автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Aunt Jane’s Nieces on the Ranch

Aunt Jane’s Nieces on the Ranch

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: Aunt Jane’s Nieces on the Ranch

Author: Edith Van Dyne

Release Date: April 12, 2011 [EBook #35859]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AUNT JANE’S NIECES ON THE RANCH ***

Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net.

AUNT JANE’S NIECES

ON THE RANCH

BY

EDITH VAN DYNE

AUTHOR OF AUNT JANE’S NIECES SERIES

THE FLYING GIRL SERIES, ETC., ETC.

The Reilly & Lee Co.

Chicago

Copyright, 1913

BY

The Reilly & Britton Co.

AUNT JANE’S NIECES ON THE RANCH

CONTENTS

- CHAPTER I—UNCLE JOHN DECIDES

- CHAPTER II—EL CAJON RANCH

- CHAPTER III—THAT BLESSED BABY!

- CHAPTER IV—LITTLE JANE’S TWO NURSES

- CHAPTER V—INEZ THREATENS

- CHAPTER VI—A DINNER WITH THE NEIGHBORS

- CHAPTER VII—GONE!

- CHAPTER VIII—VERY MYSTERIOUS

- CHAPTER IX—A FRUITLESS SEARCH

- CHAPTER X—CONJECTURES AND ABSURDITIES

- CHAPTER XI—THE MAJOR ENCOUNTERS THE GHOST

- CHAPTER XII—ANOTHER DISAPPEARANCE

- CHAPTER XIII—THE WAY IT HAPPENED

- CHAPTER XIV—PRISONERS OF THE WALL

- CHAPTER XV—MILDRED CONFIDES IN INEZ

- CHAPTER XVI—AN UNEXPECTED ARRIVAL

- CHAPTER XVII—THE PRODIGAL SON

- CHAPTER XVIII—LACES AND GOLD

- CHAPTER XIX—INEZ AND MIGUEL

- CHAPTER XX—MR. RUNYON’S DISCOVERY

- CHAPTER XXI—A FORTUNE IN TATTERS

- CHAPTER XXII—FAITHFUL AND TRUE

Aunt Jane’s Nieces on the Ranch

CHAPTER I—UNCLE JOHN DECIDES

“And now,” said Major Doyle, rubbing his hands together as he half reclined in his big chair in a corner of the sitting room, “now we shall enjoy a nice cosy winter in dear New York.”

“Cosy?” said his young daughter, Miss Patricia Doyle, raising her head from her sewing to cast a glance through the window at the whirling snowflakes.

“Ab-so-lute-ly cosy, Patsy, my dear,” responded the major. “Here we are in our own steam-heated flat—seven rooms and a bath, not counting the closets—hot water any time you turn the faucet; a telephone call brings the butcher, the baker, the candlestick-maker; latest editions of the papers chucked into the passage! What more do you want?”

“Tcha!”

This scornful ejaculation came from a little bald-headed man seated in the opposite corner, who had been calmly smoking his pipe and dreamily eyeing the flickering gas-log in the grate. The major gave a start and turned to stare fixedly at the little man. Patsy, scenting mischief, indulged in a little laugh as she threaded her needle.

“Sir! what am I to understand from that brutal interruption?” demanded Major Doyle sternly.

“You’re talking nonsense,” was the reply, uttered in a tone of cheery indifference. “New York in winter is a nightmare. Blizzards, thaws, hurricanes, ice, la grippe, shivers—grouches.”

“Drumsticks!” cried the major indignantly. “It’s the finest climate in the world—bar none. We’ve the finest restaurants, the best theatres, the biggest stores and—and the stock exchange. And then, there’s Broadway! What more can mortal desire, John Merrick?”

The little man laughed, but filled his pipe without reply.

“Uncle John is getting uneasy,” observed Patsy. “I’ve noticed it for some time. This is the first snowstorm that has caught him in New York for several years.”

“The blizzard came unusually early,” said Mr. Merrick apologetically. “It took me by surprise. But I imagine there will be a few days more of decent weather before winter finally sets in. By that time—”

“Well, what then?” asked the major in defiant accents, as his brother-in-law hesitated.

“By that time we shall be out of it, of course,” was the quiet reply.

Patsy looked at her uncle reflectively, while the major grunted and shifted uneasily in his chair. Father and daughter were alike devoted to John Merrick, whose generosity and kindliness had rescued them from poverty and thrust upon them all the comforts they now enjoyed. Even this pretty flat building in Willing Square, close to the fashionable New York residence district, belonged in fee to Miss Doyle, it having been a gift from her wealthy uncle. And Uncle John made his home with them, quite content in a seven-room-flat when his millions might have purchased the handsomest establishment in the metropolis. Down in Wall Street and throughout the financial districts the name of the great John Merrick was mentioned with awe; here in Willing Square he smoked a pipe in his corner of the modest sitting room and cheerfully argued with his irascible brother-in-law, Major Doyle, whose business it was to look after Mr. Merrick’s investments and so allow the democratic little millionaire the opportunity to come and go as he pleased.

The major’s greatest objection to Uncle John’s frequent absences from New York—especially during the winter months—was due to the fact that his beloved Patsy, whom he worshiped with a species of idolatry, usually accompanied her uncle. It was quite natural for the major to resent being left alone, and equally natural for Patsy to enjoy these travel experiences, which in Uncle John’s company were always delightful.

Patsy Doyle was an unprepossessing little thing, at first sight. She was short of stature and a bit plump; freckled and red-haired; neat and wholesome in appearance but lacking “style” in either form or apparel. But to her friends Patricia was beautiful. Her big blue eyes, mischievous and laughing, won hearts without effort, and the girl was so genuine—so natural and unaffected—that she attracted old and young alike and boasted a host of admiring friends.

This girl was Uncle John’s favorite niece, but not the only one. Beth De Graf, a year younger than her cousin Patsy, was a ward of Mr. Merrick and lived with the others in the little flat at Willing Square. Beth was not an orphan, but her father and mother, residents of an Ohio town, had treated the girl so selfishly and inconsiderately that she had passed a very unhappy life until Uncle John took her under his wing and removed Beth from her depressing environment. This niece was as beautiful in form and feature as Patsy Doyle was plain, but she did not possess Patsy’s cheerful and uniform temperament and was by nature reserved and diffident in the presence of strangers.

There was another niece, likewise dear to John Merrick’s heart, who had been Louise Merrick before she married a youth named Arthur Weldon, some two years before this story begins. A few months ago Arthur had taken his young wife to California, where he had purchased a fruit ranch, and there a baby was born to them which they named “Jane Merrick Weldon”—a rather big name for what was admitted to be a very small person.

This baby, now five months old and reported to be thriving, had been from its birth of tremendous interest to every inhabitant of the Willing Square flat. It had been discussed morning, noon and night by Uncle John and the girls, while even the grizzled major was not ashamed to admit that “that Weldon infant” was an important addition to the family. Perhaps little Jane acquired an added interest by being so far away from all her relatives, as well as from the fact that Louise wrote such glowing accounts of the baby’s beauty and witcheries that to believe a tithe of what she asserted was to establish the child as an infantile marvel.

Now, Patsy Doyle knew in her heart that Uncle John was eager to see Louise’s baby, and long ago she had confided to Beth her belief that the winter would find Mr. Merrick at Arthur Weldon’s California ranch, with all his three nieces gathered around him and the infantile marvel in his arms. The same suspicion had crept into Major Doyle’s mind, and that is why he so promptly resented the suggestion that New York was not an ideal winter resort. Somehow, the old major “felt in his bones” that his beloved Patsy would be whisked away to California, leaving her father to face the tedious winter without her; for he believed his business duties would not allow him to get away to accompany her.

Yet so far Uncle John, in planning for the winter, had not mentioned California as even a remote possibility. It was understood he would go somewhere, but up to the moment when he declared “we will be out of it, of course, when the bad weather sets in,” he had kept his own counsel and forborne to express a preference or a decision.

But now the major, being aroused, decided to “have it out” with his elusive brother-in-law.

“Where will ye go to find a better place?” he demanded.

“We’re going to Bermuda,” said Uncle John.

“For onions?” asked the major sarcastically.

“They have other things in Bermuda besides onions. A delightful climate, I’m told, is one of them.”

The major sniffed. He was surprised, it is true, and rather pleased, because Bermuda is so much nearer New York than is California; but it was his custom to object.

“Patsy can’t go,” he declared, as if that settled the question for good and all. “The sea voyage would kill her. I’m told by truthful persons that the voyage to Bermuda is the most terrible experience known to mortals. Those who don’t die on the way over positively refuse ever to come back again, and so remain forever exiled from their homes and families—until they have the good luck to die from continually eating onions.”

