автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Girl Scouts on the Ranch

THE GIRL SCOUTS

ON THE RANCH

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

Page

I

COMMENCEMENT WEEK

3II

GOODBYES

16III

THE WEEK-END AT THE SHORE

30IV

DAISY’S SISTER

42V

THE TWO LIEUTENANTS

54VI

THE RANCH

68VII

MARJORIE’S RIVAL

82VIII

THE STAMPEDE

94IX

THE PICNIC

109X

THE SCOUT MEETING

122XI

DOROTHY’S ADVICE

134XII

THE PACK TRIP

142XIII

NIGHT FEARS

154XIV

THE SEARCH

170XV

REVELATIONS

179XVI

JOHN’S MISSION

187XVII

THE SCOUT PARTY

199XVIII

THE TRIP TO YELLOWSTONE

212XIX

THE INVITATION

222XX

MARJORIE’S GOOD TURN

234XXI

THE SCOUT’S SURPRISE

246CHAPTER I.

COMMENCEMENT WEEK.

CHAPTER II.

GOODBYES.

CHAPTER III.

THE WEEK-END AT THE SHORE.

CHAPTER IV.

DAISY’S SISTER.

CHAPTER V.

THE TWO LIEUTENANTS.

CHAPTER VI.

THE RANCH.

CHAPTER VII.

MARJORIE’S RIVAL.

CHAPTER VIII.

THE STAMPEDE.

CHAPTER IX.

THE PICNIC.

CHAPTER X.

THE SCOUT MEETING.

CHAPTER XI.

DOROTHY’S ADVICE.

CHAPTER XII.

THE PACK TRIP.

CHAPTER XIII.

NIGHT FEARS.

CHAPTER XIV.

THE SEARCH.

CHAPTER XV.

REVELATIONS.

CHAPTER XVI.

JOHN’S MISSION.

CHAPTER XVII.

THE SCOUT PARTY.

CHAPTER XVIII.

THE TRIP TO YELLOWSTONE.

CHAPTER XIX.

THE INVITATION.

CHAPTER XX.

MARJORIE’S GOOD TURN.

CHAPTER XXI.

THE SCOUT’S SURPRISE.

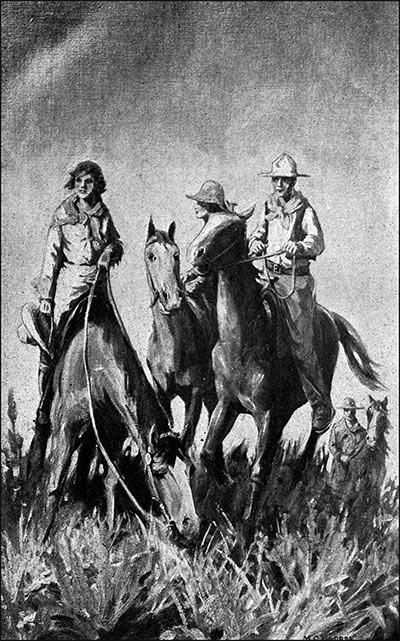

As soon as they had concluded their breakfast, Kirk, Marjorie and Daisy started back for camp.

(Page 200) (The Girl Scouts on the Ranch.)

THE GIRL SCOUTS

ON THE RANCH

By EDITH LAVELL

Author of

“The Girl Scouts at Miss Allen’s School,” “The Girl Scouts’ Good Turn,” “The Girl Scouts’ Canoe Trip,” “The Girl Scouts’ Rivals,” “The Girl Scouts at Camp.”

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers New York

THE

GIRL SCOUTS SERIES

A Series of Stories for Girl Scouts

By EDITH LAVELL

- The Girl Scouts at Miss Allen’s School

- The Girl Scouts at Camp

- The Girl Scouts’ Good Turn

- The Girl Scouts’ Canoe Trip

- The Girl Scouts’ Rivals

- The Girl Scouts on the Ranch

Copyright, 1923

By A. L. BURT COMPANY

THE GIRL SCOUTS ON THE RANCH

Made in “U. S. A.”

THE GIRL SCOUTS

ON THE RANCH.

CHAPTER I.

COMMENCEMENT WEEK.

Every door and every window of Miss Allen’s Boarding School stood wide open in hospitality to welcome the guests of the graduating class. For it was Commencement Week, and visitors were coming from far and wide to see the exercises.

Upstairs in the dormitories, confusion reigned everywhere. Trunks, half-packed, their lids wide open and their trays on the floor, lined the hallways; dresses were lying about in profusion on chairs and beds; great bunches of flowers filled the vases and pitchers; and rooms were bereft of their hangings and furnishings. Girls, girls everywhere! In party dresses or

kimonos

they rushed about their rooms or bent over their trunks in the hall. Everybody seemed in mad haste to accomplish the impossible.Marjorie Wilkinson and Lily Andrews were no less excited than the other seniors. They not only shared in the mad whirl of social events and class activities, but as officers they were responsible for their success. When dances and picnics were to be arranged, studying and packing were out of the question for them.

But that afternoon there had been a slight lull in their program, and both girls were in their room, trying to make up for lost time. Marjorie, who had been struggling for half an hour with a buckle and a satin pump, finally put it aside in disgust.

“Lil, I can’t sew that thing on, so as to have it look right! Every needle breaks, and the stitches show besides!”

“Couldn’t you wear them without the buckles?” suggested her room-mate, looking up from the floor, where she was kneeling over a bureau drawer.

“No, the marks would show where the buckles were before,” replied Marjorie, in the most mournful tone.

“Then don’t bother!” returned Lily, cheerfully. “Wear your silver slippers and stockings.”

“With pink georgette? Do you think it would look all right?”

“Yes—it would be stunning!”

“Just as you say,” agreed Marjorie, much relieved to have the matter disposed of. “I wish I had thought of that before—and not wasted a precious half hour with those old slippers!”

Lily stood up, holding a pile of clothing over her arm. She started for the trunk in the hall, but paused at the door.

“Marj, you better ‘waste’ another half hour in a nap, or you’ll be dead. You know as well as I do that tonight’s the biggest thing of the year for us.”

Marjorie smiled contentedly at this reference to the senior dance, which, as Lily had said, was the crowning event of their social career at Miss Allen’s. Later in life, Commencement itself would stand out most clearly in their memory; but now, at the age of eighteen, nothing could exceed the dance in importance. And yet Marjorie was conscious of an indefinable regret about the whole affair, as if already she knew that the realization could not equal the anticipation. The cause of this feeling could be traced to her partner. A month ago, on the spur of the moment, she had invited Griffith Hunter, a Harvard man whom she had met several years before at Silvertown, and whose acquaintance she had kept. But she was sorry not to have asked John Hadley, an older and truer friend.

“Tonight will be wonderful!” she said; “only, do you know, Lil, I do wish I had asked John instead of Griffith.”

