автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу An Epitome of the History of Medicine

AN EPITOME OF THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE

By Roswell Park, A.M., M.D.

Professor of Surgery in the Medical Department of the University of Buffalo, etc.

Based Upon A Course Of Lectures Delivered In The University Of Buffalo.

Illustrated with Portraits and Other Engravings.

1897,

The F. A. Davis Company. [Registered At Stationers' Hall. London, Eng.]

"Destiny Reserves for us Repose Enough."—Fernel.

Original

Original

TO MY COLLEAGUES

IN THE

MEDICAL FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF BUFFALO,

Who Authorized and Encouraged this First Attempt in the Medical Schools of this Country to Give Systematic Instruction in the History or the Science which they Teach,

THIS BOOK

Is Dedicated.

PREFACE.

The history of medicine has been sadly neglected in our medical schools. The valuable and fruitful lessons which it tells of what not to do have been completely disregarded, and in consequence the same gross errors have over and over been repeated. The following pages represent an effort to bring the most important facts and events comprised within such history into the compass of a medical curriculum, and, at the same time, to rehearse them in such manner that the book may be useful and acceptable to the interested layman.,—i.e., to popularize the subject. This effort first took form in a series of lectures given in the Medical Department of the University of Buffalo. The subject-matter of these lectures has been rearranged, enlarged, and edited, in order to make it more presentable for easy reading and reference. I have also tried, so far as I could in such brief space, to indicate the relationship which has ever existed between medicine, philosophy, natural science, theology, and even belles-lettres. Particularly is the history of medicine inseparable from a consideration of the various notions and beliefs that have at times shaken the very foundation of Christendom and the Church, and for reasons which appear throughout the book.

The history of medicine is really a history of human error and of human discovery. During the past two thousand years it is hard to say which has prevailed. Notwithstanding, had it not been for the latter the total of the former would have been vastly greater. A large part of my effort has been devoted to considering the causes which conspired to prevent the more rapid development of our art. If among these the frowning or forbidding attitude of the Church figures most prominently, it must not be regarded as any expression of a quarrel with the Church of to-day. But let any one interested read President White's History of the Warfare of Science with Theology, the best presentation of the subject, and he can take no issue with my statements.

Reverence for the true, the beautiful, and the good has characterized physicians in all times and climes. But little of the true, the beautiful, or the good crept into the transactions of the Church for many centuries, and we suffer, to-day, more from its interference in time past than from all other causes combined. The same may be said of theology, which is as separate from religion as darkness from light. Only when students of science emancipated themselves from the prejudices and superstitions of the theologians did medicine make more than barely perceptible progress.

In this connection I would like to quote a paragraph from an article by King, in the Nineteenth Century for 1893: "The difficulties under which medical science labored may be estimated from the fact that dissection was forbidden by the clergy of the Middle Ages on the ground that it was impious to mutilate a form made in the image of God. We do not find this pious objection interfering with such mutilation when effected by means of the rack and wheel and such other clerical, rather than medical, instruments."

Written history is, to a certain extent at least, plagiarism; and I make no apology for having borrowed my facts from whatever source could best furnish them, but wish cheerfully and publicly to acknowledge my indebtedness to the works mentioned below, those especially of Renouard, Baas, and Sprengel, and to various biographical dictionaries. I have not even scrupled to take bodily sentences or expressions from these authorities, but have tried to so indicate them when I could.

The writer takes pleasure in acknowledging here the obligations which both he and the publishers feel to Dr. Joseph H. Hunt, of Brooklyn, N. Y., from whose extensive and valuable collection have been furnished the originals for most of the portraits in the following pages, and to Dr. F. P. Henry, Honorary Librarian of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, through whose courtesy was obtained the privilege of reproducing the illustrations of instruments and operations from some of the rare old works in the college library. The kind co-operation of these gentlemen has given a distinct and added value to the contents of this little work.

LIST OF PRINCIPAL WORKS CONSULTED.

Baas, Outlines of the History of Medicine. Translated by Henderson. New York, 1889.

Berdoe, Origin and Growth of the Heeding Art. London, 1893.

Bouchut, Histoire de la Médecine. Paris, 1873.

Dezeimeris, Lettres sur VHistoire de la Médecine. Paris, 1838.

Dietionnaire Historique de la Médecine. Paris, 1828.

Haeser, Geschiehte der Medicin. Jena, 1853.

Hirsch, Biographisehes Lexikon des Hervorragendeu der Aerzte aller Zeiten und Vülker. Wien und Leipzig, 1884.

Portal, Histoire de VAnatomie et de la Chirurgie. Paris, 1770.

South, Memorials of the Craft of Surgery in England. London, 1886.

Sprexgel, Geschicute der Chirurgie. Halle, 1819.

CONTENTS

PREFACE.

LIST OF PRINCIPAL WORKS CONSULTED.

CONTENTS.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

AN EPITOME OF THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE.

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

CHAPTER IX.

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI.

CHAPTER XII.

CHAPTER XIII.

CHAPTER XIV.

INDEX.

CONTENTS.

CHAP I.

Medicine Among the Hebrews, the Egyptians, the Orientals, the Chinese,

and the Early Greeks.—The Asclepiadæ.—Further Arrangement into Periods

(Renouard's Classification). The Age of Foundation.—The Primitive;

Sacred, or Mystic; and Philosophic Periods.—Systems in

Vogue: Dogmatism, Methodism, Empiricism,

Eclecticism.—Hippocrates...................................... ...1-29

CHAP II.

AGE OF Foundation (continued).—Anatomic Period: Influence of the

Alexandrian Library. Herophilus and Erasistratus. Aretæus. Cel-sus.

Galen.—Empiricism: Asclepiades.—Methodism: Theinison.—Eclecticism.

Age of Transition.—Greek Period: Oribasins. Ætius. Alexander of

Tralles. Paulus Ægineta............ ...30-56

CHAP III.

Age of Transition (continued).—Arabic Period: Alkindus. Mesue.

Rhazes. Haly-Abbas. Avicenna. Albucassis. Avenzoar. Averroës.

Maimonides.—School of Salernum: Constantinus Africanus. Roger

of Salerno. Roland of Parma. The Four Masters. John of

Procida................................................. ...57-85

CHAP IV

Age of Transition ( concluded).—The School of Montpellier: Raimond

Lulli. John of Gaddesden. Arnold of Villanova. Establishment of Various

Universities. Gerard of Cremona. William of Salicet. Lanfranc. Mondino.

Guy de Chauliac. Age of Renovation.—Erudite Period, including the

Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Thomas Linacre. Sylvius. Vesalius.

Columbus. Eustaclius. Fallopius. Fabricius ab Aquapendente. Fabricius

Hildanus.. ...8686-113

CHAP V.

Age of Renovation (continued).—Erudite Period (continued): Beni-vieni.

Jean Fern el. Porta. Severino. Incorporation of Brother-hood of St. Come

into the University of Paris. Ambroise Paré. Guillemeau. Influence

of the Occult Sciences: Agrippa. Jerome Cardan. Paracelsus. Botal.

Joubert...................... ...114-147

CHAP VI.

Age of Renovation (continued).—Stndent-life During the Fifteenth

and Sixteenth Centuries. Ceremonials Previous to Dissection.—Reform

Period: The Seventeenth, Eighteenth, and Nineteenth Centuries. Modern

Realism in Medicine and Science. Introduction of the Cell-doctrine.

Discovery of the Circulation. William Harvey. Malpighi. Leuwenhoek.

Correct-Doctrine of Respiration. Discovery of the Lymphatic Circulation.

The Nervous System. Discovery of Cinchona. Development in Obstetric

Art, in Medical Jurisprudence, and in Oral Clinical Teaching. Van

Helmont.—The Iatrochemical System: Le Bôe. Thomas Willis......148-170

CHAP VII.

Age of Renovation (continued).—latromechanical School: Santoro.

Borelli. Sydenham. Sir Thomas Browne.—Surgery: Denis. F. Collot.

Dionis. Baulot (Frère Jacques). Scultetus. Rau. Wiseman. Cowper. Sir C.

Wren the Discoverer of Hypodermatic Medication. Anatomical Discoveries.

General Condition of the Profession During the Seventeenth Century.

The Eighteenth Century. Boerliaave. Gaub.—Animism:

Stahl.—Jlechanico-dynamic System: Hoffmann. Cullen.—Old Vienna

School: Van Swieten. De Haën.—Vitalism: Bordeu. Erasmus Darwin

..................171-202

CHAP VIII.

Age of Renovation (continued).—Animal Magnetism: Mesmer. Braid.

—Brunonianism: John Brown.—Realism: Pinel. Bichat. Avenbrugger.

Werlliof. Frank.—Surgery: Petit. Desault. Scarpa. Gimbernat. Heister.

Von Siebold. Richter. Cheselden. Monro (1st). Pott. John Hunter. B.

Bell, J. Bell, C. Bell. Smellie. Denman.—Revival of Experimental Study:

Haller. Winslow. Portal. Yieq d'Azvr. Morgagni.—Inoculation against

Smallpox: Lady Montagu. Edward Jenner.............................

...203-221

CHAP IX.

Age of Renovation (continued).—The Eighteenth Century; General

Considerations. Foundation of Learned Societies, etc. The Royal College

of Surgeons; the Josephinum.—The Nineteenth Century Realistie Reaction

Against Previous Idealism. Influence of Comte, of Claude Bernard,

and of Charles Darwin. Influence Exerted by Other Sciences.—Theory

of Excitement: Roeschlaub.—Stimolo and Contrastimolo:

Kasori.—Homoeopathy: Halineiaim.—Isopatly, Electrohomoeopathy

of Mattei.—Cranioscopy, or Phrenology: Gall and Spurzlieim.—The

Physiological Theory: Broussais.—Paris Pathological School:

Cruveillier. Andral. Louis. Magendie. Trousseau. Claude

Bernard.—British Medicine: Bell and Hall. Travel's.—Germany, School

of Natural Philosophy: Johannes Müller.—School of Natural

History: Schonlein.—New Vienna School: Rokitansky.

Skoda.................................... ...230-252

CHAP X.

Age of Transition (concluded).—New Vienna School (concluded): von

Hebra. Czermak and Türck. Juger. Arlt. Gruber. Politzer.—German

School of Physiological Medicine: Roser.—School of Rational

Medicine: Henle.—Pseudoparacelsism: Rademaeher.—Hydrotherapeutics:

Priessnitz.—Modern Vitalism: Virchow.—Seminalism: Bouchut.—Parasitism

and the Germ-theory: Davaine. Pasteur. Chauveau. Klebs. F. J.

