автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Library of the World's Best Literature, Ancient and Modern

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Library of the World's Best Literature,

Ancient and Modern, Vol. 13, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: Library of the World's Best Literature, Ancient and Modern, Vol. 13

Author: Various

Editor: Charles Dudley Warner

Release Date: November 23, 2010 [EBook #34408]

Language: English

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WORLD'S BEST LITERATURE, VOL 13 ***

Produced by Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

THE GOTHIC BIBLE OF ULFILAS. Codex Argenteus. Library of Upsala.

Socrates, a Greek ecclesiastic of the fifth century, and several other Byzantine writers, inform us, that Ulfilas, belonging to a family of Cappadocia, having been carried away captive by the Goths, when they invaded that country in A.D. 366, was subsequently elevated to the episcopal dignity in his new country, which had been converted to Christianity; that he was sent as a legate to the Emperor Valens, at Constantinople, in the year 377, to ask for a province of the empire, as a refuge for the Goths from the Huns, by whom they had been conquered; that Ulfilas obtained permission for them to settle in Moesia, on the right bank of the Danube; and that, in order to confirm them in the Christian faith, he translated the Old and New Testaments into the Gothic language, and invented for that purpose an especial alphabet; which, from this circumstance, has been named the alphabet of Ulfilas, or the alphabet of the Goths of Moesia. This translation of the Bible is the oldest existing literary monument in the Germanic languages. The principal manuscript is the Codex Argenteus, written in silver characters on a purple ground. The accompanying facsimile is from the Gospel according to St. Mark, chapter VII., beginning in the 3d verse at the words "Jews eat not," and ending in the 7th verse at "In vain do they worship me, teaching...."

LIBRARY OF THE

WORLD'S BEST LITERATURE

ANCIENT AND MODERN

CHARLES DUDLEY WARNER

EDITOR

HAMILTON WRIGHT MABIE

LUCIA GILBERT RUNKLE

GEORGE HENRY WARNER

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Connoisseur Edition

Vol. XIII.

NEW YORK

THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY

Connoisseur Edition

LIMITED TO FIVE HUNDRED COPIES IN HALF RUSSIA

No. ..........

Copyright, 1896, by

R. S. PEALE AND J. A. HILL

All rights reserved

THE ADVISORY COUNCIL

CRAWFORD H. TOY, A. M., LL. D.,

Professor of Hebrew, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

THOMAS R. LOUNSBURY, LL. D., L. H. D.,

Professor of English in the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

WILLIAM M. SLOANE, Ph. D., L. H. D.,

Professor of History and Political Science, Princeton University, Princeton, N. J.

BRANDER MATTHEWS, A. M., LL. B.,

Professor of Literature, Columbia University, New York City.

JAMES B. ANGELL, LL. D.,

President of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Mich.

WILLARD FISKE, A. M., Ph. D.,

Late Professor of the Germanic and Scandinavian Languages and Literatures, Cornell University, Ithaca, N. Y.

EDWARD S. HOLDEN, A. M., LL. D.,

Director of the Lick Observatory, and Astronomer, University of California, Berkeley, Cal.

ALCÉE FORTIER, LIT. D.,

Professor of the Romance Languages, Tulane University, New Orleans, La.

WILLIAM P. TRENT, M. A.,

Dean of the Department of Arts and Sciences, and Professor of English and History, University of the South, Sewanee, Tenn.

PAUL SHOREY, Ph. D.,

Professor of Greek and Latin Literature, University of Chicago, Chicago, Ill.

WILLIAM T. HARRIS, LL. D.,

United States Commissioner of Education, Bureau of Education, Washington, D. C.

MAURICE FRANCIS EGAN, A. M., LL. D.,

Professor of Literature in the Catholic University of America, Washington, D. C.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

VOL. XIII

LIVED PAGE Toru Dutt

1856-1877

5075 Jogadhya UmaOur Casuarina-Tree

John S. Dwight

1813-1893

5084 Music as a Means of Culture

Georg Moritz Ebers

1837-

5091 The Arrival at Babylon ('An Egyptian Princess')

José Echegaray

1832-

5101 From 'Madman or Saint?'From 'The Great Galeoto'

The Eddas

5113

BY WILLIAM H. CARPENTER

Thor's Adventures on his Journey to the Land of the Giants ('Snorra Edda')

The Lay of Thrym ('Elder Edda')

Of the Lamentation of Gudrun over Sigurd Dead: First Lay of Gudrun

Waking of Brunhilde on the Hindfell by Sigurd (Morris's 'Story of Sigurd the Völsung')

Alfred Edersheim

1825-1889

5145 The Washing of Hands ('The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah')

Maria Edgeworth

1767-1849

5151 Sir Condy's Wake ('Castle Rackrent')Sir Murtagh Rackrent and His Lady (same)

Anne Charlotte Leffler Edgren

1849-1893

5162 Open SesameA Ball in High Life ('A Rescuing Angel')

Jonathan Edwards

1703-1758

5175BY EGBERT C. SMYTH

From Narrative of His Religious History

"Written on a Blank Leaf in 1723"

The Idea of Nothing ('Of Being')

The Notion of Action and Agency Entertained by Mr. Chubb and Others ('Inquiry into the Freedom of the Will')

Excellency of Christ

Essence of True Virtue ('The Nature of True Virtue')

Georges Eekhoud

1854-

5189 Ex-VotoKors Davie

Edward Eggleston

1837-

5215 Roger Williams, the Prophet of Religious Freedom ('The Beginners of a Nation')

Egyptian Literature

5225

BY FRANCIS LLEWELLYN GRIFFITH AND KATE BRADBURY GRIFFITH

The Shipwrecked Sailor

Story of Sanehat

The Doomed Prince

Story of the Two Brothers

Story of Setna

Inscription of Una

Songs of Laborers

Love Songs: Love-Sickness; The Lucky Doorkeeper; Love's Doubts; The Unsuccessful Bird-Catcher

Hymn to Usertesen III.

Hymn to the Aten

Hymns to Amen Ra

Songs to the Harp

From an Epitaph

From a Dialogue Between a Man and His Soul

'The Negative Confession'

Teaching of Amenemhat

The Prisse Papyrus: Instruction of Ptahhetep

From the 'Maxims of Any'

Instruction of Dauf

Contrasted Lots of Scribe and Fellâh

Reproaches to a Dissipated Student

Joseph Von Eichendorff

1788-1857

5345 From 'Out of the Life of a Good-for-Nothing'Separation

Lorelei

George Eliot

1819-1880

5359BY CHARLES WALDSTEIN

The Final Rescue ('The Mill on the Floss')

Village Worthies ('Silas Marner')

The Hall Farm ('Adam Bede')

Mrs. Poyser "Has Her Say Out" (same)

The Prisoners ('Romola')

"Oh, May I Join the Choir Invisible"

Ralph Waldo Emerson

1803-1882

5421BY RICHARD GARNETT

The Times

Friendship

Nature

Compensation

Love

Circles

Self-Reliance

History

Each and All

The Rhodora

The Humble-Bee

The Problem

Days

Musketaquid

From the 'Threnody'

Concord Hymn

Ode Sung in the Town Hall, Concord, July 4, 1857

FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

VOLUME XIII

PAGE Gothic Bible of Ulfilas

Colored Plate Frontispiece

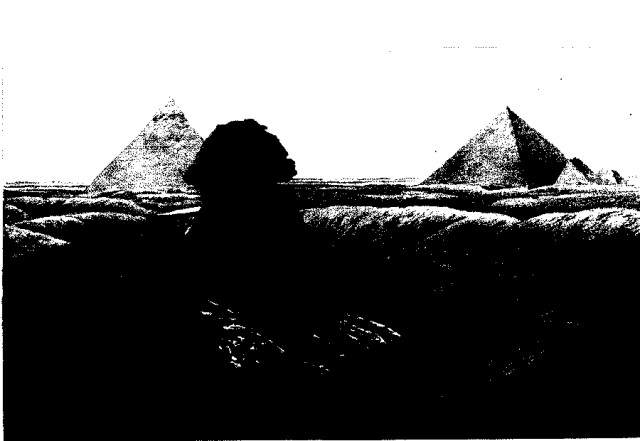

Georg Ebers (Portrait) 5091 "Babylonian Marriage Market" (Photogravure) 5098Egyptian Hieroglyphic Writing (Outline Fac-Simile)

