автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Osceola the Seminole / The Red Fawn of the Flower Land

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Osceola the Seminole, by Mayne Reid

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Osceola the Seminole

The Red Fawn of the Flower Land

Author: Mayne Reid

Illustrator: N. Orr, (Engraver)

Release Date: March 20, 2011 [EBook #35620]

Language: English

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OSCEOLA THE SEMINOLE ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Captain Mayne Reid

"Osceola the Seminole"

"The Red Fawn of the Flower Land"

Preface.

The Historical Novel has ever maintained a high rank—perhaps the highest—among works of fiction, for the reason that while it enchants the senses, it improves the mind, conveying, under a most pleasing form, much information which, perhaps, the reader would never have sought for amid the dry records of the purely historic narrative.

This fact being conceded, it needs but little argument to prove that those works are most interesting which treat of the facts and incidents pertaining to our own history, and of a date which is yet fresh in the memory of the reader.

To this class of books pre-eminently belongs the volume which is here submitted to the American reader, from the pen of a writer who has proved himself unsurpassed in the field which he has, by his various works, made peculiarly his own.

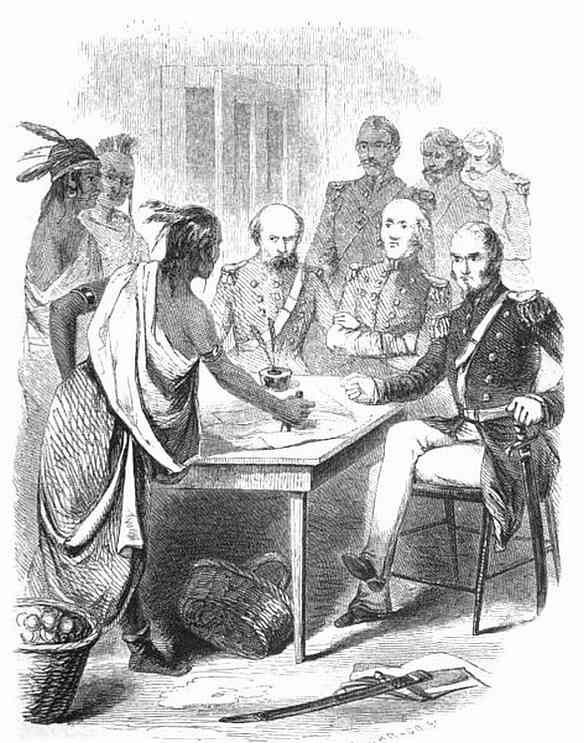

The brief but heroic struggle of the celebrated Chief, Osceola, forms the groundwork of a narrative which is equal, if not superior, to any of Mr Reid’s former productions; and while the reader’s patriotism cannot fail to be gratified at the result, his sympathy is, at the same time, awakened for the manly struggles and untimely fate of the gallant spirit, who fought so nobly for the freedom of his red brethren and the preservation of their cherished hunting-grounds.

Chapter One.

The Flowery Land.

Linda Florida! fair land of flowers!

Thus hailed thee the bold Spanish adventurer, as standing upon the prow of his caravel, he first caught sight of thy shores.

It was upon the Sunday of Palms—the festival of the flowers—and the devout Castilian beheld in thee a fit emblem of the day. Under the influence of a pious thought, he gave thee its name, and well deservedst thou the proud appellation.

That was three hundred years ago. Three full cycles have rolled past, since the hour of thy baptismal ceremony; but the title becomes thee as ever. Thy floral bloom is as bright at this hour as when Leon landed upon thy shores—ay, bright as when the breath of God first called thee into being.

Thy forests are still virgin and inviolate; verdant thy savannas; thy groves as fragrant as ever—those perfumed groves of aniseed and orange, of myrtle and magnolia. Still sparkles upon thy plains the cerulean ixia; still gleam in thy waters the golden nymphae; above thy swamps yet tower the colossal cypress, the gigantic cedar, the gum, and the bay-tree; still over thy gentle slopes of silvery sand wave long-leaved pines, mingling their acetalous foliage with the frondage of the palm. Strange anomaly of vegetation; the tree of the north, and the tree of the south—the types of the frigid and torrid—in this thy mild mid region, standing side by side, and blending their branches together!

Linda Florida! who can behold thee without peculiar emotion? without conviction that thou art a favoured land? Gazing upon thee, one ceases to wonder at the faith—the wild faith of the early adventurers—that from thy bosom gushed forth the fountain of youth, the waters of eternal life!

No wonder the sweet fancy found favour and credence; no wonder so delightful an idea had its crowds of devotees. Thousands came from afar, to find rejuvenescence by bathing in thy crystal streams—thousands sought it, with far more eagerness than the white metal of Mexico, or the yellow gold of Peru; in the search thousands grew older instead of younger, or perished in pursuit of the vain illusion; but who could wonder?

Even at this hour, one can scarcely think it an illusion; and in that age of romance, it was still easier of belief. A new world had been discovered, why not a new theory of life? Men looked upon a land where the leaves never fell, and the flowers never faded. The bloom was eternal—eternal the music of the birds. There was no winter—no signs of death or decay. Natural, then, the fancy, and easy the faith, that in such fair land man too might be immortal.

The delusion has long since died away, but not the beauty that gave birth to it. Thou, Florida, art still the same—still art thou emphatically the land of flowers. Thy groves are as green, thy skies as bright, thy waters as diaphanous as ever. There is no change in the loveliness of thy aspect.

And yet I observe a change. The scene is the same, but not the characters! Where are they of that red race who were born of thee, and nurtured on thy bosom? I see them not. In thy fields, I behold white and black, but not red—European and African, but not Indian—not one of that ancient people who were once thine own. Where are they?

Gone! all gone! No longer tread they thy flowery paths—no longer are thy crystal streams cleft by the keels of their canoes—no more upon thy spicy gale is borne the sound of their voices—the twang of their bowstrings is heard no more amid the trees of thy forest: they have parted from thee far and for ever.

But not willing went they away—for who could leave thee with a willing heart? No, fair Florida; thy red children were true to thee, and parted only in sore unwillingness. Long did they cling to the loved scenes of their youth; long continued they the conflict of despair, that has made them famous for ever. Whole armies, and many a hard straggle, it cost the pale-face to dispossess them; and then they went not willingly—they were torn from thy bosom like wolf-cubs from their dam, and forced to a far western land. Sad their hearts, and slow their steps, as they faced toward the setting sun. Silent or weeping, they moved onward. In all that band, there was not one voluntary exile.

No wonder they disliked to leave thee. I can well comprehend the poignancy of their grief. I too have enjoyed the sweets of thy flowery land, and parted from thee with like reluctance. I have walked under the shadows of thy majestic forests, and bathed my body in thy limpid streams—not with the hope of rejuvenescence, but the certainty of health and joy. Oft have I made my couch under the canopy of thy spreading palms and magnolias, or stretched myself along the greensward of thy savannas; and, with eyes bent upon the blue ether of thy heavens, have listened to my heart repeating the words of the eastern poet:

“Oh! if there can be an Elysium on earth,

It is this - it is this!”

Chapter Two.

The Indigo Plantation.

My father was an indigo planter; his name was Randolph. I bear his name in full—George Randolph.

There is Indian blood in my veins. My father was of the Randolphs of Roanoke—hence descended from the Princess Pocahontas. He was proud of his Indian ancestry—almost vain of it.

It may sound paradoxical, especially to European ears; but it is true, that white men in America, who have Indian blood in them, are proud of the taint. Even to be a “half-breed” is no badge of shame—particularly where the sang mêlé has been gifted with fortune. Not all the volumes that have been written bear such strong testimony to the grandeur of the Indian character as this one fact—we are not ashamed to acknowledge them as ancestry!

Hundreds of white families lay claim to descent from the Virginian princess. If their claims be just, then must the fair Pocahontas have been a blessing to her lord.

I think my father was of the true lineage; at all events, he belonged to a proud family in the “Old Dominion;” and during his early life had been surrounded by sable slaves in hundreds. But his rich patrimonial lands became at length worn-out—profuse hospitality well-nigh ruined him; and not brooking an inferior station, he gathered up the fragments of his fortune, and “moved” southward—there to begin the world anew.

