автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу History of the Indians, of North and South America

E-text prepared by

Cindy Horton, WebRover, Adrian Mastronardi,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

from page images generously made available by

Internet Archive

(https://archive.org)

Note:

Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See

https://archive.org/details/histindiansnorth00goodrichHISTORY

OF THE

INDIANS,

OF

NORTH AND SOUTH AMERICA.

BY THE AUTHOR OF

PETER PARLEY’S TALES.

BOSTON:

BRADBURY, SODEN & CO.

M DCCC XLIV.

Entered according to Act of Congress,

in the year 1844,

By S. G. GOODRICH,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District

Court of Massachusetts.

STEREOTYPED BY

METCALF, KEITH & NICHOLS, CAMBRIDGE.

WM. A. HALL & CO., PRINTERS,

12 Water Street.

CONTENTS.

PAGE Introduction 5 Origin of the Aborigines 10 Classification of the Indians 16 The Aborigines of the West Indies 22 The Caribs 34 Early Mexican History 41 Mexico, from the Arrival of Cortés 54 The Empire of the Incas 80 The Araucanians 98 Southern Indians of South America 112 Indians of Brazil 121 The Indians of Florida 129 The Indians of Virginia 147 The Southern Indians 160 Indians of New England 170 The Five Nations, &c.

192 The Six Nations 205 Western Indians east of the Mississippi 219 Western and Southern Indians 233 Various Tribes of Northern and Western Indians 241 The Indians west of the Mississippi 256 Present Condition of the Western Indians in The United States 287 The Prospects of the Western Tribes 297

When Velasquez set out to conquer Cuba, he had only three hundred men; and these were thought sufficient to subdue an island above seven hundred miles in length, and filled with inhabitants. From this circumstance we may understand how naturally mild and unwarlike was the character of the Indians. Indeed, they offered no opposition to the Spaniards, except in one district. Hatuey, a cacique who had fled from Hayti, had taken possession of the eastern extremity of Cuba. He stood upon the defensive, and endeavoured to drive the Spaniards back to their ships. He was soon defeated and taken prisoner.

HISTORY

OF THE

AMERICAN INDIANS.

INTRODUCTION.

When America was first discovered, it was found to be inhabited by a race of men different from any already known. They were called Indians, from the West Indies, where they were first seen, and which Columbus, according to the common opinion of that age, supposed to be a part of the East Indies. On exploring the coasts and the interior of the vast continent, the same singular people, in different varieties, were everywhere discovered. Their general conformation and features, character, habits, and customs were too evidently alike not to render it proper to class them under the same common name; and yet there were sufficient diversities, in these respects, to allow of grouping them in minor divisions, as families or tribes. These frequently took their names from the parts of the country where they lived.

The differences just mentioned were, indeed, no greater than might have been expected from the varieties of climate, modes of life, and degree of improvement which existed among them. Sometimes the Indians were found gathered in large numbers along the banks of rivers or lakes, or in the dense forest, their hunting-grounds; and not unfrequently also, scattered in little collections over the extended face of the country. As they were often engaged in wars with each other, a powerful tribe would occasionally subject to its sway numerous other lesser ones, whom it held as its vassals.

No accurate account can be given of their numbers. Some have estimated the whole amount in North and South America, at the time of the discovery of the continent, even as high as one hundred or one hundred and fifty millions. This estimate is unquestionably much too large. A more probable one would be from fifteen or twenty to twenty-five millions. But they have greatly diminished, and of all the ancient race not more than four or five millions, if so many, now remain. Pestilence, wars, hardships, and sufferings of various kinds have been their lot for nearly four hundred years; and they have melted away at the approach of the white man; so that even a lone Indian is now scarcely found beside the grave of his fathers, where once the war-whoop might have called a thousand or more valiant men to go forth to engage in the deadly fray. With them have perished, in many instances, their ancient traditions; and as they had no other means of handing down the records of their deeds, their history is lost, except here and there a fragment, which has been treasured up by some white man more curious than his fellows, in studying their present or former fates. Monuments, indeed, exist, widely scattered over the countries they once occupied; some rude and inartificial, marked by no skill or taste; and others evidently reared at not a little expense of time and labor, and characterized by all the indications of a people far in advance of their neighbours in the arts and in civilization.

By whom were these reared, when, and for what cause? How long have they been thus reposing in their undisturbed quiet, and crumbling in silent ruin? are questions that force themselves on the mind of the reflective traveller, as he stands beside or amid their strange forms, and pores over what seem the sepulchres of buried ages. But the tongue of history is mute, and they who could have answered his inquiries have long since passed away.

To give, therefore, a historical account of the American Indians is a task beset with not a few difficulties. The sources of information must be almost wholly derived from their conquerors and foes; and though the incidents related may be in the main correct, and the causes that lie on the surface be easily known, yet the more hidden ones, the secret springs of action, are beyond our reach. We have not the Indian himself recording for us the motives that have prompted his stern spirit, carefully veiling his designs from all around, nourishing the dark purpose, and maturing his plans. We are not admitted to the council of the warriors or wise men, and allowed to listen to their relation of the wrongs, real or fancied, they have suffered, or to see how one after another of the chiefs or counsellors utters his opinions, and the deep plot is laid which is to issue in wreaking a dire revenge, even to extermination, on the hated intruders.

All these various incentives to action, are nearly or quite beyond our inspection. Yet it is in the contemplation of such only, that Indian history can be truly estimated; for all these particulars throw their lights and shades across and into the portraiture of this most singular people. It could hardly be expected, that they, who suffered from the fearful revenge of the red man, who saw, as it were, the scalping-knife gleaming around the head of a beloved wife, or child, or friend, or who felt the arrow quivering in their own flesh, or who heard the war-whoop ringing terrifically on the domestic quiet of their habitation,—it could hardly, indeed, be expected, that such persons should be as truthful or impartial as if they had been called to record scenes of a more peaceful and grateful kind. Without, therefore, doing the early writers the injustice of supposing that they mean to misrepresent facts,—yet, in glancing over their descriptions of perfidy, plots, murders, cruelties, and revenge, we must remember that the red man had no one of his race to record for him his history, and be candid and just in our judgments, where there may often be not a little to extenuate, if not wholly to excuse from blame.

Let us also bear in mind one remarkable fact, that, in their first intercourse, the reception extended to the Europeans by the Americans was confiding and hospitable, and that this confidence and hospitality were generally repaid with treachery, rapine, and murder. This was the history of events for the first century, till at last the red men, over the whole continent, learned to regard the Europeans as their enemies, the plunderers of their wealth, the spoilers of their villages, the greedy usurpers of their liberty and lands. We are told of tribes of birds, in the interior of Africa, which at first permitted travellers to approach them, not having yet learned the lesson of fear; but after the fowler had scattered death among them, they discovered that man was a being to be dreaded, and fled at his approach. The natives of America had a similar lesson to learn; and though they did not always fly from the approach of their European enemy, it was not because they expected mercy at his hands.

ORIGIN OF THE ABORIGINES.

The origin of the aborigines of America is involved in mystery. Many have been the speculations indulged and the volumes written by learned and able men to establish, each one, his favorite theory. Conjecture, by a train of ingenious reasonings and comparisons, has grown into probability, and finally almost settled down into certainty. For a time, as in the case of the celebrated “Letters of Junius,” the question has seemed decided; so plausible have appeared the proofs, that it would have been deemed almost like incredulity to gainsay them. But another supposition, more likely, has been started, and has supplanted the former; each, in its turn, has passed away, and we are perhaps no nearer the truth than before. We will notice a few of the most prominent of these opinions.

