автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Works of Daniel Webster, Volume 1

Project Gutenberg's The Works of Daniel Webster, Volume 1, by Daniel Webster

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Works of Daniel Webster, Volume 1

Author: Daniel Webster

Release Date: July 25, 2011 [EBook #36843]

Language: English

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE WORKS OF DANIEL WEBSTER ***

Produced by Katherine Ward, Bryan Ness, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from scanned images of public domain

material from the Google Print project.)

THE

WORKS

OF

DANIEL WEBSTER.

VOLUME I.

EIGHTH EDITION

BOSTON:

LITTLE, BROWN AND COMPANY.

1854.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1851, by

George W. Gordon and James W. Paige,

in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

CAMBRIDGE:

STEREOTYPED BY METCALF AND COMPANY,

PRINTERS TO THE UNIVERSITY.

PRINTED AT HOUGHTON AND HAYWOOD

DEDICATION

OF THE FIRST VOLUME.

TO MY NIECES,

MRS. ALICE BRIDGE WHIPPLE,

AND

MRS. MARY ANN SANBORN:

Many of the Speeches contained in this volume were delivered and printed in the lifetime of your father whose fraternal affection led him to speak of them with approbation.

His death, which happened when he had only just past the middle period of life, left you without a father, and me without a brother.

I dedicate this volume to you, not only for the love I have for yourselves, but also as a tribute of affection to his memory, and from a desire that the name of my brother,

EZEKIEL WEBSTER,

may be associated with mine, so long as any thing written or spoken by me shall be regarded or read.

DANIEL WEBSTER.

CONTENTS OF THE FIRST VOLUME.

PAGEBIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR.

Chapter I. xiiiFormer Editions of the Works of Mr. Webster, and Plan of this Edition.—Parentage and Birth.—First Settlements in the Interior of New Hampshire.—Establishment of his Father at Salisbury.—Scanty Opportunities of Early Education.—First Teachers, and recent Letter to Master Tappan.—Placed at Exeter Academy.—Anecdotes while there.—Dartmouth College.—Study of the Law at Salisbury.—Residence at Fryeburg in Maine, and Occupations there.—Continuance of the Study of the Law at Boston, in the Office of Hon. Christopher Gore.—Admission to the Bar of Suffolk, Massachusetts.—Commencement of Practice at Boscawen, New Hampshire.—Removal to Portsmouth.—Contemporaries in the Profession.—Increasing Practice.

Chapter II. xxxiii

Entrance on Public Life.—State of Parties in 1812.—Election to Congress.—Extra Session of 1813.—Foreign Relations of the Country.—Resolutions relative to the Berlin and Milan Decrees.—Naval Defence.—Reelected to Congress in 1814.—Peace with England.—Projects for a National Bank.—Mr. Webster's Course on that Question.—Battle of New Orleans.—New Questions arising on the Return of Peace.—Course of Prominent Men of Different Parties.—Mr. Webster's Opinions on the Constitutionality of the Tariff Policy.—The Resolution to restore Specie Payments moved by Mr. Webster.—Removal to Boston.

Chapter III. xlviii

Professional Character particularly in Reference to Constitutional Law.—The Dartmouth College Case argued at Washington in 1818.—Mr. Ticknor's Description of that Argument.—The Case of Gibbons and Ogden in 1824.—Mr. Justice Wayne's Allusion to that Case in 1847.—The Case of Ogden and Saunders in 1827.—The Case of the Proprietors of the Charles River Bridge.—The Alabama Bank Case.—The Case relative to the Boundary between Massachusetts and Rhode Island.—The Girard Will Case.—The Case of the Constitution of Rhode Island.—General Remarks on Mr. Webster's Practice in the Supreme Court of the United States.—Practice in the State Courts.—The Case of Goodridge,—and the Case of Knapp.

Chapter IV. lx

The Convention to revise the Constitution of Massachusetts.—John Adams a Delegate.—Mr. Webster's Share in its Proceedings.—Speeches on Oaths of Office, Basis of Senatorial Representation, and Independence of the Judiciary.—Centennial Anniversary at Plymouth on the 22d of December, 1820.—Discourse delivered by Mr. Webster.—Bunker Hill Monument, and Address by Mr. Webster on the Laying of the Corner-Stone, 17th of June, 1825.—Discourse on the Completion of the Monument, 17th of June, 1843.—Simultaneous Decease of Adams and Jefferson on the 4th of July, 1826.—Eulogy by Mr. Webster in Faneuil Hall.—Address at the Laying of the Corner-Stone of the New Wing of the Capitol.—Remarks on the Patriotic Discourses of Mr. Webster, and on the Character of his Eloquence in Efforts of this Class.

Chapter V. lxxii

Election to Congress from Boston.—State of Parties.—Meeting of the Eighteenth Congress.—Mr. Webster's Resolution and Speech in favor of the Greeks.—Argument in the Supreme Court in the Case of Gibbons and Ogden.—Circumstances under which it was made.—Speech on the Tariff Law of 1824.—A complete Revision of the Law for the Punishment of Crimes against the United States reported by Mr. Webster, and enacted.—The Election of Mr. Adams as President of the United States.—Meeting of the Nineteenth Congress, and State of Parties.—Congress of Panama, and Mr. Webster's Speech on that Subject.—Election as a Senator of the United States.—Revision of the Tariff Law by the Twentieth Congress.—Embarrassments of the Question.—Mr. Webster's Course and Speech on this Subject.

Chapter VI. lxxxvii

Election of General Jackson.—Debate on Foot's Resolution.—Subject of the Resolution, and Objects of its Mover.—Mr. Hayne's First Speech.—Mr. Webster's original Participation in the Debate unpremeditated.—His First Speech.—Reply of Mr. Hayne with increased Asperity.—Mr. Webster's Great Speech.—Its Threefold Object.—Description of the Manner of Mr. Webster in the Delivery of this Speech, from Mr. March's "Reminiscences of Congress."—Reception of his Speech throughout the Country.—The Dinner at New York.—Chancellor Kent's Remarks.—Final Disposal of Foot's Resolution.—Report of Mr. Webster's Speech.—Mr. Healey's Painting.

Chapter VII. ci

General Character of President Jackson's Administrations.—Speedy Discord among the Parties which had united for his Elevation.—Mr. Webster's Relations to the Administration.—Veto of the Bank.—Rise and Progress of Nullification in South Carolina.—The Force Bill, and the Reliance of General Jackson's Administration on Mr. Webster's Aid.—His Speech in Defence of the Bill, and in Opposition to Mr. Calhoun's Resolutions.—Mr. Madison's Letter on Secession.—The Removal of the Deposits.—Motives for that Measure.—The Resolution of the Senate disapproving it.—The President's Protest.—Mr. Webster's Speech on the Subject of the Protest.—Opinions of Chancellor Kent and Mr. Tazewell.—The Expunging Resolution.—Mr. Webster's Protest against it.—Mr. Van Buren's Election.—The Financial Crisis and the Extra Session of Congress.—The Government Plan of Finance supported by Mr. Calhoun and opposed by Mr. Webster.—Personalities.—Mr. Webster's Visit to Europe and distinguished Reception.—The Presidential Canvass of 1840.—Election of General Harrison.

Chapter VIII. cxix

Critical State of Foreign Affairs on the Accession of General Harrison.—Mr. Webster appointed to the State Department.—Death of General Harrison.—Embarrassed Relations with England.—Formation of Sir Robert Peel's Ministry, and Appointment of Lord Ashburton as Special Minister to the United States.—Course pursued by Mr. Webster in the Negotiations.—The Northeastern Boundary.—Peculiar Difficulties in its Settlement happily overcome.—Other Subjects of Negotiation.—Extradition of Fugitives from Justice.—Suppression of the Slave-Trade on the Coast of Africa.—History of that Question.—Affair of the Caroline.—Impressment.—Other Subjects connected with the Foreign Relations of the Government.—Intercourse with China.—Independence of the Sandwich Islands.—Correspondence with Mexico.—Sound Duties and the Zoll-Verein.—Importance of Mr. Webster's Services as Secretary of State.

