автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Poems of Madison Cawein, Volume 1 (of 5)

THE POEMS OF

MADISON CAWEIN

VOLUME I

LYRICS AND OLD WORLD

IDYLLS

[See larger version]

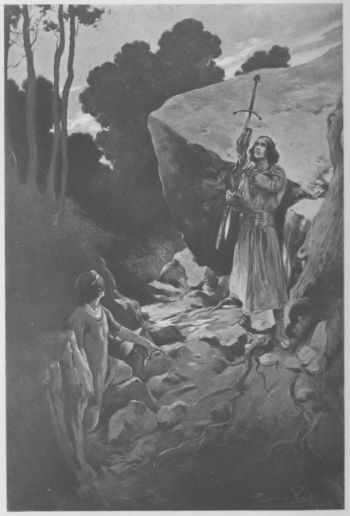

"It shall go hard with him through thee, unconquerable blade" Page 270

Accolon of Gaul

THE POEMS OF

MADISON CAWEIN

Volume I

LYRICS AND OLD

WORLD IDYLLS

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

EDMUND GOSSE

Illustrated

WITH PHOTOGRAVURES AFTER PAINTINGS BY ERIC PAPE

INDIANAPOLIS

THE BOBBS-MERRILL COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1887, 1888, 1889, 1890, 1891, 1892, 1893,

1898 and 1907, by Madison Cawein

PRESS OF

BRAUNWORTH & CO.

BOOKBINDERS AND PRINTERS

BROOKLYN, N. Y.

TO WILLIAM DEAN HOWELLS

WHO WAS THE FIRST TO RECOGNIZE AND ENCOURAGE MY ENDEAVORS, THIS VOLUME IS INSCRIBED WITH AFFECTION, ADMIRATION AND ESTEEM

PREFACE

This first collected edition of my poems contains all the verses I care to retain except the translations from the German, published in 1895 under the title of The White Snake, and some of the poems in Nature-Notes and Impressions, published in 1906.

Several of the poems which I probably would have omitted I have retained at the solicitation of friends, who have based their argument for their retention upon the generally admitted fact that a poet seldom knows his best work.

The new arrangement under new titles I found was necessary for the sake of convenience; and the poems in a manner grouped themselves in certain classes. In eliminating the old titles—some eighteen in number—I have disregarded entirely, except in the case of the first volume, the date of the appearance of each poem, placing every one, according to its subject matter, in its proper group under its corresponding title.

Most of the poems, especially the earlier ones, have been revised; many of them almost entirely rewritten and, I think, improved.

Madison Cawein.

Louisville, Kentucky.

INTRODUCTION

Since the disappearance of the latest survivors of that graceful and somewhat academic school of poets who ruled American literature so long from the shores of Massachusetts, serious poetry in the United States seems to have been passing through a crisis of languor. Perhaps there is no country on the civilized globe where, in theory, verse is treated with more respect and, in practice, with greater lack of grave consideration than in America. No conjecture as to the reason of this must be attempted here, further than to suggest that the extreme value set upon sharpness, ingenuity and rapid mobility is obviously calculated to depreciate and to condemn the quiet practice of the most meditative of the arts. Hence we find that it is what is called "humorous" verse which is mainly in fashion on the western side of the Atlantic. Those rhymes are most warmly welcomed which play the most preposterous tricks with language, which dazzle by the most mountebank swiftness of turn, and which depend most for their effect upon paradox and the negation of sober thought. It is probable that the diseased craving for what is "smart," "snappy," and wide-awake, and the impulse to see everything foreshortened and topsy-turvy, must wear themselves out before cooler and more graceful tastes again prevail in imaginative literature.

Whatever be the cause, it is certain that this is not a moment when serious poetry, of any species, is flourishing in the United States. The absence of anything like a common impulse among young writers, of any definite and intelligible, if excessive, parti pris, is immediately observable if we contrast the American, for instance, with the French poets of the last fifteen years. Where there is no school and no clear trend of executive ambition, the solitary artist, whose talent forces itself up into the light and air, suffers unusual difficulties, and runs a constant danger of being choked in the aimless mediocrity that surrounds him. We occasionally meet with a poet in the history of literature, of whom we are inclined to say: "Charming as he is, he would have developed his talent more evenly and conspicuously, if he had been accompanied from the first by other young men like-minded, who would have formed for him an atmosphere and cleared for him a space." This is the one regret I feel in contemplating, as I have done for years past, the ardent and beautiful talent of Mr. Madison Cawein. I deplore the fact that he seems to stand alone in his generation; I think his poetry would have been even better than it is, and its qualities would certainly have been more clearly perceived, and more intelligently appreciated, if he were less isolated. In his own country, at this particular moment, in this matter of serious nature-painting in lyric verse, Mr. Cawein possesses what Cowley would have called "a monopoly of wit." In one of his lyrics Mr. Cawein asks—

"The song-birds, are they flown away,

The song-birds of the summer-time,

That sang their souls into the day,

And set the laughing hours to rhyme?

No cat-bird scatters through the hush

The sparkling crystals of her song;

Within the woods no hermit-thrush

Trails an enchanted flute along."

To this inquiry, the answer is: the only hermit-thrush now audible seems to sing from Louisville, Kentucky. America will, we may be perfectly sure, calm herself into harmony again, and possess once more her school of singers. In those coming days, history may perceive in Mr. Cawein the golden link that bound the music of the past to the music of the future through an interval of comparative tunelessness.

The career of Mr. Madison Cawein is represented to me as being most uneventful. He seems to have enjoyed unusual advantages for the cultivation and protection of the poetical temperament. He was born on the 23rd of March, 1865, in the metropolis of Kentucky, the vigorous city of Louisville, on the southern side of the Ohio, in the midst of a country celebrated for tobacco and whisky and Indian corn. These are commodities which may be consumed in excess, but in moderation they make glad the heart of man. They represent a certain glow of the earth, they indicate the action of a serene and gentle climate upon a rich soil. It was in this delicate and voluptuous state of Kentucky that Mr. Cawein was born, that he was educated, that he became a poet, and that he has lived ever since. His blood is full of the color and odor of his native landscape. The solemn books of history tell us that Kentucky was discovered in 1769, by Daniel Boone, a hunter. But he first discovers a country who sees it first, and teaches the world to see it; no doubt some day the city of Louisville will erect, in one of its principal squares, a statue to "Madison Cawein, who discovered the Beauty of Kentucky." The genius of this poet is like one of those deep rivers of his native state, which cut paths through the forests of chestnut and hemlock as they hurry towards the south and west, brushing with the impulsive fringe of their currents the rhododendrons and calmias and azaleas that bend from the banks to be mirrored in their flashing waters.

Mr. Cawein's vocation to poetry was irresistible. I do not know that he even tried to resist it. I have even the idea that a little more resistance would have been salutary for a talent which nothing could have discouraged, and which opposition might have taught the arts of compression and selection. Mr. Cawein suffered at first, I think, from lack of criticism more than from lack of eulogy. From his early writings I seem to gather an impression of a Louisville more ready to praise what was second-rate than what was first-rate, and practically, indeed, without any scale of appreciation whatever. This may be a mistake of mine; at all events, Mr. Cawein has had more to gain from the passage of years in self-criticism than in inspiring enthusiasm. The fount was in him from the first; but it bubbled forth before he had digged a definite channel for it. Sometimes, to this very day, he sports with the principles of syntax, as Nature played games so long ago with the fantastic caverns of the valley of the Green River or with the coral-reefs of his own Ohio. He has bad rhymes, amazing in so delicate an ear; he has awkwardness of phrase not expected in one so plunged in contemplation of the eternal harmony of Nature. But these grow fewer and less obtrusive as the years pass by.

The virgin timber-forests of Kentucky, the woods of honey-locust and buckeye, of white oak and yellow poplar, with their clearings full of flowers unknown to us by sight or name, from which in the distance are visible the domes of the far-away Cumberland Mountains,—this seems to be the hunting-field of Mr. Cawein's imagination. Here all, it must be confessed, has hitherto been unfamiliar to the Muses. If Persephone "of our Cumnor cowslips never heard," how much less can her attention have been arrested by clusters of orchids from the Ocklawaha, or by the song of the whippoorwill, rung out when "the west was hot geranium-red" under the boughs of a black-jack on the slopes of Mount Kinnex. "Not here," one is inclined to exclaim, "not here, O Apollo, are haunts meet for thee," but the art of the poet is displayed by his skill in breaking down these prejudices of time and place. Mr. Cawein reconciles us to his strange landscape—the strangeness of which one has to admit is mainly one of nomenclature,—by the exercise of a delightful instinctive pantheism. He brings the ancient gods to Kentucky, and it is marvelous how quickly they learn to be at home there. Here is Bacchus, with a spicy fragment of calamus-root in his hand, trampling the blue-eyed grass, and skipping, with the air of a hunter born, into the hickory thicket, to escape Artemis, whose robes, as she passes swiftly with her dogs through the woods, startle the humming-birds, silence the green tree-frogs, and fill the hot still air with the perfumes of peppermint and pennyroyal. It is a queer landscape, but one of new natural beauties frankly and sympathetically discovered, and it forms a mise en scene which, I make bold to say, would have scandalized neither Keats nor Spenser.

