автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Chaucer's Works, Volume 2 (of 7) — Boethius and Troilus

Transcriber's note:

A Glossary including words from the two texts in this volume is included in Skeat's Volume VI, available from Project Gutenberg

here.

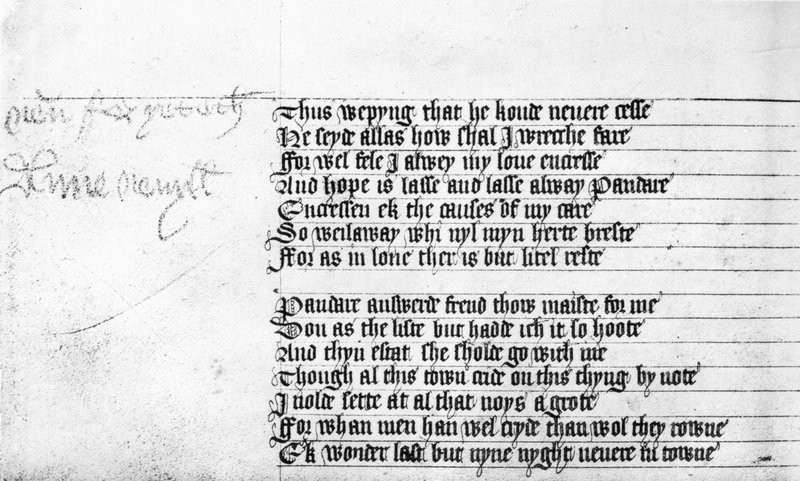

MS. Corp. Chr. Coll., Cambridge. Troil. iv. 575-588

Frontispiece**

THE COMPLETE WORKS

OF

GEOFFREY CHAUCER

EDITED, FROM NUMEROUS MANUSCRIPTS

BY THE

Rev. WALTER W. SKEAT, M.A.

Litt.D., LL.D., D.C.L., Ph.D.

ELRINGTON AND BOSWORTH PROFESSOR OF ANGLO-SAXON AND FELLOW OF CHRIST'S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE

* *

BOETHIUS AND TROILUS

'Adam scriveyn, if ever it thee befalle

Boece or Troilus to wryten newe,

Under thy lokkes thou most have the scalle,

But after my making thou wryte trewe.'

Chaucers Wordes unto Adam.

SECOND EDITION

Oxford

AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

M DCCCC

Oxford

PRINTED AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

BY HORACE HART, M.A.

PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY

CONTENTS.

PAGE

Introduction to Boethius.—§

1. Date of the Work. §

2. Boethius. §

3. The Consolation of Philosophy; and fate of its author. §

4. Jean de Meun. §

5. References by Boethius to current events. §

6. Cassiodorus. §

7. Form of the Treatise. §

8. Brief sketch of its general contents. §

9. Early translations. §

10. Translation by Ælfred. §

11. MS. copy, with A.S. glosses. §

12. Chaucer's translation mentioned. §

13. Walton's verse translation. §

14. Specimen of the same. §

15. His translation of Book ii. met. 5. §

16. M. E. prose translation; and others. §

17. Chaucer's translation and le Roman de la Rose. §

18. Chaucer's scholarship. §

19. Chaucer's prose. §

20. Some of his mistakes. §

21. Other variations considered. §

22. Imitations of Boethius in Chaucer's works. §

23. Comparison with 'Boece' of other works by Chaucer. §

24. Chronology of Chaucer's works, as illustrated by 'Boece.' §

25. The Manuscripts. §

26. The Printed Editions. §

27. The Present Edition

vii Introduction to Troilus.—§

1. Date of the Work. §

2. Sources of the Work; Boccaccio's Filostrato. §§

3,

4. Other sources. §

5. Chaucer's share in it. §

6. Vagueness of reference to sources. §

7. Medieval note-books. §

8. Lollius. §

9. Guido delle Colonne. §

10. 'Trophee.' §§

11,

12. The same continued. §§

13-

17. Passages from Guido. §§

18,

19. Dares, Dictys, and Benôit de Ste-More. §

20. The names; Troilus, &c. §

21. Roman de la Rose. §

22. Gest Historiale. §

23. Lydgate's Siege of Troye. §

24. Henrysoun's Testament of Criseyde. §

25. The MSS. §

26. The Editions. §

27. The Present Edition. §

28. Deficient lines. §

29. Proverbs. §

30. Kinaston's Latin translation. §

31. Sidnam's translation

xlix Boethius de Consolatione Philosophie 1 Book I. 1 Book II. 23 Book III. 51 Book IV. 92 Book V. 126Troilus and Criseyde

153 Book I. 153 Book II. 189 Book III. 244 Book IV. 302 Book V. 357 Notes to Boethius 419 Notes to Troilus 461INTRODUCTION TO BOETHIUS.

§ 1. Date of the Work.

In my introductory remarks to the Legend of Good Women, I refer to the close connection that is easily seen to subsist between Chaucer's translation of Boethius and his Troilus and Criseyde. All critics seem now to agree in placing these two works in close conjunction, and in making the prose work somewhat the earlier of the two; though it is not at all unlikely that, for a short time, both works were in hand together. It is also clear that they were completed before the author commenced the House of Fame, the date of which is, almost certainly, about 1383-4. Dr. Koch, in his Essay on the Chronology of Chaucer's Writings, proposes to date 'Boethius' about 1377-8, and 'Troilus' about 1380-1. It is sufficient to be able to infer, as we can with tolerable certainty, that these two works belong to the period between 1377 and 1383. And we may also feel sure that the well-known lines to Adam, beginning—

'Adam scriveyn, if ever it thee befalle

Boece or Troilus to wryten newe'—

were composed at the time when the fair copy of Troilus had just been finished, and may be dated, without fear of mistake, in 1381-3. It is not likely that we shall be able to determine these dates within closer limits; nor is it at all necessary that we should be able to do so. A few further remarks upon this subject are given below.

§ 2. Boethius.

Before proceeding to remark upon Chaucer's translation of Boethius, or (as he calls him) Boece, it is necessary to say a few words as to the original work, and its author.

Anicius Manlius Torquatus Severinus Boethius, the most learned philosopher of his time, was born at Rome about A. D. 480, and was put to death A. D. 524. In his youth, he had the advantage of a liberal training, and enjoyed the rare privilege of being able to read the Greek philosophers in their own tongue. In the particular treatise which here most concerns us, his Greek quotations are mostly taken from Plato, and there are a few references to Aristotle, Homer, and to the Andromache of Euripides. His extant works shew that he was well acquainted with geometry, mechanics, astronomy, and music, as well as with logic and theology; and it is an interesting fact that an illustration of the way in which waves of sound are propagated through the air, introduced by Chaucer into his House of Fame, ll. 788-822, is almost certainly derived from the treatise of Boethius De Musica, as pointed out in the note upon that passage. At any rate, there is an unequivocal reference to 'the felinge' of Boece 'in musik' in the Nonnes Preestes Tale, B 4484.

§ 3. The most important part of his political life was passed in the service of the celebrated Theodoric the Goth, who, after the defeat and death of Odoacer, A. D. 493, had made himself undisputed master of Italy, and had fixed the seat of his government in Ravenna. The usual account, that Boethius was twice married, is now discredited, there being no clear evidence with respect to Elpis, the name assigned to his supposed first wife; but it is certain that he married Rusticiana, the daughter of the patrician Symmachus, a man of great influence and probity, and much respected, who had been consul under Odoacer in 485. Boethius had the singular felicity of seeing his two sons, Boethius and Symmachus, raised to the consular dignity on the same day, in 522. After many years spent in indefatigable study and great public usefulness, he fell under the suspicion of Theodoric; and, notwithstanding an indignant denial of his supposed crimes, was hurried away to Pavia, where he was imprisoned in a tower, and denied the means of justifying his conduct. The rest must be told in the eloquent words of Gibbon[1].

'While Boethius, oppressed with fetters, expected each moment the sentence or the stroke of death, he composed in the tower of Pavia the "Consolation of Philosophy"; a golden volume, not unworthy of the leisure of Plato or Tully, but which claims incomparable merit from the barbarism of the times and the situation of the author. The celestial guide[2], whom he had so long invoked at Rome and at Athens, now condescended to illumine his dungeon, to revive his courage, and to pour into his wounds her salutary balm. She taught him to compare his long prosperity and his recent distress, and to conceive new hopes from the inconstancy of fortune[3]. Reason had informed him of the precarious condition of her gifts; experience had satisfied him of their real value[4]; he had enjoyed them without guilt; he might resign them without a sigh, and calmly disdain the impotent malice of his enemies, who had left him happiness, since they had left him virtue[5]. From the earth, Boethius ascended to heaven in search of the SUPREME GOOD[6], explored the metaphysical labyrinth of chance and destiny[7], of prescience and freewill, of time and eternity, and generously attempted to reconcile the perfect attributes of the Deity with the apparent disorders of his moral and physical government[8]. Such topics of consolation, so obvious, so vague, or so abstruse, are ineffectual to subdue the feelings of human nature. Yet the sense of misfortune may be diverted by the labour of thought; and the sage who could artfully combine, in the same work, the various riches of philosophy, poetry, and eloquence, must already have possessed the intrepid calmness which he affected to seek. Suspense, the worst of evils, was at length determined by the ministers of death, who executed, and perhaps exceeded, the inhuman mandate of Theodoric. A strong cord was fastened round the head of Boethius, and forcibly tightened till his eyes almost started from their sockets; and some mercy may be discovered in the milder torture of beating him with clubs till he expired. But his genius survived to diffuse a ray of knowledge over the darkest ages of the Latin world; the writings of the philosopher were translated by the most glorious of the English Kings, and the third emperor of the name of Otho removed to a more honourable tomb the bones of a catholic saint, who, from his Arian persecutors, had acquired the honours of martyrdom and the fame of miracles. In the last hours of Boethius, he derived some comfort from the safety of his two sons, of his wife, and of his father-in-law, the venerable Symmachus. But the grief of Symmachus was indiscreet, and perhaps disrespectful; he had presumed to lament, he might dare to revenge, the death of an injured friend. He was dragged in chains from Rome to the palace of Ravenna; and the suspicions of Theodoric could only be appeased by the blood of an innocent and aged senator.'

