автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Dog

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Dog, by Dinks, Mayhew, and Hutchinson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Dog

Author: Dinks, Mayhew, and Hutchinson

Editor: William Henry Herbert

Release Date: May 8, 2010 [EBook #32300]

Language: English

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DOG ***

Produced by Julia Miller, Christine D. and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber's note:

The original text was published in 1873. The contents of this text may be dated. If in doubt, consult a Canine care professional.

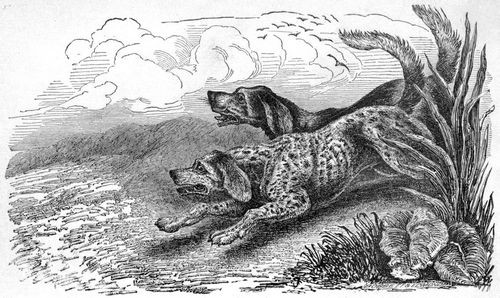

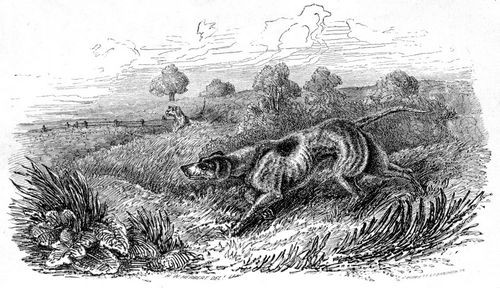

SETTER AND WOODCOCK.

THE DOG.

BY

DINKS, MAYHEW, AND HUTCHINSON.

COMPILED, ABRIDGED, EDITED, AND ILLUSTRATED

BY

FRANK FORESTER,

AUTHOR OF "FIELD SPORTS," "FISH AND FISHING," "HORSES AND HORSEMANSHIP OF THE UNITED STATES AND BRITISH PROVINCES," "THE COMPLETE MANUAL FOR YOUNG SPORTSMEN," ETC., ETC.

Complete and Revised Edition.

New York:

GEO. E. WOODWARD,

191 BROADWAY.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1873,

By GEORGE E. WOODWARD,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

EDITOR'S PREFACE.

In offering to the American public a new edition of Dinks and Mayhew on the Dog, which, I am happy to find, is largely called for, I have been induced to make a further addition, which will, I think, render this the most perfect and comprehensive work in existence for the dog fancier and dog lover.

For myself I claim no merit, since, with the exception of one or two trivial changes in unimportant recipes in Dinks, and some abridgment of the last admirable work of Col. Hutchinson on Dog Breaking, which is now included in this volume, I have found occasion to make no alterations whatever, and, save a few notes, no additions.

I will add, in brief, that while I believe the little manual of Dinks to be the best short and brief compendium on the Dog, particularly as regards his breeding, conditioning, kennel and field management, and general specialities, there can be no possible doubt that Mayhew's pages are the ne plus ultra of canine pathology. There is nothing comparable to his treatment of all diseases for gentleness, simplicity, mercy to the animal, and effect. I have no hesitation in saying, that any person with sufficient intelligence to make a diagnosis according to his showing of the symptoms, and patience to exhibit his remedies, precisely according to his directions, cannot fail of success.

I have this year treated, myself, two very unusually severe cases of distemper, one of acute dysentery, one of chronic diarrhœa, and one of most aggravated mange, implicitly after his instructions, and that with perfect, and, in three instances, most unexpected, success. The cases of distemper were got rid of with less suffering to the animals, and with less—in fact, no—prostration or emaciation than I have ever before witnessed.

I shall never attempt any practice other than that of Mayhew, for distemper; and, as he says, I am satisfied it is true, that no dog, taken in time, and treated by his rules, need die of this disease.

Colonel Hutchinson's volume, which is to dog-breaking, what Mayhew's is to dog-medicining—science, experience, patience, temper, gentleness, and judgment, against brute force and unreasoning ignorance—I have so far abridged as to omit, while retaining all the rules and precepts, such anecdotes of the habits, tricks, faults, and perfections of individual animals, and the discursive matter relative to Indian field sports, and general education of animals, as, however interesting in themselves, have no particular utility to the dog-breaker or sportsman in America. Beyond this I have done no more than to change the word September to the more general term of Autumn, in the heading of the chapters, and to add a few short notes, explanatory of the differences and comparative relations of English and American game.

I will conclude by observing, that although this work is exclusively on breaking for English shooting, there is not one word in it, which is not applicable to this country.

The methods of woodcock and snipe shooting are exactly the same in both countries, excepting only that in England there is no summer-cock shooting. Otherwise, the practice, the rules, and the qualifications of dogs are identical.

The partridge, in England, varies in few of its habits from our quail—I might almost say in none—unless that it prefers turnip fields, potatoe fields, long clover, standing beans, and the like, to bushy coverts and underwood among tall timber, and that it never takes to the tree. Like our quail, it must be hunted for and found in the open, and marked into, and followed up in, its covert, whatever that may be.

In like manner, English and American grouse-shooting may be regarded as identical, except that the former is practised on heathery mountains, the latter on grassy plains; and that pointers are preferable on the latter, owing to the drought and want of water, and to a particular kind of prickly burr, which terribly afflicts the long-haired setter. The same qualities and performances constitute the excellence of dogs for either sport, and, as there the moors, so here the prairies, are, beyond all doubt, the true field for carrying the art of dog-breaking to perfection.

To pheasant shooting we have nothing perfectly analogous. Indeed, the only sport in North America which at all resembles it, is ruffed-grouse shooting, where they abound sufficiently to make it worth the sportsman's while to pursue them alone. Where they do so, there is no difference in the mode of pursuing the two birds, however dissimilar they may be in their other habits and peculiarities.

Bearing these facts in mind, the American sportsman will have no difficulty in applying all the rules given in the admirable work in question; and the American dog-breaker can by no other means produce so perfect an animal for his pains, with so little distress to himself or his pupil.

The greatest drawback to the pleasures of dog-keeping and sporting, are the occasional sufferings of the animals, when diseased, which the owner cannot relieve, and the occasional severity with which he believes himself at times compelled to punish his friend and servant.

It may be said that, for the careful student of this volume, as it is now given entire, in its three separate parts, who has time, temper, patience, and firmness, to follow out its precepts to the letter, this drawback is abolished.

The writers are—all the three—good friends to that best of the friends of man, the faithful dog; and I feel some claim to a share in their well-doing, and to the gratitude of the good animal, and of those who love him, in bringing them thus together, in an easy compass, and a form attainable to all who love the sports of the field, and yet love mercy more.

Frank Forester.

