автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Nancy Brandon

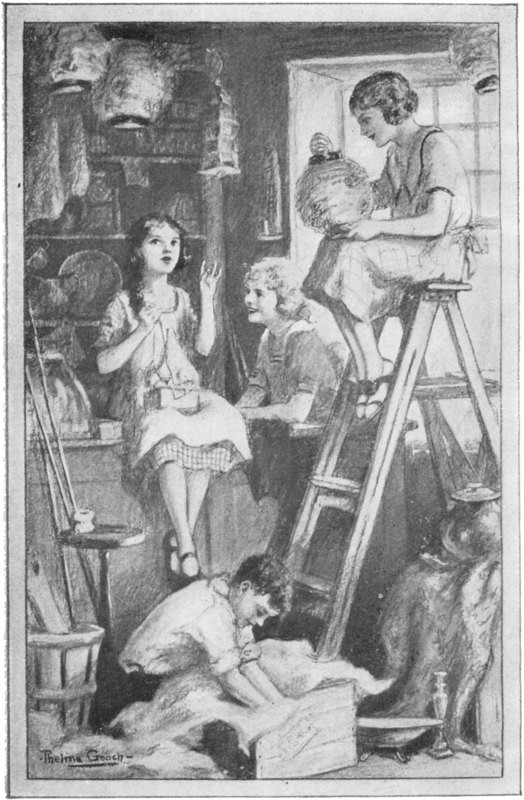

They had a merry time getting the Whatnot Shop ready.

NANCY BRANDON

By

LILIAN GARIS

Author of

“JOAN’S GARDEN OF ADVENTURE,” “GLORIA AT BOARDING

SCHOOL,” “CONNIE LORING’S AMBITION,”

“BARBARA HALE: A DOCTOR’S DAUGHTER,”

“CLEO’S MISTY RAINBOW,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

THELMA GOOCH

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Copyright, 1924

By MILTON BRADLEY COMPANY

Springfield, Massachusetts

All Rights Reserved

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

CONTENTS

I.

The Girl and the BoyII.

Dinner DifficultiesIII.

Belated HasteIV.

New FriendsV.

Original PlansVI.

Fair PlayVII.

The Special SaleVIII.

Fish Hooks and FloatersIX.

The Big DayX.

Still They CameXI.

The FailureXII.

The Virtue of ResolveXIII.

Behind the CloudXIV.

A Pleasant SurpriseXV.

Talking it OverXVI.

Just FishingXVII.

The Cave-inXVIII.

Introducing NeroXIX.

A DiscoveryXX.

The Midnight AlarmXXI.

For Value DeceivedXXII.

Tarts and Lady FingersXXIII.

The Story ToldNANCY BRANDON: ENTHUSIAST

CHAPTER I

THE GIRL AND THE BOY

The small kitchen was untidy. There were boxes empty and some crammed with loose papers, while a big clothes basket was filled—with a small boy, who took turns rolling it like a boat and bumping it up and down like a flivver. Ted Brandon was about eleven years old, full of boyhood’s importance and bristling with boyhood’s pranks.

His sister Nancy, who stood placidly reviewing the confusion, was, she claimed, in her teens. She was also just now in her glory, for after many vicissitudes and uncertainties they were actually moved into the old Townsend place at Long Leigh.

“You’re perfectly silly, Ted. You know it’s simply a wonderful idea,” she proclaimed loftily.

“Do I.” There was no question in the boy’s tone.

“Well, you ought to. But, of course, boys—”

“Oh, there you go. Boys!!” No mistaking this tone.

“Ted Brandon, you ought to be ashamed of yourself. To be so—so mean to mother.”

“Mean to mother! Who said anything about mother?”

“This is mother’s pet scheme.”

“Pretty queer scheme to keep us cooped up all vacation.” He rocked the basket vigorously.

“We won’t have to stay in much at all. Why, just odd times, and besides—” Nancy paused to pat her hair. She might have patted it without pausing but her small brother Ted would then have been less impressed by her assumed dignity, “you see, Teddy, I’m working for a principle. I don’t believe that girls should do a bit more housework than boys.”

“Oh, I know you believe that all-righty.” Ted allowed himself to sigh but did not pause to do so. He kept right on rocking and snapping the blade of his pen-knife open and shut, as if the snap meant something either useful or amusing.

“Well, I guess I know what I’m talking about,” declared Nancy, “and now, even mother has come around to agree with me. She’s going right on with her office work and you and I are to run this lovely little shop.”

“You mean you are to run the shop and I’ll wash the dishes.” Deepest scorn and seething irony hissed through Teddy’s words. He even flipped the pen-knife into the sink board and nicked, but did not break, the apple-sauce dish.

“Of course you must do your part.” Nancy lifted up two dishes and set them down again.

“And yours, if you have your say. Oh, what’s the use of talkin’ to girls?” Ted tumbled out of the basket, pushed it over until it banged into a soap box, then straightening up his firm young shoulders, he prepared to leave the scene.

“There’s no use talking to girls, Ted,” replied his sister, “if you don’t talk sense.”

“Sense!” He jammed his cap upon his head although he didn’t have any idea of wearing it on this beautiful day. The fact was, Teddy and Nancy were disagreeing. But there really wasn’t anything unusual about that, for their natures were different, they saw things differently, and if they had been polite enough to agree they would simply have been fooling each other.

Nancy smiled lovingly, however, at the boy, as he banged the door. What a darling Ted was! So honest and so scrappy! Of all things hateful to Nancy Brandon a “sissy” boy, as she described a certain type, was the worst.

“But I suppose,” she ruminated serenely, “the old breakfast dishes have got to be done.” Another lifting up and setting down of a couple of china pieces, but further than that Nancy made not the slightest headway. A small mirror hung in a small hall between the long kitchen and the store. Here Nancy betook herself and proceeded again to pat her dark hair.

She was the type of girl described as willowy, because that word is prettier than some others that might mean tall, lanky, boneless and agile. Nancy had black hair that shone with crow-black luster in spite of its pronounced curl. Her eyes were dark, snappy and meaningful. They could mean love, as when Ted slammed the door, or they could mean danger, as when a boy kicked the black and white kitten. Then again they could mean devotion, as when Nancy beheld her idolized little mother who was a business woman as well, and in that capacity, Nancy’s model.

A tingle at the bell that was set for the store alarm, sent the girl dancing away from the looking-glass.

“Funniest thing about a store,” she told herself, “there’s always someone to buy things you haven’t got.”

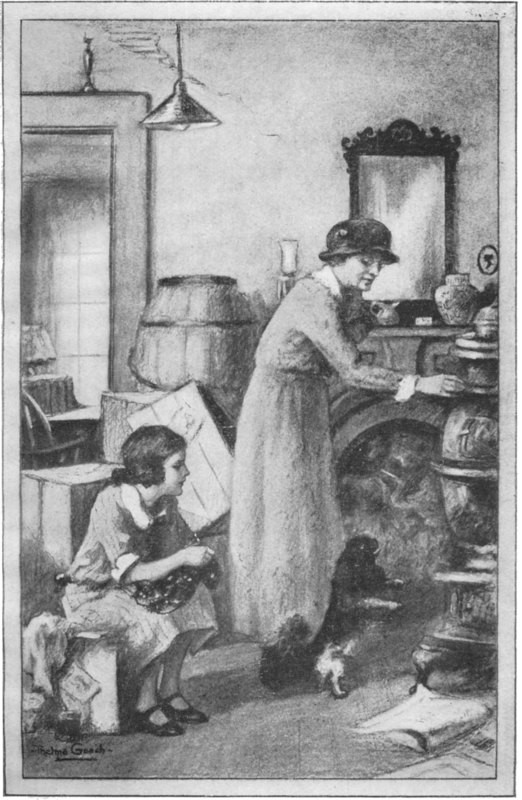

The catch was on the screen door and, as Nancy approached it, she discerned outside, the figure of an elderly woman. It was Miss Sarah Townsend from whom her mother had bought the store.

“Oh, good morning, Miss Townsend. I keep the door fastened when I’m alone, as I might be busy in the kitchen,” apologized Nancy.

“That’s right, dear, that’s right. And I wouldn’t be too much alone if I were you,” cautioned the woman who was stepping in with the air of proprietorship, and with her little brown dog sniffing at her heels. “Don’t you keep your brother with you?”

“Ted? Oh yes, sometimes. But he’s a little boy, you know, Miss Townsend, and he must enjoy his vacation.” Nancy was making friends with Tiny, the dog, but after a polite sniff or two Tiny was off frisking about happily, as any dog might be expected to do when returning to his old-time home.

Miss Townsend surveyed Nancy critically.

“Of course your brother is a little boy,” she said, “but what about you? You’re only a little girl.”

“Little! Why I’m much stronger than Ted, and years older,” declared Nancy, pulling herself up to her fullest height.

The woman smiled tolerantly. She wore glasses so securely fixed before her deep-set eyes that they seemed like a very feature of her face. She was a capable looking, elderly woman, and rather comely, but she was, as Nancy had quickly observed, “hopelessly old-fashioned.”

“We haven’t anything fixed up yet,” said Nancy apologetically. “You see, mother goes to business and that leaves the store and the house to me.”

