автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Lazy Matilda, and Other Tales

LAZY MATILDA

and OTHER TALES

[2] [3] [4]

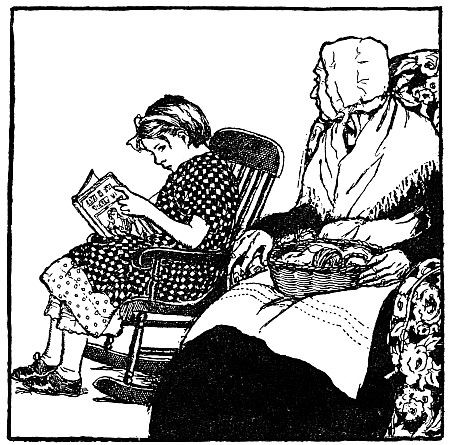

“Oh, grandmamma, I’m reading now,”

The lazy Annie said,

“I do not want to leave my book,

Mayn’t Mary go instead?”

LAZY MATILDA

and OTHER TALES

BY

KATHARINE PYLE

AUTHOR OF “CARELESS JANE AND OTHER TALES,” “WHERE THE WIND BLOWS,” “FAIRY TALES FROM MANY LANDS,” ETC.

NEW YORK

E. P. DUTTON & CO., INC.

COPYRIGHT, 1921,

BY E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

All Rights Reserved

First printingSeptember, 1921

Second printingSeptember, 1925

Third printing

March, 1926

Fourth printing

July, 1930

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

PAGE Lazy Matilda 9 The Witch and the Truant Boys 27 The Visitor 37 Daddy Crane 49 Envious Eliza 63 The Nixie 75 Stephen’s Lesson 89 The Caterpillar 99 Mischievous Jane 113 The Sweet Tooth 125 Vain Little Lucy 139 The Magic Man 161LAZY MATILDA

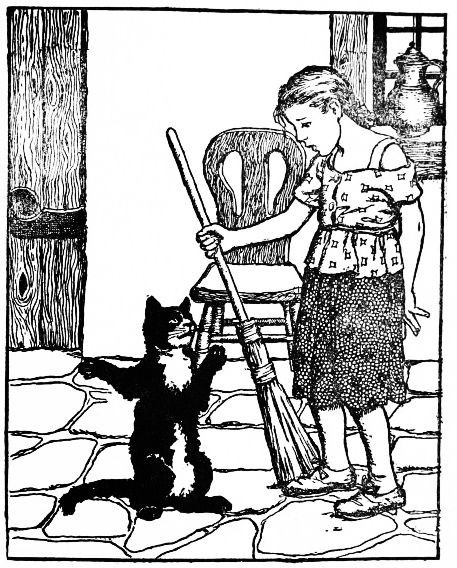

Matilda’s kind to pussy cat,

It shows her gratitude for that.

“I FEEL ashamed Matilda

To see you such a shirk!

I really think you’d run a mile

To get away from work.”

So spoke Matilda’s mother

Reprovingly one day,

But Mattie only shrugged and sulked

And turned her face away.

Soon mother left her then alone,

The door was open wide.

On tip-toes Mattie crossed the floor,

And gaily ran outside.

She left her room undusted,

She left her bed unmade,

Indeed she really was a shirk

I’m very much afraid.

With joy she gaily scampered

Across the meadows wide,

And chased the pretty butterflies

That flew from side to side.

And on and on she wandered

Until she reached a wood,

And there, deep in the shadows

A little grey house stood.

A dwarf was in the doorway,

The door stood open wide,

A lean and hungry-looking cat

Was mewing just inside.

The old dwarf grinned and beckoned,

“Come in, come in,” cried he;

“I need a little servant maid,

And you will do for me.”

“I have no wish to serve you,”

Matilda quickly cried.

But still the old dwarf beckoned her

And made her step inside.

He made her cook the dinner,

He made her work all day.

He watched her close, and left no chance

For her to run away.

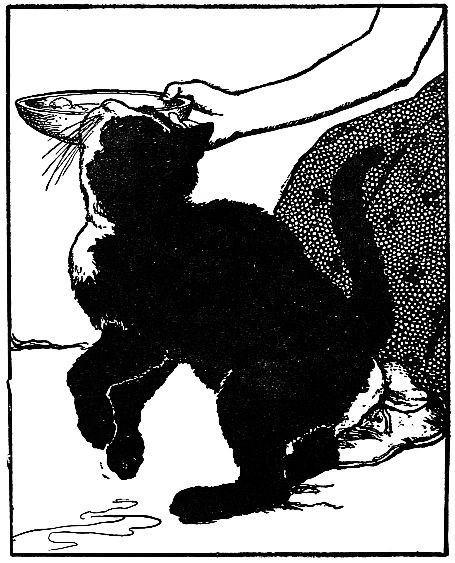

The pussy rubbed about her,

“Meow, meow,” said she.

“I’ve been so starved, please look about

And find some scraps for me.”

“Whatever I may have to eat

I’ll always share with you,”

Matilda cried, “for I can see

That you’re unhappy, too.”

One day the dwarf sat smoking

Outside the open door,

While Mattie worked about inside

And scrubbed and swept the floor.

“Matilda,” whispers pussy,

“You’ve served me well each day,

And now the dwarf is safe outside

I’ll help you run away.

“The kitchen door is open,

So now be off,” says she.

“Yes,” Mattie whispers, “but suppose

The dwarf should call to me.”

“You needn’t be afraid of that,”

The clever pussy said,

“For even if by chance he calls

I’ll answer in your stead.”

Now little Mattie’s scarcely gone

Before the old dwarf cries,

“Are you at work?” “I’m kneading bread,”

The pussy cat replies.

The old dwarf smoked and nodded,

But soon again he said,

“Are you at work?” “Oh, yes,” cried puss;

“I’m shaking up the bed.”

Again the old dwarf calls her,

“Now what are you about?”

“I’m waiting here to catch a mouse

If only he’ll come out.”

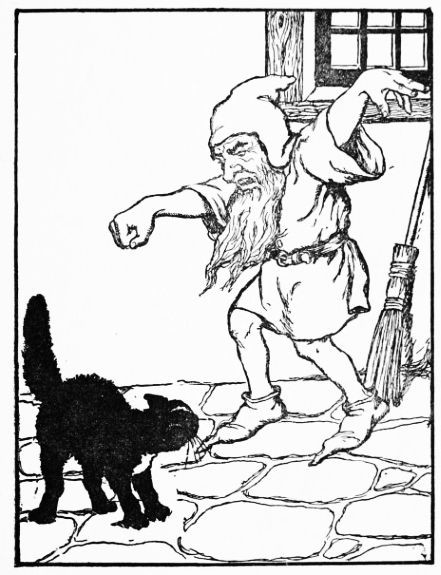

“What’s that?” the old dwarf bellows.

He bounces from his chair,

He rushes in and quickly sees

That only puss is there.

At once he knows the trick they’ve played.

He catches up the broom,

And chases poor old pussy cat

Around and around the room.

“Good-bye to you,” says pussy,

“Indeed, I’ve had my fill,”

And up she bounds and out she goes

Across the window sill.

“Come back! I will not beat you!

Come back, come back!” cries he.

“If I must lose both maid and cat

What will become of me?”

But pussy does not heed him.

Indeed, she’s far away.

She’s followed little Mattie home

And there she means to stay.

Matilda’s now a useful child,

She never tries to shirk,

But helps, with ready cheerfulness,

At any kind of work.

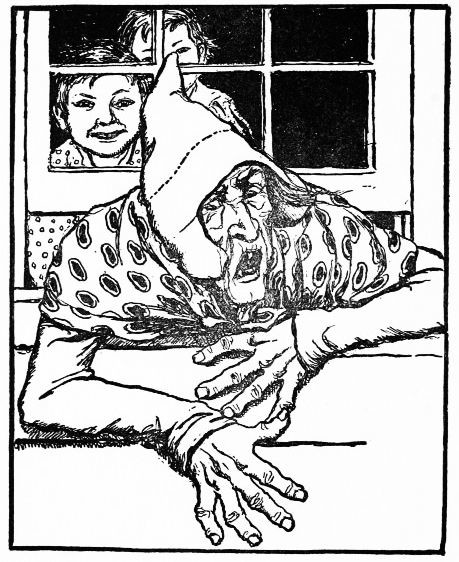

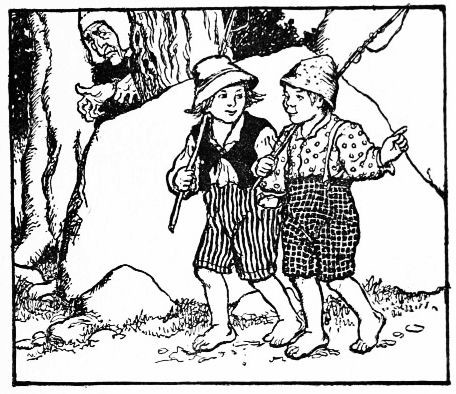

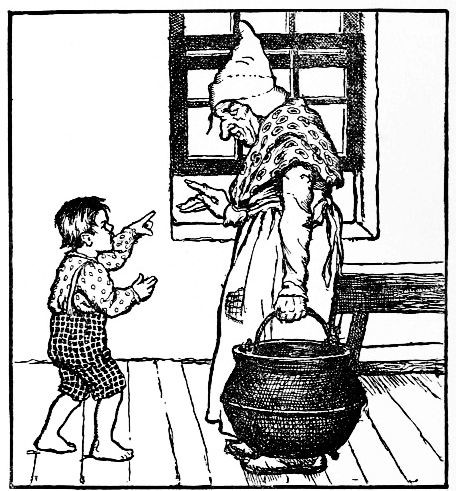

THE WITCH AND THE TRUANT BOYS

John is cleverer than the old witch

And he has her in a trap.