1. The Indians have been supposed, by certain writers, to be of Jewish origin; either descended from a portion of the ten tribes, or from the Jews of a later date. This view has been maintained by Boudinot and many others; and Catlin, in his “Letters,” has recently advocated it, especially with respect to the Indians west of the Mississippi. In proof of this opinion, reference is made to similarities, more or less striking, in many of their customs, rites, and ceremonies, sacrifices, and traditions. Thus, he has found many of their modes of worship exceedingly like those of the Mosaic institutions. He mentions a variety of particulars respecting separation, purification, feasts, and fastings, which seem to him very decisive. “These,” he says, “carry in my mind conclusive proof, that these people are tinctured with Jewish blood.” Efforts have also been made, but with little success, to detect a resemblance of words in their language to the Hebrew, and some very able writers have adopted the opinion, that this fact is established. That there may be such resemblances as are supposed is very probable, yet they are perhaps accidental, or such only as are to be found among all languages. Besides, allowance must be made for the state of the observer’s mind, and his desire to find analogies, as also for his ignorance of the Indian language in its roots, and his liability to confound their traditions with his own fancies. Many of these similarities, moreover, belong rather to the general characteristics of the Patriarchal age, than to the peculiarities of the Jewish economy. Even admitting the analogies in manners and customs mentioned by Catlin and others, they are not so striking as are those of the Greeks, as depicted by Homer, to those of the Jews, as portrayed in the Bible. There are striking resemblances between the ideas and practices of our American Indians, and those of many Eastern nations, which show them to be of Asiatic origin, but yet they do not identify them more with the Jews than with the Tartars, or Egyptians, or even the Persians.

2. Some have supposed that the ancient Phœnicians, or the Carthaginians, in their navigation of the ocean, penetrated to this Western Continent, and founded colonies. As this is mere conjecture, and is sustained by no proof in history, though here also fancied resemblances have been detected in language and some minor things, it may be dismissed as unworthy of serious consideration.

3. Others again have imagined that the Eastern and Western Continents were once united by land occupying the space which is now filled by the Atlantic Ocean; and that previous to the great disruption an emigration took place. With respect to this view, it is embarrassed by greater difficulties than the former. There is not the remotest trace of such an event recorded in history. It is only, therefore, entitled to be considered as a possible mode by which the Western Continent might have been peopled.

4. The pretensions of the Welsh have been put forth with not a little zeal, and have been considered by some as having more plausibility. They assert, that, about the year 1170, on the death of Owen Gwyneth, a strife for the succession arose among his sons; that one of them, disgusted with the quarrel, embarked in ten ships with a number of people, and sailed westward till he discovered an unknown land; that, leaving part of his people as a colony, he returned to Wales, and after a time again sailed with new recruits, and was never heard of afterwards. Southey has built on this tradition his beautiful poem of “Madoc,” the name of the fancied chieftain who was at the head of the enterprise. The writer, by whom the story was first published, is said, however, to have lived at least 400 years after the events, and discredit is thus thrown over the whole. Mr. Catlin, in the appendix to his second volume, forgetful, apparently, that he had already attributed certain rites and ceremonies of the same people to Jewish origin, seems to suppose that the Mandans are undoubted descendants of Madoc and his Welshmen, who, he thinks, entered the Gulf of Mexico, and sailed up the Mississippi even to the Ohio River, whence they afterwards emigrated to the Far West. He furnishes some words of the Mandan language, which he compares with the Welsh, and which must be allowed to have considerable resemblance to each other, for the same ideas. Still, the theory must be regarded as wholly fanciful.

5. A supposition more plausible than any other is, that America was peopled from the northeastern part of Asia. This seems to correspond with the general view of the Indians themselves, who represent their ancestors as having been formerly residents in Northwestern America. It corresponds also with history in another respect. By successive emigrations, Asia furnished Europe and Africa with their population, and why not America? If it could supply other quarters of the globe with millions, and these of various physical and moral characteristics, why not also supply America with its first inhabitants? The identity of the aborigines with the nations of Northeastern Asia cannot, indeed, be fully established; but, while many causes may have contributed to destroy this resemblance, enough is shown, with other facts, to make this theory preponderate over all others.

If this supposition be true, it is not to be imagined that the emigration to this continent all took place at once. There were doubtless successive arrivals of persons from various parts of Asia; and thus the Indian traditions, which refer to the Northwest as the country of their ancestors, and to periods and intervals separating them, in which people of various character made their appearance, one after another, and left some traces of their residence, may be accounted for.

North American Indians in Council.

CLASSIFICATION OF THE INDIANS.

In respect to the general resemblance of the Indians, an able writer of a recent date, treating of this question, says,—“The testimony of all travellers goes to prove that the native Americans are possessed of certain physical characteristics which serve to identify them in places the most remote, while they assimilate not less in their moral character. There are also, in their multitudinous languages, some traces of a common origin; and it may be assumed as a fact, that no other race of men maintains so striking an analogy through all its subdivisions, and amidst all its varieties of physical circumstances,—while, at the same time, it is distinguished from all the other races by external peculiarities of form, but still more by the internal qualities of mind and intellect.”

M. Bory de St. Vincent attempted to show that the American race includes four species besides the Esquimaux; but he appears to have failed in establishing his theory.

Dr. Morton has paid great attention to the subject. He conducted his investigations by comparisons of the skulls of a vast number of different tribes, the results of which he has given to the public in his “Crania Americana.” He considers the most natural division to be into the Toltecan and American; the former being half-civilized, and including the Peruvians and Mexicans; the latter embracing all the barbarous nations except the Esquimaux, whom he regards as of Mongolian origin.

He divides each of these into subordinate groups, those of the American class being called the Appalachian, Brazilian, Patagonian, and Fuegian.

The Appalachian includes all those of North America except the Mexicans, together with those of South America north of the Amazon and east of the Andes. They are described thus. “The head is rounded, the nose large, salient, and aquiline, the eyes dark-brown, with little or no obliquity of position, the mouth large and straight, the teeth nearly vertical, and the whole face triangular. The neck is long, the chest broad, but rarely deep, the body and limbs muscular, seldom disposed to fatness.” In character, they “are warlike cruel, and unforgiving,” averse to the restraints of civilized life, and “have made but little progress in mental culture or the mechanic arts.”

Of the Brazilian it is said, that they are spread over a great part of South America east of the Andes, including the whole of Brazil and Paraguay between the River Amazon and 35 degrees of south latitude. In physical characteristics, they resemble the Appalachian; their nose is larger and more expanded, their mouth and lips also large. Their eyes are small, more or less oblique, and farther apart, the neck short and thick, body and limbs stout and full, to clumsiness. In mental character, it is said, that none of the American race are less susceptible of civilization, and what they are taught by compulsion seldom exceeds the humblest elements of knowledge.

The Patagonian branch comprises the nations south of the River La Plata to the Straits of Magellan, and also the mountain tribes of Chili. They are chiefly distinguished by their tall stature, handsome forms, and unconquerable courage.

The Fuegians, who call themselves Yacannacunnee, rove over the sterile wastes of Terra del Fuego. Their numbers are computed by Forster to be only about 2,000. Their physical aspect is most repulsive. They are of low stature, with large heads, broad faces, and small eyes, full chests, clumsy bodies, large knees, and ill-shaped legs. Their hair is lank, black, and coarse, and their complexion a decided brown, like that of the more northern tribes. They have a vacant expression of face, and are most stupid and slow in their mental operations, destitute of curiosity, and caring for little that does not minister to their present wants.

Long, black hair, indeed, is common to all the American tribes. Their real color is not copper, but brown, most resembling cinnamon. Dr. Morton and Dr. McCulloh agree, that no epithet is so proper as the brown race.

The diversity of complexion cannot be accounted for mainly by climate; for many near the equator are not darker than those in the mountainous parts of temperate regions. The Puelches, and other Magellanic tribes beyond 35 degrees south latitude, are darker than others many degrees nearer the equator; the Botecudos, but a little distance from the tropics, are nearly white; the Guayacas, under the line, are fair, while the Charruas, at 50 degrees south latitude, are almost black, and the Californians, at 25 degrees north latitude, are almost white.

The color seems also not to depend on local situation, and in the same individual the covered parts are not fairer than those exposed to the heat and moisture. Where the differences are slight, the cause may possibly be found in partial emigrations from other countries. The characteristic brown tint is said to be occasioned by a pigment beneath the lower skin, peculiar to them with the African family, but wanting in the European.