“Yes. She explained in taking our place that she was doing it to give you a chance to try business. But for a girl so young—Come back here, Tiny,” she ordered the sniffing, snuffing, frisky little dog.

“If I’m going to be a business woman I’ve got to start in,” interrupted Nancy. “They say it’s never too early to start at housework.”

“But that’s different. Every girl has to know how to keep house,” insisted Miss Townsend. She was busy straightening a box of spools that lay upon the little counter, but from her automatic actions it was perfectly evident that Miss Townsend didn’t know she was doing anything.

“I can’t see why,” retorted Nancy. “Just look at mother. What would she have done with us if she hadn’t understood business?”

Miss Townsend sighed. “Being a widow, my dear—”

“But I may be a widow too,” breezed Nancy. “In fact I’m sure to, for everyone says I’m so much like mother. Do let me fix that box of spools, Miss Townsend. Someone came in for linen thread last night and Teddy looked for it. I’m sure he gave them a ball of cord, for all the cord was scattered around too.” She put the cover on the thread box. “Boys are rather poor at business, I think, especially boys of Teddy’s age,” orated the important Nancy.

Miss Townsend agreed without saying so. She was looking over the little place in a fidgety, nervous way. Nancy quickly decided this was due to regret that she had given the place up, and therefore sought to make her feel at ease.

The little brown dog had curled himself up in front of the fireplace on a piece of rug, evidently his own personal property. The fireplace was closed up and the stove set back against it, out of the way for summer, and handy-by for winter.

Nancy smiled at the woman who was moving about in a sort of aimless restlessness.

“It must seem natural to you to be around here,” Nancy ventured.

“Yes, after thirty years—”

“Thirty years!” repeated Nancy, incredulously. “Did you and your brother live here all that time?”

“Yes.” A prolonged sigh brought Miss Townsend down on the old hickory chair that stood by the door, just out of the way of possible customers.

“Brother Elmer and I kept on here after mother died. In fact, so far as I was concerned, we might have gone on until we died, but there was a little trouble—”

“Just like me and my brother, I suppose,” intervened Nancy, kindly. “We love each other to death, and yet we are always scrapping.”

“In children’s way, but that’s different, very different,” insisted Miss Townsend. “With me and Elmer,” she sighed again, “it became a very, very serious matter.”

“Oh,” faltered Nancy. Things were becoming uncomfortable. That kitchen work would be growing more formidable, and Nancy had really wanted to settle the store. She would love to do that, to put all the little things in their places, or in new places, as she would surely find a new method for their arrangement. She hurried over to the corner shelves.

“I hope no one comes in until I get the place fixed up,” she remarked. “Mother doesn’t intend to buy much new stock until she sees how we get along.”

“That’s wise,” remarked Miss Townsend. “I suppose I know every stick in the place,” she looked about critically, “and yet I could be just as interested. I wonder if you wouldn’t like me to help you fix things up? I’d just love to do it.”

Now this was exactly what Nancy did not want. In fact, she was wishing earnestly that the prim Miss Townsend would take herself off and leave her to do as she pleased.

“That’s kind of you, I’m sure,” she said, “but the idea was that I should be manager from the start,” Nancy laughed lightly to justify this claim, “and I’m sure mother would be better pleased if I put the shop in order. You can come in and see me again when I’m all fixed up,” (this gentle hint was tactful, thought Nancy) “and then you can tell me what you think of me as the manager of the Whatnot Shop.”

Miss Townsend was actually poking in the corner near the hearth shelf where matches, in a tin container, were kept. She heard Nancy but did not heed her.

“Looking for something?” the girl asked a little sharply.

“Looking?” Yes, that is—“Tiny keep down there,” she ordered. “I can’t see what has got into that dog of late. It was one of the things that Elmer and I were constantly fussing over. Tiny won’t let any one touch things near this chimney without barking his head off. Now just watch.”

As she went to the shelf back of the stove the dog sprang alongside of her. He barked in the happy fashion that goes with rapid tail wagging, and Nancy quickly decided that the dog knew a secret of the old chimney.

Miss Townsend pretended to take things out of the stove.

Again Miss Townsend pretended to take things out of the stove, and Tiny all but jumped into the low, broad door.

“Now, isn’t that—uncanny?” asked the woman, plainly bewildered.

“Oh, no, I don’t think so,” said Nancy. “All dogs have queer little tricks like that.”

“Do they? I’m glad to hear you say so,” sighed Miss Townsend, once more picking up a small box of notions. “You must excuse me, my dear. You see the habit of a life time—”

“Oh, that’s all right, Miss Townsend, I didn’t mean to hurry you,” spoke up Nancy. “But the morning goes so quickly, and mother may come home to lunch.” This possibility brought real anxiety to Nancy. If she had only slicked up the kitchen instead of arguing with Teddy. After all the plagued old housework did take some time, she secretly admitted.

But Miss Townsend laid down the unfinished roll of lace edging, although she had most carefully rolled all but a very small end, walked over to Nancy, who was just attempting to dust out a tray, and in the most tragic voice said:

“Nancy, I think you really have a lot of sense.”

Nancy chuckled. “I hope so, Miss Townsend.”

“I mean to say, that I think you can be trusted.”

“Well,” stammered Nancy, forcing back another chuckle, “I hope so, to that too, Miss Townsend.” She was surprised at the woman’s manner and puzzled to understand its meaning. The dog was again snoozing on the rug.

“Let’s sit down,” suggested Miss Townsend.

“Oh, all right,” faltered Nancy, in despair now of ever catching up on the delayed work.

“You see, it’s this way,” began the woman, making room for herself in the big chair that was serving as storage quarters for Teddy’s miscellany. “Some people are very proud—”

Nancy was simply choking with impatience.

“I mean to say, they are so proud they won’t or can’t ever give in to each other.”

“Stubborn,” suggested Nancy. “I’m that way sometimes.”

“And brother and sister,” sighed Miss Townsend. “I never could believe that Elmer, my own brother, could, be so—unreasonable.”

“Why, what’s the matter?” Nancy spoke up. “You seem so unhappy.”

“Unhappy is no name for it, I’m wretched.” The distress shown on Miss Townsend’s face was now unmistakable. Nancy forgot even the unwashed breakfast dishes.

“Can I help you?” she asked kindly.

“Yes, you can. What I want is to come in here sometimes—”

“Why, if you’re lonely for your old place,” interrupted Nancy.

“It isn’t that. In fact I just can’t explain,” said Miss Townsend, picking up her hand bag, nervously. “But I’m no silly woman. We’ve agreed to sell this place to your mother and I’m the last person in the world to make a nuisance of myself.”

“You needn’t worry about that,” again Nancy intervened, sympathetically.

“You are a kind girl, Nancy Brandon, and I guess your mother has made no mistake in buying the Whatnot Shop for you. You’ll be sure to make friends, and that’s what counts next to bargains, in business,” declared the woman, who had risen from the big chair and was staring at Nancy in the oddest way.

“If I had a chance—” again the woman paused and bit her thin lip. She seemed to dread what she evidently must say.

“I’ll be busy here tomorrow,” suggested Nancy briskly, “and then perhaps you would like to help me. But I really would like to get the rough dirt out first. Then we can put things to rights.”

“The fact is,” continued Miss Townsend, without appearing to hear Nancy’s suggestion, “I have a suspicion.”

“A suspicion? About this—store?”

“Yes, and about my brother. He’s an old man and we’ve never had any real trouble before, but I’m sorry to say, I can’t believe he’s telling me the truth about an important matter. That is, it’s a very important matter to me.”

“Oh,” said Nancy lamely. She was beginning to have doubts of Miss Townsend’s mental balance.

“No, Elmer is a good man. He’s been a good brother, but there are some things—” (a long, low, breathful sigh,) “some things we have individual opinions about. And, well, so you won’t think me queer if I ask you to let me tidy the shop?”

“Why—no, of course not, Miss Townsend.”

“Thank you, thank you, Nancy Brandon,” emotion was choking her words. She was really going now and Tiny with her. “And perhaps it would be just as well not to say anything about it if my brother should drop in,” concluded the strange woman.

“Oh, do you suppose he will?” asked bewildered Nancy. “I mean, will he drop in?”

“He’s apt to. Elmer is a creature of habit and he’s been around here a long time, you know.” The dark eyes were glistening behind the gold framed glasses. Miss Townsend was still preparing to depart.

Nancy opened the screen door and out darted Tiny.

“Good-bye, my dear, for the present,” murmured Miss Townsend, “and I hope you and your mother and your brother will—be happy—here,” she choked on the words and Nancy had an impression of impending tears. “We wouldn’t have sold out, we shouldn’t have sold out, but for Elmer Townsend’s foolishness.”

Back went the proud head until the lace collar on Sarah Townsend’s neck was jerked out of place, a rare thing indeed to happen to that prim lady.

“Good-bye,” said Nancy gently, “and come again, Miss Townsend.”

“Yes, yes, dear, I shall.”

CHAPTER II

DINNER DIFFICULTIES

Nancy jerked her cretonne apron first one way and then the other. Then she kicked out a few steps, still pondering. When Nancy was thinking seriously she had to be acting. This brought her to the conclusion that she should hurry out to the porch and look after Miss Townsend, but she had decided upon that move too late, for the lady in the voile dress was just turning the corner into Bender Street.

