автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу A System of Logic: Ratiocinative and Inductive / 7th Edition, Vol. I

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A System of Logic: Ratiocinative and

Inductive, by John Stuart Mill

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: A System of Logic: Ratiocinative and Inductive

7th Edition, Vol. I

Author: John Stuart Mill

Release Date: February 27, 2011 [EBook #35420]

Language: English

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A SYSTEM OF LOGIC, VOL I ***

Produced by David Clarke, Stephen H. Sentoff and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

A

SYSTEM OF LOGIC

RATIOCINATIVE AND INDUCTIVE

VOL. I.

A

SYSTEM OF LOGIC

RATIOCINATIVE AND INDUCTIVE

BEING A CONNECTED VIEW OF THE

PRINCIPLES OF EVIDENCE

AND THE

METHODS OF SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION

BY

JOHN STUART MILL

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOL. I.

SEVENTH EDITION

LONDON:

LONGMANS, GREEN, READER, AND DYER

MDCCCLXVIII

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION.

This book makes no pretence of giving to the world a new theory of the intellectual operations. Its claim to attention, if it possess any, is grounded on the fact that it is an attempt not to supersede, but to embody and systematize, the best ideas which have been either promulgated on its subject by speculative writers, or conformed to by accurate thinkers in their scientific inquiries.

To cement together the detached fragments of a subject, never yet treated as a whole; to harmonize the true portions of discordant theories, by supplying the links of thought necessary to connect them, and by disentangling them from the errors with which they are always more or less interwoven; must necessarily require a considerable amount of original speculation. To other originality than this, the present work lays no claim. In the existing state of the cultivation of the sciences, there would be a very strong presumption against any one who should imagine that he had effected a revolution in the theory of the investigation of truth, or added any fundamentally new process to the practice of it. The improvement which remains to be effected in the methods of philosophizing (and the author believes that they have much need of improvement) can only consist in performing, more systematically and accurately, operations with which, at least in their elementary form, the human intellect in some one or other of its employments is already familiar.

In the portion of the work which treats of Ratiocination, the author has not deemed it necessary to enter into technical details which may be obtained in so perfect a shape from the existing treatises on what is termed the Logic of the Schools. In the contempt entertained by many modern philosophers for the syllogistic art, it will be seen that he by no means participates; though the scientific theory on which its defence is usually rested appears to him erroneous: and the view which he has suggested of the nature and functions of the Syllogism may, perhaps, afford the means of conciliating the principles of the art with as much as is well grounded in the doctrines and objections of its assailants.

The same abstinence from details could not be observed in the First Book, on Names and Propositions; because many useful principles and distinctions which were contained in the old Logic, have been gradually omitted from the writings of its later teachers; and it appeared desirable both to revive these, and to reform and rationalize the philosophical foundation on which they stood. The earlier chapters of this preliminary Book will consequently appear, to some readers, needlessly elementary and scholastic. But those who know in what darkness the nature of our knowledge, and of the processes by which it is obtained, is often involved by a confused apprehension of the import of the different classes of Words and Assertions, will not regard these discussions as either frivolous, or irrelevant to the topics considered in the later Books.

On the subject of Induction, the task to be performed was that of generalizing the modes of investigating truth and estimating evidence, by which so many important and recondite laws of nature have, in the various sciences, been aggregated to the stock of human knowledge. That this is not a task free from difficulty may be presumed from the fact, that even at a very recent period, eminent writers (among whom it is sufficient to name Archbishop Whately, and the author of a celebrated article on Bacon in the Edinburgh Review) have not scrupled to pronounce it impossible.[1] The author has endeavoured to combat their theory in the manner in which Diogenes confuted the sceptical reasonings against the possibility of motion; remembering that Diogenes' argument would have been equally conclusive, though his individual perambulations might not have extended beyond the circuit of his own tub.

Whatever may be the value of what the author has succeeded in effecting on this branch of his subject, it is a duty to acknowledge that for much of it he has been indebted to several important treatises, partly historical and partly philosophical, on the generalities and processes of physical science, which have been published within the last few years. To these treatises, and to their authors, he has endeavoured to do justice in the body of the work. But as with one of these writers, Dr. Whewell, he has occasion frequently to express differences of opinion, it is more particularly incumbent on him in this place to declare, that without the aid derived from the facts and ideas contained in that gentleman's History of the Inductive Sciences, the corresponding portion of this work would probably not have been written.

The concluding Book is an attempt to contribute towards the solution of a question, which the decay of old opinions, and the agitation that disturbs European society to its inmost depths, render as important in the present day to the practical interests of human life, as it must at all times be to the completeness of our speculative knowledge: viz. Whether moral and social phenomena are really exceptions to the general certainty and uniformity of the course of nature; and how far the methods, by which so many of the laws of the physical world have been numbered among truths irrevocably acquired and universally assented to, can be made instrumental to the formation of a similar body of received doctrine in moral and political science.

PREFACE TO THE THIRD AND FOURTH EDITIONS.

Several criticisms, of a more or less controversial character, on this work, have appeared since the publication of the second edition; and Dr. Whewell has lately published a reply to those parts of it in which some of his opinions were controverted.[2]

I have carefully reconsidered all the points on which my conclusions have been assailed. But I have not to announce a change of opinion on any matter of importance. Such minor oversights as have been detected, either by myself or by my critics, I have, in general silently, corrected: but it is not to be inferred that I agree with the objections which have been made to a passage, in every instance in which I have altered or cancelled it. I have often done so, merely that it might not remain a stumbling-block, when the amount of discussion necessary to place the matter in its true light would have exceeded what was suitable to the occasion.

To several of the arguments which have been urged against me, I have thought it useful to reply with some degree of minuteness; not from any taste for controversy, but because the opportunity was favourable for placing my own conclusions, and the grounds of them, more clearly and completely before the reader. Truth, on these subjects, is militant, and can only establish itself by means of conflict. The most opposite opinions can make a plausible show of evidence while each has the statement of its own case; and it is only possible to ascertain which of them is in the right, after hearing and comparing what each can say against the other, and what the other can urge in its defence.

Even the criticisms from which I most dissent have been of great service to me, by showing in what places the exposition most needed to be improved, or the argument strengthened. And I should have been well pleased if the book had undergone a much greater amount of attack; as in that case I should probably have been enabled to improve it still more than I believe I have now done.

In the subsequent editions, the attempt to improve the work by additions and corrections, suggested by criticism or by thought, has been continued. In the present (seventh) edition, a few further corrections have been made, but no material additions.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] In the later editions of Archbishop Whately's Logic, he states his meaning to be, not that "rules" for the ascertainment of truths by inductive investigation cannot be laid down, or that they may not be "of eminent service," but that they "must always be comparatively vague and general, and incapable of being built up into a regular demonstrative theory like that of the Syllogism." (Book IV. ch. iv. § 3.) And he observes, that to devise a system for this purpose, capable of being "brought into a scientific form," would be an achievement which "he must be more sanguine than scientific who expects." (Book IV. ch. ii. § 4.) To effect this, however, being the express object of the portion of the present work which treats of Induction, the words in the text are no overstatement of the difference of opinion between Archbishop Whately and me on the subject.

[2] Now forming a chapter in his volume on The Philosophy of Discovery.

CONTENTS

OF

THE FIRST VOLUME.

INTRODUCTION.

