автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Rosetta Stone

THE

ROSETTA STONE

PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

London:

SOLD AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM.

1913.

Price Sixpence.

[ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.]

London:

HARRISON AND SONS,

PRINTERS IN ORDINARY TO HIS MAJESTY.

THE ROSETTA STONE.

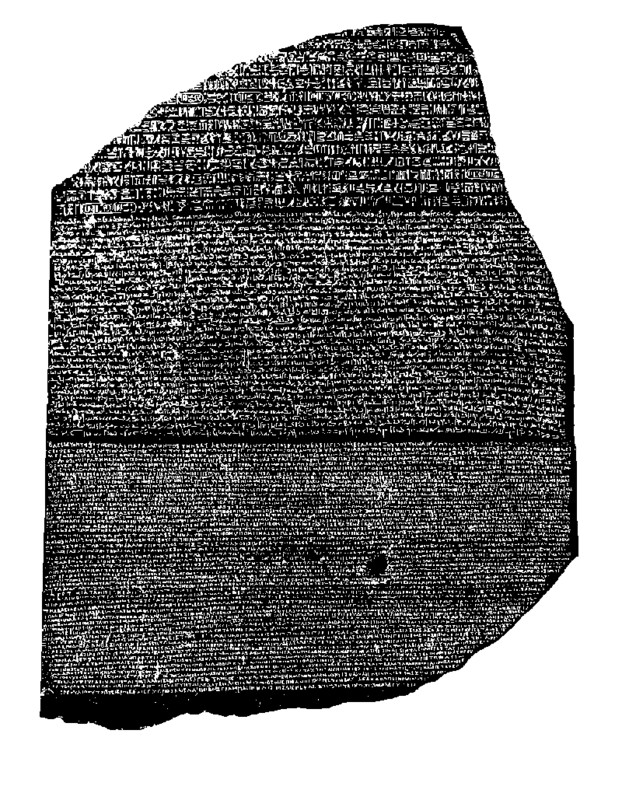

THE DISCOVERY OF THE STONE.

The famous slab of black basalt which stands at the southern end of the Egyptian Gallery in the British Museum, and which has for more than a century been universally known as the “Rosetta Stone,” was found at a spot near the mouth of the great arm of the Nile that flows through the Western Delta to the sea, not far from the town of “Rashîd,” or as Europeans call it, “Rosetta.” According to one account it was found lying on the ground, and according to another it was built into a very old wall, which a company of French soldiers had been ordered to remove in order to make way for the foundations of an addition to the fort, afterwards known as “Fort St. Julien.”[1] The actual finder of the Stone was a French Officer of Engineers, whose name is sometimes spelt Boussard, and sometimes Bouchard, who subsequently rose to the rank of General, and was alive in 1814. He made his great discovery in August, 1799. Finding that there were on one side of the Stone lines of strange characters, which it was thought might be writing, as well as long lines of Greek letters, Boussard reported his discovery to General Menou, who ordered him to bring the Stone to his house in Alexandria. This was immediately done, and the Stone was, for about two years, regarded as the General’s private property. When Napoleon heard of the Stone, he ordered it to be taken to Cairo and placed in the “Institut National,” which he had recently founded in that city. On its arrival in Cairo it became at once an object of the deepest interest to the body of learned men whom Napoleon had taken with him on his expedition to Egypt, and the Emperor himself exhibited the greatest curiosity in respect of the contents of the inscriptions cut upon it. He at once ordered a number of copies of the Stone to be made for distribution among the scholars of Europe, and two skilled lithographers, “citizens Marcel and Galland,” were specially brought to Cairo from Paris to make them. The plan which they followed was to cover the surface of the Stone with printer’s ink, and then to lay upon it a sheet of paper which they rolled with india-rubber rollers until a good impression had been taken. Several of these ink impressions were sent to scholars of great repute in many parts of Europe, and in the autumn of 1801 General Dagua took two to Paris, where he committed them to the care of “citizen Du Theil” of the Institut National of Paris.

1. This fort is marked on Napoleon’s Map of Egypt, and it stood on the left or west bank of the Rosetta arm of the Nile.

THE ARRIVAL OF THE STONE IN ENGLAND.

