автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Sound

SOUND

BY

JOHN TYNDALL, D.C.L., LL.D., F.R.S.

NEW YORK

P. F. COLLIER & SON

MCMII

7

SCIENCE

TO THE MEMORY

OF

MY FRIEND RICHARD DAWES

LATE DEAN OF HEREFORD

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED

J. T.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I

The Nerves and Sensation—Production and Propagation of Sonorous Motion—Experiments on Sounding Bodies placed in Vacuo—Deadening of Sound by Hydrogen—Action of Hydrogen on the Voice—Propagation of Sound through Air of Varying Density—Reflection of Sound—Echoes—Refraction of Sound—Diffraction of Sound; Case of Erith Village and Church—Influence of Temperature on Velocity—Influence of Density on Elasticity—Newton’s Calculation of Velocity—Thermal Changes Produced by the Sonorous Wave—Laplace’s Correction of Newton’s Formula—Ratio of Specific Heats at Constant Pressure and at Constant Volume deduced from Velocities of Sound—Mechanical Equivalent of Heat deduced from this Ratio—Inference that Atmospheric Air Possesses no Sensible Power to Radiate Heat—Velocity of Sound in Different Gases—Velocity in Liquids and Solids—Influence of Molecular Structure on the Velocity of Sound.

31 Summary of Chapter I 77CHAPTER II

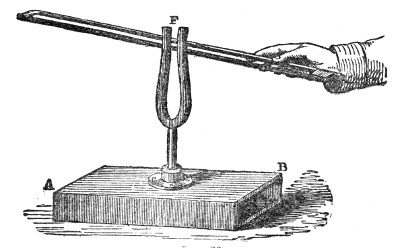

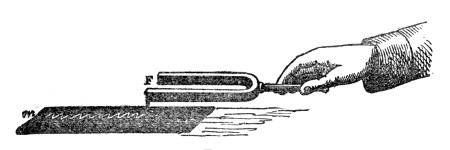

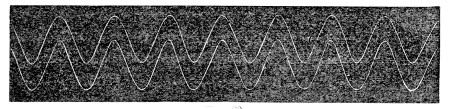

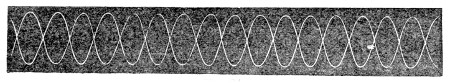

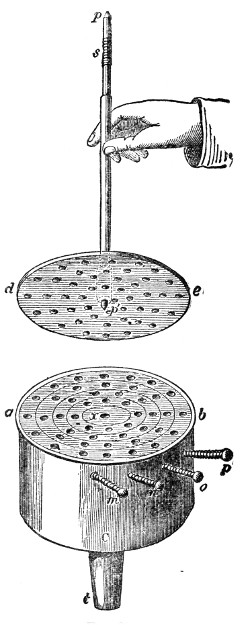

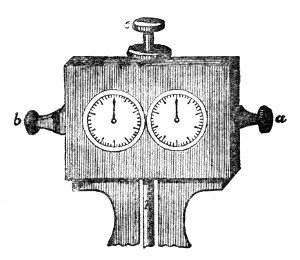

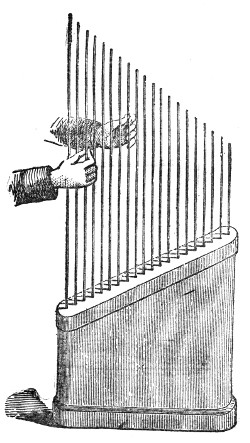

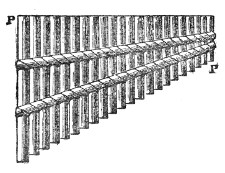

Physical Distinction between Noise and Music—A Musical Tone Produced by Periodic, Noise Produced by Unperiodic, Impulses—Production of Musical Sounds by Taps—Production of Musical Sounds by Puffs—Definition of Pitch in Music—Vibrations of a Tuning-Fork; their Graphic Representation on Smoked Glass—Optical Expression of the Vibrations of a Tuning-Fork—Description of the Siren—Limits of the Ear; Highest and Deepest Tones—Rapidity of Vibration Determined by the Siren—Determination of the Lengths of Sonorous Waves—Wave-Lengths of the Voice in Man and Woman—Transmission of Musical Sounds through Liquids and Solids.

82 Summary of Chapter II 117CHAPTER III

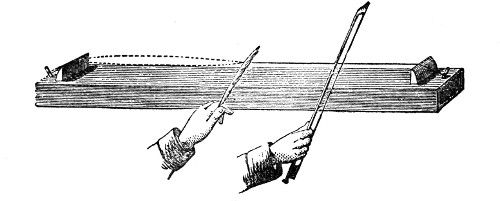

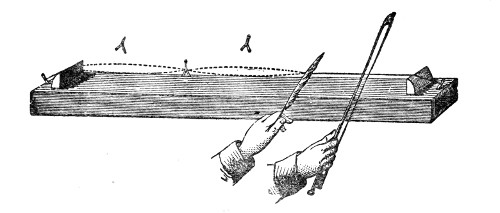

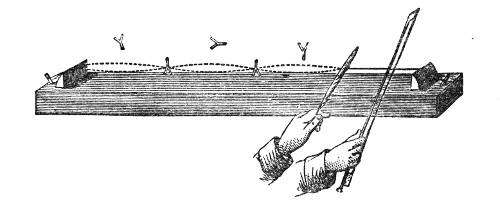

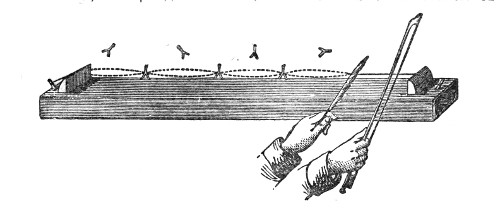

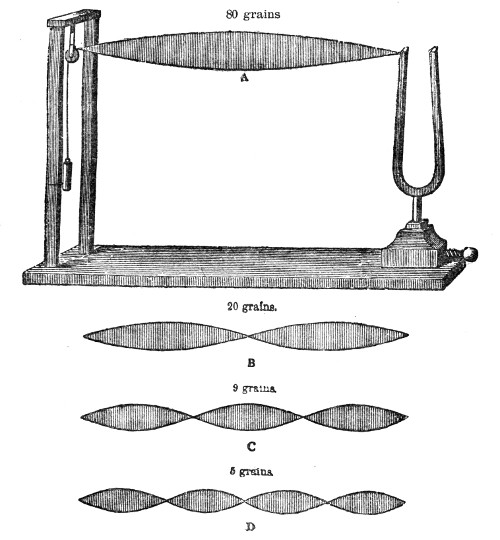

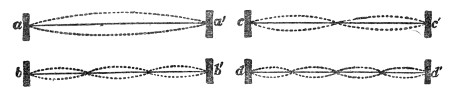

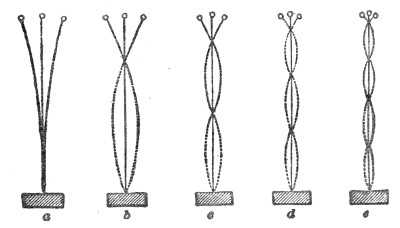

Vibration of Strings—How employed in Music—Influence of Sound-Boards—Laws of Vibrating String—Combination of Direct and Reflected Pulses—Stationary and Progressive Waves—Nodes and Ventral Segments—Application of Results to the Vibrations of Musical Strings—Experiments of Melde—Springs set in Vibration by Tuning-Forks—Laws of Vibration thus demonstrated—Harmonic Tones of Strings—Definitions of Timbre or Quality, or Overtones and Clang—Abolition of Special Harmonies—Conditions which affect the Intensity of the Harmonic Tones—Optical Examination of the Vibrations of a Piano-Wire

120 Summary of Chapter III 161CHAPTER IV

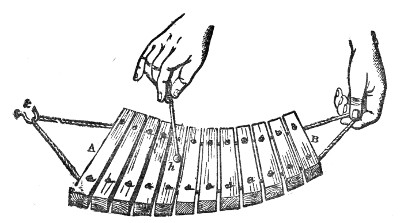

Vibrations of a Rod fixed at Both Ends: its Subdivisions and Corresponding Overtones—Vibrations of a Rod fixed at One End—The Kaleidophone—The Iron Fiddle and Musical Box—Vibrations of a Rod free at Both Ends—The Claque-bois and Glass Harmonica—Vibrations of a Tuning-Fork: its Subdivisions and Overtones—Vibrations of Square Plates—Chladni’s Discoveries—Wheatstone’s Analysis of the Vibrations of Plates—Chladni’s Figures—Vibrations of Disks and Bells—Experiments of Faraday and Strehlke.

165 Summary of Chapter IV 196CHAPTER V

Longitudinal Vibrations of a Wire—Relative Velocities of Sound in Brass and Iron—Longitudinal Vibrations of Rods fixed at One End—Of Rods free at Both Ends—Divisions and Overtones of Rods vibrating longitudinally—Examination of Vibrating Bars by Polarized Light—Determination of Velocity of Sound in Solids—Resonance—Vibrations of Stopped Pipes: their Divisions and Overtones—Relation of the Tones of Stopped Pipes to those of Open Pipes—Condition of Column of Air within a Sounding Organ-Pipe—Reeds and Reed-Pipes—The Voice—Overtones of the Vocal Chords—The Vowel Sounds—Kundt’s Experiments—New Methods of determining the Velocity of Sound.

200 Summary of Chapter V 254CHAPTER VI

Singing Flames—Influence of the Tube surrounding the Flame—Influence of Size of Flame—Harmonic Notes of Flames—Effect of Unisonant Notes on Singing Flames—Action of Sound on Naked Flames—Experiments with Fish-Tail and Bat’s-Wing Burners—Experiments on Tall Flames—Extraordinary Delicacy of Flames as Acoustic Reagents—The Vowel-Flame—Action of Conversational Tones upon Flames—Action of Musical Sounds on Smoke-Jets—Constitution of Water-Jets—Plateau’s Theory of the Resolution of a Liquid Vein into Drops—Action of Musical Sounds on Water-Jets—A Liquid Vein may compete in Point of Delicacy with the Ear

260 Summary of Chapter VI 301CHAPTER VII

PART I

RESEARCHES ON THE ACOUSTIC TRANSPARENCY OF THE ATMOSPHERE IN RELATION TO THE QUESTION OF FOG-SIGNALLING

Introduction—Instruments and Observations—Contradictory Results from the 19th of May to the 1st of July inclusive—Solution of Contradictions—Aërial Reflection and its Causes—Aërial Echoes—Acoustic Clouds—Experimental Demonstration of Stoppage of Sound by Aërial Reflection

305PART II

INVESTIGATION OF THE CAUSES WHICH HAVE HITHERTO BEEN SUPPOSED EFFECTIVE IN PREVENTING THE TRANSMISSION OF SOUND THROUGH THE ATMOSPHERE

Action of Hail and Rain—Action of Snow—Action of Fog; Observations in London—Experiments on Artificial Fogs—Observations on Fogs at the South Foreland—Action of Wind—Atmospheric Selection—Influence of Sound-Shadow

341 Summary of Chapter VII 374CHAPTER VIII

Law of Vibratory Motions in Water and Air—Superposition of Vibrations—Interference of Sonorous Waves—Destruction of Sound by Sound—Combined Action of Two Sounds nearly in Unison with each other—Theory of Beats—Optical Illustration of the Principle of Interference—Augmentation of Intensity by Partial Extinction of Vibrations—Resultant Tones—Conditions of their Production—Experimental Illustrations—Difference-Tones and Summation-Tones—Theories of Young and Helmholtz

377 Summary of Chapter VIII 407CHAPTER IX

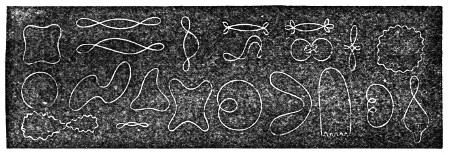

Combination of Musical Sounds—The smaller the Two Numbers which express the Ratio of their Rates of Vibration, the more perfect is the Harmony of Two Sounds—Notions of the Pythagoreans regarding Musical Consonance—Euler’s Theory of Consonance—Theory of Helmholtz—Dissonance due to Beats—Interference of Primary Tones and of Overtones—Mechanism of Hearing—Schultze’s Bristles—The Otoliths—Corti’s Fibres—Graphic Representation of Consonance and Dissonance—Musical Chords—The Diatonic Scale—Optical Illustration of Musical Intervals—Lissajous’s Figures—Sympathetic Vibrations—Various Modes of illustrating the Composition of Vibrations

410 Summary of Chapter IX 450APPENDIX I

On the Influence of Musical Sounds on the Flame of a Jet of Coal-gas. By John le Conte, M.D.

