автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Choice Readings for the Home Circle

E-text prepared by Roger Frank

and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net/)

Home, Sweet Home

CHOICE READINGS

FOR THE HOME CIRCLE

I know not where his islands lift

Their fronded palms in air,I only know I can not drift

Beyond his love and care.—

WhittierPublished By

M. A. VROMAN

2123 24th Ave. N.

Nashville, Tenn.

WESTERN OFFICES:

1650 San Jose Ave., San Francisco, Calif.

617 Chestnut St., Glendale, Calif.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1905,

by M. A. Vroman, in the Office of the Librarian of

Congress, Washington, D.C. All Rights Reserved.

Copyright 1916, by Martin A. Vroman.

PREFACE.

The compiler of this volume has been gathering a large amount of moral and religious reading, from which selections have been made, admitting only those which may be read with propriety on the Sabbath.

This volume will be found to contain the best lessons for the family circle, such as will inculcate principles of obedience to parents, kindness and affection to brothers and sisters and youthful associates, benevolence to the poor, and the requirements of the gospel. These virtuous principles are illustrated by instances of conformity to them, or departure from them, in such a manner as to lead to their love and practice.

Great care has been taken in compiling this volume to avoid introducing into it anything of a sectarian or denominational character that might hinder its free circulation among any denomination, or class of society, where there is a demand for moral and religious literature. The illustrations were made especially for this book, and are the result of much careful study.

The family circle can be instructed and impressed by high-toned moral and religious lessons in no better way during a leisure hour of the Sabbath, when not engaged in the solemn worship of God, than to listen to one of their number who shall read from this precious volume. May the blessing of God attend it to every home circle that shall give it a welcome, is the prayer of the

Publisher.

NOTE TO THE PUBLIC

This is the same book formerly known as "Sabbath Readings for the Home Circle," the subject matter remaining unchanged.

We believe all who read this book will heartily accord with us in our desire to see it placed in every home in the land, and will do their part toward this good end.

The stories and poems it contains cover nearly all phases of life's experiences. Each one presents lessons which can but tend to make the reader better and nobler.

This decidedly valuable and interesting work now enters upon its sixth edition, one hundred thirty thousand copies, with the demand rapidly increasing.

Many have joined us in canvassing for it, and it has proved to be not only a noble work and a service to the people, but it brings good financial returns. Many students have worked their way through school by using their vacations in this work.

The publisher's name and address is on the title page, and he will see that all orders are promptly and carefully filled, and all letters of inquiry cheerfully answered. Address nearest office.

Believing that the "Choice Readings for the Home Circle" will be appreciated by all lovers of the true and beautiful, and that the book will make for itself not only a place, but a warm welcome, in thousands of homes during the coming year, it is cheerfully and prayerfully sent on its mission by

The Publisher.

Contents

Affecting Scene in a Saloon

388A Good Lesson Spoiled

192A Kind Word

67A Life Lesson

178A Mountain Prayer-meeting

144An Instructive Anecdote

214Another Commandment

71A Retired Merchant

90A Rift in the Cloud

286Be Just Before Generous

99Benevolent Society

199Bread Upon the Waters

280Caught in the Quicksand

112Christ Our Refuge

47Company Manners

36Effect of Novel Reading

95Evening Prayer

342Every Heart Has Its Own Sorrow

324Grandmother's Room

230Hard Times Conquered

185Herrings for Nothing

275How It Was Blotted Out

166Live Within Your Means

127Look to Your Thoughts

397Lyman Dean's Testimonials

251Make It Plain

83"My House" and "Our House"

138Nellie Alton's Mother

393Never Indorse

170Only a Husk

151Out of the Wrong Pocket

131Over the Crossing

304Put Yourself in My Place

312Richest Man in the Parish

296Ruined at Home

157Speak to Strangers

360Story of School Life

221Success if the Reward of Perseverance

291Susie's Prayer

32The Belle of the Ballroom

40The Fence Story

310The Happy New Year

346The Indian's Revenge

11The Infidel Captain

319The Little Sisters

368The Major's Cigar

363The Premium

58The Record

25The Right Decision

29The Scripture Quilt

354The Ten Commandments

81The Widow's Christmas

374The Young Musician

244Tom's Trial

50Unforgotten Words

263With a Will, Joe

385"What Shall It Profit?"

115Why He Didn't Smoke

217Poems

A Christian Life

89Alone

341An Infinite Giver

137Believe and Trust

39Consolation

111Did You Ever Think?

279Do With Your Might

387Forgive and Forget

318Good-Bye—God Bless You!

165Life That Lasts

213Loving Words

362Mother

28"Once Again"

114Our Neighbors

66Our Record

373Reaping

216Song of the Rye

156Stop and Look Around!

309The Dark First

130The Father Is Near

285The Lord's Prayer

342The Master's Hand

49The Shadow of the Cross

46The Way to Overcome

169To-Day's Furrow

98Walking With God

303Watch Your Words

177What Counts

57What to Mind

367Your Call

274List of Illustrations

Home, Sweet Home

FrontispieceWhile He Slept His Enemy Came and Sowed Tares Among the Wheat

44Christ Blessing Little Children

76Christ the Good Shepherd

124Paul at Athens

172Pure Religion Is Visiting the Fatherless and Widows in Their Affliction

207Grandmother's Room

240Come Unto Me

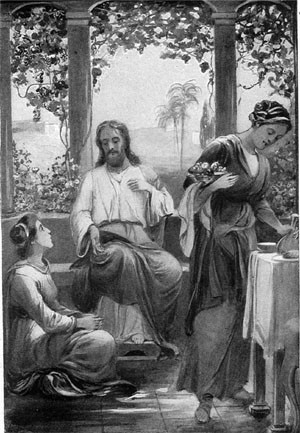

278Christ in the Home of Mary and Martha

300He Is Not Here; He Is Risen

336God Be Merciful to Me a Sinner

354Announcement to Shepherds

376Pledges

Against the use of Liquor and Tobacco

391THE SABBATH

Sabbaths, like way-marks, cheer the pilgrim's path,

His progress mark, and keep his rest in view.

In life's bleak winter, they are pleasant days,

Short foretaste of the long, long spring to come.

To every new-born soul, each hallowed morn

Seems like the first, when everything was new.

Time seems an angel come afresh from heaven,

His pinions shedding fragrance as he flies,

And his bright hour-glass running sands of gold.

—

Carlos Wilcox.

The Indian's Revenge

The beautiful precept, "Do unto others as you would that they should do unto you," is drawn from our Lord's sermon on the mount, and should be observed by all professing Christians. But unless we are truly his children, we can never observe this great command as we ought.

History records the fact that the Roman emperor Severus was so much struck with the moral beauty and purity of this sentiment, that he ordered the "Golden Rule," to be inscribed upon the public buildings erected by him. Many facts may be stated, by which untutored heathen and savage tribes in their conduct have put to shame many of those calling themselves Christians, who have indeed the form of godliness, but by their words and actions deny the power of it. One such fact we here relate.

Many years ago, on the outskirts of one of our distant new settlements, was a small but neat and pretty cottage, or homestead, which belonged to an industrious young farmer. He had, when quite a lad, left his native England, and sought a home and fortune among his American brethren. It was a sweet and quiet place; the cottage was built upon a gently rising ground, which sloped toward a sparkling rivulet, that turned a large sawmill situated a little lower down the stream. The garden was well stocked with fruit-trees and vegetables, among which the magnificent pumpkins were already conspicuous, though as yet they were wanting in the golden hue which adorns them in autumn. On the hillside was an orchard, facing the south, filled with peach and cherry-trees, the latter now richly laden with their crimson fruit. In that direction also extended the larger portion of the farm, now in a high state of cultivation, bearing heavy crops of grass, and Indian corn just coming into ear. On the north and east, the cottage was sheltered by extensive pine woods, beyond which were fine hunting-grounds, where the settlers, when their harvests were housed, frequently resorted in large numbers to lay in a stock of dried venison for winter use.