Another division of the American race has been suggested, into three great classes, according to the pursuits on which they depend for subsistence, namely, hunting, fishing, and agriculture. The American race are further said to be intellectually inferior to the Caucasian and Mongolian races. They seem incapable of a continued process of reasoning on abstract subjects. They seize easily and eagerly on simple truths, but reject those which require analysis or investigation. Their inventive faculties are small, and they generally have but little taste for the arts and sciences. A most remarkable defect is the difficulty they have of comprehending the relations of numbers. Mr. Schoolcraft assured Dr. Morton, that this was the cause of most of the misunderstandings in respect to treaties between the English and the native tribes.

The Toltecan family are considered as embracing all the semi-civilized nations of Mexico, Peru, and Bogota, reaching from the Rio Gila, in 33 degrees of north latitude, along the western shore of the continent, to the frontiers of Chili, and on the eastern coast along the Gulf of Mexico. In South America, however, they chiefly occupied a narrow strip of land between the Andes and the Pacific Ocean. The Bogotese in New Grenada were, in civilization, between the Peruvians and the Mexicans. The Toltecans were not the sole possessors of these regions, but the dominant race, while the American race composed the mass of the people.

The great difference between the Toltecan and the American races consisted in the intellectual faculties, as shown in their arts and sciences, architectural remains, pyramids, temples, grottos, bass-reliefs, and arabesques; their roads, aqueducts, fortifications, and mining operations.

With respect to the American languages, there is said to exist a remarkable similarity among them. From Cape Horn to the Arctic Sea, all the nations have languages which possess a distinctive character, but still apparently differing from all those of the Old World. This resemblance, too, is said not to be of an indefinite kind. It generally consists in the peculiar modes of conjugating the verbs by inserting syllables. Vater, a distinguished German writer on this subject, says, that this wonderful uniformity favors, in a singular manner, the supposition of a primitive people which formed the common stock of the American indigenous nations. According to M. Balbi, there are more than 438 different languages, embracing upwards of 2,000 dialects. He estimates the Indians of the brown race at 10,000,000, and the races produced by the intermixture of the pure races at 7,000,000.

We have thus given a general classification of the great American family, and the main points respecting the question of their origin. We must confess our inability wholly to lift the veil of obscurity in which their early history is involved, or answer, conclusively, the inquiry, whence they came, or when America was first peopled. We can only offer what we have already stated as the most plausible theory, that, ages ago, a great nation of Asia passed, at different times, by way of Behring’s Straits, into the American Continent, and in the course of centuries spread themselves over its surface. Here we suppose them to have become divided by the slow influences of climate, and other circumstances, into the several varieties which they display.

THE ABORIGINES OF THE WEST INDIES.

The authentic history of this remarkable and peculiar race of men opens with the morning of the 12th of October, 1492. Columbus, the discoverer of the New World, at that memorable date, landed upon the American soil, and, as if his first action was to be a type of the consequences about to follow in respect to the wondering natives who beheld him and his companions, he landed with a drawn sword in his hand. If the philanthropic spirit of the great discoverer could have shaped events, the fate of the aborigines of the new continent had been widely different; but who, that reads their history, can fail to see that the Christians of the Eastern Hemisphere have brought but the sword to the American race?

Nor were the first actions of the natives, upon beholding this advent of beings that seemed to them of heavenly birth, hardly less significant of their character and doom. They were at first filled with wonder and awe, and then, in conformity with their confiding nature, came forward and timidly welcomed the strangers. The following is Irving’s picturesque description of the scene.

“The natives of the island, when at the dawn of day they had beheld the ships hovering on the coast, had supposed them some monsters, which had issued from the deep during the night. When they beheld the boats approach the shore, and a number of strange beings, clad in glittering steel, or raiment of various colors, landing upon the beach, they fled in affright to the woods.

“Finding, however, that there was no attempt to pursue or molest them, they gradually recovered from their terror, and approached the Spaniards with great awe, frequently prostrating themselves, and making signs of adoration. During the ceremony of taking possession, they remained gazing, in timid admiration, at the complexion, the beards, the shining armor, and splendid dress of the Spaniards.

“The admiral particularly attracted their attention, from his commanding height, his air of authority, his scarlet dress, and the deference paid him by his companions; all which pointed him out to be the commander.

“When they had still further recovered from their fears, they approached the Spaniards, touched their beards, and examined their hands and faces, admiring their whiteness. Columbus was pleased with their simplicity, their gentleness, and the confidence they reposed in beings who must have appeared so strange and formidable, and he submitted to their scrutiny with perfect acquiescence.

“The wondering savages were won by this benignity. They now supposed that the ships had sailed out of the crystal firmament which bounded their horizon, or that they had descended from above on their ample wings, and that these marvellous beings were inhabitants of the skies.

“The natives of the island were no less objects of curiosity to the Spaniards, differing, as they did, from any race of men they had seen. They were entirely naked, and painted with a variety of colors and devices, so as to give them a wild and fantastic appearance. Their natural complexion was of a tawny or copper hue, and they had no beards. Their hair was straight and coarse; their features, though disfigured by paint, were agreeable; they had lofty foreheads, and remarkably fine eyes.

“They were of moderate stature, and well shaped. They appeared to be a simple and artless people, and of gentle and friendly dispositions. Their only arms were lances, hardened at the end by fire, or pointed with a flint or the bone of a fish. There was no iron among them, nor did they know its properties; for, when a drawn sword was presented to them, they unguardedly took it by the edge.

“Columbus distributed among them colored caps, glass beads, hawk’s bells, and other trifles, which they received as inestimable gifts, and, decorating themselves with them, were wonderfully delighted with their finery. In return, they brought cakes of a kind of bread called cassava, made from the yuca root, which constituted a principal part of their food.”

Thus kindly began the intercourse between the Old World and the New; but the demon of avarice soon disturbed their peace. The Spaniards perceived small ornaments of gold in the noses of some of the natives. On being asked where this precious metal was procured, they answered by signs, pointing to the south, and Columbus understood them to say, that a king resided in that quarter, of such wealth that he was served in great vessels of gold.

Columbus took seven of the Indians with him, to serve as interpreters and guides, and set sail to find the country of gold. He cruised among the beautiful islands, and stopped at three of them. These were green, fertile, and abounding with species and odoriferous trees. The inhabitants everywhere appeared the same,—simple, harmless, and happy, and totally unacquainted with civilized man.

Columbus was disappointed in his hopes of finding gold or spices in these islands; but the natives continued to point to the south, and then spoke of an island in that direction called Cuba, which the Spaniards understood them to say abounded in gold, pearls, and spices. People often believe what they earnestly wish; and Columbus sailed in search of Cuba, fully confident that he should find the land of riches. He arrived in sight of it on the 28th of October, 1492.

Here he found a most lovely country, and the houses of the Indians, neatly built of the branches of palm-trees, in the shape of pavilions, were scattered under the trees, like tents in a camp. But hearing of a province in the centre of the island, where, as he understood the Indians to say, a great prince ruled, Columbus determined to send a present to him, and one of his letters of recommendation from the king and queen of Spain.

For this purpose he chose two Spaniards, one of whom was a converted Jew, and knew Hebrew, Chaldaic, and Arabic. Columbus thought the prince must understand one or the other of these languages. Two Indians were sent with them as guides. They were furnished with strings of beads, and various trinkets, for their travelling expenses; and they were enjoined to ascertain the situation of the provinces and rivers of Asia,—for Columbus thought the West Indies were a part of the Eastern Continent.

The Jew found his Hebrew, Chaldaic, and Arabic of no avail, and the Indian interpreter was obliged to be the orator. He made a regular speech after the Indian manner, extolling the power, wealth, and generosity of the white men. When he had finished, the Indians crowded round the Spaniards, touched and examined their skin and raiment, and kissed their hands and feet in token of adoration. But they had no gold to give them.

It was here that tobacco was first discovered. When the envoys were on their return, they saw several of the natives going about with firebrands in their hands, and certain dried herbs which they rolled up in a leaf, and, lighting one end, put the other into their mouths, and continued inhaling and puffing out the smoke. A roll of this kind they called tobacco. The Spaniards were struck with astonishment at this smoking.