The Cedars, Newark, N.J.,

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

Setter and Woodcock,

FrontispieceBeagles,

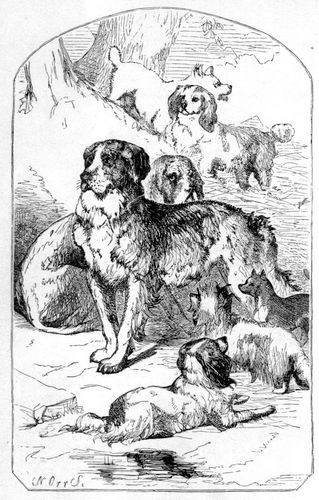

To face page 50Group of Dogs,

73The Pointer,

241Cockers—Butler and Frisk,

463Setters—Bob and Dinks,

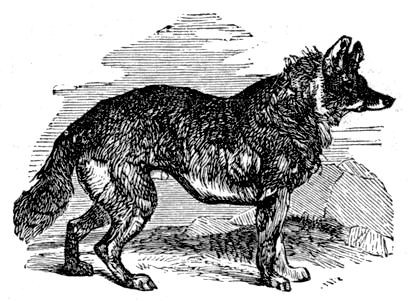

579The Wolf,

Page

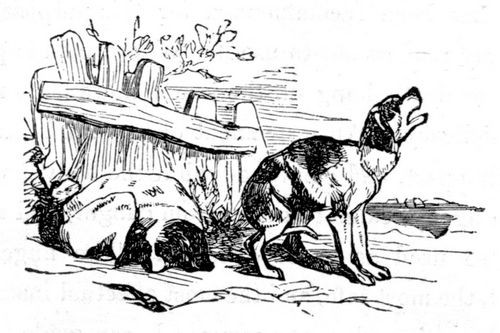

74The Jackal,

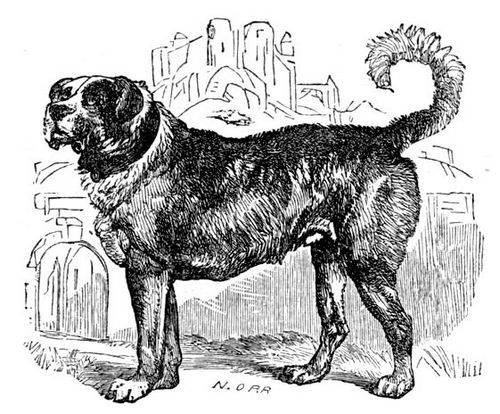

75The Mastiff,

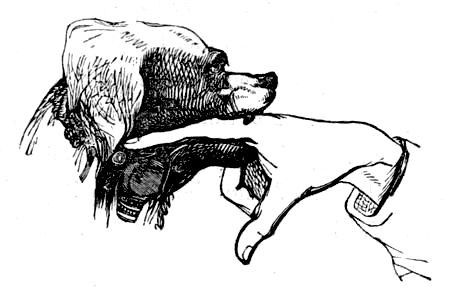

104Cuts Illustrating the Administration of Medicine to Dogs,

111,

112,

113A Dog under the Influence of an Emetic,

118Head of a Dog,

121Brush for Cleaning the Teeth of a Dog,

188A Scotch Terrier,

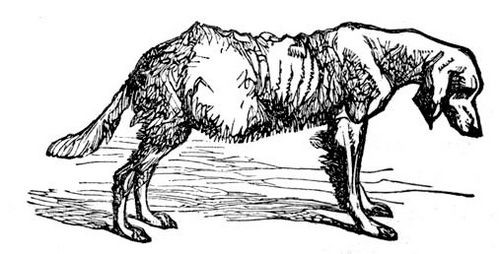

197A Dog Suffering from Inflammation of the Lung,

211A Dog with Asthma,

219" " Chronic Hepatitis,

221" " Gastritis,

233" " Colic,

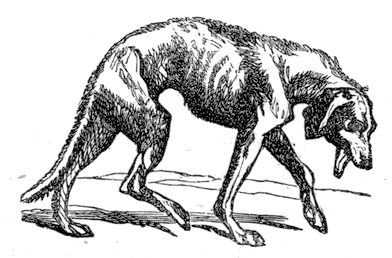

252" " Superpurgation,

263" " Acute Rheumatism,

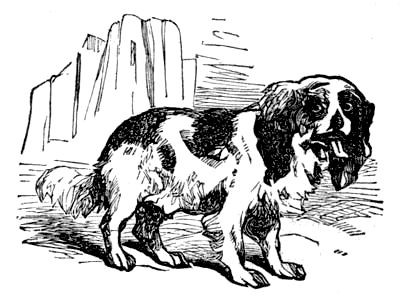

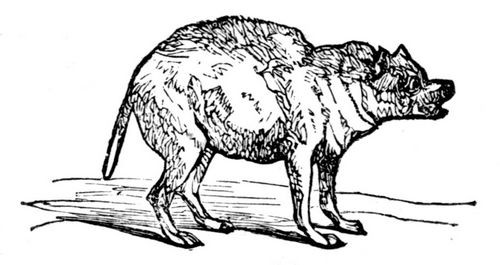

274A Rabid Dog,

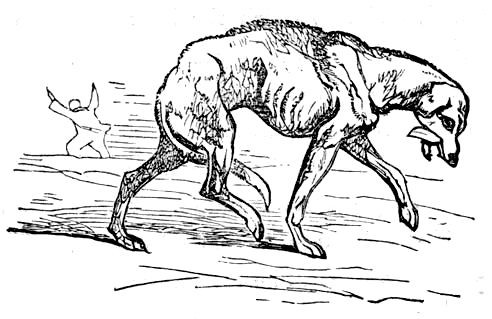

300A Mad Dog on the March,

304Head of a full-sized Pug Bitch,

348The Blood Hound,

349The Beagle,

350The Gravid Uterus,

372Parturition Instrument,

381The Crochet,

384The Bull-Dog,

404Dog with a Canker-cap on,

423A Dog Taped or Muzzled for Operation,

428Bandages for Fractured Legs,

445THE

SPORTSMAN'S VADE MECUM.

BY "DINKS."

CONTAINING FULL INSTRUCTIONS IN ALL THAT RELATES TO

THE BREEDING, REARING, BREAKING, KENNELLING, AND CONDITIONING OF DOGS.

TOGETHER WITH NUMEROUS VALUABLE RECIPES

FOR THE TREATMENT OF THE VARIOUS DISEASES

TO WHICH THE CANINE RACE IS SUBJECT.

AS ALSO

A FEW REMARKS ON GUNS, THEIR LOADING AND CARRIAGE,

DESIGNED EXPRESSLY FOR THE USE OF

YOUNG SPORTSMEN.

TO THE READER.

No one work that I am aware of contains the information that is proposed for this little treatise, which does not aspire to any great originality of idea; but the author having experienced in his early days very great difficulty in finding to his hand a concise treatise, was induced to cull, from various authors what he found most beneficial in practice, into manuscript, and this collection he is induced to make public, in the hopes that any one "who runs may read," and, without searching through many and various voluminous authors, may find the cream, leaving the skim milk behind.

Wherever any known quotation is made, credit has been given to the proper persons, but it may be as well to state that most if not all of the Receipts are copies, though from what book is in a great measure unknown to the author, who extracted them in bygone days for his own use.

With this admission, he trusts that his readers will rest satisfied with the little volume which he offers to their indulgent criticism.

"Dinks."

Fort Malden Canada West

CONTENTS OF DINKS' VADE MECUM.

Page

Breeding of Dogs in general,

15Setter,

18Setter, Russian,

19Spaniel,

20Spaniel and Cocker,

20Retriever,

21Beagles,

21Breeding,

21Bitch in Use,

24Bitches in Pup,

26Feeding Pups and Weaning.—Lice.—Teats Rubbed,

27Pointer and Setter,

28Breaking,

29Ranging, how taught,

30Quartering,

33Feeding,

40Condition,

42Kennel,

44Credit given for Recipes,

49Recipes,

50General Remarks about Dogs in Physic,

50Recipes for Diseases incident to Dogs,

51Distemper,

58Tabular Form of Game Book,

68THE

SPORTSMAN'S VADE MECUM

BREEDING OF DOGS IN GENERAL.

Before commencing to treat of the most correct methods to be observed in the breeding, it will be as well to mention the different varieties of sporting dogs, and also the various sub-genera of each species, of which every one who knows anything of the subject need not be informed; but as this work affects to be a Vade Mecum for sportsmen, young far more than old, it is as well to put before the young idea certain established rules, not to be violated with impunity, and without following which no kennel can be great or glorious. A run of luck may perhaps happen, to set at naught all well defined rules, but "breeding will tell" sooner or later; and, therefore, it behoves any person who prides himself on his kennel, to study well the qualities of his dog or bitch, his or her failings and good qualities, and so to cross with another kennel as to blend the two, and form one perfect dog. This is the great art in breeding, requiring great tact and judgment.

POINTERS.

The breed of Pointers, as now generally to be met with, is called "the English," distinguished by the lightness of limb, fineness of coat, and rattishness of tail. Fifteen or twenty years ago this style of dog was seldom seen; but, in place of it, you had a much heavier animal—heavy limbs, heavy head, deep flew-jaws, long falling ears. Which of these breeds was the best 'tis hard to say, but for America I certainly should prefer the old, heavy, English Pointer. Too much, I think, has been sacrificed to lightness, rendering him too fine for long and continued exertion, too susceptible to cold and wet, too tender skinned to bear contact with briers and thorns, in fact, far too highly bred. Not that for a moment I am going to admit that American Pointers are too highly bred; far from it, for there is hardly one that, if his or her pedigree be carefully traced up, will not be found to have some admixture of blood very far from Pointer in its veins. Now this mongrel breeding will not end well, no matter how an odd cross may succeed, and the plan to be adopted is never to breed except from the most perfect and best bitches, always having in view the making of strong, well formed, tractable dogs, bearing in mind that the bitches take after the dog, and the dog pups after the dam, that temper, ill condition, and most bad qualities are just as inherent in some breeds as good qualities are in others. Here, then, to begin with, you have a difficult problem to solve; for, in addition to the defects of your own animal, you have to make yourself acquainted with those of the one you purpose putting to it. Is your dog too timid—copulate with one of high courage. But don't misunderstand me. In this there is as much difference between a high couraged and a headstrong dog as between a well bred dog and a cur. Is your dog faulty in ranging, may be too high, or may be no ranger at all, mate with the reverse, selecting your pups according to what has been stated above. If possible, always avoid crossing colors. It is a bad plan, but cannot always be avoided, for oftentimes you may see in an animal qualities so good, that it would be wrong to let him go past you. But, then, in the offspring, keep to your color.

