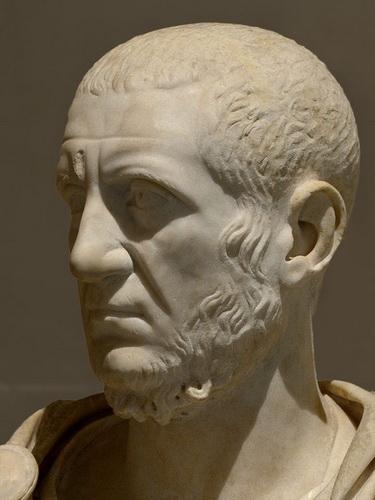

автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Complete Works of Tacitus. Illustrated

THE COMPLETE WORKS OF PUBLIUS CORNELIUS TACITUS

THE LIFE OF AGRICOLA, GERMANIA, DIALOGUE ON ORATORY, THE HISTORIES, THE ANNALS

Illustrated

Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the Annals and the Histories - examine the reigns of the emperors Tiberius, Claudius, Nero, and those who reigned in the Year of the Four Emperors (69 AD).

Tacitus' other writings discuss oratory, Germania and the life of his father-in-law, Agricola, the general responsible for much of the Roman conquest of Britain. Tacitus' works are a chief source next to the Bible and the works of Josephus for providing significant and independent extra-Biblical account of the life and crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth.

THE TRANSLATIONS

THE LIFE OF AGRICOLA

Translated by John Aikin

Written circa AD 98, this biography recounts the life of Tacitus’ father-in-law Gnaeus Julius Agricola, the eminent Roman general, and also briefly spans the geography and ethnography of ancient Britain. The Agricola was published following the assassination of Domitian in AD 96, at a time when the turmoil of the regime change allowed a new-found freedom to publish such works.

During the reign of Domitian, Agricola, a faithful imperial general, had been the most important general involved in the conquest of a large part of Britain. The proud tone of the biography recalls the style of the laudationes funebres (funeral speeches). A quick résumé of the career of Agricola prior to his mission in Britain is followed by a narration of the conquest of the island. There is a geographical and ethnological digression, taken not only from notes and memories of Agricola, but also from Caesar’s De Bello Gallico. Tacitus exalts the character of his father-in-law, by demonstrating how, as governor of Roman Britain and commander of the army, he attended to matters of state with fidelity, honesty and competence, even under the government of Domitian. Critiques of this unpopular Emperor and his regime of spying and repression come to the fore at the work’s conclusion. Agricola remained uncorrupted; in disgrace under Domitian, dying without seeking the glory of an ostentatious martyrdom. Tacitus condemns the suicide of the Stoics as of no benefit to the state. Although Tacitus makes no clear statement as to whether the death of Agricola was from natural causes or ordered by Domitian, he does state that rumours were voiced in Rome that Agricola was poisoned on the Emperor’s orders.

[This work is supposed by the commentators to have been written before the treatise on the manners of the Germans, in the third consulship of the emperor Nerva, and the second of Verginius Rufus, in the year of Rome 850, and of the Christian era 97. Brotier accedes to this opinion; but the reason which he assigns does not seem to be satisfactory. He observes that Tacitus, in the third section, mentions the emperor Nerva; but as he does not call him Divus Nerva, the deified Nerva, the learned commentator infers that Nerva was still living. This reasoning might have some weight, if we did not read, in section 44, that it was the ardent wish of Agricola that he might live to behold Trajan in the imperial seat. If Nerva was then alive, the wish to see another in his room would have been an awkward compliment to the reigning prince. It is, perhaps, for this reason that Lipsius thinks this very elegant tract was written at the same time with the Manners of the Germans, in the beginning of the emperor Trajan. The question is not very material, since conjecture alone must decide it. The piece itself is admitted to be a masterpiece in the kind. Tacitus was son-in-law to Agricola; and while filial piety breathes through his work, he never departs from the integrity of his own character. He has left an historical monument highly interesting to every Briton, who wishes to know the manners of his ancestors, and the spirit of liberty that from the earliest time distinguished the natives of Britain. “Agricola,” as Hume observes, “was the general who finally established the dominion of the Romans in this island. He governed, it in the reigns of Vespasian, Titus, and Domitian. He carried his victorious arms northward: defeated the Britons in every encounter, pierced into the forests and the mountains of Caledonia, reduced every state to subjection in the southern parts of the island, and chased before him all the men of fiercer and more intractable spirits, who deemed war and death itself less intolerable than servitude under the victors. He defeated them in a decisive action, which they fought under Galgacus; and having fixed a chain of garrisons between the friths of Clyde and Forth, he cut off the ruder and more barren parts of the island, and secured the Roman province from the incursions of the barbarous inhabitants. During these military enterprises he neglected not the arts of peace. He introduced laws and civility among the Britons; taught them to desire and raise all the conveniences of life; reconciled them to the Roman language and manners; instructed them in letters and science; and employed every expedient to render those chains, which he had forged, both easy and agreeable to them.” (Hume’s Hist. vol. i. .) In this passage Mr. Hume has given a summary of the Life of Agricola. It is extended by Tacitus in a style more open than the didactic form of the essay on the German Manners required, but still with the precision, both in sentiment and diction, peculiar to the author. In rich but subdued colors he gives a striking picture of Agricola, leaving to posterity a portion of history which it would be in vain to seek in the dry gazette style of Suetonius, or in the page of any writer of that period.]

1. The ancient custom of transmitting to posterity the actions and manners of famous men, has not been neglected even by the present age, incurious though it be about those belonging to it, whenever any exalted and noble degree of virtue has triumphed over that false estimation of merit, and that ill-will to it, by which small and great states are equally infested. In former times, however, as there was a greater propensity and freer scope for the performance of actions worthy of remembrance, so every person of distinguished abilities was induced through conscious satisfaction in the task alone, without regard to private favor or interest, to record examples of virtue. And many considered it rather as the honest confidence of integrity, than a culpable arrogance, to become their own biographers. Of this, Rutilius and Scaurus were instances; who were never yet censured on this account, nor was the fidelity of their narrative called in question; so much more candidly are virtues always estimated; in those periods which are the most favorable to their production. For myself, however, who have undertaken to be the historian of a person deceased, an apology seemed necessary; which I should not have made, had my course lain through times less cruel and hostile to virtue.

2. We read that when Arulenus Rusticus published the praises of Paetus Thrasea, and Herennius Senecio those of Priscus Helvidius, it was construed into a capital crime; and the rage of tyranny was let loose not only against the authors, but against their writings; so that those monuments of exalted genius were burnt at the place of election in the forum by triumvirs appointed for the purpose. In that fire they thought to consume the voice of the Roman people, the freedom of the senate, and the conscious emotions of all mankind; crowning the deed by the expulsion of the professors of wisdom, and the banishment of every liberal art, that nothing generous or honorable might remain. We gave, indeed, a consummate proof of our patience; and as remote ages saw the very utmost degree of liberty, so we, deprived by inquisitions of all the intercourse of conversation, experienced the utmost of slavery. With language we should have lost memory itself, had it been as much in our power to forget, as to be silent.

3. Now our spirits begin to revive. But although at the first dawning of this happy period, the emperor Nerva united two things before incompatible, monarchy and liberty; and Trajan is now daily augmenting the felicity of the empire; and the public security has not only assumed hopes and wishes, but has seen those wishes arise to confidence and stability; yet, from the nature of human infirmity, remedies are more tardy in their operation than diseases; and, as bodies slowly increase, but quickly perish, so it is more easy to suppress industry and genius, than to recall them. For indolence itself acquires a charm; and sloth, however odious at first, becomes at length engaging. During the space of fifteen years, a large portion of human life, how great a number have fallen by casual events, and, as was the fate of all the most distinguished, by the cruelty of the prince; whilst we, the few survivors, not of others alone, but, if I may be allowed the expression, of ourselves, find a void of so many years in our lives, which has silently brought us from youth to maturity, from mature age to the very verge of life! Still, however, I shall not regret having composed, though in rude and artless language, a memorial of past servitude, and a testimony of present blessings.

