автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу A Guide to the Study of Fishes, Volume 1 (of 2)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

GUIDE TO THE STUDY OF FISHES

[Pg ii] [Pg iii]

A GUIDE TO THE STUDY OF FISHES

BY

DAVID STARR JORDAN President of Leland Stanford Junior University

With Colored Frontispieces and 427 Illustrations

IN TWO VOLUMES Vol I.

"I am the wiser in respect to all knowledge and the better qualified for all fortunes for knowing that there is a minnow in that brook."—Thoreau

NEW YORK

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY 1905

Copyright, 1905

BY

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

Published March, 1905

To

Theodore Gill,

Ichthyologist, Philosopher, Critic, Master in Taxonomy,

this volume is dedicated.

[Pg vi] [Pg vii]

PREFACE

This work treats of the fish from all the varied points of view of the different branches of the study of Ichthyology. In general all traits of the fish are discussed, those which the fish shares with other animals most briefly, those which relate to the evolution of the group and the divergence of its various classes and orders most fully. The extinct forms are restored to their place in the series and discussed along with those still extant.

In general, the writer has drawn on his own experience as an ichthyologist, and with this on all the literature of the science. Special obligations are recognized in the text. To Dr. Charles H. Gilbert, he is indebted for a critical reading of most of his proof-sheets; to Dr. Bashford Dean, for criticism of the proof-sheets of the chapters on the lower fishes; to Dr. William Emerson Ritter, for assistance in the chapters on Protochordata; to Dr. George Clinton Price, for revision of the chapters on lancelets and lampreys, and to Mr. George Clark, Secretary of Stanford University, for assistance of various kinds, notably in the preparation of the index. To Dr. Theodore Gill, he has been for many years constantly indebted for illuminating suggestions, and to Dr. Barton Warren Evermann, for a variety of favors. To Dr. Richard Rathbun, the writer owes the privilege of using illustrations from the "Fishes of North and Middle America" by Jordan and Evermann. The remaining plates were drawn for this work by Mary H. Wellman, Kako Morita, and Sekko Shimada. Many of the plates are original. Those copied from other authors are so indicated in the text.

No bibliography has been included in this work. A list of writers so complete as to have value to the student would make a volume of itself. The principal works and their authors are discussed in the chapter on the History of Ichthyology, and with this for the present the reader must be contented.

The writer has hoped to make a book valuable to technical students, interesting to anglers and nature lovers, and instructive to all who open its pages.

David Starr Jordan.

Palo Alto, Santa Clara County, Cal.,

October, 1904.

ERRATA[1]

VOL. I

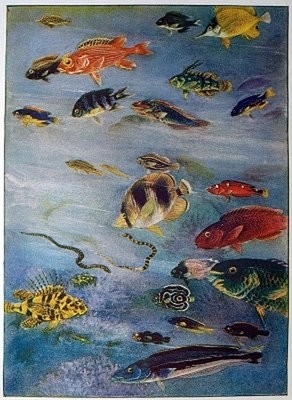

- Frontispiece, for Paramia quinqueviltata read Paramia quinquevittata

- Page xiii, line 10, for Filefish read Tilefish

- 39, " 15, for Science read Sciences

- 52, lines 4 and 5, transpose hypocoracoid and hypercoracoid

- 115, line 24, for Hexagramidæ read Hexagrammidæ

- 162, " 7, The female salmon does as much as the male in covering the eggs.

- 169, last line, for immmediately read immediately

- 189, legend, for Miaki read Misaki

- 313, line 26, for sand-pits read sand-spits

- 322, " 7 and elsewhere, for Wood's Hole read Woods Hole

- 324, " 15, for Roceus read Roccus

- 327, " next to last, for masquinonqy read masquinongy

- 357, " 5, for Filefish read Tilefish

- 361, " 26, for 255 feet read 25 feet

- 368, " 26, for infallibility read fallibility

- 414, " 22, for West Indies read East Indies

- 419, " 23, for-99 read-96

- 420, " 28, for were read are

- 428, " 24, for Geffroy, St. Hilaire read Geoffroy St. Hilaire

- 428, " 25, for William Kitchener Parker read William Kitchen Parker

- 462, " 32, for Enterpneusta read Enteropneusta

[Pg x] [Pg xi]

CONTENTS

VOL. I.

CHAPTER I.

THE LIFE OF THE FISH (

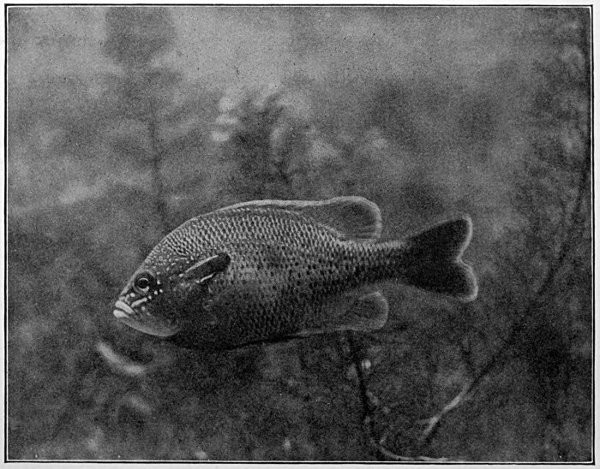

Lepomis megalotis).

PAGE

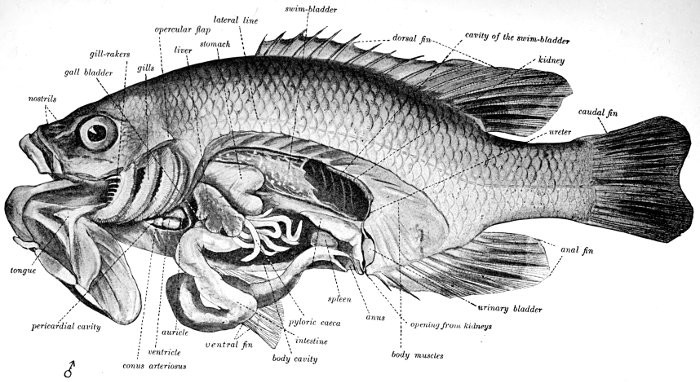

What is a Fish?—The Long-eared Sunfish.—Form of the Fish.—Face of the Fish.—How the Fish Breathes.—Teeth of the Fish.—How the Fish Sees.—Color of the Fish.—The Lateral Line.—The Fins of the Fish.—The Skeleton of the Fish.—The Fish in Action.—The Air-bladder.—The Brain of the Fish.—The Fish's Nest.

3CHAPTER II.

THE EXTERIOR OF THE FISH.

Form of Body.—Measurement of the Fish.—The Scales or Exoskeleton.—Ctenoid and Cycloid Scales.—Placoid Scales.—Bony and Prickly Scales.—Lateral Line.—Function of the Lateral Line.—The Fins of Fishes.—Muscles.

16CHAPTER III.

THE DISSECTION OF THE FISH.

The Blue-green Sunfish.—The Viscera.—Organs of Nutrition.—The Alimentary Canal.—The Spiral Valve.—Length of the Intestine.

26CHAPTER IV.

THE SKELETON OF THE FISH.

Specialization of the Skeleton.—Homologies of Bones of Fishes.—Parts of the Skeleton.—Names of Bones of Fishes.—Bones of the Cranium.—Bones of the Jaws.—The Suspensorium of the Mandible.—Membrane Bones of Head.—Branchial Bones.—The Gill-arches.—The Pharyngeals.—The Vertebral Column.—The Interneurals and Interhæmals.—The Pectoral Limb.—The Shoulder-girdle.—The Posterior Limb.—Degeneration.—The Skeleton in Primitive Fishes.—The Skeleton of Sharks.—The Archipterygium.

34CHAPTER V.

MORPHOLOGY OF THE FINS OF FISHES.

Origin of the Fins of Fishes.—Origin of the Paired Fins.—Development of the Paired Fins in the Embryo.—Evidences of Palæontology.—Current Theories as to Origin of Paired Fin.—Balfour's Theory of the Lateral Fold.—Objections.—Objections to Gegenbaur's Theory.—Kerr's Theory of Modified External Gills.—Uncertain Conclusions.—Forms of the Tail in Fishes.—Homologies of the Pectoral Limb.—The Girdle in Fishes other than Dipnoans.

62CHAPTER VI.

THE ORGANS OF RESPIRATION.

How Fishes Breathe.—The Gill Structures.—The Air-bladder.—Origin of the Air-bladder.—The Origin of Lungs.—The Heart of the Fish.—The Flow of Blood.

91CHAPTER VII.

THE NERVOUS SYSTEM.

The Nervous System.—The Brain of the Fish.—The Pineal Organ.—The Brain of Primitive Fishes.—The Spinal Cord.—The Nerves.

109CHAPTER VIII.

THE ORGANS OF SENSE.

The Organs of Smell.—The Organs of Sight.—The Organs of Hearing.—Voices of Fishes.—The Sense of Taste.—The Sense of Touch.

115CHAPTER IX.

THE ORGANS OF REPRODUCTION.

The Germ-cells.—The Eggs of Fishes.—Protection of the Eggs.—Sexual Modification.

124CHAPTER X.

THE EMBRYOLOGY AND GROWTH OF FISHES.

Post-embryonic Development.—General Laws of Development.—The Significance of Facts of Development.—The Development of the Bony Fishes.—The Larval Development of Fishes.—Peculiar Larval Forms.—The Development of Flounders.—Hybridism.—The Age of Fishes.—Tenacity of

Life.—Effect of Temperature on Fishes.—Transportation of Fishes.—Reproduction of Lost Parts.—Monstrosities among Fishes.

131CHAPTER XI.

INSTINCTS, HABITS, AND ADAPTATIONS.

The Habits of Fishes.—Irritability of Animals.—Nerve-cells and Fibers.—The Brain or Sensorium.—Reflex Action.—Instinct.—Classification of Instincts.—Variability of Instincts.—Adaptations to Environment.—Flight of Fishes.—Quiescent Fishes.—Migratory Fishes.—Anadromous Fishes.—Pugnacity of Fishes.—Fear and Anger in Fishes.—Calling the Fishes.—Sounds of Fishes.—Lurking Fishes.—The Unsymmetrical Eyes of the Flounder.—Carrying Eggs in the Mouth.

152CHAPTER XII.

ADAPTATIONS OF FISHES.

Spines of the Catfishes.—Venomous Spines.—The Lancet of the Surgeon-fish.—Spines of the Sting-ray.—Protection through Poisonous Flesh of Fishes.—Electric Fishes.—Photophores or Luminous Organs.—Photophores in the Iniomous Fishes.—Photophores of Porichthys.—Globefishes.—Remoras.—Sucking-disks of Clingfishes.—Lampreys and Hogfishes.—The Swordfishes.—The Paddle-fishes.—The Sawfishes.—Peculiarities of Jaws and Teeth.—The Angler-fishes.—Relation of Number of Vertebræ to Temperature, and the Struggle for Existence.—Number of Vertebræ: Soft-rayed Fishes; Spiny-rayed Fishes; Fresh-water Fishes; Pelagic Fishes.—Variations in Fin-rays.—Relation of Numbers to Conditions of Life.—Degeneration of Structures.—Conditions of Evolution among Fishes.

179CHAPTER XIII.

COLORS OF FISHES.

Pigmentation.—Protective Coloration.—Protective Markings.—Sexual Coloration.—Nuptial Coloration.—Coral-reef Fishes.—Recognition Marks.—Intensity of Coloration.—Fading of Pigments in Spirits.—Variation in Pattern.

226CHAPTER XIV.

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF FISHES.

Zoogeography.—General Laws of Distribution.—Species Absent through Barriers.—Species Absent through Failure to Maintain Foothold.—Species Changed through Natural Selection.—Extinction of Species.—Barriers

Checking Movements of Marine Species.—Temperature the Central Fact in Distribution.—Agency of Ocean Currents.—Centers of Distribution.—Distribution of Marine Fishes.—Pelagic Fishes.—Bassalian Fishes.—Littoral Fishes.—Distribution of Littoral Fishes by Coast Lines.—Minor Faunal Areas.—Equatorial Fishes most Specialized.—Realms of Distribution of Fresh-water Fishes.—Northern Zone.—Equatorial Zone.—Southern Zone.—Origin of the New Zealand Fauna.

237CHAPTER XV.

ISTHMUS BARRIERS SEPARATING FISH FAUNAS.

The Isthmus of Suez.—The Fish Fauna of Japan.—Fresh-water Faunas of Japan.—Faunal Areas of Marine Fishes of Japan.—Resemblance of Japanese and Mediterranean Fish Faunas.—Significance of Resemblances.—Differences between Japanese and Mediterranean Fish Faunas.—Source of Faunal Resemblances.—Effects of Direction of Shore Lines.—Numbers of Genera in Different Faunas.—Significance of Rare Forms.—Distribution of Shore-fishes.—Extension of Indian Fauna.—The Isthmus of Suez as a Barrier to Distribution.—Geological Evidences of Submergence of Isthmus of Suez.—The Cape of Good Hope as a Barrier to Fishes.—Relations of Japan to the Mediterranean Explained by Present Conditions.—The Isthmus of Panama as a Barrier to Distribution.—Unlikeness of Species on the Shores of the Isthmus of Panama.—Views of Dr. Günther on the Isthmus of Panama.—Catalogue of Fishes of Panama.—Conclusions of Evermann & Jenkins.—Conclusions of Dr. Hill.—Final Hypothesis as to Panama.

255CHAPTER XVI.

DISPERSION OF FRESH-WATER FISHES.

The Dispersion of Fishes.—The Problem of Oatka Creek.—Generalizations as to Dispersion.—Questions Raised by Agassiz.—Conclusions of Cope.—Questions Raised by Cope.—Views of Günther.—Fresh-water Fishes of North America.—Characters of Species.—Meaning of Species.—Special Creation Impossible.—Origin of American Species of Fishes.

282CHAPTER XVII.

DISPERSION OF FRESH-WATER FISHES. (

Continued.)

Barriers to Dispersion of Fresh-water Fishes: Local Barriers.—Favorable Waters Have Most Species.—Watersheds.—How Fishes Cross Watersheds.—The Suletind.—The Cassiquiare.—Two-Ocean Pass.—Mountain Chains.—Upland Fishes.—Lowland Fishes.—Cuban Fishes.—Swampy Watersheds.—The Great Basin of Utah.—Arctic Species in Lakes.—Causes of Dispersion still in Operation.

297CHAPTER XVIII.

FISHES AS FOOD FOR MAN.

The Flesh of Fishes.—Relative Rank of Food-fishes.—Abundance of Food-fishes.—Variety of Tropical Fishes.—Economic Fisheries.—Angling.

320CHAPTER XIX.

DISEASES OF FISHES.

Contagious Diseases: Crustacean Parasites.—Myxosporidia or Parasitic Protozoa.—Parasitic Worms: Trematodes, Cestodes.—The Worm of the Yellowstone.—The Heart Lake Tape-worm.—Thorn-head Worms.—Nematodes.—Parasitic Fungi.—Earthquakes.—Mortality of Filefish.

340CHAPTER XX.

THE MYTHOLOGY OF FISHES.

The Mermaid.—The Monkfish.—The Bishop-fish.—The Sea-serpent.

359CHAPTER XXI.

THE CLASSIFICATION OF FISHES.

Taxonomy.—Defects in Taxonomy.—Analogy and Homology.—Coues on Classification.—Species as Twigs of a Genealogical Tree.—Nomenclature.—The Conception of Genus and Species.—The Trunkfishes.—Trinomial Nomenclature.—Meaning of Species.—Generalization and Specialization.—High and Low Forms.—The Problem of the Highest Fishes.

367CHAPTER XXII.

THE HISTORY OF ICHTHYOLOGY.

Aristotle.—Rondelet.—Marcgraf.—Osbeck.—Artedi.—Linnæus.— Forskål.—Risso.—Bloch.—Lacépède.—Cuvier.—Valenciennes.— Agassiz.—Bonaparte.—Günther.—Boulenger.—Le Sueur.—Müller.— Gill.—Cope.—Lütken.—Steindachner.—Vaillant.—Bleeker.— Schlegel.—Poey.—Day.—Baird.—Garman.—Gilbert.—Evermann.— Eigenmann.—Zittel.—Traquair.—Woodward.—Dean.—Eastman.—Hay.— Gegenbaur.—Balfour.—Parker.—Dollo.

387CHAPTER XXIII.

THE COLLECTION OF FISHES.

How to Secure Fishes.—How to Preserve Fishes.—Value of Formalin.—Records of Fishes.—Eternal Vigilance.

429CHAPTER XXIV.

THE EVOLUTION OF FISHES.

The Geological Distribution of Fishes.—The Earliest Sharks.—Devonian Fishes.—Carboniferous Fishes.—Mesozoic Fishes.—Tertiary Fishes.—Factors of Extinction.—Fossilization of a Fish.—The Earliest Fishes.—The Cyclostomes.—The Ostracophores.—The Arthrodires.—The Sharks.—Origin of the Shark.—The Chimæras.—The Dipnoans.—The Crossopterygians.—The Actinopteri.—The Bony Fishes.

435CHAPTER XXV.

THE PROTOCHORDATA.

The Chordate Animals.—The Protochordates.—Other Terms Used in Classification.—The Enteropneusta.—Classification of Enteropneusta.—Family Harrimaniidæ.—Balanoglossidæ.—Low Organization of Harrimaniidæ.

460CHAPTER XXVI.

THE TUNICATES, OR ASCIDIANS.

Structure of Tunicates.—Development of Tunicates.—Reproduction of Tunicates.—Habits of Tunicates.—Larvacea.—Ascidiacea.—Thaliacea.—Origin of Tunicates.—Degeneration of Tunicates.

467CHAPTER XXVII.

THE LEPTOCARDII, OR LANCELETS.

The Lancelet.—Habits of Lancelets.—Species of Lancelets.—Origin of Lancelets.

482CHAPTER XXVIII.

THE CYCLOSTOMES, OR LAMPREYS.

