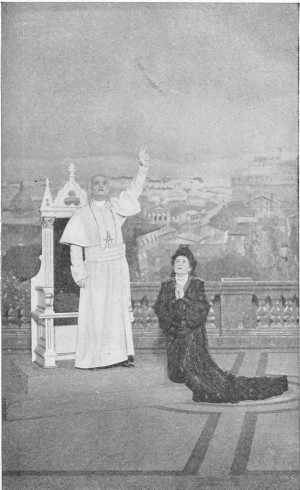

"WHAT YOU SAID SHALL BE SACRED."

The

ETERNAL CITY

By

HALL CAINE

Author of "The Christian," etc.

"He looked for a city which hath foundations

whose builder and maker is God."

GROSSET & DUNLAP

Publishers :: New York

Copyright, 1901, 1902

By HALL CAINE

Popular Edition

Published October, 1902

Table of Contents

PROLOGUE

1PART ONE—THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE

9PART TWO—THE REPUBLIC OF MAN

40PART THREE—ROMA

71PART FOUR—DAVID ROSSI

121PART FIVE—THE PRIME MINISTER

168PART SIX—THE ROMAN OF ROME

237PART SEVEN—THE POPE

298PART EIGHT—THE KING

375PART NINE—THE PEOPLE

414PREFACE TO THIS EDITION

Has a novelist a right to alter his novel after its publication, to condense it, to add to it, to modify or to heighten its situations, and otherwise so to change it that to all outward appearance it is practically a new book? I leave this point in literary ethics to the consideration of those whose business it is to discuss such questions, and content myself with telling the reader the history of the present story.

About ten years ago I went to Russia with some idea (afterwards abandoned) of writing a book that should deal with the racial struggle which culminated in the eviction of the Jews from the holy cities of that country, and the scenes of tyrannical administration which I witnessed there made a painful and lasting impression on my mind. The sights of the day often followed me through the night, and after a more than usually terrible revelation of official cruelty, I had a dream of a Jewish woman who was induced to denounce her husband to the Russian police under a promise that they would spare his life, which they said he had forfeited as the leader of a revolutionary movement. The husband came to know who his betrayer had been, and he cursed his wife as his worst enemy. She pleaded on her knees that fear for his safety had been the only motive for her conduct, and he cursed her again. His cause was lost, his hopes were dead, his people were in despair, because the one being whom heaven had given him for his support had delivered him up to his enemies out of the weakness of her womanly love. I awoke in the morning with a vivid memory of this new version of the old story of Samson and Delilah, and on my return to England I wrote the draft of a play with the incident of husband and wife as the central situation.

How from this germ came the novel which was published last year under the title of "The Eternal City" would be a long story to tell, a story of many personal experiences, of reading, of travel, of meetings in various countries with statesmen, priests, diplomats, police authorities, labour leaders, nihilists and anarchists, and of the consequent growth of my own political and religious convictions; but it will not be difficult to see where and in what way time and thought had little by little overlaid the humanities of the early sketch with many extra interests. That these interests were of the essence, clothing, and not crushing the human motive, I trust I may continue to believe, and certainly I have no reason to be dissatisfied with the reception of my book at the hands of that wide circle of general readers who care less for a contribution to a great social propaganda than for a simple tale of love.

But when the time came to return to my first draft of a play, the tale of love was the only thing to consider, and being now on the point of producing the drama in England, America, and elsewhere, and requested to prepare an edition of my story for the use of the audiences at the theatre, I have thought myself justified in eliminating the politics and religion from my book, leaving nothing but the human interests with which alone the drama is allowed to deal. This has not been an easy thing to do, and now that it is done I am by no means sure that I may not have alienated the friends whom the abstract problems won for me without conciliating the readers who called for the story only. But not to turn my back on the work of three laborious years, or to discredit that part of it which expressed, however imperfectly, my sympathy with the struggles of the poor, and my participation in the social problems with which the world is now astir, I have obtained the promise of my publisher that the original version of "The Eternal City" shall be kept in print as long as the public calls for it.

In this form of my book, the aim has been to rely solely on the humanities and to go back to the simple story of the woman who denounced her husband in order to save his life. That was the theme of the draft which was the original basis of my novel, it is the central incident of the drama which is about to be produced in New York, and the present abbreviated version of the story is intended to follow the lines of the play in all essential particulars down to the end of the last chapter but one.

H. C.

Isle of Man, Sept. 1902.

THE ETERNAL CITY

PROLOGUE

I

He was hardly fit to figure in the great review of life. A boy of ten or twelve, in tattered clothes, with an accordion in a case swung over one shoulder like a sack, and under the other arm a wooden cage containing a grey squirrel. It was a December night in London, and the Southern lad had nothing to shelter his little body from the Northern cold but his short velveteen jacket, red waistcoat, and knickerbockers. He was going home after a long day in Chelsea, and, conscious of something fantastic in his appearance, and of doubtful legality in his calling, he was dipping into side streets in order to escape the laughter of the London boys and the attentions of policemen.

Coming to the Italian quarter in Soho, he stopped at the door of a shop to see the time. It was eight o'clock. There was an hour to wait before he would be allowed to go indoors. The shop was a baker's, and the window was full of cakes and confectionery. From an iron grid on the pavement there came the warm breath of the oven underground, the red glow of the fire, and the scythe-like swish of the long shovels. The boy blocked the squirrel under his armpit, dived into his pocket, and brought out some copper coins and counted them. There was ninepence. Ninepence was the sum he had to take home every night, and there was not a halfpenny to spare. He knew that perfectly before he began to count, but his appetite had tempted him to try again if his arithmetic was not at fault.

The air grew warmer, and it began to snow. At first it was a fine sprinkle that made a snow-mist, and adhered wherever it fell. The traffic speedily became less, and things looked big in the thick air. The boy was wandering aimlessly through the streets, waiting for nine o'clock. When he thought the hour was near, he realised that he had lost his way. He screwed up his eyes to see if he knew the houses and shops and signs, but everything seemed strange.

The snow snowed on, and now it fell in large, corkscrew flakes. The boy brushed them from his face, but at the next moment they blinded him again. The few persons still in the streets loomed up on him out of the darkness, and passed in a moment like gigantic shadows. He tried to ask his way, but nobody would stand long enough to listen. One man who was putting up his shutters shouted some answer that was lost in the drumlike rumble of all voices in the falling snow.

The boy came up to a big porch with four pillars, and stepped in to rest and reflect. The long tunnels of smoking lights which had receded down the streets were not to be seen from there, and so he knew that he was in a square. It would be Soho Square, but whether he was on the south or east of it he could not tell, and consequently he was at a loss to know which way to turn. A great silence had fallen over everything, and only the sobbing nostrils of the cab-horses seemed to be audible in the hollow air.

He was very cold. The snow had got into his shoes, and through the rents in his cross-gartered stockings. His red waistcoat wanted buttons, and he could feel that his shirt was wet. He tried to shake the snow off by stamping, but it clung to his velveteens. His numbed fingers could scarcely hold the cage, which was also full of snow. By the light coming from a fanlight over the door in the porch he looked at his squirrel. The little thing was trembling pitifully in its icy bed, and he took it out and breathed on it to warm it, and then put it in his bosom. The sound of a child's voice laughing and singing came to him from within the house, muffled by the walls and the door. Across the white vapour cast outward from the fanlight he could see nothing but the crystal snowflakes falling wearily.

He grew dizzy, and sat down by one of the pillars. After a while a shiver passed along his spine, and then he became warm and felt sleepy. A church clock struck nine, and he started up with a guilty feeling, but his limbs were stiff and he sank back again, blew two or three breaths on to the squirrel inside his waistcoat, and fell into a doze. As he dropped off into unconsciousness he seemed to see the big, cheerless house, almost destitute of furniture, where he lived with thirty or forty other boys. They trooped in with their organs and accordions, counted out their coppers to a man with a clipped moustache, who was blowing whiffs of smoke from a long, black cigar, with a straw through it, and then sat down on forms to eat their plates of macaroni and cheese. The man was not in good temper to-night, and he was shouting at some who were coming in late and at others who were sharing their supper with the squirrels that nestled in their bosoms, or the monkeys, in red jacket and fez, that perched upon their shoulders. The boy was perfectly unconscious by this time, and the child within the house was singing away as if her little breast was a cage of song-birds.

