автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Sea Shore

Transcriber’s Note

There is a single footnote, which has been rendered using the original asterisk. The footnote itself has been placed after the paragraph where it is referenced. Illustrations have been re-positioned slightly.

Please see the detailed notes at the end of this text for details about the few corrections that were made during it’s preparation.

For the reader’s convenience, links have been added to the text for references to figures and pages not in the immediate vicinity.

The cover image has been fabricated and is placed in the public domain.

THE SEA SHORE

THE OUT-DOOR WORLD SERIES.

THE OUT-DOOR WORLD; or, the Young Collector’s Handbook.

By W. S. Furneaux. With 18 Plates (16 of which are Coloured), and 549 Illustrations in the Text. Crown 8vo, 6s. 6d. net.

FIELD AND WOODLAND PLANTS.

By W. S. Furneaux. With 8 Plates in Colour, and numerous other Illustrations by Patten Wilson, and from Photographs. Crown 8vo, 6s. 6d. net.

BRITISH BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS.

By W. S. Furneaux. With 12 Coloured Plates and 241 Illustrations in the Text. Crown 8vo, 6s. 6d. net.

LIFE IN PONDS AND STREAMS.

By W. S. Furneaux. With 8 Coloured Plates and 331 Illustrations in the Text. Crown 8vo, 6s. 6d. net.

THE SEA SHORE. By W. S. Furneaux.

With 8 Coloured Plates and over 300 Illustrations in the Text. Crown 8vo, 6s. 6d. net.

BRITISH BIRDS. By W. H. Hudson.

With a Chapter on Structure and Classification by Frank E. Beddard, F.R.S. With 16 Plates (8 of which are Coloured), and 103 Illustrations in the Text. Crown 8vo, 6s. 6d. net.

LONGMANS, GREEN & CO., 39 Paternoster Row, London, E.C.4 New York, Toronto, Bombay, Calcutta and Madras.

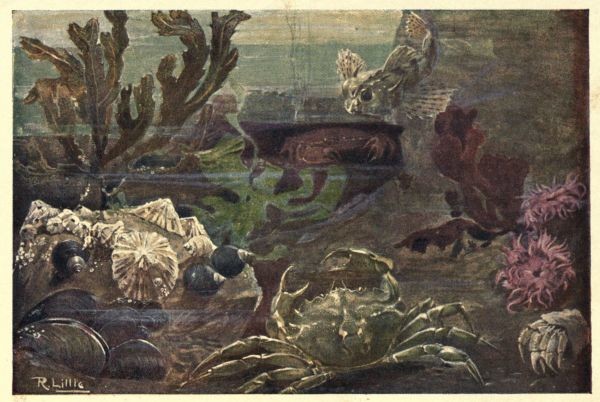

Plate I

A ROCK-POOL

THE SEA SHORE

BY

W. S. FURNEAUX

AUTHOR OF

‘THE OUTDOOR WORLD’ ‘BRITISH BUTTERFLIES AND MOTHS’

‘LIFE IN PONDS AND STREAMS’ ETC.

WITH EIGHT PLATES IN COLOUR

AND OVER THREE HUNDRED ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT

NEW IMPRESSION

LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON, E.C.4

NEW YORK, TORONTO

BOMBAY, CALCUTTA AND MADRAS

1922

All rights reserved

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE.

First published in September, 1903.

Re-issue at Cheaper Price, July, 1911.

New Impression, November, 1922.

Made in Great Britain

PREFACE

To sea-side naturalists it must be a matter of great surprise that of the inhabitants of our coast towns and villages, and of the pleasure-seekers that swarm on various parts of the coast during the holiday season, so few take a real interest in the natural history of the shore. The tide flows and ebbs and the restless waves incessantly roll on the beach without arousing a thought as to the nature and cause of their movements. The beach itself teems with peculiar forms of life that are scarcely noticed except when they disturb the peace of the resting visitor. The charming vegetation of the tranquil rock-pool receives but a passing glance, and the little world of busy creatures that people it are scarcely observed; while the wonderful forms of life that inhabit the sheltered nooks of the rugged rocks between the tide-marks are almost entirely unknown except to the comparatively few students of Nature. So general is this apparent lack of interest in the things of the shore that he who delights in the study of littoral life and scenes but seldom meets with a kindred spirit while following his pursuits, even though the crowded beach of a popular resort be situated in the immediate neighbourhood of his hunting ground. The sea-side cottager is too accustomed to the shore to suppose that he has anything to learn concerning it, and this familiarity leads, if not to contempt, most certainly to a disinclination to observe closely; and the visitor from town often considers himself to be too much in need of his hard-earned rest to undertake anything that may seem to require energy of either mind or body.

Let both, however, cast aside any predisposition to look upon the naturalist’s employment as arduous and toilsome, and make up their minds to look enquiringly into the living world around them, and they will soon find that they are led onward from the study of one object to another, the employment becoming more and more fascinating as they proceed.

Our aim in writing the following pages is to encourage the observation of the nature and life of the sea shore; to give such assistance to the beginner as will show him where the most interesting objects are to be found, and how he should set to work to obtain them. Practical hints are also furnished to enable the reader to successfully establish and maintain a salt-water aquarium for the observation of marine life at home, and to preserve various marine objects for the purpose of forming a study-collection of the common objects of the shore.

To have given a detailed description of all such objects would have been impossible in a work of this size, but a large number have been described and figured, and the broad principles of the classification of marine animals and plants have been given such prominence that, it is hoped, even the younger readers will find but little difficulty in determining the approximate positions, in the scale of life, of the various living things that come within their reach.

Of the many illustrations, which must necessarily greatly assist the reader in understanding the structure of the selected types and in the identification of the different species, a large number have been prepared especially for this work.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

PAGE

I.

THE GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE SEA SHORE

1II.

THE SEA-SIDE NATURALIST

21III.

SEA ANGLING

34IV.

THE MARINE AQUARIUM

51V.

THE PRESERVATION OF MARINE OBJECTS

71VI.

EXAMINATION OF MARINE OBJECTS—DISSECTION

91VII.

THE PROTOZOA OF THE SEA SHORE

102VIII.

BRITISH SPONGES

115IX.

THE CŒLENTERATES—JELLY-FISHES, ANEMONES, AND THEIR ALLIES

127X.

STARFISHES, SEA URCHINS, ETC.

157XI.

MARINE WORMS

172XII.

MARINE MOLLUSCS

190XIII.

MARINE ARTHROPODS

256XIV.

MARINE VERTEBRATES

306XV.

SEA WEEDS

343XVI.

THE FLOWERING PLANTS OF THE SEA-SIDE

391INDEX

425LIST OF COLOURED PLATES

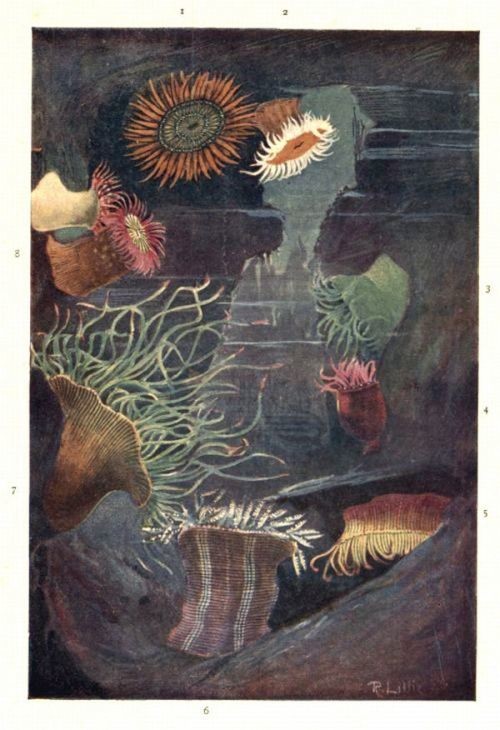

Drawn by Mr. Robert Lillie and reproduced by Messrs. André & Sleigh, Ltd., Bushey.

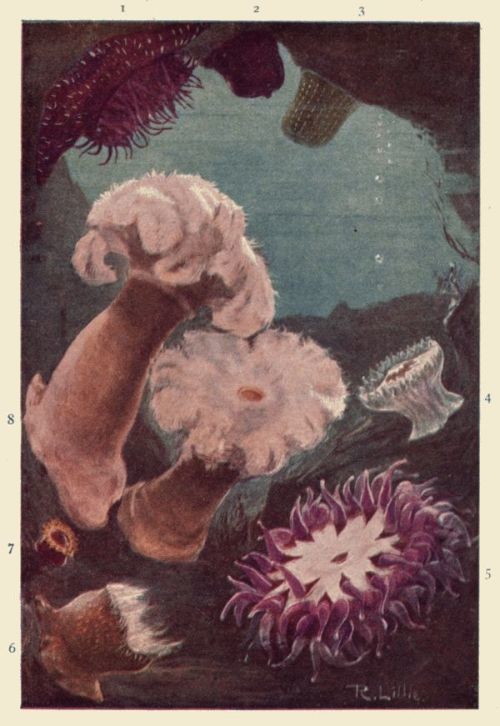

Plate I—

A ROCK-POOL Frontispiece Plate II—

SEA ANEMONES To face p. 1421, 2, 3.

Actinia mesembryanthemum.4.

Caryophyllia Smithii.5.

Tealia crassicornis.6.

Sagartia bellis.7.

Balanophyllia regia.8.

Actinoloba dianthus. Plate III—

SEA ANEMONES To face p. 1501.

Sagartia troglodytes.2. ”

venusta.3.

Actinia glauca.4. ”

chiococca.5.

Bunodes Ballii.6. ”

gemmacea.7.

Anthea cereus.8.

Sagartia rosea. Plate IV—

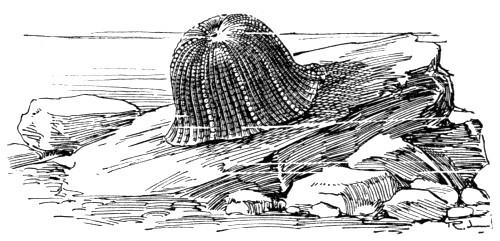

ECHINODERMS To face p. 1681.

Asterias rubens.2.

Goniaster equestris.3.

Ophiothrix fragilis.4.

Echinocardium cordatum.5.

Echinus miliaris.6. ”

esculentus. Plate V—

MOLLUSCS To face p. 2221.

Solen ensis.2.

Trivia europæa.3.

Trochus umbilicatus.4. ”

magnus.5.

Littorina littorea.6. ”

rudis.7.

Haminea(

Bulla)

hydatis.

8.

Tellina.9.

Capulus(

Pileopsis)

hungaricus.

10.

Chrysodomus(

Fusus)

antiquus.

11.

Buccinum undatum.12, 13.

Scalaria communis.14.

Pecten opercularis.15. ”

varius.16. ”

maximus. Plate VI—

CRUSTACEA To face p. 2901.

Gonoplax angulata.2.

Xantho florida.3.

Portunus puber.4.

Polybius Henslowii.5.

Porcellana platycheles. Plate VII—

SEAWEEDS To face p. 3541.

Fucus nodosus.2.

Nitophyllum laceratum.3.

Codium tomentosum.4.

Padina pavonia.5.

Porphyra laciniata(

vulgaris).

Plate VIII—

SEAWEEDS To face p. 3841.

Chorda filum.2.

Fucus vesiculosus.3.

” canaliculatus.4.

Delesseria(

Maugeria)

sanguinea.

5.

Rhodymenia palmata.6.

Chondrus crispus.7.

Ulva lactuca.OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS

Transcriber’s Note

CHAPTER I

THE GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE SEA SHORE

CHAPTER II

THE SEA-SIDE NATURALIST

CHAPTER III

SEA ANGLING

CHAPTER IV

THE MARINE AQUARIUM

CHAPTER V

THE PRESERVATION OF MARINE OBJECTS

CHAPTER VI

EXAMINATION OF MARINE OBJECTS—DISSECTION

CHAPTER VII

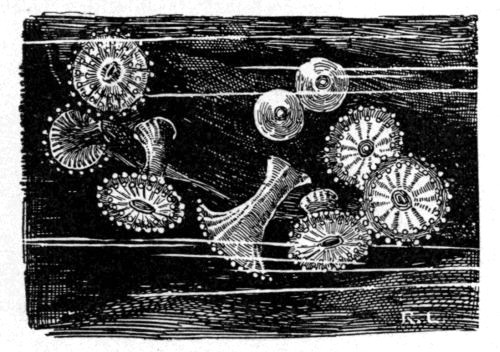

THE PROTOZOA OF THE SEA SHORE

CHAPTER VIII

BRITISH SPONGES

CHAPTER IX

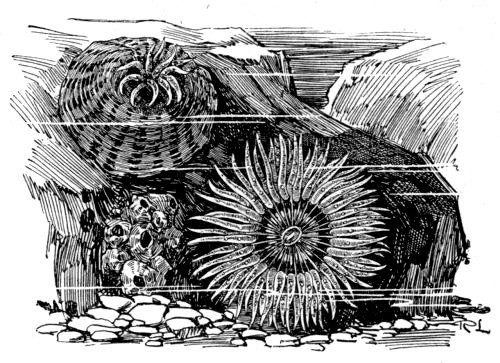

THE CŒLENTERATES—JELLY-FISHES, ANEMONES, AND THEIR ALLIES

CHAPTER X

STARFISHES, SEA URCHINS, ETC.

