автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу History of the Scottish expedition to Norway in 1612

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

Macrons over one or more characters are denoted by ̅ (utf8 hex0305); for example can̅ot and c̅o̅m̅andement.

Macrons over one or more characters are denoted in the etext by {}, since most handhelds do not handle combining diacriticals properly; for example, ca{n}ot and {com}andement.

A line of asterisks denotes omitted text. Thought breaks, and new sections, are denoted by blank lines or hr's (horizontal rules).

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources. Punctuation or lack of it in the Appendix documents has been left unchanged.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

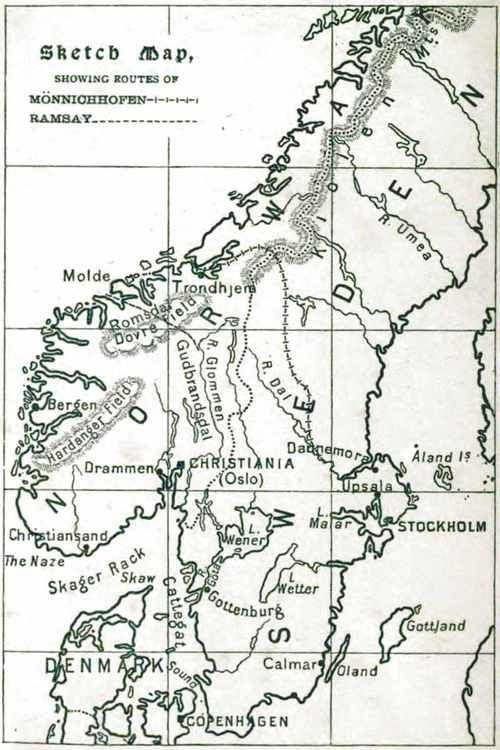

Sketch Map,

SHOWING ROUTES OF MÖNNICHHOFEN AND RAMSAY

HISTORY OF THE

Scottish Expedition

to Norway in 1612.

By

THOMAS MICHELL, C.B.,

Her Majesty's Consul General for Norway.

London:

T. NELSON AND SONS, PATERNOSTER ROW.

EDINBURGH; AND NEW YORK.

CHRISTIANIA: T. BENNETT, Tourist Agent.

1886.

Rights of Translation and Reproduction reserved for the benefit of

the Anglican Church at Christiania.

Dedicated,

BY GRACIOUS PERMISSION,

TO

His Majesty Oscar II.

KING OF SWEDEN AND NORWAY,

&c. &c. &c.

WITH THE DEEPEST GRATITUDE

AND THE MOST PROFOUND RESPECT OF

THE AUTHOR.

Preface.

The idea of investigating the story of the Scottish Expedition to Norway in 1612 occurred to the author on a trip through the beautiful valleys of Romsdal and Gudbrandsdal in the autumn of 1884—many of the statements made on that subject in guide-books, and in almost every work on Norway, having appeared incredible when he left the highway and explored the old bridle-path along which the Scots marched on their way to Sweden.

Subsequent researches in State Archives, made with the kind assistance which has been heartily acknowledged in the pages that follow, resulted in the discovery of official documents hitherto unavailable, and with their aid the traditional account of the "Skottetog" has, in its chief outlines, been reduced to strict historical proportions.

The information thus acquired was utilized by the author in a lecture delivered in 1885 at the University of Christiania, in the gracious presence of His Majesty the King of Sweden and Norway, for the benefit of the Building Fund of the Anglican Church in that city.

It is with the same practical object that, with the generous co-operation of the publishers, the lecture has been embodied in the little book now commended to the attention of those who take an interest in Scottish history, as well as to that of the British and American travellers who visit in such largely increasing numbers the beautiful and hospitable valleys and highlands of Norway, in which they find so much sympathetic evidence of a common origin of both race and language.

London, March 1886.

Contents.

PART I.—HISTORICAL.

I.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION,

11II.

THE CALMAR WAR, AND SWEDISH MEASURES FOR RAISING MERCENARIES,

18III.

SUCCESSFUL MARCH OF MÖNNICHHOFEN THROUGH NORWAY,

23IV.

ORGANIZATION OF SCOTTISH LEVIES FOR SWEDEN, AND THEIR FORCED DISBANDMENT,

32V.

ORDERS OF KING JAMES I. DISOBEYED BY A FEW SCOTTISH OFFICERS, WHO PROCEED WITH A SMALL PORTION OF THE LEVIES TO NORWAY,

42VI.

THE LANDING OF ALEXANDER RAMSAY IN ROMSDALEN,

48VII.

DESTRUCTION OF THE SCOTS IN GUDBRANDSDALEN,

52VIII.

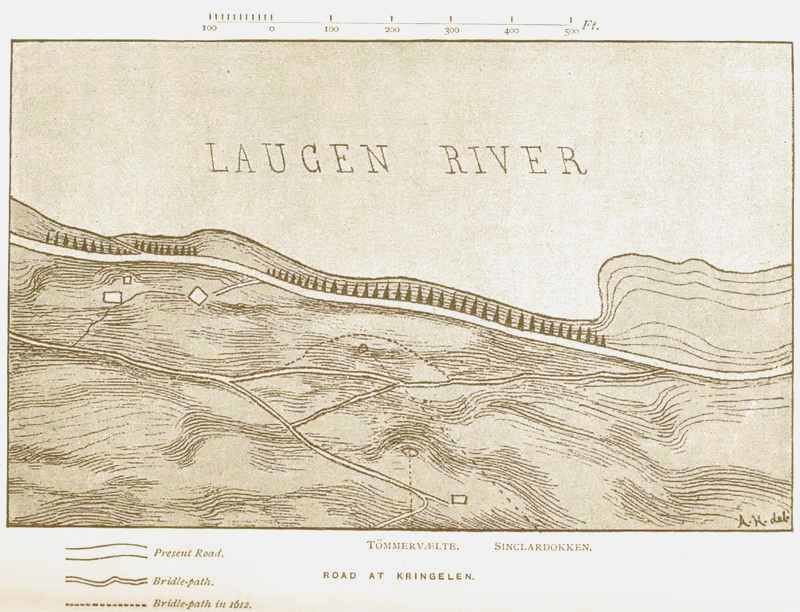

THE COMBAT AT KRINGELEN,

56———

PART II.—TRADITION.

I.

THE SINCLAIR BALLAD,

71II.

NORWEGIAN TRADITIONS COLLECTED BY THE REV. H. P. S. KRAG,

75———

PART III.—APPENDICES.

Historical Documents.

I.

EXTRACTS FROM THE "SWEDEN AND DENMARK CORRESPONDENCE, 1612," IN THE PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, LONDON,

133II.

COPIES OF DOCUMENTS FROM THE GENERAL REGISTER HOUSE, EDINBURGH,

160III.

DOCUMENTS FROM STATE ARCHIVES, STOCKHOLM,

173IV.

DOCUMENTS FROM STATE ARCHIVES, COPENHAGEN,

180———

INDEX TO NAMES OF PERSONS,

187Part I.

Historical.

I.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION.

More than two centuries and a half have elapsed since the date of the occurrence so well known in Norway as the "Skottetog," or Scottish expedition, of which but little has hitherto been authentically known in Scotland. Notwithstanding, therefore, the conspicuous position which the so-called "Sinclair Expedition" holds in the traditions,[1] and to some extent also in the literature and the art,[2] of Norway, a fresh examination of the subject by the impartial light of historical truth is justified by the recent discovery of several documents in the State Archives of England, Scotland, and Sweden.

Although Mönnichhofen's expedition through Stordalen, and the Scottish invasion of Romsdalen and Gudbrandsdalen which formed an integral but unsuccessful part of that expedition, took place in 1612, no account of the latter appeared in print earlier than the year 1688, when Puffendorff wrote his "Introduction to Swedish History;" and it was only three years later that Widikindi, another Swedish historian, gave a narrative of it in a History of Gustavus Adolphus.

Among Danish historians, Niels Slange was the first of any eminence to reproduce the now palpable errors of Puffendorff and Widikindi, in a History of Christian IV., written in 1732.

In 1782, the subject of the Skottetog first became popularized in Norway by the publication, in a periodical journal called the Dansk Museum, of the spirit-stirring poem by Edvard Storm, which Norwegian children still learn by heart and in song, and which has even been well circulated in the English and German languages.[3]

