автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Natural History of the Varieties of Man

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

THE

NATURAL HISTORY

OF

THE VARIETIES OF MAN.

[Pg ii] [Pg iii]

THE NATURAL HISTORY

OF THE VARIETIES OF MAN.

BY

ROBERT GORDON LATHAM, M.D., F.R.S.,

LATE FELLOW OF KING'S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE;

ONE OF THE VICE-PRESIDENTS OF THE ETHNOLOGICAL SOCIETY, LONDON;

CORRESPONDING MEMBER TO THE ETHNOLOGICAL SOCIETY,

NEW YORK, ETC.

LONDON:

JOHN VAN VOORST, PATERNOSTER ROW.

M.D.CCCL.

LONDON:

Printed by S. & J. Bentley and Henry Fley,

Bangor House, Shoe Lane.

TO

EDWIN NORRIS, Esq.,

OF THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY,

TO WHOSE VALUABLE INFORMATION AND SUGGESTIONS

MANY OF THE STATEMENTS AND OPINIONS OF THE PRESENT VOLUME

OWE THEIR ORIGIN,

The following Pages are Inscribed,

BY HIS FRIEND,

THE AUTHOR.

London, July 25th, 1850.

[Pg vi] [Pg vii]

PREFACE.

If the simple excellence of a book were a sufficient reason for making it the only one belonging to the sciences which it professed to illustrate, few writers would be desirous of attempting a systematic work upon the Natural History of their species, after the admirable Physical History of Mankind, by the late and lamented Dr. Prichard,—a work which even those who are most willing to defer to the supposed superior attainments of Continental scholars, are not afraid to place on an unapproached eminence in respect to both our own and other countries. The fact of its being the production of one who was at one and the same time a physiologist amongst physiologists, and a scholar amongst scholars, would have made it this; since the grand ethnological desideratum required at the time of its publication, was a work which, by combining the historical, the philological, and the anatomical methods, should command the attention of the naturalist, as well as of the scholar. Still it was a work of a rising rather than of a stationary science; and the very stimulus which it supplied, created and diffused a spirit of investigation, which—as the author himself would, above all men, have desired—rendered subsequent investigations likely to modify the preceding ones. A subject that a single book, however encyclopædic, can represent, is scarcely a subject worth taking up in earnest.

Besides this, there are two other reasons of a more special and particular nature for the present addition to the literature of Ethnology.

I. For each of the great sections of our species, the accumulation of facts, even in the eleventh hour, has out-run the anticipations of the most impatient; indeed so rapidly did it take place during the latter part of Dr. Prichard's own lifetime, that the learning which he displays in his latest edition, is, in its way, as admirable as the bold originality exhibited in the first sketch of his system, published as early as 1821; rather in the shape of a university thesis than of a full and complete production. Thus—

For Asia, there are the contributions of Rosen to the philology of Caucasus; without which (especially the grammatical sketch of the Circassian dialects) the present writer would have considered his evidence as disproportionate to his theory. Then, although matters of Archæology rather than of proper Ethnography, come in brilliant succession, the labours of Botta, Layard, and Rawlinson, on Assyrian antiquity, to which may be added the bold yet cautious criticism and varied observations of Hodgson, illustrating the obscure Ethnology of the Sub-Himalayan Indians, and preeminently confirmatory of the views of General Briggs and others as to the real affinities of the mysterious hill-tribes of Hindostan. Add to these much new matter in respect to the Indo-Chinese frontiers of China, Siam, and the Burmese Empire; and add to this the result of the labours of Fellowes, Sharpe, and Forbes, upon the monuments and language of Asia Minor. I do not say that any notable proportion of these latter investigations have been incorporated in the present work; their proper place being in a larger and more discursive work. Nevertheless, they have helped to determine those results to the general truth of which the present writer commits himself.

Africa has had a bright light thrown over more than one of its darkest portions by Krapff for the eastern coast, by Dr. Beke for Abyssinia, by the Tutsheks for the Gallas and Tumalis, by the publications of the Ethnological Society of Paris, and the researches of the American and English Missionaries for many other of its ill-understood and diversified populations, especially those to the south and west.

The copious extract from Mr. Jukes's Voyage of the Fly, show at once how much has been added; yet, at the same time, how much remains to be learned in respect to our knowledge of New Guinea; whilst the energy of the Rajah Brooke has converted Borneo, from a terra incognita, into one of the clear points of the ethnological world.

In South America, although many of the details of Sir Robert Schomburgk were laid before the world previous to the publication of the fifth volume of the Physical History, many of them, though now published, were at that time still in manuscript.

The great field, however, has been the northern half of the New World; and the researches which have illustrated this have illustrated Polynesia and Africa as well. What may be called the personal history of the United States Exploring Expedition, was published in 1845. The greatest mass, however, of philological data ever accumulated by a single enquirer—the contents of Mr. Hale's work on the philology of the voyage—is recent. The areas which this illustrates are the Oregon territory and California; and the proper complements to it are Pickering's work on the Races of Man, the Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, and the last work of the venerable Gallatin on the Semi-civilized nations of America.

Surely these are elements pregnant with modifying doctrines!

II. For each of the great sections of our species, the present classification presents some differences, which if true, are important. Whether such novelties (so to say) are of a value at all proportionate to that of the fresh data, is a matter for the reader rather than the writer to determine—the latter is satisfied with indicating them. The extension of the Seriform group, so as to include the Caucasian Georgians and Circassians on the one side, and the Indians of Hindostan on the other; the generalization of the term Oceanic so as to include the Australians and Papuans—the definitude given to the Micronesian origin of the Polynesians—the new distribution of the Siberian Samöeids, Yeniseians, and Yukahiri—the formation of the class of Peninsular Mongolidæ, so as to affiliate the Americans (previously recognised as fundamentally of one and the same stock) with the north-eastern Asiatics—the sequences in the way of transition from the Semitic Arab to the Negro—the displacement of the Celtic nations, and the geographical extension given to the original Slavonians, are points for which the present writer is responsible; not, however, without previous minute investigation. The proofs thereof lie in tables of vocabularies, analyses of grammars, and ethnological reasonings, far too elaborate to be fit for aught else than a series of special monographs; not for a general view of the human species, as classified according to its varieties.

This classification is the chief end of his work; and, more than anything else, it is this attempt at classification which has given a subordinate position to certain other departments of his subject. Where such is not the case, one of three reasons stands in its place to account for the matters enlarged upon, apparently at the expense of others.

1. The novelty of the information acquired.

2. The extent to which the subject has been previously either overlooked or thrown in the back-ground.

3. And, finally (though perhaps the plea is scarcely a legitimate one), the degree of attention which has been paid to the particular question by its expositor.

London, July 25th, 1850.

[Pg xii] [Pg xiii]

BIBLIOGRAPHY.

Notice of the chief works either used as authorities, and not particularly quoted, or else illustrative of certain portions of the subject.

Arnold.—History of Rome—Early Italian nations.

Adelung (Vater).—The Mithridates—Generally.

Baer's Beyträge, &c.—For Russian America.

Bartlett.—Report upon the present state of Ethnology. New York.

Beke.—Papers in the Transactions of the Philological and Geographical Societies—Abyssinia.

Bopp.—Vergleichende Grammatik, &c., other works.

Brooke (Keppell and Marryat).—Borneo.

Brown.—Papers in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, iv. 2.—The tribes about Manipur.

Balbi.—Atlas Ethnologique.

Bunsen.—Ægypt's Place in Universal History.

Catlin.—American Indians.

Crawford's.—Embassy to Ava, and Papers read before the Ethnological Society and the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

Dennis.—Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria.

D'Orbigny.—Homme Americain—South America. The chief authority.

Ellis.—History of Madagascar.

Ermann.—Reise in Siberian.

Fellowes, Sir C.—Travels in Lycia.

Forbes (and Spratt's), Professor E.—Ditto.

Gaimard (and Quoy).—Zoology of the Voyage de l'Astrolabe—The Papuas, Micronesians, &c.

Gallatin.—Papers in the Archæologia Americana, and the Transactions of the Ethnological Society, New York.

Grimm.—Deutsche Grammatik, Deutsche Sprache, &c.

Grote.—History of Greece—Pelasgians and other early nations.

Hodgson.—On the Kocch, Bodo, and Dhimál. Papers in the Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Bengal—Indispensable for the Sub-Himalayan Indians.

Hales.—Philology of the United States Exploring Expedition—Oregon, California, Polynesia, Australia, Africa.

Humboldt, A.—Personal Narrative—Indians of the Orinoco.

Humboldt, W.—Über die Kawisprachi—Java, and the influence of the Indian upon the Malay stock, &c.

Jukes.—Voyage of the Fly—- New Guinea.