The Lampreys.—Structure of the Lamprey.—Supposed Extinct Cyclostomes.—Conodontes.—Orders of Cyclostomes.—The Hyperotreta, or Hagfishes.—The Hyperoartia, or Lampreys.—Food of Lampreys.—Metamorphosis of Lampreys.—Mischief Done by Lampreys.—Migration or "Running" of Lampreys.—Requisite Conditions for Spawning with Lampreys.—The Spawning Process with Lampreys.—What Becomes of Lampreys after Spawning?

486CHAPTER XXIX.

THE CLASS ELASMOBRANCHII, OR SHARK-LIKE FISHES.

The Sharks.—Characters of Elasmobranchs.—Classification of Elasmobranchs.—Subclasses of Elasmobranchs.—The Selachii.—Hasse's Classification of Elasmobranchs.—Other Classifications of Elasmobranchs.—Primitive Sharks.—Order Pleuropterygii.—Order Acanthodii.—Dean on Acanthodii.—Order Ichthyotomi.

506CHAPTER XXX.

THE TRUE SHARKS.

Order Notidani.—Family Hexanchidæ.—Family Chlamydoselachidæ.—Order Asterospondyli.—Suborder Cestraciontes.—Family Heterodontidæ.—Edestus and its Allies.—Onchus.—Family Cochliodontidæ.—Suborder Galei.—Family Scyliorhinidæ.—The Lamnoid, or Mackerel-sharks.—Family Mitsukurinidæ, the Goblin-sharks.—Family Alopiidæ, or Thresher-sharks.—Family Pseudotriakidæ.—Family Lamnidæ.—Man-eating Sharks.—Family Cetorhinidæ, or Basking Sharks.—Family Rhineodontidæ.—The Carcharioid Sharks, or Requins.—Family Sphyrnidæ, or Hammer-head Sharks.—The Order of Tectospondyli.—Suborder Cyclospondyli.—Family Squalidæ.—Family Dalatiidæ.—Family Echinorhinidæ.—Suborder Rhinæ.—Family Pristiophoridæ, or Saw-sharks.—Suborder Batoidei, or Rays.—Pristididæ, or Sawfishes.—Rhinobatidæ, or Guitar-fishes.—Rajidæ, or Skates.—Narcobatidæ, or Torpedoes.—Petalodontidæ.—Dasyatidæ, or Sting-rays.—Myliobatidæ.—Family Psammodontidæ.—Family Mobulidæ. 523

CHAPTER XXXI.

THE HOLOCEPHALI, OR CHIMÆRAS.

The Chimæras.—Relationship of Chimæras.—Family Chimæridæ.—Rhinochimæridæ.—Extinct Chimæroids.—Ichthyodorulites.

561CHAPTER XXXII.

THE CLASS OSTRACOPHORI.

Ostracophores.—Nature of Ostracophores.—Orders of Ostracophores.—Order Heterostraci.—Order Osteostraci.—Order Antiarcha.—Order Anaspida.

568CHAPTER XXXIII.

ARTHRODIRES.

The Arthrodires.—Occurrence of Arthrodires.—Arthrognathi.—Anarthrodira.—Stegothalami.— Arthrodira.—Temnothoraci.—Arthrothoraci.—Relations of

Arthrodires.—Suborder Cycliæ.—Palæospondylus.—Gill on Palæospondylus.—Views as to the Relationships of Palæospondylus: Huxley, Traquair, 1890. Traquair, 1893. Traquair, 1897. Smith Woodward, 1892. Dawson, 1893. Gill, 1896. Dean, 1896. Dean, 1898. Parker & Haswell, 1897. Gegenbaur, 1898.—Relationships of Palæospondylus

581CHAPTER XXXIV.

THE CROSSOPTERYGII.

Class Teleostomi.—Subclass Crossopterygii.—Order of Amphibians.—The Fins of Crossopterygians.—Orders of Crossopterygians.—Haplistia.—Rhipidistia.—Megalichthyidæ.—Order Actinistia.—Order Cladistia.—The Polypteridæ

598CHAPTER XXXV.

SUBCLASS DIPNEUSTI, OR LUNGFISHES.

The Lungfishes.—Classification of Dipnoans.—Order Ctenodipterini.—Order Sirenoidei.—Family Ceratodontidæ.—Development of Neoceratodus.—Lepidosirenidæ.—Kerr on the Habits of Lepidosiren

609FOOTNOTES:

[1] For most of this list of errata I am indebted to the kindly interest of Dr. B. W. Evermann.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

VOL. I.

mesocoracoid

Some years since, at Madras, I (Dr. Day) obtained several specimens of a fresh-water Siluroid fish (Macrones vittatus) which is termed the "fiddler" in Mysore. I touched one which was on the wet ground, at which it appeared to become very irate, erecting its dorsal fin, making a noise resembling the buzzing of a bee. Having put some small carp into an aquarium containing one of these fishes, it rushed at a small example, seized it by the middle of its back, and shook it like a dog killing a rat; at this time its barbels were stiffened out laterally like a cat's whiskers.

It is noteworthy that the upland fishes are nearly the same in all these streams until we reach the southern limit of possible glacial influence. South of western North Carolina the faunæ of the different river basins appear to be more distinct from one another. Certain ripple-loving types are represented by closely related but unquestionably different species in each river basin, and it would appear that a thorough mingling of the upland species in these rivers has never taken place.

Very near the first among sea-fishes must come the pampano (Trachinotus carolinus) of the Gulf of Mexico, with firm, white, finely flavored flesh.

The various kinds of trout have been made famous the world over. All are attractive in form and color; all are gamey; all have the most charming of scenic surroundings, and, finally, all are excellent as food, not in the first rank perhaps, but well above the second. Notable among these are the European charr (Salvelinus alpinus), the American speckled trout or charr (Salvelinus fontinalis), the Dolly Varden or malma (Salvelinus malma), and the oquassa trout (Salvelinus oquassa). Scarcely less attractive are the true trout, the brown trout, or forelle (Salmo fario), in Europe, the rainbow-trout (Salmo irideus), the steelhead (Salmo gairdneri), the cut-throat trout (Salmo clarkii), and the Tahoe trout (Salmo henshawi), in America, and the yamabe (Salmo perryi) of Japan. Not least of all these is the flower of fishes, the grayling (Thymallus), of different species in different parts of the world.

Earthquakes.—Occasionally an earthquake has been known to kill sea-fishes in large numbers. The Albatross obtained specimens of Sternoptyx diaphana in the Japanese Kuro Shiwo, killed by the earthquakes of 1896, which destroyed fishing villages of the coast of Rikuchu in northern Japan.

A perfect taxonomy is one which would perfectly express all the facts in the evolution and development of the various forms. It would recognize all the evidence from the three ancestral documents, palæontology, morphology, and ontogeny. It would consider structure and form independently of adaptive or physiological or environmental modifications. It would regard as most important those characters which had existed longest unchanged in the history of the species or type. It would regard as of first rank those characters which appear first in the history of the embryo. It would regard as of minor importance those which had arisen recently in response to natural selection or the forced alteration through pressure of environment, while fundamental alterations as they appear one after another in geologic time would make the basal characters of corresponding groups in taxonomy. In a perfect taxonomy or natural system of classification animals would not be divided into groups nor ranged in linear series. We should imagine series variously and divergently branched, with each group at its earlier or lower end passing insensibly into the main or primitive stock. A very little alteration now and then in some structure is epoch-making, and paves the way through specialization to a new class or order. But each class or order through its lowest types is interlocked with some earlier and otherwise diverging group.

The scanty pre-Cuvieran work on the fishes of North America has been already noticed. Contemporary with the early work of Cuvier is the worthy attempt of Professor Samuel Latham Mitchill (1764-1831) to record in systematic fashion the fishes of New York. Soon after followed the admirable work of Charles Alexandre Le Sueur (1789-1840), artist and naturalist, who was the first to study the fishes of the Great Lakes and the basin of the Ohio. Le Sueur's engravings of fishes, in the early publications of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, are still among the most satisfactory representations of the species to which they refer. Constantine Samuel Rafinesque (1784-1842), the third of this remarkable but very dissimilar trio, published numerous papers descriptive of the species he had seen or heard of in his various botanical rambles. This culminated in his elaborate but untrustworthy "Ichthyologia Ohiensis." The fishes of Ohio received later a far more conscientious though less brilliant treatment at the hands of Dr. Jared Potter Kirtland (1793-1877), an eminent physician of Cleveland, Ohio. In 1842 the amiable and scholarly James Ellsworth Dekay (1799-1851) published his detailed report on the fishes of the "New York Fauna," and a little earlier (1836) in the "Fauna Boreali-Americana" Sir John Richardson (1787-1865) gave a most valuable and accurate account of the fishes of the Great Lakes and Canada. Almost simultaneously, Rev. Zadock Thompson (1796-1856) gave a catalogue of the fishes of Vermont, and David Humphreys Storer (1804-91) began his work on the fishes of Massachusetts, finally expanded into a "Synopsis of the Fishes of North America" (1846) and a "History of the Fishes of Massachusetts" (1853-67). Dr. John Edwards Holbrook (1794-1871), of Charleston, published (1855-60) his invaluable record of the fishes of South Carolina, the promise of still more important work, which was prevented by the outbreak of the Civil War in the United States. The monograph on Lake Superior (1850) and other publications of Louis Agassiz (1807-73) have been already noticed. One of the first of Agassiz's students was Charles Girard (1822-95), who came with him from Switzerland, and, in association with Spencer Fullerton Baird (1823-87), described the fishes from the United States Pacific Railway Surveys (1858) and the United States and Mexican Boundary Surveys (1859). Professor Baird, primarily an ornithologist, became occupied with executive matters, leaving Girard to finish these studies of the fishes. A large part of the work on fishes published by the United States National Museum and the United States Fish Commission has been made possible through the direct help and inspiration of Professor Baird. Among those engaged in this work, James William Milner (1841-80), Marshall Macdonald (1836-95), and Hugh M. Smith may be noted.

Other faunal writers of more or less prominence were William Dandridge Peck (1763-1822) in New Hampshire, George Suckley (1830-69) in Oregon, James William Milner (1841-80) in the Great Lake Region, Samuel Stehman Haldeman (1812-80) in Pennsylvania, William O. Ayres (1817-91) in Connecticut and California; Dr. John G. Cooper (died 1902), Dr. William P. Gibbons and Dr. William N. Lockington (died 1902) in California; Philo Romayne Hoy (1816-93) studied the fishes of Wisconsin, Charles Conrad Abbott those of New Jersey, Silas Stearns (1859-88) those of Florida, Stephen Alfred Forbes and Edward W. Nelson those of Illinois, Oliver Perry Hay, later known for his work on fossil forms, those of Mississippi, Alfredo Dugés, of Guanajuato, those of Central Mexico.

Third Period.—Morphological Work on Fossil Fishes.—Among the writers who have dealt with the problems of the relationships of the Ostracophores as well as Palæospondylus and the Arthrodires may be named Traquair, Huxley, Newberry, Smith Woodward, Rohon, Eastman, and Dean; most recently William Patten. Upon the phylogeny of the sharks Traquair, A. Fritsch, Hasse, Cope, Brongniart, Jaekel, Reis, Eastman, and Dean. On Chimæroid morphology mention may be made of the papers of A. S. Woodward, Reis, Jaekel, Eastman, C. D. Walcott, and Dean. As to Dipnoan relationships the paper of Louis Dollo is easily of the first value; of especial interest, too, is the work of Eastman as to the early derivation of the Dipnoan dentition. In this regard a paper of Rohon is noteworthy, as is also that of Richard Semon on the development of the dentition of recent Neoceratodus, since it contains a number of references to extinct types. Interest notes on Dipnoan fin characters have been given by Traquair. In the morphology of Ganoids, the work of Traquair and A. S. Woodward takes easily the foremost rank. Other important works are those of Huxley, Cope, A. Fritsch, and Oliver P. Hay.

The known branchiferous or gill-bearing chordates living and extinct may be first divided into eight classes—the Enteropneusta, the Tunicata, the Leptocardii, or lancelets, the Cyclostomi, or lampreys, the Elasmobranchii, or sharks, the Ostracophori the Arthrodira, and the Teleostomi, or true fishes. The first two groups, being very primitive and in no respect fish-like in appearance, are sometimes grouped together as Protochordata, the others with the higher Chordates constituting the Vertebrata.

[Pg 367]

ERRATA[1]

