автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Charm of Gardens

OTHER BEAUTIFUL BOOKS

ON FLOWERS AND GARDENS

Each containing full-page illustrations in

colour similar to those in this volume

Flowers and Gardens of Japan

Alpine Flowers and Gardens

British Floral Decoration

Dutch Bulbs and Gardens

Flowers and Gardens of Madeira

The Garden that I Love

Gardens of England

Kew Gardens

A. & C. BLACK, SOHO SQUARE, LONDON

THE CHARM OF GARDENS

AGENTS

AMERICA

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

64 & 66

Fifth Avenue, NEW YORK

AUSTRALASIA

THE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

205

Flinders Lane, MELBOURNE

CANADA

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF CANADA LTD.

St. Martin’s House, 70 Bond Street, TORONTO

INDIA

MACMILLAN & COMPANY LTD.

Macmillan Building, BOMBAY

309

Bow Bazaar Street, CALCUTTA

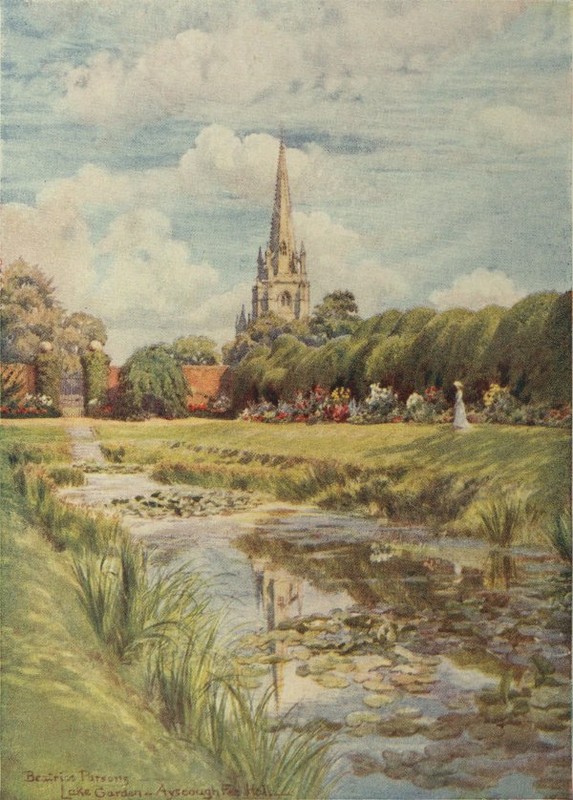

THE LAKE GARDEN AYSCOUGH FEE HALL, SPALDING.

THE

CHARM OF GARDENS

BY

DION CLAYTON CALTHROP

WITH THIRTY-TWO FULL-PAGE

ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR

PUBLISHED BY .

4 SOHO SQUARE

ADAM & CHARLES

LONDON . . W.

BLACK . . . .

MCMXI . . . .

The illustrations in this volume have been selected

from volumes in Black’s Series of Beautiful Books

TO

F. M. MARSDEN

WITHOUT WHOSE HELP THIS BOOK COULD

NEVER HAVE BEEN WRITTEN

FROM

HER AFFECTIONATE

SON-IN-LAW

CONTENTS

PART I

A VIEW OF ENGLAND

PAGE

I.

The Spirit of Gardens 3II.

The Garden of England: The Patchwork Quilt 10III.

A Country Lane: A Memory from Abroad 18IV.

Fields 23V.

Episode of the Contented Tailor 27VI.

The Bluebell Wood and the Calm Stone Dog 35VII.

The Tailor’s Sister’s Tombstone 42VIII.

The Cottage Garden 54IX.

A Feast of Wild Strawberries 64X.

The Praises of a Country Life 71PART II

GARDENS AND HISTORY

I.

The Roman Garden in England 75II.

St. Fiacre, Patron Saint of Gardeners and Cab-Drivers 88III.

Evelyn’s “Sylva” 96PART III

KALENDARIUM HORTENSE

108PART IV

GARDEN MOODS

I.

Town Gardens 151II.

The Effect of Trees 163III.

A Lover of Gardens 182IV.

Of the Crown of Thorns 185V.

Of Apples 187VI.

Of the First Gardener 189VII.

Of the First Roses 191VIII.

Of the Abbey Garden 193IX.

The Olympian Aspect 195X.

Evening Red and Morning Grey 204XI.

Garden Promises 213XII.

Garden Paths 220XIII.

The Gardens of the Dead 233I

THE SPIRIT OF GARDENS

II

THE GARDEN OF ENGLAND: THE

PATCHWORK QUILT

III

A COUNTRY LANE: A MEMORY

FROM ABROAD

IV

FIELDS

V

EPISODE OF THE CONTENTED TAILOR

VI

THE BLUEBELL WOOD AND THE CALM

STONE DOG

VII

THE TAILOR’S SISTER’S TOMBSTONE

VIII

THE COTTAGE GARDEN

IX

A FEAST OF WILD STRAWBERRIES

Sometimes he delights to lie under an aged Holm, sometimes on the matted grass: meanwhile the waters glide down from steep clefts; the birds warble in the woods; and the fountains murmur with their purling streams, which invites gentle slumbers.

I

THE ROMAN GARDEN IN ENGLAND

I have no doubt that in Roman England such wells were built where the supply of water was not equal to great distribution. But it is amazing to think that such a tiny village as Laurentium, where Pliny had one of his villas outside Rome, held three Inns, in each of which were baths always heated and ready for travellers, and that it has taken us until the present day to bring the bath into the ordinary house.

Back went Saint Fiacre to his forest clearing, to his friends the birds, his bubbling wells, his aisles of trees, his garden, now well grown, and, breaking a stick he marked out far and wide the space of land he needed, more than any man could in one day enclose with any spade. And after that into the little oratory he went and prayed for help.

PART III

KALENDARIUM HORTENSE

DECEMBER.

Our opinion has not altered in these two hundred years. The enjoyment of a garden is certainly one of the most innocent delights in human life, the enjoyment of the garden he mentions in particular is one of the most innocent pleasures in London. Kensington Gardens have inspired many people, the classic of them is undoubtedly Mr. J. M. Barrie’s “Little White Bird.” The patron Saint of them is, and I think ever will be, “Peter Pan.” One has only to walk down the Babies Mile to hear games from Peter Pan going on in all directions. This peculiar spirit haunted the Gardens long before the days of Mr. Barrie, and whispered much of his charming story in the ears of a bewigged gentleman—Mr. Tickell, by name—who, in a poem of some considerable length, sang Kensington’s praises. Those tiny fairy trumpets sounding in the walks of Kensington sounded a tune which has never left the air, and one fancies the creator of Peter Pan catching sight of a dim ghost now and again, the ghost of Mr. Tickell, Joseph Addison’s friend, as he walks in full-bottomed wig, his wide skirted coat, and sees the fairies too. He begins:

But of the effect of trees as a spiritual support no man is at variance with another. That they give courage, and help and hope, that the green sight of them is good as being reminder that Heaven is kind, and that the Winter is not always, no man doubts but, perhaps, fears to voice, feeling his neighbour will call out at him for a worshipper of Pan and of strange gods. But to the garden dweller, or to him who must perforce make his garden of one tree in a dusty court, and of one glass of flowers on his desk, these things have voices, and they are kindly voices, saying, “Despair not,” and “Regard me how I grow upright through the seasons,” and also “Give shade and shelter to all things and men equally as I do, without distinction or difference, and if the grass gives a couch, fair and embroidered with flowers, so do I give a roof of infinite variety, and a shade from the sun, and a shelter from the wind.” And again, “If a man know a tree to love it he will understand much of men, and of birds, and beasts and of all living things. And of greater things too, for in the branches is other fruit than the fruit of the tree. Just as the rainbow is set in the sky for a promise, so is fruit in a tree set there; and the leaves show how orderly is the Great Plan; and the branches show the strength of slender things, and of little things, so that a man may know how Heaven has its roots in earth, and its crest in the clouds. And a man who holds to earth with one hand, and reaches at the stars with the other, in that span he encompasses all that may be known if he but see it. But men are blind, and do not see the sky but as sky, and do not see the stars but as balls of fire, or the green grass but as a carpet, or the flowers but as a combination of chemical accidents. But over all, and through all, and in all is God, Who still speaks with Adam in the Garden.”

