автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу A Chicago Princess

Transcriber’s Note

The cover was created by the Transcriber, using an illustration from the original book, and placed in the Public Domain.

This Table of Contents was added by the Transcriber and placed in the Public Domain.

CONTENTS

PAGE

CHAPTER I1

CHAPTER II10

CHAPTER III25

CHAPTER IV37

CHAPTER V52

CHAPTER VI59

CHAPTER VII77

CHAPTER VIII90

CHAPTER IX101

CHAPTER X109

CHAPTER XI124

CHAPTER XII132

CHAPTER XIII143

CHAPTER XIV155

CHAPTER XV170

CHAPTER XVI180

CHAPTER XVII194

CHAPTER XVIII202

CHAPTER XIX219

CHAPTER XX239

CHAPTER XXI248

CHAPTER XXII264

CHAPTER XXIII274

CHAPTER XXIV288

CHAPTER XXV299

A CHICAGO PRINCESS

A CHICAGO

PRINCESS

By ROBERT BARR

Author of “Over the Border,” “The Victors,” “Tekla,”

“In the Midst of Alarms,” “A Woman Intervenes,” etc.

Illustrated by FRANCIS P. WIGHTMAN

New York · FREDERICK A.

STOKES COMPANY · Publishers

Copyright, 1904, by

ROBERT BARR

All rights reserved

This edition published in June, 1904

A CHICAGO PRINCESS

CHAPTER I

When I look back upon a certain hour of my life it fills me with wonder that I should have been so peacefully happy. Strange as it may seem, utter despair is not without its alloy of joy. The man who daintily picks his way along a muddy street is anxious lest he soil his polished boots, or turns up his coat collar to save himself from the shower that is beginning, eager then to find a shelter; but let him inadvertently step into a pool, plunging head over ears into foul water, and after that he has no more anxiety. Nothing that weather can inflict will add to his misery, and consequently a ray of happiness illumines his gloomy horizon. He has reached the limit; Fate can do no more; and there is a satisfaction in attaining the ultimate of things. So it was with me that beautiful day; I had attained my last phase.

I was living in the cheapest of all paper houses, living as the Japanese themselves do, on a handful of rice, and learning by experience how very little it requires to keep body and soul together. But now, when I had my next meal of rice, it would be at the expense of my Japanese host, who was already beginning to suspect,—so it seemed to me,—that I might be unable to liquidate whatever debt I incurred. He was very polite about it, but in his twinkling little eyes there lurked suspicion. I have travelled the whole world over, especially the East, and I find it the same everywhere. When a man comes down to his final penny, some subtle change in his deportment seems to make the whole world aware of it. But then, again, this supposed knowledge on the part of the world may have existed only in my own imagination, as the Christian Scientists tell us every ill resides in the mind. Perhaps, after all, my little bowing landlord was not troubling himself about the payment of the bill, and I only fancied him uneasy.

If an untravelled person, a lover of beauty, were sitting in my place on that little elevated veranda, it is possible the superb view spread out before him might account for serenity in circumstances which to the ordinary individual would be most depressing. But the view was an old companion of mine; goodness knows I had looked at it often enough when I climbed that weary hill and gazed upon the town below me, and the magnificent harbor of Nagasaki spreading beyond. The water was intensely blue, dotted with shipping of all nations, from the stately men-of-war to the ocean tramps and the little coasting schooners. It was an ever-changing, animated scene; but really I had had enough of it during all those ineffective months of struggle in the attempt to earn even the rice and the poor lodging which I enjoyed.

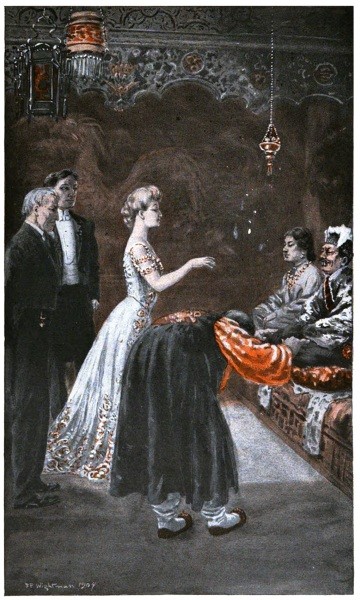

“The twinkling eyes of the Emperor fixed themselves on Miss Hemster.”

Page 144

Curiously, it was not of this harbor I was thinking, but of another in far-distant Europe, that of Boulogne in the north of France, where I spent a day with my own yacht before I sailed for America. And it was a comical thought that brought the harbor of Boulogne to my mind. I had seen a street car there, labelled “Le Dernier Sou,” which I translated as meaning “The Last Cent.” I never took a trip on this street car, but I presume somewhere in the outskirts of Boulogne there is a suburb named “The Last Cent,” and I thought now with a laugh: “Here I am in Japan, and although I did not take that street car, yet I have arrived at ‘Le Dernier Sou.’”

This morning I had not gone down to the harbor to prosecute my search for employment. As with my last cent, I had apparently given that idea up. There was no employer needing men to whom I had not applied time and again, willing to take the laborer’s wage for the laborer’s work. But all my earlier training had been by way of making me a gentleman, and the manner was still upon me in spite of my endeavors to shake it off, and I had discovered that business men do not wish gentlemen as day-laborers. There was every reason that I should be deeply depressed; yet, strange to say, I was not. Had I at last reached the lotus-eating content of the vagabond? Was this care-free condition the serenity of the tramp? Would my next step downward be the unblushing begging of food, with the confidence that if I were refused at one place I should receive at another? With later knowledge, looking back at that moment of mitigated happiness, I am forced to believe that it was the effect of coming events casting their shadows before. Some occultists tell us that every action that takes place on the earth, no matter how secretly done, leaves its impression on some ethereal atmosphere, visible to a clairvoyant, who can see and describe to us exactly what has taken place. If this be true, it is possible that our future experiences may give sub-mental warnings of their approach.

As I sat there in the warm sunlight and looked over the crowded harbor, I thought of the phrase, “When my ship comes in.” There was shipping enough in the bay, and possibly, if I could but have known where, some friend of mine might at that moment be tramping a white deck, or sitting in a steamer chair, looking up at terrace upon terrace of the toy houses among which I kept my residence. Perhaps my ship had come in already if only I knew which were she. As I lay back on the light bamboo chair, along which I had thrown myself,—a lounging, easy, half-reclining affair like those we used to have at college,—I gazed upon the lower town and harbor, taking in the vast blue surface of the bay; and there along the indigo expanse of the waters, in striking contrast to them, floated a brilliantly white ship gradually, imperceptibly approaching. The canvas, spread wing and wing, as it increased in size, gave it the appearance of a swan swimming toward me, and I thought lazily:

“It is like a dove coming to tell me that my deluge of misery is past, and there is an olive-branch of foam in its beak.”

As the whole ship became visible I saw that it, like the canvas, was pure white, and at first I took it for a large sailing yacht rapidly making Nagasaki before the gentle breeze that was blowing; but as she drew near I saw that she was a steamer, whose trim lines, despite her size, were somewhat unusual in these waters. If this were indeed a yacht she must be owned by some man of great wealth, for she undoubtedly cost a fortune to build and a very large income to maintain. As she approached the more crowded part of the bay, her sails were lowered and she came slowly in on her own momentum. I fancied I heard the rattle of the chain as her anchor plunged into the water, and now I noticed with a thrill that made me sit up in my lounging chair that the flag which flew at her stern was the Stars and Stripes. It is true that I had little cause to be grateful to the country which this piece of bunting represented, for had it not looted me of all I possessed? Nevertheless in those distant regions an Englishman regards the United States flag somewhat differently from that of any nation save his own. Perhaps there is an unconscious feeling of kinship; perhaps the similarity of language may account for it, because an Englishman understands American better than any other foreign tongue. Be that as it may, the listlessness departed from me as I gazed upon that banner, as crude and gaudy as our own, displaying the most striking of the primary colors. The yacht rested on the blue waters as gracefully as if she were a large white waterfowl, and I saw the sampans swarm around her like a fluffy brood of ducklings.