As the church clock struck nine a class of Italian lads in an upper room in Old Compton Street was breaking up for the night, and the teacher, looking out of the window, said:

"While we have been telling the story of the great road to our country a snowstorm has come, and we shall have enough to do to find our road home."

The lads laughed by way of answer, and cried: "Good-night, doctor."

"Good-night, boys, and God bless you," said the teacher.

He was an elderly man, with a noble forehead and a long beard. His face, a sad one, was lighted up by a feeble smile; his voice was soft, and his manner gentle. When the boys were gone he swung over his shoulders a black cloak with a red lining, and followed them into the street.

He had not gone far into the snowy haze before he began to realise that his playful warning had not been amiss.

"Well, well," he thought, "only a few steps, and yet so difficult to find."

He found the right turnings at last, and coming to the porch of his house in Soho Square, he almost trod on a little black and white object lying huddled at the base of one of the pillars.

"A boy," he thought, "sleeping out on a night like this! Come, come," he said severely, "this is wrong," and he shook the little fellow to waken him.

The boy did not answer, but he began to mutter in a sleepy monotone, "Don't hit me, sir. It was snow. I'll not come home late again. Ninepence, sir, and Jinny is so cold."

The man paused a moment, then turned to the door rang the bell sharply.

II

Half-an-hour later the little musician was lying on a couch in the doctor's surgery, a cheerful room with a fire and a soft lamp under a shade. He was still unconscious, but his damp clothes had been taken off and he was wrapped in blankets. The doctor sat at the boy's head and moistened his lips with brandy, while a good woman, with the face of a saint, knelt at the end of the couch and rubbed his little feet and legs. After a little while there was a perceptible quivering of the eyelids and twitching of the mouth.

"He is coming to, mother," said the doctor.

"At last," said his wife.

The boy moaned and opened his eyes, the big helpless eyes of childhood, black as a sloe, and with long black lashes. He looked at the fire, the lamp, the carpet, the blankets, the figures at either end of the couch, and with a smothered cry he raised himself as though thinking to escape.

"Carino!" said the doctor, smoothing the boy's curly hair. "Lie still a little longer."

The voice was like a caress, and the boy sank back. But presently he raised himself again, and gazed around the room as if looking for something. The good mother understood him perfectly, and from a chair on which his clothes were lying she picked up his little grey squirrel. It was frozen stiff with the cold and now quite dead, but he grasped it tightly and kissed it passionately, while big teardrops rolled on to his cheeks.

"Carino!" said the doctor again, taking the dead squirrel away, and after a while the boy lay quiet and was comforted.

"Italiano—si?"

"Si, Signore."

"From which province?"

"Campagna Romana, Signore."

"Where does he say he comes from, doctor?"

"From the country district outside Rome. And now you are living at Maccari's in Greek Street—isn't that so?"

"Yes, sir."

"How long have you been in England—one year, two years?"

"Two years and a half, sir."

"And what is your name, my son?"

"David Leone."

"A beautiful name, carino! David Le-o-ne," repeated the doctor, smoothing the curly hair.

"A beautiful boy, too! What will you do with him, doctor?"

"Keep him here to-night at all events, and to-morrow we'll see if some institution will not receive him. David Leone! Where have I heard that name before, I wonder? Your father is a farmer?"

But the boy's face had clouded like a mirror that has been breathed upon, and he made no answer.

"Isn't your father a farmer in the Campagna Romana, David?"

"I have no father," said the boy.

"Carino! But your mother is alive—yes?"

"I have no mother."

"Caro mio! Caro mio! You shall not go to the institution to-morrow, my son," said the doctor, and then the mirror cleared in a moment as if the sun had shone on it.

"Listen, father!"

Two little feet were drumming on the floor above.

"Baby hasn't gone to bed yet. She wouldn't sleep until she had seen the boy, and I had to promise she might come down presently."

"Let her come down now," said the doctor.

The boy was supping a basin of broth when the door burst open with a bang, and like a tiny cascade which leaps and bubbles in the sunlight, a little maid of three, with violet eyes, golden complexion, and glossy black hair, came bounding into the room. She was trailing behind her a train of white nightdress, hobbling on the portion in front, and carrying under her arm a cat, which, being held out by the neck, was coiling its body and kicking its legs like a rabbit.

But having entered with so fearless a front, the little woman drew up suddenly at sight of the boy, and, entrenching herself behind the doctor, began to swing by his coat-tails, and to take furtive glances at the stranger in silence and aloofness.

"Bless their hearts! what funny things they are, to be sure," said the mother. "Somebody seems to have been telling her she might have a brother some day, and when nurse said to Susanna, 'The doctor has brought a boy home with him to-night,' nothing was so sure as that this was the brother they had promised her, and yet now ... Roma, you silly child, why don't you come and speak to the poor boy who was nearly frozen to death in the snow?"

But Roma's privateering fingers were now deep in her father's pocket, in search of a specimen of the sugar-stick which seemed to live and grow there. She found two sugar-sticks this time, and sight of a second suggested a bold adventure. Sidling up toward the couch, but still holding on to the doctor's coat-tails, like a craft that swings to anchor, she tossed one of the sugar-sticks on to the floor at the boy's side. The boy smiled and picked it up, and this being taken for sufficient masculine response, the little daughter of Eve proceeded to proper overtures.

"Oo a boy?"

The boy smiled again and assented.

"Oo me brodder?"

The boy's smile paled perceptibly.

"Oo lub me?"

The tide in the boy's eyes was rising rapidly.

"Oo lub me eber and eber?"

The tears were gathering fast, when the doctor, smoothing the boy's dark curls again, said:

"You have a little sister of your own far away in the Campagna Romana—yes?"

"No, sir."

"Perhaps it's a brother?"

"I ... I have nobody," said the boy, and his voice broke on the last word with a thud.

"You shall not go to the institution at all, David," said the doctor softly.

"Doctor Roselli!" exclaimed his wife. But something in the doctor's face smote her instantly and she said no more.

"Time for bed, baby."

But baby had many excuses. There were the sugar-sticks, and the pussy, and the boy-brother, and finally her prayers to say.

"Say them here, then, sweetheart," said her mother, and with her cat pinned up again under one arm and the sugar-stick held under the other, kneeling face to the fire, but screwing her half-closed eyes at intervals in the direction of the couch, the little maid put her little waif-and-stray hands together and said:

"Our Fader oo art in Heben, alud be dy name. Dy kingum tum. Dy will be done on eard as it is in Heben. Gib us dis day our dayey bread, and forgib us our trelspasses as we forgib dem dat trelspass ayenst us. And lee us not into temstashuns, but deliber us from ebil ... for eber and eber. Amen."

The house in Soho Square was perfectly silent an hour afterward. In the surgery the lamp was turned down, the cat was winking and yawning at the fire, and the doctor sat in a chair in front of the fading glow and listened to the measured breathing of the boy behind him. It dropped at length, like a pendulum that is about to stop, into the noiseless beat of innocent sleep, and then the good man got up and looked down at the little head on the pillow.

Even with the eyes closed it was a beautiful face; one of the type which great painters have loved to paint for their saints and angels—sweet, soft, wise, and wistful. And where did it come from? From the Campagna Romana, a scene of poverty, of squalor, of fever, and of death!

The doctor thought of his own little daughter, whose life had been a long holiday, and then of the boy whose days had been an unbroken bondage.

"Yet who knows but in the rough chance of life our little Roma may not some day ... God forbid!"

The boy moved in his sleep and laughed the laugh of a dream that is like the sound of a breeze in soft summer grass, and it broke the thread of painful reverie.

"Poor little man! he has forgotten all his troubles."

Perhaps he was back in his sunny Italy by this time, among the vines and the oranges and the flowers, running barefoot with other children on the dazzling whiteness of the roads!... Perhaps his mother in heaven was praying her heart out to the Blessed Virgin to watch over her fatherless darling cast adrift upon the world!

The train of thought was interrupted by voices in the street, and the doctor drew the curtain of the window aside and looked out. The snow had ceased to fall, and the moon was shining; the leafless trees were casting their delicate black shadows on the whitened ground, and the yellow light of a lantern on the opposite angle of the square showed where a group of lads were singing a Christmas carol.