Chapter IX. cxliii

Mr. Webster resigns his Place in Mr. Tyler's Cabinet.—Attempts to draw public Attention to the projected Annexation of Texas.—Supports Mr. Clay's Nomination for the Presidency.—Causes of the Failure of that Nomination.—Mr. Webster returns to the Senate of the United States.—Admission of Texas to the Union.—The War with Mexico.—Mr. Webster's Course in Reference to the War.—Death of Major Webster in Mexico.—Mr. Webster's unfavorable Opinion of the Mexican Government.—Settlement of the Oregon Controversy.—Mr. Webster's Agency in effecting the Adjustment.—Revival of the Sub-Treasury System and Repeal of the Tariff Law of 1842.—Southern Tour.—Success of the Mexican War and Acquisition of the Mexican Provinces.—Efforts in Congress to organize a Territorial Government for these Provinces.—Great Exertions of Mr. Webster on the last Night of the Session.—Nomination of General Taylor, and Course of Mr. Webster in Reference to it.—A Constitution of State Government adopted by California prohibiting Slavery.—Increase of Antislavery Agitation.—Alarming State of Affairs.—Mr. Webster's Speech for the Union.—Circumstances under which it was made, and Motives by which he was influenced.—General Taylor's Death, and the Accession of Mr. Fillmore to the Presidency.—Mr. Webster called to the Department of State.

SPEECHES DELIVERED ON VARIOUS PUBLIC OCCASIONS.

First Settlement of New England 1 The Bunker Hill Monument 55 The Completion of the Bunker Hill Monument 79 Adams and Jefferson 109 The Election of 1825 151 Dinner at Faneuil Hall 161 The Boston Mechanics’ Institution 175 Public Dinner at New York 191 The Character of Washington. 217 National Republican Convention at Worcester 235 Reception at Buffalo 279 Reception at Pittsburg 285 Reception at Bangor 307 Presentation of a Vase 317 Reception at New York 337 Reception at Wheeling 381 Reception at Madison 395 Public Dinner in Faneuil Hall 411 Royal Agricultural Society 433 The Agriculture of England 441

BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR OF THE PUBLIC LIFE OF DANIEL WEBSTER.

BY

EDWARD EVERETT.

CHAPTER I.

Former Editions of the Works of Mr. Webster, and Plan of this Edition.—Parentage and Birth.—First Settlements in the Interior of New Hampshire.—Establishment of his Father at Salisbury.—Scanty Opportunities of Early Education.—First Teachers, and recent Letter to Master Tappan.—Placed at Exeter Academy.—Anecdotes while there.—Dartmouth College.—Study of the Law at Salisbury.—Residence at Fryeburg in Maine, and Occupations there.—Continuance of the Study of the Law at Boston, in the Office of Hon. Christopher Gore.—Admission to the Bar of Suffolk, Massachusetts.—Commencement of Practice at Boscawen, New Hampshire.—Removal to Portsmouth.—Contemporaries in the Profession.—Increasing Practice.

The first collection of Mr. Webster’s speeches in the Congress of the United States and on various public occasions was published in Boston, in one volume octavo, in 1830. This volume was more than once reprinted, and in 1835 a second volume was published, containing the speeches made up to that time, and not included in the first collection. Several impressions of these two volumes were called for by the public. In 1843 a third volume was prepared, containing a selection from the speeches of Mr. Webster from the year 1835 till his entrance into the cabinet of General Harrison. In the year 1848 appeared a fourth volume of diplomatic papers, containing a portion of Mr. Webster’s official correspondence as Secretary of State.

The great favor with which these volumes have been received throughout the country, and the importance of the subjects discussed in the Senate of the United States after Mr. Webster’s return to that body in 1845, have led his friends to think that a valuable service would be rendered to the community by bringing together his speeches of a later date than those contained in the third volume of the former collection, and on political subjects arising since that time. Few periods of our history will be entitled to be remembered by events of greater moment, such as the admission of Texas to the Union, the settlement of the Oregon controversy, the Mexican war, the acquisition of California and other Mexican provinces, and the exciting questions which have grown out of the sudden extension of the territory of the United States. Rarely have public discussions been carried on with greater earnestness, with more important consequences visibly at stake, or with greater ability. The speeches made by Mr. Webster in the Senate, and on public occasions of various kinds, during the progress of these controversies, are more than sufficient to fill two new volumes. The opportunity of their collection has been taken by the enterprising publishers, in compliance with opinions often expressed by the most respectable individuals, and with a manifest public demand, to bring out a new edition of Mr. Webster’s speeches in uniform style. Such is the object of the present publication. The first two volumes contain the speeches delivered by him on a great variety of public occasions, commencing with his discourse at Plymouth in December, 1820. Three succeeding volumes embrace the greater part of the speeches delivered in the Massachusetts Convention and in the two houses of Congress, beginning with the speech on the Bank of the United States in 1816. The sixth and last volume contains the legal arguments and addresses to the jury, the diplomatic papers, and letters addressed to various persons on important political questions.

The collection does not embrace the entire series of Mr. Webster’s writings. Such a series would have required a larger number of volumes than was deemed advisable with reference to the general circulation of the work. A few juvenile performances have accordingly been omitted, as not of sufficient importance or maturity to be included in the collection. Of the earlier speeches in Congress, some were either not reported at all, or in a manner too imperfect to be preserved without doing injustice to the author. No attempt has been made to collect from the contemporaneous newspapers or Congressional registers the short conversational speeches and remarks made by Mr. Webster, as by other prominent members of Congress, in the progress of debate, and sometimes exercising greater influence on the result than the set speeches. Of the addresses to public meetings it has been found impossible to embrace more than a selection, without swelling the work to an unreasonable size. It is believed, however, that the contents of these volumes furnish a fair specimen of Mr. Webster’s opinions and sentiments on all the subjects treated, and of his manner of discussing them. The responsibility of deciding what should be omitted and what included has been left by Mr. Webster to the friends having the charge of the publication, and his own opinion on details of this kind has rarely been taken.

In addition to such introductory notices as were deemed expedient relative to the occasions and subjects of the various speeches, it has been thought advisable that the collection should be accompanied with a Biographical Memoir, presenting a condensed view of Mr. Webster’s public career, with a few observations by way of commentary on the principal speeches. Many things which might otherwise fitly be said in such an essay must, it is true, be excluded by that delicacy which qualifies the eulogy to be awarded even to the most eminent living worth. Much may be safely omitted, as too well known to need repetition in this community, though otherwise pertaining to a full survey of Mr. Webster’s career. In preparing the following notice, free use has been made by the writer of the biographical sketches already before the public. Justice, however, requires that a specific acknowledgment should be made to an article in the American Quarterly Review for June, 1831, written, with equal accuracy and elegance, by Mr. George Ticknor, and containing a discriminating estimate of the speeches embraced in the first collection; and also to the highly spirited and vigorous work entitled “Reminiscences of Congress,” by Mr. Charles W. March. To this work the present sketch is largely indebted for the account of the parentage and early life of Mr. Webster; as well as for a very graphic description of the debate on Foot’s resolution.

The family of Daniel Webster has been established in America from a very early period. It was of Scottish origin, but passed some time in England before the final emigration. Thomas Webster, the remotest ancestor who can be traced, was settled at Hampton, on the coast of New Hampshire, as early as 1636, sixteen years after the landing at Plymouth, and six years from the arrival of Governor Winthrop in Massachusetts Bay. The descent from Thomas Webster to Daniel can be traced in the church and town records of Hampton, Kingston (now East Kingston), and Salisbury. These records and the mouldering headstones of village grave-yards are the herald’s office of the fathers of New England. Noah Webster, the learned author of the American Dictionary of the English Language, was of a collateral branch of the family.