And now I became conscious that the most polite individual in the world was making an effort to secure my attention, yet striving to accomplish his purpose in the most unobtrusive way. My patient and respected landlord, Yansan, was making deep obeisances before me, and he held in his hand a roll which I strongly suspected to be my overdue bill. I had the merit in Yansan’s eyes of being able to converse with him in his own language, and the further advantage to myself of being able to read it; therefore he bestowed upon me a respect which he did not accord to all Europeans.

“Ah, Yansan!” I cried to him, taking the bull by the horns, “I was just thinking of you. I wish you would be more prompt in presenting your account. By such delay errors creep into it which I am unable to correct.”

Yansan awarded me three bows, each lower than the one preceding it, and, while bending his back, endeavored, though with some confusion, to conceal the roll in his wide sleeve. Yansan was possessed of much shrewdness, and the bill certainly was a long standing one.

“Your Excellency,” he began, “confers too much honor on the dirt beneath your feet by mentioning the trivial sum that is owing. Nevertheless, since it is your Excellency’s command, I shall at once retire and prepare the document for you.”

“Oh, don’t trouble about that, Yansan,” I said, “just pull it out of your sleeve and let me look over it.”

The wrinkled face screwed itself up into a grimace more like that of a monkey than usual, and so, with various genuflections, Yansan withdrew the roll and proffered it to me. Therein, in Japanese characters, was set down the long array of my numerous debts to him. Now, in whatever part of the world a man wishes to delay the payment of a bill, the proper course is to dispute one or more of its items, and this accordingly I proceeded to do.

“I grieve to see, Yansan,” I began, putting my finger on the dishonest hieroglyphic, “that on the fourth day you have set down against me a repast of rice, whereas you very well know on that occasion I did myself the honor to descend into the town and lunch with his Excellency the Governor.”

Again Yansan lowered his ensign three times, then deplored the error into which he had fallen, saying it would be immediately rectified.

“There need to be no undue hurry about the rectification,” I replied, “for when it comes to a settlement I shall not be particular about the price of a plate of rice.”

Yansan was evidently much gratified to hear this, but I could see that my long delay in liquidating his account was making it increasingly difficult for him to subdue his anxiety. The fear of monetary loss was struggling with his native politeness. Then he used the formula which is correct the world over.

“Excellency, I am a poor man, and next week have heavy payments to make to a creditor who will put me in prison if I produce not the money.”

“Very well,” said I grandly, waving my hand toward the crowded harbor, “my ship has come in where you see the white against the blue. To-morrow you shall be paid.”

Yansan looked eagerly in the direction of my gesture.

“She is English,” he said.

“No, American.”

“It is a war-ship?”

“No, she belongs to a private person, not to the Government.”

“Ah, he must be a king, then,—a king of that country.”

“Not so, Yansan; he is one of many kings, a pork king, or an oil king or a railroad king.”

“Surely there cannot be but one king in a country, Excellency,” objected Yansan.

“Ah, you are thinking of a small country like Japan. One king does for such a country; but America is larger than many Japans, therefore it has numerous kings, and here below us is one of them.”

“I should think, Excellency,” said Yansan, “that they would fight with one another.”

“That they do, and bitterly, too, in a way your kings never thought of. I myself was grievously wounded in one of their slightest struggles. That flag which you see there waves over my fortune. Many a million of sen pieces which once belonged to me rest secure for other people under its folds.”

My landlord lifted his hands in amazement at my immense wealth.

“This, then, is perhaps the treasure-ship bringing money to your Excellency,” he exclaimed, awestricken.

“That’s just what it is, Yansan, and I must go down and collect it; so bring me a dinner of rice, that I may be prepared to meet the captain who carries my fortune.”

CHAPTER II

After a frugal repast I went down the hill to the lower town, and on inquiry at the custom-house learned that the yacht was named the “Michigan,” and that she was owned by Silas K. Hemster, of Chicago. So far as I could learn, the owner had not come ashore; therefore I hired a sampan from a boatman who trusted me. I was already so deeply in his debt that he was compelled to carry me, inspired by the optimistic hope that some day the tide of my fortunes would turn. I believe that commercial institutions are sometimes helped over a crisis in the same manner, as they owe so much their creditors dare not let them sink. Many a time had this lad ferried me to one steamer after another, until now his anxiety that I should obtain remunerative employment was nearly as great as my own.

As we approached the “Michigan” I saw that a rope ladder hung over the side, and there leaned against the rail a very free-and-easy sailor in white duck, who was engaged in squirting tobacco-juice into Nagasaki Bay. Intuitively I understood that he had sized up the city of Nagasaki and did not think much of it. Probably it compared unfavorably with Chicago. The seaman made no opposition to my mounting the ladder; in fact he viewed my efforts with the greatest indifference. Approaching him, I asked if Mr. Hemster was aboard, and with a nod of his head toward the after part of the vessel he said, “That’s him.”

Looking aft, I now noticed a man sitting in a cushioned cane chair, with his two feet elevated on the spotless rail before him. He also was clothed in light summer garb, and had on his head a somewhat disreputable slouch hat with a very wide brim. His back was toward Nagasaki, as if he had no interest in the place. He revolved an unlit cigar in his mouth, in a manner quite impossible to describe; but as I came to know him better I found that he never lit his weed, but kept its further end going round and round in a little circle by a peculiar motion of his lips. Though he used the very finest brand of cigars, none ever lasted him for more than ten minutes, when he would throw it away, take another, bite off the end, and go through the same process once more. What satisfaction he got out of an unlighted cigar I was never able to learn.

His was a thin, keen, business face, with no hair on it save a tuft at the chin, like the beard of a goat. As I approached him I saw that he was looking sideways at me out of the corners of his eyes, but he neither raised his head nor turned it around. I was somewhat at a loss how to greet him, but for want of a better opening I began:

“I am told you are Mr. Hemster.”

“Well!” he drawled slowly, with his cigar between his teeth, released for a moment from the circular movement of his lips, “you may thank your stars you are told something you can believe in this God-forsaken land.”

I smiled at this unexpected reply and ventured:

“As a matter of fact, the East is not renowned for its truthfulness. I know it pretty well.”

“You do, eh? Do you understand it?”

“I don’t think either an American or a European ever understands an Asiatic people.”

“Oh, yes, we do,” rejoined Mr. Hemster; “they’re liars and that’s all there is to them. Liars and lazy; that sums them up.”

As I was looking for the favor of work, it was not my place to contradict him, and the confident tone in which he spoke showed that contradiction would have availed little. He was evidently one of the men who knew it all, and success had confirmed him in his belief. I had met people of his calibre before,—to my grief.

“Well, young man, what can I do for you?” he asked, coming directly to the point.

“I am looking for a job,” I said.

“What’s your line?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“What can you do?”

“I am capable of taking charge of this ship as captain, or of working as a man before the mast.”

“You spread yourself out too thin, my son. A man who can do everything can do nothing. We specialize in our country. I hire men who can do only one thing, and do that thing better than anybody else.”

“Sir, I do not agree with you,” I could not help saying. “The most capable people in the world are the Americans. The best log house I ever saw was built by a man who owned a brown-stone front on Fifth Avenue. He simply pushed aside the guides whose specialty it was to do such things, took the axe in his own hands, and showed them how it should be accomplished.”

Mr. Hemster shoved his hat to the back of his head, and for the first time during our interview looked me squarely in the face.

“Where was that?” he inquired.

“Up in Canada.”

“Oh, well, the Fifth Avenue man had probably come from the backwoods and so knew how to handle an axe.”

“It’s more than likely,” I admitted.

“What were you doing in Canada?”

“Fishing and shooting.”

“You weren’t one of the guides he pushed aside?”

I laughed.

“No, I was one of the two who paid for the guides.”

“Well, to come back to first principles,” continued Mr. Hemster, “I’ve got a captain who gives me perfect satisfaction, and he hires the crew. What else can you do?”

“I am qualified to take a place as engineer if your present man isn’t equally efficient with the captain; and I can guarantee to give satisfaction as a stoker, although I don’t yearn for the job.”

“My present engineer I got in Glasgow,” said Mr. Hemster; “and as for stokers we have a mechanical stoker which answers the purpose reasonably well, although I have several improvements I am going to patent as soon as I get home. I believe the Scotchman I have as engineer is the best in the business. I wouldn’t interfere with him for the world.”

