автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Philippine Islands

The Philippine Islands

The Philippine Islands

By

Ramon Reyes Lala

A Native of Manila

Illustrated

MDCCCXCIX

Continental Publishing Company

25 Park Place, New York

Copyright 1898

By

Continental Publishing Co.

The Philippine Islands

TO

Rear-Admiral Dewey,

WHOSE RECENT GREAT VICTORY OVER THE

SPANISH FLEET

HAS BEGUN A NEW ERA OF FREEDOM AND PROSPERITY

FOR MY COUNTRY,

AND TO

President McKinley,

IN WHOSE HAND LIES THE DESTINY OF

EIGHT MILLIONS OF FILIPINOS,

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED.

Contents.

Preface 23

Early History of the Islands.

Discovery and Conquest—Adventures of Juan Sebastian Elcano-Legaspi, the first Governor-General—Li-ma-hong, the Chinese Pirate—The Dutch appear upon the Scene—The Japanese, and the Martyred Saints 29–48

The British Occupation.

General Draper’s Expedition—The British demand an Indemnity—Intrigues against the British 49–56

The Spanish Colonial Government.

The Encomiendoros and the Alcaldes—The Present Division and Administration—The Taxes and what became of Them—Dilatory and Abortive Courts—A New Yorker’s Experience 57–70

The Church in the Colony.

Priesthood and the People—Conflicts between Church and State—Clashing among the Friars—The Monks opposed to Reform 71–79

The Various Tribes of the Philippines.

Character of the Natives—A Native Wedding—Dress and Manners—The Half-Breeds, or Mestizos—Savage Tribes in the Interior: the Aetas, or Negritos—The Gaddanes—The Igorrotes—The Igorrote-Chinese—The Tinguianes—The Chinese: Hated but Indispensable 80–106

The Mohammedans of Sulu.

Cross or Crescent?—The Sultan’s State—The Dreaded Juramentados—The Extent of Mohammedan Rule—Sulu Customs 107–118

Manila.

The Old City—Binondo and the Suburbs—Educational and Charitable Institutions—The Cathedral and the Governor-General’s Palace—The Beautiful Luneta; the Sea Boulevard 119–137

Other Important Cities and Towns.

Iloilo; Capital of the Province of Panay—Cebú, a Mecca for many Filipinos—General Topography of the Islands 138–150

Natural Beauty of the Archipelago.

A Botanist’s Paradise—A Diadem of Island Gems—The Magnificence of Tropical Scenery—The Promise of the Future 151–158

A Village Feast.

The Morning Ceremonies—How the Afternoon is Spent—The Evening Procession—The Entertainment at Home—The Moro-Moro and the Fire-works 159–173

History of Commerce in the Philippines.

The Spanish Policy—The Treasure-Galleons—Disasters to Spanish Commerce—Other Nations enter into Competition—Fraud and Speculation—The Merchants of Cádiz—Royal Restrictions on Trade 174–187

Commerce During the Present Century.

The Royal Company—The Restrictions are gradually Abolished—Vexatious Duties on Foreign Imports—Duties made Uniform—Spanish Opposition to Foreign Trade—Trade with the Natives—The Decline of American Trade—Recent Measures and Statistics—Bad Results of Spanish Rule 188–198

Agriculture: The Sugar and Rice Crops.

Agriculture, the Chief Industry—The Principal Products of the Colony—The Cultivation of Sugar-cane—Methods of Manufacturing Sugar—The Several Systems of Labor—The Rice Crop—Methods of Rice-Cultivation—Primitive Machines, and Importance of the Rice Crop 199–213

The Hemp Plant and its Uses.

Description of the Abacá—The Process of Manufacture—Some Facts about Hemp-growing—Difficulties with Native Labor—Tricks of the Natives—Competition with Other Lands—Experience of a Planter—What the Hemp is used for 214–226

Culture and Use of Tobacco.

The Cultivation of Tobacco, a State Monopoly—Oppressive Conditions in Luzon—How Speculators take Advantage of the Natives—The Quality of Manila Tobacco—Methods of Preparing the Tobacco Leaf—Smoking, a Universal Habit 227–236

The Cultivation of Coffee.

The Origin of the Industry—Indifference of Coffee-planters—Speculation in Coffee—Methods of Cultivation—Harsh Methods of the Government 237–242

Betel-Nut, Grain, and Fruit-Growing.

The Areca Palm and the Betel Nut—The Nipa Palm and Nipa Wine—Various Fruits of the Islands—Cereals and Vegetables—Cotton and Indigo Planting—The Cocoa Industry—The Traffic in Birds’ Nests 243–250

Useful Woods and Plants.

The Huge Forests—The Bamboo Plant and its Uses—The Bejuco Rope—The Useful Cocoanut Palm—Oppressive Regulations of the Government—The Early Missionaries Beneficial to the Natives 251–259

Mineral Wealth of the Islands.

Early Search for Gold—The Mining Laws and Methods of the Colony—Where the Precious Metal is Found—The Whole Country a Virgin Mine—Precious Stones and Iron—Peculiar Method of Mining Copper—Other Materials and the Coal Fields, 260–272

Animal Life in the Colony.

The Useful Buffalo, and Other Domestic Animals—Reptiles, Bats, and Insects—A Field for the Sportsman—The Locust Scourge—The Chief Nuisances: Mosquitoes and Ants 273–283

Struggle of the Filipinos for Liberty.

Early Insurrections Against the Spaniards—The Burgos Revolt—The Present Rebellion—The Katipunan—The Black Hole of Manila—The Forbearance of the Natives—The Rebel Army—The Tagál Republic Proclaimed—Treachery of the Spaniards—Dr José Rizal and his wife Josephine—Execution of Rizal—The Philippine Joan of Arc—Rizal’s Farewell Poem—Aguinaldo Confers with Admiral Dewey—Aguinaldo as Dictator: His Proclamations—Triumphant Progress of the Rebels—The Spaniards Fortify Manila—Sketch of Aguinaldo 284–309

Dewey at Manila.

The White Squadron—Declaration of War, and Journey to the Philippines—Luzon Sighted, and Preparations for Battle—The Fleet Sails by Corregidor—First Shot of the War—The Spanish Fleet is Sighted—Dewey Attacks the Enemy—The Fate of the Reina Cristina—The Commodore Pipes all Hands to Breakfast—The Americans Renew the Battle—The Yankees are Victorious 310–325

The American Occupation.

Merritt and the Expedition—The Battle of Malate—Capture of Manila—Capitulation of the Philippines—Awaiting the Peace Commission—Instructions to Merritt 326–342

Illustrations.

- Page.

