автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Miss Leslie's New Cookery Book

MISS LESLIE'S

NEW

COOKERY BOOK.

One Volume, 652 pages, bound. Price $1.25.

T. B. Peterson, No. 102 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, has just published MISS LESLIE'S "NEW COOKERY BOOK." It comprises new and approved methods of preparing all kinds of Soups, Fish, Oysters, Beef, Mutton, Veal, Pork, Venison, Ham and Bacon, Poultry and Game, Terrapins, Turtle, Vegetables, Sauces, Bread, Pickles, Sweetmeats, Plain Cakes, Fine Cakes, Pies, Plain Desserts, Fine Desserts, Preparations for the Sick, Puddings, Confectionery, Rice, Indian Meal Preparations of all kinds, Miscellaneous Receipts, etc. etc. Also, lists of all articles in season suited to go together for breakfasts, dinners, and suppers, to suit large or small families, and much useful information and many miscellaneous subjects connected with general housewifery.

This work will have a very extensive sale, and many thousand copies will be sold, as all persons that have had Miss Leslie's former works, should get this at once, as all the receipts in this book are new, and have been fully tried and tested by the author since the publication of her former books, and none of them whatever are contained in any other work but this. It is the most complete Cook Book published in the world; and also the latest and best, as in addition to Cookery of all kinds and descriptions, its receipts for making cakes and confectionery are unequalled by any other work extant.

This new, excellent, and valuable Cook Book is published by T. B. Peterson, under the title of "MISS LESLIE'S NEW COOKERY BOOK," and is entirely different from any other work on similar subjects, under any other names, by the same author. It is an elegantly printed duodecimo volume, of 652 pages; and in it there will be found hundreds of Receipts—all useful—some ornamental—and all invaluable to every lady, miss, or family in the world.

Read what the Editors of the Leading Newspapers say of it.

From the Philadelphia Dollar Newspaper.

"This is a large, well-bound volume of near seven hundred pages, and includes in it hundreds of receipts never before published in any of Miss Leslie's other works, accompanied by a well-arranged index, by which any desired receipt may be turned to at once. The receipts are for cooking all kinds of meats, poultry, game, pies, &c., with directions for confectionery, ices, and preserves. It is entirely different from any former work by Miss Leslie, and contains new and fresh accessions of useful knowledge. The merit of these receipts is, that they have all been tried, and therefore can be recommended conscientiously. Miss Leslie has acquired great reputation among housekeepers for the excellence of her works on cookery, and this volume will doubtless enhance it. It is the best book on cookery that we know of, and while it will be useful to matrons, to young housewives we should think it quite indispensable. By the aid of this book, the young and inexperienced are brought nearly on a footing with those who have seen service in the culinary department, and by having it at hand are rendered tolerably independent of help, which sometimes becomes very refractory. The best regulated families are sometimes taken a little by surprise by the untimely stepping in of a friend to dinner—to such, Miss Leslie is the friend indeed, ready as her book is with instructions for the hasty production of various substitutes for meals requiring timely and elaborate preparation."

From the Philadelphia Daily News.

"To the housekeeper, the name of Miss Leslie is a guaranty that what comes from her hand is not only orthodox, but good; and to the young wife about to enter upon the untried scenes of catering for a family, Miss Leslie's New Cookery Book may be termed a blessing. It presents receipts, (and practical ones too,) for preparing and cooking all kinds of soups, fish, oysters, meats, game, cakes, pastry, and indeed everything which enters into the economy of housekeeping. Their recommendations are that they are all practical, and the novice of the culinary art may enter upon her important duties with 'Miss Leslie's New Cookery Book' by her side, with perfect confidence that the 'soup' will not be spoiled, and that the dinner will be what is designed. How many disappointments could be avoided, how many domestic difficulties prevented, and how many husbands made happy, instead of miserable, by the use of this 'vade mecum,' we shall not pretend to say; but as we have a sincere regard for every lady who reads the News, our advice to them all is, by all means to buy Miss Leslie's New Cookery Book. Mr. Peterson has done admirably in getting up this work: it is handsomely and substantially bound in cloth, gilt, and does credit to his business skill; the low price at which the work is sold, when we take the size of it into consideration, One Dollar and Twenty-five cents only, will doubtless give it an immense sale."

From the Philadelphia Saturday Courier.

"With such a book as Miss Leslie's New Cookery Book, published by Mr. Peterson, it is inconceivable what a vast extent of palate is destined to be astonished, and what a gastronomic multitude is to be made happy, by the delicious delicacies and substantial dishes so abundantly provided. Miss Leslie has in previous works shown how great an adept she has been in all culinary matters, and in all that relates to the comforts and the social enjoyment of the table around which cluster the good things of life. Literature is very good in its way; but such dishes as Miss Leslie gives a foretaste of, come up to a more delicious standard. Her authorship is exquisite, and is destined to diffuse the very essence of good taste among the fortunate people who sit down to good dinners and suppers, not one of whom will rise from the table without a blessing on Miss Leslie's New Cookery Book. And every taste is sure to be pleased, for all the receipts in this book are new, and to be found nowhere else, and it is the best Cook Book ever published—one which, with its hundreds of receipts, ought to be in the hands of every woman who has the slightest appreciation of convenience, comfort and economy."

From the Philadelphia Daily Sun.

"About one thousand new receipts, never before printed, appear in this work, all of which have been tried before they are recommended by the author. All kinds of cooking and pastry; rules for the preparation of dinners, breakfasts, and suppers; appropriate dishes for every meal; and a vast quantity of other useful information, are embraced in the book. It is very comprehensive, and is furnished with an index for the use of the housewife. By the aid of Miss Leslie's peculiar happy talent in giving culinary directions, our girls can acquire a branch of useful information which is generally sadly neglected in their education, and thus become fitted for their duties as wives. One great advantage in Miss Leslie's New Cookery Book, is the economy which it teaches in the management of a household, as regards the preparations for the table. Peterson has done this book up in beautiful style, and it will be sent to any part of the Union, postage paid, upon the receipt of One Dollar and Twenty-five Cents. Those who know how much of the happiness of home depends upon well-cooked viands, neatly served up, will thank the accomplished authoress for this valuable contribution to domestic science."

From the Philadelphia Saturday Evening Gazette.

"Miss Leslie's 'New Receipts for Cooking' is perhaps better known than any similar collection of receipts. The very elegant volume before us, entitled 'Miss Leslie's New Cookery Book,' is designed as a sequel and continuation to it, and should be its companion in every family, as the receipts are all new, and in no instance the same, even when their titles are similar. It contains directions for plain and fancy cooking, preserving, pickling; and commencing with soups, gives entirely new receipts for every course of an excellent dinner, to the jellies and confectionery of the dessert. Our readers are not strangers to the accuracy and minuteness of Miss Leslie's receipts, as, since the first number of the Gazette, she has contributed to our housekeepers' department. The new receipts in this volume are admirable. Many of them are modified from French sources, though foreign terms and designations are avoided. The publisher has brought it out in an extremely tasteful style, and no family in the world should be without it."

From the Pennsylvania Inquirer.

"Mr. T. B. Peterson has just published 'Miss Leslie's New Cookery Book.' This will be a truly popular work. Thousands of copies will very soon be disposed of, and other thousands will be needed. It contains directions for cooking, preserving, pickling, and preparing almost every description of dish: also receipts for preparing farina, Indian meal, fancy tea-cakes, marmalades, etc. We know of a no more useful work for families."

From the Public Ledger.

"As every woman, whether wife or maid, should be qualified for the duties of a housekeeper, a work which gives the information which acquaints her with its most important duties, will no doubt be sought after by the fair sex. This work is 'Miss Leslie's New Cookery Book.' Get it by all means."

From the Boston Evening Traveler.

"We do not claim to be deeply versed in the art of cookery; but a lady, skilled in the art, to whom we have submitted this work, assures us that there is nothing like it within the circle of her knowledge; and that having this, a housekeeper would need no other written guide to the mysteries of housekeeping. It contains hundreds of new receipts, which the author has fully tried and tested; and they relate to almost every conceivable dish—flesh, fish, and fowl, soups, sauces, and sweetmeats; puddings, pies, and pickles; cakes and confectionery. There are, too, lists of articles suitable to go together for breakfasts, dinners and suppers, at different seasons of the year, for plain family meals, and elaborate company preparations; which must be of great convenience. Indeed, there appears to be, as our lady friend remarked, everything in this book that a housekeeper needs to know; and having this book she would seem to need no other to afford her instruction about housekeeping."

MISS LESLIE'S

NEW

COOKERY

BOOK.

