автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу James Russell Lowell and His Friends

E-text prepared by

KD Weeks, Marilynda Fraser-Cunliffe, David Garcia,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

from page images generously made available by

Internet Archive

(https://archive.org)

Note:

Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See

https://archive.org/details/lowellandfriends00halerichTranscriber’s Note

Footnotes appear sparingly. The ten instances have been moved to the end of the text.

Illustrations and photographs were not included in pagination. They have been re-positioned to avoid falling mid-paragraph.

To reduce download time, the illustrations are presented as smaller images. By clicking on the image, one will open a larger image. The image will open in the current tab or window; a right click should permit one to open the image in a separate tab/window.

Please see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered during its preparation.

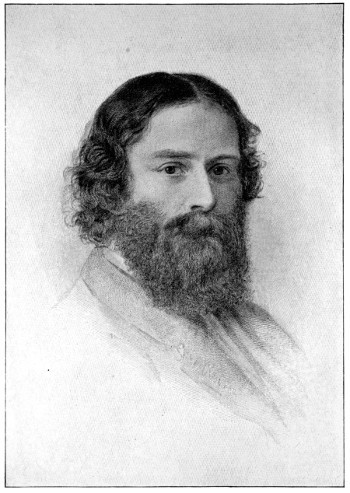

JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL

From the crayon by S.W. Rowse in the possession of Professor Charles Eliot Norton

JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL AND HIS FRIENDS

BY

EDWARD EVERETT HALE

WITH PORTRAITS, FACSIMILES, AND OTHER

ILLUSTRATIONS

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

COPYRIGHT, 1898 AND 1899, BY THE OUTLOOK COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Transcriber’s Note

Minor errors in punctuation and formatting have been silently corrected.

Minor inconsistencies and errors which are obviously due to the printer have been corrected, as noted in the table below.

Several page references in the Index were missing, and have been added. The reference to Lady Lyttelton appeared on p. 259. Likewise, the reference to ‘A Virtuoso’s Collection’ appeared on p. 84.

On p. 260, the sentence beginning ‘And Mr. Smalley at the time wrote...’ seems to call for a new paragraph.

In the final poem, ‘My Brook’, the line ‘And Will-o’-Wisp light me his lantern no more?’ was not indented, though the regular form of the poem would indicate that it should have been.

p. 115

dilustered

sic.delustered?

p. 217

show what Jef[f]erson thought

Added. Line-break error.

p. 258

Amelia [Blandford] Edwards

sic.Blanford

The following are transcriptions of the several reproduced documents given in the text. Those which are hand-written are sometimes illegible, and are annotated as such.

Transcription of document between p. 50-51.

TO THE CLASS OF ’38,

BY THEIR OSTRACIZED POET, (SO CALLED,)

J.R. L.

I.

Classmates, farewell! our journey’s done,

Our mimic life is ended,

The last long year of study’s run,

Our prayers their last have blended!

CHORUS.

Then fill the cup! fill high! fill high!

Nor spare the rosy wine!

If Death be in the cup, we’ll die!

Such death would be divine!

II.

Now forward! onward! let the past

In private claim its tear,

For while one drop of wine shall last,

We’ll have no sadness here!

CHORUS.

Then fill the cup! fill high! fill high!

Although the hour be late,

We’ll hob and nob with Destiny,

And drink the health of Fate!

III.

What though ill-luck may shake his fist,

We heed not him or his,

We’ve booked our names on Fortune’s list,

So d—n his grouty phiz!

CHORUS.

Then fill the cup! fill high! fill high!

Let joy our goblets crown,

We’ll bung Misfortune’s scowling eye,

And knock Foreboding down!

IV.

Fling out youth’s broad and snowy sail,

Life’s sea is bright before us!

Alike to us the breeze or gale,

So hope shine cheerly o’er us!

CHORUS.

Then fill the cup! fill high! fill high!

And drink to future joy,

Let thought of sorrow cloud no eye,

Here’s to our eldest boy!

V.

Hurrah! Hurrah! we’re launched at last,

To tempt the billows’ strife!

We’ll nail our pennon to the mast,

And Dare the storms of life!

CHORUS.

Then fill the cup! fill high once more!

There’s joy on time’s dark wave;

Welcome the tempest’s angry roar!

’T is music to the brave.

Transcription of document between p. 52-53.

VALEDICTORY EXERCISES OF THE HARVARD CLASS OF 1838

HARVARD UNIVERSITY.

VALEDICTORY EXERCISES OF THE SENIOR CLASS OF

1838,

TUESDAY JULY 17, 1838.

1. VOLUNTARY. By the Band.

2. PRAYER. By the Rev. Dr. Ware Jr.

3. ORATION. By James I.T. Coolidge. Boston.

4. POEM. By James R. Lowell.* Boston.

5. ODE. By John F.W. Ware. Cambridge.

Tune. “Auld Lang Syne.”

The voice of joy is hushed around,

Still is each heart and tongue;

We part for aye,—at duty’s call

We break the pleasing spell.

We meet to part,—no more to meet

Within these sacred walls,—

No longer Wisdom to her shrine

Her wayward children calls.

We met as strangers at the fount

Whence Learning’s waters flow,—

And now we part, the prayers of friends

Attend the path we go.

CHORUS.

And on the clouds that shade our way,

If Friendship’s star shine clear,

No grief shall dim a brother’s eye,

No sorrow tempt a tear.

Yet often when the soul is sad,

And worldly ills combine,

Our hearts shall hither turn, and breathe

One sigh for “Auld Lang Syne.”

Then, brothers, blessed be your lot,

May Peace forever dwell

Around the hearths of those we’ve known

And loved so long,—farewell.

CHORUS.

Farewell,—our latest voice sends up

A heartfelt wish of love,—

That we may meet again, and form

One brotherhood above.

6. BENEDICTION.

* On account of the absence of the Poet the Poem will be omitted.

Transcription of handwritten note between p. 92-93.

List of Copies of the “Conversation” to be given away

by “the Don”

1 W.L. Garrison with author’s respects.

2 C. F. Briggs by Wily & Putnam N.Y.

3 Mrs Chapman with author’s affectionate regards.

4 T. W. Parson, copy of poems & Conversations with author’s love.

(a note to go with these).

5 John S. Dwight (left at Munroe's bookstore Boston) with

author’s love.

6 W. Page with author’s love.

7 R. C. " " "

8 Revd Dr Lowell Dedication Copy. ask Owen to send it up.

9 Charles R. Lowell jr with uncle’s love (No 1, Winter Place)

10 Revd Chandler Robbins with authors sincere regard (Munroe's

bookstore)

13 J.R.L. 3 through Antislavery office Care J. M. McKim

14 Mr Nichols (printing office) with author’s sincere regards.

15 16

R.W. Emerson with author’s affectionate respects. N. Hawthorne, with author’s love.

Both then in one package directed to Hawthorne & left at Miss

Peabody’s

17 Frank Shaw with author’s love.

18 C.W. Storey jr with happy New Year.

I suppose Mr Owen will allow me 20 copies as he

did of the poems.

If the “Don” thinks of any more which I [illegible]

forgotten let him send them with judicious inscriptions.

19 “To Miss S.C. Lowell with the best newyear’s wishes of her

affectionate nephew the author.”

(Mr Owen will send this up.)

20 Joseph T. Buckingham Esq with author’s regards & thanks.

PREFACE

When my friend Mr. Howland, of the “Outlook” magazine, asked me if I could write for that magazine a Life of James Russell Lowell, I said at once that I could not. While there were certain periods of our lives when we met almost daily, for other periods we were parted, so that for many years I never saw him. I said that the materials for any Life of him were in the hands of others, who would probably use them at the proper time.

Then Mr. Howland suggested that, without attempting anything which should be called a Life of Mr. Lowell, I might write for the “Outlook” a review, as it were, of the last sixty years among literary and scientific people in Boston and its neighborhood. I do not think he wanted my autobiography, nor had I any thought of preparing it for him; but he suggested the book which is in the reader’s hands. This was in April, 1897. I began my preparation for the book with great pleasure. I was cordially helped by friends of Lowell, who opened to me their stores of memories and papers and pictures; and on the 1st of January, 1898, the first number of a series of twelve was published in the “Outlook.” This series is now collected, with such additions as seemed desirable, and such corrections as were suggested by kind and courteous readers.