This deed of injustice brought small profit to its perpetrator; for we read that Theodoric's own death took place shortly afterwards; and that, on his death-bed, 'he expressed in broken murmurs to his physician Elpidius, his deep repentance for the murders of Boethius and Symmachus.'

§ 4. For further details, I beg leave to refer the reader to the essay on 'Boethius' by H. F. Stewart, published by W. Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh and London, in 1891. We are chiefly concerned here with the 'Consolation of Philosophy,' a work which enjoyed great popularity in the middle ages, and first influenced Chaucer indirectly, through the use of it made by Jean de Meun in the poem entitled Le Roman de la Rose, as well as directly, at a later period, through his own translation of it. Indeed, I have little doubt that Chaucer's attention was drawn to it when, somewhat early in life, he first perused with diligence that remarkable poem; and that it was from the following passage that he probably drew the inference that it might be well for him to translate the whole work:—

'Ce puet l'en bien des clers enquerre

Qui Boëce de Confort lisent,

Et les sentences qui là gisent,

Dont grans biens as gens laiz feroit

Qui bien le lor translateroit' (ll. 5052-6).

I.e. in modern English:—'This can be easily ascertained from the learned men who read Boece on the Consolation of Philosophy, and the opinions which are found therein; as to which, any one who would well translate it for them would confer much benefit on the unlearned folk':—a pretty strong hint[9]!

§ 5. The chief events in the life of Boethius which are referred to in the present treatise are duly pointed out in the notes; and it may be well to bear in mind that, as to some of these, nothing further is known beyond what the author himself tells us. Most of the personal references occur in Book i. Prose 4, Book ii. Prose 3, and in Book iii. Prose 4. In the first of these passages, Boethius recalls the manner in which he withstood one Conigastus, because he oppressed the poor (l. 40); and how he defeated the iniquities of Triguilla, 'provost' (præpositus) of the royal household (l. 43). He takes credit for defending the people of Campania against a particularly obnoxious fiscal measure instituted by Theodoric, which was called 'coemption' (coemptio); (l. 59.) This Mr. Stewart describes as 'a fiscal measure which allowed the state to buy provisions for the army at something under market-price—which threatened to ruin the province.' He tells us that he rescued Decius Paulinus, who had been consul in 498, from the rapacity of the officers of the royal palace (l. 68); and that, in order to save Decius Albinus, who had been consul in 493, from wrongful punishment, he ran the risk of incurring the hate of the informer Cyprian (l. 75). In these ways, he had rendered himself odious to the court-party, whom he had declined to bribe (l. 79). His accusers were Basilius, who had been expelled from the king's service, and was impelled to accuse him by pressure of debt (l. 81); and Opilio and Gaudentius, who had been sentenced to exile by royal decree for their numberless frauds and crimes, but had escaped the sentence by taking sanctuary. 'And when,' as he tells us, 'the king discovered this evasion, he gave orders that, unless they quitted Ravenna by a given day, they should be branded on the forehead with a hot iron and driven out of the city. Nevertheless on that very day the information laid against me by these men was admitted' (ll. 89-94). He next alludes to some forged letters (l. 123), by means of which he had been accused of 'hoping for the freedom of Rome,' (which was of course interpreted to mean that he wished to deliver Rome from the tyranny of Theodoric). He then boldly declares that if he had had the opportunity of confronting his accusers, he would have answered in the words of Canius, when accused by Caligula of having been privy to a conspiracy against him—'If I had known it, thou shouldst never have known it' (ll. 126-135). This, by the way, was rather an imprudent expression, and probably told against him when his case was considered by Theodoric.

He further refers to an incident that took place at Verona (l. 153), when the king, eager for a general slaughter of his enemies, endeavoured to extend to the whole body of the senate the charge of treason, of which Albinus had been accused; on which occasion, at great personal risk, Boethius had defended the senate against so sweeping an accusation.

In Book ii. Prose 3, he refers to his former state of happiness and good fortune (l. 26), when he was blessed with rich and influential parents-in-law, with a beloved wife, and with two noble sons; in particular (l. 35), he speaks with justifiable pride of the day when his sons were both elected consuls together, and when, sitting in the Circus between them, he won general praise for his wit and eloquence.

In Book iii. Prose 4, he declaims against Decoratus, with whom he refused to be associated in office, on account of his infamous character.

§ 6. The chief source of further information about these circumstances is a collection of letters (Variæ Epistolæ) by Cassiodorus, a statesman who enjoyed the full confidence of Theodoric, and collected various state-papers under his direction. These tell us, in some measure, what can be said on the other side. Here Cyprian and his brother Opilio are spoken of with respect and honour; and the only Decoratus whose name appears is spoken of as a young man of great promise, who had won the king's sincere esteem. But when all has been said, the reader will most likely be inclined to think that, in cases of conflicting evidence, he would rather take the word of the noble Boethius than that of any of his opponents.

§ 7. The treatise 'De Consolatione Philosophiæ' is written in the form of a discourse between himself and the personification of Philosophy, who appears to him in his prison, and endeavours to soothe and console him in his time of trial. It is divided (as in this volume) into five Books; and each Book is subdivided into chapters, entitled Metres and Proses, because, in the original, the alternate chapters are written in a metrical form, the metres employed being of various kinds. Thus Metre 1 of Book I is written in alternate hexameters and pentameters; while Metre 7 consists of very short lines, each consisting of a single dactyl and spondee. The Proses contain the main arguments; the Metres serve for embellishment and recreation.

In some MSS. of Chaucer's translation, a few words of the original are quoted at the beginning of each Prose and Metre, and are duly printed in this edition, in a corrected form.

§ 8. A very brief sketch of the general contents of the volume may be of some service.

Book I. Boethius deplores his misfortunes (met. 1). Philosophy appears to him in a female form (pr. 2), and condoles with him in song (met. 2); after which she addresses him, telling him that she is willing to share his misfortunes (pr. 3). Boethius pours out his complaints, and vindicates his past conduct (pr. 4). Philosophy reminds him that he seeks a heavenly country (pr. 5). The world is not governed by chance (pr. 6). The book concludes with a lay of hope (met. 7).

Book II. Philosophy enlarges on the wiles of Fortune (pr. 1), and addresses him in Fortune's name, asserting that her mutability is natural and to be expected (pr. 2). Adversity is transient (pr. 3), and Boethius has still much to be thankful for (pr. 4). Riches only bring anxieties, and cannot confer happiness (pr. 5); they were unknown in the Golden Age (met. 5). Neither does happiness consist in honours and power (pr. 6). The power of Nero only taught him cruelty (met. 6). Fame is but vanity (pr. 7), and is ended by death (met. 7). Adversity is beneficial (pr. 8). All things are bound together by the chain of Love (met. 8).

Book III. Boethius begins to receive comfort (pr. 1). Philosophy discourses on the search for the Supreme Good (summum bonum; pr. 2). The laws of nature are immutable (met. 2). All men are engaged in the pursuit of happiness (pr. 3). Dignities properly appertain to virtue (pr. 4). Power cannot drive away care (pr. 5). Glory is deceptive, and the only true nobility is that of character (pr. 6). Happiness does not consist in corporeal pleasures (pr. 7); nor in bodily strength or beauty (pr. 8). Worldly bliss is insufficient and false; and in seeking true felicity, we must invoke God's aid (pr. 9). Boethius sings a hymn to the Creator (met. 9); and acknowledges that God alone is the Supreme Good (p. 10). The unity of soul and body is necessary to existence, and the love of life is instinctive (pr. 11). Error is dispersed by the light of Truth (met. 11). God governs the world, and is all-sufficient, whilst evil has no true existence (pr. 12). The book ends with the story of Orpheus (met. 12).