"As every woman, whether wife or maid, should be qualified for the duties of a housekeeper, a work which gives the information which acquaints her with its most important duties will no doubt be sought after by the fair sex. This work is 'Miss Leslie's New Cookery Book.' Get it by all means."—Public Ledger.

PHILADELPHIA:

T. B. PETERSON NO. 102 CHESTNUT STREET.

1857.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1857, by

ELIZA LESLIE,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States, in and for the

Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

PREFACE.

I have endeavored to render this work a complete manual of domestic cookery in all its branches. It comprises an unusual number of pages, and the receipts are all practical, and practicable—being so carefully and particularly explained as to be easily comprehended by the merest novice in the art. Also, I flatter myself that most of these preparations (if faithfully and liberally followed,) will be found very agreeable to the general taste; always, however, keeping in mind that every ingredient must be of unexceptionable quality, and that good cooking cannot be made out of bad marketing.

I hope those who consult this book will find themselves at no loss, whether required to prepare sumptuous viands "for company," or to furnish a daily supply of nice dishes for an excellent family table; or plain, yet wholesome and palatable food where economy is very expedient.

Eliza Leslie.

Philadelphia, March 28th, 1857.

WEIGHTS AND MEASURES.

Tested and Arranged by Miss Leslie.

Wheat flour

one pound of 16 ounces

is one quart.

Indian meal

one pound 2 ounces

is one quart.

Butter, when soft

one pound 1 ounce

is one quart.

Loaf sugar, broken up,

one pound

is one quart.

White sugar, powdered,

one pound 1 ounce

is one quart.

Best brown sugar,

one pound 2 ounces

is one quart.

Eggs

ten eggs

weigh one pound.

LIQUID MEASURE.

Four large table-spoonfuls

are

half a jill.

Eight large table-spoonfuls

are

one jill.

Two jills

are

half a pint.

A common-sized tumbler

holds

half a pint.

A common-sized wine-glass

holds about

half a jill.

Two pints

are

one quart.

Four quarts

are

one gallon.

About twenty-five drops of any thin liquid will fill a common-sized tea-spoon.

Four table-spoonfuls will generally fill a common-sized wine-glass.

Four wine-glasses will fill a half pint tumbler, or a large coffee-cup.

A quart black bottle holds in reality about a pint and a half; sometimes not so much.

A table-spoonful of salt is about one ounce.

DRY MEASURE.

Half a gallon

is

a quarter of a peck.

One gallon

is

half a peck.

Two gallons

are

one peck.

Four gallons

are

half a bushel.

Eight gallons

are

one bushel.

Throughout this book, the pound is avoirdupois weight—sixteen ounces.

GENERAL CONTENTS.

PAGE

Soups,33

Fish,77

Shell-Fish,108

Beef,138

Mutton,173

Veal,188

Pork,216

Ham and Bacon,235

Venison,252

Poultry and Game,265

Sauces,309

Vegetables,343

Bread, Plain Cakes, etc.,401

Plain Desserts,444

Fine Desserts,469

Fine Cakes,516

Sweetmeats,543

Pickles,568

Preparations for the Sick,581

Miscellaneous Receipts,595

Worth Knowing,645

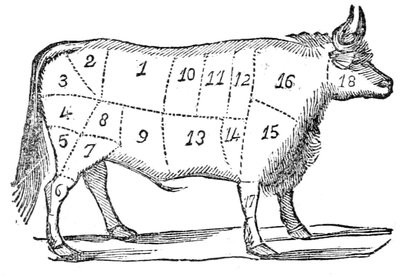

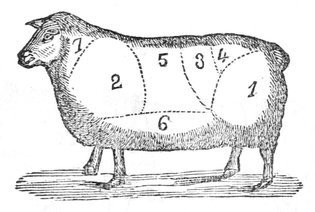

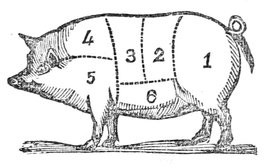

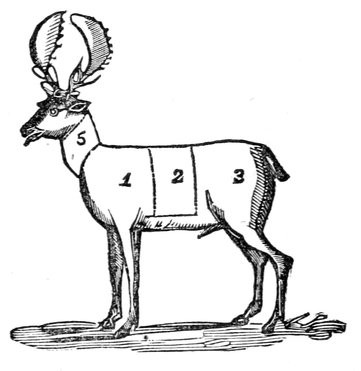

ANIMALS

FIGURES EXPLANATORY OF THE PIECES INTO WHICH THE FIVE LARGE ANIMALS ARE DIVIDED BY THE BUTCHERS.

Beef.

- 1. Sirloin.

- 2. Rump.

- 3. Edge Bone.

- 4. Buttock.

- 5. Mouse Buttock.

- 6. Leg.

- 7. Thick Flank.

- 8. Veiny Piece.

- 9. Thin Flank.

- 10. Fore Rib: 7 Ribs.

- 11. Middle Rib: 4 Ribs.

- 12. Chuck Rib: 2 Ribs.

- 13. Brisket.

- 14. Shoulder, or Leg of Mutton Piece.

- 15. Clod.

- 16. Neck, or Sticking Piece.

- 17. Shin.

- 18. Cheek.

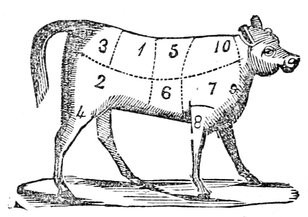

Veal.

- 1. Loin, Best End.

- 2. Fillet.

- 3. Loin, Chump End.

- 4. Hind Knuckle.

- 5. Neck, Best End.

- 6. Breast, Best End.

- 7. Blade Bone.

- 8. Fore Knuckle.

- 9. Breast, Brisket End.

- 10. Neck, Scrag End.

Mutton.

- 1. Leg.

- 2. Shoulder.

- 3. Loin, Best End.

- 4. Loin, Chump End.

- 5. Neck, Best End.

- 6. Breast.

- 7. Neck, Scrag End.

- Note.—A Chine is two Loins; and a Saddle is two Loins and two Necks of the Best End.

Pork.

- 1. Leg.

- 2. Hind Loin.

- 3. Fore Loin.

- 4. Spare Rib.

- 5. Hand.

- 6. Spring.

Venison.

- 1. Shoulder.

- 2. Neck.

- 3. Haunch.

- 4. Breast.

- 5. Scrag.

MISS LESLIE'S

NEW

COOKERY BOOK.

SOUPS.

It is impossible to have good soup, without a sufficiency of good meat; thoroughly boiled, carefully skimmed, and moderately seasoned. Meat that is too bad for any thing else, is too bad for soup. Cold meat recooked, adds little to its taste or nourishment, and it is in vain to attempt to give poor soup a factitious flavor by the disguise of strong spices, or other substances which are disagreeable or unpalatable to at least one half the eaters, and frequently unwholesome. Rice and barley add to the insipidity of weak soups, having no taste of their own. And even if the meat is good, too large a proportion of water, and too small a quantity of animal substance will render it flat and vapid.

Every family has, or ought to have, some personal knowledge of certain poor people—people to whom their broken victuals would be acceptable. Let then the most of their cold, fresh meat be set apart for those who can ill afford to buy meat in market. To them it will be an important acquisition; while those who indulge in fine clothes, fine furniture, &c., had best be consistent, and allow themselves the nourishment and enjoyment of freshly cooked food for each meal. Therefore where there is no absolute necessity of doing otherwise, let the soup always be made of meat bought expressly for the purpose, and of one sort only, except when the flavor is to be improved by the introduction of ham.

In plain cooking, every dish should have a distinct taste of its natural flavor predominating. Let the soup, for instance, be of beef, mutton, or veal, but not of all three; and a chicken, being overpowered by the meat, adds nothing to the general flavor.

Soup-meat that has been boiled long enough to extract the juices thoroughly, becomes too tasteless to furnish, afterwards, a good dish for the table; with the exception of mutton, which may be eaten very well after it has done duty in the soup-pot, when it is much liked by many persons of simple tastes. Few who are accustomed to living at hotels, can relish hotel soups, which (even in houses where most other things are unexceptionable), is seldom such as can be approved by persons who are familiar with good tables. Hotel soups and hotel hashes, (particularly those that are dignified with French names), are notoriously made of cold scraps, leavings, and in some houses, are the absolute refuse of the kitchen. In most cases, the sight of a hotel stock-pot would cause those who saw it, to forswear soup, &c.

If the directions are exactly followed, the soups contained in the following pages will be found palatable, nutritious, and easily made; but they require plenty of good ingredients.

We have heard French cooks boast of their soup being "delicate." The English would call it "soup meagre." In such a country as America, where good things are abundant, there is no necessity of imbibing the flatulency of weak washy soups.

