автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу A Visit to the Philippine Islands

A VISIT

TO

THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS.

A VISIT

TO

THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS.

BY

SIR JOHN BOWRING, LL.D., F.R.S.,

LATE GOVERNOR OF HONG KONG, H.R.M.’S PLENIPOTENTIARY IN CHINA,

HONORARY MEMBER OF THE SOCIEDAD ECONOMICA

DE LAS FILIPINAS, ETC. ETC.

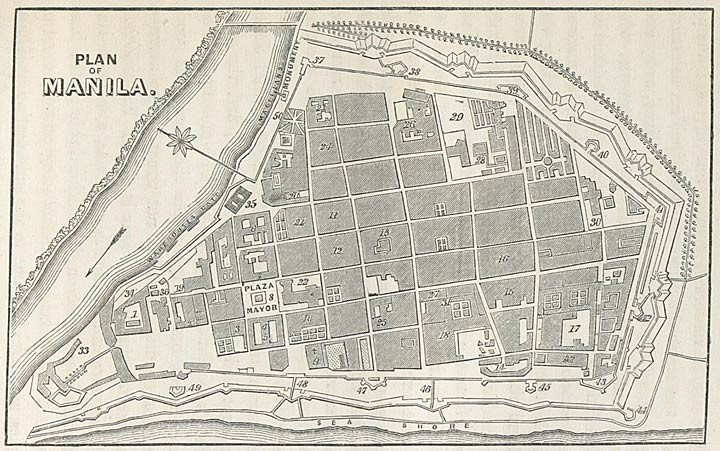

HOT SPRINGS AT TIVI.

LONDON:

SMITH, ELDER & CO., 65, CORNHILL.

M.DCCC.LIX.

[The right of Translation is reserved.]

PREFACE.

The Philippine Islands are but imperfectly known. Though my visit was a short one, I enjoyed many advantages, from immediate and constant intercourse with the various authorities and the most friendly reception by the natives of every class.

The information I sought was invariably communicated with courtesy and readiness; and by this publication something will, I hope, be contributed to the store of useful knowledge.

The mighty “tide of tendency” is giving more and more importance to the Oriental world. Its resources, as they become better known, will be more rapidly developed. They are promising fields, which will encourage and reward adventure; inviting receptacles for the superfluities of European wealth, activity, and intelligence, whose streams will flow back upon their sources with ever-augmenting contributions. Commerce will complete the work in peace and prosperity, which conquest began in perturbation and peril. Whatever clouds may hang over portions of the globe, there is a brighter dawning, a wider sunrise, over the whole; and the flights of time, and the explorings of space, are alike helping the “infinite progression” of good.

J. B.

CONTENTS.

CHAP.

PAGE

I.

Manila and Neighbourhood1

II.

Visit to La Laguna and Tayabas30

III.

History44

IV.

Geography, Climate, etc.71

V.

Government, Administration, etc.87

VI.

Population105

VII.

Manners and Superstitions of the People144

VIII.

Population—Races165

IX.

Administration of Justice186

X.

Army and Navy191

XI.

Public Instruction194

XII.

Ecclesiastical Authority199

XIII.

Languages215

XIV.

Native Produce234

XV.

Vegetables244

XVI.

Animals272

XVII.

Minerals277

XVIII.

Manufactures282

XIX.

Popular Proverbs286

XX.

Commerce292

XXI.

Finance, Taxation, etc.320

XXII.

Taxes326

XXIII.

Opening the New Ports of Iloilo, Sual and Zamboanga330

XXIV.

Zamboanga341

XXV.

Iloilo and Panay354

XXVI.

Sual425

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

- PAGE

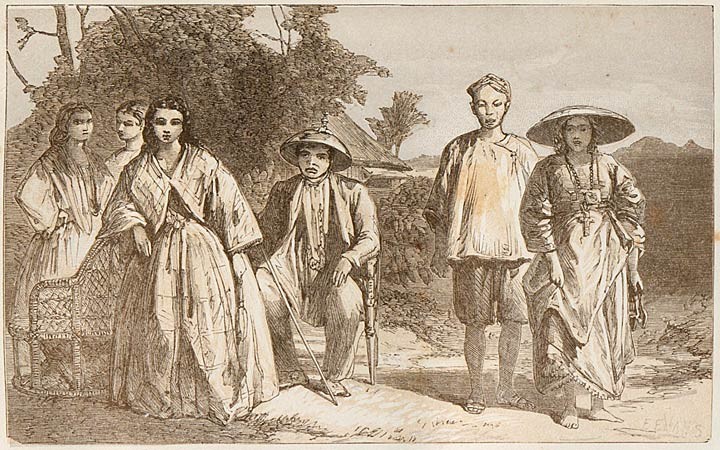

- Group of Natives (Frontispiece.)

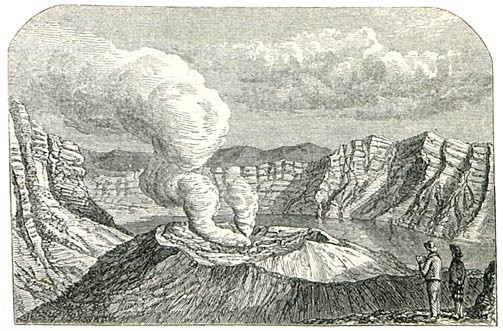

- Hot Springs at Tivi (Title-page.)

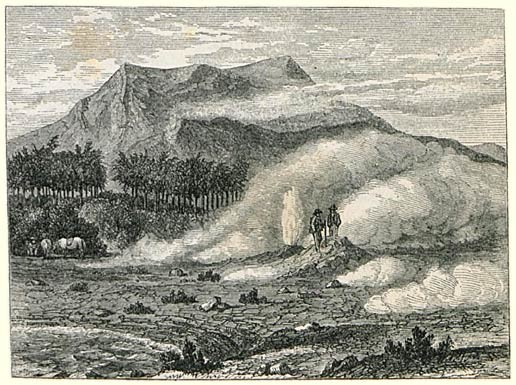

- Plan of Manila 10

- View from my Window to face page 16

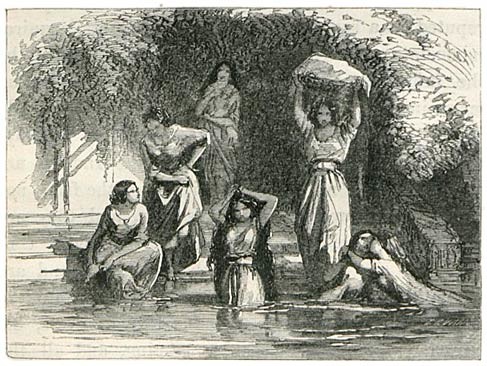

- Lavanderos, or Washerwomen ” 24

- Waterfall of the Botocan 30

- Village of Majajay to face page 36

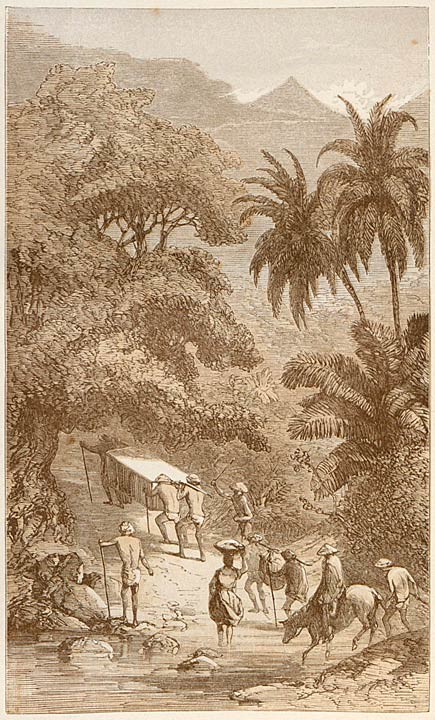

- Travelling by Palkee ” 38

- Crater of the Volcano at Taal 71

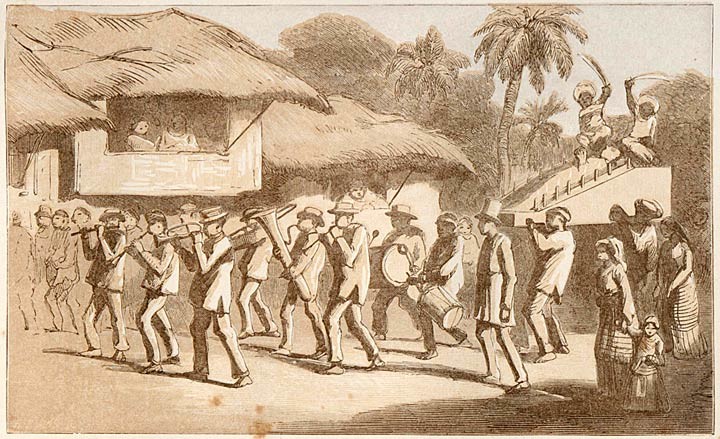

- Indian Funeral to face page 122

- Girls Bathing 134

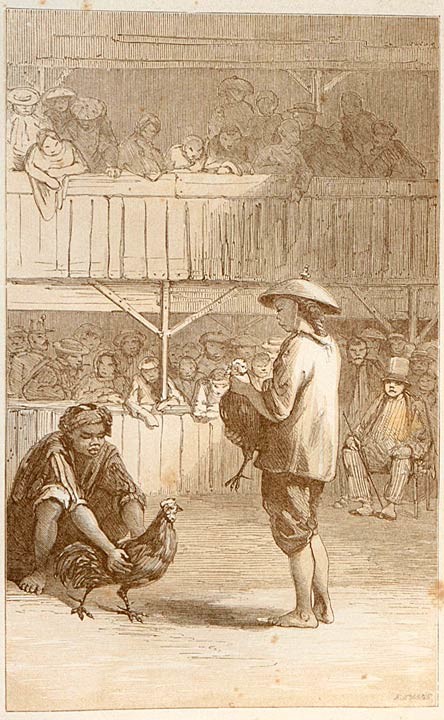

- A Gallera, or Cock-pit to face page 152

- Lake of Taal, with Volcano ” 164

- Chart of Zamboanga 341

- Chart

,,

of,,

Port Iloilo and Panay 354 - Chart

,,

of,,

Port of Sual 425 - Indian Song of the Philippines to face page 434

A VISIT

TO THE

PHILIPPINE ISLANDS.