Book IV. This book opens with a discussion of the existence of evil, and the system of rewards and punishments (pr. 1). Boethius describes the flight of Imagination through the planetary spheres till it reaches heaven itself (met. 1). The good are strong, but the wicked are powerless, having no real existence (pr. 2). Tyrants are chastised by their own passions (met. 2). Virtue secures reward; but the wicked lose even their human nature, and become as mere beasts (pr. 3). Consider the enchantments of Circe, though these merely affected the outward form (met. 4). The wicked are thrice wretched; they will to do evil, they can do evil, and they actually do it. Virtue is its own reward; so that the wicked should excite our pity (pr. 4). Here follows a poem on the folly of war (met. 4). Boethius inquires why the good suffer (pr. 5). Philosophy reminds him that the motions of the stars are inexplicable to one who does not understand astronomy (met. 5). She explains the difference between Providence and Destiny (pr. 6). In all nature we see concord, due to controlling Love (met. 6). All fortune is good; for punishment is beneficial (pr. 7). The labours of Hercules afford us an example of endurance (met. 7).

Book V. Boethius asks questions concerning Chance (pr. 1). An example from the courses of the rivers Tigris and Euphrates (met. 1). Boethius asks questions concerning Free-will (pr. 2). God, who sees all things, is the true Sun (met. 2). Boethius is puzzled by the consideration of God's Predestination and man's Free-will (pr. 3). Men are too eager to inquire into the unknown (met. 3). Philosophy replies to Boethius on the subjects of Predestination, Necessity, and the nature of true Knowledge (pr. 4); on the impressions received by the mind (met. 4); and on the powers of Sense and Imagination (pr. 5). Beasts look downward to the earth, but man is upright, and looks up to heaven (met. 5). This world is not eternal, but only God is such; whose prescience is not subject to necessity, nor altered by human intentions. He upholds the good, and condemns the wicked; therefore be constant in eschewing vice, and devote all thy powers to the love of virtue (pr. 6).

§ 9. It is unnecessary to enlarge here upon the importance of this treatise, and its influence upon medieval literature. Mr. Stewart, in the work already referred to, has an excellent chapter 'On Some Ancient Translations' of it. The number of translations that still exist, in various languages, sufficiently testify to its extraordinary popularity in the middle ages. Copies of it are found, for example, in Old High German by Notker, and in later German by Peter of Kastl; in Anglo-French by Simun de Fraisne; in continental French by Jean de Meun[10], Pierre de Paris, Jehan de Cis, Frere Renaut de Louhans, and by two anonymous authors; in Italian, by Alberto della Piagentina and several others; in Greek, by Maximus Planudes; and in Spanish, by Fra Antonio Ginebreda; besides various versions in later times. But the most interesting, to us, are those in English, which are somewhat numerous, and are worthy of some special notice. I shall here dismiss, as improbable and unnecessary, a suggestion sometimes made, that Chaucer may have consulted some French version in the hope of obtaining assistance from it; there is no sure trace of anything of the kind, and the internal evidence is, in my opinion, decisively against it.

§ 10. The earliest English translation is that by king Ælfred, which is particularly interesting from the fact that the royal author frequently deviates from his original, and introduces various notes, explanations, and allusions of his own. The opening chapter, for example, is really a preface, giving a brief account of Theodoric and of the circumstances which led to the imprisonment of Boethius. This work exists only in two MSS., neither being of early date, viz. MS. Cotton, Otho A VI, and MS. Bodley NE. C. 3. 11. It has been thrice edited; by Rawlinson, in 1698; by J. S. Cardale, in 1829; and by S. Fox, in 1864. The last of these includes a modern English translation, and forms one of the volumes of Bohn's Antiquarian Library; so that it is a cheap and accessible work. Moreover, it contains an alliterative verse translation of most of the Metres contained in Boethius (excluding the Proses), which is also attributed to Ælfred in a brief metrical preface; but whether this ascription is to be relied upon, or not, is a difficult question, which has hardly as yet been decided. A summary of the arguments, for and against Ælfred's authorship, will be found in Wülker's Grundriss zur Geschichte der angelsächsischen Litteratur, pp. 421-435.

§ 11. I may here mention that there is a manuscript copy of this work by Boethius, in the original Latin, in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, No. 214, which contains a considerable number of Anglo-Saxon glosses. A description of this MS., by Prof. J. W. Bright and myself, is printed in the American Journal of Philology, vol. v, no. 4.

§ 12. The next English translation, in point of date, is Chaucer's; concerning which I have more to say below.

§ 13. In the year 1410, we meet with a verse translation of the whole treatise, ascribed by Warton (Hist. E. Poetry, § 20, ed. 1871, iii. 39) to John Walton, Capellanus, or John the Chaplain, a canon of Oseney. 'In the British Museum,' says Warton, 'there is a correct MS. on parchment[11] of Walton's translation of Boethius; and the margin is filled throughout with the Latin text, written by Chaundler above mentioned [i. e. Thomas Chaundler, among other preferments dean of the king's chapel and of Hereford Cathedral, chancellor of Wells, and successively warden of Wykeham's two colleges at Winchester and Oxford.] There is another less elegant MS. in the same collection[12]. But at the end is this note:—'Explicit liber Boecij de Consolatione Philosophie de Latino in Anglicum translatus A.D. 1410, per Capellanum Ioannem. This is the beginning of the prologue:—"In suffisaunce of cunnyng and witte[13]." And of the translation:—"Alas, I wrecch, that whilom was in welth." I have seen a third copy in the library of Lincoln cathedral[14], and a fourth in Baliol college[15]. This is the translation of Boethius printed in the monastery of Tavistock in 1525[16], and in octave stanzas. This translation was made at the request of Elizabeth Berkeley.'

Todd, in his Illustrations of Gower and Chaucer, p. xxxi, mentions another MS. 'in the possession of Mr. G. Nicol, his Majesty's bookseller,' in which the above translation is differently attributed in the colophon, which ends thus: 'translatus anno domini millesimo ccccxo. per Capellanum Iohannem Tebaud, alius Watyrbeche.' This can hardly be correct[17].

I may here note that this verse translation has two separate Prologues. One Prologue gives a short account of Boethius and his times, and is extant in MS. Gg. iv. 18 in the Cambridge University Library. An extract from the other is quoted below. MS. E Museo 53, in the Bodleian Library, contains both of them.

§ 14. As to the work itself, Metre 1 of Book i. and Metre 5 of the same are printed entire in Wülker's Altenglisches Lesebuch, ii. 56-9. In one of the metrical prologues to the whole work the following passage occurs, which I copy from MS. Royal 18 A xiii:—

'I have herd spek and sumwhat haue y-seyne,

Of diuerse men[18], that wounder subtyllye,

In metir sum, and sum in prosë pleyne,

This book translated haue[19] suffishantlye

In-to[20] Englissh tongë, word for word, wel nye[21];

Bot I most vse the wittes that I haue;

Thogh I may noght do so, yit noght-for-thye,

With helpe of god, the sentence schall I saue.

To Chaucer, that is floure of rethoryk

In Englisshe tong, and excellent poete,

This wot I wel, no-thing may I do lyk,

Thogh so that I of makynge entyrmete:

And Gower, that so craftily doth trete,

As in his book, of moralitee,

Thogh I to theym in makyng am vnmete,

Ȝit most I schewe it forth, that is in me.'

This is an early tribute to the excellence of Chaucer and Gower as poets.

§ 15. When we examine Walton's translation a little more closely, it soon becomes apparent that he has largely availed himself of Chaucer's prose translation, which he evidently kept before him as a model of language. For example, in Bk. ii. met. 5, l. 16, Chaucer has the expression:—'tho weren the cruel clariouns ful hust and ful stille.' This reappears in one of Walton's lines in the form:—'Tho was ful huscht the cruel clarioun.' This is poetry made easy, no doubt.

In order to exhibit this a little more fully, I here transcribe the whole of Walton's translation of this metre, which may be compared with Chaucer's rendering at pp. 40, 41 below. I print in italics all the words which are common to the two versions, so as to shew this curious result, viz. that Walton was here more indebted to Chaucer, than Chaucer, when writing his poem of 'The Former Age,' was to himself. The MS. followed is the Royal MS. mentioned above (p. xvi).

§ 1. Date of the Work.

§ 2. Boethius.

§ 3. The most important part of his political life was passed in the service of the celebrated Theodoric the Goth, who, after the defeat and death of Odoacer, A. D. 493, had made himself undisputed master of Italy, and had fixed the seat of his government in Ravenna. The usual account, that Boethius was twice married, is now discredited, there being no clear evidence with respect to Elpis, the name assigned to his supposed first wife; but it is certain that he married Rusticiana, the daughter of the patrician Symmachus, a man of great influence and probity, and much respected, who had been consul under Odoacer in 485. Boethius had the singular felicity of seeing his two sons, Boethius and Symmachus, raised to the consular dignity on the same day, in 522. After many years spent in indefatigable study and great public usefulness, he fell under the suspicion of Theodoric; and, notwithstanding an indignant denial of his supposed crimes, was hurried away to Pavia, where he was imprisoned in a tower, and denied the means of justifying his conduct. The rest must be told in the eloquent words of Gibbon[1].