The present work, in the meantime, which is dedicated to the honor of my father-in-law, may be thought to merit approbation, or at least excuse, from the piety of the intention.

4. CNAEUS JULIUS AGRICOLA was born at the ancient and illustrious colony of Forumjulii. Both his grandfathers were imperial procurators, an office which confers the rank of equestrian nobility. His father, Julius Graecinus, of the senatorian order, was famous for the study of eloquence and philosophy; and by these accomplishments he drew on himself the displeasure of Caius Caesar; for, being commanded to undertake the accusation of Marcus Silanus, — on his refusal, he was put to death. His mother was Julia Procilla, a lady of exemplary chastity. Educated with tenderness in her bosom, he passed his childhood and youth in the attainment of every liberal art. He was preserved from the allurements of vice, not only by a naturally good disposition, but by being sent very early to pursue his studies at Massilia; a place where Grecian politeness and provincial frugality are happily united. I remember he was used to relate, that in his early youth he should have engaged with more ardor in philosophical speculation than was suitable to a Roman and a senator, had not the prudence of his mother restrained the warmth and vehemence of his disposition: for his lofty and upright spirit, inflamed by the charms of glory and exalted reputation, led him to the pursuit with more eagerness than discretion. Reason and riper years tempered his warmth; and from the study of wisdom, he retained what is most difficult to compass, — moderation.

5. He learned the rudiments of war in Britain, under Suetonius Paullinus, an active and prudent commander, who chose him for his tent companion, in order to form an estimate of his merit. Nor did Agricola, like many young men, who convert military service into wanton pastime, avail himself licentiously or slothfully of his tribunitial title, or his inexperience, to spend his time in pleasures and absences from duty; but he employed himself in gaining a knowledge of the country, making himself known to the army, learning from the experienced, and imitating the best; neither pressing to be employed through vainglory, nor declining it through timidity; and performing his duty with equal solicitude and spirit. At no other time in truth was Britain more agitated or in a state of greater uncertainty. Our veterans slaughtered, our colonies burnt, our armies cut off, — we were then contending for safety, afterwards for victory. During this period, although all things were transacted under the conduct and direction of another, and the stress of the whole, as well as the glory of recovering the province, fell to the general’s share, yet they imparted to the young Agricola skill, experience, and incentives; and the passion for military glory entered his soul; a passion ungrateful to the times, in which eminence was unfavorably construed, and a great reputation was no less dangerous than a bad one.

6. Departing thence to undertake the offices of magistracy in Rome, he married Domitia Decidiana, a lady of illustrious descent, from which connection he derived credit and support in his pursuit of greater things. They lived together in admirable harmony and mutual affection; each giving the preference to the other; a conduct equally laudable in both, except that a greater degree of praise is due to a good wife, in proportion as a bad one deserves the greater censure. The lot of quaestorship gave him Asia for his province, and the proconsul Salvius Titianus for his superior; by neither of which circumstances was he corrupted, although the province was wealthy and open to plunder, and the proconsul, from his rapacious disposition, would readily have agreed to a mutual concealment of guilt. His family was there increased by the birth of a daughter, who was both the support of his house, and his consolation; for he lost an elder-born son in infancy. The interval between his serving the offices of quaestor and tribune of the people, and even the year of the latter magistracy, he passed in repose and inactivity; well knowing the temper of the times under Nero, in which indolence was wisdom. He maintained the same tenor of conduct when praetor; for the judiciary part of the office did not fall to his share. In the exhibition of public games, and the idle trappings of dignity, he consulted propriety and the measure of his fortune; by no means approaching to extravagance, yet inclining rather to a popular course. When he was afterwards appointed by Galba to manage an inquest concerning the offerings which had been presented to the temples, by his strict attention and diligence he preserved the state from any further sacrilege than what it had suffered from Nero.

7. The following year inflicted a severe wound on his peace of mind, and his domestic concerns. The fleet of Otho, roving in a disorderly manner on the coast, made a hostile descent on Intemelii, a part of Liguria, in which the mother of Agricola was murdered at her own estate, her lands were ravaged, and a great part of her effects, which had invited the assassins, was carried off. As Agricola upon this event was hastening to perform the duties of filial piety, he was overtaken by the news of Vespasian’s aspiring to the empire, and immediately went over to his party. The first acts of power, and the government of the city, were entrusted to Mucianus; Domitian being at that time very young, and taking no other privilege from his father’s elevation than that of indulging his licentious tastes. Mucianus, having approved the vigor and fidelity of Agricola in the service of raising levies, gave him the command of the twentieth legion, which had appeared backward in taking the oaths, as soon as he had heard the seditious practices of his commander. This legion had been unmanageable and formidable even to the consular lieutenants; and its late commander, of praetorian rank, had not sufficient authority to keep it in obedience; though it was uncertain whether from his own disposition, or that of his soldiers. Agricola was therefore appointed as his successor and avenger; but, with an uncommon degree of moderation, he chose rather to have it appear that he had found the legion obedient, than that he had made it so.

8. Vettius Bolanus was at that time governor of Britain, and ruled with a milder sway than was suitable to so turbulent a province. Under his administration, Agricola, accustomed to obey, and taught to consult utility as well as glory, tempered his ardor, and restrained his enterprising spirit. His virtues had soon a larger field for their display, from the appointment of Petilius Cerealis, a man of consular dignity, to the government. At first he only shared the fatigues and dangers of his general; but was presently allowed to partake of his glory. Cerealis frequently entrusted him with part of his army as a trial of his abilities; and from the event sometimes enlarged his command. On these occasions, Agricola was never ostentatious in assuming to himself the merit of his exploits; but always, as a subordinate officer, gave the honor of his good fortune to his superior. Thus, by his spirit in executing orders, and his modesty in reporting his success, he avoided envy, yet did not fail of acquiring reputation.

9. On his return from commanding the legion he was raised by Vespasian to the patrician order, and then invested with the government of Aquitania, a distinguished promotion, both in respect to the office itself, and the hopes of the consulate to which it destined him. It is a common supposition that military men, habituated to the unscrupulous and summary processes of camps, where things are carried with a strong hand, are deficient in the address and subtlety of genius requisite in civil jurisdiction. Agricola, however, by his natural prudence, was enabled to act with facility and precision even among civilians. He distinguished the hours of business from those of relaxation. When the court or tribunal demanded his presence, he was grave, intent, awful, yet generally inclined to lenity. When the duties of his office were over, the man of power was instantly laid aside. Nothing of sternness, arrogance, or rapaciousness appeared; and, what was a singular felicity, his affability did not impair his authority, nor his severity render him less beloved. To mention integrity and freedom from corruption in such a man, would be an affront to his virtues. He did not even court reputation, an object to which men of worth frequently sacrifice, by ostentation or artifice: equally avoiding competition with, his colleagues, and contention with the procurators. To overcome in such a contest he thought inglorious; and to be put down, a disgrace. Somewhat less than three years were spent in this office, when he was recalled to the immediate prospect of the consulate; while at the same time a popular opinion prevailed that the government of Britain would be conferred upon him; an opinion not founded upon any suggestions of his own, but upon his being thought equal to the station. Common fame does not always err, sometimes it even directs a choice. When consul, he contracted his daughter, a lady already of the happiest promise, to myself, then a very young man; and after his office was expired I received her in marriage. He was immediately appointed governor of Britain, and the pontificate was added to his other dignities.

