автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Christmas Ghost Stories

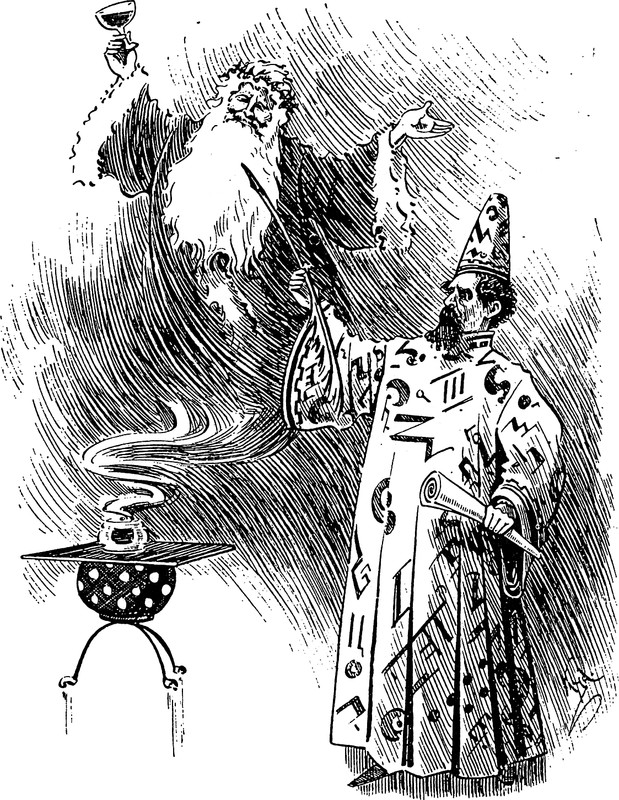

‘Dickens Invoking The Spirit Of Christmas’ – a Victorian cartoon which linked the author’s love of Christmas and ghost stories.

Charles Dickens’

Christmas Ghost Stories

Selected and introduced by

PETER HAINING

For

DAVID & ROSEMARY MIKITKA

May the spirit of Christmas be with us all year round

‘My own mind is perfectly unprejudiced and impressible on the subject of ghosts – I do not in the least pretend that such things cannot be.’

Charles Dickens, 2863

‘Christmas, as Dickens saw it, was a time for ghost stories, and he applied himself like a good journeyman to their manufacture.’

Margaret Lane, 1956

Contents

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Introduction

- 1 Ghosts at Christmas

- 2 The Goblins Who Stole a Sexton

- 3 The Mother’s Eyes

- 4 A Christmas Carol

- 5 The Haunted Man and The Ghost’s Bargain

- 6 The Rapping Spirits

- 7 The Haunted House

- 8 The Goodwood Ghost Story

- 9 The Signal Man

- 10 The Last Words of the Old Year

- Appendix: Ghosts and Ghost-seers

- Copyright

Thefrightenedrailwaymandescribestheghostlyfigurethathauntsthe tunnelnearhissignalbox in The Signal Man

Introduction

Every year, on the Saturday preceding Christmas Day, a nineteenth century coach and four carrying passengers resplendent in clothes of the period clatters through several rural Suffolk villages to the town of Eatanswill. The name of the place is doubtless familiar to readers of Charles Dickens’ classic novel, PickwickPapers. However, only those steeped in the mythology of the famous Victorian writer’s work will be aware that he actually modelled the humorously-named community on the small market town of Sudbury – earlier that century the scene of a corrupt Parliamentary election.

This annual stage coach jaunt of men and women in frock-coats and top-hats, crinolines and bonnets is looked upon by lots of people in the district as a perfect curtain-raiser to Christmas. The journey takes about three hours and includes stops at nine or so hostelries en route to raise money for local charities. It is organized by the members of the local Eatanswill Pickwick Club to ‘keep alive the true Dickensian spirit of Christmas’ – as one passenger told me the year that I joined in the event.

The Eatanswill coach outing did more than provide a nostalgic glimpse of the past for me, however – it also inspired this collection. For I couldn’t help thinking as I watched the coach swirling through a low winter mist that the men and women in their old-fashioned costumes seemed somehow like ghosts, the effect being heightened by the sound of the horses’ hooves echoing eerily as they drove towards Sudbury. Up on top beside the driver sat the figure of Ebenezer Scrooge and I was reminded of A ChristmasCarol, while beside him bounced the portly Mr Pickwick and I thought of the tale he was told about ‘The Goblins Who Stole a Sexton’. They were both Christmas stories, and I knew there were others of the same kind which the imaginative author had written during his prolific career.

By the time I parted company from the stagecoach as it was disappearing into the murk with its passengers, to keep their appointment in Sudbury with a traditional yuletide repast, this anthology was already taking shape in my head. Other ghost stories I had read during my lifelong fascination with the work of Dickens, also set at this time of the year, were flooding back into my mind: the grim novella of TheHauntedManandTheGhost’s Bargain; the mysterious events in TheHauntedHouse; and the chilling drama of TheSignalMan. As a result of these stories, written especially for Christmas publication, Dickens inaugurated a tradition of ghost story telling at this time – in books, on the stage, on radio and on television, which still continues with no sign of abatement.

‘Mr Pickwick slides’– it was Dickens’ description of a white Christmas in the Pickwick Papers which created the popular image of the season.

This is not all that we have Dickens to thank for, because in these stories he also perpetrated the idea of a ‘White Christmas’, now such a staple feature of cards, advertisements and all manner of seasonal material. If you doubt my words, the facts speak for themselves. For snowfalls at Christmas are actually very rare – in the past half century there have been only three occasions in the London area that can be regarded as matching the traditional image.

Although meteorological records of the eighteenth century indicate that a fall of snow at Christmas was generally more commonplace than today, it was Dickens who gave us the image of a countryside buried in snow and ice. The evidence is to be found right in his very first work, PickwickPapers, which contains an entire chapter about a snowbound Christmas at Dingley Dell where walks in the snow and skating on frozen ponds are complemented by enormous meals and story-telling around a roaring fire. It was during one such cosy evening that Pickwick was told the story of the mean-spirited sexton Gabriel Grub and his supernatural encounter on Christmas Eve in an icy churchyard. That this episode of the serial was published in December 1836, coinciding with one of the greatest snowstorms of the century, no doubt emphasized the image in Dickens’ mind as well as in those of his readers. As Robert Cushman wrote pointedly in the Sunday Times on December 24,1989:

Halfway through his first novel, Charles Dickens, by general consent, invented the British Christmas. There it is in the Pickwick Papers, self-proclaimed in the table of contents, ‘A good-humoured Christmas Chapter’. If the author had been running for office as the Santa Claus of English literature, he could hardly have presented more forthright credentials.

Mr Cushman could have gone on to point out that Dickens’ fascination with the spirit of Christmas remained with him throughout his writing career. For apart from the specific Christmas stories which are collected here, the season also features in several of his major works, including Great Expectations– where Mrs Joe’s joyless party contrasts sharply with Pip’s feeding of the grateful Magwitch – and his last, unfinished story, EdwinDrood, in which Jasper’s hideous crime is committed over Christmas.

This point has been well made by the author’s first biographer, John Forster, in his authoritative LifeofDickens (1874).

He had identified himself with Christmas fancies. Its life and spirits, its humour in riotous abundance, of right belonged to him. Its imaginations as well as its kindly thoughts, were his; and its privilege to light up with some sort of comfort of the squalidest places, he had made his own.

If any further proof of his fascination is needed, we have the evidence of his own daughter, Mamie, in her book My Father, As I Recall Him(1897).