My heart sank, and I began to fear that Yansan and the sampan-boy would have to wait longer for their money. It seemed that it wasn’t my ship that had come in, after all.

“Very well, Mr. Hemster,” I said, “I must congratulate you on being so well suited. I am much obliged to you for receiving me so patiently without a letter of introduction on my part, and so I bid you good-day.”

I turned for the ladder, but Mr. Hemster said, with more of animation in his tone than he had hitherto exhibited:

“Wait a moment, sonny; don’t be so hasty. You’ve asked me a good many questions about the yacht and the crew, so I should like to put some to you, and who knows but we may make a deal yet. There’s the galley and the stewards, and that sort of thing, you know. Draw up a chair and sit down.”

I did as I was requested. Mr. Hemster threw his cigar overboard and took out another. Then he held out the case toward me, saying:

“Do you smoke?”

“Thank you,” said I, selecting a cigar.

“Have you matches?” he asked, “I never carry them myself.”

“No, I haven’t,” I admitted.

He pushed a button near him, and a Japanese steward appeared.

“Bring a box of matches and a bottle of champagne,” he said.

The steward set a light wicker table at my elbow, disappeared for a few minutes, and shortly returned with a bottle of champagne and a box of matches. Did my eyes deceive me, or was this the most noted brand in the world, and of the vintage of ’78? It seemed too good to be true.

“Would you like a sandwich or two with that wine, or is it too soon after lunch?”

“I could do with a few sandwiches,” I confessed, thinking of Yansan’s frugal fare; and shortly after there were placed before me, on a dainty, white, linen-and-lace-covered plate, some of the most delicious chicken sandwiches that it has ever been my fortune to taste.

“Now,” said Mr. Hemster, when the steward had disappeared, “you’re on your uppers, I take it.”

“I don’t think I understand.”

“Why, you’re down at bed-rock. Haven’t you been in America? Don’t you know the language?”

“‘Yes’ is the answer to all your questions.”

“What’s the reason? Drink? Gambling?”

Lord, how good that champagne tasted! I laughed from the pure, dry exhilaration of it.

“I wish I could say it was drink that brought me to this pass,” I answered; “for this champagne shows it would be a tempting road to ruin. I am not a gambler, either. How I came to this pass would not interest you.”

“Well, I take it that’s just an Englishman’s way of saying it’s none of my business; but such is not the fact. You want a job, and you have come to me for it. Very well; I must know something about you. Whether I can give you a job or not will depend. You have said you could captain the ship or run her engines. What makes you so confident of your skill?”

“The fact is I possessed a yacht of my own not so very long ago, and I captained her and I ran her engines on different occasions.”

“That might be a recommendation, or it might not. If, as captain, you wrecked your vessel, or if, as engineer, you blew her up, these actions would hardly be a certificate of competency.”

“I did neither. I sold the yacht in New York for what it would bring.”

“How much money did you have when you bought your yacht?”

“I had what you would call half a million.”

“Why do you say what I would call half a million? What would you call it?”

“I should call it a hundred thousand.”

“Ah, I see. You’re talking of pounds, and I’m talking of dollars. You’re an Englishman, I suspect. Are you an educated man?”

“Moderately so. Eton and Oxford,” said I, the champagne beginning to have its usual effect on a hungry man. However, the announcement of Eton and Oxford had no effect upon Mr. Hemster, so it did not matter.

“Come, young fellow,” he said, with some impatience, “tell me all about yourself, and don’t have to be drawn out like a witness on the stand.”

“Very well,” said I, “here is my story. After I left Oxford I had some little influence, as you might call it.”

“No, a ‘pull,’ I would call it. All right, where did it land you?”

“It landed me as secretary to a Minister of the Crown.”

“You don’t mean a preacher?”

“No, I mean the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and he put me into the diplomatic service when he found the Government was going to be defeated. I was secretary of legation at Pekin and also here in Japan.”

I filled myself another glass of champagne, and, holding it up to see the sparkles, continued jauntily:

“If I may go so far as to boast, I may say I was entrusted with several delicate missions, and I carried them through with reasonable success. I can both read and write the Japanese language, and I know a smattering of Chinese and a few dialects of the East, which have stood me in good stead more than once. To tell the truth, I was in a fair way for promotion and honor when unfortunately a relative died and left me the hundred thousand pounds that I spoke of.”

“Why unfortunately? If you had had any brains you could have made that into millions.”

“Yes, I suppose I could. I thought I was going to do it. I bought myself a yacht at Southampton and sailed for New York. To make a long story short, it was a gold mine and a matter of ten weeks which were taken up with shooting and fishing in Canada. Then I had the gold mine and the experience, while the other fellow had the cash. He was good enough to pay me a trifle for my steam yacht, which, as the advertisements say, was ‘of no further use to the owner.’”

As I sipped my champagne, the incidents I was relating seemed to recede farther and farther back and become of little consequence. In fact I felt like laughing over them, and although in sober moments I should have called the action of the man who got my money a swindle, under the influence of dry ’78 his scheme became merely a very clever exercise of wit. Mr. Hemster was looking steadily at me, and for once his cigar was almost motionless.

“Well, well,” he murmured, more to himself than to me, “I have always said the geographical position of New York gives it a tremendous advantage over Chicago. They never let the fools come West. They have always the first whack at the moneyed Englishman, and will have until we get a ship canal that will let the liners through to Chicago direct. Fleeced in ten weeks! Well, well! Go on, my son. What did you do after you’d sold your yacht?”

“I took what money I had and made for the West.”

“Came to Chicago?”

“Yes, I did.”

“Just our luck. After you had been well buncoed you came to Chicago. I swear I’m tempted to settle in New York when I get back.”

“By the West I do not mean Chicago, Mr. Hemster. I went right through to San Francisco and took a steamer for Japan. I thought my knowledge of the East and of the languages might be of advantage. I was ashamed to return to England when I found I could make no headway here. I tried to bring influence to bear to get reinstated in the diplomatic service, but my brand of statesman was out of office and nothing could be done. I lived too expensively here at first, hoping to make an impression and gain a foothold that was worth having, and when I began to economize it was too late. I took to living in the native quarter, and descended from trying to get a clerkship into the position of a man who is willing to take anything. From my veranda on the hill up yonder I saw this boat come in, like a white-winged sea-gull, and so I came down, got into a sampan, and here I am, enjoying the best meal I’ve had for a long time. ‘Here endeth the first lesson,’” I concluded irreverently, pouring out another glass of champagne.

Mr. Hemster did not reply for some moments. He was evidently ruminating, and the end of his cigar went round and round quicker and quicker.

“What might your name be?” he said at last.

“Rupert Tremorne.”

“Got a handle to it?”

“A title? Oh, no! Plain Mr. Tremorne.”

“I should say, off-hand, that a title runs in your family somewhere.”

“Well; I admit that Lord Tremorne is my cousin, and we have a few others scattered about. However, there’s little danger of it ever falling upon me. To tell the truth, the family for the last few years has no idea where I am, and now that I have lost my money I don’t suppose they care very much. At least I have seen no advertisements in the papers, asking for a man of my description.”

“If you were secretary to the Minister of whatever you call it, I don’t know but what you’d do for me. I am short of a private secretary just at the present moment, and I think you’d do.”

Whether it was the champagne, or the sandwiches, or the prospect of getting something to do, and consequently being able to pay my way, or all three combined, I felt like throwing my hat into the air and uttering a war-whoop; but something of native stolidity counterbalanced the effect of the stimulant, and I was astonished to hear myself reply very quietly:

“It would be folly for a man who had just applied for the position of stoker to pretend he is not elated at being offered a secretaryship. It is needless to say, Mr. Hemster, that I accept with alacrity and gratitude.”

“Then that’s settled,” said the millionaire curtly. “As to the matter of salary, I think you would be wise to leave that to me. I have paid out a good deal of money recently and got mighty little for it. If you can turn the tide so that there is value received, you will find me liberal in the matter of wages.”

“I am quite content to leave it so,” I rejoined, “but I think I ought in honesty to tell you, if you are expecting a shrewd business man as your secretary who will turn the tide of fortune in any way, you are likely to be disappointed in me. I am afraid I am a very poor business man.”