After the successful operations of Sir Ralph Abercromby in Egypt in the spring of 1801, a Treaty of Capitulation was drawn up, and by Article XVI the Rosetta Stone and several other large and important Egyptian antiquities were surrendered to General Hutchinson at the end of August in that year. Some of these he despatched at once to England in H.M.S. “Admiral,” and others in H.M.S. “Madras,” but the Rosetta Stone did not leave Egypt until later in the year. After the ink impressions had been taken from it, the Stone was transferred from Cairo to General Menou’s house in Alexandria, where it was kept covered with cloth and under a double matting. In September, 1801, Major-General Turner claimed the Stone by virtue of the Treaty mentioned above, but as it was generally regarded as the French General’s private property, the surrender of it was accompanied by some difficulty. In the following month Major-General Turner obtained possession of the Stone, and embarked with it on H.M.S. “L’Égyptienne,” and arrived at Portsmouth in February, 1802. On March 11 it was deposited at the rooms of the Society of Antiquaries of London, where it remained for a few months, and the writings upon it were submitted to a very careful examination by many Oriental and Greek scholars. In July the President of the Society caused four plaster casts of the Stone to be made for the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh and Dublin, and had good copies of the Greek text engraved, and despatched to all the great Universities, Libraries, Academies and Societies in Europe. Towards the close of the year the Stone was removed from the Rooms of the Society of Antiquaries to the British Museum, where it was mounted and at once exhibited to the general public.

DESCRIPTION OF THE STONE.

The Rosetta Stone in its present state is an irregularly-shaped slab of compact black basalt, which measures about 3 feet 9 inches in length, 2 feet 4-1/2 inches in width, and 11 inches in thickness. The top right and left hand corners, and the right hand bottom corner, are wanting. It is not possible to say how much of the Stone is missing, but judging by the proportion which exists between the lengths of the inscriptions that are now upon it, we may assume that when it was complete it was at least 12 inches longer than it is now. The upper end of the Stone was probably rounded, and, if we may judge from the reliefs found on stelæ of this class of the Ptolemaïc Period, the front of the rounded part was sculptured with a figure of the Winged Disk of Horus of Edfû, having pendent uraei, one wearing the Crown of the South, and the other the Crown of the North. (See the Cast of the Decree of Canopus in Bay 28, No. 957.) Below the Winged Disk there may have been a relief, in which the king was seen standing, with his queen, in the presence of a series of gods, similar to that found on one of the copies mentioned below of the inscriptions on the Rosetta Stone. Whatever the sculptured decoration may have been, it is tolerably certain that, when the Stone was in a complete state, it must have been between five and six feet in height, and that when mounted upon a suitable plinth, and set up near the statue of the king in whose honour it was engraved, it formed a prominent monument in the temple in which it was set up.

The INSCRIPTION on the Rosetta Stone is written in two languages, that is to say, in EGYPTIAN and in GREEK. The EGYPTIAN portion of it is cut upon it in: I. the HIEROGLYPHIC CHARACTER, that is to say, in the old picture writing which was employed from the earliest dynasties in making copies of the Book of the Dead, and in nearly all state and ceremonial documents that were intended to be seen by the public; and II. the DEMOTIC CHARACTER, that is to say, the conventional, abbreviated and modified form of the HIERATIC character, or cursive form of hieroglyphic writing, which was in use in the Ptolemaïc Period. The GREEK portion of the inscription is cut in ordinary uncials. The hieroglyphic text consists of 14 lines only, and these correspond to the last 28 lines of the Greek text. The Demotic text consists of 32 lines, the first 14 being imperfect at the beginnings, and the Greek text consists of 54 lines, the last 26 being imperfect at the ends. A large portion of the missing lines of the hieroglyphic text can be restored from a stele discovered in 1898 at Damanhûr in the Delta (Hermopolis Parva), and now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (No. 5576), and from the copy of a text of the Decree cut on the walls of a temple at Philæ, and the correctness of the restorations of broken passages in the Demotic and Greek texts being evident, we are justified in assuming that we have the inscription of the Rosetta Stone complete both in Egyptian and Greek.

THE EARLIEST DECIPHERERS OF THE ROSETTA STONE.

The first translation of the Greek text was made by the Rev. Stephen Weston, and was read by him before the Society of Antiquaries of London in April, 1802. This was quickly followed by a French translation made by “citizen Du Theil,” who declared that the Stone was “a monument of the gratitude of some priests of Alexandria, or some neighbouring place, towards Ptolemy Epiphanes”; and a Latin translation by “citizen Ameilhon” appeared in Paris in the spring of 1803. The first studies of the Demotic text were those of Silvestre de Sacy and Åkerblad in 1802, and the latter succeeded in making out the general meaning of portions of the opening lines, and in identifying the equivalents of the names of Alexander, Alexandria, Ptolemy, Isis, etc. Both de Sacy and Åkerblad began their labours by attacking the Demotic equivalents of the cartouches, i.e. the ovals containing royal names in the hieroglyphic text. In 1818 Dr. Thomas Young compiled for the fourth volume of the “Encyclopædia Britannica” (published in 1819) the results of his studies of the texts on the Rosetta Stone, and among them was a list of several alphabetic Egyptian characters to which, in most cases, he had assigned correct values. He was the first to grasp the idea of a phonetic principle in the reading of the Egyptian hieroglyphs, and he was the first to apply it to their decipherment. Warburton, de Guignes, Barthélemy and Zoëga all suspected the existence of alphabetic hieroglyphics, and the three last-named scholars believed that the oval, or cartouche

METHOD OF DECIPHERMENT.

