автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Seven Great Monarchies Of The Ancient Eastern World, Vol 2: Assyria / The History, Geography, And Antiquities Of Chaldaea, Assyria, Babylon, Media, Persia, Parthia, And Sassanian or New Persian Empire; With Maps and Illustrations

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Seven Great Monarchies Of The Ancient

Eastern World, Vol 2. (of 7): Assyria, by George Rawlinson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: The Seven Great Monarchies Of The Ancient Eastern World, Vol 2. (of 7): Assyria

The History, Geography, And Antiquities Of Chaldaea,

Assyria, Babylon, Media, Persia, Parthia, And Sassanian

or New Persian Empire; With Maps and Illustrations.

Author: George Rawlinson

Illustrator: George Rawlinson

Release Date: July 1, 2005 [EBook #16162]

Last Updated: October 20, 2012

Language: English

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SEVEN GREAT MONARCHIES ***

Produced by David Widger

THE SEVEN GREAT MONARCHIES

OF THE ANCIENT EASTERN WORLD; OR, THE HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, AND ANTIQUITIES OF CHALDAEA, ASSYRIA BABYLON, MEDIA, PERSIA, PARTHIA, AND SASSANIAN, OR NEW PERSIAN EMPIRE. BY GEORGE RAWLINSON, M.A., CAMDEN PROFESSOR OF ANCIENT HISTORY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD IN THREE VOLUMES. VOLUME I. With Maps and Illustrations

CONTENTS

THE SECOND MONARCHY, Part 1.

CHAPTER I. DESCRIPTION OF THE COUNTRY

CHAPTER II. CLIMATE AND PRODUCTIONS

THE SECOND MONARCHY, Part 2.

CHAPTER III. THE PEOPLE

CHAPTER IV. THE CAPITAL

CHAPTER V. LANGUAGE AND WRITING

THE SECOND MONARCHY, Part 3.

CHAPTER VI. ARCHITECTURE AND OTHER ARTS.

THE SECOND MONARCHY, Part 4.

CHAPTER VII. MANNERS AND CUSTOMS.

THE SECOND MONARCHY, Part 4.

CHAPTER VIII. RELIGION

CHAPTER IX. CHRONOLOGY AND HISTORY

APPENDIX.

Illustrations

Map1

Plate 22

49. Signet of Kurri-galzu. King of Babylon

(drawn by the author from an impression in the

possession of Sir H. Rawlinson)

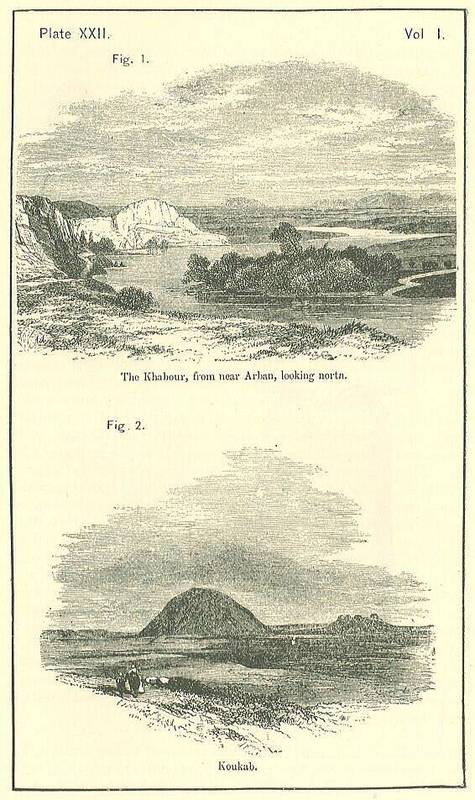

50. The Khabour, from near Arban, looking north (after Layard)

Plate 23

51. Koukab (ditto)

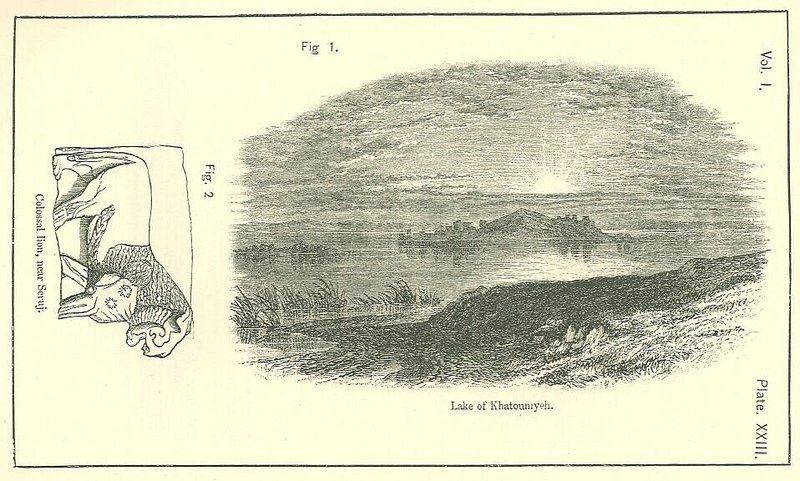

52. Lake of Khatouniyeh (ditto)

53. Colossal lion, near Seruj (after Chesney)

Plate 24

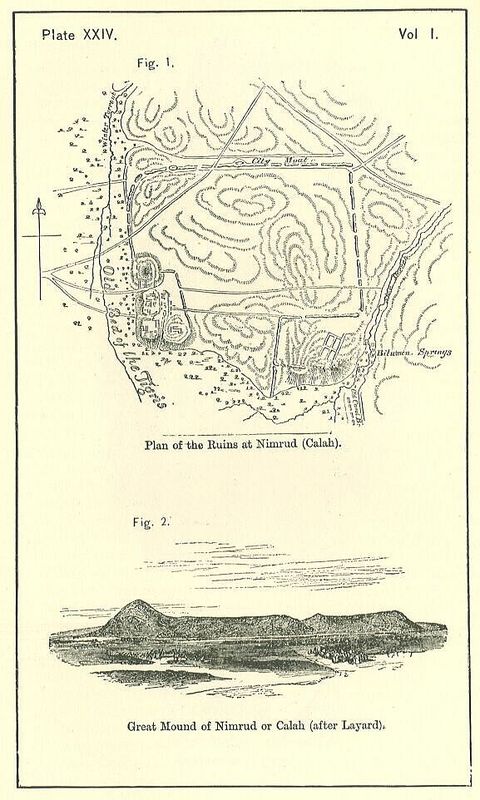

54. Plan of the ruins of Nimrud (Calah)

(reduced by the Author from Captain Jones's survey)

55. Great wound of Nimrud or Calah (after Layard)

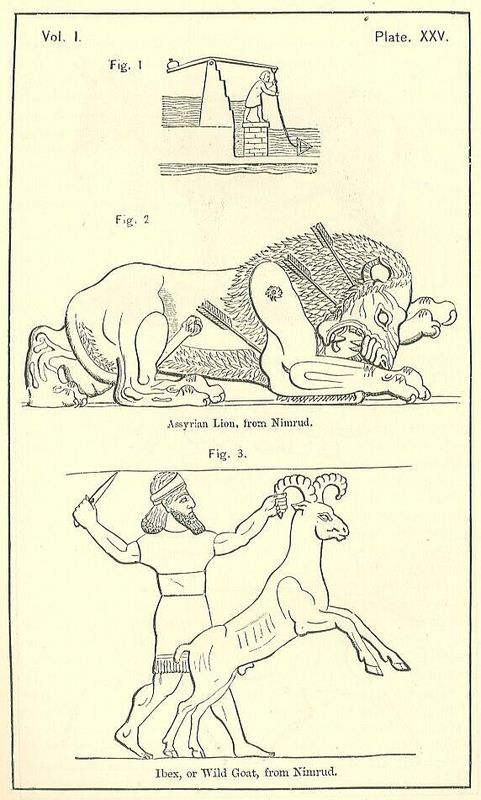

Plate 25

56. Hand-swipe, Koyunjik (ditto)

57. Assyrian lion, from Nimrud (ditto)

58. Ibex, or wild goat, from Nimrud (ditto)

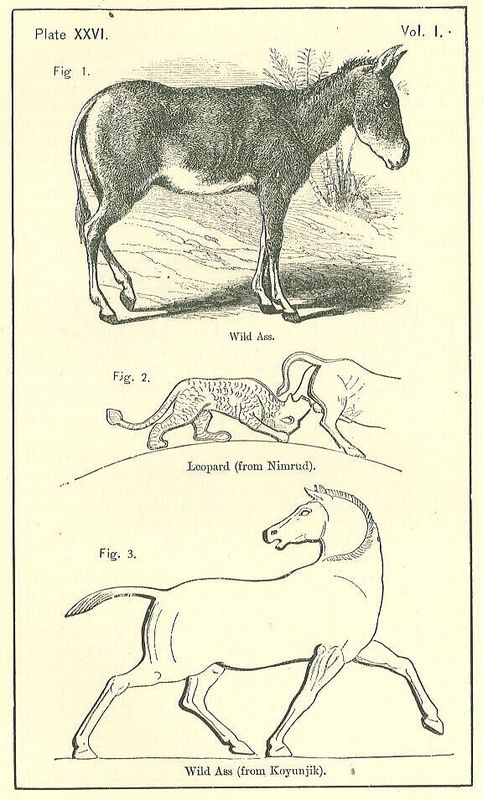

Plate 26

59. Wild ass (after Ker Porter)

60. Leopard, from Nimrud (after Layard)

61. Wild ass, from Koyunjik (from an unpublished

drawing by Mr. Boutcher in the British Museum)

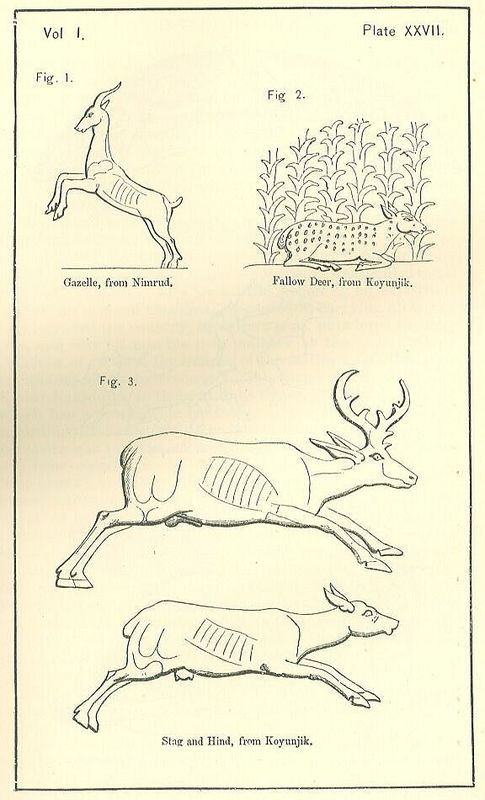

Plate 27

62. Gazelle, from Nimrud (after Layard)

63. Stag and hind, from Koyunjik (from an unpublished

drawing by Mr. Boutcher in the British Museum)

64. Fallow deer, from Koyunjik (after Layard)

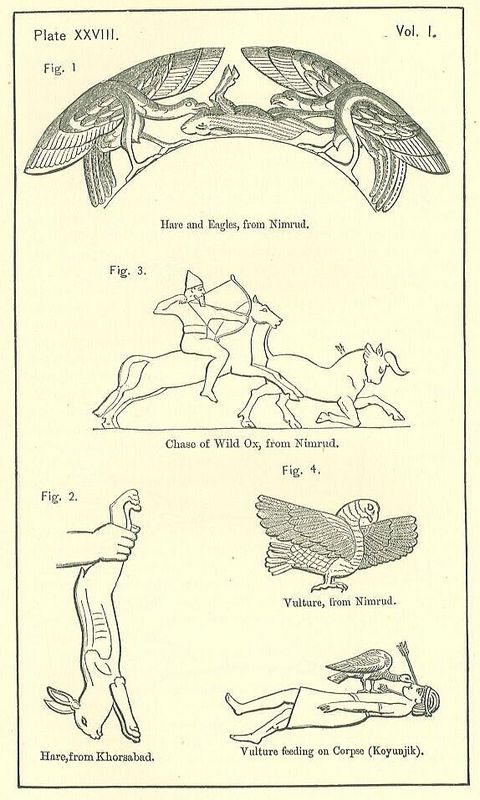

Plate 28

65. Hare and eagles, from Nimrud (ditto)

66. Hare, from Khorsabad (after Botta)

67. Chase of wild ox, from Nimrud (after Layard)

68. Vulture, from Nimrud (ditto)

69. Vulture feeding on corpse, Koyunjik (ditto)

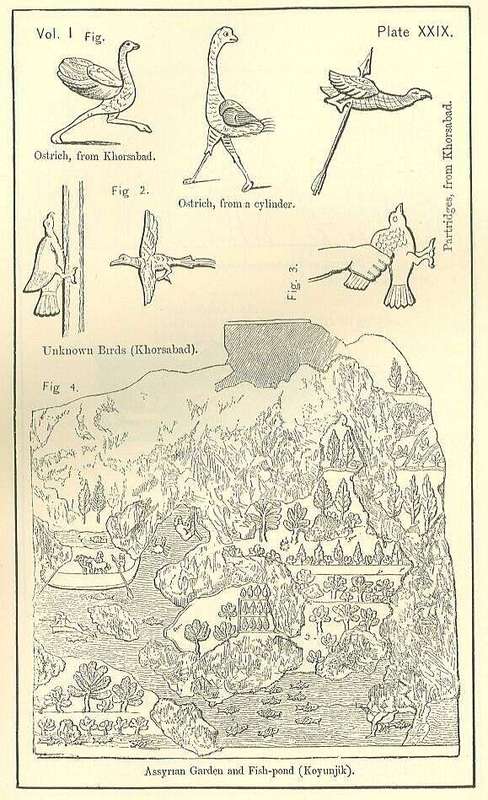

Plate 29

70. Ostrich, from a cylinder (after Cullimore)

71. Ostrich, from Nimrud (after Layard)

72. Partridges, from Khorsabad (after Botta)

73. Unknown birds, Khorsabad (ditto)

Plate 30

74. Assyrian garden and fish-pond, Koyunjik (after Layard)

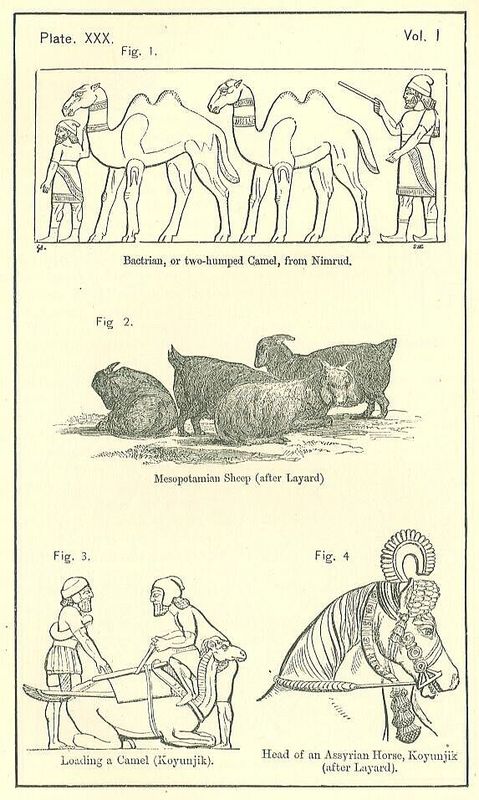

75. Bactrian or two-humped camel, from Nimrud (ditto)

76. Mesopotamian sheep (ditto)

77. Loading a camel, Koyunjik (ditto)

78. Head of an Assyrian horse, Koyunjik (ditto)

Plate 31

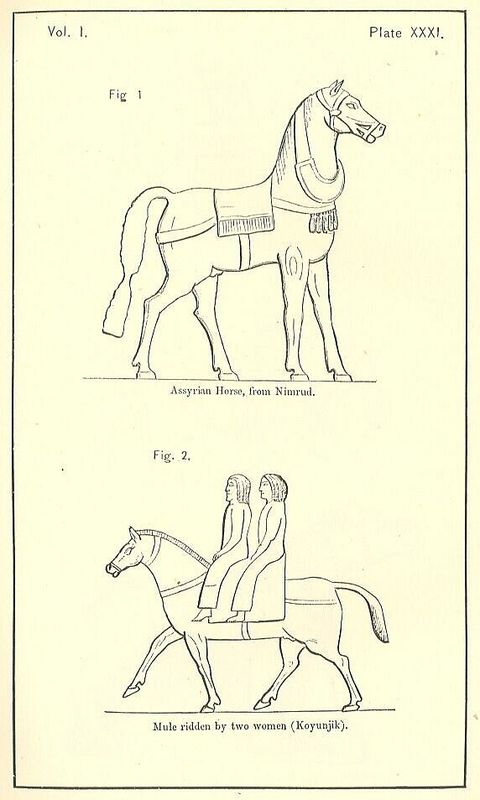

79. Assyrian horse, from Nimrud (ditto)

80. Mule ridden by two women, Koyunjik (after Layard

Plate 32

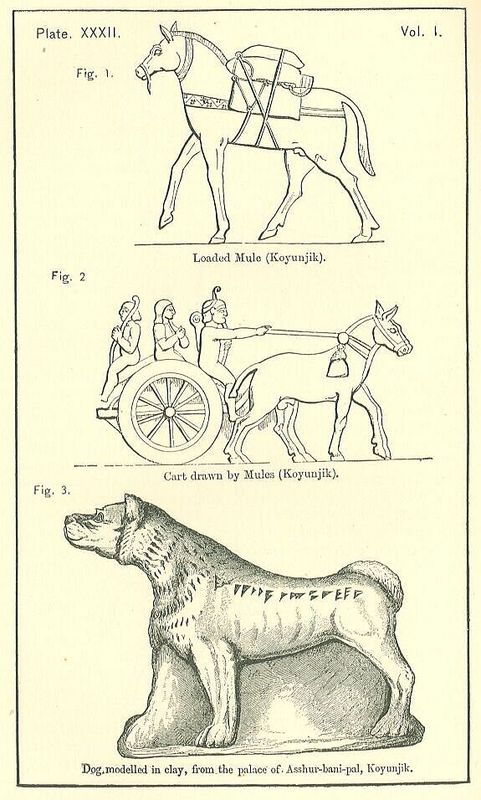

81. Loaded mule, Koyunjik (ditto)

82. Cart drawn by mules, Koyunjik (ditto)

83. Dog modelled in clay, from the palace of

Asshur-bani-pal, Koyunjik, (drawn by the Author

from the original in the British Museum)

