автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Tory Lover

THE TORY LOVER

This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Tory Lover Author: Sarah Orne Jewett Release Date: March 23, 2016 [EBook #51537] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE TORY LOVER ***

Produced by Al Haines.

Mary Hamilton

THE TORY LOVER

BY

SARAH ORNE JEWETT

BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY The Riverside Press, Cambridge 1901

COPYRIGHT, 1901, BY SARAH ORNE JEWETT AND HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & CO. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

TO T. J. E.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

-

The Sea-Wolf

-

The Parting Feast

-

A Character of Honor

-

The Flowering of whose Face

-

The Challenge

-

The Captain speaks

-

The Sailing of the Ranger

-

The Major's Hospitalities

-

Brother and Sister

-

Against Wind and Tide

-

That Time of Year

-

Between Decks

-

The Mind of the Doctor

-

To add More Grief

-

The Coast of France

-

It is the Soul that sees

-

The Remnant of Another Time

-

Oh had I wist!

-

The best laid Plans

-

Now are we Friends again?

-

The Captain gives an Order

-

The Great Commissioner

-

The Salute to the Flag

-

Whitehaven

-

A Man's Character

-

They have made Prey of him

-

A Prisoner and Captive

-

News at the Landing

-

Peggy takes the Air

-

Madam goes to Sea

-

The Mill Prison

-

The Golden Dragon

-

They come to Bristol

-

Good English Hearts

-

A Stranger at Home

-

My Lord Newburgh's Kindness

-

The Bottom of these Miseries

-

Full of Straying Streets

-

Mercy and Manly Courage

-

The Watcher's Light

-

An Offered Opportunity

-

The Passage Inn

-

They follow the Dike

-

The Road's End

-

With the Flood Tide

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

ARTIST PAGE

Mary Hamilton . . . Marcia O. Woodbury . . . Frontispiece

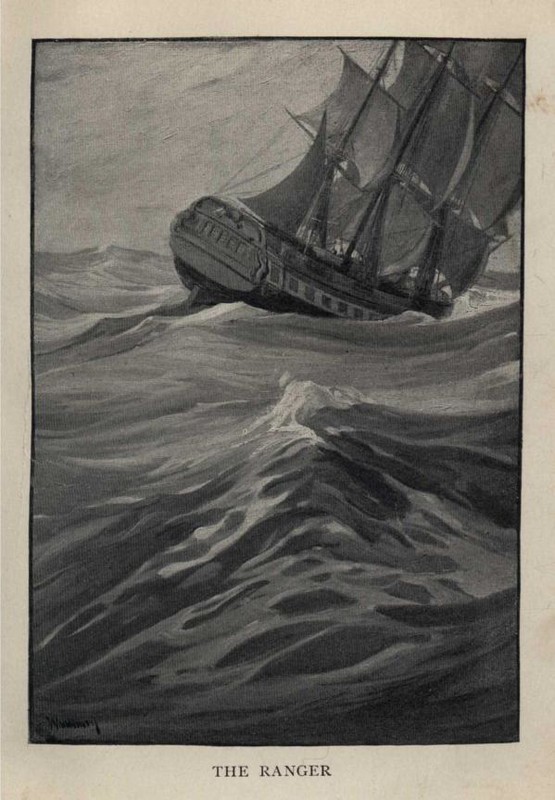

The Ranger . . . Charles H. Woodbury

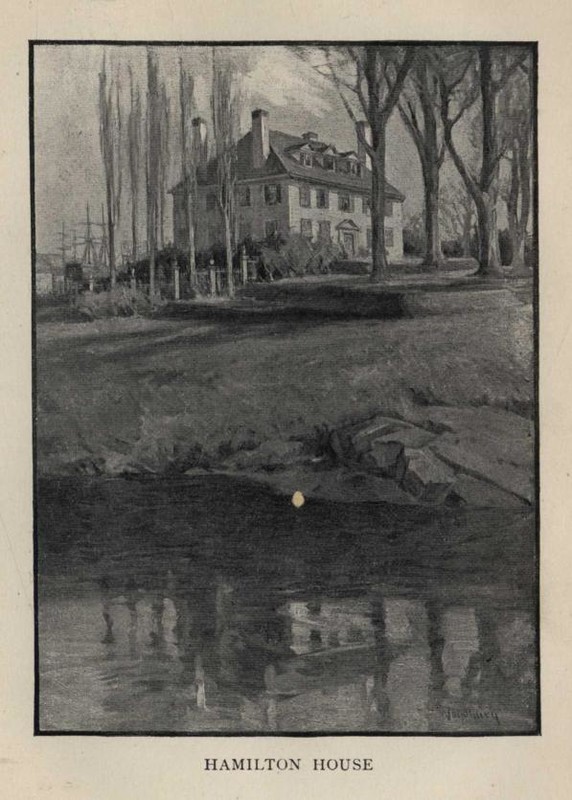

Hamilton House . . . Charles H. Woodbury

Along the Dike . . . Charles H. Woodbury

THE TORY LOVER

I

THE SEA WOLF

"By all you love most, war and this sweet lady."

The last day of October in 1777, Colonel Jonathan Hamilton came out of his high house on the river bank with a handsome, impatient company of guests, all Berwick gentlemen. They stood on the flagstones, watching a coming boat that was just within sight under the shadow of the pines of the farther shore, and eagerly passed from hand to hand a spyglass covered with worn red morocco leather. The sun had just gone down; the quick-gathering dusk of the short day was already veiling the sky before they could see the steady lift and dip of long oars, and make sure of the boat's company. While it was still a long distance away, the gentlemen turned westward and went slowly down through the terraced garden, to wait again with much formality by the gate at the garden foot.

Beside the master of the house was Judge Chadbourne, an old man of singular dignity and kindliness of look, and near them stood General Goodwin, owner of the next estate, and Major Tilly Haggens of the Indian wars, a tall, heavily made person, clumsily built, but not without a certain elegance like an old bottle of Burgundy. There was a small group behind these foremost men,—a red cloak here and a touch of dark velvet on a shoulder beyond, with plenty of well-plaited ruffles to grace the wearers. Hamilton's young associate, John Lord, merchant and gentleman, stood alone, trim-wigged and serious, with a look of discretion almost too great for his natural boyish grace. Quite the most impressive figure among them was the minister, a man of high ecclesiastical lineage, very well dressed in a three-cornered beaver hat, a large single-breasted coat sweeping down with ample curves over a long waistcoat with huge pockets and lappets, and a great white stock that held his chin high in air. This was fastened behind with a silver buckle to match the buckles on his tight knee breeches, and other buckles large and flat on his square-toed shoes; somehow he looked as like a serious book with clasps as a man could look, with an outward completeness that mated with his inner equipment of fixed Arminian opinions.

As for Colonel Hamilton, the host, a strong-looking, bright-colored man in the middle thirties, the softness of a suit of brown, and his own hair well dressed and powdered, did not lessen a certain hardness in his face, a grave determination, and maturity of appearance far beyond the due of his years. Hamilton had easily enough won the place of chief shipping merchant and prince of money-makers in that respectable group, and until these dark days of war almost every venture by land or sea had added to his fortunes. The noble house that he had built was still new enough to be the chief show and glory of a rich provincial neighborhood. With all his power of money-making,—and there were those who counted him a second Sir William Pepperrell,—Hamilton was no easy friend-maker like that great citizen of the District of Maine, nor even like his own beautiful younger sister, the house's mistress. Some strain of good blood, which they had inherited, seemed to have been saved through generations to nourish this one lovely existence, and make her seem like the single flower upon their family tree. They had come from but a meagre childhood to live here in state and luxury beside the river.

The broad green fields of Hamilton's estate climbed a long hill behind the house, hedged in by stately rows of elms and tufted by young orchards; at the western side a strong mountain stream came down its deep channel over noisy falls and rapids to meet the salt tide in the bay below. This broad sea inlet and inland harborage was too well filled in an anxious year with freightless vessels both small and great: heavy seagoing craft and lateen-sailed gundalows for the river traffic; idle enough now, and careened on the mud at half tide in picturesque confusion.