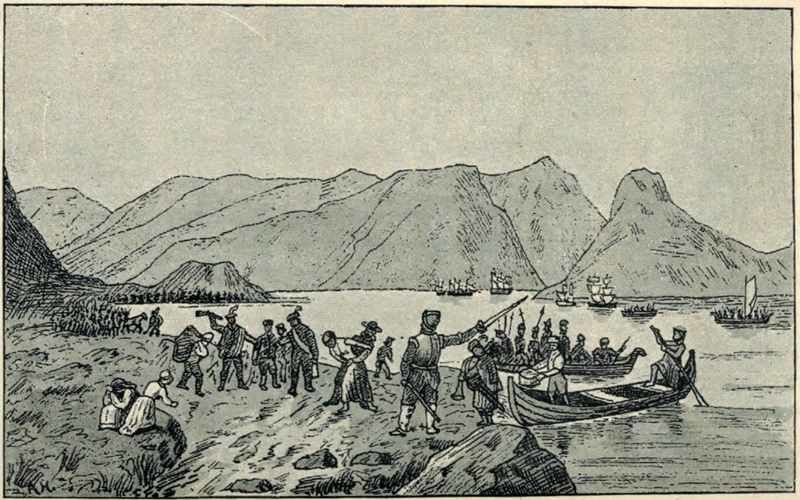

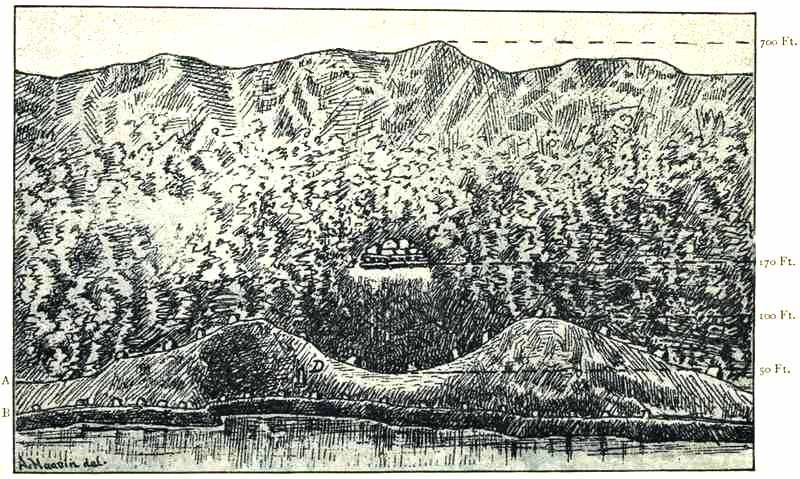

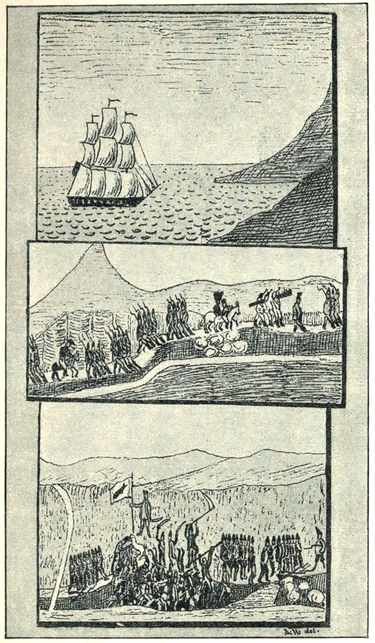

THE LANDING OF THE SCOTS IN ROMSDALEN, 1612.

Page 11. As depicted by the Norwegian artists Tiedemann and Gude.

But the first really important contribution towards the history of the event was made in 1838, when Dean Krag of Vaage dedicated to the descendants of the Bönder[4] who had fought at Kringelen the Sagas, or traditions, he had personally collected in Gudbrandsdalen, annotated with such historical references as were then available.[5]

While the traditions he has so scrupulously preserved for us are of great interest, if only because they indicate plainly the source of the information on which Swedish, Danish, and even Scottish accounts of the expedition into Romsdalen had been chiefly based, he enriched history with copies of the first and only documents that had apparently ever been drawn before his time, from State or other archives, relative to the Scots who landed in Romsdalen. Those documents were: a Report by the Norwegian Stadtholder, Envold Kruse, to the Danish Chancellor, dated Aggershuus, 17th September 1612; and three deeds of gift of land (all dated 3rd September 1613) to Lars Hage, Peder Randklev, and Berdon Sejelstad, for their bravery and loyal devotion on that occasion.

In that laborious little work Dean Krag pointed out that, with the exception of Kruse's first Report (of which he had obtained a copy from Copenhagen), all the writers after Puffendorff (1688) and Widikindi (1691) had repeated, more or less, only what those two historians had related. He also showed that Storm's poem had been preceded by a popular ballad on the same subject, and of which he collected and printed as much as was still extant in Gudbrandsdalen.

More recent historical research resulted in the discovery, also at Copenhagen, of a second Report from Envold Kruse, the Stadtholder, dated 3rd October 1612. It was first published between 1858 and 1860,[6] and was reproduced in a little work printed at Molde in 1877.[7]

The history of the Scottish expedition to Norway in 1612 has, therefore, until this day been supported in Scandinavian accounts by only two documents of indisputable authority—namely, the two Reports of Envold Kruse, of which the second was brought to light less than twenty years ago.

Nor have Scottish and English historians[8] and writers, so deeply interested in the question, been more successful in discovering and making use of authentic contemporary documents. A careful examination of their several descriptions, both of Mönnichhofen's expedition and of that of the Scots, reveals the fact that their information had been derived either from the old Danish and Swedish historians already mentioned, or more recently from the traditions current in Gudbrandsdalen. Those accounts may consequently be dismissed as unworthy of serious attention.

But the Public Record Office in London has at last delivered up its long-hidden treasures, consisting of the correspondence that passed between King James I. of England (VI. of Scotland) and Sir Robert Anstruther, his ambassador or envoy at Copenhagen, on the subject of the Scottish levies for Sweden in 1612.[9] In the General Register House, Edinburgh, have also been preserved[10] the acts and proclamations of the Scottish Privy Council in respect of those proceedings; while the keeper of the State Archives in Stockholm has supplied copies of several documents[11] that have not hitherto been published, amongst which must be mentioned a letter or commission issued by Gustavus Adolphus II.[12] to Sir James Spens of Wormiston, a Scottish officer of high rank, found sometimes in the service of James I., sometimes in that of Sweden.

That commission is of more especial value, since it explains the connection between the expedition of Mönnichhofen and that of the Scots.

The former enterprise—an important part of the famed Skottetog—is not the subject of any Norwegian Sagas, or of any popular ballads, but Scandinavian historians have dealt with it somewhat more correctly than with the Scottish expedition, probably because the Dutch contingent reached Sweden, and thereby supplied living testimony as to the circumstances that attended its march through Stordalen into Jemtland.

Nevertheless, the first documents relating to that daring exploit were not published before 1858, in a Norwegian historical magazine. These were copies of letters from Steen Bilde, amtmand, or prefect; Christian Jensson Jude, burgomaster; and Jacob Pederson, lagmand,[13] all of Trondhjem—addressed to the Danish Chancellor, and dated severally between the 15th August 1612 and the 19th February 1613.

Some years later—namely, in 1877—Dr. Yngvar Nielsen of Christiania published[14] "Some Notices respecting Johan von Mönnichhofen," derived from a series of letters from Swedish agents at Amsterdam which he found in the State Archives at Stockholm.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] For Norwegian traditions and literature, see Part II.

[2] Two of the most celebrated artists of Norway—Gude and Tiedemann—have jointly produced a very beautiful, but fanciful, picture representing the arrival of "Colonel Sinclair" on the coast of Romsdalen with five or six vessels, and the plundering of the inhabitants by his followers, one of whom, in the garb of a Calvinistic priest, is engaged in abducting a fair Norwegian maiden, while the rest are engaged in looting.

[3] A translation of it is given in Part II.

[4] The Norwegian term for peasant proprietors or yeomen; sing. Bonde.

[5] A translation in extenso is given of this work in Part II.

[6] Vol. II. of "Samlinger til det Norske Folks Sprog og Historie."

[7] "Skottetoget efter Folkesagnet og Historien." O. O. Olafsen, Molde, 1877.

[8] See Sir Robert Gordon's "History of the Earldom of Sutherland;" the "History of Caithness," by J. T. Calder; Chambers's "Domestic Annals of Scotland;" the "History of Gustavus Adolphus," by B. Chapman; "Memoirs and Adventures of Sir John Hepburn, Kt.;" Laing's "Residence in Norway;" Clarke's "Travels."

[9] Examined and kindly copied by the late Mr. Alfred Kingston of the Public Record Office, London.

[10] Communicated by Mr. T. Dickson, Curator of the Historical Department, Register House, Edinburgh, to whom the author is indebted for much valuable assistance.

[11] Search was made for those documents by the orders of the King of Sweden and Norway. In this respect the thanks of the author are due to Mr. C. G. Malmström, Keeper of the State Archives at Stockholm, and to Mr. C. H. de Lagerheim and Mr. M. de Björnstjerna of the Swedish Foreign Office, for their researches and friendly co-operation. His acknowledgments are also due to Joseph Anderson, LL.D., Keeper of the National Museum, Edinburgh.

[12] November 16, 1611, for the levying of auxiliary troops in Scotland. For copy, see p. 173.

[13] A judicial officer attached to a tribunal as a kind of witness of its proceedings.

[14] Vol. XIV. of the Historisk Tidskrift, or Historical Magazine. Dr. Nielsen's aid and advice have been invaluable to the author.

I.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION.

II.

THE CALMAR WAR, AND SWEDISH MEASURES FOR RAISING MERCENARIES.

III.

SUCCESSFUL MARCH OF MÖNNICHHOFEN THROUGH NORWAY.

IV.

ORGANIZATION OF SCOTTISH LEVIES FOR SWEDEN, AND THEIR FORCED DISBANDMENT.

V.

ORDERS OF KING JAMES I. DISOBEYED BY A FEW SCOTTISH OFFICERS, WHO PROCEED WITH A SMALL PORTION OF THE LEVIES TO NORWAY.

VI.

THE LANDING OF ALEXANDER RAMSAY IN ROMSDALEN.

VII.

DESTRUCTION OF THE SCOTS IN GUDBRANDSDALEN.

VIII.

I.

THE SINCLAIR BALLAD.[60]

II.

NORWEGIAN TRADITIONS COLLECTED BY THE REV. H. P. S. KRAG.[61]

I.

