автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу A History of Champagne, with Notes on the Other Sparkling Wines of France

Original Book Cover

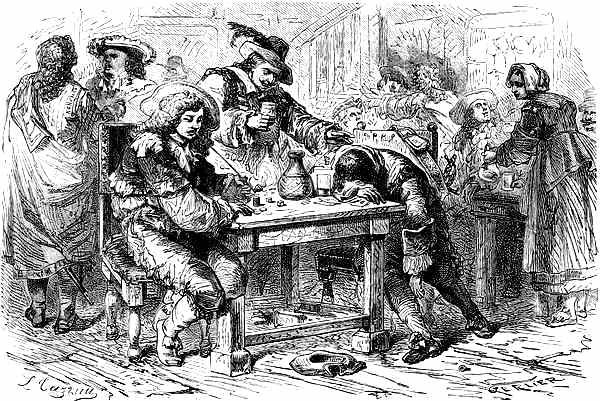

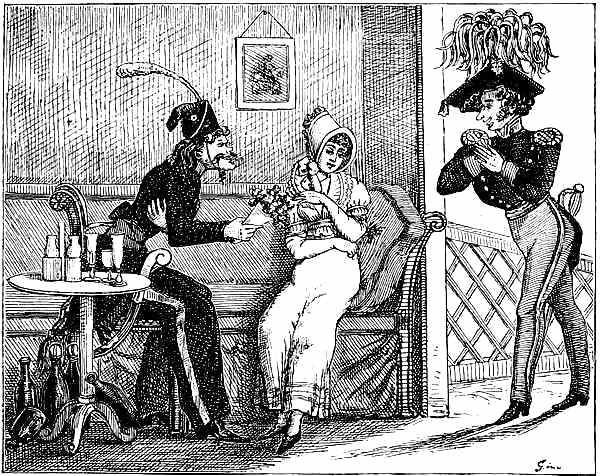

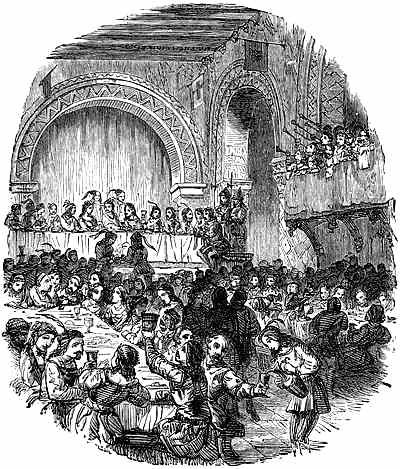

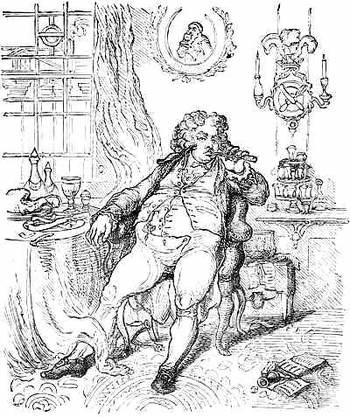

A SUPPER UNDER THE REGENCY.

Click here to view the original title page

A HISTORY

OF

CHAMPAGNE

WITH NOTES ON

THE OTHER SPARKLING WINES OF FRANCE.

BY HENRY VIZETELLY,

CHEVALIER OF THE ORDER OF FRANZ-JOSEF, AUTHOR OF ‘THE WINES OF THE WORLD CHARACTERISED AND CLASSED,’ ‘FACTS ABOUT PORT AND MADEIRA,’ ‘FACTS ABOUT CHAMPAGNE AND OTHER SPARKLING WINES,’ ‘FACTS ABOUT SHERRY,’ ETC.

ILLUSTRATED WITH 350 ENGRAVINGS.

LONDON:

VIZETELLY & CO., 42 CATHERINE STREET, STRAND.

SCRIBNER & WELFORD, NEW YORK. 1882.

LONDON:

ROBSON AND SONS, PRINTERS, PANCRAS ROAD, N.W.

Condensed Table of Contents

(added by the transcriber)

PREFACE. iv PART I. I.Early Renown of the Champagne Wines

1 II.The Wines of the Champagne from the Fourteenth to the Seventeenth Century.

12 III.Invention and Development of Sparkling Champagne.

34 IV.The Battle of the Wines.

47 V.Progress and Popularity of Sparkling Champagne.

57 VI.Champagne in England.

83 PART II. I.The Champagne Vinelands—The Vineyards of the River.

117 II.The Champagne Vinelands—The Vineyards of the Mountain.

130 III.The Vines of the Champagne and the System of Cultivation.

140 IV.The Vintage in the Champagne.

148 V.he Preparation of Champagne.

154 VI.Reims and its Champagne Establishments.

168 VII.Reims and its Champagne Establishments (

continued).