5226 "The Sphynx" (Photogravure) 5260 "Egyptian Funeral Feast" (Photogravure) 5290 "Uncial Greek Writing" (Fac-Simile) 5338 George Eliot (Portrait) 5359 Ralph Waldo Emerson (Portrait) 5421 "Concord Battle Monument" (Photogravure) 5466VIGNETTE PORTRAITS

José Echegaray

Maria Edgeworth

Jonathan Edwards

Edward Eggleston

TORU DUTT

(1856-1877)

n 1874 there appeared in the Bengal Magazine an essay upon Leconte de Lisle, which showed not only an unusual knowledge of French literature, but also decided literary qualities. The essayist was Toru Dutt, a Hindu girl of eighteen, daughter of Govin Chunder Dutt, for many years a justice of the peace at Calcutta. The family belonged to the high-caste cultivated Hindus, and Toru's education was conducted on broad lines. Her work frequently discloses charming pictures of the home life that filled the old garden house at Calcutta. Here it is easy to see the studious child poring over French, German, and English lexicons, reading every book she could lay hold of, hearing from her mother's lips those old legends of her race which had been woven into the poetry of native bards long before the civilization of modern Europe existed. In her thirteenth year Toru and her younger sister were sent to study for a few months in France, and thence to attend lectures at Cambridge and to travel in England. A memory of this visit appears in Toru's little poem, 'Near Hastings,' which shows the impressionable nature of the Indian girl, so sensitive to the romance of an alien race, and so appreciative of her friendly welcome to English soil.

After four years' travel in Europe the Dutts returned to India to resume their student life, and Toru began to learn Sanskrit. She showed great aptitude for the French language and a strong liking for the French character, and she made a special study of French romantic poetry. Her essays on Leconte de Lisle and Joséphin Soulary, and a series of English translations of poetry, were the fruit of her labor. The translations, including specimens from Béranger, Théophile Gautier, François Coppée, Sully-Prud'homme, and other popular writers, were collected in 1876 under the title 'A Sheaf Gleaned in French Fields.' A few copies found their way into Europe, and both French and English reviewers recognized the value of the harvest of this clear-sighted gleaner. One critic called these poems, in which Toru so faithfully reproduced the spirit of one alien tongue in the forms of another, transmutations rather than translations.

But marvelous as is the mastery shown over the subtleties of thought and the difficulties of translation, the achievement remains that of acquirement rather than of inspiration. But Toru's English renditions of the native Indian legends, called 'Ancient Ballads of Hindustan,' give a sense of great original power. Selected from much completed work left unpublished at her too early death, these poems are revelations of the Eastern religious thought, which loves to clothe itself in such forms of mystical beauty as haunt the memory and charm the fancy. But in these translations it is touched by the spirit of the new faith which Toru had adopted. The poems remain, however, essentially Indian. The glimpses of lovely landscape, the shining temples, the greening gloom of the jungle, the pink flush of the dreamy atmosphere, are all of the East, as is the philosophic calm that breathes through the verses. The most beautiful of the ballads is perhaps that of 'Savitri,' the king's daughter who by love wins back her husband after he has passed the gates of death. Another, 'Sindher,' re-tells the old story of that king whose great power is unavailing to avert the penalty which follows the breaking of the Vedic law, even though it was broken in ignorance. Still another, 'Prehlad,' reveals that insight into things spiritual which characterizes the true seer or "called of God." Two charming legends, 'Jogadhya Uma,' and 'Buttoo,' full of the pastoral simplicity of the early Aryan life, and a few miscellaneous poems, complete this volume upon which Toru's fame will rest.

A posthumous novel written in French makes up the sum of her contribution to letters. 'Le Journal de Mlle. D'Arvers' was found completed among her posthumous papers. It is a romance of modern French life, whose motive is the love of two brothers for the same girl. The tragic element dominates the story, and the author has managed the details with extraordinary ease without sacrificing either dignity or dramatic effect. The story was edited by Mademoiselle Bader, a correspondent of Toru, and her sole acquaintance among European authors. In 1878, the year after the poet's death, appeared a second edition of 'A Sheaf Gleaned in French Fields' containing forty-three additional poems, with a brief biographical sketch written by her father. The many translators of the 'Sakoontala' and of other Indian dramas show how difficult it is for the Western mind to express the indefinable spirituality of temper that fills ancient Hindu poetry. This remarkable quality Toru wove unconsciously into her English verse, making it seem not exotic but complementary, an echo of that far-off age when the genius of the two races was one.

JOGADHYA UMA

"Shell bracelets, ho! Shell bracelets, ho! Fair maids and matrons, come and buy!" Along the road, in morning's glow, The peddler raised his wonted cry. The road ran straight, a red, red line, To Khigoram, for cream renowned, Through pasture meadows where the kine, In knee-deep grass, stood magic bound And half awake, involved in mist That floated in dun coils profound, Till by the sudden sunbeams kist, Rich rainbow hues broke all around.

"Shell bracelets, ho! Shell bracelets, ho!" The roadside trees still dripped with dew And hung their blossoms like a show. Who heard the cry? 'Twas but a few; A ragged herd-boy, here and there, With his long stick and naked feet; A plowman wending to his care, The field from which he hopes the wheat; An early traveler, hurrying fast To the next town; an urchin slow Bound for the school; these heard and passed, Unheeding all,—"Shell bracelets, ho!"

Pellucid spread a lake-like tank Beside the road now lonelier still; High on three sides arose the bank Which fruit-trees shadowed at their will; Upon the fourth side was the ghat, With its broad stairs of marble white, And at the entrance arch there sat, Full face against the morning light, A fair young woman with large eyes, And dark hair falling to her zone; She heard the peddler's cry arise, And eager seemed his ware to own.

"Shell bracelets, ho! See, maiden; see! The rich enamel, sunbeam-kist! Happy, oh happy, shalt thou be, Let them but clasp that slender wrist; These bracelets are a mighty charm; They keep a lover ever true, And widowhood avert, and harm. Buy them, and thou shalt never rue. Just try them on!"—She stretched her hand. "Oh, what a nice and lovely fit! No fairer hand in all the land, And lo! the bracelet matches it."

Dazzled, the peddler on her gazed, Till came the shadow of a fear, While she the bracelet-arm upraised Against the sun to view more clear. Oh, she was lovely! but her look Had something of a high command That filled with awe. Aside she shook Intruding curls, by breezes fanned, And blown across her brows and face, And asked the price; which when she heard She nodded, and with quiet grace For payment to her home referred.

"And where, O maiden, is thy house? But no,—that wrist-ring has a tongue; No maiden art thou, but a spouse, Happy, and rich, and fair, and young." "Far otherwise; my lord is poor, And him at home thou shalt not find; Ask for my father; at the door Knock loudly; he is deaf, but kind. Seest thou that lofty gilded spire, Above these tufts of foliage green? That is our place; its point of fire Will guide thee o'er the tract between."

"That is the temple spire."—"Yes, there We live; my father is the priest; The manse is near, a building fair, But lowly to the temple's east. When thou hast knocked, and seen him, say, His daughter, at Dhamaser Ghat, Shell bracelets bought from thee to-day, And he must pay so much for that. Be sure, he will not let thee pass Without the value, and a meal. If he demur, or cry alas! No money hath he,—then reveal;

"Within the small box, marked with streaks Of bright vermilion, by the shrine, The key whereof has lain for weeks Untouched, he'll find some coin,—'tis mine. That will enable him to pay The bracelet's price. Now fare thee well!" She spoke; the peddler went away, Charmed with her voice as by some spell; While she, left lonely there, prepared To plunge into the water pure, And like a rose, her beauty bared, From all observance quite secure.

Not weak she seemed, nor delicate; Strong was each limb of flexile grace, And full the bust; the mien elate, Like hers, the goddess of the chase On Latmos hill,—and oh the face Framed in its cloud of floating hair! No painter's hand might hope to trace The beauty and the glory there! Well might the peddler look with awe, For though her eyes were soft, a ray Lit them at times, which kings who saw Would never dare to disobey.

Onward through groves the peddler sped, Till full in front, the sunlit spire Arose before him. Paths which led To gardens trim, in gay attire, Lay all around. And lo! the manse, Humble but neat, with open door! He paused, and blessed the lucky chance That brought his bark to such a shore. Huge straw-ricks, log huts full of grain, Sleek cattle, flowers, a tinkling bell, Spoke in a language sweet and plain, "Here smiling Peace and Plenty dwell."

Unconsciously he raised his cry, "Shell-bracelets, ho!" And at his voice Looked out the priest, with eager eye, And made his heart at once rejoice. "Ho, Sankha peddler! Pass not by, But step thou in, and share the food Just offered on our altar high, If thou art in a hungry mood. Welcome are all to this repast! The rich and poor, the high and low! Come, wash thy feet, and break thy fast; Then on thy journey strengthened go."

