автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Giovanni Boccaccio, a Biographical Study

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources.

Modern practice in Italian texts contracts (removes the space from) vowel elisions, for example l'anno not l' anno, ch'io not ch' io. This book, in common with some similar English books of the time, has a space in these elisions in the original text. This space has been retained in the etext. The only exceptions, in both the text and etext, are in French names and phrases, such as d'Aquino and d'Anjou.

More details can be found at the end of the book.

GIOVANNI BOCCACCIO

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

FREDERIC UVEDALE. A Romance. 1901.

STUDIES IN THE LIVES OF THE SAINTS. 1902.

ITALY AND THE ITALIANS. Second Edition. 1902.

THE CITIES OF UMBRIA. Third Edition. 1905.

THE CITIES OF SPAIN. Third Edition. 1906.

SIGISMONDO MALATESTA. 1906.

FLORENCE AND NORTHERN TUSCANY. Second Edition. 1907.

COUNTRY WALKS ABOUT FLORENCE. 1908.

IN UNKNOWN TUSCANY. 1909.

EDITED BY EDWARD HUTTON

MEMOIRS OF THE DUKES OF URBINO.

By James Dennistoun of Dennistoun. Illustrating the Arms, Arts, and Literature of Italy, from 1440 to 1630. New Edition, with upwards of 100 Illustrations. 3 vols. Demy 8vo. 1908.

CROWE AND CAVALCASELLE'S A NEW HISTORY OF PAINTING IN ITALY.

3 vols. 8vo. 1908-9.

Traditional Portraits of Boccaccio & Fiammetta (Maria d'Aquino)

From the Frescoes in the Spanish Chapel of S. Maria Novella, Florence.

GIOVANNI

BOCCACCIO

A BIOGRAPHICAL STUDY

BY EDWARD HUTTON

WITH PHOTOGRAVURE FRONTISPIECE

& NUMEROUS OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS

But if the love that hath and still doth burn me

No love at length return me,

Out of my thoughts I'll set her:

Heart let her go, O heart I pray thee let her!

Say shall she go?

O no, no, no, no, no!

Fix'd in the heart, how can the heart forget her.

LONDON: JOHN LANE THE BODLEY HEAD

NEW YORK: JOHN LANE COMPANY MCMX

PLYMOUTH: WM. BRENDON AND SON, LTD., PRINTERS

TO MY FRIEND

J. L. GARVIN

THIS STUDY OF AN HEROIC LIFE

PREFACE

It might seem proper, in England at least, to preface any book dealing frankly with the author of the Decameron with an apology for, and perhaps a defence of, its subject. I shall do nothing of the kind. Indeed, this is not the place, if any be, to undertake the defence of Boccaccio. His life, the facts of his life, his love, his humanity, and his labours, plentifully set forth in this work, will defend him with the simple of heart more eloquently than I could hope to do. And it might seem that one who exhausted his little patrimony in the acquirement of learning, who gave Homer back to us, who founded or certainly fixed Italian prose, who was the friend of Petrarch, the passionate defender of Dante, and who died in the pursuit of knowledge, should need no defence anywhere from any one.

This book, on which I have been at work from time to time for some years, is the result of an endeavour to set out quite frankly and in order all that may be known of Boccaccio, his life, his love for Fiammetta, and his work, so splendid in the Tuscan, the fruit of such an enthusiastic and heroic labour in the Latin. It is an attempt at a biographical and critical study of one of the greatest creative writers of Europe, of one of the earliest humanists, in which, for the first time, in England certainly, all the facts are placed before the reader, and the sources and authority for these facts quoted, cited, and named. Yet while I have tried to be as scrupulous as possible in this respect, I hope the book will be read too by those for whom notes have no attraction; for it was written first for delight.

Among other things I have dealt with, the reader will find a study of Boccaccio's attitude to Woman, and in some sort this may be said to be the true subject of the book.

I have dealt too with Boccaccio's relation to both Dante and Petrarch; and it was my intention to have written a chapter on Boccaccio and Chaucer, but interesting as that subject is—and one of the greatest desiderata in the study of Chaucer—a chapter in a long book seemed too small for it; and again, it belongs rather to a book on Chaucer than to one about Boccaccio. I have left it, then, for another opportunity, or for another and a better student than myself.

In regard to the illustrations, I may say that I hoped to make them, as it were, a chapter on Boccaccio and his work in relation to the fine arts; but I found at last that it would be impossible to carry this out. To begin with, I was unable to get permission to reproduce M. Spiridon's and Mr. V. Watney's panels by Alunno di Domenico[1] illustrating the story of Nastagio degli Onesti (Decameron, V, 8), which are perhaps the most beautiful paintings ever made in illustration of one of Boccaccio's tales. In the second place, the subject was too big to treat of in the space at my command. I wish now that I had dealt only with the Decameron; but in spite of a certain want of completeness, the examples I have been able to reproduce will give the reader a very good idea of the large and exquisite mass of material of the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries in Italy, France, Germany, and even in England which in its relation to Boccaccio has still to be dealt with. Nothing on this subject has yet been published, though something of the sort with regard to Petrarch has been attempted. Beyond the early part of the seventeenth century I have not sought to go, but an examination of the work of the eighteenth century in France at any rate should repay the student in this untouched field.

I have to thank a host of people who in many and various ways have given me their assistance in the writing of this book. It has been a labour of love for them as for me, and let us hope that Boccaccio "in the third heaven with his own Fiammetta" is as grateful for their kindness as I am.

Especially I wish to thank Mrs. Ross, of Poggio Gherardo, Mr. A. E. Benn, of Villa Ciliegio, Professor Guido Biagi, of Florence, Mr. Edmund Gardner, Professor Henri Hauvette, of Paris, Mr. William Heywood, Dr. Paget Toynbee, and Mr. Charles Whibley. And I must also express my gratitude to Messrs. J. and J. Leighton, of Brewer Street, London, W., for so kindly placing at my disposal many of the blocks which will be found in these pages.

EDWARD HUTTON.

Casa di Boccaccio,

Corbignano,

September, 1909.

INTRODUCTION

Of the three great writers who open the literature of the modern world, Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio, it is perhaps the last who has the greatest significance in the history of culture, of civilisation. Without the profound mysticism of Dante or the extraordinary sweetness and perfection of Petrarch, he was more complete than either of them, full at once of laughter and humility and love—that humanism which in him alone in his day was really a part of life. For him the centre of things was not to be found in the next world but in this. To the Divine Comedy he seems to oppose the Human Comedy, the Decameron, in which he not only created for Italy a classic prose, but gave the world an ever-living book full of men and women and the courtesy, generosity, and humanity of life, which was to be one of the greater literary influences in Europe during some three hundred years.

In England certainly, and indeed almost everywhere to-day, the name of Boccaccio stands for this book, the Decameron. Yet the volumes he wrote during a laborious and really uneventful life are very numerous both in verse and prose, in Latin and in Tuscan. He began to write before he was twenty years old, and he scarcely stayed his hand till he lay dying alone in Certaldo in 1375. That the Decameron, his greatest and most various work, should be that by which he is most widely known, is not remarkable; it is strange, however, that of all his works it should be the only one that is quite impersonal. His earlier romances are without exception romans à clef; under a transparent veil of allegory he tells us eagerly, even passionately, of himself, his love, his sufferings, his agony and delight. He too has confessed himself with the same intensity as St. Augustine; but we refuse to hear him. Over and over again he tells his story. One may follow it exactly from point to point, divide it into periods, name the beginning and the ending of his love, his enthusiasms, his youth and ripeness; yet we mark him not, but perhaps wisely reach down the Decameron from our shelves and silence him with his own words; for in the Decameron he is almost as completely hidden from us as is Shakespeare in his plays. And yet for all this, there is a profound unity in his work, which, if we can but see it, makes of all his books just the acts of a drama, the drama of his life. The Decameron is already to be found in essence in the Filocolo, as is the bitter melancholy of the Corbaccio, its mad folly too, and the sweetness of the songs. For the truth about Boccaccio can be summed up in one statement almost, he was a poet before all things, not only because he could express himself in perfect verse, nor even because of the grace and beauty of all his writing, his gifts of sentiment and sensibility, but because he is an interpreter of nature and of man, who knows that poetry is holy and sacred, and that one must accept it thankfully in fear and humility.

He was the most human writer the Renaissance produced in Italy; and since his life was so full and eager in its desire for knowledge, it is strange that nothing of any serious account has been written concerning him in English,[2] and this is even unaccountable when we remember how eagerly many among our greater poets have been his debtors. Though for no other cause yet for this it will be well to try here with what success the allegory of his life may be solved, the facts set in order, and the significance of his work expressed.

But no study of Boccaccio can be successful, or in any sense complete, without a glance at the period which produced him, and especially at those eight-and-forty years so confused in Italy, and not in Italy alone, which lie between the death of Frederic II and the birth of Dante in 1265 and the death of Henry VII and the birth of Boccaccio in 1313. This period, not less significant in the general history of Italy than in the history of her literature, begins with the fall of the Empire, its failure, that is, as the sum or at least the head, of Christendom; it includes the fall of the medieval Papacy in 1303 and the abandonment of the Eternal City, the exile of the Popes. These were years of immense disaster in which we see the passing of a whole civilisation and the birth of the modern world.

The Papacy had destroyed the Empire but had failed to establish itself in its place. It threatened a new tyranny, but already weapons were being forged to combat it, and little by little the Papal view of the world, of government, was to be met by an appeal to history, to the criticism of history, and to those political principles which were to be the result of that criticism. In this work both Petrarch and Boccaccio bear a noble part.

