автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Stolen Legacy. Illustrated

George G. M. James

STOLEN LEGACY

Illustrated

George Granville Monah James introduced the original, and rather scandalous theory, that the ancient Greeks borrowed their philosophical ideas from the Egyptians. In the book Stolen Legacy, James claims that Aristotle's ideas originated from books that were stolen when Alexander the Great looted the library in Alexandria.

James refers to Greek sources such as Herodotus, who described Greece's cultural debt to Egypt. He also mentions prominent Greek philosophers such as Pythagoras and Plato, who are said to have studied in Egypt. For example, he attributes the use of the term "atom", which means an indivisble particle, as having originated from the name of the Egyptian deity Atum, a god who symbolizes completeness and indivisibility.

The book further draws from masonic writings to support his claim that Greco-Roman mystical religion originates from the "Egyptian mystical system."

INTRODUCTION: CHARACTERISTICS OF GREEK PHILOSOPHY

The term Greek philosophy, to begin with is a misnomer, for there is no such philosophy in existence. The ancient Egyptians had developed a very complex religious system, called the Mysteries, which was also the first system of salvation.

As such, it regarded the human body as a prison house of the soul, which could be liberated from its bodily impediments, through the disciplines of the Arts and Sciences, and advanced from the level of a mortal to that of a God. This was the notion of the summum bonum or greatest good, to which all men must aspire, and it also became the basis of all ethical concepts. The Egyptian Mystery System was also a Secret Order, and membership was gained by initiation and a pledge to secrecy. The teaching was graded and delivered orally to the Neophyte; and under these circumstances of secrecy, the Egyptians developed secret systems of writing and teaching, and forbade their Initiates from writing what they had learnt.

After nearly five thousand years of prohibition against the Greeks, they were permitted to enter Egypt for the purpose of their education. First through the Persian invasion and secondly through the invasion of Alexander the Great. From the sixth century B.C. therefore to the death of Aristotle (322 B.C.) the Greeks made the best of their chance to learn all they could about Egyptian culture; most students received instructions directly from the Egyptian Priests, but after the invasion by Alexander the Great, the Royal temples and libraries were plundered and pillaged, and Aristotle’s school converted the library at Alexandria into a research centre. There is no wonder then, that the production of the unusually large number of books ascribed to Aristotle has proved a physical impossibility, for any single man within a life time.

The history of Aristotle’s life, has done him far more harm than good, since it carefully avoids any statement relating to his visit to Egypt, either on his own account or in company with Alexander the Great, when he invaded Egypt. This silence of history at once throws doubt upon the life and achievements of Aristotle. He is said to have spent twenty years under the tutorship of Plato, who is regarded as a Philosopher, yet he graduated as the greatest of Scientists of Antiquity. Two questions might be asked (a) How could Plato teach Aristotle what he himself did not know? (b) Why should Aristotle spend twenty years under a teacher from whom he could learn nothing? This bit of history sounds incredible. Again, in order to avoid suspicion over the extraordinary number of books ascribed to Aristotle, history tells us that Alexander the Great, gave him a large sum of money to get the books. Here again the history sounds incredible, and three statements must here be made.

(a) In order to purchase books on science, they must have been in circulation so as to enable Aristotle to secure them. (b) If the books were in circulation before Aristotle purchased them, and since he is not supposed to have visited Egypt at all, then the books in question must have been circulated among Greek philosophers. (c) If circulated among Greek philosophers, then we would expect the subject matter of such books to have been known before Aristotle’s time, and consequently he could not be credited either with producing them or introducing new ideas of science.

