автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Turkish Harems & Circassian Homes

TURKISH HAREMS

AND

CIRCASSIAN HOMES.

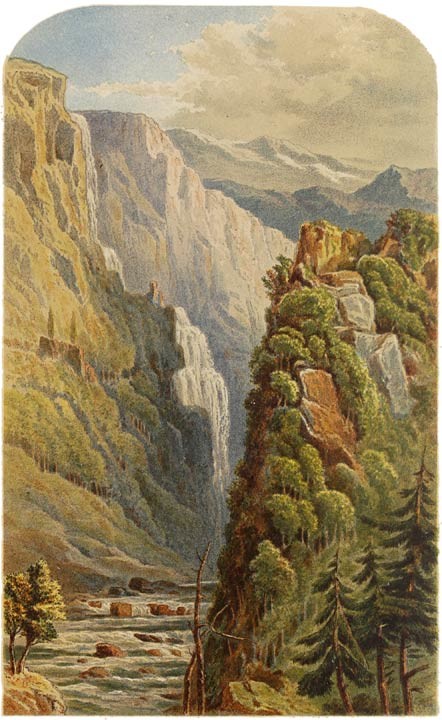

MOUNTAIN GORGE ABOVE SOUKOUM-KALE CIRCASSIA

A. HARVEY

M & N Hanhart Chromo Lith.

Turkish Harems

&

CIRCASSIAN HOMES

BY

MRS. HARVEY.

OF ICKWELL BURY.

LONDON

HURST & BLACKETT.

GREAT MARLBOROUGH STREET

1871.

M & N Hanhart Chromo Lith.

TO THE

LADY ELIZABETH RUSSELL,

THIS LITTLE VOLUME

IS AFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED.

PREFACE.

It is hoped by the Authoress that this little record of a past summer may recall some pleasant recollections to those who have already visited the sunny lands she attempts to describe; and that her accounts, though they inadequately express the beauty and charm of these distant countries, may interest those who prefer travelling for half-an-hour when seated in their arm-chairs.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I. PAGE

THE CITY OF THE SUN 1

CHAPTER II.

THE HOUR OF PRAYER 21

CHAPTER III.

SECTS 40

CHAPTER IV.

THE HAREM 54

CHAPTER V.

THE HAPPY VALLEY 82

CHAPTER VI.

AN EASTERN BANQUET 99

CHAPTER VII.

EUPATORIA 111

CHAPTER VIII.

SEVASTOPOL 125

CHAPTER IX.

TRACES OF WAR 138

CHAPTER X.

VALLEY OF TCHERNAIA 157

CHAPTER XI.

A RUSSIAN INTERIOR 172

CHAPTER XII.

CIRCASSIA 200

CHAPTER XIII.

SOUKOUM 214

CHAPTER XIV.

CIRCASSIAN MEN AND WOMEN 239

CHAPTER XV.

A LAST RIDE 259

CHAPTER XVI.

SINOPE 271

CHAPTER XVII.

STORM-CLOUDS 289

TURKISH HAREMS AND CIRCASSIAN HOMES.

CHAPTER I.

THE CITY OF THE SUN.

It was on a sunny summer morning that an English schooner yacht, that had been tossing about all night on the stormy waves of the Sea of Marmora, rounded the point opposite Scutari, and, gracefully spreading her wings like a white bird, came rapidly on under the influence of the fresh morning breeze, and cast anchor at the entrance of the Golden Horn.

The rattle of the chain had scarcely ceased when up came all the poor sea-sick folk from below, for yachting people can be sea-sick sometimes, whatever may be the popular belief to the contrary.

Never, perhaps, was a greater Babel of tongues heard on board any little vessel. The owner of the yacht, his wife and sister, were English; but there was an Italian governess, a French maid, a German bonne, a Neapolitan captain, a Maltese mate, two children speaking indifferently well most of these languages, and a crew comprising every nation bordering the Mediterranean.

(This little explanation has been given in excuse for the desultory nature of the few pages that are offered, with much diffidence, to a kind public, as they consist principally of extracts from the journals and letters of the various dwellers on board the Claymore.)

Besides these many tongues that were pouring forth expressions of joy and admiration with a vehemence of gesticulation and an energy of tone unknown in northern lands, two canaries, gifted with the most vigorous lungs and the most indefatigable throats, lifted up their shrill voices to add to the general clamour.

All this uproar, however, was but to express the delight every one felt at the unequalled beauty of the scene before them.

“Veder Napoli, e poi morir!” is a well-known saying. Put Constantinople instead of Naples, and the flattering words are equally applicable.

Constantinople has been so often written about that it is useless to describe its lovely aspect in detail. Every one knows that there are minarets and towers rising up, in fairy-like grace, from amid gardens and cypress groves; but “he who would see it aright” should have his first view in all the bright unreality of a sunny summer morning. Soon after dawn, in the tender duskiness of the early hours, when the light steals down shyly from the veiled east, and before the business and noise of a great city begin, Constantinople is like the sleeping beauty in the wood. A great hush is over everything, broken only when the sun comes up in a blaze of light, flooding sea, earth, and city with a “glory” of life and colour.

Then from each minaret is heard the voice of the muezzins, as they summon the faithful to prayers. The fairy-like caïques skim in every direction across the waters; and the beautifully-named but dirty and somewhat ugly Golden Horn is all astir with moving vessels.

Nearly opposite the yacht was a very handsome building of white Greek marble, with an immense frontage to the sea. This is the Sultan’s palace of Dolmé-Batché. The wing on the right, where the windows are closely barred and jealously latticed, contains the apartments of the ladies of the Imperial harem.

Behind the palace, stretching up the hill and crowning its summit, are seen the white, handsome houses that form the fashionable suburb of Pera. Here ambassadors and bankers have large, comfortable hotels; here, too, are the European shops, and the promenade for the Christian world. But the part to see—the part that interests—is, of course, the old Turkish quarter, Stamboul; for in Stamboul are Turks in turbans, and in Stamboul are real Turkish houses.

More tumble-down places it would be difficult to find. A man had need to be a fatalist to live in a house of which all the four walls lean at different angles. A fire, instead of a misfortune, must be a real blessing, were it only to bring some air into the dirty, narrow, ill-savoured streets.

The dirt, the narrowness, and the wretchedly bad pavement, combined with another trouble, the multitude of dogs lying about, make walking, pain and grief to the newly-arrived foreigner.

Besides these disagreeables, there is the danger of being crushed flat against a wall by human beasts of burden called “hamals” or porters. It is really frightful to see men so laden.

As they come staggering along, bent double beneath their loads, at every few steps they utter a loud cry, to warn passers-by to get out of their way. It is, however, by no means an easy matter to avoid them. The streets are so narrow and tortuous that, after jumping hastily aside to escape one monstrous package coming up the road, the unhappy stranger is nearly knocked over by another huge load coming down. Dogs’ tails, too, are always lying where dogs’ tails should not be; and in the agitation and anxiety caused by incessantly darting from side to side of the street to avoid the groaning “hamals,” it is exceedingly difficult to avoid treading occasionally on one of these inconvenient tails, and then the whole quarter resounds with hideous howlings.

The bazaars have been so well and so fully described that it is needless to say much about them. Our first sensation on seeing them was, perhaps, that of a little disappointment; but after a time we better appreciated the picturesque beauty and richness of colouring that the long dark lanes of little shops presented.

As a rule, few pretty things, excepting shoes and slippers, are exposed on the stalls. Rugs, carpets, shawls, and jewels are generally kept behind the shops in cupboards and warehouses.

Turquoises were very abundant and low in price, but all we saw were of inferior quality, and the large stones had some flaw. Pretty melon-shaped caskets are made in silver to hold cakes, and the silver rose-water bottles are charming both in design and workmanship. Foreigners are speedily attracted to the drug bazaar by the odd mixture of pungent, pleasant, and disagreeable odours that proceed from it. Here the scene is like a living picture of the “Arabian Nights’ Tales.” Like Amine in the story of “The Three Calenders,” many a veiled figure attended by her black slave may be seen making her purchases of drugs and spices of the venerable old doctors, who, with spectacles on nose, and huge musty folios at their side, look the very personification of wisdom, equally able to administer medicines and to draw the horoscopes of their patients.