Christmas was always a time which in our home was looked forward to with eagerness and delight, and to my father it was a time dearer than any other part of the year, I think. He loved Christmas for its deep significance as well as for its joy. At our holiday frolics he used sometimes to conjure for us, the equally ‘noble art’ of the prestidigitator being among his accomplishments.

(Dickens’ interest in parlour magic was, in fact, cleverly utilized by a late Victorian cartoonist named Kyd in a drawing, ‘Dickens Invoking The Spirit of Christmas’, which is reproduced as the frontispiece to this book.)

Both Forster and Mamie Dickens might have added that it was Dickens who also inextricably linked Christmas with the supernatural. An authority who has made this connection, though, is James Le Fanu, a relative of another of the great Victorian ghost story authors, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu. Writing (appropriately) in a Christmas number of TheTimes for December 28, 1991, James Le Fanu stated that a hundred years ago it had become commonplace for people to meet together at the festive season to tell each other ghost stories because, in the words of Jerome K. Jerome, ‘the close muggy atmosphere of Christmas draws up ghosts like the dampness of the summer rain brings out the frogs and snails.’

And referring specifically to Dickens’ central role in this context, James Le Fanu added;

Readers … could turn to Christmas supplements of weekly magazines such as HouseholdWords, edited by Charles Dickens, which were full of ghosts stories. Dickens’ own ghosts, such as Old Marley in AChristmasCarol, were not so much departed spirits of the dead as vehicles for his sentimental moralising. The contrast between Scrooge’s graceless Christmas Eve and his salvation on Christmas morning celebrates (through the figure of Tiny Tim) the power of innocence to redeem and bless the sinner.

There is certainly no denying that Dickens did moralise in some of his Christmas ghost stories, but he was also capable of describing the spirits of the dead in a wholly convincing way. Indeed, they are still able to produce a shiver up the spine today, as I trust the tales which follow will amply prove. A few notes about these stories may also serve to heighten the reader’s enjoyment of them …

GhostsatChristmas which opens the collection was not actually written by Dickens until 1850, but it expresses his love of the season and of ghost stories which apparently stems right back from his childhood. It seems that in his infancy Dickens was looked after by a teenage nursemaid named Mary Weller who delighted in telling him all kinds of fairytales and ghosts stories with the occasional account of death and murder thrown in for good measure. The youngster sat enraptured at Mary’s ceaseless flow of mystery and mayhem during the most formative years of his life – from five to eleven – so small wonder that he should have grown up with an enduring interest in such subjects, constantly utilizing them in his fiction.

Undoubtedly many of Mary’s stories were told to her young charge during the long, dark evenings of winter. It was probably then, too, that the first ideas for Christmas ghost stories were sown – the same stories for which in time Dickens would become the great proponent. According to G.K.Chesterton in his Criticismsof Dickens (1906), the author also evolved a unique way of combining the two elements.

When real human beings have real delights they tend to express them entirely in grotesques – I might almost say entirely in goblins. On Christmas Eve one may talk about ghosts so long as they are turnip ghosts. One would not be allowed (I hope, in any decent family) to talk on Christmas Eve about astral bodies. The boar’s head of old Yule-time was as grotesque as the donkey’s head of Bottom the Weaver. But there are only one set of goblins quite wild enough to express the wild goodwill of Christmas. Those goblins are the characters of Dickens.

The first of these goblins was, as I mentioned earlier, to be found in the earliest of Dickens’ literary creations, the great Pickwick Papers, published through the winter of 1836, making him the talk of London and a literary lion. It has been argued that because of the demands of writing a weekly serial – which, of course, PickwickPapers initially was – Dickens eased himself through moments of creative crisis by introducing short stories he had already written as a means of keeping the narrative moving. Be that as it may, TheStoryoftheGoblinsWhoStoleaSexton is certainly a highlight of the PickwickPapers as well as being a brilliantly self-contained tale in its own right.

The tale is related to Pickwick by his host at Dingley Dell, Mr Wardle, but has a far greater significance than may at first be appreciated. For in the character of the ‘morose and lonely’ Gabriel Grub – who despises the festive season, chooses to spend Christmas Eve working in a graveyard and abuses some carol singers who wish him the compliments of the season – may be seen the prototype of Ebenezer Scrooge. Even the unearthly figure who appears to Grub and warns him what the future holds unless he changes his ways clearly foreshadows one, at least, of the ghosts who so terrify the central character of AChristmasCarol. (Interestingly, the similarities between the two tales were recently emphasized in a cartoon series for television, GhostStoriesfrom ThePickwickPapers, in which this story was adapted as ‘The Goblin and the Gravedigger’ with the phantom looking for all the world like Marley’s ghost!)

TheplightofdestitutechildrenwasoneoftheinfluencesonDickensinthe creationofhismostfamousghoststory, A Christmas Carol.

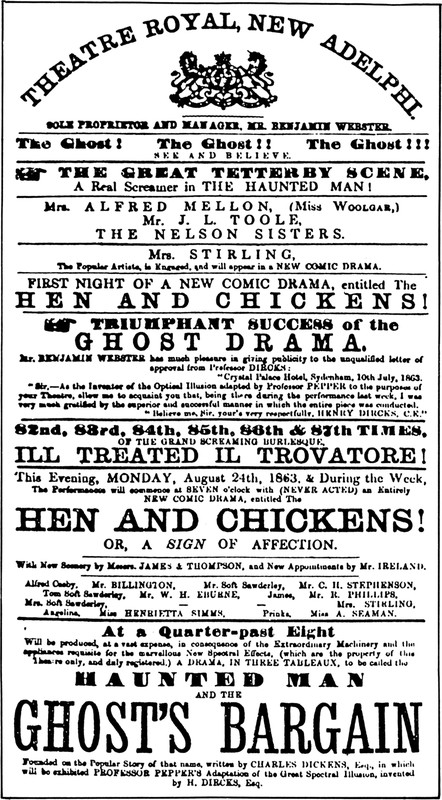

PosterforthefamousLondonproductionof The Haunted Man whichopenedatChristmas1848.

Another story of the supernatural told at Christmas which came from Dickens’ pen before he wrote AChristmasCarol was The Mother’sEyes, an episode related by a character known as the ‘Deaf Man’ in the serial, MasterHumphrey’sClock, published in 1840. Once again we find a story-teller seated beside a roaring Christmas fire relating a grim tale of retribution about a cruel-hearted man who has ill-treated his sister-in-law and her unfortunate son. In the preamble to the story, Dickens can be seen once more evoking the spirit of Christmas and the natural affinity it shares with ghost stories …

There is, of course, not a great deal new that can be written about AChristmasCarol, the tale which ensured Dickens’ place among the immortals of world literature. He apparently got the idea of writing a Christmas story while he was in Manchester in October 1843, visiting a home for destitute children, and found himself confronted by a good deal of humbug, self-seeking and rapacity among some of the local officials. Once the plot for his new story fell into place (and there are also elements of Dickens’ own life to be found in it), he composed the profoundly moving tale in a matter of days. By the end of December his GhostStoryof Christmas, as it was subtitled, was ready for press.

Successive generations have hailed the work as ‘the greatest little book in the world’ and Dickens himself as ‘The Great Apostle of Christmas’. Many believe it to be, quite simply, his greatest work and, certainly, it has had an unparalleled impact on the public consciousness. AChristmasCarol has been translated into virtually every language – including Eskimo and Esperanto – been adapted for films, television and radio programmes, ballets, pantomimes, musicals, parodies, toy theatre and puppet presentations, and even made into a special shorthand version. Scrooge, Bob Cratchit and Tiny Tim are today familiar to people in every country on earth.