Another point of considerable interest to be accounted for was the attitude of the Athenian government towards this so-called Greek philosophy, which it regarded as foreign in origin and treated it accordingly. Only a brief study of history is necessary to show that Greek philosophers were undesirable citizens, who throughout the period of their investigations were victims of relentless persecution, at the hands of the Athenian government. Anaxagoras was imprisoned and exiled; Socrates was executed; Plato was sold into slavery and Aristotle was indicted and exiled; while the earliest of them all, Pythagoras, was expelled from Croton in Italy. Can we imagine the Greeks making such an about turn, as to claim the very teachings which they had at first persecuted and openly rejected? Certainly, they knew they were usurping what they had never produced, and as we enter step by step into our study the greater do we discover evidence which leads us to the conclusion that Greek philosophers were not the authors of Greek philosophy, but the Egyptian Priests and Hierophants.

Aristotle died in 322 B.C. not many years after he had been aided by Alexander the Great to secure the largest quantity of scientific books from the Royal Libraries and Temples of Egypt. In spite however of such great intellectual treasure, the death of Aristotle marked the death of philosophy among the Greeks, who did not seem to possess the natural ability to advance these sciences. Consequently history informs us that the Greeks were forced to make a study of Ethics, which they also borrowed from the Egyptian “Summum Bonum” or greatest good. The two other Athenian Philosophers must be mentioned here, I mean Socrates and Plato; who also became famous in history as philosophers and great thinkers. Every school boy believes that when he hears or reads the command “know thyself”, he is hearing or reading words which were uttered by Socrates. But the truth is that the Egyptian temples carried inscriptions on the outside addressed to Neophytes and among them was the injunction “know thyself”. Socrates copied these words from the Egyptian Temples, and was not the author. All mystery temples, inside and outside of Egypt carried such inscriptions, just like the weekly bulletins of our modern Churches.

Similarly, every school boy believes that when he hears or reads the names of the four cardinal virtues, he is hearing or reading names of virtues determined by Plato. Nothing has been more misleading, for the Egyptian Mystery System contained ten virtues, and from this source Plato copied what have been called the four cardinal virtues, justice, wisdom,temperance, and courage. It is indeed surprising how, for centuries, the Greeks have been praised by the Western World for intellectual accomplishments which belong without a doubt to the Egyptians or the peoples of North Africa.

Another noticeable characteristic of Greek philosophy is the fact that most of the Greek philosophers used the teachings of Pythagoras as their model; and consequently they have introduced nothing new in the field of philosophy. Included in the Pythagorean system we find the doctrines of (a) opposites (b) Harmony (c) Fire (d) Mind, since it is composed of fire atoms, (e) Immortality, expressed as transmigration of Souls, (f) The Summum Bonum or the purpose of philosophy. And these of course are reflected in the systems of Heraclitus, Parmenides, Democritus, Socrates, Plato and Aristotle.

The next thing that is peculiar about Greek philosophy is its use in literature. The Egyptian Mystery System was the first secret Order of History and the publication of its teachings was strictly prohibited. This explains why Initiates like Socrates did not commit to writing their philosophy, and why the Babylonians and Chaldaeans who were very closely associated with them also refrained from publishing those teachings.

We can at once see how easy it was for an ambitious and even envious nation to claim a body of unwritten knowledge which would make them great in the eyes of the primitive world. The absurdity however, is easily recognized when we remember that the Greek language was used to translate several systems of teachings which the Greeks could not succeed in claiming. Such were the translation of Hebrew Scriptures into Greek, called the Septuagint; and the translation of the Christian Gospels, Acts and the Epistles in Greek, still called the Greek New Testament. It is only the unwritten philosophy of the Egyptians translated into Greek that has met with such an unhappy fate: a legacy stolen by the Greeks.