The arms bazaar is also attractive, not only for the magnificence and value of its contents, but from the picturesque beauty of the quaint, dark, lofty old building in which the richly-decorated weapons are displayed.

At first, the immense amount of bargaining that is required before any purchase can be effected is very amusing; but after some weeks it becomes tiresome, even to people who have had many years’ experience in Italy.

If anything of importance has to be bought, many hours, sometimes many days, elapse between the opening of the business and its conclusion.

The friends of both parties cordially assist in the affair with the utmost force of their lungs, and an amount of falsehood is told by Christians as well as Turks that ought to lie heavily on the consciences of all; but “do in Turkey as the Turks do,” is a maxim which all appear to accept, and so no one dreams of speaking the truth in a Constantinople bazaar.

When the struggle is at its height, coffee is brought, which materially recruits the strength of all concerned, and should the affair be very important, a friendly pipe is smoked; then everyone sets to work again, vowing, protesting, denying. The seller asserts by all that is holy that he will lose money, but that such is the love he feels for the stranger and the Frank, that he will sell the article to him for such and such a price (probably four times as much as the sum he means to take), and at length, after an exhausting afternoon, the foreigner retires triumphant, bearing away with him the coveted shawls or carpets, and not having paid perhaps more than double the money they are worth.

As we remained on the Bosphorus for a considerable part of the summer, we were enabled not only to see at our ease the many objects of interest to be found in Constantinople and the lovely country that surrounds it, but also to gratify the great wish we had of becoming somewhat acquainted with Turkish life, and of learning something of the realities of Turkish homes.

Every year it is more difficult for passing travellers to gain admittance to the harems. Of course the members of the principal families object to be made a show of, and equally of course the wives of the diplomatists residing in Constantinople are unwilling to intrude too frequently upon the privacy of these ladies. A Turkish visit also entails a somewhat serious loss of time, as it generally lasts from mid-day to sunset.

When royal and other very great ladies arrive at Constantinople, certain grand fêtes are given to them in different official houses, but these magnificent breakfasts and dinners do not give Europeans a better knowledge of Turkish homes than a dinner or ball at Buckingham Palace or the Tuileries would give a Turk respecting the nature of domestic life in England or France.

The wives of several diplomats had given us letters of introduction to many of their friends at Constantinople, and so kindly were these responded to by the Turkish ladies that we found ourselves received at once with the greatest cordiality, and before we left the shores of the Bosphorus had made friendships that we heartily trust we may be fortunate enough to renew at some future day.

After a stay of several months, our conviction was that it would be difficult to find people more kind-hearted, more simple-mannered, or more sweet-tempered than the Turkish women.

The servants, or slaves, are treated with a kindness and consideration that many Christian households would do well to imitate. They seem quite part of the family, and in fact a woman slave does belong to it should she have a child, as she then is entitled to her freedom, and her master is bound to accord her certain privileges which give her a position higher than that of a servant, though she does not attain the dignity of being a wife.

The greatest punishment we have heard of, and which is only inflicted on viragos whose tongues set the whole harem in a flame, is to sell (or what is still worse) to give them away to a family of inferior rank.

This is considered a frightful indignity, and one which, when seriously threatened, usually suffices to still the veriest shrew.

Of course a jealous and perhaps neglected wife may occasionally make a pretty young odalisk’s life somewhat uncomfortable, but harsh usage and cruelty are almost unknown; and in general the wife (for now there is seldom more than one) is quite satisfied if her authority is upheld, and if she remain the supreme head of the household. If content on these matters, she rarely troubles herself about the amusements of her husband.

A Turkish woman also rapidly becomes old, and after a few years of youth finds her principal happiness in the care of her children, in eating, in the gossip at the bath, and in the weekly drive to the Valley of the Sweet Waters.

A Turkish wife, whatever her rank, is always at home at sunset to receive her husband, and to present him with his pipe and slippers when, his daily work over, he comes to enjoy the repose of his harem.

In most households also the wife superintends her husband’s dinner, and has the entire control over all domestic affairs.

The greatest charm of the Turkish ladies consists in the perfect simplicity of their manners, and in the total absence of all pretence.

When we knew them better, the childlike frankness with which they talked was both amusing and pleasant; but many of them nevertheless were shrewd and intelligent, and had they received anything like adequate education, would have been able to compete with some of the most talented of their European sisters.

As mothers, their tenderness is unequalled, but their fault here is over-indulgence of the children, who, until ten or twelve years of age, are permitted to do everything they like.

Many of the ladies whose acquaintance we made showed a remarkably quick ear, and great facility in learning various songs and pieces of music that we gave them. Their voices were sweet and melodious, and it was surprising with what rapidity they caught the Italian and Neapolitan airs that they heard us sing.

The great bar to any real progress being made towards their due education, and the enlargement of their minds, is the seclusion in which they live.

Men and women are evidently not intended to live socially apart, for each deteriorates by the separation. Men who live only with other men become rough, selfish, and coarse; whilst women, when entirely limited to the conversation of their own sex, grow indolent, narrow-minded, and scandal-loving. Like flint and steel, the brilliant spark only comes forth when the necessary amount of friction has been applied.

Whatever degree of intimacy may be attained, it is rare that foreigners obtain a knowledge of more than the surface of Turkish life and manners. Strangers, therefore, should speak with much caution and reserve; but still, even a casual observer must perceive that polygamy and the singular laws regarding succession are productive of innumerable evils amongst the Turks.

The men, it is said, have but little, if any, love for their offspring. Not only do they dislike the expense of bringing up children, but fathers dread having sons who in time may become their most dangerous enemies.

In quiet families who live apart from public life the boys have a better chance of being spared. In families of very high rank but few are to be seen, whilst in the households of the relatives of the Sultan they are still more rare.

Infanticide, therefore, prevails extensively; it is hinted at without scruple; in fact, the Turks, both men and women, do not hesitate to express their surprise that Europeans encumber themselves with large families.

In the Imperial House, the throne descends in succession to each son of a deceased Sultan before any grandson can inherit. This regulation was made in order that the monarch should be the nearest living relative of the Prophet.

In olden times, therefore, the first act of a Sultan on ascending the throne was to get rid of all his brothers by imprisonment or death, not only for the purpose of securing the crown for his own children, but to prevent the risk that might accrue to himself by there being a grown-up successor ready to usurp his place.

Personal merit used to be a matter of comparative indifference to the Turks, provided the Sultan were a member of the great imperial family. Occasionally therefore monarchs, who had reason to believe themselves much hated by their subjects, have not hesitated to sacrifice their own offspring to their fears.

The late Sultan, Abd-ul-Medjid, was thought a wonder of liberality because he permitted his brother, the present Sultan, to live. But Abd-ul-Medjid’s heart had been softened by a sorrow he had had in early life. Shortly before he came to the throne he had a favourite odalisk, to whom he was much attached. In those days none of the royal princes were permitted to become fathers, and the poor girl fell a sacrifice to the State policy which forbade her becoming the mother of a living child. Within a week of her death Sultan Mahmoud died, and his son ascended the throne. Had the odalisk lived and had a son, she would have enjoyed the rank of first “Kadun” to the reigning monarch.

The Sultan’s rank is so elevated—his position is so far above that of every other mortal—that there is no woman on earth sufficiently his equal to enable him to marry her. He has, therefore, no legal wife, but his ladies are called “Kaduns,” or companions, and the mother of his eldest son is always chief kadun, a position that gives her many advantages. These ladies are not called sultanas, for only the princesses of the blood-royal enjoy that title, but the mother of the reigning sovereign is named Sultan-Validé.