179 VII.Reims and its Champagne Establishments (

continued).

188 IX.Epernay.

195 X.The Champagne Establishments of Epernay and Pierry.

205 XI.Some Champagne Establishments at Ay and Mareuil.

217 XII.Champagne Establishments at Avize and Rilly.

229 XIII.Sport in the Champagne.

235 PART III. I.Sparkling Saumur and Sparkling Sauternes.

241 II.The Sparkling Wines of Burgundy, the Jura, and the South of France.

251 III.Facts and Notes Respecting Sparkling Wines.

258 APPENDIX. 265 Advertisements. 268PREFACE.

The present is the first instance in which the history of any wine has been traced with the same degree of minuteness as the history of the still and sparkling wines of the Champagne has been traced in the following pages. And not only have the author’s investigations extended over a very wide range, as will be seen by the references contained in the footnotes to this volume, but during the past ten years he has paid frequent visits to the Champagne—to its vineyards and vendangeoirs, and to the establishments of the chief manufacturers of sparkling wine, the preparation of which he has witnessed in all its phases. Visits have, moreover, been made to various other localities where sparkling wines are produced, and more or less interesting information gathered regarding the latter. In the pursuit of his researches, the author’s position as wine juror at the Vienna and Paris Exhibitions opened up to him many sources of information inaccessible to others less favourably circumstanced, and these his general knowledge of wine, acquired during many years’ careful study, enabled him to turn to advantageous account.

The numerous illustrations scattered throughout the present volume have been derived from every available source that suggested itself. Ancient MSS., early-printed books, pictures and pieces of sculpture, engravings and caricatures, all of greater or less rarity, have been laid under contribution; and in addition, nearly two hundred original sketches have been made under the author’s immediate superintendence, with the object of illustrating the principal localities and their more picturesque features, and depicting all matters of interest connected with the growth and manipulation of the various sparkling wines which are here described.

In the preparation of this work, and more particularly the historical portions of it, the author has been largely assisted by his nephew, Mr. Montague Vizetelly, to whom he tenders his warmest acknowledgments for the valuable services rendered by him.

It should be stated that portions of the volume, relating to the vintaging and manufacture of sparkling wines generally, have been previously published under the title of Facts about Champagne and other Sparkling Wines, but they have been subjected to considerable extension and revision before being permitted to reappear in their present form.

St. Leonards-on-Sea, February 1882.

CONTENTS.

PART I.

I.

EARLY RENOWN OF THE CHAMPAGNE WINES.

P

AGEThe vine in Gaul—Domitian’s edict to uproot it—Plantation of vineyards under Probus—Early vineyards of the Champagne—Ravages by the Northern tribes repulsed for a time by the Consul Jovinus—St. Remi and the baptism of Clovis—St. Remi’s vineyards—Simultaneous progress of Christianity and the cultivation of the vine—The vine a favourite subject of ornament in the churches of the Champagne—The culture of the vine interrupted, only to be renewed with increased ardour—Early distinction between ‘Vins de la Rivière’ and ‘Vins de la Montagne’—A prelate’s counsel respecting the proper wine to drink—The Champagne desolated by war—Pope Urban II., a former Canon of Reims Cathedral—His partiality for the wine of Ay—Bequests of vineyards to religious establishments—Critical ecclesiastical topers—The wine of the Champagne causes poets to sing and rejoice—‘La Bataille des Vins’—Wines of Auviller and Espernai le Bacheler

1II.

THE WINES OF THE CHAMPAGNE FROM THE FOURTEENTH TO THE SEVENTEETH CENTURY.