454APPENDIX II

On Acoustic Reversibility 461INDEX

471ILLUSTRATION—

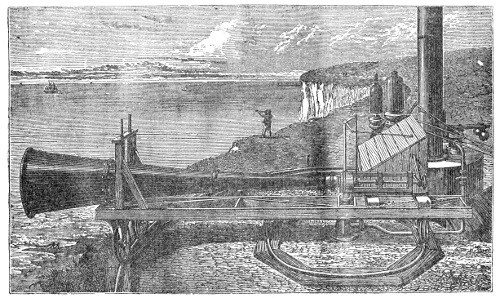

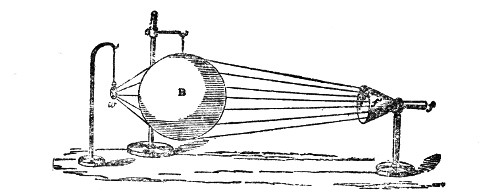

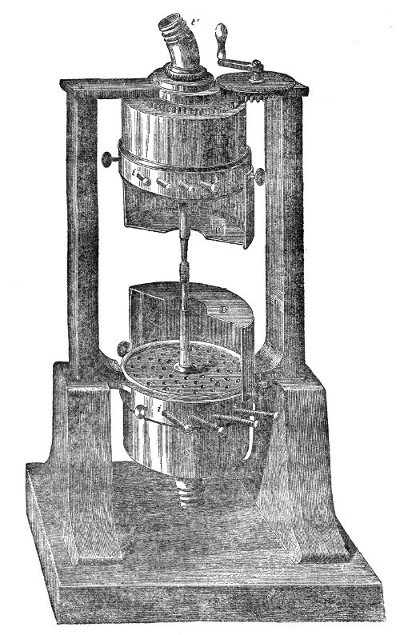

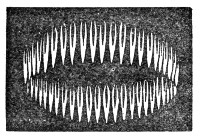

Fog-Siren Frontispiece

Fog-Siren

PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION

In preparing this new edition of “Sound,” I have carefully gone over the last one; amended, as far as possible, its defects of style and matter, and paid at the same time respectful attention to the criticisms and suggestions which the former editions called forth.

The cases are few in which I have been content to reproduce what I have read of the works of acousticians. I have sought to make myself experimentally familiar with the ground occupied; trying, in all cases, to present the illustrations in the form and connection most suitable for educational purposes.

Though bearing, it may be, an undue share of the imperfection which cleaves to all human effort, the work has already found its way into the literature of various nations of diverse intellectual standing. Last year, for example, a new German edition was published “under the special supervision” of Helmholtz and Wiedemann. That men so eminent, and so overladen with official duties, should add to these the labor of examining and correcting every proof-sheet of a work like this, shows that they consider it to be what it was meant to be—a serious attempt to improve the public knowledge of science. It is especially gratifying to me to be thus assured that not in England alone has the book met a public want, but also in that learned land to which I owe my scientific education.

Before me, on the other hand, lie two volumes of foolscap size, curiously stitched, and printed in characters the meaning of which I am incompetent to penetrate. Here and there, however, I notice the familiar figures of the former editions of “Sound.” For these volumes I am indebted to Mr. John Fryer, of Shanghai, who, along with them, favored me, a few weeks ago, with a letter from which the following is an extract: “One day,” writes Mr. Fryer, “soon after the first copy of your work on Sound reached Shanghai, I was reading it in my study, when an intelligent official, named Hsii-chung-hu, noticed some of the engravings and asked me to explain them to him. He became so deeply interested in the subject of Acoustics that nothing would satisfy him but to make a translation. Since, however, engineering and other works were then considered to be of more practical importance by the higher authorities, we agreed to translate your work during our leisure time every evening, and publish it separately ourselves. Our translation, however, when completed, and shown to the higher officials, so much interested them, and pleased them, that they at once ordered it to be published at the expense of the Government, and sold at cost price. The price is four hundred and eighty copper cash per copy, or about one shilling and eightpence. This will give you an idea of the cheapness of native printing.”

Mr. Fryer adds that his Chinese friend had no difficulty in grasping every idea in the book.

The new matter of greatest importance which has been introduced into this edition is an account of an investigation which, during the past two years, I have had the honor of conducting in connection with the Elder Brethren of the Trinity House. Under the title “Researches on the Acoustic Transparency of the Atmosphere, in Relation to the Question of Fog-signalling,” the subject is treated in Chapter VII. of this volume. It was only by Governmental appliances that such an investigation could have been made; and it gives me pleasure to believe that not only have the practical objects of the inquiry been secured, but that a crowd of scientific errors, which for more than a century and a half have surrounded this subject, have been removed, their place being now taken by the sure and certain truth of Nature. In drawing up the account of this laborious inquiry, I aimed at linking the observations so together that they alone should offer a substantial demonstration of the principles involved. Further labors enabled me to bring the whole inquiry within the firm grasp of experiment; and thus to give it a certainty which, without this final guarantee, it could scarcely have enjoyed.

Immediately after the publication of the first brief abstract of the investigation, it was subjected to criticism. To this I did not deem it necessary to reply, believing that the grounds of it would disappear in presence of the full account. The only opinion to which I thought it right to defer was to some extent a private one, communicated to me by Prof. Stokes. He considered that I had, in some cases, ascribed too exclusive an influence to the mixed currents of aqueous vapor and air, to the neglect of differences of temperature. That differences of temperature, when they come into play, are an efficient cause of acoustic opacity, I never doubted. In fact, aërial reflection arising from this cause is, in the present inquiry, for the first time made the subject of experimental demonstration. What the relative potency of differences of temperature and differences due to aqueous vapor, in the cases under consideration, may be, I do not venture to state; but as both are active, I have, in Chapter VII., referred to them jointly as concerned in the production of those “acoustic clouds” to which the stoppage of sound in the atmosphere is for the most part due.

Subsequently, however, to the publication of the full investigation another criticism appeared, to which, in consideration of its source, I would willingly pay all respect and attention. In this criticism, which reached me first through the columns of an American newspaper, differences in the amounts of aqueous vapor, and differences of temperature, are alike denied efficiency as causes of acoustic opacity. At a meeting of the Philosophical Society of Washington the emphatic opinion had, it was stated, been expressed that I was wrong in ascribing the opacity of the atmosphere to its flocculence, the really efficient cause being refraction. This view appeared to me so obviously mistaken that I assumed, for a time, the incorrectness of the newspaper account.

Recently, however, I have been favored with the “Report of the United States Lighthouse Board for 1874,” in which the account just referred to is corroborated. A brief reference to the Report will here suffice. Major Elliott, the accomplished officer and gentleman referred to at page 261, had published a record of his visit of inspection to this country, in which he spoke, with a perfectly enlightened appreciation of the facts, of the differences between our system of lighthouse illumination and that of the United States. He also embodied in his Report some account of the investigation on fog-signals, the initiation of which he had witnessed, and indeed aided, at the South Foreland.

On this able Report of their own officer the Lighthouse Board at Washington make the following remark: “Although this account is interesting in itself and to the public generally, yet, being addressed to the Lighthouse Board of the United States, it would tend to convey the idea that the facts which it states were new to the Board, and that the latter had obtained no results of a similar kind; while a reference to the appendix to this Report1 will show that the researches of our Lighthouse Board have been much more extensive on this subject than those of the Trinity House, and that the latter has established no facts of practical importance which had not been previously observed and used by the former.”

The “appendix” here referred to is from the pen of the venerable Prof. Joseph Henry, chairman of the Lighthouse Board at Washington. To his credit be it recorded that at a very early period in the history of fog-signalling Prof. Henry reported in favor of Daboll’s trumpet, though he was opposed by one of his colleagues on the ground that “fog-signals were of little importance, since the mariner should know his place by the character of his soundings.” In the appendix, he records the various efforts made in the United States with a view to the establishment of fog-signals. He describes experiments on bells, and on the employment of reflectors to reinforce their sound. These, though effectual close at hand, were found to be of no use at a distance. He corrects current errors regarding steam-whistles, which by some inventors were thought to act like ringing bells. He cites the opinion of the Rev. Peter Ferguson, that sound is better heard in fog than in clear air. This opinion is founded on observations of the noise of locomotives; in reference to which it may be said that others have drawn from similar experiments diametrically opposite conclusions. On the authority of Captain Keeney he cites an occurrence, “in the first part of which the captain was led to suppose that fog had a marked influence in deadening sound, though in a subsequent part he came to an opposite conclusion.” Prof. Henry also describes an experiment made during a fog at Washington, in which he employed “a small bell rung by clock-work, the apparatus being the part of a moderator lamp, intended to give warning to the keepers when the supply of oil ceased. The result of the experiment was, he affirms, contrary to the supposition of absorption of the sound by the fog.” This conclusion is not founded on comparative experiments, but on observations made in the fog alone; for, adds Prof. Henry, “the change in the condition of the atmosphere, as to temperature and the motion of the air, before the experiment could be repeated in clear weather, rendered the result not entirely satisfactory.”

This, I may say, is the only experiment on fog which I have found recorded in the appendix.

