автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Studies in the History and Method of Science, vol. 1 (of 2)

Transcriber’s notes:

In this transcription a black dotted underline indicates a hyperlink to a page, illustration or footnote; hyperlinks are also indicated by aqua highlighting when the mouse pointer hovers over them. A red dashed

underline

indicates the presence of a concealed comment that can be revealed by hovering the mouse pointer over the underlined text. Page numbers are shown in the right margin. Footnotes are located at the end of the book.The cover image of the book was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Potential problems:

The text contains numerous foreign and uncommon typographic characters. In addition to Greek, there are passages of Hebrew and Arabic text (which read from right-to-left and are normally right justified) that will not necessarily display correctly with all browsers. If some characters look abnormal, first ensure that the browser’s ‘character encoding’ is set to Unicode (UTF-8). You might also need to change the default font. Standard fonts such as Times New Roman, Georgia or Lucida Sans Unicode are sometimes adequate, but it might be necessary to use a less-common font such as Arial Unicode MS, DejaVu, Segoe UI Symbol or FreeSerif to see all characters correctly. Right alignment of the Hebrew and Arabic paragraphs will generally only be apparent with a monospaced font such as DejaVuSansMono.

Some diacritics don’t display consistently with all fonts and all browsers. For example, the Greek letter υ̑ occurs in several words and with some browsers and fonts the inverted breve is displaced towards the following letter (as might be the case here); the same anomaly occurs with macrons above letters in some old English words. The Hebrew passage contains several letters with single or double overhead dots (of uncertain significance) that can’t be replicated on screen – the passage is hyperlinked to an image of the original for anyone wishing to see it.

Roman numerals are widely used and often in archaic ways. Numerals followed by an italicised l, s, or d indicate monetary values in imperial pounds shillings and pence units, e.g. xxxiiil. vis. viiid. represents 33 pounds 6 shillings 8 pence (a space sometimes separates the numeral from the unit). The last ‘i’ (‘one’) in a roman numeral was often represented by the letter ‘j’; hence iiijd is equivalent to 4 pence, and ‘ij holownesses’ should be read as ‘two holownesses’.

Numerous portions of text enclosed within square brackets were inserted by the author (not the transcriber) for clarification or translation, as were several (sic) entries in the Hebrew and Arabic texts.

The index has many references to both page numbers and footnote numbers, e.g. 24 n. (a single unnumbered footnote on p. 24), 93 n. 3, 126 nn. 4, 5, (pages containing multiple footnotes), and also to numbered figures and plates. The original footnote numbering began afresh at 1. on each page, but in this transcription footnotes are numbered sequentially from the beginning of the book and the numbers no longer correspond to those shown in the index. Readers can locate a given indexed footnote by following the page hyperlink and counting through to the appropriate footnote marker on that page. Figure and plate references have been hyperlinked to the actual illustrations rather than to the original page numbers because many illustrations have been moved from their original position to be closer to the relevant text discussion.

Errors and inconsistencies:

Punctuation anomalies have been corrected silently (e.g. missing periods, commas and semicolons, incorrect or missing quotation marks, unpaired parentheses).

Unambiguous typographic errors such as the following, have been corrected silently:

Lexico nder-->Lexicon der

Aa-->As [a matter of fact]

Chiru gie-->Chirurgie

Weisbaden-->Wiesbaden

but inconsistent spellings such as those below have not been altered:

paniculi/panniculi

paniculo/panniculo

feçe/fece

Literatur/Litteratur

literae/litterae

aligati/alligati

cf./cp.

dilatare/dillatare

dilitano/dillitano

diuidendo/dividendo

judgement/judgment

Inconsistent capitalisation of Fig. and Plate has been standardised, as has inconsistent spacing of expressions such as A.D. i.e. and § 6 (a paragraph number).

STUDIES IN THE HISTORY AND METHOD OF SCIENCE

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW NEW YORK

TORONTO MELBOURNE CAPE TOWN BOMBAY

HUMPHREY MILFORD

PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY

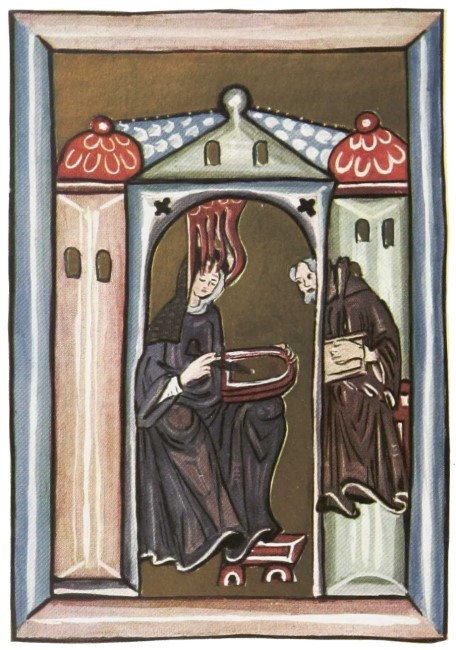

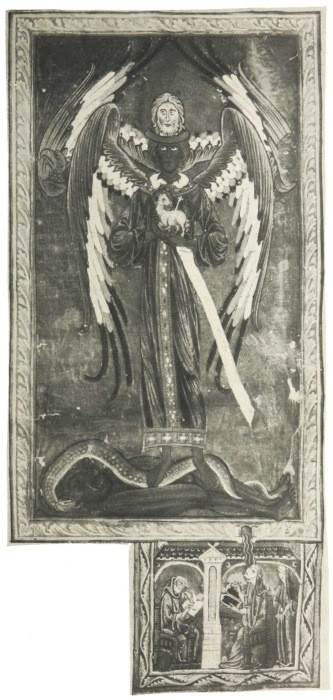

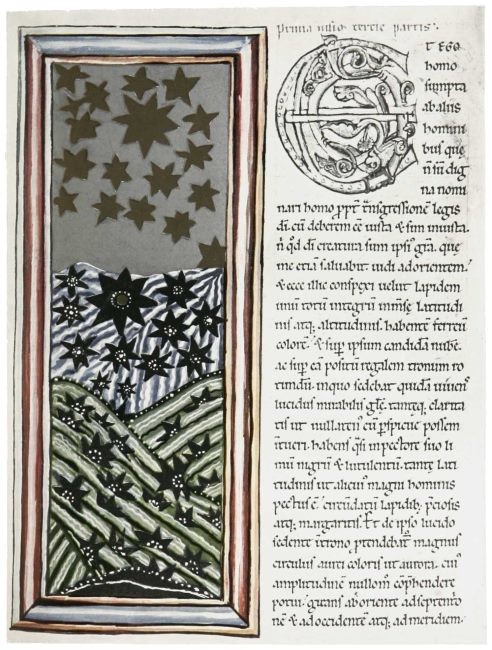

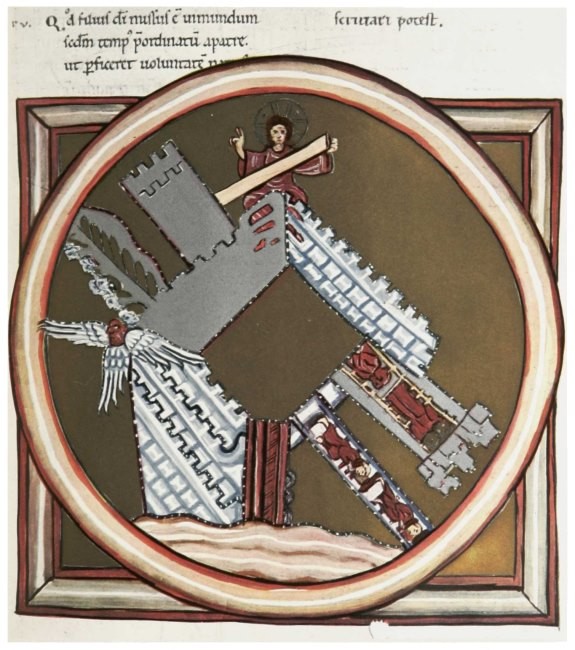

WIESBADEN CODEX B, fo. 1 r

Plate I. HILDEGARD RECEIVING THE LIGHT FROM HEAVEN

STUDIES IN THE HISTORY AND METHOD OF SCIENCE EDITED BY CHARLES SINGER

OXFORD AT THE CLARENDON PRESS 1917

PRINTED IN ENGLAND

AT THE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

INTRODUCTION

The record of men and of movements, History teaches us the growth and development of ideas. Our civilization is the final expression of the two great master-thoughts of the race. Seeking an explanation of the pressing phenomena of life, man has peopled the world with spiritual beings to whom he has assigned benign or malign influences, to be invoked or propitiated. To the great ‘uncharted region’ (Gilbert Murray) with its mysteries, his religions offer a guide; and through ‘a belief in spiritual beings’ (Tylor’s definition of religion) he has built an altar of righteousness in his heart. The birth of the other dominant idea, long delayed, is comparatively recent. ‘The discovery of things as they really are’ (Plato) by a study of nature was the great gift of the Greeks. Knowledge, scientia, knowledge of things we see, patiently acquired by searching out the secrets of nature, is the basis of our material civilization. The true and lawful goal of the sciences, seen dimly and so expressed by Bacon, is the acquisition of new powers by new discoveries—that goal has been reached. Niagara has been harnessed, and man’s dominion has extended from earth and sea to the air. The progress of physics and of chemistry has revolutionized man’s ways and works, while the new biology has changed his mental outlook.

The greater part of this progress has taken place within the memory of those living, and the mass of scientific work has accumulated at such a rate that specialism has become inevitable. While this has the obvious advantage resulting from a division of labour, there is the penalty of a narrowed horizon, and groups of men work side by side whose language is unintelligible to each other.

Here is where the historian comes in, with two definite objects, teaching the method by which the knowledge has been gained, the evolution of the subject, and correlating the innumerable subdivisions in a philosophy at once, in Plato’s words, a science in itself as well as of other sciences. For example, the student of physics may know Crookes’s tubes and their relation to Röntgen, but he cannot have a true conception of the atomic theory without a knowledge of Democritus; and the exponent of Madame Curie and of Sir J. J. Thomson will find his happiest illustrations from the writings of Lucretius. It is unfortunate that the progress of science makes useless the very works that made progress possible; and the student is too apt to think that because useless now they have never been of value.

The need of a comprehensive study of the methods of science is now widely recognized, and to recognize this need important Journals have been started, notably Isis, published by our Belgian colleague George Sarton, interrupted, temporarily we hope, by the war; and Scientia, an International Review of Scientific Synthesis published by our Italian Allies. The numerous good histories of science issued within the past few years bear witness to a real demand for a wider knowledge of the methods by which the present status has been reached. Among works from which the student may get a proper outlook on the whole question may be mentioned Dannemann’s Die Naturwissenschaften in ihrer Entwicklung und in ihrem Zusammenhang, Bd. IV; De la Méthode dans les Sciences , edited by Félix Thomas (Paris: Alcan); Marvin’s Living Past , 3rd ed. (Clarendon Press, 1917); and Libby’s Introduction to the History of Science (Houghton Mifflin & Co., 1917).

This volume of Essays is the outcome of a quiet movement on the part of a few Oxford students to stimulate a study of the history of science. Shortly after his appointment to the Philip Walker Studentship, Dr. Charles Singer (of Magdalen College) obtained leave from Bodley’s Librarian and the Curators to have a bay in the Radcliffe Camera set apart for research work in the history of science and a safe installed to hold manuscripts; and (with Mrs. Singer) offered £100 a year for five years to provide the necessary fittings, and special books not already in the Library. The works relating to the subject have been collected in the room, the objects of which are:

First, to place at the disposal of the general student a collection that will enable him to acquire a knowledge of the development of science and scientific conceptions.

Secondly, to assist the special student in research: (a) by placing him in relationship with investigations already undertaken; (b) by collecting information on the sources and accessibility of his material; and (c) by providing him with facilities to work up his material.

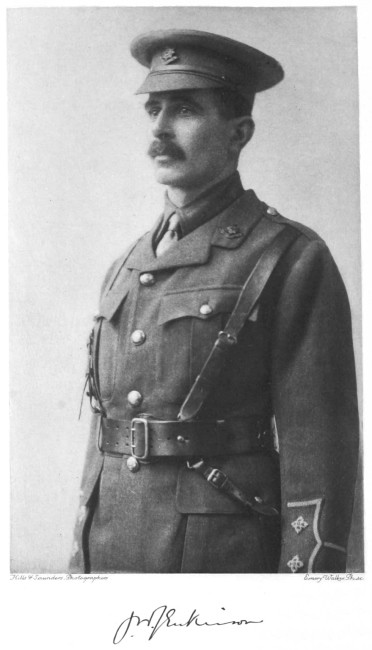

In spite of the absence of Dr. Singer on military duty for the greater part of the time, the work has been carried on with conspicuous success, to use the words of Bodley’s Librarian. Ten special students have used the room. Professor Ramsay Wright has made a study of an interesting Persian medical manuscript. Professor William Libby, of Pittsburg, during the session of 1915–16, used the room in the preparation of his admirable History of Science just issued. Dr. E. T. Withington, the well-known medical historian, is making a special study of the old Greek writers for the new edition of Liddell and Scott’s Dictionary. Miss Mildred Westland has helped Dr. Singer with the Italian medical manuscripts. Mr. Reuben Levy has worked at the Arabic medical manuscripts of Moses Maimonides. Mrs. Jenkinson is engaged on a study of early medicine and magic. Dr. J. L. E. Dreyer, the distinguished historian of Astronomy, has used the room in connexion with the preparation of the Opera Omnia of Tycho Brahe. Miss Joan Evans is engaged upon a research on mediaeval lapidaries. Mrs. Singer has begun a study of the English medical manuscripts, with a view to a complete catalogue. How important this is may be judged from the first instalment of her work dealing with the plague manuscripts in the British Museum. With rare enthusiasm and energy Dr. Singer has himself done a great deal of valuable work, and has proved an intellectual ferment working far beyond the confines of Oxford. I have myself found the science history room of the greatest convenience, and it is most helpful to have easy access on the shelves to a large collection of works on the subject. Had the war not interfered, we had hoped to start a Journal of the History and Method of Science and to organize a summer school for special students—hopes we may perhaps see realized in happier days.

Meanwhile, this volume of essays (most of which were in course of preparation when war was declared) is issued as a ballon d’essai.

WILLIAM OSLER.

CONTENTS

PAGECHARLES SINGER

The Scientific Views and Visions of Saint Hildegard(1098–1180)

1J. W. JENKINSON

Vitalism 59CHARLES SINGER

A Study in Early Renaissance Anatomy, with a new text: The ANOTHOMIA of Hieronymo Manfredi, transcribed and translated by A. Mildred Westland 79RAYMOND CRAWFURD

The Blessing of Cramp-Rings; a Chapter in the History of the Treatment of Epilepsy 165E. T. WITHINGTON

Dr. John Weyer and the Witch Mania 189REUBEN LEVY

The ‘Tractatus de Causis et Indiciis Morborum’, attributed to Maimonides 225SCHILLER, F. C. S.

Scientific Discovery and Logical Proof 235INDEX

291LIST OF PLATES

PLATE FACING PAGEI.

Hildegard receiving the Light from Heaven (Wiesbaden Codex B, fo. 1

r)

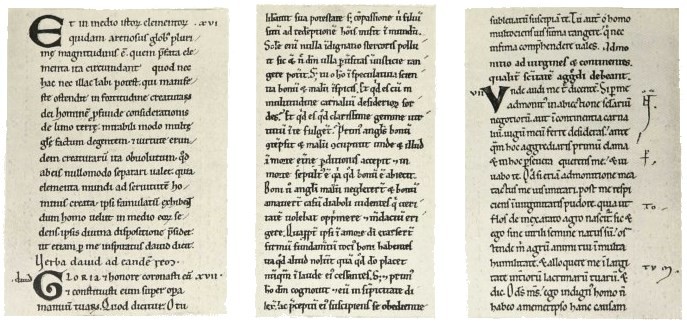

FrontispieceII.