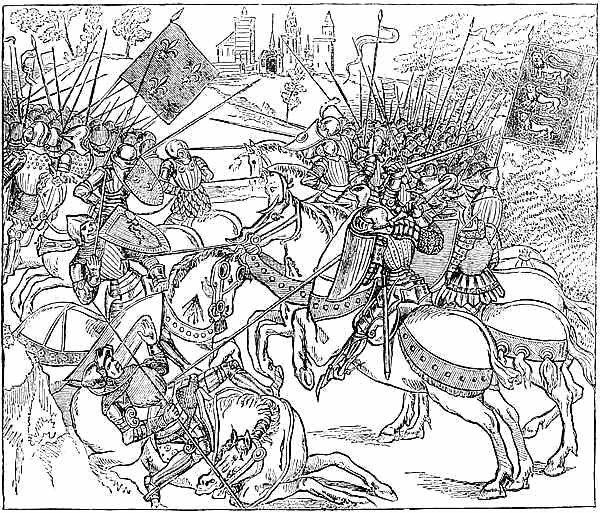

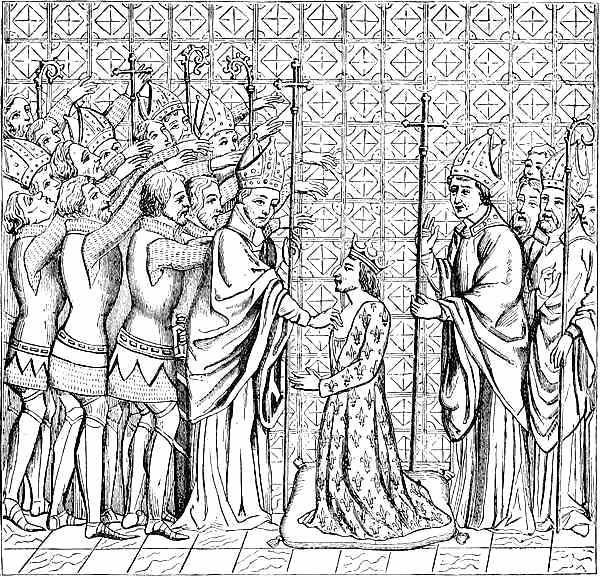

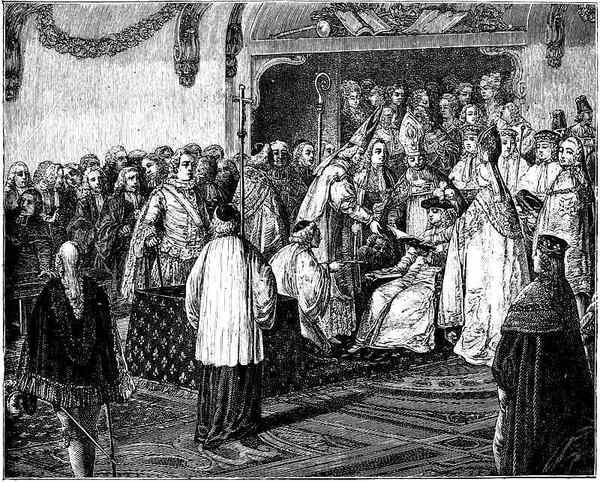

Coronations at Reims and their attendant banquets—Wine flows profusely at these entertainments—The wine-trade of Reims—Presents of wine from the Reims municipality—Cultivation of the vineyards abandoned after the battle of Poitiers—Octroi levied on wine at Reims—Coronation of Charles V.—Extension of the Champagne vineyards—Abundance of wine—Visit to Reims of the royal sot Wenceslaus of Bohemia—The Etape aux Vins at Reims—Increased consumption of beer during the English occupation of the city—The Maid of Orleans at Reims—The vineyards and wine-trade alike suffer—Louis XI. is crowned at Reims—Fresh taxes upon wine followed by the Mique-Maque revolt—The Rémois the victims of pillaging foes and extortionate defenders—The Champagne vineyards attacked by noxious insects—Coronation of Louis XII.—François Premier, the Emperor Charles V., Bluff King Hal, and Leo the Magnificent all partial to the wine of Ay—Mary Queen of Scots at Reims—State kept by the opulent and libertine Cardinal of Lorraine—Brusquet, the Court Fool—Decrease in the production of wine around Reims—Gifts of wine to newly-crowned monarchs—New restrictions on vine cultivation—The wine of the Champagne crowned at the same time as Louis XIII.—Regulation price for wine established at Reims—Imposts levied on the vineyards by the Frondeurs—The country ravaged around Reims—Sufferings of the peasantry—Presents of wine to Marshal Turenne and Charles II. of England—Perfection of the Champagne wines during the reign of Louis XIV.—St. Evremond’s high opinion of them—Other contemporary testimony in their favour—The Archbishop of Reims’s niggardly gift to James II. of England—A poet killed by Champagne—Offerings by the Rémois to Louis XIV. on his visit to their city

12III.

INVENTION AND DEVELOPMENT OF SPARKLING CHAMPAGNE.