When Columbus became convinced that there was no gold of consequence to be found in Cuba, he sailed in quest of some richer lands, and soon discovered the island of Hispaniola, or Hayti. It was a beautiful island. The high mountains swept down into luxuriant plains and green savannas, while the appearance of cultivated fields, with the numerous fires at night, and the volumes of smoke which rose in various parts by day, all showed it to be populous. Columbus immediately stood in towards the land, to the great consternation of his Indian guides, who assured him by signs that the inhabitants had but one eye, and were fierce and cruel cannibals.

Columbus entered a harbour at the western end of the island of Hayti, on the evening of the 6th of December. He gave to the harbour the name of St. Nicholas, which it bears to this day. The inhabitants were frightened at the approach of the ships, and they all fled to the mountains. It was some time before any of the natives could be found. At last three sailors succeeded in overtaking a young and beautiful female, whom they carried to the ships.

She was treated with the greatest kindness, and dismissed finely clothed, and loaded with presents of beads, hawk’s bells, and other pretty bawbles. Columbus hoped by this conduct to conciliate the Indians; and he succeeded. The next day, when the Spaniards landed, the natives permitted them to enter their houses, and set before them bread, fish, roots, and fruits of various kinds, in the most kind and hospitable manner.

Columbus sailed along the coast, continuing his intercourse with the natives, some of whom had ornaments of gold, which they readily exchanged for the merest trifle of European manufacture. These poor, simple people little thought that to obtain gold these Christians would destroy all the Indians in the islands. No,—they believed the Spaniards were more than mortal, and that the country from which they came must exist somewhere in the skies.

The generous and kind feelings of the natives were shown to great advantage when Columbus was distressed by the loss of his ship. He was sailing to visit a grand cacique or chieftain named Guacanagari, who resided on the coast to the eastward, when his ship ran aground, and, the breakers beating against her, she was entirely wrecked. He immediately sent messengers to inform Guacanagari of this misfortune.

When the cacique heard of the distress of his guest, he was so much afflicted as to shed tears; and never in any civilized country were the vaunted rites of hospitality more scrupulously observed than by this uncultivated savage. He assembled his people and sent off all his canoes to the assistance of Columbus, assuring him, at the same time, that every thing he possessed was at his service. The effects were landed from the wreck and deposited near the dwelling of the cacique, and a guard set over them, until houses could be prepared, in which they could be stored.

There seemed, however, no disposition among the natives to take advantage of the misfortune of the strangers, or to plunder the treasures thus cast upon their shores, though they must have been inestimable in their eyes. On the contrary, they manifested as deep a concern at the disaster of the Spaniards as if it had happened to themselves, and their only study was, how they could administer relief and consolation.

Columbus was greatly affected by this unexpected goodness. “These people,” said he in his journal, “love their neighbours as themselves; their discourse is ever sweet and gentle, and accompanied by a smile. There is not in the world a better nation or a better land.”

When the cacique first met Columbus, the latter appeared dejected; and the good Indian, much moved, again offered Columbus every thing he possessed that could be of service to him. He invited him on shore, where a banquet was prepared for his entertainment, consisting of various kinds of fish and fruit. After the feast, Columbus was conducted to the beautiful groves which surrounded the dwelling of the cacique, where upwards of a thousand of the natives were assembled, all perfectly naked, who performed several of their national games and dances.

Thus did this generous Indian try, by every means in his power, to cheer the melancholy of his guest, showing a warmth of sympathy, a delicacy of attention, and an innate dignity and refinement, which could not have been expected from one in his savage state. He was treated with great deference by his subjects, and conducted himself towards them with a gracious and prince-like majesty.

Three houses were given to the shipwrecked crew for their residence. Here, living on shore, and mingling freely with the natives, they became fascinated by their easy and idle mode of life. They were governed by the caciques with an absolute, but patriarchal and easy rule, and existed in that state of primitive and savage simplicity which some philosophers have fondly pictured as the most enviable on earth.

The following is the opinion of old Peter Martyr: “It is certain that the land among these people (the Indians) is as common as the sun and water, and that ‘mine and thine,’ the seeds of all mischief, have no place with them. They are content with so little, that, in so large a country, they have rather superfluity than scarceness; so that they seem to live in a golden world, without toil, in open gardens, neither intrenched nor shut up by walls or hedges. They deal truly with one another, without laws, or books, or judges.”

In fact, these Indians seemed to be perfectly contented; their few fields, cultivated almost without labor, furnished roots and vegetables; their groves were laden with delicious fruit; and the coast and rivers abounded with fish. Softened by the indulgence of nature, a great part of the day was passed by them in indolent repose. In the evening they danced in their fragrant groves to their national songs, or the rude sound of their silver drums.

Such was the character of the natives of many of the West India islands, when first discovered. Simple and ignorant they were, and indolent also, but then they were kind-hearted, generous, and happy. And their sense of justice, and of the obligations of man to do right, are beautifully set forth in the following story.

It was a custom with Columbus to erect crosses in all remarkable places, to denote the discovery of the country, and its subjugation to the Catholic faith. He once performed this ceremony on the banks of a river in Cuba. It was on a Sunday morning. The cacique attended, and also a favorite of his, a venerable Indian, fourscore years of age.

While mass was performed in a stately grove, the natives looked on with awe and reverence. When it was ended, the old man made a speech to Columbus in the Indian manner. “I am told,” said he, “that thou hast lately come to these lands with a mighty force, and hast subdued many countries, spreading great fear among the people; but be not vainglorious.

“According to our belief, the souls of men have two journeys to perform, after they have departed from the body: one to a place dismal, foul, and covered with darkness, prepared for such men as have been unjust and cruel to their fellow-men; the other full of delight, for such as have promoted peace on earth. If, then, thou art mortal, and dost expect to die, beware that thou hurt no man wrongfully, neither do harm to those who have done no harm to thee.”

When this speech was explained to Columbus by his interpreter, he was greatly moved, and rejoiced to hear this doctrine of the future state of the soul, having supposed that no belief of the kind existed among the inhabitants of these countries. He assured the old man that he had been sent by his sovereigns, to teach them the true religion, to protect them from harm, and to subdue their enemies, the Caribs.

Alas for the simple Indians who believed such professions! Columbus, no doubt, was sincere; but the adventurers who accompanied him, and the tyrants who followed him, cared only for riches for themselves. They ground down the poor, harmless red men beneath a harsh system of labor, obliging them to furnish, month by month, so much gold. This gold was found in fine grains, and it was a severe task to search the mountain-pebbles and the sands of the plains for the shining dust.

Then the islands, after they were seized upon by the Christians, were parcelled out among the leaders, and the Indians were compelled to be their slaves. No wonder deep despair fell upon the natives. Weak and indolent by nature, and brought up in the untasked idleness of their soft climate and their fruitful groves, death itself seemed preferable to a life of toil and anxiety.

The pleasant life of the island was at an end: the dream in the shade by day; the slumber during the noontide heat by the fountain, or under the spreading palm; and the song, and the dance, and the game in the mellow evening, when summoned to their simple amusements by the rude Indian drum. They spoke of the times that were past, before the white men had introduced sorrow, and slavery, and weary labor among them; and their songs were mournful, and their dances slow.

They had flattered themselves, for a time, that the visit of the strangers would be but temporary, and that, spreading their ample sails, their ships would waft them back to their home in the sky. In their simplicity, they had frequently inquired of the Spaniards when they intended to return to Turey, or the heavens. But when all such hope was at an end, they became desperate, and resorted to a forlorn and terrible alternative.

They knew the Spaniards depended chiefly on the supplies raised in the islands for a subsistence; and these poor Indians endeavoured to produce a famine. For this purpose they destroyed their fields of maize, stripped the trees of their fruit, pulled up the yuca and other roots, and then fled to the mountains.