§

1.A definition at the commencement of a subject must be provisional

1 2.Is logic the art and science of reasoning?

2 3.Or the art and science of the pursuit of truth?

3 4.Logic is concerned with inferences, not with intuitive truths

5 5.Relation of logic to the other sciences

8 6.Its utility, how shown

10 7.Definition of logic stated and illustrated

11BOOK I.

OF NAMES AND PROPOSITIONS.

Chapter I. Of the Necessity of commencing with an Analysis of Language.

§

1.Theory of names, why a necessary part of logic

17 2.First step in the analysis of Propositions

18 3.Names must be studied before Things

21Chapter II. Of Names.

§

1.Names are names of things, not of our ideas

23 2.Words which are not names, but parts of names

24 3.General and Singular names

26 4.Concrete and Abstract

29 5.Connotative and Non-connotative

31 6.Positive and Negative

42 7.Relative and Absolute

44 8.Univocal and Æquivocal

47Chapter III. Of the Things denoted by Names.

§

1.Necessity of an enumeration of Nameable Things. The Categories of Aristotle

49 2.Ambiguity of the most general names

51 3.Feelings, or states of consciousness

54 4.Feelings must be distinguished from their physical antecedents. Perceptions, what

56 5.Volitions, and Actions, what

58 6.Substance and Attribute

59 7.Body

61 8.Mind

67 9.Qualities

69 10.Relations

72 11.Resemblance

74 12.Quantity

78 13.All attributes of bodies are grounded on states of consciousness

79 14.So also all attributes of mind

80 15.Recapitulation

81Chapter IV. Of Propositions.

§

1.Nature and office of the copula

85 2.Affirmative and Negative propositions

87 3.Simple and Complex

89 4.Universal, Particular, and Singular

93Chapter V. Of the Import of Propositions.

§

1.Doctrine that a proposition is the expression of a relation between two ideas

96 2.Doctrine that it is the expression of a relation between the meanings of two names

99 3.Doctrine that it consists in referring something to, or excluding something from, a class

103 4.What it really is

107 5.It asserts (or denies) a sequence, a coexistence, a simple existence, a causation

110 6.—or a resemblance

112 7.Propositions of which the terms are abstract

115Chapter VI. Of Propositions merely Verbal.

§

1.Essential and Accidental propositions

119 2.All essential propositions are identical propositions

120 3.Individuals have no essences

124 4.Real propositions, how distinguished from verbal

126 5.Two modes of representing the import of a Real proposition

127Chapter VII. Of the Nature of Classification, and the Five Predicables.

§

1.Classification, how connected with Naming

129 2.The Predicables, what

131 3.Genus and Species

131 4.Kinds have a real existence in nature

134 5.Differentia

139 6.Differentiæ for general purposes, and differentiæ for special or technical purposes

141 7.Proprium

144 8.Accidens

146Chapter VIII. Of Definition.

§

1.A definition, what

148 2.Every name can be defined, whose meaning is susceptible of analysis

150 3.Complete, how distinguished from incomplete definitions

152 4.—and from descriptions

154 5.What are called definitions of Things, are definitions of Names with an implied assumption of the existence of Things corresponding to them

157 6.—even when such things do not in reality exist

165 7.Definitions, though of names only, must be grounded on knowledge of the corresponding Things

167BOOK II.

OF REASONING.

Chapter I. Of Inference, or Reasoning, in general.

§

1.Retrospect of the preceding book

175 2.Inferences improperly so called

177 3.Inferences proper, distinguished into inductions and ratiocinations

181Chapter II. Of Ratiocination, or Syllogism.

§

1.Analysis of the Syllogism

184 2.The

dictum de omninot the foundation of reasoning, but a mere identical proposition

191 3.What is the really fundamental axiom of Ratiocination

196 4.The other form of the axiom

199Chapter III. Of the Functions, and Logical Value, of the Syllogism.

§

1.Is the syllogism a

petitio principii?

202 2.Insufficiency of the common theory

203 3.All inference is from particulars to particulars

205 4.General propositions are a record of such inferences, and the rules of the syllogism are rules for the interpretation of the record

214 5.The syllogism not the type of reasoning, but a test of it

218 6.The true type, what

222 7.Relation between Induction and Deduction

226 8.Objections answered

227 9.Of Formal Logic, and its relation to the Logic of Truth

231Chapter IV. Of Trains of Reasoning, and Deductive Sciences.

§

1.For what purpose trains of reasoning exist

234 2.A train of reasoning is a series of inductive inferences

234 3.—from particulars to particulars through marks of marks

237 4.Why there are deductive sciences

240 5.Why other sciences still remain experimental

244 6.Experimental sciences may become deductive by the progress of experiment

246 7.In what manner this usually takes place

247Chapter V. Of Demonstration, and Necessary Truths.

§

1.The Theorems of geometry are necessary truths only in the sense of necessarily following from hypotheses

251 2.Those hypotheses are real facts with some of their circumstances exaggerated or omitted

255 3.Some of the first principles of geometry are axioms, and these are not hypothetical

256 4.—but are experimental truths

258 5.An objection answered

261 6.Dr. Whewell's opinions on axioms examined

264Chapter VI. The same Subject continued.

§

1.All deductive sciences are inductive

281 2.The propositions of the science of number are not verbal, but generalizations from experience

284 3.In what sense hypothetical

289 4.The characteristic property of demonstrative science is to be hypothetical

290 5.Definition of demonstrative evidence

292Chapter VII. Examination of some Opinions opposed to the preceding doctrines.

§

1.Doctrine of the Universal Postulate

294 2.The test of inconceivability does not represent the aggregate of past experience

296 3.—nor is implied in every process of thought

299 4.Sir W. Hamilton's opinion on the Principles of Contradiction and Excluded Middle

306BOOK III.

OF INDUCTION.

Chapter I. Preliminary Observations on Induction in general.

§

1.Importance of an Inductive Logic

313 2.The logic of science is also that of business and life

314Chapter II. Of Inductions improperly so called.

§

1.Inductions distinguished from verbal transformations

319 2.—from inductions, falsely so called, in mathematics

321 3.—and from descriptions

323 4.Examination of Dr. Whewell's theory of Induction

326 5.Further illustration of the preceding remarks

336Chapter III. On the Ground of Induction.

§

1.Axiom of the uniformity of the course of nature

341 2.Not true in every sense. Induction

per enumerationem simplicem 346 3.The question of Inductive Logic stated

348Chapter IV. Of Laws of Nature.

§

1.The general regularity in nature is a tissue of partial regularities, called laws

351 2.Scientific induction must be grounded on previous spontaneous inductions

355 3.Are there any inductions fitted to be a test of all others?

357Chapter V. Of the Law of Universal Causation.

§

1.The universal law of successive phenomena is the Law of Causation

360 2.—

i.e.the law that every consequent has an invariable antecedent

363 3.The cause of a phenomenon is the assemblage of its conditions

365 4.The distinction of agent and patient illusory

373 5.The cause is not the invariable antecedent, but the

unconditionalinvariable antecedent

375 6.Can a cause be simultaneous with its effect?

380 7.Idea of a Permanent Cause, or original natural agent

383 8.Uniformities of coexistence between effects of different permanent causes, are not laws

386 9.Doctrine that volition is an efficient cause, examined

387Chapter VI. Of the Composition of Causes.