The opposite shore was high, with farmhouses above the fields. There were many persons to be seen coming down toward the water, and when Colonel Hamilton and his guests appeared on the garden terraces, a loud cry went alongshore, and instantly the noise of mallets ceased in the shipyard beyond, where some carpenters were late at work. There was an eager, buzzing crowd growing fast about the boat landing and the wharf and warehouses which the gentlemen at the high-urned gateway looked down upon. The boat was coming up steadily, but in the middle distance it seemed to lag; the long stretch of water was greater than could be measured by the eye. Two West Indian fellows in the crowd fell to scuffling, having trodden upon each other's rights, and the on-lookers, quickly diverted from their first interest, cheered them on, and wedged themselves closer together to see the fun. Old Cæsar, the majestic negro who had attended Hamilton at respectful distance, made it his welcome duty to approach the quarrel with loud rebukes; usually the authority of this great person in matters pertaining to the estate was only second to his master's, but in such a moment of high festival and gladiatorial combat all commands fell upon deaf ears. Major Tilly Haggens burst into a hearty laugh, glad of a chance to break the tiresome formalities of his associates, and being a great admirer of a skillful fight. On any serious occasion the major always seemed a little uneasy, as if restless with unspoken jokes.

In the meantime the boat had taken its shoreward curve, and was now so near that even through the dusk the figures of the oarsmen, and of an officer, sitting alone at the stern in full uniform, could be plainly seen. The next moment the wrestling Tobago men sprang to their feet, forgetting their affront, and ran to the landing-place with the rest.

The new flag of the Congress with its unfamiliar stripes was trailing at the boat's stern; the officer bore himself with dignity, and made his salutations with much politeness. All the gentlemen on the terrace came down together to the water's edge, without haste, but with exact deference and timeliness; the officer rose quickly in the boat, and stepped ashore with ready foot and no undignified loss of balance. He wore the pleased look of a willing guest, and was gayly dressed in a bright new uniform of blue coat and breeches, with red lapels and a red waistcoat trimmed with lace. There was a noisy cheering, and the spectators fell back on either hand and made way for this very elegant company to turn again and go their ways up the river shore.

Captain Paul Jones of the Ranger bowed as a well-practiced sovereign might as he walked along, a little stiffly at first, being often vexed by boat-cramp, as he now explained cheerfully to his host. There was an eager restless look in his clear-cut sailor's face, with quick eyes that seemed not to observe things that were near by, but to look often and hopefully toward the horizon. He was a small man, but already bent in the shoulders from living between decks; his sword was long for his height and touched the ground as he walked, dragging along a gathered handful of fallen poplar leaves with its scabbard tip.

It was growing dark as they went up the long garden; a thin white mist was gathering on the river, and blurred the fields where there were marshy spots or springs. The two brigs at the moorings had strung up their dull oil lanterns to the rigging, where they twinkled like setting stars, and made faint reflections below in the rippling current. The huge elms that stood along the river shore were full of shadows, while above, the large house was growing bright with candlelight, and taking on a cheerful air of invitation. As the master and his friends went up to the wide south door, there stepped out to meet them the lovely figure of a girl, tall and charming, and ready with a gay welcome to chide the captain for his delay. She spoke affectionately to each of the others, though she avoided young Mr. Lord's beseeching eyes. The elder men had hardly time for a second look to reassure themselves of her bright beauty, before she had vanished along the lighted hall. By the time their cocked hats and plainer head gear were safely deposited, old Cæsar with a great flourish of invitation had thrown open the door of the dining parlor.

II

THE PARTING FEAST

"A little nation, but made great by liberty."

The faces gathered about the table were serious and full of character. They wore the look of men who would lay down their lives for the young country whose sons they were, and though provincial enough for the most part, so looked most of the men who sat in Parliament at Westminster, and there was no more patrician head than the old judge's to be seen upon the English bench. They were for no self-furtherance in public matters, but conscious in their hearts of some national ideas that a Greek might have cherished in his clear brain, or any citizen of the great days of Rome. They were men of a single-hearted faith in Liberty that shone bright and unassailable; there were men as good as they in a hundred other towns. It was a simple senate of New England, ready and able to serve her cause in small things and great.

The next moment after the minister had said a proper grace, the old judge had a question to ask.

"Where is Miss Mary Hamilton?" said he. "Shall we not have the pleasure of her company?"

"My sister looks for some young friends later," explained the host, but with a touch of coldness in his voice. "She begs us to join her then in her drawing-room, knowing that we are now likely to have business together and much discussion of public affairs. I bid you all welcome to my table, gentlemen; may we be here to greet Captain Paul Jones on his glorious return, as we speed him now on so high an errand!"

"You have made your house very pleasant to a homeless man, Colonel Hamilton," returned the captain, with great feeling. "And Miss Hamilton is as good a patriot as her generous brother. May Massachusetts and the Province of Maine never lack such sons and daughters! There are many of my men taking their farewell supper on either shore of your river this night. I have received my dispatches, and it is settled that we sail for France to-morrow morning at the turn of tide."

"To-morrow morning!" they exclaimed in chorus. The captain's manner gave the best of news; there was an instant shout of approval and congratulation. His own satisfaction at being finally ordered to sea after many trying delays was understood by every one, since for many months, while the Ranger was on the stocks at Portsmouth, Paul Jones had bitterly lamented the indecisions of a young government, and regretted the slipping away of great opportunities abroad and at home. To say that he had made himself as vexing as a wasp were to say the truth, but he had already proved himself a born leader with a heart on fire with patriotism and deep desire for glory, and there were those present who eagerly recognized his power and were ready to further his best endeavors. Young men had flocked to his side, sailors born and bred on the river shores, and in Portsmouth town, who could serve their country well. Berwick was in the thick of the fight from the very beginning; her company of soldiers had been among the first at Bunker's Hill, and the alarm at Lexington had shaken her very hills at home. Twin sister of Portsmouth in age, and sharer of her worldly conditions, the old ease and wealth of the town were sadly troubled now; there was many a new black gown in the parson's great parish, and many a mother's son lay dead, or suffered in an English prison. Yet the sea still beckoned with white hands, and Paul Jones might have shipped his crew on the river many times over. The ease of teaching England to let the colonies alone was not spoken of with such bold certainty as at first, and some late offenses were believed to be best revenged by such a voyage as the Ranger was about to make.

Captain Paul Jones knew his work; he was full of righteous wrath toward England, and professed a large readiness to accept the offered friendliness of France.

Colonel Jonathan Hamilton could entertain like a prince. The feast was fit for the room in which it was served, and the huge cellar beneath was well stored with casks of wine that had come from France and Spain, or from England while her ports were still home ports for the colonies. Being a Scotsman, the guest of honor was not unmindful of excellent claret, and now set down his fluted silver tumbler after a first deep draught, and paid his host a handsome compliment.

"You live like a Virginia gentleman, sir, here in your Northern home. They little know in Great Britain what stately living is among us. The noble Countess of Selkirk thought that I was come to live among the savages, instead of gratifying my wishes for that calm contemplation and poetic ease which, alas, I have ever been denied."

"They affect to wonder at the existence of American gentlemen," returned the judge. "When my father went to Court in '22, and they hinted the like, he reminded them that since they had sent over some of the best of their own gentlefolk to found the colonies, it would be strange if none but boors and clowns came back."

"In Virginia they consider that they breed the only gentlemen; that is the great pity," said Parson Tompson. "Some of my classmates at Cambridge arrived at college with far too proud a spirit. They were pleased to be amused, at first, because so many of us at the North were destined for the ministry."

"You will remember that Don Quixote speaks of the Church, the Sea, and the Court for his Spanish gentlemen," said Major Tilly Haggens, casting a glance across at the old judge. "We have had the two first to choose from in New England, if we lacked the third." The world was much with the major, and he was nothing if not eager spoken. "People forget to look at the antecedents of our various colonists; 't is the only way to understand them. In these Piscataqua neighborhoods we do not differ so much from those of Virginia; 'tis not the same pious stock as made Connecticut and the settlements of Massachusetts Bay. We are children of the Norman blood in New England and Virginia, at any rate. 'T is the Saxons who try to rule England now; there is the cause of all our troubles. Norman and Saxon have never yet learned to agree."