At that time the understanding between the whites and the Indians, was not good; and they were then far more numerous than they are at the present time, and more feared. It was not often, however, that they came into the neighborhood of the cottage which has been described, though on one or two occasions a few Minateree Indians had been seen on the outskirts of the pine forests, but had committed no outrages, as that tribe was friendly with the white men.

It was a lovely evening in June. The sun had set, though the heavens still glowed with those exquisite and radiant tints which the writer, when a child, used to imagine were vouchsafed to mortals to show them something while yet on earth, of the glories of the New Jerusalem. The moon shed her silvery light all around, distinctly revealing every feature of the beautiful scene which has been described, and showed the tall, muscular figure of William Sullivan, who was seated upon the door-steps, busily employed in preparing his scythes for the coming hay season. He was a good-looking young fellow, with a sunburnt, open countenance; but though kind-hearted in the main, he was filled with prejudices, acquired when in England, against Americans in general, and the North American Indians in particular. As a boy he had been carefully instructed by his mother, and had received more education than was common in those days; but of the sweet precepts of the gospel he was as practically ignorant as if he had never heard them, and in all respects was so thoroughly an Englishman, that he looked with contempt on all who could not boast of belonging to his own favored country. The Indians he especially despised and detested as heathenish creatures, forgetful of the fact that he who has been blessed with opportunities and privileges, and yet has abused them, is in as bad a case, and more guilty in the sight of God, than these ignorant children of the wilds.

So intent was he upon his work, that he heeded not the approach of a tall Indian, accoutred for a hunting excursion, until the words:—

"Will you give an unfortunate hunter some supper, and a lodging for the night?" in a tone of supplication, met his ear.

The young farmer raised his head; a look of contempt curling the corners of his mouth, and an angry gleam darting from his eyes, as he replied in a tone as uncourteous as his words:—

"Heathen Indian dog, you shall have nothing here; begone!"

The Indian turned away; then again facing young Sullivan, he said in a pleading voice:—

"But I am very hungry, for it is very long since I have eaten; give only a crust of bread and a bone to strengthen me for the remainder of my journey."

"Get you gone, heathen hound," said the farmer; "I have nothing for you."

A struggle seemed to rend the breast of the Indian hunter, as though pride and want were contending for the mastery; but the latter prevailed, and in a faint voice he said:—

"Give me but a cup of cold water, for I am very faint."

This appeal was no more successful than the others. With abuse he was told to drink of the river which flowed some distance off. This was all that he could obtain from one who called himself a Christian, but who allowed prejudice and obstinacy to steel his heart—which to one of his own nation would have opened at once—to the sufferings of his redskinned brother.

With a proud yet mournful air the Indian turned away, and slowly proceeded in the direction of the little river. The weak steps of the native showed plainly that his need was urgent; indeed he must have been reduced to the last extremity, ere the haughty Indian would have asked again and again for that which had been once refused.

Happily his supplicating appeal was heard by the farmer's wife. Rare indeed is it that the heart of woman is steeled to the cry of suffering humanity; even in the savage wilds of central Africa, the enterprising and unfortunate Mungo Park was over and over again rescued from almost certain death by the kind and generous care of those females whose husbands and brothers thirsted for his blood.

The farmer's wife, Mary Sullivan, heard the whole as she sat hushing her infant to rest; and from the open casement she watched the poor Indian until she saw his form sink, apparently exhausted, to the ground, at no great distance from her dwelling. Perceiving that her husband had finished his work, and was slowly bending his steps toward the stables with downcast eyes—for it must be confessed he did not feel very comfortable—she left the house, and was soon at the poor Indian's side, with a pitcher of milk in her hand, and a napkin, in which was a plentiful meal of bread and roasted kid, with a little parched corn as well.

"Will my red brother drink some milk?" said Mary, bending over the fallen Indian; and as he arose to comply with her invitation, she untied the napkin and bade him eat and be refreshed.

When he had finished, the Indian knelt at her feet, his eyes beamed with gratitude, then in his soft tone, he said: "Carcoochee protect the white dove from the pounces of the eagle; for her sake the unfledged young shall be safe in its nest, and her red brother will not seek to be revenged."

Drawing a bunch of heron's feathers from his bosom, he selected the longest, and giving it to Mary Sullivan, said: "When the white dove's mate flies over the Indian's hunting-grounds, bid him wear this on his head."

He then turned away; and gliding into the woods, was soon lost to view.

The summer passed away; harvest had come and gone; the wheat and maize, or Indian corn, was safely stored in the yard; the golden pumpkins were gathered into their winter quarters, and the forests glowed with the rich and varied tints of autumn. Preparations now began to be made for a hunting excursion, and William Sullivan was included in the number who were going to try their fortune on the hunting-grounds beyond the river and the pine forests. He was bold, active, and expert in the use of his rifle and woodman's hatchet, and hitherto had always hailed the approach of this season with peculiar enjoyment, and no fears respecting the not unusual attacks of the Indians, who frequently waylaid such parties in other and not very distant places, had troubled him.

But now, as the time of their departure drew near, strange misgivings relative to his safety filled his mind, and his imagination was haunted by the form of the Indian whom in the preceding summer he had so harshly treated. On the eve of the day on which they were to start, he made known his anxiety to his gentle wife, confessing at the same time that his conscience had never ceased to reproach him for his unkind behavior. He added, that since then all that he had learned in his youth from his mother upon our duty to our neighbors had been continually in his mind; thus increasing the burden of self-reproach, by reminding him that his conduct was displeasing in the sight of God, as well as cruel toward a suffering brother. Mary Sullivan heard her husband in silence. When he had done, she laid her hand in his, looking up into his face with a smile, which was yet not quite free from anxiety, and then she told him what she had done when the Indian fell down exhausted upon the ground, confessing at the same time that she had kept this to herself, fearing his displeasure, after hearing him refuse any aid. Going to a closet, she took out the beautiful heron's feather, repeating at the same time the parting words of the Indian, and arguing from them that her husband might go without fear.

"Nay," said Sullivan, "these Indians never forgive an injury."

"Neither do they ever forget a kindness," added Mary. "I will sew this feather in your hunting-cap, and then trust you, my own dear husband, to God's keeping; but though I know he could take care of you without it, yet I remember my dear father used to say that we were never to neglect the use of all lawful means for our safety. His maxim was, 'Trust like a child, but work like a man'; for we must help ourselves if we hope to succeed, and not expect miracles to be wrought on our behalf, while we quietly fold our arms and do nothing." "Dear William," she added, after a pause, "now that my father is dead and gone, I think much more of what he used to say than when he was with me; and I fear that we are altogether wrong in the way we are going on, and I feel that if we were treated as we deserve, God would forget us, and leave us to ourselves, because we have so forgotten him."

The tears were in Mary's eyes as she spoke; she was the only daughter of a pious English sailor, and in early girlhood had given promise of becoming all that a religious parent could desire. But her piety was then more of the head than of the heart; it could not withstand the trial of the love professed for her by Sullivan, who was anything but a serious character, and like "the morning cloud and the early dew," her profession of religion vanished away, and as his wife she lost her relish for that in which she once had taken such delight. She was very happy in appearance, yet there was a sting in all her pleasures, and that was the craving of a spirit disquieted and restless from the secret though ever-present conviction that she had sinned in departing from the living God. By degrees these impressions deepened; the Spirit of grace was at work within, and day after day was bringing to her memory the truths she had heard in childhood and was leading her back from her wanderings by a way which she knew not. A long conversation followed; and that night saw the young couple kneeling for the first time in prayer at domestic worship.

The morning that witnessed the departure of the hunters was one of surpassing beauty. No cloud was to be seen upon the brow of William Sullivan. The bright beams of the early sun seemed to have dissipated the fears which had haunted him on the previous evening, and it required an earnest entreaty on the part of his wife to prevent his removing the feather from his cap. She held his hand while she whispered in his ear, and a slight quiver agitated his lips as he said, "Well, Mary dear, if you really think this feather will protect me from the redskins, for your sake I will let it remain." William then put on his cap, shouldered his rifle, and the hunters were soon on their way seeking for game.