§

1.Two modes of the conjunct action of causes, the mechanical and the chemical

405 2.The composition of causes the general rule; the other case exceptional

408 3.Are effects proportional to their causes?

412Chapter VII. Of Observation and Experiment.

§

1.The first step of inductive inquiry is a mental analysis of complex phenomena into their elements

414 2.The next is an actual separation of those elements

416 3.Advantages of experiment over observation

417 4.Advantages of observation over experiment

420Chapter VIII. Of the Four Methods of Experimental Inquiry.

§

1.Method of Agreement

425 2.Method of Difference

428 3.Mutual relation of these two methods

429 4.Joint Method of Agreement and Difference

433 5.Method of Residues

436 6.Method of Concomitant Variations

437 7.Limitations of this last method

443Chapter IX. Miscellaneous Examples of the Four Methods.

§

1.Liebig's theory of metallic poisons

449 2.Theory of induced electricity

453 3.Dr. Wells' theory of dew

457 4.Dr. Brown-Séquard's theory of cadaveric rigidity

465 5.Examples of the Method of Residues

471 6.Dr. Whewell's objections to the Four Methods

475Chapter X. Of Plurality of Causes; and of the Intermixture of Effects.

§

1.One effect may have several causes

482 2.—which is the source of a characteristic imperfection of the Method of Agreement

483 3.Plurality of Causes, how ascertained

487 4.Concurrence of Causes which do not compound their effects

489 5.Difficulties of the investigation, when causes compound their effects

494 6.Three modes of investigating the laws of complex effects

499 7.The method of simple observation inapplicable

500 8.The purely experimental method inapplicable

501Chapter XI. Of the Deductive Method.

§

1.First stage; ascertainment of the laws of the separate causes by direct induction

507 2.Second stage; ratiocination from the simple laws of the complex cases

512 3.Third stage; verification by specific experience

514Chapter XII. Of the Explanation of Laws of Nature.

§

1.Explanation defined

518 2.First mode of explanation, by resolving the law of a complex effect into the laws of the concurrent causes and the fact of their coexistence

518 3.Second mode; by the detection of an intermediate link in the sequence

519 4.Laws are always resolved into laws more general than themselves

520 5.Third mode; the subsumption of less general laws under a more general one

524 6.What the explanation of a law of nature amounts to

526Chapter XIII. Miscellaneous Examples of the Explanation of Laws of Nature.

§

1.The general theories of the sciences

529 2.Examples from chemical speculations

531 3.Example from Dr. Brown-Séquard's researches on the nervous system

533 4.Examples of following newly-discovered laws into their complex manifestations

534 5.Examples of empirical generalizations, afterwards confirmed and explained deductively

536 6.Example from mental science

538 7.Tendency of all the sciences to become deductive

539nothing; it merely denotes the attribute corresponding to a certain sensation: but if we are making a classification of colours, and desire to justify, or even merely to point out, the particular place assigned to whiteness in our arrangement, we may define it "the colour produced by the mixture of all the simple rays;" and this fact, though by no means implied in the meaning of the word whiteness as ordinarily used, but only known by subsequent scientific investigation, is part of its meaning in the particular essay or treatise, and becomes the differentia of the species.

proportion to the pleasurable or painful character of the impressions, being felt with peculiar force in the synchronous class of associations; it is remarked by the writer referred to, that in minds of strong organic sensibility synchronous associations will be likely to predominate, producing a tendency to conceive things in pictures and in the concrete, richly clothed in attributes and circumstances, a mental habit which is commonly called Imagination, and is one of the peculiarities of the painter and the poet; while persons of more moderate susceptibility to pleasure and pain will have a tendency to associate facts chiefly in the order of their succession, and such persons, if they possess mental superiority, will addict themselves to history or science rather than to creative art. This interesting speculation the author of the present work has endeavoured, on another occasion, to pursue farther, and to examine how far it will avail towards explaining the peculiarities of the poetical temperament.

certain that 1 is always equal in number to 1; and where the mere number of objects, or of the parts of an object, without supposing them to be equivalent in any other respect, is all that is material, the conclusions of arithmetic, so far as they go to that alone, are true without mixture of hypothesis. There are a few such cases; as, for instance, an inquiry into the amount of the population of any country. It is indifferent to that inquiry whether they are grown people or children, strong or weak, tall or short; the only thing we want to ascertain is their number. But whenever, from equality or inequality of number, equality or inequality in any other respect is to be inferred, arithmetic carried into such inquiries becomes as hypothetical a science as geometry. All units must be assumed to be equal in that other respect; and this is never accurately true, for one actual pound weight is not exactly equal to another, nor one measured mile's length to another; a nicer balance, or more accurate measuring instruments, would always detect some difference.

continually take place in the less advanced branches of physical knowledge, without enabling them to throw off the character of experimental sciences. Thus with regard to the two unconnected propositions before cited, namely, Acids redden vegetable blues, Alkalies make them green; it is remarked by Liebig, that all blue colouring matters which are reddened by acids (as well as, reciprocally, all red colouring matters which are rendered blue by alkalies) contain nitrogen: and it is quite possible that this circumstance may one day furnish a bond of connexion between the two propositions in question, by showing that the antagonistic action of acids and alkalies in producing or destroying the colour blue, is the result of some one, more general, law. Although this connecting of detached generalizations is so much gain, it tends but little to give a deductive character to any science as a whole; because the new courses of observation and experiment, which thus enable us to connect together a few general truths, usually make known to us a still greater number of unconnected new ones. Hence chemistry, though similar extensions and simplifications of its generalizations are continually taking place, is still in the main an experimental science; and is likely so to continue unless some comprehensive induction should be hereafter arrived at, which, like Newton's, shall connect a vast number of the smaller known inductions together, and change the whole method of the science at once. Chemistry has already one great generalization, which, though relating to one of the subordinate aspects of chemical phenomena, possesses within its limited sphere this comprehensive character; the principle of Dalton, called the atomic theory, or the doctrine of chemical equivalents: which by enabling us to a certain extent to foresee the proportions in which two substances will combine, before the experiment has been tried, constitutes undoubtedly a source of new chemical truths obtainable by deduction, as well as a connecting principle for all truths of the same description previously obtained by experiment.

words, but that in others the source of the error is a misapprehension of things; that a person who has not the use of language at all may form propositions mentally, and that they may be untrue, that is, he may believe as matters of fact what are not really so. This last admission cannot be made in stronger terms than it is by Hobbes himself;

Let the fact be what it may, if it has begun to exist, it was preceded by some fact or facts, with which it is invariably connected. For every event there exists some combination of objects or events, some given concurrence of circumstances, positive and negative, the occurrence of which is always followed by that phenomenon. We may not have found out what this concurrence of circumstances may be; but we never doubt that there is such a one, and that it never occurs without having the phenomenon in question as its effect or consequence. On the universality of this truth depends the possibility of reducing the inductive process to rules. The undoubted assurance we have that there is a law to be found if we only knew how to find it, will be seen presently to be the source from which the canons of the Inductive Logic derive their validity.

the means which mankind possess for exploring the laws of nature by specific observation and experience.

