автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The History of Signboards, from the Earliest times to the Present Day

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

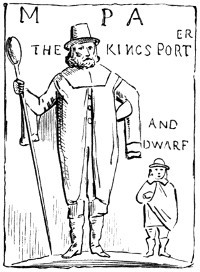

Drawn by Experience

Engraved by Sorrow

a Man Loaded with Mischief, or Matrimony.

A Monkey, a Magpie, and Wife; Is the true Emblem of Strife.

Large image (263 kB)

THE

HISTORY OF SIGNBOARDS

From the Earliest Times to the Present Day

BY JACOB LARWOOD AND

JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN

“He would name you all the signs as he went along”

BEN JONSON’S BARTHOLOMEW FAIR

“Oppida dum peragras peragranda poemata spectes”

DRUNKEN BARNABY’S TRAVELS

Cock and Bottle

TWELFTH IMPRESSION

WITH ONE HUNDRED ILLUSTRATIONS BY J. LARWOOD

LONDON

CHATTO & WINDUS

1908

To

Thomas Wright, Esq., M.A., F.S.A.,

the Accomplished Interpreter of English Popular Antiquities, this

Little Volume is Dedicated

by

THE AUTHORS.

PREFACE.

The field of history is a wide one, and when the beaten tracks have been well traversed, there will yet remain some of the lesser paths to explore. The following attempt at a “History of Signboards” may be deemed the result of an exploration in one of these by-ways.

Although from the days of Addison’s Spectator down to the present time many short articles have been written upon house-signs, nothing like a general inquiry into the subject has, as yet, been published in this country. The extraordinary number of examples and the numerous absurd combinations afforded such a mass of entangled material as doubtless deterred writers from proceeding beyond an occasional article in a magazine, or a chapter in a book,—when only the more famous signs would be cited as instances of popular humour or local renown. How best to classify and treat the thousands of single and double signs was the chief difficulty in compiling the present work. That it will in every respect satisfy the reader is more than is expected—indeed much more than could be hoped for under the best of circumstances.

In these modern days, the signboard is a very unimportant object: it was not always so. At a time when but few persons could read and write, house-signs were indispensable in city life. As education spread they were less needed; and when in the last century, the system of numbering houses was introduced, and every thoroughfare had its name painted at the beginning and end, they were no longer a positive necessity—their original value was gone, and they lingered on, not by reason of their usefulness, but as instances of the decorative humour of our ancestors, or as advertisements of established reputation and business success. For the names of many of our streets we are indebted to the sign of the old inn or public-house, which frequently was the first building in the street—commonly enough suggesting its erection, or at least a few houses by way of commencement. The huge “London Directory” contains the names of hundreds of streets in the metropolis which derived their titles from taverns or public-houses in the immediate neighbourhood. As material for the etymology of the names of persons and places, the various old signs may be studied with advantage. In many other ways the historic importance of house-signs could be shown.

Something like a classification of our subject was found absolutely necessary at the outset, although from the indefinite nature of many signs the divisions “Historic,” “Heraldic,” “Animal,” &c.—under which the various examples have been arranged—must be regarded as purely arbitrary, for in many instances it would be impossible to say whether such and such a sign should be included under the one head or under the other. The explanations offered as to origin and meaning are based rather upon conjecture and speculation than upon fact—as only in very rare instances reliable data could be produced to bear them out. Compound signs but increase the difficulty of explanation: if the road was uncertain before, almost all traces of a pathway are destroyed here. When, therefore, a solution is offered, it must be considered only as a suggestion of the possible meaning. As a rule, and unless the symbols be very obvious, the reader would do well to consider the majority of compound signs as quarterings or combinations of others, without any hidden signification. A double signboard has its parallel in commerce, where for a common advantage, two merchants will unite their interests under a double name; but as in the one case so in the other, no rule besides the immediate interests of those concerned can be laid down for such combinations.

A great many signs, both single and compound, have been omitted. To have included all, together with such particulars of their history as could be obtained, would have required at least half-a-dozen folio volumes. However, but few signs of any importance are known to have been omitted, and care has been taken to give fair samples of the numerous varieties of the compound sign. As the work progressed a large quantity of material accumulated for which no space could be found, such as “A proposal to the House of Commons for raising above half a million of money per annum, with a great ease to the subject, by a TAX upon SIGNS, London, 1695,” a very curious tract; a political jeu-d’esprit from the Harleian MSS., (5953,) entitled “The Civill Warres of the Citie,” a lengthy document prepared for a journal in the reign of William of Orange by one “E. I.,” and giving the names and whereabouts of the principal London signs at that time. Acts of Parliament for the removal or limitation of signs; and various religious pamphlets upon the subject, such as “Helps for Spiritual Meditation, earnestly Recommended to the Perusal of all those who desire to have their Hearts much with God,” a chap-book of the time of Wesley and Whitfield, in which the existing “Signs of London are Spiritualized, with an Intent, that when a person walks along the Street, instead of having their Mind fill’d with Vanity, and their Thoughts amus’d with the trifling Things that continually present themselves, they may be able to Think of something Profitable.”

Anecdotes and historical facts have been introduced with a double view; first, as authentic proofs of the existence and age of the sign; secondly, in the hope that they may afford variety and entertainment. They will call up many a picture of the olden time; many a trait of bygone manners and customs—old shops and residents, old modes of transacting business, in short, much that is now extinct and obsolete. There is a peculiar pleasure in pondering over these old houses, and picturing them to ourselves as again inhabited by the busy tenants of former years; in meeting the great names of history in the hours of relaxation, in calling up the scenes which must have been often witnessed in the haunt of the pleasure-seeker,—the tavern with its noisy company, the coffee-house with its politicians and smart beaux; and, on the other hand, the quiet, unpretending shop of the ancient bookseller filled with the monuments of departed minds. Such scraps of history may help to picture this old London as it appeared during the last three centuries. For the contemplative mind there is some charm even in getting at the names and occupations of the former inmates of the houses now only remembered by their signs; in tracing, by means of these house decorations, their modes of thought or their ideas of humour, and in rescuing from oblivion a few little anecdotes and minor facts of history connected with the house before which those signs swung in the air.

It is a pity that such a task as the following was not undertaken many years ago; it would have been much better accomplished then than now. London is so rapidly changing its aspect, that ten years hence many of the particulars here gathered could no longer be collected. Already, during the printing of this work, three old houses famous for their signs have been doomed to destruction—the Mitre in Fleet Street, the Tabard in Southwark, (where Chaucer’s pilgrims lay,) and Don Saltero’s house in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. The best existing specimens of old signboards may be seen in our cathedral towns. Antiquaries cling to these places, and the inhabitants themselves are generally animated by a strong conservative feeling. In London an entire street might be removed with far less of public discussion than would attend the taking down of an old decayed sign in one of these provincial cities. Does the reader remember an article in Punch, about two years ago, entitled “Asses in Canterbury?” It was in ridicule of the Canterbury Commissioners of Pavement, who had held grave deliberations on the well-known sign of Sir John Falstaff, hanging from the front of the hotel of that name,—a house which has been open for public entertainment these three hundred years. The knight with sword and buckler (from “Henry the Fourth,”) was suspended from some ornamental iron-work, far above the pavement, in the open thoroughfare leading to the famous Westgate, and formed one of the most noticeable objects in this part of Canterbury. In 1787, when the general order was issued for the removal of all the signs in the city—many of them obstructed the thoroughfares—this was looked upon with so much veneration that it was allowed to remain until 1863, when for no apparent reason it was sentenced to destruction. However, it was only with the greatest difficulty that men could be found to pull it down, and then several cans of beer had first to be distributed amongst them as an incentive to action—in so great veneration was the old sign held even by the lower orders of the place. Eight pounds were paid for this destruction, which, for fear of a riot, was effected at three in the morning, “amid the groans and hisses of the assembled multitude,” says a local paper. Previous to the demolition the greatest excitement had existed in the place; the newspapers were filled with articles; a petition with 400 signatures—including an M.P., the prebends, minor canons, and clergy of the cathedral—prayed the local “commissioners” that the sign might be spared; and the whole community was in an uproar. No sooner was the old portrait of Sir John removed than another was put up; but this representing the knight as seated, and with a can of ale by his side, however much it may suit the modern publican’s notion of military ardour, does not please the owner of the property, and a fac-simile of the time-honoured original is in course of preparation.

Concerning the internal arrangement of the following work, a few explanations seem necessary.

Where a street is mentioned without the town being specified, it in all cases refers to a London thoroughfare.

The trades tokens so frequently referred to, it will be scarcely necessary to state, were the brass farthings issued by shop or tavern keepers, and generally adorned with a representation of the sign of the house. Nearly all the tokens alluded to belong to the latter part of the seventeenth century, mostly to the reign of Charles II.

As the work has been two years in the press, the passing events mentioned in the earlier sheets refer to the year 1864.