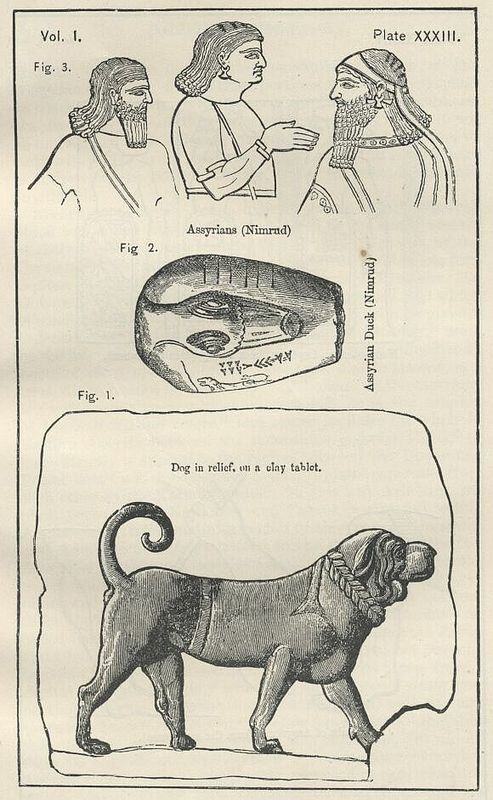

Plate 33

84. Dog in relief, on a clay tablet (after Layard)

85. Assyrian cluck, Nimrud (ditto)

86. Assyrians, Nimrud (ditto)

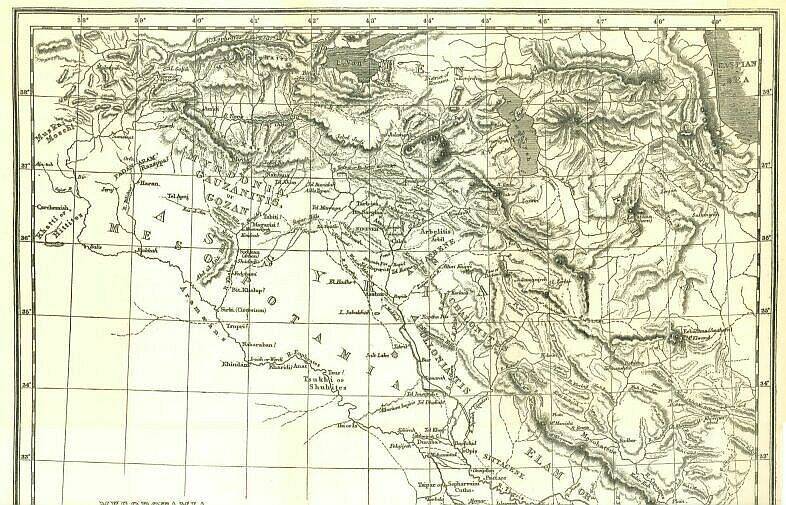

Map1

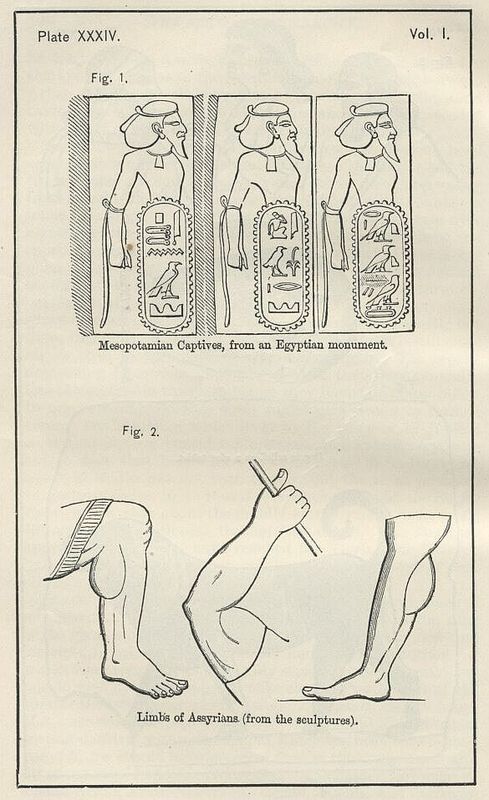

Plate 34

87. Mesopotamian captives, from an Egyptian monument (Wilkinson)

88. Limbs of Assyrians, from the sculptures (after Layard)

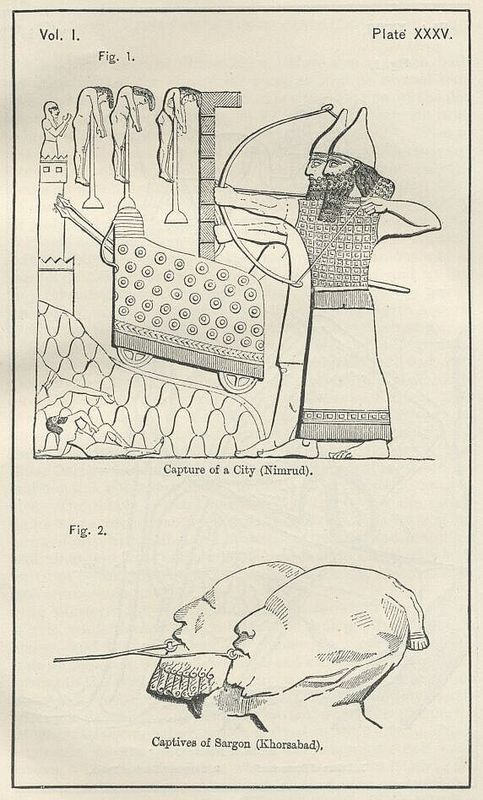

Plate 35

89. Capture of a city, Nimrud (ditto)

90. Captives of Sargon, Khorsabad (after Botta)

Plate 36

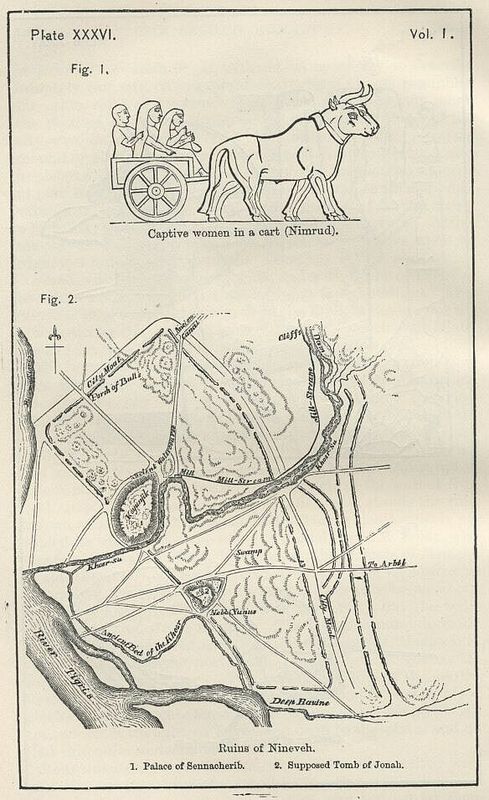

91. Captive women in a cart, Nimrud (Layard)

92. Ruins of Nineveh (reduced by the Author from Captain Jones's survey)

Plate 37

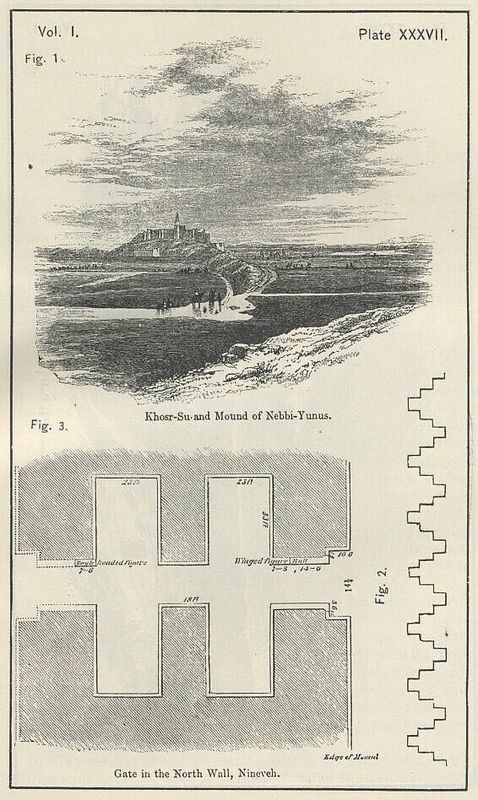

93. Khosr-Su and mound of Nebbi-Yunus (after Layard)

94. Gate in the north wall, Nineveh (ditto)

Plate 38

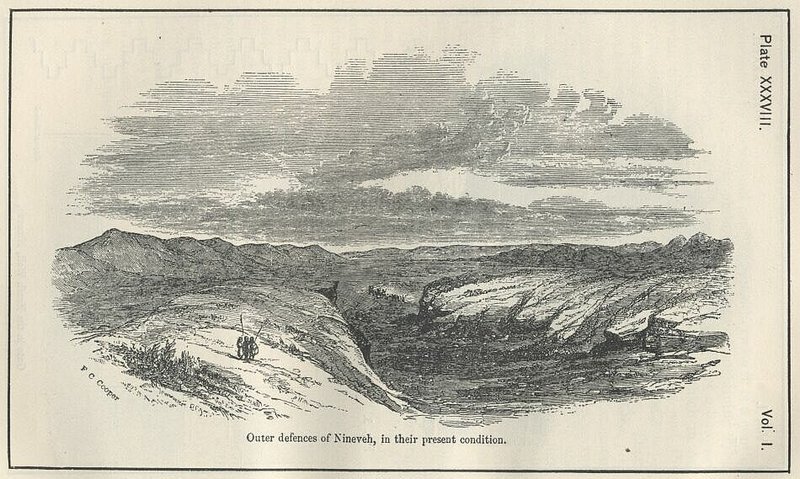

95. Outer defences of Nineveh, in their present condition (ditto)

Plate 39

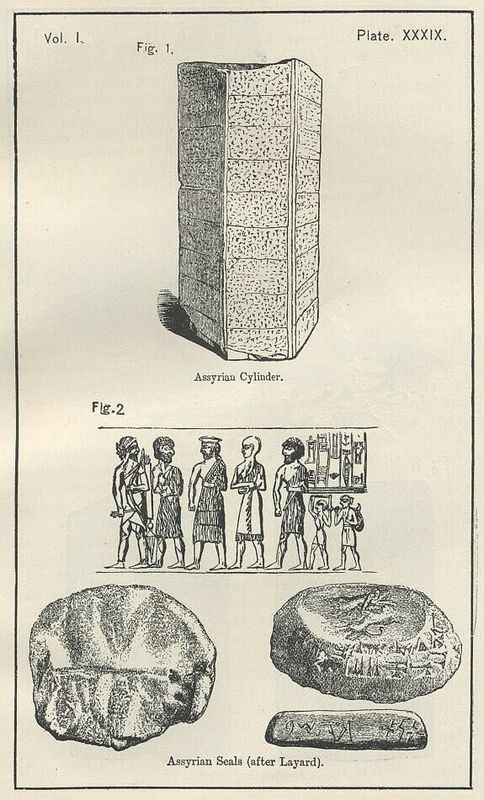

96. Assyrian cylinder (after Birch)

97. Assyrian seals (after Layard)

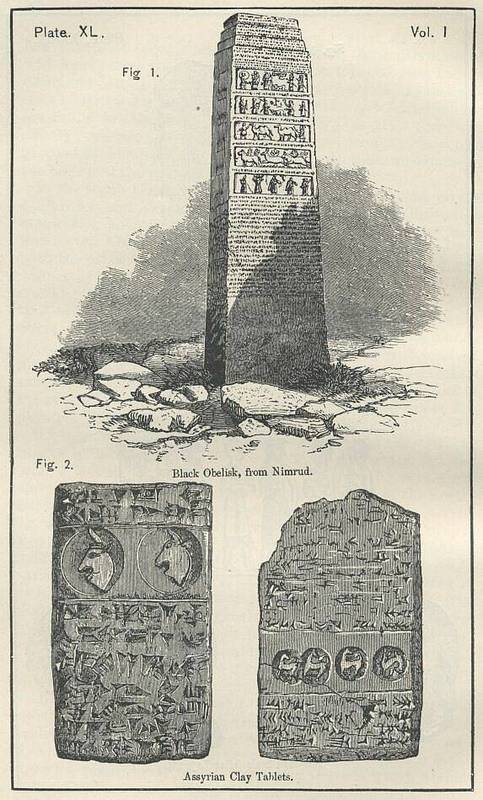

Plate 40

98. Assyrian clay tablets (ditto)

99. Black obelisk, from Nimrud (after Birch)

Partial Page 171

Partial Page 172

Partial Page 173

Partial Page 174

Page 175

Page 176

Page 177

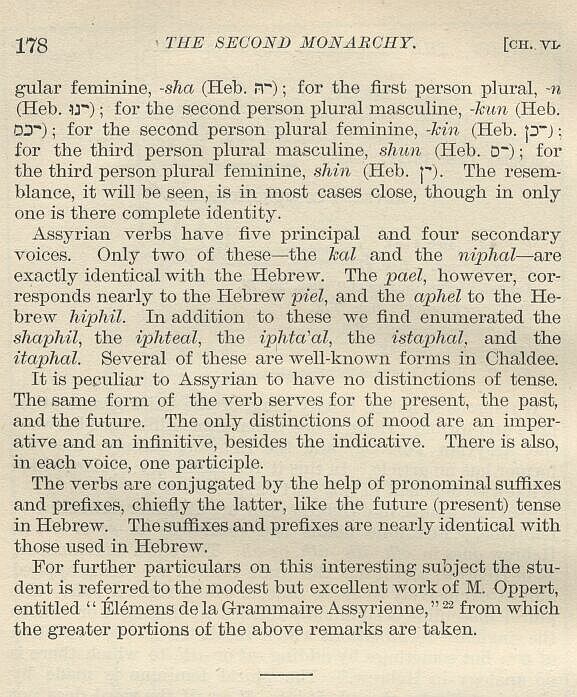

Partial Page 178

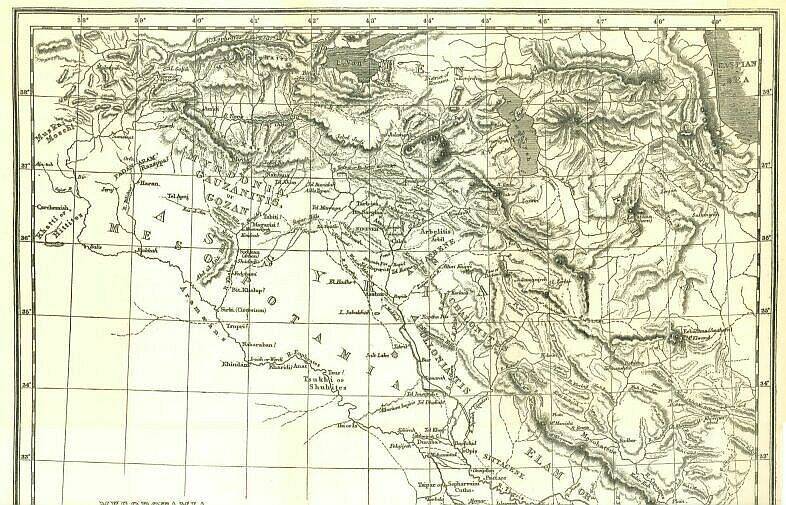

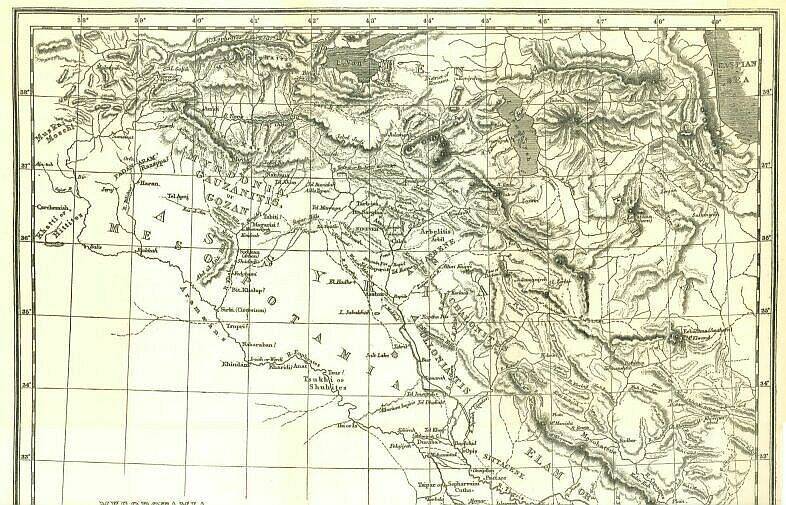

Map of Assyria

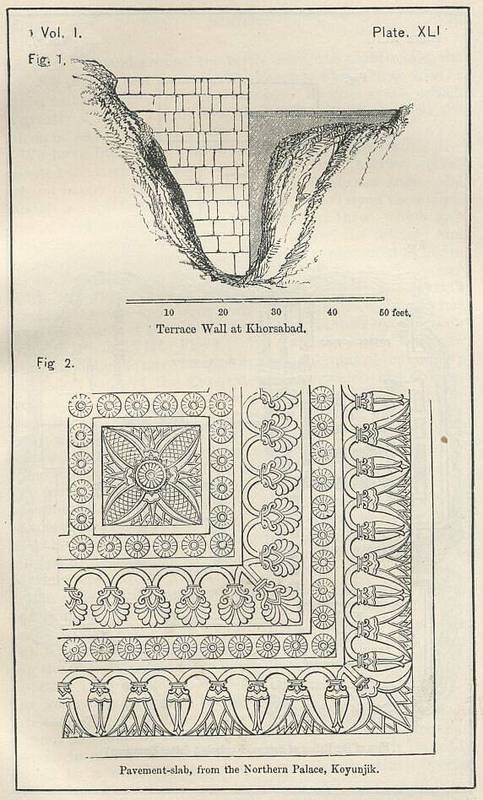

Plate 41

100. Terrace-wall at Khorsabad (after Botta)

101. Pavement-slab, from the Northern Palace.

Koyunjik (Fergusson)

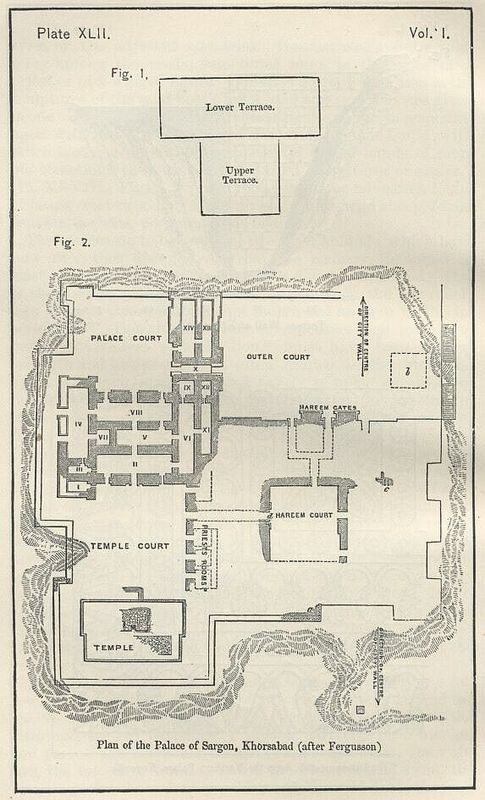

Plate 42

102. Mound of Khorsabad (ditto)

103. Plan of the Palace of Sargon, Khorsabad (ditto)

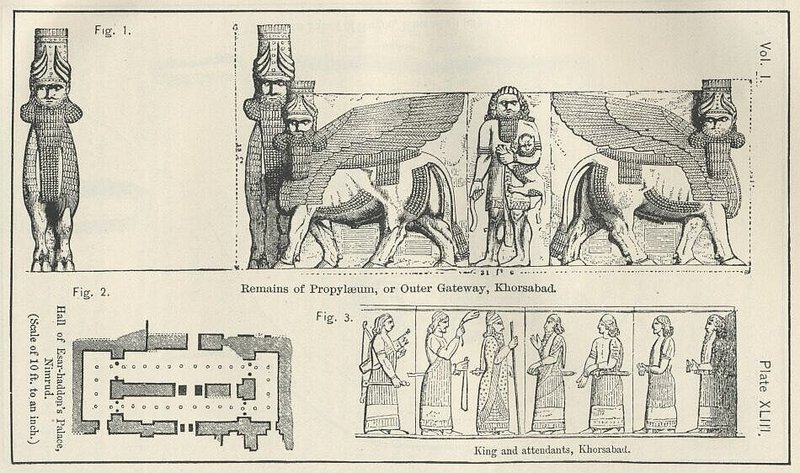

Plate 43

104. Hall of Esar-haddon's Palace, Nimrud (ditto)

106. Remains of Propyheum, or outer gateway, Khorsabad (Layard)

107. King and attendants, Khorsabad (after Botta)

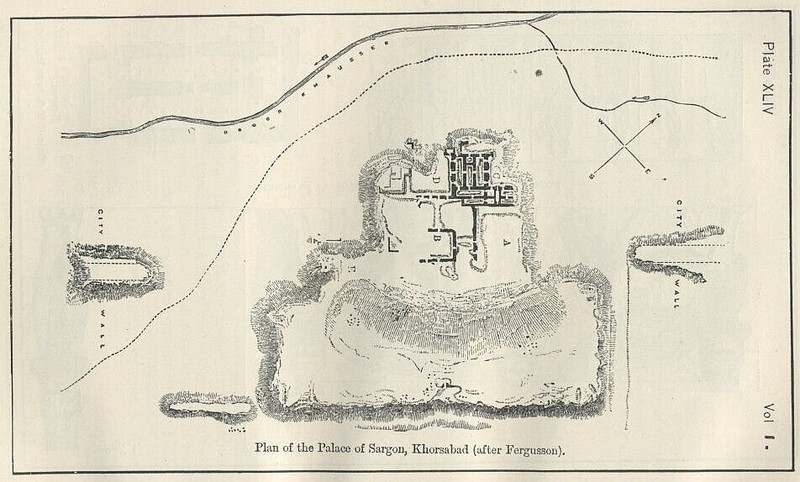

Plate 44

105. Plan of the Palace of Sargon, Khorsabad (ditto)

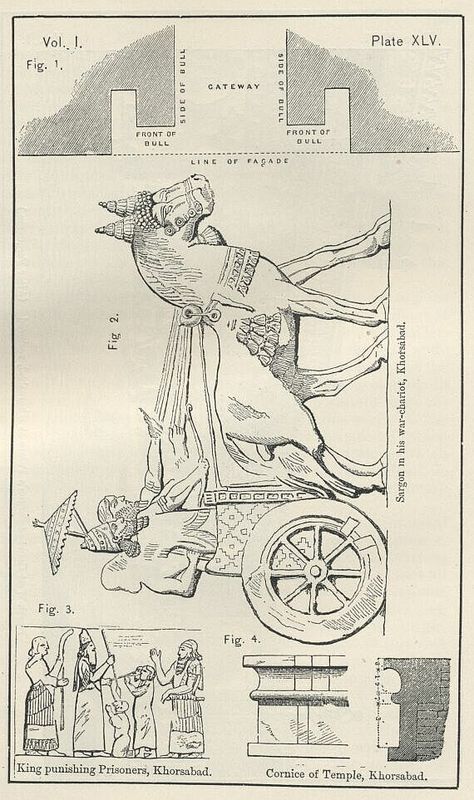

Plate 45

108. Plan of palace gateway (ditto)

109. King punishing prisoners, Khorsabad (ditto)

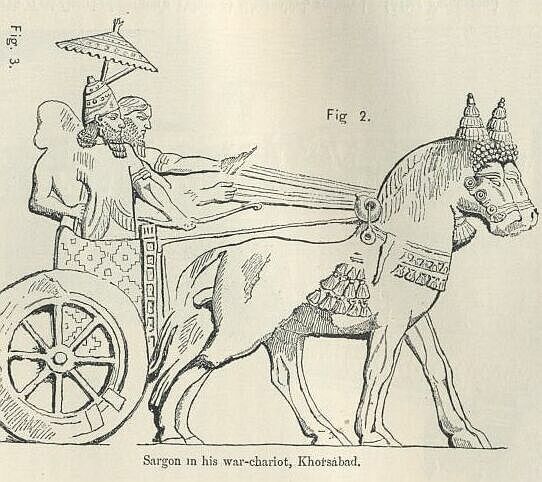

111. Sargon in his war-chariot, Khorsabad (after Botta)

112. Cornice of temple, Khorsabad (Fergusson)

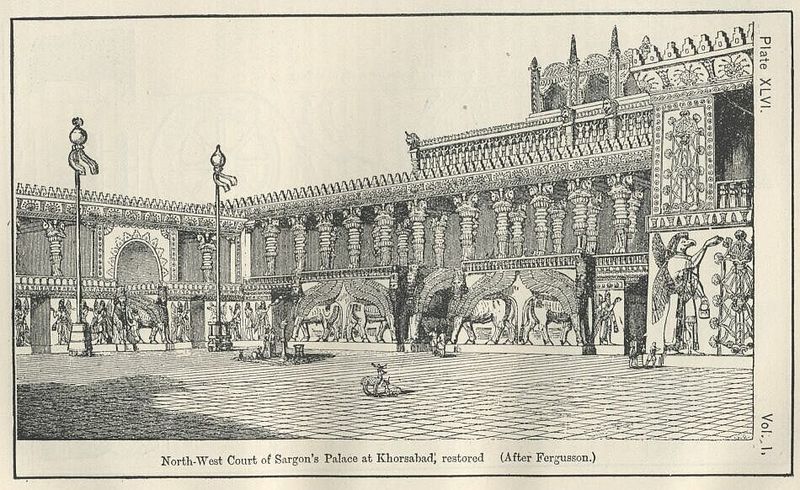

Plate 46

110. North-West Court of Sargon's Palace at

Khorsabad, restored (after Fergusson)

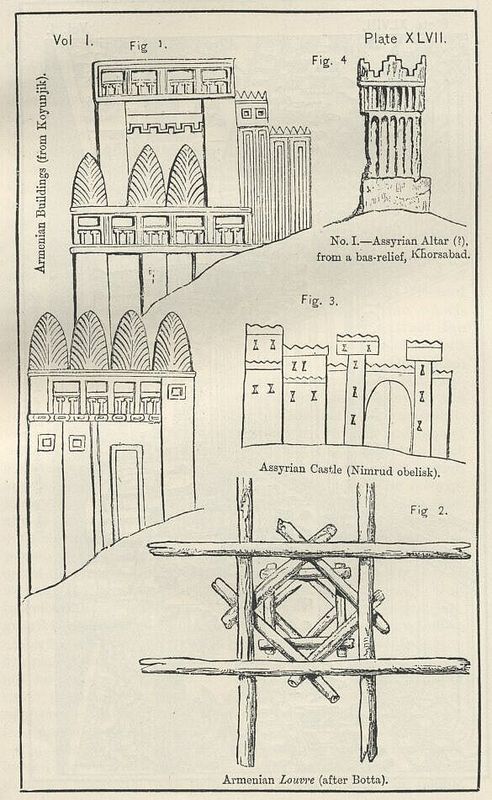

Plate 47

113. Armenian louvre ((after Botta)

114. Armenian buildings. from Koyunjik (Layard)

116. Assyrian castle on Nimrud obelisk (drawn by

the Author from the original in the British Museum)

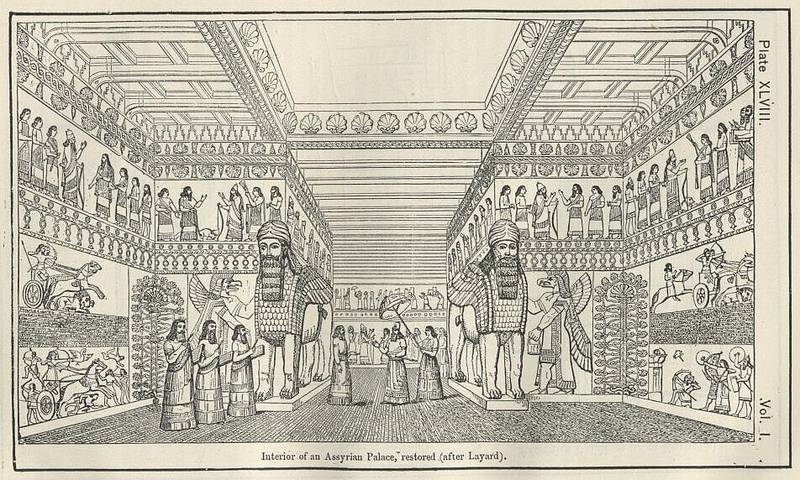

Plate 48

115. Interior of an Assyrian palace, restored (ditto)

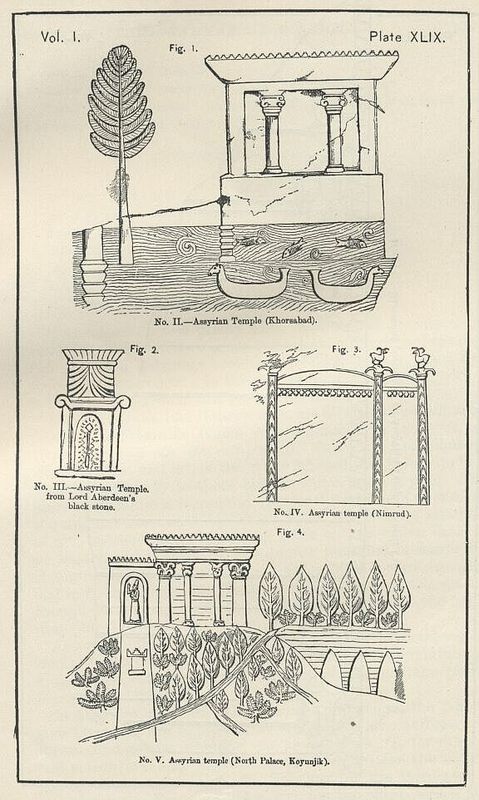

Plate 49

117. Assyrian altar, from a bas-relief, Khorsabad

(after Botta)