Kemble.—The Anglo-Saxons in England.

Krapff.—MS. vocabularies of the Pocomo and other languages of Eastern Africa.

Klaproth.—Asia Polyglotta, Sprachatlas, &c.—The chief authorities for Caucasus and Siberia.

Lesson.—Mammologie.—Classification of Man as a Mammal. Zoology of the Uranie and Physicienne—Micronesia, &c.

Leyden.—Asiatic Researches—For the Indo-Chinese Languages.

Layard.—Antiquities of Assyria.

Müller.—Die Ugrischen Völker—The Ugrian Mongolidæ.

Marsden's Sumatra.

Mallat.—Description des Isles Philippines.

Morton.—Crania Americana, Crania Ægyptiaca, &c.

Newbold.—Malacca Settlements.

Niebuhr.—Roman History—Ancient Nations of Italy, Etruscans, Pelasgi.

Newman (Francis).—Berber Grammar. Paper in the Philological Transactions. Hebrew Monarchy.

Prichard.—Physical History of Mankind. Eastern origin of the Celtic Nations.

Prescott.—History of Mexico, Peru.

Pickering.—The Races of Men. See Hales and Wilkes.

Quoy (and Gaimard).—Zoology of the Astrolabe—Papuans and Micronesians.

Retzius.—Papers in the Literary Transactions of Stockholm.

Rosen.—On the Languages of Caucasus.

Rühs.—Finnland und seine Einwohner.

Raffles.—- History of Java.

Renouard.—Abstract of Spix and Martius on the Indians of Brazil. Transactions of the Royal Geographical Society.

Rüppell.—Reise in Kordofan.

Schomburgk, Sir R.—Transactions of the Geographical, Ethnological and Philological Societies—British Guiana.

Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge.—(Squier and Davis.)—North American Archæology.

Scouler, Dr.—Papers in the Transactions of the Geographical and Ethnological Societies.—Oregon and the Hudson's Bay Territory.

Stockfleth.—Om Finnerne—Om Quänerne.—The Laplanders, and Finlanders of Scandinavia.

Sharpe.—History of Ægypt.

Sharpe (Dan.).—On the Lycian Inscriptions—Transactions of the Philological Society.

Spratt (and Forbes).—Travels in Lycia.

Transactions of the Ethnological Societies of London—Paris—New York.

Wilson, H. H.—Ariana Antiqua, &c.

Wilkes.—United States Exploring Expedition.

Zeuss.—Die Deutschen und die Nachbarstämme.

[Pg xvi] [Pg xvii]

EXPLANATION OF PLATES.

Fig. page1.

A Yakut. From Von Middendorf (

Travels in Siberia)

12.

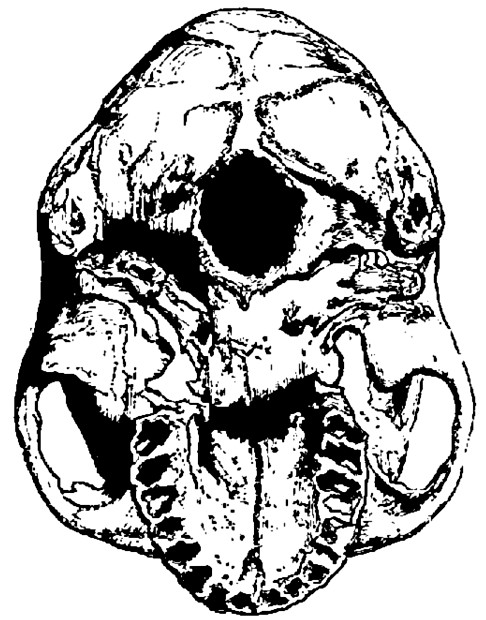

Skull of an Eskimo. From Prichard's Physical History of Mankind

53.

Skull of one of Napoleon's Guards killed at Waterloo.

Ibid.

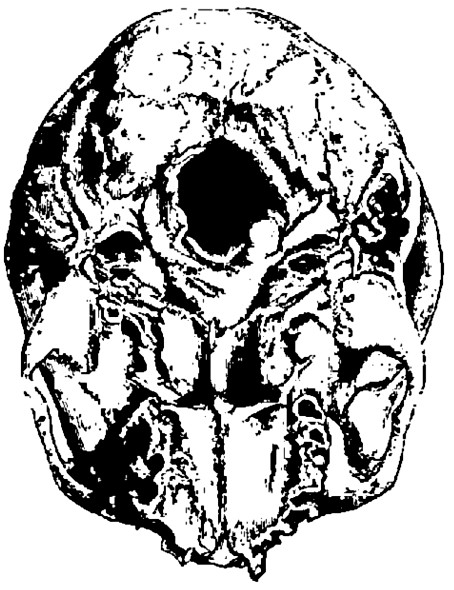

54.

Skull of a Creole Negro.

Ibid.

65.

A Yakut Female. From Von Middendorf

946, 7.

Papuan skulls. From the Voyage sur L'Uranie et La Physicienne

2138.

A Native of Van Diemen's Land. Drawn by Campbell De Morgan, Esq., from a cast belonging to the Ethnological Society

2459.

Samöeid Man. From Von Middendorf

26810.

Ground-plan of embankments in Ohio. From the Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge

36011.

Ground-plan, &c., in Wisconsin.

Ibid.

36112.

Antiquities from the Tumali of the Valley of the Mississippi.

Ibid.

36213.

Casa Grande. From a Treatise of Mr. Squier's upon the Ethnology of California and New Mexico

38814.

A Patagonian Female. From a Treatise of Professor Retzius on the Patagonians

41715.

Fac-simile of a Vei MS., in the possession of the Royal Geographical Society, taken by E. Norriss, Esq., F.A.S.

47416.

Arrow-headed Persian character. From Rawlinson. Transactions of Asiatic Society

52217.

Tuarick Alphabet. From Richardson

52318.

Specimen of the Cherokee syllabic alphabet. From a Cherokee Newspaper

52419.

Sub-Himalayan Indians. From Hodgson's Kocch, Bodo, and Dhimál

548[Pg xviii]

[Pg xix]

CONTENTS.

PAGE

Explanation of Terms

1Terms descriptive of differences in the way of physical conformation

2Typical, sub-typical, transitional, quasi-transitional

7Terms descriptive of differences in the way of language

9Terms descriptive of differences in social civilization

12The primary varieties of the human race

13PART I.

MONGOLIDÆ

15-

462A.

Altaic Mongolidæ 15-

106Seriform Altaic Mongolidæ

15-

60Chinese

16Tibetans

18Anamese

20Siamese

21Kambojians

22Burmese

23Môn

23Si-Fan

24Miaou-tse

25Lolos, &c.

25-

34Garo

34Brown's Tables

36Dhimál and Bodo

37-

53Tribes of Sikkim and Nepaul

53Antiquity of the Chinese civilization—how far indisputable

55-

60Turanian Altaic Mongolidæ

61-

106Mongolians

63-

73Tungús

74Turks

75-

95Ugrians

95-

106Voguls

96Permians

97Tcheremiss

99Finlanders

99Esthonians

101Laplanders

101Hungarians

101B.

Dioscurian Mongolidæ 107-

128Georgians

112Lesgians, Mizjeji, Irôn

115Ossetic grammar

116Circassians

119Circassian grammar

120Table of comparison between the Dioscurian and Seriform languages

123C.

Oceanic Mongolidæ 129-

264Amphinesians

133-

210Protonesians

133-

183Malacca

133Sumatra

137Mythology of the Battas

143Malay characteristics

147Java

152The Teng'ger Mountaineers

153Bali, &c.

158Languages between Sumbawa and Australia

158Timor

160Timor Laut

161The Serwatty and Ki Islands

161The Arru Isles

162Borneo

163-

169Celebes

169Bugis constitution

170The Moluccas, &c.

175The Philippines

176Philippine Blacks

177—————— languages

178Extent of Hindu influences

178Remains of original mythology

179Formosa

182Polynesians

183-

210Micronesians

186-

191Lord North's Island

186Sonsoral, The Pelews

187The Mariannes

188Carolines

189Isles of Brown, &c.

190Proper Polynesians

191-

210The mythology

191-

195Navigators' Isles

195Tonga group

ibid.

Tahitian group

196Easter Island

197The Marquesas

198Sandwich Islands

198New Zealand, &c.

203Tikopia

204Questions connected with the Ethnology of Polynesia

205-

210Kelænonesians

210-

264Papuan Branch

211-

229Waigiú

212New Guinea

213Vanikoro, &c.

222Erromango

224Tanna, Annatom

225New Caledonia

ibid.

