автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу On Growth and Form

GROWTH AND FORM

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

C. F. CLAY, MANAGER

London: FETTER LANE, E.C.

Edinburgh: 100 PRINCES STREET

New York: G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

Bombay, Calcutta and Madras: MACMILLAN AND Co., LTD.

Toronto: J. M. DENT AND SONS, LTD.

Tokyo: THE MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA

All rights reserved

ON

GROWTH AND FORM

BY

D’ARCY WENTWORTH THOMPSON

Cambridge:

at the University Press

1917

“The reasonings about the wonderful and intricate operations of nature are so full of uncertainty, that, as the Wise-man truly observes, hardly do we guess aright at the things that are upon earth, and with labour do we find the things that are before us.” Stephen Hales, Vegetable Staticks (1727), p. 318, 1738.

PREFATORY NOTE

This book of mine has little need of preface, for indeed it is “all preface” from beginning to end. I have written it as an easy introduction to the study of organic Form, by methods which are the common-places of physical science, which are by no means novel in their application to natural history, but which nevertheless naturalists are little accustomed to employ.

It is not the biologist with an inkling of mathematics, but the skilled and learned mathematician who must ultimately deal with such problems as are merely sketched and adumbrated here. I pretend to no mathematical skill, but I have made what use I could of what tools I had; I have dealt with simple cases, and the mathematical methods which I have introduced are of the easiest and simplest kind. Elementary as they are, my book has not been written without the help—the indispensable help—of many friends. Like Mr Pope translating Homer, when I felt myself deficient I sought assistance! And the experience which Johnson attributed to Pope has been mine also, that men of learning did not refuse to help me.

My debts are many, and I will not try to proclaim them all: but I beg to record my particular obligations to Professor Claxton Fidler, Sir George Greenhill, Sir Joseph Larmor, and Professor A. McKenzie; to a much younger but very helpful friend, Mr John Marshall, Scholar of Trinity; lastly, and (if I may say so) most of all, to my colleague Professor William Peddie, whose advice has made many useful additions to my book and whose criticism has spared me many a fault and blunder.

I am under obligations also to the authors and publishers of many books from which illustrations have been borrowed, and especially to the following:—

To the Controller of H.M. Stationery Office, for leave to reproduce a number of figures, chiefly of Foraminifera and of Radiolaria, from the Reports of the Challenger Expedition. {vi}

To the Council of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and to that of the Zoological Society of London:—the former for letting me reprint from their Transactions the greater part of the text and illustrations of my concluding chapter, the latter for the use of a number of figures for my chapter on Horns.

To Professor E. B. Wilson, for his well-known and all but indispensable figures of the cell (figs. 42–51, 53); to M. A. Prenant, for other figures (41, 48) in the same chapter; to Sir Donald MacAlister and Mr Edwin Arnold for certain figures (335–7), and to Sir Edward Schäfer and Messrs Longmans for another (334), illustrating the minute trabecular structure of bone. To Mr Gerhard Heilmann, of Copenhagen, for his beautiful diagrams (figs. 388–93, 401, 402) included in my last chapter. To Professor Claxton Fidler and to Messrs Griffin, for letting me use, with more or less modification or simplification, a number of illustrations (figs. 339–346) from Professor Fidler’s Textbook of Bridge Construction. To Messrs Blackwood and Sons, for several cuts (figs. 127–9, 131, 173) from Professor Alleyne Nicholson’s Palaeontology; to Mr Heinemann, for certain figures (57, 122, 123, 205) from Dr Stéphane Leduc’s Mechanism of Life; to Mr A. M. Worthington and to Messrs Longmans, for figures (71, 75) from A Study of Splashes, and to Mr C. R. Darling and to Messrs E. and S. Spon for those (fig. 85) from Mr Darling’s Liquid Drops and Globules. To Messrs Macmillan and Co. for two figures (304, 305) from Zittel’s Palaeontology, to the Oxford University Press for a diagram (fig. 28) from Mr J. W. Jenkinson’s Experimental Embryology; and to the Cambridge University Press for a number of figures from Professor Henry Woods’s Invertebrate Palaeontology, for one (fig. 210) from Dr Willey’s Zoological Results, and for another (fig. 321) from “Thomson and Tait.”

Many more, and by much the greater part of my diagrams, I owe to the untiring help of Dr Doris L. Mackinnon, D.Sc., and of Miss Helen Ogilvie, M.A., B.Sc., of this College.

D’ARCY WENTWORTH THOMPSON.

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, DUNDEE.

December, 1916.

Fig. 42.

Fig. 43.

Fig. 50.

Fig. 51.

Fig. 53. Annular chromosomes, formed in the spermatogenesis of the Mole-cricket. (From Wilson, after Vom Rath.)

Fig. 41. Caryokinetic figure in a dividing cell (or blastomere) of the Trout’s egg. (After Prenant, from a preparation by Prof. P. Bouin.)

Fig. 48.

Fig. 49.

Fig. 335. Crane-head and femur. (After Culmann and H. Meyer.)

Fig. 337. Trabecular structure of the os calcis. (From MacAlister.)

Fig. 334. Head of the human femur in section. (After Schäfer, from a photo by Prof. A. Robinson.)

Fig. 388. Pelvis of Archaeopteryx.

Fig. 393. The pelves of Archaeopteryx and of Apatornis, with three transitional types interpolated between them.

Fig. 401. A, outline diagram of the Cartesian co-ordinates of the skull of Hyracotherium or Eohippus, as shewn in Fig. 402, A. H, outline of the corresponding projection of the horse’s skull. B–G, intermediate, or interpolated, outlines.

Fig. 402. A, skull of Hyracotherium, from the Eocene, after W. B. Scott; H, skull of horse, represented as a co-ordinate transformation of that of Hyracotherium, and to the same scale of magnitude; B–G, various artificial or imaginary types, reconstructed as intermediate stages between A and H; M, skull of Mesohippus, from the Oligocene, after Scott, for comparison with C; P, skull of Protohippus, from the Miocene, after Cope, for comparison with E; Pp, lower jaw of Protohippus placidus (after Matthew and Gidley), for comparison with F; Mi, Miohippus (after Osborn), Pa, Parahippus (after Peterson), shewing resemblance, but less perfect agreement, with C and D.

Fig. 339.

Fig. 346.

Fig. 127.

Lithostrotion Martini.(After Nicholson.)

Fig. 128.

Cyathophyllum hexagonum.(From Nicholson, after Zittel.)

Fig. 9. Curve of pre-natal growth (length or stature) of child; and corresponding curve of mean monthly increments (mm.).

Fig. 131. Surface-views of Corals with undeveloped thecae and confluent septa. A, Thamnastraea; B, Comoseris. (From Nicholson, after Zittel.)

Fig. 173. Heterophyllia angulata. (After Nicholson.)

Fig. 57. Artificial caryokinesis (after Leduc), for comparison with Fig. 41, p. 169.

Fig. 122. An “artificial tissue,” formed by coloured drops of sodium chloride solution diffusing in a less dense solution of the same salt. (After Leduc.)

Fig. 123. An artificial cellular tissue, formed by the diffusion in gelatine of drops of a solution of potassium ferrocyanide. (After Leduc.)

Fig. 205. Liesegang’s Rings. (After Leduc.)

Fig. 71. A breaking wave. (From Worthington.)

Fig. 75. Various species of Vorticella. (Mostly after Saville Kent.)

Fig. 85. (After Darling.)

Fig. 304. Section of Nautilus, shewing the contour of the septa in the median plane: the septa being (in this plane) logarithmic spirals, of which the shell-spiral is the evolute.

Fig. 305. Cast of the interior of Nautilus: to shew the contours of the septa at their junction with the shell-wall.

Fig. 28. Diagram shewing time taken (in days), at various temperatures (°C.), to reach certain stages of development in the Frog: viz. I, gastrula; II, medullary plate; III, closure of medullary folds; IV, tail-bud; V, tail and gills; VI, tail-fin; VII, operculum beginning; VIII, do. closing; IX, first appearance of hind-legs. (From Jenkinson, after O. Hertwig, 1898.)

Fig. 210. Close-packed calcospherites, or so-called “spicules,” of Astrosclera. (After Lister.)

Fig. 321.

Fig. 322.

CONTENTS

CHAP.

PAGE

I.

INTRODUCTORY 1II.

ON MAGNITUDE 16III.

THE RATE OF GROWTH 50IV.

ON THE INTERNAL FORM AND STRUCTURE OF THE CELL 156V.

THE FORMS OF CELLS 201VI.

A

NOTE ON ADSORPTION 277VII.

THE FORMS OF TISSUES, OR CELL-AGGREGATES 293VIII.

THE SAME(

continued)

346IX.

ON CONCRETIONS, SPICULES, AND SPICULAR SKELETONS 411X.

A

PARENTHETIC NOTE ON GEODETICS 488XI.

THE LOGARITHMIC SPIRAL 493XII.

THE SPIRAL SHELLS OF THE FORAMINIFERA 587XIII.

THE SHAPES OF HORNS, AND OF TEETH OR TUSKS: WITH A NOTE ON TORSION 612XIV.

ON LEAF-ARRANGEMENT, OR PHYLLOTAXIS 635XV.

ON THE SHAPES OF EGGS, AND OF CERTAIN OTHER HOLLOW STRUCTURES 652XVI.

ON FORM AND MECHANICAL EFFICIENCY 670XVII.

