автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Moonlit Way

The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Moonlit Way, by Robert W. Chambers, Illustrated by A. I. Keller

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Moonlit Way

Author: Robert W. Chambers

Release Date: August 28, 2010 [eBook #33557]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MOONLIT WAY***

E-text prepared by Katherine Ward, Darleen Dove, Roger Frank,

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

The

MOONLIT WAY

A Novel

BY

ROBERT W. CHAMBERS

AUTHOR OF

“THE COMMON LAW,” “THE FIGHTING CHANCE,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

A. I. KELLER

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

1919

HIS STRAINED GAZE SOUGHT TO FIX ITSELF ON THIS FACE—(PAGE 325)

Copyright, 1919, by

ROBERT W. CHAMBERS

Copyright, 1918, 1919, by the

INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE CO.

Printed in the United States of America

TO

MY FRIEND

FRANK HITCHCOCK

CONTENTS

CHAPTERPAGE Prologue—Claire-de-Lune 1

I.

A Shadow Dance 19II.

Sunrise 28III.

Sunset 39IV.

Dusk 46V.

In Dragon Court 57VI.

Dulcie 78VII.

Opportunity Knocks 87VIII.

Dulcie Answers 102IX.

Her Day 109X.

Her Evening 123XI.

Her Night 131XII.

The Last Mail 155XIII.

A Midnight Tête-à-Tête 170XIV.

Problems 186XV.

Blackmail 194XVI.

The Watcher 205XVII.

A Conference 216XVIII.

The Babbler 233XIX.

A Chance Encounter 249XX.

Grogan’s 265XXI.

The White Blackbird 278XXII.

Foreland Farms 292XXIII.

A Lion in the Path 312XXIV.

A Silent House 328XXV.

Starlight 339XXVI.

’Be-N Eirinn I! 349XXVII.

The Moonlit Way 366XXVIII.

Green Jackets 385XXIX.

Asthore 407LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

His strained gaze sought to fix itself on this face before him

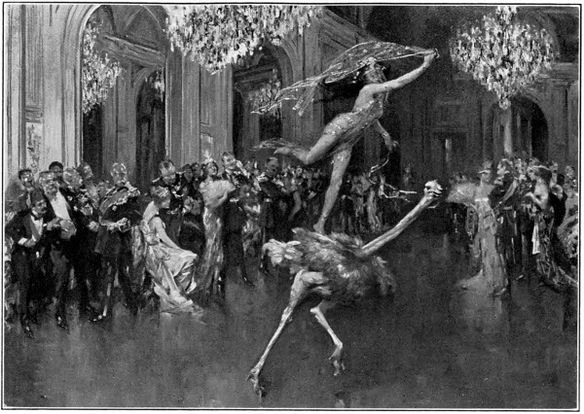

FrontispieceNihla put her feathered steed through its absurd paces

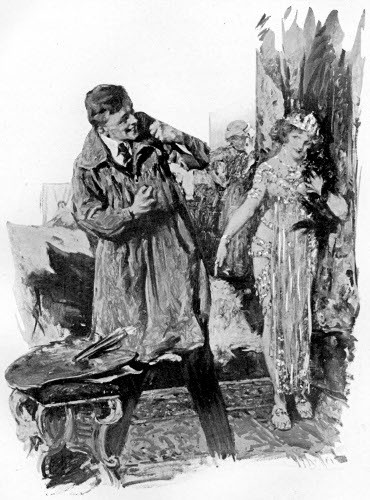

8“You little miracle!”

100He came toward her stealthily

382Novels By Robert W. Chambers

The Laughing Girl

The Restless Sex

Barbarians

The Dark Star

The Girl Philippa

Who Goes There!

Athalie

The Business of Life

The Gay Rebellion

The Streets of Ascalon

The Common Law

The Fighting Chance

The Younger Set

The Danger Mark

The Firing Line

Japonette

Quick Action

The Adventures of A Modest Man

Anne’s Bridge

Between Friends

The Better Man

Police!!!

Some Ladies in Haste

The Tree of Heaven

The Tracer of Lost Persons

The Hidden Children

The Moonlit Way

Cardigan

The Reckoning

The Maid-at-Arms

Ailsa Paige

Special Messenger

The Haunts of Men

Lorraine

Maids of Paradise

Ashes of Empire

The Red Republic

Blue-Bird Weather

A Young Man in a Hurry

The Green Mouse

Iole

The Mystery of Choice

The Cambric Mask

The Maker of Moons

The King in Yellow

In Search of the Unknown

The Conspiritors

A King and a Few Dukes

In the Quarter

Outsiders

PROLOGUE CLAIRE-DE-LUNE

There was a big moon over the Bosphorus; the limpid waters off Seraglio Point glimmered; the Golden Horn was like a sheet of beaten silver inset with topaz and ruby where lanterns on rusting Turkish warships dyed the tarnished argent of the flood. Except for these, and the fixed lights on the foreign guard-ships and on a big American steam yacht, only a pale and nebulous shoreward glow betrayed the monster city.

Over Pera the full moon’s lustre fell, silvering palace, villa, sea and coast; its rays glimmered on bridge and wharf, bastion, tower arsenal, and minarette, transforming those big, sprawling, ramshackle blotches of architecture called Constantinople into that shadowy, magnificent enchantment of the East, which all believe in, but which exists only in a poet’s heart and mind.

Night veiled the squalour of Balat, and its filth, its meanness, its flimsy sham. Moonlight made of Galata a marvel, ennobling every bastard dome, every starved façade, every unlovely and attenuated minarette, and invested with added charm each really lovely ruin, each tower, palace, mosque, garden wall and balcony, and every crenelated battlement, where the bronze bulk of ancient cannon slanted, outlined in silver under the Prophet’s moon.

Tiny moving lights twinkled on the Galata Bridge; pale points of radiance dotted Scutari; but the group of amazing cities called Constantinople lay almost blotted out under the moon.

Darker at night than any capital in the world, its huge, solid and ancient shapes bulking gigantic in the night, its noble ruins cloaked, its cheap filth hidden, its flimsy Coney Island aspect transfigured and the stylographic-pen architecture of a hundred minarettes softened into slender elegance, Constantinople lay dreaming its immemorial dreams under the black shadow of the Prussian eagle.

The German Embassy was lighted up like a Pera café; the drawing-rooms crowded with a brilliant throng where sashes, orders, epaulettes and sabre-tache glittered, and jewels blazed and aigrettes waved under the crystal chandeliers, accenting and isolating sombre civilian evening dress, which seemed mournful, rusty, and out of the picture, even when plastered over with jewelled stars.

Few Turkish officials and officers were present, but the disquieting sight of German officers in Turkish uniforms was not uncommon. And the Count d’Eblis, Senator of France, noted this phenomenon with lively curiosity, and mentioned it to his companion, Ferez Bey.

Ferez Bey, lounging in a corner with Adolf Gerhardt, for whom he had procured an invitation, and flanked by the Count d’Eblis, likewise a guest aboard the rich German-American banker’s yacht, was very much in his element as friend and mentor.

For Ferez Bey knew everybody in the Orient—knew when to cringe, when to be patronising, when to fawn, when to assert himself, when to be servile, when impudent.

He was as impudent to Adolf Gerhardt as he dared be, the banker not knowing the subtler shades and differences; he was on an equality with the French senator, Monsieur le Comte d’Eblis because he knew that d’Eblis dared not resent his familiarity.

Otherwise, in that brilliant company, Ferez Bey was a jackal—and he knew it perfectly—but a valuable jackal; and he also knew that.

So when the German Ambassador spoke pleasantly to him, his attitude was just sufficiently servile, but not overdone; and when Von-der-Hohe Pasha, in the uniform of a Turkish General of Division, graciously exchanged a polite word with him during a moment’s easy gossip with the Count d’Eblis, Ferez Bey writhed moderately under the honour, but did not exactly squirm.

To Conrad von Heimholz he ventured to present his German-American patron, Adolf Gerhardt, and the thin young military attaché condescended in his Prussian way to notice the introduction.

“Saw your yacht in the harbour,” he admitted stiffly. “It is astonishing how you Americans permit no bounds to your somewhat noticeable magnificence.”

“She’s a good boat, the Mirage,” rumbled Gerhardt, in his bushy red beard, “but there are plenty in America finer than mine.”

“Not many, Adolf,” insisted Ferez, in his flat, Eurasian voice—“not ver’ many anyw’ere so fine like your Mirage.”

“I saw none finer at Kiel,” said the attaché, staring at Gerhardt through his monocle, with the habitual insolence and disapproval of the Prussian junker. “To me it exhibits bad taste”—he turned to the Count d’Eblis—“particularly when the Meteor is there.”

“Where?” asked the Count.

“At Kiel. I speak of Kiel and the ostentation of certain foreign yacht owners at the recent regatta.”