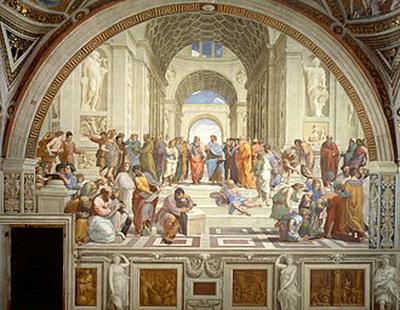

On account of reasons already given, I have been compelled to handle the subject matter of this book, in the way it has been handled: namely (a) with a frequency of repetition, because it is the method of Greek philosophy, to use a common principle to explain several different doctrines, and (b) the quotation and analysis of doctrines, because it is the object of this book to establish the Egyptian Origin and this cannot be so satisfactorily done if the doctrines are not presented. Greek philosophy is somewhat of a drama, whose chief actors were Alexander the Great, Aristotle and his successors in the peripatetic school, and the Roman Emperor Justinian. Alexander invaded Egypt and captured the Royal Library at Alexandria and plundered it. Aristotle made a library of his own with plundered books, while his school occupied the building and used it as a research centre. Finally, Justinian the Roman Emperor abolished the Temples and schools of philosophy i.e. another name for the Egyptian Mysteries which the Greeks claimed as their product, and on account of which, they have been falsely praised and honoured for centuries by the world, as its greatest philosophers and thinkers. This contribution to civilization was really and truly made by the Egyptians and the African Continent, but not by the Greeks or the European Continent. We sometimes wonder why the people of African descent find themselves in such a social plight as they do, but the answer is plain enough. Had it not been for this drama of Greek philosophy and its actors, the African Continent would have had a different reputation, and would have enjoyed a status of respect among the nations of the world. This unfortunate position of the African Continent and its peoples appears to be the result of misrepresentation upon which the structure of race prejudice has been built, i.e. the historical world opinion that the African Continent is backward, that its people are backward, and that their civilization is also backward.

Finally, the dishonesty in the movement of the publication of a Greek philosophy, becomes very glaring, when we refer to the fact, purposely that by calling the theorem of the Square on the Hypotenuse, the Pythagorean theorem, it has concealed the truth for centuries from the world, who ought to know that the Egyptians taught Pythagoras and the Greeks, what mathematics they knew.

I want to mention here that among the many books which I found helpful in my present work are “The Intellectual Adventure of Man” and “The Egyptian Religion” by Professor Henri Frankfort and “The Mediterranean World in Ancient Times” by Professor Eva Sandford.

THE AIMS OF THE BOOK

The aim of the book is to establish better race relations in the world, by revealing a fundamental truth concerning the contribution of the African Continent to civilization. It must be borne in mind that the first lesson in the Humanities is to make a people aware of their contribution to civilization; and the second lesson is to teach them about other civilizations. By this dissemination of the truth about the civilization of individual peoples, a better understanding among them, and a proper appraisal of each other should follow. This notion is based upon the notion of the Great Master Mind: Ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free. Consequently, the book is an attempt to show that the true authors of Greek philosophy were not the Greeks; but the people of North Africa, commonly called the Egyptians; and the praise and honour falsely given to the Greeks for centuries belong to the people of North Africa, and therefore to the African Continent. Consequently this theft of the African legacy by the Greeks led to the erroneous world opinion that the African Continent has made no contribution to civilization, and that its people are naturally backward. This is the misrepresentation that has become the basis of race prejudice, which has affected all people of color.

For centuries the world has been misled about the original source of the Arts and Sciences; for centuries Socrates, Plato and Aristotle have been falsely idolized as models of intellectual greatness; and for centuries the African continent has been called the Dark Continent, because Europe coveted the honor of transmitting to the world, the Arts and Sciences.

I am happy to be able to bring this information to the attention of the world, so that on the one hand, all races and creeds might know the truth and free themselves from those prejudices which have corrupted human relations; and on the other hand, that the people of African origin might be emancipated from their serfdom of inferiority complex, and enter upon a new era of freedom, in which they would feel like free men, with full human rights and privileges.