All soups should be boiled slowly at first, that the essence of the meat may be thoroughly drawn forth. The lid of the pot should be kept close, unless when it is necessary to remove it for taking off the scum, which should be done frequently and carefully. If this is neglected, the scum will boil back again into the soup, spoil it, and make it impure or muddled. When no more scum arises, and the meat is all in rags, dropping from the bones, it is time to put in the vegetables, seasoning, &c., and not till then; and if it should have boiled away too much, then is the time to add a little hot water from another kettle. Add also a large crust of bread or two. It may now be made to boil faster, and the thickening must be put in. This is a table-spoonful or more of flour mixed to a smooth paste with a little water, and enriched with a tea-spoonful of good butter, or beef-dripping. This thickening is indispensable to all soups. Let it be stirred in well. If making a rich soup that requires wine or catchup, let it be added the last thing, just before the soup is taken from the fire.

When all is quite done and thoroughly boiled, cover the bottom of a tureen with small squares of bread or toast, and dip or pour the soup into it, leaving all the bones and shreds of meat in the pot. To let any of the sediment get into the tureen is slovenly and vulgar. Not a particle of this should ever be found in a soup-plate. There are cooks who, if not prevented, will put all the refuse into the tureen; so that, when helped, the plates are half full of shreds of meat and scraps of bone, while all the best of the soup is kept back for the kitchen. This should be looked to. Servants who cannot reconcile it to their conscience to steal money or any very valuable articles, have frequently no hesitation in purloining or keeping to themselves whatever they like in the way of food.

Soup may be colored yellow with grated carrots, red with tomato juice, and green with the juice of pounded spinach—the coloring to be stirred in after the skimming is over. These colorings are improvements both to its look and flavor. It may be browned with scorched flour, kept ready always for the purpose. Never put cloves or allspice into soup—they give it a blackish ashy dirt color, and their taste is so strong as to overpower every thing else. Both these coarse spices are out of use at good tables, and none are introduced in nice cookery but mace, nutmeg, ginger, and cinnamon.

The meat boiled in soup gives out more of its essence, when cut off the bone, and divided into small pieces, always removing the fat. The bones, however, should go in, as they contain much glutinous substance, adding to the strength and thickness of the soup, which cannot be palatable or wholesome unless all the grease is carefully skimmed off. Kitchen grease is used chiefly for soap-fat.

In cold weather, good soup, if carefully covered and kept in a cool place, and boiled over again for half an hour without any additional water, will be better on the second day than on the first.

It is an excellent way in winter to boil the meat and bones on the first day, without any vegetables. Then, when very thick and rich, strain the liquid into a large pan; cover it, and set it away till next morning—it should then be found a thick jelly. Cut it in pieces, having scraped off the sediment from the bottom—then add the vegetables, and boil them in the soup.

MUSHROOM SOUP.—

Cut a knuckle of veal, or a neck of mutton, (or both, if they are small,) into large pieces, and remove the bones. Put it into a soup-pot with sufficient water to cover the whole, and season with a little salt and cayenne. Let it boil till the meat is in rags, skimming it well; then strain off the soup into another pot. Have ready a large quart, or a quart and a pint of freshly-gathered mushrooms—cut them into quarters, having removed the stalks. Put them into the soup, adding a quarter of a pound (or more) of fresh butter, divided into bits and rolled in flour. Boil the whole about half an hour longer—try if the mushrooms are tender, and do not take them up till they are perfectly so. Keep the pot lid closely covered, except when you remove the lid to try the mushrooms. Lay at the bottom of the tureen a large slice of buttered toast, (cut into small squares,) and pour the soup upon it. This is a company soup.

SWEET CORN SOUP.—

Take a knuckle of veal, and a set of calf's feet. Put them into a soup-pot with some cold boiled ham cut into pieces, and season them with pepper only. Having allowed a quart of water to each pound of meat, pour it on, and let it boil till the meat falls from the bone; strain it, and pour the liquid into a clean pot. If you live in the country, or where milk is plenty, make this soup of milk without any water. All white soups are best of milk. You may boil in this, with the veal and feet, an old fowl, (cut into pieces,) that is too tough for any other purpose. When the soup is well boiled, and the shreds all strained away, have ready (cooked by themselves in another pot) some ears of sweet corn, young and tender. Cut the grains from the cob, mix the corn with fresh butter, season it with pepper, and stir it in the strained soup. Give the whole a short boil, pour it into the tureen, and send it to table.

VENISON SOUP.—

Is excellent, made as above, with water instead of milk, and plenty of corn. And it is very convenient for a new settlement.

TOMATO SOUP.—

Take a shin or leg of beef, and cut off all the meat. Put it, with the bones, in a large soup-pot, and season it slightly with salt and pepper. Pour on a gallon of water. Boil and skim it well. Have ready half a peck of ripe tomatos, that have been quartered, and pressed or strained through a sieve, so as to be reduced to a pulp. Add half a dozen onions that have been sliced, and a table-spoonful of sugar to lessen a little the acid of the tomatos. When the meat is all to rags, and the whole thoroughly done, (which will not be in less than six hours from the commencement) strain it through a cullender, and thicken it a little with grated bread crumbs.

This soup will be much improved by the addition of a half peck of ochras, peeled, sliced thin, and boiled with the tomatos till quite dissolved.

Before it goes into the tureen, see that there are no shreds of meat or bits of bone left in the soup.

FAMILY TOMATO SOUP.—

Take four pounds of the lean of a good piece of fresh beef. The fat is of no use for soup, as it must be skimmed off when boiling. Cut the meat in pieces, season them with a little salt and pepper, and put them into a pot with three quarts of water. The tomatos will supply abundance of liquid. Of these you should have a large quarter of a peck. They should be full-grown, and quite ripe. Cut each tomato into four pieces, and put them into the soup; after it has come to a boil and been skimmed. It will be greatly improved by adding a quarter of a peck of ochras cut into thin round slices. Both tomatos and ochras require long and steady boiling with the meat. To lessen the extreme acid of the tomatos, stir in a heaped table-spoonful of sugar. Add also one large onion, peeled and minced small; and add two or three bits of fresh butter rolled in flour. The soup must boil till the meat is all to rags and the tomatos and ochras entirely dissolved, and their forms undistinguishable. Pour it off carefully from the sediment into the tureen, in the bottom of which have ready some toasted bread, cut into small squares.

FINE TOMATO SOUP.—

Take some nice fresh beef, and divest it of the bone and fat. Sprinkle it with a little salt and pepper, and pour on water, allowing to each pound of meat a pint and a half (not more) of water, and boil and skim it till it is very thick and clear, and all the essence seems to be drawn out of the meat. Scald and peel a large portion of ripe tomatos—cut them in quarters, and laying them in a stew-pan, let them cook in their own juice till they are entirely dissolved. When quite done, strain the tomato liquid, and stir into it a little sugar. In a third pan stew an equal quantity of sliced ochras with a very little water; they must be stewed till their shape can no longer be discerned. Strain separately the meat liquor, the tomatos, and the ochras. Mix butter and flour together into a lump; knead it a little, and when all the liquids are done and strained put them into a clean soup-pan, stir in the flour and butter, and give the soup one boil up. Transfer it to your tureen, and stir altogether. The soup made precisely as above will be perfectly smooth and nice. Have little rolls or milk biscuits to eat with it.

This is a tomato soup for dinner company.

GREEN PEA SOUP.—

Make a nice soup, in the usual way, of beef, mutton, or knuckle of veal, cutting off all the fat, and using only the lean and the bones, allowing a quart of water to each pound of meat. If the meat is veal, add four or six calf's feet, which will greatly improve the soup. Boil it slowly, (having slightly seasoned it with pepper and salt,) and when it has boiled, and been well skimmed, and no more scum appears, then put in a quart or more of freshly-shelled green peas, with none among them that are old, hard, and yellow; and also a sprig or two of green mint, and a little loaf sugar. Boil the peas till they are entirely dissolved. Then (having removed all the meat and bones) strain the soup through a sieve, and return it to the soup-pot, (which, in the mean time, should have been washed clean,) and stir into it a tea-cupful of green spinach juice, (obtained by pounding some spinach.) Have ready (boiled, or rather stewed in another pot) a quart of young fresh peas, enriched with a piece of fresh butter. These last peas should be boiled tender, but not to a mash. After they are in, give the soup another boil up, and then pour it off into a tureen, in the bottom of which has been laid some toast cut into square bits, with the crust removed. This soup should be of a fine green color, and very thick.