The Three Scripts of the Wiesbaden Codex B (fo. 17

r, col. b; fo. 32

v, col. b; fo. 205

r, col. b)

4III.

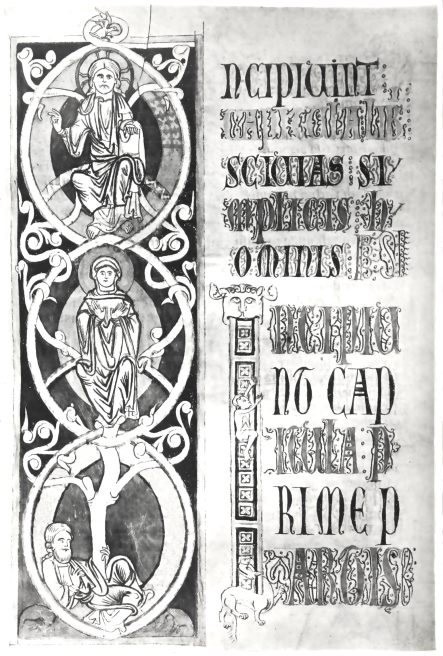

Title-page of the Heidelberg Codex of the

Scivias 5IV.

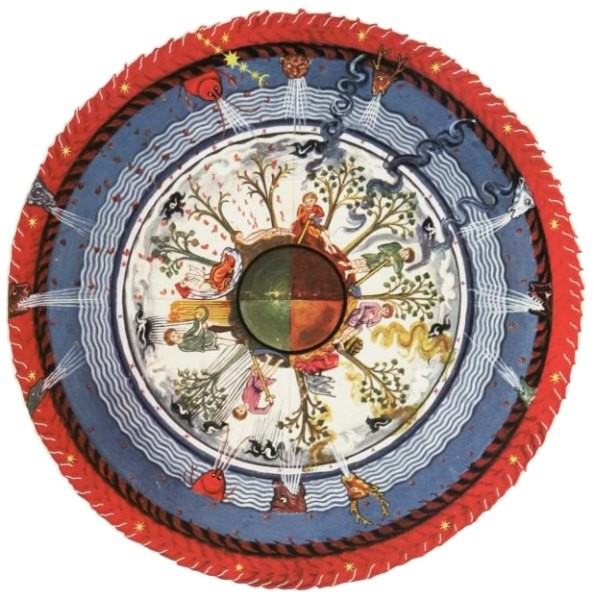

The Universe (from the Heidelberg Codex of the

Scivias)

12V.

(

a) Opening lines of the Copenhagen MS. of the

Causae et Curae. (

b) Opening lines of the Lucca MS. of the

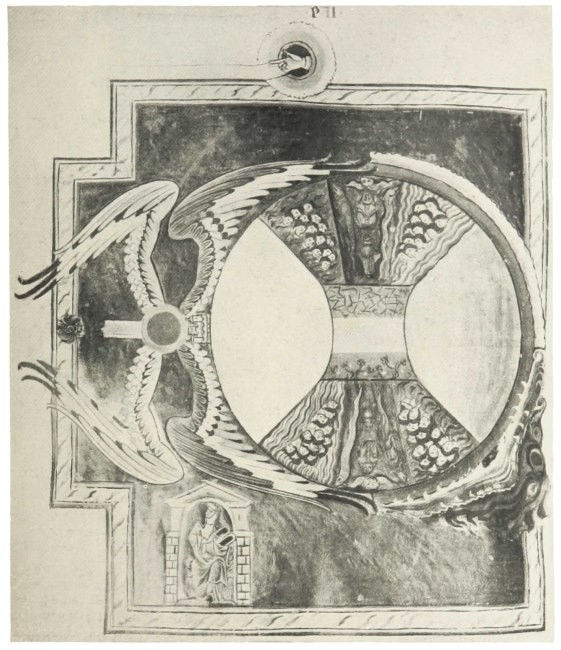

Liber divinorum operum simplicis hominis 13VI.

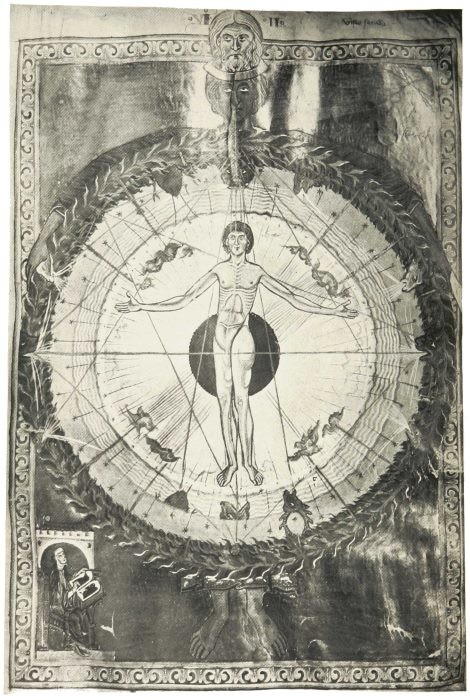

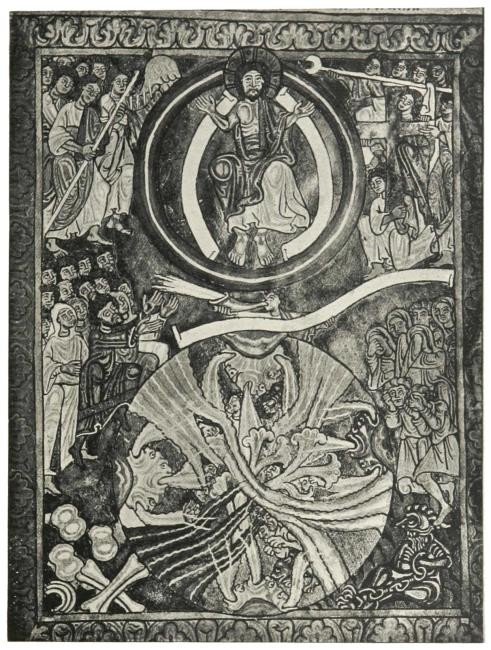

Nous pervaded by the Godhead and controlling Hyle (Lucca MS., fo. 1

v)

20VII.

Nous pervaded by the Godhead embracing the Macrocosm with the Microcosm (Lucca MS., fo. 9

r)

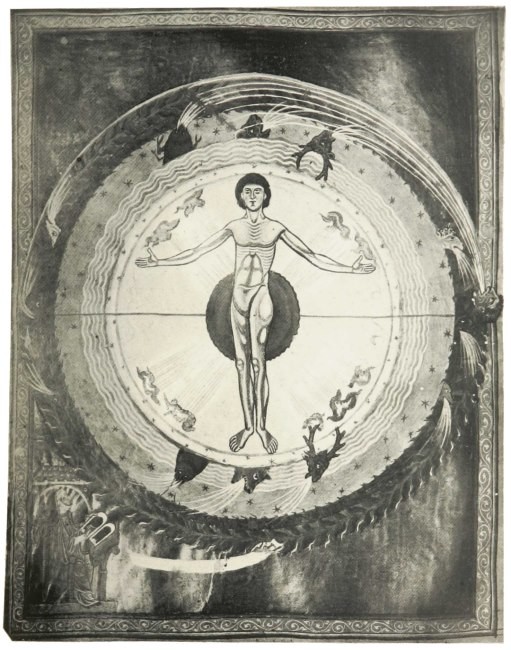

21VIII.

The Macrocosm, the Microcosm, and the Winds (Lucca MS., fo. 27

v)

28IX.

Celestial Influences on Men, Animals, and Plants (Lucca MS., fo. 371)

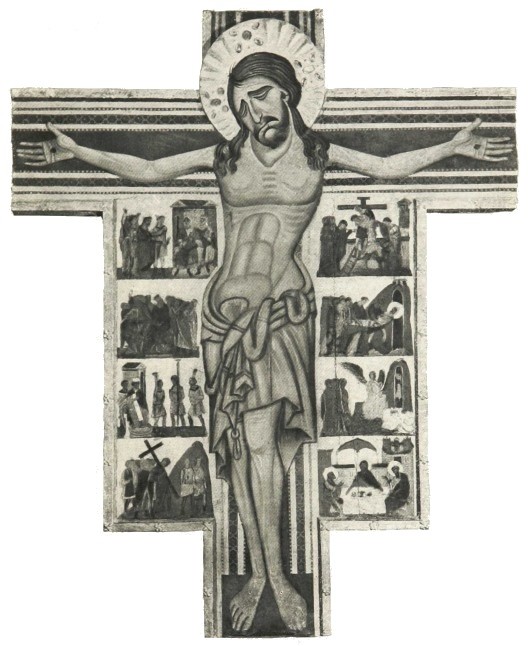

28X.

A Crucifix in the Uffizi Gallery; about the middle of the thirteenth century

30XI.

The Structure of the Mundane Sphere (Lucca MS., fo. 86

v)

32XII.

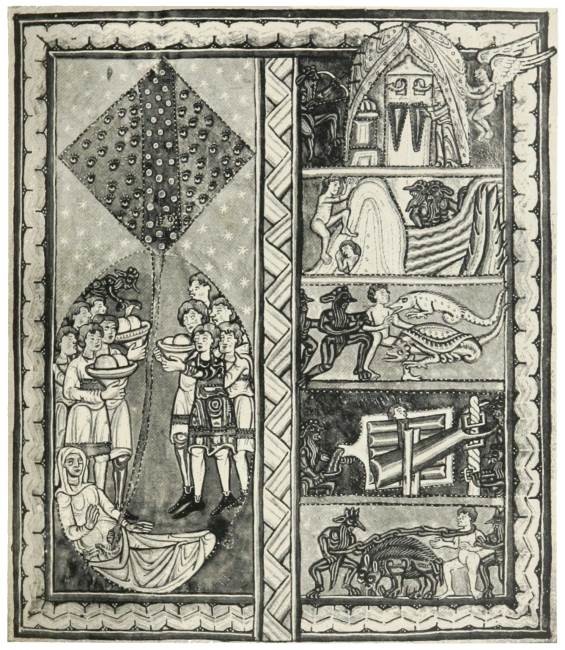

(

a) Man’s Fall and the Disturbance of the Elemental Harmony (Wiesbaden Codex B, fo. 4

r). (

b) The New Heaven and the New Earth (Wiesbaden Codex B, fo. 224

v)

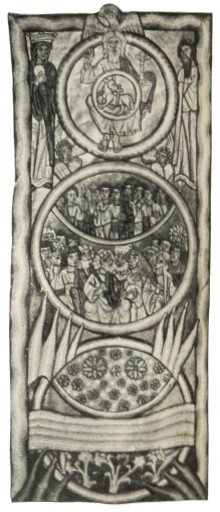

33XIII.

The Last Judgement and Fate of the Elements (Wiesbaden Codex B, fo. 224

r)

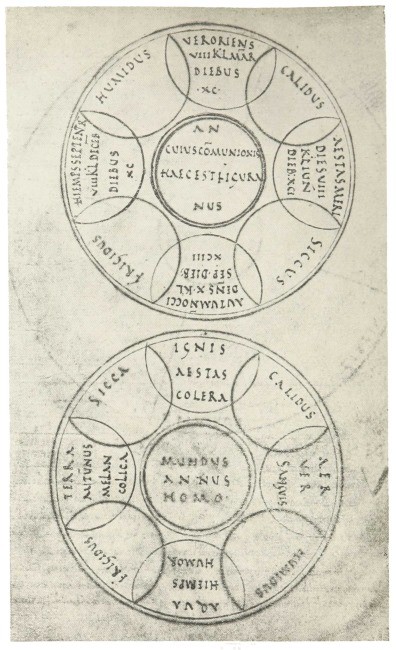

36XIV.

Diagram of the Relation of Human and Cosmic Phenomena: ninth century (Bibliothèque Nationale MS. lat. 5543, fo. 136

r)

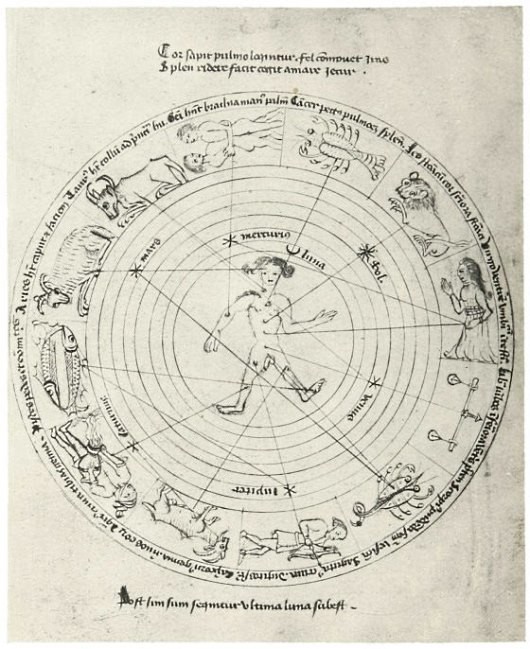

37XV.

An Eleventh-century French Melothesia (Bibliothèque Nationale MS. lat. 7028, fo. 154

r)

40XVI.

A Melothesia of about 1400 (from Bibliothèque Nationale MS. lat. 11229, fo. 45

v)

Between 40 and41

XVII.

Facsimile from the

Symbolum Apostolicorum, a German Block Book of the first half of the Fifteenth Century(Heidelberg University Library)

Between 40 and41

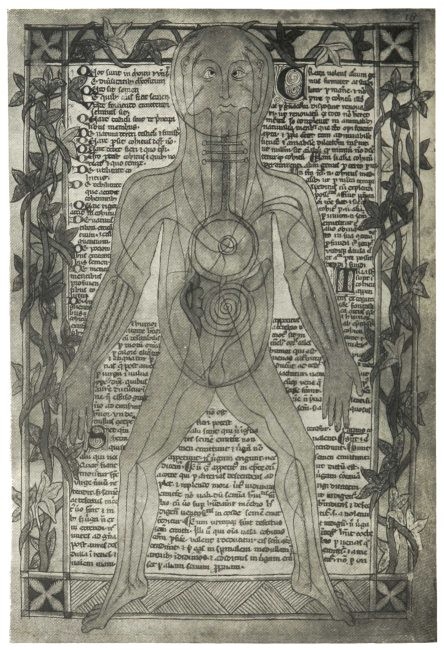

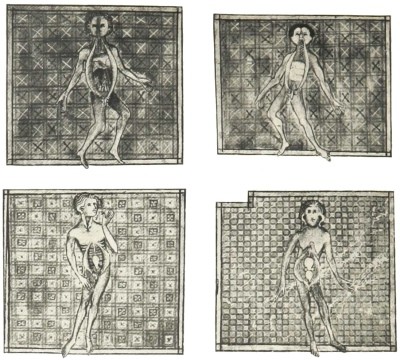

XVIII.