Gerhardt, redder than ever, was still German enough to swallow the meaningless insolence. He was not getting on very well at the Embassy of his fellow countrymen. Americans, properly presented, they endured without too open resentment; for German-Americans, even when millionaires, their contempt and bad manners were often undisguised.

“I’m going to get out of this,” growled Gerhardt, who held a good position socially in New York and in the fashionable colony at Northbrook. “I’ve seen enough puffed up Germans and over-embroidered Turks to last me. Come on, d’Eblis——”

Ferez detained them both:

“Surely,” he protested, “you would not miss Nihla!”

“Nihla?” repeated d’Eblis, who had passed his arm through Gerhardt’s. “Is that the girl who set St. Petersburg by the ears?”

“Nihla Quellen,” rumbled Gerhardt. “I’ve heard of her. She’s a dancer, isn’t she?”

Ferez, of course, knew all about her, and he drew the two men into the embrasure of a long window.

It was not happening just exactly as he and the German Ambassador had planned it together; they had intended to let Nihla burst like a flaming jewel on the vision of d’Eblis and blind him then and there.

Perhaps, after all, it was better drama to prepare her entrance. And who but Ferez was qualified to prepare that entrée, or to speak with authority concerning the history of this strange and beautiful young girl who had suddenly appeared like a burning star in the East, had passed like a meteor through St. Petersburg, leaving several susceptible young men—notably the Grand Duke Cyril—mentally unhinged and hopelessly dissatisfied with fate.

“It is ver’ fonny, d’Eblis—une histoire chic, vous savez! Figurez vous——”

“Talk English,” growled Gerhardt, eyeing the serene progress of a pretty Highness, Austrian, of course, surrounded by gorgeous uniforms and empressement.

“Who’s that?” he added.

Ferez turned; the gorgeous lady snubbed him, but bowed to d’Eblis.

“The Archduchess Zilka,” he said, not a whit abashed. “She is a ver’ great frien’ of mine.”

“Can’t you present me?” enquired Gerhardt, restlessly; “—or you, d’Eblis—can’t you ask permission?”

The Count d’Eblis nodded inattentively, then turned his heavy and rather vulgar face to Ferez, plainly interested in the “histoire” of the girl, Nihla.

“What were you going to say about that dancer?” he demanded.

Ferez pretended to forget, then, apparently recollecting:

“Ah! Apropos of Nihla? It is a ver’ piquant storee—the storee of Nihla Quellen. Zat is not ’er name. No! Her name is Dunois—Thessalie Dunois.”

“French,” nodded d’Eblis.

“Alsatian,” replied Ferez slyly. “Her fathaire was captain—Achille Dunois?—you know——?”

“What!” exclaimed d’Eblis. “Do you mean that notorious fellow, the Grand Duke Cyril’s hunting cheetah?”

“The same, dear frien’. Dunois is dead—his bullet head was crack open, doubtless by som’ ladee’s angree husban’. There are a few thousan’ roubles—not more—to stan’ between some kind gentleman and the prettee Nihla. You see?” he added to Gerhardt, who was listening without interest, “—Dunois, if he was the Gran’ Duke’s cheetah, kept all such merry gentlemen from his charming daughtaire.”

Gerhardt, whose aspirations lay higher, socially, than a dancing girl, merely grunted. But d’Eblis, whose aspirations were always below even his own level, listened with visibly increasing curiosity. And this was according to the programme of Ferez Bey and Excellenz. As the Hun has it, “according to plan.”

“Well,” enquired d’Eblis heavily, “did Cyril get her?”

“All St. Petersburg is still laughing at heem,” replied the voluble Eurasian. “Cyril indeed launched her. And that was sufficient—yet, that first night she storm St. Petersburg. And Cyril’s reward? Listen, d’Eblis, they say she slapped his sillee face. For me, I don’t know. That is the storee. And he was ver’ angree, Cyril. You know? And, by God, it was what Gerhardt calls a ‘raw deal.’ Yess? Figurez vous!—this girl, déjà lancée—and her fathaire the Grand Duke’s hunting cheetah, and her mothaire, what? Yes, mon ami, a ’andsome Géorgianne, caught quite wild, they say, by Prince Haledine! For me, I believe it. Why not?... And then the beautiful Géorgianne, she fell to Dunois—on a bet?—a service rendered?—gratitude of Cyril?——Who knows? Only that Dunois must marry her. And Nihla is their daughtaire. Voilà!”

“Then why,” demanded d’Eblis, “does she make such a fuss about being grateful? I hate ingratitude, Ferez. And how can she last, anyway? To dance for the German Ambassador in Constantinople is all very well, but unless somebody launches her properly—in Paris—she’ll end in a Pera

café.”

Ferez held his peace and listened with all his might.

“I could do that,” added d’Eblis.

“Please?” inquired Ferez suavely.

“Launch her in Paris.”

The programme of Excellenz and Ferez Bey was certainly proceeding as planned.

But Gerhardt was becoming restless and dully irritated as he began to realise more and more what caste meant to Prussians and how insignificant to these people was a German-American multimillionaire. And Ferez realised that he must do something.

There was a Bavarian Baroness there, uglier than the usual run of Bavarian baronesses; and to her Ferez nailed Gerhardt, and wriggled free himself, making his way amid the gorgeous throngs to the Count d’Eblis once more.

“I left Gerhardt planted,” he remarked with satisfaction; “by God, she is uglee like camels—the Baroness von Schaunitz! Nev’ mind. It is nobility; it is the same to Adolf Gerhardt.”

“A homely woman makes me sick!” remarked d’Eblis. “Eh, mon Dieu!—one has merely to look at these ladies to guess their nationality! Only in Germany can one gather together such a collection of horrors. The only pretty ones are Austrian.”

Perhaps even the cynicism of Excellenz had not realised the perfection of this setting, but Ferez, the nimble witted, had foreseen it.

Already the glittering crowds in the drawing rooms were drawing aside like jewelled curtains; already the stringed orchestra had become mute aloft in its gilded gallery.

The gay tumult softened; laughter, voices, the rustle of silks and fans, the metallic murmur of drawing-room equipment died away. Through the increasing stillness, from the gilded gallery a Thessalonian reed began skirling like a thrush in the underbrush.

Suddenly a sand-coloured curtain at the end of the east room twitched open, and a great desert ostrich trotted in. And, astride of the big, excited, bridled bird, sat a young girl, controlling her restless mount with disdainful indifference.

“Nihla!” whispered Ferez, in the large, fat ear of the Count d’Eblis. The latter’s pallid jowl reddened and his pendulous lips tightened to a deep-bitten crease across his face.

To the weird skirling of the Thessalonian pipe the girl, Nihla, put her feathered steed through its absurd paces, aping the haute-école.

There is little humour in your Teuton; they were too amazed to laugh; too fascinated, possibly by the girl herself, to follow the panicky gambols of the reptile-headed bird.

The girl wore absolutely nothing except a Yashmak and a zone of blue jewels across her breasts and hips.

Her childish throat, her limbs, her slim, snowy body, her little naked feet were lovely beyond words. Her thick dark hair flew loose, now framing, now veiling an oval face from which, above the gauzy Yashmak’s edge, two dark eyes coolly swept her breathless audience.

But under the frail wisp of cobweb, her cheeks glowed pink, and two full red lips parted deliciously in the half-checked laughter of confident, reckless youth.

NIHLA PUT HER FEATHERED STEED THROUGH ITS ABSURD PACES

Over hurdle after hurdle she lifted her powerful, half-terrified mount; she backed it, pirouetted, made it squat, leap, pace, trot, run with wings half spread and neck stretched level.

She rode sideways, then kneeling, standing, then poised on one foot; she threw somersaults, faced to the rear, mounted and dismounted at full speed. And through the frail, transparent Yashmak her parted red lips revealed the glimmer of teeth and her childishly engaging laughter rang delightfully.

Then, abruptly, she had enough of her bird; she wheeled, sprang to the polished parquet, and sent her feathered steed scampering away through the sand-coloured curtains, which switched into place again immediately.

Breathless, laughing that frank, youthful, irresistible laugh which was to become so celebrated in Europe, Nihla Quellen strolled leisurely around the circle of her applauding audience, carelessly blowing a kiss or two from her slim finger-tips, evidently quite unspoiled by her success and equally delighted to please and to be pleased.

Then, in the gilded gallery the strings began; and quite naturally, without any trace of preparation or self-consciousness, Nihla began to sing, dancing when the fascinating, irresponsible measure called for it, singing again as the sequence occurred. And the enchantment of it all lay in its accidental and detached allure—as though it all were quite spontaneous—the song a passing whim, the dance a capricious after-thought, and the whole thing done entirely to please herself and give vent to the sheer delight of a young girl, in her own overwhelming energy and youthful spirits.

Even the Teuton comprehended that, and the applause grew to a roar with that odd undertone of animal menace always to be detected when the German herd is gratified and expresses pleasure en masse.

