автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Makers of Modern Rome, in Four Books

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

THE MAKERS

OF

MODERN ROME

POPE GREGORY.

Frontispiece.

THE MAKERS

OF

MODERN ROME

IN FOUR BOOKS

I. HONOURABLE WOMEN NOT A FEW

II. THE POPES WHO MADE THE PAPACY

III. LO POPOLO: AND THE TRIBUNE OF THE PEOPLE

IV. THE POPES WHO MADE THE CITY

BY

MRS. OLIPHANT

AUTHOR OF "THE MAKERS OF FLORENCE"

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY HENRY P. RIVIERE, A.R.W.S. AND JOSEPH PENNELL

New York

MACMILLAN AND CO.

AND LONDON

1896

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1895,

By MACMILLAN AND CO.

Set up and electrotyped November, 1895. Reprinted January, 1896.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing & Co.—Berwick & Smith.

Norwood Mass. U.S.A.

I INSCRIBE THIS BOOK

WITH THE DEAR NAMES OF THOSE OF MINE

WHO LIE UNDER THE WALLS OF ROME:

AND OF HIM, THE LAST OF ALL,

WHO WAS BORN IN THAT SAD CITY:

ALL NOW AWAITING ME, AS I TRUST,

WHERE GOD MAY PLEASE.

F. W. O.

M. W. O.

F. R. O.

PREFACE.

Nobody will expect in this book, or from me, the results of original research, or a settlement—if any settlement is ever possible—of vexed questions which have occupied the gravest students. An individual glance at the aspect of these questions which most clearly presents itself to a mind a little exercised in the aspects of humanity, but not trained in the ways of learning, is all I attempt or desire. This humble endeavour has been conscientious at least. The work has been much interrupted by sorrow and suffering, on which account, for any slips of hers, the writer asks the indulgence of her unknown friends.

CONTENTS.

BOOK I.

HONOURABLE WOMEN NOT A FEW.

CHAPTER I.

ROME IN THE FOURTH CENTURY

page 1CHAPTER II.

THE PALACE ON THE AVENTINE

14CHAPTER III.

MELANIA

29CHAPTER IV.

THE SOCIETY OF MARCELLA

43CHAPTER V.

PAULA

65CHAPTER VI.

THE MOTHER HOUSE

89BOOK II.

THE POPES WHO MADE THE PAPACY.

CHAPTER I.

GREGORY THE GREAT

119CHAPTER II.

THE MONK HILDEBRAND

181CHAPTER III.

THE POPE GREGORY VII

230CHAPTER IV.

INNOCENT III

307BOOK III.

LO POPOLO: AND THE TRIBUNE OF THE PEOPLE.

CHAPTER I.

ROME IN THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY

381CHAPTER II.

THE DELIVERER

402CHAPTER III.

THE BUONO STATO

428CHAPTER IV.

DECLINE AND FALL

460CHAPTER V.

THE SOLDIER OF FORTUNE

486CHAPTER VI.

THE END OF THE TRAGEDY

493BOOK IV.

THE POPES WHO MADE THE CITY.

CHAPTER I.

MARTIN V.—EUGENIUS IV.—NICOLAS V.

513CHAPTER II.

CALIXTUS III.—PIUS II.—PAUL II.—SIXTUS IV.

552CHAPTER III.

JULIUS II.—LEO X.

581LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS.