"While shepherds watched their flocks by night, all seated on the ground,

The angel of the Lord came down, and glory shone around."

Doctor Roselli closed the curtain, put out the lamp, touched with his lips the forehead of the sleeping boy, and went to bed.

PART ONE—THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE

TWENTY YEARS LATER

I

It was the last day of the century. In a Bull proclaiming a Jubilee the Pope had called his faithful children to Rome, and they had come from all quarters of the globe. To salute the coming century, and to dedicate it, in pomp and solemn ceremony, to the return of the world to the Holy Church, one and universal, the people had gathered in the great Piazza of St. Peter.

Boys and women were climbing up every possible elevation, and a bright-faced girl who had conquered a high place on the base of the obelisk was chattering down at a group of her friends who were listening to their cicerone.

"Yes, that is the Vatican," said the guide, pointing to a square building at the back of the colonnade, "and the apartments of the Pope are those on the third floor, just on the level of the Loggia of Raphael. The Cardinal Secretary of State used to live in the rooms below, opening on the grand staircase that leads from the Court of Damasus. There's a private way up to the Pope's apartment, and a secret passage to the Castle of St. Angelo."

"Say, has the Pope got that secret passage still?"

"No, sir. When the Castle went over to the King the connection with the Vatican was cut off. Ah, everything is changed since those days! The Pope used to go to St. Peter's surrounded by his Cardinals and Bishops, to the roll of drums and the roar of cannon. All that is over now. The present Pope is trying to revive the old condition seemingly, but what can he do? Even the Bull proclaiming the Jubilee laments the loss of the temporal power which would have permitted him to renew the enchantments of the Holy City."

"Tell him it's just lovely as it is," said the girl on the obelisk, "and when the illuminations begin...."

"Say, friend," said her parent again, "Rome belonged to the Pope—yes? Then the Italians came in and took it and made it the capital of Italy—so?"

"Just so, and ever since then the Holy Father has been a prisoner in the Vatican, going into it as a cardinal and coming out of it as a corpse, and to-day will be the first time a Pope has set foot in the streets of Rome!"

"My! And shall we see him in his prison clothes?"

"Lilian Martha! Don't you know enough for that? Perhaps you expect to see his chains and a straw of his bed in the cell? The Pope is a king and has a court—that's the way I am figuring it."

"True, the Pope is a sovereign still, and he is surrounded by his officers of state—Cardinal Secretary, Majordomo, Master of Ceremonies, Steward, Chief of Police, Swiss Guards, Noble Guard and Palatine Guard, as well as the Papal Guard who live in the garden and patrol the precincts night and day."

"Then where the nation ... prisoner, you say?"

"Prisoner indeed! Not even able to look out of his windows on to this piazza on the 20th of September without the risk of insult and outrage—and Heaven knows what will happen when he ventures out to-day!"

"Well! this goes clear ahead of me!"

Beyond the outer cordon of troops many carriages were drawn up in positions likely to be favourable for a view of the procession. In one of these sat a Frenchman in a coat covered with medals, a florid, fiery-eyed old soldier with bristling white hair. Standing by his carriage door was a typical young Roman, fashionable, faultlessly dressed, pallid, with strong lower jaw, dark watchful eyes, twirled-up moustache and cropped black mane.

"Ah, yes," said the old Frenchman. "Much water has run under the bridge since then, sir. Changed since I was here? Rome? You're right, sir. 'When Rome falls, falls the world;' but it can alter for all that, and even this square has seen its transformations. Holy Office stands where it did, the yellow building behind there, but this palace, for instance—this one with the people in the balcony...."

The Frenchman pointed to the travertine walls of a prison-like house on the farther side of the piazza.

"Do you know whose palace that is?"

"Baron Bonelli's, President of the Council and Minister of the Interior."

"Precisely! But do you know whose palace it used to be?"

"Belonged to the English Wolsey, didn't it, in the days when he wanted the Papacy?"

"Belonged in my time to the father of the Pope, sir—old Baron Leone!"

"Leone! That's the family name of the Pope, isn't it?"

"Yes, sir, and the old Baron was a banker and a cripple. One foot in the grave, and all his hopes centred in his son. 'My son,' he used to say, 'will be the richest man in Rome some day—richer than all their Roman princes, and it will be his own fault if he doesn't make himself Pope.'"

"He has, apparently."

"Not that way, though. When his father died, he sold up everything, and having no relations looking to him, he gave away every penny to the poor. That's how the old banker's palace fell into the hands of the Prime Minister of Italy—an infidel, an Antichrist."

"So the Pope is a good man, is he?"

"Good man, sir? He's not a man at all, he's an angel! Only two aims in life—the glory of the Church and the welfare of the rising generation. Gave away half his inheritance founding homes all over the world for poor boys. Boys—that's the Pope's tender point, sir! Tell him anything tender about a boy and he breaks up like an old swordcut."

The eyes of the young Roman were straying away from the Frenchman to a rather shabby single-horse hackney carriage which had just come into the square and taken up its position in the shadow of the grim old palace. It had one occupant only—a man in a soft black hat. He was quite without a sign of a decoration, but his arrival had created a general commotion, and all faces were turning toward him.

"Do you happen to know who that is?" said the gay Roman. "That man in the cab under the balcony full of ladies? Can it be David Rossi?"

"David Rossi, the anarchist?"

"Some people call him so. Do you know him?"

"I know nothing about the man except that he is an enemy of his Holiness."

"He intends to present a petition to the Pope this morning, nevertheless."

"Impossible!"

"Haven't you heard of it? These are his followers with the banners and badges."

He pointed to the line of working-men who had ranged themselves about the cab, with banners inscribed variously, "Garibaldi Club," "Mazzini Club," "Republican Federation," and "Republic of Man."

"Your friend Antichrist," tipping a finger over his shoulder in the direction of the palace, "has been taxing bread to build more battleships, and Rossi has risen against him. But failing in the press, in Parliament and at the Quirinal, he is coming to the Pope to pray of him to let the Church play its old part of intermediary between the poor and the oppressed."

"Preposterous!"

"So?"

"To whom is the Pope to protest? To the King of Italy who robbed him of his Holy City? Pretty thing to go down on your knees to the brigand who has stripped you! And at whose bidding is he to protest? At the bidding of his bitterest enemy? Pshaw!"

"You persist that David Rossi is an enemy of the Pope?"

"The deadliest enemy the Pope has in the world."

II

The subject of the Frenchman's denunciation looked harmless enough as he sat in his hackney carriage under the shadow of old Baron Leone's gloomy palace. A first glance showed a man of thirty-odd years, tall, slightly built, inclined to stoop, with a long, clean-shaven face, large dark eyes, and dark hair which covered the head in short curls of almost African profusion. But a second glance revealed all the characteristics that give the hand-to-hand touch with the common people, without which no man can hope to lead a great movement.

From the moment of David Rossi's arrival there was a tingling movement in the air, and from time to time people approached and spoke to him, when the tired smile struggled through the jaded face and then slowly died away. After a while, as if to subdue the sense of personal observation, he took a pen and oblong notepaper and began to write on his knees.

Meantime the quick-eyed facile crowd around him beguiled the tedium of waiting with good-humoured chaff. One great creature with a shaggy mane and a sanguinary voice came up, bottle in hand, saluted the downcast head with a mixture of deference and familiarity, then climbed to the box-seat beside the driver, and in deepest bass began the rarest mimicry. He was a true son of the people, and under an appearance of ferocity he hid the heart of a child. To look at him you could hardly help laughing, and the laughter of the crowd at his daring dashes showed that he was the privileged pet of everybody. Only at intervals the downcast head was raised from its writing, and a quiet voice of warning said:

"Bruno!"

Then the shaggy head on the box-seat slewed round and bobbed downward with an apologetic gesture, and ten seconds afterwards plunged into wilder excesses.

"Pshaw!" mopping with one hand his forehead under his tipped-up billicock, and holding the bottle with the other. "It's hot! Dog of a Government, it's hot, I say! Never mind! here's to the exports of Italy, brother; and may the Government be the first of them."

"Bruno!"

"Excuse me, sir; the tongue breaks no bones, sir! All Governments are bad, and the worst Government is the best."

