автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Inhabitants of the Philippines

The Inhabitants of the Philippines

Frontispiece.

The Inhabitants of the Philippines

By

Frederic H. Sawyer

Memb. Inst. C.E., Memb. Inst. N.A.

London

Sampson Low, Marston and Company Limited

St. Dunstan’s House

Fetter Lane, Fleet Street, E.C.

1900

London:

Printed by William Clowes and Sons, Limited,

Stamford Street and Charing Cross.

Preface.

The writer feels that no English book does justice to the natives of the Philippines, and this conviction has impelled him to publish his own more favourable estimate of them. He arrived in Manila with a thorough command of the Spanish language, and soon acquired a knowledge of the Tagal dialect. His avocations brought him into contact with all classes of the community—officials, priests, land-owners, mechanics, and peasantry: giving him an unrivalled opportunity to learn their ideas and observe their manners and customs. He resided in Luzon for fourteen years, making trips either on business or for sport all over the Central and Southern Provinces, also visiting Cebú, Iloilo, and other ports in Visayas, as well as Calamianes, Cuyos, and Palawan.

Old Spanish chroniclers praise the good breeding of the natives, and remark the quick intelligence of the young.

Recent writers are less favourable; Cañamaque holds them up to ridicule, Monteverde denies them the possession of any good quality either of body or mind.

Foreman declares that a voluntary concession of justice is regarded by them as a sign of weakness; other writers judge them from a few days’ experience of some of the cross-bred corrupted denizens of Manila.

Mr. Whitelaw Reid denounces them as rebels, savages, and treacherous barbarians.

Mr. McKinley is struck by their ingratitude for American kindness and mercy.

Senator Beveridge declares that the inhabitants of Mindanao are incapable of civilisation.

It seems to have been left to French and German contemporary writers, such as Dr. Montano and Professor Blumentritt to show a more appreciative, and the author thinks, a fairer spirit, than those who have requited the hospitality of the Filipinos by painting them in the darkest colours. It will be only fair to exempt from this censure two American naval officers, Paymaster Wilcox and Mr. L. S. Sargent, who travelled in North Luzon and drew up a report of what they saw.

As regards the accusation of being savages, the Tagals can claim to have treated their prisoners of war, both Spaniards and Americans with humanity, and to be fairer fighters than the Boers.

The writer has endeavoured to describe the people as he found them. If his estimate of them is more favourable than that of others, it may be that he exercised more care in declining to do business with, or to admit to his service natives of doubtful reputation; for he found his clients punctual in their payments, and his employés, workmen and servants, skilful, industrious, and grateful for benefits bestowed.

If the natives fared badly at the hands of recent authors, the Spanish Administration fared worse, for it has been painted in the darkest tints, and unsparingly condemned.

It was indeed corrupt and defective, and what government is not? More than anything, it was behind the age, yet it was not without its good points.

Until an inept bureaucracy was substituted for the old paternal rule, and the revenue quadrupled by increased taxation, the Filipinos were as happy a community as could be found in any colony. The population greatly multiplied; they lived in competence, if not in affluence; cultivation was extended, and the exports steadily increased.

The natives were secured the perpetual usufruct of the land they tilled, they were protected against the usurer, that curse of East and West.

In guaranteeing the land to the husbandman, the “Laws of the Indies” compare favourably with the law of the United States regarding Indian land tenure. The Supreme Court in 1823 decided that “discovery gives the dominion of the land discovered to the States of which the discoverers were the subjects.”

It has been almost an axiom with some writers that no advance was made or could be made under Spanish rule.

There were difficulties indeed. The Colonial Minister, importuned on the one hand by doctrinaire liberals, whose crude schemes of reform would have set the Archipelago on fire, and confronted on the other by the serried phalanx of the Friars with their hired literary bravos, was very much in the position of being between the devil and the deep sea, or, as the Spaniards phrase it “entre la espada y la pared.”

Even thus the Administration could boast of some reforms and improvements.

The hateful slavery of the Cagayanes had been abolished; the forced cultivation of tobacco was a thing of the past, and in all the Archipelago the corvée had been reduced.

A telegraph cable connecting Manila with Hong Kong and the world’s telegraph system had been laid and subsidized. Telegraph wires were extended to all the principal towns of Luzon; lines of mail steamers to all the principal ports of the Archipelago were established and subsidized. A railway 120 miles long had been built from Manila to Dagupan under guarantee. A steam tramway had been laid to Malabon, and horse tramways through the suburbs of Manila. The Quay walls of the Pasig had been improved, and the river illuminated from its mouth to the bridge by powerful electric arc lights.

Several lighthouses had been built, others were in progress. A capacious harbour was in construction, although unfortunately defective in design and execution. The Manila waterworks had been completed and greatly reduced the mortality of the city. The schools were well attended, and a large proportion of the population could read and write. Technical schools had been established in Manila and Iloilo, and were eagerly attended. Credit appears to be due to the Administration for these measures, but it is rare to see any mention of them.

As regards the Religious Orders that have played so important a part scarcely a word has been said in their favour. Worcester declares his conviction that their influence is wholly bad. However they take a lot of killing and seem to have got round the Peace Commission and General Otis.

They are not wholly bad, and they have had a glorious history. They held the islands from 1570 to 1828, without any permanent garrison of Spanish regular troops, and from 1828 to 1883 with about 1500 artillerymen. They did not entirely rely upon brute force. They are certainly no longer suited to the circumstances of the Philippines having survived their utility. They are an anachronism. But they have brought the Philippines a long way on the path of civilisation. Let us be just; what British, French, or Dutch colony, populated by natives, can compare with the Philippines as they were till 1895?

And what about American rule? It has begun unfortunately, and has raised a feeling of hatred in the natives that will take a generation to efface. It will not be enough for the United States to beat down armed resistance. A huge army must be maintained to keep the natives down. As soon as the Americans are at war with one of the Great Powers, the natives will rise; whenever a land-tax is imposed there will be an insurrection.

The great difference between this war and former insurrections is that now for the first time the natives have rifles and ammunition, and have learned to use them. Not all the United States Navy can stop them from bringing in fresh supplies. Unless some arrangement is come to with the natives, there can be no lasting peace. Such an arrangement I believe quite possible, and that it could be brought about in a manner satisfactory to both parties.

This would not be, however, on the lines suggested in the National Review of September under the heading, “Will the United States withdraw from the Philippines?”

Three centuries of Spanish rule is not a fit preparation for undertaking the government of the Archipelago. But Central and Southern Luzon, with the adjacent islands, might be formed into a State whose inhabitants would be all Tagals and Vicols, and the northern part into another State whose most important peoples would be the Pampangos, the Pangasinanes, the Ilocanos, and the Cagayanes; the Igorrotes and other heathen having a special Protector to look after their interests.

Visayas might form a third State, all the inhabitants being of that race, whilst Mindanao and Southern Palawan should be entirely governed by Americans like a British Crown Colony.

The Sulu Sultanate could be a Protectorate similar to North Borneo or the Malay States. Manila could be a sort of Federal District, and the Consuls would be accredited to the President’s representative, the foreign relations being solely under his direction. There should be one tariff for all the islands, for revenue only, treating all nations alike, the custom houses, telegraphs, post offices, and lighthouse service being administered by United States officials, either native or American. With power thus limited, the Tagals, Pampangos, and Visayas might be entrusted with their own affairs, and no garrisons need be kept, except in certain selected healthy spots, always having transports at hand to convey them wherever they were wanted. If, as seems probable, Mr. McKinley should be re-elected, I hope he will attempt some such arrangement, and I heartily wish him success in pacifying this sorely troubled country, the scene of four years continuous massacre.

The Archipelago is at present in absolute anarchy, the exports have diminished by half, and whereas we used to travel and camp out in absolute security, now no white man dare show his face more than a mile from a garrison.

Notwithstanding this, some supporters of the Administration in the States are advising young men with capital that there is a great opening for them as planters in the Islands.

There may be when the Islands are pacified, but not before.

To all who contemplate proceeding to or doing any business, or taking stock in any company in the Philippines, I recommend a careful study of my book. They cannot fail to benefit by it.

Red Hill, Oct. 15th, 1900.

Salámat.

The author desires to express his hearty thanks to all those who have assisted him.

To Father Joaquin Sancho, S.J., Procurator of Colonial Missions, Madrid, for the books, maps and photographs relating to Mindanao, with permission to use them.

To Mr. H. W. B. Harrison of the British Embassy, Madrid, for his kindness in taking photographs and obtaining books.

To Don Francisco de P. Vigil, Director of the Colonial Museum, Madrid, for affording special facilities for photographing the Anitos and other curiosities of the Igorrotes.

To Messrs. J. Laurent and Co., Madrid, for permission to reproduce interesting photographs of savage and civilised natives.

To Mr. George Gilchrist of Manila, for photographs, and for the use of his diary with particulars of the Tagal insurrection, and for descriptions of some incidents of which he was an eye-witness.

To Mr. C. E. de Bertodano, C.E., of Victoria Street, Westminster, for the use of books of reference and for information afforded.