§ 4. For further details, I beg leave to refer the reader to the essay on 'Boethius' by H. F. Stewart, published by W. Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh and London, in 1891. We are chiefly concerned here with the 'Consolation of Philosophy,' a work which enjoyed great popularity in the middle ages, and first influenced Chaucer indirectly, through the use of it made by Jean de Meun in the poem entitled Le Roman de la Rose, as well as directly, at a later period, through his own translation of it. Indeed, I have little doubt that Chaucer's attention was drawn to it when, somewhat early in life, he first perused with diligence that remarkable poem; and that it was from the following passage that he probably drew the inference that it might be well for him to translate the whole work:—

§ 5. The chief events in the life of Boethius which are referred to in the present treatise are duly pointed out in the notes; and it may be well to bear in mind that, as to some of these, nothing further is known beyond what the author himself tells us. Most of the personal references occur in Book i. Prose 4, Book ii. Prose 3, and in Book iii. Prose 4. In the first of these passages, Boethius recalls the manner in which he withstood one Conigastus, because he oppressed the poor (l. 40); and how he defeated the iniquities of Triguilla, 'provost' (præpositus) of the royal household (l. 43). He takes credit for defending the people of Campania against a particularly obnoxious fiscal measure instituted by Theodoric, which was called 'coemption' (coemptio); (l. 59.) This Mr. Stewart describes as 'a fiscal measure which allowed the state to buy provisions for the army at something under market-price—which threatened to ruin the province.' He tells us that he rescued Decius Paulinus, who had been consul in 498, from the rapacity of the officers of the royal palace (l. 68); and that, in order to save Decius Albinus, who had been consul in 493, from wrongful punishment, he ran the risk of incurring the hate of the informer Cyprian (l. 75). In these ways, he had rendered himself odious to the court-party, whom he had declined to bribe (l. 79). His accusers were Basilius, who had been expelled from the king's service, and was impelled to accuse him by pressure of debt (l. 81); and Opilio and Gaudentius, who had been sentenced to exile by royal decree for their numberless frauds and crimes, but had escaped the sentence by taking sanctuary. 'And when,' as he tells us, 'the king discovered this evasion, he gave orders that, unless they quitted Ravenna by a given day, they should be branded on the forehead with a hot iron and driven out of the city. Nevertheless on that very day the information laid against me by these men was admitted' (ll. 89-94). He next alludes to some forged letters (l. 123), by means of which he had been accused of 'hoping for the freedom of Rome,' (which was of course interpreted to mean that he wished to deliver Rome from the tyranny of Theodoric). He then boldly declares that if he had had the opportunity of confronting his accusers, he would have answered in the words of Canius, when accused by Caligula of having been privy to a conspiracy against him—'If I had known it, thou shouldst never have known it' (ll. 126-135). This, by the way, was rather an imprudent expression, and probably told against him when his case was considered by Theodoric.

§ 6. The chief source of further information about these circumstances is a collection of letters (Variæ Epistolæ) by Cassiodorus, a statesman who enjoyed the full confidence of Theodoric, and collected various state-papers under his direction. These tell us, in some measure, what can be said on the other side. Here Cyprian and his brother Opilio are spoken of with respect and honour; and the only Decoratus whose name appears is spoken of as a young man of great promise, who had won the king's sincere esteem. But when all has been said, the reader will most likely be inclined to think that, in cases of conflicting evidence, he would rather take the word of the noble Boethius than that of any of his opponents.

§ 7. The treatise 'De Consolatione Philosophiæ' is written in the form of a discourse between himself and the personification of Philosophy, who appears to him in his prison, and endeavours to soothe and console him in his time of trial. It is divided (as in this volume) into five Books; and each Book is subdivided into chapters, entitled Metres and Proses, because, in the original, the alternate chapters are written in a metrical form, the metres employed being of various kinds. Thus Metre 1 of Book I is written in alternate hexameters and pentameters; while Metre 7 consists of very short lines, each consisting of a single dactyl and spondee. The Proses contain the main arguments; the Metres serve for embellishment and recreation.

§ 8. A very brief sketch of the general contents of the volume may be of some service.

§ 9. It is unnecessary to enlarge here upon the importance of this treatise, and its influence upon medieval literature. Mr. Stewart, in the work already referred to, has an excellent chapter 'On Some Ancient Translations' of it. The number of translations that still exist, in various languages, sufficiently testify to its extraordinary popularity in the middle ages. Copies of it are found, for example, in Old High German by Notker, and in later German by Peter of Kastl; in Anglo-French by Simun de Fraisne; in continental French by Jean de Meun[10], Pierre de Paris, Jehan de Cis, Frere Renaut de Louhans, and by two anonymous authors; in Italian, by Alberto della Piagentina and several others; in Greek, by Maximus Planudes; and in Spanish, by Fra Antonio Ginebreda; besides various versions in later times. But the most interesting, to us, are those in English, which are somewhat numerous, and are worthy of some special notice. I shall here dismiss, as improbable and unnecessary, a suggestion sometimes made, that Chaucer may have consulted some French version in the hope of obtaining assistance from it; there is no sure trace of anything of the kind, and the internal evidence is, in my opinion, decisively against it.

§ 10. The earliest English translation is that by king Ælfred, which is particularly interesting from the fact that the royal author frequently deviates from his original, and introduces various notes, explanations, and allusions of his own. The opening chapter, for example, is really a preface, giving a brief account of Theodoric and of the circumstances which led to the imprisonment of Boethius. This work exists only in two MSS., neither being of early date, viz. MS. Cotton, Otho A VI, and MS. Bodley NE. C. 3. 11. It has been thrice edited; by Rawlinson, in 1698; by J. S. Cardale, in 1829; and by S. Fox, in 1864. The last of these includes a modern English translation, and forms one of the volumes of Bohn's Antiquarian Library; so that it is a cheap and accessible work. Moreover, it contains an alliterative verse translation of most of the Metres contained in Boethius (excluding the Proses), which is also attributed to Ælfred in a brief metrical preface; but whether this ascription is to be relied upon, or not, is a difficult question, which has hardly as yet been decided. A summary of the arguments, for and against Ælfred's authorship, will be found in Wülker's Grundriss zur Geschichte der angelsächsischen Litteratur, pp. 421-435.

§ 11. I may here mention that there is a manuscript copy of this work by Boethius, in the original Latin, in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, No. 214, which contains a considerable number of Anglo-Saxon glosses. A description of this MS., by Prof. J. W. Bright and myself, is printed in the American Journal of Philology, vol. v, no. 4.

§ 12. The next English translation, in point of date, is Chaucer's; concerning which I have more to say below.

§ 13. In the year 1410, we meet with a verse translation of the whole treatise, ascribed by Warton (Hist. E. Poetry, § 20, ed. 1871, iii. 39) to John Walton, Capellanus, or John the Chaplain, a canon of Oseney. 'In the British Museum,' says Warton, 'there is a correct MS. on parchment[11] of Walton's translation of Boethius; and the margin is filled throughout with the Latin text, written by Chaundler above mentioned [i. e. Thomas Chaundler, among other preferments dean of the king's chapel and of Hereford Cathedral, chancellor of Wells, and successively warden of Wykeham's two colleges at Winchester and Oxford.] There is another less elegant MS. in the same collection[12]. But at the end is this note:—'Explicit liber Boecij de Consolatione Philosophie de Latino in Anglicum translatus A.D. 1410, per Capellanum Ioannem. This is the beginning of the prologue:—"In suffisaunce of cunnyng and witte[13]." And of the translation:—"Alas, I wrecch, that whilom was in welth." I have seen a third copy in the library of Lincoln cathedral[14], and a fourth in Baliol college[15]. This is the translation of Boethius printed in the monastery of Tavistock in 1525[16], and in octave stanzas. This translation was made at the request of Elizabeth Berkeley.'

§ 14. As to the work itself, Metre 1 of Book i. and Metre 5 of the same are printed entire in Wülker's Altenglisches Lesebuch, ii. 56-9. In one of the metrical prologues to the whole work the following passage occurs, which I copy from MS. Royal 18 A xiii:—

§ 15. When we examine Walton's translation a little more closely, it soon becomes apparent that he has largely availed himself of Chaucer's prose translation, which he evidently kept before him as a model of language. For example, in Bk. ii. met. 5, l. 16, Chaucer has the expression:—'tho weren the cruel clariouns ful hust and ful stille.' This reappears in one of Walton's lines in the form:—'Tho was ful huscht the cruel clarioun.' This is poetry made easy, no doubt.

§ 16. MS. Auct. F. 3. 5, in the Bodleian Library, contains a prose translation, different from Chaucer's. After this, the next translation seems to be one by George Colvile; the title is thus given by Lowndes: 'Boetius de Consolatione Philosophiæ, translated by George Coluile, alias Coldewel. London: by John Cawoode; 1556. 4to.' This work was dedicated to Queen Mary, and reprinted in 1561; and again, without date.

§ 17. I now return to the consideration of Chaucer's translation, as printed in the present volume.