III

A LOVER OF GARDENS

“And the Christian men, that dwell beyond the sea, in Greece, say that the Tree of the Cross, that we call Cypress, was one of that tree that Adam ate the apple off; and that find they written. And they say also, that their Scripture saith, that Adam was sick, and said to his son Seth, that he should go to the angel that kept Paradise, that he would send him the oil of mercy, for to anoint with his members, that he might have health. And Seth went. But the angel would not let him come in; but said to him, that he might not have of the oil of mercy. But he took him three grains of the same tree, that his father ate the apple off; and bade him, a soon as his father was dead, that he should put these three grains under his tongue, and grave him so; and so he did. And of these three grains sprang a tree, as the angel said it should, and bare a fruit, through the which fruit Adam should be saved.

“And ye shall understand, that our Lord Jesu, in that night that he was taken, he was led into a garden; and there he was first examined right sharply; and there the Jews scorned him, and made him a crown of the branches of the Albespine, that is White Thorn, that grew in that same garden, and set it on his head, so fast and so sore, that the blood ran down by many places of his visage, and of his neck, and of his shoulders. And therefore hath the White Thorn many virtues, for he that beareth a branch on him thereof, no thunder or no manner of tempest may dere him; nor in the house that it is in may no evil ghost enter nor come into the place that it is in. And in that same garden, Saint Peter denied our Lord thrice.

Sir John, on his constant look out lets no oddment pass him by, and the more peculiar the better. It appears he would rather see a well in a field—“that our Lord Jesu Christ made with one of his feet, when he went to play with other children”—than many things political or notable to the country. And he will never come to a country but he will mention the state of its trees and fruits, these, naturally, being important items to the traveller of his day who might at any moment have to fall back on the natural fruits of the field for his food. So, when he goes by the desert to the valley of Elim, he notes the seventy-two Palm trees there growing—“the which Moses found with the children of Israel.”

“And right fast by that place is a cave in the rock, where Adam and Eve dwelled when they were put out of Paradise; and there got they their children. And in the same place was Adam formed and made, after that some men say (for men were wont for to clept that place the field of Damascus, because that it was in the lordship of Damascus), and from thence he was translated into Paradise of delights, as they say; and after that he was driven out of Paradise he was there left. And the same day that he was put in Paradise, the same day he was put out, for anon he sinned. There beginneth the Vale of Hebron, that dureth nigh to Jerusalem. There the Angel commanded Adam that he should dwell with his wife Eve, of the which he gat Seth; of which tribe, that is to say kindred, Jesu Christ was born.”

“And other trees that bear venom, against which there is no medicine, but one; and that is to take their proper leaves and stamp them and temper them with water, and then drink it, and else he shall die; for triacle will not avail, ne none other medicine. Of this venom the Jews had let seek of one of their friends for to empoison all Christianity, as I have heard them say in their confession before their dying; but thank be to Almighty God! they failed of their purpose; but always they make great mortality of people.”

We nodded mysteriously, full of breathless expectation.

All the small birds give one joy though they be robbers or enemies to young plants, or bee eaters like the blue-tit, or strawberry robbers, or drainpipe chokers like the house-sparrows, or murderers of the summer peace like the woodpecker with his quick insistent “tap, tap.”

The stem, on which the supreme work, the flower, will be born, is, in the case of our Carnations, divided into nodes and internodes, the nodes being those solid elbows one sees. It is towards the supreme work that our eyes are turned. It is part, if not chief part, of the pleasure of our vigil to look forward to the day when the first faint colour shows in the bursting bud. It is for this moment that we wait and wear out the chill of Winter. It is towards the idea of a resurrection that our thoughts, perhaps unconsciously, are fixed, to the knowledge that our garden is to be born again, fresh and new in colour, in warmth and sunshine. The very secret workings going on before our eyes, all that Heavenly workshop where none are ’prentices and all are master-hands, where the bee, and the ant, and the unseen insect in the air, go about their exact duties, give one, as Autumn declines into Winter and Winter rouses into Spring, some vague conjecture of the mighty magic of the growing world, where no particle of energy is ever wasted.

In the ordering of paths such as I have written there are many ways, and some are for paths all of grass, and some for tiles, and some for flags of stone, some for gravel, and some for brick laid herring-bone ways. Each has its proper and appointed place, as, for instance, that flags of stone are proper by a balustrade where are also stone jars to hold flowers and stone seats arranged. And brick, which of all the others I most prefer, as it is more warm to look at and helps the garden by its rich colour, is good in intimate small gardens as well as in big, and gives a feeling of cosiness to old-fashioned borders, and is nice near to the house, and is good to set tubs for trees on, or tubs filled with gay flowers. Of grass paths, in that they are soft and inviting, I like them well enough, but they are wet underfoot after rain and dew, and need a deal of care and trimming; but in such cases as small set gardens with queer-shaped beds and low Box borders, I mean bulb gardens, to be afterwards used for carpet bedding or for a show of some one thing, as Begonias, or Zinnias, or Carnations, they are without equal. They should be kept very precious, and well free of weeds, otherwise their beauty is gone and they have a lack-lustre air, very uncomfortable. As for gravel, it is a good thing in place where the ground is low and moist, for it will remain dry better than anything if it is properly rolled and well made. Often it is not properly curved and drained, and Moss and weeds collect at the sides, whereby your garden will seem unkempt and dull. Indeed the garden paths are of supreme importance to the appearance of your garden, as if they be left dirty, or covered with leaves or moss they will spoil all the neat brightness of the flowers, and are apt to look like an unbrushed coat on a man otherwise well dressed. This is especially the case with broad paths and drives. How often one has judged of a gardener by the appearance of his drive! The first glance from the gate up the drive will give you a fair guess at the gardener and his methods, and you can tell at once if he be a man of decent and tidy habits, or a man to leave odd corners dirty and full of weeds. That last man is just such an one as will burnish up his place on the eve of a garden party, and give everything a lick and a promise, and will stand by his greenhouses with an expression on his face of an holy cherub when the visitors are being shown his stove plants. That man will be for ever complaining of overwork and will wear a face as long as a fiddle if he is asked pertinent questions of unweeded paths. “Such a work,” he will say, “should be done by an extra boy. As for me, am I not by day and by night protecting the peas from the birds, and the dahlias from earwigs, and the melons from the ravages of slugs?” And you may know from this that he is the type of man who loses grape scissors, and who leaves bast about, and mislays his trowel, and neglects to give water to your favourite plants, so that they wither and die. No. Look well that you get a man who is fond of keeping himself clean, and he will keep his paths clean, as is the case in a man I know who started a fruit garden in the country. He, it was, who showed me his men working on a Saturday afternoon at cleaning up the paths. And when I stood amazed at this he took me into the shed where the tools were kept, and there I saw spades shining like silver, and forks burnished wonderfully, and everything very orderly. I clapped my hands, and looked round still in wonder, for I marvelled to see such neatness and order in a place that is the shrine of disorder—as tool sheds, potting sheds, and the like, which are a medley of stick, earth, leafmould, old pricking-out boxes, tools, wire, and other miscellaneous objects. And I marvelled still more to see through the open door men at work—on the afternoon devoted to holiday—picking leaves from the paths, and setting the place in order.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1.

The Lake Garden, Ayscough Fee Hall, Spalding FrontispieceFacing page

2.