"You give me a new thought," said the captain.

"For me," explained the major, "I am of fighting and praying Huguenot blood, and here comes in another strain to our nation's making. I might have been a parson myself if there had not been a stray French gallant to my grandfather, who ran away with a saintly Huguenot maiden; his ghost still walks by night and puts the devil into me so that I forget my decent hymns. My family name is Huyghens; 't was a noble house of the Low Countries. Christian Huyghens, author of the Cosmotheoros, was my father's kinsman, and I was christened for the famous General Tilly of stern faith, but the gay Frenchman will ever rule me. 'Tis all settled by our antecedents," and he turned to Captain Paul Jones. "I'm for the flower-de-luce, sir; if I were a younger man I'd sail with you to-morrow! 'T is very hard for us aging men with boys' hearts in us to stay decently at home. I should have been born in France!"

"France is your country's friend, sir," said Paul Jones, bowing across the table. "Let us drink to France, gentlemen!" and the company drank the toast. Old Cæsar bowed with the rest as he stood behind his master's chair, and smacked his lips with pathetic relish of the wine which he had tasted only in imagination. The captain's quick eyes caught sight of him.

"By your leave, Colonel Hamilton!" he exclaimed heartily. "This is a toast that every American should share the pleasure of drinking. I observe that my old friend Cæsar has joined us in spirit," and he turned with a courtly bow and gave a glass to the serving man.

"You have as much at stake as we in this great enterprise," he said gently, in a tone that moved the hearts of all the supper company. "May I drink with you to France, our country's ally?"

A lesser soul might have babbled thanks, but Cæsar, who had been born a Guinea prince, drank in silence, stepped back to his place behind his master, and stood there like a king. His underlings went and came serving the supper; he ruled them like a great commander on the field of battle, and hardly demeaned himself to move again until the board was cleared.

"I seldom see a black face without remembering the worst of my boyish days when I sailed in the Two Friends, slaver," said the captain gravely, but with easy power of continuance. "Our neighbor town of Dumfries was in the tobacco trade, and all their cargoes were unloaded in Carsethorn Bay, close by my father's house. I was easily enough tempted to follow the sea; I was trading in the Betsey at seventeen, and felt myself a man of experience. I have observed too many idle young lads hanging about your Portsmouth wharves who ought to be put to sea under a smart captain. They are ready to cheer or to jeer at strangers, and take no pains to be manly. I began to follow the sea when I was but a child, yet I was always ambitious of command, and ever thinking how I might best study the art of navigation."

"There were few idlers along this river once," said General Goodwin regretfully. "The times grow worse and worse."

"You referred to the slaver, Two Friends," interrupted the minister, who had seen a shadow of disapproval on the faces of two of his parishioners (one being Colonel Hamilton's) at the captain's tone. "May I observe that there has seemed to be some manifestation of a kind Providence in bringing so many heathen souls to the influence of a Christian country?"

The fierce temper of the captain flamed to his face; he looked up at old Cæsar who well remembered the passage from his native land, and saw that black countenance set like an iron mask.

"I must beg your reverence's kind pardon if I contradict you," said Paul Jones, with scornful bitterness.

There was a murmur of protest about the table; the captain's reply was not counted to be in the best of taste. Society resents being disturbed at its pleasures, and the man who had offended was now made conscious of his rudeness. He looked up, however, and saw Miss Hamilton standing near the open doorway that led into the hall. She was gazing at him with no relic of that indifference which had lately distressed his heart, and smiled at him as she colored deeply, and disappeared.

The captain took on a more spirited manner than before, and began to speak of politics, of the late news from Long Island, where a son of old Berwick, General John Sullivan, had taken the place of Lee, and was now next in command to Washington himself. This night Paul Jones seemed to be in no danger of those fierce outbursts of temper with which he was apt to startle his more amiable and prosaic companions. There was some discussion of immediate affairs, and one of the company, Mr. Wentworth, fell upon the inevitable subject of the Tories; a topic sure to rouse much bitterness of feeling. Whatever his own principles, every man present had some tie of friendship or bond of kindred with those who were Loyalists for conscience' sake, and could easily be made ill at ease.

The moment seemed peculiarly unfortunate for such trespass, and when there came an angry lull in the storm of talk, Mr. Lord somewhat anxiously called attention to a pair of great silver candlesticks which graced the feast, and by way of compliment begged to be told their history. It was not unknown that they had been brought from England a few summers before in one of Hamilton's own ships, and that he was not without his fancy for such things as gave his house a look of rich ancestry; a stranger might well have thought himself in a good country house of Queen Anne's time near London. But this placid interlude did not rouse any genuine interest, and old Judge Chadbourne broke another awkward pause and harked back to safer ground in the conversation.

"I shall hereafter make some discrimination against men of color. I have suffered a great trial of the spirit this day," he began seriously. "I ask the kind sympathy of each friend present. I had promised my friend, President Hancock, some of our Berwick elms to plant near his house on Boston Common; he has much admired the fine natural growth of that tree in our good town here, and the beauty it lends to our high ridges of land. I gave directions to my man Ajax, known to some of you as a competent but lazy soul, and as I was leaving home he ran after me, shouting to inquire where he should find the trees. 'Oh, get them anywhere!' said I, impatient at the detention, and full of some difficult matters which were coming up at our term in York. And this morning on my return from court, I missed a well-started row of young elms, which I had selected myself and planted along the outer border of my gardens. Ajax had taken the most accessible, and they had all gone down river by the packet. I shall have a good laugh with Hancock by and by. I remember that he once praised these very trees and professed to covet them."

"'T was the evil eye," suggested Mr. Hill, laughing; but the minister slowly shook his head, contemptuous of such superstitious.

"I saw that one of our neighbor Madam Wallingford's favorite oaks was sadly broken by the recent gale," said Mr. Wentworth unguardedly, and this was sufficient to make a new name fairly leap into the conversation,—that of Mr. Roger Wallingford, the son of a widowed lady of great fortune, whose house stood not far distant, on the other side of the river in Somersworth.

General Goodwin at once dropped his voice regretfully. "I am afraid that we can have no doubt now of the young man's sympathy with our oppressors," said he. "I hear that he has been seen within a week coming out of the Earl of Halifax tavern in Portsmouth, late at night, as if from a secret conference. A friend of mine heard him say openly on the Parade that Mr. Benjamin Thompson of old Rumford had been unfairly driven to seek Royalist protection, and to flee his country, leaving wife and infant child behind him; that 't was all from the base suspicions and hounding of his neighbors, whose worst taunt had ever been that he loved and sought the company of gentlemen. 'I pity him from my heart,' says Wallingford in a loud voice; as if pity could ever belong to so vile a traitor!"

"But I fear that this was true," said Judge Chadbourne, the soundest of patriots, gravely interrupting. "They drove young Thompson away in hot haste when his country was in sorest need of all such naturally chivalrous and able men. He meant no disloyalty until his crisis came, and proved his rash young spirit too weak to meet it. He will be a great man some day, if I read men aright; we shall be proud of him in spite of everything. He had his foolish follies, and the wrong road never leads to the right place, but the taunts of the narrow-minded would have made many an older man fling himself out of reach. 'T is a sad mischance of war. Young Wallingford is a proud fellow, and has his follies too: his kindred in Boston thought themselves bound to the King; they are his elders and have been his guardians, and youth may forbid his seeing the fallacy of their arguments. Our country is above our King in such a time as this, yet I myself was of those who could not lightly throw off the allegiance of a lifetime."

"I have always said that we must have patience with such lads and not try to drive them," said Major Haggens, the least patient of all the gentlemen. Captain Paul Jones drummed on the table with one hand and rattled the links of his sword hilt with the other. The minister looked dark and unconvinced, but the old judge stood first among his parishioners; he did not answer, but threw an imploring glance toward Hamilton at the head of the table.

"We are beginning to lose the very last of our patience now with those who cry that our country is too young and poor to go alone, and urge that we should bear our wrongs and be tied to the skirts of England for fifty years more. What about our poor sailors dying like sheep in the English jails?" said Hamilton harshly. "He that is not for us is against us, and so the people feel."