CHAPTER I.

MANILA AND NEIGHBOURHOOD.

Three hundred and forty years ago, the Portuguese navigator Fernando de Magalhães, more generally known by his Spanish designation Magellanes, proposed to Carlos I. an expedition of discovery in the Eastern seas. The conditions of the contract were signed at Zaragoza, and, with a fleet of six vessels, the largest of which was only 130 tons burden, and the whole number of the crews two hundred and thirty-four men, Magalhães passed the straits which bear his name in November, 1520; in the middle of March of the following year he discovered the Mariana Islands, and a few days afterwards landed on the eastern coast of the island of Mindanao, where he was well received by the native population. He afterwards visited the island of Zebu, where, notwithstanding a menaced resistance from more than two thousand armed men, he succeeded in conciliating the king and his court, who were not only baptized into the Catholic faith, but recognised the supreme sovereignty of the crown of Spain, and took the oaths of subjection and vassalage. The king being engaged in hostilities with his neighbours, Magalhães took part therein, and died in Mactan, on the 26th April, 1521, in consequence of the wounds he received. This disaster was followed by the murder of all the leading persons of the expedition, who, being invited to a feast by their new ally, were treacherously assassinated. Guillen de Porceleto alone escaped of the twenty-six guests who formed the company. Three of the fleet had been lost before they reached the Philippines; one only returned to Spain—the Vitoria—the first that had ever made the voyage round the world, and the Spanish king conferred on her commander, Elcano, a Biscayan, an escutcheon bearing a globe, with the inscription, “Primus circumdedit me.” A second expedition, also composed of six vessels and a trader, left Spain in 1524. The whole fleet miserably perished in storms and contests with the Portuguese in the Moluccas, and the trader alone returned to the Spanish possessions in New Spain.

About one hundred and twenty of the expedition landed in Tidore, where they built themselves a fortress, and were relieved by a third fleet sent by Hernan Cortes, in 1528, to prosecute the discoveries of which Magalhães had had the initiative. This third adventure was as disastrous as those which had preceded it. It consisted of three ships and one hundred and ten men, bearing large supplies and costly presents. They took possession of the Marianas (Ladrone Islands) in the name of the king of Spain, reached Mindanao and other of the southern islands, failed twice in the attempt to reach New Spain, and finally were all victims of the climate and of the hostility of the Portuguese.

But the Spanish court determined to persevere, and the Viceroy (Mendoza) of New Spain was ordered to prepare a fourth expedition, which was to avoid the Molucca Islands, where so many misfortunes had attended the Spaniards. The fleet consisted of three ships and two traders, and the commander was Villalobos. He reached the Archipelago, and gave to the islands the name of the Philippines, in honour of the Prince of Asturias, afterwards Philip the Second. Contrary winds (in spite of the royal prohibition) drove them into the Moluccas, where they were ill received by the Portuguese, and ordered to return to Spain. Villalobos died in Amboyna, where he was attended by the famous missionary, St. Francisco Xavier. Death swept away many of the Spaniards, and the few who remained were removed from the Moluccas in Portuguese vessels.

A fifth expedition on a larger scale was ordered by Philip the Second to “conquer, pacify, and people” the islands which bore his name. They consisted of five ships and four hundred seamen and soldiers, and sailed from La Natividad (Mexico) in 1564, under the orders of Legaspi, who was nominated Governor of the Philippines, with ample powers. He reached Tandaya in February, 1565, proceeded to Cabalian, where the heir of the native king aided his views. In Bojol, he secured the aid and allegiance of the petty sovereigns of the island, and afterwards fixed himself on the island of Zebu, which for some time was the central seat of Spanish authority.1

Manila was founded in 1581.

Illness and the despotism of the doctors, who ordered me to throw off the cares of my colonial government and to undertake a sea voyage of six or seven weeks’ duration, induced me to avail myself of one of the many courtesies and kindnesses for which I am indebted to the naval commander-in-chief, Sir Michael Seymour, and to accept his friendly offer of a steamer to convey me whither I might desire. The relations of China with the Eastern Spanish Archipelago are not unimportant, and were likely to be extended in consequence of the stipulations of Lord Elgin’s Tientsin Treaty. Moreover, the slowly advancing commercial liberalism of the Spaniards has opened three additional ports to foreign trade, of which, till lately, Manila had the monopoly. I decided, therefore, after calling at the capital in order to obtain the facilities with which I doubted not the courtesy of my friend Don Francisco Norzagaray, the Captain-General of the Philippines, would favour me, to visit Zamboanga, Iloilo, and Sual. I had already experienced many attentions from him in connection with the government of Hong Kong. It will be seen that my anticipations were more than responded to by the Governor, and as I enjoyed rare advantages in obtaining the information I sought, I feel encouraged to record the impressions I received, and to give publicity to those facts which I gathered together in the course of my inquiries, assisted by such publications as have been accessible to me.

Sir Michael Seymour placed her Majesty’s ship Magicienne at my disposal. The selection was in all respects admirable. Nothing that foresight could suggest or care provide was wanting to my comfort, and I owe a great deal to Captain Vansittart, whose urbanities and attentions were followed up by all his officers and men. We left Hong Kong on the 29th of November, 1858. The China seas are, perhaps, the most tempestuous in the world, and the voyage to Manila is frequently a very disagreeable one. So it proved to us. The wild cross waves, breaking upon the bows, tossed us about with great violence; and damage to furniture, destruction of glass and earthenware, and much personal inconvenience, were among the varieties which accompanied us.

But on the fifth day we sighted the lighthouse at the entrance of the magnificent harbour of Manila, and some hours’ steaming brought us to an anchorage at about a mile distant from the city. There began the attentions which were associated with the whole of our visit to these beautiful regions. The Magicienne was visited by the various authorities, and arrangements were made for my landing and conveyance to the palace of the Governor-General. Through the capital runs a river (the Pasig), up which we rowed, till we reached, on the left bank, a handsome flight of steps, near the fortifications and close to the column which has been erected to the memory of Magellanes, the discoverer of, or, at all events, the founder of Spanish authority in, these islands. This illustrious name arrested our attention. The memorial is not worthy of that great reputation. It is a somewhat rude column of stone, crowned with a bronze armillary sphere, and decorated midway with golden dolphins and anchors wreathed in laurels: it stands upon a pedestal of marble, bearing the name of the honoured navigator, and is surrounded by an iron railing. It was originally intended to be erected in the island of Zebu, but, after a correspondence of several years with the Court of Madrid, the present site was chosen by royal authority in 1847. There was a very handsome display of cavalry and infantry, and a fine band of music played “God save the Queen.” Several carriages and four were in waiting to escort our party to the government palace, where I was most cordially received by the captain-general and the ladies of his family. A fine suite of apartments had been prepared for my occupation, and servants, under the orders of a major-domo, were ordered to attend to our requirements, while one of the Governor’s aides-de-camp was constantly at hand to aid us.

Though the name of Manila is given to the capital of the Philippine Islands, it is only the fort and garrison occupied by the authorities to which the designation was originally applied. Manila is on the left bank of the river, while, on the right, the district of Binondo is the site inhabited by almost all the merchants, and in which their business is conducted and their warehouses built. The palace fills one side of a public plaza in the fortress, the cathedral another of the same locality, resembling the squares of London, but with the advantage of having its centre adorned by the glorious vegetation of the tropics, whose leaves present all varieties of colour, from the brightest yellow to the deepest green, and whose flowers are remarkable for their splendour and beauty. There is a statue of Charles the Fourth in the centre of the garden.

The most populous and prosperous province of the Philippines takes its name from the fortification2 of Manila; and the port of Manila is among the best known and most frequented of the harbours of the Eastern world. The capital is renowned for the splendour of its religious processions; for the excellence of its cheroots, which, to the east of the Cape of Good Hope, are generally preferred to the cigars of the Havana; while the less honourable characteristics of the people are known to be a universal love of gambling, which is exhibited among the Indian races by a passion for cock-fighting, an amusement made a productive source of revenue to the State. Artists usually introduce a Philippine Indian with a game-cock under his arm, to which he seems as much attached as a Bedouin Arab to his horse. It is said that many a time an Indian has allowed his wife and children to perish in the flames when his house has taken fire, but never was known to fail in securing his favourite gallo from danger.