Occasionally, when there is a subject whom the Sultan wishes especially to honour, the favoured pasha has one of the monarch’s daughters or sisters given to him in marriage; but this great distinction is sometimes the cause of much sorrow, and uproots much domestic happiness, as all other wives must be sent away, and the children of such marriages equally banished, before the royal bride will condescend to enter the pasha’s harem. Even after marriage, the royal lady will sometimes insist upon retaining all the privileges of her rank, and in that case the husband becomes the veriest slave imaginable, never daring to enter the harem unless summoned by the princess, and when there often obliged to remain standing while receiving the orders of his imperial and imperious wife. F—— Pasha, though his ambition was gratified by becoming the brother-in-law of the Sultan, paid somewhat dearly, if reports be true, for the honour of this royal alliance, as the princess was said to be a lady of uncertain temper, or rather of a very certain temper, as Charles Dickens described it. At any rate F—— Pasha’s heart clung to the forsaken wife and children of his humbler and perhaps happier days; and sometimes in the dusk of the evening a small, undecorated caïque, containing a man closely muffled up, might be seen darting swiftly across the Bosphorus from the palace of the lordly pasha to the remote quarter of Scutari, where, in a humble house in a back street, were hid away the poor deserted wife and her little children.

All, therefore, is not gold that glitters in the lives of the members of the imperial family, and the State policy that ordains there shall not be too many heirs near the throne often wrings the heart and embitters the existence of many of the tender-hearted princesses.

Although the men probably accept the necessities of this policy with comparative indifference, the mothers do not so easily resign themselves to the loss of their infants, and many a sad story gets whispered about of the grievous struggles some of the poor creatures have made to preserve their little ones from the impending doom.

The death of one royal lady that took place while we were at Constantinople, was hastened by the grief she had gone through by thus losing her only boy.

When her marriage took place, she had obtained the promise that all her children were to be spared. In due time a boy was born, and the father received an intimation that the child had better “cease to be.” The Sultana, however, claimed the fulfilment of the promise that had been made her, and watched and guarded the little fellow most rigorously.

The Sultan’s word being inviolable, it was not possible to break it openly, but the mother was aware of the jealousy that was created by the privilege accorded to her, and knew that the child’s life was in constant peril. It is said that attempts were made both to poison and to drown him, but these cruel designs were frustrated by the vigilance of his mother, who never suffered the child to be absent from her.

When the boy was between two and three years old, two more of the Sultan’s daughters married, and many magnificent fêtes were given on the occasion. The elder sister was of course present, accompanied as usual by her little son; but one day in the crowd the child disappeared, and has never since been heard of.

Although the poor mother had another child, a girl, she never held up her head again after the disappearance of her boy, and actually pined away and died from grief at his loss.

This is not a solitary instance of the sorrows of royal Turkish ladies.

As we became more intimate with the inhabitants of the harem, and were able to understand and express ourselves a little better, our friends made themselves very merry at the expense of some of our Frank customs. Few of our habits appeared to them more ludicrous than that of the men so incessantly raising their hats.

When quarrelling, it is a common mode of abuse to say, “May your fatigued and hated soul, when it arrives in purgatory, find no more rest than a Giaour’s hat enjoys on earth!”

The Turkish language is rich and euphonious, and is capable of so much variety of expression that it is remarkably well adapted to poetry. The verses we occasionally heard recited had a rhythm that was exceedingly agreeable to the ear.

Though improvements do not march on in Turkey with giant strides, still progress is being made surely, though slowly; and many of the Turks, besides being well educated in other respects, now speak Italian, English, and French with much fluency. Some of the ladies, also, are beginning to learn these languages, although most of them, excepting those very few who have been abroad, are too shy to venture to speak in a foreign tongue.

The Sultan’s mother—the Sultan-Validé—was a very superior woman, and did much good service towards promoting education. Amongst other of her excellent deeds, she founded a college for the instruction of young candidates for public offices.

There are now in Constantinople medical, naval, and agricultural schools, all well attended, and fairly well looked after.

For the women, private tuition is of course their only means of learning, and not only is the supply of governesses very limited, but their abilities are in general of a very mediocre description.

Unless in very superior families, a little—a very little Arabic, to enable them to read, though not to understand, the Koran, working, knitting, and perhaps a slight acquaintance with French and music, is deemed amply sufficient knowledge for daughters to acquire.

CHAPTER II.

THE HOUR OF PRAYER.

There is much that is both grand and poetical in many of the practices of the Mohammedan religion; and few things strike the stranger more than the frequent calls to prayer that resound at certain hours of the day from every minaret of the city.

The formula used is simple, but heart-stirring: “Allah akbar! Allah akbar! Great God! Great God! There is no God but God! I declare that Mohammed is the apostle of God! O great Redeemer! O Ruler of the universe! Great God! Great God! There is no God but God.”

This is chanted by the muezzin in a loud but musical voice as he walks slowly around the minaret, thus summoning from every portion of the globe the faithful to join him in holy prayer.

At sunrise, at mid-day, at three o’clock, and again at nine, the sacred cry re-echoes above the city, and every true believer as it reaches his ear prostrates himself with his face towards Mecca, exclaiming: “There is no power, no might, but in God Almighty.”

All who can, perform their devotions in the mosques, although earnest prayer is quite as efficacious when made in a house or by the road-side.

One Friday, having provided ourselves with the necessary firman, we repaired to Santa Sophia, and arrived there a few minutes before the hour of mid-day prayer. Franks are now admitted into the mosque, but have to put on slippers over their boots, that they may not defile the exquisite cleanliness of the floor. As the service was about to begin, we went up to one of the galleries, and from thence had a good general view of the interior.

Nothing could be more simple. There was as little decoration as would be found in a low-church Protestant chapel. A few ostrich eggs and some large candelabra hung from the roof, but all the Christian paintings and ornaments have been destroyed or defaced. The figures and the six wings of the famous cherubim can still be seen faintly traced on the dome, but the faces of the angels have been covered with golden plates, as the Turks interpret very literally the commandment against idolatry.

Although there was but little to see in the mosque itself apart from its historical associations, the vast assemblage of worshippers that nearly filled its spacious area was most interesting to behold.

Stamboul (in which quarter is Santa Sophia) is now principally inhabited by old-fashioned Turks, and by large colonies of Circassians. Many of the worshippers, therefore, wore the flowing robe and stately turban now nearly banished from the more fashionable parts of the town. The Circassians also were habited in their picturesque national costume, and it would be impossible to see anywhere men more dignified or noble in appearance than these poor exiles.

The service is impressive from its grand simplicity. As the hour of noon is proclaimed, the Imaun places himself before a small niche called the Mihrab, that points towards Mecca, and in a loud voice proclaims, “Allah akbar! Allah akbar!” The congregation arise, respond with the same words, and the cry seems, like a mighty wave, to roll backward and forward through the vast space.

Every man then turns his eyes humbly to the ground as the Imaun recites the Fatiha or Lord’s Prayer:

“In the name of the most merciful God; praise be to God the Lord of all creatures, the most merciful, the Lord of the Day of Judgment. Thee do we worship, and of Thee do we beg help, direct us in the right way. Direct us in the way of those to whom Thou hast been gracious; not of those against whom thou art incensed, nor of those who go astray. Ameen, ameen!”

The congregation then prostrate themselves repeatedly in acknowledgment of the Almighty’s power and might. A chapter of the Koran is read, followed by more prostrations, with another prayer in which the worshippers join. Then the Imaun calls out in a loud voice that each man is to make his private prayer, and the solemn silence and perfect quiet that ensues is most impressive.

Prayers were now over, and those who wished retired. The remainder approached nearer a small pulpit into which another Imaun mounted, who, seated cross-legged on a cushion, commenced an exposition of some portion of the Koran.

No women had hitherto been present during the service, but a few now entered and seated themselves behind the men.

When we walked round the mosque to examine it in detail, we were shown the mark said to have been made by the hand of Sultan Mahmoud when he placed it upon one of the great columns in token that he took possession of the stronghold of the Christian faith. As the spot indicated, however, is at least fifteen feet from the ground, we permitted ourselves to doubt the accuracy of the statement.

After leaving Santa Sophia we passed through the largest square in Constantinople, called Ak’ Meidan, or the “place of meat.” Here it was that the Janissaries were put to death by the orders of Sultan Mahmoud. This wholesale massacre, fearful as it was, and cruel as it seemed, nevertheless delivered Turkey from one of its greatest scourges, for such was the rapacity, the cruelty, and the overbearing insolence of these famous troops, that no man’s life or property was safe for an hour, and the whole country groaned under a tyranny more oppressive than any it had ever known.