The day wore away as is usual with people on such excursions. Many animals were killed, and at night the hunters took shelter in the cave of a bear, which one of the party was fortunate enough to shoot, as he came at sunset toward the bank of the river. His flesh furnished them with some excellent steaks for supper, and his skin spread upon a bed of leaves pillowed their heads through a long November night.

With the first dawn of morning, the hunters left their rude shelter and resumed the chase. William, in consequence of following a fawn too ardently, separated from his companions, and in trying to rejoin them became bewildered. Hour after hour he sought in vain for some mark by which he might thread the intricacy of the forest, the trees of which were so thick that it was but seldom that he could catch a glimpse of the sun; and not being much accustomed to the woodman's life, he could not find his way as one of them would have done, by noticing which side of the trees was most covered with moss or lichen. Several times he started in alarm, for he fancied that he could see the glancing eyeballs of some lurking Indian, and he often raised his gun to his shoulder, prepared to sell his life as dearly as he could.

Toward sunset the trees lessened and grew thinner, and by and by he found himself upon the outskirts of an immense prairie, covered with long grass, and here and there with patches of low trees and brushwood. A river ran through this extensive tract, and toward it Sullivan directed his lagging footsteps. He was both faint and weary, not having eaten anything since the morning. On the bank of the river there were many bushes, therefore Sullivan approached with caution, having placed his rifle at half-cock, to be in readiness against any danger that might present itself. He was yet some yards from its brink, when a rustling in the underwood made him pause, and the next instant out rushed an enormous buffalo. These animals usually roam through the prairies in immense herds, sometimes amounting to many thousands in number; but occasionally they are met with singly, having been separated from the main body either by some accident, or by the Indians, who show the most wonderful dexterity in hunting these formidable creatures. The buffalo paused for a moment, and then lowering his enormous head, rushed forward toward the intruder. Sullivan took aim; but the beast was too near to enable him to do so with that calmness and certainty which would have insured success, and though slightly wounded, it still came on with increased fury. Sullivan was a very powerful man, and though weakened by his long fast and fatiguing march, despair gave him courage and nerved his arm with strength, and with great presence of mind he seized the animal as it struck him on the side with its horn, drawing out his knife with his left hand, in the faint hope of being able to strike it into his adversary's throat. But the struggle was too unequal to be successful, and the buffalo had shaken him off, and thrown him to the ground, previous to trampling him to death, when he heard the sharp crack of a rifle behind him, and in another instant the animal sprang into the air, then fell heavily close by, and indeed partly upon, the prostrate Sullivan. A dark form in the Indian garb glided by a moment after, and plunged his hunting-knife deep into the neck of the buffalo, though the shot was too true not to have taken effect, having penetrated to the brain; but the great arteries of the neck are cut, and the animal thus bled, to render the flesh more suitable for keeping a greater length of time.

The Indian then turned to Sullivan, who had now drawn himself from under the buffalo, and who, with mingled feelings of hope and fear, caused by his ignorance whether the tribe to which the Indian belonged was friendly or not, begged of him to direct him to the nearest white settlement.

"If the weary hunter will rest till morning, the eagle will show him the way to the nest of his white dove," was the reply of the Indian, in that figurative style so general among his people; and then taking him by the hand he led him through the rapidly increasing darkness, until they reached a small encampment lying near the river, and under the cover of some trees which grew upon its banks. Here the Indian gave Sullivan a plentiful supply of hominy, or bruised Indian corn boiled to a paste, and some venison; then spreading some skins of animals slain in the chase, for his bed, he signed to him to occupy it, and left him to his repose.

The light of dawn had not yet appeared in the east when the Indian awoke Sullivan; and after a slight repast, they both started for the settlement of the whites. The Indian kept in advance of his companion, and threaded his way through the still darkened forest with a precision and a rapidity which showed him to be well acquainted with its paths and secret recesses. As he took the most direct way, without fear of losing his course, being guided by signs unknown to any save some of the oldest and most experienced hunters, they traversed the forest far more quickly than Sullivan had done, and before the golden sun had sunk behind the summits of the far-off mountains, Sullivan once more stood within view of his beloved home. There it lay in calm repose, and at a sight so dear he could not restrain a cry of joy; then turning toward the Indian, he poured forth his heartfelt thanks for the service he had rendered him.

The warrior, who, till then, had not allowed his face to be seen by Sullivan, except in the imperfect light of his wigwam, now fronted him, allowing the sun's rays to fall upon his person, and revealed to the astonished young man the features of the very same Indian whom, five months before, he had so cruelly repulsed. An expression of dignified yet mild rebuke was exhibited in his face as he gazed upon the abashed Sullivan; but his voice was gentle and low as he said: "Five moons ago, when I was faint and weary, you called me 'Indian dog,' and drove me from your door. I might last night have been revenged; but the white dove fed me, and for her sake I spared her mate. Carcoochee bids you to go home, and when hereafter you see a red man in need of kindness, do to him as you have been done by. Farewell."

He waved his hand, and turned to depart, but Sullivan sprang before him, and so earnestly entreated him to go with him, as a proof that he had indeed forgiven his brutal treatment, that he at last consented, and the humbled farmer led him to his cottage. There his gentle wife's surprise at seeing him so soon was only equaled by her thankfulness at his wonderful escape from the dangers which had surrounded him, and by her gratitude to the noble savage who had thus repaid her act of kindness, forgetful of the provocation he had received from her husband. Carcoochee was treated not only as an honored guest, but as a brother; and such in time he became to them both.

Many were the visits he paid to the cottage of the once prejudiced and churlish Sullivan, now no longer so, for the practical lesson of kindness he had learned from the untutored Indian was not lost upon him. It was made the means of bringing him to a knowledge of his own sinfulness in the sight of God, and his deficiencies in duty toward his fellow men. He was led by the Holy Spirit to feel his need of Christ's atoning blood; and ere many months passed, Mary Sullivan and her husband both gave satisfactory evidence that they had indeed "passed from death unto life."

Carcoochee's kindness was repaid to him indeed a hundred fold. A long time elapsed before any vital change of heart was visible in him; but at length it pleased the Lord to bless the unwearied teaching of his white friends to his spiritual good, and to give an answer to the prayer of faith. The Indian was the first native convert baptized by the American missionary, who came about two years after to a station some few miles distant from Sullivan's cottage. After a lengthened course of instruction and trial the warrior, who once had wielded the tomahawk in mortal strife against both whites and redskins, went forth, armed with a far different weapon, "even the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God," to make known to his heathen countrymen "the glad tidings of great joy," that "Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners." He told them that "whosoever believeth on him should not perish, but have everlasting life," whether they be Jews or Gentiles, bond or free, white or red, for "we are all one in Christ." Many years he thus labored, until, worn out with toil and age, he returned to his white friend's home, where in a few months he fell asleep in Jesus, giving to his friends the certain hope of a joyful meeting hereafter at the resurrection of the just.

Many years have passed since then. There is no trace now of the cottage of the Sullivans, who both rest in the same forest churchyard, where lie the bones of Carcoochee; but their descendants still dwell in the same township. Often does the gray-haired grandsire tell this little history to his rosy grandchildren, while seated under the stately magnolia which shades the graves of the quiet sleepers of whom he speaks. And the lesson which he teaches to his youthful hearers, is one which all would do well to bear in mind, and act upon; namely, "Whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them."

Affecting Scene In A Saloon

A Good Lesson Spoiled

A Kind Word.

A Life Lesson

A Mountain Prayer Meeting

An Instructive Anecdote

Another Commandment

A Retired Merchant

A Rift in the Cloud.

Be Just Before Generous.

Benevolent Society.

Bread Upon The Waters

Caught In The Quicksand

Christ Our Refuge

Company Manners.

Effect Of Novel Reading

Evening Prayer.

Every Heart Has Its Own Sorrow

Grandmother's Room.

Hard Times Conquered.

Herrings for Nothing.

How It Was Blotted Out

Live Within Your Means.

Look to Your Thoughts.

Lyman Dean's Testimonials.

Make It Plain.

"My House" and "Our House."

Nellie Alton’s Mother

Never Indorse.

Only a Husk.

Out Of The Wrong Pocket

Over The Crossing

Put Yourself in My Place.

Richest Man in the Parish.