In a few instances it was found impossible to ascertain whether certain signs spoken of as existing really do exist, or whether those mentioned as things of the past are in reality so. The wide distances at which they are situated prevented personal examination in every case, and local histories fail to give such small particulars.

The rude unattractive woodcuts inserted in the work are in most instances fac-similes, which have been chosen as genuine examples of the style in which the various old signs were represented. The blame of the coarse and primitive execution, therefore, rests entirely with the ancient artist, whether sign painter or engraver.

Translations of the various quotations from foreign languages have been added for the following reasons:—It was necessary to translate the numerous quotations from the Dutch signboards; Latin was Englished for the benefit of the ladies, and Italian and French extracts were Anglicised to correspond with rest.

Errors, both of fact and opinion, may doubtless be discovered in the book. If, however, the compilers have erred in a statement or an explanation, they do not wish to remain in the dark, and any light thrown upon a doubtful passage will be acknowledged by them with thanks. Numerous local signs—famous in their own neighbourhood—will have been omitted, (generally, however, for the reasons mentioned on a preceding page,) whilst many curious anecdotes and particulars concerning their history may be within the knowledge of provincial readers. For any information of this kind the compilers will be much obliged; and should their work ever pass to a second edition, they hope to avail themselves of such friendly contributions.

London, June 1866.

CONTENTS.

PAGE

CHAPTER I.

GENERAL SURVEY OF SIGNBOARD HISTORY,

1CHAPTER II.

HISTORIC AND COMMEMORATIVE SIGNS,

45CHAPTER III.

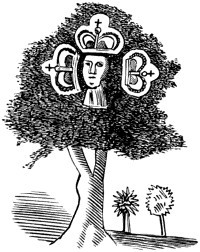

HERALDIC AND EMBLEMATIC SIGNS,

101CHAPTER IV.

SIGNS OF ANIMALS AND MONSTERS,

150CHAPTER V.

BIRDS AND FOWLS,

199CHAPTER VI.

FISHES AND INSECTS,

225CHAPTER VII.

FLOWERS, TREES, HERBS, ETC.,

233CHAPTER VIII.

BIBLICAL AND RELIGIOUS SIGNS,

253CHAPTER IX.

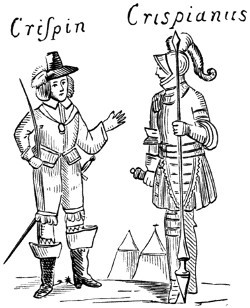

SAINTS, MARTYRS, ETC.,

279CHAPTER X.

DIGNITIES, TRADES, AND PROFESSIONS,

305CHAPTER XI.

THE HOUSE AND THE TABLE,

375CHAPTER XII.

DRESS; PLAIN AND ORNAMENTAL,

399CHAPTER XIII.

GEOGRAPHY AND TOPOGRAPHY,

414CHAPTER XIV.

HUMOROUS AND COMIC,

437CHAPTER XV.

PUNS AND REBUSES,

469CHAPTER XVI.

MISCELLANEOUS SIGNS,

476APPENDIX.

BONNELL THORNTON’S SIGNBOARD EXHIBITION,

512INDEX

OF ALL THE SIGNS MENTIONED IN THE WORK, 527PLATE I.

BAKER.

(Pompeii,

A.D.70.)

DAIRY.

(Pompeii,

A.D.70.)

SHOEMAKER.

(Herculaneum.)

WINE MERCHANT.

(Pompeii,

A.D.70.)

TWO JOLLY BREWERS.

(Banks’s Bills, 1770.)

CHAPTER I.

GENERAL SURVEY OF SIGNBOARD HISTORY.

In the cities of the East all trades are confined to certain streets, or to certain rows in the various bazars and wekalehs. Jewellers, silk-embroiderers, pipe-dealers, traders in drugs,—each of these classes has its own quarter, where, in little open shops, the merchants sit enthroned upon a kind of low counter, enjoying their pipes and their coffee with the otium cum dignitate characteristic of the Mussulman. The purchaser knows the row to go to; sees at a glance what each shop contains; and, if he be an habitué, will know the face of each particular shopkeeper, so that under these circumstances, signboards would be of no use.

With the ancient Egyptians it was much the same. As a rule, no picture or description affixed to the shop announced the trade of the owner; the goods exposed for sale were thought sufficient to attract attention. Occasionally, however, there were inscriptions denoting the trade, with the emblem which indicated it;[1] whence we may assume that this ancient nation was the first to appreciate the benefit that might be derived from signboards.

What we know of the Greek signs is very meagre and indefinite. Aristophanes, Lucian, and other writers, make frequent allusions, which seem to prove that signboards were in use with the Greeks. Thus Aristotle says: ὡσπερ επι των καπηλιων γραφομενοι, μικροι μεν εισι, φαινονται δε εχοντες πλατη και βαθη.[2] And Athenæus: εν προτεροις θηκη διδασκαλιην.[3] But what their signs were, and whether carved, painted, or the natural object, is entirely unknown.

With the Romans only we begin to have distinct data. In the Eternal City, some streets, as in our mediæval towns, derived their names from signs. Such, for instance, was the vicus Ursi Pileati, (the street of “The Bear with the Hat on,”) in the Esquiliæ. The nature of their signs, also, is well known. The Bush, their tavern-sign, gave rise to the proverb, “Vino vendibili suspensa hedera non opus est;” and hence we derive our sign of the Bush, and our proverb, “Good Wine needs no Bush.” An ansa, or handle of a pitcher, was the sign of their post-houses, (stathmoi or allagæ,) and hence these establishments were afterwards denominated ansæ.[4] That they also had painted signs, or exterior decorations which served their purpose, is clearly evident from various authors:—

“Quum victi Mures Mustelarum exercitu (Historia quorum in tabernis pingitur.)”[5]

Phædrus, lib. iv. fab. vi.

These Roman street pictures were occasionally no mean works of art, as we may learn from a passage in Horace:—

“Contento poplite miror Proelia, rubrico picta aut carbone; velut si Re vera pugnent, feriant vitentque moventes Arma viri.”[6]

Cicero also is supposed by some scholars to allude to a sign when he says:—

“Jam ostendamcujus modi sis: quum ille ‘ostende quæso’ demonstravi digito pictum Gallum in Mariano scuto Cimbrico, sub Novis, distortum ejectâ linguâ, buccis fluentibus, risus est commotus.”[7]

Pliny, after saying that Lucius Mummius was the first in Rome who affixed a picture to the outside of a house, continues:—

“Deinde video et in foro positas vulgo. Hinc enim Crassi oratoris lepos, [here follows the anecdote of the Cock of Marius the Cimberian] . . . In foro fuit et illa pastoris senis cum baculo, de qua Teutonorum legatus respondit, interrogatus quanti eum æstimaret, sibi donari nolle talem vivum verumque.”[8]

Fabius also, according to some, relates the story of the cock, and his explanation is cited:—“Taberna autem erant circa Forum, ac scutum illud signi gratia positum.”[9]

But we can judge even better from an inspection of the Roman signs themselves, as they have come down to us amongst the ruins of Herculaneum and Pompeii. A few were painted; but, as a rule, they appear to have been made of stone, or terra-cotta relievo, and let into the pilasters at the side of the open shop-fronts. Thus there have been found a goat, the sign of a dairy; a mule driving a mill, the sign of a baker, (plate 1.) At the door of a schoolmaster was the not very tempting sign of a boy receiving a good birching. Very similar to our Two Jolly Brewers, carrying a tun slung on a long pole, a Pompeian public-house keeper had two slaves represented above his door, carrying an amphora; and another wine-merchant had a painting of Bacchus pressing a bunch of grapes. At a perfumer’s shop, in the street of Mercury, were represented various items of that profession—viz., four men carrying a box with vases of perfume, men occupied in laying out and perfuming a corpse, &c. There was also a sign similar to the one mentioned by Horace, the Two Gladiators, under which, in the usual Pompeian cacography, was the following imprecation:—Abiat Venerem Pompeiianama iradam qui hoc læserit, i.e., Habeat Venerem Pompeianam iratam, &c. Besides these there were the signs of the Anchor, the Ship, (perhaps a ship-chandler’s,) a sort of a Cross, the Chequers, the Phallus on a baker’s shop, with the words, Hic habitat felicitas; whilst in Herculaneum there was a very cleverly painted Amorino, or Cupid, carrying a pair of ladies’ shoes, one on his head and the other in his hand.