CHAPTER XI

MARINE WORMS

CHAPTER XII

MARINE MOLLUSCS

CHAPTER XIII

MARINE ARTHROPODS

CHAPTER XIV

MARINE VERTEBRATES

CHAPTER XV

SEA WEEDS

CHAPTER XVI

THE FLOWERING PLANTS OF THE SEA-SIDE

INDEX

FIG.

PAGE

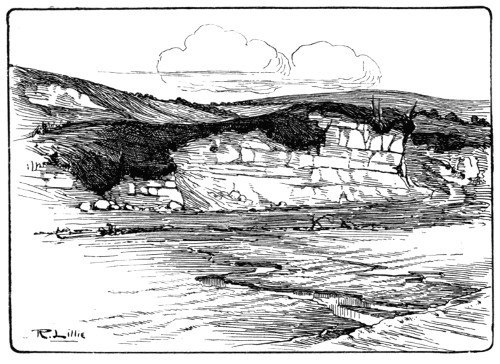

1.

Chalk Cliff 32.

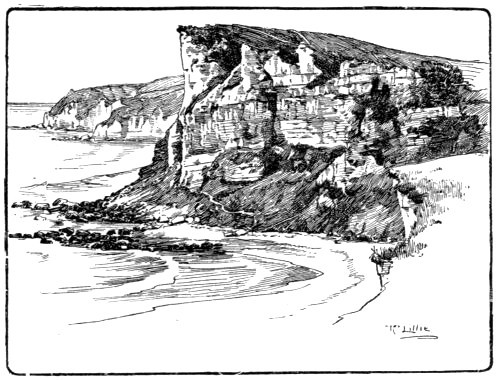

Whitecliff (Chalk), Dorset 43.

Penlee Point, Cornwall 54.

Balanus Shells 65.

A Cluster of Mussels 76.

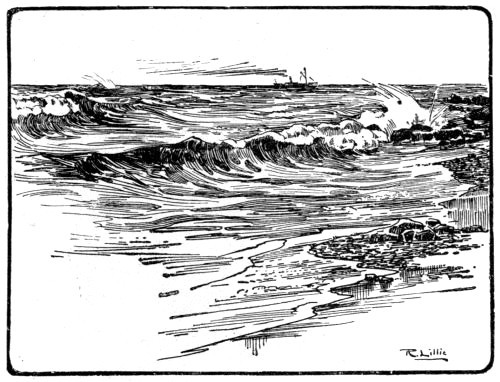

Breakers 87.

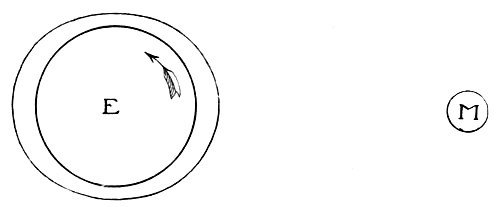

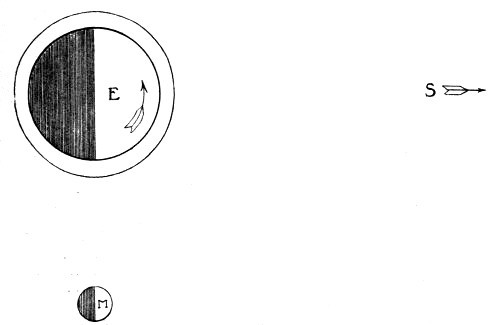

Illustrating the Tide-producing Influence of the Moon 108.

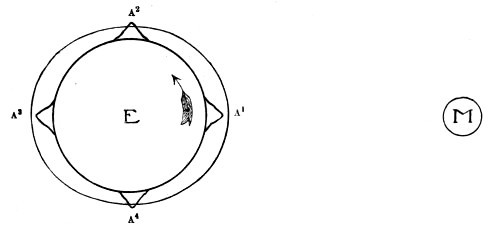

Illustrating the tides 119.

Spring Tides at Full Moon 1210.

Spring Tides at New Moon 1211.

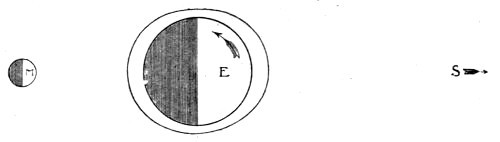

Neap Tides 1312.

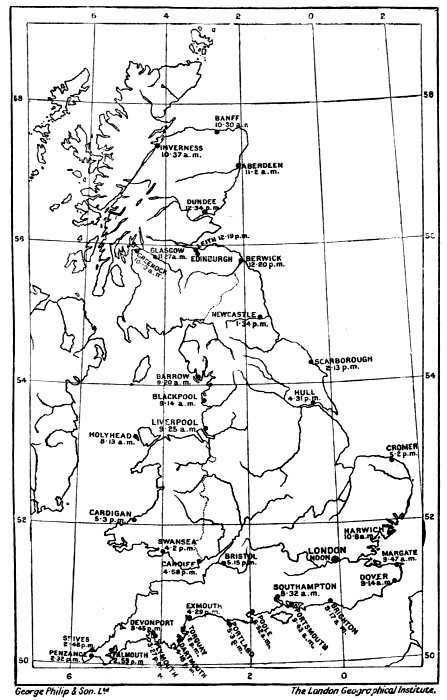

Chart showing the relative Times of High Tide on different parts of the British Coast 1613.

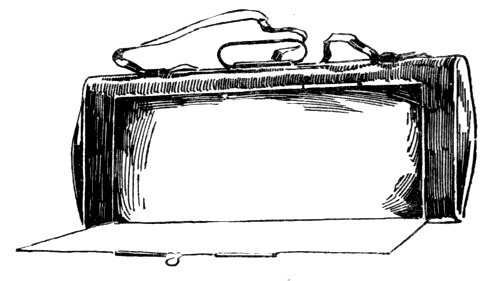

The Vasculum 2214.

Wire Ring for Net 2415.

Net Frame with Curved Point 2416.

Rhomboidal Frame for Net 2417.

Rhomboidal Net 2518.

Semicircular Net 2519.

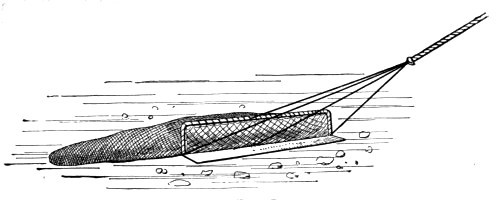

The Dredge 2520.

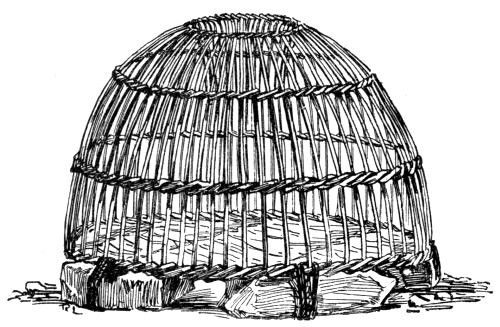

The Crab-pot 2621.

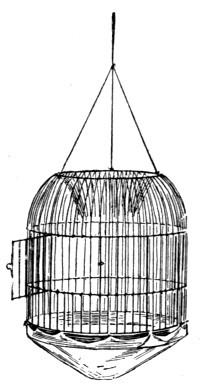

An old Bird-cage used as a Crab-pot 2722.

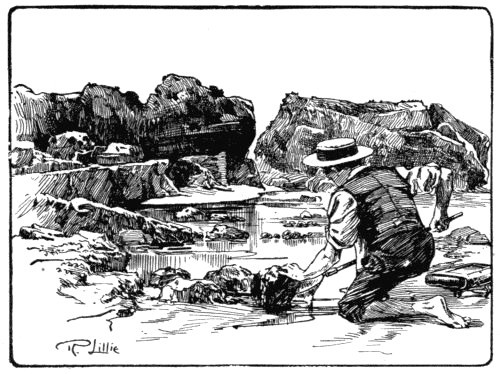

A Young Naturalist at Work 3223.

A good Hunting-ground on the Cornish Coast 3324.

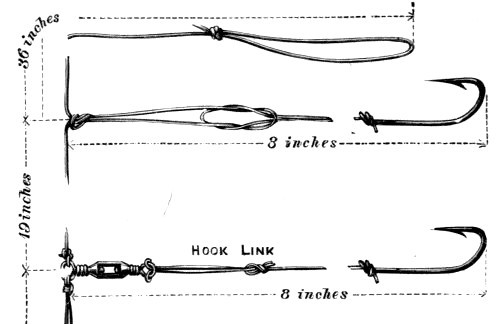

Round Bend Hook with Flattened End 3725.

Limerick Hook, eyed 3726.

Method of Attaching Snood to Flattened Hook 3827.

Method of Attaching Snood to Eyed Hook 3828.

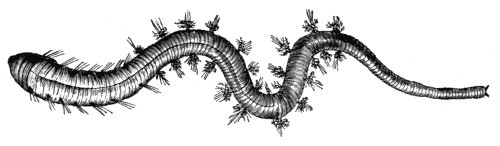

The Lugworm 3929.

The Ragworm 4030.

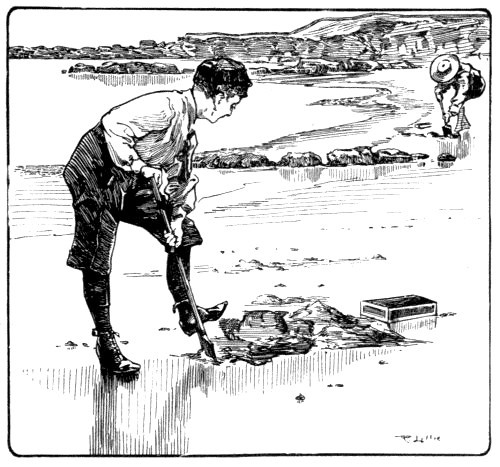

Digging for Bait 4131.

Method of Opening a Mussel 4232.

Fishing from the Rocks 4633.

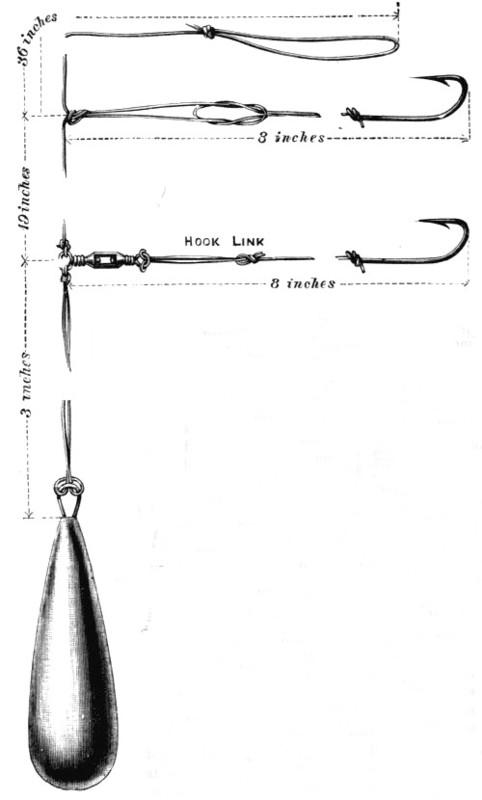

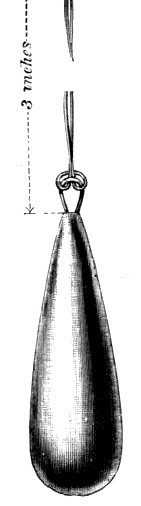

The Paternoster 4834.

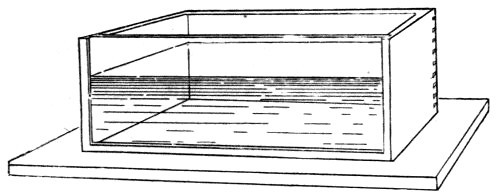

Section of an Aquarium constructed with a Mixture of Cement and Sand 5435.

Cement Aquarium with a Glass Plate in Front 5536.

Aquarium of Wood with Glass Front 5637.

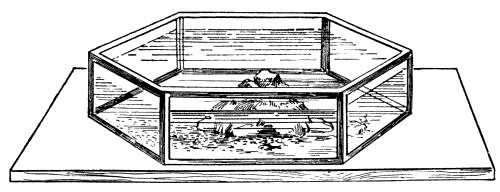

Hexagonal Aquarium constructed of Angle Zinc, with Glass Sides 5738.

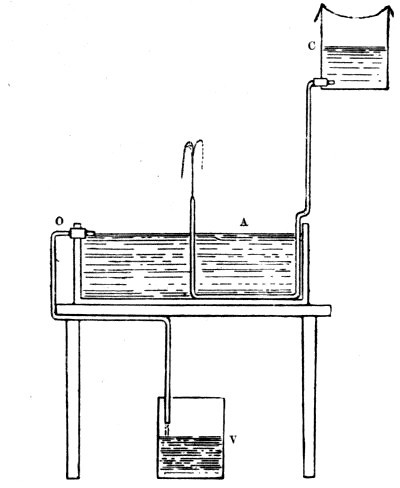

Method of Aerating the Water of an Aquarium 6539.