I was born before this removal, and am therefore a native of Virginia; but my earliest impressions of a home were formed upon the banks of the beautiful Suwanee in Florida. That was the scene of my boyhood’s life—the spot consecrated to me by the joys of youth and the charms of early love.

I would paint the picture of my boyhood’s home. Well do I remember it: so fair a scene is not easily effaced from the memory.

A handsome “frame”-house, coloured white, with green Venetians over the windows, and a wide verandah extending all round. Carved wooden porticoes support the roof of this verandah, and a low balustrade with light railing separates it from the adjoining grounds—from the flower parterre in front, the orangery on the right flank and a large garden on the left. From the outer edge of the parterre, a smooth lawn slopes gently to the bank of the river—here expanding to the dimensions of a noble lake, with distant wooded shores, islets that seem suspended in the air, wild-fowl upon the wing, and wild-fowl in the water.

Upon the lawn, behold tall tapering palms, with pinnatifid leaves—a species of oreodoxia—others with broad fan-shaped fronds—the palmettoes of the south; behold magnolias, clumps of the fragrant illicium, and radiating crowns of the yucca gloriosa—all indigenous to the soil. Another native presents itself to the eye—a huge live-oak extending its long horizontal boughs, covered thickly with evergreen coriaceous leaves, and broadly shadowing the grass beneath. Under its shade behold a beautiful girl, in light summer robes—her hair loosely coifed with a white kerchief, from the folds of which have escaped long tresses glittering with the hues of gold. That is my sister Virginia, my only sister, still younger than myself. Her golden hair bespeaks not her Indian descent, but in that she takes after our mother. She is playing with her pets, the doe of the fallow deer, and its pretty spotted fawn. She is feeding them with the pulp of the sweet orange, of which they are immoderately fond. Another favourite is by her side, led by its tiny chain. It is the black fox-squirrel, with glossy coat and quivering tail. Its eccentric gambols frighten the fawn, causing the timid creature to start over the ground, and press closer to its mother, and sometimes to my sister, for protection.

The scene has its accompaniment of music. The golden oriole, whose nest is among the orange-trees, gives out its liquid song; the mock-bird, caged in the verandah, repeats the strain with variations. The gay mimic echoes the red cardinal and the blue jay, both fluttering among the flowers of the magnolia; it mocks the chatter of the green paroquets, that are busy with the berries of the tall cypresses down by the water’s edge; at intervals it repeats the wild scream of the Spanish curlews that wave their silver wings overhead, or the cry of the tantalus heard from the far islets of the lake. The bark of the dog, the mewing of the cat, the hinny of mules, the neighing of horses, even the tones of the human voice, are all imitated by this versatile and incomparable songster.

The rear of the dwelling presents a different aspect—perhaps not so bright, though not less cheerful. Here is exhibited a scene of active life—a picture of the industry of an indigo plantation.

A spacious enclosure, with its “post-and-rail” fence, adjoins the house. Near the centre of this stands the pièce de résistance—a grand shed that covers half an acre of ground, supported upon strong pillars of wood. Underneath are seen huge oblong vats, hewn from the great trunks of the cypress. They are ranged in threes, one above the other, and communicate by means of spigots placed in their ends. In these the precious plant is macerated, and its cerulean colour extracted.

Beyond are rows of pretty little cottages, uniform in size and shape, each embowered in its grove of orange-trees, whose ripening fruit and white wax-like flowers fill the air with perfume. These are the negro-cabins. Here and there, towering above their roofs in upright attitude, or bending gently over, is the same noble palm-tree that ornaments the lawn in front. Other houses appear within the enclosure, rude structures of hewn logs, with “clap-board” roofs: they are the stable, the corn-crib, the kitchen—this last communicating with the main dwelling by a long open gallery, with shingle roof, supported upon posts of the fragrant red cedar.

Beyond the enclosure stretch wild fields, backed by a dark belt of cypress forest that shuts out the view of the horizon. These fields exhibit the staple of cultivation, the precious dye-plant, though other vegetation appears upon them. There are maize-plants and sweet potatoes (Convolvulus batatas) some rice, and sugar-cane. These are not intended for commerce, but to provision the establishment.

The indigo is sown in straight rows, with intervals between. The plants are of different ages, some just bursting through the glebe with leaves like young trefoil; others full-grown, above two feet in height, resemble ferns, and exhibit the light-green pinnated leaves which distinguish most of the leguminosa—for the indigo belongs to this tribe. Some shew their papilionaceous flowers just on the eve of bursting; but rarely are they permitted to exhibit their full bloom. Another destiny awaits them; and the hand of the reaper rudely checks their purple inflorescence.

In the inclosure, and over the indigo-fields, a hundred human forms are moving; with one or two exceptions, they are all of the African race—all slaves. They are not all of black skin—scarcely the majority of them are negroes. There are mulattoes, samboes, and quadroons. Even some who are of pure African blood are not black, only bronze-coloured; but with the exception of the “overseer” and the owner of the plantation, all are slaves. Some are hideously ugly, with thick lips, low retreating foreheads, flat noses, and ill-formed bodies! others are well proportioned; and among them are some that might be accounted good-looking. There are women nearly white—quadroons. Of the latter are several that are more than good-looking—some even beautiful.

The men are in their work-dresses: loose cotton trousers, with coarse coloured shirts, and hats of palmetto-leaf. A few display dandyism in their attire. Some are naked from the waist upwards, their black skins glistening under the sun like ebony. The women are more gaily arrayed in striped prints, and heads “toqued” with Madras kerchiefs of brilliant check. The dresses of some are tasteful and pretty. The turban-like coiffure renders them picturesque.

Both men and women are alike employed in the business of the plantation—the manufacture of the indigo. Some cut down the plants with reaping-hooks, and tie them in bundles; others carry the bundles in from the fields to the great shed; a few are employed in throwing them into the upper trough, the “steeper;” while another few are drawing off and “beating.” Some shovel the sediment into the draining-bags, while others superintend the drying and cutting out. All have their respective tasks, and all seem alike cheerful in the performance of them. They laugh, and chatter, and sing; they give back jest for jest; and scarcely a moment passes that merry voices are not ringing upon the ear.

And yet these are all slaves—the slaves of my father. He treats them well; seldom is the lash uplifted: hence the happy mood and cheerful aspect.

Such pleasant pictures are graven on my memory, sweetly and deeply impressed. They formed the mise-en-scène of my early life.

Chapter Three.

The Two Jakes.

Every plantation has its “bad fellow”—often more than one, but always one who holds pre-eminence in evil. “Yellow Jake” was the fiend of ours.

He was a young mulatto, in person not ill-looking, but of sullen habit and morose disposition. On occasions he had shewn himself capable of fierce resentment and cruelty.

Instances of such character are more common among mulattoes than negroes. Pride of colour on the part of the yellow man—confidence in a higher organism, both intellectual and physical, and consequently a keener sense of the injustice of his degraded position, explain this psychological difference.

As for the pure negro, he rarely enacts the unfeeling savage. In the drama of human life, he is the victim, not the villain. No matter where lies the scene—in his own land, or elsewhere—he has been used to play the rôle of the sufferer; yet his soul is still free from resentment or ferocity. In all the world, there is no kinder heart than that which beats within the bosom of the African black.

Yellow Jake was wicked without provocation. Cruelty was innate in his disposition—no doubt inherited. He was a Spanish mulatto; that is, paternally of Spanish blood—maternally, negro. His father had sold him to mine!

A slave-mother, a slave-son. The father’s freedom affects not the offspring. Among the black and red races of America, the child fellows the fortunes of the mother. Only she of Caucasian race can be the mother of white men.

There was another “Jacob” upon the plantation—hence the distinctive sobriquet of “Yellow Jake.” This other was “Black Jake;” and only in age and size was there any similarity between the two. In disposition they differed even more than in complexion. If Yellow Jake had the brighter skin, Black Jake had the lighter heart. Their countenances exhibited a complete contrast—the contrast between a sullen frown and a cheerful smile. The white teeth of the latter were ever set in smiles: the former smiled only when under the influence of some malicious prompting.

Black Jake was a Virginian. He was one of those belonging to the old plantation—had “moved” along with his master; and felt those ties of attachment which in many cases exist strongly between master and slave. He regarded himself as one of our family, and gloried in bearing our name. Like all negroes born in the “Old Dominion,” he was proud of his nativity. In caste, a “Vaginny nigger” takes precedence of all others.