On anchoring off the city, Captain Vansittart despatched one of his lieutenants, accompanied by my private secretary, to the British consulate, in order to announce our arrival, and to offer any facilities for consular communication with the Magicienne. They had some difficulty in discovering the consulate, which has no flag-staff, nor flag, nor other designation. The Consul was gone to his ferme modèle, where he principally passes his time among outcast Indians, in an almost inaccessible place, at some distance from Manila. The Vice-Consul said it was too hot for him to come on board, though during a great part of the day we were receiving the representatives of the highest authorities of Manila. The Consul wrote (I am bound to do him this justice) that it would “put him out” of his routine of habit and economy if he were expected to fête and entertain with formality “his Excellency the Plenipotentiary and Governor of Hong Kong.” I hastened to assure the Consul that my presence should cause him no expense, but that the absence of anything which becomingly represented consular authority on the arrival of one of Her Majesty’s large ships of war could hardly be passed unnoticed by the commander of that vessel.

Crowds of visitors honoured our arrival; among them the archbishop and the principal ecclesiastical dignitaries; deputations from the civilians, army and navy, and the various heads of departments, who invited us to visit their establishments, exhibited in their personal attentions the characteristics of ancient Castilian courtesy. A report had spread among the officers that I was a veteran warrior who had served in the Peninsular campaign, and helped to liberate Spain from the yoke of the French invaders. I had to explain that, though witness to many of the events of that exciting time, and in that romantic land, I was a peaceful spectator, and not a busy actor there. The bay of Manila, one of the finest in the world, and the river Pasig which flows into it, were, no doubt, the great recommendations of the position chosen for the capital of the Philippines. During the four months of March, April, May, and June, the heat and dust are very oppressive, and the mosquitos a fearful annoyance. To these months succeed heavy rains, but on the whole the climate is good, and the general mortality not great. The average temperature through the year is 81° 97′ Fahrenheit.

The quarantine station is at Cavite, a town of considerable importance on the southern side of the harbour. It has a large manufacturing establishment of cigars, and gives its name to the surrounding province, which has about 57,000 inhabitants, among whom are about 7,000 mestizos (mixed race). From its adjacency to the capital, the numerical proportion of persons paying tribute is larger than in any other province.

PLAN OF MANILA.

- 1 Artillery

- 2 Hall of Arms

- 3 Hall of Audience

- 4 Military Hospital

- 5 Custom House

- 6 Univ. of S. Thomas

- 7 Cabildo

- 8 Palace & Treasury

- 9 Archbishop’s Palace

- 10 Principal Accountancy

- 11 Intendance

- 12 Consulado

- 13 Bakery

- 14 Artillery Quarters

- 15 S. Potenciano’s College

- 16 Fortification Department

- 17 Barracks (Ligoros)

- 18 Barracks (Asia)

- 19 Nunnery of S. Clara

- 20 S. Domingo

- 21 Establishment of S. Rosa

- 22 Cathedral

- 23 S. John of Lateran

- 24 Establishment of S. Catherine

- 25 S. Isabella

- 26 S. Juan de Dios

- 27 S. Augustine

- 28 Orden Tercera

- 29 S. Francisco

- 30 Ricolets

- 31 S. Ignatius

- 32 Establishment of the Jesuits

- 33 Santiago Troops

- 34 Bulwark of the Torricos

- 35 Gate of S. Domingo

- 36 Custom-house Bulwark

- 37 S. Gabriel’s Bulwark

- 38 Parien Gate

- 39 Devil’s Bulwark

- 40 Postern of the Ricolets

- 41 S. Andrew’s Bulwark

- 42 Royal Gate

- 43 S. James’s Bulwark

- 44 S. Gregory’s Battery

- 45 S. Peter’s Redoubt

- 46 S. Luis Gate

- 47 Plane Bulwark

- 48 Gate of Sally-port

- 49 S. Domingo’s Redoubt

- 50 Gate of Isabella II.

The city, which is surrounded by ramparts, consists of seventeen streets, spacious and crossing at right angles. As there is little business in this part of the capital (the trade being carried on on the other side of the river), few people are seen in the streets, and the general character of the place is dull and monotonous, and forms a remarkable contrast to the activity and crowding of the commercial quarters. The cathedral, begun in 1654, and completed in 1672, is 240 feet in length and 60 in breadth. It boasts of its fourteen bells, which have little repose; and of the carvings of the fifty-two seats which are set apart for the aristocracy. The archiepiscopal palace, though sufficiently large, did not appear to me to have any architectural beauty. The apartments are furnished with simplicity, and though the archbishop is privileged, like the governor, to appear in some state, it was only on the occasion of religious ceremonies that I observed anything like display. His reception of me was that of a courteous old gentleman. He was dressed with great simplicity, and our conversation was confined to inquiries connected with ecclesiastical administration. He had been a barefooted Augustin friar (Recoleto), and was raised to the archiepiscopal dignity in 1846.

The palacio in which I was so kindly accommodated was originally built by an opulent but unfortunate protégé of one of the captains-general; it was reconstructed in 1690 by Governor Gongora. It fills a considerable space, and on the south-west side has a beautiful view of the bay and the surrounding headlands. There is a handsome Hall of Audience, and many of the departments of the government have their principal offices within its walls. The patio forms a pretty garden, and is crowded with tropical plants. It has two principal stone staircases, one leading to the private apartments, and the other to the public offices. Like all the houses at Manila, it has for windows sliding frames fitted with concha, or plates of semi-transparent oysters, which admit an imperfect light, but are impervious to the sunbeams. I do not recollect to have seen any glass windows in the Philippines. Many of the apartments are large and well furnished, but not, as often in England, over-crowded with superfluities. The courtesy of the Governor provided every day at his table seats for two officers of the Magicienne at dinner, after retiring from which there was a tertulia, or evening reception, where the notabilities of the capital afforded me many opportunities for enjoying that agreeable and lively conversation in which Spanish ladies excel. A few mestizos are among the visitors. Nothing, however, is seen but the Parisian costume; no vestiges of the recollections of my youth—the velo, the saya, and the basquiña; nor the tortoiseshell combs, high towering over the beautiful black cabellera; the fan alone remains, then, as now, the dexterously displayed weapon of womanhood. After a few complimentary salutations, most of the gentlemen gather round the card-tables.

The Calzada, a broad road a little beyond the walls of the fortress, is to Manila what Hyde Park is to London, the Champs Elysées to Paris, and the Meidan to Calcutta. It is the gathering place of the opulent classes, and from five o’clock P.M. to the nightfall is crowded with carriages, equestrians and pedestrians, whose mutual salutations seem principally to occupy their attention: the taking off hats and the responses to greetings and recognitions are sufficiently wearisome. Twice a week a band of music plays on a raised way near the extremity of the patio. Soon after sunset there is a sudden and general stoppage. Every one uncovers his head; it is the time of the oracion announced by the church bells: universal silence prevails for a few minutes, after which the promenades are resumed. There is a good deal of solemnity in the instant and accordant suspension of all locomotion, and it reminded me of the prostration of the Mussulmans when the voice of the Muezzim calls, “To prayer, to prayer.” A fine evening walk which is found on the esplanade of the fortifications, is only frequented on Sundays. It has an extensive view of the harbour and the river, and its freedom from the dust and dirt of the Calzada gives it an additional recommendation; but fashion despotically decides all such matters, and the crowds will assemble where everybody expects to meet with everybody. In visiting the fine scenery of the rivers, roads, and villages in the neighbourhood of Manila, we seldom met with a carriage, or a traveller seeking to enjoy these beauties. And in a harbour so magnificent as that of Manila one would expect to see skiffs and pleasure-boats without number, and yachts and other craft ministering to the enjoyment and adding to the variety of life; but there are none. Nobody seems to like sporting with the elements. There are no yacht regattas on the sea, as there are no horseraces on the shore. I have heard the life of Manila called intolerably monotonous; in my short stay it appeared to me full of interest and animation, but I was perhaps privileged. The city is certainly not lively, and the Spaniard is generally grave, but he is warm-hearted and hospitable, and must not be studied at a distance, nor condemned with precipitancy. He is, no doubt, susceptible and pundonoroso, but is rich in noble qualities. Confined as is the population of Manila within the fortification walls, the neighbouring country is full of attractions. To me the villages, the beautiful tropical vegetation, the banks of the rivers, and the streams adorned with scenery so picturesque and pleasing, were more inviting than the gaiety of the public parade. Every day afforded some variety, and most of the pueblos have their characteristic distinctions. Malate is filled with public offices, and women employed in ornamenting slippers with gold and silver embroidery. Santa Ana is a favourite Villagiatura for the merchants and opulent inhabitants. Near Paco is the cemetery, “where dwell the multitude,” in which are interred the remains of many of the once distinguished who have ceased to be. Guadalupe is illustrious for its miraculous image, and Paco for that of the Saviour. The Lake of Arroceros (as its name implies) is one of the principal gathering places for boats loaded with rice; near it, too, are large manufactories of paper cigars. Sampaloc is the paradise of washermen and washerwomen. La Ermita and other villages are remarkable for their bordadoras, who produce those exquisite piña handkerchiefs for which such large sums are paid. Pasay is renowned for its cultivation of the betel. Almost every house has a garden with its bamboos, plantains and cocoa-nut trees, and some with a greater variety of fruits. Nature has decorated them with spontaneous flowers, which hang from the branches or the fences, or creep up around the simple dwellings of the Indians. Edifices of superior construction are generally the abodes of the mestizos, or of the gobernadorcillos belonging to the different pueblos.

Philip the Third gave armorial bearings to the capital, and conferred on it the title of the “Very Noble City of Manila” (La mui noble Ciudad), and attached the dignity of Excellency to the Ayuntamiento (municipality).