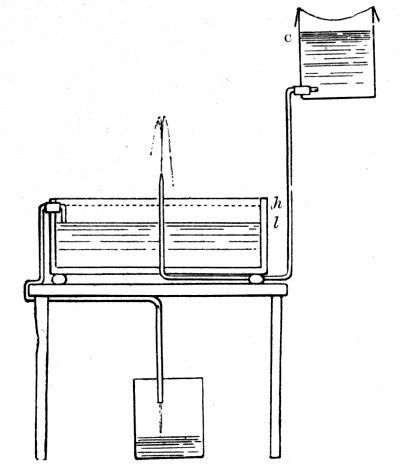

Aquarium fitted with Apparatus for Periodic Outflow 6740.

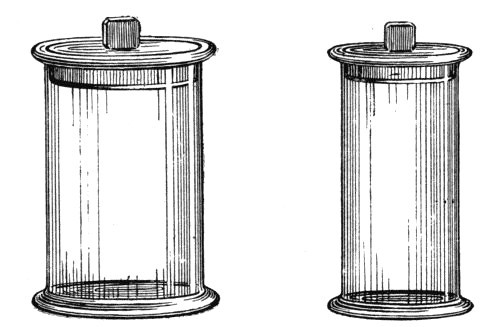

Jars for preserving Anatomical and Biological Specimens 7641.

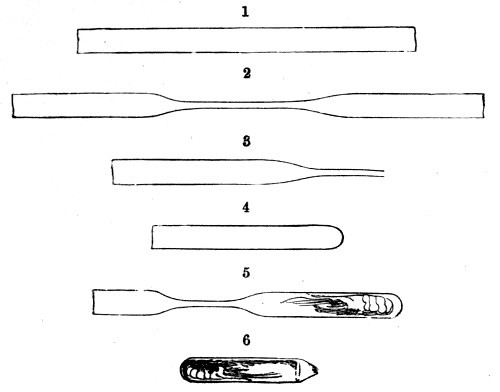

Showing the different stages in the making of a small Specimen Tube 7742.

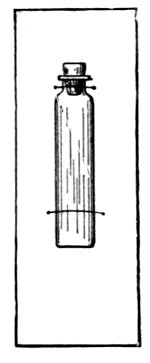

Small Specimen Tube mounted on a Card 7843.

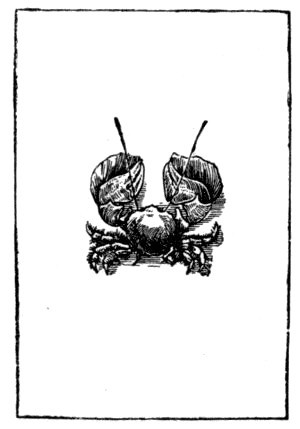

Small Crab mounted on a Card 8244.

Spring for holding together small Bivalve Shells 8445.

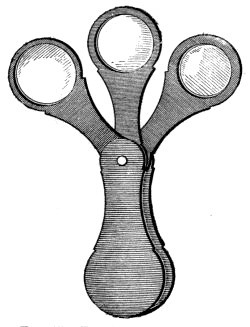

The Triplet Magnifier 9246.

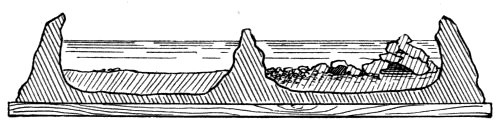

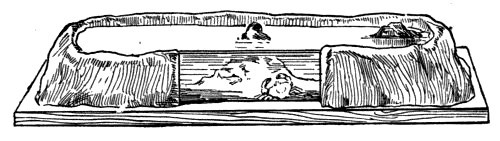

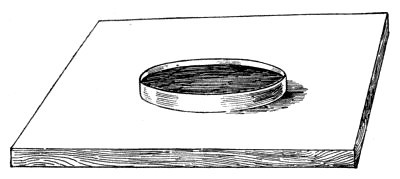

A small Dissecting Trough 9347.

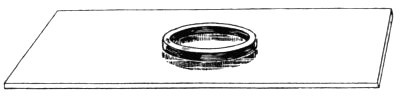

Cell for small Living Objects 9548.

Sheet of Cork on thin Sheet Lead 9949.

Weighted Cork for Dissecting Trough 9950.

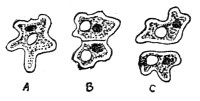

The Amœba, highly magnified 10251.

” ”

showing changes of form 10352.

” ”

feeding 10353.

” ”

dividing 10454.

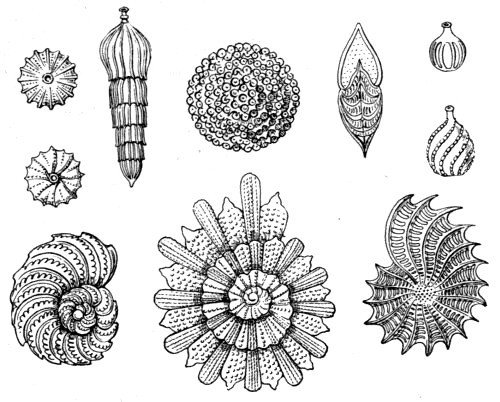

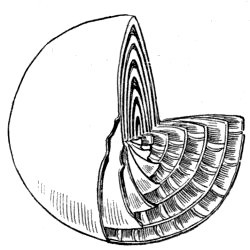

A Group of Foraminifers, magnified 10555.

A Spiral Foraminifer Shell 10656.

A Foraminifer out of its Shell 10657.

The same Foraminifer (fig. 56) as seen when alive 10758.

Section of the Shell of a Compound Foraminifer 10759.

Section of a Nummulite Shell 10860.

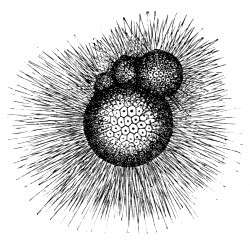

Globigerina bulloides,

as seen when alive, magnified 10861.

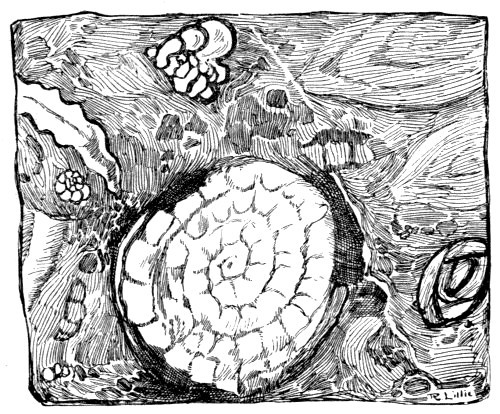

Section of a piece of Nummulitic Limestone 10962.

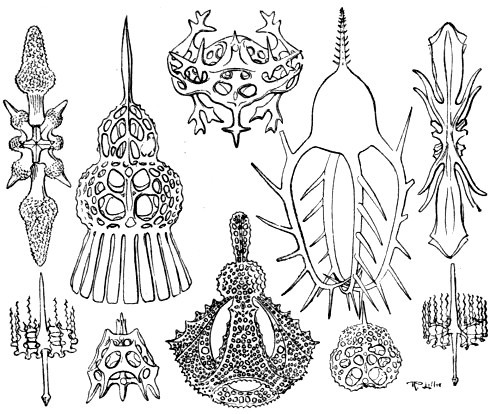

A Group of Radiolarian Shells, magnified 11163.

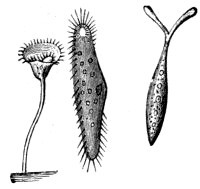

Three Infusorians, magnified 11364.

A Phosphorescent Marine Infusorian(

Noctiluca),

magnified 11465.

Section of a Simple Sponge 11666.

Diagrammatic section of a portion of a Complex Sponge 11767.

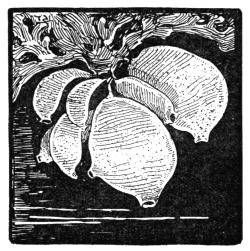

Horny Network of a Sponge, magnified 11868.

Grantia compressa 12069.

Spicules of Grantia,

magnified 12070.

Sycon ciliatum 12171.

Leucosolenia botryoides,

with portion magnified 12172.

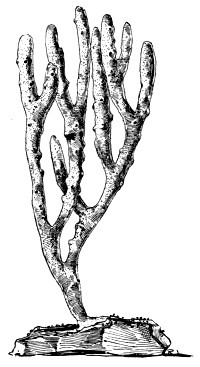

Chalina oculata 12273.

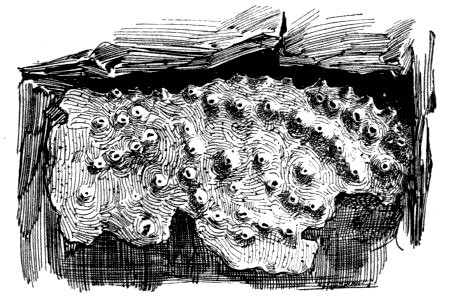

Halichondria panicea 12374.

Spicules of Halichondria,

magnified 12475.

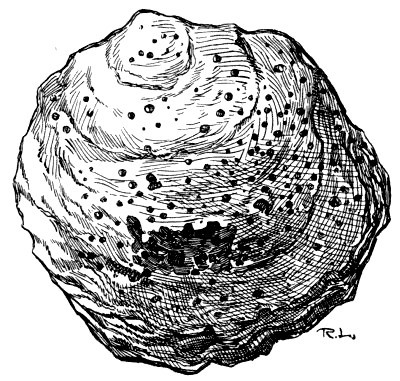

An Oyster Shell, bored by Cliona 12476.

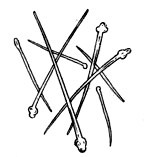

Spicules of Cliona 12577.

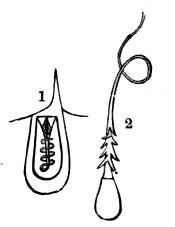

Thread Cells of a Cœlenterate, magnified 12778.

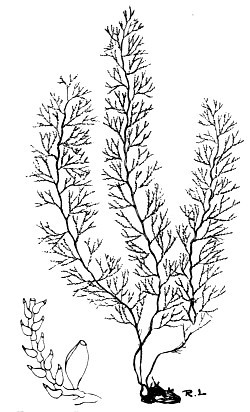

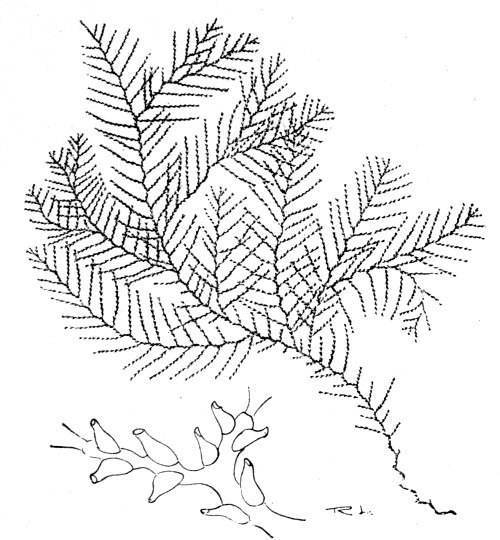

The Squirrel’s-tail Sea Fir(

Sertularia argentea),

with a portion enlarged 12879.

Sertularia filicula 12980.

”

cupressina 13081.

The Herring-bone Polype(

Halecium halecinum 13182.

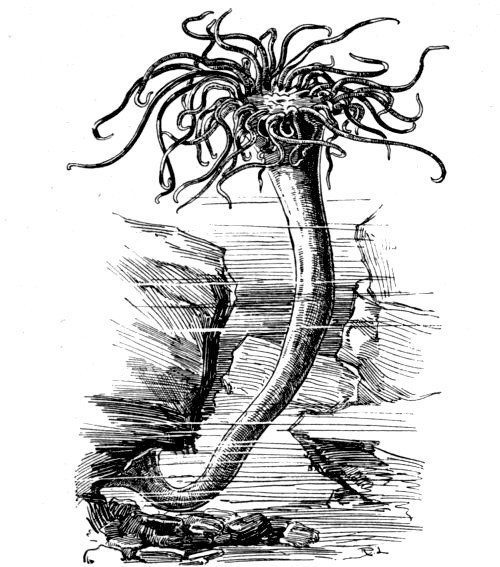

Tubularia indivisa 13283.

The Bottle Brush(

Thuiaria thuja)

13284.

Antennularia antennia 13385.

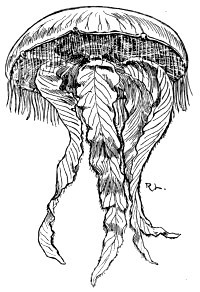

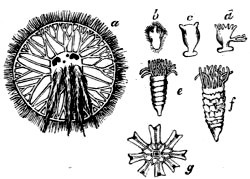

Aurelia aurita 13586.

The Early Stages of Aurelia 13687.

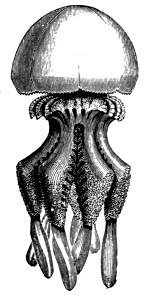

Rhizostoma 13688.

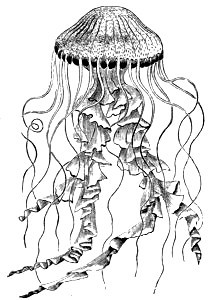

Chrysaora 13689.

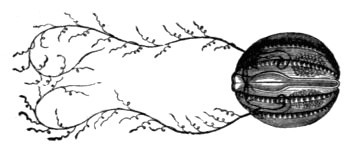

Cydippe pileus 13790.

