автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Ruthless Rhymes for Heartless Homes

Ruthless Rhymes for Heartless Homes

By

Col. D. Streamer (Harry Graham)

"I was unlucky with my wives,

So are the most of married men;

Undoubtedly they lost their lives,—"

RUTHLESS

RHYMES for

Heartless Homes

By Col. D. Streamer

New York

R. H. RUSSELL

1902

Copyright, 1901, by Robert Howard Russell

Second impression, December, 1902

Dedicated to P. P.

("Qui connait son sourire a connu le parfait.")

I NEED no Comments of the Press,

No critic's cursory caress,

No paragraphs my book to bless

With praise, or ban with curses,

So long as You, for whom I write,

Whose single notice I invite,

Are still sufficiently polite

To smile upon my verses.

If You should seek for Ruthless Rhymes

(In memory of Western climes),

And, for the sake of olden times,

Obtain this new edition,

You must not be surprised a bit,

Nor even deem the act unfit,

That I have dedicated it

To You, without permission.

P. T. O.[1]

And if You chance to ask me why,

It is sufficient, I reply,

That You are You, and I am I,—

To put the matter briefly.

That I should dedicate to You

Can only interest us two;

The fact remains, then, that I do,

Because I want to—chiefly.

And if these verses can beguile

From those grey eyes of yours a smile,

You will have made it well worth while

To seek your approbation;

No further meed

Of praise they need,

But must succeed,

And do indeed,

If they but lead

You on to read

Beyond the Dedication.

1901. H. G.

Author's Preface

WITH guilty, conscience-stricken tears

I offer up these rhymes of mine

To children of maturer years

(From Seventeen to Ninety-nine).

A special solace may they be

In days of second infancy.

The frenzied mother who observes

This volume in her offspring's hand,

And trembles for the darling's nerves,

Must please to clearly understand,

If baby suffers by-and-bye

The Artist is to blame, not I!

But should the little brat survive,

And fatten on the Ruthless Rhyme,

To raise a Heartless Home and thrive

Through a successful life of crime,

The Artist hopes that you will see

That I am to be thanked, not he!

P. T. O.[1]

Fond parent, you whose children are

Of tender age (from two to eight),

Pray keep this little volume far

From reach of such, and relegate

My verses to an upper shelf,—

Where you may study them yourself.

FOOTNOTE:

[1] Transcriber's Note: P.T.O. means please turn over. This is retained in the text although the instruction is not necessary.

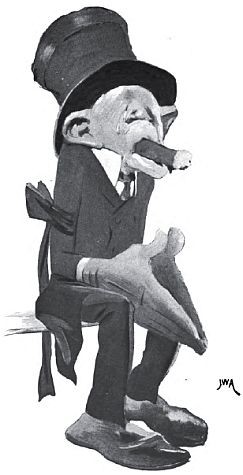

"He had such good cigars."

Uncle Joe

AN Angel bore dear Uncle Joe

To rest beyond the stars.

I miss him, oh! I miss him so,—

He had such good cigars.

Impetuous Samuel

SAM had spirits naught could check,

And to-day, at breakfast, he

Broke his baby sister's neck,

So he shan't have jam for tea!

Inconsiderate Hannah

NAUGHTY little Hannah said

She could make her grandma whistle,

So, that night, inside her bed

Placed some nettles and a thistle.

Though dear grandma quite infirm is,

Heartless Hannah watched her settle,

With her poor old epidermis

Resting up against a nettle.

Suddenly she reached the thistle!

My! you should have heard her whistle!

. . . . . . .

A successful plan was Hannah's,

But I cannot praise her manners.

Aunt Eliza

IN the drinking-well

(Which the plumber built her)

Aunt Eliza fell,—

We must buy a filter.

Self-Sacrifice

FATHER, chancing to chastise

His indignant daughter Sue,

Said, "I hope you realize

That this hurts me more than you."

Susan straightway ceased to roar.

"If that's really true," said she,

"I can stand a good deal more;

Pray go on, and don't mind me."

La Course Interrompue

I.

JEAN qui allait a Dijon

(Il montait en bicyclette)

Rencontra un gros lion

Qui se faisait la toilette.