§ 18. When we come to consider the style and manner in which Chaucer has executed his self-imposed task, we must first of all make some allowance for the difference between the scholarship of his age and of our own. One great difference is obvious, though constantly lost sight of, viz. that the teaching in those days was almost entirely oral, and that the student had to depend upon his memory to an extent which would now be regarded by many as extremely inconvenient. Suppose that, in reading Boethius, Chaucer comes across the phrase 'ueluti quidam clauus atque gubernaculum' (Bk. iii. pr. 12, note to l. 55), and does not remember the sense of clauus; what is to be done? It is quite certain, though this again is frequently lost sight of, that he had no access to a convenient and well-arranged Latin Dictionary, but only to such imperfect glossaries as were then in use. Almost the only resource, unless he had at hand a friend more learned than himself, was to guess. He guesses accordingly; and, taking clauus to mean much the same thing as clauis, puts down in his translation: 'and he is as a keye and a stere.' Some mistakes of this character were almost inevitable; and it must not greatly surprise us to be told, that the 'inaccuracy and infelicity' of Chaucer's translation 'is not that of an inexperienced Latin scholar, but rather of one who was no Latin scholar at all,' as Mr. Stewart says in his Essay, p. 226. It is useful to bear this in mind, because a similar lack of accuracy is characteristic of Chaucer's other works also; and we must not always infer that emendation is necessary, when we find in his text some curious error.

§ 19. The next passage in Mr. Stewart's Essay so well expresses the state of the case, that I do not hesitate to quote it at length. 'Given (he says) a man who is sufficiently conversant with a language to read it fluently without paying too much heed to the precise value of participle and preposition, who has the wit and the sagacity to grasp the meaning of his author, but not the intimate knowledge of his style and manner necessary to a right appreciation of either, and—especially if he set himself to write in an uncongenial and unfamiliar form—he will assuredly produce just such a result as Chaucer has done.

§ 20. Most of the instances in which Chaucer's rendering is inaccurate, unhappy, or insufficient are pointed out in the notes. I here collect some examples, many of which have already been remarked upon by Dr. Morris and Mr. Stewart.

§ 21. In the case of a few supposed errors, as pointed out by Mr. Stewart, there remains something to be said on the other side. I note the following instances.

§ 22. After all, the chief point of interest about Chaucer's translation of Boethius is the influence that this labour exercised upon his later work, owing to the close familiarity with the text which he thus acquired. I have shewn that we must not expect to find such influence upon his earliest writings; and that, in the case of the Book of the Duchesse, it affected him at second hand, through Jean de Meun. But in other poems, viz. Troilus, the House of Fame, The Legend of Good Women, some of the Balades, and in the Canterbury Tales, the influence of Boethius is frequently observable; and we may usually suppose such influence to have been direct and immediate; nevertheless, we should always keep an eye on Le Roman de la Rose, for Jean de Meun was, in like manner, influenced in no slight degree by the same work. I have often taken an opportunity of pointing out, in my Notes to Chaucer, passages of this character; and I find that Mr. Stewart, with praiseworthy diligence, has endeavoured to give (in Appendix B, following his Essay, at p. 260) 'An Index of Passages in Chaucer which seem to have been suggested by the De Consolatione Philosophiae.' Very useful, in connection with this subject, is the list of passages in which Chaucer seems to have been indebted to Le Roman de la Rose, as given by Dr. E. Köppel in Anglia, vol. xiv. 238-265. Another most useful help is the comparison between Troilus and Boccaccio's Filostrato, by Mr. W. M. Rossetti; which sometimes proves, beyond all doubt, that a passage which may seem to be due to Boethius, is really taken from the Italian poet. As this seems to be the right place for exhibiting the results thus obtained, I proceed to give them, and gladly express my thanks to the above-named authors for the opportunity thus afforded.

§ 23. Comparison with 'Boece' of other works by Chaucer.

§ 24. It is worth while to see what light is thrown upon the chronology of the Canterbury Tales by comparison with Boethius.

§ 25. The Manuscripts.

§ 26. The Printed Editions.

§ 27. The Present Edition.

§ 1. Date of the Work. The probable date is about 1380-2, and can hardly have been earlier than 1379 or later than 1383. No doubt it was in hand for a considerable time. It certainly followed close upon the translation of Boethius; see p. vii above.

§ 2. Sources of the Work. The chief authority followed by Chaucer is Boccaccio's poem named Il Filostrato, in 9 Parts or Books of very variable length, and composed in ottava rima, or stanzas containing eight lines each. I have used the copy in the Opere Volgari di G. Boccaccio; Firenze, 1832.

§ 3. I have taken occasion, at the same time, to note other passages for which Chaucer is indebted to some other authors. Of these we may particularly note the following. In Book I, lines 400-420 are translated from Petrarch's 88th Sonnet, which is quoted at length at p. 464. In Book III, lines 813-833, 1625-9, and 1744-1768 are all from the second Book of Boethius (Prose 4, 86-120 and 4-10, and Metre 8). In Book IV, lines 974-1078 are from Boethius, Book V. In Book V, lines 1-14 and 1807-27 are from various parts of Boccaccio's Teseide; and a part of the last stanza is from Dante. On account of such borrowings, we may subtract about 220 lines more from Chaucer's 'balance'; which still leaves due to him nearly 5436 lines.

§ 4. Of course it will be readily understood that, in the case of these 5436 lines, numerous short quotations and allusions occur, most of which are pointed out in the notes. Thus, in Book II, lines 402-3 are from Ovid, Art. Amat. ii. 118; lines 716-8 are from Le Roman de la Rose[47]; and so on. No particular notice need be taken of this, as similar hints are utilised in other poems by Chaucer; and, indeed, by all other poets. But there is one particular case of borrowing, of considerable importance, which will be considered below, in § 9 (p. liii).

§ 5. It is, however, necessary to observe here that, in taking his story from Boccaccio, Chaucer has so altered and adapted it as to make it peculiarly his own; precisely as he has done in the case of the Knightes Tale. Sometimes he translates very closely and even neatly, and sometimes he takes a mere hint from a long passage. He expands or condenses his material at pleasure; and even, in some cases, transposes the order of it. It is quite clear that he gave himself a free hand.

§ 6. It has been observed that, whilst Chaucer carefully read and made very good use of two of Boccaccio's works, viz. Il Filostrato and Il Teseide, he nowhere mentions Boccaccio by name; and this has occasioned some surprise. But we must not apply modern ideas to explain medieval facts, as is so frequently done. When we consider how often MSS. of works by known authors have no author's name attached to them, it becomes likely that Chaucer obtained manuscript copies of these works unmarked by the author's name; and though he must doubtless have been aware of it, there was no cogent reason why he should declare himself indebted to one in whom Englishmen were, as yet, quite uninterested. Even when he refers to Petrarch in the Clerk's Prologue (E 27-35), he has to explain who he was, and to inform readers of his recent death. In those days, there was much laxity in the mode of citing authors.

§ 7. It will help us to understand matters more clearly, if we further observe the haphazard manner in which quotations were often made. We know, for example, that no book was more accessible than the Vulgate version of the Bible; yet it is quite common to find the most curious mistakes made in reference to it. The author of Piers Plowman (B. text, iii. 93-95) attributes to Solomon a passage which he quotes from Job, and (B. vii. 123) to St. Luke, a passage from St. Matthew; and again (B. vi. 240) to St. Matthew, a passage from St. Luke. Chaucer makes many mistakes of a like nature; I will only cite here his reference to Solomon (Cant. Tales, A 4330), as the author of a passage in Ecclesiasticus. Even in modern dictionaries we find passages cited from 'Dryden' or 'Bacon' at large, without further remark; as if the verification of a reference were of slight consequence. This may help to explain to us the curious allusion to Zanzis as being the author of a passage which Chaucer must have known was from his favourite Ovid (see note to Troil. iv. 414), whilst he was, at the same time, well aware that Zanzis was not a poet, but a painter (Cant. Tales, C 16); however, in this case we have probably to do with a piece of our author's delicious banter, since he adds that Pandarus was speaking 'for the nonce.'

§ 8. The first and second scraps from Horace are hackneyed quotations. 'Multa renascentur' occurs in Troil. ii. 22 (see note, p. 468); and 'Humano capiti' in Troil. ii. 1041 (note, p. 472). In the third case (p. 464), there is no reason why we should hesitate to accept the theory, suggested by Dr. G. Latham (Athenæum, Oct. 3, 1868) and by Professor Ten Brink independently, that the well-known line (Epist. I, 2. 1)—

§ 9. I have spoken (§ 4) of 'a particular case of borrowing,' which I now propose to consider more particularly. The discovery that Chaucer mainly drew his materials from Boccaccio seems to have satisfied most enquirers; and hence it has come to pass that one of Chaucer's sources has been little regarded, though it is really of some importance. I refer to the Historia Troiana of Guido delle Colonne[49], or, as Chaucer rightly calls him, Guido de Columpnis, i.e. Columnis (House of Fame, 1469). Chaucer's obligations to this author have been insufficiently explored.

§ 10. Before answering this question, it will be best to consider the famous crux, as to the meaning of the word Trophee.