To Mr. William Harrison of Billiter Square, E.C., for the use of photographs of Vicols cleaning hemp.

To the late Mr. F. W. Campion of Trumpets Hill, Reigate, for the photograph of Salacot and Bolo taken from very fine specimens in his possession, and for the use of other photographs.

To Messrs. Smith, Bell and Co. of Manila, for the very complete table of exports which they most kindly supplied.

To Don Sixto Lopez of Balayan, for the loan of the Congressional Record, the Blue Book of the 55th Congress, 3rd Session, and other books.

To the Superintendent of the Reading Room and his Assistants for their courtesy and help when consulting the old Spanish histories in the noble library of the British Museum.

Alphabetical List of Works Cited, Referred to, or Studied whilst Preparing this Work.

Abella, Enrique—‘Informes’ (Reports).

Anonymous—‘Catálogo Oficial de la Exposicion de Filipinas’; ‘Filipinas: Problema Fundamental,’ 1887; ‘Relacion de las Yslas Filipinas,’ 1595; ‘Las Filipinas se pierden,’ a scurrilous Spanish pamphlet, Manila, 1841; ‘Aviso al publico,’ account of an attempt by the French to cause Joseph Bonaparte to be acknowledged King of the Philippines.

Barrantes Vicente—‘Guerras piraticas de Filipinas contra Mindanaos y Joloanos,’ Madrid, 1878, and other writings.

Becke, Louis—‘Wild Life in Southern Seas.’

Bent, Mrs. Theodore—‘Southern Arabia.’

Blanco, Padre—‘Flora Filipina.’

Blumentritt, Professor Ferdinand—‘Versuch einer Ethnographie der Philippinen’ (Petermann’s).

Brantôme, Abbé de—(In Motley’s ‘Rise of the Dutch Republic.’)

Cavada, Agustin de la—‘Historia, Geografica, Geologica, y estadistica de Filipinas,’ Manila, 1876, 1877.

Centeno, José—‘Informes’ (Reports).

Clifford, Hugh—‘Studies in Brown Humanity,’ ‘In Court and Kampong.’

Comyn, Tomas de.

Crawford, John—‘History of the Indian Archipelago,’ Edinburgh, 1820; ‘Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands,’ London, 1856.

Cuming, E. D.—‘With the Jungle Folk.’

Dampier, William—(from Pinkerton).

De Guignes—‘Voyage to Pekin, Manila, and Isle of France.’

D’Urville, Dumont.

Foreman, John—‘The Philippine Islands,’ first and second editions.

Garcilasso, Inca de la Vega—‘Comentarios Réales.’

Gironière, Paul de la—‘Vingt ans aux Philippines.’

Jagor, F.—‘Travels in the Philippines.’

Jesuits, Society of—‘Cartas de los P.P. de la Cia de Jesus de la mision de Filipinas,’ Cuads ix y x (1891–95); ‘Estados Generales,’ Manila, 1896, 1897; ‘Mapa Politica Hidrografica’; ‘Plano de los Distritos 2o y 5o de Mindanao’; ‘Mapa de Basilan.’

Mas, Sinibaldo de—‘Informe sobre el estado de las Yslas Filipinas en 1842.’

Montano, Dr. J.—‘Voyage aux Philippines,’ Paris, 1886.

Monteverde, Colonel Federico de—‘La Division Lachambre.’

Morga, Antonio de—‘Sucesos de las Yslas Filipinas,’ Mejico, 1609.

Motley, John Lothrop—‘Rise of the Dutch Republic.’

Navarro, Fr. Eduardo—‘Filipinas. Estudio de Asuntos de momento,’ 1897.

Nieto José—‘Mindanao, su Historia y Geographia,’ 1894.

Palgrave, W. G.—‘Ulysses, or Scenes in Many Lands’; ‘Malay Life in the Philippines.’

Petermann—‘Petermanns Mitth.’, Ergänzungsheft Nr 67, Gotha, 1882.

Pigafetta—‘Voyage Round the World,’ Pinkerton, vol. ii.

Prescott—‘Conquest of Peru.’

Posewitz, Dr. Theodor—‘Borneo, its Geology and Mineral Resources.’

Rathbone—‘Camping and Tramping in Malaya.’

Reyes, Ysabelo de los—Pamphlet.

Rizal—‘Noli me Tangere.’

St. John, Spenser—‘Life in the Forests of the Far East.’

Torquemada, Fray Juan—‘Monarquia Indiana.’

Traill, H. D.—‘Lord Cromer.’

Vila, Francisco—‘Filipinas,’ 1880.

Wallace, Alfred R.—‘The Malay Archipelago.’

Wingfield, Hon. Lewis—‘Wanderings of a Globe-trotter.’

Worcester, Dean C.—‘The Philippine Islands and their People.’

Younghusband, Major—‘The Philippines and Round About.’

Magazine Articles.

Scribner (George F. Becker)—‘Are the Philippines Worth Having?’

Blackwood (Anonymous)—‘The Case of the Philippines.’

Tennie, G. Claflin (Lady Cook)—‘Virtue Defined’ (New York Herald).

Speeches.

President McKinley: To the 10th Pennsylvania Regiment, Pittsburgh.

Mr. Whitelaw Reid: To the Miami University, Ohio.

Senator Hoar, in the Senate.

Blue Book—55th Congress, 3rd Session, Doc. No. 62, Part I.

Contents.

Introductory and Descriptive.

Chapter I.

Extent, Beauty and Fertility. Pages

Extent, beauty and fertility of the Archipelago—Variety of landscape—Vegetation—Mango trees—Bamboos 1–6

Chapter II.

Spanish Government.

Slight sketch of organization—Distribution of population—Collection of taxes—The stick 7–13

Chapter III.

Six Governors-General.

Moriones—Primo de Rivera—Jovellar—Terreros—Weyler—Despujols 14–23

Chapter IV.

Courts of Justice.

Alcaldes—The Audiencia—The Guardia Civil—Do not hesitate to shoot—Talas 24–30

Chapter V.

Tagal Crime and Spanish Justice.

The murder of a Spaniard—Promptitude of the Courts—The case of Juan de la Cruz—Twelve years in prison waiting trial—Piratical outrage in Luzon—Culprits never tried; several die in prison 31–47

Historical.

Chapter VI.

Causes of Tagal Revolt.

Corrupt officials—“Laws of the Indies”—Philippines a dependency of Mexico, up to 1800—The opening of the Suez Canal—Hordes of useless officials—The Asimilistas—Discontent, but no disturbance—Absence of crime—Natives petition for the expulsion of the Friars—Many signatories of the petition punished 48–56

Chapter VII.

The Religious Orders.

The Augustinians—Their glorious founder—Austin Friars in England—Scotland—Mexico—They sail with Villalobos for the Islands of the Setting Sun—Their disastrous voyage—Fray Andres Urdaneta and his companions—Foundation of Cebú and Manila with two hundred and forty other towns—Missions to Japan and China—The Flora Filipina—The Franciscans—The Jesuits—The Dominicans—The Recollets—Statistics of the religious orders in the islands—Turbulence of the friars—Always ready to fight for their country—Furnish a war ship and command it—Refuse to exhibit the titles of their estates in 1689—The Augustinians take up arms against the British—Ten of them fall on the field of battle—Their rectories sacked and burnt—Bravery of the archbishop and friars in 1820—Father Ibañez raises a battalion—Leads it to the assault of a Moro Cotta—Execution of native priests in 1872—Small garrison in the islands—Influence of the friars—Their behaviour—Herr Jagor—Foreman—Worcester—Younghusband—Opinion of Pope Clement X.—Tennie C. Claflin—Equality of opportunity—Statesque figures of the girls—The author’s experience of the Friars—The Philippine clergy—Who shall cast the first stone!—Constitution of the orders—Life of a friar—May become an Archbishop—The Chapter 57–70

Chapter VIII.

Their Estates.

Malinta and Piedad—Mandaloyan—San Francisco de Malabon—Irrigation works—Imus—Calamba—Cabuyao—Santa Rosa Biñan—San Pedro Tunasan—Naic—Santa Cruz—Estates a bone of contention for centuries—Principal cause of revolt of Tagals—But the Peace Commission guarantee the Orders in possession—Pacification retarded—Summary—The Orders must go!—And be replaced by natives 71–78

Chapter IX.

Secret Societies.

Masonic Lodges—Execution or exile of Masons in 1872—The “Asociacion Hispano Filipina”—The “Liga Filipina”—The Katipunan—Its programme 79–83

Chapter X.

The Insurrection of 1896–97.

Combat at San Juan del Monte—Insurrection spreading—Arrival of reinforcements from Spain—Rebel entrenchments—Rebel arms and artillery—Spaniards repulsed from Binacáyan—and from Noveleta—Mutiny of Carabineros—Prisoners at Cavite attempt to escape—Iniquities of the Spanish War Office—Lachambre’s division—Rebel organization—Rank and badges—Lachambre advances—He captures Silang—Perez Dasmariñas—Salitran—Anabo II. 84–96

Chapter XI.

The Insurrection of 1896–97—continued.