II.

Voila Jean qui tombe a terre

Et le lion le digère!

. . . . .

Mon Dieu! Que c'est embêtant!

Il me devait quatre francs.

"John had on some clothes of mine;

I can almost see them shrinking

Washed repeatedly in brine."

John

JOHN, across the broad Atlantic,

Tried to navigate a barque,

But he met an unromantic

And extremely hungry shark.

John (I blame his childhood's teachers)

Thought to treat this as a lark,

Ignorant of how these creatures

Do delight to bite a barque.

Said "This animal's a bore!" and,

With a scornful sort of grin,

Handled an adjacent oar and

Chucked it underneath the chin.

At this unexpected juncture

Which he had not reckoned on,

Mr. Shark he made a puncture

In the barque—and then in John.

Sad am I, and sore at thinking

John had on some clothes of mine;

I can almost see them shrinking,

Washed repeatedly in brine.

I shall never cease regretting

That I lent my hat to him,

For I fear a thorough wetting

Cannot well improve the brim.

Oh! to know a shark is browsing,

Boldly, blandly on my boots!

Coldly, cruelly carousing

On the choicest of my suits!

Creatures I regard with loathing

Who can calmly take their fill

Of one's Jæger underclothing:—

Down, my aching heart, be still!

The Fond Father

OF Baby I was very fond,

She'd won her father's heart;

So, when she fell into the pond,

It gave me quite a start.

Necessity

LATE last night I slew my wife,

Stretched her on the parquet flooring;

I was loath to take her life,

But I had to stop her snoring.

Unselfishness

ALL those who see my children say,

"What sweet, what kind, what charming elves!"

They are so thoughtful, too, for they

Are always thinking of themselves.

It must be ages since I ceased

To wonder which I liked the least.

Such is their generosity,

That, when the roof began to fall,

They would not share the risk with me,

But said, "No, father, take it all!"

Yet I should love them more, I know,

If I did not dislike them so.

Scorching John

JOHN, who rode his Dunlop tire

O'er the head of sweet Maria,

When she writhed in frightful pain,

Had to blow it out again.

Misfortunes Never Come Singly

MAKING toast at the fireside,

Nurse fell in the grate and died;

And, what makes it ten times worse,

All the toast was burned with nurse.

The Perils of Obesity

YESTERDAY my gun exploded

When I thought it wasn't loaded;

Near my wife I pressed the trigger,

Chipped a fragment off her figure;

'Course I'm sorry, and all that,

But she shouldn't be so fat.

"Now, although the room grows chilly,

I haven't the heart to poke poor Billy."

Tender-Heartedness

BILLY, in one of his nice new sashes,

Fell in the fire and was burnt to ashes;

Now, although the room grows chilly,

I haven't the heart to poke poor Billy.

Jim; or, the Deferred Luncheon Party

WHEN the line he tried to cross,

The express ran into Jim;

Bitterly I mourn his loss—

I was to have lunched with him.

Appreciation

AUNTIE, did you feel no pain

Falling from that apple tree?

Will you do it, please, again?

'Cos my friend here didn't see.

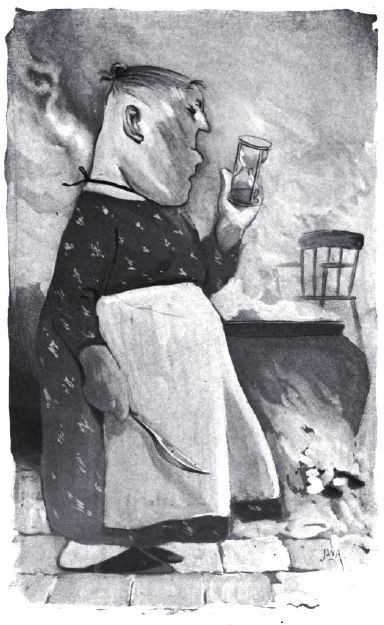

Baby

BABY in the caldron fell,—

See the grief on Mother's brow;

Mother loved her darling well,—

Darling's quite hard-boiled by now.

"Darling's quite hard-boiled by now."

