автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Normandy

NORMANDY

A NORMAN PEASANT

NORMANDY

BY NICO JUNGMAN

TEXT BY G. E. MITTON

PUBLISHED BY ADAM

AND CHARLES BLACK

SOHO SQUARE · LONDON

Published September 1905

PREFACE

Pen and brush are both necessary in the attempt to give an impression of a country; word-painting for the brain, colour for the eye. Yet even then there must be gaps and a sad lack of completeness, which is felt by no one more than by the coadjutors who have produced this book. There are so many aspects under which a country may be seen. In the case of Normandy, for instance, one man looks for magnificent architecture alone, another for country scenes, another for peasant life, and each and all will cavil at a book which does not cater for their particular taste. Cavil they must; the artist and author here have tried—knowing well how far short of the ideal they have fallen—to show Normandy as it appeared to them, and the matter must be coloured by their personalities. Thus they plead for leniency, on the ground that no one person’s view can ever exactly be that which satisfies another.

G. E. MITTON.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER IPAGE

In General1

CHAPTER II The Norman Dukes18

CHAPTER III The Mighty William34

CHAPTER IV A Mediæval City56

CHAPTER V Caen79

CHAPTER VI Falaise93

CHAPTER VII Bayeux and the Smaller Towns112

CHAPTER VIII The Famous Tapestry129

CHAPTER IX An Abbey on a Rock140

CHAPTER X The Stormy Côtentin155

CHAPTER XI Dieppe and the Coast163

CHAPTER XII Up the Seine182

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1.

A Norman Peasant

FrontispieceFACING PAGE

2.

Cherry Blossom

63.

The Harbour at Low Tide, Granville

84.

A Festival Cap

105.

A Seaside Resort

126.

Grandmother

147.

An Approach to the Abbey, Mont St Michel

228.

Entrance to Mont St Michel

289.

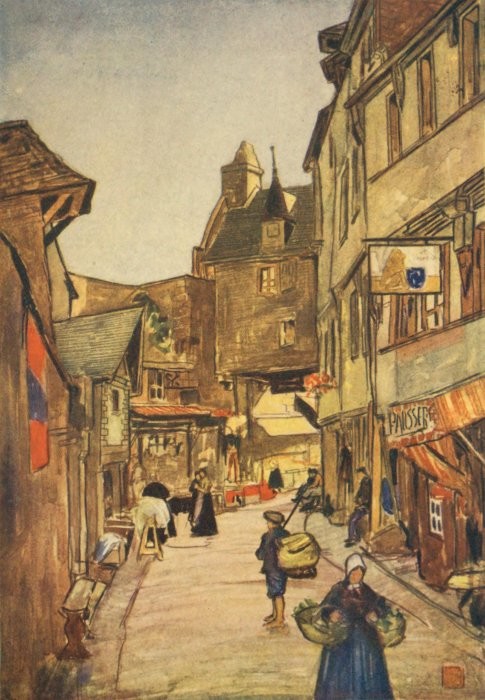

A Street, Mont St Michel

3210.

Harbour of Fécamp

3611.

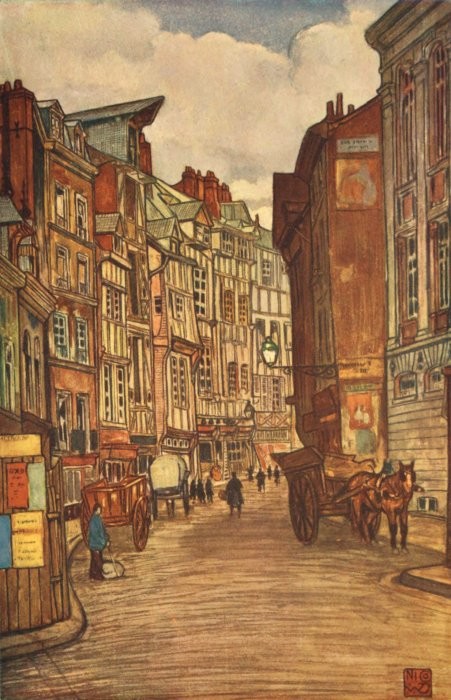

A Road near Rouen

4412.

Near Pont-Audemer

4613.

Old Houses, Rouen

5814.

A Street in Rouen

6215.

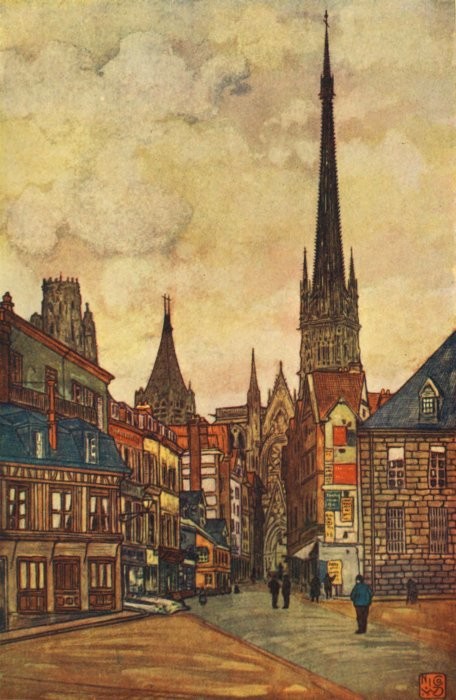

The Towers of St Ouen

6416.

An Hotel Courtyard, Rouen

7217.

The Milk Carrier

8418.

A Street Vendor, Falaise

9419.

A Little Norman Girl

9620.

Rural Scene

10221.

Starting for the Washing-Shed

10422.

Lace Making

11023.

An Ancient Inn Yard

11424.

Timber-frame House, Lisieux

12025.

Valley of the Rille

12226.

St Lo

12427.

A Street in Granville

12628.

The Spinning Wheel

13429.

Mont St Michel—Sunset

14230.

La Porte du Roi

14431.

The Street, Mont St Michel

14632.

A View from the Top of Mont St Michel

14833.

A Holiday Head-dress

15634.

Cherbourg

16035.

The Gateway, Dieppe

16436.

The Quay, Dieppe

16837.

Fishermen at Fécamp

17438.

Havre

17639.

Quai Sainte Catherine, Honfleur

18240.

Caudebec-en-Caux

186The Illustrations in this volume have been engraved and printed at the Menpes Press.

CHERRY BLOSSOM

THE HARBOUR AT LOW TIDE, GRANVILLE

A FESTIVAL CAP

A SEASIDE RESORT

GRANDMOTHER

AN APPROACH TO THE ABBEY, MONT ST MICHEL

ENTRANCE TO MONT ST MICHEL

A STREET, MONT ST MICHEL

HARBOUR OF FÉCAMP

A ROAD NEAR ROUEN

NEAR PONT-AUDEMER

OLD HOUSES, ROUEN

A STREET IN ROUEN

THE TOWERS OF ST OUEN

AN HOTEL COURTYARD, ROUEN

THE MILK CARRIER

A STREET VENDOR, FALAISE

A LITTLE NORMAN GIRL

RURAL SCENE

STARTING FOR THE WASHING-SHED

LACE MAKING

AN ANCIENT INN YARD

TIMBER-FRAME HOUSE, LISIEUX

VALLEY OF THE RILLE

ST LO

A STREET IN GRANVILLE

THE SPINNING WHEEL

MONT ST MICHEL—SUNSET

LA PORTE DU ROI

THE STREET, MONT ST MICHEL

A VIEW FROM THE TOP OF MONT ST MICHEL

A HOLIDAY HEAD-DRESS

CHERBOURG

THE GATEWAY, DIEPPE

THE QUAY, DIEPPE

FISHERMEN AT FÉCAMP

HAVRE

QUAI ST CATHERINE, HONFLEUR

CAUDEBEC-EN-CAUX

CHAPTER I

IN GENERAL

It is a task of extreme difficulty to set down on paper what may be called the character of a country; it includes so much—the historical past, the solemn and magnificent buildings, the antiquity of the towns, the nature of the landscape, the individuality of the people; and besides all these large and important facts, there must be more than a reference to distinctive customs, quaint street scenes, peculiarities in costume, manners, and style of living. Only when all these topics have been mingled and interwoven to form a comprehensive whole, can we feel that justice is done to a country. Yet when the scope of the book has been thus outlined, the manner of it remains to be considered, and on the manner depends all or nearly all the charm. It will not answer the purpose we have in view to follow the methods of guide-book writing; that careful pencil-drawing, where each small object receives the same detailed recognition in accordance with its size as does each large fact, is not for us; for it is essential that the whole must consist of wide areas of light and shade, to make definite impressions. Many people have passed through the country, guide-book in hand, have studied the style of every cathedral, have seen the spot where Joan of Arc was murdered, and where William the Conqueror was born, but have come back again without having once felt that shadowy and intangible thing, the character of Normandy, wherein lies its fascination.