The Fiji Islanders

226Australian Branch

229-

246Australians

229-

245Tasmanians

244Andaman Islanders

246Nicobarians

247Origin of the Kelænonesians

250—————— Polynesians

253Ceremonial Language

262D.

Hyperborean Mongolidæ 265-

272Samöeids

266Yeniseians

268Yukahiri

269Table of languages

270-

272E.

Peninsular Mongolidæ 273-

286Koreans

275Japanese

277Aino

281Koriaks

283Kamskadales

285F.

American Mongolidæ 287-

460Eskimo

288Kolúch

294Doubtful Kolúches

297The Nehanni

298Haidah, &c.

300Nutkans

301Athabaskans

302-

310Chippewyans, &c.

303Hare Indians

ibid.

Dog-ribs

ibid.

Carriers

304Sikani

306Southern Athabaskans

308Table of languages

308-

310Tsihaili

310-

316The Salish

311Kútanis

316Chinúks

317-

323The Lingua Franca

321Sahaptin, &c.

323-

328Algonkins

328Bethuck

330Shyennes

ibid.

Blackfoots

332Iroquois

ibid.Sioux

333Catawba, Woccoon

334Extinct tribes

ibid.

Cherokees

337Choctahs

ibid.

Uché, Coosadas, Alibamons

338Caddos

ibid.

Value of Classes

339The Natchez

340Taensas, &c.

341Ahnenin, Arrapahoes

344Riccarees and Pawnees

ibid.

The Paduca areas

345Wihinast

346Shoshonis, Cumanches

347Apaches

348Texian tribes

349-

351The unity or non-unity of the American populations

352-

380Opinions

352Vater's remark

354 Polysynthetic.—Philological paradox

356Grounds for disconnecting the Eskimo

357———————————————— Peruvians

ibid.

Archæology of the Valley of the Mississippi

359-

362American characteristics

363————— languages

365-

380Tables for simple comparison

366————— indirect

371Paucity of general terms

375Numerals

376Verb-substantive

378Negative points of agreement

ibid.

Positive

379The Californias

380-

395Description of a Casa Grande

388Pimos Indians

390Coco-Maricopas

394New Mexico

395-

398Tarahumara

398Casa Grande

399Tepeguana, &c.

400Otomi

403-

408Supposed monosyllabic character of the language

404Tables

405Mexico

408The Maya

410Indians of the Isthmus

411——————— Andes (western)

412-

414Moluché, Puelché, Huilliché

415Conventional ethnological centre

418Charruas

420Indians of Moxos

424————— Chiquitos

425————— Chaco

428————— Brazil (

notGuarani)

429Warows

438Tarumas

439Wapityan, &c.

ibid.

Atures

440Maypure

441Achagua, Yarura, Ottomacas

442Chiricoas

ibid.

Guarani

443Caribs

445Their supposed North American origin

447Indians of the Eastern Andes

448Yuracares

ibid.

Apolistas

ibid.

Northern Indians of the Eastern Andes

450Reasons for not separating the Eskimo from the other Americans

452Reasons for not separating the Peruvians, &c.

454Classification of D'Orbigny

459G.

Indian Mongolidæ. 461-

468Tamulians

462Pulindas

463Rajmahali

464Brahúi

ibid.

Indo-Gangetic Indians

465Purbutti

466Cashmirian

467Cingalese

468Maldivians

ibid.ATLANTIDÆ

469A.

Negro Atlantidæ 471Woloffs

473Sereres

ibid.

Serawolli

ibid.

Mandingos

ibid.

The Vei alphabet

474Felúps, &c.

475Fantí, &c.

476The Ghá

ibid.

Whidah, Maha, Benin tribes

477Grebo, &c.

478The Yarriba

479The Tapua

ibid.

Haussa

ibid.

Fulahs

480Cumbri

ibid.

Sungai

481Kissour

ibid.

Bornú, &c.

ibid.

Begharmi

ibid.

Mandara

ibid.

Mobba

483Furians

ibid.

Koldagi

ibid.

Shilluk, &c.

ibid.

Qamamyl

484Dallas, &c.

ibid.

Tibboo

485Gongas

ibid.

B.

Kaffre Atlantidæ 487-

494Peculiarities of Kaffre language

487Western Kaffres

489Southern Kaffres

490Eastern Kaffres

ibid.

Kazumbi, Mazenas, &c.

491Pocomo, Wanika, Wakamba, &c.

492C.

Hottentot Atlantidæ 495-

498Hottentots

496Saabs

497Dammaras

ibid.

Overlapped peripheries

498D.

Nilotic Atlantidæ 499-

506Gallas

499Agows and Falasha

500Nubians

ibid.

Bishari

501The M'Kuafi, &c.

ibid.

E.

Amazirgh Atlantidæ 507, 508

F.

Ægyptian Atlantidæ 509, 510

G.

Semitic Atlantidæ 511Syrians

ibid.

Syriac literary influence

512Assyrians

ibid.

Babylonians

ibid.

Beni Terah

513Edomites

514Beni Israel

ibid.

Samaritans

ibid.

Jews

ibid.

Arabs

515Æthiopians

517Canaanites, &c.

518Malagasi

519Question to the single origin of alphabetical writing

520On the accumulation of certain climatologic influences

524IAPETIDÆ

527A.

Occidental Iapetidæ 528Kelts

ibid.

B.

Indo-Germanic Iapetidæ 531European Class

531-

543Goths

531-

535Teutons

532-

534Mœso-Goths

ibid.

High Germans

533Franks

ibid.

Low Germans

534Batavians

ibid.

Saxons

ibid.

Frisians

ibid.

Scandinavians

ibid.

Sarmatians

535-

541Lithuanians

536Slavonians

538Russians

ibid.

Servians

ibid.

Illyrians

539Bohemians (T`sheks)

ibid.

Poles

ibid.

Serbs

ibid.

Slavonians of the Germanic frontier

ibid.

Mediterranean Indo-Germans

541Hellenic branch

ibid.

Italian branch

542Iranian class

543The Sanskrit language

ibid.

Population of Persia

546Siaposh

547Lughmani

ibid.

Dardoh

ibid.

Wokhan

ibid.

[Pg xxviii]Armenians

549Iberians

550Finnic hypothesis

552Albanians

ibid.

Pelasgi

553Etruscans

554Populations of Asia Minor

555Hybridism

ibid.

PART II.

Apophthegms on the nature of the Science of Ethnology

559-

566dolikhokephalic

2nd. That not less than one-third of the words (and some of them the names of very simple ideas) are other than Turk.[29]

The Koibals are in all probability the most advanced of the Samöeids—being the owners of herds, flocks, horses, and camels(?).

And first, as to the area over which these remains are spread.—West of the Rocky Mountains,[136] the most that has hitherto been found is a few mounds, tumuli, or barrows. They will be called mounds. North, too, of the Great Lakes, the remains are but few, and imperfectly described. On Lake Pepin, on Lake Travers (in 46° N.L.), we find notices of them; so we do for the Missouri, as much as 1000 miles above its junction with the Mississippi. Eastward, they decrease as we approach the Atlantic; i.e. on the Atlantic aspects of Pennsylvania, New York, and Virginia, they become scarcer. They become scarce, too, on the other side of the River Sabine; not that they are wanting in Texas, but that they either fall off in number or change in character as we approach Mexico.

What was the civilization? what the tribes? It is best to express both these facts in as general a way as possible. The Casas Grandes represent the first. The Pimos Indians the second.

3. That an alphabet, however much it may differ from others in the arrangement of the lines and points which form its letters, is not to be considered original if it has been framed within the literary period, and with a knowledge of previous ones—the idea of the analysis of a sentence into words, and of words into elementary articulations, being the really great achievement in the invention of an alphabet, and this, in such cases, not being original.

In justice to the classification of the so-called Indian Mongolidæ, I must here remark that the position of the Indo-Gangetic portion of it as Tamulian by no means stands or falls with the relation of its languages to the Sanskrit; since, even if an undeniably Sanskrit origin were proved for them, the evidence of physical form would still justify the inquirer in asking whether they might not still be Tamulians whose language had been replaced by an imported one.

Previous to entering upon the details connected with the varieties, and affinities of the human species, it is advisable to explain the meaning and full import of certain terms that are likely to be of frequent occurrence. It is only, however, so far as an explanation is required, that any remarks will be made. The questions themselves, although necessary and preliminary, are well capable of being isolated from the properly descriptive portions of the subject, and of forming separate sections of ethnological science; a separation which is fully justified by their great range and extent.

Upon these distinctions are founded the following forthcoming terms: occipito-frontal diameter, parietal diameter, occipito-frontal[5] profile, frontal profile, nasal profile, maxillary profile, zygomatic development.