It is also probable that, at a later period at all events, the various artificers of Rome had their tools as the sign of their house, to indicate their profession. We find that they sculptured them on their tombs in the catacombs, and may safely conclude that they would do the same on their houses in the land of the living. Thus on the tomb of Diogenes, the grave-digger, there is a pick-axe and a lamp; Bauto and Maxima have the tools of carpenters, a saw, an adze, and a chisel; Veneria, a tire-woman, has a mirror and a comb:—then there are others who have wool-combers’ implements; a physician, who has a cupping-glass; a poulterer, a case of poultry; a surveyor, a measuring rule; a baker, a bushel, a millstone, and ears of corn; in fact, almost every trade had its symbolic implements. Even that cockney custom of punning on the name, so common on signboards, finds its precedent in those mansions of the dead. Owing to this fancy, the grave of Dracontius bore a dragon; Onager, a wild ass; Umbricius, a shady tree; Leo, a lion; Doleus, father and son, two casks; Herbacia, two baskets of herbs; and Porcula, a pig. Now it seems most probable that, since these emblems were used to indicate where a baker, a carpenter, or a tire-woman was buried, they would adopt similar symbols above ground, to acquaint the public where a baker, a carpenter, or a tire-woman lived.

We may thus conclude that our forefathers adopted the signboard from the Romans; and though at first there were certainly not so many shops as to require a picture for distinction,—as the open shop-front did not necessitate any emblem to indicate the trade carried on within,—yet the inns by the road-side, and in the towns, would undoubtedly have them. There was the Roman bush of evergreens to indicate the sale of wine;[10] and certain devices would doubtless be adopted to attract the attention of the different classes of wayfarers, as the Cross for the Christian customer,[11] and the Sun or the Moon for the pagan. Then we find various emblems, or standards, to court respectively the custom of the Saxon, the Dane, or the Briton. He that desired the patronage of soldiers might put up some weapon; or, if he sought his customers among the more quiet artificers, there were the various implements of trade with which he could appeal to the different mechanics that frequented his neighbourhood.

Along with these very simple signs, at a later period, coats of arms, crests, and badges, would gradually make their appearance at the doors of shops and inns. The reasons which dictated the choice of such subjects were various. One of the principal was this. In the Middle Ages, the houses of the nobility, both in town and country, when the family was absent, were used as hostelries for travellers. The family arms always hung in front of the house, and the most conspicuous object in those arms gave a name to the establishment amongst travellers, who, unacquainted with the mysteries of heraldry, called a lion gules or azure by the vernacular name of the Red or Blue Lion.[12] Such coats of arms gradually became a very popular intimation that there was—

“Good entertainment for all that passes,— Horses, mares, men, and asses;”

and innkeepers began to adopt them, hanging out red lions and green dragons as the best way to acquaint the public that they offered food and shelter.

Still, as long as civilisation was only at a low ebb, the so-called open-houses few, and competition trifling, signs were of but little use. A few objects, typical of the trade carried on, would suffice; a knife for the cutler, a stocking for the hosier, a hand for the glover, a pair of scissors for the tailor, a bunch of grapes for the vintner, fully answered public requirements. But as luxury increased, and the number of houses or shops dealing in the same article multiplied, something more was wanted. Particular trades continued to be confined to particular streets; the desideratum then was, to give to each shop a name or token by which it might be mentioned in conversation, so that it could be recommended and customers sent to it. Reading was still a scarce acquirement; consequently, to write up the owner’s name would have been of little use. Those that could, advertised their name by a rebus; thus, a hare and a bottle stood for Harebottle, and two cocks for Cox. Others, whose names no rebus could represent, adopted pictorial objects; and, as the quantity of these augmented, new subjects were continually required. The animal kingdom was ransacked, from the mighty elephant to the humble bee, from the eagle to the sparrow; the vegetable kingdom, from the palm-tree and cedar to the marigold and daisy; everything on the earth, and in the firmament above it, was put under contribution. Portraits of the great men of all ages, and views of towns, both painted with a great deal more of fancy than of truth; articles of dress, implements of trades, domestic utensils, things visible and invisible, ea quæ sunt tamquam ea quæ non sunt, everything was attempted in order to attract attention and to obtain publicity. Finally, as all signs in a town were painted by the same small number of individuals, whose talents and imagination were limited, it followed that the same subjects were naturally often repeated, introducing only a change in the colour for a difference.

Since all the pictorial representations were, then, of much the same quality, rival tradesmen tried to outvie each other in the size of their signs, each one striving to obtrude his picture into public notice by putting it out further in the street than his neighbour’s. The “Liber Albus,” compiled in 1419, names this subject amongst the Inquisitions at the Wardmotes: “Item, if the ale-stake of any tavern is longer or extends further than ordinary.” And in book iii. part iii. p. 389, is said:—

“Also, it was ordained that, whereas the ale-stakes projecting in front of taverns in Chepe, and elsewhere in the said city, extend too far over the King’s highways, to the impeding of riders and others, and, by reason of their excessive weight, to the great deterioration of the houses in which they are fixed;—to the end that opportune remedy might be made thereof, it was by the Mayor and Aldermen granted and ordained, and, upon summons of all the taverners of the said city, it was enjoined upon them, under pain of paying forty pence[13] unto the Chamber of the Guildhall, on every occasion upon which they should transgress such ordinance, that no one of them in future should have a stake, bearing either his sign, or leaves, extending or lying over the King’s highway, of greater length than seven feet at most, and that this ordinance should begin to take effect at the Feast of Saint Michael, then next ensuing, always thereafter to be valid and of full effect.”

The booksellers generally had a woodcut of their signs for the colophon of their books, so that their shops might get known by the inspection of these cuts. For this reason, Benedict Hector, one of the early Bolognese printers, gives this advice to the buyers in his “Justinus et Florus:”—

“Emptor, attende quando vis emere libros formatos in officina mea excussoria, inspice signum quod in liminari pagina est, ita numquam falleris. Nam quidam malevoli Impressores libris suis inemendatis et maculosis apponunt nomen meum ut fiant vendibiliores.”[14]

Jodocus Badius of Paris, gives a similar caution:—

“Oratum facimus lectorem ut signum inspiciat, nam sunt qui titulum nomenque Badianum mentiantur et laborem suffurentur.”[15]

Aldus, the great Venetian printer, exposes a similar fraud, and points out how the pirate had copied the sign also in his colophon; but, by inadvertency, making a slight alteration:—

“Extremum est ut admoneamus studiosissimum quemque, Florentinos quosdam impressores, cum viderint se diligentiam nostram in castigando et imprimendo non posse assequi, ad artes confugisse solitas; hoc est Grammaticis Institutionibus Aldi in sua officina formatis, notam Delphini Anchoræ Involuti nostram apposuisse; sed ita egerunt ut quivis mediocriter versatus in libris impressionis nostræ animadvertit illos impudenter fecisse. Nam rostrum Delphini in partem sinistram vergit, cum tamen nostrum in dexteram totum demittatur.”[16]

No wonder, then, that a sign was considered an heirloom, and descended from father to son, like the coat of arms of the nobility, which was the case with the Brazen Serpent, the sign of Reynold Wolfe. “His trade was continued a good while after his demise by his wife Joan, who made her will the 1st of July 1574, whereby she desires to be buried near her husband, in St Faith’s Church, and bequeathed to her son, Robert Wolfe, the chapel-house, [their printing-office,] the Brazen Serpent, and all the prints, letters, furniture,” etc.—Dibdin’s Typ. Ant., vol. iv. p. 6.

As we observed above, directly signboards were generally adopted, quaintness became one of the desiderata, and costliness another. This last could be obtained by the quality of the picture, but, for two reasons, was not much aimed at—firstly, because good artists were scarce in those days; and even had they obtained a good picture, the ignorant crowd that daily passed underneath the sign would, in all probability, have thought the harsh and glaring daub a finer production of art than a Holy Virgin by Rafaelle himself. The other reason was the instability of such a work, exposed to sun, wind, rain, frost, and the nightly attacks of revellers and roisters. Greater care, therefore, was bestowed upon the ornamentation of the ironwork by which it was suspended; and this was perfectly in keeping with the taste of the times, when even the simplest lock or hinges could not be launched into the world without its scrolls and strapwork.

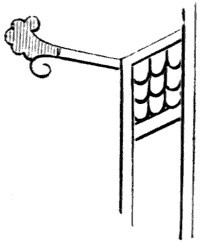

The signs then were suspended from an iron bar, fixed either in the wall of the house, or in a post or obelisk standing in front of it; in both cases the ironwork was shaped and ornamented with that taste so conspicuous in the metal-work of the Renaissance period, of which many churches, and other buildings of that period, still bear witness. In provincial towns and villages, where there was sufficient room in the streets, the sign was generally suspended from a kind of small triumphal arch, standing out in the road, partly wood, partly iron, and ornamented with all that carving, gilding, and colouring could bestow upon it, (see description of White-Hart Inn at Scole.) Some of the designs of this class of ironwork have come down to us in the works of the old masters, and are indeed exquisite.