"The true patriot is the man who risks all for love of country," said the minister, following fast behind.

"They have little to risk, some of the loudest of them," insisted Major Haggens scornfully. "They would not brook the thought of conciliation, but fire and sword and other men's money are their only sinews of war. I mean that some of those dare-devils in Boston have often made matters worse than there was any need," he added, in a calmer tone.

Paul Jones cast a look of contempt upon such a complaining old soldier.

"You must remember that many discomforts accompany a great struggle," he answered. "The lower classes, as some are pleased to call certain citizens of our Republic, must serve Liberty in their own fashion. They are used to homespun shirt-sleeves and not to lace ruffles, but they make good fighters, and their hearts are true. Sometimes their instinct gives them to see farther ahead than we can. I fear indeed that there is trouble brewing for some of your valued neighbors who are not willing to be outspoken. A certain young gentleman has of late shown some humble desires to put himself into an honorable position for safety's sake."

"You mistake us, sir," said the old judge, hastening to speak. "But we are not served in our struggle by such lawlessness of behavior; we are only hindered by it. General George Washington is our proper model, and not those men whose manners and language are not worthy of civilization."

The guest of the evening looked frankly bored, and Major Tilly Haggens came to the rescue. The captain's dark hint had set them all staring at one another.

"Some of our leaders in this struggle make me think of an old Scottish story I got from McIntire in York," said he. "There was an old farmer went to the elders to get his tokens for the Sacrament, and they propounded him his questions. 'What's your view of Adam?' says they: 'what kind of a mon?' 'Well,' says the farmer, 'I think Adam was like Jack Simpson the horse trader. Varra few got anything by him, an' a mony lost.'"

The captain laughed gayly as if with a sense of proprietorship in the joke. "T is old Scotland all over," he acknowledged, and then his face grew stern again.

"Your loud talkers are the gadflies that hurry the slowest oxen," he warned the little audience. "And we have to remember that if those who would rob America of her liberties should still prevail, we all sit here with halters round our necks!" Which caused the spirits of the company to sink so low that again the cheerful major tried to succor it.

"Shall we drink to The Ladies?" he suggested, with fine though unexpected courtesy; and they drank as if it were the first toast of the evening.

"We are in the middle of a great war now, and must do the best we can," said Hamilton, as if he wished to make peace about his table. "Last summer when things were at the darkest, Sam Adams came riding down to Exeter to plead with Mr. Gilman for money and troops on the part of their Rockingham towns. The Treasurer was away, and his wife saw Adams's great anxiety and the tears rolling down his cheeks, and heard him groan aloud as he paced to and fro in the room. 'O my God!' says he, 'and must we give it all up!' When the good lady told me there were tears in her own eyes, and I vow that I was fired as I had never been before,—I have loved the man ever since; I called him a stirrer up of frenzies once, but it fell upon my heart that, after all, it is men like Sam Adams who hold us to our duty."

"I cannot envy Sam Curwen his travels in rural England, or Gray that he moves in the best London society, but Mr. Hancock writes me 'tis thought all our best men have left us," said Judge Chadbourne.

"'T is a very genteel company now at Bristol," said John Lord.

"I hear that the East India Company is in terrible difficulties, and her warehouses in London are crammed to bursting with the tea that we have refused to drink. If they only had sense enough to lift the tax and give us liberty for our own trade, we should soon drink all their troubles dry," said Colonel Hamilton.

"'T is not because we hate England, but because we love her that we are hurt so deep," said Mr. Hill. "When a man's mother is jealous because he prospers, and turns against him, it is worst of all."

"Send your young men to sea!" cried Captain Paul Jones, who had no patience with the resettling of questions already left far behind. "Send me thoroughbred lads like your dainty young Wallingford! You must all understand how little can be done with this poor basket of a Ranger against a well-furnished British man-of-war. My reverend friend here has his heart in the matter. I myself have flung away friends and fortune for my adopted country, and she has been but a stingy young stepmother to me. I go to fight her cause on the shores that gave me birth; I trample some dear recollections under foot, and she haggles with me all summer over a paltry vessel none too smart for a fisherman, and sends me to sea in her with my gallant crew. You all know that the Ranger is crank built, and her timbers not first class,—her thin sails are but coarse hessings, with neither a spare sheet, nor stuff to make it, and there 's not even room aboard for all her guns. I sent four six-pounders ashore out of her this very day so that we can train the rest. 'T is some of your pretty Tories that have picked our knots as fast as we tied them, and some jealous hand chose poor planking for our decks and rotten red-oak knees for the frame. But, thank God, she 's a vessel at last! I would sail for France in a gundalow, so help me Heaven! and once in France I shall have a proper man-of-war."

There was a chorus of approval and applause; the listeners were deeply touched and roused; they all wished to hear something of the captain's plans, but he returned to the silver tumbler of claret, and sat for a moment as if considering; his head was held high, and his eyes flashed with excitement as he looked up at the high cornice of the room. He had borne the name of the Sea Wolf; in that moment of excitement he looked ready to spring upon any foe, but to the disappointment of every one he said no more.

"The country is drained now of ready money," said young Lord despondently; "this war goes on, as it must go on, at great sacrifice. The reserves must come out,—those who make excuse and the only sons, and even men like me, turned off at first for lack of health. We meet the strain sadly in this little town; we have done the best we could on the river, sir, in fitting out your frigate, but you must reflect upon our situation."

The captain could not resist a comprehensive glance at the richly furnished table and stately dining-room of his host, and there was not a man who saw it who did not flush with resentment.

"We are poorly off for stores," he said bitterly, "and nothing takes down the courage of a seaman like poor fare. I found to-day that we had only thirty gallons of spirits for the whole crew." At which melancholy information Major Haggens's kind heart could not forbear a groan.

General Goodwin waved his hand and took his turn to speak with much dignity.

"This is the first time that we have all been guests at this hospitable board in many long weeks," he announced gravely. "There is no doubt about the propriety of republican simplicity, or our readiness to submit to it, though our ancient Berwick traditions have taught us otherwise. But I see reason to agree with our friend and former townsman, Judge Sullivan, who lately answered John Adams for his upbraiding of President Hancock's generous way of doing things. He insists that such open hospitality is to be praised when consistent with the means of the host, and that when the people are anxious and depressed it is important to the public cheerfulness."

"'T is true. James Sullivan is right," said Major Haggens; "we are not at Poverty's back door either. You will still find a glass of decent wine in every gentleman's house in old Barvick and a mug of honest cider by every farmer's fireside. We may lack foreign luxuries, but we can well sustain ourselves. This summer has found many women active in the fields, where our men have dropped the hoe to take their old swords again that were busy in the earlier ways."

"We have quelled the savage, but the wars of civilization are not less to be dreaded," said the good minister.

"War is but war," said Colonel Hamilton. "Let us drink to Peace, gentlemen!" and they all drank heartily; but Paul Jones looked startled; as if the war might really end without having served his own ambitions.

"Nature has made a hero of him," said the judge to his neighbor, as they saw and read the emotion of the captain's look. "Circumstances have now given him the command of men and a great opportunity. We shall see the result."

"Yet 't is a contemptible force of ship and men, to think of striking terror along the strong coasts of England," observed Mr. Hill to the parson, who answered him with sympathy; and the talk broke up and was only between man and man, while the chief thought of every one was upon the venison,—a fine saddle that had come down the week before from the north country about the Saco intervales.

III

A CHARACTER OF HONOR

"Sad was I, even to pain deprest, Importunate and heavy load! The comforter hath found me here Upon this lonely road!"

"Your friend General Sullivan has had his defamers but he goes to prove himself one of our ablest men," said Paul Jones to Hamilton. "I grieve to see that his old father, that lofty spirit and fine wit, is not with us to-night. Sullivan is a soldier born."

"There is something in descent," said Hamilton eagerly. "They come of a line of fighting men famous in the Irish struggles. John Sullivan's grandfather was with Patrick Sarsfield, the great Earl of Lucan, at Limerick, and the master himself, if all tales are true, was much involved in the early plots of the old Pretender. No, sir, he was not out in the '15; he was a student at that time in France, but I dare say ready to lend himself to anything that brought revenge upon England."