During my stay at Manila, every afternoon, at five or six o’clock, the Governor-General called for me in my apartments, and escorted by cavalry lancers we were conveyed in a carriage and four to different parts of the neighbourhood, the rides lasting from one to two hours. We seldom took the same road, and thus visited not only nearly all the villages in the vicinity, but passed through much beautiful country in which the attention was constantly arrested by the groups of graceful bamboos, the tall cocoa-nut trees, the large-leafed plantains, the sugar-cane, the papaya, the green paddy fields (in which many people were fishing—and who knows, when the fields are dry, what becomes of the fish, for they never fail to appear again when irrigation has taken place?), and that wonderful variety and magnificence of tropical vegetation,—leaves and flowers so rich and gorgeous, on which one is never tired to gaze. Much of the river scenery is such as a Claude would revel in, and high indeed would be the artist’s merit who could give perpetuity to such colouring. And then the sunset skies—such as are never seen in temperate zones,—so grand, so glowing, and at times so awful! Almost every pueblo has some dwellings larger and better than the rest, occupied by the native authorities or the mixed races (mostly, however, of Chinese descent), who link the Indian to the European population. The first floor of the house is generally raised from the ground and reached by a ladder. Bamboos form the scaffolding, the floors, and principal wood-work; the nipa palm makes the walls and covers the roof. A few mats, a table, a rude chair or two, some pots and crockery, pictures of saints, a lamp, and some trifling utensils, comprise the domestic belongings, and while the children are crawling about the house or garden, and the women engaged in household cares, the master will most probably be seen with his game-cock under his arm, or meditating on the prowess of the gallo while in attendance on the gallinas.

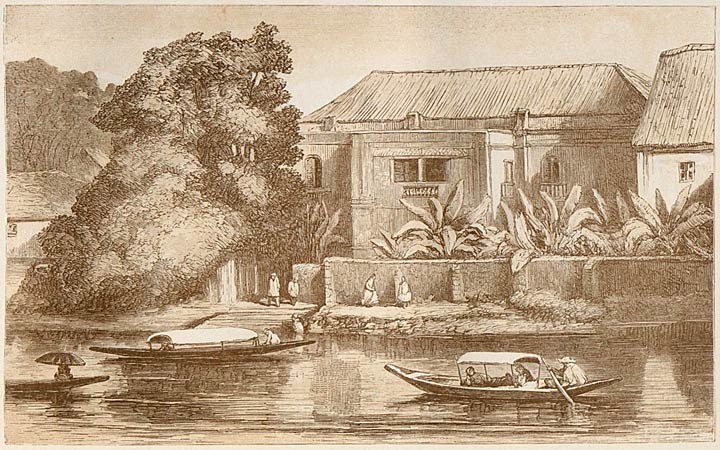

VIEW FROM MY WINDOW SAN MIGUEL.

The better class of houses in Manila are usually rectangular, having a court in the centre, round which are shops, warehouses, stables and other offices, the families occupying the first floor. Towards the street there is a corridor which communicates with the various apartments, and generally a gallery in the interior looking into the patio (court). The rooms have all sliding windows, whose small panes admit the light of day through semi-transparent oyster-shells: there are also Venetians, to help the ventilation and to exclude the sun. The kitchen is generally separated from the dwelling. A large cistern in the patio holds the water which is conveyed from the roofs in the rainy season, and the platform of the cistern is generally covered with jars of flowering plants or fruits. The first and only floor is built on piles, as the fear of earthquakes prevents the erection of elevated houses. The roofing is ordinarily of red tiles.

The apartments, as suited to a tropical climate, are large, and many European fashions have been introduced: the walls covered with painted paper, many lamps hung from the ceiling, Chinese screens, porcelain jars with natural or artificial flowers, mirrors, tables, sofas, chairs, such as are seen in European capitals; but the large rooms have not the appearance of being crowded with superfluous furniture. Carpets are rare—fire-places rarer.

Among Europeans the habits of European life are slightly modified by the climate; but it appeared to me among the Spaniards there were more of the characteristics of old Spain than would now be found in the Peninsula itself. In my youth I often heard it said—and it was said with truth—that neither Don Quixote nor Gil Blas were pictures of the past alone, but that they were faithful portraits of the Spain which I saw around me. Spain had then assuredly not been Europeanized; but fifty years—fifty years of increased and increasing intercourse with the rest of the world—have blotted out the ancient nationality, and European modes, usages and opinions, have pervaded and permeated all the upper and middling classes of Spanish society—nay, have descended deep and spread far among the people, except those of the remote and rural districts. There is little now to distinguish the aristocratical and high-bred Spaniard from his equals in other lands. In the somewhat lower grades, however, and among the whole body of clergy, the impress of the past is preserved with little change. Strangers of foreign nations, principally English and Americans, have brought with them conveniences and luxuries which have been to some extent adopted by the opulent Spaniards of Manila; and the honourable, hospitable and liberal spirit which is found among the great merchants of the East, has given them “name and fame” among Spanish colonists and native cultivators. Generally speaking, I found a kind and generous urbanity prevailing,—friendly intercourse where that intercourse had been sought,—the lines of demarcation and separation between ranks and classes less marked and impassable than in most Oriental countries. I have seen at the same table Spaniard, mestizo and Indian—priest, civilian and soldier. No doubt a common religion forms a common bond; but to him who has observed the alienations and repulsions of caste in many parts of the Eastern world—caste, the great social curse—the blending and free intercourse of man with man in the Philippines is a contrast well worth admiring. M. Mallat’s enthusiasm is unbounded in speaking of Manila. “Enchanting city!” he exclaims; “in thee are goodness, cordiality, a sweet, open, noble hospitality,—the generosity which makes our neighbour’s house our own;—in thee the difference of fortune and hierarchy disappears. Unknown to thee is etiquette. O Manila! a warm heart can never forget thy inhabitants, whose memory will be eternal for those who have known them.”

De Mas’ description of the Manila mode of life is this:—“They rise early, and take chocolate and tea (which is here called cha); breakfast composed of two or three dishes and a dessert at ten; dinner at from two to three; siesta (sleep) till five to six; horses harnessed, and an hour’s ride to the pasco; returning from which, tea, with bread and biscuits and sweets, sometimes homewards, sometimes in visit to a neighbour; the evening passes as it may (cards frequently); homewards for bed at 11 P.M.; the bed a fine mat, with mosquito curtains drawn around; one narrow and one long pillow, called an abrazador (embracer), which serves as a resting-place for the arms or the legs. It is a Chinese and a convenient appliance. No sheets—men sleep in their stockings, shirts, and loose trousers (pajamas); the ladies in garments something similar. They say ‘people must always be ready to escape into the street in case of an earthquake.’” I certainly know of an instance where a European lady was awfully perplexed when summoned to a sudden flight in the darkness, and felt that her toilette required adjustment before she could hurry forth.

Many of the pueblos which form the suburbs of Manila are very populous. Passing through Binondo we reach Tondo, which gives its name to the district, and has 31,000 inhabitants. These pueblos have their Indian gobernadorcillos. Their best houses are of European construction, occupied by Spaniards or mestizos, but these form a small proportion of the whole compared with the Indian Cabánas. Tondo is one of the principal sources for the supply of milk, butter, and cheese to the capital; it has a small manufacturing industry of silk and cotton tissues, but most of the women are engaged in the manipulation of cigars in the great establishments of Binondo. Santa Cruz has a population of about 11,000 inhabitants, many of them merchants, and there are a great number of mechanics in the pueblo. Near it is the burying-place of the Chinese, or, as they are called by the Spaniards, the Sangleyes infieles.

Santa Cruz is a favourite name in the Philippines. There are in the island of Luzon no less than four pueblos, each with a large population, called Santa Cruz, and several besides in others of the Philippines. It is the name of one of the islands, of several headlands, and of various other localities, and has been carried by the Spaniards into every region where they have established their dominion. So fond are they of the titles they find in their Calendar, that in the Philippines there are no less than sixteen places called St. John and twelve which bear the name of St. Joseph; Jesus, Santa Maria, Santa Ana, Santa Caterina, Santa Barbara, and many other saints, have given their titles to various localities, often superseding the ancient Indian names. Santa Ana is a pretty village, with about 5,500 souls. It is surrounded with cultivated lands, which, being irrigated by fertilizing streams, are productive, and give their wonted charm to the landscape—palms, mangoes, bamboos, sugar plantations, and various fruit and forest trees on every side. The district is principally devoted to agriculture. A few European houses, with their pretty gardens, contrast well with the huts of the Indian. Its climate has the reputation of salubrity.

There is a considerable demand for horses in the capital. The importation of the larger races from Australia has not been successful. They were less suited to the climate than the ponies which are now almost universally employed. The Filipinos never give pure water to their horses, but invariably mix it with miel (honey), the saccharine matter of the caña dulce, and I was informed that no horse would drink water unless it was so sweetened. This, of course, is the result of “education.” The value of horses, as compared with their cost in the remoter islands, is double or treble in the capital. In fact, nothing more distinctly proves the disadvantages of imperfect communication than the extraordinary difference of prices for the same articles in various parts of the Archipelago, even in parts which trade with one another. There have been examples of famine in a maritime district while there has been a superfluity of food in adjacent islands. No doubt the monsoons are a great impediment to regular intercourse, as they cannot be mastered by ordinary shipping; but steam has come to our aid, when commercial necessities demanded new powers and appliances, and no regions are likely to benefit by it more than those of the tropics.