The Spaniards were reduced to much distress, but were partially relieved by supplies from Spain. To revenge themselves on the Indians, they pursued them to their mountain retreats, hunted them from one dreary fastness to another, like wild beasts, until thousands perished in dens and caverns, of famine and sickness, and the survivors, yielding themselves up in despair, submitted to the yoke of slavery. But they did not long bear the burden of life under their civilized masters. In 1504, only twelve years after the discovery of Hayti, when Columbus visited it, (under the administration of Ovando,) he thus wrote to his sovereigns: “Since I left the island, six parts out of seven of the natives are dead, all through ill-treatment and inhumanity; some by the sword, others by blows and cruel usage, or by hunger.”

No wonder these oppressed Indians considered the Christians the incarnation of all evil. Their feelings were often expressed in a manner that must have touched the heart of a real Christian, if there was such a one among their oppressors.

When Velasquez set out to conquer Cuba, he had only three hundred men; and these were thought sufficient to subdue an island above seven hundred miles in length, and filled with inhabitants. From this circumstance we may understand how naturally mild and unwarlike was the character of the Indians. Indeed, they offered no opposition to the Spaniards, except in one district. Hatuey, a cacique who had fled from Hayti, had taken possession of the eastern extremity of Cuba. He stood upon the defensive, and endeavoured to drive the Spaniards back to their ships. He was soon defeated and taken prisoner.

Velasquez considered him as a slave who had taken arms against his master, and condemned him to the flames. When Hatuey was tied to the stake, a friar came forward, and told him that if he would embrace the Christian faith, he should be immediately, on his death, admitted into heaven.

“Are there any Spaniards,” says Hatuey, after some pause, “in that region of bliss you describe?”

“Yes,” replied the monk, “but only such as are worthy and good.”

“The best of them,” returned the indignant Indian, “have neither worth nor goodness; I will not go to a place where I may meet with one of that cruel race.”

THE CARIBS.

Columbus discovered the islands of the Caribs or Charibs, now called the Caribbees, during his second voyage to America, in 1493. The first island he saw he named Dominica, because he discovered it on Sunday. As the ships gently moved onward, other islands rose to sight, one after another, covered with forests, and enlivened with flocks of parrots and other tropical birds, while the whole air was sweetened by the fragrance of the breezes which passed over them.

This beautiful cluster of islands is called the Antilles. They extend from the eastern end of Porto Rico to the coast of Paria on the southern continent, forming a kind of barrier between the main ocean and the Caribbean Sea. Here was the country of the Caribs.

Columbus had heard of the Caribs during his stay at Hayti and Cuba, at the time of his first voyage. The timid and indolent race of Indians in those pleasant islands were afraid of the Caribs, and had repeatedly besought Columbus to assist them in overcoming these their ferocious enemies. The Caribs were represented as terrible warriors, and cruel cannibals, who roasted and ate their captives. This the gentle Haytians thought, truly enough, was a good pretext for warning the Christians against such foes. Columbus did not at first imagine that the beautiful paradise he saw, as he sailed onward among these green and spicy islands, could be the residence of cruel men; but on landing at Guadaloupe, he soon became convinced he was truly in a Golgotha, a place of skulls. He there saw human limbs hanging in the houses, as if curing for provisions, and some even roasting at the fire for food. He knew then that he was in the country of the Caribs.

On touching at the island of Montserrat, Columbus was informed that the Caribs had eaten up all the inhabitants. If that had been true, it seems strange how he obtained his information.

It is probable many of these stories were exaggerations. The Caribs were a warlike people, in many respects essentially differing in character from the natives of the other West India islands. They were enterprising as well as ferocious, and frequently made roving expeditions in their canoes to the distance of one hundred and fifty leagues, invading the islands, ravaging the villages, making slaves of the youngest and handsomest females, and carrying off the men to be killed and eaten.

These things were bad enough, and it is not strange report should make them more terrible than the reality. The Caribs also gave the Spaniards more trouble than did the effeminate natives of the other islands. They fought their invaders desperately. In some cases the women showed as much bravery as the men. At Santa Cruz the females plied their bows with such vigor, that one of them sent an arrow through a Spanish buckler, and wounded the soldier who bore it.

There have been many speculations respecting the origin of the Caribs. That they were a different race from the inhabitants of the other islands is generally acknowledged. They also differed from the Indians of Mexico and Peru; though some writers think they were culprits banished either from the continent or the large islands, and thus a difference of situation might have produced a difference of manners. Others think they were descended from some civilized people of Europe or Africa, and imagine that there is no difficulty attending the belief, that a Carthaginian or Phœnician vessel might have been overtaken by a storm, and blown about by the gales, till it entered the current of the trade-winds, when it would have been easily carried to the West Indies.

The Caribs possessed as many of the arts as were necessary to live at ease in that luxurious climate. Some of these have excited the admiration of Europeans.[1] In their subsequent intercourse with the Europeans, they have, in some instances, proved faithless and treacherous. In 1708, the English entered into an agreement with the Caribs in St. Vincent to attack the French colonies in Martinico. The French governor heard of the treaty, and sent Major Coullet, who was a great favorite with the savages, to persuade them to break the treaty. Coullet took with him a number of officers and servants, and a good store of provisions and liquors. He reached St. Vincent, gave a grand entertainment to the principal Caribs, and, after circulating the brandy freely, he got himself painted red, and made them a flaming speech. He urged them to break their connection with the English. How could they refuse a man who gave them brandy, and who was red as themselves? They abandoned their English friends, and burned all the timber the English had cut on the island, and butchered the first Englishmen who arrived. But their crimes were no worse than those of their Christian advisers, who, on both sides, were inciting these savages to war.

But the Caribs are all gone, perished from the earth. Their race is no more, and their name is only a remembrance. The English and the French, chiefly the latter, have destroyed them. There is, however, one pleasant reflection attending their fate. Though destroyed, they were never enslaved. None of their conquerors could compel them to labor. Even those who have attempted to hire Caribs for servants have found it impossible to derive any benefit or profit from them; they would not be commanded or reprimanded.

This independence was called pride, indolence, and stubbornness, by their conquerors. If the Caribs had had historians to record their wrongs, and their resistance to an overwhelming tyranny, they would have set the matter in a very different light. They would have expressed the sentiment which the conduct of their countrymen so steadily exemplified,—that it was better to die free than to live slaves.

So determined was their resistance to all kinds of authority, that it became a proverb among the Europeans, that to show displeasure to a Carib was the same as beating him, and to beat him was the same as to kill him. If they did any thing, it was only what they chose, how they chose, and when they chose; and when they were most wanted, it often happened that they would not do what was required, nor any thing else.

The French missionaries made many attempts to convert the Caribs to Christianity, but without success. It is true that some were apparently converted; they learned the catechism and prayers, and were baptized; but they always returned to their old habits.

A man of family and fortune, named Chateau Dubois, settled in Guadaloupe, and devoted a great part of his life to the conversion of the Caribs, particularly those of Dominica. He constantly entertained a number of them, and taught them himself. He died in the exercise of these pious and charitable offices, without the consolation of having made one single convert.

As we have said, several had been baptized, and, as he hoped, they were well instructed, and apparently well grounded in the Christian religion; but after they returned to their own people, they soon resumed all the Indian customs, and their natural indifference to all religion.

Some years after the death of Dubois, one of these Carib apostates was at Martinico. He spoke French correctly, could read and write, had been baptized, and was then upwards of fifty years old. When reminded of the truths he had been taught, and reproached for his apostasy, he replied, “that if he had been born of Christian parents, or if he had continued to live among the French, he would still have professed Christianity; but that, having returned to his own country and his own people, he could not resolve to live in a manner differing from their way of life, and by so doing expose himself to the hatred and contempt of his relations.” Alas! it is small matter of wonder that the Carib thought the Christian religion was only a profession. Had those who bore that name always been Christians in reality, and treated the poor ignorant savages with the justice, truth, and mercy which the gospel enjoins, what a different tale the settlement of the New World would have furnished!

