автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Boy Scouts on the Open Plains; Or, The Round-Up Not Ordered

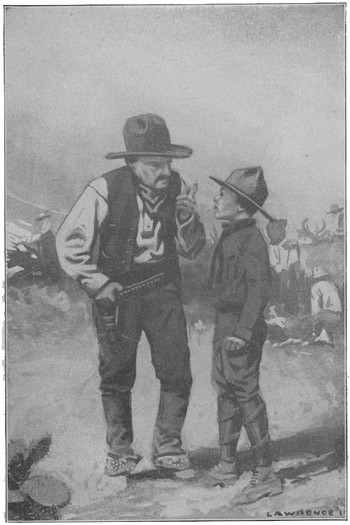

“But ain’t yuh meanin’ tuh pay me anything fo’ shootin’ up my pets thisaway?” Harkness demanded.

BOY SCOUTS ON THE OPEN PLAINS

OR

THE ROUND-UP NOT ORDERED

By

G. HARVEY RALPHSON

Author of

BOY SCOUTS IN THE CANAL ZONE

BOY SCOUTS IN THE NORTHWEST

BOY SCOUTS IN A MOTOR BOAT

BOY SCOUTS IN A SUBMARINE

Chicago

M. A. DONOHUE & COMPANY

Copyright 1914

by

M. A. Donohue & Co.

CHICAGO

Contents

I.

Over the EdgeII.

Lucky JimmyIII.

The Helping HandIV.

Picking up PointsV.

Around the Camp FireVI.

The Wolf PackVII.

Everybody BusyVIII.

An Unwelcome GuestIX.

The Homing PigeonX.

At Double Cross RanchXI.

The Sheep and the GoatsXII.

Nipping a MutinyXIII.

At Washout CoulieXIV.

Stampeding the Prize BunchXV.

Jimmy’s Unwilling RideXVI.

After the Rustlers’ RaidXVII.

The Shrewd Old FoxXVIII.

More Trouble AheadXIX.

At Bay in the CanyonXX.

Smoked OutXXI.

In the Hands of the RustlersXXII.

Coming of the Real Boss—ConclusionBoy Scouts on the Open Plains

CHAPTER I.

OVER THE EDGE.

“’Tis meself that calls this pretty tough mountain climbin’, and me athinkin’ all the while the road to Uncle Job’s cattle ranch would take us along the bully open plain all the way!”

“Hold your horses, Jimmy; we’ve got to about the end of this hill climbing. After we cross this divide it’s going to be the kind of travel you mention, all on the level. One more town to pass through, and then we strike out for the ranch. Any minute now we ought to glimpse the low country through this canyon that we’ve been following over the ridge.”

“There it is right now, Ned, and let me tell you I’m glad myself that this hard work is nearly over with. Whew! did you ever see a prettier picture than this is, with the whole country spread out like a big map?”

“And that’s where we aim to spend some little time, is it, boys?” asked a third one of the four boys who, leading a loaded pack burro apiece, had been climbing a range of rocky mountains away down in a corner of Nevada not a great distance from the Arizona border.

“Yes, that’s going to be our stamping ground, Jack, for some little time to come. My uncle Job Haines has his ranch away over there somewhere or other, in the hazy distance. His partner, another uncle of mine, James Henshaw, is with him in the business—you know my mother was married twice, and this last gentleman is the brother of her first husband, which is how I come to have so many uncles. What d’ye say to resting up a bit here before we start down the grade, Ned?”

The way three of them turned toward the other young fellow was evidence enough in itself to show that he must be the leader of the little company, which was in fact the truth.

All of the mountain climbers were wearing rather faded but serviceable khaki suits, which with the leggins and campaign hats proved that they must belong to some troop of Boy Scouts. But it was many days’ journey from their present surroundings to the scene of their home activities, for they belonged in New York City.

Those of our young readers who have had the pleasure and privilege of possessing one or more of the previous volumes connected with this series of stories will readily recognize the four lads as old and valued acquaintances. For the sake of the few who may not have enjoyed meeting the lively quartette before, a few sentences of introduction may be necessary before going on further. And while they are resting both themselves and their pack animals, at the same time drinking in the magnificent scenery that was spread out before them, looking toward the southeast, it would seem to be a fitting opportunity for this service.

The leader of the little party was Ned Nestor, who also served as assistant scout master of the troop, having duly qualified for the office according to the rules of the organization. He was a good hunter and tracker, and possessed a wide knowledge of woodcraft in its best sense.

Some time previous to this Ned had been given various chances to work for the Secret Service of the Government at Washington, and had conducted himself in such a manner as to win the confidence of the authorities. They realized that there were many opportunities when a bright lad might accomplish things unsuspected where a man would be apt to slip up. And judging from the success which had on most occasions followed Ned’s taking up a case, it appeared as though this might have been a wise move.

One of the other boys, a short chap with red hair and a freckled face, often acted as Ned’s assistant in these dangerous adventures. His name was Jimmy McGraw, and at one time he had been a regular tough little Bowery boy in New York, until he happened to meet Ned under strange conditions, and was virtually adopted by the other’s father, so that he now made his home with the Nestors. Jimmy could not entirely shake off some of the old habits; and this accounted for his making use of a little slang now and then, when trying to express himself forcibly.

The third lad was named Jack Bosworth. Jack was a splendid chum, faithful as the needle can be to the pole, and as brave as he was robust. His father being a rich corporation lawyer and capitalist, the boy had been allowed to do pretty much as he chose. Fortunately Jack was a true scout in every sense of the word, and could be depended upon to keep out of mischief. He believed Ned Nestor to be the finest patrol leader that ever wore the khaki and was ready to follow his lead, no matter where it took him.

Harry Stevens, the fourth and last of the quartette, was inclined to be a student rather than a lover of the trail and hunters’ camp. His hobby seemed to lie along the study of wild animals’ habits, and also the history of the ancient Indian tribes that, centuries back, were known to have inhabited the southwestern portion of our country. He had kept harping all the while upon the subject of the strange Zunis, the Hopis, and the Moquis, all of whom he knew had descended from the original cliff-dwellers. And he hoped before going back home again to find a chance to investigate some of their quaint rock dwellings high up in the cliffs bordering the wonderful Colorado Canyon.

Harry was really on his way to the ranch of his uncles. Not being in any hurry he and his chums had first visited San Francisco, and then Los Angeles. While here they somehow conceived the rather singular idea of crossing the desert afoot, in order to have new experiences, and be able to say that they knew what it was to find themselves alone on a sandy tract that stretched as far as the eye could see in every direction.

What remarkable adventures had come their way while carrying out this scheme have already been set down in the pages of the volume just preceding this book, under the title of “Boy Scouts in Death Valley,” so there would be no need of our repeating any of the exciting episodes here. They had purchased the four burros from a discouraged party of men who were prospecting for gold in the mountains to the west of the parched valley of the evil name.

Since they managed to escape from Death Valley, after almost leaving their bones there as the penalty of their rashness, some days had passed; in fact it was now a week later. They had done considerable traveling in that time, and overcome all obstacles with their accustomed ability.

All of them had grown weary of so much mountain climbing, and Jimmy really voiced the united sentiment of the party when he declared that he was yearning for a chance to see the open plain, with grass instead of the eternal blistering sand, and mottes of trees dotting the picture with pleasing bunches of green that would be a relief to their tortured eyes.

So they sat there and talked of the past, as well as tried to lift the veil that hid the immediate future, as though anxious to know what awaited them in the new life to which they were hastening.

Finally Ned Nestor arose and stretched himself, as he remarked:

“I think we’d better be on our way, fellows, if we hope to get down there to the level before night comes along. The sun’s headed for the west, you notice, and as this ridge will shut him out from us early, we haven’t any too much time.”

“I guess you’re about right there, Ned,” commented Jack; “and for one I want to say I’d be right glad to make camp at the foot of the mountains. We can’t say good-bye to these rocky backbones of the region any too soon to please me.”

The four burros had rested after their arduous climb, and there was not the least difficulty about getting them started moving. In fact they seemed to already scent the grass of the plains below, so different from anything that had been encountered thus far on the trip, and were showing signs of a mad desire to reach the lowlands.

Several times Ned had to caution one of the others about undue haste.