Ruined at Home.

Speak To Strangers

Story Of School Life

Success Is The Reward Of Perseverance

Susie's Prayer

The Belle of the Ballroom.

The Fence Story

The Happy New Year

The Indian's Revenge

The Infidel Captain

The Little Sisters

The Major's Cigar

The Premium.

The Record

The Right Decision.

The Scripture Quilt

THE TEN COMMANDMENTS.

The Widow’s Christmas

The Young Musician

Tom's Trial.

Unforgotten Words

With A Will, Joe

"What Shall It Profit?"

Why He Didn't Smoke.

A CHRISTIAN LIFE.

"A Christian life, have you ever thought

How much is in that name?A life like Christ, and all he taught

We must follow, to be the same.How little of ease the Saviour knew

With his life of labor and love!And if we would walk in his footsteps too,

We must look not to earth, but above.The darkest hour the Christian knows

Is just before the dawn;For as the night draws to its close,

It will bring in the morn.So if you trust, though shadows fall,

And dark your pathway be,The light, which shines from heaven for all,

Will surely fall on thee."ALONE.

"Alone with God!" the keynote this

Of every holy life,The secret power of fragrant growth,

And victory over strife."Alone with God!" in private prayer

And quietness we feelThat he draws near our waiting souls,

And doth himself reveal."Alone with God!" earth's laurels fade,

Ambition tempts not there;The world and self are judged aright,

And no false colors wear."Alone with God!" true knowledge gained,

While sitting at his feet;We learn life's greatest lessons there,

Which make for service meet.AN INFINITE GIVER.

Think you, when the stars are glinting,

Or the moonlight's shimmering gleamPaints the water's rippled surface

With a coat of silvered sheen—Think you then that God, the Painter,

Shows his masterpiece divine?That he will not hang another

Of such beauty on the line?Think you, when the air is trembling

With the birds' exultant song,And the blossoms, mutely fragrant,

Strive the anthem to prolong—Think you then that their Creator,

At the signal of his word,Fills the earth with such sweet music

As shall ne'er again be heard?He will never send a blessing

But have greater ones in store,And each oft recurring kindness

Is an earnest of still more.If the earth seems full of glory

As his purposes unfold,There is still a better country—

And the half has not been told!BELIEVE AND TRUST.

Believe and trust. Through stars and suns,

Through life and death, through soul and sense,His wise, paternal purpose runs;

The darkness of his providence Is star-lit with benign intents.O joy supreme! I know the Voice,

Like none beside on earth and sea;Yea, more, O soul of mine, rejoice!

By all that he requires of me I know what God himself must be.—

Whittier.

CONSOLATION.

"Unto those who sit in sorrow, God has sent this precious word:

Not an earnest prayer or impulse of the heart ascends unheard.

He who rides upon the tempest, heeds the sparrow when it falls,

And with mercies crowns the humblest, when before the throne he calls."

DID YOU EVER THINK?

Did you ever think what this world would be

If Christ hadn't come to save it?His hands and feet were nailed to the tree,

And his precious life—he gave it.But countless hearts would break with grief,

At the hopeless life they were given,If God had not sent the world relief,

If Jesus had stayed in heaven.Did you ever think what this world would be

With never a life hereafter?Despair in the faces of all we'd see,

And sobbing instead of laughter.In vain is beauty, and flowers' bloom,

To remove the heart's dejection,Since all would drift to a yawning tomb,

With never a resurrection.Did you ever think what this world would be.

How weary of all endeavor,If the dead unnumbered, in land and sea,

Would just sleep on forever?Only a pall over hill and plain!

And the brightest hours are dreary,Where the heart is sad, and hopes are vain,

And life is sad and weary.Did you ever think what this world would be

If Christ had stayed in heaven,—No home in bliss, no soul set free,

No life, or sins forgiven?But he came with a heart of tenderest love,

And now from on high he sees us,And mercy comes from the throne on high;

Thank God for the gift of Jesus!DO WITH YOUR MIGHT.

Whatsoe'er you find to do,

Do it, boys, with all your might!Never be a

littletrue,

Or a little in the right. Trifles even Lead to heaven,Trifles make the life of man;

So in all things, Great or small things,Be as thorough as you can.

FORGIVE AND FORGET.

Forgive and forget, it is better

To fling all ill feeling asideThan allow the deep, cankering fetter

Of revenge in your breast to abide;For your step o'er life's path will be lighter,

When the load from your bosom is cast,And the glorious sky will seem brighter,

When the cloud of displeasure has passed.Though your spirit swell high with emotion

To give back injustice again,Sink the thought in oblivion's ocean,

For remembrance increases the pain.O, why should we linger in sorrow,

When its shadow is passing away,—Or seek to encounter to-morrow,

The blast that o'erswept us to-day?Our life's stream is a varying river,

And though it may placidly glideWhen the sunbeams of joy o'er it quiver,

It must foam when the storm meets its tide.Then stir not its current to madness,

For its wrath thou wilt ever regret;Though the morning beams break on thy sadness,

Ere the sunset, forgive and forget.—

Robert Gray.GOOD-BYE—GOD BLESS YOU!

I love the words—perhaps because

When I was leaving mother,Standing at last in solemn pause,

We looked at one another;And I—I saw in mother's eyes

The love she could not tell me,A love eternal as the skies,

Whatever fate befell me.She put her arms about my neck,

And soothed the pain of leaving,And though her heart was like to break,

She spoke no word of grieving;She let no tear bedim her eye,

For fear that might distress me;But, kissing me, she said good-bye,

And asked our God to bless me.LIFE THAT LASTS.

They err who measure life by years

With false or thoughtless tongue.Some hearts grow old before their time;

Others are always young.'Tis not the number of the lines

On life's fast-filling page,'Tis not the pulse's added throbs

Which constitute their age.Some souls are serfs among the free,

While others nobly thrive;They stand just where their fathers stood,

Dead, even while they live.Others, all spirit, heart, and sense,

Theirs the mysterious powerTo live in thrills of joy or woe

A twelve-month in an hour.He liveth long who liveth well!

All other life is short and vain;He liveth longest who can tell

Of living most for heavenly gain.He liveth long who liveth well!

All else is being flung away;He liveth longest who can tell

Of true things truly done each day.LOVING WORDS.

Loving words are rays of sunshine,

Falling on the path of life,Driving out the gloom and shadow

Born of weariness and strife.Often we forget our troubles

When a friendly voice is heard,They are banished by the magic

Of a kind and helpful word.Keep not back a word of kindness

When the chance to speak it comes;Though it seems to you a trifle,

Many a heart that grief benumbsWill grow strong and brave to bear it,

And the world will brighter grow,Just because the word was spoken;

Try it—you will find it so.MOTHER.

The silvery hairs are weaving

A crown above her brow,But surely mother never seemed

One-half so sweet as now!The love-light beams from out her eyes

As clear, as sweet and true,As when, with youthful beauty crowned,

Life bloomed for her all new.No thought of self doth ever cast

A cloudlet o'er the lightThat shines afar from out her soul,

So steadfast, pure, and bright.Her love illumes the darkest hour,

Smooths all the rugged way,Makes lighter every burden,

Cheers through each weary day.More precious than the rarest gem

In all the world could be;More sweet than honor, fame, and praise,

Is mother's love to me."ONCE AGAIN."

Lord, in the silence of the night,

Lord, in the turmoil of the day;In time of rapture and delight,

In hours of sorrow and dismay;Yea, when my voice is filled with laughter,

Yea, when my lips are thinned with pain;For present joy, and joy hereafter,

Lord, I would thank thee once again.—

Elmer James Bailey.OUR NEIGHBORS.

"Somebody near you is struggling alone

Over life's desert sand;Faith, hope, and courage together are gone;

Reach him a helping hand;Turn on his darkness a beam of your light;

Kindle, to guide him, a beacon fire bright;

Cheer his discouragement, soothe his affright,

Lovingly help him to stand.Somebody near you is hungry and cold;

Send him some aid to-day;Somebody near you is feeble and old,

Left without human stay.Under his burdens put hands kind and strong;

Speak to him tenderly, sing him a song;

Haste to do something to help him along

Over his weary way.Dear one, be busy, for time fleeth fast,

Soon it will all be gone;Soon will our season of service be past,

Soon will our day be done.Somebody near you needs now a kind word;

Some one needs help, such as you can afford;

Haste to assist in the name of the Lord;

There may be a soul to be won."OUR RECORD.