The Caribs, who spread themselves over the main land contiguous to their islands, were similar in characteristics to those of the West Indies, of whom they are supposed to have been the original stock. They formed an alliance with the English under Sir Walter Raleigh, in one of his romantic expeditions on that coast, in 1595, and for a long time preserved the English colors which were presented to them on that occasion. The Caribs of the continent are said to have been divided into the Maritimos and the Mediterraneos. The former lived in plains, and upon the coast of the Atlantic, and are said to have been the most hostile of any of the Indians who infest the settlements of the missions of the River Orinoco, and have been sometimes called the Galibis. The Mediterraneos inhabited the south side of the source of the River Caroni, and are described as of a more pacific nature, and began to receive the Jesuit missionaries and embrace the Christian faith in 1738.

[1] For an account of these, see “Manners and Customs of the Indians” in “The Cabinet Library.”

EARLY MEXICAN HISTORY.

According to the annals preserved by the Mexicans, the country embraced in the vale of Mexico was formerly called Anahuac. The rest of the territory contained the kingdoms of Mexico, Acolhuacan, Tlacopan, Michuacan, and the republics of Tlaxcallan or Tlascala, Cholollan, and Huexotzinco. The people who settled the country came from the north. The first inhabitants were called Toltecs or Toltecas, who came from a distant country at the northwest in the year 472. They migrated slowly, cultivating and settling as they proceeded, so that it was 104 years before they reached a place fifty miles east of the situation where Mexico was afterwards built; there they remained for twenty years, and built a city called Tollantzinco. Thence they removed forty miles to the westward, and built another city called Tollan or Tula.

When they first commenced their migration, they had a number of chiefs, who, by the time they reached Tollantzinco, were reduced to seven. This form of government was afterwards changed to a monarchy; why, we know not, but probably some one of the chiefs was more valiant or cunning than his associates, and supplanted them. This monarchy began A. D. 607, and lasted 384 years, in which time they are said to have had only eight princes. This fact, however, is accounted for by the custom which prevailed, of keeping up the name of each king for fifty-two years.

They remained prosperous for 400 years, when a famine succeeded, occasioned by a severe drought, which was followed by a pestilence that destroyed many of them. Tradition says, that a demon appeared once at a festival ball, and with giant arms embraced the people, and suffocated them; that he appeared again as a child with a putrid head, and brought the plague; and that, by his persuasion, they abandoned Tula, and scattered themselves among various nations, by whom they were well received.

A hundred years afterwards, succeeded a more barbarous people from Amaquemecan. Who or what they were is not known, as there is no trace of them among the American nations; nor is there any reason given why they left their own country. They are said to have been eight months on their way, led by a son of their monarch, called Xolotl, who sent his son to survey the country, which he took possession of by shooting four arrows to the four winds. He chose for his capital Tenayuca, six miles north of the site of Mexico; in which direction most of the people settled. It is asserted that their numbers amounted to 1,000,000; as ascertained by twelve piles of stones which were thrown up at a review of the people; but this is probably an exaggeration.

This barbarous people formed alliances with the relics of the Toltecan race, and their prince, Nopaltzin, married a descendant of the Toltecan royal family. The effect of these intermarriages on them was a happy one, as they were civilized by the Toltecas, who were much their superiors in a knowledge of the arts. Heretofore they had subsisted only on roots and fruits, and by hunting; sucking the blood of the animals they killed, and taking their skins for clothing; but now they began to dig up and sow the ground, to work metals, and attempt other useful arts. About eighteen years after their arrival, six persons made their appearance as an embassy from a people living near Amaquemecan; a place was assigned them, and in a few years three princes came with a large army of Acolhuans, who received three princesses in marriage. The two nations gradually coalesced in one, and took the name of the new comers; the name Chechemecas being left to the ruder and more barbarous tribes who lived by hunting and on roots. These latter joined the Otomies, a barbarous people who lived farther north, in the mountains.

Xolotl divided his dominions into three states, namely, Azcapozalco, eighteen miles west of Tezcuco, Xaltocan, and Coatlichan, which he conferred, in fief, on his three sons-in-law. As was natural, various civil wars afterwards occurred during the reigns of the sovereigns who succeeded Xolotl. Nopaltzin reigned thirty-two years, and is said to have died at the advanced age of ninety-two. After him came Tlotzin, who reigned thirty-six years, and was a good prince. He was succeeded by Quinatzin, a luxurious tyrant, who, on the removal of his court from Tenayuca to Tezcuco, caused himself to be borne thither in a litter by four lords, while a fifth held an umbrella over him to keep off the sun; he is said to have reigned sixty years. In his reign, there were many rebellions, and on his death he was succeeded by a prince named Techotlala.

In the year 1160, the Mexicans, Aztecas, or Aztecs made their appearance. They are said to have come from the region north of the Gulf of California, and were induced to migrate from the country where they lived by the persuasion of Huitziton, a man of great influence among them. He is said to have observed a little singing-bird, whose notes sounded like Tihui, which in their language meant, Let us go. He led another person, also a man of influence, to observe this, and they persuaded the people to obey the suggestion, as they said, of the secret divinity. This was no difficult matter in a partially civilized and superstitious community. They proceeded, as their tradition relates, to the River Gila, where they stopped for a time, and where, it is affirmed, remains have been found at a somewhat recent date.

They then removed to a place about 250 miles from Chihuahua, toward the north-northwest, now called in Spanish Casas Grandes, on account of a large building found there, on the plan of those in New Mexico, having three floors with a terrace above them, the door for entrance opening on the second floor, to which the ascent was by a ladder. Other remains, also, of a fortress, and various utensils, have been found there. From this spot they proceeded southward, crossed the mountains, and stopped at Culiacan, a place on the Gulf of California in Lat. 24° N. Here they made a wooden image, called Huitzilopochtli, which they carried on a chair of reeds, and appointed priests for its service. When they left their country, on their migration, they consisted of seven different tribes; but here the Mexicans were left with their god by the others, called the Xochimilcas, Tepanecas, Chalchese, Colhuas, Tlahuicas, and Tlascalans, who proceeded onwards. The reason of this separation is not mentioned, except that it was at the command of the god, from which it may be conjectured that some quarrel had arisen with respect to his worship.

On their way to Tula, the Mexicans became divided into two factions; yet they kept together, for the sake of the god, while they built altars, and left their sick in different places. They remained in Tula nine years, and spent eleven more in the countries adjoining. In 1216, they reached Tzompanco, a city in the vale of Mexico, and were hospitably received by the lord of the district; his son, named Ilhuitcatl, married among them. From him have descended all the Mexican monarchs. The people continued to migrate along the Lake Tezcuco during the reign of Xolotl, but in the reign of Nopaltzin they were persecuted, and obliged, in 1245, to go to Chapoltepec, a mountain two miles from Mexico. They then took refuge in the small islands Acocolco, at the southern extremity of the Lake of Mexico. Here they lived miserably for 52 years, till the year 1314, when they were reduced to slavery by a petty king of Colhuacan, by whom they were treacherously entrapped and cruelly oppressed.

Some years after, on the occasion of a war between the Colhuas and the Xochimilcas, in which the latter were victorious, the Colhuas were obliged to release their slaves, who fought with great bravery, cutting off the ears of the enemies they had killed, which they produced on being reproached with cowardice. The effect of this was to excite such a detestation of them, that they were desired to leave the country. They did so, and went north till they came to a place called Acatzitzintlan, and afterwards Mexicaltzinco; but not liking this, they went on to Iztacalco, still nearer to the site of Mexico. Here they remained two years, and then went to a place on the lake, where they found the nopal growing on a stone, and over it the foot of an eagle; this was the place marked out by the oracle. Here they ended their wanderings, and erected an altar to their god; one of them went for a victim, and found a Colhuan, whom they killed, and offered as a sacrifice to the idol. Here, too, they built their rush huts, and formed a city, which was called Tenochtitlan, and afterwards Mexico, or the place of Mexitli, their god of war.

This was in 1325; the city was situated on a small island in the middle of a great lake, without ground sufficient for cultivation, or even to build upon. It was necessary, therefore, to enlarge it; and for this purpose they drove down piles and palisades, and with stones, turf, &c., thus united the other small islands to the larger one. To procure stone and wood, they exchanged fish and water-fowl with some other nations, and made, with incredible industry, floating gardens, on which they raised vegetable products. They here remained thirteen years at peace, but afterwards quarrels ensued, and the factions separated; one of them went to a small island a little northward, named Xaltilolco, afterwards Tlatelolco.