ON THE THEORY OF TRANSFORMATIONS, OR THE COMPARISON OF RELATED FORMS 719 EPILOGUE 778 INDEX 780CHAPTER I INTRODUCTORY

CHAPTER II. ON MAGNITUDE

CHAPTER III THE RATE OF GROWTH

CHAPTER IVON THE INTERNAL FORM AND STRUCTURE OF THE CELL

CHAPTER V THE FORMS OF CELLS

CHAPTER VI A NOTE ON ADSORPTION

CHAPTER VII THE FORMS OF TISSUES OR CELL-AGGREGATES

CHAPTER VIII THE FORMS OF TISSUES OR CELL-AGGREGATES (continued)

CHAPTER IX ON CONCRETIONS, SPICULES, AND SPICULAR SKELETONS

CHAPTER X A PARENTHETIC NOTE ON GEODETICS

CHAPTER XI THE LOGARITHMIC SPIRAL

CHAPTER XII THE SPIRAL SHELLS OF THE FORAMINIFERA

CHAPTER XIII THE SHAPES OF HORNS, AND OF TEETH OR TUSKS: WITH A NOTE ON TORSION

CHAPTER XIV ON LEAF-ARRANGEMENT, OR PHYLLOTAXIS

CHAPTER XV ON THE SHAPES OF EGGS, AND OF CERTAIN OTHER HOLLOW STRUCTURES

CHAPTER XVI ON FORM AND MECHANICAL EFFICIENCY

CHAPTER XVII ON THE THEORY OF TRANSFORMATIONS, OR THE COMPARISON OF RELATED FORMS*

EPILOGUE.

INDEX.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Fig.

Page

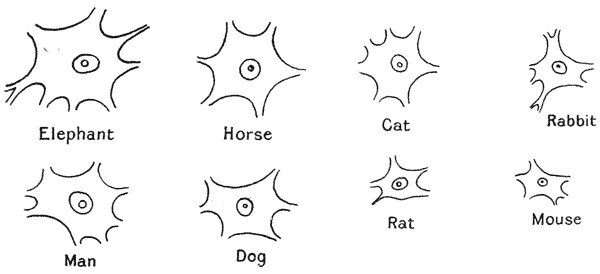

1.

Nerve-cells, from larger and smaller animals (Minot, after Irving Hardesty)

37

2.

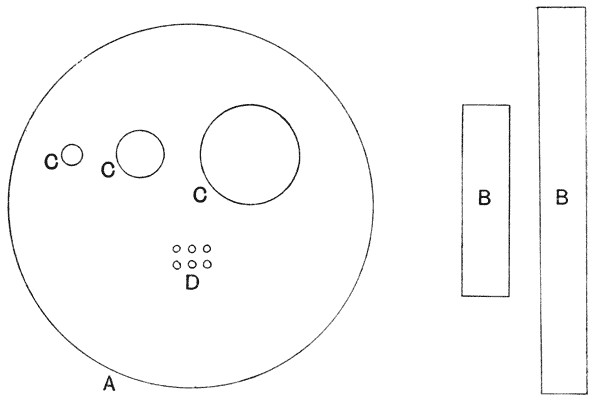

Relative magnitudes of some minute organisms (Zsigmondy)

39

3.

Curves of growth in man (Quetelet and Bowditch)

61

4, 5.

Mean annual increments of stature and weight in man (

do.)

66, 69

6.

The ratio, throughout life, of female weight to male (

do.)

71

7–9.

Curves of growth of child, before and after birth (His and Rüssow)

74–6

10.

Curve of growth of bamboo (Ostwald, after Kraus)

77

11.

Coefficients of variability in human stature (Boas and Wissler)

80

12.

Growth in weight of mouse (Wolfgang Ostwald)

83

13.

Do.of silkworm (Luciani and Lo Monaco)

84

14.

Do.of tadpole (Ostwald, after Schaper)

85

15.

Larval eels, or

Leptocephali, and young elver (Joh. Schmidt)

86

16.

Growth in length of

Spirogyra(Hofmeister)

87

17.

Pulsations of growth in

Crocus(Bose)

88

18.

Relative growth of brain, heart and body of man (Quetelet)

90

19.

Ratio of stature to span of arms (

do.)

94

20.

Rates of growth near the tip of a bean-root (Sachs)

96

21, 22.

The weight-length ratio of the plaice, and its annual periodic changes

99, 100

23.

Variability of tail-forceps in earwigs (Bateson)

104

24.

Variability of body-length in plaice

105

25.

Rate of growth in plants in relation to temperature (Sachs)

109

26.

Do.in maize, observed (Köppen), and calculated curves

112

27.

Do.in roots of peas (Miss I. Leitch)

113

28, 29.

Rate of growth of frog in relation to temperature (Jenkinson, after O. Hertwig), and calculated curves of

do.115, 6

30.

Seasonal fluctuation of rate of growth in man (Daffner)

119

31.

Do.in the rate of growth of trees (C. E. Hall)

120

32.

Long-period fluctuation in the rate of growth of Arizona trees (A. E. Douglass)

122

33, 34.

The varying form of brine-shrimps (

Artemia), in relation to salinity (Abonyi)

128, 9

35–39.

Curves of regenerative growth in tadpoles’ tails (M. L. Durbin)

140–145

40.

Relation between amount of tail removed, amount restored, and time required for restoration (M. M. Ellis)

148

41.

Caryokinesis in trout’s egg (Prenant, after Prof. P. Bouin)

169

42–51.

Diagrams of mitotic cell-division (Prof. E. B. Wilson)

171–5

52.

Chromosomes in course of splitting and separation (Hatschek and Flemming)

180

53.

Annular chromosomes of mole-cricket (Wilson, after vom Rath)

181

54–56.

Diagrams illustrating a hypothetic field of force in caryokinesis (Prof. W. Peddie)

182–4

57.

An artificial figure of caryokinesis (Leduc)

186

58.

A segmented egg of

Cerebratulus(Prenant, after Coe)

189

59.

Diagram of a field of force with two like poles

189

60.

A budding yeast-cell

213

61.

The roulettes of the conic sections

218

62.

Mode of development of an unduloid from a cylindrical tube

220

63–65.

Cylindrical, unduloid, nodoid and catenoid oil-globules (Plateau)

222, 3

66.

Diagram of the nodoid, or elastic curve

224

67.

Diagram of a cylinder capped by the corresponding portion of a sphere

226

68.

A liquid cylinder breaking up into spheres

227

69.

The same phenomenon in a protoplasmic cell of

Trianea234

70.

Some phases of a splash (A. M. Worthington)

235

71.

A breaking wave (

do.)

236

72.

The calycles of some campanularian zoophytes

237

73.

A flagellate monad,

Distigma proteus(Saville Kent)

246

74.

Noctiluca miliaris, diagrammatic

246

75.

Various species of

Vorticella(Saville Kent and others)

247

76.

Various species of

Salpingoeca(

do.)

248

77.

Species of

Tintinnus,

Dinobryonand

Codonella(

do.)

248

78.

The tube or cup of

Vaginicola248

79.

The same of

Folliculina249

80.

Trachelophyllum(Wreszniowski)

249

81.

Trichodina pediculus

252

82.

Dinenymplia gracilis(Leidy)

253

83.

A “collar-cell” of

Codosiga254

84.

Various species of

Lagena(Brady)

256

85.

Hanging drops, to illustrate the unduloid form (C. R. Darling)

257

86.

Diagram of a fluted cylinder

260

87.

Nodosaria scalaris(Brady)

262

88.

Fluted and pleated gonangia of certain Campanularians (Allman)

262

89.

Various species of

Nodosaria,

Sagrinaand

Rheophax(Brady)

263

90.

Trypanosoma tineaeand

Spirochaeta anodontae, to shew undulating membranes (Minchin and Fantham)

266

91.

Some species of

Trichomastixand

Trichomonas(Kofoid)

267

92.

Herpetomonasassuming the undulatory membrane of a Trypanosome (D. L. Mackinnon)

268

93.

Diagram of a human blood-corpuscle

271

94.

Sperm-cells of decapod crustacea,

Inachusand

Galathea(Koltzoff)

273

95.

The same, in saline solutions of varying density (

do.)

274

96.

A sperm-cell of

Dromia(

do.)

275

97.

Chondriosomes in cells of kidney and pancreas (Barratt and Mathews)

285

98.

Adsorptive concentration of potassium salts in various plant-cells (Macallum)

290

99–101.

Equilibrium of surface-tension in a floating drop

294, 5

102.

Plateau’s “bourrelet” in plant-cells; diagrammatic (Berthold)

298

103.

Parenchyma of maize, shewing the same phenomenon

298

104, 5.

Diagrams of the partition-wall between two soap-bubbles

299, 300

106.

Diagram of a partition in a conical cell

300

107.

Chains of cells in

Nostoc,

Anabaenaand other low algae

300

108.

Diagram of a symmetrically divided soap-bubble

301

109.

Arrangement of partitions in dividing spores of

Pellia(Campbell)

302

110.

Cells of

Dictyota(Reinke)

303

111, 2.

Terminal and other cells of

Chara, and young antheridium of

do.303

113.

Diagram of cell-walls and partitions under various conditions of tension

304

114, 5.

The partition-surfaces of three interconnected bubbles

307, 8

116.

Diagram of four interconnected cells or bubbles

309

117.

Various configurations of four cells in a frog’s egg (Rauber)

311

118.

Another diagram of two conjoined soap-bubbles

313

119.

A froth of bubbles, shewing its outer or “epidermal” layer

314

120.

A tetrahedron, or tetrahedral system, shewing its centre of symmetry

317

121.

A group of hexagonal cells (Bonanni)

319

122, 3.

