автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The White Prophet, Volume II (of 2)

THE WHITE PROPHET, VOLUME II

This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The White Prophet, Volume II (of 2) Author: Hall Caine Release Date: June 15, 2016 [EBook #52343] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WHITE PROPHET, VOLUME II (OF 2) ***

Produced by Al Haines.

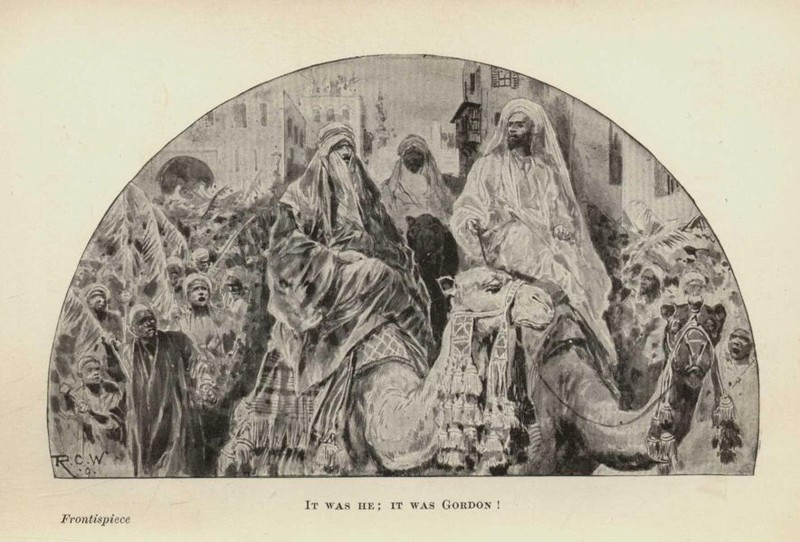

IT WAS HE; IT WAS GORDON!

THE WHITE PROPHET

BY

HALL CAINE

ILLUSTRATED BY R. CATON WOODVILLE

IN TWO VOLUMES VOL II.

LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN 1909

Copyright London 1909 by William Heinemann and

Washington U.S.A. by D. Appleton & Company

ILLUSTRATIONS

It was he! It was Gordon . . . Frontispiece

Helena was in the gallery

"Yes; conspiracy against you and against England"

The Consul-General . . . was hurling his last reproaches upon his enemies

THE WHITE PROPHET

BOOK THREE—Continued

THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD

CHAPTER XI

When Helena awoke next morning she was immediately conscious of a great commotion both within and without the house. After a moment Zenoba came into the bedroom and began to tell her what had happened.

"Have you not heard, O Rani?" said the Arab woman, in her oily voice. "No? You sleep so late, do you? When everybody is up and doing, too! Well, the Master has news that the great Bedouin is at Omdurman and he is sending the people down to the river to bring him up. The stranger is to be received in the mosque, I may tell you. Yes, indeed, in the mosque, although he is English and a Christian."

Then Ayesha came skipping into the room in wild excitement.

"Rani! Rani!" she cried. "Get up and come with us. We are going now—this minute—everybody."

Helena excused herself; she felt unwell and would stay in bed that day; so the child and the nurse went off without her.

Yet left alone she could not rest. The feverish uncertainty of the night before returned with redoubled force, and after a while she felt compelled to rise.

Going into the guest-room she found the house empty and the camp in front of it deserted. She was standing by the door, hardly knowing what to do, when the strange sound which she had heard on the night of the betrothal came from a distance.

"Lu-lu-lu-u-u!"

It was the zaghareet, the women's cry of joy, and it was mingled with the louder shouts of men. The stranger was coming! the people were bringing him on. Who would he be? Helena's anxiety was almost more than her brain and nerves could bear. She strained her eyes in the direction of the jetty, past the Abbas Barracks and the Mongers Fort.

The moments passed like hours, but at length the crowd appeared. At first sight it looked like a forest of small trees approaching. The forest seemed to sway and to send out monotonous sounds as if moved by a moaning wind. But looking again, Helena saw what was happening—the people were carrying green palm branches and strewing them on the yellow sand in front of the great stranger.

He was riding on a white camel, Ishmael's camel, and Ishmael was riding beside him.. Long before he came near to her, Helena saw him, straining her sight to do so. He was wearing the ample robes of a Bedouin, and his face was almost hidden by the sweeping shawl which covered his head and neck.

But it was he! It was Gordon! Helena could not mistake him. One glance was enough. Without looking a second time she ran back to her bedroom, and covered her eyes and ears.

For a time the voices of the people followed her through the deadening walls.

"Lu-lu-u-u!" cried the women.

"La ilaha illa-llah! La ilaha illa-llah!" shouted the men.

But after a while the muffled sounds died away, and Helena knew that the great company had passed on to the mosque. It was like a dream, a mirage of the mind. It had come and it was gone, and in the dazed condition of her senses she could almost persuade herself that she had imagined everything.

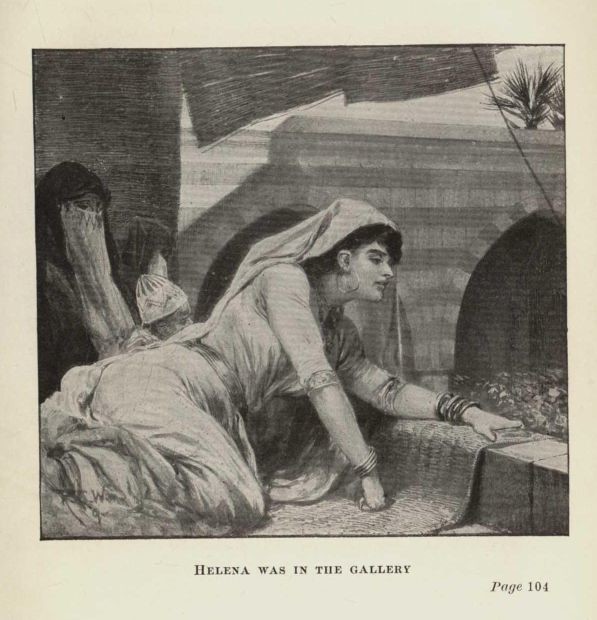

Her impatience would not permit her to remain in the house. She, too, must go to the mosque, although she had never been there before. So putting on her Indian veil she set out hurriedly. When she came to herself again she was in the gallery, people were making way for her, and she was dropping into a place. Then she realised that she was sitting between Zenoba and little Ayesha.

The mosque was a large, four-square edifice, full of columns and arches, and with a kind of inner court that was open to the sky and had minarets at every corner. The gallery looked down on this court, and Helena saw below her, half in shadow, half in sunshine, the heads of a great concourse of men in turbans, tarbooshes, and brown felt skull-caps, all kneeling in rows on bright red carpets. In the front row, with his face to the Kibleh (the niche towards Mecca), Ishmael knelt in his white caftan, and by his side, with all eyes upon him, as if every interest centred on that spot, knelt the stranger in Bedouin dress.

It was Friday, and prayers were proceeding, now surging like the sea, now silent like the desert, sometimes started, as it seemed, by the voice of the unseen muezzin on the minarets above, then echoed by the men on the carpets below. But Helena hardly heard them. Of one thing only was she conscious—that by the tragic play of destiny he was there while she was here!

After a while she became aware that Ishmael had risen and was beginning to speak, and she tried to regain composure enough to listen to what he said.

"My brothers," he said, "it is according to the precepts of the Prophet (peace to his name!) to receive the Christian in our temples if he comes with the goodwill of good Moslems and with a heart that is true to them. You know, O my brothers, whether I am a Moslem or not, and I pray to the Most Merciful to bless all such Christians as the one who is here to-day."

More of the same kind Ishmael said, but Helena found it hard, in the tumult of her brain, to follow him. She saw that both the women about her and the men below were seized with that religious fervour which comes to the human soul when it feels that something grand is being done. It was as though the memory of a thousand years of hatred between Moslem and Christian, with all its legacy of cruelty and barbarity, had been wiped out of their hearts by the stranger on whom their eyes were fixed—as though by some great act of self-sacrifice and brotherhood he had united East and West—and this fact of his presence at their prayers was the sign and symbol of an eternal truce.

The sublime spectacle seemed to capture all their souls, and when Ishmael turned towards the stranger at last and laid his hand on his head and said—

"May God and His Prophet bless you for what you have done for us and ours," the emotions of the people were raised to the highest pitch, and they rose to their feet as one man, and holding up their hands they cried, the whole congregation together, in a voice that was like the breaking of a great wave—

"You are now of us, and we are of you, and we are brothers."