The associations and recollections of my youth were revived in the hospitable entertainment of my most excellent host and the courteous and graceful ladies of his family. Nearly fifty years before I had been well acquainted with the Spanish peninsula—in the time of its sufferings for fidelity, and its struggles for freedom, and I found in Manila some of the veterans of the past, to whom the “Guerra de Independencia” was of all topics the dearest; and it was pleasant to compare the tablets of our various memories, as to persons, places and events. Of the actors we had known in those interesting scenes, scarcely any now remain—none, perhaps, of those who occupied the highest position, and played the most prominent parts; but their names still served as links to unite us in sympathizing thoughts and feelings, and having had the advantage of an early acquaintance with Spanish, all that I had forgotten was again remembered, and I found myself nearly as much at home as in former times when wandering among the mountains of Biscay, dancing on the banks of the Guadalquivir, or turning over the dusty tomes at Alcalá de Henares.3

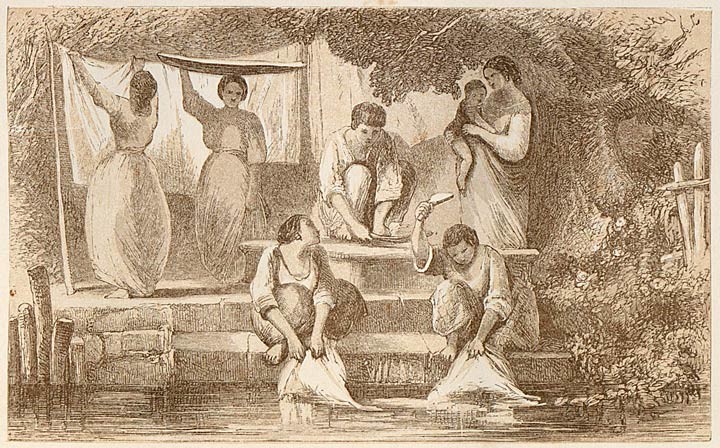

There was a village festival at Sampaloc (the Indian name for tamarinds), to which we were invited. Bright illuminations adorned the houses, triumphal arches the streets; everywhere music and gaiety and bright faces. There were several balls at the houses of the more opulent mestizos or Indians, and we joined the joyous assemblies. The rooms were crowded with Indian youths and maidens. Parisian fashions have not invaded these villages—there were no crinolines—these are confined to the capital; but in their native garments there was no small variety—the many-coloured gowns of home manufacture—the richly embroidered kerchiefs of piña—earrings and necklaces, and other adornings; and then a vivacity strongly contrasted with the characteristic indolence of the Indian races. Tables were covered with refreshments—coffee, tea, wines, fruits, cakes and sweetmeats; and there seemed just as much of flirting and coquetry as ever marked the scenes of higher civilization. To the Europeans great attentions were paid, and their presence was deemed a great honour. Our young midshipmen were among the busiest and liveliest of the throng, and even made their way, without the aid of language, to the good graces of the Zagalas. Sampaloc, inhabited principally by Indians employed as washermen and women, is sometimes called the Pueblo de los Lavanderos. The festivities continued to the matinal hours.

LAVANDEROS OR WASHERWOMEN

In 1855 the Captain-General (Crespo) caused sundry statistical returns to be published, which throw much light upon the social condition of the Philippine Islands, and afford such valuable materials for comparison with the official data of other countries, that I shall extract from them various results which appear worthy of attention.

The city of Manila contains 11 churches, with 3 convents, 363 private houses; and the other edifices, amounting in all to 88, consist of public buildings and premises appropriated to various objects. Of the private houses, 57 are occupied by their owners, and 189 are let to private tenants, while 117 are rented for corporate or public purposes. The population of the city in 1855 was 8,618 souls, as follows:—

——

Males.

Females.

Total.

European Spaniards

503

87

590

Native ditto

575

798

1,373

Indians and Mestizos

3,830

2,493

6,323

Chinese

525

7

4532

Total

5,433 3,385 8,818Far different are the proportions in another part of the capital, the Binondo district, on the other side of the river:—

——

Males.

Females.

Total.

European Spaniards

67

52

219

Native ditto

569

608

1,177

Foreigners

85

11

96

Indians and Mestizos

10,317

10,685

21,002

Chinese

5,055

8

55,063

Total

16,193 11,364 27,557Of these, one male and two females (Indian) were more than 100 years old.

The proportion of births and deaths in Manila is thus given:—

——

Spaniards.

Natives.

Total.

Births

4·38 per ct.

4·96 per ct.

4·83 per ct.

Deaths

1·68

per

,,

ct.

,,

2·72

per

,,

ct.

,,

2·48

per

,,

ct.

,,

Excess of Births over Deaths

2·70 per ct. 2·24 per ct. 2·35 per ct.In Binondo the returns are much less favourable:—

Births

5·12

Deaths

4·77

0·35The statistical commissioners state these discrepancies to be inexplicable; but attribute it in part to the stationary character of the population of the city, and the many fluctuations which take place in the commercial movements of Binondo.

Binondo is really the most important and most opulent pueblo of the Philippines, and is the real commercial capital: two-thirds of the houses are substantially built of stone, brick and tiles, and about one-third are Indian wooden houses covered with the nipa palm. The place is full of business and activity. An average was lately taken of the carriages daily passing the principal thoroughfares. Over the Puente Grande (great bridge) their number was 1,256; through the largest square, Plaza de S. Gabriel, 979; and through the main street, 915. On the Calzada, which is the great promenade of the capital, 499 carriages were counted—these represent the aristocracy of Manila. There are eight public bridges, and a suspension bridge has lately been constructed as a private speculation, on which a fee is levied for all passengers.

Binondo has some tolerably good wharfage on the bank of the Pasig, and is well supplied with warehouses for foreign commerce. That for the reception of tobacco is very extensive, and the size of the edifice where the state cigars are manufactured may be judged of from the fact that nine thousand females are therein habitually employed.

The Puente Grande (which unites Manila with Binondo) was originally built of wood upon foundations of masonry, with seven arches of different sizes, at various distances. Two of the arches were destroyed by the earthquake of 1824, since which period it has been repaired and restored. It is 457 feet in length and 24 feet in width. The views on all sides from the bridge are fine, whether of the wharves, warehouses, and busy population on the right bank of the river, or the fortifications, churches, convents, and public walks on the left.

The population of Manila and its suburbs is about 150,000.

The tobacco manufactories of Manila, being the most remarkable of the “public shows,” have been frequently described. The chattering and bustling of the thousands of women, which the constantly exerted authority of the female superintendents wholly failed to control, would have been distracting enough from the manipulation of the tobacco leaf, even had their tongues been tied, but their tongues were not tied, and they filled the place with noise. This was strangely contrasted with the absolute silence which prevailed in the rooms solely occupied by men. Most of the girls, whose numbers fluctuate from eight to ten thousand, are unmarried, and many seemed to be only ten or eleven years old. Some of them inhabit pueblos at a considerable distance from Manila, and form quite a procession either in proceeding to or returning from their employment. As we passed through the different apartments specimens were given us of the results of their labours, and on leaving the establishment beautiful bouquets of flowers were placed in our hands. We were accompanied throughout by the superior officers of the administration, explaining to us all the details with the most perfect Castilian courtesy. Of the working people I do not believe one in a hundred understood Spanish.

The river Pasig is the principal channel of communication with the interior. It passes between the commercial districts and the fortress of Manila. Its average breadth is about 350 feet, and it is navigable for about ten miles, with various depths of from 3 to 25 feet. It is crossed by three bridges, one of which is a suspension bridge. The daily average movement of boats, barges, and rafts passing with cargo under the principal bridge, was 277, escorted by 487 men and 121 women (not including passengers). The whole number of vessels belonging to the Philippines was, in 1852 (the last return I possess), 4,053, representing 81,752 tons, and navigated by 30,485 seamen. Of these, 1,532 vessels, of 74,148 tons, having 17,133 seamen, belong to the province of Manila alone, representing three-eighths of the ships, seven-eighths of the tonnage, and seventeen-thirtieths of the mercantile marine. The value of the coasting trade in 1852 is stated to have been about four and a-half millions of dollars, half this value being in abacá (Manila hemp), sugar and rice being the next articles in importance. The province of Albay, the most southern of Luzon, is represented by the largest money value, being about one-fourth of the whole. On an average of five years, from 1850 to 1854, the coasting trade is stated to have been of the value of 4,156,459 dollars, but the returns are very imperfect, and do not include all the provinces. The statistical commission reports that on an examination of all the documents and facts accessible to them, in 1855, the coasting trade might be fairly estimated at 7,200,459 dollars.

At a distance of about three miles from Binondo, on the right bank of the Pasig, is the country house of the captain-general, where he is accustomed to pass some weeks of the most oppressive season of the year: it has a nice garden, a convenient moveable bath, which is lowered into the river, an aviary, and a small collection of quadrupeds, among which I made acquaintance with a chimpanzee, who, soon after, died of a pulmonary complaint.