"Oh, thanks, good priest! Observance due And greetings! May thy name be blest! I came on business, but I knew, Here might be had both food and rest Without a charge; for all the poor Ten miles around thy sacred shrine Know that thou keepest open door, And praise that generous hand of thine. But let my errand first be told: For bracelets sold to thine this day, So much thou owest me in gold; Hast thou the ready cash to pay?

"The bracelets were enameled,—so The price is high."—"How! Sold to mine? Who bought them, I should like to know?" "Thy daughter, with the large black eyne, Now bathing at the marble ghat." Loud laughed the priest at this reply, "I shall not put up, friend, with that; No daughter in the world have I; An only son is all my stay; Some minx has played a trick, no doubt: But cheer up, let thy heart be gay, Be sure that I shall find her out."

"Nay, nay, good father! such a face Could not deceive, I must aver; At all events, she knows thy place, 'And if my father should demur To pay thee,'—thus she said,—'or cry He has no money, tell him straight The box vermilion-streaked to try, That's near the shrined'"—"Well, wait, friend, wait!" The priest said, thoughtful; and he ran And with the open box came back:— "Here is the price exact, my man,— No surplus over, and no lack.

"How strange! how strange! Oh, blest art thou To have beheld her, touched her hand, Before whom Vishnu's self must bow, And Brahma and his heavenly band! Here have I worshiped her for years, And never seen the vision bright; Vigils and fasts and secret tears Have almost quenched my outward sight; And yet that dazzling form and face I have not seen, and thou, dear friend, To thee, unsought-for, comes the grace: What may its purport be, and end?

"How strange! How strange! Oh, happy thou! And couldst thou ask no other boon Than thy poor bracelet's price? That brow Resplendent as the autumn moon Must have bewildered thee, I trow, And made thee lose thy senses all." A dim light on the peddler now Began to dawn; and he let fall His bracelet-basket in his haste, And backward ran, the way he came: What meant the vision fair and chaste; Whose eyes were they,—those eyes of flame?

Swift ran the peddler as a hind; The old priest followed on his trace; They reached the ghat, but could not find The lady of the noble face. The birds were silent in the wood; The lotus flowers exhaled a smell, Faint, over all the solitude; A heron as a sentinel Stood by the bank. They called,—in vain; No answer came from hill or fell; The landscape lay in slumber's chain; E'en Echo slept within her shell.

Broad sunshine, yet a hush profound! They turned with saddened hearts to go; Then from afar there came a sound Of silver bells;—the priest said low, "O Mother, Mother, deign to hear, The worship-hour has rung; we wait In meek humility and fear. Must we return home desolate? Oh come, as late thou cam'st unsought, Or was it but some idle dream? Give us some sign, if it was not; A word, a breath, or passing gleam."

Sudden from out the water sprung A rounded arm, on which they saw As high the lotus buds among It rose, the bracelet white, with awe. Then a wide ripple tost and swung The blossoms on that liquid plain, And lo! the arm so fair and young Sank in the waters down again. They bowed before the mystic Power, And as they home returned in thought, Each took from thence a lotus flower In memory of the day and spot.

Years, centuries, have passed away, And still before the temple shrine Descendants of the peddler pay Shell-bracelets of the old design As annual tribute. Much they own In lands and gold,—but they confess From that eventful day alone Dawned on their industry, success. Absurd may be the tale I tell, Ill-suited to the marching times; I loved the lips from which it fell, So let it stand among my rhymes.

OUR CASUARINA-TREE

thee with silver and gold, because thou bringest me to Pharaoh; for I become a great marvel, they shall rejoice for me in all the land. And thou shalt go to thy village."

Esut, appearing glorious on the throne of Horus among the living from day to day even as his father Ra; the good god, lord of the South Land, Him of Edfû

aquiline nose, and thin lips of the rider. His whole bearing bore the stamp of great power and immoderate pride.

establishing his excellence upon earth: he who knoweth hath satisfaction of his knowledge. A noble

O tenderly the haughty day Fills his blue urn with fire; One morn is in the mighty heaven, And one in our desire.

The cannon booms from town to town, Our pulses beat not less, The joy-bells chime their tidings down, Which children's voices bless.

For He that flung the broad blue fold O'er mantling land and sea, One third part of the sky unrolled For the banner of the free.

The men are ripe of Saxon kind To build an equal state,— To take the statue from the mind And make of duty fate.

United States! the ages plead,— Present and Past in under-song,— Go put your creed into your deed, Nor speak with double tongue.

For sea and land don't understand, Nor skies without a frown See rights for which the one hand fights By the other cloven down.

Be just at home; then write your scroll Of honor o'er the sea, And bid the broad Atlantic roll, A ferry of the free.

And henceforth there shall be no chain, Save underneath the sea The wires shall murmur through the main Sweet songs of liberty.

The conscious stars accord above, The waters wild below, And under, through the cable wove, Her fiery errands go.

For He that worketh high and wise, Nor pauses in his plan, Will take the sun out of the skies Ere freedom out of man.

ceeded to the camp which was on the west of the Atiu canal; he was purified in the midst of the Cool Pool, his face was washed in the stream of Nu, in which Ra washes his face. He proceeded to the sand-hill in Anu, he made a great sacrifice on the sand-hill in Anu, before the face of Ra at his rising, consisting of white bulls, milk, frankincense, incense, all woods sweet-smelling. He came, proceeding to the house of Ra; he entered the temple with rejoicings. The chief lector praised the god that warded off miscreants

Like a huge python, winding round and round The rugged trunk, indented deep with scars Up to its very summit near the stars, A creeper climbs, in whose embraces bound No other tree could live. But gallantly The giant wears the scarf, and flowers are hung In crimson clusters all the boughs among, Whereon all day are gathered bird and bee; And oft at night the garden overflows With one sweet song that seems to have no close, Sung darkling from our tree, while men repose.

Unknown, yet well known to the eye of faith! Ah, I have heard that wail far, far away In distant lands, by many a sheltered bay, When slumbered in his cave the water wraith, And the waves gently kissed the classic shore Of France or Italy, beneath the moon, When earth lay trancèd in a dreamless swoon; And every time the music rose, before Mine inner vision rose a form sublime, Thy form, O tree! as in my happy prime I saw thee in my own loved native clime.

But not because of its magnificence Dear is the Casuarina to my soul: Beneath it we have played: though years may roll, O sweet companions, loved with love intense, For your sakes shall the tree be ever dear! Blent with your images, it shall arise In memory, till the hot tears blind mine eyes. What is that dirge-like murmur that I hear Like the sea breaking on a shingle beach? It is the tree's lament, an eerie speech, That haply to the Unknown Land may reach.

When first my casement is wide open thrown At dawn, my eyes delighted on it rest; Sometimes,—and most in winter,—on its crest A gray baboon sits statue-like alone, Watching the sunrise; while on lower boughs His puny offspring leap about and play; And far and near kokilas hail the day; And to their pastures wend our sleepy cows; And in the shadow, on the broad tank cast By that hoar tree, so beautiful and vast, The water-lilies spring, like snow enmassed.

JOHN S. DWIGHT

(1813-1893)

ohn Sullivan Dwight was born in Boston, Massachusetts, May 13th, 1813. After graduation at Harvard in 1832, he studied at the Divinity School, and for two years was pastor of a Unitarian church in Northampton, Massachusetts. He then became interested in founding the famous Brook Farm community, which furnished Hawthorne with the background for 'The Blithedale Romance'; and he is mentioned in the preface to this book with Ripley, Dana, Channing, Parker, etc. This was a "community" scheme, undertaken by joint ownership in a farm in West Roxbury near Boston; associated with the names of Hawthorne, Emerson, George William Curtis, and C.A. Dana,—a scheme which Emerson called "a perpetual picnic, a French Revolution in small, an age of reason in a patty-pan." This community existed seven years, and to quote again from Emerson,—"In Brook Farm was this peculiarity, that there was no head. In every family is the father; in every factory a foreman; in a shop a master; in a boat the skipper; but in this Farm no authority; each was master or mistress of their actions; happy, hapless anarchists."

Here Mr. Dwight edited The Harbinger, a periodical published by that community; taught languages and music, besides doing his share of the manual labor. In 1848 he returned to Boston and engaged in literature and musical criticism; and in 1852 he established Dwight's Journal of Music, which he edited for thirty years. Many of his best essays appeared in the Atlantic Monthly, and he contributed to various periodicals.