“I knew you’d be sorry, Marj!” said Lily. “I never could understand why you asked Griffith.”

“I guess it’s because he’s so stunning looking, and I knew he would make a hit with the girls.”

“But John Hadley is good looking, too!”

“But not in the same way Griffith is. And you have so few dances with your partner!”

Smilingly, she threw herself down upon the bed and closed her eyes. Lily was right; she must be fresh for the dance. The class president could not afford to look weary and tired out. In a few minutes she was fast asleep.

The rest, which Marjorie so sadly needed, was the best beautifier the girl could have employed. Had her mind been on such things, her mirror would have told her, as she dressed, that she looked better. Her color was as fresh and pink as the roses she wore at her waist, and her eyes sparkled with greater brilliancy than ever.

Marjorie, modest as she always was, could not but be conscious that the eyes of everyone were turned approvingly towards her as she entered the dance hall on the arm of her handsome partner. When the music of the first dance began, and she started off with Griffith, she felt a thrill of pride at the grace of his dancing. Momentarily, she was glad that she had not invited John; no other young man of her acquaintance possessed all the social requisites to such an extent as Griffith. And, as she had remarked to Lily, they had only three dances together, and practically no intermissions, for as class president, it was her duty and her privilege to act as chief hostess. She tripped around from one group to another, introducing people, talking to everybody, sometimes taking Griffith with her, sometimes leaving him with Doris Sands or Mae Van Horn or Lily—wherever there seemed to be an interesting group. She had no time for strolls in the moonlight between dances, or intimate little tete-a-tetes on the porch; she used every minute of her evening for somebody else. When the last waltz finally started, Griffith declared that he had seen nothing of her during the evening.

“But you haven’t been bored?” she asked, with concern.

“No, indeed!” he replied, with sincerity. “Your friends are all charming!”

It was when they were strolling back to the school that Griffith asked,

“What do you intend to do this summer, Marjorie?”

“I really don’t know,” she replied. “I want to get away somewhere, and get good and strong for college next year.”

“Why not come to Maine?” suggested the young man.

“Yes, I’d like that—but I don’t know what papa is planning. It all depends upon him. But he won’t tell me a word.”

“Aren’t the Girl Scouts going camping?” asked Griffith.

“No; the captain, Mrs. Remington, couldn’t go, and at present we have no lieutenant, so we let the whole matter drop. I’m sorry, too, for I know I’m going to miss it all dreadfully.”

“And when do you expect to know your father’s plan?”

“Tomorrow, I hope,” she answered.

They had reached the school now, and they paused at the doorway. Marjorie put out her hand.

“You can’t come tomorrow?” she asked.

“No, I’m sorry,” said Griffith. “I’d love to, but we have a frat meeting. You’ll write?”

“Yes, if you write first. Well, goodnight!”

The young man pressed her hand.

“Goodnight—and thanks for a wonderful evening,” he said.

Marjorie turned about and hurried up the stairs. In spite of the rush and excitement, she was not tired. She wanted to talk it all over, to discuss the girls’ partners and dresses, the music, the flowers, the refreshments. To her joy she found Lily already in their room. She threw her arms about her in

ecstasy

.“Oh, wasn’t it all wonderful, Lil!” she cried. “Come, let’s sit down and talk it over.”

But, to her astonishment, she found Lily’s mood totally different from her own. The other girl seemed quiet, subdued, happy, but in a dreamy sort of way. And although she agreed with everything Marjorie said, she volunteered very little conversation on her own part. Apparently absorbed in her own thoughts, she began mechanically to undress. Marjorie contemplated her in amusement.

“Lil, I bet you don’t even know what color Doris’s dress was!” she said laughingly. “You’re so in the clouds.”

Lily flushed in admission of the accusation, making no attempt to deny it.

“How many dances did you have with Dick?” pursued Marjorie, teasingly. “More than the law allows, I’ll wager!”

“Why—five or six,” replied Lily. “Really, I didn’t count them.”

“No, I guess you didn’t! Well, suppose we get into bed. I won’t bother you any more—I’ll leave you to your dreams.”

“It isn’t that, Marj,” replied Lily. “But we do need the sleep. Tomorrow’s Commencement, you know.”

Marjorie’s parents were among the first guests to arrive for the exercises. Although too busy to meet each train, the girl kept a constant watch for them from the window of her room. She saw them as soon as they entered the school grounds, and bounded down the stairs, so that she might meet them before they reached the door.

“Jack is waiting for us at the out-door auditorium,” said Mrs. Wilkinson, after they had kissed each other. “He thought that he had better go and reserve seats.”

As Marjorie was all ready for the exercises, except for getting the bouquet of American beauties which John Hadley had sent her, she accompanied her parents across the campus. When they were within sight of the amphitheatre, she recognized her brother Jack, facing her, talking with a man and a woman whose backs were turned in her direction. Something in the manner in which the young man stood, and held his shoulders, gave Marjorie a thrill. It must be—it was—John Hadley!

Jack waved to her across the lawn, and instantly John Hadley turned around and greeted her cordially. In another minute the party was together.

“Perhaps we better get some seats,” suggested Jack. “At least for the ladies.”

The older people sat down, and Marjorie and the two young men stood near them. The former had only a few minutes at her disposal.

“Was your dance dress all right?” asked Mrs. Wilkinson, with motherly concern. At a glance, her experienced eye had taken in every detail of her daughter’s appearance, and she was thoroughly satisfied.

“Lovely! Perfect!” answered the girl, appreciatively. “And so were all the others. I’ll have to go somewhere very gay this summer,” she remarked with a sly, questioning look at her father, “to wear such lovely clothes!”

“Would you prefer Newport or Bar Harbor?” he asked, mischievously.

“Neither, papa, thanks. I’ve had a wonderful time this week, and, in fact all this year; but I’d be perfectly willing not to go to another party all summer. I’ve been gay enough to last a life-time.”

“Well, it certainly hasn’t seemed to hurt you,” observed Mrs. Hadley, looking approvingly at the girl’s pink cheeks.

“No; but too much of it would,” said her father. “Well, perhaps you will like my plans for your summer, then!”

Marjorie seized her father’s arm, and looked pleadingly into his eyes.

“Please tell me, papa! Please!”

“No, I can’t! It wouldn’t be fair to the rest!”

“The rest of whom?” she demanded.

“The rest of the Girl Scouts!”

Marjorie uttered a little gasp of pleasure; it was just what she wanted most of all. How she had dreaded the thought of the separation from her best friends, and the dissolution of that wonderful senior patrol of theirs which had gone together to Canada to represent the Girl Scouts of the whole United States!

“If you’re sure there are scouts in it,” she said, “I won’t ask any more. I’m perfectly satisfied!”

She turned to go, and John asked for permission to stroll back to the building with her. It was the first time he had seen her since the Spring vacation.