I should like to acknowledge here personally the courtesy and kindness of the different friends of Mr. Lowell who have rendered such cordial assistance; but really there are too many of them. In trying to prepare a list, I found that I was running up far into the hundreds, and I will not therefore name any one here. On another page the reader will see how largely we are indebted to friends of Mr. Lowell who have furnished us with pictures. To the friends who have loaned us letters or memoranda from diaries or other recollections of him, I must express in general my cordial thanks.

EDWARD E. HALE.

Roxbury, April, 1899.

CONTENTS

CHAP.

PAGE

I.

His Boyhood and Early Life 1II.

Harvard College 15III.

Literary Work in College 25IV.

Concord 43V.

Boston in the Forties 55VI.

The Brothers and Sisters 70VII.

A Man of Letters 78VIII.

Lowell as a Public Speaker 102IX.

Harvard Revisited 125X.

Lowell’s Experience as an Editor 147XI.

Politics and the War 170XII.

Twenty Years of Harvard 192XIII.

Mr. Lowell in Spain 215XIV.

Minister To England 237XV.

Home Again 262 Index 287JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL

INDEX

INDEX

ILLUSTRATIONS

James Russell LowellFrontispiece

From the crayon by S.W. Rowse in the possession of Professor Charles Eliot Norton.

Page

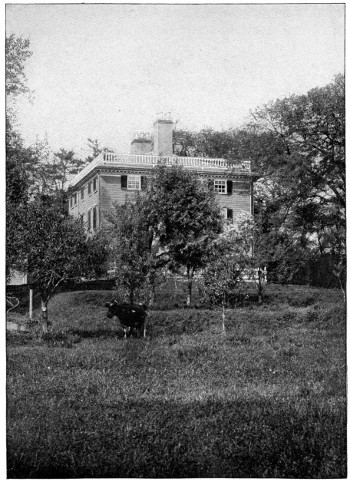

Entrance to Elmwood facing 4From a photograph by Pach Brothers.

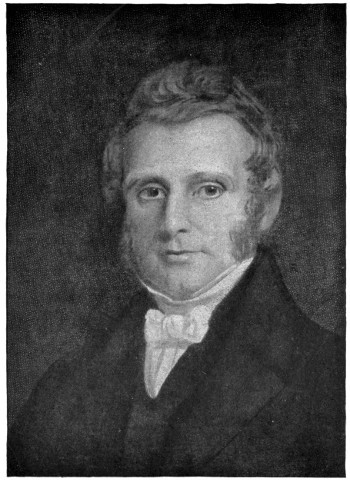

Rev. Charles Lowell 8From a painting in the possession of Charles Lowell, Boston.

The Pasture, Elmwood facing 12From a photograph by Pach Brothers.

Edward Tyrrel Channing facing 18From the painting by Healy in Memorial Hall, Harvard University.

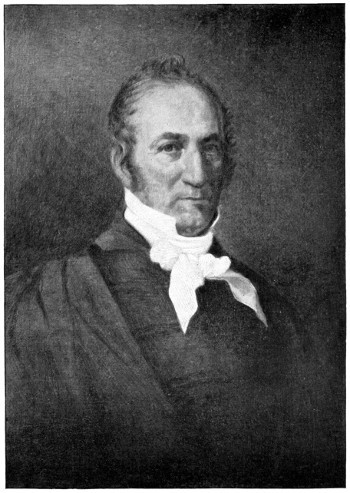

Nathan Hale facing36

From a photograph by Black.

Lowell’s Poem to his College Class facing50

From a printed copy lent by Mrs. Elizabeth Scates Beck, Germantown, Pa.

Facsimile of Programme of Valedictory Exercises of the Harvard Class of 1838 facing52

Lent by Mrs. Elizabeth Scates Beck, Germantown, Pa.

James Russell Lowell facing74

From the crayon by William Page in the possession of Mrs. Charles F. Briggs, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Maria Lowell facing 78From the crayon by S. W. Rowse in the possession of Miss Georgina Lowell Putnam, Boston.

Charles F. Briggs facing84

From an ambrotype by Brady lent by Mrs. Charles F. Briggs, Brooklyn, N.Y.

Facsimile Contents Page of the Boston Miscellany.(The Authors’ names are in the handwriting of Nathan Hale)

facing86

Facsimile of Lowell’s List of Friendsto whom he presented copies of Conversations on the Old Poets. “The Don” was Robert Carter

facing92

From the original MS. owned by General James Lowell Carter, Boston.

James Russell Lowell facing96

From a daguerreotype, taken in Philadelphia in 1844, owned by E.A. Pennock, Boston.

John Lowell, Jr. facing112

From a painting by Chester Harding in the possession of Augustus Lowell, Boston.

John Holmes, Estes Howe, Robert Carter, and James Russell Lowell facing114

From a photograph by Black owned by General James Lowell Carter, Boston.

Cornelius Conway Felton facing134

From a photograph lent by Miss Mary Sargent, Worcester,

Mass.

Elmwood facing138

From a photograph.

James T. Fields facing150

From the photograph by Mrs. Cameron.

Moses Dresser Phillips facing154

From a daguerreotype kindly lent by his daughter, Miss Sarah F. Phillips, West Medford, Mass.

Oliver Wendell Holmes facing158

From a photograph taken in 1862.

Facsimile of A Fable for Critics Proof-sheet with Lowell’s Corrections facing162

Kindly lent by Mrs. Charles F. Briggs, Brooklyn, N.Y.

William Wetmore Story facing164

From a photograph by Waldo Story lent by Miss Ellen Eldredge, Boston.

James Russell Lowell facing168

From a photograph taken by Dr. Holmes in 1864. The

print is signed by both Holmes and Lowell, and is kindly lent by Charles Akers, New York, N.Y.

Sydney Howard Gay facing178

From a photograph lent by Francis J. Garrison, Boston.

Elmwood facing182

From a photograph by Miss C.E. Peabody, Cambridge, Mass.

Robert Gould Shaw facing184

From a photograph lent by Francis J. Garrison, Boston.

William Lowell Putnam facing184

From the crayon by S.W. Rowse in the possession of Miss Georgina Lowell Putnam, Boston.

Charles Russell Lowell facing184

From the crayon by S.W. Rowse in the possession of Miss Georgina Lowell Putnam, Boston.

James Jackson Lowell facing184

From a photograph kindly lent by Miss Georgina Lowell Putnam, Boston.

Francis James Child facing186

From a photograph lent by Mrs. Child.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow facing188

From a photograph, taken in 1860, lent by Miss Longfellow.

Asa Gray facing196

From the bronze tablet by Augustus St. Gaudens in Harvard University.

Louis Agassiz facing198

From a photograph lent by Francis J. Garrison, Boston.

Charles Eliot Norton facing202

From a photograph taken in 1870.

The Hall at Elmwood facing210

From a photograph by Mrs. J.H. Thurston, Cambridge.

Whitby facing240

From a photograph kindly lent by The Outlook Company.

Thomas Hughes facing258

From a photograph.

William Page facing266

From a photograph kindly lent by Mrs. Charles F. Briggs, Brooklyn, N.Y.

James Russell Lowell in his Study at Elmwood facing268

From a copyrighted photograph taken in the spring of 1891 by Mrs. J.H. Thurston, Cambridge. This is probably the last picture of Mr. Lowell.

Room adjoining the Library at Elmwood facing270

From a photograph by Mrs. J.H. Thurston, Cambridge.

Facsimile of Letter from Mr. Lowell to Dr. Hale, November 11, 1890

facing274

First Two and Last Two Stanzas of Mr. Lowell’s Poem My Brook facing284

From the original MS. in the possession of the Rev. Minot J. Savage, New York, N.Y.

JAMES RUSSELL LOWELL

AND HIS FRIENDS

ENTRANCE TO ELMWOOD

REV. CHARLES LOWELL

From a painting in the possession of Charles Lowell, Boston

THE PASTURE, ELMWOOD

EDWARD TYRREL CHANNING

MARIA LOWELL

From the crayon by S.W. Rowse, in the possession of Miss Georgina Lowell Putnam, Boston

CHAPTER I

HIS BOYHOOD AND EARLY LIFE

One cannot conceive more fortunate or charming conditions than those of the boyhood and early education of James Russell Lowell. You may study the babyhood and boyhood of a hundred poets and not find one home like his. His father, the Rev. Charles Lowell, was the minister of a large parish in Boston for more than fifty years. Before James was born, Dr. Lowell had moved his residence from Boston to Cambridge, to the home which his children afterwards called Elmwood. So much of Mr. Lowell’s poetry refers to this beautiful place, as beautiful now as it was then, that even far-away readers will feel a personal interest in it.