Ebenezer Webster, the father of Daniel, is still recollected in Kingston and Salisbury. His personal appearance was striking. He was erect, of athletic stature, six feet high, broad and full in the chest. Long service in the wars had given him a military air and carriage. He belonged to that intrepid border race, which lined the whole frontier of the Anglo-American colonies, by turns farmers, huntsmen, and soldiers, and passing their lives in one long struggle with the hardships of an infant settlement, on the skirts of a primeval forest. Ebenezer Webster enlisted early in life as a common soldier, in one of those formidable companies of rangers, which rendered such important services under Sir Jeffrey Amherst and Wolfe in the Seven Years’ War. He followed the former distinguished leader in the invasion of Canada, attracted the attention and gained the good-will of his superior officers by his brave and faithful conduct, and rose to the rank of a captain before the end of the war.

For the first half of the last century the settlements of New Hampshire had made but little progress into the interior. Every war between France and Great Britain in Europe was the signal of an irruption of the Canadian French and their Indian allies into New England. As late as 1755 they sacked villages on the Connecticut River, and John Stark, while hunting on Baker’s River, three years before, was taken a prisoner and sold as a slave into Canada. One can scarcely believe that it is not yet a hundred years since occurrences like these took place. The cession of Canada to England by the treaty of 1763 entirely changed this state of things. It opened the pathways of the forest and the gates of the Western hills. The royal governor of New Hampshire, Benning Wentworth, began to make grants of land in the central parts of the State. Colonel Stevens of Kingston, with some of his neighbors, mostly retired officers and soldiers, obtained a grant of the town of Salisbury, which was at first called Stevenstown, from the principal grantee. This town is situated exactly at the point where the Merrimack River is formed by the confluence of the Pemigewasset and Winnipiseogee. Captain Webster was one of the settlers of the newly granted township, and received an allotment in its northerly portion. More adventurous than others of the company, he cut his way deeper into the wilderness, and made the path he could not find. At this time his nearest civilized neighbors on the northwest were at Montreal.

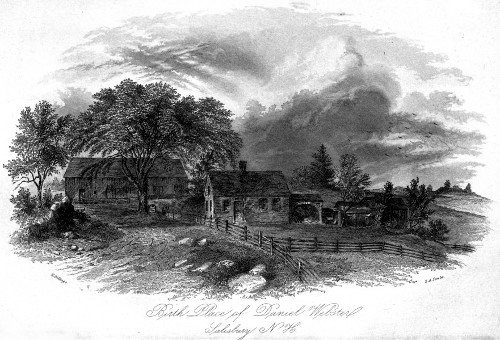

The following allusion of Mr. Webster to his birthplace will be read with interest. It is from a speech delivered before a great public assembly at Saratoga, in the year 1840.

“It did not happen to me to be born in a log cabin; but my elder brothers and sisters were born in a log cabin, raised amid the snowdrifts of New Hampshire, at a period so early that, when the smoke first rose from its rude chimney, and curled over the frozen hills, there was no similar evidence of a white man’s habitation between it and the settlements on the rivers of Canada. Its remains still exist. I make to it an annual visit. I carry my children to it to teach them the hardships endured by the generations which have gone before them. I love to dwell on the tender recollections, the kindred ties, the early affections, and the touching narratives and incidents, which mingle with all I know of this primitive family abode. I weep to think that none of those who inhabited it are now among the living; and if ever I am ashamed of it, or if I ever fail in affectionate veneration for HIM who reared and defended it against savage violence and destruction, cherished all the domestic virtues beneath its roof, and, through the fire and blood of seven years’ revolutionary war, shrunk from no danger, no toil, no sacrifice, to serve his country, and to raise his children to a condition better than his own, may my name and the name of my posterity be blotted for ever from the memory of mankind!”

Soon after his settlement in Salisbury, the first wife of Ebenezer Webster having deceased, he married Abigail Eastman, who became the mother of Ezekiel and Daniel Webster, the only sons of the second marriage. Like the mothers of so many men of eminence, she was a woman of more than ordinary intellect, and possessed a force of character which was felt throughout the humble circle in which she moved. She was proud of her sons and ambitious that they should excel. Her anticipations went beyond the narrow sphere in which their lot seemed to be cast, and the distinction attained by both, and especially by the younger, may well be traced in part to her early promptings and judicious guidance.

About the time of his second marriage, Captain Ebenezer Webster erected a frame house hard by the log cabin. He dug a well near it and planted an elm sapling. In this house Daniel Webster was born. It has long since disappeared, but the spot where it stood is well known, and is covered by a house since built. The cellar of the log cabin is still visible, though partly filled with the accumulations of seventy years. “The well still remains,” says Mr. March, “with water as pure, as cool, and as limpid as when first brought to light, and will remain in all probability for ages, to refresh hereafter the votaries of genius who make their pilgrimage hither, to visit the cradle of one of her greatest sons. The elm that shaded the boy still flourishes in vigorous leaf, and may have an existence beyond its perishable nature. Like

‘The witch-elm that guards St. Fillan’s spring,’

it may live in story long after leaf, and branch, and root have disappeared for ever.”

The interval between the peace of 1763 and the breaking out of the war of the Revolution was one of excitement and anxiety throughout the Colonies. The great political questions of the day were not only discussed in the towns and cities, but in the villages and hamlets. Captain Webster took a deep interest in those discussions. Like so many of the officers and soldiers of the former war, he obeyed the first call to arms in the new struggle. He commanded a company, chiefly composed of his own townspeople, friends, and kindred, who followed him through the greater portion of the war. He was at the battle of White Plains, and was at West Point when the treason of Arnold was discovered. He acted as a Major under Stark at Bennington, and contributed his share to the success of that eventful day.

In the last year of the Revolutionary war, on the 18th of January, 1782, Daniel Webster was born, in the home which his father had established on the outskirts of civilization. If the character and situation of the place, and the circumstances under which he passed the first years of his life, might seem adverse to the early cultivation of his extraordinary talent, it still cannot be doubted that they possessed influences favorable to elevation and strength of character. The hardships of an infant settlement and border life, the traditions of a long series of Indian wars, and of two mighty national contests, in which an honored parent had borne his part, the anecdotes of Fort William Henry, of Quebec, of Bennington, of West Point, of Wolfe and Stark and Washington, the great Iliad and Odyssey of American Independence,—this was the fireside entertainment of the long winter evenings of the secluded village home. Abroad, the uninviting landscape, the harsh and craggy outline of the hills broken and relieved only by the funereal hemlock and the “cloud seeking” pine, the lowlands traversed in every direction by unbridged streams, the tall, charred trunks in the cornfields, that told how stern had been the struggle with the boundless woods, and, at the close of the year, the dismal scene which presents itself in high latitudes in a thinly settled region, when

“the snows descend; and, foul and fierce,

All winter drives along the darkened air”;—

these are circumstances to leave an abiding impression on the mind of a thoughtful child, and induce an early maturity of character.

Mr. March has described an incident of Mr. Webster’s earliest youth in a manner so graphical, that we are tempted to repeat it in his own words:—

“In Mr. Webster’s earliest youth an

occurrence

of such a nature took place, which affected him deeply at the time, and has dwelt in his memory ever since. There was a sudden and extraordinary rise in the Merrimack River, in a spring thaw. A deluge of rain for two whole days poured down upon the houses. A mass of mingled water and snow rushed madly from the hills, inundating the fields far and wide. The highways were broken up, and rendered undistinguishable. There was no way for neighbors to interchange visits of condolence or necessity, save by boats, which came up to the very door-steps of the houses.“Many things of value were swept away, even things of bulk. A large barn, full fifty feet by twenty, crowded with hay and grain, sheep, chickens, and turkeys, sailed majestically down the river, before the eyes of the astonished inhabitants; who, no little frightened, got ready to fly to the mountains, or construct another ark.

“The roar of waters, as they rushed over precipices, casting the foam and spray far above, the crashing of the forest-trees as the storm broke through them, the immense sea everywhere in range of the eye, the sublimity, even danger, of the scene, made an indelible impression upon the mind of the youthful observer.

“Occurrences and scenes like these excite the imaginative faculty, furnish material for proper thought, call into existence new emotions, give decision to character, and a purpose to action.”—pp. 7, 8.