It was Mr. Howells,—ever as generous in discovering new talent as he is unflinching in reproof of the effeteness of European taste,—who first drew attention to the originality and beauty of Mr. Cawein's poetry. The Kentucky poet had, at that time, published but one tentative volume, the Blooms of the Berry, of 1887. This was followed, in 1888, by The Triumph of Music, and since then hardly a year has passed without a slender sheaf of verse from Mr. Cawein's garden. Among these (if a single volume is to be indicated), the quality which distinguishes him from all other poets,—the Kentucky flavor, if we may call it so,—is perhaps to be most agreeably detected in Intimations of the Beautiful.

But it is time that I should leave the American lyrist to make his own appeal, with but one additional word of explanation, namely, that in this introduction Mr. Cawein's narrative poems on medieval themes, and in general his cosmopolitan writings, have been neglected of mention in favor of such nature lyrics as would present him most vividly in his own native landscape, no visitor in spirit to Europe, but at home in that bright and exuberant West—

"Where, in the hazy morning, runs

The stony branch that pools and drips,

Where red haws and the wild-rose hips

Are strewn like pebbles; where the sun's

Own gold seems captured by the weeds;

To see, through scintillating seeds,

The hunters steal with glimmering guns.

To stand within the dewy ring

Where pale death smites the boneset's blooms,

And everlasting's flowers, and plumes

Of mint, with aromatic wing!

And hear the creek,—whose sobbing seems

A wild man murmuring in his dreams,—

And insect violins that sing!"

So sweet a voice, so consonant with the music of the singers of past times, heard in a place so fresh and strange, will surely not pass without its welcome from lovers of genuine poetry.

Edmund Gosse.

London, England.

CONTENTS

BLOOMS OF THE BERRY PAGE At Rest 45 Avatars 61 Clouds 59 Dead Lily, A 40 Dead Oread, The 41 Deficiency 50 Distance 48 Diurnal 55 Dreamer of Dreams, A 24 Dryad, The 38 Family Burying Ground, The 57 Hepaticas 17 Heron, The 60 In Late Fall 72 In Middle Spring 12 In November 71 Lillita 63 Longings 9 Loveliness 4 Midsummer 52 Midwinter 79 Mirabile Dictu 22 Miriam 65 Moonrise at Sea 69 Old Byway, The 32 Pan 27 Pax Vobiscum 43 Sound of the Sap, The 36 Spirits of Spring 19 Spring Shower, A 14 Stormy Sunset, A 29 Sweet O' the Year, The 10 Two Days 67 Tyranny 76 Waiting 7 What You Will 77 With the Seasons 73 Wood God, The 1 Woodland Grave, A 30 Woodpath, The 34 IN THE GARDENS OF FALERINA Alcalde's Daughter, The 187 Amadis at Miraflores 108 An Antique 129 Blodeuwedd 101 Epic, The 183 Ermengarde 125 Eve of All-Saints, The 164 Face to Face 160 Gardens of Falerina, The 85 Guinevere, A 153 Hackelnberg 127 Hawking 117 In Mythic Seas 193 Ishmael 189 Jaafer the Barmecide 131 King, The 138 Loké and Sigyn 197 Love as It Was in the Time of Louis XIV 171 Mater Dolorosa 169 Melancholia 141 Minstrel and the Princess, The 185 My Romance 181 Orlando 119 Perle Des Jardins 156 Pre-Existence, A 134 Romance 87 To Gertrude 83 Troubadour, The 176 Urganda 112 Valley of Music, The 90 War-Song of Harald the Red 207 Woman of the World, A 150 Yolanda of the Towers 121 Yule 209 OLD WORLD IDYLLS Accolon of Gaul 219 After the Tournament 340 An Episode 440 Arabah 458 At the Corregidor's 437 Behram and Eddetma 476 Blind Harper, The 345 Childe Ronald 347 Dark Tower, The 342 Daughter of Merlin, The 363 Demon Lover, The 358 Dream of Sir Galahad, The 335 Forester, The 371 Geraldine 431 Isolt 329 Khalif and the Arab, The 450 Knight-Errant, The 368 Lady of the Hills, The 356 Mameluke, The 466 Moated Manse, The 391 Morgan Le Fay 353 My Lady of Verne 422 Norman Knight, The 448 Old Tale Retold, An 409 Peredur, The Son of Evrawc 307 Portrait, The 471 Princess of Thule, A 360 Romaunt of the Roses 468 Rosicrucian, The 445 Seven Devils, The 460 Slave, The 443 Thamus 462 To R. E. Lee Gibson 217 Torquemada 485 Tristram to Isolt 365LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

As one hath seen a green-gowned huntress fair,

Morn in her cheeks and midnight in her hair;

Keen eyes as gray as rain, young limbs as lithe

As the wild fawn's; and silvery voice as blithe

As is the wind that breathes of flowers and dews,

Breast through the bramble-tangled avenues;

Through brier and thorn, that pluck her gown of green,

And snag it here and there,—through which the sheen

Of her white skin gleams rosy;—eyes and face,

Ardent and flushed, fixed on the lordly chase:

So came the Evening to that shadowy wood,

Or so it seemed to Accolon, who stood

Watching the sunset through the solitude.

So Evening came; and shadows cowled the way

Like ghostly pilgrims who kneel down to pray

Before a wayside shrine: and, radiant-rolled,

Along the west, the battlemented gold

Of sunset walled the opal-tinted skies,

That seemed to open gates of Paradise

On soundless hinges of the winds, and blaze

A glory, far within, of chrysoprase,

Towering in topaz through the purple haze.

And from the sunset, down the roseate ways,

To Accolon, who, with his idle lute,

Reclined in revery against the root

Of a great oak, a fragment of the west,

A dwarf, in crimson satin tightly dressed,

Skipped like a leaf the early frosts have burned,

A red oak-leaf; and like a leaf he turned,

And danced and rustled. And it seemed he came

From Camelot; from his belovéd dame,

Morgane le Fay. He on his shoulder bore

A mighty blade, wrought strangely o'er and o'er

With mystic runes, drawn from a scabbard which

Glared venomous, with angry jewels rich.

He, louting to the knight, "Sir knight," said he,

"Your Lady, with all tenderest courtesy,

Assures you—ah, unworthy bearer I

Of her good message!—of her constancy."

Then, doffing the great baldric, with the sword,

To him he gave them, saying, "From my lord,

King Arthur: even his Excalibur,

The magic blade which Merlin gat of her,

The Ladyé of the Lake, who, as you wot,

Fostered in infanthood Sir Launcelot,

Upon some isle in Briogne's tangled lands

Of meres and mists; where filmy fairy bands,

By lazy moons of summer, dancing, fill

With rings of morrice every grassy hill.

Through her fair favor is this weapon sent,

Who begged it of the King with this intent:

That, for her honor, soon would be begun

A desperate battle with a champion,

Of wondrous prowess, by Sir Accolon:

And with the sword, Excalibur, more sure

Were she that he against him would endure.

Magic the blade, and magic, too, the sheath,

Which, while 'tis worn, wards from the wearer death."

He ceased: and Accolon held up the sword

Excalibur and said, "It shall go hard

With him through thee, unconquerable blade,

Whoe'er he be, who on my Queen hath laid

Insult or injury! And hours as slow

As palsied hours in Purgatory go

For those unmassed, till I have slain this foe!—

Here, page, my purse.—And now, to her who gave,

Despatch! and say: To all commands, her slave,

To death obedient, I!—In love or war

Her love to make me all the warrior.—

Bid her have mercy, nor too long delay

From him, who dies an hourly death each day

Till, her white hands kissed, he shall kiss her face,

Through which his life lives on, and still finds grace."

Thus he commanded. And, incontinent,

The dwarf departed, like a red shaft sent

Into the sunset's sea of scarlet light

Burning through wildwood glooms. And as the night

With votaress cypress veiled the dying strife

Sadly of day, and closed his book of life

And clasped with golden stars, in dreamy thought

Of what this fight was that must soon be fought,

Belting the blade about him, Accolon,

Through the dark woods tow'rds Chariot passed on.

