автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Trails of the Pathfinders

E-text prepared by Larry B. Harrison, Charlie Howard,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

from page images generously made available by

Internet Archive

(https://archive.org)

Note:

Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See

https://archive.org/details/trailsofpathfind00grinrichIN THE SAME SERIES

Published by CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

The Boy’s Catlin. My Life Among the Indians, by George Catlin. Edited by Mary Gay Humphreys. Illustrated. 12mo. net $1.50

The Boy’s Hakluyt. English Voyages of Adventure and Discovery, retold from Hakluyt by Edwin M. Bacon. Illustrated. 12mo. net $1.50

The Boy’s Drake. By Edwin M. Bacon. Illustrated. 12mo. net $1.50

Trails of the Pathfinders. By George Bird Grinnell. Illustrated. 12mo. net $1.50

TRAILS OF THE PATHFINDERS

CAPTAINS LEWIS AND CLARK WERE MUCH PUZZLED AT THIS POINT TO KNOW WHICH OF THE RIVERS BEFORE THEM WAS THE MAIN MISSOURI.

TRAILS OF

THE PATHFINDERS

BY

GEORGE BIRD GRINNELL

AUTHOR OF “BLACKFOOT LODGE TALES,” “PAWNEE HERO STORIES AND FOLK TALES,” “THE STORY OF THE INDIAN,” “INDIANS OF TODAY,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1911

Copyright, 1911, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Published April, 1911

PREFACE

The chapters in this book appeared first as part of a series of articles under the same title contributed to Forest and Stream several years ago. At the time they aroused much interest and there was a demand that they should be put into book form.

The books from which these accounts have been drawn are good reading for all Americans. They are at once history and adventure. They deal with a time when half the continent was unknown; when the West—distant and full of romance—held for the young, the brave and the hardy, possibilities that were limitless.

The legend of the kingdom of El Dorado did not pass with the passing of the Spaniards. All through the eighteenth and a part of the nineteenth century it was recalled in another sense by the fur trader, and with the discovery of gold in California it was heard again by a great multitude—and almost with its old meaning.

Besides these old books on the West, there are many others which every American should read. They treat of that same romantic period, and describe the adventures of explorers, Indian fighters, fur hunters and fur traders. They are a part of the history of the continent.

New York, April, 1911.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

PAGE

I.

Introduction 3II.

Alexander Henry—I

13III.

Alexander Henry—II

36IV.

Jonathan Carver 57V.

Alexander Mackenzie—I

84VI.

Alexander Mackenzie—II

102VII.

Alexander Mackenzie—III

121VIII.

Lewis and Clark—I

138IX.

Lewis and Clark—II

154X.

Lewis and Clark—III

169XI.

Lewis and Clark—IV

179XII.

Lewis and Clark—V

190XIII.

Zebulon M. Pike—I

207XIV.

Zebulon M. Pike—II

226XV.

Zebulon M. Pike—III

238XVI.

Alexander Henry(

The Younger)—I

253XVII.

Alexander Henry(

The Younger)—II

271XVIII.

Alexander Henry(

The Younger)—III

287XIX.

Ross Cox—I

301XX.

Ross Cox—II

319XXI.

The Commerce of the Prairies—I

330XXII.

The Commerce of the Prairies—II

341XXIII.

Samuel Parker 359XXIV.

Thomas J. Farnham—I

372XXV.

Thomas J. Farnham—II

382XXVI.

Fremont—I

393XXVII.

Fremont—II

405XXVIII.

Fremont—III

415XXIX.

Fremont—IV

428XXX.

Fremont—V

435CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER II

ALEXANDER HENRY I

CHAPTER III

ALEXANDER HENRY II

CHAPTER IV

JONATHAN CARVER

CHAPTER V

ALEXANDER MACKENZIE I

CHAPTER VI

ALEXANDER MACKENZIE II

CHAPTER VII

ALEXANDER MACKENZIE III

CHAPTER VIII

LEWIS AND CLARK I

CHAPTER IX

LEWIS AND CLARK II

CHAPTER X

LEWIS AND CLARK III

CHAPTER XI

LEWIS AND CLARK IV

CHAPTER XII

LEWIS AND CLARK V

CHAPTER XIII

ZEBULON M. PIKE I

CHAPTER XIV

ZEBULON M. PIKE II

CHAPTER XV

ZEBULON M. PIKE III

CHAPTER XVI

ALEXANDER HENRY (THE YOUNGER) I

CHAPTER XVII

ALEXANDER HENRY (THE YOUNGER) II

CHAPTER XVIII

ALEXANDER HENRY (THE YOUNGER) III

CHAPTER XIX

ROSS COX I

CHAPTER XX

ROSS COX II

CHAPTER XXI

THE COMMERCE OF THE PRAIRIES I

CHAPTER XXII

THE COMMERCE OF THE PRAIRIES II

CHAPTER XXIII

SAMUEL PARKER

CHAPTER XXIV

THOMAS J. FARNHAM I

CHAPTER XXV

THOMAS J. FARNHAM II

CHAPTER XXVI

FREMONT I

CHAPTER XXVII

FREMONT II

CHAPTER XXVIII

FREMONT III

CHAPTER XXIX

FREMONT IV

CHAPTER XXX

FREMONT V

ILLUSTRATIONS

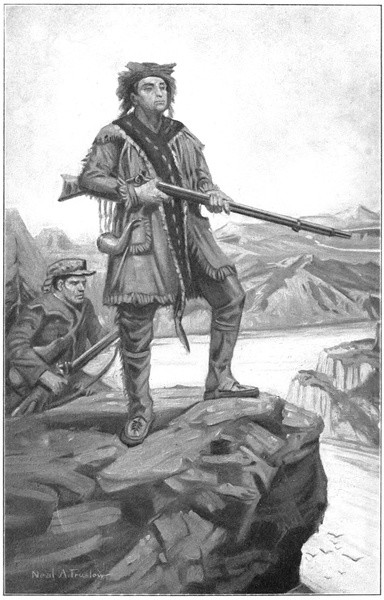

Captains Lewis and Clark Were Much Puzzled at This Point to Know Which of the Rivers Before Them Was the Main Missouri FrontispieceFACING PAGE

“

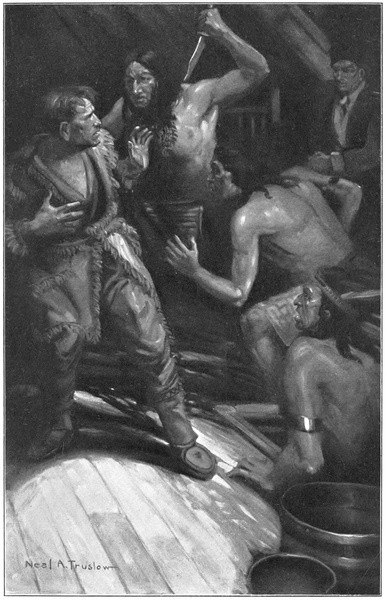

I Now Resigned Myself to the Fate with Which I Was Menaced”

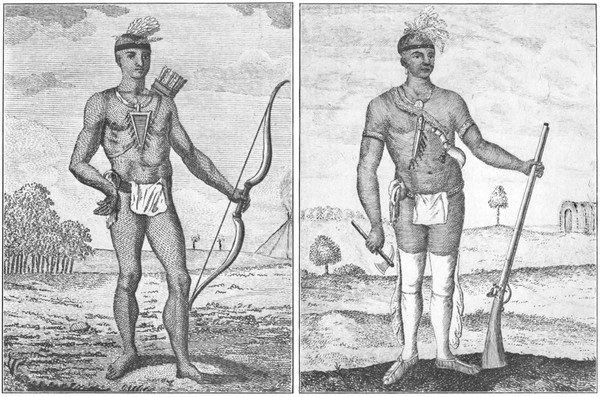

28 A Man of the NaudowessieFrom

Travels Through the Interior Parts of North America, by Jonathan Carver

62 A Man of the OttigaumiesFrom

Travels Through the Interior Parts of North America, by Jonathan Carver

62 Alexander MackenzieFrom Mackenzie’s

Voyages from Montreal Through the Continent of North America, etc.