The Division encamps at San Nicolas—Work of the native Engineer soldiers—The division marches to Salitran—Second action at Anabo II.—Crispulo Aguinaldo killed—Storming the entrenchments of Anabo I.—Burning of Imus by the rebels—Proclamation by General Polavieja—Occupation of Bacoor—Difficult march of the division—San Antonio taken by assault—Division in action with all its artillery—Capture of Noveleta—San Francisco taken by assault—Heavy loss of the Tagals—Losses of the division—The division broken up—Monteverde’s book—Polaveija returns to Spain—Primo de Rivera arrives to take his place—General Monet’s butcheries—The pact of Biak-na-Bato—The 74th Regiment joins the insurgents—The massacre of the Calle Camba—Amnesty for torturers—Torture in other countries 97–108

Chapter XII.

The Americans in the Philippines.

Manila Bay—The naval battle of Cavite—General Aguinaldo—Progress of the Tagals—The Tagal Republic—Who were the aggressors?—Requisites for a settlement—Scenes of drunkenness—The estates of the religious orders to be restored—Slow progress of the campaign—Colonel Funston’s gallant exploits—Colonel Stotsenburg’s heroic death—General Antonio Luna’s gallant rally of his troops at Macabebe—Reports manipulated—Imaginary hills and jungles—Want of co-operation between Army and Navy—Advice of Sir Andrew Clarke—Naval officers as administrators—Mr. Whitelaw Reid’s denunciations—Senator Hoar’s opinion—Mr. McKinley’s speech at Pittsburgh—The false prophets of the Philippines—Tagal opinion of American Rule—Señor Mabini’s manifesto—Don Macario Adriatico’s letter—Foreman’s prophecy—The administration misled—Racial antipathy—The curse of the Redskins—The recall of General Otis—McArthur calls for reinforcements—Sixty-five thousand men and forty ships of war—State of the islands—Aguinaldo on the Taft Commission 109–123

Chapter XIII.

Native Admiration for America.

Their fears of a corrupt government—The islands might be an earthly paradise—Wanted, the man—Rajah Brooke—Sir Andrew Clarke—Hugh Clifford—John Nicholson—Charles Gordon—Evelyn Baring—Mistakes of the Peace Commission—Government should be a Protectorate—Fighting men should be made governors—What might have been—The Malay race—Senator Hoar’s speech—Four years’ slaughter of the Tagals 124–128

Resources of the Philippines.

Chapter XIV.

Resources of the Philippines.

At the Spanish conquest—Rice—the lowest use the land can be put to—How the Americans are misled—Substitutes for rice—Wheat formerly grown—Tobacco—Compañia General de Tabacos—Abacá—Practically a monopoly of the Philippines—Sugar—Coffee—Cacao—Indigo—Cocoa-nut oil—Rafts of nuts—Copra—True localities for cocoa palm groves Summary—More sanguine forecasts—Common-sense view 129–138

Chapter XV.

Forestal.

Value exaggerated—Difficulties of labour and transport—Special sawing machinery required—Market for timber in the islands—Teak not found—Jungle produce—Warning to investors in companies—Gutta percha 139–142

Chapter XVI.

The Minerals.

Gold: Dampier—Pigafetta—De Comyn—Placers in Luzon—Gapan—River Agno—The Igorrotes—Auriferous quartz from Antaniac—Capunga—Pangutantan—Goldpits at Suyuc—Atimonan—Paracale—Mambulao—Mount Labo—Surigao River Siga—Gigaquil, Caninon-Binutong, and Cansostral Mountains—Misamis—Pighoulugan—Iponan—Pigtao—Dendritic gold from Misamis—Placer gold traded away surreptitiously—Cannot be taxed—Spanish mining laws—Pettifogging lawyers—Prospects for gold seekers. Copper: Native copper at Surigao and Torrijos (Mindoro)—Copper deposits at Mancayan worked by the Igorrotes—Spanish company—Insufficient data—Caution required. Iron: Rich ores found in the Cordillera of Luzon—Worked by natives—Some Europeans have attempted but failed—Red hematite in Cebú—Brown hematite in Paracale—Both red and brown in Capiz—Oxydised iron in Misamis—Magnetic iron in San Miguel de Mayumo—Possibilities. Coal (so called): Beds of lignite upheaved—Vertical seams at Sugud—Reason of failure—Analysis of Masbate lignite. Various minerals: Galena—Red lead—Graphite—Quicksilver—Sulphur Asbestos—Yellow ochre—Kaolin, Marble—Plastic clays—Mineral waters 143–157

Chapter XVII.

Manufactures and Industries.

Cigars and cigarettes—Textiles—Cotton—Abacá—Júsi—Rengue—Nipis—Saguran—Sinamáy—Guingon—Silk handkerchiefs—Piña—Cordage—Bayones—Esteras—Baskets—Lager beer—Alcohol—Wood oils and resins—Essence of Ylang-ilang—Salt—Bricks—Tiles—Cooking-pots—Pilones—Ollas—Embroidery—Goldsmiths’ and silversmiths’ work—Salacots—Cocoa-nut oil—Saddles and harness—Carromatas—Carriages—Schooners—Launches—Lorchas—Cascos—Pontines—Bangcas—Engines and boilers—Furniture—Fireworks—Lanterns—Brass Castings—Fish breeding—Drying sugar—Baling hemp—Repacking wet sugar—Oppressive tax on industries—Great future for manufactures—Abundant labour—Exceptional intelligence 158–163

Chapter XVIII.

Commercial and Industrial Prospects.

Philippines not a poor man’s country—Oscar F. Williams’ letter—No occupation for white mechanics—American merchants unsuccessful in the East—Difficulties of living amongst Malays—Inevitable quarrels—Unsuitable climate—The Mali-mali or Sakit-latah—The Traspaso de hambre—Chiflados—Wreck of the nervous system—Effects of abuse of alcohol—Capital the necessity—Banks—Advances to cultivators—To timber cutters—To gold miners—Central sugar factories—Paper-mills—Rice-mills—Cotton-mills—Saw-mills—Coasting steamers—Railway from Manila to Batangas—From Siniloan to the Pacific—Survey for ship canal—Bishop Gainzas’ project—Tramways for Luzon and Panay—Small steamers for Mindanao—Chief prospect is agriculture 164–172

Social.

Chapter XIX.

Life in Manila.

(A Chapter for the Ladies.)

Climate—Seasons—Terrible Month of May—Hot winds—Longing for rain—Burst of the monsoon—The Alimóom—Never sleep on the ground floor—Dress—Manila houses—Furniture—Mosquitoes—Baths—Gogo—Servants—Wages in 1892—The Maestro cook—The guild of cooks—The Mayordomo—Household budget, 1892—Diet—Drinks—Ponies—Carriage a necessity for a lady—The garden—Flowers—Shops—Pedlars—Amusements—Necessity of access to the hills—Good Friday in Manila 173–187

Chapter XX.

Sport.

(A Chapter for Men.)

The Jockey Club—Training—The races—An Archbishop presiding—The Totalisator or Pari Mutuel—The Manila Club—Boating club—Rifle clubs—Shooting—Snipe—Wild duck—Plover—Quail—Pigeons—Tabon—Labuyao, or jungle cock—Pheasants—Deer—Wild pig—No sport in fishing 188–191

Geographical.

Chapter XXI.

Brief Geographical Description of Luzon.

Irregular shape—Harbours—Bays—Mountain ranges—Blank spaces on maps—North-east coast unexplored—River and valley of Cagayan—Central valley from Bay of Lingayen to Bay of Manila—Rivers Agno, Chico, Grande—The Pinag of Candaba—Project for draining—River Pasig—Laguna de Bay—Lake of Taal—Scene of a cataclysm—Collapse of a volcanic cone 8000 feet high—Black and frowning island of Mindoro—Worcester’s pluck and endurance—Placers of Camarines—River Vicol—The wondrous purple cone of Mayon—Luxuriant vegetation 192–200

The Inhabitants of the Philippines.

Description of their appearance, dress, arms, religion, manners and customs, and the localities they inhabit, their agriculture, industries and pursuits, with suggestions as to how they can be utilised, commercially and politically. With many unpublished photographs of natives, their arms, ornaments, sepulchres and idols.

Aboriginal Inhabitants.

Scattered over the Islands.

Chapter XXII.

Aetas or Negritos.

Including Balúgas, Dumágas, Mamanúas, and Manguiánes 201–207

Part I.

Inhabitants of Luzon and Adjacent Islands.

Chapter XXIII.

Tagals (1) 208–221

Chapter XXIV.

Tagals as Soldiers and Sailors 222–237

Chapter XXV.

Pampangos (2) 238–245

Chapter XXVI.

Zambales (3)—Pangasinanes (4)—Ilocanos (5)—Ibanags or Cagayanes (6) 246–253

Chapter XXVII.

Igorrotes (7) 254–267

Chapter XXVIII.

Isinays (11)—Abacas (12)—Italones (13)—Ibilaos (14)—Ilongotes (15)—Mayoyaos and Silipanes (16)—Ifugaos (17)—Gaddanes (18)—Itetapanes (19)—Guinanes (20) 268–273

Chapter XXIX.