EXTRACTS FROM THE "SWEDEN AND DENMARK CORRESPONDENCE, 1612,"[136] IN THE PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, LONDON.

II.

COPIES OF DOCUMENTS[143] FROM THE GENERAL REGISTER HOUSE, EDINBURGH.

III.

DOCUMENTS[144] FROM STATE ARCHIVES, STOCKHOLM.

IV.

DOCUMENTS[148] FROM STATE ARCHIVES, COPENHAGEN.

Index to Names of Persons.

[1] For Norwegian traditions and literature, see Part II.

[2] Two of the most celebrated artists of Norway—Gude and Tiedemann—have jointly produced a very beautiful, but fanciful, picture representing the arrival of "Colonel Sinclair" on the coast of Romsdalen with five or six vessels, and the plundering of the inhabitants by his followers, one of whom, in the garb of a Calvinistic priest, is engaged in abducting a fair Norwegian maiden, while the rest are engaged in looting.

[3] A translation of it is given in Part II.

[4] The Norwegian term for peasant proprietors or yeomen; sing. Bonde.

[5] A translation in extenso is given of this work in Part II.

[6] Vol. II. of "Samlinger til det Norske Folks Sprog og Historie."

[7] "Skottetoget efter Folkesagnet og Historien." O. O. Olafsen, Molde, 1877.

[8] See Sir Robert Gordon's "History of the Earldom of Sutherland;" the "History of Caithness," by J. T. Calder; Chambers's "Domestic Annals of Scotland;" the "History of Gustavus Adolphus," by B. Chapman; "Memoirs and Adventures of Sir John Hepburn, Kt.;" Laing's "Residence in Norway;" Clarke's "Travels."

[9] Examined and kindly copied by the late Mr. Alfred Kingston of the Public Record Office, London.

[10] Communicated by Mr. T. Dickson, Curator of the Historical Department, Register House, Edinburgh, to whom the author is indebted for much valuable assistance.

[11] Search was made for those documents by the orders of the King of Sweden and Norway. In this respect the thanks of the author are due to Mr. C. G. Malmström, Keeper of the State Archives at Stockholm, and to Mr. C. H. de Lagerheim and Mr. M. de Björnstjerna of the Swedish Foreign Office, for their researches and friendly co-operation. His acknowledgments are also due to Joseph Anderson, LL.D., Keeper of the National Museum, Edinburgh.

[12] November 16, 1611, for the levying of auxiliary troops in Scotland. For copy, see p. 173.

[13] A judicial officer attached to a tribunal as a kind of witness of its proceedings.

[14] Vol. XIV. of the Historisk Tidskrift, or Historical Magazine. Dr. Nielsen's aid and advice have been invaluable to the author.

More than two centuries and a half have elapsed since the date of the occurrence so well known in Norway as the "Skottetog," or Scottish expedition, of which but little has hitherto been authentically known in Scotland. Notwithstanding, therefore, the conspicuous position which the so-called "Sinclair Expedition" holds in the traditions,[1] and to some extent also in the literature and the art,[2] of Norway, a fresh examination of the subject by the impartial light of historical truth is justified by the recent discovery of several documents in the State Archives of England, Scotland, and Sweden.

More than two centuries and a half have elapsed since the date of the occurrence so well known in Norway as the "Skottetog," or Scottish expedition, of which but little has hitherto been authentically known in Scotland. Notwithstanding, therefore, the conspicuous position which the so-called "Sinclair Expedition" holds in the traditions,[1] and to some extent also in the literature and the art,[2] of Norway, a fresh examination of the subject by the impartial light of historical truth is justified by the recent discovery of several documents in the State Archives of England, Scotland, and Sweden.

In 1782, the subject of the Skottetog first became popularized in Norway by the publication, in a periodical journal called the Dansk Museum, of the spirit-stirring poem by Edvard Storm, which Norwegian children still learn by heart and in song, and which has even been well circulated in the English and German languages.[3]

But the first really important contribution towards the history of the event was made in 1838, when Dean Krag of Vaage dedicated to the descendants of the Bönder[4] who had fought at Kringelen the Sagas, or traditions, he had personally collected in Gudbrandsdalen, annotated with such historical references as were then available.[5]

But the first really important contribution towards the history of the event was made in 1838, when Dean Krag of Vaage dedicated to the descendants of the Bönder[4] who had fought at Kringelen the Sagas, or traditions, he had personally collected in Gudbrandsdalen, annotated with such historical references as were then available.[5]

More recent historical research resulted in the discovery, also at Copenhagen, of a second Report from Envold Kruse, the Stadtholder, dated 3rd October 1612. It was first published between 1858 and 1860,[6] and was reproduced in a little work printed at Molde in 1877.[7]

More recent historical research resulted in the discovery, also at Copenhagen, of a second Report from Envold Kruse, the Stadtholder, dated 3rd October 1612. It was first published between 1858 and 1860,[6] and was reproduced in a little work printed at Molde in 1877.[7]

Nor have Scottish and English historians[8] and writers, so deeply interested in the question, been more successful in discovering and making use of authentic contemporary documents. A careful examination of their several descriptions, both of Mönnichhofen's expedition and of that of the Scots, reveals the fact that their information had been derived either from the old Danish and Swedish historians already mentioned, or more recently from the traditions current in Gudbrandsdalen. Those accounts may consequently be dismissed as unworthy of serious attention.

But the Public Record Office in London has at last delivered up its long-hidden treasures, consisting of the correspondence that passed between King James I. of England (VI. of Scotland) and Sir Robert Anstruther, his ambassador or envoy at Copenhagen, on the subject of the Scottish levies for Sweden in 1612.[9] In the General Register House, Edinburgh, have also been preserved[10] the acts and proclamations of the Scottish Privy Council in respect of those proceedings; while the keeper of the State Archives in Stockholm has supplied copies of several documents[11] that have not hitherto been published, amongst which must be mentioned a letter or commission issued by Gustavus Adolphus II.[12] to Sir James Spens of Wormiston, a Scottish officer of high rank, found sometimes in the service of James I., sometimes in that of Sweden.

But the Public Record Office in London has at last delivered up its long-hidden treasures, consisting of the correspondence that passed between King James I. of England (VI. of Scotland) and Sir Robert Anstruther, his ambassador or envoy at Copenhagen, on the subject of the Scottish levies for Sweden in 1612.[9] In the General Register House, Edinburgh, have also been preserved[10] the acts and proclamations of the Scottish Privy Council in respect of those proceedings; while the keeper of the State Archives in Stockholm has supplied copies of several documents[11] that have not hitherto been published, amongst which must be mentioned a letter or commission issued by Gustavus Adolphus II.[12] to Sir James Spens of Wormiston, a Scottish officer of high rank, found sometimes in the service of James I., sometimes in that of Sweden.

But the Public Record Office in London has at last delivered up its long-hidden treasures, consisting of the correspondence that passed between King James I. of England (VI. of Scotland) and Sir Robert Anstruther, his ambassador or envoy at Copenhagen, on the subject of the Scottish levies for Sweden in 1612.[9] In the General Register House, Edinburgh, have also been preserved[10] the acts and proclamations of the Scottish Privy Council in respect of those proceedings; while the keeper of the State Archives in Stockholm has supplied copies of several documents[11] that have not hitherto been published, amongst which must be mentioned a letter or commission issued by Gustavus Adolphus II.[12] to Sir James Spens of Wormiston, a Scottish officer of high rank, found sometimes in the service of James I., sometimes in that of Sweden.

But the Public Record Office in London has at last delivered up its long-hidden treasures, consisting of the correspondence that passed between King James I. of England (VI. of Scotland) and Sir Robert Anstruther, his ambassador or envoy at Copenhagen, on the subject of the Scottish levies for Sweden in 1612.[9] In the General Register House, Edinburgh, have also been preserved[10] the acts and proclamations of the Scottish Privy Council in respect of those proceedings; while the keeper of the State Archives in Stockholm has supplied copies of several documents[11] that have not hitherto been published, amongst which must be mentioned a letter or commission issued by Gustavus Adolphus II.[12] to Sir James Spens of Wormiston, a Scottish officer of high rank, found sometimes in the service of James I., sometimes in that of Sweden.

Nevertheless, the first documents relating to that daring exploit were not published before 1858, in a Norwegian historical magazine. These were copies of letters from Steen Bilde, amtmand, or prefect; Christian Jensson Jude, burgomaster; and Jacob Pederson, lagmand,[13] all of Trondhjem—addressed to the Danish Chancellor, and dated severally between the 15th August 1612 and the 19th February 1613.

Some years later—namely, in 1877—Dr. Yngvar Nielsen of Christiania published[14] "Some Notices respecting Johan von Mönnichhofen," derived from a series of letters from Swedish agents at Amsterdam which he found in the State Archives at Stockholm.

II.

THE CALMAR WAR, AND SWEDISH MEASURES FOR RAISING MERCENARIES.

Such being the documents and the information at last available in the matter of the Mönnichhofen and Scottish expeditions of 1612, it is time to narrate briefly why auxiliary troops were at that time wanted in Sweden.

When Gustavus Adolphus, on the 26th December 1611, took into his own hands, at the age of seventeen, the government of Sweden, his first step was to seek the conclusion of peace with Denmark; and with that object he formally surrendered the title of King of the Lapps, the assumption of which by his father had caused so much ill blood between Christian IV. and Charles IX. that it became one of the principal causes of the so-called Calmar War, commenced in the spring of 1611.