84 Mackenzie and the Men Jumped Overboard 118 Lieutenant Zebulon Montgomery Pike, Monument at Colorado Springs, Colorado 208 Buffalo on the Southern PlainsFrom Kendall’s

Narrative of the Texas Santa Fé Expedition 236 Two Men Mounted on Her Back, but She Was as Active with This Load as Before 270 Fur Traders of the North 280 Astoria in 1813From Franchere’s

Narrative of a Voyage to the Northwest Coast of America 302 Caravan on the MarchFrom Gregg’s

Commerce of the Prairies 334 Wagons Parked for the NightFrom Gregg’s

Commerce of the Prairies 340 Trappers Attacked by IndiansFrom an old print by A. Tait

360 Train Stampeded by Wild HorsesFrom Bartlett’s

Texas, New Mexico, California, etc.

372 Major-General John C. Fremont 394 An Oto CouncilFrom James’s

An Expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains by Major Stephen H. Long.

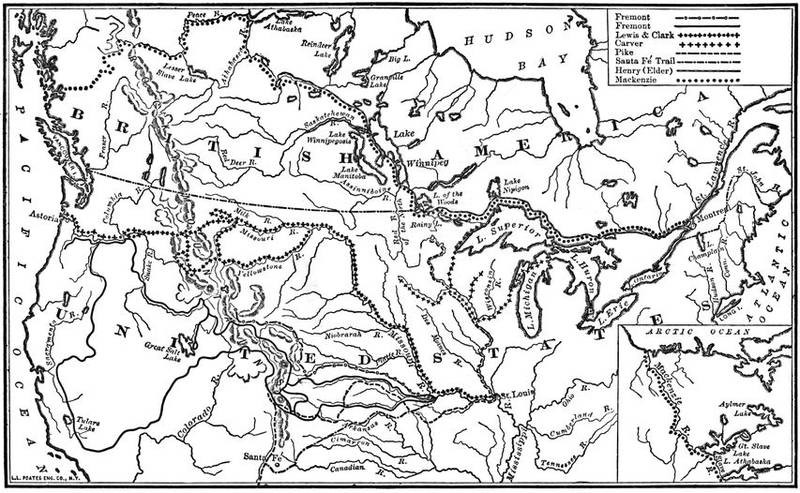

414MAP

PAGE

Routes of Some of the Pathfinders 2“I NOW RESIGNED MYSELF TO THE FATE WITH WHICH I WAS MENACED.”

A MAN OF THE NAUDOWESSIE.

A MAN OF THE OTTIGAUMIES.

From Travels Through the Interior Parts of North America, by Jonathan Carver.

ALEXANDER MACKENZIE.

From Mackenzie’s Voyages from Montreal Through the Continent of North America, etc.

MACKENZIE AND THE MEN JUMPED OVERBOARD.

LIEUTENANT ZEBULON MONTGOMERY PIKE, MONUMENT AT COLORADO SPRINGS, COLORADO.

BUFFALO ON THE SOUTHERN PLAINS.

From Kendall’s Narrative of the Texas Santa Fé Expedition.

TWO MEN MOUNTED ON HER BACK, BUT SHE WAS AS ACTIVE WITH THIS LOAD AS BEFORE.

FUR TRADERS OF THE NORTH.

ASTORIA IN 1813.

From Franchere’s Narrative of a Voyage to the Northwest Coast of America.

CARAVAN ON THE MARCH.

From Gregg’s Commerce of the Prairies.

WAGONS PARKED FOR THE NIGHT.

From Gregg’s Commerce of the Prairies.

TRAPPERS ATTACKED BY INDIANS.

From an old print by A. Tait.

TRAIN STAMPEDED BY WILD HORSES.

From Bartlett’s Texas, New Mexico, California, etc.

MAJOR-GENERAL JOHN C. FREMONT.

AN OTO COUNCIL.

From James’s An Expedition from Pittsburgh to the Rocky Mountains by Major Stephen H. Long.

ROUTES OF SOME OF THE PATHFINDERS

TRAILS OF THE PATHFINDERS

ROUTES OF SOME OF THE PATHFINDERS

TRAILS OF THE PATHFINDERS

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

Three centuries ago half a dozen tiny hamlets, peopled by white men, were scattered along the western shores of the North Atlantic Ocean. These little settlements owed allegiance to different nations of Europe, each of which had thrust out a hand to grasp some share of the wealth which might lie in the unknown wilderness which stretched away from the seashore toward the west.

The “Indies” had been discovered more than a hundred years before, but though ships had sailed north and ships had sailed south, little was known of the land, through which men were seeking a passage to share the trade which the Portuguese, long before, had opened up with the mysterious East. That passage had not been found. To the north lay ice and snow, to the south—vaguely known—lay the South Sea. What that South Sea was, what its limits, what its relations to lands already visited, were still secrets.

St. Augustine had been founded in 1565; and forty years later the French made their first settlement at Port Royal in what is now Nova Scotia. In 1607 Jamestown was settled; and a year later the French established Quebec. The Pilgrims landed in Massachusetts in 1620 and the first settlement of the Dutch on the island of Manhattan was in 1623. All these settlers establishing themselves in a new country found enough to do in the struggle to procure subsistence, to protect themselves from the elements and from the attacks of enemies, without attempting to discover what lay inland—beyond the sound of the salt waves which beat upon the coast. Not until later was any effort made to learn what lay in the vast interior.

Time went on. The settlements increased. Gradually men pushed farther and farther inland. There were wars; and one nation after another was crowded from its possessions, until, at length, the British owned all the settlements in eastern temperate America. The white men still clung chiefly to the sea-coast, and it was in western Pennsylvania that the French and Indians defeated Braddock in 1755, George Washington being an officer under his command.

A little later came the war of the Revolution, and a new people sprang into being in a land a little more than two hundred and fifty years known. This people, teeming with energy, kept reaching out in all directions for new things. As they increased in numbers they spread chiefly in the direction of least resistance. The native tribes were easier to displace than the French, who held forts to the north, and the Spanish, who possessed territory to the south; and the temperate climate toward the west attracted them more than the cold of the north or the heat of the south. So the Americans pushed on always to the setting sun, and their early movements gave truth to Bishop Berkeley’s famous line, written long before and in an altogether different connection, “Westward the course of empire takes its way.” The Mississippi was reached, and little villages, occupied by Frenchmen and their half-breed children, began to change, to be transformed into American towns. Yet in 1790, ninety-five per cent. of the population of the United States was on the Atlantic seaboard.

Now came the Louisiana Purchase, and immediately after that the expedition across the continent by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. The trip took two years’ time, and the reports brought back by the intrepid explorers, telling the wonderful story of what lay in the unknown beyond, greatly stimulated the imagination of the western people. Long before this it had become known that the western ocean—the South Sea of an earlier day—extended north along the continent, and that there was no connection here with India. It was known, too, that the Spaniards occupied the west coast. In 1790, Umfreville said: “That there are European traders settled among the Indians from the other side of the continent is without doubt. I, myself, have seen horses with Roman capitals burnt in their flanks with a hot iron. I likewise once saw a hanger with Spanish words engraved on the blade. Many other proofs have been obtained to convince us that the Spaniards on the opposite side of the continent make their inland peregrinations as well as ourselves.”

Western travel and exploration, within the United States, began soon after the return of Lewis and Clark. The trapper, seeking for peltry—the rich furs so much in demand in Europe—was the first to penetrate the unknown wilds; but close upon his heels followed the Indian trader, who used trapper and Indian alike to fill his purse. With the trapper and the trader, naturalists began to push out into the west, studying the fauna and flora of the new lands. About the same time the possibilities of trade with the Mexicans induced the beginnings of the Santa Fé trade, that Commerce of the Prairies which has been so fully written of by the intrepid spirits who took part in it. Meantime the government continued to send out expeditions, poorly provided in many ways, scarcely armed, barely furnished with provisions, without means of making their way through the unknown and dangerous regions to which they were sent, but led by heroes.

For forty years this work of investigation went on; for forty years there took place a peopling of the new West by men who were in very deed the bravest and most adventurous of our brave and hardy border population. They scattered over the plains and through the mountains; they trapped the beaver and fought the Indian and guided the explorers; and took to themselves wives from among their very enemies, and raised up broods of hardy offspring, some of whom we may yet meet as we journey through the cattle and the farming country which used to be the far West.

If ever any set of men played their part in subduing the wilderness, and in ploughing the ground to receive its seed of settlement, and to rear the crop of civilization which is now being harvested, these men did that work, and did it well. It is inconceivable that they should have had the foresight to know what they were doing; to imagine what it was that should come after them. They did not think of that. Like the bold, brave, hardy men of all times and of all countries, they did the work that lay before them, bravely, faithfully, and well, without any special thought of a distant future; surely without any regrets for the past. As the years rolled by, sickness, battle, the wild beast, starvation, murder, death in some form, whether sudden or lingering, struck them down singly or by scores; and that a man had been “rubbed out,” was cause for a sigh of regret or a word of sorrow from his companions, who forthwith saddled up and started on some journey of peril, where their fate might be what his had been.