"

It Shall go Hard With Him Through Thee, Unconquerable Blade"

Frontispiece PAGE She Raised Her Oblong Lute and Smote Some Chords(See page

230)

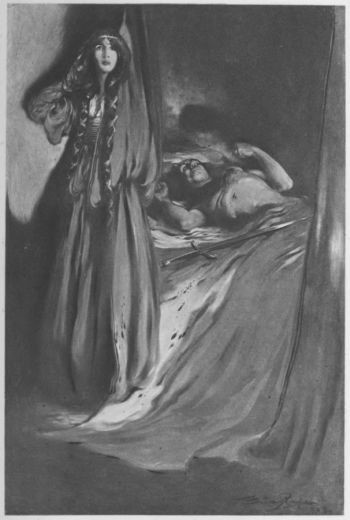

124 In Her Ecstasy a Lovely Devil(See page

303)

250 And Grasped of Both Wild Hands, Swung Trenchant(See page

285)

374LYRICS

Wine-warm winds that sigh and sing

Led me, wrapped in many moods,

Through the green, sonorous woods

Of belated spring.

Till I came where, glad with heat,

Waste and wild the fields were strewn,

Olden as the olden moon,

At my weary feet.

Wild and white with starry bloom,

One far milky-way that dashed,

When some mad wind down it flashed,

Into billowy foam.

I, bewildered, gazed around,

As one on whose heavy dreams

Comes a sudden burst of beams,

Like a mighty sound....

If the grander flowers I sought,

But these berry-blooms to you,

Evanescent as the dew,

Only these I brought.

BLOOMS OF THE BERRY.

THE WOOD GOD

I

What deity for dozing Laziness

Devised the lounging leafiness of this

Secluded nook?—And how!—did I distress

His musing ease that fled but now? or his

Communion with some forest-sister, fair

And shy as is the whippoorwill-flower there,

Did I disturb?—Still is the wild moss warm

And fragrant with late pressure,—as the palm

Of some hot Hamadryad, who, a-nap,

Props her hale cheek upon it, while her arm

Is wildflower-buried; in her hair the balm

Of a whole spring of blossoms and of sap.—

II

See, how the dented moss, that pads the hump

Of these distorted roots, elastic springs

From that god's late reclining! Lump by lump

Its points, impressed, rise in resilient rings,

As stars crowd, qualming through gray evening skies.—

Invisible presence, still I feel thy eyes

Regarding me, bringing dim dreams before

My half-closed gaze, here where great, green-veined leaves

Reach, waving at me, their innumerable hands,

Stretched towards this water where the sycamore

Stands burly guard; where every ripple weaves

A ceaseless, wavy quivering as of bands.

III

Of elfin chivalry, that, helmed with gold,

Invisible march, making a twinkling sound.—

What brought thee here?—this wind, that steals the old

Gray legends from the forests and around

Whispers them now? Or, in those purple weeds

The hermit brook so busy with his beads?—

Lulling the silence with his prayers all day,

Droning soft Aves on his rosary

Of bubbles.—Or, that butterfly didst mark

On yon hag-taper, towering by the way,

A witch's yellow torch?—Or didst, like me,

Watch, drifting by, these curled, brown bits of bark?

IV

Or con the slender gold of this dim, still

Unmoving minnow 'neath these twisted roots,

Thrust o'er the smoky topaz of this rill?—

Or, in this sunlight, did those insect flutes,

Sleepy with summer, drowsily forlorn,

Remind thee of Tithonos and the Morn?

Until thine eyes dropped dew, the dimpled stream

Crinkling with crystal o'er the winking grail?—

Or didst perplex thee with some poet plan

To drug this air with beauty to make dream,—

Presence unseen, still watching in yon vale!—

Me, wildwood-wandered from the haunts of man!

LOVELINESS

I

Now let us forth to find the young witch Spring,

Seated amid her bow'rs and birds and buds,

Busy with loveliness.—And, wandering

Among old forests that the sunlight floods,

Or vales of hermit-holy solitudes,

Dryads shall beckon us from where they cling,

Their limbs an oak-bark brown; their hair—wild woods

Have perfumed—wreathed with earliest leaves: and they,

Regarding us with a dew-sparkling eye,

Shall whispering greet us, as the rain the rye,

Or from wild lips melodious welcome fling,

Like hidden waterfalls with winds at play.

II

Let us surprise the Naiad ere she slips—

Nude at her toilette—in her fountain's glass;

With damp locks dewy and evasive hips,

Cool-dripping, but an instant seen, alas!

When from indented moss and plushy grass—

Fear in her great eyes' rainbow-blue—she dips,

Irised, the cloven water; as we pass

Making a rippled circle that shall hide,

From our exploring eyes, what watery path

She gleaming took; what crystal haunt she hath

In minnowy freshness, where her murmurous lips,

Bubbling, make merry 'neath the rocky tide.

III

Then we may meet the Oread, whose eyes

Are dewdrops where twin heavens shine confessed:

She, all the maiden modesty's surprise

Rosying her temples,—to slim loins and breast

Tempestuous, brown, bewildering tresses pressed,—

Shall stand a moment's moiety in wise

Of some delicious dream, then shrink, distressed,

Like some wild mist that, hardly seen, is gone,

Footing the ferny hillside without sound;

Or, like storm sunlight, her white limbs shall bound,

A thistle's instant, towards a woody rise,

A flying glimmer o'er the dew-drenched lawn.

IV

And we may see the Satyrs in the shades

Of drowsy dells pipe, and, goat-footed, dance;

And Pan himself reel rollicking through the glades;

Or, hidden in bosky bow'rs, the Lust, perchance,

Faun-like, that waits with heated, animal glance

The advent of the Loveliness that wades

Thigh-deep through flowers, naked as Romance,

All unsuspecting, till two hairy arms

Clasp her rebellious beauty, panting white,

Whose tearful terror, struggling into might,

Beats the brute brow resisting, but evades

Not him, for whom the gods designed her charms.

WAITING

Were it but May now, while

Our hearts are yearning,

How they would bound and smile,

The young blood burning!

Around the tedious dial

No slow hands turning.

Were it but May now!—say,

What joy to go,

Your hand in mine all day,

Where blossoms blow!

Your hand, more white than May,

May's flowers of snow.

Were it but May now!—think,

What wealth she has!

The bluet and wild-pink,

Wild flowers,—that mass

About the wood-brook's brink,—

And sassafras.

Nights, that the large stars strew,

Heaven on heaven rolled;

Nights, pearled with stars and dew,

Whose heavens hold

Aromas, and the new

Moon's curve of gold.

So mad, so wild is March!—

I long, oh, long

To see the redbud's torch

Flame far and strong;

Hear, on my vine-climbed porch,

The bluebird's song.

How slow the Hours creep,

Each with a crutch!—

Ah, could my spirit leap

Its bounds and touch

That day, no thing would keep—

Or matter much!

But now, with you away,

Time halts and crawls,

Feet clogged with winter clay,

That never falls,

While, distant still, that day

Of meeting calls.

LONGINGS

Now when the first wild violets peer

All rain-filled at blue April skies,

As on one smiles one's sweetheart dear

With the big teardrops in her eyes:

Now when the May-apples, I wis,

Bloom white along lone, greenwood creeks,

As bashful as the cheeks you kiss,

As waxen as your sweetheart's cheeks:

Within the soul what longings rise

To stamp the town-dust from the feet!

Fare forth to gaze in Spring's clean eyes,

And kiss her cheeks so cool and sweet!

THE SWEET O' THE YEAR

I

How can I help from laughing, while

The daffodillies at me smile?

The dancing dew winks tipsily

In clusters of the lilac-tree,

And crocus' mouths and hyacinths'

Storm through the grassy labyrinths

A mirth of pearl and violet;

While roses, bud by bud,

Laugh from each dainty-lacing net

Red lips of maidenhood.

II

How can I help from singing when

The swallow and the hawk again

Are noisy in the hyaline

Of happy heavens, clear as wine?

The robin, lustily and shrill,

Pipes on the timber-belted hill;

And o'er the fallow skim the bold,

Mad orioles that glow

Like shining shafts of ingot gold

Shot from the morning's bow.

III

How can I help from loving, dear,

Since love is of the sweetened year?—

The very insects feel his power,

And chirr and chirrup hour on hour;

The bee and beetle in the noon,

The cricket underneath the moon:—

What else to do but follow too,

Since youth is on the wing,

Lord Life who follows through the dew

Lord Love a-carolling.

IN MIDDLE SPRING

Now the fields are rolled into turbulent gold,

And a ripple of fire and pearl is blent

With the emerald surges of wood and of wold,

A flower-foam bursting redolent:

Now the dingles and deeps of the woodland old

Are glad with a sibilant life new sent,

Too rare to be told are the manifold,

Sweet fancies that quicken, eloquent,

In the heart that no longer is cold.