"Commend me to your ancient sage the master," said the captain. "I wish we might have had him here to-night. When we last dined here together he talked not only of our unfortunate King James, but of the great Prince of Conti and Louis Quatorze as if he had seen them yesterday. He was close to many great events in France."

"You speak of our old Master Sullivan," said Major Haggens eagerly, edging his chair a little nearer. "Yes, he knew all those great Frenchmen as he knows his Virgil and Tally; we are all his pupils here, old men and young; he is master of a little school on Pine Hill; there is no better scholar and gentleman in New England."

"Or Old England either," added Judge Chadbourne.

"They say that he had four countesses to his grandmothers, and that his grandfathers were lords of Beare and Bantry, and princes of Ireland," said the major. "His father was banished to France by the Stuarts, and died from a duel there, and the master was brought up in one of their great colleges in Paris where his house held a scholarship. He was reared among the best Frenchmen of his time. As for his coming here, there are many old stories; some say 't was being found in some treasonable plot, and some that 't was for the sake of a lady whom his mother would not let him stoop to marry. He vowed that she should never see his face again; all his fortunes depended on his mother, so he fled the country.

"With the lady?" asked the captain, with interest, and pushing along the decanter of Madeira.

"No," said the major, stopping to fill his own glass as if it were a pledge of remembrance. "No, he came to old York a bachelor, to the farm of the McIntires, Royalist exiles in the old Cromwell times, and worked there with his hands until some one asked him if he could write a letter, and he wrote it in seven languages. Then the minister, old Mr. Moody, planted him in our grammar school. There had been great lack of classical teaching in all this region for those who would be college bred, and since that early year he has kept his school for lads and now and then for a bright girl or two like Miss Mary Hamilton, and her mother before her."

"One such man who knows the world and holds that rarest jewel, the teacher's gift, can uplift a whole community," said the captain, with enthusiasm. "I see now the cause of such difference between your own and other early planted towns. Master Sullivan has proved himself a nobler prince and leader than any of his ancestry. But what of the lady? I heard many tales of him before I possessed the pleasure of his acquaintance, and so heard them with indifference."

"He had to wife a pretty child of the ship's company, an orphan whom he befriended, and later married. She was sprightly and of great beauty in her youth, and was dowered with all the energy in practical things that he had been denied," said the judge. "She came of plain peasant stock, but the poor soul has a noble heart. She flouts his idleness at one moment, and bewails their poverty, and then falls on her knees to worship him the next, and is as proud as if she had married the lord of the manor at home. The master lacked any true companionship until he bred it for himself. It has been a solitary life and hermitage for either an Irish adventurer or a French scholar and courtier."

"The master can rarely be tempted now from the little south window where he sits with his few books," said Hamilton. "I lived neighbor to him all my young days. Not long ago he went to visit his son James, and walked out with him to see the village at the falls of the Saco. There was an old woman lately come over from Ireland with her grandchildren; they said she remembered things in Charles the Second's time, and was above a hundred years of age. James Sullivan, the judge, thinking to amuse his father, stopped before the house, and out came the old creature, and fell upon her knees. 'My God! 't is the young Prince of Ardea!' says she. 'Oh, I mind me well of your lady mother, sir; 't was in Derry I was born, but I lived a year in Ardea, and yourself was a pretty boy busy with your courting!' The old man burst into tears. 'Let us go, James,' says he, 'or this will break my heart!' but he stopped and said a few words to her in a whisper, and gave the old body his blessing and all that was in his poor purse. He would listen to her no more. 'We need not speak of youth,' he told her; 'we remember it only too well!' A man told me this who stood by and heard the whole."

"'Twas most affecting; it spurs the imagination," said the captain. "If I had but an hour to spare I should ride to see him once more, even by night. You will carry the master my best respects, some of you.

"One last glass, gentlemen, to our noble cause! We may never sit in pleasant company again," he added, and they all rose in their places and stood about the table.

"Haud heigh, my old auntie used to say to me at home. Aim high's the English of it. She was of the bold clan of the MacDuffs, and 't is my own motto in these anxious days. Good-by, gentlemen all!" said the little captain. "I ask for your kind wishes and your prayers."

They all looked at Hamilton, and then at one another, but nobody took it upon himself to speak, so they shook hands warmly and drank their last toast in silence and with deep feeling. It was time to join the ladies; already there was a sound of music across the hall in a great room which had been cleared for the dancing.

IV

THE FLOWERING OF WHOSE FACE

"Dear love, for nothing less than thee Would I have broke this happy dream, * * * * * Therefore thou wak'dst me wisely; yet My dream thou breakest not, but continuest it."

While the guests went in to supper, Mary Hamilton, safe in the shelter of friendly shadows, went hurrying along the upper hall of the house to her own chamber. The coming moon was already brightening the eastern sky, so that when she opened the door the large room with its white hangings was all dimly lighted from without, and she could see the figure of a girl standing at one of the windows.

"Oh, you are here!" she cried, with sharp anxiety, and then they leaned out together, with their arms about each other's shoulders, looking down at the dark cove and at the height beyond where the tops of tall pines were silvered like a cloud. They could hear the men's voices, as if they were all talking together, in the room below.

Mary looked at her friend's face in the dim light. There were some who counted Miss Elizabeth Wyat as great a beauty as Miss Hamilton.

"Oh, Betsey dear, I can hardly bear to ask, but tell me quick now what you have heard! I must go down to Peggy; she has attempted everything for this last feast, and I promised her to trim the game pie for its proud appearing, and the great plum cake. One of her maids is ill, and she is in such a flurry!"

"'T was our own maids talking," answered Betsey Wyat slowly. "They were on the bleaching-green with their linen this morning, the sun was so hot, and I was near by among the barberry bushes in the garden. Thankful Grant was sobbing, in great distress. She said that her young man had put himself in danger; he was under a vow to come out with the mob from Dover any night now that the signal called them, to attack Madam Wallingford's house and make Mr. Roger declare his principles. They were sure he was a Tory fast enough, and they meant to knock the old nest to pieces; they are bidden to be ready with their tools; their axes, she said, and something for a torch. Thankful begged him to feign illness, but he said he did not dare, and would go with the rest at any rate. She said she fronted him with the remembrance how madam had paid his wages all last summer when he was laid by, though the hurt he got was not done in her service, but in breaking his own colt on a Sunday. Yet nothing changed him; he said he was all for Liberty, and would not play the sneak now."

"Oh, how cruel! when nobody has been so kind and generous as Madam Wallingford, so full of kind thought for the poor!" exclaimed Mary. "And Roger"—

"He would like it better if you thought first of him, not of his mother," said Betsey Wyat reproachfully.

"What can be done? It may be this very night," said Mary, in a voice of despair.

"The only thing left is to declare his principles. Things have gone so far now, they will never give him any peace. Many have come to the belief that he is in close league with our enemies."

"That he has never been!" said Mary hotly.

"He must prove it to the doubting Patriots, then; so my father says."

"But not to a mob of rascals, who will be disappointed if they cannot vex their betters, and ruin an innocent woman's home, and spoil her peace only to show their power. Oh, Betsey, what in the world shall we do? There is no place left for those who will take neither side. Oh, help me to think what we shall do; the mob may be there this very night! There was a strange crowd about the Landing just now, when the captain came. I dare not send any one across the river with such a message but old Cæsar or Peggy, and they are not to be spared from the house. I trust none of the younger people, black or white, when it comes to this."

"But he was safe in Portsmouth to-day; they will watch for his being at home; it will not be to-night, then," said Betsey Wyat hopefully. "I think that he should have spoken long ago, if only to protect his mother."

"Get ready now, dear Betty, and make yourself very fine," said Mary at last. "The people will all be coming for the dance long before supper is done. My brother was angry when I told him I should not sit at the table, but I could not. There is nobody to make it gay afterward with our beaux all gone to the army; but Captain Paul Jones begged hard for some dancing, and all the girls are coming,—the Hills and Rights, and the Lords from Somersworth. I must manage to tell my brother of this danger, but to openly protect Madam Wallingford would be openly taking the wrong side, and who will follow him in such a step?"

