автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Folk-Lore of West and Mid-Wales

FOLK-LORE

OF

WEST AND MID-WALES

BY

JONATHAN CEREDIG DAVIES

Member of the Folk-Lore Society, Author of “Adventures in the Land of Giants,” “Western Australia,” &c.

With a Preface

BY

ALICE, COUNTESS AMHERST.

“Cared doeth yr encilion.”

ABERYSTWYTH:

PRINTED AT THE “WELSH GAZETTE” OFFICES, BRIDGE STREET.

1911.

This book is respectfully dedicated by the Author

to

COUNTESS OF LISBURNE, CROSSWOOD.

ALICE, COUNTESS AMHERST.

LADY ENID VAUGHAN.

LADY WEBLEY-PARRY-PRYSE, GOGERDDAN.

LADY HILLS-JOHNES OF DOLAUCOTHY.

MRS. HERBERT DAVIES-EVANS, HIGHMEAD.

MRS. WILLIAM BEAUCLERK POWELL, NANTEOS.

PREFACE

BY

ALICE, COUNTESS AMHERST.

The writer of this book lived for many years in the Welsh Colony, Patagonia, where he was the pioneer of the Anglican Church. He published a book dealing with that part of the world, which also contained a great deal of interesting matter regarding the little known Patagonian Indians, Ideas on Religion and Customs, etc. He returned to Wales in 1891; and after spending a few years in his native land, went out to a wild part of Western Australia, and was the pioneer Christian worker in a district called Colliefields, where he also built a church. (No one had ever conducted Divine Service in that place before.)

Here again, he found time to write his experiences, and his book contained a great deal of value to the Folklorist, regarding the aborigines of that country, quite apart from the ordinary account of Missionary enterprise, history and prospects of Western Australia, etc.

In 1901, Mr. Ceredig Davies came back to live in his native country, Wales.

In Cardiganshire, and the centre of Wales, generally, there still remains a great mass of unrecorded Celtic Folk Lore, Tradition, and Custom.

Thus it was suggested that if Mr. Ceredig Davies wished again to write a book—the material for a valuable one lay at his door if he cared to undertake it. His accurate knowledge of Welsh gave him great facility for the work. He took up the idea, and this book is the result of his labours.

The main object has been to collect “verbatim,” and render the Welsh idiom into English as nearly as possible these old stories still told of times gone by.

The book is in no way written to prove, or disprove, any of the numerous theories and speculations regarding the origin of the Celtic Race, its Religion or its Traditions. The fundamental object has been to commit to writing what still remains of the unwritten Welsh Folk Lore, before it is forgotten, and this is rapidly becoming the case.

The subjects are divided on the same lines as most of the books on Highland and Irish Folk Lore, so that the student will find little trouble in tracing the resemblance, or otherwise, of the Folk Lore in Wales with that of the two sister countries.

ALICE AMHERST.

Plas Amherst, Harlech,

North Wales, 1911.

INTRODUCTION.

Welsh folk-lore is almost inexhaustible, and of great importance to the historian and others. Indeed, without a knowledge of the past traditions, customs and superstitions of the people, the history of a country is not complete.

In this book I deal chiefly with the three counties of Cardiganshire, Carmarthenshire, and Pembrokeshire, technically known in the present day as “West Wales”; but as I have introduced so many things from the counties bordering on Cardigan and Carmarthen, such as Montgomery, Radnor, Brecon, etc., I thought proper that the work should be entitled, “The Folk-Lore of West and Mid-Wales.”

Although I have been for some years abroad, in Patagonia, and Australia, yet I know almost every county in my native land; and there is hardly a spot in the three counties of Carmarthen, Cardigan, and Pembroke that I have not visited during the last nine years, gathering materials for this book from old people and others who were interested in such subject, spending three or four months in some districts. All this took considerable time and trouble, not to mention of the expenses in going about; but I generally walked much, especially in the remote country districts, but I feel I have rescued from oblivion things which are dying out, and many things which have died out already. I have written very fully concerning the old Welsh Wedding and Funeral Customs, and obtained most interesting account of them from aged persons. The “Bidder’s Song,” by Daniel Ddu, which first appeared in the “Cambrian Briton” 1822, is of special interest. Mrs. Loxdale, of Castle Hill, showed me a fine silver cup which had been presented to this celebrated poet. I have also a chapter on Fairies; but as I found that Fairy Lore has almost died out in those districts which I visited, and the traditions concerning them already recorded, I was obliged to extract much of my information on this subject from books, though I found a few new fairy stories in Cardiganshire. But as to my chapters about Witches, Wizards, Death Omens, I am indebted for almost all my information to old men and old women whom I visited in remote country districts, and I may emphatically state that I have not embellished the stories, or added to anything I have heard; and care has been taken that no statement be made conveying an idea different from what has been heard. Indeed, I have in nearly all instances given the names, and even the addresses of those from whom I obtained my information. If there are a few Welsh idioms in the work here and there, the English readers must remember that the information was given me in the Welsh language by the aged peasants, and that I have faithfully endeavoured to give a literal rendering of the narrative.

About 350 ladies and gentlemen have been pleased to give their names as subscribers to the book, and I have received kind and encouraging letters from distinguished and eminent persons from all parts of the kingdom, and I thank them all for their kind support.

I have always taken a keen interest in the History and traditions of my native land, which I love so well; and it is very gratifying that His Royal Highness, the young Prince of Wales, has so graciously accepted a genealogical table, in which I traced his descent from Cadwaladr the Blessed, the last Welsh prince who claimed the title of King of Britain.

I undertook to write this book at the suggestion and desire of Alice, Countess Amherst, to whom I am related, and who loves all Celtic things, especially Welsh traditions and legends; and about nine or ten years ago, in order to suggest the “lines of search,” her Ladyship cleverly put together for me the following interesting sketch or headings, which proved a good guide when I was beginning to gather Folk-Lore:—

(1) Traditions of Fairies. (2) Tales illustrative of Fairy Lore. (3) Tutelary Beings. (4) Mermaids and Mermen. (5) Traditions of Water Horses out of lakes, if any? (6) Superstitions about animals:—Sea Serpents, Magpie, Fish, Dog, Raven, Cuckoo, Cats, etc. (7) Miscellaneous:—Rising, Clothing, Baking, Hen’s first egg; Funerals; Corpse Candles; On first coming to a house on New Year’s Day; on going into a new house; Protection against Evil Spirits; ghosts haunting places, houses, hills and roads; Lucky times, unlucky actions. (8) Augury:—Starting on a journey; on seeing the New Moon. (9) Divination; Premonitions; Shoulder Blade Reading; Palmistry; Cup Reading. (10) Dreams and Prophecies; Prophecies of Merlin and local ones. (11) Spells and Black Art:—Spells, Black Art, Wizards, Witches. (12) Traditions of Strata Florida, King Edward burning the Abbey, etc. (13) Marriage Customs.—What the Bride brings to the house; The Bridegroom. (14) Birth Customs. (15) Death Customs. (16) Customs of the Inheritance of farms; and Sheep Shearing Customs.

Another noble lady who was greatly interested in Welsh Antiquities, was the late Dowager Lady Kensington; and her Ladyship, had she lived, intended to write down for me a few Pembrokeshire local traditions that she knew in order to record them in this book.

In an interesting long letter written to me from Bothwell Castle, Lanarkshire, dated September 9th, 1909, her Ladyship, referring to Welsh Traditions and Folk-Lore, says:—“I always think that such things should be preserved and collected now, before the next generation lets them go! ... I am leaving home in October for India, for three months.” She did leave home for India in October, but sad to say, died there in January; but her remains were brought home and buried at St. Bride’s, Pembrokeshire. On the date of her death I had a remarkable dream, which I have recorded in this book, see page 277.

I tender my very best thanks to Evelyn, Countess of Lisburne, for so much kindness and respect, and of whom I think very highly as a noble lady who deserves to be specially mentioned; and also the young Earl of Lisburne, and Lady Enid Vaughan, who have been friends to me even from the time when they were children.

I am equally indebted to Colonel Davies-Evans, the esteemed Lord Lieutenant of Cardiganshire, and Mrs. Davies-Evans, in particular, whose kindness I shall never forget. I have on several occasions had the great pleasure and honour of being their guest at Highmead.

I am also very grateful to my warm friends the Powells of Nanteos, and also to Mrs. A. Crawley-Boevey, Birchgrove, Crosswood, sister of Countess Lisburne.