PETER and John, against the rule,

Are playing truant from their school.

With eager steps away they go

To seek a fishing pool they know.

But see a witch is hiding there—

She’ll catch them if they don’t take care.

Oh boys! make haste and hurry past!

No—she has caught them tight and fast.

And now away with them she hies,

In spite of all their kicks and cries.

She hurries home and shuts the door

And then she drops them on the floor.

“These boys are plump and soft,” says she,

“A fine fat meal they’ll make for me.

I’ll fill my very biggest pot,

And cook them when the water’s hot.”

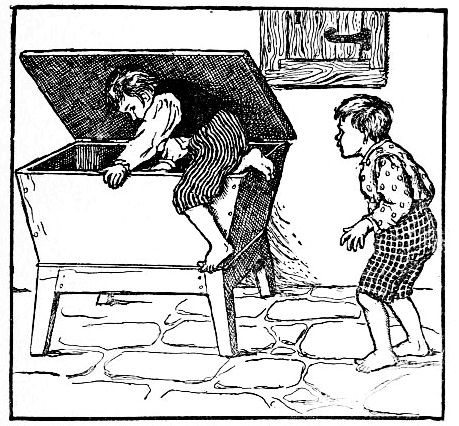

But while her pot she’s getting out,

The frightened Peter looks about.

He sees the bread trough open wide,

And into it he jumps to hide;

Then with a bump he shuts the lid.

And there he lies all safely hid.

But the old witch has heard the sound.

And quick she turns herself around.

She peers about with blinking eyes,

“Where is that other boy?” she cries.

“He can’t have run away so quick.

He must be hiding for a trick.”

“You haven’t treated me so well

That you can think I want to tell,

But if you look outside,” says John,

“Maybe you’ll see which way he’s gone.”

The old witch throws the window wide

And leans to look about outside.

But while she’s peering all around

John creeps up close without a sound,

And shuts the window on her tight,

And holds it down with all his might.

’Tis vain for her to kick and bawl,

John does not heed her cries at all.

“Quick, Peter! Bring me from the shelf

Hammer and nails. Bestir yourself.”

Out from the dough-trough Peter springs;

Quickly he fetches John the things.

“Here they are, brother!” Now, tap-tap!

John drives the nails with many a rap.

He has the window nailed at last

So tight ’twill hold the old witch fast.

No matter how she squirms and cries,

She can’t get loose howe’er she tries.

But now the little boys are free

To run on home, as you may see.

I’m sure it will be many a day

Before again from school they stay.

As for the witch, if she’s stuck tight

Until this day it serves her right.

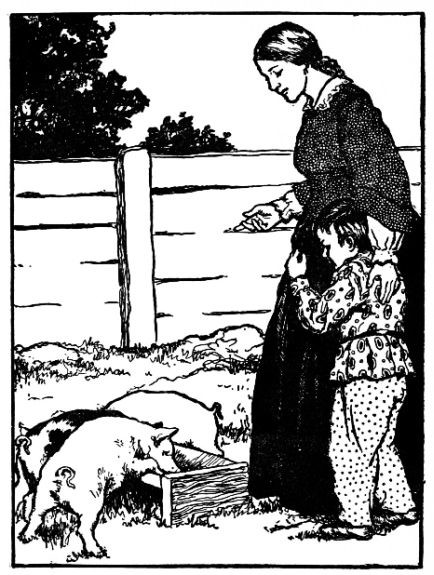

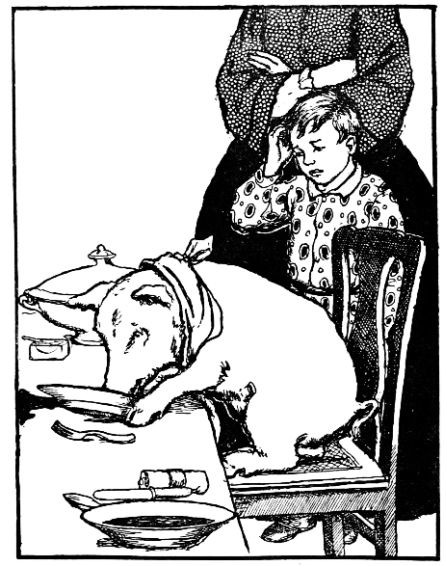

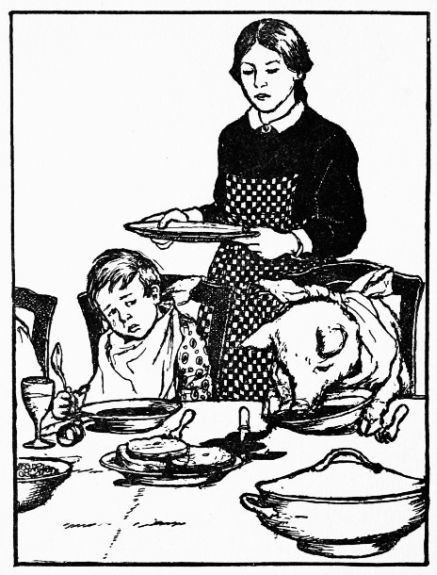

THE VISITOR

Children should never eat like this,

Although for pigs ’tis not amiss.

JOHN’S manners at the table

Were very sad to see.

You’d scarce believe a child could act

In such a way as he.

He smacked his lips and gobbled,

His nose down in his plate.

You might have thought that he was starved,

So greedily he ate.

He’d snatch for what he wanted,

And never once say “please,”

Or, elbows on the table,

He’d sit and take his ease.

In vain papa reproved him;

In vain mamma would say,

“You really ought to be ashamed

To eat in such a way.”

One day when lunch was ready,

And John came in from play,

His mother said, “A friend has come

To eat with you to-day.”

“A friend of mine?” cried Johnny,

“Whoever can it be?”

“He’s at the table,” mother said,

“You’d better come and see.”

Into the dining-room he ran.

A little pig was there.

It had a napkin round its neck,

And sat up in a chair.

“This is your friend,” his father cried,

“He’s just a pig, it’s true,

But he might really be your twin,

He acts so much like you.”

“Indeed he’s not my friend,” cried John,

With red and angry face.

“If he sits there beside my chair

I’m going to change my place.”

“No, no,” his father quickly cried,

“Indeed that will not do.

Sit down at once where you belong,

He’s come to visit you.”

Now how ashamed was little John;

But there he had to sit,

And see the piggy served with food,

And watch him gobble it.

“John,” said mamma, “I think your friend

Would like a piece of bread.”

“And pass him the potatoes, too,”

Papa politely said.

The other children laughed at this,

But father shook his head.

“Be still, or leave the room at once;

It’s not a joke,” he said.

“Oh, mother, send the pig away,”

With tears cried little John.

“I’ll never eat that way again

If only he’ll be gone.”

“Why,” said mamma, “since that’s the case,

And you your ways will mend,

Perhaps we’d better let him go.

Perhaps he’s not your friend.”

Now John has learned his lesson,

For ever since that day

He’s lost his piggish manners,

And eats the proper way.

And his papa, and mother too,

Are both rejoiced to see

How mannerly and how polite

Their little John can be.

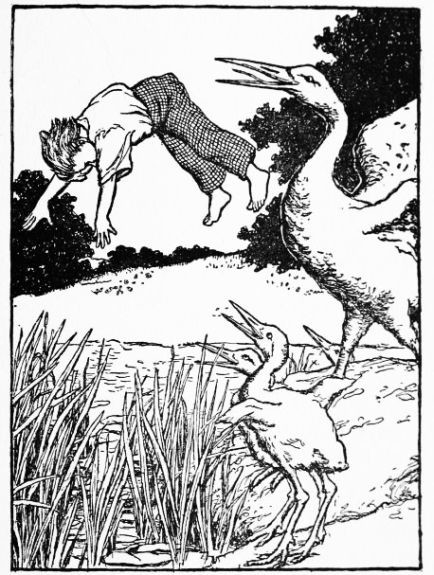

DADDY CRANE

Each child should be content to do

Some useful thing each day,

And not be thinking all the time

Of pleasure or of play.