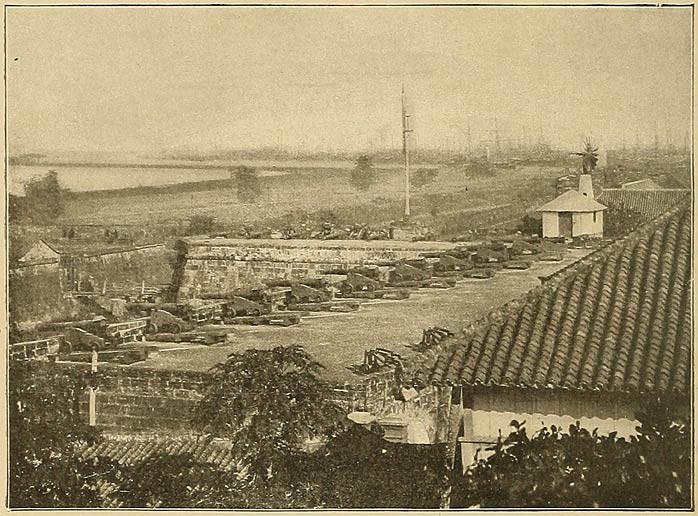

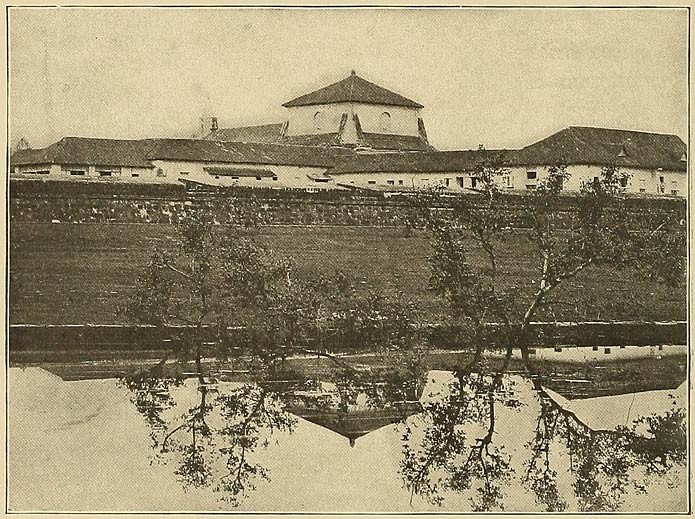

- The Fortifications of Old Manila 30

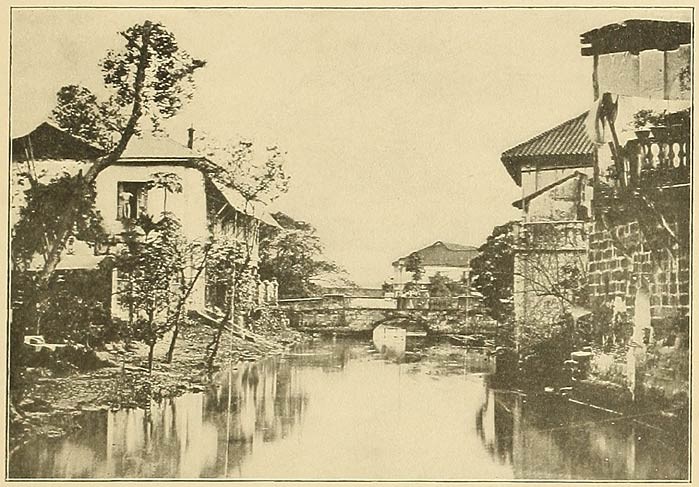

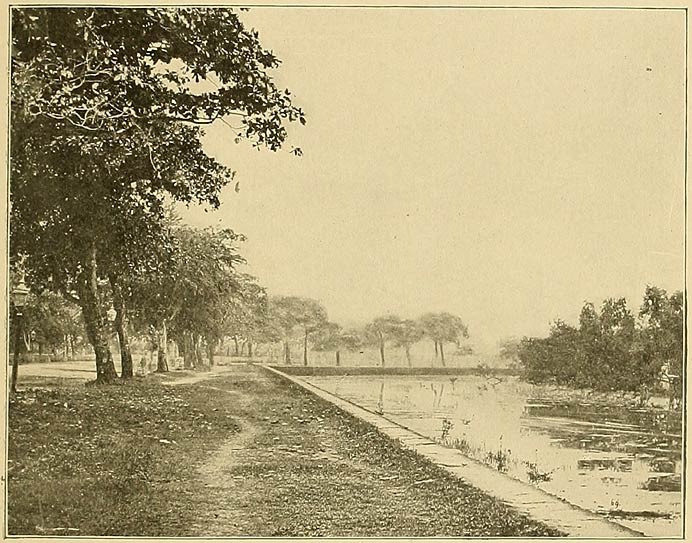

- A Glimpse of the Old Canal 35

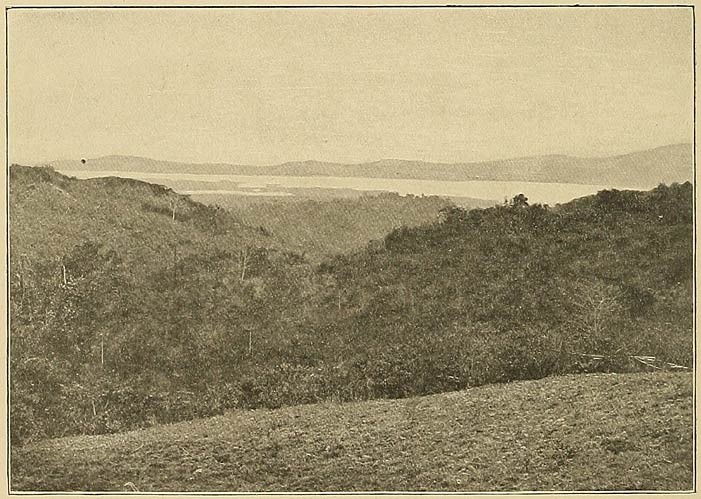

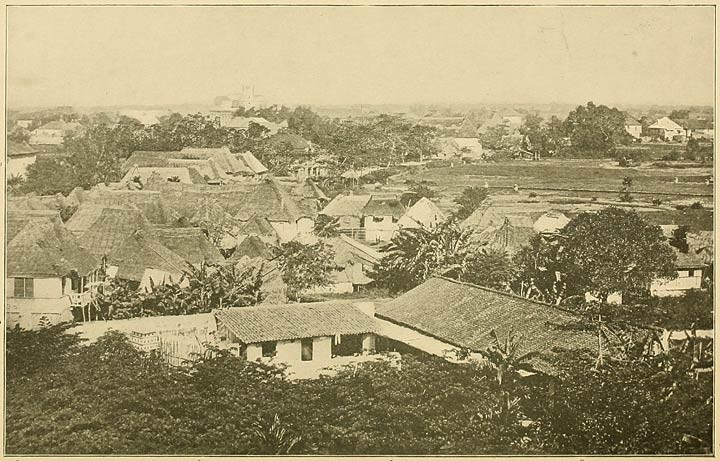

- In the Batangas Province 36

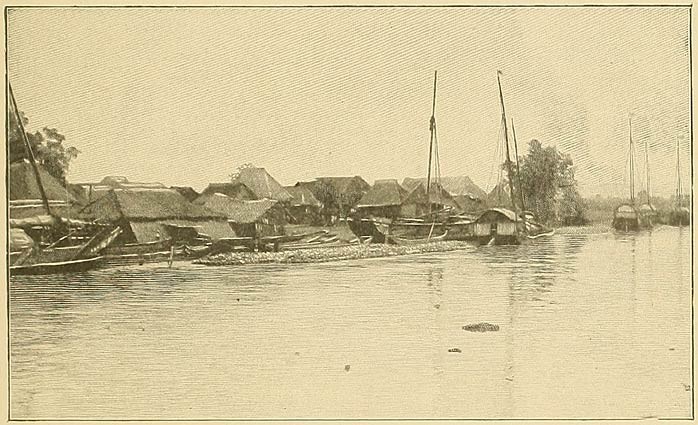

- In the Province of Pangasinan 39

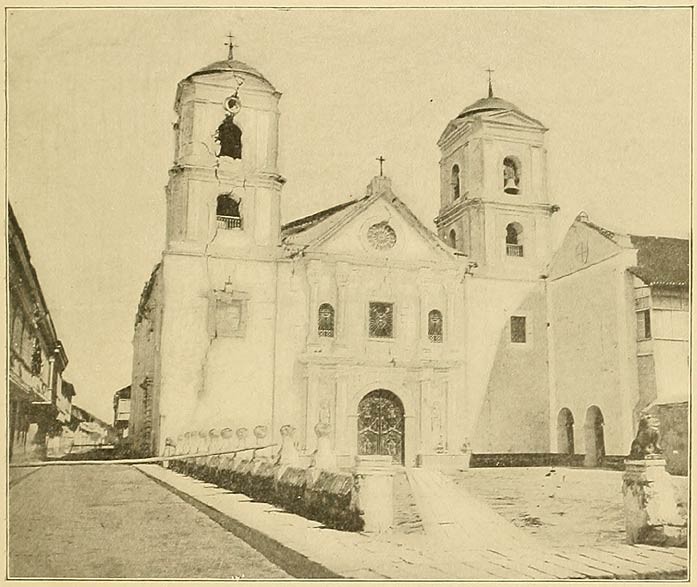

- San Augustine Church, in Old Manila 43

- A Suburb of Old Manila 45

- The Abandoned Aqueduct 47

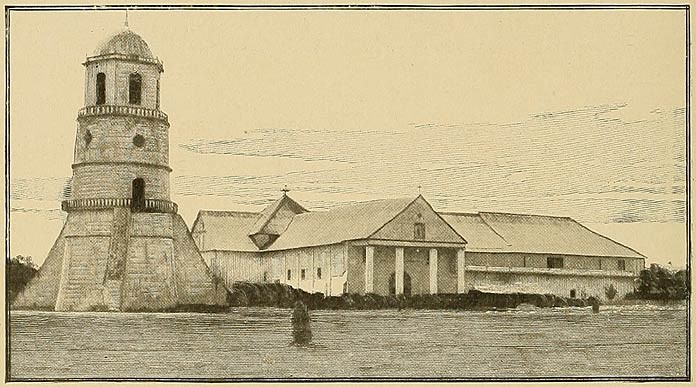

- Tower of Defense, Church, and Priest’s House 50

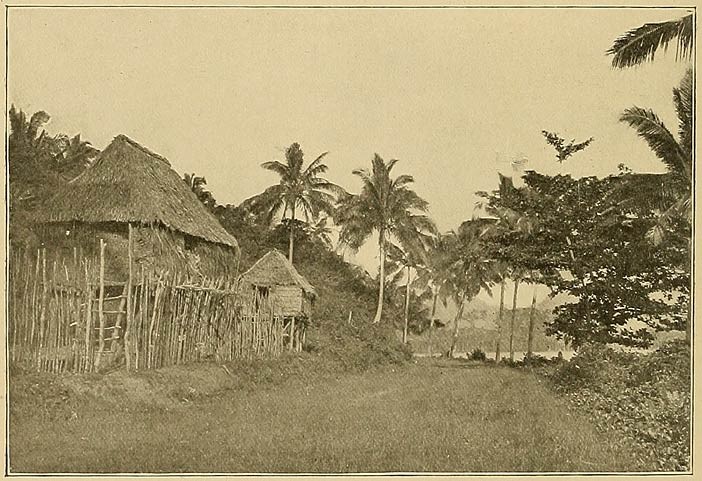

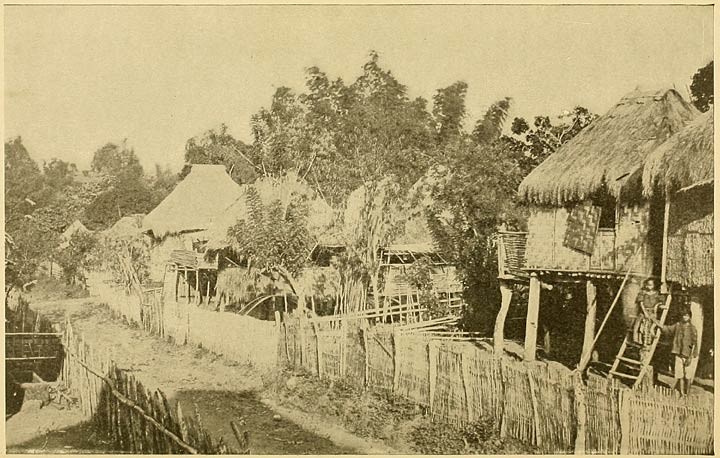

- A Native Village in the foot-hills: Old Manila 52

- A Bamboo House in Pampanga Province 54

- A Street Scene in Albay 59

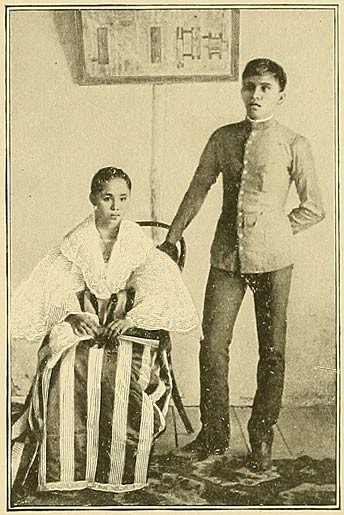

- Children of a Gobernadorcillo 61

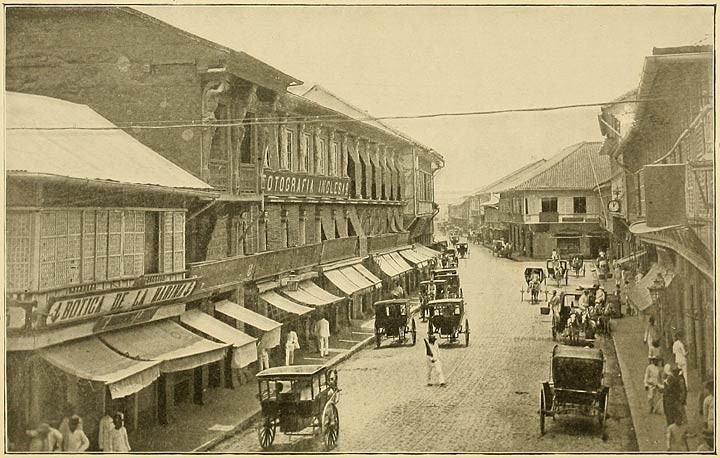

- Along the Escolta: Principal Business Street in New Manila 63

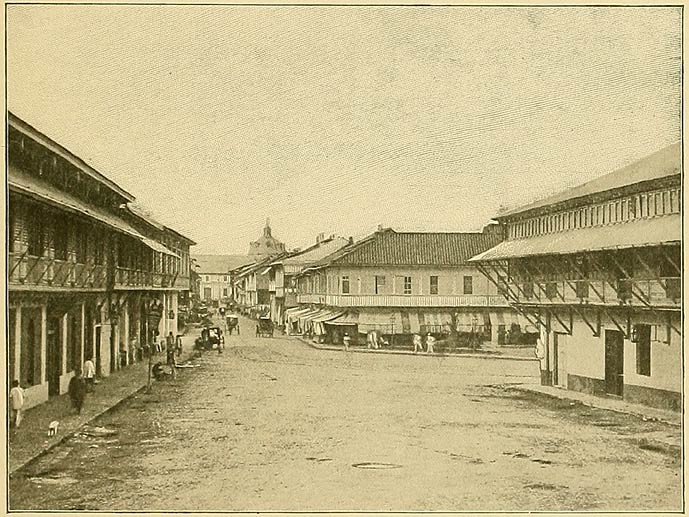

- A Business Street in Old Manila 65

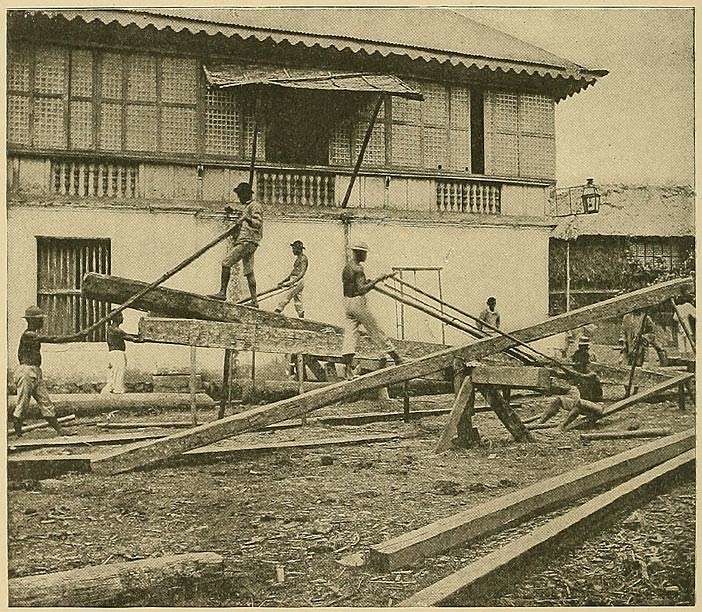

- In the Lumber District 68

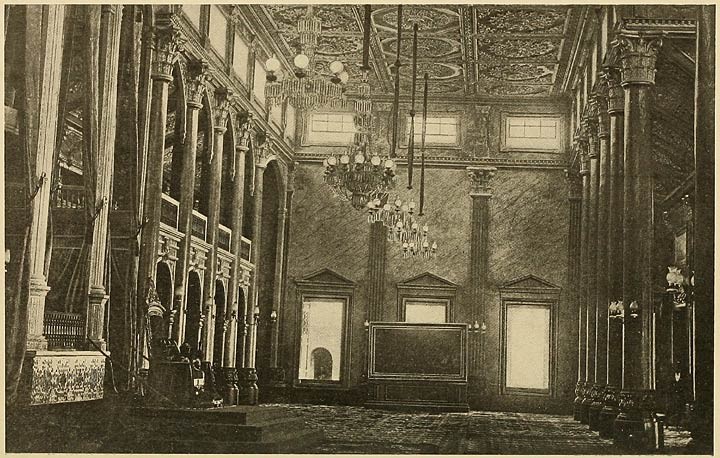

- Throne Room of the Archbishop’s Palace 72

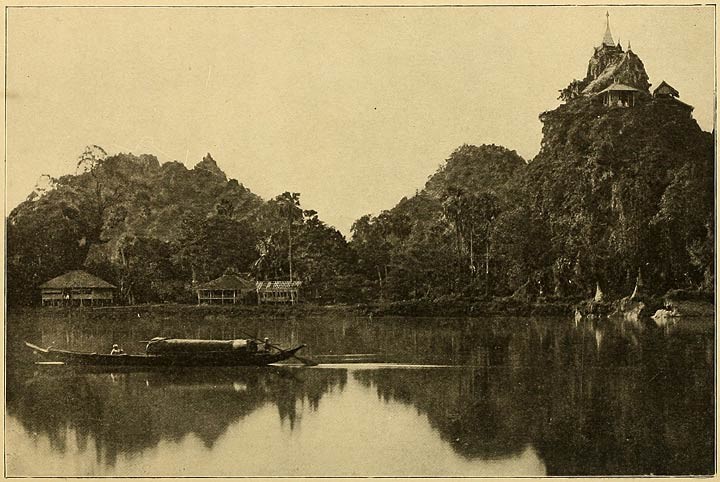

- The Famous Shrine of Antipolo 74

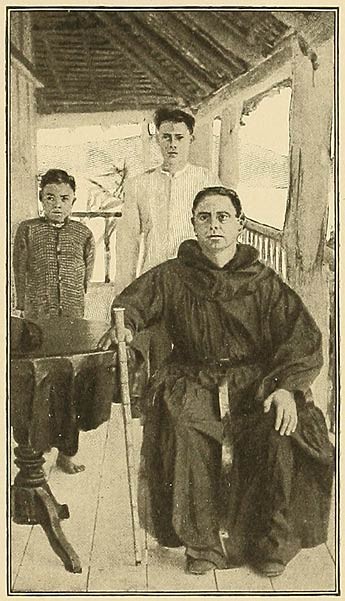

- A Parish Priest 77