At the end of forty years the first series of these exploratory journeys came to an end. Gold was discovered in California. The Mexican War took place. This was not unexpected, for in the Southwest, about the pueblos of Taos and Santa Fé, skirmishings and quarrels between the Spanish-Indian inhabitants and the rough mountaineers and teamsters from the States had already given warning of a conflict soon to come.

Now, well travelled wagon roads crossed the continent, and a stream of westward immigration that seemed to have no end. Before long there came Indian wars. The immigrants imposed upon the savages, ill-treated their wives, and were truculent and over-bearing to their men. The Indians stole from the immigrants, and drove off their horses. Then began a season of conflict which, by one tribe and another, yet with many intermissions, lasted almost down to our own day. For the most part, these Indian wars are well within the memory of living men. They have been told of by those who saw them and were a part of them.

Of the travellers who marched westward over the arid plains, during the period which intervened between the return of Lewis and Clark and the establishment of the old California trail, and of the earlier northmen who trafficked for the beaver in Canada, a few left records of their journeys; and of these records many are most interesting reading, for they are simple, faithful narratives of the every-day life of travellers through unknown regions. To Americans they are of especial interest, for they tell of a time when one-half of the continent which now teems with population had no inhabitants. The acres which now contribute freely of food that supplies the world; the mountains which now echo to the rattle of machinery, and the shot of the blasts which lay bare millions worth of precious metal; the waters which are churned by propeller blades, transporting all the varied products of the land to their markets; the forests, which, alas! in too many sections, no longer rustle to the breeze, but have been swept away to make room for farms and town sites—all these were then undisturbed and natural, as they had been for a thousand years. Of the travellers who passed over the vast stretches of prairie or mountain or woodland, many saw the possibilities of this vast land, and prophesied as to what might be wrought here, when, in the dim and distant future, which none could yet foresee, settlements should have pushed out from the east and occupied the land. Other travellers declared that these barren wastes would ever prove a barrier to westward settlement.

The books that were written concerning this new land are mostly long out of print, or difficult of access; yet each one of them is worth perusal. Of their authors, some bear names still familiar, even though their works have been lost sight of. Some of them made discoveries of great interest in one branch or other of science. At a later day some attained fame. Parkman’s first essay in literature was his story of The California and Oregon Trail, a fitting introduction to the many fascinating volumes that he contributed later to the early history of America; while in Washington Irving, historian and essayist, was found a narrator who should first tell connectedly of the fur trade of the Northwest, and the adventures of Bonneville.

Besides the books that were published in those times, there were also written accounts, usually in the form of diaries, or of notes kept from day to day of the happenings in the life of this or that individual, which are full of interest, because they give us pictures of one or another phase of early travel, or hunting adventures, or of trading with the Indians. Such private and personal accounts, never intended for the public eye, are to-day of extreme interest; and it is fortunate that an American student, the late Dr. Elliott Coues, has given us volumes which tell the stories of Lewis and Clark, Pike and Garces, of Jacob Fowler, of Alexander Henry the younger, and of Charles Larpenteur—contributions to the history of the winning of the greater West whose value is only now beginning to be appreciated.

The chapters that follow contain much of history which is old, but which, to the average American, will prove absolutely new. One may imagine himself very much interested in the old West, familiar with its history and devoted to its study, but it is not until he has gone through volume after volume of this ancient literature that he realizes how greatly his knowledge lacks precision and how much he still has to learn concerning the country he inhabits.

The work that the early travellers did, and the books they published, showed to the people of their day the conditions which existed in the far West, caused its settlement, and led to the slow discovery of its mineral treasures, and the slower appreciation of its possibilities to the farmer and stock-raiser. Each of these volumes had its readers, and of the readers of each we may be sure that a few, or many, attracted by the graphic descriptions of the new land, determined that they, too, would push out into it; they, too, would share in the wealth which it spread out with lavish hand.

It is all so long ago that we who are busy with a thousand modern interests care little about who contributed to the greatness of the country which we inhabit and the prosperity which we enjoy. But there was a day, which men alive may still remember, a day of strong men, of brave women, hardy pioneers, and true hearts, who ventured forth into the wilderness, braving many dangers that were real, and many more that were imaginary and yet to them seemed very real, occupied the land, broke up the virgin soil, and peopled a wilderness.

How can the men and women of this generation—dwellers in cities, or in peaceful villages, or on smiling farms—realize what those pioneers did—how they lived? He must have possessed stern resolution and firm courage, who, to better the condition of those dearest to him, risked their comfort—their very lives—on the hazard of a settlement in the unknown wilderness. The woman who accompanied this man bore an equal part in the struggle, with devoted helpfulness encouraging him in his strife with nature or cheering him in defeat. If the school of self-reliance and hardihood in which their children were reared gave them little of the lore of books, it built strong characters and made them worthy successors of courageous parents. We may not comprehend how long and fierce was the struggle with the elements, with the bristling forest, with the unbroken soil; how hard and wearing the annoyance of wild beasts, the anxiety as to climate, the fear of the prowling savage. Yet the work was done, and to-day, from the Alleghanies to the Pacific, we behold its results.

Through hard experience these pioneers had come to understand life. They possessed a due sense of proportion. They saw the things which were essential; they scorned those which were trivial. If, judged by certain standards, they were rough and uncouth, if they spoke a strange tongue, wore odd apparel, and lived narrow lives, they were yet practising—albeit unconsciously—the virtues—unflinching courage, sturdy independence and helpfulness to their neighbors—which have made America what it is.

In the work of travel and exploration in that far West of which we used to read, the figure which stands out boldest and most heroic of all is unnamed. Bearded, buckskin-clad, with rough fur cap, or kerchief tied about his head, wearing powder-horn and ball-pouch, and scalping-knife, and carrying his trusty Hawkins rifle, the trapper—the coureur des bois—was the man who did the first work in subduing the wild West, the man who laid the foundations on which its present civilization is built.

All honor to this nameless hero. We shall meet him often as we follow the westward trail.

CHAPTER II

ALEXANDER HENRY I

The fur trade, which occupied many worthy men during the eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth century, forms a romantic and interesting part of the early history of our country.

The traders, usually of English and American parentage, associated themselves with the French voyageurs, or coureurs des bois, whom Masson describes as “those heroes of the prairie and forest, regular mixtures of good and evil, extravagant by nature, at the same time grave and gay, cruel and compassionate; as credulous as superstitious, and always irreligious.” Traders and voyageurs alike suffered every privation, the cold of winter, the heat of summer, and finally, by incredible persistence, beat out the path of discovery during all seasons, until it became a well-worn trail; all to penetrate the great unknown, which might contain everything that the trader desired. The man who lived in those times and under those conditions was brave and enduring without trying to be; he was alert and quick to act, and unwearying in overcoming obstacles. Viewing him from the present day, we might call him cruel and without feeling; but in those times men were taught not to show their feelings. Their lives were given in great part to surmounting enormous difficulties of travel in unknown regions, and to establishing trade relations with unknown tribes of Indians, who often times were not disposed to be friendly. The fur trader was in constant danger, not only from hostile Indians, but often from starvation.

Alexander Henry was one of these fur traders. He came upon the scene just at the close of the French régime. At twenty-one he had joined Amherst’s army, not as a soldier, but in “a premature attempt to share in the fur trade of Canada, directly on the conquest of the country.” Wolfe’s victory at Quebec in the previous year had aroused the English traders to the opportunity presented of taking over the fur trade which the French had opened up, and Amherst’s large army was watched with great interest as it swept away the last remnant of French control. Henry was well fitted for the life that he intended to pursue, for he seems to have had knowledge of the trading posts of Albany and New York.

On the 3d day of August, 1761, Henry despatched his canoes from Montreal to Lachine on an expedition to the regions west of the Great Lakes. Little did he realize then that he should be gone from civilization for sixteen years; that he should suffer and want but survive; should see new and strange peoples, discover rivers and lakes, build forts, to be used by others who were to follow him, trade with the natives, and finally return to hear of the capture of Quebec by the Americans, and then go to France to tell of his adventures.