EXCELLENT BEAN SOUP.—

Early in the evening of the day before you make the soup, wash clean a large quart of dried white beans in a pan of cold water, and about bedtime pour off that water, and replace it with a fresh panful. Next morning, put on the beans to boil, with only water enough to cook them well, and keep them boiling slowly till they have all bursted, stirring them up frequently from the bottom, lest they should burn. Meantime, prepare in a larger pot, a good soup made of a shin of beef cut into pieces, and the hock of a cold ham, allowing a large quart of water to each pound of meat.

Season it with pepper only, (no salt,) and put in with it a head of celery, split and cut small. Boil the soup (skimming it well) till the meat is all in rags; then take it out, leaving not a morsel in the pot, and put in the boiled beans. Let them boil in the soup till they are undistinguishable, and the soup very thick. Put some small squares of toast in the bottom of a tureen, and pour the soup upon it.

There is said to be nothing better for making soup than the camp-kettle of the army. Many of the common soldiers make their bean soup of surpassing excellence.

SPLIT PEA SOUP.—

In buying dried or split peas, see that they are not old and worm-eaten. Wash two quarts of them over night in two or three waters. In the morning make a rich soup of the lean of beef or mutton, and the hock of a ham. Season it with pepper, but no salt. When it has boiled, and been thoroughly skimmed, put in the split peas, with a head of celery cut into small pieces, or else two table-spoonfuls of celery seed. Let it boil till the peas are entirely dissolved and undistinguishable. When it is finished strain the soup through a sieve, divesting it of the thin shreds of meat and bits of bone. Then transfer it to a tureen, in which has been laid some square bits of toast. Stir it up to the bottom directly before it goes to table.

You may boil in the soup (instead of the ham) a good piece (a rib piece, or a fillet) of corned pork, more lean than fat. When it is done, take the pork out of the soup, put it on a dish, and have ready to eat with it a pease pudding boiled by itself, cut in thick slices and laid round the pork. This pudding is made of a quart of split peas, soaked all night, mixed with four beaten eggs and a piece of fresh butter, and tied in a cloth and boiled three or four hours, or till the peas have become a mass.

ASPARAGUS SOUP.—

Make in the usual way a nice rich soup of beef or mutton, seasoned with salt and pepper. After it has been well boiled and skimmed, and the meat is all to pieces, strain the soup into another pot, or wash out the same, and return to it the liquid. Have ready a large quantity of fine fresh asparagus, with the stalks cut off close to the green tops or blossoms. It should have been lying in cold water all the time the meat was boiling. Put into the soup half of the asparagus tops, and boil them in it till entirely dissolved, adding a tea-cupful of spinach juice, obtained by pounding fresh spinach in a mortar. Stir the juice well in and it will give a fine green color. Then add the remaining half of the asparagus; having previously boiled them in a small pan by themselves, till they are quite tender, but not till they lose their shape. Give the whole one boil up together. Make some nice slices of toast, (having cut off the crust.) Dip them a minute in hot water. Butter them, lay them in the bottom of the tureen, and pour the soup upon them. This (like green peas) will do for company soup.

CABBAGE SOUP.—

Remove the fat and bone from a good piece of fresh beef, or mutton—season it with a little salt and pepper, put it into a soup-pot, with a quart of water allowed to each pound of meat. Boil, and skim it till no more scum is seen on the surface. Then strain it, and thicken it with flour and butter mixed. Have ready a fine fresh cabbage, (a young summer one is best) and after it is well washed through two cold waters, and all the leaves examined to see if any insects have crept between, quarter the cabbage, (removing the stalk) and with a cabbage-cutter, or a strong sharp knife, cut it into shreds. Or you may begin the cabbage whole and cut it into shreds, spirally, going round and round it with the knife. Put the cabbage into the clear soup, and boil it till, upon trial, by taking up a little on a fork, you find it quite tender and perfectly well cooked. Then serve it up in the tureen. This is a family soup.

RED CABBAGE SOUP.—

Red cabbages for soup should either be quartered, or cut into shreds; it is made as above, of beef or mutton, and seasoned with salt, pepper, and a jill of strong tarragon vinegar, or a table-spoonful of mixed tarragon leaves, if in summer.

FINE CABBAGE SOUP.—

Remove the outside leaves from a fine, fresh, large cabbage. Cut the stalk short, and split it half-way down so as to divide the cabbage into quarters, but do not separate it quite to the bottom. Wash the cabbage, and lay it in cold water for half an hour or more. Then set it over the fire in a pot full of water, adding a little salt, and let it boil slowly for an hour and a half, or more—skimming it well. Then take it out, drain it, and laying it in a deep pan, pour on cold water, and let it remain till the cabbage is cold all through. Next, having drained it from the cold water, cut the cabbage in shreds, (as for cold-slaw,) and put it into a clean pot containing a quart and a pint of boiling milk into which you have stirred a quarter of a pound of nice fresh butter, divided into four bits and rolled in flour, adding a little pepper and a very little salt. Boil it in the milk till thoroughly done and quite tender. Then make some nice toast, cut it into squares, lay it in the bottom of a tureen, and pour the soup on it. This being made without meat is a good soup for Lent. It will be improved by stirring in, towards the last, two or three beaten eggs.

CAULIFLOWER SOUP.—

Put into a soup-pot a knuckle of veal, and allow to each pound a quart of water. Add a set of calf's feet that have been singed and scraped, but not skinned; and the hock of a cold boiled ham. Boil it till all the meat is in rags, and the soup very thick, seasoning with cayenne and a few blades of mace, and adding, towards the last, some bits of fresh butter rolled in flour. Boil in another pot, one or two fine cauliflowers. They are best boiled in milk. When quite done and very tender, drain them, cut off the largest stalks, and divide the blossoms into small pieces; put them into a deep covered dish, lay some fresh butter among them, and keep them hot till the veal soup is boiled to its utmost thickness. Then strain it into a soup-tureen, and put into it the cauliflower, grating some nutmeg upon it. This soup will be found very fine, and is an excellent white soup for company.

For Lent this soup may be made without meat, substituting milk, butter, and flour, and eggs, as in the receipt for fine cabbage soup. Season it with mace and nutmeg. If made with milk, &c., put no water on it, but boil the cauliflower in milk from the beginning. This can easily be done where milk is plenty.

FINE ONION SOUP.—

Take a fine fresh neck of mutton, and to make a large tureen of soup, you must have a breast of mutton also. Let the meat be divided into chops, season it with a little salt, and put it in a soup-pot—allow a quart of water to each pound of mutton. Boil, and skim it till no more scum arises, and the meat drops in rags from the bones. In a small pot boil in milk a dozen large onions, (or more,) adding pepper, mace, nutmeg, and some bits of fresh butter rolled in flour. The onions should previously be peeled and sliced. When they are quite soft, transfer them to the soup, with the milk, &c., in which they were cooked. Give them one boil in the soup. Then pour it off, or strain it into the tureen, omitting all the sediment, and bones, and shreds of meat. Make some nice slices of toast, dipping each in boiling water, and trimming off all the crust. Cut the toast into small squares, lay them in the bottom of the tureen, and pour the soup upon them. Where there is no objection to onions it will be much liked.

If milk is plenty use it instead of water for onion soup. White soups are always best when made with milk.

TURNIP SOUP.—

For a very small family take a neck of mutton, and divide it into steaks, omitting all the fat. For a family of moderate size, take a breast as well as a neck. Put them into a soup-pot with sufficient water to cover them, and let them stew till well browned. Skim them carefully. Then pour on more water, in the proportion of a pint to each pound of meat, and add eight or ten turnips pared and sliced thin, with a very little pepper and salt. Let the soup boil till the turnips are all dissolved, and the meat in rags. Add, towards the last, some bits of butter rolled in flour, and in five minutes afterwards the soup will be done. Carefully remove all the bits of meat and bone before you send the soup to table. It will be found very good, and highly flavored with the turnips.

Onion soup may be made in the same manner. Parsnip soup also, cutting the parsnips into small bits. Or all three—turnips, onions and parsnips, may be used together.

PARSNIP SOUP.—

The meat for this soup may either be fresh beef, mutton, or fresh venison. Remove the fat, cut the meat into pieces, add a little salt, and put it into a soup-pot, with an allowance of rather less than a quart of water to each pound. Prepare some fine large parsnips, by first scraping and splitting them, and cutting them into pieces; then putting them into a frying pan, and frying them brown, in fresh butter or nice drippings. When the soup has been boiled till the meat is all in rags, and well skimmed—put into it the fried parsnips and let them boil about ten minutes, but not till they break or go to pieces. Just before you put in the parsnips, stir in a table-spoonful of thickening made with butter and flour, mixed to a smooth paste. When you put it into the tureen to go to table, be sure to leave in the pot all the shreds of meat and bits of bone.