"I could not pass the great window on the stairs without looking out in fear that Madam's house would be all ablaze," whispered Betsey Wyat, shuddering. "There have been such dreadful things done against the Tories in Salem and Boston!"

"My heart is stone cold with fear," said Mary Hamilton; "yet if it only does not come to-night, there may be something done."

There was a silence between the friends; they clung to each other; it was not the first time that youth and beauty knew the harsh blows of war. The loud noise of the river falls came beating into the room, echoing back from the high pines across the water.

"We must make us fine, dear, and get ready for the dancing; I have no heart for it now, I am so frightened," said Mary sadly. "But get you ready; we must do the best we can."

"You are the only one who can do anything," said little Betsey Wyat, holding her back a moment from the door. They were both silent again as a great peal of laughter sounded from below. Just then the moon came up, clear of the eastern hill, and flooded all the room.

V

THE CHALLENGE

"Thou source of all my bliss and all my woe."

An hour later there was a soft night wind blowing through the garden trees, flavored with the salt scent of the tide and the fragrance of the upland pastures and pine woods. Mary Hamilton came alone to a great arched window of the drawing-room. The lights were bright, the house looked eager for its gayeties, and there was a steady sound of voices at the supper, but she put them all behind her with impatience. She stood hesitating for a moment, and then sat down on the broad window seat to breathe the pleasant air. Betsey Wyat in the north parlor was softly touching the notes of some old country song on the spinet.

The young mistress of the house leaned her head wearily on her hand as she looked down the garden terraces to the river. She wished the long evening were at an end, but she must somehow manage to go through its perils and further all the difficult gayeties of the hour. She looked back once into the handsome empty room, and turned again toward the quiet garden. Below, on the second terrace, it was dark with shadows; there were some huge plants of box that stood solid and black, while the rosebushes and young peach-trees were but a gray mist of twigs. At the end of the terrace were some thick lilacs with a few leaves still clinging in the mild weather to shelter a man who stood there, watching Mary Hamilton as she watched the shadows and the brightening river.

There was the sharp crying of a violin from the slaves' dwellings over beyond the house. It was plain to any person of experience that the brief time of rest and informality after the evening feast would soon be over, and that the dancing was about to begin. The call of the fiddle seemed to have been heard not only through the house, but in all its neighborhood. There were voices coming down the hill and a rowboat rounding the point with a merry party. From the rooms above, gay voices helped to break the silence, while the last touches were being given to high-dressed heads and gay-colored evening gowns. But Mary Hamilton did not move until she saw a tall figure step out from among the lilacs into the white moonlight and come quickly along the lower terrace and up the steps toward the window where she was sitting. It was Mr. Roger Wallingford.

"I must speak with you," said he, forgetting to speak softly in his eagerness. "I waited for a minute to be sure there was nobody with you; I am in no trim to make one of your gay company to-night. Quick, Mary; I must speak to you alone!"

The girl had started as one does when a face comes suddenly out of the dark. She stood up and pushed away the curtain for a moment and looked behind her, then shrank into a deep alcove at the side, within the arch. She stepped forward next moment, and held the window-sill with one hand as if she feared to let go her hold. The young man bent his head and kissed her tense fingers.

"I cannot talk with you now. You are sure to be found here; I hoped that you were still in Portsmouth. Go,—it is your only safety to go away!" she protested.

"What has happened? Oh, come out to me for a moment, Mary," he answered, speaking quietly enough, but with much insistence in his imploring tone. "I must see you to-night; it is my only chance."

She nodded and warned him back, and tossed aside the curtain, turning again toward the lighted room, where sudden footsteps had startled her.

There were several guests coming in, a little perplexed, to seek their hostess, but the slight figure of Captain Paul Jones in his brilliant uniform was first at hand. The fair head turned toward him not without eagerness, and the watcher outside saw his lady smile and go readily away. It was hard enough to have patience outside in the moonlight night, until the first country dances could reach their weary end. He stood for a moment full in the light that shone from the window, his heart beating within him in heavy strokes, and then, as if there were no need of prudence, went straight along the terrace to the broad grassy court at the house's front. There was a white balustrade along the farther side, at the steep edge of the bank, and he passed the end of it and went a few steps down. The river shone below under the elms, the tide was just at the beginning of its full flood, there was a short hour at best before the ebb. Roger Wallingford folded his arms, and stood waiting with what plain patience he could gather. The shrill music jarred harshly upon his ear.

The dancing went on; there were gay girls enough, but little Betsey Wyat, that dear and happy heart, had only solemn old Jack Hamilton to her partner, and pretty Martha Hill was coquetting with the venerable judge. These were also the works of war, and some of the poor lads who had left their ladies, to fight for the rights of the colonies, would never again tread a measure in the great room at Hamilton's. Perhaps Roger Wallingford himself might not take his place at the dancing any more. He walked to and fro with his eyes ever upon the doorway, and two by two the company came in turn to stand there and to look out upon the broad river and the moon. The fiddles had a trivial sound, and the slow night breeze and the heavy monotone of the falls mocked at them, while from far down the river there came a cry of herons disturbed in their early sleep about the fishing weirs, and the mocking laughter of a loon. Nature seemed to be looking on contemptuously at the silly pleasantries of men. Nature was aware of graver things than fiddles and the dance; it seemed that night as if the time for such childish follies had passed forever from the earth.

There must have been many a moment when Mary Hamilton could have slipped away, and a cold impatience vexed the watcher's heart. At last, looking up toward the bright house, his eyes were held by a light figure that was coming round from the courtyard that lay between the house and its long row of outbuildings. He was quickly up the bank, but the figure had already flitted across the open space a little way beyond.

"Roger!" he heard her call to him. "Where are you?" and he hurried along the bank to meet her.

"Let us go farther down," she said sharply; "they may find us if they come straying out between the dances to see the moon;" and she passed him quickly, running down the bank and out beyond the edge of the elm-trees' shadow to the great rock that broke the curving shore. Here she stood and faced him, against the wide background of the river; her dress glimmered strangely white, and he could see the bright paste buckle in one of her dancing-shoes as the moonlight touched her. He came a step nearer, perplexed by such silence and unwonted coldness, but waited for her to speak, though he had begged this moment for his own errand.

"What do you want, Roger?" she asked impatiently; but the young man could not see that she was pressing both hands against her heart. She was out of breath and excited as she never had been before, but she stood there insistent as he, and held herself remote in dignity from their every-day ease and life-long habit of companionship.

"Oh, Mary!" said young Roger, his voice breaking with the uncertainty of his sorrow, "have you no kind word for me? I have had a terrible day in Portsmouth, and I came to tell you;" but still she did not speak, and he hung his head.

"Forgive me, dear," he said, "I do not understand you; but whatever it is, forgive me, so we may be friends again."

"I forgive you," said the girl. "How is it with your own conscience; can you find it so easy to forgive yourself?"

"I am ashamed of nothing," said Wallingford, and he lifted his handsome head proudly and gazed at her in wonder. "But tell me my fault, and I shall do my best to mend. Perhaps a man in such love and trouble as I"—

"You shall not speak to me of love," said Mary Hamilton, drawing back; then she came nearer with a reckless step, as if to show him how little she thought of his presence. "You are bringing sorrow and danger to those who should count upon your manliness. In another hour your mother's house may be in flames. Do not speak to me of your poor scruples any more; and as for love"—

"But it is all I have to say!" pleaded the young man. "It is all my life and thought! I do not know what you mean by these wild tales of danger. I am not going to be driven away from my rights; I must stand my own ground."

"Give me some proof that you are your country's friend and not her foe. I am tired of the old arguments! I am the last to have you cry upon patriotism because you are afraid. I cannot tell you all I know, but, indeed, there is danger; I beg you to declare yourself now; this very night! Oh, Roger, it is the only way!" and Mary could speak no more. She was trembling with fright and passion; something shook her so that she could hardly give sound to her voice; all her usual steadiness was gone.