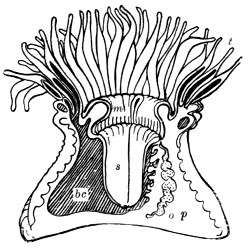

Section of an Anemone 13991.

Stinging Cells of Anemone, highly magnified 14092.

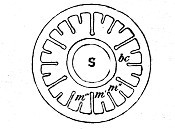

Diagrammatic transverse section of an Anemone 14093.

Larva of Anemone 14094.

The Trumpet Anemone(

Aiptasia Couchii),

Cornwall; deep water 14495.

Peachia hastata, S. Devon 14596.

Sagartia pallida, Devon and Cornwall 14697.

Sagartia nivea, Devon and Cornwall 14798.

Corynactus viridis, Devon and Cornwall 14899.

Bunodes thallia, West Coast 150100.

Bunodes gemmacea, with tentacles retracted 151101.

Caryophyllia cyathus 152102.

Sagartia parasitica 153103.

The Cloak Anemone(

Adamsia palliata)

on a Whelk Shell, with Hermit Crab 154104.

Larva of the Brittle Starfish 158105.

Larva of the Feather Star 160106.

The Rosy Feather Star 160107.

The Common Brittle Star 162108.

Section of the Spine of a Sea Urchin 165109.

Sea Urchin with Spines removed on one Side 166110.

Apex of Shell of Sea Urchin 166111.

Shell of Sea Urchin with Teeth protruding 167112.

Interior of Shell of Sea Urchin 167113.

Masticatory Apparatus of Sea Urchin 167114.

Sea Urchin Dissected, showing the Digestive Tube 168115.

The Sea Cucumber 170116.

A Turbellarian, magnified 175117.

Arenicola piscatorum 178118.

The Sea Mouse 179119.

Tube-building Worms:

Terebella, Serpula, Sabella 182120.

Terebella removed from its Tube 183121.

A tube of Serpula attached to a Shell 185122.

Serpula removed from its Tube 186123.

The Sea Mat(

Flustra)

187124.

Flustra in its Cell, magnified 188125.

Sea Squirt 189126.

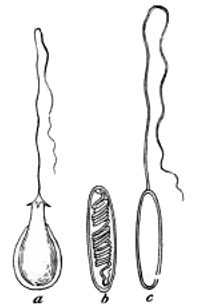

Larvæ of Molluscs 191127.

Shell of the Prickly Cockle(

Cardium aculeatum)

showing Umbo and Hinge; also the interior showing the Teeth 192128.

Interior of Bivalve Shell, showing Muscular Scars and Pallial Line 193129.

Diagram of the Anatomy of a Lamellibranch 194130.

Mytilus edulis,

with Byssus 195131.

A Bivalve Shell(

Tapes virgineana)

196132.

Pholas dactylus 199133.

” ”

interior of Valve; and Pholadidea with Animal 201134.

The Ship Worm 202135.

1.

Teredo navalis.2.

Teredo norvegica 202136.

Gastrochæna modiolina 203137.

1.

Thracia phaseolina.2.

Thracia pubescens,

showing Pallial Line 204138.

1.

Mya truncata.2.

Interior of Shell.3.

Mya arenaria.4.

Corbula nucleus 205139.

Solen siliqua 206140.

1.

Solen ensis.2.

Cerati-solen legumen.3.

Solecurtus candidus 207141.

Tellinidæ 208142.

1.

Lutraria elliptica.2.

Part of the Hinge of Lutraria,

showing the Cartilage Pit. 3.

Macra stultorum.4.

Interior of same showing Pallial Line 210143.

Veneridæ 211144.

Cyprinidæ 213145.

Galeomma Turtoni 214146.

1.

Cardium pygmæum.2.

Cardium fasciatum.3.

Cardium rusticum 215147.

Cardium aculeatum 215148.

Pectunculus glycimeris,

with portion of Valve showing Teeth, and Arca tetragona 216149.

Mytilus edulis 217150.

1.

Modiola modiolus.2.

Modiola tulipa.3.

Crenella discors 218151.

Dreissena polymorpha 219152.

Avicula,

and Pinna pectinata 220153.

1.

Anomia ephippium.2.

Pecten tigris.3.

Pecten,

animal in shell 222154.

Terebratulina. The upper figure represents the interior of the Dorsal Valve 224155.

Under side of the Shell of Natica catena,

showing the Umbilicus; and outline of the Shell, showing the Right-handed Spiral 225156.

Section of the Shell of the Whelk, showing the Columella 226157.

Diagram of the Anatomy of the Whelk, the Shell being removed 228158.

A portion of the Lingual Ribbon of the Whelk, magnified; and a single row of Teeth on a much larger scale 229159.

Egg Cases of the Whelk 230160.

Pteropods 231161.

Nudibranchs 234162.

”

235163.

Shells of Tectibranchs 236164.

Chiton Shells 238165.

Shells of Dentalium 238166.

Patellidæ 239167.

Calyptræa sinensis 241168.

Fissurellidæ 241169.

Haliotis 242170.

Ianthina fragilis 242171.

Trochus zizyphinus. 2.

Under Side of Shell.3.

Trochus magnus.4.

Adeorbis subcarinatus 244172.

Rissoa labiosa and Lacuna pallidula 244173.

Section of Shell of Turritella 245174.

Turritella communis and Cæcum trachea 245175.

Cerithium reticulatum and Aporrhais pes-pelicani 245176.

Aporrhais pes-pelicani,

showing both Shell and Animal 246177.

1.

Odostomia plicata.2.

Eulima polita.3.

Aclis supranitida 246178.

Cypræa(

Trivia)

europæa 247179.

1.

Ovulum patulum. 2.

Erato lævis 248180.

Mangelia septangularis and Mangelia turricula 248181.

1.

Purpura lapillus.2.

Egg Cases of Purpura. 3.

Nassa reticulata 249182.

Murex erinaceus 249183.

Octopus 251184.

Loligo vulgaris and its Pen 252185.

Sepiola atlantica 252186.

Sepia officinalis and its ‘Bone’ 253187.

Eggs of Sepia 254188.

The Nerve-chain of an Arthropod (Lobster) 257189.

Section through the Compound Eye of an Arthropod 260190.

Four Stages in the Development of the Common Shore Crab 261191.

The Barnacle 261192.

Four Stages in the Development of the Acorn Barnacle 262193.

A Cluster of Acorn Shells 263194.

Shell of Acorn Barnacle(

Balanus)

263195.

The Acorn Barnacle(

Balanus porcatus)

with Appendages protruded 264196.

A Group of Marine Copepods, magnified 265197.

A Group of Ostracode Shells 265198.

Evadne 266199.

Marine Isopods 267200.

Marine Amphipods 268201.

The Mantis Shrimp(

Squilla Mantis)

270202.

The Opossum Shrimp(

Mysis chamæleon)

271203.

Parts of Lobster’s Shell, separated, and viewed from above 272204.

A Segment of the Abdomen of a Lobster 272205.

Appendages of a Lobster 273206.

Longitudinal Section of the Lobster 274207.

The Spiny Lobster(

Palinurus vulgaris)

275208.

The Norway Lobster(

Nephrops norvegicus)

276209.

1.

The Mud-borer(

Gebia stellata). 2.

The Mud-borrower(

Callianassa subterranea)

277210.

The Common Shrimp(

Crangon vulgaris)

278211.

The Prawn(

Palæmon serratus)

279212.

Dromia vulgaris 282213.

The Hermit Crab in a Whelk Shell 282214.

The Long-armed Crab(

Corystes Cassivelaunus)

287215.

Spider Crabs at Home 288216.

The Thornback Crab(

Maia Squinado)

290217.

The Pea Crab(

Pinnotheres pisum)

290218.

The Common Shore Crab(

Carcinus mænas)

291219.

The Shore Spider 294220.

The Leg of an Insect 295221.

Trachea of an Insect, magnified 296222.

Sea-Shore Insects 298223.

Marine Beetles of the genus(

Bembidium)

302224.

Marine Beetles 303225.

Transverse section through the Bony Framework of a Typical Vertebrate Animal 306226.

The Sea Lamprey 309227.

The Pilchard 310228.

The Skeleton of a Fish (Perch) 315229.

The Internal Organs of the Herring 316230.

The Egg-case of the Dogfish 319231.

The Smooth Hound 320232.

The Common Eel 323233.

The Lesser Sand Eel 326234.

The Three-bearded Rockling 327235.

The Snake Pipe-fish 328236.

The Rainbow Wrass(

Labrus julis)

330237.

The Cornish Sucker 330238.

The Fifteen-spined Stickleback and Nest 331239.

The Smooth Blenny 333240.

The Butterfish 334241.

The Black Goby 335242.

The Father Lasher 335243.

The Lesser Weaver 337244.

The Common Porpoise 341245.

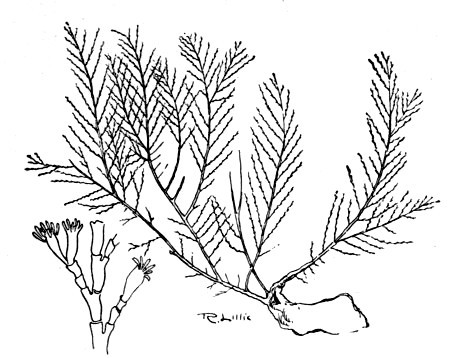

Callithamnion roseum 359246.

Callithamnion tetricum 359247.

Griffithsia corallina 361248.

Halurus equisetifolius 361249.

Pilota plumosa 361250.

Ceramium diaphanum 363251.

Plocamium 366252.

Delesseria alata 368253.

Delesseria hypoglossum 368254.

Laurencia pinnatifida 371255.

Laurencia obtusa 371256.

Polysiphonia fastigiata 373257.

Polysiphonia parasitica 374258.

Polysiphonia Brodiæi 374259.

Polysiphonia nigrescens 374260.

Ectocarpus granulosus 378261.

Ectocarpus siliculosus 378262.

Ectocarpus Mertensii 378263.

Sphacelaria cirrhosa 379264.

Sphacelaria plumosa 379265.

Sphacelaria radicans 380266.

Cladostephus spongiosus 380267.

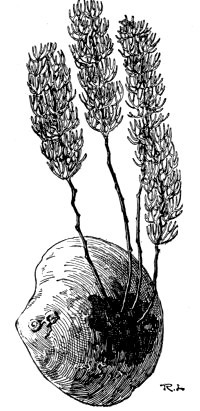

Chordaria flagelliformis 380268.

Laminaria bulbosa 384269.

Laminaria saccharina 384270.

Alaria esculenta 385271.

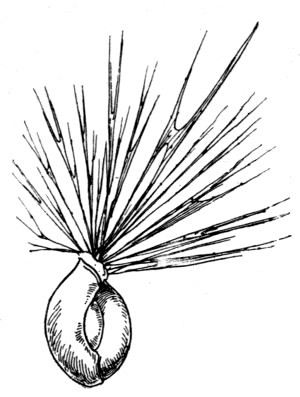

Sporochnus pedunculatus 385272.

Desmarestia ligulata 386273.

Himanthalia lorea 387274.

Cystoseira ericoides 388275.

Transverse Section of the Stem of a Monocotyledon 391276.

Leaf of a Monocotyledon 392277.

Expanded Spikelet of the Oat 393278.

The Sea Lyme Grass 395279.

Knappia agrostidea 397280.

The Dog’s-tooth Grass 397281.

The Reed Canary Grass 397282.

Male and Female Flowers of Carex, magnified 399283.

The Sea Sedge 400284.

The Curved Sedge 400285.

The Great Sea Rush 400286.

The Broad-leaved Grass Wrack 401287.

The Sea-side Arrow Grass 401288.

The Common Asparagus 401289.

The Sea Spurge 403290.

The Purple Spurge 404291.

The Sea Buckthorn 404292.

Chenopodium botryoides 405293.

The Frosted Sea Orache 406294.

The Prickly Salt Wort 406295.

The Creeping Glass Wort 407296.

The Sea-side Plantain 408297.

The Sea Lavender 408298.

The Dwarf Centaury 410299.

The Sea Samphire 412300.

The Sea-side Everlasting Pea 413301.

The Sea Stork’s-bill 414302.

The Sea Campion 416303.

The Sea Pearl Wort 417304.

The Shrubby Mignonette 417305.

The Wild Cabbage 418306.

The Isle of Man Cabbage 418307.

The Great Sea Stock 419308.

The Hoary Shrubby Stock 419309.

The Scurvy Grass 419310.

The Sea Radish 419311.

The Sea Rocket 420312.

The Sea Kale 421313.