From this general statement it will be easy to see, that in breeding dogs there is more science and skill required, more attention to minutiæ necessary, than at first sight appears to be the case. Long and deep study alone enables a person to tell whether any or what cross may be judicious, how to recover any fading excellence in his breed, or how best to acquire that of some one else. We will endeavor to give the experience of some fifteen years—devoted to this subject—to our readers, merely resting on our oars, to describe the various breeds of sporting dogs most desirable for him to possess, together with certain data on which to pin his faith in making a selection from a dealer, though as the eye may deceive, it is always as well to call in the ear as consulting physician, and by diligent inquiry endeavor to ascertain particulars.

The characteristics of a well bred Pointer may be summed up as follows: and any great deviation from them makes at once an ill bred, or, at all events, a deformed dog. To commence, then, at the head:—the head should be broad at top, long and tapering, the poll rising to a point; his nose open and large; his ears tolerably long, slightly erect, and falling between the neck and jaw bone, slightly pointed at the tip; eyes clear and bright; neck and head set on straight; his chest should be broad and deep—the contrary clearly shows want of speed and stamina; legs and arms strong, muscular, and straight; elbows well in; feet small and hard; body not over long, and well ribbed up—if not, he will be weak, and incapable of doing a day's work; loins broad at top, but thin downwards; hind quarters broad; hind legs strong and large; tail long, fine, and tapering; hair short, sleek, and close. Here you have the pure English Pointer, and as that is the best type of the dog, we shall not attempt to describe the Spanish one, which is not by any means equal to the English, and is, moreover, so quarrelsome, that he cannot be kennelled with other dogs. Good dogs are of any colors, but the most favorite ones are liver and white, white and fawn, pure black, and pure liver. The two first, however, are better adapted for this country, being more easily seen in cover.

SETTER.

We next come to the Setter. His head, like the Pointer should be broad at the top between the eyes; the muzzle though, must be longer and more tapering, and not over thick. Towards the eyes he must have a deepish indenture, and on the top of his skull a highish bony ridge. His ears should be long, pendulous, and slightly rounded. The eyes rather dark and full. His nose soft, moist, and large. Some breeds and breeders affect black noses and palates; but I must say that there are full as many good without the black as with it. I rather incline to the opinion that they are the best notwithstanding. Body like the Pointer, only deeper and broader, if anything; legs long to knee, short thence downwards; feet small, close, and thickly clothed with hair between the toes, ball and toe tufts they are termed; tail long, fine, and tapering, thickly feathered with long, soft, wavy hair; stern and legs down to feet also feathered. His body and feet also should be clothed with long, soft, silky hair, wavy, but no curl in it. This last smells badly of water spaniel. Colors, black and white, red and white, black and tan. These last I consider the finest bred ones. Roan also is good. The Irish setter is red, red and white, white and yellow spotted. The nose, lips, and palate always black. He is also rather more bony and muscular than the English breed, and ten times as headstrong and enduring. He requires constant and severe work, under most rigid discipline, to keep in anything like decent subjection.

SETTER, RUSSIAN.

The Russian Setter is as distinct from either of the above varieties as bulldog from greyhound. It is covered more profusely with long, thick, curly, soft, and silky hair, well on to the top of the head and over the eyes. He is also more bony and muscular, with a much shorter and broader head. What he wants in dash and ranging propensities, he makes up for in unwearied assiduity, extreme carefulness, and extraordinary scenting powers. The cross between this and either of the other setters is much valued by some breeders.

SPANIEL.

Of Spaniels there are several varieties, but of these the Suffolk Cocker is the only one deserving a notice. All the others are too noisy, too heedless, and too quick on their legs. It is almost impossible to keep any one of them steady, and, therefore, in this country at least, they are totally useless, since you would not see them from the beginning to the end of the day. Yaff! yaff! half a mile off, all the time putting up the birds, and you unable to stop them. The Suffolk Cocker, on the contrary, is extremely docile, can be easily broken, and kept in order. They are extremely valuable, thirty-five guineas being a low price for a brace of pure bred and well broken ones in England. The right sort are scarce, even there. Here, with two exceptions, I fancy they are not.

SPANIEL AND COCKER.

In appearance they are much like a raseed setter. The head and muzzle is much the same length and size; ears rather more rounded, but not so long; body deep, broad, and long; hair long and stiffish; legs and feet remarkably short, amounting almost to a deformity, and extraordinarily strong; tail short and bushy; it is usually curtailed a couple of joints. The purest colors are liver and white, fawn and white, and yellow and white. These dogs are slow and sure, remarkably close hunters, and obedient; just the things for cock shooting here. Too much cannot be said in their favor. They are easily taught to retrieve.

RETRIEVER.

A Retriever is a cross breed dog. There is no true type of them. Every person has a peculiar fancy regarding them. The great object is to have them tolerably small, compatible with endurance. The best I have seen were of a cross between the Labrador and water spaniel, or the pure Labrador dog.

BEAGLES.

In some parts of the States Beagles are used, and it may be as well to point out the characteristics of them. First, then, a beagle ought not to exceed fourteen inches in height; its head ought to be long and fine; its ears long, fine also, beautifully round, thin, and pendulous, rather far set back; body not too long; chest broad and deep; loins broad at top, but narrow downwards; legs strong, but short; feet small and close; hair short and close; tails curved upwards and tapering, but not too fine. There is also another sort of beagles, wire-haired, flew-jawed, heavy hung, deep-mouthed. They are very true hunters, seldom leaving the trail till dead, or run to ground.

BREEDING.

It is needless to say that at certain indefinite periods of the year a bitch comes into use, as the term is—generally twice a year, and still more generally speaking, during the time you most require her services, that is, April and September, spring snipe and grouse shooting, in consequence of which you must either sacrifice your pups or your sport. Now I am aware that in the States, for this reason, a bitch is seldom kept. For my part, I do not object to them, for from experience I can so regulate their failings as to prevent their family cares from interfering with their hunting. The knowledge of this enables me to have my pups when I want them, to get the cover of a dog I fancy, when a strange one comes my way also. The best time, then, to put the bitch to the dog is early in January. By this means you have your pups ready to wean by the middle of April. They have all summer to grow in, get strong, and large, and are fit to break in October on snipe first, and then quail, finishing off on snipe the following spring. After this litter, the bitch probably comes into use again in the end of July or in August. Young ones are not so fond of it as old ones, and, consequently, for quail shooting, your bitch is all correct and well behaved, so far as regards the dam. I look upon the breeding of dogs from any except the best and most perfectly formed of their species, as an act of great folly. There are times when it must be done to keep up the breed, or to acquire one; for no one drafts his best bitches unless he is an ass. For my part, I keep five or six constantly, and draft yearly all my dog pups but two or three, say one pointer, setter, and cocker. By this means I have the pick out of a large number of well bred ones for myself, while the drafts pay the expenses of keep and breaking. This is impossible for every one to do, and they must pick up their dogs the best way they can. It is my intention for the future to draft my setters to New York and my pointers westward. My cockers, I fear, will not go off yet, my imported dog having taken it into his head to die, and, until he is replaced from England—I have no stock for breed. I could only get a chance of four while last there out of many valuable kennels. However, I have promises of drafts from two or three parties, and ere summer cock come in, doubtless a brace or so will dare the perils of the sea for me; I have no hesitation in saying that, unless most amply remunerated, I would as soon sell my nose as the best pup in the litter, if I wanted it, nor would I advise any one else to do it. If done, you have to put up with inferior dogs. No; I breed to put a brace or so of the best young dogs yearly into my kennel, for my own use, and, while doing this, I also have, probably, ten good, well formed dogs to pick from, any one of which were one in want, would gladden the heart to get hold of. Sir William Stanley used to breed some fifty pointers yearly. Out of this lot, two brace were culled for his use. The rest were sold. They paid expenses. Many were excellent dogs, but he got the tip-top ones, and so he ought. This is the way a man who cannot afford to give great prices for good dogs must do, if he is much addicted to shooting. It requires two brace of dogs to do a day's shooting as it ought to be done. Each dog at full gallop the whole time, except, of course, when on birds; and to do this he must be shut off work about noon. Few dogs can go from morn till night without extreme fatigue. I never yet saw the dog that I could not hunt off his legs in a fortnight's hunt, taking him out every second day only, and feeding him on the best and strongest food. However, for general purposes, three brace of dogs are sufficient, and, when not often used, two are plenty; but no one ought ever to have less than two brace. It may be managed by always going out with a friend, he keeping one brace, you the other; he shooting to your dogs, you to his. For my part, give me three brace of my own, and let those be the best shaped, strongest, best bred, and best workers there can be. That is my weakness, and to achieve this I yearly sink a sufficient number of dollars to keep a poor man. But all this is digressing most fearfully from the nursery of young pointers and setters.