After Santa Sophia, the finest mosque in Constantinople is that of Sultan Ahmed. It is a large and handsome building; its six tall, graceful minarets giving much beauty to the exterior, whilst the interior is chiefly remarkable for the eleven gigantic columns that support the roof. The mosque possesses some very fine Korans all richly bound in velvet, some of them even encrusted with pearls and precious stones. There is also a magnificent collection of jewelled cups that have been presented by various sultans and by many rich pashas.

When we issued forth from the cool freshness of the shady mosque, the burning glare of the sun seemed doubly oppressive. We were thankful even to climb into the little telega that was awaiting us; fleas and tight squeezing seeming slight evils compared with the scorching heat and blinding vividness of the sun’s rays.

When we halted at the beautiful fountain of Ahmed the Third, never did water and marble look more delicious and refreshing.

This celebrated fountain is one of the most beautiful little buildings in Constantinople. It is an octagon made of white marble, the projecting roof extending far beyond the walls. Where gilt lattice-work has not been let into the sides they are covered with inscriptions in gold letters, extolling the virtues of the treasure it contains; for the waters of the Fountain of Ahmed are said to excel in freshness and purity even those of the Holy Well of the Prophet at Mecca, and have been in many poems compared to the Sacred Fount whose eternal spring has its rise in Paradise itself.

On a little marble slab outside the building are arranged rows of brass cups full of the fresh water so precious to the hot and weary passenger in Constantinople.

As we lingered in the grateful shade, thankful to escape, even for a few minutes, from the scorching heat, two poor hamals came staggering down the street, bent nearly double beneath their terrible loads. With almost a groan of relief they came beneath the shelter of the projecting roof, and, dropping their packs, seated themselves on the fresh, cool marble pavement. It was now three o’clock, and, pouring a few cups of water over their hands and feet, they prostrated themselves towards Mecca, and remained an instant in silent prayer.

These poor fellows, notwithstanding their galling toil, are a merry, contented race of people. From dawn to sunset they work like beasts of burden, and are satisfied with food that would kill an English workman in a week. Our two neighbours each pulled a very small bit of black bread from his pocket, got a slice of melon from an adjacent fruit stall, and this slender fare, washed down by a few cups of water, made their dinner for the day. The repast, slight as it was, was eaten with a cheerfulness and satisfaction that might have been envied by many a gourmand.

At sunset, however, they feel themselves amply repaid for the fatigues of the day if they can but gain enough to indulge in an infinite number of cups of the strongest coffee, which, with the soothing pipe, gives them strength to sustain their prodigious toil.

One ought to visit the East to appreciate, to its full extent, the blessing of an abundance of fresh and pure water. No wonder that the Prophet says that he who bestows the treasure of a fountain on his fellow-men shall be sustained by the supporting hand of the Angel of Mercy as he traverses the perilous bridge made of a single hair, by which alone the gates of Paradise can be reached.

Fresh springs of water, also, are doubly dear to the hearts of the faithful, as by the direct miracle of sending water in the wilderness was the life of Ishmael saved when Sarai succeeded in having the child and his mother Hagar banished from the tents of Abraham.

Wandering far into the recesses of the desert, the small bottle of water with which she had been provided speedily became empty, and the sorrowing and forsaken woman found herself in the terrible wilderness alone, and far from the aid of man. She placed her hapless infant beneath some shrubs, and, retiring to a distance that she might not see the little creature die, the unhappy mother lifted up her voice and wept.

But when was the Almighty deaf to the cry of the afflicted and oppressed? He hears when men’s ears and hearts are closed; and, swift as thought, the Angel of Compassion, that watches day and night at the foot of God’s throne, sped from his heavenly post and touched the barren earth. The faint flutter of the angel’s wings roused the poor mother from her grief: she turned and beheld, gushing brightly from the rock, the stream whose crystal waters brought salvation to herself and to her child.

Although it is the custom to inveigh energetically against the folly of seeing too many sights at once, yet old travellers know full well that no town is really enjoyable until all the wonders of it have been visited.

Then, and not till then, is there rest for mind and body, as, all necessary sights seen, the traveller can seek again the especial objects of his fancy, and in peace and ease make more intimate acquaintance with the scenes of nature, or of art, that have the most charm for him.

Most people, probably, will acknowledge that the former have a considerable supremacy over the latter in Constantinople. There are no picture-galleries, and, excepting some of the mosques, a few palaces, and the Seraglio, there are few buildings to interest a lover of architecture.

The Seraglio, however, is well worth a visit, for, though neither grand, nor beautiful, it is interesting in many ways; and the position it occupies on rising ground at the entrance of the Golden Horn (thus commanding the Bosphorus both east and west) makes the views from its gardens quite unequalled in beauty.

The summer was unusually hot, so that it was often quite an effort to tear ourselves away from the cool rooms and delightful garden of the Embassy at Therapia, where we were staying, and undertake a regular afternoon of sight-seeing, especially also as it was necessary to go to Stamboul, or Pera, in one of the hot little steamers that ply incessantly up and down the Bosphorus.

One intensely hot day, however, we set off for the Seraglio, and the thermometer being at any number of degrees, and the deck of the steamer so crowded that there was barely standing room, we arrived at the gate of the Palace in a very exhausted state. When we entered the first court therefore, and found ourselves under the shade of a gigantic plane-tree, a faint breeze every now and then rustling amongst the leaves, the change was so pleasant that we thought we would give up sight seeing, and stay there till night.

Not only was the cool shade very grateful to our feelings, but the pretty scene before us was very pleasant to the eyes. Beneath the tree was a small fountain, its stream trickling into a shallow marble basin, and on its brink were seated groups of gaily-dressed women, chattering merrily as they ate melon and sweetmeats.

Having never been in Spain, we are ignorant of the witching grace bestowed upon the fair or unfair Spaniard by the magic folds of the mantilla; but not having had that good fortune, we all agreed that no head-dress is so becoming to the female face as the Turkish veil, worn as it is arranged at Constantinople.

Great art and much consideration are bestowed upon the arrangement of the folds; and in this respect a lady of Constantinople is as much superior to her Eastern compeers as a “lionne” in Paris would be above her provincial rivals.

So coquettishly is the transparent muslin folded over the nose and mouth, so tenderly does it veil the forehead, that the delicate cloud seems but to heighten and increase each charm. Far, very far is it from hiding the features from the profaning gaze of man, as was so savagely ordained by Mohammed.

Nose, mouth, and forehead being thus softly shadowed, the great luminous eyes shine out with doubled brilliancy and effect.

It is some consolation to Frank ladies to know that, excepting that never-to-be-sufficiently praised veil, Turkish out-door costume is absolutely hideous.

A large loose cloak called a “feredje” is thrown over the in-door dress, and this is so long that it has to be gathered up in front when the wearer walks, thus giving her the appearance of a moving bag or bundle. The huge, unshapely yellow boots also give a very ungainly appearance. Some of the fashionable ladies, however, are discarding these ugly over-alls, and are adopting French boots without heels.

Near the wall were drawn up “arabas” waiting for the ladies, and very magnificent “turn-outs” they were.

An araba is a native carriage that is much used by women, as it easily contains eight or ten persons. In shape it is something between a char-à-banc and a waggon, but is without springs. It is generally very gaily decorated and painted, and is comfortably cushioned inside. The top is covered with a thick red, green, or blue cloth that is fringed with gold. The white oxen that draw the carriages are generally beautiful creatures, and are also brilliantly adorned with red trappings and tassels, and have sometimes their foreheads painted bright pink or blue.

After a time our exhausted bodies became somewhat refreshed, and our crushed minds began to revive, and to face more courageously the duties of the day; so at last, summoning a strong resolution, we rushed across the hot court and over another burning “place,” where the gravel felt as if it had been baked in an oven, and found ourselves in the Imperial armoury.

It was formerly an old chapel, and the remains of a great white marble cross at one end seemed to rebuke the desecration it is suffering.