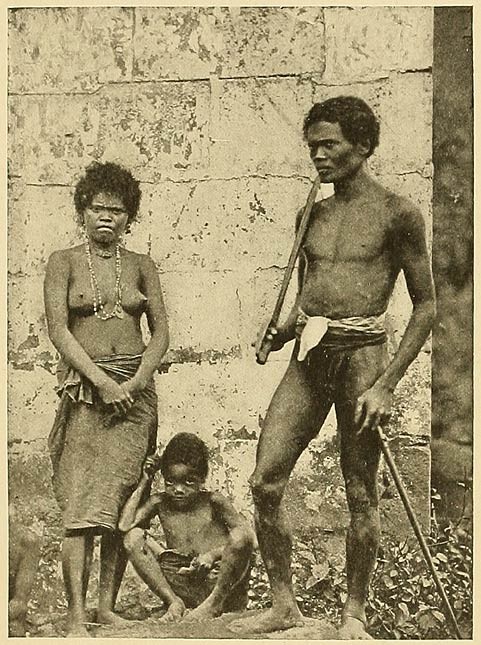

- Negritos of Pampanga 81

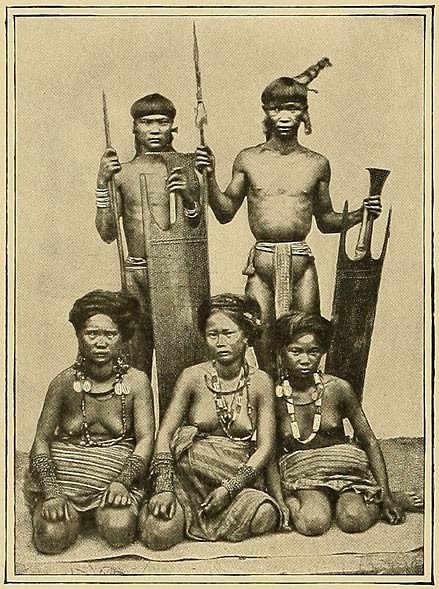

- The Igorrotes 82

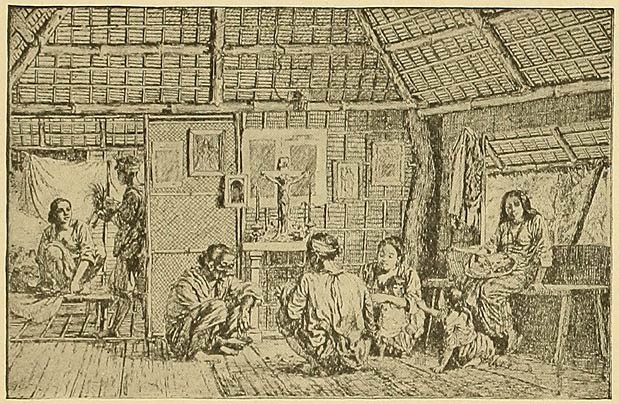

- Interior of a Native Hut 85

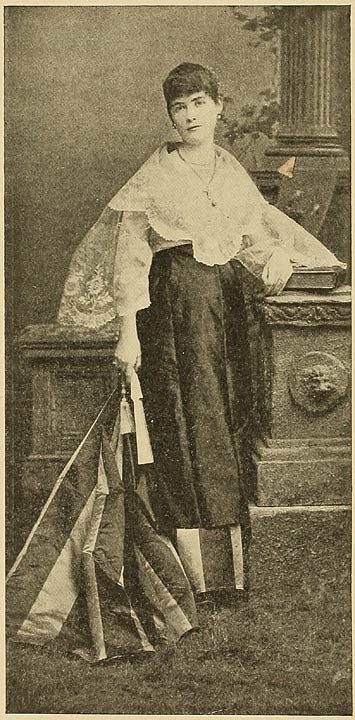

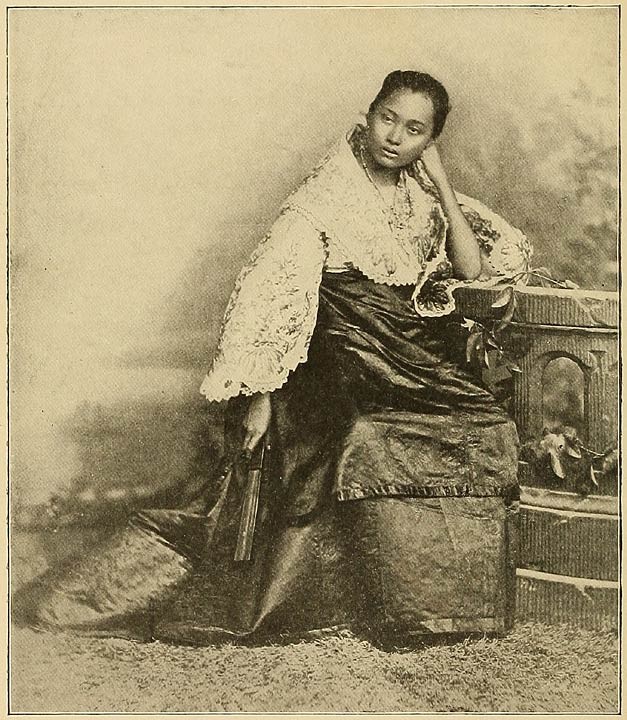

- A High-born Filipina—upper garment of costly Piña 86

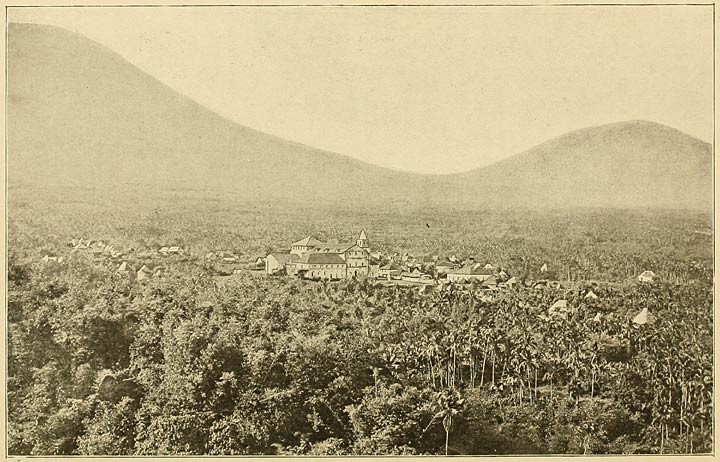

- The Fashionable Church and the Village of Majayjay 89

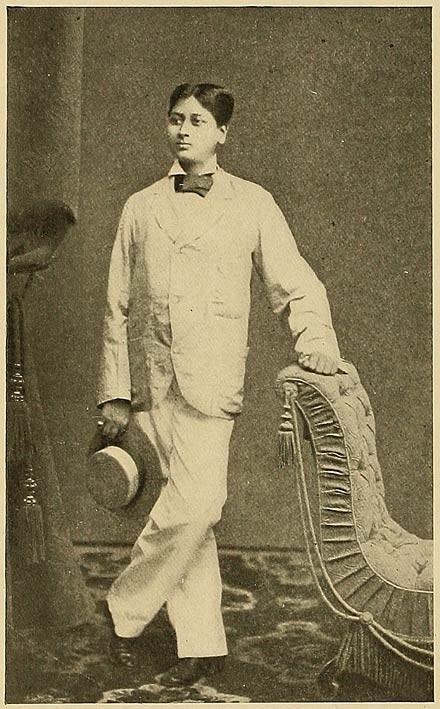

- Author in Silken Suit: kind worn by high-class natives 90

- Full-blooded Native Girl in Reception Attire 92

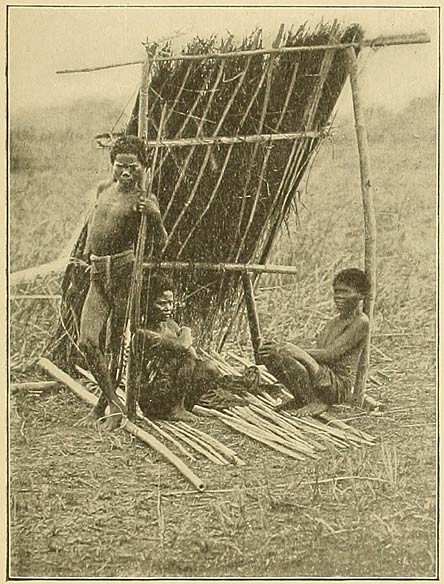

- Negritos Enjoying a Primitive Sun-shade 95

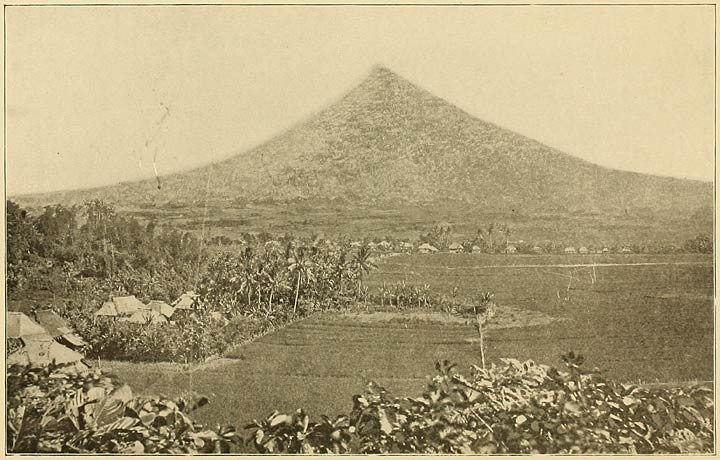

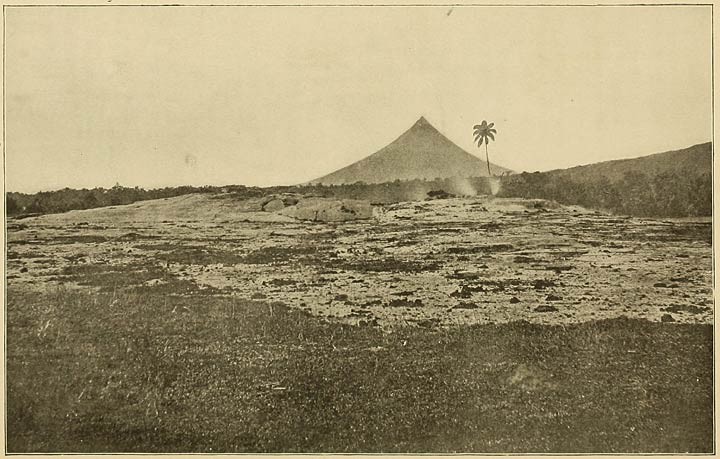

- Volcano of Albay—a near view 97

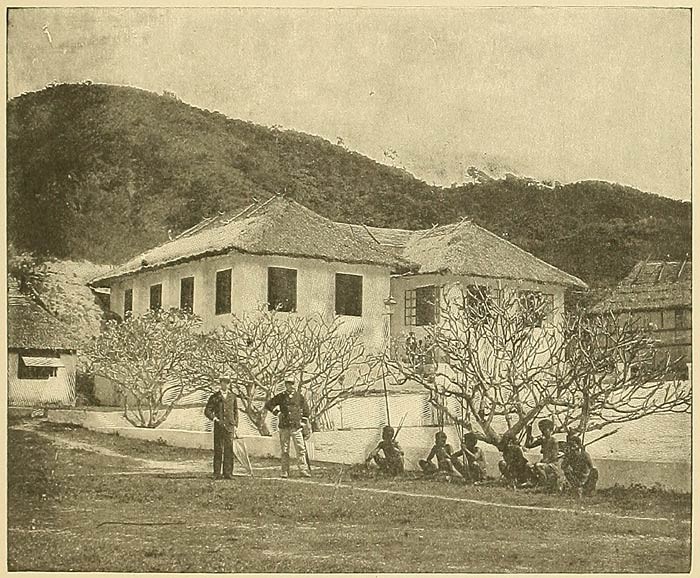

- A Body-guard of Igorrotes 99

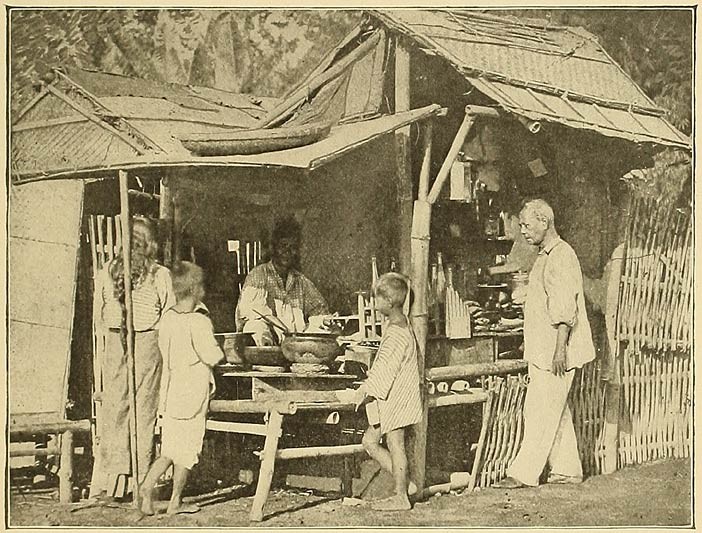

- A Native Restaurant, in Binondo 101

- Chinese Merchants on their way to the Joss House 103

- A Chinese Chocolate-maker 105

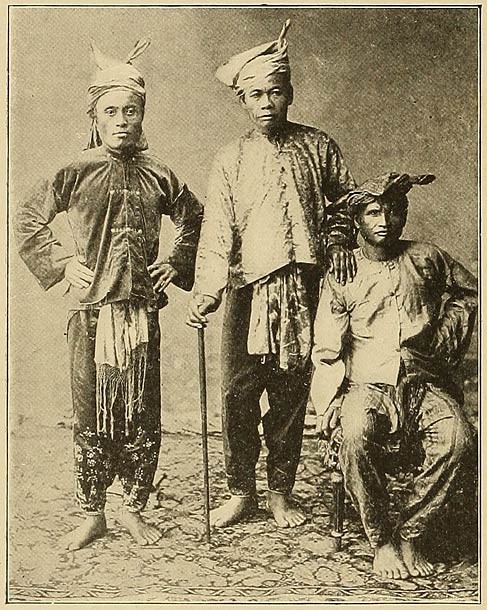

- Chieftains of Sulu 108

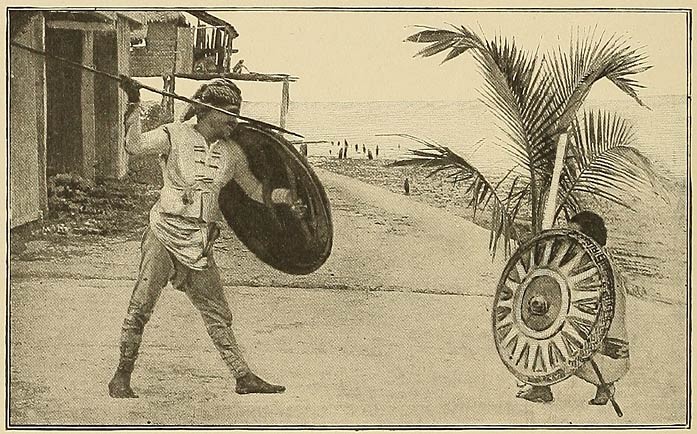

- Sulu Warriors in Fighting Attitude 110

- A Bamboo Thicket in Sulu 112

- The Devil’s Bridge, in Wild Laguna 114

- A Jungle in Luzon 116

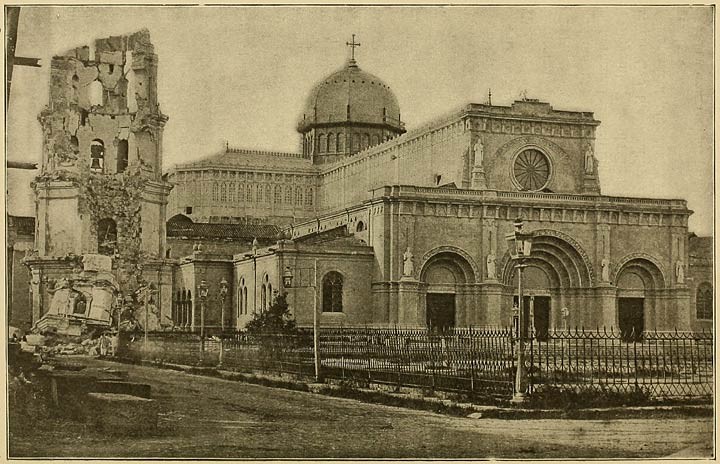

- The Magnificent New Cathedral in Old Manila, and Ruins of the Old Cathedral, Destroyed by Earthquake 1863 121