118. Assyrian temple, Khorsabad (ditto)

119. Assyrian temple, from Lord Aberdeen's

black stone (after Fergusson)

120. Assyrian temple, Nimrud (drawn by

the Author from the original in the British Museum)

121. Assyrian temple, North Palace, Koyunjik (ditto)

Plate 50

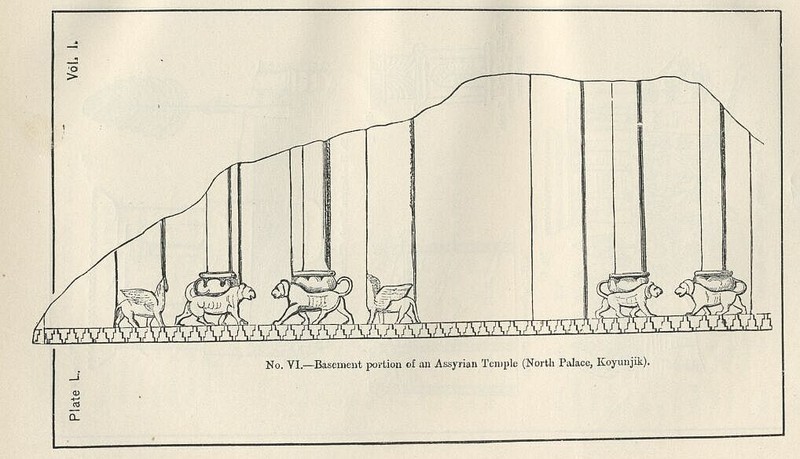

123. Basement portion of an Assyrian temple,

North Palace. Koyunjik (drawn by the Author

from the original in the British Museum)

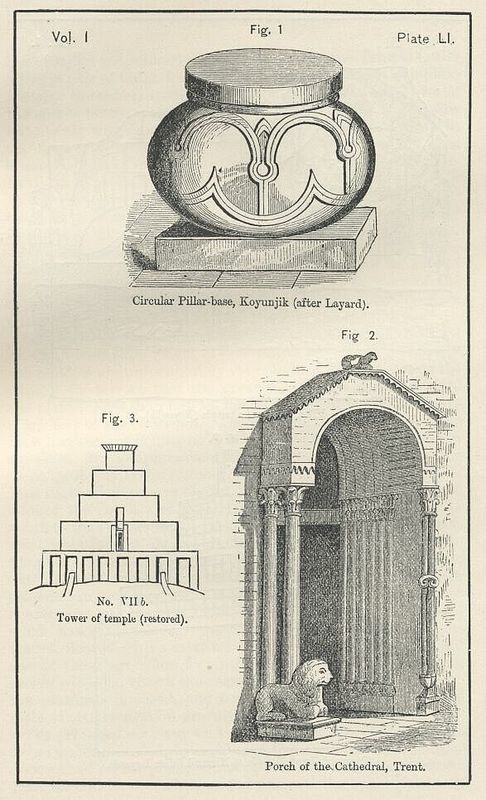

Plate 51

122. Circular pillar-base, Koyunjik (after Layard)

124. Porch of the Cathedral, Trent (from an

original sketch made by the Author)

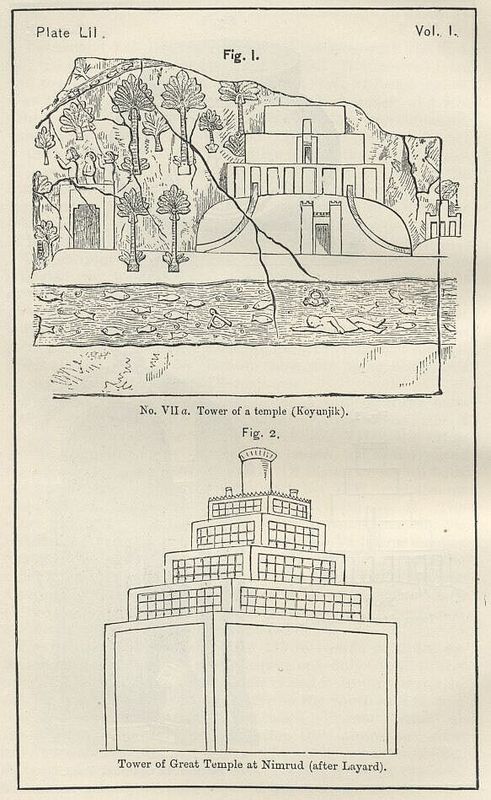

Plate 52

125. Tower of a temple, Koyunjik (after Layard)

126. Tower of ditto, restored (by the Author)

127. Tower of great temple at Nimrud (after Layard)

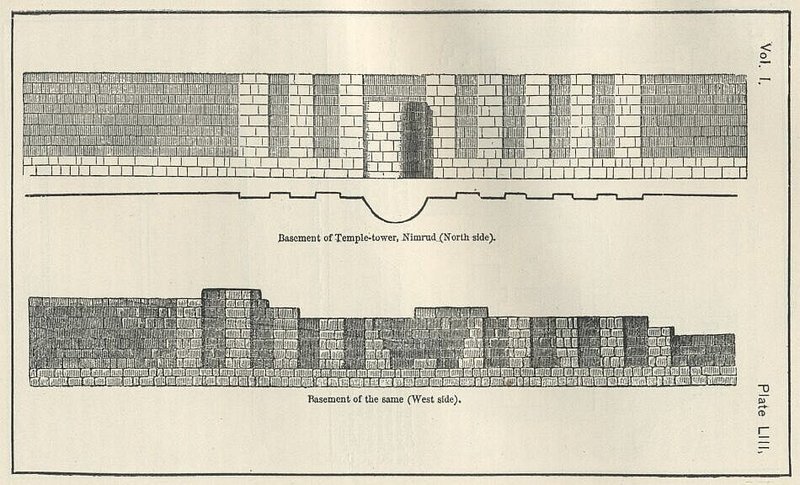

Plate 53

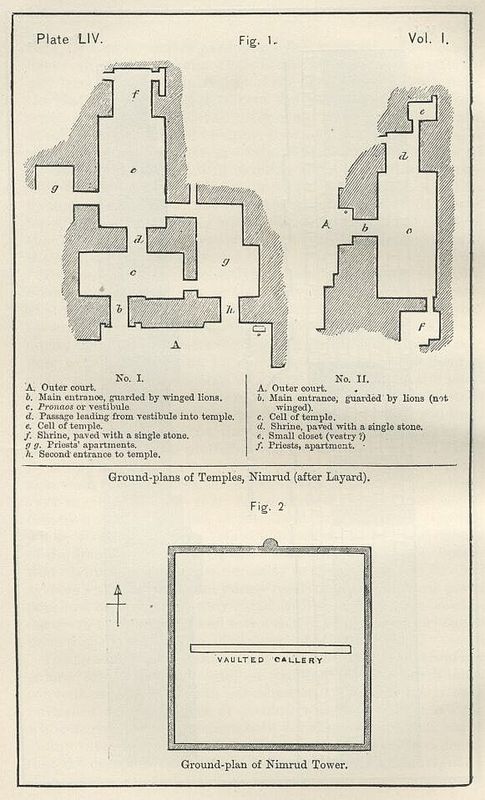

Plate 54

128. Basement of temple-tower, Nimrud,

north and west sides (ditto)

129. Ground-plan of Nimrud Tower (ditto)

130. Ground-plans of temples, Nimrud (ditto)

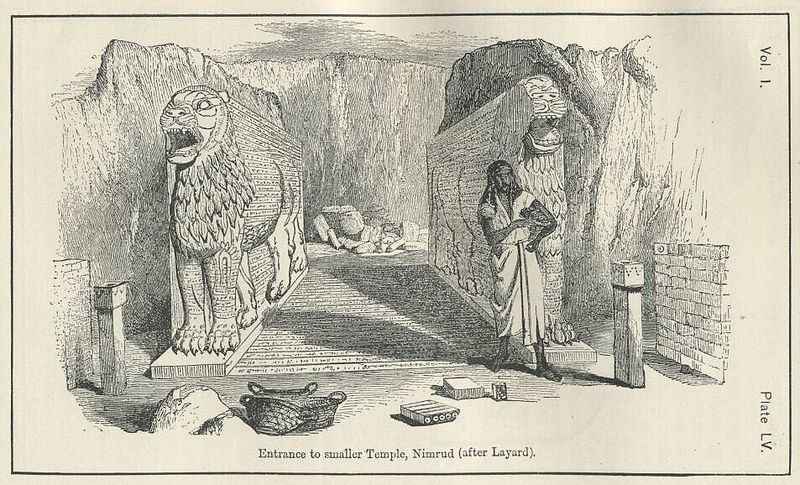

Plate 55

131. Entrance to smaller temple. Nimrud(ditto)

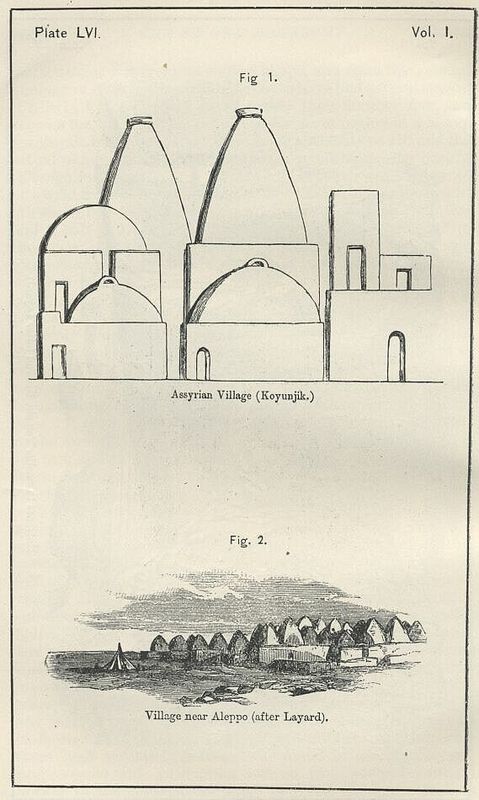

Plate 56

132. Assyrian village. Koyunjik (ditto)

133. Village near Aleppo (ditto)

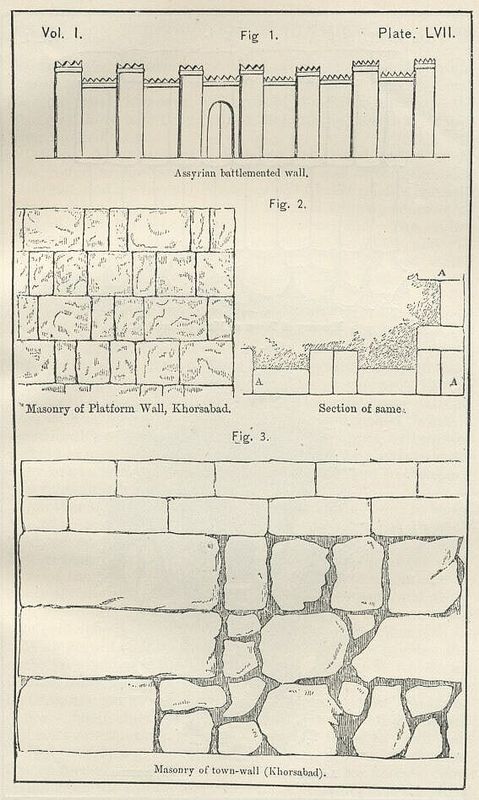

Plate 57

134. Assyrian hattlemented wall (ditto)

135. Masonry and section of platform wall.

Khorsabad (after Botta)

136. Masonry of town-wall. Khorsabad (ditto)

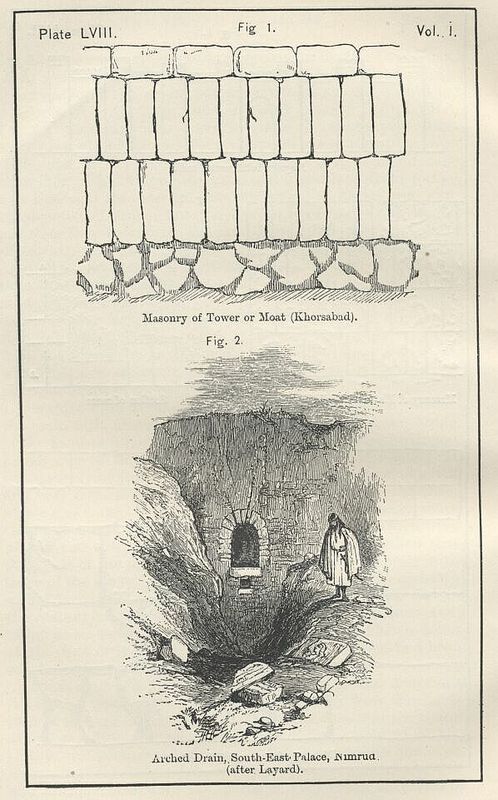

Plate 58

137. Masonry of tower or moat, Khorsabad (ditto)

139. Arched drain, South-East Palace, Nimrud (ditto)

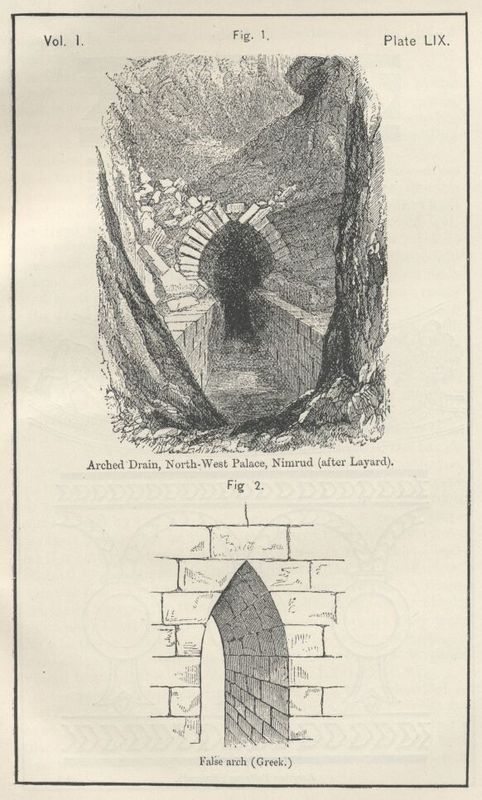

Plate 59

138. Arched drain, North-West Palace, Nimrud (after Layard)

140. False arch (Greek)

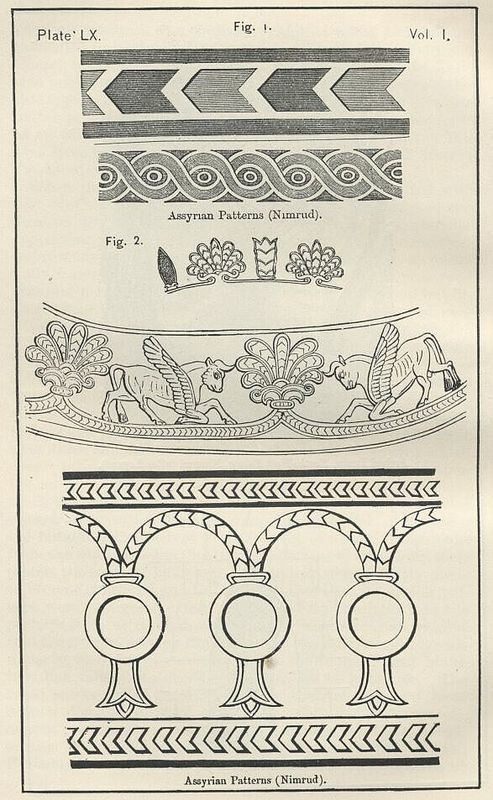

Plate 60

141. Assyrian patterns, Nimrud (Layard)

142. Ditto (ditto)

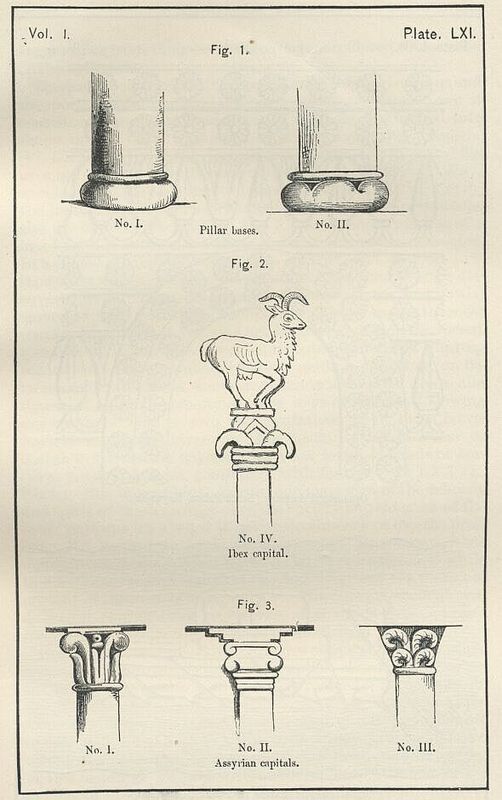

Plate 61

143. Bases and capitals of pillars (chiefly

drawn by the Author from bas-reliefs

in the British Museum)

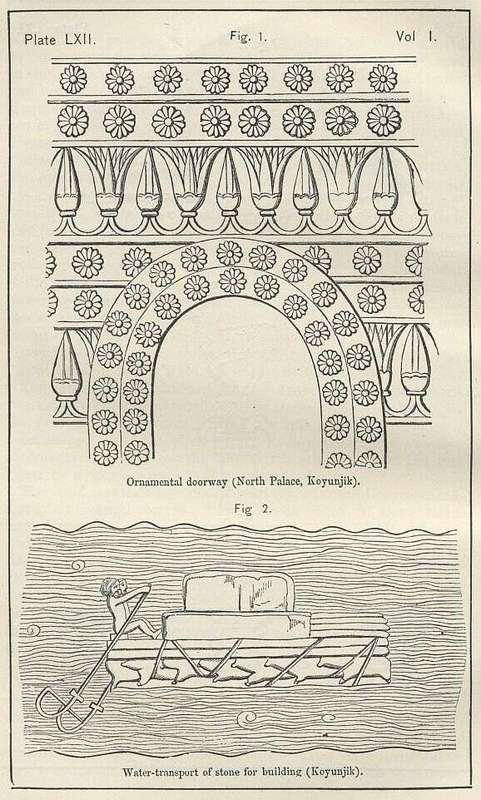

Plate 62

144. Ornamental doorway, North Palace, Koyunjik

(from an unpublished drawing'by Mr. Boutcher

in the British Museum)

145. Water transport of stone for building,

Koyunjik (after Layard)

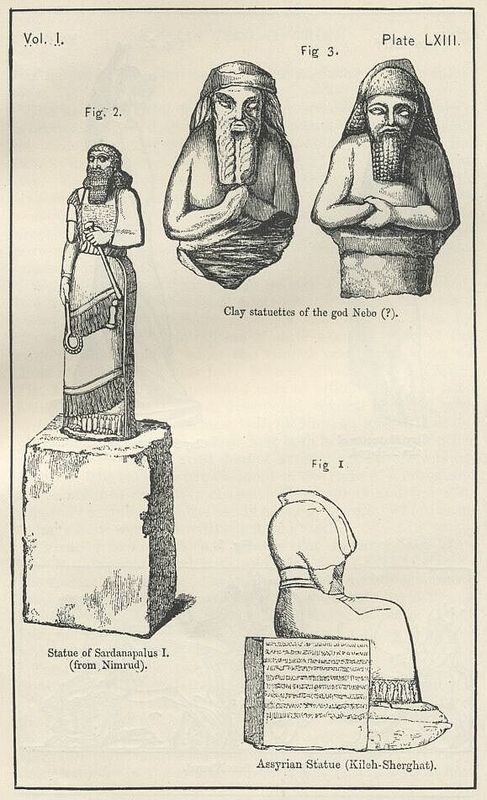

Plate 63

146. Assyrian statue from Kileh-Sherghat (ditto)

147. Statue of Sardanapalus I., from Nimrud (ditto)

148. Clay statuettes of the god Nebo (after Botta)

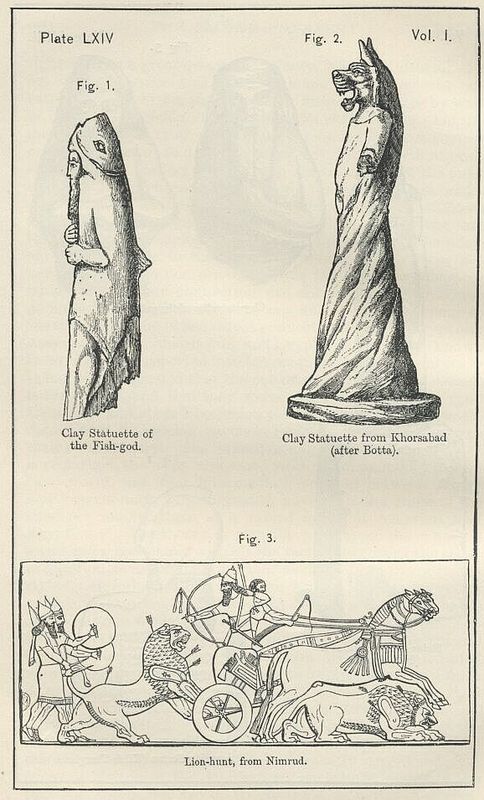

Plate 64

149. Clay statuette of the Fish-God (drawn by

the Author from the original in the British Museum)