BITCH IN USE.

By receipt on a subsequent page, you will see how your bitch is to be brought into use. We will suppose her well formed and well bred. If faultless, put her to a dog nearly equal, if you cannot get one equal. Save the dog pups which will take after the dam. It is well understood that by breeding from young bitches you have faster and higher rangers; and this also reminds me to say that no bitch ought to be bred from till she is full grown, that is to say, till she is two years old. Many people breed at twelve months, but it is wrong. The bitch is not full grown, and, consequently, the puppies are poor, weak, and miserable. If the bitch has faults, find a dog of the same appearance as her, while he excels in those points she is deficient in. The bitches are partakers of his qualities. Are you short of bone, nose, size, form, temper, look for the excess of these. The cross, or, at all events, the next remove from it, will be just as you wish. Any peculiarity may be made inherent in a breed by sedulously cultivating that peculiarity. Avoid above all things breeding in and in brother and sister, mother and son, father and daughter—all bad, but the first far worse than either of the others, since the blood of each is the same. The other two are only half so. To perfect form should be added high ranging qualities, high courage, great docility, keen nose, and great endurance. That is the acme of breeding. A few judicious crosses will enable you to acquire it for your kennel. To the inattention and carelessness of sportsmen to these points are to be attributed the innumerable curs we nowadays see in comparison to well bred dogs. Anything that will find a bird will do. Far otherwise, to my mind. "Nothing is worth doing at all if it is not to be well done," and I would as soon pot a bevy of quail on the ground, as think of following an ill bred, ill broken, obstinate cur. It may perhaps be as well to state, that when I spoke of "crosses," I had not the slightest intention of recommending a cross of pointer and setter or bull dog. Far otherwise. Let each breed be distinct, but cultivate a "cross," be they pointer or spaniel, from another kennel of another breed of the same class of dogs.

With regard to setters, a little separate talk is necessary, for we have three sorts, English, Irish, and Russian. The cross of English and Irish may and does often benefit both races. So also does the Russian, but I would be extremely careful how I put him to one or the other. Extreme cases may and do justify the admixture, but the old blood ought to be got back as soon as possible. He is of quite a different species to the other, though with the same types or characteristics, yet this cross is rather approaching to mongrel. Having descanted somewhat largely on the preliminary portion, we will pass on to the rearing of the progeny.

BITCHES IN PUP.

Bitches in pup ought to be well fed, and suffered to run at large, and I am rather of opinion that by hunting them occasionally, or rather, by letting them see game while in this state, does not "set the young back any." Every one is aware of the sympathy between the mother and the unborn fœtus, and I for one rather do think it of use.

Few bitches can rear more than six pups, many only four, and do them justice. Cull out, therefore, the ill colored, ugly marked bitches first, and if you find too many left, after a few days you must exercise your judgment on the dogs. I don't like, however, this murdering, and prefer, by extra feeding while suckling, and afterwards, to make up for pulling the mother down, which having to nurse six or seven pups does terribly. My idea always is in the matter, that the pup I drown is to be, or rather would be, the best in the litter. It is humbug, I know, but I cannot help it. At that age all else but color and markings is a lottery. Oft have I seen the poor, miserable little one turn out not only the best, but biggest dog. Therefore, I recommend the keeping of as many as possible.

Let the bitch have a warm kennel, with plenty of straw and shavings, or shavings alone. Let her be loose, free to go or come. Feed her well with boiled oatmeal in preference to corn meal—more of this anon in the feeding department, mixed in good rich broth, just lukewarm, twice a day; About the ninth day the pups begin to see, and at a month old they will lap milk. This they ought to be encouraged to do as soon as possible, as it saves the mother vastly. At six weeks, or at most seven, they are fit to wean.

FEEDING PUPS AND WEANING.—LICE.—TEATS RUBBED.

Feed them entirely on bread and milk, boiled together to pulp. Shut them in a warm place, the spare stall of a stable, boarded up at the end. Examine them to see whether they are lousy, as they almost always are. A decoction of tobacco water (vide receipt) kills them off. Rub the bitch's teats with warm vinegar twice a day till they are dried up. If this be not done, there is great danger of their becoming caked, besides causing her to suffer severely. She must have a mild dose of salts, say half an ounce, repeated after the third day. When the weather is fine, the young pups should be turned out of doors to run about. Knock out the head of a barrel, in which put a little straw, so that they may retire to sleep when they feel disposed. Feed them three times a day, and encourage them to run about as much as possible. Nothing produces crooked legs more than confinement, nothing ill grown weeds more than starvation; so that air, liberty, exercise, and plenty of food are all equally essential to the successful rearing of fine, handsome dogs. Above all things, never frighten, nor yet take undue notice of one over the rest. Accustom them to yourself and strangers. This gives them courage and confidence. Remember, if you ever should have to select a pup in this early stage, to get them all together, fondle them a little; the one that does not skulk will be the highest couraged dog, the rest much in the same proportion, as they display fear or not. This I have invariably noticed is the case, and on this I invariably act when I have to select a pup, provided always he is not mis-formed. We have now brought our pups on till they can take care of themselves, and while they grow and prosper and get over the distemper, we will hark back a little, and say why we object to fall puppies,—simply because they are generally stunted by the cold, unless they are house-reared. They come in better, certainly, for breaking, but it is not so good to have them after September at the latest, unless it be down South, where, I fancy, the order of things would, or rather should, be reversed.

POINTER AND SETTER.

Hitherto I have omitted to compare the respective merits of pointer and setter. This I had intended to have done altogether, but fearful lest fault should be found with me for doing so, I state it as my deliberate opinion, that there is nothing to choose between them "year in and year out." A setter may stand the cold better and may stand the briers better, but the heat and want of water he cannot stand. A pointer, I admit, cannot quite stand cold so well, but he will face thorns quite as well, if he be the right sort, and pure bred, but he don't come out quite so well from it as the setter does. The one does it because it don't hurt him, the other does it because he is told so to do, and his pluck, his high moral courage won't let him say no. For heat and drought he don't care a rush, comparatively, and will kill a setter dead, were he to attempt to follow him. Westward, in the neighborhood of Detroit, the pros and cons are pretty equal. I hunt both indiscriminately, and see no difference either in their powers of endurance, see exceptions above, or hunting qualifications. For the prairies, however, I should say the pointer was infinitely superior, for there the shooting—of prairie hen—is in the two hottest months of the year, and the ground almost, if not quite, devoid of water. Therefore, the pointer there is the dog, and if well and purely bred, he is as gallant a ranger as the setter. Eastward, in New Jersey and Maryland, I am led to believe that setters may be the best there. Except "summer cock," all the shooting is in spring or late fall. Westward, we commence quail shooting on September the first. There, I believe, not until November the first. Here we have few or no briers or thorned things, save and except an odd blackberry or raspberry bush. There they have these and cat briers also, and that infernal young locust tree almost would skin a pointer. Therefore, for those regions, a setter is more preferable. Still more so the real springer.

BREAKING.

We will now pass on to the breaking of our young dogs. This may be begun when they are four or five months old, to a certain extent They may be taught to "charge" and obey a trifle, but it must be done so discreetly that it were almost better left alone. Nevertheless, I generally teach them some little, taking care never to cow them, one by one. This down-charging must be taught them in a room or any convenient place. Put them into the proper position, hind legs under the body, nose on the ground between their fore-paws. Retaining them so with one hand on their head, your feet one on each side their hind quarters, with the other hand pat and encourage them. Do not persist at this early age more than a few minutes at a time, and after it is over, play with and fondle them. At this time also teach them to fetch and carry; to know their names. Recollect that any name ending in o, as "Ponto," "Cato," &c., very common ones by the way, is bad. The only word ending in o ought to be "Toho," often abbreviated into "ho." This objection will be evident to any person who reflects for a moment, and a dog will answer to any other short two syllable word equally as well. These two lessons, and answering to the whistle, are about all that can or should be taught them.

RANGING, HOW TAUGHT.