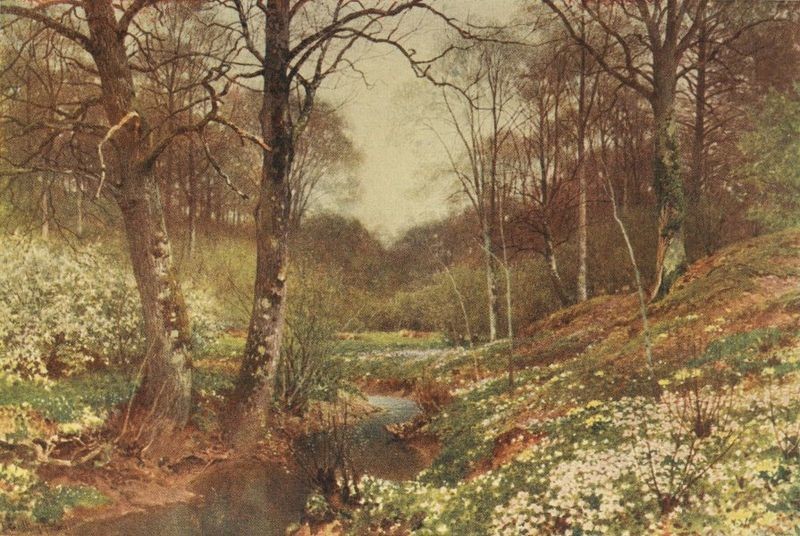

A Primrose Bank near Dorking vi3.

Sir Walter’s Sundial, Abbotsford 94.

The Weald of Kent, showing the Country like a Patchwork Quilt 165.

Poppies in Surrey 256.

Porches grown over with Honeysuckle and Roses at Broadway in the Cotswolds 327.

Bluebells in Surrey 418.

A Cottage Garden 489.

A Surrey Cottage 5710.

Patches of Heather 6411.

A Pergola in an English Garden 7312.

Entrance to the Gardens, Ayscough Fee Hall, Spalding 8013.

A Cab-Driver in Piccadilly 8914.

A Wood at Wotton, the Home of John Evelyn 9615.

Tulips in the “Garden of Peace” 10516.

Apple Trees 11217.

Daffodils in a Middlesex Garden 12118.

A Poet’s Orchard in Kent 12819.

A Kentish Garden in Autumn 13720.

A Hampstead Garden in Winter 14421.

Azaleas in Bloom, Rotten Row 15322.

In Hyde Park 16023.

The Seat beneath the Oak in the Poet Laureate’s Garden 16924.

In the Botanic Garden, Oxford 17625.

The Pride of Spring, Surrey 18526.

A Rose Garden in Berkshire 19227.

A Shepherd of Coniston 20128.

A Dovecote in a Sussex Garden 20829.

A Northamptonshire Garden 21730.

A Path in a Rose Garden 22431.

A Churchyard in the Cotswolds 23532.

Autumn Colour at Bonchurch Old Church near Ventnor 238SIR WALTER’S SUNDIAL, ABBOTSFORD.

THE WEALD OF KENT SHOWING THE COUNTRY LIKE A PATCHWORK QUILT.

POPPIES IN SURREY.

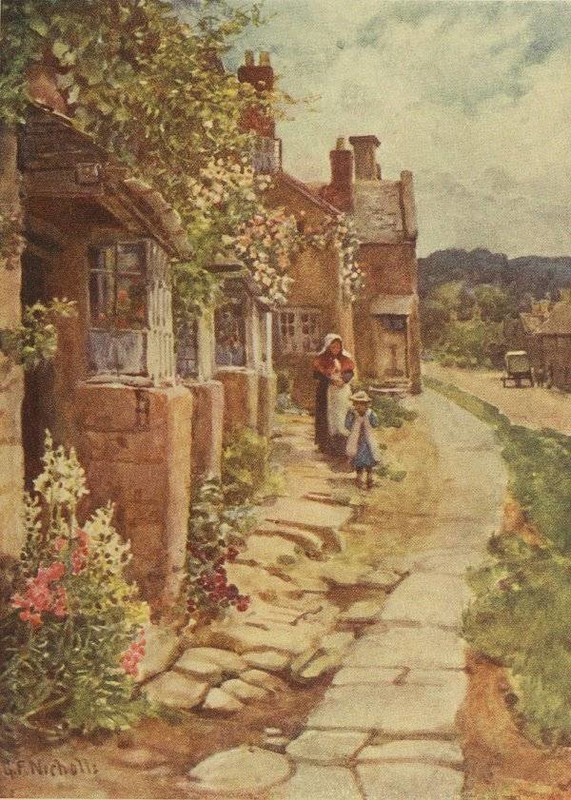

PORCHES GROWN OVER WITH HONEYSUCKLE AND ROSES AT BROADWAY IN THE COTSWOLDS.

BLUEBELLS IN SURREY.

A COTTAGE GARDEN.

A SURREY COTTAGE.

PATCHES OF HEATHER.

A PERGOLA IN AN ENGLISH GARDEN.

ENTRANCE TO THE GARDENS, AYSCOUGH FEE HALL, SPALDING.

A CAB-DRIVER IN PICCADILLY.

A WOOD AT WOTTON, THE HOME OF JOHN EVELYN.

TULIPS IN “THE GARDEN OF PEACE.”

APPLE TREES.

DAFFODILS IN A MIDDLESEX GARDEN.

A POET’S ORCHARD IN KENT.

A KENTISH GARDEN IN AUTUMN.

A HAMPSTEAD GARDEN IN WINTER.

AZALEAS IN BLOOM, ROTTEN ROW.

IN HYDE PARK.

THE SEAT BENEATH THE OAK IN THE POET LAUREATE’S GARDEN.

IN THE BOTANIC GARDEN, OXFORD.

THE PRIDE OF SPRING, SURREY.

A ROSE GARDEN IN BERKSHIRE.

A SHEPHERD OF CONISTON.

A DOVECOTE IN A SUSSEX GARDEN.

A NORTHAMPTONSHIRE GARDEN.

A PATH IN A ROSE GARDEN.

A CHURCHYARD IN THE COTSWOLDS.

AUTUMN COLOUR AT BONCHURCH OLD CHURCH, NEAR VENTNOR.

PART I

A VIEW OF ENGLAND

I

THE SPIRIT OF GARDENS

Once, I remember well, when I was hungering for a breath of country air, a woman, brown with the caresses of the wind and sun, brought the Spring to my door and sold it to me for a penny. The husky rough scent of those Primroses gave me news of England that I longed to hear. When I had placed my flowers in a bowl and put them on the table where I worked, they told me stories of the lanes and woods, how thrushes sang, and the wild Cherry Blossom flared delicately across the purpling trees.

A flower often will reclaim a mood when nothing else will bring it back.

To garden, to garner up the seasons in a little space, is part of every wise man’s philosophy. To sow the seeds, to watch the tender shoots come out and brave the light and rain, to see the buds lift up their heads, and then to catch one’s breath as the flowers open and display their precious colours, living, breathing jewels, is enough to live for. But there is more than that. A man may choose the feast to spread before his eyes, may sow old memories and see them grow, and feel the answering colours in his heart. This Rose he used to pass on his way to school; it nodded to him over the high red wall, while next to it a Purple Clematis clung, arching over, so that, by standing on his pile of school-books, he could reach the flowers. This patch of Golden Marigolds reminds him of a long border in the garden where he spent his boyhood (they used to grow behind the bee skeps, had a little place to themselves next to the Horseradish and the early Lettuces). There’s a hedge of Lavender full of association, he may remember how he was allowed (or was it set him for a task?) to cut great sheaves of it and take them to the Apple-room, and hang them up to dry over old newspapers. To look at Lavender brings back the curious musty smell of that store-room, where Apples wintered on long shelves; where the lawn-mower stood, and the brooms, and the scythe (to cut the orchard grass), and untidy bundles of bass hung with string and coils of wire. What a wonderful place that store-room was, with the broken door and the rusty lock that creaked as the big key turned to let him in: to reach the latch he had to stand on tip-toe, and to turn the key seemed quite a grown-up task. There was all a garden needs stored in that room. It had been a dining-room once, a hundred years ago, a room where the members of a bowling club convivially met and fought old games; bias, twist, jack, all the terms ring in his ears, even the click of the bowls, sharp on the summer air, comes back; and the plastered ornamental ceiling had sagged and dropped away here and there, showing the laths. There was a big dusty window, across which the twisted arms of a Wisteria stretched, and a broken window seat in it that opened like a box to hold the bowls. Just the hedge of Lavender brings back the picture of the boy whose cherished dreams hung about those four walls; who, having strung his bunches, neatly tied, on wooden pegs along the walls, and spread his papers underneath to catch the falling seeds, sat, book in hand, and travelled into foreign lands with Mungo Park. There, on his left, and facing him as well, shelves lined the walls, and Pears, Apples and Medlars were arranged in rows, while by his side, placed on the window ledge to catch the sun, were fallen Nectarines, Peaches and big yellow Plums set to ripen.