150. Clay statuette from Khorsabad (after Botto)

151. Lion hunt, from Nimrud (after Layard)

Plate 65

152. Assyrian seizing a wild bull, Nimrud (ditto)

153. Hawk-headed figure and sphinx, Nimrud (ditto)

154. Death of a wild bull, Nimrud(ditto)

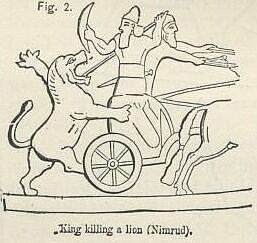

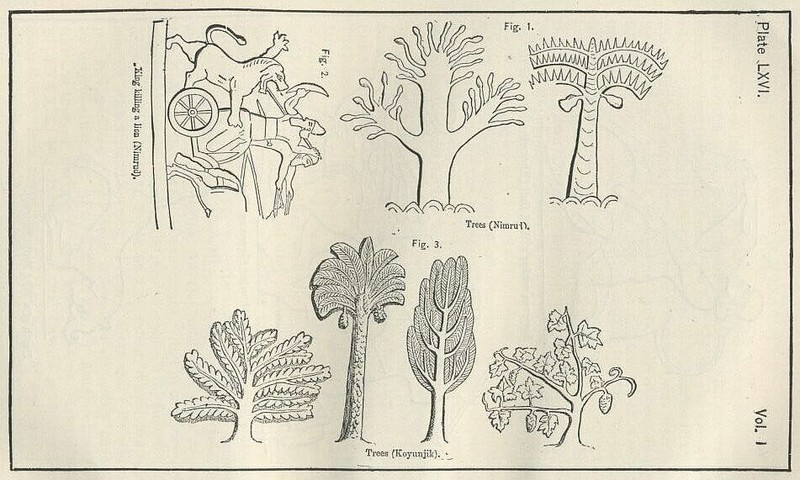

Plate 66

155. King killing a lion, Nimrud (ditto)

156. Trees from Nimrud (ditto)

157. Trees from Koyunjik (ditto)

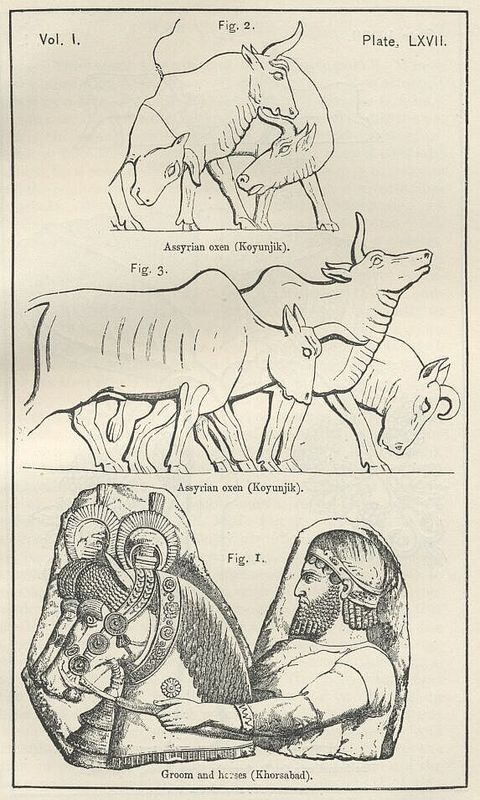

Plate 67

158. Groom and horses, Khorsabad (ditto)

159., 160. Assyrian oxen, Koyunjik (ditto)

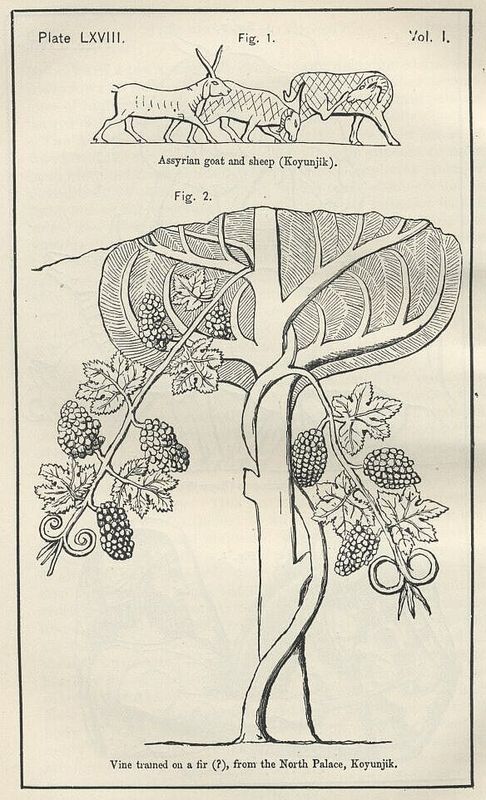

Plate 68

161. Assyrian goat and sheep, Koyunjik (ditto)

162. Vine trained on a fir, from the North Palace,

Koyunjik (drawn by the Author from a bas-relief

in the British Museum)

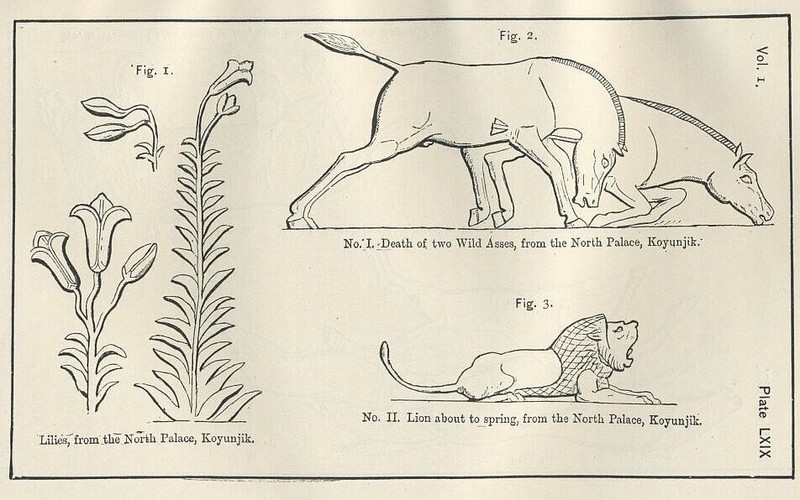

Plate 69

163. Lilies, from the North Palace, Koyunjik (ditto)

164. Death of two wild asses, from the North Palace,

Koyunjik (from an unpublished drawing by Mr. Boutcher

in the British Museum)

165. Lion about to spring, from the North Palace,

Koyunjik (ditto)

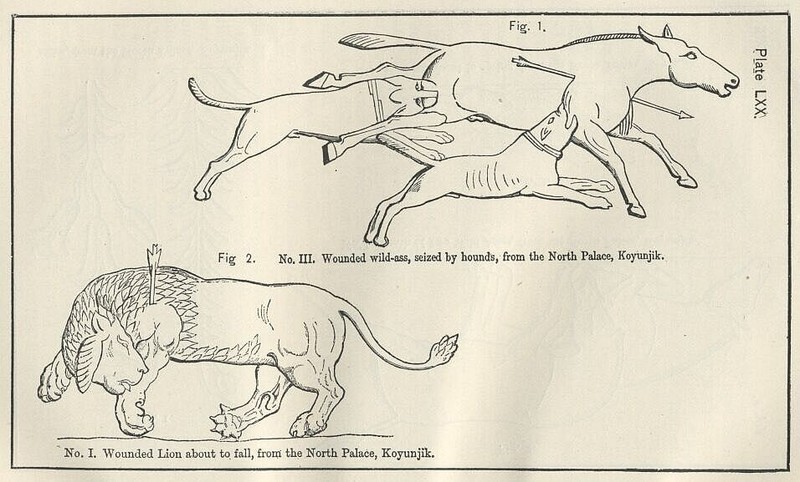

Plate 70

166. Wounded wild ass seized by hounds,

from the North Palace, Koyunjik

167. Wounded lion about to fall,from the North Palace,

Koyunjik (from an unpublished drawing by Mr. Boutcher,

in the British Museum)

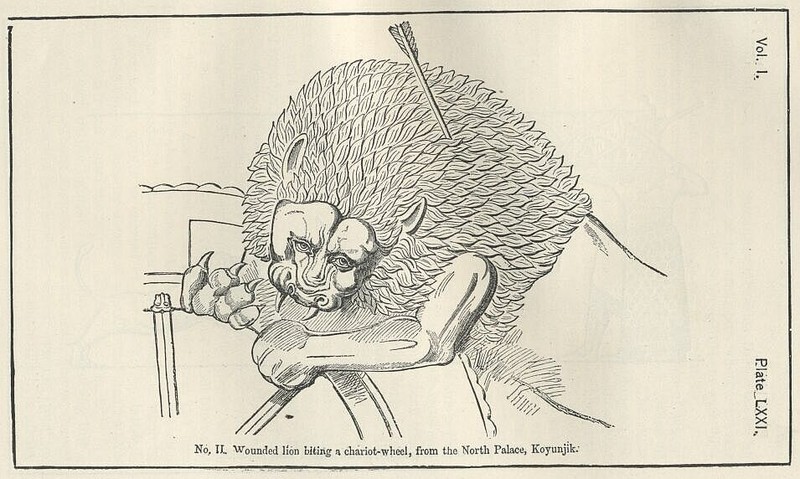

Plate 71

168. Wounded lion biting a chariot-wheel,

from the North Palace, Koyunjik

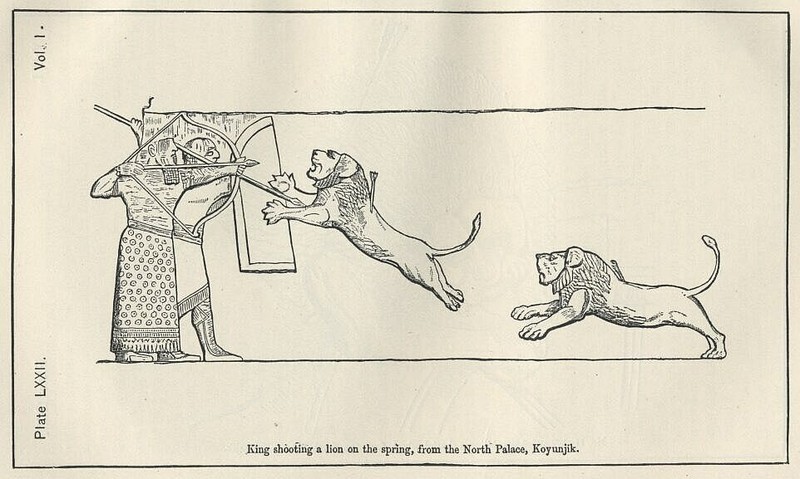

Plate 72

169. King shooting a lion on the spring,

from the North Palace, Koyunjik (ditto)

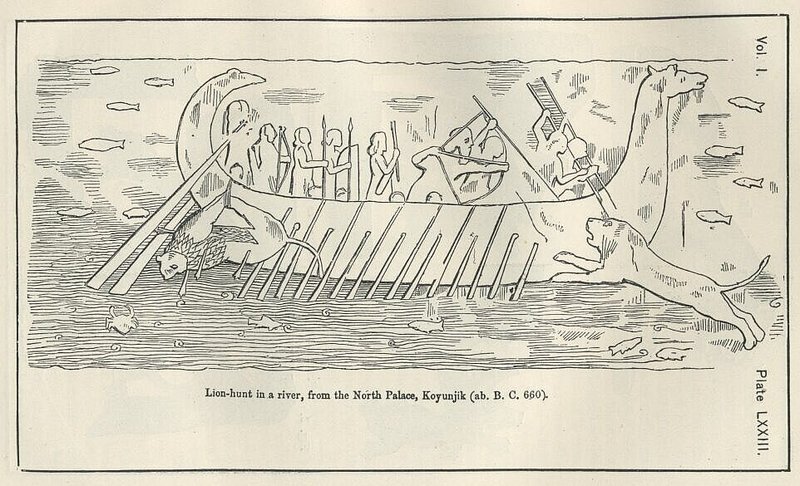

Plate 73

170. Lion-hunt in a river. from the

North Palace, Koyunjik (ditto)

Plate 74

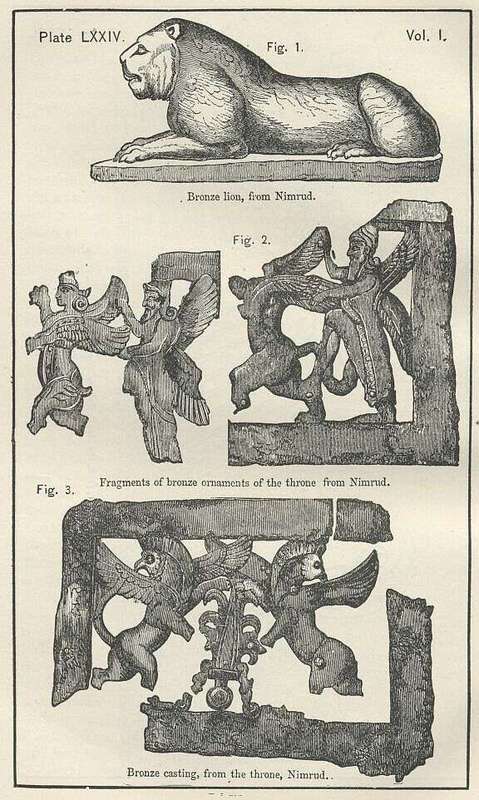

171. Bronze lion, from Nimrud (after Layard)

172. Fragments of bronze ornaments of the throne,

from Nimrud (ditto)

173. Bronze casting, from the throne, Nimrud (ditto)

Plate 75

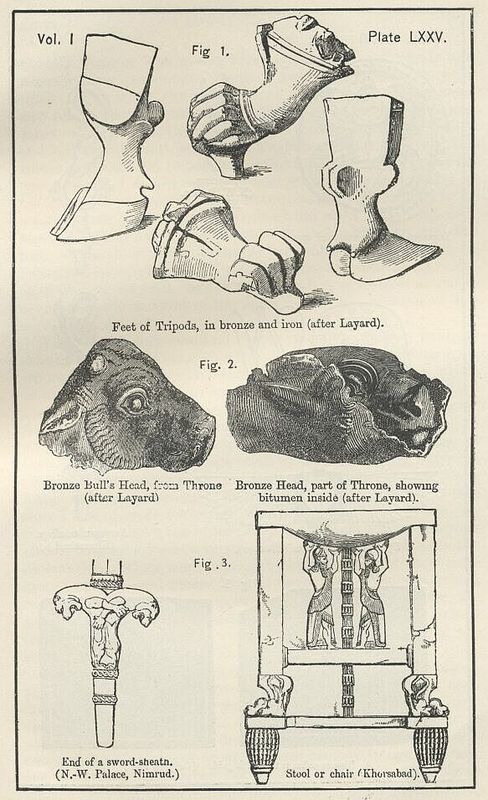

174. Feet of tripods in bronze and iron (ditto)

175. Bronze bull's head, from thethrone (ditto)

176. Bronze head, part of throne,

showing bitumen inside (ditto)

177. End of a sword-sheath, from

the N. W. Palace, Nimrud (ditto)

178. Stool or chair, Khorsabad (after Botta)

Plate 76

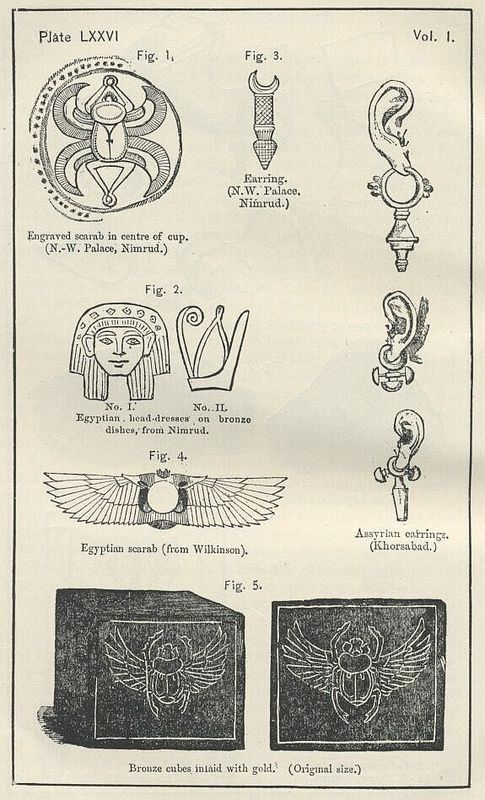

179. Engraved scarab in centre of cup,

from the N. W. Palace, Nimrud (Layard)

180. Egyptian head-dresses on bronze dishes,

from Nimrud (ditto)

181. Ear-rings from Nimrud and Khorsabad (ditto)

182. Bronze cubes inlaid with gold, original size (ditto)

183. Egyptian scarab (from Wilkinson)

onk (Page 223)

Plate 77

184. Fragment of ivory panel, from Nimrod (after Layard)

185. Fragment of a lion in ivory, Nimrud (ditto)

187. Fragment of a stag in ivory, Nimrud (ditto)

188. Royal attendant, Nimrud (ditto)

Plate 78

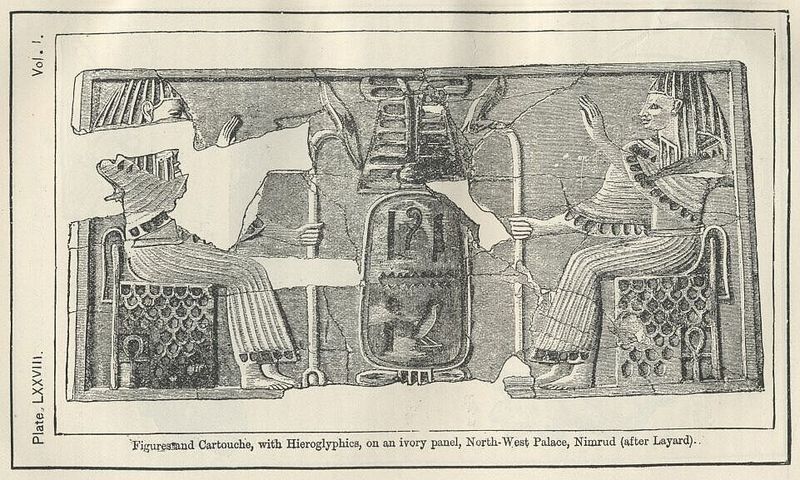

186. Figures and cartouche with hieroglyphics,

on an ivory panel, from the N.W. Palace, Nimrud (ditto)

Plate 79

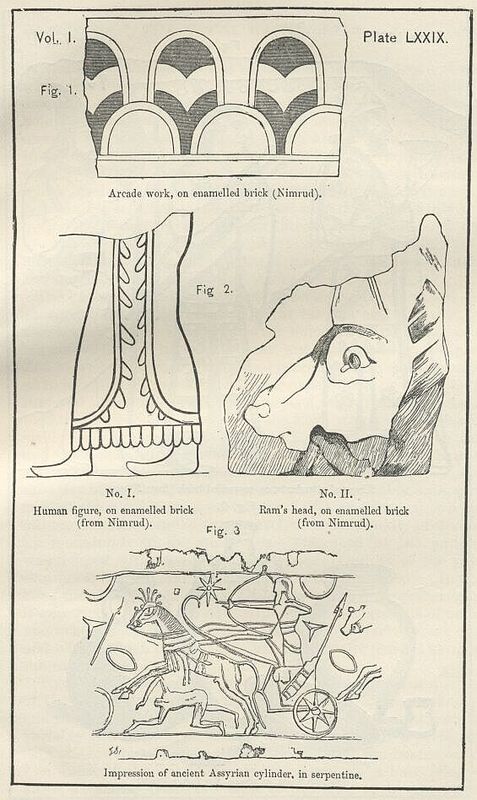

189. Arcade work, on enamelled brick, Nimrud (ditto)

190. Human figure, on enamelled brick, from Nimrud (ditto)

191. Ram's head, on enamelled brick, from Nimrud (ditto)

193. Impression of ancient Assyrian cylinder,

in serpentine (ditto)

Plate 80

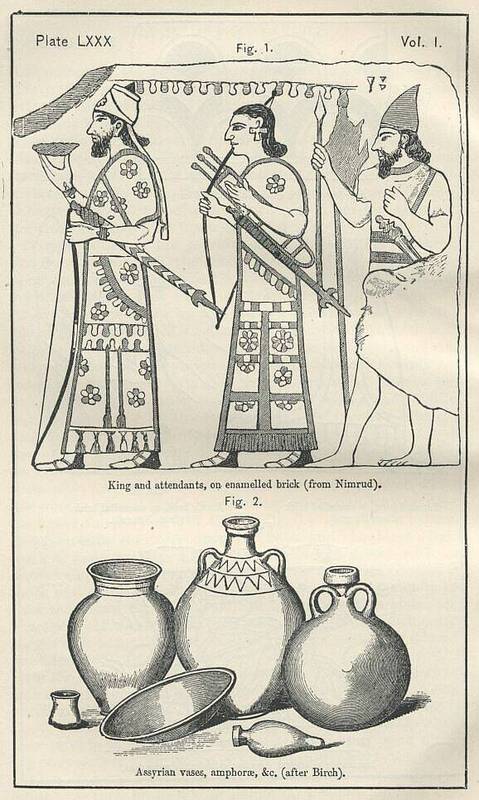

192. King and attendants, on enamelled brick,

from Nimrud (ditto)

197. Assyrian vases. amphorae, etc. (after Birch)

Plate 81

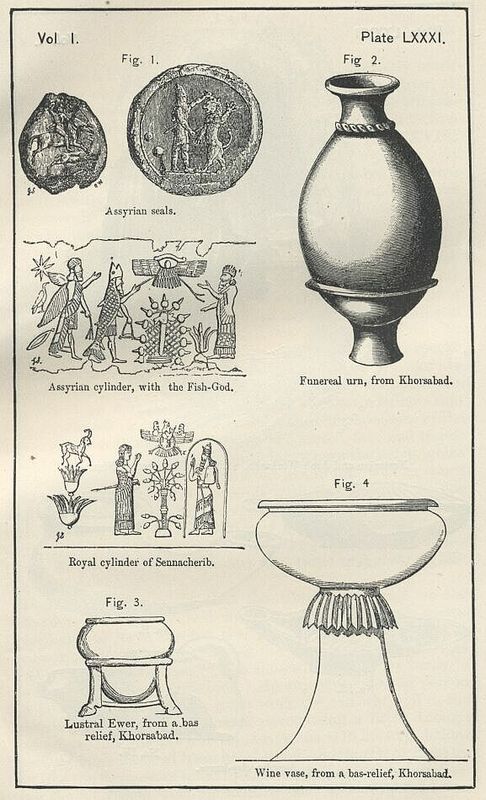

194. Assyrian seals (ditto)

195. Assyrian cylinder, with Fish-God (ditto)

196. Royal cylinder of Sennacherib (ditto)

198. Funereal Urn from Khorsabad (after Botta)

200. Lustral ewer, from a bas relief, Khorsabad (after Botta)

201. Wine vase, from a bas-relief, Khorsabad (ditto)

Plate 82

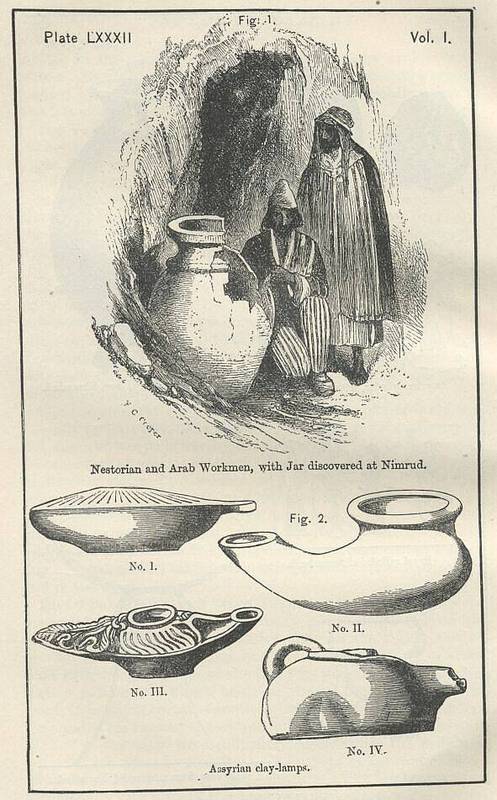

199. Nestorian and Arab workmen,

with jar discovered at Nimrud (Layard)

202. Assyrian clay-lamp, (after Layard and Birch)

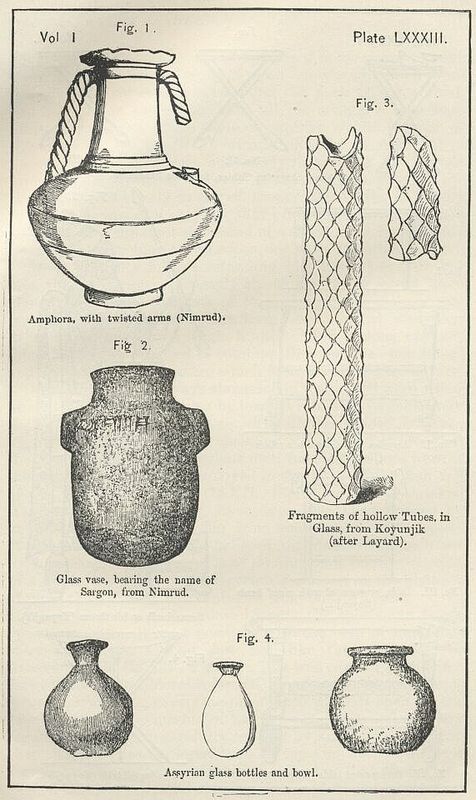

Plate 83

203. Amphora, with twisted arrns, Ninirud (Birch)

201. Assyrian glass bottles and bowl (after Layard)

205. Glass vase, bearing the name of Sargon,

from Nimrud (ditto)