The overtures of Sweden and the offered mediation of Great Britain and other powers were rejected by Denmark, and the war was thereupon continued with great vigour, but with varying success on either side. However, in the early summer of 1612 the Danes took the important fortresses of Elfsborg and Gullberg, and having the entire command of the Cattegat and the Belts, cut off Sweden from the sea. Later, the Danish fleet anchored inside the rocks at Stockholm, of which the seizure was averted only by the bold strategy of Gustavus Adolphus.

This abortive attempt on the capital of Sweden practically concluded the war. Peace was ultimately signed at Knäröd, in Halland, January 18, 1613.[15]

During that war the Danish monarch had in his service about eighteen thousand English,[16] French, and German mercenaries; while Gustavus Adolphus, having on his side[17] only one foreign regiment of eight or nine companies, soon found himself "in need of foreign soldiers as well, wherewith to check the attacks of the enemy."[18] Charles IX. had indeed foreseen such a necessity, but no action was apparently taken in that direction until the month of November 1611, when Gustavus Adolphus addressed to Sir James Spens the letter or commission already mentioned, and when also the Queen Dowager of Sweden issued an order[19] for the payment of 10,500 rigsdaller out of a fund at Lübeck to Mönnichhofen, then preparing to proceed to the Netherlands for the enlistment of men, who, according to the letter addressed to Sir James Spens, were to have joined the Scottish auxiliary contingent at Elfsborg. On the 2nd December 1611 Mönnichhofen[20] was appointed commander-in-chief of the Swedish ships-of-war with which he was to have sailed from Elfsborg and brought back his levies. Money being apparently scarce, orders were given that he should be supplied with a certain quantity of ox-hides, for sale on his arrival in Holland, to meet the further expenses of his expedition. But the original plan of fetching and transporting the Netherlands levies in Swedish ships-of-war was ultimately abandoned, and Mönnichhofen reached Holland by another route.

The letters discovered at Stockholm by Dr. Yngvar Nielsen prove that Mönnichhofen had by the 1st June 1612 embarked a force of about twelve hundred men at Amsterdam on board four ships, which were detained for five weeks by contrary winds. Mönnichhofen had, therefore, the Swedish agent writes, incurred "extraordinary expenses, to the extent of at least four thousand thalers, in providing the men in the small ships with food and drink, and had consequently to pledge and mortgage all he possessed." He had "also encountered much difficulty and incurred great expense in keeping his men together even before the ships lay wind-bound."

Although in most Danish and Swedish histories the troops enlisted by Mönnichhofen in Holland are stated to have been Scottish, there is no documentary proof of such having been their nationality. The Netherlands were at the time full of foreign auxiliary troops, the republic having, on the signature of the truce of 17th June 1609, retained in its service 6,000 French, 3,000 English, and 3,000 Germans, but only 2,000 Scots. The absence of all mention of Scottish officers being with Mönnichhofen; the rivalry that existed between the military adventurers of that period; the circumstance that General Halkett,[21] a Scottish officer, was in Amsterdam at about the same period, engaged, not in enlisting Scots, but in hiring a ship to transport levies from Scotland; and more especially the fact that Mönnichhofen had been instructed to procure arms for the men simultaneously levied in Scotland;—all this leads us to infer that Mönnichhofen, himself a Fleming, enlisted Hollanders, and perhaps Germans.

FOOTNOTES:

[15] In that treaty of peace, King James I. of England, whose ambassador had assisted at its negotiation, was described as "a friendly broker and negotiator"—a phrase which, slightly varied, Prince Bismarck applied to himself at the late Congress of Berlin. King James I. is mentioned as "the general peace-broker of Europe." (Jahn's "History of the Calmar War.") The king himself aspired to be called "Rex Pacificus."

[16] "His M. doth holde that their are not a thousand strong fighting men of Inglysh soiours heere; and doeth wonder of my Lord Willowbeis staying."—Sir R. Anstruther to King James I., from the "Camp at Golberg," July 5, 1612.

[17] The alien officers were General Rutherford and Lieutenant Learmonth, Captain Wauchope, and Greig, who commanded the artillery—all Scotsmen; also General Due, Caspar Matzen, and Mönnichhofen. (Deposition of Andrew Ramsay and Robert Douglas, Copenhagen, December 19, 1611.) In 1613 Mönnichhofen and Rutherford were employed with Swedish troops in Russia. (Cronholm's "History of Sweden.")

[18] Gustavus Adolphus to Sir James Spens, November 16, 1611.

[19] November 26, 1611.

[20] Johann von Mönnichhofen was an officer of high rank in the Swedish service. In the documents preserved in the Swedish State Archives he is indifferently styled "Quartermaster-General and Chief" and "Chief Quartermaster." Together with the other foreign officers in the pay of Sweden, he was at the siege of Calmar, at which they were all, with the solitary exception of himself, wounded. A Scottish officer deponed at Copenhagen that Mönnichhofen had alone escaped on that occasion "because he surpassed the others in prudence, and knew how to fight from a distance." This disparaging observation may be due to jealousy on the part of his Scottish brethren in arms, for he certainly showed great daring in planning and executing successfully his march through Norway.

[21] Called in some documents "Colonel" and "Lieut.-Colonel."

[15] In that treaty of peace, King James I. of England, whose ambassador had assisted at its negotiation, was described as "a friendly broker and negotiator"—a phrase which, slightly varied, Prince Bismarck applied to himself at the late Congress of Berlin. King James I. is mentioned as "the general peace-broker of Europe." (Jahn's "History of the Calmar War.") The king himself aspired to be called "Rex Pacificus."

[16] "His M. doth holde that their are not a thousand strong fighting men of Inglysh soiours heere; and doeth wonder of my Lord Willowbeis staying."—Sir R. Anstruther to King James I., from the "Camp at Golberg," July 5, 1612.

[17] The alien officers were General Rutherford and Lieutenant Learmonth, Captain Wauchope, and Greig, who commanded the artillery—all Scotsmen; also General Due, Caspar Matzen, and Mönnichhofen. (Deposition of Andrew Ramsay and Robert Douglas, Copenhagen, December 19, 1611.) In 1613 Mönnichhofen and Rutherford were employed with Swedish troops in Russia. (Cronholm's "History of Sweden.")

[18] Gustavus Adolphus to Sir James Spens, November 16, 1611.

[19] November 26, 1611.

[20] Johann von Mönnichhofen was an officer of high rank in the Swedish service. In the documents preserved in the Swedish State Archives he is indifferently styled "Quartermaster-General and Chief" and "Chief Quartermaster." Together with the other foreign officers in the pay of Sweden, he was at the siege of Calmar, at which they were all, with the solitary exception of himself, wounded. A Scottish officer deponed at Copenhagen that Mönnichhofen had alone escaped on that occasion "because he surpassed the others in prudence, and knew how to fight from a distance." This disparaging observation may be due to jealousy on the part of his Scottish brethren in arms, for he certainly showed great daring in planning and executing successfully his march through Norway.

[21] Called in some documents "Colonel" and "Lieut.-Colonel."

This abortive attempt on the capital of Sweden practically concluded the war. Peace was ultimately signed at Knäröd, in Halland, January 18, 1613.[15]

During that war the Danish monarch had in his service about eighteen thousand English,[16] French, and German mercenaries; while Gustavus Adolphus, having on his side[17] only one foreign regiment of eight or nine companies, soon found himself "in need of foreign soldiers as well, wherewith to check the attacks of the enemy."[18] Charles IX. had indeed foreseen such a necessity, but no action was apparently taken in that direction until the month of November 1611, when Gustavus Adolphus addressed to Sir James Spens the letter or commission already mentioned, and when also the Queen Dowager of Sweden issued an order[19] for the payment of 10,500 rigsdaller out of a fund at Lübeck to Mönnichhofen, then preparing to proceed to the Netherlands for the enlistment of men, who, according to the letter addressed to Sir James Spens, were to have joined the Scottish auxiliary contingent at Elfsborg. On the 2nd December 1611 Mönnichhofen[20] was appointed commander-in-chief of the Swedish ships-of-war with which he was to have sailed from Elfsborg and brought back his levies. Money being apparently scarce, orders were given that he should be supplied with a certain quantity of ox-hides, for sale on his arrival in Holland, to meet the further expenses of his expedition. But the original plan of fetching and transporting the Netherlands levies in Swedish ships-of-war was ultimately abandoned, and Mönnichhofen reached Holland by another route.

During that war the Danish monarch had in his service about eighteen thousand English,[16] French, and German mercenaries; while Gustavus Adolphus, having on his side[17] only one foreign regiment of eight or nine companies, soon found himself "in need of foreign soldiers as well, wherewith to check the attacks of the enemy."[18] Charles IX. had indeed foreseen such a necessity, but no action was apparently taken in that direction until the month of November 1611, when Gustavus Adolphus addressed to Sir James Spens the letter or commission already mentioned, and when also the Queen Dowager of Sweden issued an order[19] for the payment of 10,500 rigsdaller out of a fund at Lübeck to Mönnichhofen, then preparing to proceed to the Netherlands for the enlistment of men, who, according to the letter addressed to Sir James Spens, were to have joined the Scottish auxiliary contingent at Elfsborg. On the 2nd December 1611 Mönnichhofen[20] was appointed commander-in-chief of the Swedish ships-of-war with which he was to have sailed from Elfsborg and brought back his levies. Money being apparently scarce, orders were given that he should be supplied with a certain quantity of ox-hides, for sale on his arrival in Holland, to meet the further expenses of his expedition. But the original plan of fetching and transporting the Netherlands levies in Swedish ships-of-war was ultimately abandoned, and Mönnichhofen reached Holland by another route.