A feeble old man was at that moment crushing his way up to the cab. Seeing him approach, David Rossi rose and held out his hand. The old man took it, but did not speak.

"Did you wish to speak to me, father?"

"I can't yet," said the old man, and his voice shook and his eyes were moist.

David Rossi stepped out of the cab, and with gentle force, against many protests, put the old man in his place.

"I come from Carrara, sir, and when I go home and tell them I've seen David Rossi, and spoken to him, they won't believe me. 'He sees the future clear,' they say, 'as an almanack made by God.'"

Just then there was a commotion in the crowd, an imperious voice cried, "Clear out," and the next instant David Rossi, who was standing by the step of his cab, was all but run down by a magnificent equipage with two high-stepping horses and a fat English coachman in livery of scarlet and gold.

His face darkened for a moment with some powerful emotion, then resumed its kindly aspect, and he turned back to the old man without looking at the occupant of the carriage.

It was a lady. She was tall, with a bold sweep of fulness in figure, which was on a large scale of beauty. Her hair, which was abundant and worn full over the forehead, was raven black and glossy, and it threw off the sunshine that fell on her face. Her complexion had a golden tint, and her eyes, which were violet, had a slight recklessness of expression. Her carriage drew up at the entrance of the palace, and the porter, with the silver-headed staff, came running and bowing to receive her. She rose to her feet with a consciousness of many eyes upon her, and with an unabashed glance she looked around on the crowd.

There was a sulky silence among the people, almost a sense of antagonism, and if anybody had cheered there might have been a counter demonstration. At the same time, there was a certain daring in that marked brow and steadfast smile which seemed to say that if anybody had hissed she would have stood her ground.

She lifted from the blue silk cushions of the carriage a small half-clipped black poodle with a bow of blue ribbon on its forehead, tucked it under her arm, stepped down to the street, and passed into the courtyard, leaving an odour of ottar of roses behind her.

Only then did the people speak.

"Donna Roma!"

The name seemed to pass over the crowd in a breathless whisper, soundless, supernatural, like the flight of a bat in the dark.

III

The Baron Bonelli had invited certain of his friends to witness the Pope's procession from the windows and balconies of his palace overlooking the piazza, and they had begun to arrive as early as half-past nine.

In the green courtyard they were received by the porter in the cocked hat, on the dark stone staircase by lackeys in knee-breeches and yellow stockings, in the outer hall, intended for coats and hats, by more lackeys in powdered wigs, and in the first reception-room, gorgeously decorated in the yellow and gold of the middle ages, by Felice, in a dress coat, the Baron's solemn personal servant, who said, in sepulchral tones:

"The Baron's excuses, Excellency! Engaged in the Council-room with some of the Ministers, but expects to be out presently. Sit in the Loggia, Excellency?"

"So our host is holding a Cabinet Council, General?" said the English Ambassador.

"A sort of scratch council, seemingly. Something that concerns the day's doings, I guess, and is urgent and important."

"A great man, General, if half one hears about him is true."

"Great?" said the American. "Yes, and no, Sir Evelyn, according as you regard him. In the opinion of some of his followers the Baron Bonelli is the greatest man in the country—greater than the King himself—and a statesman too big for Italy. One of those commanding personages who carry everything before them, so that when they speak even monarchs are bound to obey. That's one view of his picture, Sir Evelyn."

"And the other view?"

General Potter glanced in the direction of a door hung with curtains, from which there came at intervals the deadened drumming of voices, and then he said:

"A man of implacable temper and imperious soul, an infidel of hard and cynical spirit, a sceptic and a tyrant."

"Which view do the people take?"

"Can you ask? The people hate him for the heavy burden of taxation with which he is destroying the nation in his attempt to build it up."

"And the clergy, and the Court, and the aristocracy?"

"The clergy fear him, the Court detests him, and the Roman aristocracy are rancorously hostile."

"Yet he rules them all, nevertheless?"

"Yes, sir, with a rod of iron—people, Court, princes, Parliament, King as well—and seems to have only one unsatisfied desire, to break up the last remaining rights of the Vatican and rule the old Pope himself."

"And yet he invites us to sit in his Loggia and look at the Pope's procession."

"Perhaps because he intends it shall be the last we may ever see of it."

"The Princess Bellini and Don Camillo Murelli," said Felice's sepulchral voice from the door.

An elderly aristocratic beauty wearing nodding white plumes came in with a pallid young Roman noble dressed in the English fashion.

"You come to church, Don Camillo?"

"Heard it was a service which happened only once in a hundred years, dear General, and thought it mightn't be convenient to come next time," said the young Roman.

"And you, Princess! Come now, confess, is it the perfume of the incense which brings you to the Pope's procession, or the perfume of the promenaders?"

"Nonsense, General!" said the little woman, tapping the American with the tip of her lorgnette. "Who comes to a ceremony like this to say her prayers? Nobody whatever, and if the Holy Father himself were to say...."

"Oh! oh!"

"Which reminds me," said the little lady, "where is Donna Roma?"

"Yes, indeed, where is Donna Roma?" said the young Roman.

"Who is Donna Roma?" said the Englishman.

"Santo Dio! the man doesn't know Donna Roma!"

The white plumes bobbed up, the powdered face fell back, the little twinkling eyes closed, and the company laughed and seated themselves in the Loggia.

"Donna Roma, dear sir," said the young Roman, "is a type of the fair lady who has appeared in the history of every nation since the days of Helen of Troy."

"Has a woman of this type, then, identified herself with the story of Rome at a moment like the present?" said the Englishman.

The young Roman smiled.

"Why did the Prime Minister appoint so-and-so?—Donna Roma! Why did he dismiss such-and-such?—Donna Roma! What feminine influence imposed upon the nation this or that?—Donna Roma! Through whom come titles, decorations, honours?—Donna Roma! Who pacifies intractable politicians and makes them the devoted followers of the Ministers?—Donna Roma! Who organises the great charitable committees, collects funds and distributes them?—Donna Roma! Always, always Donna Roma!"

"So the day of the petticoat politician is not over in Italy yet?"

"Over? It will only end with the last trump. But dear Donna Roma is hardly that. With her light play of grace and a whole artillery of love in her lovely eyes, she only intoxicates a great capital and"—with a glance towards the curtained door—"takes captive a great Minister."

"Just that," and the white plumes bobbed up and down.

"Hence she defies conventions, and no one dares to question her actions on her scene of gallantry."

"Drives a pair of thoroughbreds in the Corso every afternoon, and threatens to buy an automobile."

"Has debts enough to sink a ship, but floats through life as if she had never known what it was to be poor."

"And has she?"

The voices from behind the curtained door were louder than usual at that moment, and the young Roman drew his chair closer.

"Donna Roma, dear sir, was the only child of Prince Volonna. Nobody mentions him now, so speak of him in a whisper. The Volonnas were an old papal family, holding office in the Pope's household, but the young Prince of the house was a Liberal, and his youth was cast in the stormy days of the middle of the century. As a son of the revolution he was expelled from Rome for conspiracy against the papal Government, and when the Pope went out and the King came in, he was still a republican, conspiring against the reigning sovereign, and, as such, a rebel. Meanwhile he had wandered over Europe, going from Geneva to Berlin, from Berlin to Paris. Finally he took refuge in London, the home of all the homeless, and there he was lost and forgotten. Some say he practised as a doctor, passing under another name; others say that he spent his life as a poor man in your Italian quarter of Soho, nursing rebellion among the exiles from his own country. Only one thing is certain: late in life he came back to Italy as a conspirator—enticed back, his friends say—was arrested on a charge of attempted regicide, and deported to the island of Elba without a word of public report or trial."

"Domicilio Coatto—a devilish and insane device," said the American Ambassador.

"Was that the fate of Prince Volonna?"

"Just so," said the Roman. "But ten or twelve years after he disappeared from the scene a beautiful girl was brought to Rome and presented as his daughter."

"Donna Roma?"

"Yes. It turned out that the Baron was a kinsman of the refugee, and going to London he discovered that the Prince had married an English wife during the period of his exile, and left a friendless daughter. Out of pity for a great name he undertook the guardianship of the girl, sent her to school in France, finally brought her to Rome, and established her in an apartment on the Trinità de' Monti, under the care of an old aunt, poor as herself, and once a great coquette, but now a faded rose which has long since seen its June."