Artificial cellular tissues (Leduc)

320

124.

Epidermis of

Girardia(Goebel)

321

125.

Soap-froth, and the same under compression (Rhumbler)

322

126.

Epidermal cells of

Elodea canadensis(Berthold)

322

127.

Lithostrotion Martini(Nicholson)

325

128.

Cyathophyllum hexagonum(Nicholson, after Zittel)

325

129.

Arachnophyllum pentagonum(Nicholson)

326

130.

Heliolites(Woods)

326

131.

Confluent septa in

Thamnastraeaand

Comoseris(Nicholson, after Zittel)

327

132.

Geometrical construction of a bee’s cell

330

133.

Stellate cells in the pith of a rush; diagrammatic

335

134.

Diagram of soap-films formed in a cubical wire skeleton (Plateau)

337

135.

Polar furrows in systems of four soap-bubbles (Robert)

341

136–8.

Diagrams illustrating the division of a cube by partitions of minimal area

347–50

139.

Cells from hairs of

Sphacelaria(Berthold)

351

140.

The bisection of an isosceles triangle by minimal partitions

353

141.

The similar partitioning of spheroidal and conical cells

353

142.

S-shaped partitions from cells of algae and mosses (Reinke and others)

355

143.

Diagrammatic explanation of the S-shaped partitions

356

144.

Development of

Erythrotrichia(Berthold)

359

145.

Periclinal, anticlinal and radial partitioning of a quadrant

359

146.

Construction for the minimal partitioning of a quadrant

361

147.

Another diagram of anticlinal and periclinal partitions

362

148.

Mode of segmentation of an artificially flattened frog’s egg (Roux)

363

149.

The bisection, by minimal partitions, of a prism of small angle

364

150.

Comparative diagram of the various modes of bisection of a prismatic sector

365

151.

Diagram of the further growth of the two halves of a quadrantal cell

367

152.

Diagram of the origin of an epidermic layer of cells

370

153.

A discoidal cell dividing into octants

371

154.

A germinating spore of

Riccia(after Campbell), to shew the manner of space-partitioning in the cellular tissue

372

155, 6.

Theoretical arrangement of successive partitions in a discoidal cell

373

157.

Sections of a moss-embryo (Kienitz-Gerloff)

374

158.

Various possible arrangements of partitions in groups of four to eight cells

375

159.

Three modes of partitioning in a system of six cells

376

160, 1.

Segmenting eggs of

Trochus(Robert), and of

Cynthia(Conklin)

377

162.

Section of the apical cone of

Salvinia(Pringsheim)

377

163, 4.

Segmenting eggs of

Pyrosoma(Korotneff), and of

Echinus(Driesch)

377

165.

Segmenting egg of a cephalopod (Watase)

378

166, 7.

Eggs segmenting under pressure: of

Echinusand

Nereis(Driesch), and of a frog (Roux)

378

168.

Various arrangements of a group of eight cells on the surface of a frog’s egg (Rauber)

381

169.

Diagram of the partitions and interfacial contacts in a system of eight cells

383

170.

Various modes of aggregation of eight oil-drops (Roux)

384

171.

Forms, or species, of

Asterolampra(Greville)

386

172.

Diagrammatic section of an alcyonarian polype

387

173, 4.

Sections of

Heterophyllia(Nicholson and Martin Duncan)

388, 9

175.

Diagrammatic section of a ctenophore (

Eucharis)

391

176, 7.

Diagrams of the construction of a Pluteus larva

392, 3

178, 9.

Diagrams of the development of stomata, in

Sedumand in the hyacinth

394

180.

Various spores and pollen-grains (Berthold and others)

396

181.

Spore of

Anthoceros(Campbell)

397

182, 4, 9.

Diagrammatic modes of division of a cell under certain conditions of asymmetry

400–5

183.

Development of the embryo of

Sphagnum(Campbell)

402

185.

The gemma of a moss (

do.)

403

186.

The antheridium of

Riccia(

do.)

404

187.

Section of growing shoot of

Selaginella, diagrammatic

404

188.

An embryo of

Jungermannia(Kienitz-Gerloff)

404

190.

Development of the sporangium of

Osmunda(Bower)

406

191.

Embryos of

Phascumand of

Adiantum(Kienitz-Gerloff)

408

192.

A section of

Girardia(Goebel)

408

193.

An antheridium of

Pteris(Strasburger)

409

194.

Spicules of

Siphonogorgiaand

Anthogorgia(Studer)

413

195–7.

Calcospherites, deposited in white of egg (Harting)

421, 2

198.

Sections of the shell of

Mya(Carpenter)

422

199.

Concretions, or spicules, artificially deposited in cartilage (Harting)

423

200.

Further illustrations of alcyonarian spicules:

Eunicea(Studer)

424

201–3.

Associated, aggregated and composite calcospherites (Harting)

425, 6

204.

Harting’s “conostats”

427

205.

Liesegang’s rings (Leduc)

428

206.

Relay-crystals of common salt (Bowman)

429

207.

Wheel-like crystals in a colloid medium (

do.)

429

208.

A concentrically striated calcospherite or spherocrystal (Harting)

432

209.

Otoliths of plaice, shewing “age-rings” (Wallace)

432

210.

Spicules, or calcospherites, of

Astrosclera(Lister)

436

211. 2.

C- and S-shaped spicules of sponges and holothurians (Sollas and Théel)

442

213.

An amphidisc of

Hyalonema442

214–7.

Spicules of calcareous, tetractinellid and hexactinellid sponges, and of various holothurians (Haeckel, Schultze, Sollas and Théel)

445–452

218.

Diagram of a solid body confined by surface-energy to a liquid boundary-film

460

219.

Astrorhiza limicolaand

arenaria(Brady)

464

220.

A nuclear “

reticulum plasmatique” (Carnoy)

468

221.

A spherical radiolarian,

Aulonia hexagona(Haeckel)

469

222.

Actinomma arcadophorum(

do.)

469

223.

Ethmosphaera conosiphonia(

do.)

470

224.

Portions of shells of

Cenosphaera favosaand

vesparia(

do.)

470

225.

Aulastrum triceros(

do.)

471

226.

Part of the skeleton of

Cannorhaphis(

do.)

472

227.

A Nassellarian skeleton,

Callimitra carolotae(

do.)

472

228, 9.

Portions of

Dictyocha stapedia(

do.)

474

230.

Diagram to illustrate the conformation of

Callimitra476

231.

Skeletons of various radiolarians (Haeckel)

479

232.

Diagrammatic structure of the skeleton of

Dorataspis(

do.)

481

233, 4.

Phatnaspis cristata(Haeckel), and a diagram of the same

483

235.

Phractaspis prototypus(Haeckel)

484

236.

Annular and spiral thickenings in the walls of plant-cells

488

237.

A radiograph of the shell of

Nautilus(Green and Gardiner)

494

238.

A spiral foraminifer,

Globigerina(Brady)

495

239–42.

Diagrams to illustrate the development or growth of a logarithmic spiral

407–501

243.

A helicoid and a scorpioid cyme

502

244.

An Archimedean spiral

503

245–7.

More diagrams of the development of a logarithmic spiral

505, 6

248–57.

Various diagrams illustrating the mathematical theory of gnomons

508–13

258.

A shell of

Haliotis, to shew how each increment of the shell constitutes a gnomon to the preexisting structure

514

259, 60.

Spiral foraminifera,

Pulvinulinaand

Cristellaria, to illustrate the same principle

514, 5

261.

Another diagram of a logarithmic spiral

517

262.

A diagram of the logarithmic spiral of

Nautilus(Moseley)

519

263, 4.

Opercula of

Turboand of

Nerita(Moseley)

521, 2

265.

A section of the shell of

Melo ethiopicus525

266.

Shells of

Harpaand

Dolium, to illustrate generating curves and gene

526

267.

D’Orbigny’s Helicometer

529

268.

Section of a nautiloid shell, to shew the “protoconch”

531

269–73.

Diagrams of logarithmic spirals, of various angles

532–5

274, 6, 7.

Constructions for determining the angle of a logarithmic spiral

537, 8

275.

An ammonite, to shew its corrugated surface pattern

537

278–80.

Illustrations of the “angle of retardation”

542–4

281.

A shell of

Macroscaphites, to shew change of curvature

550

282.

Construction for determining the length of the coiled spire

551

283.

Section of the shell of

Triton corrugatus(Woodward)

554

284.

Lamellaria perspicuaand

Sigaretus haliotoides(

do.)

555

285, 6.

Sections of the shells of

Terebra maculataand

Trochus niloticus559, 60

287–9.

Diagrams illustrating the lines of growth on a lamellibranch shell

563–5

290.

Caprinella adversa(Woodward)

567

291.

Section of the shell of

Productus(Woods)

567

292.

The “skeletal loop” of

Terebratula(

do.)

568

293, 4.

The spiral arms of

Spiriferand of

Atrypa(

do.)

569

295–7.

Shells of

Cleodora,

Hyalaeaand other pteropods (Boas)

570, 1

298, 9.

Coordinate diagrams of the shell-outline in certain pteropods

572, 3

300.

Development of the shell of

Hyalaea tridentata(Tesch)

573

301.

Pteropod shells, of

Cleodoraand

Hyalaea, viewed from the side (Boas)

575

302, 3.

Diagrams of septa in a conical shell

579

304.

A section of

Nautilus, shewing the logarithmic spirals of the septa to which the shell-spiral is the evolute

581

305.

Cast of the interior of the shell of

Nautilus, to shew the contours of the septa at their junction with the shell-wall

582

306.