There are some magnificent scimitars, made of the finest Damascus steel, and some of the hilts and scabbards are of gold, thickly encrusted with precious stones, but beyond these valuable decorations the collection of arms did not appear to be of much value. There are some hundreds of old matchlocks of an obsolete form, and probably of doubtful utility.

Amongst the curiosities are shown the Bells of Santa Sophia when it was a Christian church, the ancient keys of Constantinople, and the gorgeous scimitar of Sultan Mahmoud.

The Palace is but an assemblage of small buildings joined together by passages, and added to, from time to time, by successive sovereigns.

We passed through many large rooms or saloons, very handsome as to size, and richly ornamented with painting and gilding; but we thought them too low for their length, a defect that is increased by the heavy decorations of the ceilings.

There was but little furniture—only a few hard chairs besides the usual divan, and sometimes a console table with a French clock upon it.

Some of the smaller rooms were painted in arabesques, and had portières of blue or red satin over the doors.

From the position of the Palace, however, the views from the great recesses, full of windows, were quite enchanting.

A long low passage, hung with indifferent French and English prints, representing naval battles, storms at sea, &c., led to the bath-rooms—a pretty little set of apartments, with domed ceilings, beautifully fretted and painted.

The Sultan, however, has long ceased to reside here, and only comes on certain stated occasions, such as after the feast of the Bairam.

The grand procession from the mosque on that day is a magnificent pageant.

A crowd of court pages, resplendent with gold embroidery and brilliant dresses, precede the monarch, who, mounted on a matchless snow-white Arabian steed, rides slowly on, surrounded by all the great dignitaries of the Empire. The Pashas, habited in their state uniforms, are a mass of gold and precious stones, their saddles and the trappings of their horses being equally gorgeous.

Amidst all the magnificence of this group the Sultan alone is dressed with simplicity. He wears a dark frock coat with but little embroidery about it; but on the front of his fez and on the hilt of his sword blaze the enormous diamonds that are the pride of the Imperial treasury, while the housings of his Arab are almost hidden by the pearls and precious stones by which they are adorned.

On arriving at the Seraglio the Sultan proceeds to the throne-room, and there receives all his great officers of state. Ambassadors and foreign ministers are received at other times.

The Sultan goes in state to the mosque every Friday, and when he is then passing through the streets his people may approach him to present petitions.

The “temennah,” as the ordinary mode of salutation is termed, is a very graceful gesticulation. The hand is bent towards the ground, as if to take up the hem of the superior’s garment, and then pressed on the heart, forehead, and lips, to signify both humility and affection.

To call the pleasure-grounds that surround the Seraglio gardens, is a misnomer according to the European idea of what a garden should be, for there is scarcely a flower to be seen. They are a series of beautiful wildernesses, where the nightingales sing from the tangled thickets, and where each turn in the pathway, each opening amongst the trees, discloses some enchanting view, either of the bright blue Bosphorus, or of the misty grey of the distant mountains, or gives a peep of the city itself, whose innumerable domes and minarets rise dazzlingly white above the dark masses of cypress, their gilded crescents flashing brightly in the brilliant sunshine.

The soft rustling of the breeze amongst the trees, the sweet scent of the cypresses and flowering shrubs, all invited to a halt, and we seated ourselves on a piece of old wall, and idly watched the caïques as they glided across the Bosphorus.

Near us was a low gateway projecting over the sea, and in olden times its portals never opened, save when the sack was borne forth, that contained sometimes the living body of those odalisks whose conduct had not been sans reproche. In later years it is believed that these unhappy women were taken to a fortress called Roumel-Hissei, or Castles in Europe, and there strangled. Their bodies, sewn up in a sack, were then thrown into the middle of the stream, where the strength of the current would rapidly carry them out to sea. At any rate, whatever their punishment, the extent of it is never known beyond the walls of the Imperial Harem.

The flocks of little birds that are seen skimming so rapidly and so restlessly over the waves of the Bosphorus, are supposed by the Turks to be the souls of these unfortunates, who, for their great sin, are for ever condemned to seek in vain the lover who had led them astray.

CHAPTER III.

SECTS.

Although in olden times the Moslems were both cruel and fanatical in forcing their religion upon conquered nations, the Turks of to-day are exceedingly tolerant, and unlike the Mohammedans of Syria and Asia Minor, who abhor every denomination of Christians, permit Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Greek chapels to be erected without opposition in the neighbourhood of Constantinople.

Indeed, at this present time, the Sheyees, as the followers of Ali are called, are hated by the orthodox party, or Sünnees, far more intensely than any sects of Christians are.

However, notwithstanding the religious warfare that rages between the heads of these two great parties, almost every description of worship is tolerated by the Government, and there are as many Dissenters therefore in Constantinople as could be found in London. One of the most popular sects, especially amongst the lower classes, is that of the Dancing Dervishes, and it is a curious though a somewhat humiliating spectacle, to see by what extraordinary means men seek to do homage to their Creator.

The Dervishes assemble every Tuesday and Friday, the ceremonial being the same on both days. On arriving at the Tekké, or place of worship, we were taken to a large room on the upper storey. A gallery ran round three sides of this apartment, portions of it being partitioned off for the use of the Sultan and of Turkish ladies.

A large circular space is railed off in the centre of the room and reserved for the Dervishes. A few women and children, some Turkish officers and soldiers, were also seated in the gallery near us. No other foreigners were present besides ourselves.

About twenty Dervishes speedily arrived, and their Mollah or Sheik, a venerable old man, with a long white beard, seated himself before the niche that indicated the direction of Mecca. The Dervishes stood before him in a semicircle, without shoes, their arms crossed upon their breasts, and their eyes humbly cast upon the ground. They were all without exception pallid and haggard, and apparently belonged to quite the lower classes. One was a mere boy of about thirteen or fourteen, another was blind, a third was a negro.

After a few sentences, recited from the Koran, the Dervishes, headed by their mollah, began to march slowly round and round the enclosure, adapting their steps to the music (if it could be so called) of a tom-tom and a sort of flute, that from time to time uttered a low melancholy wail.

After having made four or five rounds, the mollah returned to his seat, and the Dervishes, throwing off their cloaks, appeared in white jackets and long yellow petticoats.

The mollah began to pray aloud, and, as if inspired by the prayer to which they listened with upturned faces, the Dervishes began to turn round; slowly at first, but then as the heavenly visions became more and more vivid, they extended their arms above their heads, they closed their eyes, and their countenances showed that they were in a trance of ecstatic joy.

The mollah ceased to pray, but round and round went the whirling figures, faster and faster. It was a wonderful sight, so many men moving with such rapidity, all apparently unconscious, yet never did one touch the other.

The only sound heard was the occasional flutter of a petticoat, and the unearthly noise of the music from the gallery, for as the movements became more rapid, so did the tom-tom increase in vehemence, and the wailings of the flute became more and more dismally dreadful.

The effect was singular upon us spectators in the gallery. After a time many of our neighbours seemed to become, as it were, infected with the extraordinary scene below, their eyes became fixed, and they began rocking themselves to and fro in rhythm with the movements of the Dervishes.

We were also becoming quite giddy from assisting at such a fatiguing religion, when, happily for us, the mollah bowed his head; in an instant each man stopped short, and bowed as quietly as if nothing had happened.

A few prayers and some sentences from the Koran were again recited, and the Dervishes, who were in a state of heat and exhaustion quite distressing to see, resumed their cloaks. They then knelt while more prayers were said. Each man then kissed the hand of the sheik and those of his brother Dervishes. A blessing was pronounced, to which the Dervishes responded by a cry, or rather howl, of Allah-il-Allah, and the ceremony was over. Having seen it, we no longer wondered at the pallid worn-out appearance of the worshippers, for the exhaustion both of mind and body must be very great. The object of the whirling is to distract the mind from earthly things, so as to enable the worshipper to concentrate himself upon the inexpressible joys of Paradise.

The exhibition, however, on the whole was painful. It is always sad to see Our Heavenly Father worshipped in a degrading manner by His children.

The Dancing Dervishes are said to be popular. They mostly lead blameless, inoffensive lives, and are very charitable.