Nancy’s face was a bed of smiles. They were tucked away in the corners of her mouth, they blinked out through her eyes and were having lots of fun teasing her two deep cheek dimples. She was literally all smiles.

“What a lark! Won’t Ted howl? The dog and the—the chimney secret,” she chuckled. “And dogs know. You can’t fool them.” She came back into the store and gazed ruefully at the squatty stove that mutely stood guard.

“I don’t suppose mother will want that left there all summer,” Nancy further considered. “It might just as well be put out in the shed, and the store would look lots better.”

She could not help thinking of Miss Townsend’s strange visit. The lady was unmistakably worried, and her worry surely had to do with the Whatnot Shop.

“But I do hope we don’t run into any old spooky stories about this place,” Nancy pondered, “for mother hates that sort of thing and so do I—if they’re the foolish, silly kind,” she admitted, still staring at the questionable fireplace.

“What-ever can Miss Townsend want to be around here for? No hidden treasures surely, or she would say so and start in to dig them up,” decided the practical Nancy. The clock struck one!

“One o’clock!” she said this aloud. “Of course it isn’t,” laughed the girl. “That clock has been going since the moving and it hasn’t unpacked its strike carefully. But, just the same, it must be eleven o’clock, and as for the morning’s work! However shall I catch up?”

One hour later Ted was in looking for lunch. He had been out “exploring” and had, he explained, met some fine fellows who were “brigand scouts.”

“I’m goin’ to join,” he declared. “They’re goin’ to let me in and I’m goin’ to bring a lot of my things over to the den.”

“Den?” questioned Nancy. “Where’s that?”

“Secret,” answered Ted. “An’ anyhow, it isn’t for girls.” This was said in a pay-you-back manner that Nancy quickly challenged.

“Oh, all right. Very well. Just as you say, keep it secret if you like,” she taunted, “but I’ve got a real one.” The potatoes were burning but neither of the children seemed to care.

Ted looked closely at his sister and was convinced. She really was serious. Then too, everything was on end, no dinner ready, nothing done, the place all boxes, just as they were when he left. Something must have been going on all morning, reasoned Ted.

“Good thing mother didn’t come home, Sis,” he remarked amicably. “Say, how about—chow?”

“Chow?”

“Yes. Don’t you know that means food in the military, and I’m as starved as a bear.”

“Well, why don’t you get something to eat? I understood we were to camp, share and share alike,” Nancy reminded him, giving the simmering potatoes a shake that sent the little pot-cover flying to the floor.

“That was your idea. But mother said you had to be sure we ate our meals,” contended Ted. “I’ll get the meat. It’s meat balls, isn’t it?”

“It will be, I suppose, when I make them,” said Nancy, deliberately shoving everything from one end of the table with a sweep that rattled together dishes, glasses and various other breakable articles.

There was no doubt about it, Nancy Brandon did hate housework. Every thing she did was done with that degree of scorn absolutely fatal to the result. Perhaps this was just why her mother was allowing her to try out the pet summer scheme.

“I’d go mad if I had to stick in a kitchen,” Nancy declared theatrically. “I’m so glad we’ve got the store.”

“But we can’t eat the store,” replied Ted. “Here’s the meat. Do get it going, Sis. I’ve got to get back to the fellows.”

“Ted Brandon! You’ve got to help me this afternoon. Do you think, for one instant, I’m going to do everything?”

“'Course not, I’ll do my share,” promised the unsuspecting boy. “But just today we’ve got something big on. Here’s the meat.”

“Big or little you have just got to help me, Ted. Look at this place! It seems to me things walk out of the boxes and heap themselves up all over. Now, we didn’t take those pans out, did we?”

“I don’t know, don’t think so. But here’s a good one. It’s the meat kind, isn’t it?”

“Yes. Give it here.” Nancy took from his hand a perfectly flat iron griddle. “I’ll fix up the cakes if you make place on the table. We’ll eat out here.”

“All right.” Ted flew to the task. “But you know, Sis, mother said we might eat in that sun porch. It’s a dandy place to read. Look at the windows.”

Nancy had flattened the chopped meat into four balls and was pressing them on the griddle.

“There. What did you do with the potatoes?”

“Nothing. I didn’t take them.”

“But we had potatoes—” She lighted the gas under the meat.

“Sure. I smelled them burning.”

“Well, hunt around and see if you can smell them now,” ordered Ted’s sister. “I can’t eat meat without potatoes.”

Ted dropped his two plates and actually went sniffing about in search of the lost food. Meanwhile Nancy was standing at the stove, a magazine in one hand and the griddle handle in the other. Her eyes, however, were not upon the griddle.

Presently the meat was sizzling and its odor cheered Ted considerably.

“Don’t let’s mind the potatoes,” he suggested. “I can’t find them.”

“Can’t find them? And I peeled three! We’ve got to find them.”

“Then you look and I’ll stir the meat.”

“It doesn’t have to be stirred.” But Nancy stood over the stove just the same.

“Then what are you watching it for?”

“So it won’t burn, like the potatoes.”

“Maybe they all burned up.” Ted didn’t care much for potatoes.

“Oh, don’t be silly. Where’s the pan?”

“Which pan?”

“Oh, Ted Brandon! The potato pan, of course!”

“Oh, Nancy Brandon! What potato pan, of course! Has it got a name on it?”

Nancy dropped her magazine on a littered chair, in sheer disgust. She realized the meat was cooking; (it splattered and spluttered merrily on the shallow griddle,) and she too was hungry. Ted might be satisfied to eat just bread and meat, but she simply had to have freshly cooked potatoes. Wasn’t housework awful? Especially cooking?

There was a jangle of the store bell, actually some one coming at that critical moment.

“Oh, dear!” groaned Nancy. “What a nuisance! I suppose I’ll have to go—”

“But the meat?” Ted was getting desperate.

“It’s almost ready.” Nancy wiped her hands on the dish towel and hurried to the store.

“A man!” she announced, as she went to open the screen door.

Ted left his post and cautiously stole after her. A customer was a real novelty and Ted didn’t want to miss the excitement. A pleasant voice filled in the moment. A gentleman was talking to Nancy.

“I’m glad to find some one in,” he was saying. “Since my friend, Elmer Townsend, left here I’ve been rather—that is, I’ve missed the little place,” explained the man. Ted could see that he was very tall and looked, he thought, like a school teacher, having no hat on and not much hair either.

“We’ve just been unpacking,” Nancy replied. She was conscious of the confusion in the store as well as she had been of things upset in the kitchen.

“Oh, yes,” drawled the man, stepping behind the counter. “It will take you some time to go over everything. But you see, Mr. Townsend and I are great friends, and I know where most of the things are kept. You don’t mind if I take a look for a ball of twine?”

“No, certainly not,” agreed Nancy.

“I can get you that,” spoke up Ted. “I had it out last night,” and he jumped behind the counter to the littered cord and twine box.

Nancy pulled herself up to that famous height of hers. She smelled—something burning!

“Ted!” she screamed. “It’s a-fire! The kitchen! I see the blaze!”

“The meat!” yelled Ted, springing over the low counter and following his sister toward the smoke filling place.

“Oh-h-h-!” Nancy continued to yell. “What shall we do!”

“Don’t get excited,” ordered the stranger. “And don’t go near that blazing pan. Let me go in there,” and he brushed Nancy aside making his way into the untidy place, which now seemed, to the frightened girl, all in flames.

“The meat—gosh!” moaned poor Ted, for the stranger had opened the back door, and having grabbed the flaming pan with that same towel Nancy had tossed on the chair, he was now tossing the blazing pan as far out from the house as his best fling permitted.

“There!” he exclaimed, brushing one hand with the other. “I guess we’re safe now.”

“Oh, thank you, Mister, Mister—” Nancy waited for him to supply the name, but he only smiled broadly.

“Just call me Sam,” he said pleasantly.

“Sam?” echoed Ted.

“Yes, sonny. Isn’t that all right?” asked the stranger.

They were within the cluttered kitchen now and, as is usually the case with girls of Nancy’s temperament, she was much distressed at the looks of the place. In fact, she was making frantic but futile efforts to right things.

“What’s the matter with Sam?” again asked the man, curiously.

“Oh, nothing,” replied Ted. “Only it isn’t your name.”

“No? How do you know?” persisted the stranger, quizzically.

“You don’t look like a Sam,” said Ted, kicking one heel against the other to hide his embarrassment. He hadn’t intended saying all that.

The man laughed heartily, and for the moment Nancy forgot the upset kitchen. But the dinner!

“I hope your dinner isn’t gone,” remarked the stranger who wanted to be called Sam.

“Oh, no,” replied Nancy laconically, avoiding Ted’s discouraged look. “That was only some—some meat we were cooking.”

“Can’t keep house and 'tend store without spoiling something. But I feel it was somewhat my fault. Suppose we lock up and trot down to the corner for a dish of ice cream?” he suggested. “It’s just warm enough today for cream; don’t you think so?”

“Oh, let’s!” chirped Ted. A hungry boy is ever an object of pity.