How it knows of the wings of the hawk ere it swings

From the drippled dew scintillant seen!

Where the redbird hides, ere it flies or sings,

In melodious quiverings of green!

How the sun to the dogwood such kisses brings

That it laughs into blossoms of wonderful sheen;

While the wind, to the strings of his lute that rings,

Makes love to apple and nectarine,

Till the sap in them rosily springs.

Go seek in the ray for a sworded fay,

The chestnut's buds into blooms that rips;

And look in the brook, that runs laughing gay,

For the Nymph with the laughing lips;

In the brake for the Dryad whose eyes are gray,

From whose bosom the perfume drips;

The Faun hid away, where the branches sway,

Thick ivy low down on his hips,

Pursed lips on a syrinx at play.

So, ho! for the rose, the Romeo rose,

And the lyric it hides in its heart!

And, oh, for the epic the oak-tree knows,

Sonorous as Homer in art!

And it's ho! for the prose of the weed that grows

Green-writing Earth's commonest part!—

What God may propose let us learn of those,

The songs and the dreams that start

In the heart of each blossom that blows.

A SPRING SHOWER

We stood where the fields were beryl,

The redolent woodland was warm;

And the heaven above us, now sterile,

Was alive with the pulse-winds of storm.

We had watched the green wheat brighten

And gloom as it winced at each gust;

And the turbulent maples whiten

As the lane blew gray with dust.

White flakes from the blossoming cherry,

Pink snows of the peaches were blown,

And star-bloom wrecks of the berry

And dogwood petals were sown.

Then instantly heaven was sullied,

And earth was thrilled with alarm,

As a cloud, that the thunder had gullied,

Thrust over the sunlight its arm.

The birds to dry coverts had hurried,

And hid in their leafy-built rooms;

And the bees and the hornets had buried

Themselves in the bells of the blooms.

Then down from the clouds, as from towers,

Rode slant the tall lancers of rain,

And charged the fair troops of the flowers,

And trampled the grass of the plain.

And the armies of blossoms were scattered;

Their standards hung draggled and lank;

And the rose and the lily were shattered,

And the iris lay crushed on its bank.

But high in the storm was the swallow,

And the rock-loud voice of the fall,

From its ramparts of forest, rang hollow

Defiance and challenge o'er all.

But the storm and its clouds passed over,

And left but one cloud in the west,

Wet wafts that were fragrant with clover,

And the sun slow-sinking to rest.

Rain-drippings and rain in the poppies,

And scents as of honey and bees;

A touch of wild light on the coppice,

That turned into flames the drenched trees.

Then the cloud in the sunset was riven,

And bubbled and rippled with gold,

And over the gorges of heaven,

Like a gonfalon vast was unrolled.

HEPATICAS

In the frail hepaticas—

That the early Springtide tossed,

Sapphire-like, along the ways

Of the woodlands that she crossed—

I behold, with other eyes,

Footprints of a dream that flies.

One who leads me; whom I seek:

In whose loveliness there is

All the glamour that the Greek

Knew as wind-borne Artemis.—

I am mortal. Woe is me!

Her sweet immortality!

Spirit, must I always fare,

Following thy averted looks?

Now thy white arm, now thy hair,

Glimpsed among the trees and brooks?

Thou who hauntest, whispering,

All the slopes and vales of Spring.

Cease to lure! or grant to me

All thy beauty! though it pain,

Slay with splendor utterly!

Flash revealment on my brain!

And one moment let me see

All thy immortality!

SPIRITS OF SPRING

I

Over the summer seas,

From the Hesperides,

Warm as the southern breeze,

Gather the Spirits,

Clad on with sun and rain,

Fire in each ardent vein,

Who, with a wild refrain,

Waken the germs that the Season inherits.

II

See, where they come, like mist,

Gleaming with amethyst,

Trailing the light that kissed

Vine-tangled mountains

Looming o'er tropic lakes,

Where every wind, that shakes

Tamarisk coverts, makes

Music that haunts like the falling of fountains.

III

You may behold the beat

Of their wild hearts of heat,

And their rose-flashing feet

Flying before us:

Hear them among the trees

Whispering like far-off seas,

Waking the drowsy bees,

Wild-birds and flowers and torrents sonorous.

IV

You may behold their eyes,

Star-like, that sapphire dyes,

To which the blossoms rise

Star-like; and shadows

Flee from: and, golden deep,

As through the woods they sweep,

See their wild curls that keep

Asphodel memories that kindle the meadows.

V

Music of forest-streams,

Fragrance and dewy gleams,

Daybreak and dawn and dreams,

High things and lowly,

Mix in their limbs of light,

Which, what they touch of blight,

Quicken to blossom white,

Raise to be beautiful, perfect, and holy.

VI

Come! do not sit and wait

Now that once desolate

Fields are intoxicate

With birds and flowers!

And all the woods are rife

With resurrected life,

Passion and purple strife

Of the warm winds and the turbulent showers.

VII

Come! let us lie and dream

Here by the wildwood stream,

Where many a twinkling gleam

Falls on the rooty

Banks; and the forest glooms

Rain down their redbud blooms,

Armfuls of wild perfumes—

Winds! or Auloniads busy with beauty.

MIRABILE DICTU

I

There dwells a goddess in the West,

An Island in death-lonesome seas;

No towered towns are hers confessed,

No castled forts or palaces;

Hers, simple worshipers at best,

The buds, the birds, the bees.

II

And she hath wonder-words of song,

So heavenly beautiful and shed

So sweetly from her honeyed tongue,

The savage creatures, it is said,

Hark, marble-still, their wilds among,

And nightingales fall dead.

III

I know her not, nor have I known:

I only feel that she is there:

For when my heart is most alone,

Her deep communion fills the air,—

Her influence calls me from my own,—

Miraculously fair.

IV

Then fain am I to sing and sing,

And then again to fly and fly,

Beyond the flight of cloud or wing,

Far under azure arcs of sky;

My love at her chaste feet to fling,

Behold her face and—die.

A DREAMER OF DREAMS

He lived beyond men, and so stood

Admitted to the brotherhood

Of beauty; dreams, with which he trod

Companioned as some sylvan god.

And oft men wondered, when his thought

Made all their knowledge seem as naught,

If he, like Uther's mystic son,

Had not been born for Avalon.

When wandering 'mid the whispering trees,

His soul communed with every breeze;

Heard voices calling from the glades,

Bloom-words of the Leimoniads;

Or Dryads of the ash and oak,

Who syllabled his name and spoke

With him of presences and powers

That glimpsed in sunbeams, gloomed in showers.

By every violet-hallowed brook,

Where every bramble-matted nook

Rippled and laughed with water sounds,

He walked like one on sainted grounds,

Fearing intrusion on the spell

That kept some fountain-spirit's well,

Or woodland genius, sitting where

Red, racy berries kissed his hair.

Once when the wind, far o'er the hill,

Had fall'n and left the wildwood still

For Dawn's dim feet to glide across,—

Beneath the gnarled boughs, on the moss,

The air around him golden ripe

With daybreak,—there, with oaten pipe,

His eyes beheld the wood-god, Pan,

Goat-bearded, and half-brute, half-man;

Who, shaggy-haunched, a savage rhyme

Blew in his reed to rudest time;

And swollen-jowled, with rolling eye—

Beneath the slowly silvering sky,

Whose light shone through the forest's roof—

Danced, while beneath his boisterous hoof

The branch was snapped, and, interfused

Between great roots, the moss was bruised.

And often when he wandered through

Old forests at the fall of dew—

A new Endymion who sought

A beauty higher than all thought—

Some night, men said, most surely he

Would favored be of deity:

That in the holy solitude

Her sudden presence, long pursued,

Unto his gaze would be confessed;

The awful moonlight of her breast

Come, high with majesty, and hold

His heart's blood till his heart were cold,

Unpulsed, unsinewed, and undone,

And snatch his soul to Avalon.

PAN

I

Haunter of green intricácies

Where the sunlight's amber laces

Deeps of darkest violet;

Where the shaggy Satyr chases

Nymphs and Dryads, fair as Graces,

Whose white limbs with dew are wet:

Piper in hid mountain places,

Where the blue-eyed Oread braces

Winds which in her sweet cheeks set

Of Aurora rosy traces;

While the Faun from myrtle mazes

Watches with an eye of jet:

What art thou and these dim races,

Thou, O Pan, of many faces,

Who art ruler yet?

II

Tell me, piper, have I ever

Heard thy hollow syrinx quiver

Trickling music in the trees?

Where the hazel copses shiver,

Have I heard its dronings sever

The warm silence, or the bees?