“I suppose you are still working hard?” she asked, casually.

“Yes—so—so,” he replied, lightly dismissing her question. He was more interested in the subject she had been discussing with her father.

“Marj, don’t you really know where you are going this summer?” he inquired.

“I haven’t the faintest idea,” replied the girl. “I know only just what papa said, which you heard: somewhere with the Girl Scouts.”

“Well, whenever you do go, I wish I could spend my two weeks vacation at the same place!”

“Probably you can, for I don’t think we are going to any girls’ camp, or anything like that.”

“But you might be going to Europe, or California,” he observed.

“No, I wouldn’t want to travel this summer—I’m too tired. And I’m sure mother realizes that, if papa doesn’t.”

John looked at her seriously.

“I wouldn’t be in your way, Marjorie?”

“No indeed!” she replied, heartily. “Let’s make it a bargain! We’ll have

our

vacation together—provided, of course, your mother is well enough to go.”“Oh thanks!” he said, fervently.

They had reached the main building now, and Marjorie stopped at the door-step.

“Come see me next Sunday!” she said, cordially. “Lily will be there, and perhaps some more young people.”

“I’d be delighted!” said John, turning to leave her. But he would have preferred to have an invitation for a time when he might see her alone.

Marjorie entered the building, and made her way to the room where the rest of the graduating class were gathered. With a sharp pang of regret she realized that this was the last time they would ever be together as students of Miss Allen’s school. No doubt they would often meet later as

alumnae

, but it would never be the same. It seemed such a short time since they had entered as freshmen—when she and Ruth Henry had ridden up from their home town together, wondering what it would all be like. She was so thankful that Ruth had not dared to come back to the school after her expulsion from the Girl Scouts the preceding summer; her absence had made the year singularly pleasant and peaceful. Yes, Marjorie Wilkinson had been happy during those four years of boarding school life, and she was sorry that it was all over.As soon as she had entered the room, Lily rushed forward with her bouquet.

“Marj! You forgot your flowers!”

“Oh, thanks, Lil!” cried the other, gratefully. “And I forgot to thank John, too. But I’ll see him again.”

She arranged the American beauties on her arm, and fell into her place in the procession of girls who were to walk, two by two, to that pretty stage in the wooded part of the campus.

During the first part of the exercises, she kept her eyes steadfastly in front of her, listening with

rapt

attention to the speaker, as he droned through his dry address. But it did not seem long to her; somehow she wished that he might go on forever, thus, by his act, keeping her a student at Miss Allen’s. But, like everything else, it was over at last, and the principal gave the signal for the singing of the Alma Mater, which was to mark the conclusion of the exercises.It was then that Marjorie looked about the audience, and allowed her eyes to rest upon John Hadley’s. Dropping them for a moment, she looked at him again, mutely trying to make up for her omission in thanking him.

The young man understood her meaning, and was happy.

CHAPTER II.

GOODBYES.

Marjorie saw her parents and the Hadleys only for a few minutes after the exercises were over, for almost immediately Mae and Lily came to drag her off to a luncheon, which was to be followed by the last class meeting.

As president, Marjorie naturally took the chair. Calling the meeting to order, she put through the necessary details, that the girls might return to their visitors as soon as possible. It was only when she mentioned the formation of some sort of permanent organization, whose purpose it would be to arrange for reunions and other activities, that she realized that the girls were in no hurry to adjourn.

“Is it your pleasure to elect officers, and frame a constitution?” she asked.

Immediately several girls rose to their feet in hearty approval of the suggestion. Discussion followed, and a unanimous acceptance of the proposition. Almost before she realized it, Marjorie was re-elected president for the coming year.

It was after three o’clock when the meeting broke up, and Marjorie and Lily decided to go straight to their room. Lily’s parents had gone home immediately after the exercises were over, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilkinson had invited the girls to supper at the inn with them that evening, so they had not planned to be with Marjorie in the afternoon. Both girls, therefore, felt that they were free for the remainder of the time.

Marjorie opened the door rather listlessly, picturing to herself the confusion of the room, and wishing to keep away from it as long as possible. But the packing had to be done, and there would be no opportunity so good as this one.

“Lil!” she exclaimed, as soon as they were both inside the door, “What are those suit-boxes on our beds?”

“I don’t know,” replied the other girl, going over to examine them. “They don’t belong to me—” she paused, and looked at one of them closely—“yes, this one does, too! It has my name on it!”

“And the other has my name on it!” cried Marjorie. “They must be Commencement presents!”

With trembling fingers the girls pulled at the string and succeeded in loosening it. In a moment each had made her discovery. A brand new riding-habit of the most fashionable cut lay folded in each box.

“How wonderful!” cried Marjorie. “Yes, here’s a card—from mother. But when are we supposed to wear them? I haven’t any horse—”

“It must have something to do with our vacation this summer,” surmised Lily. “Or maybe our parents are going to let us go riding every day.”

“Let’s put them on!” suggested Marjorie, holding hers up for a closer examination.

“No, we better not, Marj. Let’s pack first, and get our work all done. I simply can’t rest in all this mess.”

“Righto!” agreed her room-mate.

The girls substituted middy blouses and bloomers for the Commencement dresses, and then fell to work with a will. Order began to come from chaos, and the room took on that bare appearance of the deserted dormitory in summer time. As they surveyed the results of their labor, both Marjorie and Lily grew increasingly cheerful; they began to forget that this day was their last at Miss Allen’s, among so many dear friends, and their thoughts instead were of the future.

“Don’t you wish we knew what we were going to do this summer?” asked Marjorie, for perhaps the tenth time that week.

“Yes, but I do love a mystery. Remember last summer—how we didn’t know whether we were going to the training camp or not—and then later when we hardly dared dream that Pansy Girl Scouts would be the ones to go to Canada.”

“Yes,” said Marjorie; “and everything always seems more thrilling in reality than we ever hoped it would be. So perhaps, this summer will be, too.”

“Your father said something about Girl Scouts—oh, don’t you wish the whole senior patrol could be together?”

“It is my dearest wish,” replied Marjorie, earnestly.

The appearance of a maid at the door to remind them that the man would call for their trunks in ten minutes put an abrupt end to this pleasant conversation. Without another word, both girls set themselves to finish their task.

“There’s just time for a nap before we dress for supper,” said Lily, dropping on the bed.

“Of course I wouldn’t have said anything to mother or papa,” said Marjorie thoughtfully, “but I do wish we didn’t have to go to the inn tonight. It’s our last supper here, so I care more about the companionship with the girls than about having good food. I want to be with our best friends—Alice, and Doris, and the rest.”

“Cheer up, you’ll have breakfast with them tomorrow,” reminded Lily. “And we can come back early this evening, and maybe wear our riding-habits to visit them.”

Marjorie’s face brightened at the suggestion.