The tremendous public reception for AChristmasCarol naturally encouraged Dickens to produce more stories for publication at the same time of the year – four in all. The titles of these ‘Christmas Books’ as they were later to become generically referred to are: TheChimes (1844), TheCricketontheHearth (1845), TheBattleofLife (1846) and TheHauntedManandThe Ghost’sBargain (1848). The sum total of them was to have a profound effect on readers – an effect graphically described by one enthusiastic reader, the novelist Robert Louis Stevenson. He wrote in a letter to a friend, Mrs Stilwell, in September 1874:

I wonder if you have ever read Dickens’ Christmas book? I don’t know that I would recommend you to read them because they are too much perhaps. I have only read two of them yet, and feel so good after them and would do anything; yes, and shall do everything to make it a little better for people. I wish I could lose no time; I want to go out and comfort someone. I shall never listen to the nonsense they tell me about not giving money – I shall give money; not that I haven’t done so always, but I shall do it with a high hand now. Oh, what a jolly thing it is for a man to have written books like these!

It is perhaps not surprising to learn that because of Stevenson’s interest in the supernatural, it was the first and last of these works, AChristmasCarol and TheHauntedManandTheGhost’s Bargain, that he had read. And of all five, only these two are true Christmas ghost stories and therefore eligible for inclusion in this collection.

The idea for TheHauntedMan crept into Dickens’ consciousness in much the same way as AChristmasCarol, according to his first biographer. John Forster recounts in his book how the author told him during the year preceding its publication, ‘I have been dimly conceiving a very ghostly and wild idea which I must now reserve for the next Christmas book.’

This time Dickens created a story about a sad and sombre professor of chemistry named Redlaw who is haunted by a far more malevolent figure than any of those which pursued Scrooge. Pubished on December 19, 1848, TheHauntedMan (as it is often shortened) was enthusiastically greeted by the reading public, and that same month presented on the London stage in an adaptation by Mark Lemon at the Adelphi Theatre.

Lemon, a journalist and playwright who seven years earlier had helped to launch Punch magazine, had received proofs of the story some weeks earlier in order to prepare the dramatization. If this speed of production was not remarkable enough in itself, the fact that the play contained a unique ghostly appearance (acclaimed in much the same way as the special effects in today’s great theatrical extravaganzas like LesMiserables and ThePhantomoftheOpera) certainly was extraordinary! Redlaw was played in the production by the versatile Henry Hughes, with the ghost enacted by the sepulchral O. Smith, who first appeared gliding from the roof and caught the breath of every member of the audience. ‘I well remember the strangely weird effect of the very cleverly-managed first appearance of O. Smith as the ghost,’ Dickens himself wrote later.

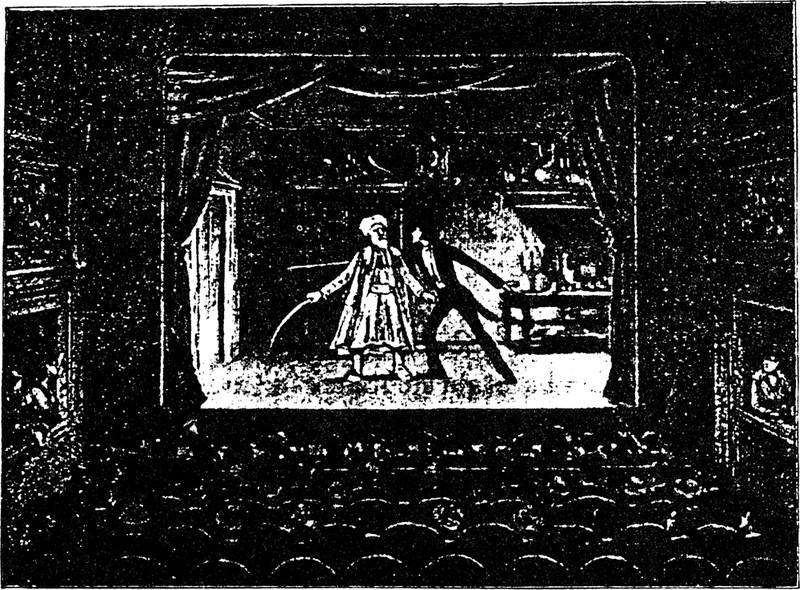

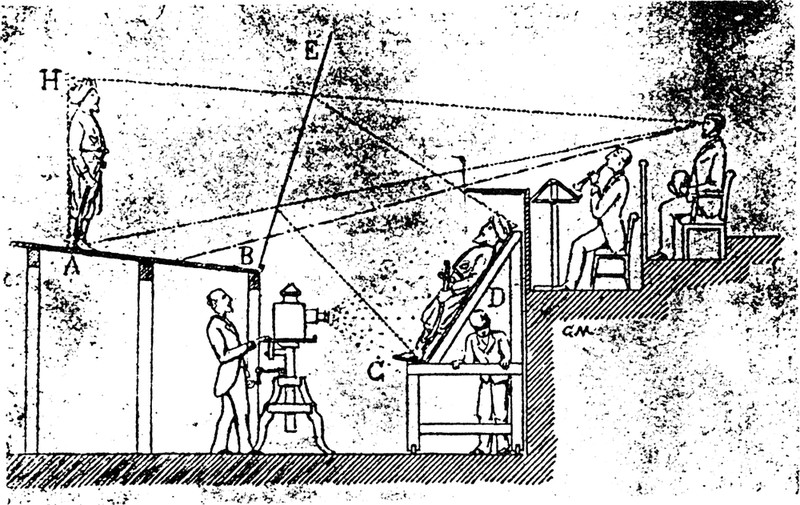

The secret of how the ‘ghost’ materialized by an optical illusion in the 1863 production ofThe Haunted Man.

In June 1863, however, another production of TheHaunted Man at the Adelphi introduced an even more startling illusion which gave the impression of the ghost actually materializing on stage. This, it was later revealed, was achieved by a sheet of glass, invisible to the audience, set at an angle on the stage above a concealed trap. When the ‘ghost’ stood on the trap and was illuminated by a strong light (as the illustrations here show) the eerily realistic figure seemed to be actually on stage confronting the startled Redlaw. The figure could thus seemingly move through tables, chairs and even pieces of scenery with stunning effect, undoubtedly helping to make this one of the longest theatrical runs of the time as theatre-goers clamoured for tickets.

If TheHauntedMan was to be the last of Dickens’ ‘Christmas books’, it was not the last of his Christmas stories. In December 1858 he wrote for HouseholdWords, ‘The Rapping Spirits’ – a satire about the current public interest in Spiritualism and the methods being employed by mediums to contact the spirits of the dead. The story is actually set on Boxing Day and is enlivened by some very pertinent comments about overeating on the previous day!

The following year, to mark the retitling of his magazine as All TheYearRound, Dickens produced TheHauntedHouse, an altogether more substantial work in the style of his earlier Christmas offerings. Writer Margaret Lane, however, commented in a preface to a reprint of the story in 1956;

It is no more genuinely haunted than Borley Rectory (unless, like some of the investigators of Borley, we can seriously accept an ’ooded woman with a howl’ and other capital nonsense) and the spiritualist encountered in the train on the way there provides evidence worthy of the archives of a psychical research society.

TheGoodwoodGhost which follows this has also been extracted from the pages of AllTheYearRound where it appeared anonymously in December 1862. It is, though, the subject of some argument and debate. The story seems quite clearly to fit the pattern of Dickens’ Christmas contributions, but the authorship has been disputed by some experts because of the lack of confirmation of this in the magazine’s records.