M. Comte, limit the sphere of scientific investigation to Laws of Phenomena, and speak of the inquiry into causes as vain and futile. The causes which M. Comte designates as inaccessible, are efficient causes. The investigation of physical, as opposed to efficient, causes (including the study of all the active forces in Nature, considered as facts of observation) is as important a part of M. Comte's conception of science as of Dr. Whewell's. His objection to the word cause is a mere matter of nomenclature, in which, as a matter of nomenclature, I consider him to be entirely wrong. "Those," it is justly remarked by Mr. Bailey,

this would be an exact parallel to his doctrine about the belief in matter.

pupil to put away the glasses which distort the object, and to use those which are adapted to his purpose in such a manner as to assist, not perplex, his vision; he would not be in a condition to practise the remaining part of their discipline with any prospect of advantage. Therefore it is that an inquiry into language, so far as is needful to guard against the errors to which it gives rise, has at all times been deemed a necessary preliminary to the study of logic.

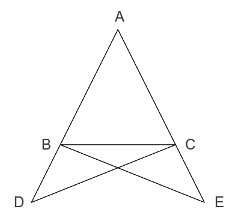

the fundamental axiom concerning straight lines, is a mark that the reflected rays pass through the focus. Most chains of physical deduction are of this more complicated type; and even in mathematics such are abundant, as in all propositions where the hypothesis includes numerous conditions: "If a circle be taken, and if within that circle a point be taken, not the centre, and if straight lines be drawn from that point to the circumference, then," &c.

origin, very frequently excites a similar affection in the other eye, which may be cured by section of the intervening nerve:

we may affirm simple existence. But what is a noumenon? An unknown cause. In affirming, therefore, the existence of a noumenon, we affirm causation. Here, therefore, are two additional kinds of fact, capable of being asserted in a proposition. Besides the propositions which assert Sequence or Coexistence, there are some which assert simple Existence; and others assert Causation, which, subject to the explanations which will follow in the Third Book, must be considered provisionally as a distinct and peculiar kind of assertion.

without being connoted by the word, it follows from an attribute which the word does connote, viz. from the attribute of rationality. But this is a Proprium of the second kind, which follows by way of causation. How it is that one property of a thing follows, or can be inferred, from another; under what conditions this is possible, and what is the exact meaning of the phrase; are among the questions which will occupy us in the two succeeding Books. At present it needs only be said, that whether a Proprium follows by demonstration or by causation, it follows necessarily; that is to say, its not following would be inconsistent with some law which we regard as a part of the constitution either of our thinking faculty or of the universe.

and simultaneity, of likeness and unlikeness. These, not being grounded on any fact or phenomenon distinct from the related objects themselves, do not admit of the same kind of analysis. But these relations, though not, like other relations, grounded on states of consciousness, are themselves states of consciousness: resemblance is nothing but our feeling of resemblance; succession is nothing but our feeling of succession. Or, if this be disputed (and we cannot, without transgressing the bounds of our science, discuss it here), at least our knowledge of these relations, and even our possibility of knowledge, is confined to those which subsist between sensations, or other states of consciousness; for, though we ascribe resemblance, or succession, or simultaneity, to objects and to attributes, it is always in virtue of resemblance or succession or simultaneity in the sensations or states of consciousness which those objects excite, and on which those attributes are grounded.

evident that the effect of A is a. So again, if we begin at the other end, and desire to investigate the cause of an effect a, we must select an instance, as a b c, in which the effect occurs, and in which the antecedents were A B C, and we must look out for another instance in which the remaining circumstances, b c, occur without a. If the antecedents, in that instance, are B C, we know that the cause of a must be A: either A alone, or A in conjunction with some of the other circumstances present.

likeness and unlikeness I do not pretend to explain, no more than any other kind of likeness or unlikeness. But my object is to show, that when we say of two things that they differ in quantity, just as when we say that they differ in quality, the assertion is always grounded on a difference in the sensations which they excite. Nobody, I presume, will say, that to see, or to lift, or to drink, ten gallons of water, does not include in itself a different set of sensations from those of seeing, lifting, or drinking one gallon; or that to see or handle a foot-rule, and to see or handle a yard-measure made exactly like it, are the same sensations. I do not undertake to say what the difference in the sensations is. Everybody knows, and nobody can tell; no more than any one could tell what white is to a person who had never had the sensation. But the difference, so far as cognizable by our faculties, lies in the sensations. Whatever difference we say there is in the things themselves, is, in this as in all other cases, grounded, and grounded exclusively, on a difference in the sensations excited by them.

which tends to produce an accelerating motion towards the sun; the real motion being a compound of the two.

ascertaining what kinds of uniformities have been found perfectly invariable, pervading all nature, and what are those which have been found to vary with difference of time, place, or other changeable circumstances.

excitement of the other and opposite kind: that both are effects of the same cause; that the possibility of the one is a condition of the possibility of the other, and the quantity of the one an impassable limit to the quantity of the other. A scientific result of considerable interest in itself, and illustrating those three methods in a manner both characteristic and easily intelligible.

and one or more Syncategorematic words, as A heavy body, or A court of justice, they sometimes called a mixed term; but this seems a needless multiplication of technical expressions. A mixed term is, in the only useful sense of the word, Categorematic. It belongs to the class of what have been called many-worded names.

apprehended in any particular case which can occur. In this respect, however, these axioms of logic are on a level with those of mathematics. That things which are equal to the same thing are equal to one another, is as obvious in any particular case as it is in the general statement: and if no such general maxim had ever been laid down, the demonstrations in Euclid would never have halted for any difficulty in stepping across the gap which this axiom at present serves to bridge over. Yet no one has ever censured writers on geometry, for placing a list of these elementary generalizations at the head of their treatises, as a first exercise to the learner of the faculty which will be required in him at every step, that of apprehending a general truth. And the student of logic, in the discussion even of such truths as we have cited above, acquires habits of circumspect interpretation of words, and of exactly measuring the length and breadth of his assertions, which are among the most indispensable conditions of any considerable mental attainment, and which it is one of the primary objects of logical discipline to cultivate.

corresponds, on different occasions, to different words in another. When not thus exercised, even the strongest understandings find it difficult to believe that things which have a common name, have not in some respect or other a common nature; and often expend much labour very unprofitably (as was frequently done by the two philosophers just mentioned) in vain attempts to discover in what this common nature consists. But, the habit once formed, intellects much inferior are capable of detecting even ambiguities which are common to many languages: and it is surprising that the one now under consideration, though it exists in the modern languages as well as in the ancient, should have been overlooked by almost all authors. The quantity of futile speculation which had been caused by a misapprehension of the nature of the copula, was hinted at by Hobbes; but Mr. James Mill

(that is, in which the predicate connotes the whole or part of what the subject connotes, but nothing besides) answer no purpose but that of unfolding the whole or some part of the meaning of the name, to those who did not previously know it. Accordingly, the most useful, and in strictness the only useful kind of essential propositions, are Definitions: which, to be complete, should unfold the whole of what is involved in the meaning of the word defined; that is, (when it is a connotative word,) the whole of what it connotes. In defining a name, however, it is not usual to specify its entire connotation, but so much only as is sufficient to mark out the objects usually denoted by it from all other known objects. And sometimes a merely accidental property, not involved in the meaning of the name, answers this purpose equally well. The various kinds of definition which these distinctions give rise to, and the purposes to which they are respectively subservient, will be minutely considered in the proper place.