“You go,” suggested Nancy, “but I think I had better stay here.”

“Oh, no. You’ve got to come along. Let me see. If you call me Uncle Sam what shall I call you?”

“I’m Nancy Brandon and this is my brother Ted,” replied Nancy. “But I’d like much better to call you by your real name.”

“Real name,” and he laughed again. “I see we are going to be critical friends. Now then, since you insist Sam won’t do suppose we make it Sanders. Mr. Sanders. How does that name suit?” and he clapped Ted’s shoulders jovially.

“Then Mr. Sanders, you and Ted go along and get your cream. I really must attend to things here,” insisted Nancy. “We are all so upset and mother will expect us to have things in some sort of order.”

“Oh, Sis, come along” begged Ted. “I’ll help you when we get back. It won’t take a minute.”

Hunger is a poor argument against food, and presently the back door was locked, the front door was locked, and the two Brandons with the man who called himself Mr. Sanders, because they refused to call him Uncle Sam, were making tracks for the ice cream store.

Burnt potatoes, burnt meat with ice cream for dessert, thought Nancy. But she was still convinced that business was more important than housekeeping.

“Glad we didn’t burn up,” remarked Ted, as he trotted along beside Mr. Sanders.

“Never want to throw water on burning grease,” they were advised. “And always keep a thing at full arm’s length, if you must pick it up. Of course, if you turned out the gas and pushed the pan well in on the stove it would eventually burn out, but think of the smoke!”

“You bet!” declared Ted, as they reached the little country ice cream parlor. Two girls, whom Nancy had seen several times since she came to Long Leigh, were just leaving the place and she thought they looked at her very curiously as they passed out. Then, she distinctly heard one of them say:

“Fancy! With him!”

And Nancy knew she had made some sort of mistake in accepting the well-intentioned invitation.

CHAPTER III

BELATED HASTE

Instinctively Nancy sought a sheltered corner of the ice cream room. She was greatly embarrassed to have come along the road with a stranger whom she knew nothing about, and now she was determined to leave him alone with Teddy. There must be something odd about him, to have drawn that remark from the girls. Nancy looked at him critically from her place below the decorated looking glass, and decided he did appear queer to her.

“But I’m just starved,” she told herself, “and I’ve got to have something to eat.” The girl in the gingham dress, with a great wide muslin apron, took an order for cake and cream and a glass of milk. Fortunately, Nancy had her purse along with her. That much, at least, she had already learned about being a business woman.

Teddy was chatting gaily with the man down near the door. They seemed to be having a great time over their stories, and Nancy rightly suspected the stories concerned Ted’s favorite sport, camping.

She ate her lunch rather solemnly. Everything seemed to be going wrong, but the escape from fire, with the frying meat on a shallow griddle, was surely something to be thankful for.

Oh, well! Only half a day had been lost, and she really couldn’t have done more when Miss Townsend took all that precious time with her lamentations.

Miss Townsend! Nancy sipped the last of her milk as she reflected on the little dog’s interest in the old fireplace. Of course, Miss Townsend would come again, and Tiny would always be along with her. And Nancy hadn’t yet told Ted about that experience.

“Just buying a country store didn’t seem to mean buying a lot of freaks along with the bargain,” Nancy speculated. “And now here’s Mr. Baldy who wants to be called after Uncle Sam, going right in back of my counter and helping himself—”

“Ready, Sis!” called out Teddy, as he waited for Mr. Sanders to pay his bill.

“You go along, Ted,” called back Nancy. “I’ve got to stop some place, but I’ll be there in time to open the door for you.”

Ted never questioned one of those queer decisions of Nancy’s. He knew how useless such a thing would be; so off he went with the man in the short sleeved shirt, while Nancy tarried long enough to give them a fair start.

Then, easily finding a way through the fields, she raced off herself, although getting through thick hedges and climbing an occasional rail fence, proved rather tantalizing.

In front of the store she found Mr. Sanders just leaving Ted. They were both talking and laughing as if the acquaintance had proved highly satisfactory, but it irritated Nancy.

“Now, I suppose, he’ll come snooping around,” she grumbled. “Well, there’s one thing certain, I’m not going to keep an old-fashioned country store. No hanging around my cracker barrels,” she told herself, although there was not, and likely never would be a cracker barrel in the Whatnot Shop.

Once more left to themselves, the burnt dinner was not referred to, as Ted helped at last to clear up the disordered kitchen. Not even the lost potatoes came in for mention as brother and sister “made things fly,” as most belated workers find themselves obliged to do.

“Here, Ted, get the broom.”

Ted grabbed the broom.

“No, let me sweep. You empty those baskets of excelsior.”

“Where?”

“Where?”

“Yes. Can we burn it?”

“No, never. No more fire for us,” groaned Nancy. “Just dump the stuff some where.”

“But we can’t, Sis,” objected Ted. “Mother 'specially said nothing could be dumped around.”

“Well, do anything you like with it, but just get it out of the way,” and Nancy’s excited broom made jabs and stabs at corners without quite reaching them.

Ted was much more methodical. He really would do things right, if only Nancy would give him a chance. Just now he was carefully packing the excelsior in a big clothes basket.

“You know, Nan,” he remarked, “Mr. Sanders is awfully funny.”

“How funny?” asked Nancy crisply.

“Oh, he knows an awful lot.”

“He ought to, he’s bald headed,” answered Nancy, implying there-by that Mr. Sanders was an old man and ought to be wise.

“Is he?” asked Ted innocently.

“For lands sake! Ted Brandon!” exclaimed Nancy. “Can’t you think what you’re saying? Is he what?”

The thread of the argument thus entirely lost, Ted just crammed away at the excelsior.

“I’m just dying to get at the store,” said Nancy next. “I want to fix that all up so that mother will buy more things to put in stock.”

“She’s going to bring home fishing rods. I’m goin’ to have a corner for sport stuff, you know,” Ted reminded the whirl-wind Nancy.

“Oh, yes, of course, that’s all right. But we’ll have to see which corner we can spare best. The store isn’t any too big, is it?”

“Big enough,” agreed the affable boy. “And I’ll bet, Nan, we’ll have heaps of sport around here this summer. There’s fine fellows over by the big hill. That’s more of a summer place than this is, I guess.”

“Where does your friend Uncle Sam live?”

“You mean Mr. Sanders. Why, he didn’t say, but he went up the hill toward that old stone place.”

“Yes. I wouldn’t wonder but he would live in an old stone place,” echoed Nancy sarcastically.

“Why, don’t you like him?”

“Like him?”

“I mean—do you hate him?” laughed Ted. His basket was filled and he was gathering up the loose ends of the splintered fibers upon a tin cover.

“I don’t like him and I don’t hate him, but I do hope he won’t come snooping around my store,” returned Nancy.

Teddy stopped short with a frying pan raised in mid air. He swung it at an imaginary ball, then put it down in the still packed peach basket.

“Now, Nan,” he protested, “don’t you go kickin’ up any fuss about Mr. Sanders. He always came around here; he’s a great friend of the Townsends.”

“Ted Brandon!” Nancy flirted the dust brush at the gas stove, “do you think I am going to take all that with this store? Did we buy all the Townsends’ old—old cronies along with the Whatnot Shop?”

“There’s someone,” Ted interrupted, as the store bell jangled timidly.

“Oh, you go please, Ted,” begged Nancy, who had glimpsed girls’ skirts without. “I’m too untidy to tend store this afternoon.”

CHAPTER IV

NEW FRIENDS

Nancy never looked as untidy as she really felt. In fact, she always looked “interesting and human,” as her friends might say, but she was sensitive about the disorder she pretended to despise. Now, here were those two girls! She simply could not go in the store as she looked.

“You’re all right,” Ted insisted, as they both listened to the jangling bell. “You look good in that yellow dress.”

“Good?” she took time to correct. “You mean—something else. And it isn’t yellow,” she countered. “But please, Ted, you go. There’s a dear. I’ll do something for you—”

Ted started off dutifully. “But I won’t know,” he argued.

“Run along, like a dear,” whispered Nancy, for persons were now within the store, she could easily hear them talking and could even see their reflections in the little hall mirror.

Ted went. He was such a good-natured boy, and Nancy was glad to notice once more “so good-looking.”

After exchanging a few questions and answers with the girls in the store, Ted was presently back again in the kitchen.

“Blue silk!” he sort of hissed at Nancy. “They want—blue silk.”

“We haven’t any. Tell them we’re out of it.”

Ted went forth with a protest.

A few seconds later he again confronted Nancy.

“Blue twist then. What ever on earth is blue twist?”

“We haven’t any!” Nancy told him sharply. “We’re all out of sewing stuff, except black and white.”

“Oh, you come on. They’re just laughin’ at me. It’s your store. You go ahead and 'tend it.” Ted was on a strike now. He wasn’t going to be that kind of store keeper. Twist and silk!

“But I’m so dirty,” complained Nancy, brushing at her skirt and then patting her disordered hair. She had been rushing around at a mad rate since noon hour and naturally felt untidy.

“Well, any how, go tell them,” suggested Ted. “They’re just girls like you. You needn’t worry about your looks.” His eyes paid Nancy a decided compliment with the careless speech. Evidently she was not the only one who found good looks in the family.