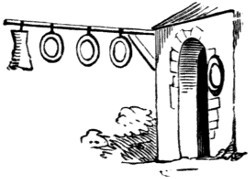

Painted signs then, suspended in the way we have just pointed out, were more common than those of any other kind; yet not a few shops simply suspended at their doors some prominent article in their trade, which custom has outlived the more elegant signboards, and may be daily witnessed in our streets, where the ironmonger’s frying-pan, or dust-pan, the hardware-dealer’s teapot, the grocer’s tea-canister, the shoemaker’s last or clog, with the Golden Boot, and many similar objects, bear witness to this old custom.

Lastly, there was in London another class of houses that had a peculiar way of placing their signs—viz., the Stews upon the Bankside, which were, by a proclamation of 37 Hen. VIII., “whited and painted with signs on the front, for a token of the said houses.” Stow enumerates some of these symbols, such as the Cross-Keys, the Gun, the Castle, the Crane, the Cardinal’s Hat, the Bell, the Swan, &c.

Still greater variety in the construction of the signs existed in France; for besides the painted signs in the iron frames, the shopkeepers in Paris, according to H. Sauval, (“Antiquités de la Ville de Paris,”) had anciently banners hanging above their doors, or from their windows, with the sign of the shop painted on them; whilst in the sixteenth century carved wooden signs were very common. These, however, were not suspended, but formed part of the wooden construction of the house; some of them were really chefs-d’œuvres, and as careful in design as a carved cathedral stall. Several of them are still remaining in Rouen and other old towns; many also have been removed and placed in various local museums of antiquities. The most general rule, however, on the Continent, as in England, was to have the painted signboard suspended across the streets.

An observer of James I.’s time has jotted down the names of all the inns, taverns, and side streets in the line of road between Charing Cross and the old Tower of London, which document lies now embalmed amongst the Harl. MS., 6850, fol. 31. In imagination we can walk with him through the metropolis:—

“On the way from Whitehall to Charing Cross we pass: the White Hart, the Red Lion, the Mairmade, iij. Tuns, Salutation, the Graihound, the Bell, the Golden Lyon. In sight of Charing Crosse: the Garter, the Crown, the Bear and Ragged Staffe, the Angel, the King Harry Head. Then from Charing Cross towards ye cittie: another White Hart, the Eagle and Child, the Helmet, the Swan, the Bell, King Harry Head, the Flower-de-luce, Angel, the Holy Lambe, the Bear and Harroe, the Plough, the Shippe, the Black Bell, another King Harry Head, the Bull Head, the Golden Bull, ‘a sixpenny ordinarye,’ another Flower-de-luce, the Red Lyon, the Horns, the White Hors, the Prince’s Arms, Bell Savadge’s In, the S. John the Baptist, the Talbot, the Shipp of War, the S. Dunstan, the Hercules or the Owld Man Tavern, the Mitar, another iij. Tunnes Inn, and a iij. Tunnes Tavern, and a Graihound, another Mitar, another King Harry Head, iij. Tunnes, and the iij. Cranes.”

Having walked from Whitechapel “straight forward to the Tower,” the good citizen got tired, and so we hear no more of him.

In the next reign we find the following enumerated by Taylor the water-poet, in one of his facetious pamphlets:—5 Angels, 4 Anchors, 6 Bells, 5 Bullsheads, 4 Black Bulls, 4 Bears, 5 Bears and Dolphins, 10 Castles, 4 Crosses, (red or white,) 7 Three Crowns, 7 Green Dragons, 6 Dogs, 5 Fountains, 3 Fleeces, 8 Globes, 5 Greyhounds, 9 White Harts, 4 White Horses, 5 Harrows, 20 King’s Heads, 7 King’s Arms, 1 Queen’s Head, 8 Golden Lyons, 6 Red Lyons, 7 Halfmoons, 10 Mitres, 33 Maidenheads, 10 Mermaids, 2 Mouths, 8 Nagsheads, 8 Prince’s Arms, 4 Pope’s Heads, 13 Suns, 8 Stars, &c. Besides these he mentions an Adam and Eve, an Antwerp Tavern, a Cat, a Christopher, a Cooper’s Hoop, a Goat, a Garter, a Hart’s Horn, a Mitre, &c. These were all taverns in London; and it will be observed that their signs were very similar to those seen at the present day—a remark applicable to the taverns not only of England, but of Europe generally, at this period. In another work Taylor gives us the signs of the taverns[17] and alehouses in ten shires and counties about London, all similar to those we have just enumerated; but amongst the number, it may be noted, there is not one combination of two objects, except the Eagle and Child, and the Bear and Ragged Staff. In a black-letter tract entitled “Newes from Bartholomew Fayre,” the following are named:—

In old times the ale-house windows were generally open, so that the company within might enjoy the fresh air, and see all that was going on in the street; but, as the scenes within were not always fit to be seen by the “profanum vulgus” that passed by, a trellis was put up in the open window. This trellis, or lattice, was generally painted red, to the intent, it has been jocularly suggested, that it might harmonise with the rich hue of the customers’ noses; which effect, at all events, was obtained by the choice of this colour. Thus Pistol says:—

[1] Sir Gardiner Wilkinson’s Ancient Egyptians, vol. iii. p. 158. Also, Rosellini Monumenti dell’Egitto e della Nubia.

[2] Aristotle, Problematum x. 14: “As with the things drawn above the shops, which, though they are small, appear to have breadth and depth.”

[3] “He hung the well-known sign in the front of his house.”

[4] Hearne, Antiq. Disc., i. 39.

[5] “When the mice were conquered by the army of the weasels, (a story which we see painted on the taverns.)”

[6] Lib. ii. sat. vii.: “I admire the position of the men that are fighting, painted in red or in black, as if they were really alive; striking and avoiding each other’s weapons, as if they were actually moving.”

[7] De Oratore, lib. ii. ch. 71: “Now I shall shew you how you are, to which he answered, ‘Do, please.’ Then I pointed with my finger towards the Cock painted on the signboard of Marius the Cimberian, on the New Forum, distorted, with his tongue out and hanging cheeks. Everybody began to laugh.”

[8] Hist. Nat., xxxv. ch. 8: “After this I find that they were also commonly placed on the Forum. Hence that joke of Crassus, the orator. . . . On the Forum was also that of an old shepherd with a staff, concerning which a German legate, being asked at how much he valued it, answered that he would not care to have such a man given to him as a present, even if he were real and alive.”

[9] “There were, namely, taverns round about the Forum, and that picture [the Cock] had been put up as a sign.”

[10] The Bush certainly must be counted amongst the most ancient and popular of signs. Traces of its use are not only found among Roman and other old-world remains, but during the Middle Ages we have evidence of its display. Indications of it are to be seen in the Bayeux tapestry, in that part where a house is set on fire, with the inscription, Hic domus incenditur, next to which appears a large building, from which projects something very like a pole and a bush, both at the front and the back of the building.

[11] In Cædmon’s Metrical Paraphrase of Scripture History, (circa A.D. 1000,) in the drawings relating to the history of Abraham, there are distinctly represented certain cruciform ornaments painted on the walls, which might serve the purpose of signs. (See upon this subject under “Religious Signs.”)

[12] The palace of St Laurence Poulteney, the town residence of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, and also of the Dukes of Buckingham, was called the Rose, from that badge being hung up in front of the house:—

[13] Rather a heavy fine, as the best ale at that time was not to be sold for more than three-halfpence a gallon.

[14] “Purchaser, be aware when you wish to buy books issued from my printing-office. Look at my sign, which is represented on the title-page, and you can never be mistaken. For some evil-disposed printers have affixed my name to their uncorrected and faulty works, in order to secure a better sale for them.”

[15] “We beg the reader to notice the sign, for there are men who have adopted the same title, and the name of Badius, and so filch our labour.”

[16] “Lastly, I must draw the attention of the student to the fact that some Florentine printers, seeing that they could not equal our diligence in correcting and printing, have resorted to their usual artifices. To Aldus’s Institutiones Grammaticæ, printed in their offices, they have affixed our well-known sign of the Dolphin wound round the Anchor. But they have so managed, that any person who is in the least acquainted with the books of our production, cannot fail to observe that this is an impudent fraud. For the head of the Dolphin is turned to the left, whereas that of ours is well known to be turned to the right.”—Preface to Aldus’s Livy, 1518.

[17] The number of taverns in these ten shires was “686, or thereabouts.”

“There has been great sale and utterance of Wine, Besides Beer, Ale, and Hippocrass fine, In every Country, Region, and Nation, Chiefly at Billingsgate, at the Salutation;[10] And Boreshead near London Stone, The Swan at Dowgate, a tavern well knowne; The Mitre in Cheap, and the Bullhead, And many like places that make noses red; The Boreshead in Old Fish Street, Three Cranes in the Vintree, And now, of late, Saint Martin’s in the Sentree; The Windmill in Lothbury, the Ship at the Exchange, King’s Head in New Fish Street, where Roysters do range; The Mermaid in Cornhill, Red Lion in the Strand, Three Tuns in Newgate Market, in Old Fish Street the Swan.”