"And then?"

"Then? Ah, who shall say what then, dear friend? We can only judge by what appears—Donna Roma's elegant figure, dressed in silk by the best milliners Paris can provide, queening it over half the women of Rome."

"And now her aunt is conveniently bedridden," said the little Princess, "and she goes about alone like an Englishwoman; and to account for her extravagance, while everybody knows her father's estate was confiscated, she is by way of being a sculptor, and has set up a gorgeous studio, full of nymphs and cupids and limbs."

"And all by virtue of—what?" said the Englishman.

"By virtue of being—the good friend of the Baron Bonelli!"

"Meaning by that?"

"Nothing—and everything!" said the Princess with another trill of laughter.

"In Rome, dear friend," said Don Camillo, "a woman can do anything she likes as long as she can keep people from talking about her."

"Oh, you never do that apparently," said the Englishman. "But why doesn't the Baron make her a Baroness and have done with the danger?"

"Because the Baron has a Baroness already."

"A wife living?"

"Living and yet dead—an imbecile, a maniac, twenty years a prisoner in his castle in the Alban hills."

IV

The curtain parted over the inner doorway, and three gentlemen came out. The first was a tall, spare man, about fifty years of age, with an intellectual head, features cut clear and hard like granite, glittering eyes under overhanging brows, black moustaches turned up at the ends, and iron-grey hair cropped very short over a high forehead. It was the Baron Bonelli.

One of the two men with him had a face which looked as if it had been carved by a sword or an adze, good and honest but blunt and rugged; and the other had a long, narrow head, like the head of a hen—a lanky person with a certain mixture of arrogance and servility in his expression.

The company rose from their places in the Loggia, and there were greetings and introductions.

"Sir Evelyn Wise, gentlemen, the new British Ambassador—General Morra, our Minister of War; Commendatore Angelelli, our Chief of Police. A thousand apologies, ladies! A Minister of the Interior is one of the human atoms that live from minute to minute and are always at the mercy of events. You must excuse the Commendatore, gentlemen; he has urgent duties outside."

The Prime Minister spoke with the lucidity and emphasis of a man accustomed to command, and when Angelelli had bowed all round he crossed with him to the door.

"If there is any suspicion of commotion, arrest the ringleaders at once. Let there be no trifling with disorder, by whomsoever begun. The first to offend must be the first to be arrested, whether he wears cap or cassock."

"Good, your Excellency," and the Chief of Police went out.

"Commotion! Disorder! Madonna mia!" cried the little Princess.

"Calm yourselves, ladies. It's nothing! Only it came to the knowledge of the Government that the Pope's procession this morning might be made the excuse for a disorderly demonstration, and of course order must not be disturbed even under the pretext of liberty and religion."

"So that was the public business which deprived us of your society?" said the Princess.

"And left my womanless house the duty of receiving you in my absence," said the Baron.

The Baron bowed his guests to their seats, stood with his back to a wide ingle, and began to sketch the Pope's career.

"His father was a Roman banker—lived in this house, indeed—and the young Leone was brought up in the Jesuit schools and became a member of the Noble Guard: handsome, accomplished, fond of society and social admiration, a man of the world. This was a cause of disappointment to his father, who has intended him for a great career in the Church. They had their differences, and finally a mission was found for him and he lived a year abroad. The death of the old banker brought him back to Rome, and then, to the astonishment of society, he renounced the world and took holy orders. Why he gave up his life of gallantry did not appear...."

"Some affair of the heart, dear Baron," said the little Princess, with a melting look.

"No, there was no talk of that kind, Princess, and not a whisper of scandal. Some said the young soldier had married in England, and lost his wife there, but nobody knew for certain. There was less doubt about his religious vocation, and when by help of his princely inheritance he turned his mind to the difficult task of reforming vice and ministering to the lowest aspects of misery in the slums of Rome, society said he had turned Socialist. His popularity with the people was unbounded, but in the midst of it all he begged to be removed to London. There he set up the same enterprises, and tramped the streets in search of his waifs and outcasts, night and day, year in, year out, as if driven on by a consuming passion of pity for the lost and fallen. In the interests of his health he was called back to Rome—and returned here a white-haired man of forty."

"Ah! what did I say, dear Baron? The apple falls near the tree, you know!"

"By this time he had given away millions, and the Pope wished to make him President of his Academy of Noble Ecclesiastics, but he begged to be excused. Then Apostolic Delegate to the United States, and he prayed off. Then Nuncio to Spain, and he went on his knees to remain in the Campagna Romana, and do the work of a simple priest among a simple people. At last, without consulting him they made him Bishop, and afterwards Cardinal, and, on the death of the Pope, he was Scrutator to the Conclave, and fainted when he read out his own name as that of Sovereign Pontiff of the Church."

The little Princess was wiping her eyes.

"Then—all the world was changed. The priest of the future disappeared in a Pope who was the incarnation of the past. Authority was now his watchword. What was the highest authority on earth? The Holy See! Therefore, the greatest thing for the world was the domination of the Pope. If anybody should say that the power conferred by Christ on his Vicar was only spiritual, let him be accursed! In Christ's name the Pope was sovereign—supreme sovereign over the bodies and souls of men—acknowledging no superior, holding the right to make and depose kings, and claiming to be supreme judge over the consciences and crimes of all—the peasant that tills the soil, and the prince that sits on the throne!"

"Tre-men-jous!" said the American.

"But, dear Baron," said the little Princess, "don't you think there was an affair of the heart after all?" and the little plumes bobbed sideways.

The Baron laughed again. "The Pope seems to have half of humanity on his side already—he has the women apparently."

All this time there had risen from the piazza into the room a humming noise like the swarming of bees, but now a shrill voice came up from the crowd with the sudden swish of a rocket.

"Look out!"

The young Roman, who had been looking over the balcony, turned his head back and said:

"Donna Roma, Excellency."

But the Baron had gone from the room.

"He knew her carriage wheels apparently," said Don Camillo, and the lips of the little Princess closed tight as if from sudden pain.

V

The return of the Baron was announced by the faint rustle of a silk under-skirt and a light yet decided step keeping pace with his own. He came back with Donna Roma on his arm, and over his coolness and calm dignity he looked pleased and proud.

The lady herself was brilliantly animated and happy. A certain swing in her graceful carriage gave an instant impression of perfect health, and there was physical health also in the brightness of her eyes and the gaiety of her expression. Her face was lighted up by a smile which seemed to pervade her whole person and make it radiant with overflowing joy. A vivacity which was at the same time dignified and spontaneous appeared in every movement of her harmonious figure, and as she came into the room there was a glow of health and happiness that filled the air like the glow of sunlight through a veil of soft red gauze.

She saluted the Baron's guests with a smile that fascinated everybody. There was a modified air of freedom about her, as of one who has a right to make advances, a manner which captivates all women in a queen and all men in a lovely woman.

"Ah, it is you, General Potter? And my dear General Morra? Camillo mio!" (The Italian had rushed upon her and kissed her hand.) "Sir Evelyn Wise, from England, isn't it? I'm half an Englishwoman myself, and I'm very proud of it."

She had smiled frankly into Sir Evelyn's face, and he had smiled back without knowing it. There was something contagious about her smile. The rosy mouth with its pearly teeth seemed to smile of itself, and the lovely eyes had their separate art of smiling. Her lips parted of themselves, and then you felt your own lips parting.

"You were to have been busy with your fountain to-day...." began the Baron.

"So I expected," she said in a voice that was soft yet full, "and I did not think I should care to see any more spectacles in Rome, where the people are going in procession all the year through—but what do you think has brought me?"

"The artist's instinct, of course," said Don Camillo.

"No, just the woman's—to see a man!"

"Lucky fellow, whoever he is!" said the American. "He'll see something better than you will, though," and then the golden complexion gleamed up at him under a smile like sunshine.

"But who is he?" said the young Roman.

"I'll tell you. Bruno—you remember Bruno?"

"Bruno!" cried the Baron.