It seems, then, that the only possible way to aim at this high ideal will be to exercise the principle of selection; to choose those things which are typical and representative, whether of a particular town or the whole country, to describe in detail some points which may be found in many places, and to leave the rest. A town-to-town tour, with everything minute, accurate, at the same level, would be wearisome and unimpressive, however useful as a guide-book. Here we shall wander and ramble, selecting one or two objects for special attention, perhaps by reason of their singularity, perhaps for the opposite reason, because they are typical of many of their kind, and by this method we shall gain some general idea of the country, without becoming tedious by reason of too much detail, or vague for lack of it.

It has often been said that Normandy is a beautiful country, or as it is less happily expressed, “So pretty,” and this is not altogether true; no doubt there are parts of Normandy which are beautiful, such as the banks of the Seine, and the country about Mortain and Domfront, but there are also parts as dully monotonous as the worst of Holland or Picardy. To know the country, one must see all kinds, and perhaps with knowledge we shall get to feel even for the plainer parts that affection which comes with knowledge of a dear but plain face.

The present chapter, however, is merely preliminary and discursive, with the object of giving some general idea of the country as a background before filling in the groups destined for the foreground. The place where the majority of English people first strike Normandy is Dieppe. The coast-line running north and south of Dieppe is famous for its bathing-places and pleasure resorts, and it will be dealt with later on.

The district lying between Dieppe and the Seine is known as Caux. The route from Dieppe to Paris is well known to many a traveller, and the feeling of anyone who sees it for the first time will probably be surprise at its likeness to England. If the journey be in the spring-time, he will see cowslips and cuckoo flowers in the lush green grass, amid which stand cows of English breed. The woods will be spangled with starry-eyed primrose and anemones, while long bramble creepers trail over the sprouting hedges. Even the cottages, red-tiled or thatched, are quite familiar specimens; and it is only when some rigid chateau, in the hideous style most affected by modern France, built of glaring brick, and with an utter absence of all attempt at architectural grace, is seen up a vista of formal trees, that he will realise he is not in the Midlands.

Then we come to the banks of the Seine. Perhaps if one had to choose out of all Normandy, one would select the country lying within and around those great horseshoe loops of the river as admittedly the most beautiful part. So full of interest and variety is the course of the Seine, that we have reserved a special chapter for an account of it between Havre and Vernon. However, beautiful as it is, this part is not quite so characteristically Norman as some other districts. The Seine itself, though it flows for so long through Normandy, does not belong to it, but to France; the people who live on its banks are more French than Norman, and we have to go farther westward to find more typical scenery. The country lying about Gisors, and between that town and the Seine, was called the Vexin, and formed a debatable ground on which many a contest was fought, and which was held by France and Normandy in turn.

To the west of the Seine the country varies. Some towns, like Lisieux, lie surrounded by broken ground well clothed by trees, while much of the district, notably that south of Evreux, is monotonous and almost devoid of hills at all.

We find here some instances of those long, straight roads which it seems to be the highest ideal of the Vicinal Committee to make. We shall meet them again in plenty elsewhere, but may as well describe them here. Take for instance that road running between Evreux and Lisieux; it undulates slightly, and at each little crest the white ribbon can be seen rising and falling, and growing at last so small in the endless perspective, that it almost vanishes from sight. Six miles from any town a man is found carefully brushing the dust from this road, though what good he can possibly do by the clouds he raises with his long, pliant sweep is a mystery. On each side of the road there is a broad ribbon of green, and in this case it is overhung by a double row of trees that really do give some shade. The peasants walk in this green aisle, but even with the grass underfoot the patience needed to traverse perpetually such monotonous roads must be great; it is the quality often found in those whose lives know little variety. Sometimes these high roads are planted with poplars, which mock the wayfarer, for like so many other trees in France, these poplars are stripped of all their boughs almost to the top, and the little tuft of light leaves remaining gives no relief to sight or sense on a glaring road under a summer sun; oaks, horse-chestnuts, beeches—almost any other tree, and all seem to grow well—would have been far better for shade and comfort; yet for one road planted with these umbrageous trees a dozen are lined by the scanty and disappointing poplar. Along them pass the market carts with hoods like those of a victoria; and even the drivers of slow travelling carts supply themselves with miniature hoods, exactly like those of perambulators, to cover their seats, for no one could endure the hours passed in the sun without some protection.

A great deal of Normandy is flat and bare; the flint and trefoil style is common. Wide fields of mustard of a crude raw yellow, not golden like the Pomeranian lupin fields, are often to be seen. The flat landscapes are broken by a few stiff or scraggy trees, tethered cows, or cottages of lathe and clay; yet, we hear the song of the lark and scent the breath of roses, and in the spring and early summer orchards of cherry blossom make gleaming sheets of white on many a roadside.

The valley of the River Rille, up which Pont Audemer lies, is of a different style altogether, still it has characteristics in common with other districts. The valley is flat, and from it on each side so steeply rise the fir-crowned hills that in describing them one could almost use the word rectangular. Though the trees are fairly thick there is a ragged, unfinished, rather scrubby look, very often seen in Normandy.

CHERRY BLOSSOM

If we spring westward now to Caen, we find the flat and bald landscape everywhere. The country is almost incredibly dull, and this is the reason why Caen, such an interesting town in itself, makes so small an appeal as headquarters. The long, straight roads radiate from it in all directions. Here and there there is a lining of trees, but generally only a green ditch, waterless, and a line of cornfield, blue-green or yellow as the season may be, with perhaps a ragged fringe of gnarled apple-trees standing ankle-deep in the corn, and the wide sky, like a great inverted bowl of clear blue, fitting every way to the horizon. There may be fields of deep crimson trefoil to vary the colouring, or there may be fields yet unplanted in which the bare brown earth seems to stretch to eternity, and far away in the midst are the stooping figures of two or three men and women busily working with bent backs on a shadeless plain. Yet in this wide flat country there is a freshness and an openness that one might imagine could permeate the blood, so that the peasants who were born and reared here might suffocate and die in a mountainous country, as the mountaineers are said to pine and die in a plain. This flat plain to the westward of Caen, and surrounding Bayeux in the district of the Bessin, has been, so long as history has any record, a prime agricultural country with magnificent pasturage. The most notable points in the little villages which stud it are the wonderful churches, out of all proportion to the size of the hamlets they represent. Of course this feature is found all over the country, and in almost every small town there is a cathedral, so that one cannot but wonder where the money came from which built such glorious monuments to piety. The line going to Bayeux runs at about seven or eight miles from Caen, between two little villages, Bretteville and Norrey, which share a station between them. The church at Norrey, built in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, is a very model of architectural perfection and simplicity, the tall spire is something in the style of the marvellous St Pierre in Caen itself. Bretteville falls not far short of it, though the tower is after a different pattern. A very few miles on, at Andrieu, is a church with a splendid tower of the same date as Norrey, and about two miles south, at Tilly aux Seulles, a church of which the nave is eleventh century, the choir twelfth, the tower fourteenth, and the portal fifteenth, all in the artistic and finished style we associate with that period when there seems to have been nothing but good work. This group of churches is worth mentioning as striking, even in the profusion to be found in Normandy. Leaving Caen and going southward, we plunge before very long into the hilly country from which the Orne rises. This is known as the Bocage, a name which suggests rich foliage. The part of the country in which Mortain and Domfront lie has been called the Alps of Normandy, and certainly it can hold its own for picturesqueness. It is, however, comparatively little known; the line of the quick-trip-man may touch Falaise, but it goes no further south. Yet even at Falaise one can see part of a ridge extending for many kilometres, a ridge which has been so magnificently utilised as the site of the castle where William was born. The hills through Mortain and Domfront run parallel with this ridge, and are of the same description. Indeed the positions of the castles at Domfront and Falaise are very similar.