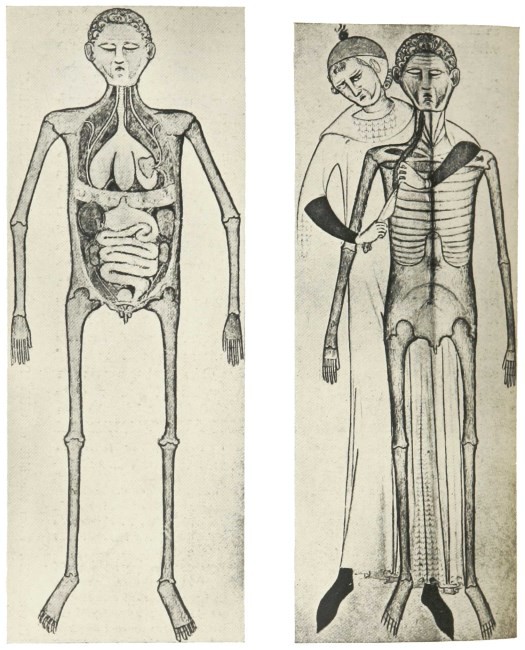

An Anatomical Diagram of about 1298 (Bodleian MS.Ashmole 399, fo. 18

r)

41XIX.

Birth. The Arrival and Trials of the Soul (Wiesbaden Codex B, fo. 22

r)

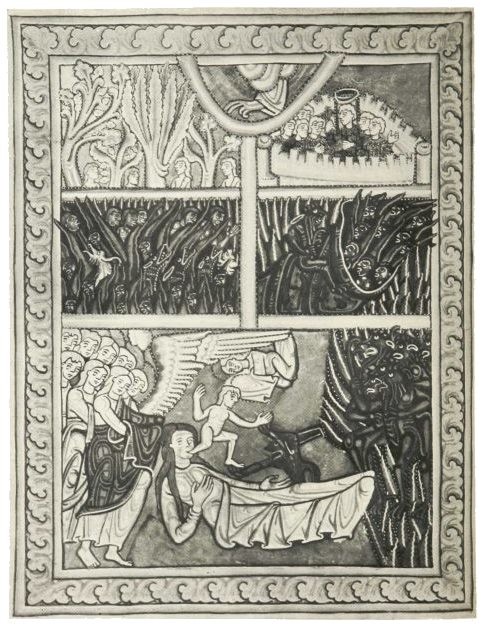

44XX.

Death. The Departure and Fate of the Soul (Wiesbaden Codex B, fo. 25

r)

45XXI.

The Fall of the Angels (Wiesbaden Codex B, fo. 123

r)

46XXII.

The Days of Creation and the Fall of Man (Wiesbaden Codex B, fo. 41

v)

48XXIII.

The Vision of the Trinity (Wiesbaden Codex B, fo. 471)

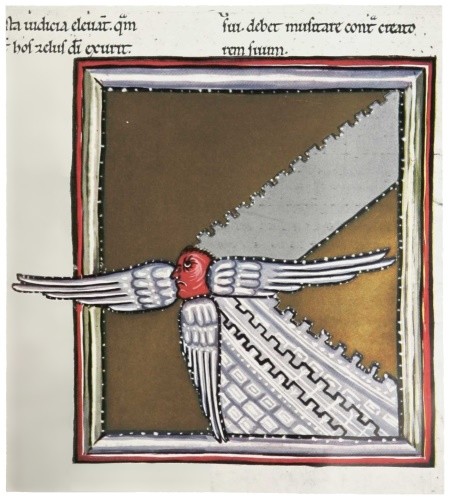

50XXIV.

(

a) Sedens Lucidus (Wiesbaden Codex B, fo. 213

v). (

b) Zelus Dei (Wiesbaden Codex B, fo. 153

r)

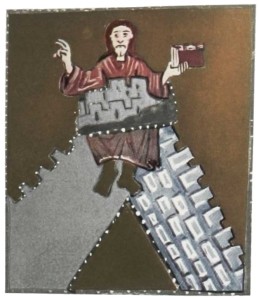

52XXV.

The Heavenly City (Wiesbaden Codex B, fo. 30

r)

54XXVI.

John Wilfred Jenkinson

57XXVII.

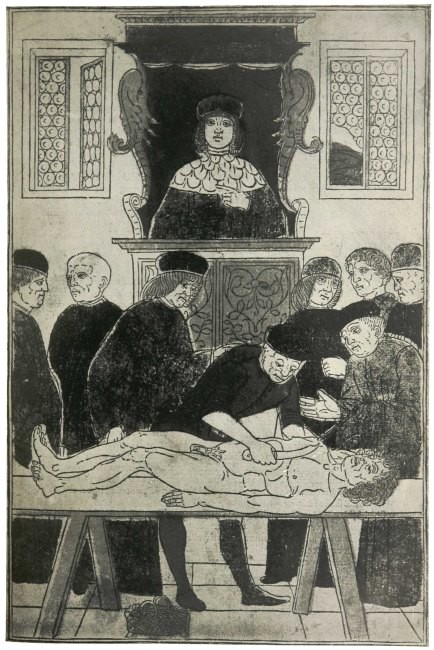

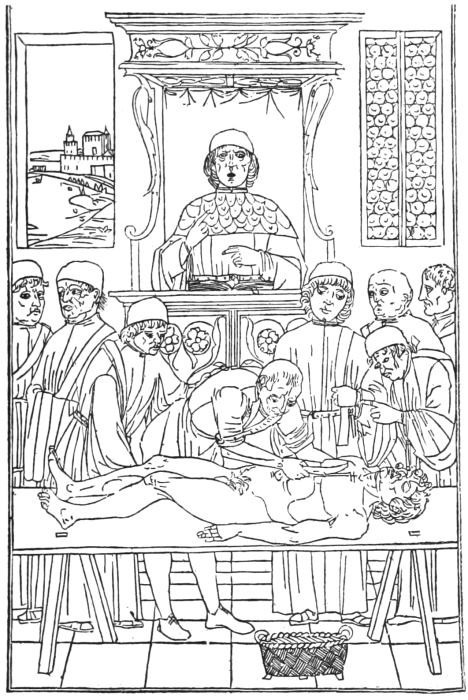

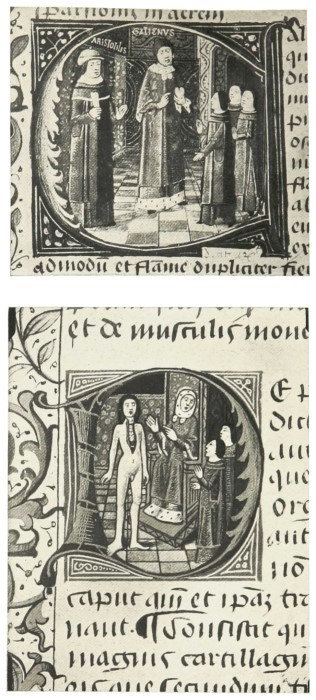

Mundinus (?) lecturing on Anatomy (from the 1493 edition of ‘Ketham’)

78XXVIII.

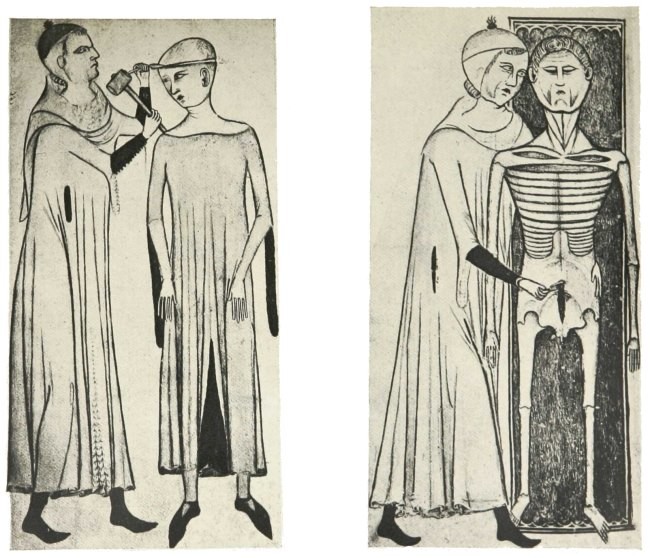

(

a) Four Diagrams, to illustrate the Anatomy of Henri de Mondeville (Bibliothèque Nationale MS. fr. 2030, written in 1314). (

b) A Dissection Scene,

circa1298 (Bodleian MS. Ashmole 399, fo. 34

r)

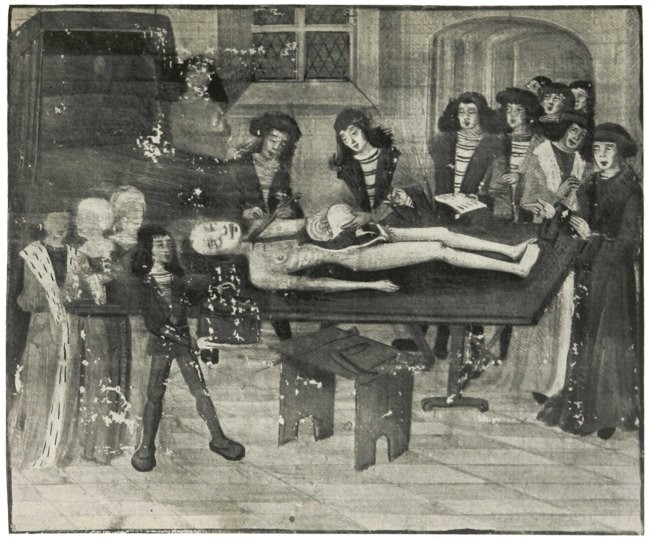

79XXIX.

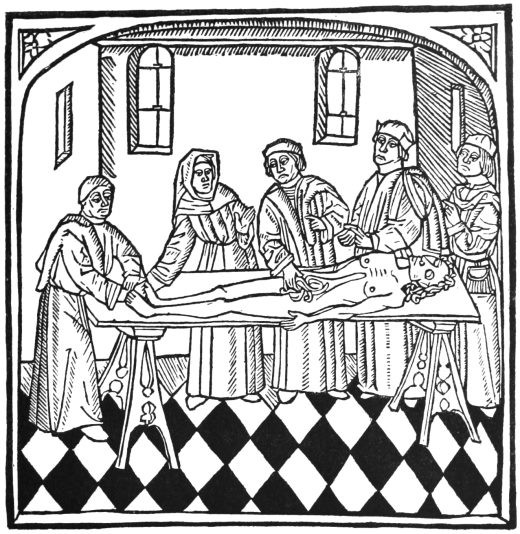

A Post-Mortem Examination: late fourteenth century to illustrate Guy de Chauliac (Montpellier, Bibliothèque de la Faculté de Médecine MS. fr. 184, fo. 14

r)

80XXX.

(

a) A Demonstration of Surface Markings: second half of fifteenth century (Vatican MS. Hispanice 4804, fo. 8

r). (

b) A Demonstration of the Bones to illustrate Guy de Chauliac: first half of fifteenth century (Bristol Reference Library MS., fo. 25

r)

81XXXI.

Anatomical Sketches from the MS. of Guy de Vigevano of 1345 at Chantilly

84XXXII.

Anatomical Sketches from the MS. of Guy de Vigevano of 1345 at Chantilly

85XXXIII.

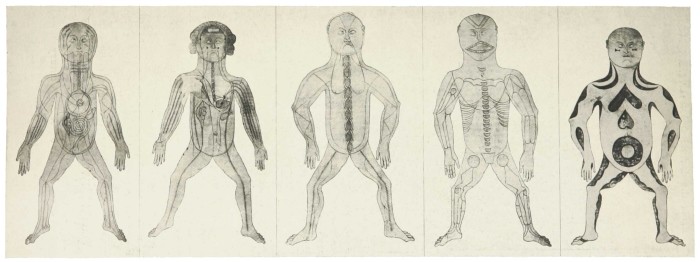

The Five-Figure Series: Veins, &c., Arteries, Nerves, Bones, Muscles (Bodleian MS. Ashmole 399, fos. 18

r–22

r): about 1298

92XXXIV.

Demonstrations of Anatomy: second half of fifteenth century (Dresden Galen MS.)

93XXXV.

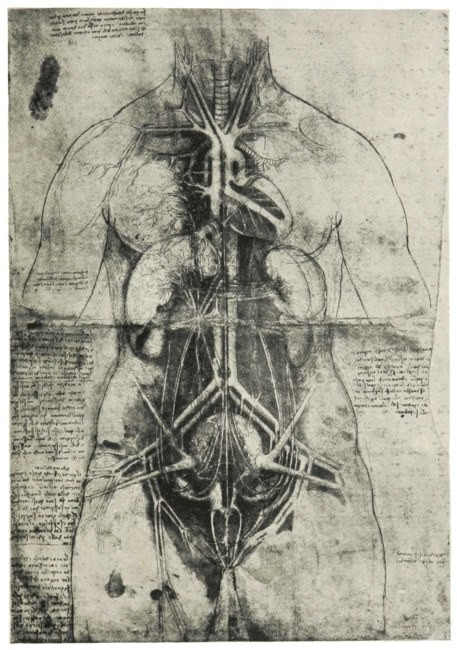

A View of the Internal Organs: Leonardo da Vinci (from a drawing in the Library, Windsor Castle)

96XXXVI.

Two Persons dissecting, traditionally said to represent Michelangelo and Antonio della Torre (from a drawing in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, attributed to Bartolomeo Manfredi (1574?–1602))

97XXXVII.

Portrait of Giovanni Bentivoglio II, from his tomb in the Church of S. Giacomo Maggiore at Bologna

102XXXVIII.

(

a) Roger Bacon’s Diagram of the Eye: thirteenth century (British Museum MS. Roy. 7 F.

VIII, fo. 50

v). (

b) Leonardo da Vinci’s Diagram of the Heart: early sixteenth century (from a drawing in Windsor Castle)

103XXXIX.

Miracles at the Tomb of Edward the Confessor, from Norman-French thirteenth-century MS. (University Library, Cambridge, MS. Ee. iii. 59)

166XL.

Queen Mary Tudor blessing Cramp-Rings (from Queen Mary’s Illuminated MS. Manual, in the Library of the Roman Catholic Cathedral at Westminster)

178XLI.

Facsimile of the

Tractatus de Causis et Indiciis Morborum, attributed to Maimonides (Bodleian MS., Marsh 379)

225ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT

SCIENTIFIC VIEWS AND VISIONS OF SAINT HILDEGARD

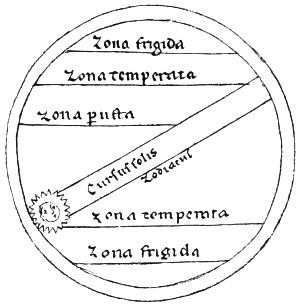

FIGURE PAGE1.

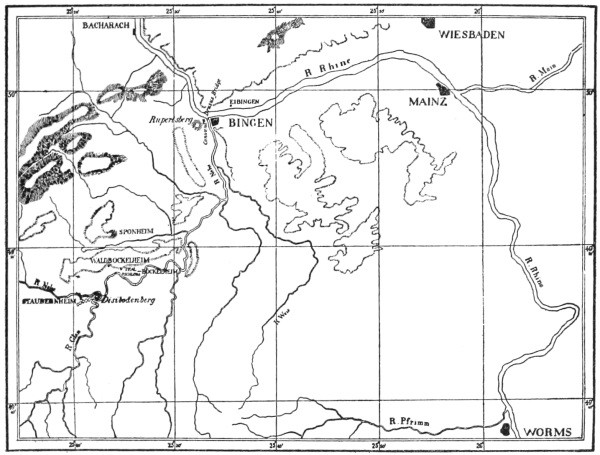

The Hildegard Country

32.