“Hold your burro in more, Jimmy,” he would say; “there are too many precipices on our trail to take chances of his slipping, and dragging you over with him. To be sure mules and donkeys are clever about keeping their footing and almost equal Rocky Mountain sheep, or the chamois of the Alps that way; but they can stumble, we know, and it might come at a bad time. They’re wild to get down out of this; but for one I don’t care to take a short cut by plunging over a three hundred foot precipice. Easy now, Teddy; behave yourself, old boy. That’s an ugly hole we’re passing right now, and we want to go slow.”

Jimmy himself was apt to be a reckless sort of a chap; and many a time did Ned have to check his impatience in days gone by. Jack, too, often did things without sufficient consideration, though he could hold himself in on occasion; while Harry seldom if ever had to be cautioned, for he was inclined to be slow.

They often found themselves put to it to make progress, for while they followed what seemed to be a trail over the ridge, it had been seldom used, and many obstructions often blocked the way.

Once they had to get wooden crowbars and pry a huge boulder loose that had fallen so as to completely block progress. Fortunately it had been easy to move it a few inches at a time, until they sent it into a gulf that yawned alongside the trail, to hear it crash downward for hundreds of feet, and make the face of the mountain quiver under the shock.

In this fashion they had managed to get a third of the way down from the apex of the ridge, and Ned, comparing the time with the progress made, announced it as his opinion that he believed they would be easily able to make the bottom before night came on.

“That sounds all to the good to me, Ned,” declared Jimmy, with a broad grin on his freckled face.

“Hope you’re a true prophet, that’s all,” said Harry.

“I agree with Ned,” Jack broke in with, “and say, we ought to make the foot of the range before night, the way we’re going, unless we hit up against some bad spot that’ll hold us up worse than we’ve struck yet.”

“That isn’t likely to happen,” Ned observed, “because the further down we get the easier the going ought to be.”

“But I notice that the holes are just as deep,” Harry told him.

“And a fall would jolt a feller as hard too, seems like,” Jimmy admitted as he craned his neck to look over at a place where the trail was only a few feet wide with a blank wall on the right and an empty void on the left.

Harry nervously caught his breath, and called out:

“Better be careful there, Jimmy, how you bend over and look down. You might get dizzy and take a lurch or the frisky burro give a lug just then and upset you. We all think too much of you to want to gather up your remains down at the bottom of a precipice.”

Jimmy laughed and seemed pleased at the compliment. He did not again bother about looking over, but occupied himself with managing his pack animal, which kept showing an increasing desire to hasten. At one point Ned had stopped to tighten the ropes that held the pack on his burro, and in some manner Jimmy managed to get at the head of the little procession that wound, single file, down that steep mountain trail.

It was Ned’s intention to assume the lead again at the first opportunity, when he could pass the others. Meantime he thought he could keep an observant eye on Jimmy, so as to restrain him in case he began to show any sign of rashness.

After all it was not so much Jimmy’s fault that it happened, but the fact that his burro had quite lost its head in the growing desire to get down to the green pastures from which it had been debarred so very long, and for which it was undoubtedly hungering greatly.

That the unlucky animal should chance to make that stumble just at the time of passing another narrow place in the trail, where the conditions again caused them to move in single file, was one of those strange happenings which sometimes spring unannounced upon the unwary traveler.

Jimmy at one time even walked along with the end of the rope wound about his waist in a lazy fashion; but Ned had immediately told him never to think of doing such a thing again, when there was even the slightest chance of the burro slipping over the edge of the sloping platform and dragging his master along. But right then Jimmy had such a rigid clutch upon the rope that he did not seem to know enough to let go when the pack animal stumbled, tried to cling desperately to the rocky edge, and then vanished from sight into the gulf.

In fact Jimmy’s first idea seemed to be a desire to drag the tottering animal back to safety, and it was because he was tugging for all he was worth on the rope that he was pulled over the edge himself.

The other three scouts seemed to be petrified with horror when they saw their plucky but rash chum dragged over. None of them could jump to his assistance on account of the burros being in the way and plunging and kicking wildly, as though terrified at the fate that had overtaken their mate.

Ned was at the end of the line, and Harry, though not far from the spot where the terrible accident happened, seemed to be too terrified to know what to do, until it was all over, and poor Jimmy had vanished from their view.

CHAPTER II.

LUCKY JIMMY.

“Oh! Ned, he’s gone—poor Jimmy—pulled right over by that burro!” Harry was crying as he stood there almost petrified with horror, while his own pack animal acted as though it might be terrified by the fate that had overtaken its mate, for it snorted and pulled back strenuously.

Ned knew that unless the remaining three burros were quieted a still greater disaster was apt to overtake them.

“Speak to your animal, Harry; get him soothed right away! Easy now, Teddy, stand still where you are! It’s all right, old fellow! Back up against the rock and stand still there.”

Ned as he spoke in this strain managed to throw a coil or two of the leading rope over a jutting spur of rock. Then turning round, he crept on hands and knees to the edge of the yawning precipice and looked over, shuddering to note that while not nearly so high as that other precipice had been, at the same time the fall must be all of seventy feet.

There at the foot he could see the unfortunate burro on his back and with never a sign of life about him. Doubtless that tumble must have effectually broken his neck and ended his days of usefulness.

“Do you see him, Ned?” asked a trembling voice close by, and the scout leader knew that Jack too had crawled to the edge in order to discover what had become of poor Jimmy McGraw.

“Not yet,” replied Ned, sadly; “he may be hidden under the burro, or lying in among that clump of bushes.”

“But glory be, he ain’t, all the same!” said a voice just then that thrilled them all. “If ye be lookin’ over this way ye’ll discover the same Jimmy aholdin’ on with a death grip to a fine old rock that sticks out from the face of the precipice. But ’tis me arms that feel like they was pulled part way out of the sockets with the jerk; and I’d thank ye to pass a rope down as soon as ye get over the surprise of havin’ a ghost address ye.”

“Bully for you, Jimmy!” exclaimed Jack; “seems like you’ve got nearly as many lives as a cat. Hold on like anything, because Ned’s getting a rope right now, and he’ll heave it over in three shakes of a lamb’s tail. Don’t look down, Jimmy, but keep your eye on me. We’ll pull you out of that in a jiffy, sure we will. And here comes Ned right now with the rope. He’s even made a noose at the end, so as to let you put your foot in the same. Keep holding on, Jimmy, old fellow!”

In this manner, then, did Jack try to encourage the one in peril, so as to stiffen his muscles, and cause him to keep his grip on that friendly crag that had saved him from sharing the dreadful fate of the wretched burro.

Jimmy had fortunately kept his wits about him, and although the strain was very great, because he could find no rest for his dangling feet, he managed to hold his awkward position until the rope came within reach.

“Be careful, now, how you manage!” called Ned, from his position fifteen feet above the head of the imperiled scout. “Let me angle for your foot, and once I get the noose fast around it, you can rest your weight safely. But Jimmy, remember not to let go with one hand, because your other might slip. Leave it all to me.”

Ned was already working the rope so that the open noose twirled slowly around, coming in contact with Jimmy’s foot, which the other thrust out purposely. While no expert in such angling and more or less worked up with fears lest Jimmy suddenly lose his precarious hold, and go down to his death, Ned presently met with success. The noose passed over the waiting foot, and was instantly jerked tight by a quick movement from above.

By then Jack was alongside the scout master eager to lend his assistance when it came to the point of lifting Jimmy. Harry, too, hovered just behind them, unable to look over because it made him dizzy when so terribly excited, but only too ready to take hold of the end of the rope and bracing his feet against some projection of the rocky trail, throw all his weight into the endeavor to draw the one they meant to rescue to the safety of the path.

It was speedily but cautiously accomplished, for Ned would not allow himself to be needlessly hurried, knowing how disasters so often result from not taking the proper care.

Jimmy was looking a trifle peaked and worried as he came clambering over the edge of the narrow path, assisted by Ned, who as soon as he could get a grip on the other scout’s jacket knew that all was well. No sooner did Jimmy realize that he was surely safe than he proceeded to indulge on one of his favorite grins, although they could see that a deep sigh of gratitude accompanied the same.

The very first thing he did was to turn around, and lying flat on his chest, look back down into that gulf from which he had just been dragged.