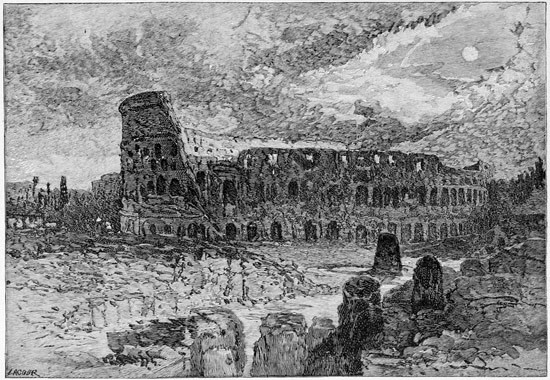

page Pope Gregory Frontispiece Colosseum by Moonlight,

by H. P. Riviere 37 Temple of Venus and River from the Colosseum(1860),

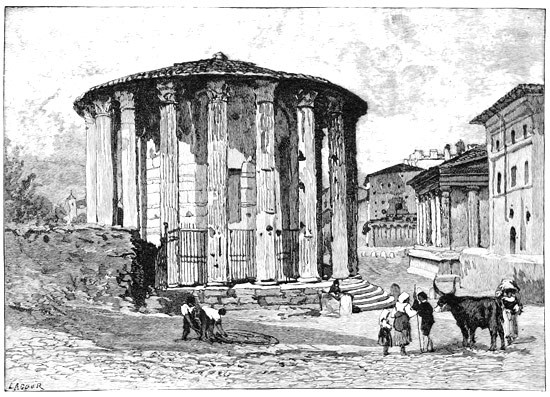

by H. P. Riviere 73 Temple of Vesta,

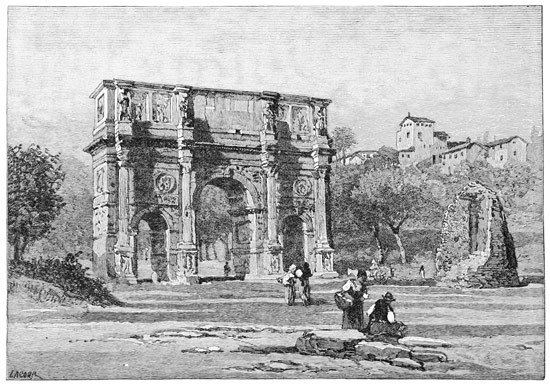

by H. P. Riviere 111 Arch of Constantine,

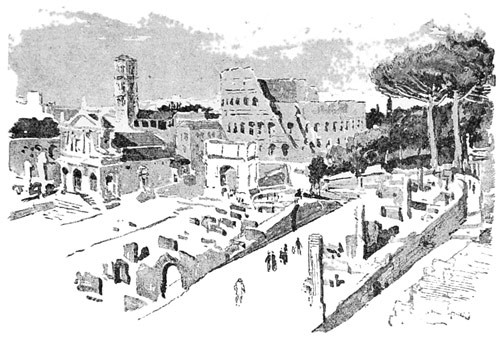

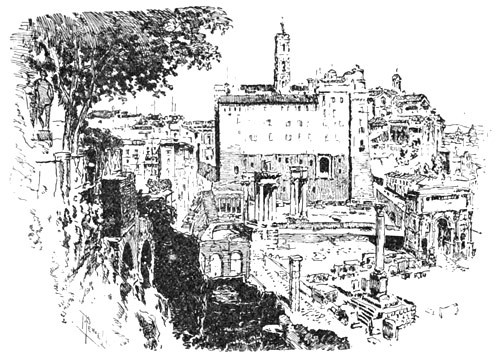

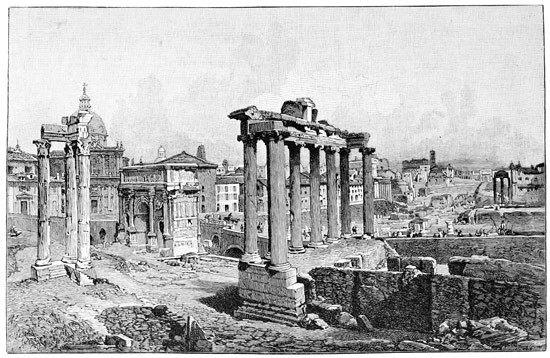

by H. P. Riviere 153 The Forum,

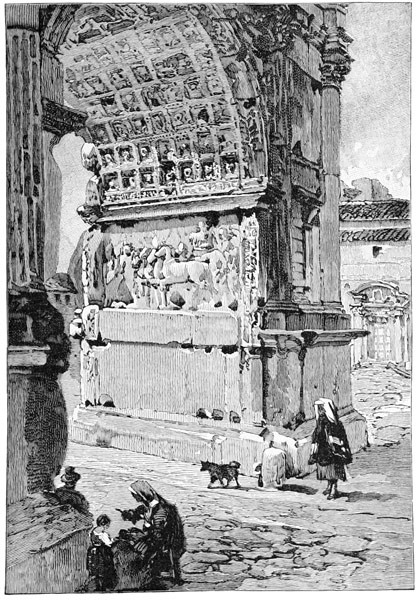

by H. P. Riviere 171 Arch of Titus,

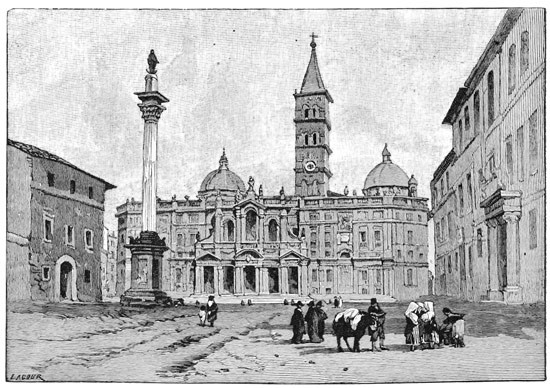

by H. P. Riviere 209 Santa Maria Maggiore,

by H. P. Riviere 247 Arch of Drusus(1860),

by H. P. Riviere 267 Island on Tiber,

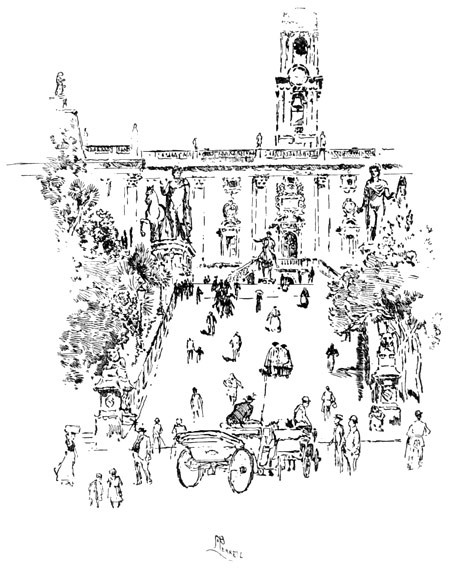

by H. P. Riviere 287 The Capitol,

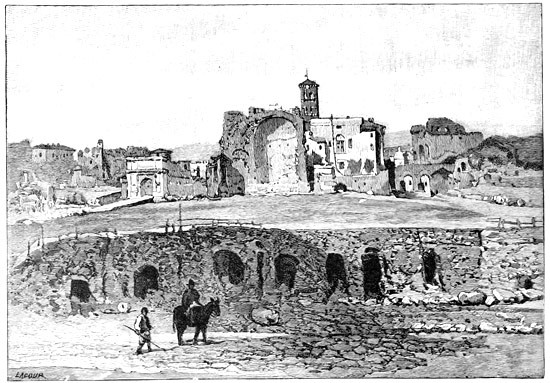

by J. Pennell 317 Porta Maggiore,

by H. P. Riviere 327 In the Campagna(1860),

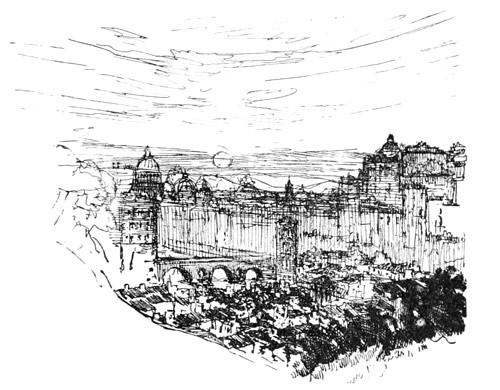

by H. P. Riviere 347 St. Peter's and the Castle of St. Angelo,

by H. P. Riviere 367 Approach to the Capitol(1860),

by H. P. Riviere 387 Theatre of Marcellus,

by J. Pennell 407 Aqua Felice,

by H. P. Riviere 463 The Tarpeian Rock,

by J. Pennell 481 Ancient, Mediæval, and Modern Rome,

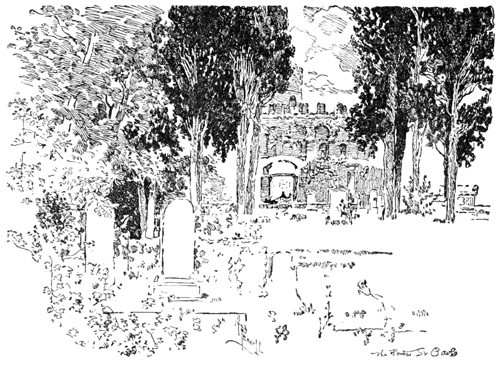

by J. Pennell 503 Modern Rome: Shelley's Tomb,

by J. Pennell 519 Fountain of Trevi,

by H. P. Riviere 527 Santa Maria del Popolo,

by H. P. Riviere 547 Piazza Colonna,

by J. Pennell 565 Old St. Peter's,

from the engraving by Campini 585 Modern Rome: The Grave of Keats,

by J. Pennell 593ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT.

The Colosseum,

by J. Pennell 1 The Palatine, from the Aventine,

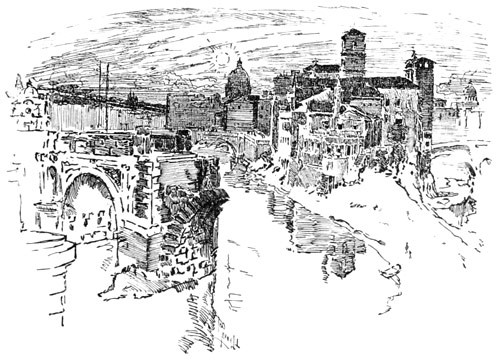

by J. Pennell 13 The Ripetta,

by J. Pennell 14 On the Palatine,

by J. Pennell 27 The Walls by St. John Lateran,

by J. Pennell 29 The Temple of Vesta,

by J. Pennell 42 Churches on the Aventine,

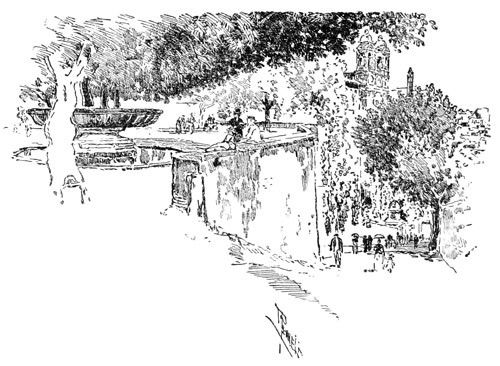

by J. Pennell 43 The Steps of the Capitol,

by J. Pennell 51 The Lateran from the Aventine,

by J. Pennell 64 Portico of Octavia,

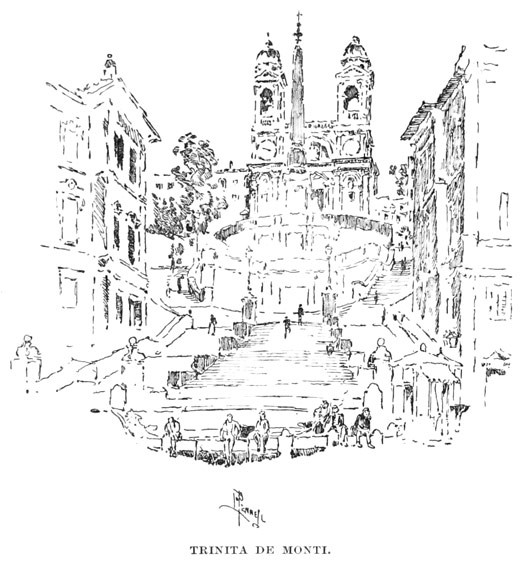

by J. Pennell 65 Trinita de' Monti,

by J. Pennell 76 From the Aventine,

by J. Pennell 87 The Capitol from the Palatine,

by J. Pennell 89 San Bartolommeo,

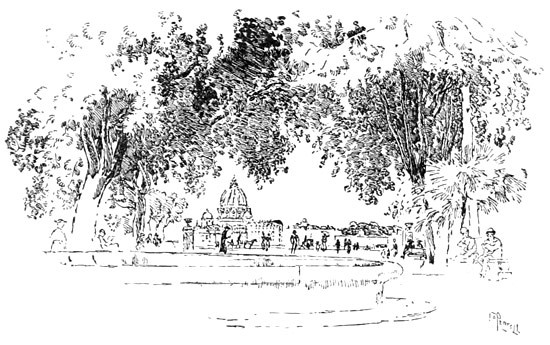

by J. Pennell 97 St. Peter's, from the Janiculum,

by J. Pennell 103 St. Peter's, from the Pincio,

by J. Pennell 107 Porta San Paola,

by J. Pennell 115 The Steps of San Gregorio,

by J. Pennell 119 Villa de' Medici,

by J. Pennell 133 San Gregorio Magno, and St. John and St. Paul,

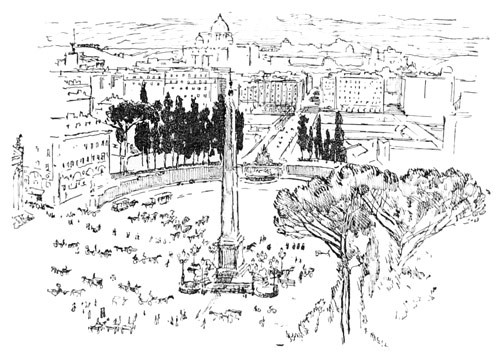

by J. Pennell 145 The Piazza del Popolo,

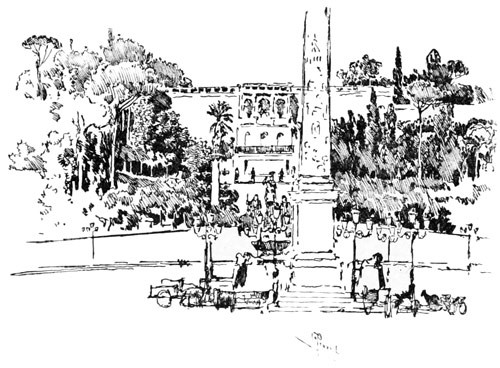

by J. Pennell 157 Monte Pincio, from the Piazza del Popolo,

by J. Pennell 167 Ponte Molle,

by J. Pennell 180 The Palatine,

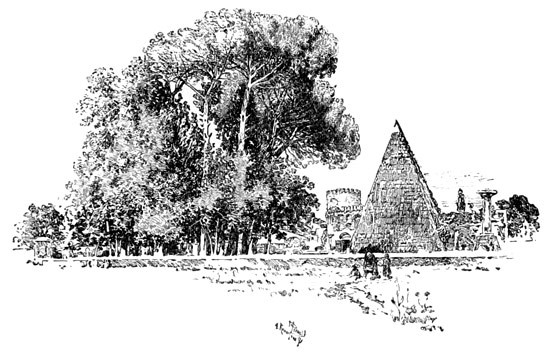

by J. Pennell 181 Pyramid of Caius Cestius,

by J. Pennell 197 Trinita de' Monti,

by J. Pennell 207 The Villa Borghese,

by J. Pennell 220 Where the Ghetto stood,

by J. Pennell 228 From San Gregorio Magno,

by J. Pennell 230 In the Villa Borghese,

by J. Pennell 306 The Fountain of the Tortoise,

by J. Pennell 307 All that is left of the Ghetto,

by J. Pennell 377 On the Tiber,

by J. Pennell 381 On the Pincio,

by J. Pennell 402 The Lungara,

by J. Pennell 428 Porta del Popolo (Flaminian Gate),

by J. Pennell 459 Theatre of Marcellus,

by J. Pennell 460 The Borghese Gardens,

by J. Pennell 486 Tomb of Cecilia Metella,

by J. Pennell 493 Letter Writer,

by J. Pennell 510 Piazza del Popolo,

by J. Pennell 513 On the Pincio,

by J. Pennell 533 In the Corso: Church Doors,

by J. Pennell 542 Modern Degradation of a Palace,

by J. Pennell 552 Fountain of Trevi,

by J. Pennell 581 A Bric-a-brac Shop,

by J. Pennell 600BOOK I.