Area.—Hindustan, Cashmere, Ceylon, the Maldives and Laccadives, part of Beloochistan.

Conterminous with the Iapetidæ(?) of Beloochistan and Cabúl, the Seriform tribes of Little Tibet and the Sub-Himalayan countries of Bisahur, Nepaul, Sikkim, the Koch and Bodo country, the Garo country, Assam, and Aracan.

Political relations.—Chiefly either English or Independent. Partially French, Dutch, Danish, and Portuguese.

Religions.—Brahminism, Buddism, with a variety of eclectic and intermediate creeds, Parsi fireworship, Mahometanism, with creeds intermediate to it and Brahminism or Buddhism, Paganism, fragments or rudiments of Judaism and Christianity.

Physical condition of country.—Chiefly intertropical, with a. Fluviatile alluvia (deltas of the Indus and Ganges). b. Mountain and forest ranges (the Ghants, &c.). c. Sandy steppes (Ajmeer and the Punjaub). d. Portions of the Himalayan range (Cashmere).

Social and civilizational influences.—a. Ante-Mahometan; Persian, and Greek. b. Mahometan; Arabic, Persian, Turk, Mongol. c. Recent; Portuguese, Dutch, French, Danish, British.

Physical conformation.—The two extreme forms.—a. Colour dark, or even black, skin coarse, nasal profile flattened, cheek-bones prominent, lips thick, hair coarse and generally straight, beard scanty, limbs oftener slender than massive, stature oftener short than tall.

b. Colour brunette, sometimes of great clearness and delicacy, skin delicate, nose aquiline, eyebrows arched and delicate, frontal profile perpendicular, cranium dolikhokephalic, zygomatic development moderate, lips thin, stature sometimes tall, limbs often powerful, the whole body being well-formed, even when not muscular, and the face oval, with regular and expressive features.

Habits.—Agricultural and industrial. More rarely pastoral. Sometimes predatory.

Nutrition.—Varied. Sometimes nearly wholly vegetable; sometimes almost exclusively animal.

Social constitution.—Castes; the higher the caste, the more predominant the second type of physical conformation.

Intermixture.—Arabs on the western, Malays, Indo-Chinese, on the eastern coast. In earlier time, Turanian Turks, Mongols, Scythians(?), Persians.

Emigrant and Indians.—1. The Gypsies. 2. Hindu traders in different parts of Asia.

Frontier.—Partly encroaching on that of the Sub-Himalayan Seriform tribes (i.e., in Kumaon, Gurhwhal, and Bisahur), partly receding, i.e. in Nepaul.

Antiquities.—Rock temples, tombs, columns, coins, inscriptions in the Pali. Ancient literature in the Sanskrit language.

Epochs.—1. Ante-historical Persian, i.e. the epoch of the introduction of the languages represented by the Sanskrit, and the germs of the Brahminical system. 2. Macedonian, from the time of Alexander to the breaking-up of the Indo-Bactrian kingdom. 3. Mahometan. 4. European.

Alphabets.—1. With the letters more square than round, manifestly derived from the Sanskrit. 2. With the letters more round than square, derived from the Sanskrit, but not so visibly as the former.

Divisions.—1. The Tamul. 2. The Pulinda. 3. The Brahúi. 4. The Indo-Gangetic. 5. The Purbutti. 6. The Cashmirian. 7. The Cingalese. 8. The Maldivian.

In the ethnology of Scandinavia—in the skilful and industrious hands of Retzius, Eschricht, Nilson, Kaiser, and others—Ugrian archæology, and Ugrian craniology, are preeminently prominent. The numerous barrows of Scandinavia are attentively studied; and observation has shown that the older the tomb, and the greater the proportion of instruments found within it not made of iron (but of greater antiquity than the art of forging that metal) the less dolikhokephalic, and the more brakhykephalic, (or Ugrian,) is the skull. Hence comes the inference that the southward extension of barrows, containing remains of the sort in question, is a measure of the southward extension of the Ugrian family.

I have begun with the nations and tribes represented by the Chinese, Tibetans, and Indo-Chinese, on the strength of the primitive condition of their languages. This represents the earliest known stage of human speech; by which I mean, not that it was spoken earlier than the other tongues of the world, but only that it has changed, or grown, more slowly. I should also add, that over and above the fact of these languages being destitute of true inflection, the separate words generally consist of only a single syllable. Hence the class has been called monosyllabic. This latter character, however, has no essential connection with the aptotic form. A language of dissyllables or trisyllables may, for any thing known to the contrary, be as destitute of inflections as a monosyllabic one. Still, it must be admitted that no such tongue has yet been discovered.

In physical conformation the Chinese have a yellow-brown complexion, a broad face, and a scanty beard, lank black hair, dark irides, and a stature below that of the European. This is what we expect, as part and parcel of the common Mongol characteristics. Harshness of feature they have in a less degree than the true Mongolians; a tendency to obesity in a greater. In this respect, they have been called Mongols softened down. This is what they really are. One point of physiognomy, however, is more peculiarly Chinese than aught else,—viz. the linear character, and oblique direction of the opening of the eyes. This is narrow, so that little of the eye is seen. It is also drawn upwards at its outer angle, and so becomes oblique in its position. Sometimes in addition to this the upper eyelid hangs heavy and tumid over the eyeball; and sometimes the skin forms a crescentic fold between the inner angle of the eye and the nose; as may be seen in individuals out of China, and which is not uncommon in England.

4.—The Bulti of Bultistan, or Little Tibet.—The most differential characteristic of the Bulti Tibetans, is that they are no Buddhists, but Mahometans, of the Shia persuasion, their conversion having come from Persia. It has been already stated that the Bulti enjoy a political independence.

Physical Appearance.—Like that of the Chinese, except that the average height is somewhat less. Upper extremities long, lower, short and stout. Form of the skull more globular than square. Eyelids less turned than that of the Chinese. Mouth large; lips prominent, but not thick; moustache more abundant than beard; beard scanty, though encouraged. Colour more yellow than either brown or blackish. Clothing abundant.—Finlayson from Prichard.

The Khamti.—In the North Eastern corner of Assam, the Khamti are conterminous with the Singpho, Mishimi, and Miri, and are traditionally reported to have emigrated from the head-waters of the Irawaddi. In physical appearance they are middle-sized, more resembling the Chinese than any tribe on the frontier. Perhaps, a shade darker in complexion. Their alphabet is Siamese; and their language, far north as it is spoken, when compared with the Siamese of Bankok, closely resembles that dialect. In Brown's[11] Vocabularies the proportion of words, similar or identical, in Khamti and Siamese, is 92 per cent.

The notices hitherto given have applied only to the great political divisions of the variety speaking monosyllabic languages; and have referred to nations of a known and similar degree of civilization. It would be an error, however, to suppose that they supply a complete enumeration. Hardly an empire mentioned will not exhibit some instance of a new series of phenomena standing over for investigation. The Chinese, the Burmese, and the Siamese, represent merely the dominant tribes of their several areas; those whereof the civilization and territorial power have given their possessors a certain degree of prominence in the history of the world. The intermixed tribes, sometimes imperfectly subdued, always imperfectly civilized, inhabiting barren tracts or mountain fastnesses, have a value in ethnology which they cannot command in history. In these we see the original substratum of the different national characters, as it may be supposed to have shown itself, before it was modified by foreign influences. In a more advanced stage of our knowledge, these tribes will probably be brought under one of the sub-divisions already noticed. At present, even when in some cases they may be so placed, it is best to take them in detail; premising that, the list does not pretend to be exhaustive, that, from the fluctuations of the geographical nomenclature, the same tribe may be mentioned twice over, and, lastly, that partly from imperfect knowledge, and partly from changes of locality, arising from migrations of the tribes themselves, the geographical position is, in many cases, difficult to fix.

We are now in that part of the Indian side of the Himalayan range, which lies between Assam on the east, and Sikkim on the west, and which is bounded on the north by Bhután. This is the area where the aboriginal Indian and the Tibetan most intermix.

2. The converted Kooch.—Residents, in contact with the Bodo and Dhimál, of the Sub-Himalayan range, between the north-west corner of Assam and Sikkim. The higher class of the converted Kooch are Brahminists: the lower Mahometans. Both call themselves Raibansi. The notice of the Kooch kingdom of Hájo, explains this term.

We know, too, (though in a less degree) what modifies language. New wants gratified by objects with new names, new ideas requiring new terms, increased intercourse between man and man, tribe and tribe, nation and nation, &c. do this; all (or nearly all) such changes being of a moral nature.

Persia.—By Persia, is meant the half-restored empire of the Kalifs, so that it includes the whole country from Bokhara to Arabia, from Samarcand to Bagdad. Holagou is the grandson identified with this series of conquests; which embrace Syria, Asia Minor, and Armenia, and do not embrace Ægypt. There the Mongolian was met and repulsed by the Mameluke.