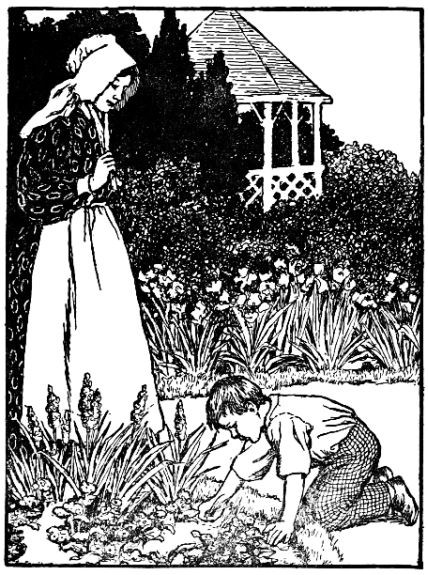

DADDY CRANE

NED was so fond of swimming

No punishment nor rule

That mother made could keep him long

Out of the swimming pool.

One morning she had set him

To clear a flower bed,

“And do not stop till every weed

Is out of it,” she said.

But oh, that naughty Edward!

She scarce had turned away

When up he rose, and off he ran;

He did not stop nor stay.

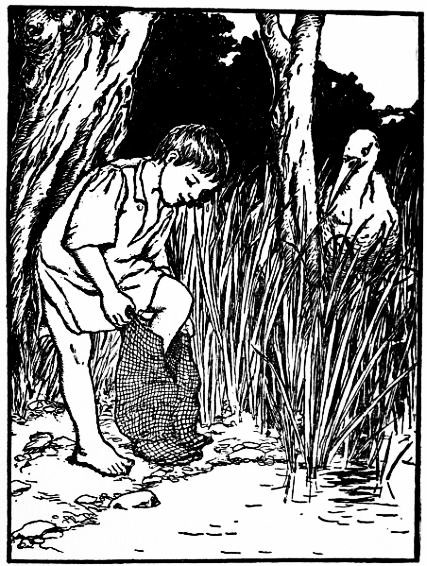

Soon, naked as a little frog,

With many a joyous shout,

He jumped into the swimming pool,

And kicked and swam about.

But while he played so gaily

Old Daddy Crane, unseen,

Stood watching him, and grinning,

Among the rushes green.

“I’ll wait until that funny thing

Has dressed, and then,” says he,

“I’ll catch him by the trousers seat

And take him home with me.”

Soon, cooled and freshened by his swim,

Young Ned comes splashing out.

In haste he gets into his clothes

And never looks about.

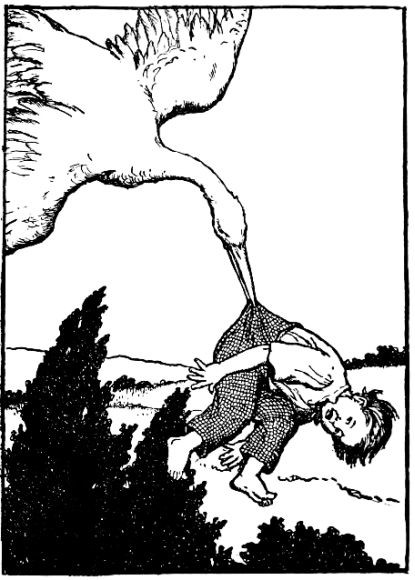

Now Daddy stretches out his neck!

“Oh! Oh,” poor Edward cries,

For Daddy has him in his beak,

And off with him he flies.

Far, far off by a river,

Where no one comes to see,

Old Daddy lives among the reeds,

He and his children three.

’Tis there he carries Edward.

“Look children! Look!” cries he.

“I’ve brought you such a funny thing.

It swims, as you shall see.”

And now with cackling laughter

He throws poor little Ned

Far, far out in the river,

Ker-splash! heels over head.

Then how the young ones clap their wings,

And laugh and dance about,

As, blowing water from his nose,

Poor Ned comes scrabbling out.

“Quick, Daddy, throw him in again,”

The youngsters cry with glee.

“There never was a froggy thing

As comical as he.”

In vain poor Edward struggles.

His cries are all in vain.

No sooner does he get on shore

Than splash! he’s in again.

“Oh dear!” he cries, while water

Is mingled with his tears,

“I’ve had enough of swimming

To last for years and years.”

And so, next time they throw him in,

Instead of swimming round

He hides himself among the reeds,

And hopes he won’t be found.

He hears old Daddy calling,

“Hi there! You frog, come out!

You needn’t try to hide from me.

I know what you’re about.”

He hears the young ones rustle round,

They bitterly complain,

“Oh Daddy, find our frog for us.

We want him back again.”

But quick Ned gathers lily leaves,

All broad and green and flat,

And fixes them to hide his head

As though they were a hat.

[112]

[113]

[124]

[125]

[160]

[161]

Then out beyond the reeds he floats;

The green leaves hide him still

As down the stream he swims away

Past meadow, wood and hill.

In vain old Daddy hunts about,

And little does he dream

That Ned was underneath the leaves

That floated down the stream.

Now Edward’s reached his home again.

He runs in through the door,

Leaving a trail of water

Across the kitchen floor.

“You need not scold me mother,”

With chattering teeth he says.

“I’ve had enough of swimming now

To last me all my days.”

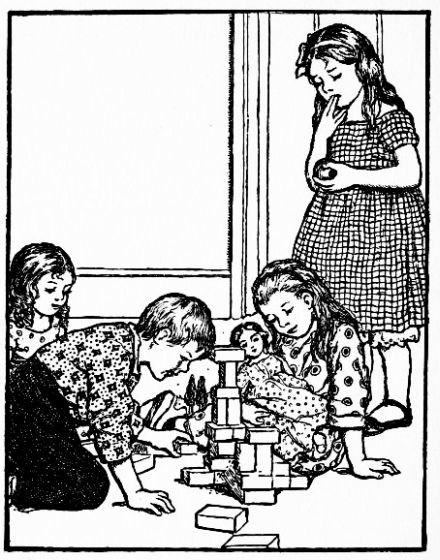

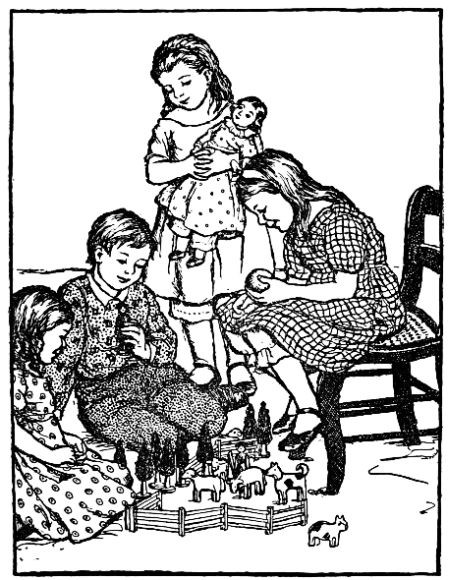

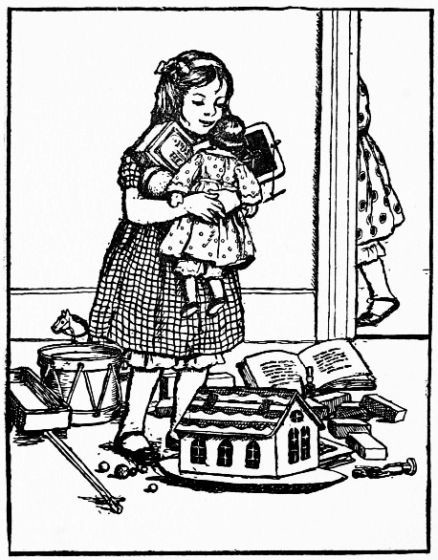

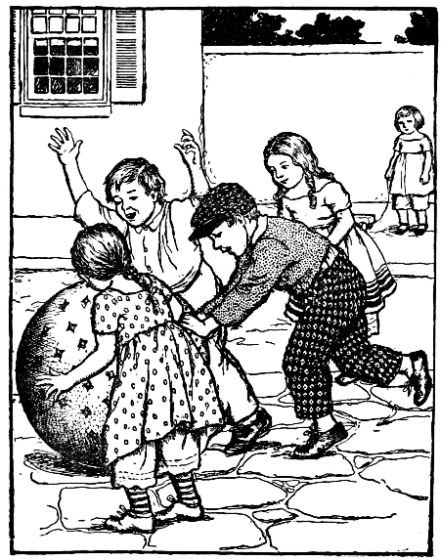

ENVIOUS ELIZA

Eliza never was content.

Indeed ’twas very sad

That any child could envy so

The things that others had.

ENVIOUS ELIZA

ELIZA was an envious child,

Indeed ’twas very sad

To see the way she wished for things

That other children had.

Instead of playing like the rest,

She’d stand about and whine,

“I do not see why every one

Has better things than mine.

“Jane’s doll is prettier than mine.

John has a better ball.

The one Aunt Sarah gave to me

Will hardly bounce at all.

“My picture book is old and torn

And Mary’s looks quite new.

And Tom has all the building blocks.

I wish I had some, too.”

’Twas thus the envious little girl

Complained day after day.

She made herself unhappy,

And spoiled the fun and play.

At last one day when she began

With her complaints once more,

John quickly gathered up his toys

And games from off the floor.

“Here, you may have my things,” he said,

“I’ll give them all to you.”