Cohn. Koch. Lister.—Advances in Physical Diagnosis: Laënnec.

Piorry.—Surgery: Delpecli. Stro-meyer. Sims. Bozeman. McDowell. Boyer.

Larrey. Dupuytren. Cloquet. Civiale. Vidal. Velpeau. Malgaigne.

Nélaton. Sir Astley Cooper. Brodie. Guthrie. Syme. Simpson. Langenbeck.

Billroth.................................................. ...253-275

CHAP XI.

History of Medicine in America.—The Colonial Physicians. Medical Study

under Preceptors. Inoculation against Small-pox. Military Surgery During

the Revolutionary War. Earliest Medical Teaching and Teachers in this

Country. The First Medical Schools. Benjamin Rush. The First Medical

Journals. Brief List of the Best-Known American Physicians and

Surgeons.... ...276-299

CHAP XII.

The History of Anæsthesia.—Anæsthesia and Analgesia. Drugs Possessing

Narcotic Properties in use since Prehistoric Times. Mandragora; Hemp;

Hasheesh. Sulphuric Ether and the Men Concerned in its Introduction as

an Anæsthetic—Long, Jackson, Wells, and Morton. Morton's First Public

Demonstration of the Value of Ether. Morton Entitled to the Credit of

its Introduction. Chloroform and Sir Janies Simpson. Cocaine and Karl

Koller.............................................. ...300-315

CHAP XIII.

The History of Antisepsis.—Sepsis, Asepsis, and Antisepsis. The

Germ-theory of Disease. Gay-Lussac's Researches. Schwann. Tyndall.

Pasteur. Davaine. Lord Lister and his Epoch-making Revolution in

Surgical Methods. Modifications of his Earlier Technique without Change

in Underlying Principles, which Still Remain Unshaken. Changes Effected

in Consequence. Comparison of Old and Modern Statistics...........

...316-329

CHAP XIV.

Ax Epitome of the History of Dentistry.—Rude Dentistry of Prehistoric

Times. Early Instruments for Extraction Made of Lead. Dentistry on the

Same Low Plane as Medicine During the First. Half of the Christian Era.