“Gee, whiz! but that was somethin’ of a drop, believe me!” he remarked, trying to keep his voice from trembling. “And there lies me silly old burro on his back with never a sign of a kick acomin’. He’s sure on the blink and whatever am I agoin’ to do now, without any Navajo blanket to sleep in nights? Mebbe we might have ropes aplenty to lower me down there, so I could recover me valuables. ’Tis a piece of great luck I had me Marlin gun in me hands at the time and dropped it on the ledge, so I did.”

“If we couldn’t get the things any other way, Jimmy,” announced Ned, “perhaps I’d agree to that spliced rope business, because we’ve got more than thirty yards of good line with us, but I’d go down myself and not let you try a second time. Still I don’t think it’ll be necessary. From what I see of the lay of the mountain we can reach that place after we leave this narrow trail.”

Jimmy did not insist. Perhaps his nerves had been more roughly shaken by his recent experience than he cared to admit; and the possibility of again finding himself dangling in space did not appeal very strongly to him.

It was just as well that Ned decided the matter as he did, for they found that once the end of the narrow stretch of rock was gained it was no great task to creep along the side of the mountain to the place where the dead pack animal lay.

Ned and Jack made the little journey and in due time turned up again carrying with them all that had been upon the burro, save the water keg.

“We left that behind,” explained Ned, “because as we are done with desert travel for this trip we won’t find any need of such a thing. But here’s your precious Navajo colored blanket, Jimmy; likewise we’ve saved what grub there was in the pack.”

“Good for you, Ned; I’d hated to lose that blanket the worst kind, you know; and as for the food end of the deal, well, what’s the use telling you how I feel about that when you all know that I’m the candy boy when the dinner horn blows.”

Jimmy was a great “feeder,” as Jack called it, and on many an occasion this weakness on his part had made him the butt of practical jokes on the part of his chums. But Jimmy was not the one to give up any cherished object simply because some one laughed at him on account of it. He was more apt to join in the merriment and consider it all a good joke.

The journey was now resumed, and the balance of the afternoon they met with no new hardships or perils worth recording. When the day was done and the shadows of coming night began to steal forth from all their hiding places where the bright sunlight had failed to locate them, the four scouts had reached the foot of the rocky mountain range and looked out upon the plain.

Here they made camp and passed a pleasant night with nothing to disturb their slumbers save the distant howl of a wolf, which was a familiar sound in the ears of these lads, since they had roughed it on many occasions in the past in more than a few strange parts of the world.

Although they had recently passed through some very arduous experiences these were only looked on as vague reminiscences by these energetic chums. The future beckoned with rosy fingers and that level plain looked very attractive in their eyes, after such a long and painful trip across the burning deserts and through that terrible Death Valley, where so many venturesome prospectors, gold-mad, have left their bones as a monument to their folly.

When morning came again they cooked breakfast with new vim. And the fragrant odor of the coffee seemed to appeal to them with more than ordinary force because of the bright prospect that opened before them.

“Ned says it might be only two more days before we get close to Uncle Job’s ranch,” remarked Harry, as he assisted Jimmy in getting breakfast; for since the latter was so fond of eating his comrades always saw to it that he had a hand in the preparation of the meals, to which Jimmy was never heard to offer the slightest objection.

“Then it’s me that will have to be studying harder on all them cowboy terms so they won’t take me for a greeny,” Jimmy went on to say in reply. “You just wait and see how I branch out a full-blown puncher. Right now I c’n ride a bucking pony and stick in the saddle like a leech; and I’m practicin’ how to throw a rope, though I must say I don’t get it very good and sometimes drop the old loop over my own coco instead of the post I’m aimin’ to lasso. But I’ll never give it up till I get there. That’s the way with the McGraws, we’re all set in our way and want baseball championships and everything else that’s good to own.”

“Jimmy,” called out Jack just then, “I think if you didn’t talk so much we’d be getting our breakfast sooner, because you kind of cool things off. There, see how the coffee boils like mad whenever you hold up. How about it, Harry, isn’t it nearly done? I’m feeling half-starved, to tell you the truth.”

“Then I’m not the only pebble on the beach this time, it seems,” chuckled Jimmy, who was so used to being made fun of on account of his voracious appetite that he felt happy to find that someone else could also get hungry on occasion.

“In three minutes we’ll give you the high sign, Jack,” Harry announced and he was as good as his word, for it was not long before the chums might have been seen discussing the food that had been prepared and making merry over the meal as was their usual custom.

Starting forth in high spirits they began to head across the plain and at about noon all of them were electrified on hearing the distant but unmistakable whistle of a locomotive, showing that they were approaching the railroad.

After their recent experiences in the dead lands this sign of civilization was enough to thrill them through and through. Jimmy was immediately waving his hat and letting off a few yells to denote his overwhelming joy; while even Ned looked around with more or less of a smile on his face.

“Sounds like home, don’t it?” asked Jack, beaming on the rest. “Takes you back to good old New York, where you can sit down next to a plate of ice cream when your tongue feels thick from the heat and cool off. Seems like I’d never get my fill of cold stuff again.”

Pushing on they presently sighted the railroad and also discovered that just as Ned had figured would be the case, they were approaching a town.

“That’s where we ordered our mail to be sent on from Los Angeles, up to the tenth, and I hope we find letters waiting for us,” Harry remarked; for he was quite a correspondent, though not in the same class with Frank Shaw, another member of the Black Bear Patrol, whose father owned a big daily in New York and who often contributed letters to its columns when he was away on trips with Ned.

Ned on his part was wondering whether he would receive anything in the way of business communications from the Government people in Washington, for it would be forwarded on from Los Angeles if such a message did come in cipher.

So anxious were the boys to reach the settlement on the railroad that it was decided not to stop for any lunch at noon but to push right along. If there was any eating place in the town they could get a bite before leaving; and the change from camp fare might be agreeable to them all.

At two o’clock they reached the place, which was hardly of respectable size, although it had a station and post office. The first thing the boys did was to head for this latter place and ask for mail, which was handed out after the old man had slowly gone over several packages. Strangers were such a novelty in that Nevada railroad settlement that the postmaster evidently was consumed with curiosity to know what could have brought four lively looking boys dressed in khaki suits very much on the same pattern as United States regulars, to that jumping-off place. But they did not bother themselves explaining and he had to take it out in guessing that the Government was so hard pushed for recruits now in the army that they had to enlist boys not fully grown.

While the other boys were eagerly devouring the contents of the various envelopes they had received, bearing the New York post mark, Ned, who had put his own letters in his pocket for later reading, sauntered over to the station to interview the telegraph agent, who was also the ticket man, express agent and filled various other offices as well after the usual custom of these small towns.

It was only a short time later that Jack, Harry and Jimmy, still devouring the long letters they had received, in which all the news of the home circles was retailed, saw Ned walking briskly toward them.

“He’s struck something or other that’s given him reason to chirk up,” announced the observant Jimmy, as he took a shrewd look at Ned’s face on the scout master drawing near. “Ten to one he’s had word from the head of the Secret Service in Washington. It’d sure be pretty punk now if after comin’ so far over deserts and the like to visit your uncle, we had to drop off here and take the train back to Los Angeles, so Ned could help gather in some gang of counterfeiters or look up a bunch of smugglers bringing the Heathen Chinese across the Mexican border while all that fighting is goin’ on down there between Villa and Huerta.”

Ned quickly joined them. They could see from the alert look on his face that something must have happened since he left them shortly before to arouse Ned. His eyes shone with resolution and he had the look that appears on a hunter’s face when he discovers the track of the animal he had long wanted to bag.

“Did you find a message waiting for you here, Ned?” asked Harry.

“Just what I did,” came the reply.

“Then it must have been from Washington?” suggested Jack, anxiously. “But let’s hope for Harry’s sake it won’t call you off from this scheme we’ve got started.”

“That’s the strangest thing of it all,” replied Ned; “because, you see, this message was meant to send me from Los Angeles straight down into this very section of the Colorado River country.”

CHAPTER III.

THE HELPING HAND.

When Ned made this announcement the others exchanged looks in which wonder struggled with curiosity.