“I am aware of that already,” replied Hemster. “I can supply all the business qualifications that are needed in this new combination. What I want of you is something entirely different. You said you could speak more languages than your own?”

“Yes, I am very familiar with French and German, and have also a smattering of Spanish and Italian. I can read and write Japanese, speaking that language and Chinese with reasonable fluency, and can even jabber a little in Corean.”

“Then you’re my man,” said my host firmly. “I suppose now you would not object to a little something on account?”

“I should be very much obliged indeed if you have confidence enough in me to make an advance. There are some things I should like to buy before I come aboard, and, not to put too fine a point to it, there are some debts I should like to settle.”

“That’s all right,” commented Hemster shortly, thrusting his hand deep in his trousers pocket, and bringing out a handful of money which he threw on the wicker table. “There ought to be something like two hundred dollars there. Just count it and see, and write me a receipt for it.”

I counted it, and, as I did so, thought he watched me rather keenly out of the corner of his eye. There was more than two hundred dollars in the heap, and I told him the amount. The Japanese brought up a sheet of paper headed with a gorgeous gilt and scarlet monogram and a picture of the yacht, and I wrote and signed the receipt.

“Do you know anything about the stores in town?” he asked, nodding his head toward Nagasaki.

“Oh, yes!”

“They tell me Nagasaki is a great place for buying crockery. I wish you would order sent to the yacht three complete dinner sets, three tea sets, and three luncheon sets. There is always a good deal of breakage on a sea-going yacht.”

“Quite so,” I replied. “Is there any particular pattern you wish, or any limit to the price?”

“Oh, I don’t need expensive sets; anything will do. I’m not particular; in fact, I don’t care even to see them; I leave that entirely to you, but tell the man to pack them securely, each in a separate box. He is to bring them aboard at half-past five this afternoon precisely, and ask for me. Now, when can you join us?”

“To-morrow morning, if that will be soon enough.”

“Very well; to-morrow morning at ten.”

I saw that he wished the interview terminated, as, for the last few minutes, he had exhibited signs of uneasiness. I therefore rose and said,—rather stammeringly, I am afraid:

“Mr. Hemster, I don’t know how to thank you for your kindness in——”

“Oh, that’s all right; that’s all right,” he replied hastily, waving his hand; but before anything further could be spoken there came up on deck the most beautiful and stately creature I had ever beheld, superbly attired. She cast not even a glance at me, but hurried toward Mr. Hemster, crying impetuously:

“Oh, Poppa! I want to go into the town and shop!”

“Quite right, my dear,” said the old man; “I wonder you’ve been so long about it. We’ve been in harbor two or three hours. This is Mr. Rupert Tremorne, my new private secretary. Mr. Tremorne, my daughter.”

I made my bow, but it seemed to pass unnoticed.

“How do you do,” said the girl hastily; then, to her father, “Poppa, I want some money!”

“Certainly, certainly, certainly,” repeated the old gentleman, plunging his hand into his other pocket and pulling out another handful of the “necessary.” As I learned afterward, each of his pockets seemed to be a sort of safe depository, which would turn forth any amount of capital when searched. He handed the accumulation to her, and she stuffed it hastily into a small satchel that hung at her side.

“You are going to take Miss Stretton with you?” he asked.

“Why, of course.”

“Mr. Tremorne is cousin to Lord Tremorne, of England,” said the old gentleman very slowly and solemnly.

I had been standing there rather stupidly, instead of taking my departure, as I should have done, for I may as well confess that I was astounded at the sumptuous beauty of the girl before me, who had hitherto cast not even a look in my direction. Now she raised her lovely, indescribable eyes to mine, and I felt a thrill extend to my finger-tips. Many handsome women have I seen in my day, but none to compare with this superb daughter of the West.

“Really!” she exclaimed with a most charming intonation of surprise. Then she extended a white and slim hand to me, and continued, “I am very glad to meet you, Mr. Tremorne. Do you live in Nagasaki?”

“I have done so for the past year.”

“Then you know the town well?”

“I know it very well indeed.”

At this juncture another young woman came on deck, and Miss Hemster turned quickly toward her.

“Oh, Hilda!” she cried, “I shall not need you to-day. Thanks ever so much.”

“Not need her?” exclaimed her father. “Why, you can’t go into Nagasaki alone, my dear.”

“I have no intention of doing so,” she replied amiably, “if Mr. Tremorne will be good enough to escort me.”

“I shall be delighted,” I gasped, expecting an expostulation from her father; but the old gentleman merely said:

“All right, my dear; just as you please.”

“Rupert, my boy!” I said to my amazed self; “your ship has come in with a vengeance.”

CHAPTER III

A stairway was slung on the other side of the yacht from that on which I had ascended, and at its foot lay a large and comfortable boat belonging to the yacht, manned by four stout seamen. Down this stairway and into the boat I escorted Miss Hemster. She seated herself in the stern and took the tiller-ropes in her hands, now daintily gloved. I sat down opposite to her and was about to give a command to the men to give way when she forestalled me, and the oars struck the water simultaneously. As soon as we had rounded the bow of the yacht there was a sudden outcry from a half-naked Japanese boy who was sculling about in a sampan.

“What’s the matter with him?” asked Miss Hemster with a little laugh. “Does he think we’re going to desert this boat and take that floating coffin of his?”

“I think it is my own man,” I said; “and he fears that his fare is leaving him without settling up. Have I your permission to stop these men till he comes alongside? He has been waiting patiently for me while I talked with Mr. Hemster.”

“Why, certainly,” said the girl, and in obedience to her order the crew held water, and as the boy came alongside I handed him more than double what I owed him, and he nearly upset his craft by bowing in amazed acknowledgment.

“You’re an Englishman, I suppose,” said Miss Hemster.

“In a sort of way I am, but really a citizen of the world. For many years past I have been less in England than in other countries.”

“For many years? Why, you talk as if you were an old man, and you don’t look a day more than thirty.”

“My looks do not libel me, Miss Hemster,” I replied with a laugh, “for I am not yet thirty.”

“I am twenty-one,” she said carelessly, “but every one says I don’t look more than seventeen.”

“I thought you were younger than seventeen,” said I, “when I first saw you a moment ago.”

“Did you really? I think it is very flattering of you to say so, and I hope you mean it.”

“I do, indeed, Miss Hemster.”

“Do you think I look younger than Hilda?” she asked archly, “most people do.”

“Hilda!” said I. “What Hilda?”

“Why, Hilda Stretton, my companion.”

“I have never seen her.”

“Oh, yes, you did; she was standing at the companion-way and was coming with me when I preferred to come with you.”

“I did not see her,” I said, shaking my head; “I saw no one but you.”

The young lady laughed merrily,—a melodious ripple of sound. I have heard women’s laughter compared to the tinkle of silver bells, but to that musical tintinnabulation was now added something so deliciously human and girlish that the whole effect was nothing short of enchanting. Conversation now ceased, for we were drawing close to the shore. I directed the crew where to land, and the young lady sprang up the steps without assistance from me,—before, indeed, I could proffer any. I was about to follow when one of the sailors touched me on the shoulder.

“The old man,” he said in a husky whisper, nodding his head toward the yacht, “told me to tell you that when you buy that crockery you’re not to let Miss Hemster know anything about it.”

“Aren’t you coming?” cried Miss Hemster to me from the top of the wharf.

I ascended the steps with celerity and begged her pardon for my delay.

“I am not sprightly seventeen, you see,” I said.

She laughed, and I put her in a ’rickshaw drawn by a stalwart Japanese, got into one myself, and we set off for the main shopping street. I was rather at a loss to know exactly what the sailor’s message meant, but I took it to be that for some reason Mr. Hemster did not wish his daughter to learn that he was indulging so freely in dinner sets. As it was already three o’clock in the afternoon, I realized that there would be some difficulty in getting the goods aboard by five o’clock, unless the young lady dismissed me when we arrived at the shops. This, however, did not appear to be her intention in the least; when our human steeds stopped, she gave me her hand lightly as she descended, and then said, with her captivating smile:

“I want you to take me at once to a china shop.”

“To a what?” I cried.

“To a shop where they sell dishes,—dinner sets and that sort of thing. You know what I mean,—a crockery store.”