By this time the women in the gallery were weeping audibly, and Helena, from quite other causes, was scarcely able to control her feelings. "Why did I come here?" she asked herself, and then, seeing that the Arab woman was watching her through the slits of her jealous eyes, she got up and pushed her way out of the mosque.

Back in her room, lying face down upon the bed, she sought in vain to collect her faculties sufficiently to follow and comprehend the course of events. Yes, it was Gordon. He had come to join Ishmael. Why had she never thought of that as a probable sequel to what had occurred in Cairo? Had he not been turned out by his own? In effect cashiered from the army? Forbidden his father's house? And had she not herself driven him away from her? What sequel was more natural—more plainly inevitable?

Then she grew hot and cold at a new and still more terrifying thought—Gordon would come there! How could she meet him? How look into his face? A momentary impulse to deny her own identity was put aside immediately. Impossible! Useless! Then how could she account to Gordon for her presence in that house? Ishmael's wife! According to Mohammedan law and custom not only betrothed but married to him!

When she put her position to herself so, the thread of her thoughts seemed to snap in her brain. She could not disentangle the knot of them. A sense of infidelity to Gordon, to the very spirit of love itself, brought her for a moment the self-reproach and the despair of a woman who has sinned.

In the midst of her pain she heard the light voices of people returning to the house, and at the next moment Ayesha and Zenoba came into her room. The child was skipping about, full of high spirits, and the Arab woman was bitterly merry.

"Rani will be happy to hear that the Master is bringing the stranger home," said Zenoba.

Helena turned and gazed at the woman with a stupefied expression. What she had foreseen as a terrifying possibility was about to come to pass! She opened her mouth as if to speak but said nothing.

Meantime the Arab woman, in a significant tone that was meant to cut to the core, went on to say that this was the highest honour the Moslem could show the unbeliever, as well as the greatest trust he could repose in him.

"Have you never heard of that in your country, O Rani? No? It is true, though! Quite true!"

People supposed that every Moslem guarded his house so jealously that no strange man might look upon his wife, but among the Arabs of the desert, when a traveller, tired and weary, sought food and rest, the Sheikh would sometimes send him into his harem and leave him there for three days with full permission to do as he thought well.

"But he must never wrong that harem, O lady! If he does the Arab husband will kill him! Yes, and the faithless wife as well!"

So violent was the conflict going on within her that Helena hardly heard the woman's words, though the jealous spirit behind them was piercing her heart like needles. She became conscious of the great crowd returning, and it was making the same ululation as before, mingled with the same shouts. At the next moment there came a knock at the bedroom door and Abdullah's voice, crying—

"Lady! Lady!"

Helena reeled a little in rising to reply, and it was with difficulty that she reached the door.

"Master has brought Sheikh Omar Benani back and is calling for the lady. What shall I say?"

Helena fumbled the hem of her handkerchief in her fingers, as she was wont to do in moments of great agitation. She was asking herself what would happen if she obeyed Ishmael's summons. Would Gordon see through her motive in being there? If so, would he betray her to Ishmael?

Already she could hear a confused murmur in the guest-room, and out of that murmur her memory seemed to grasp back, as from a vanishing dream, the sound of a voice that had been lost to her.

She felt as if she were suffocating. Her breathing was coming rapidly from the depth of her throat. Yet the Arab woman was watching her, and while a whirlwind was going on within she had to preserve a complete tranquillity without.

"Say I am coming," she said.

The supreme moment had arrived. With a great effort she gathered up all her strength, drew her Indian shawl over her head in such a way that it partly concealed her face, and then, pallid, trembling, and with downcast eyes she walked out of the room.

CHAPTER XII

Gordon had that day experienced emotions only less poignant than those of Helena. In the early morning, after parting with Osman, the devoted comrade of his desert journey, he had encountered the British Sub-Governor of Omdurman, a young Captain of Cavalry who had once served under himself but now spoke to him, in his assumed character as a Bedouin, with a certain air of command.

This brought him some twinges of wounded pride, which were complicated by qualms of conscience, as he rode through the streets, past the silversmiths' shops, where grave-looking Arabs sold bracelets and necklets; past the weaving quarter, where men and boys were industriously driving the shuttle through the strings of their flimsy looms; past the potter's bazaar and the grain market, all so sweet and so free from their former smell of sun-dried filth and warm humanity packed close together.

"Am I coming here to oppose the power that in so few years has turned chaos into order?" he asked himself, but more personal emotions came later.

They came in full flood when the ferry steamer, by which he crossed the river, approached the bank on the other side, and he saw standing there, near to the spot on which the dervishes landed on the black night of the fall of Khartoum, a vast crowd of their sons and their sons' sons who were waiting to receive him.

Again came qualms of conscience when out of this crowd stepped Ishmael Ameer, who kissed him on both cheeks and led him forward to his own camel amid the people's shouts of welcome. Was he, as a British soldier, throwing in his lot with the enemies of his country? As an Englishman and a Christian was he siding with the adversaries of religion and civilisation?

The journey through the town to the mosque, with the lu-lu-ing and the throwing of palm branches before his camel's feet, was less of a triumphal progress than an abject penance. He could hardly hold up his head. Sight of the bronze and black faces about him, shouting for him.—for him of another race and creed—making that act his glory which had led to his crime—this was almost more than he could bear.

But when he reached the mosque; when he found himself, unbeliever though he was, kneeling in front of the Kibleh; when Ishmael laid his hand on his head and called on God to bless him, and the people cried with one voice, "You are of us and we are brothers," the sense of human sympathy swept down every other emotion, and he felt as if at any moment he might burst into tears.

And then, when prayers were over and Ishmael brought up his uncle, and the patriarchal old man, with a beard like a flowing fleece, said he was to lodge at his house; and finally when Ishmael led him home and took him to his own chamber and called to Abdullah to set up another angerib, saying they were to sleep in the same room, Gordon's twinges of pride and qualms of conscience were swallowed up in one great wave of human brotherhood.

But both came back, with a sudden bound, when Ishmael began to talk of his wife, and sent the servant to fetch her. They were sitting in the guest-room by this time, waiting for the lady to come to them, and Gordon felt himself moved by the inexplicable impulse of anxiety he had felt before. Who was this Mohammedan woman who had prompted Ishmael to a scheme that must so surely lead to disaster? Did she know what she was doing? Was she betraying him?

Then a door on the women's side of the house opened slowly and he saw a woman enter the room. He did not look into her face. His distrust of her, whereof he was now half ashamed, made him keep his head down while he bowed low during the little formal ceremony of Ishmael's presentation. But instantly a certain indefinite memory of height and step and general bearing made his blood flow fast, and he felt the perspiration breaking out on his forehead.

A moment afterwards he raised his eyes, and then it seemed as if his hair stood upright. He was like a man who has been made colour-blind by some bright light. He could not at first believe the evidence of his senses that she who appeared to be before him was actually there.

He did not speak or utter a sound, but his embarrassment was not observed by Ishmael, who was clapping his hands to call for food. During the next few minutes there was a little confusion in the room—Black Zogal and Abdullah were laying a big brass tray on tressels and covering it with dishes. Then came the ablutions and the sitting down to eat—Gordon at the head of the table, with Ishmael on his right and old Mahmud on his left, and Helena next to Ishmael.

The meal began with the beautiful Eastern custom of the host handing the first mouthful of food to his guest as a pledge of peace and brotherhood, faith and trust. This kept Gordon occupied for the moment, but Helena had time for observation. In the midst of her agitation she could not help seeing that Gordon had grown thinner, that his eyes were bloodshot and his nostrils pinched as if by physical or moral suffering. After a while she saw that he was looking across at her with increasing eagerness, and under his glances she became nervous and almost hysterical.

Gordon, on his part, had now not the shadow of a doubt of Helena's identity, but still he did not speak. He, too, noticed a change—Helena's profile had grown more severe, and there were dark rims under her large eyes. He could not help seeing these signs of the pain she had gone through, though his mind was going like a windmill under constantly changing winds. Why was she there? Could it be that the great sorrow which fell upon her at the death of her father had made her fly to the consolation of religion?