demonstrated from the definition of the triangle. I shall have occasion to revert to this theory in treating of Demonstration, and of the conditions under which one property of a thing admits of being demonstrated from another property. It is enough here to remark that, according to this definition, the real essence of an object has, in the progress of physics, come to be conceived as nearly equivalent, in the case of bodies, to their corpuscular structure: what it is now supposed to mean in the case of any other entities, I would not take upon myself to define.

towards the sun. It was this which determined astronomers to consider the law of gravitation as obtaining between all bodies whatever, and therefore between all particles of matter; their first tendency having been to regard it as a force acting only between each planet or satellite and the central body to whose system it belonged. Again, the catastrophists, in geology, be their opinion right or wrong, support it on the plea, that after the effect of all causes now in operation has been allowed for, there remains in the existing constitution of the earth a large residue of facts, proving the existence at former periods either of other forces, or of the same forces in a much greater degree of intensity. To add one more example: those who assert, what no one has shown any real ground for believing, that there is in one human individual, one sex, or one race of mankind over another, an inherent and inexplicable superiority in mental faculties, could only substantiate their proposition by subtracting from the differences of intellect which we in fact see, all that can be traced by known laws either to the ascertained differences of physical organization, or to the differences which have existed in the outward circumstances in which the subjects of the comparison have hitherto been placed. What these causes might fail to account for, would constitute a residual phenomenon, which and which alone would be evidence of an ulterior original distinction, and the measure of its amount. But the assertors of such supposed differences have not provided themselves with these necessary logical conditions of the establishment of their doctrine.

[1] In the later editions of Archbishop Whately's Logic, he states his meaning to be, not that "rules" for the ascertainment of truths by inductive investigation cannot be laid down, or that they may not be "of eminent service," but that they "must always be comparatively vague and general, and incapable of being built up into a regular demonstrative theory like that of the Syllogism." (Book IV. ch. iv. § 3.) And he observes, that to devise a system for this purpose, capable of being "brought into a scientific form," would be an achievement which "he must be more sanguine than scientific who expects." (Book IV. ch. ii. § 4.) To effect this, however, being the express object of the portion of the present work which treats of Induction, the words in the text are no overstatement of the difference of opinion between Archbishop Whately and me on the subject.

instance to the contrary, we must have reason to believe that if there were in nature any instances to the contrary, we should have known of them. This assurance, in the great majority of cases, we cannot have, or can have only in a very moderate degree. The possibility of having it, is the foundation on which we shall see hereafter that induction by simple enumeration may in some remarkable cases amount practically to proof.

These are reducible to two, which I shall endeavour to state as clearly and as forcibly as possible.

universe at any particular moment is impossible, but would also be useless. In making chemical experiments, we do not think it necessary to note the position of the planets; because experience has shown, as a very superficial experience is sufficient to show, that in such cases that circumstance is not material to the result: and, accordingly, in the ages when men believed in the occult influences of the heavenly bodies, it might have been unphilosophical to omit ascertaining the precise condition of those bodies at the moment of the experiment. As to the degree of minuteness of the mental subdivision; if we were obliged to break down what we observe into its very simplest elements, that is, literally into single facts, it would be difficult to say where we should find them: we can hardly ever affirm that our divisions of any kind have reached the ultimate unit. But this too is fortunately unnecessary. The only object of the mental separation is to suggest the requisite physical separation, so that we may either accomplish it ourselves, or seek for it in nature; and we have done enough when we have carried the subdivision as far as the point at which we are able to see what observations or experiments we require. It is only essential, at whatever point our mental decomposition of facts may for the present have stopped, that we should hold ourselves ready and able to carry it farther as occasion requires, and should not allow the freedom of our discriminating faculty to be imprisoned by the swathes and bands of ordinary classification; as was the case with all early speculative inquirers, not excepting the Greeks, to whom it seldom occurred that what was called by one abstract name might, in reality, be several phenomena, or that there was a possibility of decomposing the facts of the universe into any elements but those which ordinary language already recognised.

which we had not already calculated and subducted the effect. But as we can never be quite certain of this, the evidence derived from the Method of Residues is not complete unless we can obtain C artificially and try it separately, or unless its agency, when once suggested, can be accounted for, and proved deductively from known laws.

and prolongation of the cadaveric rigidity. This investigation places in a strong light the value and efficacy of the Joint Method. For, as we have already seen, the defect of that Method is, that like the Method of Agreement, of which it is only an improved form, it cannot prove causation. But in the present case (as in one of the steps in the argument which led up to it) causation is already proved; since there could never be any doubt that the rigidity altogether, and the putrefaction which follows it, are caused by the fact of death: the observations and experiments on which this rests are too familiar to need analysis, and fall under the Method of Difference. It being, therefore, beyond doubt that the aggregate antecedent, the death, is the actual cause of the whole train of consequents, whatever of the circumstances attending the death can be shown to be followed in all its variations by variations in the effect under investigation, must be the particular feature of the fact of death on which that effect depends. The degree of muscular irritability at the time of death fulfils this condition. The only point that could be brought into question, would be whether the effect depended on the irritability itself, or on something which always accompanied the irritability: and this doubt is set at rest by establishing, as the instances do, that by whatever cause the high or low irritability is produced, the effect equally follows; and cannot, therefore, depend upon the causes of irritability, nor upon the other effects of those causes, which are as various as the causes themselves; but upon the irritability, solely.

of our not being able to produce them by art is, that in every instance in which we see a human mind developing itself, or acting upon other things, we see it surrounded and obscured by an indefinite multitude of unascertainable circumstances, rendering the use of the common experimental methods almost delusive. We may conceive to what extent this is true, if we consider, among other things, that whenever nature produces a human mind, she produces, in close connexion with it, a body; that is, a vast complication of physical facts, in no two cases perhaps exactly similar, and most of which (except the mere structure, which we can examine in a sort of coarse way after it has ceased to act), are radically out of the reach of our means of exploration. If, instead of a human mind, we suppose the subject of investigation to be a human society or State, all the same difficulties recur in a greatly augmented degree.

they arrived at their conclusions as deserving of study, independently of the conclusions themselves.

which must be made to use vague words so as to convey a precise meaning, is not wholly a matter of regret. It is not unfitting that logical treatises should afford an example of that, to facilitate which is among the most important uses of logic. Philosophical language will for a long time, and popular language still longer, retain so much of vagueness and ambiguity, that logic would be of little value if it did not, among its other advantages, exercise the understanding in doing its work neatly and correctly with these imperfect tools.

comparative anatomy and physiology, the characteristic organic structure corresponding to each class of functions has been determined with considerable precision. Whether these organic conditions are the whole of the conditions, and in many cases whether they are conditions at all, or mere collateral effects of some common cause, we are quite ignorant: nor are we ever likely to know, unless we could construct an organized body, and try whether it would live.

square" does not include the meaning of "a round square exists," for it does not and cannot exist. When I say "the sun," "my father," or a "round square," I do not call upon the hearer for any belief or disbelief, nor can either the one or the other be afforded me; but if I say, "the sun exists," "my father exists," or "a round square exists," I call for belief; and should, in the first of the three instances, meet with it; in the second, with belief or disbelief, as the case might be; in the third, with disbelief.

which presented themselves, in an examination extending to a great number of instances, were cases in which mercury had been administered, we might generalize with confidence from this experience, and should have obtained a conclusion of real value. But no such basis for generalization can we, in a case of this description, hope to obtain. The reason is that which we have spoken of as constituting the characteristic imperfection of the Method of Agreement; Plurality of Causes. Supposing even that mercury does tend to cure the disease, so many other causes, both natural and artificial, also tend to cure it, that there are sure to be abundant instances of recovery in which mercury has not been administered: unless, indeed, the practice be to administer it in all cases; on which supposition it will equally be found in the cases of failure.

the ladder from a to e by a process of ratiocination; we can conclude that a is a mark of e, and that every object which has the mark a has the property e, although, perhaps, we never were able to observe a and e together, and although even d, our only direct mark of e, may not be perceptible in those objects, but only inferrible. Or, varying the first metaphor, we may be said to get from a to e underground: the marks b, c, d, which indicate the route, must all be possessed somewhere by the objects concerning which we are inquiring; but they are below the surface: a is the only mark that is visible, and by it we are able to trace in succession all the rest.