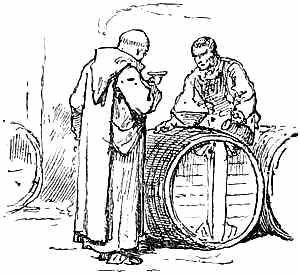

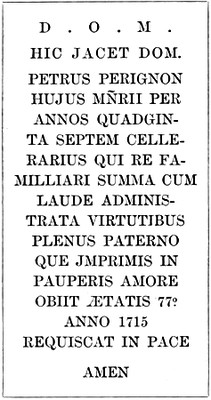

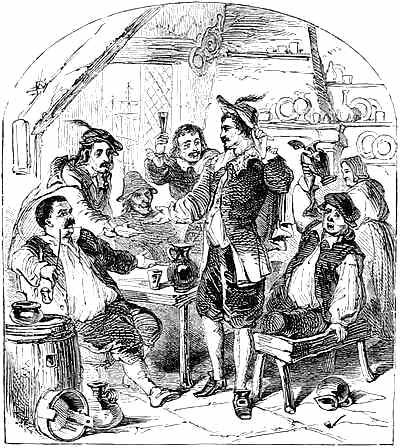

The ancients acquainted with sparkling wines—Tendency of Champagne wines to effervesce noted at an early period—Obscurity enveloping the discovery of what we now know as sparkling Champagne—The Royal Abbey of Hautvillers—Legend of its foundation by St. Nivard and St. Berchier—Its territorial possessions and vineyards—The monks the great viticulturists of the Middle Ages—Dom Perignon—He marries wines differing in character—His discovery of sparkling white wine—He is the first to use corks to bottles—His secret for clearing the wine revealed only to his successors Frère Philippe and Dom Grossart—Result of Dom Perignon’s discoveries—The wine of Hautvillers sold at 1000 livres the queue—Dom Perignon’s memorial in the Abbey-Church—Wine flavoured with peaches—The effervescence ascribed to drugs, to the period of the moon, and to the action of the sap in the vine—The fame of sparkling wine rapidly spreads—The Vin de Perignon makes its appearance at the Court of the Grand Monarque—Is welcomed by the young courtiers—It figures at the suppers of Anet and Chantilly, and at the orgies of the Temple and the Palais Royal—The rapturous strophes of Chaulieu and Rousseau—Frederick William I. and the Berlin Academicians—Augustus the Strong and the page who pilfered his Champagne—Horror of the old-fashioned gourmets at the innovation—Bertin du Rocheret and the Marshal d’Artagnan—System of wine-making in the Champagne early in the eighteenth century—Bottling of the wine in flasks—Icing Champagne with the corks loosened

34IV.

THE BATTLE OF THE WINES.

Temporary check to the popularity of sparkling Champagne—Doctors disagree—The champions of Champagne and Burgundy—Péna and his patient—A young Burgundian student attacks the wine of Reims—The Faculty of Reims in arms—A local Old Parr cited as an example in favour of the wines of the Champagne—Salins of Beaune and Le Pescheur of Reims engage warmly in the dispute—A pelting with pamphlets—Burgundy sounds a war-note—The Sapphics of Benigné Grenan—An asp beneath the flowers—The gauntlet picked up—Carols from a coffin—Champagne extolled as superior to all other wines—It inspires the heart and stirs the brain—The apotheosis of Champagne foam—Burgundy, an invalid, seeks a prescription—Impartially appreciative drinkers of both wines—Bold Burgundian and stout Rémois, each a jolly tippling fellow—Canon Maucroix’s parallel between Burgundy and Demosthenes and Champagne and Cicero—Champagne a panacea for gout and stone—Final decision in favour of Champagne by the medical faculty of Paris—Pluche’s opinion on the controversy—Champagne a lively wit and Burgundy a solid understanding—Champagne commands double the price of the best Burgundy—Zealots reconciled at table

47V.

PROGRESS AND POPULARITY OF SPARKLING CHAMPAGNE.