If we turn to the history of Florence we shall find that the last thirty-five years of the thirteenth century had been, perhaps, the happiest in her history. From the triumph of the Guelfs at Benevento to the quarrel of Neri and Bianchi she was at least at peace with herself, while in her relations with her sister cities she became the greatest power in Tuscany. Art and Poetry flourished within her walls. Dante, Cavalcanti, Giotto, the Pisani, and Arnolfo di Cambio were busy with their work, and the great churches we know so well, the beautiful palaces of the officers of the Republic were then built with pride and enthusiasm. In 1289, the last sparks, as it was thought, of Tuscan Ghibellinism had been stamped out at Campaldino. There followed the old quarrel and Dante's exile.

The Ghibellines were no more, but the Grandi, those Guelf magnates who had done so well at Campaldino, hating the burgher rule as bitterly as the old nobility had done, began to exert themselves. In the very year of the great battle we find that the peasants of the contrada were enfranchised to combat them. In 1293 the famous Ordinances of Justice which excluded them from office were passed, and the Gonfaloniere was appointed to enforce these laws against them. A temporary alliance of burghers and Grandi in 1295 drove Giano della Bella, the hero of these reforms, into exile, and the government remained in the hands of the Grandi. That year saw Dante's entrance into public life.

The quarrel thus begun came to crisis in 1300, the famous year of the jubilee, when Boniface VIII seemed to hold the whole world in his hands. The dissensions in Florence had not been lost upon the Pope, who, apparently hoping to repress the Republic altogether and win the obedience of the city, intrigued with the Neri, those among the magnates who, unlike their fellows of the Bianchi faction, among whom Dante is the most conspicuous figure, refused to admit the Ordinances of Justice, even in their revised form, and wished for the tyrannical rule of the old Parte Guelfa. Already, as was well known, the Pope was pressing Albert of Austria for a renunciation of the Imperial claim over Tuscany in favour of the Holy See; and Florence, finally distracted now by the quarrels of Neri and Bianchi, seemed to be in imminent danger of losing her liberty. It became necessary to redress the balance of power, destroyed at Benevento, by an attempt to recreate the Empire. This was the real work of the Bianchi—their solution of the greatest question of their time. The actual solution was to come, however, from their opponents: not from the leaders of the Neri it is true, but from the people themselves. These leaders were but tyrants in disguise: they served any cause to establish their own lordship. Corso Donati, for instance, the head and front of the Neri, was of an old Ghibelline stock, yet he trafficked with the Pope, not for the Church, we may be sure, nor to give Florence to the Holy See, but that he might himself rule the city. Nor did the Pope disdain to use him. Alarmed even in Rome by the republican sentiments of the populace, who wished to rule themselves even as the Florentines, he desired above all things to bring Florence into his power. On May 15, 1300, the Pope despatched a letter to the Bishop of Florence, in which he asked: "Is not the Pontiff supreme lord over all, and particularly over Florence, which for especial reasons is bound to be subject to him? Do not emperors and kings of the Romans yield submission to us, yet are they not superior to Florence? During the vacancy of the Imperial throne, did not the Holy See appoint King Charles of Anjou Vicar-General of Tuscany?" Thus as Villari says, "in a rising crescendo," he threatened the Florentines that he would "not only launch his interdict and excommunication against them, but inflict the utmost injury on their citizens and merchants, cause their property to be pillaged and confiscated in all parts of the world, and release all their debtors from the duty of payment." The Neri, fearing the people might, with that impudent claim before them, side with the Bianchi, induced the Pope to send the Cardinal of Acquasparta to arrange a pacification. But though the city gave him many promises, she would not invest him with the Balia.

Meanwhile the Pope, set on the subjection of Florence, without counting the cost, urged Charles of Valois, the brother of Philip IV of France, to march into Tuscany. Nor was Charles of Anjou, King of Naples, less eager to have his aid against the Sicilians. Joined by the exiles in November, 1301, he entered Florence with some 1200 horse, part French, part Italian. His mission was to crush the Bianchi and the people, and to uplift the Neri. He came at the request of the Pope, and, so far as he himself was interested, for booty; yet he swore in S. Maria Novella to keep the peace. On that same day, November 5, Corso Donati entered the city with an armed force. The French joined in the riot, the Priors were driven from their new palace, and the city sacked by the soldiers with the help of the Neri. The Pope had succeeded in substituting black for white, that was all. A new "peace-maker" failed altogether. The proscription, already begun, continued, and before January 27, 1302, Dante went into exile.

But if the Pope had failed to do more than establish the Neri in the government of Florence, Corso Donati had failed also; he had not won the lordship of the city. He tried again, splitting the Neri into two factions, and Florence was not to possess herself in peace till his death in a last attempt in 1308. It was during these years so full of disaster that Petrarch was born at Arezzo on July 20, 1304.

The medieval idea of the Papacy has been expressed once and for all by S. Thomas Aquinas. In his mind so profoundly theological, abhorring variety, the world was to be governed, if at all, by a constitutional monarchy, strong enough to enforce order, but not to establish a tyranny. The first object of every Christian society, the salvation of the soul, was to be achieved by the priest under the absolute rule of the Pope. Under the old dispensation, as he admitted, the priest had been subject to the king, but under the new dispensation the king was subject to the priest in matters touching the law of Christ. Thus if the king were careless of religion or schismatic or heretical, the Church might deprive him of his power and by excommunication release his subjects from their allegiance. This supreme authority is vested in the Pope, who is infallible, and from whom there can be no appeal at any time as to what is to be believed or what condemned.

Before these claims the Empire had fallen in 1266; but a reaction, the result of the success of Boniface, soon set in, and we find the most perfect expression of the revived and reformed claims of the Empire in the De Monarchia, which Dante Alighieri wrote in exile. Dante's Empire was by no means merely a revival of what the Imperial idea had become in its conflicts with the Holy See. It was nevertheless as hopeless an anachronism as the dream of S. Thomas Aquinas, and even less clairvoyant of the future, for it disregarded altogether the spirit to which the future belonged, the spirit of nationalism. With a mind as theological as S. Thomas's, Dante hated variety not less than he, and rather than tolerate the confusion of the innumerable cities and communes into which Italy was divided, where there was life, he would have thrust the world back into Feudalism and the Middle Age from which it was already emerging, he would have established over all Italy a German king. He was dreaming of the Roman Empire. The end for which we must strive, he would seem to say in the De Monarchia, that epitaph of the Empire, is unity; let that

be granted

. And since that is the end of all society, how shall we obtain it but by obedience to one head—the Emperor. And this Empire—so easy is it to mistake the past for the future—belongs of right to the Roman people who won it long ago. And what they won Christ sanctioned, for He was born within its confines. And yet again He recognised it, for He received at the hands of a Roman judge the sentence under which He bore our sorrows. Nor does the Empire derive from the Pope or through the Pope, but from God immediately; for the foundation of the Church is Christ, but the Empire was before the Church. Yet let Cæsar be reverent to Peter, as the first-born should be reverent to his father.So much for the philosophical defence of the reaction. It is rarely, after all, that a rigidly logical conception of society, of the State, has any existence in reality. The future, as we know, lay with quite another theory. Yet which of us to-day but in his secret heart dreams ever more hopefully of a new unity, that is indeed no stranger to the old, but in fact the resurrection of the Empire, of Christendom, in which alone we can be one? After all, is it not now as then, the noblest hope that can inspire our lives?

Already, before the death of Boniface VIII, the last Pope to die in Rome for nearly a hundred years, Philip IV of France had asserted the rights of the State against the claims of the Papal monarchy. The future was his, and his success was to be so great that for more than seventy years the Papacy was altogether under the influence of France, the first of the great nations of the Continent to become self-conscious. Thus when Boniface died broken-hearted in 1303, it was the medieval Papacy which lay in state beside him. Two years later, after the pathetic and ineffectual nine months' reign of Benedict XI, Clement V, Bertrand de Goth, an Aquitanian, was elected, and, like his predecessor, fearful before the turbulent Romans and the confusion of Italy, in 1305 fled away to Avignon, which King Charles II of Naples held as Count of Anjou on the borders of the French kingdom. The Papacy had abandoned the Eternal City and had come under the influence of the French king. Yet in spite of every disaster the Pope and the Emperor remained the opposed centres of European affairs. No one as yet realised the possibility of doing without them, but each power sought rather to use them for its own end. In this political struggle France held the best position; the Pope was a Frenchman and so her son; there remained as spoil, the Empire.

On May 1, 1308, Albert of Hapsburg had been murdered by his nephew; the election of a new King of the Romans, the future Emperor, fell pat to Philip's ambitions. He immediately supported the candidature of his brother, Charles of Valois; but in this he reckoned without the Pope, who with the Angevins in Naples and himself in Avignon had no wish to see the Empire also in the hands of France. His position forbade him openly to oppose Philip, but secretly he gave his support to Henry of Luxemburg, who was elected as Henry VII on 27 November, 1308.

A German educated in France, the lord of a petty state, Henry, in spite of the nobility of his nature, of which we hear so much and see so little, had but feeble Latin sympathies and no real power of his own. He dreamed of the universal empire like a true German, believing that the feudal union of Germany and Italy which had always been impossible was the future of the world. With this mirage before his eyes he raised the imperial flag and set out southward; and for a moment it seemed as though the stars had stopped in their courses.

For he was by no means alone in his dream. Every disappointed ambition in Italy, noble and ignoble, greeted him with a feverish enthusiasm. The Bianchi and the exiled Ghibellines joined hands, enormous hopes were conceived, and in his triumph private vengeance and public hate thought to find achievement. But when Henry entered Italy in September, 1310, he soon found he had reckoned without the Florentines, who had called together the Guelf cities, and, leaguing themselves with King Robert the Wise of Naples, formed what was, in fact, an Italian confederation to defend freedom and their common independence. It is true that in these acts Florence thought only of present safety: she was both right and fortunate; but in allying herself with King Robert and espousing the cause of France and the Pope she contributed to that triumph which was to prove for centuries the most dangerous of all to Italian liberty and independence.