Caláuas or Itaves (21)—Camuangas and Bayabonanes (22)—Dadayags (23)—Nabayuganes (24)—Aripas (25)—Calingas (26)—Tinguianes (27)—Adangs (28)—Apayaos (29)—Catalanganes and Irayas (30–31) 274–282

Chapter XXX.

Catubanganes (32)—Vicols (33) 283–287

Chapter XXXI.

The Chinese in Luzon.

Mestizos or half-breeds 288–294

Part II.

The Visayas and Palawan.

Chapter XXXII.

The Visayas Islands.

Area and population—Panay—Negros—Cebú—Bohol—Leyte—Samar 295–299

Chapter XXXIII.

The Visayas Race.

Appearance—Dress—Look upon Tagals as foreigners—Favourable opinion of Tomas de Comyn—Old Christians—Constant wars with the Moro pirates and Sea Dayaks—Secret heathen rites—Accusation of indolence unfounded—Exports of hemp and sugar—Ilo-ilo sugar—Cebú sugar—Textiles—A promising race 300–306

Chapter XXXIV.

The Island of Palawan, or Paragua.

The Tagbanúas—Tandulanos—Manguianes—Negritos—Moros of southern Palawan—Tagbanúa alphabet 307–320

Part III.

Mindanao, Including Basilan.

Chapter XXXV.

Brief Geographical Description.

Configuration—Mountains—Rivers—Lakes—Division into districts—Administration—Productions—Basilan 321–330

Chapter XXXVI.

The Tribes of Mindanao.

Visayas (1) [Old Christians]—Mamanúas (2)—Manobos (3)—Mandayas (4)—Manguángas (5)—Montéses or Buquidnónes(6)—Atás or Ata-as (7)—Guiangas (8)—Bagobos (9) 331–351

Chapter XXXVII.

The Tribes of Mindanao—continued.

Calaganes (10)—Tagacaolos (11)—Dulanganes (12)—Tirurayes (13)—Tagabelies (14)—Samales (15)—Vilanes (16)—Subanos (17) 352–360

Chapter XXXVIII.

The Moros, or Mahometan Malays (18 to 23).

Illanos (18)—Sanguiles (19)—Lutangas (20)—Calibuganes (21) Yacanes (22)—Samales (23) 361–373

Chapter XXXIX.

Tagabáuas (24) 374–375

The Chinese in Mindanao.

N.B.—The territory occupied by each tribe is shown on the general map of Mindanao by the number on this list.

Chapter XL.

The Political Condition of Mindanao, 1899.

Relapse into savagery—Moros the great danger—Visayas the mainstay—Confederation of Lake Lanao—Recall of the Missionaries—Murder and pillage in Davao—Eastern Mindanao—Western Mindanao—The three courses—Orphanage of Tamontaca—Fugitive slaves—Polygamy an impediment to conversion—Labours of the Jesuits—American Roman Catholics should send them help 376–388

Appendix.

Chronological Table 389

Table of Exports for twelve Years 411

Estimate of Population 415

Philippine Budget of 1897 compared with Revenue of 1887 416, 417

Value of Land in several Provinces of Luzon 418

List of Spanish and Filipino Words used in the Work 419

Cardinal Numbers in Seven Malay Dialects 422

List of Illustrations.

- Portrait of the Author Frontispiece

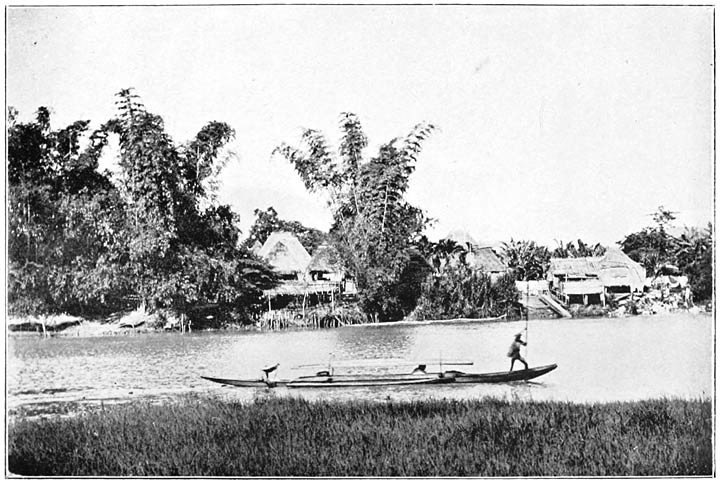

- View on the Pasig with Bamboos and Canoe To face p. 6

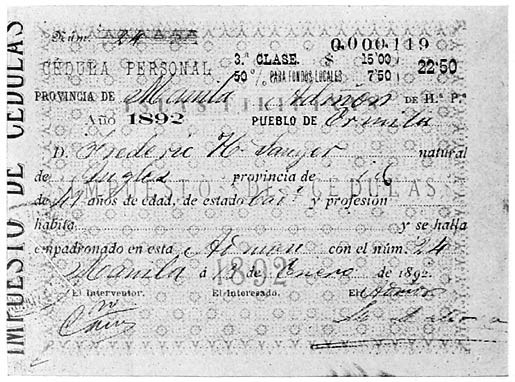

- Facsimile of Cédula Personal To face p. 53

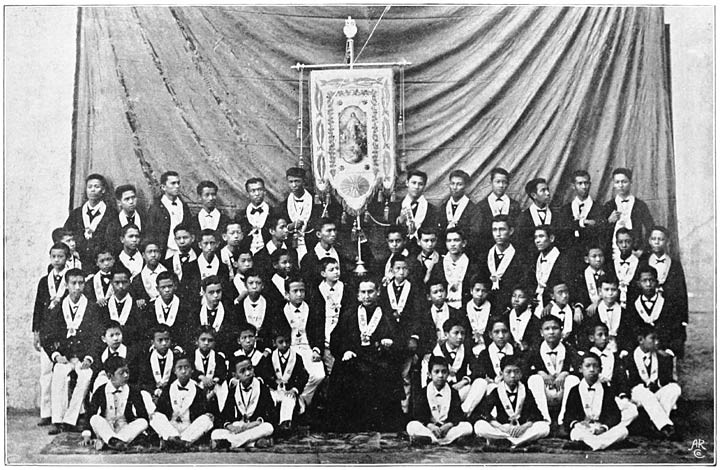

- Some of the rising generation in the Philippines To face p. 75

- Map of the Philippine Islands To face p. 150

- Group of women making Cigars To face p. 158

- Salacots and Women’s Hats To face p. 160

- Author’s office, Muelle Del Rey, ss. Salvadora, and Lighters called “Cascos” To face p. 161

- River Pasio showing Russell and Sturgis’s former office To face p. 166

- Tower of Manila Cathedral after the Earthquakes, 1880 Between pp. 168–9

- Suburb of Malate after a typhoon, October 1882, When thirteen ships were driven ashore

- Author’s house at Ermita To face p. 177

- Fernery at Ermita To face p. 185

- A Negrito from Negros Island To face p. 207

- A Manila Man Between pp. 208–9

- A Manila Girl

- Tagal Girl wearing Scapulary To face p. 216

- Carabao harnessed to native Plough; Ploughman, Village, and Church Between pp. 226–7

- Paddy Field recently planted

- Paulino Marillo, a Tagal of Laguna, Butler to the author To face p. 229

- A Farderia, or Sugar Drying and Packing Place To face p. 240

- Igorrote Spearmen and Negriot Archer To face p. 254

- Anitos of Northern Tribes To face p. 258

- Aitos of the Igorrotes To face p. 258

- Coffin of an Igorrote Noble, with his Coronets and other Ornaments To face p. 259

- Weapons of the Highlands of Luzon To face p. 261

- Igorrote Dresses and Ornaments, Water-Jar, Dripstones, Pipes, and Baskets To face p. 264

- Anitos, Highlands To face p. 266

- Anito of the Igorrotes To face p. 266

- Igorrote Drums To face p. 266

- Tinguianes, Aeta, and Igorrotes To face p. 276

- Vicols Preparing Hemp:— To face p. 287

- Cutting the Plant

- Separating the Petioles

- Adjusting under the Knife

- Drawing out the Fibre

- Visayas Women at a Loom To face p. 305

- Lieut. P. Garcia and Local Militia of Baganga, Caraga (East Coast) To face p. 333

- Atás from the Back Slopes of the Apo To face p. 347

- Heathen Guiangas, from the Slopes of the Apo To face p. 349

- Father Gisbert, S.J. exhorting a Bagobo Datto and his Followers to Abandon their custom of making Human Sacrifices Between pp. 350–1

- The Datto Manib, Principal Bagani of the Bagabos, with some Wives and Followers and Two Missionaries Between pp. 350–1

- The Moro Sword and Spear To face p. 363

- Moros of the Bay of Mayo To face p. 367

- Moro Lantacas and Coat of Mail To face p. 373

- Seat of the Moro Power, Lake Lanao To face p. 377

- Double-barrelled Lantaca of Artistic Design and Moro Arms To face p. 387

The Inhabitants of the Philippines.

Chapter I.

Extent, Beauty and Fertility.