§ 11. If we examine the sources of the story of Hercules in the Monkes Tale, we see that all the supposed facts except the one mentioned in the two lines above quoted are taken from Boethius and Ovid (see the Notes). Now the next most obvious source of information was Guido's work, since the very first Book has a good deal about Hercules, and the Legend of Hypsipyle clearly shews us that Chaucer was aware of this. And, although neither Ovid (in Met. ix.) nor Boethius has any allusion to the Pillars of Hercules, they are expressly mentioned by Guido. In the English translation called the Gest Historiale of the Destruction of Troy, ed. Panton and Donaldson (which I call, for brevity, the alliterative Troy-book), l. 308, we read:—

§ 12. Why this particular book was so called, we have no means of knowing[51]; but this does not invalidate the fact here pointed out. Of course the Latin side-note in some of the MSS. of the Monkes Tale, which explains 'Trophee' as referring to 'ille vates Chaldeorum Tropheus,' must be due to some mistake, even if it emanated (as is possible) from Chaucer himself. It is probable that, when the former part of the Monkes Tale was written, Chaucer did not know much about Guido's work; for the account of Hercules occurs in the very first chapter. Perhaps he confused the name of Tropheus with that of Trogus, i.e. Pompeius Trogus the historian, whose work is one of the authorities for the history of the Assyrian monarchy.

§ 13. It remains for me to point out some of the passages in Troilus which are clearly due to Guido, and are not found in Boccaccio at all.

§ 17. With regard to the statement in Guido, that Achilles slew Hector treacherously, we must remember how much turns upon this assertion. His object was to glorify the Trojans, the supposed ancestors of the Roman race, and to depreciate the Greeks. The following passage from Guido, Book XXV, is too characteristic to be omitted. 'Set o Homere, qui in libris tuis Achillem tot laudibus, tot preconiis extulisti, que probabilis racio te induxit, vt Achillem tantis probitatis meritis vel titulis exultasses?' Such was the general opinion about Homer in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

§ 18. This is not the place for a full consideration of the further question, as to the sources of information whence Boccaccio and Guido respectively drew their stories. Nor is it profitable to search the supposed works of Dares and Dictys for the passages to which Chaucer appears to refer; since he merely knew those authors by name, owing to Guido's frequent appeals to them. Nevertheless, it is interesting to find that Guido was quite as innocent as were Chaucer and Lydgate of any knowledge of Dares and Dictys at first hand. He acquired his great reputation in the simplest possible way, by stealing the whole of his 'History' bodily, from a French romance by Benoît de Sainte-More, entitled Le Roman de Troie, which has been well edited and discussed by Mons. A. Joly. Mons. Joly has shewn that the Roman de Troie first appeared between the years 1175 and 1185; and that Guido's Historia Troiana is little more than an adaptation of it, which was completed in the year 1287, without any acknowledgment as to its true source.

§ 19. The whole question of the various early romances that relate to Troy is well considered in a work entitled 'Testi Inediti di Storia Trojana, preceduti da uno studio sulla Leggenda Trojana in Italia, per Egidio Gorra; Torino, 1887'; where various authorities are cited, and specimens of several texts are given. At p. 136 are given the very lines of Benoît's Roman (ll. 795-6) where Guido found a reference to the columns of Hercules:—

§ 20. A few words may be said as to the names of the characters. Troilus is only once mentioned in Homer, where he is said to be one of the sons of Priam, who were slain in battle, Iliad, xxiv. 257; so that his story is of medieval invention, except as to the circumstance of his slayer being Achilles, as stated by Vergil, Æn. i. 474, 475; cf. Horace, Carm. ii. 9. 16. Pandarus occurs as the name of two distinct personages; (1) a Lycian archer, who wounded Menelaus; see Homer, Il. iv. 88, Vergil, Æn. 5. 496; and (2) a companion of Æneas, slain by Turnus; see Vergil, Æn. ix. 672, xi. 396. Diomede is a well-known hero in the Iliad, but his love-story is of late invention. The heroine of Benoît's poem is Briseida, of whom Dares (c. 13) has merely the following brief account: 'Briseidam formosam, alta statura, candidam, capillo flauo et molli, superciliis junctis[59], oculis venustis, corpore aequali, blandam, affabilem, uerecundam, animo simplici, piam'; but he records nothing more about her. The name is simply copied from Homer's Βρισηΐδα, Il. i. 184, the accusative being taken (as often) as a new nominative case; this Briseis was the captive assigned to Achilles. But Boccaccio substitutes for this the form Griseida, taken from the accusative of Homer's Chryseis, mentioned just two lines above, Il. i. 182. For this Italian form Chaucer substituted Criseyde, a trisyllabic form, with the ey pronounced as the ey in prey. He probably was led to this correction by observing the form Chryseida in his favourite author, Ovid; see Remed. Amoris, 469. Calchas, in Homer, Il. i. 69, is a Grecian priest; but in the later story he becomes a Trojan soothsayer, who, foreseeing the destruction of Troy, secedes to the Greek side, and is looked upon as a traitor. Cf. Vergil, Æn. ii. 176; Ovid, Art. Amat. ii. 737.

§ 21. In Anglia, xiv. 241, there is a useful comparison, by Dr. E. Köppel, of the parallel passages in Troilus and the French Roman de la Rose, ed. Méon, Paris, 1814, which I shall denote by 'R.' These are mostly pointed out in the Notes. Köppel's list is as follows:—

§ 22. I have frequently alluded above to the alliterative 'Troy-book,' or 'Gest Historiale,' edited for the Early English Text Society, in 1869-74, by Panton and Donaldson. This is useful for reference, as being a tolerably close translation of Guido, although a little imperfect, owing to the loss of some leaves and some slight omissions (probably) on the part of the scribe. It is divided into 36 Books, which agree, very nearly, with the Books into which the original text is divided. The most important passages for comparison with Troilus are lines 3922-34 (description of Troilus); 3794-3803 (Diomede); 7268-89 (fight between Troilus and Diomede); 7886-7905 (Briseida and her dismissal from Troy); 8026-8181 (sorrow of Troilus and Briseida, her departure, and the interviews between Briseida and Diomede, and between her and Calchas her father); 8296-8317 (Diomede captures Troilus' horse, and presents it to Briseida); 8643-60 (death of Hector); 9671-7, 9864-82, 9926-9 (deeds of Troilus); 9942-59 (Briseida visits the wounded Diomede); 10055-85, 10252-10311 (deeds of Troilus, and his death); 10312-62 (reproof of Homer for his false statements).

§ 23. Another useful book, frequently mentioned above, is Lydgate's Siege of Troye[61], of which I possess a copy printed in 1555. This contains several allusions to Chaucer's Troilus, and more than one passage in praise of Chaucer's poetical powers, two of which are quoted in Mr. Rossetti's remarks on MS. Harl. 3943 (Chaucer Soc. 1875), pp. x, xi. These passages are not very helpful, though it is curious to observe that he speaks of Chaucer not only as 'my maister Chaucer,' but as 'noble Galfride, chefe Poete of Brytaine,' and 'my maister Galfride.' The most notable passages occur in cap. xv, fol. K 2; cap. xxv, fol. R 2, back; and near the end, fol. Ee 2. Lydgate's translation is much more free than the preceding one, and he frequently interpolates long passages, besides borrowing a large number of poetical expressions from his 'maister.'

§ 24. Finally, I must not omit to mention the remarkable poem by Robert Henrysoun, called the Testament and Complaint of Criseyde, which forms a sequel to Chaucer's story. Thynne actually printed this, in his edition of 1532, as one of Chaucer's poems, immediately after Troilus; and all the black-letter editions follow suit. Yet the 9th and 10th stanzas contain these words, according to the edition of 1532:—

§ 25. The Manuscripts.

§ 26. The Editions. 'Troilus' was first printed by Caxton, about 1484; but without printer's name, place, or date. See the description in Blades' Life of Caxton, p. 297. There is no title-page. Each page contains five stanzas. Two copies are in the British Museum; one at St. John's College, Oxford; and one (till lately) was at Althorp. The second edition is by Wynkyn de Worde, in 1517. The third, by Pynson, in 1526. These three editions present Troilus as a separate work. After this, it was included in Thynne's edition of 1532, and in all the subsequent editions of Chaucer's Works.

§ 27. The Present Edition. The present edition has the great advantage of being founded upon Cl. and Cp., neither of which have been previously made use of, though they are the two best. Bell's text is founded upon the Harleian MSS. numbered 1239, 2280, and 3943, in separate fragments; hence the text is neither uniform nor very good. Morris's text is much better, being founded upon H. (closely related to Cl. and Cp.), with a few corrections from other unnamed sources.

§ 28. It is worth notice that Troilus contains about fifty lines in which the first foot consists of a single syllable. Examples in Book I are:—

§ 29. Proverbs. Troilus contains a considerable number of proverbs and proverbial phrases or similes. See, e. g., I. 257, 300, 631, 638, 694, 708, 731, 740, 946-952, 960, 964, 1002, 1024; II. 343, 398, 403, 585, 784, 804, 807, 861, 867, 1022, 1030, 1041, 1238, 1245, 1332, 1335, 1380, 1387, 1553, 1745; III. 35, 198, 294, 308, 329, 405, 526, 711, 764, 775, 859, 861, 931, 1625, 1633; IV. 184, 415, 421, 460, 588, 595, 622, 728, 836, 1098, 1105, 1374, 1456, 1584; V. 484, 505, 784, 899, 971, 1174, 1265, 1433.