Dentistry Taught at the School of Salernum. Progress of the Art on the

Continent. Prosthesis and Substitutes for Human Teeth. Introduction of

Porcelain for Artificial Teeth; of Metal and of Vulcanized Rubber for

Plates; of Plaster for Impressions. From being a Trade, Dentistry is now

a Profession, in which Americans lead the World. Statistics... ...330-341

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

1. Æsculapius,...................................007

2. Offering to Æsculapius,.......................009

3. Hippocrates,..................................019

4. Aulus Cornelius Celsus,.......................035

5. The Conversion of Galen,......................037

6. Averroës,.....................................064

7. Andreas Vesalius,.............................105

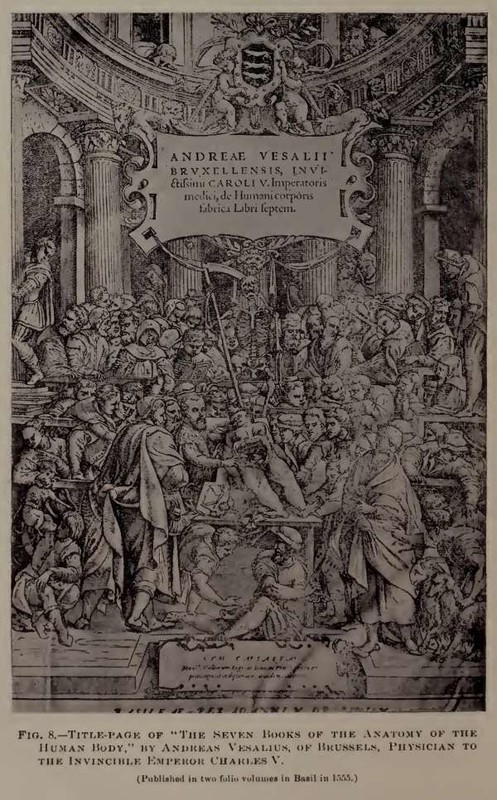

8. Title-page, Seven Books of the Anatomy,.......106

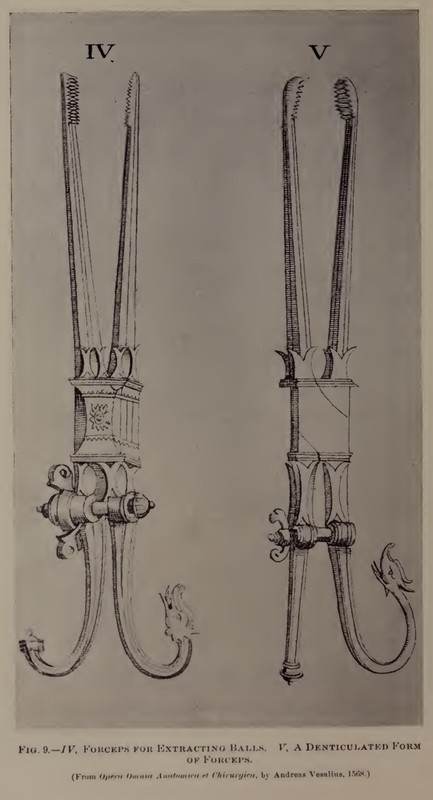

9. IV, Forceps for Extracting Balls..............108

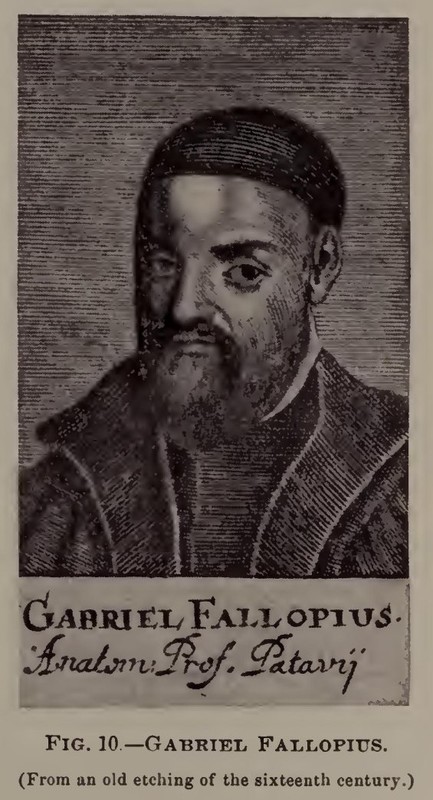

10. Gabriel Fallopius,...........................109

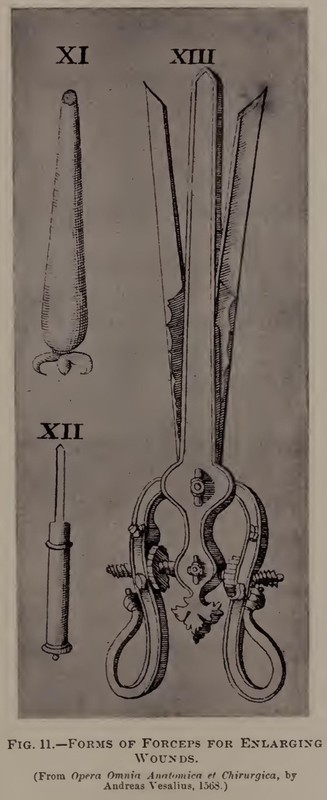

11. Forms of Forceps for Enlarging Wounds,.......111

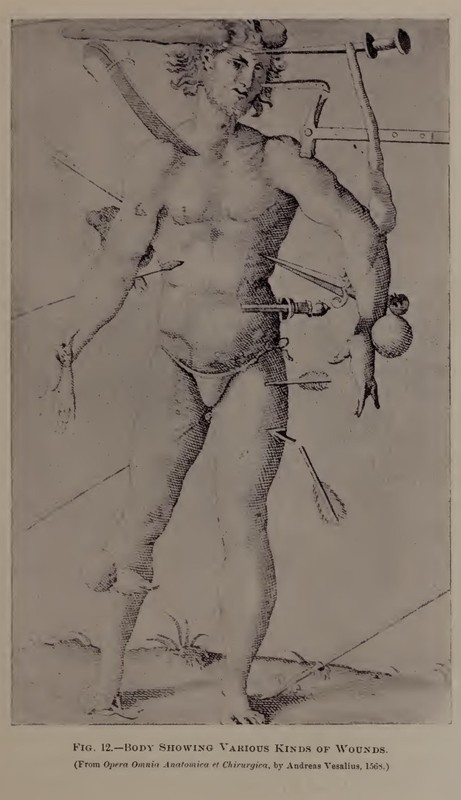

12. Body Showing Various Kinds of Wounds,........117

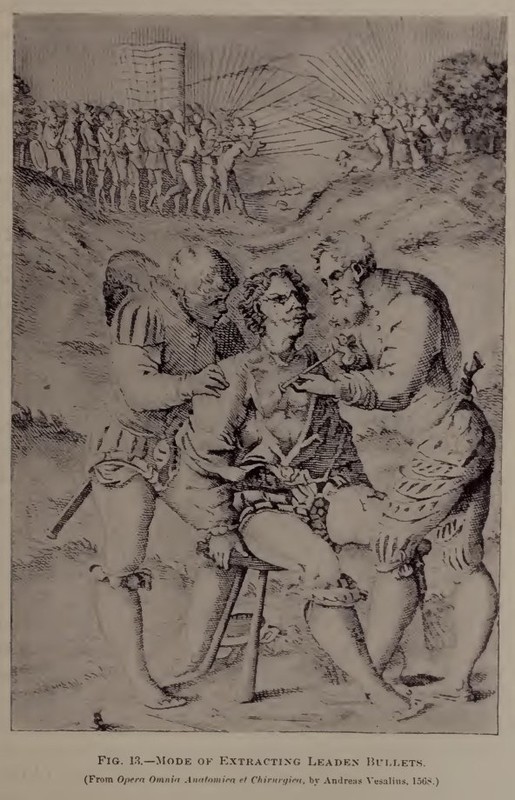

13. Mode of Extracting Leaden Bullets,...........121

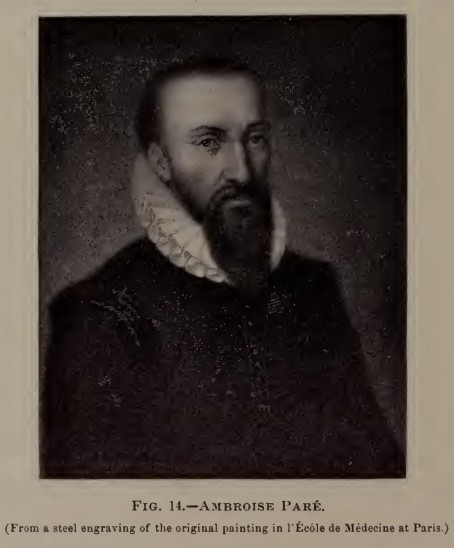

14. Ambroise Pare,...............................124

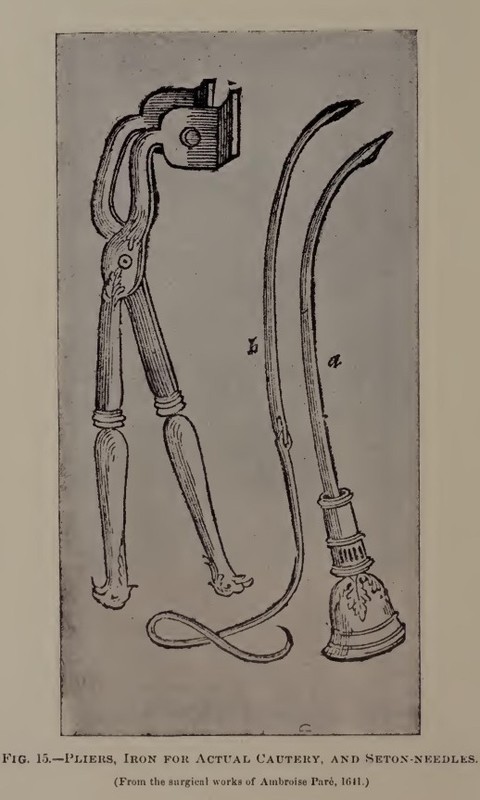

15. Pliers, Iron for Actual Cautery,.............126

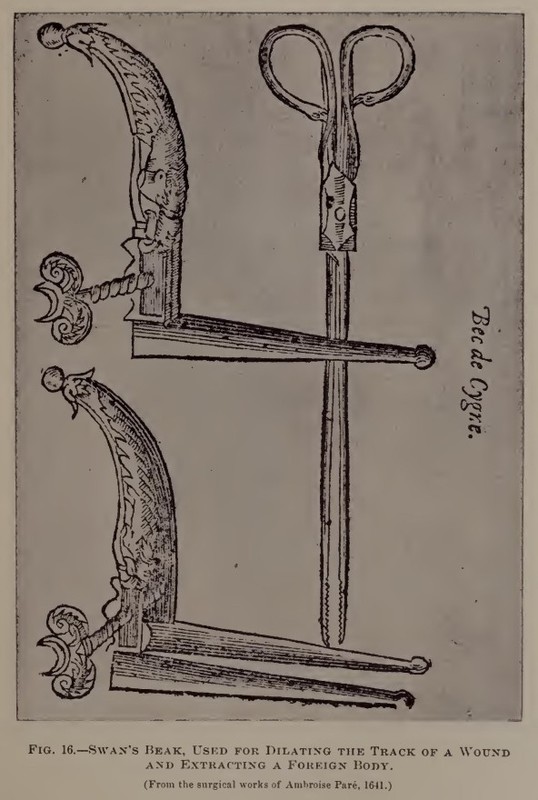

16. Swan's Beak, Used for Dilating...............132

17. Instruments for the Extraction of Balls,.....133

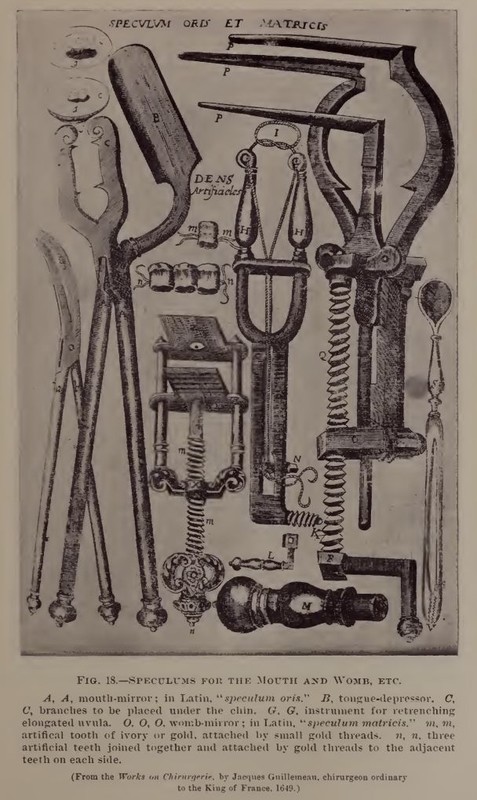

18. Spéculums for the Mouth and Womb, etc.,......135

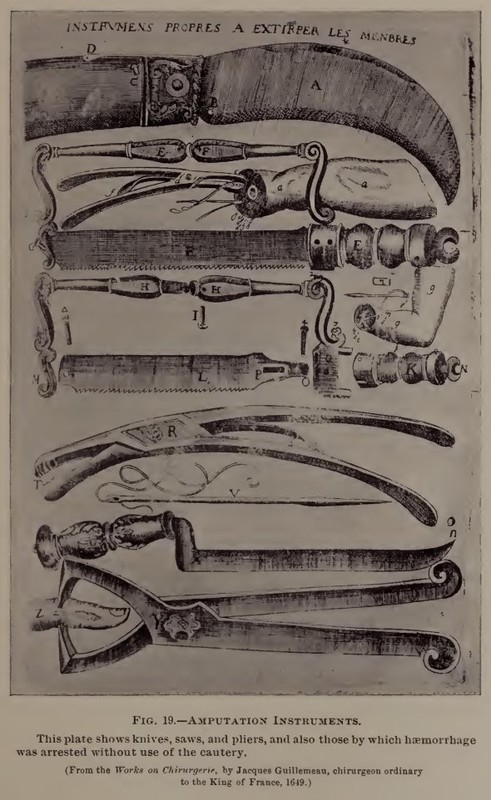

19. Amputation Instruments,......................136

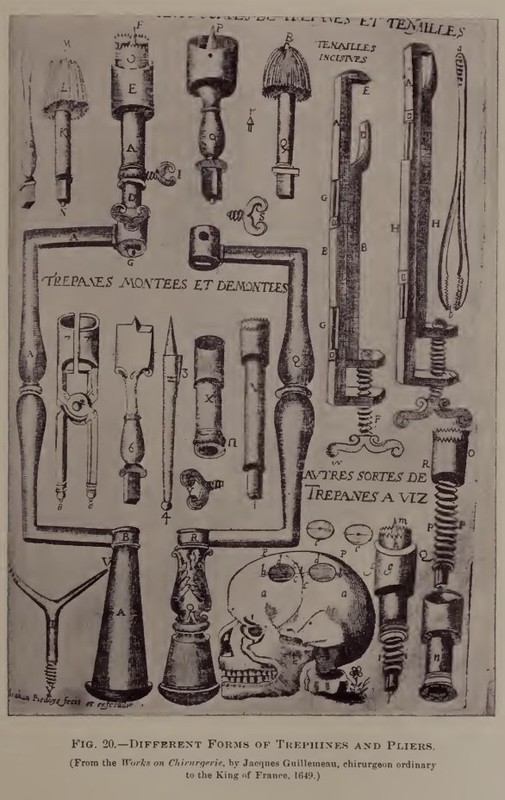

20. Different Forms of Trephines and Pliers,.....137

21. Philip Theophrastus Paracelsus,..............143

22. William Harvey, M.D.,........................156

23. Thomas Sydenham,.............................173

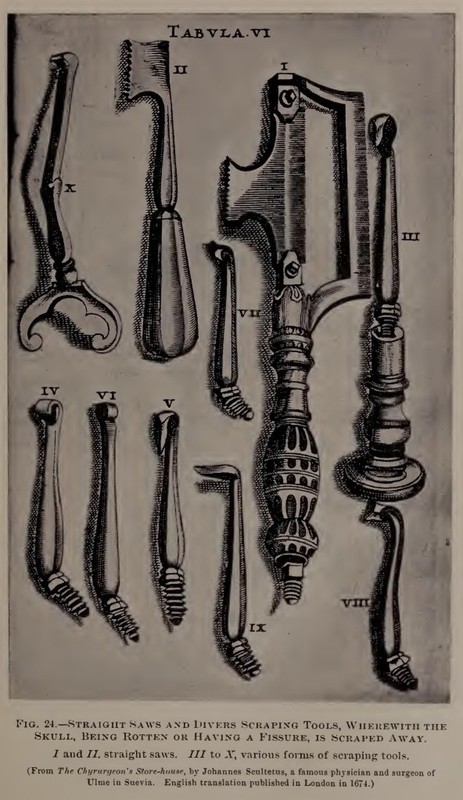

24. Straight Saws and Divers Scraping Tools,.....179

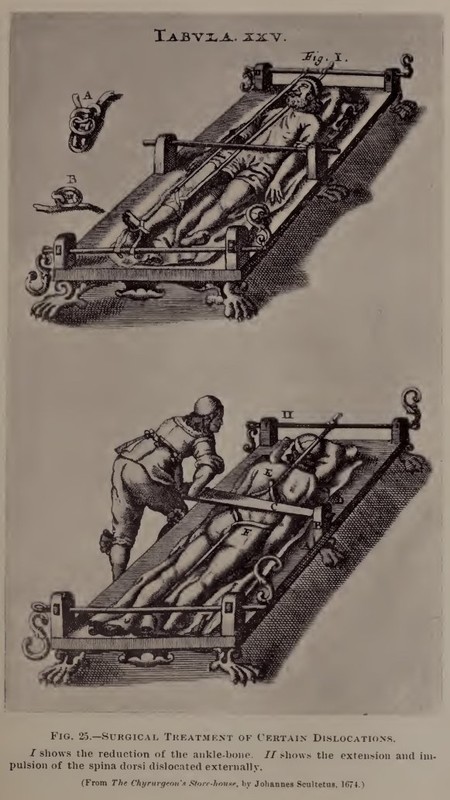

25. Surgical Treatment of Dislocations,..........181

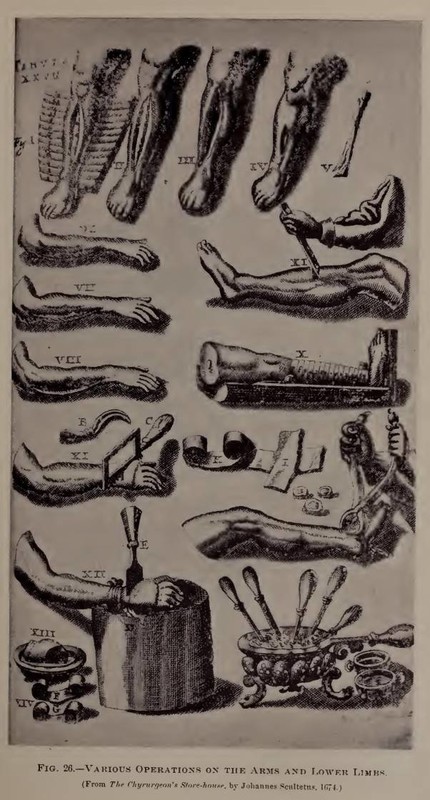

26. Operations on the Arms and Lower Limbs,......185

27. Surgical Operations on the Breast, etc.,.....187

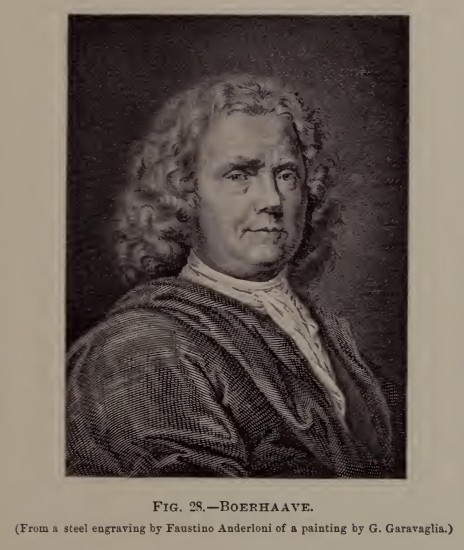

28. Boerhaave,...................................193

29. John Brown, M.D.,............................205

30. Ph. Pinel,...................................207

31. Marie François Xavier Bicliat, M.D.,.........208

32. William Hunter, M.D., F.R.S.,................217

33. John Hunter,.................................219

34. J. F. Blumenbacli,...........................223

35. Edward Jenner, M.D.,.........................227

36. Samuel Hahnemann,............................242

37. Rudolph Virchow,.............................257

38. Bernhard von Langenbeck,.....................265

39. Theodor Billroth,............................266

40. Sir Astley Cooper, Bart.,....................272

41. Sir Benjamin Collins Brodie, F.R.S.,.........273

42. B. Waterhouse, M.D.,.........................280

43. Surgeon's Hall,..............................281

44. Benjamin Rush, M.D.,.........................284

45. George B. Wood, M.D.,........................287

46. Robley Dunglison, M.D.,......................287b

47. Austin Flint, M.D.,..........................288

48. Isaac Ray, M.D.,.............................289

49. Philip Sung Physick, M.D.,...................291

50. Ephraim McDowell, M.D.,......................292

51. S. D. Gross, M.D., LL.D.,....................294

52. J. Marion Sims, M.D.,........................296

53. D. Hayes Agnew, M.D., LL.D.,.................297

54. William T. G. Morton, M.D.,..................307

55. Dr. Morton, October 16, 1846,................308

56. Lord Lister, M.D., D.C.L., LL.D.,............323

AN EPITOME OF THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE.

CHAPTER I.

Medicine Among the Hebrews, the Egyptians, the Orientals, the Chinese, and the Early Greeks.—The Asclepiadæ.—Further Arrangement into Periods ( Renouard's Classification). The Age of Foundation.—The Primitive; Sacred, or Mystic; and Philosophic Periods.—Systems in Vogue: Dogmatism, Methodism, Empiricism, Eclecticism.—Hippocrates, born 460 B.C.

Of the origin of medicine but little need be said by way of preface, save that it must have been nearly contemporaneous with the origin of civilization. The lower animals when sick or wounded instinctively lessen or alter their diet, seek seclusion and rest, and even in certain cases seek out some particular herb or healing substance. Thus, too, does the savage in his primitive state; and experience and superstition together have led nearly all the savage tribes into certain habits and forms in case of injury or disease. For us the history of medicine must necessarily begin with the written history of events, and its earliest endeavors need detain us but a very short time. Its earliest period is enveloped in profound obscurity, and so mingled with myth and table as to be very uncertain. It embraces an indefinite time, during which medicine was not a science, but an undigested collection of experimental notions,—vaguely described, disfigured by tradition, and often made inutile by superstition and ignorance. The earliest records of probable authenticity are perhaps to be met with in the Scriptures, from which may be gathered here and there a fair notion of Egyptian knowledge and practice. Thus we read that Joseph commanded his servants and physicians to embalm him, this being about 1700 B.C.. It shows that Egypt at that time possessed a class of men who practiced the healing art, and that they also embalmed the dead, which must have both required and furnished a crude idea of general anatomy. We are also informed from other sources that so superstitious were the Egyptians that they not only scoffed at, but would stone, the embalmers, for whom they had sent, after the completion of their task. The probably mythical being whom the Egyptians called Thoth, whom the Greeks named Hermes and the Latins