It may well be supposed that Mr. Webster’s early opportunities for education were very scanty. It is indeed correctly remarked by Mr. Ticknor, in reference to this point, that “in New England, ever since the first free school was established amidst the woods that covered the peninsula of Boston in 1636, the schoolmaster has been found on the border line between savage and civilized life, often indeed with an axe to open his own path, but always looked up to with respect, and always carrying with him a valuable and preponderating influence.” Still, however, compared with any thing that would be called a good school in this region and at the present time, the schools which existed on the frontier sixty years ago were sadly defective. Many of our district schools even now are below their reputation. The Swedish Chancellor’s exclamation of wonder at the little wisdom with which the world is governed, might well be repeated at the little learning and skill with which the scholastic world in too many parts of our country is still taught. In Mr. Webster’s boyhood it was much worse. Something that was called a school was kept for two or three months in the winter, frequently by an itinerant, too often a pretender, claiming only to teach a little reading, writing, and ciphering, and wholly incompetent to give any valuable assistance to a clever youth in learning either.

Such as the village school was, Mr. Webster enjoyed its advantages, if they could be called by that name. It was, however, of a migratory character. When it was near his father’s residence it was easy to attend; but it was sometimes in a distant part of the town, and sometimes in another town. While he was quite young, he was daily sent two miles and a half or three miles to school in mid-winter and on foot. If the school-house lay in the same direction with the miller or the blacksmith, an occasional ride might be hoped for. If the school was removed to a still greater distance, he was boarded at a neighbor’s. Poor as these opportunities of education were, they were bestowed on Mr. Webster more liberally than on his brothers. He showed a greater eagerness for learning; and he was thought of too frail a constitution for any robust pursuit. An older half-brother good-humoredly said, that “Dan was sent to school that he might get to know as much as the other boys.” It is probable that the best part of his education was derived from the judicious and experienced father, and the strong-minded, affectionate, and ambitious mother.

Mr. Webster’s first master was Thomas Chase. He could read tolerably well, and wrote a fair hand; but spelling was not his forte. His second master was James Tappan, now living at an advanced age in Gloucester, Massachusetts. His qualifications as a teacher far exceeded those of Master Chase. The worthy veteran, now dignified with the title of Colonel, feels a pride, it may well be supposed, in the fame of his quondam pupil. He lately addressed a letter to him, recounting some of the incidents of his own life since he taught school at Salisbury. This unexpected communication from his aged teacher drew from Mr. Webster the following answer, in which a handsome gratuity was inclosed, more, probably, than the old gentleman ever received for a winter’s teaching at “New Salisbury.”[1]

“Washington, February 26, 1851.

“Master Tappan,—I thank you for your letter, and am rejoiced to know that you are among the living. I remember you perfectly well as a teacher of my infant years. I suppose my mother must have taught me to read very early, as I have never been able to recollect the time when I could not read the Bible. I think Master Chase was my earliest schoolmaster, probably when I was three or four years old. Then came Master Tappan. You boarded at our house, and sometimes, I think, in the family of Mr. Benjamin Sanborn, our neighbor, the lame man. Most of those whom you knew in ‘New Salisbury’ have gone to their graves. Mr. John Sanborn, the son of Benjamin, is yet living, and is about your age. Mr. John Colby, who married my oldest sister, Susannah, is also living. On the ‘North Road’ is Mr. Benjamin Hunton, and on the ‘South Road’ is Mr. Benjamin Pettengil. I think of none else among the living whom you would probably remember.

“You have indeed lived a checkered life. I hope you have been able to bear prosperity with meekness, and adversity with patience. These things are all ordered for us far better than we could order them for ourselves. We may pray for our daily bread; we may pray for the forgiveness of sins; we may pray to be kept from temptation, and that the kingdom of God may come, in us, and in all men, and his will everywhere be done. Beyond this, we hardly know for what good to supplicate the Divine Mercy. Our Heavenly Father knoweth what we have need of better than we know ourselves, and we are sure that his eye and his loving-kindness are upon us and around us every moment.

“I thank you again my good old schoolmaster, for your kind letter, which has awakened many sleeping recollections; and, with all good wishes, I remain your friend and pupil,

“Daniel Webster.

To “Mr. James Tappan.”

He derived, also, no small benefit from the little social library, which, chiefly by the exertions of Mr. Thompson (the intelligent lawyer of the place), the clergyman, and Mr. Webster’s father, had been founded in Salisbury. The attention of the people of New Hampshire had been called to this mode of promoting general and popular education by Dr. Belknap. In the patriotic address to the people of New Hampshire, at the close of his excellent History, he says:—

“This (the establishment of social libraries) is the easiest, the cheapest, and the most effectual mode of diffusing knowledge among the people. For the sum of six or eight dollars at once, and a small annual payment besides, a man may be supplied with the means of literary improvement during his life, and his children may inherit the blessing.”[2]

From the village library at Salisbury, founded on recommendations like these, Mr. Webster was able to obtain a moderate supply of good reading. It is quite worth noticing, that his attention, like that of Franklin, was in early boyhood attracted to the Spectator. Franklin, as is well known, studiously formed his style on that of Addison;—and a considerable resemblance may be traced between them. There is no such resemblance between Mr. Webster’s style and that of Addison, unless it be the negative merit of freedom from balanced sentences, hard words, and inversions. It may, no doubt, have been partly owing to his early familiarity with the Spectator, that he escaped in youth from the turgidity and pomp of the Johnsonian school, and grew up to the mastery of that direct and forcible, but not harsh and affected sententiousness, that masculine simplicity, with which his speeches and writings are so strongly marked.

The year before Mr. Webster was born was rendered memorable in New Hampshire by the foundation of the Academy at Exeter, through the munificence of the Honorable John Phillips. His original endowment is estimated by Dr. Belknap at nearly ten thousand pounds, which, in the comparative scarcity of money in 1781, cannot be considered as less than three times that amount at the present day. Few events are more likely to be regarded as eras in the history of that State. In the year 1788, Dr. Benjamin Abbot, soon afterwards its principal, became connected with the Academy as an instructor, and from that time it assumed the rank which it still maintains among the schools of the country. To this Academy Mr. Webster was taken by his father in May, 1796. He enjoyed the advantage of only a few months’ instruction in this excellent school; but, short as the period was, his mind appears to have received an impulse of a most genial and quickening character. Nothing could be more graceful or honorable to both parties than the tribute paid by Mr. Webster to his ancient instructor, at the festival at Exeter, in 1838, in honor of Dr. Abbot’s jubilee. While at the Academy, his studies were aided and his efforts encouraged by a pupil younger than himself, but who, having enjoyed better advantages of education in boyhood, was now in the senior class at Exeter, the early celebrated and lamented Joseph Stevens Buckminster. The following anecdote from Mr. March’s work will not be thought out of place in this connection:—

“It may appear somewhat singular that the greatest orator of modern times should have evinced in his boyhood the strongest antipathy to public declamation. This fact, however, is established by his own words, which have recently appeared in print. ‘I believe,’ says Mr. Webster, ‘I made tolerable progress in most branches which I attended to while in this school; but there was one thing I could not do. I could not make a declamation. I could not speak before the school. The kind and excellent Buckminster sought especially to persuade me to perform the exercise of declamation, like other boys, but I could not do it. Many a piece did I commit to memory, and recite and rehearse in my own room, over and over again; yet when the day came, when the school collected to hear declamations, when my name was called, and I saw all eyes turned to my seat, I could not raise myself from it. Sometimes the instructors frowned, sometimes they smiled. Mr. Buckminster always pressed and entreated, most winningly, that I would venture. But I never could command sufficient resolution.’ Such diffidence of its own powers may be natural to genius, nervously fearful of being unable to reach that ideal which it proposes as the only full consummation of its wishes. It is fortunate, however, for the age, fortunate for all ages, that Mr. Webster by determined will and frequent trial overcame this moral incapacity, as his great prototype, the Grecian orator, subdued his physical defect.”—pp. 12, 13.