What curious things a garden store-room holds! The tins, slopped over, of weed-killer, of patent plant foods, of fine white sand. The twisted string, criss-crossed upon a peg of wood, covered with whitewash, the string that serves to guide the marker for the tennis-court. Then an array of nets to cover Currant bushes, and bid birds beware of Gooseberries, Cherries and ripe Strawberries. A barrow, full of odds and ends, baskets, queer little bags of seeds, a heap of Groundsel gathered for a bird and lying there forgotten. Like a Dutch picture, half in gloom with bright lights on the shears, and along the edge of the scythe, and on the curved wire mesh made to guard young seedlings. Empty seed packets on the floor, bright coloured pictures of the flowers on the outsides, a little soiled by the earth and the gardener’s thumb.

Plant memories, indeed! A man may plant a host of them and never then recapture all his joys. There’s his first love garnishing a rustic arch, a deep yellow Rose, beautiful in the bud—William Allen Richardson: she wore them in her sash. He can laugh now and see the long yellow hair floating in a cloud behind her as she ran, and the twinkling black legs, and the merry pretty face looking down on him from between the leaves of the Apple-tree she climbed. He grows that Apple in his orchard now, and toasts her memory when the first ripe fruit of it shines on the dish before him at dessert.

The Clove Carnation with its spice-like scent he bought from a barrow in a London slum, brought with care—wrapped in paper on the rack of the railway carriage—and planted it here. This Picotee he hailed with joy in the flower-market at Saint Malo and carried it across the sea, each bloom tied up to a friendly length of cane. His neighbours marvel at his pains, but it recalls many a happy day to him.

There, in a corner under a nut-tree, is a grass bank thick with Primrose plants—another memory. A picture comes to him from the Primroses very clear, very distinct, a picture of the world gone black, of a day when a boy thought heaven and earth purposeless, cruel; when he ran from a garden to the woods and threw himself on a bank, covered with Primroses, sobbing and weeping till the world was blotted out with his tears, because his dog had died. It had been the first thing he had learnt to love, the first thing he had had to care for, to look after. All his childish ideas were whispered into the big retriever’s silky coat. They had secret understandings, a different language, ideas in common, and the dog’s death was his first hint of death in the world. Years after, when he planted this garden, he gave a place to Don, and planted the Primroses himself. The earth was kindly and the flowers flourished. The earth is kindly, even your cynic knows that and marks the spot where he hopes to lie, and thinks, not sourly, of the Daisies over his head.

There is something more than memory in a garden. There is that urgent need man has to be part of growing life. He must have open spaces, he takes health from the sight of a tree in bud, from the sight of a newly ploughed field, from a plant or so in a window-box, a flower in his button-hole. Men, who by a thousand ties are held at desks in cities, look up and hear a caged thrush sing, and their thoughts fly out to fields and the common wayside flowers, and, for a moment, the offices are filled with the perfume—indescribable—of the open road.

A PRIMROSE BANK NEAR DORKING.

There is that in the hum and business of a garden that makes for peace; the senses are softly stirred even as the heart finds wings. No greeting is as sweet as the drowsy murmur of bees, in garden, lane or open heath. No day so good as that which breaks to song of birds. No sight so happy as the elegant confusion of flower-border still wet and glistening with the morning dew.

I heard a man once deliver a learned lecture on the Persian character, full of history, romance and thoughtful ideas. Towards the end of his discourse I began to feel that he, indeed, knew the Persian inside out, but that I could catch but a fleeting and momentary glimpse of his knowledge. Then, by way of background to an anecdote, he mirrored, with loving care and wealth of detail, Oriental in its imagery and elaboration, the gardens in a palace. There was a stream of clear water running through the garden, and the owner had paved the bed of the stream with exquisite old tiles; white Irises bloomed along the banks, white Roses, growing thickly, dropped scented petals in the stream. I have as good as lived in that garden; I saw it so well, and what little I know of the Persian I know from that description. Omar is more than a dead poet to me now; I can smell the Roses blooming over his grave.

There should be a sundial in every garden to mark the true beginning and the end of day; some noise of water somewhere; bees; good trees to give shade to us and shelter to the birds; a garden-house with proper amount of flower-lore on shelves within; a walk for scent alone, flowers grown perfume-wise; a solitary place, if possible, where should be a nest of owls; a spread of lawn to rest the eyes, no cut beds in it to spoil the symmetry, and at least one border for herbaceous plants. If this is greedy of good things leave out the owls—that’s but a fanciful thought. Do you know what a small space this requires? Those who might be free and yet choose to live in towns might have it all for the price of the rent of the ground their kitchen covers.

SIR WALTER’S SUNDIAL, ABBOTSFORD.

There are those aching spirits to whom no land is home, whose feet go wandering over the world; gipsy-spirits searching one must suppose for peace of mind in constant new sights. For them the well-ordered garden with its high walls, its neat lawn, its fair carriage-drive, is but a dull prison-house, and even if in the course of their wanderings they stray into such a place their talk is all of other lands; of scarlet twisted flowers in Cashmere; of fields of Arum Lilies near Table Mountain; of the sad-grey Olives and the gorgeous Orange groves of Spain; the Poppy fields of China, or the brightly painted Tulips growing orderly in Holland. We with our ancestral rookery near by, our talk of last year’s nests, or overweening pride in the soft snows of Mrs. Simpkin’s Pinks, seem to these folk like prisoners, who having tamed a mouse proclaim it chief of all the animal world. But ask of the Garden of England and the flowers it affords and see their eyes take on a far-away look as the road calls to them, and hear them at their own lore of roadside flowers, praising and loving Traveller’s Joy, the gilt array of Buttercups, the dusty pink of Ragged Robin, and the like sweet joys the vagabond holds dear. This one can whistle like a blackbird; that one has boiled the roots of Dandelions (Dent de Lion, a charming name) and has been cured by their juices. He knows that if he sees the delicate parachutes of Dandelion, Coltsfoot, or of Thistle-fly when there is not a breath of wind, then there will be rain. They read the skies, hear voices in the wind, take courses from the stars, and know the time of day from flowers. These men, having none of the spirit that inspires your gardener, see the results of the work and smile pleasantly, ask, perhaps, the name of some flower, to please you, know something of soils, praise your Mulberries, and admire your collection of Violas, but soon they are off and away, breathing more freely for leaving the sheltered peace of your well-kept place, and vanish to Spitzbergen or the Chinese desert in search of what their souls crave. We are different; we sit in the cool of the evening, overlooking our sweet-scented borders, gaining joy from the gathering night that paints out the detail of our world, and hope quietly for a soft, gentle rain in the night to stiffen the flowers’ drooping heads. We English are gardeners by nature: perhaps the greyness of our skies accounts for our desire to make our gardens blaze with colours.

We have our memories, our desire for peace, our love of colour, and, at the back of all, something infinitely more grand.

“No lily muffled hum of a summer bee

But finds some coupling with the spinning stars;

No pebble at your foot, but proves a sphere;

... Earth’s crammed with heaven,

And every common bush afire with God:

But only he who knows takes off his shoes.”

II

THE GARDEN OF ENGLAND: THE

PATCHWORK QUILT

Even your most unadventurous fellow can hardly look on a fair prospect of fields and meadows, woods, villages with smoking chimneys, a river, and a road, without a certain feeling rising in him that he would like to tread the road that winds so dapperly through the country, and discover for himself where it leads.