However, Ernest Rhys, the Anglo-Welsh editor and poet who became famous as the editor of the EverymanLibraryofClassics, was convinced that TheGoodwoodGhost was the work of Dickens and included it in his superlative anthology, TheHauntersandThe Haunted, published in 1921. I share Mr Rhys’s opinion and have duly reprinted this now rare story herein.

There is also an intriguing mystery about the background to The SignalMan, a story which first appeared in the Christmas Extra number of AllTheYearRound for 1866 – although the argument is not about the authorship. This issue of the magazine was taken up by a series of stories about events concerning a railway line known as Mugby Junction. Dickens’ contribution about a man in charge of a signal box who keeps seeing a strange apparition at the site of a fatal accident, was firmly written in the supernatural tradition for which he was now acknowledged as a master. What intrigued experts was where Dickens had got his idea.

Several railway accidents in the middle years of the nineteenth century have been cited as the inspiration for TheSignalMan, but the most likely one seems to be the crash which occurred on 25 August, 1861 between two excursion trains on the London to Brighton line in the Claydon tunnel, under the South Downs. This collision, which resulted in the death of twenty-three passengers, was later said to have been caused by a misunderstanding between the two signalmen at each end of the deep cutting through which the tunnel ran. They had allowed the trains to proceed along the single line at the same time with a horrifying result.

Reading Dickens’ story, the reader will soon discover elements in it which fit the pattern of the official reports of this tragedy. As it would certainly have come to the attention of Dickens in newspaper reports and concerned an area with which he was familiar, its influence upon the story of TheSignalMan is not difficult to imagine. The tale itself has proved something of a favourite with the media of late, having first been broadcast in a radio version in California by Clarence Roach in 1949. This was followed in 1952 by a London stage presentation entitled DeathontheLine starring Eric Jones-Evans; while most recently a BBC adaptation was screened especially for Christmas 1990 with Denholm Elliott as the fear-wracked signalman.

My final selection, TheLastWordsoftheOldYear, actually appeared in HouseholdWords on 4 January 1851, but as it is a grim and timeless little fable reflecting on the bad events of the previous year and expressing a hope for better things to come in the new, it must surely round off the book as Dickens intended it to do in his magazine.

Towards the end of his life, we know that Dickens became increasingly disillusioned about the commercialization of the Christmas he so loved. As Katherine Carolan wrote in her essay, ‘Dicken’s Last Christmases’ in TheDalhousieReview, Autumn 1972;

The Christmas scenes in GreatExpectations (1861) and the unfinished EdwinDrood (1870) point up how Dickens’ attitudes towards the seasonal festivity had soured in accordance with his growing pessimism over a society which had failed to heed (his) Christmas message of love and communion in contrast with Dingley Dell and the Cratchits.

Her point has also been emphasized by F.J.Brown in his reflections on ‘Those Dickens Christmases’ in TheDickensian (January 1964) when he wrote;

The three main Christmases of the Dickens’s books, at the beginning, zenith and end of his working life, mirror a profound change in the social attitude towards Christmas. The Christmas of PickwickPapers belongs to an age as remote from our own as the mail coaches which rumble through it; the Christmas of Edwin Drood, on the other hand, is as recognisably the ancestor of our own day as is the train that puffs into an unfinished fragment of main line.

Though the magic of all Dickens’ seasonal tales has remained undiminished through the passing years – making them as enjoyable fireside Christmas reading now as they were a hundred years and more ago – their author would surely be even more horrified to see how well-founded his pessimism has proved. With Christmas arriving in the shops before autumn is barely over and the ‘celebrations’ beginning when December is only a few days old, he was right to wonder if anyone had really appreciated what he was trying to say through the medium of his stories.

Perhaps this might explain the recent sightings of a ghost in Tavistock Square where Dickens once lived? According to a report in the DailyTelegraph of 4 January 1977 a figure has been repeatedly seen at BMA House which stands on the site of Tavistock House, once the author’s home. The report continues:

Evidence of the ghost’s presence has been detailed by Ellen Newman, a cockney cleaner who repeatedly saw ‘a veiled figure’ in the library in the early hours of the morning; from Alice Stenning, her predecessor; from Joan Stevenson, a cloakroom attendant, who heard footsteps in the Great Hall but saw no-one; from Shirley Ireland, the BMA housekeeper, who recalled vividly ‘a mysterious swaying of the heavy curtains in the library and an opening of the door’: and from others.

Suggestions have, of course, abounded about the cause of this haunting, some of them rational and some of them supernatural. But on reading the report I could not help wondering if perhaps Dickens himself had decided to return like one of those phantoms in AChristmasCarol, to warn us all of the same fate predicted for Scrooge if he did not mend his ways? In any event, I have no intention of going too close to that neighbourhood on Christmas Eve to find out …

PETER HAINING

February 1992

1 Ghosts at Christmas

I like to come home at Christmas. We all do, or we all should. We ought to come home for a holiday – the longer the better – from the great boarding school where we are for ever working at our arithmetical slates, to take and give a rest.

We travel home across a winter prospect; by low-lying mist grounds, through fens and fogs, up long hills, winding dark as caverns between thick plantations, almost shutting out the sparkling stars; so, out on broad heights, until we stop at last, with sudden silence, at an avenue. The gate bell has a deep, half-awful sound in the frosty air; the gate swings open on its hinges; and, as we drive up to a great house, the glancing lights grow larger in the windows, and the opposing rows of trees seem to fall solemnly back on either side, to give us place. At intervals, all day, a frightened hare has shot across this whitened turf; or the distant clatter of a herd of deer trampling the hard frost has, for the minute, crushed the silence too. Their watchful eyes beneath the fern may be shining now, if we could see them, like the icy dewdrops on the leaves; but they are still, and all is still. And so, the lights growing larger, and the trees falling back before us, and closing up again behind us, as if to forbid retreat, we come to the house.

There is probably a smell of roasted chestnuts and other good comfortable things all the time, for we are telling Winter Stories – Ghost Stories, or more shame for us – round the Christmas fire; and we have never stirred, except to draw a little nearer to it. But, no matter for that. We come to the house, and it is an old house, full of great chimneys where wood is burnt on ancient dogs upon the hearth, and grim portraits (some of them with grim legends, too) lower distrustfully from the oaken panels of the walls. We are a middle-aged nobleman, and we make a generous supper with our host and hostess and their guests – it being Christmas-time, and the old house full of company – and then we go to bed. Our room is a very old room. It is hung with tapestry. We don’t like the portrait of a cavalier in green, over the fire-place. There are great black beams in the ceiling, and there is a great black bedstead, supported at the foot by two great black figures, who seem to have come off a couple of tombs in the old baronial church in the park, for our particular accommodation. But, we are not a superstitious nobleman, and we don’t mind. Well! we dismiss our servant, lock the door, and sit before the fire in our dressing-gown, musing about a great many things. At length we go to bed. Well! we can’t sleep. We toss and tumble, and can’t sleep. The embers on the hearth burn fitfully, and make the room look ghostly. We can’t help peeping out, over the counterpane, at the two black figures and the cavalier – that wicked-looking cavalier in green. In the flickering light they seem to advance and retire: which, though we are not by any means a superstitious nobleman, is not agreeable. Well! we get nervous – more and more nervous. We say, ‘This is very foolish, but we can’t stand this; we’ll pretend to be ill, and knock up somebody.’ Well! we are just going to do it, when the locked door opens, and there comes in a young woman, deadly pale, and with long fair hair, who glides to the fire, and sits down in the chair we have left there, wringing her hands. Then, we notice that her clothes are wet. Our tongue cleaves to the roof of our mouth, and we can’t speak; but, we observe her accurately. Her clothes are wet; her long hair is dabbled with moist mud; she is dressed in the fashion of two hundred years ago; and she has at her girdle a bunch of rusty keys. Well! there she sits, and we can’t even faint, we are in such a state about it. Presently she gets up, and tries all the locks in the room with the rusty keys, which won’t fit one of them; then, she fixes her eyes on the portrait of the cavalier in green, and says, in a low, terrible voice. ‘The stags know it!’ After that, she wrings her hands again, passes the bedside, and goes out at the door. We hurry on our dressing-gown, seize our pistols (we always travel with pistols), and are following, when we find the door locked. We turn the key, look out into the dark gallery; no one there. We wander away, and try to find our servant. Can’t be done. We pace the gallery till daybreak; then return to our deserted room, fall asleep, and are awakened by our servants (nothing ever haunts him) and the shining sun. Well! we make a wretched breakfast, and all the company say we look queer. After breakfast, we go over the house with our host, and then we take him to the portrait of the cavalier in green, and then it all comes out. He was false to a young housekeeper once attached to that family, and famous for her beauty, who drowned herself in a pond, and whose body was discovered, after a long time, because the stags refused to drink the water. Since which, it has been whispered that she traverses the house at midnight (but goes especially to that room, where the cavalier in green was wont to sleep), trying the old locks with the rusty keys. Well! we tell our host of what we have seen, and a shade comes over his features, and he begs it may be hushed up, and so it is. But, it’s all true; and we said so, before we died (we are dead now), to many responsible people.