The house, not much changed in the last century, was one of the Cambridge houses deserted by the Tory refugees at the time of the Revolution. On the steps of this house Thomas Oliver, who lived there in 1774, stood and heard the demand of the freeholders of Middlesex County when they came to bid him resign George the Third’s commission. The king had appointed him lieutenant-governor of Massachusetts and president of the council. But by the charter of the province councilors were to be elected. Thomas Oliver became, therefore, an object of public resentment. A committee of gentlemen of the county waited on him on the morning of September 2, 1774, at this house, not then called Elmwood. At their request he waited at once on General Gage in Boston, to prevent the coming of any troops out from town to meet the Middlesex yeomanry. And he was able to report to them in the afternoon that no troops had been ordered, “and, from the account I had given his Excellency, none would be ordered.” The same afternoon, however, four or five thousand men appeared, not from the town but from the country—“a quarter part in arms.” For in truth this was a rehearsal for the minute-men’s gathering of the next spring, on the morning of the battle of Lexington. They insisted on Oliver’s resignation of his commission from the crown, and he at last signed the resignation they had prepared, with this addition: “My house at Cambridge being surrounded by five thousand people, in compliance with their command, I sign my name.”

But for Thomas Oliver’s intercession with General Gage and the Admiral of the English fleet, the English troops would have marched to Cambridge that day, and Elmwood would have been the battleground of the First Encounter.

The state confiscated his house after Governor Oliver left for England. Elbridge Gerry, one of the signers of the Declaration, occupied it afterward.

Readers must remember that in Cambridge were Washington’s headquarters, and that the centre of the American army lay in Cambridge. During this time the large, airy rooms of Elmwood were used for the hospital service of the centre. Three or four acres of land belonged to the estate. Since those early days a shorter road than the old road from Watertown to Cambridge has been cut through on the south of the house, which stands, therefore, in the midst of a triangle of garden and meadow. But it was and is well screened from observation by high lilac hedges and by trees, mostly elms and pines. It is better worth while to say all this than it might be were we speaking of some other life, for, as the reader will see, the method of education which was followed out with James Russell Lowell and his brothers and sisters made a little world for them within the confines, not too narrow, of the garden and meadow of Elmwood.

In this home James Russell Lowell was born, on the 22d of February, 1819. There is more than one reference in his letters to his being born on Washington’s birthday. His father, as has been said, was the Rev. Charles Lowell. His mother before her marriage was Harriet Spence, daughter of Mary Traill, who was the daughter of Robert Traill, of Orkney. They were of the same family to which Minna Troil, of Scott’s novel of “The Pirate,” belongs. Some of us like to think that the second-sight and the weird fancies without which a poet’s life is not fully rounded came to the child of Elmwood direct by the blood and traditions of Norna and the Fitful Head. Anyway, Mrs. Lowell was a person of remarkable nature and accomplishments. In the very close of her life her health failed, from difficulties brought on by the bad food and other exposure of desert travel in the East with her husband. Those were the prehistoric days when travelers in Elijah’s deserts did not carry with them a cook from the Palais Royal. But such delicate health was not a condition of the early days of the poet’s life.

His mother had the sense, the courage, and exquisite foresight which placed the little boy, almost from his birth, under the personal charge of a sister eight years older. Mrs. Putnam died on the 1st of June, 1898, loving and beloved, after showing the world in a thousand ways how well she was fitted for the privileges and duties of the nurse, playmate, companion, philosopher, and friend of a poet. She entered into this charge, I do not know how early—I suppose from his birth. I hope that we shall hear that she left in such form that they may be printed her notes on James’s childhood and her care of it.

ENTRANCE TO ELMWOOD

Certain general instructions were given by father and mother, and under these the young Mentor was largely left to her own genius and inspiration. A daily element in the business was the little boy’s nap. He was to lie in his cradle for three hours every morning. His little nurse, eleven or twelve years old, might sing to him if she chose, but she generally preferred to read to him from the poets who interested her. The cadences of verse were soothing, and so the little boy fell asleep every day quieted by the rhythm of Shakespeare or Spenser. By the time a boy is three years old he does not feel much like sleeping three hours in the forenoon. Also, by that time this little James began to be interested in the stories in Spenser, and Mrs. Putnam once gave me a most amusing account of the struggle of this little blue-eyed fellow to resist the coming of sleep and to preserve his consciousness so that he might not lose any of the poem.

Of course the older sister had to determine, in doubtful cases, whether this or that pastime or occupation conflicted with the general rules which had been laid down for them. In all the years of this tender intimacy they never had but one misunderstanding. He was quite clear that he had a right to do this; she was equally sure that he must do that. For a minute it seemed as if there were a parting of the ways. There was no assertion of authority on her part; there could be none. But he saw the dejection of sorrow on her face. And this was enough. He rushed back to her, yielded the whole point, and their one dispute was at an end. The story is worth telling, if only as an early and exquisite exhibition of the profound affection for others which is at the basis of Lowell’s life. If to this loving-kindness you add an extraordinary self-control, you have the leading characteristics of his nature as it appears to those who knew him earliest and best, and who have such right to know where the motives of his life are to be found.

I am eager to go on in some reminiscences of the little Arcadia of Elmwood. But I must not do this till I have said something of the noble characteristics of the boy’s father. Indeed, I must speak of the blood which was in the veins of father and son, that readers at a distance from Boston may be reminded of a certain responsibility which attaches in Massachusetts to any one who bears the Lowell name.

I will go back only four generations, when the Rev. John Lowell was the Congregational minister of Newburyport, and so became a leader of opinion in Essex County. This man’s son, James Lowell’s grandfather, the second John Lowell, is the Lowell who as early as 1772 satisfied himself that, at the common law, slavery could not stand in Massachusetts. It is believed that he offered to a negro, while Massachusetts was still a province of the Crown, to try if the courts could not be made to liberate him as entitled to the rights of Englishmen. This motion of his may have been suggested by Lord Mansfield’s decision in 1772, in the Somerset case, which determined, from that day to this day, that—

“Slaves cannot breathe in England; if their lungs

Receive our air, that moment they are free!

They touch our country, and their shackles fall!”

But in that year John Lowell lost his chance. In 1779, however, he introduced the clause in our Massachusetts Bill of Rights under which the Supreme Court of Massachusetts freed every slave in the state who sought his freedom. Let me say in passing that some verses of his, written when he was quite a young man, are preserved in the “Pietas et Gratulatio.” This was an elegant volume which Harvard College prepared and sent to George III. in 1760 on his accession to the crown. They are written with the exaggeration of a young man’s verse; but they show, not only that he had the ear for rhythm and something of what I call the “lyric swing,” but also that he had the rare art of putting things. There is snap and epigram in the lines. Here they differ by the whole sky from the verses of James Russell, who was also a great-grandfather of our poet Lowell. This gentleman, a resident of Charlestown, printed a volume of poems, which is now very rare. I am, very probably, the only person in the world who has ever read it, and I can testify that there is not one line in the book which is worth remembering, if, indeed, any one could remember a line of it.

John Lowell, the emancipator, became a judge. He had three sons,—John Lowell, who, without office, for many years led Massachusetts in her political trials; Francis Cabot Lowell, the founder of the city of Lowell; and Charles Lowell, the father of the poet. It is Francis Lowell’s son who founded the Lowell Institute, the great popular university of Boston. It is Judge John Lowell’s grandson who directs that institution with wonderful wisdom; and it is his son who gives us from day to day the last intelligence about the crops in Mars, or reverses the opinions of centuries as to the daily duties of Mercury and Venus. I say all this by way of illustration as to what we have a right to expect of a Lowell, and, if you please, of what James Russell Lowell demanded of himself as soon as he knew what blood ran in his veins.

In this connection one thing must be said with a certain emphasis; for the impression has been given that James Russell Lowell took up his anti-slavery sentiment from lessons which he learned from the outside after he left college.

The truth is that Wilberforce’s portrait hung opposite his father’s face in the dining-room. And it was not likely that in that house people had forgotten who wrote the anti-slavery clauses in the Massachusetts Bill of Rights only forty years before Lowell was born.