Nine months, or better, twelve, is soon enough to enter into the serious part of breaking. This is more to be effected by kind determination than by brute force. Avoid the use of the whip. Indeed, it never in my opinion ought to be seen, except in real shooting, instead of which we would use a cord about five or ten yards long. Fasten one end round the dog's neck, the other to a peg firmly staked in the ground; before doing this, however, your young dogs should, along with a high ranging dog, be taken out into a field where there is no game, and suffered to run at large without control until they are well practised in ranging. Too much stress cannot be laid on this point, as on this first step in a great measure depends the future ranging propensities of the dog. Where a youngster sees the old one galloping about as hard as he can, he soon takes the hint and follows. After a few days, the old one may be left behind, when the pups will gallop about equally as well. These lessons should never be too long as to time, else the effect is lost. Another good plan also is to accustom them to follow you on horseback at a good rate. They will learn by this to gallop, not to trot, than which nothing is more disgusting in a dog. When you have your pup well "confirmed in ranging," take the cord, as above directed, peg him down. Probably he will attempt to follow you as you leave him, in which case the cord will check him with more or less force, according to the pace he goes at. The more he resists the more he punishes himself. At last he finds that by being still he is best off. Generally he lies down. At all events, he stands still. This is just what you desire. Without your intervention he punishes himself, and learns a lesson of great value, without attributing it to you, and consequently fearing you, to wit:—that he is not to have his own way always. After repeating this lesson a few times, you may take him to the peg, and "down" or "charge," as you like the term best, close to the peg in the proper position. Move away, but if he stirs one single inch, check him by the cord and drag him back, crying "down" or "charge." For the future I shall use the word "down." You can in practice which you please. Leave him again, checking him when he moves, or letting him do it for himself when he gets to the end of it, always bringing him, however, back to the peg, jerking the cord with more or less severity. Do this for eight or ten times, and he will not stir. You must now walk quite out of sight, round him, run at him, in fact, do anything you can to make him move, when, if he moves, he must be checked as before, until he is perfectly steady. It is essential in this system of breaking that this first lesson should be so effectually taught that nothing shall induce the dog to move, and one quarter of an hour will generally effect this. In all probability, the dog will be much cowed by this treatment. Go up to him, pat him, lift him up, caress him, and take him home for that day. Half an hour per day for each dog will soon get over a long list of them. There is no more severe, I may as well remark here, or more gentle method of breaking than this; more or less vim being put into the check, according to the nature of the beast. I never saw it fail to daunt the most resolute, audacious devil, nor yet to cow the most timid after the first or second attempt, for it is essential in the first instance that they should obey. The next day, and for many days, you commence as at first. Peg him down, &c., and after he does this properly lift him up and walk him about, holding on to the cord still pegged in the ground, suddenly cry "Down!" accompanying the word with a check more or less severe, as requisite, till he does go down. Leave him as before. If he don't move, go up to him, pat him—a young dog ought never to move while breaking until he is touched—lift him up, if necessary, lead him about, again cry "down," and check him until he falls instantly at the word. This will do for lesson No. 2. The next day commence at the beginning, following up with lesson 2, making him steady at each. Before proceeding to the next step, release the one end of the cord from the peg, take it in your hand, cry "down;" if he goes down, well; if not, check him, pat him, loose the end of cord in the hand, let him run about, occasionally crying "down," sometimes when he is close at hand, at other times further off, visiting any disobedience with a check, until he will drop at the word anywhere immediately. At these times his lesson may last for an hour twice a day. He will get steady more quickly and better.

QUARTERING.

His next step is to learn to quarter his ground thoroughly and properly. It is the most difficult to teach, and requires more care and ability, than any other part of his acquirements, on the part of the preceptor. For this purpose select a moderately sized field, say one hundred or two hundred yards wide, where you are certain there is no game. Cast him off at the word "hold up" to the right or left, up wind. This is essential, to prevent their turning inwards, and so going over the same ground twice. (I forgot to say that a cord fifteen feet is long enough now; it does not impede his ranging, and he is nearly as much at command with it as with one twice as long.) If a dog is inclined to this fault of turning inwards, you must get before him up wind, and whistle him just before he turns. This will in the end break him of that habit. If he takes too much ground up wind, call "down," and start him off, after you get to him, in the way he should go. You ought also yourself to walk on a line with the direction the dog is going. This will accustom him to take his beat right through to the fence, and not in irregular zigzags, as he otherwise would do. He must now be kept at these lessons in "down," charging, and quartering, till he is quite perfect and confirmed, setting him off indiscriminately to the right or left, so that when you hunt with another, both may not start one way. Much time will be gained, and the dog rendered by far more perfect by continuing this practice for some time. It is far better to render him au fait at his work by slight punishments, frequently repeated, and by that means more strongly impressed on his memory, than by a severe cowhiding. This latter process is apt to make him cowed, than which there is nothing worse. Many a fine dog is ruined by it. The punishment of the check is severe, and, as I said before, whilst it never fails to daunt the most resolute, so also it can be so administered as not in the end to cow the most timid.

Here it is you are to use your discretion so to temper justice and mercy that you cause yourself to be obeyed without spoiling your creature. For full a month this ought daily to be done, if fine. It is a good plan to feed your young dogs at this stage all together, with a cord round each of their necks, making them "down" several times between the trough and their kennel. Pat one dog, and let him feed awhile. The rest being "down," call him back and make him "down" also, checking him if he does not instantly obey. Pat another now, and let him feed awhile, and so on all through one day, sending one first then another. They learn by this a daily lesson of obedience, and also to let another dog pass them when at point. After your dog is perfectly steady, take him out as before, and when he has run off what is termed the wire edge, introduce him to where there are birds. Set him off up wind, and most probably he will spring the first bird, and chase. Follow him, crying "down." This, in the first ardor of the moment, he is not expected to do, but sooner or later he will. You must now pull him back to where he sprung the birds. By repeatedly doing this, he will chase less and less, always pulling him back to where the bird rises, crying "down." Gradually, by this, he will learn to drop at the rise of the bird, and ultimately to make a point; though most well bred dogs do this the first time. When they do so, cry "down," very slightly checking them if they do not. Great caution is necessary here to prevent their blinking. It is always advisable to teach all young dogs to "down" when they point. When once down, they will lie there as long as you please, and are less likely to blink, run in, chase. You ought, if possible, to get before the dog when you cry "down." It is less likely also to make him blink.