10. The situation and inhabitants of Britain have been described by many writers; and I shall not add to the number with the view of vying with them in accuracy and ingenuity, but because it was first thoroughly subdued in the period of the present history. Those things which, while yet unascertained, they embellished with their eloquence, shall here be related with a faithful adherence to known facts. Britain, the largest of all the islands which have come within the knowledge of the Romans, stretches on the east towards Germany, on the west towards Spain, and on the south it is even within sight of Gaul. Its northern extremity has no opposite land, but is washed by a wide and open sea. Livy, the most eloquent of ancient, and Fabius Rusticus, of modern writers, have likened the figure of Britain to an oblong target, or a two-edged axe. And this is in reality its appearance, exclusive of Caledonia; whence it has been popularly attributed to the whole island. But that tract of country, irregularly stretching out to an immense length towards the furthest shore, is gradually contracted in form of a wedge. The Roman fleet, at this period first sailing round this remotest coast, gave certain proof that Britain was an island; and at the same time discovered and subdued the Orcades, islands till then unknown. Thule was also distinctly seen, which winter and eternal snow had hitherto concealed. The sea is reported to be sluggish and laborious to the rower; and even to be scarcely agitated by winds. The cause of this stagnation I imagine to be the deficiency of land and mountains where tempests are generated; and the difficulty with which such a mighty mass of waters, in an uninterrupted main, is put in motion. It is not the business of this work to investigate the nature of the ocean and the tides; a subject which many writers have already undertaken. I shall only add one circumstance: that the dominion of the sea is nowhere more extensive; that it carries many currents in this direction and in that; and its ebbings and flowings are not confined to the shore, but it penetrates into the heart of the country, and works its way among hills and mountains, as though it were in its own domain.

11. Who were the first inhabitants of Britain, whether indigenous or immigrants, is a question involved in the obscurity usual among barbarians. Their temperament of body is various, whence deductions are formed of their different origin. Thus, the ruddy hair and large limbs of the Caledonians point out a German derivation. The swarthy complexion and curled hair of the Silures, together with their situation opposite to Spain, render it probable that a colony of the ancient Iberi possessed themselves of that territory. They who are nearest Gaul resemble the inhabitants of that country; whether from the duration of hereditary influence, or whether it be that when lands jut forward in opposite directions, climate gives the same condition of body to the inhabitants of both. On a general survey, however, it appears probable that the Gauls originally took possession of the neighboring coast. The sacred rites and superstitions of these people are discernible among the Britons. The languages of the two nations do not greatly differ. The same audacity in provoking danger, and irresolution in facing it when present, is observable in both. The Britons, however, display more ferocity, not being yet softened by a long peace: for it appears from history that the Gauls were once renowned in war, till, losing their valor with their liberty, languor and indolence entered amongst them. The same change has also taken place among those of the Britons who have been long subdued; but the rest continue such as the Gauls formerly were.

12. Their military strength consists in infantry; some nations also make use of chariots in war; in the management of which, the most honorable person guides the reins, while his dependents fight from the chariot. The Britons were formerly governed by kings, but at present they are divided in factions and parties among their chiefs; and this want of union for concerting some general plan is the most favorable circumstance to us, in our designs against so powerful a people. It is seldom that two or three communities concur in repelling the common danger; and thus, while they engage singly, they are all subdued. The sky in this country is deformed by clouds and frequent rains; but the cold is never extremely rigorous. The length of the days greatly exceeds that in our part of the world. The nights are bright, and, at the extremity of the island, so short, that the close and return of day is scarcely distinguished by a perceptible interval. It is even asserted that, when clouds do not intervene, the splendor of the sun is visible during the whole night, and that it does not appear to rise and set, but to move across. The cause of this is, that the extreme and flat parts of the earth, casting a low shadow, do not throw up the darkness, and so night falls beneath the sky and the stars. The soil, though improper for the olive, the vine, and other productions of warmer climates, is fertile, and suitable for corn. Growth is quick, but maturation slow; both from the same cause, the great humidity of the ground and the atmosphere. The earth yields gold and silver and other metals, the rewards of victory. The ocean produces pearls, but of a cloudy and livid hue; which some impute to unskilfulness in the gatherers; for in the Red Sea the fish are plucked from the rocks alive and vigorous, but in Britain they are collected as the sea throws them up. For my own part, I can more readily conceive that the defect is in the nature of the pearls, than in our avarice.

13. The Britons cheerfully submit to levies, tributes, and the other services of government, if they are not treated injuriously; but such treatment they bear with impatience, their subjection only extending to obedience, not to servitude. Accordingly Julius Caesar, the first Roman who entered Britain with an army, although he terrified the inhabitants by a successful engagement, and became master of the shore, may be considered rather to have transmitted the discovery than the possession of the country to posterity. The civil wars soon succeeded; the arms of the leaders were turned against their country; and a long neglect of Britain ensued, which continued even after the establishment of peace. This Augustus attributed to policy; and Tiberius to the injunctions of his predecessor. It is certain that Caius Caesar meditated an expedition into Britain; but his temper, precipitate in forming schemes, and unsteady in pursuing them, together with the ill success of his mighty attempts against Germany, rendered the design abortive. Claudius accomplished the undertaking, transporting his legions and auxiliaries, and associating Vespasian in the direction of affairs, which laid the foundation of his future fortune. In this expedition, nations were subdued, kings made captive, and Vespasian was held forth to the fates.

14. Aulus Plautius, the first consular governor, and his successor, Ostorius Scapula, were both eminent for military abilities. Under them, the nearest part of Britain was gradually reduced into the form of a province, and a colony of veterans was settled. Certain districts were bestowed upon king Cogidunus, a prince who continued in perfect fidelity within our own memory. This was done agreeably to the ancient and long established practice of the Romans, to make even kings the instruments of servitude. Didius Gallus, the next governor, preserved the acquisitions of his predecessors, and added a very few fortified posts in the remoter parts, for the reputation of enlarging his province. Veranius succeeded, but died within the year. Suetonius Paullinus then commanded with success for two years, subduing various nations, and establishing garrisons. In the confidence with which this inspired him, he undertook an expedition against the island Mona, which had furnished the revolters with supplies; and thereby exposed the settlements behind him to a surprise.

15. For the Britons, relieved from present dread by the absence of the governor, began to hold conferences, in which they painted the miseries of servitude, compared their several injuries, and inflamed each other with such representations as these: “That the only effects of their patience were more grievous impositions upon a people who submitted with such facility. Formerly they had one king respectively; now two were set over them, the lieutenant and the procurator, the former of whom vented his rage upon their life’s blood, the latter upon their properties; the union or discord of these governors was equally fatal to those whom they ruled, while the officers of the one, and the centurions of the other, joined in oppressing them by all kinds of violence and contumely; so that nothing was exempted from their avarice, nothing from their lust. In battle it was the bravest who took spoils; but those whom they suffered to seize their houses, force away their children, and exact levies, were, for the most part, the cowardly and effeminate; as if the only lesson of suffering of which they were ignorant was how to die for their country. Yet how inconsiderable would the number of invaders appear did the Britons but compute their own forces! From considerations like these, Germany had thrown off the yoke, though a river and not the ocean was its barrier. The welfare of their country, their wives, and their parents called them to arms, while avarice and luxury alone incited their enemies; who would withdraw as even the deified Julius had done, if the present race of Britons would emulate the valor of their ancestors, and not be dismayed at the event of the first or second engagement. Superior spirit and perseverence were always the share of the wretched; and the gods themselves now seemed to compassionate the Britons, by ordaining the absence of the general, and the detention of his army in another island. The most difficult point, assembling for the purpose of deliberation, was already accomplished; and there was always more danger from the discovery of designs like these, than from their execution.”