Before he was a year old the Missouri Compromise passed Congress. The only outburst of rage remembered in that household was when Charles Lowell, the father, lost his self-control, on the morning when he read his newspaper announcing that capitulation of the North to its Southern masters. It took more than forty years before that same household had to send its noblest offering to the war which should undo that capitulation. It was forty-five years before Lowell delivered the Harvard Commemoration Ode under the college elms.

REV. CHARLES LOWELL

From a painting in the possession of Charles Lowell, Boston

We are permitted to publish for the first time a beautiful portrait of the Rev. Charles Lowell when he was at his prime. The picture does more than I can do to give an impression of what manner of man he was, and to account for the regard, which amounts to reverence, with which people who knew him speak of him to this hour. The reader at a distance must try to imagine what we mean when we speak of a Congregational minister in New England at the end of the last century and at the beginning of this. We mean a man who had been chosen by a congregation of men to be their spiritual teacher for his life through, and, at the same time, the director of sundry important functions in the administration of public affairs. When one speaks of the choice of Charles Lowell to be a minister in Boston, it is meant that the selection was made by men who were his seniors, perhaps twice his age, among whom were statesmen, men of science, leaders at the bar, and merchants whose sails whitened all the ocean. Such men made the selection of their minister from the young men best educated, from the most distinguished families of the State.

In 1805 Charles Lowell returned from professional study in Edinburgh. He had been traveling that summer with Mr. John Lowell, his oldest brother. In London he had seen Wilberforce, who introduced him into the House of Commons, where he heard Fox and Sheridan. Soon after he arrived in Boston he was invited to preach at the West Church.

This church was the church of Mayhew, who was the Theodore Parker of his time. Mayhew was in the advance in the Revolutionary sentiment of his day, and Samuel Adams gave to him the credit of having first suggested the federation of the Colonies: “Adams, we have a communion of churches; why do we not make a communion of states?” This he said after leaving the communion table. In such a parish young Charles Lowell preached in 1805, from the text, “Rejoice in the Lord alway.” Soon after, he was unanimously invited to settle as its minister, and in that important charge he remained until he died, on the 20th of January, 1861.

Mr. Lowell was always one of those who interpreted most broadly and liberally the history and principles of the Christian religion. But he was never willing to join in the unfortunate schism which divided the Congregational churches between Orthodox and Unitarian. He and Dr. John Pierce, of Brookline, to their very death, succeeded in maintaining a certain nominal connection with the Evangelical part of the Congregational body.

The following note, written thirty-six years after James Lowell was born, describes his position in the disputes of “denominationalists”:—

My dear Sir: You must allow me to say that, whilst I am most happy to have my name announced as a contributor toward any fund that may aid in securing freedom and religious instruction to Kansas, I do not consent to its being announced as the minister of a Unitarian or Trinitarian church, in the common acceptation of those terms. If there is anything which I have uniformly, distinctly, and emphatically declared, it is that I have adopted no other religious creed than the Bible, and no other name than Christian as denoting my religious faith.

Very affectionately your friend and brother,

Cha. Lowell.

Elmwood, Cambridge,

December 19, 1855.

It may be said that he was more known as a minister than as a preacher. There was no branch of ministerial duty in which he did not practically engage. His relations with his people, from the beginning to the end, were those of entire confidence. But it must be understood, while this is said, that he was a highly popular preacher everywhere, and every congregation, as well as that of the West Church, was glad if by any accident of courtesy or of duty he appeared in the pulpit.

The interesting and amusing life by which the children of the family made a world of the gardens of Elmwood was in itself an education. The garden and grounds, as measured by a surveyor, were only a few acres. But for a circle of imaginative children, as well led as the Lowell children were, this is a little world. One is reminded of that fine passage in Miss Trimmers’s “Robins,” where, when the four little birds have made their first flight from the nest into the orchard, Pecksy says: “Mamma, what a large place the world is!” Practically, I think, for the earlier years of James Lowell’s life, Elmwood furnished as large a world as he wanted. Within its hedges and fences the young people might do much what they chose. They were Mary, who was the guardian; then came William; afterwards Robert, whose name is well known in our literature; and then James. The four children were much together; they found nothing difficult, for work or for pastime. Another daughter, Rebecca, was the songstress of the home; with a sweet flexible voice she sang, in her childhood, hymns, and afterwards the Scotch melodies and the other popular music of the day.

The different parts of the grounds of Elmwood became to these children different cities of the world, and they made journeys from one to another. Their elder brother Charles, until he went to Exeter to school, joined in this geographical play.

The father and mother differed from each other, but were allied in essentials; they enjoyed the same tastes and followed the same pursuits in literature and art. Dr. Lowell was intimate with Allston, the artist, whose studio was not far away, and the progress of his work was a matter of home conversation.

Mrs. Putnam told me that in “The First Snowfall” would be found a reference to Lowell’s elder brother William, who died when the poet himself was but five years old; another trace of this early memory appears again in the poem “Music,” in “A Year’s Life.”

To such open-air life we may refer the pleasure he always took in the study of birds, their seasons and habits, and the accuracy of his knowledge with regard to trees and wild flowers.

THE PASTURE, ELMWOOD

In the simple customs of those days, when one clergyman exchanged pulpits with another, Dr. Lowell would drive in his own “chaise” to the parsonage of his friend, would spend the day there, and return probably on Monday morning. He soon found that James was a good companion in such rides, and the little fellow had many reminiscences of these early travels. It would be easy to quote hundreds of references in his poems and essays to the simple Cambridge life of these days before college. Thus here are some lines from the poem hardly known, on “The Power of Music.”

“When, with feuds like Ghibelline and Guelf,

Each parish did its music for itself,

A parson’s son, through tree-arched country ways,

I rode exchanges oft in dear old days,

Ere yet the boys forgot, with reverent eye,

To doff their hats as the black coat went by,

Ere skirts expanding in their apogee

Turned girls to bells without the second e;

Still in my teens, I felt the varied woes

Of volunteers, each singing as he chose,

Till much experience left me no desire

To learn new species of the village choir.”

So soon as the boy was old enough he was sent to the school of Mr. William Wells, an English gentleman who kept a classical school in Cambridge, not far from Dr. Lowell’s house. Of this school Dr. Holmes and Mr. Higginson have printed some of their memories. All the Cambridge boys who were going to college were sent there. Mr. Wells was a good Latin scholar, and on the shelves of old-fashioned men will still be found his edition of Tacitus, printed under his own eye in Cambridge, and one of the tokens of that “Renaissance” in which Cambridge and Boston meant to show that they could push such things with as much vigor and success as they showed in the fur trade or in privateering. A very good piece of scholarly work it is. Mr. Wells was a well-trained Latinist from the English schools, and his boys learned their Latin well. And it is worth the while of young people to observe that in the group of men of letters at Cambridge and Boston, before and after James Lowell’s time, Samuel Eliot, William Orne White, James Freeman Clarke, Charles and James Lowell, John and Wendell Holmes, Charles Sumner, Wentworth Higginson, and other such men never speak with contempt of the niceties of classical scholarship. You would not catch one of them in a bad quantity, as you sometimes do catch to-day even a college president, if you are away from Cambridge, in the mechanical Latin of his Commencement duty.

But though the boys might become good Latinists and good Grecians, the school has not a savory memory as to the personal relations between master and pupils. James Lowell, however, knew but little of its hardships, as he was but a day scholar. Dr. Samuel Eliot, who attended the school as a little boy, tells me that Lowell delighted to tell the boys imaginative tales, and the little fellows, or many of them, took pleasure in listening to the more stirring stories. “I remember nothing of them except one, which rejoiced in the central interest of a trap in the playground, which opened to subterranean marvels of various kinds.”

CHAPTER II

HARVARD COLLEGE

From such life, quite familiar with Cambridge and its interests, Lowell presented himself for entrance at Harvard College in the summer of 1834, and readily passed the somewhat strict examination which was required.