Apart from his complexion, Black Jake was not ill-looking. His features were as good as those of the mulatto. He had neither the thick lips, flat nose, nor retreating forehead of his race—for these characteristics are not universal. I have known negroes of pure African blood with features perfectly regular, and such a one was Black Jake. In form, he might have passed for the Ethiopian Apollo.

There was one who thought him handsome—handsomer than his yellow namesake. This was the quadroon Viola, the belle of the plantation. For Viola’s hand, the two Jakes had long time been rival suitors. Both had assiduously courted her smiles—somewhat capricious they were, for Viola was not without coquetry—but she had at length exhibited a marked preference for the black. I need not add that there was jealousy between the negro and mulatto—on the part of the latter, rank hatred of his rival—which Viola’s preference had kindled into fierce resentment.

More than once had the two measured their strength, and on each occasion had the black been victorious. Perhaps to this cause, more than to his personal appearance, was he indebted for the smiles of Viola. Throughout all the world, throughout all time, beauty has bowed down before courage and strength.

Yellow Jake was our woodman; Black Jake, the curator of the horses, the driver of “white massa’s” barouche.

The story of the two Jakes—their loves and their jealousies—is but a common affair in the petite politique of plantation-life. I have singled it out, not from any separate interest it may possess, but as leading to a series of events that exercised an important influence on my own subsequent history.

The first of these events was as follows; Yellow Jake, burning with jealousy at the success of his rival, had grown spiteful with Viola. Meeting her by some chance in the woods, and far from the house, he had offered her a dire insult. Resentment had rendered him reckless. The opportune arrival of my sister had prevented him from using violence, but the intent could not be overlooked; and chiefly through my sister’s influence, the mulatto was brought to punishment.

It was the first time that Yellow Jake had received chastisement, though not the first time he had deserved it. My father had been indulgent with him; too indulgent, all said. He had often pardoned him when guilty of faults—of crimes. My father was of an easy temper, and had an exceeding dislike to proceed to the extremity of the lash; but in this case my sister had urged, with some spirit, the necessity of the punishment. Viola was her maid; and the wicked conduct of the mulatto could not be overlooked.

The castigation did not cure him of his propensity to evil. An event occurred shortly after, that proved he was vindictive. My sister’s pretty fawn was found dead by the shore of the lake. It could not have died from any natural cause—for it was seen alive, and skipping over the lawn but the hour before. No alligator could have done it, nor yet a wolf. There was neither scratch nor tear upon it; no signs of blood! It must have been strangled.

It was strangled, as proved in the sequel. Yellow Jake had done it, and Black Jake had seen him. From the orange grove, where the latter chanced to be at work, he had been witness of the tragic scene; and his testimony procured a second flogging for the mulatto.

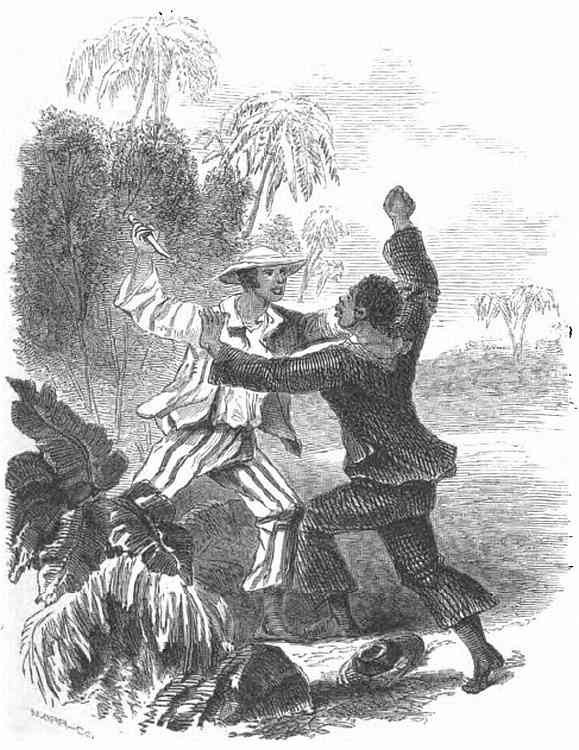

A third event followed close upon the heels of this—a quarrel between negro and mulatto, that came to blows. It had been sought by the latter to revenge himself, at once upon his rival in love, and the witness of his late crime.

The conflict did not end in mere blows. Yellow Jake, with an instinct derived from his Spanish paternity, drew his knife, and inflicted a severe wound upon his unarmed antagonist.

This time his punishment was more severe. I was myself enraged, for Black Jake was my “body guard” and favourite. Though his skin was black, and his intellect but little cultivated, his cheerful disposition rendered him a pleasant companion; he was, in fact, the chosen associate of my boyish days—my comrade upon the water, and in the woods.

Justice required satisfaction, and Yellow Jake caught it in earnest.

The punishment proved of no avail. He was incorrigible. The demon spirit was too strong within him: it was part of his nature.

Chapter Four.

The Hommock.

Just outside the orangery was one of those singular formations—peculiar, I believe, to Florida.

A circular basin, like a vast sugar-pan, opens into the earth, to the depth of many feet, and having a diameter of forty yards or more. In the bottom of this, several cavities are seen, about the size and of the appearance of dug wells, regularly cylindrical—except where their sides have fallen in, or the rocky partition between them has given way, in which case they resemble a vast honeycomb with broken cells.

The wells are sometimes found dry; but more commonly there is water in the bottom, and often filling the great tank itself.

Such natural reservoirs, although occurring in the midst of level plains, are always partially surrounded by eminences—knolls, and detached masses of testaceous rocks; all of which are covered by an evergreen thicket of native trees, as magnolia grandiflora, red bay, zanthoxylon, live-oak, mulberry, and several species of fan-palms (palmettoes). Sometimes these shadowy coverts are found among the trees of the pine-forests, and sometimes they appear in the midst of green savannas, like islets in the ocean.

They constitute the “hommocks” of Florida—famed in the story of its Indian wars.

One of these, then, was situated just outside the orangery; with groups of testaceous rocks forming a half-circle around its edge; and draped with the dark foliage of evergreen trees, of the species already mentioned. The water contained in the basin was sweet and limpid; and far down in its crystal depths might be seen gold and red fish, with yellow bream, spotted bass, and many other beautiful varieties of the finny tribe, disporting themselves all day long. The tank was in reality a natural fishpond; and, moreover, it was used as the family bathing-place—for, under the hot sun of Florida, the bath is a necessity as well as a luxury.

From the house, it was approached by a sanded walk that led across the orangery, and some large stone-flags enabled the bather to descend conveniently into the water. Of course, only the white members of the family were allowed the freedom of this charming sanctuary.

Outside the hommock extended the fields under cultivation, until bounded in the distance by tall forests of cypress and white cedar—a sort of impenetrable morass that covered the country for miles beyond.

On one side of the plantation-fields was a wide plain, covered with grassy turf, and without enclosure of any kind. This was the savanna, a natural meadow where the horses and cattle of the plantation were freely pastured. Deer often appeared upon this plain, and flocks of the wild turkey.

I was just of that age to be enamoured of the chase. Like most youth of the southern states who have little else to do, hunting was my chief occupation; and I was passionately fond of it. My father had procured for me a brace of splendid greyhounds; and it was a favourite pastime with me to conceal myself in the hommock, wait for the deer and turkeys as they approached, and then course them across the savanna. In this manner I made many a capture of both species of game; for the wild turkey can easily be run down with fleet dogs.

The hour at which I was accustomed to enjoy this amusement was early in the morning, before any of the family were astir. That was the best time to find the game upon the savanna.

One morning, as usual, I repaired to my stand in the covert. I climbed upon a rock, whose flat top afforded footing both to myself and my dogs. From this elevated position I had the whole plain under view, and could observe any object that might be moving upon it, while I was myself secure from observation. The broad leaves of the magnolia formed a bower around me, leaving a break in the foliage, through which I could make my reconnoissance.

On this particular morning I had arrived before sunrise. The horses were still in their stables, and the cattle in the enclosure. Even by the deer, the savanna was untenanted, as I could perceive at the first glance. Over all its wide extent not an antler was to be seen.