The effect produced, even at that early period of Mr. Webster’s life, on the mind of a close observer of his mental powers, is strikingly illustrated by the following anecdote. Mr. Nicholas Emery, afterwards a distinguished lawyer and judge, and now living in Portland, was temporarily employed, at that time, as an usher in the Academy. On entering the Academy, Mr. Webster was placed in the lowest class, which consisted of half a dozen boys, of no remarkable brightness of intellect. Mr. Emery was the instructor of this class, among others. At the end of a month, after morning recitations, “Webster,” said Mr. Emery, “you will pass into the other room and join a higher class”; and added, “Boys, you will take your final leave of Webster, you will never see him again.”

After a few months well spent at Exeter, Mr. Webster returned home, and in February, 1797, was placed by his father under the Rev. Samuel Wood, the minister of the neighboring town of Boscawen. He lived in Mr. Wood’s family, and for board and instruction the entire charge was one dollar per week.

On their way to Mr. Wood’s, Mr. Webster’s father first opened to his son, now fifteen years old, the design of sending him to college, the thought of which had never before entered his mind. The advantages of a college education were a privilege to which he had never aspired in his most ambitious dreams. “I remember,” says Mr. Webster, in an autobiographical memorandum of his boyhood, “the very hill which we were ascending, through deep snows, in a New England sleigh, when my father made known this purpose to me. I could not speak. How could he, I thought, with so large a family and in such narrow circumstances, think of incurring so great an expense for me. A warm glow ran all over me, and I laid my head on my father’s shoulder and wept.”

In truth, a college education was a far different affair fifty years ago from what it has since become, by the multiplication of collegiate institutions, and the establishment of public funds in aid of those who need assistance. It constituted a person at once a member of an intellectual aristocracy. In many cases it really conferred qualifications, and in all was supposed to do so, without which professional and public life could not be entered upon with any hope of success. In New England, at that time, it was not a common occurrence that any one attained a respectable position in either of the professions without this advantage. In selecting the member of the family who should enjoy this privilege, the choice not unfrequently fell upon the son whose slender frame and early indications of disease unfitted him for the laborious life of our New England yeomanry.

From February till August, 1797, Mr. Webster remained under the instruction of Mr. Wood, at Boscawen, and completed his preparation for college. It is hardly necessary to say, that the preparation was imperfect. There is probably no period in the history of the country at which the standard of classical literature stood lower than it did at the close of the last century. The knowledge of Greek and Latin brought by our forefathers from England had almost run out in the lapse of nearly two centuries, and the signal revival which has taken place within the last thirty years had not yet begun. Still, however, when we hear of a youth of fifteen preparing himself for college by a year’s study of Greek and Latin, we must recollect that the attainments which may be made in that time by a young man of distinguished talent, at the period of life when the faculties develop themselves with the greatest energy, studying night and day, summer and winter, under the master influence of hope, ambition, and necessity, are not to be measured by the tardy progress of the thoughtless or languid children of prosperity, sent to school from the time they are able to go alone, and carried along by routine and discipline from year to year, in the majority of cases without strong personal motives to diligence. Besides this, it is to be considered that the studies which occupy this usually prolonged novitiate are those which are required for the acquisition of grammatical and metrical niceties, the elegancies and the luxuries of scholarship. Short as was his period of preparation, it enabled Mr. Webster to lay the foundation of a knowledge of the classical writers, especially the Latin, which was greatly increased in college, and which has been kept up by constant recurrence to the great models of antiquity, during the busiest periods of active life. The happiness of Mr. Webster’s occasional citations from the Latin classics is a striking feature of his oratory.

Mr. Webster entered college in 1797, and passed the four academic years in assiduous study. He was not only distinguished for his attention to the prescribed studies, but devoted himself to general reading, especially to English history and literature. He took part in the publication of a little weekly newspaper, furnishing selections from books and magazines, with an occasional article from his own pen. He delivered addresses, also, before the college societies, some of which were published. The winter vacations brought no relaxation. Like those of so many of the meritorious students at our places of education, they were employed in teaching school, for the purpose of eking out his own frugal means and aiding his brother to prepare himself for college. The attachment between the two brothers was of the most affectionate kind, and it was by the persuasion of Daniel that the father had been induced to extend to Ezekiel also the benefits of a college education.

The genial and companionable spirit of Mr. Webster is still remembered by his classmates, and by the close of his first college year he had given proof of powers and aspirations which placed him far above rivalry among his associates. “It is known,” says Mr. Ticknor, “in many ways, that, by those who were acquainted with him at this period of life, he was already regarded as a marked man, and that to the more sagacious of them the honors of his subsequent career have not been unexpected.”

Mr. Webster completed his college course in August, 1801, and immediately entered the office of Mr. Thompson, the next-door neighbor of his father, as a student of law. Mr. Thompson was a gentleman of education and intelligence, and, at a later period, a respectable member, successively, of the House of Representatives and Senate of the United States. He maintained a high character till his death. Mr. Webster remained in his office as a student till, in the words of Mr. March, “he felt it necessary to go somewhere and do something to earn a little money.” In this emergency, application was made to him to take charge of an academy at Fryeburg in Maine, upon a salary of about one dollar per diem, being what is now paid for the coarsest kind of unskilled manual labor. As he was able, besides, to earn enough to pay for his board and to defray his other expenses by acting as assistant to the register of deeds for the county, his salary was all saved,—a fund for his own professional education and to help his brother through college.

Mr. Webster’s son and one of his friends have lately visited Fryeburg and examined these records of deeds. They are still preserved in two huge folio volumes, in Mr. Webster’s handwriting, exciting wonder how so much work could be done in the evening, after days of close confinement to the business of the school. They looked also at the records of the trustees of the academy and found in them a most respectful and affectionate vote of thanks and good-will to Mr. Webster when he took leave of the employment.[3]

These humble details need no apology. They relate to trials, hardships, and efforts which constitute no small part of the discipline by which a great character is formed. During his residence at Fryeburg, Mr. Webster borrowed (he was too poor to buy) Blackstone’s Commentaries, and read them for the first time. “Among other mental exercises,” says Mr. March, “he committed to memory Mr. Ames’s celebrated speech on the British treaty.” In after life he has been heard to say, that few things moved him more than the perusal and reperusal of this celebrated speech.

In September, 1802, Mr. Webster returned to Salisbury, and resumed his studies under Mr. Thompson, in whose office he remained for eighteen months. Mr. Thompson, though, as we have said, a person of excellent character and a good lawyer, yet seems not to have kept pace in his profession with the progress of improvement. Although Blackstone’s Commentaries had been known in this country for a full generation, Mr. Thompson still directed the reading of his pupils on the principle of the hardest book first. Coke’s Littleton was still the work with which his students were broken into the study of the profession. Mr. Webster has condemned this practice. “A boy of twenty,” says he, “with no previous knowledge of such subjects, cannot understand Coke. It is folly to set him upon such an author. There are propositions in Coke so abstract, and distinctions so nice, and doctrines embracing so many distinctions and qualifications, that it requires an effort not only of a mature mind, but of a mind both strong and mature, to understand him. Why disgust and discourage a young man by telling him he must break into his profession through such a wall as this?” Acting upon these views, even in his youth, Mr. Webster gave his attention to more intelligible authors, and to titles of law of greater importance in this country than the curious learning of tenures, many of which are antiquated, even in England. He also gave a good deal of time to general reading, and especially the study of the Latin classics, English history, and the volumes of Shakespeare. In order to obtain a wider compass of knowledge, and to learn something of the language not to be gained from the classics, he read through attentively Puffendorff’s Latin History of England.

In July, 1804, he took up his residence in Boston. Before entering upon the practice of his profession, he enjoyed the advantage of pursuing his legal studies for six or eight months in the office of the Hon. Christopher Gore. This was a fortunate event for Mr. Webster. Mr. Gore, afterwards Governor of Massachusetts, was a lawyer of eminence, a statesman and a civilian, a gentleman of the old school of manners, and a rare example of distinguished intellectual qualities, united with practical good sense and judgment. He had passed several years in England as a commissioner, under Jay’s treaty, for liquidating the claims of citizens of the United States for seizures by British cruisers in the early wars of the French Revolution. His library, amply furnished with works of professional and general literature, his large experience of men and things at home and abroad, and his uncommon amenity of temper, combined to make the period passed by Mr. Webster in his office one of the pleasantest in his life. These advantages, it hardly need be said, were not thrown away. He diligently attended the sessions of the courts and reported their decisions. He read with care the leading elementary works of the common and municipal law, with the best authors on the law of nations, some of them for a second and third time; diversifying these professional studies with a great amount and variety of general reading. His chief study, however, was the common law, and more especially that part of it which relates to the now unfashionable science of special pleading. He regarded this, not only as a most refined and ingenious, but a highly instructive and useful branch of the law. Besides mastering all that could be derived from more obvious sources, he waded through Saunders’s Reports in the original edition, and abstracted and translated into English from the Latin and Norman French all the pleadings contained in the two folio volumes. This manuscript still remains.