The route of the expedition was the usual one. Almost immediately after leaving Lachine they came to the broad stretch of Lake Saint Louis. At St. Anne’s the men used to go to confession, as the voyageurs were almost all Catholics, and at the same time offered up their vows; “for the saint from which this parish derives its name, and to whom its church is dedicated, is the patroness of the Canadians in all their travels by water.” “There is still a further custom to be observed on arriving at Saint-Anne’s,” Henry relates, “which is that of distributing eight gallons of rum to each canoe for consumption during the voyage; nor is it less according to custom to drink the whole of this liquor upon the spot. The saint, therefore, and the priest were no sooner dismissed than a scene of intoxication began in which my men surpassed, if possible, the drunken Indian in singing, fighting, and the display of savage gesture and conceit.”

Continuing up the river, and carrying over many portages, they at last reached the Ottawa, and soon ascended the Mattawa. Hitherto the French were the only white men that had been known in this region. Their relations with the Indians were friendly, and the Indians were well aware of the enmity existing between the French and the English. In the Lac des Chats Henry met several canoes of Indians returning from their winter hunt. They recognized him as an Englishman, and cautioned him, declaring that the upper Indians would kill him when they saw him, and said that the Englishmen were crazy to go so far after beaver. The expedition came at last to Lake Huron, which “lay stretched across our horizon like an ocean.” It was, perhaps, the largest water Henry had yet seen, and the prospect was alarming, but the canoes rode with the ease of a sea-bird, and his fears subsided. Coming to the island called La Cloche, because “there is here a rock standing on a plain, which, being struck, rings like a bell,” he found Indians, with whom he traded, and to whom he gave some rum, and who, recognizing him as an Englishman, told his men that the Indians at Michilimackinac would certainly kill him. On the advice of his friend Campion, Henry changed his garb, assuming the dress usually worn by the Canadians, and, smearing his face with dirt and grease, believed himself thoroughly disguised.

Passing the mouth of the river Missisaki, he found the Indians inhabiting the north side of Lake Superior cultivating corn in small quantities.

As he went on, the lake before him to the westward seemed to become less and less broad, and at last he could see the high back of the island of Michilimackinac, commonly interpreted to mean the great turtle. He found here a large village of Chippewas, and leaving as soon as possible, pushed on about two leagues farther to the fort, where there was a stockade of thirty houses and a church.

For years now Fort Michilimackinac had been a scene of great activity. Established by Father Marquette, and kept up by succeeding missionaries, the first men to brave the unknown terrors of the interior, it was from here in 1731 that the brave and adventurous Verendryes set out on their long journey to the Forks of the Saskatchewan, and to the Missouri River.

This was the half-way house for all the westward pushing and eastward coming traders, and a meeting place for all the tribes living on the Great Lakes. Here were fur traders, trappers, voyageurs, and Indians, hurrying to and fro, dressed in motley and picturesque attire. Some were bringing in furs from long and perilous journeys from the west, while others were on the eve of departure westward, and others still were leaving for Montreal. The scene must have been gay and active almost beyond our powers to imagine. Henry was in the midst of all this when the word came to him that a band of Chippewas wished to speak with him; and, however unwillingly, he was obliged to meet them, sixty in number, headed by Minavavana, their chief. “They walked in single file, each with a tomahawk in one hand and scalping-knife in the other. Their bodies were naked from the waist upward, except in a few examples, where blankets were thrown loosely over the shoulders.” Their faces were painted with charcoal, their bodies with white clay, and feathers were tied in the heads of some, and thrust through the noses of others. Before the opening of the council, the chief held a conference with Campion, asking how long it was since Henry had left Montreal, and observing that the English must be brave men and not afraid of death, since they thus ventured to come fearlessly among their enemies. After the pipe had been smoked, while Henry “inwardly endured the tortures of suspense,” the chief addressed him, saying:

“Englishman, our father, the King of France, employed our young men to make war upon your nation. In this warfare many of them have been killed; and it is our custom to retaliate, until such time as the spirits of the slain are satisfied. But the spirits of the slain are to be satisfied in either of two ways: the first is by the spilling of the blood of the nation by which they fell; the other, by covering the bodies of the dead, and thus allaying the resentment of their relations. This is done by making presents.

“Englishman, your King has never sent us any presents, nor entered into any treaty with us, wherefore he and we are still at war; and, until he does these things, we must consider that we have no other father nor friend among the white men than the King of France; but, for you, we have taken into consideration that you have ventured your life among us, in the expectation that we should not molest you. You do not come armed, with an intention to make war; you come in peace, to trade with us, and supply us with necessaries, of which we are in much want. We shall regard you, therefore, as a brother, and you may sleep tranquilly, without fear of the Chippewas. As a token of our friendship, we present you with this pipe to smoke.”

In reply, Henry told them that their late father, the King of France, had surrendered Canada to the King of England, whom they should now regard as their father, and that he, Henry, had come to furnish them with what they needed. Things were thus very satisfactory, and when the Chippewas went away they were given a small quantity of rum.

Henry was now busily at work assorting his goods, preparatory to starting on his expedition, when two hundred Ottawas entered the fort and demanded speech with him. They insisted that he should give credit to every one of their young men to the amount of fifty beaver skins, but as this demand would have stripped him of all his merchandise, he refused to comply with the request. What the Ottawas might have done is uncertain. They did nothing, because that very day word was brought that a detachment of English soldiers, sent to garrison the fort, was distant only five miles, and would be there the next day. At daybreak the Ottawas were seen preparing to depart, and by sunrise not one of them was left in the fort.

Although it was now the middle of September, the traders sent off their canoes on the different trading expeditions. These canoes were victualled largely with Indian corn at the neighboring village of L’Arbre Croche, occupied by the Ottawas. This corn was prepared for use by boiling it in a strong lye which removed the husk, after which it was pounded and dried, making a meal. “The allowance for each man on the voyage is a quart a day, and a bushel, with two pounds of prepared fat, is reckoned to be a month’s subsistence. No other allowance is made of any kind, not even of salt, and bread is never thought of. The men, nevertheless, are healthy, and capable of performing their heavy labor. This mode of victualling is essential to the trade, which, being pursued at great distances, and in vessels so small as canoes, will not admit of the use of other food. If the men were to be supplied with bread and pork, the canoes could not carry a sufficiency for six months; and the ordinary duration of the voyage is not less than fourteen.”

The food of the garrison consisted largely of small game, partridges and hares, and of fish, especially trout, whitefish, and sturgeon. Trout were caught with set lines and bait, and whitefish with nets under the ice. Should this fishery fail, it was necessary to purchase grain, which, however, was very expensive, costing forty livres, or forty shillings, Canadian currency; though there was no money in Michilimackinac, and the circulating medium consisted solely of furs. A pound of beaver was worth about sixty cents, an otter skin six shillings Canadian, and marten skins about thirty cents each.

Having wintered at Michilimackinac, Henry set out in May for the Sault de Sainte-Marie. Here there was a stockaded fort, with four houses, one of which was occupied by Monsieur Cadotte, the interpreter, and his Chippewa wife. The Indians had an important whitefish fishery at the rapids, taking the fish in dip nets. In the autumn Henry and the other whites did much fishing; and in the winter they hunted, and took large trout with the spear through the ice in this way: “In order to spear trout under the ice, holes being first cut of two yards in circumference, cabins of about two feet in height are built over them of small branches of trees; and these are further covered with skins so as to wholly exclude the light. The design and result of this contrivance is to render it practicable to discern objects in the water at a very considerable depth; for the reflection of light from the water gives that element an opaque appearance, and hides all objects from the eye at a small distance beneath its surface. A spear head of iron is fastened on a pole of about ten feet in length. This instrument is lowered into the water, and the fisherman, lying upon his belly, with his head under the cabin or cover, and therefore over the hole, lets down the figure of a fish in wood and filled with lead. Round the middle of the fish is tied a small pack thread, and, when at the depth of ten fathoms, where it is intended to be employed, it is made, by drawing the string and by the simultaneous pressure of the water, to move forward, after the manner of a real fish. Trout and other large fish, deceived by its resemblance, spring toward it to seize it, but, by a dexterous jerk of the string, it is instantly taken out of their reach. The decoy is now drawn nearer to the surface, and the fish takes some time to renew the attack, during which the spear is raised and held conveniently for striking. On the return of the fish, the spear is plunged into its back, and, the spear being barbed, it is easily drawn out of the water. So completely do the rays of the light pervade the element that in three-fathom water I have often seen the shadows of the fish on the bottom, following them as they moved; and this when the ice itself was two feet in thickness.”