Mr. Merrick smiled as he glanced at the major’s severe countenance.

“It can’t be as bad as that,” said he. “I know a man who has taken his family to Bermuda for five winters, in succession.”

“And brought ’em back alive each time?”

“Certainly. Otherwise, you will admit he couldn’t take them again.”

“That family,” asserted the major seriously, “must be made of cast-iron, with clockwork stomachs.”

Patsy gave one of her low, musical laughs.

“I think I would like Bermuda,” she said. “Anyhow, whatever pleases Uncle John will please me, so long as we get away from New York.”

“Why, ye female traitor!” cried the major; and added, for Uncle John’s benefit: “New York is admitted by men of discretion to be the modern Garden of Eden. It’s the one desideratum of—”

Here the door opened abruptly and Beth came in. Her cheeks were glowing red from contact with the wind and her dark tailor-suit glistened with tiny drops left by the melted snow. In her mittened hand she waved a letter.

“From Louise, Patsy!” she exclaimed, tossing it toward her cousin; “but don’t you dare read it till I’ve changed my things.”

Then she disappeared into an inner room and Patsy, disregarding the injunction, caught up the epistle and tore open the envelope.

Uncle John refilled his pipe and looked at Patsy’s tense face inquiringly. The major stiffened, but could not wholly repress his curiosity. After a moment he said:

“All well, Patsy?”

“How’s the baby?” asked Uncle John.

“Dear me!” cried Patsy, with a distressed face; “and no doctor nearer than five miles!”

Both men leaped from their chairs.

“Why don’t they keep a doctor in the house?” roared the major.

“Suppose we send Dr. Lawson, right away!” suggested Uncle John.

Patsy, still holding up the letter, turned her eyes upon them reproachfully.

“It’s all over,” she said with a sigh.

The major dropped into a chair, limp and inert. Uncle John paled.

“The—the baby isn’t—dead!” he gasped.

“No, indeed,” returned Patsy, again reading. “But it had colic most dreadfully, and Louise was in despair. But the nurse, a dark-skinned Mexican creature, gave it a dose of some horrid hot stuff—”

“Chile con carne, most likely!” ejaculated the major.

“Horrible!” cried Uncle John.

“And that cured the colic but almost burned poor little Jane’s insides out.”

“Insides out!”

“However, Louise says the dear baby is now quite well again,” continued the girl.

“Perhaps so, when she wrote,” commented the major, wiping his forehead with a handkerchief; “but that’s a week ago, at least. A thousand things might have happened to that child since then. Why was Arthur Weldon such a fool as to settle in a desert place, far away from all civilization? He ought to be prosecuted for cruelty.”

“The baby’s all right,” said Patsy, soothingly. “If anything serious happened, Louise would telegraph.”

“I doubt it,” said the major, walking the floor. “I doubt if there’s such a thing as a telegraph in all that forsaken country.”

Uncle John frowned.

“You are getting imbecile, Major. They’ve a lot more comforts and conveniences on that ranch than we have here in New York.”

“Name ’em!” shouted the Major. “I challenge ye to mention one thing we haven’t right here in this flat.”

“Chickens!” said Beth, re-entering the room in time to hear this challenge. “How’s the baby, Patsy?”

“Growing like a weed, dear, and getting more lovely and cunning every second. Here—read the letter yourself.”

While Beth devoured the news from California Uncle John replied to the major.

“At El Cajon Ranch,” said he, “there’s a fine big house where the sunshine peeps in and floods the rooms every day in the year. Hear that blizzard howl outside, and think of the roses blooming this instant on the trellis of Louise’s window. Arthur has two automobiles and can get to town in twenty minutes. They’ve a long-distance telephone and I’ve talked with ’em over the line several times.”

“You have!” This in a surprised chorus.

“I have. Only last week I called Louise up.”

“An expensive amusement, John,” said the major grimly.

“Yes; but I figured I could afford it. I own some telephone stock, you know, so I may get part of that investment back. They have their own cows, and chickens—as Beth truly says—and any morning they can pick oranges and grapefruit from their own trees for breakfast.”

“I’d like to see that precious baby,” remarked Beth, laying the letter on her lap to glance pleadingly at her uncle.

“Uncle John is going to take us to Bermuda,” said Patsy in a serious voice.

The little man flushed and sat down abruptly. The major, noting his attitude, became disturbed.

“You’ve all made the California trip,” said he. “It doesn’t pay to see any country twice.”

“But we haven’t seen Arthur’s ranch,” Beth reminded him.

“Nor the baby,” added Patsy, regarding the back of Uncle John’s head somewhat wistfully.

The silence that followed was broken only by the major’s low growls. The poor man already knew his fate.

“That chile-con-carne nurse ought to be discharged,” mumbled Uncle John, half audibly. “Mexicans are stupid creatures to have around. I think we ought to take with us an experienced nurse, who is intelligent and up-to-date.”

“Oh, I know the very one!” exclaimed Beth. “Mildred Travers. She’s perfectly splendid. I’ve watched her with that poor girl who was hurt at the school, and she’s as gentle and skillful as she is refined. Mildred would bring up that baby to be as hearty and healthful as a young savage.”

“How soon could she go?” asked Uncle John.

“At an hour’s notice, I’m sure. Trained nurses are used to sudden calls, you know. I’ll see her to-morrow—if it’s better weather.”

“Do,” said Uncle John. “I suppose you girls can get ready by Saturday?”

“Of course!” cried Patsy and Beth in one voice.

“Then I’ll make the reservations. Major Doyle, you will arrange your business to accompany us.”

“I won’t!”

“You will, or I’ll discharge you. You’re working for me, aren’t you?”

“I am, sir.”

“Then obey orders.”

CHAPTER II—EL CAJON RANCH

Uncle John always traveled comfortably and even luxuriously, but without ostentation. Such conveniences as were offered the general public he indulged in, but no one would suspect him of being a multi-millionaire who might have ordered a special train of private cars had the inclination seized him. A modest little man, who had made an enormous fortune in the far Northwest—almost before he realized it—John Merrick had never allowed the possession of money to deprive him of his simple tastes or to alter his kindly nature. He loved to be of the people and to mingle with his fellows on an equal footing, and nothing distressed him more than to be recognized by some one as the great New York financier. It is true that he had practically retired from business, but his huge fortune was invested in so many channels that his name remained prominent among men of affairs and this notoriety he was unable wholly to escape.

The trip to California was a delight because none of his fellow passengers knew his identity. During the three days’ jaunt from Chicago to Los Angeles he was recognized only as an engaging little man who was conducting a party of three charming girls, as well as a sedate, soldierly old gentleman, into the sunny Southland for a winter’s recreation.

Of these three girls we already know Patsy Doyle and Beth DeGraf, but Mildred Travers remains to be introduced. The trained nurse whom Beth had secured was tall and slight, with a sweet face, a gentle expression and eyes so calm and deep that a stranger found it disconcerting to gaze within them. Beth herself had similar eyes—big and fathomless—yet they were so expressive as to allure and bewitch the beholder, while Mildred Travers’ eyes repelled one as being masked—as concealing some well guarded secret. Both the major and Uncle John had felt this and it made the latter somewhat uneasy when he reflected that he was taking this girl to be the trusted nurse of Louise’s precious baby. He questioned Beth closely concerning Mildred and his niece declared that no kindlier, more sympathetic or more skillful nurse was ever granted a diploma. Of Mildred’s history she was ignorant, except that the girl had confided to her the story of her struggles to obtain recognition and to get remunerative work after graduating from the training school.

“Once, you know,” explained Beth, “trained nurses were in such demand that none were ever idle; but the training schools have been turning them out in such vast numbers that only those with family influence are now sure of work. Mildred is by instinct helpful and sympathetic—a natural born nurse, Uncle John—but because she was practically a stranger in New York she was forced to do charity and hospital work, and that is how I became acquainted with her.”

“She seems to bear out your endorsement, except for her eyes,” said Uncle John. “I—I don’t like—her eyes. They’re hard. At times they seem vengeful and cruel, like tigers’ eyes.”

“Oh, you wrong Mildred, I’m sure!” exclaimed Beth, and Uncle John reluctantly accepted her verdict. On the journey Miss Travers appeared well bred and cultured, conversing easily and intelligently on a variety of subjects, yet always exhibiting a reserve, as if she held herself to be one apart from the others. Indeed, the girl proved so agreeable a companion that Mr. Merrick’s misgivings gradually subsided. Even the major, still suspicious and doubtful, admitted that Mildred was “quite a superior person.”

Louise had been notified by telegraph of the coming of her relatives, but they had withheld from her the fact that they were bringing a “proper” nurse to care for the Weldon baby. The party rested a day in Los Angeles and then journeyed on to Escondido, near which town the Weldon ranch was located.