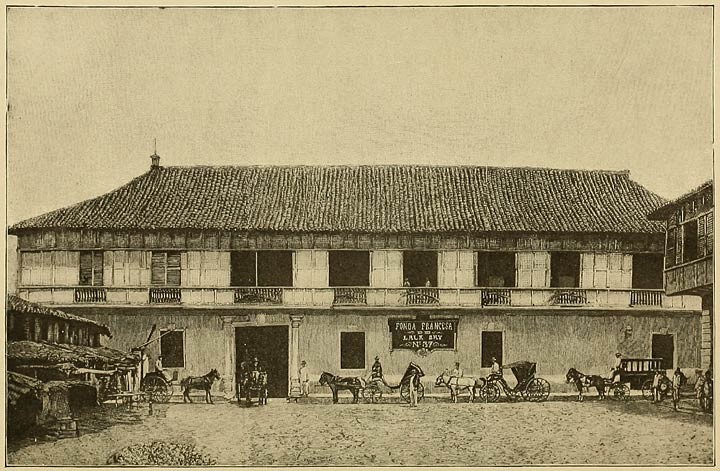

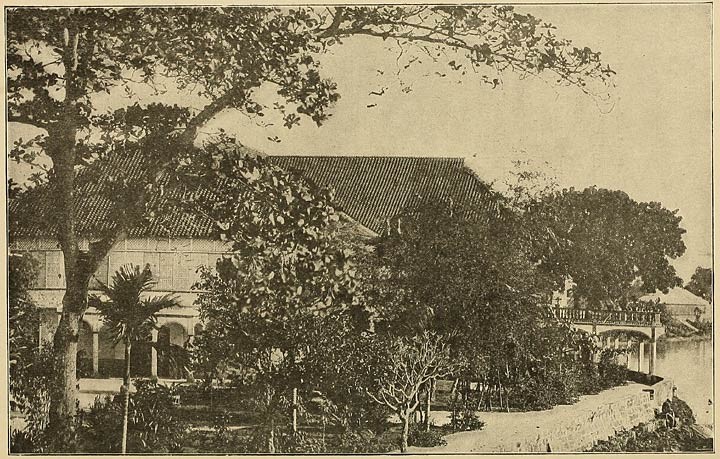

- Commercial House of Russell & Sturgis; First American Merchants; Later, Lala’s Hotel 123