He was one of the pioneers of scholarly, intelligent, original, and literary musical criticism in America, and he possessed fine general attainments and a distinct style. It is because of his clear perception of the indispensableness of the arts—and especially of the art of music—to life, and because of his clear statement of their vital relationship, that his work belongs to literature.

MUSIC AS A MEANS OF CULTURE

From the Atlantic Monthly, 1870, by permission of Houghton, Mifflin and Company

We as a democratic people, a great mixed people of all races, overrunning a vast continent, need music even more than others. We need some ever-present, ever-welcome influence that shall insensibly tone down our self-asserting and aggressive manners, round off the sharp, offensive angularity of character, subdue and harmonize the free and ceaseless conflict of opinions, warm out the genial individual humanity of each and every unit of society, lest he become a mere member of a party, or a sharer of business or fashion. This rampant liberty will rush to its own ruin, unless there shall be found some gentler, harmonizing, humanizing culture, such as may pervade whole masses with a fine enthusiasm, a sweet sense of reverence for something far above us, beautiful and pure; awakening some ideality in every soul, and often lifting us out of the hard hopeless prose of daily life. We need this beautiful corrective of our crudities. Our radicalism will pull itself up by the roots, if it do not cultivate the instinct of reverence. The first impulse of freedom is centrifugal,—to fly off the handle,—unless it be restrained by a no less free impassioned love of order. We need to be so enamored of the divine idea of unity, that that alone—the enriching of that—shall be the real motive for assertion of our individuality. What shall so temper and tone down our "fierce democracy"? It must be something better, lovelier, more congenial to human nature than mere stern prohibition, cold Puritanic "Thou shalt not!" What can so quickly magnetize a people into this harmonic mood as music? Have we not seen it, felt it?

The hard-working, jaded millions need expansion, need the rejuvenating, the ennobling experience of joy. Their toil, their church, their creed perhaps, their party livery, and very vote, are narrowing; they need to taste, to breathe a larger, freer life. Has it not come to thousands, while they have listened to or joined their voices in some thrilling chorus that made the heavens seem to open and come down? The governments of the Old World do much to make the people cheerful and contented; here it is all laissez-faire, each for himself, in an ever keener strife of competition. We must look very much to music to do this good work for us; we are open to that appeal; we can forget ourselves in that; we blend in joyous fellowship when we can sing together; perhaps quite as much so when we can listen together to a noble orchestra of instruments interpreting the highest inspirations of a master. The higher and purer the character and kind of music, the more of real genius there is in it, the deeper will this influence be.

Judge of what can be done, by what already, within our own experience, has been done and daily is done. Think what the children in our schools are getting, through the little that they learn of vocal music,—elasticity of spirit, joy in harmonious co-operation, in the blending of each happy life in others; a rhythmical instinct of order and of measure in all movement; a quickening of ear and sense, whereby they will grow up susceptible to music, as well as with some use of their own voices, so that they may take part in it; for from these spacious nurseries (loveliest flower gardens, apple orchards in full bloom, say, on their annual fête days) shall our future choirs and oratorio choruses be replenished with good sound material....

We esteem ourselves the freest people on this planet; yet perhaps we have as little real freedom as any other, for we are the slaves of our own feverish enterprise, and of a barren theory of discipline, which would fain make us virtuous to a fault through abstinence from very life. We are afraid to give ourselves up to the free and happy instincts of our nature. All that is not pursuit of advancement in some good, conventional, approved way of business, or politics, or fashion, or intellectual reputation, or professed religion, we count waste. We lack geniality; nor do we as a people understand the meaning of the word. We ought to learn it practically of our Germans. It comes of the same root with the word genius. Genius is the spontaneous principle; it is free and happy in its work; it is artist and not drudge; its whole activity is reconciliation of the heartiest pleasure with the purest loyalty to conscience, with the most holy, universal, and disinterested ends. Genius, as Beethoven gloriously illustrates in his Choral Symphony (indeed, in all his symphonies), finds the keynote and solution of the problem of the highest state in "Joy," taking his text from Schiller's Hymn. Now, all may not be geniuses in the sense that we call Shakespeare, Mozart, Raphael, men of genius. But all should be partakers of this spontaneous, free, and happy method of genius; all should live childlike, genial lives, and not wear all the time the consequential livery of their unrelaxing business, nor the badge of party and profession, in every line and feature of their faces. This genial, childlike faculty of social enjoyment, this happy art of life, is just what our countrymen may learn from the social "Liedertafel" and the summer singing-festivals of which the Germans are so fond. There is no element of national character which we so much need; and there is no class of citizens whom we should be more glad to adopt and own than those who set us such examples. So far as it is a matter of culture, it is through art chiefly that the desiderated genial era must be ushered in. The Germans have the sentiment of art, the feeling of the beautiful in art, and consequently in nature, more developed than we have. Above all, music offers itself as the most available, most popular, most influential of the fine arts,—music, which is the art and language of the feelings, the sentiments, the spiritual instincts of the soul; and so becomes a universal language, tending to unite and blend and harmonize all who may come within its sphere.

Such civilizing, educating power has music for society at large. Now, in the finer sense of culture, such as we look for in more private and select "society," as it is called, music in the salon, in the small chamber concert, where congenial spirits are assembled in its name—good music of course—does it not create a finer sphere of social sympathy and courtesy? Does it not better mold the tone and manners from within than any imitative "fashion" from without? What society, upon the whole, is quite so sweet, so satisfactory, so refined, as the best musical society, if only Mozart, Mendelssohn, Franz, Chopin, set the tone! The finer the kind of music heard or made together, the better the society. This bond of union only reaches the few; coarser, meaner, more prosaic natures are not drawn to it. Wealth and fashion may not dictate who shall be of it. Here congenial spirits meet in a way at once free, happy, and instructive, meet with an object which insures "society"; whereas so-called society, as such, is often aimless, vague, modifying and fatiguing, for the want of any subject-matter. Here one gets ideas of beauty which are not mere arbitrary fashions, ugly often to the eye of taste. Here you may escape vulgarity by a way not vulgar in itself, like that of fashion, which makes wealth and family and means of dress its passports. Here you can be as exclusive as you please, by the soul's light, not wronging any one; here learn gentle manners, and the quiet ease and courtesy with which cultivated people move, without in the same process learning insincerity.

Of course the same remarks apply to similar sincere reunions in the name of any other art, or of poetry. But music is the most social of them all, even if each listener find nothing set down to his part (or even hers!) but tacet.

We have fancied ourselves entertaining a musical house together, but we must leave it with no time to make report or picture out the scene. Now, could we only enter the chamber, the inner sanctum, the private inner life of a thoroughly musical person, one who is wont to live in music! Could we know him in his solitude! (You can only know him in yourself, unless he be a poet and creator in his art, and bequeath himself in that form in his works for any who know how to read.) If the best of all society is musical society, we go further and say: The sweetest of all solitude is when one is alone with music. One gets the best of music, the sincerest part, when he is alone. Our poet-philosopher has told us to secure solitude at any cost; there's nothing which we can so ill afford to do without. It is a great vice of our society, that it provides for and disposes to so little solitude, ignoring the fact that there is more loneliness in company than out of it. Now, to a musical person, in the mood of it, in the sweet hours by himself, comes music as the nearest friend, nearer and dearer than ever before; and he soon finds that he never was in such good company. I doubt if symphony of Beethoven, opera of Mozart, Passion Music of Bach, was ever so enjoyed or felt in grandest public rendering, as one may feel it while he recalls its outline by himself at his piano (even if he be a slow and bungling reader and may get it out by piecemeal). I doubt if such an one can carry home from the performance, in presence of the applauding crowd, nearly so much as he may take to it from such inward, private preparation.