Louise and Arthur were both at the station with their big seven-passenger touring car. The young mother was promptly smothered in embraces by Patsy and Beth, but when she emerged from this ordeal to be hugged and kissed by Uncle John, that observing little gentleman decided that she looked exactly as girlish and lovely as on her wedding day.

This eldest niece was, in fact, only twenty years of age—quite too young to be a wife and mother. She was of that feminine type which matures slowly and seems to bear the mark of perpetual youth. Mrs. Weldon’s slight, willowy form was still almost childlike in its lines, and the sunny, happy smile upon her face seemed that of a school-maid.

That tall, boyish figure beside her, now heartily welcoming the guests, would scarcely be recognized as belonging to a husband and father. These two were more like children playing at “keeping house” than sedate married people. Mildred Travers observed the couple with evident surprise; but the others, familiar with the love story of Arthur and Louise, were merely glad to find them unchanged and enjoying their former health and good spirits.

“The baby!”

That was naturally the first inquiry, voiced in concert by the late arrivals; and Louise, blushing prettily and with a delightful air of proprietorship, laughingly assured them that “Toodlums” was very well.

“This is such a glorious country,” she added as the big car started off with its load, to be followed by a wagon with the baggage, “that every living thing flourishes here like the green bay trees—and baby is no exception. Oh, you’ll love our quaint old home, Uncle John! And, Patsy, we’ve got such a flock of white chickens! And there’s a new baby calf, Beth! And the major shall sleep in the Haunted Room, and—”

“Haunted?” asked the major, his eyes twinkling.

“I’m sure they’re rats,” said the little wife, “but the Mexicans claim it’s the old miser himself. And the oranges are just in their prime and the roses are simply magnificent!”

So she rambled on, enthusiastic over her ranch home one moment and the next asking eager questions about New York and her old friends there. Louise had a mother, who was just now living in Paris, much to Arthur Weldon’s satisfaction. Even Louise did not miss the worldly-minded, self-centered mother with whom she had so little in common, and perhaps Uncle John and his nieces would never have ventured on this visit had Mrs. Merrick been at the ranch.

The California country roads are all “boulevards,” although they are nothing more than native earth, rolled smooth and saturated with heavy oil until they resemble asphalt. The automobile was a fast one and it swept through the beautiful country, all fresh and green in spite of the fact that it was December, and fragrant with the scent of roses and carnations, which bloomed on every side, until a twenty-minute run brought them to an avenue of gigantic palms which led from the road up to the ranch house of El Cajon.

Originally El Cajon had been a Spanish grant of several thousand acres, and three generations of Spanish dons had resided there. The last of these Cristovals had erected the present mansion—a splendid, rambling dwelling built around an open court where a fountain splashed and tall palms shot their swaying crowns far above the housetop. The South Wing was the old dwelling which the builder had incorporated into the present scheme, but the newer part was the more imposing.

The walls were of great thickness and composed of adobe blocks of huge size. These were not sun-baked, as is usual in adobe dwellings, but had been burned like brick in a furnace constructed for the purpose by the first proprietor, and were therefore much stronger and harder than ordinary brick. In this climate there is no dampness clinging to such a structure and the rooms were extraordinarily cool in summer and warm in the chill winter season. Surrounding the house were many magnificent trees of tropical and semi-tropical nature, all of which had now attained their full prime. On the south and east sides were extensive rose gardens and beds of flowers in wonderful variety.

It was here that the last Señor Cristoval had brought his young bride, a lady of Madrid who was reputed to have possessed great beauty; but seclusion in this retired spot, then much isolated, rendered her so unhappy that she became mentally unbalanced and in a fit of depression took her own life. Cristoval, until then a generous and noble man, was completely changed by this catastrophe. During the remainder of his life he was noted for parsimony and greed for money, not unmixed with cruelty. He worked his ignorant Indian and Mexican servants mercilessly, denying them proper food or wage, and his death was a relief to all. Afterward the big estate was cut up and passed into various hands. Three hundred acres of fine orange and olive groves, including the spacious mansion, were finally sold to young Arthur Weldon.

“It’s an awfully big place,” said Louise, as the party alighted and stood upon the broad stone veranda, “but it is so quaint and charming that I love every stick and stone of it.”

“The baby!” shrieked Patsy.

“Where’s that blessed baby?” cried Beth.

Then came from the house a dusky maid bearing in her arms a soft, fluffy bundle that was instantly pounced upon by the two girls, to Uncle John’s horror and dismay.

“Be careful, there!” he called. “You’ll smother the poor thing.” But Louise laughed and regarded the scene delightedly. And little Jane seemed to appreciate the importance of the occasion, for she waved her tiny hands and cooed a welcome to her two new aunties.

CHAPTER III—THAT BLESSED BABY!

“Oh, you darling!”

“It’s my turn, Patsy! Don’t be selfish. Let me kiss her again.”

“That’s enough, Beth. Here—give me my niece!”

“She’s mine, too.”

“Give me that baby! There; you’ve made her cry.”

“I haven’t; she’s laughing because I kissed her wee nose.”

“Isn’t she a dear, though?”

“Now, girls,” suggested Louise, “suppose we give Uncle John and the major a peep at her.”

Reluctantly the bundle was abandoned to its mother, who carried it to where Mr. Merrick was nervously standing. “Yes, yes,” he said, touching one cheek gently with the tip of his finger. “It—it’s a fine child, Louise; really a—a—creditable child. But—eh—isn’t it rather—soft?”

“Of course, Uncle John. All babies are soft. Aren’t you going to kiss little Jane?”

“It—won’t—hurt it?”

“Not a bit. Haven’t Beth and Patsy nearly kissed its skin off?”

“Babies,” asserted Major Doyle, stiffly, “were made to be kissed. Anyhow, that’s the penalty they pay for being born helpless.” And with this he kissed little Jane on both cheeks with evident satisfaction.

This bravado encouraged Uncle John to do likewise, but after the operation he looked sheepish and awkward, as if he felt that he had taken an unfair advantage of the wee lady.

“She seems very red, Louise,” he remarked, to cover his embarrassment.

“Oh, no, Uncle! Everyone says she’s the whitest baby of her age they ever saw. She’s only five months old, remember.”

“Dear me; how very young.”

“But she’s getting older every day,” said Arthur, coming in from the garage. “What do you folks think of her, anyhow?”

The rhapsodies were fairly bewildering, yet very pleasant to the young father and mother. While they continued, Mildred Travers quietly took the child from Louise and tenderly bent over it. Only the major noted the little scene that ensued.

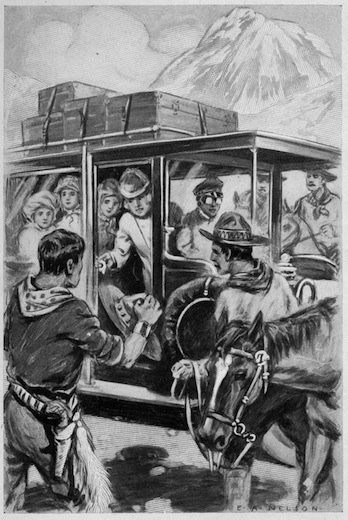

The eyes of the dark-skinned Mexican girl flashed sudden fire. She pulled Mildred’s sleeve and then fell back discomfited as the cold, fathomless eyes of the trained nurse met her own. For an instant the girl stood irresolute; then with a quick, unexpected motion she tore the infant from Mildred’s arms and rushed into the house with it.

Arthur, noticing this last action, laughed lightly. The major frowned. Mildred folded her arms and stood in the background unmoved and unobtrusive. Louise was chatting volubly with her two cousins.

“Was that the same Mexican girl who fed the baby chile con carne?” inquired Uncle John anxiously.

“Mercy, no!” cried Arthur. “What ever put such an idea into your head?”

“I believe the major suggested it,” replied the little man. “Anyhow, it was something hot, so Louise wrote.”

“Oh, yes; when Toodlums had the colic. It was some queer Mexican remedy, but I’m confident it saved the child’s life. The girl is a treasure.”

Uncle John coughed and glanced uneasily at Miss Travers, who pretended not to have overheard this conversation. But the major was highly amused and decided it was a good joke on Mr. Merrick. It was so good a joke that it might serve as a basis for many cutting remarks in future discussions. His brother-in-law was so seldom guilty of an error in judgment that Major Doyle, who loved to oppose him because he was so fond of him, hailed Uncle John’s present predicament with pure joy.

Louise created a welcome diversion by ushering them all into the house and through the stately rooms to the open court, where a luncheon table was set beneath the shade of the palms.

Here was the baby again, with the Mexican girl, Inez, hugging it defiantly to her bosom as she sat upon a stone bench.