Drunken Barnaby, (1634,) in his travels, called at several of the London taverns, which he has recorded in his vinous flights:—

“Country left I in a fury, To the Axe in Aldermanbury First arrived, that place slighted, I at the Rose in Holborn lighted. From the Rose in Flaggons sail I To the Griffin i’ th’ Old Bailey, Where no sooner do I waken, Than to Three Cranes I am taken, Where I lodge and am no starter. ...... Yea, my merry mates and I, too, Oft the Cardinal’s Hat do fly to. There at Hart’s Horns we carouse,” &c.

Already, in very early times, publicans were compelled by law to have a sign; for we find that in the 16 Richard II., (1393,) Florence North, a brewer of Chelsea, was “presented” “for not putting up the usual sign.”[18] In Cambridge the regulations were equally severe; by an Act of Parliament, 9 Henry VI., it was enacted: “Quicunq; de villa Cantebrigg ‘braciaverit ad vendend’ exponat signum suum, alioquin omittat cervisiam.”—Rolls of Parliament, vol. v. fol. 426 a.[19] But with the other trades it was always optional. Hence Charles I., on his accession to the throne, gave the inhabitants of London a charter by which, amongst other favours, he granted them the right to hang out signboards:—

“And further, we do give and grant to the said Mayor, and Commonalty, and Citizens of the said city, and their successors, that it may and shall be lawful to the Citizens of the same city and any of them, for the time being, to expose and hang in and over the streets, and ways, and alleys of the said city and suburbs of the same, signs, and posts of signs, affixed to their houses and shops, for the better finding out such citizens’ dwellings, shops, arts, or occupations, without impediment, molestation, or interruption of his heirs or successors.”

In France, the innkeepers were under the same regulations as in England; for there also, by the edict of Moulins, in 1567, all innkeepers were ordered to acquaint the magistrates with their name and address, and their “affectes et enseignes;” and Henri III., by an edict of March 1577, ordered that all innkeepers should place a sign on the most conspicuous part of their houses, “aux lieux les plus apparents;” so that everybody, even those that could not read, should be aware of their profession. Louis XIV., by an ordnance of 1693, again ordered signs to be put up, and also the price of the articles they were entitled to sell:—

“Art. XXIII.—Taverniers metront enseignes et bouchons. . . . Nul ne pourra tenir taverne en cette dite ville et faubourgs, sans mettre enseigne et bouchon.”[20]

Hence, the taking away of a publican’s licence was accompanied by the taking away of his sign:—

“For this gross fault I here do damn thy licence, Forbidding thee ever to tap or draw; For instantly I will in mine own person, Command the constables to pull down thy sign.”

Massinger, A New Way to Pay Old Debts, iv. 2.

At the time of the great Civil War, house-signs played no inconsiderable part in the changes and convulsions of the state, and took a prominent place in the politics of the day. We may cite an earlier example, where a sign was made a matter of high treason—namely, in the case of that unfortunate fellow in Cheapside, who, in the reign of Edward IV., kept the sign of the Crown, and lost his head for saying he would “make his son heir to the Crown.” But more general examples are to be met with in the history of the Commonwealth troubles. At the death of Charles I., John Taylor the water-poet, a Royalist to the backbone, boldly shewed his opinion of that act, by taking as a sign for his alehouse in Phœnix Alley, Long Acre, the Mourning Crown; but he was soon compelled to take it down. Richard Flecknoe, in his “Ænigmatical Characters,” (1665,) tells us how many of the severe Puritans were shocked at anything smelling of Popery:—“As for the signs, they have pretty well begun their reformation already, changing the sign of the Salutation of Our Lady into the Souldier and Citizen, and the Catherine Wheel into the Cat and Wheel; such ridiculous work they make of this reformation, and so jealous they are against all mirth and jollity, as they would pluck down the Cat and Fiddle too, if it durst but play so loud as they might hear it.” No doubt they invented very godly signs, but these have not come down to us.

At that time, also, a fashion prevailed which continued, indeed, as long as the signboard was an important institution—of using house-signs to typify political ideas. Imaginary signs, as a part of secret imprints, conveying most unmistakably the sentiments of the book, were often used in the old days of political plots and violent lampoons. Instance the following:—

“Vox Borealis, or a Northerne Discoverie, by Way of Dialogue, between Jamie and Willie. Amidst the Babylonians—printed by Margery Marprelate, in Thwack Coat Lane, at the sign of the Crab-Tree Cudgell, without any privilege of the Catercaps. 1641.”

“Articles of High Treason made and enacted by the late Halfquarter usurping Convention, and now presented to the publick view for a general satisfaction of all true Englishmen. Imprinted for Erasmus Thorogood, and to be sold at the signe of the Roasted Rump. 1659.”

“A Catalogue of Books of the Newest Fashion, to be sold by auction at the Whigs’ Coffeehouse, at the sign of the Jackanapes in Prating Alley, near the Deanery of Saint Paul’s.”

“The Censure of the Rota upon Mr Milton’s book, entitled ‘The Ready and Easy Way to Establish a Free Commonwealth,’ &c. Printed at London by Paul Giddy, Printer to the Rota, at the sign of the Windmill, in Turn-again Lane. 1660.”

“An Address from the Ladies of the Provinces of Munster and Leinster to their Graces the Duke and Duchess of D——t, Lord G——, and Caiaphas the High Priest, with sixty original toasts, drank by the Ladies at their last Assembly, with Love-letters added. London: Printed for John Pro Patria, at the sign of Vivat Rex. 1754.”

“Chivalry no Trifle, or the Knight and his Lady: a Tale. To which is added the Hue and Cry after Touzer and Spitfire, the Lady’s two lapdogs. Dublin: Printed at the sign of Sir Tady’s Press, etc. 1754.”

“An Address from the Influential Electors of the County and City of Galway, with a Collection of 60 Original Patriot Toasts and 48 Munster Toasts, with Intelligence from the Kingdom of Eutopia. Printed at the sign of the Pirate’s Sword in the Captain’s Scabbard. London, 1754.”

“The C——t’s Apology to the Freeholders of this Kingdom for their conduct, containing some Pieces of Humour, to which is added a Bill of C——t Morality. London: Printed at the sign of Betty Ireland, d——d of a Tyrant in Purple, a Monster in Black, etc.”

In the newspapers of the eighteenth century, we find that signs were constantly used as emblems of, or as sharp hits at, the politics of the day; thus, in the Weekly Journal for August 17, 1718, allusions are made to the sign of the Salutation, in Newgate Street, by the opposition party, to which the Original Weekly Journal, the week after, retaliates by a description and explanation of an indelicate sign said to be in King Street, Westminster. In 1763, the following pasquinade went the round of the newspapers, said to have been sent over from Holland:—

“HÔTELS POUR LES MINISTRES DES COURS ETRANGÈRES AU FUTUR CONGRESS.

De l’Empereur,

À la Bonne Volonté; rue d’Impuissance.

De Russie,

Au Chimère; rue des Caprices.

De France,

Au Coq déplumé; rue de Canada.

D’Autriche,

À la Mauvaise Alliance, rue des Invalides.

D’Angleterre,

À la Fortune, Place des Victoires, rue des Subsides.

De Prusse,

Aux Quatre vents, rue des Renards, près la Place des Guinées.

De Suede,

Au Passage des Courtisans, rue des Visionaires.

De Pologne,

Au Sacrifice d’Abraham, rue des Innocents, près la Place des Devôts.

Des Princes de l’Empire,

Au Roitelêt, près de l’Hôpital des Incurables, rue des Charlatans.

De Wirtemberg,

Au Don Quichotte, rue des Fantômes près de la Montagne en Couche.

D’Hollande,

À la Baleine, sur le Marché aux Fromages, près du Grand Observatoire.”

On the morning of September 28, 1736, all the tavern-signs in London were in deep mourning; and no wonder, their dearly beloved patron and friend Gin was defunct,—killed by the new Act against spirituous liquors! But they soon dropped their mourning, for Gin had only been in a lethargic fit, and woke up much refreshed by his sleep. Fifteen years after, when Hogarth painted his “Gin Lane,” royal gin was to be had cheap enough, if we may believe the signboard in that picture, which informs us that “gentlemen and others” could get “drunk for a penny,” and “dead drunk for twopence,” in which last emergency, “clean straw for nothing” was provided.

Of the signs which were to be seen in London at the period of the Restoration,—to return to the subject we were originally considering,—we find a goodly collection of them in one of the “Roxburghe Ballads,” (vol. i. 212,) entitled:—

“LONDON’S ORDINARIE, OR EVERY MAN IN HIS HUMOUR

THROUGH the Royal Exchange as I walked, Where Gallants in sattin doe shine,[14] At midst of the day, they parted away, To seaverall places to dine.

The Gentrie went to the King’s Head, The Nobles unto the Crowne: The Knights went to the Golden Fleece, And the Ploughmen to the Clowne.