"Oh! Bruno is all right," she said, and, turning to the others, "Bruno is my man in the studio—my marble pointer, you know. Bruno Rocco, and nobody was ever so rightly named. A big, shaggy, good-natured bear, always singing or growling or laughing, and as true as steel. A terrible Liberal, though; a socialist, an anarchist, a nihilist, and everything that's shocking."

"Well?"

"Well, ever since I began my fountain ... I'm making a fountain for the Municipality—it is to be erected in the new part of the Piazza Colonna. I expect to finish it in a fortnight. You would like to see it? Yes? I'll send you cards—a little private view, you know."

"But Bruno?"

"Ah! yes, Bruno! Well, I've been at a loss for a model for one of my figures ... figures all round the dish, you know. They represent the Twelve Apostles, with Christ in the centre giving out the water of life."

"But Bruno! Bruno! Bruno!"

She laughed, and the merry ring of her laughter set them all laughing.

"Well, Bruno has sung the praises of one of his friends until I'm crazy ... crazy, that's English, isn't it? I told you I was half an Englishwoman. American? Thanks, General! I'm 'just crazy' to get him in."

"Simple enough—hire him to sit to you," said the Princess.

"Oh," with a mock solemnity, "he is far too grand a person for that! A member of Parliament, a leader of the Left, a prophet, a person with a mission, and I daren't even dream of it. But this morning, Bruno tells me, his friend, his idol, is to stop the Pope's procession, and present a petition, so I thought I would kill two birds with one stone—see my man and see the spectacle—and here I am to see them!"

"And who is this paragon of yours, my dear?"

"The great David Rossi!"

"That man!"

The white plumes were going like a fan.

"The man is a public nuisance and ought to be put down by the police," said the little Princess, beating her foot on the floor.

"He has a tongue like a sword and a pen like a dagger," said the young Roman.

Donna Roma's eyes began to flash with a new expression.

"Ah, yes, he is a journalist, isn't he, and libels people in his paper?"

"The creature has ruined more reputations than anybody else in Europe," said the little Princess.

"I remember now. He made a terrible attack on our young old women and our old young men. Declared they were meddling with everything—called them a museum of mummies, and said they were symbolical of the ruin that was coming on the country. Shameful, wasn't it? Nobody likes to be talked about, especially in Rome, where it's the end of everything. But what matter? The young man has perhaps learned freedom of speech in some free country. We can afford to forgive him, can't we? And then he is so interesting and so handsome!"

"An attempt to stop the Pope's procession might end in tumult," said the American General to the Italian General. "Was that the danger the Baron spoke about?"

"Yes," said General Morra. "The Government have been compelled to tax bread, and of course that has been a signal for the enemies of the national spirit to say that we are starving the people. This David Rossi is the worst Roman in Rome. He opposed us in Parliament and lost. Petitioned the King and lost again. Now he intends to petition the Pope—with what hope, Heaven knows."

"With the hope of playing on public opinion, of course," said the Baron cynically.

"Public opinion is a great force, your Excellency," said the Englishman.

"A great pestilence," said the Baron warmly.

"What is David Rossi?"

"An anarchist, a republican, a nihilist, anything as old as the hills, dear friend, only everything in a new way," said the young Roman.

"David Rossi is the politician who proposes to govern the world by the precepts of the Lord's Prayer," said the American.

"The Lord's Prayer!"

The Baron paraded on the hearthrug. "David Rossi," he said compassionately, "is a creature of his age. A man of generous impulses and wide sympathies, moved to indignation at the extremes of poverty and wealth, and carried away by the promptings of the eternal religion in the human soul. A dreamer, of course, a dreamer like the Holy Father himself, only his dream is different, and neither could succeed without destroying the other. In the millennium Rossi looks for, not only are kings and princes to disappear, but popes and prelates as well."

"And where does this unpractical politician come from?" said the Englishman.

"We must ask you to tell us that, Sir Evelyn, for though he is supposed to be a Roman, he seems to have lived most of his life in your country. As silent as an owl and as inscrutable as a sphinx. Nobody in Rome knows certainly who his father was, nobody knows certainly who his mother was. Some say his father was an Englishman, some say a Jew, and some say his mother was a gipsy. A self-centred man, who never talks about himself, and cannot be got to lift the veil which surrounds his birth and early life. Came back to Rome eight years ago, and made a vast noise by propounding his platonic scheme of politics—was called up for his term of military service, refused to serve, got himself imprisoned for six months and came out a mighty hero—was returned to Parliament for no fewer than three constituencies, sat for Rome, took his place on the Extreme Left, and attacked every Minister and every measure which favoured the interest of the army—encouraged the workmen not to pay their taxes and the farmers not to pay their rents—and thus became the leader of a noisy faction, and is now surrounded by the degenerate class throughout Italy which dreams of reconstructing society by burying it under ruins."

"Lived in England, you say?"

"Apparently, and if his early life could be traced it would probably be found that he was brought up in an atmosphere of conspiracy—perhaps under the influence of some vile revolutionary living in London under the protection of your too liberal laws."

Donna Roma sprang up with a movement full of grace and energy. "Anyhow," she said, "he is young and good-looking and romantic and mysterious, and I'm head over ears in love with him already."

"Well, every man is a world," said the American.

"And what about woman?" said Roma.

He threw up his hands, she smiled full into his face, and they laughed together.

VI

A fanfare of trumpets came from the piazza, and with a cry of delight Roma ran into the balcony, followed by all the women and most of the men.

"Only the signal that the cortège has started," said Don Camillo. "They'll be some minutes still."

"Santo Dio!" cried Roma. "What a sight! It dazzles me; it makes me dizzy!"

Her face beamed, her eyes danced, and she was all aglow from head to foot. The American Ambassador stood behind her, and, as permitted by his greater age, he tossed back the shuttlecock of her playful talk with chaff and laughter.

"How patient the people are! See the little groups on camp-stools munching biscuits and reading the journals. 'La Vera Roma!'" (mimicking the cry of the newspaper sellers). "Look at that pretty girl—the fair one with the young man in the Homburg hat! She has climbed up the obelisk, and is inviting him to sit on an inch and a half of corbel beside her."

"Ah, those who love take up little room!"

"Don't they? What a lovely world it is! I'll tell you what this makes me think about—a wedding! Glorious morning, beautiful sunshine, flowers, wreaths, bridesmaids ready; coachman all a posy, only waiting for the bride!"

"A wedding is what you women are always dreaming about—you begin dreaming about it in your cradles—it's in a woman's bones, I do believe," said the American.

"Must be the ones she got from Adam, then," said Roma.

Meantime the Baron was still parading the hearthrug inside and listening to the warnings of his Minister of War.

"You are resolved to arrest the man?"

"If he gives us an opportunity—yes."

"You do not forget that he is a Deputy?"

"It is because I remember it that my resolution is fixed. In Parliament he is a privileged person; let him make half as much disorder outside and you shall see where he will be."

"Anarchists!" said Roma. "That group below the balcony? Is David Rossi among them? Yes? Which of them? Which? Which? Which? The tall man in the black hat with his back to us? Oh! why doesn't he turn his face? Should I shout?"

"Roma!" from the little Princess.

"I know; I'll faint, and you'll catch me, and the Princess will cry 'Madonna mia!' and then he'll turn round and look up."

"My child!"

"He'll see through you, though, and then where will you be?"

"See through me, indeed!" and she laughed the laugh a man loves to hear, half-raillery, half-caress.

"Donna Roma Volonna, daughter of a line of princes, making love to a nameless nobody!"

"Shows what a heavenly character she is, then! See how good I am at throwing bouquets at myself?"

"Well, what is love, anyway? A certain boy and a certain girl agree to go for a row in the same boat to the same place, and if they pull together, what does it matter where they come from?"

"What, indeed?" she said, and a smile, partly serious, played about the parted mouth.

"Could you think like that?"

"I could! I could! I could!"

The clock struck eleven. Another fanfare of trumpets came from the direction of the Vatican, and then the confused noises in the square suddenly ceased and a broad "Ah!" passed over it, as of a vast living creature taking breath.

"They're coming!" cried Roma. "Baron, the cortège is coming."

"Presently," the Baron answered from within.

Roma's dog, which had slept on a chair through the tumult, was awakened by the lull and began to bark. She picked it up, tucked it under her arm and ran back to the balcony, where she stood by the parapet, in full view of the people below, with the young Roman on one side, the American on the other, and the ladies seated around.