Every dog, old or young, ought to be broken to drop when a bird rises, not at the report of the gun. It renders them far more steady. A young dog ought to be hunted alone till he is perfectly confirmed in these points. It is a very absurd idea to suppose that killing birds prevents their chasing, quite "au contraire." Seeing the bird fall in its flight encourages them to chase. It is far better to get a bird and peg it down so as to flutter and run about before the dog when he is "down." This persisted in soon brings them steady. The other plan takes a much longer time to accomplish. A young dog may easily be taught to back. Make one dog down, and then cry "down" to him, checking him if he does not, and pulling him to where he ought to drop. In the field, after a time, you use the word "toho," at which also he drops or points. A young dog ought never to be hunted with an old one. The latter always has tricks; in fact, is cunning; and at that age a bad fault is easily learnt, but not so easily forgotten. This is Lloyd's art of breaking. A more sensible one I have never seen, nor do I believe is. I have broken many dogs on it, and never saw it fail. Patience, practice, and temper are all that is required, for dogs can only be taught by lessons frequently repeated. When first you shoot over a young dog, an assistant should hold the end of the long line to check him, should he attempt to run in when the bird falls. Lloyd says further, "I never use a whip on any occasion whatever." He trusts to the cord. This is all right while breaking and finishing off a dog, but after that one cannot be expected to lug fifteen feet of cord in one's pocket, though, doubtless, it is very true that it is more efficacious than the whip, and does not make them so apt to blink. Some will sneak away, and are not easily caught, after committing a fault, and others are so shy, that they would not bear a lash, and yet are readily broken with the cord. By this means also dogs are broken to fetch a soft substance, for instance, a glove stuffed with wool is put in their mouths, checking them till they hold it, calling them to you, checking them if they drop it. By degrees you get them not only to hold and bring, but also to fetch it. Practice and patience only are required. Any one possessing them, and with but a slight knowledge of sporting matters, by following the above plain and precise rules, may break his own dogs. I have much pleasure in making it known to the American public. Where the article is taken from I cannot say. I got it a few years ago in manuscript, and Lloyd, Sir J. Sebright's keeper, is the author, and very creditable it is to him. The springer is broken by this equally well with the pointer or setter, omitting the pointing part; teaching, however, the quartering and "down," in the open, most perfectly and thoroughly before ever he goes into covert—till steady on birds, dropping the moment a bird rises and a gun is fired—observing, though, to teach him to take his quarters much closer and shorter. The cocker ought never to be fifteen yards from the shooter, and when two are shooting, should take his quarters from one to the other, turning at the whistle, and only gaining a few yards each turn. For beagles, kennel discipline is of more avail than out-door teaching. They must be taught to come and go, when called. To such perfection is this kennel discipline carried in England, that I have seen fifty couples of hounds waiting in a yard to be fed; the door open, each one coming when called by name; leaving his food when ordered "to bed" or "kennel." "Dogs come over," all the dogs coming over "Bitches come over," when all the bitches come. To do this requires time and patience. Out doors they are taught to follow the huntsman to cover, receiving a hearty cut of the whip if they lag or loiter by the way, whipped up if they neglect to come to the pipe of the horn, if they run to heel, hang too long on the scent, follow false scent, fox, rabbit, or anything else they be not hunted to. With them the whip is used, and severely too, sometimes. And now I have done with the training of dogs, all but the retriever. The cord will apply for him, though in addition to this he must be taught to "seek lost" in any direction you wave your hand. His lessons, however, will extend over a far greater length of time than the others. Age only increases his abilities. The more of a companion you make of him, the more tricks in seeking lost you teach him, the more valuable he becomes. My brother has one that can be sent miles to the house for any article almost, and he brings it. Last winter he sent him for the roast before the fire, and after a tussle with the cook it came sure enough. He is one of the most knowing dogs I ever saw. A large black fellow, of what breed I know not, Newfoundland and setter though, I fancy. Four pounds was his price. He is well worth five times four. For wounded birds he is invaluable, and has only one fault; he does not "charge," which all retrievers, as well as every other sporting dog, should do; else while you are loading, and they rushing about like mad, the birds get up, and you lose a chance, from either not being ready, or your gun being empty. Before concluding, I will state all the words and motions requisite to teach your pointers and setters. "Down," "Hold up," "Toho." Holding up your hand open means "down," or "Toho," where another dog is pointing. A whistle solus to come in "to heel"—that word for them to get behind you; a whistle and a wave of the hand to the right for them to quarter that way; ditto whistle and wave to the left to quarter to the left. Avoid shouting as much as possible. Nothing is more disgusting than to be bawling all the time. If your dog don't heed your whistle, get him to heel as fast and as quietly as possible, and administer a little strap, whistling to them sharply to impress it on their mind. Never pass by a single fault without either rating or flogging. Always make your dogs point a dead bird before retrieving it; and nothing is more insane than to loo on your dogs, after a wing-tipped bird. Hunt it quietly and deliberately. I know it is difficult to restrain yourself sometimes. How much more difficult, then, to restrain your dogs. Far better to lose a bird, a thing I detest doing, than run the chance of spoiling a young dog. Never take a liberty with him, however you may do so with an old one, though even he can and will be made unsteady, by letting him chase or have his own way. One thing leads to another. I thought I had got through, but methinks it is as well to state the best plan to find a dead bird in cover, or out also, for that matter. Walk as nearly as possible to where you fancy the bird fell; there stand, nor move a step, making the dogs circle round you till they find it. Practise them at this as much as any other part of their education, calling them constantly back if they move off. Should you find a dog going off, notice the direction, but call him back. If he should still return there, you may presume it is a runner. Let him try to puzzle it out, while you keep the other dog at work close to you. By this plan it is extraordinary what few birds you will lose in a season. Always hunt a brace of dogs. More are too many; one is just one too few. It is too pot-hunterish, too slow. You lose half the beauties of the sport seeing your dogs quartering their fields, crossing one another in the centre, or thereby, without jealousy, backing one another's points—both dropping "to shot" as if shot. You get over twice as much ground in a day. This, in a thinly sprinkled game country, is something. Where very plentiful, you find them all the quicker.

FEEDING.

With regard to the feeding of dogs, some few words are necessary, and we will endeavor to point out the best way to manage them properly, and with a due regard to economy. Where only one or two dogs are kept, it is presumed that the refuse of the house is ample for them. It will keep them in good order and condition; but where more are kept, it will be necessary to look further for their supplies. We will therefore treat them as one would a kennel, distinguishing town from country; for in the one what would be extremely cheap, in the other would be dear. For ordinary feeding, then, in town, purchase beef heads, sheep ditto, offal, i.e. feet, bellies, &c., which clean. Chop them up and boil to rags in a copper, filling up your copper as the water boils away. You may add to this a little salt, cabbage, parsnips, potatoes, carrots, turnips, or any other cheap vegetable. Put this soup aside, and then boil old Indian meal till it is quite stiff. Let it also get cold. Take of the boiled meal as much as you think requisite, adding sufficient of the broth to liquefy it. This is the cheapest town food. In the country during the summer, skimmed milk, sour milk, buttermilk, or whey, may be used in place of the soup. In the winter, it is as well to give soup occasionally for a change. Never use new Indian flour. It scours the dogs dreadfully. Old does not. The plan I adopt is, to buy Indian corn this year for use next, store it, and send it to grind as I require it; and as the millers have no object in boning the old meal, returning new for it, I insure by this means no illness from feeding in my kennel. Although Indian corn has not either so much albumen or saccharine matter in it as oats, it does tolerably well with broth; but when the greatest amount of work is required in a certain given time from a certain quantity of dogs, as in a week's, fortnight's, or month's shooting excursion, I always use oatmeal, for two reasons:—1st, it is far more nourishing in itself, a less bulk of it going further than corn meal:—2nd, you cannot depend on getting old meal in the country, nor yet meat always to make soup. The dogs fed on oatmeal porridge and milk, which you always can get, do a vast deal of work, and have good scenting powers. Using these different articles, I calculate each dog to cost me one shilling York currency per week, and I pay fifty cents per bushel for Indian corn, six dollars per barrel for oatmeal (old), one York shilling for beef head, milk three cents per quart for new, probably, one and a half for skim. In a house there are always bones, potatoe peelings, and pot liquor. By cleaning the potatoes before peeling, and popping all into the dog pot, a considerable saving is effected in a year, and the dogs are benefited thereby. Mangel Wurtzel and Ruta Bagas, I believe they call them this side the water, are easily grown, and are good food, boiled up with soup.

bring me an animal affected with this complaint, that if my directions are strictly followed, the creature "shall not die." When saying this, I pretend not to have life or death at my command, and the mildest affections will sometimes terminate fatally; but I merely mean to imply, that when proper measures are adopted, distemper is less likely to destroy than the majority of those diseases to which the dog is liable.

and in wet, than in dry. When dampness and heat are combined, the mischief is yet augmented; and, probably, the worst conditions that can be supposed are when, to dampness and heat, a salt atmosphere is superadded.

better left alone. Nevertheless, I generally teach them some little, taking care never to cow them, one by one. This down-charging must be taught them in a room or any convenient place. Put them into the proper position, hind legs under the body, nose on the ground between their fore-paws. Retaining them so with one hand on their head, your feet one on each side their hind quarters, with the other hand pat and encourage them. Do not persist at this early age more than a few minutes at a time, and after it is over, play with and fondle them. At this time also teach them to fetch and carry; to know their names. Recollect that any name ending in o, as "Ponto," "Cato," &c., very common ones by the way, is bad. The only word ending in o ought to be "Toho," often abbreviated into "ho." This objection will be evident to any person who reflects for a moment, and a dog will answer to any other short two syllable word equally as well. These two lessons, and answering to the whistle, are about all that can or should be taught them.

have elapsed. Where the system is vigorous, expectorants and sedatives, with leeches to the chest, may be used. Turpentine liniment to the sides, throat, and under the jaws, may also be freely rubbed in, and the diet in quantity restricted. Tartar emetic in very minute doses may be exhibited three times daily.

breeds and breeders affect black noses and palates; but I must say that there are full as many good without the black as with it. I rather incline to the opinion that they are the best notwithstanding. Body like the Pointer, only deeper and broader, if anything; legs long to knee, short thence downwards; feet small, close, and thickly clothed with hair between the toes, ball and toe tufts they are termed; tail long, fine, and tapering, thickly feathered with long, soft, wavy hair; stern and legs down to feet also feathered. His body and feet also should be clothed with long, soft, silky hair, wavy, but no curl in it. This last smells badly of water spaniel. Colors, black and white, red and white, black and tan. These last I consider the finest bred ones. Roan also is good. The Irish setter is red, red and white, white and yellow spotted. The nose, lips, and palate always black. He is also rather more bony and muscular than the English breed, and ten times as headstrong and enduring. He requires constant and severe work, under most rigid discipline, to keep in anything like decent subjection.

of the ear, it would not be so easy to cut speedily from below upward, as to push the blade from above downwards. Well, the opening being made with the lancet, a little fluid escapes; but no pressure being put on the sac, the major portion is retained. The operator then takes a straight probe-pointed bistoury, and having introduced it into the orifice, by making only pressure, instantly divides the sac. Frequently considerable fluid escapes; the beast operated upon makes up its mind for a good howl; but, finding the affair over before its mouth was moulded to emit the sound, the cry is cut short, and the dog returns to have the tape removed, that it may lick the hand that pained it.

attack mostly yields to treatment. The third is less certain, and so is each following visitation; the chances of restoration being remote, just in proportion as the assault is removed from the original affliction.

greater force to the jackal. However, to settle the dispute, we here give the likeness of the beast, and leave to the reader to point out the particular breed of dogs to which it belongs.

for cock shooting here. Too much cannot be said in their favor. They are easily taught to retrieve.