Hildegard’s First Scheme of the Universe (slightly simplified from the Wiesbaden Codex B, fo. 14

r)

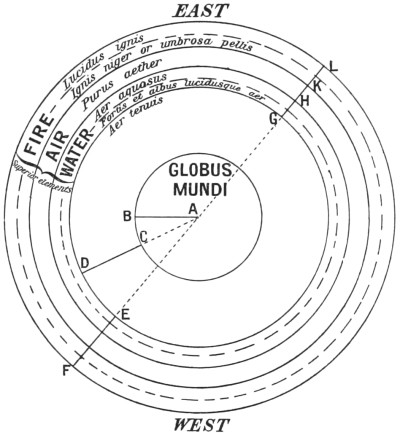

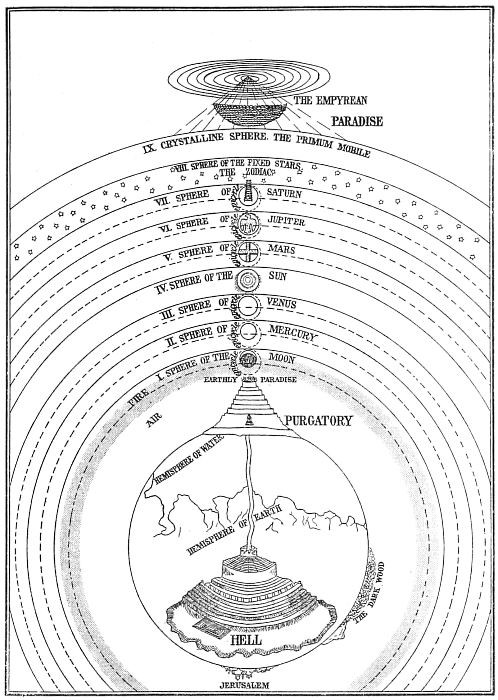

93.

Hildegard’s Second Scheme of the Universe (reconstructed from her measurements)

294.

Dante’s Scheme of the Universe (slightly modified from Michelangelo Caetani, duca di Sermoneta,

La materia della Divina Commedia di Dante Allighieri dichiarata in VI tavole)

315.

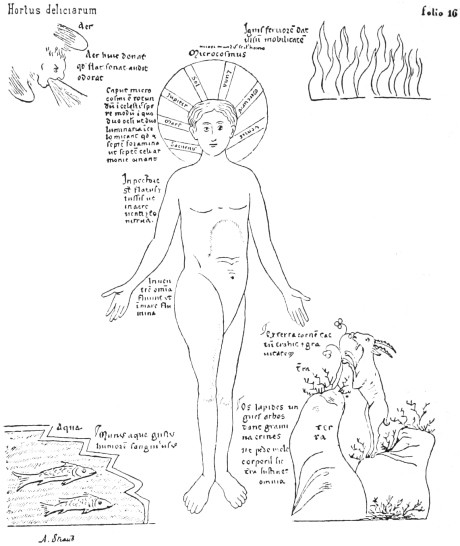

Diagram of the Zones (from Herrade de Landsberg,

Hortus deliciarum)

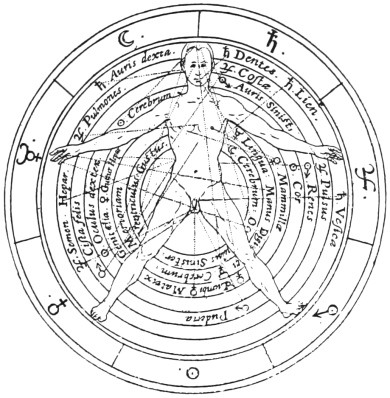

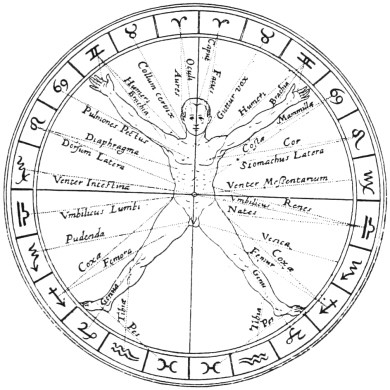

406, 7.

Melothesiae (from R. Fludd,

Historia utriusque cosmi, 1619)

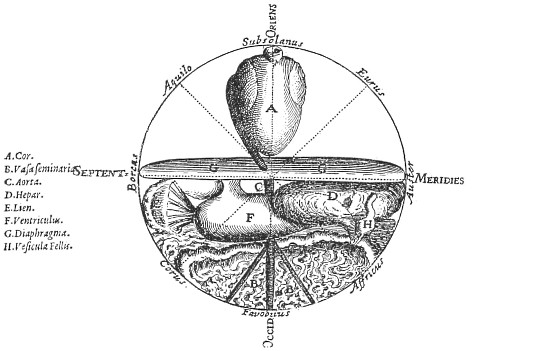

418.

The Microcosm (from R. Fludd,

Philosophia sacra seu astrologia cosmica, 1628)

429.

Diagram illustrating the relationship of the Planets to the Brain (from Herrade de Landsberg,

Hortus deliciarum)

48A STUDY IN EARLY RENAISSANCE ANATOMY

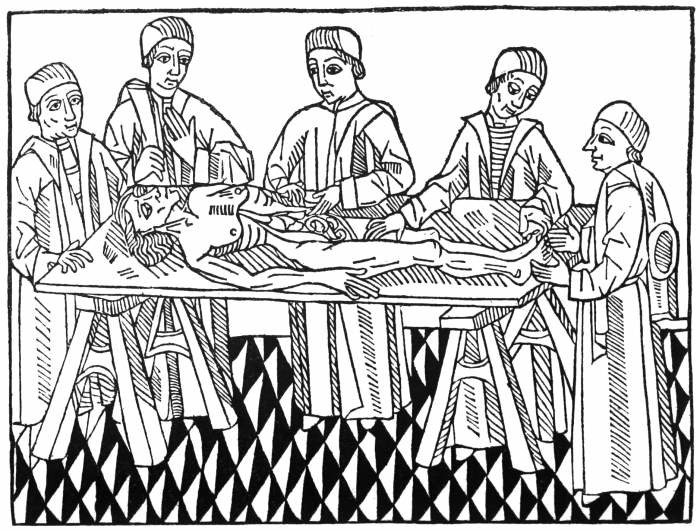

1.

The first printed picture of Dissection (from the French translation of Bartholomaeus Anglicus, 1482)

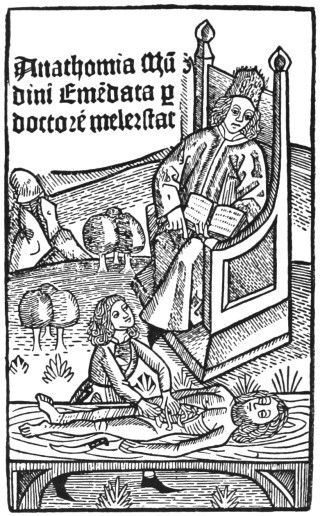

802.

Dissection Scene in the open air (Title-page of Mellerstadt’s edition of the

Anatomyof Mondino, 1493)

823.

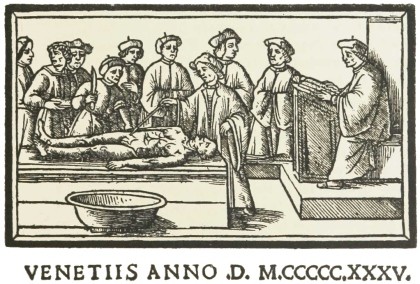

Dissection Scene (from the 1495 edition of ‘Ketham’)

834.

The first picture of Dissection in an English-printed book (from the English translation of Bartholomaeus Anglicus, printed by Wynkyn de Worde, 1495)

855.

A Lecture on Anatomy (from the 1535 edition of Berengar of Carpi’s Commentary on Mondino)

856.

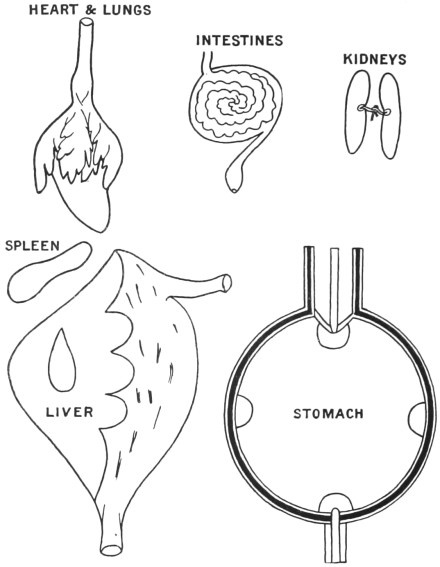

Diagrams of the Internal Organs (after Bodleian MS. Ashmole 399, of about 1298)

887.

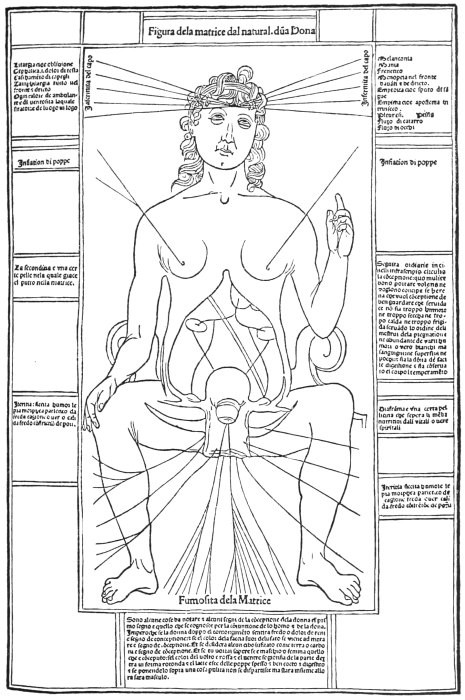

A Female Figure laid open to show the Womb and other Organs (from the 1493 edition of ‘Ketham’)

918.

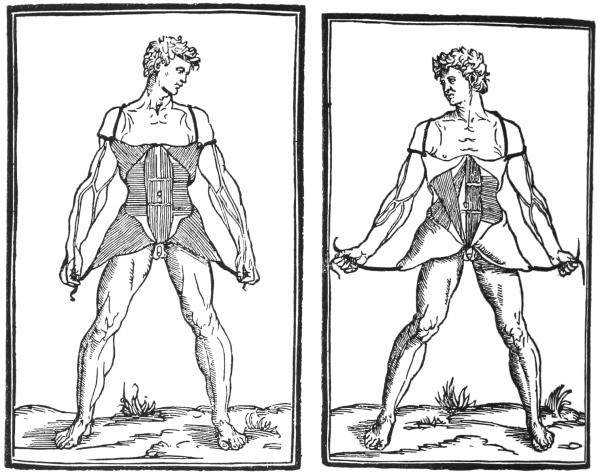

The Abdominal Muscles (from Berengar of Carpi’s Commentary on Mondino, 1521)

969.

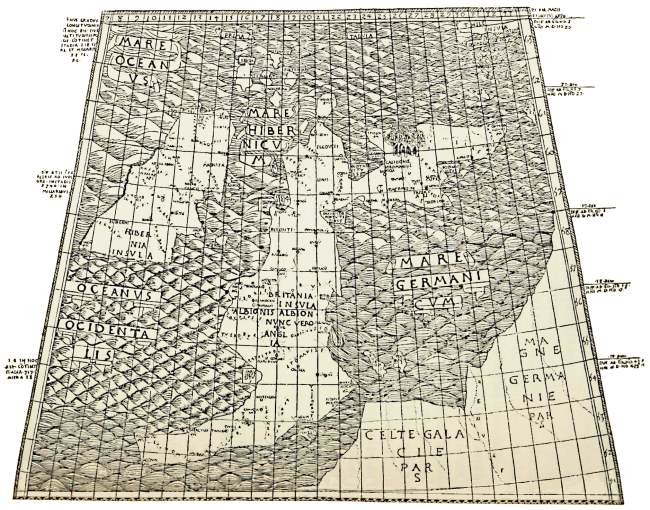

The first printed Map of England (from the 1472(?) Bologna

Ptolemy, edited by Manfredi and others)

10010.

Facsimile of the last page of Manfredi’s

Prognosticon ad annum 1479 10211.

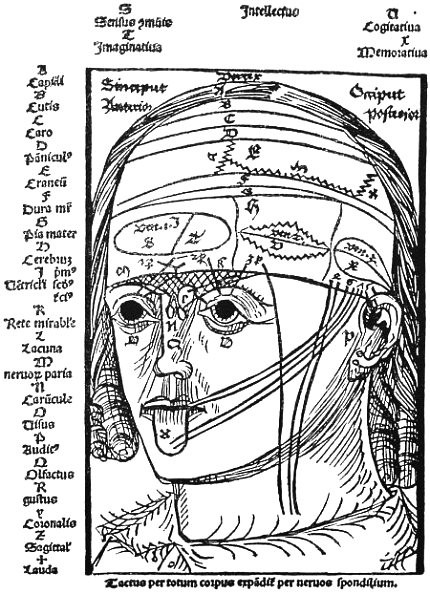

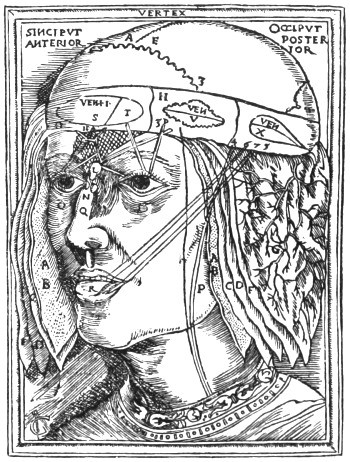

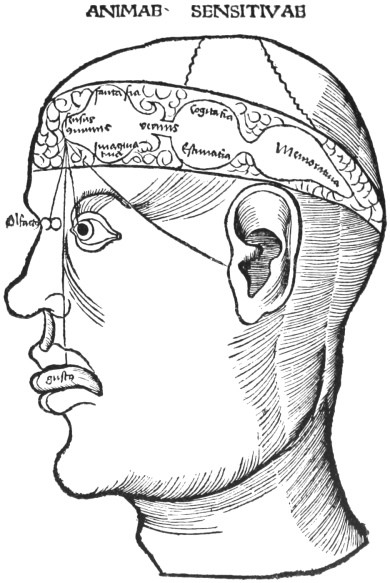

Diagram showing the ten Layers of the Head, the Cerebral Ventricles and Cranial Nerves, and the Relation of the Nerves to the Senses (from M. Hundt,

Antropologium, 1501)

11212.

The Layers of the Head (from the

Anatomiaof Johannes Dryander, 1537)

11213.

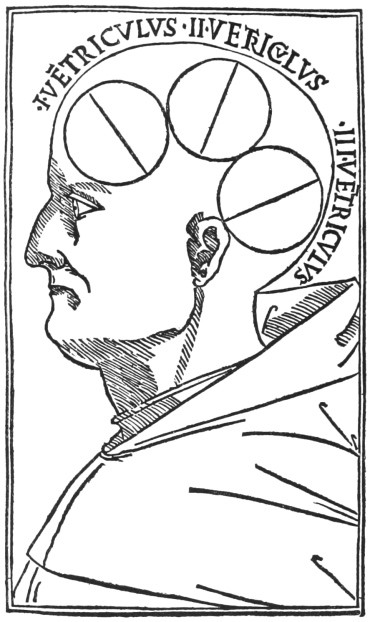

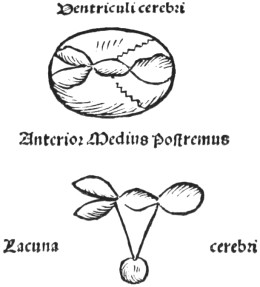

Diagram showing the Ventricles of the Brain (from

Illustrissimi philosophi et theologi domini Alberti magni compendiosum insigne ac perutile opus Philosophiae naturalis, 1496)

11414.