Nurse's Mistake

NURSE, who peppered baby's face

(She mistook it for a muffin),

Held her tongue and kept her place,

"Laying low and sayin' nuffin'";

Mother, seeing baby blinded,

Said, "Oh, nurse, how absent-minded!"

The Stern Parent

FATHER heard his Children scream,

So he threw them in the stream,

Saying, as he drowned the third,

"Children should be seen, not heard!"

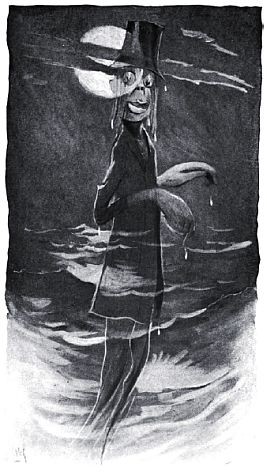

"Bluebeard"

YES, I am Bluebeard, and my name

Is one that children cannot stand;

Yet once I used to be so tame

I'd eat out of a person's hand;

So gentle was I wont to be

A Curate might have played with me.

People accord me little praise,

Yet I am not the least alarming;

I can recall, in bygone days,

A maid once said she thought me charming.

She was my friend,—no more I vow,—

And—she's in an asylum now.

Girls used to clamour for my hand,

Girls I refused in simple dozens;

I said I'd be their brother, and

They promised they would be my cousins.

(One, I accepted,—more or less—

But I've forgotten her address.)

They worried me like anything

By their proposals ev'ry day,

Until at last I had to ring

The bell, and have them cleared away;

(I often pondered on the cost

Of getting them completely lost.)

To share my somewhat lofty rank

Was what they panted for, like mad;

You see my balance at the bank

Was not so small, and, I may add,

A Castle, Gothic and immense,

Is my Official Residence.

It overlooks a many a mile

Of park, of gardens and domains;

I'm staying now in lodgings, while

They're doing up the—well—the drains,—

For they began to give offence

At my Official Residence.

And, when I entertain at home,

I hardly ever fail to please,

The "upper tens" alone may come

To join in my "recherché" teas;

I am a King in ev'ry sense

At my Official Residence.

My dances, on a parquet floor,

My royal dinners, which consist

Of fifteen courses, sometimes more,

Are things that are not lightly missed;

In fact I do not spare expense

At my Official Residence.

My hospitality to those

Whom I invite to come and stay

Is famed; my wine like water flows,

Exactly like, some people say,

But this is mere impertinence

At my Official Residence.

When through the streets I walk about

My subjects stand and kiss their hands,

Raise a refined metallic shout,

Wave flags and warble tunes on bands,

While bunting hangs on ev'ry front,—

With my commands to let it bunt.

When I come home again, of course,

Retainers are employed to cheer,

My paid domestics get quite hoarse

Acclaiming me, and you can hear

The welkin ringing to the sky,—

Aye, aye, and let it welk, say I!

And yet, in spite of this, there are

Some persons who, at diff'rent times,

—(Because I am so popular)—

Accuse me of most awful crimes;

A girl once said I was a flirt!

Oh my! how the expression hurt!

I never flirted in the least,

Never for very long, I mean,—

Ask any lady (now deceased)

Who partner of my life has been;—

Oh well, of course, sometimes, perhaps,

I meet a girl, like other chaps.

And, if I like her very much,

And if she cares for me a bit,

Where is the harm of look or touch

If neither of us mentions it?

It isn't right, I don't suppose,

But no one's hurt if no one knows!

And, if I placed my hand below

Her chin and raised her face an inch,

And then proceeded—well, you know,—

(Excuse the vulgarism)—to clinch;

It would be wrong without a doubt,

That is, if anyone found out.

But then, remember, Life is short

And Woman's Arts are very long,

And sometimes when one didn't ought

One knowingly commits a wrong;

Well—speaking for myself, of course,

I almost always feel remorse.

One should not break one's self too fast

Of little habits of this sort,

Which may be definitely classed

With gambling or a taste for port;

They should be slowly dropped, until

The Heart is subject to the Will.

I knew a man on Seventh Street

Who, at a very slight expense,

By persevering, was complete-

Ly cured of total abstinence;

An altered life he has begun

And takes a horn with anyone.