VOL. I

PAGE

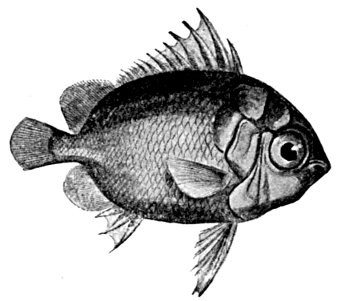

Lepomis megalotis, Long-eared Sunfish

2 Lepomis megalotis, Long-eared Sunfish

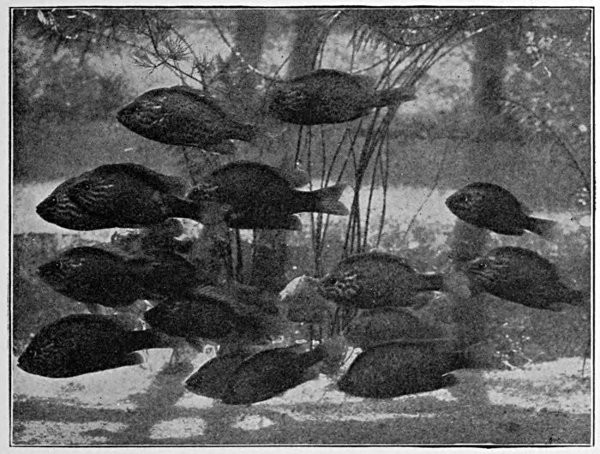

4 Eupomotis gibbosus, Common Sunfish

7 Ozorthe dictyogramma, a Japanese Blenny

9 Eupomotis gibbosus, Common Sunfish

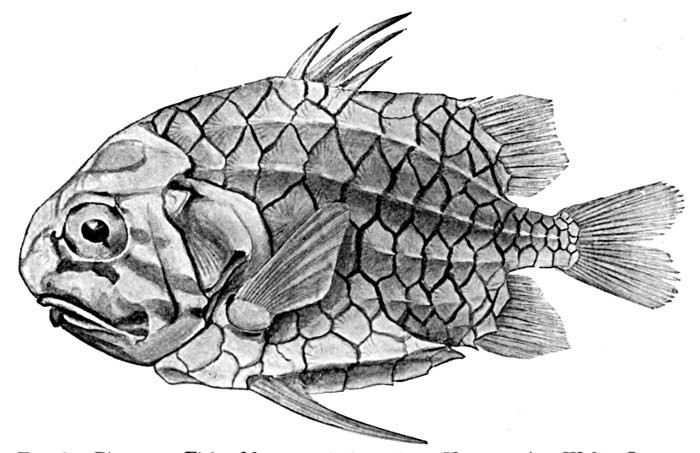

13 Monocentris japonicas, Pine-cone Fish

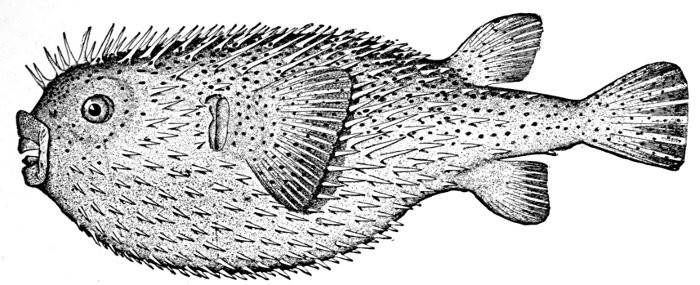

16 Diodon hystrix, Porcupine-fish

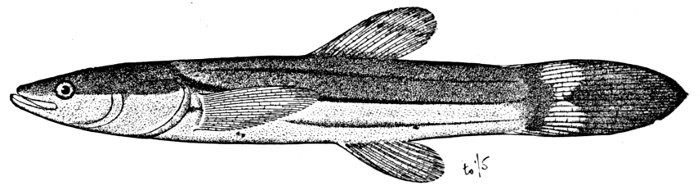

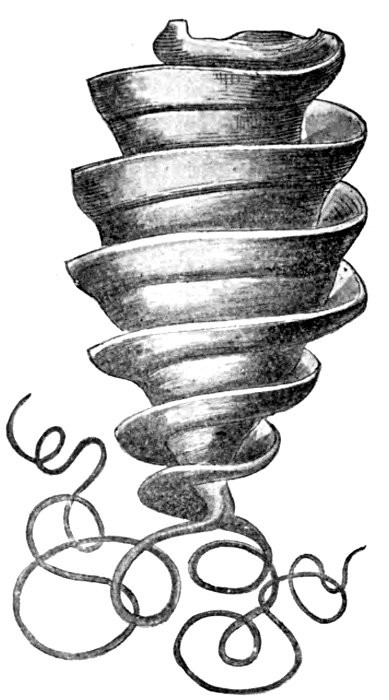

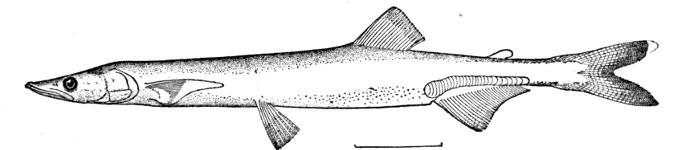

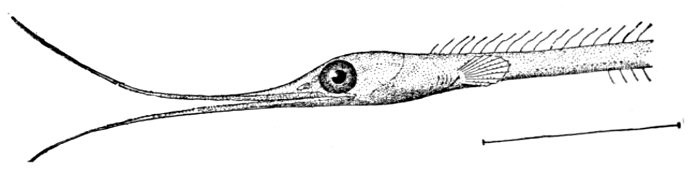

17 Nemichthys avocetta, Thread-eel

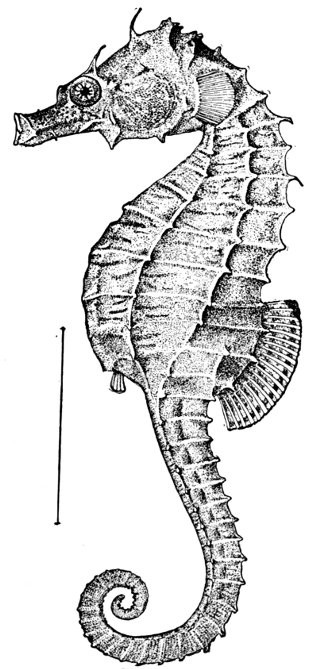

17 Hippocampus hudsonius, Sea-horse

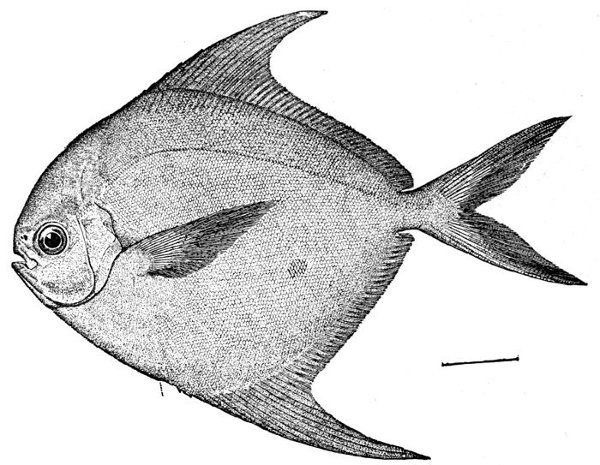

17 Peprilus paru, Harvest-fish

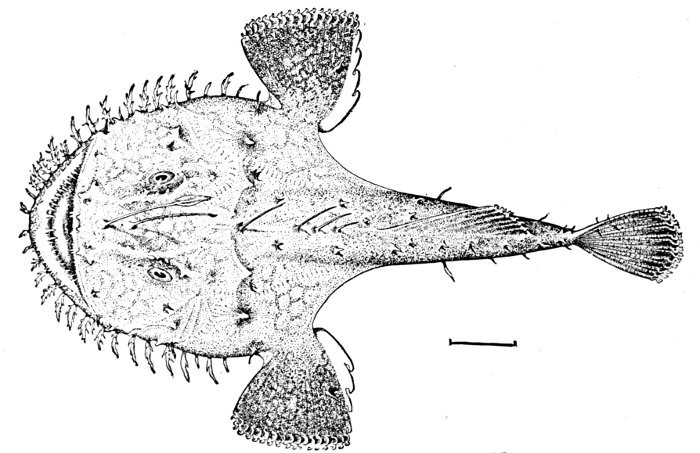

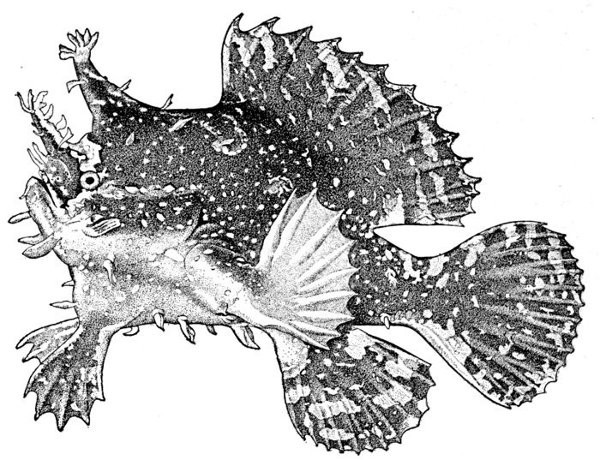

18 Lophius litulon, Anko or Fishing-frog

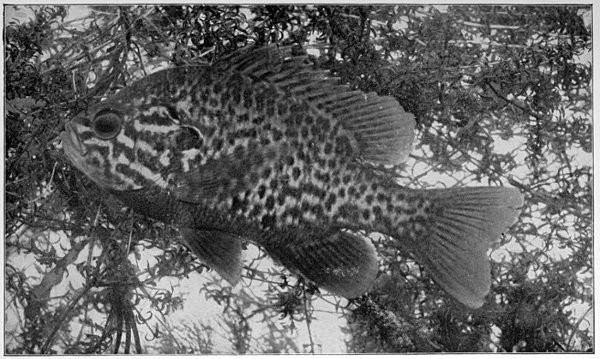

18 Epinephelus adscensionis, Rock-hind or Cabra Mora

20Scales of

Acanthoessus bronni 21Cycloid Scale

22 Porichthys porosissimus, Singing-fish

23 Apomotis cyanellus, Blue-green Sunfish

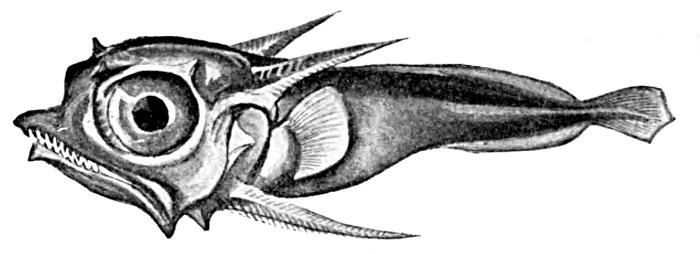

27 Chiasmodon niger, Black Swallower

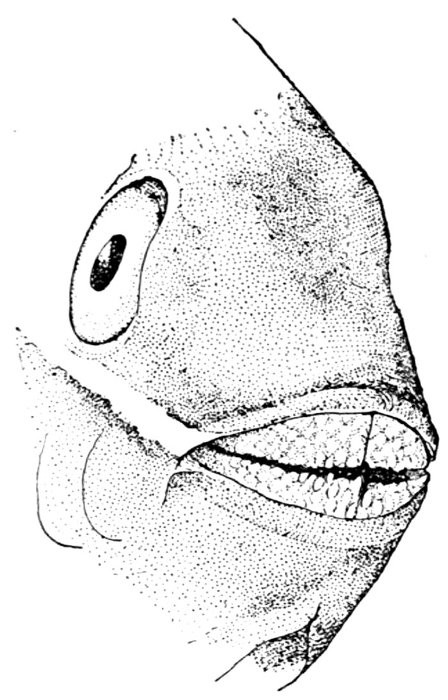

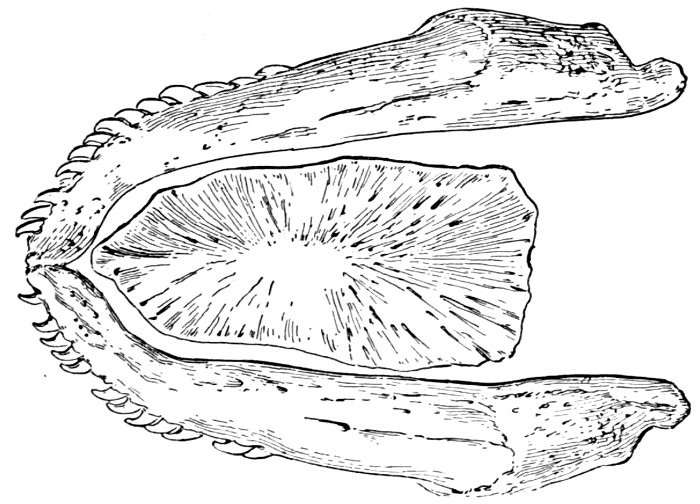

29Jaws of a Parrot-fish,

Sparisoma aurofrenatum 30 Archosargus probatocephalus, Sheepshead

31 Campostoma anomalum, Stone-roller

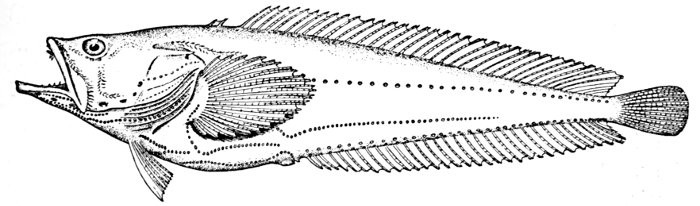

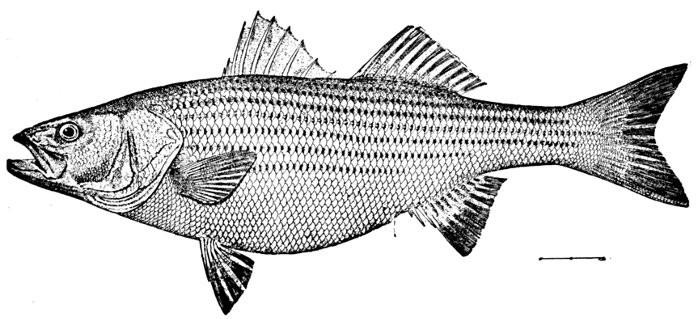

33 Roccus lineatus, Striped Bass

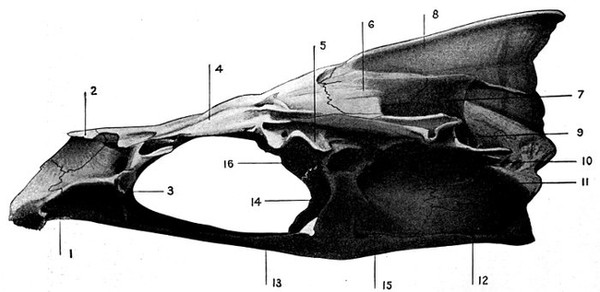

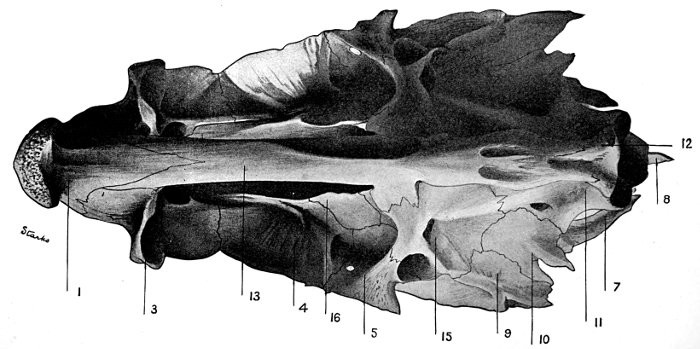

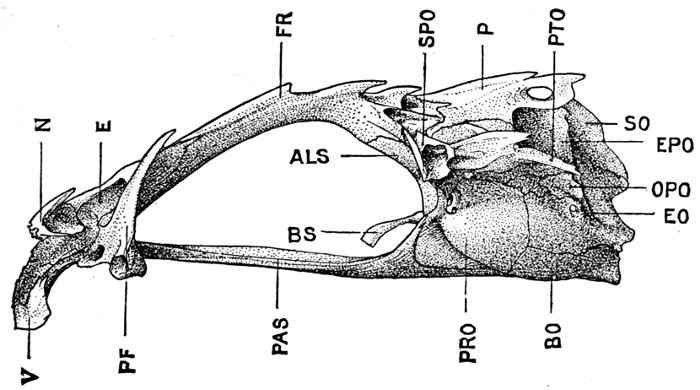

35 Roccus lineatus.Lateral View of Cranium

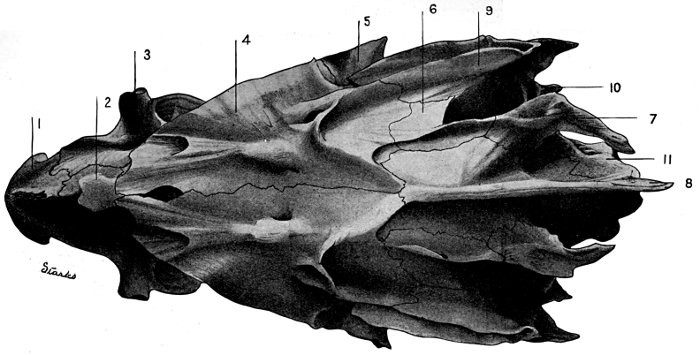

36 Roccus lineatus.Superior View of Cranium

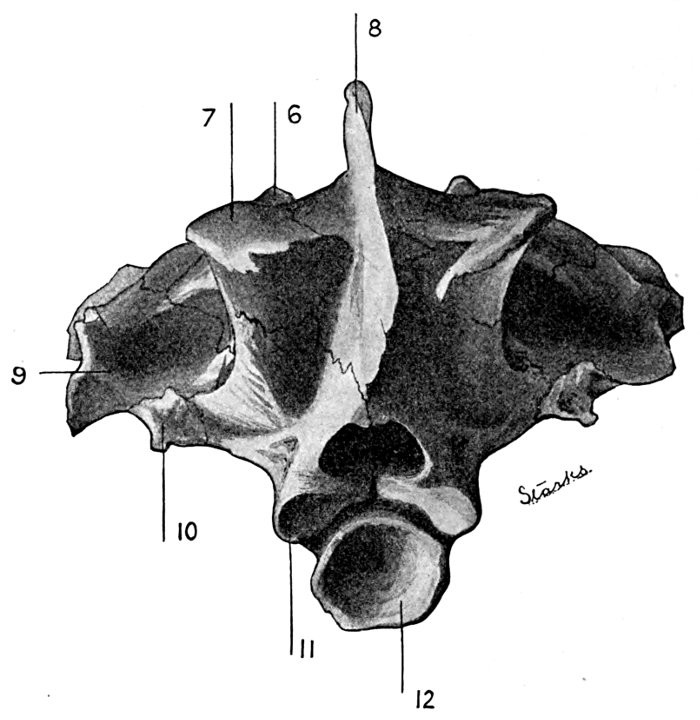

37 Roccus lineatus.Inferior View of Cranium

38 Roccus lineatus. Posterior View of Cranium

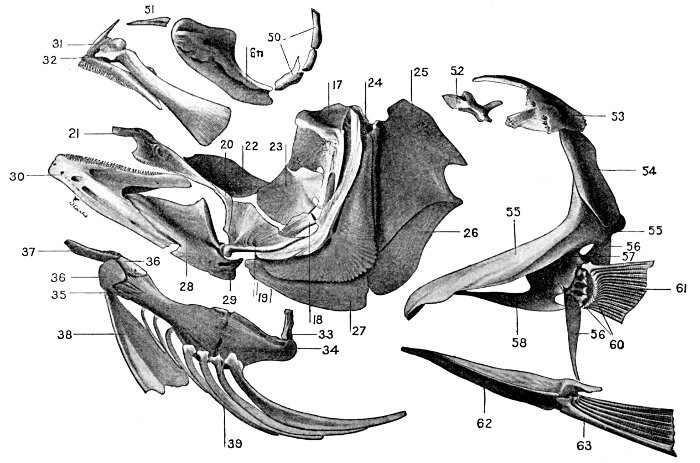

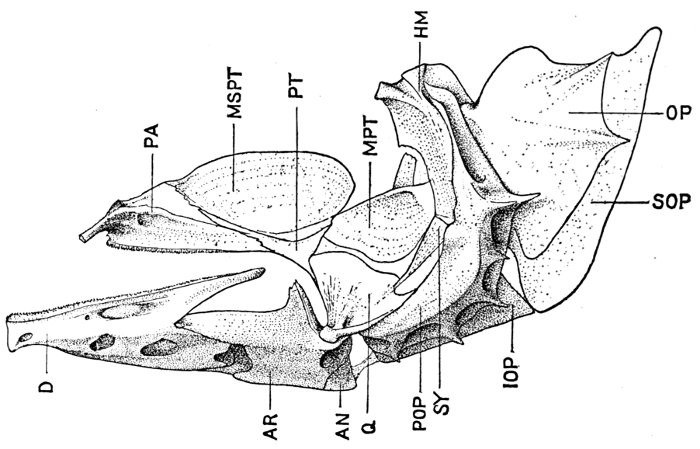

40 Roccus lineatus.Face-bones, Shoulder and Pelvic Girdles, and Hyoid Arch

42Lower Jaw of

Amia calva, showing Gular Plate

43 Roccus lineatus.Branchial Arches

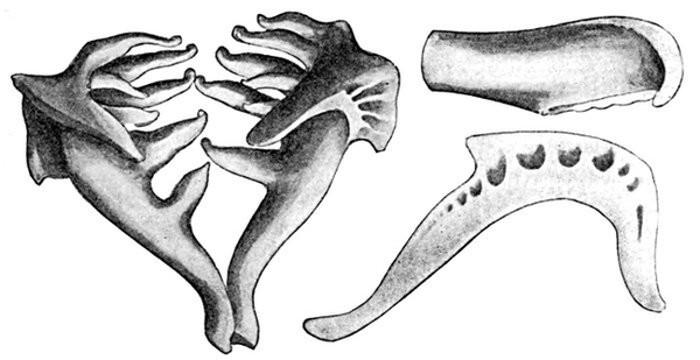

46Pharyngeal Bone and Teeth of European Chub,

Leuciscus cephalus 47Upper Pharyngeals of Parrot-fish,

Scarus strongylocephalus 47Lower Pharyngeal Teeth of Parrot-fish,

Scarus strongylocephalus 47Pharyngeals of Italian Parrot-fish,

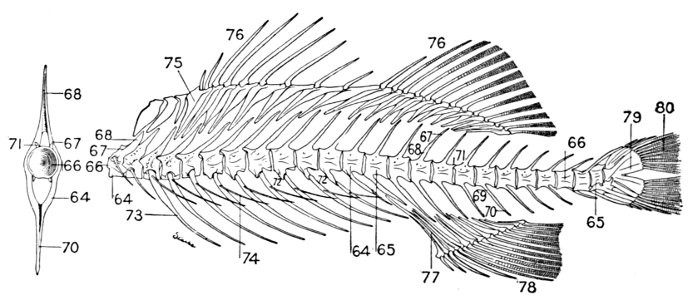

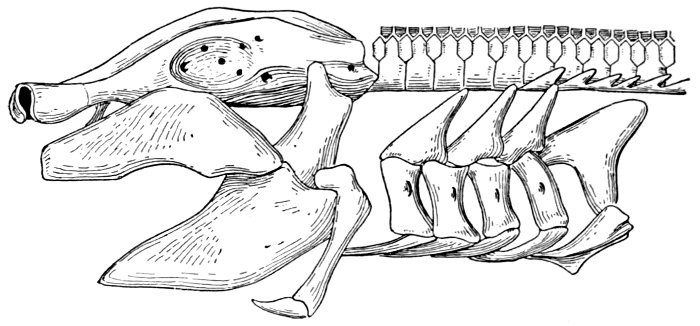

Sparisoma cretense 48 Roccus lineatus, Vertebral Column and Appendages

48Basal Bone of Dorsal Fin,

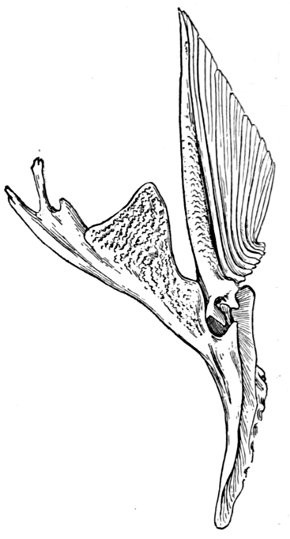

Holoptychius leptopterus 49Inner View of Shoulder-girdle of Buffalo-fish,

Ictiobus bubalus 51 Pterophryne tumida, Sargassum-fish.