Between the infant, the excitement of arrival and admiration for the Weldon establishment, so far surpassing their most ardent anticipations, Beth and Patsy had little desire for food. Uncle John and the major, however, did ample justice to an excellent repast, which was served by two more Mexican maids.

“Do you employ only Mexicans for servants?” inquired Uncle John, when finally the men were left alone to smoke while the girls, under Louise’s guidance, explored the house.

“Only Mexicans, except for the Chinese cook,” replied Arthur. “It is impossible to get American help and the Japs I won’t have. Some of the ranch hands have been on the place for years, but the house servants I hired after I come here.”

“A lazy lot, eh?” suggested the major.

“Quite right, sir. But I find them faithful and easy to manage. You will notice that I keep two or three times as many house servants as a similar establishment would require in the east; but they are content with much smaller wages. It’s the same way on the ranch. Yet without the Mexicans the help problem would be a serious one out here.”

“Does the ranch pay?” asked Mr. Merrick.

“I haven’t been here long enough to find out,” answered Arthur, with a smile. “So far, I’ve done all the paying. We shall harvest a big orange crop next month, and in time the olives will mature; but I’ve an idea the expenses will eat up the receipts, by the end of the year.”

“No money in a California ranch, eh?”

“Why, some of my neighbors are making fortunes, I hear; but they are experienced ranchers. On the other hand, my next neighbor at the north is nearly bankrupt, because he’s a greenhorn from the east. Some time, when I’ve learned the game, I hope to make this place something more than a plaything.”

“You’ll stay here, then?” asked the major, with astonishment. “It’s the most delightful country on earth, for a residence. You’ll admit that, sir, when you know it better.”

Meantime the baggage wagon arrived and Patsy and Beth, having picked out their rooms, began to unpack and “settle” in their new quarters.

CHAPTER IV—LITTLE JANE’S TWO NURSES

Louise had been considerably puzzled to account for the presence of the strange girl in Uncle John’s party. At first she did not know whether to receive Mildred Travers as an equal or a dependent. Not until the three nieces were seated together in Louise’s own room, exchanging girlish confidences, was Mildred’s status clearly defined to the young mother.

“You see,” explained Patsy, “Uncle John was dreadfully worried over the baby. When you wrote of that terrible time the dear little one had with the colic, and how you were dependent on a Mexican girl who fed the innocent lamb some horrid hot stuff, Uncle declared it was a shame to imperil such a precious life, and that you must have a thoroughly competent nurse.”

“But,” said Louise, quite bewildered, “I’m afraid you don’t understand that—”

“And so,” broke in Beth, “I told him I knew of a perfect jewel of a trained nurse, who knows as much as most doctors and could guard the baby from a thousand dangers. I’d watched her care for one of our poor girls who was knocked down by an automobile and badly injured, and Mildred was so skillful and sympathetic that she quite won my heart. I wasn’t sure, at first, she’d come way out to California, to stay, but when I broached the subject she cried out: ‘Thank heaven!’ in such a heart-felt, joyous tone that I was greatly relieved. So we brought her along, and—”

“Really, Beth, I don’t need her,” protested Louise. “The Mexicans are considered the best nurses in the world, and Inez is perfectly devoted to baby and worships her most sinfully. I got her from a woman who formerly employed her as a nurse and she gave Inez a splendid recommendation. Both Arthur and I believe she saved baby’s life by her prompt action when the colic caught her.”

“But the hot stuff!” cried Patsy.

“It might have ruined baby’s stomach for life,” asserted Beth.

“No; it’s a simple Mexican remedy that is very efficient. Perhaps, in my anxiety, I wrote more forcibly than the occasion justified,” admitted Louise; “but I have every confidence in Inez.”

The girls were really dismayed and frankly displayed their chagrin. Louise laughed at them.

“Never mind,” she said; “it’s just one of dear Uncle John’s blunders in trying to be good to me; so let’s endeavor to wiggle out of the hole as gracefully as possible.”

“I don’t see how you’ll do it,” confessed Patsy. “Here’s Mildred, permanently engaged and all expenses paid.”

“She is really a superior person, as you’ll presently discover,” added Beth. “I’ve never dared question her as to her family history, but I venture to say she is well born and with just as good antecedents as we have—perhaps better.”

“She’s very quiet and undemonstrative,” said Patsy musingly.

“Naturally, being a trained nurse. I liked her face,” said Louise, “but her eyes puzzle me.”

“They are her one unfortunate feature,” Beth agreed.

“They’re cold,” said Patsy; “that’s the trouble. You never get into her eyes, somehow. They repel you.”

“I never look at them,” said Beth. “Her mouth is sweet and sensitive and her facial expression pleasant. She moves as gracefully and silently as—as—”

“As a cat,” suggested Patsy.

“And she is acquainted with all the modern methods of nursing, although she’s done a lot of hospital work, too.”

“Well,” said Louise, reflectively, “I’ll talk it over with Arthur and see what we can do. Perhaps baby needs two nurses. We can’t discharge Inez, for Toodlums is even more contented with her than with me; but I admit it will be a satisfaction to have so thoroughly competent a nurse as Miss Travers at hand in case of emergency. And, above all else, I don’t want to hurt dear Uncle John’s feelings.”

She did talk it over with Arthur, an hour later, and her boy husband declared he had “sized up the situation” the moment he laid eyes on Mildred at the depot. They owed a lot to Uncle John, he added, and the most graceful thing they could do, under the circumstances, was to instal Miss Travers as head nurse and retain Inez as her assistant.

“The chances are,” said Arthur laughingly, “that the Mexican girl will have most of the care of Toodlums, as she does now, while the superior will remain content to advise Inez and keep a general supervision over the nursery. So fix it up that way, Louise, and everybody will be happy.”

Uncle John was thanked so heartily for his thoughtfulness by the young couple that his kindly face glowed with satisfaction, and then Louise began the task of reconciling the two nurses to the proposed arrangement and defining the duties of each. Mildred Travers inclined her head graciously and said it was an admirable arrangement and quite satisfactory to her. But Inez listened sullenly and her dark eyes glowed with resentment.

“You not trust me more, then?” she added.

“Oh, yes, Inez; we trust you as much as ever,” Louise assured her.

“Then why you hire this strange woman?”

“She is a present to us, from my Uncle John, who came this morning. He didn’t know you were here, you see, or he would not have brought her.”

Inez remained unmollified.

“Miss Travers is a very skillful baby doctor,” continued Louise, “and she can mend broken bones, cure diseases and make the sick well.”

Inez nodded.

“I know. A witch-woman,” she said in a whisper. “You can trust me señora, but you cannot trust her. No witch-woman can be trusted.”

Louise smiled but thought best not to argue the point farther. Inez went back to the nursery hugging Toodlums as jealously as if she feared some one would snatch the little one from her arms.

Next morning Mildred said to Beth, in whom she confided most:

“The Mexican girl does not like me. She is devotedly attached to the baby and fears I will supplant her.”

“That is true,” admitted Beth, who had conceived the same idea; “but you mustn’t mind her, Mildred. The poor thing’s only half civilized and doesn’t understand our ways very well. What do you think of little Jane?”

“I never knew a sweeter, healthier or more contented baby. She smiles and sleeps perpetually and seems thoroughly wholesome. Were she to remain in her present robust condition there would be little need of my services, I assure you. But—”

“But what?” asked Beth anxiously, as the nurse hesitated.

“All babies have their ills, and little Jane cannot escape them. The rainy season is approaching and dampness is trying to infants. There will be months of moisture, and then—I shall be needed.”

“Have you been in California before?” asked Beth, impressed by Mildred’s positive assertion.

The girl hesitated a moment, looking down.

“I was born here,” she said in low, tense tones.

“Indeed! Why, I thought all the white people in California came from the east. I had no idea there could be such a thing as a white native.”

Mildred smiled with her lips. Her imperturbable eyes never smiled.

“I am only nineteen, in spite of my years of training and hard work,” she said, a touch of bitterness in her voice. “My father came here nearly thirty years ago.”

“To Southern California?”

“Yes.”

“Did you live near here, then?”

Mildred looked around her.

“I have been in this house often, as a girl,” she said slowly. “Señor Cristoval was—an acquaintance of my father.”

Beth stared at her, greatly interested.

“How strange!” she exclaimed. “You cannot be far from your own family, then,” she added.

Mildred shivered a little, twisting her fingers nervously together. She was indeed sensitive, despite that calm, repellent look in her eyes.

“I hope,” she said, evading Beth’s remark, “to be of real use to this dear baby, whom I already love. The Mexican girl, Inez, is well enough as a caretaker, but her judgment could not be trusted in emergencies. These Mexicans lose their heads easily and in crises are liable to do more harm than good. Mrs. Weldon’s arrangement is an admirable one and I confess it relieves me of much drudgery and confinement. I shall keep a watchful supervision over my charge and be prepared to meet any emergency.”