Although the ceremonies of the Howling Dervishes have been much modified, and though many of the revolting cruelties they inflicted upon themselves have been suppressed by law, still the hideous howls and frantic actions to which they yield, as the inspiration possesses them, make their mode of worship a scene at which no woman can properly assist.

Passing one day in a caïque by a Tekké where the service of Howling Dervishes was going on, we were arrested by the most tremendous and savage yell that imagination can picture. So hideous and prolonged was the howl, that it seemed as if it must have come from a menagerie of wild beasts rather than from the throats of human beings.

These miserable fanatics begin their worship by placing their arms on each other’s shoulders, they then draw back a step, and advancing suddenly, each man with a tremendous and savage yell howls forth, “Allah-Allah-Allah-hoo!” which must be repeated a thousand times uninterruptedly. Their countenances become livid, the foam flies from their lips, many of them fall on the floor in strong convulsions, from which they only rise to inflict cruel and horrid tortures upon their own wretched bodies.

The stream that runs through the Bosphorus from the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmora is so strong that it is almost impossible for a vessel to stem the current unless aided by steam. We thankfully, therefore, accepted the kind offer of the captain of the English man-of-war to take us in tow up to Beyuk’dere, a village near the entrance of the Black Sea.

The yacht was made fast apparently to the frigate, and off we set, but such was the force of the stream that, at an awkward corner near Bebek, the immense hawser, that looked as if nothing could break it, snapped in two like a bit of thread, and the yacht spun round with the velocity of an opera-dancer. Happily the danger had been foreseen and guarded against, but we were swept so close in against the shore that the jib-boom knocked down a piece of garden railing, and nearly spitted a most respectable old Turk, who was sitting calmly smoking on his terrace. Some time and much patience were required before the yacht could be again attached to the frigate, but at last two hawsers made her fast, and we proceeded on our way up the Bosphorus.

This beautiful stream is very unique in its characteristics, for while the waters have the depth, brilliancy, and life of the sea, its shores are cultivated and wooded like the banks of a river. The gentle sloping hills are covered with dwelling-houses and kiosks, while the terraces and gardens of stately palaces line the shore. The Turks have much taste, and are also great lovers of flowers. The gardens, therefore, are well laid out, and generally well kept. The climate also is favourable, though the winters are cold, snow sometimes lying on the ground for many days. The beautiful American trumpet-creeper grows in perfection, and may be seen hanging over almost every garden wall, its large bunches of orange-coloured flowers being in lovely contrast with the brilliant green foliage. Orange trees and myrtles do well, although they do not attain the same size and luxuriance as in Sicily and Greece.

Turkish houses are exceedingly picturesque in appearance. They are seldom more than two storeys high, have many irregular projections, and the overhanging roofs extend considerably beyond the walls. They are usually built of wood, and are painted white, stone colour, or pale yellow.

Both inside and out they look exquisitely clean; indeed, inside not a speck of dust is to be seen, the floors are covered with beautiful matting, and the walls are usually painted a delicate cream colour. But, alas! a Turkish house is but a whited sepulchre, for beneath this pure surface vermin prevail to such an extent that at night they come out by hundreds. It is a horrible plague, but by constantly painting and the free use of turpentine, most foreigners succeed in time in ridding their houses of these torments.

We once made a painful experience of the deceptiveness of appearances. During the summer, our evil angel induced us, and the Countess S—, the wife of one of the diplomats, to accept an invitation from a very rich Armenian merchant to assist at the marriage of his daughter. The fêtes were as usual to extend over three days, and we were to be his guests for that period.

The house was magnificent in size, and gorgeously decorated with gold, and velvet, and satin. The dinner, or supper, also was as grand as French and Turkish culinary art could make it. Our entertainers were kind and agreeable people, so we looked forward to a very pleasant visit.

We three Frank ladies had assigned to us as a sleeping apartment an immense saloon, superbly gilt and painted, but having little furniture besides a crimson satin divan, trimmed with gold fringe, that ran round three sides of the room. Adjoining was a small bath-room, and our maids had a room at some distance in another wing of the house.

On retiring to our apartment at night, we found three comfortable-looking beds had been prepared for us in the usual Eastern fashion—that is, laid on the floor.

Each bed had two thick soft mattresses, covered with pale green satin; the pillows were of the same rich material, and covered with cambric; the sheets were also of cambric, beautifully fine and white, and trimmed with broad lace. The coverlets were of green satin, embroidered, and fringed with gold.

Altogether our couches looked very inviting, especially after a long afternoon of civilities, and talk, besides the great dinner, and the long wedding ceremony, which did not take place till midnight.

The lights were put out, and we had just sunk into the pleasant half-conscious dreaminess of a first sleep, when we were thoroughly awakened by a sudden pattering and rush of little feet behind the walls, around, above, and below us, while sundry sharp squeaks announced the neighbourhood of rats.

However, travellers do not allow their night’s rest to be disturbed for trifles; so, covering up our heads, in order to shut out the disagreeable noise, we resolved not to hear, and tried to go to sleep.

But it would not do; an unendurably loud squeal close to Madame S.’s head made her jump up hastily, thinking the rats must be in the room.

We lighted the candles, and then—our feelings can better be imagined than described, when we beheld an invading army of horrors worse than rats, descending the walls, marching over the floor, and creeping out of every little crack and hollow in the woodwork.

In blank dismay we looked at each other. What was to be done? The divans and ottomans had already been taken possession of by the enemy. There was not a cane chair or a table in the room, or we would have mounted upon them.

Help was impossible; there were no bells, we did not feel justified in disturbing the household, and we were ignorant of the whereabouts of our maids’ room.

We were in despair, when a sudden bright inspiration flashed into the mind of one of us. The bath, the clean white marble, seemed to offer a safe refuge. In an instant we were there, and wrapping ourselves up as well as we could, there we remained till morning. Luckily for us it was a warm summer’s night, or we should have caught our deaths of cold, for we were so eager to escape from our hateful enemies that we should have accepted any risk.

There we sat in forlorn discomfort—melancholy warning of the usual end of a party of pleasure. Luckily a sense of the ludicrousness of our position made us merry, for as each caught sight of the other’s dismayed white face, we could not help bursting into fits of laughter, especially when we thought what our friends would have said could they have seen us.

When day came the foe retired; but as speedily as ordinary civility would permit, we took our leave, obliged to pretend important business in Constantinople, and resisting all the kind pressing of our host and his family, for nothing would have induced us to pass another night in such a chamber of horrors.

Our poor maids had slept, but showed lamentable traces of the presence of the foe, who evince decided partiality for fresh and newly-arrived foreigners.

An Armenian wedding has many forms that are akin to those of both the Turkish and Christian services. The ceremony is performed at midnight. The bride is so muffled up in shawls, and veils, and flowing garments, that face and figure are alike invisible. The fair damsel is not seen, but the mass of superb silk, lace, and flashing jewels placed in the middle of the room, indicate her presence. The bridegroom is asked, as he stands opposite to her, “Will you take this girl to be your wife, even if she be lame, deaf, deformed, or blind?” to which, with admirable courage and resignation, he replies, “I will take her.” The officiating priest then joins their hands, a silk cord is tied round the head of each, and, after many prayers and much singing, they are pronounced man and wife.

CHAPTER IV.

THE HAREM.

The first visit to a Harem is a very exhausting business, for everyone feels shy, and everyone is stupid, and the stupidity and shyness last many hours.

We were fortunate, however, in paying our first ceremonious visit to the Harem of R—— Pasha, whose wife enjoys, and deservedly, the reputation of being as kind in manner as she is in heart. Madame P. was so good as to go with us as interpreter. We were afterwards accompanied by a nice old Armenian woman, well known amongst the Turkish ladies, as she attends many of them in their confinements, and is always summoned to assist at weddings and other festivals, besides being often trusted as the confidential agent for making the first overtures in arranging marriages.