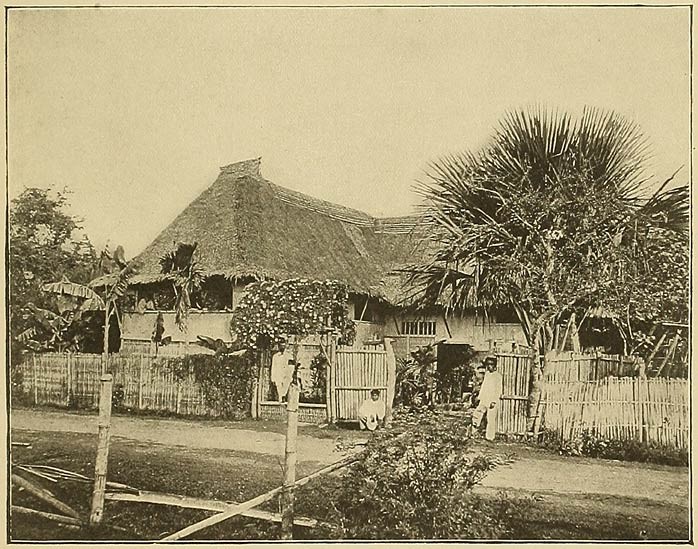

- “Home, Sweet Home,” as the Filipino knows it 125

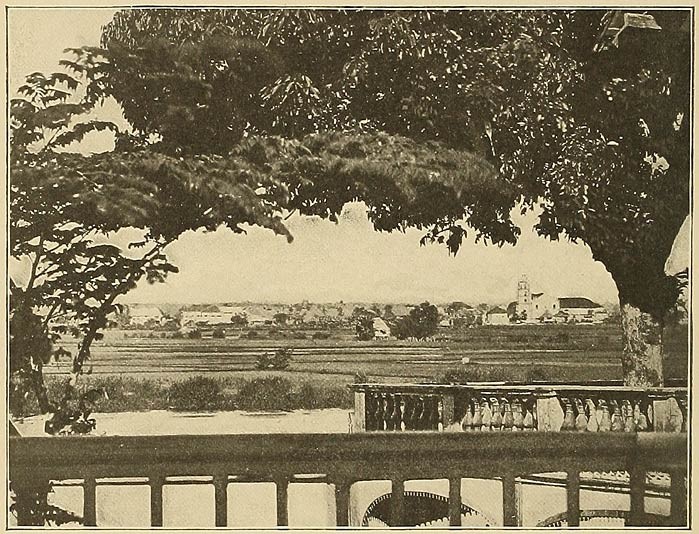

- Balcony of Manila Jockey Club, overlooking Pandacan 126

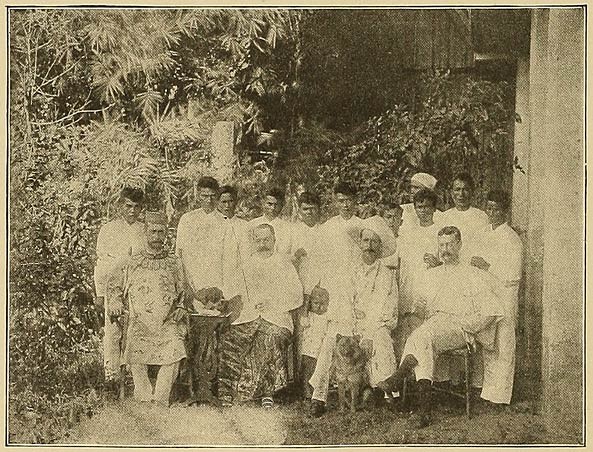

- The Nactajan Mess: Manila Jockey Club 128

- Church of San Francisco, and the Old City Walls 130

- A Rear View of the Governor-General’s Palace 132

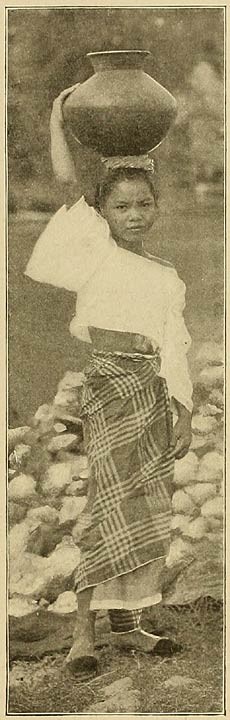

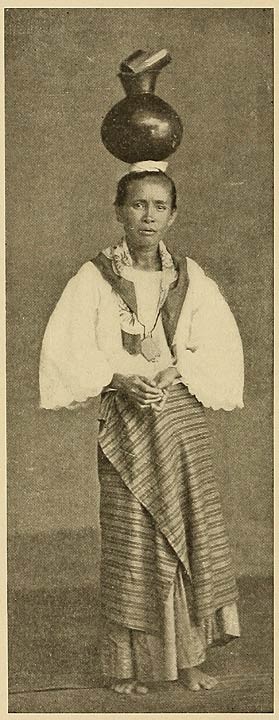

- A Water-girl 133

- The Garrote, Manila Method of Capital Punishment 135

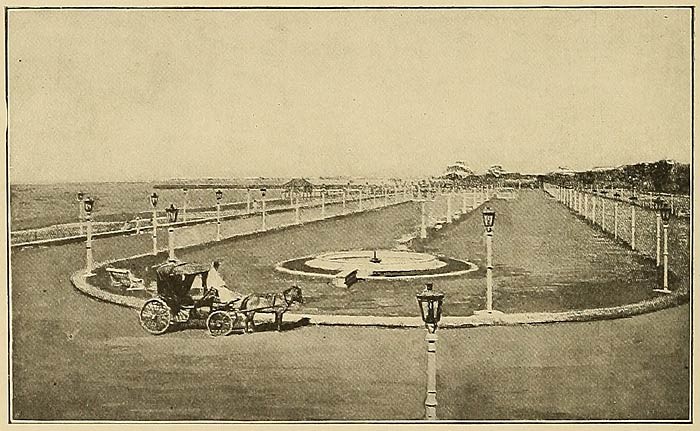

- The Beautiful Luneta 136

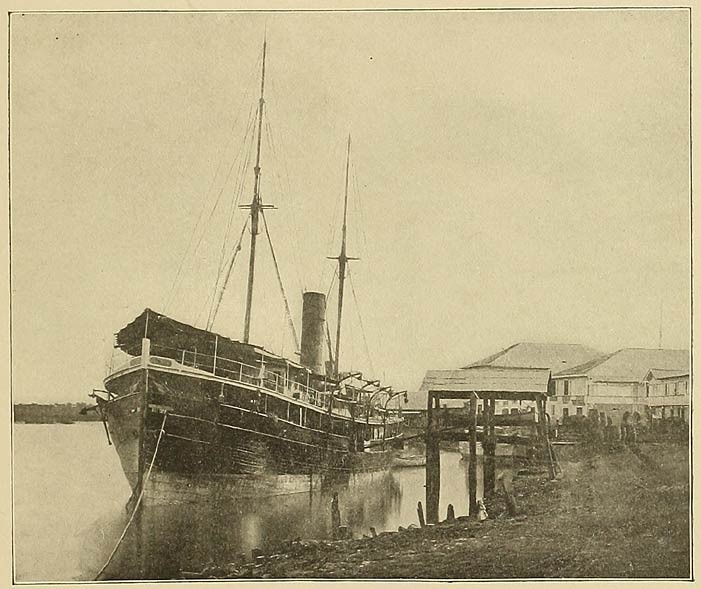

- At the Port of Iloilo 139

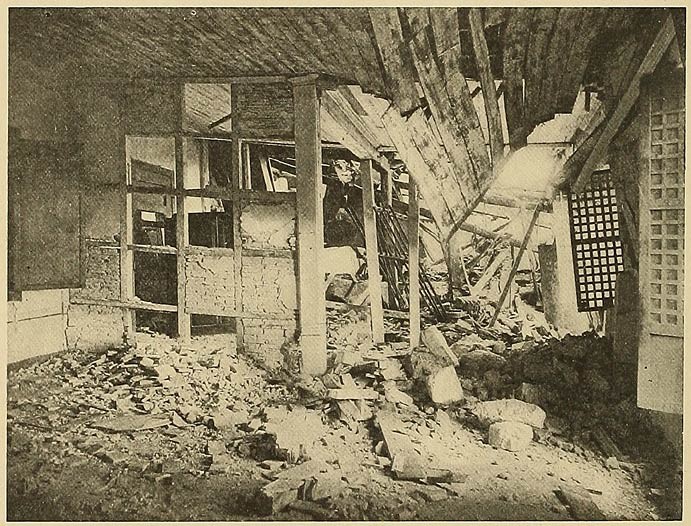

- Interior of a House Destroyed by an Earthquake 140

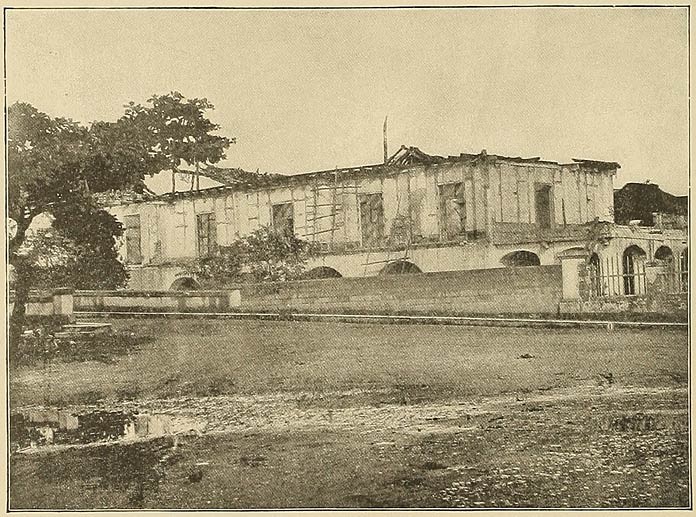

- Open-air View of an Earthquake’s Violence 142

- A Milkwoman of Calamba 144

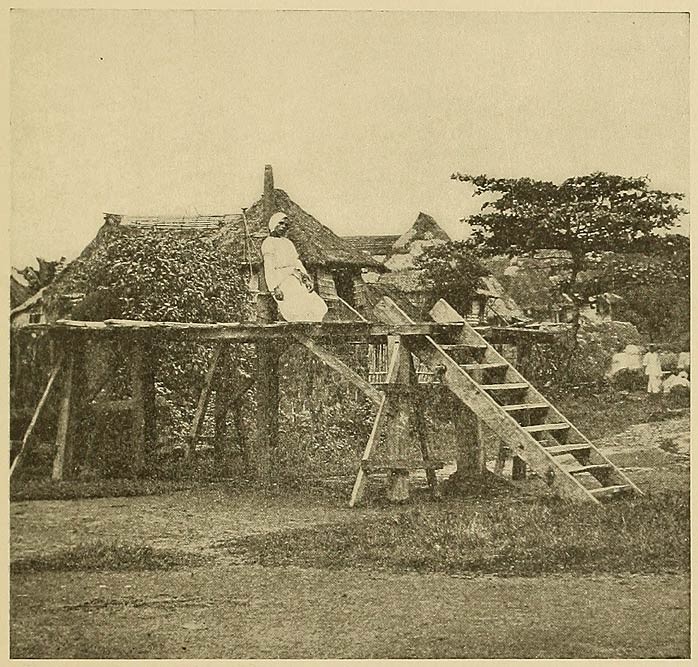

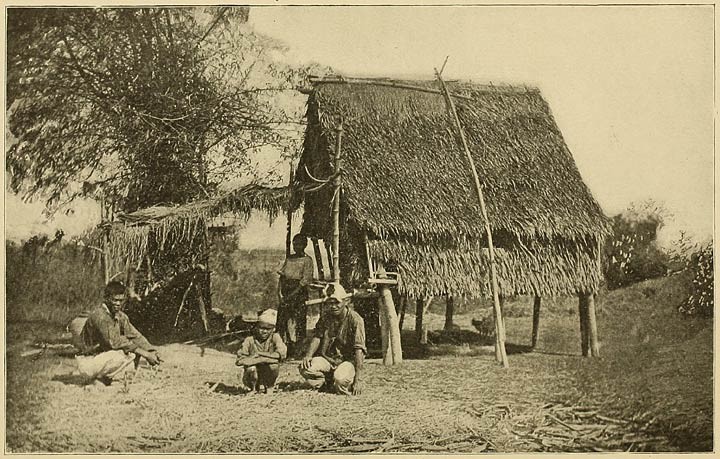

- A Native Hut in the Interior 147

- Hot Water Springs, Albay; and Mayon Volcano 149

- The Once-beautiful Botanical Gardens 152

- Malecon Promenade, along Manila Bay 154

- A Mestiza Flower-girl 157

- A Village Feast 160

- A Fashionable Church in Majayjay, Near Manila 162

- Home of a well-to-do Manila Merchant 164

- Cock-fighting: the Supreme Enjoyment 166

- Interior of the Cathedral, where all Processions Begin And End 168

- Square of Cervantes: Fashionable Quarter of Manila 170

- A Scene From the Moro-Moro Play 172

- The Puente de España: Stone Bridge, Replacing the Old Wooden One 175

- Square of Cervantes—New Manila 178

- Tondo: The Ancient Quarter of Native Fishermen 180

- Water-Carriers and Fruit-Vender 182

- Ancient and Present Method of Washing Clothes 184

- A Procession of Natives Carrying Fish 186

- A Mestizo Merchant 189

- The Escolta: Looking Toward Santa Cruz 191

- A Milkman on his Rounds 193

- A Village of Santa Ana 195

- A Water-Carrier and Customer 196

- Weaving the Beautiful Piña Cloth 200

- Women Employed in a Piña Shop 202

- Natives Preparing the Ground for Sugar-Cane Planting 204

- Old-fashioned Process of Drying Black Sugar 206

- Cane-stalk Yard, Tanduay; Drying Crushed Cane for Fuel 208

- Native Women Hulling Rice 211

- Mayon Volcano, Albay; in the Hemp-producing District 215

- A Hemp Warehouse, Manila 217

- A Hemp Press at a Busy Hour 219

- A Chinese Hemp Merchant in Gala Attire 221

- A Wealthy Spanish Merchant of Albay 223

- A Bamboo Bridge in Albay 225

- A Cigar and Cigarette Factory in Manila 228

- A View of the Suspension Bridge, Manila; over the Pasig River 230

- Native Girls Making Manila Cheroots 233

- Spanish Luxury in the Old Days 234

- District of Taäl: in the Batangas Province 238

- The Useful Buffalo: for all Hauling Purposes 240

- A Betel-Nut Gatherer of Luzon 244

- A Typical Native Fruit-Girl 246

- “La Belle Chocolatière” of Luzon 248

- Shifting Lumber in a Forest of Tayabas 252

- Natives Transporting Lumber to the Coast 254

- The Young Proprietor of a Cocoanut Grove Gathering Tuba 256

- A Wealthy Mestiza of the Upper Class 258

- A Group of Tagals Employed by a Mining Company 262

- Another Glimpse of the Great Stone Bridge 264

- La Laguna Lake; the Neighborhood of a Gold Discovery 266

- A Country House in Tanguet Village 268

- House of Native Coal-Laborer of Cebú 270

- A Buffalo in Harness; Harrowing the Soil 274

- Grand Stand, Santa Mesa, where the Pony Races are run 276

- At the National Sport; Just Before the Contest 278

- A Wayside Restaurant 281

- A Native Servant-Girl 282

- Buffalo Transporting Lumber in Pampanga 285

- Enterprising Sugar Refineries, Tanduay 287

- La Bella Filipina in Troubadour Costume 290

- Foreigners at Tiffin in Manila 292

- Dr José Rizal, Martyred Leader of the Present Insurrection 295

- An Execution of Insurgent Chiefs on the Luneta 296

- Entrance of the River Pasig, Manila 299

- The President of the United States and His War-Cabinet 300

- Andres Bonifacio, sometime Rebel President of so-called Tagal Republic 303

- Emilio Aguinaldo 305

- Native Women: their Upper Garment—Pañuelo—of Piña 306

- Types of the Tagbanua Tribe 308

- A Battery at the Corner of the Old Fortifications, Manila; Facing the Bay 313

- The Spanish Fleet as it Appeared in the Philippine Waters 315

- The Hot Springs of Luzon Province 317

- The Reina Cristina, Flagship of Admiral Montojo 318

- The Isla de Cuba; To it the Spanish Flag was Transferred 322

- The Olympia; Admiral Dewey’s Flagship 324

- Admiral Montojo, Commander of Spanish Fleet at Manila 327

- Cavité; a Rebel Stronghold, Noted for its Arsenal 328

- Alfonzo XIII., the Boy King of Spain 330

- The Queen-Regent of Spain 333

- Rear-Admiral George Dewey 334

- Don Basilo Augustine, Spanish Captain-General of the Philippine Islands 338

- General Wesley Merritt, American Commander of Military Forces at Manila 340

Maps 343

Introduction.

The absolute present necessity for accurate information by the people of the United States respecting the Philippines has been met in no more satisfactory manner than by this book.

The author, Mr. Ramon Reyes Lala, is a Filipino and was born in Manila. His collegiate education was completed in England and Switzerland. A long sojourn in Europe has instructed him in European thought, tendencies, and methods. He has lived in the United States for many years, and has become, by naturalization, a citizen of this country.

He collected the historical material for this work largely from the Spanish archives in Manila before the last rising of the people of Luzon in rebellion against Spain. His mastery of the English language is that of the thorough scholar. His qualifications for his work are those of the student, trained by many studies. He possesses by nativity the gift, incommunicable to any alien, of giving a true color and duly proportioned form to his delineations of his own people. These endowments have enabled him to produce a work of striking and permanent value.

The most meritorious feature of Mr. Lala’s book is unquestionably its impartiality of statement and judgment. This is particularly apparent in his descriptions of the moral and intellectual character of his countrymen. No defect is extenuated, nor is there any patriotic exaggeration of merits. The capacities and limitations of the Filipinos are plainly and photographically depicted. The difficulties and the facilities of their political control by the United States are weighed in a just balance by the reader himself in considering these portrayals of national character.

This colorless truth of statement appears not alone in Mr. Lala’s special descriptions of the character of his people. It is also manifest, as it is incidentally displayed, in his many expositions of the systems and methods of labor, of social usages, of domestic life, of civil administration, of military capacity, of popular amusements and of religious faith. The result is that he has communicated to the reader an unusually distinct conception of national and ethnic character. This is always a very difficult task. The most graphic portrayal in this respect most commonly enables the reader merely to perceive indistinctly, but not clearly to see.

The book is of a most practical character. Its statements of commercial history and methods, and of past and present business and industrial conditions, are most satisfactory. Such an exposition is at this time most indispensably needed. Everybody knows, in a general way, that the Philippine Islands produce sugar, rice, hemp, tobacco, coffee, and many other agricultural staples, and that they are rich in minerals and valuable woods. But heretofore it has been very difficult to obtain specific information upon these subjects. Mr. Lala has given this information. The practical man, the farmer, the manufacturer, the merchant, the miner is here informed concerning resources, methods, prices, labor, wages, profits, and roads. While this information is not technical, it is instructively full and is evidently reliable.

The descriptions of the processes of cultivating and preparing hemp, sugar, coffee, rice, and tobacco, and the suggestions of the ways by which these methods can be easily improved, and the products made more profitable, are, in every way, most satisfactory.

The Philippines began to come under European control with the administration of Legaspi, the first Governor-General, in 1565, long before the English had colonized any portion of North America.

For about three hundred and fifty years the Spanish system has been in contrast with that of every other colonizing nation. It has been worse than the worst of any of these. While there is no elaborate contrast of these systems in Mr. Lala’s book, he nevertheless depicts so thoroughly the manifold and inveterate rapacity, cruelty, corruption, and imbecility of Spanish colonial administration, that he also discloses the vast possibilities of the better contrasted systems.

No war was ever yet waged in the interests of humanity, as the war against Spain unquestionably was, that did not produce consequences entirely unforeseen at its beginning. This truth was never more convincingly confirmed than by the war just ended. The United States demanded the evacuation by Spain of Cuba and Cuban waters. Compliance by Spain would have limited the consequences to the evacuation. She did not comply. She chose the arbitrament of war, and the result was her extirpation from her insular possessions in the West Indies and the Philippines.

This providential and revolutionary event imposed upon the United States duties unforeseen, but none the less imperious. As to the Philippines, those duties are complicated by the irresistible tendencies which seem to make certain the dismemberment of China, and the subjection of that immemorial empire to all the influences of Western civilization. This is an event not inferior in importance to the discovery of America by Columbus, and the interest of the United States in its consequences is of incalculable importance. With this interest its relations to the Philippines is inseparably connected, and those relations present for consideration policies which disenchant the situation of all idealism and make it intensely practical. To this possible result the war waged against the United States by Aguinaldo and his followers has decisively contributed.

But, in any event, whatever the relations of the United States to the Philippines may finally become, the book of Mr. Lala will undoubtedly influence and assist the considerate judgment of those whose duty shall call them to determine the momentous questions which are now enforcing themselves for solution upon the attention of the American people.

Washington, March 22d, 1899.

[Cushman Kellogg Davis, U. S. Senate, Minnesota, 1887 to ——; Chairman Committee on Foreign Relations; Member of the Commission that met at Paris, September 1898, to arrange terms of peace between the United States and Spain.]

Preface.

About twenty years ago, when a student at St. John’s College, London, I was frequently asked by people I met in society for information regarding the Philippines and the Filipinos. Many also, who showed considerable interest, and who wished, for various reasons, to carry their investigations further, complained that there was in English no good book on the subject. Afterward, when I continued my studies at a French college in Neûchatel, Switzerland, I met with many similar inquiries, and here too in America I found demand for a comprehensive, reliable work upon my country.

But it was not until I had traveled considerably through Europe, studying the history of the various States and peoples, that the idea of writing a history of my own fatherland occurred to me. It was mortifying then to think that the glories of my native land were no better known. Accordingly, I resolved to become the chronicler, and I began at once to collect material for a work on the Philippines, that should, I trusted, be deemed a permanent contribution to historical literature.

Upon my return to Manila from Europe, I immediately began a study of the Colonial archives in the office of the Governor-General. From these I gathered many valuable data about the early history of the colony, and also much information that would be locked to the curious traveler. And on account of my knowledge of Spanish, and because of my friendship with the Governor-General Moriones, I was enabled to do this thoroughly. Thus I gradually laid the foundation for the present work.

When, a few years later,—in 1887,—because of my sympathy with the rising cause of the insurgents, Spanish tyrants banished me from my country and my kindred, I carried away all the manuscripts I had already written, resolved to finish the task I had set before me amid a more congenial environment.

I came to the United States. Of this country I, in due time, became a citizen. However, I kept up my relations with friends in Manila; for I still felt an interest in the fate of my native land. Though I have since revisited the Orient, I preferred to retain my American citizenship, rather than again put myself under the iron yoke of Spain. I have, nevertheless, kept pace with the march of events in the colony, and had, indeed, about completed my history when Dewey’s grand victory denoted a new era for the Filipinos, and, hence, made the addition of several chapters necessary. I have thus added much of supreme interest to Americans; bringing the book to the capture of Manila by the American forces.

My acquaintance with the leading insurgents,—Rizal, Aguinaldo, Agoncillo, the Lunas, and others,—has also enabled me to speak with authority about them and the cause for which they have fought.

In writing this work I have consulted all previous historians, the old Spanish chroniclers, Gaspar de San Agustin, Juan de la Concepcion, Martinez Zuñiga, Bowring, Foreman, and various treatises, anthropological and historical, in French, Spanish, and English.

To all these writers I am indebted for many valuable facts.

It has been my aim to give—rather than a long, detailed account—a concise, but true, comprehensive, and interesting history of the Philippine Islands; one, too, covering every phase of the subject, and giving also every important fact.

And my animating spirit of loyalty for my own countrymen makes me feel that I cannot more clearly and fully manifest my affection for them and my native land than by writing this book.

Many of the pictures are photographs taken by myself. The rest were selected from a great number of others, that were accessible, as being most typical of Philippine life and scenery.

The student of history, and he that would learn something about the customs of the people, and the natural resources of the country, may, I trust, find the perusal of this work not without profit and interest.

I desire to attest here my gratitude for the many courtesies shown me, and for the hearty manner in which I have been received, in this great, free country.

Everywhere it was the same.

And I would say to all loyal, ardent Filipinos, that I believe that they eventually will not regret the day when Commodore Dewey sundered the galling chains of Spanish dominance, and when General Merritt, later, hoisted the Stars and Stripes over the Archipelago.

They will, rather, most surely live to recognize and appreciate the unsullied manifold advantages and benefits incident to American occupation and to a close contact with this honest, vigorous type of manhood.

The Author.

New York December, 1898.

Early History of the Islands.

Discovery and Conquest.

When Magellan in the spring of 1521 took formal possession of Mindanao, one of the largest of the Philippine group, he was surrounded by crowds of the curious brown-skinned natives of that island; with sensations of awe, they watched their strange white visitors, believing them to be angels of light. It was Easter-week, and the Spanish discoverers, with all the ritualistic splendor of the mass, dedicated the newly-found islands to God and the Church.

The natives, too, manifested great friendliness to the tempest-tossed mariners. Indeed, one of their most prominent chieftains himself piloted the exploring party to Cebú, where thousands of natives, arrayed in all the barbarous paraphernalia of savagery, stood on the beach, and, with their spears and shields, menaced the strangers.