THE HARBOUR AT LOW TIDE, GRANVILLE

Turning now to a new district westward, we find a rugged granite coast, chiefly notable for the splendid views it affords of the bay of Mont St Michel and its famous rock, and on a wider scale of the Channel, where lie the Iles Causey and Iles Normandes (Channel Isles). There are here a group of fine towns, Avranches, Granville, Coutances, and St Lo. The first named is the capital of the Avranchin district, which stretches up to the little stream Couesnon, separating Normandy and Brittany. Thus we are almost at the end of a general topographical survey; there remains only that peninsula of the Côtentin, very little visited, and entirely off the tourist track, yet in itself delightful. The hills rise and fall, and are well covered with trees, which, though not of a great height, grow warmly and bushily. The roads are good, and the country is studded with ancient chateaux, now for the most part farmhouses, which shall have, as they deserve, a chapter to themselves. We have thus run very quickly over Normandy in a general survey, gaining some idea of the characteristics of the districts, and calling them by the ancient names they bore in the days of the Norman dukes.

In regard to the people, what there is to say has been said in the various local chapters. The quaint costumes, which are familiar to us from many a picture, are fast dying out; in Normandy one sees less of them than in Brittany; here and there, it is true, we find a local fashion in caps, as at Valognes; and still on feast-days and fair-days some damsel appears in the wonderful erection of stiffening and beautiful hand-made lace which her grandmother wore, to be the envy of her neighbours; but in an ordinary way these things are not seen. “On y cherchent vainement ces riches fermiéres de la plaine et du Bessin, dont les hautes coiffes garnies de dentelles et les bijoux Normandes attiraient tous les regards.”

A FESTIVAL CAP

And what is said of costumes may be said also of customs. Le Hericher, who has made a study of racial characteristics, says that the Normans are not a people of imagination and idealism like the Celtic races. “Il y a en Normandie deux localités où on remarque une population exotique, exotique de costume, exotique de langue; c’est Granville à quatre lieues de Cancale, son berceau, son point de départ; Cancalaises et Granvillaises sont des sœurs séparées par un bras de mer. L’autre c’est le faubourg de Dieppe, celui des pêcheuses, le Pollet. Ces deux localités où la race est Celtique, se distinguent par un esprit pieux qui, comme cela se fait chez les Bretons, mêle la religion aux actes de la vie civile et de l’existence maritime.” He adds, “Le Normand chante peu et ne danse pas du tout. Son voisin le Breton chante beaucoup, danse un peu.”

Nevertheless a dancing-match may still be found in some obscure corners of Normandy.

The Norman has the love of country strongly developed and though settlers have gone forth to other lands, especially to Canada, the mother-country retains their hearts in a peculiar way. One of the most popular of the national songs carried overseas runs:—

“À la Claire fontaine, Les mains me mis lavé. Sur la plus haute branche La rossignol chantait, Chante, rossignol chante Puisque t’as le cœur gai, Le mien n’est pas de même Il est bien affligé.”

Longfellow’s Evangeline is full of the spirit of the exile and his picture of the girl herself:—

“Wearing her Norman cap, and her kirtle of blue, and the earrings, Brought in the olden time from France, and since as an heirloom Handed down from mother to child through long generations,”

gives us a clear-cut vision of a type of Norman girl now growing every day more rare.

A great many people who could visit Normandy as easily as one of our own coast towns are deterred by the difficulty of knowing where to begin, and what route to take. Normandy is the easiest of all countries to visit. One may begin anywhere with the certainty of finding interest and enjoyment, especially those who are cyclists, for the roads are as a rule excellent, much better than those in Brittany, and one may stay for a longer or shorter time with equal pleasure, for the country furnishes material for many a month, and yet much can be seen in ten days or a fortnight.

The best known starting-place, as we have said, is Dieppe, and of the hundreds who enter Normandy yearly, at least eighty per cent. come in by this gate. A very usual route for a first trip is by Rouen, Evreux, Lisieux, Caen, Bayeux, St Lo, Coutances, Avranches, and St Mont Michel, returning from St Malo. This for a preliminary survey is good, and having once been in the country it is almost certain that the traveller will go again, given the opportunity.

A SEASIDE RESORT

There are of course many people who are content with the sea-coast, and wish to penetrate no further than Dieppe or Trouville, to mention the two largest of the coast resorts. There is much to be said for these places. There is a brilliance in the sunny air, a gaiety in the mingling crowds, a completeness in the round of amusements, and the opportunities for observing one’s fellow-creatures, that are grand elements in the tonic of change. The bathing, the bands, the casinos, the toilets, are all excellent of their kind, and many a tired worker goes back to that office in the city, where his view is limited by his neighbour’s window-reflectors, a new man for the busy idleness of a fortnight at one of these holiday resorts. Unfortunately for those who have not much to spend, the prices at the best hotels at these places in the season are almost prohibitive. However, the season is late, not beginning until July, and there are sunny months before that. There are also countless places along the coast less known, and having the primary advantages of the others; where the sands are just as stoneless and shadeless, and where the sea-air is as fresh and the sky as blue, but where the hotels are not so exorbitant, and the villas and pensions are innumerable also. Such, to take only one example, are the places that line the coast near Caen.

But this is the merest fringe of the subject. One who has sampled the coast towns, and rushed over the main route above described, has hardly begun to know Normandy. He has endless choice left for future holidays. He may make his headquarters at Valognes to explore the Côtentin; he may settle down at Domfront, and wander throughout that lovely district; or he may devote himself to the country around Les Andelys and Gisors; and everywhere he will find opportunity for enjoyment.

The difficulty in passing quickly through Normandy on a cycling or pedestrian tour is to get food when and where you want it. To make any progress at all in summer, it is necessary to start in good time after a substantial meal, then to take a very light luncheon, perhaps carried with one, and to arrive in time for a good dinner at the day’s end. This is very difficult of accomplishment. Such a thing as that which an Englishman calls a good breakfast is almost out of the question, and the probability is that the cyclist riding off the beaten tracks cannot get anything at all for the rest of the day; for of all hopeless places for eatable food, the small villages in Normandy are the worst. Drink of some kind, vermouth, and the sweet syrupy grenadine, can be had at every little shanty, marked “Debit du Boisson,” but there is nothing to eat.

GRANDMOTHER

I can recall one scene which could never have taken place anywhere save in Normandy. An old farmhouse with half-door, which, being opened, admitted one to an old room toned in browns of all shades, heavy beams, walls, and floor alike. A few boughs, green-encrusted, and sending up a thick smoke, lie on the open hearth. A little old dame, of any age one likes to guess, with wizened nut-brown face encircled by a spotless close-fitting coif, is the lady of the house. Her face is one to which Rembrandt alone could have done justice, with an expression at once kindly, dignified, and shrewd. On the rough table, hacked and hewed by many a knife, are set bowls of milk strongly tasting of wood smoke. Sour cream is spread like jam on slices roughly carved from a loaf the size of a bicycle wheel, and about as hard as deal wood. The cream is very sour, and a few lumps of sugar are served out with it to be grated over it. The old dame sits by with folded hands while the party laugh over their strange meal, but as the laughter continues she grows slightly anxious, and asks to be assured that she is not the object of it; a royal compliment in the best French at the command of the best linguist of the party chases away anxiety, and also for the moment dignity and shrewdness, leaving nothing but delight pure and simple on that dear old work-worn face.