The locality of the Yakuts is remarkable. It is that of a weak section of the human race, pressed into an inhospitable climate by a stronger one. Yet the Turks have ever been the people to displace others, rather than to be displaced themselves. On the other hand, the traditions of the country speak expressly to a southern origin.

1. Present distribution—continuous.—West and East—From Norway to the Yenisey. North and South (South-East)—From the North Cape to the Russian governments of Simbirsk, Saratof, and Astrakhan. The Volga south of its confluence with the Kama.

2. Isolated portion.—Hungary.

3. Ancient distribution.—Further southwards along the whole frontier, i.e., in Scandinavia, Russia, and Siberia. The Eastward extension probably less than at present.

4. As portions of a mixed population beyond their proper area—In Sweden and Norway.

Religion.—Lutheranism, Romanism, Greek Church, Imperfect Christianity, Shamanism.

Physical conformation.—Chief departure from the Mongol type, the frequency of blue eyes, and light (red) hair.

Conterminous with.—1. Goths of the Scandinavian group in Norway and Sweden; 2. Slavonians in Russia; 3. Lithuanians in Esthonia; 4, 5, 6. Turks, Yeniseians, and Tungús in Siberia. In Europe, in contact with the North Sea. East of Archangel, separated therefrom by the Samöeids.

- Divisions.—1. Trans-Uralian Ugrians.—Between the Ural Mountains and the Yenisey. Voguls and Ostiaks.

- 2. Permian Finns.—Permians, Siranians, Votiaks.

- 3. Finns of the Volga.—Morduins, Tcheremiss, Tshuvatsh.

- 4. Finlanders of Finland.

- 5. Esthonians of Esthonia.

- 6. Laplanders of Sweden and Finmark.

- 7. Majiars of Hungary.

The Voguls are very nearly on the low level of a tribe of fishers and hunters. Except towards the south, where they are partially Russianized, and where they have also partially adopted the manners of the Bashkirs, there is but little pasturage, and no agriculture. The horse is not in use amongst them—the rein-deer being the nearest approach to a domestic animal. Their tribute is paid in its skins.

For the metals, and agriculture, the terms are almost always native. Cheese, however, on the one side, and gold, tin, and lead, on the other, have Swedish names. So have oats and rye.

·Tibetan, shjanggu

2. The Orpelian settlement from China.—In the thirteenth century, according to those who are most willing to allow a comparatively high antiquity to Armenian literature, a work was composed in Armenian, by Stephen, Archbishop of Siounia. In this, it is stated that a noble family, called Ouhrbélêan, or Orpelian, entered Georgia, settled on the frontiers of Orpeth, and became the founders of one of the great families of Georgia; to which family the historian himself belonged. Finally, it is added, that this family came from Djenasdan or China. This is probably a mere tradition; one which, even if true, would denote an immigration wholly unconnected with the real ante-historical relations between Caucasus and the Seriform area.

As the single skull of the Georgian female did all the mischief in the physiological ethnography of Caucasus, an Irôn vocabulary has been the prime source of error in the way of its philology. Klaproth considered that the number of words common to the Irôn[40] and Persian languages was sufficient to place the former amongst the Indo-European languages. More than this, there were historical grounds for believing that the Irôn was the ancient language of Media[41]—also of the Alani of the later Roman empire. No man believed all this more than the present writer until the appearance of Rosen's sketch of the Irôn (Ossetic) grammar. He now believes that the Irôn is more Chinese than Indo-European.

Qus-inc`.

The declensional inflections are preeminently scanty. In English substantives there is a sign for the possessive case, and for none other. In Absné there is not even this—ab=father, ácĕ=horse; ab ácĕ=father's horse, (verbally, father horse). In expressions like these, position does the work of an inflection.

"The Papuan race exclusively possesses the islands on the north-east of Australia, namely, New Guinea with New Britain and New Ireland, the Solomon Islands, the islands called Tierra Austral del Espiritu Santo, and the New Hebrides, and New Caledonia. It extends also to the Feejee Islands, where it is more or less mingled with the Polynesian race, and where the language appears to be of Polynesian origin. It is probable that from New Caledonia proceeded the colony, or whatever it was, that reached Tasmania, and there mingled with the Australian race. To the westward of New Guinea scattered tribes, apparently of Papuan race, are said to occur in the interior of many islands as far west as that called Endé Flores or Mangeray, and as far north as the Philippine Islands. It has even been said that the Andaman Islands, in the Bay of Bengal, are inhabited by a people much resembling the Papuans, and I have been struck with the similarity of many of their customs to those which are said to characterize some of the wild hill tribes in the centre of India. I believe, however, that many of the stories of tribes of people being found in the various parts of the Archipelago, must be received with much caution, and that most of the wild people so described will be found, like the Dyaks of Borneo, or the wild tribes of the Malacca Peninsula, to be really of Polynesian race. A mingling of the Papuan race with the Australian, probably takes place at the present day in the neighbourhood of Torres Strait, but not, perhaps, to so great an extent as might be expected, for I am inclined to think that the Australians give way and retreat before the islanders. * * * * Whatever may have been the origin of the Polynesians, it is certainly most probable that their reason for going round these Papuan islands (whether from the east or west), and not taking possession of them, was the fact of their being previously inhabited by the Papuans."[86]

That an island so near as Formosa should have been so long unknown to the Chinese, surprises Klaproth; who reasonably thinks that it was known at an earlier period, but known under a different name. The more so, as the Pescadores islands, half-way between, are within sight of the mainland.

Dr. Prichard would study the three forms of Malay development in Sumatra, in Java, and in the Philippines. In Sumatra for the Mahometan aspect, in Java for the Indian, and in the Philippines for the phenomena of indigenous growth and progress. In the main, this view is a right one. A Philippine language, of all the Malay language, is the richest in inflections, perhaps also in vocables; and the Philippine civilization, as found by the first Spanish missionaries, was on a level with that of any other non-Mahometan or non-Indianized tribe. It was also essentially Malay. Marsden remarks upon the great similarity between the few facts known of the early Philippine Mythology and that of the Battas. So that thus far the Philippines are Malay; and Malay in its most developed form; also in its more indigenous form. Still they are not wholly Malay; at least their development is not wholly independent of extraneous influences. Though there is little about them Mahometan, their alphabet is Indian in origin.

Head-hunting.—No trophy is more honourable, either among the Battas of Sumatra, or the Dyaks of Borneo, than a human head; the head of a conquered enemy. These are preserved in the houses as tokens; so that the number of skulls is a measure of the prowess of the possessor. In tribes, where this feeling becomes morbid, no young man can marry before he has presented his future bride with a human head, cut off by himself. Hence, for a marriage to take place, an enemy must be either found or made. To this subject I shall return when treating of Borneo.

"Their language does not differ much from the Javan of the present day, though more gutturally pronounced. Upon a comparison of about a hundred words with the Javan vernacular two only were found to differ. They do not marry or intermix with the people of the low-lands, priding themselves on their independence and purity in this respect."

"We have rarely met with any Negrito language, in which many corrupt Polynesian words might not be detected. In those of New Holland or Australia, such a mixture is not found. Among them no foreign terms that connect them with the languages, even of other Papua or Negrito countries, can be discovered; with regard to the physical qualities of the natives, it is nearly superfluous to state, that they are Negritos of the most decided class."

Timor, and the Arru Islands bring us to Australia, and New Guinea, parts of Kelænonesia, or true Negrito areas. How far the transition from the Oceanic tribes of the Protonesian to the Oceanic tribes of the Negrito type, both in the way of language and physical conformation, is abrupt or gradual, is to be studied in the islands last enumerated. At present we will return to Java, and follow the Malay population in a different direction, i.e. from south to north, rather than from east to west.

The tribes described by Mr. Brooke are chiefly the Lundu, Sakarran, the Sarebas, the Suntah, Sow, Sibnow, Meri, Millanow, and Kayan; also the Bajow, or Sea-Gipsies, who live as wanderers (pilots or pirates, as the case may be) on the ocean, and are found on Borneo, the Sulu islands, Celebes, and elsewhere.

"The office itself is called 'Manang;' and no particular age is specified, the 'Manang' being young or old, as chance may determine. The present occupier of this important post became so when quite a child, and he is now well stricken in years, and much respected by his tribe."[58]

Divisions.—1. The southern island of Magindano, or Mindanao. 2. The northern island of Luçon, or Luçonia. 3. The Bissayan Archipelago between the two. Of this last, the most important islands are Mindoro, Samar, Leyte, Panay, and the Isola de Negros.