He dismissed that thought the instant it came to him, for behind it, close behind it, came the recollection of Helena's hatred of Ishmael Ameer and of the jealousy which had been the first cause of the separation between themselves. "Smash the Mahdi," she had said, not altogether in play. Then why was she there? Great God! could it be possible ... that after the death of the General ... she had——

Gordon felt at that moment as if the world were reeling round him.

Helena, glancing furtively across the table, was sure she could read Gordon's thoughts. With the certainty that he knew what had brought her to Khartoum she felt at first a crushing sense of shame. What a fatality! If anybody had told her that she would be overwhelmed with confusion by the very person she had been trying to avenge, she would have thought him mad, yet that was precisely what Providence had permitted to come to pass.

The sense of her blindness and helplessness in the hands of destiny was so painful as to reach the point of tears. When Gordon spoke in reply to Ishmael's or old Mahmud's questions the very sound of his voice brought memories of their happy days together, and, looking back on the past of their lives and thinking where they were now, she wanted to run away and cry.

All this time Ishmael saw nothing, for he was talking rapturously of the great hope, the great expectation, the near approach of the time when the people's sufferings would end. A sort of radiance was about him, and his face shone with the joy and the majesty of the dreamer in the full flood of his dream.

When the meal was over the old man, who had been too busy with his food to see anything else, went off to his siesta, and then, the dishes being removed and the servants gone, Ishmael talked in lower tones of the details of his scheme—how he was to go into Cairo, in advance, in the habit of a Bedouin such as Gordon wore, in order to win the confidence of the Egyptian Army, so that they should throw down the arms which no man ought to bear, and thus permit the people of the pilgrimage, coming behind, to take possession of the city, the citadel, the arsenal, and the engines of war, in the name of God and His Expected One.

All this he poured out in the rapturous language of one who saw no impediments, no dangers, no perils from chance or treachery, and then, turning to where Helena sat with her face aflame and her eyes cast down, he gave her the credit of everything that had been thought of, everything that was to be done.

"Yes, it was the Rani who suggested it," he said, "and when the triumph of peace is won God will write it on her forehead."

The afternoon had passed by this time, and the sun, which had gone far round to the West, was glistening like hammered gold along the river, in the line of the forts of Omdurman. It was near to the hour for evening prayers, and Helena was now trembling under a new thought—the thought that Ishmael would soon be called out to speak to the people who gathered in the evening in front of the house, and then she and Gordon would be left alone.

When she thought of that she felt a desire which she had never felt before and never expected to feel—a desire that Ishmael might remain to protect her from the shock of the first word that would be spoken when he was gone.

Gordon on his part, too, was feeling a thrill of the heart from his fear of the truth that must fall on him the moment he and Helena were left together.

But Black Zogal came to the open door of the guest-room, and Ishmael, who was still on the heights of his fanatical rapture, rose to go.

"Talk to him, Rani! Tell him everything! About the kufiah you intend to make, and all the good plans you proposed to prevent bloodshed."

The two unhappy souls, still sitting at the empty table, heard his sandalled footsteps pass out behind them.

Then they raised their eyes and for the first time looked into each other's faces.

CHAPTER XIII

When they began to speak it was in scarcely audible whispers.

"Helena!"

"Gordon!"

"Why are you here, Helena? What have you come for? You disliked and distrusted Ishmael Ameer when you heard about him first. You used to say you hated him. What does it all mean?"

Helena did not answer immediately.

"Tell me, Helena. Don't let me go on thinking these cruel thoughts. Why are you here with Ishmael in Khartoum?"

Still Helena did not answer. She was now sitting with her eyes down, and her hands tightly folded in her lap. There was a moment of silence while he waited for her to speak, and in that silence there came the muffled sound of Ishmael's voice outside, reciting the Fatihah—

"Praise be to God, the Lord of all creatures——"

When the whole body of the people had repeated the solemn words there was silence in the guest-room again, and, in the same hushed whisper as before, but more eagerly, more impetuously, Gordon said—

"He says you put this scheme into his mind, Helena. If so, you must know quite well what it will lead to. It will lead to ruin—inevitable ruin; bloodshed—perhaps great bloodshed."

Helena found her voice at last. A spirit of defiance took possession of her for a moment, and she said firmly—

"No, it will never come to that. It will all end before it goes so far."

"You mean that he will be ... will be taken?"

"Yes, he will be taken the moment he sets foot in Cairo. Therefore the rest of the plan will never be carried out, and consequently there will be no bloodshed."

"Do you know that, Helena?"

Her lips were compressed; she made a silent motion of her head.

"How do you know it?"

"I have written to your father."

"You have ... written ... to my father?"

"Yes," she said, still more firmly. "He will know everything before Ishmael arrives, and will act as he thinks best."

"Helena! Hel——"

But he was struck breathless both by what she said and by the relentless strength with which she said it. There was silence again for some moments, and once more the voice of Ishmael came from without—

"There are three holy books, O my brothers—the took of Moses and the Hebrew prophets, the book of the Gospel of the Lord Jesus, and the plain book of the Koran. In the first of these it is written: 'I know that my Redeemer liveth and that He shall stand at the latter day upon the earth.'"

Gordon reached over to where Helena sat at the side of the table, with her eyes fixed steadfastly before her, and touching her arm he said in a whisper so low that he seemed to be afraid the very air would hear—

"Then ... then .... you are sending him to his death!"

She shuddered for an instant as if cut to the quick; then she braced herself up.

"Isn't that so, Helena? Isn't it?"

With her lips still firmly compressed she made the same silent motion of her head.

"Is that what you came here to do?"

"Yes."

"To possess yourself of his secrets and then——?"

"There was no other way," she answered, biting her under-lip.

"Helena! Can it be possible that you have deliberately——"

He stopped, as if afraid to utter the word that was trembling on his tongue, and then said in a softer voice—

"But why, Helena? Why?"

The spirit of defiance took possession of her again, and she said—

"Wasn't it enough that he came between you and me, and that our love——"

"Love! Helena! Helena! Can you talk of our love here ... now?"

She dropped her head before his flashing eyes, and again he reached over to her and said in the same breathless whisper—

"Is this love ... for me ... to become the wife of another man? ... Helena, what are you saying?"

She did not speak; only her hard breathing told how much she suffered.

"Then think of the other man! His wife! When a woman becomes a man's wife they are one. And to marry a man in order to ... to ... Oh, it is impossible! I cannot believe it of you, Helena."

Suddenly, without warning, she burst into tears, for something in the tone of his voice rather than the strength of his words had made her feel the shame of the position she occupied in his eyes.

After a moment she recovered herself, and, in wild anger at her own weakness, she flamed out at him, saying that if she was Ishmael's wife it was in name only, that if she had married Ishmael it was only as a matter of form, at best a betrothal, in order to meet his own wish and to make it possible for her to go on with her purpose.

"As for love ... our love ... it is not I who have been false to it. No, never for one single moment ... although ... in spite of everything ... for even when you were gone ... when you had abandoned me ... in the hour of my trouble, too ... and I had lost all hope of you ... I——"

"Then why, Helena? You hated Ishmael and wished to put him down while you thought he was coming between you and me. But why ... when all seemed to be over between us——"

Her lips were twitching and her eyes were ablaze.

"You ask me why I wished to punish him?" she said. "Very well, I will tell you. Because—" she paused, hesitated, breathed hard, and then said, "because he killed my father."

Gordon gasped, his face became distorted, his lips grew pale, he tried to speak but could only stammer out broken exclamations.

"Great God! Hele——"

"Oh, you may not believe it, but I know," said Helena.

And then, with a rush of emotion, in a torrent of hot words, she told him how Ishmael Ameer had been the last man seen in her father's company; how she had seen them together and they were quarrelling; how her father had been found dead a few minutes after Ishmael had left him; how she had found him; how other evidence gave proof, abundant proof, that violence, as a contributory means at least, had been the cause of her father's death; and how the authorities knew this perfectly, but were afraid, in the absence of conclusive evidence, to risk a charge against one whom the people in their blindness worshipped.

"So I was left alone—quite alone—for you were gone too—and therefore I vowed that if there was no one else I would punish him."

"And that is what you——"

"Yes."

"O God! O God!"

Gordon hid his face in his hands, being made speechless by the awful strength of the blind force which had governed her life and led her into the tragic tangle of her error. But she misunderstood his feeling, and with flashing, almost blazing eyes, though sobs choked her voice for a moment, she turned on him and said—

"Why not? Think of what my father had been to me and say if I was not justified. Nobody ever loved me as he did—nobody. He was old, too, and weak, for he was ill, though nobody knew it. And then this ... this barbarian ... this hypocritical ... Oh, when I think of it I have such a feeling of physical repulsion for the man that I can scarcely sit by his side."