Ammonites Sowerbyi, to shew septal outlines (Zittel, after Steinmann and Döderlein)

584

307.

Suture-line of

Pinacoceras(Zittel, after Hauer)

584

308.

Shells of

Hastigerina, to shew the “mouth” (Brady)

588

309.

Nummulina antiquior(V. von Möller)

591

310.

Cornuspira foliaceaand

Operculina complanata(Brady)

594

311.

Miliolina pulchellaand

linnaeana(Brady)

596

312, 3.

Cyclammina cancellata(

do.), and diagrammatic figure of the same

596, 7

314.

Orbulina universa(Brady)

598

315.

Cristellaria reniformis(

do.)

600

316.

Discorbina bertheloti(

do.)

603

317.

Textularia trochusand

concava(

do.)

604

318.

Diagrammatic figure of a ram’s horns (Sir V. Brooke)

615

319.

Head of an Arabian wild goat (Sclater)

616

320.

Head of

Ovis Ammon, shewing St Venant’s curves

621

321.

St Venant’s diagram of a triangular prism under torsion (Thomson and Tait)

623

322.

Diagram of the same phenomenon in a ram’s horn

623

323.

Antlers of a Swedish elk (Lönnberg)

629

324.

Head and antlers of

Cervus duvauceli(Lydekker)

630

325, 6.

Diagrams of spiral phyllotaxis (P. G. Tait)

644, 5

327.

Further diagrams of phyllotaxis, to shew how various spiral appearances may arise out of one and the same angular leaf-divergence

648

328.

Diagrammatic outlines of various sea-urchins

664

329, 30.

Diagrams of the angle of branching in blood-vessels (Hess)

667, 8

331, 2.

Diagrams illustrating the flexure of a beam

674, 8

Fig. 1. Motor ganglion-cells, from the cervical spinal cord.

(From Minot, after Irving Hardesty.)

Fig. 2. Relative magnitudes of: A, human blood-corpuscle (7·5 µ in diameter); B, Bacillus anthracis (4 – 15 µ × 1 µ); C, various Micrococci (diam. 0·5 – 1 µ, rarely 2 µ); D, Micromonas progrediens, Schröter (diam. 0·15 µ).

Fig. 3. Curve of Growth in Man, from birth to 20 yrs ();) from Quetelet’s Belgian data. The upper curve of stature from Bowditch’s Boston data.

Fig. 4. Mean annual increments of stature (), Belgian and American.

Fig. 6. Percentage ratio, throughout life, of female weight to male; from Quetelet’s data.

Fig. 7. Curve of growth (in length or stature) of child, before and after birth. (From His and Rüssow’s data.)

Fig. 10. Curve of growth of bamboo (from Ostwald, after Kraus).

Fig. 11. Coefficients of variability of stature in Man (). from Boas and Wissler’s data.

Fig. 12. Growth in weight of Mouse. (After W. Ostwald.)

Fig. 13. Growth in weight of Silkworm. (From Ostwald, after Luciani and Lo Monaco.)

Fig. 14. Growth in weight of Tadpole. (From Ostwald, after Schaper.)

Fig. 15. Development of Eel; from Leptocephalus larvae to young Elver. (From Ostwald after Joh. Schmidt.)

Fig. 16. Growth in length of Spirogyra. (From Ostwald, after Hofmeister.)

Fig. 17. Pulsations of growth in Crocus, in micro-millimetres. (After Bose.)

Fig. 18. Relative growth in weight (in Man) of Brain, Heart, and whole Body.

Fig. 19. Ratio of stature in Man, to span of outstretched arms.

(From Quetelet’s data.)

Fig. 20. Rate of growth in successive zones near the tip of the bean-root.

Fig. 21. Changes in the weight-length ratio of Plaice, with increasing size.

Fig. 23. Variability of length of tail-forceps in a sample of Earwigs. (After Bateson, P. Z. S. 1892, p. 588.)

Fig. 24. Variability of length of body in a sample of Plaice.

Fig. 25. Relation of rate of growth to temperature in certain plants. (From Sachs’s data.)

Fig. 26. Relation of rate of growth to temperature in Maize. Observed values (after Köppen), and calculated curve.

Fig. 27. Relation of rate of growth to temperature in rootlets of Pea. (From Miss I. Leitch’s data.)

Fig. 28. Diagram shewing time taken (in days), at various temperatures (°C.), to reach certain stages of development in the Frog: viz. I, gastrula; II, medullary plate; III, closure of medullary folds; IV, tail-bud; V, tail and gills; VI, tail-fin; VII, operculum beginning; VIII, do. closing; IX, first appearance of hind-legs. (From Jenkinson, after O. Hertwig, 1898.)

Fig. 30. Half-yearly increments of growth, in cadets of various ages. (From Daffner’s data.)

Fig. 31. Periodic annual fluctuation in rate of growth of trees (in the southern hemisphere).

Fig. 32. Long-period fluctuation in rate of growth of Arizona trees (smoothed in 100-year periods), from A.D. 1390–1490 to A.D. 1810–1910.

Fig. 33. Brine-shrimps (Artemia), from more or less saline water. Upper figures shew tail-segment and tail-fins; lower figures, relative length of cephalothorax and abdomen. (After Abonyi.)

Fig. 35. Curve of regenerative growth in tadpoles’ tails. (From M. L. Durbin’s data.)

Fig. 40. Relation between the percentage amount of tail removed, the percentage restored, and the time required for its restoration. (From M. M. Ellis’s data.)

Fig. 41. Caryokinetic figure in a dividing cell (or blastomere) of the Trout’s egg. (After Prenant, from a preparation by Prof. P. Bouin.)

Fig. 42.

Fig. 43.

Fig. 52. Chromosomes, undergoing splitting and separation.

(After Hatschek and Flemming, diagrammatised.)

Fig. 53. Annular chromosomes, formed in the spermatogenesis of the Mole-cricket. (From Wilson, after Vom Rath.)

Fig. 54.

Fig. 57. Artificial caryokinesis (after Leduc), for comparison with Fig. 41, p. 169.

Fig. 58. Final stage in the first segmentation of the egg of Cerebratulus. (From Prenant, after Coe.)245

Fig. 59. Diagram of field of force with two similar poles.

Fig. 58. Final stage in the first segmentation of the egg of Cerebratulus. (From Prenant, after Coe.)245

Fig. 59. Diagram of field of force with two similar poles.

Fig. 60.

Fig. 61.

Fig. 62.

Fig. 63.

Fig. 66.

Fig. 67.

Fig. 68.

Fig. 69. Hair of Trianea, in glycerine. (After Berthold.)

Fig. 70. Phases of a Splash. (From Worthington.)

Fig. 71. A breaking wave. (From Worthington.)

Fig. 72. Calycles of Campanularian zoophytes. (A) C. integra; (B) C. groenlandica; (C) C. bispinosa; (D) C. raridentata.

Fig. 73. A flagellate “monad,”

Distigma proteus, Ehr. (After Saville Kent.)

Fig. 74.

Noctiluca miliaris.Fig. 73. A flagellate “monad,”

Distigma proteus, Ehr. (After Saville Kent.)

Fig. 74.

Noctiluca miliaris.Fig. 75. Various species of Vorticella. (Mostly after Saville Kent.)

Fig. 76. Various species of Salpingoeca.

Fig. 77. Various species of Tintinnus, Dinobryon and Codonella.

(After Saville Kent and others.)

Fig. 78. Vaginicola.

Fig. 79. Folliculina.

Fig. 80. Trachelophyllum. (After Wreszniowski.)

Fig. 81.

Fig. 82. Dinenympha gracilis, Leidy.

Fig. 83.

Fig. 84. Various species of Lagena. (After Brady.)

Fig. 85. (After Darling.)

Fig. 86.

Fig. 87.

Nodosaria scalaris, Batsch.

Fig. 88. Gonangia of Campanularians. (

a)

C. gracilis; (

b)

C. grandis. (After Allman.)

Fig. 87.

Nodosaria scalaris, Batsch.

Fig. 88. Gonangia of Campanularians. (

a)

C. gracilis; (

b)

C. grandis. (After Allman.)

Fig. 89. Various Foraminifera (after Brady), a, Nodosaria simplex; b, N. pygmaea; c, N. costulata; e, N. hispida; f, N. elata; d, Rheophax (Lituola) distans; g, Sagrina virgata.

Fig. 90. A, Trypanosoma tineae (after Minchin); B, Spirochaeta anodontae (after Fantham).

Fig. 91. A, Trichomonas muris, Hartmann; B, Trichomastix serpentis, Dobell; C, Trichomonas angusta, Alexeieff. (After Kofoid.)

Fig. 92. Herpetomonas assuming the undulatory membrane of a Trypanosome. (After D. L. Mackinnon.)

Fig. 93.

Fig. 94. Sperm-cells of Decapod Crustacea (after Koltzoff). a, Inachus scorpio; b, Galathea squamifera; c, do. after maceration, to shew spiral fibrillae.

Fig. 95. Sperm-cells of Inachus, as they appear in saline solutions of varying density. (After Koltzoff.)

Fig. 96. Sperm-cell of Dromia. (After Koltzoff.)

Fig. 97. A, B, Chondriosomes in kidney-cells, prior to and during secretory activity (after Barratt); C, do. in pancreas of frog (after Mathews).

Fig. 98. Adsorptive concentration of potassium salts in (1) cell of Pleurocarpus about to conjugate; (2) conjugating cells of Mesocarpus; (3) sprouting spores of Equisetum. (After Macallum.)

Fig. 99.