There is no end to the old houses, with resounding galleries, and dismal state bedchambers, and haunted wings shut up for many years, through which we may ramble, with an agreeable creeping up our back, and encounter any number of ghosts, but (it is worthy of remark perhaps) reducible to a very few general types and classes; for, ghosts have little originality, and ‘walk’ in a beaten track. Thus, it comes to pass that a certain room in a certain old hall, where a certain bad lord, baronet, knight, or gentleman shot himself, has certain planks in the floor from which the blood will not be taken out. You may scrape and scrape, as the present owner has done, or plane and plane, as his father did, or scrub and scrub, as his grandfather did, or burn and burn with strong acids, as his great-grandfather did, but there the blood will still be – no redder and no paler – no more and no less – always just the same. Thus, in such another house there is a haunted door that never will keep open; or another door that never will keep shut; or a haunted sound of a spinning-wheel, or a hammer, or a footstep, or a cry, or a sigh, or a horse’s tramp, or the rattling of a chain. Or else there is a turret clock, which, at the midnight hour, strikes thirteen when the head of the family is going to die; or a shadowy, immovable black carriage which at such a time is always seen by somebody, waiting near the great gates in the stable-yard. Or thus, it came to pass how Lady Mary went to pay a visit at a large wild house in the Scottish Highlands, and, being fatigued with her long journey, retired to bed early, and innocently said, next morning, at the breakfast-table, ‘How odd to have so late a party last night in this remote place, and not to tell me of it before I went to bed!’ Then, every one asked Lady Mary what she meant. Then, Lady Mary replied, ‘Why, all night long, the carriages were driving round and round the terrace, underneath my window!’ Then, the owner of the house turned pale, and so did his Lady, and Charles Macdoodle of Macdoodle signed to Lady Mary to say no more, and everyone was silent. After breakfast, Charles Macdoodle told Lady Mary that it was a tradition in the family that those rumbling carriages on the terrace betokened death. And so it proved, for, two months afterwards, the Lady of the mansion died. And Lady Mary, who was a Maid of Honour at Court, often told this story to the old Queen Charlotte; by this token, that the old King always said, ‘Eh, eh? What, what? Ghosts, ghosts? No such thing, no such thing!’ And never left off saying so until he went to bed.

Ghosts at Christmas – anevocativepictureofaseasonalhauntingfromone oftheleastknownofDickens’ supernaturalstories.

Or, a friend of somebody’s, whom most of us know, when he was a young man at college, had a particular friend, with whom he made the compact that, if it were possible for the Spirit to return to this earth after its separation from the body, he of the twain who first died should reappear to the other. In course of time this compact was forgotten by our friend; the two young men having progressed in life, and taken diverging paths that were wide asunder. But one night, many years afterwards, our friend being in the North of England, and staying for the night in an inn on the Yorkshire Moors, happened to look out of bed; and there, in the moonlight, leaning on a bureau near the window, steadfastly regarding him, saw his old college friend! The appearance being solemnly addressed, replied, in a kind of whisper, but very audibly, ‘Do not come near me. I am dead. I am here to redeem my promise. I come from another world, but may not disclose its secrets!’ Then, the whole form becoming paler, melted, as it were, into the moonlight, and faded away.

Or, there was the daughter of the first occupier of the picturesque Elizabethan house, so famous in our neighbourhood. You have heard about her? No! Why, she went out one summer evening at twilight, when she was a beautiful girl, just seventeen years of age, to gather flowers in the garden; and presently came running, terrified, into the hall to her father, saying, ‘Oh, dear father, I have met myself!’ He took her in his arms, and told her it was fancy, but she said, ‘Oh no! I met myself in the broad walk, and I was pale and gathering withered flowers, and I turned my head, and held them up!’ And, that night, she died; and a picture of her story was begun, though never finished, and they say it is somewhere in the house to this day, with its face to the wall.

Or, the uncle of my brother’s wife was riding home on horseback, one mellow evening at sunset, when, in a green lane close to his own house, he saw a man standing before him, in the very centre of the narrow way. ‘Why does that man in the cloak stand there?’ he thought. ‘Does he want me to ride over him?’ But the figure never moved. He felt a strange sensation at seeing it so still, but slackened his trot and rode forward. When he was so close to it as almost to touch it with his stirrup, his horse shied, and the figure glided up the bank in a curious, unearthly manner – backward, and without seeming to use its feet – and was gone. The uncle of my brother’s wife exclaiming, ‘Good Heaven! It’s my cousin Harry, from Bombay!’ put spurs to his horse, which was suddenly in a profuse sweat, and, wondering at such strange behaviour, dashed round to the front of his house. There, he saw the same figure, just passing in at the long French window of the drawing-room opening on the ground. He threw his bridle to a servant, and hastened in after it. His sister was sitting there alone.

‘Alice, where’s my cousin Harry?’

‘Your cousin Harry, John?’

‘Yes. From Bombay. I met him in the lane just now, and saw him enter here this instant.’

Not a creature had been seen by any one; and in that hour and minute, as it afterwards appeared, this cousin died in India.

Or, it was a certain sensible old maiden lady, who died at ninety-nine, and retained her faculties to the last, who really did see the Orphan Boy; a story which has often been incorrectly told, but of which the real truth is this – because it is, in fact, a story belonging to our family – and she was a connection of our family. When she was about forty years of age, and still an uncommonly fine woman (her lover died young, which was the reason why she never married, though she had many offers), she went to stay at a place in Kent, which her brother, an Indian merchant, had newly bought.

There was a story that this place had once been held in trust by the guardian of a young boy; who was himself the next heir, and who killed the young boy by harsh and cruel treatment. She knew nothing of that. It has been said that there was a cage in her bedroom, in which the guardian used to put the boy. There was no such thing. There was only a closet. She went to bed, made no alarm whatever in the night, and in the morning said composedly to her maid, when she came in, ‘Who is the pretty forlorn-looking child who has been peeping out of that closet all night?’ The maid replied by giving a loud scream, and instantly decamping. She was surprised; but, she was a woman of remarkable strength of mind, and she dressed herself and went downstairs, and closeted herself with her brother. ‘Now, Walter,’ she said, ‘I have been disturbed all night by a pretty, forlorn-looking boy, who has been constantly peeping out of that closet in my room, which I can’t open. This is some trick.’