Other friends who deserve to be mentioned are, Sir Edward and Lady Webley-Parry-Pryse, of Gogerddan; Sir John and Lady Williams, Plas, Llanstephan (now of Aberystwyth); General Sir James and Lady Hills-Johnes, and Mrs. Johnes of Dolaucothy (who have been my friends for nearly twenty years); the late Sir Lewis Morris, Penbryn; Lady Evans, Lovesgrove; Colonel Lambton, Brownslade, Pem.; Colonel and Mrs. Gwynne-Hughes, of Glancothy; Mrs. Wilmot Inglis-Jones; Capt. and Mrs. Bertie Davies-Evans; Mr. and Mrs. Loxdale, Castle Hill, Llanilar; Mr. and Mrs. Lloyd, Waunifor; Mrs. Webley-Tyler, of Glanhelig; Archdeacon Williams, of Aberystwyth; Professor Tyrrell Green, Lampeter; Dr. Hughes, and Dr. Rees, of Llanilar; Rev. J. F. Lloyd, vicar of Llanilar, the energetic secretary of the Cardiganshire Antiquarian Society; Rev. Joseph Evans, Rector of Jordanston, Fishguard; Rev. W. J. Williams, Vicar of Llanafan; Rev. H. M. Williams, Vicar of Lledrod; Rev. J. N. Evans, Vicar of Llangybi; Rev. T. Davies, Vicar of Llanddewi Brefi; Rev. Rhys Morgan, C. M. Minister, Llanddewi Brefi; Rev. J. Phillips, Vicar of Llancynfelyn; Rev. J. Morris, Vicar, Llanybyther; Rev. W. M. Morgan-Jones (late of Washington, U.S.A.); Rev. G. Eyre Evans, Aberystwyth; Rev. Z. M. Davies, Vicar of Llanfihangel Geneu’r Glyn; Rev. J. Jones, Curate of Nantgaredig; Rev. Prys Williams (Brythonydd) Baptist Minister in Carmarthenshire; Rev. D. G. Williams, Congregational Minister, St. Clears (winner of the prize at the National Eisteddfod, for the best essay on the Folk-Lore of Carmarthen); Mr. William Davies, Talybont (winner of the prize at the National Eisteddfod for the best essay on the Folk-Lore of Merioneth); Mr. Roderick Evans, J. P., Lampeter; Rev. G. Davies, Vicar of Blaenpenal; Mr. Stedman-Thomas (deceased), Carmarthen, and others in all parts of the country too numerous to be mentioned here. Many other names appear in the body of my book, more especially aged persons from whom I obtained information.

JONATHAN CEREDIG DAVIES.

Llanilar, Cardiganshire.

March 18th, 1911.

CONTENTS.

PAGE.

DedicationIII.

PrefaceV.

IntroductionVII.

I.

Love Customs, etc.1

II.

Wedding Customs16

III.

Funeral Customs39

IV.

Other Customs59

V.

Fairies and Mermaids88

VI

. Ghost Stories148

VII.

Death Portents192

VIII.

Miscellaneous Beliefs, Birds, etc.215

IX.

Witches and Wizards, etc.230

X.

Folk-Healing281

XI.

Fountains, Lakes, and Caves ...298

XII.

Local Traditions315

Index335

CHAPTER I.

LOVE CUSTOMS AND OMEN SEEKING.

“Pwy sy’n caru, a phwy sy’n peidio,

A phwy sy’n troi hen gariad heibio.”

Who loves, and who loves not,

And who puts off his old love?

Undoubtedly, young men and young women all over the world from the time of Adam to the present day, always had, and still have, their modes or ways of associating or keeping company with one another whilst they are in love, and waiting for, and looking forward to, the bright wedding day. In Wales, different modes of courting prevail; but I am happy to state the old disgraceful custom of bundling, which was once so common in some rural districts, has entirely died out, or at least we do not hear anything about it nowadays. I believe Wirt Sikes is right in his remarks when he says that such a custom has had its origin in primitive times, when, out of the necessities of existence, a whole household lay down together for greater warmth, with their usual clothing on.

Giraldus Cambrensis, 700 years ago, writes of this custom in these words:—

“Propinquo concubantium calore multum adjuti.”

Of course, ministers of religion, both the Clergy of the Church of England and Nonconformist ministers condemned such practice very sternly, but about two generations ago, there were many respectable farmers who more or less defended the custom, and it continued to a certain extent until very recently, even without hardly any immoral consequences, owing to the high moral standard and the religious tendencies of the Welsh people.

One reason for the prevalence of such custom was that in times past in Wales, both farm servants and farmers’ sons and daughters were so busy, from early dawn till a late hour in the evening that they had hardly time or an opportunity to attend to their love affairs, except in the night time. Within the memory of hundreds who are still alive, it was the common practice of many of the young men in Cardiganshire and other parts of West Wales, to go on a journey for miles in the depth of night to see the fair maidens, and on their way home, perhaps, about 3 o’clock in the morning they would see a ghost or an apparition! but that did not keep them from going out at night to see the girls they loved, or to try to make love. Sometimes, several young men would proceed together on a courting expedition, as it were, if we may use such a term, and after a good deal of idle talk about the young ladies, some of them would direct their steps towards a certain farmhouse in one direction, and others in another direction in order to see their respective sweethearts, and this late at night as I have already mentioned.

It was very often the case that a farmer’s son and the servant would go together to a neighbouring farm house, a few miles off, the farmer’s son to see the daughter of the house, and the servant to see the servant maid, and when this happened it was most convenient and suited them both. After approaching the house very quietly, they would knock at the window of the young woman’s room, very cautiously, however, so as not to arouse the farmer and his wife.

I heard the following story when a boy:—A young farmer, who lived somewhere between Tregaron and Lampeter, in Cardiganshire, rode one night to a certain farm-house, some miles off, to have a talk with the young woman of his affection, and after arriving at his destination, he left his horse in a stable and then entered the house to see his sweetheart. Meanwhile, a farm servant played him a trick by taking the horse out of the stable, and putting a bull there instead. About 3 o’clock in the morning the young lover decided to go home, and went to the stable for his horse. It was very dark, and as he entered the stable he left the door wide open, through which an animal rushed wildly out, which he took for his horse. He ran after the animal for hours, but at daybreak, to his great disappointment, found that he had been running after a bull!

Another common practice is to meet at the fairs, or on the way home from the fairs. In most of the country towns and villages there are special fairs for farm servants, both male and female, to resort to; and many farmers’ sons and daughters attend them as well. These fairs give abundant opportunity for association and intimacy between young men and women.

Indeed, it is at these fairs that hundreds of boys and girls meet for the first time. A young man comes in contact with a young girl, he gives her some “fairings” or offers her a glass of something to drink, and accompanies her home in the evening. Sometimes when it happens that there should be a prettier and more attractive maiden than the rest present at the fair, occasionally a scuffle or perhaps a fight takes place, between several young men in trying to secure her society, and on such occasions, of course, the best young man in her sight is to have the privilege of her company.

As to whether the Welsh maidens are prettier or not so pretty as English girls, I am not able to express an opinion; but that many of them were both handsome and attractive in the old times, at least, is an historical fact; for we know that it was a very common thing among the old Norman Nobles, after the Conquest, to marry Welsh ladies, whilst they reduced the Anglo-Saxons almost to slavery. Who has not heard the beautiful old Welsh Air, “Morwynion Glan Meirionydd” (“The Pretty Maidens of Merioneth”)?

Good many men tell me that the young women of the County of Merioneth are much more handsome than those of Cardiganshire; but that Cardiganshire women make the best wives.

Myddfai Parish in Carmarthenshire was in former times celebrated for its fair maidens, according to an old rhyme which records their beauty thus:—

“Mae eira gwyn ar ben y bryn,

A’r glasgoed yn y Ferdre,

Mae bedw mân ynghanol Cwm-bran,

A merched glân yn Myddfe.”

Principal Sir John Rhys translates this as follows:—

“There is white snow on the mountain’s brow,

And greenwood at the Verdre,

Young birch so good in Cwm-bran wood,

And lovely girls in Myddfe.”

In the time of King Arthur of old, the fairest maiden in Wales was the beautiful Olwen, whom the young Prince Kilhwch married after many adventures. In the Mabinogion we are informed that “more yellow was her hair than the flowers of the broom, and her skin was whiter than the foam of the wave, and fairer were her hands and her fingers than the blossoms of the wood-anemone, amidst the spray of the meadow fountain. The eye of the trained hawk, the glance of the three-mewed falcon, was not brighter than hers. Her bosom was more snowy than the breast of the white swan; her cheek was redder than the reddest roses. Those who beheld her were filled with her love. Four white trefoils sprang up wherever she trod. She was clothed in a robe of flame-coloured silk, and about her neck was a collar of ruddy gold, on which were precious emeralds and rubies.”

A good deal of courting is done at the present day while going home from church or chapel as the case may be. The Welsh people are very religious, and almost everybody attends a place of worship, and going home from church gives young people of both sexes abundant opportunities of becoming intimate with one another. Indeed, it is almost a general custom now for a young man to accompany a young lady home from church.