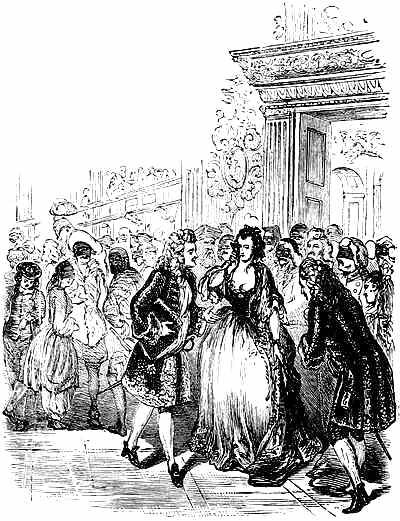

Sparkling Champagne intoxicates the Regent d’Orléans and the roués of the Palais Royal—It is drunk by Peter the Great at Reims—A horse trained on Champagne and biscuits—Decree of Louis XV. regarding the transport of Champagne—Wine for the petits cabinets du Roi—The petits soupers and Champagne orgies of the royal household—A bibulous royal mistress—The Well-Beloved at Reims—Frederick the Great, George II., Stanislas Leczinski, and Marshal Saxe all drink Champagne—Voltaire sings the praises of the effervescing wine of Ay—The Commander Descartes and Lebatteux extol the charms of sparkling Champagne—Bertin du Rocheret and his balsamic molecules—The Bacchanalian poet Panard chants the inspiring effects of the vintages of the Marne—Marmontel is jointly inspired by Mademoiselle de Navarre and the wine of Avenay—The Abbé de l’Attaignant and his fair hostesses—Breakages of bottles in the manufacturers’ cellars—Attempts to obviate them—The early sparkling wines merely crémant—Saute bouchon and demi-mousseux—Prices of Champagne in the eighteenth century—Preference given to light acid wines for sparkling Champagne—Lingering relics of prejudice against vin mousseux—The secret addition of sugar—Originally the wine not cleared in bottle—Its transfer to other bottles necessary—Adoption of the present method of ridding the wine of its deposit—The vine-cultivators the last to profit by the popularity of sparkling Champagne—Marie Antoinette welcomed to Reims—Reception and coronation of Louis XVI. at Reims—‘The crown, it hurts me!’—Oppressive dues and tithes of the ancien régime—The Fermiers Généraux and their hôtel at Reims—Champagne under the Revolution—Napoleon at Epernay—Champagne included in the equipment of his satraps—The Allies in the Champagne—Drunkenness and pillaging—Appreciation of Champagne by the invading troops—The beneficial results which followed—Universal popularity of Champagne—The wine a favourite with kings and potentates—Its traces to be met with everywhere

57VI.

CHAMPAGNE IN ENGLAND.

The strong and foaming wine of the Champagne forbidden his troops by Henry V.—The English carrying off wine when evacuating Reims on the approach of Jeanne Darc—A legend of the siege of Epernay—Henry VIII. and his vineyard at Ay—Louis XIV.’s present of Champagne to Charles II.—The courtiers of the Merry Monarch retain the taste for French wine acquired in exile—St. Evremond makes the Champagne flute the glass of fashion—Still Champagne quaffed by the beaux of the Mall and the rakes of the Mulberry Gardens—It inspires the poets and dramatists of the Restoration—Is drank by James II. and William III.—The advent of sparkling Champagne in England—Farquhar’s Love and a Bottle—Mockmode the Country Squire and the witty liquor—Champagne the source of wit—Port-wine and war combine against it, but it helps Marlborough’s downfall—Coffin’s poetical invitation to the English on the return of peace—A fraternity of chemical operators who draw Champagne from an apple—The influence of Champagne in the Augustan age of English literature—Extolled by Gay and Prior—Shenstone’s verses at an inn—Renders Vanbrugh’s comedies lighter than his edifices—Swift preaches temperance in Champagne to Bolingbroke—Champagne the most fashionable wine of the eighteenth century—Bertin du Rocheret sends it in cask and bottle to the King’s wine-merchant—Champagne at Vauxhall in Horace Walpole’s day—Old Q. gets Champagne from M. de Puissieux—Lady Mary’s Champagne and chicken—Champagne plays its part at masquerades and bacchanalian suppers—Becomes the beverage of the ultra-fashionables above and below stairs—Figures in the comedies of Foote, Garrick, Coleman, and Holcroft—Champagne and real pain—Sir Edward Barry’s learned remarks on Champagne—Pitt and Dundas drunk on Jenkinson’s Champagne—Fox and the Champagne from Brooks’s—Champagne smuggled from Jersey—Grown in England—Experiences of a traveller in the Champagne trade in England at the close of the century—Sillery the favourite wine—Nelson and the ‘fair Emma’ under the influence of Champagne—The Prince Regent’s partiality for Champagne punch—Brummell’s Champagne blacking—The Duke of Clarence overcome by Champagne—Curran and Canning on the wine—Henderson’s praise of Sillery—Tom Moore’s summer fête inspired by Pink Champagne—Scott’s Muse dips her wing in Champagne—Byron’s sparkling metaphors—A joint-stock poem in praise of Pink Champagne—The wheels of social life in England oiled by Champagne—It flows at public banquets and inaugurations—Plays its part in the City, on the Turf, and in the theatrical world—Imparts a charm to the dinners of Belgravia and the suppers of Bohemia—Champagne the ladies’ wine par excellence—Its influence as a matrimonial agent—‘O the wildfire wine of France!’