I was somewhat disappointed on observing this. My mother expected a party upon that day. She had expressed a wish to have venison at dinner: I had promised her she should have it; and on seeing the savanna empty, I felt disappointment.

I was a little surprised, too; the sight was unusual. Almost every morning, there were deer upon this wide pasture, at one point or another.

Had some early stalker been before me? Probable enough. Perhaps young Ringgold from the next plantation; or maybe one of the Indian hunters, who seemed never to sleep? Certainly, some one had been over the ground, and frightened off the game?

The savanna was a free range, and all who chose might hunt or pasture upon it. It was a tract of common ground, belonging to no one of the plantations—government land not yet purchased.

Certainly Ringgold had been there? or old Hickman, the alligator-hunter, who lived upon the skirt of our plantation? or it might be an Indian from the other side of the swamp?

With such conjectures did I account for the absence of the game.

I felt chagrin. I should not be able to keep my promise; there would be no venison for dinner. A turkey I might obtain; the hour for chasing them had not yet arrived. I could hear them calling from the tall tree-tops—their loud “gobbling” borne far and clear upon the still air of the morning. I did not care for these—the larder was already stocked with them; I had killed a brace on the preceding day. I did not want more—I wanted venison.

To procure it, I must needs try some other mode than coursing. I had my rifle with me; I could try a “still-hunt” in the woods. Better still, I would go in the direction of old Hickman’s cabin; he might help me in my dilemma. Perhaps he had been out already? if so, he would be sure to bring home venison. I could procure a supply from him, and keep my promise.—The sun was just shewing his disc above the horizon; his rays were tingeing the tops of the distant cypresses, whose light-green leaves shone with the lines of gold.

I gave one more glance over the savanna, before descending from my elevated position; in that glance I saw what caused me to change my resolution, and remain upon the rock.

A herd of deer was trooping out from the edge of the cypress woods—at that corner where the rail-fence separated the savanna from the cultivated fields.

“Ha!” thought I, “they have been poaching upon the young maize-plants.”

I bent my eyes towards the point whence, as I supposed, they had issued from the fields. I knew there was a gap near the corner, with movable bars. I could see it from where I stood, but I now perceived that the bars were in their places! The deer could not have been in the fields then? It was not likely they had leaped either the bars or the fence. It was a high rail-fence, with “stakes and riders.” The bars were as high as the fence. The deer must have come out of the woods?

This observation was instantly followed by another. The animals were running rapidly, as if alarmed by the presence of some enemy.

A hunter is behind them? Old Hickman? Ringgold? Who?

I gazed eagerly, sweeping my eyes along the edge of the timber, but for a while saw no one.

“A lynx or a bear may have startled them? If so, they will not go far; I shall have a chance with my greyhounds yet. Perhaps—”

My reflections were brought to a sudden termination, on perceiving what had caused the stampede of the deer. It was neither bear nor lynx, but a human being.

A man was just emerging from out the dark shadow of the cypresses. The sun as yet only touched the tops of the trees; but there was light enough below to enable me to make out the figure of a man—still more, to recognise the individual. It was neither Ringgold nor Hickman, nor yet an Indian. The dress I knew well—the blue cottonade trousers, the striped shirt, and palmetto hat. The dress was that worn by our woodman. The man was Yellow Jake.

Chapter Five.

Yellow Jake.

Not without some surprise did I make this discovery. What was the mulatto doing in the woods at such an hour? It was not his habit to be so thrifty; on the contrary, it was difficult to rouse him to his daily work. He was not a hunter—had no taste for it. I never saw him go after game—though, from being always in the woods, he was well acquainted with the haunts and habits of every animal that dwelt there. What was he doing abroad on this particular morning?

I remained on my perch to watch him, at the same time keeping an eye upon the deer.

It soon became evident that the mulatto was not after these; for, on coming out of the timber, he turned along its edge, in a direction opposite to that in which the deer had gone. He went straight towards the gap that fed into the maize-field.

I noticed that he moved slowly and in a crouching attitude. I thought there was some object near his feet: it appeared to be a dog, but a very small one. Perhaps an opossum, thought I. It was of whitish colour, as these creatures are; but in the distance I could not distinguish between an opossum and a puppy. I fancied, however, that it was the pouched animal; that he had caught it in the woods, and was leading it along in a string.

There was nothing remarkable or improbable in all this behaviour. The mulatto may have discovered an opossum-cave the day before, and set a trap for the animal. It may have been caught in the night, and he was now on his way home with it. The only point that surprised me was, that the fellow had turned hunter; but I explained this upon another hypothesis. I remembered how fond the negroes are of the flesh of the opossum, and Yellow Jake was no exception to the rule. Perhaps he had seen, the day before, that this one could be easily obtained, and had resolved upon having a roast?

But why was he not carrying it in a proper manner? He appeared to be leading, or dragging it rather—for I knew the creature would not be led—and every now and then I observed him stoop towards it, as if caressing it.

I was puzzled; it could not be an opossum.

I watched the man narrowly till he arrived opposite the gap in the fence. I expected to see him step over the bars—since through the maize-field was the nearest way to the house. Certainly he entered the field; but, to my astonishment, instead of climbing over in the usual manner, I saw him take out bar after bar, down to the very lowest. I observed, moreover, that he flung the bars to one side, leaving the gap quite open!

He then passed through, and entering among the corn, in the same crouching attitude, disappeared behind the broad blades of the young maize-plants—

For a while I saw no more of him, or the white object that he “toated” along with him in such a singular fashion.

I turned my attention to the deer: they had got over their alarm, and had halted near the middle of the savanna, where they were now quietly browsing.

But I could not help pondering upon the eccentric manoeuvres I had just been witness of; and once more I bent my eyes toward the place, where I had last seen the mulatto.

He was still among the maize-plants. I could see nothing of him; but at that moment my eyes rested upon an object that filled me with fresh surprise.

Just at the point where Yellow Jake had emerged from the woods, something else appeared in motion—also coming out into the open savanna. It was a dark object, and from its prostrate attitude, resembled a man crawling forward upon his hands, and dragging his limbs after him.

For a moment or two, I believed it to be a man—not a white man—but a negro or an Indian. The tactics were Indian, but we were at peace with these people, and why should one of them be thus trailing the mulatto? I say “trailing” for the attitude and motions, of whatever creature I saw, plainly indicated that it was following upon the track which Yellow Jake had just passed over.

Was it Black Jake who was after him?

This idea came suddenly into my mind: I remembered the vendetta that existed between them; I remembered the conflict in which Yellow Jake had used his knife. True, he had been punished, but not by Black Jake himself. Was the latter now seeking to revenge himself in person?

This might have appeared the easiest explanation of the scene that was mystifying me; had it not been for the improbability of the black acting in such a manner. I could not think that the noble fellow would seek any mean mode of retaliation, however revengeful he might feel against one who had so basely attacked him. It was not in keeping with his character. No. It could not be he who was crawling out of the bushes.

Nor he, nor any one.

At that moment, the golden sun flashed over the savanna. His beams glanced along the greensward, lighting the trees to their bases. The dark form emerged from out of the shadow, and turned head towards the maize-field. The long prostrate body glittered under the sun with a sheen like scaled armour. It was easily recognised. It was not negro—not Indian—not human: it was the hideous form of an alligator!

Chapter Six.

The Alligator.

To one brought up—born, I might almost say—upon the banks of a Floridian river, there is nothing remarkable in the sight of an alligator. Nothing very terrible either; for ugly as is the great saurian—certainly the most repulsive form in the animal kingdom—it is least dreaded by those who know it best. For all that, it is seldom approached without some feeling of fear. The stranger to its haunts and habits, abhors and flees from it; and even the native—be he red, white, or black—whose home borders the swamp and the lagoon, approaches this gigantic lizard with caution.

Some closet naturalists have asserted that the alligator will not attack man, and yet they admit that it will destroy horses and horned cattle. A like allegation is made of the jaguar and vampire bat. Strange assertions, in the teeth of a thousand testimonies to the contrary.

It is true the alligator does not always attack man when an opportunity offers—nor does the lion, nor yet the tiger—but even the false Buffon would scarcely be bold enough to declare that the alligator is innocuous. If a list could be furnished of human beings who have fallen victims to the voracity of this creature, since the days of Columbus, it would be found to be something enormous—quite equal to the havoc made in the same period of time by the Indian tiger or the African lion. Humboldt, during his short stay in South America, was well informed of many instances; and for my part, I know of more than one case of actual death, and many of lacerated limbs, received at the jaws of the American alligator.