The burning of the post at the Sault forced all hands to return next winter to Michilimackinac, where the early spring was devoted to the manufacture of maple sugar, an important article of diet in the northern country.

That spring Indians gathered about the fort in such large numbers as to make Henry fearful that something unusual lay behind the concourse. He spoke about it to the commanding officer, who laughed at him for his timidity. The Indians seemed to be passing to and fro in the most friendly manner, selling their fur and attending to their business altogether in a natural way.

About a year before an Indian named Wawatam had come into Henry’s house, expressed a strong liking for him, and, having explained that years before, after a fast, he had dreamed of adopting an Englishman as his son, brother, and friend, told Henry that in him he recognized the person whom the Great Spirit had pointed out to him for a brother, and that he hoped Henry would become one of his family, and at the same time he made him a large present. Henry accepted these friendly overtures, and made a handsome present in return, and the two parted for the time.

Henry had almost forgotten his brother, when, on the second day of June, twelve months later, Wawatam again came to his house and expressed great regret that Henry had returned from the Sault. Wawatam stated that he intended to go there at once, and begged Henry to accompany him. He asked, also, whether the commandant had heard bad news, saying that during the winter he himself had been much disturbed by the noises of evil birds, and that there were many Indians around the fort who had never shown themselves within it. Both the chief and his wife strove earnestly to persuade Henry to accompany them at once, but he paid little attention to their requests, and they finally took their departure, very much depressed—in fact, even weeping. The next day Henry received from a Chippewa an invitation to come out and see the great game of baggatiway, or lacrosse, which his people were going to play that day with the Sacs. But as a canoe was about to start for Montreal, Henry was busy writing letters, and although urged by a friend to go out and meet another canoe just arrived from Detroit, he nevertheless remained in his room, writing. Suddenly he heard the Indian war-cry, and, looking out of the window, saw a crowd of Indians within the fort furiously cutting down and scalping every Englishman they found. He noticed, too, many of the Canadian inhabitants of the fort quietly looking on, neither trying to stop the Indians nor suffering injury from them; and from the fact that these people were not being attacked, he conceived the hope of finding security in one of their houses. This is as he tells it:

“Between the yard-door of my own house and that of M. Langlade, my next neighbor, there was only a low fence, over which I easily climbed. At my entrance I found the whole family at the windows, gazing at the scene of blood before them. I addressed myself immediately to M. Langlade, begging that he would put me into some place of safety until the heat of the affair should be over, an act of charity by which he might perhaps preserve me from the general massacre; but, while I uttered my petition, M. Langlade, who had looked for a moment at me, turned again to the window, shrugging his shoulders and intimating that he could do nothing for me—‘Que voudriez-vous que j’en ferais?’

“This was a moment for despair; but the next a Pani woman, a slave of M. Langlade’s, beckoned to me to follow her. She brought me to a door, which she opened, desiring me to enter, and telling me that it led to the garret, where I must go and conceal myself. I joyfully obeyed her directions and she, having followed me up to the garret door, locked it after me, and with great presence of mind took away the key.

“This shelter obtained, if shelter I could hope to find it, I was naturally anxious to know what might still be passing without. Through an aperture which afforded me a view of the area of the fort, I beheld, in shapes the foulest and most terrible, the ferocious triumphs of barbarian conquerors. The dead were scalped and mangled; the dying were writhing and shrieking under the unsatiated knife and tomahawk, and, from the bodies of some ripped open, their butchers were drinking the blood, scooped up in the hollow of joined hands and quaffed amid shouts of rage and victory. I was shaken, not only with horror, but with fear. The sufferings which I witnessed, I seemed on the point of experiencing. No long time elapsed before every one being destroyed who could be found, there was a general cry of ‘All is finished!’ At the same instant I heard some of the Indians enter the house in which I was.

“The garret was separated from the room below only by a layer of single boards, at once the flooring of the one and the ceiling of the other. I could therefore hear everything that passed; and, the Indians no sooner in than they inquired whether or not any Englishmen were in the house? M. Langlade replied that ‘He could not say—he did not know of any’—answers in which he did not exceed the truth, for the Pani woman had not only hidden me by stealth, but had kept my secret and her own; M. Langlade was therefore, as I presume, as far from a wish to destroy me as he was careless about saving me, when he added to these answers that ‘They might examine for themselves, and would soon be satisfied as to the object of their question.’ Saying this, he brought them to the garret door.

“The state of my mind will be imagined. Arrived at the door, some delay was occasioned by the absence of the key, and a few moments were thus allowed me in which to look around for a hiding place. In one corner of the garret was a heap of vessels of birch-bark, used in maple-sugar making.

“The door was unlocked, and opening, and the Indians ascending the stairs, before I had completely crept into a small opening which presented itself at one end of the heap. An instant after four Indians entered the room, all armed with tomahawks, and all besmeared with blood upon every part of their bodies.

“The die appeared to be cast. I could scarcely breathe: but I thought that the throbbing of my heart occasioned a noise loud enough to betray me. The Indians walked in every direction about the garret, and one of them approached me so closely that at a particular moment, had he put forth his hand, he must have touched me. Still, I remained undiscovered, a circumstance to which the dark color of my clothes and the want of light, in a room which had no window, and in the corner in which I was, must have contributed. In a word, after taking several turns in the room, during which they told M. Langlade how many they had killed and how many scalps they had taken, they returned down-stairs, and I with sensations not to be expressed heard the door, which was the barrier between me and fate, locked for the second time.

“There was a feather bed on the floor, and on this, exhausted as I was by the agitation of my mind, I threw myself down and fell asleep. In this state I remained till the dusk of the evening, when I was awakened by a second opening of the door. The person that now entered was M. Langlade’s wife, who was much surprised at finding me, but advised me not to be uneasy, observing that the Indians had killed most of the English, but that she hoped I might myself escape. A shower of rain having begun to fall, she had come to stop a hole in the roof. On her going away, I begged her to send me a little water to drink, which she did.

“As night was now advancing, I continued to lie on the bed, ruminating on my condition but unable to discover a resource from which I could hope for life. A flight to Detroit had no probable chance of success. The distance from Michilimackinac was four hundred miles; I was without provisions, and the whole length of the road lay through Indian countries, countries of an enemy in arms, where the first man whom I should meet would kill me. To stay where I was threatened nearly the same issue. As before, fatigue of mind and not tranquillity, suspended my cares and procured me further sleep....

“The respite which sleep afforded me during the night was put an end to by the return of morning. I was again on the rack of apprehension. At sunrise I heard the family stirring, and, presently after, Indian voices, informing M. Langlade that they had not found my hapless self among the dead, and that they supposed me to be somewhere concealed. M. Langlade appeared, from what followed, to be by this time acquainted with the place of my retreat, of which, no doubt, he had been informed by his wife. The poor woman, as soon as the Indians mentioned me, declared to her husband, in the French tongue, that he should no longer keep me in his house, but deliver me up to my pursuers; giving as a reason for this measure that should the Indians discover his instrumentality in my concealment they might revenge it on her children, and that it was better that I should die than they. M. Langlade resisted at first this sentence of his wife’s; but soon suffered her to prevail, informing the Indians that he had been told I was in his house; that I had come there without his knowledge, and that he would put me into their hands. This was no sooner expressed than he began to ascend the stairs, the Indians following upon his heels.

“I now resigned myself to the fate with which I was menaced; and regarding every attempt at concealment as vain, I arose from the bed and presented myself full in view to the Indians who were entering the room. They were all in a state of intoxication, and entirely naked, except about the middle. One of them, named Wenniway, whom I had previously known and who was upward of six feet in height, had his entire face and body covered with charcoal and grease, only that a white spot of two inches in diameter encircled either eye. This man, walking up to me, seized me with one hand by the collar of the coat, while in the other he held a large carving knife, as if to plunge it into my breast; his eyes, meanwhile, were fixed steadfastly on mine. At length, after some seconds of the most anxious suspense he dropped his arm, saying, ‘I won’t kill you!’ To this he added that he had been frequently engaged in wars against the English, and had brought away many scalps; that, on a certain occasion, he had lost a brother, whose name was Musingon, and that I should be called after him.”

“I NOW RESIGNED MYSELF TO THE FATE WITH WHICH I WAS MENACED.”

Several times within the next two or three days Henry had narrow escapes from death at the hands of drunken Indians; but finally his captors, having stripped him of all his clothing save an old shirt, took him, with other prisoners, and set out for the Isles du Castor, in Lake Michigan.