Several criticisms, of a more or less controversial character, on this work, have appeared since the publication of the second edition; and Dr. Whewell has lately published a reply to those parts of it in which some of his opinions were controverted.[2]

possible, when we find that not only one substance, but many substances, possess the capacity of acting as antidotes to metallic poisons, and that all these agree in the property of forming insoluble compounds with the poisons, while they cannot be ascertained to agree in any other property whatsoever. We have thus, in favour of the theory, all the evidence which can be obtained by what we termed the Indirect Method of Difference, or the Joint Method of Agreement and Difference; the evidence of which, though it never can amount to that of the Method of Difference properly so called, may approach indefinitely near to it.

name taken together; being the name of something which has once had a particular attribute, or for some other reason might have been expected to have it, but which has it not. Such is the word blind, which is not equivalent to not seeing, or to not capable of seeing, for it would not, except by a poetical or rhetorical figure, be applied to stocks and stones. A thing is not usually said to be blind, unless the class to which it is most familiarly referred, or to which it is referred on the particular occasion, be chiefly composed of things which can see, as in the case of a blind man, or a blind horse; or unless it is supposed for any reason that it ought to see; as in saying of a man, that he rushed blindly into an abyss, or of philosophers or the clergy that the greater part of them are blind guides. The names called privative, therefore, connote two things: the absence of certain attributes, and the presence of others, from which the presence also of the former might naturally have been expected.

sensation; that is, not the cause, properly speaking, but the cause of the cause;—the real cause of the sensation is the change in the state of the nerve. Future experience may not only give us more knowledge than we now have of the particular nature of this change, but may also interpolate another link: between the contact (for example) of the object with our outward organs, and the production of the change of state in the nerve, there may take place some electric phenomenon; or some phenomenon of a nature not resembling the effects of any known agency. Hitherto, however, no such intermediate link has been discovered; and the touch of the object must be considered, provisionally, as the proximate cause of the affection of the nerve. The sequence, therefore, of a sensation of touch on contact with an object, is ascertained not to be an ultimate law; it is resolved, as the phrase is, into two other laws,—the law, that contact with an object produces an affection of the nerve; and the law, that an affection of the nerve produces sensation.

received, and is still far from being altogether exploded, among metaphysicians.

At present it is of more importance to understand thoroughly the import of the axiom itself. For the proposition, that the course of nature is uniform, possesses rather the brevity suitable to popular, than the precision requisite in philosophical language: its terms require to be explained, and a stricter than their ordinary signification given to them, before the truth of the assertion can be admitted.

consequents. If those antecedents could not be severed from one another except in thought, or if those consequents never were found apart, it would be impossible for us to distinguish (à posteriori at least) the real laws, or to assign to any cause its effect, or to any effect its cause. To do so, we must be able to meet with some of the antecedents apart from the rest, and observe what follows from them; or some of the consequents, and observe by what they are preceded. We must, in short, follow the Baconian rule of varying the circumstances. This is, indeed, only the first rule of physical inquiry, and not, as some have thought, the sole rule; but it is the foundation of all the rest.

Diamond and Combustible first received their meaning; and could not have been discovered by the most ingenious and refined analysis of the signification of those words. It was found out by a very different process, namely, by exerting the senses, and learning from them, that the attribute of combustibility existed in the diamonds upon which the experiment was tried; the number or character of the experiments being such, that what was true of those individuals might be concluded to be true of all substances "called by the name," that is, of all substances possessing the attributes which the name connotes. The assertion, therefore, when analysed, is, that wherever we find certain attributes, there will be found a certain other attribute: which is not a question of the signification of names, but of laws of nature; the order existing among phenomena.

that it was found possible to frame a rational definition of chemistry; and the definition of the science of life and organization is still a matter of dispute. So long as the sciences are imperfect, the definitions must partake of their imperfection; and if the former are progressive, the latter ought to be so too. As much, therefore, as is to be expected from a definition placed at the commencement of a subject, is that it should define the scope of our inquiries: and the definition which I am about to offer of the science of logic, pretends to nothing more, than to be a statement of the question which I have put to myself, and which this book is an attempt to resolve. The reader is at liberty to object to it as a definition of logic; but it is at all events a correct definition of the subject of these volumes.

differences, like that between affirmation and negation, might be glossed over by considering the incident of time as a mere modification of the predicate: thus, The sun is an object having risen, The sun is an object now rising, The sun is an object to rise hereafter. But the simplification would be merely verbal. Past, present, and future, do not constitute so many different kinds of rising; they are designations belonging to the event asserted, to the sun's rising to-day. They affect, not the predicate, but the applicability of the predicate to the particular subject. That which we affirm to be past, present, or future, is not what the subject signifies, nor what the predicate signifies, but specifically and expressly what the predication signifies; what is expressed only by the proposition as such, and not by either or both of the terms. Therefore the circumstance of time is properly considered as attaching to the copula, which is the sign of predication, and not to the predicate. If the same cannot be said of such modifications as these, Cæsar may be dead; Cæsar is perhaps dead; it is possible that Cæsar is dead; it is only because these fall altogether under another head, being properly assertions not of anything relating to the fact itself, but of the state of our own mind in regard to it; namely, our absence of disbelief of it. Thus "Cæsar may be dead" means "I am not sure that Cæsar is alive."

constitutes an immense advantage of the joint method over the simple Method of Agreement. It may seem, indeed, that the advantage does not belong so much to the joint method, as to one of its two premises, (if they may be so called,) the negative premise. The Method of Agreement, when applied to negative instances, or those in which a phenomenon does not take place, is certainly free from the characteristic imperfection which affects it in the affirmative case. The negative premise, it might therefore be supposed, could be worked as a simple case of the Method of Agreement, without requiring an affirmative premise to be joined with it. But though this is true in principle, it is generally altogether impossible to work the Method of Agreement by negative instances without positive ones: it is so much more difficult to exhaust the field of negation than that of affirmation. For instance, let the question be, what is the cause of the transparency of bodies; with what prospect of success could we set ourselves to inquire directly in what the multifarious substances which are not transparent, agree? But we might hope much sooner to seize some point of resemblance among the comparatively few and definite species of objects which are transparent; and this being attained, we should quite naturally be put upon examining whether the absence of this one circumstance be not precisely the point in which all opaque substances will be found to resemble.