To those who love their country the road is but a garden path running between borders of fair flowers whose names and virtues should be known to every child.

A poet can weave a story from the speck of mud on a fellow traveller’s boot—the red soil of a Devonshire lane calls up such pictures of fern-covered banks, such rushing streams, as make a poem in themselves.

It strikes one from the very first how neatly most of England is kept. The dip and rise of softly swelling hills across which the curling ribbon of the road winds leisurely between neat hedges, the fields in patches, coloured brown and green, golden with Corn, scarlet with Poppies, yellow with Buttercups; the circular bunches of trees under whose shade fat cattle stand lazily switching their tails at flies; the woods, hangers, shaws and coppices, glades, dells, dingles and combes, all set out so orderly and precise that, from a hill, the country has the appearance of a patchwork quilt set in a pleasant irregularity, studded with straggling farms, and little sleepy villages where the resonant note of the church clock checks off the drowsy hours. The road that runs through this quilt land seems like a thread on which villages and market towns are strung, beads of endless variety, some huddled in a bunch upon a hill, some long and straggling, some thatched and warm, red-bricked and creeper-covered, others white with roofs of purple slate, others of grey stone, others of warm yellow. All alive with birds and flowers and village children, butterflies and trees; fed by broad rivers, or hanging over singing streams or deep in the lush grass of water meadows gay with kingcups.

This garden is for us who care to know it. We can take the road, our garden path, and pluck, as we will, flowers of all kinds from our borders; sleep in our garden on beds of bracken pulled and piled high under trees; or on soft heaps of heather heaped under sheltering stones. If we know our garden well enough it will give us food—salads, fruits and nuts; it will cure us of our ills by its herbs; feed our imagination by the quaint names of flower and herb. Here’s a small list that will sing a man to sleep, dreaming of England.

Poet’s Asphodel.

Shepherd’s Purse.

Our Lady’s Bedstraw.

Water Soldier.

Rowan.

Hound’s Tongue.

Gipsy Rose.

Fool’s Parsley.

Celandine.

Columbine.

Adder’s Tongue.

Speedwell.

Thorn Apple.

Virgin Bower.

Whin.

These alone of hundreds give a lift to the day: there’s a story to each of them.

Take our England as a garden and let the eye roam over the land. Here’s the flat country of the Fens, long, long vistas of fields, with spires and towers sticking up against the sky. Plenty of rare flowers there for your gardener, marsh flowers, water plants galore. That’s the place to see the sky, to watch a summer storm across the plain, to see the Poplars bending in an angry wind, and the white windmills glare against purple rain clouds. Few hedges here but plenty of banks and dykes, and canals they call drains. Here you may find Marsh Valerian, Water Crowsfoot, Frogbit, pink Cuckoo-flowers, Bog Bean, Sundews, Sea Lavender, and Bladder-worts. The Sundews alone will give you an hour’s pleasure with their glistening red glands tricked out to catch unwary flies and midges.

Then there’s a wild garden waiting you by stone walls in the dales of Derbyshire, or in the Yorkshire wolds, or the Lancashire fells. On the open heaths, where the grey roads wind through warm carpets of ling and heather, you can fill your nostrils with the sweet scent of Gorse and Thyme.

I was sitting one hot afternoon, drawing the twisted bole of a Beech tree. All the wood in which I sat was stirring with life; the dingle below me a mist of flowers, Primroses, Wind-flowers, Hyacinths whose bells made the air softly fragrant. Above me the sky showed through a trellis-work of young leaves, the distance of the wood was purple with opening buds, and the floor was a swaying sea of Bluebells dancing in a gentle breeze. Squirrels chattered in the trees; now and then a wood pigeon flopped out of a tree, and a blackbird whistled in some hidden place.

All absorbed in my work, following the grotesquely beautiful curves of the beech roots, I heard no sound of approaching footsteps. A voice behind me said “Good,” and I started, dropping my pencil in my confusion.

“Sorry. Didn’t mean to startle you,” said the voice.

I turned round and saw a man standing behind me, a man without a cap, with curly brown hair, and a face coloured deep brown by the sun. He was dressed in a faded suit of greenish tweed, wore a blue flannel shirt, carried a thick stick in his hand, and had a worn-looking box slung over his shoulders by a stained leather strap.

I suppose my surprise showed in my face in some comic way, for he laughed heartily, showing a set of strong white teeth.

“No, I’m not Pan,” he said laughing, “or a keeper, or a vision. I’m a gardener.”

His admirable assurance and pleasant address were very captivating.

I asked him what he did there, and he immediately sat down by me, pulled out a black clay pipe, and lit up before replying. He extended the honours of his match to my cigarette and I noticed that his hands were well formed, and that he wore a silver ring on the little finger of his right hand.

When he had arranged himself to his comfort, propping his back against a tree and crossing his legs, he told me he was a gardener on a very large scale.

I wished him joy of his garden, at which he smiled broadly, and informed me in the most matter-of-fact way that he gardened the whole of Great Britain.

For a moment I wondered if I had fallen in with an amiable lunatic, but a closer inspection of his face showed me he was sane, uncommonly healthy, and, I judged, a clever man.

“A vast garden?” I said.

Without exactly replying to my remark, which was put half in the manner of a question, he said, partly to himself, “The slight fingers of April. Do you notice how delicate everything is?”

I had noticed. The air was full of suggestion, the flowers were very fairylike, the green of the trees very tender.

“Pied April,” said I.

Instead of answering me again he unstrapped the box that now lay beside him on the grass, opened it and took from it a beautiful Fritillaria.

“There’s one of the April Princesses, if you like,” he said. “There are not many about here, just an odd one or two; plenty near Oxford though.”

“You know Oxford?” said I.

“Guess again,” he said, smiling. “I’m no Oxford man, but I know the woods about there well. Please go on working; I’ll talk.”

I was about to look at my watch when he stopped me.

“It’s half-past two,” he said. “The slant of the sun on the leaves ought to tell you that.”

I was amused, interested in the man; he was so odd and quaint. “I’ve not eaten my lunch yet,” I said. “Perhaps you’ll share it with me.”

“I was wondering if you’d invite me,” he replied. “I’m rather hungry.”

I had, luckily, enough for two. Slices of ham, some cheese, a loaf of new bread, and a full flask. Very soon we were eating together like old friends.

In an inconsequent way he asked me what I thought of the name of Noakes.

I said it was as good as any other.

“Let’s have it Noakes, then,” he said, laughing again. A very merry man.

“About this garden of yours, Mr. Noakes?” I asked.

He tapped his wooden box and said, “If you want to know, I’m a herbalist. You can scarcely call me a civilised being, except on occasions when I do go among my fellow men to winter.” He pulled a cap and a pair of gloves out of his pocket. “My titles to respectability,” he said.

“And in the Spring?”

“I take to the road with the Coltsfoot and the Butterburrs. I come out with the first Violet, and the Pussy-cat Willow. I wander, all through the year, up and down the length and breadth of England, with my box of herbs. I get my bread and cheese that way—while you draw for pleasure.”

“Partly.”

“It must be for pleasure, or you wouldn’t take so much pains. I suppose you think I’m a very disgraceful person, a bad citizen, a worse patriot. But I know the news of the world better than those who read newspapers. Although I trade on superstitions, I do no harm.”

“Do you sell your herbs?”

“Colchicum for gout—Autumn Crocus, you know it,” he replied. “Willow-bark quinine; Violet distilled, for coughs. Not a bad trade—besides, it keeps me free.”

I hazarded a question. “Tell me—you must observe these things—do swifts drink as they fly? It has often puzzled me.”

“I don’t know,” said he. “Ask Mother Nature. Some of these things are the province of professors. I’m not a learned man; just a herbalist.”

At that moment a thrush began to sing in a tree overhead. My friend cocked his head, just like an animal.

“There’s the wise thrush,” he quoted softly, “he sings his song twice over.”