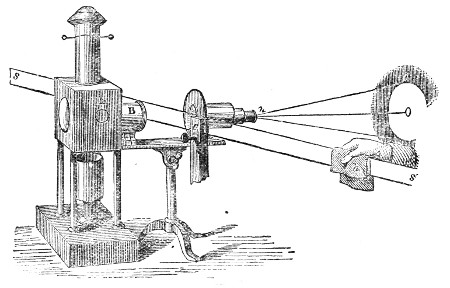

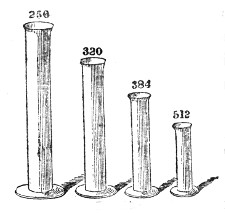

In 1867 the steam-siren was mounted at Sandy Hook, and examined by Prof. Henry. He compared its action with that of a Daboll trumpet, employing for this purpose a stretched membrane covered with sand, and placed at the small end of a tapering tube which concentrated the sonorous motion upon the membrane. The siren proved most powerful. “At a distance of 50, the trumpet produced a decided motion of the sand, while the siren gave a similar result at a distance of 58.” Prof. Henry also varied the pitch of the siren, and found that in association with its trumpet 400 impulses per second yielded the maximum sound; while the best result with the unaided siren was obtained when the impulses were 360 a second. Experiments were also made on the influence of pressure; from which it appeared that when the pressure varied from 100 lbs. to 20 lbs., the distance reached by the sound (as determined by the vibrating membrane) varied only in the ratio of 61 to 51. Prof. Henry also showed the sound of the fog-trumpet to be independent of the material employed in its construction; and he furthermore observed the decay of the sound when the angular distance from the axis of the instrument was increased. Further observations were made by Prof. Henry and his colleagues in August, 1873, and in August, and September, 1874. In the brief but interesting account of these experiments a hypothetical element appears, which is absent from the record of the earlier observations.

It is quite evident from the foregoing that, in regard to the question of fog-signalling, the Lighthouse Board of Washington have not been idle. Add to this the fact that their eminent chairman gives his services gratuitously, conducting without fee or reward experiments and observations of the character here revealed, and I think it will be conceded that he not only deserves well of his own country, but also sets his younger scientific contemporaries, both in his country and ours, an example of high-minded devotion.

I was quite aware, in a general way, that labors like those now for the first time made public had been conducted in the United States, and this knowledge was not without influence upon my conduct. The first instruments mounted at the South Foreland were of English manufacture; and I, on various accounts, entertained a strong sympathy for their able constructor, Mr. Holmes. From the outset, however, I resolved to suppress such feelings, as well as all other extraneous considerations, individual or national; and to aim at obtaining the best instruments, irrespective of the country which produced them. In reporting, accordingly, on the observations of May 19 and 20, 1873 (our first two days at the South Foreland), these were my words to the Elder Brethren of the Trinity House:

“In view of the reported performance of horns and whistles in other places, the question arises whether those mounted at the South Foreland, and to which the foregoing remarks refer, are of the best possible description.... I think our first duty is to make ourselves acquainted with the best instruments hitherto made, no matter where made; and then, if home genius can transcend them, to give it all encouragement. Great and unnecessary expense may be incurred, through our not availing ourselves of the results of existing experience.

“I have always sympathized, and I shall always sympathize, with the desire of the Elder Brethren to encourage the inventor who first made the magneto-electric light available for lighthouse purposes. I regard his aid and counsel as, in many respects, invaluable to the corporation. But, however original he may be, our duty is to demand that his genius shall be expended in making advances on that which has been already achieved elsewhere. If the whistles and horns that we heard on the 19th and 20th be the very best hitherto constructed, my views have been already complied with; but if they be not—and I am strongly inclined to think that they are not—then I would submit that it behooves us to have the best, and to aim at making the South Foreland, both as regards light and sound, a station not excelled by any other in the world.”

On this score it gives me pleasure to say that I never had a difficulty with the Elder Brethren. They agreed with me; and two powerful steam-whistles, the one from Canada, the other from the United States, together with a steam-siren—also an American instrument—were in due time mounted at the South Foreland. It will be seen in Chapter VII. that my strongest recommendation applies to an instrument for which we are indebted to the United States.

In presence of these facts, it will hardly be assumed that I wish to withhold from the Lighthouse Board of Washington any credit that they may fairly claim. My desire is to be strictly just; and this desire compels me to express the opinion that their Report fails to establish the inordinate claim made in its first paragraph. It contains observations, but contradictory observations; while as regards the establishment of any principle which should reconcile the conflicting results, it leaves our condition unimproved.

But I willingly turn aside from the discussion of “claims” to the discussion of science. Inserted, as a kind of intrusive element, into the Report of Prof. Henry, is a second Report by General Duane, founded on an extensive series of observations made by him in 1870 and 1871. After stating with distinctness the points requiring decision, the General makes the following remarks:

“Before giving the results of these experiments, some facts will be stated which will explain the difficulties of determining the power of a fog-signal.

“There are six steam fog-whistles on the coast of Maine: these have been frequently heard at a distance of twenty miles, and as frequently cannot be heard at the distance of two miles, and this with no perceptible difference in the state of the atmosphere.

“The signal is often heard at a great distance in one direction, while in another it will be scarcely audible at the distance of a mile. This is not the effect of wind, as the signal is frequently heard much further against the wind than with it.2 For example, the whistle on Cape Elizabeth can always be distinctly heard in Portland, a distance of nine miles, during a heavy northeast snowstorm, the wind blowing a gale directly from Portland toward the whistle.3

“The most perplexing difficulties, however, arise from the fact that the signal often appears to be surrounded by a belt, varying in radius from one mile to one mile and a half, from which the sound appears to be entirely absent. Thus, in moving directly from a station the sound is audible for the distance of a mile, is then lost for about the same distance, after which it is again distinctly heard for a long time. This action is common to all ear-signals, and has been at times observed at all the stations, at one of which the signal is situated on a bare rock twenty miles from the mainland, with no surrounding objects to affect the sound.”

It is not necessary to assume here the existence of a “belt,” at some distance from the station. The passage of an acoustic cloud over the station itself would produce the observed phenomenon.

Passing over the record of many other valuable observations in the Report of General Duane, I come to a few very important remarks which have a direct bearing upon the present question:

“From an attentive observation,” writes the General, “during three years, of the fog-signals on this coast, and from the reports received from the captains and pilots of coasting vessels, I am convinced that, in some conditions of the atmosphere, the most powerful signals will be at times unreliable.4

“Now it frequently occurs that a signal which, under ordinary circumstances, would be audible at the distance of fifteen miles, cannot be heard from a vessel at the distance of a single mile. This is probably due to the reflection mentioned by Humboldt.

“The temperature of the air over the land where the fog-signal is located being very different from that over the sea, the sound, in passing from the former to the latter, undergoes reflection at their surface of contact. The correctness of this view is rendered more probable by the fact that, when the sound is thus impeded in the direction of the sea, it has been observed to be much stronger inland.

“Experiments and observation lead to the conclusion that these anomalies in the penetration and direction of sound from fog-signals are to be attributed mainly to the want of uniformity in the surrounding atmosphere, and that snow, rain, and fog, and the direction of the wind, have much less influence than has been generally supposed.”

The Report of General Duane is marked throughout by fidelity to facts, rare sagacity, and soberness of speculation. The last three of the paragraphs just quoted exhibit, in my opinion, the only approach to a true explanation of the phenomena which the Washington Report reveals. At this point, however, the eminent Chairman of the Lighthouse Board strikes in with the following criticism:

“In the foregoing I differ entirely in opinion from General Duane as to the cause of extinction of powerful sounds being due to the unequal density of the atmosphere. The velocity of sound is not at all affected by barometric pressure; but if the difference in pressure is caused by a difference in heat, or by the expansive power of vapor mingled with the air, a slight degree of obstruction of sound may be observed. But this effect we think is entirely too minute to produce the results noted by General Duane and Dr. Tyndall, while we shall find in the action of currents above and below a true and efficient cause.”

I have already cited the remarkable observation of General Duane, that with a snowstorm from the northeast blowing against the sound, the signal at Cape Elizabeth is always heard at Portland, a distance of nine miles. The observations at the South Foreland, where the sound has-been proved to reach a distance of more than twelve miles against the wind, backed by decisive experiments, reduce to certainty the surmises of General Duane. It has, for example, been proved that a couple of gas-flames placed in a chamber can, in a minute or two, render its air so non-homogeneous as to cut a sound practically off; while the same sound passes without sensible impediment through showers of paper-scraps, seeds, bran, raindrops, and through fumes and fogs of the densest description. The sound also passes through thick layers of calico, silk, serge, flannel, baize, close felt, and through pads of cotton-net impervious to the strongest light.

As long, indeed, as the air on which snow, hail, rain or fog is suspended is homogeneous, so long will sound pass through the air, sensibly heedless of the suspended matter.5 This point is illustrated upon a large scale by my own observations on the Mer de Glace, and by those of General Duane, at Portland, which prove the snow-laden air from the northeast to be a highly homogeneous medium. Prof. Henry thus accounts for the fact that the northeast snow-wind renders the sound of Cape Elizabeth audible at Portland: In the higher regions of the atmosphere he places an ideal wind, blowing in a direction opposed to the real one, which always accompanies the latter, and which more than neutralizes its action. In speculating thus he bases himself on the reasoning of Prof. Stokes, according to which a sound-wave moving against the wind is tilted upward. The upper, and opposing wind, is invented for the purpose of tilting again the already lifted sound-wave downward. Prof. Henry does not explain how the sound-wave recrosses the hostile lower current, nor does he give any definite notion of the conditions under which it can be shown that it will reach the observer.

This, so far as I know, is the only theoretic gleam cast by the Washington Report on the conflicting results which have hitherto rendered experiments on fog-signals so bewildering. I fear it is an ignis fatuus, instead of a safe guiding light. Prof. Henry, however, boldly applies the hypothesis in a variety of instances. But he dwells with particular emphasis upon a case of non-reciprocity which he considers absolutely fatal to my views regarding the flocculence of the atmosphere. The observation was made on board the steamer “City of Richmond,” during a thick fog in a night of 1872. “The vessel was approaching Whitehead from the southwestward, when, at a distance of about six miles from the station, the fog-signal, which is a 10-inch steam-whistle, was distinctly perceived, and continued to be heard with increasing intensity of sound until within about three miles, when the sound suddenly ceased to be heard, and was not perceived again until the vessel approached within a quarter of a mile of the station, although from conclusive evidence, furnished by the keeper, it was shown that the signal had been sounding during the whole time.”

But while the 10-inch shore-signal thus failed to make itself heard at sea, a 6-inch whistle on board the steamer made itself heard on shore. Prof. Henry thus turns this fact against me. “It is evident,” he writes, “that this result could not be due to any mottled condition or want of acoustic transparency in the atmosphere, since this would absorb the sound equally in both directions.” Had the observation been made in a still atmosphere, this argument would, at one time, have had great force. But the atmosphere was not still, and a sufficient reason for the observed non-reciprocity is to be found in the recorded fact that the wind was blowing against the shore-signal, and in favor of the ship-signal.

But the argument of Prof. Henry, on which he places his main reliance, would be untenable, even had the air been still. By the very aërial reflection which he practically ignores, reciprocity may be destroyed in a calm atmosphere. In proof of this assertion I would refer him to a short paper on “Acoustic Reversibility,” printed at the end of this volume.6 The most remarkable case of non-reciprocity on record, and which, prior to the demonstration of the existence and power of acoustic clouds, remained an insoluble enigma, is there shown to be capable of satisfactory solution. These clouds explain perfectly the “abnormal phenomena” of Prof. Henry. Aware of their existence, the falling off and subsequent recovery of a signal-sound, as noticed by him and General Duane, is no more a mystery than the interception of the solar light by a common cloud, and its restoration after the cloud has moved or melted away.