HONOURABLE WOMEN NOT A FEW.

THE COLOSSEUM.

BOOK I.

HONOURABLE WOMEN NOT A FEW.

CHAPTER I.

ROME IN THE FOURTH CENTURY.

There is no place in the world of which it is less necessary to attempt description (or of which so many descriptions have been attempted) than the once capital of that world, the supreme and eternal city, the seat of empire, the home of the conqueror, the greatest human centre of power and influence which our race has ever known. Its history is unique and its position. Twice over in circumstances and by means as different as can be imagined it has conquered and held subject the world. All that was known to man in their age gave tribute and acknowledgment to the Cæsars; and an ever-widening circle, taking in countries and races unknown to the Cæsars, have looked to the spiritual sovereigns who succeeded them as to the first and highest of authorities on earth. The reader knows, or at least is assisted on all hands to have some idea and conception of the classical city—to be citizens of which was the aim of the whole world's ambition, and whose institutions and laws, and even its architecture and domestic customs, were the only rule of civilisation—with its noble and grandiose edifices, its splendid streets, the magnificence and largeness of its life; while on the other hand most people are able to form some idea of what was the Rome of the Popes, the superb yet squalid mediæval city with its great palaces and its dens of poverty, and that conjunction of exuberance and want which does not strike the eye while the bulk of a population remains in a state of slavery. But there is a period between, which has not attracted much attention from English writers, and which the reader passes by as a time in which there is little desirable to dwell upon, though it is in reality the moment of transition when the old is about to be replaced by the new, and when already the energy and enthusiasm of a new influence is making its appearance among the tragic dregs and abysses of the past. An ancient civilisation dying in the impotence of luxury and wealth from which all active power or influence over the world had departed, and a new and profound internal revolt, breaking up its false calm from within, before the raging forces of another rising power had yet begun to thunder at its gates without—form however a spectacle full of interest, especially when the scene of so many conflicts is traversed and lighted up by the most lifelike figures, and has left its record, both of good and evil, in authentic and detailed chronicles, full of individual character and life, in which the men and women of the age stand before us, occupied and surrounded by circumstances which are very different from our own, yet linked to us by that unfailing unity of human life and feeling which makes the farthest off foreigner a brother, and the most distant of our primeval predecessors like a neighbour of to-day.

The circumstances of Rome in the middle and end of the fourth century were singular in every point of view. With all its prestige and all its memories, it was a city from which power and the dominant forces of life had faded. The body was there, the great town with its high places made to give law and judgment to the world, even the officials and executors of the codes which had dispensed justice throughout the universe; but the spirit of dominion and empire had passed away. A great aristocracy, accustomed to the first place everywhere, full of wealth, full of leisure, remained; but with nothing to do to justify this greatness, nothing but luxury, the prize and accompaniment of it, now turned into its sole object and meaning. The patrician class had grown by use, by the high capability to fill every post and lead every expedition which they had constantly shown, which was their original cause and the reason of their existence, into a position of unusual superiority and splendour. But that reason had died away, the empire had departed from them, the world had a new centre: and the sons of the men who had conducted all the immense enterprises of Rome were left behind with the burden of their great names, and the weight of their great wealth, and nothing to do but to enjoy and amuse themselves: no vocations to fulfil, no important public functions to occupy their time and their powers. Such a position is perhaps the most dreadful that can come to any class in the history of a nation. Great and irresponsible wealth, the supremacy of high place, without those bonds of practical affairs which, in the case of all rulers—even of estates or of factories—preserve the equilibrium of humanity, are instruments of degradation rather than of elevation. To have something to do for it, something to do with it, is the condition which alone makes boundless wealth wholesome. And this had altogether failed in the imperial city. Pleasure and display had taken the place of work and duty. Rome had no longer any imperial affairs in hand. Her day was over: the absence of a court and all its intrigues might have been little loss to any community—but that those threads of universal dominion which had hitherto occupied them had been transferred to other hands, and that all the struggles, the great questions, the causes, the pleas, the ordinances of the world were now decided and given forth at Constantinople, was ruin to the once masters of the world. It was worse than destruction, a more dreadful overthrow than anything that the Goths and barbarians could bring—not death which brings a satisfaction of all necessities in making an end of them—but that death in life which fills men's blood with cold.

The pictures left us of this condition of affairs do indeed chill the blood. It is natural that there should be a certain amount of exaggeration in them. We read daily in our own contemporary annals, records of society of which we are perfectly competent to judge, that though true to fact in many points, they give a picture too dark in all its shadows, too garish in its lights, to afford a just view of the state of any existing condition of things. Contemporaries know how much to receive and how much to reject, and are apt to smile at the possibility of any permanent impression upon the face of history being made by lights and darks beyond the habit of nature. But yet when every allowance has been made, the contemporary pictures of Rome at this unhappy period leave an impression on the mind which is not contradicted but supported and enforced by the incidents of the time and the course of history. The populace, which had for ages been fed and nourished upon the bread of public doles and those entertainments of ferocious gaiety which deadened every higher sense, had sunk into complete debasement. Honest work and honest purpose, or any hope of improving their own position, elevating themselves or training their children, do not seem to have existed among them. A half-ludicrous detail, which reminds us that the true Roman had always a trifle of pedantry in his pride, is noted with disgust and disdain even by serious writers—which is that the common people bore no longer their proper names, but were known among each other by nicknames, such as those of Cabbage-eaters, Sausage-mongers, and other coarse familiar vulgarisms. This might be pardoned to the crowd which spent its idle days at the circus or spectacle, and its nights on the benches in the Colosseum or in the porch of a palace; but it is difficult to exaggerate the debasement of a populace which lived for amusement alone, picking up the miserable morsels which kept it alive from any chance or tainted source, without work to do or hope of amelioration. They formed the shouting, hoarse accompaniment of every pageant, they swarmed on the lower seats of every amphitheatre, howling much criticism as well as boisterous applause, and keeping in fear, and disgusted yet forced compliance with their coarse exactions, the players and showmen who supplied their lives with an object. According to all the representations that have reached us, nothing more degraded than this populace—encumbering every portico and marble stair, swarming over the benches of the Colosseum, basking in filth and idleness in the brilliant sun of Rome, or seeking, among the empty glories of a triumphal age gone by, a lazy shelter from it—has ever been known.

The higher classes suffered in their way as profoundly, and with a deeper consciousness, from the same debasing influences of stagnation. The descriptions of their useless life of luxury are almost too extravagant to quote. "A loose silken robe," says the critic and historian of the time, Ammianus Marcellinus, speaking of a Roman noble,—"for a toga of the lightest tissue would have been too heavy for him—linen so transparent that the air blew through it, fans and parasols to protect him from the light, a troop of eunuchs always round him." This was the appearance and costume of a son of the great and famous senators of Rome. "When he was not at the bath, or at the circus to maintain the cause of some charioteer, or to inspect some new horses, he lay half asleep upon a luxurious couch in great rooms paved with marble, panelled with mosaic." The luxurious heat implied, which makes the freshness of the marble, the thinness of the linen, so desirable, as in a picture of Mr. Alma Tadema's, bids us at the same time pause in receiving the whole of this description as unquestionable; for Rome has its seasons in which vast chambers paved with marble are no longer agreeable, though the manners and utterances of the race still tend to a complete ignoring of this other side of the picture: but yet no doubt its general features are true.

When this Sybarite went out it was upon a lofty chariot, where he reclined negligently, showing off himself, his curled and perfumed locks, his robes, with their wonderful embroideries and tissues of silk and gold, to the admiration of the world; his horses' harness were covered with ornaments of gold, his coachman armed with a golden wand instead of a whip, and the whole equipage followed by a procession of attendants, slaves, freedmen, eunuchs, down to the knaves of the kitchen, the hewers of wood and drawers of water, to give importance to the retinue, which pushed along through the streets with all the brutality which is the reverse side of senseless display, pushing citizens and passers-by out of the way. The dinner parties of the evening were equally childish in their extravagance: the tables covered with strange dishes, monsters of the sea and of the mountains, fishes and birds of unknown kinds and unequalled size. The latter seems to have been a special subject of pride, for we are told of the servants bringing scales to weigh them, and notaries crowding round with their tablets and styles to record the weight. After the feast came a "hydraulic organ," and other instruments of corresponding magnitude, to fill the great hall with resounding music, and pantomimical plays and dances to enliven the dulness of the luxurious spectators on their couches—"women with long hair, who might have married and given subjects to the state," were thus employed, to the indignation of the critic.