1 A recent History of the Conquest of the Islands, and of the Spanish rule, is given by Buzeta, vol. i., pp. 57–98. ↑

2 I visited some Cochin Chinese prisoners in the fortification. They had been taken at Turon, and one of them was a mandarin, who had exercised some authority there,—said to have been the commandant of the place. They wrote the Chinese characters, but were unable to understand the spoken language. ↑

3 Among my early literary efforts was an essay by which the strange story was utterly disproved of the destruction of the MSS. which had served Cardinal Ximenes in preparing his Polyglot Bible. ↑

4 One woman, six children. ↑

5 All children. ↑

1 A recent History of the Conquest of the Islands, and of the Spanish rule, is given by Buzeta, vol. i., pp. 57–98. ↑

2 I visited some Cochin Chinese prisoners in the fortification. They had been taken at Turon, and one of them was a mandarin, who had exercised some authority there,—said to have been the commandant of the place. They wrote the Chinese characters, but were unable to understand the spoken language. ↑

3 Among my early literary efforts was an essay by which the strange story was utterly disproved of the destruction of the MSS. which had served Cardinal Ximenes in preparing his Polyglot Bible. ↑

4 One woman, six children. ↑

5 All children. ↑

CHAPTER II.

VISIT TO LA LAGUNA AND TAYABAS.

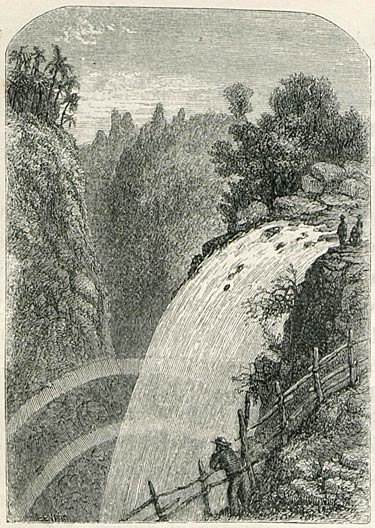

WATERFALL OF THE BOTOCAN.

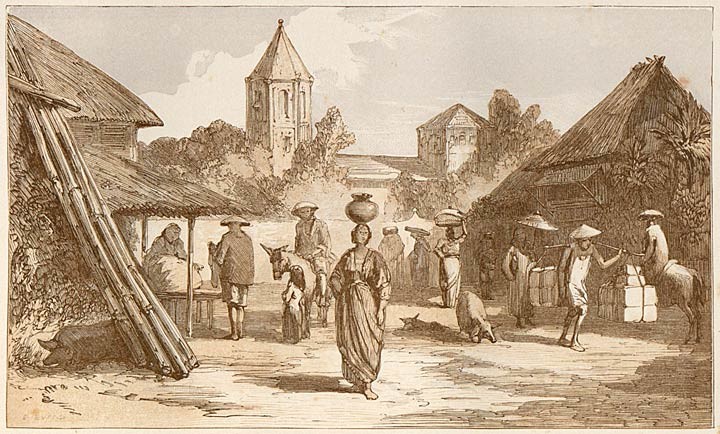

Having arranged for a visit to the Laguna and the surrounding hills, whose beautiful scenery has given to the island of Luzon a widely-spread celebrity, we started accompanied by the Alcalde Mayor, De la Herran, Colonel Trasierra, an aide-de-camp of the Governor, appointed to be my special guide and guardian, my kind friend and gentlemanly companion Captain Vansittart, and some other gentlemen. The inhabitants of the Laguna are called by the Indians of Manila Tagasilañgan, or Orientals. As we reached the various villages, the Principalia, or native authorities, came out to meet us, and musical bands escorted us into and out of all the pueblos. We found the Indian villages decorated with coloured flags and embroidered kerchiefs, and the firing of guns announced our arrival. The roads were prettily decorated with bamboos and flowers, and everything proclaimed a hearty, however simple welcome. The thick and many-tinted foliage of the mango—the tall bamboos shaking their feathery heads aloft—the cocoa-nut loftier still—the areca and the nipa palms—the plantains, whose huge green leaves give such richness to a tropical landscape—the bread-fruit, the papaya, and the bright-coloured wild-flowers, which stray at will over banks and branches—the river every now and then visible, with its canoes and cottages, and Indian men, women, and children scattered along its banks. Over an excellent road, we passed through Santa Ana to Taguig, where a bamboo bridge had been somewhat precipitately erected to facilitate our passage over the stream: the first carriage got over in safety; with the second the bridge broke down, and some delay was experienced in repairing the disaster, and enabling the other carriages to come forward. Taguig is a pretty village, with thermal baths, and about 4,000 inhabitants; its fish is said to be particularly fine. Near it is Pateros, which no doubt takes its name from the enormous quantity of artificially hatched ducks (patos) which are bred there, and which are seen in incredible numbers on the banks of the river. They are fed by small shell-fish found abundantly in the neighbouring lake, and which are brought in boats to the paterias on the banks of the Pasig. This duck-raising is called Itig by the Indians. Each pateria is separated from its neighbour by a bamboo enclosure on the river, and at sunset the ducks withdraw from the water to adjacent buildings, where they deposit their eggs during the night, and in the morning return in long procession to the river. The eggs being collected are placed in large receptacles containing warm paddy husks, which are kept at the same temperature; the whole is covered with cloth, and they are removed by their owners as fast as they are hatched. We saw hundreds of the ducklings running about in shallow bamboo baskets, waiting to be transferred to the banks of the river. The friar at Pasig came out from his convent to receive us. It is a populous pueblo, containing more than 22,000 souls. There is a school for Indian women. It has stone quarries worked for consumption in Manila, but the stone is soft and brittle. The neighbourhood is adorned with gardens. Our host the friar had prepared for us in the convent a collation, which was served with much neatness and attention, and with cordial hospitality. Having reached the limits of his alcadia, the kind magistrate and his attendants left us, and we entered a falua (felucca) provided for us by the Intendente de Marina, with a goodly number of rowers, and furnished with a carpet, cushions, curtains, and other comfortable appliances. In this we started for the Laguna, heralded by a band of musicians. The rowers stand erect, and at every stroke of the oar fling themselves back upon their seats; they thus give a great impulse to the boat; the exertion appears very laborious, yet their work was done with admirable good-humour, and when they were drenched with rain there was not a murmur. In the lake (which is called Bay) is an island, between which and the main land is a deep and dangerous channel named Quinabatasan, through which we passed. The stream rushes by with great rapidity, and vessels are often lost in the passage. The banks are covered with fine fruit trees, and the hills rise grandly on all sides. Our destination was Santa Cruz, and long before we arrived a pilot boat had been despatched in order to herald our coming. The sun had set, but we perceived, as we approached, that the streets were illuminated, and we heard the wonted Indian music in the distance. Reaching the river, we were conducted to a gaily-lighted and decorated raft, which landed us,—and a suite of carriages, in one of which was the Alcalde, who had come from his Cabacera, or head quarters, to take charge of us,—conducted the party to a handsome house belonging to an opulent Indian, where we found, in the course of preparation, a very handsome dinner or supper, and all the notables of the locality, the priest, as a matter of course, among them, assembled to welcome the strangers. We passed a theatre, which appeared hastily erected and grotesquely adorned, where, as we were informed, it was intended to exhibit an Indian play in the Tagál language, for our edification and amusement. I was too unwell to attend, but I heard there was much talk on the stage (unintelligible, of course, to our party), and brandishing of swords, and frowns and fierce fighting, and genii hunting women into wild forests, and kings and queens gaily dressed. The stage was open from the street to the multitude, of whom many thousands were reported to be present, showing great interest and excitement. I was told that some of the actors had been imported from Manila. The hospitality of our host was super-abundant, and his table crowded not only with native but with many European luxuries. He was dressed as an Indian, and exhibited his wardrobe with some pride. He himself served us at his own table, and looked and moved about as if he were greatly honoured by the service. His name, which I gratefully record, is Valentin Valenzuela, and his brother has reached the distinction of being an ordained priest.

Santa Cruz has a population of about 10,000 souls. Many of its inhabitants are said to be opulent. The church is handsome; the roads in the neighbourhood broad and in good repair. There is much game in the adjacent forests, but there is not much devotion to the chase. Almost every variety of tropical produce grows in the vicinity. Wild honey is collected by the natives of the interior, and stuffs of cotton and abacá are woven for domestic use. The house to which we were invited was well furnished, but with the usual adornings of saints’ images and vessels for holy water. In the evening the Tagála ladies of the town and neighbourhood were invited to a ball, and the day was closed with the accustomed light-heartedness and festivity: the bolero and the jota seemed the favourite attractions. Dance and music are the Indians’ delight, and very many of the evenings we passed in the Philippines were devoted to these enjoyments. Next morning the carriages of the Alcalde, drawn by the pretty little ponies of Luzon, conducted us to the casa real at Pagsanjan, the seat of the government, or Cabacera, of the province, where we met with the usual warm reception from our escort Señor Tafalla, the Alcalde. Pagsanjan has about 5,000 inhabitants, being less populous than Biñan and other pueblos in the province. Hospitality was here, as everywhere, the order of the day and of the night, all the more to be valued as there are no inns out of the capital, and no places of reception for travellers; but he who is recommended to the authorities and patronized by the friars will find nothing wanting for his accommodation and comfort, and will rather be surprised at the superfluities of good living than struck with the absence of anything necessary. I have been sometimes amazed when the stores of the convent furnished wines which had been kept from twenty to twenty-five years; and to say that the cigars and chocolate provided by the good friars would satisfy the most critical of critics, is only to do justice to the gifts and the givers.

We made an excursion to the pretty village of Lumbang, having, as customary, been escorted to the banks of the river, which forms the limit of the pueblo, by the mounted principalia of Pagsanjan. The current was strong, but a barge awaited us and conveyed us to the front of the convent on the other side, where the principal ecclesiastic, a friar, conducted us to the reception rooms. We walked through the pueblo, whose inhabitants amount to 5,000 Indians, occupying one long broad street, where many coloured handkerchiefs and garments were hung out as flags from the windows, which were crowded with spectators. We returned to the Cabacera, where we slept. Early in the morning we took our departure from Pagsanjan.