The clew to all the difficulties and anomalies of this question is to be found in the aërial echoes, the significance of which has been overlooked by General Duane, and misinterpreted by Prof. Henry. And here a word might be said with regard to the injurious influence still exercised by authority in science. The affirmations of the highest authorities, that from clear air no sensible echo ever comes, were so distinct that my mind for a time refused to entertain the idea. Authority caused me for weeks to depart from the truth, and to seek counsel among delusions. On the day our observations at the South Foreland began I heard the echoes. They perplexed me. I heard them again and again, and listened to the explanations offered by some ingenious persons at the Foreland. They were an “ocean-echo”: this is the very phraseology now used by Prof. Henry. They were echoes “from the crests and slopes of the waves”: these are the words of the hypothesis which he now espouses. Through a portion of the month of May, through the whole of June, and through nearly the whole of July, 1873, I was occupied with these echoes; one of the phases of thought then passed through, one of the solutions then weighed in the balance and found wanting, being identical with that which Prof. Henry now offers for acceptation.

But though it thus deflected me from the proper track, shall I say that authority in science is injurious? Not without some qualification. It is not only injurious, but deadly, when it cows the intellect into fear of questioning it. But the authority which so merits our respect as to compel us to test and overthrow all its supports, before accepting a conclusion opposed to it, is not wholly noxious. On the contrary, the disciplines it imposes may be in the highest degree salutary, though they may end, as in the present case, in the ruin of authority. The truth thus established is rendered firmer by our struggles to reach it. I groped day after day, carrying this problem of aërial echoes in my mind; to the weariness, I fear, of some of my colleagues who did not know my object. The ships and boats afloat, the “slopes and crests of the waves,” the visible clouds, the cliffs, the adjacent lighthouses, the objects landward, were all in turn taken into account, and all in turn rejected.

With regard to the particular notion which now finds favor with Prof. Henry, it suggests the thought that his observations, notwithstanding their apparent variety and extent, were really limited as regards the weather. For did they, like ours, embrace weather of all kinds, it is not likely that he would have ascribed to the sea-waves an action which often reaches its maximum intensity when waves are entirely absent. I will not multiply instances, but confine myself to the definite statement that the echoes have often manifested an astonishing strength when the sea was of glassy smoothness. On days when the echoes were powerful, I have seen the southern cumuli mirrored in the waveless ocean, in forms almost as definite as the clouds themselves. By no possible application of the law of incidence and reflection could the echoes from such a sea return to the shore; and if we accept for a moment a statement which Prof. Henry seems to indorse, that sound-waves of great intensity, when they impinge upon a solid or liquid surface, do not obey the law of incidence and reflection, but “roll along the surface like a cloud of smoke,” it only increases the difficulty. Such a “cloud,” instead of returning to the coast of England, would, in our case, have rolled toward the coast of France. Nothing that I could say in addition could strengthen the case here presented. I will only add one further remark. When the sun shines uniformly on a smooth sea, thus producing a practically uniform distribution of the aërial currents to which the echoes are due, the direction in which the trumpet-echoes reach the shore is always that in which the axis of the instrument is pointed. At Dungeness this was proved to be the case throughout an arc of 210°—an impossible result, if the direction of reflection were determined by that of the ocean waves.

Rightly interpreted and followed out, these aërial echoes lead to a solution which penetrates and reconciles the phenomena from beginning to end. On this point I would stake the issue of the whole inquiry, and to this point I would, with special earnestness, direct the attention of the Lighthouse Board of Washington. Let them prolong their observations into calm weather: if their atmosphere resembles ours—which I cannot doubt—then I affirm that they will infallibly find the echoes strong on days when all thought of reflection “from the crests and slopes of the waves” must be discarded. The echoes afford the easiest access to the core of this question, and it is for this reason that I dwell upon them thus emphatically. It requires no refined skill or profound knowledge to master the conditions of their production; and these once mastered, the Lighthouse Board of Washington will find themselves in the real current of the phenomena, outside of which—I say it with respect—they are now vainly speculating. The acoustic deportment of the atmosphere in haze, fog, sleet, snow, rain, and hail will be no longer a mystery; even those “abnormal phenomena” which are now referred to an imaginary cause, or reserved for future investigation, will be found to fall naturally into place, as illustrations of a principle as simple as it is universal.

“With the instruments now at our disposal wisely established along our coasts, I venture to think that the saving of property, in ten years, will be an exceedingly large multiple of the outlay necessary for the establishment of such signals. The saving of life appeals to the higher motives of humanity.” Such were the words with which I wound up my Report on Fog-Signals.7 One year after their utterance, the “Schiller” goes to pieces on the Scilly rocks. A single calamity covers the predicted multiple, while the sea receives three hundred and thirty-three victims. As regards the establishment of fog-signals, energy has been hitherto paralyzed by their reputed uncertainty. We now know both the reason and the range of their variations; and such knowledge places it within our power to prevent disasters like the recent one. The inefficiency of bells, which caused their exclusion from our inquiry, was sadly illustrated in the case of the “Schiller.”

JOHN TYNDALL.

Royal institution, June, 1875.

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION

In the following pages I have tried to render the science of Acoustics interesting to all intelligent persons, including those who do not possess any special scientific culture.

The subject is treated experimentally throughout, and I have endeavored so to place each experiment before the reader that he should realize it as an actual operation. My desire, indeed, has been to give distinct images of the various phenomena of acoustics, and to cause them to be seen mentally in their true relations.

I have been indebted to the kindness of some of my English friends for a more or less complete examination of the proof-sheets of this work. To my celebrated German friend Clausius, who has given himself the trouble of reading the proofs from beginning to end, my especial thanks are due and tendered.

There is a growing desire for scientific culture throughout the civilized world. The feeling is natural, and, under the circumstances, inevitable. For a power which influences so mightily the intellectual and material action of the age could not fail to arrest attention and challenge examination. In our schools and universities a movement in favor of science has begun which, no doubt, will end in the recognition of its claims, both as a source of knowledge and as a means of discipline. If by showing, however inadequately, the methods and results of physical science to men of influence, who derive their culture from another source, this book should indirectly aid in promoting the movement referred to, it will not have been written in vain.

SOUND

CHAPTER I

The Nerves and Sensation—Production and Propagation of Sonorous Motion—Experiments on Sounding Bodies placed in Vacuo—Deadening of Sound by Hydrogen—Action of Hydrogen on the Voice—Propagation of Sound through Air of Varying Density—Reflection of Sound—Echoes—Refraction of Sound—Diffraction of Sound; Case of Erith Village and Church—Influence of Temperature on Velocity—Influence of Density on Elasticity—Newton’s Calculation of Velocity—Thermal Changes Produced by the Sonorous Wave—Laplace’s Correction of Newton’s Formula—Ratio of Specific Heats at Constant Pressure and at Constant Volume deduced from Velocities of Sound—Mechanical Equivalent of Heat deduced from this Ratio—Inference that Atmospheric Air Possesses no Sensible Power to Radiate Heat—Velocity of Sound in Different Gases—Velocity in Liquids and Solids—Influence of Molecular Structure on the Velocity of Sound

§ 1. Introduction: Character of Sonorous Motion. Experimental Illustrations

THE various nerves of the human body have their origin in the brain, which is the seat of sensation. When the finger is wounded, the sensor nerves convey to the brain intelligence of the injury, and if these nerves be severed, however serious the hurt may be, no pain is experienced. We have the strongest reason for believing that what the nerves convey to the brain is in all cases motion. The motion here meant is not, however, that of the nerve as a whole, but of its molecules or smallest particles.8

Different nerves are appropriated to the transmission of different kinds of molecular motion. The nerves of taste, for example, are not competent to transmit the tremors of light, nor is the optic nerve competent to transmit sonorous vibrations. For these a special nerve is necessary, which passes from the brain into one of the cavities of the ear, and there divides into a multitude of filaments. It is the motion imparted to this, the auditory nerve, which, in the brain, is translated into sound.

Applying a flame to a small collodion balloon which contains a mixture of oxygen and hydrogen, the gases explode, and every ear in this room is conscious of a shock, which we name a sound. How was this shock transmitted from the balloon to our organs of hearing? Have the exploding gases shot the air-particles against the auditory nerve as a gun shoots a ball against a target? No doubt, in the neighborhood of the balloon, there is to some extent a propulsion of particles; but no particle of air from the vicinity of the balloon reached the ear of any person here present. The process was this: When the flame touched the mixed gases they combined chemically, and their union was accompanied by the development of intense heat. The heated air expanded suddenly, forcing the surrounding air violently away on all sides. This motion of the air close to the balloon was rapidly imparted to that a little further off, the air first set in motion coming at the same time to rest. The air, at a little distance, passed its motion on to the air at a greater distance, and came also in its turn to rest. Thus each shell of air, if I may use the term, surrounding the balloon took up the motion of the shell next preceding, and transmitted it to the next succeeding shell, the motion being thus propagated as a pulse or wave through the air.

The motion of the pulse must not be confounded with the motion of the particles which at any moment constitute the pulse. For while the wave moves forward through considerable distances, each particular particle of air makes only a small excursion to and fro.

What a curious transference of action is here presented to the mind! At the command of the musician’s will, the fingers strike the keys; the hammers strike the strings, by which the rude mechanical shock is converted into tremors. The vibrations are communicated to the sound-board of the piano. Upon that board rests the end of the deal rod, thinned off to a sharp edge to make it fit more easily between the wires. Through the edge, and afterward along the rod, are poured with unfailing precision the entangled pulsations produced by the shocks of those ten agile fingers. To the sound-board of the harp before you the rod faithfully delivers up the vibrations of which it is the vehicle. This second sound-board transfers the motion to the air, carving it and chasing it into forms so transcendently complicated that confusion alone could be anticipated from the shock and jostle of the sonorous waves. But the marvellous human ear accepts every feature of the motion, and all the strife and struggle and confusion melt finally into music upon the brain.32