Beth was not wholly satisfied with this interview. Mildred had told her just enough to render her curious, but had withheld any information as to how a California girl happened to be in New York working as a trained nurse. She remembered the girl’s fervent exclamation: “Thank heaven!” when asked if she would go to Southern California, to a ranch called El Cajon, to take care of a new baby. Beth judged from this that Mildred was eager to get back home again; yet she had evaded any reference to her family or former friends, and since her arrival had expressed no wish to visit them.

There was something strange and unaccountable about the affair, and for this reason Beth refrained from mentioning to her cousins that Mildred Travers was a Californian by birth and was familiar with the scenes around El Cajon ranch and even with the old house itself. Perhaps some day the girl would tell her more, when she would be able to relate the whole story to Patsy and Louise.

Of course the new arrivals were eager to inspect the orange and olive groves, so on the day following that of their arrival the entire party prepared to join Arthur Weldon in a tramp over the three hundred acre ranch.

A little way back of the grounds devoted to the residence and gardens began the orange groves, the dark green foliage just now hung thick with fruit, some green, some pale yellow and others of that deep orange hue which denotes full maturity. “They consider five acres of oranges a pretty fair ranch, out here,” said the young proprietor; “but I have a hundred and ten acres of bearing trees. It will take a good many freight cars to carry my oranges to the eastern markets.”

“And what a job to pick them all!” exclaimed Patsy.

“We don’t pick them,” said Arthur. “I sell the crop on the trees and the purchaser sends a crew of men who gather the fruit in quick order. They are taken to big warehouses and sorted into sizes, wrapped and packed and loaded onto cars. That is a separate branch of the business with which we growers have nothing to do.”

Between the orange and the olive groves, and facing a little lane, they came upon a group of adobe huts—a little village in itself. Many children were playing about the yards, while several stalwart Mexicans lounged in the shade quietly smoking their eternal cigarettes. Women appeared in the doorways, shading their eyes with their hands as they curiously examined the approaching strangers.

Only one man, a small, wiry fellow with plump brown cheeks and hair and beard of snowy whiteness, detached himself from the group and advanced to meet his master. Removing his wide sombrero he made a sweeping bow, a gesture so comical that Patsy nearly laughed aloud.

“This is Miguel Zaloa, the ranchero, who has charge of all my men,” said Arthur. Then, addressing the man, he asked: “Any news, Miguel?”

“Ever’thing all right, Meest Weld,” replied the ranchero, his bright eyes earnestly fixed upon his employer’s face. “Some pardon, señor; but—Mees Jane is well?”

“Quite well, thank you, Miguel.”

“Mees Jane,” said the man, shyly twirling his hat in his hands as he cast an upward glance at the young ladies, “ees cherub young lade; much love an’ beaut’ful. Ees not?”

“She’s a dear,” replied Patsy, with ready sympathy for the sentiment and greatly pleased to find the man so ardent an admirer of the baby.

“Ever’bod’ love Mees Jane,” continued old Miguel, simply. “Since she have came, sun ees more bright, air ees more good, tamale ees more sweet. Will Inez bring Mees Jane to see us to-day, Meest Weld?”

“Perhaps so,” laughed Arthur; and then, as he turned to lead them to the olive trees, Louise, blushing prettily at the praise bestowed upon her darling, pressed a piece of shining silver into old Miguel’s hand—which he grasped with alacrity and another low bow.

“No doubt he’s right about little Jane,” remarked the major, when they had passed beyond earshot, “but I’ve a faint suspicion the old bandit praised her in order to get the money.”

“Oh, no!” cried Louise; “he’s really sincere. It is quite wonderful how completely all our Mexicans are wrapped up in baby. If Inez doesn’t wheel the baby-cab over to the quarters every day, they come to the house in droves to inquire if ‘Mees Jane’ is well. Their love for her is almost pathetic.”

“Don’t the fellows ever work?” inquired Uncle John.

“Yes, indeed,” said Arthur. “Have you any fault to find with the condition of this ranch? As compared with many others it is a model of perfection. At daybreak the mules are cultivating the earth around the trees; when the sun gets low the irrigating begins. We keep the harrows and the pumps busy every day. But during the hours when the sun shines brightest the Mexicans do not love to work, and it is policy—so long as they accomplish their tasks—to allow them to choose their own hours for labor.”

“They seem a shiftless lot,” said the major.

“They’re as good as their average type. But some—old Miguel, for instance—are better than the ordinary. Miguel is really a clever and industrious fellow. He has lived here practically all his life and knows intimately every tree on the place.”

“Did he serve the old Spanish don—Cristoval?” asked Beth.

“Yes; and his father before him. I’ve often wondered how old Miguel is. According to his own story he must be nearly a hundred; but that’s absurd. Anyhow, he’s a faithful, capable fellow, and rules the others with the rigor of an autocrat. I don’t know what I should do without him.”

“You seem to have purchased a lot of things with this ranch,” observed Uncle John. “A capital old mansion, a band of trained servants, and—a ghost.”

“Oh, yes!” exclaimed Louise. “Major, did the ghost bother you last night?”

“Not to my knowledge,” said the old soldier. “I was too tired to keep awake, you know; therefore his ghostship could not have disturbed me without being unusually energetic.”

“Have you ever seen the ghost, Louise?” inquired Patsy.

“No, dear, nor even heard it. But Arthur has. It’s in the blue room, you know, near Arthur’s study—one of the prettiest rooms in the house.”

“That’s why we gave it to the major,” added Arthur. “Once or twice, when I’ve been sitting in the study, at about midnight, reading and smoking my pipe, I’ve heard some queer noises coming from the blue room; but I attribute them to rats. These old houses are full of the pests and we can’t manage to get rid of them.”

“I imagine the walls are not all solid,” explained Louise, “for some of those on the outside are from six to eight feet in thickness, and it would be folly to make them of solid adobe.”

“As for that, adobe costs nothing,” said Arthur, “and it would be far cheaper to make a solid wall than a hollow one. But between the blocks are a lot of spaces favored as residences by our enemies the rats, and there they are safe from our reach.”

“But the ghost?” demanded Patsy.

“Oh, the ghost exists merely in the minds of the simple Mexicans, over there at the quarters. Most of them were here when that rascally old Cristoval died, and no money would hire one of them to sleep in the house. You see, they feared and hated the old fellow, who doubtless treated them cruelly. That is why we had to get our house servants from a distance, and even then we had some difficulty in quieting their fears when they heard the ghost tales. Little Inez,” added Louise, “is especially superstitious, and I’m sure if she were not so devoted to baby she would have left us weeks ago.”

“Inez told me this morning,” said Beth, “that the major must be a very brave man and possessed some charm that protected him from ghosts, or he would never dare sleep in the blue room.”

“I have a charm,” declared the major, gravely, “and it’s just common sense.”

But now they were among the graceful, broad-spreading olives, at this season barren of fruit but very attractive in their gray-green foliage. Arthur had to explain all about olive culture to the ignorant Easterners and he did this with much satisfaction because he had so recently acquired the knowledge himself.

“I can see,” said Uncle John, “that your ranch is to be a great gamble. In good years, you win; a crop failure will cost you a fortune.”

“True,” admitted the young man; “but an absolute crop failure is unknown in this section. Some years are better than others, but all are good years.”

It was quite a long tramp, but a very pleasant one, and by the time they returned to the house everyone was ready for luncheon, which awaited them in the shady court, beside the splashing fountain. Patsy and Beth demanded the baby, so presently Inez came with little Jane, and Mildred Travers followed after. The two nurses did not seem on very friendly terms, for the Mexican girl glared fiercely at her rival and Mildred returned a basilisk stare that would have confounded anyone less defiant.

This evident hostility amused Patsy, annoyed Beth and worried Louise; but the baby was impartial. From her seat on Inez’ lap little Jane stretched out her tiny hands to Mildred, smiling divinely, and the nurse took the child in spite of Inez’ weak resistance, fondling the little one lovingly. There was a sharp contrast between Mildred’s expert and adroit handling of the child and Inez’ tender awkwardness, and this was so evident that all present noticed it.

Perhaps Inez herself felt this difference as, sullen and jealous, she eyed the other intently. Then little Jane transferred her favors to her former nurse and held out her hands to Inez. With a cry that was half a sob the girl caught the baby in her arms and held it so closely that Patsy had hard work to make her give it up.

By the time Uncle John had finished his lunch both Patsy and Beth had taken turns holding the fascinating “Toodlums,” and now the latter plunged Jane into Mr. Merrick’s lap and warned him to be very careful.