“And you may have my doll,” said Jane,

“And all her dresses, too.”

“Yes,” Mary cried, “and take my books,

”My grace-hoop, sticks and all,

And Noah’s Ark.“ ”And here!“ said Tom,

”Here are my blocks and ball.“

Eliza scarce believed her ears,

“You’ll give them all to me,—

The books and games and toys? Oh dear!

How happy I shall be.”

The other children ran away,

And left her standing there,

But since they’d also left their things

But little did she care.

Quite happily, all by herself,

She played that afternoon,

It seemed to her that supper time

Had never come so soon.

Next day, all by herself again;

She settled down to play,

But oh! the room seemed strangely still

With all the rest away.

“I wonder what they’re all about,

And where they are,” thought she;

And then she called them, “Come in here

And play awhile with me.”

“We can’t,” she heard them answer back,

“There’s nothing we can do

Now we have given all our toys

And games and books to you!”

“But oh! I cannot always play

All by myself,” cried she,

“Come here, and you shall have again

The things you gave to me.

“The toys and books and dolls and games—

Each one shall take his own,

I’d rather never have a thing

Than always play alone.”

The children now have taken back

The toys they gave to her,

The nursery’s full of merriment

And fun and cheerful stir.

Eliza now is quite content

To play like all the rest,

And never gives a single thought

To which one has the best.

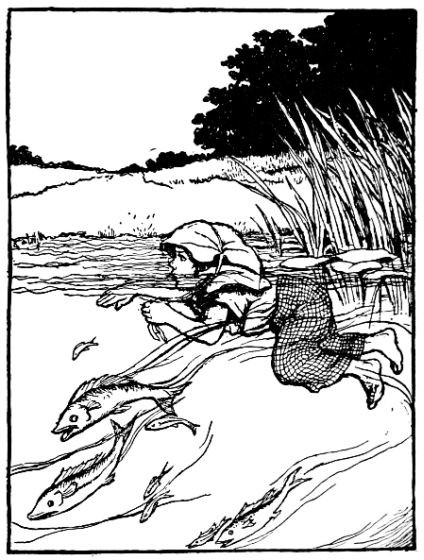

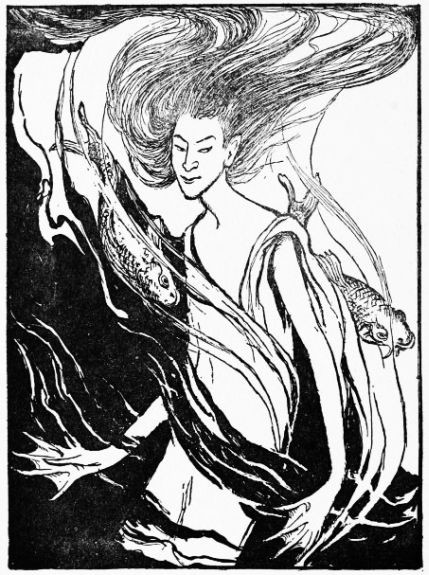

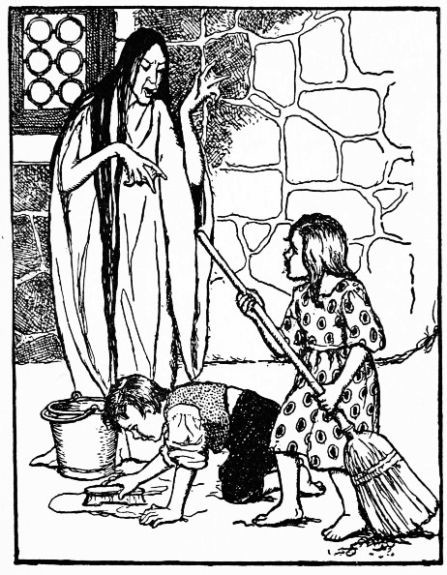

THE NIXIE

Up through the water see her rise,

The nixie with her sea-green eyes.

ONCE John and Jane were playing

Beside a shining lake

When suddenly the waters

Began to stir and shake.

And up there rose a nixie

From out the waters green.

She was the strangest looking thing

That they had ever seen.

She called the children gently.

She coaxed them, “Come with me,

And I will show you castles,

And gardens fair to see.”

“Our mother’s often told us,”

The children both replied,

“We must not go with strangers,

Or evil may betide.”

But still the nixie coaxed them.

“Come see my lovely things.

I’ll show you strings of shining shells,

And fishes that have wings.”

She took them by their shoulders,

She took them by the hands,

She drew them down beneath the lake

To where her castle stands.

But now the nixie had them

She lost her pleasant smile.

She set the children both to work

And scolded all the while.

“Now scrub about, and sweep about,

And fill the iron pot,

And hang it up above the fire

To make the water hot.

“No idling now, you lazy ones;

Be quick and stir your feet,

The while I go outside a bit

And catch some fish to eat.”

Soon as the nixie leaves them

The children set to work.

Indeed they’re both so frightened

They do not dare to shirk.

Just as the work is finished

The nixie comes once more,

And leaves a trail of water

Across the kitchen floor.

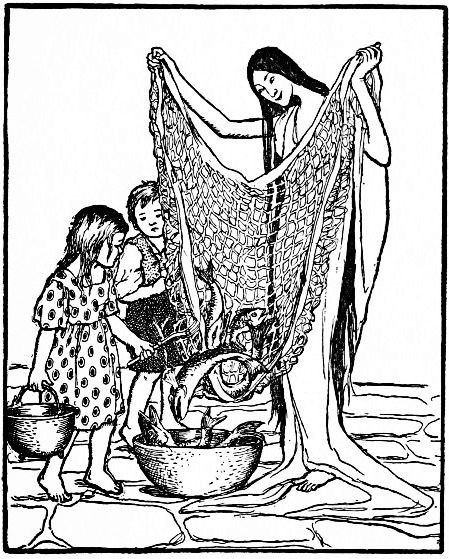

Her net is full of fishes.

“Here, child! be quick,” cries she,

“Now clean these fish and cook them,

And serve them up to me.”

Quick little Janie sets to work,

She cooks the fish in haste,

The greedy nixie eats them all;

She does not leave a taste.

Then after she has finished

She lies down on the bed,

And snores so loud the rafters

Are shaken overhead.

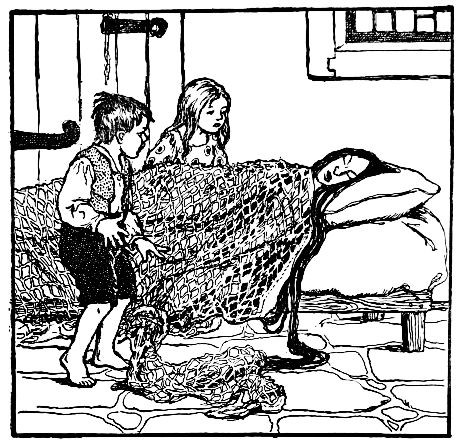

Then Janie beckons Johnnie,

And whispers in his ear,

“Now, John, I’m going to run away.

I will not stay down here.”

But little John is frightened.

“Oh dear! I’d be afraid.

I know she’d come and catch us,

This cruel water-maid.”

“But I’ve a plan,” says Janie,

“It just came in my head.

We’ll take the nixie’s fishing-net

And tie her down in bed.

“Be quick or she may waken,

We have no time to waste.”

So now the little children

Have set to work in haste.

They wrap her net about her,

They tie her tight in bed.

Now, even if she wakened

She scarce could lift her head!

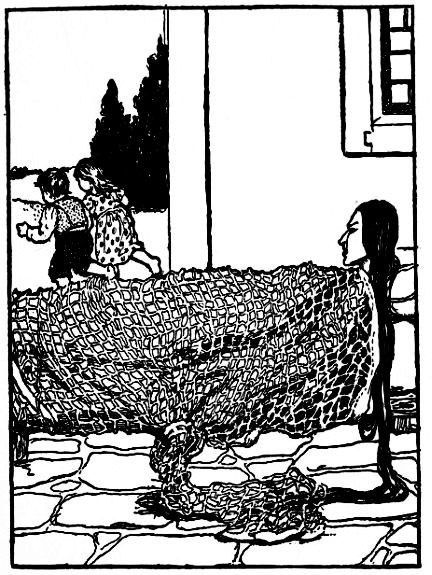

“So there! that job is finished,”

Cries little Jane with glee.

“Unless someone unties her

She never can get free.”

Now quick the little children

Run tip-toe out the door,

And never stop nor turn about

Till they are home once more.

But for the cruel nixie,

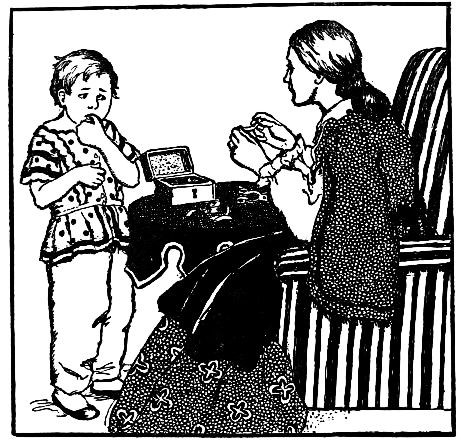

Whether she’s still in bed,

Or whether she has wriggled out

No one has ever said.