“It’s Friday night, Lil!” she exclaimed, suddenly. “Oh, if our senior patrol could only get together for one last meeting! Just think—is it possible we’re out of active membership of the Girl Scouts forever?” Her voice became disconsolate, and she uttered the last word almost in a whisper.

“But we won’t be,” said Lily, reassuringly. “We’re both going to start troops of our own in the fall. And besides, I shan’t give up hopes for this summer until I hear what your father tells you tonight.”

Both girls were in their

kimonos

, ready for their brief nap. Almost as soon as they stopped talking and closed their eyes, they fell asleep, exhausted from the strain and excitement of the week.Neither realized how long she had been asleep; each sat up at the same moment, awakened by a continuous knocking. Someone was at the door.

“My gracious, what’s that?” cried Lily. “It must be late, Marj! How long do you suppose we have slept?”

Mechanically, patiently, the knocking persisted. Whoever the visitor was, she evidently did not intend to give up until she received an answer.

“We’ve got to open the door, though, goodness knows, we haven’t any time for callers,” said Marjorie, pulling on her slippers.

Before she reached the door there came another volley of knocks, then a whisper, followed by sounds of smothered laughter. The visitors were evidently in high good humor. Sleepily, and with an excuse half-formed on her lips, Marjorie opened the door. To her immense surprise, not one, but five girls confronted her—her five best friends in the Girl Scout troop. She burst into laughter.

“Do come in!” she exclaimed.

“We were sure you were dead!” said Alice Endicott, one of the most vivacious girls in the troop. “We’ve been knocking for hours!”

“Not really?” asked Marjorie, seriously. “Oh, what time is it?”

“Quarter of six!” answered Doris Sands, consulting her watch.

“And we’re to be at the inn at quarter past for dinner with your father and mother!” cried Lily, in alarm. “Marj, we certainly will have to rush!”

“Yes,” announced Alice, “we’re all going—that’s the reason we are here. I’ve heard of parties where nobody came but the hostess, but a party without the hostess would be rather odd!”

She seated herself comfortably on the couch, and the others followed her example. Marjorie listened incredulously to what she had told them.

“You’re invited too? Why, that’s perfect! But why didn’t papa tells us?”

“Oh, you know he’s always strong on surprises,” remarked Lily. “I think this is a dandy. But don’t stand there like a bump on a log, Marj! We’ve got to dress.”

In less than ten minutes the girls announced their readiness to start. Florence Evans reminded them both, however, not to forget their flowers.

“Flowers?” repeated Lily. “Oh, yes, I’d forgotten. Of course we seniors all have them.”

“Seniors?” questioned Marjorie, a trifle regretfully. “We’re graduates now, Lil. Florence and Alice and Daisy are the seniors now.”

But in spite of the imminence of the separation, Marjorie became gay again. The evening promised to be very enjoyable, almost, it would seem, a repetition of old good times. Mae Van Horn, Doris Sands, Alice Endicott, Florence Evans, Daisy Gravers, Lily, and herself—with the exception of Ethel Todd, all of the dear old senior patrol that shared the wonderful experiences of last summer would be together. Surely it was no time for regrets!

Linking arms, and humming the Girl Scout Marching-song, they proceeded across the campus to the village. All the girls wore dainty summer dresses, with light wraps or silk sweaters, and went without hats. There were no bobbed heads now among the group; the style was considered passé, and the girls with short locks disguised them with nets.

They reached the inn just in time, and found Mr. and Mrs. Wilkinson waiting for them on the porch. Two tall white benches on either side of the door seemed to invite them hospitably to be seated. The girls gratefully dropped into seats.

“Why is the door closed?” asked Marjorie, after she had expressed to her parents her appreciation of the delightful surprise party.

“I guess it’s cold inside,” replied Mr. Wilkinson, with a twinkle in his merry brown eyes.

“Oh it isn’t, papa! You’re hiding something!” cried his delighted daughter. “I know you!”

“You aren’t satisfied, then?” he asked. “You want something more? Some young men, I suppose?”

“No I don’t!” protested Marjorie, emphatically. “I hope John and Jack went home, as they expected, for I’d rather have the girls all to myself tonight!”

“Well then, what is it you do want?” he pursued.

“Nothing, papa. I’m perfectly happy. But I just asked a simple question: why, on such a warm night as this, should the door be closed, when there is a perfectly good screen-door in front of it?”

“Don’t tease her any more, dear!” remonstrated Mrs. Wilkinson. “There is a reason for having it closed, Marjorie, and it is another surprise for all of you. Two more guests are waiting for you inside, but they’re of the feminine gender, as you seem to desire.”

“Oh, who?” demanded all the girls at once.

“What two people would you most rather have with you tonight?” asked the older woman.

“Ethel Todd, for one!” cried Marjorie.

“And Mrs. Remington!” put in Lily and Alice, both in the same breath.

At this dramatic moment, Mr. Wilkinson threw open the door, revealing the very two people desired, smiling at the girls’ surprised expressions. The scouts all jumped up and rushed forward, and a great confusion of embracing followed. Before they had calmed down, the landlady appeared to announce supper.

Following her into a private dining-room beyond the main tea-room, they found a charming table set for ten. A big bowl of purple pansies stood in the center, surrounded by candles of the same color; and at the four corners of the table there were bows of purple ribbon. The place-cards represented hand-painted scout hats, decorated with wreaths of the same troop flower.

“It’s lovely! I feel just as if it were a real scout party again!” cried Marjorie, joyfully.

“That’s exactly what we’ve tried to make it,” explained her father, gratified at her obvious pleasure.

“And so many surprises in one day,” continued the girl, after everyone was seated. “Our riding-habits—you must see them, girls—and this party, and Ethel and Mrs. Remington—”

“And flowers from John,” teased Alice.

“Well, I simply couldn’t stand anything more!” concluded Marjorie. “I’d just die!”

“And here I was just about to tell you about the best one of all!” interrupted her father. “But now I guess it wouldn’t be safe.”

“Oh, you simply must now!” urged Marjorie. “It isn’t fair to keep us all in suspense!”

“But you said you couldn’t stand any more!”

“I could stand that one!” laughed Marjorie.

“Well, I’m going to let Mrs. Remington tell you this one,” he said. “But wouldn’t it be better, perhaps, to have some dinner first?”

The girls

acquiesced

, and gave their attention to the inviting fruit-cups before them. In the conversation that ensued the graduates, who had been the recipients of all the attention for the past week, were glad to retire to the background, to give Ethel Todd and Mrs. Remington the center of the stage. They talked about college, and the future of Pansy troop without its distinguished leaders. Almost every possible subject was discussed except the one in which the girls were most interested: namely, their captain’s plans for their vacation.When they had finally finished their ice-cream, served in such beautiful pansy-forms that they hated to eat them, and the candies and nuts were being passed, Mr. Wilkinson called upon Mrs. Remington for her announcement. Eight eager pairs of eyes turned hopefully towards their captain, for somehow all the girls felt that in some way their own fate was connected with the surprise Mr. Wilkinson had planned for his daughter.