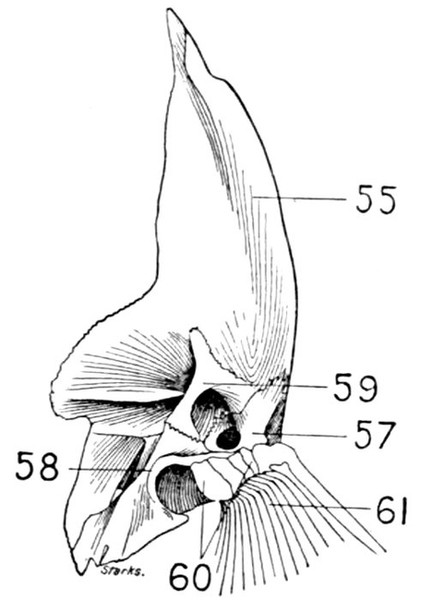

52Shoulder-girdle of

Sebastolobus alascanus.

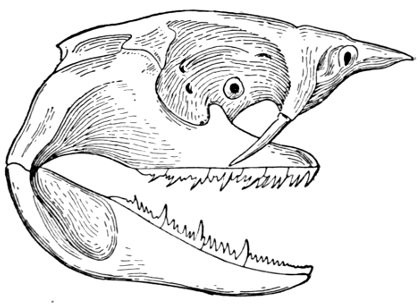

52Cranium of

Sebastolobus alascanus.

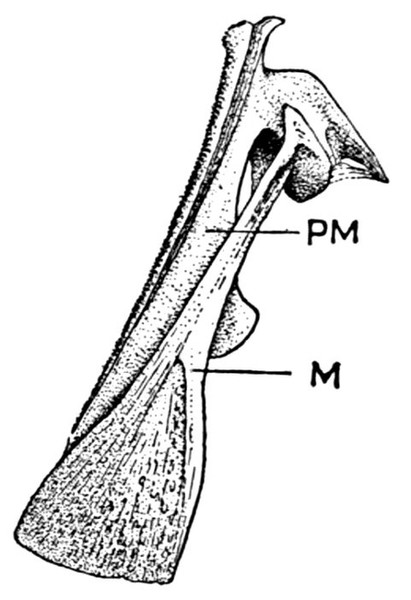

53Lower Jaw and Palate of

Sebastolobus alascanus.

54Maxillary and Premaxillary of

Sebastolobus alascanus.

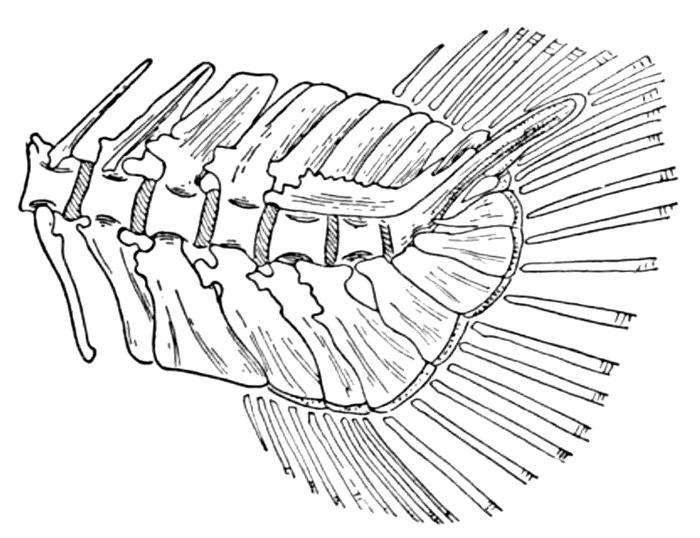

55Part of Skeleton of

Selene vomer.

55Hyostylic Skull of

Chiloscyllium indicum, a Scyliorhinoid Shark.

56Skull of

Heptranchias indicus, a Notidanoid Shark.

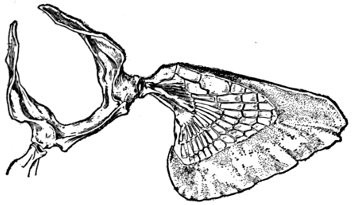

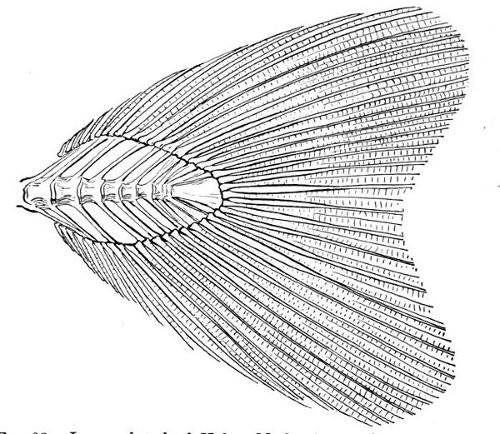

56Basal Bones of Pectoral Fin of Monkfish,

Squatina.

56Pectoral Fin of

Heterodontus philippi.

57Pectoral Fin of

Heptranchias indicus.

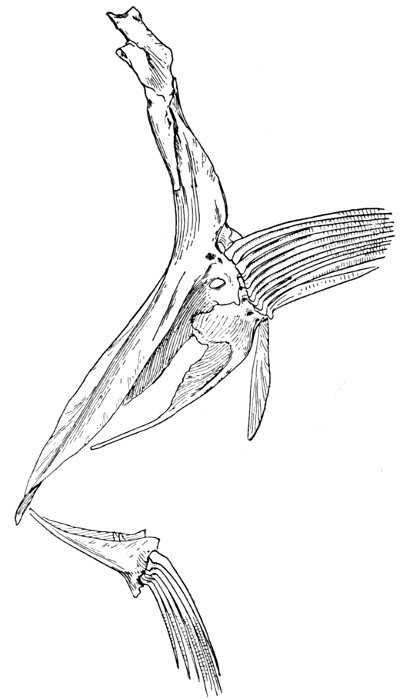

57Shoulder-girdle of a Flounder,

Paralichthys californicus.

58Shoulder-girdle of a Toadfish,

Batrachoides pacifici.

59Shoulder-girdle of a Garfish,

Tylosurus fodiator.

59Shoulder-girdle of a Hake,

Merluccius productus.

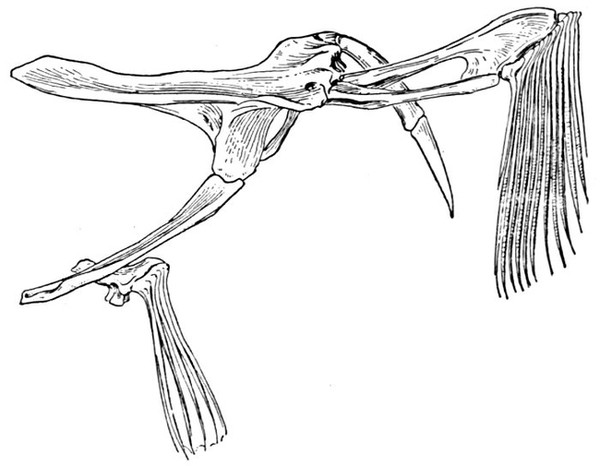

60 Cladoselache fyleri, Restored.

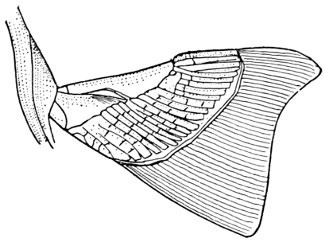

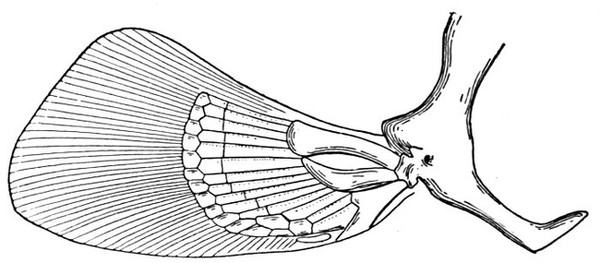

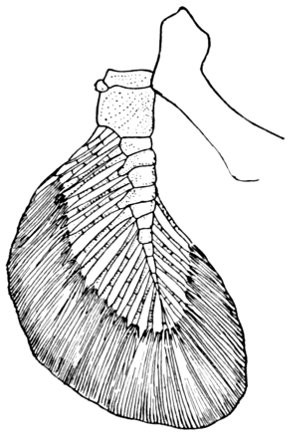

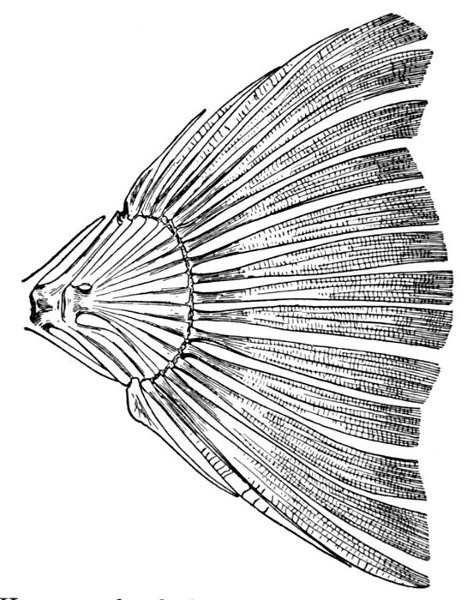

65Fold-like Pectoral and Ventral Fins of

Cladoselache fyleri.

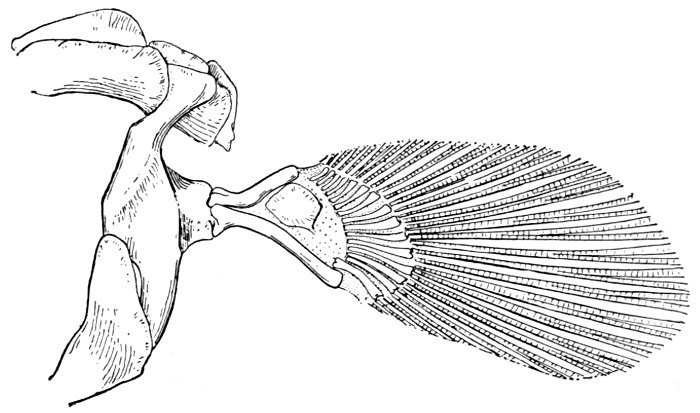

65Pectoral Fin of a Shark,

Chiloscyllium.

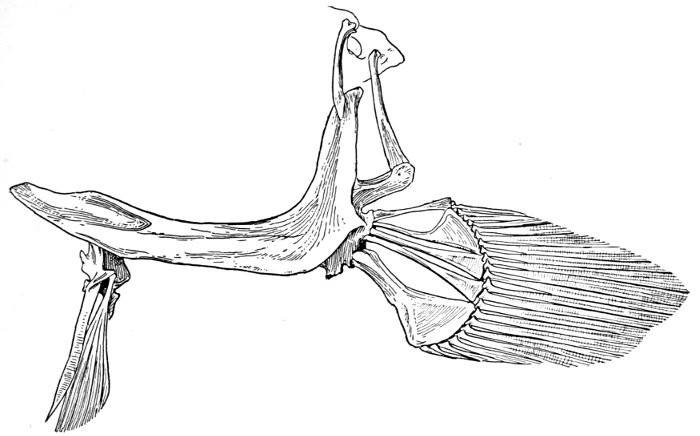

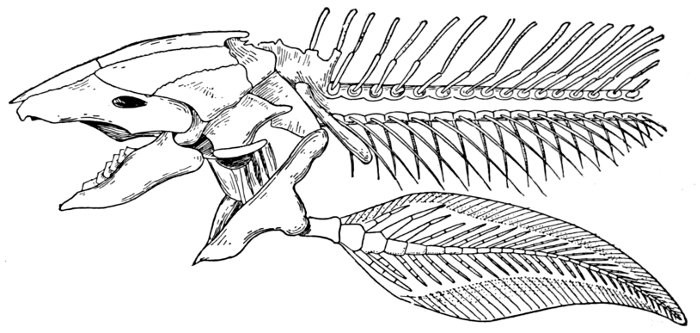

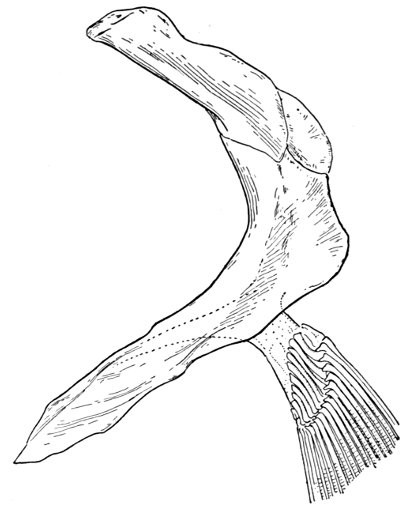

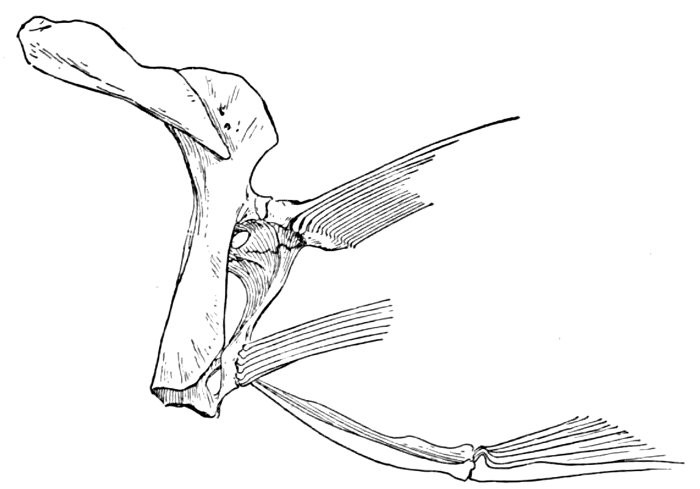

66Skull and Shoulder-girdle of

Neoceratodus forsteri, showing archipterygium.

68 Acanthoessus wardi.

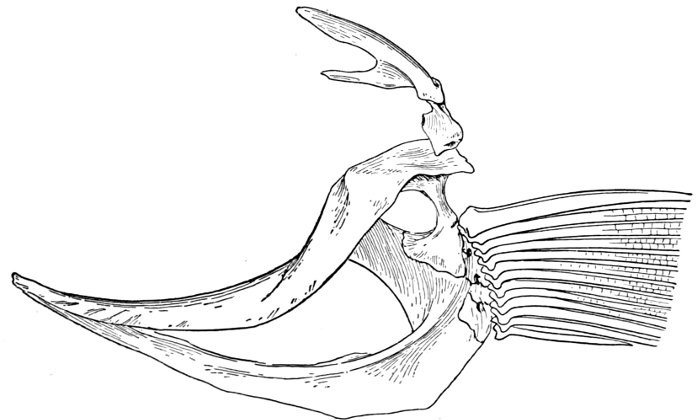

69Shoulder-girdle of

Acanthoessus.

69Pectoral Fin of

Pleuracanthus.

69Shoulder-girdle of

Polypterus bichir.

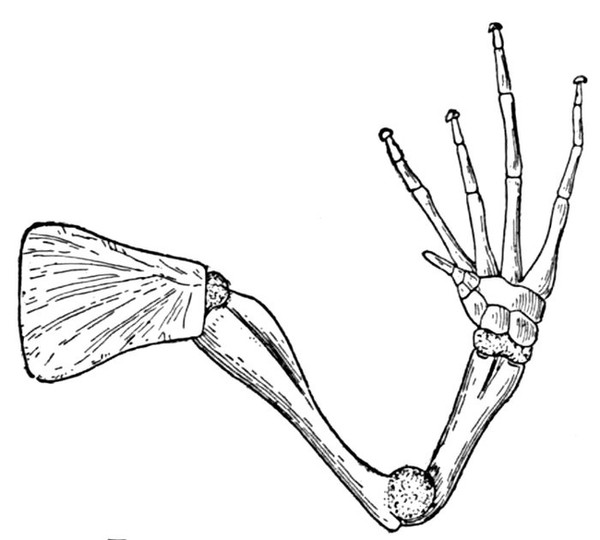

70Arm of a Frog.

71 Pleuracanthus decheni.

74Embryos of

Heterodontus japonicas, a Cestraciont Shark.

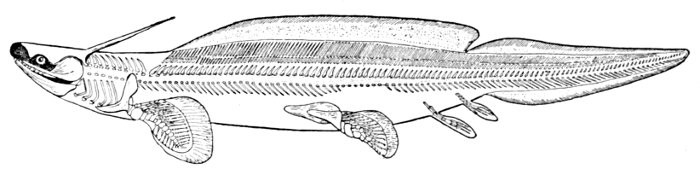

75 Polypterus congicus, a Crossopterygian Fish with External Gills.

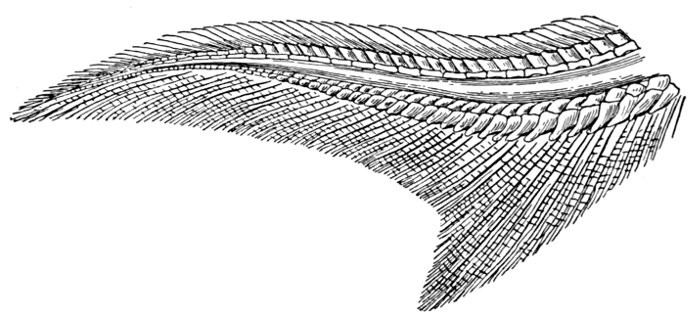

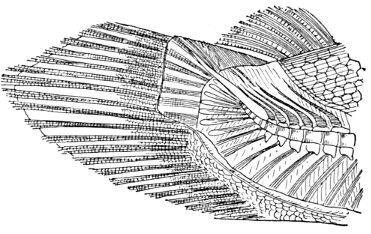

78Heterocercal Tail of Sturgeon,

Acipenser sturio.