We built us grand, gorgeous towers

Out toward the western sea,And said in a dream of the summer hours,

Thus fair should our record be.We would strike the bravest chords

That ever rebuked the wrong;And through them should tremble all loving words

That would make the weary strong.There entered not into our thought

The dangers the way led through,We saw but the gifts of the good we sought,

And the good we would strive to do.Here trace we a hurried line,

There blush or a blotted leaf;And tears, vain tears, on the eyelids shine,

That the record is so brief.REAPING.

While the years are swiftly passing,

As we watch them come and go,Do we realize the maxim,

We must reap whate'er we sow?When the past comes up before us,

All our thoughts, our acts and deeds,Shall they glean for us fair roses,

Or a harvest bear of weeds?Are we sowing seeds to blossom?

We shall reap some day,—somewhere,Just what here we have been sowing,

Worthless weeds or roses fair.All around us whispering ever,

Hear the voice of Nature speak,Teaching all the self-same lesson,

"As you sow so shall you reap."Though there's pardon for each sinner

In God's mercy vast and mild,Yet the law that governs Nature,

Governs e'en fair Nature's child.SONG OF THE RYE.

I was made to be eaten,

And not to be drank;To be thrashed in a barn,

Not soaked in a tank.I come as a blessing

When put through a mill,As a blight and a curse

When run through a still.Make me up into loaves,

And the children are fed;But if into drink,

I'll starve them instead.In bread I'm a servant,

The eater shall rule;In drink I am master,

The drinker a fool.STOP AND LOOK AROUND!

Life is full of passing pleasures

That are never seen or heard,Little things that go unheeded—

Blooming flower and song of bird;Overhead, a sky of beauty;

Underneath, a changing ground;And we'd be the better for it

If we'd stop and look around!Oh, there's much of toil and worry

In the duties we must meet;But we've time to see the beauty

That lies underneath our feet.We can tune our ears to listen

To a joyous burst of sound,And we know that God intended

We should stop and look around!Drop the care a while, and listen

When the sparrow sings his best;Turn aside, and watch the building

Of some little wayside nest;See the wild flower ope its petals,

Gather moss from stump and mound;And you'll be the better for it

If you stop and look around!THE DARK FIRST.

Not first the glad and then the sorrowful—

But first the sorrowful, and then the glad;Tears for a day—for earth of tears is full:

Then we forget that we were ever sad.Not first the bright, and after that the dark—

But first the dark, and after that the bright;First the thick cloud, and then the rainbow's arc:

First the dark grave, and then resurrection light.—

Horatius Bonar.

THE FATHER IS NEAR.

A wee little child in its dreaming one night

Was startled by some awful ogre of fright,

And called for its father, who quickly arose

And hastened to quiet the little one's woes.

"Dear child, what's the matter?" he lovingly said,

And smoothed back the curls from the fair little head;

"Don't cry any more, there is nothing to fear,

Don't cry any more, for your papa is here."

Ah, well! and how often we cry in the dark,

Though God in His love is so near to us! Hark!

How His loving words, solacing, float to the ear,

Saying, "Lo! I am with you: 'tis I, do not fear."

God is here in the world as thy Father and mine,

Ever watching and ready with love-words divine.

And while erring oft, through the darkness I hear

In my soul the sweet message: "Thy Father is near."

"Our Father."

THE MASTER'S HAND.

"In the still air the music lies unheard;

In the rough marble beauty hides unseen;To make the music and the beauty needs

A master's touch, the sculptor's chisel keen.Great Master, touch us with Thy skilled hand:

Let not the music that is in us die!Great Sculptor, hew and polish us, nor let

Hidden and lost, Thy form within us lie!Spare not the stroke! Do with us as thou wilt!

Let there be naught unfinished, broken, marred;Complete Thy purpose, that we may become

Thy perfect image, Thou our God and Lord!"THE SHADOW OF THE CROSS.

"Aye, and the race is just begun,

The world is all before me now,

The sun is in the eastern sky,

And long the shadows westward lie;

In everything that meets my eye

A splendor and a joy I mind

A glory that is undesigned."

Ah! youth, attempt that path with care,

The shadow of the cross is there.

"I've time," he said, "to rest awhile,

And sip the fragrant wine of life,

My lute to pleasure's halls I'll bring

And while the sun ascends I'll sing,

And all my world without shall ring

Like merry chiming bells that peal

Not half the rapture that they feel."

Alas! he found but tangled moss,

Above the shadow of the cross.

THE WAY TO OVERCOME.

When first from slumber waking,

No matter what the hour,If you will say, "Dear Jesus,

Come, fill me with thy power,"You'll find that every trouble

And every care and sinWill vanish, surely, fully,

Because Christ enters in.It may be late in morning,

Or in the dark before,When first you hear his knocking;

But open wide the door,And say to him, "Dear Jesus,

Come in and take the throne,Lest Satan with his angels

Should claim it for his own."For we are weak and sinful,

"Led captive at his will."But thou canst "bind the strong man,"

Our heart with sweetness fill.So would we have "thy presence"

From our first waking hour;All through the swift day's moments,

Dwell thou with us in power.TO-DAY'S FURROW.

Sow the shining seeds of service

In the furrows of each day,Plant each one with serious purpose,

In a hopeful, tender way.Never lose one seed, nor cast it

Wrongly with an hurried hand;Take full time to lay it wisely,

Where and how thy God hath planned.This the blessed way of sharing

With another soul your gains,While, though losing life, you find it

Yielding fruit on golden plains;For the soul which sows its blessings

Great or small, in word or smile,Gathers as the Master promised,

Either here or afterwhile.WALKING WITH GOD.

Walking with God in sorrow's dark hour,

Calm and serene in his infinite power;

Walking with him, I am free from all dread,

Filled with his Spirit, O! softly I tread.

Walking with God, O! fellowship sweet,

Thus to know God, and in him be complete;

Walking with him whom the world can not know,

O! it is sweet through life thus to go.

Walking with God in sorrow's dark hour,

Soothed and sustained by his infinite power;

O! it is sweet to my soul thus to live,

Filled with a peace which the world can not give.

Walking with God, O! may my life be

Such that my Lord can walk always with me;

Walking with him, I shall know, day by day,

That he is my Father, and leads all the way.

WATCH YOUR WORDS.

Keep a watch on your words, my darling,

For words are wonderful things;They are sweet like the bee's fresh honey—

Like the bees, they have terrible stings;They can bless, like the warm, glad sunshine,

And brighten a lonely life;They can cut in the strife of anger,

Like an open two-edged knife.Let them pass through your lips unchallenged,

If their errand is true and kind—If they come to support the weary,

To comfort and help the blind;If a bitter, revengeful spirit

Prompt the words, let them be unsaid;They may flash through a brain like lightning,

Or fall on a heart like lead.Keep them back, if they are cold and cruel,

Under bar and lock and seal;The wounds they make, my darling,

Are always slow to heal.May peace guard your life, and ever,

From the time of your early youth,May the words that you daily utter

Be the words of beautiful truth.WHAT COUNTS.

Did you tackle the trouble that came your way,

With a resolute heart and cheerful,Or hide your face from the light of day

With a craven face and fearful.O, a trouble's a ton, or a trouble's an ounce.

A trouble is what you make it.It isn't the fact that you're hurt that counts,

But only, HOW DID YOU TAKE IT?You are beaten to the earth? Well, what of that?

Come up with a smiling face.It's nothing against you to fall down

flat;

But to LIE THERE—that's disgrace.The harder you're thrown, the higher you'll bounce,

Be proud of your blackened eye.It isn't the fact that you're licked that counts,

But, HOW did you fight, and WHY?And though you be down to death, what then?

If you battled the best that you could,If you played your part in the world of men,

The Critic will call it good.Death comes with a crawl, or comes with a pounce,

And whether he's slow or spry,It isn't the fact that you're DEAD that counts,

But only HOW DID YOU DIE?—

Cooke.