Bitter with loneliness, imprisoned in the adamant of his personality, Dante, amid the rocks of the Casentino, hurled his curses on Florence, and not on Florence alone. Is there, I wonder, anything but hatred and abuse of the cities of his Fatherland in all his work? He has judged his country as God Himself will not judge it, and he kept his anger for ever. In the astonishing and disgraceful letters written in the spring of 1311 he urged Henry to attack his native city. Hailing this German king—and the Florentines would call him nothing else—as the "Lamb of God Who taketh away the sins of the world," he asks him: "What may it profit thee to subdue Cremona? Brescia, Bergamo, and other cities will continue to revolt until thou hast extirpated the root of the evil. Art thou ignorant perhaps where the rank fox lurketh in hiding? The beast drinketh from the Arno, polluting the waters with its jaws. Knowest thou not that Florence is its name?..." Henry, however, took no heed as yet of that terrible voice crying in the wilderness. He entered Rome before attacking Florence, in May, 1312. He easily won the Capitol, but was fiercely opposed by King Robert when he tried to reach S. Peter's to win the imperial crown, and from Castel S. Angelo he was repulsed with heavy loss. The Roman people, however, presently took his part, and by threats and violence compelled the bishops to crown him in the Lateran on June 29.

If Rome greeted him, however, she was alone. Florence remained the head and front of the unbroken League. Those scelestissimi Florentini, as Dante calls them, still refused to hail him as anything but Enemy, German King and Tyrant. The fine political sagacity of Florence, which makes hers the only history worth reading among the cities of Central Italy, was never shown to better advantage or more fully justified in the event than when she dared to send her greatest son into exile and to proclaim his Emperor "German king" and "enemy." "Remember," she wrote to the people of Brescia, "that the safety of all Italy and all the Guelfs depends on your resistance. The Latins must always hold the Germans in enmity, seeing that they are opposed in act and deed, in manners and soul; not only is it impossible to serve, but even to hold any intercourse with that race."

At last the Emperor decided to follow Dante's advice and "slay the new Goliath." This was easier to talk of in the Casentino than to do. From mid-September to the end of October the Imperial army lay about the City of the Lily, never daring to attack. Then the Emperor raised the siege and set out for Poggibonsi, his health ruined by anxiety and hardship, and his army, as was always the case both before and since, broken and spoiled by the Italian summer. He spent the winter and spring between Poggibonsi and Pisa, then with some idea of retrieving all by invading Naples, he set off southward in August to meet his death on S. Bartholomew's Day, poisoned, as some say, at Buonconvento.

And Florence announced to her allies: "Jesus Christ hath procured the death of that most haughty tyrant Henry, late Count of Luxemburg, whom the rebellious persecutors of the Church and the treacherous foes of ourselves and you call King of the Romans and Emperor."

In the very year of Henry's death, as we suppose, Boccaccio was born in Paris. The Middle Age had come to an end. The morning of the Renaissance had already broken on the world.

CONTENTS

PAGE

Preface vii Introduction xiCHAPTER

I.

Boccaccio's Parentage, Birth, and Childhood 3II.

His Arrival in Naples—His Years with the Merchant—His Abandonment of Trade and Entry on the Study of Canon Law 15III.

His Meeting with Fiammetta and the Periods of their Love Story 27IV.

The Years of Courtship—The Reward—The Betrayal—The Return To Florence 41V.

Boccaccio's Early Works—The Filocolo—The Filostrato—The Teseide—The Ameto—The Fiammetta—The Ninfale Fiesolano 61VI.

In Florence—His Father's Second Marriage—The Duke of Athens 96VII.

In Naples—The Accession of Giovanna—The Murder of Andrew of Hungary—The Vengeance 108VIII.

In Romagna—The Plague—The Death of Fiammetta 119IX.

The Rime—The Sonnets To Fiammetta 130X.

Boccaccio as Ambassador—The Meeting with Petrarch 145XI.

Two Embassies 162XII.

Boccaccio's Attitude to Woman—The Corbaccio 170XIII.

Leon Pilatus and the Translation of Homer—The Conversion of Boccaccio 189XIV.

The Embassies

to the Pope—Visits to Venice and Naples—Boccaccio's Love of Children 207XV.

Petrarch and Boccaccio—The Latin Works 223XVI.

Dante and Boccaccio—The Vita—and the Comento 249XVII.

Illness and Death 279XVIII.

The Decameron 291APPENDICES

I.

The Dates of Boccaccio's Arrival in Naples and of his Meeting with Fiammetta 319II.

Document of the Sale of "Corbignano" (called now "Casa di Boccaccio") by Boccaccio in 1336 325III.

From "La Villeggiatura di Maiano," a MS. by Ruberto Gherardi; a Copy of which is in Possession of Mrs. Ross, of Poggio Gherardo, near Settignano, Florence 335IV.

The Acrostic of the Amorosa Visione dedicating the Poem to Fiammetta 348V.

The Will of Giovanni Boccaccio 350VI.

English Works on Boccaccio 355VII.

Boccaccio and Chaucer and Shakespeare 360VIII.

Synopsis of the Decameron, together with some Works to be consulted 367IX.

An Index to the Decameron 394 Index 409ILLUSTRATIONS

Traditional Portraits of Boccaccio and Fiammetta (Maria d'Aquino)

Frontispiece

From the frescoes in the Spanish Chapel at S. Maria Novella, Florence. Photogravure.

To face page

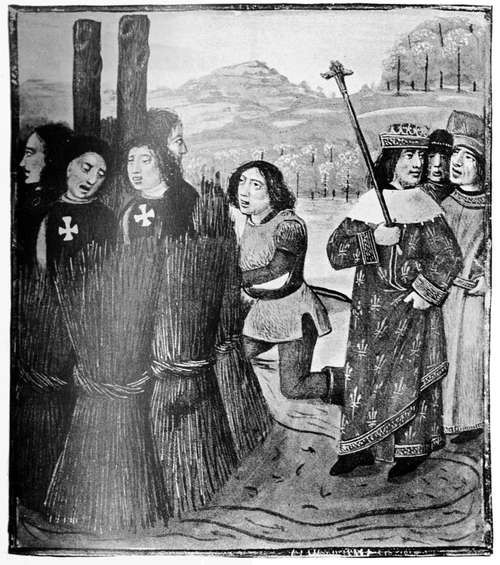

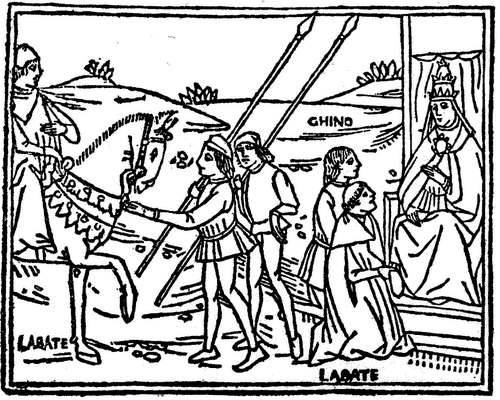

The Burning of the Master of the Temple

6From a miniature in the French version of the

De Casibus Virorum, made in 1409 by Laurent le Premierfait. MS. late XV century. (Brit. Mus. Showcase V, MS. 126.)

Casa di Boccaccio, Corbignano, near Florence

12King Robert of Naples crowned by S. Louis of Toulouse

18From the fresco by Simone Martini in S. Lorenzo, Naples.

Pope Joan

24A woodcut from the

De Claris Mulieribus. (Berne, 1539.) (By the courtesy of Messrs. J. and J. Leighton.)

Lucrece

30A woodcut from

De Claris Mulieribus. (Berne, 1539.) (By the courtesy of Messrs. J. and J. Leighton.)

Boccaccio and Mainardi Cavalcanti

36By the Dutch engraver called "The Master of the Subjects in the Boccaccio."

De Casibus Virorum.(Strasburg, 1476.)

Sapor mounting over the prostrate Valerian

42By the Dutch engraver called "The Master of the Subjects in the Boccaccio."

De Casibus Virorum.(Strasburg, 1476.)

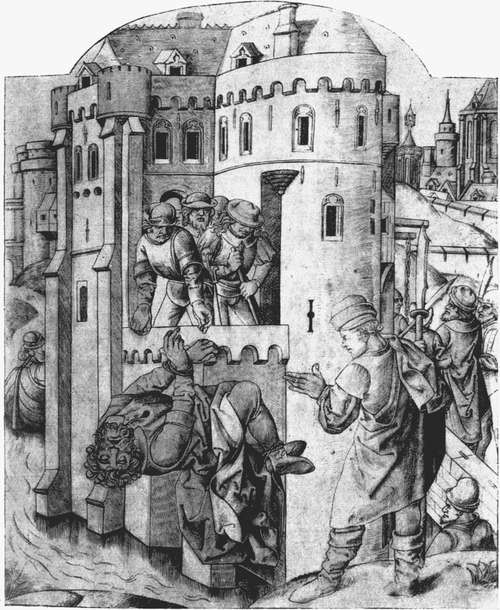

Manlius thrown into the Tiber

48By the Dutch engraver called "The Master of the Subjects in the Boccaccio."

De Casibus Virorum.(Strasburg, 1476.)

Allegory of Wealth and Poverty

54From a miniature in the French version of the

De Casibus Virorum, made in 1409 by Laurent le Premierfait. MS. late XV century. (Brit. Mus. Rothschild Bequest. MS. XII.)