Are you alone? What spirits can you summon up to fill the vacancy, and people it with life and love and beauty! Take down the volume of sonatas, the arrangement of the great Symphony, the recorded reveries of Chopin, the songs of Schubert, Schumann, Franz, or even the chorals, with the harmony of Bach, in which the four parts blend their several individual melodies together in such loving service of the whole, that the plain people's tune becomes a germ unfolding into endless wealth and beauty of meaning; and you have the very essence of all prayer, and praise, and gratitude, as if you were a worshiper in the ideal church. Nothing like music, then, to banish the benumbing ghost of ennui. It lends secret sympathy, relief, expression, to all one's moods, loves, longings, sorrows; comes nearer to the soul or to the secret wound than any friend or healing sunshine from without. It nourishes and feeds the hidden springs of hope and love and faith; renews the old conviction of life's springtime,—that the world is ruled by love, that God is good, that beauty is a divine end of life, and not a snare and an illusion. It floods out of sight the unsightly, muddy grounds of life's petty, anxious, doubting moments, and makes immortality a present fact, lived in and realized. It locks the door against the outer world of discords, contradictions, importunities, beneath the notice of a soul so richly occupied: lets "Fate knock at the door" (as Beethoven said in explanation of his symphony),—Fate and the pursuing Furies,—and even welcomes them, and turns them into gracious goddesses,—Eumenides! Music, in this way, is a marvelous elixir to keep off old age. Youth returns in solitary hours with Beethoven and Mozart. Touching the chords of the 'Moonlight Sonata,' the old man is once more a lover; with the andante of the 'Pastoral Symphony' he loiters by the shady brookside, hand in hand with his fresh heart's first angel. You are past the sentimental age, yet you can weep alone in music,—not weep exactly, but find outlet more expressive and more worthy of your manly faith.

A great grief comes, an inconsolable bereavement, a humiliating, paralyzing reverse, a blow of Fate, giving the lie to your best plans and bringing your best powers into discredit with yourself; then you are best prepared and best entitled to receive the secret visitations of these tuneful goddesses and muses.

"Who never ate his bread in tears, He knows you not, ye heavenly powers!"

So sings the German poet. It is the want of inward, deep experience, it is innocence of sorrow and of trial, more than the lack of any special cultivation of musical taste and knowledge, that debars many people—naturally most young people, and all who are what we call shallow natures—from the feeling and enjoyment of many of the truest, deepest, and most heavenly of all the works of music. Take the Passion Music of Bach, for instance; if you can sit down alone at your piano and decipher strains and pieces of it when you need such music, you shall find that in its quiet quaintness, its sincerity and tenderness, its abstinence from all striving for effect, it speaks to you and entwines itself about your heart, like the sweetest, deepest verses in the Bible; when "the soul muses till the fire burns."

Such a panacea is this art for loneliness. But sometimes too it may intensify the sense of loneliness, only for more heavenly relief at last. Think of the deep composer, of lonely, sad Beethoven, wreaking his pain upon expression in those impatient chords and modulations, putting his sorrows into sonatas, and wringing triumph always out of all! Look at him as he was then,—morose, they say, and lonely and tormented; look where he is now, as the whole world knows him, feels him, seeks him for its joy and inspiration—and who can doubt of immortality?

Now, in such private solace, in such solitary joys, is there not culture? Can one rise from such communings with the good spirits of the tone-world and go out, without new peace, new faith, new hope, and good-will in his soul? He goes forth in the spirit of reconciliation and of patience, however much he may hate the wrong he sees about him, or however little he accept authorities and creeds that make war on his freedom. The man who has tasted such life, and courted it till he has become acclimated in it, whether he be of this party or that, or none at all; whether he be believer or "heretic," conservative or radical, follower of Christ by name or "Free Religionist,"—belongs to the harmonic and anointed body-guard of peace, fraternity, good-will; his instincts have all caught the rhythm of that holy march; the good genius leads, he has but to follow cheerfully and humbly. For somehow the minutest fibres, the infinitesimal atoms of his being, have got magnetized as it were into a loyal, positive direction towards the pole-star of unity; he has grown attuned to a believing, loving mood, just as the body of a violin, the walls of a music hall, by much music-making become gradually seasoned into smooth vibration.

GEORG EBERS.

GEORG MORITZ EBERS

(1837-)

eorg Ebers, distinguished as an Egyptian archaeologist and as a historical novelist, was born in Berlin in 1837. At ten years of age he was sent to school in Keilhau, where under the direction of Froebel he was taught the delights of nature and the pleasure of study. His university career at Göttingen was interrupted by a long and serious illness. During his convalescence he pursued with avidity his study of Egyptian archæology, and with neither dictionary nor grammar to help him in the mastery of hieroglyphics, he acquired to some degree this ancient language. Later, under the learned Lepsius, he became a thorough and brilliant scholar in the science which is his specialty. It was at this epoch that he wrote 'An Egyptian Princess,' for the purpose of realizing to himself a period which he was studying. Thirteen years later his second work, 'Uarda' was published. When restored to health, he launched himself with enthusiasm on the life of a university professor. He taught for a time at Jena, and in 1870 removed to Leipsic. He has made several journeys into Egypt, sharing his experiences with the public.

'The Egyptian Princess' is Ebers's most representative romance. It is perhaps the subtle quality of popularity, rather than exceptional merit, which has insured its success. The scene of the story is laid at the time when Egypt drew its last free breath, unconscious that at the very height of its intellectual vigor its national life was to be cut off; the time when Amasis held the throne of the Pharaohs, and Cambyses was king of Persia. 'Uarda' gives a picture of Egypt under one of the Rameses. 'Homo Sum,' a tale of the desert anchorites in the fourth century, is filled with the spirit of the early Christians. In the story of 'Die Schwestern' (The Sisters) Ebers takes the reader to Memphis, the temple of Serapis, and the palace of the Ptolemies. The ethical element enters largely into the novel 'Der Kaiser' (The Emperor), of Christianity in the time of Hadrian.

In the 'Frau Bürgermeisterin' (The Burgomaster's Wife), Ebers leaves behind him the world of antiquity, and deals with the heroic struggle against the Spanish rule made in 1547 by the city of Leyden. 'Gred,' a long and quiet novel, most carefully executed, is a minute picture of middle-class Nürnberg, some centuries ago. 'Ein Wort' (A Word: Only a Word) also stands apart from the historical romances. It is a psychological and ethical story, working out the development of inconspicuous character. Both in 'Serapis' and 'The Bride of the Nile,' the victory of Christianity over heathenism is celebrated. Not less interesting than his fiction is his book of travels called 'Durch Gosen zum Sinai' (Through Goshen to Sinai). In 1889, on account of his health, Ebers resigned his professorship. He now passes his winters in Munich, where his life is that of a scholar and a writer.

THE ARRIVAL AT BABYLON

From 'An Egyptian Princess'

Seven weeks later, a long line of chariots and riders of every description wound along the great highway that led from the west to Babylon, the gigantic city which could be seen from a long distance.

Nitetis, the Egyptian princess, sat in a gilt four-wheeled chariot, called a "Harmamaxa." The cushions were covered with gold brocade; the roof was supported by wooden columns; its sides could be closed by means of curtains.

Her companions, the Persian nobles, the dethroned King of Lydia and his son, rode by the side of her chariot. Fifty carriages and six hundred sumpter-horses followed, and a regiment of Persian soldiers on splendid horses preceded the procession.

The road lay along the Euphrates, through luxuriant fields of wheat, barley, and sesame, which yielded two or even three hundredfold. Slender date-palms, with heavy clusters of fruit, stood in the fields, which were intersected in all directions by canals and conduits. Although it was winter, the sun shone warm and clear in the cloudless sky. The mighty river was crowded with barges and boats, which brought the produce of the Armenian highlands to the Mesopotamian plain, and forwarded to Babylon the greater part of the wares which were brought to Thapsacus from Greece.

Engines, pumps, and water-wheels poured refreshing moisture on the fields and plantations along the banks, which were dotted with numerous villages. Everything indicated that the capital of a civilized and well-governed country was close at hand.

The carriage and suite of Nitetis stopped before a long building of brick covered with bitumen, by the side of which grew numerous plane-trees. Croesus was helped from his horse, approached the carriage of the Egyptian princess, and cried to her:—"We have reached the last station-house. The high tower that stands out against the horizon is the famous tower of Bel, like your Pyramids one of the greatest achievements of mortal hands. Before the sun sets we shall reach the brazen gates of Babylon. Permit me to help you from the carriage, and to send your women to you into the house. To-day you must dress yourself according to the custom of Persian queens, so that you may be pleasant in the eyes of Cambyses. In a few hours you will stand before your husband. How pale you are! See that your women skillfully paint joyous excitement on your cheeks. The first impression is often decisive, and this is the case with your future husband, more than with any one else. If, as I do not doubt, you please him at first sight, you have won his heart forever. If you displease him, he will, in accordance with his rough habits, scarcely deign to look on you again with kindness. Courage, my daughter. Above all things, remember what I have taught you."

Nitetis wiped away a tear, and returned:—"How shall I thank you for all your kindness, Croesus, my second father, my protector and adviser! Oh, do not ever desert me! When the path of my poor life passes through sorrow and grief, remain my guide and protector, as you have been during this long journey over dangerous mountain passes. Thank you, my father, thank you a thousand times."