Ripple murmurings that never

Could be born of fall or river,

Or the whispering breeze.

III

Once in tempest it was given

Me to see thee,—where the leven

Lit the craggy wood with glare,—

Dancing, while,—like wedges driven,—

Thunder split the deeps of heaven,

And the wild rain swept thy hair.—

What art thou, whose presence, even

While with fear my heart was riven,

Healed it as with prayer?

A STORMY SUNSET

I

Soul of my body! what a death

For such a day of grief and gloom,

Unbroken sorrow of the sky!—

'Tis as if God's own loving breath

Had swept the piled-up thunder by,

And, bursting through the tempest's sheath,

Cleft from its pod a giant bloom.

II

See how the glory grows! unrolled,

Expanding length on radiant length

Of cloud-wrought petals.—Vast, a rose

The western heavens of flame unfold,

Where, sparkling thro' the splendor, glows

The evening star, fresh-faced with strength—

A raindrop in its heart of gold.

A WOODLAND GRAVE

White moons may come, white moons may go,

She sleeps where early blossoms blow;

Knows nothing of the leafy June,

That leans above her, night and noon,

Crowned now with sunbeam, now with moon,

Watching her roses grow.

The downy moth at evening comes

And flutters round their honeyed blooms:

Long, languid clouds, like ivory,

That isle the blue lagoons of sky,

Grow red as molten gold and dye

With flame the pine-dark glooms.

Dew, dripping from wet fern and leaf;

The wind, that shakes the blossom's sheaf;

The slender sound of water lone,

That makes a harp-string of some stone,

And now a wood-bird's twilight moan,

Seem whisp'rings there of grief.

Her garden, where the lilacs grew,

Where, on old walls, old roses blew,

Head-heavy with their mellow musk,

Where, when the beetle's drone was husk,

She lingered in the dying dusk,

No more shall know that knew.

Her orchard,—where the Spring and she

Stood listening to each bird and bee,—

That, from its fragrant firmament,

Snowed blossoms on her as she went,

(A blossom with their blossoms blent)

No more her face shall see.

White moons may come, white moons may go,

She sleeps where early blossoms blow;

Around her headstone many a seed

Shall sow itself; and briar and weed

Shall grow to hide it from men's heed,

And none will care or know.

THE OLD BYWAY

Its rotting fence one scarcely sees

Through sumac and wild blackberries.

Thick elder and the bramble-rose,

Big ox-eyed daisies where the bees

Hang droning in repose.

The little lizards lie all day

Gray on its rocks of lichen-gray;

And there, gay Ariels of the sun,

The butterflies make bright its way,

And paths where chipmunks run.

Its lyric there the redbird lifts,

While, overhead, the swallow drifts

'Neath sun-soaked clouds of palest cream,—

In which the wind makes azure rifts,—

And there the wood-doves dream.

The brown grasshoppers rasp and bound

'Mid weeds and briars that hedge it round;

And in its grass-grown ruts,—where stirs

The harmless snake,—mole-crickets sound;

O'erhead the locust whirs.

At evening, when the sad west turns

To lonely night a cheek that burns,

The tree-toads in the wild-plum sing;

And ghosts of long-dead flowers and ferns

The wind wakes, whispering.

THE WOODPATH

Here Spring her first frail violets blows;

Broadcast her whitest wind-flowers sows

Through starry mosses amber-fair,

And fronded ferns and briar-rose,

Hart's-tongue and maidenhair.

Here fungus life is beautiful;

Slim mushroom and the thick toadstool,—

As various colored as are blooms,—

Dot their damp cones through shadows cool,

And breathe forth rain perfumes.

Here stray the wandering cows to rest;

The calling cat-bird builds its nest

In spicewood bushes dark and deep;

Here raps the woodpecker its best,

And here young rabbits leap.

Beech, oak, and cedar; hickories;

The pawpaw and persimmon trees;

And tangled vines and sumac-brush,

Make dark the daylight, where the bees

Drone, and the wood-springs gush.

Here to pale melancholy moons,

In haunted nights of dreamy Junes,

Wails wildly the weird whippoorwill,

Whose strains, like those the owlet croons,

Wild woods with phantoms fill.

THE SOUND OF THE SAP

When the ice was thick on the flower-beds,

And the sleet was caked on the briar;

When the frost was down in the brown bulb's heads,

And the ways were clogged with mire:

When the snow on syringa and spiræa-tree

Seemed the ghosts of perished flowers;

And the days were sorry as sorry could be,

And Time limped, cursing his fardel of hours:

Heigh-ho! had I not a book and the logs,

That chirped with the sap in the burning?—

Or was it the frogs in the far-off bogs?

Or the bush-sparrow's song at the turning?

And I strolled by ways that the Springtime knows,

In her mossy dells, and her ferny passes;

Where the earth was holy with lily and rose,

And the myriad life of the grasses.

And I spoke with the Spring as a lover, who speaks

To his sweetheart; to whom he has given

A kiss that has kindled the rose of her cheeks,

And her eyes with the laughter of heaven.

The sound of the sap!—What a simple thing!—

But the sound of the sap had the power

To make the song-sparrow come and sing,

And the winter woodlands flower!

THE DRYAD

I have seen her limpid eyes,

Large with gradual laughter, rise

In the wild-rose nettles;

Slowly, like twin flowers, unfold,

Smiling,—when the wind, behold!

Whisked them into petals.

I have seen her hardy cheek,

Like a molten coral, leak

Through the leaves around it

Of thick Chickasaws; but so,

When I made more certain, lo!

A red plum I found it.

I have found her racy lips,

And her roguish finger-tips,

But a haw or berry;

Glimmers of her there and here,

Just, forsooth, enough to cheer,

And to make me merry.

Often from the ferny rocks

Dazzling rimples of her locks

At me she hath shaken;

And I've followed—but in vain!—

They had trickled into rain,

Sunlit, on the braken.

Once her full limbs flashed on me,

Naked, where a royal tree

Checkered mossy places

With soft sunlight and dim shade,—

Such a haunt as myths have made

For the Satyr races.

There, it seemed, hid amorous Pan;

For a sudden pleading ran

Through the thicket, wooing

Me to search and, suddenly,

From the swaying elder-tree,

Flew a wild-dove, cooing.

A DEAD LILY

With shadowy eyes long, long she gazed in his,

Then whispered dreamily the one word, "Bliss."

And like an echo on his sad mouth sate

The answer:—"Bliss?—deep have we drunk of late!

But death, I feel, some stealthy-footed death

Draws near! whose claws will clutch away—whose breath?...

I dreamed last night thou gather'dst flowers with me,

Fairer than those of earth. And I did see

How woolly gold they were, how woven through

With fluffy flame, and webby with spun dew:

And 'Asphodels' I murmured: then, 'These sure

Are Eden amaranths, so angel pure

That love alone may touch them.'—Thou didst lay

The flowers in my hands; alas! then gray

The world grew; and, meseemed, I passed away.

In some strange manner on a misty brook,

Between us flowing, striving still to look

Beyond it, while, around, the wild air shook

With torn farewells of pensive melody,

Aching with tears and hopeless utterly;

So merciless near, meseemed that I did hear

That music in those flowers, and yearned to tear

Their ingot-cored and gold-crowned hearts, and hush

Their voices into silence and to crush:

Yet o'er me was a something that restrained:

The melancholy presence of two pained

And awful, burning eyes that cowed and held

My spirit while that music died or swelled

Far out on shoreless waters, borne away—

Like some wild-bird, that, blinded with the ray

Of dawn it wings tow'rds, lifting high its crest,

The glory round it, sings its heavenliest,

When suddenly all's changed; with drooping head,

Daggered of thorns it plunged on, fluttering, dead,

Still, still it seems to sing, though wrapped in night,

The slow blood beading on its breast of white.—

And then I knew the flowers which thou hadst given

Were strays of parting grief and waifs of heaven

For tears and memories. Importunate

They spoke to me of loves that separate!—

But, God! ah God! my God! thus was I left!

And these were with me who was so bereft.

The haunting torment of that dream of grief

Weighs on my soul and gives me no relief."

And this is she God made

Of sunlight and of flowers

For love and kisses and fond caresses—

Yolanda of the Towers.

O'er his heart

The long blade paused and—then descended hard.

Unfleshed, she flung it by her murdered lord,

And watched the blood spread darkly through the sheet,

And drip, a horror, at impassive feet

Pooling the polished oak. Regretless she

Stood, and relentless; in her ecstasy

A lovely devil: demon crowned, that cried

For Accolon, with passion that defied

Control in all her senses; clamorous as

A torrent in a cavernous mountain pass

That sweeps to wreck and ruin; at that hour

So swept her longing tow'rds her paramour.