to light, there are very few which have any, even apparent, pretension to this rigorous indefeasibility: and of those few, one only has been found capable of completely sustaining it. In that one, however, we recognise a law which is universal also in another sense; it is coextensive with the entire field of successive phenomena, all instances whatever of succession being examples of it. This law is the Law of Causation. The truth that every fact which has a beginning has a cause, is coextensive with human experience.

entering into chemical combination with any other substance whatever.

phenomena; as when a complex passion is formed by the coalition of several elementary impulses, or a complex emotion by several simple pleasures or pains, of which it is the result without being the aggregate, or in any respect homogeneous with them. The product, in these cases, is generated by its various factors; but the factors cannot be reproduced from the product; just as a youth can grow into an old man, but an old man cannot grow into a youth. We cannot ascertain from what simple feelings any of our complex states of mind are generated, as we ascertain the ingredients of a chemical compound, by making it, in its turn, generate them. We can only, therefore, discover these laws by the slow process of studying the simple feelings themselves, and ascertaining synthetically, by experimenting on the various combinations of which they are susceptible, what they, by their mutual action upon one another, are capable of generating.

without the aid of any other premises; whether the definition expresses them in two or three words, or in a larger number. It is, therefore, not without reason that Condillac and other writers have affirmed a definition to be an analysis. To resolve any complex whole into the elements of which it is compounded, is the meaning of analysis: and this we do when we replace one word which connotes a set of attributes collectively, by two or more which connote the same attributes singly, or in smaller groups.

with which the four only possible methods of directly inductive investigation by observation and experiment, are for the most part, as will appear presently, quite unequal to cope. The instrument of Deduction alone is adequate to unravel the complexities proceeding from this source; and the four methods have little more in their power than to supply premises for, and a verification of, our deductions.

in this multiplicity of acceptations, distinguishing these so clearly as to prevent their being confounded with one another. Such a word may be considered as two or more names, accidentally written and spoken alike.

exactly true; and that the peculiar certainty ascribed to it, on account of which its propositions are called Necessary Truths, is fictitious and hypothetical, being true in no other sense than that those propositions legitimately follow from the hypothesis of the truth of premises which are avowedly mere approximations to truth.

of all physical objects in so far as possessing length. But even what I hold to be the false doctrine on the subject, leaves the conclusion that our reasonings are grounded on the matters of fact postulated in definitions, and not on the definitions themselves, entirely unaffected; and accordingly this conclusion is one which I have in common with Dr. Whewell, in his Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences: though, on the nature of demonstrative truth, Dr. Whewell's opinions are greatly at variance with mine. And here, as in many other instances, I gladly acknowledge that his writings are eminently serviceable in clearing from confusion the initial steps in the analysis of the mental processes, even where his views respecting the ultimate analysis are such as (though with unfeigned respect) I cannot but regard as fundamentally erroneous.

The quadrature of the cycloid is said to have been first effected by measurement, or rather by weighing a cycloidal card, and comparing its weight with that of a piece of similar card of known dimensions.

must be made. If in concluding that all animals have a nervous system, we mean the same thing and no more as if we had said "all known animals," the proposition is not general, and the process by which it is arrived at is not induction. But if our meaning is that the observations made of the various species of animals have discovered to us a law of animal nature, and that we are in a condition to say that a nervous system will be found even in animals yet undiscovered, this indeed is an induction; but in this case the general proposition contains more than the sum of the special propositions from which it is inferred. The distinction is still more forcibly brought out when we consider, that if this real generalization be legitimate at all, its legitimacy probably does not require that we should have examined without exception every known species. It is the number and nature of the instances, and not their being the whole of those which happen to be known, that makes them sufficient evidence to prove a general law: while the more limited assertion, which stops at all known animals, cannot be made unless we have rigorously verified it in every species. In like manner (to return to a former example) we might have inferred, not that all the planets, but that all planets, shine by reflected light: the former is no induction; the latter is an induction, and a bad one, being disproved by the case of double stars—self-luminous bodies which are properly planets, since they revolve round a centre.

meaning do these words convey, but that of innumerable actions, done or to be done by the sovereign and the subjects, to or in regard to one another reciprocally? So with the words physician and patient, leader and follower, tutor and pupil. In many cases the words also connote actions which would be done under certain contingencies by persons other than those denoted: as the words mortgagor and mortgagee, obligor and obligee, and many other words expressive of legal relation, which connote what a court of justice would do to enforce the legal obligation if not fulfilled. There are also words which connote actions previously done by persons other than those denoted either by the name itself or by its correlative; as the word brother. From these instances, it may be seen how large a portion of the connotation of names consists of actions. Now what is an action? Not one thing, but a series of two things: the state of mind called a volition, followed by an effect. The volition or intention to produce the effect, is one thing; the effect produced in consequence of the intention, is another thing; the two together constitute the action. I form the purpose of instantly moving my arm; that is a state of my mind: my arm (not being tied or paralytic) moves in obedience to my purpose; that is a physical fact, consequent on a state of mind. The intention, followed by the fact, or (if we prefer the expression) the fact when preceded and caused by the intention, is called the action of moving my arm.

entire universe could ever recur a second time, all subsequent states would return too, and history would, like a circulating decimal of many figures, periodically repeat itself:—

are fulfilled; the effect is the same as if the drain had been open for half an hour first,

permeates its membranes, and rapidly spreads through the system. 3rd. Alcohol taken into the stomach passes into vapour and spreads through the system with great rapidity; (which, combined with the high combustibility of alcohol, or in other words its ready combination with oxygen, may perhaps help to explain the bodily warmth immediately consequent on drinking spirituous liquors.) 4th. In any state of the body in which peculiar gases are formed within it, these will rapidly exhale through all parts of the body; and hence the rapidity with which, in certain states of disease, the surrounding atmosphere becomes tainted. 5th. The putrefaction of the interior parts of a carcase will proceed as rapidly as that of the exterior, from the ready passage outwards of the gaseous products. 6th. The exchange of oxygen and carbonic acid in the lungs is not prevented, but rather promoted, by the intervention of the membrane of the lungs and the coats of the blood-vessels between the blood and the air. It is necessary, however, that there should be a substance in the blood with which the oxygen of the air may immediately combine; otherwise instead of passing into the blood, it would permeate the whole organism: and it is necessary that the carbonic acid, as it is formed in the capillaries, should also find a substance in the blood with which it can combine; otherwise it would leave the body at all points, instead of being discharged through the lungs.

fact taking place, and all reasoning as carried on in the form into which it must necessarily be thrown to enable us to apply to it any test of its correct performance.

of truths whose negations are inconceivable. But occasional failure, he says, is incident to all tests. If such failure vitiates "the test of inconceivableness," it "must similarly vitiate all tests whatever. We consider an inference logically drawn from established premises to be true. Yet in millions of cases men have been wrong in the inferences they have thought thus drawn. Do we therefore argue that it is absurd to consider an inference true on no other ground than that it is logically drawn from established premises? No: we say that though men may have taken for logical inferences, inferences that were not logical, there nevertheless are logical inferences, and that we are justified in assuming the truth of what seem to us such, until better instructed. Similarly, though men may have thought some things inconceivable which were not so, there may still be inconceivable things; and the inability to conceive the negation of a thing, may still be our best warrant for believing it.... Though occasionally it may prove an imperfect test, yet, as our most certain beliefs are capable of no better, to doubt any one belief because we have no higher guarantee for it, is really to doubt all beliefs." Mr. Spencer's doctrine, therefore, does not erect the curable, but only the incurable limitations of the human conceptive faculty, into laws of the outward universe.

of the syllogism to its legitimate corollary, have been led to impute uselessness and frivolity to the syllogistic theory itself, on the ground of the petitio principii which they allege to be inherent in every syllogism. As I believe both these opinions to be fundamentally erroneous, I must request the attention of the reader to certain considerations, without which any just appreciation of the true character of the syllogism, and the functions it performs in philosophy, appears to me impossible; but which seem to have been either overlooked, or insufficiently adverted to, both by the defenders of the syllogistic theory and by its assailants.