VILLAGE OF MAJAJAY

We next advanced into the more elevated regions, growing more wild and wonderful in their beauties. As we proceeded the roads became worse and worse, and our horses had some difficulty in dragging the carriages through the deep mud. We had often to ask for assistance from the Indians to extricate us from the ruts, and they came to our aid with patient and persevering cheerfulness. When the main road was absolutely impassable, we deviated into the forest, and the Indians, with large knives—their constant companions—chopped down the impeding bushes and branches, and made for us a practicable way. After some hours’ journey we arrived at Majayjay, and between files of Indians, with their flags and music, were escorted to the convent, whence the good Franciscan friar Maximo Rico came to meet us, and led us up the wide staircase to the vast apartments above. The pueblo has about 8,500 inhabitants; the climate is humid, and its effects are seen in the magnificent vegetation which surrounds the place. The church and convent are by far the most remarkable of its edifices. Here we are surrounded by mountain scenery, and the forest trees present beautiful and various pictures. In addition to leaves, flowers and fruits of novel shapes and colours, the grotesque forms which the trunks and branches of tropical trees assume, as if encouraged to indulge in a thousand odd caprices, are among the characteristics of these regions. The native population availed themselves of the rude and rugged character of the region to offer a long resistance to the Spaniards on their first invasion, and its traditional means of defence were reported to be so great that the treasures of Manila were ordered to be transported thither on the landing of the English in 1762. Fortunately, say the Spanish historians, the arrangement was not carried out, as the English had taken their measures for the seizure of the spoils, and it was found the locality could not have been defended against them.

We were now about to ascend the mountains, and were obliged to abandon our carriages. Palanquins, in which we had to stretch ourselves at full length, borne each by eight bearers, and relays of an equal number, were provided for our accommodation. The Alcalde of the adjacent province of Tayabas had come down to Majayjay to invite us into his district, where, he said, the people were on the tiptoe of expectation, had made arrangements for our reception, and would be sadly disappointed if we failed to visit Lucban. We could not resist the kind urgency of his representations, and deposited ourselves in the palanquins, which had been got ready for us, and were indeed well rewarded. The paths through the mountains are such as have been made by the torrents, and are frequently almost impassable from the masses of rock brought down by the rushing waters. Sometimes we had to turn back from the selected road, and choose another less impracticable. In some places the mud was so deep that our bearers were immersed far above their knees, and nothing but long practice and the assistance of their companions could have enabled them to extricate themselves or us from so disagreeable a condition. But cheerfulness and buoyancy of spirits, exclamations of encouragement, loud laughter, and a general and brotherly co-operation surmounted every difficulty. Around us all was solitude, all silence, but the hum of the bees and the shrieks of the birds; deep ravines below, covered with forest trees, which no axe of the woodman would ever disturb; heights above still more difficult to explore, crowned with arboreous glories; brooks and rivulets noisily descending to larger streams, and then making their quiet way to the ocean receptacle. At last we reached a plain on the top of a mountain, where two grandly adorned litters, with a great number of bearers, were waiting, and we were welcomed by a gathering of graceful young women, all on ponies, which they managed with admirable agility. They were clad in the gayest dresses. The Alcalde called them his Amazonas; and a pretty spokeswoman informed us, in very pure Castilian, that they were come to escort us to Lucban, which was about a league distant. The welcome was as novel as it was unexpected. I observed the Tagálas mounted indifferently on the off or near side of their horses. Excellent equestrians were they; and they galloped and caracolled to the right and the left, and flirted with their embellished whips. A band of music headed us; and the Indian houses which we passed bore the accustomed demonstrations of welcome. The roads had even a greater number of decorations—arches of ornamented bamboos on both sides of the way, and firing of guns announcing our approach. The Amazonas wore bonnets adorned with ribands and flowers,—all had kerchiefs of embroidered piña on their shoulders, and variously coloured skirts and gowns of native manufacture added to the picturesque effect. So they gambolled along—before, behind, or at our sides where the roads permitted it—and seemed quite at ease in all their movements. The convent was, as usual, our destination; the presiding friar—quite a man of the world—cordial, amusing, even witty in his colloquies. He had most hospitably provided for our advent. All the principal people were invited to dinner. Many a joke went round, to which the friar contributed more than his share. Talking of the fair (if Indian girls can be so called), Captain Vansittart said he had thirty unmarried officers on board the Magicienne.

TRAVELLING BY PALKEE.

“A bargain,” exclaimed the friar; “send them hither,—I will find pretty wives for all of them.”

“But you must convert them first.”

“Ay! that is my part of the bargain.”

“And you will get the marriage fees.”

“Do you think I forgot that?”

After dinner, or supper, as it was called, the Amazonas who had escorted us in the morning, accompanied by many more, were introduced; the tables were cleared away; and when I left the hall for my bedroom, the dancing was going on in full energy.

Newspapers and books were lying about the rooms of the convent. The friar had more curiosity than most of his order: conversation with him was not without interest and instruction.

We returned by a different road to Majayjay, for the purpose of visiting a splendid waterfall, where the descent of the river is reported to be 300 feet. We approached on a ledge of rock as near as we could to the cataract, the roar of which was awful; but the quantity of mist and steam, which soon soaked our garments, obscured the vision and made it impossible for us to form any estimate of the depth of the fall. It is surrounded by characteristic scenery—mountains and woods—which we had no time to explore, and of which the natives could give us only an imperfect account: they knew there were deer, wild boars, buffaloes, and other game, but none had penetrated the wilder regions. A traveller now and then had scrambled over the rocks from the foot to the top of the waterfall

We returned to Majayjay again to be welcomed and entertained by our hosts at the convent with the wonted hospitality; and taking leave of our Alcalde, we proceeded to Santa Cruz, where, embarking in our felucca, we coasted along the lake and landed at Calamba, a pueblo of about 4,000 inhabitants; carriages were waiting to convey us to Biñan, stopping a short time at Santa Rosa, where the Dominican friars, who are the proprietors of large estates in the neighbourhood, invited us as usual to their convent. We tarried there but a short time. The roads are generally good on the borders of the Laguna, and we reached Biñan before sunset, the Indians having in the main street formed themselves in procession as we passed along. Flags, branches of flowering forest trees, and other devices, were displayed. First we passed between files of youths, then of maidens; and through a triumphal arch we reached the handsome dwelling of a rich mestizo, whom we found decorated with a Spanish order, which had been granted to his father before him. He spoke English, having been educated at Calcutta, and his house—a very large one—gave abundant evidence that he had not studied in vain the arts of domestic civilization. The furniture, the beds, the tables, the cookery, were all in good taste, and the obvious sincerity of the kind reception added to its agreeableness. Great crowds were gathered together in the square which fronts the house of Don José Alberto. Indians brought their game-cocks to be admired, but we did not encourage the display of their warlike virtues. There was much firing of guns, and a pyrotechnic display when the sun had gone down, and a large fire balloon, bearing the inscription, “The people of Biñan to their illustrious visitors,” was successfully inflated, and soaring aloft, was lost sight of in the distance, but was expected to tell the tale of our arrival to the Magicienne in Manila Bay. Biñan is a place of some importance. In it many rich mestizos and Indians dwell. It has more than 10,000 inhabitants. Large estates there are possessed by the Dominican friars, and the principal of them was among our earliest visitors. There, as elsewhere, the principalia, having conducted us to our head-quarters, came in a body to present their respects, the gobernadorcillo, who usually speaks Spanish, being the organ of the rest. Inquiries about the locality, thanks for the honours done us, were the commonplaces of our intercourse, but the natives were always pleased when “the strangers from afar” seemed to take an interest in their concerns. Nowhere did we see any marks of poverty; nowhere was there any crowding, or rudeness, or annoyance, in any shape. Actors and spectators seemed equally pleased; in fact, our presence only gave them another holiday, making but a small addition to their regular and appointed festivals. Biñan is divided by a river, and is about a mile from the Laguna. Its streets are of considerable width, and the neighbouring roads excellent. Generally the houses have gardens attached to them; some on a large scale. They are abundant in fruits of great variety. Rice is largely cultivated, as the river with its confluents affords ample means of irrigation. The lands are usually rented from the Dominicans, and the large extent of some of the properties assists economical cultivation. Until the lands are brought into productiveness, little rent is demanded, and when they become productive the friars have the reputation of being liberal landlords and allowing their tenants to reap large profits. It is said they are satisfied with one-tenth of the gross produce. A tenant is seldom disturbed in possession if his rent be regularly paid. Much land is held by associations or companies known by the title of Casamahanes. There is an active trade between Biñan and Manila.

Greatly gratified with all we had seen, we again embarked and crossed the Laguna to Pasig. Descending by that charming river, we reached Manila in the afternoon.

CHAPTER III.

HISTORY.