These divided their city into four parts, each quarter having its tutelar deity. In the midst of the city, Mexitli was worshipped with horrible rites, and the sacrifice of prisoners. Under pretence of consecrating her to be the mother of their god, they sought the presence of a Colhuan princess at their rites; and when the request was granted, they put her to death, flayed her body, and dressed one of their brave men in her skin. The father was invited to be present and officiate as the priest. All was darkness, till, on lighting the copal in his censer to begin the rites of worship, he saw the horrible spectacle of his immolated daughter.

In 1352, the Mexicans changed their aristocracy of twenty lords for a monarchy, and elected as their king Acamapitzin, who married a daughter of the lord of Coatlichan. The Tlatelolcos also chose a king, who was a son of the king of the Tepanecas. The king of the Tepanecas was persuaded by them to double the tributes of the Mexicans, and oppress them. They were commanded to transport to his capital, Azcapozalco, a great floating garden, producing every kind of vegetable known in Anahuac; when this was done, the next year, another garden was required, with a duck and a swan in it sitting on their eggs, ready to hatch on arriving at Azcapozalco; and then again, a garden was exacted from them having a live stag, which they were obliged to hunt in the mountains, among their enemies.

Acamapitzin, the king of Mexico, reigned thirty-seven years, and died in 1389, and, after an interregnum of four months, his son Huitzilihuitl succeeded him. He requested, for a wife, one of the daughters of the king of Azcapozalco, on which occasion the ambassadors are said to have made the following speech: “We beseech you, with the most profound respect, to take compassion on our master and your servant, Huitzilihuitl. He is without a wife, and we are without a queen. Vouchsafe, Sire, to part with one of your jewels or most precious feathers. Give us one of your daughters, who may come and reign over us in a country which belongs to you.” This request was granted.

It will be recollected that the Acolhuans were under the government of Techotlala, son of Quinatzin. After a thirty years’ peace, a revolt was begun by a prince called Tzompan, a descendant of one of the three original Acolhuan princes. The rebel was defeated and put to death. The Mexicans, in this war, were the allies of Techotlala, and showed great valor.

The son of the king of the Tepanecas, Maxtlaton, fearing that his sister’s son by the Mexican king might obtain the Tepanecan crown, began to oppress the Mexicans, and sent assassins to murder his nephew. The Mexicans, however, were too weak to resent this baseness.

The rival Mexicans and Tlatelolcos advanced together in wealth and power. Techotlala, the Acolhuan king, was succeeded by Ixtlilxochitl in 1406. The king of Azcapozalco, his vassal, sought to stir up rebellion, but he was defeated, and compelled to sue for peace. The same year in which this occurred, the Mexican king died, and his son, Chimalpopoca, was chosen his successor.

The king of the Acolhuans, mentioned above, was driven from his kingdom, and both he and one of his grandsons were cut off by the treachery of the Tepanecas. The rebels, led on by their king, Tezozomoc, poured in, and conquered Acolhuacan. Tezozomoc then gave Tezcuco to the Mexican king, Chimalpopoca, and other portions to the king of Tlatelolco, and proclaimed his own capital, Azcapozalco, the metropolis of all the kingdoms of Acolhuacan. He was a great tyrant, and was tormented with dreams, that the son of the murdered king of the Acolhuans, Nezahualcoyotl, transformed into an eagle, had eaten out his heart, or, in the shape of a lion, had sucked his blood. He enjoined it, therefore, on his sons, to put the prince, of whom he had dreamed, to death. He survived his dreams but a year, and died in 1422.

He was succeeded by his son Tajatzin, but the throne was at once usurped by another son, Maxtlaton, and Tajatzin took refuge with Chimalpopoca, who advised him to invite his brother to a feast, and murder him. This being overheard and told to Maxtlaton, he pretended not to believe it, but took the same means to get rid of Tajatzin. The king of Mexico declined the invitation, and escaped for a time; but his wife having been ravished by Maxtlaton, he resolved not to survive his dishonor, but to offer himself in sacrifice to his god, Huitzilopochtli. In the midst of the ceremonies, Maxtlaton burst in, took him, carried him off, and caged him like a criminal.

This success excited afresh in the mind of Maxtlaton the desire to get the Acolhuan prince, Nezahualcoyotl, into his power. He, discovering the designs of the tyrant, went boldly to him and told him he had heard that he wished his life also, and he had therefore come to offer it. Maxtlaton, struck by his conduct, assured him he had no designs against him, nor was it his purpose to put the king of Mexico to death. He then gave orders that he should be hospitably entertained, and even allowed him to visit Chimalpopoca in prison. The Mexican king, however, soon after, hanged himself with his girdle; and Nezahualcoyotl, suspecting the sincerity of Maxtlaton’s professions, left the court. After wandering about for some time, exposed to various dangers from his inveterate foe, he finally took refuge among the Cholulans, who agreed to assist him with an army for the purpose of overthrowing Maxtlaton, and restoring him to the throne, which had been usurped by the father of the tyrant.

On the death of their king, the Mexicans raised to the throne Itzcoatl, a son of their first monarch, Acamapitzin, a brave, prudent, and just prince. This choice was offensive to Maxtlaton,—but to Nezahualcoyotl, on the contrary, it afforded the highest satisfaction. The new monarch, immediately on his elevation to the throne, resolved to unite all his forces with this prince against the tyrant Maxtlaton. On a certain occasion, he sent an ambassador to Nezahualcoyotl, named Montezuma, who, with another nobleman, was taken captive on the way, and carried to Chalco. They were then sent to the Huexotzincas to be sacrificed. This people, however, spurned the barbarous proposal. Maxtlaton was then informed of their capture; but he commanded the lord of Chalco, whom he called a double-minded traitor, to set them both at liberty. Before this, however, they had escaped, by the connivance of the man to whom they had been intrusted, and returned to Mexico. Maxtlaton then made war against Mexico. Montezuma offered to challenge him, which he did by presenting to him certain defensive weapons, anointing his head, and fixing feathers on it. Maxtlaton, in turn, commissioned him in like manner to bear a challenge from himself to the king of Mexico. A terrible battle ensued; the tyrant was defeated, his city taken, and himself killed, being beaten to death while attempting to escape. His people, the Tepanecas, were entirely subdued.

The Mexican king now replaced the Acolhuan prince on the throne of his ancestors, and carried on his conquests by his general, Montezuma. On his death in 1436, he was succeeded by Montezuma the First. This monarch was the greatest that ever sat on the throne of Mexico. He engaged in a war with Chalco, the king of which city had taken three Mexican lords, and two sons of the king of Tezcuco, put them to death, salted and dried their bodies, and placed them in his hall as supporters to torches! Montezuma took the city, and executed vengeance on the barbarous people. He then reduced Tlatelolco, whose king had conspired against the late king of Mexico. He also subdued the Mixtecas, and thus enlarged his dominions.

In 1457, he sent an expedition against the Cotastese, and took 6,200 prisoners, whom he sacrificed to his god. He also took signal vengeance again on the Chalchese, who had rebelled, and had sought to make one of his brothers king in his stead. The brother pretended to comply; but mounting a scaffold which he ordered to be erected, and taking a bunch of flowers in his hand, then urging his attendant Mexicans to be faithful to their king, he threw himself from the scaffold. This enraged the Chalchese so much that they put the Mexicans to death, for which Montezuma made war against them till he had almost exterminated them. He finally, however, proclaimed a general amnesty. He constructed a dike, nine miles long and eleven cubits broad, to prevent the recurrence of an inundation which had happened, and which was followed by a famine. He died in 1464.