But she wouldn’t stay, wouldn’t return. Like one of those beautiful Persian cats, she had lingered long enough to arouse delight. Then she went, deaf to recall, to persuasion, to caress—indifferent to praise, to blandishment, to entreaty. Cat and dancer were similar; Nihla, like the Persian puss, knew when she had had enough. That was sufficient for her: nothing could stop her, nothing lure her to return.

Beads of sweat were glistening upon the heavy features of the Count d’Eblis. Von-der-Goltz Pasha, strolling near, did him the honour to remember him, but d’Eblis seemed dazed and unresponsive; and the old Pasha understood, perhaps, when he caught the beady and expressive eyes of Ferez fixed on him in exultation.

“Whose is she?” demanded d’Eblis abruptly. His voice was hoarse and evidently out of control, for he spoke too loudly to please Ferez, who took him by the arm and led him out to the moonlit terrace.

“Mon pauvere ami,” he said soothingly, “she is actually the propertee of nobodee at present. Cyril, they say, is following her—quite ready for anything—marriage——”

“What!”

Ferez shrugged:

“That is the gosseep. No doubt som’ man of wealth, more acceptable to her——”

“I wish to meet her!” said d’Eblis.

“Ah! That is, of course, not easee——”

“Why?”

Ferez laughed:

“Ask yo’self the question again! Excellenz and his guests have gone quite mad ovaire Nihla——”

“I care nothing for them,” retorted d’Eblis thickly; “I wish to know her.... I wish to know her!... Do you understand?”

After a silence, Ferez turned in the moonlight and looked at the Count d’Eblis.

“And your newspapaire—Le Mot d’Ordre?”

“Yes.... If you get her for me.”

“You sell to me for two million francs the control stock in Le Mot d’Ordre?”

“Yes.”

“An’ the two million, eh?”

“I shall use my influence with Gerhardt. That is all I can do. If your Emperor chooses to decorate him—something—the Red Eagle, third class, perhaps——”

“I attend to those,” smiled Ferez. “Hit’s ver’ fonny, d’Eblis, how I am thinking about those Red Eagles all time since I know Gerhardt. I spik to Von-der-Goltz de votre part, si vous le voulez? Oui? Alors——”

“Ask her to supper aboard the yacht.”

“God knows——”

The Count d’Eblis said through closed teeth:

“There is the first woman I ever really wanted in all my life!... I am standing here now waiting for her—waiting to be presented to her now.”

“I spik to Von-der-Goltz Pasha,” said Ferez; and he slipped through the palms and orange trees and vanished.

For half an hour the Count d’Eblis stood there, motionless in the moonlight.

She came about that time, on the arm of Ferez Bey, her father’s friend of many years.

And Ferez left her there in the creamy Turkish moonlight on the flowering terrace, alone with the Count d’Eblis.

When Ferez came again, long after midnight, with Excellenz on one arm and the proud and happy Adolf Gerhardt on the other, the whole cycle of a little drama had been played to a conclusion between those two shadowy figures under the flowering almonds on the terrace—between this slender, dark-eyed girl and this big, bulky, heavy-visaged man of the world.

And the man had been beaten and the girl had laid down every term. And the compact was this: that she was to be launched in Paris; she was merely to borrow any sum needed, with privilege to acquit the debt within the year; that, if she ever came to care for this man sufficiently, she was to become only one species of masculine property—a legal wife.

And to every condition—and finally even to the last, the man had bowed his heavy, burning head.

“D’Eblis!” began Gerhardt, almost stammering in his joy and pride. “His highness tells me that I am to have an order—an Imperial d-decoration——”

D’Eblis stared at him out of unseeing eyes; Nihla laughed outright, alas, too early wise and not even troubling her lovely head to wonder why a decoration had been asked for this burly, bushy-bearded man from nowhere.

But within his sinuous, twisted soul Ferez writhed exultingly, and patted Gerhardt on the arm, and patted d’Eblis, too—dared even to squirm visibly closer to Excellenz, like a fawning dog that fears too much to venture contact in his wriggling demonstrations.

“You take with you our pretty wonder-child to Paris to be launched, I hear,” remarked Excellenz, most affably, to d’Eblis. And to Nihla: “And upon a yacht fit for an emperor, I understand. Ach! Such a going forth is only heard of in the Arabian Nights. Eh bien, ma petite, go West, conquer, and reign! It is a prophecy!”

And Nihla threw back her head and laughed her full-throated laughter under the Turkish moon.

Later, Ferez, walking with the Ambassador, replied humbly to the curt question:

“Yes, I have become his jackal. But always at the orders of Excellenz.”

Later still, aboard the Mirage, Ferez stood alone by the after-rail, staring with ratty eyes at the blackness beyond the New Bridge.

“Oh, God, be merciful!” he whispered. He had often said it on the eve of crime. Even an Eurasian rat has emotions. And Ferez had been in love with Nihla many years, and was selling her now at a price—selling her and Adolf Gerhardt and the Count d’Eblis and France—all he had to barter—for he had sold his soul too long ago to remember even what he got for it.

The silence seemed more intense for the sounds that made it audible. From, the unlighted cities on the seven hills came an unbroken howling of dogs; transparent waves of the limpid Bosphorus slapped the vessel’s sides, making a mellow and ceaseless clatter. Far away beyond Galata Quay, in the inner reek of unseen Stamboul, the notes of a Turkish flute stole out across the darkness, where some Tzigane—some unseen wretch in rags—was playing the melancholy song of Mourad. And, mournfully responsive to the reedy complaint of a homeless wanderer from a nation without a home, the homeless dogs of Islam wailed their miserere under the Prophet’s moon.

The tragic wolf-song wavered from hill to hill; from the Fields of the Dead to the Seven Towers, from Kassim to Tophane, seeming to swell into one dreadful, endless plaint:

“My God, why hast Thou forsaken me?”

“And me!” muttered Ferez, shivering in the windy vapours from the Black Sea, which already dampened his face with their creeping summer chill.

“Ferez!”

He turned slowly. Swathed in a white wool bernous, Nihla stood there in the foggy moonlight.

“Why?” she enquired, without preliminaries and with the unfeigned curiosity of a child.

He did not pretend to misunderstand her in French:

“Thou knowest, Nihla. I have never touched thy heart. I could do nothing for thee——”

“Except to sell me,” she smiled, interrupting him in English, without the slightest trace of accent.

But Ferez preferred the refuge of French:

“Except to launch thee and make possible thy career,” he corrected her very gently.

“I thought you were in love with me?”

“I have loved thee, Nihla, since thy childhood.”

“Is there anything on earth or in paradise, Ferez, that you would not sell for a price?”

“I tell thee——”

“Zut! I know thee, Ferez!” she mocked him, slipping easily into French. “What was my price? Who pays thee, Colonel Ferez? This big, shambling, world-wearied Count, who is, nevertheless, afraid of me? Did he pay thee? Or was it this rich American, Gerhardt? Or was it Von-der-Goltz? Or Excellenz?”

“Nihla! Thou knowest me——”

Her clear, untroubled laughter checked him:

“I know you, Ferez. That is why I ask. That is why I shall have no reply from you. Only my wits can ever answer me any questions.”

She stood laughing at him, swathed in her white wool, looming like some mocking spectre in the misty moonlight of the after-deck.

“Oh, Ferez,” she said in her sweet, malicious voice, “there was a curse on Midas, too! You play at high finance; you sell what you never had to sell, and you are paid for it. All your life you have been busy selling, re-selling, bargaining, betraying, seeking always gain where only loss is possible—loss of all that justifies a man in daring to stand alive before the God that made him!... And yet—that which you call love—that shadowy emotion which you have also sold to-night—I think you really feel for me.... Yes, I believe it.... But it, too, has its price.... What was that price, Ferez?”

“Believe me, Nihla——”

“Oh, Ferez, you ask too much! No! Let me tell you, then. The price was paid by that American, who is not one but a German.”

“That is absurd!”

“Why the Red Eagle, then? And the friendship of Excellenz? What is he then, this Gerhardt, but a millionaire? Why is nobility so gracious then? What does Gerhardt give for his Red Eagle?—for the politeness of Excellenz?—for the crooked smile of a Bavarian Baroness and the lifted lorgnette of Austria? What does he give for me? Who buys me after all? Enver? Talaat? Hilmi? Who sells me? Excellenz? Von-der-Goltz? You? And who pays for me? Gerhardt, who takes his profit in Red Eagles and offers me to d’Eblis for something in exchange to please Excellenz—and you? And what, at the end of the bargaining, does d’Eblis pay for me—pay through Gerhardt to you, and through you to Excellenz, and through Excellenz to the Kaiser Wilhelm II——”

Ferez, showing his teeth, came close to her and spoke very softly:

“See how white is the moonlight off Seraglio Point, my Nihla!... It is no whiter than those loveliest ones who lie fathoms deep below these little silver waves.... Each with her bowstring snug about her snowy neck.... As fair and young, as warm and fresh and sweet as thou, my Nihla.”