WHAT TO MIND.

Mind your tongue!Don't let it speak

An angry, an unkind,A cruel, or a wicked word;

Don't let it, boys—now, mind! Mind eyes and ears!Don't ever look

At wicked books or boys.From wicked pictures turn away—

All sinful acts despise. And mind your lips!Tobacco stains;

Strong drink, too, keep away;And let no bad words pass your lips—

Mind everything you say. Mind hands and feet!Don't let them do

A single wicked thing;Don't steal or strike, don't kick or fight,

Don't walk in paths of sin.YOUR CALL.

The world is dark, but you are called to brighten

Some little corner, some secluded glen;Somewhere a burden rests that you may lighten,

And thus reflect the Master's love for men.Is there a brother drifting on life's ocean,

Who might be saved if you but speak a word?Speak it to-day. The testing of devotion

Is our response when duty's call is heard.While He Slept His Enemy Came and Sowed Tares Among the Wheat

Christ Blessing Little Children

Christ the Good Shepherd.

Paul at Athens

Pure Religion Is Visiting the Fatherless and Widows in Their Affliction

Grandmother’s Room

Come Unto Me.

Christ in the Home of Mary and Martha

He Is Not Here; He Is Risen

God Be Merciful to Me a Sinner.

Announcement to Shepherds

Against Liquor

Recognizing in alcoholic beverages a deadly enemy to the delicate functions of the human system, a menace to the home, and their use as a drink an outrage against society, the State and the Nation, I hereby promise to not only abstain from them myself, but to use my influence against their manufacture, sale, and consumption.

Name______________________________

Address___________________________

Date______________________________

Against Tobacco

Acknowledging smoking, chewing, or snuffing tobacco to be always detrimental to the human system, an enemy to perfect health and happiness, and an offense against good form and respectable society, I hereby express myself against the use of this vile poison. I shall also endeavor to discourage its use among my friends and associates.

Name_________________________

Address______________________

Date_________________________

"If any man defile the temple of God, him shall God destroy; for the temple of God is holy, which temple ye are." I Cor. 3:17.

"Be not deceived: neither fornicators, nor idolators, nor adulterers, nor effeminate, nor abusers of themselves with mankind, nor thieves, nor covetous, nor drunkards, nor revilers, nor extortioners, shall inherit the kingdom of God." I Cor. 6:9, 10.

Speak not harshly—learn to feel

Another's woes, another's weal;

Of malice, hate, and guile, instead,

By friendship's holy bonds be led;

For sorrow is man's heritage

From early youth to hoary age.

The Record

"The hours are viewless angels, that still go gliding by,

And bear each moment's record up to Him that sits on high."

A mother wrote a story about her daughter in which she represented her as making some unkind and rude remarks to her sister. Julia was a reader of the newspapers, and it did not escape her notice. The incident was a true one, but it was one she did not care to remember, much less did she like to see it in print.

"Oh! mother, mother," she exclaimed, "I do not think you are kind to write such stories about me. I do not like to have you publish it when I say anything wrong."

"How do you know it is you? It is not your name." Julia then read the story aloud.

"It is I. I know it is I, mother. I shall be afraid of you if you write such stories about me, I shall not dare to speak before you."

"Remember, my child, that God requireth the past, and nothing which you say, or do, or think, is lost to him."

Poor Julia was quite grieved that her mother should record the unpleasant and unsisterly words which fell from her lips. She did not like to have any memorial of her ill-nature preserved. Perhaps she would never have thought of those words again in this life; but had she never read this passage of fearful import, the language of Jesus Christ: "But I say unto you that for every idle word that men shall speak, they shall give account thereof in the day of judgment"? Julia thought that the careless words which had passed her lips would be forgotten, but she should have known that every word and act of our lives is to be recorded and brought to our remembrance.

I have known children to be very much interested, and to be influenced to make a great effort to do right, by an account-book which was kept by their mothers. When such a book is kept at school, and every act is recorded, the pupils are much more likely to make an effort to perform the duties required of them. So it is in Sabbath-schools. I recently heard a Sabbath-school superintendent remark that the school could not be well sustained unless accounts were kept of the attendance, etc., of the pupils.

Many years ago a man, brought before a tribunal, was told to relate his story freely without fear, as it should not be used against him. He commenced to do so, but had not proceeded far before he heard the scratching of a pen behind a curtain. In an instant he was on his guard, for by that sound he knew that, notwithstanding their promise, a record was being taken of what he said.

Silently and unseen by us the angel secretaries are taking a faithful record of our words and actions, and even of our thoughts. Do we realize this? and a more solemn question is, What is the record they are making?

Not long ago I read of a strange list. It was an exact catalogue of the crimes committed by a man who was at last executed in Norfolk Island, with the various punishments he had received for his different offenses. It was written out in small hand by the chaplain, and was nearly three yards long.

What a sickening catalogue to be crowded into one brief life. Yet this man was once an innocent child. A mother no doubt bent lovingly over him, a father perhaps looked upon him in pride and joy, and imagination saw him rise to manhood honored and trusted by his fellow-men. But the boy chose the path of evil and wrong-doing regardless of the record he was making, and finally committed an act, the penalty for which was death, and he perished miserably upon the scaffold.

Dear readers, most of you are young, and your record is but just commenced. Oh, be warned in time, and seek to have a list of which you will not be ashamed when scanned by Jehovah, angels, and men. Speak none but kind, loving words, have your thoughts and aspirations pure and noble, crowd into your life all the good deeds you can, and thus crowd out evil ones.

We should not forget that an account-book is kept by God, in which all the events of our lives are recorded, and that even every thought will be brought before us at the day of judgment. In that day God will judge the secrets of men: he will bring to light the hidden things of darkness, and will make manifest the counsels of the heart.

There is another book spoken of in the Bible. The book of life, and it is said that no one can enter heaven whose name is not written in the Lamb's book of life.

Angels are now weighing moral worth. The record will soon close, either by death or the decree, "He that is unjust, let him be unjust still, and he which is filthy, let him be filthy still; and he that is righteous, let him be righteous still; and he that is holy let him be holy still." We have but one short, preparing hour in which to redeem the past and get ready for the future. Our life record will soon be examined. What shall it be!

MOTHER.

The silvery hairs are weaving

A crown above her brow,But surely mother never seemed

One-half so sweet as now!The love-light beams from out her eyes

As clear, as sweet and true,As when, with youthful beauty crowned,

Life bloomed for her all new.No thought of self doth ever cast

A cloudlet o'er the lightThat shines afar from out her soul,

So steadfast, pure, and bright.Her love illumes the darkest hour,

Smooths all the rugged way,Makes lighter every burden,

Cheers through each weary day.More precious than the rarest gem

In all the world could be;More sweet than honor, fame, and praise,

Is mother's love to me.The Right Decision.

It was the beginning of vacation when Mr. Davis, a friend of my father, came to see us, and asked to let me go home with him. I was much pleased with the thought of going out of town. The journey was delightful, and when we reached Mr. Davis' house everything looked as if I were going to have a fine time. Fred Davis, a boy about my own age, took me cordially by the hand, and all the family soon seemed like old friends. "This is going to be a vacation worth having," I said to myself several times during the evening, as we all played games, told riddles, and laughed and chatted merrily as could be.

At last Mrs. Davis said it was almost bedtime. Then I expected family prayers, but we were very soon directed to our chambers. How strange it seemed to me, for I had never before been in a household without the family altar. "Come," said Fred, "mother says you and I are going to be bedfellows," and I followed him up two pair of stairs to a nice little chamber which he called his room; and he opened a drawer and showed me a box, and boat, and knives, and powder-horn, and all his treasures, and told me a world of new things about what the boys did there. He undressed first and jumped into bed. I was much longer about it, for a new set of thoughts began to rise in my mind.