Diagram of the Senses, the Humours, the Cerebral Ventricles, and the Intellectual Faculties. To illustrate Roger Bacon,

De Scientia Perspectiva, (British Museum MS. Sloane 2156, fo. 11

r)

11615.

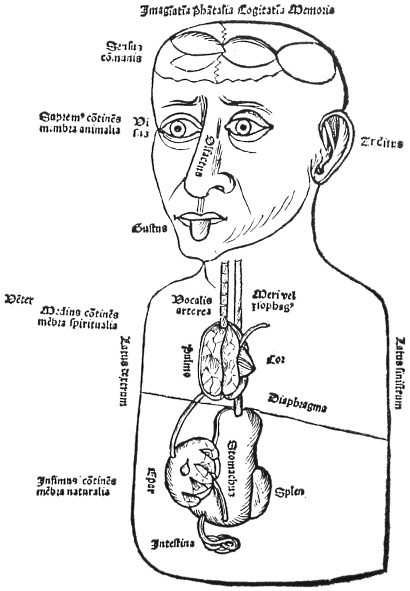

Diagram illustrating the general ideas on Anatomy current at the Renaissance (from K. Peyligk.

Philosophiae naturalis compendium, 1489)

11616.

Diagrams of the Cerebral Ventricles viewed from above and from the side (from K. Peyligk,

Philosophiae naturalis compendium, 1489)

11717.

The Localization of Cerebral Functions (from the 1493 edition of ‘Ketham’)

11718.

Diagram of the Ventricles and the Senses, with their relation to the intellectual processes, according to the doctrine of the Renaissance anatomists (from G. Reisch,

Margarita philosophiae, 1503)

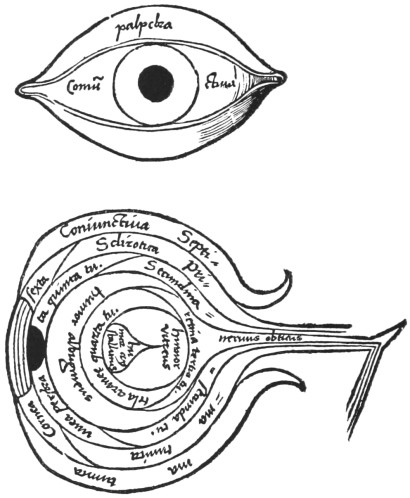

11719.

The Anatomy of the Eye (from G. Reisch,

Margarita philosophiae, 1503)

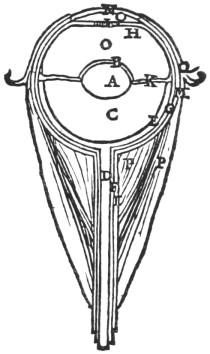

12020.

The Anatomy of the Eye (from Vesalius,

De humani corporis fabrica, 1543)

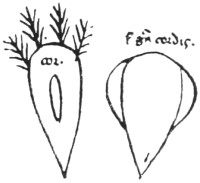

12121.

The Heart (from the Roncioni MS., Pisa 99)

12722.

Diagram showing the two Lateral Ventricles and the ‘Central’ Ventricle, (from Johannes Adelphus,

Mundini de omnibus humani corporis interioribus menbris Anathomia, 1513)

12823.

The Heart (from Hans von Gersdorff,

Feldt- und Stattbüch bewerter Wundartznei, 1556)

129DR. JOHN WEYER AND THE WITCH MANIA

Portrait of Dr. John Weyer at the age of 60, 1576

189THE SCIENTIFIC VIEWS AND VISIONS OF SAINT HILDEGARD (1098–1180)

By Charles Singer

PAGEI.

Introduction

1II.

Life and Works

2III.

Bibliographical Note

6IV.

The Spurious Scientific Works of Hildegard

12V.

Sources of Hildegard’s Scientific Knowledge

15VI.

The Structure of the Material Universe

22VII.

Macrocosm and Microcosm

30VIII.

Anatomy and Physiology

43IX.

Birth and Death and the Nature of the Soul

49X.

The Visions and their Pathological Basis

51I. Introduction

In attempting to interpret the views of Hildegard on scientific subjects, certain special difficulties present themselves. First is the confusion arising from the writings to which her name has been erroneously attached. To obtain a true view of the scope of her work, it is necessary to discuss the authenticity of some of the material before us. A second difficulty is due to the receptivity of her mind, so that views and theories that she accepts in her earlier works become modified, altered, and developed in her later writings. A third difficulty, perhaps less real than the others, is the visionary and involved form in which her thoughts are cast.

But a fourth and more vital difficulty is the attitude that she adopts towards phenomena in general. To her mind there is no distinction between physical events, moral truths, and spiritual experiences. This view, which our children share with their mediaeval ancestors, was developed but not transformed by the virile power of her intellect. Her fusion of internal and external universe links Hildegard indeed to a whole series of mediaeval visionaries, culminating with Dante. In Hildegard, as in her fellow mystics, we find that ideas on Nature and Man, the Moral World and the Material Universe, the Spheres, the Winds, and the Humours, Birth and Death, and even on the Soul, the Resurrection of the Dead, and the Nature of God, are not only interdependent, but closely interwoven. Nowadays we are well accustomed to separate our ideas into categories, scientific, ethical, theological, philosophical, and so forth, and we even esteem it a virtue to retain and restrain our thoughts within limits that we deliberately set for them. To Hildegard such classification would have been impossible and probably incomprehensible. Nor do such terms as parallelism or allegory adequately cover her view of the relation of the material and spiritual. In her mind they are really interfused, or rather they have not yet been separated.

Therefore, although in the following pages an attempt is made to estimate her scientific views, yet the writer is conscious that such a method must needs interpret her thought in a partial manner. Hildegard, indeed, presents to us scientific thought as an undifferentiated factor, and an attempt is here made to separate it by the artificial but not unscientific process of dissection from the organic matrix in which it is embedded.

The extensive literature that has risen around the life and works of Hildegard has come from the hands of writers who have shown no interest in natural knowledge, while those who have occupied themselves with the history of science have, on their side, largely neglected the period to which Hildegard belongs, allured by the richer harvest of the full scholastic age which followed. This essay is an attempt to fill in a small part of the lacuna.

II. Life and Works

Hildegard of Bingen was born in 1098, of noble parentage, at Böckelheim, on the river Nahe, near Sponheim. Destined from an early age to a religious life, she passed nearly all her days within the walls of Benedictine houses. She was educated and commenced her career in the isolated convent of Disibodenberg, at the junction of the Nahe and the Glan, where she rose to be abbess. In 1147 she and some of her nuns migrated to a new convent on the Rupertsberg, a finely placed site, where the smoky railway junction of Bingerbrück now mars the landscape. Between the little settlement and the important mediaeval town of Bingen flowed the river Nahe, spanned by a bridge to which still clung the name of the pagan Drusus (see Fig. 1). At this spot, a place of ancient memories, secluded and yet linked to the world, our abbess passed the main portion of her life, and here she closed her eyes in the eighty-second year of her age on September 17, 1180.

Folio 17 r col. b Folio 32 v col. b Folio 205 r col. b

Plate II. THE THREE SCRIPTS OF THE WIESBADEN CODEX B

Plate III. TITLE PAGE OF THE HEIDELBERG CODEX OF THE SCIVIAS

From the HEIDELBERG CODEX OF THE SCIVIAS

Plate IV. THE UNIVERSE

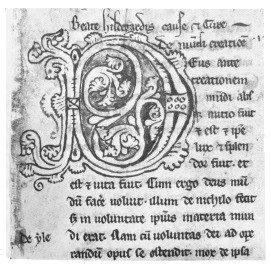

Plate V a. OPENING LINES OF THE COPENHAGEN MS. OF THE CAUSAE ET CURAE

From the LUCCA MS. fo. 1 v

Plate VI. NOUS PERVADED BY THE GODHEAD AND CONTROLLING HYLE

From the LUCCA MS. fo. 9 r

Plate VII. NOUS PERVADED BY THE GODHEAD EMBRACING THE MACROCOSM WITH THE MICROCOSM

From the LUCCA MS. fo. 27 v

Plate VIII. THE MACROCOSM THE MICROCOSM AND THE WINDS

Plate IX. From THE LUCCA MS fo. 37 r

CELESTIAL INFLUENCES ON MEN ANIMALS AND PLANTS

Plate X. A CRUCIFIX IN THE UFFIZI GALLERY About the middle of the XIIIth Century.

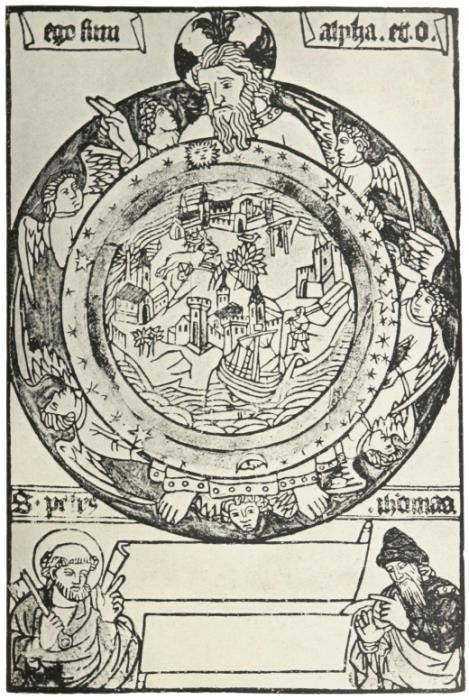

From the LUCCA MS. fo. 86 v

Plate XI. THE STRUCTURE OF THE MUNDANE SPHERE

WIESB. COD. B. fo. 4 r

Plate XIIa. MAN’S FALL AND THE DISTURBANCE OF THE ELEMENTAL HARMONY

From WIESBADEN CODEX B fo. 224 r

Plate XIII. THE LAST JUDGEMENT AND FATE OF THE ELEMENTS

From BIBL. NAT. MS. LAT. 5543 fo. 136 r

Plate XIV. DIAGRAM OF THE RELATION OF HUMAN AND COSMIC PHENOMENA IXth Century

From BIBL. NAT. MS. LAT. 7028 fo. 154 r

Plate XV. AN XIth CENTURY FRENCH MELOTHESIA

From BIBL. NAT. MS. LAT. 11229 fo. 45 v

Plate XVI. A MELOTHESIA OF ABOUT 1400

From the SYMBOLUM APOSTOLICORUM

Plate XVII. A GERMAN BLOCK BOOK First Half of XVth Century. Heidelberg University Library

From BODLEIAN MS. ASHMOLE 399 fo. 18 r

Plate XVIII. AN ANATOMICAL DIAGRAM OF ABOUT 1298 From the Five-Figure Series. Cp. Plate XXXIII

From WIESBADEN CODEX B fo. 22 r

Plate XIX. BIRTH. THE ARRIVAL AND TRIALS OF THE SOUL

From WIESBADEN CODEX B fo. 25 r

Plate XX. DEATH. THE DEPARTURE AND FATE OF THE SOUL

From WIESBADEN CODEX B, fo. 123 r

Plate XXI. THE FALL OF THE ANGELS

From WIESBADEN CODEX B fo. 41 v

Plate XXII. THE DAYS OF CREATION AND THE FALL OF MAN

From WIESBADEN CODEX B. fo. 47 r

Plate XXIII. THE VISION OF THE TRINITY

WIESB. COD. B. fo. 213 v

SEDENS LUCIDUS

From THE WIESBADEN CODEX B fo. 30 r

Plate XXV. THE HEAVENLY CITY

From the Italian translation of ‘KETHAM’, VENICE 1493

Plate XXVII. MUNDINUS(?) LECTURING ON ANATOMY

BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE MS. fr. 2030 Written in 1314

TO ILLUSTRATE THE ANATOMY OF HENRI DE MONDEVILLE

MS. fr. 184 fo. 14 r

Plate XXIX. A POST-MORTEM EXAMINATION. Late XIVth Century

VATICAN MS. HISPANICE 4804 fo. 8 r

Plate XXX a. A DEMONSTRATION OF SURFACE MARKINGS

Plate XXXI. From the MS. of GUY DE VIGEVANO of 1345 at CHANTILLY

Plate XXXII. From the MS. of GUY DE VIGEVANO of 1345 at CHANTILLY

Plate XXXIII. The FIVE-FIGURE SERIES BODLEIAN MS. ASHMOLE 399, about 1292 Fos. 18 r–22 r

VEINS, &c. ARTERIES NERVES BONES MUSCLES

From the DRESDEN GALEN MS.

Plate XXXIV. DEMONSTRATIONS OF ANATOMY Second half of XVth Century

From a drawing in the Library, WINDSOR CASTLE

Plate XXXV. VIEW OF THE INTERNAL ORGANS LEONARDO DA VINCI

From a Drawing in the ASHMOLEAN MUSEUM, OXFORD, attributed to BARTOLOMEO MANFREDI (1574?–1602)

Plate XXXVI. THE TWO FIGURES DISSECTING ARE TRADITIONALLY SAID TO REPRESENT MICHELANGELO AND ANTONIO DELLA TORRE

From his tomb in the Church of S. Giacomo Maggiore at Bologna

Plate XXXVII. GIOVANNI BENTIVOGLIO II

BRIT. MUS. MS. ROY. 7 F VIII, fo. 50 v

Plate XXXVIII a. ROGER BACON’S DIAGRAM OF THE EYE. XIIIth Century

From CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY MS. Ec. iii. 59

Plate XXXIX. MIRACLES AT THE TOMB OF EDWARD THE CONFESSOR XIIIth Century

Plate XL. QUEEN MARY TUDOR BLESSING CRAMP-RINGS

From QUEEN MARY’S MS. MANUAL fo. iv Library of the Roman Catholic Cathedral at WESTMINSTER

Plate XLI. THE BODLEIAN MANUSCRIPT MS. MARSH 379 fo. 73

Fig. 1. THE HILDEGARD COUNTRY

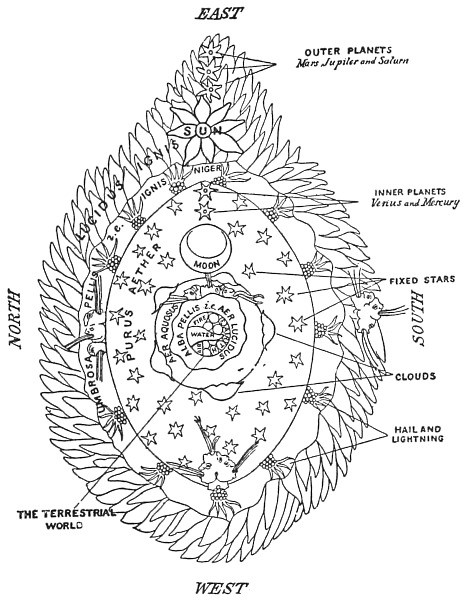

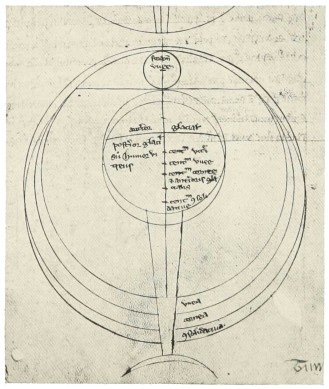

Fig. 2. HILDEGARD’S FIRST SCHEME OF THE UNIVERSE

Slightly simplified from the Wiesbaden Codex B, folio 14 r.

Fig. 3. HILDEGARD’S SECOND SCHEME OF THE UNIVERSE

Reconstructed from her measurements. AB, CD, and EF are all equal to each other, as are also GH, HK, and KL. The clouds are situated in the outer part of the aer tenuis, and form a prolongation downwards from the aer aquosus towards the earth.