Remember, if you please, or learn now, if you never knew, that “Harvard College” was a college by itself, or “seminary,” as President Quincy used to call it, and had no vital connection with the law school, the school of medicine, or the divinity school,—though they were governed by the same Board of Fellows, and, with the college, made up Harvard University. Harvard College was made of four classes,—numbering, all told, some two hundred and fifty young men, of all ages from fourteen to thirty-five. Most of them were between sixteen and twenty-two. In this college they studied Latin, Greek, and mathematics chiefly. But on “modern language days,” which were Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, there appeared teachers of French, Italian, Spanish, German, and Portuguese; and everybody not a freshman must take his choice in these studies. They were called “voluntaries,” not because you could shirk if you wanted to, for you could not, but because you chose German or Italian or Spanish or French or Portuguese. When you had once chosen, you had to keep on for four terms. But as to college “marks” and the rank which followed, a modern language was “worth” only half a classical language.

Beside these studies, as you advanced you read more or less in rhetoric, logic, moral philosophy, political economy, chemistry, and natural history,—less rather than more. There was no study whatever of English literature, but the best possible drill in the writing of the English language. There was a well selected library of about fifty thousand volumes, into which you might go on any week-day at any time before four o’clock and read anything you wanted. You took down the book with your own red right hand, and you put it back when you were done.

Then there were three or four society libraries. To these you contributed an entrance fee, when you were chosen a member, and an annual fee of perhaps two dollars. With this money the society bought almost all the current novels of the time. Novels were then published in America in two volumes, and they cost more than any individual student liked to pay. One great object in joining a college society was to have a steady supply of novels. For my part, I undoubtedly averaged eighty novels a year in my college course. They were much better novels, in my judgment, than the average novels of to-day are, and I know I received great advantage from the time I devoted to reading them. I think Lowell would have said the same thing. But I do not mean to imply that such reading was his principal reading. He very soon began delving in the stores which the college library afforded him of the older literature of England.

You had to attend morning chapel and evening chapel. Half the year these offices were at six in the morning and six at night. But as the days shortened, morning prayers came later and later,—even as late as half past seven in the morning,—while afternoon prayers came as early as quarter past four, so that the chapel need not be artificially lighted. On this it followed that breakfast, which was an hour and twenty minutes after prayers, might be long after eight in the morning, and supper at half past four in the afternoon. This left enormously long evenings for winter reading.

Lowell found in the government some interesting and remarkable men.

Josiah Quincy, the president, had been the mayor of Boston who had to do with ordering the system and precedents of its government under the new city charter. From a New England town, governed by the fierce democracy of town meetings, he changed it into a “city,” as America calls it, ruled by an intricate system of mayor, aldermen, council, school committee, and overseers of the poor. Of a distinguished patriot family, Mr. Quincy had been, for years of gallant battle, a leader in Congress of the defeated and disconcerted wrecks of the Federal party. His white plume never went down, and he fought the Southern oligarchy as cheerfully as Amadis ever fought with his uncounted enemies. He was old enough to have been an aide to Governor Hancock when Washington visited Boston in 1792. In Congress he had defied John Randolph, who was an antagonist worthy of him; and he hated Jefferson, and despised him, I think, with a happy union of scorn and hatred, till he died. When he was more than ninety, after the civil war began, I had my last interview with him. He was rejoiced that the boil had at last suppurated and was ready to be lanced, and that the thing was to be settled in the right way. He said: “Gouverneur Morris once said to me that we made our mistake when we began, when we united eight republics with five oligarchies.”

It is interesting now to know, what I did not know till after his death, that this gallant leader of men believed that he was directed, in important crises, by his own “Daimon,” quite as Socrates believed. In the choice of his wife, which proved indeed to have been made in heaven, he knew he was so led. And, in after life, he ascribed some measures of importance and success to his prompt obedience to the wise Daimon’s directions.

His wife was most amiable in her kind interest in the students’ lives. The daughters who resided with him were favorites in the social circles of Cambridge.

EDWARD TYRREL CHANNING

Most of the work of the college was then done in rather dreary recitations, such as you might expect in a somewhat mechanical school for boys to-day. But Edward Tyrrel Channing, brother of the great divine, met his pupils face to face and hand to hand. He deserves the credit of the English of Emerson, Holmes, Sumner, Clarke, Bellows, Lowell, Higginson, and other men whom he trained. Their English did more credit to Harvard College, I think, than any other of its achievements for those thirty-two years. You sat, physically, at his side. He read your theme aloud with you,—so loud, if he pleased, that all of the class who were present could hear his remarks of praise or ridicule,—“Yes, we used to have white paper and black ink; now we have blue paper, blue ink.” I wonder if Mr. Emerson did not get from him the oracle, “Leave out the adjectives, and let the nouns do the fighting.” I think that is Emerson’s. Or whose is it?

In 1836, when Lowell was a sophomore, Mr. Longfellow came to Cambridge, a young man, to begin his long and valuable life in the college. His presence there proved a benediction, and, I might say, marks an epoch in the history of Harvard. In the first place, he was fresh from Europe, and he gave the best possible stimulus to the budding interest in German literature. In the second place, he came from Bowdoin College, and in those days it was a very good thing for a Harvard undergraduate to know that there were people not bred in Cambridge quite as well read, as intelligent, as elegant and accomplished as any Harvard graduate. In the third place, Longfellow, though he was so young, ranked already distinctly as a man of letters. This was no broken-winded minister who had been made professor. He was not a lawyer without clients, or a doctor without patients, for whom “a place” had to be found. He was already known as a poet by all educated people in America. The boys had read in their “First Class Book” his “Summer Shower” verses. By literature, pure and simple, and the work of literature, he had won his way to the chair of the Smith professorship of modern literature, to which Mr. George Ticknor had already given distinction. Every undergraduate knew all this, and felt that young Longfellow’s presence was a new feather in our cap, as one did not feel when one of our own seniors was made a tutor, or one of our own tutors was made a professor.

But, better than this for the college, Longfellow succeeded, as no other man did, in breaking that line of belt ice which parted the students from their teachers. Partly, perhaps, because he was so young; partly because he was agreeable and charming; partly because he had the manners of a man of the world, because he had spoken French in Paris and Italian in Florence; but chief of all because he chose, he was companion and friend of the undergraduates. He would talk with them and walk with them; would sit with them and smoke with them. You played whist with him if you met him of an evening. You never spoke contemptuously of him, and he never patronized you.

Lowell intimates, however, in some of his letters, that he had no close companionship with Longfellow in those boyish days. He shared, of course, as every one could, in the little Renaissance, if one may call it so, of interest in modern Continental literature, on Longfellow’s arrival in Cambridge.

I cannot remember—I wish I could—whether it were Longfellow or Emerson who introduced Tennyson in college. That first little, thin volume of Tennyson’s poems, with “Airy, fairy Lillian” and the rest, was printed in London in 1830. It was not at once reprinted in America. It was Emerson’s copy which somebody borrowed in Cambridge and which we passed reverently from hand to hand.[1] Everybody who had any sense knew that a great poet had been born as well as we know it now. And it is always pleasant to me to remember that those first poems of his were handed about in manuscript as a new ode of Horace might have been handed round among the young gentlemen of Rome.

Carlyle’s books were reprinted in America, thanks to Emerson, as fast as they were written. Lowell read them attentively, and the traces of Carlyle study are to be found in all Lowell’s life, as in the life of all well educated Americans of his time.

I have written what I have of Channing and Longfellow with the feeling that Lowell would himself have said much more of the good which they did to all of us. I do not know how much his clear, simple, unaffected English style owes to Channing, but I am quite sure that he would have spoken most gratefully of his teacher.

Now as to the atmosphere of the college itself. I write these words in the same weeks in which I am reading the life of Jowett at Oxford. It is curious, it is pathetic, to compare Balliol College in 1836-7 with Harvard College at the same time. So clear is it that the impulse and direction were given in Oxford by the teachers, while with us the impulse and direction were given by the boys. The boys invariably called themselves “men,” even when they were, as Lowell was when he entered, but fifteen years old.

Let it be remembered, then, that the whole drift of fashion, occupation, and habit among the undergraduates ran in lines suggested by literature. Athletics and sociology are, I suppose, now the fashion at Cambridge. But literature was the fashion then. In November, when the state election came round, there would be the least possible spasm of political interest, but you might really say that nobody cared for politics. Not five “men” in college saw a daily newspaper. My classmate, William Francis Channing, would have been spoken of, I think, as the only Abolitionist in college in 1838, the year when Lowell graduated. I remember that Dr. Walter Channing, the brother of our professor, came out to lecture one day on temperance. There was a decent attendance of the undergraduates, but it was an attendance of pure condescension on their part.