Out in the store the girls were waiting, and when she finally walked up to them, Nancy was instantly at ease.

“Oh, hello!” greeted the stouter one. She was genuinely pleasant and Nancy at once liked her. “You’re the girl we’ve been trying to meet. This is Vera Johns and I’m Ruth Ashley. We live over on North Road and we’ve been wanting to meet you.”

“I’m Nancy Brandon,” replied Nancy pleasantly, “and I’m glad to meet you, too. I was wondering if I would get acquainted away out here. Won’t you sit down? Here’s a bench,” brushing aside the papers. “It takes so long to get things straightened out.”

The girls murmured their understanding of the moving problem, and after Teddy had called out from the back door, that he was going “over to see the fellows,” all three girls settled down to chat.

“Is it really your own store?” asked Ruth. She had reddish-brown hair, gray eyes and the brightest smile.

“Yes,” replied Nancy. “Just a little summer experiment. You see, I perfectly despise housework and mother believes I should learn something practical. I just begged for a little country store. I’ve always been so interested reading about them.”

“How quaint!” murmured Vera Johns. Her tone of voice seemed so affected that Nancy glanced quickly at her. Was she fooling? Could any girl mean so senseless a remark as “How quaint!” to Nancy’s telling of her practical experiment?

“Do you mean,” murmured Nancy, “why, just—how quaint?”

“Yes, isn’t it?” Vera again sort of lisped. At this Nancy was convinced. Vera was that sort of girl. She would be apt to say any silly little thing that had the fewest words in it. Just jerky little exclamations, such as Nancy’s mother had taught her to avoid as affectations.

Vera’s hair was of a toneless blonde hue, cut “classic” and plastered down like that of an Egyptian slave. Her eyes, Nancy noticed were a faded blue, and her form—Nancy hoped that she, being tall herself, did not sag at all corners, as did Vera Johns.

“I think it’s a wonderful idea,” chimed in Ruth, “to have a chance really to try out business. Just as you say, Nancy, we learn to wash doll dishes as soon as we can reach a kitchen chair. Then why shouldn’t we learn to make and count pennies as early as we possibly can?”

“Do you hate housework too, Ruth?” Nancy asked, hoping for the joy of finding a mutual understanding. “Are you also anxious to try business?”

“I hate housework, abhor it,” admitted Ruth, dimpling prettily, “but mother says we just have to get used to it, so we won’t know we’re doing it. You would be surprised, Nancy, how easy it is to wash dishes and dream of babbling brooks.”

“Really!” That was Vera again. “I adore dishes, but I won’t dream of bobbling brooks, ever.”

“Bobbling,” repeated Ruth. “That’s good, Vera. I suppose they bobble more than they babble. But I guess you’re not much of a dreamer, Vera,” she finished, in a doubtful compliment.

Nancy was amused. Ruth was going to be “good fun” and Vera was already proving a pretty good joke. Their acquaintance was surely promising, and Nancy responded fittingly.

She had time to notice in detail each of these new friends. Ruth was dimply and just fat enough to be happily plump. She also was correspondingly sunny in her disposition. She wore her hair twisted into three or four “Spring Maids” and it gave her the effect of short, curled hair. Her summer dress was a simple blue ratine, and Nancy admired it frankly.

Vera was affected in manner, in style, in dress and every way. Her hair was so arranged Nancy couldn’t be sure just how it was done, but it looked like a model in a hairdresser’s window. Also, she wore, bound around it a Roman ribbon, with a wonderful assortment of rainbow colors. Her costume was sport, with a very fancy jacket and a light silk and wool plaid skirt. That she had plenty of money was rather too obviously apparent, and Nancy wondered just how she and Ruth were connected.

They were inspecting the newly acquired little store.

“And you are the manager, the proprietor—”

“The clerk and the cashier,” Nancy interrupted Ruth. “I’ve always loved to play store, so now, mother says, she hopes I’ll be satisfied. But this is a very old-timey place. I don’t see how the Townsends ever made it pay.”

“Miss Townsend is a queer old lady,” replied Ruth. “I guess of late years they didn’t have to worry about making things pay in the store.”

“Why Ruthie!” exclaimed Vera. “Don’t you know every body says they went bankrupt?”

“Oh, that,” laughed Ruth. “I guess Mr. Townsend lent out his money and couldn’t get it back handy.”

“But he and his sister had a perfectly desperate fight over it,” insisted Vera, eyes wide with curious interest.

“Desperate,” repeated Ruth, as if trying to give Nancy a cue to Vera’s queer vocabulary. “I can imagine their sort of desperate fight. Sister Sarah would say to Brother Elmer: 'Elmer dear, you really can’t mean a thing like that,’” imitated Ruth, “and Brother Elmer would clasp and unclasp his thin hands as he replied: 'I’m sorry, Sister Sarah, but it looks that way.’”

Ruth and Nancy laughed merrily as the little sketch ended.

“That’s about how desperate those two would fight,” Ruth declared.

“Then why did they sell out?” demanded Vera. “Every body knows they lost everything.”

“We haven’t actually bought the place,” Nancy explained, “just have an option on it. You see, we had to go to the country every summer, and mother thought this might suit us. It is so convenient for her to commute, and Ted and I can’t get into a lot of mischief in a place like this. So it seems, at least,” she hastened to add.

“Well, if you let your brother go around with that queer old fellow we saw him with today, he may get into mischief,” intimated Vera, mysteriously, with a wag of her bobbed head.

“Mr. Sanders? What’s the matter with Mr. Sanders?” demanded Nancy, rather sharply.

“Oh talk, talk, and gossip,” Ruth interposed. “Just because he sees fit to keep his business to himself—”

“You know perfectly well, Ruth, that is more than gossip,” insisted Vera.

“What is? What’s the mystery?” again demanded Nancy, dropping her box of lead pencils rather suddenly.

“Well,” drawled Vera, getting up with a tantalizing deliberateness, “if you were to see a person in front of you one minute and have him vanish the next—”

A peal of laughter from Nancy broke in rudely upon Vera’s recitation.

“All right,” Vera added, in a hurt tone. “Don’t believe me if you don’t want to, but just wait and see.”

“Disappearing Dick?” chanted Nancy gaily. “Do you mean to say he’s one of those so-called miracle men?”

“Oh, no, nothing of the sort,” protested Ruth. “But there is something—different about him. A lot of people say he does disappear, but of course, there’s nothing uncanny about it. It’s probably just clever,” Ruth tried to explain.

“Rather,” drawled Vera.

And Nancy could not suppress an impolite but insistent chuckle.

CHAPTER V

ORIGINAL PLANS

During the next half hour the girls busied themselves playing store. Ruth was almost as keenly interested in the little place as was Nancy, herself, but it was noticeable that Vera was more curious. She poked into the farthest corners, even opening obscure little cubby-holes that Nancy had not yet discovered. All the while they talked about the Townsends and the mysterious Mr. Sanders, declaring that something around the Whatnot Shop held the clue to the Townsend disagreement, and Mr. Sanders’ mysterious power of disappearing.

“I think it’s the funniest thing,” ruminated Nancy, clapping the wrong cover on the white thread box, “here we came away out here to be peaceful, quiet and studious. Mother looked for a place just to keep Ted and me busy, and then we run into a regular hornet’s nest of rumors.”

“Don’t you know,” replied Ruth, “that still waters run deepest?”

“But I didn’t know we had to take on a whole Mother Goose set of fairy tales with a little two cent shoe-string shop,” protested Nancy. “Of course it will serve me right if I get into an awful squall. My rebellion against the long-loved house-work idea, is sure to get me into some trouble, isn’t it?”

“Who doesn’t rebel secretly?” admitted Ruth. “Isn’t it fairer to up and say so than to be always hoping the dishpan will spring a leak, and dish-towels will blow away?” Ruth was making rapid strides in gaining Nancy’s affection. She was so unaffected, so frank, and so sensible.

Vera wasn’t saying much but she was poking a lot. Just now she was fussing with some discarded and disabled toys. She held up a helpless windmill.

“Imagine!” she said, simply.

“Well, what of it?” asked Ruth. “It was pretty—once!”

“Pretty! As if anyone around here would ever buy a thing like that.”

“Let me see it,” Nancy said. “I’m sure Ted would love 'a thing like that.’ He’d spend days tinkering with it.” Nancy took the red and blue tin toy and inspected it critically. As she wound a tiny key a little bell tinkled.

“Lovel-lee!” cried Ruth. “That’s a merry wind. Or is it a tinkle-ly wind? Anyway it’s cute. Save it for the small brother, Nancy. And I think he’s awfully cute. Here’s something else for his camp,” she offered, handing Nancy over a red, white and blue popgun.

“Great!” declared Nancy. “Ted has been too busy to rummage yet, but he’s sure to be thrilled when he does go at it. Yes, I think Ted is cute, and I hope the disappearing man won’t cast a spell on him,” she finished, laughing at the idea, and meanwhile inspecting the toy windmill.

“You can joke,” warned Vera, “but my grandmother insists that what everyone says must be true, and everyone says Baldy Sanders is freakish.”

“Baldy,” repeated Nancy gaily. “I noticed that. But he has enough of eyes to make up for the lost hair. I never saw such merry twinkling eyes.”