16. Instigated by such suggestions, they unanimously rose in arms, led by Boadicea, a woman of royal descent (for they make no distinction between the sexes in succession to the throne), and attacking the soldiers dispersed through the garrisons, stormed the fortified posts, and invaded the colony itself, as the seat of slavery. They omitted no species of cruelty with which rage and victory could inspire barbarians; and had not Paullinus, on being acquainted with the commotion of the province, marched speedily to its relief, Britain would have been lost. The fortune of a single battle, however, reduced it to its former subjection; though many still remained in arms, whom the consciousness of revolt, and particular dread of the governor, had driven to despair. Paullinus, although otherwise exemplary in his administration, having treated those who surrendered with severity, and having pursued too rigorous measures, as one who was revenging his own personal injury also, Petronius Turpilianus was sent in his stead, as a person more inclined to lenity, and one who, being unacquainted with the enemy’s delinquency, could more easily accept their penitence. After having restored things to their former quiet state, he delivered the command to Trebellius Maximus. Trebellius, indolent, and inexperienced in military affairs, maintained the tranquillity of the province by popular manners; for even the barbarians had now learned to pardon under the seductive influence of vices; and the intervention of the civil wars afforded a legitimate excuse for his inactivity. Sedition however infected the soldiers, who, instead of their usual military services, were rioting in idleness. Trebellius, after escaping the fury of his army by flight and concealment, dishonored and abased, regained a precarious authority; and a kind of tacit compact took place, of safety to the general, and licentiousness to the army. This mutiny was not attended with bloodshed. Vettius Bolanus, succeeding during the continuance of the civil wars, was unable to introduce discipline into Britain. The same inaction towards the enemy, and the same insolence in the camp, continued; except that Bolanus, unblemished in his character, and not obnoxious by any crime, in some measure substituted affection in the place of authority.

17. At length, when Vespasian received the possession of Britain together with the rest of the world, the great commanders and well-appointed armies which were sent over abated the confidence of the enemy; and Petilius Cerealis struck terror by an attack upon the Brigantes, who are reputed to compose the most populous state in the whole province. Many battles were fought, some of them attended with much bloodshed; and the greater part of the Brigantes were either brought into subjection, or involved in the ravages of war. The conduct and reputation of Cerealis were so brilliant that they might have eclipsed the splendor of a successor; yet Julius Frontinus, a truly great man, supported the arduous competition, as far as circumstances would permit. He subdued the strong and warlike nation of the Silures, in which expedition, besides the valor of the enemy, he had the difficulties of the country to struggle with.

18. Such was the state of Britain, and such had been the vicissitudes of warfare, when Agricola arrived in the middle of summer; at a time when the Roman soldiers, supposing the expeditions of the year were concluded, were thinking of enjoying themselves without care, and the natives, of seizing the opportunity thus afforded them. Not long before his arrival, the Ordovices had cut off almost an entire corps of cavalry stationed on their frontiers; and the inhabitants of the province being thrown into a state of anxious suspense by this beginning, inasmuch as war was what they wished for, either approved of the example, or waited to discover the disposition of the new governor. The season was now far advanced, the troops dispersed through the country, and possessed with the idea of being suffered to remain inactive during the rest of the year; circumstances which tended to retard and discourage any military enterprise; so that it was generally thought most advisable to be contented with defending the suspected posts: yet Agricola determined to march out and meet the approaching danger. For this purpose, he drew together the detachments from the legions, and a small body of auxiliaries; and when he perceived that the Ordovices would not venture to descend into the plain, he led an advanced party in person to the attack, in order to inspire the rest of his troops with equal ardor. The result of the action was almost the total extirpation of the Ordovices; when Agricola, sensible that renown must be followed up, and that the future events of the war would be determined by the first success, resolved to make an attempt upon the island Mona, from the occupation of which Paullinus had been summoned by the general rebellion of Britain, as before related. The usual deficiency of an unforeseen expedition appearing in the want of transport vessels, the ability and resolution of the general were exerted to supply this defect. A select body of auxiliaries, disencumbered of their baggage, who were well acquainted with the fords, and accustomed, after the manner of their country, to direct their horses and manage their arms while swimming, were ordered suddenly to plunge into the channel; by which movement, the enemy, who expected the arrival of a fleet, and a formal invasion by sea, were struck with terror and astonishment, conceiving nothing arduous or insuperable to troops who thus advanced to the attack. They were therefore induced to sue for peace, and make a surrender of the island; an event which threw lustre on the name of Agricola, who, on the very entrance upon his province, had employed in toils and dangers that time which is usually devoted to ostentatious parade, and the compliments of office. Nor was he tempted, in the pride of success, to term that an expedition or a victory; which was only bridling the vanquished; nor even to announce his success in laureate despatches. But this concealment of his glory served to augment it; since men were led to entertain a high idea of the grandeur of his future views, when such important services were passed over in silence.

19. Well acquainted with the temper of the province, and taught by the experience of former governors how little proficiency had been made by arms, when success was followed by injuries, he next undertook to eradicate the causes of war. And beginning with himself, and those next to him, he first laid restrictions upon his own household, a task no less arduous to most governors than the administration of the province. He suffered no public business to pass through the hands of his slaves or freedmen. In admitting soldiers into regular service, to attendance about his person, he was not influenced by private favor, or the recommendation or solicitation of the centurions, but considered the best men as likely to prove the most faithful. He would know everything; but was content to let some things pass unnoticed. He could pardon small faults, and use severity to great ones; yet did not always punish, but was frequently satisfied with penitence. He chose rather to confer offices and employments upon such as would not offend, than to condemn those who had offended. The augmentation of tributes and contributions he mitigated by a just and equal assessment, abolishing those private exactions which were more grievous to be borne than the taxes themselves. For the inhabitants had been compelled in mockery to sit by their own locked-up granaries, to buy corn needlessly, and to sell it again at a stated price. Long and difficult journeys had also been imposed upon them; for the several districts, instead of being allowed to supply the nearest winter quarters, were forced to carry their corn to remote and devious places; by which means, what was easy to be procured by all, was converted into an article of gain to a few.

20. By suppressing these abuses in the first year of his administration, he established a favorable idea of peace, which, through the negligence or oppression of his predecessors, had been no less dreaded than war. At the return of summer he assembled his army. On their march, he commended the regular and orderly, and restrained the stragglers; he marked out the encampments, and explored in person the estuaries and forests. At the same time he perpetually harassed the enemy by sudden incursions; and, after sufficiently alarming them, by an interval of forbearance, he held to their view the allurements of peace. By this management, many states, which till that time had asserted their independence, were now induced to lay aside their animosity, and to deliver hostages. These districts were surrounded with castles and forts, disposed with so much attention and judgment, that no part of Britain, hitherto new to the Roman arms, escaped unmolested.

21. The succeeding winter was employed in the most salutary measures. In order, by a taste of pleasures, to reclaim the natives from that rude and unsettled state which prompted them to war, and reconcile them to quiet and tranquillity, he incited them, by private instigations and public encouragements, to erect temples, courts of justice, and dwelling-houses. He bestowed commendations upon those who were prompt in complying with his intentions, and reprimanded such as were dilatory; thus promoting a spirit of emulation which had all the force of necessity. He was also attentive to provide a liberal education for the sons of their chieftains, preferring the natural genius of the Britons to the attainments of the Gauls; and his attempts were attended with such success, that they who lately disdained to make use of the Roman language, were now ambitious of becoming eloquent. Hence the Roman habit began to be held in honor, and the toga was frequently worn. At length they gradually deviated into a taste for those luxuries which stimulate to vice; porticos, and baths, and the elegancies of the table; and this, from their inexperience, they termed politeness, whilst, in reality, it constituted a part of their slavery.