The Horned Poppy 422Fig. 1.—Chalk Cliff

Fig. 2.—Whitecliff (Chalk), Dorset

Fig. 3.—Penlee Point, Cornwall

Fig. 4.—Balanus Shells

Fig. 5.—A Cluster of Mussels

Fig. 6.—Breakers

Fig. 7.—Illustrating the Tide-producing Influence of the Moon

Fig. 8.—Illustrating the Tides

Fig. 9.—Spring Tides at Full Moon

Fig. 10.—Spring Tides at New Moon

Fig. 11.—Neap Tides

Fig. 12.—Chart showing the relative Times of High Tide on different parts of the British Coast

Fig. 13.—The Vasculum

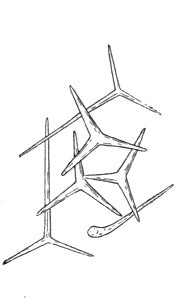

Fig. 14.—Wire Ring for Net

Fig. 15.—Net Frame with Curved Point

Fig. 16.—Rhomboidal Frame for Net

Fig. 17.—Rhomboidal Net

Fig. 18.—Semicircular Net

Fig. 19.—The Dredge

Fig. 20.—The Crab-pot

Fig. 21.—An old Bird-cage used as a Crab-pot

Fig. 22.—A Young Naturalist at Work

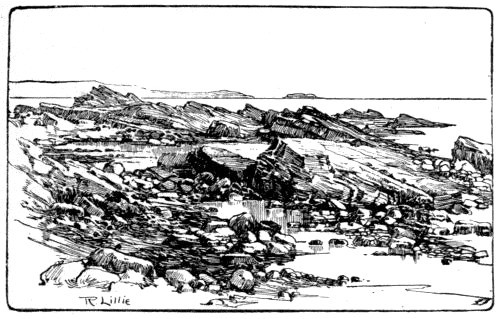

Fig. 23.—A good Hunting-ground on the Cornish Coast

Fig. 24.—Round Bend Hook with Flattened End

Fig. 25.—Limerick Hook, eyed

Fig. 26.—Method of attaching Snood to Flattened Hook

Fig. 27.—Method of attaching Snood to Eyed Hook

Fig. 28.—The Lugworm

Fig. 29.—The Ragworm

Fig. 30.—Digging for Bait

Fig. 31.—Method of Opening a Mussel

Fig. 32.—Fishing from the Rocks

Fig. 34.—Section of an Aquarium constructed with a mixture of Cement and Sand

Fig. 35.—Cement Aquarium with a Glass Plate in Front

Fig. 36.—Aquarium of Wood with Glass Front

Fig. 37.—Hexagonal Aquarium constructed of Angle Zinc, with Glass Sides

Fig. 38.—Method of aërating the Water of an Aquarium

a, aquarium with fountain; c, cistern to supply the fountain; o, pipe for overflow; v, vessel for overflow

Fig. 39.—Aquarium fitted with Apparatus for Periodic Outflow

Fig. 40.—Jars for preserving Anatomical and Biological Specimens

Fig. 41.—Showing the different stages in the making of a small Specimen Tube

Fig. 42.—Small Specimen Tube mounted on a Card

Fig. 43.—Small Crab mounted on a Card

Fig. 44.—Spring for holding together small Bivalve Shells

Fig. 45—The Triplet Magnifier

Fig. 46.—A small Dissecting Trough

Fig. 47.—Cell for small Living Objects

Fig. 48.—Sheet of Cork on thin Sheet Lead

Fig. 49.—Weighted Cork for Dissecting Trough

Fig. 50.—The Amœba, highly magnified

Fig. 51.—The Amœba, showing changes of form

Fig. 52.—The Amœba, feeding

Fig. 53.—The Amœba, dividing

Fig. 54.—A group of Foraminifers, magnified

Fig. 55.—A Spiral Foraminifer Shell

Fig. 56.—A Foraminifer out of its shell

Fig. 57.—The same Foraminifer (Fig. 56) as seen when alive

Fig. 58.—Section of the Shell of a Compound Foraminifer

Fig. 59.—Section of a Nummulite Shell

Fig. 60.—Globigerina bulloides, as seen when alive, magnified

Fig. 61.—Section of a piece of Nummulitic Limestone

Fig. 62.—A Group of Radiolarian Shells, magnified

Fig. 63.—Three Infusorians magnified

Fig. 64.—A Phosphorescent Marine Infusorian (Noctiluca), magnified

Fig. 65.—Section of a Simple Sponge

Fig. 66.—Diagrammatic section of a portion of a Complex Sponge

Fig. 67.—Horny Network of a Sponge, magnified

Fig. 68.—Grantia compressa

Fig. 69.—Spicules of Grantia, magnified

Fig. 70.—Sycon ciliatum

Fig. 71.—Leucosolenia botryoides, with portion magnified

Fig. 72.—Chalina oculata

Fig. 73.—Halichondria panicea

Fig. 74.—Spicules of Halichondria, magnified

Fig. 75.—An Oyster Shell bored by Cliona

Fig. 76.—Spicules of Cliona

Fig. 77.—Thread Cells of a Cœlenterate, magnified

1. Thread retracted 2. Thread protruded

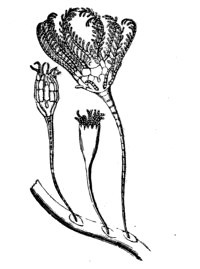

Fig. 78.—The Squirrel’s-tail Sea Fir (Sertularia argentea), with a portion enlarged

Fig. 79.—Sertularia filicula

Fig. 80.—Sertularia cupressina

Fig. 81.—The Herring-bone Polype (Halecium halecinum)

Fig. 82.—Tubularia indivisa

Fig. 83.—The Bottle Brush

(Thuiaria thuja)

Fig. 84.—Antennularia antennia

Fig. 85.—Aurelia aurita

Fig. 86.—The early Stages of Aurelia

Fig. 87.—Rhizostoma

Fig. 88.—Chrysaora

Fig. 89.—Cydippe pileus

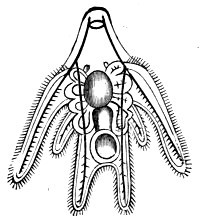

Fig. 90.—Section of an Anemone

t, tentacles; m, mouth; s, stomach; b c, body-cavity p, mesentery; o, egg-producing organ

Fig. 91.—Stinging Cells of Anemone, highly magnified

a and c, with thread protruded; b, with cell retracted

Fig. 92.—Diagrammatic transverse section of an Anemone

S, stomach; bc, body-cavity; m′, m″, m‴, primary, secondary, and tertiary mesenteries

Fig. 93.—Larva of Anemone

Fig. 94.—The Trumpet Anemone (Aiptasia Couchii), Cornwall; deep water

Fig. 95.—Peachia hastata, S. Devon

Fig. 96.—Sagartia pallida, Devon and Cornwall

Fig. 97.—Sagartia nivea, Devon and Cornwall

Fig. 98.—Corynactus viridis, Devon and Cornwall

Fig. 99.—Bunodes thallia, West Coast

Fig. 100.—Bunodes gemmacea, with tentacles retracted

Fig. 101.—Caryophyllia cyathus

Fig. 102.—Sagartia parasitica

Fig. 103.—The Cloak Anemone (Adamsia palliata) on a Whelk Shell, with Hermit Crab

Fig. 104.—Larva of the Brittle Starfish

Fig. 105.—Larva of the Feather Star

Fig. 106.—The Rosy Feather Star

Fig. 107.—The Common Brittle Star

Fig. 108.—Section of the Spine of a Sea Urchin

Fig. 109.—Sea Urchin with Spines Removed on one side

Fig. 110.—Apex of Shell of Sea Urchin

Fig. 111.—Shell of Sea Urchin with Teeth protruding

Fig. 112.—Interior of Shell or Sea Urchin

Fig. 113.—Masticatory Apparatus of Sea Urchin

Fig. 114.—Sea Urchin Dissected, showing the Digestive Tube

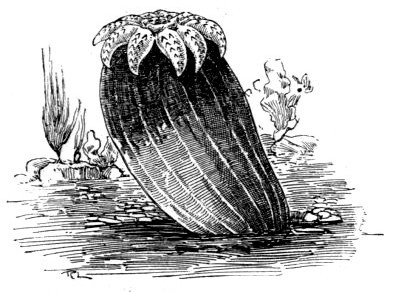

Fig. 115.—The Sea Cucumber

Fig. 116.—A Turbellarian, magnified

a, mouth; b, cavity of mouth; c, gullet; d, stomach; e, branches of stomach; f, nerve ganglion; g to m, reproductive organs.

Fig. 117.—Arenicola piscatorum

Fig. 118.—The Sea Mouse

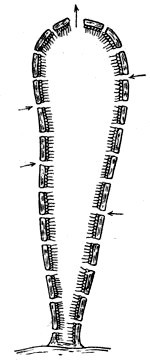

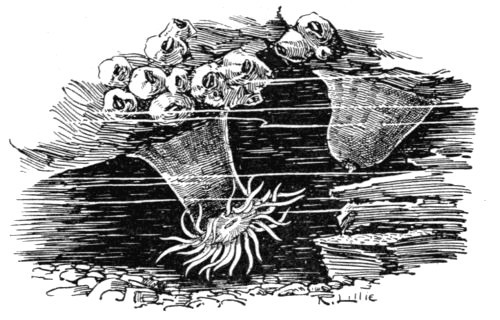

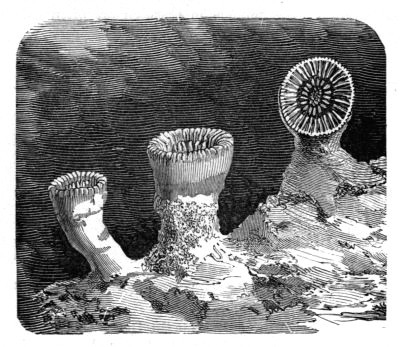

Fig. 119.—Tube-building Worms: Terebella (left), Serpula (middle), Sabella (right)

Fig. 120.—Terebella removed from its tube

Fig. 121.—A tube of Serpula attached to a Shell

Fig. 122.—Serpula removed from its Tube

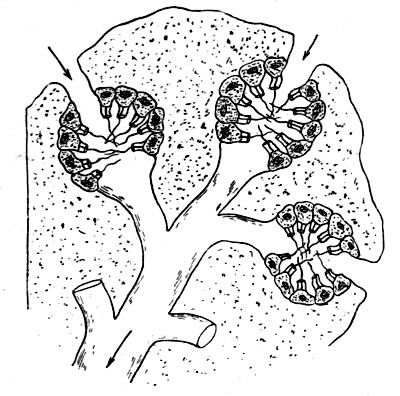

Fig. 123.—The Sea Mat (Flustra)

Fig. 124.—Flustra in its Cell, magnified

Fig. 125.—Sea Squirt

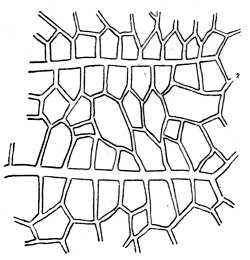

Fig. 126.—Larvæ of Molluscs

v, ciliated ‘velum’; f, rudimental foot

Fig. 127.—Shell of the Prickly Cockle (Cardium aculeatum) showing Umbo and Hinge; also the interior showing the Teeth

Fig. 128.—Interior of Bivalve Shell, showing Muscular Scars and Pallial Line

Fig. 129.—Diagram of the Anatomy of a Lamellibranch

f, mouth, with labial palps; g, stomach; i, intestine, surrounded by the liver; a, anus; r, posterior adductor muscle; e, anterior adductor muscle; c, heart; d, nerve ganglion; m, mantle (the right lobe has been removed); s, siphons; h, gills; ft, foot

Fig. 130.—Mytilus edulis, with Byssus

Fig. 131.—A Bivalve Shell

(Tapes virgineana)

a, anterior; p, posterior; l, left valve; r, right valve; u, umbo, on dorsal side

Fig. 132.—Pholas dactylus

1, ventral aspect, with animal; 2, dorsal side of shell showing accessory valves

Fig. 133.—Pholas dactylus, interior of Valve; and Pholadidea with Animal

Fig. 134.—The Ship Worm

Fig. 135.—1. Teredo navalis. 2. Teredo norvegica

Fig. 136.—Gastrochæna modiolina

1, Animal in shell; 2, shell; 3, cell

Fig. 137.—1. Thracia phaseolina. 2. Thracia pubescens, showing Pallial Line

Fig. 138.—1. Mya truncata. 2. Interior of Shell. 3. Mya arenaria. 4. Corbula nucleus

Fig. 139.—Solen siliqua

The valves have been separated and the mantle divided to expose the large foot

Fig. 140.—1. Solen ensis. 2. Cerati-solen legumen. 3. Solecurtus candidus

Fig. 141.—Tellinidæ

1. Psammobia ferroensis. 2. Donax anatinus. 3. Tellina crassa. 4. Tellina tenuis. 5. Donax politus

Fig. 142.—1. Lutraria elliptica. 2. Part of the Hinge of Lutraria, showing the Cartilage Pit. 3. Macra stultorum. 4. Interior of same showing Pallial Line

Fig. 143.—Veneridæ

1. Venus fasciata. 2. Venus striatula. 3. Tapes virgineana. 4. Tapes aurea

Fig. 144.—Cyprinidæ

1. Cyprina islandica. 2. Teeth of Cyprina. 3. Astarte compressa. 4. Circe minima. 5. Isocardia cor

Fig. 145.—Galeomma Turtoni

Fig. 146.—1. Cardium pygmæum. 2. Cardium fasciatum. 3. Cardium rusticum

Fig. 147.—Cardium aculeatum

Fig. 148.—Pectunculus glycimeris, with portion of Valve showing Teeth, and Arca tetragona

Fig. 149.—Mytilus edulis

Fig. 150.—1. Modiola modiolus. 2. Modiola tulipa. 3. Crenella discors

Fig. 151.—Dreissena polymorpha

Fig. 152.—Avicula, and Pinna pectinata

Fig. 153.—1. Anomia ephippium. 2. Pecten tigris. 3. Pecten, animal in shell

Fig. 154.—Terebratulina. The upper figure represents the interior of the Dorsal Valve