STEPHEN’S LESSON

Poor Stephen is in such disgrace

He is ashamed to show his face.

’TIS very very sad indeed

When little children choose

To say the naughty, ugly words

That no one ought to use.

That was the way with Stephen,

Such naughty words he said

That grandmamma looked shocked and grieved,

And auntie shook her head.

Mamma said, “Son, I’ve told you

Such words you must not say,

And yet, in spite of warnings,

I hear them every day.

“So now, my child, I’m taking

These sticking plaster strips.

I’m going to put them on your mouth

And seal those naughty lips.”

“But mother, how then shall I eat?”

Cries Stephen anxiously.

“Oh, I will take them off for meals.

’Twill not be hard,” says she.

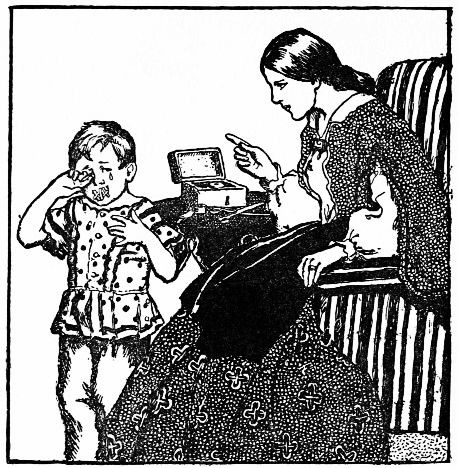

In vain poor Stephen pleads with her;

In vain he sobs and cries.

She lays the strips across his lips

In straight and criss-cross wise.

Now only sounds like “Um! Um-hum!”

From Stephen’s lips are heard,

Because, with all those plasters on

He cannot speak a word.

Now Stephen cannot go to school,

He sits at home all day.

He feels ashamed to go outside,

Or join the boys at play.

And if he’s at the window,

And some one passes by,

He quickly turns aside his head,

Lest they the plasters spy.

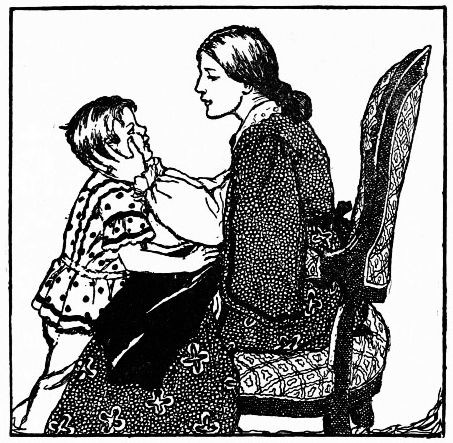

One day, when mother changed the strips

In haste poor Stephen cried,

“I do not think my lips could say

Those words now if I tried.”

“If that’s the case,” cried mother,

“No need to use these slips,”

And with a smile of joy she kissed

The one-time naughty lips.

Indeed the lesson had been learned,

For Stephen nevermore

Was heard to say those naughty words

That he had used before.

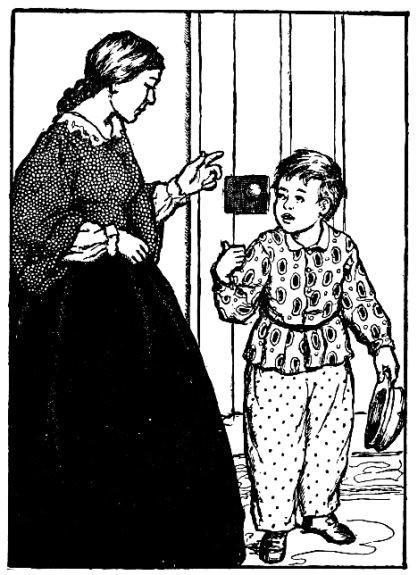

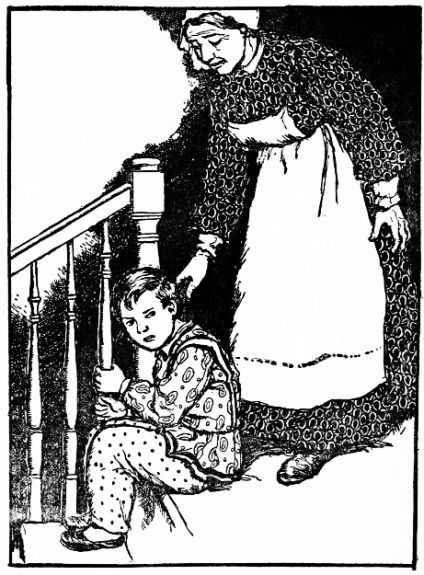

THE CATERPILLAR

The Caterpillar has to crawl.

He cannot run or jump at all.

ANNE was a lively child at play,

And quick as she could be,

But when an errand must be run

Ah, slow of foot was she.

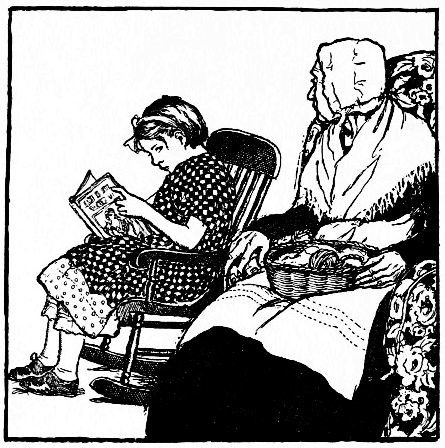

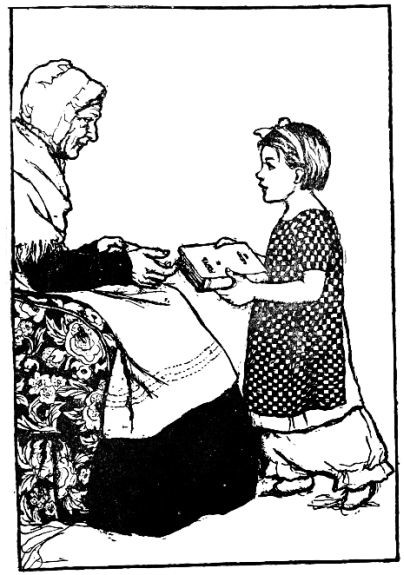

“My child,” said grandmamma one day,

“Run to my room and look,

And bring me, from my bureau there,

My spectacles and book.”

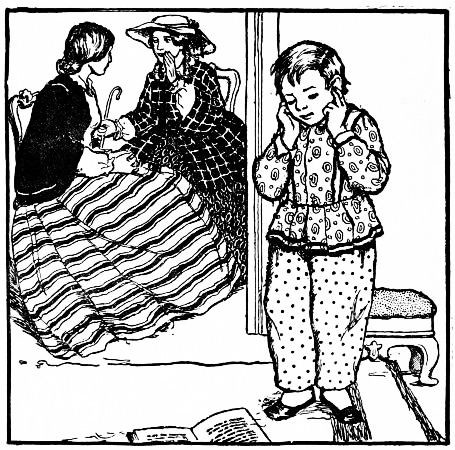

“Oh, grandmamma, I’m reading now,”

The lazy Annie said,

“I do not want to leave my book,

Mayn’t Mary go instead?”

No wonder grandmamma looked pained

When Annie answered so,

But little Mary cried, “Why, yes!

Of course I’d love to go.”

“Come little Anne,” her mother called,

“Run down the street for me,

And get some thread to sew your frock.

Let’s see how quick you’ll be.”

“Oh dear! I’m tired,” Anne replied,

“Why cannot Mary go?

Or nurse? She’s not been out all day,

Indeed she told me so.”

“My child, my child!” her mother said,

“Whatever shall I do?

You’re such a lazy, useless girl

I feel ashamed of you.

“Your little feet run fast enough

For pleasure or for fun,

But you can hardly crawl about

When errands must be run.”

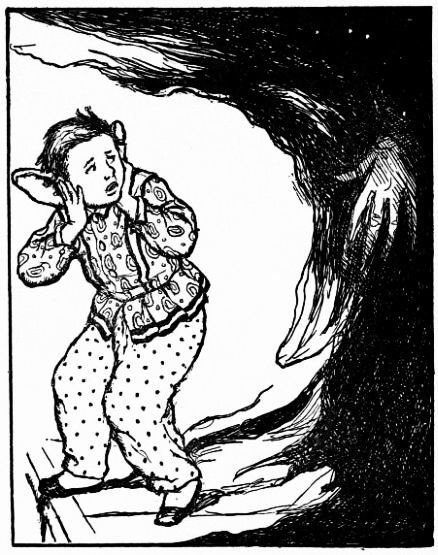

But listen now! One day Anne woke

And felt quite strange and queer.

“Whatever’s happened to me now,”

She cried; “Oh dear, oh dear!

“Oh mother! nurse! Come in here quick

And tell me what is wrong.

I seem to have so many feet—

My body feels so long.”