The Cleargie will dine at the Miter, The Vintners at the Three Tunnes, The Usurers to the Devill will goe, And the Fryers to the Nunnes.

The Ladyes will dine at the Feathers, The Globe no Captaine will scorne, The Huntsmen will goe to the Grayhound below, And some Townes-men to the Horne.

The Plummers will dine at the Fountaine, The Cookes at the Holly Lambe, The Drunkerds by noone, to the Man in the Moone, And the Cuckholdes to the Ramme.

The Roarers will dine at the Lyon, The Watermen at the Old Swan; And Bawdes will to the Negro goe, And Whores to the Naked Man.

The Keepers will to the White Hart, The Marchants unto the Shippe, The Beggars they must take their way To the Egge-shell and the Whippe.

The Farryers will to the Horse, The Blackesmith unto the Locke, The Butchers unto the Bull will goe, And the Carmen to Bridewell Clocke.

The Fishmongers unto the Dolphin, The Barbers to the Cheat Loafe,[21] The Turners unto the Ladle will goe, Where they may merrylie quaffe.

The Taylors will dine at the Sheeres, The Shooemakers will to the Boote, The Welshmen they will take their way, And dine at the signe of the Gote.

The Hosiers will dine at the Legge, The Drapers at the signe of the Brush. The Fletchers to Robin Hood will goe, And the Spendthrift to Begger’s Bush.

The Pewterers to the Quarte Pot, The Coopers will dine at the Hoope, The Coblers to the Last will goe, And the Bargemen to the Sloope.[15]

The Carpenters will to the Axe, The Colliers will dine at the Sacke, Your Fruterer he to the Cherry-Tree, Good fellowes no liquor will lacke.

The Goldsmith will to the Three Cups, For money they hold it as drosse; Your Puritan to the Pewter Canne, And your Papists to the Crosse.

The Weavers will dine at the Shuttle, The Glovers will unto the Glove, The Maydens all to the Mayden Head, And true Louers unto the Doue.

The Sadlers will dine at the Saddle, The Painters will to the Greene Dragon, The Dutchmen will go to the Froe,[22] Where each man will drinke his Flagon.

The Chandlers will dine at the Skales, The Salters at the signe of the Bagge; The Porters take pain at the Labour in Vaine, And the Horse-Courser to the White Nagge.

Thus every Man in his humour, That comes from the North or the South, But he that has no money in his purse, May dine at the signe of the Mouth.

The Swaggerers will dine at the Fencers, But those that have lost their wits: With Bedlam Tom let that be their home, And the Drumme the Drummers best fits.

The Cheter will dine at the Checker, The Picke-pockets in a blind alehouse, Tel on and tride then up Holborne they ride, And they there end at the Gallowes.”

Thomas Heywood introduced a similar song in his “Rape of Lucrece.” This, the first of the kind we have met with, is in all probability the original, unless the ballad be a reprint from an older one; but the term Puritan used in it, seems to fix its date to the seventeenth century.

“THE Gintry to the Kings Head, The Nobles to the Crown, The Knights unto the Golden Fleece, And to the Plough the Clowne.

The Churchmen to the Mitre, The Shepheard to the Star, The Gardener hies him to the Rose, To the Drum the Man of War.[16]

The Huntsmen to the White Hart, To the Ship the Merchants goe, But you that doe the Muses love, The sign called River Po.

The Banquerout to the World’s End, The Fool to the Fortune his, Unto the Mouth the Oyster-wife, The Fiddler to the Pie.

The Punk unto the Cockatrice,[23] The Drunkard to the Vine, The Begger to the Bush, there meet, And with Duke Humphrey dine.”[24]

After the great fire of 1666, many of the houses that were rebuilt, instead of the former wooden signboards projecting in the streets, adopted signs carved in stone, and generally painted or gilt, let into the front of the house, beneath the first floor windows. Many of these signs are still to be seen, and will be noticed in their respective places. But in those streets not visited by the fire, things continued on the old footing, each shopkeeper being fired with a noble ambition to project his sign a few inches farther than his neighbour. The consequence was that, what with the narrow streets, the penthouses, and the signboards, the air and light of the heavens were well-nigh intercepted from the luckless wayfarers through the streets of London. We can picture to ourselves the unfortunate plumed, feathered, silken gallant of the period walking, in his low shoes and silk stockings, through the ill-paved dirty streets, on a stormy November day, when the honours were equally divided between fog, sleet, snow, and rain, (and no umbrellas, be it remembered,) with flower-pots blown from the penthouses, spouts sending down shower-baths from almost every house, and the streaming signs swinging overhead on their rusty, creaking hinges. Certainly the evil was great, and demanded that redress which Charles II. gave in the seventh year of his reign, when a new Act “ordered that in all the streets no signboard shall hang across, but that the sign shall be fixed against the balconies, or some convenient part of the side of the house.”

The Parisians, also, were suffering from the same enormities; everything was of Brobdignagian proportions. “J’ai vu,” says an essayist of the middle of the seventeenth century, “suspendu aux boutiques des volants de six pieds de hauteur, des perles grosses comme des tonneaux, des plumes qui allaient au troisième étage.”[25] There, also, the scalpel of the law was at last applied to the evil; for, in 1669, a royal order was issued to prohibit these monstrous signs, and the practice of advancing them too far into the streets, “which made the thoroughfares close in the daytime, and prevented the lights of the lamps from spreading properly at night.”

PLATE II.

BUSH.

(MS. of the 14th century.)

BUSH.

(Bayeux tapestry, 11th cent.)

CROSS.

(Luttrell Psalter, 11th century.)

ALE-POLE.

(Picture of Wouwverman, 17th cent.)

BLACK JACK AND PEWTER PLATTER.

(Print by Schavelin, 1480.)

NAG’S HEAD.

(Cheapside. 1640.)

BUSH.

(MS. of the 15th cent.)

Still, with all their faults, the signs had some advantages for the wayfarer; even their dissonant creaking, according to the old weather proverb, was not without its use:—

“But when the swinging signs your ears offend With creaking noise, then rainy floods impend.”

Gay’s Trivia, canto i.

This indeed, from the various allusions made to it in the literature of the last century, was regarded as a very general hint to the lounger, either to hurry home, or hail a sedan-chair or coach. Gay, in his didactic—flâneur—poem, points out another benefit to be derived from the signboards:—

“If drawn by Bus’ness to a street unknown, Let the sworn Porter point thee through the town; Be sure observe the Signs, for Signs remain Like faithful Landmarks to the walking Train.”

Besides, they offered constant matter of thought, speculation, and amusement to the curious observer. Even Dean Swift, and the Lord High Treasurer Harley,

“Would try to read the lines Writ underneath the country signs.”

And certainly these productions of the country muse are often highly amusing. Unfortunately for the compilers of the present work, they have never been collected and preserved; although they would form a not unimportant and characteristic contribution to our popular literature. Our Dutch neighbours have paid more attention to this subject, and a great number of their signboard inscriptions were, towards the close of the seventeenth century, gathered in a curious little 12mo volume,[26] to which we shall often refer. Nay, so much attention was devoted to this branch of literature in that country, that a certain H. van den Berg, in 1693, wrote a little volume,[27] which he entitled a “Banquet,” giving verses adapted for all manner of shops and signboards; so that a shopkeeper at a loss for an inscription had only to open the book and make his selection; for there were rhymes in it both serious and jocular, suitable to everybody’s taste. The majority of the Dutch signboard inscriptions of that day seem to have been eminently characteristic of the spirit of the nation. No such inscriptions could be brought before “a discerning public,” without the patronage of some holy man mentioned in the Scriptures, whose name was to stand there for no other purpose than to give the Dutch poet an opportunity of making a jingling rhyme; thus, for instance,—

“Jacob was David’s neef maar ’t waren geen Zwagers. Hier slypt men allerhande Barbiers gereedschappen, ook voor vischwyven en slagers.”[28]

Or another example:—

“Men vischte Moses uit de Biezen, Hier trekt men tanden en Kiezen.”[29]

In the beginning of the eighteenth century, we find the following signs named, which puzzled a person of an inquisitive turn of mind, who wrote to the British Apollo,[30] (the meagre Notes and Queries of those days,) in the hope of eliciting an explanation of their quaint combination:—

“I’m amazed at the Signs As I pass through the Town, To see the odd mixture: A Magpie and Crown, The Whale and the Crow, The Razor and Hen, The Leg and Seven Stars, The Axe and the Bottle, The Tun and the Lute, The Eagle and Child, The Shovel and Boot.”

All these signs are also named by Tom Brown:[31]—“The first amusements we encountered were the variety and contradictory language of the signs, enough to persuade a man there were no rules of concord among the citizens. Here we saw Joseph’s Dream, the Bull and Mouth, the Whale and Crow, the Shovel and Boot, the Leg and Star, the Bible and Swan, the Frying-pan and Drum, the Lute and Tun, the Hog in Armour, and a thousand others that the wise men that put them there can give no reason for.”