The Welsh people are of an affectionate disposition, and thoroughly enjoy the pleasures of love, but they keep their love more secret, perhaps, than the English; and Welsh bards at all times have been celebrated for singing in praise of female beauty. Davydd Ap Gwilym, the chief poet of Wales, sang at least one hundred love songs to his beloved Morfudd.

This celebrated bard flourished in the fourteenth century, and he belonged to a good family, for his father, Gwilym Gam, was a direct descendant from Llywarch Ap Bran, chief of one of the fifteen royal tribes of North Wales; and his mother was a descendant of the Princes of South Wales. According to the traditions of Cardiganshire people, Davydd was born at Bro-Gynin, near Gogerddan, in the Parish of Llanbadarn-Fawr, and only a few miles from the spot where the town of Aberystwyth is situated at present.

An ancient bard informs us that Taliesin of old had foretold the honour to be conferred on Bro-Gynin, in being the birthplace of a poet whose muse should be as the sweetness of wine:—

“Am Dafydd, gelfydd goelin—praff awdwr,

Prophwydodd Taliesin,

Y genid ym mro Gynin,

Brydydd a’i gywydd fel gwin.”

The poet, Davydd Ap Gwilym, is represented as a fair young man who loved many, or that many were the young maidens who fell in love with him, and there is one most amusing tradition of his love adventures. It is said that on one occasion he went to visit about twenty young ladies about the same time, and that he appointed a meeting with each of them under an oak-tree—all of them at the same hour. Meanwhile, the young bard had secretly climbed up the tree and concealed himself among the branches, so that he might see the event of this meeting. Every one of the young girls was there punctually at the appointed time, and equally astonished to perceive any female there besides herself. They looked at one another in surprise, and at last one of them asked another, “What brought you here?” “to keep an appointment with Dafydd ap Gwilym” was the reply. “That’s how I came also” said the other “and I” added a third girl, and all of them had the same tale. They then discovered the trick which Dafydd had played with them, and all of them agreed together to punish him, and even to kill him, if they could get hold of him. Dafydd, who was peeping from his hiding-place amongst the branches of the tree, replied as follows in rhyme:—

“Y butein wen fain fwynnf—o honoch

I hono maddeuaf,

Tan frig pren a heulwen haf,

Teg anterth, t’rawed gyntaf!”

The words have been translated by someone something as follows:—

“If you can be so cruel,

Let the kind wanton jade,

Who oftenest met me in this shade,

On summer’s morn, by love inclined,

Let her strike first, and I’m resigned.”

Dafydd’s words had the desired effect. The young women began to question each other’s purity, which led to a regular quarrel between them, and, during the scuffle, the poet escaped safe and sound.

After this the Poet fell in love with the daughter of one Madog Lawgam, whose name was Morfudd, and in her honour he wrote many songs, and it seems that he ever remained true to this lady. They were secretly married in the woodland; but Morfudd’s parents disliked the Poet so much for some reason or other, that the beautiful young lady was taken away from him and compelled to marry an old man known as Bwa Bach, or Little Hunchback. Dafydd was tempted to elope with Morfudd, but he was found, fined and put in prison; but through the kindness of the men of Glamorgan, who highly esteemed the Poet, he was released. After this, it seems that Dafydd was love-sick as long as he lived, and at last died of love, and he left the following directions for his funeral:—

“My spotless shroud shall be of summer flowers,

My coffin from out the woodland bowers:

The flowers of wood and wild shall be my pall,

My bier, light forest branches green and tall;

And thou shalt see the white gulls of the main

In thousands gather then to bear my train!”

One of Dafydd’s chief patrons was his kinsman, the famous and noble Ivor Hael, Lord of Macsaleg, from whose stock the present Viscount Tredegar is a direct descendant, and, in judging the character of the Poet we must take into consideration what was the moral condition of the country in the fourteenth century.

But to come to more modern times, tradition has it that a young man named Morgan Jones of Dolau Gwyrddon, in the Vale of Teivi, fell in love with the Squire of Dyffryn Llynod’s daughter. The young man and the young woman were passionately in love with each other; but the Squire, who was a staunch Royalist, refused to give his consent to his daughter’s marriage with Morgan Jones, as the young man’s grandfather had fought for Cromwell. The courtship between the lovers was kept on for years in secret, and the Squire banished his daughter to France more than once. At last the young lady fell a victim to the small pox, and died. Just before her death, her lover came to see her, and caught the fever from her, and he also died. His last wish was that he should be buried in the same grave as the one he had loved so dearly, but this was denied him.

In Merionethshire there is a tradition that many generations ago a Squire of Gorsygedol, near Harlech, had a beautiful daughter who fell in love with a shepherd boy. To prevent her seeing the young man, her father locked his daughter in a garret, but a secret correspondence was carried on between the lovers by means of a dove she had taught to carry the letters. The young lady at last died broken-hearted, and soon after her burial the dove was found dead upon her grave! And the young man with a sad heart left his native land for ever.

More happy, though not less romantic, was the lot of a young man who was shipwrecked on the coast of Pembrokeshire, and washed up more dead than alive on the seashore, where he was found by the daughter and heiress of Sir John de St. Bride’s, who caused him to be carried to her father’s house where he was hospitably entertained. The young man, of course, was soon head and ears in love with his fair deliverer, and the lady being in nowise backward in response to his suit, they married and founded a family of Laugharnes, and their descendants for generations resided at Orlandon, near St. Bride’s.

The Rev. D. G. Williams in his interesting Welsh collection of the Folk-lore of Carmarthenshire says that in that part of the county which borders on Pembrokeshire, there is a strange custom of presenting a rejected lover with a yellow flower, or should it happen at the time of year when there are no flowers, to give a yellow ribbon.

This reminds us of a curious old custom which was formerly very common everywhere in Wales; that of presenting a rejected lover, whether male or female, with a stick or sprig of hazel-tree. According to the “Cambro Briton,” for November, 1821, this was often done at a “Cyfarfod Cymhorth,” or a meeting held for the benefit of a poor person, at whose house or at that of a neighbour, a number of young women, mostly servants, used to meet by permission of their respective employers, in order to give a day’s work, either in spinning or knitting, according as there was need of their assistance, and, towards the close of the day, when their task was ended, dancing and singing were usually introduced, and the evening spent with glee and conviviality. At the early part of the day, it was customary for the young women to receive some presents from their several suitors, as a token of their truth or inconstancy. On this occasion the lover could not present anything more odious to the fair one than the sprig of a “collen,” or hazel-tree, which was always a well-known sign of a change of mind on the part of the young man, and, consequently, that the maiden could no longer expect to be the real object of his choice. The presents, in general, consisted of cakes, silver spoons, etc., and agreeably to the respectability of the sweetheart, and were highly decorated with all manner of flowers; and if it was the lover’s intention to break off his engagement with the young lady, he had only to add a sprig of hazel. These pledges were handed to the respective lasses by the different “Caisars,” or Merry Andrews,—persons dressed in disguise for the occasion, who, in their turn, used to take each his young woman by the hand to an adjoining room where they would deliver the “pwysi,” or nose-gay, as it was called, and afterwards immediately retire upon having mentioned the giver’s name.

When a young woman also had made up her mind to have nothing further to do with a young man who had been her lover, or proposed to become one, she used to give him a “ffon wen,” (white wand) from an hazel tree, decorated with white ribbons. This was a sign to the young man that she did not love him.

The Welsh name for hazel-tree is “collen.” Now the word “coll” has a double meaning; it means to lose anything, as well as a name for the hazel, and it is the opinion of some that this double meaning of the word gave the origin to the custom of making use of the hazel-tree as a sign of the loss of a lover.

It is also worthy of notice, that, whilst the hazel indicated the rejection of a lover, the birch tree, on the other hand, was used as an emblem of love, or in other words that a lover was accepted. Among the Welsh young persons of both sexes were able to make known their love to one another without speaking, only by presenting a Birchen-Wreath. This curious old custom of presenting a rejected lover with a white wand was known at Pontrhydfendigaid, in Cardiganshire until only a few years ago. My informant was Dr. Morgan, Pontrhydygroes. Mrs. Hughes, Cwrtycadno, Llanilar, also informed me that she had heard something about such custom at Tregaron, when she was young.

It was also the custom to adorn a mixture of birch and quicken-tree with flowers and a ribbon, and leave it where it was most likely to be found by the person intended on May-morning. Dafydd ap Gwilym, the poet, I have just referred to, mentions of this in singing to Morfudd.

Young people of both sexes, are very anxious to know whether they are to marry the lady or the gentleman they now love, or who is to be their future partner in life, or are they to die single. Young people have good many most curious and different ways to decide all such interesting and important questions, by resorting to uncanny and romantic charms and incantations. To seek hidden information by incantation was very often resorted to in times past, especially about a hundred years ago, and even at the present day, but not as much as in former times. It was believed, and is perhaps, still believed by some, that the spirit of a person could be invoked, and that it would appear, and that young women by performing certain ceremonies could obtain a sight of the young men they were to marry.