80Heterocercal Tail of Bowfin,

Amia calva.

82Heterocercal Tail of Garpike,

Lepisosteus osseus.

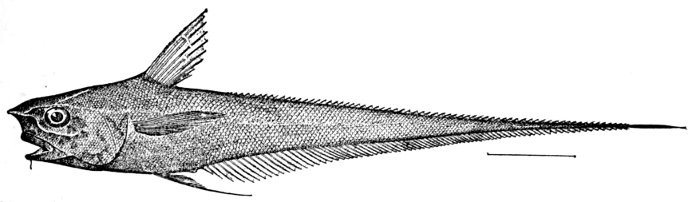

82 Coryphænoides carapinus, showing Leptocercal Tail.

83Heterocercal Tail of Young Trout,

Salmo fario.

83Isocercal Tail of Hake,

Merluccius productus.

84Homocercal Tail of a Flounder,

Paralichthys californicus.

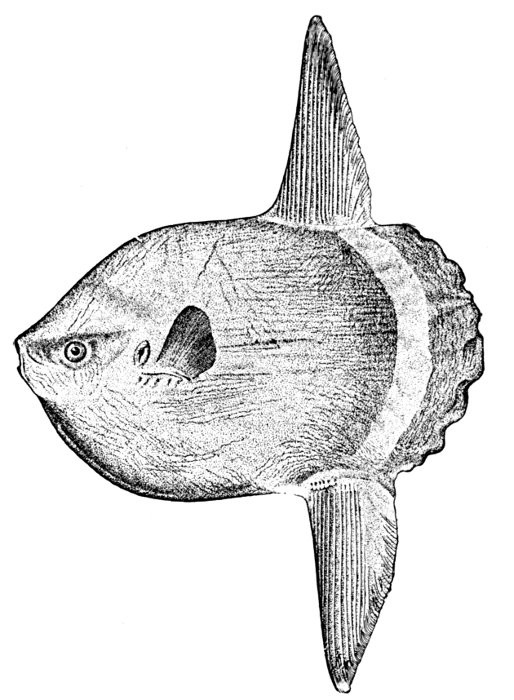

84Gephyrocercal Tail of

Mola mola.

85Shoulder-girdle of

Amia calva.

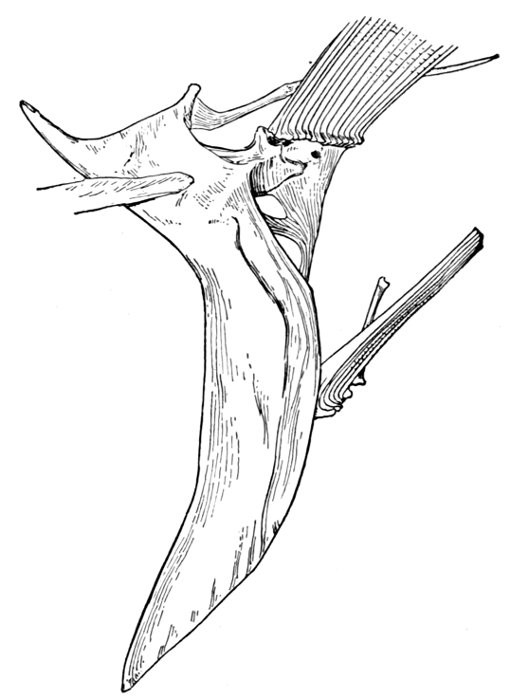

86Shoulder-girdle of a Sea-catfish,

Selenaspis dowi.

86Clavicles of a Sea-catfish,

Selenaspis dowi.

87Shoulder-girdle of a Batfish,

Ogcocephalus radiatus.

88Shoulder-girdle of a Threadfin,

Polydactylus approximans.

89Gill-basket of Lamprey.

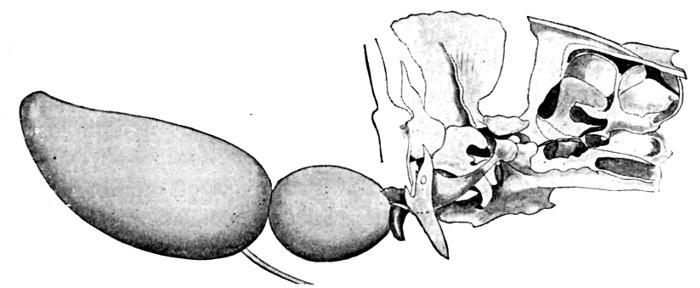

92Weberian Apparatus and Air-bladder of Carp.

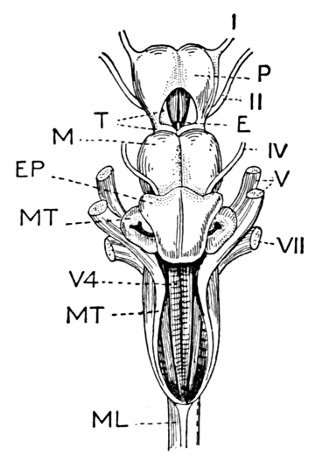

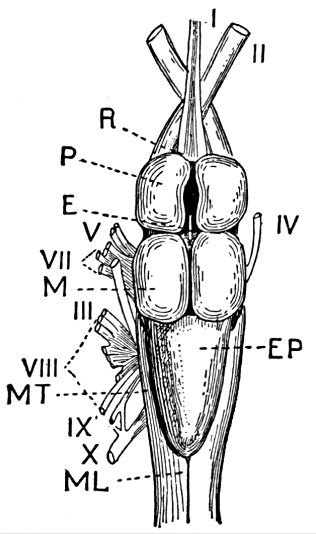

93Brain of a Shark,

Squatina squatina.

110Brain of

Chimæra monstrosa.

110Brain of

Polypterus annectens.

110Brain of a Perch,

Perca flavescens.

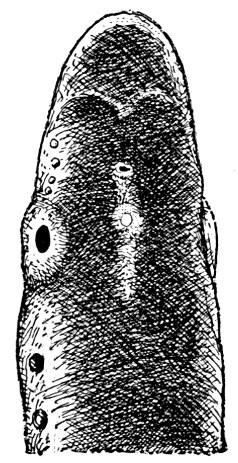

111 Petromyzon marinus unicolor.Head of Lake Lamprey, showing Pineal Body.

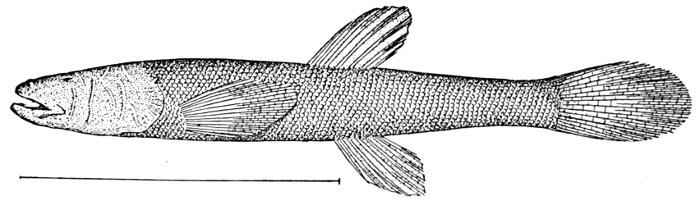

111 Chologaster cornutus, Dismal-swamp Fish.

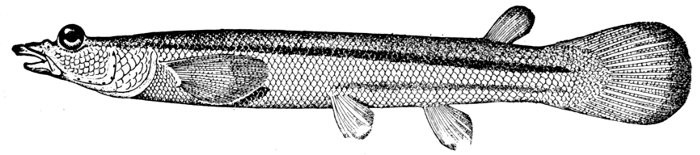

116 Typhlichthys subterraneus, Blind Cavefish.

116 Anableps dovii, Four-eyed Fish.

117Ipnops murrayi.

118 Boleophthalmus chinensis, Pond-skipper.

118 Lampetra wilderi, Brook Lamprey.

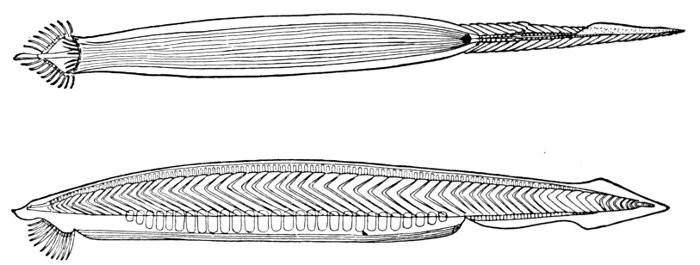

120 Branchiostoma lanceolatum, European Lancelet.

120 Pseudupeneus maculatus, Goatfish.

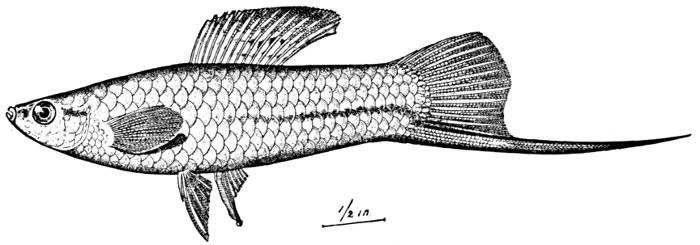

122 Xiphophorus helleri, Sword-tail Minnow.

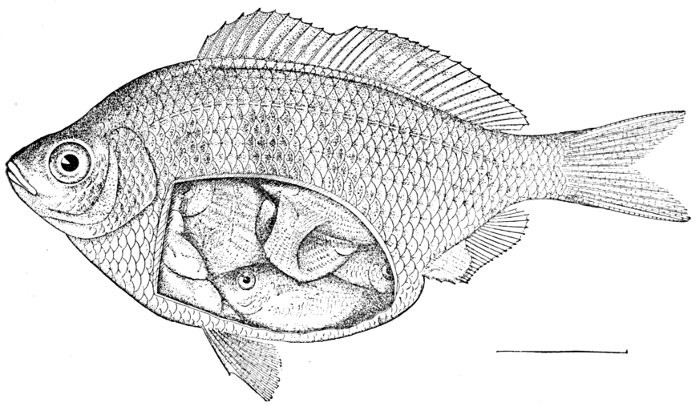

124 Cymatogaster aggregatus, White Surf-fish, Viviparous, with Young.

125 Goodea luitpoldi, a Viviparous Fish.

126Egg of

Callorhynchus antarcticus, the Bottle-nosed Chimæra.

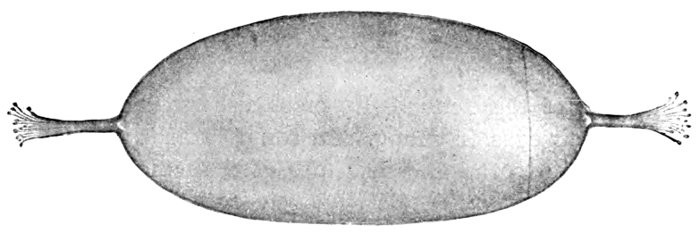

127Egg of the Hagfish,

Myxine limosa.

127Egg of Port Jackson Shark,

Heterodontus philippi.

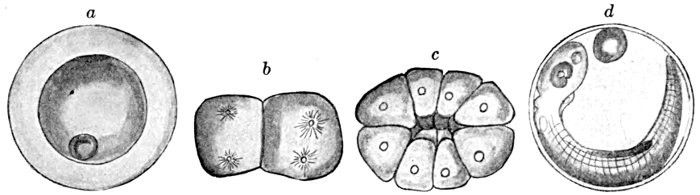

128Development of Sea-bass,

Centropristes striatus.

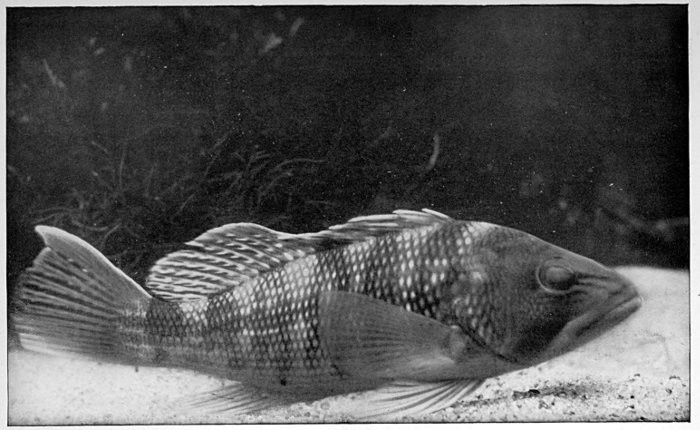

135 Centropristes striatus, Sea-bass.

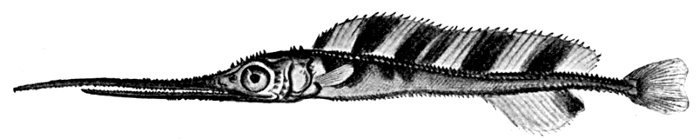

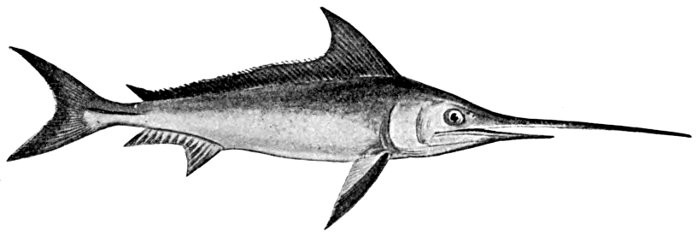

137 Xiphias gladius, Young Sword-fish.

139 Xiphias gladius, Sword-fish.

139Larva of the Sail-fish,

Istiophorus, Very Young.

140Larva of Brook Lamprey,

Lampetra wilderi, before Transformation.

140 Anguilla chrisypa, Common Eel.

140Larva of Common Eel,

Anguilla chrisypa, called

Leptocephalus grassii.

141Larva of Sturgeon,

Acipenser sturio.

141Larva of

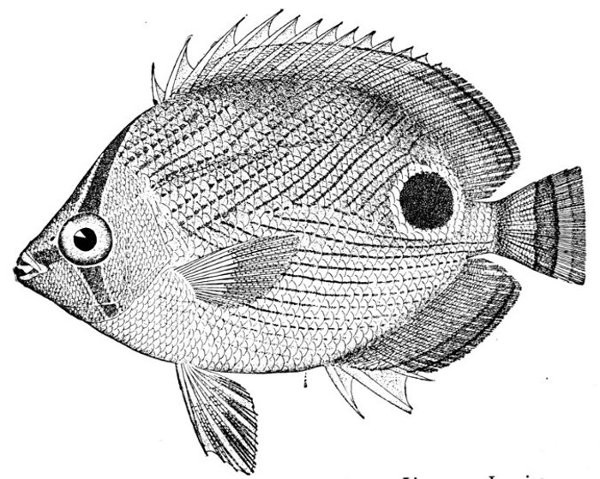

Chætodon sedentarius.

142 Chætodon capistratus, Butterfly-fish.

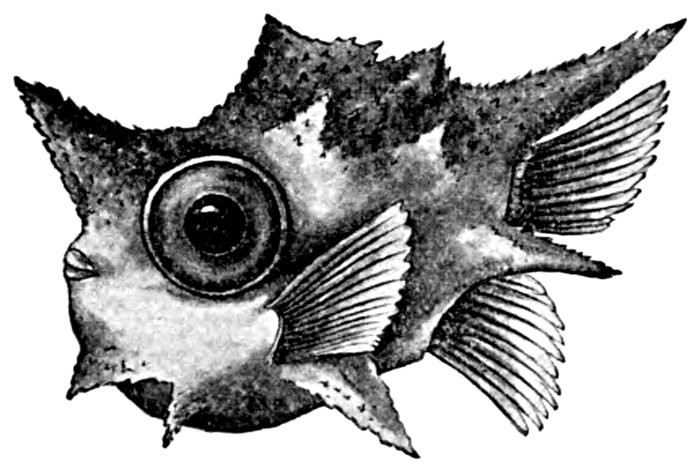

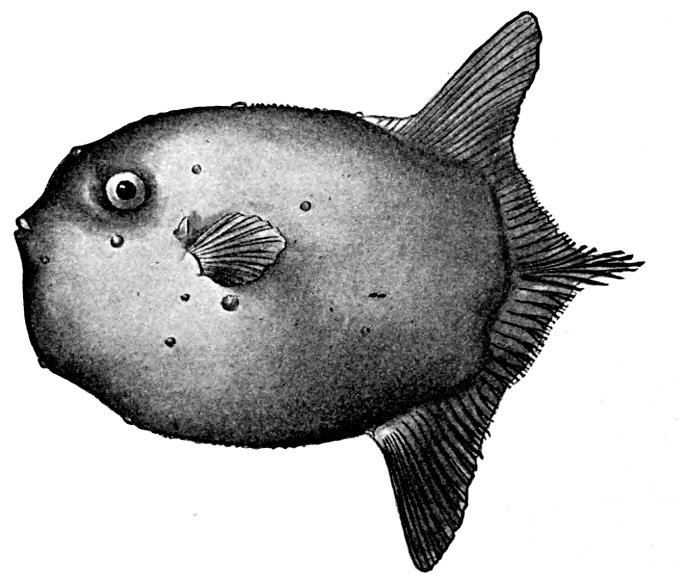

142 Mola mola, Very Early Larval Stage of Headfish, called

Centaurus boöps.

143 Mola mola, Early Larval Stage called

Molacanthus nummularis.