3. The Extent of Hindu influences.—These are less in the Philippines than in Celebes, and much less than in Java and Bali. Still the Philippines have a native alphabet, and this native alphabet has the same origin with the alphabets of Sumatra, Java, and Celebes; viz. the Hindu Devanagari.

The recognition of this conflict between the two probabilities, has determined me to consider the Micronesian Archipelago, as that part of Polynesia which is the part most likely to have been first peopled; and hence comes a reason for taking it first in order.

The paucity of quadrupeds, and the abundance of tropical vegetables is common to the Pelew Islands, and the whole of Polynesia. Hence, it is mentioned once for all. The chief exception, however, is an important one. The hog will be found to be partially distributed; and the partial character of its distribution has been one of the instruments of ethnological criticism (especially in the hands of the French naturalists), by means of which the order of succession in which the different islands have been peopled has been investigated.

Direction.—West to east.

Extent.—From 140° to 15° E. L. from Paris. Under 5° N. L.

Particular islands.—Lamoursek, Satawal, Faroilep (the most northern), Aurupig (the most southern).

Physical conformation of the natives.—Stature average, hair black, beard scanty, only in some cases thick, forehead narrow, eyes oblique, nose somewhat flattened, face broad, complexion clear yellow (citron), lightest in the case of the chiefs.—Lesson.

From the feeling of pedigree, and from the belief that the nobler families become spirits after death, we have the belief in ghosts, and the reverence for the dead. Whoever studies the details of the Polynesian creeds and traditions will find abundant instances of this; and in such detail they should be studied. To exhibit them (as has just been attempted) in a general point of view, can only be done by applying terms adapted to a different system, and, as such, only partially appropriate. It can only be done at the sacrifice of those special elements which give life and individuality to a description. Such, however, as it is, the previous sketch is the only one that could be admitted into a work like the present.

Synonym.—The Hapai Islands; the Friendly Islands.

ISLANDS.

POPULATION.

Eooa

200

Hapai

4,000

Vavao

4,000

Keppell's Islan

1,000

Boscawen's Islan

1,300

Tonga-tabú

8,000

Total

18,500

Said to be on the increase. Number of Christians, about 4,500.

Pantheon.—Múoi.—The Hotooas, Táli-y-tobú, Higooléo, Tooboo-toti, Alaivaloo, Ali-ali, Tangaloa—Tangaloa's sons, Toobó, and Váca-ácow-ooli, &c. Bolotoo=the Happy Island.

Term for

the Tonga

chiefs—

Egi.

"

"

councillors—

Mataboulai.

"

"

king—

How.

"

"

lower classes—

Mooa.

"

"

lowest—

Tooa.

Real or supposed peculiarities.—Infant sacrifices; the cutting off of a finger on the death of relatives; domestic architecture on a scale approaching that of Borneo. Remains of stone architecture; probably the tombs of the chiefs.

That they are not objects of worship is inferred from the extent to which they are neglected. When fallen, or broken they are not repaired; neither are they connected with the burial-places.

"Here," Sir G. Simpson continues, "is an average of one person under eighteen, to rather more than three persons above it—a state of things which would carry depopulation written on its very face, unless every creature, without exception, were to attain the good old age of seventy-five." To this we add a remark upon the bearing of the early period of marriages throughout Polynesia. Not one—but two—generations are included in the population under eighteen years; since before that time boys and girls have begun to have boys and girls of their own.

On the other hand, they use the bow and arrow, and raise cicatrices by burning—both of which habits are Kelænonesian.

Physical conformation.—Modified Amphinesian Negrito. Skin rough and harsh, black rather than brown or olive. Hair crisp, curly, frizzy, and woolly(?) rather than straight; black. Stature from five feet, or under, to six(?).

Languages.—Not generally admitted to contain a certain proportion of Malay words—but really containing it.

Distribution.—Wholly insular; islands often large.

Area.—New Guinea, New Ireland, Solomon's Isles, Louisiade, New Hebrides, New Caledonia, Australia, Tasmania.

Aliment.—Mammalian fauna considerable. In parts, deficient in ruminants and pachydermata.

Religion.—Paganism.

Social and physical development.—Maritime habits rare and partial. Industrial arts limited. Foreign influences of all sorts inconsiderable.

Divisions.—1. The Papua Branch. 2. The Australian Branch. 3. The Tasmanian Branch(?).

"The colour of the Feejeeans is a chocolate-brown, or a hue mid-way between the jet-black of the Negro, and the brownish yellow of the Polynesian. There are, however, two shades very distinctly marked, like the blonde and brunette complexions in the white race; besides all the intermediate gradations. In one of these shades the brown predominates, and in the other the copper. They do not belong to distinct castes or classes, but are found indiscriminately among all ranks and in all tribes. The natives are aware of the distinction, and call the lighter coloured people, Viti ndamundamu, "red Feejeeans;" but they do not seem to regard it as anything which requires or admits of explanation. These red-skinned natives must not be confounded with the Tonga-Viti, or individuals of mixed Tongan and Feejeean blood, of whom there are many on some parts of the group."

The probable source, however, of the Papuan population must be sought for in the parts about Gilolo. Here the distinction between those islands which constitute the more eastern and northern portions of the Moluccas, and those which are considered to belong to New Guinea, is difficult to be drawn. In Guebé, for instance, the natives are described by M. Freycinet as having flat noses and projecting lips. To this it may be added, that their colour is dark. On the other hand, however, the facial angle is from ten to twelve degrees higher than that of the Negrito of New Guinea. Mr. Crawford, who rarely either overlooks or undervalues physical distinctions, adopts Freycinet's notice as descriptive of a second variety of the true Malay type, and suggests the likelihood of there being an intermediate race between the lank and the woolly-haired families.

b. Vanikoro is the Kelænonesian Island, which, by its vicinity, gives to[71] Tikopia, which is Polynesian, its peculiarity of distribution.

Erromango Native as described by Hales.—"He was about five feet high, slender and long limbed. He had close woolly hair, and retreating arched forehead, short and scanty eyebrows, and small snub-nose, thick lips (especially the upper), a retreating chin, and that projection of the jaws and lower part of the face, which is one of the distinctive characteristics of the Negro race. His limbs and body were covered with fine short hairs, made conspicuous by their light colour. On his left side were many small round cicatrices burnt into the skin, which he said was a mode of marking common amongst his people. Placed in a crowd of African blacks, there was nothing about him by which he could have been distinguished from the rest."—Vol. 6. p. 44.

Of this Island I have seen no definite account. Such notices, however, as I have met with, make the population what we should expect it to be—Papua-Kelænonesian.

Writers who are not, otherwise, over-prone to exaggerate differences, have separated the Tasmanians from the Australians; and this arrangement is followed in the present work. The physical difference is chiefly that of the hair. The language, as far as the imperfect vocabularies have allowed me to examine it, has fewer affinities with the southern dialects of Australia than even the known amount of dissimilarity between fundamentally allied languages prepares us for.

"The two armies (usually from fifty to two hundred each) meet, and after a great deal of mutual vituperation, the combat commences. From their singular dexterity in avoiding or parrying the missiles of their adversaries, the engagement usually continues a long time without any fatal result. When a man is killed (and sometimes before), a cessation takes place; another scene of recrimination, abuse, and explanation ensues, and the affair commonly terminates. All hostility is at an end, and the two parties mix amicably together, bury the dead, and join in a general dance.

One of the most remarkable of their customs is the way in which they celebrate the anniversary of the burial of any near relation, when "their houses are decorated with garlands of flowers, fruits, and branches of trees. The people of each village assemble, dressed in their best attire, at the principal house in the place, where they spend the day in a convivial manner; the men, sitting apart from the women, smoke tobacco and intoxicate themselves, while the latter are nursing their children, and employed in preparations for the mournful business of the night. At a certain hour of the afternoon, announced by striking the coung, the women set up the most dismal howls and lamentations, which they continue without intermission till about sunset; when the whole party gets up, and walks in procession to the burying-ground. Arrived at the place, they form a circle around one of the graves, when the stake, planted exactly over the head of the corpse, is pulled up. The woman who is nearest of kin to the deceased, steps out from the crowd, digs up the skull, and draws it up with her hands. At sight of the bones, her strength seems to fail her; she shrieks, she sobs, and tears of anguish abundantly fall to the mouldering object of her pious care. She clears it from the earth, scrapes off the festering flesh, and laves it plentifully with the milk of fresh coco-nuts, supplied by the bystanders; after which she rubs it over with an infusion of saffron, and wraps it carefully in a piece of new cloth. It is then deposited again in the earth, and covered up; the stake is replanted, and hung with the various trappings and implements belonging to the deceased. They proceed then to the other graves, and the whole night is spent in repetitions of these dismal and disgustful rites."[82]

The distinction just indicated is of more importance, as illustrative of a general principle, than as a fact affecting the particular point in question. The special facts of the case are, in the mind of the present writer, in favour of Timor and not New Guinea, having been the quarter from whence Australia was peopled, the particular part of the Timorian stock being, of course, the darker, wilder, and, apparently, more ancient tribes of the west and of the interior.