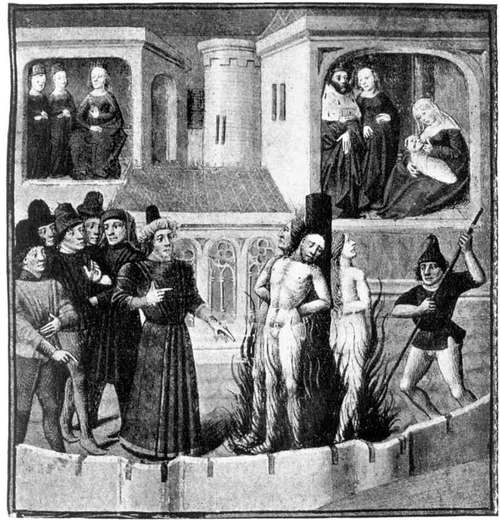

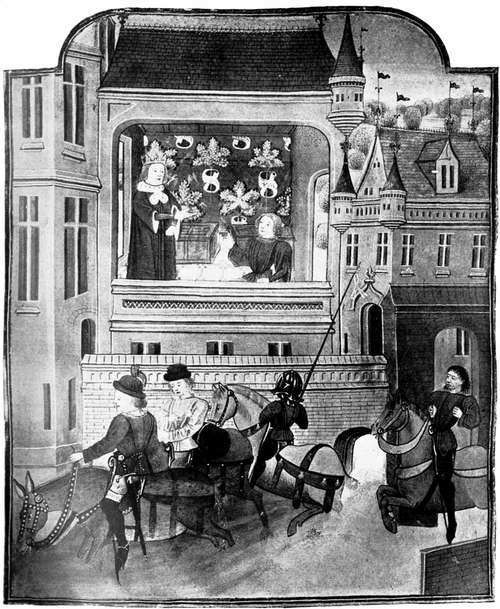

The Murder of the Emperor and Empress

62From a miniature in the French version of the

De Casibus Virorum, made in 1409 by Laurent le Premierfait. MS. late XV century. (Brit. Mus. Showcase V, MS. 126.)

A Woodcut from

Des Nobles Malheureux(

De Casibus Virorum). Paris, 1515

68This cut originally appears in the

Troy Book. (T. Bonhomme, Paris, 1484.) Unique copy at Dresden. (By the courtesy of Messrs. J. and J. Leighton.)

Marcus Manlius hurled from the Tarpeian Rock

74An English woodcut from Lydgate's

Falles of Princes. (Pynson, London, 1527.) It is a copy in reverse from the French translation of the

De Casibus. (Du Pré, Paris, 1483.) (By the courtesy of Messrs. J. and J. Leighton.)

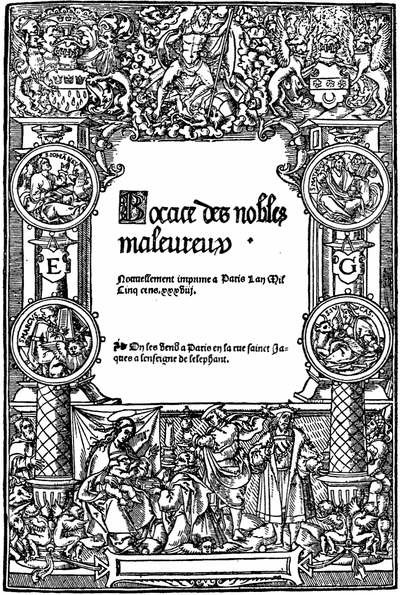

The Title of the

Nobles Malheureux(

De Casibus). Paris, 1538

80(By the Courtesy of Messrs. J. and J. Leighton.)

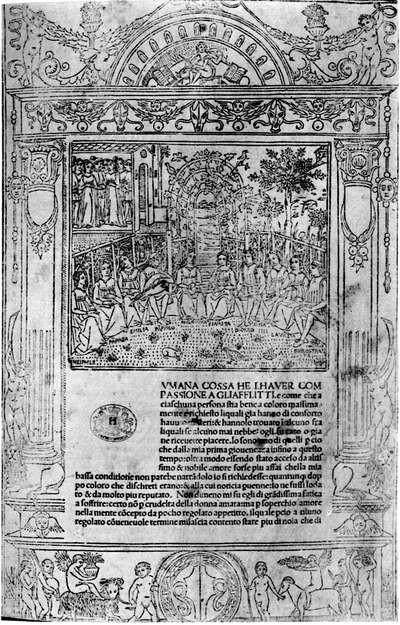

Frontispiece of the

Decameron. Venice, 1492

86Chapter Heading from the

Decameron. Venice, 1492

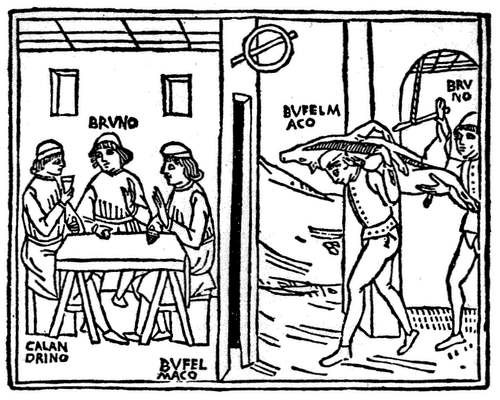

92the Theft of Calandrino's Pig (

Dec., viii, 6)

98Ghino and the Abbot (

Dec., x, 2)

98Woodcuts from the

Decameron. (Venice, 1492.)

The Duke of Athens

104The Execution of Filippa la Catanese

104From miniatures in the French version of the

De Casibus Virorum, made in 1409 by Laurent le Premierfait. Ms. Late XV century. (Brit. Mus. Rothschild Bequest. Ms. XII.)

Cimon and Iphigenia (

Dec., v, 1)

110From a miniature in the French version of the

Decameron, made in 1414 by Laurent le Premierfait. MS. late XV century. (Brit. Mus. Rothschild Bequest. MS. XIII.)

Gulfardo and Guasparruolo (

Dec., viii, 1)

116From a miniature in the French version of the

Decameron, made in 1414 by Laurent le Premierfait. MS. late XV century. (Brit. Museum. Rothschild Bequest, MS. XIV.)

Madonna Francesca and her Lovers (

Dec., ix, 1)

124From a miniature in the French version of the

Decameron, made in 1414 by Laurent le Premierfait. MS. late XV century. (Brit. Mus. Rothschild Bequest. MS. XIV.)

The Knight who thought himself ill-rewarded (

Dec., x, 1)

132From a miniature in the French version of the

Decameron, made in 1414 by Laurent le Premierfait. MS. late XV century. (Brit. Mus. Rothschild Bequest. MS. XIV.)

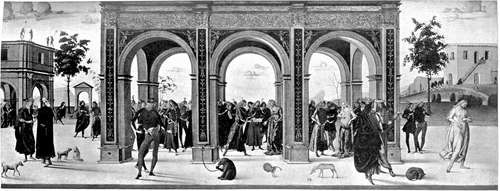

The Story of Griselda (

Dec., x, 10)

138From the picture by Pesellino in the Morelli Gallery at Bergamo.

The Story of Griselda (

Dec., x, 10)

146i. The Marquis of Saluzzo, while out hunting, meets with Griselda, a peasant girl, and falls in love; he clothes her in fine things. From the picture in the National Gallery by (?) Bernardino Fungai.

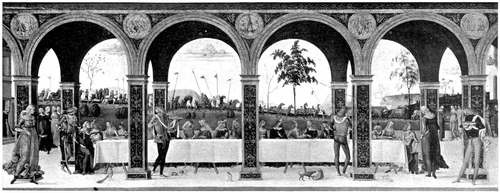

The Story of Griselda (

Dec., x, 10)

152ii. Her two children are taken from her, she is divorced, stripped, and sent back to her father's house. From the picture in the National Gallery by (?) Bernardino Fungai.

The Story of Griselda (

Dec., x, 10)

158iii. A banquet is prepared for the new bride; Griselda is sent for to serve, but is reinstated in her husband's affections and finds her children. From the picture in the National Gallery by (?) Bernardino Fungai.

The Palace of the Popes at Avignon

164Masetto and the Nuns (

Dec., iii, 1)

174In 1538 this woodcut appears in Tansillo's

Stanze. (By the courtesy of Messrs. J. and J. Leighton.)

Masetto and the Nuns (

Dec., iii, 1)

174A woodcut from

Le Cento Novellein ottava rima. (Venice, 1554.) (By the courtesy of Messrs. J. and J. Leighton.)

Monna Tessa Exorcising the Devil. (

Dec., vii, 1)

184A woodcut from the

Decameron. (Venice, 1525.)

Monna Tessa Exorcising the Devil. (

Dec., vii, 1)

184Appeared in Sansovino's

Le Cento Novelle(Venice, 1571.) (By the courtesy of Messrs. J. and J. Leighton.)

A Woodcut from the

Decameron. (Strasburg, 1535)

194(By the courtesy of Messrs. J. and J. Leighton.)

Title of the Spanish Translation of the

Decameron(Valladolid, 1539)

204(By the courtesy of Messrs. J. and J. Leighton.)

A Woodcut from the

Decameron(Venice, 1602.) Title to Day V

214(By the courtesy of Messrs. J. and J. Leighton.)

Petrarch and Boccaccio Discussing

224From a miniature in the French version of the

De Casibus Virorum, made in 1409 by Laurent le Premierfait. MS. late XV century. (Brit. Mus. Showcase V, MS. 126.)

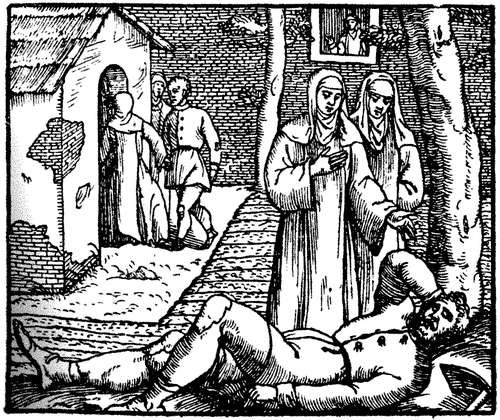

Pompeia, Paulina, and Seneca

230A woodcut from the

De Claris Mulieribus(Ulm, 1473), cap. 92. (By the courtesy of Messrs. J and J. Leighton.)