Fig. 4. DANTE’S SCHEME OF THE UNIVERSE

Slightly modified from Michelangelo Caetani, duca di Sermoneta, La materia della Divina Commedia di Dante Allighieri dichiarata in VI tavole, Monte Cassino, 1855.

Fig. 5. From Herrade de Landsberg’s Hortus deliciarum, after Straub and Keller.

Fig. 6.

Fig. 8. THE MICROCOSM

From R. Fludd, Philosophia sacra seu astrologia cosmica, Frankfurt, 1628, p. 52.

Fig. 9. From Herrade de Landsberg’s Hortus deliciarum, after Straub and Keller’s reproduction.107

Fig. 1. From the French translation of Bartholomaeus Anglicus, Lyons, 1482. The first printed picture of dissection.

Fig. 2. Title-page of Mellerstadt’s edition of the Anatomy of Mondino, Leipzig, 1493. The scene is laid in the open air.131

Fig. 3. A DISSECTION SCENE

From the Venice 1495 edition of ‘Ketham’ (compare Plate XXVII).

Fig. 4. From the English translation of Bartholomaeus Anglicus, printed by Wynkyn de Worde, 1495. The first picture of dissection in an English-printed book.

Fig. 5. A LECTURE ON ANATOMY

From the 1535 Venice edition of Berengar of Carpi’s Commentary on Mondino.

Fig. 6. DIAGRAMS OF THE INTERNAL ORGANS

After Bodleian Library MS. Ashmole 399 of about 1298, fos. 23 recto–24 recto.

Fig. 7. A FEMALE FIGURE LAID OPEN TO SHOW THE WOMB AND OTHER ORGANS

From the 1493 Venice edition of ‘Ketham’ translated into Italian. This is the first printed anatomical figure drawn from the object.

Fig. 8. THE ABDOMINAL MUSCLES

From Berengar of Carpi’s Commentary on Mondino, Bologna, 1521.

THE FIRST PRINTED MAP OF ENGLAND.

From the 1472 (?) Bologna Ptolemy, edited by Manfredi and others.

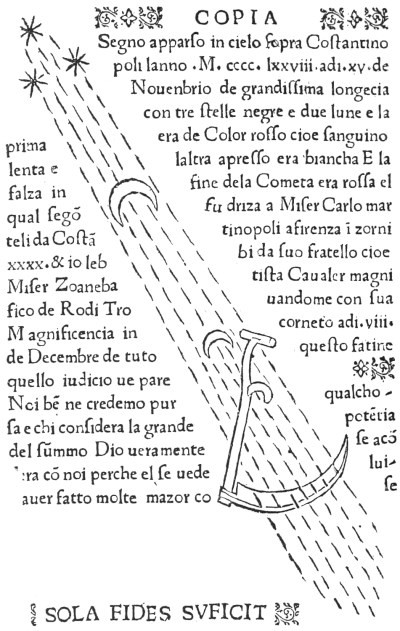

Fig. 10. The last page of Manfredi’s Prognosticon ad annum 1479, Bologna, 1478.

Fig. 11. From M. Hundt, Antropologium, de hominis dignitate natura et proprietatibus, Leipzig, 1501. The figure shows the ten layers of the head, the cerebral ventricles and cranial nerves, and the relation of the nerves to the senses.

Fig. 12. THE LAYERS OF THE HEAD

From the Anatomia of Johannes Dryander, Marburg, 1537.

Fig. 13. From Illustrissimi philosophi et theologi domini Alberti magni compendiosum insigne ac perutile opus Philosophiae naturalis, Venice, 1496, showing the ventricles of the brain.

Fig. 14. Diagram of the senses, the humours, the cerebral ventricles, and the intellectual faculties. MS. Sloane 2156, folio 11 recto, in the British Museum, being a copy written in 1428 of the De Scientia Perpectiva of Roger Bacon

Fig. 15. From K. Peyligk’s Philosophiae naturalis compendium, Leipzig, 1489. Illustrating the general ideas on anatomy current at the Renaissance.

Fig. 16. The cerebral ventricles from above and from the side. According to K. Peyligk, Philosophiae naturalis compendium, Leipzig, 1489.

Fig. 17. The localization of cerebral functions. From the Italian edition of ‘Ketham’, Fasciculus Medicinae, Venice, 1493.

Fig. 18. From G. Reisch, Margarita philosophiae, Leipzig,? 1503. Diagram of the ventricles and the senses with their relation to the intellectual processes according to the doctrine of the Renaissance anatomists.

Fig. 19. THE ANATOMY OF THE EYE

From G. Reisch, Margarita philosophiae, Leipzig,? 1503. Showing the seven tunics and three humours of the eye according to the doctrines of Renaissance anatomists.196

Fig. 20. THE ANATOMY OF THE EYE

From Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica, Basel, 1543, p. 643. A, Crystalline humour; O, Albugineous humour; C, Vitreous humour; N, Cornea; Q, Conjunctiva; M, Sclerotica; G, Secundina; H, Uvea; K, Arachnoidea; E, Retina.

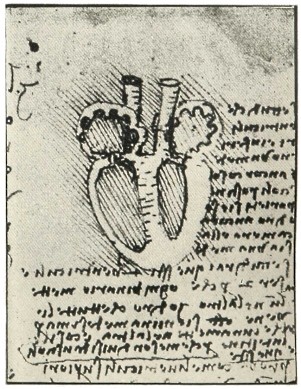

Fig. 21. THE HEART

From the Roncioni MS. (Pisa 99) after Sudhoff.

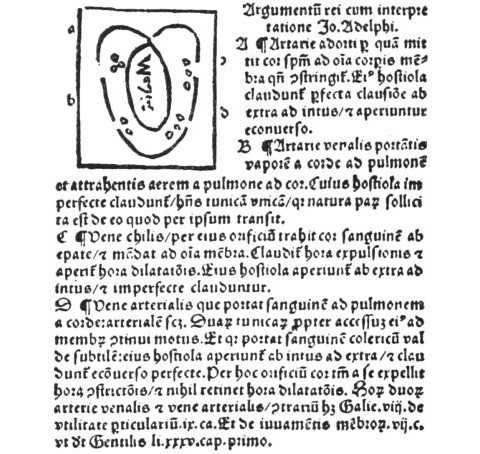

Fig. 22. From Johannes Adelphus, Mundini de omnibus humani corporis interioribus menbris Anathomia, Strassburg, 1513. The diagram shows the two lateral ventricles and the ‘central’ ventricle. By a printer’s error the letters c and d are transposed. The arteria adorti is the aorta, the arteria venalis the pulmonary vein, the vena chilis the vena cava, and the vena arterialis the pulmonary artery. The auricles are ignored, as is frequently the case in works of the period, and the pulmonary veins are represented as opening directly into the ventricles.

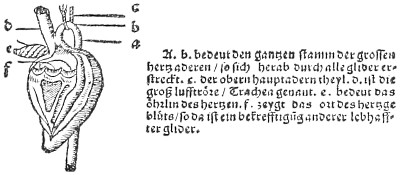

Fig. 23. From Hans von Gersdorff, Feldt und Stattbüch bewerter Wundartznei, Frankfurt, 1556. The trachea (d) is represented as opening directly into the heart.

Introduction

But a fourth and more vital difficulty is the attitude that she adopts towards phenomena in general. To her mind there is no distinction between physical events, moral truths, and spiritual experiences. This view, which our children share with their mediaeval ancestors, was developed but not transformed by the virile power of her intellect. Her fusion of internal and external universe links Hildegard indeed to a whole series of mediaeval visionaries, culminating with Dante. In Hildegard, as in her fellow mystics, we find that ideas on Nature and Man, the Moral World and the Material Universe, the Spheres, the Winds, and the Humours, Birth and Death, and even on the Soul, the Resurrection of the Dead, and the Nature of God, are not only interdependent, but closely interwoven. Nowadays we are well accustomed to separate our ideas into categories, scientific, ethical, theological, philosophical, and so forth, and we even esteem it a virtue to retain and restrain our thoughts within limits that we deliberately set for them. To Hildegard such classification would have been impossible and probably incomprehensible. Nor do such terms as parallelism or allegory adequately cover her view of the relation of the material and spiritual. In her mind they are really interfused, or rather they have not yet been separated.

Whatever the date of these miniatures, however, they reproduce the meaning of the text of the Liber divinorum operum with a convincing certainty and sureness of touch. This work is the most difficult of all Hildegard’s mystical writings. Without the clues provided by the miniatures, many passages in it are wholly incomprehensible. It appears to us therefore by no means improbable that the traditional interpretation of Hildegard’s works, thus preserved to our time by these miniatures and by them alone, may have had its origin from the mouth of the prophetess herself, perhaps through another set of miniatures that has disappeared or has not yet come to light.19

(f) Furthermore, although that spurious work has a chapter De elementis, it reveals none of Hildegard’s most peculiar and definite views as to their nature, origin, and fate,28 nor does it refer to the sphericity of the earth, to the vascular system of man, to the humours and their relation to the winds and the elements, or to a dozen other points on which, as we shall see, Hildegard had views of her own.

The contemporaries of Hildegard who provide the closest analogy to her are Elizabeth of Schönau (died 1165), whose visions are recounted in her life by Eckbertus;50 and Herrade de Landsberg, Abbess of Hohenburg in Alsace, the priceless MS. of whose Hortus Deliciarum was destroyed by the Germans in the siege of Strasbourg in 1870.51 With Elizabeth of Schönau, who lived in her neighbourhood, Hildegard was in frequent correspondence. With Herrade she had, so far as is known, no direct communication; but the two were contemporary, lived not very far apart, and under similar political and cultural conditions. Elizabeth’s visions present some striking analogies to those of Hildegard, while the figures of Herrade, of which copies have fortunately survived, often suggest the illustrations of the Wiesbaden or of the Lucca MSS.

These curious passages were written at some date after 1163, when Hildegard was at least 65 years old. They reveal our prophetess attempting to revise much of her earlier theory of the universe, and while seeking to justify her earlier views, endeavouring also to bring them into line with the new science that was now just beginning to reach her world. Note that (a) the universe has become round; (b) there is an attempt to arrange the zones according to their density, i.e. from without inwards, fire, air (ether), water, earth; (c) exact measurements are given; (d) the watery zone is continued earthward so as to mingle with the central circle. In all these and other respects she is joining the general current of mediaeval science then beginning to be moulded by works translated from the Arabic. Her knowledge of the movements of the heavenly bodies is entirely innocent of the doctrine of epicycles, but in other respects her views have come to resemble those, for instance, of Messahalah, one of the simplest and easiest writers on the sphere available in her day. Furthermore, her conceptions have developed so as to fit in with the macrocosm-microcosm scheme which she grasped about the year 1158. Even in her latest work, however, her theory of the universe exhibits differences from that adopted by the schoolmen, as may be seen by comparing her diagram with, for example, the scheme of Dante (Fig. 4).

Macrocosmic schemes of the type illustrated by the text of Hildegard and by the figures of the Lucca MS. had a great vogue in mediaeval times, and were passed on to later ages. Some passages in Hildegard’s work read curiously like Paracelsus (1491–1541),93 and it is not hard to find a link between these two difficult and mystical writers. Trithemius, the teacher of Paracelsus, was abbot of Sponheim, an important settlement almost within sight of Hildegard’s convents on the Rupertsberg and Disibodenberg. Trithemius studied Hildegard’s writings with great care and attached much importance to them, so that they may well have influenced his pupil. The influence of mediaeval theories of the relation of macrocosm and microcosm is encountered among numerous Renaissance writers besides Paracelsus, and is presented to us, for instance, by such a cautious, balanced, and scientifically-minded humanist as Fracastor. But as the years went on, the difficulty in applying the details of the theory became ever greater and greater. Facts were strained and mutilated more and more to make them fit the Procrustean bed of an outworn theory, which at length became untenable when the heliocentric system of Copernicus and Galileo replaced the geocentric and anthropocentric systems of an earlier age. The idea of a close parallelism between the structure of man and of the wider universe was gradually abandoned by the scientific, while among the unscientific it degenerated and became little better than an insane obsession. As such it appears in the ingenious ravings of the English follower of Paracelsus, the Rosicrucian, Robert Fludd, who reproduced, often with fidelity, the systems which had some novelty five centuries before his time (Figs. 6, 7, and 8). As a similar fantastic obsession this once fruitful hypothesis still occasionally appears even in modern works of learning and industry.94

When the body has thus taken shape there enters into it the soul which, though at first shapeless, gradually assumes the form of its host, the earthly tabernacle; and at death the soul departs through the mouth with the last breath, as a fully developed naked human shape, to be received by devils or angels as the case may be (Plate XX).

Fig. 1. THE HILDEGARD COUNTRY

Hildegard was a woman of extraordinarily active and independent mind. She was not only gifted with a thoroughly efficient intellect, but was possessed of great energy and considerable literary power, and her writings cover a wide range, betraying the most varied activities and remarkable imaginative faculty. The best known, and in a literary sense the most valuable of her works, are the books of visions. She was before all things an ecstatic, and both her Scivias (1141–50) and her Liber divinorum operum simplicis hominis (1163–70) contain passages of real power and beauty. Less valuable, perhaps, is her third long mystical work (the second in point of time), the Liber vitae meritorum (1158–62). She is credited with the authorship of an interesting mystery-play and of a collection of musical compositions, while her life of St. Disibode, the Irish missionary (594–674) to whom her part of the Rhineland owes its Christianity, and her account of St. Rupert, a local saint commemorated in the name ‘Rupertsberg’, both bear witness alike to her narrative powers, her capacity for systematic arrangement, and her historical interests. Her extensive correspondence demonstrates the influence that she wielded in her own day and country, while her Quaestionum solutiones triginta octo, her Explanatio regulae sancti Benedicti, and her Explanatio symboli sancti Athanasii ad congregationem sororum suorum give us glimpses of her activities as head of a religious house.

Her biographer, the monk Theodoric, records that she also busied herself with the treatment of the sick, and credits her with miraculous powers of healing.1 Some of the cited instances of this faculty, as the curing of a love-sick maid,2 are, however, but manifestations of personal ascendancy over weaker minds; notwithstanding her undoubted acquaintance with the science of her day, and the claims made for her as a pioneer of the hospital system, there is no serious evidence that her treatment extended beyond exorcism and prayer.

For her time and circumstance Hildegard had seen a fair amount of the world. Living on the Rhine, the highway of Western Germany, she was well placed for observing the traffic and activities of men. She had journeyed at least as far north as Cologne, and had traversed the eastern tributary of the great river to Frankfort on the Main and to Rothenburg on Taube.3 Her own country, the basin of the Nahe and the Glan, she knew intimately. She was, moreover, in constant communication with Mayence, the seat of the archbishopric in which Bingen was situated, and there has survived an extensive correspondence with the ecclesiastics of Cologne, Speyer, Hildesheim, Trèves, Bamberg, Prague, Nürnberg, Utrecht, and numerous other towns of Germany, the Low Countries, and Central Europe.

Folio 17 r col. b Folio 32 v col. b Folio 205 r col. b

Plate II. THE THREE SCRIPTS OF THE WIESBADEN CODEX B

Hildegard’s journeys, undertaken with the object of stimulating spiritual revival, were of the nature of religious progresses, but, like those of her contemporary, Bernard of Clairvaux, they were in fact largely directed against the heretical and most cruelly persecuted Cathari, an Albigensian sect widely spread in the Rhine country of the twelfth century, whom Hildegard regarded as ‘worse than the Jews’.4 In justice to her memory it is to be recalled that she herself was ever against the shedding of blood, and had her less ferocious views prevailed, some more substantial relic than the groans and tears of this people had reached our time, while the annals of the Church had been spared the defilement of an inexpiable stain.