Pustoserk, pirçe

Respecting the extent to which the Yeniseian, the Samöeid, and Yukahiri, are isolated languages; the classification of the present writer is opposed to that of the Asia Polyglotta. Klaproth raises each to the rank of a separate family, and neither admits any definite relationship between the three, as compared with each other, nor yet between any one of them and any of the neighbouring languages. Still he indicates some important general and miscellaneous affinities; and Prichard does the same. The following table helps to verify the present classification.

"According to Steller, the Kamtschatkans have no idea of a Supreme Being, but this must have been true only in some peculiar sense of the expression, for he adds an account of their mythology, which in part contradicts the above statement. They believe, as he says, in the immortality of souls. All creatures, even to the smallest fly, are destined, as they believe, to another eternal life under the earth, where they are to meet with similar adventures to those of their present state of existence, but never to suffer hunger. In that world there is no punishment of crimes, which, in the opinion of the Kamskadales, meet their chastisement in the present life, but the rich are destined to become poor and the poor here are to be enriched. The sky and stars existed before the earth, which was made by Katchu, or, as others say, brought by Katchu and his sister Katligith with them from heaven and fastened upon the sea. After Katchu had made the earth he left heaven and came to dwell in Kamtschatka. He had a son, Tigil, and a daughter, Sidanka, who married and became parents of offspring: the latter clothed themselves with the leaves of trees and fed upon the bark, for beasts were not yet made, and the gods knew not how to catch fish. When Katchu went to drink, the hills and valleys were formed under his feet, for the earth had till then been a flat surface. Tigil finding his family increase invented nets and betook himself to fishing. The Kamtschatkans have, like other pagans, images of their gods."[102]

"The Kamis or gods of the original Japanese, were, according to a collection of the national traditions, not eternal. The first five gods originated at the separation of elements in which the world began: they are the Amatsukami. A bud, similar to that of the Asi, the Erianthus Japonicus, expanded itself between heaven and earth and produced Kuni-soko-tatsino-mi-koto, or the 'Maker of the dry land,' who governed the world, as yet unfashioned, during an immeasurable space of time, which was more than a hundred thousand millions of years. This kami had many successors whose reigns were nearly as long. Their temples are still places of worship in Oomi and Ise, districts of Japan. There were seven dynasties of celestial gods. The last, Iza-na-gi, standing on a bridge that floated between heaven and earth, said to his wife, Iza-na-mi, 'Come on; there must be some habitable land: let us try to find it.' He dipped his pike, ornamented with precious stones, into the surrounding waters and agitated the waves: the drops which fell from his pike when he raised it thickened and formed an island, named 'Ono-koro-sima.' On this island Iza-na-gi and his wife descended, and made the other provinces of the Japanese empire. From them descended the five dynasties or reigns of earthly gods. From the last of these originated Zin-moo-teu-woo, the ruler of men, who, as above mentioned, founded the empire of Japan, and conquered the aboriginal tribes. From Zin-moo's reign is dated the first year of the epoch of Japanese chronology, coinciding with the seventh year of the Chinese emperor Hoéï-wâng, B. C. 660. Such is the cosmogony of the Japanese. Their highest adoration is given to the deity of the sun, offspring of Iza-na-gi and Iza-na-mi: to him are subordinate all the genii or demons which govern the elements and all the operations of nature, as well as the souls of men, who after death go to the gods or to an infernal place of punishment, according to their actions on earth. Sacred festivals are held at certain seasons of the year and at changes of the moon. The whole number of kamis or gods worshipped by the Japanese amounts to three thousand one hundred and thirty-two. These gods are worshipped in different temples without idols."

So great is the influence of the Shamans, or so low is the value set upon human life, that in 1814, after a terrible storm, followed by a fatal epidemic, and by a murrain among the cattle, the result of a general consultation having been, that one of the most respected of the chiefs, named Kotshen, must be sacrificed, to appease the irritated spirits, the sacrifice took place accordingly. In the first instance, indeed, the commands of the Shamans were rejected. The plague, however, continued, when Kotshen at last declared his willingness to submit. No one, however, could be found to be his executioner; until his own son plunged a knife in his heart, and gave his body to the Shamans.

b. Antisian branch.—Colour, varying from a deep olive to nearly white; form, not massive; forehead, not retreating; physiognomy, lively, mild.—Yuracares, Mocéténès, Tacanas, Maropas, and Apolistas.

Furthermore—when the American languages differ from one another, they differ in a manner to which Asia has supplied no parallel.

The Tungaas.—Of this we have only a short vocabulary of Mr. Tolmic, which is stated by Dr. Scouler, to exhibit affinities with the Sitkan. This is the case. Whether, however, these affinities with the languages to the north of the Tungaas localities, are so much greater than those with the tongues spoken southwards, as to justify us in drawing a line between the true Kolúch dialects and those that will soon be enumerated, has yet to be ascertained. Assuming, however, that this is the case, and, again, insisting upon the conventional character of the present class, and the transitional nature of the Kolúch languages, I consider that the undoubted Kolúch dialects end in the neighbourhood of Queen Charlotte's Islands.

tchon

[105]thun-agalgus.

The languages which now follow are known but imperfectly; so that the classes which they form are all provisional, and of uncertain value. It is certainly not safe to call them Kolúch, although they all contain a notable per-centage of Kolúch words; nor yet is it advisable to throw them all together as members of a separate division—equivalent to, but distinct from, the Kolúch. For this, they are hardly sufficiently like each other, and hardly sufficiently unlike those spoken to the north of them. In other words we are now in one of those difficult ethnological areas, where we have no broad and trenchant lines of demarcation, but the phenomena of intermixture instead. This is the coast and a little beyond the coast of the Pacific, where the common climatologic conditions presented by a deeply-indented sea-board, make this arrangement natural as well as convenient.

nakhuk.

The Dog-ribs.—Due-east of the Hare Indians.—"They live upon the rein-deer, which frequent their lands in great numbers, following the migrations of these animals as closely as if they formed part and parcel of the herd. They are almost entirely independent of the whites, and present a marked contrast with their neighbours of the Hare Tribe. They are well-clothed in the skins of the rein-deer, and have all the elements of comfort and Indian prosperity within their reach. They are a healthy, vigorous, but not very active race, of a mild and peaceful disposition, but very low in the mental scale, and apparently of very inferior capacity. There is no reason to think that they are decreasing in numbers. They receive the name of the Dog-ribs, from a tradition that they are descended from the dog."

"The natives are prone to sensuality, and chastity among the women is unknown. At the same time, they seem to be almost devoid of natural affection. Children are considered by them a burden, and they often use means to destroy them before birth. Their religious ideas are very gross and confused. It is not known that they have any distinct ideas of a God, or of the existence of the soul. They have priests, or doctors, whose art consists in certain mummeries, intended for incantations. When a corpse is burned, which is the ordinary mode of disposing of the dead, the priest, with many gesticulations and contortions, pretends to receive in his closed hands something, perhaps the life of the deceased, which he communicates to some living person, by throwing his hands towards him, and at the same time blowing upon him. This person then takes the rank of the deceased, and assumes his name in addition to his own. Of course the priest always understands to whom this succession is properly due.

Sub-divisions.—Value of the classification unascertained. a. Continuous Tsihaili. 1. Shushwap. 2. Salish. 3. Skitsuish. 4. Piskwaus. 5. Kawitchen. 6. Skwali. 7. Checheeli. 8. Kowelits. 9. Noosdalum.

The Kútanis are described by Simpson as undersized, irregularly fed, poor, and squalid; the women being plainer than the men. Irregularly fed upon fish and venison, they dig up the kammas and mash it into a pulp. This, in times of unusual scarcity, they flavour with a sort of moss or lichen collected from the trees. On the other hand they are sharp-sighted in making bargains, prudent enough to be the best economisers in their district of the fur-animals, steady in their fidelity to the whites, and so brave, under attacks, as to hold their own against the powerful Blackfoots of the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains.