When my mother put my portmanteau into my hand, just before the coach started, she said tenderly, in a low tone, "Remember, Robert, that you are a Christian boy." I knew very well what that meant, and I had now just come to a point of time when her words were to be minded. At home I was taught the duties of a Christian child; abroad I must not neglect them, and one of these was evening prayer. From a very little boy I had been in the habit of kneeling and asking the forgiveness of God, for Jesus' sake, acknowledging his mercies, and seeking his protection and blessing.

"Why don't you come to bed, Robert?" cried Fred. "What are you sitting there for?" I was afraid to pray, and afraid not to pray. It seemed that I could not kneel down and pray before Fred. What would he say? Would he not laugh? The fear of Fred made me a coward. Yet I could not lie down on a prayerless bed. If I needed the protection of my heavenly Father at home, how much more abroad. I wished many wishes; that I had slept alone, that Fred would go to sleep, or something else, I hardly knew what. But Fred would not go to sleep.

Perhaps struggles like these take place in the bosom of every one when he leaves home and begins to act for himself, and on his decision may depend his character for time, and for eternity. With me the struggle was severe. At last, to Fred's cry, "Come, boy, come to bed," I mustered courage to say, "I will kneel down and pray first; that is always my custom." "Pray?" said Fred, turning himself over on his pillow, and saying no more. His propriety of conduct made me ashamed. Here I had long been afraid of him, and yet when he knew my wishes he was quiet and left me to myself. How thankful I was that duty and conscience triumphed.

That settled my future course. It gave me strength for time to come. I believe that the decision of the "Christian boy," by God's blessing, made me the Christian man; for in after years I was thrown amid trials and temptations which must have drawn me away from God and from virtue, had it not been for my settled habit of secret prayer.

Let every boy who has pious parents, read and think about this. You have been trained in Christian duties and principles. When you go from home do not leave them behind you. Carry them with you and stand by them, and then in weakness and temptation, by God's help, they will stand by you. Take a manly stand on the side of your God and Saviour, of your father's God. It is by abandoning their Christian birthright that so many boys go astray, and grow up to be young men dishonoring parents, without hope and without God in the world.

Yes, we are boys, always playing with tongue or with pen,

And I sometimes have asked, shall we ever be men?

Will we always be youthful, and laughing and gay,

Till the last dear companions drop smiling away?

Then here's to our boyhood, its gold and its gray,

The stars of its winter, the dews of its May.

And when we have done with our life-lasting toys,

Dear Father, take care of thy children, the boys.

—

Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Susie's Prayer

It was a half-holiday. The children were gathered on the green and a right merry time they were having.

"Come, girls and boys," called out Ned Graham, "let's play hunt the squirrel."

All assented eagerly, and a large circle was formed with Ned Graham for leader, because he was the largest.

"Come, Susie," said one of the boys, to a little girl who stood on one side, and seemed to shrink from joining them.

"Oh, never mind her!" said Ned, with a little toss of his head, "she's nobody, anyhow. Her father drinks."

A quick flush crept over the child's pale face as she heard the cruel, thoughtless words.

She was very sensitive, and the arrow had touched her heart in its tenderest place.

Her father was a drunkard, she knew, but to be taunted with it before so many was more than she could bear; and with great sobs heaving from her bosom, and hot tears filling her eyes, she turned and ran away from the playground.

Her mother was sitting by the window when she reached home, and the tearful face of the little girl told that something had happened to disturb her.

"What is the matter, Susie?" she asked, kindly.

"Oh mother," Susie said, with the tears dropping down her cheeks, as she hid her face in her mother's lap, "Ned Graham said such a cruel thing about me," and here the sobs choked her voice so that she could hardly speak; "He said that I wasn't anybody, and that father drinks."

"My poor little girl," Mrs. Ellet said, very sadly. There were tears in her eyes, too.

Such taunts as this were nothing new.

"Oh, mother," Susie said, as she lifted her face, wet with tears, from her mother's lap, "I can't bear to have them say so, and just as if I had done something wicked. I wish father wouldn't drink! Do you suppose he'll ever leave it off?"

"I hope so," Mrs. Ellet answered, as she kissed Susie's face where the tears clung like drops of dew on a rose. "I pray that he may break off the habit, and I can do nothing but pray, and leave the rest to God."

That night Mr. Ellet came home to supper, as usual. He was a hard-working man, and a good neighbor. So everybody said, but he had the habit of intemperance so firmly fixed upon him that everybody thought he would end his days in the drunkard's grave. Susie kissed him when he came through the gate, as she always did, but there was something in her face that went to his heart—a look so sad, and full of touching sorrow for one so young as she!

"What ails my little girl?" he asked as he patted her curly head.

"I can't tell you, father," she answered, slowly.

"Why?" he asked.

"Because it would make you feel bad." Susie replied.

"I guess not," he said, as they walked up to the door together. "What is it, Susie?"

"Oh, father," and Susie burst into tears again as the memory of Ned Graham's words came up freshly in her mind, "I wish you wouldn't drink any more, for the boys and girls don't like to play with me, 'cause you do."

Mr. Ellet made no reply. But something stirred in his heart that made him ashamed of himself; ashamed that he was the cause of so much sorrow and misery. After supper he took his hat, and Mrs. Ellet knew only too well where he was going.

At first he had resolved to stay at home that evening, but the force of habit was so strong that he could not resist, and he yielded, promising himself that he would not drink more than once or twice.

Susie had left the table before he had finished his supper, and as he passed the great clump of lilacs by the path, on his way to the gate, he heard her voice and stopped to listen to what she was saying.

"Oh, good Jesus, please don't let father drink any more. Make him just as he used to be when I was a baby, and then the boys and girls can't call me a drunkard's child, or say such bad things about me. Please, dear Jesus, for mother's sake and mine."

Susie's father listened to her simple prayer with a great lump swelling in his throat.

And when it was ended he went up to her, and knelt down by her side, and put his arm around her, oh, so lovingly!

"God in Heaven," he said, very solemnly, "I promise to-night, never to touch another drop of liquor as long as I live. Give me strength to keep my pledge, and help me to be a better man."

"Oh, father," Susie cried, her arms about his neck, and her head upon his breast, "I'm so glad! I shan't care about anything they say to me now, for I know you won't be a drunkard any more."

"God helping me, I will be a man!" he answered, as, taking Susie by the hand he went back into the house where his wife was sitting with the old patient look of sorrow on her face.—the look that had become so habitual.

I cannot tell you of the joy and thanksgiving that went up from that hearthstone that night. I wish I could, but it was too deep a joy which filled the hearts of Susie and her mother to be described.

Was not Susie's prayer answered?

There is never a day so dreary,

But God can make it bright.And unto the soul that trusts him

He giveth songs in the night.There is never a path so hidden,

But God will show the way,If we seek the Spirit's guidance,

And patiently watch and pray.Company Manners.

"Well," said Bessie, very emphatically, "I think Russell Morton is the best boy there is, anyhow."

"Why so, pet?" I asked, settling myself in the midst of the busy group gathered around in the firelight.

"I can tell," interrupted Wilfred, "Bessie likes Russ because he is so polite."

"I don't care, you may laugh," said frank little Bess; "that is the reason—at least, one of them. He's nice; he don't stamp and hoot in the house—and he never says, 'Halloo Bess,' or laughs when I fall on the ice."

"Bessie wants company manners all the time," said Wilfred. And Bell added: "We should all act grown up, if she had her fastidiousness suited."

Bell, be it said in passing, is very fond of long words, and has asked for a dictionary for her next birthday present.

Dauntless Bessie made haste to retort, "Well, if growing up would make some folks more agreeable, it's a pity we can't hurry about it."

"Wilfred, what are company manners?" interposed I from the depths of my easy chair.

"Why—why—they're—It's behaving, you know, when folks are here, or we go a visiting."

"Company manners are good manners," said Horace,

"Oh yes," answered I, meditating on it. "I see; manners that are too good—for mamma—but just right for Mrs. Jones."

"That's it," cried Bess.

"But let us talk it over a bit. Seriously, why should you be more polite to Mrs. Jones than to mamma? You don't love her better?"

"Oh my! no indeed," chorused the voices.

"Well, then, I don't see why Mrs. Jones should have all that's agreeable; why the hats should come off, and the tones soften, and 'please,' and 'thank you,' and 'excuse me,' should abound in her house, and not in mamma's."