Saying this she rose to her feet, and standing before Gordon, as he sat with his face covered by his hands, she said, with intense bitterness, as if exulting in the righteousness of her vengeance—

"Let him go to Damietta or to death itself if need be. Doesn't he deserve it? Doesn't he? Uncover your face and tell me. Tell me if ... if ... tell me if——"

She was approaching Gordon as if to draw away his hands when she began to gasp and stammer as though she had experienced a sudden electric shock. Her eyes had fallen on the third finger of his left hand, and they fixed themselves upon it with the fascination of fear. She saw that it was shorter than the rest, and that, since she had seen it before, it had been injured and amputated.

Her breath, which had been labouring heavily, seemed to stop altogether, and there was silence once more, in which the voice of Ishmael came again—

"When the Deliverer comes will he find peace on the earth? Will he find war? Will he find corruption and the worship of false gods? Will he find hatred and vengeance? Beware of vengeance, O my brothers! It corrupts the heart; it pulls down the pillars of the soul! Vengeance belongs to God, and when men take it out of His hands He writes black marks upon their faces."

The two unhappy people sitting together in the guest-room seemed to hear their very hearts beat. At length Gordon, making a great call on his resolution, began to speak.

"Helena!"

"Well?"

"It is all a mistake—a fearful, frightful mistake."

She listened without drawing breath—a vague foreshadowing of the truth coming over her.

"Ishmael Ameer did not kill your father."

Her lips trembled convulsively; she grew paler and paler every moment.

"I know he did not, Helena, because—" (he covered his face again) "because I know who did."

"Then who ... who was it?"

"He did not intend to do it, Helena."

"Who was it?"

"It was all in the heat of blood."

"Who was——"

He hesitated, then stammered out, "Don't you see, Helena?—it was I."

She had known in advance what he was going to say, but not until he had said it did the whole truth fall on her. Then in a moment the world itself seemed to reel. A moral earthquake, upheaving everything, had brought all her aims to ashes. The mighty force which had guided and sustained her soul (the sense of doing a necessary and a righteous thing) had collapsed without an instant's warning. Another force, the powerful, almost brutal force of fate, had broken it to pieces.

"My God! My God! What has become of me?" she thought, and without speaking she gazed blankly at Gordon as he sat with his eyes hidden by his injured hand.

Then in broken words, with gasps of breath, he told her what had happened, beginning with the torture of his separation from her at the door of the General's house.

"You said I had not really loved you—that you had been mistaken and were punished and ... and that was the end."

Going away with the memory of these words in his mind, his wretched soul had been on the edge of a vortex of madness in which all its anger, all its hatred, had been directed against the General. In the blind leading of his passion, torn to the heart's core, he had then returned to the Citadel to accuse the General of injustice and tyranny.

"'Helena was mine,' I said, 'and you have taken her from, me, and broken her heart as well as my own. Is that the act of a father?'"

Other words he had also said, in the delirium of his rage, mad and insulting words such as no father could bear; then the General had snatched up the broken sword from the floor and fallen on him, hacking at his hand—see!

"I didn't want to do it, God knows I did not, for he was an old man and I was no coward, but the hot blood was in my head, and I laid hold of him by the throat to hold him off."

He uncovered his face—it was full of humility and pain.

"God forgive me, I didn't know my strength. I flung him away; he fell. I had killed him—my General, my friend!"

Tears filled his eyes. In her eyes, also, tears were gathering.

"Then you came to the door and knocked. 'Father!' you said. 'Are you alone? May I come in?' Those were your words, and how often I have heard them since! In the middle of the night, in my dreams, O God, how many times!"

He dropped his head and stretched a helpless arm along the table.

"I wanted to open the door and say, 'Helena, forgive me, I didn't mean to do it, and that is the truth, as God is my witness.' But I was afraid—I fled away."

She was now sitting with her hands clasped in her lap and her eyelids tightly closed.

"Next day I wanted to go back to you, but I dared not do so. I wanted to comfort you—I could not. I wanted to give myself up to justice—it was impossible, there was nothing for me to do except to fly away."

The tears were rolling down his thin face to his pinched nostrils.

"But I could not fly from myself or from ... from my love for you. They told me you had gone to England. 'Where is she to-night?' I thought. If I had never really loved you before I loved you now. And you were gone! I had lost you for ever."

Emotion choked his voice; tears were forcing themselves through her closed eyelids. There was another moment of silence and then, nervously, hesitatingly, she put out her hand to where his hand was lying on the table and clasped it.

The two unhappy creatures, like wrecked souls about to be swallowed up in a tempestuous ocean, saw one raft of hope—their love for each other, which had survived all the storms of their fate.

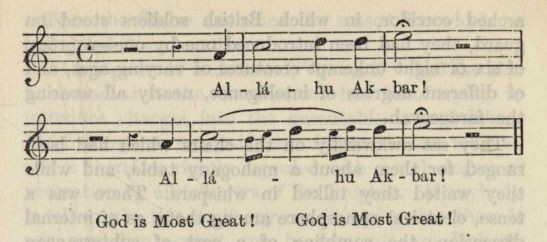

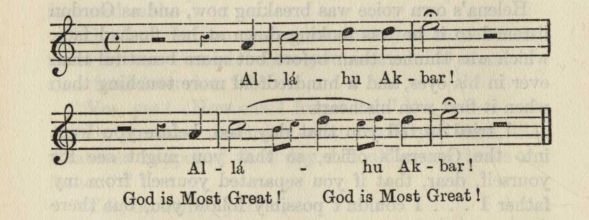

But just as their hands were burning as if with fever, and quivering in each other's clasp like the bosom of a captured bird, a voice from without fell on their ears like a trumpet from the skies. It was the voice of the muezzin calling to evening prayers from the minaret of the neighbouring mosque:—

Music fragment: God is Most Great! God is Most Great!

It seemed to be a supernatural voice, the voice of an accusing angel, calling them back to their present position. Ishmael—Helena—the betrothal!

Their hands separated and they rose to their feet. One moment they stood with bowed heads, at opposite sides of the table, listening to the voice outside, and then, without a word more, they went their different ways—he to his room, she to hers.

Into the empty guest-room, a moment afterwards, came the rumbling and rolling sound of the voices of the people, repeating the Fatihah after Ishmael—

"Praise be to God, the Lord of all creatures.... Direct us in the right way, O Lord ... not the way of those who go astray."

CHAPTER XIV

That day the Sirdar had held his secret meeting of the Ulema, the Sheikhs and Notables of Khartoum. Into a room on the ground floor of the Palace, down a dark, arched corridor, in which British soldiers stood on guard, they had been introduced one by one—a group of six or eight unkempt creatures of varying ages, and of different degrees of intelligence, nearly all wearing the farageeyah.

They sat awkwardly on the chairs which had been ranged for them about a mahogany table, and while they waited they talked in whispers. There was a tense, electrical atmosphere among them, as of internal dissension, the rumbling of a sort of subterranean thunder.

But this subsided instantly, when the voice of the sergeant outside, and the clash of saluting arms, announced the coming of the Sirdar. The Governor-General, who was in uniform and booted and spurred as if returning from a ride, was accompanied by his Inspector-General, his Financial Secretary, the Governor of the town, and various minor officers.

He was received by the Sheikhs, all standing, with sweeping salaams from floor to forehead, a circle of smiles and looks of complete accord.

The Sirdar, with his ruddy and cheerful face, took his seat at the head of the table and began by asking, as if casually, who was the stranger that had arrived that day in Khartoum.

"A Bedouin," said the Cadi. "One whom Ishmael Ameer loves and who loves him."

"Yet a Bedouin, you say?" asked the Sirdar, in an incredulous tone, and with a certain elevation of the eyebrows.

"A Bedouin, O Excellency," repeated the Cadi, whereupon the others, without a word of further explanation, bent their turbaned heads in assent.

Then the Sirdar explained the reason for which he had called them together.

"I am given to understand," he said, "that the idea is abroad that the Government has been trying to introduce changes into the immutable law of Islam, which forms an integral part of your Moslem religion, and is therefore rightly regarded with a high degree of veneration by all followers of the Prophet. If anybody is telling you this, or if any one is saying that there is any prejudice against you because you are Mohammedans, he is a wicked and mischievous person, and I beg of you to tell me who he is."