“Tell me about that, now,” muttered Jimmy; “was there ever anything like the luck that chases after us all the while? Here we start out to visit Harry’s uncle, so he might carry out a mission that his folks sent him on, and of course the Government must a guessed all about it, since they went and laid a game to be hatched out right in the same part of the Wild and Wooly West. Can you beat it?”

“Let Ned tell us what the game is, can’t you, Jimmy?” demanded Harry.

“Yes, and please don’t break in again with your remarks until he’s all through,” added Jack. “It bothers a fellow to make connections when you get started. If you must talk, why, we’ll throw in and hire a hall for the occasion. Now, Ned, tell us what the Secret Service folks want you to do.”

“I’ve had a message in cipher from my people in Washington, telling me that while I’m out in this section they’d like me to look up one Clem Parsons, who’s been wanted for a long time on the charge of counterfeiting Government notes. When last heard from he was running a stage line somewhere in the country of the Colorado and doing a little in the way of fleecing unsuspecting travelers who come out here to see the wonders of the Canyon. So from now on we’ll begin to ask questions and see whether we can get on the trail of this gentleman who’s given some of the smartest agents in the Secret Service the call-down.”

“And then they have to depend on Ned Nestor and his able assistant, Jimmy McGraw,” remarked the last mentioned scout; “excuse me, fellers, but if you don’t blow your own horn, who d’ye reckon’ll be fool enough to do it for you? But Ned, if our luck holds as good as it generally does, chances are ten to one this same Clem Parsons will come tumbling right up against us. It seems like you might be a magnet and they all have to come our way sooner or later.”

“Any description of what he looks like?” asked Jack, who had known Ned to get similar orders on previous occasions and could guess that it was not all left to his imagination.

“Yes, they tell me he is tall and thin and has a scar on his left cheek. He used to be a cow puncher at one time and might be working at his old trade now. That’s a point to remember when we get to the Double Cross Ranch. Every puncher will have to run the gantlet of our eyes and if one of them happens to be marked with a scar on his left cheek, it’ll be a bad day for him.”

“Now, wouldn’t it be queer if we did run across the mutt there at your uncle’s place, Harry?” remarked Jimmy. “But here we are again, Ned, uniting business with pleasure like we’ve done heaps of times before now. Mr. Clem Parsons, I’m sure sorry for you when this combination gets started to work, because you’ve got to come in out of the wet and that’s all there is to it!”

It might appear that Jimmy was much given to boasting; but as a rule he made good, so that this failing might be forgiven by those who knew him and his propensity for joking.

They moved out of town after getting a pretty poor apology for a lunch at the tavern. Jimmy declared that he would starve on such fare and announced his intention of immediately opening a box of crackers he had purchased at a local store so as to keep himself from suffering.

Ned, as was his habit, had interviewed about everybody that crossed his path, so as to improve upon the rude map he carried and which he had found to be faulty on several occasions, which fact caused him to distrust it as a guide.

“We ought to make the ranch by tomorrow evening, if all goes well,” he told his three chums, as they walked onward over the plain, still heading almost due southwest.

“Not much danger of anything upsetting our calculations from now on,” observed Jack, “unless we meet up with drunken punchers, run across some bad men who have been chased by the sheriff’s posse out of the railroad towns and who try to make a living by holding up travelers once in six months; or else get caught in a fine old prairie fire.”

“Say, that last could happen, that’s right,” Jack went on to exclaim, looking a little uneasily at the dead grass that in places completely concealed the greener growth underneath. “If a big gale was blowing and a spark should get into this stuff she would go awhooping along as fast as a train could run. That’s something I’ve often read about and thought I’d like to see, but come to think of it, now that I’m on the ground, I don’t believe I care much about it after all.”

“They say it’s a grand sight,” Harry volunteered; “but according to my mind a whole lot depends on which side of the fire you happen to be. What’s interesting to some might even mean death to others.”

“Yes, I’ve read lots about the same,” admitted Jack, “and of the trouble people have had in saving themselves when chased by one of these fires on the plains. If we do see one of the same here’s hoping we are to windward of the big blaze.”

When the sun sank that evening they were hurrying to reach what seemed to be a stream of some sort, judging from the line of trees that cut across the plain and which only grow where there is more or less water to be had.

The three burros must have scented the presence of water, for there was no keeping the animals within bounds. They increased their pace until they were almost on the run; and Jimmy threw away the fag end of a whip with which he had been amusing himself by tickling the haunches of the burro in his charge and urging him to move along faster.

One of the animals started to bray in a fashion that could have been easily heard half a mile or more away.

Hardly had the discordant sounds died away than the boys were considerably surprised to hear a shrill voice coming from directly ahead, as though the exultant bray of the pack animal had given warning of their presence to some one who needed assistance the worst kind.

“Help! Come quick and get me! Help—help!” came the words as clear as a bell and causing Harry and Jimmy to stare at each other as though their first thought might have been along the line of some deception that was being practiced upon them.

But there was Ned already on the jump and shouting over his shoulder as he ran:

“Jimmy, give your burro over to Harry to look after; you too, Jack and follow me on the run!”

“That suits me all right!” cried Jack; “here Harry, please look after my pack!” and with these words he was off at full speed.

Jimmy was close at his heels. He had only waited long enough to snatch his rifle from the top of the pack on the burro that had been given into his charge after his own had been lost in the mountain disaster. Jimmy was always thinking they might be attacked by Indians off their reservation or else run across some bad men who liked to play their guns on strangers just to see them dance. For that reason he seldom if ever allowed himself to be caught far away from his repeating Marlin these days.

When they had pushed into the patch of cottonwoods they found that Ned was already at work trying to lend the assistance that had been so lustily called for in that childish treble.

A figure was in the stream, although just his head and a small portion of his body could be seen. He was stretching out his hands towards Ned in a beseeching manner that at first puzzled Jimmy.

“Why, I declare if it ain’t a little boy!” he exclaimed; “but what’s he doin’ out there, I want to know? Why don’t he come ashore if the water’s too deep. What ails the cub, d’ye think, Jack?”

“Don’t know—might be quicksand!” snapped the other, as he once more started to hurry forward.

Ned was talking with the stranger now, evidently assuring him that there was no further need of anxiety since they had reached the spot.

“Can’t you budge at all?” they heard him ask.

“Not a foot,” came the reply; “seems like I mout be jest glued down here for keeps and that’s a fact, stranger.”

“How long have you been caught there?” asked the scout master.

“Reckon as it mout be half hour er thereabouts,” the boy who was held fast in the iron grip of the treacherous quicksand told him; and so far as Jack could see he did not exhibit any startling signs of fright, for he was a boy of the plains and evidently used to running into trouble as well as perilous traps.

“But,” Jack broke in with, “you never shouted all that time, or we’d have heard you long before we did?”

“Never let out a yip till I ketched that burro speakin’,” the boy replied; “what was the use when I didn’t think there was a single person inside o’ five mile? I jest tried and tried to git out but she hung on all the tighter; and the water kept acreepin’ up till it’d been over my mouth in ten minutes more I reckon.”

“Well, we are going to get you out of that in a hurry, now,” Ned told him in a reassuring tone; “Jack, climb up after me, to help pull. Jimmy, you stand by to do anything else that’s wanted.”

Ned, being a born woodsman, had immediately noted the fact that the limb of a tree exactly overhung the spot where the boy had been trapped in the shifting sand. This made his task the easier; but had it been otherwise he would have found some means for accomplishing his ends, even though he had to make a mattress of bushes and branches on which to safely approach the one in deadly peril.

Creeping out on that stout limb Ned dropped the noose of his rope down to the boy, who was only some six feet below him.

“Put it around under your arms,” Ned told him; but as though he understood the method of procedure already, the boy in the sand was even in the act of doing this when Ned spoke.

“Tie the end around the limb and let me pull myself up, Mister, won’t you?” the boy pleaded, as though ashamed of having been caught in a trap, and wishing to do something looking to his own release.

This suited Ned just as well, though he meant to have a hand in the pulling process himself and also give Jack a chance. So when he fastened the rope to the limb of the tree he did so at a point midway between himself and Jack.

“Get hold and pull!” he said in a low tone to his chum; for already was the boy below straining himself with might and main to effect his own release.