By this time the procession had begun to appear, issuing from a bronze gate under the right arm of the colonnade, and passing down the channel which had been kept open by the cordon of infantry.

Roma abandoned herself to the fascinations of the scene, and her gaiety infected everybody.

"Camillo, you must tell me who they all are. There now—those men who come first in black and red?"

"Laymen," said the young Roman. "They're called the Apostolic Cursori. When a Cardinal is nominated they take him the news, and get two or three thousand francs for their trouble."

"And these little fat folk in white lace pinafores?"

"Singers of the Sistine Chapel. That's the Director, old Maestro Mustafa—used to be the greatest soprano of the century."

"And this dear old friar with the mittens and rosary and the comfortable linsey-woolsey sort of face?"

"That's Father Pifferi of San Lorenzo, confessor to the Pope. He knows all the Pope's sins."

PROLOGUE

PART ONE—THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE

PART TWO—THE REPUBLIC OF MAN

PART THREE—ROMA

PART FOUR—DAVID ROSSI

PART FIVE—THE PRIME MINISTER

PART SIX—THE ROMAN OF ROME

PART SEVEN—THE POPE

PART EIGHT—THE KING

PART NINE—THE PEOPLE

"Oh!" said Roma.

At that moment her dog barked furiously, and the old friar looked up at her, whereupon she smiled down on him, and then a half-smile played about his good-natured face.

"He is a Capuchin, and those Frati in different colours coming behind him...."

"I know them; see if I don't," she cried, as there passed under the balcony a double file of friars and monks. "The brown ones—Capuchins and Franciscans! Brown and white—Carmelites! Black—Augustinians and Benedictines! Black with a white cross—Passionists! And the monks all white are Trappists. I know the Trappists best, because I drive out to Tre Fontane to buy eucalyptus and flirt with Father John."

"Shocking!" said the American.

"Why not? What are their vows of celibacy but conspiracies against us poor women? Nearly every man a woman wants is either mated or has sworn off in some way. Oh, how I should love to meet one of those anchorites in real life and make him fly!"

"Well, I dare say the whisk of a petticoat would be more frightening than all his doctors of divinity."

"Listen!"

From a part of the procession which had passed the balcony there came the sound of harmonious voices.

"The singers of the Sistine Chapel! They're singing a hymn."

"I know it. 'Veni, Creator!' How splendid! How glorious! I feel as if I wanted to cry!"

All at once the singing stopped, the murmuring and speaking of the crowd ceased too, and there was a breathless moment, such as comes before the first blast of a storm. A nervous quiver, like the shudder that passes over the earth at sundown, swept across the piazza, and the people stood motionless, every neck stretched, and every eye turned in the direction of the bronze gate, as if God were about to reveal Himself from the Holy of Holies. Then in that grand silence there came the clear call of silver trumpets, and at the next instant the Presence itself.

"The Pope! Baron, the Pope!"

The atmosphere was charged with electricity. A great roar of cheering went up from below like the roaring of surf, and it was followed by a clapping of hands like the running of the sea off a shingly beach after the boom of a tremendous breaker.

An old man, dressed wholly in white, carried shoulder-high on a chair glittering with purple and crimson, and having a canopy of silver and gold above him. He wore a triple crown, which glistened in the sunlight, and but for the delicate white hand which he upraised to bless the people, he might have been mistaken for an image.

His face was beautiful, and had a ray of beatified light on it—a face of marvellous sweetness and great spirituality.

It was a thrilling moment, and Roma's excitement was intense. "There he is! All in white! He's on a gilded chair under the silken canopy! The canopy is held up by prelates, and the chairmen are in knee-breeches and red velvet. Look at the great waving plumes on either side!"

"Peacock's feathers!" said a voice behind her, but she paid no heed.

"Look at the acolytes swinging incense, and the golden cross coming before! What thunders of applause—I can hardly hear myself speak. It's like standing on a cliff while the sea below is running mountains high. No, it's like no other sound on earth; it's human—fifty thousand unloosed throats of men! That's the clapping of ladies—listen to the weak applause of their white-gloved fingers. Now they're waving their handkerchiefs. Look! Like the wings of ten thousand butterflies fluttering up from a meadow."

Roma's abandonment was by this time complete; she was waving her handkerchief and crying "Viva il Papa Re!"

"They're bearing him slowly along. He's coming this way. Look at the Noble Guard in their helmets and jackboots. And there are the Swiss Guard in Joseph's coat of many colours! We can see him plainly now. Do you smell the incense? It's like the ribbon of Bruges. The pluviale? That gold vestment? It's studded on his breast with precious stones. How they blaze in the sunshine! He is blessing the people, and they are falling on their knees before him."

"Like the grass before the scythe!"

"How tired he looks! How white his face is! No, not white—ivory! No, marble—Carrara marble! He might be Lazarus who was dead and has come back from the tomb! No humanity left in him! A saint! An angel!"

"The spiritual autocrat of the world!"

"Viva il Papa Re! He's going by! Viva il Papa Re! He has gone.... Well!"

She was rising from her knees and wiping her eyes, trying to cover up with laughter the confusion of her rapture.

"What is that?"

There was a sound of voices in the distance chanting dolorously.

"The cantors intoning Tu es Petrus," said Don Camillo.

"No, I mean the commotion down there. Somebody is pushing through the Guard."

"It's David Rossi," said the American.

"Is that David Rossi? Oh, dear me! I had forgotten all about him." She moved forward to see his face. "Why ... where have I ... I've seen him before somewhere."

A strange physical sensation tingled all over her at that moment, and she shuddered as if with sudden cold.

"What's amiss?"

"Nothing! But I like him. Do you know, I really like him."

"Women are funny things," said the American.

"They're nice, though, aren't they?" And two rows of pearly teeth between parted lips gleamed up at him with gay raillery.

Again she craned forward. "He is on his knees to the Pope! Now he'll present the petition. No ... yes ... the brutes! They're dragging him away! The procession is going on! Disgraceful!"

"Long live the Workmen's Pope!" came up from the piazza, and under the shrill shouts of the pilgrims were heard the monotonous voices of the monks as they passed through the open doors of the Basilica intoning the praises of God.

"They're lifting him on to a car," said the American.

"David Rossi?"

"Yes; he is going to speak."

"How delightful! Shall we hear him? Good! How glad I am that I came! He is facing this way! Oh, yes; those are his own people with the banners! Baron, the Holy Father has gone on to St. Peter's, and David Rossi is going to speak."

"Hush!"

A quivering, vibrating voice came up from below, and in a moment there was a dead silence.

VII

"Brothers, when Christ Himself was on the earth going up to Jerusalem, He rode on the colt of an ass, and the blind and the lame and the sick came to Him, and He healed them. Humanity is sick and blind and lame to-day, brothers, but the Vicar of Christ goes on."

At the words an audible murmur came from the crowd, such as goes before the clapping of hands in a Roman theatre, a great upheaval of the heart of the audience to the actor who has touched and stirred it.

"Brothers, in a little Eastern village a long time ago, there arose among the poor and lowly a great Teacher, and the only prayer He taught His followers was the prayer 'Our Father who art in Heaven.' It was the expression of man's utmost need, the expression of man's utmost hope. And not only did the Teacher teach that prayer—He lived according to the light of it. All men were His brothers, all women His sisters; He was poor, He had no home, no purse, and no second coat; when He was smitten He did not smite back, and when He was unjustly accused He did not defend Himself. Nineteen hundred years have passed since then, brothers, and the Teacher who arose among the poor and lowly is now a great Prophet. All the world knows and honours Him, and civilised nations have built themselves upon the religion He founded. A great Church calls itself by His name, and a mighty kingdom, known as Christendom, owes allegiance to His faith. But what of His teaching? He said: 'Resist not evil,' yet all Christian nations maintain standing armies. He said: 'Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth,' yet the wealthiest men are Christian men, and the richest organisation in the world is the Christian Church. He said: 'Our Father who art in Heaven,' yet men who ought to be brothers are divided into states, and hate each other as enemies. He said: 'Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done on earth as it is done in Heaven,' yet he who believes it ever will come is called a fanatic and a fool."

Some murmurs of dissent were drowned in cries of "Go on!" "Speak!" "Silence!"