During that war the Danish monarch had in his service about eighteen thousand English,[16] French, and German mercenaries; while Gustavus Adolphus, having on his side[17] only one foreign regiment of eight or nine companies, soon found himself "in need of foreign soldiers as well, wherewith to check the attacks of the enemy."[18] Charles IX. had indeed foreseen such a necessity, but no action was apparently taken in that direction until the month of November 1611, when Gustavus Adolphus addressed to Sir James Spens the letter or commission already mentioned, and when also the Queen Dowager of Sweden issued an order[19] for the payment of 10,500 rigsdaller out of a fund at Lübeck to Mönnichhofen, then preparing to proceed to the Netherlands for the enlistment of men, who, according to the letter addressed to Sir James Spens, were to have joined the Scottish auxiliary contingent at Elfsborg. On the 2nd December 1611 Mönnichhofen[20] was appointed commander-in-chief of the Swedish ships-of-war with which he was to have sailed from Elfsborg and brought back his levies. Money being apparently scarce, orders were given that he should be supplied with a certain quantity of ox-hides, for sale on his arrival in Holland, to meet the further expenses of his expedition. But the original plan of fetching and transporting the Netherlands levies in Swedish ships-of-war was ultimately abandoned, and Mönnichhofen reached Holland by another route.

During that war the Danish monarch had in his service about eighteen thousand English,[16] French, and German mercenaries; while Gustavus Adolphus, having on his side[17] only one foreign regiment of eight or nine companies, soon found himself "in need of foreign soldiers as well, wherewith to check the attacks of the enemy."[18] Charles IX. had indeed foreseen such a necessity, but no action was apparently taken in that direction until the month of November 1611, when Gustavus Adolphus addressed to Sir James Spens the letter or commission already mentioned, and when also the Queen Dowager of Sweden issued an order[19] for the payment of 10,500 rigsdaller out of a fund at Lübeck to Mönnichhofen, then preparing to proceed to the Netherlands for the enlistment of men, who, according to the letter addressed to Sir James Spens, were to have joined the Scottish auxiliary contingent at Elfsborg. On the 2nd December 1611 Mönnichhofen[20] was appointed commander-in-chief of the Swedish ships-of-war with which he was to have sailed from Elfsborg and brought back his levies. Money being apparently scarce, orders were given that he should be supplied with a certain quantity of ox-hides, for sale on his arrival in Holland, to meet the further expenses of his expedition. But the original plan of fetching and transporting the Netherlands levies in Swedish ships-of-war was ultimately abandoned, and Mönnichhofen reached Holland by another route.

During that war the Danish monarch had in his service about eighteen thousand English,[16] French, and German mercenaries; while Gustavus Adolphus, having on his side[17] only one foreign regiment of eight or nine companies, soon found himself "in need of foreign soldiers as well, wherewith to check the attacks of the enemy."[18] Charles IX. had indeed foreseen such a necessity, but no action was apparently taken in that direction until the month of November 1611, when Gustavus Adolphus addressed to Sir James Spens the letter or commission already mentioned, and when also the Queen Dowager of Sweden issued an order[19] for the payment of 10,500 rigsdaller out of a fund at Lübeck to Mönnichhofen, then preparing to proceed to the Netherlands for the enlistment of men, who, according to the letter addressed to Sir James Spens, were to have joined the Scottish auxiliary contingent at Elfsborg. On the 2nd December 1611 Mönnichhofen[20] was appointed commander-in-chief of the Swedish ships-of-war with which he was to have sailed from Elfsborg and brought back his levies. Money being apparently scarce, orders were given that he should be supplied with a certain quantity of ox-hides, for sale on his arrival in Holland, to meet the further expenses of his expedition. But the original plan of fetching and transporting the Netherlands levies in Swedish ships-of-war was ultimately abandoned, and Mönnichhofen reached Holland by another route.

Although in most Danish and Swedish histories the troops enlisted by Mönnichhofen in Holland are stated to have been Scottish, there is no documentary proof of such having been their nationality. The Netherlands were at the time full of foreign auxiliary troops, the republic having, on the signature of the truce of 17th June 1609, retained in its service 6,000 French, 3,000 English, and 3,000 Germans, but only 2,000 Scots. The absence of all mention of Scottish officers being with Mönnichhofen; the rivalry that existed between the military adventurers of that period; the circumstance that General Halkett,[21] a Scottish officer, was in Amsterdam at about the same period, engaged, not in enlisting Scots, but in hiring a ship to transport levies from Scotland; and more especially the fact that Mönnichhofen had been instructed to procure arms for the men simultaneously levied in Scotland;—all this leads us to infer that Mönnichhofen, himself a Fleming, enlisted Hollanders, and perhaps Germans.

III.

SUCCESSFUL MARCH OF MÖNNICHHOFEN THROUGH NORWAY.

According to the Report of the same Swedish agent, Mönnichhofen sailed at last on the 14th July from Amsterdam,[22] and landed five days later in Stordalen, on the coast of Norway—at that time united with the Crown of Denmark—without combining, as originally intended, with the levies made in Scotland, although measures for their detention were taken only on the 4th August following.

The ships (evidently Dutch) which had transported his troops to Norway returned safely to Amsterdam with the information that Mönnichhofen had disembarked "three or four miles above Trondhjem, in Moersdall," and that his men had landed in such an ill-conditioned state that they "could not reach Sweden without great difficulty and danger."

When read in connection with the Reports of the Swedish agents at Amsterdam, first discovered and made known by Dr. Yngvar Nielsen in 1877, the letters of Steen Bilde, C. J. Jude, and J. Pederson[23] afford a credible and fairly complete account of that expedition. Those collective documents show that it was not composed, as alleged by Niels Slange, of "about fourteen hundred soldiers, or Scots," enlisted in Scotland, but nominally of twelve hundred men raised in the Netherlands under the circumstances already described.

The burgomaster of Trondhjem (who, like Bilde and the other Danish officials, was interested in over-rating rather than in under-rating the strength of the invaders,) reported, on 15th August 1612, that the expedition consisted of "eight hundred soldiers, besides their women and boys;" and according to Cronholm,[24] Gustavus Adolphus himself wrote that the number of those men, when they arrived in Jemtland, out of all further danger, amounted to eight hundred.[25] The four small Dutch ships could scarcely have carried more, especially if the men were accompanied by their women and children, as alleged by the burgomaster.

The Swedish and Danish historians relate that Mönnichhofen took his men to Scotland, and sailed from thence, in command of a combined force, for the coast of Norway; but all these statements only serve to prove yet more conclusively that the true history of the foreign levies made for Sweden in 1612 has until quite recently lain hidden in State Archives.

Mönnichhofen sailed from Amsterdam on the 14th July 1612, and having landed in Norway on the 19th July, could not possibly have carried out the original plan of joining his levies with those made in Scotland. Besides, the documents now brought to light prove that the small portion of the intended Scottish contingent that escaped the vigilance of the Scottish Council of State did not sail for Norway until the 2nd of August.

According to the Reports of the Trondhjem officials above mentioned, Mönnichhofen seized two other ships off Giske (which place he plundered), put some of his soldiers on board, and compelled the Norwegian vessels to pilot his own fleet of four ships into Trondhjem roads. In order to prevent the enemy from entering the river, Steen Bilde removed the poles and buoys that marked the channel, brought six iron cannon down to the sea-shore, and hastily made many other arrangements for repelling an anticipated attack on the city. As it grew dark soon after the ships had anchored, the fire opened upon them from the shore was harmless; and at daybreak they set sail again, after firing a few shots in return.

The wind being favourable, they soon rounded a point on which stood a farm called Viig, where the soldiers were quickly disembarked and marched towards Meragerfjeld, four or five Norwegian (twenty-eight to thirty-five English) miles distant.

They reached the summit of the fjeld without much molestation from the three military officers in command of the "frontier guard" of about two hundred soldiers or militia, reinforced by three hundred mounted Bönder. Steen Bilde and the three officers had collected a considerable number of peasants (the burgomaster says fifteen hundred) to repel the invasion; but according to the prefect, when a part of those levies reached the enemy, the captain of the frontier guard "could not get them forward where they were wanted." The enemy kept them off with their muskets, which the peasants mistook for cannon, probably because they were fired from rests, while their own firearms they considered to be relatively "pop-guns" (Snap-bosser).

Moreover, provisions were unobtainable, as the local Bönder had fled on the approach of the troops, after hiding their scanty supplies of food in the woods. A panic ensued, the common people insisting that the invaders were "very strong, and picked soldiers and warriors."

Steen Bilde was subsequently tried and punished for his alleged remissness in not repelling the enemy, and therefore some caution is necessary in receiving the official complaints made by the burgomaster and lagmand against the peasantry on that occasion, and which were to the following effect: "How can we carry on war in this country with peasants? It suffices to see how they conducted themselves against the soldiers." Steen Bilde affirmed that the lagmand had to "ride and walk about the whole of the night to get those peasants and ill-disposed persons into order; and yet nothing can be accomplished with them, as they do not stand, but run away at once when they see the enemy." He urged in his own defence: "I did my best, diligently, according to the counsel and means at hand, and according to what could be accomplished with those peasants. God comfort those who have no other help than peasants on such an occasion!"

It would appear at this distance of time that both Steen Bilde and the peasants were unfairly reproached for their conduct. The sudden landing of so many armed men was quite sufficient to create a panic, while the burning of "four farms in Stordalen, and of all the farms (twelve in all) which lay towards the river at Merager," was well calculated to strike terror into and to paralyze a peaceful population.[26] Under such circumstances, it would have been difficult to drive the men back to their ships, even with the fifteen hundred peasants hastily collected, under the command of three captains, and supported only by two hundred soldiers or militia.