The Mindanao chieftain, who had acted as pilot, thereupon went on shore and volunteered an explanation: these strange voyagers were seeking rest and provisions, having been many weary months away from their own country.

A treaty of amity was then ratified according to their native custom, each party thereto simultaneously drawing and drinking blood from the breast of the other. Magellan then caused a rude chapel to be built on this new and hospitable shore, and here the natives witnessed the first rites of that Church that, within a century, extended its oppressive sway from one end of the Archipelago to the other.

The King and Queen of the natives were soon persuaded to accept the rite of baptism. This they seemed to enjoy greatly. To persuade the good-natured savages to take the oath of allegiance to the King of far-away Spain was but a step farther. One ceremony was probably as intelligible to them as the other; and thus the first two links in the fetters of the Filipinos had been forged.

The Fortifications of Old Manila.

With characteristic arrogance the Spaniards henceforth conducted themselves as the rightful masters of both the confiding natives and their opulent country.

It appears, now, that the natives of Cebú were engaged in war with another tribe on the island of Magtan. The adventurous Magellan, beholding an opportunity for conquest, and, perhaps, for profit, accompanied his allies into battle, where he was mortally wounded by an arrow.

Thus perished the brave and brilliant discoverer, in the very bloom of life, when both fame and fortune seemed to have laid their most precious offerings at his feet.

Posterity has erected a monument on the very spot where this hero was slain. Cebú also boasts an obelisk that commemorates the discovery; while on the left bank of the Pasig river, Manila, stands another testimonial to the splendid achievements of the intrepid Magellan.

Duarte de Barbosa was now chosen leader of the expedition, and he, with twenty-six companions, was invited to a banquet by Hamabar, the King of the island. In the midst of the royal festivities the Spaniards were treacherously murdered. Juan Serrano alone—so the old chronicles relate—was spared. He had, in some way, secured the favor of the natives, and now, stripped of his clothing and his armor, he was made to walk up and down the beach, in full view of his companions on board the ships.

For his person the natives shrewdly demanded a ransom of two of the Spanish cannon. A consultation was held among the Spaniards, and it was decided that it was better that one should perish than that the lives of all be jeoparded. And so Serrano was left to his fate.

Adventures of Juan Sebastian Elcano.

Reduced, at last, to about 100 men and two ships, the Spaniards decided to return home. The captain of one of these—of the Victoria—was Juan Sebastian Elcano. This gallant sailor, after losing many brave companions and meeting many thrilling adventures, at last brought his ship safely to a Spanish port—three years after he had embarked, en route to the Moluccas, under his first commander, the unfortunate Magellan.

When Elcano and his seventeen companions landed in Spain, they were mere skeletons, so reduced were they by hunger and disease. Everywhere they were received with acclamations of joy, and upon their arrival in Seville they straightway proceeded to the Cathedral, where, amid grand Te Deums, they gave thanks to God for their return.

It must, indeed, have been a strange sight to see this remnant, these gaunt survivors of the splendid company of adventurers that had left that city but three years before,—flaming with zeal for the spread of the Church, and glowing in the desire of conquest,—these few half-starved wretches, now walking barefooted, with lighted candles, through the streets,—all that was left of that eager throng.

And yet, pitiable as they were, they must have been conscious of an achievement that meant glory for their country and immortality for themselves.

Nor were they unrewarded. All received food and money, and Elcano, the leader, was voted a life-pension of 500 ducats; and, in token of his great accomplishment in having first circumnavigated the globe, the King knighted him, awarding him, as his escutcheon, a globe with the motto: “Primus circundedit me.”

The cargo of the Victoria consisted of 26½ tons of cloves and other spices: cinnamon, sandalwood, nutmegs, and so forth. It is said that one of the Tidor islanders, brought back with the expedition, who was presented to the King, was never permitted to return to his home, because he had committed the blunder of making inquiry regarding the value of spices in the Spanish markets.

The Trinidad, the other vessel of this remarkable expedition, after many terrible hardships, fell into the hands of the Portuguese, who sent the survivors to Lisbon. They reached that port five years after their departure with Magellan.

The enthusiasm of the Spanish monarch and his subjects on account of these remarkable discoveries was unbounded. Other expeditions to the islands were soon fitted out. One, under the leadership of Ruy Lopez de Villalobos, gave to them the name of the Philippine Islands. This was in honor of Philip, Prince of Austria, the son of King Charles I., heir-apparent to the throne of Castile; to which, in 1555, upon the abdication of his father, he succeeded as Philip II.

This bigot, convinced by his religious advisers of the importance of winning the newly-discovered islands for the Church, caused another expedition to be fitted out from Navidad, in the South Sea.

Legaspi, the First Governor-General.

Accordingly, Miguel Lopez de Legaspi, a well-known Basque navigator, of great piety, and with a reputation for probity and ability, set out with four ships and one frigate, all well armed and carrying 800 soldiers and sailors. Six priests also accompanied them. One was Urdaneta, who had formerly sailed as a captain to the Moluccas. The avowed object of the expedition was to subjugate and to Christianize the benighted natives of those islands.

After a propitious voyage, not without incident, General Legaspi resolved to cast anchor at Cebú, a safe port. On the way the ships stopped at the port of Dapitan, on the island of Mindanao. Prince Pagbuaya, the ruler of this island, was so astonished at the sight of these large ships off the coast of his country, that he commanded one of his subjects, who had some reputation for boldness, to observe their movements and to report his observations.

He did. They were manned, he said, by enormous men with long, pointed noses; that these strange beings were dressed in fine robes, and actually ate stones (hard sea-biscuits); most wonderful of all, they drank fire, and blew smoke out of their mouths and through their nostrils—referring, of course, to their drinking and smoking. He also said that they could command the thunder and the lightning—meaning their fire-arms;—that their proud bearing, their bearded faces, and splendid attire, moreover, surely proclaimed them to be gods.

Having heard this report, the Prince, accordingly, thought it not unwise to treat with these wonderful beings. Legaspi not only succeeded in obtaining provisions—in barter for European wares—from this chief, but he also obtained much useful information about his destination, Cebú. He learnt that it was considered a powerful kingdom, whose greatness was much feared by other States, and that its port was not only safe, but also favorably situated.

The General, therefore, determined to annex it to the Crown of Castile at the earliest opportunity. He landed at Cebú April 27th, 1565, and immediately began negotiations with the natives.

These, however, remembering their successful resistance to Magellan’s party but a generation before, opposed every advance of the Spaniards. The latter, notwithstanding, finally took possession of the town, and sacked it; but for months they were so harassed by the chief and his subjects that they were several times on the point of retiring. Legaspi, however, decided to remain, and the natives, growing accustomed to their presence, gradually yielded to the new order of things; and thus the first step in the conquest of the islands was made. The people were declared Spanish subjects. Happy at his success, Legaspi determined to send the news at once to Spain. Urdaneta was therefore commissioned to bear the despatches. In due time he arrived at his destination.

Legaspi, meanwhile, steadily and successfully pursued the conquest of Cebú and surrounding islands. He succeeded most admirably also in winning the confidence of the natives. Their dethroned King Tupas was baptized, and his daughter married one of the Spaniards. Other alliances also were made, which bound the two races together.

The Portuguese, the natural enemies of Spanish exploration and conquest, now appeared on the scene and attempted, in vain, to dispute the possession of the successful invaders. The Spaniards then built a fort, and plots of land were marked out for the building of houses for the colonists. In 1570 Cebú was declared a city, and Legaspi, by special grant from the King, received the title of Governor-General of all the lands that he might be so fortunate as to conquer.

A Glimpse of the Old Canal.

Soon afterward, Captain Juan Saicedo, Legaspi’s grandson, was sent to the island of Luzon to reconnoiter the territory and to bring it into subjection to Spain. Martin de Goiti and a few soldiers accompanied him. They were well received by the various chiefs they visited. Among these were King Lacandola, the Rajah of Tondo, and his nephew, the stern young Rajah Soliman, of Manila. Intimidated by the countenances of the warlike-looking foreigners, and awed by the mysterious symbols of their priests, these superstitious chiefs agreed forever, for no consideration, and without reservation, to yield up their independence, to pay tribute, and to aid in the subjugation of their own countrymen. A treaty of peace having been made, the Spaniards acted as if they were the natural owners of the soil.

Young Soliman, however, soon found occasion to demonstrate that he, at least, had no intention of carrying out his part of this enforced contract. He sowed the seeds of insurrection broadcast among the various surrounding tribes, and not only carried on an offensive warfare against the invaders, but set fire to his capital, Manila, that it might not become the spoil of the invaders. Soliman and his little army were put to flight by Salcedo, who generously pardoned the young chief upon his again swearing fealty to the King of Spain. Then, while Goiti with his forces remained in the vicinity of Manila, Salcedo pursued his adventurous way as far as the Taal district. All the country of the Batangas province was also subdued by him. About this time Salcedo himself, severely wounded by an arrow, returned to Manila.

In the Batangas Province.

Legaspi being informed of the occurrences in Luzon, soon joined Salcedo at Cavité, where chief Lacondola gave his submission. Legaspi, continuing his journey to Manila, was there received with much pomp and acclamation. He not only took formal possession of all the surrounding territory, but also declared Manila to be the capital of the whole Archipelago. He next publicly proclaimed the sovereignty of the King of Spain over all the islands.

Speaking of this period, the old chronicler, Gaspar de San Agustin, says: “He (Legaspi) ordered them (the natives) to finish the building of the fort in construction at the mouth of the river (Pasig), so that His Majesty’s artillery might be mounted therein for the defense of the port and the town. He also ordered them to build a large house inside the battlement walls for Legaspi’s own residence, and another large house and church for the priests.

“Besides building these two large houses, he told them to erect 150 dwellings of moderate size for the remainder of the Spaniards to live in. All this they promptly promised to do; but they did not obey; for the Spaniards were themselves obliged to complete the work of the fortifications.”

The City Council of Manila was constituted on the 24th June, 1571. On the 20th of August of the following year Miguel Lopez de Legaspi died. His was a most eventful, arduous life. His career was honorable, and he occupied a prominent place in the colonial history of his country. He was buried in the Augustine chapel of San Fausto in Manila, where his royal standard and armorial bearings hung until the occupation of the city by the British in 1763.

Li-ma-hong, the Chinese Pirate.

Guido de Lavezares succeeded Legaspi as Governor of the islands, and had not long taken possession when he had to defend them against the assaults of the celebrated Chinese corsair, Li-ma-hong.

This redoubtable Celestial had early shown a martial spirit, and became a member of a band of pirates that for many years infested the seas. Here he so distinguished himself by his prowess and cruelty that, upon the death of the leader, he was at once elected chief of the buccaneers. At length this Celestial Viking essayed an attack on the Philippines. It is said that he first heard of the remarkable wealth of the islands from the crew of a Chinese merchantman returning from Manila. After committing a few depredations along the coast, this Captain Kidd of the Chinese Main appeared before Manila on the 29th of November, 1594, with a fleet of 62 armed junks, manned by more than 2,000 sailors. Twenty-five hundred soldiers were also on board for effective warfare, and more than 2,000 Chinese artisans and women, with which he intended to found the colony that was to be the capital of his new Empire.

So secret was the landing of the Chinese, and so sudden was their attack, that they were already within the gates of the city before the Spaniards knew that they were at hand.

Martin de Goiti, second in command to the Governor, was the first to receive their attack; and, after a brave defense, he was killed with many of his soldiers. The flames from his burning residence gave the Governor himself his first intimation of the enemy’s presence. Flushed with success, Sioco, the Japanese leader of the buccaneers, then stormed the Fort of Santiago, where many Spanish soldiers had taken refuge. A small body of fresh troops coming to the aid of the besieged, the Chinese, after considerable loss, retreated, fearing that other reinforcements might follow and cut off their return to the ships.

It was now reported that Li-ma-hong himself, who, with the greater part of his force, was at Cavité, would lead the next assault. The inhabitants of Manila, therefore, awaited him in great terror.

Fortunately, however, that intrepid warrior, Juan Salcedo, fresh from his conquests in the north, now came to the city’s aid. Just about sunrise on the 3d of December the Chinese squadron again appeared in the bay near the capital. The Celestials disembarked, and, it is said, their leader, in an eloquent speech, incited his followers to the assault, with glowing promises of plunder.

Meantime, while the Chinese were forming into battle-line, within the walls of the city the drums and the trumpets of the Spaniards kept up an inspiring din, and all that were able to bear arms hastened to the defense. It was an important moment in the history of the colony,—an hour big with fate; for the coming battle would decide for either European or Asiatic domination.

Again Li-ma-hong chose his trusted lieutenant to lead the attack; and fifteen hundred picked troops, armed to the teeth, followed him, swearing to take the fort or leave their corpses as a testimonial to their valor.

In the Province of Pangasinan.

The city was then set on fire in several places, and in three divisions the Chinese advanced to the attack, Li-ma-hong himself from the outside supporting them with a well-directed cannonade against the walls.

After a spirited assault, Sioco succeeded in entering the fort, and here a bloody hand-to-hand conflict took place. Again and again the Spaniards forced their fierce assailants over the walls; again and again the Chinese poured into the breaches, while the trembling non-combatants within the city awaited the result in agonized suspense.

Salcedo was at the front and everywhere. Time and again, with indomitable courage, he rallied his men; and splendidly did they respond to his magnificent leadership. The old Governor himself was at the front, shouting encouragement; and many prominent citizens also distinguished themselves by feats of remarkable heroism. The Chinese, once more, gathering their shattered numbers together, plunged into the ranks of their enemies, and it was not until after the loss of their daring leader that the few that remained turned their repulse into a disorderly flight, and Manila and the Philippines were saved to Spain and America. Salcedo now eagerly took the offensive and pursued the panic-stricken fugitives back to their ships, killing great numbers on the way.

In vain Li-ma-hong tried to regain his advantage. Troop after troop were sent ashore, only to join the rout and return confused and disorganized back to the fleet. The Spaniards had conquered.

Li-ma-hong, nevertheless, was determined to found his Empire and to set up his capital in another part of the islands—in the province of Pangasinan. Salcedo was accordingly despatched against him, but was unable to dislodge him. Hearing, however, that the Chinese Emperor also was about to send an expedition against him, the wily pirate secretly departed, leaving his Spanish enemies not at all displeased at being thus cheaply rid of his presence.