Fig. 102. (After Berthold.)

Fig. 103. Parenchyma of Maize.

Fig. 102. (After Berthold.)

Fig. 103. Parenchyma of Maize.

Fig. 104.

Fig. 105.

Fig. 106.

Fig. 107. Filaments, or chains of cells, in various lower Algae. (A) Nostoc; (B) Anabaena; (C) Rivularia; (D) Oscillatoria.

Fig. 108.

Fig. 109. Spore of Pellia. (After Campbell.)

Fig. 110. Cells of

Dictyota. (After Reinke.)

Fig. 111. Terminal and other cells of

Chara.

Fig. 110. Cells of

Dictyota. (After Reinke.)

Fig. 111. Terminal and other cells of

Chara.

Fig. 113.

Fig. 114.

Fig. 116.

Fig. 117. Various ways in which the four cells are co-arranged in the four-celled stage of the frog’s egg. (After Rauber.)

Fig. 118.

Fig. 119.

Fig. 120.

Fig. 121. Diagram of hexagonal cells. (After Bonanni.)

Fig. 122. An “artificial tissue,” formed by coloured drops of sodium chloride solution diffusing in a less dense solution of the same salt. (After Leduc.)

Fig. 124. Epidermis of Girardia. (After Goebel.)

Fig. 125. Soap-froth under pressure. (After Rhumbler.)

Fig. 126. From leaf of Elodea canadensis. (After Berthold.)

Fig. 127.

Lithostrotion Martini.(After Nicholson.)

Fig. 128.

Cyathophyllum hexagonum.(From Nicholson, after Zittel.)

Fig. 127.

Lithostrotion Martini.(After Nicholson.)

Fig. 128.

Cyathophyllum hexagonum.(From Nicholson, after Zittel.)

Fig. 129.

Arachnophyllum pentagonum.(After Nicholson.)

Fig. 130.

Heliolites.(After Woods.)

Fig. 129.

Arachnophyllum pentagonum.(After Nicholson.)

Fig. 130.

Heliolites.(After Woods.)

Fig. 131. Surface-views of Corals with undeveloped thecae and confluent septa. A, Thamnastraea; B, Comoseris. (From Nicholson, after Zittel.)

Fig. 132.

Fig. 133. Diagram of development of “stellate cells,” in pith of Juncus. (The dark, or shaded, areas represent the cells; the light areas being the gradually enlarging “intercellular spaces.”)

Fig. 134.

Fig. 135. Aggregations of four soap-bubbles, to shew various arrangements of the intermediate partition and polar furrows. (After Robert.)

Fig. 136. (After Berthold.)

Fig. 139.

Fig. 140.

Fig. 141.

Fig. 142. -shaped partitions: A, from Taonia atomaria (after Reinke); B, from paraphyses of Fucus; C, from rhizoids of Moss; D, from paraphyses of Polytrichum.

Fig. 143. Diagrammatic explanation of -shaped partition.

Fig. 144. Development of Erythrotrichia. (After Berthold.)

Fig. 145.

Fig. 146.

Fig. 147.

Fig. 148. Segmentation of frog’s egg, under artificial compression. (After Roux.)

Fig. 149.

Fig. 150.

Fig. 151.

Fig. 152.

Fig. 153. Diagram of flattened or discoid cell dividing into octants: to shew gradual tendency towards a position of equilibrium.

Fig. 154.

Fig. 155. Theoretical arrangement of successive partitions in a discoid cell; for comparison with Fig. 144.

Fig. 157. Sections of embryo of a moss. (After Kienitz-Gerloff.)

Fig. 158. Various possible arrangements of intermediate partitions, in groups of 4, 5, 6, 7 or 8 cells.

Fig. 159.

Fig. 160. Segmenting egg of

Trochus. (After Robert.)

Fig. 161. Two views of segmenting egg of

Cynthia partita. (After Conklin.)

Fig. 162. (a) Section of apical cone of Salvinia. (After Pringsheim394.) (b) Diagram of probable actual arrangement.

Fig. 163. Egg of

Pyrosoma. (After Korotneff).

Fig. 164. Egg of

Echinus, segmenting under pressure. (After Driesch.)

Fig. 165. (a) Part of segmenting egg of Cephalopod (after Watase); (b) probable actual arrangement.

Fig. 166. (a) Egg of Echinus; (b) do. of Nereis, under pressure. (After Driesch).

Fig. 168. Various modes of grouping of eight cells, at the dorsal or epiblastic pole of the frog’s egg. (After Rauber.)

Fig. 169.

Fig. 170. Aggregations of oil-drops. (After Roux.) Figs. 4–6 represent successive changes in a single system.

Fig. 171. (A) Asterolampra marylandica, Ehr.; (B, C) A. variabilis, Grev. (After Greville.)

Fig. 172. Section of Alcyonarian polype.

Fig. 173. Heterophyllia angulata. (After Nicholson.)

Fig. 175. Diagrammatic section of a Ctenophore (Eucharis).

Fig. 176. Diagrammatic arrangement of partitions, represented by skeletal rods, in larval Echinoderm (Ophiura).

Fig. 178. Diagrammatic development of Stomata in Sedum. (Cf. fig. in Sachs’s Botany, 1882, p. 103.)

Fig. 180. Various pollen-grains and spores (after Berthold, Campbell, Goebel and others). (1) Epilobium; (2) Passiflora; (3) Neottia; (4) Periploca graeca; (5) Apocynum; (6) Erica; (7) Spore of Osmunda; (8) Tetraspore of Callithamnion.

Fig. 181. Dividing spore of Anthoceros. (After Campbell.)

Fig. 182.

Fig. 183. Development of Sphagnum. (After Campbell.)

Fig. 185. Gemma of Moss. (After Campbell.)

Fig. 186. Development of antheridium of Riccia. (After Campbell.)

Fig. 187. Section of growing shoot of Selaginella, diagrammatic.

Fig. 188. Embryo of Jungermannia. (After Kienitz-Gerloff.)

Fig. 187. Section of growing shoot of Selaginella, diagrammatic.

Fig. 188. Embryo of Jungermannia. (After Kienitz-Gerloff.)

Fig. 190. Development of sporangium of Osmunda. (After Bower.)

Fig. 191. (A, B,) Sections of younger and older embryos of Phascum; (C) do. of Adiantum. (After Kienitz-Gerloff.)

Fig. 192. Section through frond of Girardia sphacelaria. (After Goebel.)

Fig. 193. Development of antheridium of Pteris. (After Strasbürger.)

Fig. 194. Alcyonarian spicules: Siphonogorgia and Anthogorgia. (After Studer.)

Fig. 195. Calcospherites, or concretions of calcium carbonate, deposited in white of egg. (After Harting.)

Fig. 196. A single calcospherite, with central “nucleus,” and striated, iridescent border. (After Harting.)

Fig. 198, A. Section of shell of Mya; B. Section of hinge-tooth of do. (After Carpenter.)

Fig. 199. Large irregular calcareous concretions, or spicules, deposited in a piece of dead cartilage, in presence of calcium phosphate. (After Harting.)

Fig. 200. Additional illustrations of Alcyonarian spicules: Eunicea. (After Studer.)

Fig. 201. A “crust” of close-packed calcareous concretions, precipitated at the surface of an albuminous solution. (After Harting.)

Fig. 202. Aggregated calcospherites. (After Harting.)

Fig. 204. Conostats. (After Harting.)

Fig. 205. Liesegang’s Rings. (After Leduc.)

Fig. 206. Relay-crystals of common salt. (After Bowman.)

Fig. 207. Wheel-like crystals in a colloid. (After Bowman.)

Fig. 208.

Fig. 209. Otoliths of Plaice, showing four zones or “age-rings.” (After Wallace.)

Fig. 210. Close-packed calcospherites, or so-called “spicules,” of Astrosclera. (After Lister.)

Fig. 211. Sponge and Holothurian spicules.

Fig. 213. An “amphidisc” of Hyalonema.

Fig. 214. Spicules of Grantia and other calcareous sponges. (After Haeckel.)

Fig. 218.

Fig. 219. Arenaceous Foraminifera; Astrorhiza limicola and arenaria. (From Brady’s Challenger Monograph.)

Fig. 220. “Reticulum plasmatique.” (After Carnoy.)

Fig. 221. Aulonia hexagona, Hkl.

Fig. 222. Actinomma arcadophorum, Hkl.

Fig. 223.

Ethmosphaera conosiphonia, Hkl.

Fig. 224. Portions of shells of two “species” of

Cenosphaera: upper figure,

C. favosa, lower,

C. vesparia, Hkl.

Fig. 223.

Ethmosphaera conosiphonia, Hkl.

Fig. 224. Portions of shells of two “species” of

Cenosphaera: upper figure,

C. favosa, lower,

C. vesparia, Hkl.

Fig. 225. Aulastrum triceros, Hkl.

Fig. 226.

Fig. 227. A Nassellarian skeleton,

Callimitra carolotae, Hkl.

Fig. 226.

Fig. 227. A Nassellarian skeleton,

Callimitra carolotae, Hkl.

Fig. 228. An isolated portion of the skeleton of Dictyocha.

Fig. 230.

Fig. 231. Skeletons of various Radiolarians, after Haeckel. 1. Circoporus sexfurcus; 2. C. octahedrus; 3. Circogonia icosahedra; 4. Circospathis novena; 5. Circorrhegma dodecahedra.

Fig. 232. Dorataspis sp.; diagrammatic.

Fig. 233. Phatnaspis cristata, Hkl.

Fig. 235. Phractaspis prototypus, Hkl.