This chronicler of folly and bad manners would not be human if he omitted the noble woman of Rome from his picture. Her rooms full of obsequious attendants, slaves, and eunuchs, half of her time was occupied by the monstrous toilette which annulled all natural charms to give to the Society beauty a fictitious and artificial display of red and white, of painted eyelids, tortured hair, and extravagant dress. An authority still more trenchant than the heathen historian, Jerome, describes even one of the noble ladies who headed the Christian society of Rome as spending most of the day before the mirror. Like the ladies of Venice in a later age, these women, laden with ornaments, attired in cloth of gold, and with shoes that crackled under their feet with the stiffness of metallic decorations, were almost incapacitated from walking, even with the support of their attendants; and a life so accoutred was naturally spent in the display of the charms and wealth thus painfully set forth.

The fairer side of the picture, the revolt of the higher nature from such a life, brings us into the very heart of this society: and nothing can be more curious than the gradual penetration of a different and indeed sharply contrary sentiment, the impulse of asceticism and the rudest personal self-deprivation, amid a community spoilt by such a training, yet not incapable of disgust and impatience with the very luxury which had seemed essential to its being. The picturesqueness and attraction of the picture lies here, as in so many cases, chiefly on the women's side.

It is necessary to note, however, the curious mixture which existed in this Roman society, where Christianity as a system was already strong, and the high officials of the Church were beginning to take gradually and by slow degrees the places abandoned by the functionaries of the empire. Though the hierarchy was already established, and the Bishop of Rome had assumed a special importance in the Church, Paganism still held in the high places that sway of the old economy giving place to the new, which is at once so desperate and so nerveless—impotence and bitterness mingling with the false tolerance of cynicism. The worship of the gods had dropped into a survival of certain habits of mind and life, to which some clung with the angry revulsion of terror against a new revolutionary power at first despised: and some held with the loose grasp of an imaginative and poetical system, and some with a sense of the intellectual superiority of art and philosophy over the arguments and motives that moved the crowd. Life had ebbed away from these religions of the past. The fictitious attempt of Julian to re-establish the worship of the gods, and bring new blood into the exhausted veins of the mythological system, had in reality given the last proof of its extinction as a power in the world: but still it remained lingering out its last, holding a place, sometimes dignified by a gleam of noble manners and the graces of intellectual life—and often, it must be allowed, justified by the failure of the Church to embody that purity and elevation which its doctrines, but scarcely its morals or life, professed. Thus the faith in Christ, often real, but very faulty—and the faith in Apollo, almost always fictitious, but sometimes dignified and superior—existed side by side. The father might hold the latter with a superb indifference to its rites, and a contemptuous tolerance for its opponents, while the mother held the first with occasional hot impulses of devotion, and performances of penance for the pardon of those worldly amusements and dissipations to which she returned with all the more zest when her vigils and prayers were over.

This conjunction of two systems so opposite in every impulse, proceeding from foundations so absolutely contrary to each other, could not fail to have an extraordinary effect upon the minds of the generations moved by it, and affords, I think, an explanation of some events very difficult to explain on ordinary principles, and particularly the abandonment of what would appear the most unquestionable duties, by some of the personages, especially the women whose histories and manners fill this chapter of the great records of Rome. Some of them deserted their children to bury themselves in the deserts, to withdraw to the mountains, placing leagues of land and sea between themselves and their dearest duties—why? the reader asks. At the bidding of a priest, at the selfish impulse of that desire to save their own souls, which in our own day at least has come to mean a degrading motive—is the general answer. It would not be difficult, however, to paint on the other side a picture of the struggle with the authorities of her family for the training of a son, for the marriage of a daughter, from which a woman might shrink with a sense of impotence, knowing the prestige of the noble guardian against whom she would have to contend, and all the forces of family pride, of tradition and use and wont, that would be arrayed against her. Better perhaps, the mother might think, to abandon that warfare, to leave the conflict for which she was not strong enough, than to lose the love of her child as well, and become to him the emblem of an opposing faction attempting to turn him from those delights of youth which the hereditary authority of his house encouraged instead of opposing. It is difficult perhaps for the historians to take such motives into consideration, but I think the student of human nature may feel them to be worth a thought, and receive them as some justification, or at least apology, for the actions of some of the Roman women who fill the story of the time.

Unfortunately it is not possible to leave out the Church in Rome when we collect the details of depravity and folly in Society. One cannot but feel how robust is the faith which goes back to these ages for guidance and example when one sees the image in St. Jerome's pages of a period so early in the history of Christianity. "Could ye not watch with me one hour?" our Lord said to the chosen disciples, His nearest friends and followers, in the moment of His own exceeding anguish, with a reproach so sorrowful, yet so conscious of the weakness of humanity, that it silences every excuse. We may say, for a poor four hundred years could not the Church keep the impress of His teaching, the reality of the faith of those who had themselves fallen and fainted, yet found grace to live and die for their Master? But four centuries are a long time, and men are but men even with the inheritance of Christians. They belonged to their race, their age, and the manifold influences which modify in the crowd everything it believes or wishes. And they were exposed to many temptations which were doubly strong in that world to which by birth and training they belonged. How is an ordinary man to despise wealth in the midst of a society corrupted by it, and in which it is supreme? how learn to be indifferent to rank and prestige in a city where without these every other claim was trampled under foot? "The virtues of the primitive Church," says Villemain of a still later period, "had been under the guard of poverty and persecution: they were weak in success and triumph. Enthusiasm became less pure, the rules of life less severe. In the always increasing crowd of proselytes were many unworthy persons, who turned to Christianity for reasons of ambition and self-interest, to make way at Court, to appear faithful to the emperor. The Church, enriched at once by the spoil of the temples and the offerings of the Christian crowd, began to clothe itself in profane magnificence." Those who attained the higher clerical honours were sure, according to the evidence of Ammianus, "of being enriched by the offerings of the Roman ladies, and drove forth like noblemen in lofty chariots, clothed magnificently, and sat down at tables worthy of kings." The Church, endowed in an earlier period by converts, who offered sometimes all their living for the sustenance of the community which gave them home and refuge, had continued to receive the gifts of the pious after the rules of ordinary life regained their force; and now when she had yielded to a great extent to the prevailing temptations of the age, found a large means of endowment in the gifts of deathbed repentance and the weakness of dying penitents, of which she was reputed to take large advantage: wealth grew within her borders, and luxury with it, according to the example of surrounding society. It is Jerome himself who reports the saying of one of the highest of Roman officials to Bishop Damasus. "If you will undertake to make me Bishop of Rome, I will be a Christian to-morrow." Not even the highest place in the Government was so valuable and so great. It is Jerome also who traces for us—the fierce indignation of his natural temper, mingling with an involuntary perception of the ludicrous side of the picture—a popular young priest of his time, whose greatest solicitude was to have perfumed robes, a well fitting shoe, hair beautifully curled, and fingers glittering with jewels, and who walked on tip-toe lest he should soil his feet.

They died all three, one after another, and were laid to rest in the pure and wholesome rock near the sacred spot of the Nativity. There is a touching story told of how Eustochium, after her mother's death, when Jerome was overwhelmed with grief and unable to return to any of his former occupations, came to him with the book of Ruth still untranslated in her hand, at once a promise and an entreaty. "Where thou goest I will go. Where thou dwellest I will dwell"—and a continuation at the same time of the blessed work which kept their souls alive.

In the very age that produced the Borgias, and himself the head of that band of elegant scholars and connoisseurs, everything but Christian, to whom Rome owes so much of her external beauty and splendour, it is pathetic to stand by this kind and gentle spirit as he pauses on the threshold of a higher life, subduing the astute and worldly minded Churchmen round him with the tender appeal of the dying father, their Papa Niccolajo, familiar and persuasive—beseeching them to be of one accord without so much as saying it, turning his own weakness to account to touch their hearts, for the honour of the Church and the welfare of the flock.

COLOSSEUM BY MOONLIGHT.

To face page 36.

TEMPLE OF VENUS AND ROME FROM THE COLOSSEUM (1860).

To face page 72.

TEMPLE OF VESTA.

To face page 110.

ARCH OF CONSTANTINE.

To face page 152.

THE FORUM

To face page 170.

ARCH OF TITUS.

To face page 208.

SANTA MARIA MAGGIORE.

To face page 246.

ARCH OF DRUSUS (1860)

To face page 266.

ISLAND ON TIBER.

To face page 286.

THE CAPITOL.

To face page 316.

PORTA MAGGIORE.

To face page 326.

IN THE CAMPAGNA (1860)

To face page 346.

ST. PETER'S AND THE CASTLE OF ST. ANGELO.

To face page 366.

APPROACH TO THE CAPITOL (1860).

APPROACH TO THE CAPITOL (1860).

THEATRE OF MARCELLUS.

To face page 406.

AQUA FELICE

To face page 462.

THE TARPEIAN ROCK.

To face page 480.

ANCIENT, MEDIÆVAL, AND MODERN ROME.

To face page 502.

MODERN ROME: SHELLEY'S TOMB.

To face page 518.

FOUNTAIN OF TREVI.

To face page 526.

SANTA MARIA DEL POPOLO.

To face page 546.

PIAZZA COLONNA,

To face page 564.

OLD ST. PETER'S.

To face page 584.

MODERN ROME: THE GRAVE OF KEATS.

To face page 592.

THE COLOSSEUM.

THE PALATINE, FROM THE AVENTINE.

THE RIPETTA.

ON THE PALATINE.

THE WALLS BY ST. JOHN LATERAN.

THE TEMPLE OF VESTA

CHURCHES ON THE AVENTINE

THE STEPS OF THE CAPITOL.