206. Fragments of hollow tubes, in glass,

from Koyunjik (ditto)

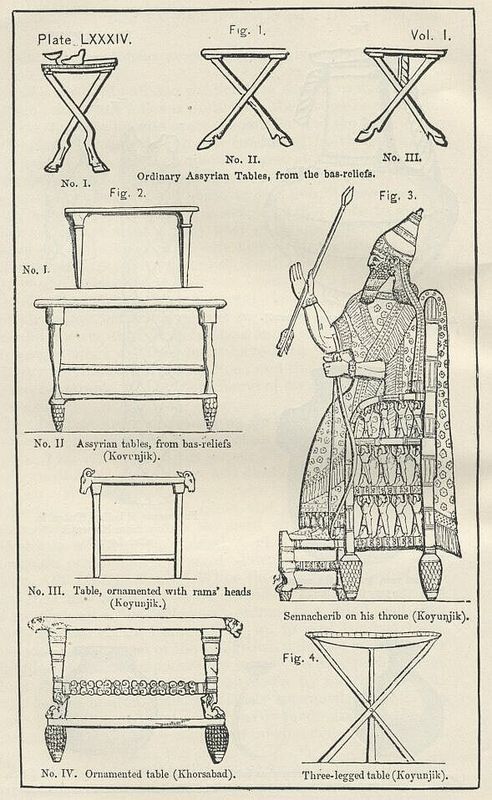

Plate 84

207. Ordinary Assyrian tables, from the bas-reliefs

(by the Author)

208, 209. Assyrian tables, from bas-reliefs,

Koymrjik (ditto)

210. Table, ornamented with rain's heads,

Koyunjik (after Layard)

211. Ornamented table, Khorsabad (ditto)

212. Three-legged table, Koyunjik (ditto)

213. Sennacherib on his throne. Koyunjilc(ditto)

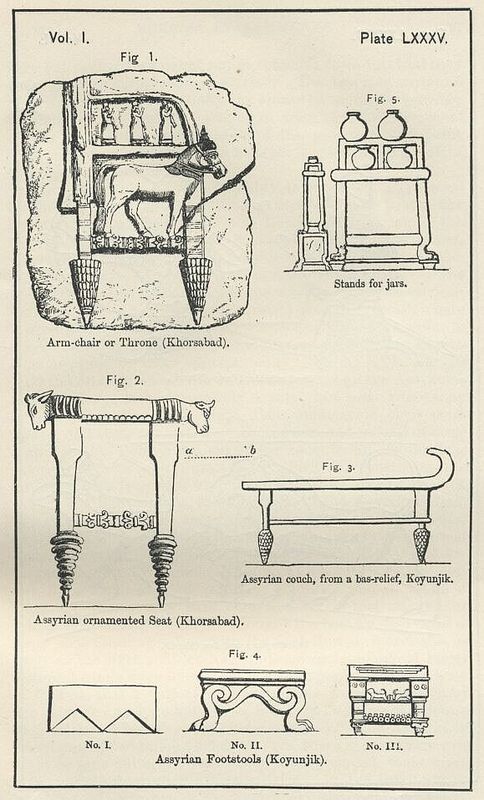

Plate 85

214. Arm-chair or throne, Khorsahad (after Botta)

215. Assyrian ornamented seat, Khorsabad (ditto)

216. Assyrian couch, from a bas-relief.

Koyunjik (by the Author)

217. Assyrian footstools, Koynnjik (ditto)

218. Stands for jars (Layyard)

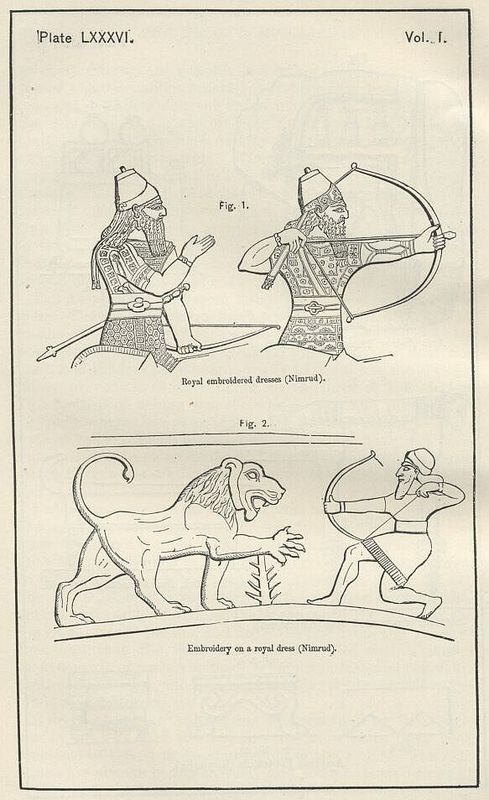

Plate 86

219. Royal embroidered dresses, Nimrud (ditto)

220. Embroidery on a royal dress, Nimrud (ditto)

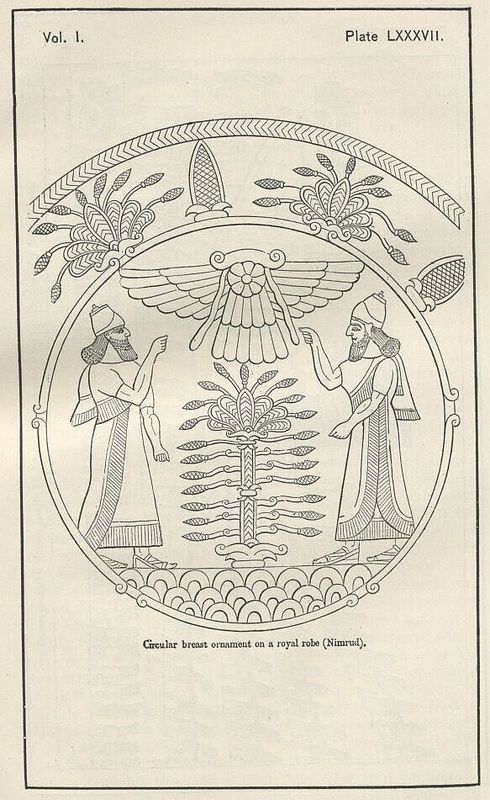

Plate 87

221. Circular breast ornament on a royal robe,

Nimrud (ditto)

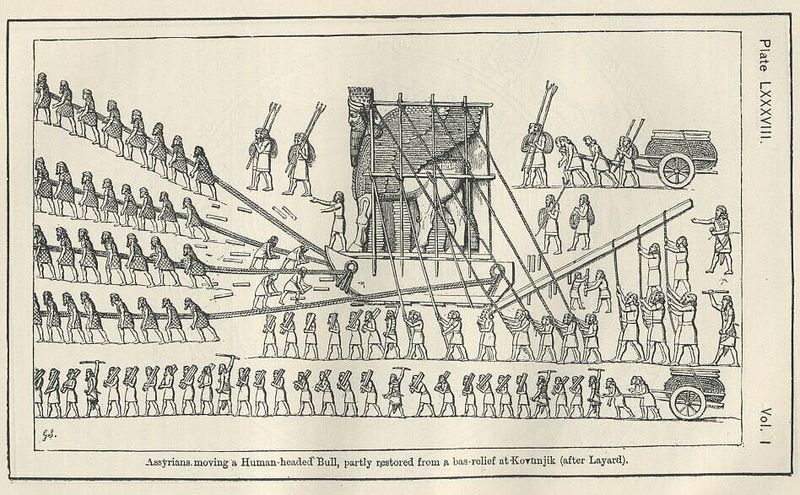

Plate 88

222. Assyrians moving a human-headed bull, partly

restored from a bas-relief at Koyunjik (ditto)

225. Part of a bas-relief, showing a pulley and

a warrior cutting a bucket from the rope (ditto)

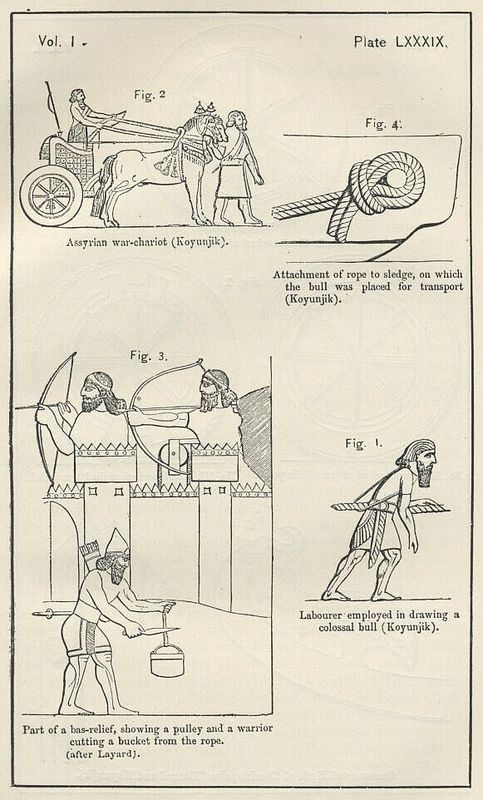

Plate 89

223. Laborer employed in drawing a colossal bull,

Koyunjik (ditto)

224. Attachment of rope to sledge, on which the bull

was placed for transport, Koyunjik (ditto)

226. Assyrian war-chariot, Koyunjik

from the original in the British Museum)

Map1

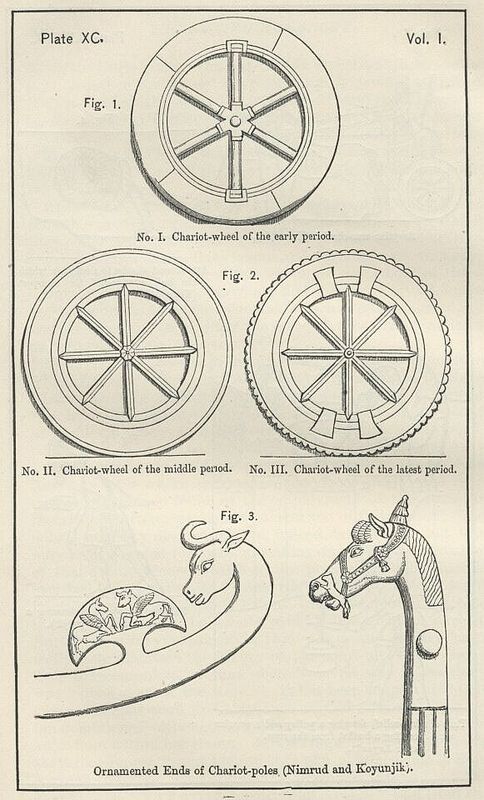

Plate 90

227. Chariot-wheel of the early period, Nimrud

(from the original in the British Museum)

228. Chariot-wheel of the middle period, Koyunjik (ditto)

229. Chariot-wheel of the latest period, Koyunjik (ditto)

230. Ornamented ends of chariot poles, Nimrud and Koyunjik ditto

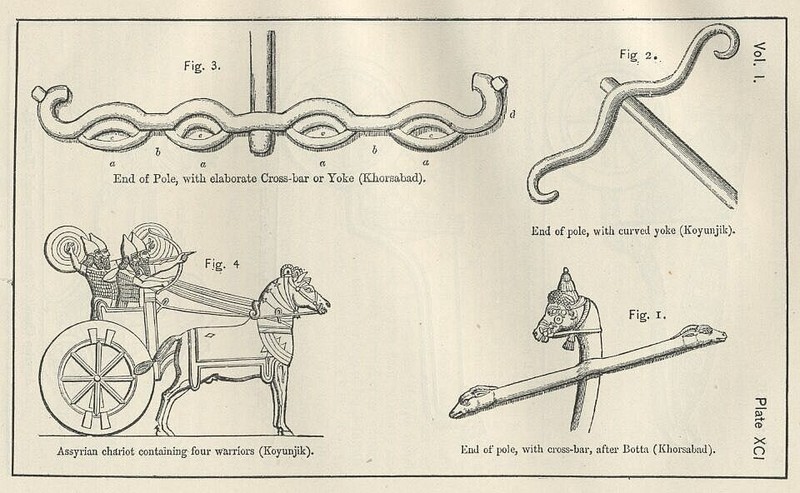

Plate 91

231. End of pole, with cross-bar, Khorsabad (after Botta

232. End of pole, with curved yoke, Koyunjik (after Layard)

233. End of pole, with elaborate cross-bar or yoke, Khorsabad

(after Botta)

234. Assyrian chariot containing four warriors, Koyunjik

(after Boutcher)

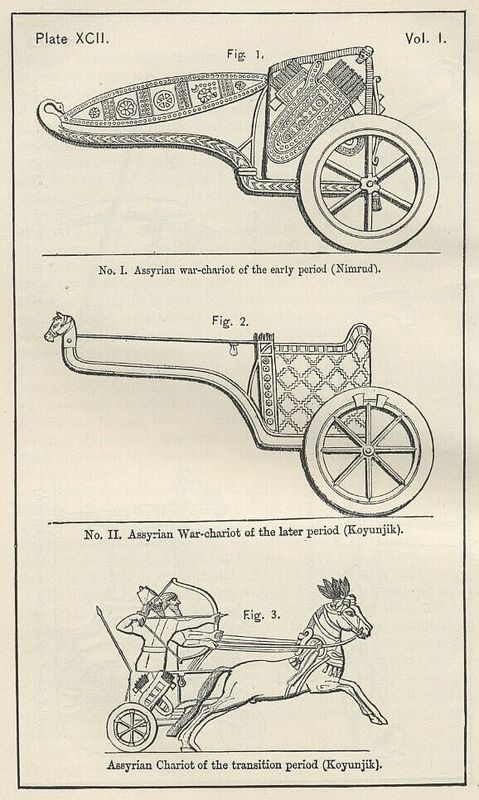

Plate 92

235. Assyrian war-chariot of the early period, Nimrud

(from the original in the British Museum)

236. Assyrian war-chariot of the later period,

Koyunjik (ditto)

237. Assyrian chariot of the transition period,

Koyunjik (after Boutcher)

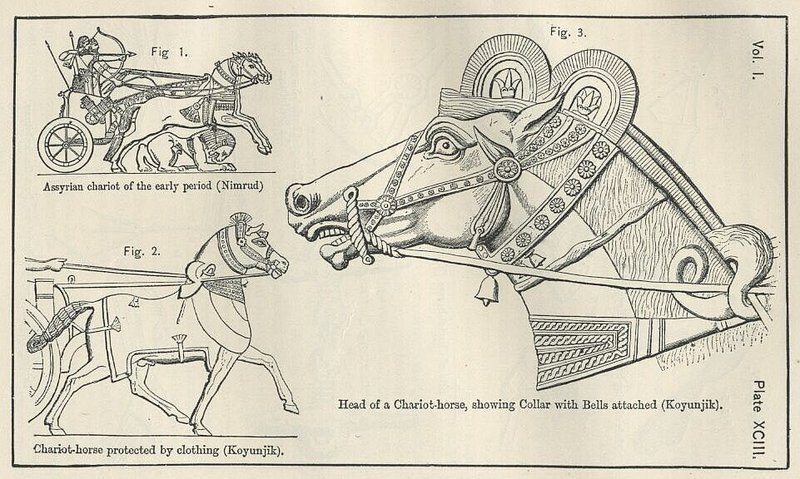

Plate 93

238. Assyrian chariot of the early period, Nimrud

(from the original in the British Museum)

239. Chariot-horse protected by clothing, Koyunjik (ditto)

240. Head of a chariot-horse, showing collar with

bells attached, Koyunjik(after Boutcher)

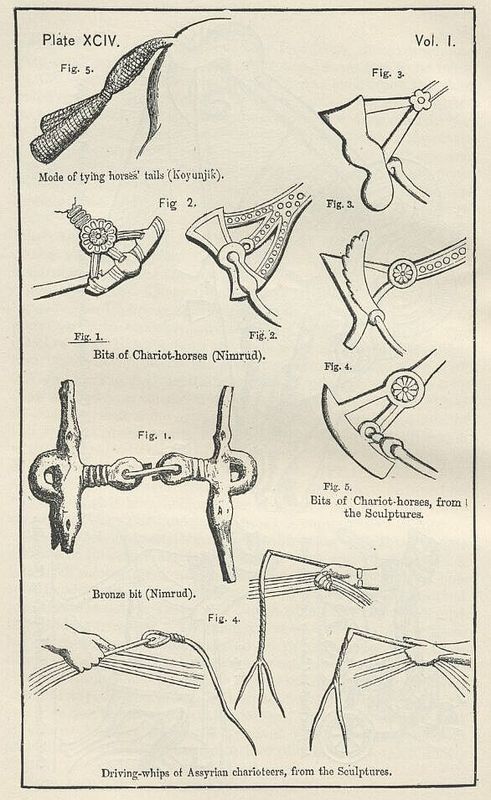

Plate 94

241. Bronze bit, Nimrud (from the original

in the British Museum)

242. Bits of chariot-horses, from the sculptures,

Nimrud and Koyunjik (ditto)

243. Driving-whips of Assyrian charioteers,

from the sculptures (ditto)

244. Mode of tying horses' tails, Koyunjik (ditto)

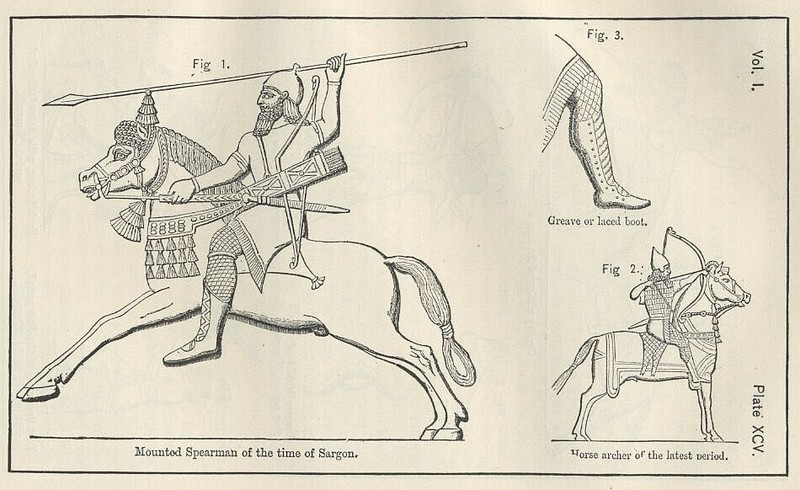

Plate 95

245. Mounted spearmen of the time of Sargon,

Khorsabad (after Botta)

246. Greave or laced boot of a horseman,

Khorsabad (ditto)

248. Horse archer of the latest period, Koyunjik

(from the original in the British Museum)

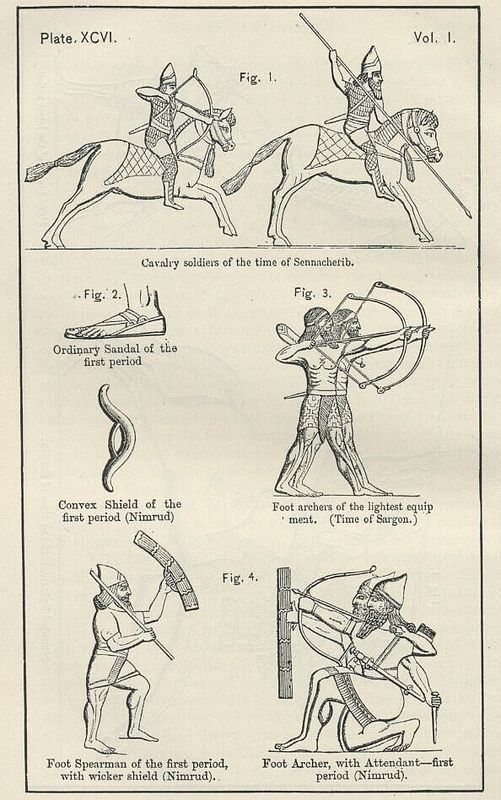

Plate 96

247. Cavalry soldiers of the time of Sennacherib,

Koyunjik (after Layard)

249. Ordinary sandal of the first period, Nimrud (ditto)

250. Convex shield of the first period, Nimrud (after Layard)

251. Foot spearmen of the first period, with wicker shield,

Nimrud (from the original in the British Museum)

252. Foot archer with attendant, first period, Nimrud (ditto)

253. Foot archer of the lightest equipment, time of Sargon,

Khorsabad (after Botta)

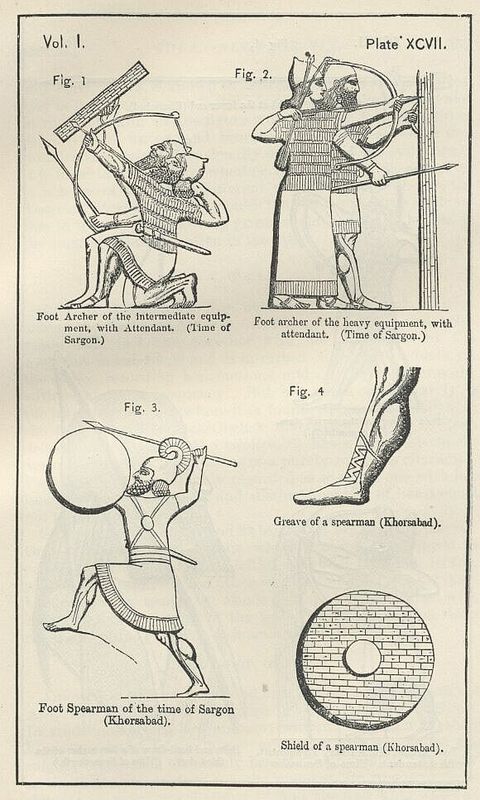

Plate 97

254. Foot archer of the intermediate equipment,

with attendant, time of Sargon, Khorsabad (after Botta)

255. Foot archer of the heavy equipment, with attendant,

time of Sargon, Khorsabad (ditto)

256. Foot spearman of the time of Sargon, Khorsabad (ditto)

257. Shield and greave of a spearman, Khorsabad (ditto)

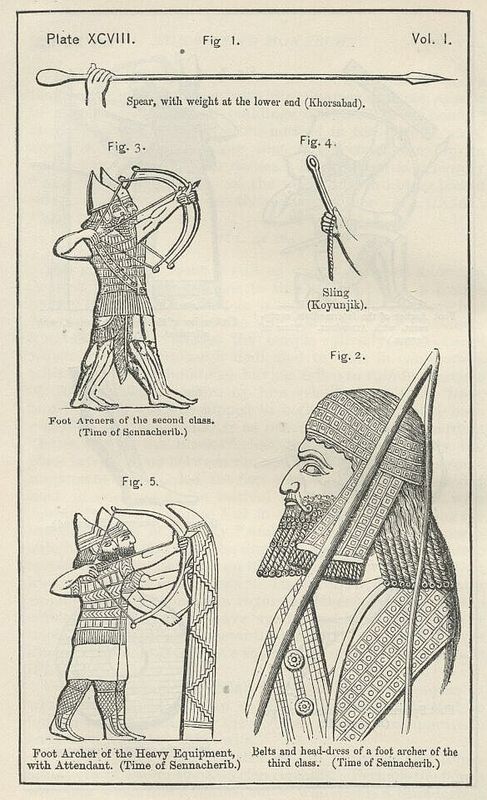

Plate 98

258. Spear, with weight at the lower end, Khorsabad (ditto)

259. Sling, Koyunjik (from the original in the British Museum)

260. Foot archer of the heavy equipment, with attendant,

time of Sennacherib, Koyunjik (ditto)