The friars, ever on the lookout for their own interests, attributed their deliverance to the aid of St. Andrew. He, therefore, was declared the Patron Saint of Manila—high mass in his honor being celebrated at 8 A. M. in the Cathedral every 30th of November.

The old chroniclers relate that some of the native chiefs took advantage of the disturbance to foment a rebellion against their Spanish conquerors; but all other disturbances were speedily quelled.

Civil disturbances, civil conflicts, now followed in the wake of these struggles against foreign aggression and domestic insurrection. In these internal dissensions, all branches of the Government took part. It was the Governor-General against the Supreme Court, the Supreme Court against the Clergy, the Clergy against All.

The Governor was censured for alleged undue exercise of arbitrary authority. The Supreme Court, patterned after the one in Mexico, was also accused of seeking to overstep the limits of its functions. Every law was reduced to the practise of a quibble, every quibble was administered with a dilatoriness that was destructive not only to all legitimate industry, but also to the encouragement and maintenance of order. To make matters even worse, the clergy, with their pretense of immunity from all State-control, interfered in all matters that promised profit. Indeed, there were few things out of which these wily friars were unable to extract a generous tithe.

The Dutch Appear upon the Scene.

The Chinese pirate had been taught a severe lesson, and had departed. The memory of his ravages, however, was still fresh in the minds of his conquerors when other buccaneers, far mere formidable and dangerous, appeared in the waters of the Philippines, threatening the peace and safety of the colonists.

Kindling with a desire for vengeance on their ancient foes the Spaniards, and flaming with greed for the richly-freighted Spanish argosies, the Dutch made repeated sallies from their secure retreat in the Moluccas, spreading terror in their wake. The galleons full of silver from Mexico, the ships laden with the comforts and luxuries of far-away Spain, fell a delightful prey into the hands of these remorseless freebooters, that never gave nor asked quarter. Many were the conflicts with these ruthless invaders, and many a rich prize did they tow away from the Philippine waters, while the angry Spaniards on shore stood transfixed,—in helpless misery.

Millions of dollars intended for the salaries of the Government officials and the troops, were thus stolen, and though the colonists were often victorious, yet the enemy, with characteristic Dutch audacity, refused to be defeated; in fact, he invariably reappeared with a new demonstration of bloody rapacity.

Upon one occasion a Dutch squadron anchored at the entrance of Manila Bay. It remained several months, seizing from time to time the merchantmen on their way to the Manila market. It thus secured an immense booty; its presence, too, becoming extremely prejudicial to trade and to the interests of the colony.

Juan de Silva, the Governor, therefore began to prepare an armament to drive these freebooters from the bay. One night he dreamt that St. Mark had offered to help him. Awaking, he consulted a priest about his dream, who interpreted it to be an omen of victory. On St. Mark’s day, accordingly, the Spaniards sallied forth to meet their hereditary foe; they sailed from Cavité with ten ships, carrying twenty guns. Over 1,000 Europeans and a large number of natives manned this fleet, the latter being religiously told that the Dutch were infidels, and, therefore, deserved extermination.

Once more the possession of the colony was to be decided. This time the conflict was to be between two rival nations from the same continent,—between Protestant and Catholic. The clergy, hence, were keenly alive to its importance: mass was said in all the churches, bells were tolled, and images of the Patron Saints of the colony were daily paraded through the streets.

The Governor himself took command, and incited his followers to martial order by proclaiming St. Mark’s promised intercession. From his ship he unfurled the royal standard,—on which the image of the Virgin was conspicuously embroidered,—to give encouragement to the eyes of the faithful. He then gave the signal for the advance, and they swiftly bore down upon the enemy. The Dutch were quietly awaiting the attack, and the conflict was fierce and sanguinary. It was a calm, beautiful day; but the calmness soon gave place to the thundering turbulence of battle, and the beauty soon became the ugliness of war.

The contest lasted about six hours, and the Dutch, unable longer to cope against odds so overwhelming, were finally vanquished; their three ships were destroyed, and their flags, artillery, and plundered merchandise to the value of $300,000 were seized.

San Augustine Church, in Old Manila.

This important struggle is known in the history of the islands as the battle of Playa Honda. Had it ended otherwise, it is probable that the Philippines would have been for the Dutch another Java, and a most interesting problem would not have sought solution at the hands of the American people.

Several other engagements with the Dutch occurred at different times; first one, then the other side being victorious. And thus for over a century the contest continued, until by the Peace of Westphalia, in 1648, Holland’s independence was fully established, her impoverished and weakened foe being forced to a tardy recognition of what had been an obstinate fact for many years.

The Japanese, and the Martyred Saints.

The struggling colony was menaced by yet another foe. Early commercial relations had been entered into with the Japanese, who had established one or two trading-settlements in different parts of Luzon. It was not long, therefore, before the news of the Spanish occupation of the Philippines reached the Emperor of Japan. Accordingly, in 1593, he sent an ultimatum to the Governor-General, demanding his surrender, and that he acknowledge him as his liege lord.

The Japanese Ambassador, Farranda Kiemon, was received with great honor, and treated with all the deference due to a royal envoy: the colonists were not yet strong enough to manifest a high degree of independence when threatened by so powerful a foe. So the Governor prudently resorted to diplomacy. He replied, that, being but a vassal of the King of Spain, a most powerful and opulent sovereign, he was prevented from giving homage to any other monarch; that his first duty, naturally, was to defend the colony against invasion; that he should, however, be happy to make a Treaty of Commerce with His Majesty, and would, accordingly, send several envoys to his capital to treat concerning the same.

This done, it is related, the Spaniards were received in great state. The treaty was then adjusted to the satisfaction of both parties.

A Suburb of Old Manila.

Unfortunately, however, these envoys, returning homeward, were drowned, and shortly afterward two religious embassies were sent to Japan to renew the treaty and to convert the benighted inhabitants of that country to God and the true Church. After thirty days, sailing they arrived at their destination. The friar Pedro Bautista, chief of the embassy, was now presented to the Emperor Taycosama, and the treaty was renewed. The most important feature of this agreement was the permission to build a chapel at Meaco, near Osaka. This was opened with ceremonial pomp in 1594.

Now the chief of the Jesuits—the sect were by royal favor allowed to follow their calling among the Portuguese traders in Nagasaki—bitterly opposed what he deemed the exclusive right of his order, conceded by Pope Gregory XIII., and confirmed by Imperial decree.

The Portuguese traders, foreseeing that the arrival of Bautista and his priests was but a prelude to Spanish domination,—when they, naturally, would be the sufferers,—forewarned the Governor of Nagasaki.

The Emperor was alarmed; for he now also became convinced that the Philippine Ambassadors were actuated to missionary zeal by ulterior motives; and, fearing that the priests, by their doctrines, might pollute the fountain of his ancient religion,—thus paving the way for their domination and his own ultimate ruin,—he at once commanded that all attempts to convert the natives must cease. Bautista, in holy zeal, not heeding the Imperial injunction, was expelled, and retired to Luzon, leaving several of his embassy behind. Some of these also, obstinately persisting in violating the Imperial mandate, were arrested and imprisoned.

Upon his arrival in Manila, Bautista fitted out another expedition, and soon again landed in Japan with a company of Franciscans.

The indignant Emperor, convinced of the duplicity of the Spaniards, caused them to be seized and cast into prison. A few natives, who had forsaken the religion of their forefathers for the discord-breeding doctrines of the foreigners, were also apprehended. All—twenty-six in number—were then condemned to death. After their ears and noses had been cut off, they were exhibited in various towns, as a warning to the other foreigners and to the populace. Upon the breast of each hung a board, that announced the sentence of the wearer and the reasons for his punishment. They were then crucified, and, after lingering for several hours in great agony, were speared to death.

The colony was much perturbed when the news of the sad fate of the zealous Franciscans reached Manila. Special masses were said, and processions of monks daily paraded through the streets.

The Abandoned Acqueduct.

The Governor was finally prevailed on to send a deputation to Japan for the bodies of the executed priests; for the relics of these martyrs were fraught with too many possibilities of profit to their co-religionists to be left in a foreign country in ignominious sepulture. It is related, also, that these envoys were entertained most royally, and the Emperor gave them a long letter to the Governor, justifying with many reasons the late execution and his vigorous policy. It seems, however, that the relics were lost on the homeward voyage. Notwithstanding, many priests soon ventured to Japan, to court a martyr’s doom and to furnish relics for the adoration of their superstitious countrymen. Hence, it is not surprising that a great many other similar executions afterward took place.

Incensed at these frequent and persistent violations of his well-founded prohibition, the Emperor finally refused to treat with the embassies sent from the colony; and, as he and his successors continued to enforce their stern decrees, the transportation of Spanish priests to Japan was finally prohibited. Had the Japanese been less severe, less astute, it is highly probable that all the evil consequences that they foresaw,—as a result of the Christian propaganda,—would really have taken place. As it was, they saved both their religion and their Empire.

The British Occupation.

General Draper’s Expedition.

The affairs of the colony—now directed by custom and precedence into the narrow channel of official routine—flowed placidly along in undisturbed monotony. But in 1762 another enemy appeared before the walls of Manila; an enemy more powerful than any that had heretofore threatened the peace of that tropical capital. War had been declared by Spain against England, and the enterprising inhabitants of that little isle were not slow in following their traditional policy of striking the first blow. Rodney and Monckton were sent to Havana. This they took without great difficulty, and soon a British squadron, composed of thirteen ships, under the command of Admiral Cornish, was despatched to Manila.

It was the evening of the 22nd of September when the English fleet arrived in the bay, and the following morning Admiral Cornish sent an officer to the Governor, demanding the surrender of the citadel. At this peremptory proceeding the haughty Spaniard was highly incensed, and his refusal was couched in terms no less indignant than defiant.

Words having signally failed to bring the Spanish to terms, a demonstration of force was decided upon, and Brigadier-General Draper was sent on shore with a large body of troops. The garrison, however, treated this display with counter demonstrations, and Draper’s threats with lofty disdain. Draper therefore resolved to parley no longer, and the bombardment began the next day.

Tower of Defense, Church, and Priest’s House.

The British forces consisted of 1600 European troops, nearly 3000 seamen, and about 800 Sepoys—about 5000 fighting men. The forces in Manila, on the other hand, were only 603 Spaniards and 77 small guns. In the meantime, the ardor of the British had been inflamed by the capture of a Spanish galleon containing $2,500,000 in specie.

The Archbishop, Manuel Antonio Rojo, who acted also as Governor,—the seat of that functionary being vacant at the time,—seeing the hopelessness of the conflict, and desiring to avert unavailing bloodshed, counseled surrender. But the soldiers in the garrison, under their fiery leader Simon de Anda, were utterly intractable, and prepared vigorously for the defense. After a few unsuccessful sorties, the Spanish batteries, on the 24th September, began a rapid but harmless cannonade. Again a company sallied forth from the garrison to attack the invaders, but this also was repulsed, with considerable loss to the Spanish. The English now renewed the bombardment, and terrific havoc was made among the ranks of the enemy. Some two thousand natives, in three columns, advanced toward the three improvised redoubts held by the British, and were driven back with great loss and confusion. Panic-stricken, the natives fled back to their villages, and on the 5th of October the besieging forces entered the walled city. The bombardment, meanwhile, continued. Nor did it cease until the forts were demolished and most of the Spanish artillerymen killed. It is estimated that 20,000 cannon-balls and 5000 shells were thrown into the city.

The military men among the Spanish now counseled surrender. The civilians, contrariwise, were eager to continue the defense. But as most of the fortifications were destroyed, and since “confusion worse confounded” already reigned in the city, many fled to the surrounding villages.

The opposing civilians having barricaded and otherwise obstructed the streets, the British advanced into the heart of the city, clearing the way before them with a raking fire of musketry.

General Draper now sent Colonel Monson to the Archbishop, demanding instant and absolute surrender. The Archbishop appeared and offered himself as a prisoner, also presenting terms of capitulation. These provided for the free exercise of religion, the security of private property, unrestricted commerce between the Spaniards and the natives, and the English support of the Supreme Court in its attempts to preserve order.

The British Demand an Indemnity.

General Draper readily granted these terms, but demanded an indemnity of $4,000,000. To this the Spanish agreed, and these terms were then signed by both parties to the compact.

When the Union Jack was first unfurled from Fort Santiago, it is said that the British burst forth into a chorus of ringing cheers.

But their joy was not unmixed with sensations of sorrow; for, it is reported, over 1500 men, and many gallant officers, were lost in the assault. The city was then given over to the mercy of the victorious troops, and a riotous scene of pillage ensued; many excesses were committed, the Sepoys, in particular, committing many atrocities. General Draper forthwith gave the command that these outrages should cease; and guards were at once placed at the doors of the convents and the nunneries to prevent outrages on the women. A few thieving Chinamen, who had taken advantage of the confusion to add to their own profit, were hanged; and the General, it is said, with his own hand cut down a soldier that he caught stealing after his inhibition had been proclaimed.

A Native Village in the Foot-hills: Old Manila.

The English now demanded the payment of the stipulated indemnity, but the enforced contributions from the wealthy inhabitants, with the silver from the churches—all that the Spaniards professed to be able to collect—amounted to only a little more than half a million dollars,—but one-eighth of the stipulated sum. Threat and force were alike unavailing to produce the other monies promised, although the friars, it is believed, had secreted immense sums, determined at all hazards to preserve their accumulated store from the rapacity of their Protestant enemy.

By the terms of the capitulation the entire Archipelago had been surrendered to the British; but Simon de Anda, who commanded the Spanish forces during the siege, had now established himself in Bulacan as Provisional Governor, in opposition to the authority of the Archbishop who had bitterly denounced the surrender. The clergy, however, were the more influential part of the Colonial Government, and General Draper accordingly treated with them alone, obtaining their consent to a cession of all the islands to the King of England. Draper himself then returned to England, leaving behind a Provisional Military Government.

Admiral Cornish now demanded the payment of the million dollars that the British had finally decided to accept as full indemnity.

The Spaniard, however, continued to plead poverty, and the money was not forthcoming. Several thousands of dollars were eventually unearthed in the convent where the friars had hidden it. The British, though convinced of the deception that these holy brethren had practised to save these dollars,—wrung from the hearts of the poor,—were, however, unable to lay their hands upon the treasure.