At the village of L’Arbre Croche, the Ottawas forcibly took away their prisoners from the Chippewas, but the Chippewas made violent complaint, while the Ottawas explained to the prisoners that they had taken them from the Chippewas to save their lives, it being the practice of the Chippewas to eat their enemies, in order to give them courage in battle. A council was held between the Chippewas and Ottawas, the result of which was that the prisoners were handed over to their original captors. But before they had left this place, while Henry was sitting in the lodge with his captor, his friend and brother, Wawatam, suddenly entered. As he passed Henry he shook hands with him, but went toward the great chief, by whom he sat down, and after smoking, rose again and left the lodge, saying to Henry as he passed him, “Take courage.”

A little later, Wawatam and his wife entered the lodge, bringing large presents, which they threw down before the chiefs. Wawatam explained that Henry was his brother, and therefore a relative to the whole tribe, and asked that he be turned over to him, which was done.

Henry now went with Wawatam to his lodge, and thereafter lived with him. The Indians were very much afraid that the English would send to revenge the killing of their troops, and they shortly moved to the Island of Michilimackinac. A little later a brigade of canoes, containing goods and abundant liquor, was captured: and Wawatam, fearing the results of the drink on the Indians, took Henry away and concealed him in a cave, where he remained for two days.

The head chief of the village of Michilimackinac now recommended to Wawatam and Henry that, on account of the frequent arrival of Indians from Montreal, some of whom had lost relatives or friends in the war, Henry should be dressed like an Indian, and the wisdom of this advice was recognized. His hair was cut off, his head shaved, except for a scalp-lock, his face painted, and Indian clothing given him. Wawatam helped him to visit Michilimackinac, where Henry found one of his clerks, but none of his property. Soon after this they moved away to Wawatam’s wintering ground, which Henry was very willing to visit, because in the main camp he was constantly subjected to insults from the Indians who knew of his race.

Henry writes fully of the customs of the Indians, of the habits of many of the animals which they pursued, and of the life he led. He says that during this winter “Raccoon hunting was my more particular and daily employ. I usually went out at the first dawn of day, and seldom returned till sunset, or till I had laden myself with as many animals as I could carry. By degrees I became familiarized with this kind of life; and had it not been for the idea, of which I could not divest my mind, that I was living among savages, and for the whispers of a lingering hope that I should one day be released from it, or if I could have forgotten that I had ever been otherwise than as I then was, I could have enjoyed as much happiness in this as in any other situation.”

Among the interesting hunting occurrences narrated is one of the killing of a bear, and of the ceremonies subsequent to this killing performed by the Indians. He says:

“In the course of the month of January I happened to observe that the trunk of a very large pine tree was much torn by the claws of a bear, made both in going up and down. On further examination, I saw that there was a large opening in the upper part, near which the smaller branches were broken. From these marks, and from the additional circumstance that there were no tracks in the snow, there was reason to believe that a bear lay concealed in the tree.

“On returning to the lodge, I communicated my discovery, and it was agreed that all the family should go together in the morning to assist in cutting down the tree, the girth of which was not less than three fathom. Accordingly, in the morning we surrounded the tree, both men and women, as many at a time as could conveniently work at it, and here we toiled like beaver till the sun went down. This day’s work carried us about half way through the trunk; and the next morning we renewed the attack, continuing it till about two o’clock in the afternoon, when the tree fell to the ground. For a few minutes everything remained quiet, and I feared that all our expectations were disappointed; but, as I advanced to the opening, there came out, to the great satisfaction of all our party, a bear of extraordinary size, which, before she had proceeded many yards, I shot.

“The bear being dead, all my assistants approached, and all, but more particularly my old mother (as I was wont to call her), took her head in their hands, stroking and kissing it several times, begging a thousand pardons for taking away her life; calling her their relation and grandmother, and requesting her not to lay the fault upon them, since it was truly an Englishman that had put her to death.

“This ceremony was not of long duration, and if it was I that killed their grandmother, they were not themselves behindhand in what remained to be performed. The skin being taken off, we found the fat in several places six inches deep. This, being divided into two parts, loaded two persons, and the flesh parts were as much as four persons could carry. In all, the carcass must have exceeded five hundredweight.

“As soon as we reached the lodge, the bear’s head was adorned with all the trinkets in the possession of the family, such as silver arm-bands and wrist-bands, and belts of wampum, and then laid upon a scaffold set up for its reception within the lodge. Near the nose was placed a large quantity of tobacco.

“The next morning no sooner appeared than preparations were made for a feast to the manes. The lodge was cleaned and swept, and the head of the bear lifted up and a new stroud blanket, which had never been used before, spread under it. The pipes were now lit, and Wawatam blew tobacco smoke into the nostrils of the bear, telling me to do the same, and thus appease the anger of the bear on account of my having killed her. I endeavored to persuade my benefactor and friendly adviser that she no longer had any life, and assured him that I was under no apprehension from her displeasure; but the first proposition obtained no credit, and the second gave but little satisfaction.

“At length, the feast being ready, Wawatam commenced a speech, resembling, in many things, his address to the manes of his relations and departed companions, but having this peculiarity, that he here deplored the necessity under which men labored thus to destroy their friends. He represented, however, that the misfortune was unavoidable, since without doing so they could by no means subsist. The speech ended, we all ate heartily of the bear’s flesh, and even the head itself, after remaining three days on the scaffold, was put into the kettle.

“It is only the female bear that makes her winter lodging in the upper parts of trees, a practice by which her young are secured from the attacks of wolves and other animals. She brings forth in the winter season, and remains in her lodge till the cubs have gained some strength.

“The male always lodges in the ground, under the roots of trees. He takes to this habitation as soon as the snow falls, and remains there till it has disappeared. The Indians remark that the bear comes out in the spring with the same fat which he carried in in the autumn; but, after exercise of only a few days, becomes lean. Excepting for a short part of the season, the male lives constantly alone.

“The fat of our bear was melted down, and the oil filled six porcupine skins. A part of the meat was cut into strips and fire-dried, after which it was put into the vessels containing the oil, where it remained in perfect preservation until the middle of summer.”

When spring came, and they returned to the more travelled routes and met other Indians, it was seen that these people were all anxious lest the English should this summer avenge the outbreak of the Indians of the previous year. Henry was exceedingly anxious to escape from his present life, and his brother was willing that he should go, but this appeared difficult. At last, however, a Canadian canoe, carrying Madame Cadotte, came along, and this good woman was willing to assist Henry so far as she could. He and his brother parted rather sadly, and Henry, now under the guise of a Canadian, took a paddle in Madame Cadotte’s canoe. She took him safely to the Sault, where he was welcomed by Monsieur Cadotte, whose great influence among the Indians was easily sufficient to protect him. Soon after this there came an embassy from Sir William Johnson, calling the Indians to come to Niagara and make peace with the English; and after consulting the Great Turtle, who was the guardian spirit of the Chippewas, a number of young men volunteered to go to Niagara, and among them Henry.

After a long voyage they reached Niagara, where Henry was very kindly received by Sir William Johnson and subsequently was appointed by General Bradstreet, commander of an Indian battalion of ninety-six men, among whom were many of the Indians who, not long before, had been ready and eager to kill him. With this command he moved westward, and after peace had been made with Pontiac at Detroit, with a detachment of troops reached Michilimackinac, where he recovered a part of his property.

CHAPTER III

ALEXANDER HENRY II

The French Government had established regulations governing the fur trade in Canada, and in 1765, when Henry made his second expedition, some features of the old system were still preserved. No person was permitted to enter the countries lying north-west of Detroit unless furnished with a license, and military commanders had the privilege of granting to any individual the exclusive trade of particular districts.

At this time beaver were worth two shillings and sixpence per pound; otter skins, six shillings each; martens, one shilling and sixpence; all this in nominal Michilimackinac currency, although here fur was still the current coin. Henry loaded his four canoes with the value of ten thousand pounds’ weight of good and merchantable beaver. For provision he purchased fifty bushels of corn, at ten pounds of beaver per bushel. He took into partnership Monsieur Cadotte, and leaving Michilimackinac July 14, and Sault Sainte-Marie the 26th, he proceeded to his wintering ground at Chagouemig. On the 19th of August he reached the river Ontonagan, notable for its abundance of native copper, which the Indians used to manufacture into spoons and bracelets for themselves. This they did by the mere process of hammering it out. Not far beyond this river he met Indians, to whom he gave credit. “The prices were for a stroud blanket, ten beaver skins; for a white blanket, eight; a pound of powder, two; a pound of shot or of ball, one; a gun, twenty; an axe of one pound weight, two; a knife, one.” As the value of a skin was about one dollar, the prices to the Indians were fairly high.