Uncle John was embarrassed but greatly delighted. He cooed and clucked to the baby until it fairly laughed aloud with glee, and then he made faces until the infant became startled and regarded him with grave suspicion.

“If you’ve done making an old fool of yourself, sir,” said the major severely, “you’ll oblige me by handing over my niece.”

“Your niece!” was the indignant reply; “she’s nothing of the sort. Jane is my niece.”

“No more than mine,” insisted the major; “and you’re worrying her. Will you hand her over, you selfish man, or must I take her by force?”

Uncle John reluctantly submitted to the divorce and the major handled the baby as if she had been glass.

“Ye see,” he remarked, lapsing slightly into his Irish brogue, as he was apt to do when much interested, “I’ve raised a daughter meself, which John Merrick hasn’t, and I know the ways of the wee women. They know very well when a friend has ’em, and—Ouch! Leg-go, I say!”

Little Jane had his grizzly moustache fast in two chubby fists and the major’s howls aroused peals of laughter.

Uncle John nearly rolled from his chair in an ecstacy of delight and he could have shaken Mildred Travers for releasing the grip of the baby fingers and rescuing the major from torture.

“Laugh, ye satyr!” growled the major, wiping the tears from his own eyes. “It’s lucky you have no hair nor whiskers—any more than an egg—or you’d be writhing in agony before now.” He turned to look wonderingly at the crowing baby in Mildred’s arms. “It’s a female Sandow!” he averred. “The grip of her hands is something marvelous!”

CHAPTER V—INEZ THREATENS

“Yes,” said Louise, a week later, “we all make fools of ourselves over Toodlums, Really, girls, Jane is a very winning baby. I don’t say that because I’m her mother, understand. If she were anyone else’s baby, I’d say the same thing.”

“Of course,” agreed Patsy. “I don’t believe such a baby was ever before born. She’s so happy, and sweet, and—and—”

“And comfortable,” said Beth. “Indeed, Jane is a born sorceress; she bewitches everyone who beholds her dear dimpled face. This is an impartial opinion, you know; I’d say the same thing if I were not her adoring auntie.”

“It’s true,” Patsy declared. “Even the Mexicans worship her. And Mildred Travers—the sphinx—whose blood I am sure is ice-water, displays a devotion for baby that is absolutely amazing. I don’t blame her, you know, for it must be a real delight to care for such a fairy. I’m surprised, Louise, that you can bear to have baby out of your sight so much of the time.”

Louise laughed lightly.

“I’m not such an unfeeling mother as you think,” she answered. “I know just where baby is every minute and she is never out of my thoughts. However, with two nurses, both very competent, to care for Toodlums, I do not think it necessary to hold her in my lap every moment.”

Here Uncle John and the major approached the palm, under which the three nieces were sitting, and Mr. Merrick exclaimed:

“I’ll bet a cookie you were talking of baby Jane.”

“You’d win, then,” replied Patsy. “There’s no other topic of conversation half so delightful.”

“Jane,” observed the major, musingly, as he seated himself in a rustic chair. “A queer name for a baby, Louise. Whatever possessed you to burden the poor infant with it?”

“Burden? Nonsense, Major! It’s a charming name,” cried Patsy.

“She is named after poor Aunt Jane,” said Louise.

A silence somewhat awkward followed.

“My sister Jane,” remarked Uncle John gravely, “was in some respects an admirable woman.”

“And in many others detestable,” said Beth in frank protest. “The only good thing I can remember about Aunt Jane,” she added, “is that she brought us three girls together, when we had previously been almost unaware of one anothers’ existence. And she made us acquainted with Uncle John.”

“Then she did us another favor,” added Patsy. “She died.”

“Poor Aunt Jane!” sighed Louise. “I wish I could say something to prove that I revere her memory. Had the baby been a boy, its name would have been John; but being a girl I named her for Uncle John’s sister—the highest compliment I could conceive.”

Uncle John nodded gratefully. “I wasn’t especially fond of Jane, myself,” said he, “but it’s a family name and I’m glad you gave it to baby.”

“Jane Merrick,” said the major, “was very cruel to Patsy and to me, and so I’m sorry you gave her name to baby.”

“Always contrary, eh?” returned Uncle John, with a tolerant smile, for he was in no wise disturbed by this adverse criticism of his defunct sister—a criticism that in fact admitted little argument. “But it occurs to me that the most peculiar thing about this name is that you three girls, who were once Aunt Jane’s nieces, are now Niece Jane’s aunts!”

“Except me,” smiled Louise. “I’m happy to claim a closer relationship. But returning to our discussion of Aunt Jane. She was really instrumental in making our fortunes as well as in promoting our happiness, so I have no regret because I made baby her namesake.”

“The name of Jane,” said Patsy, “is in itself beautiful, because it is simple and old-fashioned. Now that it is connected with my chubby niece it will derive a new and added luster.”

“Quite true,” declared Uncle John.

“Where is Arthur?” inquired the major.

“Writing his weekly batch of letters,” replied Arthur’s wife. “When they are ready he is to drive us all over to town in the big car, and we have planned to have lunch there and to return home in the cool of the evening. Will that program please our guests?”

All voiced their approval and presently Arthur appeared with his letters and bade them get ready for the ride, while he brought out the car. He always drove the machine himself, as no one on the place was competent to act as chauffeur; but he managed it admirably and enjoyed driving.

Louise went to the nursery to kiss little Jane. The baby lay in her crib, fast asleep. Near her sat Mildred Travers, reading a book. Crouched in the window-seat was Inez, hugging her knees and gazing moodily out into the garden.

The nursery was in the East Wing, facing the courtyard but also looking upon the rose garden, its one deep-set window being near a corner of the room. On one side it connected with a small chamber used by Inez, which occupied half the depth of the wing and faced the garden. The other half of the space was taken by a small sewing-room letting out upon the court.

At the opposite side of little Jane’s nursery was a roomy chamber which had been given up to Mildred, and still beyond this were the rooms occupied by Arthur and Louise, all upon the ground floor. By this arrangement the baby had a nurse on either side and was only one room removed from its parents.

This wing was said to be the oldest part of the mansion, a fact attested by the great thickness of the walls. Just above was the famous blue room occupied by the major, where ghosts were supposed at times to hold their revels. Yet, despite its clumsy construction, the East Wing was cheery and pleasant in all its rooms and sunlight flooded it the year round.

After the master and mistress had driven away to town with their guests, Inez sat for a time by the window, still motionless save for an occasional wicked glance over her shoulder at Mildred, who read placidly as she rocked to and fro in her chair. The presence of the American nurse seemed to oppress the girl, for not a semblance of friendship had yet developed between the two; so presently Inez rose and glided softly out into the court, leaving Mildred to watch the sleeping baby.

She took the path that led to the Mexican quarters and ten minutes later entered the hut where Bella, the skinny old hag who was the wife to Miguel Zaloa, was busy with her work.

“Ah, Inez. But where ees Mees Jane?” was the eager inquiry.

Inez glanced around to find several moustached faces in the doorway. Every dark, earnest eye repeated the old woman’s question. The girl shrugged her shoulders.

“She is care for by the new nurse, Meeldred. I left her sleeping.”

“Who sleeps, Inez?” demanded the aged Miguel. “Ees it the new nurse, or Mees Jane?”

“Both, perhap.” She laughed scornfully and went out to the shed that connected two of the adobe dwellings and served as a shady lounging place. Here a group quickly formed around her, including those who followed from the hut.

“I shall kill her, some day,” declared the girl, showing her gleaming teeth. “What right have she to come an’ take our baby?”

Miguel stroked his white moustache reflectively.

“Ees this Meeldred good to Mees Jane?” he asked.

“When anyone looks, yes,” replied Inez reluctantly. “She fool even baby, some time, who laugh at her. But poor baby do not know. I know. This Meeldred ees a devil!” she hissed.

The listening group displayed no emotion at this avowal. They eyed the girl attentively, as if expecting to hear more. But Inez, having vented her spite, now sulked.

“Where she came from?” asked Miguel, the recognized spokesman.

“Back there. New York,” tossing her head in an easterly direction.

“Why she come?” continued the old man.

“The little mans with no hair—Meest Merrick—he think I not know about babies. He think this girl who learns babies in school, an’ from books, know more than me who has care for many baby—but for none like our Mees Jane. Mees Jane ees angel!”

They all nodded in unison, approving her assertion.

“Eet ees not bad thought, that,” remarked old Bella. “Books an’ schools ees good to teach wisdom.”

“Pah! Not for babies,” objected her husband, shaking his head. “Book an’ school can not grow orange, either. To do a thing many time ees to know it better than a book can know.”

“Besides,” said Inez, “this Meeldred ees witch-woman.”