It would have proved a much harder task than he contemplated; but the scouts did not mean that he should exhaust himself any further in trying. They managed to get some sort of grip on the rope and then Ned called out cheerily:

“Yo heave-o! here he comes! Yo-heave-o! up with him, Jack! Now, once more, all together for a grand pull—yo-heave-o! Hurrah, he’s nearly out of the sand!”

Five seconds later and the energetic boy was scrambling across the limb of the tree; and in as many minutes all of them had descended to the ground, the end accomplished and nobody much the worse for the experience.

“It was a close call for me, that’s sure,” the boy was saying, as he gravely went around and shook hands with each one of the scouts, not excepting Harry, who had meanwhile come up, leading the three burros; “an’ I want you all to know I’m glad that donkey let out his whoop when he did. Why, I might a been all under when you got here; but say, I lost my gun and that makes me mad.”

Looking at the boy more closely they were struck with the fact that while he did not seem to be more than nine years old, he was dressed like a cow-puncher and had a resolute air. How much of this was assumed in order to impress them with the idea that he had not been alarmed in the least by his recent peril, of course no one could say. Ned was wondering how the boy, brought up undoubtedly amidst such perils and on the lookout for danger all the while, could have fallen into such a silly little trap as this.

“What were you doing in the stream that you stood there and let the sand suck you in?” he asked as he proceeded to help the boy scrape himself off so as to appear more presentable.

“I was a little fool, all right,” the kid immediately answered, with an expression of absolute disgust on his sharp face; “you see, I glimpsed a bunch of deer feeding just over yonder to windward and as they were headin’ in this way I thought I’d lie low under the river bank and wait till they got inside easy gunshot. I tied my pony over in the thickest place of the timber and then walked out to where the water jest come to my knees, where I got low down to wait. Say, I was that taken up with watchin’ them deer afeedin’ up that I forgets all about everything else and was some s’prised to feel the water tricklin’ around my waist like. After that I knowed the huntin’ game was all up, and that less I wanted to be smothered I’d have to get out in a hurry. But it didn’t matter much how I pulled, an’ heaved and tried to swim I jest stuck like I was bolted down to a snubbin’ post and somebody had cinched the girth on me. Then, after a while, when I was expectin’ to swaller water, I heard that burro singin’ and afore I could help it I jest hollored out. Guess you must a thought it was a maverick. I could a kicked myself right away afterwards ’cause I give tongue so wild like!”

Ned smiled. He realized that the cub had imbibed the spirit of the Indian warrior who disdains to display any weakness of the flesh. No matter how much he may have been frightened by his recent terrible predicament, he did not choose any one to know about it. Indians may feel fear but they have learned never to show it by look or action and to go to their deaths, if need be, taunting the foe.

“Well,” he told the small boy, “we intended to camp for the night here close to the river and we’d be glad to have you stay over with us. Plenty of grub for everybody and it might be much more pleasant than being by yourself. We are not Western boys but then we’ve been around more or less and know something about how things are done out here. Will you join us—er—”

“My name is Amos, Amos Adams, and I’ll be right well pleased to stay over with you to-night, sure I will,” the boy went on to say.

So it was settled, and out of just such small things as their meeting Amos in such a strange way great events sometimes spring. But none of the scouts so much as suspected this when they busied themselves preparing the camp, building the cooking fire, and seeing that all the animals were staked out to feed, after watering them.

CHAPTER IV.

PICKING UP POINTS.

“Ned, whatever do you imagine this kid is doing out here all by himself?”

Jack asked this question in a low tone. They had cooked supper, and disposed of it promptly; and there had been an abundance for the guest, as well as the four chums. And now the two scouts were lounging near the fire, while Jimmy and Amos cleaned up the tin dishes and cooking utensils; Harry meanwhile being busily engaged with some notes he wanted to jot down for future use, in comparing his recent experiences with those of others who had suffered tortures in the notorious Death Valley.

“Well, you’ve heard as much of his talk as any of us, Jack,” replied the leader of the expedition, quietly, “and so far there’s been nothing said about himself. I’m going to beckon to Amos to come over here, and put a few leading questions to him. Out here when a fellow is entertained at the camp fire, it’s only fair that he give some sort of an account of himself. Besides, Amos looks so much like a kid, just as you say, that it makes the thing seem queer.”

A minute later, catching the eye of the boy, he crooked his finger and nodded his head. Plainly Amos understood, for he immediately came across.

“Sit down, Amos,” Ned told him.

The small boy in the cowboy suit did so, at the same time allowing a sort of smile to come upon his bronzed face.

“Want to know somethin’ about me, I reckon?” he remarked, keenly.

Jack chuckled as though amused at his shrewdness; but Ned only said:

“Well, ordinarily out here on the plains I understand that men seldom express any curiosity about their chance guests; it isn’t always a safe thing to do. But you see, Amos, in your case it’s different.”

“Sure it is; I get on to that, Mr. Scout Master,” replied the boy, readily; for he had ere this noticed the emblem which Ned bore upon his khaki coat, and which stamped him as authorized to answer to this name, which would indicate that Amos knew something about the Boy Scout business.

“In the first place we chanced to be of some little assistance to you.”

“A heap!” broke in the other, quickly.

“And then, excuse me for saying it, but you are such a kid that anybody would be surprised to run across you out by yourself, carrying a gun, riding a pony like the smartest puncher going, and after big game at the time you got stuck in that quicksand—all of which, Amos, must be our excuse for feeling that we’d like to hear something about you.”

“That’s only fair and square, Ned,” the boy spoke up immediately; “Jimmy there has been telling me the greatest lot of stuff about what you fellows have been doing all over, that I’d think he was stuffing me, only he held up his hand right in the start, and declared he never told anything but the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so help him. And I’m ready to tell you who I am, and what I’m adoin’ out here.”

“Not that we think you’re anything that you shouldn’t be, Amos,” put in Jack.

“Well, my name’s Amos Adams, just like I said, and all my life I’ve been around a cattle ranch. That’s why I know so much about roping steers, and riding buckin’ broncs. I guess I was in a saddle before my ma weaned me. There are a few things mebbe I can’t quite do as well as some of these here prize punchers, but it’s only because I ain’t as strong as them, that’s all.”

Looking at his confident face the scouts believed that Amos was only speaking the plain truth.

“My dad’s name is Hy Adams,” continued the kid puncher. “I guess you ain’t been around these diggin’s much yet, or you’d a heard who he is. They call him the Bad Man of the Bittersweets, and when he raises his fog-horn of a voice lots of men that think themselves brave just give a hitch to their shoulders this way,” and he imitated it to the life as he spoke, “and does what he tells ’em. That’s when he’s been drinkin’. But then there are other times—oh, well, I reckon, I hadn’t ought to tell family secrets.

“We live in a cabin, ’bout ten miles away from here. My dad, he’s in the cattle business, when he don’t loaf. Sometimes he’s ’round home, and agin he ain’t, just ’cordin’ to how things are agoin’. Mam, she’s a little woman, but she knows how to run the house. I gotter sister, too, younger’n me, and her name it’s Polly. I ain’t gone to school any to speak of, but mam, she kinder teaches me, when I ain’t ridin’ out on the range, or totin’ my gun on a hunt. That makes me mad to think I lost my gun in the drink there.”

“No use hunting for it in the morning, I should think?” suggested Jack.

“Nary bit,” the boy replied quickly; “it’s down under that shiftin’ sand long before now. But then she was an old gun, and I’m savin’ up to git a new six-shot rifle, so it don’t need to be long now before I’ll be heeled agin.”

“Is your father a rancher, then, Amos?” Jack went on to ask, idly.

The boy grinned and looked at him queerly.

“Well,” he replied, with a quaint drawl that amused the scouts, “I don’t know as you could call him that way, exactly. He’s been cow puncher, and nigh everything else a man c’n be down thisaway to make a livin’. Me and my awful dad we don’t git on well. That’s one reason I gen’rally skips out when he takes a notion to lay ’round home for a spell. He knows right well I ain’t afeard of him, if he has got the name of bein’ a holy terror. I happen to belong to the same fambly. ’Sides, he ain’t what you’d call my real and true dad.”

“Oh! I see, you adopted him, did you, Amos?” Jack asked, laughingly.