Literature was, as I said, the fashion. The books which the fellows took out of the library, the books which they bought for their own subscription libraries, were not books of science, nor history, nor sociology, nor politics; they were books of literature. Some Philadelphia publisher had printed in one volume Coleridge’s poems, Shelley’s, and Keats’s—a queer enough combination, but for its chronological fitness. And you saw this book pretty much everywhere. At this hour you will find men of seventy who can quote their Shelley as the youngsters of to-day cannot quote, shall I say, their Swinburne, their Watson, or their Walt Whitman. In the way of what is now called science (we then spoke of the moral sciences also) Daniel Treadwell read once a year some interesting technological lectures. The Natural History Society founded itself while Lowell was in college; but there was no general interest in science, except so far as it came in by way of the pure mathematics.

In the year 1840 I was at West Point for the first time, with William Story, Lowell’s classmate and friend, and with Story’s sister and mine. We enjoyed to the full the matchless hospitality of West Point, seeing its lions under the special care of two young officers of our own age. They had just finished their course, as we had recently finished ours at Harvard. One day when Story and I were by ourselves, after we had been talking of our studies with these gentlemen, Story said to me: “Ned, it is all very well to keep a stiff upper lip with these fellows, but how did you dare tell them that we studied about projectiles at Cambridge?”

“Because we did,” said I.

“Did I ever study projectiles?” asked Story, puzzled.

“Certainly you did,” said I. “You used to go up to Peirce Tuesday and Thursday afternoons in the summer when you were a junior, with a blue book which had a white back.”

“I know I did,” said Story; “and was I studying projectiles then? This is the first time I ever heard of it.”

And I tell that story because it illustrates well enough the divorce between theory and fact which is possible in education. I do not tell it by way of blaming Professor Peirce or Harvard College. Story was not to be an artilleryman, nor were any of the rest of us, so far as we knew. Anyway, the choice of our specialty in life was to be kept as far distant as was possible.

1. That copy is still preserved,—among the treasures of Mr. Emerson’s library in Concord,—beautifully bound, for such was his habit with books which he specially loved.

CHAPTER III

LITERARY WORK IN COLLEGE

“Harvardiana,” a college magazine which ran for four years, belongs exactly to the period of Lowell’s college life. Looking over it now, it seems to me like all the rest of them. That is, it is as good as the best and as bad as the worst.

There is not any great range for such magazines. The articles have to be short. And the writers know very little of life. All the same, a college magazine gives excellent training. Lowell was one editor of the fourth volume of “Harvardiana.” I suppose he then read proof for the first time, and in a small way it introduced him into the life of an editor,—a life in which he afterwards did a great deal of hard work, which he did extremely well, as we shall presently see.

The editorial board of the year before, from whose hands the five editors of the class of ’38 took “Harvardiana,” was a very interesting circle of young men. They were, by the way, classmates and friends of Thoreau, who lived to be better known than they; but I think he was not of the editorial committee. The magazine was really edited in that year entirely by Charles Hayward, Samuel Tenney Hildreth, and Charles Stearns Wheeler. Horatio Hale, the philologist, was in the same class and belonged to the same set. He was named as one of the editors. But he was appointed to Wilkes’s exploring expedition a year before he graduated,—a remarkable testimony, this, to his early ability in the lines of study in which he won such distinction afterwards. It is interesting and amusing to observe that his first printed work was a vocabulary of the language of some Micmac Indians, who camped upon the college grounds in the summer of 1834. Hale learned the language from them, made a vocabulary, and then set up the type and printed the book with his own hand. Hayward, Hildreth, and Wheeler, who carried on the magazine for its third volume, all died young, before the age of thirty. Hayward had written one or more of the lives in Sparks’s “American Biography,” Wheeler had distinguished himself as a Greek scholar here and in Europe, and Hildreth, as a young poet, had given promise for what we all supposed was to be a remarkable future.

To this little circle somebody addressed himself who wanted to establish a chapter of Alpha Delta Phi in Cambridge in 1836. Who this somebody was, I do not know. I wish I did. But he came to Cambridge and met these leaders of the literary work of the classes of ’37 and ’38, and among them they agreed on the charter members for the formation of the Alpha Delta Phi chapter at Harvard. The list of the members from the Harvard classes of 1837 and 1838 shows that these youngsters knew already who their men of letters were. It consists of fourteen names: John Bacon, John Fenwick Eustis, Horatio Hale, Charles Hayward, Samuel Tenney Hildreth, Charles Stearns Wheeler, Henry Williams, James Ivers Trecothick Coolidge, Henry Lawrence Eustis, Nathan Hale, Rufus King, George Warren Lippitt, James Russell Lowell, and Charles Woodman Scates.

This is no place for a history of Alpha Delta Phi. At the moment when the Phi Beta Kappa fraternity, the oldest of the confederated college societies, gave up its secrets, Alpha Delta Phi was formed in Hamilton College of New York. I shall violate none of her secrets if I say, what the history of literature in America shows, that, in the earlier days at least, interest in literature was considered by those who directed the society as a very important condition in the selection of its members.

At Cambridge, when Lowell became one of its first members, there was a special charm in membership. Such societies were absolutely forbidden by a hard and fast rule. They must not be in Harvard College. The existence of the Alpha Delta chapter, therefore, was not to be known, even to the great body of the undergraduates. It had no public exercises. There was no public intimation of meetings. In truth, if its existence had been known, everybody connected with it would have been severely punished, under the college code of that day.

This element of secrecy gave, of course, a special charm to membership. I ought to say that, after sixty years, it makes it more difficult to write of its history. I was myself a member in ’37, ’38, and ’39. Yet, in a somewhat full private diary which I kept in those days, I do not find one reference to my attendance at any meeting; so great was the peril, to my boyish imagination, lest the myrmidons of the “Faculty” should seize upon my papers and examine them, and should learn from them any fact regarding the history of this secret society.

But now, after sixty years, I will risk the vengeance of the authorities of the university. Perhaps they will take away all our degrees, honorary and otherwise; but we will venture. This very secret society, after it was well at work, may have counted at once twenty members,—seniors, juniors, and sophomores. They clubbed their scanty means and hired a small student’s room in what is now Holyoke Street, put in a table and stove and some chairs, and subscribed for the English quarterlies and Blackwood. This room was very near the elegant and convenient club-house owned by the society to-day, if indeed this do not occupy the same ground, as I think it does. Everybody had a pass-key. It was thus a place where you could loaf and be quiet and read, and where once a week we held our literary meetings. Of other meetings, the obligations of secrecy do not permit me to speak. One of my friends, the other day, said that his earliest recollection of Lowell was finding him alone in this modest club-room reading some article in an English review. What happened was that we all took much more interest in the work which the Alpha Delta provided for us than we did in most of the work required of us by the college.

At that time the conventional division of classes at Cambridge made very hard and fast distinctions between students of different classes. Alpha Delta broke up all this and brought us together as gentlemen; and, naturally, the younger fellows did their very best when they were to read in the presence of their seniors. I think, though I am not certain, that I heard Lowell read there the first draft of his papers on Old English Dramatists, which he published afterwards in my brother’s magazine, the “Boston Miscellany,” and which were the subject of the last course of lectures which he delivered. –– From this little group of Alpha Delta men were selected the editors of “Harvardiana” for 1837–38. I suppose, indeed, that in some informal way Alpha Delta chose them. They were Rufus King, afterwards a leader of the bar in Ohio; George Warren Lippitt, so long our secretary of legation at Vienna; Charles Woodman Scates, who went into the practice of law in Carolina; James Russell Lowell; and my brother, Nathan Hale, Jr. All of them stood, when chosen, in what we call the first half of the class. This meant that they were within the number of twenty-four students who had had honors at the several exhibitions up to that time. In point of fact, twenty-four was not half the class. But that phrase long existed; I do not know how long. Practically, to say of a graduate that he was in “the first half of his class” meant that at these exhibitions, or at Commencement, he had received some college honor.

I rather think that the average senior of that year approved this selection of editors, and he would have said in a general way that King and Lippitt were expected to do that heavy work of long eight-page articles which is supposed by boys to make such magazines respected among the graduates; that Scates was relied upon for critical work; that my brother was supposed to have inherited a faculty for editing, and that on him and Lowell, in the general verdict of the class, was imposed the privilege of furnishing the poetry for the magazine and making it entertaining. Of course it was expected that their year’s “Harvardiana” would be better than those of any before.