Mönnichhofen's troops appear to have had the same difficulty as the peasant levies in providing themselves with food; for the men sent by Steen Bilde into the mountains as scouts found some of the soldiers dead from hunger, and many pieces of armour as well as pikes and other weapons thrown away by them.

On the other hand, Cronholm[27] asserts that the progress of the troops, which, laden with booty, were driving before them the cattle robbed from farms, was arrested in numerous mountain passes, where the soldiers were slaughtered by a host of peasants. But this statement is not in harmony with the Official Reports made to the Danish Chancellor, or with the punishment inflicted on Steen Bilde. The latter pointed out, on the contrary, that if some armed bands of peasants had understood how to utilize the advantages afforded by the physical conditions of the highlands, the rocks and precipices over which the bold Mönnichhofen and his men made their way "might easily have become their graves."

However, it is on historical record that the expedition reached Jemtland, where it found itself on Swedish soil, the population having previously taken an oath of allegiance to the Swedish Crown, which at the end of the war acquired permanently that Danish province.

Gustavus Adolphus occupied Herjedalen and Jemtland in pursuance of a threat made (March 1612) in a proclamation to the Norwegian peasantry, who yet spurned the idea of seceding from Denmark, and had attacked in force the lands on the Swedish borders, when, according to a contemporaneous writer, Dal and Vemland bore the brunt of the Norse onslaught.[28]

In that proclamation Gustavus Adolphus attributed the war to the Danish king, "whose aim," he said, "was war and bloodshed, and who had caused, menaced, and forced both his late father and himself to have recourse to self-defence." He reminded the Norwegians how "Sweden and Norway had from the most ancient days been united by relationship of descent and language; how there was a time when they had one and the same king; how the bond that should unite Norwegians and Swedes was, after all, closer and more natural than anything that could unite Norwegians with Danes; and how even geographical conditions seemed to witness that it was the will of Fate that Norway and Sweden should be united."

That far-seeing sovereign therefore called upon the Norwegians to submit to him as their lord and king, promising to confirm all their rights and privileges, and to restore to their legitimate position the remnants of the old aristocracy of Norway.

This appeal produced gradually the desired effect both in Herjedalen and Jemtland. The march of Mönnichhofen towards the old Swedish provinces was thus rendered easy; and on receipt of orders from Gustavus Adolphus, he took the direct road to Stockholm, then seriously threatened by the fleet of Christian IV.

Gustavus led in person the Netherlands contingent to Waxholm, a few miles from Stockholm, in order to attack the Danes, and in a month or so the Calmar War came to an end.

FOOTNOTES:

[22] Steen Bilde reported that Mönnichhofen's ships had sailed from Emden.

[23] Published about 1858.

[24] "Sveriges Historia under Gustav II Adolph's Regering." Stockholm. Part I., p. 175.

[25] In his letter to Sir J. Spens, Gustavus Adolphus speaks only of one thousand infantry to be raised by Mönnichhofen.

[26] F. H. Jahn, the Danish historian of the Calmar War, says the Bönder were so stricken with fear that they allowed the transport ships, which they might have taken, to sail back.

[27] "Sveriges Historia under Gustav II Adolph's Regering."

[28] "Nordens Historie." N. Bache, Copenhagen, 1884.

[22] Steen Bilde reported that Mönnichhofen's ships had sailed from Emden.

[23] Published about 1858.

[24] "Sveriges Historia under Gustav II Adolph's Regering." Stockholm. Part I., p. 175.

[25] In his letter to Sir J. Spens, Gustavus Adolphus speaks only of one thousand infantry to be raised by Mönnichhofen.

[26] F. H. Jahn, the Danish historian of the Calmar War, says the Bönder were so stricken with fear that they allowed the transport ships, which they might have taken, to sail back.

[27] "Sveriges Historia under Gustav II Adolph's Regering."

[28] "Nordens Historie." N. Bache, Copenhagen, 1884.

According to the Report of the same Swedish agent, Mönnichhofen sailed at last on the 14th July from Amsterdam,[22] and landed five days later in Stordalen, on the coast of Norway—at that time united with the Crown of Denmark—without combining, as originally intended, with the levies made in Scotland, although measures for their detention were taken only on the 4th August following.

When read in connection with the Reports of the Swedish agents at Amsterdam, first discovered and made known by Dr. Yngvar Nielsen in 1877, the letters of Steen Bilde, C. J. Jude, and J. Pederson[23] afford a credible and fairly complete account of that expedition. Those collective documents show that it was not composed, as alleged by Niels Slange, of "about fourteen hundred soldiers, or Scots," enlisted in Scotland, but nominally of twelve hundred men raised in the Netherlands under the circumstances already described.

The burgomaster of Trondhjem (who, like Bilde and the other Danish officials, was interested in over-rating rather than in under-rating the strength of the invaders,) reported, on 15th August 1612, that the expedition consisted of "eight hundred soldiers, besides their women and boys;" and according to Cronholm,[24] Gustavus Adolphus himself wrote that the number of those men, when they arrived in Jemtland, out of all further danger, amounted to eight hundred.[25] The four small Dutch ships could scarcely have carried more, especially if the men were accompanied by their women and children, as alleged by the burgomaster.

The burgomaster of Trondhjem (who, like Bilde and the other Danish officials, was interested in over-rating rather than in under-rating the strength of the invaders,) reported, on 15th August 1612, that the expedition consisted of "eight hundred soldiers, besides their women and boys;" and according to Cronholm,[24] Gustavus Adolphus himself wrote that the number of those men, when they arrived in Jemtland, out of all further danger, amounted to eight hundred.[25] The four small Dutch ships could scarcely have carried more, especially if the men were accompanied by their women and children, as alleged by the burgomaster.

It would appear at this distance of time that both Steen Bilde and the peasants were unfairly reproached for their conduct. The sudden landing of so many armed men was quite sufficient to create a panic, while the burning of "four farms in Stordalen, and of all the farms (twelve in all) which lay towards the river at Merager," was well calculated to strike terror into and to paralyze a peaceful population.[26] Under such circumstances, it would have been difficult to drive the men back to their ships, even with the fifteen hundred peasants hastily collected, under the command of three captains, and supported only by two hundred soldiers or militia.

On the other hand, Cronholm[27] asserts that the progress of the troops, which, laden with booty, were driving before them the cattle robbed from farms, was arrested in numerous mountain passes, where the soldiers were slaughtered by a host of peasants. But this statement is not in harmony with the Official Reports made to the Danish Chancellor, or with the punishment inflicted on Steen Bilde. The latter pointed out, on the contrary, that if some armed bands of peasants had understood how to utilize the advantages afforded by the physical conditions of the highlands, the rocks and precipices over which the bold Mönnichhofen and his men made their way "might easily have become their graves."

Gustavus Adolphus occupied Herjedalen and Jemtland in pursuance of a threat made (March 1612) in a proclamation to the Norwegian peasantry, who yet spurned the idea of seceding from Denmark, and had attacked in force the lands on the Swedish borders, when, according to a contemporaneous writer, Dal and Vemland bore the brunt of the Norse onslaught.[28]

IV.

ORGANIZATION OF SCOTTISH LEVIES FOR SWEDEN, AND THEIR FORCED DISBANDMENT.

Having dealt with that part of the general plan of bringing foreign troops to the aid of Sweden which was so successfully carried out by Mönnichhofen, we approach the main subject of this little work—namely, the history of the Scottish levies, and of the disaster that befell the very small portion of them that succeeded in leaving Scotland and landing in Norway.

Our starting-point in this part of the inquiry must be the commission addressed by Gustavus Adolphus to Sir James Spens, Laird of Wormiston.[29]

It gives an authentic indication of the measures subsequently adopted for obtaining levies in Scotland as well as in Holland. The young warrior and statesman refers to promises made by Sir James Spens to Charles IX., and to the services which his father had required of him, urging him to hasten his return (evidently from Scotland) with the "promised three thousand soldiers of proved faithfulness and bravery." He wished them to be infantry, not cavalry. The main object was the arrival of Sir James Spens at Elfsborg, by the 1st of April 1612, "with the before-mentioned number of troops, properly equipped with the needful accoutrements." Spens was to be paid at Hamburg the sum of 20,000 imperials, and was assured that any further expense he might incur in the matter of the levies would be repaid to him punctually and with the greatest cheerfulness. Gustavus Adolphus added: "Furthermore, we have thought (right) that it should be notified to you that we have arranged with our general (duce), our truly-beloved Johannes Mœnichovius, that he is to transport his thousand infantry, fully furnished with necessary arms, from Holland to Elfsborg, in the beginning of spring. If, therefore, you combine your fleet and army with the ships of the aforesaid Mœnichovius, we shall be extremely glad."

The execution of this part of the plan was subsequently rendered impossible by the fall of Elfsborg and the command which the Danes obtained of the approaches to Sweden by sea.

The proceedings of Spens in this matter are not disclosed in the documents so far discovered,[30] which prove that Colonel Andrew Ramsay was the active organizer of the levies in Scotland. King James I. in one of his letters calls him "the chief of the business, whose brother all men know what place he hath with us." The influence Andrew Ramsay possessed at the Court of King James probably caused him to be engaged by Spens. One of his brothers was Sir John Ramsey, a favourite of King James, and who, while one of the royal pages, in the year 1600, was instrumental in rescuing the king from assassination at Gowrie House, near Perth. It was another brother of his—Alexander Ramsay—who was the leader of the small detachment of Scots destroyed at Kringelen, in Norway, and not George Sinclair, as hitherto assumed.