Mercury, passed among the Egyptians as the inventor of all sciences and arts. To him are attributed an enormous number of writings concerning all subjects. Some have considered him as identical with Bacchus, Zoroaster, Osiris, Isis, Serapis, Apollo, and even Shem, the son of Xoah. Others have thought him to be a god. It is now almost certain that the books attributed to Hermes were not the work of anyone hand or of any one age. The-last six volumes of the forty-two composing the encyclopaedia, with which Hermes is credited, refer to medicine, and embrace a body of doctrines fairly complete and well arranged. Of these six, the first treats of anatomy; the second, of diseases; the third, of instruments; the fourth, of remedies; the fifth, of diseases of the eye; and the sixth, of diseases of women. In completeness and arrangement it rivals, if not surpasses, the Hippocratic collection, which it antedated by perhaps a thousand years. The Egyptians appear at first to have exposed their sick in public (at least, so says Strabo), so that if any of those who passed by had been similarly attacked they might give their advice for the benefit of the sufferers. In fact, according to Herodotus, the same custom prevailed among the Babylonians and Lusitanians. At a later date all who were thus cured were required to go to the temples and there inscribe their symptoms and what had helped them. The temples of Canopus and Vulcan at Memphis became the principal depots for these records, which were kept as carefully as were the archives of the nation, and were open for public reference. These records, being under the control of the priests, were mainly studied by them, who later collected a great mass of facts of more or less importance, and endeavored to found upon the knowledge thus collected an exclusive practice of the art of medicine. In this way they formed their medical code, which was called by Diodorus the Hiera Sacra, Sacred Book, from whose directions they were never allowed to swerve. It was perhaps this code which was later attributed to Hermes, and that made up the collection spoken of by Clement of Alexandria. If in following these rules they could not save their patients they were held blameless, but were punished with death if any departure from them were not followed by success.

I have spoken of embalming as practiced by the Egyptians. It was of three grades: the first reserved for men of position and means, which cost one talent, and according to which the brain was removed by an opening through the nasal fossæ, and the intestines through an opening on the left side of the abdomen, after which both cavities were stuffed with spices and aromatics; then the body was washed and spread over with gum and wrapped in bandages of linen. The second grade was adopted by families of moderate means; and the third was resorted to by the poor, consisting simply in the washing of the body and maceration in lye for seventy days.

Pliny assures us that the kings of Egypt permitted the opening of corpses for the purpose of discovering the causes of disease, but this was only permitted by the Ptolemies, under whose reign anatomy was carried to a very high degree of cultivation.

The medicine of the Hebrews is known generally through the Sacred Scriptures, especially through the writings attributed to Moses, which embraced rules of the highest sagacity, especially in public hygiene. The book of Leviticus is largely made up of rules concerning matters of public health. In the eleventh chapter, for instance, meat of the rabbit and the hog is proscribed, as apparently injurious in the climate of Egypt and India; it, however, has been suggested that there was such variation of names or interpretation thereof as to make it possible that our rabbit and hog are not the animals alluded to by Moses. The twelfth and fifteenth chapters of the same book were designed to regulate the relation of man and wife and the purification of women, their outlines being still observed in some localities by certain sects, while the hygienic measure of circumcision then insisted upon is still observed as a religious rite among the descendants of Moses. For the prevention of the spread of leprosy, the measures suggested by Moses could not now be surpassed, although ancient authors have confounded under this name divers affections, probably including syphilis, to which, however, the same hygienic rules should apply. Next to Moses in medical lore should be mentioned Solomon, to whom is attributed a very high degree of knowledge of natural history, and who, Josephus claimed, had such perfect knowledge of the properties of all the productions of nature that he availed himself of it to compound remedies extremely useful, some of which had even the virtues necessary to cast out devils.

The most conspicuous feature in the life of the Indian races is their division into castes, of which the most noble is that of the priests, or Brahmins, who in ancient times alone had the privilege of practicing medicine. Their Organon of Medicine, or collection of medical knowledge, was a hook which they called Vagadasastir. It was not systematically arranged, and in it demonology played a large rôle. They held the human body to consist of 100,000 parts, of which 17,000 were vessels, each one of which was composed of seven tubes, giving passage to ten species of gases, which by their conflicts engendered a number of diseases. They placed the origin of the pulse in a reservoir located behind the umbilicus. This was four fingers wide by two long, and divided into 72,000 canals, distributed to all parts of the body. The physician examined not only the pulse of his patient, but the dejecta, consulted the stars, the flight of birds, noted any incidental occurrence during his visits, and made up his prognosis from a multitude of varying circumstances, omitting only those which were really valuable, namely, the symptoms indicating the state of the organs. Ancient Hindoo charlatan priests let fall from the end of a straw a drop of oil into the patient's water. If the oil was precipitated and attached itself to the bottom of the vessel, they predicted an unfavorable result; if, on the contrary, it floated, they gave a favorable prognosis. This is, so far as we know, the earliest recorded way of testing the specific gravity of the urine.