Him whom, King Arthur had commanded when

Borne from the lists, she should receive again;

Her lover, her dear Accolon, as was just,

As was but due her for her love—and lust.

And while she stood revolving if her deed's

Secret were safe, behold! a noise of steeds,

Arms, jingling stirrups, voices loud that cursed

Fierce in the northern court. To her, athirst

For him her lover, war and power it spoke,

Him victor and so king. And then awoke

Desire to see and greet him: and she fled,

Like some wild spectre, down the stairs; and, red,

Burst on a glare of links and glittering mail,

That shrunk her eyes and made her senses quail.

To her a bulk of iron, bearded fierce,

Down from a steaming steed into her ears,

"This from the King, O Queen!" laughed harsh and hoarse:

Two henchmen beckoned, who pitched sheer, with force,

Loud clanging at her feet, hacked, hewn, and red,

Crusted with blood, a knight in armor—dead:

Her Accolon, flung in his battered arms

By what to her seemed fiends and demon forms,

Wild-torched, who mocked; then, with the parting scoff,

"This from the King!" phantoms in fog, rode off.

Beyond, the hart a tangled labyrinth weaves

Through deeper boscage; and it seems the sun

Makes many shadowy stags of this wild one,

That lead in different trails the foresters:

And in the trees the ceaseless wind, that stirs,

Seems some strange witchcraft, that, with baffling mirth,

Mocks them the unbayed hart, and fills the earth

With rustling sounds of running.—Hastening thence,

Galloped King Arthur and King Urience,

With one small brachet-hound. Now far away

They heard their fellowship's faint horns; and day

Wore on to noon; yet, there before them, they

Still saw the hart plunge bravely through the brake,

Leaving the bracken shaking in his wake:

And on they followed; on, through many a copse,

Above whose brush, close on before, the tops

Of the great antlers swelled anon, then, lo,

Were gone where beat the heather to and fro.

But still they drave him hard; and ever near

Seemed that great hart unwearied, and 'twas clear

The chase would yet be long, when Arthur's horse

Gasped mightily and, lunging in his course,

Lay dead, a lordly bay; and Urience

Reined his gray hunter, laboring. And thence

King Arthur went afoot. When suddenly

He was aware of a wide waste of sea,

And, near the wood, the hart upon the sward,

Bayed, panting unto death and winded hard.

So with his sword he slew him; then the pryce

Wound loudly on his hunting-bugle thrice.

Then Arthur drew aside to rest upon

His falchion for a space. But Accolon,

As yet,—through virtue of that magic sheath,—

Fresh and almighty, and no nearer death

Now than when first the fight to death begun,

Chafed at delay. But Arthur, with the sun,

His heavy mail, his wounds, and loss of blood,

Made weary, ceased and for a moment stood

Leaning upon his sword. Then, "Dost thou tire?"

Sneered Accolon. And then, with fiercer fire,

"Defend thee! yield thee! or die recreant!"

And at the King aimed a wild blow, aslant,

That beat a flying fire from the steel.

Stunned by that blow, the King, with brain a-reel,

Sank on one knee; then rose, infuriate,

Nerved with new vigor; and with heat and hate

Gnarled all his strength into one blow of might,

And in both fists his huge blade knotted tight,

And swung, terrific, for a final stroke,—

And,—as the lightning flames upon an oak,—

Boomed on the burgonet his foeman wore;

Hacked through and through its crest, and cleanly shore,

With hollow clamor, from his head and ears,

The brag and boasting of that griffin fierce:

Then, in an instant, as if made of glass,

That brittle blade burst, shattered; and the grass

Shone, strewn with shards; as 'twere a broken ray,

It fell and bright in feverish fragments lay.

Then groaned the King, disarmed. And straight he knew

This sword was not Excalibur: too true

And perfect tempered, runed and mystical,

That weapon of old wars! and then withal,

Looking upon his foe, who still with stress

Fought on, untiring, and with no distress

Of wounds or heat, he thought, "I am betrayed!"

Then as the sunlight struck along that blade,

He knew it, by the hilt, for his own brand,

The true Excalibur, that high in hand

Now rose avenging. For Sir Accolon

In madness urged th' unequal battle on

His King defenseless; who, the hilted cross

Of that false weapon grasped, beneath the boss

Of his deep-dented shield crouched; and around,

Like some great beetle, labored o'er the ground,

Whereon the shards of shattered spears and bits

Of shivered steel and gold made sombre fits

Of flame, 'mid which, hard-pressed and cowering

Beneath his shield's defense, the dauntless King

Crawled still defiant. And, devising still

How to secure his sword and by what skill,

Him thus it fortuned when most desperate:

In that close chase they came where, shattered late,

Lay, tossed, the truncheon of a bursten lance,

Which, deftly seized, to Accolon's advance

He wielded with effect. Against the fist

Smote, where the gauntlet clasped the nervous wrist,

That heaved Excalibur for one last blow;

Sudden the palsied sinews of his foe

Relaxed in effort, and, the great sword seized,

Was wrenched away: and straight the wroth King eased

Himself of his huge shield, and hurled it far;

And clasping in both arms of wiry war

His foe, Sir Accolon,—as one hath seen

A strong wind take an ash tree, rocking green,

And swing its sappy bulk, then, trunk and boughs,

Crash down its thundering height in wild carouse

And wrath of tempest,—so King Arthur shook

And headlong flung Sir Accolon. Then took,

Tearing away, that scabbard from his side

And hurled it through the lists, that far and wide

Gulped in the battle breathless. Then, still wroth,

He seized Excalibur; and grasped of both

Wild hands, swung trenchant, and brought glittering down

On rising Accolon. Steel, bone and brawn

That blow hewed through. Unsettled every sense.

Bathed in a world of blood, his limbs lay tense

A moment, then grew limp, relaxed in death.

And bending o'er him, from the brow beneath,

The King unlaced the helm. When dark, uncasqued,

The knight's slow eyelids opened, Arthur asked:

"Say, ere thou diest, whence and who thou art!

What king, what court is thine? And from what part

Of Britain dost thou come? Speak!—for, methinks,

I have beheld thee—where? Some memory links

Me strangely with thy face, thy eyes ... thou art—

Who art thou?—speak!"—

And then his smile! a thrust-like thing that curled

His lips with heresy and incredible lore

When Christ's or th' Virgin's holy name was said,

Exclaimed in reverence or admonishment:

And once he sneered,—"What is this God you mouth,

Employ whose name to bless yourselves or damn?

A curse or blessing?—It hath passed my skill

T' interpret what He is. And then your faith—

What is this faith that helps you unto Him?

Distinguishment unseen, design unlawed.

Why, earth, air, fire, and water, heat and cold,

Hint not at Him: and man alone it is

Who needs must worship something. And for me—

No God like that whom man hath kinged and crowned!

Rather your Satan cramped in Hell—the Fiend!

God-countenanced as he is, and tricked with horns.

No God for me, bearded as Charlemagne,

Throned on a tinsel throne of gold and jade,

Earth's pygmy monarchs imitate in mien

And mind and tyranny and majesty,

Aping a God in a sonorous Heaven.

Give me the Devil in all mercy then,

Bad as he is! for I will none of such!"

And laughed an oily laugh of easy jest

To bow out God and let the Devil in.

The South saluted her mouth

Till her breath was sweet with the South.

The North in her ear breathed low,

Till her veins ran crystal and snow.

The West 'neath her eyelids blew,

Till her heart beat honey and dew.

And the East with his magic old

Changed her body to pearl and gold.

And she stood like a beautiful thought

That a godhead of love had wrought....

How strange that the Power begot it

Only to kill it and rot it!

THE DEAD OREAD

Her heart is still and leaps no more

With holy passion when the breeze,

Her whilom playmate, as before,

Comes with the language of the bees,

Sad songs her mountain cedars sing,

And water-music murmuring.

Her calm, white feet,—once fleet and fast

As Daphne's when a god pursued,—

No more will dance like sunlight past

The gold-green vistas of the wood,

Where every quailing floweret

Smiled into life where they were set.

Hers were the limbs of living light,

And breasts of snow, as virginal

As mountain drifts; and throat as white

As foam of mountain waterfall;

And hyacinthine curls, that streamed

Like mountain mists, and gloomed and gleamed.

Her presence breathed such scents as haunt

Deep mountain dells and solitudes,

Aromas wild,—like some wild plant

That fills with sweetness all the woods;—

And comradeship with stars and skies

Shone in the azure of her eyes.

Her grave be by a mossy rock

Upon the top of some high hill,

Removed, remote from men who mock

The myths, the dreams of life they kill;

Where all of love and naught of lust

May guard her solitary dust.