“Well, girls,” she began, as she looked from one to another of the expectant faces about the table, “Mr. Wilkinson asked me what he thought Marjorie would like to do best this summer, and I replied, without the least hesitation: something with the Girl Scouts—and particularly with the members of the senior patrol. Was I right, Marjorie?” she asked, turning to the girl.

“Yes, yes,” cried Marjorie. “Go on, please!”

“So you see that naturally necessitated my working out a plan and consulting the other girls’ parents. I thought of a great many places to go, but I wanted something entirely different, and yet, at the same time, some out-door vacation. So finally I hit upon a plan which I hope will suit you all. At least, it suits your parents; I have their consent for every girl here—including Ethel.”

“And it is—” cried two or three scouts at once.

“Something to do with horseback-riding!” ventured Lily, thinking of her own and Marjorie’s latest graduating presents.

“Yes. You are all to spend July and August on a ranch in Wyoming!” said Mrs. Remington.

“July and August?” repeated Marjorie, jumping out of her seat, and rushing toward her father’s chair. “Two whole months?”

“It isn’t too long, is it?” he asked.

“It’s heaven!” she cried, throwing her arms about his neck.

The candles were burning low now, so Mrs. Wilkinson suggested that the party adjourn to the porch to enjoy the moonlight, while they discussed the proposition to their hearts’ content. The girls asked innumerable questions, many of which, however, Mrs. Remington could only partially answer.

“I’m sorry, girls, that I shall not be able to go with you,” she said, “but I couldn’t possibly leave home that long. But you will get along all right. The ranch is almost like a private place, and Mrs. Hilton, the proprietor’s wife, will act as chaperone. And you only need one in name.”

“And when do we start?” asked Lily.

“The very first day of July,” replied the captain.

The girls fell to discussing what clothing they should take, and Mrs. Remington told them, to their surprise, that they would live almost entirely in riding breeches. Warm, sensible clothing, and undergarments that could be easily laundered, were necessities; and perhaps a silk dress to wear on the trains. But they would find no use for fancy summer costumes, she said.

“Suppose all our Commencement dresses are out of style when we get home!” wailed Lily. “Won’t it be a shame!”

“Well, you can still go to Newport, if you prefer!” teased Mr. Wilkinson; but Lily was horrified at the thought.

“But what I like best,” said Marjorie, as the girls made a move to go, “is the fact that we’ll be together for two months—the longest vacation we have ever had!”

“Do you suppose you can stand it all that time away from John Hadley?” asked Mae, in a low voice, at her side. “That will be too far for him to visit you, you know.”

Marjorie frowned; the remark recalled her promise to John that very morning to go to a place where he and his mother might join her. A wave of regret spread over her; she hated to go back on her promise, but of course it was too late to change the plans now, even if she had wanted to. Anyone would be foolish to give up a whole summer for the sake of a two weeks’ vacation.

“Oh, I guess we’ll meet lots of Western boys,” she answered, carelessly. “I don’t expect to pine away.”

Mr. Wilkinson accompanied the girls back to the school, and although it was nearly half past ten, Marjorie and Lily insisted that he wait down stairs while they put on their riding-habits and returned, proudly, to show themselves to him. Then they made the round of the scouts.

CHAPTER III.

THE WEEK-END AT THE SHORE.

Commencement was over, and Miss Allen’s Boarding School had been closed for a week. Marjorie Wilkinson was home again.

For the last few days everything seemed strangely quiet and unnatural. No bells rang in the morning to arouse Marjorie from her much needed rest; there were no classes or meetings to attend; no gay functions at night that kept her up till the small hours. She accomplished her unpacking in less than an hour and arranged her room so that it seemed as if she had never been gone. Her old favorite books were back in her secretary-desk; her pictures were in their former places on the walls; her school pillows were again on the wide window-seat, and her

monogrammed

ivory set on the bureau. As far as outward appearance went, the girl was perfectly at home.And yet the strangeness of the life, in spite of the familiarity of her surroundings, impressed her as it had never done before during a summer vacation. Her old friends had vanished, and her new ones were too far away to take their places. Ruth Henry, her chum from childhood, who had afterward proved herself to be such a traitor, had moved to New York to finish at a fashionable boarding school. Harold Mason was spending his summer at a young men’s camp, and her brother Jack had taken a vacation position at a hotel in Atlantic City. There was no one left in town whom she knew intimately.

For a while, however, Marjorie was too tired to deplore this absence of friends and excitement. She was glad of the chance to sleep, to read, and to visit with her mother. She went over her college catalogues, marking the studies she intended to take in the Fall, and she examined her wardrobe with the view of selecting the things she would like to take with her to the ranch.

But when the week had finally passed, and Lily Andrews arrived for the promised visit, she knew she was thankful for the companionship.

The girls greeted each other as effusively as if it had been a month, instead of a week, that had separated them.

“But I’m afraid it will be pretty slow for you, till the week end, at least,” said Marjorie, apologetically, as she started the motor. “There isn’t a thing doing—the town’s practically dead.”

“Why, isn’t there tennis—and driving—and canoeing, an—?” asked Lily.

“Oh, certainly!” interrupted Marjorie. “But I mean no dances or parties, or even young men to call!”

“I don’t believe that will worry me much,” laughed the other. “But say, Marj, couldn’t we go horseback riding—just to practice up a little, you know?”

“Yes, we can hire horses, of course. That’s a dandy idea!”

Marjorie said nothing more about the week-end until they were comfortably established on the porch after Lily’s things had been disposed of. Then she mentioned it again.

“You don’t seem a bit excited about the week-end,” she remarked. “We’re going away!”

“Why, of course I’m thrilled!” Lily hastened to assure her. “Where are we going?”

“To Atlantic City—the hotel where Jack is clerking. And mother has invited Mrs. Hadley and John.”

“That’s great!” cried Lily, rapturously. She had loved the seashore from childhood. Then, at the mention of John Hadley, she asked whether Marjorie had told him of her plans for the summer.

“No, I haven’t,” replied her companion. “I tried to when I wrote to thank him for the roses. But somehow I didn’t know how to tell him, because you know we had partly arranged to go to the same place this summer. It seems sort of like going back on my promise!”

“Well, you couldn’t help that,” returned Lily, consolingly. “But I’m sure he won’t be angry.”

“No, maybe not angry, but hurt, perhaps. Still—scouts have to come first, don’t they, Lil?”

“You bet they do! Particularly as this is probably the last thing you and I shall ever do as members of Pansy troop!”