The five editors had the further privilege of assuming the whole pecuniary responsibility for the undertaking. How this came out I do not know; perhaps I never did. I do not think they ever printed three hundred copies. I do not think they ever had two hundred and fifty subscribers. The volume contains the earliest of Lowell’s printed poems, some of which have never been reprinted, and a copy is regarded by collectors as one of the exceptionally rare nuggets in our literary history.

When this choice of editors was made, I lived with my brother in Stoughton 22. In September, at the time when the first number was published, we had moved to Massachusetts 27, where I lived for two years. Lowell had always been intimate in our room, and from this time until the next March he was there once or twice a day. Indeed, it was a good editor’s room,—we called it the best room in college; and all of them made it their headquarters.

Unfortunately for my readers, the daguerreotype and photograph had not even begun in their benevolent and beneficent career. It was in the next year that Daguerre, in Paris, first exhibited his pictures. The French government rewarded him for his great discovery and published his process to the world. His announcements compelled Mr. Talbot, in England, to make public his processes on paper, which were the beginning of what we now call photography. I think my classmate, Samuel Longfellow, and I took from the window of this same room, Massachusetts 27, the first photograph which was taken in New England. It was made by a little camera intended for draughtsmen. The picture was of Harvard Hall, opposite. And the first portrait taken in Massachusetts was the copy in this picture of a bust of Apollo standing in the window of the college library, in Harvard Hall.

The daguerreotype was announced by Daguerre in January, 1839. He thus forced W.H. Fox Talbot’s hand, and he read his paper on photographic drawings on January 31 of that year. This paper was at once published, and Longfellow and I worked from its suggestions.

Rufus King afterwards won for himself distinction and respect as a lawyer of eminence in Cincinnati. He was the grandson of the great Rufus King, the natural leader of the Federalists and of the North in the dark period of the reign of the House of Virginia. Our Rufus King’s mother was the daughter of Governor Worthington, of Ohio. King had begun his early education at Kenyon College, but came to Cambridge to complete his undergraduate course, and remained there in the law school under Story and Greenleaf. He then returned to Cincinnati, where he lived in distinguished practice in his profession until his death in 1891. “His junior partners were many of them men in the first rank of political, judicial, and professional eminence. But he himself steadily declined all political or even judicial trusts until, in 1874, he became a member of the Constitutional Convention of Ohio. Over this body he presided. He did not shrink from any work in education. He was active in the public schools. He was the chief workman in creating the Cincinnati Public Library, and, as one of the trustees of the McMicken bequest, he nursed it into the foundation of the University of Cincinnati. In 1875 he became Dean of the Faculty of the Law School, and served in that office for five years. Until his death he continued his lectures on Constitutional Law and the Law of Real Property. No citizen of Cincinnati was more useful or more honored.”

Lowell was with Mr. King in the Cambridge law school.

Of the five editors, four became lawyers—so far, at least, as to take the degree of Bachelor of Laws at Cambridge. The fifth, George Warren Lippitt, from Rhode Island, remained in Cambridge after he graduated and studied at the divinity school.

There were other clergymen in his class, who attained, as they deserved, distinction afterwards. Lowell frequently refers in his correspondence to Coolidge, Ellis, Renouf, and Washburn. Lippitt’s articles in “Harvardiana” show more maturity, perhaps, than those of any of the others. He had entered the class as a sophomore, and was the oldest, I believe, of the five. For ten years, from 1842 to 1852, he was a valuable preacher in the Unitarian church, quite unconventional, courageous, candid, and outspoken. He was without a trace of that ecclesiasticism, which the New Testament writers would call accursed, which is the greatest enemy of Christianity to-day, and does more to hinder it than any other device of Satan. In 1852 Lippitt sought and accepted an appointment as secretary of legation to Vienna. He married an Austrian lady, and represented the United States at the imperial court there in one and another capacity for the greater part of the rest of his life. He died there in 1891.

Charles Woodman Scates, also, like King and Lippitt, entered the class after the freshman year. There was a tender regard between him and Lowell. When they graduated, Scates went to South Carolina to study law. But for his delicate health, I think his name would be as widely known in the Southern states as Rufus King’s is in the valley of the Ohio. I count it as a great misfortune that almost all of Lowell’s letters to him, in an intimate and serious correspondence which covered many years, were lost when the house in Germantown was burned where he spent the last part of his life. Fortunately, however, Mr. Norton had made considerable extracts from them in the volume of Lowell’s published letters. From one of these letters which has been preserved, I copy a little poem, which I believe has never been printed. Lowell writes:—

“I will copy you a midnight improvisation, which must be judged kindly accordingly. It is a mere direct transcript of actual feelings, and so far good:—

“What is there in the midnight breeze

That tells of things gone by?

Why does the murmur of the trees

Bring tears into my eye?

O Night! my heart doth pant for thee,

Thy stars are lights of memory!

“What is there in the setting moon

Behind yon gloomy pine,

That bringeth back the broad high noon

Of hopes that once were mine?

Seemeth my heart like that pale flower

That opes not till the midnight hour.

“The day may make the eyes run o’er

From hearts that laden be,

The sunset doth a music pour

Round rock and hill and tree;

But in the night wind’s mournful blast

There cometh somewhat of the Past.

“In garish day I often feel

The Present’s full excess,

And o’er my outer soul doth steal

A deep life-weariness.

But the great thoughts that midnight brings

Look calmly down on earthly things.

“Oh, who may know the spell that lies

In a few bygone years!

These lines may one day fill my eyes

With Memory’s doubtful tears—

Tears which we know not if they be

Of happiness or agony.

“Open thy melancholy eyes,

O Night! and gaze on me!

That I may feel the charm that lies

In their dim mystery.

Unveil thine eyes so gloomy bright

And look upon my soul, O Night!”

“Have you ever felt this? I have, many and many a time.”

Of my dear brother, Nathan Hale, Jr., I will not permit myself to speak at any length. We shall meet him once and again as our sketch of Lowell’s life goes on. It is enough for our purpose now that, though he prepared himself carefully for the bar, and, as a young man, opened a lawyer’s office, the most of his life, until he died in 1872, was spent in the work of an editor. Our father had been an editor from 1809, and of all his children, boys and girls, it might be said that they were cradled in the sheets of a newspaper.

My brother was the editor of the “Boston Miscellany” in 1841, when Lowell and Story of their class were his chief coöperators. From that time forward he served the Boston “Advertiser,” frequently as its chief; and when he died, he was one of the editors of “Old and New,” his admirable literary taste and his delicate judgment presiding over that discrimination, so terrible to magazine editors, in the accepting or rejecting of the work of contributors.

All of these five boys, or young men, were favorite pupils of Professor Edward Tyrrell Channing. When, in September, 1837, they undertook the publication of “Harvardiana,” Lowell was eighteen, Hale was eighteen, Scates, King, and Lippitt but little older.

With such recourse the fourth volume started. It cost each subscriber two dollars a year. I suppose the whole volume contained about as much “reading matter,” as a cold world calls it, as one number of “Harper’s Magazine.” These young fellows’ reputations were not then made. But as times have gone by, the people who “do the magazines” in newspaper offices would have felt a certain wave of languid interest if a single number of “Harper” should bring them a story and a poem and a criticism by Lowell; something like this from William Story; a political paper by Rufus King; with General Loring, Dr. Washburn, Dr. Coolidge, and Dr. Ellis to make up the number.

Lowell’s intimate relations with George Bailey Loring began, I think, even earlier than their meeting in college. They continued long after his college life, and I may refer to them better in another chapter.

The year worked along. They had the dignity of seniors now, and the wider range of seniors. This means that they no longer had to construe Latin and Greek, and that the college studies were of rather a broader scope than before. It meant with these young fellows that they took more liberty in long excursions from Cambridge, which would sacrifice two or three recitations for a sea-beach in the afternoon, or perhaps for an evening party twenty miles away.

NATHAN HALE

Young editors always think that they have a great deal of unpublished writing in their desks or portfolios, which is of the very best type, and which, “with a little dressing over,” will bring great credit to the magazine. Alas! the first and second numbers always exhaust these reserves. Yet in the case of “Harvardiana” no eager body of contributors appeared, and the table of contents shows that the five editors contributed much more than half the volume.