PAX VOBISCUM

I

I know that from thine eyes

The Spring her violets grew;

Those bits of April skies,

On which the green turf lies,

Whereon they blossom blue.

II

I know that Summer wrought

From thy sweet heart that rose,

With such faint fragrance fraught,—

Its pale, poetic thought

Of peace and deep repose.—

III

That Autumn, like some god,

From thy delicious hair,—

Lost sunlight 'neath the sod,—

Shot up this goldenrod

To toss it everywhere.

IV

That Winter from thy breast

The snowdrop's whiteness stole—

Much kinder than the rest—

Thy innocence confessed,

The pureness of thy soul.

AT REST

I heard the dead man, where he lay

Within the open coffin, say:—

"Why do they come to weep and cry

Around me now?—Because I lie

So silent, and my heart's at rest?

Because the pistons of my blood

No more in this machinery thud?

And on these eyes, that once were blessed

With magnetism and fire, are pressed

The soldered eyelids, like a sheath?

On which the icy hand of Death

Hath laid invisible coins of lead

Stamped with the image of his head?

"Why will they weep and not have done?

Why sorrow so? and all for one,

Who, they believe, hath found the best

God gives to us,—and that is rest.

Why grieve?—Yea, rather let them lift

The voice in thanks for such a gift,

That leaves the worn hands, long that wrought,

And weary feet, that sought and sought,

At peace; and makes what came to naught,

In life, more real now than all

The good men strive for here on Earth:

The love they seek; the things they call

Desirable and full of worth;

Yea, wisdom ev'n; and, like the South,

The dreams that dewed the soul's sick drouth,

And heart's sad barrenness.—God's rest,

With every sigh and every tear,

By them who weep above me here,

Despite their Faith and Hope, 's confessed

A doubt; a thing to dread and fear.

"Before them peacefully I lie.

But, haply, not for me they sigh,

But for themselves,—their loss. The round

Of daily labor still to do

For them, while for myself 'tis through;

And all the unknown, too, is found,

The bourn for which all hopes are bound,

Where dreams are all made manifest:

For this they grieve, perhaps. 'Tis well;

Since 'tis through grief the soul is blessed,

Not joy;—and yet, we can not tell,

We do not know, we can not prove,

We only feel that there is love,

And something we call Heaven and Hell.

"Howbeit, here, you see, I lie,

As all shall lie—for all must die—

A cast-off, useless, empty shell,

In which an essence once did dwell;

That once, like fruit, the spirit held,

And with its husk of flesh compelled:

The mask of mind, the world of will,

That laughed and wept and labored till

The thing within, that never slept,

The life essential, from it stept;

The ichor-veined inhabitant

Who made it all it was; in all

Its aims the thing original,

That held its course, like any star,

Among its fellows; or a plant,

Among its brother plants; 'mid whom,—

The same and yet dissimilar,—

Distinct and individual,

It grew to microcosmic bloom."

These were the words the dead man said

To me who stood beside the dead.

DISTANCE

I

I dreamed last night once more I stood

Knee-deep on purple clover leas;

Her old home glimmered through its wood

Of dark and melancholy trees:

And on my brow I felt the breeze

That blew from out the solitude,

With sounds of waters that pursued,

And sleepy hummings of the bees.

II

And ankle-deep in violet blooms

Methought I saw her standing there,

A lawny light among the glooms,

A crown of sunlight on her hair;

The wood-birds, warbling everywhere,

Above her head flashed happy plumes;

About her clung the wild perfumes,

And woodland gleams of shimmering air.

III

And then she called me: in my ears

Her voice was music; and it led

My sad soul back with all its fears;

Recalled my spirit that had fled.—

And in my dream it seemed she said,

"Our hearts keep true through all the years;"

And on my face I felt the tears,

The blinding tears of her long dead.

DEFICIENCY

Ah, God! were I away, away

By woodland-belted hills!

There might be more in this bright day

Than my poor spirit thrills.

The elder coppice, banks of blooms;

The spicewood brush; the field

Of tumbled clover, and perfumes

Hot, weedy pastures yield.

The old rail-fence, whose angles hold

Bright briar and sassafras;

Sweet, priceless wildflowers, blue and gold,

Starred through the moss and grass.

The ragged path that winds unto

Lone, bird-melodious nooks,

Through brambles to the shade and dew

Of rocks and woody brooks.

To see the minnows flash and gleam

Like sparkling prisms; all

Shoot in gray schools adown the stream

Let but a dead leaf fall!

To feel the buoyance and delight

Of floating, feathered seeds!

Capricious wisps of wandering white

Born of silk-bearing weeds.

Ah, God! were I away, away

Among wild woods and birds,

There were more soul in this bright day

Than one could bless with words.

MIDSUMMER

The red blood stings through her cheeks and clings

In their tan with a fever that lightens;

And the clearness of heaven-born mountain springs

In her dark eyes dusks and brightens:

Her limbs are the limbs of an Atalanta who swings

With the youths in the sinewy games,

When the hot wind sings through the hair it flings,

And the circus roars hoarse with their names,

As they fly to the goal that flames.

Her voice is as deep as the waters that sweep

Through the musical reeds of a river;

A voice as of reapers who bind and reap,

With the ring of curved scythes that quiver:

A voice, singing ripe the orchards that heap

With crimson and gold the ground;

That whispers like sleep, till the briars weep

Their berries, all ruby round,

And vineyards are purple-crowned.

Right sweet is the beat of her glowing feet,

And her smile, as Heaven's, is gracious;

The creating might of her hands of heat

As a god's or a goddess's spacious:

The odorous blood in her heart a-beat

Is rich with a perishless fire;

And her bosom, most sweet, is the ardent seat

Of a mother who never will tire,

While the world has a breath to suspire.

Wherever she fares her soft voice bears

Fecundity; powers that thicken

The fruits,—as the wind made Thessalian mares

Of old mysteriously quicken:—

The apricots' honey, the milk of the pears,

The wine, great grape-clusters hold,

These, these are her cares, and her wealth she declares

In the corn's long billows of gold,

And flowers that jewel the wold.

So, hail to her lips, and her sun-girt hips,

And the glory she wears in her tresses!

All hail to the balsam that dreams and drips

From her breasts that the light caresses!

Midsummer! whose fair arm lovingly slips

Round the Earth's great waist of green,

From whose mouth's aroma his hot mouth sips

The life that is love unseen,

And the beauty that God may mean.

DIURNAL

I

With molten ruby, clear as wine,

The East's great cup of daybreak brims;

The morning-glories swing and shine;

The night-dews bead their satin rims;

The bees are busy in flower and vine,

And load with gold their limbs.

Sweet Morn, the South

A loyal lover,

Kisses thy mouth,

Thy rosy mouth,

And over and over

Wooes thee with scents of wild-honey and clover.

II

Beside the wall the roses blow

That Noon's hot breezes scarcely shake;

Beside the wall the poppies glow,

So full of fire their deep hearts ache;

The drowsy butterflies fly slow,

Half sleeping, half awake.

Sweet Noontide, Rest,—

A reaper sleeping,—

His head on thy breast,

Thy redolent breast,

Dreams of the reaping,

While sounds of the scythes all around him are sweeping.

III

Along lone paths the cricket cries,

Where Night distils dim scent and dew;

One mad star 'thwart the heaven flies,

A glittering curve of molten blue;

Now grows the big moon in the skies;

The stars are faint and few.

Sweet Night, the vows

Of love long taken,

Against thy brows

Lay their pale brows,

Till thy soul is shaken

Of amorous dreams that make it awaken.

THE FAMILY BURYING GROUND

A wall of crumbling stones doth keep

Watch o'er long barrows where they sleep,

Old, chronicled grave-stones of its dead,

On which oblivion's mosses creep

And lichens gray as lead.

Warm days, the lost cows, as they pass,

Rest here and browse the juicy grass

That springs about its sun-scorched stones;

Afar one hears their bells' deep brass

Waft melancholy tones.

Here the wild morning-glory goes

A-rambling, and the myrtle grows;

Wild morning-glories, pale as pain,

With holy urns, that hint at woes,

The night hath filled with rain.

Here are the largest berries seen,

Rich, winey-dark, whereon the lean

Black hornet sucks; noons, sick with heat,

That bend not to the shadowed green

The heavy, bearded wheat.

At night, for its forgotten dead,

A requiem, of no known wind said,

Through ghostly cedars moans and throbs,

While to the starlight overhead

The shivering screech-owl sobs.

CLOUDS

All through the tepid summer night

The starless sky had poured a cool

Monotony of pleasant rain

In music beautiful.

And for an hour I sat to watch

Clouds moving on majestic feet;

And heard down avenues of night

Their hearts of thunder beat.