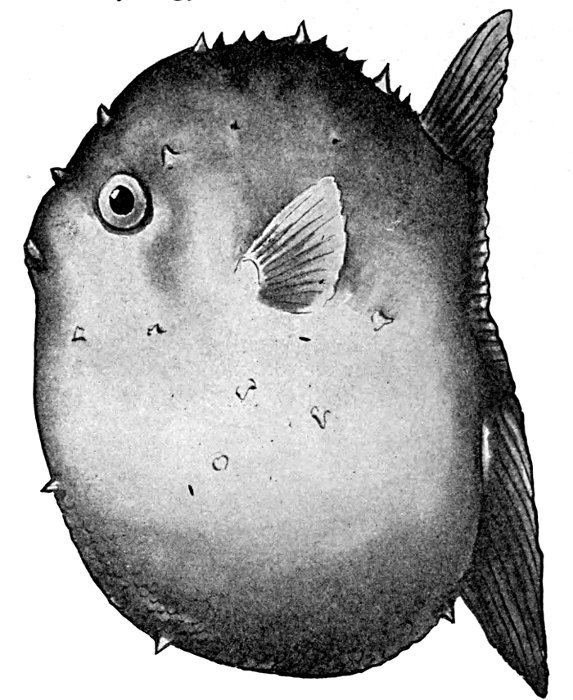

144 Mola mola, Advanced Larval Stage.

144 Mola mola, Headfish, Adult.

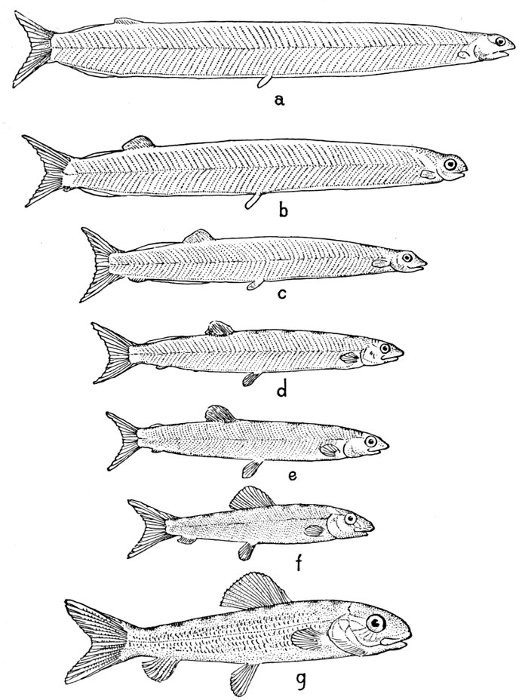

146 Albula vulpes, Transformation of Ladyfish from Larva to Young.

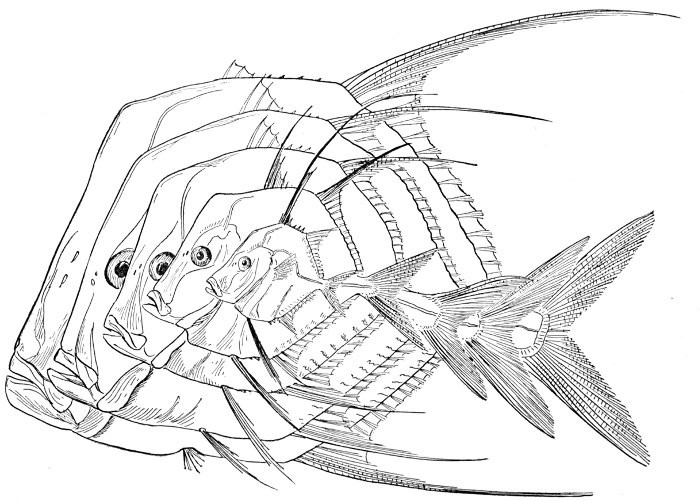

147Development of the Horsehead-fish,

Selene vomer.

148 Salanx hyalocranius, Ice-fish.

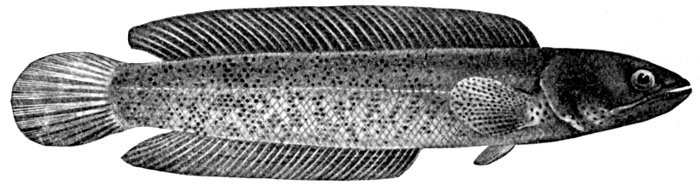

149 Dallia pectoralis, Alaska Blackfish.

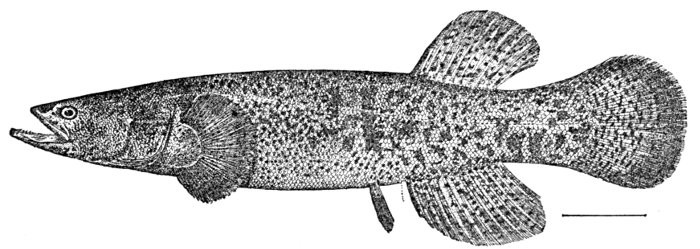

149 Ophiocephalus barca, Snake-headed China-fish.

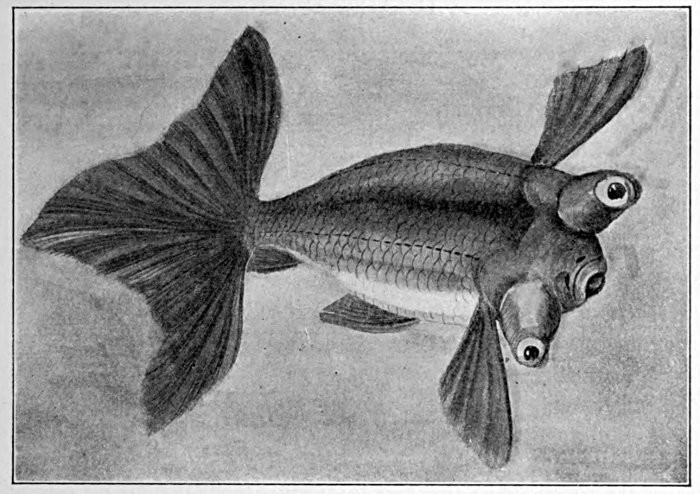

150 Carassius auratus, Monstrous Goldfish.

151Jaws of

Nemichthys avocetta.

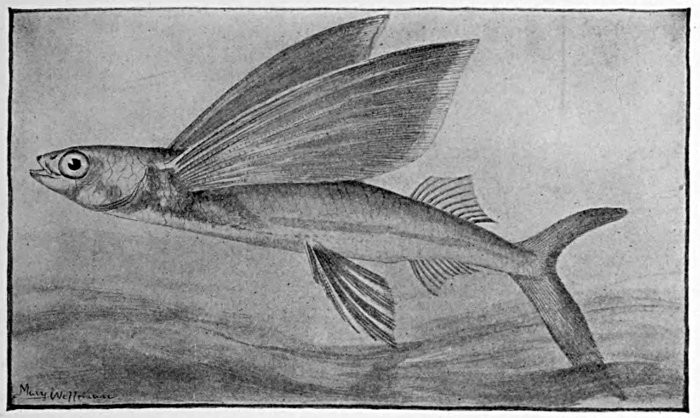

156 Cypsilurus californicus, Flying-fish.

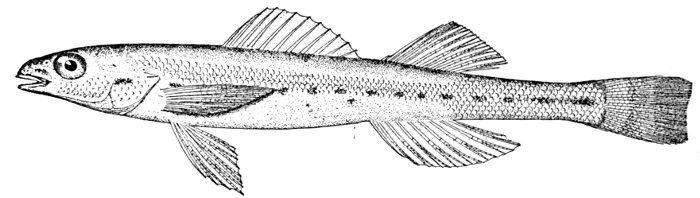

157 Ammocrypta clara, Sand-darter.

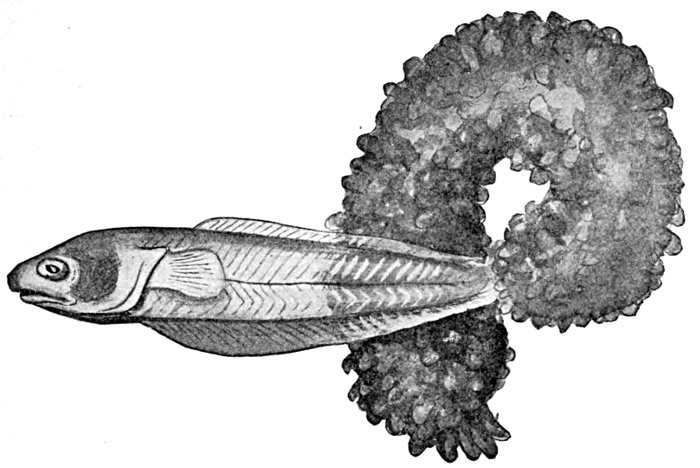

158 Fierasfer acus, Pearl-fish, issuing from a Holothurian.

159 Gobiomorus gronovii, Portuguese Man-of-war Fish.

160Tide Pools of Misaki.

161 Ptychocheilus oregonensis, Squaw-fish.

162 Ptychocheilus grandis, Squaw-fish, Stranded as the Water Falls.

164Larval Stages of

Platophrys podas, a Flounder of the Mediterranean, showing Migration of Eye.

174 Platophrys lunatus, the Wide-eyed Flounder.

175Young Flounder Just Hatched, with Symmetrical Eyes.

175 Pseudopleuronectes americanus, Larval Flounder.

176 Pseudopleuronectes americanus, Larval Flounder (more advanced stage).

176Face View of Recently-hatched Flounder.

177 Schilbeodes furiosus, Mad-Tom.

179 Emmydrichthys vulcanus, Black Nohu or Poison-fish.

180 Teuthis bahianus, Brown Tang.

181 Stephanolepis hispidus, Common Filefish.

182Tetraodon meleagris.

183 Balistes carolinensis, the Trigger-fish.

184 Narcine brasiliensis, Numbfish.

185 Torpedo electricus, Electric Catfish.

186 Astroscopus guttatus, Star-gazer.

187 Æthoprora lucida, Headlight-fish.

188 Corynolophus reinhardti, showing Luminous Bulb.

188Etmopterus lucifer.

189Argyropelecus olfersi.

190Luminous Organs and Lateral Line of Midshipman,

Porichthys notatus.

192Cross-section of Ventral Phosphorescent Organ of Midshipman,

Porichthys notatus.

193Section of Deeper Portion of Phosphorescent Organ,

Porichthys notatus.

194 Leptecheneis naucrates, Sucking-fish or Pegador.

197 Caularchus mæandricus, Clingfish.

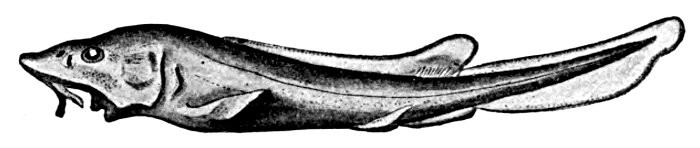

198 Polistotrema stouti, Hagfish.

199 Pristis zysron, Indian Sawfish.

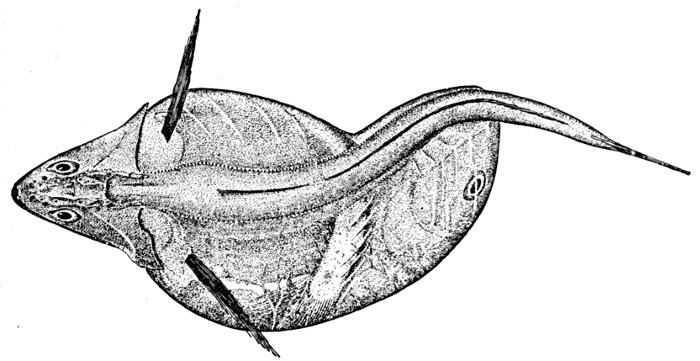

200 Pristiophorus japonicus, Saw-shark.

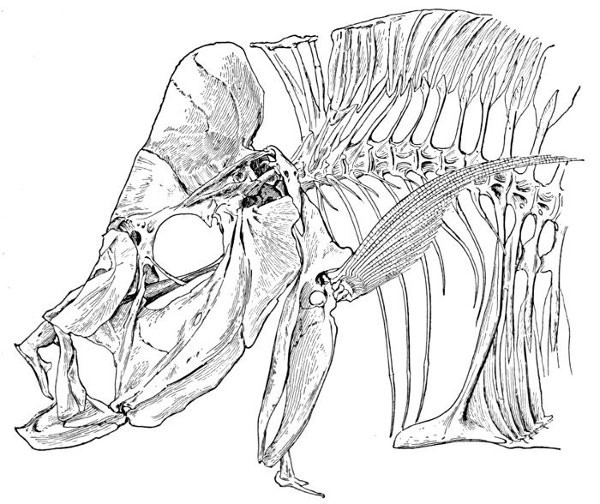

201Skeleton of Pike,

Esox lucius.

203Skeleton of Red Rockfish,

Sebastodes miniatus.

214Skeleton of a Spiny-rayed Fish of the Tropics,

Holacanthus ciliaris.

214Skeleton of the Cowfish,

Lactophrys tricornis.

215 Crystallias matsushimæ, Liparid.

218 Sebastichthys maliger, Yellow-backed Rockfish.

218 Myoxocephalus scorpius, European Sculpin.

219 Hemitripterus americanus, Sea-raven.

220 Cyclopterus lumpus, Lumpfish.

220 Psychrolutes paradoxus, Sleek Sculpin.

221 Pallasina barbata, Agonoid-fish.

221 Amblyopsis spelæus, Blindfish of the Mammoth Cave.

221 Lucifuga subterranea, Blind Brotula.

222 Hypsypops rubicunda, Garibaldi.

227 Synanceia verrucosa, Gofu or Poison-fish.

229 Alticus saliens, Lizard-skipper.

230 Etheostoma camurum, Blue-breasted Darter.

231 Liuranus semicinctusand

Chlevastes colubrinus, Snake-eels.

233Coral Reef at Apia.

234 Rudarius ercodes, Japanese Filefish.

241 Tetraodon setosus, Globefish.

244 Dasyatis sabina, Sting-ray.

246 Diplesion blennioides, Green-sided Darter.

247 Hippocampus mohnikei, Japanese Sea-horse.

250 Archoplites interruptus, Sacramento Perch.

258Map of the Continents, Eocene Time.

270 Caulophryne jordani, Deep-sea Fish of Gulf Stream.

276 Exerpes asper, Fish of Rock-pools, Mexico.

276Xenocys jessiæ.

279 Ictalurus punctatus, Channel Catfish.

280Drawing the Net on the Beach of Hilo, Hawaii.

281 Semotilus atromaculatus, Horned Dace.

285 Leuciscus lineatus, Chub of the Great Basin.

287 Melletes papilio, Butterfly Sculpin.

288 Scartichthys enosimæ, a Fish of the Rock-pools of the Sacred Island of Enoshima, Japan.

294 Halichœres bivittatus, the Slippery Dick.

297Peristedion miniatum.

299Outlet of Lake Bonneville.

303 Hypocritichthys analis, Silver Surf-fish.

309 Erimyzon sucetta, Creekfish or Chub-sucker.

315 Thaleichthys pretiosus, Eulachon or Ulchen.

320 Plecoglossus altivelis, the Japanese Ayu.

321 Coregonus clupeiformis, the Whitefish.

321 Mullus auratus, the Golden Surmullet.

322 Scomberomorus maculatus, the Spanish Mackerel.

322 Lampris luna, the Opah or Moonfish.

323 Pomatomus saltatrix, the Bluefish.

324 Centropomus undecimalis, the Robalo.

324 Chætodipterus faber, the Spadefish.

325 Micropterus dolomieu, the Small-mouthed Black Bass.

325 Salvelinus fontinalis, the Speckled Trout.

326 Salmo irideus, the Rainbow Trout.

326 Salvelinus oquassa, the Rangeley Trout.

326 Salmo gairdneri, the Steelhead Trout.

327 Salmo henshawi, the Tahoe Trout.

327 Salvelinus malma, the Dolly Varden Trout.

327 Thymallus signifer, the Alaska Grayling.

328 Esox lucius, the Pike.

328 Pleurogrammus monopterygius, the Atka-fish.

328 Chirostoma humboldtianum, the Pescado blanco.

329 Pseudupeneus maculatus, the Red Goatfish.

329 Pseudoscarus guacamaia, Great Parrot-fish.

330 Mugil cephalus, Striped Mullet.

330 Lutianus analis, Mutton-snapper.

331 Clupea harengus, Herring.

331 Gadus callarias, Codfish.

331 Scomber scombrus, Mackerel.

332 Hippoglossus hippoglossus, Halibut.

332Fishing for Ayu with Cormorants.

333Fishing for Ayu. Emptying Pouch of Cormorant.

335Fishing for Tai, Tokyo Bay.

338 Brevoortia tyrannus, Menhaden.

340 Exonautes unicolor, Australian Flying-fish.

341 Rhinichthys atronasus, Black-nosed Dace.

342 Notropis hudsonius, White Shiner.

343 Ameiurus catus, White Catfish.

344 Catostomus ardens, Sucker.

348 Oncorhynchus tschawytscha, Quinnat Salmon.

354 Oncorhynchus tschawytscha, Young Male.

355 Ameiurus nebulosus, Catfishes.

358"Le Monstre Marin en Habit de Moine".

360"Le Monstre Marin en Habit d'Évêque".

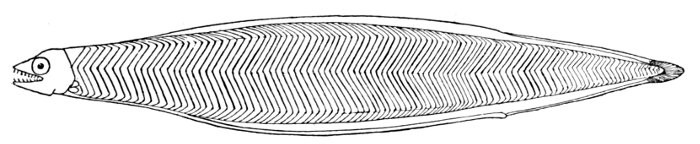

361 Regalecus russelli, Oarfish.

362 Regalecus glesne, Glesnæs Oarfish.

363 Nemichthys avocetta, Thread-eel.

365 Lactophrys tricornis, Horned Trunkfish.

373 Ostracion cornutum, Horned Trunkfish.

376 Lactophrys bicaudalis, Spotted Trunkfish.

377 Lactophrys bicaudalis, Spotted Trunkfish (Face).

377 Lactophrys triqueter, Spineless Trunkfish.

378 Lactophrys trigonus, Hornless Trunkfish.

378 Lactophrys trigonus, Hornless Trunkfish (Face).

379Bernard Germain de Lacépède.

399Georges Dagobert Cuvier.

399Louis Agassiz.

399Johannes Müller.

399Albert Günther.

403Franz Steindachner.

403George Albert Boulenger.

403Robert Collett.

403Spencer Fullerton Baird.

407Edward Drinker Cope.

407Theodore Nicholas Gill.

407George Brown Goode.

407Johann Reinhardt.

409Edward Waller Claypole.

409Carlos Berg.

409Edgar R. Waite.

409Felipe Poey y Aloy.

413Léon Vaillant.

413Louis Dollo.

413Decio Vinciguerra.

413Bashford Dean.

417Kakichi Mitsukuri.

417Carl H. Eigenmann.

417Franz Hilgendorf.

417David Starr Jordan.

421Herbert Edson Copeland.

421Charles Henry Gilbert.

421Barton Warren Evermann.