Chagouemig, where Henry wintered, is now known as Chequamegon. It is in Wisconsin, a bay which partly divides Bayfield from Ashland county, and seems always to have been a great gathering place for Indians. There were now about fifty lodges here, making, with those who had followed Henry, about one hundred families. All were poor, their trade having been interfered with by the English invasion of Canada and by Pontiac’s war. Henry was obliged to distribute goods to them to the amount of three thousand beaver skins, and this done, the Indians separated to look for fur. Henry sent a clerk to Fond du Lac with two loaded canoes; Fond du Lac being, roughly, the site of the present city of Duluth. As soon as Henry was fairly settled, he built a house, and began to collect fish from the lake as food for the winter. Before long he had two thousand trout and whitefish, the former frequently weighing fifty pounds each, the latter from four to six. They were preserved by being hung up by the tail and did not thaw during the winter. When the bay froze over, Henry amused himself by spearing trout, and sometimes caught a hundred in a day, each weighing on an average twenty pounds.

He had some difficulty with the first hunting party which brought furs. The men crowded into his house and demanded rum, and when he refused it, they threatened to take all he had. His men were frightened and all abandoned him. He got hold of a gun, however, and on threatening to shoot the first who should lay hands on anything, the disturbance began to subside and was presently at an end. He now buried the liquor that he had, and when the Indians were finally persuaded that he had none to give them, they went and came very peaceably, paying their debts and purchasing goods.

The ice broke up in April, and by the middle of May the Indians began to come in with their furs, so that by the close of the spring Henry found himself with a hundred and fifty packs of beaver, weighing a hundred pounds each, besides twenty-five packs of otter and marten skins. These he took to Michilimackinac, accompanied by fifty canoes of Indians, who still had a hundred packs of beaver that they did not sell. It appears, therefore, that Henry’s ten thousand pounds of beaver brought him fifty per cent. profit in beaver, besides the otter and the marten skins which he had.

On his way back he went up the Ontonagan River to see the celebrated mass of copper there, which he estimated to weigh no less than five tons. So pure was it that with an axe he chopped off a piece weighing a hundred pounds. This great mass of copper, which had been worked at for no one knows how long by Indians and by early explorers, lay there for eighty years after Henry saw it; and finally, in 1843, was removed to the Smithsonian Institution at Washington. It was then estimated to weigh between three and four tons, and the cost of transporting it to the national capital was about $3,500.

The following winter was passed at Sault Sainte-Marie, and was rather an unhappy one, as the fishery failed, and there was great suffering from hunger. Canadians and Indians gathered there from the surrounding country, driven in by lack of food. Among the incidents of the winter was the arrival of a young man who had been guilty of cannibalism. He was killed by the Indians, not so much as punishment, as from the fear that he would kill and eat some of their children.

A journey to a neighboring bay resulted in no great catch of fish, and returning to the Sault, Henry started for Michilimackinac. At the first encampment, an hour’s fishing procured them seven trout, of from ten to twenty pounds’ weight. A little later they met a camp of Indians who had fish, and shared with them; and the following day Henry killed a caribou, by which they camped and on which they subsisted for two days.

The following winter Henry stopped at Michipicoten, on the north side of Lake Superior, and about a hundred and fifty miles from the Sault. Here there were a few people known as Gens des Terres, a tribe of Algonquins, living in middle Canada, and ranging from the Athabasca country east to Lake Temiscamingue. A few of them still live near the St. Maurice River, in the Province of Quebec. These people, though miserably poor, and occupying a country containing very few animals, had a high reputation for honesty and worth. Therefore, Henry gave to every man credit for one hundred beaver skins, and to every woman thirty—a very large credit.

There was some game in this country, a few caribou, and some hares and partridges. The hills were well wooded with sugar-maples, and from these, when spring came, Henry made sugar; and for a time this was their sole provision, each man consuming a pound a day, desiring no other food, and being visibly nourished by the sugar. Soon after this, wildfowl appeared in such abundance that subsistence for fifty could without difficulty be shot daily by one man, but this lasted only for a week, by which time the birds all departed. By the end of May all to whom Henry had advanced goods returned, and of the two thousand skins for which he had given them credit, not thirty remained unpaid. The small loss that he did suffer was occasioned by the death of one of the Indians, whose family brought all the skins of which he died possessed, and offered to contribute among themselves the balance.

The following winter was also to be passed at Michipicoten, and in the month of October, after all the Indians had received their goods and had gone away, Henry set out for the Sault on a visit. He took little provision, only a quart of corn for each person.

On the first night they camped on an island sacred to Nanibojou, one of the Chippewa gods, and failed to offer the tobacco which an Indian would always have presented to the spirit. In the night a violent storm arose which continued for three days. When it abated on the third day they went to examine the net which they had set for fish, and found it gone. The wind was ahead to return to Michipicoten, and they steered for the Sault; but that night the wind shifted and blew a gale for nine days following. They soon began to starve, and though Henry hunted faithfully, he killed nothing more than two snowbirds. One of his men informed him that the other two had proposed to kill and eat a young woman, whom they were taking to the Sault, and when taxed with the proposition, these two men had the hardihood to acknowledge it. The next morning, Henry, still searching for food, found on a rock the tripe de roche, a lichen, which, when cooked, yields a jelly which will support life. The discovery of this food, on which they supported themselves thereafter, undoubtedly saved the life of the poor woman. When they embarked on the evening of the ninth day they were weak and miserable; but, luckily, the next morning, meeting two canoes of Indians, they received a gift of fish, and at once landed to feast on them.

In the spring of 1769, and for some years afterward, Henry turned his attention more or less to mines. He visited the Ile de Maurepas, said to contain shining rocks and stones of rare description, but was much disappointed in the island, which seemed commonplace enough. A year later Mr. Baxter, with whom Henry had formed a partnership for copper mining, returned, and during the following winter, at Sault Sainte-Marie, they built vessels for navigating the lakes. Henry had heard of an island (Caribou Island) in Lake Superior described as covered with a heavy yellow sand like gold-dust, and guarded by enormous snakes. With Mr. Baxter he searched for this island and finally found it, but neither yellow sands nor snakes nor gold. Hawks there were in abundance, and one of them picked Henry’s cap from his head. There were also caribou, and they killed thirteen, and found many complete and undisturbed skeletons. Continuing their investigations into the mines about the lakes, they found abundant copper ore, and some supposed to contain silver. But their final conclusion was that the cost of carrying the copper ore to Montreal must exceed its marketable value.

In June, 1775, Henry left Sault Sainte-Marie with four large canoes and twelve small ones, carrying goods and provisions to the value of three thousand pounds sterling. He passed west, over the Grand Portage, entered Lac à la Pluie, passed down to the Lake of the Woods, and finally reached Lake Winipegon. Here there were Crees, variously known as Christinaux, Kinistineaux, Killistinoes, and Killistinaux. Lake Winipegon is sometimes called the Lake of the Crees. These people were primitive. Almost entirely naked, the whole body was painted with red ochre; the head was wholly shaved, or the hair was plucked out, except a spot on the crown, where it grew long and was rolled and gathered into a tuft; the ears were pierced, and filled with bones of fishes and land animals. The women, on the other hand, had long hair, which was gathered into a roll on either side of the head above the ear, and was covered with a piece of skin, painted or ornamented with beads of various colors. The traditions of the Cheyennes of to-day point back to precisely similar methods of dressing the hair of the women and of painting the men.