Such charms were performed sometimes on certain Saints’ Days, or on one of the “Three Spirits’ Nights,” or on a certain day of the moon; but more frequently on “Nos Calan Gauaf” or All Hallows Eve—the 31st. of October. All Hallows was one of the “Three Spirits’ Nights,” and an important night in the calendar of young maidens anxious to see the spirits of their future husbands.

In Cardiganshire, divination by means of a ball of yarn, known as “coel yr edau Wlan” is practised, and indeed in many other parts of Wales. A young unmarried woman in going to her bedroom would take with her a ball of yarn, and double the threads, and then she would tie small pieces of wool along these threads, so as to form a small thread ladder, and, opening her bedroom window threw this miniature ladder out to the ground, and then winding back the yarn, and at the same time saying the following words:—

“Y fi sy’n dirwyn

Pwy sy’n dal”

which means:

“I am winding,

Who is holding?”

Then the spirit of the future husband of the girl who was performing the ceremony was supposed to mount this little ladder and appear to her. But if the spirit did not appear, the charm was repeated over again, and even a third time. If no spirit was to be seen after performing such ceremony three times, the young lady had no hope of a husband. In some places, young girls do not take the trouble to make this ladder, but, simply throw out through the open window, a ball of yarn, and saying the words:

“I am winding, who is holding.”

Another custom among the young ladies of Cardiganshire in order to see their future husbands is to walk nine times round the house with a glove in the hand, saying the while—“Dyma’r faneg, lle mae’r llaw.”—“Here’s the glove, where is the hand?” Others again would walk round the dungheap, holding a shoe in the left hand, and saying “Here’s the shoe, where is the foot?” Happy is the young woman who sees the young man she loves, for he is to be her future husband.

In Carmarthenshire young girls desirous of seeing their future partners in life, walk round a leek bed, carrying seed in their hand, and saying as follows:—

“Hadau, hadau, hau,

Sawl sy’n cam, doed i grynhoi.”

“Seed, seed, sowing.

He that loves, let him come to gather.”

It was also the custom in the same county for young men and young women to go round a grove and take a handful of moss, in which was found the colour of the future wife or husband’s hair.

In Pembrokeshire, it is the custom for young girls to put under their pillow at night, a shoulder of mutton, with nine holes bored in the blade bone, and at the same time they put their shoes at the foot of the bed in the shape of the letter T, and an incantation is said over them. By doing this, they are supposed to see their future husbands in their dreams, and that in their everyday clothes. This curious custom of placing shoes at the foot of the bed was very common till very recently, and, probably, it is still so, not only in Pembrokeshire, but with Welsh girls all over South Wales. A woman who is well and alive told me once, that many years ago she had tried the experiment herself, and she positively asserted that she actually saw the spirit of the man who became her husband, coming near her bed, and that happened when she was only a young girl, and some time before she ever met the man. When she was telling me this, she had been married for many years and had grown-up children, and I may add that her husband was a particular friend of mine.

Another well-known form of divination, often practised by the young girls in Carmarthenshire, Cardiganshire and Pembrokeshire, is for a young woman to wash her shirt or whatever article of clothing she happens to wear next to the skin, and having turned it inside out, place it before the fire to dry, and then watch to see who should come at midnight to turn it. If the young woman is to marry, the spirit of her future husband is supposed to appear and perform the work for the young woman, but if she is to die single, a coffin is seen moving along the room, and many a young girl has been frightened almost to death in performing these uncanny ceremonies. The Rev. D. G. Williams in his excellent Welsh essay on the Folk-lore of Carmarthenshire, mentions a farmer’s daughter who practised this form of divination whilst she was away from home at school. A young farmer had fallen in love with her, but she hated him with all her heart. Whilst she was performing this ceremony at midnight, another girl, from mere mischief dressed herself in man’s clothing, exactly the same kind as the clothes generally worn by the young farmer I have mentioned, and, trying to appear as like him as possible, entered the room at the very moment when the charm of invoking the spirit of a future husband was being performed by the farmer’s daughter, who went half mad when she saw, as she thought, the very one whom she hated so much, making his appearance.

The other girls had to arouse their schoolmistress from her bed immediately so that she might try and convince the young girl that she had seen nothing, but another girl in man’s clothes. But nothing availed. The doctor was sent for, but he also failed to do anything to bring her to herself, and very soon the poor young woman died through fright and disappointment.

Another common practice in West Wales is for a young woman to peel an apple at twelve o’clock, before a looking glass in order to see the spirit of her future husband. This also is done on All Hallow’s Eve. Sowing Hemp Seed is also a well-known ceremony among the young ladies of Wales, as well as England.

THE CANDLE AND PIN DIVINATION.

It was also the custom, at least many years ago, if not now, for a young woman, or two of them together to stick pins at midnight in a candle, all in a row, right from its top to the bottom, and then to watch the candle burning and the pins dropping one by one, till the last pin had dropped, and then the future husband of the girl to whom the pin belonged, was supposed to appear; but if she was destined to die single, she would see a coffin.

Another form of Divination, was to put the plates on the dining-room table upside down, and at midnight the spirit of the future husband was supposed to come and arrange them in their proper order.

Another custom resorted to in Cardiganshire and other parts in order to see a future husband, or rather to dream of him, was to eat a hen’s first egg; but no one was to know the secret, and absolute silence was to be observed, and the egg was to be eaten in bed.

GOING ROUND THE CHURCH.

This kind of divination was perhaps of a more uncanny character than anything I have hitherto mentioned, and a custom which both young men and young women very commonly practised, even within the last 50 years as I have been told by old people. This weird practice was to go round the parish church seven times, some say nine times, whilst others again say nine times-and-half, and holding a knife in the hand saying the while:—

“Dyma’r twca, lle mae’r wain?”

“Here’s the knife, where is the sheath?”

It was also the practice to look in through the key-hole of the church door each time whilst going round, and many people assert to this very day that whoever performed this mode of divination in proper order, that the spirit of his or her future wife or husband would appear with a sheath to fit the knife; but, if the young man or woman was to die single, a coffin would meet him or her. Mr. John Jones, of Pontrhydfendigaid, an intelligent old man of 95, with a wonderful memory, told me that, when a boy, he had heard his mother giving a most sad account of what happened to a young woman who did this at Ystrad Meurig in Cardiganshire about the year 1800. She was the daughter of a public house in the village, and the name of her mother was Catherine Dafydd Evan. Mr. Jones’s mother knew the family well; some of them emigrated to America.

This young woman was in love with one of the students of St. John’s College, in the neighbourhood, and being anxious to know whether he was to be her husband or not, she resorted to this uncanny practice of walking nine times round Ystrad Meurig Church. Around and round she went, holding the knife in her hand and repeating the words of incantation, “Here’s the knife, where is the sheath?” And whilst she was performing her weird adventure, to her great alarm, she perceived a clergyman coming out to meet her through the church door with his white surplice on, as if coming to meet a funeral procession. The frightened young woman fell down in a swoon, almost half dead, as she imagined that the one she met with a surplice on was an apparition or the spirit of a clergyman officiating at the phantom funeral of herself, which prognosticated that instead of going to be married, she was doomed to die.

It turned out that the apparition she had seen was only one of the students, who, in order to frighten her, had secretly entered the Church for the purpose. But the poor girl recovered not, and she died very soon afterwards.

I heard the following story from my mother when I was a boy. A girl had determined to obtain a sight of her future husband by going round the parish church nine times at All Hallows’ Eve in the same manner as the young woman I mentioned in the above story, but with more fortunate results. This also happened somewhere in Cardiganshire or Carmarthenshire. Just as the young woman was walking round the ninth time, she saw, to her great surprise, her own master (for she was a servant maid) coming to meet her. She immediately ran home and asked her mistress why she had sent her master after her to frighten her. But the master had not gone out from the house. On hearing the girl’s account, the mistress was greatly alarmed and was taken ill, and she apprehended that she herself was doomed to die, and that her husband was going to marry this servant girl, ultimately. Then the poor woman on her death bed begged the young woman to be kind to her children, “For you are to become the mistress here,” said she, “when I am gone.”

It was also a custom in Wales once for nine young girls to meet together to make a pancake, with nine different things, and share it between them, that is, each of the girls taking a piece before going to bed in order to dream of their future husbands.

Another practice among young girls was to sleep on a bit of wedding cake.

WATER IN DISH DIVINATION.