“Yes?”

“I know it. She come from New York. But yesterday she say to me: ‘Let us wheel leetle Jane to the live oak at Burney’s.’ How can she know there is live oak at Burney’s? Then, the first day she come, she say: ‘Take baby’s milk into vault under your room an’ put on stone shelf to keep cool.’ I, who live here, do not know of such a vault. She show me some stone steps in one corner, an’ she push against stone wall. Then wall open like door, an’ I find vault. But how she know it, unless she is witch-woman?”

There was a murmur of astonishment. Old Miguel scratched his head as if puzzled.

“I, too, know about thees vault,” said he; “but then, eet ees I know all of the old house, as no one else know. Once I live there with Señor Cristoval. But how can thees New York girl know?”

There was no answer. Merely puzzled looks.

“What name has she, Inez?” suddenly asked Miguel.

“Travers. Meeldred Travers.”

The old man thought deeply and then shook his head with a sigh.

“In seexty year there be no Travers near El Cajon,” he asserted. “I thought maybe she have been here before. But no. Even in old days there ees no Travers come here.”

“There ees a Travers Ranch over at the north,” asserted Bella.

“Eet ees a name; there be no Travers live there,” declared Miguel, still with that puzzled look upon his plump features.

Inez laughed at him.

“She is witch-woman, I tell you. I know it! Look in her eyes, an’ see.”

The group of Mexicans moved uneasily. Old Miguel deliberately rolled a cigarette and lighted it.

“Thees woman I have not yet see,” he announced, after due reflection. “But, if she ees witch-woman, eet ees bad for Mees Jane to be near her.”

“That is what I say!” cried Inez eagerly. She spoke better English than the others. “She will bewitch my baby; she will make it sickly, so it will die!” And she wrung her hands in piteous misery.

The Mexicans exchanged frightened looks. Old Bella alone seemed unaffected.

“Mees Weld own her baby—not us,” suggested Miguel’s wife. “If Mees Weld theenk thees girl is safe nurse, what have we to say—eh?”

“I say she shall not kill my baby!” cried Inez fiercely. “That is what I say, Bella. Before she do that, I kill thees Meeldred Travers.”

Miguel examined the girl’s face intently.

“You are fool, Inez,” he asserted. “It ees bad to keel anything—even thees New York witch-woman. Be compose an’ keep watch. Nothing harm Mees Jane if you watch. Where are your folks, girl?”

“Live in San Diego,” replied Inez, again sullen.

“Once I know your father. He ees good man, but drink too much. If you make quarrel about thees new nurse, you get sent home. Then you lose Mees Jane. So keep compose, an’ watch. If you see anything wrong, come to me an’ tell it. That ees best.”

Inez glanced around the group defiantly, but all nodded approval of old Miguel’s advice. She rose from the bench where she was seated, shrugged her shoulders disdainfully and walked away without a word.

CHAPTER VI—A DINNER WITH THE NEIGHBORS

Escondido, the nearest town and post office to El Cajon Ranch, is a quaint little place with a decided Mexican atmosphere. Those California inhabitants whom we call, for convenience, “Mexicans,” are not all natives of Mexico, by any means. Most of them are a mixed breed derived from the early Spanish settlers and the native Indian tribes—both alike practically extinct in this locality—and have never stepped foot in Mexican territory, although the boundary line is not far distant. Because the true Mexican is generally a similar admixture of Indian and Spaniard, it is customary to call these Californians by the same appellation. The early Spaniards left a strong impress upon this state, and even in the newly settled districts the Spanish architecture appropriately prevails, as typical of a semi-tropical country which owed its first civilizing influences to old Spain.

The houses of Escondido are a queer mingling of modern bungalows and antique adobe dwellings. Even the business street shows many adobe structures. A quiet, dreamy little town, with a comfortable hotel and excellent stores, it is much frequented by the wealthy ranchers in its neighborhood.

After stopping at the post office, Arthur drove down a little side street to a weather-beaten, unprepossessing building which bore the word “Restaurant” painted in dim white letters upon its one window. Here he halted the machine.

“Oh,” said Beth, drawing a long breath. “Is this one of your little jokes, Arthur?”

“A joke? Didn’t we come for luncheon, then?”

“We did, and I’m ravenous,” said Patsy. “But you informed us that there is a good hotel here, on the main street.”

“So there is,” admitted Arthur; “but it’s like all hotels. Now, this is—different. If you’re hungry; if you want a treat—something out of the ordinary—just follow me.”

Louise was laughing at their doubting expressions and this care-free levity led them to obey their host’s injunction. Then the dingy door opened and out stepped a young fellow whom the girls decided must be either a cowboy or a clever imitation of one.

He seemed very young—a mere boy—for all his stout little form. He was bareheaded and a shock of light, tow-colored hair was in picturesque disarray. A blue flannel shirt, rolled up at the sleeves, a pair of drab corduroy trousers and rough shoes completed his attire. Pausing awkwardly in the doorway, he first flushed red and then advanced boldly to shake Arthur’s hand.

“Why, Weldon, this is an unexpected pleasure,” he exclaimed in a pleasant voice that belied his rude costume, for its tones were well modulated and cultured. “I’ve been trying to call you up for three days, but something is wrong with the line. How’s baby?”

This last question was addressed to Louise, who shook the youth’s hand cordially.

“Baby is thriving finely,” she reported, and then introduced her friends to Mr. Rudolph Hahn, who, she explained, was one of their nearest neighbors.

“We almost crowd the Weldons,” he said, “for our house is only five miles distant from theirs; so we’ve been getting quite chummy since they moved to El Cajon. Helen—that’s my wife, you know—is an humble worshiper at the shrine of Miss Jane Weldon, as we all are, in fact.”

“Your wife!” cried Patsy in surprise.

He laughed.

“You think I’m an infant, only fit to play with Jane,” said he; “but I assure you I could vote, if I wanted to—which I don’t. I think, sir,” turning to Uncle John, “that my father knows you quite well.”

“Why, surely you’re not the son of Andy Hahn, the steel king?”

“I believe they do give him that royal title; but Dad is only a monarch in finance, and when he visits my ranch he’s as much a boy as his son.”

“It scarcely seems possible,” declared Mr. Merrick, eyeing the rough costume wonderingly but also with approval. “How long have you lived out here?”

“Six years, sir. I’m an old inhabitant. Weldon, here, has only been alive for six months.”

“Alive?”

“Of course. One breathes, back east, but only lives in California.”

During the laughter that followed this enthusiastic epigram Arthur ushered the party into the quaint Spanish restaurant. The room was clean and neat, despite the fact that the floor was strewn with sawdust and the tables covered with white oilcloth. An anxious-eyed, dapper little man with a foreign face and manner greeted them effusively and asked in broken English their commands.

Arthur ordered the specialties of the house. “These friends, Castro, are from the far East, and I’ve told them of your famous cuisine. Don’t disappoint them.”

“May I join you?” asked Rudolph Hahn. “I wish I’d brought Nell over to-day; she’d have been delighted with this meeting. But we didn’t know you were coming. That confounded telephone doesn’t reach you at all.”

“I’m going over to the office to see about that telephone,” said Arthur. “I believe I’ll do the errand while Castro is preparing his compounds. I’m always uneasy when the telephone is out of order.”

“You ought to be,” said Rudolph, “with that blessed baby in the house. It might save you thirty precious minutes in getting a doctor.”

“Does your line work?” asked Louise.

“Yes; it seems to get all connections but yours. So I imagine something is wrong with your phone, or near the house.”

“I’ll have them send a repair man out at once,” said Arthur, and departed for the telephone office, accompanied by his fellow rancher.

While they were gone Louise told them something of young Hahn’s history. He had eloped, at seventeen years of age, with his father’s stenographer, a charming girl of eighteen who belonged to one of the best families in Washington. Old Hahn was at first furious and threatened to disinherit the boy, but when he found the young bride’s family still more furious and preparing to annul the marriage on the grounds of the groom’s youth, the great financier’s mood changed and he whisked the pair off to California and bought for them a half-million-dollar ranch, where they had lived for six years a life of unalloyed bliss. Having no children of their own, the Hahns were devoted to little Jane and it was Rudolph who had given the baby the sobriquet of “Toodlums.” At almost any time, night or day, the Hahn automobile was liable to arrive at El Cajon for a sight of the baby.

“Rudolph—we call him ‘Dolph,’ you know—has not a particle of business instinct,” said Louise, “so he will never be able to take his father’s place in the financial world. And he runs his ranch so extravagantly that it costs the pater a small fortune every year. Yet they are agreeable neighbors, artless and unconventional as children, and surely the great Hahn fortune won’t suffer much through their inroads.”