Just as he was about to be admitted to practise in the Suffolk Court of Common Pleas in Massachusetts, an incident occurred which came near affecting his career for life. The place of clerk in the Court of Common Pleas for the county of Hillsborough, in New Hampshire, became vacant. Of this court Mr. Webster’s father had been made one of the judges, in conformity with a very common practice at that time, of placing on the side bench of the lower courts men of intelligence and respectability, though not lawyers. From regard to Judge Webster, the vacant clerkship was offered by his colleagues to his son. It was what the father had for some time looked forward to and desired. The fees of the office were about fifteen hundred dollars per annum, which in those days and in that region was not so much a competence as a fortune. Mr. Webster himself was disposed to accept the office. It promised an immediate provision in lieu of a distant and doubtful prospect. It enabled him at once to bring comfort into his father’s family, while to refuse it was to condemn himself and them to an uncertain and probably harassing future. He was willing to sacrifice his hopes of professional eminence to the welfare of those whom he held most dear. But the earnest dissuasions of Mr. Gore, who saw in this step the certain postponement, perhaps the final defeat, of all hopes of professional advancement, prevented his accepting the office. His aged father was, in a personal interview with his son, if not reconciled to the refusal, at least induced to bury his regrets in his own bosom. The subject was never mentioned by him again. In the spring of the same year (1805), Mr. Webster was admitted to the practice of the law in the Court of Common Pleas for Suffolk county, Boston. According to the custom of that day, Mr. Gore accompanied the motion for his admission with a brief speech in recommendation of the candidate. The remarks of Mr. Gore on this occasion are well remembered by those present. He dwelt with emphasis on the remarkable attainments and uncommon promise of his pupil, and closed with a prediction of his future eminence.

Immediately on his admission to the bar, Mr. Webster went to Amherst, in New Hampshire, where his father’s court was in session; from that place he went home with his father. He had intended to establish himself at Portsmouth, which, as the largest town and the seat of the foreign commerce of the State, opened the widest field for practice. But filial duty kept him nearer home. His father was now infirm from the advance of years, and had no other son at home. Under these circumstances Mr. Webster opened an office at Boscawen, not far from his father’s residence, and commenced the practice of the law in this retired spot. Judge Webster lived but a year after his son’s entrance upon the practice of his profession; long enough, however, to hear his first argument in court, and to be gratified with the confident predictions of his future success.

In May, 1807, Mr. Webster was admitted as an attorney and counsellor of the Superior Court in New Hampshire, and in September of that year, relinquishing his office in Boscawen to his brother Ezekiel, he removed to Portsmouth, in conformity with his original intention. Here he remained in the practice of his profession for nine successive years. They were years of assiduous labor, and of unremitted devotion to the study and practice of the law. He was associated with several persons of great eminence, citizens of New Hampshire or of Massachusetts occasionally practising at the Portsmouth bar. Among the latter were Samuel Dexter and Joseph Story; of the residents of New Hampshire, Jeremiah Mason was the most distinguished. Often opposed to each other as lawyers, a strong personal friendship grew up between them, which ended only with the death of Mr. Mason. Mr. Webster’s eulogy on Mr. Mason will be found in one of the volumes of this collection, and will descend to posterity an enduring monument of both. Had a more active temperament led Mr. Mason to embark earlier and continue longer in public life, he would have achieved a distinction shared by few of his contemporaries. Mr. Webster, in the lapse of time, was called to perform the same melancholy office for Judge Story.

During the greater part of Mr. Webster’s practice of the law in New Hampshire, Jeremiah Smith was Chief Justice of the State, a learned and excellent judge, whose biography has been written by the Rev. John H. Morison, and will well repay perusal. Judge Smith was an early and warm friend of Judge Webster, and this friendship descended to the son, and glowed in his breast with fervor till he went to his grave.

Although dividing with Mr. Mason the best of the business of Portsmouth, and indeed of all the eastern portion of the State, Mr. Webster’s practice was mostly on the circuit. He followed the Superior Court through the principal counties of the State, and was retained in nearly every important cause. It is mentioned by Mr. March, as a somewhat singular fact in his professional life, that, with the exception of the occasions on which he has been associated with the Attorney-General of the United States for the time being, he has hardly appeared ten times as junior counsel. Within the sphere in which he was placed, he may be said to have risen at once to the head of his profession; not, however, like Erskine and some other celebrated British lawyers, by one and the same bound, at once to fame and fortune. The American bar holds forth no such golden prizes, certainly not in the smaller States. Mr. Webster’s practice in New Hampshire, though probably as good as that of any of his contemporaries, was never lucrative. Clients were not very rich, nor the concerns litigated such as would carry heavy fees. Although exclusively devoted to his profession, it afforded him no more than a bare livelihood.

But the time for which he practised at the New Hampshire bar was probably not lost with reference to his future professional and political eminence. His own standard of legal attainment was high. He was associated with professional brethren fully competent to put his powers to their best proof, and to prevent him from settling down in early life into an easy routine of ordinary professional practice. It was no disadvantage, under these circumstances, (except in reference to immediate pecuniary benefit,) to enjoy some portion of that leisure for general reading, which is almost wholly denied to the lawyer of commanding talents, who steps immediately into full practice in a large city.

FOOTNOTES

RECEPTION AT BUFFALO.[101]

THE BUNKER HILL MONUMENT.

PUBLIC DINNER AT NEW YORK.

[3]

The old school-house was burned down many years ago. The spot on which it stood belongs to Mr. Robert J. Bradley, who has inherited from his father a devoted friendship for Mr. Webster, and who would never suffer any other building to be erected on the spot, and says that none shall be during his life.

ADAMS AND JEFFERSON.

FIRST SETTLEMENT OF NEW ENGLAND.

THE AGRICULTURE OF ENGLAND.[118]

ROYAL AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY.[117]

THE ELECTION OF 1825.

RECEPTION AT BANGOR.[103]

RECEPTION AT MADISON.

PRESENTATION OF A VASE.

DINNER AT FANEUIL HALL.

THE CHARACTER OF WASHINGTON.[94]

[1]

Fifty dollars. The knowledge of this fact is derived from the “Gloucester News,” to which it was no doubt communicated by Master Tappan.

RECEPTION AT PITTSBURG.

PUBLIC DINNER IN FANEUIL HALL.

RECEPTION AT NEW YORK.

RECEPTION AT WHEELING.[108]

NATIONAL REPUBLICAN CONVENTION AT WORCESTER.[96]

[2]

Belknap’s History of New Hampshire, Vol. III. p. 328.

THE BOSTON MECHANICS’ INSTITUTION.[88]

THE COMPLETION

OF

THE BUNKER HILL MONUMENT.

Fifty dollars. The knowledge of this fact is derived from the “Gloucester News,” to which it was no doubt communicated by Master Tappan.

Belknap’s History of New Hampshire, Vol. III. p. 328.

The old school-house was burned down many years ago. The spot on which it stood belongs to Mr. Robert J. Bradley, who has inherited from his father a devoted friendship for Mr. Webster, and who would never suffer any other building to be erected on the spot, and says that none shall be during his life.

CHAPTER II.