I did, but I was so astonished by the request coming right on the heels of the message from her father, and taken in conjunction with his previous order, that I am afraid I stood looking very much like a fool, whereupon she laughed heartily, and I joined her. I saw she was quite a merry young lady, with a keen sense of the humour of things.

“Haven’t they any crockery stores in this town?” she asked.

“Oh, there are plenty of them,” I replied.

“Why, you look as if you had never heard of such a thing before. Take me, then, to whichever is the best. I want to buy a dinner set and a tea set the very first thing.”

I bowed, and, somewhat to my embarrassment, she took my arm, tripping along by my side as if she were a little girl of ten, overjoyed at her outing, to which feeling she gave immediate expression.

“Isn’t this jolly?” she cried.

“It is the most undeniably jolly shopping excursion I ever engaged in,” said I, fervently and truthfully.

“You see,” she went on, “the delight of this sort of thing is that we are in an utterly foreign country and can do just as we please. That is why I did not wish Hilda to come with us. She is rather prim and has notions of propriety which are all right at home, but what is the use of coming to foreign countries if you cannot enjoy them as you wish to?”

“I think that is a very sensible idea,” said I.

“Why, it seems as if you and I were members of a travelling theatrical company, and were taking part in ‘The Mikado,’ doesn’t it? What funny little people they are all around us! Nagasaki doesn’t seem real. It looks as if it were set on a stage,—don’t you think so?”

“Well, you know, I am rather accustomed to it. I have lived here for more than a year, as I told you.”

“Oh, so you said. I have not got used to it yet. Have you ever seen ‘The Mikado?’”

“Do you mean the Emperor or the play?”

“At the moment I was thinking of the play.”

“Yes, I have seen it, and the real Mikado, too, and spoken with him.”

“Have you, indeed? How lucky you are!”

“You speak truly, Miss Hemster, and I never knew how lucky I was until to-day.”

She bent her head and laughed quietly to herself. I thought we were more like a couple of school children than members of a theatrical troupe, but as I never was an actor I cannot say how the latter behave when they are on the streets of a strange town.

“Oh, I have met your kind of man before, Mr. Tremorne. You don’t mind what you say when you are talking to a lady as long as it is something flattering.”

“I assure you, Miss Hemster, that quite the contrary is the case. I never flatter; and if I have been using a congratulatory tone it has been directed entirely to myself and to my own good fortune.”

“There you go again. How did you come to meet the Mikado?”

“I used to be in the diplomatic service in Japan, and my duties on several occasions brought me the honor of an audience with His Majesty.”

“How charmingly you say that, and I can see that you believe it from your heart; and although we are democratic, I believe it, too. I always love diplomatic society, and enjoyed a good deal of it in Washington, and my imagination always pictured behind them the majesty of royalty, so I have come abroad to see the real thing. I was presented at Court in London, Mr. Tremorne. Now, please don’t say that you congratulate the Court!”

“There is no need of my saying it, as it has already been said; or perhaps I should say ‘it goes without saying.’”

“Thank you very much, Mr. Tremorne; I think you are the most polite man I ever met. I want you to do me a very great favor and introduce me to the higher grades of diplomatic society in Nagasaki during our stay here.”

“I regret, Miss Hemster, that that is impossible, because I have been out of the service for some years now. Besides, the society here is consular rather than diplomatic. The Legation is at the capital, you know. Nagasaki is merely a commercial city.”

“Oh, is it? I thought perhaps you had been seeing my father to-day because of some consular business, or that sort of thing, pertaining to the yacht.”

As the girl said this I realized, with a suddenness that was disconcerting, the fact that I was practically acting under false pretences. I was her father’s humble employee, and she did not know it. I remembered with a pang when her father first mentioned my name she paid not the slightest attention to it; but when he said I was the cousin of Lord Tremorne the young lady had favored me with a glance I was not soon to forget. Therefore, seeing that Mr. Hemster had neglected to make my position clear, it now became my duty to give some necessary explanation, so that his daughter might not continue an acquaintance that was rapidly growing almost intimate under her misapprehension as to who I was. I saw with a pang that a humiliation was in store for me such as always lies in wait for a man who momentarily steps out of his place and receives consideration which is not his social due.

I had once before suffered the experience which was now ahead of me, and it was an episode I did not care to repeat, although I failed to see how it could be honestly avoided. On my return to Japan I sought out the man in the diplomatic service who had been my greatest friend and for whom I had in former days accomplished some slight services, because my status in the ranks was superior to his own. Now that there was an opportunity for a return of these services, I called upon him, and was received with a cordiality that went to my discouraged heart; but the moment he learned I was in need, and that I could not regain the place I had formerly held, he congealed in the most tactful manner possible. It was an interesting study in human deportment. His manner and words were simply unimpeachable, but there gathered around him a mantle of impenetrable frigidity the collection of which was a triumph in tactful intercourse. As he grew colder and colder, I grew hotter and hotter. I managed to withdraw without showing, I hope, the deep humiliation I felt. Since that time I had never sought a former acquaintance, or indeed any countryman of my own, preferring to be indebted to my old friend Yansan on the terrace above or the sampan-boy on the waters below. The man I speak of has risen high and is rising higher in my old profession, and every now and then his last words ring in my ears and warm them,—words of counterfeit cordiality as he realized they were the last that he should probably ever speak to me:

“Well, my dear fellow, I’m ever so glad you called. If I can do anything for you, you must be sure and let me know.”

As I had already let him know, my reply that I should certainly do so must have sounded as hollow as his own smooth phrase.

Unpleasant as that episode was, the situation was now ten times worse, as it involved a woman,—and a lovely woman at that,—who had treated me with a kindness she would feel misplaced when she understood the truth. However, there was no help for it, so, clearing my throat, I began:

“Miss Hemster, when I took the liberty of calling on your father this morning, I was a man penniless and out of work. I went to the yacht in the hope that I might find something to do. I was fortunate enough to be offered the position of private secretary to Mr. Hemster, which position I have accepted.”

The young lady, as I expected, instantly withdrew her hand from my arm, and stood there facing me, I also coming to a halt; and thus we confronted each other in the crowded street of Nagasaki. Undeniable amazement overspread her beautiful countenance.

“Why!” she gasped, “you are, then, Poppa’s hired man?”

I winced a trifle, but bowed low to her.

“Madam,” I replied, “you have stated the fact with great truth and terseness.”

“Do you mean to say,” she said, “that you are to be with us after this on the yacht?”

“I suspect such to be your father’s intention.” Then, to my amazement, she impulsively thrust forth both her hands and clasped mine.

“Why, how perfectly lovely!” she exclaimed. “I haven’t had a white man to talk with except Poppa for ages and ages. But you must remember that everything I want you to do, you are to do. You are to be my hired man; Poppa won’t mind.”

“You will find me a most devoted retainer, Miss Hemster.”

“I do love that word ‘retainer,’” she cried enthusiastically. “It is like the magic talisman of the ‘Arabian Nights,’ and conjures up at once visions of a historic tower, mullioned windows, and all that sort of thing. When you were made a bankrupt, Mr. Tremorne, was there one faithful old retainer who refused to desert you as the others had done?”

“Ah, my dear young lady, you are thinking of the romantic drama now, as you were alluding to comic opera a little while ago. I believe, in the romantic drama, the retainer, like the man with the mortgage, never lets go. I am thankful to say I had no such person in my employ. He would have been an awful nuisance. It was hard enough to provide for myself, not to mention a retainer. But here we are at the crockery shop.”

I escorted her in, and she was soon deeply absorbed in the mysteries of this pattern or that of the various wares exposed to her choice. Meanwhile I took the opportunity to give the proprietor instructions in his own language to send to the yacht before five o’clock what Mr. Hemster had ordered, and I warned the man he was not to mix up the order I had just given him with that of the young lady. The Japanese are very quick at comprehension, and when Miss Hemster and I left the place I had no fear of any complication arising through my instructions.

We wandered from shop to shop, the girl enthusiastic over Nagasaki, much to my wonder, for there are other places in Japan more attractive than this commercial town; but the glamor of the East cast its spell over the young woman, and, although I was rather tired of the Orient, I must admit that the infection of her high spirits extended to my own feelings. A week ago it would have appeared impossible that I should be enjoying myself so thoroughly as I was now doing. It seemed as if years had rolled from my shoulders, and I was a boy once more, living in a world where conventionality was unknown.