THE LATERAN FROM THE AVENTINE.

PORTICO OF OCTAVIA.

TRINITA DE' MONTI.

FROM THE AVENTINE.

THE CAPITOL FROM THE PALATINE.

SAN BARTOLOMMEO.

ST. PETER'S, FROM THE JANICULUM.

ST. PETER'S, FROM THE PINCIO.

PORTA SAN PAOLO.

THE STEPS OF SAN GREGORIO.

VILLA DE' MEDICI.

SAN GREGORIO MAGNO, AND ST. JOHN AND ST. PAUL.

THE PIAZZA DEL POPOLO.

MONTE PINCIO, FROM THE PIAZZA DEL POPOLO.

PONTE MOLLE.

THE PALATINE.

PYRAMID OF CAIUS CESTIUS.

TRINITA DE MONTI.

THE VILLA BORGHESE.

WHERE THE GHETTO STOOD.

FROM SAN GREGORIO MAGNO

IN THE VILLA BORGHESE.

THE FOUNTAIN OF THE TORTOISE

ALL THAT IS LEFT OF THE GHETTO.

ON THE TIBER.

ON THE PINCIO.

THE LUNGARA

PORTA DEL POPOLO (FLAMINIAN GATE).

THEATRE OF MARCELLUS.

THE BORGHESE GARDENS

TOMB OF CECILIA METELLA

LETTER WRITER.

PIAZZA DEL POPOLO.

ON THE PINCIO.

IN THE CORSO: CHURCH DOORS.

MODERN DEGRADATION OF A PALACE.

FOUNTAIN OF TREVI.

A BRIC-A-BRAC SHOP.

"What are these men? To those who see them pass they are more like bridegrooms than priests. Some among them devote their life and energies to the single object of knowing the names, the houses, the habits, the disposition of all the ladies in Rome. I will sketch for you, dear Eustochium, in a few lines, the day's work of one of them, great in the arts of which I speak, that by means of the master you may the more easily recognise his disciples.

"Our hero rises with the sun: he regulates the order of his visits, studies the shortest ways, and arrives before he is wanted, almost before his friends are awake. If he perceives anything that strikes his fancy, a pretty piece of furniture or an elegant marble, he gazes at it, praises it, turns it over in his hands, and grieves that he has not one like it—thus extorting rather than obtaining the object of his desires; for what woman would not hesitate to offend the universal gossip of the town? Temperance, modesty (castitas), and fasting are his sworn enemies. He smells out a feast and loves savoury meats.

"Wherever one goes one is sure to meet him; he is always there before you. He knows all the news, proclaims it in an authoritative tone, and is better informed than any one else can be. The horses which carry him to the four quarters of Rome in pursuit of this honest task are the finest you can see anywhere; you would say he was the brother of that King of Thrace known in story by the speed of his coursers.

"This man," adds the implacable satirist in another letter, "was born in the deepest poverty, brought up under the thatch of a peasant's cottage, with scarcely enough of black bread and millet to satisfy the cravings of his appetite; yet now he is fastidious and hard to please, disdaining honey and the finest flour. An expert in the science of the table, he knows every kind of fish by name, and whence come the best oysters, and what district produces the birds of finest savour. He cares only for what is rare and unwholesome. In another kind of vice he is not less remarkable; his mania is to lie in wait for old men and women without children. He besieges their beds when they are ill, serves them in the most disgusting offices, more humble and servile than any nurse. When the doctor enters he trembles, asking with a faltering voice how the patient is, if there is any hope of saving him. If there is any hope, if the disease is cured, the priest disappears with regrets for his loss of time, cursing the wretched old man who insists on living to be as old as Methusalem."

The last accusation, which has been the reproach of the Church in many different ages, had just been specially condemned by a law of the Emperor Valentinian I., declaring null and void all legacies made to priests, a law which called forth Jerome's furious denunciation, not of itself, but of the abuse which called it forth. This was a graver matter than the onslaught upon the curled darlings of the priesthood, more like bridegrooms than priests, who carried the news from boudoir to boudoir, and laid their entertainers under contribution for the bibelots and ancient bric-a-brac which their hearts desired. Thus wherever the eye turned there was nothing but luxury and the love of luxury, foolish display, extravagance and emulation in all the arts of prodigality, a life without gravity, without serious occupation, with nothing in it to justify the existence of those human creatures standing between earth and heaven, and capable of so many better things. The revulsion, a revulsion inspired by disgust and not without extravagance in its new way, was sure to come.

THE PALATINE, FROM THE AVENTINE.

THE RIPETTA.

CHAPTER II.

THE PALACE ON THE AVENTINE.

The strong recoil of human nature from those fatal elements which time after time have threatened the destruction of all society is one of the noblest things in history, as it is one of the most divine in life. There are evidences that it exists even in the most wicked individuals, and it very evidently comes uppermost in every commonwealth from century to century to save again and again from utter debasement a community or a nation. When depravity becomes the rule instead of the exception, and sober principle appears on the point of yielding altogether to the whirl of folly or the thirst of self-indulgence, then it may always be expected that some ember of divine indignation, some thrill of high disgust with the miserable satisfactions of the world will kindle in one quarter or another and set light to a thousand smouldering tires over all the face of the earth. It is one of the highest evidences of that charter of our being which is our most precious possession, the reflection of that image of God which amid all degradations still holds its place in human nature, and will not be destroyed. We may mourn indeed that so short a span of centuries had so effaced the recollection of the brightest light that ever shone among men, as to make the extravagance of a human revulsion and revolution necessary in order to preserve and restore the better life of Christendom. At the same time it is our salvation as a race that such revolutions, however imperfect they may be in themselves, are sure to come.

This revulsion from vice, degradation, and evil of every kind, public and personal, had already come with the utmost excess of self-punishment and austerity in the East, where already the deserts were mined with caverns and holes in the sand, to which hermits and cœ;nobites, the one class scarcely less exalted in religious passion and suffering than the other, had escaped from the current of evil which they did not feel themselves capable of facing, and lived and starved and agonised for the salvation of their own souls and for a world lying in wickedness. The fame of the Thebaid and its saints and martyrs, slowly making itself known through the great distances and silences, had already breathed over the world, when Athanasius, driven by persecution from his see and his country, came to Rome, accompanied by two of the monks whose character was scarcely understood as yet in the West, and bringing with him his own book, the life of St. Antony of the desert, a work which had as great an effect in that time as the most popular of publications, spread over the world in thousands of copies, could have now. It puzzles the modern reader to think how a book should thus have moved the world and revolutionised hundreds of lives, while it existed only in manuscript and every example had to be carefully and tediously copied before it could touch even those who were wealthy enough to secure themselves such a luxury. What readings in common, what earnest circles of auditors, what rapt intense hanging upon the lips of the reader, there must have been before any work, even the most sacred, penetrated to the crowd!—but to us no doubt the process seems more slow and difficult than it really was when scribes were to be found everywhere, and manuscripts were treated with reverence and respect. When Athanasius found refuge in Rome, which was during the pontificate, or rather—for the full papal authority had as yet been claimed by no one—the primacy—of Liberius, and about the year 341, he was received by all that was best in Rome with great hospitality and sympathy. Rome so far as it was Christian was entirely orthodox, the Arian heresy having gained no part of the Christian society there—and a man of genius and imposing character, who brought into that stagnant atmosphere the breath of a larger world, who had shared the councils of the emperor and lived in the cells of Egypt—an orator, a traveller, an exile, with every kind of interest attaching to him, was such a visitor as seldom appeared in the city deserted by empire. Something like the man who nine centuries later went about the Italian streets with the signs upon him of one who had been through heaven and hell, the Eastern bishop must have appeared to the languid citizens, with the brown of the desert still on his cheeks, yet something of the air of a courtly prelate, a friend of princes; while his attendants, one with all the wildness of a hermit from the desert in his eyes and aspect, in the unfamiliar robe and cowl—and the other mild and young like the ideal youth, shy and simple as a girl—were wonderful apparitions in the fatigued and blasé society, which longed above everything for something new, something real, among all the mocks and shows of their impotent life.

One of the houses in which Athanasius and his monks were most welcome was the palace of a noble widow, Albina, who lived the large and luxurious life of her class in the perfect freedom of a Roman matron, Christian, yet with no idea in her mind of retirement from the world, or renunciation of its pleasures. A woman of a more or less instructive mind and lively intelligence, she received with the greatest interest and pleasure these strangers who had so much to tell, the great bishop flying from his enemies, the monks from the desert. That she and her circle gathered round him with that rapt and flattering attention which not the most abstracted saint any more than the sternest general can resist, is evident from the story, and it throws a gleam of softer light upon the impassioned theologian who stood fast, "I, Athanasius, against the world" for that mysterious splendour of the Trinity, against which the heretical East had risen. In the Roman lady's withdrawingroom, in his dark and flowing Eastern robes, we find him amid the eager questionings of the women, describing to them the strange life of the desert which it was such a wonder to hear of—the evensong that rose as from every crevice of the earth, while the Egyptian after-glow burned in one great circle of colour round the vast globe of sky, diffusing an illumination weird and mystic over the fantastic rocks and dark openings where the singers lived unseen. What a picture to be set before that soft, eager circle, half rising from silken couches, clothed with tissues of gold, blazing with jewels, their delicate cheeks glowing in artificial red and white, their crisped and curled tresses surmounted by the fantastic towering headdress which weighed them down!