22. The military expeditions of the third year discovered new nations to the Romans, and their ravages extended as far as the estuary of the Tay. The enemies were thereby struck with such terror that they did not venture to molest the army though harassed by violent tempests; so that they had sufficient opportunity for the erection of fortresses. Persons of experience remarked, that no general had ever shown greater skill in the choice of advantageous situations than Agricola; for not one of his fortified posts was either taken by storm, or surrendered by capitulation. The garrisons made frequent sallies; for they were secured against a blockade by a year’s provision in their stores. Thus the winter passed without alarm, and each garrison proved sufficient for its own defence; while the enemy, who were generally accustomed to repair the losses of the summer by the successes of the winter, now equally unfortunate in both seasons, were baffled and driven to despair. In these transactions, Agricola never attempted to arrogate to himself the glory of others; but always bore an impartial testimony to the meritorious actions of his officers, from the centurion to the commander of a legion. He was represented by some as rather harsh in reproof; as if the same disposition which made him affable to the deserving, had inclined him to austerity towards the worthless. But his anger left no relics behind; his silence and reserve were not to be dreaded; and he esteemed it more honorable to show marks of open displeasure, than to entertain secret hatred.

23. The fourth summer was spent in securing the country which had been overrun; and if the valor of the army and the glory of the Roman name had permitted it, our conquests would have found a limit within Britain itself. For the tides of the opposite seas, flowing very far up the estuaries of Clota and Bodotria, almost intersect the country; leaving only a narrow neck of land, which was then defended by a chain of forts. Thus all the territory on this side was held in subjection, and the remaining enemies were removed, as it were, into another island.

24. In the fifth campaign, Agricola, crossing over in the first ship, subdued, by frequent and successful engagements, several nations till then unknown; and stationed troops in that part of Britain which is opposite to Ireland, rather with a view to future advantage, than from any apprehension of danger from that quarter. For the possession of Ireland, situated between Britain and Spain, and lying commodiously to the Gallic sea, would have formed a very beneficial connection between the most powerful parts of the empire. This island is less than Britain, but larger than those of our sea. Its soil, climate, and the manners and dispositions of its inhabitants, are little different from those of Britain. Its ports and harbors are better known, from the concourse of merchants for the purposes of commerce. Agricola had received into his protection one of its petty kings, who had been expelled by a domestic sedition; and detained him, under the semblance of friendship, till an occasion should offer of making use of him. I have frequently heard him assert, that a single legion and a few auxiliaries would be sufficient entirely to conquer Ireland and keep it in subjection; and that such an event would also have contributed to restrain the Britons, by awing them with the prospect of the Roman arms all around them, and, as it were, banishing liberty from their sight.

25. In the summer which began the sixth year of Agricola’s administration, extending his views to the countries situated beyond Bodotria, as a general insurrection of the remoter nations was apprehended, and the enemy’s army rendered marching unsafe, he caused the harbors to be explored by his fleet, which, now first acting in aid of the land-forces gave the formidable spectacle of war at once pushed on by sea and land. The cavalry, infantry, and marines were frequently mingled in the same camp, and recounted with mutual pleasure their several exploits and adventures; comparing, in the boastful language of military men, the dark recesses of woods and mountains, with the horrors of waves and tempests; and the land and enemy subdued, with the conquered ocean. It was also discovered from the captives, that the Britons had been struck with consternation at the view of the fleet, conceiving the last refuge of the vanquished to be cut off, now the secret retreats of their seas were disclosed. The various inhabitants of Caledonia immediately took up arms, with great preparations, magnified, however, by report, as usual where the truth is unknown; and by beginning hostilities, and attacking our fortresses, they inspired terror as daring to act offensively; insomuch that some persons, disguising their timidity under the mask of prudence, were for instantly retreating on this side the firth, and relinquishing the country rather than waiting to be driven out. Agricola, in the meantime, being informed that the enemy intended to bear down in several bodies, distributed his army into three divisions, that his inferiority of numbers, and ignorance of the country, might not give them an opportunity of surrounding him.

26. When this was known to the enemy, they suddenly changed their design; and making a general attack in the night upon the ninth legion, which was the weakest, in the confusion of sleep and consternation they slaughtered the sentinels, and burst through the intrenchments. They were now fighting within the camp, when Agricola, who had received information of their march from his scouts, and followed close upon their track, gave orders for the swiftest of his horse and foot to charge the enemy’s rear. Presently the whole army raised a general shout; and the standards now glittered at the approach of day. The Britons were distracted by opposite dangers; whilst the Romans in the camp resumed their courage, and secure of safety, began to contend for glory. They now in their turns rushed forwards to the attack, and a furious engagement ensued in the gates of the camp; till by the emulous efforts of both Roman armies, one to give assistance, the other to appear not to need it, the enemy was routed: and had not the woods and marshes sheltered the fugitives, that day would have terminated the war.

27. The soldiers, inspirited by the steadfastness which characterized and the fame which attended this victory, cried out that “nothing could resist their valor; now was the time to penetrate into the heart of Caledonia, and in a continued series of engagements at length to discover the utmost limits of Britain.” Those even who had before recommended caution and prudence, were now rendered rash and boastful by success. It is the hard condition of military command, that a share in prosperous events is claimed by all, but misfortunes are imputed to one alone. The Britons meantime, attributing their defeat not to the superior bravery of their adversaries, but to chance, and the skill of the general, remitted nothing of their confidence; but proceeded to arm their youth, to send their wives and children to places of safety, and to ratify the confederacy of their several states by solemn assemblies and sacrifices. Thus the parties separated with minds mutually irritated.

28. During the same summer, a cohort of Usipii, which had been levied in Germany, and sent over into Britain, performed an extremely daring and memorable action. After murdering a centurion and some soldiers who had been incorporated with them for the purpose of instructing them in military discipline, they seized upon three light vessels, and compelled the masters to go on board with them. One of these, however, escaping to shore, they killed the other two upon suspicion; and before the affair was publicly known, they sailed away, as it were by miracle. They were presently driven at the mercy of the waves; and had frequent conflicts, with various success, with the Britons, defending their property from plunder. At length they were reduced to such extremity of distress as to be obliged to feed upon each other; the weakest being first sacrificed, and then such as were taken by lot. In this manner having sailed round the island, they lost their ships through want of skill; and, being regarded as pirates, were intercepted, first by the Suevi, then by the Frisii. Some of them, after being sold for slaves, by the change of masters were brought to the Roman side of the river, and became notorious from the relation of their extraordinary adventures.