“My mam she married agin after pop he was planted, and they went an’ changed my name from Scroggins to Adams. I don’t know which I likes best; but Scroggins that’s honest, anyway, which Adams ain’t—leastways some people around this region say it ain’t. When I grows up I reckon I’ll be a Scroggins, or else get a new name.”

Again the scouts exchanged amused glances. Amos was certainly a most entertaining little chap, with his quaint sayings.

“Now, you see, dad never comes home alone any more, but fetches some of his cronies along with him, and there’s unpleasant scenes ahappenin’ all the time; which is one of the reasons why I skip out. They gets to drinkin’, too, purty hard, till mam she has to douse a bucket of water over each puncher, and start ’em off. Mam she don’t approve of the kinds of business that dad takes up. But he keeps amakin’ these here visits to home further apart all the while, ’cause things ain’t as pleasant as they might be. Some time mebbe he won’t come no more. I’m bankin’ on that, which is one reason I ain’t never laid a hand on him when he gets roarin’ like a mad bull. There are others, too, but I wont mention the same.”

Amos had apparently been very frank with his new friends. He seemed to have taken a great fancy for them all, and, in turn, asked many questions concerning their expected visit to Harry’s uncle on Double Cross Ranch, which place he knew very well.

The conversation by degrees became general, and finally the scouts went on to talk about their own affairs. During this exchange of opinions, it happened that the name of Clem Parsons was mentioned by Ned. Perhaps it would be hardly fair to call it “chance,” when in reality the scout master wanted to find out whether the kid puncher seemed to be familiar with the name of the man whom the Government authorities in Washington wished him to round up.

The bait took, for immediately he heard Amos say:

“What’s that, Clem Parsons? Say, I happen to know a man by that name, and he’s been over to our house lots of times, too.”

“Then he’s a puncher, is he?” asked Ned.

“Well, I reckon he has been ’bout everything in his day, for I’ve heard him say so,” came the reply. “He rides with my awful dad, an’ they seem to git on together, which is some queer, because most of ’em is that skeered o’ dad they tries to steer clear o’ him.”

“My! but this dad of yours must be a grizzly bear, Amos?” remarked Jimmy, who had been greatly impressed with what he heard the boy say.

“Just you wait till you see him, that’s all,” was what Amos told him. “Mam, she reckons as how ’twas this same Clem Parsons as had got dad to ridin’ ’round the kentry doin’ things that might git him into trouble, an’ she hates him like pizen, for the same. Since they got to goin’ together, dad he’s allers showing plenty of the long-green, which he never handled before. But I ain’t tellin’ fambly secrets, and I reckons I’d better shut up shop.”

He had said enough, however, to convince Ned and Jack that he strongly suspected his step-father of having joined forces with a band of cattle thieves who were stealing the fattest beeves neighboring ranchers owned, and selling them on the side.

There is always this temptation existing when cattle are raised on the range, often feeding for days and weeks many miles away from the ranch house, and scattered among the little valleys where the grass grows greenest. In the darkness of the night, a few of these experienced rustlers can cut out what they want of a herd, and drive them far away, effectually concealing the trail. Then the brands are changed adroitly, and the cattle shipped away to be sold in a distant market.

So long as this lawless business can be carried on successfully, it brings in big money to the reckless rustlers; but if discovered in the act they are usually treated with scant ceremony by the angry punchers and shot down like wolves.

To some men the fascination of the life causes them to ignore its perils. Then besides, the fact that money pours in upon them with so little effort, is a temptation they are unable to resist. So long as there are ranches, and cattle to be raised for the market, there will be men who go wrong and try to get a fat living off those who do the work.

It did not surprise Ned to learn that this clever rascal, whom he had been asked to look up and apprehend if possible, had for the time being forsaken the counterfeiting game and started on a new lay. Clem Parsons was no one idea man. His past fairly bristled with shrewd devices, whereby he deluded the simple public and eluded the detectives sent out by the Secret Service to enmesh him.

He had played the part of moonshiner, smuggler, and bogus moneymaker for years, and snapped his fingers at the best men on the pay roll of the Government. Now, if as seemed possible, he had turned cattle rustler, perhaps there might come a complete change in the programme; for if the irate ranchmen and their faithful punchers only got on a hot trail with Clem at the other end, the authorities at Washington might be saved much further anxiety; for a man who has been strung up to a telegraph pole and riddled with bullets is not apt to give any one trouble again.

Ned had learned some important facts that were apt to prove more or less valuable to him presently. Already he felt that they had been paid many times over for the little effort it had taken to rescue Amos from the sand of the shallow river.

Scouts are taught to do a good deed without any thought of a return; but all the same, it is pleasant to know that the reward does often come, and if any of the four chums had failed to find a chance to turn his badge right-side up that day, on account of having given a helping hand to some one, certainly they must feel entitled to that privilege after lifting Amos out of his sad predicament. Saving a precious human life must surely be counted as answering the requirements of the scout law.

When Amos, a little later, left them to saunter down to the brink of the river, in order to give his mottled pony a last drink before leaving him at the end of his rope to crop grass the remainder of the night, Jack turned to the scout master and gave expression to his convictions as follows:

“Well, it looks like your old luck holds good, Ned, and that you stand a chance of running across your game the very first thing after getting here. If this Clem Parsons Amos tells us about turns out to be the same man the Government wants you to tackle, he’ll be walking into the net any old time from now on. Why, we may run across him tomorrow or the day afterwards, who knows?”

“He’s the right party,” said Ned, quietly. “I asked Amos if he had a scar on his cheek, and he said it gave Clem a look as though he was grinning all the time, a sort of sneering expression, I imagine. And as you say, Jack, I’m in great luck to strike a hot trail so early in the hunt. Given the chance, and I’ll have Mr. Clem Parsons on the way to Los Angeles, by rail, with a hop, skip and a jump.”

“He’s a nifty character, all right,” remarked Jimmy; “and trains with a hard crowd out here, so we’ll all have to pitch in and help lift him. Four of us, armed with rifles as we are, ought to be enough to flag him.”

“One thing in our favor,” ventured Jack, “is that he’ll never for a minute dream of being afraid of a pack of Boy Scouts. While he might keep a suspicious eye on every strange man he meets, and his hand ready to draw a gun, he’ll hardly give us a second look. That’s where we can get the bulge on Clem, and his ignorance is going to be his undoing yet.”

“Perhaps we’d better be a little careful how we mention these things while Amos is around,” Ned went on to say.

“But sure, you don’t think that little runt would peach on us, do you?” demanded Jimmy, who had apparently taken a great liking for the diminutive puncher.

“Certainly not,” answered Ned, “but you understand one of the things that goes to make a successful Secret Service operator is in knowing how to keep his own counsel. He’s got to learn all he can about others, and tell as little about himself as will carry him through. So please keep quiet about my wanting to invite this Clem Parsons to an interview with the Collector in Los Angeles.”

Jimmy promptly raised his hand.

“I’m on,” he said. “Mum’s the word till you lift the embargo, Ned. But it begins to look like we might have some interestin’ happenings ahead of us, from what we know about this Clem Parsons, and what we guess is agoin’ on between the ranchers and the cattle rustlers. I thought all the froth had blown off the top, after we quit that Death Valley, but now I’m beginnin’ to believe we’re agoin’ to scratch gravel again right smart. Which suits Jimmy McGraw all right, because he’s built that way, and never did like to see the green mould set on top of the pond. Keep things astirrin’, that’s my way. When folks go to sleep, give the same a punch, and start something doin’.”

“Well,” said Harry, looking up from his work close by, “if you have a few more narrow squeaks like that one to-day up on the mountain trail, it won’t be long before they plant you under the daisies,” but Jimmy only laughed at the warning.

CHAPTER V.

AROUND THE CAMP FIRE.

It was a lovely night, with the moon looking almost as round as a big yellow cart-wheel when it rose in the east, where the horizon lay low, with the level plain and sky meeting.

Besides, it was not nearly as hot there on the plains as they had found it back where the sands of the Mojave Desert shifted with the terrible winds that seemed to come from the regions of everlasting fire, they scorched so.

The scouts appeared to be enjoying themselves so much that even Jimmy, usually the sleepy member of the party, gave no sign of wanting to crawl under his brilliant and beloved Navajo blanket.