“And that reminds me,” said Marjorie, “I wanted to ask you whether you thought we couldn’t keep our organization, and have regular scout meetings at the ranch. And we could wear our uniforms once in a while, just for old time’s sake, you know.”

“Indeed I do approve of that idea!” cried Lily, with spirit. “Let’s keep our senior patrol as long as we possibly can.”

“I sort of hesitated to suggest it,” continued Marjorie, “because I am senior patrol leader, and I was afraid it might look as if I were trying to keep all the power I could get.”

As Lily listened to these words, a new thought came into her mind. She seized upon it immediately; it was a veritable inspiration.

“Marj! I have it! You’re eighteen now—let’s get you commissioned as lieutenant!”

“Lieutenant—of—Pansy—troop?” repeated Marjorie, overcome by the wonder of such a proposal. When the older girls had received their commissions, she had looked upon them with awe and admiration, but it never seemed possible to her that she could hold the same office as Edith Evans and Frances Wright. She had always dreamed of becoming an officer—perhaps, in time, a captain—over a troop of little girls. But to be first lieutenant of her own troop—that seemed utterly out of the question.

“Certainly,” replied Lily. “I’ll write to Mrs. Remington this very minute, and she’ll get your examination papers.” She was on her feet now, starting towards the door. “We have ten days yet,” she added, “we can easily put it through.”

But Marjorie still seemed reluctant.

“It wouldn’t be fair, Lil—without consulting the other girls.”

“Nonsense! Would they have elected you senior patrol leader, two years in succession, if they didn’t want you? Would you have been made class president and first alumnae president, if you weren’t popular? Why, they’ll be tickled to death! And won’t it be fun to spring a surprise on them!”

“You mean not say a word about it to them, till everything is settled?” Marjorie showed plainly that she disapproved of the suggestion.

“Of course! Tell them that Mrs. Remington wouldn’t let us go without an officer, and that some awful stick of an old maid has been made our lieutenant, and will join us somewhere on our trip out. Oh, I can just see Alice’s expression now! Won’t she be furious!”

The humor of such a situation dawned upon Marjorie, and she joined in Lily’s amusement. Then, after a little more persuasion, she consented to the writing of the letter.

The girls did not have to wait long for the answer; indeed, they were surprised at the rapidity with which it came. But then Mrs. Remington always attended to matters promptly, and this all the more so because she approved so heartily of the proposal.

Marjorie was delighted to find that the examination was comparatively easy; after the more difficult merit-badge tests she had taken the previous summer at training camp, this one seemed almost like child’s play. She took it into the library, signed the pledge of honor to answer the questions without assistance, and set immediately to work. Inside of an hour the paper was finished, sealed in an envelope, and dropped into the mail-box.

On Friday afternoon the whole family went in the automobile to Atlantic City. Marjorie and Lily occupied the front seat, with the former at the wheel, while Mr. and Mrs. Wilkinson rode in the tonneau.

The girls were not very talkative; both were absorbed in their own thoughts. Marjorie went over and over in her own mind the best way to tell John her plans for the summer. Probably it would make no difference to him, and yet she wished the ordeal were over. She would hate so to offend him.

A slight accident to the motor delayed them for a couple of hours at a garage, bringing them to the hotel in Atlantic City at something after five o’clock. Jack met them and informed them that the Hadleys had already arrived, and had gone to their rooms. They would meet in the lobby at six o’clock to go into the dining-room together.

“Don’t say a word about our trip to the ranch, Lil,” pleaded Marjorie, as the girls were unpacking their suit-case. “I want to break it to him gently—in case he should be peeved.”

“I know he’s going to be terribly disappointed,” said Lily. “But I’ll be very careful, Marj.”

Reassured by her chum’s promise, Marjorie went gaily down to the lobby at the appointed time. John’s first words, however, took her somewhat aback; he had not forgotten her promise.

“This certainly is jolly of your mother,” he said. “And more than I ever dreamed of. An extra week-end with you—besides our two weeks in August.”

Marjorie winced at the reference, and closed her lips tightly. She could not tell him now, before all those people, that her plans were changed. So she merely smiled, and turned to Mrs. Hadley.

Having secured permission for extra time off, Jack felt particularly gay, and acted as host of the party. Mr. Wilkinson noticed with what genuine courtesy he carried the thing off, and judiciously retired to the background. Indeed, it seemed as if the boy even regarded his father and mother as guests.

The others of the party responded to his mood, and the meal was a jolly one. It was only when he announced that he had procured seats for Keith’s theatre that evening, that the girls found their spirits sinking. For Lily would have preferred to spend the time looking at the ocean, and Marjorie longed for the opportunity to have a tete-a-tete with John.

But if the girls were disappointed at this announcement, they were dismayed at the young man’s next remark. All unconscious of the situation, he blurted out to John’s surprised ears the unwelcome news of the girls’ project.

“What do you think of these wild girls, Hadley?” he asked, while they were all waiting for their dessert. “Imagine them strutting around in trousers all summer, on a ranch in Wyoming! I’ll bet they join the cowboys, and never come back!”

“What? What?” demanded John, in a most perplexed tone. Marjorie had said nothing about any such plans.

“Oh—haven’t the girls told you yet? Well, there hasn’t been much time. Still—I thought you and Marj kept up a steady correspondence!”

“The steadiness is all on my side,” replied the young man, quietly. Then, louder, “No, I didn’t know a word about it. Tell me!”

Marjorie hastened to relate all there was to tell: her father’s desire to plan something particularly nice for her for this vacation, Mrs. Remington’s suggestion, and the Girl Scout party. John said nothing about his shattered hopes, but Marjorie saw that the slight had cut deeply. If only she had written to him! But it was too late now for regrets.

She did not find an opportunity until the following afternoon to apologize for her failure to explain the project to John. The party, which had stayed together all morning on the beach and in the ocean, decided to go their separate ways after luncheon. Mr. Wilkinson joined a fishing excursion, and Lily and the two older women planned to take naps. Jack found it his duty to be in the office if he wanted the evening off, so John seized the chance to ask Marjorie to go walking. She was only too glad to accept.

Taking the car as far as Ventnor, so that they might avoid the crowd and the shops, they started their walk in the prettier part of the town. Marjorie plunged immediately into the subject that was uppermost in both minds.

“John,” she began, “I didn’t mean to go back on my promise, and I wanted to tell you all about it before anybody else did. But you see papa and Mrs. Remington planned everything; I had practically no say in the matter.”

John regarded her intently, wishing that he might believe that she was as keenly disappointed as he was because they were not to be able to spend the vacation together. But no; she certainly did not appear heart-broken.

“You’re not sorry, though,” he said, somewhat bitterly. “The whole thing suits you exactly.”

“It would be a lie to say it didn’t,” laughed Marjorie, good-naturedly. “You know how I adore that sort of thing.”