§ 30. A translation of the first two books of Troilus into Latin verse, by Sir Francis Kinaston, was printed at Oxford in 1635. The volume also contains a few notes, but I do not find in them anything of value. The author tries to reproduce the English stanza, as thus:—

§ 31. Hazlitt's Handbook to Popular Literature records the following title:—'A Paraphrase vpon the 3 first bookes of Chaucer's Troilus and Cressida. Translated into modern English ... by J[onathan] S[idnam]. About 1630. Folio; 70 leaves; in 7-line stanzas.'

mountaignes, is arested and resisted ofte tyme by the encountringe

covere al the erthe:—al this acordaunce of thinges is bounden with

the yifte: that is to seyn, that, til he be out of helle, yif he loke

and brende the venim. And Achelous the flood, defouled in his

[1]

Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, chap. xxxix. See the whole chapter.

[2]

Philosophy personified; see Book i, Prose 1, l. 3.

[3]

See Book ii, Prose 1.

[4]

See Book ii, Proses 5, 6.

[5]

See Book iii, Prose 9.

[6]

See Book iv, Metre 1.

[7]

See Book iv, Prose 6.

[8]

See Book v.

[9]

See the Romaunt of the Rose (in vol. i.), ll. 5659-5666; and the note to l. 5661. It is also tolerably obvious, that Chaucer selected Metre 5 of Book ii. of Boethius for poetical treatment in his 'Former Age,' because Jean de Meun had selected for similar treatment the very same passage; see Rom. de la Rose, ll. 8395-8406.

[10]

There is a copy of this in the British Museum, MS. Addit. 10341.

[11]

MS. Harl. 44 (Wülker); not MS. Harl. 43, as in Warton, who has confused this MS. with that next mentioned.

[12]

MS. Harl. 43 (Wülker); not MS. Harl. 44, as in Warton.

[13]

There is a better copy than either of the above in MS. Royal 18 A. xiii. The B. M. Catalogue of the Royal MSS., by Casley, erroneously attributes this translation to Lydgate. And there is yet a fourth copy, in MS. Sloane 554. The Royal MS. begins, more correctly:—'In suffisaunce of cunnyng and of wyt.'

[14]

MS. i. 53.

[15]

MS. B. 5. There is yet another MS. in the library of Trinity College, Oxford, no. 75; and others in the Bodleian Library (MS. Rawlinson 151), in the Cambridge University Library (Gg. iv. 18), and in the Phillipps collection (as in note 5 below).

[16]

'The Boke of Comfort, translated into Englesse tonge. Enprented in the exempt Monastery of Tavestok in Denshyre, by me, Dan Thomas Rychard, Monke; 1525. 4to.'—Lowndes.

[17]

The MS. is now in the collection of Sir Thomas Phillipps; no. 1099.

[18]

He here implies that Chaucer's translation was by no means the only one then in existence; a remarkable statement.

[19]

MS. inserts full, needlessly.

[20]

Perhaps read In.

[21]

MS. neye.

Boethius: Book II: Meter V.

A verse translation by John Walton.

Full wonder blisseful was that rather age,

When mortal men couthe holde hem-selven[22] payed

To fede hem-selve[23] with-oute suche outerage,

With mete that trewe feeldes[24] have arrayed;

With acorne[s] thaire hunger was alayed,

And so thei couthe sese thaire talent;

Thei had[den] yit no queynt[e] craft assayed,

As clarry for to make ne pyment[25].

To de[y]en purpure couthe thei noght be-thynke,

The white flees, with venym Tyryen;

The rennyng ryver yaf hem lusty drynke,

And holsom sleep the[y] took vpon the grene.

The pynes, that so full of braunches been,

That was thaire hous, to kepe[n] vnder schade.

The see[26] to kerve no schippes were there seen;

Ther was no man that marchaundise made.

They liked not to sailen vp and doun,

But kepe hem-selven[27] where thei weren bred;

Tho was ful huscht the cruel clarioun,

For eger hate ther was no blood I-sched,

Ne therwith was non armour yet be-bled;

For in that tyme who durst have be so wood

Suche bitter woundes that he nold have dred,

With-outen réward, for to lese his blood.

I wold oure tyme myght turne certanly,

And wise[28] maneres alwey with vs dwelle;

But love of hauyng brenneth feruently,

More fersere than the verray fuyre of helle.

Allas! who was that man that wold him melle

With[29] gold and gemmes that were kevered thus[30],

That first began to myne; I can not telle,

But that he fond a perel[31] precious.

§ 16. MS. Auct. F. 3. 5, in the Bodleian Library, contains a prose translation, different from Chaucer's. After this, the next translation seems to be one by George Colvile; the title is thus given by Lowndes: 'Boetius de Consolatione Philosophiæ, translated by George Coluile, alias Coldewel. London: by John Cawoode; 1556. 4to.' This work was dedicated to Queen Mary, and reprinted in 1561; and again, without date.

There is an unprinted translation, in hexameters and other metres, in the British Museum (MS. Addit. 11401), by Bracegirdle, temp. Elizabeth. See Warton, ed. Hazlitt, iii. 39, note 6.

Lowndes next mentions a translation by J. T., printed at London in 1609, 12mo.

A translation 'Anglo-Latine expressus per S. E. M.' was printed at London in quarto, in 1654, according to Hazlitt's Hand-book to Popular Literature.

Next, a translation into English verse by H. Conningesbye, in 1664, 12mo.

The next is thus described: 'Of the Consolation of Philosophy, made English and illustrated with Notes by the Right Hon. Richard (Graham) Lord Viscount Preston. London; 1695, 8vo. Second edition, corrected; London; 1712, 8vo.'

A translation by W. Causton was printed in London in 1730; 8vo.

A translation by the Rev. Philip Ridpath, printed in London in 1785, 8vo., is described by Lowndes as 'an excellent translation with very useful notes, and a life of Boethius, drawn up with great accuracy and fidelity.'

A translation by R. Duncan was printed at Edinburgh in 1789, 8vo.; and an anonymous translation, described by Lowndes as 'a pitiful performance,' was printed in London in 1792, 8vo.

In a list of works which the Early English Text Society proposes shortly to print, we are told that 'Miss Pemberton has sent to press her edition of the fragments of Queen Elizabeth's Englishings (in the Record Office) from Boethius, Plutarch, &c.'

§ 17. I now return to the consideration of Chaucer's translation, as printed in the present volume.

I do not think the question as to the probable date of its composition need detain us long. It is so obviously connected with 'Troilus' and the 'House of Fame,' which it probably did not long precede, that we can hardly be wrong in dating it, as said above, about 1377-1380; or, in round numbers, about 1380 or a little earlier. I quite agree with Mr. Stewart (Essay, p. 226), that, 'it is surely most reasonable to connect its composition with those poems which contain the greatest number of recollections and imitations of his original;' and I see no reason for ascribing it, with Professor Morley (English Writers, v. 144), to Chaucer's youth. Even Mr. Stewart is so incautious as to suggest that Chaucer's 'acquaintance with the works of the Roman philosopher ... would seem to date from about the year 1369, when he wrote the Deth of Blaunche.' When we ask for some tangible evidence of this statement, we are simply referred to the following passages in that poem, viz. the mention of 'Tityus (588); of Fortune the debonaire (623); Fortune the monster (627); Fortune's capriciousness and her rolling wheel (634, 642); Tantalus (708); the mind compared to a clean parchment (778); and Alcibiades (1055-6);' see Essay, p. 267. In every one of these instances, I believe the inference to be fallacious, and that Chaucer got all these illustrations, at second hand, from Le Roman de la Rose. As a matter of fact, they are all to be found there; and I find, on reference, that I have, in most instances, already given the parallel passages in my notes. However, to make the matter clearer, I repeat them here.

Book Duch. 588. Cf. Comment li juisier Ticius

Book Duch. 588. Cf. S'efforcent ostoir de mangier;

Book Duch. 588. Cf. Rom. Rom. Rose, 19506.

Book Duch. 588. Cf. Si cum tu fez, las Sisifus, &c.;

Book Duch. 588. Cf. Rom. R. R. 19499.

Book Duch. 623. The dispitouse debonaire,

Book Duch. 623. That scorneth many a creature.

I cannot give the exact reference, because Jean de Meun's description of the various moods of Fortune extends to a portentous length. Chaucer reproduces the general impression which a perusal of the poem leaves on the mind. However, take ll. 4860-62 of Le Roman:—

Que miex vaut asses et profite

Fortune perverse et contraire

Que la mole et la debonnaire.

Surely 'debonaire' in Chaucer is rather French than Latin. And see debonaire in the E. version of the Romaunt, l. 5412.

Book Duch. 627. She is the monstres heed y-wryen,

Book Duch. 627. As filth over y-strawed with floures.

Book Duch. 627. Si di, par ma parole ovrir,

Book Duch. 627. Qui vodroit un femier covrir

Book Duch. 627. De dras de soie ou de floretes; R. R. 8995.

As the second of the above lines from the Book of the Duchesse is obviously taken from Le Roman, it is probable that the first is also; but it is a hard task to discover the particular word monstre in this vast poem. However, I find it, in l. 4917, with reference to Fortune; and her wheel is not far off, six lines above.