Epitharis

234A woodcut from the

De Claris Mulieribus(Ulm, 1493), cap. 91. (By the courtesy of Messrs. J. and J. Leighton.)

Paulina, Mundus, and the God Anubis

238A woodcut from the

De Claris Mulieribus(Ulm, 1473), cap. 89. (By the courtesy of Messrs. J. and J. Leighton.)

The Torture of Regulus

244A woodcut from Lydgate's

Falle of Princes of John Bochas. (London, 1494.)

Boccaccio Discussing

250From a miniature in the French version of the

De Casibus Virorum, made in 1409 by Laurent le Premierfait. MS. late XV century. (Brit. Mus. Rothschild Bequest. MS. XII.)

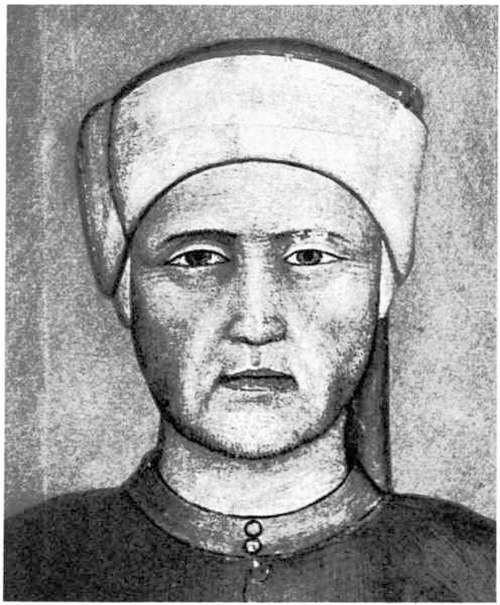

Giovanni Boccaccio

265From the fresco in S. Apollonia, Florence. By Andrea dal Castagno (1396(?)-1457).

Certaldo

280Boccaccio's House in Certaldo

284Room in Boccaccio's House at Certaldo

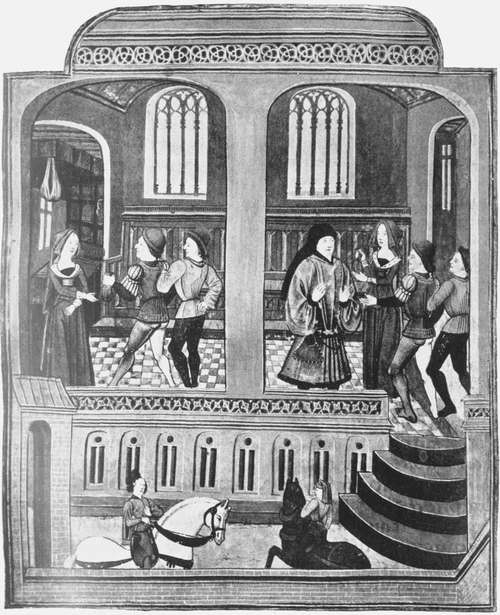

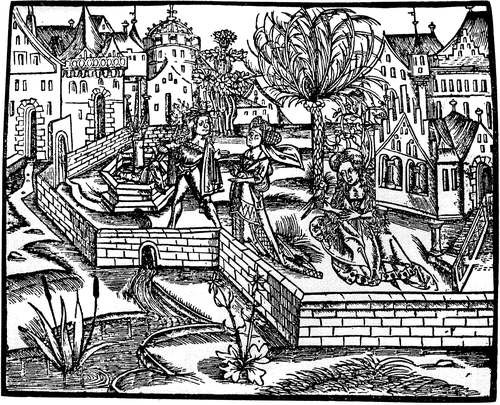

288The Ladies and Youths of the

Decameronleaving Florence

292From a miniature in the French version of the

Decameron, made in 1414 by Laurent le Premierfait. MS. late XV century. (Brit. Mus. Rothschild Bequest. MS. XIV.)

Poggio Gherardo, near Settignano, Florence

298(The scene of the first two days of the

Decameron.)

Villa Palmieri, near Florence

302(The scene of the third and following days of the

Decameron.)

La Valle Delle Donne

306From a print of the XVIII century in Baldelli's

Vita di Gio. Boccaccio.

Title Page of Volume II of the First English Edition of the

Decameron(Isaac Jaggard, 1620.)

312

GIOVANNI BOCCACCIO

GIOVANNI BOCCACCIO

CHAPTER I

1313-1323

BOCCACCIO'S PARENTAGE, BIRTH, AND CHILDHOOD

The facts concerning the life and work of Giovanni Boccaccio, though they have been traversed over and over again by modern students,[3] are still for the most part insecure and doubtful; while certain questions, of chronology especially, seem to be almost insoluble. To begin with, we are uncertain of the place of his birth and of the identity of his mother, of whom in his own person he never speaks. And though it is true that he calls himself "of Certaldo,"[4] a small town at that time in the Florentine contado where he had some property, and where indeed he came at last to die, we have reason to believe that it was not his birthplace. The opinion now most generally professed by Italian scholars is that he was born in Paris of a French mother; and, while we cannot assert this as a fact, very strong evidence, both from within and from without his work, can be brought to support it. It will be best, perhaps, to examine this evidence, whose corner-stone is his assertion to Petrarch that he was born in 1313,[5] as briefly as possible.

The family of Boccaccio[6] was originally from Certaldo in Valdelsa,[7] his father being the Florentine banker and money-changer Boccaccio di Chellino da Certaldo, commonly called Boccaccino.[8] We know very little about him, but we are always told that he was of very humble condition. That he was of humble birth seems certain, but his career, what we know of his career, would suggest that he was in a position of considerable importance. We know that in 1318 he was in business in Florence, the name of his firm being Simon Jannis Orlandini, Cante et Jacobus fratres et filii q. Ammannati et Boccaccinus Chelini de Certaldo. In the first half of 1324 he was among the aggiunti deputati of the Arte del Cambio for the election of the Consiglieri della Mercanzia;[9] in 1326 he was himself one of the five Consiglieri; in the latter part of 1327 he represented the Società de' Bardi in Naples, and was very well known to King Robert;[10] while in 1332 he was one of the Fattori for the same Società in Paris, a post at least equivalent to that of a director of a bank to-day. These were positions of importance, and could not have been held by a person of no account.

As a young man, in 1310, we know he was in business in Paris, for on May 12 in that year fifty-four Knights Templars were slaughtered there,[11] and this Boccaccio tells us his father saw.[12] That there was at that time a considerable Florentine business in France in spite of those years of disaster—Henry VII had just entered Italy—is certain. In 1311, indeed, we find the Florentines addressing a letter to the King of France,[13] lamenting that at such a moment His Majesty should have taken measures hurtful to the interests of their merchants, upon whom the prosperity of their city so largely depended.

Boccaccio di Chellino seems to have remained in Paris in business;[14] that he was still there in 1313 we know, for in that year, on March 11, Jacques de Molay, Master of the Templars, was executed, and Giovanni tells us that his father was present.[15] If, then, Boccaccio was speaking the truth when he told Petrarch he was born in 1313, he must have been conceived, and was almost certainly born, in Paris.

[1] Mr. Berenson (Burlington Magazine, Vol. I (1903), p. 1 et seq.) gives these panels to Alunno di Domenico; Mr. Horne to Botticelli. See Crowe and Cavalcaselle (ed. E. Hutton), A New History of Painting in Italy (Dent, 1909), Vol. II, pp. 409 and 471, and works there cited.

[2] The best study is that of J. A. Symonds's Boccaccio as Man and Author (Nimmo, 1896). It is unfortunately among the less serious works of that scholar.

Boccaccio di Chellino seems to have remained in Paris in business;[14] that he was still there in 1313 we know, for in that year, on March 11, Jacques de Molay, Master of the Templars, was executed, and Giovanni tells us that his father was present.[15] If, then, Boccaccio was speaking the truth when he told Petrarch he was born in 1313, he must have been conceived, and was almost certainly born, in Paris.

It is, then, to the hills about Settignano, to the woods above the Mensola and the valley of the Affrico, that we should naturally turn to look for the scenes of his boyhood. And indeed any doubt of his presence there might seem to be dismissed by a document discovered by Gherardi, which proves that on the 18th of May, 1336, by a contract drawn up by Ser Salvi di Dini, Messer Boccaccio di Chellino da Certaldo, lately dwelling in the parish of S. Pier Maggiore and then in that of S. Felicità, sold to Niccolò di Vegna, who bought for Niccolò the son of Paolo his nephew, the poderi with houses called Corbignano, partly in the parish of S. Martino a Mensola and partly in that of S. Maria a Settignano.[35] This villa of old Boccaccio's exists to-day at Corbignano, and bears his name, Casa di Boccaccio, and though it has been rebuilt much remains from his day—part of the old tower that has been broken down and turned into a loggia, here a ruined fresco, there a spoiled inscription.[36] Here, doubtless, within sound of Mensola and Affrico, within sight of Florence and Fiesole, "not too far from the city nor too near the gate," Giovanni's childhood was passed.

wrote Petrarch of him later—"full of virtue." While in a letter written in 1340 to Cardinal Colonna he says that of all men he would most readily have accepted King Robert as a judge of his ability. Nor were they poets and men of learning alone whom he gathered about him. In 1330 Giotto, who had known Charles of Calabria in Florence in 1328,[54] came to Naples on his invitation; while so early as 1310, certainly, Simone Martini was known to him, and seems about that time to have painted his portrait, later representing him in S. Chiara as crowned by his brother S. Louis of Toulouse.[55] It was then into a city where learning and the arts were the fashion that Boccaccio came in 1323.