The girl herself was in a whirlwind of glee, and it was not often that the shopkeepers of Nagasaki met so easy a victim. She seemed absolutely reckless in the use of money, paying whatever was asked for anything that took her fancy. In a very short time all her ready cash was gone, but that made not the slightest difference. She ordered here and there with the extravagance of a queen, on what she called the “C. O. D.” plan, which I afterward learned was an American phrase meaning, “Collect on delivery.” Her peregrinations would have tired out half-a-dozen men, but she showed no signs of fatigue. I felt a hesitation about inviting her to partake of refreshment, but I need not have been so backward.

“Talking of comic operas,” she exclaimed as we came out of the last place, “Aren’t there any tea-houses here, such as we see on the stage?”

“Yes, plenty of them,” I replied.

“Well,” she exclaimed with a ripple of laughter, “take me to the wickedest of them. What is the use of going around the world in a big yacht if you don’t see life?”

I wondered what her father would say if he knew, but I acted the faithful retainer to the last, and did as I was bid. She expressed the utmost delight in everything she saw, and it was well after six o’clock when we descended from our ’rickshaw at the landing. The boat was awaiting us, and in a short time we were alongside the yacht once more. It had been a wild, tempestuous outing, and I somewhat feared the stern disapproval of an angry parent. He was leaning over the rail revolving an unlit cigar.

“Oh, Poppa!” she cried up at him with enthusiasm, “I have had a perfectly splendid time. Mr. Tremorne knows Nagasaki like a book. He has taken me everywhere,” she cried, with unnecessary emphasis on the last word.

The millionaire was entirely unperturbed.

“That’s all right,” he said. “I hope you haven’t tired yourself out.”

“Oh, no! I should be delighted to do it all over again! Has anybody sent anything aboard for me?”

“Yes,” said the old man, “there’s been a procession of people here since you left. Dinner’s ready, Mr. Tremorne. You’ll come aboard, of course, and take pot-luck with us?”

“No, thank you, Mr. Hemster,” I said; “I must get a sampan and make my way into town again.”

“Just as you say; but you don’t need a sampan, these men will row you back again. See you to-morrow at ten, then.”

Miss Hemster, now on deck, leaned over the rail and daintily blew me a kiss from the tips of her slender fingers.

“Thank you so much, retainer,” she cried, as I lifted my hat in token of farewell.

CHAPTER IV

I was speedily rowed ashore in a state of great exaltation. The sudden change in my expectations was bewilderingly Eastern in its completeness. The astonishingly intimate companionship of this buoyant, effervescent girl had affected me as did the bottle of champagne earlier in the day. I was well aware that many of my former acquaintances would have raised their hands in horror at the thought of a girl wandering about an Eastern city with me, entirely unchaperoned; but I had been so long down on my luck, and the experiences I had encountered with so-called fashionable friends had been so bitter, that the little finicky rules of society seemed of small account when compared with the realities of life. The girl was perfectly untrained and impulsive, but that she was a true-hearted woman I had not the slightest doubt. Was I in love with her? I asked myself, and at that moment my brain was in too great a whirl to be able to answer the question satisfactorily to myself. My short ten weeks in America had given me no such acquaintance as this, although the two months and a half had cost me fifty thousand dollars a week, certainly the most expensive living that any man is likely to encounter. I had met a few American women, but they all seemed as cold and indifferent as our own, while here was a veritable child of nature, as untrammelled by the little rules of society as could well be imagined. After all, were these rules so important as I had hitherto supposed them to be? Certainly not, I replied to myself, as I stepped ashore.

I climbed the steep hill to my former residence with my head in the air in every sense of the word. Many a weary journey I had taken up that forlorn path, and it had often been the up-hill road of discouragement; but to-night Japan was indeed the land of enchantment which so many romantic writers have depicted it. I thought of the girl and thought of her father, wondering what my new duties were to be. If to-day were a sample of them then truly was Paradise regained, as the poet has it. I had told Mr. Hemster that I needed time to purchase necessary things for the voyage, but this would take me to very few shops. I had in store in Nagasaki a large trunk filled with various suits of clothing, a trunk of that comprehensive kind which one buys in America. This was really in pawn. I had delivered it to a shopkeeper who had given me a line of credit now long since ended, but I knew I should find my goods and chattels safe when I came with the money, as indeed proved to be the case.

It was a great pleasure to meet Yansan once more, bowing as lowly as if I were in truth a millionaire. I had often wondered what would happen if I had been compelled to tell the grimacing old fellow I had no money to pay him. Would his excessive politeness have stood the strain? Perhaps so, but luckily his good nature was not to be put to the test. I could scarcely refrain from grasping his two hands, as Miss Hemster had grasped mine, and dancing with him around the bare habitation which he owned and which had so long been my shelter. However, I said calmly to him:

“Yansan, my ship has come in, as I told you this morning; and now, if you will bring me that bill, errors and all, I will pay you three times its amount.”

Speechless, the old man dropped on his knees and beat his forehead against the floor.

“Excellency has always been too good to me!” he exclaimed.

I tried to induce good old Yansan to share supper with me; but he was too much impressed with my greatness and could do nothing but bow and bow and serve me.

After the repast I went down into the town again, redeemed my trunk and its contents, bought what I needed, and ordered everything forwarded to the yacht before seven o’clock next morning. Then I went to a tea-house, and drank tea, and thought over the wonderful events of the day, after which I climbed the hill again for a night’s rest.

I was very sorry to bid farewell to old Yansan next morning, and I believe he was very sorry to part with his lodger. Once more at the waterside I hailed my sampan-boy, who was now all eagerness to serve me, and he took me out to the yacht, which was evidently ready for an early departure. Her whole crew was now aboard, and most of them had had a day’s leave in Nagasaki yesterday. The captain was pacing up and down the bridge, and smoke was lazily trailing from the funnel.

Arrived on deck I found Mr. Hemster in his former position in the cane chair, with his back still toward Nagasaki, which town I believe he never glanced at all the time his yacht was in harbor. I learned afterward that he thought it compared very unfavorably with Chicago. His unlighted cigar was describing circles in the air, and all in all I might have imagined he had not changed from the position I left him in the day before if I had not seen him leaning over the rail when I escorted his daughter back to the yacht. He gave me no further greeting than a nod, which did not err on the side of effusiveness.

I inquired of the Japanese boy, who stood ready to receive me with all the courtesy of his race, whether my luggage had come aboard, and he informed me that it had. I approached Mr. Hemster, bidding him good-morning, but he gave a side nod of his head toward the Japanese boy and said, “He’ll show you to your cabin,” so I followed the youth down the companion-way to my quarters. The yacht, as I have said, was very big. The main saloon extended from side to side, and was nearly as large as the dining-room of an ocean liner. Two servants with caps and aprons, exactly like English housemaids, were dusting and putting things to rights as I passed through.

My cabin proved ample in size, and was even more comfortably equipped than I expected to find it. My luggage was there, and I took the opportunity of changing my present costume for one of more nautical cut, and, placing a yachting-cap on my head, I went on deck again. I had expected, from all the preparedness I had seen, to hear the anchor-chain rattle up before I was equipped, and feared for the moment that I had delayed the sailing of the yacht; but on looking at my watch as I went on deck I found it was not yet ten o’clock, so I was in ample time, as had been arranged.

I had seen nothing of Miss Hemster, and began to suspect that she had gone ashore and that the yacht was awaiting her return; but a glance showed me that all the yacht’s boats were in place, so if the young woman had indulged in a supplementary shopping-tour it must have been in a sampan, which was unlikely.

The old gentleman, as I approached him, eyed my yachting toggery with what seemed to me critical disapproval.

“Well,” he said, “you’re all fitted out for a cruise, aren’t you? Have a cigar,”—and he offered me his case.

I took the weed and replied:

“Yes, and you seem ready to begin a cruise. May I ask where you are going?”

“I don’t know exactly,” he replied carelessly. “I haven’t quite made up my mind yet. I thought perhaps you might be able to decide the matter.”