“Really!” Vera commented. “I never notice men’s eyes.”

“Just their bald heads,” teased Ruth. “Now Vera, if Mr. Sanders is a professor, as some folks claim, and if he ever gets our class in chemistry, I’m afraid you would just have to notice his merry, twinkling eyes. Anyhow,” and Ruth cocked up a faded little blue muslin pussy cat, “he’s merry, and that is in his favor. What are you doing with that windmill, Nancy?”

“Inspecting it. It’s a queer kind of windmill. Look at the cross pieces on top and this tin cup.”

All three girls gave their attention to the queer toy. It was, as Nancy had said, different from the usual model. It had cross pieces on top instead of on the side, and one piece was capped off with a metal cup.

“I’ll save it for Ted,” Nancy concluded. “But I hope it isn’t dangerous. It takes boys to find out the worst of everything. Just before we moved, most of our furniture is in storage you know,” she put in to explain the scarcity of things at the country place, “Ted went up to the attic and found an old wooden gun. It would shoot peas, and what those boys didn’t shoot peas at wasn’t worth mentioning. I’ll put the freak windmill away for him, though. It looks quite harmless.”

“Oh, I think it’s just joyous to have a shop,” exclaimed Ruth, “and if you’ll let me, Nancy, I’ll come in and 'tend sometimes.”

“I’d love to have you,” replied Nancy earnestly. “I did expect my chum, Bonny Davis, to visit me, but she’s gone down to the shore first. Bonny’s lots of fun. I’m sure you’d like her if she does come,” declared Nancy, loyally.

“I like her name,” Ruth answered. “What is it? Bonita?”

“No, it’s really Charlotte, but she’s so black we’ve always called her Bonny from ebony, you know. Now Vera, what have you discovered?” broke off Nancy, looking over to the comer in which Vera was plainly interested. “Anything spooky?”

“Not spooky,” replied Vera, “but I never saw such odd looking fishing things. No wonder the Townsends went bankrupt. Here are boxes and boxes of wires and weights, and I don’t know what all. Oh, I’ll tell you!” she exclaimed, in a rare burst of enthusiasm. “Let’s have a fishing sale?”

“And sell fish!” teased Ruth.

“No,” objected Nancy, taking Vera’s part. “I think a special sale of fishing and sport supplies would be great. Let’s see what we’ve got toward it.”

“It would draw the boys and that’s something,” joked Ruth. “But I’ll tell you what, Nancy, you had better be careful what you try to sell to the young fishermen around here. They’re pretty particular and rather good at the sport. I like to fish myself.”

“Oh, I’d love to,” declared Nancy. “Where do you go?”

“Dyke’s pond and sometimes the old mill creek,” replied Ruth. “But we only get sunnies there. There’s perch in the pond, though.”

This led to discussing the fishing prospects in brooks, ponds and other waterways around Long Leigh, until it was being promptly decided that Ruth and Vera should very soon introduce Nancy to the sport. The idea of having a sale of the outfit at the shop was also entered upon enthusiastically, until the afternoon was melting into shadows before the girls realized it.

“But what ever you do,” Ruth cautioned Nancy, “don’t let any one induce you to take the Whatnot out of the window. That’s the sign of this old shop that’s known for miles and miles.”

“I think a cute little windmill would be lots nicer,” suggested Vera. “That Whatnot is—atrocious.”

“Windmill!” repeated Ruth. “But we don’t sell windmills.”

“Certainly not. Neither do we sell Whatnots,” contended Vera.

“But we sell the things that are on the Whatnot,” argued Ruth. “And besides Whatnot stands for What Not!”

It was amusing Nancy to listen to their assumed partnership. They were both talking about “our shop” and insisting upon what “we sell.” This established at once a comradeship among all three, and Nancy was convinced that her own desire to go into business was not, after all, very queer. Other girls, no doubt, shared it as well, but the difference was—Nancy’s mother. She was the “angel of the enterprise,” as Nancy had declared more than once.

“And I’ll tell you,” confided Vera, quite surprisingly, “if you’ll let me, I’ll help you with your housework. I don’t mind it a bit, and you hate it so.”

“Oh, that’s just lovely of you, Vera,” Nancy replied, while a sense of fear seized her, “but I really must do some of it, you know. Even a good store keeper should know how to cook a little,” she pretended, vowing that her house would be in some kind of order before Vera ever even got a peek into the living rooms.

When they were finally gone Nancy stood alone in the little store, too excited to decide at once which way to turn. She liked the girls, especially Ruth, and even Vera had her interesting features. At least she said odd things in an odd way, and her drawl was “delicious,” Nancy admitted. Of course she was gossipy. There was all that nonsense about Mr. Sanders. As if any human being could really disappear. Ted would just howl at the idea, Nancy knew, and if the man were really a professor of some sort, that ought to make him interesting, she reflected. At any rate, he was, the girls had said, a friend of the Townsends, and Nancy would make it her business to ask Miss Townsend about him the very next time she came into the store.

Her mind busy with such reflections, Nancy hooked the screen door, (the shop was not yet supposed to be open for business) and turned toward the upset kitchen.

“I’ve just got to do something with it,” she promised, “before mother comes. I wish Ted would hurry along home. Of course, he’s a boy and boys don’t have to worry about kitchens.”

Nevertheless, as Nancy dashed around she did make a real effort to adjust the disordered room, for her pride was now prompting her. Whatever would Vera Johns say to such a looking place? And was all this fair to a mother so thoughtful and so good-natured as was Nancy’s?

“I begin right here at this door,” she decided, feeling she had to begin at a definite spot, “and I just straighten out every single thing from here to the back door.”

Peach baskets idling with the odds and ends of packing, Ted’s red sweater, Nancy’s blue one, Nancy’s straw hat that she felt she must have within reach and which therefore had been “parked” on the floor, safe, however, under a big chair, and a paste-board box of books that she also didn’t want to lose track of, the portable phonograph cover, the phonograph itself was reposing safely on the corner of the sink where Ted had been trying a new record; all these and as many more miscellaneous articles Nancy was briefly encountering in her general clearing up plan “from one door to the other.”

But she forged on, the old broom doing heroic duty as a plough cutting through the débris. Finally, having gotten most of the stuff into a corner, she undertook to scatter it in a way peculiar to one with business, rather than domestic, instincts.

“I’ll need the baskets, all of them, when I’m settling the store,” she promptly decided, “and I’ll get Ted to put the box of books in there too, so I can read while I’m waiting. Then the phonograph—That can go in there just as well, it may draw customers.” At this Nancy laughed, but she picked up the little black box, it had been her birthday present, and put it right on the small table under the old mantle in the store. A phonograph in the store seemed attractive.

“I guess we’ll find the store handy for lots of things,” Nancy was thinking, for the difference in the size of their old home, and the limits of this new one, was not easy to adjust.

With a sort of flourish of the broom at the papers and bits of excelsior that were still an eyesore about, Nancy at length managed to “make a path,” as she expressed it, through the kitchen.

“And I’ll gather some flowers to greet mother with,” she insisted. “There’s no reason why we shouldn’t make a pretty room of a kitchen like this, with one, two, three, good sized windows,” she counted.

But the glorious bunch of early roses must have felt rather out of place, trying to conserve their wondrous perfume from contamination with the remains of a smudgy odor from burnt potatoes—which by-the-way, had not yet come to light, not to say anything of the real fire smell of burnt meat, that ran over from a pan-cake griddle into a seething gas flame.

“Oh, those flowers!” exhaled the triumphant Nancy, pushing the dishpan away so as not to bend the longest stalk, which was brushed against it. “Won’t mother just love it here?”

After all, is not the soul of the poet more valuable than the skill of a prospective housewife?

CHAPTER VI

FAIR PLAY

Mrs. Brandon was such a mother as one might readily imagine would be the parent of Nancy and Ted. In the first place she was young, so young as to be mistaken often for Nancy’s big sister. Then she was lively, a real chum with her two children, but more important than these qualities, perhaps, was her sense of tolerance.

Fair play, she called it, believing that the children would more surely and more correctly learn from experience than from continuous preaching. Perhaps this was due to her own experience. She had been a girl much like Nancy. She had not inherited the so-called domestic instinct; no more did Nancy. To that cause was ascribed Nancy’s unusual disposition toward business and her dislike for all kitchens.

“Those roses!” she breathed deeply over the scented mass Nancy had gathered. “Aren’t they just um-um? Wonderful?”

“I knew you would like them, mother,” responded Nancy happily. “I’m sorry we couldn’t get things slicked up better today, but we were so constantly interrupted.”

“You will be, Nan dear. It is always just like that when business runs into housework.”

“Oh, but say, Mother,” interrupted Ted. “It’s just great here. There’s the best lot of boys. And we’ve got a camp, a regular brigand camp—”

“Look out for mischief, Teddy boy,” replied his mother fondly. “I want you both to have a fine time, but a little mischief goes a long ways toward spoiling things, you know,” she warned, earnestly.