421Ramsay Heatley Traquair.

425Arthur Smith Woodward.

425Karl A. Zittel.

425Charles R. Eastman.

425Fragment of Sandstone from Ordovician Deposits.

435Fossil Fish Remains from Ordovician Rocks.

436Dipterus valenciennesi.

437Hoplopteryx lewesiensis.

438 Paratrachichthys prosthemius, Berycoid fish.

439 Cypsilurus heterurus, Flying-fish.

440 Lutianidæ, Schoolmaster Snapper.

440 Pleuronichthys decurrens, Decurrent Flounder.

441 Cephalaspis lyelli, Ostracophore.

444 Dinichthys intermedius, Arthrodire.

445 Lamna cornubica, Mackerel-shark or Salmon-shark.

447 Raja stellulata, Star-spined Ray.

448 Harriotta raleighiana, Deep-sea Chimæra.

449 Dipterus valenciennesi, Extinct Dipnoan.

449 Holoptychius giganteus, Extinct Crossopterygian.

451 Platysomus gibbosus, Ancient Ganoid fish.

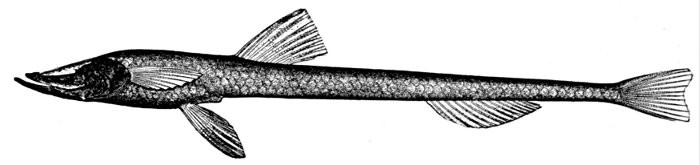

452 Lepisosteus platystomus, Short-nosed Gar.

452 Palæoniscum macropomum, Primitive Ganoid fish.

453 Diplomystus humilis, Fossil Herring.

453 Holcolepis lewesiensis.

454 Elops saurus, Ten-pounder.

454 Apogon semilineatus, Cardinal-fish.

455 Pomolobus æstivalis, Summer Herring.

455Bassozetus catena.

456Trachicephalus uranoscopus.

456 Chlarias breviceps, African Catfish.

457 Notropis whipplii, Silverfin.

457Gymnothorax moringa.

458 Seriola lalandi, Amber-fish.

458Geological Distribution of the Families of Elasmobranchs.

459"Tornaria" Larva of

Glossobalanus minutus.

463Glossobalanus minutus.

464Harrimania maculosa.

465Development of Larval Tunicate to Fixed Condition.

471Anatomy of Tunicate.

472Ascidia adhærens.

474Styela yacutatensis.

475Styela greeleyi.

476Cynthia superba.

476 Botryllus magnus, Compound Ascidian.

477Botryllus magnus.

478 Botryllus magnus, a Single Zooid.

479 Aplidiopsis jordani, a Compound Ascidian.

479 Oikopleura, Adult Tunicate of Group Larvacea.

480 Branchiostoma californiense, California Lancelet.

484Gill-basket of Lamprey.

485Polygnathus dubium.

488 Polistotrema stouti, Hagfish.

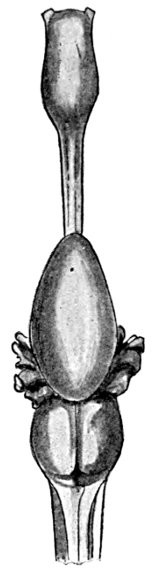

489 Petromyzon marinus, Lamprey.

491 Petromyzon marinus unicolor, Mouth Lake Lamprey.

492 Lampetra wilderi, Sea Larvæ Brook Lamprey.

492 Lampetra wilderi, Mouth Brook Lamprey.

492 Lampetra camtschatica, Kamchatka Lamprey.

495 Entosphenus tridentatus, Oregon Lamprey.

496 Lampetra wilderi, Brook Lamprey.

505Fin-spine of

Onchus tenuistriatus.

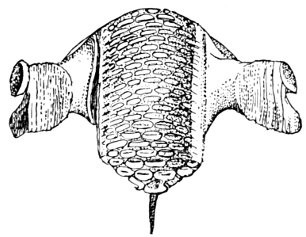

509Section of Vertebræ of Sharks, showing Calcification.

510Cladoselache fyleri.

514 Cladoselache fyleri, Ventral View.

515Teeth of

Cladoselache fyleri.

515Acanthoessus wardi.

515Diplacanthus crassissimus.

517Climatius scutiger.

518Pleuracanthus decheni.

519 Pleuracanthus decheni, Restored.

520Head-bones and Teeth of

Pleuracanthus decheni.

520Teeth of

Didymodus bohemicus.

520Shoulder-girdle and Pectoral Fins of

Cladodus neilsoni.

521Teeth of

Cladodus striatus.

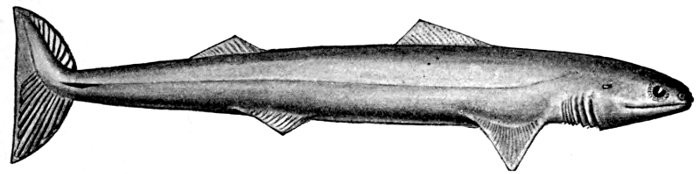

522 Hexanchus griseus, Griset or Cow-shark.

523Teeth of

Heptranchias indicus.

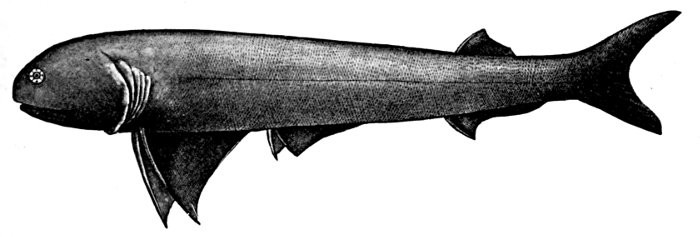

524 Chlamydoselachus anguineus, Frill-shark.

525 Heterodontus francisci, Bullhead-shark.

526Lower Jaw of

Heterodontus philippi.

526Teeth of Cestraciont Sharks.

527Egg of Port Jackson Shark,

Heterodontus philippi.

527Tooth of

Hybodus delabechei.

528Fin-spine of

Hybodus basanus.

528Fin-spine of

Hybodus reticulatus.

528Fin-spine of

Hybodus canaliculatus.

529Teeth of Cestraciont Sharks.

529 Edestus vorax, Supposed to be a Whorl of Teeth.

529 Helicoprion bessonowi, Teeth of.

530Lower Jaw of

Cochliodus contortus.

531 Mitsukurina owstoni, Goblin-shark.

535 Scapanorhynchus lewisi, Under Side of Snout.

536Tooth of

Lamna cuspidata.

537 Isuropsis dekayi, Mackerel-shark.

537Tooth of

Isurus hastalis.

538[Pg 2]

The Long-eared Sunfish.—If we would understand a fish, we must first go and catch one. This is not very hard to do, for there are plenty of them in the little rushing brook or among the lilies of the pond. Let us take a small hook, put on it an angleworm or a grasshopper,—no need to seek an elaborate artificial fly,—and we will go out to the old "swimming-hole" or the deep eddy at the root of the old stump where the stream has gnawed away the bank in changing its course. Here we will find fishes, and one of them will take the bait very soon. In one part of the country the first fish that bites will be different from the first one taken in some other. But as we are fishing in the United States, we will locate our brook in the centre of population of our country. This will be to the northwest of Cincinnati, among the low wooded hills from which clear brooks flow over gravelly bottoms toward the Ohio River. Here we will catch sunfishes of certain species, or maybe rock bass or catfish: any of these will do for our purpose. But one of our sunfishes is especially beautiful—mottled blue and golden and scarlet, with a long, black, ear-like appendage backward from his gill-covers—and this one we will keep and hold for our first lesson in fishes. It is a small fish, not longer than your hand most likely, but it can take the bait as savagely as the best, swimming away with it with such force that you might think from the vigor of its pull that you have a pickerel or a bass. But when it comes out of the water you see a little, flapping, unhappy, living plate of brown and blue and orange, with fins wide-spread and eyes red with rage.

Color of the Fish.—Behind the eye there are several bones on the side of the head which are more or less distinct from the skull itself. These are called membrane bones because they are formed of membrane which has become bony by the deposition in it of salts of lime. One of these is called the opercle, or gill-cover, and before it, forming a right angle, is the preopercle, or false gill-cover. On our sunfish we see that the opercle ends behind in a long and narrow flap, which looks like an ear. This is black in color, with an edging of scarlet as though a drop of blood had spread along its margin. When the fish is in the water its back is dark greenish-looking, like the weeds and the sticks in the bottom, so that we cannot see it very plainly. This is the way the fish looks to the fishhawks or herons in the air above it who may come to the stream to look for fish. Those fishes which from above look most like the bottom can most readily hide and save themselves. The under side of the sunfish is paler, and most fishes have the belly white. Fishes with white bellies swim high in the water, and the fishes who would catch them lie below. To the fish in the water all outside the water looks white, and so the white-bellied fishes are hard for other fishes to see, just as it is hard for us to see a white rabbit bounding over the snow.

When the sunfish is taken out of the water its colors seem to fade. In the aquarium it is generally paler, but it will sometimes brighten up when another of its own species is placed beside it. A cause of this may lie in the nervous control of the muscles at the base of the scales. When the scales lie very flat the color has one appearance. When they rise a little the shade of color seems to change. If you let fall some ink-drops between two panes of glass, then spread them apart or press them together, you will see changes in the color and size of the spots. Of this nature is the apparent change in the colors of fishes under different conditions. Where the fish feels at its best the colors are the richest. There are some fishes, too, in which the male grows very brilliant in the breeding season through the deposition of red, white, black, or blue pigments, or coloring matter, on its scales or on its head or fins, this pigment being absorbed when the mating season is over. This is not true of the sunfish, who remains just about the same at all seasons. The male and female are colored alike and are not to be distinguished without dissection. If we examine the scales, we shall find that these are marked with fine lines and concentric striæ, and part of the apparent color is due to the effect of the fine lines on the light. This gives the bluish lustre or sheen which we can see in certain lights, although we shall find no real blue pigment under it. The inner edge of each scale is usually scalloped or crinkled, and the outer margin of most of them has little prickly points which make the fish seem rough when we pass our hand along his sides.

The Brain of the Fish.—The movements of the fish, like those of every other complex animal, are directed by a central nervous system, of which the principal part is in the head and is known as the brain. From the eye of the fish a large nerve goes to the brain to report what is in sight. Other nerves go from the nostrils, the ears, the skin, and every part which has any sort of capacity for feeling. These nerves carry their messages inward, and when they reach the brain they may be transformed into movement. The brain sends back messages to the muscles, directing them to contract. Their contraction moves the fins, and the fish is shoved along through the water. To scare the fish or to attract it to its food or to its mate is about the whole range of the effect that sight or touch has on the animal. These sensations changed into movement constitute what is called reflex action, performance without thinking of what is being done. With a boy, many familiar actions may be equally reflex. The boy can also do many other things "of his own accord," that is, by conscious effort. He can choose among a great many possible actions. But a fish cannot. If he is scared, he must swim away, and he has no way to stop himself. If he is hungry, and most fishes are so all the time, he will spring at the bait. If he is thirsty, he will gasp, and there is nothing else for him to do. In other words, the activities of a fish are nearly all reflex, most of them being suggested and immediately directed by the influence of external things. Because its actions are all reflex the brain is very small, very primitive, and very simple, nothing more being needed for automatic movement. Small as the fish's skull-cavity is, the brain does not half fill it.

Thus, again, the length of the muzzle, the diameter of the eye, and other dimensions may be compared with the length of the head. In the Rock Hind, fig. 12, the eye is 5 in head, the snout is 4-2/5 in head, and the maxillary 2-3/5. Young fishes have the eye larger, the body slenderer, and the head larger in proportion than old fishes of the same kind. The mouth grows larger with age, and is sometimes larger also in the male sex. The development of the fins often varies a good deal in some fishes with age, old fishes and male fishes having higher fins when such differences exist. These variations are soon understood by the student of fishes and cause little doubt or confusion in the study of fishes.

Ctenoid and Cycloid Scales.—Normally formed scales are rounded in outline, marked by fine concentric rings, and crossed on the inner side by a few strong radiating ridges and folds. They usually cover the body more or less evenly and are imbricated like shingles on a roof, the free edge being turned backward. Such normal scales are of two types, ctenoid or cycloid. Ctenoid scales have a comb-edge of fine prickles or cilia; cycloid scales have the edges smooth. These two types are not very different, and the one readily passes into the other, both being sometimes seen on different parts of the same fish. In general, however, the more primitive representatives of the typical fishes, those with abdominal ventrals and without spines in the fins, have cycloid or smooth scales. Examples are the salmon, herring, minnow, and carp. Some of the more specialized spiny-rayed fishes, as the parrot-fishes, have, however, scales equally smooth, although somewhat different in structure. Sometimes, as in the eel, the cycloid scales may be reduced to mere rudiments buried in the skin.

Bony and Prickly Scales.—Bony and prickly scales are found in great variety, and scarcely admit of description or classification. In general, prickly points on the skin are modifications of ctenoid scales. Ganoid scales are thickened and covered with bony enamel, much like that seen in teeth, otherwise essentially like cycloid scales. These are found in the garpike and in many genera of extinct Ganoid and Crossopterygian fishes. In the line of descent the placoid scale preceded the ganoid, which in turn was followed by the cycloid and lastly by the ctenoid scale. Bony scales in other types of fishes may have nothing structurally in common with ganoid scales or plates, however great may be the superficial resemblance.

The Lateral Line as a Mucous Channel.—The more primitive condition of the lateral line is seen in the sharks and chimæras, in which fishes it appears as a series of channels in or under the skin. These channels are filled with mucus, which exudes through occasional open pores. In many fishes the bones of the skull are cavernous, that is, provided with cavities filled with mucus. Analogous to these cavities are the mucous channels which in primitive fishes constitute the lateral line.

The lancelets, lampreys, and hagfishes possess no genital ducts. In the former the germ cells are shed into the atrial cavity, and from there find their way to the exterior either through the mouth or the atrial pore; in the latter they are shed directly into the body cavity, from which they escape through the abdominal pores. In the sharks and skates the Wolffian duct in the male, in addition to its function as an excretory duct, serves also as a passage for the sperm, the testes having a direct connection with the kidneys. In these forms there is a pair of Müllerian ducts which serve as oviducts in the females; they extend the length of the body cavity, and at their anterior end have an opening which receives the eggs which have escaped from the ovary into the body cavity. In some bony fishes as the eels and female salmon the germ cells are shed into the body cavity and escape through genital pores, which, however, may not be homologous with abdominal pores. In most other bony fishes the testes and ovaries are continued directly into ducts which open to the outside.

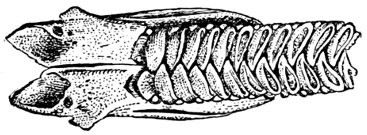

The most usual type of teeth among fishes is that of villiform bands. Villiform teeth are short, slender, even, close-set, making a rough velvety surface. When the teeth are larger and more widely separated, they are called cardiform, like the teeth of a wool-card. Granular teeth are small, blunt, and sand-like. Canine teeth are those projecting above the level of the others, usually sharp, curved, and in some species barbed. Sometimes the canines are in front. In some families the last tooth in either jaw may be a "posterior canine," serving to hold small animals in place while the anterior teeth crush them. Canine teeth are often depressible, having a hinge at base.

Teeth very slender and brush-like are called setiform. Teeth with blunt tips are molar. These are usually enlarged and fitted for crushing shells. Flat teeth set in mosaic, as in many rays and in the pharyngeals of parrot-fishes, are said to be paved or tessellated. Knife-like teeth, occasionally with serrated edges, are found in many sharks. Many fishes have incisor-like teeth, some flattened and truncate like human teeth, as in the sheepshead, sometimes with serrated edges. Often these teeth are movable, implanted only in the skin of the lips. In other cases they are set fast in the jaw. Most species with movable teeth or teeth with serrated edges are herbivorous, while strong incisors may indicate the choice of snails and crabs as food. Two or more of these different types may be found in the same fish. The knife-like teeth of the sharks are progressively shed, new ones being constantly formed on the inner margins of the jaw, so that the teeth are marching to be lost over the edge of the jaw as soon as each has fulfilled its function. In general the more distinctly a species is a fish-eater, the sharper are the teeth. Usually fishes show little discrimination in their choice of food; often they devour the young of their own species as readily as any other. The digestive process is rapid, and most fishes rapidly increase in size in the process of development. When food ceases to be abundant the fishes grow more slowly. For this reason the same species will grow to a larger size in large streams than in small ones, in lakes than in brooks. In most cases there is no absolute limit to growth, the species growing as long as it lives. But while some species endure many years, others are certainly very shortlived, and some may be even annual, dying after spawning, perhaps at the end of the first season.

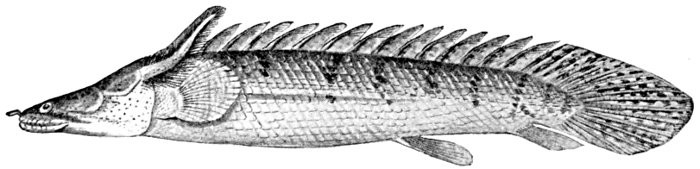

Lepisosteus

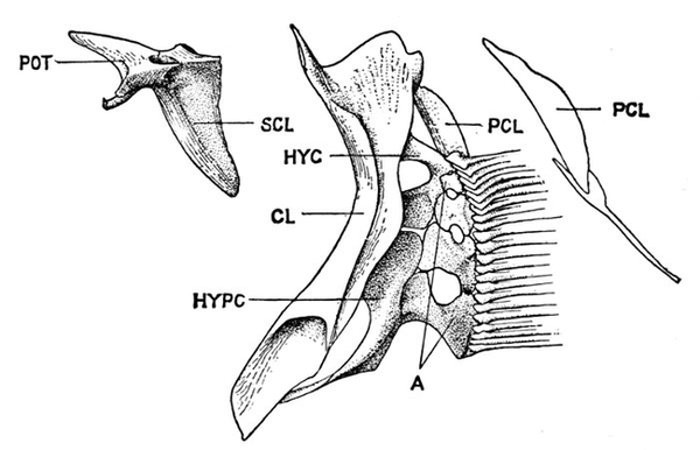

The assumption that each element in the shoulder-girdle and the pectoral fin of the fish must correspond in detail to the arm of man has led to great confusion in naming the different bones. Among the many bones of the fish's shoulder-girdle and pectoral fin, three or four different ones have successively borne the names of scapula, clavicle, coracoid, humerus, radius, and ulna. None of these terms, unless it be clavicle, ought by rights apply to the fish, for no bone of the fish is a true homologue of any of these as seen in man. The land vertebrates and the fishes have doubtless sprung from a common stock, but this stock, related to the crossopterygians of the present day, was unspecialized in the details of its skeleton, and from it the fishes and the higher vertebrates have developed the widely diverging lines.