PART I

CHAPTER I: Greek Philosophy is Stolen Egyptian Philosophy

1. The Teachings of the Egyptian Mysteries Reached Other Lands Many Centuries Before It Reached Athens.

According to history, Pythagoras after receiving his training in Egypt, returned to his native island, Samos, where he established his order for a short time, after which he migrated to Croton (540 B.C.) in Southern Italy, where his order grew to enormous proportions, until his final expulsion from that country. We are also told that Thales (640 B.C.) who had also received his education in Egypt, and his associates: Anaximander, and Anaximenes, were natives of Ionia in Asia Minor, which was a stronghold of the Egyptian Mystery schools, which they carried on. (Sandford’s The Mediterranean World, p. 195–205). Similarly, we are told that Xenophanes (576 B.C.), Parmenides, Zeno and Melissus were also natives of Ionia and that they migrated to Elea in Italy and established themselves and spread the teachings of the Mysteries.

In like manner we are informed that Heraclitus (530 B.C.), Empedocles, Anaxagoras and Democritus were also natives of Ionia who were interested in physics. Hence in tracing the course of the so-called Greek philosophy, we find that Ionian students after obtaining their education from the Egyptian priests returned to their native land, while some of them migrated to different parts of Italy, where they established themselves.

Consequently, history makes it clear that the surrounding neighbours of Egypt had all become familiar with the teachings of Egyptian Mysteries many centuries before the Athenians, who in 399 B.C. sentenced Socrates to death (Zeller’s Hist. of Phil., p. 112; 127; 170–172) and subsequently caused Plato and Aristotle to flee for their lives from Athens, because philosophy was something foreign and unknown to them. For this same reason, we would expect either the Ionians or the Italians to exert their prior claim to philosophy, since it made contact with them long before it did with the Athenians, who were always its greatest enemies, until Alexander’s conquest of Egypt, which provided for Aristotle free access to the Library of Alexandria.

The Ionians and Italians made no attempt to claim the authorship of philosophy, because they were well aware that the Egyptians were the true authors. On the other hand, after the death of Aristotle, his Athenian pupils, without the authority of the state, undertook to compile a history of philosophy, recognized at that time as the Sophia or Wisdom of the Egyptians, which had become current and traditional in the ancient world, which compilation, because it was produced by pupils who had belonged to Aristotle’s school, later history has erroneously called Greek philosophy, in spite of the fact that the Greeks were its greatest enemies and persecutors, and had persistently treated it as a foreign innovation. For this reason, the so-called Greek philosophy is stolen Egyptian philosophy, which first spread to Ionia, thence to Italy and thence to Athens. And it must be remembered that at this remote period of Greek history, i.e., Thales to Aristotle 640 B.C.–322 B.C., the Ionians were not Greek citizens, but at first Egyptian subjects and later Persian subjects.

Zeller’s Hist. of Phil.: p. 37; 46; 58; 66–83; 112; 127; 170172.

William Turner’s Hist. of Phil.: p 34; 39; 45; 53.

Roger’s Student Hist. of Phil.: p. 15.

B. D. Alexander’s Hist. of Phil.: p. 13; 21.

Sandford’s The Mediterranean World p. 157; 195–205.

A brief sketch of the ancient Egyptian Empire would also make it clear that Asia Minor or Ionia was the ancient land of the Hittites, who were not known by any other name in ancient days.

According to Diodorus and Manetho, High Priest in Egypt, two columns were found at Nysa Arabia; one of the Goddess Isis and the other of the God Osiris, on the latter of which the God declared that he had led an army into India, to the sources of the Danube, and as far as the ocean. This means of course, that the Egyptian Empire, at a very early date, included not only the islands of the Aegean sea and Ionia, but also extended to the extremities of the East.

We are also informed that Senusert I, during the 12th Dynasty (i.e., about 1900 B.C.) conquered the whole sea coast of India, beyond the Ganges to the Eastern ocean. He is also said to have included the Cyclades and a great part of Europe in his conquests.

Secondly, the “Amarna Letters” found in the government offices of the Egyptian King, Iknaton, testify to the fact, that the Egyptian Empire had extended to western Asia, Syria and Palestine, and that for centuries Egyptian power had been supreme in the ancient world. This was in the 18th Dynasty i.e., about 1500 B.C.