Simon de Anda, the self-constituted Governor, now became unusually active in the provinces, and several expeditions were sent out to quell the various insurrections that he had been stirring up. One of these, numbering 600 men, under the leadership of Captain Eslay, in the province of Bulacan, assaulted and took a fortified convent. They were also victorious in some engagements with a body of natives, several thousand strong, under the command of Lieutenant Bustos, a Spanish officer. As several Austin friars had been found among the slain, the British rightly believed that their order had been conspiring against them. Many, therefore, were arrested. Eleven were sent back to Europe.

Naturally suspicious of all the friars, the English now entered the Augustine convent and found that these priests had been no less deceitful than their brethren in the other orders. Six thousand, five hundred dollars in coin were found hidden in the garden, and large quantities of wrought silver elsewhere. The convent itself was then searched and all the valuables found therein taken.

A Bamboo House in Pampanga Province.

About this time the Spaniards professed to have discovered a conspiracy among the Chinese in the province of Pampanga, the object being, they said, to murder Anda and his Spanish followers. The Chinese had raised extensive fortifications, saying that these preparations were all made as a defense against an expected attack from the British.

The Spaniards, however, suspecting sympathy with their enemies, attacked the Celestials and a general massacre of the Chinese followed. Many thousands, too, were killed that had taken no part in the war.

Admiral Cornish, disgusted and infuriated with their obvious deception and palpable dilly-dallying, again demanded the payment of the indemnity. But he was forced to content himself with a bill on the Madrid Treasury.

Anda now appointed Bustos Alcalde of Bulacan: he hoped great things of his seditious and unscrupulous lieutenant; he knew that he would resort to every means to harass the enemy: he therefore, accordingly, ordered him to recruit and train troops.

For Anda still cherished the hope of confining the British, perhaps, even, of driving them from the colony. So, with practiced subtlety and with masked deviltry, he set about accomplishing his grim purpose.

Intrigues Against the British.

The British were now kept busy suppressing the numerous intrigues against their power that sprang up among the Spanish residents everywhere. Many sorties also were made to dislodge the persistent and irrepressible Anda and his lieutenant Bustos, now encamped at Malinta, a village a few miles from Manila. Most of those assaults, however, proved indecisive and ineffectual. The priests proved troublesome, and were the cause of much bloodshed, teaching the natives that the British were infidels.

The Augustine friars were especially hostile, many laying aside the cowl for the helmet. At Masilo, indeed, the British were defeated by an Austin friar, who, with a small band of natives, attacked them from ambush.

The Austin friars, however, had some cause for grievance. For, according to a recent historian, they had lost nearly a quarter of a million dollars, fifteen of their convents were destroyed, several valuable estates despoiled, ten of the members killed in the battle, and nineteen were taken prisoners and sent as exiles to India and Europe.

On the 23d of July, 1763, an English vessel brought news of an armistice between the conflicting Powers. And in the latter part of August the British Commander received notice of the articles of peace, by which Manila was to be evacuated (Peace of Paris, 10th of Feb., 1763).

It was several months, however, before peace was finally established in the island, fierce quarrels having arisen among the rival factions of the Spaniards as to who should be Governor and receive the city officially from the British. The Archbishop having died, Anda, who was in actual command of the troops, was fully recognized by the British as Governor. Don Francisco de La Torre arriving at this time from Spain with a commission as Governor-General, Anda resigned the Government to him on the 17th of March, 1764. Several serious quarrels now took place, due to jealousy among the English officers; but Anda, on behalf of the new Governor, formally received the city from the British, who embarked for India, after having met all claims that could be justly established against them.

The Spanish Colonial Government.

The Encomiendoros and the Alcaldes.

In the early days of the colony there were, besides the Governor-General, the sub-governors, known as Encomiendoros, who rented their provinces at so much per annum, called Encomiendas, from the General Government. These Encomiendoros were usually men of wealth, that entered into politics as a speculation. More properly, I should say, as a peculation; for it became their policy to fleece the natives and to extort as much money as possible during the term of their incumbency. Few, indeed, left the scene of their civil brigandage without full coffers; and as enormous fortunes were to be made during a few years sojourn in the islands, no wonder that this office was eagerly sought after in Spain.

This imitation of the methods of the Roman tax-payers, however, became so demoralizing to the morale of the Spaniards themselves, and so ruinous to the colony and to the natives, that a more equitable policy was introduced. The Encomiendoros were succeeded by Judicial Governors, called Alcaldes, to whom was paid a small salary, from $300 upward a year, according to the prominence of the province.

This office, however, proved almost equally remunerative to the holders; for, by means of a Government license to trade, they were able to create, to their own advantage, monopolies in every line of industry, thus freezing out all competitors. Though each was responsible to the Central Government for the taxes of his provinces, yet this did not prevent the shrewd and unprincipled from finding profit here also. For, by a system of false weights and measures, the native, who, in lieu of silver, brought his produce in payment for taxes, was shamefully defrauded, the Alcalde sending the indebted amount to the Government storehouse and selling the rest to his own profit. In addition, many of these Alcaldes, by arbitrary decrees and despotic methods, conducted a system of public robbery that in a few years enriched them at the expense of the long-suffering natives; for them there was no redress, inasmuch as each Alcalde was also the head of the Legal Tribunal in his own province. These abuses, however, became so flagrant that the Alcaldes were finally forbidden to trade; but as this measure was not as effectual as had been expected, sweeping reforms were instituted.

To recount what these were; to mention in detail what malignant opposition was manifested by a large body of natives and resident Spaniards toward the purposed overthrow of the old system, would be only to reiterate well-known characteristics and abnormalities of the Spanish nature; placed, too, in but a slightly different setting.

I will merely add that these Alcaldes, these perpetrators and beneficiaries of wholesale misrule and dishonor, yielded finally to the reform-wave, and, accordingly, fell away before their own judicial perversion. And the new system, it must be confessed, is a great improvement upon the old.

But the evil wrought upon the Filipino mind and character was deep-planted. For, by the despotic and summary disposing of his labor and chattels, in the name of the King,—abetted frequently, too, by seemingly supernatural means,—respect for the Spaniard and the white man in general had fled, fear and distrust supplanting it.

A Street Scene in Albay.

In the new order of things,—instituted by a decree from the Queen-Regent Maria Cristina, the 26th of February, 1886,—18 Civil Governorships were created, and the Alcaldes’ functions were confined to their Judgeships. And thus the former frightful distortion of justice was overcome and banished.

So, too, under this law of 1886 each Civil Governor has a Secretary, who serves as a check upon his chief, if he be illegally inclined.

Accordingly, two new official safeguards were thus erected in the fabric of Colonial Administration in these 18 different provinces.

The Present Division and Administration.

The colony was then divided into 19 civil provinces, including Sulu, and into 3 grand military divisions.

As before, at the head was the Governor-General,—the supervising and executive officer of the province,—directly responsible to Spain. His salary is $40,000 a year. He is assisted by an Executive Cabinet and by an Administrative Council. The Provincial Governor, the successor to the Alcalde, must be a Spaniard, and at least 30 years old. He is the direct representative of the Governor-General and it is his duty to execute his decrees and to maintain order. He also has the power of appointment and removal, presides over provincial elections, controls the civil and local guard, interprets the laws,—usually to suit his own profit or convenience,—supervises the balloting for military conscription, can assess fines to the amount of $50, or imprison for 30 days, is Superintendent of Public Instruction, issues licenses and collects taxes. It is his duty also to furnish statistics and to control the Postal and Telegraph service. He is the Superintendent of health, prisons, charities, agriculture, forestry, and of manufactures. It will thus be seen that his duties are as diverse as they are important. He is now allowed no percentage, nor other emolument than his salary. At the same time, a shrewd Governor is yet able to reap a golden harvest. This, however, can be done only in conjunction with other Government officers.

Owing to the extreme shortness of his term of office—three years only—there is no incentive for the improvement of his province, as his successors would reap the results as well as the credit of his industry. Besides, he has no reason to hope that a good work begun will be a good work continued; for the next Governor may be averse to exertion, or may be at variance with his policy.

Children of a Gobernadorcillo.

Most of the Governors live in good style; as a rule they spend about two hours a day in Government employ. Is it to be wondered at, then, that this office is so eagerly sought after in Spain?

There are about 750 towns in the colony; each governed by a Gobernadorcillo, “Little Governor,” called Capitan; usually a native or half-caste. This office is elected every two years, and is to the Provincial Governor what the latter is to the Governor-General. He is the tax-collector of his district, and is, furthermore, responsible for the amount apportioned to his district. If he fails to collect this, he must make the deficit good out of his own pocket. Under him are a number of deputies, called Cabezas, each likewise responsible for another division of the population called a Barangay,—a collection of forty or fifty families. If the individuals of this group are unable to pay, the property is distrained and sold by the deputy, who would otherwise have to make good the amount himself. If the proceeds of the sale fail to equal the indebtedness of the delinquent, he is cast into prison.

I have often seen respectable men deported to the penal settlements; and for no other offense than inability to pay the oppressive tax laid upon their shoulders, regardless of the season,—whether productive or not. Their families, meanwhile, left without a head, were thrown into the most woeful destitution.

The Gobernadorcillo gets the munificent salary of $200 a year, though his expenses, for clerk-hire, for presents to his chief, and for entertainments in his honor, are often many times greater. A shrewd Gobernadorcillo, however, manages to make something out of the place, which, in some districts, is eagerly sought after by rich planters. The official dress of this worthy is a short black jacket, the tail worn over the trousers. He also carries a stick as a sign of authority. To him is entrusted the apprehension of criminals, and he has command of the local guards, or cuadrilleros, the police of the towns.

The Taxes and What Became of Them.

It can easily be guessed that the taxes are not inconsiderable, when I simply mention a few things that are assessed: There is a tax on the ownership and sale of live-stock and vehicles, on realty, and on all private industries and manufactures. Opium, liquors, stamps, tobacco, and lotteries yield an immense revenue. Then there is a Community-fund, which is usually several hundred thousand dollars a year in each province, and is supposed to be spent in the interest of the community. The Chinese Capitation tax also brings in a large amount. But the most common and onerous tax of all is that arising from the Government sale of Cédulas, or documents of identity, which is a poll-tax from $25 down. The individual paying less than $3.50 is subject to 15 days’ hard labor each year and to a fine of 50 cents for each day that he shall fail to work. Those whose cédulas have cost more than $3.50 must also pay a municipal tax of $1.50. The cédula is also used as a passport, and must be brought into court to render legal instruments effective.

Along the Escolta; Principal Business Street in New Manila.

From this brief and imperfect survey of the system of provincial taxation, it can easily be gathered that the revenues are considerable; and yet, of the hundreds of thousands of dollars extorted from the natives in each province, under the plausible pretexts of an avaricious policy, it is safe to say that not a dollar is expended for any local improvements. No building of bridges, no constructing of highways, no public schools, nor halls of justice must mar the stagnant serenity of provincial life. Nothing is ever repaired; a system of “let alone” blights every aspiration, and is fatal to the extension of commerce and industry. Consequently, in the wet season, for vehicles, the public roads are impassable, and, in many parts of the country, for months transportation is practically at a stand-still. As if effectually to close every door to progress, private individuals, too, are forbidden by law to repair the highways.

Did any government ever foster a more imbecile and iniquitous policy for its own damnation?

Although the speculations in the colony are not so enormous as formerly, yet there is no doubt that they still amount to several millions annually; mostly, however, at the seat of Government in Manila. It is indeed notorious that General Weyler, during his brief incumbency of the office, succeeded in placing several millions of dollars to his credit—I should have said to his dishonor!

Dilatory and Abortive Courts.

Perhaps no feature of Colonial life is fraught with more evil and is so disgusting, as the process of the courts. The Supreme Court of the early years of the colony was modeled after the one in Majorca, and on several occasions when the Governorship has been left vacant, it has assumed the functions of the executive—pro-tem.

There are two Supreme Law Courts in the colony: one in Manila; the other in Cebú. The President of the one in Manila has a salary of $7,000 a year; that of Cebú, $6,000. There are also 41 Superior Courts, of various degrees of importance, the salary of the judges ranging from $2,000 to $4,000 per annum. The department of Justice alone costs the colony about $350,000 a year.

The dilatoriness of the courts has become proverbial. It is, in fact, years before a case can be brought to a close. Meantime, the litigant has been fleeced out of an amount perhaps a hundred times the value of the article under litigation. The islands are full of native pettifoggers from the law schools of Manila, who have learned too well the meaning of the Spanish mañana. A suit can never be considered as disposed of; for another judge, scenting the faint possibility of a fee, may again have it retried. Thus I have seen the lives of acquitted persons again brought into jeopardy by the meddlesome officiousness and the grasping greed of a new judge. He that goes to court in the Philippines must not do so without reckoning the cost.

A Business Street in Old Manila.

Commenting on this, a recent English traveler says: “Availing one self of the dilatoriness of the Spanish law, it is possible for a man to occupy a house, pay no rent, and refuse to quit on legal grounds during a couple of years or more.” A person who has not a cent to lose can persecute another by means of a trumped up accusation, until he is ruined by an “informacion de pobreza”—a declaration of poverty—which enables the persecutor to keep the case going as long as he chooses, without needing money for fees.

A New Yorker’s Experience.

The following experience of an American friend of mine, whom I knew very well in Manila, will bring out in a graphic way the course of justice in the Philippines. Nor is his experience uncommon. It is, in fact, the usual one of the stranger or the native who goes to the fountain of Justice for the redress of a grievance.

I quote part of his letter written to a common friend:

In 1871 I joined Mr. William Morton Clark of Philadelphia, who had a large timber business on the island of Luzon, and started cutting some timber contracted for by the Chinese government.

I soon discovered that I was interfering with the business of a certain priest, who was also in the same line of business.

Shortly before this, this priest and an inspector of roads had loaded the Spanish bark Santa Lucia for Hong-Kong, and had made things so disagreeable for others who had tried to ship merchandise that foreigners were becoming afraid to risk their capital.

Mr. Clark finding how things were going on soon abandoned the enterprise, and I then determined to fight the thing out on my own account.

At this time I had 25,000 cubic feet of hard timber, cut and squared, for a foreign market, eighty-two buffaloes for hauling, and a plant of machinery and appliances valued at $7,000.

I had a license for carrying on my business, duly granted by the superior government, and in 1874 chartered a vessel at Manila to carry my timber to Hong-Kong, and then went to the port of Love, where my timber was, taking with me $940 in gold to prepare for the vessel’s arrival and to continue cutting.