Turkish babies have a hard time of it during the first month of their existence. Soon after their birth they are rubbed down with salt, and tightly swaddled in the Italian fashion. The pressure of these bandages is often so great that the circulation becomes impeded, and incisions and scarifications are then made on the hands, feet, and spine, to let out what Turkish doctors and nurses call “the bad blood.” The unhappy little creature is only occasionally released from its bonds, and never thoroughly washed until the sacred month of thirty days has expired, when it is taken with its mother to the bath. No wonder that the sickly and ailing sink under such treatment, and that the mortality amongst infants should be frightful.

Scarcely had our caïque touched the terrace that extends before R—— Pasha’s handsome palace, when a small door, that was hardly noticed in the long line of blank wall, opened as if by magic. We passed through, and found ourselves in a small shady court surrounded by arcades, up the columns of which climbing plants were trained. In the centre was a fountain, with orange trees and masses of flowers arranged around its basin. A broad flight of steps at the end of the court led to the principal apartments.

We were received at the foot of the stairs by two black slaves and several young girls dressed in white, who escorted us to a large saloon on the upper floor. The ceiling of this room was quite magnificent, so richly was it painted and gilt. There was the usual divan, and the floor was covered with delicate matting, but there was no other furniture of any sort.

The walls were exceedingly pretty, being painted cream colour, and bordered with Turkish sentences, laid on in mat or dead gold, a mode of decoration both novel and graceful. We learnt afterwards that many of the phrases were extracts from the Koran; others set forth the name and titles of the hanoum’s father, who had been a minister of much influence and importance.

The windows were closely latticed, but notwithstanding the jealous bars, the views over the Bosphorus and the opposite shore of Asia were enchanting.

Here we were met by H—— Bey, the Pasha’s eldest son, a good-looking boy, about eleven or twelve years of age, also dressed in white, but wearing some magnificent jewels in his fez, and by him conducted to another and smaller apartment, somewhat more furnished than the first, as it had a console table, with the usual clock, a piano, and some stiff hard chairs ranged against the walls.

As we entered the room, the folding-doors opposite were thrown open, and the hanoum (lady of the house), accompanied by her daughter, and attended by a train of women, advanced to meet us.

We had heard that this lady had once been a famous beauty. She was still of an age “à prétention,” that is to say, about thirty-three or five, so we had pictured to ourselves something handsome, graceful, and dignified. We were stricken, therefore, almost dumb with surprise when we saw a woman, apparently nearer sixty than thirty, very short, and enormously fat, roll rather than walk into the room. Her awkward movements were probably as much caused by the extraordinary shape of her gown, as by her unusual size. Her dress, which is called an “enterree,” and was but a slight and slender garment, was made of thin pink silk. It was open to the waist, very scanty in the skirt, and ended in three long tails, each about a yard wide, and which, passing on each side and between her feet, must have made walking quite a matter of difficulty.

This singular robe was fastened round the waist by a white scarf, and certainly did not embellish, nor even conceal the too great exuberance of figure.

To show that she received us as equals and friends, the hanoum wore no stockings, only slippers. When the mistress of the house enters in stockings it is a sign that she considers her visitors to be of inferior rank.

We thought the hanoum’s head-dress as unbecoming as her gown. Her hair was combed down straight on each side of her face, and then cut off short; and she had a coloured gauze handkerchief tied round her head. The eyebrows were painted with antimony, about the width of a finger, from the nose to the roots of the hair, and the eyes were blackened all round the lids. Had the face, however, not been such an enormous size, it would have been handsome, for the eyes were large, black, and well shaped, and the complexion was fair and good; but the nose was too large, and the mouth was spoiled from there being no front teeth. However, she seemed a most good-tempered, kind, merry creature, and she nodded her head and smiled upon us, while uttering a thousand welcoming compliments, as if she were really glad to see her stranger guests.

The daughter was a nice-looking girl, about fourteen or fifteen, with a face that was more bright and intelligent than actually pretty. Her figure was slight and graceful, but nevertheless showed indications that in a few years she, like her mother, might become prematurely fat and faded.

The eyes were marvellously beautiful—so large and lustrous, that they seemed like lamps when the long black lashes were raised; but her mouth was quite spoiled by bad teeth, a singular defect in one so young. But Turkish women almost always lose their teeth early. They seldom use tooth-brushes, and are inordinately fond of sweetmeats, which they eat from morning till night.

The young lady also wore the “enterree,” or tailed dress, which seemed to be a mark of distinction, for all the attendants wore short coats and full white trousers.

Mother and daughter were both dressed with studied simplicity, as Turkish ladies receive at home “en negligé.” It is only when they pay visits that they array themselves sumptuously.

On the present occasion the slaves and women were gorgeously apparelled, and most magnificent was their attire—velvet, satin, cloth of gold, and precious stones quite dazzled the eye. It was in very earnest a scene from the “Arabian Nights.”

When we had been duly placed on the divan, a young slave brought in a tray, on which were a bowl containing a compote of white grapes, another full of gold spoons, several glasses of iced water, &c.

Etiquette requires that a spoonful of the sweetmeat should be eaten, and the spoon then placed in the left-hand bowl. Some iced water is drunk, and then the tips of the fingers only should be delicately wiped with an embroidered napkin presented for the purpose.

A calm and graceful performance of this ceremony marks the “grande dame” amongst Turkish ladies, and many a foreigner has come to grief from being unacquainted with these little details.

In the story of Ivanhoe, Cedric the Saxon is described as having been despised by the Norman courtiers, because he wiped his hands with the napkin, instead of drying them in courtly fashion by waving them in the air; so likewise does a lady lose caste for ever in a Turkish Harem should she rub her hands with the napkin instead of daintily passing it over the tips of her fingers.

Now came more slaves bringing coffee. One carried a silver brazier, on which were smoking several small coffee-pots; another had the cups—lovely little things, made of exquisitely transparent china, and mounted on gold filigree stands; a third carried a round black velvet cloth, embroidered all over in silver. This is used to cover the cups as they are carried away empty.

Narghilés were now brought, and for some minutes we all solemnly puffed away in silence. For myself, personally, this was an anxious moment, for I very much doubted whether my powers as a smoker would enable me to undertake a narghilé, very few whiffs being often enough to make a neophyte faint. I looked at my sister; she was calmly smoking with the serenity and gravity of a Turk. The hanoum’s eyes were fixed on vacancy. She had evidently arrived at her fifth heaven at least. The pretty daughter was looking at me, but I did not dare look at her; so, as there was no escape, I boldly drew in a whiff. Things around looked rather indistinct; however, I mustered up my courage and drew in another. It was not as disagreeable as the first, but the indistinct things seemed to get even fainter, and were, besides, becoming a little black, so I took the hint, and, finding nature had not intended me for a smoker, quietly let my pipe go out. Narghilés are now seldom used in harems except for occasions of ceremony. On all subsequent visits cigarettes were brought, which were much more easily managed.

When the pipes were finished we began to talk, and mutually inquired the names and ages of our respective children. The hanoum has three—the eldest son, H—— Bey, the daughter named Nadèje, and a little fellow about five years old, who came running in very grandly dressed, and with a great aigrette of diamonds in his little fez—evidently mamma’s pet.

H—— Bey wanted very much to talk. But, alas! our Turkish words were sadly few, and conversation through an interpreter soon languishes and becomes irksome. We asked him his age, but he did not know. No Turk ever troubles himself or herself about so trivial a matter. They are satisfied to exist, and think it quite immaterial how many years they may have been in the world.

Amongst the attendants were two very old women, so dried up and so withered that they scarcely looked like women. One of them, who was blind, had been nurse to the hanoum. It was quite charming to see the kindness and tenderness with which these poor old creatures were treated. The blind nurse was carefully placed in a comfortable corner near the windows. H—— Bey constantly went to her, and from time to time, affectionately putting his arm round her neck, seemed to be describing the visitors to her. These old women were the only persons who were allowed to sit in the hanoum’s presence; all the others remained standing in a respectful attitude, their arms crossed, and generally so motionless that they might have been statues but for the restless movement of their eyes.

Remembering the piano, we asked Nadèje if she liked music, and after some persuasion she played some wild Turkish airs with considerable facility and expression.