He smiled at her; and if the smile stiffened an instant on her lips, the next instant her light, dauntless laughter mocked him.

“For a price,” she said, “you would sell even Life to that old miser, Death! Then listen what you have done, little smiling, whining jackal of his Excellency! I go to Paris and to my career, certain of my happy destiny, sure of myself! For my opportunity I pay if I choose—pay what I choose—when and where it suits me to pay!——”

She slipped into French with a little laugh:

“Now go and lick thy fingers of whatever crumbs have stuck there. The Count d’Eblis is doubtless licking his. Good appetite, my Ferez! Lick away lustily, for God does not temper the jackal’s appetite to his opportunities!”

Ferez let his level gaze rest on her in silence.

“Well, trafficker in Eagles, dealer in love, vendor of youth, merchant of souls, what strikes you silent?”

But he was thinking of something sharper than her tongue and less subtle, which one day might strike her silent if she laughed too much at Fate.

And, thinking, he showed his teeth again in that noiseless snicker which was his smile and laughter too.

The girl regarded him for a moment, then deliberately mimicked his smile:

“The dogs of Stamboul laugh that way, too,” she said, baring her pretty teeth. “What amuses you? Did the silly old Von-der-Goltz Pasha promise you, also, a dish of Eagle?—old Von-der-Goltz with his spectacles an inch thick and nothing living within what he carries about on his two doddering old legs! There’s a German!—who died twenty years ago and still walks like a damned man—jingling his iron crosses and mumbling his gums! Is it a resurrection from 1870 come to foretell another war? And why are these Prussian vultures gathering here in Stamboul? Can you tell me, Ferez?—these Prussians in Turkish uniforms! Is there anything dying or dead here, that these buzzards appear from the sky and alight? Why do they crowd and huddle in a circle around Constantinople? Is there something dead in Persia? Is the Bagdad railroad dying? Is Enver Bey at his last gasp? Is Talaat? Or perhaps the savoury odour comes from the Yildiz——”

“Nihla! Is there nothing sacred—nothing thou fearest on earth?”

“Only old age—and thy smile, my Ferez. Neither agrees with me.” She stretched her arms lazily.

“Allons,” she said, stifling a pleasant yawn with one slim hand,“—my maid will wake below and miss me; and then the dogs of Stamboul yonder will hear a solo such as they never heard before.... Tell me, Ferez, do you know when we are to weigh anchor?”

“At sunrise.”

“It is the same to me,”—she yawned again—“my maid is aboard and all my luggage. And my Ferez, also.... Mon dieu! And what will Cyril have to say when he arrives to find me vanished! It is, perhaps, well for us that we shall be at sea!”

Her quick laughter pealed; she turned with a careless gesture of salute, friendly and contemptuous; and her white bernous faded away in the moonlit fog.

And Ferez Bey stood staring after her out of his near-set, beady eyes, loving her, desiring her, fearing her, unrepentant that he had sold her, wondering whether the day might dawn when he would find it best to kill her for the prosperity and peace of mind of the only living being in whose service he never tired—himself.

XXV STARLIGHT

XXVI ’BE-N EIRINN I!

VIII DULCIE ANSWERS

XVIII THE BABBLER

XXVII THE MOONLIT WAY

V IN DRAGON COURT

XVI THE WATCHER

XXIV A SILENT HOUSE

XIX A CHANCE ENCOUNTER

VI DULCIE

XXIII A LION IN THE PATH

IX HER DAY

XIV PROBLEMS

XII THE LAST MAIL

IV DUSK

XX GROGAN’S

II SUNRISE

HE CAME TOWARD HER STEALTHILY

XXIX ASTHORE

XXII FORELAND FARMS

XVII A CONFERENCE

PROLOGUE CLAIRE-DE-LUNE

“YOU LITTLE MIRACLE!”

X HER EVENING

III SUNSET

XXVIII GREEN JACKETS

NIHLA PUT HER FEATHERED STEED THROUGH ITS ABSURD PACES

I A SHADOW DANCE

XXI THE WHITE BLACKBIRD

XIII A MIDNIGHT TÊTE-À-TÊTE

XI HER NIGHT

XV BLACKMAIL

VII OPPORTUNITY KNOCKS

I A SHADOW DANCE

Three years later Destiny still wore a rosy face for Nihla Quellen. And, for a young American of whom Nihla had never even heard, Destiny still remained the laughing jade he had always known, beckoning him ever nearer, with the coquettish promise of her curved forefinger, to fame and wealth immeasurable.

Seated now on a moonlit lawn, before his sketching easel, this optimistic young man, whose name was Barres, continued to observe the movements of a dim white figure which had emerged from the villa opposite, and was now stealing toward him across the dew-drenched grass.

When the white figure was quite near it halted, holding up filmy skirts and peering intently at him.

“May one look?” she inquired, in that now celebrated voice of hers, through which ever seemed to sound a hint of hidden laughter.

“Certainly,” he replied, rising from his folding camp stool.

She tiptoed over the wet grass, came up beside him, gazed down at the canvas on his easel.

“Can you really see to paint? Is the moon bright enough?” she asked.

“Yes. But one has to be familiar with one’s palette.”

“Oh. You seem to know yours quite perfectly, monsieur.”

“Enough to mix colours properly.”

“I didn’t realise that painters ever actually painted pictures by moonlight.”

“It’s a sort of hit or miss business, but the notes made are interesting,” he explained.

“What do you do with these moonlight studies?”

“Use them as notes in the studio when a moonlight picture is to be painted.”

“Are you then a realist, monsieur?”

“As much of a realist as anybody with imagination can be,” he replied, smiling at her charming, moonlit face.

“I understand. Realism is merely honesty plus the imagination of the individual.”

“A delightful mot, madam——”

“Mademoiselle,” she corrected him demurely. “Are you English?”

“American.”

“Oh. Then may I venture to converse with you in English?” She said it in exquisite English, entirely without accent.

“You are English!” he exclaimed under his breath.

“No ... I don’t know what I am.... Isn’t it charming out here? What particular view are you painting?”

“The Seine, yonder.”

She bent daintily over his sketch, holding up the skirts of her ball-gown.

“Your sketch isn’t very far advanced, is it?” she inquired seriously.

“Not very,” he smiled.

They stood there together in silence for a while, looking out over the moonlit river to the misty, tree-covered heights.

Through lighted rows of open windows in the elaborate little villa across the lawn came lively music and the distant noise of animated voices.

“Do you know,” he ventured smilingly, “that your skirts and slippers are soaking wet?”

“I don’t care. Isn’t this June night heavenly?”

She glanced across at the lighted house. “It’s so hot and noisy in there; one dances only with discomfort. A distaste for it all sent me out on the terrace. Then I walked on the lawn. Then I beheld you!... Am I interrupting your work, monsieur? I suppose I am.” She looked up at him naïvely.

He said something polite. An odd sense of having seen her somewhere possessed him now. From the distant house came the noisy American music of a two-step. With charming grace, still inspecting him out of her dark eyes, the girl began to move her pretty feet in rhythm with the music.

“Shall we?” she inquired mischievously.... “Unless you are too busy——”

The next moment they were dancing together there on the wet lawn, under the high lustre of the moon, her fresh young face and fragrant figure close to his.

During their second dance she said serenely:

“They’ll raise the dickens if I stay here any longer. Do you know the Comte d’Eblis?”

“The Senator? The numismatist?”

“Yes.”

“No, I don’t know him. I am only a Latin Quarter student.”

“Well, he is giving that party. He is giving it for me—in my honour. That is his villa. And I”—she laughed—“am going to marry him—perhaps! Isn’t this a delightful escapade of mine?”

“Isn’t it rather an indiscreet one?” he asked smilingly.

“Frightfully. But I like it. How did you happen to pitch your easel on his lawn?”

“The river and the hills—their composition appealed to me from here. It is the best view of the Seine.”

“Are you glad you came?”

They both laughed at the mischievous question.

During their third dance she became a little apprehensive and kept looking over her shoulder toward the house.

“There’s a man expected there,” she whispered, “Ferez Bey. He’s as soft-footed as a cat and he always prowls in my vicinity. At times it almost seems to me as though he were slyly watching me—as though he were employed to keep an eye on me.”

“A Turk?”

“Eurasian.... I wonder what they think of my absence? Alexandre—the Comte d’Eblis—won’t like it.”

“Had you better go?”

“Yes; I ought to, but I won’t.... Wait a moment!” She disengaged herself from his arms. “Hide your easel and colour-box in the shrubbery, in case anybody comes to look for me.”