We are also told that during the reign of Tuthmosis III, the dominion of Egypt extended not only along the coast of Palestine: but also from Nubia to Northern Asia.

(Breadsted’s Conquest of Civilization p. 84; Diodorus 128; Manetho; Strabo; Dicaearchus; John Kendrick’s Ancient Egypt vol. I).

2. The Authorship of the Individual Doctrines Is Extremely Doubtful.

As one attempts to read the history of Greek philosophy, one discovers a complete absence of essential information concerning the early life and training of the so-called Greek philosophers, from Thales to Aristotle. No writer or historian professes to know anything about their early education. All they tell us about them consists of (a) a doubtful date and place of birth and (b) their doctrines; but the world is left to wonder who they were and from what source they got their early education, and would naturally expect that men who rose to the position of a Teacher among relatives, friends and associates, would be well-known, not only by them, but by the whole community.

On the contrary, men who might well be placed among the earliest Teachers in history, who had grown up from childhood to manhood, and had taught pupils, are represented as unknown, being without any domestic, social or early educational traces.

This is unbelievable, and yet it is a fact that the history of Greek philosophy has presented to the world a number of men whose lives it knows little or nothing about; but expects the world to accept them as the true authors of the doctrines which are alleged to be theirs.

In the absence of essential evidence, the world hesitates to recognise them as such, because the truth of this whole matter of Greek philosophy points to a very different direction.

The Book on nature entitled peri physeos was the common name under which Greek students interested in nature-study wrote. The earliest copy is said to date back to the sixth century B.C. and it is customary to refer to the remnants of peri physeos as the Fragments. (William Turner’s History of Philosophy p. 62). We do not believe that genuine Initiates produced the Book on nature, since this was contrary to the rules of the Egyptian Mysteries, in connexion with which the Philosophical Schools conducted their work. Egypt was the centre of the body of ancient wisdom, and knowledge, religious, philosophical and scientific spread to other lands through student Initiates. Such teachings remained for generations and centuries in the form of tradition, until the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great, and the movement of Aristotle and his school to compile Egyptian teaching and claim it as Greek Philosophy. (Ancient Mysteries by C. H. Vail p. 16.)

Consequently, as a source of authority of authorships, peri physeos, is of little value, if any, since history mentions only four names as authors of it, namely, Anaximander, Heraclitus, Parmenides, Anaxagoras; and asks the world to accept their authorship of philosophy, because Theophrastus, Sextus, Proclus and Simplicius, of the school at Alexandria are said to have preserved small remnants of it (the Fragments). If peri physeos is the criterion to the authorship of Greek Philosophy, then it falls short in its purpose by a long way, since only four philosophers are alleged to have written this book, and to have remnants of their work. According to this idea all the other philosophers, who failed to write peri physeos and to have remnants of it, also failed to write Greek philosophy. This is the reductio ad absurdum to which peri physeos leads us.

The schools of philosophy, Chaldean, Greek and Persian, were part of the Ancient Mystery System of Egypt. They were conducted in secrecy according to the demands of the Osiriaca, whose teachings became common to all the schools. In keeping with the demands for secrecy, the writing and publication of teachings were strictly forbidden and consequently, Initiates who had developed satisfactorily in their training, and had been advanced to the rank of Master or Teacher, refrained from publishing the teachings of the Mysteries or philosophy.

Consequently any publication of philosophy could not have come from the pen of the original philosophers themselves, but either from their close friends who knew their views, as in the case of Pythagoras and Socrates, or from interested persons who made a record of those philosophical teachings that had become popular opinion and tradition. There is no wonder then, that in the absence of original authorship, history has had to resort to the strategy of accepting Aristotle’s opinion as the sole authority in determining the authorship of Greek Philosophy (Introduction to Alfred Weber’s History of Philosophy). It is for these reasons that great doubt surrounds the so-called Greek authorship of philosophy. (William Turner’s History of Philosophy p. 35; 39; 47; 53; 62; 79; 210–211; 627. Ancient Mysteries by C. H. Vail p. 16. Theophrastus: Fragment 2 apud Diels. Introduction to Alfred Weber’s History of Philosophy.)