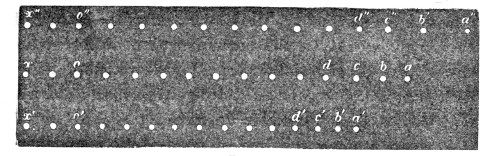

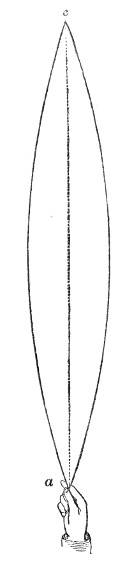

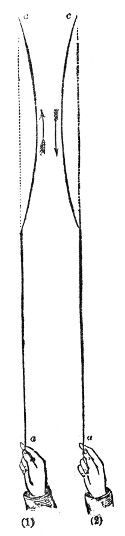

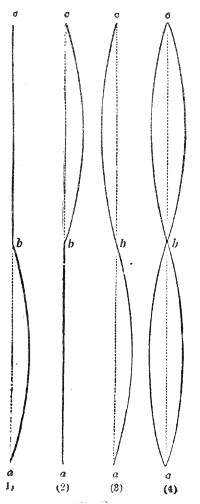

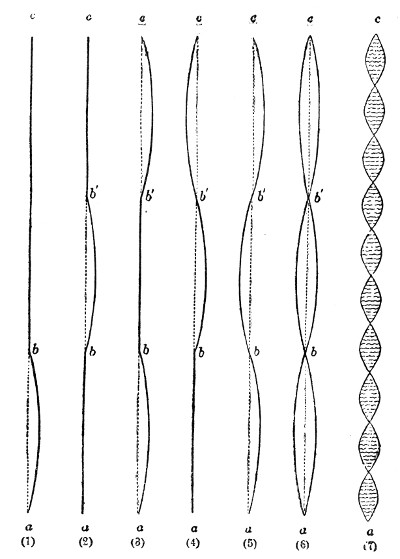

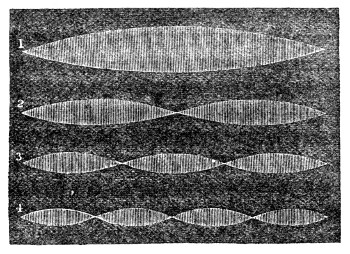

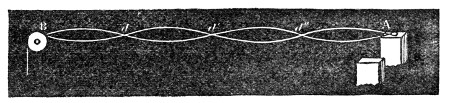

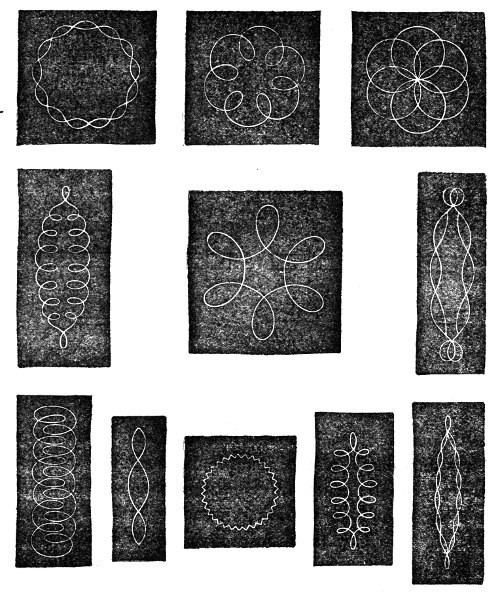

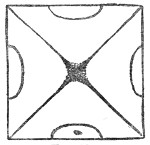

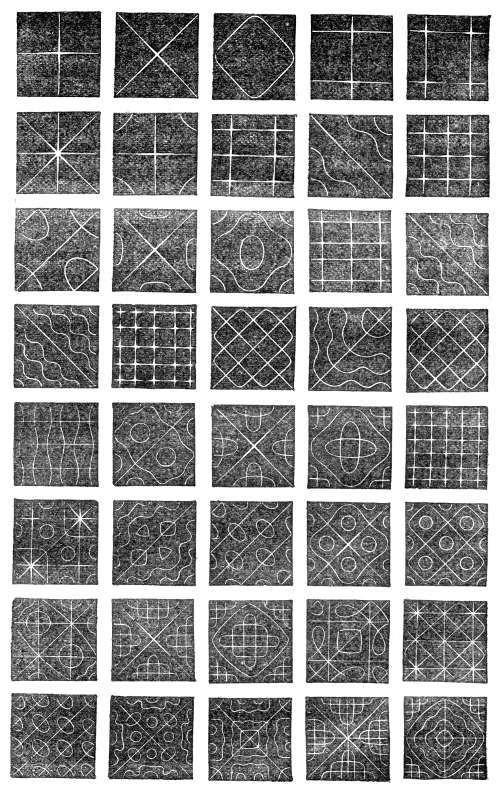

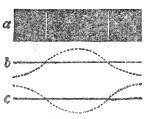

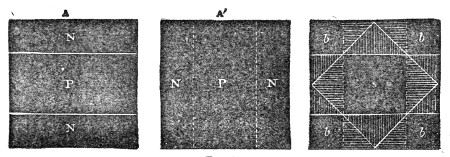

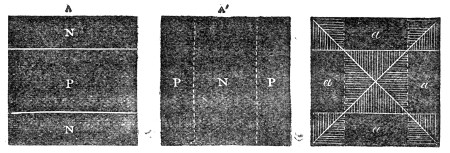

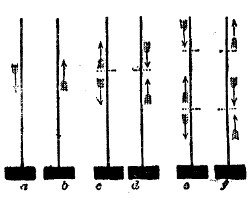

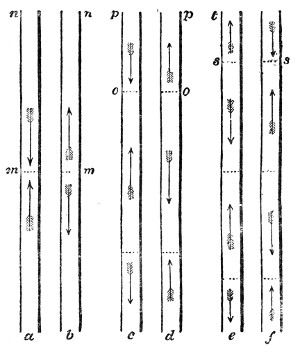

Finally, with regard to the vibrations of a wire, the experiments of Dr. Young, who was the first to employ optical methods in such experiments, must be mentioned. He allowed a sheet of sunlight to cross a pianoforte-wire, and obtained thus a brilliant dot. Striking the wire he caused it to vibrate, the dot described a luminous line like that produced by the whirling of a burning coal in the air, and the form of this line revealed the character of the vibration. It was rendered manifest by these experiments that the oscillations of the wire were not confined to a single plane, but that it described in its vibrations curves of greater or less complexity. Superposed upon the vibration of the whole string were partial vibrations, which revealed themselves as loops and sinuosities. Some of the lines observed by Dr. Young are given in Fig. 51. Every one of these figures corresponds to a distinct impression made by the wire upon the surrounding air. The form of the sonorous wave is affected by these superposed vibrations, and thus they influence the clang-tint or quality of the sound.

The resonance of caves and of rocky inclosures is well known. Bunsen notices the thunder-like sound produced when one of the steam jets of Iceland breaks out near the mouth of a cavern. Most travellers in Switzerland have noticed the deafening sound produced by the fall of the Reuss at the Devil’s Bridge. The sound heard when a hollow shell is placed close to the ear is a case of resonance. Children think they hear in it the sound of the sea. The noise is really due to the reinforcement of the feeble sounds with which even the stillest air is pervaded, and also in part to the noise produced by the pressure of the shell against the ear itself. By using tubes of different lengths, the variation of the resonance with the length of the tube may be studied. The channel of the ear itself is also a resonant cavity. When a poker is held by two strings, and when the fingers of the hands holding the poker are thrust into the ears on striking the poker against a piece of wood, a sound is heard as deep and sonorous as that of a cathedral bell. When open, the channel of the ear resounds to notes whose periods of vibration are about 3,000 per second. This has been shown by Helmholtz, and Madame Seiler has found that dogs which howl to music are particularly sensitive to the same notes. We may expect from Mr. Francis Galton interesting results in connection with this subject.

By introducing a Leyden-jar into the circuit of a powerful induction-coil, a series of dense and dazzling flashes of light, each of momentary duration, is obtained. Every such flash in a darkened room renders the drops distinct, each drop being transformed into a little star of intense brilliancy. If the vein be then acted on by a sound of the proper pitch, it instantly gathers its drops together into a necklace of inimitable beauty.

“An illustration is here afforded of the perfect analogy between light and sound; for if a beam of light be projected from B to F′, and a plate of glass be introduced at A in the exact position of the reflecting layer of gas, the beam will be divided, one portion being reflected in the direction A F, and the other portion transmitted through the glass toward F′, exactly as the sound-wave is divided into a reflected and transmitted portion by the layer of heated gas or flame.”

In the subsequent experimental treatment of the subject I have been most ably aided by my excellent assistant, Mr. John Cottrell.

These considerations make it probably evident to you that a coalescence of musical sounds is a far more complicated dynamical condition than you have hitherto supposed it to be. In the music of an orchestra, not only have we the fundamental tones of every pipe and of every string, but we have the overtones of each, sometimes audible as far as the sixteenth in the series. We have also resultant tones; both difference-tones and summation-tones; all trembling through the same air, all knocking at the self-same tympanic membrane. We have fundamental tone interfering with fundamental tone; overtone with overtone; resultant tone with resultant tone. And, besides this, we have the members of each class interfering with the members of every other class. The imagination retires baffled from any attempt to realize the physical condition of the atmosphere through which these sounds are passing. And, as we shall immediately learn, the aim of music, through the centuries during which it has ministered to the pleasure of man, has been to arrange matters empirically, so that the ear shall not suffer from the discordance produced by this multitudinous interference. The musicians engaged in this work knew nothing of the physical facts and principles involved in their efforts; they knew no more about it than the inventors of gunpowder knew about the law of atomic proportions. They tried and tried till they obtained a satisfactory result; and now, when the scientific mind is brought to bear upon the subject, order is seen rising through the confusion, and the results of pure empiricism are found to be in harmony with natural law.

I close these remarks on the combination of rectangular vibrations with a brief reference to an apparatus constructed by Mr. A. E. Donkin, of Exeter College, Oxford, and described in the “Proceedings of the Royal Society,” vol. xxii., p. 196. In its construction great mechanical knowledge is associated with consummate skill. I saw the apparatus as a wooden model, before it quitted the hands of its inventor, and was charmed with its performance. It is now constructed by Messrs. Tisley and Spiller.

1 It will be borne in mind that the Washington Appendix was published nearly a year after my Report to the Trinity House.

2 That is to say, homogeneous air with an opposing wind is frequently more favorable to sound than non-homogeneous air with a favoring wind. We had the same experience at the South Foreland.—J. T.

3 Had this observation been published, it could only have given me pleasure to refer to it in my recent writings. It is a striking confirmation of my observations on the Mer de Glace in 1859.

4 Had I been aware of its existence I might have used the language of General Duane to express my views on the point here adverted to. See Chap. VII., pp. 340-341.

5 This does not seem more surprising than the passage of light, or radiant heat, through rock salt.

6 Also “Proceedings of the Royal Society,” vol. xxiii., p. 159, and “Proceedings of the Royal Institution,” vol. vii., p. 344.

7 See page 372 of this volume.

8 The rapidity with which an impression is transmitted through the nerves, as first determined by Helmholtz, and confirmed by Du Bois-Reymond, is 93 feet a second.

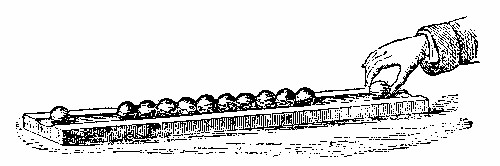

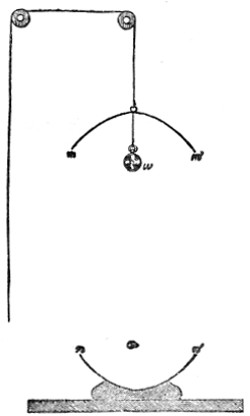

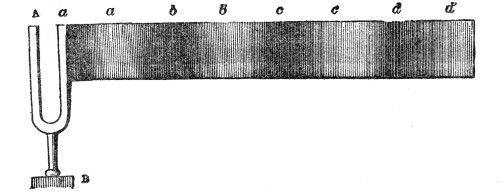

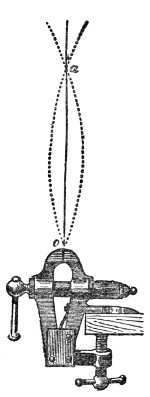

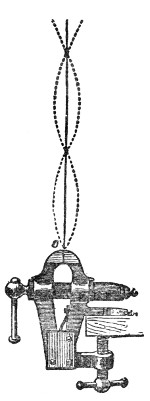

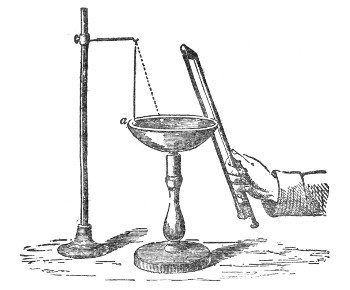

Fig. 1.