She helped him strap up and fasten the telescope-easel; they placed the paraphernalia behind the blossoming screen of syringa. Then, coming together, she gave herself to him again, nestling between his arms with a little laugh; and they fell into step once more with the distant dance-music. Over the grass their united shadows glided, swaying, gracefully interlocked—moon-born phantoms which dogged their light young feet....

A man came out on the stone terrace under the Chinese lanterns. When they saw him they hastily backed into the obscurity of the shrubbery.

“Nihla!” he called, and his heavy voice was vibrant with irritation and impatience.

He was a big man. He walked with a bulky, awkward gait—a few paces only, out across the terrace.

“Nihla!” he bawled hoarsely.

Then two other men and a woman appeared on the terrace where the lanterns were strung. The woman called aloud in the darkness:

“Nihla! Nihla! Where are you, little devil?” Then she and the two men with her went indoors, laughing and skylarking, leaving the bulky man there alone.

The young fellow in the shrubbery felt the girl’s hand tighten on his coat sleeve, felt her slender body quiver with stifled laughter. The desire to laugh seized him, too; and they clung there together, choking back their mirth while the big man who had first appeared waddled out across the lawn toward the shrubbery, shouting:

“Nihla! Where are you then?” He came quite close to where they stood, then turned, shouted once or twice and presently disappeared across the lawn toward a walled garden. Later, several other people came out on the terrace, calling, “Nihla, Nihla,” and then went indoors, laughing boisterously.

The young fellow and the girl beside him were now quite weak and trembling with suppressed mirth.

They had not dared venture out on the lawn, although dance music had begun again.

“Is it your name they called?” he asked, his eyes very intent upon her face.

“Yes, Nihla.”

“I recognise you now,” he said, with a little thrill of wonder.

“I suppose so,” she replied with amiable indifference. “Everybody knows me.”

She did not ask his name; he did not offer to enlighten her. What difference, after all, could the name of an American student make to the idol of Europe, Nihla Quellen?

“I’m in a mess,” she remarked presently. “He will be quite furious with me. It is going to be most disagreeable for me to go back into that house. He has really an atrocious temper when made ridiculous.”

“I’m awfully sorry,” he said, sobered by her seriousness.

She laughed:

“Oh, pouf! I really don’t care. But perhaps you had better leave me now. I’ve spoiled your moonlight picture, haven’t I?”

“But think what you have given me to make amends!” he replied.

She turned and caught his hands in hers with adorable impulsiveness:

“You’re a sweet boy—do you know it! We’ve had a heavenly time, haven’t we? Do you really think you ought to go—so soon?”

“Don’t you think so, Nihla?”

“I don’t want you to go. Anyway, there’s a train every two hours——”

“I’ve a canoe down by the landing. I shall paddle back as I came——”

“A canoe!” she exclaimed, enchanted. “Will you take me with you?”

“To Paris?”

“Of course! Will you?”

“In your ball-gown?”

“I’d adore it! Will you?”

“That is an absolutely crazy suggestion,” he said.

“I know it. The world is only a big asylum. There’s a path to the river behind these bushes. Quick—pick up your painting traps——”

“But, Nihla, dear——”

“Oh, please! I’m dying to run away with you!”

“To Paris?” he demanded, still incredulous that the girl really meant it.

“Of course! You can get a taxi at the Pont-au-Change and take me home. Will you?”

“It would be wonderful, of course——”

“It will be paradise!” she exclaimed, slipping her hand into his. “Now, let us run like the dickens!”

In the uncertain moonlight, filtering through the shrubbery, they found a hidden path to the river; and they took it together, lightly, swiftly, speeding down the slope, all breathless with laughter, along the moonlit way.

In the suburban villa of the Comte d’Eblis a wine-flushed and very noisy company danced on, supped at midnight, continued the revel into the starlit morning hours. The place was a jungle of confetti.

Their host, restless, mortified, angry, perplexed by turns, was becoming obsessed at length with dull premonitions and vaguer alarms.

He waddled out to the lawn several times, still wearing his fancy gilt and tissue cap, and called:

“Nihla! Damnation! Answer me, you little fool!”

He went down to the river, where the gaily painted row-boats and punts lay, and scanned the silvered flood, tortured by indefinite apprehensions. About dawn he started toward the weed-grown, slippery river-stairs for the last time, still crowned with his tinsel cap; and there in the darkness he found his aged boat-man, fishing for gudgeon with a four-cornered net suspended to the end of a bamboo pole.

“Have you see anything of Mademoiselle Nihla?” he demanded, in a heavy, unsteady voice, tremulous with indefinable fears.

“Monsieur le Comte, Mademoiselle Quellen went out in a canoe with a young gentleman.”

“W-what is that you tell me!” faltered the Comte d’Eblis, turning grey in the face.

“Last night, about ten o’clock, M’sieu le Comte. I was out in the moonlight fishing for eels. She came down to the shore—took a canoe yonder by the willows. The young man had a double-bladed paddle. They were singing.”

“They—they have not returned?”

“No, M’sieu le Comte——”

“Who was the—man?”

“I could not see——”

“Very well.” He turned and looked down the dusky river out of light-coloured, murderous eyes. Then, always awkward in his gait, he retraced his steps to the house. There a servant accosted him on the terrace:

“The telephone, if Monsieur le Comte pleases——”

“Who is calling?” he demanded with a flare of fury.

“Paris, if it pleases Monsieur le Comte.”

The Count d’Eblis went to his own quarters, seated himself, and picked up the receiver:

“Who is it?” he asked thickly.

“Max Freund.”

“What has h-happened?” he stammered in sudden terror.

Over the wire came the distant reply, perfectly clear and distinct:

“Ferez Bey was arrested in his own house at dinner last evening, and was immediately conducted to the frontier, escorted by Government detectives.... Is Nihla with you?”

The Count’s teeth were chattering now. He managed to say:

“No, I don’t know where she is. She was dancing. Then, all at once, she was gone. Of what was Colonel Ferez suspected?”

“I don’t know. But perhaps we might guess.”

“Are you followed?”

“Yes.”

“By—by whom?”

“By Souchez.... Good-bye, if I don’t see you. I join Ferez. And look out for Nihla. She’ll trick you yet!”

The Count d’Eblis called:

“Wait, for God’s sake, Max!”—listened; called again in vain. “The one-eyed rabbit!” he panted, breathing hard and irregularly. His large hand shook as he replaced the instrument. He sat there as though paralysed, for a moment or two. Mechanically he removed his tinsel cap and thrust it into the pocket of his evening coat. Suddenly the dull hue of anger dyed neck, ears and temple:

“By God!” he gasped. “What is that she-devil trying to do to me? What has she done!”

After another moment of staring fixedly at nothing, he opened the table drawer, picked up a pistol and poked it into his breast pocket.

Then he rose, heavily, and stood looking out of the window at the paling east, his pendulous under lip aquiver.

II SUNRISE

The first sunbeams had already gilded her bedroom windows, barring the drawn curtains with light, when the man arrived. He was still wearing his disordered evening dress under a light overcoat; his soiled shirt front was still crossed by the red ribbon of watered silk; third class orders striped his breast, where also the brand new Turkish sunburst glimmered.

A sleepy maid in night attire answered his furious ringing; the man pushed her aside with an oath and strode into the semi-darkness of the corridor. He was nearly six feet tall, bulky; but his legs were either too short or something else was the matter with them, for when he walked he waddled, breathing noisily from the ascent of the stairs.

“Is your mistress here?” he demanded, hoarse with his effort.

“Y—yes, monsieur——”

“When did she come in?” And, as the scared and bewildered maid hesitated: “Damn you, answer me! When did Mademoiselle Quellen come in? I’ll wring your neck if you lie to me!”

The maid began to whimper:

“Monsieur le Comte—I do not wish to lie to you.... Mademoiselle Nihla came back with the dawn——”

“Alone?”

The maid wrung her hands:

“Does Monsieur le Comte m-mean to harm her?”

“Will you answer me, you snivelling cat!” he panted between his big, discoloured teeth. He had fished out a pistol from his breast pocket, dragging with it a silk handkerchief, a fancy cap of tissue and gilt, and some streamers of confetti which fell to the carpet around his feet.

“Now,” he breathed in a half-strangled voice, “answer my questions. Was she alone when she came in?”

“N-no.”

“Who was with her?”

“A—a——”

“A man?”

The maid trembled violently and nodded.

“What man?”

“M-Monsieur le Comte, I have never before beheld him——”

“You lie!”

“I do not lie! I have never before seen him, Monsieur le——”

“Did you learn his name?”

“No——”

“Did you hear what they said?”

“They spoke in English——”

“What!” The man’s puffy face went flabby white, and his big, badly made frame seemed to sag for a moment. He laid a large fat hand flat against the wall, as though to support and steady himself, and gazed dully at the terrified maid.

And she, shivering in her night-robe and naked feet, stared back into the pallid face, with its coarse, greyish moustache and little short side-whiskers which vulgarized it completely—gazed in unfeigned terror at the sagging, deadly, lead-coloured eyes.