I remember the following test or divination resorted to in Cardiganshire only about twelve years ago. It was tried by young maidens who wished to know whether their husbands were to be bachelors, and by young men who wished to know whether their wives were to be spinsters. Those who performed this ceremony were blindfolded. Then three basins or dishes were placed on the table, one filled with clean water, the other with dirty water, and the third empty. Then the young man or young woman as the case might be advanced to the table blindfolded and put their hand in the dish; and the one who placed his hands in the clean water was to marry a maiden; if into the foul water, a widow; but if into the empty basin, he was doomed to remain single all his life. Another way for a young maiden to dream of her future husband was to put salt in a thimble, and place the same in her stockings, laying them under her pillow, and repeat an incantation when going to bed. Meyrick in his History of Cardiganshire states that “Ivy leaves are gathered, those pointed are called males, and those rounded are females, and should they jump towards each other, then the parties who had placed them in the fire will be believed by and married by their sweethearts; but should they jump away from one another, then, hatred will be the portion of the anxious person.”

Testing a lover’s love by cracking of nuts is also well known in West and Mid-Wales.

It was also a custom in the old times for a young girl on St. John’s Eve to go out at midnight to search for St. John’s Wort in the light of a glow worm which they carried in the palm of their hand. After finding some, a bunch of it was taken home and hung in her bedroom. Next morning, if the leaves still appeared fresh, it was a good omen; the girl was to marry within that same year; but, on the other hand, if the leaves were dead, it was a sign that the girl should die, or at least she was not to marry that year.

THE BIBLE AND KEY DIVINATION.

The Bible and Key Divination, or how to find out the two first letters of a future Wife’s or Husband’s name is very commonly practised, even now, by both young men and young women. A small Bible is taken, and having opened it, the key of the front door is placed on the 16th verse of the 1st Chapter of Ruth:—“And Ruth said, intreat me not to leave thee, or to return from following after thee; for whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest I will lodge; thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God.” Some take Solomon’s Songs, Chapter viii., verses 6 and 7 instead of the above verse from the Book of Ruth. Then the Bible is closed, and tied round with the garter taken off the left leg of him or her who wishes to know his or her future wife or husband’s initials. A person cannot perform this ceremony himself; he must get a friend with him to assist him. The young man must put the middle finger of his right hand on the key underneath the loop, and take care to keep the Bible steady. Then the man, who does not consult the future, repeats the above verse or verses, and when he comes to the appointed letter, that is the first letter of the future wife’s name, the Bible will turn round under the finger. I was told at Ystrad Meurig, that a few years ago, a young woman, a farmer’s daughter, tried this Bible and key divination; and whilst the ceremony was going on, and her sister assisting her to hold the key under the Bible and repeating the words, instead of the book turning round as she expected, she saw a coffin moving along the room, which was a sign that she was doomed to die single; and so it came to pass! The farmhouse where this young woman lived is situated in the neighbourhood of Strata Florida, Cardiganshire; but I do not wish to name the house. I have myself once or twice witnessed this divination practised, but I never heard of a coffin appearing, except in the case of the young woman just mentioned.

DIVINATION BY THE TEA-CUP.

Tea-cup divination is also very much practised by young girls in Wales in order to find out some future events concerning love affairs, future husbands, etc. There was a woman, who only died a few years ago, in the parish of Llandyssul, near a small village called Pontshan in Cardiganshire, who was considered an expert in the art of fortune telling by a tea cup, at least young women and young men thought so, and many of them resorted to her, especially those who were in love or intending to marry. There was another one near Llandovery in Carmarthenshire, and there are a few even at present to whom the maidens go for consultation.

But Welsh women, who are so fond of tea, can find out many things themselves by means of the tea cup without resorting to those who are considered experts in the art. When several of them meet together to tea they help one another in divining their cups, and tea drinking or sipping is the order of the day among the females of Wales. After having emptied the cup, it is turned round three times in the left hand, so that the tea-leaves may cover the surface of the whole cup. Then the cup is placed in the saucer, bottom upwards, to drain, for a few minutes before inspection. If the leaves are scattered evenly round the sides of the cup, leaving the bottom perfectly clear, it is considered a very good sign; but on the other hand when the bottom of the cup appears very black with leaves, it is a very bad sign: some trouble or some misfortune is near. When the leaves form a ring on the side of the cup, it means that the girl who consults is to marry very soon; but if the ring is at the bottom of the cup, disappointment in love awaits her, or she is doomed to die single. When the tea leaves form a cross or a coffin, that also is considered a bad sign; but as a rule, a horse, a dog, or a bird portends good. Two leaves seen in close proximity on the side of the cup foretell a letter bringing good news. When there is a speck floating on the surface of a cup of tea before drinking, some people say it means a letter, a parcel, or a visitor, but a young girl takes it to represent her lover, and she proves his faithfulness by placing the speck on the back of her left hand, and striking it with the back of her right hand. Should the speck or the small tea leaves stick to the back of the left hand and cling or stick fast to the right hand when striking it, it means that the young man is faithful; but on the other hand, should it happen that the tea still remain on the left hand where it was first placed, especially after striking it three times, the young man is not to be depended upon. Some women can even tell by means of the tea-cup what trade their admirer follows, the colour of their future husband’s hair, and many other such things.

A lily is considered a most lucky emblem, if it be at the top, or in the middle of the cup, for this is considered a sign that the young man, or the young woman who consults, will have a good and kind wife, or husband, who will make him or her happy in the marriage estate, but on the other hand, a lily at the bottom of the cup, portends trouble, especially if clouded, or in the thick.

A heart, especially in the clear, is also a very good sign, for it signifies joy and future happiness. Two hearts seen together in the cup, the young man, or the young woman’s wedding is about to take place. Tea-cup divination is well-known all over the Kingdom; and in the Colonies, especially Australia, it is by far more popular than in England.

DIVINATION BY CARDS.

Divination by cards is not so much known in Wales as in England, and this is more popular in towns than country places.

CHAPTER II.

WEDDING CUSTOMS.

In times past, Wales had peculiar and most interesting, if not excellent, Wedding Customs, and in no part of the country were these old quaint customs more popular, and survived to a more recent date than in Cardiganshire and Carmarthenshire. Therefore this book would be incomplete without giving a full description of them.

When a young man and a young woman had agreed together to marry “for better for worse,” they were first of all to inform their parents of the important fact. Then in due time, the young man’s father, taking a friend with him, proceeded to interview the young woman’s father, so as to have a proper understanding on the subject and to arrange different matters, especially concerning dowry, etc. I am writing more especially of a rural wedding among the farmers.

The young woman’s father would agree to give with his daughter, as her portion, household goods of so much value, a certain sum of money, and so many cows, pigs, etc.; and the young man’s father, on his part, would agree to grant his son so much money, horses, sheep, hay, wheat and other things, so that the young couple might have a good start in the married life, “i ddechreu eu byd,”—to begin their world, as we say in Welsh. Sometimes the young man’s father on such occasions met with opposition on the part of the young woman’s father or mother or other relations, at least we read that it happened so in the case of the heir of Ffynonbedr, near Lampeter, long ago; for it seems that when he tried to secure the daughter of Dyffryn Llynod, in the parish of Llandyssul, as his bride, the reply was in Welsh rhyme as follow:—

“Deunaw gwr a deunaw cledde,

Deunaw gwas yn gwisgo lifre,

Deunaw march o liw’r scythanod,

Cyn codi’r ferch o Ddyffryn Llynod.”

Anglicised, this meant that she could not be secured without coming for her with eighteen gentlemen bearing eighteen swords; eighteen servants wearing livery; and eighteen horses of the colour of the woodpigeon.

But such opposition was not often to be met with.

After the parents had arranged these matters satisfactorily, the next preliminary and important step was to send forth a gwahoddwr, or Bidder, from house to house, to bid or invite the guests to the Bidding and the Wedding.

In connection with these old interesting customs, there were the Bidding or invitation to the wedding; the Bidder, whose duty it was formally to invite the guests; the Ystafell, or the bride’s goods and presents; the purse and girdle; the Pwython; and the Neithior.

The Bidding was a general invitation to all the friends of the bride and bridegroom-elect to meet them at the houses of their respective parents or any other house appointed for the occasion. All were welcomed to attend, even a stranger who should happen to be staying in the neighbourhood at the time, but it was an understood thing that every person who did attend, whether male or female, contributed something, however small, in order to make a purse for the young couple, who, on the other hand, naturally expected donations from those whose weddings they had attended themselves. So it was to the advantage of the bride and bridegroom-elect to make their wedding as public as possible, as the greater the number of guests, the greater the donation, so it was the custom to send the “Gwahoddwr,” or Bidder all round the surrounding districts to invite the neighbours and friends about three weeks, more or less, before the wedding took place. The banns were, of course, published as in England.

The Gwahoddwr or Bidder’s circuit was one of the most pleasant and merry features of the rural weddings in South Wales in times past, and he was greeted everywhere, especially when it happened that he was, as such often was the case, a merry wag with fluent speech and a poet; but it was necessary that he should be a real friend to the young couple on whose behalf he invited the guests. This important wedding official as he went from house to house, carried a staff of office in his hand, a long pole, or a white wand, as a rule a willow-wand, from which the bark had been peeled off. This white stick was decorated with coloured ribbons plying at the end of it; his hat also, and often his breast was gaily decorated in a similar manner.