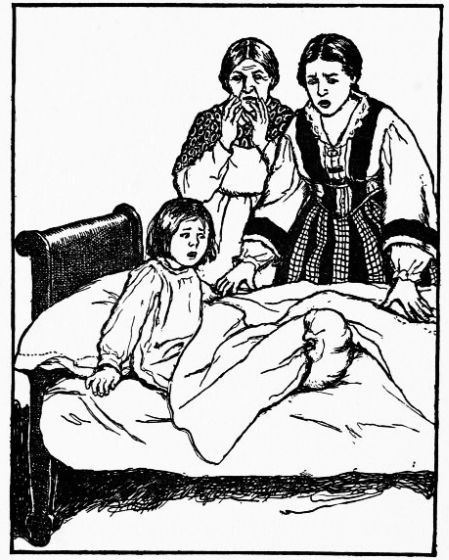

Mamma and nurse came hurrying in,

Ah what a sight to see!

Poor Anne! A caterpillar’s legs

And stubby feet had she.

She scarce knew how to turn herself

Nor how to climb from bed.

“However shall I run or play!”

The poor child sadly said.

Mamma and nurse were shocked and grieved,

And so was grandma, too,

While little Mary sobbed, “Oh dear!

Whatever will she do!”

But like a caterpillar soon

She learned to crawl around,

Although her legs were now so short

She almost touched the ground.

’Twas sad indeed to be so slow

When she had been so fleet.

No longer could she play about

Nor run out in the street.

Her greatest pleasure was to find

Some errand she could go,

And up and down the stairs she’d trudge

With patient steps and slow.

She waited on her grandmamma,

And on her mother, too.

No one could ask her anything

She was not glad to do.

One day her watchful mother said,

“It really seems to me

Anne’s legs are growing long and slim,

More like they used to be.

“She does not have so many now.

Her body’s shorter, too.

I saw her standing up to-day

Quite as she used to do.”

“I’ve noticed that,” her grandma said,

“Indeed I hope some day

To see our Anne herself again,

And fit for work and play.”

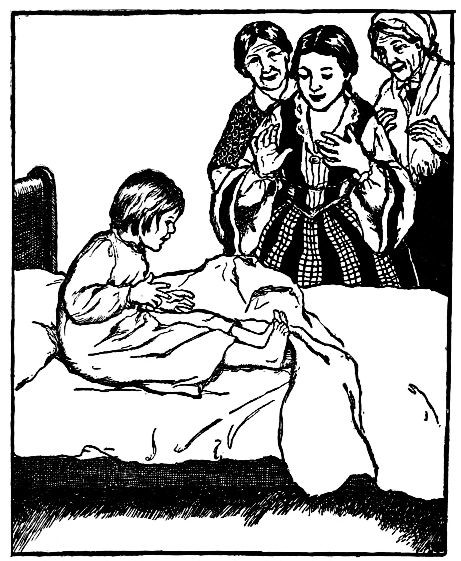

And so it was. For one day Anne

Awoke to find once more

She was the selfsame nimble child

That she had been before.

Then what rejoicings filled the house,

All gathered round to see;

And as for Anne, as you may guess,

A thankful child was she.

And never since has Annie lost

Her willing, useful ways,

And her mamma and every one

All speak of her with praise.

[112] [113]

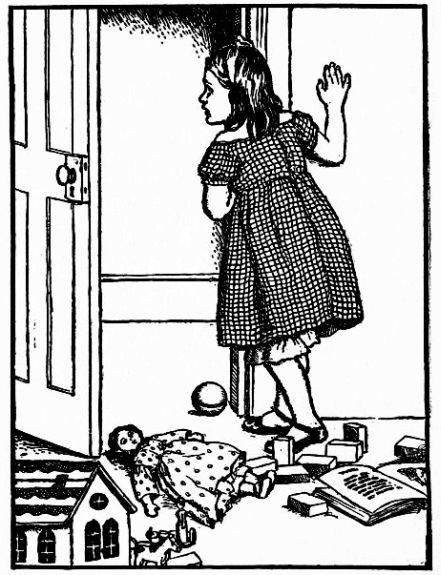

MISCHIEVOUS JANE

Only see how this naughty Jane

Is frightening her nurse again.

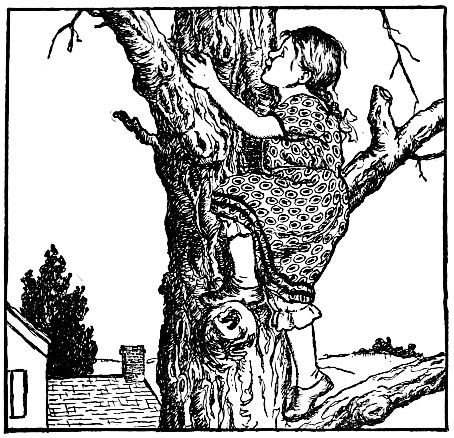

JANE’S greatest pleasure and delight

Was putting others in a fright.

She loved to bounce and scream and climb,

She kept nurse nervous all the time.

Her dear mamma was worried, too,

She never knew what Jane would do.

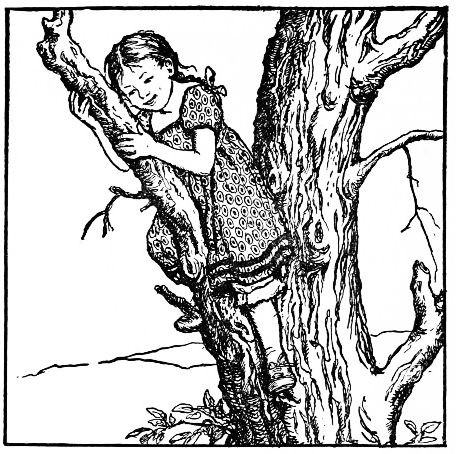

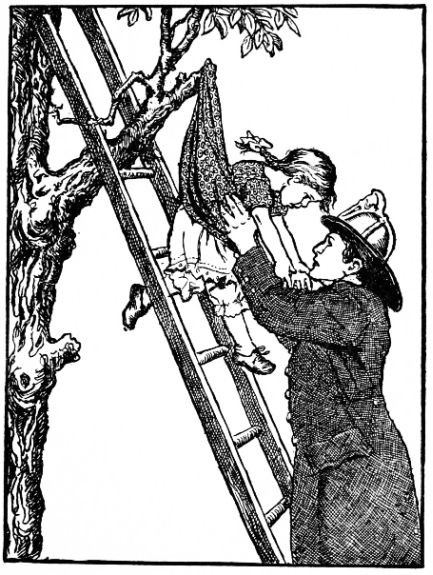

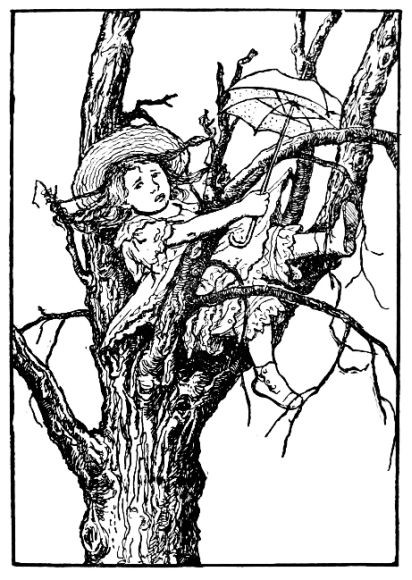

One day she climbed up in a tree.

A very daring child was she.

Then she began to scream and call,

“Oh nurse, come quick! Oh! Oh! I’ll fall!”

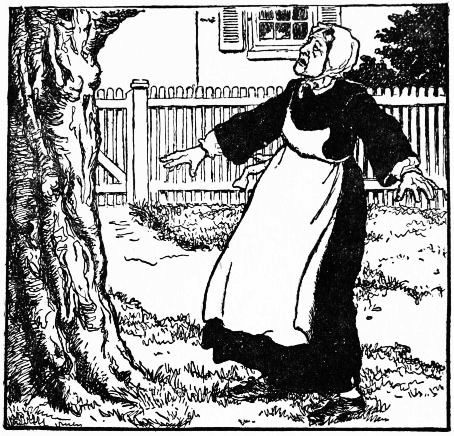

Quickly her nurse came running out,

And anxiously she looked about.

“Where are you, Jane? Where can you be?”

“Here I am, nurse, up in the tree.”

Poor nurse was in a dreadful fright.

“Oh Jane!” she cried. “That is not right.”

“Come down! If your mamma should see

You know how worried she would be.”

Jane laughed aloud to see her fright,

She thought it such a funny sight.

Now higher up the tree she went,

On nurse’s further torment bent.

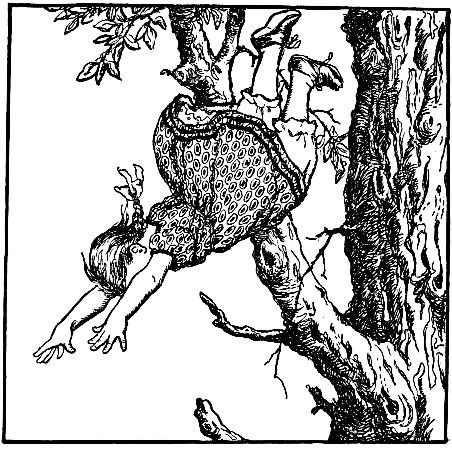

“Now look!” she cried. But as she spoke

The branch where she was standing broke,

And then—a fearful sight to see—

Down she came crashing through the tree.