29. In the beginning of the next summer, Agricola received a severe domestic wound in the loss of a son, about a year old. He bore this calamity, not with the ostentatious firmness which many have affected, nor yet with the tears and lamentations of feminine sorrow; and war was one of the remedies of his grief. Having sent forwards his fleet to spread its ravages through various parts of the coast, in order to excite an extensive and dubious alarm, he marched with an army equipped for expedition, to which he had joined the bravest of the Britons whose fidelity had been approved by a long allegiance, and arrived at the Grampian hills, where the enemy was already encamped. For the Britons, undismayed by the event of the former action, expecting revenge or slavery, and at length taught that the common danger was to be repelled by union alone, had assembled the strength of all their tribes by embassies and confederacies. Upwards of thirty thousand men in arms were now descried; and the youth, together with those of a hale and vigorous age, renowned in war, and bearing their several honorary decorations, were still flocking in; when Calgacus, the most distinguished for birth and valor among the chieftans, is said to have harangued the multitude, gathering round, and eager for battle, after the following manner: —

30. “When I reflect on the causes of the war, and the circumstances of our situation, I feel a strong persuasion that our united efforts on the present day will prove the beginning of universal liberty to Britain. For we are all undebased by slavery; and there is no land behind us, nor does even the sea afford a refuge, whilst the Roman fleet hovers around. Thus the use of arms, which is at all times honorable to the brave, now offers the only safety even to cowards. In all the battles which have yet been fought, with various success, against the Romans, our countrymen may be deemed to have reposed their final hopes and resources in us: for we, the noblest sons of Britain, and therefore stationed in its last recesses, far from the view of servile shores, have preserved even our eyes unpolluted by the contact of subjection. We, at the furthest limits both of land and liberty, have been defended to this day by the remoteness of our situation and of our fame. The extremity of Britain is now disclosed; and whatever is unknown becomes an object of magnitude. But there is no nation beyond us; nothing but waves and rocks, and the still more hostile Romans, whose arrogance we cannot escape by obsequiousness and submission. These plunderers of the world, after exhausting the land by their devastations, are rifling the ocean: stimulated by avarice, if their enemy be rich; by ambition, if poor; unsatiated by the East and by the West: the only people who behold wealth and indigence with equal avidity. To ravage, to slaughter, to usurp under false titles, they call empire; and where they make a desert, they call it peace.

31. “Our children and relations are by the appointment of nature the dearest of all things to us. These are torn away by levies to serve in foreign lands. Our wives and sisters, though they should escape the violation of hostile force, are polluted under names of friendship and hospitality. Our estates and possessions are consumed in tributes; our grain in contributions. Even our bodies are worn down amidst stripes and insults in clearing woods and draining marshes. Wretches born to slavery are once bought, and afterwards maintained by their masters: Britain every day buys, every day feeds, her own servitude. And as among domestic slaves every new comer serves for the scorn and derision of his fellows; so, in this ancient household of the world, we, as the newest and vilest, are sought out to destruction. For we have neither cultivated lands, nor mines, nor harbors, which can induce them to preserve us for our labors. The valor too and unsubmitting spirit of subjects only render them more obnoxious to their masters; while remoteness and secrecy of situation itself, in proportion as it conduces to security, tends to inspire suspicion. Since then all Lopes of mercy are vain, at length assume courage, both you to whom safety and you to whom glory is dear. The Trinobantes, even under a female leader, had force enough to burn a colony, to storm camps, and, if success had not damped their vigor, would have been able entirely to throw off the yoke; and shall not we, untouched, unsubdued, and struggling not for the acquisition but the security of liberty, show at the very first onset what men Caledonia has reserved for her defence?

32. “Can you imagine that the Romans are as brave in war as they are licentious in peace? Acquiring renown from our discords and dissensions, they convert the faults of their enemies to the glory of their own army; an army compounded of the most different nations, which success alone has kept together, and which misfortune will as certainly dissipate. Unless, indeed, you can suppose that Gauls, and Germans, and (I blush to say it) even Britons, who, though they expend their blood to establish a foreign dominion, have been longer its foes than its subjects, will be retained by loyalty and affection! Terror and dread alone are the weak bonds of attachment; which once broken, they who cease to fear will begin to hate. Every incitement to victory is on our side. The Romans have no wives to animate them; no parents to upbraid their flight. Most of them have either no home, or a distant one. Few in number, ignorant of the country, looking around in silent horror at woods, seas, and a heaven itself unknown to them, they are delivered by the gods, as it were imprisoned and bound, into our hands. Be not terrified with an idle show, and the glitter of silver and gold, which can neither protect nor wound. In the very ranks of the enemy we shall find our own bands. The Britons will acknowledge their own cause. The Gauls will recollect their former liberty. The rest of the Germans will desert them, as the Usipii have lately done. Nor is there anything formidable behind them: ungarrisoned forts; colonies of old men; municipal towns distempered and distracted between unjust masters and ill-obeying subjects. Here is a general; here an army. There, tributes, mines, and all the train of punishments inflicted on slaves; which whether to bear eternally, or instantly to revenge, this field must determine. March then to battle, and think of your ancestors and your posterity.”

33. They received this harangue with alacrity, and testified their applause after the barbarian manner, with songs, and yells, and dissonant shouts. And now the several divisions were in motion, the glittering of arms was beheld, while the most daring and impetuous were hurrying to the front, and the line of battle was forming; when Agricola, although his soldiers were in high spirits, and scarcely to be kept within their intrenchments, kindled additional ardor by these words: —

“It is now the eighth year, my fellow-soldiers, in which, under the high auspices of the Roman empire, by your valor and perseverance you have been conquering Britain. In so many expeditions, in so many battles, whether you have been required to exert your courage against the enemy, or your patient labors against the very nature of the country, neither have I ever been dissatisfied with my soldiers, nor you with your general. In this mutual confidence, we have proceeded beyond the limits of former commanders and former armies; and are now become acquainted with the extremity of the island, not by uncertain rumor, but by actual possession with our arms and encampments. Britain is discovered and subdued. How often on a march, when embarrassed with mountains, bogs and rivers, have I heard the bravest among you exclaim, ‘When shall we descry the enemy? when shall we be led to the field of battle?’ At length they are unharbored from their retreats; your wishes and your valor have now free scope; and every circumstance is equally propitious to the victor, and ruinous to the vanquished. For, the greater our glory in having marched over vast tracts of land, penetrated forests, and crossed arms of the sea, while advancing towards the foe, the greater will be our danger and difficulty if we should attempt a retreat. We are inferior to our enemies in knowledge of the country, and less able to command supplies of provision; but we have arms in our hands, and in these we have everything. For myself, it has long been my principle, that a retiring general or army is never safe. Hot only, then, are we to reflect that death with honor is preferable to life with ignominy, but to remember that security and glory are seated in the same place. Even to fall in this extremest verge of earth and of nature cannot be thought an inglorious fate.

34. “If unknown nations or untried troops were drawn up against you, I would exhort you from the example of other armies. At present, recollect your own honors, question your own eyes. These are they, who, the last year, attacking by surprise a single legion in the obscurity of the night, were put to flight by a shout: the greatest fugitives of all the Britons, and therefore the longest survivors. As in penetrating woods and thickets the fiercest animals boldly rush on the hunters, while the weak and timorous fly at their very noise; so the bravest of the Britons have long since fallen: the remaining number consists solely of the cowardly and spiritless; whom you see at length within your reach, not because they have stood their ground, but because they are overtaken. Torpid with fear, their bodies are fixed and chained down in yonder field, which to you will speedily be the scene of a glorious and memorable victory. Here bring your toils and services to a conclusion; close a struggle of fifty years with one great day; and convince your country-men, that to the army ought not to be imputed either the protraction of war, or the causes of rebellion.”

35. Whilst Agricola was yet speaking, the ardor of the soldiers declared itself; and as soon as he had finished, they burst forth into cheerful acclamations, and instantly flew to arms. Thus eager and impetuous, he formed them so that the centre was occupied by the auxiliary infantry, in number eight thousand, and three thousand horse were spread in the wings. The legions were stationed in the rear, before the intrenchments; a disposition which would render the victory signally glorious, if it were obtained without the expense of Roman blood; and would ensure support if the rest of the army were repulsed. The British troops, for the greater display of their numbers, and more formidable appearance, were ranged upon the rising grounds, so that the first line stood upon the plain, the rest, as if linked together, rose above one another upon the ascent. The charioteers and horsemen filled the middle of the field with their tumult and careering. Then Agricola, fearing from the superior number of the enemy lest he should be obliged to fight as well on his flanks as in front, extended his ranks; and although this rendered his line of battle less firm, and several of his officers advised him to bring up the legions, yet, filled with hope, and resolute in danger, he dismissed his horse and took his station on foot before the colors.