With these words, the girl put her beautiful arms round the old man's neck and kissed him like an affectionate daughter.

When she entered the court of the gloomy house, a man came towards her, followed by a train of Asiatic serving-women. The leader, the chief eunuch, one of the most important Persian court officials, was tall and stout. There was a sweet smile on his beardless face; valuable rings hung from his ears; his arms and legs, his neck, his long womanish garments, were covered with gold ornaments, and his stiff artificial curls were surrounded by a purple fillet, and sent forth a pungent odor. Boges, for this was the eunuch's name, bowed respectfully to the Egyptian and said, holding his fleshy hand covered with rings before his mouth:—"Cambyses, the ruler of the world, sends me to meet you, O queen, that I may refresh your heart with the dew of his greetings. He further sends to you through me, his poorest slave, the garments of Persian women, that you may approach the gate of the Achæmenidæ in Median dress, as beseems the wife of the greatest of rulers. These women your servants await your commands. They will transform you from an Egyptian emerald into a Persian diamond." Boges drew back, and with a condescending movement of his hand allowed the host of the inn to present the princess with a most tastefully arranged basket of fruit.

Nitetis thanked both men with friendly words, entered the house, and tearfully put off the robes of her home; the thick plait, the mark of an Egyptian princess, was unfastened, and strange hands clad her in Median fashion.

Meanwhile her companions commanded a meal to be prepared. Nimble servants fetched chairs, tables, and golden utensils from the wagon; the cooks bustled about, and were so ready and eager to help each other that soon, as if by magic, a splendidly laid table where nothing was wanting, down to the very flowers, awaited the hungry travelers.

The same luxury had been displayed during the whole journey, for the sumpter-horses that followed the royal travelers carried every imaginable convenience, from gold-woven water-proof tents down to silver footstools, and the carts that accompanied them bore bakers, cooks, cup-bearers, carvers, men to prepare ointment, wreath-winders, and hair-dressers.

Well-appointed inns were established at regular intervals along the high-road. Here the horses that had fallen on the way were replaced by fresh ones, shady trees offered a pleasant shelter from the heat of the sun, and on the mountains the fires of the inns protected the traveler from cold and snow.

The Persian inns, which resembled our post-houses, were first established by Cyrus the Great, who sought to shorten the enormous distances between the different parts of his realm by means of well-kept roads. He had also organized a regular postal service. At every station the riders with their knapsacks found substitutes on fresh horses ready for instant departure, who, after receiving the letters which were to be forwarded, galloped off post-haste, and when they reached the next inn threw their knapsacks to other riders who stood in readiness. These couriers were called Angares, and were considered the swiftest horsemen in the world.

When the company, who had been joined by Boges the eunuch, rose from table, the door of the inn opened. A long-drawn sigh of admiration was heard, for Nitetis stood before the Persians in the splendid Median court dress, proudly exultant in the consciousness of her beauty, and yet suffused with blushes at her friends' astonishment.

The servants involuntarily prostrated themselves in the Asiatic manner, but the noble Achæmenidæ bowed low and reverently. It was as if the princess had laid aside all shyness with the simple dress of her home, and assumed the pride and dignity of a queen with the silken garments, heavy with gold and jewels, of a Persian princess.

The deep respect which had just been shown her seemed to please her. With a condescending movement of her hand she thanked her admiring friends; then she turned to the chief eunuch and said to him kindly but proudly:—"You have done your duty. I am not dissatisfied with the robes and the slaves you have provided for me. I shall duly praise your care to my husband. Meanwhile, receive this golden chain as a sign of my gratitude."

The powerful overseer of the king's wives kissed her hand and silently accepted the gift. None of his charges had yet treated him with such pride. All the wives whom Cambyses had owned till now were Asiatics, and as they were acquainted with the full power of the chief eunuch, they were accustomed to do all they could to win his favor by means of flattery and submission.

Boges again bowed low to Nitetis; but without paying any further attention to him, she turned to Croesus and said in a low tone:—"I cannot thank you, my gracious friend, with word or gift for what you have done for me; it will be owing to you alone if my life at this court becomes, if not happy, at least peaceful." Then she continued in a louder voice, audible to her traveling companions:—"Take this ring, which has not left my hand since our departure from Egypt. Its value is small, its significance great. Pythagoras, the noblest of all the Greeks, gave it to my mother when he came to Egypt to listen to the wise teachings of our priests. She gave it to me when I left home. There is a seven engraved on this simple turquoise. This number, which is indivisible, represents the health of body and soul, for nothing is less divisible than health. If but a small portion of the body suffers, the whole body is ill; if one evil thought nestles in our heart, the harmony of the soul is disturbed. Whenever you look at this seven, let it remind you that I wish you perfect enjoyment of bodily health, and the continuance of that benignity which makes you the most virtuous and therefore the most healthy of men. No thanks, my father, for I should remain in your debt though I should restore to Croesus the wealth of Croesus. Gyges, take this Lydian lyre of ivory, and when its strings give forth music, remember the giver. To you, Zopyrus, I give this chain, for I have noticed that you are the most faithful friend of your friends, and we Egyptians put bonds and ropes into the fair hands of our goddess of love and friendship, beautiful Hathor, as a symbol of her binding qualities. To you, Darius, the friend of Egyptian lore and the starry firmament, I give for a keepsake this golden ring, on which you will find the Zodiac engraved by a skillful hand. Bartja, my dear brother-in-law, you shall receive the most precious treasure I possess. Take this amulet of blue stone. My sister Tachot put it round my neck when for the last time I pressed a kiss upon her lips before we fell asleep. She told me this talisman would bring sweet happiness in love to him who wore it. She wept as she spoke, Bartja. I do not know what she was thinking of, but I hope I am carrying out her wish when I lay this treasure in your hand. Think that Tachot is giving it to you through me her sister, and think sometimes of the garden of Sais."

She had spoken in Greek till then. Now she turned to the servants, who were waiting at a respectful distance, and said in broken Persian:—"You too must accept my thanks. You shall receive a thousand gold staters. Boges," she added, turning to the eunuch, "I command you to see that the sum is distributed not later than the day after to-morrow! Lead me to my carriage, Croesus!"

The old man hastened to comply with her request. While he conducted Nitetis to the carriage, she pressed his arm against her breast and whispered, "Are you satisfied with me, my father?"

"I tell you, maiden," returned the old man, "you will be the first at this court after the king's mother, for true regal pride is on your brow, and you possess the art of doing great things with small means. Believe me, a trifling gift, chosen as you can choose, will cause greater pleasure to a nobleman than a heap of gold flung down before him. The Persians are accustomed to bestow and to receive costly gifts. They know how to enrich one another. You will teach them to make each other happy. How beautiful you are! Is that right, or do you desire higher cushions? But what is that! Do you not see clouds of dust rolling hither from the town? That must be Cambyses, who is coming to meet you. Keep yourself upright, girl. Above all, try to bear your husband's glance and return it. Few can bear the fire of his eye. If you succeed in meeting it without fear or embarrassment, you have conquered. Courage, courage, my daughter! May Aphrodite adorn you with her loveliest charms! To horse, my friends! I think the King is coming to meet us."

Nitetis sat very erect in the golden carriage, and pressed her hands on her heart. The cloud of dust came nearer and nearer. Now bright sunbeams were reflected in the weapons of the approaching host, and darted from the cloud of dust like lightning from a stormy sky. Now the cloud divided, and figures could be distinguished; now the approaching procession vanished behind the thick bushes at a turn of the road; and now, not a hundred feet away, the galloping riders were seen distinctly as they approached nearer and nearer.

The whole procession seemed to consist of a gay crowd of horses, men, purple, gold, silver, and jewels. More than two hundred riders, all on snow-white Nisæan steeds, whose bridles and caparisons glittered with gold bells and buckles, feathers, tassels, and embroidery, were followed by a man who was often carried away by the powerful coal-black horse on which he rode, but who generally proved to the unmanageable, foaming animal that he was strong enough to tame its wildness. The rider, whose knees pressed the horse so that the animal trembled and panted, wore a garment with a scarlet and white pattern, which was embroidered with silver eagles and falcons. His trousers were of purple, his boots of yellow leather. He wore a golden belt round his waist, in which was a short dagger-like sword, whose hilt and sheath were incrusted with jewels. The rest of his dress resembled Bartja's. His tiara also was surrounded by the blue-and-white fillet of the Achæmenidæ. Thick jet-black hair streamed from it. A thick beard of the same color covered the whole lower portion of his hale, rigid face. His eyes were even darker than his hair and beard, and glittered with a fire that burned instead of warming. A deep red scar, caused by the sword of a Massagetian warrior, marked the lofty brow, large aquiline nose, and thin lips of the rider. His whole bearing bore the stamp of great power and immoderate pride.