It is the fashion to praise French cooking, but to an Englishman who has passed the day bicycling with nothing but a couple of soft-boiled eggs and some sour cream, there is something unsatisfying about the ordinary dinner menu at a French hotel. The monotonous soup, always maigre; the dull variety of nameless white fish, which seems to be kept in stock as a staple; the little tasteless pieces of veal, all the same size and shape cut on a dish; the leathery and half-raw mutton, also cut in the same way; the very small variety of vegetables, and utter absence of attempt at sweets—is not an appetising menu. The French are apparently very conservative in their food. A traveller of eighty years ago tells us: “The breakfast at the table d’hôte at Argentan, as at every other place where I stopped, was of exactly the same nature as their dinners. That is, soup, fish, meat of different kinds, eggs, salad, and a dessert with cider; no potatoes or any other vegetable but asparagus at any meal,” and this would be a very fair account of an hotel menu nowadays. The worst fault seems to be monotony, always chicken, gigot, or veal. Of course, at the very first-class hotels, at places such as Dieppe, where English influence has penetrated, things are certainly better, but in the ordinary best hotel in a second-class town, the food is very unsatisfactory, and the meat always tough and bad, in spite of the splendid pasture lands and the fine fat beasts one sees grazing; good beef is very rare, and good mutton unknown. In this respect Normandy seems to have been unvaryingly the same, for the traveller above quoted writes also: “With occasional exceptions, the meat in this part of Normandy (Caen) is of inferior quality, more particularly the mutton, which is generally as lean and tough as an old shoe.” So often has the praise of French vegetables been repeated, that one has learned to take it as an axiom, until one goes and finds out for oneself. The truth is there is less, not more variety, than with us; such a thing as a good spring cabbage is unknown, and cauliflower is served only au gratin. Yet the hotels have improved enormously in many points in the last seven or eight years. They have their advantages, and in some ways every French hotel, even the poorest, can beat its English compeers. The great advantage of cheap wine is felt at every hotel in Normandy; the question of what to drink at dinner, usually such a difficult one, is solved for you. On the table, almost everywhere, are red and white wine and seltzer water “compris”; and at every hotel, without exception, cider, varying it is true greatly as to quality, can be had for the asking.

The hotels are also cheap. At those of the first class, 1 franc is the average charge for the petit déjeuner meal; the déjeuner is generally 3; and the dinner 3.50; while the room may be taken at an average price of 3 francs. Therefore a full day at an hotel usually costs 10.50 francs, or en pension 10 francs, equalling between 8 and 9 shillings; but at fashionable coast resorts in the season 15 francs per day is the lowest rate, and in the out-of-the-way districts, and off the beaten tracks, 7 and 8 francs a day are the usual charges. At any rate, in Normandy one is free from the ridiculous impost called “attendance,” which entails an additional 1s. 6d. a day in many English and Scotch hotels, while tipping is expected just the same.

Many of the hotels have a forbidding aspect outside; until one is used to it, it is a little damping to enter under a low archway leading to a stableyard, but the entry is often the worst part of it. An Englishman touring through the country will find as a rule he is able to find without difficulty quarters which possess all requisites though not luxuries.

CHAPTER II

THE NORMAN DUKES

Normandy is probably at the same time the best and the least known place on the Continent to Englishmen: the best known, because the most accessible; the least known, because, beyond the fact that the Duke of Normandy conquered England in the year 1066, and that it is in consequence from Normandy that our line of kings is derived, the average Englishman knows little or nothing of its history or associations. Ask him plainly: What is the extent of Normandy? and he will answer vaguely, “It is the north of France.” So it is, a part of the north of France, but not the whole. As a matter of fact, the term Normandy has now little geographical meaning. Normandy is not a province for practical purposes, nor does it carry any civil boundaries marking customs, or law, or government. Normandy embraces the departments of Manche, Orne, Eure, Calvados, and Seine Inférieure; that is to say, it reaches from Eu and its port Le Tréport on the east; to the stream Couesnon, which flows into the English Channel a little beyond Mont St Michel on the west; and southward it just takes in Alençon, dips down to a point near La Ferté Bernard, returning with a wavering north-eastward line across the Seine at Vernon, and by Gisors to Eu aforesaid. It answers also to the modern dioceses of Rouen, Evreux, Séez, Bayeux, and Coutances. The Archbishop of Rouen still keeps the title of Primate of Normandy, otherwise the name has gone out of formal use, and Normandy is merged in France.

Yet it is extraordinary with what tenacity and affection Englishmen regard a name which links the dwellers in the land to them as kin, and it is still more extraordinary how, after centuries of submersion, beneath a rule entirely French, the kinship makes itself felt in manner and character as well as in memory. The qualities of the sturdy northmen whose bravery and roving dispositions led them to lands far from their own, and made them at home everywhere, still exist in their descendants, as the colonies of England testify. When the Danes had settled down upon the north of France “they were,” says Freeman, “no longer Northmen but Normans; the change in the form of the name aptly expresses the change in those who bore it.” Yet many and many a vessel full of vikings discharged itself on that land without making any impression, until one came bearing the mighty Rollo, who was destined to stay and make a permanent mark.

The France of those days, torn by dissensions, was not the homogeneous country we now know. Long before Cæsar first conquered Gaul, and in the time of his successor Augustus, Lyons was the capital; then came the Germans and Goths, who began to overrun the land, and a little later the low German tribe of the Franks came also; they were destined to give their name to a land alien from their own, just as the modern name of Scotland was brought over the sea originally by the men of Ireland. It was in the beginning of the sixth century that the greater part of Gaul lay under the dominion of Clovis, King of the Franks. Yet after his death, in accordance with the German custom, the kingdom was divided among his sons, one province being Neustria, which included what we know as Normandy, and endless struggles ensued, until in the middle of the seventh century arose the great Charlemagne, who ruled by his might over all central Europe, now divided into many nations. But in the struggle between his grandsons, his great dominion was split up, one grandson taking what is now Germany, another Italy, and the third, and most powerful, Charles the Bald, holding France. He had for his kingdom “all Gaul west of the Scheldt, the Meuse, the Saône, and the Rhone; it ran down to the Mediterranean, and was thence bounded by the Pyrenees and the Atlantic.” Brittany was still savagely independent, however, and the northern coasts of Neustria were ravaged by the Northmen. The county of Paris became part of the possessions of the duchy of France, and Robert the Strong, made duke by Charles the Bald, was set to fight against the northern marauders, who had penetrated even to Paris. But the descendants of the great Charles were weak and feeble, and as his house declined that of Robert the Strong grew, culminating in his great-grandson, Hugh Capet, who, on the death of the last of the direct line of degenerate Carlovingians, became king of the France that we know.

But before Capet had succeeded in seating himself on the throne, the Northmen had settled permanently in France. In the reign of Charles the Bald’s grandson, Charles the Simple, Rollo or Rolf, the Northman, had established himself at Rouen, and the king had made terms with him, giving him his daughter to wife, and granting him a tract of land from the Epte to the sea, with Rouen as its heart. This was in 912, and is the first recognised settlement of the Northmen. Rollo himself is a fine bold figure, only surpassed by one other among his descendants. His frame was gigantic, and when in full armour no horse could carry him. He seems to have combined, with the strenuous virile qualities of the northerners, the capacity for organisation and settled government belonging to a later period, and a more civilised people. He embraced the faith of his wife Gisella, and was baptized under the name of Robert, though it is as Rollo he will be known and remembered. He was the founder of Normandy, and under his government, learning and industry sprang up and flourished. His followers received the softening influences of the French, and the French language began to be spoken in Normandy.

The first Normandy was, as has been said, the district lying around Rouen, but in 924 the district of Bayeux was added to it, hereafter to become a stronghold of the older language and customs against the Frenchified influences of Rouen. Freeman says: “Nowhere out of old Saxon or Frisian lands can we find another portion of continental Europe which is so truly a brother land of our own. The district of Bayeux, occupied by a Saxon colony in the latest days of the old Roman empire, occupied again by a Scandinavian colony as the result of its conquest by Rolf, has retained to this day a character which distinguishes it from any other Romance-speaking portion of the Continent.”