“Is the man there—in there now—with her?” demanded the Comte d’Eblis heavily.

“No, monsieur.”

“Gone?”

“Oh, Monsieur le Comte, the young man stayed but a moment——”

“Where were they? In her bedroom?”

“In the salon. I—I served a pâté—a glass of wine—and the young gentleman was gone the next minute——”

A dull red discoloured the neck and features of the Count.

“That’s enough,” he said; and waddled past her along the corridor to the furthest door; and wrenched it open with one powerful jerk.

In the still, golden gloom of the drawn curtains, now striped with sunlight, a young girl suddenly sat up in bed.

“Alexandre!” she exclaimed in angry astonishment.

“You slut!” he said, already enraged again at the mere sight of her. “Where did you go last night!”

“What are you doing in my bedroom?” she demanded, confused but flushed with anger. “Leave it! Do you hear!—” She caught sight of the pistol in his hand and stiffened.

He stepped nearer; her dark, dilated gaze remained fixed on the pistol.

“Answer me,” he said, the menacing roar rising in his voice. “Where did you go last night when you left the house?”

“I—I went out—on the lawn.”

“And then?”

“I had had enough of your party: I came back to Paris.”

“And then?”

“I came here, of course.”

“Who was with you?”

Then, for the first time, she began to comprehend. She swallowed desperately.

“Who was your companion?” he repeated.

“A—man.”

“You brought him here?”

“He—came in—for a moment.”

“Who was he?”

“I—never before saw him.”

“You picked up a man in the street and brought him here with you?”

“N-not on the street——”

“Where?”

“On the lawn—while your guests were dancing——”

“And you came to Paris with him?”

“Y-yes.”

“Who was he?”

“I don’t know——”

“If you don’t name him, I’ll kill you!” he yelled, losing the last vestige of self-control. “What kind of story are you trying to tell me, you lying drab! You’ve got a lover! Confess it!”

“I have not!”

“Liar! So this is how you’ve laughed at me, mocked me, betrayed me, made a fool of me! You!—with your fierce little snappish ways of a virgin! You with your dangerous airs of a tiger-cat if a man so much as laid a finger on your vicious body! So Mademoiselle-Don’t-touch-me had a lover all the while. Max Freund warned me to keep an eye on you!” He lost control of himself again; his voice became a hoarse shout: “Max Freund begged me not to trust you! You filthy little beast! Good God! Was I crazy to believe in you—to talk without reserve in your presence! What kind of imbecile was I to offer you marriage because I was crazy enough to believe that there was no other way to possess you! You—a Levantine dancing girl—a common painted thing of the public footlights—a creature of brasserie and cabaret! And you posed as Mademoiselle Nitouche! A novice! A devotee of chastity! And, by God, your devilish ingenuity at last persuaded me that you actually were what you said you were. And all Paris knew you were fooling me—all Paris was laughing in its dirty sleeve—mocking me—spitting on me——”

“All Paris,” she said, in an unsteady voice, “gave you credit for being my lover. And I endured it. And you knew it was not true. Yet you never denied it.... But as for me, I never had a lover. When I told you that I told you the truth. And it is true to-day as it was yesterday. Nobody believes it of a dancing girl. Now, you no longer believe it. Very well, there is no occasion for melodrama. I tried to fall in love with you: I couldn’t. I did not desire to marry you. You insisted. Very well; you can go.”

“Not before I learn the name of your lover of last night!” he retorted, now almost beside himself with fury, and once more menacing her with his pistol. “I’ll get that much change out of all the money I’ve lavished on you!” he yelled. “Tell me his name or I’ll kill you!”

She reached under her pillow, clutched a jewelled watch and purse, and hurled them at him. She twisted from her arm a gemmed bracelet, tore every flashing ring from her fingers, and flung them in a handful straight at his head.

“There’s some more change for you!” she panted. “Now, leave my bedroom!”

“I’ll have that man’s name first!”

The girl laughed in his distorted face. He was within an ace of shooting her—of firing point-blank into the lovely, flushed features, merely to shatter them, destroy, annihilate. He had the desire to do it. But her breathless, contemptuous laugh broke that impulse—relaxed it, leaving it flaccid. And after an interval something else intervened to stay his hand at the trigger—something that crept into his mind; something he had begun to suspect that she knew. Suddenly he became convinced that she did know it—that she believed that he dared not kill her and stand the investigation of a public trial before a juge d’instruction—that he could not afford to have his own personal affairs scrutinised too closely.

He still wanted to kill her—shoot her there where she sat in bed, watching him out of scornful young eyes. So intense was his need to slay—to disfigure, brutalise this girl who had mocked him, that the raging desire hurt him physically. He leaned back, resting against the silken wall, momentarily weakened by the violence of passion. But his pistol still threatened her.

No; he dared not. There was a better, surer way to utterly destroy her,—a way he had long ago prepared,—not expecting any such contingency as this, but merely as a matter of self-insurance.

His levelled weapon wavered, dropped, held loosely now. He still glared at her out of pallid and blood-shot eyes in silence. After a while:

“You hell-cat,” he said slowly and distinctly. “Who is your English lover? Tell me his name or I’ll beat your face to a pulp!”

“I have no English lover.”

“Do you think,” he went on heavily, disregarding her reply, “that I don’t know why you chose an Englishman? You thought you could blackmail me, didn’t you?”

“How?” she demanded wearily.

Again he ignored her reply:

“Is he one of the Embassy?” he demanded. “Is he some emissary of Grey’s? Does he come from their intelligence department? Or is he only a police jackal? Or some lesser rat?”

She shrugged; her night-robe slipped and she drew it over her shoulder with a quick movement. And the man saw the deep blush spreading over face and throat.

“By God!” he said, “you are an actress! I admit it. But now you are going to learn something about real life. You think you’ve got me, don’t you?—you and your Englishman? Because I have been fool enough to trust you—hide nothing from you—act frankly and openly in your presence. You thought you’d get a hold on me, so that if I ever caught you at your treacherous game you could defy me and extort from me the last penny! You thought all that out—very thriftily and cleverly—you and your Englishman between you—didn’t you?”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“Don’t you? Then why did you ask me the other day whether it was not German money which was paying for the newspaper which I bought?”

“The Mot d’Ordre?”

“Certainly.”

“I asked you that because Ferez Bey is notoriously in Germany’s pay. And Ferez Bey financed the affair. You said so. Besides, you and he discussed it before me in my own salon.”

“And you suspected that I bought the Mot d’Ordre with German money for the purpose of carrying out German propaganda in a Paris daily paper?”

“I don’t know why Ferez Bey gave you the money to buy it.”

“He did not give me the money.”

“You said so. Who did?”

“You!” he fairly yelled.

“W-what!” stammered the girl, confounded.

“Listen to me, you rat!” he said fiercely. “I was not such a fool as you believed me to be. I lavished money on you; you made a fortune for yourself out of your popularity, too. Do you remember endorsing a cheque drawn to your order by Ferez Bey?”

“Yes. You had borrowed every penny I possessed. You said that Ferez Bey owed you as much. So I accepted his cheque——”

“That cheque paid for the Mot d’Ordre. It is drawn to your order; it bears your endorsement; the Mot d’Ordre was purchased in your name. And it was Max Freund who insisted that I take that precaution. Now, try to blackmail me!—you and your English spy!” he cried triumphantly, his voice breaking into a squeak.

Not yet understanding, merely conscious of some vague and monstrous danger, the girl sat motionless, regarding him intently out of beautiful, intelligent eyes.

He burst into laughter, made falsetto by the hysteria of sheer hatred:

“That’s where you are now!” he said, leering down at her. “Every paper I ever made you sign incriminates you; your cancelled cheque is in the same packet; your dossier is damning and complete. You didn’t know that Ferez Bey was sent across the frontier yesterday, did you? Your English spy didn’t inform you last night, did he?”

“N-no.”

“You lie! You did know it! That was why you stole away last night and met your jackal—to sell him something besides yourself, this time! You knew they had arrested Ferez! I don’t know how you knew it, but you did. And you told your lover. And both of you thought you had me at last, didn’t you?”

“I—what are you trying to say to me—do to me?” she stammered, losing colour for the first time.

“Put you where you belong—you dirty spy!” he said with grinning ferocity. “If there is to be trouble, I’ve prepared for it. When they try you for espionage, they’ll try you as a foreigner—a dancing girl in the pay of Germany—as my mistress whom Max Freund and I discover in treachery to France, and whom I instantly denounce to the proper authorities!”

He shoved his pistol into his breast pocket and put on his marred silk hat.