“Marjorie,” he pursued, “do you think that—that—” he hesitated, as if he did not know how to put his thought—“that sports, and Girl Scouts, and things like that, will always come first with you?”

Marjorie seemed hurt at his words; he was accusing her of being cold and unfeeling.

“I don’t know what you mean!” she returned, sharply. “Do you imply that I care more for things like that than for people? That I like

horseback-riding

and hiking better than mother and father and Lily—”“No, no! I didn’t mean that. Of course I know your family and Lily come first. But men, for instance? It seems to me you’d always rather go off with a pack of girls on some escapade than see any of your men friends.”

“Maybe I would,” laughed the girl, heartlessly. “But,” she added, “perhaps I’ll wake up some time!”

“When?” he asked, seriously.

“Maybe when I fall in love!” she returned, teasingly.

John knew that now she had adopted this frivolous manner, it would be useless to pursue the subject further. So he put the thing out of his mind temporarily, forcing himself to talk of other things.

But when, an hour later, he was alone in his room, he made a new resolution. Marjorie had treated him shamefully by not writing to him of her plans, by allowing his hopes to be dashed so rudely to the ground by a third person. It was evident that she did not care for him—that she had never cared, and it was foolish of him to pursue her. In the future, therefore, he meant to treat her with the same polite indifference with which he accorded the other members of her sex; if he was nothing to her, he would show her that she was nothing to him!

That evening and the following day, he shared his attentions equally with both girls, and although nothing was said, when Marjorie drove away in the car, she felt that something was wrong. She feared she had lost the friendship of a young man for whom she had the utmost regard and respect. And she was sorry—but not sorry enough to make an effort to re-establish it on the old footing.

Resolutely, she thought of the ranch and the Girl Scouts, and talked volubly to Lily on both subjects. She was rewarded, it seemed; for when she reached her home, she found her lieutenant’s commission waiting in the mail-box!

CHAPTER IV.

DAISY’S SISTER.

The eight Girl Scouts who were going to the ranch met at the Grand Central Station of New York. Although there were to be only eight travellers, there seemed to be about thirty or forty people in the party, so many friends and relatives had come to see them off.

Luckily, the girls’ luggage was all cared for by someone else, for there was not a scout in the party who was not laden down with baskets of fruit or boxes of candy. Doris Sands and Marjorie Wilkinson each wore bunches of roses—those of the latter however were a gift, not from John Hadley, but from Griffith Hunter.

The girls themselves seemed almost too excited to give much thought to their presents. They tried to listen to innumerable admonitions and messages at the last minute, and finally got into the train with only a hazy idea of what everyone had said. But they all looked supremely happy.

As soon as they were comfortably settled, and the excitement had died down so that normal conversation was in order again, Marjorie began to wish she might tell the others about her commission. It was only with the greatest effort that she restrained herself.

Neither had Lily forgotten the all important subject; so as soon as she found a chance, she blurted out her announcement.

“Girls!” she said. “I have the most exciting news to tell you! Guess what it is!”

“What? What?” demanded two or three at once.

“Marj is engaged?” suggested Alice, always anxious for romance.

“Don’t be silly!” said Marjorie, frigidly.

“Well, you’ll never guess, so I might as well tell you,” said Lily, amused at Marjorie’s indignation. “We are to have a scout lieutenant to chaperone us this summer.”

“Who?” demanded Florence Evans, excitedly. “Not my sister Edith?”

“No—nobody like her. You couldn’t imagine two people more different; in fact this woman is different from anybody else we ever had in the troop. She is really an awful old maid—about seventy, I guess—and wears spectacles, and thinks girls of seventeen or eighteen are mere infants. She—”

Lily rejoiced to see the girls all growing furiously angry. How did such a thing ever happen? Was this Mrs. Remington’s doing? Ethel interrupted Lily by demanding, sharply,

“What’s this dreadful person’s name?”

Lily had not thought of a name for her. So, under the necessity of inventing one on the spur of the moment, it sounded perhaps a trifle too prim.

“Miss Prudence Proctor!” she announced, avoiding Marjorie’s eyes.

Florence let out a soft whistle. The others looked equally dismayed. It was Alice who demanded a full explanation.

“Mrs. Remington wrote for us to keep a watch for her, that she might join us anywhere from New York to the ranch.”

“How are we to know her?” asked Ethel.

“I’ll know her,” answered Lily. “I met her once.”

“And is she really so awful?” asked Alice, a little more hopefully.

“She’s dreadful!”

“Marj,” said Ethel, suddenly suspicious, “why aren’t you saying anything? What do you know about her?”

Marjorie could hardly keep from laughing; in her struggle with the corners of her mouth, the tears came into her eyes.

“She’s—she’s impossible!” she stammered, hiding behind her handkerchief. “She’s really the most disagreeable person I know.”

“Worse than Ruth Henry?” asked Alice.

“Yes,” murmured Marjorie, again almost losing control of herself.

“Girls,” said Doris, who was always sensitive to another’s discomfort, “let’s change the subject. I don’t understand it, but Mrs. Remington must have had a reason for putting this woman over us. Anyway, we can’t make it any better by talking about it.”

“It looks like one of Ruth Henry’s tricks to me,” said Alice, bitterly.

All this finally became too much for Lily; she was choking now, and she feared that if she stayed another minute she would give way entirely. Rising hastily, she made some excuse about getting a glass of water, and disappeared into her own compartment.

By making their reservations early all the Girl Scouts had managed to travel in the same car. Lily and Marjorie had one compartment together, and Ethel and Doris another; the rest of the party had been satisfied to travel in berths.

Although Doris, Alice and Lily had all been to the coast before, they had taken the trip during their childhood, with their parents, and had forgotten most of the details. Everything, therefore, seemed new and fascinating to them all; they were in no hurry for the days to pass which would be spent so enjoyably before they even reached the ranch. They would read and play cards to their hearts’ content; and then, when they were tired of everything else, they could always talk with each other.

To many people much older than these Girl Scouts the novelty of eating on a train has never lost its charm, so it is little wonder that they looked forward to each occasion with a keen sense of pleasure. They were thankful, too, as they entered the diner for their first meal, that there were eight in their party; it would mean that they might always eat by themselves, if they were fortunate enough to secure two tables. They were careful to keep their voices low, and to avoid drawing any undue attention to themselves; but, in spite of this, more than one fellow-passenger looked enviously at the happy party.

When supper was over that first night, the girls, by general consent, congregated in Marjorie’s compartment. It was the larger, more comfortable of the two, and afforded a lovely private sitting-room.

“Shall we play bridge?” asked Doris.

“No, let’s just talk,” replied Marjorie, who sensed the prevailing sentiment of the group. “Only—not about the lieutenant! I couldn’t bear that!”

“We’ll never mention her till she appears!” exclaimed Alice, loyally. “There—will that be a relief to you?”