I knew another man whose wife

Was an invet'rate suicide,

She daily strove to take her life

And (naturally) nearly died;

But some such system she essayed,

And now she's eighty in the shade.

Ah, the new leaves I try to turn,

But, like so many men in town,

I seem, as with regret I learn,

Merely to turn the corner down;

A habit which I fear, alack!

Makes it more easy to turn back.

I have been criticised a lot;

I venture to enquire what for;

Because, forsooth, I have not got

The instincts of a bachelor!

Just hear my story, you will find

How grossly I have been maligned.

I was unlucky with my wives,

So are the most of married men;

Undoubtedly they lost their lives,—

Of course, but even so, what then?

I loved them dearly, understand,

And I can love, to beat the band.

My first was little Emmeline,

More beautiful than day was she;

Her proud, aristocratic mien

Was what at once attracted me.

I naturally did not know

That I should soon dislike her so.

But there it was! And you'll infer

I had not very long to wait

Before my red-hot love for her

Turned to unutterable hate.

So, when this state of things I found,

I naturally had her drowned.

My next was Sarah, sweet but shy,

And quite inordinately meek;

Yes, even now I wonder why

I had her hanged within the week.

Perhaps I felt a bit upset,

Or else she bored me, I forget.

Then came Evangeline, my third,

And, when I chanced to be away,

She, so I subsequently heard,

Was wont (I deeply grieve to say)

With my small retinue to flirt.

I strangled her. I hope it hurt.

Isabel was, I think, my next,—

(That is, if I remember right)—

And I was really very vexed

To find her hair come off at night;

To falsehood I could not connive,

And so I had her boiled alive.

Then came Sophia, I believe,

Her coiffure was at least her own,

Alas! she fancied to deceive

Her friends by altering its tone.

She dyed her locks a flaming red!

I suffocated her in bed.

Susannah Maud was number six;

But she did not survive a day;

Poor Sue, she had no parlour tricks

And hardly anything to say.

A little strychnine in her tea

Finished her off, and I was free.

Yet I did not despair, and soon!

In spite of failures, started off

Upon my seventh honeymoon

With Jane; but could not stand her cough.

'Twas chronic. Kindness was in vain.

I pushed her underneath the train.

Well, after her, I married Kate.

A most unpleasant woman. Oh!

I caught her at the garden gate

Kissing a man I didn't know;

And, as that didn't suit me quite,

I blew her up with dynamite.

Most married men, so sorely tried

As this, would have been rather bored.

Not I, but chose another bride

And married Ruth. Alas! she snored!

I served her just the same as Kate,

And so she joined the other eight.

My last was Grace; I am not clear,

I think she didn't like me much;

She used to scream when I came near,

And shuddered at my lightest touch.

She seemed to wish to keep aloof,

And so I threw her off the roof.

This is the point I wish to make:—

From all the wives for whom I grieve,

Whose lives I had perforce to take,

Not one complaint did I receive;

And no expense was spared to please

My spouses at their obsequies.

My habits, I would have you know,

Are perfect, as they've always been;

You ask if I am good, and go

To church, and keep my fingers clean?

I do, I mean to say I am,

I have the morals of a lamb.

In my domains there is no sin,

Virtue is rampant all the time,

Since I so thoughtfully brought in

A bill which legalizes crime;

Committing things that are not wrong

Must pall before so very long.

And if what you imagine vice

Is not considered so at all,

Crime doesn't seem the least bit nice,

There's no temptation then to fall;

For half the charm of things we do

Is knowing that we oughtn't to.

Believe me, then, I am not bad,

Though in my youth I had to trek

Because I happened to have had

Some difficulties with a cheque.

What forgery in some might be

Is absentmindedness in me!

I know that I was much abused,

No doubt when I was young and rash,

But I should not have been accused

Of misappropriating cash.

I may have sneaked a silver dish;—

Well, you may search me if you wish!

So, now you see me, more or less,

As I would figure in your thoughts;

A trifle given to excess

And prone perhaps to vice of sorts;

When tempted, rather apt to fall,

But still—a good chap after all!