"My love has come to be the whole of life," said Roger Wallingford slowly. "I am here to show you how much I love you, though you think that I have been putting you to shame. All day I have been closeted with Mr. Langdon and his officers in Portsmouth. I have told them the truth, that my heart and my principles were all against this war, and I would not be driven by any man living; but I have come to see that since there is a war and a division my place is with my countrymen. Listen, dear! I shall take your challenge since you throw it down," and his face grew hard and pale. "I am going to sail on board the Ranger, and she sails to-morrow. There was a commission still in Mr. Langdon's hands, and he gave it me, though your noble captain took it upon himself to object. I have been ready to give it up at every step when I was alone again, riding home from Portsmouth; I could not beg any man's permission, and we parted in a heat. Now I go to say farewell to my poor mother, and I fear 't will break her heart. I can even make my peace with the commander, if it is your pleasure. Will this prove to you that I am a true American? I came to tell you this."

"To-morrow, to sail on board the Ranger," she repeated under her breath. She gave a strange sigh of relief, and looked up at the lighted house as if she were dreaming. Then a thought came over her and turned her sick with dread. If Paul Jones should refuse; if he should say that he dared not risk the presence of a man who was believed to be so close to the Tory plots! The very necessities of danger must hold her resolute while she shrank, womanlike, from the harsh immediateness of decision. For if Paul Jones should refuse this officer, and being in power should turn him back at the very last, there lay ready the awful opportunity of the mob, and Roger Wallingford was a ruined man and an exile from that time.

"You shall not give one thought to that adventurer!" cried the angry lover, whose quick instinct knew where Mary's thoughts had gone. "He has boldness enough, but only for his own advance. He makes light jokes of those"—

"Stop; I must hear no more!" said the young queen coldly. "It would ill befit you now. Farewell for the present; I go to speak with the captain. I have duties to my guests;" but the tears shone in her eyes. She was for flitting past him like a fawn, as they climbed the high bank together. The pebbles rattled down under their hurrying feet, and the dry elm twigs snapped as if with fire, but Wallingford kept close at her side.

"Oh, my darling!" he said, and his changed voice easily enough touched her heart and made her stand still. "Do not forgive me, then, until you have better reason to trust me. Only do not say that I must never speak. We may be together now for the last time; I may never see you again."

"If you can bear you like a man, if you can take a man's brave part"—and again her voice fell silent.

"Then I may come?"

"Then you may come, Mr. Wallingford," she answered proudly.

For one moment his heart was warm with the happiness of hope,—she herself stood irresolute,—but they heard heavy footsteps, and she was gone from his vision like a flash of light.

Then the pain and seizure of his fate were upon him, the break with his old life and all its conditions. Love would now walk ever by his side, though Mary Hamilton herself had gone. She had not even given him her dear hand at parting.

VI

THE CAPTAIN SPEAKS

"The Hous of Fame to descrive,— Thou shalt see me go as blyve Unto the next laure I see And kisse it, for it is thy tree."

At this moment the drawing-room was lively enough, whatever anxieties might have been known under the elms, and two deep-arched windows on either side of the great fireplace were filled with ladies who looked on at the dancing. A fine group of elderly gentlewomen, dressed in the highest French fashion of five years back, sat together, with nodding turbans and swaying fans, and faced the doorway as Miss Hamilton came in. They had begun to comment upon her absence, but something could be forgiven a young hostess who might be having a thoughtful eye to her trays of refreshment.

There was still an anxious look on many faces, as if this show of finery and gayety were out of keeping with the country's sad distresses. Though Hamilton, like Nero, fiddled while Rome was burning, everybody had come to look on: the surrender of Burgoyne had put new heart into everybody, and the evening was a pleasant relief to the dark apprehension and cheerless economies of many lives. Most persons were rich in anticipation of the success of Paul Jones's enterprise; as if he were a sort of lucky lottery in which every one was sure of a handsome prize. The winning of large prize money in the capture of richly laden British vessels had already been a very heartening incident of this most difficult and dreary time of war.

When Mary Hamilton came in, there happened to be a pause between the dances, and an instant murmur of delight ran from chair to chair of those who were seated about the room. She had looked pale and downcast in the early evening, but was rosy-cheeked now, and there was a new light in her eyes; it seemed as if the charm of her beauty had never shone so bright. She crossed the open space of the floor, unconscious as a child, and Captain Paul Jones stepped out to meet her. The pink brocaded flowers of her shimmering satin gown bloomed the better for the evening air, and a fall of splendid lace of a light, frosty pattern only half hid her white throat. It was her brother's pleasure to command such marvels of French gowns, and to send orders by his captains for Mary's adorning; she was part of the splendor of his house, moreover, and his heart was filled with perfect satisfaction as she went down the room.

The simpler figures of the first dances were over, the country dances and reels, and now Mr. Lord and Miss Betsey Wyat took their places with Mary and the captain, and made their courtesies at the beginning of an old French dance of great elegance which was known to be the favorite of the old Judge. They stood before him in a pretty row, like courtiers who would offer pleasure to their rightful king, and made their obeisance, all living color and fine clothes and affectionate intent. The captain was scarcely so tall as his partner, but gallant enough in his uniform, and took his steps with beautiful grace and the least fling of carelessness, while Mr. John Lord moved with the precision of a French abbé, always responsible for outward decorum whatever might be the fire within his heart.

The captain was taking his fill of pleasure for once; he had danced many a time with Mary Hamilton, that spring, in the great houses of Portsmouth and York, and still oftener here in Berwick, where he had never felt his hostess so charming or so approachable as to-night. At last, when the music stopped, they left the room together, while their companions were still blushing at so much applause, and went out through the crowded hall. There was a cry of admiration as they passed among the guests; they were carried on the swift current of this evident delight and their own excitement. It is easy for any girl to make a hero of a gallant sailor,—for any girl who is wholly a patriot at heart to do honor to the cordial ally of her country.

They walked together out of the south door, where Mary had so lately entered alone, and went across the broad terrace to the balustrade which overhung the steep bank of the river. Mary Hamilton was most exquisite to see in the moonlight; her dress softened and shimmered the more, and her eyes had a brightness now that was lost in the lighted room. The captain was always a man of impulse; in one moment more he could have dared to kiss the face that shone, eager, warm, and blooming like a flower, close to his own. He was not unskilled in love-making, but he had never been so fettered by the spell of love itself or the royalty of beauty as he was that night.

"This air is very sweet after an arduous day," said he, looking up for an instant through the elm boughs to the moon.

"You must be much fatigued, Sir Captain," said Mary kindly; she looked at the moon longer than he, but looked at him at last.

"'No, noble mistress, 't is fresh morning with me,'" he answered gently, and added the rest of the lovely words under his breath, as if he said them only to himself.

"I think that you will never have any mistress save Glory," said Mary. She knew The Tempest, too; but this brave little man, this world-circling sailor, what Calibans and Ariels might he not have known!

"This is my last night on land," he answered, with affecting directness. "Will you bid me go my lonely way unblest, or shall I dare to say what is in my heart now, my dear and noble mistress?"

Mary looked at him with most straightforward earnestness as he spoke; there was so great a force in her shining eyes that this time it was his own that turned away.

"Will you do a great kindness, if I ask you now?" she begged him; and he promised with his hand upon his heart.

"You sail to-morrow?"

"Yes, and your image shall go always with me, and smile at me in a thousand gloomy hours. I am often a sad and lonely man upon the sea."

"There has been talk of Mr. Wallingford's taking the last commission."

"How have you learned what only a few trusted men were told?" the captain demanded fiercely, forgetting his play of lover in a jealous guarding of high affairs.

"I know, and by no man's wrongful betraying. I give you my deepest proof of friendship now," said the eager girl. "I ask now if you will befriend our neighbor, my dear friend and playmate in childhood. He has been much misjudged and has come to stand in danger, with his dear mother whom I love almost as my own."

"Not your young rascal of a Tory!" the captain interrupted, in a towering rage. "I know him to be a rascal and a spy, madam!"

"A loyal gentleman I believe him in my heart," said Mary proudly, but she took a step backward as they faced each other,—"a loyal gentleman who will serve our cause with entire devotion since he gives his word. His hesitations have been the fault of his advisers, old men who cannot but hold to early prejudice and narrow views. With you at sea, his own right instincts must be confirmed; he will serve his country well. I come to you to beg from my very heart that you will stand his friend."