There are many species, both of the caïman or alligator, and of the true crocodile, in the waters of tropical America. They are more or less fierce, and hence the difference of “travellers’ tales” in relation to them. Even the same species in two different rivers is not always of like disposition. The individuals are affected by outward circumstances, as other animals are. Size, climate, colonisation, all produce their effect; and, what may appear still more singular, their disposition is influenced by the character of the race of men that chances to dwell near them!

On some of the South-American rivers—whose banks are the home of the ill-armed apathetic Indian—the caimans are exceedingly bold, and dangerous to approach. Just so were their congeners, the alligators of the north, till the stalwart backwoodsman, with his axe in one hand, and his rifle in the other, taught them to fear the upright form—a proof that these crawling creatures possess the powers of reason. Even to this hour, in many of the swamps and streams of Florida, full-grown alligators cannot be approached without peril; this is especially the case daring the season of the sexes, and still more where these reptiles are encountered remote from the habitations of man. In Florida are rivers and lagoons where a swimmer would have no more chance of life, than if he had plunged into a sea of sharks.

Notwithstanding all this, use brings one to look lightly even upon real danger—particularly when that danger is almost continuous; and the denizen of the cyprière and the white cedar swamp is accustomed to regard without much emotion the menace of the ugly alligator. To the native of Florida, its presence is no novelty, and its going or coming excites but little interest—except perhaps in the bosom of the black man who feeds upon its tail; or the alligator-hunter, who makes a living out of its leather.

The appearance of one on the edge of the savanna would not have caused me a second thought, had it not been for its peculiar movements, as well as those I had just observed on the part of the mulatto. I could not help fancying that there was some connexion between them; at all events it appeared certain, that the reptile was following the man!

Whether it had him in view, or whether trailing him by the scent, I could not tell. The latter I fancied to be the case; for the mulatto had entered under cover of the maize-plants, before the other appeared outside the timber; and it could hardly have seen him as it turned towards the gap. It might, but I fancied not. More like, it was trailing him by the scent; but whether the creature was capable of doing so, I did not stay to inquire.

On it crawled over the sward—crossing the corner of the meadow, and directly upon the track which the man had taken. At intervals, it paused, flattened its breast against the earth, and remained for some seconds in this attitude, as if resting itself. Then it would raise its body to nearly a yard in height, and move forward with apparent eagerness—as if in obedience to some attractive power in advance of it? The alligator progresses but slowly upon dry ground—not faster than a duck or goose. The water is its true element, where it makes way almost with the rapidity of a fish.

At length it approached the gap; and, after another pause, it drew its long dark body within the enclosure. I saw it enter among the maize-plants, at the exact point where the mulatto had disappeared! Of course, it was now also hidden from my view.

I no longer doubted that the monster was following the man; and equally certain was I that the latter knew that he was followed! How could I doubt either of these facts? To the former, I was an eye-witness; of the latter, I had circumstantial proofs. The singular attitudes and actions of the mulatto; his taking out the bars and leaving the gap free; his occasional glances backward—which I had observed as he was crossing the open ground—these were my proofs that he knew what was coming behind him—undoubtedly he knew.

But my conviction upon these two points in nowise helped to elucidate the mystery—for a mystery it had become. Beyond a doubt, the reptile was drawn after by some attraction, which it appeared unable to resist—its eagerness in advancing was evidence of this, and proved that the man was exercising some influence over it that lured it forward.

What influence? Was he beguiling it by some charm of Obeah?

A superstitious shudder came over me, as I asked myself the question. I really had such fancies at the moment. Brought up, as I had been, among Africans, dandled in the arms—perhaps nourished from the bosom—of many a sable nurse, it is not to be wondered at that my young mind was tainted with the superstitions of Bonny and Benin. I knew there were alligators in the cypress swamp—in its more remote recesses, some of enormous size—but how Yellow Jake had contrived to lure one out, and cause it to follow him over the dry cultivated ground, was a puzzle I could not explain to myself. I could think of no natural cause; I was therefore forced into the regions of the weird and supernatural.

I stood for a long while watching and wondering. The deer had passed out of my mind. They fed unnoticed: I was too much absorbed in the mysterious movements of the half-breed and his amphibious follower.

Chapter Seven.

The Turtle-Crawl.

So long as they remained in the maize-field, I saw nothing of either. The direction of my view was slightly oblique to the rows of the plants. The corn was at full growth, and its tall culms and broad lanceolate leaves would have overtopped the head of a man on horseback. A thicket of evergreen trees would not have been more impenetrable to the eye.

By going a little to the right, I should have become aligned with the rows, and could have seen far down the avenues between them; but this would have carried me out of the cover, and the mulatto might then have seen me. For certain reasons, I did not desire he should; and I remained where I had hitherto been standing.

I was satisfied that the man was still making his way up the field, and would in due time discover himself in the open ground.

An indigo flat lay between the hommock and the maize. To approach the house, it would be necessary for him to pass through the indigo; and, as the plants were but a little over two feet in height, I could not fail to observe him as he came through. I waited, therefore, with a feeling of curious anticipation—my thoughts still wearing a tinge of the weird!

He came on slowly—very slowly; but I knew that he was advancing. I could trace his progress by an occasional movement which I observed among the leaves and tassels of the maize. The morning was still—not a breath of air stirred; and consequently the motion must have been caused by some one passing among the plants—of course by the mulatto himself. The oscillation observed farther off, told that the alligator was still following.

Again and again I observed this movement among the maize-blades. It was evident the man was not following the direction of the rows, but crossing diagonally through them! For what purpose? I could not guess. Any one of the intervals would have conducted him in a direct line towards the house—whither I supposed him to be moving. Why, then, should he adopt a more difficult course, by crossing them? It was not till afterwards that I discovered his object in this zigzag movement.

He had now advanced almost to the nether edge of the cornfield. The indigo flat was of no great breadth, and he was already so near, that I could hear the rustling of the cornstalks as they switched against each other.

Another sound I could now hear; it resembled the howling of a dog. I heard it again, and, after an interval, again. It was not the voice of a full-grown dog, but rather the weak whimper of a puppy.

At first, I fancied that the sounds came from the alligator: for these reptiles make exactly such a noise—but only when young. The one following the mulatto was full-grown; the cries could not proceed from it. Moreover, the sounds came from a point nearer me—from the place where the man himself was moving.

I now remembered the white object I had observed as the man was crossing the corner of the savanna. It was not an opossum, then, but a young dog.

Yes. I heard the cry again: it was the whining of a whelp—nothing else.

If I could have doubted the evidence of my ears, my eyes would soon have convinced me; for, just then, I saw the man emerge from out the maize with a dog by his side—a small white cur, and apparently a young one. He was leading the creature upon a string, half-dragging it after him. I had now a full view of the individual, and saw to a certainty that he was our woodman, Yellow Jake.

Before coming out from the cover of the corn, he halted for a moment—as if to reconnoitre the ground before him. He was upon his feet, and in an erect attitude. Whatever motive he had for concealment, he needed not to crouch amid the tall plants of maize; but the indigo did not promise so good a shelter, and he was evidently considering how to advance through it without being perceived. Plainly, he had a motive for concealing himself—his every movement proved this—but with what object I could not divine.

The indigo was of the kind known as the “false Guatemala.” There were several species cultivated upon the plantation; but this grew tallest; and some of the plants, now in their full purple bloom, stood nearly three feet from the surface of the soil. A man passing through them in an erect attitude, could, of coarse, have been seen from any part of the field; but it was possible for one to crouch down, and move, between the rows unobserved. This possibility seemed to occur to the woodman; for, after a short pause, he dropped to his hands and knees, and commenced crawling forward among the indigo.

There was no fence for him to cross—the cultivated ground was all under one enclosure—and an open ridge alone formed the dividing-line between the two kinds of crop.

Had I been upon the same level with the field, the skulker would have been now hidden from my sight; but my elevated position enabled me to command a view of the intervals between the rows, and I could note every movement he was making.

Every now and then he paused, caught up the cur, and held it for a few seconds in his hands—during which the animal continued to howl as if in pain!

As he drew nearer, and repeated this operation, I saw that he was pinching its ears!