“Which do you think they will believe—you or the Count d’Eblis?” he demanded, the nervous leer twitching at his heavy lips. “Which do you think they will believe—your denials and counter-accusations against me, or Max Freund’s corroboration, and the evidence of the packet I shall now deliver to the authorities—the packet containing every cursed document necessary to convict you!—you filthy little——”

The girl bounded from her bed to the floor, her dark eyes blazing:

“Damn you!” she said. “Get out of my bedroom!”

Taken aback, he retreated a pace or two, and, at the furious menace of the little clenched fist, stepped another pace out into the corridor. The door crashed in his face; the bolt shot home.

In twenty minutes Nihla Quellen, the celebrated and adored of European capitals, crept out of the street door. She wore the dress of a Finistère peasant; her hair was grey, her step infirm.

The commissaire, two agents de police, and a Government detective, one Souchez, already on their way to identify and arrest her, never even glanced at the shabby, infirm figure which hobbled past them on the sidewalk and feebly mounted an omnibus marked Gare du Nord.

For a long time Paris was carefully combed for the dancer, Nihla Quellen, until more serious affairs occupied the authorities, and presently the world at large. For, in a few weeks, war burst like a clap of thunder over Europe, leaving the whole world stunned and reeling. The dossier of Nihla Quellen, the dancing girl, was tossed into secret archives, together with the dossier of one Ferez Bey, an Eurasian, now far beyond French jurisdiction, and already very industrious in the United States about God knows what, in company with one Max Freund.

As for Monsieur the Count d’Eblis, he remained a senator, an owner of many third-rate decorations, and of the Mot d’Ordre.

And he remained on excellent terms with everybody at the Swedish, Greek, and Bulgarian legations, and the Turkish Embassy, too. And continued in cipher communication with Max Freund and Ferez Bey in America.

Otherwise, he was still president of the Numismatic Society of Spain, and he continued to add to his wonderful collection of coins, and to keep up his voluminous numismatic correspondence.

He was growing stouter, too, which increased his spinal waddle when he walked; and he became very prosperous financially, through fortunate “operations,” as he explained, with one Bolo Pasha.

He had only one regret to interfere with his sleep and his digestion; he was sorry he had not fired his pistol into the youthful face of Nihla Quellen. He should have avenged himself, taken his chances, and above everything else he should have destroyed her beauty. His timidity and caution still caused him deep and bitter chagrin.

For nearly a year he heard absolutely nothing concerning her. Then one day a letter arrived from Ferez Bey through Max Freund, both being in New York. And when, using his key to the cipher, he extracted the message it contained, he had learned, among other things, that Nihla Quellen was in New York, employed as a teacher in a school for dancing.

The gist of his reply to Ferez Bey was that Nihla Quellen had already outlived her usefulness on earth, and that Max Freund should attend to the matter at the first favourable opportunity.

III SUNSET

On the edge of evening she came out of the Palace of Mirrors and crossed the wet asphalt, which already reflected primrose lights from a clearing western sky.

A few moments before, he had been thinking of her, never dreaming that she was in America. But he knew her instantly, there amid the rush and clatter of the street, recognised her even in the twilight of the passing storm—perhaps not alone from the half-caught glimpse of her shadowy, averted face, nor even from that young, lissome figure so celebrated in Europe. There is a sixth sense—the sense of nearness to what is familiar. When it awakes we call it premonition.

The shock of seeing her, the moment’s exciting incredulity, passed before he became aware that he was already following her through swarming metropolitan throngs released from the toil of a long, wet day in early spring.

Through every twilit avenue poured the crowds; through every cross-street a rosy glory from the west was streaming; and in its magic he saw her immortally transfigured, where the pink light suffused the crossings, only to put on again her lovely mortality in the shadowy avenue.

At Times Square she turned west, straight into the dazzling fire of sunset, and he at her slender heels, not knowing why, not even asking it of himself, not thinking, not caring.

A third figure followed them both.

The bronze giants south of them stirred, swung their great hammers against the iron bell; strokes of the hour rang out above the din of Herald Square, inaudible in the traffic roar another square away, lost, drowned out long before the pleasant bell-notes penetrated to Forty-second Street, into which they both had turned.

Yet, as though occultly conscious that some hour had struck on earth, significant to her, she stopped, turned, and looked back—looked quite through him, seeing neither him nor the one-eyed man who followed them both—as though her line of vision were the East itself, where, across the grey sea’s peril, a thousand miles of cannon were sounding the hour from the North Sea to the Alps.

He passed her at her very elbow—aware of her nearness, as though suddenly close to a young orchard in April. The girl, too, resumed her way, unconscious of him, of his youthful face set hard with controlled emotion.

The one-eyed man followed them both.

A few steps further and she turned into the entrance to one of those sprawling, pretentious restaurants, the sham magnificence of which becomes grimy overnight. He halted, swung around, retraced his steps and followed her. And at his heels two shapes followed them very silently—her shadow and his own—so close together now, against the stucco wall that they seemed like Destiny and Fate linked arm in arm.

The one-eyed man halted at the door for a few moments. Then he, too, went in, dogged by his sinister shadow.

The red sunset’s rays penetrated to the rotunda and were quenched there in a flood of artificial light; and there their sun-born shadows vanished, and three strange new shadows, twisted and grotesque, took their places.

She continued on into the almost empty restaurant, looming dimly beyond. He followed; the one-eyed man followed both.

The place into which they stepped was circular, centred by a waterfall splashing over concrete rocks. In the ruffled pool goldfish glimmered, nearly motionless, and mandarin ducks floated, preening exotic plumage.

A wilderness of tables surrounded the pool, set for the expected patronage of the coming evening. The girl seated herself at one of these.

At the next table he found a place for himself, entirely unnoticed by her. The one-eyed man took the table behind them. A waiter presented himself to take her order; another waiter came up leisurely to attend to him. A third served the one-eyed man. There were only a few inches between the three tables. Yet the girl, deeply preoccupied, paid no attention to either man, although both kept their eyes on her.

But already, under the younger man’s spellbound eyes, an odd and unforeseen thing was occurring: he gradually became aware that, almost imperceptibly, the girl and the table where she sat, and the sleepy waiter who was taking her orders, were slowly moving nearer to him on a floor which was moving, too.

He had never before been in that particular restaurant, and it took him a moment or two to realise that the floor was one of those trick floors, the central part of which slowly revolves.

Her table stood on the revolving part of the floor, his upon fixed terrain; and he now beheld her moving toward him, as the circle of tables rotated on its axis, which was the waterfall and pool in the middle of the restaurant.

A few people began to arrive—theatrical people, who are obliged to dine early. Some took seats at tables placed upon the revolving section of the floor, others preferred the outer circles, where he sat in a fixed position.

Her table was already abreast of his, with only the circular crack in the floor between them; he could easily have touched her.

As the distance began to widen between them, the girl, her gloved hands clasped in her lap, and studying the table-cloth with unseeing gaze, lifted her dark eyes—looked at him without seeing, and once more gazed through him at something invisible upon which her thoughts remained fixed—something absorbing, vital, perhaps tragic—for her face had become as colourless, now, as one of those translucent marbles, vaguely warmed by some buried vein of rose beneath the snowy surface.

Slowly she was being swept away from him—his gaze following—hers lost in concentrated abstraction.

He saw her slipping away, disappearing behind the noisy waterfall. Around him the restaurant continued to fill, slowly at first, then more rapidly after the orchestra had entered its marble gallery.

The music began with something Russian, plaintive at first, then beguiling, then noisy, savage in its brutal precision—something sinister—a trampling melody that was turning into thunder with the throb of doom all through it. And out of the vicious, Asiatic clangour, from behind the dash of too obvious waterfalls, glided the girl he had followed, now on her way toward him again, still seated at her table, still gazing at nothing out of dark, unseeing eyes.

It seemed to him an hour before her table approached his own again. Already she had been served by a waiter—was eating.

He became aware, then, that somebody had also served him. But he could not even pretend to eat, so preoccupied was he by her approach.

Scarcely seeming to move at all, the revolving floor was steadily drawing her table closer and closer to his. She was not looking at the strawberries which she was leisurely eating—did not lift her eyes as her table swept smoothly abreast of his.

Scarcely aware that he spoke aloud, he said:

“Nihla—Nihla Quellen!...”

Like a flash the girl wheeled in her chair to face him. She had lost all her colour. Her fork had dropped and a blood-red berry rolled over the table-cloth toward him.

“I’m sorry,” he said, flushing. “I did not mean to startle you——”

The girl did not utter a word, nor did she move; but in her dark eyes he seemed to see her every sense concentrated upon him to identify his features, made shadowy by the lighted candles behind his head.

By degrees, smoothly, silently, her table swept nearer, nearer, bringing with it her chair, her slender person, her dark, intelligent eyes, so unsmilingly and steadily intent on him.

He began to stammer:

“—Two years ago—at—the Villa Tresse d’Or—on the Seine.... And we promised to see each other—in the morning——”

She said coolly:

“My name is Thessalie Dunois. You mistake me for another.”