“So you read Browning,” I said.

“I have a garret and a library,” he said. “Winter quarters. We shall meet one day, and you’ll be surprised. I actually possess two dress suits. It’s a mad world.” He stopped abruptly to listen to the thrush. “This is better than the Carlton or Delmonico’s, anyhow!”

“What do you do?” I asked. “Go from village to village selling herbs?”

“That’s about it. Lord! Listen to that bird. I heard and saw a nightingale sing once in a shaw near Ewelme. I think a thrush is the better musician, though. Yes, I sell my herbs, all sorts and kinds. Drugs and ointments, very simple I assure you—Hemlock and Poppy to cure the toothache. Wood Sorrel—full of oxalic acid, you know, like Rhubarb—for fevers. Aconite for rheumatics—very popular medicine I make of that, sells like hot cakes in water meadow land, so does Agrimony for Fen ague. Tansy and Camomile for liver—excellent. Hellebore for blisters, and Cowslip pips for measles—I’m a regular quack, you see.”

“And it’s worth doing, is it?”

He leaned back, his pipe between his lips, a very contented man. “Worth doing!” he said. “Worth owning England, with all the wonderful mornings, and the clean air; worth waking up to the scent of Violets; worth lying on your back near a Bean field on a summer day; worth seeing the Bracken fronds uncurl; watching kingfishers; worth having the fields and hedgerows for a garden, full of flowers always—I should think so. I earn my bread, and I’m happy, far happier than most men. I can lend a hand at haymaking, at the harvest; at sheep-shearing, at the cider press, at hoeing, when I’m tired of my own company. I’ve worked the seines in the mackerel season on the South coast—do you know the bend of shore by Lyme and Charmouth? I’ve ploughed in the Lowlands, and found lost sheep in the Lake Country; caught moles for a living in Norfolk, and cut Hop-poles in Kent, and Heather in the Highlands.—And I’m not forty, and I’m never ill.”

THE WEALD OF KENT SHOWING THE COUNTRY LIKE A PATCHWORK QUILT.

“It sounds delightful.”

He rose to his feet and gave me his hand.

“We shall meet again,” he said laughing. “Perhaps in the conventional armour of starched shirts and inky black. For the present—to my work,” he pointed over his shoulder. “I’m building hen-coops for a widow. Hasta luego.”

With that he vanished as quietly as he came. Almost as soon as the trees had hidden him from my sight, a blackbird began to whistle, then stopped, and a laugh came out of the woods.

Altogether a very strange man.

I found, when he had gone, that he had written something on a piece of paper and had pinned it to the tree with a long thorn. It was this:

“I think, very likely, you may not know Ben Jonson’s ‘Gipsy Benediction.’ If you don’t, accept the offering as a return for my excellent lunch.

“The faerybeam upon you—

The stars to glisten on you—

A moon of light

In the noon of night,

Till the firedrake hath o’er gone you!

The wheel of fortune guide you;

The boy with the bow beside you;

Run aye in the way

Till the bird of day,

And the luckier lot, betide you.”

He signed, at the foot, “Noakes, Under the Greenwood Tree.” And he seemed to have written some of his clear laughter into it.

III

A COUNTRY LANE: A MEMORY

FROM ABROAD

I was looking at a vision of the world upside down, mirrored in the deep blue of a still sea. Where the inverted picture of my boat gleamed white, and the rope that moored her to a tree showed grey, I saw the dark fir trees growing upside down, the bank of emerald grass looking more brilliant because of the grey-green lichened rocks; a black rock, glistening, hung with brown seaweed, made the vision clear, and, over all, clouds chased each other in the sky, seemingly below me. They were those round fleecy clouds, like sheep, and they reminded me of something I could not quite arrest.

A fish swam—dash—across my mirror, another and another, rippling the sky, the trees, the bank, distorting everything. Then I looked up and saw a fishing-boat come sailing by with its great orange and tawny sails all set out to catch the land breeze; and bright blue nets hung out ready, floating and billowing in the slight wind. There was a creaking of ropes and a hum of Breton as the sailors talked. From my moorings by the island I watched her sail—Saint Nicholas she was called, and had a little figure of the Madonna on her stern. Out of the land-locked harbour she slipped, tacking to make the neck that led to the outer harbour, and there she was going to meet other gaily coloured ships and sail with them to the sardine grounds off the coast of Spain.

After she had passed, leaving her wide white wake in the still waters, I followed her in my mind, seeing the nets cast and the shimmering silver fish drawn up, and the long loaves of bread eaten, with wine and onions, until the waters round me were quiet again, and I could look once more into my mirror and wonder what it was the flocks of clouds said to my brain.

It came in a flash. Big Claus said to Little Claus, “After I threw you into the river in the sack, where did you get all those sheep and cattle?” And Little Claus said, “Out of the river, brother, for there I came upon a man in beautiful meadows, and he was tending the sheep and cattle. There were so many that he gave me a flock of sheep and a herd of cattle for myself, and I drove them out of the river and up here to graze.” Now they were looking over the bridge at the time, and the description Little Claus gave of the meadows and the sheep below in the river made the mouth of Big Claus begin to water with greed. As they looked, Little Claus pointed excitedly at the water, and said, “Look, brother, there go a flock of sheep under your very nose.” It was, really, nothing but the reflection of the clouds in the water, but Big Claus was too interested to think of this, and he implored his brother to tie him in a sack and push him into the water, that he, too, might get some of these wonderful herds. This Little Claus did, and that was the end of Big Claus.

How well I remember now—so well that when I looked into the water and saw the fleecy clouds go floating by, the picture changed for me and I saw an English country lane, and a small boy sitting under a hedge out of a summer shower, and he was deep in dreams over an old brown volume of “Grimm’s Fairy Tales.”

How wonderful the lane smelt after the rain! The Honeysuckle filled the air and mingled with the smell of warm wet earth. It was a deep lane, with the high hedges grown so rank and wild that they nearly crossed overhead, and the curved arms of the Dog Roses criss-crossed against the patch of turquoise sky. The thin new thread of a single wire crossed high overhead, shining like gold in the sun. It went, I knew, to the Coast Guard Station below me, and I remember clearly how I used to wonder what flashed across the wire to those fortunate men: news of thrilling wrecks, of smugglers creeping round the point, of battle-ships put out to sea, and other tales the sailors told me.

The lane was deep and twisted, and so narrow that when a flock of sheep was driven down it, the dogs ran across the backs of the sheep to head off stragglers. What a cloud of white dust they made, and how thick it lay on the leaves and flowers until the rain washed them clean again.

On the day of which I was dreaming, there had been one of those sharp angry storms, very short and fierce, with growling thunder in the distance, and purple and deep grey clouds flying along with torn, rust-coloured edges. I had sheltered under a quick-set hedge (set, that is, while the thorn was alive—quick, and bent into a kind of wattle pattern by men with sheepskin gloves) and where I sat, under a wayfaring tree (the Guelder Rose), the lane had a double turn, fore and aft, so that a space of it was quite shut off, like an island. I had my garden here and knew all the flowers and the butterflies.

On this day the rain washed the Foxgloves and made them gay and bright, each bell with a sparkling drop of water on its lips. The Brambles had long rows of drops on them, all shining like jewels, until a yellow-hammer perched on one of the arched sprays and shook all the raindrops off in a fluster of bright light.

Behind me, and in front, trailing Black Bryony twisted its arms round Traveller’s Joy, Honeysuckle and Wild Roses. Here and there, pink and white Bindweed hung, clinging to the hedge. By me, on the bank, Monkshood, Our Lady’s Cushion, and Butterfly Orchis grew, all shining with the rain, and the Silverweed shone better than them all.