Montezuma the First was succeeded by Axayacatl, who pursued the conquests so successfully begun by the late king. A war broke out between the Mexicans and Tlatelolcos, which ended in the final subjection of the latter. Their king was killed, and carried to the Mexican monarch, who, with his own hand, cut open his breast, and tore out his heart. He also fought the Otomies, and gained a complete victory, making 11,060 prisoners, among whom were three chiefs. He died in 1477, and was succeeded by his oldest brother, Tizoc, who was probably cut off by poison. Tizoc was succeeded by another brother, named Ahuitzotl, who finished the great temple begun by his predecessor, and, having reserved the prisoners taken in his wars for this purpose, he sacrificed, at its dedication, as Torquemada asserts, 72,344; others say, 64,060. This was in the year 1486. He carried on his conquests even as far as Guatemala, 900 miles south of Mexico. He was only once defeated; this was in 1496, by Toltecatl, a Huexotzincan chief. He died in 1502, in consequence of striking his head against a door. Two years previous to his death there was an inundation, which was followed by a famine, proceeding, it is said, from the decay of the grain.

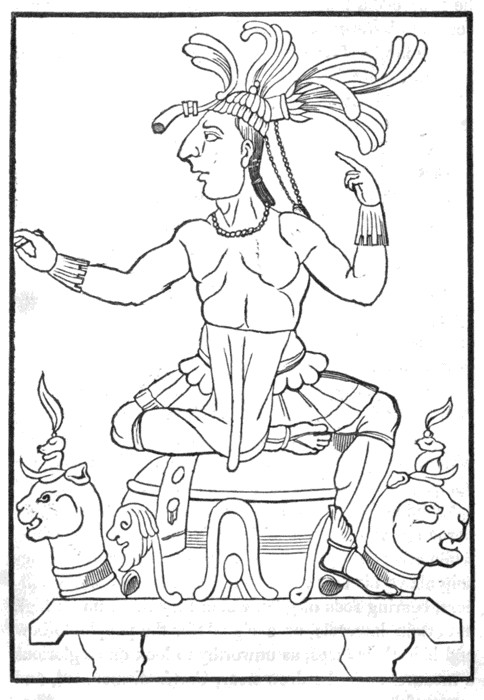

Ahuitzotl was succeeded by Montezuma the Second, a man of great bravery, and also a priest, but excessively haughty. His coronation was attended with the greatest display and pomp. He lived in exceeding splendor; lords were his servants, and no one was permitted to enter his palace without putting off his shoes and stockings. Even the meanest utensils of his service were of gold plate and sea-shell. His dinner was carried in by 300 or 400 of his young nobles, and he pointed with a rod to such dishes as he chose. He was served with water for washing by four of his most beautiful women. The vast expenses necessary to support such luxury displeased his subjects. He was, however, munificent in rewarding his generals, by which means he retained their services, and still further secured the soldiery by appointing a hospital for invalids. Unsuccessful for a time in a war with the Tlascalans, he finally took captive a brave Tlascalan general, named Tlahuicol, and put him into a cage. When, however, he gave him his liberty to return home, Tlahuicol wished to sacrifice himself, and perished in a gladiatorial combat, after having killed eight men, and wounded twenty more.

In his reign, the conquest of Mexico was effected by Cortés. Previous to the arrival of the Spaniards, a vague apprehension seems to have troubled the minds of Montezuma and his people, respecting the downfall of their empire, an event which was supposed likewise to be portended by a comet. But the history of this catastrophe must be reserved for another chapter.

MEXICO, FROM THE ARRIVAL OF CORTÉS.

Mexico was first discovered by Juan de Grijalva. He, however, seems to have made no attempt to penetrate into the interior from the sea-coast. In 1518, when its conquest was undertaken by Cortés, the Mexican empire is said to have extended 230 leagues from east to west, and 140 from north to south. After arranging his expedition, on the 10th of February, 1519, Cortés set sail from Havana, in Cuba, and landed at the island of Cozumel, on the coast of Yucatan. His whole army consisted of but 553 soldiers, 16 horsemen, and 110 mechanics, pilots, and mariners. Having released some Spanish captives whom he found there, he proceeded to Tabasco. Here he was attacked by the natives, but defeated them, and then pursued his course north-west to San Juan de Ulua, where he arrived on the 20th of April.

Hardly had the Spaniards cast anchor, when they saw two canoes, filled with Indians, put off from the shore, and steer directly for the general’s ship. Cortés received his visiters courteously, and, in exchange for the presents of fruit, flowers, and little ornaments of gold which they brought, gave them a few trinkets, of European fabric, with which they seemed to be greatly pleased. Through the medium of an interpreter, whom he chanced to have on board, a Mexican female slave, the celebrated Marina, he learned from the Indians that they belonged to a neighbouring province which was subject to the emperor of Mexico, a mighty monarch who lived far in the interior, called Montezuma; and that they had been sent to ascertain who the strangers were, and what they wanted. Cortés replied, that he had come only with the most friendly purposes, and expressed a desire for an interview with the governor of their province. Their inquiries being satisfied, his guests shortly afterwards took their leave, and returned to the shore.

The next morning, Cortés landed with all his troops and munitions of war, and immediately set to work, with the assistance of the natives, in erecting barracks. One can scarcely help being reminded, on reading the account of the readiness with which the simple Indians engaged in this object, of the fatal alacrity with which the Trojans are said to have received within their walls the wooden horse that was so soon to prove their ruin.

Once on shore, Cortés informed the governor, Teuhtlile, that he must go to the capital. He said that he came as the ambassador of a great monarch, and must see Montezuma himself. To this the governor replied, that he would send couriers to the capital, to convey his request to the emperor, and so soon as he had learned Montezuma’s will he would communicate it to him. He then ordered his attendants to bring forward some presents which he had prepared, the richness and splendor of which only confirmed Cortés in the determination to prosecute his schemes. In the mean while, some Mexican painters who accompanied the governor were employed in depicting the appearance of the Spaniards, their ships and horses; and Cortés, to render the intelligence to be thus conveyed to the emperor more striking, arrayed his horsemen, commanded his trumpets to sound, and the guns to be fired, by which display the Mexicans were deeply impressed with the idea of the greatness of the Spaniards.

Couriers, stationed in relays along the whole line of the distance, in a day or two informed Montezuma of these things, though it was 180 miles to the capital. The monarch, who, in the midst of his fears, seems to have summoned somewhat more resolution, commanded Cortés to leave his dominions. He likewise sent him more presents; fine cotton stuffs resembling silk, pictures, gold and silver plates representing the sun and moon, bracelets, and other costly things. Cortés, however, still persisted in his purpose; on hearing which, the Mexican ambassadors turned away with surprise and resentment, and all the natives deserted the camp of the Spaniards, nor came any more to trade with them. Cortés, already threatened with a mutiny among his soldiers, evidently felt his situation to be critical, but he nevertheless went on to found a city, and establish a government for his colony.

In this juncture of his affairs, he was visited by some people from Cempoalla and Chiahuitztla, two small cities or villages tributary to Montezuma. With the caciques of these places he formed a treaty of alliance, and agreed to protect them against Montezuma. Encouraged by his promises, they went so far as to insult the Mexican power, of which they had before stood in the greatest dread. Having secured their submission, Cortés, to take away all hope of a return to Cuba, and inspire his soldiers with a desperate courage, burned his fleet; and, leaving a garrison in his new city, called Vera Cruz, he set out for the capital of the Mexican empire with 400 infantry, 15 horsemen, and seven field-pieces, having also been furnished by the Cempoallans with 1300 warriors and 1000 tamanes, or men of burden, to carry the baggage.

On the route to Mexico lay the little republic of Tlascala, and between these two powers there had existed for a long period an inextinguishable feud. On arriving near the confines of the republic, therefore, Cortés sent forward an embassy of Cempoallans inviting the Tlascalans to an alliance, and requesting, that, at least, he might be allowed to pass through their territories. The senate was immediately convened to decide upon this application. Maxicatzin, one of the oldest of the senators, alluded to a tradition respecting the coming of white men, and favored the request. He was opposed by Xicotencatl, who sought to prove that the Spaniards were magicians, and asserted, as they had pulled down the images in Cempoalla, that the gods would be against them. They resolved therefore on war; seized the ambassadors, and placed them in confinement.