In the sharks, dipnoans, crossopterygians, ganoids, and teleosts or bony fishes, jaws are developed as well as a variety of other bones around the mouth and throat. The jaw-bearing forms are sometimes known by the general name of gnathostomes. In the sharks and their relatives (rays, chimæras, etc.) all the skeleton is composed of cartilage. In the more specialized bony fishes, besides these bones we find also series of membrane bones, more or less external to the skull and composed of ossified dermal tissues. Membrane bones are not found in the sharks and lampreys, but are developed in an elaborate coat of mail in some extinct forms.

basisphenoid

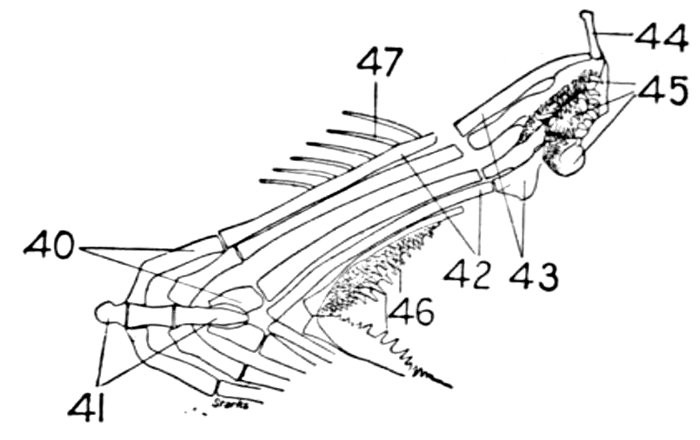

The gill-arches are suspended to the cranium from above by the suspensory pharyngeal (44). Each arch contains three parts—the epibranchial (43), above, the ceratobranchial (42), forming the middle part, and the hypobranchial (41), the lower part articulating with the series of basibranchials (40) which lie behind the epihyal of the tongue. On the three bones forming the first gill-arch are attached numerous appendages called gill-rakers (47). These gill-rakers vary very greatly in number and form. In the striped bass they are few and spear-shaped. In the shad they are very many and almost as fine as hairs. In some fishes they form an effective strainer in separating the food, or perhaps in keeping extraneous matter from the gills. In some fishes they are short and lumpy, in others wanting altogether.

The anterior vertebræ known as abdominal vertebræ, bounding the body-cavity, possess neural spines similar to those of the caudal vertebræ. In place, however, of the hæmapophyses are projections known as parapophyses (72), which do not meet below, but extend outward, forming the upper part of the wall of the abdominal cavity.

In the garpike the vertebræ are convex anteriorly, concave behind, being joined by ball-and-socket joints (opisthocœlian). In most other fishes they are double concave (amplicœlian). In sharks the vertebræ are imperfectly ossified, a number of terms, asterospondylous, cyclospondylous, tectospondylous, being applied to the different stages of ossification, these terms referring to the different modes of arrangement of the calcareous material within the vertebra.

The post-temporal sometimes projects behind through the skin and may bear spines or serrations. In front of the post-temporal and a little to the outside of it is the small supratemporal (52) also usually connecting the shoulder-girdle with the skull. Below the post-temporal, extending downward and backward, is the flattish supraclavicle (posterotemporal) (54). To this is joined the long clavicle (proscapula) (55), which runs forward and downward in the bony fishes, meeting its fellow on the opposite side in a manner suggesting the wishbone of a fowl. Behind the base of the clavicle, the sword-shaped post-clavicle (56) extends downward through the muscles behind the base of the pectoral fin. In some fishes, as the stickleback and the trumpet-fish, a pair of flattish or elongate bones called interclavicles (infraclavicles) lie between and behind the lower part of the clavicle. These are not found in most fishes and are wanting in the striped bass. They are probably in all cases merely extensions of the hypocoracoid.

mesocoracoid

In the shark the pelvic girdle is rather largely developed, but in the more specialized fishes it loses its importance. In the less specialized of the bony fishes the pelvis is attached at a distance from the head among the muscles of the side, and free from the shoulder-girdle and other parts of the skeleton. The ventral fins are then said to be abdominal. When very close to the clavicle, but not connected with it, as in the mullet, the fin is still said to be abdominal or subabdominal. In the striped bass the pelvis is joined by ligament between the clavicles, near their tip. The ventral fins thus connected, as seen in most spiny-rayed fishes, are said to be thoracic. In certain forms the pelvis is thrown still farther forward and attached at the throat or even to the chin. When the ventral fins are thus inserted before the shoulder-girdle, they are said to be jugular. Most of the fishes with spines in the fins have thoracic ventrals. In the fishes with jugular ventrals these fins have begun a process of degeneration by which the spines or soft rays or both are lost or atrophied.

The Skeleton in Primitive Fishes.—To learn the names of bones we can deal most satisfactorily with the higher fishes, those in which the bony framework has attained completion. But to understand the origin and relation of parts we must begin with the lowest types, tracing the different stages in the development of each part of the system.

In the embryo of the bony fish a similar notochord precedes the segmentation and ossification of the vertebral column. In most of the extinct types of fishes a notochord more or less modified persisted through life, the vertebræ being strung upon it spool fashion in various stages of development. In the Cyclostomi (lampreys and hagfishes) the limbs and lower jaw are still wanting, but a distinct skull is developed. The notochord is still present, but its anterior pointed end is wedged into the base of a cranial capsule, partly membranous, partly cartilaginous. There is no trace of segmentation in the notochord itself in these or any other fishes, but neutral arches are foreshadowed in a series of cartilages on each side of the spinal chord. The top of the head is protected by broad plates. There are ring-like cartilages supporting the mouth and other cartilages in connection with the tongue and gill structures.

The shoulder-girdle is made of a single cartilage, touching the back-bone at a distance behind the head. To this cartilage three smaller ones are attached, forming the base of the pectoral fin. These are called mesopterygium, propterygium, and metapterygium, the first named being in the middle and more distinctly basal. These three segments are subject to much variation. Sometimes one of them is wanting; sometimes two are grown together. Behind these the fin-rays are attached. In most of the skates the shoulder-girdle is more closely connected with the anterior vertebræ, which are more or less fused together.

Evidence of Paleontology.—If we had representations of all the early forms of fishes arranged in proper sequence, we could decide once for all, by evidence of paleontology, which form of fin appears first and what is the order of appearance. As to this, it is plain that we do not know the most primitive form of fin. Sharks of unknown character must have existed long before the earliest remains accessible to us. Hence the evidence of paleontology seems conflicting and uncertain. On the whole it lends most support to the fin-fold theory. In the later Devonian, a shark, Cladoselache fyleri, is found in which the paired fins are lappet-shaped, so formed and placed as to suggest their origin from a continuous fold of skin. In this species the dorsal fins show much the same form. Other early sharks, constituting the order of Acanthodei, have fins somewhat similar, but each preceded by a stiff spine, which may be formed from coalescent rays.

Long after these appears another type of sharks represented by Pleuracanthus and Cladodus, in which the pectoral fin is a jointed organ fringed with rays arranged serially in one or two rows. This form of fin has no resemblance to a fold of skin, but accords better with Gegenbaur's theory that the pectoral limb was at first a modified gill-arch. In the Coal Measures are found also teeth of sharks (Orodontidæ) which bear a strong resemblance to still existing forms of the family of Heterodontidæ, which originates in the Permian. The existing Heterodontidæ have the usual specialized form of shark-fin, with three of the basal segments especially enlarged and placed side by side, the type seen in modern sharks. Whatever the primitive form of shark-fin, it may well be doubted whether any one of these three (Cladoselache, Pleuracanthus, or Heterodontus) actually represents it. The beginning is therefore unknown, though there is some evidence that Cladoselache is actually more nearly primitive than any of the others. As we shall see, the evidence of comparative anatomy may be consistent with either of the two chief theories, while that of ontogeny or embryology is apparently inconclusive, and that of paleontology is apparently most easily reconciled with the theory of the fin-fold.

Current Theories as to Origin of Paired Fins.—There are three chief theories as to the morphology and origin of the paired fins. The earliest is that of Dr. Karl Gegenbaur, supported by various workers among his students and colleagues. In his view the pectoral and ventral fins are derived from modifications of primitive gill-arches. According to this theory, the skeletal arrangements of the vertebrate limb are derived from modifications of one primitive form, a structure made up of successive joints, with a series of fin-rays on one or both sides of it. To this structure Gegenbaur gives the name of archipterygium. It is found in the shark, Pleuracanthus, in Cladodus, and in all the Dipnoan and Crossopterygian fishes, its primitive form being still retained in the Australian genus of Dipnoans, Neoceratodus. This biserial archipterygium with its limb-girdle is derived from a series of gill-rays attached to a branchial arch. The backward position of the ventral fin is due to a succession of migrations in the individual and in the species.

"This view is based on the skeletal structures within the fin. It rests upon (1) the assumption that the archipterygium is the primitive type of fin, and (2) the fact that amongst the Selachians is found a tendency for one branchial ray to become larger than the others, and, when this has happened, for the base of attachment of neighboring rays to show a tendency to migrate from the branchial arch on to the base of the larger or, as we may call it, primary ray; a condition coming about which, were the process to continue rather farther than it is known to do in actual fact, would obviously result in a structure practically identical with the archipterygium. Gegenbaur suggests that the archipterygium actually has arisen in this way in phylogeny."

"This view, in its modern form, was based by Balfour on his observation that in the embryos of certain Elasmobranchs the rudiments of the pectoral and pelvic fins are at a very early period connected together by a longitudinal ridge of thickened epiblast—of which indeed they are but exaggerations. In Balfour's own words referring to these observations: 'If the account just given of the development of the limb is an accurate record of what really takes place, it is not possible to deny that some light is thrown by it upon the first origin of the vertebrate limbs. The facts can only bear one interpretation, viz., that the limbs are the remnants of continuous lateral fins.'

We may now take up the evidence in regard to each of the different theories, using in part the language of Kerr, the paragraphs in quotation-marks being taken from his paper. We may first consider Balfour's theory of the lateral fold.

"The portion of Gegenbaur's view which asserts that the biserial archipterygial fin is of an extremely primitive character is supported by a large body of anatomical facts, and is rendered further probable by the great frequency with which fins apparently of this character occur amongst the oldest known fishes. On the lateral-fold view we should have to regard these as independently evolved, which would imply that fins of this type are of a very perfect character, and in that case we may be indeed surprised at their so complete disappearance in the more highly developed forms, which followed later on."

As to Gegenbaur's theory it is urged that no form is known in which a gill-septum develops into a limb during the growth of the individual. The main thesis, according to Professor Kerr, "that the archipterygium was derived from gill-rays, is supported only by evidence of an indirect character. Gegenbaur in his very first suggestion of his theory pointed out, as a great difficulty in the way of its acceptance, the position of the limbs, especially of the pelvic limbs, in a position far removed from that of the branchial arches. This difficulty has been entirely removed by the brilliant work of Gegenbaur's followers, who have shown from the facts of comparative anatomy and embryology that the limbs, and the hind limbs especially, actually have undergone, and in ontogeny do undergo, an extensive backward migration. In some cases Braus has been able to find traces of this migration as far forward as a point just behind the branchial arches. Now, when we consider the numbers, the enthusiasm, and the ability of Gegenbaur's disciples, we cannot help being struck by the fact that the only evidence in favor of this derivation of the limbs has been that which tends to show that a migration of the limbs backwards has taken place from a region somewhere near the last branchial arch, and that they have failed utterly to discover any intermediate steps between gill-rays and archipterygial fin. And if for a moment we apply the test of common sense we cannot but be impressed by the improbability of the evolution of a gill-septum, which in all the lower forms of fishes is fixed firmly in the body-wall, and beneath its surface, into an organ of locomotion.

"No doubt these external gills are absent also in a few of the admittedly primitive forms such as, e.g., (Neo-) Ceratodus. But I would ask that in this connection one should bear in mind one of the marked characteristics of external gills—their great regenerative power. This involves their being extremely liable to injury and consequently a source of danger to their possessor. Their absence, therefore, in certain cases may well have been due to natural selection. On the other hand, the presence in so many lowly forms of these organs, the general close similarity in structure that runs through them in different forms, and the exact correspondence in their position and relations to the body can, it seems to me, only be adequately explained by looking on them as being homologous structures inherited from a common ancestor and consequently of great antiquity in the vertebrate stem."

To the same type of tail Mr. Alexander Agassiz gave, in 1877, the name of leptocardial, on the supposition that it represented the adult condition of the lancelet. In this creature, however, rudimentary basal rays are present, a condition differing from that of the early embryos.

The term gephyrocercal is devised by Ryder for fishes in which the end of the vertebral axis is aborted in the adult, leaving the caudal elements to be inserted on the end of this axis, thus bridging over the interval between the vertical fins, as the name (γεφύρος, bridge; κέρκος, tail) is intended to indicate. Such a tail has been recognized in four genera only, Mola, Ranzania, Fierasfer, and Echiodon, the head-fishes and the pearl-fishes.

"1. The forms that are best comparable and that are most nearly related to each other are the Dipnoi, an order of fishes at present represented by Lepidosiren, Protopterus, and Ceratodus, and the Batrachians as represented by the Ganocephala, Salamanders, and Salamander-like animals.

"The scapula in the Urodele and other Batrachians is entirely or almost wholly excluded from the glenoid foramen, and above the coracoid. Therefore the corresponding element in Dipnoi must be the scapula.

"Neither the scapula in Batrachians nor the cartilaginous extension thereof, designated suprascapula, is dissevered from the coracoid. Therefore there is an a priori improbability against the homology with the scapula of any part having a distant and merely ligamentous connection with the humerus-bearing element. Consequently, as an element better representing the scapula exists, the element named scapula (by Owen, Günther, etc.) cannot be the homologue of the scapula of Batrachians. On the other hand, its more intimate relations with the skull and the mode of development indicate that it is rather an element originating and developed in more intimate connection with the skull. It may therefore be considered, with Parker, as a post-temporal.

"With the humerus of the Dipnoans, the element of the Polypterids (single at the base, but immediately divaricating and with its limbs bordering an intervening cartilage which supports the pectoral and its basilar ossicles) must be homologous. But it is evident that the external elements of the so-called carpus of the teleosteoid Ganoids are homologous with that element in Polypterids. Therefore those elements cannot be carpal, but must represent the humerus.

The gills, or branchiæ, are primarily folds of the skin lining the branchial cavity. In most fishes they form fleshy fringes or laminæ throughout which the capillaries are distributed. In the embryos of sharks, skates, chimæras, lung-fishes, and Crossopterygians external gills are developed, but in the more specialized forms these do not appear outside the gill-cavity. In some of the sharks, and especially the rays, a spiracle or open foramen remains behind the eye. Through this spiracle, leading from the outside into the cavity of the mouth, water is drawn downwards to pass outward over the gills. The presence of this breathing-hole permits these animals to lie on the bottom without danger of inhaling sand.

The Air-bladder.—The air-bladder, or swim-bladder, must be classed among the organs of respiration, although in the higher fishes its functions in this regard are rudimentary, and in some cases it has taken collateral functions (as a hydrostatic organ of equilibrium, or perhaps as an organ of hearing) which have no relation to its original purpose.

In front of the cerebellum lies the largest pair of lobes, each of them hollow, the optic nerves being attached to the lower surface. These are known as the optic lobes, or mesencephalon. In front of these lie the two lobes of the cerebrum, also called the hemispheres, or prosencephalon. These lobes are usually smaller than the optic lobes and solid. In some fishes they are crossed by a furrow, but are never corrugated as in the brain of the higher animals. In front of the cerebrum lie the two small olfactory lobes, which receive the large olfactory nerve from the nostrils. From its lower surface is suspended the hypophysis or pituitary gland.

In most of the bony fishes the structure of the brain does not differ materially from that seen in the perch. In the sturgeon, however, the parts are more widely separated. In the Dipnoans the cerebral hemispheres are united, while the optic lobe and cerebellum are very small. In the sharks and rays the large cerebral hemispheres are usually coalescent into one, and the olfactory nerves dilate into large ganglia below the nostrils. The optic lobes are smaller than the hemispheres and also coalescent. The cerebellum is very large, and the surface of the medulla oblongata is more or less modified or specialized. The brain of the shark is relatively more highly developed than that of the bony fishes, although in most other regards the latter are more distinctly specialized.

In the lancelet there is a single median organ supposed to be a nostril, a small depression at the front of the head, covered by ciliated membrane. In the hagfish the single median nostril pierces the roof of the mouth, and is strengthened by cartilaginous rings, like those of the windpipe. In the lamprey the single median nostril leads to a blind sac. In the Barramunda (Neoceratodus) there are both external and internal nares, the former being situated just within the upper lip. In all other fishes there is a nasal sac on either side of the head. This has usually, but not always, two openings.

The Organs of Sight.—The eyes of fishes differ from those of the higher vertebrates mainly in the spherical form of the crystalline lens. This extreme convexity is necessary because the lens itself is not very much denser than the fluid in which the fishes live. The eyes vary very much in size and somewhat in form and position. They are larger in fishes living at a moderate depth than in shore fishes or river fishes. At great depths, as a mile or more, where all light is lost, they may become aborted or rudimentary, and may be covered by the skin. Often species with very large eyes, making the most of a little light or of light from their own luminous spots, will inhabit the same depths with fishes having very small eyes or eyes apparently useless for seeing, retained as vestigial structures through heredity. Fishes which live in caves become also blind, the structures showing every possible phase of degradation. The details of this gradual loss of eyes, whether through reversed selection or hypothetically through inheritance of atrophy produced by disuse, have been given in a number of memoirs on the blind fishes of the Mississippi Valley by Dr. Carl H. Eigenmann.