She stood waiting for assurance: there was a lovely smile on her face; it would be like refusing some easy benefaction to a child. Mary Hamilton knew her country's troubles, great and small; she had listened to the most serious plans and secret conferences at her brother's side: but the captain forgot all this, and only hated to crush so innocent a childish hope. He also moved a step backward, with an impatient gesture; she did not know what she was asking; then, still looking at her, he drew nearer than before. The captain was a man of quick decisions. He put his arm about her as if she were a child indeed. She shrank from this, but stood still and waited for him to speak.

"My dear," he said, speaking eagerly, so that she must listen and would not draw away, "my dear, you ask an almost impossible thing; you should see that a suspected man were better left ashore, on such a voyage as this. Do you not discern that he may even turn my crew against me? He has been the young squire and benefactor of a good third of my men, and can you not see that I must always be on my guard?"

"But we must not distrust his word," begged Mary again, a little shaken.

"I have followed the sea, boy and man, since I was twelve years old. I have been a seafarer all my days," said Paul Jones. "I know all the sad experiences of human nature that a man may learn. I trust no man in war and danger and these days of self-advancement, so far that I am not always on the alert against treachery. Too many have failed me whom I counted my sure friends. I am going out now, only half trusted here at home, to the coasts where treason can hurt me most. I myself am still a suspected and envied man by those beneath me. I am given only this poor ship, after many generous promises. I fear a curse goes with it."

"You shall have our hopes and prayers," faltered Mary, with a quivering lip. The bitterness of his speech moved her deepest feelings; she was overstrung, and she was but a girl, and they stood in the moonlight together.

"Do not ask me again what I must only deny you, even in this happy moment of nearness," he said sadly, and watched her face fall and all the light go out of it. He knew all that she knew, and even more, of Wallingford's dangerous position, and pitied her for a single moment with all the pity that belonged to his heart. A lonely man, solitary in his very nature, and always foreboding with a kind of hopelessness the sorrows that must fall to him by reason of an unkindness that his nature stirred in the hearts of his fellows, his very soul had lain bare to her trusting look.

He stood there for one moment self-arraigned before Mary Hamilton, and knowing that what he lacked was love. He was the captain of the Ranger; it was true that Glory was his mistress. In that moment the heavens had opened, and his own hand had shut the gates.

The smile came back to Mary's face, so strange a flash of tenderness had brightened his own. When that unforgettable light went out, she did not know that all the jealousy of a lonely heart began to burn within him.

"I have changed my mind. I will take your friend," he said suddenly, with a new tone of authority and coldness. "And I shall endeavor to remember that he is your friend. May I win your faith and patience, 't is a hard ploy."

Then Mary, of her own accord, put her hand into the captain's and he bent and kissed it.

"I shall watch a star in the sky for you every night," she told him, "and say my prayers for the Ranger till you come sailing home."

"God grant I may tread the deck of another and a better ship," said the captain hastily. Now he was himself again, and again they both heard the music in the house.

"Will you keep this ring for me, and give me yours?" he asked. "'T will be but a talisman to keep me to my best. I am humble, and I ask no more."

"No," said the girl, whose awakened feeling assured her of his own. She was light-headed with happiness; she could have thrown herself into the arms of such a hero,—of a man so noble, who had done a hard and unwelcome thing for her poor asking. She had failed to do him rightful honor until now, and this beautiful kindness was his revenge. "No," she entreated him, "not your own ring; you have done too much for me; but if you wish it, I shall give you mine. 'T is but a poor ring when you have done so great a kindness."

She gave it as a child might give away a treasure; not as a woman gives, who loves and gives a ring for token. The captain sighed; being no victor after all, his face grew sombre. He must try what a great conqueror might do when he came back next year with Glory all his own; and yet again he lingered to plead with her once more.

"Dear Mary," he said, as he lifted her hand again, "you will not forget me? I shall be far from this to-morrow night, and you will remember that a wanderer like me must sometimes be cruel to his own heart, and cold to the one woman he truly loves."

Something stirred now in Mary Hamilton's breast that had always slept before, and, frightened and disturbed, she drew her hand away. She was like a snared bird that he could have pinched to death a moment before: now a fury of disappointment possessed him, for she was as far away as if she had flown into the open sky beyond his reach.

"Glory is your mistress; it is Glory whom you must win," she whispered, thinking to comfort him.

"When I come back," he said sadly, "if I come back, I hope that you will have a welcome for me." He spoke formally now, and there was a haggard look upon his face. There had come into his heart a strange longing to forget ambition. The thought of his past had strangely afflicted him in that clear moment of life and vision; but the light faded, the dark current of his life flowed on, and there was no reflection upon it of Mary Hamilton's sweet eyes. "If I carry that cursed young Tory away to sea," he said to himself, "I shall know where he is; not here, at any rate, to have this angel for his asking!"

They were on their way to the house again.

"Alas," said Paul Jones once more, with a sad bitterness in his voice, "a home like this can never be for me: the Fates are my enemies; let us hope 't is for the happiness of others that they lure me on!"

Mary cast a piteous, appealing glance at this lonely hero. He was no more the Sea Wolf or the chief among pleasure-makers ashore, but an unloved, unloving man, conscious of heavy burdens and vexed by his very dreams. At least he could remember this last kindness and her grateful heart.

Colonel Hamilton was standing in the wide hall with a group of friends about him. Old Cæsar and his underservants were busy with some heavy-laden silver trays. The captain approached his host with outstretched hands, to speak his farewells.

"I must be off, gentlemen. I must take my boat," said he, in a manly tone that was heard and repeated along the rooms. It brought many of the company to their feet and to surround him, with a new sense of his high commission and authority. "I ask again for your kind wishes, Colonel Hamilton, and yours, Mr. Justice, and for your blessing on my voyage, reverend sir;" and saluting those of the elder ladies who had been most kind, and kissing his hand to some younger friends and partners of the dance, he turned to go. Then, with his fine laced hat in hand, the captain waved for silence and hushed the friendly voices that would speak a last word of confidence in his high success.

"These friends of his and mine who are assembled here should know that your neighbor, Mr. Wallingford, sails with me in the morning. I count my crew well, now, from your noble river! Farewell, dear ladies; farewell, my good friends and gentlemen."

There was a sudden shout in the hushed house, and a loud murmur of talk among the guests, and Hamilton himself stepped forward and began to speak excitedly; but the captain stayed for neither question nor answer, and they saw him go away hurriedly, bowing stiffly to either hand on his way toward the door. Mary had been standing there, with a proud smile and gentle dignity in her look of attendance, since they had come in together, and he stopped one moment more to take her hand with a low and formal bow, to lift it to his lips, and give one quick regretful look at her happy face. Then Hamilton and some of the younger men followed him down through the gardens to the boat landing. The fleet tide of the river was setting seaward; the captain's boat swept quickly out from shore, and the oars flashed away in the moonlight. There were ladies on the terrace, and on the broad lookout of the housetop within the high railing; there were rounds upon rounds of cheers from the men who stood on the shore, black and white together. The captain turned once when he was well out into the river bay and waved his hand. It was as if the spectators were standing on the edge of a great future, to bid a hero hail and farewell.

The whole countryside was awake and busy in the moonlight. So late at night as this there were lights still shining in one low farmhouse after another, as the captain went away. The large new boat of the Ranger was rowed by man-of-war's men in trim rig, who were leaving their homes on the river shores for perhaps the last time; a second boat was to join them at Stiles's Cove, heaped with sea chests and sailors' bags. The great stream lay shining and still under the moon, a glorious track of light lay ready to lead them on, and the dark pines stood high on the eastern shore to watch them pass. The little captain, wrapped in his boat cloak, sat thoughtful and gloomy at the stern. The gold lace glittered on his hat, and the new flag trailed aft. This was the first reach of a voyage that would go down in history. He was not familiar with many of his men, but in this hour he saw their young faces before him, and remembered his own going from home. The Scottish bay of Carsethom, the laird's house at Arbigland, the far heights of the Cumberland coast, rose again to the vision of a hopeful young adventurer to Virginia and the southern seas.