Fifty paces in his rear, the great lizard appeared coming out of the corn. It scarcely made pause in the open ground, but still following the track, entered among the indigo.

At this moment, a light broke upon me; I no longer speculated on the power of Obeah. The mystery was dissolved: the alligator was lured forward by the cries of the dog!

I might have thought of the thing before, for I had heard of it before. I had heard from good authority—the alligator-hunter himself, who had often captured them by such a decoy—that these reptiles will follow a howling dog for miles through the forest, and that the old males especially are addicted to this habit. Hickman’s belief was that they mistake the voice of the dog for that of their own offspring, which these unnatural parents eagerly devour.

But, independently of this monstrous propensity, it is well-known that dogs are the favourite prey of the alligator; and the unfortunate beagle that, in the heat of the chase, ventures across creek or lagoon, is certain to be attacked by these ugly amphibia.

The huge reptile, then, was being lured forward by the voice of the puppy; and this accounted for the grand overland journey he was making.

There was no longer a mystery—at least, about the mode in which the alligator was attracted onward; the only thing that remained for explanation was, what motive had the mulatto in carrying out this singular manoeuvre?

When I saw him take to his hands and knees, I had been under the impression that he did so to approach the house, without being observed. But as I continued to watch him, I changed my mind. I noticed that he looked oftener, and with more anxiety behind him, as if he was only desirous of being concealed from the eyes of the alligator. I observed, too, that he changed frequently from place to place, as if he aimed at keeping a screen of the plants between himself and his follower. This would also account for his having crossed the rows of the maize-plants, as already noticed.

After all, it was only some freak that had entered the fellow’s brain. He had learned this curious mode of coaxing the alligator from its haunts—perhaps old Hickman had shown him how—or he may have gathered it from his own observation, while wood-chopping in the swamps. He was taking the reptile to the house from some eccentric motive?—to make exhibition of it among his fellows?—to have a “lark” with it? or a combat between it and the house-dogs? or for some like purpose?

I could not divine his intention, and would have thought no more of it, had it not been that one or two little circumstances had made an impression upon me. I was struck by the peculiar pains which the fellow was taking to accomplish his purpose with success. He was sparing neither trouble nor time. True, it was not to be a work-day upon the plantation; it was a holiday, and the time was his own; but it was not the habit of Yellow Jake to be abroad at so early an hour, and the trouble he was taking was not in consonance with his character of habitual insouciance and idleness. Some strong motive, then, must have been urging him to the act. What motive?

I pondered upon it, but could not make it out.

And yet I felt uneasiness, as I watched him. It was an undefined feeling, and I could assign no reason for it—beyond the fact that the mulatto was a bad fellow, and I knew him to be capable of almost any wickedness. But if his design was a wicked one, what evil could he effect with the alligator? No one would fear the reptile upon dry ground?—it could hurt no one?

Thus I reflected, and still did I feel some indefinite apprehensions.

But for this feeling I should have given over observing his movements, and turned my attention to the herd of deer—which I now perceived approaching up the savanna, and coming close to my place of concealment.

I resisted the temptation, and continued to watch the mulatto a little longer.

I was not kept much longer in suspense. He had now arrived upon the outer edge of the hommock, which he did not enter. I saw him turn round the thicket, and keep on towards the orangery. There was a wicket at this corner which he passed through, leaving the gate open behind him. At short intervals, he still caused the dog to utter its involuntary howlings.

It no longer needed to cry loudly, for the alligator was now close in the rear.

I obtained a full view of the monster as it passed under my position. It was not one of the largest, though it was several yards in length. There are some that measure more than a statute pole. This one was full twelve feet, from its snout to the extremity of its tail. It clutched the ground with its broad webbed feet as it crawled forward. Its corrugated skin of bluish brown colour was coated with slippery mucus, that glittered under the sun as it moved; and large masses of the swamp-slime rested in the concavities between its rhomboid scales. It seemed greatly excited; and whenever it heard the voice of the dog, exhibited fresh symptoms of rage. It would erect itself upon its muscular arms, raise its head aloft—as if to get a view of the prey—lash its plaited tail into the air, and swell its body almost to double its natural dimensions. At the same time, it emitted loud noises from its throat and nostrils, that resembled the rumbling of distant thunder, and its musky smell filled the air with a sickening effluvium. A more monstrous creature it would be impossible to conceive. Even the fabled dragon could not have been more horrible to behold.

Without stopping, it dragged its long body through the gate, still following the direction of the noise. The leaves of the evergreens intervened, and hid the hideous reptile from my sight.

I turned my face in the opposite direction—towards the house—to watch the further movements of the mulatto. From my position, I commanded a view of the tank, and could see nearly all around it. The inner side was especially under my view, as it lay opposite, and could only be approached through the orangery.

Between the grove and the edge of the great basin, was an open space. Here there was an artificial pond only a few yards in width, and with a little water at the bottom, which was supplied by means of a pump, from the main reservoir. This pond, or rather enclosure, was the “turtle-crawl,” a place in which turtle were fed and kept, to be ready at all times for the table. My father still continued his habits of Virginian hospitality; and in Florida these aldermanic delicacies are easily obtained.

The embankment of this turtle-crawl formed the direct path to the water-basin; and as I turned, I saw Yellow Jake upon it, and just approaching the pond. He still carried the cur in his arms; I saw that he was causing it to utter a continuous howling.

On reaching the steps, that led down, he paused a moment, and looked back. I noticed that he looked back in both ways—first towards the house, and then, with a satisfied air, in the direction whence he had come. No doubt he saw the alligator close at hand; for, without further hesitation, he flung the puppy far out into the water; and then, retreating along the embankment of the turtle-crawl, he entered among the orange-trees, and was out of sight.

The whelp, thus suddenly plunged into the cool tank, kept up a constant howling, at the same time beating the water violently with its feet, in the endeavour to keep itself afloat.

Its struggles were of short duration. The alligator, now guided by the well-known noise of moving water, as well as the cries of the dog, advanced rapidly to the edge; and without hesitating a moment, sprang forward into the pond. With the rapidity of an arrow, it darted out to the centre; and, seizing the victim between its bony jaws, dived instantaneously under the surface.

I could for some time trace its monstrous form far down in the diaphanous water; but guided by instinct, it soon entered one of the deep wells, amidst the darkness of which it sank out of sight.

Chapter Eight.

The King Vultures.

“So, then, my yellow friend, that is the intention!—a bit of revenge after all. I’ll make you pay for it, you spiteful ruffian! You little thought you were observed. Ha! you shall rue this cunning deviltry before night.”

Some such soliloquy escaped my lips, as soon as I comprehended the design of the mulatto’s manoeuvre—for I now understood it—at least I thought so. The tank was full of beautiful fish. There were gold fish and silver fish, hyodons, and red trout. They were my sister’s especial pets. She was very fond of them. It was her custom to visit them daily, give them food, and watch their gambols. Many an aquatic cotillon had she superintended. They knew her person, would follow her around the tank, and take food out of her fingers. She delighted in thus serving them.

The revenge lay in this. The mulatto well knew that the alligator lives upon fish—they are his natural food; and that those in the tank, pent up as they were, would soon become his prey. So strong a tyrant would soon ravage the preserve, killing the helpless creatures by scores—of course to the chagrin and grief of their fond mistress, and the joy of Yellow Jake.

I knew that the fellow disliked my little sister. The spirited part she had played, in having him punished for the affair with Viola, had kindled his resentment against her; but since then, there had been other little incidents to increase it. She had favoured the suit of his rival with the quadroon, and had forbidden the woodman to approach Viola in her presence. These circumstances had certainly rendered the fellow hostile to her; and although there was no outward show of this feeling—there dared not be—I was nevertheless aware of the fact. His killing the fawn had proved it, and the present was a fresh instance of the implacable spirit of the man.

He calculated upon the alligator soon making havoc among the fish. Of course he knew it would in time be discovered and killed; but likely not before many of the finest should be destroyed.

No one would ever dream that the creature had been brought there—for on more than one occasion, alligators had found their way into the tank—having strayed from the river, or the neighbouring lagoons—or rather having been guided thither by an unexplained instinct, which enables these creatures to travel straight in the direction of water.

Such, thought I, were the designs and conjectures of Yellow Jake.