Presently came two great cart horses, their trappings jingling, down my lane, and on the back of one, riding sideways, a small boy, swaying as he rode. His face was a perfect country poem, blue eyes, shaded by a battered hat of felt, into the band of which a Dog Rose was stuck. His hair, like Corn, shone in the sun, and his face, red and freckled, a blue shirt, faded by many washings and sun-bleached to a fine colour, thick boots, a hard horny young fist, and in his mouth a long stem of feathery grass. He looked as much part of Nature as the flowers themselves. There was some sort of greeting as he passed. I can see the group now; the slow patient horses, the boy, the yellow canvas coat slung to dry across the horse’s neck, a straw basket, from which a bottle neck protruded, hitched on the horse’s collar. They passed the bend in the lane and the boy began to whistle an aimless tune, but very good to hear. And it was England, every bit of it, the kind of thing one hungers for when a southern sun is beating pitilessly on one’s head, or when the rains in the tropics bring out overpowering scents, heavy and stifling.

So I might have dreamed on about this garden lane I carried in my mind, had not the tide turned and little waves begun to lop the sides of my boat.

I slipped my moorings, shipped the oars, and sailed home quietly on the tide under a clear blue sky from which all the clouds had vanished like my dream.

IV

FIELDS

A man will tell you how he has walked to such and such a place “across the fields,” with an air of saying, “You, I suppose, not knowing the country, painfully pursue the highroad.” He has the look of one who has made the discovery that it is good and wise to leave the beaten track, the cart rut, and the plain and obvious road, and has adventured in a daring spirit from stile to stile, from gate to ditch, where only the knowing ones may go. He is generally so occupied in the pride of reaching his destination by these means, that he has had little time to look about him and enjoy the expanse of country. For all that, he is a man after my own heart for, in a sense, he becomes part owner of England with me as soon as he puts his leg across a stile and begins to cast an eye across country.

There is an extraordinary satisfaction in following a footpath, that is made doubly sweet if one sucks in the joy of the day, and the blitheness of that through which we pass. To be knee-high in a bean field in flower is as good a thing as I know, more especially if it be on a hillside overlooking the sea.

I sat once on the polished rail of a stile (very well made with cross arms to hold by, like two short step-ladders, each with one long arm) and looked at a path I had taken that lay through a field of whispering oats. They seemed to hold a thousand secrets that they passed from ear to ear all down the field, and when the breeze came, and blew birds across the hedge, the whole field swayed, showing a rustling, silken surface, as if it enjoyed a great joke. The Poppies and Cornflowers and the White Convolvulus had no part in the conversation of the Oats, but field mice had, and ran across the path hurrying like urgent messengers, and once a mole nosed its way from the earth by my stile and vanished grumbling—like some gruff old gentleman—along the hedgerow. I never saw a field laugh as much as that field, or be so frivolous, or so feminine. The field at my back was more like a great lady in a green velvet gown, embroidered with Daisies. There, at the bottom of the field, was a pond like a bright blue eye in the green, and lazy cattle, red and white, stood in it, while others lay under a chestnut tree near by.

Down in the valley, a long undulating spread before me, fields of different hues, some green, some brown, some golden with ripe Corn, lay baked in the heat, quivering under a calm blue sky. In one field a man was sharpening a scythe with a whetstone—the rasp came floating up to me clearly, and presently he began to open a field of wheat for the reaping machine I could see, with men round her, under a clump of trees. Next to this field was a narrow strip of coarse grass all aglow with Buttercups, then a wide triangular field, with a pit in the corner of it, snowed over with Daisies, and then a farm looking like a toy place, neat with white painted railings, and a dovecote, and a long barn covered over with yellow Stone Crop. I could see—all in miniature—the farmer come out of his house door, beckon to a dog, and walk past a row of Hollyhocks and a flush of pink Sweet Williams, open the gate and cross a road to the Corn-field. The dog leapt ahead of him, barking joyously.

POPPIES IN SURREY.

A little further down, and cut off partly from view by the May tree that sheltered me, was a village, white and grey, sheltered by Elm trees. In the midst of the handful of cottages the square-towered flint church stood with Ivy on the tower and dark Yews in the churchyard. The graves in the churchyard looked like the Daisies in the distant field, as if they grew there. At the back of the church, and facing the high road, was a line of trees from whence came an incessant noise of rooks.

Very few things moved on the high road, a lumbering waggon, the doctor’s trap, a bicycle, and then the carrier’s cart with a man I knew driving it, a very pleasant man who preached in the Sion Chapel on Sundays and chalked up texts in the tilt of his waggon—but with a shrewd eye to business: a man who never forgave a debt.

As I sat on my stile I felt this was all mine: no person there knew the beauty of it as I did, or cared to capture its sweetness as I did. No one but I saw the field of Oats laugh, or cared to note the business of the dragon fly, or the flashing patterns of the butterflies. I had seen these fields turned up, rich and brown, under the plough, and tender green when the seeds came up, and waving green, and gold when they bore their harvest of Corn, or silver and green with roots and red with Beets. I had counted the sheep on the hillsides, and watched the cattle stray in a long line to be milked at milking time, and though I did not farm an acre of it, I owned it with my heart, and gathered its harvest with my eyes.

Every field footpath had its story, the road was rich in old romance, and hidden by the trees at the head of the valley was the big house where my hostess lived and with a loving hand directed all this little world—but I doubt if she owned it more than I.

To end all this, comes a little maid through the Oats, almost hidden by them, her face quivering with tears because of a misplaced trust in a bunch of Nettles. So we apply Dock leaves and a penny, and a farthing’s worth of country wisdom, and part friends—I to the head of the valley, she to her father’s farm on the other side of the hill.

V

EPISODE OF THE CONTENTED TAILOR

Not a hundred yards out of a certain village I came across a little man dressed in grey. We were alone on the road, we were going in the same direction, and I came to learn that he travelled with as little purpose as I.

As soon as I saw his face, his jaunty walk, his knapsack and his stick, I knew him for a friend.

I hailed him. He stopped, smiled pleasantly, and fell in with my stride. We soon found a mutual bond of esteem. It appeared we were out in search of adventures.

He explained to me, quite simply, that he was not going anywhere, and that he proposed to be some four months about it.

“Just walking about looking at things,” he volunteered.

“That is my case,” I replied.

“I’m a tailor, sir,” said he.

“Having a look at the cut of the country?”

He gave a little friendly nod.

“And do you tailor as you go along?” I asked, for I had never met a travelling tailor before: tinkers galore; haberdashers aplenty; patent medicine men a few; sailors; old soldiers (the worst); apothecaries I have mentioned; gentlemen, many; ploughboys, purse thieves, one or two, and ugly customers—they were in a dark lane—but a tailor, never. It seemed all the world could tread the high road but a tailor. Then I remembered my fairy tales—“Seven at a Blow”—and laughed aloud.

“I’ve given up my trade,” he explained, as we began to mount the hill. “No more sitting on a bench for me in the spring or summer. I do a bit in the winter, but I’m a free man on two pounds ten a week.”

And he was young—forty at the most.

“Put by?” said I.

He smiled again. “Not quite, sir. I had a little bit put by, but a brother of mine went to Australia, and made a fortune—he died, poor Tom, and left his money to me and my sister. Two pound ten a week for each of us.”

“And it has brought you—this,” I explained, pointing with my stick at the expanse of country. “It’s like a romance.”

“Isn’t it?”

“Then you read romances?” I asked quickly.

“I read all I can lay hands on,” he replied. “I’m living just as my sister and I dreamed we’d live if ever something wonderful happened.”

“And it has happened?”

“You’re right, sir. My sister lives in the little cottage I bought with my savings. She’s got all she wants—all anybody might want, you might say. A cottage, six-roomed, all white, with a Pink Rose growing over the porch, and a canary in a cage in the parlour. Then there’s a garden, and a bit of orchard, and bees and a river at the bottom of the little meadow, and a Catholic Church within a stone’s throw—so it’s all right. She’s a rare good gardener, is my sister.”

“I envy you both,” I said.

He looked me up and down for a moment before speaking. “No cause for you to do that, I expect, sir.”

“Well, you know what you want, and you’ve got it.”

We had reached the crest of the hill now after a longish climb. It was a hot day and I proposed a rest. Besides, it was one o’clock and I was hungry.