Fig. 236. Annular and spiral thickenings in the walls of plant-cells.

Fig. 237. The shell of Nautilus pompilius, from a radiograph: to shew the logarithmic spiral of the shell, together with the arrangement of the internal septa. (From Messrs Green and Gardiner, in Proc. Malacol. Soc. II, 1897.)

Fig. 238. A Foraminiferal shell (Globigerina).

Fig. 239.

Fig. 243. A, a helicoid, B, a scorpioid cyme.

Fig. 244.

Fig. 245.

Fig. 248.

Fig. 258. A shell of Haliotis, with two of the many lines of growth, or generating curves, marked out in black: the areas bounded by these lines of growth being in all cases “gnomons” to the pre-existing shell.

Fig. 259. A spiral foraminifer (Pulvinulina), to show how each successive chamber continues the symmetry of, or constitutes a gnomon to, the rest of the structure.

Fig. 261.

Fig. 262.

Fig. 263. Operculum of Turbo.

Fig. 265. Melo ethiopicus, L.

Fig. 266. 1, Harpa; 2, Dolium. The ridges on the shell correspond in (1) to generating curves, in (2) to generating spirals.

Fig. 267. D’Orbigny’s Helicometer.

Fig. 268.

Fig. 269.

Fig. 274.

Fig. 275. An Ammonite, to shew corrugated surface-pattern.

Fig. 276.

Fig. 278.

Fig. 281. An ammonitoid shell (Macroscaphites) to shew change of curvature.

Fig. 282.

Fig. 283. Section of a spiral, or turbinate, univalve, Triton corrugatus, Lam. (From Woodward.)

Fig. 284. A, Lamellaria perspicua; B, Sigaretus haliotoides.

(After Woodward.)

Fig. 285. Terebra maculata, L.

Fig. 287.

Fig. 290.

Caprinella adversa.(After Woodward.)

Fig. 291. Section of

Productus(

Strophomena) sp. (From Woods.)

Fig. 290.

Caprinella adversa.(After Woodward.)

Fig. 291. Section of

Productus(

Strophomena) sp. (From Woods.)

Fig. 292. Skeletal loop of Terebratula. (From Woods.)

Fig. 293. Spiral arms of

Spirifer. (From Woods.)

Fig. 294. Inwardly directed spiral arms of

Atrypa.

Fig. 295. Pteropod shells: (1) Cuvierina columnella; (2) Cleodora chierchiae; (3) C. pygmaea. (After Boas.)

Fig. 298. Cleodora cuspidata.

Fig. 300. Development of the shell of Hyalaea (Cavolinia) tridentata, Forskal: the earlier stages being the “Pleuropus longifilis” of Troschel. (After Tesch.)

Fig. 301. Pteropod shells, from the side: (1) Cleodora cuspidata; (2) Hyalaea longirostris; (3) H. trispinosa. (After Boas.)

Fig. 302.

Fig. 304. Section of Nautilus, shewing the contour of the septa in the median plane: the septa being (in this plane) logarithmic spirals, of which the shell-spiral is the evolute.

Fig. 305. Cast of the interior of Nautilus: to shew the contours of the septa at their junction with the shell-wall.

Fig. 306. Ammonites (Sonninia) Sowerbyi. (From Zittel, after Steinmann and Döderlein.)

Fig. 307. Suture-line of a Triassic Ammonite (Pinacoceras). (From Zittel, after Hauer.)

Fig. 308. Hastigerina sp.; to shew the “mouth.”

Fig. 309. Nummulina antiquior, R. and V. (After V. von Möller.)

Fig. 310. A, Cornuspira foliacea, Phil.; B, Operculina complanata, Defr.

Fig. 311. 1, 2, Miliolina pulchella, d’Orb.; 3–5, M. linnaeana, d’Orb. (After Brady.)

Fig. 312. Cyclammina cancellata, Brady.

Fig. 314. Orbulina universa, d’Orb.

Fig. 315. Cristellaria reniformis, d’Orb.

Fig. 316. Discorbina bertheloti, d’Orb.

Fig. 317. A, Tertularia trochus, d’Orb. B, T. concava, Karrer.

Fig. 318. Diagram of Ram’s horns. (After Sir Vincent Brooke, from P.Z.S.) a, frontal; b, orbital; c, nuchal surface.

Fig. 319. Head of Arabian Wild Goat, Capra sinaitica. (After Sclater, from P.Z.S.)

Fig. 320. Head of Ovis Ammon, shewing St Venant’s curves.

Fig. 321.

Fig. 322.

Fig. 321.

Fig. 322.

Fig. 323. Antlers of Swedish Elk. (After Lönnberg, from P.Z.S.)

Fig. 324. Head and antlers of a Stag (Cervus Duvauceli). (After Lydekker, from P.Z.S.)

Fig. 325.

Fig. 327.

Fig. 328. Diagrammatic vertical outlines of various Sea-urchins: A, Palaeechinus; B, Echinus acutus; C, Cidaris; D, D′ Coelopleurus; E, E′ Genicopatagus; F, Phormosoma luculenter; G, P. tenuis; H, Asthenosoma; I, Urechinus.

Fig. 329.

Fig. 331.

.

An example of the mode of arrangement of bast-fibres in a plant-stem (Schwendener)

680

334.

Section of the head of a femur, to shew its trabecular structure (Schäfer, after Robinson)

681

335.

Comparative diagrams of a crane-head and the head of a femur (Culmann and H. Meyer)

682

336.

Diagram of stress-lines in the human foot (Sir D. MacAlister, after H. Meyer)

684

337.

Trabecular structure of the

os calcis(

do.)

685

338.

Diagram of shearing-stress in a loaded pillar

686

339.

Diagrams of tied arch, and bowstring girder (Fidler)

693

340, 1.

Diagrams of a bridge: shewing proposed span, the corresponding stress-diagram and reciprocal plan of construction (

do.)

696

342.

A loaded bracket and its reciprocal construction-diagram (Culmann)

697

343, 4.

A cantilever bridge, with its reciprocal diagrams (Fidler)

698

345.

A two-armed cantilever of the Forth Bridge (

do.)

700

346.

A two-armed cantilever with load distributed over two pier-heads, as in the quadrupedal skeleton

700

347–9.

Stress-diagrams. or diagrams of bending moments, in the backbones of the horse, of a Dinosaur, and of

Titanotherium701–4

350.

The skeleton of

Stegosaurus707

351.

Bending-moments in a beam with fixed ends, to illustrate the mechanics of chevron-bones

709

352, 3.

Coordinate diagrams of a circle, and its deformation into an ellipse

729

354.

Comparison, by means of Cartesian coordinates, of the cannon-bones of various ruminant animals

729

355, 6.

Logarithmic coordinates, and the circle of Fig. 352 inscribed therein

729, 31

357, 8.

Diagrams of oblique and radial coordinates

731

359.

Lanceolate, ovate and cordate leaves, compared by the help of radial coordinates

732

360.

A leaf of

Begonia daedalea733

361.

A network of logarithmic spiral coordinates

735

362, 3.

Feet of ox, sheep and giraffe, compared by means of Cartesian coordinates

738, 40

364, 6.

“Proportional diagrams” of human physiognomy (Albert Dürer)

740, 2

365.

Median and lateral toes of a tapir, compared by means of rectangular and oblique coordinates

741

367, 8.

A comparison of the copepods

Oithonaand

Sapphirina742

369.

The carapaces of certain crabs,

Geryon,

Corystesand others, compared by means of rectilinear and curvilinear coordinates

744

370.

A comparison of certain amphipods,

Harpinia,

Stegocephalusand

Hyperia746

371.

The calycles of certain campanularian zoophytes, inscribed in corresponding Cartesian networks

747

372.

The calycles of certain species of

Aglaophenia, similarly compared by means of curvilinear coordinates

748

373, 4.

The fishes

Argyropelecusand

Sternoptyx, compared by means of rectangular and oblique coordinate systems

748

375, 6.

Scarusand

Pomacanthus, similarly compared by means of rectangular and coaxial systems

749

377–80.

A comparison of the fishes

Polyprion,

Pseudopriacanthus,

Scorpaenaand

Antigonia750

381, 2.

A similar comparison of

Diodonand

Orthagoriscus751

383.

The same of various crocodiles:

C. porosus,

C. americanusand

Notosuchus terrestris753

384.

The pelvic girdles of

Stegosaurusand

Camptosaurus754

385, 6.

The shoulder-girdles of

Cryptocleidusand of

Ichthyosaurus755

387.

The skulls of

Dimorphodonand of

Pteranodon756

388–92.

The pelves of

Archaeopteryxand of

Apatorniscompared, and a method illustrated whereby intermediate configurations may be found by interpolation (G. Heilmann)

757–9

393.

The same pelves, together with three of the intermediate or interpolated forms

760

394, 5.

Comparison of the skulls of two extinct rhinoceroses,

Hyrachyusand

Aceratherium(Osborn)

761

396.

Occipital views of various extinct rhinoceroses (

do.)

762

397–400.

Comparison with each other, and with the skull of

Hyrachyus, of the skulls of

Titanotherium, tapir, horse and rabbit

763, 4

401, 2.

Coordinate diagrams of the skulls of

Eohippusand of

Equus, with various actual and hypothetical intermediate types (Heilmann)

765–7

403.

A comparison of various human scapulae (Dwight)

769

404.

A human skull, inscribed in Cartesian coordinates

770

405.

The same coordinates on a new projection, adapted to the skull of the chimpanzee

770

406.

Chimpanzee’s skull, inscribed in the network of Fig. 405

771

407, 8.