CARROT SOUP.—

Take a good piece of fresh beef that has not been previously cooked. Remove the fat. It is of no use in making soup; and as it must all be skimmed off when boiling, it is better to clear it away before the meat goes into the pot. Season the beef with a very little salt and pepper, and allow a small quart of water to each pound. Grate half a dozen or more large carrots on a coarse grater, and put them to boil in the soup with some other carrots; cut them into pieces about two inches long. When all the meat is boiled to rags, and has left the bone, pour off the soup from the sediment, transferring it to a tureen, and sending it to table with bread cut into it.

POTATO SOUP.—

Pare and slice thin half a dozen fine potatos and a small onion. Boil them in three large pints of water, till so soft that you can pulp them through a cullender. When returned to the pot add a very little salt and cayenne, and a quarter of a pound of fresh butter, divided into bits, and boil it ten minutes longer. When you put it into the tureen, stir in two table-spoonfuls or more of good cream. This is a soup for fast-days, or for invalids.

CHESTNUT SOUP.—

Make, in the best manner, a soup of the lean of fresh beef, mutton, or venison, (seasoned with cayenne and a little salt,) allowing rather less than a quart of water to each pound of meat, skimming and boiling it well, till the meat is all in rags, and drops from the bone. Strain it, and put it into a clean pot. Have ready a quart or more of large chestnuts, boiled and peeled. If roasted, they will be still better. They should be the large Spanish chestnuts. Put the chestnuts into the soup, with some small bits of fresh butter rolled in flour. Boil the soup ten minutes longer, before it goes to table.

PORTABLE SOUP.—

This is a very good and nutritious soup, made first into a jelly, and then congealed into hard cakes, resembling glue. If well made, it will keep for many months in a cool, dry place, and when dissolved in hot water or gravy, will afford a fine liquid soup, very convenient to carry in a box on a journey or sea voyage, or to use in a remote place, where fresh meat for soup is not to be had. A piece of this glue, the size of a large walnut, will, when melted in water, become a pint bowl of soup; or by using less water, you may have it much richer. If there is time and opportunity, boil with the piece of soup a seasoning of sliced onion, sweet marjoram, sweet basil, or any herbs you choose. Also, a bit of butter rolled in flour.

To make portable soup, take two shins or legs of beef, two knuckles of veal, and four unskinned calves' feet. Have the bones broken or cracked. Put the whole into a large clean pot that will hold four gallons of water. Pour in, at beginning, only as much water as will cover the meat well, and set it over the fire, to heat gradually till it almost boils. Watch and skim it carefully while any scum rises. Then pour in a quart of cold water to make it throw up all the remaining scum, and then let it come to a good boil, continuing to skim as long as the least scum appears. In this be particular. When the liquid appears perfectly clear and free from grease, pour in the remainder of the water, and let it boil very gently for eight hours. Strain it through a very clean hair sieve into a large stoneware pan, and set it where it will cool quickly. Next day, remove all the remaining grease, and pour the liquid, as quickly as possible, into a three-gallon stew-pan, taking care not to disturb the settlings at the bottom. Keep the pan uncovered, and let it boil as fast as possible over a quick fire. Next, transfer it to a three-quart stew-pan, and skim it again, if necessary. Watch it well, and see that it does not burn, as that would spoil the whole. Take out a little in a spoon, and hold it in the air, to see if it will jelly. If it will not, boil it a little longer. Till it jellies, it is not done.

Have ready some small white ware preserve pots, clean, and quite dry. Fill them with the soup, and let them stand undisturbed till next day. Set, over a slow fire, a large flat-bottomed stew-pan, one-third filled with boiling water. Place in it the pots of soup, seeing it does not reach within two inches of their rims. Let the pots stand uncovered in this water, hot, but without boiling, for six or seven hours. This will bring the soup to a proper thickness, which should be that of a stiff jelly, when hot; and when cold, it should be like hard glue. When finished turn out the moulds of soup, and wrap them up separately in new brownish paper, and put them up in boxes, breaking off a piece when wanted to dissolve the soup.

Portable soup may be improved by the addition of three pounds of nice lean beef, to the shins, knuckles, calves' feet, &c. The beef must be cut into bits.

If you have any friends going the overland journey to the Pacific, a box of portable soup may be a most useful present to them.

PEPPER-POT.—

Have ready a small half pound of very nice white tripe, that has been thoroughly boiled and skinned, in a pot by itself, till quite soft and tender. It should be cut into very small strips or mouthfuls. Put into another pot a neck of mutton, and a pound of lean ham, and pour on it a large gallon of water. Boil it slowly, and skim it. When the scum has ceased to rise, put in two large onions sliced, four potatos quartered, and four sliced turnips. Season with a very small piece of red pepper or capsicum, taking care not to make it too hot. Then add the boiled tripe. Make a quart bowlful of small dumplings of butter and flour, mixed with a very little water; and throw them into the pepper-pot, which should afterwards boil about an hour. Then take it up, and remove the meat before it is put into the tureen. Leave in the bits of tripe.

NOODLE SOUP.—

This soup may be made with either beef or mutton, but the meat must be fresh for the purpose, and not cold meat, re-cooked. Cut off all the fat, and break the bones. If boiled in the soup they improve it. To each pound of meat allow a small quart of water. Boil and skim it, till the meat drops from the bone. Put in with the meat, after the scum has ceased to rise, some turnips, carrots and onions, cut in slices, and boil them till all to pieces. Strain the soup, and return the liquid to a clean pot. Have ready a large quantity of noodles, (in French nouillés,) and put them into the strained soup; let them boil in it ten minutes. The noodles are composed of beaten eggs, made into a paste or dough, with flour and a very little fresh butter. This paste is rolled out thin into a square sheet. This sheet is then closely rolled up like a scroll or quire of thick paper, and then with a sharp knife cut round into shreds, or shavings, as cabbage is cut for slaw. These cuttings must be dredged with flour to prevent their sticking. Throw them into the soup while boiling the second time, and let it boil for ten minutes longer.

CHICKEN SOUP.—

Cut up two large fine fowls, as if carving them for the table, and wash the pieces in cold water. Take half a dozen thin slices of cold ham, and lay them in a soup-pot, mixed among the pieces of chicken. Season them with a very little cayenne, a little nutmeg, and a few blades of mace, but no salt, as the ham will make it salt enough. Add a head of celery, split and cut into long bits, a quarter of a pound of butter, divided in two, and rolled in flour. Pour on three quarts of milk. Set the soup-pot over the fire, and let it boil rather slowly, skimming it well. When it has boiled an hour, put in some small round dumplings, made of half a pound of flour mixed with a quarter of a pound of butter; divide this dough into equal portions, and roll them in your hands into little balls about the size of a large hickory nut. The soup must boil till the flesh of the fowls is loose on the bones, but not till it drops off. Stir in, at the last, the beaten yolks of three or four eggs; and let the soup remain about five minutes longer over the fire. Then take it up. Cut off from the bones the flesh of the fowls, and divide it into mouthfuls. Cut up the slices of ham in the same manner. Mince the livers and gizzards. Put the bits of fowl and ham in the bottom of a large tureen, and pour the soup upon it.

This soup will be found excellent, and may be made of large old fowls, that cannot be cooked in any other way. If they are so old that when the soup is finished they still continue tough, remove them entirely, and do not serve them up at all.

Similar soup may be made of a large old turkey. Also, of four rabbits.

DUCK SOUP.—

Half roast a pair of fine large tame ducks, keeping them half an hour at the fire, and saving the gravy, the fat of which must be carefully skimmed off. Then cut them up; season them with black pepper; and put them into a soup-pot with four or five small onions sliced thin, a small bunch of sage, a thin slice of cold ham cut into pieces, a grated nutmeg, and the yellow rind of a lemon grated. Add the gravy of the ducks. Pour on, slowly, three quarts of boiling water from a kettle. Cover the soup-pot, and set it over a moderate fire. Simmer it slowly (skimming it well) for about four hours, or till the flesh of the ducks is dissolved into small shreds. When done, strain it through a tureen, the bottom of which is covered with toasted bread, cut into square dice about two inches in size.

FRENCH WHITE SOUP.—

Boil a knuckle of veal and four calves' feet in five quarts of water, with three onions sliced, a bunch of sweet herbs, four heads of white celery cut small, a table-spoonful of whole pepper, and a small tea-spoonful of salt, adding five or six large blades of mace. Let it boil very slowly, till the meat is in rags and has dropped from the bone, and till the gristle has quite dissolved. Skim it well while boiling. When done, strain it through a sieve into a tureen, or a deep white-ware pan. Next day, take off all the fat, and put the jelly (for such it ought to be) into a clean soup-pot with two ounces of vermicelli, and set it over the fire. When the vermicelli is dissolved, stir in, gradually, a pint of thick cream, while the soup is quite hot; but do not let it come to a boil after the cream is in, lest it should curdle. Cut up one or two French rolls in the bottom of a tureen, pour in the soup, and send it to table.