AN APPROACH TO THE ABBEY, MONT ST MICHEL

As we have seen, at the time of Rolf’s settlement in Neustria there were two powers in France, the King of France, Charles the Simple, and the powerful Duke of the French, who included in his dominions the future capital, Paris. It was to the King of France that Rolf did homage as overlord; and the story goes that the proud Northman, on being told to kiss the monarch’s foot by way of homage, deputed one of his men to act as his proxy, and that this man, no humbler than his master, contemptuously raised the king’s foot to his own mouth, thereby oversetting the monarch. The story is probably apocryphal, but it has lived with odd persistence.

Rollo died in 931, and a few years after his death his son William Longsword had the satisfaction of adding to his lands the district of Côntentin, including the peninsula and the land as far south as Granville. He obtained this additional land when he was suppressing what was called a revolt of the Bretons—for the Dukes of Normandy held shadowy rights over Brittany, rights which they were never able to enforce. By his new conquest the Channel Isles were included in Normandy, and oddly enough it was thus they became attached to the English crown, for when the Norman dukes, as kings of England, lost all their other French possessions, they retained the islands. William Longsword was of a softer mould than his father, and from what can be gathered from the chronicles of the time he was a man of a thoughtful cast of mind, serious and gentle, a character rare enough in his age. He was succeeded by his son Richard, who, of all the Norman dukes except the Conqueror himself, is the best known to English people from Miss Yonge’s charming story, The Little Duke, in which it is to be feared she regards both father and son through a haze of idealisation; but it is indeed difficult if not impossible to make sufficient allowances for the radically different cast of thought in a bygone age, and to draw men as they really were. Richard the Fearless reigned for more than fifty years, and it was ten years before his death that Hugh Capet combined in himself the power of the kings and dukes of France, and became the first king of consolidated France. Richard had been sent as a lad to Bayeux, in order that he might be brought up under the influences of the country of his ancestors instead of becoming too much Frenchified; but he was of a vigorous disposition, and there seems to have been no reason to believe that he would have suffered unduly from any softening influence.

Nothing is more striking in the early annals of France than the succession of weak rulers she produced; occasionally there arose a man of capacity and power, but his sons were invariably weaklings. France does not seem to have been able to carry on a strong ruling race. In contrast to this, note the towering figures of the Norman dukes—the gigantic Rolf, the wise William Longsword, Richard the Fearless, Robert the Devil, William the Conqueror—all men of exceptional power and capacity. The infusion of Norman blood seems to have given just that basic power of endurance needed in the Teutonic nation. Richard the Fearless was succeeded by his son Richard the Good, and he by two of his sons successively, another Richard, and Robert the Devil or the Magnificent (see p. 34). It was Roberts son William, who, left as a child to his inheritance, became the most famous of his race. No story of romance or legend is more wonderful than that of the Conqueror. At present we leave it aside to form the theme of a separate chapter, so as not to prolong too far this sketch of Norman history, which is necessary for any understanding of the topographical allusions.

With the Conquest, Normandy began to sink in importance; as in the case of a mother who has brought forth a son, destined to wield power and occupy positions far beyond her capacity, she herself took a secondary place. To be the independent King of England was grander than to be Duke of Normandy subject to the kings of France, and it needed but a generation or two to make the English forget the fact of their being conquered, and to look upon Normandy as a appanage of the English crown. It was a strange position altogether; the best blood of Normandy was emptied into England at the Conquest; abbots, warriors, nobles, men of learning and men of birth settled in the new country and became the English, and England found herself so much Normanised as to be transformed.

It is customary to consider that the history of Normandy ends with the conquest of England, being thenceforth merged in that of the greater country; but though the importance of Normandy as a country was lessened by the union, her history is by no means identical with that of England. Normandy several times enjoyed a sovereign prince altogether distinct from him who wore the crown of England, and this state of affairs began immediately after the death of William the Conqueror, who left the duchy to his eldest son Robert, while the second son William became King of England. Of Robert we know chiefly that he suffered from an incurable “mollesse,” and further, as regards personal details, that as “Jambes eût cortes, gros les os,” he earned the nickname of Court-hose. This son of a famous father and admirable mother, was a libertine, given over to pleasure, incapable of taking decisive action, one of those weak characters on which experience cannot engrave permanent lines, but withal full of the courage of his race. He was, however, unable to hold what had been left him. William had prophesied that his youngest son Henry should be greater than both his brothers, and Henry soon began to fulfil the parental prophecy by seizing and holding for himself the Côtentin peninsula, and with it the lordship of Mortain. Nothing is more significant of the grasping natures of the trio of brothers than the way in which they changed over, first one couple joining against the remaining one, and then almost immediately breaking up for a fresh combination. William and Henry warred against Robert; Henry and Robert combined to thwart William; William and Robert mutually agreed to keep Henry out of the succession, and so on; exactly as self-interest dictated for the moment. Finally William came uppermost, and Robert submitted, and henceforth practically held his duchy at the pleasure of his brother. It was Henry’s turn to be the “odd man out,” and he fled before his elder brothers, taking refuge in Mont St Michel, where they both besieged him. He had to submit, and, yielding up the fortress, retired a penniless adventurer. But in some way he afterwards regained the whole of the Côtentin. When the crusading mania began, Robert was seized with it; under his rule Normandy had been wretchedly governed, and little he cared. For a comparatively small sum he mortgaged his duchy to his brother William the Red, for six years, and went off to the Holy Land. Normandy was probably the better for his action. In returning from the Holy Land, he managed to occupy a year in the journey, and on the way he married Sybilla, daughter of Count Geoffrey of Flanders. He had already, it may be stated, two sons and a daughter, who seem to have inherited the best of the traits of his house. One of the sons, Richard, while on a visit to his uncle William in England, was accidentally killed in the New Forest.