With all their absurdities, however, the Indians appear to have done some things that we scarcely do to-day: they arè said to have had an ointment that caused the cicatrices of variola to disappear, and they cured the bites of venomous serpents with remedies whose composition has been lost.

The antiquity of the Chinese is simply lost in tradition and fable. From time immemorial their rulers have taken extraordinary care to prevent contact and interchange of ideas with foreigners. For 4000 years their manners, laws, religious beliefs, language, and territory have scarcely changed. In this respect they stand alone among the nations of the earth. They attribute the invention of medicine to one of their emperors named Hoam-ti, who was the third of the first dynasty, and whose supposititious date is 2687 B.C. He is considered to be the author of the work which still serves them as a medical guide. It is, however, more probably an apochryphal book. Its philosophy was of a sphygmic kind,—i.e., based upon the pulse, which they divided into the supreme or celestial, the middle, and the inferior or terrestrial; by the examination of which the Chinese physician was supposed not only to show the seat of disease, but to judge of its duration and gravity. It is related that one of the ancient Chinese emperors directed the dead bodies of criminals to be opened, but this is questionable, since it is certain that they have the most profound ignorance of rudimentary anatomy, and glaring errors abound in their system. Being thus replete with errors, and possessing no anatomical knowledge, their surgery was of the most barbarous type. No one dared attempt a bloody operation; the reduction of hernia was unknown; a cataract was regarded as beyond their resources; and even venesection was never practiced. On the other hand, they employed cups, and acupuncture, fomentation, plasters of all kinds, lotions, and baths. The moxa, or red-hot button, was in constant use, and they had their magnetizers, who appear to have been convulsionists. For a long time there existed at Pekin an Imperial School of Medicine, but now there is no such organization nor any regulation for the privilege of practicing medicine or surgery since 1792. At least until lately the country and the cities were infested with quacks, who dealt out poison and death with impunity. They practiced most murderous methods in place of the principles of midwifery. Only since the civilized missionaries have penetrated into their country has there been any improvement in this condition of affairs.

It is Greece which furnishes us with the most interesting and the most significant remains of the history of medicine during antiquity, as she furnishes every other art with the same historical advantages. During the period preceding the Trojan War there is little hut myth and tradition. Leclerc catalogued some thirty divinities, heroes or heroines, who were supposed to have invented or cultivated some of the branches of medicine. Melampus is perhaps the first of these who immortalized himself by extraordinary cures, especially on the daughters of Proetus, King of Argos. These young princesses, having taken vows of celibacy, became subjects of hysterical monomania, with delusions, during which they imagined themselves transformed into cows and roamed the forests instead of the palaces. This nervous delusion spread to and involved many other women, and became a serious matter.

Original

Melampus, the shepherd, having observed the purgative effects upon goats of white hellebore, gave to the young women milk in which this plant had been steeped, thereby speedily effecting a cure. Scarcely less distinguished than Melampus was Chiron. He was mainly distinguished because he was the preceptor of Æsculapius, the most eminent of early Greeks in this field. By some Æsculapius was considered the son of Apollo by the nymph Coronis.

Several cities of Greece contended for the honor of his birthplace, as they did for that of Homer. That he was famous at the time of the Argonautic expedition is seen by the fact that the twins Castor and Pollux desired him to accompany the expedition as surgeon. Be his origin what it may, Æsculapius was the leading character in medicine of all the ancients, with the possible exception of Hermes among the Egyptians; in fact, some scholars consider the two identical. Temples were erected in his honor, priests were consecrated to them, and schools of instruction were there established. It is related that Pluto, god of hell, alarmed at the diminishing number of his daily arrivals, complained to Jupiter, who destroyed the audacious healer—on which account, some wit has said, "the modern children of Æsculapius abstain from performing prodigies," But the true Æsculapians, the successors of the demigod, wrere imitated or copied by the crowd of charlatans and quacks, calling themselves theosophs, thaumaturgs, and so on, and not alone at that date, but for generations and centuries thereafter, Paracelsus and Mesmer being fair examples of this class. The poet Pindar, who lived seven or eight hundred years after Æsculapius, says that he cured ulcers, wounds, fever, and pain of all who applied to him by enchantment, potions, incisions, and by external applications. *

* Third Pythian Ode,

The followers of Æsculapius, and the priests in the temples dedicated to him, soon formed a separate caste, transmitting from one to another, as a family heritage, their medical knowledge. At first no one was admitted to practice the sacred science unless lie joined the priesthood, although later this secrecy was relaxed. They initiated strangers, provided they fulfilled the test which they made. Some kind of medical instruction was given in each temple. The three most celebrated temples to Æsculapius were that of Rhodes, already extinct by the time of Hippocrates; that of Cnidus, which published a small repertory; and finally that of Cos, most celebrated of all, because of the illustrious men who emanated from this school. In these temples votive tablets were fastened in large numbers, after the fashion of the Egyptians, the same giving the name of the patient, his affliction, and the manner of his cure. For example, such a one as this: "Julien vomited blood, and appeared lost beyond recovery. The oracle ordered him to take the pine-seeds from the altar, which they had three days mingled with honey; he did so, and was cured."

Original

Having solemnly thanked the god, he went away. There is reason to think that the priests of these temples made for their own uses much more minute and accurate accounts, which should be of some real service, since the writings which have come down to us evince a habit of close observation and clear description of disease. During the Trojan War two men are frequently mentioned by Homer as possessing great surgical skill. These were Machaon and Podalirius. They were regarded as sons of Æsculapius, the former being the elder. The first account of venesection, although not authentic, refers to the bleeding practiced by the latter upon the daughter of the King of Caria, upon whose shores Podalirius was cast by tempest after the ruin of Priam's kingdom. Whether he was the first of all men to practice it or not, it is certain that the act of venesection goes back long prior to the era of Hippocrates, who speaks of it as frequently performed.

Many of the deities upon Olympus seem at one time or another to have usurped medical functions. Apollo, the reputed father of Æsculapius, appropriated nearly everything under the name of Pæon, who assumed the privilege of exciting or subduing epidemics. Juno was supposed to preside at accouchements, and in both the Iliad and Odyssey it is indicated that Apollo was considered as the cause of all the natural deaths among men, and Diana of those among women.

The long Trojan War appears to have been an epoch-making event in the medical and surgical history of those times, as was the Civil War recently in our country. Certain vague and indefinite practices then took more fixed form, and from that time on medicine may be said to have been furnished with a history. After the dethronement of Priam and the destruction of his capital, navigation was free and unrestricted. The Hellenists covered with their colonies both shores of the Mediterranean, and their navigators even passed the pillars of Hercules. By these means the worship of Æsculapius passed from Greece into what is now Asia, Africa, and Italy. In his temple at Epidaurus was a statue of colossal size made of gold and ivory. The dialogues of Plato, especially the Phædo, make it apparent that the cock was the animal sacrificed to him, and hence sacred to the god of medicine. The priests attached to his worship were called Asclepiacloe, or descendants of Æsculapius. The temples were usually hygienically located near thermal springs or fountains and among groves. Pilgrimages were made from all quarters, and these localities became veritable health-resorts. A well-regulated dietary, pure air, temperate habits, and faith stimulated to a fanatical degree combined and sufficed for cures which even nowadays would be regarded as wonderful. The priests prescribed venesection, purgatives, emetics, friction, sea-baths, and mineral waters, as they appeared to be indicated. The imagination of the patient was continually stimulated, and at the same time controlled. Before interrogating the oracles they must be purified by abstinence, prayer, and sacrifice. Sometimes they were obliged to lie in the temple for one or more nights. The gods sometimes revealed themselves in mysterious ways, at times devouring the cakes upon the altars under the guise of a serpent, or again causing dreams which were to be interpreted by^the priests. There can be no doubt that sometimes, at least, the grossest frauds and the basest trickery were relied upon for the purpose of impressing the minds of those weakened by abstinence or influenced by drugs. Mercenary considerations were not lacking; moreover, cures were often not obtained until zeal had been redoubled by largely increased contributions to the treasury of the temples. In the neighborhood of many of these temples serpents abounded, non-venomous and easily tamed. These were employed by the priests in various supernatural performances by which the ignorant people were astonished and profoundly impressed. In fact, the serpent and the serpent-myth played a very large rôle in the early history of medicine as well as that of religion and religious symbolism.

It will thus be seen that during the space of about 700 years medicine underwent a transformation in Greece. It was first domestic and popular, practiced by shepherds, soldiers, and others; then became sacerdotal; after the Trojan War it was confined to the vicinity of the temples and practiced in the name of some divinity; and finally it was wrapped in mystery and mystic symbolism, where superstition was played upon and credulity made to pay its reward. Down to the time of Hippocrates the Asclep-iadæ rendered some genuine service to science, especially by inculcating habits of observation, in which Hippocrates excelled above all. Later, however, down to the time of the Christian era, medicine in the temples declined, and became, in fact, a system based upon the grossest jugglery.

It is time now that we make a systematic attempt to classify events in the history of medicine, and to recognize certain distinct epochs as they have occurred. For this purpose I know of no better arrangement than that of Renouard, which, in the main, I shall follow, at least during the forepart of this book. In this sense he divides the past into three ages, known, respectively, as the Age of Foundation, the Age of Transition, and the Age of Renovation. Each of these chronological divisions is subdivided into periods, of which the first contains four:—

AGE OF FOUNDATION.

1. The Primitive Period, or that of Instinct, beginning with myth, and ending with the destruction of Troy 1184 years before Christ.

2. The Sacred, or Mystic, Period, ending with the dispersion of the Pythagorean Society, 500 years before Christ.

3. The Philosophic Period, terminating with the foundation of the Alexandrian library, 320 years before Christ.

4. The Anatomic Period, ending with the death of Galen, about A.D. 200.

THE SECOND AGE, OR THAT OF TRANSITION, is divided into a fifth, or Greek Period, ending at the burning of the Alexandrian library, A.D. 640, and a sixth, Arabic Period, ending with the revival of letters, A.D. 1400.

THE THIRD AGE, OR THAT OF RENOVATION, includes the seventh, or Erudite Period, comprising the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and eighth, or Reform Period, comprising the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries.