The Gwahoddwr, thus attired, knocked at the door of each guest and entered the house amidst the smiles of the old people and the giggling of the young. Then he would take his stand in the centre of the house, and strike the floor with his staff to enforce silence, and announce the wedding, and the names of bride and bridegroom-elect, their place of abode, and enumerate the great preparations made to entertain the guests, etc. As a rule, the Gwahoddwr made this announcement in a set speech of prose, and often repeated a rhyme also on the occasion.

The following was the speech of a Gwahoddwr in Llanbadarn Fawr, Cardiganshire in 1762, quoted in Meyrick’s “History of Cardiganshire,” from the miscellaneous papers of Mr. Lewis Morris:—

“Speech of the Bidder in Llanbadarn Fawr, 1762.”

“The intention of the bidder is this; with kindness and amity, with decency and liberality for Einion Owain and Llio Ellis, he invites you to come with your good will on the plate; bring current money; a shilling, or two, or three, or four, or five; with cheese and butter. We invite the husband and wife, and children, and man-servants, and maid-servants, from the greatest to the least. Come there early, you shall have victuals freely, and drink cheap, stools to sit on, and fish if we can catch them; but if not, hold us excusable; and they will attend on you when you call upon them in return. They set out from such a place to such a place.”

The following which appeared in a Welsh Quarterly “Y Beirniad,” for July, 1878, gives a characteristic account of a typical Bidder of a much later date in Carmarthenshire:—

“Am Tomos fel gwahoddwr, yr wyf yn ei weled yn awr o flaen llygaid fy meddwl.

“Dyn byr, llydan, baglog, yn gwisgo coat o frethyn lliw yr awyr, breeches penglin corduog, gwasgod wlanen fraith, a rhuban glas yn hongian ar ei fynwes, yn dangos natur ei swydd a’i genadwri dros y wlad a dramwyid ganddo; hosanau gwlan du’r ddafad am ei goesau, a dwy esgid o ledr cryf am ei draed; het o frethyn garw am ei ben haner moel; dwy ffrwd felingoch o hylif y dybaco yn ymlithro dros ei en; pastwn cryf a garw yn ei ddeheulaw. Cerddai yn mlaen i’r ty lle y delai heb gyfarch neb, tarawai ei ffon deirgwaith yn erbyn y llawr, tynai ei het a gosodai hi dan y gesail chwith, sych besychai er clirio ei geg, a llefarai yn debyg i hyn:—‘At wr a gwraig y ty, y plant a’r gwasanaethyddion, a phawb o honoch sydd yma yn cysgu ac yn codi. ‘Rwy’n genad ac yn wahoddwr dros John Jones o’r Bryntirion, a Mary Davies o Bantyblodau; ‘rwy’n eich gwahodd yn hen ac yn ifanc i daith a phriodas y par ifanc yna a enwais, y rhai sydd yn priodi dydd Mercher, tair wythnos i’r nesaf, yn Eglwys Llansadwrn. Bydd y gwr ifanc a’i gwmp’ni yn codi ma’s y bore hwnw o dy ei dad a’i fam yn Bryntirion, plwyf Llansadwrn; a’r ferch ifanc yn codi ma’s y bore hwnw o dy ei thad a’i mam, sef Pantyblodau, yn mhlwyf Llanwrda. Bydd gwyr y “shigouts” yn myned y bore hwnw dros y mab ifanc i ‘mofyn y ferch ifanc; a bydd y mab ifanc a’i gwmp’ni yn cwrdd a’r ferch ifanc a’i chwmp-ni wrth ben Heolgelli, a byddant yno ar draed ac ar geffylau yn myned gyda’r par ifanc i gael eu priodi yn Eglwys Llansadwrn. Wedi hyny bydd y gwr a’r wraig ifanc, a chwmp’ni y bobol ifanc, yn myned gyda’u gilydd i dy y gwr a’r wraig ifanc, sef Llety’r Gofid, plwyf Talyllechau, lle y bydd y gwr ifanc, tad a mam y gwr ifanc, a Daniel Jones, brawd y gwr ifanc, a Jane Jones, chwaer y gwr ifanc, yn dymuno am i bob rhoddion a phwython dyledus iddynt hwy gael eu talu y prydnawn hwnw i law y gwr ifanc; a bydd y gwr ifanc a’i dad a’i fam, a’i frawd a’i chwaer, Dafydd Shon William Evan, ewyrth y gwr ifanc, yn ddiolchgar am bob rhoddion ychwanegol a welwch yn dda eu rhoddi yn ffafr y gwr ifanc ar y diwrnod hwnw.

“‘Hefyd, bydd y wraig ifanc, yn nghyd a’i thad a’i mam, Dafydd a Gwenllian Davies, yn nghyd a’i brodyr a’i chwiorydd, y wraig ifanc a Dafydd William Shinkin Dafydd o’r Cwm, tadcu y wraig ifanc, yn galw mewn bob rhoddion a phwython, dyledus iddynt hwy, i gael eu talu y prydnawn hwnw i law y gwr a’r wraig ifanc yn Llety’r Gofid. Y mae’r gwr a’r wraig ifanc a’r hwyaf fo byw, yn addo talu ’nol i chwithau bob rhoddion a weloch yn dda eu rhoddi i’r tylwyth ifanc, pryd bynag y bo galw, tae hyny bore dranoeth, neu ryw amser arall.’”

Rendered into English the above reads as follows:—

“I can see Thomas, in the capacity of a Gwahoddwr,—Bidder,—before me now in my mind’s eye. A short man, broad, clumsy, wearing a coat of sky-blue cloth, corduroy breeches to the knee, a motley woollen waistcoat, and a blue ribbon hanging on his breast, indicating the nature of his office and message through the country which he tramped; black-woollen stockings on his legs, and two strong leathern boots on his feet; a hat made of rough cloth on his half-bare head; two yellow-red streams of tobacco moisture running down his chin; a rough, strong staff in his right hand. He walked into the house he came to without saluting any one, and struck the floor three times with his staff, took off his hat, and put it under his left arm, and having coughed in order to clear his throat, he delivered himself somewhat as follows:—

“To the husband and wife of the house, the children and the servants, and all of you who are here sleeping and getting up. I am a messenger and a bidder for John Jones of Bryntirion and Mary Davies of Pantyblodau; I beg to invite you, both old and young, to the bidding and wedding of the young couple I have just mentioned, who intend to marry on Wednesday, three weeks to the next, at Llansadwrn Church. The young man and his company on that morning will be leaving his father and mother’s house at Bryntirion, in the parish of Llansadwrn; and the young woman will be leaving that same morning from the house of her father and mother, that is Pantyblodau, in the parish of Llanwrda. On that morning the shigouts (seekouts) men will go on behalf of the young man to seek for the young woman; and the young man and his company will meet the young woman and her company at the top of Heolgelli, and there they will be, on foot and on horses, going with the young couple who are to be married at Llansadwrn Church. After that, the young husband and wife, and the young people’s company, will be going together to the house of the young husband and wife, to wit, Llety’r Gofid, in the parish of Tally, where the young man, the young man’s father and mother, and Daniel Jones, brother of the young man, and Jane Jones, the young man’s sister, desire that all donations and pwython due to them be paid that afternoon to the hands of the young man; and the young man, his father and mother, his brother and sister, and Dafydd Shon William Evan, uncle of the young man, will be very thankful for every additional gifts you will be pleased to give in favour of the young man that day.

“Also, the young wife, together with her father and mother, Dafydd and Gwenllian Davies, together with her brothers and sisters, the young wife and Dafydd William Shinkin Dafydd of Cwm, the young wife’s grandfather, desire that all donations and pwython, due to them, be paid that afternoon to the hand of the young husband and wife at Llety’r Gofid.

“The young husband and wife and those who’ll live the longest, do promise to repay you every gift you will be pleased to give to the young couple, whenever called upon to do so, should that happen next morning or at any other time?”

The Bidder then repeated in Welsh a most comic and humorous song for the occasion.

Another well-known “Gwahoddwr,” or Bidder in Cardiganshire was an old man named Stephen, who flourished at the end of the eighteenth, and the beginning of the nineteenth century.