Saying this, the Sirdar looked sharply round the table, but met nothing but blank and expressionless faces. Then turning to the Cadi, who as Chief Judge of the Mohammedan law-courts had been constituted spokesman, he asked pointedly what Ishmael Ameer was saying.

"Nothing, O Excellency," said the Cadi; "nothing that is contrary to the Sharia—the religious law of Islam."

"Is he telling the people to resist the Government?"

The grave company about the table silently shook their heads.

"Do you know if he has anything to do with a conspiracy to resist the payment of taxes?"

The grave company knew nothing.

"Then what is he doing, and why has he come to Khartoum? Pasha, have you no explanation to make to me?" asked the Sirdar, singling out a vivacious old gentleman, with a short, white, carefully oiled beard—a person of doubtful repute who had once been a slave-dealer and was now living patriarchally, under the protection of the Government, with his many wives and concubines.

The old black sinner cast his little glittering eyes around the room and then said—

"If you ask me, O Master, I say, Ishmael Ameer is putting down polygamy and divorce and ought himself to be put down."

At that there was some clamour among the Ulema, and the Sirdar thought he saw a rift through which he might discover the truth, but the Pasha was soon silenced, and in a moment there was the same unanimity as before.

"Then what is he?" asked the Sirdar, whereupon a venerable old Sheikh, after the usual Arabic compliments and apologies, said that, having seen the new teacher with his own eyes and talked with him, he had now not the slightest doubt that Ishmael was a man sent from God, and therefore that all who resisted him, all who tried to put him down, would perish miserably. At these words the electrical atmosphere which had been held in subjection seemed to burst into flame. In a moment six tongues were talking together. One Sheikh, with wild eyes, told of Ishmael's intercourse with angels. Another knew a man who had seen him riding with the Prophet in the desert. A third had spoken to somebody who had seen angels, in the form of doves, descending upon him from the skies, and a fourth was ready to swear that one day, while Ishmael was preaching in the mosque, people heard a voice from heaven crying, "Hear him! He is My messenger!"

"What was he preaching about?" said the Sirdar.

"The last days, the coming of the Deliverer," said the Sheikh with the wild eyes, in an awesome whisper.

"What Deliverer?"

"Seyidna Isa—our Lord Jesus—the White Christ that is to come."

"Is this to be soon?"

"Soon, O Excellency, very soon."

After this outburst there was a moment of tense and breathless silence, during which the Sirdar sat with his serious eyes fixed on the table, and his officers, standing behind, glanced at each other and smiled.

Immediately afterwards the Sirdar put an end to the interview.

"Tell your people," he said, "that the Government has no wish to interfere with your religious beliefs and feelings, whatever they may be; but tell them also, that it intends to have its orders obeyed, and that any suspicion of conspiracy, still more of rebellion, will be instantly put down."

The group of unkempt creatures went off with sweeping salaams, and then the Sirdar dismissed his officers also, saying—

"Bear in mind that you are the recognised agents of a just and merciful Government, and whatever your personal opinions may be of these Arabs and their superstitions, please understand that you are to give no anti-Islamic colour to your British feelings. At the same time remember that we have worked for the redemption of the Soudan from a state of savagery, and we cannot allow it to be turned back to barbarism in the name of religion."

Both the Ulema and the other British officials being gone, the Sirdar was alone with his Inspector-General.

"Well?" he said.

"Well?" repeated the Inspector-General, biting the ends of his close-cropped moustache. "What more did you expect, sir? Naturally the man's own people were not going to give him away. They nearly did so, though. You heard what old Zewar Pasha said?"

"Tut! I take no account of that," said the Sirdar. "The brothers of Christ Himself would have put Him down, too—locked Him up in an asylum, I dare say."

"That's exactly what I would do with Ishmael Ameer, anyway," said the Inspector-General. "Of course he performs no miracles, and is attended by no angels. His removal to Torah, and his inability to free himself from a Government jail, would soon dispel the belief in his supernatural agencies."

"But how can we do it? Under what pretext? We can't imprison a man for preaching the second coming of Christ. If we did, our jails would be pretty full at home, I'm thinking."

The Inspector-General laughed. "Your old error, dear Sirdar. You can't apply the same principles to East and West."

"And your old Parliamentary cant, dear friend! I'm sick to death of it."

There was a moment of strained silence, and then the Inspector-General said—

"Ah well, I know these holy men, with their sham inspirations and their so-called heavenly messages. They develop by degrees, sir. This one has begun by proclaiming the advent of the Lord Jesus, and he will end by hoisting a flag and claiming to be the Lord Jesus himself."

"When he does that, Colonel, we'll consider our position afresh. Meantime it may do us no mischief to remember that if the family of Jesus could have dealt with the founder of our own religion as you would deal with this olive-faced Arab there would probably be no Christianity in the world to-day."

The Inspector-General shrugged his shoulders and rose to go.

"Good-night, sir."

"Good-night, Colonel," said the Sirdar, and then he sat down to draft a dispatch to the Consul-General—

"Nothing to report since the marriage, betrothal, or whatever it was, of the 'Rani' to the man in question. Undoubtedly he is laying a strong hold on the imagination of the natives and acquiring the allegiance of large bodies of workers; but I cannot connect him with any conspiracy to persuade people not to pay taxes or with any organised scheme that is frankly hostile to the continuance of British rule.

"Will continue to watch him, but find myself at fearful odds owing to difference of faith. It is one of the disadvantages of Christian Governments among people of alien race and religion, that methods of revolt are not always visible to the naked eye, and God knows what is going on in the sealed chambers of the mosque.

"That only shows the danger of curtailing the liberty of the vernacular press, whatever the violence of its sporadic and muddled anarchy. Leave the press alone, I say. Instead of chloroforming it into silence give it a tonic if need be, or you drive your trouble underground. Such is the common sense and practical wisdom of how to deal with sedition in a Mohammedan country, let some of the logger-headed dunces who write leading articles in England say what they will.

"If this man should develop supernatural pretensions I shall know what to do. But without that, whether he claim divine inspiration or not, if his people should come to regard him as divine, the very name and idea of his divinity may become a danger, and I suppose I shall have to put him under arrest."

Then remembering that he was addressing not only the Consul-General but a friend, the Sirdar wrote—

"'Art Thou a King?' Strange that the question of Pontius Pilate is precisely what we may find in our own mouths soon! And stranger still, almost ludicrous, even farcical and hideously ironical, that though for two thousand years Christendom has been spitting on the pusillanimity of the old pagan, the representative of a Christian Empire will have to do precisely what he did.

"Short of Pilate's situation, though, I see no right to take this man, so I am not taking him. Sorry to tell you so, but I cannot help it.

"Our love from both to both. Trust Janet is feeling better. No news of our poor boy, I suppose?"

"Our boy" had for thirty years been another name for Gordon.

CHAPTER XV

Grave as was the gathering in the Sirdar's Palace at Khartoum, there was a still graver gathering that day at the British Agency in Cairo—the gathering of the wings of Death.

Lady Nuneham was nearing her end. Since Gordon's disgrace and disappearance she had been visibly fading away under a burden too heavy for her to bear.

The Consul-General had been trying hard to shut his eyes to this fact. More than ever before, he had immersed himself in his work, being plainly impelled to fresh efforts by hatred of the man who had robbed him of his son.

Through the Soudan Intelligence Department in Cairo he had watched Ishmael's movements in Khartoum, expecting him to develop the traits of the Mahdi and thus throw himself into the hands of the Sirdar.

It was a deep disappointment to the Consul-General that this did not occur. The same report came to him. again and again. The man was doing nothing to justify his arrest. Although surrounded by fanatical folk, whose minds were easily inflamed, he was not trying to upset governors or giving "divine" sanction for the removal of officials.

But meantime some mischief was manifestly at work all over the country. From day to day Inspectors had been coming in to say that the people were not paying their taxes. Convinced that this was the result of conspiracy, the Consul-General had shown no mercy.

"Sell them up," he had said, and the Inspectors, taking their cue from his own spirit but exceeding his orders, had done his work without remorse.

Week by week the trouble had deepened, and when disturbances had been threatened he had asked the British Army of Occupation, meaning no violence, to go out into the country and show the people England's power.

Then grumblings had come down on him from the representatives of foreign nations. If the people were so discontented with British rule that they were refusing to pay their taxes, there would be a deficit in the Egyptian treasury—how then were Egypt's creditors to be paid?