What are we to think of these visions? Did they really happen, or are they merely an artistic method of stating certain facts—among the rest that Fiammetta was about to renew his life? But we have gone too far to turn back now; we have already relied so much on the allegories of the Ameto, the Filocolo, and the Fiammetta, that we dare not at this point question them too curiously. The visions are all probably true in substance if not in detail. We must accept them, though not necessarily the explanations that have been offered of them.[75]

When she saw that he continued to stare at her, she screened herself with her veil.[97] But he changed his position and found a place by a column whence he could see her very well—"dirittissimamente opposto, ... appoggiato ad una colonna marmorea"—and there, while the priest sang the Office, "con canto pieno di dolce melodia,"[98] he drank in her blonde beauty which the dark clothes made more splendid—the golden hair and the milk-white skin, the shining eyes and the mouth like a rose in a field of lilies.[99] Once she looked at him,—"Li occhi, con debita gravità elevati, in tra la moltitudine de' circostanti giovani, con acuto ragguardamento distesi."[100] So he stayed where he was till the service was over, "senza mutare luogo." Then he joined his companions, waiting with them at the door to see the girls pass out. And it was then, in the midst of other ladies, that he saw her for the second time, watching her pass out of S. Lorenzo on her way home. When she was gone he went back to his room with his friends, who remained a short time with him. These, as soon as might be, excusing himself, he sent away, and remained alone with his thoughts.

Thus, says Crescini, we have twenty-four days from the first meeting to the acceptance of his court, and 135 days thenceforward to the possession, that is 159 days.[131]

What happened is described in the forty-fourth chapter of the Amorosa Visione. The twelve days were passed, he tells us in this allegory, when he heard a voice like a terrible thunder cry to him:—

In this feverish state of mind, of soul, sometimes hopeful, sometimes in despair, Boccaccio passed the next five years of his life, from the spring of 1331 to the spring of 1336. It was during this time, in 1335[167] it seems, that with his father's unwilling permission he discontinued the law studies he had begun in 1329, but had for long neglected, and gave himself up to literature, "without a master," but not without a counsellor—his old companion in the study of astronomy, Calmeta. Other friends, too, were able to assist him, among them Giovanni Barrili, the jurisconsult, a man of fine culture, later Seneschal of King Robert for the kingdom of Provence,[168] and Paolo da Perugia, King Robert's learned librarian, elected to that office in 1332. Him Boccaccio held in the highest veneration, and no doubt Paolo was very useful to him.[169]

That year so full of wild joy soon passed away. With the dawn of 1338 his troubles began. At first jealousy. He found it waiting to torture him on returning from a journey we know not whither,[188] in which he had encountered dangers by flood and field; a winter journey then, doubtless. He came home to find Fiammetta disdainful, angry, even indifferent. All the annoyance of the road came back to him threefold:—[189]

but also from the letters he sent to Niccolò Acciaiuoli,[213] in which he says: "I can write nothing here where I am in Florence, for if I should, I must write not in ink, but in tears. My only hope is in you—you alone can change my unhappy fate." That he was very poor we may be certain, and though he was not compelled to work at business, the abomination of his youth, no doubt he had to listen to the regrets, and perhaps to the reproaches, of an old man whom misfortune had soured. His father, however, seems to have left him quite free to work as he wished, satisfying himself with his mere presence and company. And then the worst was soon over, for, by what means we know not, by December, 1342, he was able to buy a house in the parish of S. Ambrogio, and to live in his own way.[214]

After these adventures Florio, with Biancofiore and his companions, goes on to Rome, where, like a modern tourist, he visits all the sights. In the Lateran he meets the monk Ilario, who discourses on religion, dealing severely with paganism, and recounting briefly the contents of the Old and New Testaments. He speaks also of the history of the Greeks and Romans, and at last converts Florio and his companions to Christianity.[221] Then follows the reconciliation with Biancofiore's relations and the return to Spain, where, Felice being dead, Florio inherits his kingdom, and with Biancofiore lives happily ever after.

"Pensato ancora avea di domandarla

Di grazia al padre mio che la mi desse;

Poi penso questo fora un accusarla,

E far palese le cose commesse;

Nè spero ancora ch' el dovesse darla,

Sì per non romper le cose promesse,

E perchè la direbbe diseguale

A me, al qual vuol dar donna reale."[239]

Scarcely is he come to Athens when he is urged by a deputation of the Greek princesses to declare war on Creon, who will not permit the burial rites to be performed for those who fell in the war of succession. Theseus conquers Thebes and Creon is killed, the bodies of the Greek princes are solemnly burned and their ashes conserved.

The book, however, full as it is of imitations of Dante, is an allegory within an allegory. The nymphs and shepherds are not real people, but it seems personifications of the four cardinal virtues and the three theological virtues and their opposites. Thus Mopsa is Wisdom, and she loves Afron, Foolishness; Emilia is Justice, and she loves Ibrida, Pride; Adiona is Temperance, and she loves Dioneo, Licence; Acrimonia is Fortitude, and she loves Apaten, Insensibility; Agapes is Charity, and she loves Apiros, Indifference; Fiammetta is Hope, and she loves Caleone, Despair; Lia is Faith, and she loves Ameto, Ignorance. In their songs the seven nymphs praise and exalt the seven divinities that correspond to the seven virtues which they impersonate; thus Pallas is praised by Mopsa (Wisdom), Diana by Emilia (Justice), Pomona by Adiona (Temperance), Bellona by Acrimonia (Fortitude), Venus by Agapes (Charity), Vesta by Fiammetta (Hope), and Cibele by Lia (Faith). The whole action of the work then becomes symbolical, and Boccaccio, it has been said, had the intention of showing that a man, however rude and savage, can find God only by means of the seven virtues which are the foundation of all morals. If such were his intention he has indeed chosen strange means of carrying it out. The stories of the seven nymphs are extremely licentious, and all confess that they do not love their husbands and are seeking to make the shepherds fall in love with them. All this is, as we see, obscure, medieval, and far-fetched. Let it be what it may be. It is not in this allegory we shall find much to interest us, but in certain other allusions in which the work is rich. Thus we shall note that Fiammetta is Hope, and that she gives Hope to Caleone, who is Despair. That Caleone is Boccaccio himself there can be no manner of doubt. We see then that at the time the Ameto was written he still had some hope of winning Fiammetta again. In fact in the Ameto Fiammetta has the mission of saving Caleone from death, for he is resolved to kill himself. I have spoken of the autobiographical allusions in the Ameto, however, elsewhere.[274] It will be sufficient to say here that the Ameto was written, as Boccaccio himself tells us, in order that he might tell freely without regret or fear what he had seen and heard. It is all his life that we find in the stories of the nymphs. Emilia tells of Boccaccino's love for Jeanne (Gannai), his desertion of her, his marriage, and his ruin. Fiammetta tells how her mother was seduced by King Robert, who is here called Midas.[275] Then she describes the passion of Caleone (Boccaccio), his nocturnal surprise of her, and his triumph. The work is in fact a complete biography; and since this is so, there are in fact no sources from which it can be said to be derived. We find there some imitations of the Divine Comedy, some hints from Ovid and Virgil, of Moschus and Theocritus. The Ameto was dedicated to Niccola di Bartolo del Bruno, his "only friend in time of trouble." It was first published in small quarto in Rome in 1478. It has never been translated into any language.

All alone she passes her days and nights in weeping. The four months pass and Panfilo does not come back to her. One day she hears from a merchant that he has taken a wife in Florence. This news increases her agony, and she asks aid of Venus. Then her husband, seeing her to be ill, but unaware of the cause of her sufferings, takes her to Baia; but no distraction helps her, and Baia only reminds her of the bygone days she spent there with Panfilo. At last she hears from a faithful servant come from Florence that Panfilo has not taken a wife, that the young woman in his house is the new wife of his old father; but it seems though he be unmarried he is in love with another lady, which is even worse. New jealousy and lamentations of Fiammetta. She refuses to be comforted and thinks only of death and suicide, and even tries to throw herself from her window, but is prevented. Finally the return of Panfilo is announced. Fiammetta thanks Venus and adorns herself again. She waits; but Panfilo does not come, and at last she is reduced to comforting herself by thinking of all those who suffer from love even as she. The work closes with a sort of epilogue.

It will be remembered that in the romance which passes under her name Fiammetta tells us that Panfilo (Giovanni), when he deserted her, promised to return in four months. Later[309] she says, when the promised time of his return had passed by more than a month, she heard from a merchant lately arrived in Naples that her lover fifteen days before had taken a wife in Florence.[310] Great distress on the part of Fiammetta; but, as she soon learnt, it was not Giovanni, but his father, who had married himself.

The Duke was no sooner secure in his dominion than he forbade the Signori to meet in the Palazzo, recalled the Baldi and the Frescobaldi, made peace with the Pisans, and took away their bills and assignments from the merchants who had lent money in the war of Lucca. He dissolved the authority of the Signori and set up in their place three Rettori, with whom he constantly advised. The taxes he laid upon the people were great, all his judgments were unjust, and all men saw his cruelty and pride, while many citizens of the more noble and wealthy sort were condemned, executed, and tortured. He was jealous of the nobili, so he applied himself to the people, cajoling them and scheming into their favour, hoping thus to secure his tyranny for ever. In the month of May, for instance, when the people were wont to be merry, he caused the common people to be disposed into several companies, gave them ensigns and money, so that half the city went up and down feasting and junketing, while the other half was busy to entertain them. And his fame grew abroad, so that many persons of French extraction repaired to him, and he preferred them all, for they were his faithful friends; so that in a short while Florence was not only subject to Frenchmen, but to French customs and garb, men and women both, without decency or moderation, imitating them in all things. But that which was incomparably the most displeasing was the violence he and his creatures used to the women. In these conditions it is not surprising that plots to get rid of him grew and multiplied. He cared not. When Matteo di Morrozzo, to ingratiate himself with the Duke, discovered to him a plot which the Medici had contrived with others against him, he caused him to be put to death. And when Bettone Cini spoke against the taxes he caused his tongue to be pulled out by the roots so that he died of it. Such was his cruelty and folly. But indeed this last outrage completed the rest. The people grew mad, for they who had been used to speak of everything freely could not brook to have their mouths stopped up by a stranger. "When," asks Machiavelli, "did the Florentines know how to maintain liberty or to endure slavery?" However, things were indeed at such a pass that the most servile people would have tried to recover its freedom.