To Soften Boots.—Use hog's lard, half a pound; mutton suet, quarter of a pound; and bees' wax, quarter of a pound. Melt well, and rub well in before the fire; or currier's oil is as good, barring the smell.

fed yourself. No servant will do it as it should be done. Ten minutes or a quarter of an hour devoted to this as soon as you return from the field, will be more than repaid when next you use them. If you ride, or rather drive to your ground, as is best to do when more than a mile away, ride your dogs also; ditto as you return. Every little helps, and this short ride wonderfully saves your animals. I invariably do this. But when I drive, say twenty miles or so, to a shooting station, I generally run one brace or so the whole way, and the other brace perhaps ten miles, taking out next day that brace which only ran the short distance. Always on a trip of this kind take a bag of meal with you also. You are then safe. The neglect of this precaution in one or two instances has obliged me to use boiled beef alone, to the very great detriment of the olfactory senses of my dogs. Their noses, on this kind of food, completely fail them. Greasy substances also are objectionable for the same cause, unless very well incorporated with meal. For this reason I object to "tallow scrap" or chandlers' graves; but this I sometimes use in summer. Regular work, correct feeding, and regular hours, that is the great secret of one man's dogs standing harder work than others. A little attention to the subject will enable any one to keep his animals pretty near the mark. Amongst the receipts will be found one used in England for feeding greyhounds when in training, if any one likes to go to the expense of it.

give temporary ease; but the last-named medicines are to be resorted to only after due consideration, as they greatly lower the strength. Stomachics and mild tonics at the same time are to be employed; but a cure is not to be expected. The treatment cannot be absolutely laid down; but the judgment must be exercised, and whenever the slightest improvement is remarked every effort must be made to prevent a relapse.

him back. If he should still return there, you may presume it is a runner. Let him try to puzzle it out, while you keep the other dog at work close to you. By this plan it is extraordinary what few birds you will lose in a season. Always hunt a brace of dogs. More are too many; one is just one too few. It is too pot-hunterish, too slow. You lose half the beauties of the sport seeing your dogs quartering their fields, crossing one another in the centre, or thereby, without jealousy, backing one another's points—both dropping "to shot" as if shot. You get over twice as much ground in a day. This, in a thinly sprinkled game country, is something. Where very plentiful, you find them all the quicker.

resorted to. It is of much service when the skin is hot and inflamed, but after it, exercise ought not to be neglected. For healthy animals the hot or warm bath should never be employed; but the sea is frequently as beneficial to dogs as to their owners; only always bearing in mind that the head should be preserved dry.

and I consequently no longer use it. To supply its place, I had the following very simple instrument made; and it answers every intention, although it is but seldom required:—

animals thus afflicted are always gross and fat. The disorder comes on gradually in most instances, though the fit is usually sudden. The appetite is not affected, or rather it is increased often to an extraordinary degree. The craving is great, and flesh is always preferred, while sweet and seasoned articles are much relished. On examination, the signs denoting the digestion to be deranged will be discovered. Piles are nearly constantly met with; the coat is generally in a bad condition, and the hair off in places. The nose may be dry; the membrane of the eyes congested; the teeth covered with tartar, and the breath offensive. The dog is slothful, and exertion is followed by distress. Cough may or may not exist; but it usually appears towards the latter period of the attack.

liquor. By cleaning the potatoes before peeling, and popping all into the dog pot, a considerable saving is effected in a year, and the dogs are benefited thereby. Mangel Wurtzel and Ruta Bagas, I believe they call them this side the water, are easily grown, and are good food, boiled up with soup.

does not run. That would be too great an exertion for an animal whose body is the abode of a deadly sickness. He proceeds in a slouching manner, in a kind of trot; a movement neither run nor walk, and his aspect is dejected. His eyes do not glare and stare, but they are dull and retracted. His appearance is very characteristic, and if once seen, can never afterwards be mistaken. In this state he will travel the most dusty roads, his tongue hanging dry from his open mouth, from which, however, there drops no foam. His course is not straight. How could it be, since it is doubtful whether at this period he sees at all? His desire is to journey unnoticed. If no one notices him, he gladly passes by them. He is very ill. He cannot stay to bite. If, nevertheless, anything oppose his progress, he will, as if by impulse, snap—as a man in a similar state might strike, and tell the person "to get out of the way." He may take his road across a field in which there are a flock of sheep. Could these creatures only make room for him, and stand motionless, the dog would pass on and leave them behind uninjured. But they begin, to run, and at the sound, the dog pricks up. His entire aspect changes. Rage takes possession of him. What made that noise? He pursues it with all the energy of madness. He flies at one, then at another. He does not mangle, nor is his bite, simply considered, terrible. He cannot pause to tear the creature he has caught. He snaps and then rushes onward, till, fairly exhausted and unable longer to follow, he sinks down, and the sheep pass forward to be no more molested. He may have bitten twenty or thirty in his mad onslaught; and would have worried more had his strength lasted, for the furor of madness then had possession of him.

strengthening but entirely fluid. The warm bath is here highly injurious; and bleeding or purging out of the question. When the distension of the stomach is so great as to threaten suffocation, the tube of the stomach-pump may be introduced; but, unless danger be present, the practitioner ought to depend upon the efforts of nature, to support which all his measures should be directed. After recovery, meat scraped as for potting, without any admixture of vegetables, must constitute the diet; and while a sufficiency is given, a very little only must be allowed at a time. With these precautions the life may be prolonged, but the restoration of health is not to be expected.

them between the posterior molar teeth. A firm hold of the head will thus be gained, and the jaws are prevented from being closed by the pain which every effort to shut the mouth produces. No time should be lost, but the pill ought to be dropped as far as possible into the mouth, and with the finger of the right hand it ought to be pushed the entire length down the throat. This will not inconvenience the dog. The epiglottis is of such a size that the finger does not excite a desire to vomit; and the pharynx and œsophagus are so lax that the passage presents no obstruction.

pectoral sound, and only after this has repeatedly been heard is the stomach able to cast off its contents.

will best save themselves by not hitting the dog; for the teeth are almost certain to mark the hand that strikes. Firmness will gain submission; cruelty will only get up a quarrel, in which the dog will conquer, and the man, even if he prove victorious, can win nothing. He who is cleaning canine teeth must not expect to earn the love of his patient; the liberty taken is so great that it is never afterwards pardoned. I scarcely ever yet have known the dog to which I was not subsequently an object of dread and hatred. Grateful and intelligent as these creatures are, I have not found one simple or noble-minded enough to appreciate a dentist.