Plate III. TITLE PAGE OF THE HEIDELBERG CODEX OF THE SCIVIAS

Hildegard’s correspondence with St. Bernard, then preaching his crusade, with four popes, Eugenius III, Anastasius IV, Adrian IV, and Alexander III, and with the emperors Conrad and Frederic Barbarossa, brings her into the current of general European history, while she comes into some slight contact with the story of our own country by her hortatory letters to Henry II and to his consort Eleanor, the divorced wife of Louis VII.5

To complete a sketch of her literary activities, mention should perhaps be made of a secret script and language, the lingua ignota, attributed to her. It is a transparent and to modern eyes a foolishly empty device that hardly merits the dignity of the term ‘mystical’. It has, however, exercised the ingenuity of several writers, and has been honoured by analysis at the hands of Wilhelm Grimm.6

Ample material exists for a full biography of Hildegard, and a number of accounts of her have appeared in the vulgar tongue. Nearly all are marred by a lack of critical judgement that makes their perusal a weary task, and indeed it would need considerable skill to interest a detached reader in the minutiae of monastic disputes that undoubtedly absorbed a considerable part of her activities. Perhaps the best life of her is the earliest; it is certainly neither the least critical nor the most credulous, and is by her contemporaries, the monks Godefrid and Theodoric.7

The title of ‘saint’ is usually given to Hildegard, but she was not in fact canonized. Attempts towards that end were made under Gregory IX (1237), Innocent IV (1243), and John XXII (1317). Miraculous cures and other works of wonder were claimed for her, but either they were insufficiently miraculous or insufficiently attested.8 Those who have impartially traced her life in her documents will agree with the verdict of the Church. Hers was a fiery, a prophetic, in many ways a singularly noble spirit, but she was not a saint in any intelligible sense of the word.

III. Bibliographical Note

There is no complete edition of the works of Hildegard. For the majority of readers the most convenient collection will doubtless be vol. 197 of Migne, Patrologia Latina. This can be supplemented from Cardinal J. B. Pitra’s well-edited Analecta sacra, the eighth volume of which contains certain otherwise inaccessible works of Hildegard,9 and is the only available edition of the Liber vitae meritorum per simplicem hominem a vivente luce, revelatorum.

Manuscripts of the writings of our abbess are numerous and are widely scattered over Europe. Four of them are of special importance for our purpose, and are here briefly described.

(A) is a vast parchment of 480 folios in the Nassauische Landesbibliothek at Wiesbaden. This much-thumbed volume, still bearing the chain that once tethered it to some monastic desk, is written in a thirteenth-century script. There is evidence that it was prepared in the neighbourhood of Hildegard’s convent, if not in that convent itself. It is interesting as a collection of those works that the immediate local tradition attributed to her, and is thus useful as a standard of genuineness.10 Reference will be made to it in the following pages as the Wiesbaden Codex A. Its contents are as follows:

1. Liber Scivias.

2. Liber vitae meritorum.

3. Liber divinorum operum.

4. Ad praelatos moguntienses.

5. Vita sanctae Hildegardis. By Godefrid and Theodoric.

6. Liber epistolarum et orationum. This collection contains 292 items, and includes the Explanatio symboli Athanasii, the Exposition of the Rule of St. Benedict, and the Lives of St. Disibode and St. Rupert.

7. Expositiones evangeliorum.

8. Ignota lingua and Ignotae litterae.

9. Litterae villarenses.

10. Symphonia harmoniae celestum revelationum.

(B) is also at Wiesbaden, and will be cited here as the Wiesbaden Codex B. It contains the Scivias only, and is a truly noble volume of 235 folios, beautifully illuminated, in excellent preservation, and of the highest value for the history of mediaeval art. It has been thoroughly investigated by the late Dom Louis Baillet,11 who concluded that it was written in or near Bingen between the dates 1160 and 1180. Its miniatures help greatly in the interpretation of the visions, illustrating them often in the minutest and most unexpected details. In view of the great difficulty of visualizing much of her narrative, these miniatures afford to our mind strong evidence that the MS. was supervised by the prophetess herself, or was at least prepared under her immediate tradition. This view is confirmed by comparing the miniatures with those of the somewhat similar but inferior Heidelberg MS. (C).

Both the miniatures and the script of the Wiesbaden Codex B are the work of several hands. There are three distinct handwritings discernible (Plate II). The earliest is attributed by Baillet in his careful work to the twelfth century, while the later writing is in thirteenth-century hands.12 It thus appears to us that while Hildegard herself probably supervised the earlier stages of the preparation of this volume, its completion took place subsequent to her death. This view is sustained by the fact that some of the later miniatures are far less successful than the earlier figures in aiding the interpretation of her text.

The two Wiesbaden MSS. appear to have remained at the convent on the Rupertsberg opposite Bingen until the seventeenth century. They were studied there by Trithemius in the fifteenth century, and one of them at least was seen by the Mayence Commission of 1489. Later they were noted by the theologians Osiander (1527) and Wicelius (Weitzel, 1554), and by the antiquary Nicolaus Serarius (1604). In 1632, during the Thirty Years’ War, the Rupertsberg buildings were destroyed, the MSS. being removed to a place of safety in the neighbouring settlement at Eibingen, where they were again recorded in 1660 by the Jesuits Papenbroch and Henschen.13 At some unknown date they were transferred to Wiesbaden, where they were examined in 1814 by Goethe,14 and a few years later by Wilhelm Grimm,15 and where they have since remained.

Fig. 2. HILDEGARD’S FIRST SCHEME OF THE UNIVERSE

Slightly simplified from the Wiesbaden Codex B, folio 14 r.

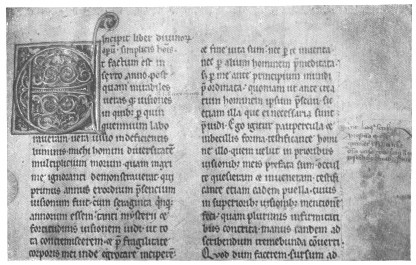

(C) This MS. is at the University Library at Heidelberg. It also contains only the Scivias, and it is the only known illuminated MS. of that work except the Wiesbaden Codex B. The Heidelberg MS. was prepared with great care in the early thirteenth century, only a little later than its fellow, but its figures afford little aid in the interpretation of the text. Thus, for instance, the Heidelberg diagram of the universe (Plate IV) is of a fairly conventional type which quite fails to illustrate the difficult description. The obscurities of the text are, however, at once explained by a figure in the Wiesbaden Codex B (Fig. 2): we thus obtain further indirect evidence of the personal influence of Hildegard in the preparation of that MS. The representation of Hildegard in the Heidelberg MS. (Plate III) shows no resemblance to those in the Wiesbaden Codex B (Plate I) or in the Lucca MS. (Plates VI to IX), which will now be described.

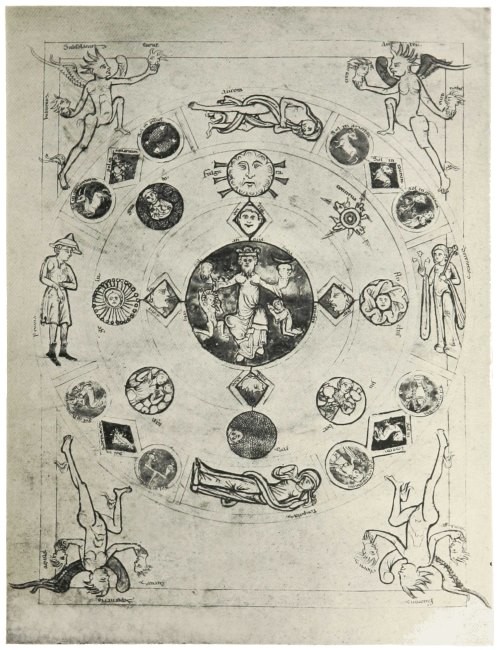

(D) is an illustrated codex of the Liber divinorum operum simplicis hominis at the Municipal Library at Lucca. It contains ten beautiful miniatures, some of which are here reproduced (Plates VI to IX and XI), as they are of special value for the interpretation of Hildegard’s theories on the relation of macrocosm and microcosm.

This Lucca MS. was described and its text printed in 1761 by Giovanni Domenico Mansi,16 a careful scholar, who was himself sometime Archbishop of Lucca. Mansi concluded that it was written at the end of the twelfth or the beginning of the thirteenth century. On palaeographical grounds a slightly later date would nowadays probably be preferred (Plate V b).

The work consists of ten visions, each illustrated by a figure. The date, character, and meaning of these miniatures raise special problems to which only very superficial reference can here be made. Unfortunately but little work has been done on early Italian schools of miniaturists, and it is not a subject on which any exact knowledge can yet be said to exist.17

Of these ten miniatures we may dismiss the last five in a few words. The sixth to the tenth visions are of purely theological interest, and the miniatures illustrating them are by a different hand to the rest. They are all relatively crude products, which appear to us to resemble other Italian work of the period at which the MS. was written. We shall concentrate our attention on the first five miniatures.

The first three miniatures of the Lucca MS. (Plates VI to VIII) may be attributed to the same hand on the following grounds:

1. All have a very similar inset figure of the prophetess below the main picture.

2. The character of the principal figure of the first miniature (Plate VI) is almost identical with the curious universe-embracing double-headed figure of the second miniature (Plate VII).

3. The features and draughtsmanship of the central figure of the second miniature (Plate VII) are identical with those of the third (Plate VIII).

4. The beasts’ heads arranged round the second miniature (Plate VII) are exactly reproduced in the third miniature (Plate VIII).

Now although these three miniatures are in some respects unique, they contain elements enabling us to date them with an approach to accuracy. These elements are to be found especially in the central figure of the second and third miniatures (Plates VII and VIII).

About the middle of the thirteenth century, as Venturi has shown,18 there was a well-marked change in Northern Italy in the traditional representation of the form on the Cross. This change was followed with almost slavish accuracy, and the new form is well represented by a painting in the Uffizi Gallery (Plate X). It is this figure of Christ which is reproduced by our miniaturist. The central figure of Plates VII and VIII resembles that of the Uffizi crucifix, for instance, in the general pose of the body, in the position of the legs and of the arms, in the treatment of the abdominal musculature, in the method of outlining the muscles of the legs and of the arms, and in a minute and very constant detail by which the outline of the left side is continued with the fold of the groin, thus giving an impression of the left thigh being advanced on the right. Furthermore, the somewhat Byzantine cast of countenance of the figure can be closely paralleled from Northern Italian work of the same period. We therefore regard these first three miniatures of the Lucca MS. as dating from about the middle of the thirteenth century.

The remaining two miniatures (Plates IX and XI) offer special difficulties. Plate XI (illustrating the fifth vision) presents us with no complete human figures, except the small and probably copied inset of the prophetess below the miniature. The faces bear some resemblance to those of the last five miniatures; the wings, on the other hand, to those of the first miniature (Plate VI). It is perhaps possible that this miniature was the work of an early thirteenth-century artist, and that the wings and some other details were added by a later hand. The abnormal orientation, east to the left and south above, suggests that we have here to do with some special influence.

The most anomalous of all is, however, the beautiful fourth miniature (Plate IX). This picture has a general feeling of the early Renaissance, though it is hard to find in it any definite humanistic element. The nude female figure in the upper left quadrant is especially striking. No parallel to it is to be found in the thirteenth-century Italian miniatures that have so far been reproduced, and it appears to us difficult to date the miniature anterior to the fourteenth century at the very earliest. It is, in any event, by a different hand to the others. The rashes on the patients in the two upper and the right lower quadrants are perhaps an attempt to render the fatal ‘God’s tokens’ of those waves of pestilence that devastated the Italian peninsula in the fourteenth century.

Whatever the date of these miniatures, however, they reproduce the meaning of the text of the Liber divinorum operum with a convincing certainty and sureness of touch. This work is the most difficult of all Hildegard’s mystical writings. Without the clues provided by the miniatures, many passages in it are wholly incomprehensible. It appears to us therefore by no means improbable that the traditional interpretation of Hildegard’s works, thus preserved to our time by these miniatures and by them alone, may have had its origin from the mouth of the prophetess herself, perhaps through another set of miniatures that has disappeared or has not yet come to light.19

IV. The Spurious Scientific Works of Hildegard

The scientific views of Hildegard are embedded in a theological setting, and are mainly encountered in the Scivias and the Liber divinorum operum simplicis hominis. To a less extent they appear occasionally in her Epistolae and in the Liber vitae meritorum.

From the HEIDELBERG CODEX OF THE SCIVIAS

Plate IV. THE UNIVERSE

Two works of non-theological tone and definitely scientific character have been printed in her name. One of these was recently edited under the title Beatae Hildegardis causae et curae.20 A single MS. only of this work is known to exist, and is now deposited in the Royal Library of Copenhagen.21 It is an ill-written document of the thirteenth century, and the original work probably dates from this period. It has none of the characteristics of the acknowledged work of Hildegard, and indeed the only link with her name is the title, which is written in a hand different from that of the text (Plate V a). Nothing could be more unlike the ecstatic but well-ordered and systematic work of the prophetess of Bingen than the prosy disorder of the Causae et curae. Linguistically, also, it differs entirely from the typical writings of Hildegard, for it is full of Germanisms, which never interrupt the eloquence of her authentic works. Again, Hildegard’s tendency to theoretical speculation, as for instance on the nature of the elements or on the form of the Universe, finds no place in the scrappy paragraphs of this apocryphal compilation.

Plate V a. OPENING LINES OF THE COPENHAGEN MS. OF THE CAUSAE ET CURAE

Plate V b. OPENING LINES OF THE LUCCA MS. OF THE LIBER DIVINORUM OPERUM SIMPLICIS HOMINIS

A second work, of somewhat similar character, is entitled Subtilitatum diversarumque creaturarum libri novem. This is clearly a compilation, and numerous passages in it can be traced to such sources as Pliny, Walafrid Strabus, Marbod, Macer, the Physiologus, Isidore Hispalensis, Constantine the African, and the Regimen Sanitatis Salerni, only the last three of which exerted a traceable influence on the genuine works of our authoress. Nevertheless this Liber subtilitatum was early printed as Hildegard’s work, along with a treatise attributed with as little justification to another woman writer, Trotula, one of the ladies of Salerno, whose name was also a household word in the Middle Ages, and was freely attached to medical writings with which she had little or nothing to do.22 It is true that Hildegard’s contemporary biographer, the monk Theodoric, assures us that she had written De natura hominis et elementorum, diversarumque creaturarum,23 but there is nothing to suggest that the Liber subtilitatum is intended thereby.

The modern scholars Daremberg and Reuss have edited the Liber subtilitatum as Hildegard’s composition,24 and the work attracted the attention of Virchow,25 but notwithstanding the authority of these names, the objections which apply to the genuineness of the Causae et curae are also valid here:

(a) The Liber subtilitatum is not included in the Wiesbaden Codex A.

(b) The phrase De natura hominis et elementorum diversarumque creaturarum, used by Theodoric as a description and by Reuss as a title,26 would lead one to expect great emphasis on the nature of the elements and their entry into the human frame. Such emphasis is not, in fact, discoverable in the Liber subtilitatum, which, moreover, does not treat of human anatomy or physiology.

(c) On the other hand, the genuine Liber divinorum operum simplicis hominis does lay stress on these points. This is possibly therefore the work to which Theodoric refers, and to it his description certainly applies well.