A few sketches of the personal history of some of the captains-general of Manila will be an apt illustration of the general character of the government, which, with some remarkable exceptions, appears to have been of a mild and paternal character; while the Indians exhibit, when not severely dealt with, much meekness and docility, and a generally willing obedience. The subjugation of the wild tribes of the interior has not made the progress which might have been fairly looked for; but the military and naval forces at the disposal of the captain-general have always been small when the extent of his authority is considered. In fact, many conquests have had to be abandoned from inadequacy of strength to maintain them. The ecclesiastical influences, which have been established among the idolatrous tribes, are weak when they come in contact with any of the forms of Mahomedanism, as in the island of Mindanao, where the fanaticism of Mussulman faith is quite as strong as that among the Catholics themselves. Misunderstandings between the Church and State could hardly be avoided where each has asserted a predominant power, and such misunderstandings have often led to the effusion of blood and the dislocation of government. Mutual jealousies exist to the present hour, and as the friars, in what they deem the interests of the people, are sometimes hostile to the views of the civil authority, that authority has frequently a right to complain of being thwarted, or feebly aided, by the local clergy.

While shortly recording the names of the captains-general to whom the government of the Philippines has been confided, I will select a few episodes from the history of the islands, which will show the character of the administration, and assist the better understanding of the position of the people.

Miguel Lope de Legaspi, a Biscayan, upon whom the title of Conqueror of the Philippines has been conferred, was the first governor, and was nominated in 1565. He took possession of Manila in 1571, and died, it is said, of disgust and disappointment the following year. The city was invaded by Chinese pirates during the government of his successor Guido de Lavezares, who repulsed them, and received high honours from his sovereign, Philip II. Francisco de Saude founded in Camarines the city of Nueva Caceres, to which he gave the name of the place of his birth. He was a man of great ambition, who deposed one and enthroned another sultan of Borneo, and modestly asked from the king of Spain authority to conquer China, but was recommended to be less ambitious, and to keep peace with surrounding nations. Rinquillo de Peñarosa rescued Cagayan from a Japanese pirate, and founded New Segovia and Arévalo in Panay; his nephew succeeded him, and in doing honour to his memory set the Church of St. Augustin on fire; it spread to the city, of which a large part was destroyed. In 1589, during the rule of Santiago de Vera, the only two ships which carried on the trade with New Spain were destroyed by a hurricane in the port of Cavite. The next governor, Gomez Perez Dasmariñas, sent to Japan the missionaries who were afterwards put to death; he headed an expedition to Moluco, but on leaving the port of Mariveles his galley was separated from the rest of the fleet; the Chinese crew rose, murdered him, and fled in his vessel to Cochin China. His son Luis followed him as governor. A Franciscan friar, who had accompanied the unfortunate expedition of his father, informed him that he would find, as he did, his patent of appointment in a box which the Chinese had landed in the province of Ilocos, and his title was in consequence recognised. Francisco Tello de Guzman, who entered upon the government in 1596, was unfortunate in his attempts to subdue the natives of Mindanao, as was one of his captains, who had been sent to drive away the Dutch from Mariveles.

In the year 1603 three mandarins arrived in Manila from China. They said that a Chinaman, whom they brought as a prisoner, had assured the Emperor that the island of Cavite was of gold, that the Chinaman had staked his life upon his veracity, and that they had come to learn the truth of his story. They soon after left, having been conducted by the governor to examine Cavite for themselves. A report speedily spread that an invasion of the Philippines by a Chinese army of 100,000 was in contemplation, and a Chinese called Eng Kang, who was supposed to be a great friend of the Europeans, was charged with a portion of the defences. A number of Japanese, the avowed enemies of the Chinese, were admitted to the confidence of the governor, and communicated to the Chinese the information that the government suspected a plot. A plot there was, and it was said the Chinese determined on a rising, and a general massacre of the Spaniards on the vespers of St. Francis’ day. A Philippine woman, who was living with a Chinaman, denounced the project to the curate of Quiapo, who advised the governor. A number of the conspirators were assembled at a half-league’s distance from Manila, and Eng Kang was sent with some Spaniards to put down the movement. The attempt failed, and Eng Kang was afterwards discovered to have been one of the principal promoters of the insurrection. In the evening the Chinese attacked Quiapo and Tondo, murdering many of the natives. They were met by a body of 130 Spaniards, nearly all of whom perished, and their heads were sent to Parian, which the insurgents captured, and besieged the city of Manila from Dilao. The danger led to great exertions on the part of the Spaniards, the ecclesiastics taking a very active part. The Chinese endeavoured to scale the walls, but were repulsed. The monks declared that St. Francis had appeared in person to encourage them. The Chinese withdrew to their positions, but the Spaniards sallied out from the citadel, burnt and destroyed Parian, and pursued the flying Chinese to Cabuyao. New reinforcements arrived, and the flight of the Chinese continued as far as the province of Batangas, where they were again attacked and dispersed. It is said that of 24,000 revolted Chinese only one hundred escaped, who were reserved for the galleys. About 2,000 Chinese were left, who had not involved themselves in the movement. Eng Kang was decapitated, and his head exposed in an iron cage. It was three years after this insurrection that the Court of Madrid had the first knowledge of its existence.

Pedro de Acuña, after the suppression of this revolt, conquered Ternate, and carried away the king, but died suddenly, in 1606, after governing four years. Cristobal Tellez, during his short rule, destroyed a settlement of the Japanese in Dilao. Juan de Silva brought with him, in 1609, reinforcements of European troops, and in the seventh year of his government, made great preparations for attacking the Dutch, but died after a short illness. In 1618, Alonzo Fajardo came to the Philippines, with conciliatory orders as regarded the natives, and was popular among them. He punished a revolt in Buhol, sent an unsuccessful mission to Japan, and in a fit of jealousy killed his wife. Suspecting her infidelity, he surprised her at night in a house, where she had been accustomed to give rendezvous to her paramour, and found her in a dress which left no doubt of her crime. The governor called in a priest, commanded him to administer the sacrament, and, spite of the prayers of the ecclesiastic, he put her to death by a stab from his own dagger. This was in 1622. Melancholy took possession of him, and he died in 1624. Two interim governors followed. Juan Niño de Tabera arrived in 1626. He brought with him 600 troops, drove the Dutch from their holds, and sent Olaso, a soldier, celebrated for his deeds in Flanders, against the Jolo Indians; but Olaso failed utterly, and returned to Manila upon his discomfiture.

A strange event took place in 1630. The holy sacrament had been stolen in a glass vase, from the cathedral. A general supplication (rogativa) was ordered; the archbishop issued from his palace barefooted, his head covered with ashes, and a rope round his neck, wandering about to discover where the vase was concealed. All attempts having failed, so heavy were the penitences, and so intolerable the grief of the holy man, that he sank under the calamity, and a fierce contest between the ecclesiastical and civil functionaries was the consequence of his death.

In 1635 there was a large arrival of rich converted Japanese, who fled from the fierce persecutions to which the Christians had been subjected in Japan; but a great many Catholic missionaries hastened to that country, in order to be honoured with the crown of martyrdom. Another remarkable ecclesiastical quarrel took place at this time. A commissary, lately arrived from Europe, ordered that all the friars with beards should be charged with the missions to China and Japan; and all the shorn friars should remain in the Philippines. The archbishop opposed this, as the Pope’s bulls had no regulations about beards. Fierce debates were also excited by the exercise of the right of asylum to criminals, having committed offences, either against the military or the civil authority. The archbishop excommunicated—the commandant of artillery rebelled. The archbishop fined him—the vicar apostolic confirmed the sentence. The Audiencia annulled the proceedings—the Bishop of Camarines was called on as the arbiter, and absolved the commandant. Appeals followed, and one of the parties was accused of slandering the Most Holy Father. The Jesuits took part against the archbishop, who called all the monks together, and they fined the Jesuits 4,000 dollars. The governor defended the Jesuits, and required the revocation of the sentence in six hours. The quarrel did not end here: but there was a final compromise, each party making some concessions to the other.

The disasters which followed the insurrection of Eng Kang did not prevent the influx of Chinese into the islands, and especially into the province of Laguna, where another outbreak, in which it is said 30,000 Chinese took part, occurred in 1639. They divided themselves into guerrillas, who devastated the country; but were subdued in the following year, seven thousand having surrendered at discretion. Spanish historians say that the hatred of the Indians to the Chinese awaked them from their habitual apathy, and that in the destruction of the intruders they exhibited infinite zeal and activity.

In the struggles between the natives and the Spaniards, even the missionaries were not always safe, and the Spaniards were often betrayed by those in whom they placed the greatest confidence. The heavy exactions and gabelles inflicted on the Indians under Fajardo led to a rising in Palopag, when the Jesuit curate was killed and the convent and church sacked. The movement spread through several of the islands, and many of the prisoners were delivered in Caraga to the keeping of an Indian, called Dabao, who so well fulfilled his mission, that when the governor came to the fortress, to claim the captives, Dabao seized and beheaded his Excellency, and, with the aid of the prisoners, destroyed most of the Spaniards in the neighbourhood, including the priests; so that only six, among whom was an Augustine barefooted friar, escaped, and fled to the capital. Reinforcements having arrived from Manila, the Indians surrendered, being promised a general pardon. “The promise,” says the Spanish historian, “was not kept; but the leaders of the insurrection were hanged, and multitudes of the Indians sent to prison.” The governor-general “did not approve of this violation of a promise made in the king’s name,” but ordered the punishment of the Spanish chiefs, and the release of such natives as remained in prison.

In 1645, for two months there was a succession of fearful earthquakes. In Cagayan a mountain was overturned, and a whole town engulfed at its foot. Torrents of water and mud burst forth in many places. All the public buildings in the capital were destroyed, except the convent and the church of the Augustines, and that of the Jesuits. Six hundred persons were buried in Manila under the ruins of their houses, and 3,000 altogether are said to have lost their lives.