Extent, beauty, and fertility of the Archipelago—Variety of landscape—Vegetation—Mango trees—Bamboos.

Extent.

The Philippine Archipelago, in which I include the Sulu group, lies entirely within the northern tropic; the southernmost island of the Tawi-tawi group called Sibutu reaches down to 4° 38′ N., whilst Yami, the northernmost islet of the Batanes group, lies in 21° 7′ N. This gives an extreme length of 1100 miles, whilst the extreme breadth is about 680 miles, measured a little below the 8th parallel from the Island of Balábac to the east coast of Mindanao.

Various authorities give the number of islands and islets at 1200 and upwards; many have probably never been visited by a white man. We need only concern ourselves with the principal islands and those adjacent to them.

From the hydrographic survey carried out by officers of the Spanish Navy, the following areas have been calculated and are considered official, except those marked with an asterisk, which are only estimated.

Sq. Miles.

Sq. Miles.

Luzon

42,458

Babuyanes Islands

272

Batanes Islands

104

Mindoro

4,153

Catanduanes

721

Marinduque

332

Polillo

300

Buriás

116

Ticao.

144

Masbate

1,642

——

7,784

——

Total Luzon and adjacent islands

50,242

Visayas, etc.

Panay

4,898

Negros

3,592

Cebú

2,285

Bohol

1,226

Leyte

3,706

Samar

5,182

——

20,889

Mindanao

34,456

Palawan and Balabac

5,963

Calamianes Islands

640

——

Area of principal islands

112,190

The Spanish official estimate of the area of the whole Archipelago is 114,214 square miles1 equivalent to 73,000,000 acres, so that the remaining islands ought to measure between them something over 2000 square miles.

Beauty and Fertility.

Lest I should be taxed with exaggeration when I record my impressions of the beauty and potential wealth of the Archipelago, so far as I have seen it; I shall commence by citing the opinions of some who, at different times, have visited the islands.

I think I cannot do better than give precedence to the impressions of two French gentlemen who seem to me to have done justice to the subject, then cite the calm judgment of a learned and sagacious Teuton, and lastly quote from the laboured paragraphs of a much-travelled cosmopolite, at one time Her Britannic Majesty’s Consul at Manila.

Monsieur Dumont D’Urville says: “The Philippines, and above all Luzon, have nothing in this world to equal them in climate, beauty of landscape, and fertility of soil. Luzon is the finest diamond that the Spanish adventurers have ever found.

“It has remained uncut in their hands; but deliver over Luzon to British activity and tolerance, or else to the laborious tenacity of the Dutch Creoles, and you will see what will come out of this marvellous gem.”

Monsieur de Guignes says: “Of the numerous colonies belonging to the Spaniards, as one of the most important must indisputably be reckoned the Philippines. Their position, their great fertility, and the nature of their productions, render them admirably adapted for active commerce, and if the Spaniards have not derived much benefit from them, to themselves and to their manner of training is the fault to be ascribed.”

Herr Jagor, speaking of the Province of Bulacan, says the roads were good and were continuously shaded by fruit trees, cocoa and areca palms, and the aspect of this fruitful province reminded him of the richest districts in Java, but he found the pueblos here exhibited more comfort than the desas there.

Mr. Gifford Palgrave says: “Not the Ægean, not the West Indian, not the Samoan, not any other of the fair island clusters by which our terraqueous planet half atones for her dreary expanses of grey ocean and monotonous desert elsewhere, can rival in manifold beauties of earth, sea, sky, the Philippine Archipelago; nor in all that Archipelago, lovely as it is through its entire extent, can any island vie with the glories of Luzon.”

Variety of Landscape.

If I may without presumption add my testimony to that of these illustrious travellers, I would say that, having been over a great part of South America, from Olinda Point to the Straits of Magellan, from Tierra del Fuego to Panama, not only on the coasts but in the interior, from the Pampas of the Argentine and the swamps of the Gran Chaco to where

“The roots of the Andes strike deep in the earth

As their summits to heaven shoot soaringly forth;”

having traversed the fairest gems of the Antilles and seen some of the loveliest landscapes in Japan, I know of no land more beautiful than Luzon, certainly of none possessing more varied features or offering more striking contrasts.

Limestone cliffs and pinnacles, cracked and hollowed into labyrinthine caves, sharp basalt peaks, great ranges of mountains, isolated volcanic cones, cool crystalline springs, jets of boiling water, cascades, rivers, lakes, swamps, narrow valleys and broad plains, rocky promontories and coral reefs, every feature is present, except the snow-clad peak and the glacier.

Vegetation.

Vegetation here runs riot, hardly checked by the devastating typhoon, or the fall of volcanic ashes. From the cocoa-nut palm growing on the coral strand, from the mangrove, building its pyramid of roots upon the ooze, to the giant bamboo on the banks of the streams, and the noble mango tree adorning the plains, every tropical species flourishes in endless variety, and forests of conifers2 clothe the summits of the Zambales and Ilocan mountains.

As for the forest wealth, the trees yielding indestructible timber for ships, houses or furniture, those giving valuable drugs and healing oils, gums and pigments, varnishes, pitch and resin, dyes, sap for fermenting or distilling, oil for burning, water, vinegar, milk, fibre, charcoal, pitch, fecula, edible fungi, tubers, bark and fruits, it would take a larger book than this to enumerate them in their incredible variety.

Mango Trees.

A notable feature of the Philippine landscape is the mango tree. This truly magnificent tree is often of perfect symmetry, and rears aloft on its massive trunk and wide-spreading branches a perfect dome of green and glistening leaves, adorned in season with countless strings of sweet-scented blossom and pendent clusters of green and golden fruit, incomparably luscious, unsurpassed, unequalled.

Beneath that shapely vault of verdure the feathered tribes find shelter. The restless mango bird3 displays his contrasted plumage of black and yellow as he flits from bough to bough, the crimson-breasted pigeon and the ring-dove rest secure.

These glorious trees are pleasing objects for the eye to rest on. All through the fertile valleys of Luzon they stand singly or in groups, and give a character to the landscape which would otherwise be lacking. Only the largest and finest English oaks can compare with the mango trees in appearance; but whilst the former yield nothing of value, one or two mango trees will keep a native family in comfort and even affluence with their generous crop.

Bamboos.

On the banks of the Philippine streams and rivers that giant grass, the thorny bamboo, grows and thrives. It grows in clumps of twenty, forty, fifty stems. Starting from the ground, some four to six inches in diameter, it shoots aloft for perhaps seventy feet, tapering to the thickness of a match at its extremity, putting forth from each joint slender and thorny branches, carrying small, thin, and pointed leaves, so delicately poised as to rustle with the least breath of air.

The canes naturally take a gradual curve which becomes more and more accentuated as their diameter diminishes, until they bend over at their tops and sway freely in the breeze.

I can only compare a fine clump of bamboos to a giant plume of green ostrich feathers. Nothing in the vegetable kingdom is more graceful, nothing can be more useful. Under the blast of a typhoon the bamboo bends so low that it defies all but the most sudden and violent gusts. If, however, it succumbs, it is generally the earth under it that gives way, and the whole clump falls, raising its interlaced roots and a thick wall of earth adhering to and embraced by them.

Piercing the hard earth, shoving aside the stones with irresistible force, comes the new bamboo, its head emerging like a giant artichoke.

Each flinty-headed shoot soars aloft with a rapidity astonishing to those who have only witnessed the tardy growth of vegetation in the temperate zone. I carefully measured a shoot of bamboo in my garden in Santa Ana and found that it grew two feet in three days, that is, eight inches a day, ⅓ inch per hour. I could see it grow. When I commenced to measure the shoot it was eighteen inches high and was four inches in diameter. This rapid growth, which, considering the extraordinary usefulness of the bamboo ought to excite man’s gratitude to Almighty Providence, has, to the shame of human nature, led the Malay and the Chinaman to utilise the bamboo to inflict death by hideous torture on his fellow men. (See Tûkang Bûrok’s story in Hugh Clifford’s ‘Studies of Brown Humanity.’)

Each joint is carefully enveloped by nature in a wrapper as tough as parchment, covered, especially round the edges, with millions of small spines. The wrapper, when dry, is brown, edged with black, but when fresh the colours are remarkable, pale yellow, dark yellow, orange, brown, black, pale green, dark green, black; all shaded or contrasted in a way to make a Parisian dress designer feel sick with envy.

This wrapper does not fall off till the joint has hardened and acquired its flinty armour so as to be safe from damage by any animal.

It would take a whole chapter to enumerate the many and varied uses of the bamboo.

Suffice it to say that I cannot conceive how the Philippine native could do without it.

Everlastingly renewing its youth, perpetually soaring to the sky, proudly overtopping all that grows, splendidly flourishing when meaner plants must fade from drought, this giant grass, which delights the eyes, takes rank as one of God’s noblest gifts to tropical man.

View on the Pasig with Bamboos and Canoe.

To face p. 6.

1 England has 51,000 square miles area; Wales, 7378; Ireland, 31,759; Scotland, nearly 30,000. Total, Great Britain and Ireland, etc., 121,000 square miles.