From this enumeration, we see that a century had worked great changes in the signs. Those of the beginning of the seventeenth century were all simple, and had no combinations. But now we meet very heterogeneous objects joined together. Various reasons can be found to account for this. First, it must be borne in mind that most of the London signs had no inscription to tell the public “this is a lion,” or, “this is a bear;” hence the vulgar could easily make mistakes, and call an object by a wrong name, which might give rise to an absurd combination, as in the case of the Leg and Star; which, perhaps, was nothing else but the two insignia of the order of the Garter; the garter being represented in its natural place, on the leg, and the star of the order beside it. Secondly, the name might be corrupted through faulty pronunciation; and when the sign was to be repainted, or imitated in another street, those objects would be represented by which it was best known. Thus the Shovel and Boot might have been a corruption of the Shovel and Boat, since the Shovel and Ship is still a very common sign in places where grain is carried by canal boats; whilst the Bull and Mouth is said to be a corruption of the Boulogne Mouth—the Mouth of Boulogne Harbour. Finally, whimsical shopkeepers would frequently aim at the most odd combination they could imagine, for no other reason but to attract attention. Taking these premises into consideration, some of the signs which so puzzled Tom Brown might be easily accounted for; the Axe and Bottle, in this way, might have been a corruption of the Battle-axe. The Bible and Swan, a sign in honour of Luther, who is generally represented by the symbol of a swan, a figure of which many Lutheran Churches have on their steeple instead of a weathercock; whilst the Lute and Tun was clearly a pun on the name of Luton, similar to the Bolt and Tun of Prior Bolton, who adopted this device as his rebus.

Other causes of combinations, and many very amusing and instructive remarks about signs, are given in the following from the Spectator, No. 28, April 2, 1710:—

“There is nothing like sound literature and good sense to be met with in those objects, that are everywhere thrusting themselves out to the eye and endeavouring to become visible. Our streets are filled with blue boars, black swans, and red lions, not to mention flying-pigs and hogs in armour, with many creatures more extraordinary than any in the deserts of Africa. Strange that one, who has all the birds and beasts in nature to choose out of, should live at the sign of an ens rationis.

“My first task, therefore, should be like that of Hercules, to clear the city from monsters. In the second place, I should forbid that creatures of jarring and incongruous natures should be joined together in the same sign; such as the Bell and the Neat’s Tongue, the Dog and the Gridiron. The Fox and the Goose may be supposed to have met, but what has the Fox and the Seven Stars to do together? And when did the Lamb and Dolphin ever meet except upon a signpost? As for the Cat and Fiddle, there is a conceit in it, and therefore I do not intend that anything I have here said should affect it. I must, however, observe to you upon this subject, that it is usual for a young tradesman, at his first setting up, to add to his own sign that of the master whom he served, as the husband, after marriage, gives a place to his mistress’s arms in his own coat. This I take to have given rise to many of those absurdities which are committed over our heads; and, as I am informed, first occasioned the Three Nuns and a Hare, which we see so frequently joined together. I would therefore establish certain rules for the determining how far one tradesman may give the sign of another, and in what case he may be allowed to quarter it with his own.

“In the third place, I would enjoin every shop to make use of a sign which bears some affinity to the wares in which it deals. What can be more inconsistent than to see a bawd at the sign of the Angel, or a tailor at the Lion? A cook should not live at the Boot, nor a shoemaker at the Roasted Pig; and yet, for want of this regulation, I have seen a Goat set up before the door of a perfumer, and the French King’s Head at a sword-cutler’s.

“An ingenious foreigner observes that several of those gentlemen who value themselves upon their families, and overlook such as are bred to trades, bear the tools of their forefathers in their coats of arms. I will not examine how true this is in fact; but though it may not be necessary for posterity thus to set up the sign of their forefathers, I think it highly proper that those who actually profess the trade should shew some such mark of it before their doors.

“When the name gives an occasion for an ingenious signpost, I would likewise advise the owner to take that opportunity of letting the world know who he is. It would have been ridiculous for the ingenious Mrs Salmon to have lived at the sign of the trout, for which reason she has erected before her house the figure of the fish that is her namesake. Mr Bell has likewise distinguished himself by a device of the same nature. And here, sir, I must beg leave to observe to you, that this particular figure of a Bell has given occasion to several pieces of wit in this head. A man of your reading must know that Abel Drugger gained great applause by it in the time of Ben Jonson. Our Apocryphal heathen god is also represented by this figure, which, in conjunction with the Dragon,[32] makes a very handsome picture in several of our streets. As for the Bell Savage, which is the sign of a savage man standing by a bell, I was formerly very much puzzled upon the conceit of it, till I accidentally fell into the reading of an old romance translated out of the French, which gives an account of a very beautiful woman, who was found in a wilderness, and is called la Belle Sauvage, and is everywhere translated by our countrymen the Bell Savage.[33] This piece of philology will, I hope, convince you that I have made signposts my study, and consequently qualified myself for the employment which I solicit at your hands. But before I conclude my letter, I must communicate to you another remark which I have made upon the subject with which I am now entertaining you—namely, that I can give a shrewd guess at the humour of the inhabitant by the sign that hangs before his door. A surly, choleric fellow generally makes choice of a Bear, as men of milder dispositions frequently live at the Lamb. Seeing a Punchbowl painted upon a sign near Charing Cross, and very curiously garnished, with a couple of angels hovering over it and squeezing a lemon into it, I had the curiosity to ask after the master of the house, and found upon inquiry, as I had guessed by the little agrémens upon his sign, that he was a Frenchman.”

Another reason for “quartering” signs was on removing from one shop to another, when it was customary to add the sign of the old shop to that of the new one.

“WHEREAS Anthony Wilton, who lived at the Green Cross publick-house against the new Turnpike on New Cross Hill, has been removed for two years past to the new boarded house now the sign of the[22] Green Cross and Kross Keyes on the same hill,” &c.—Weekly Journal, November 22, 1718.

“THOMAS BLACKALL and Francis Ives, Mercers, are removed from the Seven Stars on Ludgate Hill to the Black Lion and Seven Stars over the way.”—Daily Courant, November 17, 1718.

“PETER DUNCOMBE and Saunders Dancer, who lived at the Naked Boy in Great Russell Street, Covent Garden, removed to the Naked Boy and Mitre, near Sommerset House, Strand,” &c.—Postboy, January 2-4, 1711.

“RICHARD MEARES, Musical Instrument maker, is removed from y’ Golden Viol in Leaden Hall Street to y’ North side of St Paul’s Churchyard, at y’ Golden Viol and Hautboy, where he sells all sorts of musical instruments,” &c.—[Bagford bills.]

To increase this complexity still more, came the corruption of names arising from pronunciation; thus Mr Burn, in his introduction to the “Beaufoy Tokens,” mentions the sign of Pique and Carreau, on a gambling-house at Newport, Isle of Wight, which was Englished into the Pig and Carrot; again, the same sign at Godmanchester was still more obliterated into the Pig and Checkers. The sign of the Island Queen I have frequently heard, either in jest or in ignorance, called the Iceland Queen. The editor of the recently-published “Slang Dictionary” remarks that he has seen the name of the once popular premier, George Canning, metamorphosed on an alehouse-sign into the George and Cannon; so the Golden Farmer became the Jolly Farmer; whilst the Four Alls, in Whitechapel, were altered into the Four Awls. Along with this practice, there is a tendency to translate a sign into a sort of jocular slang phrase; thus, in the seventeenth century, the Blackmoorshead and Woolpack, in Pimlico, was called the Devil and Bag of Nails by those that frequented that tavern, and by the last part of that name the house is still called at the present day. Thus the Elephant and Castle is vulgarly rendered as the Pig and Tinderbox; the Bear and Ragged Staff, the Angel and Flute; the Eagle and Child, the Bird and Bantling; the Hog in Armour, the Pig in Misery; the Pig in the Pound, the Gentleman in Trouble, &c.

Some further information, in illustration of the different signboards, is to be obtained from the Adventurer, No. 9, (1752:)—

“It cannot be doubted but that signs were intended originally to express the several occupations of their owners, and to bear some affinity in their external designations with the wares to be disposed of, or the business carried on within. Hence the Hand and Shears is justly appropriated to tailors, and the Hand and Pen to writing-masters; though the very reverend and right worthy order of my neighbours, the Fleet-parsons, have assumed it to themselves as a mark of ‘marriages performed without imposition.’ The Woolpack plainly points out to us a woollen draper; the Naked Boy elegantly reminds us of the necessity of clothing; and the Golden Fleece figuratively denotes the riches of our staple commodity; but are not the Hen and Chickens and the Three Pigeons the unquestionable right of the poulterer, and not to be usurped by the vender of silk or linen?