"Time enough to cross the bridge when you come to it, gentlemen," said the Consul-General, in his stinging tone and with a curl of his iron lip.

If the worst came to the worst England would pay, but England should not be asked to do so because Egypt must meet the cost of her own government. Hence more distraining and some inevitable violence in suppressing the riots that resulted from evictions.

Finally came a hubbub in Parliament, with the customary "Christian" prattlers prating again. Fools! They did not know what a subtle and secret conspiracy he had to deal with while they were crying out against his means of killing it.

He must kill it! This form of passive resistance, this attack on the Treasury, was the deadliest blow that had ever yet been aimed at England's power in Egypt.

But he must not let Europe see it! He must make believe that nothing was happening to occasion the least alarm. Therefore to drown the cries of the people who were suffering not because they were poor and could not pay, but because they were perverse and would not, he must organise some immense demonstration.

Thus came to the Consul-General the scheme of the combined festival of the King's Birthday and the —th anniversary of the British Occupation of Egypt. It would do good to foreign Powers, for it would make them feel that, not for the first time, England had been the torch-bearer in a dark country. It would do good to the Egyptians, too, for it would force their youngsters (born since Tel-el-Kebir) to realise the strength of England's arm.

Thus had the Consul-General occupied himself while his wife had faded away. But at length he had been compelled to see that the end was near, and towards the close of every day he had gone to her room and sat almost in silence, with bowed head, in the chair by her side.

The great man, who for forty years had been the virtual ruler of millions, had no wisdom that told him what to say to a dying woman; but at last, seeing that her pallor had become whiteness, and that she was sinking rapidly and hungering for the consolations of her religion, he asked her if she would like to take the sacrament.

"It is just what I wish, dear," she answered, with the nervous smile of one who had been afraid to ask.

At heart the Consul-General had been an agnostic all his life, looking upon religion as no better than a civilising superstition, but all the same he went downstairs and sent one of his secretaries for the Chaplain of St. Mary's—the English Church.

The moment he had gone out of the door Fatimah, under the direction of the dying woman, began to prepare the bedroom for the reception of the clergyman by laying a side-table with a fair white cloth, a large prayer-book, and two silver candlesticks containing new candles.

While the Egyptian nurse did this the old lady looked on with her deep, slow, weary eyes, and talked in whispers, as if the wings of the august Presence that was soon to come were already rustling in the room. When all was done she looked very happy.

"Everything is nice and comfortable now," she said, as she lay back to wait for the clergyman.

But even then she could not help thinking the one thought that made a tug at her resignation. It was about Gordon.

"I am quite ready to die, Fatimah," she said, "but I should have loved to see my dear Gordon once more."

This was what she had been waiting for, praying for, eating her heart and her life out for.

"Only to see and kiss my boy! It would have been so easy to go then."

Fatimah, who was snuffling audibly, as she straightened the eider-down coverlet over the bed, began to hint that if her "sweet eyes" could not see her son she could send him a message.

"Perhaps I know somebody who could see it reaches him, too," said Fatimah, in a husky whisper.

The old lady understood her instantly.

"You mean Hafiz! I always thought as much. Bring me my writing-case—quick!"

The writing-case was brought and laid open before her, and she made some effort to write a letter, but the power of life in her was low, and after a moment the shaking pen dropped from her fingers.

"Ma'aleysh, my lady!" said Fatimah soothingly. "Tell me what you wish to say. I will remember everything."

Then the dying mother sent a few touching words as her last message to her beloved son.

"Wait! Let me think. My head is a little ... just a little ... Yes, this is what I wish to say, Fatimah. Tell my boy that my last thoughts were about him. Though I am sorry he took the side of the false prophet, say I am certain he did what he thought was right. Be sure you tell him I die happy, because I know I shall see him again. If I am never to see him in this world I shall do so in the world to come. Say I shall be waiting for him there. And tell him it will not seem long."

"Could you sign your name for him, my heart?" said Fatimah, in her husky voice.

"Yes, oh yes, easily," said the old lady, and then with an awful effort she wrote—

"Your ever-loving Mother."

At that moment Ibrahim in his green caftan, carrying a small black bag, brought the English chaplain into the room.

"Peace be to this house," said the clergyman, using the words of his Church ritual, and the Egyptian nurse, thinking it was an Eastern salutation, answered, "Peace!"

The Chaplain went into the "boys' room" to put on his surplice, and when he came out, robed in white, and began to light the candles and prepare the vessels which he placed on the side-table, the old lady was talking to Fatimah in nervous whispers—

"His lordship?" "Yes!" "Do you think, my lady——"

She wanted the Consul-General to be present and was half afraid to send for him; but just at that instant the door opened again, and her pale, spiritual face lit up with a smile as she saw her husband come into the room.

The clergyman was now ready to begin, and the old lady looked timidly across the bed at the Consul-General as if there were something she wished to ask and dared not.

"Yes, I will take the sacrament with you, Janet," said the old man, and then the old lady's face shone like the face of an angel.

The Consul-General took the chair by the side of the bed and the Chaplain began the service—

"Almighty, ever-living God, Maker of mankind, who dost correct those whom Thou dost love——"

All the time the triumphant words reverberated through the room the dying woman was praying fervently, her lips moving to her unspoken words and her eyes shining as if the Lord of Life she had always loved was with her now and she was giving herself to Him—her soul, her all.

The Consul-General was praying too—praying for the first time to the God he did not know and had never looked to—

"If Thou art God, let her die in peace. It is all I ask—all I wish."

Thus the two old people took the sacrament together, and when the Communion Service came to a close, the old lady looked again at the Consul-General and asked, with a little confusion, if they might sing a hymn.

The old man bent his head, and a moment later the Chaplain, after a whispered word from the dying woman, began to sing—

"Sun of my soul, Thou Saviour dear,

It is not night if Thou be near ..."

At the second bar the old lady joined him in her breaking, cracking voice, and the Consul-General, albeit his throat was choking him, forced himself to sing with her—

"When the soft dews of kindly sleep

My wearied eyelids gently steep..."

It was as much as the Consul-General could do to sing of a faith he did not feel, but he felt tenderly to it for his wife's sake now, and with a great effort he went on with her to the end—

"If some poor wandering child of Thine

Have spurned to-day the voice divine ..."

The light of another world was in the old lady's eyes when all was over, and she seemed to be already half way to heaven.

CHAPTER XVI

All the same there was a sweet humanity left in her, and when the Chaplain was gone and the side-table had been cleared, and she was left alone with her old husband, there came little gleams of the woman who wanted to be loved to the last.

"How are you now?" he asked.

"Better so much better," she said, smiling upon him, and caressing with her wrinkled hand the other wrinkled hand that lay on the eider-down quilt.

The great Consul-General, sitting on the chair by the side of the bed, felt as helpless as before, as ignorant as ever of what millions of simple people know—how to talk to those they love when the wings of Death are hovering over them. But the sweet old lady, with the wisdom and the courage which God gives to His own on the verge of eternity, began to speak in a lively and natural voice of the end that was coming and what was to follow it.

He was not to allow any of his arrangements to be interfered with, and, above all, the festivities appointed for the King's Birthday were not to be disturbed.

"They must be necessary or you would not have them, especially now," she said, "and I shall not be happy if I know that on my account they are not coming off."

And then, with the sweet childishness which the feebleness of illness brings, she talked of the last King's Birthday, and of the ball they had given in honour of it.

That had been in their own house, and the dancing had been in the drawing-room, and the Consul-General had told Ibrahim to set the big green arm-chair for her in the alcove, and sitting there she had seen everything. What a spectacle! Ministers Plenipotentiary, Egyptian Ministers, ladies, soldiers! Such gorgeous uniforms! Such glittering orders! Such beautiful toilets!

The old lady's pale face filled with light as she thought of all this, but the Consul-General dropped his head, for he knew well what was coming next.

"And, John, don't you remember? Gordon was there that night, and Helena—dear Helena! How lovely they looked! Among all those lovely people, dear.... He was wearing every one of his medals that night, you know. So tall, so brave-looking, a soldier every inch of him, and such a perfect English gentleman! Was there ever anything in the world so beautiful? And Helena, too! She wore a silvery silk, and a kind of coif on her beautiful black hair. Oh, she was the loveliest thing in all the room, I thought! And when they led the cotillion—don't you remember they led the cotillion, dear?—I could have cried, I was so proud of them."