2 Worcester, p. 446, mentions Conifers at sea level in Sibuyan Island, province of Romblon.

3 Called in Spanish the oropéndola (Broderipus achrorchus).

1 England has 51,000 square miles area; Wales, 7378; Ireland, 31,759; Scotland, nearly 30,000. Total, Great Britain and Ireland, etc., 121,000 square miles.

2 Worcester, p. 446, mentions Conifers at sea level in Sibuyan Island, province of Romblon.

3 Called in Spanish the oropéndola (Broderipus achrorchus).

Chapter II.

Spanish Government.

Slight sketch of organization—Distribution of population—Collection of taxes—The stick.

The supreme head of the administration was a Governor-General or Captain-General of the Philippines. The British Colonial Office has preserved this Spanish title in Jamaica where the supreme authority is still styled Captain-General and Governor-in-Chief.

In recent years no civilian has been Governor-General of the Philippines, the appointment being given or sold to a Lieutenant-General, though in 1883 a Field-Marshal was sent out. But in 1874 Rear-Admiral Malcampo obtained the post, and a very weak and foolish Governor-General he turned out to be.

In former times military men did not have a monopoly of such posts, and civilians, judges, priests, and bishops have held this appointment.

The Governor-General had great powers. Practically, if not legally, he had the power of life and death, for he could proclaim martial law and try offenders by court-martial. He was ex officio president of every corporation or commission, and he could expel from the Islands any person, whether Spaniard, native, or foreigner, by a decree declaring that his presence was inconvenient.

Slight Sketch of Organization.

He could suspend or remove any official, and in fact was almost despotic. On the other hand he had to remember two important limitations. Unless he supported the religious orders against all comers he would have the Procurators of these wealthy corporations, who reside in Madrid, denouncing him to the Ministry as an anti-clerical, and a freemason, and perhaps offering a heavy bribe for his removal. If he made an attempt to put down corruption and embezzlement in the Administration, his endeavours would be thwarted in every possible way by the officials, and a formidable campaign of calumny and detraction would be inaugurated against him. The appointment was for a term of three years at a salary of $40,000 per annum, and certain very liberal travelling allowances.

Since the earthquake of 1863 the official residence of the Governors-General was at Malacañan, on the River Pasig in the ward of San Miguel. This is now the residence of the American Governor. He had a troop of native Lancers to escort him when he drove out, and a small corps of Halberdiers for duty within the palace and grounds. These latter wore a white uniform with red facings, and were armed with a long rapier and a halberd. They were also furnished with rifles and bayonets for use in case of an emergency.

When the Governor-General drove out, every man saluted him by raising his hat—and when he went to the Cathedral he was received by the clergy at the door, and, on account of being the Vice-Regal Patron, was conducted under a canopy along the nave to a seat of honour.

His position was in fact one of great power and dignity, and it was felt necessary to surround the representative of the king with much pomp and state in order to impress the natives with his importance and authority.

There was a Governor-General of Visayas who resided at Cebu, and was naturally subordinate to the Governor-General of the Philippines. He was usually a Brigadier-General.

In case of the death or absence of the Governor-General, the temporary command devolved upon the Segundo Cabo, a general officer in immediate command of the military forces. Failing him, the Acting Governor-Generalship passed to the Admiral commanding the station.

The two principal departments of the administration were the Intendencia or Treasury, and the Direction of Civil Administration.

The Archipelago is divided into fifty-one provinces or districts, according to the accompanying table and map.

Distribution of Population.

Provinces.

Males.

Females.

Total.Abra

21,631

21,016

42,647

Albay

127,413

130,120

257,533

Antique

60,193

63,910

124,103

Balábac

1,912

27

1,939

Bataán

25,603

24,396

49,999

Batangas

137,143

137,932

275,075

Benguet (district)

8,206

12,104

20,310

Bohol

109,472

117,074

226,546

Bontoc

40,515

41,914

82,429

Bulacán

127,455

124,694

252,149

Burías

84

44

128

Cagayán

37,157

35,540

72,697

Calamianes

8,227

8,814

17,041

Camarines Norte

15,931

14,730

30,661

Camarines Sur

78,545

77,852

156,400

Cápiz

114,827

128,417

243,244

Cavite

66,523

65,541

132,064

Cebú

201,066

202,230

403,296

Corregidor (island of)

216

203

419

Cottabato

788

494

1,282

Dávao

983

712

1,695

Ilocos Norte

76,913

79,802

156,715

Ilocos Sur

97,916

103,133

201,049

Ilo-Ilo

203,879

206,551

410,430

Infanta (district)

4,947

4,947

9,894

Isabela de Basilan

454

338

792

Isabela de Luzon

20,251

18,365

38,616

Islas Batanes

4,004

4,741

8,745

Isla de Negros

106,851

97,818

204,669

Laguna

66,332

66,172

132,504

Lepanto

8,255

16,219

24,474

Leyte

113,275

107,240

220,515

Manila

137,280

120,994

258,274

Masbate and Ticao

8,835

8,336

17,171

Mindoro

29,220

28,908

58,128

Misamis

46,020

42,356

88,376

Mórong

21,506

21,556

43,062

Nueva Ecija

63,456

60,315

123,771

Nueva Vizcaya

8,495

7,612

16,107

Pampanga

114,425

111,884

226,309

Pangasinán

149,141

144,150

293,291

Principe (district)

2,085

2,073

4,158

Puerto Princesa

350

228

578

Romblón

14,528

13,626

28,154

Samar

92,330

86,560

178,890

Surigao

28,371

27,875

56,246

Tarlac

42,432

40,325

82,757

Tayabas

27,886

25,782

53,668

Unión

55,802

57,568

113,370

Zambales

49,617

44,934

94,551

Zamboanga

7,683

6,461

14,144

2,794,876

2,762,743

5,557,619

The above figures are taken from the official census of 1877.

This is the latest I have been able to find.

In the Appendix is given an estimate of the population in 1890, the author puts the number at 8,000,000, and at this date there may well be 9,000,000 inhabitants in the Philippines and Sulus.

It will be seen that these provinces are of very different extent, and vary still more in population, for some have only a few hundred inhabitants, whilst others, for instance, Cebú and Ilo-Ilo have half-a-million.

Each province was under a Governor, either civil or military. Those provinces which were entirely pacified had Civil Governors, whilst those more liable to disturbance or attack from independent tribes or from the Moors had Military Governors. Up to 1886 the pacified provinces were governed by Alcaldes-Mayores, who were both governors and judges. An appeal from their decisions could be made to the Audiencia or High Court at Manila.

From the earliest times of their appointment, the Alcaldes were allowed to trade. Some appointments carried the right to trade, but most of the Alcaldes had to covenant to forego a large proportion of their very modest stipends in order to obtain this privilege. By trade and by the fees and squeezes of their law courts they usually managed to amass fortunes. In 1844 the Alcaldes were finally prohibited from trading.

This was a rude system of government, but it was cheap, and a populous province might only have to maintain half-a-dozen Spaniards.

Each town has its municipality consisting of twelve principales, all natives, six are chosen from those who have already been Gobernadorcillos. They are called past-captains, and correspond to aldermen who have passed the chair. The other six are chosen from amongst the Barangay headmen. From these twelve are elected all the officials, the Gobernadorcillo or Capitan, the 1st, 2nd and 3rd lieutenants, the alguaciles (constables), the judges of the fields, of cattle, and of police. The Capitan appoints and pays the directorcillo or town clerk, who attends to the routine business.

For the maintenance of order, and for protecting the town against attack, there is a body of local police called Cuadrilleros. These are armed with bolos and lances in the smaller and poorer towns, but in more important places they have fire-arms usually of obsolete pattern. But in towns exposed to Moro attack the cuadrilleros are more numerous, and carry Remington rifles.

The Gobernadorcillos of towns were directly responsible to the governor of the province, the governor in case of emergency reported direct to the Governor-General, but for routine business through the Director-General of Civil Administration, which embraced the departments of Public Works, Inspection of Mines and Forests, Public Instruction, Model Farms, etc.

The collection of taxes was under the governors of provinces assisted by delegates of the Intendant-General. It was directly effected by the Barangay headman each of whom was supposed to answer for fifty families, the individuals of which were spoken of as his sácopes. His eldest son was recognised as his chief assistant, and he, like his father, was exempt from the tribute or capitation tax.

The office was hereditary, and was not usually desired, but like the post of sheriff in an English county it had to be accepted nolens volens.

No doubt a great deal of latitude was allowed to the Barangay Chiefs in order that they might collect the tax, and the stick was often in requisition. In fact the chiefs had to pay the tax somehow, and it is not surprising that they took steps to oblige their sácopes to pay.

I, however, in my fourteen years’ experience, never came across such a case as that mentioned by Worcester, p. 295, where he states that in consequence of a deficiency of $7000, forty-four headmen of Siquijor were seized and exiled, their lands, houses and cattle confiscated, and those dependent on them left to shift for themselves. The amount owing by each headman was under $160 Mexican, equal to $80 gold, and it would not take much in the way of lands, houses, and cattle to pay off this sum. However, it is true that Siquijor is a poor island. But on page 284 he maintains that the inhabitants of Siquijor had plenty of money to back their fighting-cocks, and paid but little attention to the rule limiting each man’s bet on one fight to $50. From this we may infer that they could find money to bet with, but not to pay their taxes.