Fig. 155.—Under side of the Shell of Natica catena, showing the Umbilicus; and outline of the Shell, showing the Right handed Spiral

Fig. 156.—Section of the Shell of the Whelk, showing the Columella

Fig. 157.—Diagram of the Anatomy of the Whelk, the Shell being removed

c, stomach; e, end of intestine; g, gills; h, ventricle of the heart; a, auricle; f, nerve ganglia; b, digestive gland; ft, foot; o, operculum; d, liver

Fig. 158.—A portion of the Lingual Ribbon of the Whelk, magnified; and a single row of Teeth on a much larger Scale

b, medial teeth; a and c, lateral teeth

Fig. 159.—Egg Cases of the Whelk

Fig. 160.—Pteropods

Fig. 161.—Nudibranchs

1. Doto coronata. 2. Elysia viridis. 3. Proctonotus mucroniferus. 4. Embletonia pulchra

Fig. 162.—Nudibranchs

1. Dendronotus arborescens. 2. Tritonia plebeia. 3. Triopa claviger. 4. Ægirus punctilucens

Fig. 163.—Shells of Tectibranchs

Fig. 164.—Chiton Shells

Fig. 165.—Shells of Dentalium

Fig. 166.—Patellidæ

1. Patella vulgata. 2. P. pellucida. 3. P. athletica. 4. Acmæa testudinalis

Fig. 167.—Calyptræa sinensis

Fig. 168.—Fissurellidæ

1. Puncturella noachina. 2. Emarginula reticulata. 3. Fissurella reticulata

Fig. 169.—Haliotis

Fig. 170.—Ianthina fragilis

Fig. 171.—1. Trochus zizyphinus. 2. Under side of Shell. 3. Trochus magnus. 4. Adeorbis subcarinatus

Fig. 172.—Rissoa labiosa and Lacuna pallidula

Fig. 173.—Section of Shell of Turritella

Fig. 174.—Turritella communis and Cæcum trachea

Fig. 175.—Cerithium reticulatum and Aporrhais pes-pelicani

Fig. 176.—Aporrhais pes-pelicani, showing both shell and animal

Fig. 177.—1. Odostomia plicata. 2. Eulima polita. 3. Aclis supranitida

Fig. 178.—Cypræa (Trivia) europæa

Fig. 179.—1. Ovulum patulum. 2. Erato lævis

Fig. 180.—Mangelia septangularis and Mangelia turricula

Fig. 181.—1. Purpura lapillus. 2. Egg Cases of Purpura. 3. Nassa reticulata

Fig. 182.—Murex erinaceus

Fig. 183.—Octopus

Fig. 184.—Loligo vulgaris and its Pen

Fig. 185.—Sepiola atlantica

Fig. 186.—Sepia officinalis and its ‘Bone’

Fig. 187.—Eggs of Sepia

Fig. 188.—The Nerve-chain of an Arthropod (Lobster)

o, optic nerve; c, cerebral ganglion; i, large ganglion behind the œsophagus; th, ganglia of the thorax; ab, ganglia of the abdomen

Fig. 189.—Section through the Compound Eye of an Arthropod

Fig. 190.—Four Stages in the development of the Common Shore Crab

Fig. 191. The Barnacle

Fig. 192.—Four Stages in the development of the Acorn Barnacle

a, newly hatched larva; b, larva after second moult; c, side view of same; d, stage immediately preceding loss of activity; a, stomach; b, base of future attachment. All magnified

Fig. 193.—A Cluster of Acorn Shells

Fig. 194.—Shell of Acorn Barnacle (Balanus)

Fig. 195.—The Acorn Barnacle (Balanus porcatus) with Appendages protruded

Fig. 196.—A group of Marine Copepods, magnified

Fig. 197.—A group of Ostracode Shells

Fig. 198.—Evadne

Fig. 199.—Marine Isopod

1. Sphæroma serratum. 2. Limnoria lignorum. 3. Ligia oceanica. 4. Nesæa bidentata. 5. Oniscoda maculosa

Fig. 200.—Marine Amphipods

1. The spined sea screw (Dexamine spinosa). 2. Westwoodia cœcula. 3. Tetromatus typicus. 4. The sandhopper (Orchestia littorea). 5. Montagua monoculoides. 6. Iphimedia obesa. All enlarged

Fig. 201.—The Mantis Shrimp (Squilla Mantis)

Fig. 202.—The Opossum Shrimp (Mysis chamæleon)

Fig. 203.—Parts of Lobster’s Shell, separated, and viewed from above

Fig. 204.—A Segment of the Abdomen of a Lobster

t, tergum; s, sternum, bearing a pair of swimmerets; h, bloodvessel; d, digestive tube; n, nerve chain

Fig. 205.—Appendages of a Lobster

1. Second maxilla. 2. Third foot-jaw. 3. Third walking leg. 4. Fifth walking leg

Fig. 206.—Longitudinal Section of the Lobster

a, antenna; r, rostrum or beak; o, eye; m, mouth; s, stomach; in, intestine; l, liver; gl, gills; h, heart; g, genital organ; ar, artery; n, nerve ganglia

Fig. 207.—The Spiny Lobster (Palinurus vulgaris)

Fig. 208.—The Norway Lobster (Nephrops norvegicus)

Fig. 209.—The Mud-borer (Gebia stellata) (1) and the Mud-burrower (Callianassa subterranea) (2)

Fig. 210.—The Common Shrimp (Crangon vulgaris)

Fig. 211.—The Prawn (Palæmon serratus)

Fig. 212.—Dromia vulgaris

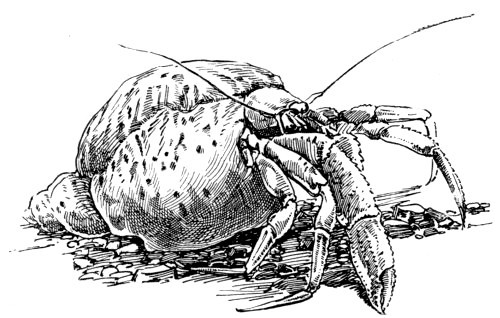

Fig. 213.—The Hermit Crab in a Whelk Shell

Fig. 214.—The Long-armed Crab (Corystes Cassivelaunus)

Fig. 215.—Spider Crabs at Home

Fig. 216.—The Thornback Crab (Maia Squinado)

Fig. 217.—The Pea Crab (Pinnotheres pisum)

Fig. 218.—The Common Shore Crab (Carcinus mænas)

Fig. 219.—The Shore Spider

Fig. 220.—The Leg of an Insect

Fig. 221.—Trachea of an Insect, magnified

Fig. 222.—Sea Shore Insects

1. Æpophilus. 2. Machilis maritima. 3. Isotoma maritima. 4. Cœlopa

Fig. 223.—Marine Beetles of the genus Bembidium

1. B. biguttatum. 2. B. pallidipenne. 3. B. fumigatum. 4. B. quadriguttatum

Fig. 224.—Marine Beetles

1. Æpys marinus. 2. Micralymma brevipenne

Fig. 225.—Transverse section through the Bony Framework of a Typical Vertebrate Animal

1. Spinous process of the vertebra. 2. Neural arch. 3. Transverse process. 5. Body of the vertebra. 6. Breast-bone. 7. Rib. The space between 2 and 5 is the neural cavity; and that between 5 and 6 is the visceral cavity

Fig. 226.—The Sea Lamprey

Fig. 227.—The Pilchard

1. Dorsal fin. 2. Pectoral fin. 3. Pelvic fin. 4. Ventral or anal fin. 5. Caudal fin.

Fig. 228.—The Skeleton of a Fish (Perch)

d, dorsal fin; p, pectoral fin; v, pelvic fin; t, tail fin; a, anal fin

Fig. 229.—The Internal Organs of the Herring

a, œsophagus; bc, stomach; e, intestine; l, duct of swimming bladder; k, air-bladder; h, ovary

Fig. 230.—The Egg-case of Dogfish

Fig. 231.—The Smooth Hound

Fig. 232.—The Common Eel

Fig. 233.—The Lesser Sand Eel

Fig. 234.—The Three-bearded Rockling

Fig. 235.—The Snake Pipe-fish

Fig. 236.—The Rainbow Wrass (Labrus julis)

Fig. 237.—The Cornish Sucker

Fig. 238.—The Fifteen-spined Stickleback and Nest

Fig. 239.—The Smooth Blenny

Fig. 240.—The Butterfish

Fig. 241.—The Black Goby

Fig. 242.—The Father Lasher

Fig. 243.—The Lesser Weaver

Fig. 244.—The Common Porpoise

Fig. 245.—Callithamnion roseum

Fig. 246.—Callithamnion tetricum

Fig. 247.—Griffithsia corallina

Fig. 248.—Halurus equisetifolius

Fig. 249.—Pilota plumosa

Fig. 250.—Ceramium diaphanum

Fig 251..—Plocamium

Fig. 252.—Delesseria alata

Fig. 253.—Delesseria hypoglossum

Fig. 254.—Laurencia pinnatifida

Fig. 255.—Laurencia obtusa

Fig. 256.—Polysiphonia fastigiata

Fig. 257.—Polysiphonia parasitica

Fig. 258.—Polysiphonia Brodiæi

Fig. 259.—Polysiphonia nigrescens

Fig. 260.—Ectocarpus granulosus

Fig. 261.—Ectocarpus siliculosus

Fig. 262.—Ectocarpus Mertensii

Fig. 263.—Sphacelaria cirrhosa

Fig. 264.—Sphacelaria plumosa

Fig. 265.—Sphacelaria radicans

Fig. 266.—Cladostephus spongiosus

Fig. 267.—Chordaria flagelliformis

Fig. 268.—Laminaria bulbosa

Fig. 269.—Laminaria saccharina

Fig. 270.—Alaria esculenta

Fig. 271.—Sporochnus pedunculatus

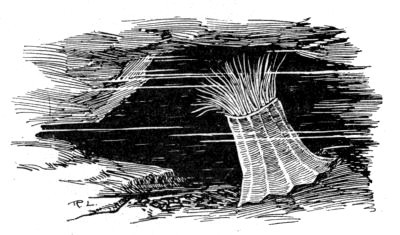

Fig. 272.—Desmarestia ligulata

Fig. 273.—Himanthalia lorea

Fig. 274.—Cystoseira ericoides

Fig. 275.—Transverse Section of the Stem of a Monocotyledon

Fig. 276.—Leaf of a Monocotyledon

Fig. 277.—Expanded Spikelet of the Oat

G. glumes; P.e, outer pale; P.i, inner pale; A, awn; F.S, a sterile flower. The stamens and the feathery stigmas of the fertile flower are also shown

Fig. 278.—The Sea Lyme Grass

Fig. 279.—Knappia agrostidea

Fig. 280.—The Dog’s-tooth Grass

Fig. 281.—The Reed Canary Grass

Fig. 282.—Male and Female Flowers of Carex, magnified

Fig. 283.—The Sea Sedge

Fig. 284.—The Curved Sedge

Fig. 285.—The Great Sea Rush

Fig. 286.—The Broad-leaved Grass Whack

Fig. 287.—The Sea-side Arrow Grass

Fig. 288.—The Common Asparagus

Fig. 289.—The Sea Spurge

Fig. 290.—The Purple Spurge

Fig. 291.—The Sea Buckthorn

Fig. 292.—Chenopodium botryoides

Fig. 293.—The Frosted Sea Orache

Fig. 294.—The Prickly Salt Wort

Fig. 295.—The Creeping Glass Wort

Fig. 296.—The Sea-side Plantain

Fig. 297.—The Sea Lavender

Fig. 298.—The Dwarf Centaury

Fig. 299.—The Sea Samphire

Fig. 300.—The Sea-side Everlasting Pea

Fig. 301.—The Sea Stork’s-bill

Fig. 302.—The Sea Campion

Fig. 303.—The Sea Pearl Wort

Fig. 304.—The Shrubby Mignonette

Fig. 305.—The Wild Cabbage

Fig. 306.—The Isle of Man Cabbage

Fig. 307.—The Great Sea Stock

Fig. 308.—The Hoary Shrubby Stock

Fig. 309.—The Scurvy Grass

Fig. 310.—The Sea Radish

Fig. 311.—The Sea Rocket

Fig. 312.—The Sea Kale

Fig. 313.—The Horned Poppy

THE SEA SHORE

CHAPTER I

THE GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE SEA SHORE

What are the attractions which so often entice us to the sea shore, which give such charm to a ramble along the cliffs or the beach, and which will so frequently constrain the most active wanderer to rest and admire the scene before him? The chief of these attractions is undoubtedly the incessant motion of the water and the constant change of scene presented to his view. As we ramble along a beaten track at the edge of the cliff, new and varied features of the coast are constantly opening up before us. Each little headland passed reveals a sheltered picturesque cove or a gentle bay with its line of yellow sands backed by the cliffs and washed by the foaming waves; while now and again our path slopes down to a peaceful valley with its cluster of pretty cottages, and the rippling stream winding its way towards the sea. On the one hand is the blue sea, full of life and motion as far as the eye can reach, and on the other the cultivated fields or the wild and rugged downs.

The variety of these scenes is further increased by the frequent changes in the character of the cliffs themselves. Where they are composed of soft material we find the coast-line washed into gentle curves, and the beach formed of a continuous stretch of fine sand; but where harder rocks exist the scenery is wild and varied, and the beach usually strewn with irregular masses of all sizes.