"Oh! that's very different."

"And mamma knows we mean all right. Besides, you are not fair, cousin; we were talking about boys and girls—not grown up people."

Thus my little audience assailed me, and I was forced to a change of base.

"Well, about boys and girls, then. Can not a boy be just as happy, if, like our friend Russell, he is gentle to the little girls, doesn't pitch his little brother in the snow, and respects the rights of his cousins and intimate friends? It seems to me that politeness is just as suitable to the playground as to the parlor."

"Oh, of course; if you'd have a fellow give up all fun," said Wilfred.

"My dear boy," said I, "that isn't what I want. Run, and jump, and shout as much as you please; skate, and slide, and snowball; but do it with politeness to other boys and girls, and I'll agree you will find just as much fun in it. You sometimes say I pet Burke Holland more than any of my child-friends. Can I help it? For though he is lively and sometimes frolicsome, his manners are always good. You never see him with his chair tipped up, or his hat on in the house. He never pushes ahead of you to get first out of the room. If you are going out, he holds open the door; if weary, it is Burke who brings a glass of water, places a chair, hands a fan, springs to pick up your handkerchief—and all this without being told to do so, or interfering with his own gaiety in the least.

"This attention isn't only given to me as the guest, or to Mrs. Jones when he visits her, but to mamma, Aunt Jennie, and little sister, just as carefully; at home, in school, or at play, there is always just as much guard against rudeness. His courtesy is not merely for state occasions, but a well-fitting garment worn constantly. His manliness is genuine loving-kindness. In fact, that is exactly what real politeness is; carefulness for others, and watchfulness over ourselves, lest our angles shall interfere with their comfort."

It is impossible for boys and girls to realize, until they have grown too old to easily adopt new ones, how important it is to guard against contracting carelessness and awkward habits of speech and manners. Some very unwisely think it is not necessary to be so very particular about these things except when company is present. But this is a grave mistake, for coarseness will betray itself in spite of the most watchful sentinelship.

It is impossible to indulge in one form of speech, or have one set of manners at home, and another abroad, because in moments of confusion or bashfulness, such as every young person feels sometimes who is sensitive and modest, the habitual mode of expression will discover itself.

It is not, however, merely because refinement of speech and grace of manners are pleasing to the sense, that our young friends are recommended to cultivate and practice them, but because outward refinement of any sort reacts as it were on the character and makes it more sweet and gentle and lovable, and these are qualities that attract and draw about the possessor a host of kind friends. Then again they increase self-respect.

The very consciousness that one prepossesses and pleases people, makes most persons feel more respect for themselves, just as the knowledge of being well dressed makes them feel more respectable. You can see by this simple example, how every effort persons make toward perfecting themselves brings some pleasant reward.

BELIEVE AND TRUST.

Believe and trust. Through stars and suns,

Through life and death, through soul and sense,His wise, paternal purpose runs;

The darkness of his providence Is star-lit with benign intents.O joy supreme! I know the Voice,

Like none beside on earth and sea;Yea, more, O soul of mine, rejoice!

By all that he requires of me I know what God himself must be.—

Whittier.

The Belle of the Ballroom.

"Only this once," said Edward Allston, fixing a pair of loving eyes on the beautiful girl beside him—"only this once, sister mine. Your dress will be my gift, and will not, therefore, diminish your charity fund; and besides, if the influences of which you have spoken, do, indeed, hang so alluringly about a ballroom, should you not seek to guard me from their power? You will go, will you not? For me—for me?"

The Saviour, too, whispered to the maiden, "Decide for me—for me." But her spirit did not recognize the tones, for of late it had been bewildered with earthly music.

She paused, however, and her brother waited her reply in silence.

Beware! Helen Allston, beware! The sin is not lessened that the tempter is so near to thee. Like the sparkle of the red wine to the inebriate are the seductive influences of the ballroom. Thy foot will fall upon roses, but they will be roses of this world, not those that bloom for eternity. Thou wilt lose the fervor and purity of thy love, the promptness of thy obedience, the consolation of thy trust. The holy calm of thy closet will become irksome to thee, and thy power of resistance will be diminished many fold, for this is the first great temptation. But Helen will not beware. She forgets her Saviour. The melody of that rich voice is dearer to her than the pleadings of gospel memories.

Two years previous to the scene just described, Helen Allston hoped she had been converted. For a time she was exact in the discharge of her social duties, regular in her closet exercises, ardent, yet equable, in her love. Conscious of her weakness, she diligently used all those aids, so fitted to sustain and cheer. Day by day, she rekindled her torch at the holy fire which comes streaming on to us from the luminaries of the past—from Baxter, Taylor, and Flavel, and many a compeer whose names live in our hearts, and linger on our lips. She was alive to the present also. Upon her table a beautiful commentary, upon the yet unfulfilled prophecies, lay, the records of missionary labor and success. The sewing circle busied her active fingers, and the Sabbath-school kept her affections warm, and rendered her knowledge practical and thorough. But at length the things of the world began insensibly to win upon her regard. She was the child of wealth, and fashion spoke of her taste and elegance. She was very lovely, and the voice of flattery mingled with the accents of honest praise. She was agreeable in manners, sprightly in conversation, and was courted and caressed. She heard with more complacency, reports from the gay circles she had once frequented, and noted with more interest the ever-shifting pageantry of folly. Then she lessened her charities, furnished her wardrobe more lavishly, and was less scrupulous in the disposal of her time. She formed acquaintances among the light and frivolous, and to fit herself for intercourse with them, read the books they read, until others became insipid.

Edward Allston was proud of his sister, and loved her, too, almost to idolatry.

They had scarcely been separated from childhood, and it was a severe blow to him when she shunned the amusements they had so long shared together. He admired indeed the excellency of her second life, the beauty of her aspirations, the loftiness of her aims, but he felt deeply the want of that unity in hope and purpose which had existed between them. He felt, at times, indignant, as if something had been taken from himself. Therefore, he strove by many a device to lure her into the path he was treading. He was very selfish in this, but he was unconscious of it. He would have climbed precipices, traversed continents, braved the ocean in its wrath, to have rescued her from physical danger, but, like many others, thoughtless as himself, he did not dream of the fearful importance of the result; did not know that the Infinite alone could compute the hazard of the tempted one. Thus far had he succeeded, that she had consented to attend with him a brilliant ball.

"It will be a superb affair," he said, half aloud, as he walked down the street. "The music will be divine, too. And she used to be so fond of dancing! 'T was a lovely girl spoiled, when the black-coated gentry preached her into their notions. And yet—and yet—pshaw!—all cant!—all cant! What harm can there be in it? And if she does withstand all this, I will yield the point that there is something—yes, a great deal in her religion."

So musing, he proceeded to the shop of Mrs. Crofton, the most fashionable dressmaker in the place, and forgot his momentary scruples in the consultation as to the proper materials for Helen's dress, which was to be a present from him, and which he determined should be worthy her grace and beauty.

The ball was over, and Helen stood in her festal costume, before the ample mirror in her chamber, holding in one hand a white kid glove she had just withdrawn. She had indeed been the belle of the ballroom. Simplicity of life, and a joyous spirit, are the wonder-workers, and she was irresistibly bright and fresh among the faded and hackneyed of heated assembly rooms. The most delicate and intoxicating flattery had been offered her, and wherever she turned, she met the glances of admiration. Her brother, too, had been proudly assiduous, had followed her with his eyes so perpetually as to seem scarcely conscious of the presence of another; and there she stood, minute after minute, lost in the recollections of her evening triumph.

Almost queenlike looked she, the rich folds of her satin robe giving fullness to her slender form, and glittering as if woven with silver threads. A chain of pearls lay on her neck, and gleamed amid the shading curls, which floated from beneath a chaplet of white roses. She looked up at length, smiled at her lovely reflection in the mirror, and then wrapping herself in her dressing-gown, took up a volume of sacred poems. But when she attempted to read, her mind wandered to the dazzling scene she had just quitted. She knelt to pray, but the brilliant vision haunted her still, and ever as the wind stirred the vines about the window, there came back that alluring music.