83PART II.

I.

THE CHAMPAGNE VINELANDS—THE VINEYARDS OF THE RIVER.

The vinelands in the neighbourhood of Epernay—Viticultural area of the Champagne—A visit to the vineyards of ‘golden plants’—The Dizy vineyards—Antiquity of the Ay vineyards—St. Tresain and the wine-growers of Ay—The Ay vintage of 1871—The Mareuil vineyards and their produce—Avernay; its vineyards, wines, and ancient abbey—The vineyards of Mutigny and Cumières—Damery and ‘la belle hôtesse’ of Henri Quatre—Adrienne Lecouvreur and the Maréchal de Saxe’s matrimonial schemes—Pilgrimage to Hautvillers—Remains of the Royal Abbey of St. Peter—The ancient church—Its quaint decorations and monuments—The view from the heights of Hautvillers—The abbey vineyards and wine-cellars in the days of Dom Perignon—The vinelands of the Côte d’Epernay—Pierry and its vineyard cellars—The Moussy, Vinay, and Ablois St. Martin vineyards—The Côte d’Avize—Chavot, Monthelon, Grauves, and Cuis—The vineyards of Cramant and Avize, and their light delicate white wines—The Oger and Le Mesnil vineyards—Vertus and its picturesque ancient remains—Its vineyards planted with Burgundy grapes from Beaune—The red wine of Vertus a favourite beverage of William III. of England

117II.

THE CHAMPAGNE VINELANDS—THE VINEYARDS OF THE MOUNTAIN.

The wine of Sillery—Origin of its renown—The Maréchale d’Estrées a successful Marchande de Vin—The Marquis de Sillery the greatest wine-farmer in the Champagne—Cossack appreciation of the Sillery produce—The route from Reims to Sillery—Henri Quatre and the Taissy wines—Failure of the Jacquesson system of vine cultivation—Château of Sillery—Wine-making at M. Fortel’s—Sillery sec—The vintage at Verzenay and the vendangeoirs—Renown of the Verzenay wine—The Verzy vineyards—Edward III. at the Abbey of St. Basle—Excursion from Reims to Bouzy—The herring procession at St. Remi—Rilly, Chigny, and Ludes—The Knights Templars’ ‘pot’ of wine—Mailly and the view over the Champagne plains—Wine-making at Mailly—The village in the wood—Château and park of Louvois, Louis le Grand’s War Minister—The vineyards of Bouzy—Its church-steeple, and the lottery of the great gold ingot—Pressing grapes at the Werlé vendangeoir—Still red Bouzy—Ambonnay—A pattern peasant vine-proprietor—The Ambonnay vintage—The vineyards of Ville-Dommange and Sacy, Hermonville and St. Thierry—The still red wine of the latter

130III.

THE VINES OF THE CHAMPAGNE AND THE SYSTEM OF CULTIVATION.

A combination of circumstances essential to the production of good Champagne—Varieties of vines cultivated in the Champagne vineyards—Different classes of vine-proprietors—Cost of cultivation—The soil of the vineyards—Period and system of planting the vines—The operation of ‘provenage’—The ‘taille’ or pruning, the ‘bêchage’ or digging—Fixing the vine-stakes—Great cost of the latter—Manuring and shortening back the vines—The summer hoeing around the plants—Removal of the stakes after the vintage—Precautions adopted against spring frosts—The Guyot system of roofing the vines with matting—Forms a shelter from rain, hail, and frost, and aids the ripening of the grapes—Various pests that prey upon the Champagne vines—Destruction caused by the Eumolpe, the Chabot, the Bêche, the Cochylus, and the Pyrale—Attempts made to check the ravages of the latter with the electric light

140IV.

THE VINTAGE IN THE CHAMPAGNE.

Period of the Champagne vintage—Vintagers summoned by beat of drum—Early morning the best time for plucking the grapes—Excitement in the neighbouring villages at vintage-time—Vintagers at work—Mules employed to convey the gathered grapes down the steeper slopes—The fruit carefully examined before being taken to the wine-press—Arrival of the grapes at the vendangeoir—They are subjected to three squeezes, and then to the ‘rébêche’—The must is pumped into casks and left to ferment—Only a few of the vine-proprietors in the Champagne press their own grapes—The prices the grapes command—Air of jollity throughout the district during the vintage—Every one is interested in it, and profits by it—Vintagers’ fête on St. Vincent’s-day—Endless philandering between the sturdy sons of toil and the sunburnt daughters of labour

148V.