ENTRANCE TO MONT ST MICHEL

Sybilla attempted to reclaim her husband from the crowd of bad companions who gathered round him on his re-entry into Normandy, and when Robert was tired of her, as he soon became of everything, he found this inconvenient, so in less than two years she died suddenly of poison. Robert had returned too late to put in a bid for the throne of England! which was already occupied by Henry; but the death of William freed him from any obligation to pay back the debt on his duchy, and Sybilla’s dowry went in other directions. Henry now made a treaty with his brother, by which he delivered up the Côtentin, but kept Domfront and Mortain. However, becoming once more embroiled with Robert, he quickly won for himself the whole duchy, clinching the matter at the famous battle of Tinchebray, whereby the process of his father was reversed, and the King of England now conquered Normandy as the Duke of Normandy had then conquered England. After the terrible death of his son near Barfleur, Henry set his heart on the succession of his daughter Maude, who had been married first to the Emperor of Germany, and afterwards on his death, evidently by her father’s choice, to Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou and Maine, one of the most powerful of the rulers who might have opposed her succession in Normandy. Yet Maude never ascended the throne that her father had so carefully guarded for her. It is true that a claimant who might have proved very formidable, William, the remaining son of Robert, had died seven years before his uncle Henry, but there remained the two sons of Adela, daughter of the Conqueror; of these the younger, Stephen, was determined to oust his cousin. During the weary civil war that followed, Normandy was many times traversed by one party or the other, but on the whole the country declared for Stephen. The Count of Anjou was an hereditary enemy, and the Normans did not relish the idea of being governed by him in his wife’s name. When at last, after the death of Stephen’s son Eustace, it was settled that Henry should be recognised as next heir to his cousin, the land enjoyed peace. With the accession of Henry a fresh era began, for the new king held in France not only Normandy, but in right of his mother and his wife, Touraine, Anjou, Maine, and Acquitaine—together more than half the country—a formidable vassal for the French king! Henry was tenacious of his rights, and it was only as his turbulent sons grew older, and displayed to the full those unfilial dispositions so common in their race, that he consented to divide some of his possessions among them, to be held from him as lord. His gifts were many times changed, but it seems certain that Richard had ruled in Acquitaine as an independent sovereign before his father’s death, while Geoffrey, by his marriage with Constance, heiress of Brittany, became Duke of Brittany. Henry gave to his youngest and best loved John the title of Count of Mortain, and with it the vicounty of the Côtentin; and in 1181 he made his eldest son, Henry, Duke of Normandy. But Henry the younger did not long survive, dying at the early age of twenty-eight, after rebelling against his father almost continuously since his attainment of manhood. Therefore, at the death of the king, Richard came to the throne. John still continued ruler of Mortain and the Côtentin under his brother, and these dominions gave him an opportunity for putting in practice those treasonable conspiracies by which he hoped to throw off Richard’s yoke, and become an independent sovereign. Richard, however, was too strong for him; he marched into Normandy, and speedily showed himself master. Thereupon John came humbly to ask forgiveness at Lisieux. The story goes that Richard, with the open-minded heartiness which won him so much more love than his worse qualities merited, exclaimed that he forgave him freely, and set his behaviour down to bad influence, as he was only a child. As John was then six-and-twenty, this reason must have galled him had he possessed an atom of pride, but we have reason to think he did not. While Richard was otherwise engaged in the Holy Land and on the Continent, John made a second attempt to win his realms, which was brought to an end by a knowledge of his brother’s death. He heard this while at Carentan, and gleefully hastened to take advantage of it. True, there was still a boy to be reckoned with, young Arthur, son of his dead brother Geoffrey—a boy who was already Duke of Brittany, and who inherited to the full the proud fierce temper of his mother Constance. But John had two points in his favour: first, that in the old days a brother was often considered to have a better right to a throne, especially if he were a man, than a nephew who was still a child, and this idea had not altogether died out; secondly, the Normans of all people would have been the last to yield homage to the duke of the hated Bretons, their nearest neighbours, with whom they had been perpetually at war, and for whom they felt a fierce jealousy. On the other hand, Arthur had a powerful ally in Philip, King of France, who saw that it would be much more to his own advantage to have a weak boy as ruler of Normandy than a man equal to himself in cunning and craftiness. Therefore Philip helped Arthur, and even promised him his little daughter in marriage. But unluckily for the boy who was the principal actor in the drama, he fell into the hands of his uncle,—some say he was captured by treachery while asleep,—however that may be, he was in John’s clutches, and little chance was there for him to get out again. This was in August 1202. John carried his prisoner at once to one of the strongest castles in his dominions, namely Falaise. Arthur was now between fourteen and fifteen years of age, and John, reckoning without that stubborn courage of nature which the boy inherited, attempted to make him abdicate his rights, in vain. Finding this hopeless, he hurried him away to Rouen, there to dispose of him finally. Arthur’s incarceration at Falaise is dealt with in the chapter on Falaise, and his captivity at Rouen is treated in the chapter on Rouen. The fury of the Bretons, who saw the last of their ruling race, a promising boy, thus foully murdered by the duke of the Normans, their life-long foes, may be imagined; it hardly needed the French king’s call to arms to make them rise in their wrath and flood in upon the neighbouring towns of Normandy. The conduct of John after this displays a pitiable weakness. He alone of all the Conqueror’s line showed a lack of courage; others had been weak, vacillating, unfilial, cruel, vicious, but it remained for John to combine all these qualities in himself. His movements were like those of a timid animal who knows the huntsmen are closing in on him, but has not courage to make a dash through the ring. He hurried from Rouen to Caen, from Caen to Brix, and Brix to Valognes. Back again to Caen, and then to Domfront. He returned to the Côtentin, and at last embarked at Barfleur without striking a blow to save that land, which he had not hesitated to gain by murdering a boy, when he thought there was no personal danger in the action. He did indeed return in 1206 for a short time, but never in such a spirit as to make the retrieving of his dominions possible. Meantime the Normans did not submit so quietly; they could not endure the entry of the Bretons, and sternly defended themselves at Mont St Michel, which was set on fire, and at Caen; but it was of no use; the Bretons, after a triumphal progress, met the French king, who had received the submission of Caen as well as Lisieux and Bayeux, and thus with hardly a struggle there fell into the hands of France that territory which she had so long and so jealously regarded. If ever a king deserved to lose his land, it was the craven John.

A STREET, MONT ST MICHEL

By a curious oversight in the ratification and the submission which followed this conquest, the Channel Islands were overlooked. It has been suggested they were simply forgotten; if so, the event proved fortunate for them, for they have remained ever since in the happy independence granted them by England. The title of Duke of Normandy was dropped by Henry III., John’s son, at the Treaty of Saintes in 1259, when it was agreed that Acquitaine should remain an English possession, and the title was afterwards borne by a scion of the ruling French house. But the tale of Normandy’s wars is not ended. For in the time of Edward, that monarch was set upon recovering not only the territory lost by his grandfather, but, if possible, the French crown for himself; he landed at Barfleur, and, quickly subduing the Côtentin, passed on to St Lo, Coutances, and Caen, taking towns and seizing vast quantities of precious stuffs wherever he went. These triumphs were followed by the famous battles of Crécy and Poitiers, and the historic siege of Calais. However, his conquest left no permanent mark on Normandy, for by the Treaty of Bretigny in 1360, though he received much else, he resigned Normandy with his claim to the French crown, and it was reserved for his great-grandson, Henry V., to recover the duchy by the sword. This he actually did, after a brilliant series of victories; so that in the years 1417 and 1418 Normandy became an appanage of the English crown, but under the rule of the weak Henry VI. his father’s conquests lapsed, and by 1450 Normandy was once more included in the dominions of France, never again to be severed.

CHAPTER III

THE MIGHTY WILLIAM

William’s father was the fifth Duke of Normandy, and if the story of how he attained that dignity be true, certain it is that his nickname “Le Diable” was more fitting than the other, “Magnifique,” which he earned by his lavishness. His elder brother, Richard, was Duke of Normandy when Robert set up the standard of rebellion at Falaise. But Richard was no weakling, and did not suffer the disaffection to spread; he appeared before the walls with all the forces at his disposal, and soon compelled his younger brother to sue for peace. Then an arrangement was made by which a certain grant of land was conferred on the rebel, while the castle of Falaise, a powerful stronghold, was recognised as the property of the reigning duke. To celebrate the occasion the two brothers repaired in amity to Rouen, and there in the castle fortress, then standing on the site of the markets near the river, a banquet was held, to cement the new friendship and understanding. But suddenly Richard turned pale and sickened, and before nightfall he was dead. There was little doubt that poison had been in his cup; put there by whom but the man who was now duke, and held the power of life and death in his hands! None dare speak to accuse him, and, like many another in the Dark Ages, he reaped the full reward of his crime in perfect security. There were others of his family alive, uncles as powerful, and, had occasion arisen, doubtless as unscrupulous as himself; but Robert was on the spot, he held possession, and apparently without a word being raised in protest, he occupied his murdered brother’s place. An illegitimate son of his brother’s, named Nicholas, he placed in the abbey at Fécamp to be trained as a monk, a method often made use of by half savage kings to soften youthful rivals, still susceptible of being taught the hollowness of worldly ambition and the wickedness of rebellion against authority. It may be thought that this youth can hardly have been regarded as a serious rival, but in those days the marriage-tie was not deemed essential to inheritance. From William Longsword every Norman duke so far had been born out of wedlock, and though they had been legitimatised afterwards by some ceremony between their parents, this was rather a concession than a necessity. It is said that Nicholas entered with zest into his holy vocation, and was himself the architect of the first church of St Ouen at Rouen, of which there remains only the beautiful apse, known as the Tour aux Clercs. He was fourth abbot, and was buried in the church.