261. Foot archers of the second class, time of Sennacherib,

Koyunjik (ditto)

262. Belts and head-dress of a foot archer of the third class,

time of Sennacherib, Koyunjik (after Boutcher)

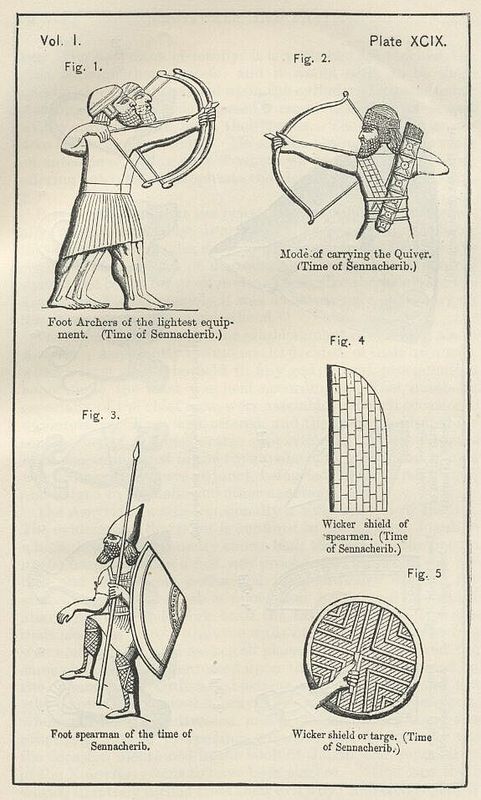

Plate 99

263. Mode of carrying the quiver, time of Sennacherib,

Koyunjik (from the original in the British Museum)

264. Foot archers of the lightest equipment,

time of Sennacherib, Koyunjik

266. Wicker shields, time of Sennacherib, Koyunjik

(from the originals in the British Museum)

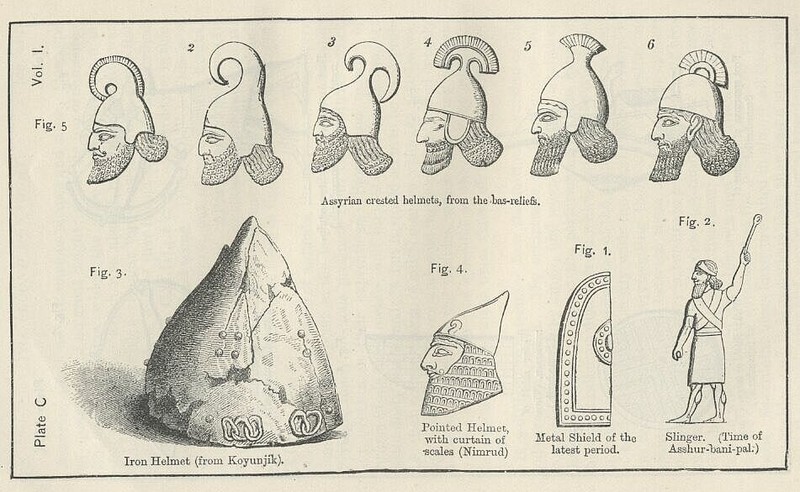

Plate 100

267. Metal shield of the latest period, Koyunjik (ditto)

268. Slinger, time of Asshur-bani-pal, Koyunjik (after Boutcher)

269. Pointed helmet, with curtain of scales, Nimrud (after Layard)

270. Iron helmet, from Koyunjik, now in the British Museum

(by the Author)

271. Assyrian crested helmets, from the bas-reliefs,

Khorsabad and Koyunjik (from the originals in the British Museum)

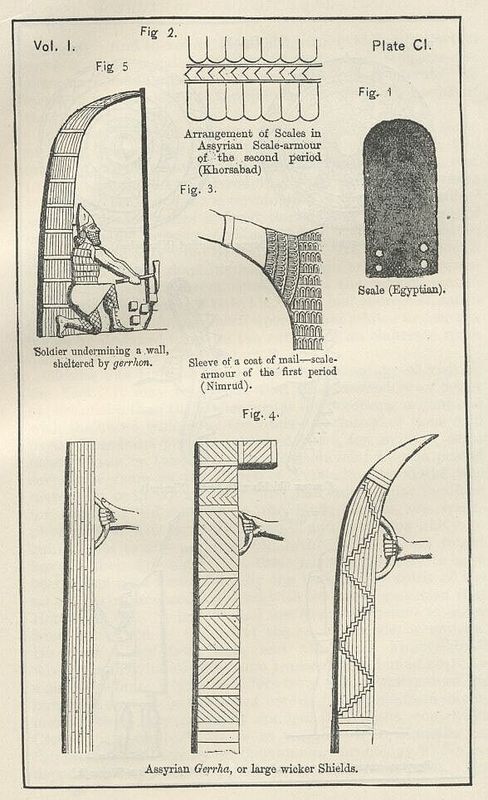

Plate 101

272. Scale, Egyptian (after Sir G. Wilkinson)

273. Arrangement of scales in Assyrian scale-armour

of the second period, Khorsabad (after Botta)

274. Sleeve of a coat of mail-scale-armor of the first period,

Nimrud (from the original in the British Museum)

275. Assyrian gerrha, or large wicker shields (ditto)

276. Soldier undermining a wall, sheltered by gerrhon,

Koyunjik (ditto)

Plate 102

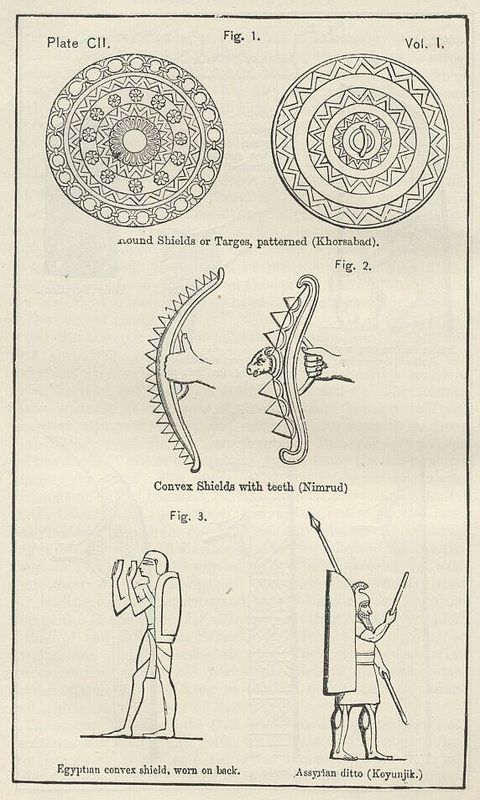

277. Round shields or targes, patterned, Khorsabad (after Botta)

278. Convex shields with teeth, Nimrud (from the originals

in the British Museum)

279. Egyptian convex shield, worn on back (after Sir G. Wilkinson)

280. Assyrian ditto, Koyunjik (from the original in the British Museum

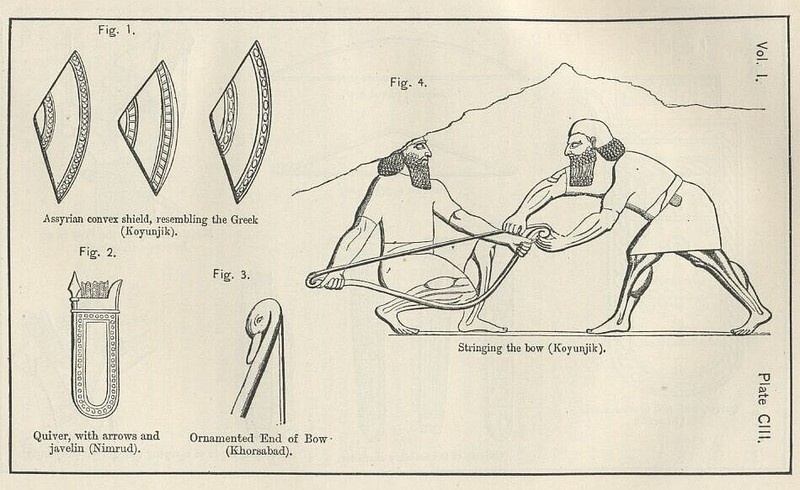

Plate 103

281. Assyrian convex shield, resembling the Greek, Koyunjik (ditto)

282. Quiver, with arrows and javelin, Nimrud (ditto)

283. Ornamented end of bow, Khorsabad (after Botta)

284. Stringing the bow, Koyunjik (from the original

in the British Museum)

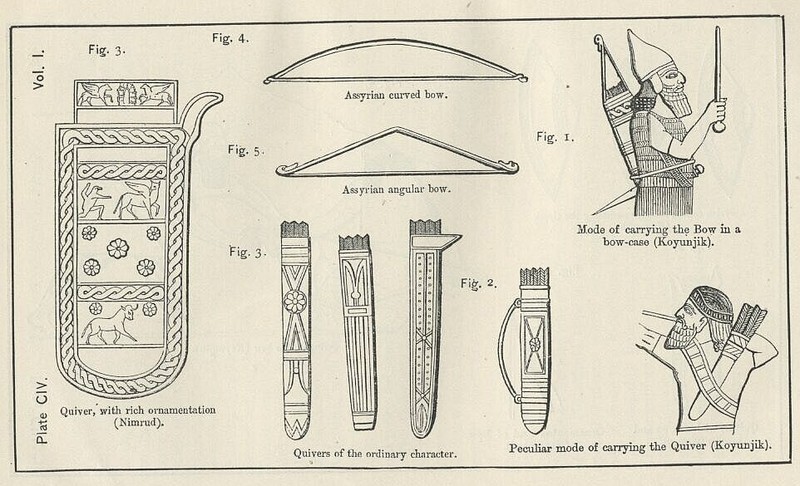

Plate 104

285. Assyrian curved bow (ditto)

286. Assyrian angular bow, Khorsabad (after Botta)

287. Mode of carrying the bow in a bow-case, Koyunjik

(from the original in the British Museum)

288. Peculiar mode of carrying the quiver, Koyunjik (ditto)

289. Quiver, with rich ornamentation, Nimrud (after Layard)

290. Quivers of the ordinary character, Koyunjik

(from the originals in the British Museum)

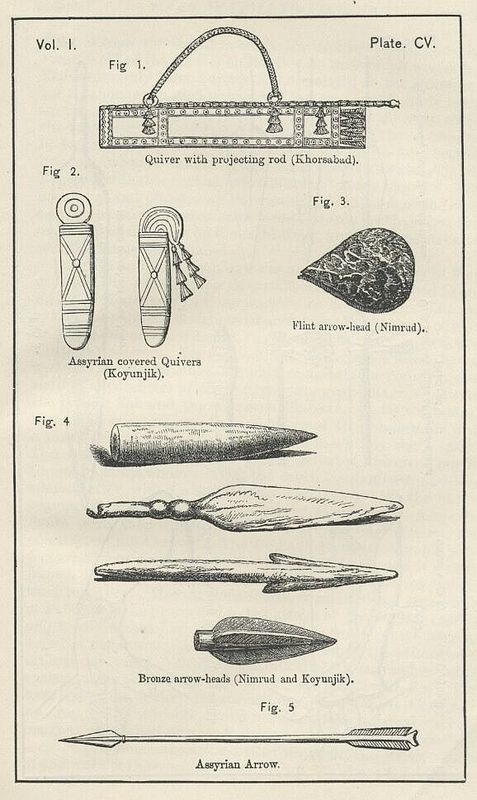

Plate 105

291. Quiver with projecting rod, Khorsabad (after Botta)

292. Assyrian covered quivers, Koyunjik

(from the originals in the British Museum)

293. Bronze arrow-heads, Nimrud and Koyunjik (ditto)

294. Flint arrow-brad; Nimrud (ditto)

295. Assyrian arrow (ditto)

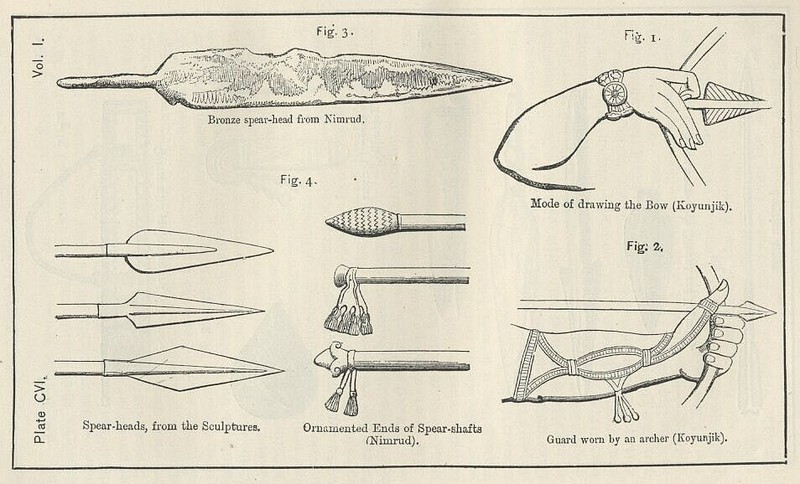

Plate 106

296. Mode of drawing the bow, Koyunjik (after Boutcher)

297. Guard worn by an archer, Koyunjik (ditto)

298. Bronze spear-head, Nimrud (from the original

in the British Museum)

299. Spear-heads (from the Sculptures)

300. Ornamented ends of spear-shafts, Nimrud (after Layard)

Plate 107

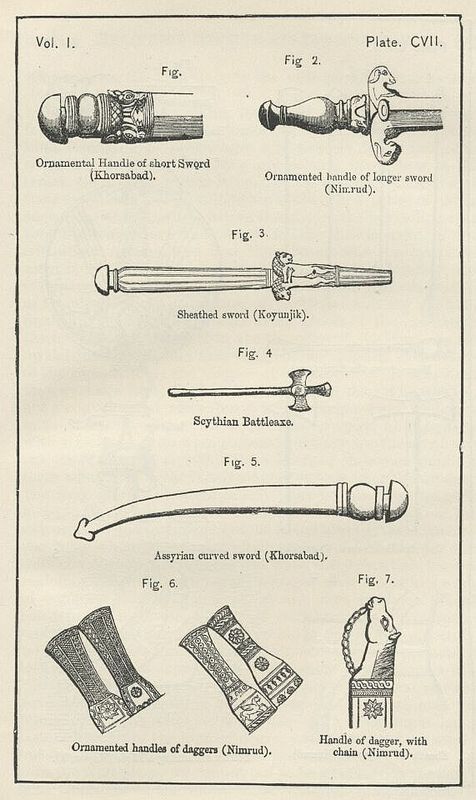

301. Ornamented handle of short sword, Khorsabad (after Botta)

302. Sheathed sword, Koyunjik (after Boutcher)

303. Ornamented handle of longer sword, Nimrud

(from the original in the British Museum?

304. Assyrian curved sword, Khorsabad (after Botta)

308. Scythian battle-axe (after Tester)

309. Ornamented handles of daggers, Nimrud (after Layard)

310. Handle of dagger, with chain, Nimrud (ditto)

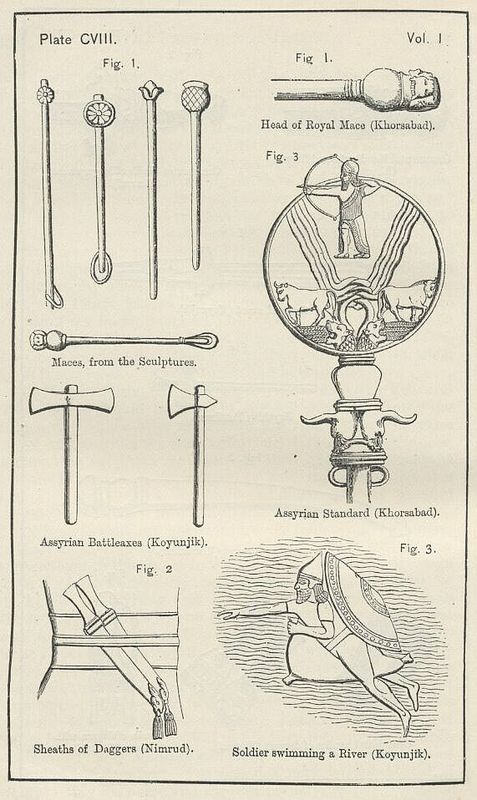

Plate 108

305. Head of royal mace, Khorsabad (ditto)

306. Maces, from the Sculptures

307. Assyrian battle-axes, Koyunjik

(from the originals in the British Museum)

311. Sheaths of daggers, Nimrud

312. Assyrian standard, Khorsabad (after Botta)

313. Soldier swimming a river, Koyunjik (after Layard)

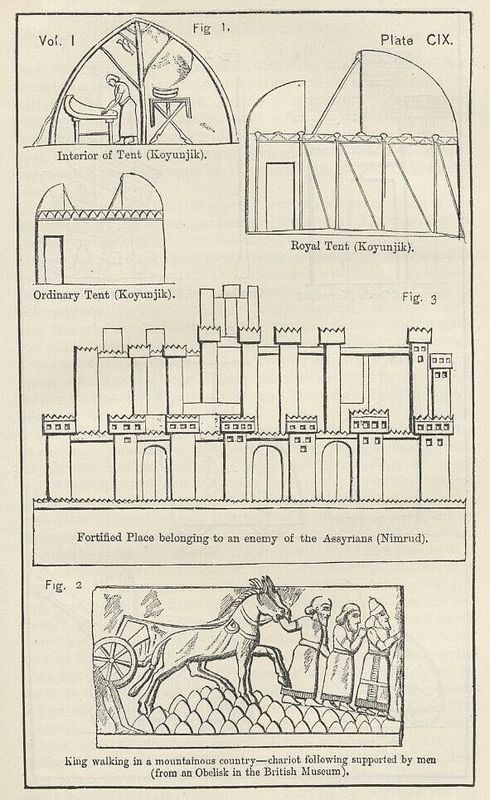

Plate 109

314. Royal tent, Koyunjik (from the original in the British Museum)

315. Ordinary tent, Koyunjik (after Boutcher)

316. Interior of tent, Koyunjik (ditto)

317. King walking in a mountainous country, chariot following,

supported by men, Koyunjik (from an obelisk in the British Museum,

after Boutcher)

318. Fortified place belonging to an enemy of the Assyrians,

Nimrud (after Layard)

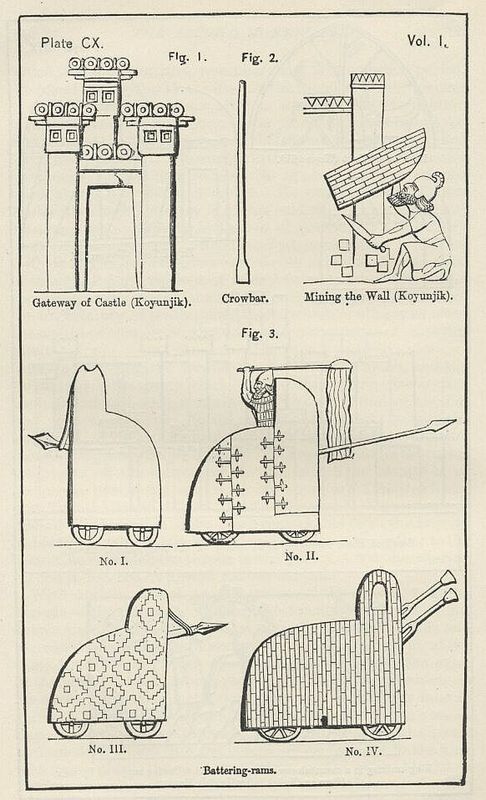

Plate 110

319. Gateway of castle, Koyunjik (after Boutcher)

320. Battering-rams, Khorsabad and Koyunjik (partly after Botta)

322. Crowbar, and mining the wall, Koyunjik (ditto)

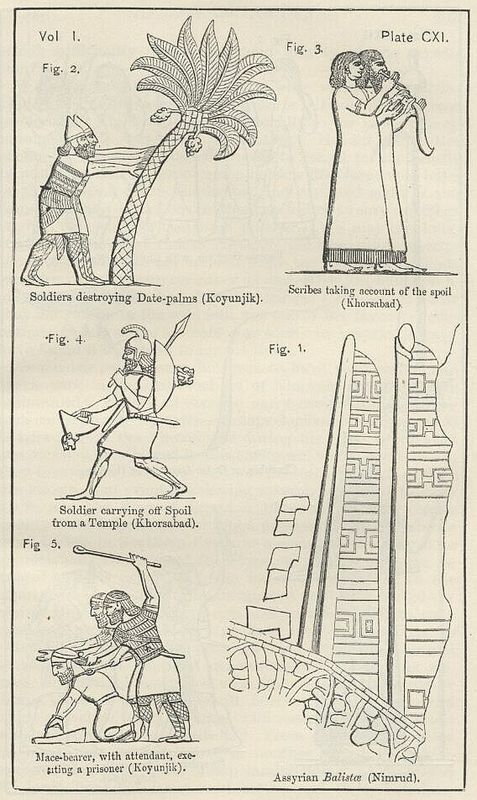

Plate 111

321. Assyrian balistce, Nimrud (after Layard)

324. Soldiers destroying date-palms, Koyunjik (after Layard)

325. Soldier carrying off spoil from a temple, Khorsabad (after Botta)

326. Scribes taking account of the spoil, Khorsabad (ditto)

327. Mace-bearer, with attendant, executing a prisoner,

Koyunjtk (from the original in the British Museum)

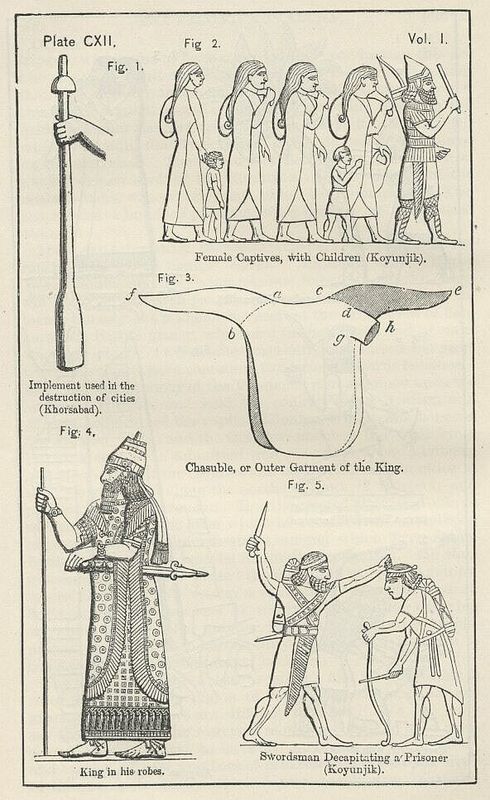

Plate 112

323. Implement used in the destruction of cities,

Khorsabad (after Botta)

328. Swordsman decapitating a prisoner, Koyunjik (ditto)

329. Female captives, with children, Koyunjik (after Layard)

330. Chasuble or outer garment of the king (chiefly after Botta)

331. King in his robes, Khorsabad (after Botta)

Plate 113

332. Tiaras of the later and earlier Periods,

Koyunjik and Nimrud (Layard and Boutcher)

333. Fillet worn by the king, Nimrud (after Layard)

334. Royal sandals, times of Sargon and Asshur-izir-pal

(from the originals in the British Museum)

335. Royal shoe, time of Sennacherib, Koyunjik (ditto)

336. Royal necklace, Nimrud (ditto)

337. Royal collar, Nimrud (ditto)

Plate 114

338. Royal armlets, Khorsabad (after Botta)

339. Royal bracelets, Khorsabad and Koyunjik

(after Botta and Boutcher)

340. Royal ear-rings, Nimrud (from the originals

in the British Museum)