The Consul-General continued to sit with his head down, listening to the old lady and saying nothing, yet seeing the scene as she depicted it and feeling again the tingling pride which he, too, had felt that night but permitted nobody to know.

After a moment the beaming face on the bed became clouded over, as if that memory had brought other memories less easy to bear—dreams of happy days to come, of honours and of children.

"Ah well, God knows best," she said in a tremulous voice, releasing the Consul-General's hand.

The old man felt as if he would have to hurry out of the room without uttering another word, but, as well as he could, he controlled himself and said—

"You are agitating yourself, Janet. You must lie quiet now."

"Yes, I must lie quiet now, and think of ... of other things," she answered.

He was stepping away when she called on him to turn her on her right side, for that was how she always slept, and upon the Egyptian nurse coming hurrying up to help, she said—

"No, no, not you, Fatimah—his lordship."

Then the Consul-General put his arms about her—feeling how thin and wasted she was, and how little of her was left to die—and turning her gently round he laid her back on the pillow which Fatimah had in the meantime shaken out.

While he did so her dim eyes brightened again, and stretching her white hands out of her silk nightdress she clasped them about his neck, with the last tender efforts of the woman who wanted to be fondled to the end.

The strain of talking had been too much for her, and after a few minutes she sank into a restless doze, in which the perspiration broke out on her forehead and her face acquired an expression of pain, for sleep knows no pretences. But at length her features became more composed and her breathing more regular, and then the Consul-General, who had been standing aside, mute with anguish, said in a low tone to Fatimah—

"She is sleeping quietly now," and then he turned to go.

Fatimah followed him to the head of the stairs and said in a husky whisper—

"It will be all over to-night, though—you'll see it will."

For a moment he looked steadfastly into the woman's eyes, and then, without answering her, walked heavily down the stairs.

Back in the library, he stood for some time with his face to the empty fireplace. Over the mantelpiece there hung a little picture, in a black-and-gilt frame, of a bright-faced boy in an Arab fez. It was more than he could do to look at that portrait now, so he took it off its nail and laid it, face down, on the marble mantel-shelf.

Just at that moment one of his secretaries brought in a despatch. It was the despatch from the Sirdar, sent in cypher but now written out at length. The Consul-General read it without any apparent emotion and put it aside without a word.

The hours passed slowly; the night was very long; the old man did not go to bed. Not for the first time, he was asking himself searching questions about the mystery of life and death, but the great enigma was still baffling him. Could it be possible that while he had occupied himself with the mere shows and semblance of things, calling them by great names—Civilisation and Progress—that simple soul upstairs had been grasping the eternal realities?

There were questions that cut deeper even than that, and now they faced him one by one. Was it true that he had married merely in the hope of having some one to carry on his name and thus fulfil the aspirations of his pride? Had he for nearly forty years locked his heart away from the woman who had been starving for his love, and was it only by the loss of the son who was to have been the crown of his life that they were brought together in the end?

Thus the hoofs of the dark hours beat heavily on the great Proconsul's brain, and in the awful light that came to him from an open grave, the triumphs of the life behind him looked poor and small.

But meantime the palpitating air of the room upstairs was full of a different spirit. The old lady had apparently awakened from her restless sleep, for she had opened her eyes and was talking in a bright and happy voice. Her cheeks were tinged with the glow of health, and her whole face was filled with light.

"I knew I should see them," she said.

"See whom, my heart?" asked Fatimah, but without answering her, the old lady, with the same rapturous expression, went on talking.

"I knew I should, and I have! I have seen both of them!"

"Whom have you seen, my lady?" asked Fatimah again, but once more the dying woman paid no heed to her.

"I saw them as plainly as I see you now, dear. It was in a place I did not know. The sun was so hot, and the room was so close. There was a rush roof and divans all round the walls. But Gordon and Helena were there together, sitting at opposite sides of a table and holding each other's hands."

"Allah! Allah!" muttered Fatimah, with upraised hands.

The old lady seemed to hear her, for an indulgent smile passed over her radiant face and she said in a tone of tender remonstrance—

"Don't be foolish, Fatimah! Of course I saw him. The Lord said I should, and He never breaks His promises. 'Help me, O God, for Christ's sake,' I said. 'Shall I see my dear son again? O God, give me a sign.' And He did! Yes, it was in the middle of the night. 'Janet,' said a voice, and I was not afraid. 'Be patient, Janet. You shall see your dear boy before you die.'"

Her face was full of happy visions. The life of this world seemed to be no longer there. A kind of life from the other world appeared to reanimate the sinking woman. The near approach of eternity illumined her whole being with a supernatural light. She was dying in a flood of joy.

"Oh, how good the Lord is! It is so easy to go now! ... John, you must not think I suffer any longer, because I don't. I have no pain now, dear—none whatever."

Then she clasped her wasted hands together in the attitude of prayer and said in a rustling whisper—

"To-night, Lord Jesus! Let it be to-night!"

After that her rapturous voice died away and her ecstatic eyes gently closed, but an ineffable smile continued to play on her faintly-tinted face, as if she were looking on the wings that were waiting to bear her away.

The doctor came in at that moment, and was told what had occurred.

"Delirium, of course," he said. A change had come; the crisis was approaching. If the same thing happened at the supreme moment the patient was not to be contradicted; her delusion was to be indulged.

It did not happen.

In the early hours of the morning the Consul-General was called upstairs. There was a deep silence in the bedroom, as if the air had suddenly become empty and void. The day was breaking, and through the windows that looked over to the Nile the white sails of a line of boats gliding by seemed like the passing of angels' wings. Sparrows were twittering in the eaves, and through the windows to the east the first streamers of the sunrise were rising in the sky.

The Consul-General approached the bed and looked down at the pallid face on the pillow. He wanted to stoop and kiss it, but he felt as if it would be a profanation to do so now. His own face was full of suffering, for the sealed chambers of his iron soul had been broken open at last.

With his hands clasped behind his back he stood for some minutes quite motionless. Then laying one hand on the brass head-rail of the bed, he leaned over his dead wife and spoke to her as if she could hear.

"Forgive me, Janet! Forgive me!" he said in a low voice that was like a sob.

Did she hear him? Who can say she did not? Was it only a ray from the sunrise that made the Egyptian woman think that over the dead face of the careworn and weary one, whose sweet soul was even then winging its way to heaven, there passed the light of a loving smile?

CHAPTER XVII

Within three days the softening effects on the Consul-General of Lady Nuneham's death were lost. Out of his very bereavement and the sense of being left friendless and alone he became a harder and severer man than before. His secretaries were more than ever afraid of him, and his servants trembled as they entered his room.

It heightened his anger against Gordon to believe that by his conduct he had hastened his mother's end. In his absolute self-abasement there were moments when he would have found it easier to forgive Gordon if he had been a prodigal, a wastrel, prompted to do what he had done by the grossest selfishness; but deep down in some obscure depths of the father's heart the worst suffering came of the certainty that his son had been moved by that tragic earnestness which belongs only to the greatest and noblest souls.

Still more hardening and embittering to the Consul-General than the memory of Gordon was the thought of Ishmael. It intensified his anger against the Egyptian to feel that having first by his "visionary mummery," by his "manoeuvring and quackery," robbed him of his son, he had now, by direct consequence, robbed him of his wife also.

All the Consul-General's bull-necked strength, all his force of soul, were roused to fury when he thought of that. He was old and tired and he needed rest, but before he permitted himself to think of retirement, he must crush Ishmael Ameer.

Not that he allowed himself to recognise his vindictiveness. Shutting his eyes to his personal motive, he believed he was thinking of England only. Ishmael was the head-centre of an anarchical conspiracy which was using secret and stealthy weapons that were more deadly than bombs; therefore Ishmael must be put down, he must be trampled into the earth, and his movement must be destroyed.

But how?

Within a few hours after Lady Nuneham's funeral the Grand Cadi came by night, and with many vague accusations against "the Arab innovator," repeated his former warning—

"I tell you again, O Excellency, if you permit that man to go on it will be death to the rule of England in Egypt."

"Then prove what you say—prove it, prove it," cried the Consul-General, raising his impatient voice.

But the suave old Moslem judge either could not or would not do so. Indeed, being a Turkish official, accustomed to quite different procedure, he was at a loss to understand why the Consul-General wanted proof.

"Arrest the offender first and you'll find evidence enough afterwards," he said.