The process may be rudely represented by the propagation of motion through a row of glass balls, such as are employed in the game of solitaire. Placing the balls along a groove thus, Fig. 1, each of them touching its neighbor, and urging one of them against the end of the row: the motion thus imparted to the first ball is delivered up to the second, the motion of the second is delivered up to the third, the motion of the third is imparted to the fourth; each ball, after having given up its motion, returning itself to rest. The last ball only of the row flies away. In a similar way is sound conveyed from particle to particle through the air. The particles which fill the cavity of the ear are finally driven against the tympanic membrane, which is stretched across the passage leading from the external ear toward the brain. This membrane, which closes outwardly the “drum” of the ear, is thrown into vibration, its motion is transmitted to the ends of the auditory nerve, and afterward along that nerve to the brain, where the vibrations are translated into sound. How it is that the motion of the nervous matter can thus excite the consciousness of sound is a mystery which the human mind cannot fathom.

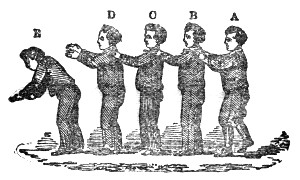

Fig. 2.

The propagation of sound may be illustrated by another homely but useful illustration. I have here five young assistants, A, B, C, D, and E, Fig. 2, placed in a row, one behind the other, each boy’s hands resting against the back of the boy in front of him. E is now foremost, and A finishes the row behind. I suddenly push A, A pushes B, and regains his upright position; B pushes C; C pushes D; D pushes E; each boy, after the transmission of the push, becoming himself erect. E, having nobody in front, is thrown forward. Had he been standing on the edge of a precipice, he would have fallen over; had he stood in contact with a window, he would have broken the glass; had he been close to a drumhead, he would have shaken the drum. “We could thus transmit a push through a row of a hundred boys, each particular boy, however, only swaying to and fro. Thus, also, we send sound through the air, and shake the drum of a distant ear, while each particular particle of the air concerned in the transmission of the pulse makes only a small oscillation.

But we have not yet extracted from our row of boys all that they can teach us. When A is pushed he may yield languidly, and thus tardily deliver up the motion to his neighbor B. B may do the same to C, C to D, and D to E. In this way the motion might be transmitted with comparative slowness along the line. But A, when pushed, may, by a sharp muscular effort and sudden recoil, deliver up promptly his motion to B, and come himself to rest; B may do the same to C, C to D, and D to E, the motion being thus transmitted rapidly along the line. Now this sharp muscular effort and sudden recoil is analogous to the elasticity of the air in the case of sound. In a wave of sound, a lamina of air, when urged against its neighbor lamina, delivers up its motion and recoils, in virtue of the elastic force exerted between them; and the more rapid this delivery and recoil, or in other words the greater the elasticity of the air, the greater is the velocity of the sound.

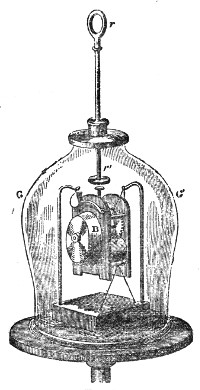

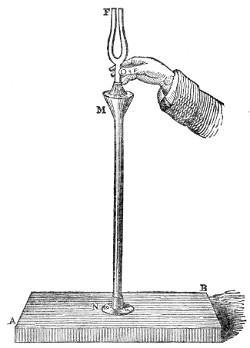

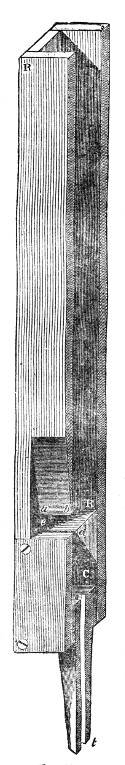

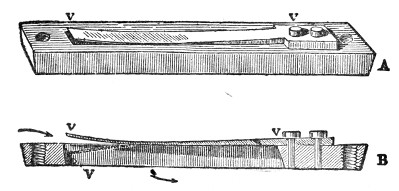

Fig. 3.

A very instructive mode of illustrating the transmission of a sound-pulse is furnished by the apparatus represented in Fig. 3, devised by my assistant, Mr. Cottrell. It consists of a series of wooden balls separated from each other by spiral springs. On striking the knob A, a rod attached to it impinges upon the first ball B, which transmits its motion to C, thence it passes to E, and so on through the entire series. The arrival at D is announced by the shock of the terminal ball against the wood, or, if we wish, by the ringing of a bell. Here the elasticity of the air is represented by that of the springs. The pulse may be rendered slow enough to be followed by the eye.

Scientific education ought to teach us to see the invisible as well as the visible in nature, to picture with the vision of the mind those operations which entirely elude bodily vision; to look at the very atoms of matter in motion and at rest, and to follow them forth, without ever once losing sight of them, into the world of the senses, and see them there integrating themselves in natural phenomena. With regard to the point now under consideration, we must endeavor to form a definite image of a wave of sound. We ought to see mentally the air-particles, when urged outward by the explosion of our balloon, crowding closely together; but immediately behind this condensation we ought to see the particles separated more widely apart. We must, in short, to be able to seize the conception that a sonorous wave consists of two portions, in the one of which the air is more dense, and in the other of which it is less dense than usual. A condensation and a rarefaction, then, are the two constituents of a wave of sound. This conception shall be rendered more complete in our next lecture.

§ 2. Experiments in Vacuo, in Hydrogen, and on Mountains

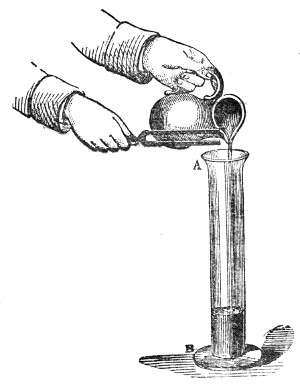

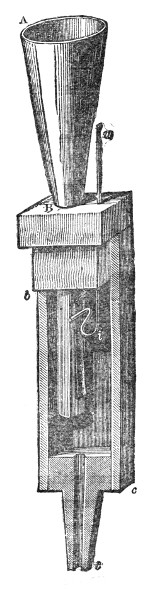

That air is thus necessary to the propagation of sound was proved by a celebrated experiment made before the Royal Society, by a philosopher named Hawksbee, in 1705.9 He so fixed a bell within the receiver of an air-pump that he could ring the bell when the receiver was exhausted. Before the air was withdrawn the sound of the bell was heard within the receiver; after the air was withdrawn the sound became so faint as to be hardly perceptible. An arrangement is before you which enables us to repeat in a very perfect manner the experiment of Hawksbee. Within this jar, G G′, Fig. 4, resting on the plate of an air-pump is a

Sir John Leslie found hydrogen singularly incompetent to act as the vehicle of the sound of a bell rung in the gas. More than this, he emptied a receiver like that before you of half its air, and plainly heard the ringing of the bell. On permitting hydrogen to enter the half-filled receiver until it was wholly filled, the sound sank until it was scarcely audible. This result remained an enigma until it received a simple and satisfactory explanation at the hands of Prof. Stokes. When a common pendulum oscillates it tends to form a condensation in front and a rarefaction behind. But it is only a tendency; the motion is so slow, and the air is so elastic, that it moves away in front before it is sensibly condensed, and fills the space behind before it can become sensibly dilated. Hence waves or pulses are not generated by the pendulum. It requires a certain sharpness of shock to produce the condensation and rarefaction which constitute a wave of sound in air.

The more elastic and mobile the gas, the more able will it be to move away in front and to fill the space behind, and thus to oppose the formation of rarefactions and condensations by a vibrating body. Now hydrogen is much more mobile than air; and hence the production of sonorous waves in it is attended with greater difficulty than in air. A rate of vibration quite competent to produce sound-waves in the one may be wholly incompetent to produce them in the other. Both calculation and observation prove the correctness of this explanation, to which we shall again refer.

At great elevations in the atmosphere sound is sensibly diminished in loudness. De Saussure thought the explosion of a pistol at the summit of Mont Blanc to be about equal to that of a common cracker below. I have several times repeated this experiment; first, in default of anything better, with a little tin cannon, the torn remnants of which are now before you, and afterward with pistols. What struck me was the absence of that density and sharpness in the sound which characterize it at lower elevations. The pistol-shot resembled the explosion of a champagne bottle, but it was still loud. The withdrawal of half an atmosphere does not very materially affect our ringing bell, and air of the density found at the top of Mont Blanc is still capable of powerfully affecting the auditory nerve. That highly attenuated air is able to convey sound of great intensity is forcibly illustrated by the explosion of meteorites at elevations where the tenuity of the atmosphere must be almost infinite. Here, however, the initial disturbance must be exceedingly great.

The motion of sound, like all other motion, is enfeebled by its transference from a light body to a heavy one. When the receiver which has hitherto covered our bell is removed you hear how much more loudly it rings in the open air. When the bell was covered the aërial vibrations were first communicated to the heavy glass jar, and afterward by the jar to the air outside; a great diminution of intensity being the consequence. The action of hydrogen gas upon the voice is an illustration of the same kind. The voice is formed by urging air from the lungs through an organ called the larynx, where it is thrown into vibration by the vocal chords which thus generate sound. But when the lungs are filled with hydrogen, the vocal chords on speaking produce a vibratory motion in the hydrogen, which then transfers the motion to the outer air. By this transference from a light gas to a heavy one the voice is so weakened as to become a mere squeak.12

The intensity of a sound depends on the density of the air in which the sound is generated, and not on that of the air in which it is heard.13 Supposing the summit of Mont Blanc to be equally distant from the top of the Aiguille Verte and the bridge at Chamouni; and supposing two observers stationed, the one upon the bridge and the other upon the Aiguille: the report of a cannon fired on Mont Blanc would reach both observers with the same intensity, though in the one case the sound would pursue its way through the rare air above, while in the other it would descend though the denser air below. Again, let a straight line equal to that from the bridge at Chamouni to the summit of Mont Blanc be measured along the earth’s surface in the valley of Chamouni, and let two observers be stationed, the one on the summit and the other at the end of the line: the report of a cannon fired on the bridge would reach both observers with the same intensity, though in the one case the sound would be propagated through the dense air of the valley, and in the other case would ascend through the rarer air of the mountain. Finally, charge two cannon equally, and fire one of them at Chamouni and the other at the top of Mont Blanc: the one fired in the heavy air below may be heard above, while the one fired in the light air above is unheard below.