HARBOUR OF FÉCAMP

What always strikes one as remarkable in reading history, is the youth of the principal actors. Robert was but twenty-two when he murdered his brother for the ducal crown. Falaise was one of his favourite seats, the hunting was good, the country pleasant, and the security of the stronghold reassuring. Once, as he returned from hunting, he had espied a tanner’s daughter, of rare beauty, washing clothes in the little stream that runs beneath the mighty rock; when he looked out of the high narrow window the next day, he had no difficulty in recognising the same girl again; and subsequently he introduced himself to her in the guise of a lover. Tanning was looked upon by the Normans as being a very low trade indeed, and though Fulbert, the Conqueror’s grandsire, added to it the avocation of brewing, he could never shake off the odium which clung to his name on account of his principal business. The base-born brat of the tanner’s daughter would hardly be considered at first as even a pawn in the great game of statecraft. But the boy was dear to his father’s heart. His mother, Arlotta, was taken into the castle, and there was none to rival her, for Robert was not married. Yet strangely enough he did not make her his wife, and so render brighter the prospects of the sturdy boy, whom he regarded with much affection. He could not bring himself to recognise Arlotta even by the sort of ceremony his ancestors had considered sufficient; his pride was too great to give the tanner’s daughter a right to share his throne, and he preferred that his son should start more heavily weighted for the race than he need have been. When Robert made up his mind to go on a crusade to the Holy Land, the position became one of great difficulty; he was worse than childless, and men began dimly to foresee that this only son of his would prove a heavy stumbling-block in the way of any other succession. But Robert’s selfishness being immeasurably stronger than his paternal love, he departed, leaving it to be well understood that in case of accidents William was to be his heir. But there were a number of the descendants of the great Rollo still alive, strong men, soldiers, nobles with retinues of their own, and each and all put his own claim prior to that of this nameless boy. Looked at thus, it seems little short of miraculous that William should ever have raised himself to the throne at all, a more wonderful feat than even his conquest of England in later years. The boy was but eight when, after various warning rumours of failing health, the news came definitely that his father was dead. Duke Robert had left him in charge of Alain, Count of Brittany, who, though a relative, could not himself hope to ascend the throne, and the choice was wise. Alain fulfilled his trust loyally, and the exceptional talent and courage of the young duke seem from the first to have attached to him a number of nobles, so that his position gradually gained solidarity, though the marvel that he should have escaped knife or poison in an age where such means of riddance were frequently employed remains the same. Full credit for his safety at this dangerous time must be given to the nobles of the Côtentin, especially to Neel of St Sauveur, who is mentioned again in the chapter on that district. The bitterness of the stain upon his birth was early felt by William, and there are instances in his career which point to the smarting of a hidden sore shown by a man ordinarily self-possessed. His treatment of the burghers of Alençon, because they had openly taunted him with his birth, is one case in point; the other is his own unexampled domestic life, which stands out in strong contrast with those of his predecessors; he seems early to have made up his mind with iron will that what he had suffered through his father, none should suffer through him.

At thirteen he took upon himself responsibility, and really began to rule. His mother had been separated from him, and had no share in the government. She had married a knight named Herlouin, by whom she had two children, of both of whom we hear much in history. The elder, Odo, became Bishop of Bayeux. He it was who encouraged his half-brother’s troops at Hastings, going before and calling them on. As Odo’s dealings had more to do with England than Normandy, we may dispose of him here in a few words. After the Conquest, vast wealth and many estates were bestowed upon him; he was viceroy in William’s absence, and second in power to the king himself. His overweening pride made him overbearing; he aspired to sit on the papal throne. William, discovering in him many treasonable practices, kept him prisoner at Rouen. On his half-brother’s death, however, he once more became prominent, led insurrections against his nephew William the Red, and joined with Duke Robert in his fraternal wars. At last this turbulent, vigorous, astute man went crusading with Robert, and died at Palermo in 1097.

Arlotta’s other son, Robert of Mortain, was a loyal brother; he prepared a hundred and twenty ships for the great flotilla, and lived peaceably during the Conqueror’s lifetime, though he too warred against William the Red. He is mentioned again in connection with Mortain.

The generally received opinion of William the Conqueror in England is, that he was a stern and cruel man; stern he certainly was, stern with the sternness of strength which serves as a shield against familiarity, and enables its possessor to go straight on his own way, regardless of unfavourable opinions or specious arguments.

“This King William that we speak about,” says the chronicler, “was a very wise man, and very rich; more worshipful and strong than any of his foregangers were. He was mild to the good men that loved God, and beyond all metes stark to them who withstood his will. Else, he was very worshipful.” This is the testimony of one who was almost his contemporary, and who had nothing to fear from him, nor aught to gain by praising him.

The idea of William’s cruelty is based on his harrying of Northumberland, an act that could never have originated in the mind of a soft-hearted or imaginative man; but William’s bent was not toward cruelty, and considering the age in which he lived, the well-authenticated cases which we have of his clemency are remarkable. When he was only twenty, an age when if there be any hardness in a man’s nature it is at its worst, unsoftened by personal experience of sorrow, he spared the lives of those of his vassals who had risen against him not openly but with treachery. The manner of it was thus. Guy of Burgundy, William’s first cousin, entered into a conspiracy with many of the most powerful nobles of Normandy to assassinate the duke. It is easy to be seen what was Guy’s motive; though he could only claim through his mother, he meant to make himself Duke of Normandy; but it is more difficult to see what the others expected to gain by a move which proposed to substitute one duke for another. It was not the first time that rebellion and revolt against the duke had risen, but it was the most serious plot, and the turning-point of William’s career.

So secretly had the conspiracy been planned that he was all unaware of it. He was at this time in his twentieth year, and, as Wace tells us, “the barons’ feuds continued; they had no regard for him; everyone according to his means made castles and fortresses.” Up till now William had lived, but he had not been master. “Affrays and jealousies, maraudings and challengings” had continued in spite of him, but this deadly conspiracy was to bring matters to a head in a way its projectors little thought. William was in the castle of Alleaumes close to Valognes; he had retired for the night, when he was awakened by the agonised entreaties of the court fool, who told him that the nobles were even now on the point of arriving in order to seize him unprepared, and murder him. William must have had great confidence in his jester, for he rose straightway, and apparently without waiting for attendants saddled his horse, and rode off into the dark night. The whole story is mysterious; were there then no men-at-arms to guard the duke, no attendant to go with him? would it not have been safer to barricade the castle rather than to have fled alone? Whatever the cause, William’s midnight ride is a matter of history. There were no smooth, easy roads then; the country, from various accounts in charters and deeds of the tenth century, was covered with woods, and much waste ground; and, as we know, wolves abounded, for much later (1326), forty-five wolves were taken in the district of Coutances, twenty-two in that of Carentan, and nineteen in that of Valognes, in the Easter term alone. The young duke could only have had the stars to guide him, and safety was far off. He meant to get to Falaise, where he could feel tolerably secure; but even as the crow flies Falaise is over seventy miles from Valognes, and the way would be difficult to find. The account of this dramatic episode is circumstantially given by the old chronicler, who tells us that even as William left the town he heard the clatter of the enemies’ horses entering it. The enemy, finding he had fled, and knowing they had implicated themselves far too deeply to think of pardon, set off in hot pursuit, and the duke was only saved by hiding in a thicket, whence he saw them go by. He did not follow the direct route, but kept along by the sea-coast, until the next morning on a worn and jaded steed he found himself at Ryes, between Bayeux and the coast, where he revealed himself to the lord of the manor-house, a man named Hubert. Hubert promptly rehorsed him, and sent him on his way with two of his own sons as guides. Thus the duke managed to reach the stronghold of Falaise in safety.

Later on William constructed a raised road, running through the country in the direction of his flight; it ran from Valognes to Bayeux and thence to Falaise, part of it may still be seen between Quilly-le-Tessin, Caitheoux, and Fresni-le-Pucceux. It is said that it was the forced task of the very conspirators who had compelled the fight, an instance of grim justice!

The malcontents must have trembled when they knew that their powerful overlord was free, and fully aware of their guilt; there was no escape now, open revolt was their only chance, so they gathered their forces and attacked Caen.

William, for his part, collected his men, and leaving a garrison in Falaise, marched to Rouen; but too much depended on a battle, to risk it against a greatly superior and better prepared force. He resolved on a stroke of policy, no less than to call for protection from his own overlord the King of France, who had formerly been his invader and enemy. King Henry responded to the appeal, possibly feeling that Normandy might slip from him altogether, and France itself be menaced, were the handful of nobles to win power by their swords.