Nitetis could not turn her eyes from his form. She had never seen any one like him. She thought she saw the essence of all manliness in the intensely proud face. It seemed to her as if the whole world, but especially she herself, had been created to serve this man. She feared him, and yet her humble woman's heart longed to cling to this strong man as the vine clings to the elm. She did not know whether the father of all evil, terrible Seth, or the giver of all light, great Ra, was to be imagined in this form.

As light and shade alternate when the heavens are clouded at noon, so did deep red and ashy pallor appear on her face. She forgot the precepts of her fatherly friend; and yet when Cambyses forced his wild snorting steed to stand still by the side of her carriage, she gazed breathlessly into the flashing eyes of the man, for she knew that he was the King, though no one had told her.

The stern face of the ruler of half the world softened more and more, the longer she, urged by a strange impulse, endured his piercing glance. At last he waved his hand in welcome and rode towards her companions, who had dismounted, and who either prostrated themselves in the dust before the King, or stood bowing low, in accordance with Persian custom, hiding their hands in the sleeves of their garments.

Now he himself sprang from his horse. At the same time all his followers swung themselves out of the saddle. The carpet-bearers in his train spread, quick as thought, a heavy purple carpet on the road, so that the King's foot should not touch the dust. A few seconds later, Cambyses greeted his friends and relations with a kiss.

Then he shook Croesus's hand, and ordered him to mount again and accompany him to Nitetis as interpreter.

The highest dignitaries hastened up and helped the King to mount. He gave the signal, and the whole procession moved on. Croesus rode beside Cambyses by the golden carriage.

"She is beautiful, and pleasing to my heart," cried the Persian to his Lydian friend. "Now translate to me faithfully what she says in answer to my questions, for I understand only Persian, Babylonian, and Median."

BABYLONIAN MARRIAGE MARKET.

Photogravure from a Painting by Edwin Long, R.A.

"Once a year in each village the maidens of age to marry were collected all together into one place, while the men stood round them in a circle. Then a herald called up the damsels one by one and offered them for sale. He began with the most beautiful; when she was sold for no small sum, he offered for sale the one who came next to her in beauty. All of them were sold to be wives. The richest of the Babylonians who wished to wed, bid against each other for the loveliest maidens, while the humbler wife-seekers who were indifferent about beauty took the more homely damsels with a marriage portion.... The marriage portions were furnished by the money paid for the beautiful damsels, and thus the fairer maidens portioned out the uglier.

No one was allowed to give his daughter in marriage to the man of his choice, nor might any one carry away the damsel whom he had purchased without finding bail really and truly to make her his wife. If, however, it turned out that they did not agree, the money might be paid back."—Herodotus, Book I. Sec. 196.

Nitetis had understood his words. Inexpressible joy filled her heart, and before Croesus could answer the King she said in a low tone, in broken Persian, "How shall I thank the gods, who let me find favor in your eyes? I am not ignorant of the language of my lord, for this noble old man has instructed me in the Persian language during our long journey. Pardon me if I can answer in broken words only. My time for instruction was short, and my understanding is only that of a poor ignorant maiden."

The usually stern King smiled. His vanity was flattered by Nitetis's eagerness to gain his approbation, and this diligence in a woman seemed as strange as it was praiseworthy to the Persian, who was used to see women grow up in ignorance and idleness, thinking of nothing but dress and intrigue.

He therefore answered with evident satisfaction, "I am glad that I can speak to you without an interpreter. Continue to try to learn the beautiful language of my fathers. My companion Croesus shall remain your teacher in the future."

"Your command fills me with joy," said the old man, "for I could not desire a more grateful or more eager pupil than the daughter of Amasis."

"She confirms the ancient fame of Egyptian wisdom," returned the King; "and I think that she will soon understand and accept with all her soul the teachings of the magi, who will instruct her in our religion."

Nitetis looked down. The dreaded moment was approaching. She was henceforth to serve strange gods in place of the Egyptian deities.

Cambyses did not observe her emotion, and continued:—"My mother Cassandane shall initiate you in your duties as my wife. I will conduct you to her myself to-morrow. I repeat what you accidentally overheard: you please me. Look to it that you keep my favor. We will try to make you like our country; and because I am your friend I advise you to treat Boges, whom I sent to meet you, graciously, for you will have to obey him in many things, as he is the superintendent of the harem."

"He may be the head of the women's house," returned Nitetis. "But it seems to me that no mortal but you has a right to command your wife. Give but a sign and I will obey, but consider that I am a princess, and come from a land where weak woman shares the rights of strong men; that the same pride fills my breast which shines in your eyes, my beloved! I will gladly obey you the great man, my husband and ruler; but it is as impossible for me to sue for the favor of the unmanliest of men, a bought servant, as it is for me to obey his commands."

Cambyses's astonishment and satisfaction increased. He had never heard any woman save his mother speak like this, and the subtle way in which Nitetis unconsciously recognized and exalted his power over her whole existence satisfied his self-complacency. The proud man liked her pride. He nodded approvingly and said, "You are right. I will have a special house prepared for you. I alone will command you. The pleasant house in the hanging gardens shall be prepared for you to-day."

"I thank you a thousand times!" cried Nitetis. "If you but knew how you delight me by your gift! Your brother Bartja told me much of the hanging gardens, and none of the splendors of your great realm pleased us as much as the love of the king who built the green mountain."

"To-morrow you will be able to enter your new dwelling. Tell me how you and the Egyptians liked my envoys?"

"How can you ask! Who could become acquainted with noble Croesus without loving him? Who could help admiring the excellent qualities of the young heroes, your friends? They have become dear to our house, especially your beautiful brother Bartja, who won all hearts. The Egyptians are averse to strangers, but whenever Bartja appeared among them a murmur of admiration arose from the gaping throng."

At these words the King's face grew dark. He gave his horse a heavy blow, so that it reared, turned its head, galloped in front of his retinue, and in a few minutes reached the walls of Babylon....

The walls seemed perfectly impregnable, for they were two hundred cubits high, and their breadth was so great that two carriages could easily pass each other. Two hundred and fifty high towers surmounted and fortified this huge rampart. A greater number of these citadels would have been necessary if Babylon had not been protected on one side by impenetrable marshes. The enormous city lay on both sides of the Euphrates. It was more than nine miles in circumference, and the walls protected buildings which surpassed even the pyramids and the temples of Thebes and Memphis in size....

Nitetis looked with astonishment at this huge gate; with joyful emotion she gazed at the long wide street, which was festively decked in her honor.

JOSÉ ECHEGARAY

(1832-)

he period of political disorder and disturbance which followed the revolution of 1868 in Spain was also a period of disorder and decline for the Spanish stage. The drama—throwing off the fetters of French classicism that paralyzed inspiration at the beginning of the century—had revived for a time. But after its rejuvenescence of the glories of the Golden Age of Spanish literature, uniting a new beauty of form with truth to nature in the Classic-Romantic School, it sank into a debasement hitherto unknown. Meretricious sentiment, dullness, or buffoonery, chiefly of foreign production, occupied the scene before adorned by the imagination, the wisdom, and the wit, of a Zorilla, a Tamayo, a Ventura de la Vega.

José Echegaray

It was at this period of dramatic decadence that Echegaray appeared to revive once more the romantic traditions of the Spanish stage, peopling it again with noble and heroic figures,—in whom, however, the chivalric spirit of the Middle Ages is at times strangely joined to the casuistic modern conscience. The explanation of this is perhaps to be found in part in the mental constitution of the dramatist, in whom the analytic and the imaginative faculties are united in marked degree, and who had acquired a distinguished reputation as a civil engineer long before he entered the lists as an aspirant for dramatic honors. Born in Madrid in 1832, his earlier years were passed in Murcia, where he took his degree of bachelor of arts, applying himself afterward with notable success to the study of the exact sciences. Returning to Madrid, after enlarging his knowledge of his profession of civil engineer by practical study in various provinces of Spain, he was appointed a professor in the School of Engineers, where he taught theoretical and applied mathematics, finding time however for the production of important scientific works, and for the study of political economy and general literature. On the breaking out of the revolution of 1868 he joined actively in the movement, taking office under the new government as Director of Public Works, and holding a ministerial portfolio. He took office a second time in 1872, and later filled the post of Minister of Finance, which he resigned on the proclamation of the Republic. Retiring from public life, he went to Paris; and while there wrote, being then a little past forty, his first dramatic work, 'The Check-Book,' a domestic drama in one act, which was represented anonymously in Madrid two years later, when the author for the third time held a ministerial portfolio.