“Oh, I know. I’ll be careful. We won’t have any real guns nor knives, nor swords—”

“Ted Brandon! I should hope not!” cried Nancy. “Real guns and swords and knives, indeed! If you go out playing with that sort of ruffian—”

“But they aren’t. We don’t have them. No real firearms at-all,” protested Ted. “And the boys are nice fellows.”

“But just imagine what I would do if you came in hurt. And mother away and everything,” reasoned Nancy foolishly, as if she enjoyed the sensation. “It is not like it was when Anna was with us. Mother,” Nancy asked, “don’t you really think we should have someone in Anna’s place?”

“No, girlie, I don’t,” promptly replied the mother, who was just taking from the gas oven a deliciously broiled steak. “While we had Anna you never had a chance to find out all the simple things that you didn’t know. Anna was an ideal maid, but maids are not educators and none of us can learn without being given a chance. Ted, please get the ice water. And I would try, Nancy, to have every meal, no matter how simple it is, served either on the side porch or in the dining room,” counselled Mrs. Brandon. “Nothing so demoralizes us as upset kitchen meals.”

“Yes, mother, I know that,” admitted Nancy, who, with her mother nearby for inspection, was daintily arranging the salad. “As a matter of fact, I lose things in the kitchen. Imagine losing the potatoes, pan and all!”

A hearty laugh followed the recalling of Nancy’s and Ted’s dinner disaster. But even to that accident Mrs. Brandon insisted that her daughter was one of the girls who must learn by experience, so there were no long arguments given to point out her weakness.

“But Anna is coming back, isn’t she?” Ted pleaded. A boy wants to be sure of his meals in spite of all the educational processes necessary for training obdurate sisters.

“Yes, dear. I expect she will be back to us in the autumn, and I’m sure she will be benefited by her vacation,” said Mrs. Brandon. “Anna does not really have to work now. The salary and light expenses of maids soon place them in a position to retire, you know,” she pointed out practically.

“And besides,” chimed in Nancy, “it’s lots of fun to live all alone for the summer, at least. Why, if Anna were here she would be forever poking in and out of the store, and really mother,” Nancy’s voice fell to a very serious tone, “when I get things going, I intend to make you take a vacation. I’m going to make that store pay.”

“That’s lovely, girlie,” replied the mother, “and I’m sure you and Ted are going to be wonderful little helpers. Now, come eat dinner. You must be ravenous. Here, Nancy, carry along the beans with the butter. Make each hand do its share to help out each foot, you know,” she teased.

“But I’m starved,” declared Ted, making a rather risky dive for the three dinner plates and hurrying into the little dining room with them. “That ice cream was good while we were eating it, but it doesn’t last long, does it, Nan?”

This brought up the story of Mr. Sanders’ treat, and as her children related it, each outdoing the other in vivid description and volumes of parentheses, Mrs. Brandon listened with but few interruptions. When the story was told, however, she gave her version of the gossip concerning the stranger.

“He is really a professor, I’m sure,” she stated, “for Miss Townsend told me that much. Of course professors can be as queer as other folks—”

“Queer?” interrupted Ted, holding his plate out for another new potato.

“Yes, they are often odd,” admitted his mother, smiling at the boy’s joke. “But then, too, we expect to depend upon their intelligence for reasonable explanations.”

“Mother, anyone would know you were a librarian, the way you talk,” said Nancy. “I suppose we act booky too, only we can’t realize it ourselves. Ted, your knife is playing toboggan—”

“I’m too starved to notice,” said Ted. “Hope you won’t lose the potatoes and burn the meat again, Sis,” he added, “I can’t stand starvation.”

“I didn’t do it, we did it,” insisted Nancy. “I’m sure we were both getting dinner—”

“But about Miss Townsend, dear,” her mother forestalled their argument. “Did she say she regretted agreeing to sell?”

“No, mother; that’s the queer part of it all,” Nancy replied. They were now settled at their meal and could chat happily. “She acted so mysterious about everything. And you should see her little dog, Tiny, sniff around! Honestly, I thought he’d sniff his little stumpy nose off at the fireplace. By the way, mother, can’t we have the old stove moved out into the back storeroom? We don’t want it standing around all summer waiting for a blizzard next Christmas, do we?”

“No. But I’m afraid we will have to put off that sort of work until my vacation, Nancy. You must remember, dear, we have only agreed to let you run the little store practically as it is, to sell out Miss Townsend’s stuff and to give you some experience.”

“Oh, yes. I know,” said Nancy a little ruefully. “But mother—” she hesitated. Then began again, “Mother, I simply can’t have the girls come in and have things so upset, and I won’t, positively won’t have Miss Townsend fussing around—”

“You can’t be rude to her, Nan,” the mother said rather decidedly. “And, after all, there is nothing here she doesn’t know about.”

“Well, there seems to be,” sighed Nancy, “or else what did she start right in to search for? And the very first time she met me, too.”

“Perhaps her brother lost some papers, or something like that,” suggested Mrs. Brandon. “I do know he is a little odd in his manner.”

“But if it were only that she wouldn’t need to act so mysteriously about it, would she, mother?”

“And the dog,” put in Ted. “He couldn’t know about papers, could he? Dogs are awfully wise, I know that much, and I’m going to get one—”

Paying no attention to Ted’s last sentence, Nancy continued to deplore Miss Townsend’s threat of more visits to her shop.

“And the girls, that is Vera, said that she and her brother had a quarrel about the place before they left,” Nancy continued. “Vera is talkative, but I could see myself that Miss Townsend was awfully unhappy about something.”

“Yes,” snapped Ted, again allowing his fork to rest in the prohibited sliding position from his plate, “and she’s the one who talks about Mr. Sanders, too. That girl Veera—”

“Vera, Ted. Just like very,” said Nancy critically.

“Yeah,” groaned Ted. “Just like scary, too. That’s what she is, scary. And the fellows say Mr. Sanders is a first-rate scout, a real scout. They say he’s even a scoutmaster—”

“Did they say anything about his habit of disappearing?” asked Nancy, quizzically.

“Now, Nan. You know very well that isn’t so. It couldn’t be. How could any one dis-sa-peer?” inquired Ted, emphatically.

“That wasn’t the question, brother,” insisted Nancy. “I just asked you if the boys spoke of his reputation as Disappearing Dick?”

This was too much for Ted, and again his mother was forced to intervene.

“Anyway,” the boy managed to interject, “if they did say something about it they didn’t say he was a spook, like your old Very-scary girl told it.”

“Ted Brandon! Nothing about spooks! We never even mentioned them, that I remember. But they said that Mr. Sanders lived somewhere around here but no one knew where, that he went right up the hill to the stone house and never went in the house nor in the barn nor anyplace but just disappeared,” rattled off Nancy.

“Why daughter!” protested Mrs. Brandon, “how perfectly absurd. I’m surprised that you should listen to such truck.”

“But of course I don’t believe it, Mother, it’s just funny, that’s all,” explained Nancy, who had begun to carry the dishes to the kitchen quite as if she just loved to do it.

According to their new schedule, both Ted and Nancy were expected to do their part in the clearing of the table, and washing the dishes, and as this was a beautiful summer evening, the children “fell to” very promptly.

“It’s too lovely to stay inside,” remarked Nancy. “You’ll come out with us, won’t you Mother? There’s heaps of things you haven’t yet had a chance to see around here,” she pleaded.

“But we really must get things in order,” declared the mother. “You and Ted hurry along with your work—Ted will dry and you wash tonight, Nancy, and meanwhile I’ll sort of dig in—”

“Mother! You can’t. You have just got to have your evenings free,” protested Nancy. “You need lots of fresh air out here—”

“I know, dear, but after all we are just ordinary mortals and we must live as such. That means—civilization, around here,” laughed Mrs. Brandon, who was already “digging in.”

“I’ll put these pans away first.” She paused. “Whatever is this? I do declare, children, here are your lost potatoes, packed away in among the empty pans. Now, who could have done that?”

“Ted did,” replied Nancy. “He was sorting the tins. But Mother,” she said, in a grieved tone, “I know I did waste a lot of time today.”

Nancy was carrying out a tray but she had stopped abruptly. No punishment could be greater to her than the loss of a summer evening out of doors, except it was her mother’s loss of that self-same evening.

“I’m so sorry,” she sighed. “I know I did idle my time today, Mother dear, but I can’t bear to have you—pay for it.”

“Nonsense, dear, I don’t mind. Really the exercise will do me good,” insisted Mrs. Brandon. “Just attend to the dishes and you won’t know these quarters presently. I’m glad we found the potatoes,” she said, but Nancy was now too serious to joke.

A call from the side porch checked their argument. It was Ruth calling to Nancy.

“Come along!” she shrilled through the screen door. “There’s going to be a band concert—”

“Oh, I can’t, Ruth,” Nancy called back. “I must do—”

“You must go, dear,” interrupted her mother.

At this Ruth came in to wait. Ted was already off—he did not need to be coaxed to give up his task, and when dishes were not being washed surely they could not be dried.

But Nancy felt guilty. In fact the band concert, novelty though it was, with firemen and a baseball team making up the “scrambled” programme, was not loud enough to still the voice of regret.

“I can’t bear to think of mother doing, now on this beautiful evening, what I should have done today,” she confided to Ruth, as they waited between numbers.