COCOA-NUT SOUP.—

Take eight calves' feet (two sets) that have been scalded and scraped, but not skinned; and put them into a soup-kettle with six or seven blades of mace, and the yellow rind of a lemon grated. Pour on a gallon of water; cover the kettle, and let it boil very slowly (skimming it well) till the flesh is reduced to rags and has dropped entirely from the bones. Then strain it into a broad white-ware pan, and set it away to get cold. When it has congealed, scrape off the fat and sediment, cut up the cake of jelly, (or stock,) and put it into a clean porcelain or enameled kettle. Have ready half a pound of very finely grated cocoa-nut. Mix it with a pint of cream. If you cannot obtain cream, take rich unskimmed milk, and add to it three ounces of the best fresh butter divided into three parts, each bit rolled in arrow-root or rice-flour. Mix it, gradually, with the cocoa-nut, and add it to the calves-feet-stock in the kettle, seasoned with a small nutmeg grated. Set it over the fire, and boil it, slowly, about a quarter of an hour; stirring it well. Then transfer it to a tureen, and serve it up. Have ready small French rolls, or light milk biscuit to eat with it; also powdered sugar in case any of the company should wish to sweeten it.

ALMOND SOUP

is made in the above manner, substituting pounded almonds for the grated cocoa-nut. You must have half a pound of shelled sweet almonds, mixed with two ounces of shelled bitter almonds. After blanching them in hot water, they must be pounded to a smooth paste (one at a time) in a marble mortar; adding frequently a little rose-water to prevent their oiling, and becoming heavy. Or you may use peach-water for this purpose; in which case omit the bitter almonds, as the peach-water will give the desired flavor. When the pounded almonds are ready, mix them with the other ingredients, as above.

The calves' feet for these soups should be boiled either very early in the morning, or the day before.

SPRING SOUP.—

Unless your dinner hour is very late, the stock for this soup should be made the day before it is wanted, and set away in a stone pan, closely covered. To make the stock take a knuckle of veal, break the bones, and cut it into several pieces. Allow a quart of water to each pound of veal. Put it into a soup-pot, with a set of calves' feet,[A] and some bits of cold ham, cut off near the hock. If you have no ham, sprinkle in a tea-spoonful of salt, and a salt-spoon of cayenne. Place the pot over a moderate fire, and let it simmer slowly (skimming it well) for several hours, till the veal is all to rags and the flesh of the calves' feet has dropped in shreds from the bones. Then strain the soup; and if not wanted that day, set it away in a stone pan, as above mentioned.

Next day have, ready boiled, two quarts or more of green peas, (they must on no account be old,) and a pint of the green tops cut off from asparagus boiled for the purpose. Pound a handful of raw spinach till you have extracted a tea-cupful of the juice. Set the soup or stock over the fire; add the peas, asparagus, and spinach juice, stirring them well in; also a quarter of a pound of fresh butter, divided into four bits, and rolled in flour. Let the whole come to a boil; and then take it off and transfer it to a tureen. It will be found excellent.

In boiling the peas for this soup, you may put with them half a dozen sprigs of green mint, to be afterwards taken out.

Late in the spring you may add to the other vegetables two cucumbers, pared and sliced, and the whitest part or heart of a lettuce, boiled together; then well drained, and put into the soup with the peas and asparagus. It must be very thick with vegetables.

SUMMER SOUP.—

Take a large neck of mutton, and hack it so as nearly to cut it apart, but not quite. Allow a small quart of water to each pound of meat, and sprinkle on a tea-spoonful of salt and a very little black pepper. Put it into a soup-pot, and boil it slowly (skimming it well) till the meat is reduced to rags. Then strain the liquid, return it to the soup-pot, and carefully remove all the fat from the surface. Have ready half a dozen small turnips sliced thin, two young onions sliced, a table-spoonful of sweet marjoram leaves picked from the stalks, and a quart of shelled Lima beans. Put in the vegetables, and boil them in the soup till they are thoroughly done. You may add to them two table-spoonfuls of green nasturtion seeds, either fresh or pickled. Put in also some little dumplings, (made of flour and butter,) about ten minutes before the soup is done.

Instead of Lima beans, you may divide a cauliflower or two broccolis into sprigs, and boil them in the soup with the other vegetables.

This soup may be made of a shoulder of mutton, cut into pieces and the bones cracked. For a large potful add also the breast to the neck, cutting the bones apart.

AUTUMN SOUP.—

Begin this soup as early in the day as possible. Take six pounds of the lean of fine fresh beef; cut it into small pieces; sprinkle it with a tea-spoonful of salt, (not more); put it into a soup-pot, and pour on six quarts of water. The hock of a cold ham will greatly improve it. Set it over a moderate fire, and let it boil slowly. After it comes to a boil, skim it well. Have ready a quarter of a peck of ochras cut into very thin round slices, and a quarter of a peck of tomatos cut into pieces; also a quart of shelled Lima beans. Season them with pepper. Put them in; and after the whole has boiled three hours at least, take four ears of young Indian corn, and having grated off all the grains, add them to the soup and boil it an hour longer. Before you serve up the soup remove from it all the bits of meat, which, if the soup is sufficiently cooked, will be reduced to shreds.

You may put in with the ochras and tomatos one or two sliced onions. The soup, when done, should be as thick as a jelly.

Ochras for soup may be kept all winter, by tying them separately to a line stretched high across the store room.

WINTER SOUP.—

The day before you make the soup, get a leg or shin of beef. Have the bone sawed through in several places, and the meat notched or scored down to the bone. This will cause the juice or essence to come out more freely, when cooked. Rub it slightly with salt; cover it, and set it away. Next morning, early as possible, as soon as the fire is well made up, put the beef into a large soup-pot, allowing to each pound a small quart of water. Then taste the water, and if the salt that has been rubbed on the meat is not sufficient, add a very little more. Throw in also a tea-spoonful of whole pepper-corns; and you may add half a dozen blades of mace. Let it simmer slowly till it comes to a boil; then skim it well. After it boils, you may quicken the fire. At nine o'clock put in a large head of cabbage cut fine as for cold-slaw; six carrots grated; the leaves stripped from a bunch of sweet marjoram; and the leaves of a sprig of parsley. An hour afterwards, add six turnips, and three potatoes, all cut into four or eight pieces. Also two onions, which will be better if previously roasted brown, and then sliced. Keep the soup boiling steadily, but not hard, unless the dinner hour is very early. For a late dinner, there will be time to boil it slowly all the while; and all soups are the better for long and slow boiling. See that it is well skimmed, so that, when done, there will be not a particle of fat or scum on the surface. At dinner-time take it up with a large ladle, and transfer it to a tureen. In doing so, carefully avoid the shreds of meat and bone. Leave them all in the bottom of the pot, pressing them down with the ladle. A mass of shreds in the tureen or soup-plate looks slovenly and disgusting, and should never be seen at the table; also, they absorb too much of the liquid. Let the vegetables remain in the soup when it is served up, but pick out every shred of meat or bone that may be found in the tureen when ready to go to table.

In very cold weather, what is left of this soup will keep till the second day; when it must be simmered again over the fire, till it just comes to a boil. Put it away in a tin or stone vessel. The lead which is used in glazing earthen jars frequently communicates its poison to liquids that are kept in them.

VEGETABLE SOUP—

(very good.)—Soak all night, in cold water, either two quarts of yellow split peas, or two quarts of dried white beans. In the morning drain them, and season them with a very little salt and cayenne, and a head of minced celery, or else a heaped table-spoonful of celery seed. Put them into a soup-pot with four quarts of water, and boil them slowly till they are all dissolved and undistinguishable. Stir them frequently. Have ready a profuse quantity of fresh vegetables, such as turnips, carrots, parsnips, potatos, onions, and cauliflowers; also, salsify, and asparagus tops. Put in, first, the vegetables that require the longest boiling. They should all be cut into small pieces. Enrich the whole with some bits of fresh butter rolled in flour. Boil these vegetables in the soup till they are all quite tender. Then transfer it to a tureen, and serve it up hot.

The foundation being of dried peas or beans, makes it very thick and smooth, and the fresh vegetables improve its flavor. It is a good soup for Lent, or for any time, if properly and liberally made.

All vegetable soups can be made in Lent without meat, if milk is substituted for water, and with butter, beaten eggs and spice, to flavor and enrich it.