Collection of Taxes.

Natives of the gorgeous East very commonly require a little persuasion to make them pay their taxes, and I have read of American millionaires who, in the absence of this system, could not be got to pay at all. Not many years ago, there was an enquiry as to certain practices resorted to by native tax-collectors in British India to induce the poor Indian to pay up; anybody who is curious to know the particulars can hunt them up in the Blue Books—they are unsuitable for publication.

In Egypt, up to 1887, or thereabouts, the “courbash”1 was in use for this purpose. I quote from a speech by Lord Cromer delivered about that time (’Lord Cromer,’ by H. D. Traill): “The courbash used to be very frequently employed for two main objects, viz.: the collection of taxes, and the extortion of evidence. I think I may say with confidence that the use of the courbash as a general practice in connection either with collection of taxes or the extortion of evidence has ceased.”

But we need not go so far East for examples of collecting taxes by means of the stick. The headmen of the village communities in Russia freely apply the lash to recalcitrant defaulters.

It would seem, therefore, that the Spaniards erred in company with many other nations. It was by no means an invention of theirs, and it will be remembered that some of our early kings used to persuade the Jews to pay up by drawing their teeth.

Its Good Points.

The Government and the laws partook of a patriarchal character, and notwithstanding certain exactions, the Spanish officials and the natives got on very well together. The Alcaldes remained for many years in one province, and knew all the principal people intimately. I doubt if there was any colony in the world where as much intercourse took place between the governors and the natives, certainly not in any British colony, nor in British India, where the gulf ever widens. In this case, governors and governed professed the same religion, and no caste distinctions prevailed to raise a barrier between them. They could worship together, they could eat together, and marriages between Spaniards and the daughters of the native landowners were not unfrequent. These must be considered good points, and although the general corruption and ineptitude of the administration was undeniable, yet, bad as it was, it must be admitted that it was immeasurably superior to any government that any Malay community had ever established.

1 A whip made from hippopotamus hide.

1 A whip made from hippopotamus hide.

Chapter III.

Six Governors-General.

Moriones—Primo de Rivera—Jovellar—Terreros—Weyler—Despujols.

Moriones.

During my residence in the Islands—from 1877 to 1892—there were six Governors-General, and they differed very widely in character and ideas.

The first was Don Domingo Moriones y Murillo, Marquis of Oroquieto, an austere soldier, and a stern disciplinarian. He showed himself to be a man of undaunted courage, and of absolutely incorruptible honesty.

When he landed in Manila he found that, owing to the weakness of Admiral Malcampo, his predecessor, the Peninsular Regiment of Artillery had been in open mutiny, and that the matter had been hushed up. After taking the oath of office, and attending a Te Deum at the Cathedral, he mounted his horse, and, attended by his aides-de-camp, rode to the barracks, and ordered the regiment to parade under arms. He rode down the ranks, and recognised many soldiers who had served under him in the Carlist wars.

He then stationed himself in front of the regiment, and delivered a remarkable and most stirring oration. He said that it grieved him to the heart to think that Spanish soldiers, sent to the Philippines to maintain the authority of their king and country, many of whom had with him faced the awful fusillade of Somorrostro, and had bravely done their duty, could fall so low as to become callous mutineers, deaf to the calls of duty, and by their bad conduct tarnish the glory of the Spanish Army in the eyes of all the world. Such as they deserved no mercy; their lives were all forfeited. Still he was willing to believe that they were not entirely vicious, that repentance and reform were still possible to the great majority. He would, therefore, spare the lives of most of them in the hope that they might once more become worthy soldiers of Spain. But he would decimate them; every tenth man must die.

He then directed the lieutenant-colonel in command to number off the regiment by tens from the right.

Let the reader ponder upon the situation. Here was a mutinous veteran regiment that for months had been the terror of the city, and had frightened the Governor-General and all the authorities into condoning its crimes.

In front of it sat upon his horse one withered old man. But that man’s record was such that he seemed to those reckless mutineers to be transfigured into some awful avenging angel. His modest stature grew to a gigantic size in their eyes; the whole regiment seemed hypnotized. They commenced numbering. It was an impressive scene—the word ten meant death. The men on the extreme right felt happy; they were sure to escape. Confidently rang out their voices: one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine—then a stop. The doomed wretch standing next would not say the fatal word. Moriones turned his glance upon the captain of the right company, and that officer perceived that the crisis of his life had arrived, and that the next few seconds would make or mar him; one instant’s hesitation would cost him his commission. Drawing and cocking his revolver, he held it in front of the forehead of the tenth man, and ordered him to call out ten. Placed thus between the alternative of instant death or obedience, the unhappy gunner complied, and the numbering of the whole line was accomplished. The number tens were ordered to step out of the ranks, were disarmed, placed under arrest, and notified that they would be shot next morning. As regards the others, all leave was stopped, and extra drills ordered. Great interest was exerted with Moriones to pardon the condemned men, and he did commute the death sentence on most of them, but the ring-leaders were shot the following morning, others imprisoned, and fifty were sent back to Spain in the same vessel as Admiral Malcampo, whose pampering of them had ruined their discipline. So much for the courage of Moriones. It was a wonderful example of the prestige of lawful authority, but of course the risk was great.

To him was due the construction of the Manila Waterworks. A sum of money had been left a century before by Don Francisco Carriedo, who had been general of a galleon, to accumulate until it was sufficient to pay for the waterworks, which ought to have been begun years before. However, the parties who held these funds, like certain Commissioners we know of at home, had little desire to part with the capital, and it was only the determination of General Moriones that triumphed over their reluctance.

Manila ought to be ever grateful to Moriones for this. He also tried to get some work out of the Obras Publicas Department, and, in fact, he did frighten them into exerting themselves for a time, by threatening to ship the Inspector-General of Public Works back to Spain, unless the Ayala bridges were completed on a certain day.

But the greatest thing that Moriones did for the Philippines was when he prevented the sale of the Government tobacco-culture monopoly to some Paris Jews. Whilst he was staying at the Convent of Guadalupe he received a letter from Cánovas, at the time Prime Minister of Spain. It informed him that a project was entertained of selling the Crown monopoly of the cultivation and manufacture of tobacco in the Philippines to a Franco-Spanish syndicate, and added, “The palace is very interested,” meaning that the King and the Infantas were in the affair. It announced that a Commission was about to be sent by the capitalists to enquire into the business, and wound up by requesting Moriones to report favourably on the affair, for which service he might ask any reward he liked. The carrying out of this project meant selling the inhabitants of Cagayan into slavery.

I had this information from a gentleman of unblemished truth and honour, who was present at the receipt of the letter, and it was confirmed by two friars of the Augustinian Order under circumstances that left no doubt upon my mind as to their accuracy.

Although Cánovas was at the time in the height of his power, and although the King was interested in the matter going through, Moriones indignantly refused to back up the proposal. He wrote or cabled to Cánovas not to send out the Commission, for if it came he would send it back by the same vessel. He reported dead against the concession, and told the Prime Minister that he was quite prepared to resign, and return to Spain, to explain his reasons from his seat in the Senate. What a contrast this brave soldier made to the general run of men; how few in any country would have behaved as he did!

This was not the only benefit Moriones conferred upon the tobacco cultivators of Cagayán, for he did what he could to pay off the debt owing to them by the Treasury.

Primo de Rivera.

The next Governor-General was Don Fernando Primo de Rivera, Marquis of Estella, and he was the only one with whom I was not personally acquainted. During the cholera epidemic of 1882, when 30,000 persons died in the city and province of Manila, he showed ability and firmness in the arrangements he made, and he deserves great credit for this. But corruption and embezzlement was rampant during his time. Gambling was tolerated in Manila and it was currently reported that twenty-five gambling houses were licensed and that each paid $50 per day, which was supposed to go to the Governor-General. Emissaries from these houses were stationed near the banks and mercantile offices, and whenever a collector was seen entering or leaving carrying a bag of dollars, an endeavour was made to entice him to the gambling table, and owing to the curious inability of the native to resist temptation, these overtures were too frequently successful.

The whole city became demoralised, servants and dependants stole from their employers and sold the articles to receivers for a tenth of their value in order to try their luck at the gaming table. A sum of $1250 per day was derived from the gambling-houses and was collected every evening.

Notwithstanding all these abuses, Primo de Rivera maintained good relations with the natives; he was not unpopular, and no disturbances occurred during his first government. He owed his appointment to King Alfonso XII., being granted three years’ pillage of the Philippine Islands as a reward for having made the pronunciamento in favour of that monarch, which greatly contributed to putting him upon the throne. He and his friends must have amassed an enormous sum of money, for scarcely a cent was expended on roads or bridges during his government, the provincial governors simply pocketed every dollar.

Jovellar.