§ 3. Intensity of Sound. Law of Inverse Squares

In the case of our exploding balloon the wave of sound expands on all sides, the motion produced by the explosion being thus diffused over a continually augmenting mass of air. It is perfectly manifest that this cannot occur without an enfeeblement of the motion. Take the case of a thin shell of air with a radius of one foot, reckoned from the centre of explosion. A shell of air of the same thickness, but of two feet radius, will contain four times the quantity of matter; if its radius be three feet, it will contain nine times the quantity of matter; if four feet, it will contain sixteen times the quantity of matter, and so on. Thus the quantity of matter set in motion augments as the square of the distance from the centre of explosion. The intensity or loudness of sound diminishes in the same proportion. We express this law by saying that the intensity of the sound varies inversely as the square of the distance.

Let us look at the matter in another light. The mechanical effect of a ball striking a target depends on two things—the weight of the ball, and the velocity with which it moves. The effect is proportional to the weight simply; but it is proportional to the square of the velocity. The proof of this is easy, but it belongs to ordinary mechanics rather than to our present subject. Now what is true of the cannon-ball striking a target is also true of an air-particle striking the tympanum of the ear. Fix your attention upon a particle of air as the sound-wave passes over it; it is urged from its position of rest toward a neighbor particle, first with an accelerated motion, and then with a retarded one. The force which first urges it is opposed by the resistance of the air, which finally stops the particle and causes it to recoil. At a certain point of its excursion the velocity of the particle is its maximum. The intensity of the sound is proportional to the square of this maximum velocity.

The distance through which the air-particle moves to and fro, when the sound-wave passes it, is called the amplitude of the vibration. The intensity of the sound is proportional to the square of the amplitude.

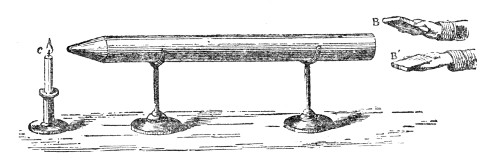

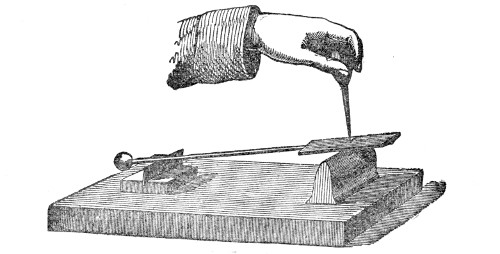

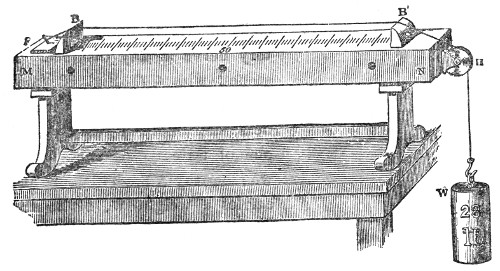

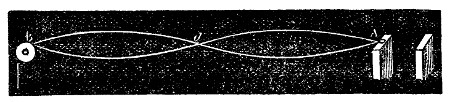

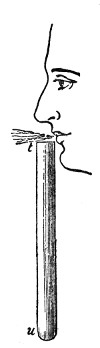

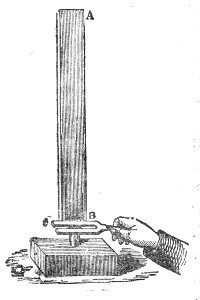

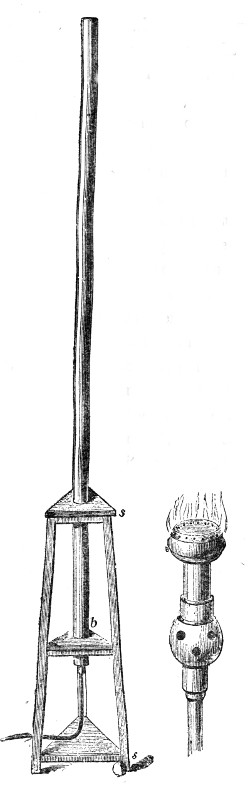

§ 4. Confinement of Sound-waves in Tubes

This weakening of the sound, according to the law of inverse squares, would not take place if the sound-wave were so confined as to prevent its lateral diffusion. By sending it through a tube with a smooth interior surface we accomplish this, and the wave thus confined may be transmitted to great distances with very little diminution of intensity. Into one end of this tin tube, fifteen feet long, I whisper in a manner quite inaudible to the people nearest to me, but a listener at the other end hears me distinctly. If a watch be placed at one end of the tube, a person at the other end hears the ticks, though nobody else does. At the distant end of the tube is now placed a lighted candle, c, Fig. 5. When the hands are clapped at this end, the flame instantly ducks down at the other. It is not quite extinguished, but it is forcibly depressed. When two books, B B′, Fig. 5, are clapped together, the candle is blown out.14 You may here observe, in a rough way, the speed with which the sound-wave is propagated. The instant the clap is heard the flame is extinguished. I do not say that the time required by the sound to travel this tube is immeasurably short, but simply that the interval is too short for your senses to appreciate it.

Fig. 5.

That it is a pulse and not a puff of air is proved by filling one end of the tube with the smoke of brown paper. On clapping the books together no trace of this smoke is ejected from the other end. The pulse has passed through both smoke and air without carrying either of them along with it.

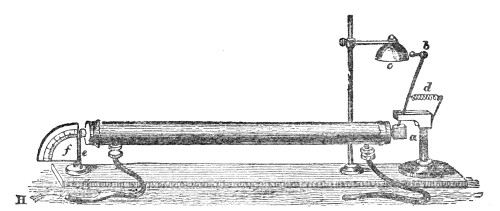

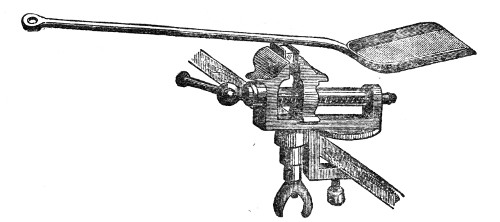

An effective mode of throwing the propagation of a pulse through air has been devised by my assistant. The two ends of a tin tube fifteen feet long are stopped by sheet India-rubber stretched across them. At one end, e, a hammer with a spring handle rests against the India-rubber; at the other end is an arrangement for the striking of a bell, c. Drawing back the hammer e to a distance measured on the graduated circle and liberating it, the generated pulse is propagated through the tube, strikes the other end, drives away the cork termination a of the lever a b, and causes the hammer b to strike the bell. The rapidity of propagation is well illustrated here. When hydrogen (sent through the India-rubber tube H) is substituted for air the bell does not ring.

Fig. 6.

The celebrated French philosopher, Biot, observed the transmission of sound through the empty water-pipes of Paris, and found that he could hold a conversation in a low voice through an iron tube 3,120 feet in length. The lowest possible whisper, indeed, could be heard at this distance, while the firing of a pistol into one end of the tube quenched a lighted candle at the other.

§ 5. The Reflection of Sound. Resemblances to Light

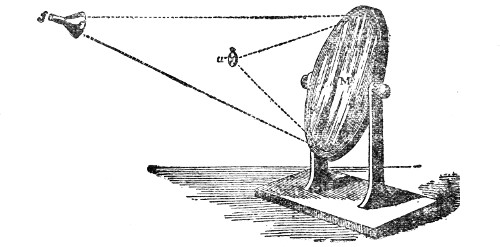

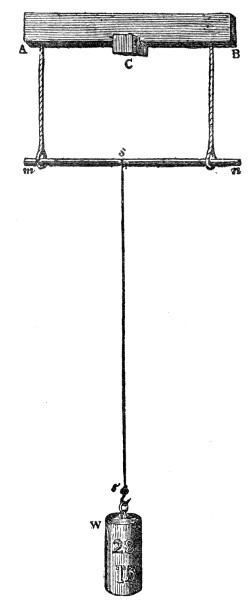

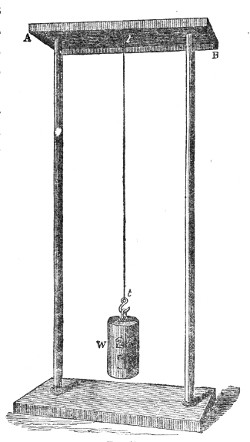

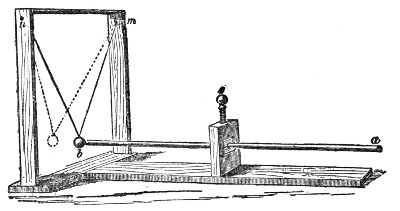

The action of sound thus illustrated is exactly the same as that of light and radiant heat. They, like sound, are wave-motions. Like sound they diffuse themselves in space, diminishing in intensity according to the same law. Like sound also, light and radiant heat, when sent through a tube with a reflecting interior surface, may be conveyed to great distances with comparatively little loss. In fact, every experiment on the reflection of light has its analogy in the reflection of sound. On yonder gallery stands an electric lamp, placed close to the clock of this lecture-room. An assistant in the gallery ignites the lamp, and directs its powerful beam upon a mirror placed here behind the lecture-table. By the act of reflection the divergent beam is converted into this splendid luminous cone traced out upon the dust of the room. The point of convergence being marked and the lamp extinguished, I place my ear at that point. Here every sound-wave sent forth by the clock and reflected by the mirror is gathered up, and the ticks are heard as if they came, not from the clock, but from the mirror. Let us stop the clock, and place a watch w, Fig. 7, at the place occupied a moment ago by the electric light. At this great distance the ticking of the watch is distinctly heard. The hearing is much aided by introducing the end f of a glass funnel into the ear, the funnel here acting the part of an ear-trumpet. We know, moreover, that in optics the positions of a body and of its image are reversible. When a candle is placed at this lower focus, you see its image on the gallery above, and I have only to turn the mirror on its stand to make the image of the flame fall upon any one of the row of persons who occupy the front seat in the gallery. Removing the candle, and putting the watch, w, Fig. 8, in its place, the person on whom the light falls distinctly hears the sound. When the ear is assisted by the glass funnel, the reflected ticks of the clock in our first experiment are so powerful as to suggest the idea of something pounding against the tympanum, while the direct ticks are scarcely if at all, heard.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 8.