Among the ladies was the child of the house, the little girl who was her mother's excuse for retaining the freedom of her widowhood, Marcella: a thoughtful and pensive child, devouring all these wonderful tales, listening to everything and laying up a store of silent resolutions and fancies in her heart. Her elder sister Asella would seem to have already secluded herself in precocious devotion from the family, or at least is not referred to. The story which touched the general mind of the time with so strange and strong an enthusiasm, fell into the virgin soil of this young spirit like the seed of a new life. But the little Roman maiden was no ascetic. She had evidently no impulse, as some young devotees have had, to set out barefoot in search of suffering. When Athanasius left Rome, he left in the house which had received him so kindly his life of St. Antony, the first copy which had been seen in the Western world. This manuscript, written perhaps by the hand of one of those wonderful monks, the strangest figures in her luxurious world whom Marcella knew, became the treasure of her youth. Such a present, at such a time, was enough to occupy the visionary silence of a girl's life, often so full of dreams unknown and unsearchable even to her nearest surroundings. She went through however the usual routine of a young lady's life in Rome. Madame Albina the mother, though full of interest and curiosity in respect to all things intellectual and Christian, held still more dearly a mother's natural desire to see her only remaining child nobly married and established in the splendour and eminence to which she was born. We are told that Marcella grew up to be one of the beauties of Rome, but as this is an inalienable qualification of all these beautiful souls, it is not necessary to believe that the "insignem decorem corporis" meant any extraordinary distinction. She carried out at all events her natural fate and married a rich and noble husband, of whom however we know no details, except that he died some months after, leaving her without child or tie to the ordinary life of the world, in all the freedom of widowhood, at a very early age.

Thus placed in full command of her fate, she never seems to have hesitated as to what she should do with herself. She was, as a matter of course, assailed by many new suitors, among whom her historian, who is no other than St. Jerome himself, makes special mention of the exceptionally wealthy Cerealis ("whose name is great among the consuls"), and who was so splendid a suitor that the fact that he was old scarcely seems to have told against him. Marcella's refusal of this great match and of all the others offered to her, offended and alienated her friends and even her mother, and there followed a moment of pain and perplexity in her life. She is said to have made a sacrifice of a part of her possessions to relatives to whom, failing herself, it fell to keep up the continuance of the family name, hoping thus to secure their tolerance. And she acquired the reputation of an eccentric, and probably of a poseuse, so general in all times when a young woman forsakes the beaten way, as she had done by giving up the ridiculous fashions and toilettes of the time, putting aside the rouge and antimony, the disabling splendour of cloth of gold, and assuming a simple dress of a dark colour, a thing which shocked her generation profoundly. The gossip rose and flew from mouth to mouth among the marble salons where the Roman ladies languished for a new subject, or in the ante-rooms, where young priests and deacons awaited or forestalled the awakening of their patronesses. It might be the Hôtel Rambouillet of which we are reading, and a fine lady taking refuge at Port Royal who was being discussed and torn to pieces in those antique palaces. What was the meaning that lay beneath that brown gown? Was it some unavowed disappointment, or, more exciting still, some secret intrigue, some low-placed love which she dared not acknowledge? Withdrawn into a villa had she, into the solitude of a suburban garden, hid from every eye? and who then was the companion of Marcella's solitude? The ladies who discussed her had small faith in austerities, nor in the desire of a young and attractive woman to live altogether alone.

It is very likely that Marcella herself, as well as her critics, soon began to feel that the mock desert into which she had made the gardens of her villa was indeed a fictitious way of living the holy life, and the calumny was more ready and likely to take hold of this artificial retirement, than of a course of existence led within sight of the world. She finally took a wiser and more reasonable way. Her natural home was a palace upon the Aventine to which she returned, consecrating a portion of it to pious uses, a chapel for common worship and much accommodation for the friends of similar views and purposes who immediately began to gather about her. It is evident that there were already many of these women in the best society of Rome. A lively sentiment of feminine society, of the multiplied and endless talks, consultations, speculations, of a community of women, open to every pleasant curiosity and quick to every new interest, rises immediately before us in that first settlement of monasticism—or, as the ecclesiastical historians call it, the first convent of Rome, before our eyes. It was not a convent after all so much as a large and hospitable feminine house, possessing the great luxury of beautiful rooms and furniture, and the liberal ways of a large and wealthy family, with everything that was most elegant, most cultured, most elevated, as well as most devout and pious. The "Souls," to use our own jargon of the moment, would seem indeed to have been more truly represented there than the Sisters of our modern understanding, though we may acknowledge that there are few communities of Sisters in which this element does not more or less flourish. Christian ladies who were touched like herself with the desire of a truer and purer life, gathered about her, as did the French ladies about Port Royal, and women of the same class everywhere, wherever a woman of influential character leads the way.

The character and position of these ladies was not perhaps so much different as we might suppose from those of the court of Louis XIV. or any other historical period in which great luxuries and much dissipation had sickened the heart of all that was good and noble. Yet there were very special characteristics in their lot. Some of them were the wives of pagan officials of the empire, holding a sometimes devious and always agitated course through the troubles of a divided household: and there were many young widows perplexed with projects of remarriage, of whom some would be tempted by the prospects of a triumphant re-entry into the full enjoyments of life, although a larger number were probably resistant and alarmed, anxious to retain their freedom, or to devote themselves as Marcella had done to a higher life. Women of fashion not unwilling to add a devotion à la mode to their other distractions, women of intellectual aspirations, lovers of the higher education, seekers after a society altogether brilliant and new, without any special emotions of religious feeling, no doubt filled up the ranks. "A society," says Thierry, in his Life of Jerome, "of rich and influential women, belonging for the great part to patrician families, thus organised itself, and the oratory on the Aventine became a seat of lay influence and power which the clergy themselves were soon compelled to reckon with."

The heads of the community bore the noblest names in Rome, which however at that period of universal deterioration was not always a guarantee of noble birth, since the greatest names were sometimes assumed with the slenderest of claims to their honours. Marcella's sister, Asella, older than the rest, and a sort of mother among them, had for a long time before "lived the life" in obscurity and humbleness, and several others not remarkable in the record, were prominent associates. The actual members of the community, however, are not so much remarked or dwelt upon as the visitors who came and went, not all of them of consistent religious character, ladies of the great world. One of these, Fabiola, affords an amusing episode in the graver tale, the contrast of a butterfly of society, a grande dame of fascinating manners, airs, and graces, unfortunate in her husbands, of whom she had two, one of them divorced—and not quite unwilling to divorce the second and try her luck again. Another, one of the most important of all in family and pretensions, and by far the most important in history of these constant visitors, was Paula, a descendant (collateral, the link being of the lightest and easiest kind, as was characteristic of the time) of the great Æmilius Paulus, the daughter of a distinguished Greek who claimed to be descended from Agamemnon, and widow of another who claimed Æneas as his ancestor. These large claims apart, she was certainly a great lady in every sense of the word, delicate, luxurious, following all the fashions of the time. She too was a widow, with a family of young daughters, in that enviable state of freedom which the Roman ladies give every sign of having used and enjoyed to the utmost, the only condition in which they were quite at liberty to regulate their own fate. Paula is the most interesting of the community, as she is the one of whom we know the most. No fine lady more exquisite, more fastidious, more splendid than she. Not even her Christianity had beguiled her from the superlative finery of her Roman habits. She was one of the fine ladies who could not walk abroad without the support of her servants, nor scarcely cross the marble floor from one silken couch to another without tottering, as well she might, under the weight of the heavy tissues interwoven with gold, of which her robes were made. A widow at thirty-five, she was still in full possession of the charms of womanhood, and the sunshine of life (though we are told that her grief for her husband was profound and sincere)—with her young daughters growing up round her, more like her sisters than her children, and sharing every thought. Blæsilla, the eldest, a widow at twenty, was, like her mother, a Roman exquisite, loving everything that was beautiful and soft and luxurious. In the affectionate gibes of the family she is described as spending entire days before her mirror, giving herself up to all the extravagances of dress and personal decoration, the tower of curls upon her head, the touch of rouge on her cheeks. A second daughter, Paulina, was on the eve of marriage with a young patrician, as noble, as rich, and, as was afterwards proved, as devoutly Christian as the family into which he married. The third member of the family, Eustochium, a girl of sixteen, of a character contrasting strongly with those of her beautiful mother and sister, a saint from her birth, was the favourite, and almost the child, of Marcella, instructed by her from her earliest years, and had already fixed her choice upon a monastic life, and would seem to have been a resident in the Aventine palace to which the others were such frequent visitors. Of all this delightful and brilliant party she is the one born recluse, severe in youthful virtue, untouched by any of the fascinations of the world. The following very pretty and graphic story is told of her, in which we have a curious glimpse into the strangely mixed society of the time.