Corresponding diagrams of a baboon’s skull, and of a dog’s

771, 3

Fig. 333.

Fig. 334. Head of the human femur in section. (After Schäfer, from a photo by Prof. A. Robinson.)

Fig. 335. Crane-head and femur. (After Culmann and H. Meyer.)

Fig. 336. Diagram of stress-lines in the human foot. (From Sir D. MacAlister, after H. Meyer.)

Fig. 337. Trabecular structure of the os calcis. (From MacAlister.)

Fig. 338.

Fig. 339.

Fig. 340. A, Span of proposed bridge. B, Stress diagram, or diagram of bending-moments628.

Fig. 342.

Fig. 343.

Fig. 345. A two-armed cantilever of the Forth Bridge. Thick lines, compression-members (bones); thin lines, tension-members (ligaments).

Fig. 346.

Fig. 347. Stress-diagram of horse’s backbone.

Fig. 350. Diagram of Stegosaurus.

Fig. 351.

Fig. 352.

Fig. 353.

Fig. 354.

Fig. 355.

Fig. 354.

Fig. 355.

Fig. 357.

Fig. 359.

Fig. 360. Begonia daedalea.

Fig. 361.

Fig. 362.

Fig. 364. (After Albert Dürer.)

Fig. 365.

Fig. 367.

Oithona nana.Fig. 368.

Sapphirina.Fig. 369. Carapaces of various crabs. 1, Geryon; 2, Corystes; 3, Scyramathia; 4, Paralomis; 5, Lupa; 6, Chorinus.

Fig 370. 1. Harpinia plumosa Kr. 2. Stegocephalus inflatus Kr. 3. Hyperia galba.

Fig. 371. a, Campanularia macroscyphus, Allm.; b, Gonothyraea hyalina, Hincks; c, Clytia Johnstoni, Alder.

Fig. 372. a, Cladocarpus crenatus, F.; b, Aglaophenia pluma, L.; c, A. rhynchocarpa, A.; d, A cornuta, K.; e, A. ramulosa, K.

Fig. 373.

Argyropelecus Olfersi.Fig. 374.

Sternoptyx diaphana.Fig. 375.

Scarussp.

Fig. 376.

Pomacanthus.Fig. 377.

Polyprion.Fig. 378.

Pseudopriacanthus altus.Fig. 381.

Diodon.Fig. 382.

Orthagoriscus.Fig. 383. A, Crocodilus porosus. B, C. americanus. C, Notosuchus terrestris.

Fig. 384. Pelvis of (A) Stegosaurus; (B) Camptosaurus.

Fig. 385. Shoulder-girdle of Cryptocleidus. a, young; b, adult.

Fig. 387. a, Skull of Dimorphodon. b, Skull of Pteranodon.

Fig. 388. Pelvis of Archaeopteryx.

Fig. 393. The pelves of Archaeopteryx and of Apatornis, with three transitional types interpolated between them.

Fig. 394. Skull of Hyrachyus agrarius. (After Osborn.)

Fig. 396. Occipital view of the skulls of various extinct rhinoceroses (Aceratherium spp.). (After Osborn.)

Fig. 397.

Titanotherium robustum.

Fig. 398. Tapir’s skull.

Fig. 401. A, outline diagram of the Cartesian co-ordinates of the skull of Hyracotherium or Eohippus, as shewn in Fig. 402, A. H, outline of the corresponding projection of the horse’s skull. B–G, intermediate, or interpolated, outlines.

Fig. 403. Human scapulae (after Dwight). A, Caucasian; B, Negro; C, North American Indian (from Kentucky Mountains).

Fig. 404. Human skull.

Fig. 405. Co-ordinates of chimpanzee’s skull, as a projection of the Cartesian co-ordinates of Fig. 404.

Fig. 406. Skull of chimpanzee.

Fig. 407. Skull of baboon.

Fig. 406. Skull of chimpanzee.

Fig. 407. Skull of baboon.

“Cum formarum naturalium et corporalium esse non consistat nisi in unione ad materiam, ejusdem agentis esse videtur eas producere cujus est materiam transmutare. Secundo, quia cum hujusmodi formae non excedant virtutem et ordinem et facultatem principiorum agentium in natura, nulla videtur necessitas eorum originem in principia reducere altiora.” Aquinas, De Pot. Q. iii, a, 11. (Quoted in Brit. Assoc. Address, Section D, 1911.)

“...I would that all other natural phenomena might similarly be deduced from mechanical principles. For many things move me to suspect that everything depends upon certain forces, in virtue of which the particles of bodies, through forces not yet understood, are either impelled together so as to cohere in regular figures, or are repelled and recede from one another.” Newton, in Preface to the Principia. (Quoted by Mr W. Spottiswoode, Brit. Assoc. Presidential Address, 1878.)

“When Science shall have subjected all natural phenomena to the laws of Theoretical Mechanics, when she shall be able to predict the result of every combination as unerringly as Hamilton predicted conical refraction, or Adams revealed to us the existence of Neptune,—that we cannot say. That day may never come, and it is certainly far in the dim future. We may not anticipate it, we may not even call it possible. But none the less are we bound to look to that day, and to labour for it as the crowning triumph of Science:—when Theoretical Mechanics shall be recognised as the key to every physical enigma, the chart for every traveller through the dark Infinite of Nature.” J. H. Jellett, in Brit. Assoc. Address, Section A, 1874.

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTORY

Of the chemistry of his day and generation, Kant declared that it was “a science, but not science,”—“eine Wissenschaft, aber nicht Wissenschaft”; for that the criterion of physical science lay in its relation to mathematics. And a hundred years later Du Bois Reymond, profound student of the many sciences on which physiology is based, recalled and reiterated the old saying, declaring that chemistry would only reach the rank of science, in the high and strict sense, when it should be found possible to explain chemical reactions in the light of their causal relation to the velocities, tensions and conditions of equilibrium of the component molecules; that, in short, the chemistry of the future must deal with molecular mechanics, by the methods and in the strict language of mathematics, as the astronomy of Newton and Laplace dealt with the stars in their courses. We know how great a step has been made towards this distant and once hopeless goal, as Kant defined it, since van’t Hoff laid the firm foundations of a mathematical chemistry, and earned his proud epitaph, Physicam chemiae adiunxit1.

We need not wait for the full realisation of Kant’s desire, in order to apply to the natural sciences the principle which he urged. Though chemistry fall short of its ultimate goal in mathematical mechanics, nevertheless physiology is vastly strengthened and enlarged by making use of the chemistry, as of the physics, of the age. Little by little it draws nearer to our conception of a true science, with each branch of physical science which it {2} brings into relation with itself: with every physical law and every mathematical theorem which it learns to take into its employ. Between the physiology of Haller, fine as it was, and that of Helmholtz, Ludwig, Claude Bernard, there was all the difference in the world.

As soon as we adventure on the paths of the physicist, we learn to weigh and to measure, to deal with time and space and mass and their related concepts, and to find more and more our knowledge expressed and our needs satisfied through the concept of number, as in the dreams and visions of Plato and Pythagoras; for modern chemistry would have gladdened the hearts of those great philosophic dreamers.

But the zoologist or morphologist has been slow, where the physiologist has long been eager, to invoke the aid of the physical or mathematical sciences; and the reasons for this difference lie deep, and in part are rooted in old traditions. The zoologist has scarce begun to dream of defining, in mathematical language, even the simpler organic forms. When he finds a simple geometrical construction, for instance in the honey-comb, he would fain refer it to psychical instinct or design rather than to the operation of physical forces; when he sees in snail, or nautilus, or tiny foraminiferal or radiolarian shell, a close approach to the perfect sphere or spiral, he is prone, of old habit, to believe that it is after all something more than a spiral or a sphere, and that in this “something more” there lies what neither physics nor mathematics can explain. In short he is deeply reluctant to compare the living with the dead, or to explain by geometry or by dynamics the things which have their part in the mystery of life. Moreover he is little inclined to feel the need of such explanations or of such extension of his field of thought. He is not without some justification if he feels that in admiration of nature’s handiwork he has an horizon open before his eyes as wide as any man requires. He has the help of many fascinating theories within the bounds of his own science, which, though a little lacking in precision, serve the purpose of ordering his thoughts and of suggesting new objects of enquiry. His art of classification becomes a ceaseless and an endless search after the blood-relationships of things living, and the pedigrees of things {3} dead and gone. The facts of embryology become for him, as Wolff, von Baer and Fritz Müller proclaimed, a record not only of the life-history of the individual but of the annals of its race. The facts of geographical distribution or even of the migration of birds lead on and on to speculations regarding lost continents, sunken islands, or bridges across ancient seas. Every nesting bird, every ant-hill or spider’s web displays its psychological problems of instinct or intelligence. Above all, in things both great and small, the naturalist is rightfully impressed, and finally engrossed, by the peculiar beauty which is manifested in apparent fitness or “adaptation,”—the flower for the bee, the berry for the bird.

Time out of mind, it has been by way of the “final cause,” by the teleological concept of “end,” of “purpose,” or of “design,” in one or another of its many forms (for its moods are many), that men have been chiefly wont to explain the phenomena of the living world; and it will be so while men have eyes to see and ears to hear withal. With Galen, as with Aristotle, it was the physician’s way; with John Ray, as with Aristotle, it was the naturalist’s way; with Kant, as with Aristotle, it was the philosopher’s way. It was the old Hebrew way, and has its splendid setting in the story that God made “every plant of the field before it was in the earth, and every herb of the field before it grew.” It is a common way, and a great way; for it brings with it a glimpse of a great vision, and it lies deep as the love of nature in the hearts of men.