When Arthur returned he brought with him still another neighboring ranchman, an enormous individual fully six feet tall and broad in proportion, who fairly filled the doorway as he entered. This man was about thirty years of age, stern of feature and with shaggy brows that overhung a pair of peaceful blue eyes which ought to have been set in the face of some child. This gave him a whimsical look that almost invariably evoked a smile when anyone observed him for the first time. He walked with a vigorous, aggressive stride and handled his big body with consummate grace and ease. His bow, when Arthur introduced him, was that of an old world cavalier.

“Here is another of our good friends for you to know. He’s our neighbor at the north and is considered the most enterprising orange grower in all California,” announced Weldon, with a chuckle that indicated he had said something funny.

“Lemon,” said the man, speaking in such a shrill, high-pitched tenor voice that the sound was positively startling, coming from so massive a chest.

“I meant lemon,” Arthur hastened to say. “Permit me to introduce Mr. Bulwer Runyon, formerly of New York but now the pride of the Pacific coast, where his superb oranges—”

“Lemons,” piped the high, childish voice.

“Whose lemons are the sourest and—and—juiciest ever grown.”

“What there are of them,” added the man in a wailing tenor.

“We are highly honored to meet Mr. Bulwer Runyon,” said the major, noticing that the girls were for once really embarrassed how to greet this new acquaintance.

“Out here,” remarked Dolph Hahn, with a grin, “we drop the handle to his name and call him ‘Bul Run’ for short. Sounds sort of patriotic, you know, and it’s not inappropriate.”

“You wrong me,” said the big rancher, squeaking the words cheerfully but at the same time frowning in a way that might well have terrified a pirate. “I’m not a bull and I don’t run. It’s enough exertion to walk. Therefore I ride. My new car is equipped with one of those remarkable—”

“Pardon me; we will not discuss your new car, if you please,” said Arthur. “We wish to talk of agreeable things. The marvelous Castro is concocting some of his mysterious dishes and we wish you to assist us in judging their merits.”

“I shall be glad to, for I’m pitifully hungry,” said the tenor voice. “I had breakfast at seven, you know—like a working man—and the ride over here in my new six-cylinder machine, which has a wonderful—”

“Never mind the machine, please. Forget it, and try to be sociable,” begged Dolph.

“How is the baby, Mrs. Weldon?”

“Well and hearty, Bulwer,” replied Louise. “Why haven’t you been to see little Jane lately?”

“I heard you had company,” said Mr. Runyon; “and the last time I came I stayed three days and forgot all about my ranch. I’ve made a will, Mrs. Weldon.”

“A will! You’re not going to die, I hope?”

“I join you in that hope, most fervently, for I’d hate to leave the new machine and its—”

“Go on, Bulwer.”

“But life is fleeting, and no one knows just when it’ll get to the end of its fleet. Therefore, as I love the baby better than any other object on earth—animate or inanimate—except—”

“Never mind your new car.”

He sighed.

“Therefore, Mrs. Weldon, I’ve made Jane my heiress.”

“Oh, Bul! Aren’t you dreadfully in debt?”

“Yes’m.”

“Is the place worth the mortgage?” inquired Arthur.

“Just about, although the money sharks don’t think so. But all property out here is rapidly increasing in value,” declared Runyon, earnestly, “so, if I can manage to hold on a while longer, Toodlums will inherit a—a—several fine lemon trees, at least.”

Uncle John was delighted with the big fellow with the small voice. Even the major clapped Bul Run on the shoulder and said the sentiment did him credit, however big the mortgage might be.

By the time Castro brought in his first surprise—a delicious soup—a jovial and friendly party was gathered around the oilcloth board. Even the paper napkins could not dampen the joy of the occasion, or detract from the exquisite flavor of the broth.

The boyish Dolph bewailed anon the absence of his “Nell,” who loved Castro’s cookery above everything else, while every endeavor of Mr. Runyon to explain the self-starter on his new car was so adroitly headed off by his fellow ranchers that the poor fellow was in despair. The “lunch” turned out to be a seven course dinner and each course introduced such an enticing and unusual dish that every member of the party became an audacious gormandizer. None of the girls—except Louise—had ever tasted such concoctions before, or might even guess what many of them were composed of; but all agreed with Patsy when she energetically asserted that “Castro out-cheffed both Rector and Sherry.”

“If only he would have tablecloths and napkins, and decent rugs upon the floor,” added dainty Louise.

“Oh, that would ruin the charm of the place,” protested Uncle John. “Don’t suggest such a horror to Castro, Louise; at least until after we have returned to New York.”

“I’ll take you riding in my car,” piped Runyon to Beth, who sat beside him. “I don’t have to crank it, you know; I just—”

“Have you sold your orange crop yet?” asked Arthur.

“Lemons, sir!” said the other reproachfully. And the laugh that followed again prevented his explaining the self-starter.

The porch was shady and cool when they emerged from the feast room and Arthur Weldon, as host, proposed they sit on the benches with their coffee and cigars and have a social chat. But both Runyon and Hahn protested this delay. They suggested, instead, that all ride back to El Cajon and play with the baby, and so earnest were they in this desire that the proud young father and mother had not the grace to refuse.

Both men had their cars at the village garage and an hour later the procession started. Beth riding beside “Bul Run” and Patsy accompanying the jolly “Dolph.”

“We must stop and pick up Nell,” said the latter, “for she’d be mad as hops if I went to see Toodlums without her.”

“I don’t wonder,” replied Patsy. “Isn’t my niece a dear baby?”

“Never was one born like her. She’s the only woman I ever knew who refuses to talk.”

“She crows, though.”

“To signify she agrees with everyone on every question; and her angelic smile is so genuine and constant that it gets to your heart in spite of all resistance.”

“And she’s so soft and mushy, as it were,” continued Patsy enthusiastically; “but I suppose she’ll outgrow that, in time.”

Mrs. Helen Hahn, when the three automobiles drew up before her young husband’s handsome residence, promptly agreed to join Rudolph in a visit to the baby. She proved to be a retiring and rather shy young woman, but she was very beautiful and her personality was most attractive. Both Patsy and Beth were delighted to find that Louise had so charming a neighbor, of nearly her own age.

Rudolph would not permit the party to proceed further until all had partaken of a refreshing glass of lemonade, and as this entailed more or less delay the sun was getting low as they traversed the five miles to El Cajon, traveling slowly that they might enjoy the exquisite tintings of the sky. Runyon, who was a bachelor, lived a few miles the other side of Arthur’s ranch. All three ranches had at one time been part of the Spanish grant to the Cristovals, and while Arthur now possessed the old mansion, the greatest number of acres had been acquired by Rudolph Hahn, who had preferred to build for himself and his bride a more modern residence.

CHAPTER VII—GONE!

The Weldons and their guests were greeted at their door by a maid, for there were no men among the house servants, and as Louise ushered the party into the living room she said to the girl:

“Ask Miss Travers to bring the baby here.”

The maid departed and was gone so long that Louise started out to see why her order was not obeyed. She met the woman coming back with a puzzled face.

“Mees Traver not here, señora,” she said.

“Then tell Inez to fetch the baby.”

“Inez not here, señora,” returned the woman.

“Indeed! Then where is baby?”

“Mees Jane not here, señora.”

Louise rushed to the nursery, followed by Arthur, whose quick ears had overheard the statement. The young mother bent over the crib, the covers of which were thrown back as if the infant had been quickly caught up—perhaps from a sound sleep.

“Good gracious!” cried Louise, despairingly; “she’s gone—my baby’s gone!”

“Gone?” echoed Arthur, in a distracted tone. “What does it mean, Louise? Where can she be?”

A gentle hand was laid on his shoulder and Uncle John, who had followed them to the room, said soothingly:

“Don’t get excited, my boy; there’s nothing to worry about. Your two nurses have probably taken little Jane out for a ride.”

“At this time of night?” exclaimed Louise. “Impossible!”

“It is merely twilight; they may have been delayed,” replied Mr. Merrick.

“But the air grows chill at this hour, and—”

“And there is the baby-cab!” added Arthur, pointing to a corner.

Louise and her husband looked into one another’s eyes and their faces grew rigid and white. Uncle John, noting their terror, spoke again.

“This is absurd,” said he. “Two competent nurses, both devoted to little Jane, would not allow the baby to come to harm, I assure you.”

“Where is she, then?” demanded Arthur.

“Hello; what’s up?” called Patsy Doyle, entering the room with Beth to see what was keeping them from their guests.

“Baby’s gone!” wailed Louise, falling into a chair promptly to indulge in a flood of tears.

“Gone? Nonsense,” said Beth, gazing into the empty cradle. Then she put down her hand and felt of the bedding. It had no warmth. Evidently the child had been removed long ago.