Near by the three pack animals were tethered, along with the calico pony owned by Amos. They cropped the grass as though they could never get enough of the same. Everything seemed so very peaceful that one would find it difficult to imagine that there could come any change to the scene.

Amos had joined the circle again, and once more the conversation had become general. Ned asked numerous questions concerning the ranch which they expected to visit, and in this way they learned in advance considerable about the puncher gang, some of the peculiarities of various members of the same, as well as the floating news of the region.

When Amos was asked about the hunting he gave glowing accounts of the sport to be had by those willing to ride twenty miles or more to the coulies of the foothills, where a panther or a grizzly bear might be run across, and deer were to be stalked.

“How about wolves?” Jimmy wanted to know.

Jimmy always declared war on wolves. He had had some experiences with the treacherous animals in the past, and could not forget. There was a standing grudge between them, and every time Jimmy found a chance he liked to knock over a gray prowler.

Amos shrugged his narrow shoulders as though he took very little stock in such cowardly animals.

“Oh! the punchers they have a round-up for the critters every fall, an’ so you see they kind of keep ’em low in stock. Then besides, ever since they took to payin’ a bounty for wolf scalps, men go out to hunt for the same when they ain’t got nothin’ else to do. They ain’t aplenty about this part of the country nowadays. I reckon as how that’s why Wolf Harkness took to raisin’ the critters.”

“What’s that, raising wolves, do you mean, Amos? Sure you must be kiddin’?” was the way Jimmy greeted this announcement.

“Not me, Jimmy; it’s plain United States I’m giving you, sure I am,” the other insisted.

“But there ain’t no great call for wolf pelts, like there is for black fox and ’coon, and otter, and skunks and that sort of thing. How d’ye s’pose this Wolf Harkness makes it pay?”

“Oh! that’s easy,” replied Amos, carelessly. “You see, he kills off a certain number of his stock once in so often and sells the skins. Then later on they reckon that he collects the bounty for wolf scalps from the State.”

“But say, that looks kind of queer for any man to raise pests, and then expect to make the State pay him so much for every one he kills,” Jimmy remarked, shaking his head as though he found it difficult to believe.

“Don’t know how he manages,” the boy continued. “Heard some say that the law, it left a loophole for such practices, and that they couldn’t stop him. Others kind of think he sells the scalps to some hunter, who collects for the same. But everybody just knows Harkness does get a heap of cash out of his queer business.”

“Ever been to his pen and seen his stock?” asked Jimmy.

“Yes, once I happened that way, but the smell drove me away. There must have been thirty or more wolves in the stockade right then, and they looked like they was pretty nigh starved, too. I dreamed that night they broke loose and got me cornered in an empty cabin. I barred the door, but they pushed underneath and clumb through the broken windows, and everywhere I looked I saw red tongues and pale yellow eyes! Then I woke up, and was scared near stiff, for there was a pair of eyes in the dark right alongside me in the loft at home. But say, that turned out to be only our old black cat.”

All of them laughed with Amos, as though they could fully appreciate the scare he must have received on that occasion.

The subject of the wolf farm seemed to have interested Jimmy intensely, for he went on asking more questions concerning the raising of the animals, what they were fed on, the price of wolf pelts, and a lot more along the same lines until finally Harry turned to Ned and complained.

“Tell him to change the subject, won’t you, Ned? He’ll have the lot of us dreaming we’re beset by a horde of wolves. And you’d better make him draw all the charges out of his gun to-night, because he’s sure to sit up and begin blazing away, to keep from being dragged off. Jimmy’s got a big imagination, you know, and every once in a while it runs away with him.”

“Tell me,” announced Jimmy, rather indignantly, “who’s got a better right to be askin’ questions about the habits of the animals than me, who’s a member of that same Wolf Patrol? How can you expect a feller to give the right kind of a howl when he wants to signal to his mates, unless he finds out all these things.”

“Oh! if that’s the worst you are after, Jimmy, go ahead and find out,” Jack was heard to say, condescendingly. “I thought you had a more serious scheme in that head of yours than just accumulating knowledge.”

Jimmy turned and looked at him suspiciously.

“And what did you think I had up me sleeve, if it’s a fair question?” he asked.

“Why, you see,” began Jack, with a twinkle in his eye, “I was afraid that you might want to invest what money you’ve got saved in starting a wolf ranch of your own, or trying to buy this old man Harkness out. I supposed that was why you wanted to know the exact value of wolf hides, and what the State paid bounty on scalps. But I’m just as glad to find that you’re not bothering your head over the business part of the game. Perhaps you’d like to meet up with this Harkness, thinking he might give you a chance to shoot his collection of hungry wolves. That would be a snap for a fellow who hates the beasts like you do, and has made a vow to never let one get past him, when he had a gun handy or a stone to heave.”

Jimmy only grinned. He did not know whether Jack was joking or not, but there seemed to be something complimentary in his way of talking; and Jimmy was not at all averse to being known as a champion wolf killer.

“I only hope I get a chance to see this Harkness and his bunch of slick critters before we quit this neck of the woods,” he remarked. “But as I ain’t a butcher you needn’t think that I’d ask him to let me cut down his list with my new Marlin gun. Out in the open I’m death on the sneakers every time; but it’d go against my grain to knock ’em over, when they hadn’t got any show for their money. I never could do the axe business for a chicken at home, even when we were livin’ in the country.”

“Oh! well, you must excuse me for speaking of such a thing, Jimmy,” said Jack, with assumed gravity; “I was mistaken, that’s all, in sizing you up. Appearances are often deceitful, you know, and things don’t always turn out as they seem. Now, few people looking at you would ever dream that they were gazing on a marvelous phenomenon. I guess you caught that trick from association with Ned, here,” and Jack might have continued along that vein still further had he not been nudged sharply by the scout master, and heard Ned mutter:

“Mum’s the word, Jack. Don’t tell all you know!”

This brought him to his senses, for he remembered that there was a stranger present, and that it had been decided not to expose their full hand to the gaze of Amos, at least for the present.

In this fashion the time passed.

All of the scouts were in a humor to vote that one of the most delightful camps they had ever been in. Perhaps this partly arose from the great contrast it afforded when compared with recent nights passed under the most trying of conditions, when crossing the desert, and the terrible valley lying to the east of it.

Amos had a blanket along with him. Apparently the lad was accustomed to sleeping by himself on the open plain, and always went prepared. Things were not as pleasant as they might be at his cabin home, frequently enough; and besides this, he must be possessed of a wandering nature, feeling perfectly satisfied to take care of himself, and capable of doing it, too.

They were still lying around the dying fire, and each waiting for some one else to take the lead in mentioning such a thing as going to sleep, when Amos suddenly sat upright.

Ned noticed that he had his head cocked on one side, and appeared to be in the attitude of listening for a repetition of some sound that may have struck his acute hearing.

“There it comes again,” Amos remarked. “You see, the wind has veered around that way more or less; but say, twelve miles as the crow flies is pretty hefty of a distance to hear that pack give tongue, seems to me.”

Ned had caught it that time.

“You must mean the wolves that Harkness keeps shut up in his pen for breeding purposes, is that it, Amos?” he inquired.

“Nothing more nor less than that,” came the reply.

“There, I caught it as plain as anything then!” acknowledged Jimmy, with a vein of triumph and satisfaction in his voice, as though he did not mean to be left at the post, when the whole bunch was running swiftly.

“Whew! they do make a racket, when they’re excited, for a fact!” declared Jack.

“Is it the wolves you’re talking about?” asked Harry.

“Don’t you be hearing the noise beyond there?” Jimmy asked him. “P’raps now, meat is so scarce that the old man’s put his pets on half rations, and the whoopin’ we hear is meant for a protest.”

“Well, what of that?” Jack wanted to know; “I guess you’d raise a bigger howl than that, Jimmy, if we tried to put you on half rations. I can fancy how you’d be trying to lift the roof off, and they’d have to call the fire company out to soak you with their hose so as to make you stop. But don’t get alarmed, Jimmy, because none of us have any intention that way.”

They sat there and listened for several minutes. No doubt, Jimmy was endeavoring to picture in his mind what the den of trapped wolves must look like; and at the same time, he was promising himself once more to try and visit the Harkness place before leaving the country. He would like to be able to say he had set eyes on so strange a thing as a wolf ranch.