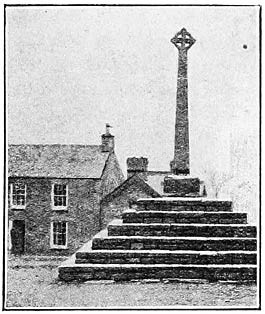

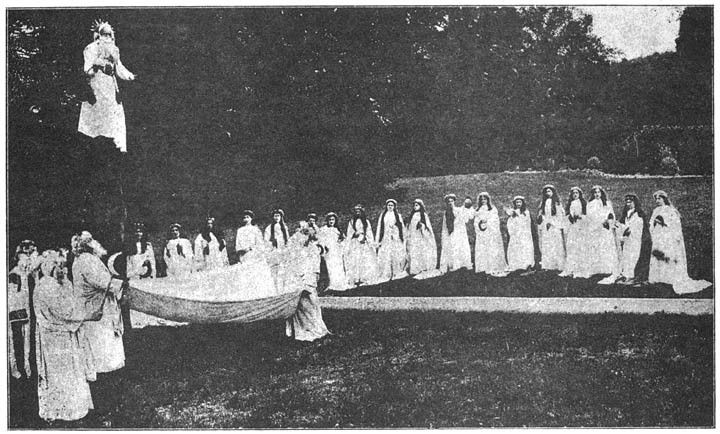

THE BIDDER, OR GWAHODDWR,

(Reproduced from an old picture in the “Hynafion Cymreig,” published in 1823).

He was commonly known as Stephen Wahoddwr, or Stephen the Bidder, and concerning whom the celebrated poet “Daniel Ddu o Geredigion,” wrote to the “Cambrian Briton,” in March, 1822, as follows:—

“There is an old man in this neighbourhood of the name of Stephen, employed in the vocation of ‘Gwahoddwr,’ who displayed, in my hearing, so much comic talent and humour in the recitation of his Bidding-song (which he complained, was, by repetition, become uninteresting to his auditors) as to induce me to furnish him with some kind of fresh matter. My humble composition, adapted, in language and conceptions, as far as I could make it, to common taste and capacities, this man now delivers in his rounds; and I send it you as a specimen of a Bidder’s Song, hoping that your readers will be in some measure amused by its perusal:—

“Dydd da i chwi, bobl, o’r hynaf i’r baban,

Mae Stephan Wahoddwr a chwi am ymddiddan,

Gyfeillion da mwynaidd, os felly’ch dymuniad,

Cewch genyf fy neges yn gynhes ar gariad.

Y mae rhyw greadur trwy’r byd yn grwydredig,

Nis gwn i yn hollol ai glanwedd ai hyllig,

Ag sydd i laweroedd yn gwneuthur doluriad,

Ar bawb yn goncwerwr, a’i enw yw Cariad.

Yr ifanc yn awchus wna daro fynycha’,

A’i saeth trwy ei asen mewn modd truenusa’;

Ond weithiau a’i fwa fe ddwg yn o fuan

O dan ei lywodraeth y rhai canol oedran.

Weithiau mae’n taro yn lled annaturiol,

Nes byddant yn babwyr yn wir yr hen bobl,

Mi glywais am rywun a gas yn aflawen

Y bendro’n ei wegil yn ol pedwar ugain.

A thyma’r creadur trwy’r byd wrth garwyro

A d’rawodd y ddeu-ddyn wyf trostynt yn teithio,

I hel eich cynorthwy a’ch nodded i’w nerthu,

Yn ol a gewch chwithau pan ddel hwn i’ch brathu.

Ymdrechwch i ddala i fyny yn ddilys,

Bawb oll yr hen gystwm, nid yw yn rhy gostus—

Sef rhoddi rhyw sylltach, rai ‘nol eu cysylltu,

Fe fydd y gwyr ifainc yn foddgar o’u meddu.

Can’ brynu rhyw bethau yn nghyd gan obeithio

Byw yn o dawel a’u plant yn blodeuo;

Dwyn bywyd mor ddewis wrth drin yr hen ddaear,

A Brenhin y Saeson, neu gynt yr hen Sesar.

Can’s nid wyf i’n meddwl mae golud a moddion

Sy’n gwneuthur dedwyddwch, dyweden hwy wedo’n;

Mae gofid i’r dynion, sy’n byw mewn sidanau,

Gwir mae’r byd hawsaf yw byw heb ddim eisiau.

‘Roedd Brenhin mawr Lloegr a’i wraig yn alluog,

A chig yn eu crochan, ond eto’n byw’n ‘ysgrechog;

Pe cawsai y dwliaid y gaib yn eu dwylo,

Yr wyf yn ystyried y buasai llai stwrio.

Cynal rhyw gweryl yr aent am y goron,

Ac ymladd a’u gilydd a hyny o’r galon;

‘Rwy’n barod i dyngu er cymaint eu hanghen

Nad o’ent hwy mor ddedwydd a Stephen a Madlen.

Yr wyf yn attolwg i bob un o’r teulu,

I gofio fy neges wyf wedi fynegu;

Rhag i’r gwr ifanc a’i wraig y pryd hyny,

Os na chan’ ddim digon ddweyd mai fi fu’n diogi.

Chwi gewch yno roeso, ‘rwy’n gwybod o’r hawsaf,

A bara chaws ddigon, onide mi a ddigiaf,

Caiff pawb eu hewyllys, dybacco, a phibelli,

A diod hoff ryfedd, ‘rwyf wedi ei phrofi.

Gwel’d digrif gwmpeini wy’n garu’n rhagorol,

Nid gwiw ini gofio bob amser ei gofol;

Mae amser i gwyno mae amser i ganu,

Gwir yw mae hen hanes a ddywed in’ hyny.

Cwpanau da fawrion a dynion difyrus,

I mi sy’n rhyw olwg o’r hen amser hwylus;

Ac nid wyf fi’n digio os gwaeddi wna rhywun,

Yn nghornel y ‘stafell, “A yfwch chwi, Styfyn?”

Dydd da i chwi weithian, mae’n rhaid i mi deithio

Dros fryniau, a broydd, a gwaunydd, dan gwyno;

Gan stormydd tra awchus, a chan y glaw uchel,

Caf lawer cernod, a chwithau’n y gornel.”

The above has been translated into English by one Mair Arfon as follows, and appeared in “Cymru Fu,” Cardiff, August 9th, 1888:—

“Here’s Stephen the Bidder! Good day to you all,

To baby and daddy, old, young, great and small;

Good friends if you like, in a warm poet’s lay

My message to you I’ll deliver to-day.

Some creature there is who roams the world through

Working mischief to many and joy to a few,

But conquering all, whether hell or above

Be his home, I am not certain; his name though is love.

The young he most frequently marks as his game,

Strikes them straight through the heart with an unerring aim;

Though the middle age, too, if he gets in his way,

With his bow he will cover and bend to his sway.

And sometimes the rogue with an aim somewhat absurd,

Makes fools of old people. Indeed, I have heard

Of one hapless wight, who, though over four score,

He hit in the head, making one victim more.

And this is the creature, who, when on his way

Through the world, struck the couple in whose cause to-day,

I ask for your help and your patronage, too;

And they’ll give you back when he comes to bite you.

And now let each one of us struggle to keep

The old custom up, so time-honoured and cheap;

Of jointly, or singly, some small trifle giving,

To start the young pair on their way to a living.

They’ll buy a few things, with a confidence clear,

Of living in peace as their children they rear;

Stealing and content, out of Mother Earth’s hand,

Blest as Cæsar of old, or the King of our land.

I do not consider that riches or gold

Ensure contentment; a wise man of old

Tells us men in soft raiment of grief have their share,

And a life without wants is the lightest to bear.

Once a great English King1 and his talented wife,

Though they had meat in their pan, led a bickering life;

Were the dullards compelled to work, him and her,

With a hoe in their hands it would lessen their stir.

The quarrel arose from some fight for the Crown

And at it they went like some cats of renown;

And although we are poor, I am ready to swear

That Stephen and Madlen are freer from care.

Now let me impress on this whole family,

To think on the message delivered by me;

Lest the youth and his wife, through not getting enough,

Should say that my idleness caused lack of stuff.

A welcome you’ll get there I guarantee you,

With bread and cheese plenty, and prime beer, too;

I know, for I have tried it, and everybody there

Can have ‘bacco and pipes enough and to spare.

It delights me a jovial assembly to see,

For it is wiser sometimes to forget misery;

There are times for complaining and song, too we’re told,

In the proverb of old, which is true as it’s old.

A bumping big cup and a lot of bright men,

Bring before me the jolly old times o’er again,

And I wouldn’t be angry if some one now even

Would shout from some corner “Will you have a glass Stephen?”

Good day to you now, for away I must hie,

Over mountains and hillocks with often a sigh,

Exposed as I am to keen storms, rain, and sleet,

While you cosily sit in your warm corner seat.”

Another well-known Gwahoddwr about 50 years ago was Thomas Parry, who lived at the small village of Pontshan in the parish of Llandyssul. A short time ago, when I was staying in that neighbourhood in quest for materials for my present work, I came across a few old people who well-remembered him, especially Mr. Thomas Evans, Gwaralltyryn, and the Rev. T. Thomas, J.P., Greenpark, both of whom, as well as one or two others, told me a good deal about him.