“It would be useless to enumerate the gross blunders committed in this point by almost every branch of trade. I shall therefore confine myself chiefly to the numerous fraternity of publicans, whose extravagance in this affair calls aloud for reprehension and restraint. Their modest ancestors were contented with a plain Bough stuck up before their doors, whence arose the wise proverb, ‘Good Wine needs no Bush;’ but how have they since deviated from their ancient simplicity! They have ransacked earth, air, and seas, called down sun, moon, and stars to their assistance, and exhibited all the monsters that ever teemed from fantastic imagination. Their Hogs in Armour, their Blue Boars, Black Bears, Green Dragons, and Golden Lions, have already been sufficiently exposed by your brother essay-writers:—

‘Sus horridus, atraque Tigris, Squamosusque Draco, et fulva cervice Leæna.

Virgil.

‘With foamy tusks to seem a bristly boar, Or imitate the lion’s angry roar; Or kiss a dragon, or a tiger stare.’—Dryden.

“It is no wonder that these gentlemen who indulged themselves in such unwarrantable liberties, should have so little regard to the choice of signs adapted to their mystery. There can be no objection made to the Bunch of Grapes, the Rummer, or the Tuns; but would not any one inquire for a hosier at the Leg, or for a locksmith at the Cross Keys? and who would expect anything but water to be sold at the Fountain? The Turkshead may fairly intimate that a seraglio is kept within; the Rose may be strained to some propriety of meaning, as the business transacted there may be said to be done ‘under the rose;’ but why must the Angel, the Lamb, and the Mitre be the designations of the seats of drunkenness or prostitution?

“Some regard should likewise be paid by tradesmen to their situation; or, in other words, to the propriety of the place; and in this, too, the publicans are notoriously faulty. The King’s Arms, and the Star and Garter, are aptly enough placed at the court end of the town, and in the neighbourhood of the royal palace; Shakespeare’s Head takes his station by one playhouse, and Ben Jonson’s by the other; Hell is a public-house adjoining to Westminster Hall, as the Devil Tavern is to the lawyers’ quarter in the Temple: but what has the Crown to do by the ’Change, or the Gun, the Ship, or the Anchor anywhere but at Tower Hill, at Wapping, or Deptford?

“It was certainly from a noble spirit of doing honour to a superior desert, that our forefathers used to hang out the heads of those who were particularly eminent in their professions. Hence we see Galen and Paracelsus exalted before the shops of chemists; and the great names of Tully, Dryden, and Pope, &c., immortalised on the rubric posts[34] of booksellers, while their heads denominate the learned repositors of their works. But I know not whence it happens that publicans have claimed a right to the physiognomies of kings and heroes, as I cannot find out, by the most painful researches, that there is any alliance between them. Lebec, as he was an excellent cook, is the fit representative of luxury; and Broughton, that renowned athletic champion, has an indisputable right to put up his own head if he pleases; but what reason can there be why the glorious Duke William should draw porter, or the brave Admiral Vernon retail flip? Why must Queen Anne keep a ginshop, and King Charles inform us of a skittle-ground? Propriety of character, I think, require that these illustrious personages should be deposed from their lofty stations, and I would recommend hereafter that the alderman’s effigy should accompany his Intire Butt Beer, and that the comely face of that public-spirited patriot who first reduced the price of punch and raised its reputation Pro Bono Publico, should be set up wherever three penn’orth of warm rum is to be sold.

“I have been used to consider several signs, for the frequency of which it is difficult to give any other reason, as so many hieroglyphics with a hidden meaning, satirising the follies of the people, or conveying instruction to the passer-by. I am afraid that the stale jest on our citizens gave rise to so many Horns in public streets; and the number of Castles floating with the wind was probably designed as a ridicule on those erected by soaring projectors. Tumbledown Dick, in the borough of Southwark, is a fine moral on the instability of greatness, and the consequences of ambition; but there is a most ill-natured sarcasm against the fair sex exhibited on a sign in Broad Street, St Giles’s, of a headless female figure called the Good Woman.

[18] “The original court roll of this presentation is still to be found amongst the records of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster.”—Lyson’s Env. of London, vol. iii. p. 74.

[19] “Whosoever shall brew ale in the town of Cambridge, with intention of selling it, must hang out a sign, otherwise he shall forfeit his ale.”

[20] “Art. XXIII.—Tavernkeepers must put up signboards and a bush. . . . Nobody shall be allowed to open a tavern in the said city and its suburbs without having a sign and a bush.”

[21] A Cheat loaf was a household loaf, “wheaten seconds bread.”—Nares’s Glossary.

[22] Froe—i.e. Vrouw, woman.

[23] This was in those days a slang term for a mistress.

[24] i.e. Walk about in St Paul’s during the dinner hour.

[25] “I have seen, hanging from the shops, shuttlecocks six feet high, pearls as large as a hogshead, and feathers reaching up to the third story.”

[26] “Koddige en ernstige opschriften op Luiffels, wagens, glazen, uithangborden en andere tafereelen door Jeroen Jeroense. Amsterdam, 1682.”

[27] “Het gestoffeerde Winkelen en Luifelen Banquet. H. van den Berg. Amsterdam, 1693.”

[1] Sir Gardiner Wilkinson’s Ancient Egyptians, vol. iii. p. 158. Also, Rosellini Monumenti dell’Egitto e della Nubia.

[2] Aristotle, Problematum x. 14: “As with the things drawn above the shops, which, though they are small, appear to have breadth and depth.”

[3] “He hung the well-known sign in the front of his house.”

[4] Hearne, Antiq. Disc., i. 39.

[5] “When the mice were conquered by the army of the weasels, (a story which we see painted on the taverns.)”

[6] Lib. ii. sat. vii.: “I admire the position of the men that are fighting, painted in red or in black, as if they were really alive; striking and avoiding each other’s weapons, as if they were actually moving.”

[7] De Oratore, lib. ii. ch. 71: “Now I shall shew you how you are, to which he answered, ‘Do, please.’ Then I pointed with my finger towards the Cock painted on the signboard of Marius the Cimberian, on the New Forum, distorted, with his tongue out and hanging cheeks. Everybody began to laugh.”

[8] Hist. Nat., xxxv. ch. 8: “After this I find that they were also commonly placed on the Forum. Hence that joke of Crassus, the orator. . . . On the Forum was also that of an old shepherd with a staff, concerning which a German legate, being asked at how much he valued it, answered that he would not care to have such a man given to him as a present, even if he were real and alive.”

[9] “There were, namely, taverns round about the Forum, and that picture [the Cock] had been put up as a sign.”

[10] The Bush certainly must be counted amongst the most ancient and popular of signs. Traces of its use are not only found among Roman and other old-world remains, but during the Middle Ages we have evidence of its display. Indications of it are to be seen in the Bayeux tapestry, in that part where a house is set on fire, with the inscription, Hic domus incenditur, next to which appears a large building, from which projects something very like a pole and a bush, both at the front and the back of the building.

[11] In Cædmon’s Metrical Paraphrase of Scripture History, (circa A.D. 1000,) in the drawings relating to the history of Abraham, there are distinctly represented certain cruciform ornaments painted on the walls, which might serve the purpose of signs. (See upon this subject under “Religious Signs.”)

[12] The palace of St Laurence Poulteney, the town residence of Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, and also of the Dukes of Buckingham, was called the Rose, from that badge being hung up in front of the house:—

“The Duke being at the Rose, within the parish Of St Laurence Poultney.”—Henry VIII., a. i. s. 2.

“A house in the town of Lewes was formerly known as The Three Pelicans, the fact of those birds constituting the arms of Pelham having been lost sight of. Another is still called The Cats,” which is nothing more than “the arms of the Dorset family, whose supporters are two leopards argent, spotted sable.”—Lower, Curiosities of Heraldry.

[13] Rather a heavy fine, as the best ale at that time was not to be sold for more than three-halfpence a gallon.

[14] “Purchaser, be aware when you wish to buy books issued from my printing-office. Look at my sign, which is represented on the title-page, and you can never be mistaken. For some evil-disposed printers have affixed my name to their uncorrected and faulty works, in order to secure a better sale for them.”

[15] “We beg the reader to notice the sign, for there are men who have adopted the same title, and the name of Badius, and so filch our labour.”

[16] “Lastly, I must draw the attention of the student to the fact that some Florentine printers, seeing that they could not equal our diligence in correcting and printing, have resorted to their usual artifices. To Aldus’s Institutiones Grammaticæ, printed in their offices, they have affixed our well-known sign of the Dolphin wound round the Anchor. But they have so managed, that any person who is in the least acquainted with the books of our production, cannot fail to observe that this is an impudent fraud. For the head of the Dolphin is turned to the left, whereas that of ours is well known to be turned to the right.”—Preface to Aldus’s Livy, 1518.

[17] The number of taverns in these ten shires was “686, or thereabouts.”