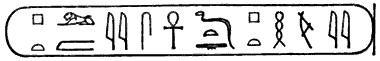

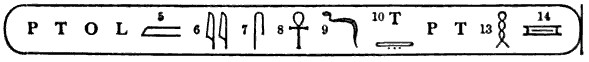

The method by which the greater part of the Egyptian alphabet was recovered is this: It was assumed correctly that the oval

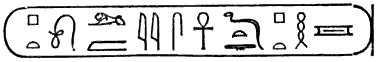

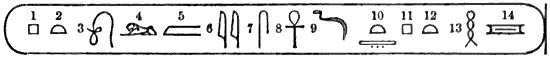

On the Rosetta Stone

On the Obelisk from Philæ

The second of these cartouches contains the sign

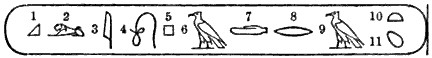

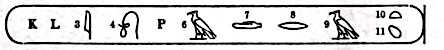

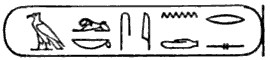

Taking the cartouches which were supposed to contain the names of Ptolemy and Cleopatra from the Philæ Obelisk, and numbering the signs we have:

Ptolemy, A.

Cleopatra, B.

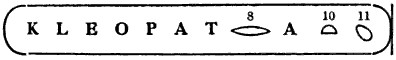

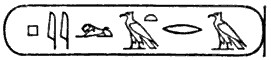

Now we see at a glance that No. 1 in A and No. 5 in B are identical, and judging by their position only in the names they must represent the letter P. No. 4 in A and No. 2 in B are identical, and arguing as before from their position they must represent the letter L. As L is the second letter in the name of Cleopatra, the sign No. 1

In the Greek form of the name of Cleopatra there are two vowels between the L and the P, and in the hieroglyphic form there are two hieroglyphs,

Thomas Young noticed that the two signs

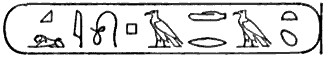

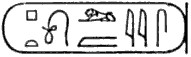

We now see that the cartouche must be that of Ptolemy, but it is also clear that there must be contained in it many other hieroglyphs which do not form part of his name. Champollion found other forms of the cartouche of Ptolemy, and the simplest of them was written thus:

1.

2.

Now, in No. 1, we can at once write down the values of all the signs, viz., P . I . L . A . T . R . A, which is obviously the Greek name Philotera. In No. 2 we only know some of the hieroglyphs, and we write the cartouche thus:

which is clearly meant to represent the name “Alexandros,” or Alexander. The position of the sign

Returning to the signs

THE CONTENTS OF THE INSCRIPTION ON THE ROSETTA STONE.

The inscription on the Rosetta Stone is a copy of the Decree passed by the General Council of Egyptian priests assembled at Memphis to celebrate the first commemoration of the coronation of Ptolemy V, Epiphanes, king of all Egypt. The young king had been crowned in the eighth year of his reign, therefore the first commemoration took place in the ninth year, in the spring of the year B.C. 196. The original form of the Decree is given by the Demotic section, and the Hieroglyphic and Greek versions were made from it.

The inscription is dated on the fourth day of the Greek month Xandikos (April), corresponding to the eighteenth day of the Egyptian month Meshir, or Mekhir, of the ninth year of the reign of Ptolemy V, Epiphanes, the year in which Aetus, the son of Aetus, was chief priest and Pyrrha, the daughter of Philinus, and Areia, the daughter of Diogenes, and Irene, the daughter of Ptolemy, were chief priestesses. The opening lines are filled with a list of the titles of Ptolemy V, and a series of epithets which proclaim the king’s piety towards the gods, and his love for the Egyptians and his country. In the second section of the inscription the priests enumerate the benefits which he had conferred upon Egypt, and which may be thus summarized:

1.

Gifts of money and corn to the temples.

2.

Gifts of endowments to temples.

3.

Remission of one half of taxes due to the Government.

4.

Abolition of one half of the taxes.

5.

Forgiveness of debts owed by the people to the Government.

6.

Release of the prisoners who had been languishing in gaol for years.