"The place at which the jargon is most in use is at Fort Vancouver. At this establishment five languages are spoken by about five hundred persons—namely, the English, the Canadian French, the Tshinúk, the Cree or Knisteneau, and the Hawaiian. The three former are already accounted for; the Cree is the language spoken in the families of many officers and men belonging to the Hudson's Bay Company, who have married half-breed wives at the posts east of the Rocky Mountains. The Hawaiian is in use among about a hundred natives of the Sandwich Islands, who are employed as labourers about the fort. Besides these five languages there are many others—the Tsihailish, Wallawalla, Kalapuya, Naskwali, &c., which are daily heard from natives who visit the fort for the purpose of trading. Among all these individuals, there are very few who understand more than two languages, and many who speak only their own. The general communication is, therefore, maintained chiefly by means of the jargon, which may be said to be the prevailing idiom. There are Canadians and half-breeds married to Chinook women, who can only converse with their wives in this speech; and it is the fact, strange as it may seem, that many young children are growing up to whom this factitious language is really the mother tongue, and who speak it with more readiness and perfection than any other."

The divisions of the American population that occupy, or occupied, this area, are of unascertained value; I shall give them, in the first instance, nearly according to the classification and nomenclature of Gallatin's standard dissertation in the Archæologia Americana. Some of these will be large, some small; some like the Turk, some like the Dioscurian; phænomena for which we are now prepared. The first in the list, single handed, takes up more than half the whole area.

That the evidence of the Shyenne numerals, the only part of Lieut. Abert's vocabulary then known to him, made the Shyennes Algonkin, was also stated by the present writer at the meeting of the British Association, in 1847, at Oxford.—Transactions of the Sections, p. 123.

Area.—Central North America, between the Mississippi and the Rocky Mountains, east and west. Between Lake Winebago and the Arkansas, north and south. The valley of the Missouri. The water-system of Lake Winebago. One division east of the Mississippi.

Divisions.—1. Winnebagoes, Hochungohrah=Trout Nation. 2. Dakotas, Sioux, or Nadowessiou. 3. Assineboins, or Stone Indians. 4. Upsaroka, or Crows. 5. Mandans. 6. Minetari. 7. Osage.

Sub-divisions.—a. Of the Dahcota—1. Yanktons. 2. Yanktoanans(?) 3. Tetons. 4. Proper Sioux.

b. Of the Osage.—1. Konzas. 2. Missouris. 3. Ottos. 4. Omahaws. 5. Puncas. 6. Ioways. 7. Quappas. 8. Osage Proper.

Again, not only have whole tribes become extinct since the settlement of Europeans, but at the very beginning of the American historical period, tribes were found mutually exterminating each other. The empire of Powhattan was founded upon the annihilation of some tribes, and the incorporation of others. The Huron Iroquois were nearly extinguished by the Five Nations. The Mandans, within the last decennium, after being thinned and weakened by the small-pox, were, as a separate tribe, destroyed by the Sioux, who incorporated with themselves those who were not killed in the attack.

The Choctah family has, probably, been a family of encroaching area, the population which it displaced being represented by—

The provisional character of all these groups has been noticed. This is so great that scarcely two inquirers would give the same answer to the question, "What is the difference between a member of (say) the Algonkin and one of (say) the Cherokee, Choctah, or Iroquois class?" The most extreme opinions are, perhaps, those of Gallatin, as expressed in the Synopsis, and the present writer. According to the former, the Algonkin, Iroquois, Sioux, Catawba, Cherokee, Choctah, and Caddo, and Uché languages differ from one another, as the English and Turkish, or the Greek and Lapplandic, i.e. as languages reducible to no common class, a view which makes divisions so large as the Algonkin, and so small as the Uché, equally equivalent to the great class denominated Indo-European—a doctrine by no means improbable in itself, since it differs in degree rather than in kind, from the similar juxtaposition of large and small, simple and sub-divided classes, which we find in Europe; where the isolated Basque and Albanian are, in the present state of our knowledge, co-extensive in the way of classification with the wide and varied Indo-European, Semitic, and Ugrian groups.

The present writer allows a value, equal to that expressed by the term Indo-European to three groups only, the first of which contains the Algonkin, which is apparently more different from the others than they are from each other; the second, the Uché, which, although it has several miscellaneous affinities, is not at present subordinated to any other class; and the third, the remainder, i.e. the Iroquois, Sioux, Catawba, Cherokee, Choctah, and Caddo, or (probably) the Iroquois, Sioux, and Cherokee, as primary divisions, to the last of which the Catawba, Choctah, and Caddo are subordinate. This is the very utmost he would do, in the way of recognising differences. He will, however, hereafter give reasons for doing less. At present the notification of fresh divisions of the population is continued.

Westward we come to Texas. Now the imperfect and fragmentary character of our information makes the consideration of the Texian Indians (known by little beyond their names) most conveniently follow the enumeration of the tribes to the north and west of them—besides which, four unplaced families have still to be enumerated as belonging to, and interrupting the great Algonkin and Sioux areas.

Now all this is the case with the great Paduca area. Spreading from the Pacific to the Atlantic, it has to the north developments like those of the Oregon and the valley of the Mississippi: to the south those of Mexico, Guatimala, and Yucatan.

Wihinast.—Called by Mr. Hales, Western Shoshonis, and unequivocally members of that division. Locality 45° N.L. 117° W.L., on the southern bank of the Snake or Lewis River, and conterminous with the Wailatpu. Of the Northern Paducas, these are the nearest to the Pacific, from which they are separated by the Lutuami, Umkwa and Saintskla. The evidence that the Wihinast are Shoshoni is derived from a vocabulary of their language.—Philology of the U.S.E.E.

Cumanches.—The chief Indians of Texas.—It is the ethnological position of the Cumanches that determines the extent of the Paduca group. That the Kiaways, &c., are Cumanche is believed on external evidence, and on the a priori probability. That the Cumanche are Shoshoni is believed upon external evidence by those Americans who have had means of forming an opinion, and also upon the evidence of a short MS. vocabulary of the Cumanche, with which the present writer was favoured by Mr. Bollaert, compared with an equally short one of the Shoshoni in Gallatin's Synopsis. This was in 1844;[130] since which time, although the data for the Shoshoni have greatly increased, those of the Cumanche are as imperfect as ever. Still the author has but little doubt as to the truth of the opinion of the Shoshoni affinity with the Cumanche, or (changing the expression) of the common Paduca character of the two.

The Cumanches are the chief Indians of Texas; hence, from the north and west of that state they form an ethnological boundary. The names (all that the author can give) of the Texian tribes not already included in the several extensions of the Cumanche, Pawnee, Sioux, Cherokee, Choctah, Natchez, and other smaller families, are—

b. The incorporation of the possessive pronoun.—Certain words like hand, father, son, express, all the world over, objects which are rarely mentioned except in relation to some other object to which they belong—a hand, for instance, is mine, thine, his, and so is a father, a son, a wife, &c. In other words there is almost always a pronoun[141] attached to them. Now in the American languages this is almost always incorporated with the substantive; so that an American can only talk of my father, thy father, &c., being incapable of using the substantive in a sense sufficiently abstract to dispense with the pronoun.

The phænomena, however, which the multiplicity of mutually unintelligible tongues spoken within limited areas exhibited, were first made known in the case of the languages of America; and, as new facts, they were not likely to be undervalued. On the contrary, another natural tendency of the human mind, viz., a readiness to exaggerate difference in cases where similarity had been expected, was allowed full play; and not only were the really remarkable phænomena of philological diversity overstated, but the inferences from them rather exceeded than fell short of their legitimate compass. A measure of the extent to which this was carried may be collected from the following extract from Prichard,—"We owe the earliest information respecting the languages of America to the missionaries sent from time to time by the kings of Spain at the instigation of the Pope, with the view of converting the native inhabitants to the Christian religion. Many of these persons devoted immense labour to the acquisition of the idioms of various tribes, with the intention of qualifying themselves for the effectual performance of their duties. They represent the number of distinct languages spoken in the New World as very great. Abbé Gilii, who wrote a history of the Orinoco and collected specimens of the languages spoken in different districts with which he was acquainted, says that if a catalogue were formed of all the idioms of the continent, they would be found to be 'non molte moltissime,' but 'infinite, innumerabili.' Abbé Clavigero declares that he had cognisance of thirty-five different idioms spoken by races within the jurisdiction of Mexico. Father Kircher, a celebrated philologer of his time, after consulting the Jesuits assembled in Rome on the occasion of a general congregation of the order in 1676, informs us that those missionaries who had been in the New World supposed the number of languages, of which they had some notices in South America, to be five hundred. But the Abbé Royo, who had made diligent inquiries about the language of Peru, where he had dwelt, asserts that the whole people of America spoke not less than two thousand languages. The learned Francisco Lopez, a native of South America, who had extensive knowledge of that country as well as of the northern continent, a great part of which was traversed by the Jesuits, thought it no rash assertion to say that the idioms, 'notabilmente diversi,' of the whole country were not less than fifteen hundred."