An English statesman could not act on lines like those, so the Consul-General turned back to the despatches of the Sirdar. The last of them—the one received during the dark hours preceding his wife's death—contained significant passages—

"If this man should develop supernatural pretensions I shall know what to do."

Ha! There was hope in that! The charlatan element in Ishmael Ameer might carry him far if only the temptation of popular idolatry were strong enough.

Once let a man deceive himself with the idea that he was divine, nay, once let his followers delude themselves with the notion of his divinity, and a civilised Government would be bound to make short work of him. Whosoever and whatsoever he might be, that man must die!

A sudden cloud passed over the face of the Consul-General as he glanced again at the Sirdar's despatch and saw its references to Christ.

"How senseless everybody is becoming in this world," he thought.

Pontius Pilate! Pshaw! When would religious hypocrisy open its eyes and see that, according to all the laws of civilised states, the Roman Governor had done right? Jesus claimed to be divine, His people were ready to recognise Him as King; and whether His kingdom was of this world or another, what did it matter? If His pretensions had been permitted they would have led to wild, chaotic, shapeless anarchy. Therefore Pilate crucified Jesus, and, scorned though he had been through all the ages, he had done no more than any so-called "Christian" governor would be compelled to do to-day.

"Jesus of Nazareth, the King of the Jews." Why would not people understand that these words were written not in derision but in self-defence? There could be only one authority in Palestine then, and there could be only one authority in Egypt now.

"If this visionary mummer, with his empty quackeries, should develop the idea that he is divine, or even the messenger of divinity, I will hang him like a dog!" thought the Consul-General.

CHAPTER XVIII

Five days after the death of Lady Nuneham the Consul-General was reading at his breakfast the last copy of the Times to arrive in Cairo. It contained an anticipatory announcement of a forthcoming Mansion House Banquet in honour of the King's Birthday. The Foreign Minister was expected to speak on the "unrest in the East, with special reference to the affair of El Azhar."

The Consul-General's face frowned darkly, and he began to picture the scene as it would occur. The gilded hall, the crowd of distinguished persons eating in public, the mixed odours of many dishes, the pop of champagne corks, the smoke of cigars, the buzz of chatter like the gobbling of geese on a green, and then the Minister, with his hand on his heart, uttering timorous apologies for his Proconsul's policy, and pouring out pompous platitudes as if he had newly discovered the Decalogue.

The Consul-General's gorge rose at the thought. Oh, when would these people, who stayed comfortably at home and lived by the votes of the factory-hands of Lancashire and Yorkshire, and hungered for the shouts of the mob, understand the position of men like himself, who, in foreign lands, among alien races, encompassed by secret conspiracies, were spending their strength in holding high the banner of Empire?

"Having chosen a good man, why can't they leave him alone?" thought the Consul-General.

And then, his personal feelings getting the better of his patriotism, he almost wished that the charlatan element in Ishmael Ameer might develop speedily; that he might draw off the allegiance of the native soldiers in the Soudan and break out, like the Mahdi, into open rebellion. That would bring the Secretary of State to his senses, make him realise a real danger, and see in the everlasting "affair of El Azhar" if not light, then lightning.

The door of the breakfast-room opened and Ibrahim entered.

"Well, what is it?" demanded the Consul-General with a frown.

Ibrahim answered in some confusion that a small boy was in the hall, asking to see the English lord. He said he brought an urgent message, but would not tell what it was or where it came from. Had been there three times before, slept last night on the ground outside the gate, and could not be driven away—would his lordship see the lad?

"What is his race? Egyptian?"

"Nubian, my lord."

"Ever seen the boy before?"

"No ... yes ... that is to say ... well, now that your lordship mentions it, I think ... yes I think he came here once with Miss Hel ... I mean General Graves's daughter."

"Bring him up immediately," said the Consul-General.

At the next moment a black boy stepped boldly into the room. It was Mosie. His clothes were dirty, and his pudgy face was like a block of dark soap splashed with stale lather, but his eyes were clear and alert and his manner was eager.

"Well, my boy, what do you want?" asked the Consul-General.

Mosie looked fearlessly up into the stern face with its iron jaw, and tipped his black thumb over his shoulder to where Ibrahim, in his gorgeous green caftan, stood timidly behind him.

At a sign from the Consul-General, the Egyptian servant left the room, and then, quick as light, Mosie slipped off his sandal, ripped open its inner sole, and plucked out a letter stained with grease.

It was the letter which Helena had written in Khartoum.

The Consul-General read it rapidly, with an eagerness which even he could not conceal. So great, indeed, was his excitement that he did not see that a second paper (Ishmael's letter to the Chancellor of El Azhar) had fallen to the floor until Mosie picked it up and held it out to him.

"Good boy," said the Consul-General—the cloud had passed and his face bore an expression of joy.

Instantly apprehending the dim purport of Helena's hasty letter, the Consul-General saw that what he had predicted and half hoped for was already coming to pass. It was to be open conspiracy now, not passive conspiracy any longer. The man Ishmael was falling a victim to the most fatal of all mental maladies. The Mahdist delusion was taking possession of him, and he was throwing himself into the Government's hands.

Hurriedly ringing his bell, the Consul-General committed Mosie to Ibrahim's care, whereupon the small black boy, in his soiled clothes, with his dirty face and hands, strutted out of the room in front of the Egyptian servant, looking as proud as a peacock and feeling like sixteen feet tall. Then the Consul-General called for one of his secretaries and sent him for the Commandant of Police.

The Commandant came in hot haste. He was a big and rather corpulent Englishman, wearing a blue-braided uniform and a fez—naturally a blusterous person with his own people, but as soft-voiced as a woman and as obsequious as a slave before his chief.

"Draw up your chair, Commandant—closer; now listen," said the Consul-General.

And then in a low tone he repeated what he had already learned from Helena's letter, and added what he had instantly divined from it—that Ishmael Ameer was to return to Cairo; that he was to come back in the disguise of a Bedouin Sheikh; that his object was to draw off the allegiance of the Egyptian army in order that a vast horde of his followers might take possession of the city; that this was to be done during the period of the forthcoming festivities, while the British army was still in the provinces, and that the conspiracy was to reach its treacherous climax on the night of the King's Birthday.

The Commandant listened with a gloomy face, and, looking timidly into the flashing eyes before him, he asked if his Excellency could rely on the source of his information.

"Absolutely! Infallibly!" said the Consul-General.

"Then," said the Commandant nervously, "I presume the festivities must be postponed?"

"Certainly not, sir."

"Or perhaps your Excellency intends to have the British army called back to Cairo?"

"Not that either."

"At least you will arrest the 'Bedouin'?"

"Not yet at all events."

The policy to be pursued was to be something quite different.

Everything was to go on as usual. Sports, golf, cricket, croquet, tennis-tournaments, polo-matches, race-meetings, automobile-meetings, "all the usual fooleries and frivolities"—with crowds of sight-seers, men in flannels and ladies in beautiful toilets—were to be encouraged to proceed. The police-bands were to play in the public gardens, the squares, the streets, everywhere.

"Say nothing to anybody. Give no sign of any kind. Let the conspiracy go on as if we knew nothing about it. But——"

"Yes, my lord? Yes?"

"Keep an eye on the 'Bedouin.' Let every train that arrives at the railway-station and every boat that comes down the river be watched. As soon as you have spotted your man, see where he goes. He may be a fanatical fool, miscalculating his 'divine' influence with the native soldier, but he cannot be working alone. Therefore find out who visit him, learn all their movements, let their plans come to a head, and, when the proper time arrives, in one hour, at one blow we will crush their conspiracy and clap our hands upon the whole of them."

"Splendid! An inspiration, my lord!"

"I've always said it would some day be necessary to forge a special weapon to meet special needs, and the time has come to forge it. Meantime undertake nothing hurriedly. Make no mistakes, and see that your men make none."

"Certainly, my lord."

"Investigate every detail for yourself, and above all hold your tongue and guard your information with inviolable secrecy."

"Surely, my lord."

"You can go now. I'm busy. Good-morning!"

"Wonderful man!" thought the Commandant, as he went out at the porch. "Seems to have taken a new lease of life! Wonderful!"

The Consul-General spent the whole of that day in thinking out his scheme for a "special weapon," and when night came and he went upstairs—through the great echoing house that was like the bureau of a department of state now, being so empty and so cheerless, and past the dark and silent room whereof the door was always closed—he felt conscious of a firmer and lighter step than he had known for years.