That the king's name was privately but unjustifiably used in the proceedings of Colonel Andrew Ramsay, was subsequently acknowledged by the latter, and hence the suspicion arose in Denmark that King James was cognizant of those proceedings. But the documents preserved in Edinburgh show that King James did not become aware of what Andrew Ramsay and the officers with him were doing in Scotland until about the 31st July 1612, the date on which the king wrote to his Scottish Privy Council as follows:—

"Whereas it is said there is a colonel and certain captains levying men to go to Sweden, we wonder that any subject of ours dare presume in that kind to serve any foreign prince, not only without our licence but directly against our meaning and special promise made to our dear brother the King of Denmark[31].... It is therefore our pleasure that ye certify as to what that levying of soldiers meaneth; by what authority it is done; and that ye make stay of all proceedings therein till ye shall be advertised of our further pleasure concerning that matter."

Nine days later, the king wrote to his envoy at Copenhagen[32] that he had heard, "by mere accident, of levies in Scotland ready to embark under Ramsay, Steward, and some other captains;" and "being displeased, gave order presently for the stay of the levy. And whereas good numbers of them were already embarked before His Majesty heard the news, or ready to embark, His Highness hath given order to discharge them, and doth utterly disavow any acts of theirs," etc.

But the Danish king was already well acquainted with those proceedings; for the British envoy at Copenhagen wrote to King James on the 10th August 1612 (the king had written to him on the 9th August) that the King of Denmark was informed that "one Menigowe, a Fleming, having in company with him fifteen hundred men, is to meet with Andrew Ramsay in some part of the north of Scotland, about Caithness or Orkney, who has more than a thousand Scottish men with him; and so they mind to join their forces together, and to fall upon Norway and spoil some towns, and so go into Sweden." The King of Denmark, added the envoy, had been informed by persons from Scotland that Ramsay had levied men about Edinburgh and embarked them at Leith; and His Majesty argued that "such levies so near Edinburgh could not be done without permission of the State."

Indeed, the excuses of the Scottish Privy Council, to the effect that the levies had been made secretly, did not satisfy even King James, who wrote to his envoy that, to quote his own expression, he "misliked some dulness of theirs."

The action taken by the Scottish Privy Council immediately on receipt of the peremptory orders of the king was as follows:—

On the 4th August 1612 a proclamation was issued "discharging the transporting of soldiers to Sweden," and another "against the soldiers enlisted for Sweden;" while two acts were passed—the one "charging" or accusing "Captains Hay, Ker, and Sinclair" of having enlisted men for the wars of Sweden, and ordering them to desist from their enterprise, etc.; the other summoning Colonel Andrew Ramsay to appear before the Council to "hear and see His Majesty's will, pleasure, and direction" in respect of the men of war enlisted under his pay and command to be transported to Sweden. Next day the Lords of the Council ordered officers of arms "to pass, command, and charge the masters, owners, skippers, and mariners of ships and vessels freighted for transport of soldiers to Sweden, that they bring in their ships to the harbour of Leith, and there suffer them to lie," and not to set sail until they know the Council's will and pleasure towards them, under pain of being denounced as rebels and "put to the horn."[33]

On the 15th August an act was passed by the Council, ordering that "the companies of men lately enlisted under the charge and commandment of Colonel Ramsay and some other captains, for the wars of Sweden, be broken up, and that they shall in no wise be transported to Sweden;" and on the same day another act, ordaining that the companies under Colonel Ramsay, who had meanwhile professed his willingness to render obedience to the king by disbanding them, should be landed, one half at Leith, the other half at Brunt or Burnt Island, on the other side of the Forth.

The latest document regarding these matters, obtained from the General Register Office in Edinburgh, is dated the 18th September 1612. Colonel Andrew Ramsay had been summoned to appear before the Council on the latter date, to answer regarding the unlawful levying of troops; and having failed to do so, he was forthwith denounced as a rebel.

Those acts and proclamations[34] give a very interesting and, indeed, important insight into the methods Colonel Andrew Ramsay and his confederates had adopted in Scotland.

We first of all find that Sir Robert Ker had apprehended in the middle shires[35] of Scotland a number of malefactors, part of whom he sent, or rather intended to send, to Sweden. In the second place, the proclamations assert that the Scottish officers therein named "have violently pressed and taken a great many honest men's sons, and have carried them to their ships against their will, of purpose to transport them to Sweden." They are accused of going "about the country in a swaggering manner, awaiting the time and occasion how and where they may apprehend any persons travelling on their lawful adois,[36] and if they be masters of them they immediately lay hands on them and by force and violence convey them to the next shore, where they have their boats in readiness to take them on board of their ships.... So that there is such a fear and dread arising among the common people that none of them dare travel," unless they be "able to withstand and resist the violence and injury of the said persons." ... "And divers young fellows," continues the proclamation, "who were resolved to have come to these parts to have awaited upon the harvest and cutting down of the corn are," for those reasons, "afraid to come here." In the charge against Captains Hay, Ker, and Sinclair, it is alleged that the "honest men's bairns and servants" are detained on board the ships "as slaves and captives."

Any person disobeying the orders of the Council was threatened with the penalty of death. The levies were to be discontinued, the ships seized, their sails taken from the yards, and the men on board set at liberty; but not before the local authorities had visited the vessels, and taken out of them and delivered over to the bailies of Edinburgh "the persons who had been delivered to them by the Commissioners of the late Borders," as well as the persons whom Colonel Ramsay and his captains had received out of the tolbooths of Edinburgh and Dunbar.

The remainder of the companies were ordered to be landed, as already said, at Leith and Burntisland, but on condition that the men should not remain together or travel back in groups of more than two after their disembarkation, under penalty of death, to obviate the possibility of their committing acts of violence on passing through the country.

The remarkable fact that, in all these stringent and detailed regulations for the disbanding and landing of so many men, no mention whatever is made of the most ordinary military precaution of disarming them will be noticed in a succeeding chapter.

FOOTNOTES:

[29] Sir James Spens was the son of "Spens of Wormiston," who made Lennox, the regent of Scotland, captive at the seizure of Stirling by the forces of Kirkaldy in 1571, and who was slain at the same time while protecting his prisoner. The personage in question, so high in the favour of Gustavus Adolphus, was a prominent type of the Scottish adventurer of that age. He went to Sweden in 1610 as envoy from King James I., there being at the time a question of betrothing Gustavus Adolphus, then Crown Prince, to an English princess—namely, to Elizabeth, the daughter of James I., married subsequently to Frederick, the Elector Palatine of the German Empire. We find him later in Denmark, offering the mediation of England between Christian IV. and Charles IX. On this occasion he was so ungraciously received at Copenhagen that he narrowly escaped with his life. Sir James Spens entered the Swedish military service, from which, however, he was recalled by King James, who, a short time after, sent him back to Stockholm as ambassador, in which character he invested Gustavus Adolphus with the Order of the Garter, and took part in the negotiations that resulted in the Peace of Knäröd. On one occasion he went to England as ambassador from the Swedish Court. In 1622 he was created Baron Spens of Orreholmen, in Vestergotland. He died at Stockholm in 1632, after having been made, in 1629, General in Command of the English and Scottish regiments in the pay of Sweden.

[30] It appears from the correspondence of Sir Robert Anstruther that the "Lord of Wormiston" landed at Elsinore on the 4th June 1612, having been sent simultaneously with Sir Robert Anstruther to arrange a peace between Denmark and Sweden. The Danish Chancellor was induced to grant him a safe-conduct into Sweden; "whereupon a nvmber hath wondred and thinks he shall haue small thank for his panis." F. H. Jahn, the Danish historian of the Calmar War, asserts that Spens was "secretly supported in his recruiting business."

[31] When as yet only King of Scotland, James was married (November 24, 1589) at Oslo, now a suburb of Christiania, to Anne, sister of Christian IV. of Denmark. She had previously gone through the ceremony of marriage with Earl-Marshal Keith, as proxy for the king, at the castle of Cronenberg; but on their way to Scotland the Danish ships, driven by storms to the coast of Norway, landed the princess at Oslo. With great gallantry King James came over to fetch her with a large fleet, and remained at Oslo, after his marriage there (performed by Robert Bruce, court chaplain), until the 21st January 1590, when he sailed with his bride for Copenhagen. The ties of relationship, and the duties and obligations of King James towards his "good brother" the King of Denmark, are fully recognized in the documents now published; but the impartial historian cannot fail to take into consideration the character of that sovereign and his conduct in other matters, such as the negotiations with Spain and the family interests connected with them.

[32] King's Secretary to Sir Robert Anstruther, 9th August 1612.

[33] The latter threat meant, in Scottish law, a declaration of outlawry, after three blasts of a horn, and the putting up of a citation at the quay, pier, or shore in Leith, or at the market cross in Edinburgh.

[34] Vide text in Appendix.

[35] The Border counties of Scotland were ordered to be called the middle shires on the union of the two kingdoms.

[36] Plural of ado, business.