‘I am afraid not, Charlotte,’ said he, ‘for it is the legend of the house. It is the Orphan Boy. What did he do?’

‘He opened the door softly,’ said she, ‘and peeped out. Sometimes, he came a step or two into the room. Then, I called to him, to encourage him, and he shrunk, and shuddered, and crept in again, and shut the door.’

‘The closet has no communication, Charlotte,’ said her brother, ‘with any other part of the house, and it’s nailed up.’

This was undeniably true, and it took two carpenters a whole forenoon to get it open for examination. Then, she was satisfied that she had seen the Orphan Boy. But the wild and terrible part of the story is, that he was also seen by three of her brother’s sons in succession, who all died young. On the occasion of each child being taken ill, he came home in a heat, twelve hours before, and said, Oh, mamma, he had been playing under a particular oak-tree, in a certain meadow, with a strange boy – a pretty, forlorn-looking boy, who was very timid, and made signs! From fatal experience, the parents came to know that this was the Orphan Boy, and that the course of that child whom he chose for his little playmate was surely run.

2 The Goblins Who Stole a Sexton

In an old abbey town, down in this part of the country, a long, long while ago – so long, that the story must be a true one, because our great grandfathers implicitly believed it – there officiated as sexton and grave-digger in the church-yard, one Gabriel Grub. It by no means follows that because a man is a sexton, and constantly surrounded by emblems of mortality, therefore he should be a morose and melancholy man; your undertakers are the merriest fellows in the world, and I once had the honour of being on intimate terms with a mute, who in private life, and off duty, was as comical and jocose a little fellow as ever chirped out a devil-may-care song, without a hitch in his memory, or drained off a good stiff glass of grog without stopping for breath. But not withstanding these precedents to the contrary, Gabriel Grub was an ill-conditioned, cross-grained, surly fellow – a morose and lonely man, who consorted with nobody but himself, and an old wicker bottle which fitted into his large deep waistcoat pocket; and who eyed each merry face as it passed him by, with such a deep scowl of malice and ill-humour, as it was difficult to meet without feeling something the worse for.

A little before twilight one Christmas Eve, Gabriel shouldered his spade, lighted his lantern, and betook himself towards the old church-yard, for he had got a grave to finish by next morning, and feeling very low he thought it might raise his spirits perhaps, if he went on with his work at once. As he wended his way, up the ancient street, he saw the cheerful light of the blazing fires gleam through the old casements, and heard the loud laugh and the cheerful shouts of those who were assembled around them; he marked the bustling preparations for next day’s good cheer, and smelt the numerous savoury odours consequent thereupon, as they steamed up from the kitchen windows in clouds. All this was gall and wormwood to the heart of Gabriel Grub; and as groups of children, bounded out of the houses, tripped across the road, and were met, before they could knock at the opposite door, by half-a-dozen curly-headed little rascals who crowded them as they flocked up stairs to spend the evening in their Christmas games, Gabriel smiled grimly, and clutched the handle of his spade with a firmer grasp, as he thought of measles, scarlet-fever, thrush, hooping-cough, and a good many other sources of consolation beside.

In this happy frame of mind, Gabriel strode along, returning a short, sullen growl to the good-humoured greetings of such of his neighbours as now and then passed him, until he turned into the dark lane which led to the church-yard. Now Gabriel had been looking forward to reaching the dark lane, because it was, generally speaking, a nice gloomy mournful place, into which the townspeople did not much care to go, except in broad daylight, and when the sun was shining; consequently he was not a little indignant to hear a young urchin roaring out some jolly song about a merry Christmas, in this very sanctuary, which had been called Coffin Lane ever since the days of the old abbey, and the time of the shaven-headed monks. As Gabriel walked on, and the voice drew nearer, he found it proceeded from a small boy, who was hurrying along, to join one of the little parties in the old street, and who, partly to keep himself company, and partly to prepare himself for the occasion, was shouting out the song at the highest pitch of his lungs. So Gabriel waited till the boy came up, and then dodged him into a corner, and rapped him over the head with his lantern five or six times, just to teach him to modulate his voice. And as the boy hurried away with his hand to his head, singing quite a different sort of tune, Gabriel Grub chuckled very heartily to himself, and entered the church-yard, locking the gate behind him.

He took off his coat, set down his lantern, and getting into the unfinished grave, worked at it for an hour or so, with right good will. But the earth was hardened with frost, and it was no very easy matter to break it up, and shovel it out; and although there was a moon, it was a very young one, and shed little light upon the grave, which was in the shadow of the church. At any other time, these obstacles would have made Gabriel Grub very moody and miserable, but he was so well pleased with having stopped the small boy’s singing, that he took little heed of the scanty progress he had made, and looked down into the grave when he had finished work for the night, with grim satisfaction, murmuring as he gathering up his things –

Brave lodgings for one, brave lodgings for one,

A few feet of cold earth, when life is done;

A stone at the head, a stone at the feet,

A rich, juicy meal for the worms to eat;

Rank grass over head, and damp clay around,

Brave lodgings for one, these, in holy ground!

‘Ho! ho!’ laughed Gabriel Grub, as he sat himself down on a flat tombstone which was a favourite resting-place of his; and drew forth his wicker bottle. ‘A coffin at Christmas – a Christmas Box. Ho! ho! ho!’

‘Ho! ho! ho!’ repeated a voice which sounded close behind him.

Gabriel paused in some alarm, in the act of raising the wicker bottle to his lips, and looked round. The bottom of the oldest grave about him, was not more still and quiet, than the church-yard in the pale moonlight. The cold hoar frost glistened on the tombstones, and sparkled like rows of gems among the stone carvings of the old church. The snow lay hard and crisp upon the ground, and spread over the thickly-strewn mounds of earth, so white and smooth a cover, that it seemed as if corpses lay there, hidden only by their winding sheets. Not the faintest rustle broke the profound tranquility of the solemn scene. Sound itself appeared to be frozen up, all was so cold and still.

‘It was the echoes,’ said Gabriel Grub, raising the bottle to his lips again.

‘It was not,’ said a deep voice.

Gabriel started up, and stood rooted to the spot with astonishment and terror; for his eyes rested on a form which made his blood run cold.

Seated on an upright tombstone, close to him, was a strange unearthly figure, whom Gabriel felt at once, was no being of this world. His long fantastic legs which might have reached the ground, were cocked up, and crossed after a quaint, fantastic fashion; his sinewy arms were bare, and his hands rested on his knees. On his short round body he wore a close covering, ornamented with small slashes; and a short cloak dangled at his back; the collar was cut into curious peaks, which served the goblin in lieu of ruff or neckerchief; and his shoes curled up at the toes into long points. On his head he wore a broad-brimmed sugar-loaf hat, garnished with a single feather. The hat was covered with the white frost, and the goblin looked as if he had sat on the same tombstone very comfortably, for two or three hundred years. He was sitting perfectly still; his tongue was put out, as if in derision; and he was grinning at Gabriel Grub with such a grin as only a goblin could call up.

‘It was not the echoes,’ said the goblin.

Gabriel Grub was paralysed, and could make no reply.

‘What do you do here on Christmas eve?’ said the goblin sternly.

‘I came to dig a grave, Sir,’ stammered Gabriel Grub.

‘What man wanders among graves and church-yards on such a night as this?’ said the goblin.