Examining this table for a moment, it will be seen that so far we have dealt with the Primitive Period and the Sacred, or Mystic, Period. Before passing on to the Philosophic Period let us for a moment follow Renouard, who likens the three schools of medical belief in the earlier part of the Primary Age, or the Age of Foundation, to the three schools of cosmogony, which obtained among the Greeks. The first of these was headed by Pythagoras, who regarded the universe as inhabited by acknowledged sentient principles which governed all substances in a determined way for preconceived purposes. Animals, plants, and even minerals were supposed to possess vivifying spirits, and above them all was a supreme principle. To this school corresponded the so-called Dogmatic School of medicine, attributed to Hippocrates, which was the precursor of modern vitalism, and regarded diseases as indivisible units from beginning to termination; in other words, they consisted of a regular programme of characteristic systems, successive periods, and of long course, either for the better or worse; that was one of the characteristic dogmas of the Hippocratic teaching. The Second System of cosmogony was that founded by Leucippus and Democritus, who explained all natural phenomena without recourse to the intervention of intelligent principles. All things for them existed as the necessary result of the eternal laws of matter. They denied preconceived purposes and ridiculed final causes. To this system corresponded that in medicine which has been termed Methodism (medically and literally speaking) and which recognized as its founders Æsculapius and Themison. The believers in this doctrine attempted to apply the atomic theory of Democritus and Epicurus to the theory and practice of medicine. Atoms of various size were supposed to pass and repass without cessation through cavities or pores in the human body. So long as the atoms and pores maintained a normal relationship of size and proportion health was maintained, but it was deranged so soon as the exactness of these relations was destroyed or interfered with. The Dogmatists considered vital reaction as a primary phenomenon, while with the Methodists it was secondary. The Third System of cosmogony, founded by Parmenides and Pyrrho, believed in the natural improvement of bodies in their endless reproduction and change, and concluded that wisdom consisted in remaining in doubt; in other words, they were the agnostics of that day. "What is the use," said they, "of fatiguing the mind in endeavoring to comprehend what is beyond its capability." Later they were known as Skeptics and Zetetics, to indicate that they were always in search of truth without flattering them selves that they had found it. To them corresponded a third class of physicians, with Philinus and Serapis at their head, who deemed that proximate causes and primitive phenomena of disease were inaccessible to observation; that all that is affirmed on these subjects is purely hypothetical, and hence unworthy of consideration in choosing treatment. For them objective symptoms—or, as we would say, signs—constituted the natural history of disease, they thus believing that their remedies could only be suggested by experience, since nothing else could reveal itself to them. They therefore took the name of Empirics.

Finally a fourth class of physicians arose who would not adopt any one of these systems exclusively, but chose from each what seemed to them most reasonable and satisfactory. They called themselves Eclectics, wishing thereby to imply that they made rational choice of what seemed best. The idea conveyed in the term "eclecticism" has been fairly criticised for this reason: eclecticism is in reality neither a system nor a theory; it is individual pretension elevated to the dignity of dogma. The true eclectic recognizes no other rule than his particular taste, reason, or fancy, and two or more eclectics have little or nothing in common. If that were true two thousand years ago, it is not much less so to-day. The eclectic carefully avoids the discussion of principles, and has neither taste nor capacity for abstract reasoning, although he may be a good practitioner; not that he has no ideas, but that his ideas form no working system. With him medical tact—i.e., cultivated instinct—replaces principle.

The eclectic of our day, however, is only an empiric in disguise,—that is, a man whose opinions are based on comparison of observed facts, but whose theoretical ideas do not go beyond phenomena.

In older days philosophy embraced the whole of human knowledge, and the philosopher was not permitted to be unacquainted with any of its branches. Now physics, metaphysics, natural history, etc., are arranged into separate sciences, and the sum-total of knowledge is too great to be compassed by any one man.

Pythagoras was the last of the Greek sages who made use of hieroglyphic writings and transmitted his doctrine in ancient language. Born at Samos, he was, first of all, an athlete; but one day, hearing a lecture no immortality of the soul, he was thereby so strongly attracted to philosophy that he renounced all other occupation to devote himself to it. He studied arduously in Egypt, in Phoenicia, in Chaldea, and even, it is said, in India, where he was initiated into the secrets of the Brahmins and Magi. Finally, returning to his own country, he was received by the tyrant Polycrates, but not made to feel at home. Starting on his travels again, he assisted at one of the Olympic games, and, being recognized, was warmly greeted. He sailed to the south of Italy, landed at Crotona, and lodged with Milo, the athlete. Commencing here his lectures, he soon gathered around him a great number of disciples, of whom he required a very severe novitiate, lasting even five or six years, during which they had to abstain almost entirely from conversation, and live upon a very frugal diet. Those only who persevered were initiated later into the mysteries of the order. His disciples had for him most profound veneration, and were accustomed to decide all disputes witlr: "The master has said it." Pythagoras possessed immense knowledge; he invented the theorem of the square of the hypothenuse, and he first divided the year into 365 days and 6 hours. He seems to have suspected the movements of our planetary system. He traveled from place to place, and founded schools and communities wherever he went, which exercised, at least at first, only the happiest influence; but the success and influence which their learning gave them later made his disciples bold, and then dishonest, and his communities were finally dispersed by angry mobs, which forced their members to conceal or expatriate themselves; and so, even during the life-time of its founder, the Pythagorean Society was destroyed, and never reconstructed.

With Pythagoras and his disciples numbers played a very important rôle, and the so-called language of numbers was first taught by him. He considered the unit as the essential principle of all things, and designated God by the figure 1 and matter by the figure 2, and then he expressed the universe by 12, as representing the juxtaposition of 1 and 2. As 12 results from multiplying 3 by 4, he conceived the universe as composed of three distinct worlds, each of which was developed in four concentric spheres, and these spheres corresponded to the primitive elements of fire, air, earth, and water. The application of the number 12 to express the universe Pythagoras had received from the Chaldeans and Egyptians—it being the origin of the institution of the zodiac. Although this is digressing, it serves to show what enormous importance the people of that time attached to numbers, especially to the ternary and quarternary periods in the determination of critical days in illness. Pythagoras was the founder of a philosophic system of great grandeur, beauty, and, in one sense, completion, embracing, as it does, and uniting by common bounds God, the universe, time, and eternity; furnishing an explanation of all natural phenomena, which, if not true, was at that time acceptable, and which appears in strong and favorable contrast as against the mythological systems of pagan priests. No wonder that it captivated the imagination and understanding of the thinking young men of that day. Had they continued in the original purity of life and thought in which he indoctrinated them there is no knowing how long the Pythagorean school might have continued. But after it had been dissolved by the storm of persecution, its members were scattered all over Greece and even beyond. Now no longer held by any bonds, many of them revealed the secrets of their doctrine, to which circumstance we owe the little knowledge thereof we now possess.

The Pythagoreans apparently first introduced the custom of visiting patients in their own homes, and they went from city to city and house to house in performance of this duty. On this account they were called Periodic or Ambulant physicians, in opposition to the Asclepiadæ, who prescribed only in the temples. Empedocles, of Agrigentum, well known in the history of philosophy, was perhaps the most famous of these physicians. Let the following incident witness his sagacity: Pestilential fevers periodically ravaged his native city. He observed that their appearance coincided with the return of the sirocco, which blows in Sicily on its western side. He therefore advised to close by a wall, as by a dam, the narrow gorge from which this wind blew upon Agrigentum. His advice was followed and his city was made free from the pestilence.

Again, the inhabitants of Selinus were ravaged by epidemic disease. A sluggish stream filled the city with stagnant water from which mephitic vapors arose. Empedocles caused two small rivulets to be conducted into it, which made its current more rapid; the noxious vapors dispersed and the scourge subsided.

The Gymnasia.—Before we proceed to a somewhat more detailed, but brief, account of Hippocrates, it is necessary to say a word or two of the ancient gymnasia of Greece, which were used long before the Asclepiadæ had practiced or begun to teach. In these gymnasia were three orders of physicians: first, the director, called the Gym-nasiarch; second, the subdirector, or Gymnast, who directed the pharmaceutical treatment of the sick; and, lastly, the Iatroliptes, who put up prescriptions, anointed, bled, gave massage, dressed wounds and ulcers, reduced dislocations, treated abscesses, etc. Of the gymnasiarclis wonderful stories are told evincing their sagacity, which, though somewhat fabulous, indicate the possession of a very high degree of skill of a certain kind. Of one of the most celebrated of these, Herodicus, we may recall Plato's accusation, who reprimanded him severely for succeeding too well in prolonging the lives of the aged. Whatever else may be said, we must acknowledge that above all others the Greeks recognized the value of physical culture in the prevention of infirmity, and of all physical methods in the treatment of disease. By their wise enactments with reference to these matters they set an example which modern legislators have rarely, if ever, been wise enough to follow,—an example of compulsory physical training for the young,—and thereby built up a nation of athletes and a people of rugged constitution among whom disease was almost unknown.

I come now to the so-called Philosophic Period, or the third period in the Age of Foundation, which is inseparably connected with the name of Hippocrates. This central figure in the history of ancient medicine was born on the Island of Cos, of a family in which the practice of medicine was hereditary, who traced their ancestors on the male side to Æsculapius, and on the female side to Hercules. The individual to whom every one refers under this name was the second of seven; the date of his birth goes back to 460 B.C., but of his life and his age at death we do not know; some say he lived to be over one hundred years of age. It is certain that he traveled widely, since his writings evince the knowledge thus gained. He was a contemporary of Socrates, although somewhat younger, and lived in the age of Pericles,—the golden age for science and art in Greece.

Original

The Island of Cos is now called Stan-Co, and is situated not far from the coast of Ionia. Formerly it was considered as having a most salubrious climate; now that it is under the dominion of the Turks, it is considered most unhealthy. It possessed a temple dedicated to Æsculapius and a celebrated medical school. But Hippocrates, not satisfied with what he could learn here, visited the principal foreign cities, and seems to have been a most accurate and painstaking observer and collector of notes. That he achieved great renown in his life is known, since Plato and even Aristotle refer to him as their authority in very many matters. His children and grandchildren followed in his footsteps, and published their writings under the same name; it has, therefore, become difficult to distinguish his works from theirs. Finally, authors more unscrupulous, who bore no relationship to him, attached his name to their own writings. But the true were, as a rule, easily distinguished from the spurious, and were carefully separated by those in charge of the Alexandrian library.