The Crees were friendly, and gave the traveller presents of wild rice and dried meat. He kept on along the lake and soon joined Peter Pond, a well-known trader of early days. A little later, in early September, the two Frobishers and Mr. Patterson overtook them. On the 1st of October they reached the River de Bourbon, now known as the Saskatchewan, and proceeded up it, using the tow-line to overcome the Great Rapids. They passed on into Lake de Bourbon, now Cedar Lake, and by old Fort Bourbon, built by the Sieur de Vérendrye. At the mouth of the Pasquayah River they found a village of Swampy Crees, the chief of whom expressed his gratification at their coming, but remarked that, as it would be possible for him to kill them all when they returned, he expected them to be extremely liberal with their presents. He then specified what it was that he desired, namely, three casks of gunpowder, four bags of shot and ball, two bales of tobacco, three kegs of rum, and three guns, together with many smaller articles. Finally he declared that he was a peaceable man, and always tried to get along without quarrels. The traders were obliged to submit to being thus robbed, and passed on up the river to Cumberland House. Here they separated, M. Cadotte going on with four canoes to the Fort des Prairies, a name given then and later to many of the trading posts built on the prairie. This one is probably that Fort des Prairies which was situated just below the junction of the north and south forks of the Saskatchewan River, and was known as Fort Nippewen. Mr. Pond, with two canoes, went to Fort Dauphin, on Lake Dauphin, while the Messrs. Frobisher and Henry agreed to winter together on Beaver Lake. Here they found a good place for a post, and were soon well lodged. Fish were abundant, and the post soon assumed the appearance of a settlement. Owing to the lateness of the season, their canoes could not be buried in the ground, as was the common practice, and they were therefore placed on scaffolds. The fishing here was very successful, and moose were killed. The Indians brought in beaver and bear’s meat, and some skins for sale.

In January, 1776, Henry left the fort on Beaver Lake, attended by two men, and provided with dried meat, frozen fish, and cornmeal, to make an excursion over the plains, “or, as the French denominate them, the Prairies, or Meadows.” There was snow on the ground, and the baggage was hauled by the men on sledges. The cold was bitter, but they were provided with “ox skins, which the traders call buffalo robes.”

Beaver Lake was in the wooded country, and, indeed, all Henry’s journeyings hitherto had been through a region that was timbered; but here, striking south and west, by way of Cumberland House, he says, “I was not far advanced before the country betrayed some approaches to the characteristic nakedness of the plains. The wood dwindled away, both in size and quantity, so that it was with difficulty we could collect sufficient for making a fire, and without fire we could not drink, for melted snow was our only resource, the ice on the river being too thick to be penetrated by the axe.” Moreover, the weather was bitterly cold, and after a time provisions grew scanty. No game was seen and no trace of anything human. The men began to starve and to grow weak, but as tracks of elk and moose were seen, Henry cheered them up by telling them that they would certainly kill something before long.

“On the twentieth, the last remains of our provisions were expended; but I had taken the precaution to conceal a cake of chocolate in reserve for an occasion like that which was now arrived. Toward evening my men, after walking the whole day, began to lose their strength, but we nevertheless kept on our feet till it was late, and when we encamped I informed them of the treasure which was still in store. I desired them to fill the kettle with snow, and argued with them the while that the chocolate would keep us alive for five days at least, an interval in which we should surely meet with some Indian at the chase. Their spirits revived at the suggestion, and, the kettle being filled with two gallons of water, I put into it one square of the chocolate. The quantity was scarcely sufficient to alter the color of the water, but each of us drank half a gallon of the warm liquor, by which we were much refreshed, and in its enjoyment felt no more of the fatigues of the day. In the morning we allowed ourselves a similar repast, after finishing which we marched vigorously for six hours. But now the spirits of my companions again deserted them, and they declared that they neither would, nor could, proceed any further. For myself, they advised me to leave them, and accomplish the journey as I could; but for themselves, they said, that they must die soon, and might as well die where they were as anywhere else.

“While things were in this melancholy posture, I filled the kettle and boiled another square of chocolate. When prepared I prevailed upon my desponding companions to return to their warm beverage. On taking it they recovered inconceivably, and, after smoking a pipe, consented to go forward. While their stomachs were comforted by the warm water they walked well, but as evening approached fatigue overcame them, and they relapsed into their former condition, and, the chocolate being now almost entirely consumed, I began to fear that I must really abandon them, for I was able to endure more hardship than they, and, had it not been for keeping company with them, I could have advanced double the distance within the time which had been spent. To my great joy, however, the usual quantity of warm water revived them.

“For breakfast the next morning I put the last square of chocolate into the kettle, and, our meal finished, we began our march in but very indifferent spirits. We were surrounded by large herds of wolves which sometimes came close upon us, and who knew, as we were prone to think, the extremity in which we were, and marked us for their prey; but I carried a gun, and this was our protection. I fired several times, but unfortunately missed at each, for a morsel of wolf’s flesh would have afforded us a banquet.

“Our misery, nevertheless, was still nearer its end than we imagined, and the event was such as to give one of the innumerable proofs that despair is not made for man. Before sunset we discovered on the ice some remains of the bones of an elk left there by the wolves. Having instantly gathered them, we encamped, and, filling our kettle, prepared ourselves a meal of strong and excellent soup. The greater part of the night was passed in boiling and regaling on our booty, and early in the morning we felt ourselves strong enough to proceed.

“This day, the twenty-fifth, we found the borders of the plains reaching to the very banks of the river, which were two hundred feet above the level of the ice. Water marks presented themselves at twenty feet above the actual level.

“Want had lost his dominion over us. At noon we saw the horns of a red deer [an elk or wapiti] standing in the snow on the river. On examination we found that the whole carcass was with them, the animal having broke through the ice in the beginning of the winter in attempting to cross the river too early in the season, while his horns, fastening themselves in the ice, had prevented him from sinking. By cutting away the ice we were enabled to lay bare a part of the back and shoulders, and thus procure a stock of food amply sufficient for the rest of our journey. We accordingly encamped and employed our kettle to good purpose, forgot all our misfortunes, and prepared to walk with cheerfulness the twenty leagues which, as we reckoned, still lay between ourselves and Fort des Prairies.

“Though the deer must have been in this situation ever since the month of November, yet its flesh was perfectly good. Its horns alone were five foot high or more, and it will therefore not appear extraordinary that they should be seen above the snow.

“On the twenty-seventh, in the morning, we discovered the print of snow-shoes, demonstrating that several persons had passed that way the day before. These were the first marks of other human feet than our own which we had seen since our leaving Cumberland House, and it was much to feel that we had fellow-creatures in the wide waste surrounding us. In the evening we reached the fort.”

At Fort des Prairies, Henry saw more provisions than he had ever before dreamed of. In one heap he saw fifty tons of buffalo meat, so fat that the men could hardly find meat lean enough to eat. Immediately south of this plains country, which he was on the edge of, was the land of the Osinipoilles [Assiniboines, a tribe of the Dakota or Sioux nation], and some of these people being at the fort, Henry determined to visit them at their village, and on the 5th of February set out to do so. The Indians whom they accompanied carried their baggage on dog travois. They used snow-shoes and travelled swiftly, and at night camped in the shelter of a little grove of wood. There were fourteen people in the tent in which Henry slept that night, but these were not enough to keep each other warm. They started each morning at daylight, and travelled as long as they could, and over snow that was often four feet deep. During the journey they saw buffalo, which Henry calls wild oxen, but did not disturb them, as they had no time to do so, and no means of carrying the flesh if they had killed any. One night they met two young men who had come out to meet the party. They had not known that there were white men with it, and announced that they must return to advise the chief of this; but before they could start, a storm came up which prevented their departure. All that night and part of the next day the wind blew fiercely, with drifting snow. “In the morning we were alarmed by the approach of a herd of oxen, who came from the open ground to shelter themselves in the wood. Their numbers were so great that we dreaded lest they should fairly trample down the camp; nor could it have happened otherwise but for the dogs, almost as numerous as they, who were able to keep them in check. The Indians killed several when close upon their tents, but neither the fire of the Indians nor the noise of the dogs could soon drive them away. Whatever were the terrors which filled the wood, they had no other escape from the terrors of the storm.”

Two days later they reached the neighborhood of the camp, which was situated in a woody island. Messengers came to welcome them, and a guard armed with bows and spears, evidently the soldiers, to escort them to the home which had been assigned them. They were quartered in a comfortable skin lodge, seated on buffalo robes; women brought them water for washing, and presently a man invited them to a feast, himself showing them the way to the head chief’s tent. The usual smoking, feasting, and speech-making followed.

These Osinipoilles seemed not before to have seen white men, for when walking about the camp, crowds of women and children followed them, very respectfully, but evidently devoured by insatiable curiosity. Water here was obtained by hanging a buffalo paunch kettle filled with snow in the smoke of the fire, and, as the snow melted, more and more was added, until the paunch was full of water. During their stay they never had occasion to cook in the lodge, being constantly invited to feasts. They had with them always the guard of soldiers, who were careful to allow no one to crowd upon or annoy the travellers. They had been here but a short time when the head chief sent them word that he was going to hunt buffalo the next day, and asked them to be of the party.