We were then invited to see the house, which was large and very handsome. Strangers are always at first, however, somewhat bewildered by finding there are no bedrooms; but, in fact, every room is a bedroom, according to necessity or the season.

Hospitality is almost a religious duty amongst the Turks, and every room is surrounded by cupboards, in which are stowed away vast numbers of mattresses and pillows ready for any chance guest who may arrive.

The mattresses are thick and comfortable, and are generally covered with some pale-coloured satin or silk. The beds are made upon the floor, and, besides the mattresses and pillows, have cambric or fine linen sheets and a silk coverlet.

Excepting the bathing apartments attached to the house, no appliances for washing were to be seen anywhere; and these ladies seemed surprised that we considered daily ablution necessary. They assured us that the bath twice a week was quite as much as was good for the health. Daily washing they consider a work of supererogation, so they satisfy themselves with pouring a little rose-water from time to time over their hands and faces.

Upon our expressing a wish to know how the “yashmak,” or veil, was arranged, Nadèje immediately had one put on, to show how it ought to be folded and pinned; and as by this time we had become great friends, it was good-naturedly proposed that we should try the effects of yashmak and “feredje,” and the most beautiful dresses were brought, in which we were to be arrayed.

Further acquaintance with the yashmak increases our admiration for it. The filmy delicacy of the muslin makes it like a vapour, and the exquisite softness of its texture causes it to fall into the most graceful folds.

Some of the feredjes, or cloaks, were magnificent garments. One was made of the richest purple satin, with a broad border of embroidered flowers; another of brocade, so thick that it stood alone; another of blue satin worked with seed pearls.

The jackets, “enterrees,” &c. &c., were brought in piled upon trays and in numbers that seemed countless. A Parisian’s wardrobe would be as nothing compared with the multitude and magnificence of the toilettes spread before us.

The jewels were then exhibited. Turkish jewellers generally mount their stones too heavily, and the cutting is far inferior to that of Amsterdam; but the hanoum had some very fine diamonds, really well set. One aigrette for the hair was exceedingly beautiful. The diamonds were mounted as a bunch of guelder-roses, each rose trembling on its stem. We also much admired a circlet of lilies and butterflies, the antennæ of the butterflies ending in a brilliant of the finest water. There was also a charming ornament for the waist, an immense clasp, made of branches of roses in diamonds, surrounded with wreaths of leaves in pearls and emeralds, a large pear-shaped pearl hanging from each point.

Having inspected the house we paid a visit to the garden, now as full of roses as an eastern garden should be. Terraces made shady by trellises of vines and fig-trees hung over the Bosphorus, and to every pretty view the falling waters of streams and fountains added their pleasant music to aid the soothing influence of the scene. At the end of one terrace was a large conservatory full of beautiful climbing plants; but we were afraid of admiring too much, for H—— Bey had accompanied us, and, after the manner of eastern tales, whenever we praised anything insisted upon giving it to us.

We were now preparing to take leave, but our friend’s hospitality was not yet exhausted; and the hanoum, taking my sister and myself each by the hand, led us into the smaller saloon, where a collation had been prepared.

On a low circular table, or stool, a large tray had been placed, on which were a number of dishes containing melons, grapes, peaches, vegetable marrows, thin slices of cheese, and a variety of sweetmeats. Piles of bread cut into slices were also arranged round the tray. There were forks, but the bread supplied the place of spoons.

When we were all seated, rice, pillau, and little birds roasted in vine leaves were brought in, à la Française. The kabobs and maccaroni had too much garlic in them for our taste, but a very light sort of pastry called “paklava” was excellent, and the rice was perfection. The cooking we thought very good, and a great contrast to an experiment we had made a few days previously, in order to see what ordinary Turkish cookery was like.

One day during our many expeditions for sight-seeing in Constantinople, we were seized by the pangs of hunger several hours before we had arranged to return to Therapia, so espying a very nice clean-looking cook-shop, where a number of cooks, neatly dressed in white, were chopping and frying little scraps of meat, we proceeded there and ordered a dish of kabobs à la Turque. The kabobs in themselves might have been good, and also the fried bread that accompanied them, but a sauce of fat and garlic had been poured over both that made the dish not only uneatable, but unendurable. The good-natured cook seemed surprised at our bad taste, but yielded to European prejudices, and at last brought some plain rice and tomatoes, with which we made an excellent luncheon. The favourite Turkish sweetmeat, called “Rahat-la-Koum,” or Lumps of Delight, is excellent when quite fresh, and makes much better eau sucrée than plain sugar, as there is a slight flavour of orange-peel and roses given to the water.

To return, however, to our little breakfast at R—— Pasha’s; between each course of meat every one took what pleased her from the dishes on the table—fruits, sweetmeats, or cheese, though the latter was the favourite, as it is supposed not only to increase the appetite, but to improve the taste.

Both before and after eating, gold basins and ewers were brought round, and as we held our hands over the former perfumed water was poured upon them. The napkins were so beautifully embroidered in gold thread and coloured silks that it seemed quite a pity to use them for drying the hands. The repast over, coffee and cigarettes again appeared, and then, with many friendly invitations and kindly expressions, we parted.

The hanoum offers us her bath-room, her caïques, and her carriages, and proposes also to teach us Turkish.

In this harem, as is now generally the case in the best Turkish families, there is but one wife.

Our friend, the hanoum, had been a well-portioned bride. She brought her husband, besides the house we had seen, another at Beyuk’dere, considerable property in land, and a large sum of money. Where a daughter is so richly dowered, the father usually stipulates that no other wife shall be taken.

Wives also, in Constantinople, as elsewhere, are expensive luxuries, for each lady must have a separate establishment, besides retinue and carriages.

Marriage in Turkey is not a religious ceremony; it is merely a civil covenant that can be annulled for very trivial reasons by either party. Public opinion, however, pronounces such separations disgraceful, and they are seldom resorted to unless for grave reasons.

A man can put away his wife by pronouncing before a third person that his marriage is “void,” but must in that case resign all the property that his wife has ever possessed. A woman can only obtain a divorce by going before a cadi, and declaring that she yields all her dower and property, and claims her freedom. Should there be children, the mother, if she so elects, can retain the girls with her until they are seven years old; after that age they return to their father’s house, unless an especial arrangement has been made to the contrary.

A Turkish bath, when taken in a private house, is but a repetition of the ceremony that may be gone through in any of the principal bathing establishments in London and Paris; but public Turkish baths are quite national institutions, and often afford so many amusing and interesting scenes of real life that no foreigner should omit to visit them.

Wednesday is the day usually set apart for the Turkish women; Greek women have Saturday; the other days are allotted to the men.

The first time we went to the bath, we were quite oppressed with the extent of the preparations that our friends seemed to think absolutely necessary. Ladies are always attended by their own servants, and besides providing themselves with the necessary linen and toilet appendages, bring all the materials for the subsequent repast, with coffee and pipes.

Besides several dressing-gowns, there was quite a mountain of towels, so large that they might almost be called sheets; some of them long and narrow for wrapping round the head and drying the hair. There were wonderful-looking yellow gloves, of various degrees of coarseness, for rubbing. As we looked at them we quite shuddered at the thought of what we should have to endure. Then there were tall wooden clogs, to enable us to walk across the heated floors; and bowls of metal for pouring boiling water upon us. Besides these and many other implements apparently for torture, there were brushes and combs, various sorts of soap for washing, for rubbing, and for perfuming; bottles of scented waters, rugs, mattresses, looking-glasses; and, in addition to the basket containing cups, plates, and dishes, with all the paraphernalia for luncheon, there was a large box full of perfumes.

Perfumes in the East are not only countless in number, but of a strength almost overpowering to Western nerves. Literally, not only every flower, but every fruit, is pressed into the service of the perfumer.

First in rank and potency is the far-famed attar-gûl, of which one pure drop suffices to scent for years the stuff on which it is poured. The fine aromatic perfume of the orange and cinnamon flowers is well known, and the more delicate fragrance of the violet is preserved with all its fresh charm. Still, a box of Turkish perfumes is almost overpowering from its excess of sweetness; and, with the exception of the violets, we preferred the bottles unopened.