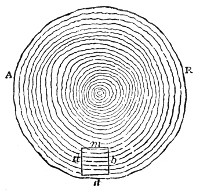

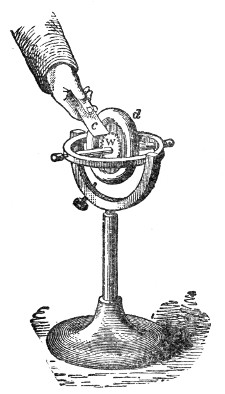

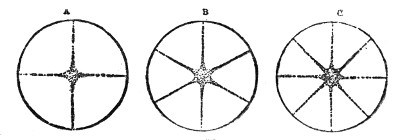

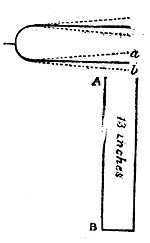

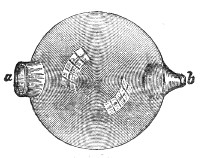

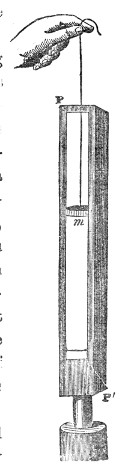

One of these two parabolic mirrors, n n′, Fig. 9, is placed upon the table, the other, m m′, being drawn up to the ceiling of this theatre; they are five-and-twenty feet apart. When the carbon-points of the electric light are placed in the focus a of the lower mirror and ignited, a fine luminous cylinder rises like a pillar to the upper

Curved roofs and ceilings and bellying sails act as mirrors upon sound. In our old laboratory, for example, the singing of a kettle seemed, in certain positions, to come, not from the fire on which it was placed, but from the ceiling. Inconvenient secrets have been thus revealed, an instance of which has been cited by Sir John Herschel.16 In one of the cathedrals in Sicily the confessional was so placed that the whispers of the penitents were reflected by the curved roof, and brought to a focus at a distant part of the edifice. The focus was discovered by accident, and for some time the person who discovered it took pleasure in hearing, and in bringing his friends to hear, utterances intended for the priest alone. One day, it is said, his own wife occupied the penitential stool, and both he and his friends were thus made acquainted with secrets which were the reverse of amusing to one of the party.

When a sufficient interval exists between a direct and a reflected sound, we hear the latter as an echo.

Sound, like light, may be reflected several times in succession, and, as the reflected light under these circumstances becomes gradually feebler to the eye, so the successive echoes become gradually feebler to the ear. In mountain regions this repetition and decay of sound produce wonderful and pleasing effects. Visitors to Killarney will remember the fine echo in the Gap of Dunloe. When a trumpet is sounded in the proper place in the Gap, the sonorous waves reach the ear in succession after one, two, three, or more reflections from the adjacent cliffs, and thus die away in the sweetest cadences. There is a deep cul-de-sac, called the Ochsenthal, formed by the great cliffs of the Engelhörner, near Rosenlaui, in Switzerland, where the echoes warble in a wonderful manner.

The sound of the Alpine horn, echoed from the rocks of the Wetterhorn or the Jungfrau, is in the first instance heard roughly. But by successive reflections the notes are rendered more soft and flute-like, the gradual diminution of intensity giving the impression that the source of sound is retreating further and further into the solitudes of ice and snow. The repetition of echoes is also in part due to the fact that the reflecting surfaces are at different distances from the hearer.

In large, unfurnished rooms the mixture of direct and reflected sound sometimes produces very curious effects. Standing, for example, in the gallery of the Bourse at Paris, you hear the confused vociferation of the excited multitude below. You see all the motions—of their lips as well as of their hands and arms. You know they are speaking—often, indeed, with vehemence—but what they say you know not. The voices mix with their echoes into a chaos of noise, out of which no intelligible utterance can emerge. The echoes of a room are materially damped by its furniture. The presence of an audience may also render intelligible speech possible where, without an audience, the definition of the direct voice is destroyed by its echoes. On the 16th of May, 1865, having to lecture in the Senate House of the University of Cambridge, I first made some experiments as to the loudness of voice necessary to fill the room, and was dismayed to find that a friend, placed at a distant part of the hall, could not follow me because of the echoes. The assembled audience, however, so quenched the sonorous waves that the echoes were practically absent, and my voice was plainly heard in all parts of the Senate House.

Sounds are also said to be reflected from the clouds. Arago reports that, when the sky is clear, the report of a cannon on an open plain is short and sharp, while a cloud is sufficient to produce an echo like the rolling of distant thunder. The subject of aërial echoes will be subsequently treated at length, when it will be shown that Arago’s conclusion requires correction.

Sir John Herschel, in his excellent article “Sound,” In the “Encyclopædia Metropolitana,” has collected with others the following instances of echoes. An echo in Woodstock Park repeats seventeen syllables by day and twenty by night; one, on the banks of the Lago del Lupo, above the fall of Terni, repeats fifteen. The tick of a watch may be heard from one end of the abbey church of St. Albans to the other. In Gloucester Cathedral, a gallery of an octagonal form conveys a whisper seventy-five feet across the nave. In the whispering-gallery of St. Paul’s, the faintest sound is conveyed from one side to the other of the dome, but is not heard at any intermediate point. At Carisbrook Castle, in the Isle of Wight, is a well two hundred and ten feet deep and twelve wide. The interior is lined by smooth masonry; when a pin is dropped into the well it is distinctly heard to strike the water. Shouting or coughing into this well produces a resonant ring of some duration.17

§ 6. Refraction of Sound

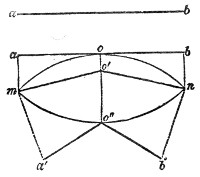

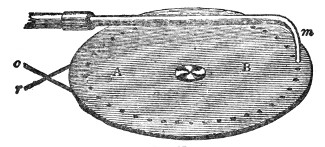

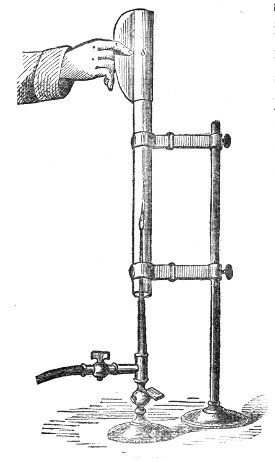

Fig. 10.

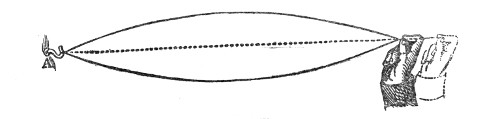

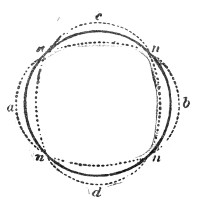

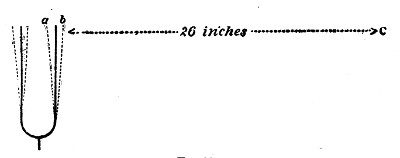

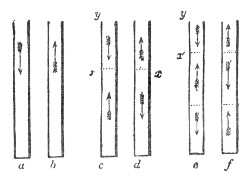

Another important analogy between sound and light has been established by M. Sondhauss.18 When a large lens is placed in front of our lamp, the lens compels the rays of light that fall upon it to deviate from their direct and divergent course, and to form a convergent cone behind it. This refraction of the luminous beam is a consequence of the retardation suffered by the light in passing through the glass. Sound may be similarly refracted by causing it to pass through a lens which retards its motion. Such a lens is formed when we fill a thin balloon with some gas heavier than air. A collodion balloon, B, Fig. 10, filled with carbonic-acid gas, the envelope being so thin as to yield readily to the pulses which strike against it, answers the purpose.19 A watch, w, is hung up close to the lens, beyond which, and at a distance of four or five feet from the lens, is placed the ear, assisted by the glass funnel f f′. By moving the head about, a position is soon discovered in which the ticking is particularly loud. This, in fact, is the focus of the lens. If the ear be moved from this focus the intensity of the sound falls; if, when the ear is at the focus, the balloon be removed, the ticks are enfeebled; on replacing the balloon their force is restored. The lens, in fact, enables us to hear the ticks distinctly when they are perfectly inaudible to the unaided ear.

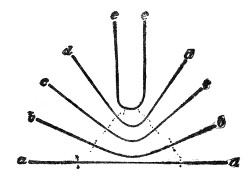

How a sound-wave is thus converged may be comprehended by reference to Fig. 11. Let m o n o″ be a section of the sound-lens, and a b a portion of a sonorous wave approaching it from a distance. The middle point, o, of the wave first touches the lens, and is first retarded

§ 7. Diffraction of Sound: illustrations offered by great Explosions

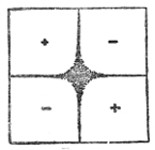

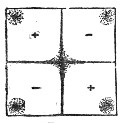

When a long sea-roller meets an isolated rock in its passage, it rises against the rock and embraces it all round. Facts of this nature caused Newton to reject the undulatory theory of light. He contended that if light were a product of wave-motion we could have no shadows, because the waves of light would propagate themselves round opaque bodies as a wave of water round a rock. It has been proved since his time that the waves of light do bend round opaque bodies; but with that we have nothing now to do. A sound-wave certainly bends thus round an obstacle, though as it diffuses itself in the air at the back of the obstacle it is enfeebled in power, the obstacle thus producing a partial shadow of the sound. A railway train passing through cuttings and long embankments exhibits great variations in the intensity of the sound. The interposition of a hill in the Alps suffices to diminish materially the sound of a cataract; it is able sensibly to extinguish the tinkle of the cowbells. Still the sound-shadow is but partial, and the marker at the rifle-butts never fails to hear the explosion, though he is well protected from the ball. A striking example of this diffraction of a sonorous wave was exhibited at Erith after the tremendous explosion of a powder magazine which occurred there in 1864. The village of Erith was some miles distant from the magazine, but in nearly all cases the windows were shattered; and it was noticeable that the windows turned away from the origin of the explosion suffered almost as much as those which faced it. Lead sashes were employed in Erith Church, and these, being in some degree flexible, enabled the windows to yield to pressure without much fracture of the glass. As the sound-wave reached the church it separated right and left, and, for a moment, the edifice was clasped by a girdle of intensely compressed air, every window in the church, front and back, being bent inward. After compression, the air within the church no doubt dilated, tending to restore the windows to their first condition. The bending in of the windows, however, produced but a small condensation of the whole mass of air within the church; the recoil was therefore feeble in comparison with the pressure, and insufficient to undo what the latter had accomplished.

§ 8. Velocity of Sound: relation to Density and Elasticity of Air

Two conditions determine the velocity of propagation of a sonorous wave; namely, the elasticity and the density of the medium through which the wave passes. The elasticity of air is measured by the pressure which it sustains or can hold in equilibrium. At the sea-level this pressure is equal to that of a stratum of mercury about thirty inches high. At the summit of Mont Blanc the barometric column is not much more than half this height; and, consequently, the elasticity of the air upon the summit of the mountain is not much more than half what it is at the sea-level.

If we could augment the elasticity of air, without at the same time augmenting its density, we should augment the velocity of sound. Or, if allowing the elasticity to remain constant we could diminish the density, we should augment the velocity. Now, air in a closed vessel, where it cannot expand, has its elasticity augmented by heat, while its density remains unchanged. Through such heated air sound travels more rapidly than through cold air. Again, air free to expand has its density lessened by warming, its elasticity remaining the same, and through such air sound travels more rapidly than through cold air. This is the case with our atmosphere when heated by the sun.

The velocity of sound in air, at the freezing temperature, is 1,090 feet a second.

At all lower temperatures the velocity is less than this, and at all higher temperatures it is greater. The late M. Wertheim has determined the velocity of sound in air of different temperatures, and here are some of his results:

Temperature of air

Velocity of sound

0·5°

centigrade

1,089 feet

2·10

”

1,091 ”

8·5

”

1,109 ”

12·0

”

1,113 ”

26·6

”

1,140 ”