THE PREPARATION OF CHAMPAGNE.

The treatment of Champagne after it comes from the wine-press—The racking and blending of the wine—The proportions of red and white vintages composing the ‘cuvée’—Deficiency and excess of effervescence—Strength and form of Champagne bottles—The ‘tirage’ or bottling of the wine—The process of gas-making commences—Details of the origin and development of the effervescent properties of Champagne—The inevitable breakage of bottles which ensues—This remedied by transferring the wine to a lower temperature—The wine stacked in piles—Formation of sediment—Bottles placed ‘sur pointe’ and daily shaken to detach the deposit—Effect of this occupation on those incessantly engaged in it—The present system originated by a workman of Madame Clicquot’s—‘Claws’ and ‘masks’—Champagne cellars—Their construction and aspect—Raw recruits for the ‘Regiment de Champagne’—Transforming the ‘vin brut’ into Champagne—Disgorging and liqueuring the wine—The composition of the liqueur—Variation in the quantity added to suit diverse national tastes—The corking, stringing, wiring, and amalgamating—The wine’s agitated existence comes to an end—The bottles have their toilettes made—Champagne sets out on its beneficial pilgrimage round the world

154VI.

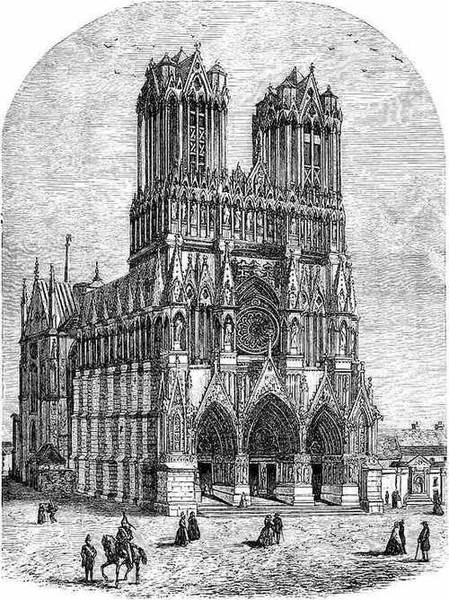

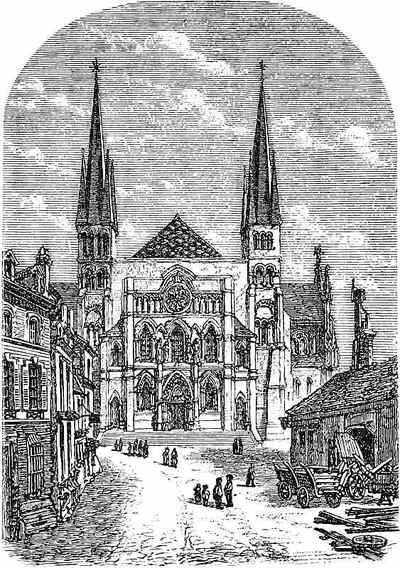

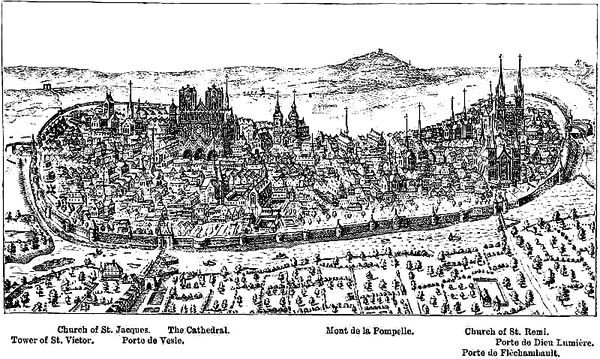

REIMS AND ITS CHAMPAGNE ESTABLISHMENTS.