B. D. 634, 642. Fortune's capriciousness is treated of by Jean de Meun at intolerable length, ll. 4863-8492; and elsewhere. As to her wheel, it is continually rolling through his verses; see ll. 4911, 5366, 5870, 5925, 6172, 6434, 6648, 6880, &c.

B. D. 708. Cf. Et de fain avec Tentalus; R. R. 19482.

B. D. 778. Not from Le Roman, nor from Boethius, but from Machault's Remède de Fortune, as pointed out by M. Sandras long ago; see my note.

B. D. 1055-6. Cf. Car le cors Alcipiades

B. D. 1055-6. Cf. Qui de biauté avoit adés ...

B. D. 1055-6. Cf. Ainsinc le raconte Boece; R. R. 8981.

See my note on the line; and note the spelling of Alcipiades with a p, as in the English MSS.

We thus see that all these passages (except l. 778) are really taken from Le Roman, not to mention many more, already pointed out by Dr. Köppel (Anglia, xiv. 238). And, this being so, we may safely conclude that they were not taken from Boethius directly. Hence we may further infer that, in all probability, Chaucer, in 1369, was not very familiar with Boethius in the Latin original. And this accounts at once for the fact that he seldom quotes Boethius at first hand, perhaps not at all, in any of his earlier poems, such as the Complaint unto Pite, the Complaint of Mars, or Anelida and Arcite, or the Lyf of St. Cecilie. I see no reason for supposing that he had closely studied Boethius before (let us say) 1375; though it is extremely probable, as was said above, that Jean de Meun inspired him with the idea of reading it, to see whether it was really worth translating, as the French poet said it was.

§ 18. When we come to consider the style and manner in which Chaucer has executed his self-imposed task, we must first of all make some allowance for the difference between the scholarship of his age and of our own. One great difference is obvious, though constantly lost sight of, viz. that the teaching in those days was almost entirely oral, and that the student had to depend upon his memory to an extent which would now be regarded by many as extremely inconvenient. Suppose that, in reading Boethius, Chaucer comes across the phrase 'ueluti quidam clauus atque gubernaculum' (Bk. iii. pr. 12, note to l. 55), and does not remember the sense of clauus; what is to be done? It is quite certain, though this again is frequently lost sight of, that he had no access to a convenient and well-arranged Latin Dictionary, but only to such imperfect glossaries as were then in use. Almost the only resource, unless he had at hand a friend more learned than himself, was to guess. He guesses accordingly; and, taking clauus to mean much the same thing as clauis, puts down in his translation: 'and he is as a keye and a stere.' Some mistakes of this character were almost inevitable; and it must not greatly surprise us to be told, that the 'inaccuracy and infelicity' of Chaucer's translation 'is not that of an inexperienced Latin scholar, but rather of one who was no Latin scholar at all,' as Mr. Stewart says in his Essay, p. 226. It is useful to bear this in mind, because a similar lack of accuracy is characteristic of Chaucer's other works also; and we must not always infer that emendation is necessary, when we find in his text some curious error.

§ 19. The next passage in Mr. Stewart's Essay so well expresses the state of the case, that I do not hesitate to quote it at length. 'Given (he says) a man who is sufficiently conversant with a language to read it fluently without paying too much heed to the precise value of participle and preposition, who has the wit and the sagacity to grasp the meaning of his author, but not the intimate knowledge of his style and manner necessary to a right appreciation of either, and—especially if he set himself to write in an uncongenial and unfamiliar form—he will assuredly produce just such a result as Chaucer has done.

'We must now glance (he adds) at the literary style of the translation. As Ten Brink has observed, we can here see as clearly as in any work of the middle ages what a high cultivation is requisite for the production of a good prose. Verse, and not prose, is the natural vehicle for the expression of every language in its infancy, and it is certainly not in prose that Chaucer's genius shews to best advantage. The restrictions of metre were indeed to him as silken fetters, while the freedom of prose only served to embarrass him; just as a bird that has been born and bred in captivity, whose traditions are all domestic, finds itself at a sad loss when it escapes from its cage and has to fall back on its own resources for sustenance. In reading "Boece," we have often as it were to pause and look on while Chaucer has a desperate wrestle with a tough sentence; but though now he may appear to be down, with a victorious knee upon him, next moment he is on his feet again, disclaiming defeat in a gloss which makes us doubt whether his adversary had so much the best of it after all. But such strenuous endeavour, even when it is crowned with success, is strange in a writer one of whose chief charms is the delightful ease, the complete absence of effort, with which he says his best things. It is only necessary to compare the passages in Boethius in the prose version with the same when they reappear in the poems, to realise how much better they look in their verse dress. Let the reader take Troilus' soliloquy on Freewill and Predestination (Bk. iv. ll. 958-1078), and read it side by side with the corresponding passage in "Boece" (Bk. v. proses 2 and 3), and he cannot fail to feel the superiority of the former to the latter. With what clearness and precision does the argument unfold itself, how close is the reasoning, how vigorous and yet graceful is the language! It is to be regretted that Chaucer did not do for all the Metra of the "Consolation" what he did for the fifth of the second book. A solitary gem like "The Former Age" makes us long for a whole set[32]. Sometimes, whether unconsciously or of set purpose, it is difficult to decide, his prose slips into verse:—

It lyketh me to shewe, by subtil song,

With slakke and délitáble soun of strenges (Bk. iii. met. 2. 1).

Whan Fortune, with a proud right hand (Bk. ii. met. 1. 1)[33].'

The reader should also consult Ten Brink's History of English Literature, Book iv. sect. 7. I here give a useful extract.

'This version is complete, and faithful in all essential points. Chaucer had no other purpose than to disclose, if possible wholly, the meaning of this famous work to his contemporaries; and notwithstanding many errors in single points, he has fairly well succeeded in reproducing the sense of the original. He often employs for this purpose periphrastic turns, and for the explanation of difficult passages, poetical figures, mythological and historical allusions; and he even incorporates a number of notes in his text. His version thus becomes somewhat diffuse, and, in the undeveloped state of prose composition so characteristic of that age, often quite unwieldy. But there is no lack of warmth, and even of a certain colouring....

'The language of the translation shews many a peculiarity; viz. numerous Latinisms, and even Roman idioms in synthesis, inflexion, or syntax, which are either wholly absent or at least found very rarely in Chaucer's poems. The labour of this translation proved a school for the poet, from which his powers of speech came forth not only more elevated but more self-reliant; and above all, with a greater aptitude to express thoughts of a deeper nature.'

§ 20. Most of the instances in which Chaucer's rendering is inaccurate, unhappy, or insufficient are pointed out in the notes. I here collect some examples, many of which have already been remarked upon by Dr. Morris and Mr. Stewart.

i. met. 1. 3. rendinge Muses: 'lacerae Camenae.'

i. "et. 1. 20. unagreable dwellinges[34]: 'ingratas moras.'

i. pr. 1. 49. til it be at the laste: 'usque in exitium;' (but see the note).

i. pr. 3. 2. I took hevene: 'hausi caelum.'

i. met. 4. 5. hete: 'aestum;' (see the note). So again, in met. 7. 3.

i. pr. 4. 83. for nede of foreine moneye: 'alienae aeris necessitate.'

i. pr. 4. 93. lykned: 'astrui;' (see the note).

i. met. 5. 9. cometh eft ayein hir used cours: 'Solitas iterum mutet habenas;' (see the note).

ii. pr. 1. 22. entree: 'adyto;' (see the note).

ii. pr. 1. 45. use hir maneres: 'utere moribus.'

ii. pr. 5. 10. to hem that despenden it: 'effundendo.'

ii. "r. 5. 11. to thilke folk that mokeren it: 'coaceruando.'

ii. "r. 5. 90. subgit: 'sepositis;' (see the note).

ii. met. 6. 21. the gloss is wrong; (see the note).

ii. met. 7. 20. cruel day: 'sera dies;' (see the note).

iii. pr. 2. 57. birefte awey: 'adferre.' Here MS. C. has afferre, and Chaucer seems to have resolved this into ab-ferre.

iii. pr. 3. 48. foreyne: 'forenses.'

iii. pr. 4. 42. many maner dignitees of consules: 'multiplici consulatu.'

iii. pr. 4. 64. of usaunces: 'utentium.'

iii. pr. 8. 11. anoyously: 'obnoxius;' (see the note).

iii. "r. 8. 29. of a beest that highte lynx: 'Lynceis;' (see the note).

iii. pr. 9. 16. Wenest thou that he, that hath nede of power, that him ne lakketh no-thing? 'An tu arbitraris quod nihilo indigeat egere potentia?' On this Mr. Stewart remarks that 'it is easy to see that indigeat and egere have changed places.' To me, it is not quite easy; for the senses of the M.E. nede and lakken are very slippery. Suppose we make them change places, and read:—'Wenest thou that he, that hath lak of power, that him ne nedeth no-thing?' This may be better, but it is not wholly satisfactory.

iii. pr.9. 39-41. that he ... yif him nedeth = whether he needeth. A very clumsy passage; see the Latin quoted in the note.