Then, when we approach the water’s edge, we find a delight in watching the approaching waves as they roll over the sandy or pebbly beach, or embrace an outlying rock, gently raising its olive covering of dangling weeds.

Such attractions will allure the ordinary lover of Nature—the mere seeker after the picturesque—but to the true naturalist there are many others. The latter loves to read in the cliffs their past history, to observe to what extent the general scenery of the coast is due to the nature of the rocks, and to learn the action of the waves from the character of the cliffs and beach, and from the changes which are known to have taken place in the contour of the land in past years. He also delights to study those plants and flowers which are peculiar to the coast, and to observe how the influences of the sea have produced interesting modifications in certain of our flowering plants, as may be seen by comparing them with the same species from inland districts. The sea birds, too, differing so much as they do from our other feathered friends in structure and habit, provide a new field for study; while the remarkably varied character of the forms of life met with on the beach and in the shallow waters fringing the land is in itself sufficient to supply the most active naturalist with material for prolonged and constant work.

Let us first observe some of the general features of the coast itself, and see how far we can account for the great diversity of character presented to us, and for the continual changes and incessant motions that add such a charm to the sea-side ramble.

Here we stand on the top of a cliff composed of a soft calcareous rock—on the exposed edge of a bed of chalk that extends far inland. All the country round is gently undulating, and devoid of any of the features that make up a wild and romantic scene. The coast-line, too, is wrought into a series of gentle bays, separated by inconspicuous promontories where the rock, being slightly harder, has better withstood the eroding action of the sea; or where a current, washing the neighbouring shore, has been by some force deflected seaward. The cliff, though not high, rises almost perpendicularly from the beach, and presents to the sea a face which is but little broken, and which in itself shows no strong evidence of the action of raging, tempestuous seas; its chief diversity being its gradual rise and fall with each successive undulation of the land. The same soft and gentle nature characterises the beach below. Beyond a few small blocks of freshly-loosened chalk, with here and there a liberated nodule of flint, we find nothing but a continuous, fine, siliceous sand, the surface of which is but seldom broken by the protrusion of masses from below. Such cliffs and beaches do not in themselves suggest any violent action on the part of the sea, and yet it is here that the ocean is enabled to make its destructive efforts with the greatest effect. The soft rock is gradually but surely reduced, partly by the mechanical action of the waves and partly by the chemical action of the sea-water. The rock being almost uniformly soft, it is uniformly worn away, thus presenting a comparatively unbroken face. Its material is gradually dissolved in the sea; and the calcareous matter being thus removed, we have a beach composed of the remains of the flints which have been pulverised by the action of the waves. Thus slowly but surely the sea gains upon the land. Thus it is that many a famous landmark, once hundreds of yards from the coast, now stands so near the edge of the cliff as to be threatened by every storm; or some ancient castle, once miles from the shore, lies entirely buried by the encroaching sea.

Fig. 1.—Chalk Cliff

The coast we have described is most certainly not the one with the fullest attractions for the naturalist, for the cliffs lack those nooks that provide so much shelter for bird and beast, and the rugged coves and rock pools in which we find such a wonderful variety of marine life are nowhere to be seen. But, although it represents a typical shore for a chalky district, yet we may find others of a very different nature even where the same rock exists. Thus, at Flamborough in Yorkshire, and St. Alban’s Head in Dorset, we find the hardened, exposed edge of the chalk formation terminating in bold and majestic promontories, while the inner edge surrounding the Weald gives rise to the famous cliffs of Dover and the dizzy heights of Beachy Head. The hard chalk of the Isle of Wight, too, which has so well withstood the repeated attacks of the Atlantic waves, presents a bold barrier to the sea on the south and east coasts, and terminates in the west with the majestic stacks of the Needles.

Fig. 2.—Whitecliff (Chalk), Dorset

Where this harder chalk exists the coast is rugged and irregular. Sea birds find a home in the sheltered ledges and in the protected nooks of its serrated edge; and the countless wave-resisting blocks of weathered chalk that have been hurled from the heights above, together with the many remnants of former cliffs that have at last succumbed to the attacks of the boisterous sea, all form abundant shelter for a variety of marine plants and animals.

Fig. 3.—Penlee Point, Cornwall

But it is in the west and south-west of our island that we find both the most furious waves and the rocks that are best able to resist their attacks. Here we are exposed to the full force of the frontal attacks of the Atlantic, and it is here that the dashing breakers seek out the weaker portions of the upturned and contorted strata, eating out deep inlets, and often loosening enormous blocks of the hardest material, hurling them on the rugged beach, where they are eventually to be reduced to small fragments by the continual clashing and grinding action of the smaller masses as they are thrown up by the angry sea. Here it is that we find the most rugged and precipitous cliffs, bordering a more or less wild and desolate country, now broken by a deep and narrow chasm where the resonant roar of the sea ascends to the dizzy heights above, and anon stretching seaward into a rocky headland, whose former greatness is marked by a continuation of fantastic outliers and smaller wave-worn masses of the harder strata. Here, too, we find that the unyielding rocks give a permanent attachment to the red and olive weeds which clothe them, and which provide a home for so many inhabitants of our shallow waters. It is here, also, that we see those picturesque rock pools of all sizes, formed by the removal of the softer material of the rocks, and converted into so many miniature seas by the receding of the tide.

Fig. 4.—Balanus Shells

A more lovely sight than the typical rock pool of the West coast one can hardly imagine. Around lies the rugged but sea-worn rock, partly hidden by dense patches of the conical shells of the Balanus, with here and there a snug cluster of young mussels held together by their intertwining silken byssi. The surface is further relieved by the clinging limpet, the beautifully banded shells of the variable dog-periwinkle, the pretty top shells, and a variety of other common but interesting molluscs. Clusters of the common bladdery weeds are also suspended from the dry rock, and hang gracefully into the still water below, where the mantled cowry may be seen slowly gliding over the olive fronds. Submerged in the peaceful pool are beautiful tufts of white and pink corallines, among which a number of small and slender starfishes may climb unnoticed by the casual observer; while the scene is brightened by the numerous patches of slender green and red algæ, the thread-like fronds of which are occasionally disturbed as the lively little blenny darts among them to evade the intruder’s glance. Dotted here and there are the beautiful anemones—the variously-hued animal flowers of the sea, with expanded tentacles gently and gracefully swaying, ready to grasp and paralyse any small living being that may wander within their reach. Here, under a projecting ledge of the rock, partly hidden by pale green threads, are the glaring eyes of the voracious bullhead, eager to pounce on almost any moving object; while above it the five-fingered starfish slowly climbs among the dangling weeds by means of its innumerable suckers. In yonder shady corner, where the overhanging rock cuts off all direct rays of the sun from the deeper water of the pool, are the pink and yellow incrustations of little sponges, some of the latter colour resembling a group of miniature inverted volcanic cones, while on the sandy floor of the pool itself may be seen the transparent phantom-like prawn, with its rapidly moving spinnerets and gently-waving antennæ, suddenly darting backward when disturbed by the incautious approach of the observer; and the spotted sand-crab, entirely buried with the exception of its upper surface, and so closely imitating its surroundings as to be quite invisible except on the closest inspection. Finally, the scene is greatly enlivened by the active movements of the hermit-crab, that appropriates to its own use the shell which once covered the body of a mollusc, and by the erratic excursions of its cousin crabs as they climb over the weedy banks of the pool in search of food.

Fig. 5.—A Cluster of Mussels

Thus we may find much to admire and study on the sea shore at all times, but there are attractions of quite another nature that call for notice on a stormy day, especially on the wilder and more desolate western coasts. At such times we delight to watch the distant waves as they approach the shore, to see how they become gradually converted into the foaming breakers that dash against the standing rocks and wash the rattling pebbles high on the beach. The powerful effects of the sea in wearing away the cliffs are now apparent, and we can well understand that even the most obdurate of rocks must sooner or later break away beneath its mighty waves.

Fig. 6.—Breakers

The extreme mobility of the sea is displayed not only by the storm waves, and by the soft ripples of the calm day, but is seen in the gentle currents that almost imperceptibly wash our shores, and more manifestly in the perpetual motions of the tides.

This last-named phenomenon is one of extreme interest to the sea-side rambler, and also one of such great importance to the naturalist that we cannot do better than spend a few moments in trying to understand how the swaying of the waters of the ocean is brought about, and to see what determines the period and intensity of its pulsations, as well as some of the variations in the daily motions which are to be observed on our own shores.

In doing this we shall, of course, not enter fully into the technical theories of the tides, for which the reader should refer to authoritative works on the subject, but merely endeavour to briefly explain the observed oscillations of the sea and the general laws which govern them.

The most casual observer must have noticed the close connection between the movements of the ocean and the position of the moon, while those who have given closer attention to the subject will have seen that the relative heights of the tides vary regularly with the relative positions of the sun, moon, and earth.

In the first place, then, we notice that the time of high tide in any given place is always the same at the same period of the cycle of the moon; that is, it is always the same at the time of new moon, full moon, &c. Hence it becomes evident that the moon is the prime mover in the formation of tides. Now, it is a fact that the sun, though about ninety-three millions of miles from the earth, has a much greater attractive influence on the earth and its oceans than the moon has, although the distance of the latter is only about a quarter of a million miles: but this is due to the vastly superior mass of the sun, which is about twenty-six million times the mass of the moon. How is it, then, that we find the tides apparently regulated by the moon rather than by the sun? The reason is that the tide-producing influence is due not to the actual attractive force exerted on the earth as a whole, but to the difference between the attraction for one side of the globe and that for the opposite side. Now, it will be seen that the diameter of the earth—about eight thousand miles—is an appreciable fraction of the moon’s distance, and thus the attractive influence of the moon for the side of the earth nearest to it will be appreciably greater than that for the opposite side; while in the case of the sun, the earth’s diameter is such a small fraction of the distance from the sun that the difference in the attractive force for the two opposite sides of the earth is comparatively small.

Omitting, then, for the present the minor tide-producing influence of the sun, let us see how the incessant rising and falling of the water of the ocean are brought about; and, to simplify our explanation, we will imagine the earth to be a globe entirely covered with water of uniform depth.

The moon attracts the water on the side nearest to it with a greater force than that exerted on the earth itself; hence the water is caused to bulge out slightly on that side. Again, since the attractive force of the moon for the earth as a whole is greater than that for the water on the opposite side, the earth is pulled away, as it were, from the water on that side, causing it to bulge out there also. Hence high tides are produced on two opposite sides of the earth at the same time, while the level of the water is correspondingly reduced at two other parts at right angles with these sides.

This being the case, how are we to account for the observed changes in the level of the sea that occur every day on our shores?

Let us first see the exact nature of these changes:—At a certain time we find the water high on the beach; and, soon after reaching its highest limit, a gradual descent takes place, generally extending over a period of a little more than six hours. This is then followed by another rise, occupying about the same time, and the oscillations are repeated indefinitely with remarkable regularity as to time.

Fig. 7.—Illustrating the Tide-producing Influence of the Moon

Now, from what has been previously said with regard to the tidal influence of the moon, we see that the tide must necessarily be high under the moon, as well as on the side of the earth directly opposite this body, and that the high tides must follow the moon in its regular motion. But we must not forget that the earth itself is continually turning on its axis, making a complete rotation in about twenty-four hours; while the moon, which revolves round the earth in about twenty-eight days, describes only a small portion of its orbit in the same time; thus, while the tidal wave slowly follows the moon as it travels in its orbit, the earth slips round, as it were, under the tidal wave, causing four changes of tide in approximately the period of one rotation. Suppose, for example, the earth to be performing its daily rotation in the direction indicated by the arrow (fig. 8), and the tide high at the place markedÛuccessively, where the tide is high and low respectively. Hence the daily changes are to a great extent determined by the rotation of the earth.

But we have already observed that each change of tide occupies a little more than six hours, the average time being nearly six hours and a quarter, and so we find that the high and low tides occur nearly an hour later every day. This is due to the fact that, owing to the revolution of the moon round the earth in the same direction as that of the rotation of the earth itself, the day as measured by the moon is nearly an hour longer than the average solar day as given by the clock.

Fig. 8.—Illustrating the Tides

There is yet another point worth noting with regard to the relation between the moon and the tidal movements of the water, which is that the high tides are never exactly under the moon, but always occur some time after the moon has passed the meridian. This is due to the inertia of the ocean, and to the resistance offered by the land to its movements.

Now, in addition to these diurnal changes of the tide, there are others, extending over longer periods, and which must be more or less familiar to everyone who has spent some time on the coast. On a certain day, for instance, we observe that the high tide flows very far up the beach, and that this is followed, a few hours later, by an unusually low ebb, exposing rocks or sand-banks that are not frequently visible. Careful observations of the motions of the water for some days after will show that this great difference between the levels of high and low-water gradually decreases until, about a week later, it is considerably reduced, the high tide not flowing so far inland and the low-water mark not extending so far seaward. Then, from this time, the difference increases again, till, after about two weeks from the commencement of our observations, we find it at the maximum again.

Fig. 9.—Spring Tides at Full Moon

Here again we find that the changes exactly coincide with changes in the position of the moon with regard to the sun and the earth. Thus, the spring tides—those which rise very high and fall very low—always occur when the moon is full or new; while the less vigorous neap tides occur when the moon is in her quarters and presents only one-half of her illuminated disc to the earth. And, as the moon passes through a complete cycle of changes from new to first-quarter, full, last-quarter, and then to new again in about twenty-nine days, so the tides run through four changes from spring to neap, spring, neap, and then to spring again in the same period.