341. Early king in his war-costume, Nimrud (ditto)

Plate 115

342. King, queen, and attendants, Koyunjik (ditto)

343. Enlarged figure of the queen, Koyunjik (ditto)

345. Heads of eunuchs, Nimrud (ditto)

Plate 116

344. Royal parasols, Nimrud and Koyunjik (ditto)

316. The chief eunuch, Nimrud (ditto)

347. Head-dress of the vizier, Khorsabad (after Botta)

Plate 117

348. Costumes of the vizier, times of Sennacherib and

Asshur-izir-pal, Nimrud and Koyunjik (from the originals

in the British Museum)

Plate 118

349. Tribute-bearers presented by the chief eunuch,

Nimrud obelisk (ditto)

350. Fans or fly-flappers, Nimrud and Koyunjik

351. King killing a lion, Nimrud (after Layard)

352. King, with attendants, spearing a lion, Koyunjik

(after Boutcher)

Plate 119

353. King, with attendant, stabbing a lion, Koyunjik (ditto)

354. Lion let out of trap, Koyunjik (ditto)

Plate 120

355. Hound held in leash, Koyunjik (from the original

in the British Museum)

356. Wounded lioness, Koyunjik (ditto)

351. Fight of lion and bull, Nimrud (after Layard)

358. King hunting the wild bull, Nimrud (ditto)

359. King pouring libation over four dead lions,

Koyunjik (from the original in the British Museum)

Plate 121

360. Hound chasing a wild ass colt, Koyunjik (after Boutcher)

361. Dead wild ass, Koyunjik (ditto)

362. Hounds pulling down a wild ass, Koyunjik (ditto)

563. Wild ass taken with a rope, Koyunjik

(from the original in the British Museum)

Plate 122

364. Hound chasing a doe, Koyunjik (after Boutcher)

365. Hunted stag taking the water, Koyunjik (ditto)

Plate 123

366. Net spread to take deer, Koyunjik (from the original

in the British Museum)

367. Portion of net showing the arrangement of the meshes

and the pegs, Koyunjik (ditto)

368. Hunted ibex, flying at full speed. Koyunjik

(after Boutcher)

369. Ibex transfixed with arrow-falling (ditto)

Plate 124

370. Sportsman carrying a, gazelle, Khorsabad

(from the original in the British Museum)

371. Sportsman shooting, Khorsabad (after Bntta)

372. Greyhound and hare, Niunrud (from a bronze bowl

in the British Museum)

373. Nets, pegs, and balls of string, Koyunjik

(after Boutcher)

Plate 125

374. Man fishing, Nimrud (after Layard)

375. Man fishing, Koyunjik (ditto)

Plate 126

376. Man fishing, seated on skin, Koyunjik

(from the original in the British Museum)

377. Bear standing, Nimrud (from a bronze bowl

in the British Museum)

378. Ancient Assyrian harp and harper, Nimrud

(from the originals in the British Museum)

330. Triangular lyre, Koyunjik (ditto)

Plate 127

379. Later Assyrian harps and harpers, Koyunjik (ditto)

381. Lyre with ten strings, Khorsabad (after Botta)

Plate 128

382. Lyres with five and seven strings, Koyunjik

(from the originals in the British Museurn)

383. Guitar or tamboura, Koyunjik (ditto)

384. Player on the double pipe. Koyunjik (ditto)

Plate 129

385. Tambourine player and other musicians, Koyunjik (ditto)

387. Assyrian tubbuls, or drums, Koyunjik

(from the originals in the British Museum)

Plate 130

386. Eunuch playing on the cymbals, Koyunjik (after Boutcher)

388. Musician playing the dulcimer, Koyunjik (ditto)

389. Roman trumpet (Column of Trajan)

390. Assyrian ditto, Koyunjik (after Layard)

391. Portion of an Assyrian trumpet (from the original

in the British Museum)

Plate 131

392. Captives playing on lyres, Koyunjik (ditto)

Plate 132

333. Lyre on a Hebrew coin (ditto)

394. Baud of twenty-six musicians, Koyunjik (ditto)

Plate 133

395. Time-keepers, Koyunjik (after Boutcher)

396. Assyrian coracle, Nimrud (from the original

in the British Museum)

397. Common oar, time of Sennacherib, Koyunjik (ditto)

398. Steering oar, time of Asshur-izir-pal, Nimrud (ditto)

399. Early long boat, Nimrud (ditto)

400. Later long boat, Khorsabad (after Botta)

401. Phoenician bireme, Koyunjik (after Layard)

402. Oar kept in place by pegs, Koyunjik

(from the original in the British Museum)

Plate 134

403. Chart of the district about Nimrud, showing the

course of the ancient canal and conduit (after the

survey of Captain Jones)

404. Assyrian drill-plough (from Lori Aberdeen's

black stone, after Fergusson.

405. Modern Turkish plough (after Sir C. Fellows)

406. Modern Arab plough (after C. Niebuhr)

Plate 135

407. Ornamental belt or girdle, Koyunjik

(from the original in the British Museum)

408. Ornamental cross-belt, Khorsabad (after Botta)

409. Armlets of Assyrian grandees, Khorsabad (ditto)

410. Head-dresses of various officials, Koyunjik

(from the originals in the British Musemn)

411. Curious mode of arranging the hair, Koyunjik

(from the originals in the British Museum)

412. Female seated (from an ivory in the British Museum)

Plate 136

413. Females gathering grapes

(from some ivory fragments in the British Museum)

414. Necklace of flat glass beads (from the original

in the British Museum)

415. Metal mirror (ditto)

Plate 137

416. Combs in iron and lapis lazuli (from the original

in the British Museum)

417. Assyrian joints of meat (from the Sculptures)

418. Killing the sheep, Koyunjik (after Boutcher)

419. Cooking meat in caldron, Koyunjik (after Layard)

420. Frying, Nimrud (from the original in the British Museum)

421. Assyrian fruits (from the Monuments)

Plate 138

422. Drinking scene, Khorsabad (after Botta)

423. Ornamental wine-cup, Khorsabad (ditto)

424. Attendant bringing flowers to a banquet, Koyunjik

(after Layard)

425. Socket of hinge, Nimrud (ditto)

Map1

Page 358

Plate 143

448. Evil genii contending, Koyunjik (after Boutcher)

450. Triangular altar, Khorsabad (after Botta)

451. Portable altar in an Assyrian camp,

with priests offering, Khorsabad (ditto)

Plate 144

449. Sacrificial scene, from an obelisk found

at Nimrud (ditto)

452. Worshipper bringing an offering,

from a cylinder (after Lajard)

453. Figure of Tiglath-Pileser I.

(from an original drawing by Mr. John Taylor)

Page 371

Page 372

Plate 145

454. Plan of the palace of Asshur-izir-pal (after Fergusson)

455. Stele of Asshur-izir-pal with an altar in front, Nimrud

(from the original in the British Museum)

Plate 146

456. Israelites bringing tribute to Shalmaneser II.,

Nimrud (ditto)

457. Assyrian sphinx, time of Asshur-bani-pal

(after Layard)

458. Scythian soldiers, from a vase found in a Scythian tomb

Page 508

Page 509

Page 510

Page 511

Page 512

Page 513

Map of Media

THE SECOND MONARCHY

ASSYRIA

ENLARGE TO FULL SIZE

CHAPTER I.

DESCRIPTION OF THE COUNTRY.

"Greek phrase[—]"—HEROD. i. 192.

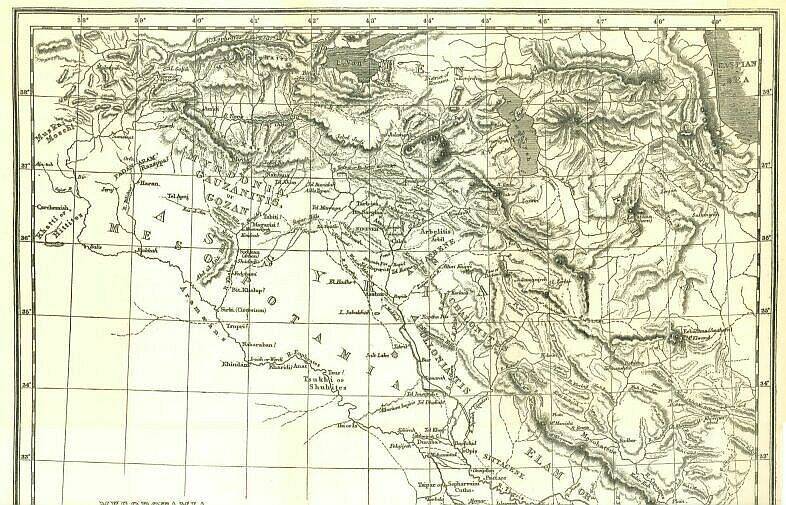

The site of the second—or great Assyrian-monarchy was the upper portion of the Mesopotamian valley. The cities which successively formed its capitals lay, all of them, upon the middle Tigris; and the heart of the country was a district on either side that river, enclosed within the thirty-fifth and thirty-seventh parallels. By degrees these limits were enlarged; and the term Assyria came to be used, in a loose and vague way, of a vast and ill-defined tract extending on all sides from this central region. Herodotus considered the whole of Babylonia to be a mere district of Assyria. Pliny reckoned to it all Mesopotamia. Strabo gave it, besides these regions, a great portion of Mount Zagros (the modern Kurdistan), and all Syria as far as Cilicia, Judaea, and Phoenicia.

If, leaving the conventional, which is thus vague and unsatisfactory, we seek to find certain natural limits which we may regard as the proper boundaries of the country, in two directions we seem to perceive an almost unmistakable line of demarcation. On the east the high mountain-chain of Zagros. penetrable only in one or two places, forms a barrier of the most marked character, and is beyond a doubt the natural limit for which we are looking. On the south a less striking, but not less clearly defined, line—formed by the abutment of the upper and slightly elevated plain on the alluvium of the lower valley—separates Assyria from Babylonia, which is best regarded as a distinct country. In the two remaining directions, there is more doubt as to the most proper limit. Northwards,we may either view Mount Masius as the natural boundary, or the course of the Tigris from Diarbekr to Til, or even perhaps the Armenian mountain-chain north of this portion of the Tigris, from whence that river receives its early tributaries. Westward, we might confine Assyria to the country watered by the affluents of the Tigris, or extend it so as to in elude the Khabour and its tributaries, or finally venture to carry it across the whole of Mesopotamia, and make it be bounded by the Euphrates. On the whole it is thought that in both the doubted cases the wider limits are historically the truer ones. Assyrian remains cover the entire country between the Tigris and the Khabour, and are frequent on both banks of the latter stream, giving unmistakable indications of a long occupation of that region by the great Mesopotamian people. The inscriptions show that even a wider tract was in process of time absorbed by the conquerors; and if we are to draw a line between the country actually taken into Assyria, and that which was merely conquered and held in subjection, we can select no better boundary than the Euphrates westward, and northward the snowy mountain-chain known to the ancients as Mons Niphates.

If Assyria be allowed the extent which is here assigned to her, she will be a country, not only very much larger than Chaldaea or Babylonia, but positively of considerable dimensions. Reaching on the north to the thirty-eighth and on the south to the thirty-fourth parallel, she had a length diagonally from Diarbekr to the alluvium of 350 miles, and a breadth between the Euphrates and Mount Zagros varying from about 300 to 170 miles. Her area was probably not less than 75,000 square miles, which is more than double that of Portugal, and not much below that of Great Britain. She would thus from her mere size be calculated to play an important (part) in history; and the more so, as during the period of her greatness scarcely any nation with which she came in contact possessed nearly so extensive a territory.

Within the limits here assigned to Assyria, the face of the country is tolerably varied. Possessing, on the whole, perhaps, a predominant character of flatness, the territory still includes some important ranges of hills, while on the two sides it abuts upon lofty mountain-chains. Towards the north and east it is provided by nature with an ample supply of water, rills everywhere flowing from the Armenian and Kurdish ranges, which soon collect into rapid and abundant rivers. The central, southern, and western regions are, however, less bountifully supplied; for though the Euphrates washes the whole western and south-western frontier, it spreads fertility only along its banks; and though Mount Masius sends down upon the Mesopotamian plain a considerable number of streams, they form in the space of 200 miles between Balls and Mosul but two rivers, leaving thus large tracts to languish for want of the precious fluid. The vicinity of the Arabian and Syrian deserts is likewise felt in these regions, which, left to themselves, tend to acquire the desert character, and have occasionally been regarded as actual parts of Arabia.

The chief natural division of the country is that made by the Tigris, which, having a course nearly from north to south, between Til and Samarah, separates Assyria into a western and an eastern district. Of these two, the eastern or that upon the left bank of the Tigris, although considerably the smaller, has always been the more important region. Comparatively narrow at first, it broadens as the course of the river is descended, till it attains about the thirty-fifth parallel a width of 130 or 140 miles. It consists chiefly of a series of rich and productive plains, lying along the courses of the various tributaries which flow from Mount Zagros into the Tigris, and often of a semi-alluvial character. These plains are not, however, continuous. Detached ranges of hills, with a general direction parallel to the Zagros chain, intersect the flat rich country, separating the plains from one another, and supplying small streams and brooks in addition to the various rivers, which, rising within or beyond the great mountain barriers, traverse the plains on their way to the Tigris. The hills themselves—known now as the Jebel Maklub, the Ain-es-sufra, the Karachok, etc.—are for the most part bare and sterile. In form they are hogbacked, and viewed from a distance have a smooth and even outline but on a nearer approach they are found to be rocky and rugged. Their limestone sides are furrowed by innumerable ravines, and have a dry and parched appearance, being even in spring generally naked and without vegetation. The sterility is most marked on the western flank, which faces the hot rays of the afternoon sun; the eastern slope is occasionally robed with a scanty covering of dwarf oak or stunted brushwood. In the fat soil of the plains the rivers commonly run deep and concealed from view, unless in the spring and the early summer, when through the rains and the melting of the snows in the mountains they are greatly swollen, and run bank full, or even overflow the level country.

The most important of these rivers are the following:—the Kurnib or Eastern Khabour, which joins the Tigris in lat. 37° 12'; the Greater Zab (Zab Ala), which washes the ruins of Nimrud, and enters the main stream almost exactly in lat. 30°; the Lesser Zab (Zab Asfal), which effects its junction about lat. 35° 15'; the Adhem, which is received a little below Samarah, about lat. 34°; and the Diyaleh, which now joins below Baghdad, but from which branches have sometimes entered the Tigris a very little below the mouth of the Adhem. Of these streams the most northern, the Khabour, runs chiefly in an untraversed country—the district between Julamerik and the Tigris. It rises a little west of Julamerik in one of the highest mountain districts of Kurdistan, and runs with a general south-westerly course to its junction with another large branch, which reaches it from the district immediately west of Amadiyeh; it then flows due west, or a little north of west, to Zakko, and, bending to the north after passing that place, flows once more in a south-westerly direction until it reaches the Tigris. The direct distance from its source to its embouchure is about 80 miles; but that distance is more than doubled by its windings. It is a stream of considerable size, broad and rapid; at many seasons not fordable at all, and always forded with difficulty.

The Greater Zab is the most important of all the tributaries of the Tigris. It rises near Konia, in the district of Karasu, about lat. 32° 20', long. 44° 30', a little west of the watershed which divides the basins of Lakes Van and Urymiyeh. Its general course for the first 150 miles is S.S.W., after which for 25 or 30 miles it runs almost due south through the country of the Tiyari. Near Amadiyeh it makes a sudden turn, and flows S.E. or S.S.E. to its junction with the Rowandiz branch whence, finally, it resumes its old direction, and runs south-west past the Nimrud ruins into the Tigris. Its entire course, exclusive of small windings, is above 350 miles, and of these nearly 100 are across the plain country, which it enters soon after receiving the Rowandiz stream. Like the Khabour, it is fordable at certain places and during the summer season; but even then the water reaches above the bellies of horses. It is 20 yards wide a little above its junction with the main steam. On account of its strength and rapidity the Arabs sometimes call it the "Mad River."

The Lesser Zab has its principal source near Legwin, about twenty miles south of Lake Urumiyeh, in lat. 36° 40', long. 46° 25'. The source is to the east of the great Zagros chain; and it might have been supposed that the waters would necessarily flow northward or eastward, towards Lake Urumiyeh, or towards the Caspian. But the Legwin river, called even at its source the Zei or Zab, flows from the first westward, as if determined to pierce the mountain barrier. Failing, however, to find an opening where it meets the range, the Little Zab turns south and even south-east along its base, till about 25 or 30 miles from its source it suddenly resumes its original direction, enters the mountains in lat. 36° 20', and forces its way through the numerous parallel ranges, flowing generally to the S.S.W., till it debouches upon the plain near Arbela, after which it runs S.W. and S.W. by S. to the Tigris. Its course among the mountains is from 80 to 90 miles, exclusive of small windings; and it runs more than 100 miles through the plain. Its ordinary width, just above its confluence with the Tigris, is 25 feet.

The Diyaleh, which lies mostly within the limits that have been here assigned to Assyria, is formed by the confluence of two principal streams, known respectively as the Holwan, and the Shirwan, river. Of these, the Shirwan seems to be the main branch. This stream rises from the most eastern and highest of the Zagros ranges, in lat. 34° 45', long. 47° 40' nearly. It flows at first west, and then north-west, parallel to the chain, but on entering the plain of Shahrizur, where tributaries join it from the north-east and the north-west, the Shirwan changes its course and begins to run south of west, a direction, which, it pursues till it enters the low country, about lat. 35° 5', near Semiram. Thence to the Tigris it has a course which in direct distance is 150 miles, and 200 if we include only main windings. The whole course cannot be less than 380 miles, which is about the length of the Great Zab river. The width attained before the confluence with the Tigris is 60 yards, or three times the width of the Greater, and seven times that of the Lesser Zab.

On the opposite side of the Tigris, the traveller comes upon a region far less favored by nature than that of which we have been lately speaking. Western Assyria has but a scanty supply of water; and unless the labor of man is skilfully applied to compensate this natural deficiency, the greater part of the region tends to be, for ten months out of the twelve, a desert. The general character of the country is level, but not alluvial. A line of mountains, rocky and precipitous, but of no great elevation, stretches across the northern part of the region, running nearly due east and west, and extending from the Euphrates at Rum-kaleh to Til and Chelek upon the Tigris. Below this, a vast slightly undulating plain extends from the northern mountains to the Babylonian alluvium, only interrupted about midway by a range of low limestone hills called the Sinjar, which leaving the Tigris near Mosul runs nearly from east to west across central Mesopotamia, and strikes the Euphrates half-way between Rakkeh and Kerkesiyeh, nearly in long. 40°.

The northern mountain region, called by Strabo "Mons Masius," and by the Arabs the Karajah Dagh towards the west, and towards the east the Jebel Tur, is on the whole a tolerably fertile country. It contains a good deal of rocky land; but has abundant springs, and in many parts is well wooded. Towards the west it is rather hilly than mountainous; but towards the east it rises considerably, and the cone above Mardin is both lofty and striking. The waters flowing from the range consist, on the north, of a small number of brooks, which after a short course fall into the Tigris; on the south, of more numerous and more copious streams, which gradually unite, and eventually form two rather important rivers. These rivers are the Belik, known anciently as the Bileeha, and the Western Khabour, called Habor in Scripture, and by the classical writers Aborrhas or Chaboras. [PLATE XXII., Fig. 1.]

The Belik rises among the hills east of Orfa, about long. 39°, lat. 37° 10'. Its course is at first somewhat east of south; but it soon sweeps round, and, passing by the city of Harran—the Haran of Scripture and the classical Carrh—proceeds nearly due south to its junction, a few miles below Rakkah, with the Euphrates. It is a small stream throughout its whole course, which may be reckoned at 100 or 120 miles.

The Khabour is a much more considerable river. It collects the waters which flow southward from at least two-thirds of the Mons Masius, and has, besides, an important source, which the Arabs regard as the true "head of the spring," derived apparently from a spur of the Sinjar range. This stream, which rises about lat. 36° 40', long. 40°, flows a little south of east to its junction near Koukab with the Jerujer or river Nisi-his, which comes down from Mons Masius with a course not much west of south. Both of these branches are formed by the union of a number of streams. Neither of them is fordable for some distance above their junction; and below it, they constitute a river of such magnitude as to be navigable for a considerable distance by steamers. The course of the Khabour below Koukab is tortuous; but its general direction is S.S.W. The entire length of the stream is certainly not less than 200 miles.

The country between the "Mons Masius" and the Sinjar range is an undulating plain, from 60 to 70 miles in width, almost as devoid of geographical features as the alluvium of Babylonia. From a height the whole appears to be a dead level: but the traveller finds, on descending, that the surface, like that of the American prairies and the Roman Campagna, really rises and falls in a manner which offers a decided contrast to the alluvial flats nearer the sea. Great portions of the tract are very deficient in water. Only small streams descend from the Sinjar range, and these are soon absorbed by the thirsty soil; so that except in the immediate vicinity of the hills north and south, and along the courses of the Khabour, the Belik, and their affluents, there is little natural fertility, and cultivation is difficult. The soil too is often gypsiferous, and its salt and nitrous exudations destroy vegetation; while at the same time the streams and springs are from the same cause for the most part brackish and unpalatable. Volcanic action probably did not cease in the region very much, if at all, before the historical period. Fragments of basalt in many places strew the plain; and near the confluence of the two chief branches of the Khabour, not only are old craters of volcanoes distinctly visible, but a cone still rises from the centre of one, precisely like the cones in the craters of Etna and Vesuvius, composed entirely of loose lava, scorim, and ashes, and rising to the height of 300 feet. The name of this remarkable hill, which is Koukab, is even thought to imply that the volcano may have been active within the time to which the traditions of the country extend. [PLATE XXII., Fig. 2.]

Sheets of water are so rare in this region that the small lake of Khatouniyeh seems to deserve especial description. This lake is situated near the point where the Sinjar changes its character, and from a high rocky range subsides into low broken hills. It is of oblong shape, with its greater axis pointing nearly due east and west, in length about four miles, and in its greatest breadth somewhat less than three. [PLATE XXIII., Fig. 1] The banks are low and parts marshy, more especially on the side towards the Khabour, which is not more than ten miles distant. In the middle of the lake is a hilly peninsula, joined to the mainland by a narrow causeway, and beyond it a small island covered with trees. The lake abounds with fish and waterfowl; and its water, though brackish, is regarded as remarkably wholesome both for man and beast.

The Sinjar range, which divides Western Assyria into two plains, a northern and a southern, is a solitary limestone ridge, rising up abruptly from the flat country, which it commands to a vast distance on both sides. The limestone of which it is composed is white, soft, and fossiliferous; it detaches itself in enormous flakes from the mountain-sides, which are sometimes broken into a succession of gigantic steps, while occasionally they present the columnar appearance of basalt. The flanks of the Sinjar are seamed with innumerable ravines, and from these small brooks issue, which are soon dispersed by irrigation, or absorbed in the thirsty plains. The sides of the mountain are capable of being cultivated by means of terraces, and produce fair crops of corn and excellent fruit; the top is often wooded with fruit trees or forest-trees. Geographically, the Sinjar may be regarded as the continuation of that range of hills which shuts in the Tigris on the west, from Tekrit nearly to Mosul, and then leaving the river strikes across the plain in a direction almost from east to west as far as the town of Sinjar. Here the mountains change their course and bend to the south-west, till having passed the little lake described above, they somewhat suddenly subside, sinking from a high ridge into low undulating hills, which pass to the south of the lake, and then disappear in the plain altogether. According to some, the Sinjar here terminates; but perhaps it is best to regard it as rising again in the Abd-el-aziz hills, which, intervening between the Khabour and the Euphrates, run in the same south-west direction from Arban to Zelabi. If this be accepted as the true course of the Sinjar, we must view it as throwing out two important spurs. One of these is near its eastern extremity, and runs to the south-east, dividing the plain of Zerga from the great central level. Like the main chain, it is of limestone; and, though low, has several remarkable peaks which serve as landmarks from a vast distance. The Arabs call it Kebritiyeh, or "the Sulphur range," from a sulphurous spring which rises at its foot. The other spur is thrown out near the western extremity, and runs towards the north-west, parallel to the course of the upper Khabour, which rises from its flank at Ras-el-Ain. The name of Abd-el-aziz is applied to this spur, as well as to the continuation of the Sinjar between Arban and Halebi. It is broken into innumerable valleys and ravines, abounding with wild animals, and is scantily wooded with dwarf oak. Streams of water abound in it.