FRENCH POT AU FEU.—

This is one of the national dishes of France. The following is a genuine French receipt, and it would be found very palatable and very convenient if tried in our own land of plenty. The true French way to cook it is in an earthen pipkin, such as can be had in any pottery shop. The French vessel has a wide mouth, and close-fitting lid, with a handle at each side, in the form of circular ears. It is large and swelling in the middle, and narrows down towards the bottom. The American pipkin has a short thick spout at one side, and stands on three or four low feet. No kitchen should be without these vessels, which are cheap, very strong, and easily kept clean. They can sit on a stove, or in the corner of the fire, and are excellent for slow cooking.

The wife of a French artisan commences her pot au feu soon after breakfast, prepares the ingredients, puts them, by degrees, into the pot, attends to it during the day; and when her husband has done his work she has ready for him an excellent and substantial repast, far superior to what in our country is called a tea-dinner. Men frequently indemnify themselves for the poorness of a tea-dinner by taking a dram of whiskey afterwards. A Frenchman is satisfied with his excellent pot au feu and some fruit afterwards. The French are noted as a temperate nation. If they have eaten to their satisfaction they have little craving for drink. Yet there is no country in the world where so much good eating might be had as in America. But to live well, and wholesomely, there should also be good cooking, and the wives of our artisans must learn to think more of the comfort, health, and cheerfulness of him who in Scotland is called the bread-winner, than of their own finery, and their children's uncomfortable frippery.

Receipt.—For a large pot au feu, put into the pipkin six pounds of good fresh beef cut up, and pour on it four quarts of water. Set it near the fire, skim it when it simmers, and when nearly boiling, add a tea-spoonful of salt, half a pound of liver cut in pieces, and some black pepper. Then add two or three large carrots, sliced or grated on a coarse grater; four turnips, pared and quartered; eight young onions peeled and sliced thick, two of the onions roasted whole; a head of celery cut up; a parsnip split and cut up; and six potatos, pared, sliced, or quartered. In short any good vegetables now in season, including tomatos in summer and autumn. Also a bunch of sweet herbs, chopped small. Let the whole continue to boil slowly and steadily; remembering to skim well. Let it simmer slowly five or six hours. Then, having laid some large slices of bread in the bottom of a tureen, or a very large pan or bowl, pour the stew or soup upon it; all the meat, and all the vegetables. If you have any left, recook it the next morning for breakfast, and that day you may prepare something else for dinner.

For beef you may substitute mutton, or fresh venison, if you live in a venison country, and can get it newly killed.

WILD DUCK SOUP.—

This is a company soup. If you live where wild ducks are abundant, it will afford an agreeable variety occasionally to make soup of some of them. If you suspect them to be sedgy or fishy, (you can ascertain by the smell when drawing or cleaning them,) parboil each duck, with a carrot put into his body. Then take out the carrot and throw it away. You will find that the unpleasant flavor has left the ducks, and been entirely absorbed by the carrots. To make the soup—cut up the ducks, season the pieces with a little salt and pepper, and lay them in a soup-pot. For a good pot of soup you should have four wild ducks. Add two or three sliced onions, and a table-spoonful of minced sage. Also a quarter of a pound of butter divided into four, and each piece rolled in flour. Pour in water enough to make a rich soup, and let it boil slowly till all the flesh has left the bones,—skim it well. Thicken it with boiled or roasted chestnuts, peeled, and then mashed with a potato beetle. A glass of Madeira or sherry will be found an improvement, stirred in at the last, or the juice and grated peel of a lemon. In taking it up for the tureen, be careful to leave all the bones and bits of meat in the bottom of the pot.

VENISON SOUP.—

Take a large fine piece of freshly killed venison. It is best at the season when the deer are fat and juicy, from having plenty of wild berries to feed on. I do not consider winter-venison worth eating, when the meat is poor and hard, and affords no gravy, and also is black from being kept too long. When venison is fresh and in good order it yields a fine soup, allowing a small quart of water to each pound of meat. When it has boiled well, and been skimmed, put in some small dumplings made of flour and minced suet, or drippings. Also, boiled sweet potatos, cut into round thick slices. You may add boiled sweet corn cut off the cob; and, indeed, whatever vegetables are in season. The soup-meat should boil till all the flesh is loose on the bones, and the bits and shreds should not be served up.

The best pieces of buffalo make good soup.

GAME SOUP.—

Take partridges, pheasants, grouse, quails, or any of the birds considered as game. You may put in here as many different sorts as you can procure. They must all be fresh killed. When they are cleaned and plucked, cut them in pieces as for carving, and put them into a soup-pot, with four calves' feet and some slices of ham, two sticks of celery, and a bundle of sweet herbs chopped small, and water enough to cover the whole well. Boil and skim well, till all the flesh is loose from the bones. Strain the liquid through a sieve into a clean pot, then thicken it with fresh butter rolled in flour. Add some force-meat balls that have been already fried; or else some hard-boiled yolks of eggs; some currant jelly, or some good wine into which a half-nutmeg has been grated; the juice of two oranges or lemons, and the grated yellow peel of one lemon. Give the soup another boil up, and then send it to table, having bread rolls to eat with it.

This is a fine soup for company. Venison soup may be made in this manner. Hare soup also.

SQUATTER'S SOUP.—

Take plenty of fresh-killed venison, as fat and juicy as you can get it. Cut the meat off the bones and put it (with the bones) into a large pot. Season it with pepper and salt, and pour on sufficient water to make a good rich soup. Boil it slowly (remembering to skim it well) till the meat is all in rags. Have ready some ears of young sweet corn. Boil them in a pot by themselves till they are quite soft. Cut the grains off the cob into a deep dish. Having cleared the soup from shreds and bits of bone left at the bottom of the pot, stir in a thickening made of indian meal mixed to a paste with a little fresh lard, or venison gravy. And afterwards throw in, by degrees, the cut corn. Let all boil together, till the corn is soft, or for about half an hour. Then take it up in a large pan. It will be found very good by persons who never were squatters. This soup, with a wild turkey or a buffalo hump roasted, and stewed grapes sweetened well with maple sugar, will make a good backwoods dinner.

MOCK TURTLE SOUP.—

Boil together a knuckle of veal (cut up) and a set of calves' feet, split. Also the hock of a cold boiled ham. Season it with cayenne pepper; but the ham will render it salt enough. You may add a smoked tongue. Allow, to each pound of meat, a small quart of water. After the meat has come to a boil and been well skimmed, add half a dozen sliced parsnips, three sliced onions, and a head of celery cut small, with a large bunch of sweet marjoram, and two large carrots sliced. Boil all together till the vegetables are nearly dissolved and the meat falls from the bone. Then strain the whole through a cullender, and transfer the liquid to a clean pot. Have ready some fine large sweetbreads that have been soaked in warm water for an hour till all the blood was disgorged; then transferred to boiling water for ten minutes, and then taken out and laid in very cold water. This will blanch them, and all sweetbreads should look white. Take them out; and remove carefully all the pipe or gristle. Cut the sweetbreads in pieces or mouthfuls, and put them into the pot of strained soup. Have ready about two or three dozen (or more) of force-meat balls, made of cold minced veal and ham seasoned with nutmeg and mace, enriched with butter, and mixed with grated lemon-peel, bread-crumbs, chopped marjoram and beaten eggs, to make the whole into smooth balls about the size of a hickory nut. Throw the balls into the soup, and add a fresh lemon, sliced thin, and a pint of Madeira wine. Give it one more boil up; then put it into a tureen and send it to table.

This ought to be a rich soup, and is seldom made except for dinner company.

If the above method is exactly followed, there will be found no necessity for taking the trouble and enduring the disgust and tediousness of cleaning and preparing a calf's head for mock turtle soup—a very unpleasant process, which too much resembles the horrors of a dissecting room. And when all is done a calf's head is a very insipid article.

It will be found that the above is superior to any mock turtle. Made of shin beef, with all these ingredients, it is very rich and fine.

[A] In buying calves' feet always get those that are singed, not skinned. Much of the glutinous or jelly property resides in the skin.

FISH SOUP.—

All fish soups should be made with milk, (if unskimmed so much the better,) using no water whatever. The best fish for soup are the small sort of cat-fish; also tutaug, porgie, blue fish, white fish, black fish or sea-bass. Cut off their heads, tails, and fins, and remove the skin, and the backbone, and cut the fish into pieces. To each pound of fish allow a quart of rich milk. Put into the soup-pot some pieces of cold boiled ham. No salt will then be required; but season with cayenne pepper, and a few blades of mace and some grated nutmeg. Add a bunch of sweet marjoram, the leaves stripped from the stalks and chopped. Make some little dumplings of flour and butter, and put them in when the soup is about half done. Half an hour's steady boiling will be sufficient. Serve up in the tureen the pieces of fish and ham. Also some toast cut in dice.