[29] Sir James Spens was the son of "Spens of Wormiston," who made Lennox, the regent of Scotland, captive at the seizure of Stirling by the forces of Kirkaldy in 1571, and who was slain at the same time while protecting his prisoner. The personage in question, so high in the favour of Gustavus Adolphus, was a prominent type of the Scottish adventurer of that age. He went to Sweden in 1610 as envoy from King James I., there being at the time a question of betrothing Gustavus Adolphus, then Crown Prince, to an English princess—namely, to Elizabeth, the daughter of James I., married subsequently to Frederick, the Elector Palatine of the German Empire. We find him later in Denmark, offering the mediation of England between Christian IV. and Charles IX. On this occasion he was so ungraciously received at Copenhagen that he narrowly escaped with his life. Sir James Spens entered the Swedish military service, from which, however, he was recalled by King James, who, a short time after, sent him back to Stockholm as ambassador, in which character he invested Gustavus Adolphus with the Order of the Garter, and took part in the negotiations that resulted in the Peace of Knäröd. On one occasion he went to England as ambassador from the Swedish Court. In 1622 he was created Baron Spens of Orreholmen, in Vestergotland. He died at Stockholm in 1632, after having been made, in 1629, General in Command of the English and Scottish regiments in the pay of Sweden.

[30] It appears from the correspondence of Sir Robert Anstruther that the "Lord of Wormiston" landed at Elsinore on the 4th June 1612, having been sent simultaneously with Sir Robert Anstruther to arrange a peace between Denmark and Sweden. The Danish Chancellor was induced to grant him a safe-conduct into Sweden; "whereupon a nvmber hath wondred and thinks he shall haue small thank for his panis." F. H. Jahn, the Danish historian of the Calmar War, asserts that Spens was "secretly supported in his recruiting business."

[31] When as yet only King of Scotland, James was married (November 24, 1589) at Oslo, now a suburb of Christiania, to Anne, sister of Christian IV. of Denmark. She had previously gone through the ceremony of marriage with Earl-Marshal Keith, as proxy for the king, at the castle of Cronenberg; but on their way to Scotland the Danish ships, driven by storms to the coast of Norway, landed the princess at Oslo. With great gallantry King James came over to fetch her with a large fleet, and remained at Oslo, after his marriage there (performed by Robert Bruce, court chaplain), until the 21st January 1590, when he sailed with his bride for Copenhagen. The ties of relationship, and the duties and obligations of King James towards his "good brother" the King of Denmark, are fully recognized in the documents now published; but the impartial historian cannot fail to take into consideration the character of that sovereign and his conduct in other matters, such as the negotiations with Spain and the family interests connected with them.

[32] King's Secretary to Sir Robert Anstruther, 9th August 1612.

[33] The latter threat meant, in Scottish law, a declaration of outlawry, after three blasts of a horn, and the putting up of a citation at the quay, pier, or shore in Leith, or at the market cross in Edinburgh.

[34] Vide text in Appendix.

[35] The Border counties of Scotland were ordered to be called the middle shires on the union of the two kingdoms.

[36] Plural of ado, business.

Our starting-point in this part of the inquiry must be the commission addressed by Gustavus Adolphus to Sir James Spens, Laird of Wormiston.[29]

The proceedings of Spens in this matter are not disclosed in the documents so far discovered,[30] which prove that Colonel Andrew Ramsay was the active organizer of the levies in Scotland. King James I. in one of his letters calls him "the chief of the business, whose brother all men know what place he hath with us." The influence Andrew Ramsay possessed at the Court of King James probably caused him to be engaged by Spens. One of his brothers was Sir John Ramsey, a favourite of King James, and who, while one of the royal pages, in the year 1600, was instrumental in rescuing the king from assassination at Gowrie House, near Perth. It was another brother of his—Alexander Ramsay—who was the leader of the small detachment of Scots destroyed at Kringelen, in Norway, and not George Sinclair, as hitherto assumed.

"Whereas it is said there is a colonel and certain captains levying men to go to Sweden, we wonder that any subject of ours dare presume in that kind to serve any foreign prince, not only without our licence but directly against our meaning and special promise made to our dear brother the King of Denmark[31].... It is therefore our pleasure that ye certify as to what that levying of soldiers meaneth; by what authority it is done; and that ye make stay of all proceedings therein till ye shall be advertised of our further pleasure concerning that matter."

Nine days later, the king wrote to his envoy at Copenhagen[32] that he had heard, "by mere accident, of levies in Scotland ready to embark under Ramsay, Steward, and some other captains;" and "being displeased, gave order presently for the stay of the levy. And whereas good numbers of them were already embarked before His Majesty heard the news, or ready to embark, His Highness hath given order to discharge them, and doth utterly disavow any acts of theirs," etc.

On the 4th August 1612 a proclamation was issued "discharging the transporting of soldiers to Sweden," and another "against the soldiers enlisted for Sweden;" while two acts were passed—the one "charging" or accusing "Captains Hay, Ker, and Sinclair" of having enlisted men for the wars of Sweden, and ordering them to desist from their enterprise, etc.; the other summoning Colonel Andrew Ramsay to appear before the Council to "hear and see His Majesty's will, pleasure, and direction" in respect of the men of war enlisted under his pay and command to be transported to Sweden. Next day the Lords of the Council ordered officers of arms "to pass, command, and charge the masters, owners, skippers, and mariners of ships and vessels freighted for transport of soldiers to Sweden, that they bring in their ships to the harbour of Leith, and there suffer them to lie," and not to set sail until they know the Council's will and pleasure towards them, under pain of being denounced as rebels and "put to the horn."[33]

Those acts and proclamations[34] give a very interesting and, indeed, important insight into the methods Colonel Andrew Ramsay and his confederates had adopted in Scotland.

We first of all find that Sir Robert Ker had apprehended in the middle shires[35] of Scotland a number of malefactors, part of whom he sent, or rather intended to send, to Sweden. In the second place, the proclamations assert that the Scottish officers therein named "have violently pressed and taken a great many honest men's sons, and have carried them to their ships against their will, of purpose to transport them to Sweden." They are accused of going "about the country in a swaggering manner, awaiting the time and occasion how and where they may apprehend any persons travelling on their lawful adois,[36] and if they be masters of them they immediately lay hands on them and by force and violence convey them to the next shore, where they have their boats in readiness to take them on board of their ships.... So that there is such a fear and dread arising among the common people that none of them dare travel," unless they be "able to withstand and resist the violence and injury of the said persons." ... "And divers young fellows," continues the proclamation, "who were resolved to have come to these parts to have awaited upon the harvest and cutting down of the corn are," for those reasons, "afraid to come here." In the charge against Captains Hay, Ker, and Sinclair, it is alleged that the "honest men's bairns and servants" are detained on board the ships "as slaves and captives."

We first of all find that Sir Robert Ker had apprehended in the middle shires[35] of Scotland a number of malefactors, part of whom he sent, or rather intended to send, to Sweden. In the second place, the proclamations assert that the Scottish officers therein named "have violently pressed and taken a great many honest men's sons, and have carried them to their ships against their will, of purpose to transport them to Sweden." They are accused of going "about the country in a swaggering manner, awaiting the time and occasion how and where they may apprehend any persons travelling on their lawful adois,[36] and if they be masters of them they immediately lay hands on them and by force and violence convey them to the next shore, where they have their boats in readiness to take them on board of their ships.... So that there is such a fear and dread arising among the common people that none of them dare travel," unless they be "able to withstand and resist the violence and injury of the said persons." ... "And divers young fellows," continues the proclamation, "who were resolved to have come to these parts to have awaited upon the harvest and cutting down of the corn are," for those reasons, "afraid to come here." In the charge against Captains Hay, Ker, and Sinclair, it is alleged that the "honest men's bairns and servants" are detained on board the ships "as slaves and captives."

V.

ORDERS OF KING JAMES I. DISOBEYED BY A FEW SCOTTISH OFFICERS, WHO PROCEED WITH A SMALL PORTION OF THE LEVIES TO NORWAY.

The vigorous measures of the Council were not, however, adopted in sufficient time to prevent a small contingent of the Scottish levies from crossing over to Norway.

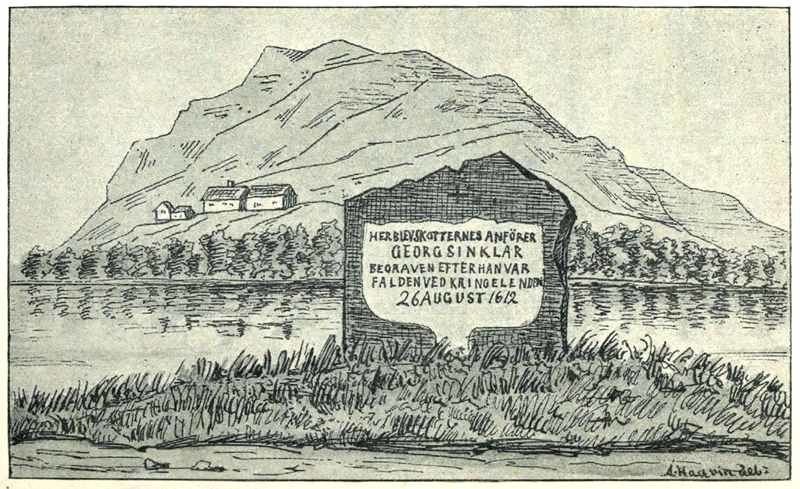

On the 17th September 1612, the Norwegian Stadtholder Kruse announced to the Danish Chancellor the arrival of two Scottish ships at Romsdalen between the 19th and 20th August, and the destruction at Kringelen, on the 26th August, of all the men, except eighteen, that had landed from those vessels.

On the 26th October 1612, Sir Robert Anstruther reported the matter in the following terms to King James:—