36. At first the action was carried on at a distance. The Britons, armed with long swords and short targets, with steadiness and dexterity avoided or struck down our missile weapons, and at the same time poured in a torrent of their own. Agricola then encouraged three Batavian and two Tungrian cohorts to fall in and come to close quarters; a method of fighting familiar to these veteran soldiers, but embarrassing to the enemy from the nature of their armor; for the enormous British swords, blunt at the point, are unfit for close grappling, and engaging in a confined space. When the Batavians; therefore, began to redouble their blows, to strike with the bosses of their shields, and mangle the faces of the enemy; and, bearing down all those who resisted them on the plain, were advancing their lines up the ascent; the other cohorts, fired with ardor and emulation, joined in the charge, and overthrew all who came in their way: and so great was their impetuosity in the pursuit of victory, that they left many of their foes half dead or unhurt behind them. In the meantime the troops of cavalry took to flight, and the armed chariots mingled in the engagement of the infantry; but although their first shock occasioned some consternation, they were soon entangled among the close ranks of the cohorts, and the inequalities of the ground. Not the least appearance was left of an engagement of cavalry; since the men, long keeping their ground with difficulty, were forced along with the bodies of the horses; and frequently, straggling chariots, and affrighted horses without their riders, flying variously as terror impelled them, rushed obliquely athwart or directly through the lines.

37. Those of the Britons who, yet disengaged from the fight, sat on the summits of the hills, and looked with careless contempt on the smallness of our numbers, now began gradually to descend; and would have fallen on the rear of the conquering troops, had not Agricola, apprehending this very event, opposed four reserved squadron of horse to their attack, which, the more furiously they had advanced, drove them back with the greater celerity. Their project was thus turned against themselves; and the squadrons were ordered to wheel from the front of the battle and fall upon the enemy’s rear. A striking and hideous spectacle now appeared on the plain: some pursuing; some striking: some making prisoners, whom they slaughtered as others came in their way. Now, as their several dispositions prompted, crowds of armed Britons fled before inferior numbers, or a few, even unarmed, rushed upon their foes, and offered themselves to a voluntary death. Arms, and carcasses, and mangled limbs, were promiscuously strewed, and the field was dyed in blood. Even among the vanquished were seen instances of rage and valor. When the fugitives approached the woods, they collected, and surrounded the foremost of the pursuers, advancing incautiously, and unacquainted with the country; and had not Agricola, who was everywhere present, caused some strong and lightly-equipped cohorts to encompass the ground, while part of the cavalry dismounted made way through the thickets, and part on horseback scoured the open woods, some disaster would have proceeded from the excess of confidence. But when the enemy saw their pursuers again formed in compact order, they renewed their flight, not in bodies as before, or waiting for their companions, but scattered and mutually avoiding each other; and thus took their way to the most distant and devious retreats. Night and satiety of slaughter put an end to the pursuit. Of the enemy ten thousand were slain: on our part three hundred and sixty fell; among whom was Aulus Atticus, the praefect of a cohort, who, by his juvenile ardor, and the fire of his horse, was borne into the midst of the enemy.

38. Success and plunder contributed to render the night joyful to the victors; whilst the Britons, wandering and forlorn, amid the promiscuous lamentations of men and women, were dragging along the wounded; calling out to the unhurt; abandoning their habitations, and in the rage of despair setting them on fire; choosing places of concealment, and then deserting them; consulting together, and then separating. Sometimes, on beholding the dear pledges of kindred and affection, they were melted into tenderness, or more frequently roused into fury; insomuch that several, according to authentic information, instigated by a savage compassion, laid violent hands upon their own wives and children. On the succeeding day, a vast silence all around, desolate hills, the distant smoke of burning houses, and not a living soul descried by the scouts, displayed more amply the face of victory. After parties had been detached to all quarters without discovering any certain tracks of the enemy’s flight, or any bodies of them still in arms, as the lateness of the season rendered it impracticable to spread the war through the country, Agricola led his army to the confines of the Horesti. Having received hostages from this people, he ordered the commander of the fleet to sail round the island; for which expedition he was furnished with sufficient force, and preceded by the terror of the Roman name. Pie himself then led back the cavalry and infantry, marching slowly, that he might impress a deeper awe on the newly conquered nations; and at length distributed his troops into their winter-quarters. The fleet, about the same time, with prosperous gales and renown, entered the Trutulensian harbor, whence, coasting all the hither shore of Britain, it returned entire to its former station.

39. The account of these transactions, although unadorned with the pomp of words in the letters of Agricola, was received by Domitian, as was customary with that prince, with outward expressions of joy, but inward anxiety. He was conscious that his late mock-triumph over Germany, in which he had exhibited purchased slaves, whose habits and hair were contrived to give them the resemblance of captives, was a subject of derision; whereas here, a real and important victory, in which so many thousands of the enemy were slain, was celebrated with universal applause. His greatest dread was that the name of a private man should be exalted above that of the prince. In vain had he silenced the eloquence of the forum, and cast a shade upon all civil honors, if military glory were still in possession of another. Other accomplishments might more easily be connived at, but the talents of a great general were truly imperial. Tortured with such anxious thoughts, and brooding over them in secret, a certain indication of some malignant intention, he judged it most prudent for the present to suspend his rancor, tilt the first burst of glory and the affections of the army should remit: for Agricola still possessed the command in Britain.

40. He therefore caused the senate to decree him triumphal ornaments, — a statue crowned with laurel, and all the other honors which are substituted for a real triumph, together with a profusion of complimentary expressions; and also directed an expectation to be raised that the province of Syria, vacant by the death of Atilius Rufus, a consular man, and usually reserved for persons of the greatest distinction, was designed for Agricola. It was commonly believed that one of the freedmen, who were employed in confidential services, was despatched with the instrument appointing Agricola to the government of Syria, with orders to deliver it if he should be still in Britain; but that this messenger, meeting Agricola in the straits, returned directly to Domitian without so much as accosting him. Whether this was really the fact, or only a fiction founded on the genius and character of the prince, is uncertain. Agricola, in the meantime, had delivered the province, in peace and security, to his successor; and lest his entry into the city should be rendered too conspicuous by the concourse and acclamations of the people, he declined the salutation of his friends by arriving in the night; and went by night, as he was commanded, to the palace. There, after being received with a slight embrace, but not a word spoken, he was mingled with the servile throng. In this situation, he endeavored to soften the glare of military reputation, which is offensive to those who themselves live in indolence, by the practice of virtues of a different cast. He resigned himself to ease and tranquillity, was modest in his garb and equipage, affable in conversation, and in public was only accompanied by one or two of his friends; insomuch that the many, who are accustomed to form their ideas of great men from their retinue and figure, when they beheld Agricola, were apt to call in question his renown: few could interpret his conduct.

41. He was frequently, during that period, accused in his absence before Domitian, and in his absence also acquitted. The source of his danger was not any criminal action, nor the complaint of any injured person; but a prince hostile to virtue, and his own high reputation, and the worst kind of enemies, eulogists. For the situation of public affairs which ensued was such as would not permit the name of Agricola to rest in silence: so many armies in Moesia, Dacia, Germany, and Pannonia lost through the temerity or cowardice of their generals; so many men of military character, with numerous cohorts, defeated and taken prisoners; whilst a dubious contest was maintained, not for the boundaries, of the empire, and the banks of the bordering rivers, but for the winter-quarters of the legions, and the possession of our territories. In this state of things, when loss succeeded loss, and every year was signalized by disasters and slaughters, the public voice loudly demanded Agricola for general: every one comparing his vigor, firmness, and experience in war, with the indolence and pusillanimity of the others. It is certain that the ears of Domitian himself were assailed by such discourses, while the best of his freedmen pressed him to the choice through motives of fidelity and affection, and the worst through envy and malignity, emotions to which he was of himself sufficiently prone. Thus Agricola, as well by his own virtues as the vices of others, was urged on precipitously to glory.