7.

Abolition of the press-gang for sailors.

8.

Reduction of fees payable by candidates for the priesthood.

9.

Reduction of the dues payable by the temples to the Government.

10.

Restoration of the services in the temples.

11.

Forgiveness of rebels, who were permitted to return to Egypt and live there.

12.

Despatch of troops by sea and land against the enemies of Egypt.

13.

The siege and conquest of the town of Shekan (Lycopolis).

14.

Forgiveness of the debts owed by the priests to him.

15.

Reduction of the tax on byssus.

16.

Reduction of the tax on corn lands.

17.

Restoration of the temples of the Apis and Mnevis Bulls, and of the other sacred animals.

18.

Rebuilding of ruined shrines and sacred buildings, and providing them with endowments.

As a mark of the gratitude of the priesthood to the king for all these gracious acts of Ptolemy V, it was decided by the General Council of the priests of Egypt to “increase the ceremonial observances of honour which are paid to Ptolemy, the ever-living, in the temples.” With this object in view it was decided:

1.

To make statues of Ptolemy in his character of “Saviour of Egypt,” and to set up one in every temple of Egypt for the priests and people to worship.

2.

To make figures of Ptolemy [in gold], and to place them in gold shrines, which are to be set side by side with the shrines of the gods, and carried about in procession with them.

3.

To distinguish the shrine of Ptolemy by means of ten double-crowns of gold which are to be placed upon it.

4.

To make the anniversaries of the birthday and coronation days of Ptolemy, viz., the XVIIth and the XXXth days of the month Mesore, festival days for ever.

5.

To make the first five days of the month of Thoth days of festival for ever; offerings shall be made in the temples, and all the people shall wear garlands.

6.

To add a new title to the titles of the priests, viz., “Priests of the beneficent god Ptolemy Epiphanes, who appeareth on earth,” which is to be cut upon the ring of every priest of Ptolemy, and inserted in every priestly document.

7.

That the soldiers may borrow the shrines with figures of Ptolemy inside them from the temples, and may take them to their quarters, and carry them about in procession.

8.

That copies of this Decree shall be cut upon slabs of basalt in the “writing of the speech of the god,” i.e. hieroglyphs, and in the writing of the books, i.e. demotic, and in the writing of the Ueienin, i.e. Greek. “And a basalt slab on which a copy of this Decree is cut shall be set up in the temples of the first, second and third orders, side by side with the statue of Ptolemy, the ever-living god.”

E. A. WALLIS BUDGE.

Department of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities,

July 12th, 1913.

1. This fort is marked on Napoleon’s Map of Egypt, and it stood on the left or west bank of the Rosetta arm of the Nile.

The famous slab of black basalt which stands at the southern end of the Egyptian Gallery in the British Museum, and which has for more than a century been universally known as the “Rosetta Stone,” was found at a spot near the mouth of the great arm of the Nile that flows through the Western Delta to the sea, not far from the town of “Rashîd,” or as Europeans call it, “Rosetta.” According to one account it was found lying on the ground, and according to another it was built into a very old wall, which a company of French soldiers had been ordered to remove in order to make way for the foundations of an addition to the fort, afterwards known as “Fort St. Julien.”[1] The actual finder of the Stone was a French Officer of Engineers, whose name is sometimes spelt Boussard, and sometimes Bouchard, who subsequently rose to the rank of General, and was alive in 1814. He made his great discovery in August, 1799. Finding that there were on one side of the Stone lines of strange characters, which it was thought might be writing, as well as long lines of Greek letters, Boussard reported his discovery to General Menou, who ordered him to bring the Stone to his house in Alexandria. This was immediately done, and the Stone was, for about two years, regarded as the General’s private property. When Napoleon heard of the Stone, he ordered it to be taken to Cairo and placed in the “Institut National,” which he had recently founded in that city. On its arrival in Cairo it became at once an object of the deepest interest to the body of learned men whom Napoleon had taken with him on his expedition to Egypt, and the Emperor himself exhibited the greatest curiosity in respect of the contents of the inscriptions cut upon it. He at once ordered a number of copies of the Stone to be made for distribution among the scholars of Europe, and two skilled lithographers, “citizens Marcel and Galland,” were specially brought to Cairo from Paris to make them. The plan which they followed was to cover the surface of the Stone with printer’s ink, and then to lay upon it a sheet of paper which they rolled with india-rubber rollers until a good impression had been taken. Several of these ink impressions were sent to scholars of great repute in many parts of Europe, and in the autumn of 1801 General Dagua took two to Paris, where he committed them to the care of “citizen Du Theil” of the Institut National of Paris.