The enumeration of his writings by different authors varies very much. Renouard, who seems to have studied the subject very carefully, gives the following as appearing to him to be the authentic list of writings of Hippocrates the Second,—i.e., the Great: The Prognostic, the Aphorisms, the first and third books of Epidemics, that on Regimen in Acute Disease, that on Airs, Waters, and Places, that on Articulations and Luxations, that on Fractures, and the Mochlic, or the treatise on instruments and reduction. This list does not comprise the fourth part of the entire Hippocratic collection, but its authenticity appears to be undoubted, and it suffices, as Renouard says, to justify the enthusiasm of his contemporaries and the admiration of posterity. Later, joined with the writings of Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, and others, they constituted the so-called Hippocratic collection, which was a definite part of the great libraries of Alexandria and Pergamos, and formed the most ancient authentic monument of medical science.

Respect for the bodies of the dead was a religious observance in all Greece, and prevented the dissection of the human body. Consequently the knowledge of anatomy possessed by Hippocrates must have been meagre. Nevertheless, he described lesions, like wounds of the head, of the heart, the glands, the nature of bones, etc. It being impossible to establish a physiology without an anatomical basis, it is not strange that we find but little physiology in the Hippocratic writings, and that this little is very crude and incorrect. Arteries and veins were confounded, and nerves, tendons, ligaments, and membranes were represented as analogous or interchangeable tissues. The physiologists of those days abandoned themselves to transcendental speculation concerning the nature and principles of life, which some placed in moisture, others in fire, etc. Speculation, thus run wild, prevented such accurate observation as might have greatly enhanced the progress of physiological knowledge.

Hippocrates wrote at least three treatises concerning hygiene: The first, on Airs, Waters, and Places; the second, on Regimen; the third, on Salubrious Diet,—practically an abridgement of the preceding, in which he recommends the habit of taking one or two vomits systematically every month. The classification of diseases into internal or medical, and external or surgical, is not modern, but is due to Hippocrates; neither is it philosophic, although it is very convenient.

With so little knowledge of physiology and pathology as the ancients had, it is not strange that they ascribed undue importance to external appearance; in other words, to what has been termed semeiotics, which occupies a very considerable place in the medical treatises of the Asclep-iadæ. Indeed, the writings on this subject constitute more than one-eighth part of the entire Hippocratic collection. To prognosis, also, Hippocrates ascribed very great importance, saying that "The best physician is the one who is able to establish a prognosis, penetrating and exposing first of all, at the bedside, the present, the past, and the future of his patients, and adding what they omit in their statements. He gains their confidence, and being convinced of his superiority of knowledge they do not hesitate to commit themselves entirely into his hands. He can treat, also, so much better their present condition in proportion as he shall be able from it to foresee the future," etc.

To the careful scrutiny of facial appearances, the position, and other body-marks about the patient he attributed very great importance; in fact, so positive was he about these matters that he embodied the principal rules of semeiotics into aphorisms, to which, however, there came later so many exceptions that they lost much of their value. From certain passages in his book on Prediction, and from the book on Treatment, which is a part of the Hippocratic collection, it appears that it was the custom then of physicians to announce the probable issue of the disease upon the first or second visit,—a custom which still prevails in China and in Turkey, It gave the medical man the dignity of an oracle when right, but left him in a very awkward position when wrong.

To Hippocrates we are indebted for the classification of sporadic, epidemic, and endemic forms, as well as for the division of disease into acute and chronic. Hippocrates wrote extensively on internal disease, including some particular forms of it, such as epilepsy, which was called the sacred disease; also fragments on diseases of girls, relating particularly to hysteria; also a book on the nature of woman, an extensive treatise on diseases of women, and a monograph on sterility. That Hippocrates was a remarkably close observer of disease as it appeared to him his books amply prove; in fact, they almost make one think that close observation is one of the lost arts, being only open to the objection that too much weight was attached to insignificant external appearances, speculation on which detracted from consideration of the serious feature of the case. His therapeutics, considering the crude information of the time, was a vast improvement on that which had preceded, and really entitled him to his title of "Great Physician."

Of external diseases and their surgical therapeutics he wrote fully: on The Laboratory of the Surgeon, dealing with dressings, bandaging, and operating; on Fractures; and on Articulations and Dislocations; showing much more anatomical knowledge than was possessed by his contemporaries. The Mochlic was an abridgment of former treatises; in Wounds of the Head he formulated the dictum concerning the possible danger of trifling wounds and the possible recovery from those most serious, so often ascribed to Sir Astlev Cooper. Other monographs, also, he wrote, on Diseases of the Eye, on Fistula, and on Hoemorrhoids. He described only a small number of operations, however, and all the Hippocratic writings on surgery would make but a very incomplete treatise as compared with those that belong to the next historical epoch; all of which we have to ascribe—in the main—to prejudice against dissection and ignorance of anatomy.

From the earliest times physicians and writers occupied themselves largely with obstetrics, as was most natural. The Hippocratic collection includes monographs on Generation; the Nature of the Infant; the Seventh Month of Pregnancy; the Eighth Month of Pregnancy; on Accouchement; Superfoetation; on Dentition; on Diseases of Women; on Extraction of the Dead Foetus. The treatise on superfcetation concerned itself mainly with obstetrics.

On epidemics Hippocrates writes extensively, showing that he had studied them carefully. He was among the first to connect meteorological phenomena with those of disease during given seasons of the year, expressing the hope that by the study of storms it would be possible to foresee the advent of the latter, and prepare for them. Seven books of the Hippocratic collection bear the title of Epidemics, although only two of them are exclusively devoted to this subject. In these books were contained a long list of clinical observations relating to various diseases. They constituted really a clinical study of disease.

The collection of Hippocrates's Aphorisms fills seven of the books; no medical work of antiquity can compare with these. Physicians and philosophers of many centuries have professed for them the same veneration as the Pythagoreans manifested for their golden verses. They were considered the crowning glory of the collection. Even within a short time past the Faculty of Paris required aspirants for the medical degree to insert a certain number of these in their theses, and only the political revolution of France served to cause a discontinuance of this custom. These aphorisms formed, says Littré, "a succession of propositions in juxtaposition, but not united." It has always been and always will be disadvantageous for a work to be written in that style, since such aphorisms lose all their general significance; and that which seems isolated in itself becomes more so when introduced into modern science, with which it has but little practical relationship. But not so if the mind conceive of the ideas which prevailed when these aphorisms were written; in this light, when they seem most disjoined they are most related to a common doctrine by which they are united, and in this view they no longer appear as detached sentences.

The school of the Asclepiadæ has been responsible for certain theories which have been more or less prominent during the earlier historical days. One of these which prevailed throughout the Hippocratic works is that of Coction and Crisis. By the former term is meant thickening or elaboration of the humors in the body, which was supposed to be necessary for their elimination in some tangible form. Disease was regarded as an association of phenomena resulting from efforts made by the conservative principles of life to effect a coction,—i.e., a combination of the morbific matter in the economy, it being held that the latter could not be properly expelled until thus united and prepared so as to form excrementitious material. This elaboration was supposed to be brought about by the vital principles, which some called nature (Physis), some spirit (Psyche), some breath (Pneuma), and some heat (Thermon).

The gradual climax of morbid phenomena has, since the days of Hippocrates, been commonly known as Crisis; it was regarded as the announcement of the completion of the union by coction. The day on which it was accomplished was termed critical, as were also the signs which preceded or accompanied it, and for the crisis the physician anxiously watched. Coction having been effected and crisis occurring, it only remained to evacuate the morbific material—which nature sometimes spontaneously accomplished by the critical sweat, urination, or stools, or sometimes the physician had to come to her relief by the administration of diuretics, purgatives, etc. The term "critical period" was given to the number of days necessary for coction, which in its perfection was supposed to be four, the so-called quarternary, while the septenary was also held in high consideration. Combination of figures after the Pythagorean fashion produced many complicated periods, however, and so periods of 34, 40, and 60 days were common. This doctrine of crisis in disease left an impress upon the medical mind not yet fully eliminated. Celsus was the most illustrious of its adherents, but it can be recognized plainly in the teachings of Galen, Sydenham, Stahl, Van Swieten, and many others. In explanation, it must be said that there have always existed diseases of nearly constant periods, these being nearly all of the infectious form, and that the whole "critical" doctrine is founded upon the recognition of this natural phenomenon.

The Hippocratic books are full, also, of the four elements,—earth, water, air, and fire; four elementary qualities,—namely, heat, cold, dryness, and moisture; and the four cardinal humors,—blood, bile, atrabile, and phlegm.

Owing to the poverty of knowledge of physics and chemistry possessed by the ancients, and notwithstanding their errors and imperfections, the doctrine of Dogmatism, founded upon the theory of coction and humors, was the most intelligible and complete among the medical doctrines of antiquity, responding better, as it did, to the demands of the science of that day. That Hippocrates was a profound observer is shown in this: that he reminds both philosophers and physicians that the nature of man cannot be well known without the aid of medical observation, and that nothing should be affirmed concerning that nature until by our senses we have become certain of it. In this maxim he took position opposed to the Pythagorean doctrine, and included therein the germ of a new philosophy of which Plato misconceived, and of which Aristotle had a very faint glimpse.

Another prominent theory throughout the Hippocratic books is that of Fluxions, meaning thereby about what we would call congestions, or conditions which we would say were ordinarily caused by cold, though certain fluxions were supposed to be caused by heat, because the tissues thereby became rarefied, their pores enlarged, and their humor attenuated so that it flowed easily when compressed. The whole theorv of fluxion was founded on the densest ignorance of tissues and the laws of physics, the body of man being sometimes likened to a sponge and sometimes to a sieve. The treatment recommended was almost as crazy as the theory. Certain other theories have complicated or disfigured the Hippocratic writings, and certain have been founded on the consideration of two elements—i.e., fire and earth—or on the consideration of one single element which was supposed to be air,—the breath, or pneuma; and there was—lastly—the theory of any excedent, which is very vague; of all of these we may say that they are not of sufficient interest to demand expenditure of our time.

The eclat which the second (i.e., the Great) Hippocrates gave to the school of Asclepiadæ in the Island of Cos long survived, and many members of his family followed in his footsteps. Among his most prominent successors were Polybius, Diodes, and Praxagoras, also of Cos,—the last of the Asclepiadæ mentioned in history. Praxagoras was distinguished principally for his anatomical knowledge; like Aristotle, he supposed that the veins originated from the heart, but did not confound these vessels with the arteries, as his predecessors had done, but supposed that they contained only air, or the vital spirit. It has been claimed that he dissected the human body. He laid the foundation of sphygmology, or study of the pulse, since Hippocratic writers rarely alluded to arterial pulsations and described them as of only secondary importance.