Soup may be made in this manner, of chickens or rabbits, using always milk enriched with bits of butter rolled in flour and flavored with bits of cold ham.

LOBSTER SOUP.—

This is a fine soup for company. Take two or three fine fresh lobsters, (the middle sized are the best.) Heat a large pot of water, throwing in a large handful of salt. When it is boiling hard put in the lobsters, head foremost, that they may die immediately. They will require at least half an hour's fast boiling; if large, three quarters. When done, take them out, wipe off the scum that has collected on the shell, and drain the lobster. First break off the large claws, and crack them, then split the body, and extract all the white meat, and the red coral—nothing else—and cut it into small pieces. Mash the coral into smooth bits with the back of a large spoon, mixing with it plenty of sweet oil; and, gradually, adding it to the bits of chopped lobster. Put into a clear soup-pot two quarts, or more, of good milk, and thicken it with half a dozen crackers or butter-biscuit, pounded fine; or the grated crumbs of two or three small rolls, and stir in a quarter of a pound of fresh butter made into a paste with two spoonfuls of flour. Put in the chopped lobster, seasoned with nutmeg, a few blades of mace powdered, and a little cayenne. Let all boil together, slowly, for half an hour, keeping it closely covered. Towards the last, stir in two beaten eggs. Lay some very small soda biscuit in the bottom of a tureen, and pour the soup upon them. Nasturtion flowers strewed at the last thickly over the surface of this soup, when in the tureen, are an improvement both to its appearance and flavor. So is peppergrass.

CRAB SOUP.—

Take the meat of two dozen boiled crabs, cut it small, and give it a boil in two quarts of milk. Season it with powdered mace, nutmeg, and a little cayenne, and thicken it with butter mixed in flour; or, make the flour and butter into little dumplings. Have ready half a dozen yolks of hard-boiled eggs, and crumble them into the soup just before you take it from the fire. Add the heart of a fresh green lettuce, cut small and strewed over the surface of the soup, after it is poured into the tureen.

OYSTER SOUP.—

Strain the liquor from one hundred oysters, and carefully remove any bits of shell or particles of sea-weed. To every pint of oyster liquor allow an equal quantity of rich milk. Season it with whole pepper and some blades of mace. Add a head of celery, washed, scraped, and minced small. Put the whole into a soup-pot, and boil and skim it well. When it boils put in the oysters. Also, a quarter of a pound of fresh butter; divide into four pieces, each piece rolled in flour. If you can procure cream, add a half-pint, otherwise boil some six eggs hard, and crumble the yolks into the soup. After the oysters are in give them but one boil up, just sufficient to plump them. If boiled longer they will shrink and shrivel and lose their taste. Take them all out and set them away to cool. When the soup is done, place in the bottom of the tureen some small square pieces of nicely toasted bread cut into dice, and pour on the soup; grate in a nutmeg and then add the oysters. Serve it up very hot.

Another way is to chop or cut small the oysters, omitting the hard part. Make the soup as above, and put in the minced oysters at the last, letting them boil but five minutes. Mix the powdered nutmeg with them. This is a good way, if you make but a small quantity of soup.

CLAM SOUP.—

Having washed clean the outside shells of a hundred small sand clams, (or scrubbed them with a brush,) put them into a large pot of boiling water. When they open their shells take them out with a ladle, and as you do so, put them into a cullender to drain off the liquor. Then extract the clams from the shells with a knife. Save a quart of the liquor, putting the clams in a pitcher by themselves. Mix with the quart of liquor, in a clean pot, two quarts of rich milk. Put in the clams, and add some pepper-corns and some blades of mace. Also, a bunch of sweet marjoram, the leaves stripped off and minced. After all has boiled well for an hour, add half a pound, or more, of nice fresh butter, made into little dumplings with flour; also a pint of grated bread-crumbs. Let it boil a quarter of an hour longer. Then pour the soup off from the clams and leave them in the bottom of the pot. They will not now be worth eating. If you cannot obtain small clams, you may cut large ones in pieces, but they are very coarse and tough.

FAST-DAY SOUP.—

For winter.—Having soaked all night two quarts of split peas, put them into a soup-pot, adding a sliced onion, two heads of celery, the stalks split and cut small; a table-spoonful of chopped mint, another of marjoram, and two beets, that have been previously boiled and sliced. Mix all these with half a pound of fresh butter cut into pieces and dredged with flour. Season with a little salt and pepper. Pour on rather more than water enough to cover the whole. Let them boil till all the things are quite tender, and the peas dissolved. When done, cover the bottom of a tureen with small square bits of toast, and pour in the contents of the soup-pot.

It is a good way to boil the split peas in a pot by themselves, till they are quite dissolved, and then add them to the ingredients in the other pot.

Vegetable soups require a large portion of vegetables, and butter always, as a substitute for meat.

FRIDAY SOUP.—

For summer.—This is a fast-day soup. Pare and slice six cucumbers, and cut up the white part or heart of six lettuces; slice two onions, and cut small the leaves of six sprigs of fresh green mint, unless mint is disliked by the persons that are to eat the soup; in which case, substitute parsley. Add a quart of young green peas. Put the whole into a soup-pot, with as much water as will more than cover them well. Season slightly with salt and a little cayenne, and add half a pound of nice fresh butter, divided into six, each piece dredged well with flour. Boil the whole for an hour and a half. Then serve it up, without straining; having colored it green with a tea-cup of pounded spinach juice.

When green peas are out of season, you may substitute tomatos peeled and quartered.

This soup, having no meat, is chiefly for fast days, but will be found good at any time.

BAKED SOUP.—

On the days that you bake bread, you may have a dish of thick soup with very little trouble, by putting into a large earthen jug or pipkin, or covered pan, the following articles:—Two pounds of fresh beef, or mutton, cut into small slices, having first removed the fat; two sliced onions and four carrots, and four parsnips cut in four; also, four turnips, six potatos pared and cut up, and half a dozen tomatos, peeled and quartered. Season the whole with a little salt and pepper. A large beet, scraped and cut up, will be an improvement. To these things pour on three quarts of water. Cover the earthen vessel, and set it in the oven with the bread, and let the soup bake at the same time.

If the bread is done before the dinner hour, you must keep the soup still longer in the oven.

Do not use cold meat for this or any other soup, unless you are very poor.

FISH.

TO CLEAN FISH.—

This must always be done with the greatest care and nicety. If sent to table imperfectly cleaned, they are disgraceful to the cook, and disgusting to the sight and taste. Handle the fish lightly; not roughly so as to bruise it. Wash it well, but do not leave it in the water longer than is needful. It will lose its flavor, and become insipid, if soaked. To scale it, lay the fish flat upon one side, holding it firmly in the left hand, and with the right taking off the scales by means of a knife. When both sides are done, pour sufficient cold water over it to float off all the loose scales that may have escaped your notice. It is best to pump on it. Then proceed to open and empty the fish. Be sure that not the smallest particle of the entrails is left in. Scrape all carefully from the backbone. Wash out all the blood from the inside. A dexterous cook can draw a fish without splitting it entirely down, all the way from head to tail. Smelts and other small fish are drawn or emptied at the gills.

All fish should be cleaned or drawn as soon as they are brought in, and then kept on ice, till the moment for cooking.

TO BOIL FISH.—

No fish can be fit to eat unless the eyes are prominent and lively, the gills very red, and the body firm and stiff, springing back immediately when bent round to try them. Every scale must be carefully scraped off, and the entrails entirely extracted; not the smallest portion being carelessly left sticking to the backbone. Previous to cooking, fish of every kind should be laid in cold water, and the blood thoroughly washed from the inside. Few fish are not the better for being put on to boil in cold water, heating gradually with it till it comes to a boil. If you put it on in boiling water, the outside becomes boiling hot too soon; and is apt to break and come off in flakes, while the inside still remains hard and underdone: halibut, salmon, cod, and other large thick fish must be boiled slowly and thoroughly throughout, taking nearly as long as meat. Always put salt into the water at the commencement, and a little vinegar towards the last. In every kitchen should be a large oval kettle purposely for boiling fish. This kettle has a movable strainer inside. The fish lies on the strainer. To try if it is done, run a thin sharp knife in it, till it reaches the backbone; and see if the flesh will loosen or separate easily. If it adheres to the bone it requires more boiling. When quite done, leave it no longer in the kettle, or it will lose its flavor and get a woolly look. Take out the strainer with the fish upon it. Drain off the water through the strainer, cover the fish with a folded napkin or fine towel, doubled thick; transfer it to a heated dish, and keep it warm and dry till it goes to table, directly after the soup. In the mean time prepare the sauce to be served up along with the fish.

FRYING FISH.—