“To decide!” I answered in surprise.

“Yes,” he said, sitting up suddenly and throwing the cigar overboard. “What nonsense were you talking to my daughter yesterday?”

I was so taken aback at this unexpected and gruff inquiry that I fear I stood there looking rather idiotic, which was evidently the old man’s own impression of me, for he scowled in a manner that was extremely disconcerting. I had no wish to adopt the Adam-like expedient of blaming the woman; but, after all, he had been there when I went off alone with her, and it was really not my fault that I was the girl’s sole companion in Nagasaki. All my own early training and later social prejudices led me to sympathize with Mr. Hemster’s evident ill-humour regarding our shore excursion, but nevertheless it struck me as a trifle belated. He should have objected when the proposal was made.

“Really, sir,” I stammered at last, “I’m afraid I must say I don’t exactly know what you mean.”

“I think I spoke plainly enough,” he answered. “I want you to be careful what you say, and if you come with me to my office, where we shall not be interrupted, I’ll give you a straight talking to, so that we may avoid trouble in the future.”

I was speechless with amazement, and also somewhat indignant. If he took this tone with me, my place was evidently going to be one of some difficulty. However, needs must when the devil drives, even if he comes from Chicago; and although his words were bitter to endure, I was in a manner helpless and forced to remember my subordinate position, which, in truth, I had perhaps forgotten during my shopping experiences with his impulsive daughter. Yet I had myself made her aware of my situation, and if our conversation at times had been a trifle free and easy I think the fault——but there—there—there——I’m at the Adam business again. The woman tempted me, and I did talk. I felt humiliated that even to myself I placed any blame upon her.

Mr. Hemster rose, nipped off the point of another cigar, and strode along the deck to the companion-way, I following him like a confessed culprit. He led me to what he called his office, a room not very much larger than my own, but without the bunk that took up part of the space in my cabin; in fact a door led out of it which, I afterward learned, communicated with his bedroom. The office was fitted up with an American roll-top desk fastened to the floor, a copying-press, a typewriter, filing-cases from floor to ceiling, and other paraphernalia of a completely equipped business establishment. There was a swivelled armchair before the desk, into which Mr. Hemster dropped and leaned back, the springs creaking as he did so. There was but one other chair in the room, and he motioned me into it.

“See here!” he began abruptly. “Did you tell my daughter yesterday that you were a friend of the Mikado’s?”

“God bless me, no!” I was surprised into replying. “I said nothing of the sort.”

“Well, you left her under that impression.”

“I cannot see, Mr. Hemster, how such can be the case. I told Miss Hemster that I had met the Mikado on several occasions, but I explained to her that these occasions were entirely official, and each time I merely accompanied a superior officer in the diplomatic service. Although I have spoken with His Majesty, it was merely because questions were addressed to me, and because I was the only person present sufficiently conversant with the Japanese language to make him a reply in his own tongue.”

“I see, I see,” mused the old gentleman; “but Gertie somehow got it into her head that you could introduce us personally to the Mikado. I told her it was not likely that a fellow I had picked up strapped from the streets of Nagasaki, as one might say, would be able to give us an introduction that would amount to anything.”

I felt myself getting red behind the ears as Mr. Hemster put my situation with, what seemed to me, such unnecessary brutality. Yet, after all, what he had said was the exact truth, and I had no right to complain of it, for if there was money in my pocket at that moment it was because he had placed it there; and then I saw intuitively that he meant no offence, but was merely repeating what he had said to his daughter, placing the case in a way that would be convincing to a man, whatever effect it might have on a woman’s mind.

“I am afraid,” I said, “that I must have expressed myself clumsily to Miss Hemster. I think I told her,—but I make the statement subject to correction,—that I had so long since severed my connection with diplomatic service in Tokio that even the slight power I then possessed no longer exists. If I still retained my former position I should scarcely be more helpless than I am now, so far as what you require is concerned.”

“That’s exactly what I told her,” growled the old man. “I suppose you haven’t any suggestion to make that would help me out at all?”

“The only suggestion I can make is this, and indeed I think the way seems perfectly clear. You no doubt know your own Ambassador,—perhaps have letters of introduction to him,—and he may very easily arrange for you to have an audience with His Majesty the Mikado.”

“Oh! our Ambassador!” growled Mr. Hemster in tones of great contempt; “he’s nothing but a one-horse politician.”

“Nevertheless,” said I, “his position is such that by merely exercising the prerogatives of his office he could get you what you wanted.”

“No, he can’t,” maintained the old gentleman stoutly. “Still, I shouldn’t say anything against him; he’s all right. He did his best for us, and if we could have waited long enough at Yokohama perhaps he might have fixed up an audience with the Mikado. But I’d had enough of hanging on around there, and so I sailed away. Now, my son, I said I was going to give you a talking to, and I am. I’ll tell you just how the land lies, so you can be of some help to me and not a drawback. I want you to be careful of what you say to Gertie about such people as the Mikado, because it excites her and makes her think certain things are easy when they’re not.”

“I am very sorry if I have said anything that led to a misapprehension. I certainly did not intend to.”

“No, no! I understand that. I am not blaming you a bit. I just want you to catch on to the situation, that’s all. Gertie likes you first rate; she told me so, and I’m ever so much obliged to you for the trouble you took yesterday afternoon in entertaining her. She told me everything you said and did, and it was all right. Now Gertie has always been accustomed to moving in the very highest society. She doesn’t care for anything else, and she took to you from the very first. I was glad of that, because I should have consulted her before I hired you. Nevertheless, I knew the moment you spoke that you were the man I wanted, and so I took the risk. I never cared for high society myself; my intercourse has been with business men. I understand them, and I like them; but I don’t cut any figure in high society, and I don’t care to, either. Now, with Gertie it’s different. She’s been educated at the finest schools, and I’ve taken her all over Europe, where we stayed at the very best hotels and met the very best people in both Europe and America. Why, we’ve met more Sirs and Lords and Barons and High Mightinesses than you can shake a stick at. Gertie, she’s right at home among those kind of people, and, if I do say it myself, she’s quite capable of taking her place among the best of them, and she knows it. There never was a time we came in to the best table d’hôte in Europe that every eye wasn’t turned toward her, and she’s been the life of the most noted hotels that exist, no matter where they are, and no matter what their price is.”

I ventured to remark that I could well believe this to have been the case.

“Yes, and you don’t need to take my word for it,” continued the old man with quite perceptible pride; “you may ask any one that was there. Whether it was a British Lord, or a French Count, or a German Baron, or an Italian Prince, it was just the same. I admit that it seemed to me that some of those nobles didn’t amount to much. But that’s neither here nor there; as I told you before, I’m no judge. I suppose they have their usefulness in creation, even though I’m not able to see it. But the result of it all was that Gertie got tired of them, and, as she is an ambitious girl and a real lady, she determined to strike higher, and so, when we bought this yacht and came abroad again, she determined to go in for Kings, so I’ve been on a King hunt ever since, and to tell the truth it has cost me a lot of money and I don’t like it. Not that I mind the money if it resulted in anything, but it hasn’t resulted in anything; that is, it hasn’t amounted to much. Gertie doesn’t care for the ordinary presentation at Court, for nearly anybody can have that. What she wants is to get a King or an Emperor right here on board this yacht at lunch or tea, or whatever he wants, and enjoy an intimate conversation with him, just like she’s had with them no-account Princes. Then she wants a column or two account of that written up for the Paris edition of the “New York Herald,” and she wants to have it cabled over to America. Now she’s the only chick or child I’ve got. Her mother’s been dead these fifteen years, and Gertie is all I have in the world, so I’m willing to do anything she wants done, no matter whether I like it or not. But I don’t want to engage in anything that doesn’t succeed. Success is the one thing that amounts to anything. The man who is a failure cuts no ice. And so it rather grinds me to confess that I’ve been a failure in this King business. Now I don’t know much about Kings, but it strikes me they’re just like other things in this world. If you want to get along with them, you must study them. It’s like climbing a stair; if you want to get to the top you must begin at the lowest step. If you try to take one stride up to the top landing, why you’re apt to come down on your head. I told Gertie it was no use beginning with the German Emperor, for we’d have to get accustomed to the low-down Kings and gradually work up. She believes in aiming high. That’s all right ordinarily, but it isn’t a practical proposition. Still, I let her have her way and did the best I could, but it was no use. I paid a German Baron a certain sum for getting the Emperor on board my yacht, but he didn’t deliver the goods. So I said to Gertie: ‘My girl, we’d better go to India, or some place where Kings are cheap, and practise on them first.’ She hated to give in, but she’s a reasonable young woman if you take her the right way. Well, the long and the short of it was that we sent the yacht around to Marseilles, and went down from Paris to meet her there, and sailed to Egypt, and, just as I said, we had no difficulty at all in raking in the Khedive. But that wasn’t very satisfactory when all’s said and done. Gertie claimed he wasn’t a real king, and I say he’s not a real gentleman. We had a little unpleasantness there, and he became altogether too friendly, so we sailed off down through the Canal a hunting Kings, till at last we got here to Japan. Now we’re up against it once more, and I suppose this here Mikado has hobnobbed so much with real Emperors and that sort of thing that he thinks himself a white man like the rest. So I says to Gertie, ‘There’s a genuine Emperor in Corea, good enough to begin on, and we’ll go there,’ and that’s how we came round from Yokohama to Nagasaki, and dropped in here to get a few things we might not be able to obtain in Corea. The moment I saw you and learned that you knew a good deal about the East, it struck me that if I took you on as private secretary you would be able to give me a few points, and perhaps take charge of this business altogether. Do you think you’d be able to do that?”