Lily looked distressed. Was all her fun going to be denied her in this fashion? But Marjorie good-naturedly came to her rescue.

“No, Alice, I’d rather get used to talking about her now, so that I won’t make a fool of myself when she does appear. You can say whatever you like; it really doesn’t matter to me!”

“Well, don’t let’s talk about her, anyway,” said Doris. “I’m sure we can find a more agreeable topic of conversation. Let’s everybody tell what she is going to do next year!”

“That will be interesting!” cried Lily, enthusiastically. “Where shall we begin?”

“With the oldest,” answered Doris. “That’s you, Ethel.”

“Well, you all know about me,” said the girl. “I’ll be a sophomore at Bryn Mawr.”

“And I’m going to a finishing school outside of Boston,” volunteered Doris, briefly. “Who’s next—Marj or Lil?”

“I am,” said Lily. “I’m not sure what I am going to do. I’d like to go to college, but I’m the only child in my family, you know, and mother wants me home—papa travels so much.”

“I’m entered at Turner College,” said Marjorie. “And if I have anything to say about it, Lily will go too!”

“But how about her mother?” asked Mae.

“Her mother can have her all the rest of her life!”

“It’s likely,” laughed Mae. “She’d be married the week after college closed!”

“Mae!” remonstrated Lily, “don’t judge others by yourself! Now—what are you going to do?”

“I’m going to business college, and I hope to take a position by the first of the year.”

“That certainly sounds interesting,” said Doris. “Well, I suppose there isn’t any use asking our seniors. You three are all going back to Miss Allen’s, aren’t you?” she asked, turning to the youngest girls in the party.

Florence and Alice both nodded assent; but Daisy sat still, staring into space. It was evident from her attitude that something was troubling her.

“I’m sorry,” she said, quietly, after the short pause, “but I can’t go back.”

“Why not?” demanded two or three of the girls at once. Mae was just about to make some teasing remark about getting married, when, catching sight of the girl’s expression, she took the warning to be careful.

“We can’t afford it,” said Daisy, sadly. “Mother had to choose between this trip and my last year at school, and, for the sake of my health, she chose this. I’m really glad, for my best friends are here, and I can get my diploma later at night school.”

The girls were absolutely silent for a moment, nonplussed at their chum’s announcement. No one had had the slightest idea of the change in her circumstances, and, although Marjorie and Alice had both remarked about something strange in Daisy’s manner, both had attributed it to ill health.

And while no one asked any questions, Daisy was started now, and meant to go on with the whole story.

“You see, our family have been under tremendous expense lately,” she explained, fingering the tatting on her handkerchief, and avoiding the girls’ eyes. “My sister—she’s only twenty—always was very excitable, and we sort of expected her to do something crazy. Well, she did! Last Easter she went to the seashore with another girl, but she didn’t come back with her. Instead, she ran off and married a man she had known only three days!”

“My gracious!” cried Alice, who was now sitting on the edge of her chair, “How thrilling!”

“And did your father have to support him?” asked Florence, jumping to the natural conclusion.

Daisy shook her head sadly. How she wished their problem were as simple as that!

“No, he turned out to be a splendid young man—papa met him afterwards, though of course I never saw him. Well, to get back to the story, Olive—that’s my sister, you know—sent a telegram to say they were married, giving the man’s name. But unfortunately it was Smith—a Thomas Smith!”

“Why unfortunately?” asked Alice. She could see no dishonor in marrying a man of that name.

“Because, as you’ll see later, we had to trace her, and the name is too common. It was in April that we received this telegram; in May, Thomas Smith came to see the family alone. Olive had disappeared, and he didn’t know where.”

“But why did she run away?” asked Alice, incredulously. “Was he cruel to her?”

“No; as I said before, papa said he was lovely. Of course, I was at school myself, and didn’t meet him, but I’d trust papa’s judgment any day. And he said he had never seen anybody look so sad. The poor young man seemed to take all the blame on himself.”

“I wonder why!” exclaimed Doris, with pity.

“Well, it seems that he had teased her about a poorly cooked dinner, and it turned out that she was really very sick, with a fever. She took his teasing to heart, and ran out without any coat or hat. He naturally thought she would come right back, but she didn’t. Then he began to phone to all her friends, and to us, but nobody has seen her since. We don’t know whether she’s dead or not!”

“How dreadful!” whispered several of the girls, sympathetically.

“And so, ever since then, papa and Mr. Smith have both spent a great deal of money in trying to trace her; but no detectives have ever found a clue. Mr. Smith finally became discouraged, and went away, giving her up as dead. But we have never given up hope.”

“Surely she’ll turn up,” said Doris, consolingly. “Why, if she had died, somebody, somehow, would have sent word.”

“Except that there was no way to identify her. Well, papa has another theory. He thinks her exposure while she was so sick made her temporarily lose her mind, and probably even now she is an amnesia victim, wandering around trying to find out who she is.”

“Wouldn’t it be great if we’d find her!” cried Alice, who was always looking for adventure.

“We’d never find her this far away,” said Daisy, sadly. “If Olive’s alive, she’s somewhere in the East. Mr. Smith said she couldn’t have had more than ten or fifteen dollars in her purse.”

“Anyway, I’m going to watch for her all the time!” declared Alice. “I’d rather watch for her than for that old stick of a lieutenant!”

“Tell us what she looks like!” begged Marjorie.

“She’s very striking looking. You

couldn’t

miss her. She has dark, wavy hair, and very pink cheeks. Her eyes are blue, and she has a dimple in her right cheek. She’s medium height, and slender.”“Have you a picture of her?” asked Lily.

“I’m afraid I haven’t,” sighed Daisy. “I didn’t bring any pictures at all with me. I thought we might live in tents, and wouldn’t want anything that wasn’t absolutely necessary.”

“Well, let’s look at every girl we see, every time the train slows down. And we can go in the diner in relays tomorrow, and look over everybody on the train!” said Alice.

“Now Alice, that’s too foolish!” cried practical Florence Evans. “Imagine finding her right on this train! You sound like a dime novel!”

“But she must be somewhere!” persisted Alice, stubbornly.

This discussion was interrupted by Marjorie’s asking Daisy what she was planning to do next year.

“I’ve been studying stenography,” replied the girl, “and I have a position waiting for me at home in the principal’s office of the public school. I’m very lucky, because that will allow me to be with mother, and help a little besides.”

“I think you’re wonderful to be so cheerful!” said Marjorie, admiringly. “And think of keeping it from us all this time!”

“Well, I always hoped the thing would solve itself, and that there would be no need of explanations. But now I’m getting pretty hopeless too.”

“Whom do you bet we find first?” asked Alice, in spite of Florence’s rebuke, “Daisy’s sister, or the lieutenant?”

“Daisy’s sister, I hope,” replied Doris, with a yawn. “Come girls, let’s go away and let these people go to bed!”