“I’ll help you tomorrow,” offered Ruth kindly. “And I won’t bring Vera. She’s rather critical—”

“I’ll be up at daybreak,” resolved Nancy, really determined now to get the little country home in order.

A band concert in Long Leigh was plainly an important event, and the numbers of persons crowding about the band-stand on the village green attested hearty appreciation for the musical efforts. The firemen, however, seemed to draw out the heaviest applause, but that was because old Jake Jacobs, the best piccolo player around, had been training them. Still, there was Pete Van Riper, the drummer on the baseball side of the platform. He certainly could drum, and the small boys around kept calling to him in baseball parlance such encouragements as “Make it a homer, Pete! Hug the mat! Hit her hard!” and such outfield coaching.

Ruth had met a number of her friends and some she introduced to Nancy, but the concert was spoiled for Nancy. She could see and actually feel her mother working in that little country place to which she had come, just to give Ted and Nancy a happy vacation.

When her worry was becoming so keen that she felt she must ask Ruth to go home with her, there pushed into the crowd an old man in a broad-brimmed straw hat, although the sun was well out of all mischief.

“Look!” whispered Ruth. “There’s Mr. Townsend! And that’s Mr. Sanders—with him!”

Just then the two men stepped over to the little mound where the girls were. They did not see the girls, but Mr. Sanders drew Mr. Townsend to a sudden stop in a space directly in front of Nancy and Ruth.

“I tell you, Sanders,” Mr. Townsend said, in a voice not at all suitable for his surroundings, “the whole town is talkin’. They say all kinds of things and you had better out with the whole thing.”

Mr. Sanders laughed as if he enjoyed the joke.

“Keep cool, keep cool, friend,” he said.

But Mr. Townsend was by no means keeping cool, and he said so, sharply.

“And I’ve left my home, got my sister on her ear, made a poor man’s name for myself—”

Mr. Sanders grasped his arm with a sudden movement, perfectly evident to the astounded girls.

“When you are tired of your bargain, Elmer Townsend,” he said, “just let me know.”

CHAPTER VII

THE SPECIAL SALE

They had worked like slaves, according to Nancy, while Ted insisted he was too tired even to eat.

“But it’s going to be a grand success,” promised Ruth. “I can hardly wait until morning for the doors to open.”

“Sale now going on!” chanted Isabel, a friend of Ruth’s, who had come in to help. “Ladies and gentlemen! Step this way for your fish lines!” she called out, testing the possibilities of the next day’s special sale. “Here’s where you get your fish-hooks that never slip, and your tackle that always tacks, and as for sinkers—”

“You’ll sink, first shot,” Ruth interrupted, from her perch on the stepladder, where she was waving a Japanese lantern as if that flimsy article had anything to do with fishing tackle.

“Oh say! Look here! Who took my best reel?” cried Ted. “I want that for myself. It was in a dollar box—”

“Then it’s got to be sold,” called back Nancy. She was sitting on the counter counting fish lines, a dozen to each box.

“Sold nothing!” retorted Ted. “I’d like to know why I can’t have the best—”

“You can, Teddy dear,” Ruth told him. “You have been a perfect lamb to help us all afternoon, and I never did see two legs do more trotting than yours have done since Nancy locked the front doors and put us all to work like prisoners. You may certainly have the reel, and there’s a wonderful pole back of the empty cigar boxes—there on that first shelf. See it? It’s in a gray case—”

“Ruth Ashley! Whose store is this?” Nancy pretended to be very severe but her jolly little laugh filtered through the words in giggles and titters. “If you are going to give things away, why not start in with the perishables? There’s a basket of apples, Ted himself bought out of the general fund, and unless they can be sold as bait, I don’t see what we’re going to do with them.” She had counted out all the fish lines and was resting against the old-time candy glass case, now neatly filled with post cards and stationery supplies.

They had had a merry time getting the Whatnot Shop ready for the first special sale, and girl-like, had expended a lot of energy upon pretty effects in the arrangements of articles. Mrs. Brandon “chipped in” as Ted expressed it, and Nancy was able to supplement her stock considerably. She had also made a very attractive poster for the big front window, in fact, it was so attractive that Ruth put another sign right alongside of it which stated:

This poster, handmade, for sale

Price $2.00

“We always sell our charity posters,” she insisted, “and they are never as pretty as this. Just look at that fish. What is he, Nancy? A cat-fish or a pickerel?”

“I’m totally ignorant of the varieties,” replied Nancy grandly. “But I like the flecks on his back so I made him up flecked.”

“The fellows will be here awfully early,” Ted warned the girls, “so you better be ready to sell, quick as the door’s opened.”

“We’ll be here,” sang out Ruth. “And Ted, be sure to tell them this is a strictly cash sale. No charging and no refunds. If you buy a fish pole and find it’s a curtain rod you’ve got to go fishing with the curtain rod. Nancy, here’s those fancy little colored bags to fool the poor fish with. Where do you want them put? Some place very safe, for they’re easily broken, you know,” Ruth cautioned.

“Right here in the show case,” Nancy directed. “They’re too cute to be stuck away on a shelf. Ted, you better run off and have some fun. I don’t want mother to think we’ve been stunting your growth. You know how particular she is about exercise.”

“Exercise!” repeated Isabel. “As if the poor child hasn’t been stretching every muscle to its utmost all afternoon. Take my advice, Ted, and lie down. I’ll make an ice bag out of an old bathing cap—”

But Ted was not waiting to hear Isabel’s kind, if foolish, offer. His merry shout as he rounded the corner, however, spoke decidedly against ice bags as well as couches.

“Let’s quit,” suggested Nancy. “Honestly girls, I thought housework was tedious, but I can’t see much difference. I believe I’ll be winding fish lines all night, I’ve got them tangled in my brain.”

“Then you’re the one for the ice bags,” pronounced Isabel. “I love to make them and I love to put them on pretty heads. Here Ruth, let’s put her on the couch. I think she looks a bit feverish.”

Kicking and protesting Nancy was forced to get down from “her perch,” and stretch out on the little leather couch in a favorite corner of the sun porch. Then, while Ruth literally held her there, Isabel cracked ice, put it in a green rubber bathing cap, that leaked like a sieve, tied it up most imperfectly, and presently clapped it on Nancy’s head.

“Oh, please! It’s leaking! I’m all wet. Isabel, you’re freezing my—my thinker!” yelled Nancy, as she struggled to free herself from her playful companions.

“That’s the idea,” replied Isabel. “We’ve got to freeze your thinker to make you forget your fish lines. Here now, dearie,” she mocked “lie perfectly still—”

“You’re spoiling my pretty new gown,” yelled Nancy, referring to the oldest and most faded gown she could find that morning, in preparation for the extra work.

But Isabel held the bag in the general direction of Nancy’s forehead, while little icy cold streams tinkled down her neck and into her ears. Ruth served as body guard, and almost kept Nancy on the couch, her feet, arms, and other “loose ends” hanging over untidily.

The store bell was jerked suddenly and violently.

“Oh me, oh my!” groaned Nancy, jumping up so as to smash the ice bag to the floor, cut its string loose and send the remaining chunks of ice flying. “I can’t go. Ruth, will you—”

“Love to,” chanted Ruth, starting off promptly.

“Look at the puddle,” bewailed Isabel, but Nancy interrupted her.

“No one, simply no one can come in to-day. Do run out, Belle and restrain Ruth. Just listen to her sweetest tones—”

Isabel went. She liked to “'tend store” and each possible customer represented to her, as well as to Ruth, a possible adventure.

“No, I’m not the proprietor,” Nancy heard Ruth saying.

“No, she really can’t see you,” was Isabel’s contribution.

A man’s voice, full, rich, persuasive, was speaking in so low a tone that his words did not convey meaning to the listening Nancy.

She listened! She crept nearer, and finally realizing that both Ruth and Isabel were not being able to dismiss the stranger, she attempted to right her rumpled self, to pat the unruly hair into place, and not knowing that her forehead looked like a beefsteak from the ice freeze, she sauntered out into the store.

“This is Miss Brandon,” announced Ruth as she entered. “She is the proprietor.”

Nancy found herself in the presence of a very important looking young man. His Panama hat was on the counter, his suitcase was on the floor, and he stood in the most attentive, courteous attitude, bowing as if she were meeting him in a reception room.

“I’ve heard of your store, Miss Brandon,” he said. “In fact, its fame has travelled far and wide, and I’m here representing a Boston firm of sporting goods. I would like you to see—”

“Really,” faltered Nancy, “this is only sort of a play store. We are doing it for a vacation experience.”

“Exactly the thing,” insisted the young man, who was not polite to the point of affectation but simply polite as a gentleman. “I know this territory pretty well, and you will possibly be surprised at the class of customers who will, doubtless, seek you out. The motor people come along here from Gretna Lake. There’s good fishing on that lake, and fishing supplies have a way of giving out suddenly when the inexperienced handle them. If you will let me—” he was tackling the suitcase.

“But you see,” protested Nancy, much embarrassed, “I really have no authority to—buy. Mother is not here—”

“You assume no obligation,” insisted the man. “As this is your store we are glad, in fact anxious, to leave you a sample line. If you sell them you make a very fair commission, if you do not I pick them up and try something else on my next trip.”