“Well,” I said hesitatingly, “I’m not sure, but if I can be of any use to you on such a quest it will be in Corea. I’ve been there on two or three occasions, and each time had an audience with the King.”

“Why do you call him the King? Isn’t he an Emperor?”

“Well, I’ve always called him the King, but I’ve heard people term him the Emperor.”

“The American papers always call him an Emperor. So you think you could manage it, eh?”

“I don’t know that there would be any difficulty about the matter. Of course you are aware he is merely a savage.”

“Well, they’re all savages out here, aren’t they? I don’t suppose he’s any worse or any better than the Mikado.”

“Oh, the Mikado belongs to one of the most ancient civilizations in the world. I don’t think the two potentates are at all on a par.”

“Well, that’s all right. That just bears out what I was saying, that it’s the correct thing to begin with the lowest of them. You see I hate to admit I’m too old to learn anything, and I think I can learn this King business if I stick long enough at it. But I don’t believe in a man trying to make a grand piano before he knows how to handle a saw. So you see, Mr. Tremorne, the position is just this. I want to sail for Corea, and Gertie, she wants to go back to Yokohama and tackle the Mikado again, thinking you can pull it off this time.”

“I dislike very much to disagree with a lady,” I said, “but I think your plan is the more feasible of the two. I do not think it would be possible to get the Mikado to come aboard this yacht, but it might be that the King of Corea would accept your invitation.”

“What’s the name of the capital of that place?” asked Mr. Hemster.

“It is spelled S-e-o-u-l, and is pronounced ‘Sool.’”

“How far is it from here?”

“I don’t know exactly, but it must be something like four hundred miles, perhaps a little more.”

“It is on the sea?”

“No. It lies some twenty-six miles inland by road, and more than double that distance by the winding river Han.”

“Can I steam up that river with this yacht to the capital?”

“No, I don’t think you could. You could go part way, perhaps, but I imagine your better plan would be to moor at the port of Chemulpo and go to Seoul by road, although the road is none of the best.”

“I’ve got a little naphtha launch on board. I suppose the river is big enough for us to go up to the capital in that?”

“Yes, I suppose you could do it in a small launch, but the river is so crooked that I doubt if you would gain much time, although you might gain in comfort.”

“Very well, we’ll make for that port, whatever you call it,” said Hemster, rising. “Now, if you’ll just take an armchair on deck, and smoke, I’ll give instructions to the captain.”

CHAPTER V

We had been a long time together in the little office, longer even than this extended conversation would lead a reader to imagine, and as I went through the saloon I saw that they were laying the table for lunch, a sight by no means ungrateful to me, for I had risen early and enjoyed but a small and frugal breakfast. I surmised from the preparations going forward that I should in the near future have something better than rice. When I reached the deck I saw the captain smoking a pipe and still pacing the bridge with his hands in his pockets. He was a grizzled old sea-dog, who, I found later, had come from the Cape Cod district, and was what he looked, a most capable man. I went aft and sat down, not wishing to go forward and became acquainted with the captain, as I expected every moment that Mr. Hemster would come up and give him his sailing-orders. But time passed on and nothing happened, merely the same state of tension that occurs when every one is ready to move and no move is made. At last the gong sounded for lunch. I saw the captain pause in his promenade, knock the ashes out of his pipe into the palm of his hand, and prepare to go down. So I rose and descended the stairway, giving a nod of recognition to the captain, who followed at my heels. The table was laid for five persons. Mr. Hemster occupied the position at the head of it, and on his right sat his daughter, her head bent down over the tablecloth. On the opposite side, at Mr. Hemster’s left, sat the young lady of whom I had had a glimpse the afternoon before. The captain pushed past me with a gruff, “How de do, all,” which was not responded to. He took the place at the farther end of the table. If I have described the situation on deck as a state of tension, much more so was the atmosphere of the dining-saloon. The silence was painful, and, not knowing what better to do, I approached Miss Hemster and said pleasantly:

“Good-morning. I hope you are none the worse for your shopping expedition of yesterday.”

The young woman did not look up or reply till her father said in beseeching tones:

“Gertie, Mr. Tremorne is speaking to you.”

Then she glanced at me with eyes that seemed to sparkle dangerously.

“Oh, how do you do?” she said rapidly. “Your place is over there by Miss Stretton.”

There was something so insulting in the tone and inflection that it made the words, simple as they were, seem like a slap in the face. Their purport seemed to be to put me in my proper position in that society, to warn me that, if I had been treated as a friend the day before, conditions were now changed, and I was merely, as she had previously remarked, her father’s hired man. My situation was anything but an enviable one, and as there was nothing to say I merely bowed low to the girl, walked around behind the captain, and took my place beside Miss Stretton, as I had been commanded to do. I confess I was deeply hurt by the studied insolence of look and voice; but a moment later I felt that I was probably making a mountain of a molehill, for the good, bluff captain said, as if nothing unusual had happened:

“That’s right, young man; I see you have been correctly brought up. Always do what the women tell you. Obey orders if you break owners. That’s what we do in our country. In our country, sir, we allow the women to rule, and their word is law, even though the men vote.”

“Such is not the case in the East,” I could not help replying.

“Why,” said the captain, “it’s the East I’m talking about. All throughout the Eastern States, yes, and the Western States, too.”

“Oh, I beg your pardon,” I replied, “I was referring to the East of Asia. The women don’t rule in these countries.”

“Well,” said the staunch captain, “then that’s the reason they amount to so little. I never knew an Eastern country yet that was worth the powder to blow it up.”

“I’m afraid,” said I, “that your rule does not prove universally good. It’s a woman who reigns in China, and I shouldn’t hold that Empire up as an example to others.”

The captain laughed heartily.

“Young man, you’re contradicting yourself. You’re excited, I guess. You said a minute ago that women didn’t rule in the East, and now you show that the largest country in the East is ruled by a woman. You can’t have it both ways, you know.”

I laughed somewhat dismally in sympathy with him, and, lunch now being served, the good man devoted his entire attention to eating. As no one else said a word except the captain and myself, I made a feeble but futile attempt to cause the conversation to become general. I glanced at my fair neighbor to the right, who had not looked up once since I entered. Miss Stretton was not nearly so handsome a girl as Miss Hemster, yet nevertheless in any ordinary company she would be regarded as very good-looking. She had a sweet and sympathetic face, and at the present moment it was rosy red.

“Have you been in Nagasaki?” I asked, which was a stupid question, for I knew she had not visited the town the day before, and unless she had gone very early there was no time for her to have been ashore before I came aboard.

She answered “No” in such low tones that, fearing I had not heard it, she cleared her throat, and said “No” again. Then she raised her eyes for one brief second, cast a sidelong glance at me, so appealing and so vivid with intelligence, that I read it at once to mean, “Oh, please do not talk to me.”