We shall select for this purpose a case which as yet furnishes no very brilliant example of the success of any of the three methods, but which is all the more suited to illustrate the difficulties inherent in them. Let the subject of inquiry be, the conditions of health and disease in the human body; or (for greater simplicity) the conditions of recovery from a given disease; and in order to narrow the question still more, let it be limited, in the first instance, to this one inquiry: Is, or is not some particular medicament (mercury, for instance) a remedy for the given disease.

the acceptation in which the speaker or writer desires to use them. These propositions occupy, however, a conspicuous place in philosophy; and their nature and characteristics are of as much importance in logic, as those of any of the other classes of propositions previously adverted to.

to prevent it from denoting individuals not included in the genus. And it must connote something besides, otherwise it would include the whole genus. Animal denotes all the individuals denoted by man, and many more. Man, therefore, must connote all that animal connotes, otherwise there might be men who are not animals; and it must connote something more than animal connotes, otherwise all animals would be men. This surplus of connotation—this which the species connotes over and above the connotation of the genus—is the Differentia, or specific difference; or, to state the same proposition in other words, the Differentia is that which must be added to the connotation of the genus, to complete the connotation of the species.

to itself, I can see only cases of belief; but of belief which claims to be intuitive, or independent of external evidence. When a stone lies before me, I am conscious of certain sensations which I receive from it; but if I say that these sensations come to me from an external object which I perceive, the meaning of these words is, that receiving the sensations, I intuitively believe that an external cause of those sensations exists. The laws of intuitive belief, and the conditions under which it is legitimate, are a subject which, as we have already so often remarked, belongs not to logic, but to the science of the ultimate laws of the human mind.

seemed to be so; the reason perhaps is, that men's logical notions have not yet acquired the degree of extension, or of accuracy, requisite for the estimation of the evidence proper to those particular departments of knowledge.

induction left for Kepler to make, nor did he make any further induction. He merely applied his new conception to the facts inferred, as he did to the facts observed. Knowing already that the planets continued to move in the same paths; when he found that an ellipse correctly represented the past path, he knew that it would represent the future path. In finding a compendious expression for the one set of facts, he found one for the other: but he found the expression only, not the inference; nor did he (which is the true test of a general truth) add anything to the power of prediction already possessed.

of nomenclature and arrangement. An effect of precisely the same kind, and arising from the same cause, ought not to be placed in two different categories, merely as there does or does not exist another cause preponderating over it."

respecting an idea, the assumption on which it depends may be merely that of the existence of an idea. But when the conclusion is a proposition concerning a Thing, the postulate involved in the definition which stands as the apparent premise, is the existence of a thing conformable to the definition, and not merely of an idea conformable to it. This assumption of real existence will always convey the impression that we intend to make, when we profess to define any name which is already known to be a name of really existing objects. On this account it is, that the assumption was not necessarily implied in the definition of a dragon, while there was no doubt of its being included in the definition of a circle.

particular science. And therefore the conclusions of all deductive sciences were said by the ancients to be necessary propositions. We have observed already that to be predicated necessarily was characteristic of the predicable Proprium, and that a proprium was any property of a thing which could be deduced from its essence, that is, from the properties included in its definition.

may produce not a and b, but different portions of an effect a. The obscurity and difficulty of the investigation of the laws of phenomena is singularly increased by the necessity of adverting to these two circumstances; Intermixture of Effects, and Plurality of Causes. To the latter, being the simpler of the two considerations, we shall first direct our attention.

strange that a modified cause, which is in truth a different cause, should produce a different effect.

relate to something which has real existence, (for there can be no science respecting non-entities,) it follows that any hypothesis we make respecting an object, to facilitate our study of it, must not involve anything which is distinctly false, and repugnant to its real nature: we must not ascribe to the thing any property which it has not; our liberty extends only to slightly exaggerating some of those which it has, (by assuming it to be completely what it really is very nearly,) and suppressing others, under the indispensable obligation of restoring them whenever, and in as far as, their presence or absence would make any material difference in the truth of our conclusions. Of this nature, accordingly, are the first principles involved in the definitions of geometry. That the hypotheses should be of this particular character, is however no further necessary, than inasmuch as no others could enable us to deduce conclusions which, with due corrections, would be true of real objects: and in fact, when our aim is only to illustrate truths, and not to investigate them, we are not under any such restriction. We might suppose an imaginary animal, and work out by deduction, from the known laws of physiology, its natural history; or an imaginary commonwealth, and from the elements composing it, might argue what would be its fate. And the conclusions which we might thus draw from purely arbitrary hypotheses, might form a highly useful intellectual exercise: but as they could only teach us what would be the properties of objects which do not really exist, they would not constitute any addition to our knowledge of nature: while on the contrary, if the hypothesis merely divests a real object of some portion of its properties, without clothing it in false ones, the conclusions will always express, under known liability to correction, actual truth.

sensation of white, or The sensation of whiteness; we must denominate the sensation either from the object, or from the attribute, by which it is excited. Yet the sensation, though it never does, might very well be conceived to exist, without anything whatever to excite it. We can conceive it as arising spontaneously in the mind. But if it so arose, we should have no name to denote it which would not be a misnomer. In the case of our sensations of hearing we are better provided; we have the word Sound, and a whole vocabulary of words to denote the various kinds of sounds. For as we are often conscious of these sensations in the absence of any perceptible object, we can more easily conceive having them in the absence of any object whatever. We need only shut our eyes and listen to music, to have a conception of an universe with nothing in it except sounds, and ourselves hearing them: and what is easily conceived separately, easily obtains a separate name. But in general our names of sensations denote indiscriminately the sensation and the attribute. Thus, colour stands for the sensations of white, red, &c., but also for the quality in the coloured object. We talk of the colours of things as among their properties.

who studied terrestrial phenomena; and had, indeed, been a matter of great interest at a time when the idea of explaining celestial facts by terrestrial laws was looked upon as the confounding of an indefeasible distinction. When, however, the celestial motions were accurately ascertained, and the deductive processes performed, from which it appeared that their laws and those of terrestrial gravity corresponded, those celestial observations became a set of instances which exactly eliminated the circumstance of proximity to the earth; and proved that in the original case, that of terrestrial objects, it was not the earth, as such, that caused the motion or the pressure, but the circumstance common to that case with the celestial instances, namely, the presence of some great body within certain limits of distance.

done, for the purpose of showing the falsity of the assumption; which is called a reductio ad absurdum. In such cases, the reasoning is as follows: a is a mark of b, and b of c; now if c were also a mark of d, a would be a mark of d; but d is known to be a mark of the absence of a; consequently a would be a mark of its own absence, which is a contradiction; therefore c is not a mark of d.

directions were framed by ourselves as the result of induction, or were received by us from an authority competent to give them.