The predominating theory in the Island of Cos was that which made health dependent on the exact proportion and play of the elements of the body, and on perfect combination of the four cardinal humors. This was the prevailing doctrine,—i.e., the Ancient Medical Dogmatism, so named because it embraced the most profound dogmas in medicine, and was taught exclusively until the foundation of the school at Alexandria.

Two men, however, more commonly ranked among philosophers than among physicians of antiquity, dissected the statements of Hippocrates, and embodied them more or less in their own teachings, and thus exercised a great influence on the progress of the human mind, particularly in the direction of medical study. The first of these was Plato, profound moralist, eloquent writer, and most versatile thinker of his day or any other. He undertook the study of disease, not by observation (the empirical or experimental method), but by pure intuition. He seemed to have never discovered that his meditations were taken in the wrong direction, and that the method did not conduce to the discovery of abstract truths. He gave beauty an abstract existence, and affirmed that all things beautiful are beautiful because of the presence of beauty. This reminds one of that famous response in the school of the Middle Ages to a question: "Why does opium produce sleep?" the answer being: "Because it possesses the sleepy principle." Plato introduced into natural science a doctrine of final causes. He borrowed from Pythagoras the dogma of homogeneity of matter, and claimed that it had a triangular form.

Aristotle, equally great thinker with Plato, but whose mental activity was manifest in other channels, was born in Stagyrus, in Macedonia. He was fascinated by the teachings of Plato, and attained such eminence as a student that King Philip of Macedon made him preceptor to his son Alexander, subsequently the Great, by whom he was later furnished with sufficient funds to form the first known museum in natural history.—a collection of rare objects of every sort, transmitted, many of them, by the royal hands of his former student from the remote depths of Asia. Aristotle, by long odds the greatest naturalist of antiquity, laid the first philosophic basis for empiricism. He admitted four elements—fire, air, earth, and water—and believed them susceptible of mutual transmutation. He studied the nature of the soul and that of the animal body; regarded heat and moisture as two conditions indispensable to life; described the brain with some accuracy, but without the least idea of its true function; said that the nerves proceeded from the heart; termed the aorta a nervous vein; and made various other mistakes which to us seem inexcusable. Nevertheless, he was rich in many merits, and no one of his age studied or searched more things than he, nor introduced so many new facts. Although he never dissected human bodies, he nevertheless corrected errors in anatomy held to by the Hippocratic school. He dissected a large number of animals of every species, and noted the varieties of size and shape of hearts of various animals and birds. In other words, he created a comparative anatomy and physiology, and the plan that he traced was so complete that two thousand years later the great French naturalist Cuvier followed it quite closely. If he be charged with having propagated a taste for scholastic subtleties, he also furnished an example of patient and attentive observation of Nature. His history of animals is a storehouse of knowledge, and his disciples cultivated with zeal anatomy, physiology, and natural history. His successor, Theophrastus, was the most eminent botanist of antiquity.

It will thus be seen that Plato and Aristotle were the eminent propagators of two antagonistic opinions. One supposed knowledge to be derived by mental intuition, and the other that all ideas are due to sensation. Both count among moderns some partisans of the greatest acumen: Descartes, Leibnitz, and Kant being followers of Plato, and Bacon, Locke, Hume, and Condillac, of Aristotle.

The excuse for stating these things, which apparently do not so closely concern the history of medicine, must be that of the learned interpreter of the doctrine of Cuvier, that "The first question in science is always a question of method."

Hippocrates formed a transition between a period of mythology and that of history. His doctrine was received by contemporaries and by posterity with a veneration akin to worship. No other man ever obtained homage so elevated, constant, and universal. A little later ignorance reigned in the school that he made celebrated. Methods and theories were propagated there under the shadow of his name which he would have disowned.

Medical science now changes its habitation as well as its aspect, and from the record of Hippocrates and his work we turn to the fourth period of the Age of Foundation,—namely, the Anatomic, which extends from the foundation of the Alexandrian library, 320 B.C., up to the death of Galen, about the year A.D. 200.

CHAPTER II.

Age of Foundation (continued).—Anatomic Period: Influence of the Alexandrian Library. Herophilus and Erasistratus. Aretæus, f B.C. 170. Celsus, A.D. 1-65 (?). Galen.—Empiricism: Asclepiades B.C. 100 (?).—Methodism: Theinison, B.C. 50 (?).—Eclecticism. Age of Transition, A.D. 201-1400.—Greek Period: Oribasius, 326-403. Ætius, 502-575. Alexander of Tralles, 525-605. Paul us Ægineta, 625-690.

Fourth, or Anatomic, Period.—As already seen, Alexander the Great and his successors collected the intellectual and natural riches of the universe, as they knew them, and placed them at the disposal of studious men to benefit humanity; their complete value has not yet been exhausted, and never can be. This undertaking was carried out under conditions that made it one of extreme difficulty. Manuscripts were then rare and most costly; but few copies of a given work were in existence, often only one, and these were held almost priceless. Under these circumstances the establishment of a public library and of a museum was an act of philanthropy and liberality simply beyond eulogy, and did more to immortalize the founder of the collection than all his victories and other achievements.

This appears to have also occurred to two of Alexander's lieutenants—one Eumenes, Governor of Pergamos, and the other, Ptolemy, Governor of Egypt. After the death of the conqueror his generals shook of all dependence upon the central government, and endeavored to centralize their own authority. But these two were the only ones among so many leaders who did not devote all their attention to armies and invasion, but interested themselves in commerce and arts. So active were they in the enterprise that Eumenes had gathered two hundred thousand volumes for the library at Pergamos, and Ptolemy six to seven hundred thousand for that of Alexandria. The latter was divided into two parts, the greater and the lesser, the latter of which was kept in the temple of Serapis, hence known as the Serapium. These notable efforts to found enormous collections first excited praiseworthy rivalry among contemporaries and rulers, which, however, degenerated into contemptible jealousy, so that some of the rulers of Alexandria even went so far as to interdict the exportation of papyrus, in order to prevent the making of copies for the library of Pergamos. But the effect was unexpected, since it led to the invention of the paper of Pergamos, otherwise called parchment, which completely displaced the bark from which papyri were made. Be this as it was, the collection at Alexandria had a much more marked influence on the medical study of the future than that of Pergamos, and calls for our particular notice. About it sprang up first a collection of learned men, and then the inevitable result—a school of learning. It was Ptolemy Soter who called around him the most renowned men of his day. He provided them with homes adjoining the library, endowed them with salaries, and charged them with the classification and collation of manuscripts, or with the giving of instruction by lectures and discussions. Ptolemy himself sometimes took part in these feasts of reason, which became still more frequent and formal under his son Ptolemy Philadelphia. These were called the Feasts of the Muses and of Apollo,—i.e., ludi musarum,—and, consequently, the place where they were held came to be termed the "museum." Often the subjects for discussion were announced in advance, and those who gained the most applause received rewards in accordance with the merits of their work. Among those who enjoyed these advantages under the reign of these two Ptolemies are prominently named two physicians, Herophilus and Erasistratus, the latter said to be the grandson of Aristotle. It was under this Philadelphus that the Hebrew wise men translated into Greek the Holy Scriptures, which translation has since been called the Septuagint—so called because it is supposed to have been translated by the members of the Sanhedrim, which was composed of about seventy men, or because, according to another legend, it was translated by seventy-two men in seventy-two hours. These savants of ancient Egypt, thus supported by the dynasty of the Lagides, gave the first place to the science of medicine. As regards this study, the school of Alexandria eclipsed almost from its origin the ancient schools of Cos and Pergamos, and during its existence was the leading institution of its kind in the world. At the time of Galen it was sufficient to have studied there, and even to have resided a short time in Alexandria, to obtain the reputation of being a physician. Nearly all the scholars of these five centuries had received instruction in this school. The principal reason for its eminence in medical instruction was the practice of dissection of human bodies, which, under the Ptolemies, was allowed and recommended, and by which the science of medicine received an extraordinary impulse. Although the prejudice of Egyptians was very strong against those who touched a dead body, the Ptolemies themselves are said to have participated in this kind of anatomical study, thus destroying by their example the odium previously attached to dissection. Strange to say, however, the practice of dissection fell into disuse toward the end of this Anatomic Period, and scholars preferred to indulge in subtle metaphysical discussions rather than study human tissues. But the principal reason for giving up this practice was the Roman domination of Egypt, the Romans, inconsistently, being perfectly willing to see any amount of bloodshed in the arena, and all sorts of inhumanities practiced upon living human beings, but holding that contact with a corpse was profanation; so that not a single anatomist of reputation had his origin in ancient Rome. "If on any occasion," says Renouard, "a foreign physician attached to the king or general desired to avail himself of the occasions that were afforded to examine the structures of the internal parts of the human body, he was obliged to conceal and carry off during the night some body abandoned to the birds of prey." To complete the melancholy termination of the Anatomic Period, the labors of the writers of those days were all lost by the burning of the great library by Julius Cæsar, which was the beginning of the chain of disasters with which Egypt was accursed under Roman dominion. Although Mark Antony, induced thereto by the endearments and solicitations of Cleopatra, transported the library of Pergamos to Alexandria, even this was unavailing to restore the position of the school, since the atrocious and imbecile Caracalla took from the pensioners of the museum their privileges of common residence and every other advantage, and suppressed all public exhibitions and discussions. I can mention but few of the names most eminent during this Anatomic Period, and but a short account of the life and work of each.

The first deserving of mention was Herophilus, who was born in Chalcedon about the end of the fourth century before Christ, and supposed to be the first to undertake systematic dissection of the human body. The so-called Torcular Herophili, or common meeting-place of the sinuses at the occiput, named after him, gives evidence of his influence upon the study of anatomy. He wrote on all departments of medical science, concerning the eyes, the pulse, midwifery, etc., as well as numerous commentaries upon the Hippocratic writings,—describing the membranes of the brain and its vessels, the choroid plexus, the ventricles of the brain, the tunics of the eye, the intestinal canal, and certain portions of the vascular system. He alluded to the thoracic duct without knowing its purpose, and gave a more accurate description of the genitalia than any previous writer. Strange to say, but little is known of his later life, and of his death absolutely nothing.