Harry began to yawn, and stretch tremendously.

“What ails you fellows; don’t any of you expect to crawl into your blankets and pick up a little sleep? Talking may be all very well, but it doesn’t rest you up any. Ned, why don’t you tell Jimmy to sound taps, all lights out so the rest of us can adjourn? As long as Jimmy’s afloat to do the grand talking act, it isn’t any use trying to go to sleep, because you just can’t.”

Jimmy seemed ready to take up that challenge, and entered upon an argument calculated to prove that he was a mild mannered individual alongside of some people he could mention, though not wanting to give names. Ned, however, put his foot down.

“Harry’s right this time, Jimmy, and you know it. So make up your mind to simmer down, and keep the rest for another time. We’ll find a soft spot and see how well this ground lies. And we ought to make up some for lost sleep to-night, with that soft breeze blowing, and the air getting fresher right along.”

At that plain invitation Jimmy began to make his blanket ready, for he never liked seeing any one crawl in ahead of him any more than he did to be the first one up in the morning.

Amos still sat there. Ned, looking at the boy, saw that there was a little frown on his forehead, as though he did not exactly like something or other.

“What’s wrong, Amos?” he asked, quietly.

“The breeze, it is no stronger than before, you can see, Ned,” the kid puncher replied, as he held up his wet forefinger, after the fashion of range riders and plainsmen in general.

“That’s true enough,” replied the scout master, always willing to pick up points in woodcraft, for he did not pretend to know everything there was going.

“But listen!” added Amos; “it is much louder now, you see.”

Ned became intensely interested at once.

“You are right,” he remarked, “the sound of that wolfish howling does come three times as loud as in the start, and yet the wind couldn’t be the reason of that. Do you know what makes it, Amos?”

“I could give a guess, mebbe.”

“As how?” continued Ned, while Jack and Jimmy and Harry all stopped their preparations for fixing their blankets to suit their individual wants, in order to hear what the kid puncher would say.

“When I was over there at the wolf ranch,” Amos commenced, “I remember now that I noticed the pen looked old and weak. I asked the hunter about it, and he said it’d hold, he guessed; that wolves, they didn’t have the intelligence of hosses, or even cattle, so as to make a combined rush at a weak place.”

“Well?” Ned remarked, as Amos paused.

“It might be that somethin’ happened to make that weak place in the big pen give way, and the whole pack is loose, acomin’ for the river, hungry as all get-out, and ready to attack anything that walks on two legs, because they are nearly starved!”

When Amos gave this as his opinion, the scouts who had been getting their blankets ready for a quiet night’s sleep seemed suddenly to lose all interest in the proceedings. Instead Jimmy started reaching around him for that new Marlin repeating rifle, which had already proven its worth on several occasions.

“Whew!” they could hear him saying, almost breathlessly to himself; “thirty hungry wolves, all at a pop, hey? That’s what I call crowding the mourners. I may be set on knockin’ over an occasional critter when I run across the same; but say, I ain’t so greedy as all that. Think I’m in the wholesale line, do you? Well, you’ve got another guess acomin’ to you, that’s all!”

CHAPTER VI.

THE WOLF PACK.

“What can we do, Ned?” asked Jack.

Jimmy was not the only one now who had seized hold of his gun, for the other three scouts could be seen gripping their rifles. Only poor Amos was without his rifle, though he carried a revolver, cowboy fashion, attached to his belt.

“It’s out of the question for us to get away,” replied the scout master; “because we only have three poor burros, and they’d be overtaken before they’d gone a mile.”

“Yes,” added Jimmy, “and don’t forget there’s four of us, Ned, darlint.”

“Amos could skip out if he feels like it, because his pony has fleet heels, and might outrun the wolf pack?” Jack suggested.

“But all the same Amos is agoin’ to hang around, and take pot luck with the rest of the bunch,” remarked the kid puncher, quietly.

“But how about the animals,” asked Harry, nervously; “do we leave them to be pulled down by the savage beasts of prey? All of us could shinny up some of these trees, but burros can’t climb.”

“Huh, I’ve seen the time when I thought they could do everything but fly,” grunted Jimmy; “and I wasn’t so sure about that, either.”

“We might bring them in close and stand guard over the poor things,” Ned went on to say.

At that they hurried to where the four animals were tethered. Already something seemed to have told the burros and the calico pony that danger hovered in that breeze, for they were beginning to show signs of excitement, and it was not such an easy job after all to lead them in close to the dying camp fire.

Hastily they were firmly secured.

“Will the ropes hold if they get to cutting up?” Harry asked, after he had tied his as many as five different times, to make sure there would be no slipping of the knot.

“They are all good and practically new,” Ned informed him, “and I think there’s no doubt about their holding. Now to get ourselves fixed. Pick your tree, everybody, but let it be where you can keep watch over the animals, so as to knock over every wolf that makes a jump for them.”

They caught on to the idea Ned had in mind. This was to occupy, say as many as three trees that chanced to grow in a triangle around the fire and the spot where the burros and pony had been fastened.

The bright moon would give them all needed opportunity to see any movement on the part of the assailants, and woe to the daring wolf that ventured to cross the dead line.

Ned waited to see which trees the others would pick out before choosing his own place of refuge. He did this because he thought it good policy to have their forces scattered, as by that means they could guard the camp more surely.

As they went on with these preparations, looking to the repulse of invading hosts of sleek gray-coated beasts of prey, they could hear the fiendish chorus of wolfish howls drawing steadily nearer all the while. There may have been a lingering doubt in the mind of Jack or Harry concerning the accuracy of that guess on the part of Amos, but it was gone by this time. Those constantly increasing howls had convinced them beyond all question.

Jimmy had picked out his tree easily enough. Indeed, it was a habit of his these times to settle in his mind just what tree would make the best harbor of refuge in case of a sudden necessity. This he always did as soon as a camp had been decided upon. Jimmy was wont to say with considerable pride that he was only following out the customary scout law “be prepared,” which might cover the case, as it does many others.

He seemed to have little trouble about climbing into this tree, first pushing up his Marlin gun, and then the beloved Navajo blanket with its bright colors; for Jimmy did not mean to leave his personal possessions to the mercy of the thievish pack that had broken bounds and was wildly hunting for food.

He climbed after the rest, and it happened that no one else had picked on that particular tree for their refuge, so that Jimmy was going to have it all to himself.

The lower limbs grew rather close to the ground, Jimmy now realized; and he began to wonder whether he had after all been wise in choosing such a tree. Would he be in any danger from the sharp teeth and claws of the wolves when they came rushing up? Jimmy did not believe that wolves could climb trees; but all the same he did not feel altogether easy about it. Still, when he found himself clutching his trusty gun new confidence seemed to be born in his soul.

“Let ’em come if they want to,” he said aloud, between his set teeth. “If they will have it, I guess I’ll be able to take care of the lot. Every bullet ought to count for a victim; and, mebbe, now I’ll be able to see if the bully gun can’t send the lead through a couple at one time. It’s passed through a six-inch tree, and that’s goin’ some, let me tell you. My stars! but don’t they yap to beat the band. And say, they can’t be more’n a mile away right now, I should think.”

The thought was enough to make his blood leap through his veins with renewed excitement. In imagination, Jimmy already began to picture himself blazing away as fast as he could work the mechanism of his modern firearm; and, of course, bowling over a fresh victim with every discharge.

“Jimmy!”

That was Harry calling.

“Hello, there!” replied the one addressed.

“Did you think to grab up the grub and take it up with you?” continued Harry.

“Oh! thunder!”

Jimmy was all broken up by this sudden intelligence. The others had apparently expected him to look out for the food supply, because Jimmy was always ready to take this burden on his shoulders.

And now, alas, what had seemed to be everyone’s duty had proved to be no one’s; their precious supply of food was left unguarded at the foot of that central tree, close to which the burros and pony had been hitched.

Could he reach it, and get back before the advance gray runner arrived on the scene, bringing his appetite with him and, likewise, his teeth well sharpened for business?

Jimmy came to a conclusion almost instantly, and having a convenient crotch in which he could leave his gun and blanket, he dropped down from his perch.

“Hey! get back there!” shouted Jack; “don’t you hear the pack coming along? They’ll get you, Jimmy! Climb up again!”