Entrance on Public Life.—State of Parties in 1812.—Election to Congress.—Extra Session of 1813.—Foreign Relations of the Country.—Resolutions relative to the Berlin and Milan Decrees.—Naval Defence.—Reelected to Congress in 1814.—Peace with England.—Projects for a National Bank.—Mr. Webster’s Course on that Question.—Battle of New Orleans.—New Questions arising on the Return of Peace.—Course of Prominent Men of Different Parties.—Mr. Webster’s Opinions on the Constitutionality of the Tariff Policy.—The Resolution to restore Specie Payments moved by Mr. Webster.—Removal to Boston.

Mr. Webster had hitherto taken less interest in politics than has been usual with the young men of talent, at least with the young lawyers, of America. In fact, at the time to which the preceding narrative refers, the politics of the country were in such a state, that there was scarce any course which could be pursued with entire satisfaction by a patriotic young man sagacious enough to penetrate behind mere party names, and to view public questions in their true light. Party spirit ran high; errors had been committed by ardent men on both sides; and extreme opinions had been advanced on most questions, which no wise and well-informed person at the present day would probably be willing to espouse. The United States, although not actually drawn to any great depth into the vortex of the French Revolution, were powerfully affected by it. The deadly struggle of the two great European belligerents, in which the neutral rights of this country were grossly violated by both, gave a complexion to our domestic politics. A change of administration, mainly resulting from difference of opinion in respect to our foreign relations, had taken place in 1801. If we may consider President Jefferson’s inaugural address as the indication of the principles on which he intended to conduct his administration, it was his purpose to take a new departure, and to disregard the former party divisions. “We have,” said he, in that eloquent state paper, “called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all republicans, we are all federalists.”

At the time these significant expressions were uttered, Mr. Webster, at the age of nineteen, was just leaving college and preparing to embark on the voyage of life. A sentiment so liberal was not only in accordance with the generous temper of youth, but highly congenial with the spirit of enlarged patriotism which has ever guided his public course. There is certainly no individual who has filled a prominent place in our political history who has shown himself more devoted to principle and less to party. While no man has clung with greater tenacity to the friendships which spring from agreement in political opinion (the idem sentire de republica), no man has been less disposed to find in these associations an instrument of monopoly or exclusion in favor of individuals, interests, or sections of the country.

But however catholic may have been the intentions and wishes of Mr. Jefferson, events both at home and abroad were too strong for him, and defeated that policy of blending the great parties into one, which has always been a favorite, perhaps we must add, a visionary project, with statesmen of elevated and generous characters. The aggressions of the belligerents on our neutral commerce still continued, and, by the joint effect of the Berlin and Milan Decrees and the Orders in Council, it was all but swept from the ocean. In this state of things two courses were open to the United States, as a growing neutral power: one, that of prompt resistance to the aggressive policy of the belligerents; the other, that which was called “the restrictive system,” which consisted in an embargo on our own vessels, with a view to withdraw them from the grasp of foreign cruisers, and in laws inhibiting commercial intercourse with England and France. There was a division of opinion in the cabinet of Mr. Jefferson and in the country at large. The latter policy was finally adopted. It fell in with the general views of Mr. Jefferson against committing the country to the risks of foreign war. His administration was also strongly pledged to retrenchment and economy, in the pursuit of which a portion of our little navy had been brought to the hammer, and a species of shore defence substituted, which can now be thought of only with mortification and astonishment.

Although the discipline of party was sufficiently strong to cause this system of measures to be adopted and pursued for years, it was never cordially approved by the people of the United States of any party. Leading Republicans both at the South and at the North denounced it. With Mr. Jefferson’s retirement from office it fell rapidly into disrepute. It continued, however, to form the basis of our party divisions till the war of 1812. In these divisions, as has been intimated, both parties were in a false position; the one supporting and forcing upon the country a system of measures not cordially approved, even by themselves; the other, a powerless minority, zealously opposing those measures, but liable for that reason to be thought backward in asserting the neutral rights of the country. A few men of well-balanced minds, true patriotism, and sound statesmanship, in all sections of the country, were able to unite fidelity to their party associations with a comprehensive view to the good of the country. Among these, mature beyond his years, was Mr. Webster. As early as 1806 he had, in a public oration, presented an impartial view of the foreign relations of the country in reference to both belligerents, of the importance of our commercial interests and the duty of protecting them. “Nothing is plainer,” said he, “than this: if we will have commerce, we must protect it. This country is commercial as well as agricultural. Indissoluble bonds connect him who ploughs the land with him who ploughs the sea. Nature has placed us in a situation favorable to commercial pursuits, and no government can alter the destination. Habits confirmed by two centuries are not to be changed. An immense portion of our property is on the waves. Sixty or eighty thousand of our most useful citizens are there, and are entitled to such protection from the government as their case requires.”

At length the foreign belligerents themselves perceived the folly and injustice of their measures. In the strife which should inflict the greatest injury on the other, they had paralyzed the commerce of the world and embittered the minds of all the neutral powers. The Berlin and Milan Decrees were revoked, but in a manner so unsatisfactory as in a great degree to impair the pacific tendency of the measure. The Orders in Council were also rescinded in the summer of 1812. War, however, justly provoked by each and both of the parties, had meantime been declared by Congress against England, and active hostilities had been commenced on the frontier. At the elections next ensuing, Mr. Webster was brought forward as a candidate for Congress of the Federal party of that day, and, having been chosen in the month of November, 1812, he took his seat at the first session of the Thirteenth Congress, which was an extra session called in May, 1813. Although his course of life hitherto had been in what may be called a provincial sphere, and he had never been a member even of the legislature of his native State, a presentiment of his ability seems to have gone before him to Washington. He was, in the organization of the House, placed by Mr. Clay, its Speaker, upon the Committee of Foreign Affairs, a select committee at that time, and of necessity the leading committee in a state of war.

There were many men of uncommon ability in the Thirteenth Congress. Rarely has so much talent been found at any one time in the House of Representatives. It contained Clay, Calhoun, Lowndes, Pickering, Gaston, Forsyth, in the front rank; Macon, Benson, J. W. Taylor, Oakley, Grundy, Grosvenor, W. R. King, Kent of Maryland, C. J. Ingersoll of Pennsylvania, Pitkin of Connecticut, and others of scarcely inferior note. Although among the youngest and least experienced members of the body, Mr. Webster rose, from the first, to a position of undisputed equality with the most distinguished. The times were critical. The immediate business to be attended to was the financial and military conduct of the war, a subject of difficulty and importance. The position of Mr. Webster was not such as to require or permit him to take a lead; but it was his steady aim, without the sacrifice of his principles, to pursue such a course as would tend most effectually to extricate the country from the embarrassments of her present position, and to lead to peace upon honorable terms.

As the repeal of the Orders in Council was nearly simultaneous with the declaration of war, the delay of a few weeks might have led to an amicable adjustment. Whatever regret on the score of humanity this circumstance may now inspire, the war must be looked upon, in reviewing the past, as a great chapter in the progress of the country, which could not be passed over. When we reflect on the influence of the conflict, in its general results, upon the national character; its importance as a demonstration to the belligerent powers of the world that the rights of neutrals must be respected; and more especially, when we consider the position among the nations of the earth which the United States have been enabled to take, in consequence of the capacity for naval achievement which the war displayed, we shall readily acknowledge it to be a part of that great training, by which the country was prepared to take the station which she now occupies.

Mr. Webster was not a member of Congress when war was declared, nor in any other public station. He was too deeply read in the law of nations, and regarded that august code with too much respect, not to contemplate with indignation its infraction by both the belligerents. With respect to the Orders in Council, the highest judicial magistrate in England (Lord Chief Justice Campbell) has lately admitted that they were contrary to the law of nations.[4] As little doubt can exist that the French decrees were equally at variance with the public law. But however strong his convictions of this truth, Mr. Webster’s sagacity and practical sense pointed out the inadequacy, and what may be called the political irrelevancy, of the restrictive system, as a measure of defence or retaliation. He could not but feel that it was a policy which tended at once to cripple the national resources, and abase the public sentiment, with an effect upon the foreign powers doubtful and at best indirect. In the state of the military resources of the country at that time, he discerned, in common with many independent men of all parties, that less was to be hoped from the attempted conquest of foreign territory, than from a gallant assault upon the fancied supremacy of the enemy at sea. It is unnecessary to state, that the whole course of the war confirmed the justice of these views. They furnish the key to Mr. Webster’s course in the Thirteenth Congress.