It proved afterwards that I had fathomed but half his plan. I was too young, too innocent of wickedness, even to guess at the intense malice of which the human heart is capable.

My first impulse was to follow the mulatto to the house—make known what he had done—have him punished; and then return with a party to destroy the alligator, before he could do any damage among the fish.

At this crisis, the deer claimed my attention. The herd—an antlered buck with several does—had browsed close up to the hommock. They were within two hundred yards of where I stood. The sight was too tempting. I remembered the promise to my mother; it must be kept; venison must be obtained at all hazards!

But there was no hazard. The alligator had already eaten his breakfast. With a whole dog in his maw, it was not likely he would disturb the finny denizens of the tank for some hours to come; and as for Yellow Jake, I saw he had proceeded on to the house; he could be found at any moment; his chastisement could stand over till my return.

With these reflections passing through my mind, I abandoned my first design, and turned my attention exclusively to the game.

They were too distant for the range of my rifle; and I waited a while in the hope that they would move nearer.

But I waited in vain. The deer is shy of the hommock. It regards the evergreen islet as dangerous ground, and habitually keeps aloof from it. Natural enough, since there the creature is oft saluted by the twang of the Indian bow, or the whip-like crack of the hunter’s rifle. Thence often reaches it the deadly missile.

Perceiving that the game was getting no nearer, but the contrary, I resolved to course them; and, gliding down from the rock, I descended through the copsewood to the edge of plain.

On reaching the open ground, I rushed forward—at the same time unleashing the dogs, and crying the “view hilloo.”

It was a splendid chase—led on by the old buck—the dogs following tail-on-end. I thought I never saw deer run so fleetly; it appeared as if scarcely a score of seconds had transpired while they were crossing the savanna—more than a mile in width. I had a full and perfect view of the whole; there was no obstruction either to run of the animals or the eye of the observer; the grass had been browsed short by the cattle, and not a bush grew upon the green plain; so that it was a trial of pure speed between dogs and deer. So swiftly ran the deer, I began to feel apprehensive about the venison.

My apprehensions were speedily at an end. Just on the farther edge of the savanna, the chase ended—so far at least as the dogs were concerned, and one of the deer. I saw that they had flung a doe, and were standing over her, one of them holding her by the throat.

I hurried forward. Ten minutes brought me to the spot; and after a short struggle, the quarry was killed, and bled.

I was satisfied with my dogs, with the sport, with my own exploits. I was happy at the prospect of being able to redeem my promise; and with the carcass across my shoulders, I turned triumphantly homeward.

As I faced round, I saw the shadow of wings moving over the sunlit savanna. I looked upward. Two large birds were above me in the air; they were at no great height, nor were they endeavouring to mount higher. On the contrary, they were wheeling in spiral rings, that seemed to incline downward at each successive circuit they made around me.

At first glance, the sun’s beams were in my eyes, and I could not tell what birds were flapping above me. On facing round, I had the sun in my favour; and his rays, glancing full upon the soft cream-coloured plumage, enabled me to recognise the species—they were king vultures—the most beautiful birds of their tribe, I am almost tempted to say the most beautiful birds in creation; certainly they take rank, among those most distinguished in the world of ornithology.

These birds are natives of the flowery land, but stray no farther north. Their haunt is on the green “everglades” and wide savannas of Florida, on the llanos of the Orinoco, and the plains of the Apure. In Florida they are rare, though not in all parts of it; but their appearance in the neighbourhood of the plantations excites an interest similar to that which is occasioned by the flight of an eagle. Not so with the other vultures—Cathartes aura and atratus—both of which are as common as crows.

In proof that the king vultures are rare, I may state that my sister had never seen one—except at a great distance off; yet this young lady was twelve years of age, and a native of the land. True, she had not gone much abroad—seldom beyond the bounds of the plantation. I remembered her expressing an ardent desire to view more closely one of these beautiful birds. I remembered it that moment; and at once formed the design of gratifying her wish.

The birds were near enough—so near that I could distinguish the deep yellow colour of their throats, the coral red upon their crowns, and the orange lappets that drooped along their beaks. They were near enough—within half reach of my rifle—but moving about as they were, it would have required a better marksman than I to have brought one of them down with a bullet.

I did not think of trying it in that way. Another idea was in my mind; and without farther pause, I proceeded to carry it out.

I saw that the vultures had espied the body of the doe, where it lay across my shoulders. That was why they were hovering above me. My plan was simple enough. I laid the carcass upon the earth; and, taking my rifle, walked away towards the timber.

Trees grew at fifty yards’ distance from where I had placed the doe; and behind the nearest of these I took my stand.

I had not long to wait. The unconscious birds wheeled lower and lower, and at length one alighted on the earth. Its companion had not time to join it before the rifle cracked, and laid the beautiful creature lifeless upon the grass.

The other, frighted by the sound, rose higher and higher, and then flew away over the tops of the cypresses.

Again I shouldered my venison; and carrying the bird in my hand started homeward.

My heart was full of exultation. I anticipated a double pleasure—from the double pleasure I was to create. I should make happy the two beings that, of all on earth, were dearest to me—my fond mother, my beautiful sister.

I soon recrossed the savanna, and entered the orangery. I did not stay to go round by the wicket, but climbed over the fence at its lower end. So happy was I that my load felt light as a feather. Exultingly I strode forward, dashing the loaded boughs from my path. I sent their golden globes rolling hither and thither. What mattered a bushel of oranges?

I reached the parterre. My mother was in the verandah; she saw me as I approached, and uttered an exclamation of joy. I flung the spoils of the chase at her feet. I had kept my promise.

“What is that?—a bird?”

“Yes the king vulture—a present for Virgine. Where is she? Not up yet? Ha! the little sluggard—I shall soon arouse her. Still abed and on such a beautiful morning!”

“You wrong her, George; she has been up on hour or more. She has been playing; and has just this moment left off.”

“But where is she now? In the drawing-room?”

“No; she has gone to the bath.”

“To the bath!”

“Yes, she and Viola. What—”

“O mother—mother—”

“Tell me, George—”

“O heavens—the alligator!”

Chapter Nine.

The Bath.

“Yellow Jake! the alligator!”

They were all the words I could utter. My mother entreated an explanation; I could not stay to give it. Frantic with apprehension, I tore myself away, leaving her in a state of terror that rivalled my own.

I ran towards the hommock—the bath. I wait not to follow the devious route of the walk, but keep straight on, leaping over such obstacles as present themselves. I spring across the paling, and rush through the orangery, causing the branches to crackle and the fruit to fall. My ears are keenly bent to catch every sound.

Behind are sounds enough: I hear my mother’s voice uttered in accents of terror. Already have her cries alarmed the house, and are echoed and answered by the domestics, both females and men. Dogs, startled by the sudden excitement, are baying within the enclosure, and fowls and caged birds screech in concert.

From behind come all these noises. It is not for them my ears are bent; I am listening before me.

In this direction I now hear sounds. The plashing of water is in my ears, and mingling with the tones of a clear silvery voice—it is the voice of my sister! “Ha, ha, ha!” The ring of laughter! Thank Heaven, she is safe!

I stay my step under the influence of a delicate thought; I call aloud:

“Virgine! Virgine!”

Impatiently I wait the reply. None reaches me; the noise of the water has drowned my voice!

I call again, and louder: “Virgine! sister! Virgine!”

I am heard, and hear:

“Who calls? You, Georgy?”

“Yes; it is I, Virgine.”

“And pray, what want you, brother?”

“O sister! come out of the bath.”

“For what reason should I? Our friends come? They are early: let them wait, my Georgy. Go you and entertain them. I mean to enjoy myself this most beautiful of mornings; the water’s just right—delightful! Isn’t it, Viola? Ho! I shall have a swim round the pond: here goes?”

And then there was a fresh plashing in the water, mingled with a cheerful abandon of laughter in the voices of my sister and her maid.

I shouted at the top of my voice:

“Hear me, Virgine, dear sister! For Heaven’s sake, come out! come—”

There was a sudden cessation of the merry tones; then came a short sharp ejaculation, followed almost instantaneously by a wild scream. I perceived that neither was a reply to my appeal. I had called out in a tone of entreaty sufficient to have raised apprehension; but the voices that now reached me were uttered in accents of terror. In my sister’s voice I heard the words:

“See, Viola! O mercy—the monster! Ha! he is coming this way! O mercy! Help, George, help! Save—save me!”