South of the Sinjar range, the country resumes the same level appearance which characterizes it between the Sinjar and the Mons Masius. A low limestone ridge skirts the Tigris valley from Mosul to Tekrit, and near the Euphrates the country is sometimes slightly hilly; but generally the eye travels over a vast slightly undulating level, unbroken by eminences, and supporting but a scanty vegetation. The description of Xenophon a little exaggerates the flatness, but is otherwise faithful enough:—"In these parts the country was a plain throughout, as smooth as the sea, and full of wormwood; if any other shrub or reed grew there, it had a sweet aromatic smell; but there was not a tree in the whole region." Water is still more scarce than in the plains north of the Sinjar. The brooks descending from that range are so weak that they generally lose themselves in the plain before they have run many miles. In one case only do they seem sufficiently strong to form a river. The Tharthar, which flows by the ruins of El Hadhr, is at that place a considerable stream, not indeed very wide but so deep that horses have to swim across it. Its course above El Hadhr has not been traced; but the most probable conjecture seems to be that it is a continuation of the Sinjar river, which rises about the middle of the range, in long. 41° 50', and flows south-east through the desert. The Tharthar appears at one time to have reached the Tigris near Tekrit, but it now ends in a marsh or lake to the south-west of that city.

The political geography of Assyria need not occupy much of our attention. There is no native evidence that in the time of the great monarchy the country was formally divided into districts, to which any particular names were attached, or which were regarded as politically separate from one another; nor do such divisions appear in the classical writers until the time of the later geographers, Strabo, Dionysius, and Ptolemy. If it were not that mention is made in the Old Testament of certain districts within the region which has been here termed Assyria, we should have no proof that in the early times any divisions at all had been recognized. The names, however, of Padan-Aram, Aram-Naharaim, Gozan, Halah, and (perhaps) Huzzab, designate in Scripture particular portions of the Assyrian territory; and as these portions appear to correspond in some degree with the divisions of the classical geographers, we are led to suspect that these writers may in many, if not in most cases, have followed ancient and native traditions or authorities. The principal divisions of the classical geographers will therefore be noticed briefly, so far at least as they are intelligible.

According to Strabo, the district within which Nineveh stood was called Aturia, which seems to be the word Assyria slightly corrupted, as we know that it habitually was by the Persians. The neighboring plain country he divides into four regions—Dolomene, Calachene, Chazene, and Adiabene. Of Dolomene, which Strabo mentions but in one place, and which is wholly omitted by other authors, no account can be given. Calachene, which is perhaps the Calacine of Ptolemy, must be the tract about Calah (Nimrud), or the country immediately north of the Upper Zab river. Chazene, like Dolomene, is a term which cannot be explained. Adiabene, on the contrary, is a well-known geographical expression. It is the country of the Zab or Diab rivers, and either includes the whole of Eastern Assyria between the mountains and the Tigris, or more strictly is applied to the region between the Upper and Lower Zab, which consists of two large plains separated from each other by the Karachok hills. In this way Arbelitis, the plain between the Karachok and Zagros, would fall within Adiabene, but it is sometimes made a distinct region, in which case Adiabene must be restricted to the flat between the two Zabs, the Tigris, and the harachok. Chalonitis and Apolloniatis, which Strabo seems to place between these northern plains and Susiana, must be regarded as dividing between them the country south of the Lesser Zab, Apolloniatis (so called from its Greek capital, Apollonia) lying along the Tigris, and Chalonitis along the mountains from the pass of Derbend to Gilan. Chalonitis seems to have taken its name from a capital city called Chala, which lay on the great route connecting Babylon with the southern Ecbatana, and in later times was known as Holwan. Below Apolloniatis, and (like that district) skirting the Tigris, was Sittacene, (so named from its capital, Sittace which is commonly reckoned to Assyria, but seems more properly regarded as Susianian territory.) Such are the chief divisions of Assyria east of the Tigris.

West of the Tigris, the name Mesopotamia is commonly used, like the Aram-Naharaim of the Hebrews, for the whole country between the two great rivers. Here are again several districts, of which little is known, as Acabene, Tigene, and Ancobaritis. Towards the north, along the flanks of Mons Masius from Nisibis to the Euphrates, Strabo seems to place the Mygdonians, and to regard the country as Mygdonia. Below Mygdonia, towards the west, he puts Anthemusia, which he extends as far as the Khabour river. The region south of the Khabour and the Sinjar he seems to regard as inhabited entirely by Arabs. Ptolemy has, in lieu of the Mygdonia of Strabo, a district which he calls Gauzanitis; and this name is on good grounds identified with the Gozan of Scripture, the true original probably of the "Mygdonia" of the Greeks. Gozan appears to represent the whole of the upper country from which the longer affluents of the Khabour spring; while Halah, which is coupled with it in Scripture, and which Ptolemy calls Chalcitis, and makes border on Gauzanitis, may designate the tract upon the main stream, as it comes down from Ras-el-Ain. The region about the upper sources of the Belik has no special designation in Strabo, but in Scripture it seems to be called Padan-Aram, a name which has been explained as "the flat Syria," or "the country stretching out from the foot of the hills." In the later Roman times it was known as Osrhoene; but this name was scarcely in use before the time of the Antonines.

The true heart of Assyria was the country close along the Tigris, from lat. 35° to 36° 30'. Within these limits were the four great cities, marked by the mounds at Khorsabad, Mosul, Nimrud, and Kileh-Sherghat, besides a multitude of places of inferior consequence. It has been generally supposed that the left bank of the river was more properly Assyria than the right; and the idea is so far correct, as that the left bank was in truth of primary value and importance, whence it naturally happened that three out of the four capitals were built on that side of the stream. Still the very fact that one early capital was on the right bank is enough to show that both shores of the stream were alike occupied by the race from the first; and this conclusion is abundantly confirmed by other indications throughout the region. Assyrian ruins, the remains of considerable towns, strew the whole country between the Tigris and Khabour, both north and south of the Sin jar range. On the banks of the Lower Khabour are the remains of a royal palace, besides many other traces of the tract through which it runs having been permanently occupied by the Assyrian people. Mounds, probably Assyrian, are known to exist along the course of the Khabour's great western affluent; and even near Seruj, in the country between Harlan and the Euphrates some evidence has been found not only of conquest but of occupation. Remains are perhaps more frequent on the opposite side of the Tigris; at any rate they are more striking and more important. Bavian, Khorsabad, Shereef-Khan, Neb-bi-Yunus, Koyunjik, and Nimrud, which have furnished by far the most valuable and interesting of the Assyrian monuments, all lie east of the Tigris; while on the west two places only have yielded relics worthy to be compared with these, Arban and Kileh-Sherghat.

It is curious that in Assyria, as in early Chaldaea, there is a special pre-eminence of four cities. An indication of this might seem to be contained in Genesis, where Asshur is said to have "builded Nineveh," and the city Rehoboth, and Calah, and Resen; but on the whole it is more probable that we have here a mistranslation (which is corrected for us in the margin), and that three cities only are ascribed by Moses to the great patriarch. In the flourishing period of the empire, however, we actually find four capitals, of which the native names seem to have been Ninua, Calah, Asshur, and Bit-Sargina, or Dur-Sargina (the city of Sargon)—all places of first-rate consequence. Besides these principal cities, which were the sole seats of government, Assyria contained a vast number of large towns, few of which it is possible to name, but so numerous that they cover the whole face of the country with their ruins. Amomig; them were Tarbisa, Arbil, Arapkha, and Khazeh, in the tract between the Tigris and Mount Zagros; Haran, Tel-Apni, Razappa (Rezeph), and Amida, towards the north-west frontier; Nazibina (Nisibis), on the eastern branch of the Khabour; Sirki (Circesium), at the confluence of the Khabour with the Euphrates; Anat, on the Euphrates, some way below this junction; Tabiti, Magarisi, Sidikan, Katni, Beth-Khalupi,etc., in the district south of the Sinjar, between the lower course of the Khabour and the Tigris. Here, again, as in the case of Chaldaea, it is impossible at present to locate with accuracy all the cities. We must once more confine ourselves to the most important, mind seek to determine, either absolutely or with a certain vagueness, their several positions.

It admits of no reasonable doubt that the ruins opposite Mosul are those of Nineveh. The name of Nineveh is read on the bricks; and a uniform tradition, reaching from the Arab conquest to comparatively recent times, attaches to the mounds themselves the same title. They are the most extensive ruins in Assyria; and their geographical position suits perfectly all the notices of the geographers and historians with respect to the great Assyrian capital. As a subsequent chapter will be devoted to a description of this famous city, it is enough in this place to observe that it was situated on the left or east bank of the Tigris, in lat. 36° 21', at the point where a considerable brook, the Khosr-su, falls into the main stream. On its west flank flowed the broad and rapid Tigris, the "arrow-stream," as we may translate the word; while north, east, and south, expanded the vast undulating plain which intervenes between the river and the Zagros mountain-range. Mid-way in this plain, at the distance of from 15 to 18 miles from the city, stood boldly up the Jabel Maklub and Ain Sufra hills, calcareous ridges rising nearly 2000 feet above the level of the Tigris, and forming by far the most prominent objects in the natural landscape. Inside the Ain Sufra, and parallel to it, ran the small stream of the Gomel, or Ghazir, like a ditch skirting a wall, an additional defence in that quarter. On the south-east and south, distant about fifteen miles, was the strong and impetuous current of the Upper Zab, completing the natural defences of the position which was excellently chosen to be the site of a great capital.

South of Nineveh, at the distance of about twenty miles by the direct route and thirty by the course of the Tigris, stood the second city of the empire, Calah, the site of which is marked by the extensive ruins at Nimrud. [PLATE XXIV., Fig. 1.] Broadly, this place may be said to have been built at the confluence of the Tigris with the Upper Zab; but in strictness it was on the Tigris only, the Zab flowing five or six miles further to the south, and entering the Tigris at least nine miles below the Nimrud ruins. These ruins at present occupy an area somewhat short of a thousand English acres, which is little more than one-half of the area of the ruins of Nineveh; but it is thought that the place was in ancient times considerably larger, and that the united action of the Tigris and some winter streams has swept away no small portion of the ruins. They form at present an irregular quadrangle, the sides of which face the four cardinal points. On the north and east the rampart may still be distinctly traced. It was flanked with towers along its whole course, and pierced at uncertain intervals by gates, but was nowhere of very great strength or dimensions. On the south side it must have been especially weak, for there it has disappeared altogether. Here, however, it seems probable that the Tigris and the Shor Derreh stream, to which the present obliteration of the wall may be ascribed, formed in ancient times a sufficient protection. Towards the west, it seems to be certain that the Tigris (which is now a mile off) anciently flowed close to the city. On this side, directly facing the river, and extending along it a distance of 600 yards, or more than a third of a mile, was the royal quarter, or portion of the city occupied by the palaces of the kings. It consisted of a raised platform, forty feet above the level of the plain, composed in some parts of rubbish, in others of regular layers of sun-dried bricks, and cased on every side with solid stone masonry, containing an area of sixty English acres, and in shape almost a regular rectangle, 560 yards long, and from 350 to 450 broad. The platform was protected at its edges by a parapet, and is thought to have been ascended in various places by wide staircases, or inclined ways, leading up from the plain. The greater part of its area is occupied by the remains of palaces constructed by various native kings, of which a more particular account will be given in the chapter on the architecture and other arts of the Assyrians. It contains also the ruins of two small temples, and abuts at its north-western angle on the most singular structure which has as yet been discovered among the remains of the Assyrian cities. This is the famous tower or pyramid which looms so conspicuously over the Assyrian plams, and which has always attracted the special notice of the traveller. [PLATE XXIV., Fig. 2.] An exact description of this remarkable edifice will be given hereafter.

It appears from the inscriptions on its bricks to have been commenced by one of the early kings, and completed by another. Its internal structure has led to the supposition that it was designed to be a place of burial for one or other of these monarchs. Another conjecture is, that it was a watch-tower; but this seems very unlikely, since no trace of any mode by which it could be ascended has been discovered.

Forty miles below Calah, on the opposite bank of the Tigris, was a third great city, the native name of which appears to have been Asshur. This place is represented by the ruins at Kileh-Sherghat, which are scarcely inferior in extent to those at Nimrud or Calah. It will not be necessary to describe minutely this site, as in general character it closely resembles the other ruins of Assyria. Long lines of low mounds mark the position of the old walls, and show that the shape of the city was quadrangular. The chief object is a large square mound or platform, two miles and a half in circumference, and in places a hundred feet above the level of the plain, composed in part of sun-dried bricks, in part of natural eminences, and exhibiting occasionally remains of a casing of hewn stone, which may once have encircled the whole structure. About midway on the north side of the platform, and close upon its edge, is a high cone or pyramid. The rest of the platform is covered with the remains of walls and with heaps of rubbish, but does not show much trace of important buildings. This city has been supposed to represent the Biblical Resen; but the description of that place as lying "between Nineveh and Calah" seems to render the identification worse than uncertain.

The ruins at Kileh-Sherghat are the last of any extent towards the south, possessing a decidedly Assyrian character. To complete our survey, therefore of the chief Assyrian towns, we must return northwards, and, passing Nineveh, direct our attention to the magnificent ruins on the small stream of the Khosrsu, which have made the Arab village of Khorsabad one of the best known names in Oriental topography. About nine miles from the north-east angle of the wall of Nineveh, in a direction a very little east of north, stands the ruin known as Khorsabad, from a small village which formerly occupied its summit—the scene of the labors of M. Botta, who was the first to disentomb from among the mounds of Mesopotamia the relics of an Assyrian palace. The enclosure at Khorsabad is nearly square in shape, each side being about 2000 yards long. No part of it is very lofty, but the walls are on every side well marked. Their angles point towards the cardinal points, or nearly so; and the walls themselves consequently face the north-east, the north-west, the south-west, and the south-east. Towards the middle of the north-west wall, and projecting considerably beyond it, was a raised platform of the usual character; and here stood the great palace, which is thought to have been open to the plain, and on that side quite undefended.

Four miles only from Khorsabad, in a direction a little west of north, are the ruins of a smaller Assyrian city, whose native name appears to have been Tarbisa, situated not far from the modern village of Sherif-khan. Here was a palace, built by Esarhaddon for one of his sons, as well as several temples and other edifices. In the opposite direction at the distance of about twenty miles, is Keremles, an Assyrian ruin, whose name cannot yet be rendered phonetically. West of this site, and about half-way between the ruins of Nineveh and Nimrud or Calah, is Selamiyah, a village of some size, the walls of which are thought to be of Assyrian construction. We may conjecture that this place was the Resen, or Dase, of Holy Scripture, which is said to have been a large city, interposed between Nineveh and Calah. In the same latitude, but considerably further to the east, was the famous city of Arabil or Arbil, known to the Greeks as Arbela, and to this day retaining its ancient appellation. These were the principal towns, whose positions can be fixed, belonging to Assyria Proper, or the tract in the immediate vicinity of Nineveh.

Besides these places, the inscriptions mention a large number of cities which we cannot definitely connect with any particular site. Such are Zaban and Zadu, beyond the Lower Zab, probably somewhere in the vicinity of Kerkuk; Kurban, Tidu (?), Napulu, Kapa, in Adiabene; Arapkha and Khaparkhu, the former of which names recalls the Arrapachitis of Ptolemy, in the district about Arbela; Hurakha, Sallat (?), Dur-Tila, Dariga, Lupdu, and many others, concerning whose situations it is not even possible to make any reasonable conjecture. The whole country between the Tigris and the mountains was evidently studded thickly with towns, as it is at the present day with ruins; but until a minute and searching examination of the entire region has taken place, it is idle to attempt an assignment to particular localities of these comparatively obscure names.

In Western Assyria, or the tract on the right bank of the Tigris, while there is reason to believe that population was as dense, and that cities were as numerous, as on the opposite side of the river, even fewer sites can be determinately fixed, owing to the early decay of population in those parts, which seem to have fallen into their present desert condition shortly after the destruction of the Assyrian empire by the conquering Medes. Besides Asshur, which is fixed to the ruins at Kileh-Sherghat, we can only locate with certainty some half-dozen places. These are Nazibina, which is the modern Nisibin, the Nisibis of the Greeks; Amidi, which is Amida or Diarbekr; Haran, which retains its name unchanged; Sirki, which is the Greek Circesium, now Kerkesiyeh; Anat, now Anah, on an island in the Euphrates; and Sidikan, now Arban, on the Lower Khabour. The other known towns of this region, whose exact position is more or less uncertain, are the following:—Tavnusir, which is perhaps Dunisir, near Mardin; Guzana, or Gozan, in the vicinity of Nisibin; Razappa, or Rezeph, probably not far from Harran; Tel Apni, about Orfah or Ras-el-Ain; Tabiti and Magarisi, on the Jerujer, or river of Nisibin; Katni and Beth-Khalupi, on the Lower Khabour; Tsupri and Nakarabani, on the Euphrates, between its junction with the Khabour and Allah; and Khuzirina, in the mountains near the source of the Tigris. Besides these, the inscriptions contain a mention of some scores of towns wholly obscure, concerning which we cannot even determine whether they lay west or east of the Tigris.

Such are the chief geographical features of Assyria. It remains to notice briefly the countries by which it was bordered. To the east lay the mountain region of Zagros, inhabited principally, during the earlier times of the Empire, by the Zimri, and afterwards occupied by the Medes, and known as a portion of Media. This region is one of great strength, and at the same time of much productiveness and fertility. Composed of a large number of parallel ridges. Zagros contains, besides rocky and snow-clad summits, a multitude of fertile valleys, watered by the great affluents of the Tigris or their tributaries, and capable of producing rich crops with very little cultivation. The sides of the hills are in most parts clothed with forests of walnut, oak, ash, plane, and sycamore, while mulberries, olives, and other fruit-trees abound; in many places the pasturage is excellent; and thus, notwithstanding its mountainous character, the tract will bear a large population. Its defensive strength is immense, equalling that of Switzerland before military roads were constructed across the High Alps. The few passes by which it can be traversed seem, according to the graphic phraseology of the ancients, to be carried up ladders; they surmount six or seven successive ridges, often reaching the elevation of 10,000 feet, and are only open during seven months of the year. Nature appears to have intended Zagros as a seven fold wall for the protection of the fertile Mesopotamian lowland from the marauding tribes inhabiting the bare plateau of Iran.

North of Assyria lays a country very similar to the Zagros region. Armenia, like Kurdistan, consists, for the most part of a number of parallel mountain ranges, with deep valleys between them, watered by great rivers or their affluents. Its highest peaks, like those of Zagros, ascend considerably above the snow-line. It has the same abundance of wood, especially in the more northern parts; and though its valleys are scarcely so fertile, or its products so abundant and varied, it is still a country where a numerous population may find subsistence. The most striking contrast which it offers to the Zagros region is in the direction of its mountain ranges. The Zagros ridges run from north-west to south-east, like the principal mountains of Italy, Greece, Arabia, Hindustan, and Cochin China; those of Armenia have a course from a little north of east to a little south of west, like the Spanish Sierras, the Swiss and Tyrolese Alps, the Southern Carpathians, the Greater Balkan, the Cilician Taurus, the Cyprian Olympus, and the Thian Chan. Thus the axes of the two chains are nearly at right angles to one another, the triangular basin of Van occurring at the point of contact, and softening the abruptness of the transition. Again, whereas the Zagros mountains present their gradual slope to the Mesopotamian lowland, and rise in higher and higher ridges as they recede from the mountains of Armenia ascend at once to their full heignt from the level of the Tigris, and the ridges then gradually decline towards the Euxine. It follows from this last contrast, that, while Zagros invites the inhabitants of the Mesopotamian plain to penetrate its recesses, which are at first readily accessible, and only grow wild and savage towards the interior, the Armenian mountains repel by presenting their greatest difficulties and most barren aspect at once, seeming, with their rocky sides and snow-clad summits, to form an almost insurmountable obstacle to an invading host. Assyrian history bears traces of this difference; for while the mountain region to the east is gradually subdued and occupied by the people of the plain, that on the north continues to the last in a state of hostility and semi-independence.

West of Assyria (according to the extent which has here been given to it), the border countries were, towards the south, Arabia, and towards the north, Syria. A desert region, similar to that which bounds Chaldaea in this direction, extends along the Euphrates as far north as the 36th parallel, approaching commonly within a very short distance of the river. This has been at all times the country of the wandering Arabs. It is traversed in places by rocky ridges of a low elevation, and intercepted by occasional wadys, but otherwise it is a continuous gravelly or sandy plain, incapable of sustaining a settled population. Between the desert and the river intervenes commonly a narrow strip of fertile territory, which in Assyrian times was held by the Tsukhi or Shuhites, and the Aramaeans or Syrians. North of the 36th parallel, the general elevation of the country west of the Euphrates rises. There is an alternation of bare undulating hills and dry plains, producing wormwood and other aromatic plants. Permanent rivers are found, which either terminate in salt lakes or run into the Euphrates. In places the land is tolerably fertile, and produces good crops of grain, besides mulberries, pears, figs, pomegranates, olives, vines, and pistachio-nuts. Here dwelt, in the time of the Assyrian Empire, the Khatti, or Hittites, whose chief city, Carchemish, appears to have occupied the site of Hierapolis, now Bambuk. In a military point of view, the tract is very much less strong than either Armenia or Kurdistan, and presents but slight difficulties to invading armies.

The tract south of Assyria was Chaldaea, of which a description has been given in an earlier portion of this volume. Naturally it was at once the weakest of the border countries, and the one possessing the greatest attractions to a conqueror. Nature had indeed left it wholly without defence; and though art was probably soon called in to remedy this defect, yet it could not but continue the most open to attack of the various regions by which Assyria was surrounded. Syria was defended by the Euphrates—at all times a strong barrier; Arabia, not only by this great stream, but by her arid sands and burning climate; Armenia and Kurdistan had the protection of their lofty mountain ranges. Chaldaea was naturally without either land or water barrier; and the mounds and dykes whereby she strove to supply her wants were at the best poor substitutes for Nature's bulwarks. Here again geographical features will be found to have had an important bearing on the course of history, the close connection of the two countries, in almost every age, resulting from their physical conformation.

CHAPTER II.

CLIMATE AND PRODUCTIONS.

"Assyria, celebritate et magnitudine, et multiformi feracitate ditissima."—AMM. MARC. xxiii

In describing the climate and productions of Assyria, it will be necessary to divide it into regions, since the country is so large, and the physical geography so varied, that a single description would necessarily be both incomplete and untrue. Eastern Assyria has a climate of its own, the result of its position at the foot of Zagros. In Western Assyria we may distinguish three climates, that of the upper or mountainous country extending from Bir to Til and Jezireh, that of the middle region on either side of the Sinjar range, and that of the lower region immediately bordering on Babylonia. The climatic differences depend in part on latitude; but probably in a greater degree on differences of elevation, distance or vicinity of mountains, and the like.

Eastern Assyria, from its vicinity to the high and snow-clad range of Zagros, has a climate at once cooler and moister than Assyria west of the Tigris. The summer heats are tempered by breezes from the adjacent mountains, and, though trying to the constitution of an European, are far less oppressive than the torrid blasts which prevail on the other side of the river. A good deal of rain falls in the winter, and even in the spring; while, after the rains are past, there is frequently an abundant dew, which supports vegetation and helps to give coolness to the air. The winters are moderately severe.