“No,” he said, in a low voice, “I am not mistaken.”

Her brown eyes seemed to plunge their clear regard into the depths of his very soul—not in recognition, but in watchful, dangerous defiance.

He began again, still stammering a trifle:

“—In the morning, we were to—to meet—at eleven—near the fountain of Marie de Médicis—unless you do not care to remember——”

At that her gaze altered swiftly, melted into the exquisite relief of recognition. Suspended breath, released, parted her blanched lips; her little guardian heart, relieved of fear, beat more freely.

“Are you Garry?”

“Yes.”

“I know you now,” she murmured. “You are Garret Barres, of the rue d’Eryx.... You are Garry!” A smile already haunted her dark young eyes; colour was returning to lip and cheek. She drew a deep, noiseless breath.

The table where she sat continued to slip past him; the distance between them was widening. She had to turn her head a little to face him.

“You do remember me then, Nihla?”

The girl inclined her head a trifle. A smile curved her lips—lips now vivid but still a little tremulous from the shock of the encounter.

“May I join you at your table?”

She smiled, drew a deeper breath, looked down at the strawberry on the cloth, looked over her shoulder at him.

“You owe me an explanation,” he insisted, leaning forward to span the increasing distance between them.

“Do I?”

“Ask yourself.”

After a moment, still studying him, she nodded as though the nod answered some silent question of her own:

“Yes, I owe you one.”

“Then may I join you?”

“My table is more prudent than I. It is running away from an explanation.” She fixed her eyes on her tightly clasped hands, as though to concentrate thought. He could see only the back of her head, white neck and lovely dark hair.

Her table was quite a distance away when she turned, leisurely, and looked back at him.

“May I come?” he asked.

She lifted her delicate brows in demure surprise.

“I’ve been waiting for you,” she said, amiably.

The one-eyed man had never taken his eyes off them.

IV DUSK

She had offered him her hand; he had bent over it, seated himself, and they smilingly exchanged the formal banalities of a pleasantly renewed acquaintance.

A waiter laid a cover for him. She continued to concern herself, leisurely, with her strawberries.

“When did you leave Paris?” she enquired.

“Nearly two years ago.”

“Before war was declared?”

“Yes, in June of that year.”

She looked up at him very seriously; but they both smiled as she said:

“It was a momentous month for you then—the month of June, 1914?”

“Very. A charming young girl broke my heart in 1914; and so I came home, a wreck—to recuperate.”

At that she laughed outright, glancing at his youthful, sunburnt face and lean, vigorous figure.

“When did you come over?” he asked curiously.

“I have been here longer than you have. In fact, I left France the day I last saw you.”

“The same day?”

“I started that very same day—shortly after sunrise. I crossed the Belgian frontier that night, and I sailed for New York the morning after. I landed here a week later, and I’ve been here ever since. That, monsieur, is my history.”

“You’ve been here in New York for two years!” he repeated in astonishment. “Have you really left the stage then? I supposed you had just arrived to fill an engagement here.”

“They gave me a try-out this afternoon.”

“You? A try-out!” he exclaimed, amazed.

She carelessly transfixed a berry with her fork:

“If I secure an engagement I shall be very glad to fill it ... and my stomach, also. If I don’t secure one—well—charity or starvation confronts me.”

He smiled at her with easy incredulity.

“I had not heard that you were here!” he repeated. “I’ve read nothing at all about you in the papers——”

“No ... I am here incognito.... I have taken my sister’s name. After all, your American public does not know me.”

“But——”

“Wait! I don’t wish it to know me!”

“But if you——”

The girl’s slight gesture checked him, although her smile became humorous and friendly:

“Please! We need not discuss my future. Only the past!” She laughed: “How it all comes back to me now, as you speak—that crazy evening of ours together! What children we were—two years ago!”

Smilingly she clasped her hands together on the table’s edge, regarding him with that winning directness which was a celebrated part of her celebrated personality; and happened to be natural to her.

“Why did I not recognise you immediately?” she demanded of herself, frowning in self-reproof. “I am stupid! Also I have, now and then, thought about you——” She shrugged her shoulders, and again her face faltered subtly:

“Much has happened to distract my memories,” she added carelessly, impaling a strawberry, “—since you and I took the key to the fields and the road to the moon—like the pair of irresponsibles we were that night in June.”

“Have you really had trouble?”

Her slim figure straightened as at a challenge, then became adorably supple again; and she rested her elbows on the table’s edge and took her cheeks between her hands.

“Trouble?” she repeated, studying his face. “I don’t know that word, trouble. I don’t admit such a word to the honour of my happy vocabulary.”

They both laughed a little.

She said, still looking at him, and at first speaking as though to herself:

“Of course, you are that same, delightful Garry! My youthful American accomplice!... Quite unspoiled, still, but very, very irresponsible ... like all painters—like all students. And the mischief which is in me recognised the mischief in you, I suppose.... I did surprise you that night, didn’t I?... And what a night! What a moon! And how we danced there on the wet lawn until my skirts and slippers and stockings were drenched with dew!... And how we laughed! Oh, that full-hearted, full-throated laughter of ours! How wonderful that we have lived to laugh like that! It is something to remember after death. Just think of it!—you and I, absolute strangers, dancing every dance there in the drenched grass to the music that came through the open windows.... And do you remember how we hid in the flowering bushes when my sister and the others came out to look for me? How they called, ‘Nihla! Nihla! Little devil, where are you?’ Oh, it was funny—funny! And to see him come out on the lawn—do you remember? He looked so fat and stupid and anxious and bad-tempered! And you and I expiring with stifled laughter! And he, with his sash, his decorations and his academic palms! He’d have shot us both, you know....”

They were laughing unrestrainedly now at the memory of that impossible night a year ago; and the girl seemed suddenly transformed into an irresponsible gamine of eighteen. Her eyes grew brighter with mischief and laughter—laughter, the greatest magician and doctor emeritus of them all! The immortal restorer of youth and beauty.

Bluish shadows had gone from under her lower lashes; her eyes were starry as a child’s.

“Oh, Garry,” she gasped, laying one slim hand across his on the table-cloth, “it was one of those encounters—one of those heavenly accidents that reconcile one to living.... I think the moon had made me a perfect lunatic.... Because you don’t yet know what I risked.... Garry!... It ruined me—ruined me utterly—our night together under the June moon!”

“What!” he exclaimed, incredulously.

But she only laughed her gay, undaunted little laugh:

“It was worth it! Such moments are worth anything we pay for them! I laughed; I pay. What of it?”

“But if I am partly responsible I wish to know——”

“You shall know nothing about it! As for me, I care nothing about it. I’d do it again to-night! That is living—to go forward, laugh, and accept what comes—to have heart enough, gaiety enough, brains enough to seize the few rare dispensations that the niggardly gods fling across this calvary which we call life! Tenez, that alone is living; the rest is making the endless stations on bleeding knees.”

“Yet, if I thought—” he began, perplexed and troubled, “—if I thought that through my folly——”

“Folly! Non pas! Wisdom! Oh, my blessed accomplice! And do you remember the canoe? Were we indeed quite mad to embark for Paris on the moonlit Seine, you and I?—I in evening gown, soaked with dew to the knees!—you with your sketching block and easel! Quelle déménagement en famille! Oh, Garry, my friend of gayer days, was that really folly! No, no, no, it was infinite wisdom; and its memory is helping me to live through this very moment!”

She leaned there on her elbows and laughed across the cloth at him. The mockery began to dance again and glimmer in her eyes:

“After all I’ve told you,” she added, “you are no wiser, are you? You don’t know why I never went to the Fountain of Marie de Médicis—whether I forgot to go—whether I remembered but decided that I had had quite enough of you. You don’t know, do you?”

He shook his head, smiling. The girl’s face grew gradually serious:

“And you never heard anything more about me?” she demanded.

“No. Your name simply disappeared from the billboards, kiosques, and newspapers.”

“And you heard no malicious gossip? None about my sister, either?”

“None.”

She nodded:

“Europe is a senile creature which forgets overnight. Tant mieux.... You know, I shall sing and dance under my sister’s name here. I told you that, didn’t I?”

“Oh! That would be a great mistake——”

“Listen! Nihla Quellen disappeared—married some fat bourgeois, died, perhaps,”—she shrugged,—“anything you wish, my friend. Who cares to listen to what is said about a dancing girl in all this din of war? Who is interested?”

It was scarcely a question, yet her eyes seemed to make it so.

“Who cares?” she repeated impatiently. “Who remembers?”

“I have remembered you,” he said, meeting her intently questioning gaze.

“You? Oh, you are not like those others over there. Your country is not at war. You still have leisure to remember. But they forget. They haven’t time to remember anything—anybody—over there. Don’t you think so?” She turned in her chair unconsciously, and gazed eastward. “—They have forgotten me over there—” And her lips tightened, contracted, bitten into silence.