The family of Paula though Christian, and full of religious fervour, or at least imbued with the new spirit of revolt against the corruption of the time, was closely connected with the still existing pagan society of Rome. Her sister-in-law, sister of her husband and aunt of her children, was a certain lady named Prætextata, the wife of Hymettius, a high official under the Emperor Julian the Apostate, both of them belonging, with something of the fictitious enthusiasm of their master, to the faith of the old gods. No doubt one of the severest critics of that society on the Aventine, Prætextata saw with impatience and wrath, what no doubt she considered the artificial gravity, inspired by her surroundings, of the young niece who had already announced her intention never to marry, and to withdraw altogether from the world. Such resolutions on the part of girls who know nothing of the world they abandon have exasperated the most devout of parents, and it was not wonderful if this pagan lady thought it preposterous. The little plot which she formed against the serious girl was, however, of the most good-natured and innocent kind. Finding that words had no effect upon her, the elder lady invited Eustochium to her house on a visit. The young vestal came all unsuspicious in her little brown gown, the costume of humility, but had scarcely entered her aunt's house when she was seized by the caressing and flattering hands of the attendants, interested in the plot as the favourite maids of such an establishment would be, who unloosed her long hair and twisted it into curls and plaits, took away her humble dress, clothed her in silk and cloth of gold, covered her with ornaments and led her before the mirror which reflected all these charms, to dazzle her eyes with the apparition of herself, so different from the schoolroom figure with which she was acquainted. The little plot was clever as well as innocent, and might, no doubt, have made a heart of sixteen beat high. But Eustochium with her Greek name, and her virgin heart, was the grave girl we all know, the one here and there among the garden of girls, born to a natural seriousness which is beyond such temptations. She let them turn her round and round, received sweetly in her gentle calm the applauses of the collected household, looked at her image in the mirror as at a picture—and went home again in her little brown gown with her story to tell, which, no doubt, was an endless amusement and triumph to the ladies on the Aventine, repeated to every new-comer with many a laugh at the foolishness of the clever aunt who had hoped by such means to seduce Eustochium—Eustochium, the most serious of them all!

Such was the first religious community in Rome. It was the natural home of Marcella to which her friends gathered, without in most cases deserting their own palaces, or forsaking their own place in the world—a centre and home of the heart, where they met constantly, the residents ever ready to receive, not only their closer associates, but all the society of Roman ladies, who might be attracted by the higher aspirations of intellect and piety. Not a stone exists of that noble mansion now, but it is supposed to have stood close to the existing church of Sta. Sabina, an unrivalled mount of vision. From that mount now covered with so many ruins the ladies looked out upon the yet unbroken splendour of the city, Tiber far below sweeping round under the walls. Palatinus, with the "white roofs" of that home to which Horatius looked before he plunged into the yellow river, still stood intact at their right hand: and, older far, and longer surviving, the wealth of nature, the glory of the Roman sky and air, the white-blossomed daphne and the starry myrtle, and those roses which are as ancient inhabitants of the world as any we know flinging their glories about the marble balustrades and making the terraces sweet. There would they walk and talk, the recluses at ease and simple in their brown gowns, the great ladies uneasy under the weight of their toilettes, but all eager to hear, to tell, to read the last letter from the East, from the desert or the cloister, to exchange their experiences and plan their charities. There is nothing ascetic in the picture, which is a very different one from that of those austere solitudes of the desert, which had suggested and inspired it—the lady Paula tottering in, with a servant on either side to conduct her to the nearest couch, and young Blæsilla making a brilliant irruption in all her bravery, with her jewels sparkling and her transparent veil floating, and her golden heels tapping upon the marble floor. This is not how we understand the atmosphere of a convent; yet, if fact were taken into due consideration, the greatest convents have been very like it, in all ages—the finest ladies having always loved that intercourse and contrast, half envious of the peace of their cloistered sisters, half pleased to dazzle them with a splendour which never could be theirs.

"No fixed rule," says Thierry, in his Life of St. Jerome, "existed in this assembly, where there was so much individuality, and where monastic life was not even attempted. They read the Holy Scriptures together, sang psalms, organised good works, discussed the condition of the Church, the progress of spiritual life in Italy and in the provinces, and kept up a correspondence with the brothers and sisters outside of a more strictly monastic character. Those of the associates who carried on the ordinary life of the world came from time to time to refresh their spirits in these holy meetings, then returned to their families. Those who were free gave themselves up to devotional exercises, according to their taste and inclination, and Marcella retired into her desert. In a short time these exercises were varied by the pursuit of knowledge. All Roman ladies of rank knew a little Greek, if only to be able to say to their favourites, according to the mot of Juvenal, repeated by a father of the Church, Ζωὴ καὶ ψυχὴ, my life and my soul: the Christian ladies studied it better and with a higher motive. Several later versions of the Old and New Testament were in general circulation in Italy, differing considerably from each other, and this very difference interested anxious minds in referring to the original Greek for the Gospels, and for the Hebrew books to the Greek of the Septuagint, the favourite guide of Western translators. The Christian ladies accordingly set themselves to perfect their knowledge of Greek, and many, among whom were Marcella and Paula, added the Hebrew language, in order that they might sing the psalms in the very words of the prophet-king. Marcella even became, by intelligent comparison of the texts, so strong in exegetical knowledge that she was often consulted by the priests themselves."

It was about the year 380 that this establishment was formed. "The desert of Marcella" above referred to was, as the reader will remember, a great garden in a suburb of Rome, which she had pleased herself by allowing to run wild, and where occasionally this great Roman lady played at a hermit's life in solitude and abstinence. Paula's desert, perhaps not so easy a one, was in her own house, where, besides the three daughters already mentioned, she had a younger girl Rufina, not yet of an age to show any marked tendencies, and a small boy Toxotius, her only son, who was jealously looked after by his pagan relatives, to keep him from being swept away by this tide of Christianity.

ON THE PALATINE.

Such was the condition of the circle on the Aventine, when a great event happened in Rome. Following many struggles and disasters in the East, chiefly the continually recurring misfortune of a breach of unity, a diocese here and there exhibiting its freedom by choosing two bishops representing different parties at the same time, and thus calling for the exercise of some central authority—Pope Damasus had called a council in Rome. He was so well qualified to be a judge in such cases that he had himself won his see at the point of the sword, after a stoutly contested fight in which much blood was shed, and the church of S. Lorenzo, the scene of the struggle, was besieged and taken like a castle. If he had hoped by this means to establish the universal authority of his see, a pretension as yet undeveloped, it was immediately forestalled by the Bishop of Constantinople, who at once called together a rival council in that place. The Council of Rome, however, is of so much more importance to us that it called into full light in the Western world the great and remarkable figure of Jerome: and still more to our record of the Roman ladies of the Aventine, since it suddenly introduced to them the man whose name is for ever connected with theirs, who is supposed erroneously, as the reader will see, to have been the founder of their community, but who henceforward became its most trusted leader and guide in the spiritual life.

THE WALLS BY ST. JOHN LATERAN.

CHAPTER III.

MELANIA.

It may be well, however, before continuing this narrative to tell the story of another Roman lady, not of their band, nor in any harmony with them, which had already echoed through the Christian world, a wild romance of enthusiasm and adventure in which the breach of all the decorums of life was no less remarkable than the abandonment of its duties. Some ten years before the formation of Marcella's religious household (the dates are of the last uncertainty) a young lady of Rome, of Spanish origin, rich and noble and of the highest existing rank, found herself suddenly left in the beginning of a splendid and happy life, in desolation and bereavement. Her husband, whose name is unrecorded, died early leaving her with three little children, and shortly after, while yet unrecovered from this crushing blow, another came upon her in the death of her two eldest children, one following the other. The young woman, only twenty-three, thus terribly stricken, seems to have been roused into a fever of excitement and passion by a series of disasters enough to crush any spirit. It is recorded of her that she neither wept nor tore her hair, but advancing towards the crucifix with her arms extended, her head high, her eyes tearless, and something like a smile upon her lips, thanked God who had now delivered her from all ties and left her free to serve Himself. Whether she had previously entertained this desire, or whether it was only the despair of the distracted mother which expressed itself in such words, we are not told. In the haste and restlessness of her anguish she arranged everything for a great funeral, and placing the three corpses on one bier followed them to Rome to the family mausoleum alone, holding her infant son, the only thing left to her, in her arms. The populace of Rome, eager for any public show, had crowded upon the course of many a triumph, and watched many a high-placed Cæsar return in victory to the applauding city, but never had seen such a triumphal procession as this, Death the Conqueror leading his captives. We are not told whether it was attended by the overflowing charities, extravagant doles and offerings to the poor with which other mourners attempted to assuage their grief, or whether Melania's splendour and solitude of mourning was unsoftened by any ministrations of charity; but the latter is more in accordance with the extraordinary fury and passion of grief, as of a woman injured and outraged by heaven to which she thus called the attention of the spheres.

The impression made by that funeral splendour and by the sight of the young woman following tearless and despairing with her one remaining infant in her arms, had not faded from the minds of the spectators when it was rumoured through Rome that Melania had abandoned her one remaining tie to life and gone forth into the outside world no one knew where, leaving her child so entirely without any arrangement for its welfare that the official charged with the care of orphans had to select a guardian for this son of senators and consuls as if he had been a nameless foundling. What bitterness of soul lay underneath such an incomprehensible desertion, who could say? It might be a sense of doom such as overwhelms some sensitive minds, as if everything belonging to them were fated and nothing left them but the tragic expedient of Hagar in the desert, "Let me not see the child die." Perhaps the courage of the heartbroken young woman sank before the struggle with pagan relations, who would leave no stone unturned to bring up this last scion of the family in the faith or no-faith of his ancestors; perhaps she was in reality devoid of those maternal instincts which make the child set upon the knee the best comforter of the woman to whom they have brought home her warrior dead. This was the explanation given by the world which tore the unhappy Melania to pieces and held her up to universal indignation. Not even the Christians already touched with the enthusiasm and passion of the pilgrim and ascetic could justify the sudden and mysterious disappearance of a woman who still had so strong a natural bond to keep her in her home. But whatever the character of Melania might be, whether destitute of tenderness, or only distracted by grief and bereavement, and hastening to take her fatal shadow away from the cradle of her child, she was at least invulnerable to any argument or persuasion. "God will take care of him better than I can," she said as she left the infant to his fate. It was probably a better one than had he been the charge of this apparently friendless young woman, with her pagan relations, her uncompromising enthusiasm and self-will, and with all the risks surrounding her feet which made the path of a young widow in Rome so full of danger; but it is fortunate for the world that few mothers are capable of counting those risks or of turning their backs upon a duty which is usually their best consolation.