I had four hard boiled eggs, and he had bread and cheese—we divided our goods evenly, and ate comfortably under a hedge in a field.

“I’ve often sat on my bench,” he said, “and looked out at the sun in the dusty street and wondered if I should ever be able to sit out in it on the grass and have nothing to do. We used to go for a day in the country, I and my sister, whenever I could spare the money, and it was a holiday. You wouldn’t believe what the sight of green fields and trees meant to me and my sister: you see the hedgerows were the only garden we could afford, and we could ill-afford that. My sister used to talk about the Roses she’d have, and the Carnations, and the Sunflowers and Asters, when our ship came home. It came home—think of that.” He stretched his limbs luxuriously. “And here we are with everything, and more.”

“And more?” I asked.

“Well, you see, it is more, somehow. I’m ‘me’ now—do you follow the idea? I never knew what it was to be on my own: just ‘me.’ I can lie abed now as long as I want to, I can wear what I like, do what I like. And I’ve a garden of my own.”

“But you don’t stop there,” I said.

“Well,” he said, “I wonder if you’d know what I meant if I said that a garden and sitting about is a bit too much for me for the present. I want to walk and walk in the open air, and see things, and stretch my legs a bit to get rid of twenty odd years of the bench. I want to run up the top of hills and shout because—well, because I feel as if I had a right to shout when the sun is shining.”

“I quite understand that,” I said.

“And then,” he went on, and his face showed the joy he felt, “everything is so wonderful. Look at that village we came through: those people there feel the same as you and me. They’ve got to express themselves somehow, so they grow flowers right out into the road, just as a gift to you and me. A sort of something comes to them that they must have flowers at the front door. Whenever I see a good garden, full of Pinks and Roses and Larkspur, I get a bed at that cottage, if I can. I’ve slept all over the place, all over England, you might say; and cheap, too.”

“That was a beautiful village, below there,” I said.

He nodded wisely. “Seems as if they’d decorated the street on purpose to make the cottages look as if they grew like the flowers. All the porches covered with Honeysuckle and Roses, and everlasting Peas, and flowers up against the windows. I’ve a perfect craze for flowers—can’t think where I get it from.”

“You are the real gardener,” said I.

“I believe I am,” he said. “And why I took to tailoring beats me, now. My father was a butcher.”

I pointed over my shoulder towards the village. “Do you live in a place like that?” I asked.

“Better than that,” he answered proudly. “It took me nearly two years to find the place my sister and I had dreamed of. We wanted a cottage in a county as much like a garden as possible. I found it—in Devonshire; my eye, it’s a wonderful place, all orchards. In the blossom time it looks like—well, as if it was expecting somebody, it’s so beautiful.”

“I know,” I said. “Sometimes the country dresses itself as if a lover were coming.”

“Do you ever read Browning?” he asked. “Because he answers a lot of questions for me.”

“For me too.”

“Well,” he said, and reddened shyly as he said it; “do you remember the poem that ends

‘What if that friend happened to be God?’”

I understood perfectly. He was a man of soul, my tailor.

“I expect you are surprised to find I read a lot,” he went on in his artless way. “But when I was a boy I was in a book shop, before my father lost all his money, and put me out to be a tailor. My mother was a lady’s maid, and she encouraged me to read. There was a priest, Father Brown, who helped me too; it was from him I first learned to love flowers.”

“Then, as you are a Catholic, you know what to-day is,” said I.

“The twenty-ninth of August. No, sir, I’m afraid I don’t.”

“It is dedicated to one of our patron Saints—there are two for gardeners—Saint Phocas, a Greek, and Saint Fiacre, an Irishman. To-day is the day of Saint Phocas.”

The tailor crossed himself reverently.

“I’ll tell you the story if you like.” And, as he lay on his back, I told him the little legend of

Saint Phocas: Patron Saint of Gardeners.

“At the end of the third century there lived a certain good man called Phocas, who had a little dwelling outside the gates of the city of Sinope, in Pontus. He had a small garden in which he grew flowers and vegetables for the poor and for his own needs. Prayer, love of his labour, and care for the things he grew filled his life.”

My tailor interrupted here to ask, apologetically, what manner of garden Saint Phocas would have.

“Neat beds,” said I—for I had gone into the matter myself—“edged with box. The flowers and vegetables growing together. Violets, Leeks, Onions, with Crocuses, Narcissus, and Lilies. Then, in their season, Gladiolus, Hyacinths, Iris, Poppies, and plenty of Roses. Melons, also, and Gherkins, Peaches, Plums, Apples and Pomegranates, Olives, Almonds, Medlars, Cherries, and Pears, of which quite thirty kinds were known. In his house, on the window ledge, if he had one, he may have grown Violets and Lilies in window pots, for they did that in those days.”

“Now, isn’t that interesting?” said the tailor. “My sister will care to know that. I shouldn’t be a bit surprised to find her putting a statue of Saint Phocas over the door. She’s all for figures.”

“I’m afraid,” said I, “there will be some trouble over that. There is a statue of him in Saint Mark’s in Venice, a great old man with a fine beard, dressed like a gardener, and holding a spade in his hand. There’s one of him, too, in the Cathedral at Palermo, but I have never seen them copied. Now I must tell you the rest of the story.

“There were days, you know, when Christians were hunted out and killed. One evening there came to the house of the Saint, two strangers. It was the habit of this good man to give of what he had to all travellers, food, rest, water to bathe their feet, and a kindly welcome. On this occasion the Saint performed his hospitable offices as usual—set the strangers at his board, prepared a meal for them, and led them afterwards to a place where they might sleep. Before going to rest they told him their errand; they were searching for a certain man of the name of Phocas, a Christian, and, having found him, they were to slay him. When they were asleep, the Saint, after offering up his prayers, went into his garden and dug a grave in the middle of the flower beds.

“The morning came, and the strangers prepared to depart, but the Saint, standing before them, told them he was the very man whom they sought. A horror seized them that they should have eaten with the man they had set out to kill, but Saint Phocas, leading them to the grave among the flowers, bid them do their work. They cut off his head, and buried him in his own garden, in the grave he had dug.”

PORCHES GROWN OVER WITH HONEYSUCKLE AND ROSES AT BROADWAY IN THE COTSWOLDS.

The little tailor was silent. I lit my pipe, and began to put my traps together.

Then he spoke. “I couldn’t do that, you know. Those martyrs—by gum!”

“Death,” said I, “was life to them. Their life was only a preparation for death.”

The tailor sat up. “My sister’s like that,” he said. “She’s bought a tombstone—think of that. Said she’d like to have it by her. She’s a one for a bargain, if you like; saw this tombstone marked ‘Cheap,’ in a stonemason’s yard down our way, and went in at once to ask the price. She’d price anything, my sister would. You’ve only got to mark a thing down ‘Cheap’ and she’s after the price in a minute.”

“How did the tombstone come to be marked ‘cheap’?” I asked, laughing with him.

“It was this way,” said the tailor. Then he turned, in his inconsequent way to me. “I wonder,” he said, “if, as you’re so kind as to take an interest, you’d care to see our cottage. We’d be proud, my sister and I, if you would come. If you are just walking about for pleasure, perhaps you’d come down as far as that one day and—and, well, sir, it’s very humble, but we’d do our best.”

“When shall you be there?” I said. “Because I want to come very much.”

“I’m going back; I’m on my way now,” he said; “I always go back two or three times in the summer just to tell her the news. I tell her what’s happened, and what flowers they grow where I’ve been. If you would really come, sir, perhaps you’d come in three weeks from now, if you have nothing better to do. I’d let her know.”

“Then she could tell me the story of the tombstone herself?” I said.

It ended at that. He wrote the address for me in my sketch-book, and took his leave of me in characteristic fashion.

“I hope I’m not taking a liberty,” he said, as he jerked his knapsack into a comfortable place between his shoulders.

“There’s nothing I should like better,” said I.

“You’ll like the garden,” he said as an inducement.

And this was how I came to hear the story of the “Tailor’s Sister’s Tombstone.”