Prodigious limbs, far-veined with gold,

Pulsed fiery life o'er wood and plain,

While, scattered, fell from giant hands

The largess of the rain.

Beholding at each lightning flash

Their generous silver on the sod,

In meek devotion bowed, I thanked

These almoners of God.

THE HERON

I

EVENING

A vein of flame, the long creek crawls

Beneath dark brows of woodland walls,

Red where the sunset's crimson falls.

One wiry leg drawn to his breast,

Neck-shrunk, at solitary rest,

The heron stands among the bars.

II

NIGHT

The whimpering creek breaks on the stone,

Where for a while the new moon shone

With one white star and one alone.

Lank haunter of lone marshy lands

The melancholy heron stands,

Then, clamoring, dives into the stars.

AVATARS

I

When the moon hangs low

Over an afterglow,

Lilac and lily;

When the stars are high,

Wisps in a windless sky,

Silverly stilly:—

He, who will lean, his inner ear compelling,

May hear the spirit of the forest stream

Its story to a wildwood flower telling,

That is no flower but some ascended dream.

II

When the dawn's first lines

Show dimly through the pines

Along the mountain;

When the stars are few,

And starry lies the dew

Around the fountain:—

Who will, may hear, within her leafy dwelling,

The spirit of the oak-tree, great and strong,

Its romance to the wildwood streamlet telling,

That is no stream but some descended song.

LILLITA

Can I forget how, when you stood

'Mid orchards whence the bloom had fled,

Stars made the orchards seem a-bud,

And weighed the sighing boughs o'erhead

With shining ghosts of blossoms dead?

Or when you bowed, a lily tall,

Above your drowsy lilies, slim,

Transparent pale, that by the wall

Like cups of moonlight seemed to swim,

Brimmed with faint fragrance to the brim?

And in the cloud that lingered low—

A silent pallor in the west—

There stirred and beat a golden glow,

Like some great heart that could not rest,

A heart of gold within its breast.

Your heart, your soul were in the wild:

You loved to hear the whippoorwill

Lament its love, when, dewy mild,

The harvest scent made musk the hill.

You loved to walk, where oft had trod

The red deer, o'er the fallen hush

Of Fall's torn leaves, when th' ivy-tod

Hung frosty by each berried bush.

Still do the whippoorwills complain

Above your listless lilies, where

The moonlight their white faces stain;

Still flows the dreaming streamlet there,

Whispering of rest an easeful air....

O music of the falling rain,

At night unto her painless rest

Sound sweet not sad! and make her fain

To feel the wildflowers on her breast

Lift moist, pure faces up again

To breathe a prayer in fragrance blessed.

Thick-pleated beeches long have crossed

Old, gnarly arms above her tomb,

Where oft I sit and dream her ghost

Smiles, like a blossom, through the gloom;

Dim as a mist,—that summer lost,—

Of tangled starbeam and perfume.

MIRIAM

White clouds and buds and birds and bees,

Low wind-notes, piped down southern seas,

Brought thee, a rose-white offering,

A flower-like baby with the spring.

She, with her April, gave to thee

A soul of winsome witchery;

Large, heavenly eyes and sparkling whence

Shines the young mind's soft influence;

Where love's eternal innocence,

And smiles and tears of maidenhood,

Gleam with the dreams of hope and good.

She, with the dower of her May

Gave thee a nature strong to sway

Man's higher feelings; and a pride

Where all pride's smallness is denied.

Limbs wrought of lilies; and a face

Made of a rose-bloom; and the grace

Of water, that thy limbs express

In each chaste billow of thy dress.

She, with her dreamy June, brought down

Night-deeps of hair that are thy crown;

A voice like low winds musical,

Or streams that in the moonlight fall

O'er bars of pearl; and in thy heart,—

True gold,—she set Joy's counterpart,

A gem, that in thy fair face gleams,

All radiance, when it speaks or dreams;

And in thy soul the jewel Truth

Whose beauty is perpetual youth.

TWO DAYS

I

The slanted storm tossed at their feet

The frost-nipped autumn leaves;

The park's high pines were caked with sleet,

And ice-spears armed the eaves.

They strolled adown the pillared pines,

To part where wet and twisted vines

About the gate-posts blew and beat.

She watched him riding through the rain

Along the river's misty shore,

And turned with lips that laughed disdain:

"To meet no more!"

II

'Mid heavy roses weighed with dew

The chirping crickets hid;

I' the honeysuckle avenue

Sang the green katydid.

Soft southern stars smiled through the pines.

Through stately windows, draped with vines,

The drifting moonlight's silver blew.

She stared upon a face, now dead,

A soldier calm that wore;

Despair sobbed on the lips that said,

"To meet no more."

MOONRISE AT SEA

I

With lips that had hushed all their fury

Of foam and of winds that were strewn,

Of storm and of turbulent hurry,

The ocean sighed; heralding soon

A ship of miraculous glory,

Of pearl and of fire—the moon.

II

And up from the East, with a slipping

And shudder and clinging of light,

With a loos'ning of clouds and a dipping,

Outbound for the Havens of Night,

With a silence of sails and a dripping,

The vessel came, wonderful white.

III

Then heaven and ocean were sprinkled

With splendor; for every sheet

And spar, and its hollow hull twinkled

With mother-of-pearl. And the feet

Of spirits, that followed it, crinkled

The billows that under it beat.

IN NOVEMBER

No windy white of wind-blown clouds is thine!

No windy white, but low and sodden gray,

That holds the melancholy skies and kills

The wild song and the wild-bird. Yet, ah me!

Thy melancholy skies and mournful woods,

Brown, sighing forests dying that I love!

Thy long, dead leaves, deep, deep about my feet,

Slow, dragging feet that halt or wander on;

Thy deep, sweet, crimson leaves that burn and die

With silent fever of the sickened wood.

I love to hear in all thy wind-swept coignes,

Rain-wet and choked with bleached and ruined weeds,

The withered whisper of the many leaves,

That, fallen on barren ways—like fallen hopes—

Once held so high upon the Summer's heart

Of stalwart trees, now seem the desolate voice

Of Earth lamenting in hushed undertones

Her green departed glory vanished so.

IN LATE FALL

O days, that break the wild-bird's heart,

That slay the wild-bird and its songs!

Why should death play so sad a part

With you to whom such sweet belongs?

Why are your eyes so filled with tears,

As with the rain the frozen flowers?

Why are your hearts so swept with fears,

Like winds among the ruined bowers?

Farewell! farewell! for she is dead,

The old gray month; I saw her die:

Go, light your torches round her head,

The last red leaves, and let her lie.

WITH THE SEASONS

I

You will not love me, sweet,

When this brief year is past;

Or love, now at my feet,

At other feet you'll cast,

At fairer feet you'll cast.

You will not love me, sweet,

When this brief year is past.

II

Now 'tis the Springtime, dear,

And crocus-cups hold flame,

Brimmed to the pregnant year,

All bashful as with shame,

Who blushes as with shame.

Now 'tis the Springtime, dear,

And crocus-cups hold flame.

III

Soon Summer will be queen,

At her brown throat one rose,

And poppy-pod, and bean,

Will rustle as she goes,

As down the garth she goes.

Soon Summer will be queen,

At her brown throat one rose.

IV

Then Autumn come, a prince,

A gipsy crowned with gold;

Gold weight the fruited quince,

Gold strew the leafy wold,

The wild and wind-swept wold.

Then Autumn come, a prince,

A gipsy crowned with gold.

V

Then Winter will be king,

Snow-driven from feet to head;

No song-birds then will sing,

The winds will wail instead,

The wild winds weep instead.

Then Winter will be king,

Snow-driven from feet to head.

VI

Then shall I weep, who smiled,

And curse the coming years,

You and myself, and child,

Born unto shame and tears,

A mother's shame and tears.

Then shall I weep, who smiled,

And curse the coming years.

TYRANNY

What is there now more merciless

Than such fast lips that will not speak;

That stir not if one curse or bless

A God who made them weak?

More maddening to one there is naught

Than such white eyelids sealed on eyes,

Eyes vacant of the thing named thought,

An exile in the skies.

Ah, silent tongue! ah, dull, closed ear!

What angel utterances low

Have wooed you? so you may not hear

Our mortal words of woe!

WHAT YOU WILL

I

When the season was dry and the sun was hot,

And the hornet sucked, gaunt on the apricot,

And the ripe peach dropped, to its seed a-rot,

With a lean, red wasp that stung and clung:

When the hollyhocks, ranked in the garden plot,

More seed-pods had than blossoms, I wot,

Then all had been said and been sung,

And meseemed that my heart had forgot.

II

When the black grape bulged with the juice that burst

Through its thick blue skin that was cracked with thirst,