‘Gabriel Grub! Gabriel Grub!’ screamed a wild chorus of voices that seemed to fill the church-yard. Gabriel looked fearfully round – nothing was to be seen.

‘What have you got in that bottle?’ said the goblin.

‘Hollands, Sir,’ replied the sexton, trembling more than ever; for he had bought it off the smugglers, and he thought that perhaps his questioner might be in the excise department of the goblins.

‘Who drinks Hollands alone, and in a church-yard, on such a night as this?’ said the goblin.

‘Gabriel Grub! Gabriel Grub!’ exclaimed the wild voices again.

The goblin leered maliciously at the terrified sexton, and then raising his voice, exclaimed –

‘And who, then, is our fair and lawful prize?’

To this inquiry the invisible chorus replied, in a strain that sounded like the voices of many choristers singing to the mighty swell of the old church organ – a strain that seemed borne to the sexton’s ears upon a gentle wind, and to die away as its soft breath passed onward – but the burden of the reply was still the same, ‘Gabriel Grub! Gabriel Grub!’

The goblin grinned a broader grin than before, as he said, ‘Well, Gabriel, what do you say to this?’

The sexton gasped for breath.

‘What do you think of this, Gabriel?’ said the goblin, kicking up his feet in the air on either side the tombstone, and looking at the turned-up points with as much complacency as if he had been contemplating the most fashionable pair of Wellingtons in all Bond Street.

‘It’s – it’s – very curious, Sir,’ replied the sexton, half-dead with fright, ‘very curious, and very pretty, but I think I’ll go back and finish my work, Sir, if you please.’

‘Work!’ said the goblin, ‘what work?’

‘The grave, Sir, making the grave,’ stammered the sexton.

‘Oh, the grave, eh?’ said the goblin, ‘who makes graves at a time when all other men are merry, and takes a pleasure in it?’

Again the mysterious voices replied, ‘Gabriel Grub! Gabriel Grub!’

‘I’m afraid my friends want you, Gabriel,’ said the goblin, thrusting his tongue further into his cheek than ever – and a most astonishing tongue it was – ‘I’m afraid my friends want you, Gabriel,’ said the goblin.

‘Under favour, Sir,’ replied the horror-struck sexton, ‘I don’t think they can, Sir; they don’t know me, Sir; I don’t think the gentlemen have ever seen me, Sir.’

‘Oh yes, they have,’ replied the goblin; ‘we know the man with the sulky face and the grim scowl, that came down the street to-night, throwing his evil looks at the children, and grasping his burying spade the tighter. We know the man that struck the boy in the envious malice of his heart, because the boy could be merry, and he could not. We know him, we know him.’

Here the goblin gave a loud shrill laugh, that the echoes returned twenty-fold, and throwing his legs up in the air, stood upon his head, or rather upon the very point of his sugar-loaf hat, on the narrow edge of the tombstone, from whence he threw a summerset with extraordinary agility, right to the sexton’s feet, at which he planted himself in the attitude in which tailors generally sit upon the shop-board.

‘I – I – am afraid I must leave you, Sir,’ said the sexton, making an effort to move.

‘Leave us!’ said the goblin, ‘Gabriel Grub going to leave us. Ho! ho! ho!’

As the goblin laughed, the sexton observed for one instant a brilliant illumination within the windows of the church, as if the whole building were lighted up; it disappeared, the organ pealed forth a lively air, and whole troops of goblins, the very counterpart of the first one, poured into the church-yard, and began playing at leap-frog with the tombstones, never stopping for an instant to take breath, but overing the highest among them, one after the other, with the most marvellous dexterity. The first goblin was a most astonishing leaper, and none of the others could come near him; even in the extremity of his terror the sexton could not help observing, that while his friends were content to leap over the common-sized gravestones, the first one took the family vaults, iron railing and all, with as much ease as if they had been so many street posts.

At last the game reached to a most exciting pitch; the organ played quicker and quicker, and the goblins leaped faster and faster, coiling themselves up, rolling head over heels upon the ground, and bounding over the tombstones like foot-balls. The sexton’s brain whirled round with the rapidity of the motion he beheld, and his legs reeled beneath him, as the spirits flew before his eyes, when the goblin king suddenly darting towards him, laid his hand upon his collar, and sank with him through the earth.

When Gabriel Grub had had time to fetch his breath, which the rapidity of his descent had for the moment taken away, he found himself in what appeared to be a large cavern, surrounded on all sides by crowds of goblins, ugly and grim; in the centre of the room, on an elevated seat, was stationed his friend of the church-yard; and close beside him stood Gabriel Grub himself, without the power of motion.

‘Cold to-night,’ said the king of the goblins, ‘very cold. A glass of something warm, here.’

At this command, half-a-dozen officious goblins, with a perpetual smile upon their faces, whom Gabriel Grub imagined to be courtiers, on that account, hastily disappeared, and presently returned with a goblet of liquid fire, which they presented to the king.

‘Ah!’ said the goblin, whose cheeks and throat were quite transparent, as he tossed down the flame, ‘This warms one indeed: bring a bumper of the same, for Mr Grub.’

It was in vain for the unfortunate sexton to protest that he was not in the habit of taking anything warm at night; for one of the goblins held him while another poured the blazing liquid down his throat, and the whole assembly screeched with laughter as he coughed and choked, and wiped away the tears which gushed plentifully from his eyes, after swallowing the burning draught.

‘And now,’ said the king, fantastically poking the taper corner of his sugar-loaf hat into the sexton’s eye, and there-by occasioning him the most exquisite pain – ‘And now, show the man of misery and gloom a few of the pictures from our own great storehouse.’

As the goblins said this, a thick cloud which obscured the further end of the cavern, rolled gradually away, and disclosed, apparently at a great distance, a small and scantily furnished, but neat and clean apartment. A crowd of little children were gathered round a bright fire, clinging to their mother’s gown, and gambolling round her chair. The mother occasionally rose, and drew aside the window-curtain as if to look for some expected object; a frugal meal was ready spread upon the table, and an elbow chair was placed near the fire. A knock was heard at the door: the mother opened it, and the children crowded round her, and clapped their hands for joy, as their father entered. He was wet and weary, and shook the snow from his garments, as the children crowded round him, and seizing his cloak, hat, stick, and gloves, with busy zeal, ran with them from the room. Then as he sat down to his meal before the fire, the children climbed about his knee, and the mother sat by his side, and all seemed happiness and comfort.

But a change came upon the view, almost imperceptibly. The scene was altered to a small bedroom, where the fairest and youngest child lay dying; the roses had fled from his cheek, and the light from his eye; and even as the sexton looked upon him with an interest he had never felt or known before, he died. His young brothers and sisters crowded round his little bed, and seized his tiny hand, so cold and heavy; but they shrank back from its touch, and looked with awe on his infant face; for calm and tranquil as it was, and sleeping in rest and peace as the beautiful child seemed to be, they saw that he was dead, and they knew that he was an angel looking down upon, and blessing them, from a bright and happy Heaven.