Fig. 10.—Spring Tides at New Moon

The reason for this is not far to seek, for we have already seen that both sun and moon exert a tide-producing influence on the earth, though that of the moon is considerably greater than that of the sun; hence, if the sun, earth, and moon are in a straight line, as they are when the moon is full, at which time she and the sun are on opposite sides of the earth, and also when new, at which time she is between the earth and sun, the sun’s tide is added to the moon’s tide, thus producing the well-marked spring tides; while, when the moon is in her quarters, occupying a position at right angles from the sun as viewed from the earth, the two bodies tend to produce high tides on different parts of the earth at the same time, and thus we have the moon’s greater tides reduced by the amount of the lesser tides of the sun, with the result that the difference between high and low tides is much lessened.

Fig. 11.—Neap Tides

Again, the difference between high and low water marks is not always exactly the same for the same kind of tide—the spring tide for a certain period, for example, not having the same limits as the same tide of another time. This is due to the fact that the moon revolves round the sun in an elliptical orbit, while the earth, at the same time, revolves round the sun in a similar path, so that the distances of both moon and sun from the earth vary at different times. And, since the tide-producing influences of both these bodies must increase as their distance from the earth diminishes, it follows that there must be occasional appreciable variations in the vigour of the tidal movements of the ocean.

As the earth rotates on its axis, while at the same time the tidal wave must necessarily keep its position under the moon, this wave appears to sweep round the earth with considerable velocity. The differences in the level of the ocean thus produced would hardly be appreciable if the earth were entirely covered with water; but, owing to the very irregular distribution of the land, the movements of the tidal wave become exceedingly complex; and, when it breaks an entrance into a gradually narrowing channel, the water is compressed laterally, and correspondingly increased in height. It is thus that we find a much greater difference between the levels of high and low tides in continental seas than are to be observed on the shores of oceanic islands.

We have occupied so much of our time and space in explanation of the movements of the tides not only because we think it desirable that all who delight in sea-side rambles should understand something of the varied motions which help to give such a charm to the sea, but also because, as we shall observe later, these motions are a matter of great importance to those who are interested in the observation and study of marine life. And, seeing that we are writing more particularly for the young naturalists of our own island, we must devote a little space to the study of the movements of the tidal wave round Great Britain, in order that we may understand the great diversity in the time of high tide on any one day on different parts of the coast, and see how the time of high tide for one part may be calculated from that of any other locality.

Were it not for the inertia of the ocean and the resistance offered by the irregular continents, high tide would always exist exactly under the moon, and we should have high water at any place just at the time when the moon is in the south and crossing the meridian of that place. But while the inertia of the water tends to make all tides late, the irregular distribution of the land breaks up the tidal wave into so many wave-crests and greatly retards their progress.

Thus, the tidal wave entering the Atlantic round the Cape of Good Hope mingles with another wave that flows round Cape Horn, and the combined wave travels northward at the rate of several hundred miles an hour. On reaching the British Isles it is broken up, one wave-crest travelling up the English Channel, while another flows round Scotland and then southwards into the North Sea.

The former branch, taking the shorter course, determines the time of high tide along the Channel coast. Passing the Land’s End, it reaches Plymouth in about an hour, Torquay in about an hour and a half, the Isle of Portland in two hours and a half, Brighton in about seven hours, and London in about nine hours and a half. The other branch, taking a much longer course, makes its arrival in the southern part of the North Sea about twelve hours later, thus mingling at that point with the Channel wave of the next tide. It takes about twenty hours to travel from the south-west coast of Ireland, round Scotland, and then to the mouth of the Thames. Where the two waves meet, the height of the tides is considerably increased; and it will be understood that, at certain points, where the rising of one tide coincides with the falling of another, the two may partially or entirely neutralise each other. Further, the flow and the ebb of the tide are subject to numerous variations and complications in places where two distinct tidal wave-crests arrive at different times. Thus, the ebbing of the tide may be retarded by the approach of a second crest a few hours after the first, so that the ebb and the flow do not occupy equal times. At Eastbourne, for example, the water flows for about five hours, and ebbs for about seven and a half. Or, the approach of the second wave may even arrest the ebbing waters, and produce a second high tide during the course of six hours, as is the case at some places along the Hampshire and Dorset coasts.

Fig. 12.—Chart showing the relative Times of High Tide on different parts of the British Coast

Those who visit various places on our own coasts will probably be interested in tracing the course of the tidal crests by the aid of the accompanying map of the British Isles, on which the time of high tide at several ports for the same time of day is marked. It will be seen from this that the main tidal wave from the Atlantic approaches our islands from the south-west, and divides into lesser waves, one of which passes up the Channel, and another round Scotland and into the North Sea, as previously mentioned, while minor wave-crests flow northward into the Irish Sea and the Bristol Channel. The chart thus supplies the data by means of which we can calculate the approximate time of high tide for any one port from that of another.

Although the time of high water varies so greatly on the same day over such a small area of country, yet that time for any one place is always approximately the same during the same relative positions of the sun, earth, and moon; that is, for the same ‘age’ of the moon; so that it is possible to determine the time of high water at any port from the moon’s age.

The time of high tide is generally given for the current year in the local calendars of our principal seaports, and many guide-books supply a table from which the time may be calculated from the age of the moon.

At every port the observed high water follows the meridional passage of the moon by a fixed interval of time, which, as we have seen, varies considerably in places within a small area of the globe. This interval is known as the establishment of the port, and provides a means by which the time of high water may be calculated.

Before closing this short chapter on the general characteristics of the sea shore we ought to make a few observations on the nature of the water of the sea. Almost everyone is acquainted with the saltness while many bathers have noticed the superior buoyancy of salt water as compared with the fresh water of our rivers and lakes. The dissolved salts contained in sea water give it a greater density than that of pure water; and, since all floating bodies displace their own weight of the liquid in which they float, it is clear that they will not sink so far in the denser water of the sea as they would in fresh water.

If we evaporate a known weight of sea water to dryness and weigh the solid residue of sea salt that remains, we find that this residue forms about three and a half per cent. of the original weight. Then, supposing that the evaporation has been conducted very slowly, the residue is crystalline in structure, and a careful examination with the aid of a lens will reveal crystals of various shapes, but by far the larger number of them cubical in form. These cubical crystals consist of common salt (sodium chloride), which constitutes about three-fourths of the entire residue, while the remainder of the three and a half per cent. consists principally of various salts of magnesium, calcium, and sodium.

Sea salt may be obtained ready prepared in any quantity, as it is manufactured for the convenience of those who desire a sea bath at home; and it will be seen from what has been said that the artificial sea-water may be prepared, to correspond almost exactly with that of the sea, by the addition of three and a half pounds of sea salt to about ninety-six and a half pounds of water.

This is often a matter of no little importance to the sea-side naturalist, who may require to keep marine animals alive for some time at considerable distance from the sea shore, while their growth and habits are observed. Hence we shall refer to this subject again when dealing with the management of the salt-water aquarium.

The attractions of the sea coast are undoubtedly greater by day than at night, especially in the summer season, when the excessive heat of the land is tempered by the cool sea breezes, and when life, both on the cliffs and among the rocks, is at its maximum. But the sea is grand at night, when its gentle ripples flicker in the silvery light of the full moon. No phenomenon of the sea, however, is more interesting than the beautiful phosphorescence to be observed on a dark summer’s night. At times the breaking ripples flash with a soft bluish light, and the water in the wake of a boat is illuminated by what appears to be liquid fire. The advancing ripples, as they embrace a standing rock, surround it with a ring of flame; while streaks and flashes alternately appear and disappear in the open water where there is apparently no disturbance of any kind.

These effects are all produced by the agency of certain marine animals, some of which display a phosphorescent light over the whole surface of their bodies, while in others the light-giving power is restricted to certain organs or to certain well-defined areas of the body; and in some cases it even appears as if the creatures concerned have the power of ejecting from their bodies a phosphorescent fluid.

It was once supposed that the phosphorescence of the sea was produced by only a few of the lower forms of life, but it is well known now that quite a large number of animals, belonging to widely different classes, play a part in this phenomenon. Many of these are minute creatures, hardly to be seen without the aid of some magnifying power, while others are of considerable size.

Among the peculiar features of the phosphorescence of the sea are the suddenness with which it sometimes appears and disappears, and its very irregular variations both at different seasons and at different hours of the same night. On certain nights the sea is apparently full of living fire when, almost suddenly the light vanishes and hardly a trace of phosphorescence remains; while, on other occasions, the phenomenon is observed only on certain patches of water, the areas of which are so well defined that one passes suddenly from or into a luminous sea.

The actual nature of the light and the manner in which it is produced are but ill understood, but the variations and fitfulness of its appearances can be to a certain extent conjectured from our knowledge of some of the animals that produce it.

In our own seas the luminosity is undoubtedly caused principally by the presence of myriads of minute floating or free-swimming organisms that inhabit the surface waters. Of these each one has its own season, in which it appears in vast numbers. Some appear to live entirely at or near the surface, but others apparently remain near the surface only during the night, or only while certain conditions favourable to their mode of life prevail. And further, it is possible that these minute creatures, produced as they generally are in vast numbers at about the same time, and being more or less local, are greatly influenced by changes of temperature, changes in the nature of the wind, and the periodic changes in the tides; and it is probable that we are to look to these circumstances for the explanations of the sudden changes so frequently observed.

In warmer seas the phenomenon of phosphorescence is much more striking than in our own, the brilliancy of the light being much stronger, and also produced by a greater variety of living beings, some of which are of great size, and embrace species belonging to the vertebrates and the higher invertebrate animals.

Those interested in the investigation of this subject should make it a rule to collect the forms of life that inhabit the water at a time when the sea is unusually luminous. A sample of the water may be taken away for the purpose of examination, and this should be viewed in a good light, both with and without a magnifying lens. It is probable, too, that a very productive haul may be obtained by drawing a fine muslin net very slowly through the water. After some time the net should be emptied and gently washed in a small quantity of sea water to remove the smaller forms of life contained, and the water then examined at leisure.

Of course it must not be assumed that all the species so obtained are concerned in any way with the phosphorescence of the sea, but any one form turning up in abundance when collected under the conditions named will probably have some connection with the phenomenon.

One may well ask ‘What is the use of this light-emitting power to the animals who possess it?’ but this question is not easily answered. The light produced by the glow-worm and other luminous insects is evidently a signal by means of which they call their mates, and this may be the case with many of the marine luminous animals, but it is evidently not so with those which live in such immense numbers that they are simply crowded together; nor can it be so with the many luminous creatures that are hermaphrodite. It is a fact, however, that numbers of deep-sea species possess the power of emitting light to a striking extent; and the use of this power is in such cases obvious, for since the rays of the sun do not penetrate to great depths in the ocean, these luminous species are enabled to illuminate their own surroundings while in search of food, and, in many cases at least, to quench their lights suddenly at such times as they themselves are in danger.

CHAPTER II

THE SEA-SIDE NATURALIST

Outdoor Work

Assuming that the reader is one who desires to become intimately acquainted with the wonderful and varied forms of life to be met with on the sea shore, or, hoping that he may be lured into the interesting and profitable pastimes of the sea-side naturalist, we shall now devote a chapter to the consideration of the appliances required for the collection and examination of marine life, and to general instructions as to the methods by which we may best search out the principal and most interesting objects of the shore.

First, then, we shall describe the equipment of an enthusiastic and all-round admirer of Nature—he who is interested in plant forms from the flowering species down to the ‘meanest weed that grows,’ and is always ready to learn something of any member of the animal world that may happen to come within his reach. And this, not because we hope, or even desire, that every reader may develop into an all-round naturalist, but so that each may be able to select from the various appliances named just those which would be useful for the collection and observation of the objects which are to form his pet study.

The most generally useful of all these appliances is undoubtedly some kind of case of the ‘hold-all’ type, a case into which specimens in general may be placed for transmission from the hunting-ground in order that they may be studied at leisure, and we know of nothing more satisfactory than the botanist’s ‘vasculum.’ This is an oblong box of japanned tin, fitted with a hinged front, and having both handle and strap, so that it can be either carried in the hand or slung over the shoulder. Of course almost any kind of non-collapsible box or basket will answer the purpose, but we know of no utensils so convenient as the one we have named. It is perfectly satisfactory for the temporary storage of the wild flowers gathered on the cliffs, as it will keep them moist and fresh for some considerable time; and for the reception of sea weeds of all kinds it is all that could be desired, for it will preserve them in splendid condition, and is so constructed that there is no possibility of the inconvenience arising from the dripping of salt water on the lower garments. Then, as regards marine animal-life in general—starfishes, urchins, anemones, molluscs, crustaceans, fishes, &c.—these may be conveyed away in it with a liberal packing of moist weeds not only without injury, but in such a satisfactory condition that nearly all may be turned out alive at the end of a day’s work; and this must be looked upon as a very important matter to him who aims at becoming a naturalist rather than a mere collector, for while the latter is content with a museum of empty shells and dried specimens, the former will endeavour to keep many of the creatures alive for a time in some kind of artificial rock pool in order that he may have the opportunity of studying their development and their habits at times when he has not the chance of visiting the sea shore for the purpose.

Fig. 13.—The Vasculum