Half overshadowing the “efficient” or physical cause, the argument of the final cause appears in eighteenth century physics, in the hands of such men as Euler2 and Maupertuis, to whom Leibniz3 had passed it on. Half overshadowed by the mechanical concept, it runs through Claude Bernard’s Leçons sur les {4} phénomènes de la Vie4, and abides in much of modern physiology5. Inherited from Hegel, it dominated Oken’s Naturphilosophie and lingered among his later disciples, who were wont to liken the course of organic evolution not to the straggling branches of a tree, but to the building of a temple, divinely planned, and the crowning of it with its polished minarets6.

It is retained, somewhat crudely, in modern embryology, by those who see in the early processes of growth a significance “rather prospective than retrospective,” such that the embryonic phenomena must be “referred directly to their usefulness in building the body of the future animal7”:—which is no more, and no less, than to say, with Aristotle, that the organism is the τέλος, or final cause, of its own processes of generation and development. It is writ large in that Entelechy8 which Driesch rediscovered, and which he made known to many who had neither learned of it from Aristotle, nor studied it with Leibniz, nor laughed at it with Voltaire. And, though it is in a very curious way, we are told that teleology was “refounded, reformed or rehabilitated9” by Darwin’s theory of natural selection, whereby “every variety of form and colour was urgently and absolutely called upon to produce its title to existence either as an active useful agent, or as a survival” of such active usefulness in the past. But in this last, and very important case, we have reached a “teleology” without a τέλος, {5} as men like Butler and Janet have been prompt to shew: a teleology in which the final cause becomes little more, if anything, than the mere expression or resultant of a process of sifting out of the good from the bad, or of the better from the worse, in short of a process of mechanism10. The apparent manifestations of “purpose” or adaptation become part of a mechanical philosophy, according to which “chaque chose finit toujours par s’accommoder à son milieu11.” In short, by a road which resembles but is not the same as Maupertuis’s road, we find our way to the very world in which we are living, and find that if it be not, it is ever tending to become, “the best of all possible worlds12.”

But the use of the teleological principle is but one way, not the whole or the only way, by which we may seek to learn how things came to be, and to take their places in the harmonious complexity of the world. To seek not for ends but for “antecedents” is the way of the physicist, who finds “causes” in what he has learned to recognise as fundamental properties, or inseparable concomitants, or unchanging laws, of matter and of energy. In Aristotle’s parable, the house is there that men may live in it; but it is also there because the builders have laid one stone upon another: and it is as a mechanism, or a mechanical construction, that the physicist looks upon the world. Like warp and woof, mechanism and teleology are interwoven together, and we must not cleave to the one and despise the other; for their union is “rooted in the very nature of totality13.”

Nevertheless, when philosophy bids us hearken and obey the lessons both of mechanical and of teleological interpretation, the precept is hard to follow: so that oftentimes it has come to pass, just as in Bacon’s day, that a leaning to the side of the final cause “hath intercepted the severe and diligent inquiry of all {6} real and physical causes,” and has brought it about that “the search of the physical cause hath been neglected and passed in silence.” So long and so far as “fortuitous variation14” and the “survival of the fittest” remain engrained as fundamental and satisfactory hypotheses in the philosophy of biology, so long will these “satisfactory and specious causes” tend to stay “severe and diligent inquiry,” “to the great arrest and prejudice of future discovery.”

The difficulties which surround the concept of active or “real” causation, in Bacon’s sense of the word, difficulties of which Hume and Locke and Aristotle were little aware, need scarcely hinder us in our physical enquiry. As students of mathematical and of empirical physics, we are content to deal with those antecedents, or concomitants, of our phenomena, without which the phenomenon does not occur,—with causes, in short, which, aliae ex aliis aptae et necessitate nexae, are no more, and no less, than conditions sine quâ non. Our purpose is still adequately fulfilled: inasmuch as we are still enabled to correlate, and to equate, our particular phenomena with more and ever more of the physical phenomena around, and so to weave a web of connection and interdependence which shall serve our turn, though the metaphysician withhold from that interdependence the title of causality. We come in touch with what the schoolmen called a ratio cognoscendi, though the true ratio efficiendi is still enwrapped in many mysteries. And so handled, the quest of physical causes merges with another great Aristotelian theme,—the search for relations between things apparently disconnected, and for “similitude in things to common view unlike.” Newton did not shew the cause of the apple falling, but he shewed a similitude between the apple and the stars.

Moreover, the naturalist and the physicist will continue to speak of “causes,” just as of old, though it may be with some mental reservations: for, as a French philosopher said, in a kindred difficulty: “ce sont là des manières de s’exprimer, {7} et si elles sont interdites il faut renoncer à parler de ces choses.”

The search for differences or essential contrasts between the phenomena of organic and inorganic, of animate and inanimate things has occupied many mens’ minds, while the search for community of principles, or essential similitudes, has been followed by few; and the contrasts are apt to loom too large, great as they may be. M. Dunan, discussing the “Problème de la Vie15” in an essay which M. Bergson greatly commends, declares: “Les lois physico-chimiques sont aveugles et brutales; là où elles règnent seules, au lieu d’un ordre et d’un concert, il ne peut y avoir qu’incohérence et chaos.” But the physicist proclaims aloud that the physical phenomena which meet us by the way have their manifestations of form, not less beautiful and scarce less varied than those which move us to admiration among living things. The waves of the sea, the little ripples on the shore, the sweeping curve of the sandy bay between its headlands, the outline of the hills, the shape of the clouds, all these are so many riddles of form, so many problems of morphology, and all of them the physicist can more or less easily read and adequately solve: solving them by reference to their antecedent phenomena, in the material system of mechanical forces to which they belong, and to which we interpret them as being due. They have also, doubtless, their immanent teleological significance; but it is on another plane of thought from the physicist’s that we contemplate their intrinsic harmony and perfection, and “see that they are good.”

Nor is it otherwise with the material forms of living things. Cell and tissue, shell and bone, leaf and flower, are so many portions of matter, and it is in obedience to the laws of physics that their particles have been moved, moulded and conformed16. {8} They are no exception to the rule that Θεὸς ἀεὶ γεωμετρεῖ. Their problems of form are in the first instance mathematical problems, and their problems of growth are essentially physical problems; and the morphologist is, ipso facto, a student of physical science.

Apart from the physico-chemical problems of modern physiology, the road of physico-mathematical or dynamical investigation in morphology has had few to follow it; but the pathway is old. The way of the old Ionian physicians, of Anaxagoras17, of Empedocles and his disciples in the days before Aristotle, lay just by that highwayside. It was Galileo’s and Borelli’s way. It was little trodden for long afterwards, but once in a while Swammerdam and Réaumur looked that way. And of later years, Moseley and Meyer, Berthold, Errera and Roux have been among the little band of travellers. We need not wonder if the way be hard to follow, and if these wayfarers have yet gathered little. A harvest has been reaped by others, and the gleaning of the grapes is slow.

It behoves us always to remember that in physics it has taken great men to discover simple things. They are very great names indeed that we couple with the explanation of the path of a stone, the droop of a chain, the tints of a bubble, the shadows in a cup. It is but the slightest adumbration of a dynamical morphology that we can hope to have, until the physicist and the mathematician shall have made these problems of ours their own, or till a new Boscovich shall have written for the naturalist the new Theoria Philosophiae Naturalis.

How far, even then, mathematics will suffice to describe, and physics to explain, the fabric of the body no man can foresee. It may be that all the laws of energy, and all the properties of matter, and all the chemistry of all the colloids are as powerless to explain the body as they are impotent to comprehend the soul. For my part, I think it is not so. Of how it is that the soul informs the body, physical science teaches me nothing: consciousness is not explained to my comprehension by all the nerve-paths and “neurones” of the physiologist; nor do I ask of physics how goodness shines in one man’s face, and evil betrays itself in another. But of the construction and growth and working {9} of the body, as of all that is of the earth earthy, physical science is, in my humble opinion, our only teacher and guide18.

Often and often it happens that our physical knowledge is inadequate to explain the mechanical working of the organism; the phenomena are superlatively complex, the procedure is involved and entangled, and the investigation has occupied but a few short lives of men. When physical science falls short of explaining the order which reigns throughout these manifold phenomena,—an order more characteristic in its totality than any of its phenomena in themselves,—men hasten to invoke a guiding principle, an entelechy, or call it what you will. But all the while, so far as I am aware, no physical law, any more than that of gravity itself, not even among the puzzles of chemical “stereometry,” or of physiological “surface-action” or “osmosis,” is known to be transgressed by the bodily mechanism.

Some physicists declare, as Maxwell did, that atoms or molecules more complicated by far than the chemist’s hypotheses demand are requisite to explain the phenomena of life. If what is implied be an explanation of psychical phenomena, let the point be granted at once; we may go yet further, and decline, with Maxwell, to believe that anything of the nature of physical complexity, however exalted, could ever suffice. Other physicists, like Auerbach19, or Larmor20, or Joly21, assure us that our laws of thermodynamics do not suffice, or are “inappropriate,” to explain the maintenance or (in Joly’s phrase) the “accelerative absorption” {10} of the bodily energies, and the long battle against the cold and darkness which is death. With these weighty problems I am not for the moment concerned. My sole purpose is to correlate with mathematical statement and physical law certain of the simpler outward phenomena of organic growth and structure or form: while all the while regarding, ex hypothesi, for the purposes of this correlation, the fabric of the organism as a material and mechanical configuration.