(d) As in the Causae et curae, there are linguistic difficulties that prevent us attributing the Liber subtilitatum to Hildegard. Such, for instance, is the number of Germanisms as well as the marked difference from the style and method of her acknowledged work.

(e) There are statements in the Liber subtilitatum that can scarcely be attributed to our authoress. Having largely explored the Rhine basin, and corresponding constantly with writers beyond the Alps, how could she possibly derive all rivers, Rhine and Danube, Meuse and Moselle, Nahe and Glan, from the same lake (of Constance) as does the author of the Liber subtilitatum?27

(f) Furthermore, although that spurious work has a chapter De elementis, it reveals none of Hildegard’s most peculiar and definite views as to their nature, origin, and fate,28 nor does it refer to the sphericity of the earth, to the vascular system of man, to the humours and their relation to the winds and the elements, or to a dozen other points on which, as we shall see, Hildegard had views of her own.

Before leaving the subject of Hildegard’s apocryphal works, brief reference may be made to the Speculum futurorum temporum, a spurious production to which her name is often attached. It exists in innumerable MSS., and has been frequently edited and translated. It is the work of Gebeno, prior of Eberbach, who wrote it in 1220, claiming that he extracted it from Hildegard’s writings. Another work erroneously attributed to Hildegard is entitled Revelatio de fratribus quatuor mendicantium ordinum, and is directed against the four mendicant orders—Franciscans, Dominicans, Carmelites, and Augustinians. It also has been printed, but is wholly spurious, and was probably composed towards the latter part of the thirteenth century.

V. Sources of Hildegard’s Scientific Knowledge

In the works of Hildegard we are dealing with the products of a peculiarly original intellect, and her imaginative power and mystical tendency make an exhaustive search into the origin of her ideas by no means an easy task. With her theological standpoint, as such, we are not here concerned, and unfortunately she does not herself refer to any of her sources other than the Biblical books; to have cited profane writers would indeed have involved the abandonment of her claim that her knowledge was derived by immediate inspiration from on high. Nevertheless it is possible to form some idea, on internal evidence, of the origin of many of her scientific conceptions.

The most striking point concerning the sources of Hildegard is negative. There is no German linguistic element distinguishable in her writings, and they show little or no trace of native German folk-lore.29 It is true that Trithemius of Sponheim (1462–1516), who is often a very inaccurate chronicler, tells us that Hildegard ‘composed works in German as well as in Latin, although she had neither learned nor used the latter tongue except for simple psalmody’.30 But with the testimony before us of the writings themselves and of her skilful use of Latin, the statement of Trithemius and even the hints of Hildegard31 may be safely discounted and set down to the wish to magnify the element of inspiration.32 So far from her having been illiterate, we shall show that the structure and details of her works betray a considerable degree of learning and much painstaking study of the works of others. Thus, for instance, she skilfully manipulates the Hippocratic doctrines of miasma and the humours, and elaborates a theory of the interrelation of the two which, though developed on a plan of her own, is yet clearly borrowed in its broad outline from such a writer as Isidore of Seville. Again, as we shall see, some of her ideas on anatomy seem to have been derived from Constantine the African, who belonged to the Benedictine monastery of Monte Cassino.33

Hildegard lived at rather too early a date to drink from the broad stream of new knowledge that was soon to flow into Europe through Paris from its reservoir in Moslem Spain. Such drops from that source as may have reached her must have trickled in either from the earlier Italian translators or from the Jews who had settled in the Upper Rhineland, for it is very unlikely that she was influenced by the earlier twelfth-century translations of Averroes, Avicenna, Avicebron, and Avempace, that passed into France from the Jews of Marseilles, Montpellier, and Andalusia.34 Her intellectual field was thus far more patristic than would have been the case had her life-course been even a quarter of a century later.

Her science is primarily of the usual degenerate Greek type, disintegrated fragments of Aristotle and Galen coloured and altered by the customary mediaeval attempts to bring theory into line with scriptural phraseology, though a high degree of independence is obtained by the visionary form in which her views are set. She exhibits, like all mediaeval writers on science, the Aristotelian theory of the elements, but her statement of the doctrine is illuminated by flashes of her own thoughts and is coloured by suggestions from St. Augustine, Isidore Hispalensis, Bernard Sylvestris of Tours, and perhaps from writings attributed to Boethius.

The translator Gerard of Cremona (1114–87) was her contemporary, and his labours made available for western readers a number of scientific works which had previously circulated only among Arabic-speaking peoples.35 Several of these works, notably Ptolemy’s Almagest, Messahalah’s De Orbe, and the Aristotelian De Caelo et Mundo, contain material on the form of the universe and on the nature of the elements, and some of them probably reached the Rhineland in time to be used by Hildegard. The Almagest, however, was not translated until 1175, and was thus inaccessible to Hildegard.36 Moreover, as she never uses an Arabic medical term, it is reasonably certain that she did not consult Gerard’s translation of Avicenna, which is crowded with Arabisms.

On the other hand, the influence of the Salernitan school may be discerned in several of her scientific ideas. The Regimen Sanitatis of Salerno, written about 1101, was rapidly diffused throughout Europe, and must have reached the Rhineland at least a generation before the Liber Divinorum Operum was composed. This cycle of verses may well have reinforced some of her microcosmic ideas,37 and suggested also her views on the generation of man,38 on the effects of wind on health,39 and on the influence of the stars.40

On the subject of the form of the earth Hildegard expressed herself definitely as a spherist,41 a point of view more widely accepted in the earlier Middle Ages than is perhaps generally supposed. She considers in the usual mediaeval fashion that this globe is surrounded by celestial spheres that influence terrestrial events.42 But while she claims that human affairs, and especially human diseases, are controlled, under God, by the heavenly cosmos, she yet commits herself to none of that more detailed astrological doctrine that was developing in her time, and came to efflorescence in the following centuries. In this respect she follows the earlier and somewhat more scientific spirit of such writers as Messahalah, rather than the wilder theories of her own age. The shortness and simplicity of Messahalah’s tract on the sphere made it very popular. It was probably one of the earliest to be translated into Latin; and its contents would account for the change which, as we shall see, came over Hildegard’s scientific views in her later years.

The general conception of the universe as a series of concentric elemental spheres had certainly penetrated to Western Europe centuries before Hildegard’s time. Nevertheless the prophetess presents it to her audience as a new and striking revelation. We may thus suppose that translations of Messahalah, or of whatever other work she drew upon for the purpose, did not reach the Upper Rhineland, or rather did not become accepted by the circles in which Hildegard moved, until about the decade 1141–50, during which she was occupied in the composition of her Scivias.

There is another cosmic theory, the advent of which to her country, or at least to her circle, can be approximately dated from her work. Hildegard exhibits in a pronounced but peculiar and original form the doctrine of the macrocosm and microcosm. Hardly distinguishable in the Scivias (1141–50), it appears definitely in the Liber Vitae Meritorum (1158–62),43 in which work, however, it takes no very prominent place, and is largely overlaid and concealed by other lines of thought. But in the Liber Divinorum Operum (1163–70) this belief is the main theme. The book is indeed an elaborate attempt to demonstrate a similarity and relationship between the nature of the Godhead, the constitution of the universe, and the structure of man, and it thus forms a valuable compendium of the science of the day viewed from the standpoint of this theory.

From whence did she derive the theory of macrocosm and microcosm? In outline its elements were easily accessible to her in Isidore’s De Rerum Natura as well as in the Salernitan poems. But the work of Bernard Sylvestris of Tours, De mundi universitate sive megacosmus et microcosmus,44 corresponds so closely both in form, in spirit, and sometimes even in phraseology, to the Liber Divinorum Operum that it appears to us certain that Hildegard must have had access to it also. Bernard’s work can be dated between the years 1145–53 from his reference to the papacy of Eugenius III. This would correspond well with the appearance of his doctrines in the Liber Vitae Meritorum (1158–62) and their full development in the Liber Divinorum Operum (1163–70).

Another contemporary writer with whom Hildegard presents points of contact is Hugh of St. Victor (1095–1141).45 In his writings the doctrine of the relation of macrocosm and microcosm is more veiled than with Bernard Sylvestris. Nevertheless, his symbolic universe is on the lines of Hildegard’s belief, and the plan of his De arca Noe mystica presents many parallels both to the Scivias and to the Liber Divinorum Operum. If these do not owe anything directly to Hugh, they are at least products of the same mystical movement as were his works.

We may also recall that at Hildegard’s date very complex cabalistic systems involving the doctrine of macrocosm and microcosm were being elaborated by the Jews, and that she lived in a district where Rabbinic mysticism specially flourished.46 Benjamin of Tudela, who visited Bingen during Hildegard’s lifetime, tells us that he found there a congregation of his people. Since we know, moreover, that she was familiar with the Jews,47 it is possible that she may have derived some of the very complex macrocosmic conceptions with which her last work is crowded from local Jewish students.

The Alsatian Herrade de Landsberg (died 1195), a contemporary of Hildegard, developed the microcosm theory along lines similar to those of our abbess, and it is probable that the theory, in the form in which these writers present it, reached the Upper Rhineland somewhere about the middle or latter half of the twelfth century.

1 Vita Sanctae Hildegardis auctoribus Godefrido et Theodorico monachis, lib. iii, cap. 1. The work has been frequently reprinted and is in Migne, Patrologia Latina, vol. 197, col. 91 ff. This volume will be quoted here simply as ‘Migne’.

2 Migne, col. 119.

3 The erroneous statement in some of her biographies that she journeyed to Paris is based on a misunderstanding.

4 Cardinal J. B. Pitra, Analecta sacra, vol. viii, p. 350, Paris, 1882. This volume will here be quoted simply as ‘Pitra’.

5 Pitra, p. 556.

6 Wilhelm Grimm, ‘Wiesbader Glossen’, in Moriz Haupt’s Zeitschrift für deutsches Alterthum, Leipzig, 1848, vol. vi, p. 321. The script is reproduced in the ill-arranged and irritating work of J. P. Schmelzeis, Das Leben und Wirken der heiligen Hildegardis, Freiburg im Breisgau, 1879; and in Pitra, p. 497. The subject has been summarized by F. W. E. Roth in his Lieder und unbekannte Sprache der h. Hildegardis, Wiesbaden, 1880.

7 A short sketch of her life of yet earlier date has survived. It is from the hand of the monk Guibert and was probably written in 1180: Pitra, p. 407. The best modern account of her is by F. W. E. Roth in the Zeitschrift für kirchliche Wissenschaft und kirchliches Leben, vol. ix, p. 453, Leipzig, 1888. Less critical but more readable is the essay by Albert Battandier, ‘Sainte Hildegarde, sa vie et ses œuvres’, in the Revue des questions historiques, vol. xxxiii, pp. 395–425, Paris, 1883.

8 The ‘Acta inquisitionis de virtutibus et miraculis sanctae Hildegardis’ are reprinted in Migne, col. 131.

9 This volume is supplemented by ‘Annotationes ad Nova S. Hildegardis Opera’ in Analecta Bollandiana, vol. i, p. 597, Brussels, 1882.

10 This Wiesbaden MS. has been fully described by Antonius van der Linde, Die Handschriften der Königlichen Landesbibliothek in Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden, 1877.

11 Louis Baillet, ‘Les Miniatures du Scivias de sainte Hildegarde’, in the Monuments et Mémoires publiés par l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, Paris, 1912, especially pp. 139 and 145.

12 We are inclined to place the preparation of this remarkable MS. at a slightly later date than that attributed to it by Baillet. As Wiesbaden is at present inaccessible we have reproduced the facsimiles in Plate II from Baillet’s monograph.

13 For the history of these MSS. see A. van der Linde, loc. cit., pp. 30–6.

14 Goethe, ‘Am Rhein, Main und Neckar’, Cotta’s Jubiläums-Ausgabe, vol. xxix, p. 258.

15 Wilhelm Grimm in M. Haupt’s Zeitschrift für deutsches Alterthum, vi, p. 321, Leipzig, 1847.

16 In Étienne Baluze, Miscellanea novo ordine digesta et non paucis ineditis monumentis opportunisque animadversionibus aucta opera ac studio J. D. Mansi, 4 vols., Lucca, 1761–6; see vol. ii, p. 377.

17 Cf. J. A. Herbert, Illuminated Manuscripts, London, 1911, p. 160.

18 A. Venturi, Storia dell’ arte italiana, Milan, in progress, vol. v, p. 16.

19 We are unable to concur with Baillet, however, that there is enough evidence to suggest that the miniaturists of the Lucca MS. had consulted the Wiesbaden illuminations. Baillet, loc. cit., p. 147.

20 Hildegardis causae et curae edidit Paulus Kaiser, Leipzig, B. G. Teubner, 1903. The MS. was brought to light by C. Jessen in the Sitzungsberichte der kaiserl. Akademie der Wissenschaften, Mathematisch-naturwissenschaftliche Klasse, Band xlv, Heft 1, p. 97, Vienna, 1862. See also the same author in Botanik in kulturhistorischer Entwickelung, pp. 124–6, Leipzig, 1862, and in the Anzeiger für Kunde der deutschen Vorzeit, 1875, p. 175. An imperfect edition appeared in 1882 in Pitra, p. 468, under the title Liber compositae medicinae de aegritudinum causis signis atque curis.

21 Royal Library of Copenhagen, MS. Ny. Kgl. Saml., No. 90 b.

22 Experimentarius medicinae continens Trotulae curandarum Aegritudinum muliebrium ... item quatuor Hildegardis de elementorum, fluminum aliquot Germaniae, metallorum,... herbarum, piscium & animantium terrae, naturis et operationibus. Edited by G. Kraut, Strasbourg, J. Schott, 1544. The work often ascribed to Trotula is somewhat similar to the spurious medical works of Hildegard. Like them, it was probably written early in the thirteenth century. Trotula herself lived in the eleventh century, a generation or two before Hildegard. On Trotula see Salvatore de Renzi, Collectio Salernitana, vol. i, p. 149, Naples, 1852.

23 In the Vita, lib. ii, cap. 1; Migne, col. 101.

24 Migne, col. 1125. See also F. A. Reuss, De Libris physicis S. Hildegardis commentatio historico-medica, Würzburg, 1835, and ‘Der heiligen Hildegard Subtilitatum diversarum naturarum creaturarum libri novem, die werthvollste Urkunde deutscher Natur- und Heilkunde aus dem Mittelalter’ in the Annalen des Vereins für Nassauische Alterthumskunde und Geschichtsforschung, Band vi, Heft 1, Wiesbaden, 1859.

25 Rudolf Virchow, ‘Zur Geschichte des Aussatzes und der Spitäler, besonders in Deutschland’, in Virchow’s Archiv für Pathologie, vol. xviii, p. 285, &c., Berlin, 1860.

26 Reuss, in Migne, cols. 1121 and 1122, states on Theodoric’s authority that Hildegard had written a book on this subject: ‘Exstat inter libros virginis fatidicae superstites opus argumenti partim physici partim medici, “De natura hominis, elementorum diversarumque creaturarum” in quo, ut Theodoricus idem fusius exponit, secreta naturae prophetico spiritu manifestavit.’ But Theodoric does not in fact anywhere speak of a special work with this title or of this character. What he does write is as follows (Vita, lib. ii, cap. i, Migne, col. 101): ‘Igitur beata virgo ... librum visionum ... consummavit et quaedam de natura hominis et elementorum, diversarumque creaturarum, et quomodo homini ex his succurrendum sit, aliaque multa secreta prophetico spiritu manifestavit.’

27 Migne, cols. 1212 and 1213.

28 As detailed in the Liber vitae meritorum, Pitra, p. 228, and in many places in the Liber divinorum operum and Scivias.