Her nursie screamed so loud with fear

That all the neighborhood could hear.

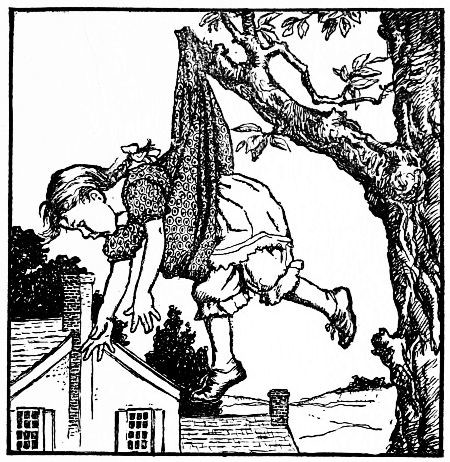

But luckily, when half way down

A ragged branch caught Janie’s gown.

It stopped her fall, and held her there

Swinging and turning in the air.

Her nurse’s cries brought mother out,

And neighbors ran from all about.

They talked and made a great to-do,

But how to reach her no one knew.

Till some one cried, “Without a doubt

We’ll have to call the firemen out.

“They have a ladder that’s so high

It almost reaches to the sky.”

Mamma cries, “Oh, for mercy’s sake

Be quick! Suppose the branch should break?”

Now clang! clang! clang! the fire-bells go.

People are running to and fro,

And down the street—ah only see!

There comes the fire company.

“Quick! Get the ladder up!” “Look out!”

“Be careful there what you’re about.”

Now up, up, up, the ladder goes.

It’s up as high as Janie’s toes.

Up further still; it’s resting now

Its topmost rung against a bough.

Then quick a fireman, strong and brown

Runs up and lifts the poor child down.

And listen how the anxious crowd

That has been watching shouts aloud.

No need for any more alarms.

He’s placed her in her mother’s arms.

“Oh dear! I’ll never try,” sobs Jane

“To frighten any one again.”

[124] [125]

THE SWEET TOOTH

Alas poor Fred! So fat is he,

Only a pig could fatter be.

THE SWEET TOOTH

A SWEET-TOOTH was our Frederick.

He scorned the bread and meat

And all the other wholesome things

That children ought to eat.

He ate the sugar from the bowl;

He fed on cakes and pies,

The very sight of lollipops

Brought water to his eyes.

He grew too fat to play about,

Too fat to run or jump,

On either side his arms stuck out

Like handles of a pump.

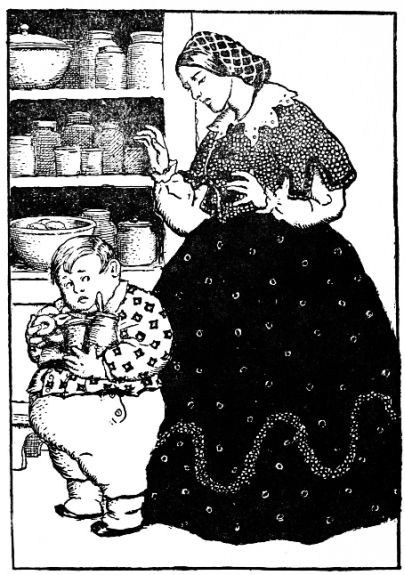

It grieved his kind mamma to see

How fat and fatter grew

Her little Fred, in spite of all

That she could say or do.

One day, with pennies in his hand

He set out for a shop,

To buy himself some sugar-cakes

Or tart or lollipop.

But oh the day was very hot,

The sun a fiery ball,

And soon the heat made Fred so soft

He scarce could walk at all.

“Oh dear, oh dear! I feel so queer;

What’s happening?” cried he.

“If I should melt in all this heat

How dreadful it would be!”

It is a sorry tale to tell,

But greedy ones take heed!

Fred’s arms and legs and all of him

Were melting down indeed.

They melted till you scarce could tell

Fred was a boy at all,

For now he looked all smooth and round

As though he were a ball.

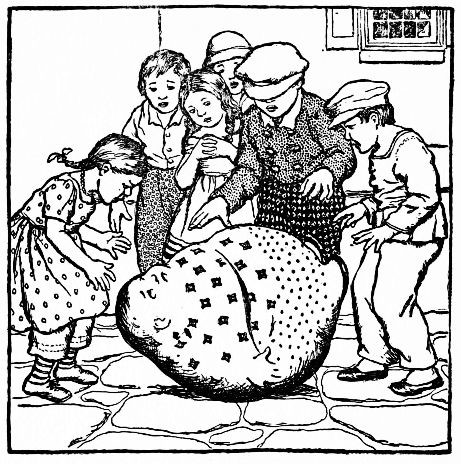

That afternoon the girls and boys

Came running out to play,

And wondering they gathered round

The place where Frederick lay.

“Oh what a great enormous ball!

”Let’s play with it,“ they cried;

And then they rolled and pushed poor Fred

About from side to side.

Hither and yon, in giddy round

The wretched Frederick sped,

And sometimes he was on his heels,

And sometimes on his head.

At supper time the mothers called,

“Now put your ball away.

To-morrow you can get it out

And have another play.”

Ah Frederick, poor Frederick!

Though he lay quiet now

He could not even lift his hand

To wipe his heated brow,

And now each day they came to play

With Fred, until at last

His fat began to wear away

They rolled him round so fast.

The disappointed children said,

“Someone has spoiled our ball.

It’s growing such a funny shape

It scarcely rolls at all.”

One time when they had stopped to rest

Fred’s little brother said,

“It’s queer, but don’t you think our ball

Looks very much like Fred?”

“Why it is Fred,” his sister cried.

“I know his eyes and nose.

And only see! Those are his hands,

And down there are his toes.”

They called his mother out to see.

With eager steps she came,

At once she knew her Frederick,

And called him by his name.

And now he found that he could turn,

That he could move and rise.

He stood before his mother

With shamed and tearful eyes.

“Oh, mother, mother, dear, I’ve had

A dreadful time!” cried he,

“But now that I’m a boy again

Less greedy I will be.”

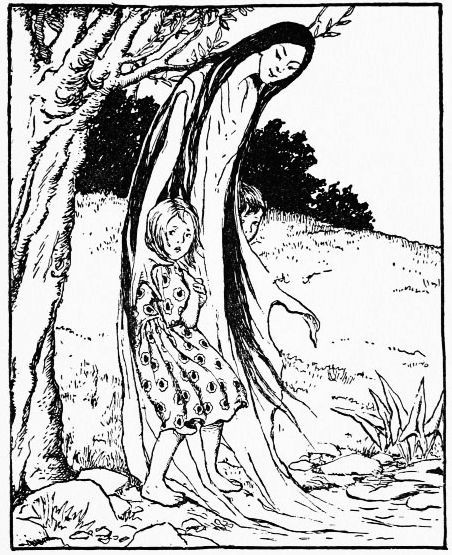

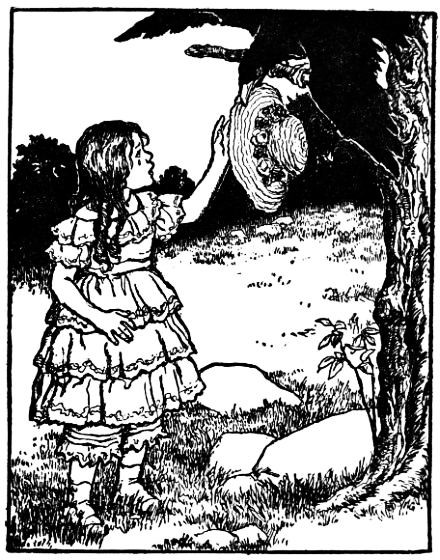

VAIN LITTLE LUCY

Her godmamma once sent to her

A frock of ruffled lace.

VAIN LITTLE LUCY

MISS LUCY was a pretty child,

But vain as she could be,

She loved all sorts of furbelows,

And frills and finery.

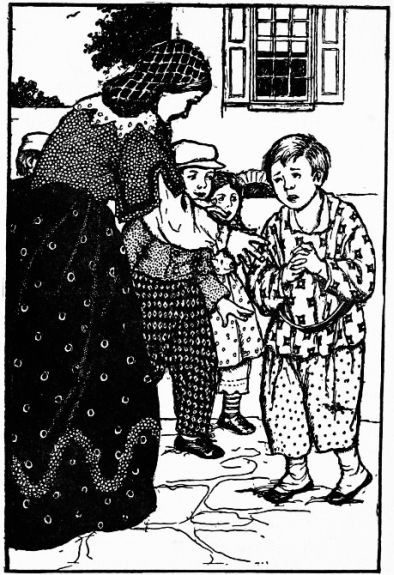

Her godmamma once sent to her

A frock of ruffed lace,

A flowered hat, and parasol

With which to shade her face.