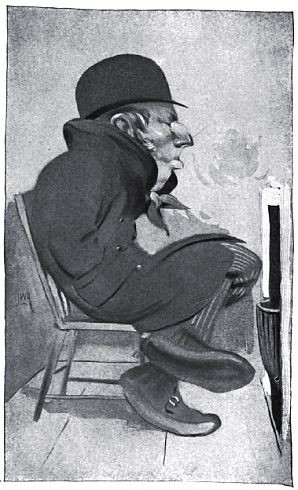

The Cat

(Advice to the Young)

MY children, you should imitate

The harmless, necessary cat,

Who eats whatever's on his plate,

And doesn't even leave the fat;

Who never stays in bed too late,

Or does immoral things like that;

Instead of saying "Shan't!" or "Bosh!"

He'll sit and wash, and wash, and wash!

When shadows fall and lights grow dim

He sits beneath the kitchen stair;

Regardless as to life and limb,

A simple couch he chooses there;

And if you tumble over him,

He simply loves to hear you swear.

And, while bad language you prefer,

He'll sit and purr, and purr, and purr!

The Cat.

The Children's "Don't"

DON'T tell Papa his nose is red

As any rosebud or geranium,

Forbear to eye his hairless head

Or criticise his cootlike cranium;

'Tis years of sorrow and of care

Have made his head come through his hair.

Don't give your endless guinea-pig

(Wherein that animal may build a

Sufficient nest) the Sunday wig

Of poor, dear, dull, deaf Aunt Matilda.

Oh, don't tie strings across her path,

Or empty beetles in her bath!

Don't ask your uncle why he's fat;

Avoid upon his toe-joints treading;

Don't hide a hedgehog in his hat,

Or bury bushes in his bedding.

He will not see the slightest sport

In pepper put into his port!

Don't pull away the cherished chair

On which Mamma intended sitting,

Nor yet prepare her session there

By setting on the seat her knitting;

Pause ere you hurt her spine, I pray—

That is a game that two can play.

My children, never, never steal!

To know their offspring is a thief

Will often make a father feel

Annoyed and cause a mother grief;

So never steal, but, when you do,

Be sure there's no one watching you.

"Don't hide a hedgehog in his hat."

Perhaps you have a turn for what

Is known as "misappropriation,"

Attractions this has doubtless got

For persons of a certain station,

But prevalent 'twill never be

Among the aristocracy.

Of course, suppose you want a thing

(The owner's absent), and you borrow

A ruby ring; you mean to bring

Your friend his trinket back to-morrow

Meanwhile you have the stones reset,

Lest he forget! Lest he forget!

And if some rude detective's hand

Should find beneath your cloak a roll

Of muslin, or a cruet-stand

That's labelled "Hotel Metropole,"

With kindly smile you hand them back,

A harmless Kleptomaniac!

. . . . .

Don't tell a lie! Some men I've known

Commit the most appalling acts,

Because they happen to be prone

To an economy of facts;

And if to lie is bad, no doubt

'Tis even worse to get found out!

. . . . .

Don't take the life of any one,

However horrid he may be;

That sort of thing is never done,

Not in the best society,

Where even parricide is thought

A most unfilial kind of sport.

Among the "Upper Ten" to-day,

It is considered want of tact

To slay one's kith and kin, and may

Be classed as an "unfriendly act."

Oh, yes, of course I know that this

Is merely public prejudice.

"Or empty beetles in her bath!"

But ever since the world began,

Howe'er well meant his motives are,

The man who slays his fellow man

Is never really popular,

Whether he sins from love of crime,

Or merely just to pass the time.

Envoi

SPEED, Ruthless Rhymes; throughout the land

Disperse yourselves with patient zeal!

Go, perch upon the Critic's hand,

Just after he has had a meal.

But should he still unkindly be,

Unperch and hasten back to me.

And, wheresoever you may roam,

Remember the secluded shelf

(Where, sitting in his Heartless Home,

The author chortles to himself),

There, in the distant by-and-bye,

You still may flutter back—to die.

[1] Transcriber's Note: P.T.O. means please turn over. This is retained in the text although the instruction is not necessary.

P. T. O.[1]