'The Check-Book' was followed in rapid succession by a series of productions whose titles, 'La Esposa del Vengador' (The Avenger's Bride), 'La Ultima Noche' (The Last Night), 'En el Puño de la Espada' (In the Hilt of the Sword), 'Como Empieza y Como Acaba' (How it Begins and How it Ends), sufficiently indicate their character. They are of unequal merit, but all show dramatic power of a high order. But on the representation in 1877 of 'Locura o Santidad?' (Madman or Saint?), the fame of the statesman and the scientist was completely and finally eclipsed by that of the dramatist, in whom the press and public of Madrid unanimously recognized a new and vital force in the Spanish drama. In this tragedy the keynote of Echegaray's philosophy is clearly struck. Moral perfection, unfaltering obedience to the right, is the end and aim of man; and the catastrophe is brought about by the inability of the hero to make those nearest to him accept this ideal of life. "Then virtue is but a lie," he cries, when the conviction of his moral isolation is forced upon him; "and you, all of you whom I have most loved in this world, perceiving what I regarded as divinity in you, are only miserable egoists, incapable of sacrifice, a prey to greed and the mere playthings of passion! Then you are all of you but clay; you resolve yourselves to dust and let the wind of the tempest carry you off! ... Beings shaped without conscience or free-will are simply atoms that meet to-day and separate to-morrow. Such is matter—then let it go!"

But the punishment of sin, in Echegaray's moral code, is visited upon the innocent equally with the guilty; and the guilty are never allowed to escape the retributive consequences of their wrong-doing. The pessimistic coloring of the picture would be at times unendurably oppressive, were it not relieved and lightened by the moral dignity of the hero. Echegaray's pessimism is, so to say, altruistic, never egoistic; and the compensating sense of righteousness vindicated rarely fails to explain, if not to justify, his darkest scenes.

Judged by the canons of art, Echegaray's dramatic productions will be found to have many imperfections. But their defects are the defects of genius, not of mediocrity, and spring generally from an excess of imagination, not from poverty of invention or faulty insight. The plot is often overweighted with an accumulation of incidents, and the means employed to bring about the desired end are often lacking in verisimilitude. Synthetic rather than analytic in his methods, and a master in producing contrasts, Echegaray captivates the imagination by arts which the cooler judgment not seldom condemns. His characters too are not always inhabitants of the real world, and not infrequently act contrary to the laws which govern it. The secondary characters are too often carelessly drawn, sometimes being mere shadowy outlines, while an altogether disproportionate part of the development of the plot is intrusted to them.

On the other hand, in the world of the passions Echegaray treads with secure step. Its labyrinthine windings, its depths and its heights, are all familiar to him. Here every accent uttered is the accent of truth; every act is prompted by unerring instinct. Nothing is false; nothing is trivial; nothing is strained. The elemental forces of nature seem to be at work, and the catastrophe results as inevitably from their action as if decreed by fate.

The genius of Echegaray, which in its irregular grandeur and its ethical tendency has been not inaptly likened by a Spanish critic to that of Victor Hugo, rarely descends from the tragic heights on which it achieved its first and its greatest triumphs; but that its range has been limited by choice, not nature, is abundantly proved in the best of his lighter productions, 'Un Critico Incipiente' (An Embryo Critic). Of his achievement in tragedy the culminating point was reached—after a second series of noteworthy productions, among them 'Lo Que no Puede Decirse' (What Cannot be Told), 'Mar Sin Orillas' (A Shoreless Sea), and 'En el Seno de la Muerte' (In the Bosom of Death)—in 'El Gran Galeoto' (The Great Galeoto), represented in 1881 before an audience which hailed its author as a "prodigy of genius," a second Shakespeare. Other notable works followed,—'Conflicto entre Dos Deberes' (Conflict between Two Duties), 'Vida Alegre y Muerte Triste' (A Merry Life and a Sad Death), 'Lo Sublime en lo Vulgar' (The Sublime in the Commonplace); but 'El Gran Galeoto' has remained thus far its author's supreme dramatic achievement. In its title is personified the evil speaking which not always with evil intent, sometimes even with the best motives, slays, with a venom surer than that of the adder's tongue, the reputation which it attacks; turning innocence itself by its contaminating power into guilt.

FROM 'MADMAN OR SAINT?'

[Don Lorenzo, a man of wealth and position living in Madrid, has discovered that he is the son, not as he and all the world had supposed, of the lady whose wealth and name he has inherited, but of his nurse Juana, who dies after she has revealed to him the secret of his birth. In consequence he resolves publicly to renounce his name and his possessions, although by doing so he will prevent the marriage of his daughter Inez to Edward, the son of the Duchess of Almonte. The mother will consent to Don Lorenzo's renunciation of his possessions but not of his name, as this would throw a stigma on Inez's origin. He refuses to listen either to the reasoning or to the entreaties of his wife, the duchess, Edward, and Dr. Tomás. Finally they are persuaded that he is mad, and Dr. Tomás calls in a specialist to examine him. The specialist, with two keepers, arrives at the house at the same time with the notary, whom Don Lorenzo has sent for to make before him a formal act of renunciation of his name and possessions.]

Don Lorenzo enters and stands listening to Inez

Don Lorenzo [aside]—"Die," she said!

Edward—You to die! No, Inez, not that; do not say that.

Inez—And why not? If I do not die of grief—if happiness could ever visit me again—I should die of remorse.

Lorenzo [aside]—"Of remorse!" She! "If happiness could ever visit her again!" What new fatality floats in the air and hangs threateningly above my head? Remorse! I have surprised another word in passing! I traverse rooms and halls, and I go from one place to another, urged by intolerable anguish, and I hear words that I do not understand, and I meet glances that I do not understand, and tears greet me here and smiles there, and no one opposes me, and every one avoids me or watches me. [Aloud.] What is this? What is this?

Inez [hurrying to him and throwing herself into his arms]—Father!

Lorenzo—Inez! How pale you are! Why are your lips drawn as if with pain? Why do you feign smiles that end in sighs!—How lovely in her sorrow! And I am to blame for all!

Inez—No, father.

Lorenzo—How cruel I am! Ah! you think it, although you do not say it.

Edward—Inez is an angel. Rebellious thoughts can find no place in her heart; but who that sees her can fail to think it and to say it?

Lorenzo—No one; you are right.

Edward [with energy]—If I am right, then you are wrong.

Lorenzo—I am right also. There is something more pallid than the pallid brow of a lovesick maiden; there is something sadder than the sad tears that fall from her beautiful eyes; something more bitter than the smile that contracts her lips; something more tragic than the death of her beloved.

Edward [with scornful vehemence]—And what is that pallor, what are those tears, and what the tragedies you speak of?

Lorenzo—Insensate! [Seizing him by the arm.] The pallor of crime, the tears of remorse, the consciousness of our own vileness.

Edward—And it would be vile, and criminal, and a source of remorse, to make Inez happy?

Lorenzo [despairingly]—It ought not to be so—but it would! [Pause.] And this it is that tortures me. This is the thought that is driving me mad!

Inez—No, father, do not say that! Follow the path you have marked out for yourself, without thought of me. What does it matter whether I live or die?

Lorenzo—Inez!

Inez—But do not vacillate—and above all, let no one see that you vacillate; let your speech be clear and convincing as it is now; let not anger blind you. Be calm, be calm, father; I implore it of you in the name of God.

Lorenzo—What do you mean by those words? I do not understand you.

Inez—Do I rightly know myself what I mean? There—I am going. I do not wish to pain you.

Edward [to Lorenzo]—Ah, if you would but listen to your heart; if you would but silence the cavilings of your conscience.

Inez [to Edward]—Leave him in peace—come with me; do not anger him, or you will make him hate you.

Lorenzo—Poor girl! She too struggles, but she too will conquer! [With an outburst of pride.] She will show that she is indeed my daughter!

[Inez and Edward go up the stage; passing the study door, Inez sees the keepers and gives a start of horror.]

Inez—What sinister vision affrights my gaze!—No, father, do not enter there.

Edward—Come, come, my Inez!

Inez [to her father]—No, no, I entreat you!

Lorenzo [approaching her]—Inez!

Inez—Those men there—look!