3. The Chronology of Greek Philosophers Is Mere Speculation.

History knows nothing about the early life and training of the Greek philosophers and this is true not only of the pre-Socratic philosophers: but also of Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, who appear in history about the age of eighteen and begin to teach at forty.

As a body of men they were undesirable to the state, (personae non gratae) and were consequently persecuted and driven into hiding and secrecy. Under such circumstances they kept no records of their activities and this was done in order to conceal their identity. After the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great, and the seizure and looting of the Royal Library at Alexandria, Aristotle’s plan to usurp Egyptian philosophy, was subsequently carried out by members of his school: Theophrastus, Andronicus of Rhodes and Eudemus, who soon found themselves confronted with the problem of a chronology for a history of philosophy. (Introduction of Zeller’s Hist. of Phil. p. 13).

Throughout this effort there has been much speculation concerning the date of birth of philosophers, whom the public knew very little about. As early as the third century B.C. (274–194 B.C.) Eratosthenes, a Stoic drew up a chronology of Greek philosophers and in the second century B.C. (140) Apollodorus also drew up another. The effort continued, and in the first century B.C. (60–70 B.C.) Andronicus, the eleventh Head of the Peripatetic school, also drew up another.

This difficulty continued throughout the early centuries, and has come down to the present time for it appears that all modern writers on Greek Philosophy are unable to agree on the dates that should be assigned to the nativity of the philosophers. The only exception appears to occur with reference to the three Athenian philosophers, i.e., Socrates, Plato and Aristotle, the date of whose nativity is believed to be certain, and concerning which there is general agreement among historians.

However, when we come to deal with the pre-Socratic philosophers, we are confronted with confusion and uncertainty, and a few examples would serve to illustrate the untrustworthy nature of the chronology of Greek Philosophers.

(1) Diogenes Laertius places the birth of Thales at 640 B.C., while William Turner’s History of Philosophy places it as 620 B.C.; that of Frank Thilly at 624 B.C.; that of A. K. Rogers at early in the sixth century B.C.; and that of W. G. Tennemann at 600 B.C.

(2) Diogenes Laertius places the birth of Anaximenes at 546 B.C.; while W. Windelbrand places it at the sixth century B.C.; that of Frank Thilly at 588 B.C.; that of B. D. Alexander at 560 B.C.; while that of A. K. Rogers at the sixth century B.C.

(3) Parmenides is credited by Diogenes as being born at 500 B.C.; while Fuller, Thilly and Rogers omit a date of birth, because they say it is unknown.

(4) Zeller places the birth of Xenophanes at 576 B.C.; while Diogenes gives 570 B C.; and the majority of the other historians declare that the date of birth is unknown.

(5) With reference to Xeno, Diogenes who does not know the date of his birth, says that he flourished between B.C. 464–460; while William Turner places it at 490 B.C.; like Frank Thilly and B. D. Alexander; while Fuller, A. K. Rogers and W. G. Tennemann declare it is unknown.

(6) With references to Heraclitus, Zeller makes the following suppositions: if he died in 475 B.C. and if he was sixty years old when he died, then he must have been born in 535 B.C.; similarly Diogenes supposes that he flourished between B.C. 504–500; and while William Turner places his birth at 530 B.C.; Windelbrand places it at 536 B.C.; and Fuller and Tennemann declare that he flourished in 500 B.C.

(7) With reference to Pythagoras, Zeller who does not know the date of his birth supposes that it occurred between the years 580–570 B.C.; and while Diogenes also supposes that it occurred between the years 582–500 B.C.; William Turner, Fuller, Rogers, and Tennemann declare that it is unknown.