There is, however, an interest in the character and proceedings of such an exceptional woman which has always excited the world, and which the thoughtful spectator will scarcely dismiss with the common imputation of simple heartlessness and want of feeling. Melania was a proud patrician notwithstanding that she flung from her every trace of earthly rank or wealth, and a high-spirited, high-tempered individual notwithstanding her subsequent plunge into the most self-abasing ministrations of charity. And these features of character were not altered by her sudden renunciation of all things. She went forth a masterful personage determined, though no doubt unconsciously, to sway all circumstances to her will, though in the utmost self-denial and with all the appearances and surroundings of humility. This is a paradox which meets us on every side, in the records of such world-abandonment as are familiar in every history of the beginnings of the monastic system, in which continually both men and women give up all things while giving up nothing, and carry their individual will and way through circumstances which seem to preclude the exercise of either.

The disappearance of Melania made a great sensation in Rome, and no doubt discouraged Christian zeal and woke doubts in many minds even while proving to others the height of sacrifice which could be made for the faith. On the other hand the adversary had boundless occasion to blaspheme and denounce the doctrines which, as he had some warrant for saying, thus struck at the very basis of society and weakened every bond of nature. What more dreadful influence could be than one which made a woman forsake her child, the infant whom she had carried in her arms to the great funeral, in the sight of all Rome, the son of her sorrow? Nobody except a hot-headed enthusiast could take her part even among her fellow-Christians, nor does it appear that she sought any support or made any apology for herself. Jerome, then a young student and scholar from the East, was in Rome, in obscurity, still a catechumen preparing for his baptism, at the time of Melania's flight; and though there is no proof that he was even known to her, and no probability that so unknown a person could have anything to do with her resolution, or could have influenced her mind, it was suggested in later times when he was well known, that probably he had much to do—who can tell if not the most powerful and guilty of motives?—in determining her flight. Such a vulgar explanation is always adapted to the humour of the crowd, and gives an easy solution of the problems which are otherwise so difficult to solve. As a matter of fact these two personages, not unlike each other in force and spirit, had much to do with each other, though mostly in a hostile sense, in the after part of their life.

We find Melania again in Egypt, to which presumably she at once directed her flight as the headquarters of austere devotion and self-sacrifice, on leaving Rome—alone so far as appears. This was in the year 372 (nothing can be more delightful than to encounter from time to time a date, like an angel, in the vague wilderness of letters and narratives), when Athanasius the great Bishop was near his end. The young fugitive, whose arrival in Alexandria would not be attended by such mystery as shrouded her departure from Rome, was received kindly by the dying saint, to whom she had probably been known in her better days, and who in his enthusiasm for the life of monastic privation and sacrifice probably considered her flight and her resolution alike inspired by heaven. He gave her, let us hope, his blessing, and much good counsel—in addition to the sacred sheepskin which had formed the sole garment of the holy Macarius in his cell in the desert, which she carried away with her as her most valued possession. The great Roman lady then pursued her way into the wilderness, which was indeed a wilderness rather in name than in fact, being peopled on every side by communities both of men and women, while in every rocky fissure and cavern were hermits jealously shut each in his hole, the more inaccessible the better. Nothing can be more contradictory than the terms used. This desert of solitaries gave forth the evening hymn over all its extent as if the very sands and rocks sang, so many were the unseen worshippers. And the traveller went into the wilderness alone so to speak, in the utmost self-abnegation and humility, yet attended by an endless retinue of servants whose attendance was indispensable, if only to convey and protect the store of provisions and presents which she carried with her.

The conception of a lonely figure on the edge of a trackless sandy waste facing all perils, and encountering perhaps after toilsome days of solitude a still more lonely anchorite in his cell, to give her the hospitality of a handful of peas, and a shrine of prayer, which is the natural picture which rises before us—changes greatly when the details are examined. Melania evidently travelled with a great caravanserai, with camels laden with grain and every kind of provision that was necessary to sustain life in those regions. The times were more troublous even than usual. The death of Athanasius was the signal for one of those outbursts of persecution which rent the Christian world in its very earliest ages, and which alas! the Church herself has never been slow to learn the use of. The underground or overground population of the Egyptian desert was orthodox; the powers that were, were Arian; and hermits and cœnobites alike were hunted out of their refuges and dragged before tribunals, where their case was decided before it was heard and every ferocity used against them. In a country so rent by the most violent of agitations Melania passed like an angel of charity. She became the providence of the hunted and suffering monks. She is said for a short period to have provided for five thousand in Nitria, which proves that however secret her disappearance from Rome had been, her address as we should say must have been well known to her bankers, or their equivalent. Thus it is evident that a robe of sackcloth need not necessarily imply poverty, much less humility, and that a woman may ride about on the most sorry horse (chosen it would seem because it was a more abject thing than the well-conditioned ass of the East) and yet demean herself like a princess.

There is one story told of this primitive Lady Bountiful by Palladius which if it did not recall the action of St. Paul in somewhat similar circumstances would be highly picturesque. The proconsul in Palestine, not at all aware who was the pestilent woman who persisted in supplying and defending the population of the religious which it was his mission to get rid of—even going so far as to visit and nourish them in his prisons—had her arrested to answer for her interference. There is nothing more likely than that Melania remembered the method adopted by St. Paul to bring his judges to his feet. She sent the consul a message in which a certain compassionate scorn mingles with pride. "You esteem me by my present dress," she said, "which it is quite in my power to change when I will. Take care lest you bring yourself into trouble by what you do in your ignorance." This incident happened at Cæsarea, the great city on the Mediterranean shore which Herod had built, and where the prodigious ruins still lie in sombre grandeur capable of restoration to the uses of life. The governor of the Syrian city trembled in his gilded chair. The names which Melania quoted were enough to unseat him half a dozen times over, though, truth to tell, they are not very clearly revealed to the distant student. He hastened to set free the sunburnt pilgrim in her brown gown, and leave her to her own devices. "One must answer a fool according to his folly," she said disdainfully, as she accepted her freedom. This lady's progress through the haunted deserts, her entrance into town after town, with the shield of rank ready for use in any emergency, attended by continual supplies from the stewards of her estates, and the power of shedding abundance round her wherever she went, could hardly be said to merit the rewards of privation and austerity even if her delicate feet were encased in rude sandals and the cloth of gold replaced by a tunic of rough wool.

COLOSSEUM BY MOONLIGHT.

To face page 36.

Melania had been, presumably for some time before this incident, accompanied by a priest named Rufinus, a fellow-countryman, schoolfellow and dear friend of Jerome, the future Father of the Church, at this period a young religious adventurer if we may use the word:—which indeed seems the only description applicable to the bands of young, devout enthusiasts, who roamed about the world, not bound to any special duties, supporting themselves one knows not how, aiming at one knows not what, except some devotion of mystical religious life, or indefinite Christian service to the world. The object of saving their souls was perhaps for most the prevailing object, and the greater part of them had at least passed a year or two in those Eastern deserts where renunciation of the world had been pushed to its furthest possibilities. But they were also hungry for learning, for knowledge, for disciples, and full of that activity of youth which is bound to go everywhere and see everything whether with possible means and motives or not. Whatever they were, they were not so far as can be made out missionaries in any sense of the word. They were received wherever they went, in devout households here and there, in any of the early essays at monasteries which existed by bounty and Christian charity, among the abounding dependents of great houses, or by the bishop or other ecclesiastical

functionary. They were this man's secretary, that man's tutor—seldom so far as we can see were they employed as chaplains. Rufinus indeed was a priest, but few of the others were so, Jerome himself only having consented to be ordained from courtesy, and in no way fulfilling the duties of the priesthood. There were, however, many offices no doubt appropriate to them in the household of a bishop, who was often the distributor of great charities and the administrator of great possessions. But it is evident that there were always a number of these scholar-student monks available to join any travelling party, to serve their patron with their knowledge of the desert and their general experience of the ways of the world. "To lead about a sister":—St. Paul perhaps had already in his time some knowledge of the usefulness of such a functionary, and of the perfectly legitimate character of his office. Rufinus joined Melania in this way, to all appearance as the other head of the expedition, on perfectly equal terms, though it was her purse which supplied everything necessary. Jerome himself (with a train of brethren behind him) travelled in the same way with Paula—Oceanus with Fabiola. Nothing could be more completely in accordance with the fashion of the time. Perhaps the young men provided for their own expenses as we say, but the caravan was the lady's and all the immense and indiscriminate charity which flowed from it.

It is not necessary for us to follow the career of Rufinus any more than we intend to follow that of Jerome, into the violent controversy which is the chief link which connects their names, or indeed in any way except that of their association with the women of our tale. Rufinus was a Dalmatian from the shores of the Adriatic, learned enough according to the fashion of his time, though not such a scholar as Jerome, and apt to despise those elegances of literature which he was incapable of appreciating. He too, no doubt, like Jerome, had some following of other men like himself, ready for any adventure, and glad to make themselves the almoners of Melania and form a portion of her train. It is a strange conjunction according to our modern ideas, and no doubt there were vague and flying slanders, such as exist in all ages, accounting for anything that is unusual or mysterious by the worse reasons. But it must be remembered that such partnerships were habitual in those days, permitted by the usage of a time of which absolute purity was the craze and monomania, if we may so speak, as well as the ideal: and also that the solitude of those pilgrims was at all times that of a crowd—the supposed fugitive flying forth alone being in reality, as has been explained already, accompanied on every stage of the way by attendants enough to fill her ship and form her caravan wherever she went.