Well knew I the meaning of the summons; too well could I comprehend the half-coherent words, and the continued screaming that succeeded them.

“Sister, I come, I come!”

Quick as thought, I dashed forward, breaking through the boughs that still intercepted my view.

“Oh, perhaps I shall be too late! She screams in agony; she is already in the grasp of the alligator?”

A dozen bounds carried me clear of the grove; and, gliding along the embankment of the turtle-crawl, I stood by the edge of the tank. A fearful tableau was before me.

My sister was near the centre of the basin, swimming towards the edge. There stood the quadroon—knee deep—screeching and flinging her arms frantically in the air. Beyond, appeared the gigantic lizard; his whole body, arms, hands, and claws clearly traceable in the pellucid water, above the surface of which rose the scaly serrature of his back and shoulders. His snout and tail projected still higher; and with the latter he was lashing the water into white froth, that already mottled the surface of the pond. He was not ten feet from his intended victim. His gaunt jaws almost touched the green baize skirt that floated train-like behind her. At any moment, he might have darted forward and seized her.

My sister was swimming with all her might. She was a capital swimmer; but what could it avail? Her bathing-dress was impeding her; but what mattered that? The alligator might have seized her at any moment; with a single effort, could have caught her, and yet he had not made it.

I wondered why he had not; I wondered that he still held back. I wonder to this hour, for it is not yet explained. I can account for it only on one supposition: that he felt that his victim was perfectly within his power; and as the cat cajoles with the mouse, so was he indulging in the plenitude of his tyrant strength.

These observations were made in a single second of time—while I was cocking my rifle.

I aimed, and fired. There were but two places where the shot could have proved fatal—the eye or behind the forearm. I aimed for the eye. I hit the shoulder; but from that hard corrugated skin, my bullet glinted as from a granite rock. Among the rhomboid protuberances it made a whitish score, and that was all.

The play of the monster was brought to a termination. The shot appeared to have given him pain. At all events, it roused him to more earnest action, and perhaps impelled him to the final spring. He made it the instant after.

Lashing the water with his broad tail—as if to gain impetus—he darted forward; his huge jaw hinged vertically upward, till the red throat showed wide agape; and the next moment the floating skirt—and oh! the limbs of my sister, were in his horrid gripe!

I plunged in, and swam towards them. The gun I still carried in my grasp. It hindered me. I dropped it to the bottom, and swam on.

I caught Virgine in my arms. I was just in time, for the alligator was dragging her below.

With all my strength, I held her up. It needed all to keep us above the surface. I had no weapon; and if I had been armed, I could not have spared a hand to strike.

I shouted with all my voice, in the hope of intimidating the assailant, and causing him to let go his hold. It was to no purpose: he still held on.

O Heavens! we shall both be dragged under—drowned—devoured—

A plunge, as of one leaping from a high elevation into the pond—a quick, bold swimmer from the shore—a dark-skinned face, with long black hair that floats behind it on the water—a breast gleaming with bright spangles—a body clad in bead-embroidered garments—a man? a boy!

Who is this strange youth that rushes to our rescue?

He is already by our side—by the side of our terrible antagonist. With all the earnest energy of his look, he utters not a word. He rests one hand upon the shoulder of the huge lizard, and with a sudden spring places himself upon its back. A rider could not have leaped more adroitly to the saddle.

A knife gleams in his uplifted hand. It descends—its blade is buried in the eye of the alligator!

The roar of the saurian betokens its pain. The earth vibrates with the sound; the froth flies up under the lashings of its tail, and a cloud of spray is flung over us. But the monster has now relaxed its gripe, and I am swimming with my sister to the shore.

A glance backward reveals to me a strange sight—I see the alligator diving to the bottom with the bold rider upon its back! He is lost—he is lost!

With painful thoughts, I swim on. I climb out, and place my fainting sister upon the bank. I again look back.

Joy, joy! the strange youth is once more above the surface, and swimming freely to the shore. Upon the further side of the pond, the hideous form is also above water, struggling by the edge—frantic and furious with the agony of its wounds.

Joy, joy! my sister is unharmed. The floating skirt has saved her; scarcely a scratch shows upon her delicate limbs; and now in tender arms, amidst sweet words and looks of kind sympathy, she is borne away from the scene of her peril.

Chapter Ten.

The “Half-Blood.”

The alligator was soon clubbed to death, and dragged to the shore—a work of delight to the blacks of the plantation.

No one suspected how the reptile had got to the pond—for I had not said a word to any one. The belief was that it had wandered there from the river, or the lagoons—as others had done before; and Yellow Jake, the most active of all in its destruction, was heard several times repeating this hypothesis! Little did the villain suspect that his secret was known. I thought that besides himself I was the only one privy to it; in this, however, I was mistaken.

The domestics had gone back to the house, “toating” the huge carcass with ropes, and uttering shouts of triumph. I was alone with our gallant preserver. I stayed behind purposely to thank him.

Mother, father, all had given expression to their gratitude; all had signified their admiration of his gallant conduct: even my sister, who had recovered consciousness before being carried away, had thanked him with kind words.

He made no reply, further than to acknowledge the compliments paid him; and this he did either by a smile or a simple inclination of the head. With the years of a boy, he seemed to possess the gravity of a man.

He appeared about my own age and size. His figure was perfectly proportioned, and his face handsome. The complexion was not that of a pure Indian, though the style of his dress was so. His skin was nearer brunette than bronze: he was evidently a “half-blood.”

His nose was slightly aquiline, which gave him that fine eagle-look peculiar to some of the North American tribes; and his eye, though mild in common mood, was easily lighted up. Under excitement, as I had just witnessed, it shone with the brilliancy of fire.

The admixture of Caucasian blood had tamed down the prominence of Indian features to a perfect regularity, without robbing them of their heroic grandeur of expression; and the black hair was finer than that of the pure native, though equally shining and luxuriant. In short, the tout ensemble of this strange youth was that of a noble and handsome boy that another brace of summers would develop into a splendid-looking man. Even as a boy, there was an individuality about him, that, when once seen, was not to be forgotten.

I have said that his costume was Indian. So was it—purely Indian—not made up altogether of the spoils of the chase, for the buckskin has long, ceased to be the wear of the aborigines of Florida. His moccasins alone were of dressed deer’s hide; his leggings were of scarlet cloth; and his tunic of figured cotton stuff—all three elaborately beaded and embroidered. With these he wore a wampum belt, and a fillet encircled his head, above which rose erect three plumes from the tail of the king vulture—which among Indians is an eagle. Around his neck were strings of party-coloured beads, and upon his breast three demi-lunes of silver, suspended one above the other.

Thus was the youth attired, and, despite the soaking which his garments had received, he presented an aspect as once noble and picturesque.

“You are sure you have received no injury?” I inquired for the second time.

“Quite sure—not the slightest injury.”

“But you are wet through and through; let me offer you a change of clothes: mine, I think, would about fit you.”

“Thank you. I should not know how to wear them. The sun is strong: my own will soon be dry again.”

“You will come up to the house, and eat something?”

“I have eaten but a short while ago. I thank you. I am not in need.”

“Some wine?”

“Again I thank you—water is my only drink.”

I scarcely knew what to say to my new acquaintance. He refused all my offers of hospitality, and yet he remained by me. He would not accompany me to the house; and still he showed no signs of taking his departure.

Was he expecting something else? A reward for his services? Something more substantial than complimentary phrases?

The thought was not unnatural. Handsome as was the youth, he was but an Indian. Of compliments he had had enough. Indians care little for idle words. It might be that he waited for something more; it was but natural for one in his condition to do so, and equally natural for one in mine to think so.

In an instant my purse was out; in the next it was in his hands—and in the next it was at the bottom of the pond!

“I did not ask you for money,” said he, as he flung the dollars indignantly into the water.

I felt pique and shame; the latter predominated. I plunged into the pond, and dived under the surface. It was not after my purse, but my rifle, which I saw lying upon the rocks at the bottom. I gained the piece, and, carrying it ashore, handed it to him.

The peculiar smile with which he received it, told me that I had well corrected my error, and subdued the capricious pride of the singular youth.

“It is my turn to make reparation,” said he. “Permit me to restore you your purse, and to ask pardon for my rudeness.”