And in the box was also packed

A pair of pink kid shoes.

“Oh dear!” her mother sighed; “they all

Are quite too fine to use.”

But Lucy cried, “Oh mother, no!

I’m sure they’re what I need.

When I am dressed and walking out

I will look fine indeed.”

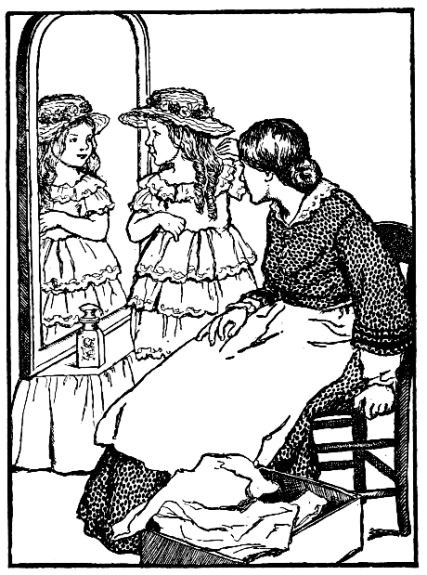

And then she begged to put them on,

And with a peacock pride

She stood before the looking-glass

And turned from side to side.

“May I go out and show them off?”

Cried Lucy eagerly.

“How all the little girls will stare!

And how they’ll envy me!”

“Why Lucy! What a way to speak!”

Her loving mother cried.

“I am surprised my child should show

Such vain and silly pride.”

“Now go put on your calico,

And run outdoors and play.

These things were meant for special times,

And not for every day.”

But Lucy has another plan.

She sulks, and hangs about,

Till later in the afternoon,

When her mamma goes out.

Then quick she dresses up again

In all her frills and lace,

And out she runs, to trip along

With air of dainty grace.

She walked with such a haughty air,

She held her head so high,

The other children scarcely dared

To speak as she passed by.

But even as, with scornful air,

She minced along the street,

There came a sudden rushing wind

That swept her from her feet.

It caught her by her parasol,

It caught her by her frills,

It swept her up into the sky,

And off across the hills.

No knowing where she would have gone,

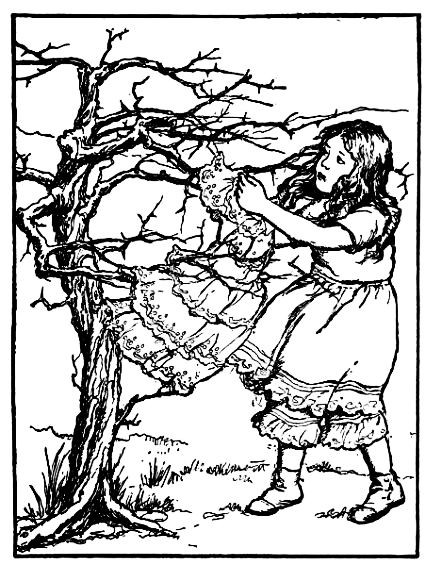

Still driven by the blast,

But luckily a branching tree

Has caught her skirts at last.

It catches her and holds to her,—

It will not let her go;

Whatever will become of her

Poor Lucy does not know.

In vain she twists herself about

And strives with all her might.

“Oh, dear kind tree,” she says to it,

“Don’t hold me quite so tight.”

The tree replies, “My branches

Shall quickly set you free

If you’ll give me your parasol

To wear as finery.”

“Oh, take it, do,” cries Lucy.

“I do not care at all,

If you will only set me free;

But do not let me fall.”

So now the twigs and branches

Bend back to let her go,

And safely Lucy clambers down

Into the field below.

Now Lucy looks about her

With frightened, tearful eyes.

“Oh dear, oh dear, I’m lost I fear!

What shall I do!” she cries.

High overhead a raven

Is sitting in the tree,

“I know the way you ought to go.”

Cries Lucy, “Tell it me!”

“Oh it is not for nothing

I tell the things I know,

But if you’ll let me have your hat

I’ll tell you how to go.”

“Alas, I meant to keep it,

And wear it for my best.

But take it,” cries poor Lucy.

“’Twill make a pretty nest.”

Now with his wing the raven points,

“There yonder lies your way.”

And off Miss Lucy runs in haste.

She does not stop nor stay.

But see! across the pathway

A thorn tree towers high.

Its thorns will surely catch her

Before she can go by.

“Oh prickly, stickly thorn-tree,

That stands to bar the way,

Draw back your boughs,” cries Lucy,

“And let me pass, I pray.”

The thorn replies, “My blossoms

Have dropped and left me bare,

I’ll let you pass if I may have

That little frock you wear.”

“Here take my frock,” cries Lucy,

And gives it to the tree,

Then quick it draws aside its thorns

And leaves the pathway free.

Now on again runs Lucy.

Indeed she is in haste.

If she would reach her home by dark

She has no time to waste.

And now she sees a river,

It flows so deep and wide

There seems no way for Lucy

To reach the other side.

But look! A duck is sailing

Upon the flowing tide,

His legs are strong for swimming,

His back is flat and wide.

“Oh pretty duck,” cries Lucy,

“Come here, come here to me.

If you will carry me across

How thankful I will be.”

“In winter time,” replies the duck,

“My toes get nipped with frost.

If you will give your shoes to me

I’ll carry you across.”

“Here! Take them quick,” cries Lucy.

“Indeed I do not care!

I have a stouter pair at home,

And they will do to wear.”

And now see little Lucy

On ducky’s back astride,

As steadily he swims across

Unto the other side.

Now on she runs—she reaches home—

In through the door she creeps,

“Oh mother dear, I’m back again,”

With joyful tears she weeps.

Now Lucy’s grown more sensible,

She’s quite content when dressed

In just the plain and simple things

That mother thinks are best.

[160] [161]

THE MAGIC MAN

Be careful, children, lest some day

The Magic Man should come your way.

’TIS very naughty for a child

To try to hang about

And overhear what people say,

And find their secrets out.

Our James was such a child as that.

He loved to overhear

The very things he knew were not

Intended for his ear.

The older people often said,

“Now James, please run away.

You’re always, always hanging round

To hear what we may say.”

Once mother asked some ladies in

To drink a cup of tea,

And nurse said, “James, don’t go downstairs;

Come in the room with me.”

“I want to hear them talk,” said James.

“I like to listen, too.”

“But that’s exactly what mamma

Has told you not to do.”

“I’ll stay here, anyway,” said James,

And sat down on the stair,

And when nurse found he would not move

She went and left him there.

“And now she’s gone, I’ll creep downstairs

Into the hall,” thought he,

“And listen at the parlor door,

I’m sure no one will see.”

But James had hardly risen up

Before, all silently,

Some one came stealing down the hall

As soft as soft could be.

And then James felt that somebody

Had caught him by each ear,

“Ho!” cried a voice, “so you’re the boy

Who always wants to hear.”

Quite suddenly he felt his ears

Begin to stretch and spread.

Until, like any elephant’s

They stood out from his head.

“Let go!” cried James, “Let go, I say!

Take care what you’re about!”

And then the hands had set him free,

And quick he turned about.

He peered around with frightened eyes.

No one at all was there,—

Only the clock that said tick-tock,

And shadows on the stair.

Into the nursery quick he ran,

“Oh, nursie! Only see!

Somebody came and stretched my ears

And scared me terribly.”

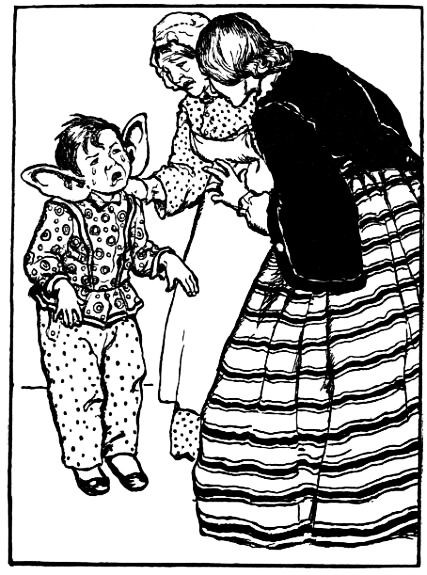

Nurse looked at him and gave a cry.

“Oh James! What shall we do!

It must have been the Magic Man

Who did this thing to you.

“I know when children misbehave

He often comes about,

And punishes their naughty ways

If he can find them out.”

And now mamma is called in haste.

She comes, and “Oh!” cries she,

“Whatever’s happened to your ears?

They are a sight to see!”

James tells her all the doleful tale,

But ah, ’tis very plain

The only thing is just to wait

And hope they’ll shrink again.

“If you are very patient, James,

And if you will be good,

Perhaps some day your ears once more

Will look the way they should.”

Now James is different indeed,

For ever since that day

He’s never wished to overhear

What other people say,

And if a secret’s being told

That he perchance might hear

He runs away, or else he stuffs

A finger in each ear.

His ears are shrinking day by day,

And soon I hope we’ll see

They are as small as any lad

Could wish his ears to be.