He was succeeded by Field-Marshal Don Joaquim Jovellar, during whose time the tribute was abolished and the Cédulas Personales tax instituted. Jovellar appeared to me to be a strictly honourable man, he refused the customary presents from the Chinese, and bore himself with much dignity. His entourage was, however, deplorable, and he placed too much confidence in Ruiz Martinez, the Director of Civil Administration. The result was that things soon became as bad as in the previous governor’s time. Jovellar was well advanced in years, being nearly seventy. He had many family troubles, and the climate did not agree with him.

I remember one stifling night, when I was present at Malacañan at a ball and water fête, given to Prince Oscar, a son of the King of Sweden. The Governor-General had hardly recovered from an illness, and had that day received most distressing news about two of his sons, and his daughter Doña Rosita, who was married to Colonel Arsenio Linares, was laid up and in danger of losing her sight.

Yet in that oppressive heat, and buttoned up in the full dress uniform of a field-marshal, Jovellar went round the rooms and found a kind word or compliment for every lady present. I ventured to remark how fatigued he must be, to which he replied, “Yes, but make no mistake, a public man is like a public woman, and must smile on everybody.”

During his time, owing to symptoms of unrest amongst the natives, the garrison of Manila and Cavite was reinforced by two battalions of marines.

Terrero.

He was succeeded by Don Emilio Terrero y Perinat, a thorough soldier and a great martinet. I found him a kind and courteous gentleman, and deeply regretted the unfortunate and tragic end that befell him after his return to Spain. I saw a good deal of Field-Marshal Jovellar and of General Terrero, having been Acting British Consul at the end of Jovellar’s and the beginning of Terrero’s Government. I kept up my acquaintance with General Terrero all the time he was in the islands, and was favoured with frequent invitations to his table, where I met all the principal officials.

Things went on quietly in his time and there was little to record except successful expeditions to Joló and Mindanao, causing an extension of Spanish influence in both places.

Weyler.

Terrero was succeeded by Don Valeriano Weyler, Marquis of Ténérife, the son of a German doctor, born in Majorca, who brought with him a reputation for cruelties practised on the Cuban insurgents during the first war.

Weyler was said to have purchased the appointment from the wife of a great minister too honest to accept bribes himself, and the price was commonly reported to have been $30,000 paid down and an undertaking to pay the lady an equal sum every year of his term of office.

Weyler is a small man who does not look like a soldier. He is clever, but it is more the cleverness of a sharp attorney than of a general or statesman.

Curiously enough the Segundo Cabo at this time was an absolute contrast. Don Manuel Giron y Aragon, Marquis of Ahumada, is descended from the Kings of Aragon, and to that illustrious lineage he unites a noble presence and a charm of manner that render him instantly popular with all who have the good fortune to meet him. No more dignified representative of his country could be found, and I send him my cordial salutation wherever he is serving.

During Weyler’s term another expedition to Mindanao was made and some advantages secured. Some disturbances occurred which will be mentioned in another chapter, and secret societies were instituted amongst the natives. Otherwise the usual bribery and corruption continued unchecked.

There was a great increase in the smuggling of Mexican dollars from Hong Kong into Manila, where they were worth 10 per cent. more. The freight and charges amounted to 2 per cent., leaving 8 per cent. profit, and according to rumour 4 per cent. was paid to the authorities to insure against seizure, as the importation was prohibited under heavy penalties.

At this time I was Government Surveyor of Shipping, and one day received an order from the captain of the port to proceed on board the steamer España with the colonel of carbineers and point out to him all hollow places in the ship’s construction where anything could be concealed. This I did, but remembering Talleyrand’s injunction, and not liking the duty, showed no zeal, but contented myself with obeying orders. The carbineers having searched every part of the ship below, we came on deck where the captain’s cabin was. A corporal entered the cabin and pulled open one of the large drawers. I only took one glimpse at it and looked away. It was chock full of small canvas bags, and no doubt the other drawers and lockers were also full. Yet it did not seem to occur to any of the searchers that there might be dollars in the bags, and it was no business of mine. Nothing contraband had been found in the ship, and a report to that effect was sent in. I sent the colonel an account for my fee, which was duly paid from the funds of the corps.

Weyler returned to Spain with a large sum of money, a far larger sum than the whole of his emoluments. He had remitted large sums in bills, and having fallen out with one of his confederates who had handled some of the money, this man exhibited the seconds of exchange to certain parties inimical to Weyler, with the result that the latter was openly denounced as a thief in capital letters in a leading article of the Correspondencia Militar of Madrid. Weyler’s attorneys threatened to prosecute for libel, but the editor defied them and declared that he held the documents and was prepared to prove his statement. The matter was allowed to drop. Weyler was thought to have received large sums of money from the Augustinians and Dominicans for his armed support against their tenants. It was said that the Chinese furnished him with a first-rate cook, and provided food for his whole household gratis, besides making presents of diamonds to his wife. And for holding back certain laws which would have pressed very hardly upon them, it was asserted that the Celestials paid him no less than $80,000. This is the man who afterwards carried out the reconcentrado policy in Cuba at the cost of thousands of lives, and subsequently returning with a colossal fortune to Spain, posed as a patriot and as chief of the military party.

Despujols.

To Weyler succeeded a man very different in appearance and character, Don Emilio Despujols, Conde de Caspe.

Belonging to an ancient and noble family of Catalonia, holding his honour dear, endowed with a noble presence and possessed of an ample fortune, he came out to uplift and uphold the great charge committed to him, and rather to give lustre to his office by expending his own means than to economise from his pay, as so many colonial governors are accustomed to do. He established his household upon a splendid scale, and seconded by his distinguished countess, whose goodness and munificent charities will ever be remembered, he entertained on a scale worthy of a viceroy and in a manner never before seen in Manila.

Despujols rendered justice to all. Several Spaniards whose lives were an open scandal, were by his order put on board ship and sent back to Spain. Amongst these was one who bore the title of count, but who lived by gambling.

Another was a doctor who openly plundered the natives. Like a Mahometan Sultan of the old times, Despujols was accessible to the poorest who had a tale of injustice and oppression to relate.

The news that a native could obtain justice from a governor-general flew with incredible rapidity. At last a new era seemed to be opening. A trifling event aroused the enthusiasm of the people. Despujols and his countess drove to the Manila races with their postillions dressed in shirts of Júsi and wearing silver-mounted salacots instead of their usual livery. I was present on this occasion and was struck with the unwonted warmth of the governor-general’s reception from the usually phlegmatic natives. Despujols became popular to an extent never before reached. He could do anything with the natives. Whenever his splendid equipages appeared in public he received an ovation. Quite a different spirit now seemed to possess the natives. But not all the Spaniards viewed this with satisfaction; many whose career of corruption had been checked, who found their illicit gains decreased, and the victims of their extortion beginning to resist them, bitterly criticised the new governor-general.

The religious orders finding Despujols incorruptible and indisposed to place military forces at the disposal of the Augustinians and Dominicans to coerce or evict refractory tenants, then took action. Their procurators in Madrid made a combined attack on Despujols, both in the reptile press and by representations to the ministry. They succeeded, and Despujols was dismissed from office by cable. Rumour has it that the Orders paid $100,000 for Despujols’s recall. For my own part I think this very likely, and few who know Madrid will suppose that this decree could be obtained by any other means.

He laboured under a disadvantage, for he did not pay for his appointment as some others did. If he had been paying $30,000 a year to the wife of a powerful minister, he would not have been easily recalled. Or if, like another governor-general, he had been in debt up to the eyes to influential creditors, these would have kept him in power till he had amassed enough to pay them off.

I am of opinion that had Despujols been retained in Manila, and had he been given time to reform and purify the administration, the chain of events which has now torn the Philippines for ever from the grasp of Spain would never have been welded. Whoever received the priests’ money, whoever they were who divided that Judas-bribe, they deserve to be held in perpetual execration by their fellow-countrymen, and to have their names handed down to everlasting infamy.

Despujols left Manila under a manifestation of respect and devotion from the foreign residents, from the best Spaniards and from every class of the natives of the Philippines, that might well go far to console him for his unmerited dismissal. He must have bitterly felt the injustice with which he was treated, but still he left carrying with him a clear conscience and a harvest of love and admiration that no previous governor-general had ever inspired.

For if Moriones manifested courage, energy and incorruptible honesty under what would have been an irresistible temptation to many another man, that rude soldier was far from possessing those personal gifts, the fine presence and the sympathetic address of Despujols, and inspired fear rather than affection.

Yet both were worthy representatives of their country; both were men any land might be proud to send forth. Those two noble names are sufficient to redeem the Spanish Government of the Philippines from the accusation of being entirely corrupt, too frequently made against it. They deserve an abler pen than mine to extol their merits and to exalt them as they deserve above the swarm of pilferers, and sham patriots, who preceded and succeeded them. To use an Eastern image, they may be compared to two noble trees towering above the rank vegetation of some poisonous swamp. For the honour of Spain and of human nature in general, I have always felt grateful that I could say that amongst the governors-general of the Philippines whom I had known there were at least two entitled to the respect of every honest man.

Chapter IV.

Courts of Justice.

Alcaldes—The Audiencia—The Guardia Civil—Do not hesitate to shoot—Talas.