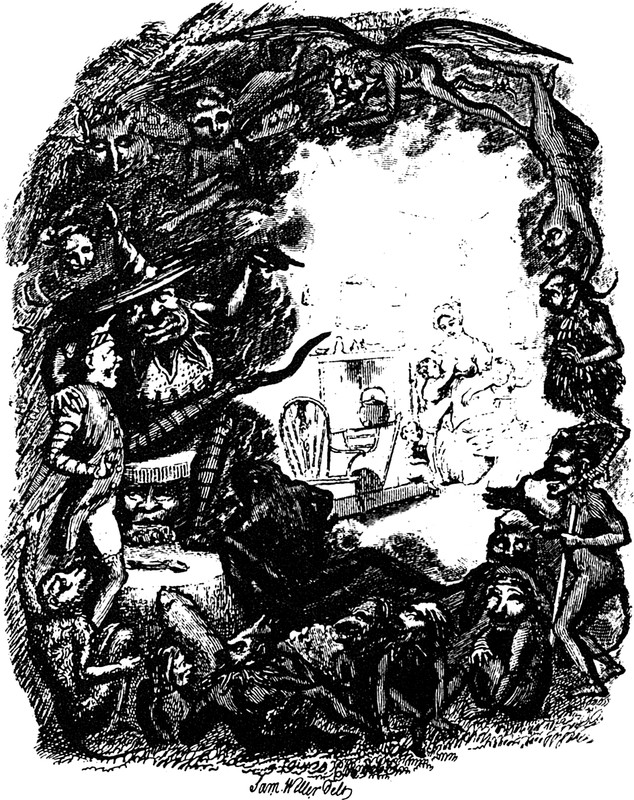

Thegoblinswhorevealthefuturetothemean-spiritedsexton,Gabriel Grub, inTheGoblinsWhoStoleaSexton.

Again the light cloud passed across the picture, and again the subject changed. The father and mother were old and helpless now, and the number of those about them was diminished more than half; but content and cheerfulness sat on every face, and beamed in every eye, as they crowded round the fireside, and told and listened to old stories of earlier and bygone days. Slowly and peacefully the father sank into the grave, and soon after, the sharer of all his cares and troubles followed him to a place of rest and peace. The few, who yet survived them, knelt by their tomb, and watered the green turf which covered it with their tears; then rose and turned away, sadly and mournfully, but not with bitter cries or despairing lamentations, for they knew that they should one day meet again; and once more they mixed with the busy world, and their content and cheerfulness were restored. The cloud settled upon the picture, and concealed it from the sexton’s view.

‘What do you think of that?’ said the goblin, turning his large face towards Gabriel Grub.

Gabriel murmured out something about its being very pretty, and looked somewhat ashamed, as the goblin bent his fiery eyes upon him.

‘You miserable man!’ said the goblin, in a tone of excessive contempt. ‘You!’ He appeared disposed to add more, but indignation choked his utterance, so he lifted up one of his very pliable legs, and flourishing it above his head a little, to insure his aim, administered a good sound kick to Gabriel Grub; immediately after which, all the goblins in waiting crowded round the wretched sexton, and kicked him without mercy, according to the established and invariable custom of courtiers upon earth, who kick whom royalty kicks, and hug whom royalty hugs.

‘Show him some more,’ said the king of the goblins.

At these words the cloud was again dispelled, and a rich and beautiful landscape was disclosed to view – there is just such another to this day, within half-a-mile of the old abbey town. The sun shone from out the clear blue sky, the water sparkled beneath his rays, and the trees looked greener, and the flowers more gay, beneath his cheering influence. The water rippled on, with a pleasant sound, the trees rustled in the light wind that murmured among their leaves, the birds sang upon the boughs, and the lark carolled on high her welcome to the morning. Yes, it was morning, the bright, balmy morning of summer; the minutest leaf, the smallest blade of grass, was instinct with life. The ant crept forth to her daily toil, the butterfly fluttered and basked in the warm rays of the sun; myriads of insects spread their transparent wings, and revelled in their brief but happy existence. Man walked forth, elated with the scene; and all was brightness and splendour.

‘You miserable man!’ said the king of the goblins, in a more contemptuous tone than before. And again the king of the goblins gave his leg a flourish; again it descended on the shoulders of the sexton; and again the attendant goblins imitated the example of their chief.

Many a time the cloud went and came, and many a lesson it taught to Gabriel Grub, who although his shoulders smarted with pain from the frequent applications of the goblins’ feet thereunto, looked on with an interest which nothing could diminish. He saw that men who worked hard, and earned their scanty bread with lives of labour, were cheerful and happy; and that to the most ignorant, the sweet face of nature was a never-failing source of cheerfulness and joy. He saw those who had been delicately nurtured, and tenderly brought up, cheerful under privations, and superior to suffering, that would have crushed many of a rougher grain, because they bore within their own bosoms the materials of happiness, contentment, and peace. He saw that women, the tenderest and most fragile of all God’s creatures, were the oftenest superior to sorrow, adversity, and distress; and he saw that it was because they bore in their own hearts an inexhaustible well-spring of affection and devotedness. Above all, he saw that men like himself, who snarled at the mirth and cheerfulness of others, were the foulest weeds on the fair surface of the earth; and setting all the good of the world against the evil, he came to the conclusion that it was a very decent and respectable sort of world after all. No sooner had he formed it, than the cloud which had closed over the last picture, seemed to settle on his senses, and lull him to repose. One by one, the goblins faded from his sight, and as the last one disappeared, he sank to sleep.

The day had broken when Gabriel Grub awoke, and found himself lying at full length on the flat gravestone in the church-yard, with the wicker bottle lying empty by his side, and his coat, spade, and lantern, all well whitened by the last night’s frost, scattered on the ground. The stone on which he had first seen the goblin seated, stood bolt upright before him, and the grave at which he had worked, the night before, was not far off. At first he began to doubt the reality of his adventures, but the acute pain in his shoulders when he attempted to rise, assured him that the kicking of the goblins was certainly not ideal. He was staggered again, by observing no traces of footsteps in the snow on which the goblins had played at leap-frog with the gravestones, but he speedily accounted for this circumstance when he remembered that being spirits they would leave no visible impression behind them. So Gabriel Grub got on his feet as well as he could, for the pain in his back; and brushing the frost off his coat, put it on, and turned his face towards the town.

But he was an altered man and he could not bear the thought of returning to a place where his repentance would be scoffed at, and his reformation disbelieved. He hesitated for a few moments; and then turned away to wander where he might, and seek his bread elsewhere.

The lantern, the spade, and the wicker bottle, were found that day in the church-yard. There were a great many speculations about the sexton’s fate at first, but it was speedily determined that he had been carried away by the goblins; and there were not wanting some very credible witnesses who had distinctly seen him whisked through the air on the back of a chestnut horse blind of one eye, with the hind quarters of a lion, and the tail of a bear. At length all this was devoutly believed; and the new sexton used to exhibit to the curious for a trifling emolument, a good-sized piece of the church weathercock which had been accidentally kicked off by the aforesaid horse in his aerial flight, and picked up by himself in the church-yard a year or two afterwards.

Unfortunately these stories were somewhat disturbed by the unlooked-for reappearance of Gabriel Grub himself, some ten years afterwards, a ragged, contented, rheumatic old man. He told his story to the clergyman, and also to the mayor; and in course of time it began to be received as a matter of history, in which form it has continued down to this very day. The believers in the weathercock tale, having misplaced their confidence once, were not easily prevailed upon to part with it again, so they looked as wise as they could, shrugged their shoulders, touched their foreheads, and murmured something about Gabriel Grub’s having drunk all the Hollands, and then fallen asleep on the flat tombstone; and they affected to explain what he supposed he had witnessed in the goblin’s cavern, by saying that he had seen the world, and grown wiser. But this opinion, which was by no means a popular one at any time, gradually died off; and be the matter how it may, as Gabriel Grub was afflicted with rheumatism to the end of his days, this story has at least one moral, if it teach no better one – and that is, that if a man turns sulky and drinks by himself at Christmas time, he may make up his mind to be not a bit the better for it, let the spirits be ever so good, or let them be even as many degrees beyond proof, as those which Gabriel Grub saw, in the goblin’s cavern.