Lowell’s connection with this volume ought to rescue it from oblivion. It has a curiously old-fashioned engraving on the meagre title-page. It represents University Hall as it then was—before the convenient shelter of the corridor in front was removed. “Blackwood,” and perhaps other magazines, had given popularity to the plan, which all young editors like, of an imagined conference between readers and editors, in which the editors tell what is passing in the month. Christopher North had given an appetite among youngsters for this sort of thing, and the new editors fancied that “Skillygoliana,” such an imagined dialogue, would be very bright, funny, and attractive. But the fun has long since evaporated; the brightness has long since tarnished. I think they themselves found that the papers became a bore to them, and did not attract the readers.

The choice of the title “Skillygoliana” was, without doubt, Lowell’s own. “Skillygolee” is defined in the Century Dictionary in words which give the point to his use of it: “A poor, thin, watery kind of broth or soup ... served out to prisoners in the hulks, paupers in workhouses, and the like; a drink made of oatmeal, sugar, and water, formerly served out to sailors in the British navy.”

Here is a scrap which must serve as a bit of mosaic carried off from this half-built temple:—

SKILLYGOLIANA—III.

Since Friday morning, on each busy tongue,

“Shameful!” “Outrageous!” has incessant rung.

But what’s the matter? Why should words like these

Of dreadful omen hang on every breeze?

Has our Bank failed, and shown, to cash her notes,

Not cents enough to buy three Irish votes?

Or, worse than that, and worst of human ills,

Will not the lordly Suffolk take her bills?

Sooner expect, than see her credit die,

Proud Bunker’s pile to creep an inch more high.

Has want of patronage, or payments lean,

Put out the rushlight of our Magazine?

No, though Penumbra swears “the thing is flat,”

Thank Heaven, taste has not sunk so low as that!

... Has Texas, freed by Samuel the great,

Entered the Union as another State?

No, still she trades in slaves as free as air,

And Sam still fills the presidential chair,

Rules o’er the realm, the freeman’s proudest hope,

In dread of naught but bailiffs and a rope.

... What is the matter, then? Why, Thursday night

Some chap or other strove to vent his spite

By blowing up the chapel with a shell,

But unsuccessfully—he might as well

With popgun threat the noble bird of Jove,

Or warm his fingers at a patent stove,

As try to shake old Harvard’s deep foundations

With such poor, despicable machinations....

Long may she live, and Harvard’s morning star

Light learning’s wearied pilgrims from afar!

Long may the chapel echo to the sound

Of sermon lengthy or of part profound,

And long may Dana’s gowns survive to grace

Each future runner in the learned race!

I believe Lowell afterwards printed among his collected poems one or two which first appeared in “Harvardiana.” Here is a specimen which I believe has never been reprinted until now:—

“Perchance improvement, in some future time,

May soften down the rugged path of rhyme,

Build a nice railroad to the sacred mount,

And run a steamboat to the muses’ fount!

* * * * * * * *

Fain would I more—but could my muse aspire

To praise in fitting strains our College choir?

Ah, happy band! securely hid from sight,

Ye pour your melting strains with all your might;

And as the prince, on Prosper’s magic isle,

Stood spellbound, listening with a raptured smile

To Ariel’s witching notes, as through the trees

They stole like angel voices on the breeze,

So when some strange divine the hymn gives out,

Pleased with the strains he casts his eyes about,

All round the chapel gives an earnest stare,

And wonders where the deuce the singers are,

Nor dreams that o’er his own bewildered pate

There hangs suspended such a tuneful weight!”

From “A Hasty Pudding Poem.”

In the winter of the senior year the class made its selection of its permanent committees and of the orator, poet, and other officers for “Class Day,” already the greatest, or one of the greatest, of the Cambridge festivals. I do not remember that there was any controversy as to the selection of either orator or poet. It seemed quite of course that James Ivers Trecothick Coolidge, now the Rev. Dr. Coolidge, should be the orator; and no opposition was possible to the choice of Lowell as poet.

Some thirty years later, in Lowell’s absence from Cambridge, I had to take his place as president of a Phi Beta Kappa dinner at Cambridge. One of those young friends to whom I always give the privilege of advising me begged me with some feeling, before the dinner, not to be satisfied with “trotting out the old war-horses,” but to be sure to call out enough of the younger men to speak or to read verses. I said, in reply, that the old war-horses were not a bad set after all, that I had Longfellow and Holmes and Joe Choate and James Carter and President Eliot and Professor Thayer and Dr. Everett on my string, of whom I was sure. But I added, “The year Lowell graduated we were as sure as we are now that in him was firstrate poetical genius and that here was to be one of the leaders of the literature of the time.” And I said, “You know this year’s senior class better than I do, and if you will name to me the man who is going to fill that bill twenty years hence, you may be sure that I will call upon him to-morrow.”

I like to recall this conversation here, because it describes precisely the confidence which we who then knew Lowell had in his future. I think that the government of the college, that “Faculty” of which undergraduates always talk so absurdly, was to be counted among those who knew him. I think they thought of his power as highly as we did. I think they did all that they could in decency to bring Lowell through his undergraduate course without public disapprobation. President Quincy would send for him to give him what we called “privates,” by which we meant private admonitions. But Lowell somehow hardened himself to these, the more so because he found them in themselves easy to bear.

The Faculty had in it such men as Quincy, Sparks and Felton, who were Quincy’s successors; Peirce and Longfellow and Channing, all of them men of genius and foresight; and I think they meant to pull Lowell through. In Lowell’s case it was simply indifference to college regulations which they were compelled to notice. He would not go to morning prayers. We used to think he meant to go. The fellows said he would screw himself up to go on Monday morning, as if his presence there might propitiate the Faculty, who met always on Monday night. How could they be hard on him, if he had been at chapel that very morning! But, of course, if they meant to have any discipline, if there were to be any rule for attendance at chapel, the absence of a senior six days in seven must be noticed.

And so, to the horror of all of us, of his nearest friends most of all, Lowell was “rusticated,” as the old phrase was. That meant that he was told that he must reside in Concord until Commencement, which would come in the last week in August. It meant no class poet, no good-by suppers, no vacation rambles in the six weeks preceding Commencement. It meant regular study in the house of the Rev. Barzillai Frost, of Concord, until Commencement Day! And it meant that he was not even to come to Cambridge in the interval.

I have gone into this detail because I have once or twice stumbled upon perfectly absurd stories about Lowell’s suspension. And it is as well to put your thumb upon them at once. Thus, I have heard it said that there was some mysterious offense which he had committed. And, again, I have heard it said that he had become grossly intemperate; all of which is the sheerest nonsense. I think I saw him every day of his life for the first six months of his senior year, frequently half a dozen times a day, excepting in the winter vacation. He lived out of college; our room was in college, and it was a convenient loafing place. Now, let me say that from his birth to his death I never saw him in the least under any influence of liquor which could be detected in any way. I never, till within five years, heard any suggestion of the gossip which I have referred to above. There is in the letters boyish joking about cocktails and glasses of beer. But here there is nothing more than might ordinarily come into the foolery of anybody in college familiarly addressing a classmate.

It is as well to say here that a careful examination of the private records of the Faculty of the time entirely confirms the statement I have made above.

CHAPTER IV

CONCORD

Concord was then and is now one of the most charming places in the world. But to poor Lowell it was exile. He must leave all the gayeties of the life of a college senior, just ready to graduate, and he must give up what he valued more—the freedom of that life as he had chosen to conduct it. He was but just nineteen years old. And even to the gravest critic or biographer, though writing after half a century, there seems something droll in the idea of directing such a boy as that, with his head full of Tennyson and Wordsworth, provoked that he had to leave Beaumont and Fletcher and Massinger behind him—to set him to reciting every day ten pages of “Locke on the Human Understanding” in the quiet study of the Rev. Barzillai Frost. So is it,—as one has to say that Lowell hated Concord when he went there, and when he came away he was quite satisfied that he had had a very agreeable visit among very agreeable people.

Concord is now a place of curious interest to travelers, and the stream of intelligent visitors from all parts of the English-speaking world passes through it daily. It has been the home, first of all, of Emerson and then of the poet Channing, of Alcott, of Thoreau, of Hawthorne, known by their writings to almost every one who dabbles in literature. It has been the home of the Hoars, father and sons, honored and valued in government and in law. Two railways carry the stream of pilgrims there daily, and at each station you find two or three carriages ready to take you to the different shrines, with friendly, well-read “drivers” quite as intelligent as you are yourself, and well informed as to the interests which bring you there.