"Pastorum Rex Argus erat: cui lumina centum

The murder of Andrew, whose handiwork soever, effectually divided the Kingdom into two parties, to wit those of Durazzo and Taranto; the former demanding punishment of the murderers. Two Cardinals, di S. Clemente and di S. Marco, were appointed by the Pope to rule in Naples and to exact vengeance. The Queen was helpless. On December 25th her son was born and named Charles Martel. As time went on and none of the assassins were brought to justice, the Hungarians became furious, and at last requested the custody of the young prince; and this request became a demand when it was known that Giovanna was being sought in marriage by Robert of Taranto, who, with his mother and his half-brother Louis, had been covertly associated with the Catanesi. Something had to be done, and early in 1346 we find Charles of Durazzo with Robert of Taranto and Ugo del Balzo seizing Raimondo the seneschal, as one of the guilty persons. Under torture he confessed that he had knowledge of the plot and assisted those who committed the murder. Among his accomplices he named the Count of Terlizzi, Roberto de Cabannis, Giovanni and Rostaino di Lagonessa, Niccolò di Melezino, Filippa Catanese, and Sancia de Cabannis.

If that letter is authentic,[347] then Boccaccio not only met King Louis of Hungary[348] at Forlì, but accompanied him and Francesco degli Ordelaffi into the Kingdom in the end of the year 1347 and the beginning of 1348.[349] His sentiments with regard to the murder and the war which followed it are clearly expressed there. He speaks of the King's arms as "arma justissima," and though it surprises us to find Boccaccio on that side, the letter only states clearly the sentiments already set down in allegory in the third and eighth Eclogues, and clearly but more discreetly stated in the De Casibus Virorum. In the fourth Eclogue, however, he commiserates the unhappy fate of Louis of Taranto, and hymns his return. Can it be that, at first persuaded of the Queen's guilt, he learned better later? We do not know. The whole affair of the murder, as of Boccaccio's actions at this time and of his sentiments with regard to it, are mysterious. If in the third and eighth Eclogues he tells us that Giovanna and Louis of Taranto were the real murderers of Andrew and wishes success to the arms of the avenger; in the fourth, fifth, and sixth Eclogues he sympathises with Louis and tells of the misery of the Kingdom after the descent of the Hungarians, and at last joyfully celebrates the return of Giovanna and her husband.[350] And this contradiction is emphasised by his actions. So far as we may follow him at all in these years, we see him in Naples horrified and disgusted at the state of affairs, leaving the city after the torture and death of the Catanesi and repairing to the courts of the Polenta and of the Ordelaffi, the enemies of the Church which held Giovanna innocent, and of the champions of the Church, Robert and Naples. Nor does he stop there, but apparently follows Ordelaffo in his descent with King Louis on Naples in the end of 1347 and the beginning of 1348. Yet in 1350 he was in Naples, and in 1352 he was celebrating the return of those against whom he had sided and written. The contradiction is evident, and we cannot explain it; but in a manner it gives us the reason why, when Frate Martino da Segna asked for an explanation and key to the Eclogues, he supplied him with one so meagre and imperfect.[351]

But then, the dissenters continue, none of the contemporary biographers, such as Villani and Bandino,[362] say anything of the matter. Our answer to that is that they had nothing to say for the same reason that a modern biographer would have or should have nothing to say in similar circumstances. But in spite of the diversity of opinion which we find for these and similar reasons, we must suppose, that even to-day, to every type of mind and soul save the critic of literature it must be evident that the love of Boccaccio for Fiammetta was an absolutely real thing, so real that it made Boccaccio what he was, and led him to write those early works which we have already examined and to compose the majority of the poems which we are now about to consider and to enjoy.[363]

Crescini tells us that it is only just to admit that atleast the greater part of the love poems of Boccaccio refer to Fiammetta. Landau is more precise, and Antona Traversi follows him in naming sonnets c. and ci. (the latter we do not call a love poem) as written for Pampinea or Abrotonia. To these Antona Traversi adds sonnets xii. and xvii. (the former we do not call a love poem), which he thinks were written for one of the ladies Boccaccio loved before he met Fiammetta.[371] I give them both in Rossetti's translation:—

As we have seen, Boccaccio returned to Florence probably in the end of 1349. His father, who was certainly living in July, 1348, for he then added a codicil to his Will,[387] seems still to have been alive in May, 1349,[388] but by January, 1350, he is spoken of as dead and Giovanni is named as one of his heirs.[389] And in the same month of January, 1350, on the 26th of the month, Boccaccio was appointed guardian of his brother Jacopo,[390] then still a child. But these were not the only duties which fell to him in that year, which, as it proved, was to mark a new departure in his life. It is in 1350 that we find him, for the first time as we may think, acting as ambassador for the Florentine Republic, and it is in 1350 that he first met Petrarch face to face and entertained him in his house in Florence.

Putting aside Baldelli's assertion, we may take it on the evidence as most probable that Boccaccio was the ambassador of Florence in Romagna at some time between March and October, 1350. If we are right in thinking so, his mission was of very great importance. What Florence feared, as we have seen, was the growing power of Milan, and, after the sale of Bologna, the loss of her trade routes north, and finally perhaps even her liberty. Already, in the latter part of 1349,[401] she had offered again and again to mediate between the Pope and Bologna and Romagna, fearing that in their distraction Milan would be tempted to interfere for her own ends. In the first months of 1350 she had written to the Pope, to Perugia, Siena, and to the Senate of Rome, that they should send ambassadors to the congress at Arezzo to form a confederation for their common protection.[402] In September she wrote the Pope more than once explaining affairs to him; but he had touched Visconti gold, and far away in Avignon cared nothing and paid but little heed. The sale of Bologna, however, brought things to a crisis so far as the policy of Florence was concerned, and having secured Prato, Pistoia, and the passes, her ambassadors in Romagna had apparently induced the Pepoli to replace Bologna under the protection of the communes of Florence, Siena, and Perugia, till the Papal army was ready to act. But the Papal army was not likely to be ready so long as Visconti was willing to pay,[403] and we find the Pope, while he thanks Florence effusively, refusing to acknowledge the claim of the League to protect Bologna. The sale of Bologna to Milan, its seizure by the Visconti, brought all the diplomacy of Florence to naught for the moment, and in another letter, written on November 9, 1350,[404] she returns once more to plead with the Pope and to point out to him the danger of the invasions of the Visconti in Lombardy and in Bologna, which placed in peril not only the Parte Guelfa, but the territories of the Church and the Florentine contado. By the time that letter was written Boccaccio was back in Florence, and it must have been evident to the Florentines that the Pope had no intention of giving them any assistance and that they must look elsewhere for an ally.

It was doubtless this consideration and some remembrance of her humiliation before the contempt of that other exile who had died in Ravenna, that prompted Florence, always so business-like, to try to repair the wrong she had done to Petrarch. So she decided to return him in money the value of the property confiscated from his father, and to send Boccaccio on the delicate mission of persuading him to accept the offer she now made him of a chair in her university.[414] With a letter then from the Republic, Boccaccio set out for Padua in the spring of 1351, meeting Petrarch there, as De Sade tells us, on April 6, the anniversary of the day of Petrarch's first meeting with Laura and of her death.

That a Guelf republic should turn for assistance to the head of the Ghibelline cause seems perhaps more strange than in fact it was. Guelf and Ghibelline had become mere names beneath which local jealousies hid and flourished, caring nothing for the greater but less real quarrel between Empire and Papacy. Charles, however, was to fail Florence; for at the last moment he withdrew from the treaty, fearing to leave Germany; when he did descend later, things had so far improved for her that she was anything but glad to see him especially when she was forced to remember that it was she who had called him there. After these two failures Florence was compelled to make terms with the Visconti at Sarzana in April, 1353, promising not to interfere in Lombardy or Bologna, while Visconti for his part undertook not to molest Tuscany.[425] But by this treaty the Visconti gained a recognition of their hold in Bologna from the only power that wished to dispute it. They profited too by the peace, extending their dominion in Northern Italy. In this, though fortune favoured them, they began to threaten others who had looked on with composure when they were busy with Tuscany. Among these were the Venetians, who made an alliance with Mantua, Verona, Ferrara, and Padua, and were soon trying to persuade Florence, Siena, and Perugia to join them.[426] Nor did they stop there, for in December, 1353, they too tried to interest Charles IV in Italian affairs. When it was seen that Charles was likely to listen to the Venetians the Visconti too sent ambassadors to him, nor was the Papacy slow to make friends.