"Foremost and grandest of the teachings of Christ are two inseparable truths—the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. But in Italy, as elsewhere, the people are starved that king may contend with king, and when we appeal to the Pope to protest in the name of the Prince of Peace, he remembers his temporalities and passes on!"

At these words the emotion of the crowd broke into loud shouts of approval, with which some groans were mingled.

Roma had turned her face aside from the speaker, and her profile was changed—the gay, sprightly, airy, radiant look had given way to a serious, almost a melancholy expression.

"We have two sovereigns in Rome, brothers, a great State and a great Church, with a perishing people. We have soldiers enough to kill us, priests enough to tell us how to die, but no one to show us how to live."

"Corruption! Corruption!"

"Corruption indeed, brothers; and who is there among us to whom the corruptions of our rulers are unknown? Who cannot point to the wars made that should not have been made? to the banks broken that should not have broken? And who in Rome cannot point to the Ministers who allow their mistresses to meddle in public affairs and enrich themselves by the ruin of all around?"

The little Princess on the balcony was twisting about.

"What! Are you deserting us, Roma?"

And Roma answered from within the house, in a voice that sounded strange and muffled:

"It was cold on the balcony, I think."

The little Princess laughed a bitter laugh, and David Rossi heard it and misunderstood it, and his nostrils quivered like the nostrils of a horse, and when he spoke again his voice shook with passion.

"Who has not seen the splendid equipages of these privileged ones of fortune—their gorgeous liveries of scarlet and gold—emblems of the acid which is eating into the public organs? Has Providence raised this country from the dead only to be dizzied in a whirlpool of scandal, hypocrisy, and fraud—only to fall a prey to an infamous traffic without a name between high officials of low desires and women whose reputations are long since lost? It is men and women like these who destroy their country for their own selfish ends. Very well, let them destroy her; but before they do so, let them hear what one of her children says: The Government you are building up on the whitened bones of the people shall be overthrown—the King who countenances you, and the Pope who will not condemn you, shall be overthrown, and then—and not till then—will the nation be free."

At this there was a terrific clamour. The square resounded with confused voices. "Bravo!" "Dog!" "Dog's murderer!" "Traitor!" "Long live David Rossi!" "Down with the Vampire!"

The ladies had fled from the balcony back to the room with cries of alarm. "There will be a riot." "The man is inciting the people to rebellion!" "This house will be first to be attacked!"

"Calm yourselves, ladies. No harm shall come to you," said the Baron, and he rang the bell.

There came from below a babel of shouts and screams.

"Madonna mia! What is that?" cried the Princess, wringing her hands; and the American Ambassador, who had remained on the balcony, said:

"The Carabineers have charged the crowd and arrested David Rossi."

"Thank God!"

"They're going through the Borgo," said Don Camillo, "and kicking and cuffing and jostling and hustling all the way."

"Don't be alarmed! There's the Hospital of Santo Spirito round the corner, and stations of the Red Cross Society everywhere," said the Baron, and then Felice answered the bell.

"See our friends out by the street at the back, Felice. Good-bye, ladies! Have no fear! The Government does not mean to blunt the weapons it uses against the malefactors who insult the doctrines of the State."

"Excellent Minister!" said the Princess. "Such canaglia are not fit to have their liberty, and I would lock them all up in prison."

And then Don Camillo offered his arm to the little lady with the white plumes, and they came almost face to face with Roma, who was standing by the door hung with curtains, fanning herself with her handkerchief, and parting from the English Ambassador.

"Donna Roma," he was saying, "if I can ever be of use to you, either now or in the future, I beg of you to command me."

"Look at her!" whispered the Princess. "How agitated she is! A moment ago she was finding it cold in the Loggia! I'm so happy!"

At the next instant she ran up to Roma and kissed her. "Poor child! How sorry I am! You have my sympathy, my dear! But didn't I tell you the man was a public nuisance, and ought to be put down by the police?"

"Shameful, isn't it?" said Don Camillo. "Calumny is a little wind, but it raises such a terrible tempest."

"Nobody likes to be talked about," said the Princess, "especially in Rome, where it is the end of everything."

"But what matter? Perhaps the young man has learned freedom of speech in a free country!" said Don Camillo.

"And then he is so interesting and so handsome," said the Princess.

Roma made no answer. There was a slight drooping of the lovely eyes and a trembling of the lips and nostrils. For a moment she stood absolutely impassive, and then with a flash of disdain she flung round into the inner room.

VIII

Roma had taken refuge in the council-room. There had been much business that morning, and a copy of the constitutional statute lay open on a large table, which had a plate-glass top with photographs under the surface.

In this passionless atmosphere, so little accustomed to such scenes, Roma sat in her wounded pride and humiliation, with her head down, and her beautiful white hands over her face.

She heard measured footsteps approaching, and then a hand touched her on the shoulder. She looked up and drew back as if the touch stung her. Her lips closed sternly, and she got up and began to walk about the room, and then she burst into a torrent of anger.

"Did you hear them? The cats! How they loved to claw me, and still purr and purr! Before the sun is set the story will be all over Rome! It has run off already on the hoofs of that woman's English horses. To-morrow morning it will be in every newspaper in the kingdom. Olga and Lena and every woman of them all who lives in a glass house will throw stones. 'The new Pompadour! Who is she?' Oh, I could die of vexation and shame!"

The Baron leaned against the table and listened, twisting the ends of his moustache.

"The Court will turn its back on me now. They only wanted a good excuse to put their humiliations upon me. It's horrible! I can't bear it. I won't. I tell you, I won't!"

But the lips, compressed with scorn, began to quiver visibly, and she threw herself into a chair, took out her handkerchief, and hid her face on the table.

At that moment Felice came into the room to say that the Commendatore Angelelli had returned and wished to speak with his Excellency.

"I will see him presently," said the Baron, with an impassive expression, and Felice went out silently, as one who had seen nothing.

The Baron's calm dignity was wounded. "Be so good as to have some regard for me in the presence of my servants," he said. "I understand your feelings, but you are much too excited to see things in their proper light. You have been publicly insulted and degraded, but you must not talk to me as if it were my fault."

"Then whose is it? If it is not your fault, whose fault is it?" she said, and the Baron thought her red eyes flashed up at him with an expression of hate. He took the blow full in the face, but made no reply, and his silence broke her answer.

"No, no, that was too bad," she said, and she reached over to him, and he kissed her and then sat down beside her and took her hand and held it. At the next moment her brilliant eyes had filled with tears and her head was down and the hot drops were falling on to the back of his hand.

"I suppose it is all over," she said.

"Don't say that," he answered. "We don't know what a day may bring forth. Before long I may have it in my power to silence every slander and justify you in the eyes of all."

At that she raised her head with a smile and seemed to look beyond the Baron at something in the vague distance, while the glass top of the table, which had been clouded by her breath, cleared gradually, and revealed a large house almost hidden among trees. It was a photograph of the Baron's castle in the Alban hills.

"Only," continued the Baron, "you must get rid of that man Bruno."

"I will discharge him this very day—I will! I will! I will!"

There was an intense bitterness in the thought that what David Rossi had said must have come of what her own servant told him—that Bruno had watched her in her own house day by day, and that time after time the two men had discussed her between them.

"I could kill him," she said.

"Bruno Rocco?"

"No, David Rossi."

"Have patience; he shall be punished," said the Baron.

"How?"

"He shall be put on his trial."

"What for?"

"Sedition. The law allows a man to say what he will about a Prime Minister, but he must not foretell the overthrow of the King. The fellow has gone too far at last. He shall go to Santo Stefano."

"What good will that do?"

"He will be silenced—and crushed."

She looked at the Baron with a sidelong smile, and something in her heart, which she did not understand, made her laugh at him.

"Do you imagine you can crush a man like that by trying and condemning him?" she said. "He has insulted and humiliated me, but I'm not silly enough to deceive myself. Try him, condemn him, and he will be greater in his prison than the King on his throne."

The Baron twisted the ends of his moustache again.

"Besides," she said, "what benefit will it be to me if you put him on trial for inciting the people to rebellion against the King? The public will say it was for insulting yourself, and everybody will think he was punished for telling the truth."

The Baron continued to twist the ends of his moustache.