Like a good many of the Gwahoddwyr or Bidders, he seemed to have been a most eccentric character, of a ready wit and full of humour, especially when more or less under the influence of a glass of ale. Mr. Rees Jones, Pwllffein, a poet of considerable repute in the Vale of Cletwr, composed for T. Parry, a “Can y Gwahoddwr,” or the Bidder’s Song, which song in a very short time, became most popular in that part of Cardiganshire, and the adjoining districts of Carmarthenshire. This Parry the Bidder, whenever he was sent by those intending to marry, went from house to house, through the surrounding districts, proclaiming the particulars, and inviting all to the Bidding and the Weddings, and he was greeted with smiles wherever he went, especially by the young men and young women, who always looked forward to a wedding with great delight, as it was an occasion for so much merriment and enjoyment, and where lovers and sweethearts met. Food was set before the Gwahoddwr almost in every house, bread and cheese and beer, so that it is not to be wondered at that he felt a bit merry before night. He tramped through his circuit through storms and rain, but like most Bidders, he was but poorly paid, so he was often engaged as a mole trapper as well.

On one occasion, he had set down a trap in a neighbouring field in the evening expecting to find a mole entrapped in it next morning. Next morning came, and off went the old man to see the trap, but when he arrived on the spot, to his great surprise, instead of a mole in the trap, there was a fish in it! The famous entrapper of moles could not imagine how a fish could get into a trap on dry land, but he found out afterwards that some mischievous boys had been there early in the morning before him, who, to have a bit of fun at the expense of the old man, had taken out the mole from the trap and put a fish in it instead.

Thus we see that the modern Gwahoddwr was generally a poor man; but in the old times, on the other hand, he was a person of importance, skilled in pedigrees and family traditions, and himself of good family; for, undoubtedly, these old wedding customs which have survived in some localities in Cardiganshire and Carmarthenshire and other parts of Wales even down almost to the present time, are of a very ancient origin, coming down even from the time of the Druids, and this proves the wisdom and knowledge of the original legislators of the Celtic tribes; for they were instituted in order to encourage wedlock so as to increase the population of the country, and to repair the losses occasioned by plagues and wars. A chieftain would frequently assume the character of a Bidder on behalf of his vassal, and hostile clans respected his person as he went about from castle to castle, or from mansion to mansion.

Old people who well remember the time when the quaint old wedding customs were very general throughout West Wales, informed me that it was in some localities the custom sometimes to have two or more Gwahoddwyr to invite to the wedding; this was especially the case when the bride and bridegroom-elect did not reside in the same part of the country; for it happened sometimes that the young man engaged to be married lived in a certain part of Carmarthenshire, whilst his bride perhaps lived some way off in Cardiganshire or Pembrokeshire.

In such cases it was necessary to appoint two Bidders, one for the young man, and another for the young woman, to go round the respective districts in which each of them lived.

An old man in Carmarthenshire informed me that many years ago a friend of his, a farmer in the parish of Llanycrwys married a young lady from Pencarreg, two Bidders were sent forth to tramp the country; one going round the parish of Llanycrwys where the bridegroom lived, and the other’s circuit was the parish of Pencarreg, the native parish of the bride.

Another custom in some places, especially round Llandyssul and Llangeler, which took place before appointing the Gwahoddwr, was for the neighbours and friends to come together of an evening to the house of the bride or bridegroom’s parents, or any other place fixed upon for that purpose. On such occasion a good deal of drinking home-brewed beer was indulged in, “Er lles y par ifanc,” that is, for the benefit of the young couple. All the profit made out of this beer drinking at a private house went to the young man and the young woman as a help to begin their married life. At such a meeting also very often the day of the wedding was fixed, and the Bidder appointed, and should he happen to be an inexperienced one he was urged to repeat his Bidding speech before the company present, in order to test him whether he had enough wit and humour to perform his office satisfactorily in going round to invite to the wedding.

When the young people engaged to be married were sons and daughters of well-to-do farmers, it was the custom to send by this Bidder in his rounds, a circular letter, or a written note in English; and this note or circular in course of time became so fashionable that the occupation of a Bidder gradually fell to decay; that is, it became a custom to send a circular letter instead of a Bidder. The following Bidding Letter, which is not a fictitious one, but a real document, appeared in an interesting book, entitled “The Vale of Towy,” published in 1844:—

“Being betrothed to each other, we design to ratify the plighted vow by entering under the sanction of wedlock; and as a prevalent custom exists from time immemorial amongst “Plant y Cymry” of making a bidding on the occurrence of a hymeneal occasion, we have a tendency to the manner of the oulden tyme, and incited by friends as well as relations to do the same, avail ourselves of this suitableness of circumstances of humbly inviting your agreeable and pleasing presence on Thursday, the 29th day of December next, at Mr. Shenkin’s, in the parish of Llangathen, and whatever your propensities then feel to grant will meet with an acceptance of the most grateful with an acknowledgement of the most warmly, carefully registered, and retaliated with promptitude and alacrity, whenever an occurrence of a similar nature present itself, by

“Your most obedient servants,

William Howells,

Sarah Lewis.

“The young man, with his father and mother (David and Ann Howells), his brother (John Howells), and his cousin (Edward Howells), desire that all claims of the above nature due to them be returned to the young man on the above day, and will feel grateful for the bestowments of all kindness conferred upon him.

“The young woman, with her father and mother (Thomas and Letice Lewis), her sisters (Elizabeth and Margaret Lewis), and her cousins (William and Mary Morgan), desire that all claims of the above nature due to them be returned to the young woman on the above day, and will feel grateful for the bestowments of all kindness conferred upon her.”

The following Bidding Letter I copied from an old manuscript in possession of that eminent Antiquarian, the Rev. D. H. Davies, once Vicar of Cenarth, but who lives at present at Newcastle Emlyn:—

“To Mr. Griffith Jenkins.

“Sir,—As my daughter’s Bidding is fixed to be the Eighth day of February next, I humbly beg the favour of your good company according to custom, on the occasion, which shall be most gratefully acknowledged and retaliated by

“Yours most obedient and humble Servant,

Joshua Jones.

“Penrallt,

Jan. 23rd, 1770.”

The following also is another specimen of such circular, a copy of which came into my possession through the kindness of the esteemed lady, Mrs. Webley-Tyler, Glanhelig, near Cardigan:—

“February 1, 1841.

“As we intend to enter the Matrimonial State, on Thursday, the 11th day of February instant, we purpose to make a Bidding on the occasion, the same day, at the young woman’s Father and Mother’s House, called Llechryd Mill; When and where the favour of your good company is most humbly solicited, and whatever donation you will be pleased to confer on us that day, will be thankfully received and cheerfully repaid whenever called for on a similar occasion,

“By your obedient humble Servants,

John Stephens,

Ann Davies.

“The young man’s Father and Mother (John and Elizabeth Stephens, Pen’rallt-y-felin), together with his brother (David Stephens), desire that all gifts of the above nature due to them be returned to the Young Man, on the said day, and will be thankful for all favours granted.—Also the Young Woman’s Father and Mother (David and Hannah Davies, Llechryd Mill), desire that all gifts of the above nature due to them, be returned to the young woman on the said day, and will be thankful for all favours granted.”

The day before the Wedding was once allotted to bringing home the “Ystafell,” or household goods and furniture, of the young couple; but these customs varied considerably in different parts of the country. The furniture of the bride, as a rule, consisted of a feather bed and bed clothes, one or two large oaken chests to keep clothes in, and a few other things; and it was customary for the bridegroom to find or provide tables, chairs, bedstead, and a dresser. The dresser was perhaps the most interesting relic of family property, and is still to be seen in Welsh farm-houses, and is greatly valued as a thing which has been an heirloom in the family for generations. It consists of two or more stages, and the upper compartments, which are open, are always decked with specimens of useful and ornamental old Welsh ware, which are getting very rare now, and people offer a high price for them as curiosities.

It was also customary on the same day for the young man and the young woman to receive gifts of various kinds, such as money, flour, cheese, butter, bacon, hens, and sometimes even a cow or a pig, also a good many useful things for house-keeping. This was called “Pwrs a Gwregys”—a purse and a girdle. But these gifts were to be re-paid when demanded on similar occasions; and, upon a refusal, were even recoverable by law; and sometimes this was done.

About a hundred years ago, and previous to that date, the day before the wedding, as a rule, was allotted to the “Ystafell,” or bringing home of the furniture, etc.; but more recently it became the custom to appoint a day for that purpose at other times in some districts, that is, it took place whenever the young married couple went to live at a house of their own; this would be perhaps three or six months after the wedding. In Wales it is very common to see a young married couple among the farmers remaining with the parents of the young man, or with the young wife’s parents until it is a convenient time for them to take up a farm of their own.