Early in the session, he moved a series of resolutions of inquiry, relative to the repeal of the Berlin and Milan Decrees. The object of these resolutions was to elicit a communication on this subject from the executive, which would unfold the proximate causes of the war, as far as they were to be sought in those famous Decrees, and in the Orders in Council. On the 10th of June, 1813, Mr. Webster delivered his maiden speech on these resolutions. No full report of this speech has been preserved. It is known only from extremely imperfect sketches, contained in the contemporaneous newspaper accounts of the proceedings of Congress, from the recollection of those who heard it, and from general tradition. It was a calm and statesmanlike exposition of the objects of the resolutions; and was listened to with profound attention by the House. It was marked by all the characteristics of Mr. Webster’s maturest parliamentary efforts,—moderation of tone, precision of statement, force of reasoning, absence of ambitious rhetoric and high-flown language, occasional bursts of true eloquence, and, pervading the whole, a genuine and fervid patriotism. We have reason to believe that its effect upon the House is accurately described in the following extract from Mr. March’s work.

“The speech took the House by surprise, not so much from its eloquence as from the vast amount of historical knowledge and illustrative ability displayed in it. How a person, untrained to forensic contests and unused to public affairs, could exhibit so much parliamentary tact, such nice appreciation of the difficulties of a difficult question, and such quiet facility in surmounting them, puzzled the mind. The age and inexperience of the speaker had prepared the House for no such display, and astonishment for a time subdued the expression of its admiration.

“‘No member before,’ says a person then in the House, ‘ever riveted the attention of the House so closely, in his first speech. Members left their seats, where they could not see the speaker face to face, and sat down, or stood on the floor, fronting him. All listened attentively and silently, during the whole speech; and when it was over, many went up and warmly congratulated the orator; among whom were some, not the most niggard of their compliments, who most dissented from the views he had expressed.’

“Chief Justice Marshall, writing to a friend some time after this speech, says: ‘At the time when this speech was delivered, I did not know Mr. Webster, but I was so much struck with it, that I did not hesitate then to state, that Mr. Webster was a very able man, and would become one of the very first statesmen in America, and perhaps the very first.’”—pp. 35, 36.[5]

The resolutions moved by Mr. Webster prevailed by a large majority, and drew forth from Mr. Monroe, then Secretary of State, an elaborate and instructive report upon the subject to which they referred.

We have already observed, that, as early as 1806, Mr. Webster had expressed himself in favor of the protection of our commerce against the aggressions of both the belligerents. Some years later, before the war was declared, but when it was visibly impending, he had put forth some vigorous articles to the same effect. In an oration delivered in 1812, he had said: “A navy sufficient for the defence of our coasts and harbors, for the convoy of important branches of our trade, and sufficient also to give our enemies to understand, when they injure us, that they too are vulnerable, and that we have the power of retaliation as well as of defence, seems to be the plain, necessary, indispensable policy of the nation. It is the dictate of nature and common sense, that means of defence shall have relation to the danger.” In accordance with these views, first announced by Mr. Webster a considerable time before Hull, Decatur, and Bainbridge had broken the spell of British naval supremacy, he used the following language in his speech on encouraging enlistments in 1814:—

“The humble aid which it would be in my power to render to measures of government shall be given cheerfully, if government will pursue measures which I can conscientiously support. If even now, failing in an honest and sincere attempt to procure an honorable peace, it will return to measures of defence and protection, such as reason and common sense and the public opinion all call for, my vote shall not be withholden from the means. Give up your futile projects of invasion. Extinguish the fires which blaze on your inland frontiers. Establish perfect safety and defence there by adequate force. Let every man that sleeps on your soil sleep in security. Stop the blood that flows from the veins of unarmed yeomanry, and women and children. Give to the living time to bury and lament their dead, in the quietness of private sorrow. Having performed this work of beneficence and mercy on your inland border, turn and look with the eye of justice and compassion on your vast population along the coast. Unclench the iron grasp of your embargo. Take measures for that end before another sun sets upon you. With all the war of the enemy on your commerce, if you would cease to make war upon it yourselves, you would still have some commerce. That commerce would give you some revenue. Apply that revenue to the augmentation of your navy. That navy in turn will protect your commerce. Let it no longer be said, that not one ship of force, built by your hands since the war, yet floats upon the ocean. Turn the current of your efforts into the channel which national sentiment has already worn broad and deep to receive it. A naval force competent to defend your coasts against considerable armaments, to convoy your trade, and perhaps raise the blockade of your rivers, is not a chimera. It may be realized. If then the war must continue, go to the ocean. If you are seriously contending for maritime rights, go to the theatre where alone those rights can be defended. Thither every indication of your fortune points you. There the united wishes and exertions of the nation will go with you. Even our party divisions, acrimonious as they are, cease at the water’s edge. They are lost in attachment to the national character, on the element where that character is made respectable. In protecting naval interests by naval means, you will arm yourselves with the whole power of national sentiment, and may command the whole abundance of the national resources. In time you may be able to redress injuries in the place where they may be offered; and, if need be, to accompany your own flag throughout the world with the protection of your own cannon.”

The principal subjects on which Mr. Webster addressed the House during the Thirteenth Congress were his own resolutions, the increase of the navy, the repeal of the embargo, and an appeal from the decision of the chair on a motion for the previous question. His speeches on those questions raised him to the front rank of debaters. He manifested upon his entrance into public life that variety of knowledge, familiarity with the history and traditions of the government, and self-possession on the floor, which in most cases are acquired by time and long experience. They gained for him the reputation indicated by the well-known remark of Mr. Lowndes, that “the North had not his equal, nor the South his superior.” It was not the least conspicuous of the strongly marked qualities of his character as a public man, disclosed at this early period, and uniformly preserved throughout his career, that, at a time when party spirit went to great lengths, he never permitted himself to be infected with its contagion. His opinions were firmly maintained and boldly expressed; but without bitterness toward those who differed from him. He cultivated friendly relations on both sides of the House, and gained the personal respect even of those with whom he most differed.

In August, 1814, Mr. Webster was reëlected to Congress. The treaty of Ghent, as is well known, was signed in December, 1814, and the prospect of peace, universally welcomed by the country, opened on the Thirteenth Congress toward the close of its third session. Earlier in the season a project for a Bank of the United States was introduced into the House of Representatives on the recommendation of Mr. Dallas, Secretary of the Treasury. The charter of the first incorporated bank of the United States had expired in 1811. No general complaints of mismanagement or abuse had been raised against this institution; but the opinions entertained by what has been called the “Virginia School” of politicians, against the constitutionality of a national bank, prevented the renewal of the charter. The want of such an institution was severely felt in the war of 1812, although it is probable that the amount of assistance which it could have afforded the financial operations of the government was greatly overrated. Be this as it may, both the Treasury Department and Congress were now strongly disposed to create a bank. Its capital was to consist of forty-five millions of the public stocks and five millions of specie, and it was to be under obligation to lend the government thirty millions of dollars on demand. To enable it to exist under these conditions, it was relieved from the necessity of redeeming its notes in specie. In other words, it was an arrangement for the issue of an irredeemable paper currency. It was opposed mainly on this ground by Mr. Calhoun, Mr. Webster, Mr. Lowndes, and others of the ablest men on both sides of the House, as a project not only unsound in its principles, but sure to increase the derangement of the currency already existing. The speech of Mr. Webster against the bill will be found in one of these volumes, and it will be generally admitted to display a mastery of the somewhat difficult subjects of banking and finance, rarely to be found in the debates in Congress. The project was supported as an administration measure, but the leading members from South Carolina and their friends united with the regular opposition against it, and it was lost by the casting vote of the Speaker, Mr. Cheves. It was revived by reconsideration, on motion of Mr. Webster, and such amendments introduced that it passed the House by a large majority. It was carried through the Senate in this amended form with difficulty, but it was negatived by Mr. Madison, being one of the two cases in which he exercised the veto power during his eight years’ administration.