42. The year now arrived in which the proconsulate of Asia or Africa must fall by lot upon Agricola; and as Civica had lately been put to death, Agricola was not unprovided with a lesson, nor Domitian with an example. Some persons, acquainted with the secret inclinations of the emperor, came to Agricola, and inquired whether he intended to go to his province; and first, somewhat distantly, began to commend a life of leisure and tranquillity; then offered their services in procuring him to be excused from the office; and at length, throwing off all disguise, after using arguments both to persuade and intimidate him, compelled him to accompany them to Domitian. The emperor, prepared to dissemble, and assuming an air of stateliness, received his petition for excuse, and suffered himself to be formally thanked for granting it, without blushing at so invidious a favor. He did not, however, bestow on Agricola the salary usually offered to a proconsul, and which he himself had granted to others; either taking offence that it was not requested, or feeling a consciousness that it would seem a bribe for what he had in reality extorted by his authority. It is a principle of human nature to hate those whom we have injured; and Domitian was constitutionally inclined to anger, which was the more difficult to be averted, in proportion as it was the more disguised. Yet he was softened by the temper and prudence of Agricola; who did not think it necessary, by a contumacious spirit, or a vain ostentation of liberty, to challenge fame or urge his fate. Let those be apprised, who are accustomed to admire every opposition to control, that even under a bad prince men may be truly great; that submission and modesty, if accompanied with vigor and industry, will elevate a character to a height of public esteem equal to that which many, through abrupt and dangerous paths, have attained, without benefit to their country, by an ambitious death.

43. His decease was a severe affliction to his family, a grief to his friends, and a subject of regret even to foreigners, and those who had no personal knowledge of him. The common people too, and the class who little interest themselves about public concerns, were frequent in their inquiries at his house during his sickness, and made him the subject of conversation at the forum and in private circles; nor did any person either rejoice at the news of his death, or speedily forget it. Their commiseration was aggravated by a prevailing report that he was taken off by poison. I cannot venture to affirm anything certain of this matter; yet, during the whole course of his illness, the principal of the imperial freedmen and the most confidential of the physicians was sent much more frequently than was customary with a court whose visits were chiefly paid by messages; whether that was done out of real solicitude, or for the purposes of state inquisition. On the day of his decease, it is certain that accounts of his approaching dissolution were every instant transmitted to the emperor by couriers stationed for the purpose; and no one believed that the information, which so much pains was taken to accelerate, could be received with regret. He put on, however, in his countenance and demeanor, the semblance of grief: for he was now secured from an object of hatred, and could more easily conceal his joy than his fear. It was well known that on reading the will, in which he was nominated co-heir with the excellent wife and most dutiful daughter of Agricola, he expressed great satisfaction, as if it had been a voluntary testimony of honor and esteem: so blind and corrupt had his mind been rendered by continual adulation, that he was ignorant none but a bad prince could be nominated heir to a good father.

44. Agricola was born in the ides of June, during the third consulate of Caius Caesar; he died in his fifty-sixth year, on the tenth of the calends of September, when Collega and Priscus were consuls. Posterity may wish to form an idea of his person. His figure was comely rather than majestic. In his countenance there was nothing to inspire awe; its character was gracious and engaging. You would readily have believed him a good man, and willingly a great one. And indeed, although he was snatched away in the midst of a vigorous age, yet if his life be measured by his glory, it was a period of the greatest extent. For after the full enjoyment of all that is truly good, which is found in virtuous pursuits alone, decorated with consular and triumphal ornaments, what more could fortune contribute to his elevation? Immoderate wealth did not fall to his share, yet he possessed a decent affluence. His wife and daughter surviving, his dignity unimpaired, his reputation flourishing, and his kindred and friends yet in safety, it may even be thought an additional felicity that he was thus withdrawn from impending evils. For, as we have heard him express his wishes of continuing to the dawn of the present auspicious day, and beholding Trajan in the imperial seat, — wishes in which he formed a certain presage of the event; so it is a great consolation, that by his untimely end he escaped that latter period, in which Domitian, not by intervals and remissions, but by a continued, and, as it were, a single act, aimed at the destruction of the commonwealth.

45. Agricola did not behold the senate-house besieged, and the senators enclosed by a circle of arms; and in one havoc the massacre of so many consular men, the flight and banishment of so many honorable women. As yet Carus Metius was distinguished only by a single victory; the counsels of Messalinus resounded only through the Albanian citadel; and Massa Baebius was himself among the accused. Soon after, our own hands dragged Helvidius to prison; ourselves were tortured with the spectacle of Mauricus and Rusticus, and sprinkled with the innocent blood of Senecio.

Even Nero withdrew his eyes from the cruelties he commanded. Under Domitian, it was the principal part of our miseries to behold and to be beheld: when our sighs were registered; and that stern countenance, with its settled redness, his defence against shame, was employed in noting the pallid horror of so many spectators. Happy, O Agricola! not only in the splendor of your life, but in the seasonableness of your death. With resignation and cheerfulness, from the testimony of those who were present in your last moments, did you meet your fate, as if striving to the utmost of your power to make the emperor appear guiltless. But to myself and your daughter, besides the anguish of losing a parent, the aggravating affliction remains, that it was not our lot to watch over your sick-bed, to support you when languishing, and to satiate ourselves with beholding and embracing you. With what attention should we have received your last instructions, and engraven them on our hearts! This is our sorrow; this is our wound: to us you were lost four years before by a tedious absence. Everything, doubtless, O best of parents! was administered for your comfort and honor, while a most affectionate wife sat beside you; yet fewer tears were shed upon your bier, and in the last light which your eyes beheld, something was still wanting.

46. If there be any habitation for the shades of the virtuous; if, as philosophers suppose, exalted souls do not perish with the body; may you repose in peace, and call us, your household, from vain regret and feminine lamentations, to the contemplation of your virtues, which allow no place for mourning or complaining! Let us rather adorn your memory by our admiration, by our short-lived praises, and, as far as our natures will permit, by an imitation of your example. This is truly to honor the dead; this is the piety of every near relation. I would also recommend it to the wife and daughter of this great man, to show their veneration of a husband’s and a father’s memory by revolving his actions and words in their breasts, and endeavoring to retain an idea of the form and features of his mind, rather than of his person. Not that I would reject those resemblances of the human figure which are engraven in brass or marbles but as their originals are frail and perishable, so likewise are they: while the form of the mind is eternal, and not to be retained or expressed by any foreign matter, or the artist’s skill, but by the manners of the survivors. Whatever in Agricola was the object of our love, of our admiration, remains, and will remain in the minds of men, transmitted in the records of fame, through an eternity of years. For, while many great personages of antiquity will be involved in a common oblivion with the mean and inglorious, Agricola shall survive, represented and consigned to future ages.

GERMANIA

Translated by John Aikin

The Germania, an ethnographic work on the Germanic tribes outside the Roman Empire, was composed by Tacitus circa AD 98. Beginning with a description of the lands, laws and customs of the Germanic people, it then moves into descriptions of individual tribes, starting with those dwelling closest to Roman lands and ending on the uttermost shores of the Baltic, among the amber-gathering Aesti, the Fenni and the unknown tribes beyond them.