We cannot, I think, remind ourselves too often in our attempts—and after all they can never be more than attempts—to understand the development of Boccaccio's mind, of his soul even, that he had but one really profound passion in his life, his love for Fiammetta. And as that had been one of those strong and persistent sensual passions which are among the strangest and bitterest things in the world,[432] his passing love affairs—and doubtless they were not few—with other women had seemed scarcely worth recounting.[433] That he never forgot Fiammetta, that he never freed himself from her remembrance, are among the few things concerning his spiritual life which we may assert with a real confidence. It is true that in the Proem to the Decameron he would have it otherwise, but who will believe him? There he says—let us note as we read that even here he cannot but return to it—that: "It is human to have compassion on the afflicted; and as it shows very well in all, so it is especially demanded of those who have had need of comfort and have found it in others: among whom, if any had ever need thereof or found it precious or delectable, I may be numbered; seeing that from my early youth even to the present,[434] I was beyond measure aflame with a most aspiring and noble love, more perhaps than were I to enlarge upon it would seem to accord with my lowly condition. Whereby, among people of discernment to whose knowledge it had come, I had much praise and high esteem, but nevertheless extreme discomfort and suffering, not indeed by reason of cruelty on the part of the beloved lady, but through superabundant ardour engendered in the soul by ill-bridled desire; the which, as it allowed me no reasonable period of quiescence, frequently occasioned me an inordinate distress. In which distress so much relief was afforded me by the delectable discourse of a friend and his commendable consolations that I entertain a very solid conviction that I owe it to him that I am not dead. But as it pleased Him who, being infinite, has assigned by immutable law an end to all things mundane, my love, beyond all other fervent, and neither to be broken nor bent by any force of determination, or counsel of prudence, or fear of manifest shame or ensuing danger, did nevertheless in course of time abate of its own accord, in such wise that it has now left naught of itself in my mind but that pleasure which it is wont to afford to him who does not adventure too far out in navigating its deep seas; so that, whereas it was used to be grievous, now, all discomfort being done away, I find that which remains to be delightful ... now I may call myself free."

The Corbaccio, however, was not the only work in which his pessimism and hatred of woman showed itself. It is visible also in the Vita di Dante, which was written about this time or a little later than the Corbaccio,[444] perhaps in 1356-7. All goes well till we come to Dante's marriage, when there follows a magnificent piece of invective which, while it expresses admirably Boccaccio's mood and helps us to date the book, has little or nothing to do with Dante. Indeed, we seem to learn there, reading a little between the lines, more of Boccaccio himself than of the husband of Gemma Donati.

This man who makes such a bizarre figure in Boccaccio's life seems to have belonged to that numerous race of adventurers half Greek, half Calabrian, needy, unscrupulous, casual, and avaricious, who ceaselessly wandered about Europe in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries seeking fortune. It might seem strange that such an one should play the part of a teacher and professor, but he certainly was not particular, and Petrarch and Boccaccio were compelled to put up with what they could get. Pilatus, however, seems to have wearied and disgusted Petrarch; it was Boccaccio, more gentle and more heroic, who devoted himself to him for the sake of learning. Having persuaded Pilatus to follow him to Florence, he caused a Chair of Greek to be given to him in the university, and for almost four years imposed upon himself the society of this disagreeable barbarian. For as it seems he was nothing else; his one claim on the attention of Petrarch and Boccaccio being that he could, or said he could, speak Greek.

"I have always thought," Petrarch writes to him after his return to Tuscany,[476] "I have always thought that your presence would give me pleasure, I knew it would, and I felt that it would please you too. What I did not know, however, was that it would bring good fortune. For during the very few months, gone so quickly, that you have cared to dwell with me in this house that I call mine, and which is yours, it seems to me, in truth, that I have contracted a truce with fortune who, while you were here, dared not spoil my happiness...."

"Presently we were talking in your charming little garden with some friends, and she offered me with matronly serenity your house, your books, and all your things there. Suddenly little footsteps—and there came towards us thy Eletta, my delight, who, without knowing who I was, looked at me smiling. I was not only delighted, I greedily took her in my arms, imagining that I held my little one (virgunculam olim meam) that is lost to me. What shall I say? If you do not believe me, you will believe Guglielmo da Ravenna, the physician, and our Donato, who knew her. Your little one has the same aspect that she had who was my Eletta, the same expression, the same light in the eyes, the same laughter there, the same gestures, the same way of walking, the same way of carrying all her little person; only my Eletta was, it is true, a little taller when at the age of five and a half I saw her for the last time.[491] Besides, she talks in the same way, uses the same words, and has the same simplicity. Indeed, indeed, there is no difference save that thy little one is golden-haired, while mine had chestnut tresses (aurea cesaries tuæ est, meæ inter nigram rufamque fuit). Ah me! how many times when I have held thine in my arms listening to her prattle the memory of my baby stolen away from me has brought tears to my eyes—which I let no one see."

Those ten years from 1363 to 1372 had not only been given by Boccaccio to the study of Greek and the service of his country, they had also been devoted to a vast and general accumulation of learning such as was possessed by only one other man of his time, his master and friend Petrarch. It might seem that ever since Boccaccio had met Petrarch he had come under his influence, and in intellectual matters, at any rate, had been very largely swayed by him. In accordance with the unfortunate doctrine of his master, we see him, after 1355, giving up all work in the vulgar, and setting all his energy on work in the Latin tongue, in the study of antiquity and the acquirement of knowledge. From a creative writer of splendid genius he gradually became a scholar of vast reading but of mediocre achievement. He seems to have read without ceasing the works of antiquity, annotating as he read. His learning, such as it was, became prodigious, immense, and, in a sense, universal, and little by little he seems to have gathered his notes into the volumes we know as De Montibus, Sylvis, Fontibus, Lacubus, Fluminibus, Stagnis seu Paludibus, De Nominibus Maris Liber, a sort of dictionary of Geography;[504] the De Casibus Virorum Illustrium, in nine books, which deals with the vanity of human affairs from Adam to Petrarch;[505] the De Claris Mulieribus, which he dedicated to Acciaiuoli's sister, and which begins with Eve and comes down to Giovanna, Queen of Naples;[506] and the De Genealogiis Deorum, in fifteen books, dedicated to Ugo, King of Cyprus and Jerusalem, who had begged him to write this work, which is a marvellous cyclopædia of learning concerning mythology[507] and a defence of poetry and poets.[508] In all these works it must be admitted that we see Boccaccio as Petrarch's disciple, a pupil who lagged very far behind his master.

"Petrarch," he tells us,[526] "living from his youth up as a celibate, had such a horror of the impurities of the excess of love that for those who know him he is the best example of honesty. A mortal enemy of liars, he detests all vices. For he is a venerable sanctuary of truth, and honours and joys in virtue, the model of Catholic holiness. Pious, gentle, and full of devotion, he is so modest that one might name him a second Parthenias [i.e. Virgil]. He is too the glory of the poetic art. An agreeable and eloquent orator, philosophy has for him no secrets. His spirit is of a superhuman perspicacity; his mind is tenacious and full of all knowledge that man may have. It is for this reason that his writings, both in prose and in verse, numerous as they are, shine so brilliantly, breathe so much charm, are adorned with so many flowers, enclosing in their words so sweet a harmony, and in their thoughts an essence so marvellous that one believes them the work of a divine genius rather than the work of a man. In short he is assuredly more than a man and far surpasses human powers. I am not singing the praises of some ancient, long since dead. On the contrary, I am speaking of the merits of a living man.... If you do not believe these words, you can go and see him with your eyes. I do not fear that it will happen to him as to so many famous men, as Claudius says, 'Their presence diminishes their reputation.' Rather I affirm boldly that he surpasses his reputation. He is distinguished by such dignity of character, by an eloquence so charming, by an urbanity and old age so well ordered, that one can say of him what Seneca said of Socrates, that 'one learns more from his manners than from his discourse.'"

Nor is Petrarch deceived in his own superiority. He was by far the most cultured man of his time; as a critic he had already for himself disposed of the much-abused claims of the Church and the Empire. For instance, with what assurance he recognises as pure invention, with what certainty he annihilates with his criticism the privileges the Austrians claimed to hold from Cæsar and Nero.[532] And even face to face with antiquity he is not afraid; he is sure of the integrity of his mind; he analyses and weighs, yes, already in a just balance, the opinions of the writers of antiquity; while Boccaccio mixes up in the most extraordinary way the various antiquities of all sorts of epochs. Nor has Boccaccio the courage of his opinions; all seems to him worthy of faith, of acceptance. He cannot, even in an elementary way, discern the false from the true; and even when he seems on the point of doing so he has not the courage to express himself. When he reads in Vincent de Beauvais that the Franks came from Franc the son of Hector, he does not accept it altogether, it is true, but, on the other hand, he dare not deny it, "because nothing is impossible to the omnipotence of God."[533] He accepts the gods and heroes of antiquity; the characters in Homer and the writers of Greece, of Rome, are equally real, equally authentic, equally worthy of faith, and we might add equally unintelligible. They are as wonderful, as delightful, as impossible to judge as the saints. What they do or say he accepts with the same credulity as that with which he accepted the visions of Blessed Pietro. Petrarch only had to look Blessed Pietro in the eye, and he shrivelled up into lies and absurdities. But to dispose of a charlatan and a rascal of one's own day is comparatively easy: the true superiority of Petrarch is shown when he is face to face with the realities of antiquity—when, for instance, venerating Cicero as he did, he does not hesitate to blame him on a question of morals. But Boccaccio speaks of Cicero as though he scarcely knew him;[534] he praises him as though he were a mere abstraction, calls him "a divine spirit," a "luminous star whose light still waxes."[535] He does not know him. He goes to him for certain details because Petrarch has told him to do so.

"Paolina, the Roman lady," says Boccaccio, "lived in the reign of Tiberius Cæsar, and above all the ladies of her time she was famous for the beauty of her body and the loveliness of her face, and, married as she was, she was reputed the especial mirror of modesty. She cared for nothing else, she studied no other thing, save to please her husband and to worship and reverence Anubis, god of the Egyptians, for whom she had so much devotion, that in everything she did she hoped to merit his grace whom she so much venerated. But, as we know, wherever there is a beautiful woman there are young men who would be her lovers, and especially if she be reputed chaste and honest, so here a young Roman fell in love beyond hope of redemption with the beautiful Paolina. His name was Mundo, he was very rich, and of the noblest family in Rome. He followed her with his eyes, and with much amorous and humble service as lovers are wont to do, and with prayers too, and with promises and presents, but he found her not to be won, for that she, modest and pure as she was, placed all her affection in her husband, and considered all those words and promises as nothing but air. Mundo, seeing all this, almost hopeless at last, turned all his thoughts to wickedness and fraud."