Sporting dogs are frequently sent to me suffering under what the proprietors are pleased to term "Foul." The history of these cases is soon known. They have been withdrawn from the field at the close of the season, and have ever since been shut up in close confinement, while the working diet has been persevered with. The poor beast is supposed capable of vegetating until the return of the period for shooting requires his services. He remains chained up till he acquires every outward disease to which his kind are liable; and then, when he stinks the place out, his owner is surprised at his condition, pronouncing his misused animal to be "very foul." "Foul" is not one disease, but an accumulation of disorders brought on by the absence of exercise with a stimulating diet. The sporting dog, when really at work, may have all the flesh it can consume; but at the termination of that period its food should consist wholly of vegetable substances, while a little exercise daily is necessary, not to health, but absolutely for life. The dog with "foul" requires each seat of disease to be treated separately; beginning of course with the dressing for mange or for lice, one or the other of which the animal is certain to display.

approach the bitch whose mother was large, or whose brothers and sisters stand much higher than herself. Let the reader look at the two portraits that follow. They are evidently of one and the same family. They both had a common progenitor. The beagle is the blood-hound, only of smaller size; and often these beautiful diminutive creatures suffer in parturition, or throw pups whose size takes from them all value. However, for the chance of security, if for no more tangible object; let the dog, in every instance, be smaller than the bitch; and let it also have no disease, but be in perfect health, strong and lively. A dog in any way deformed or affected with any disorder ought to be avoided. Blindness, skin eruptions, piles, paralysis of the tongue, and a host of other annoyances, I more than suspect to be hereditary. The mental qualities are transmitted, as well as physical beauties and defects. Sagacity, health, and beauty are to be sought for, and if all cannot be obtained, those most desired must be selected. Where shape is wanted, let the dog possess such form as the bitch is deficient in; thus the female having a long-nose or legs, may be put to a male short in these respects; and the rule may be applied in other instances.

out every second day only, and feeding him on the best and strongest food. However, for general purposes, three brace of dogs are sufficient, and, when not often used, two are plenty; but no one ought ever to have less than two brace. It may be managed by always going out with a friend, he keeping one brace, you the other; he shooting to your dogs, you to his. For my part, give me three brace of my own, and let those be the best shaped, strongest, best bred, and best workers there can be. That is my weakness, and to achieve this I yearly sink a sufficient number of dollars to keep a poor man. But all this is digressing most fearfully from the nursery of young pointers and setters.

and strangers. This gives them courage and confidence. Remember, if you ever should have to select a pup in this early stage, to get them all together, fondle them a little; the one that does not skulk will be the highest couraged dog, the rest much in the same proportion, as they display fear or not. This I have invariably noticed is the case, and on this I invariably act when I have to select a pup, provided always he is not mis-formed. We have now brought our pups on till they can take care of themselves, and while they grow and prosper and get over the distemper, we will hark back a little, and say why we object to fall puppies,—simply because they are generally stunted by the cold, unless they are house-reared. They come in better, certainly, for breaking, but it is not so good to have them after September at the latest, unless it be down South, where, I fancy, the order of things would, or rather should, be reversed.

really don't know to whom the credit is due for each individual one, I trust to be forgiven. This much, however, I can say, there are not more than one or two of my own. I have tried most, if not all, and found them good. Some are not quite as in the original, having been amended by a sporting medical man, a friend of mine, to suit the new fashion of preparing medicines.

aspect; but however painful it may be to look at, there seems to be but little suffering attending it. The animal permits it to be freely handled, and does not resist even when sharp dressings are applied.

and either of the other setters is much valued by some breeders.

top, long and tapering, the poll rising to a point; his nose open and large; his ears tolerably long, slightly erect, and falling between the neck and jaw bone, slightly pointed at the tip; eyes clear and bright; neck and head set on straight; his chest should be broad and deep—the contrary clearly shows want of speed and stamina; legs and arms strong, muscular, and straight; elbows well in; feet small and hard; body not over long, and well ribbed up—if not, he will be weak, and incapable of doing a day's work; loins broad at top, but thin downwards; hind quarters broad; hind legs strong and large; tail long, fine, and tapering; hair short, sleek, and close. Here you have the pure English Pointer, and as that is the best type of the dog, we shall not attempt to describe the Spanish one, which is not by any means equal to the English, and is, moreover, so quarrelsome, that he cannot be kennelled with other dogs. Good dogs are of any colors, but the most favorite ones are liver and white, white and fawn, pure black, and pure liver. The two first, however, are better adapted for this country, being more easily seen in cover.

about the dog. It does not, therefore, depend solely upon the testimony of the present writer; but sad is the reflection, that all the pain and suffering thus occasioned was unnecessary. Canker without the ear cannot be established unless canker within the ear, in the first instance, exists. It may not be violent; it may be present only in an incipient stage, and never get beyond it; but in this state it is sufficient to annoy the animal, and make it shake its head. Doing this, however, it does enough to mislead the practitioner, and cause the death of the unfortunate animal.

Half an ounce of salts is a fair dose for a dog from nine months to any age. No. 2 is particularly recommended, whenever an early action is required. It is essentially short, sharp and decisive.

the pup being reached by instruments. The horns, in consequence of their greater length, become bent, or folded upon themselves; so that an instrument which should drag the pups to light, where more than two or three are present, should be made to pass forward in the first instance, and then be constructed to take a backward direction. Those who invented these instruments to deliver bitches with, would seem to have been ignorant of this necessity; and I here mention it to prove how perfectly inadequate such things are for the purpose intended.

accomplished. There will, however, then only be a distant chance of success; and where these indications have been remarked, the life of the mother has generally been lost. If a portion of the litter has been born, and, on the appearance of the symptoms just described, the pups refuse to suck, and when placed to the teats turn from them, the termination will be fatal. The milk seems to have lost its inviting properties, and to be rendered disgusting by the approach of death; and the sign is as conclusive as the departure of vermin from the carcase of an animal.

go or come. Feed her well with boiled oatmeal in preference to corn meal—more of this anon in the feeding department, mixed in good rich broth, just lukewarm, twice a day; About the ninth day the pups begin to see, and at a month old they will lap milk. This they ought to be encouraged to do as soon as possible, as it saves the mother vastly. At six weeks, or at most seven, they are fit to wean.

to be got back as soon as possible. He is of quite a different species to the other, though with the same types or characteristics, yet this cross is rather approaching to mongrel. Having descanted somewhat largely on the preliminary portion, we will pass on to the rearing of the progeny.

he is touched—lift him up, if necessary, lead him about, again cry "down," and check him until he falls instantly at the word. This will do for lesson No. 2. The next day commence at the beginning, following up with lesson 2, making him steady at each. Before proceeding to the next step, release the one end of the cord from the peg, take it in your hand, cry "down;" if he goes down, well; if not, check him, pat him, loose the end of cord in the hand, let him run about, occasionally crying "down," sometimes when he is close at hand, at other times further off, visiting any disobedience with a check, until he will drop at the word anywhere immediately. At these times his lesson may last for an hour twice a day. He will get steady more quickly and better.

waistcoat, rub his little body against my head and face, lick the hand lifted up to return his caresses, and then scamper off, and perhaps not come near me again the whole of that afternoon. What was this but an affectionate impulse seeking a nervous development? The way to manage an animal of this description is, to respect his evident excitability. The instant a dog appears to be getting excited, there should be a sign given, commanding a stop to be put to all further proceedings. If the respect of the animal be habitual, the person who mildly enforces it may enter a room, where the same dog is in a rabid state, and come forth unscathed.

time of breeding does not agree,—their habits are opposite, and their outward and inward character is entirely dissimilar. The above engraving is the portrait of the wolf. Is the reader in any danger of mistaking it for that of a dog?

In the chronic form, the membrane of the eye is pallid; the nose often moist; the breath offensive; the appetite ravenous; the pulse quick and weak; the anus inflamed; mostly protruding, and usually disfigured by piles; the fæces liquid, and of various hues; sometimes black, occasionally lighter than usual, very generally mixed with much mucus and a small quantity of blood, so that the leading symptoms are those of weakness, accompanied with purgation.

Here is a portrait of a Scotch terrier, and the reader will perceive the coat is by the artist truthfully depicted as remarkably long, full, and hairy.

him, the other does it because he is told so to do, and his pluck, his high moral courage won't let him say no. For heat and drought he don't care a rush, comparatively, and will kill a setter dead, were he to attempt to follow him. Westward, in the neighborhood of Detroit, the pros and cons are pretty equal. I hunt both indiscriminately, and see no difference either in their powers of endurance, see exceptions above, or hunting qualifications. For the prairies, however, I should say the pointer was infinitely superior, for there the shooting—of prairie hen—is in the two hottest months of the year, and the ground almost, if not quite, devoid of water. Therefore, the pointer there is the dog, and if well and purely bred, he is as gallant a ranger as the setter. Eastward, in New Jersey and Maryland, I am led to believe that setters may be the best there. Except "summer cock," all the shooting is in spring or late fall. Westward, we commence quail shooting on September the first. There, I believe, not until November the first. Here we have few or no briers or thorned things, save and except an odd blackberry or raspberry bush. There they have these and cat briers also, and that infernal young locust tree almost would skin a pointer. Therefore, for those regions, a setter is more preferable. Still more so the real springer.

it to be the violent division of a bone into two or more parts.

given to unload the cæcum. The medicine having acted freely, the food must be amended, the treatment altered, and such other measures taken as the digestion may require for its restoration.