Then was fought, at Val-ès-dunes, about nine miles from Caen, one of the most memorable battles in the history of Normandy.

A picturesque incident marked the beginning of the battle. A splendid company of knights, carrying devices on their lances, were seen in the forefront of the nobles’ ranks, and William, advancing, cried out that they were his friends. The leader, De Gesson, was so much touched by this, that though he had banded himself with the insurgents, and taken a fearful oath to be the first to strike William in the mêlée, he satisfied his conscience by one of those transparent evasions common to superstitious ages, and considered he had redeemed his word by striking William gently on the shoulder with his gauntlet, and then immediately transferring himself and his followers to the side against which he had come out to fight.

It is said the army of the nobles numbered 20,000, but figures seen through such a distance of time have generally suffered from a little extension. The fight was fierce, and hand to hand; battle-axes and swords played greater part than arrows. It is impossible to better the picturesque account given by Wace. “There was great stir over the field, horses were to be seen curvetting, the pikes were raised, the lances brandished, and shields and helmets glistened. As they gallop they cry their various war-cries: those of France cry ‘Montjoie!’ the sound whereof is pleasant to them. William cries ‘Dex Aie!’ the swords are drawn, the lances clash. Many were the vassals to be seen there fighting, serjeants and knights overthrowing one another. The king himself was struck and beat down off his horse.”

A ROAD NEAR ROUEN

But in the end William and his ally triumphed, and the nobles fled in confusion from the field. Yet, when he seized the arch-traitor Guy of Burgundy, he treated him as we have said with extraordinary leniency, and except for taking from him the territory which had enabled him to play such a part, he suffered him to go unpunished, and even provided for him otherwise. This treatment bore fruit, for Guy became a good subject, and led troops at Hastings with distinction. The other leaders were deprived of their estates, and one was imprisoned, but none were executed, while the smaller men escaped scot-free. When the duke had come to his full stature he was a mighty man, some say seven feet in height, and unwieldy in bulk; none could wield his axe; in battle, horse and man went down before him, cloven by the strength of his mighty arm. And not alone in strength was he more than a match for his fellows, but let a man as much as whisper treason, and he heard of it; those who plotted were reached surely by that penetrating power, and lived to rue their folly. He was a kingly man, born to rule.

But though the victory at Val-ès-dunes made him duke de facto, his work was far from being done, insurrection continued in other parts of the duchy, and shortly after he was called to subdue Alençon, which held out against him. “He found the inhabitants all ready to greet him: calthrops sown, fosses deepened, walls heightened, palisades bristling all around ... to spite the Tanner’s grandson, the walls were tapestried with raw hides, the filthy gore-besmeared skins hung out, and as he drew nigh, they whacked them and they thwacked them; ‘plenty of work for the tanner,’ they sang out, shouting and hooting, mocking their enemies” (Palgrave).

Then in an ineffectual sortie some of the townsmen fell into William’s hands, and terrible was the vengeance which fell on them for their savage joke. Their eyes were spiked out, their hands and feet chopped off, and the mangled limbs were flung into the town. Soon after, no doubt awed by an anger so much fiercer than they had reckoned on, a cruelty so merciless when aroused, the people made terms, and William, victorious, once again returned to Rouen.

NEAR PONT-AUDEMER

The next rebel was William’s own uncle, of the same name as himself, his father’s half-brother. He trusted to the strength of the castle of Arques, near Dieppe, which had been given him by his nephew. But the young duke was in the heyday of his vigour. The news was brought to him at Valognes at midday one Thursday, and by Friday evening he was before the gates of Arques, having come by way of Bayeux, Caen, and Pont-Audemer. The castle was stoutly defended, and so impregnable by position, that the only method was to sit down before it and wait; a method adopted with complete success, though the arch-traitor himself managed to escape and fly. Many other smaller risings occurred which kept the great Conqueror in practice, and then came the second great battle in Normandy, that of Mortèmer, at which he was not present himself. He had shown his diplomacy in using the King of France as an ally against the men of the Côtentin, now it was the same King of France, Henry, who, being jealous of the power of this great vassal, fomented insurrection among his subjects and entered that part of the duchy known as the Vexin, in a hostile spirit. To the French, the Normans were even yet pirates, and pirates they continued to be called until the end. Wace says that the Frenchmen would call the Normans “Bigoz,” a corruption of their war-cry, “By God,” from which comes our word bigot; and they would ask the king, “Sire, why do you not chase the Bigoz out of the country? Their ancestors were robbers, who came by sea, and stole the land from our forefathers and us.”

So the French marched as far as Mortèmer, and began to pillage. But after pillage came revelry, as it so frequently does, and the Normans, who had been watchful but unseen, fell upon the French and routed them hip and thigh. With the blithe exaggeration of days before statistics were known, the old chronicler says, “nor was there a prison in all Normandy which was not full of the Frenchmen. They were to be seen fleeing around, skulking in the woods and bushes, and the dead and wounded lay amid the burning ruins, and upon the dunghills, and about the fields, and in the bye-paths.”

As we have said, at this battle William personally was not present, and the French king was not taken prisoner.

Record states that William broke into poetry, apparently the only time he was so seized: the very words of his poem are preserved; here is a verse of it:—

“Réveillez vous et vous levez Guerriers qui trop dormi avez Allez bientôt voir vos amys Que les Normands ont à mort mys Entre Ecouys et Mortèmer Là les vous convient les inhumer.”

After this, negotiations were concluded, and the French prisoners restored; nevertheless the French again soon after entered Normandy, and ravaged the country, even so far as the coast. The River Dive, lying to the east of Caen, is considered the dividing line between Upper and Lower Normandy, and it was at this river that William came up with the main body of the French, including the king himself. William’s strokes generally owed as much to their policy as their strength, and this time was no exception. He waited in ambush until half the French had crossed the stream, and then falling suddenly on the remainder, cut them off, and totally routed them. Those in advance, taken in the rear, fled in confusion, and vast quantities of spoil fell into the duke’s hands, though the French king himself escaped. After this, peace was concluded at Fécamp.

But still fighting did not cease. The Counts of Anjou had been a perpetual thorn in William’s side, and the most formidable of all was Geoffrey Martel, who seized Maine, and held it as well as his own territory; but buoyant with victory, the Norman troops advanced upon the principal city, Le Mans, and took it without difficulty, and Geoffrey Martel was quieted for a while; he died four years before the Conquest of England.

But now we must turn for a moment from William’s battles to his domestic life. His romantic marriage is an outstanding incident in his career. He did not marry until he was twenty-six, a considerable age for a king. But in that as in other matters he had a mind of his own, and one lady and one only would satisfy him, and she kept him waiting for seven years. She was his own first cousin, Matilda of Flanders, daughter of Baldwin V., Earl of Flanders, but neither she nor her relatives cared for the match. There are various tales concerning her, one of which says she was already a widow when William expressed his preference, and had two children of her own. Another story says she favoured another suitor, who, however, was perhaps well advised in declining the perilous position of husband to the lady of William’s choice, however flattering that lady’s preference for himself. After waiting with more or less patience for seven years, William took summary methods. He went to Bruges, where his ladylove lived, and meeting her as she returned from church, rolled her in the mud of the street, humiliating her in the eyes of all, and ruining her gay and beautiful clothes. This Petruchio-like method served the purpose. In a very short time Matilda consented to marry the man who had shown her his determination in so unequivocal a manner. This particular marriage seems to have been a brilliant exception in an age when marriage vows were held in scant respect. Yet, when he won Matilda’s consent, all William’s troubles, in regard to the alliance, were by no means at an end. By the tenets of the Church to which he and his bride belonged, they were within the prohibited degree of consanguinity. This difficulty was surmounted by their gaining absolution on the condition that they erected two religious houses at Caen, houses which stand to this day, and are mentioned more particularly in the chapter on that city.