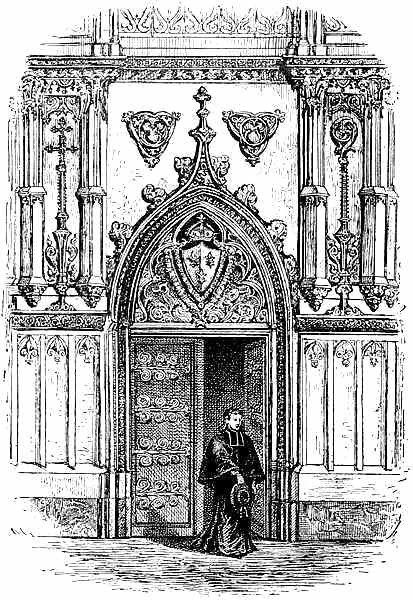

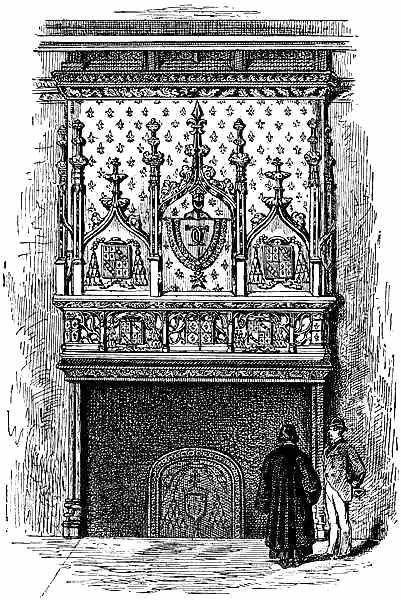

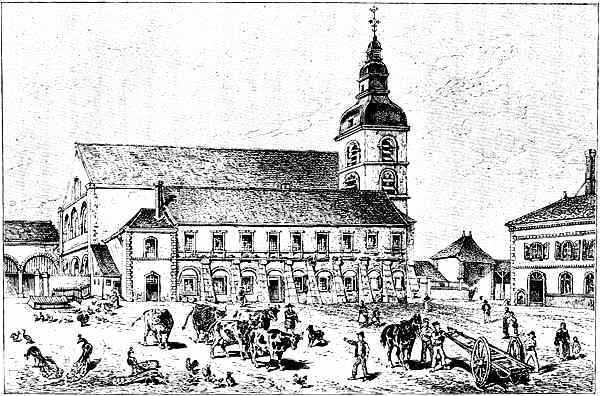

The city of Reims—Its historical associations—The Cathedral—Its western front one of the most splendid conceptions of the thirteenth century—The sovereigns crowned within its walls—Present aspect of the ancient archiepiscopal city—The woollen manufactures and other industries of Reims—The city undermined with the cellars of the great Champagne firms—Reims hotels—Gothic house in the Rue du Bourg St. Denis—Renaissance house in the Rue de Vesle—Church of St. Jacques: its gateway and quaint weathercock—The Rue des Tapissiers and the Chapter Court—The long tapers used at religious processions—The Place des Marchés and its ancient houses—The Hôtel de Ville—Statue of Louis XIII.—The Rues de la Prison and du Temple—Messrs. Werlé & Co., successors to the Veuve Clicquot-Ponsardin—Their offices and cellars on the site of a former Commanderie of the Templars—Origin of the celebrity of Madame Clicquot’s wines—M. Werlé and his son—Remains of the Commanderie—The forty-five cellars of the Clicquot-Werlé establishment—Our tour of inspection through them—Ingenious dosing machine—An explosion and its consequences—M. Werlé’s gallery of paintings—Madame Clicquot’s Renaissance house and its picturesque bas-reliefs—The Werlé vineyards and vendangeoirs

168VII.

REIMS AND ITS CHAMPAGNE ESTABLISHMENTS (continued).

The house of Louis Roederer founded by a plodding German named Schreider—The central and other establishments of the firm—Ancient house in the Rue des Elus—The gloomy-looking Rue des Deux Anges and prison-like aspect of its houses—Inside their courts the scene changes—Handsome Renaissance house and garden, a former abode of the canons of the Cathedral—The Place Royale—The Hôtel des Fermes and the statue of the ‘wise, virtuous, and magnanimous Louis XV.’—Birthplace of Colbert in the Rue de Cérès—Quaint Adam and Eve gateway in the Rue de l’Arbalète—Heidsieck & Co.’s central establishment in the Rue de Sedan—Their famous ‘Monopole’ brand—The firm founded in the last century—Their extensive cellars inside and outside Reims—The matured wines shipped by them—The Boulevard du Temple—M. Ernest Irroy’s cellars, vineyards, and vendangeoirs—Recognition by the Reims Agricultural Association of his plantations of vines—His wines and their popularity at the best London clubs—Various Champagne firms located in this quarter of Reims—The Rue du Tambour and the famous House of the Musicians—The Counts de la Marck assumed former occupants of the latter—The Brotherhood of Minstrels of Reims—Périnet & Fils’ establishment in the Rue St. Hilaire—Their cellars of three stories in solid masonry—Their soft, light, and delicate wines—A rare still Verzenay—The firm’s high-class Extra Sec

179VIII.

REIMS AND ITS CHAMPAGNE ESTABLISHMENTS (continued).

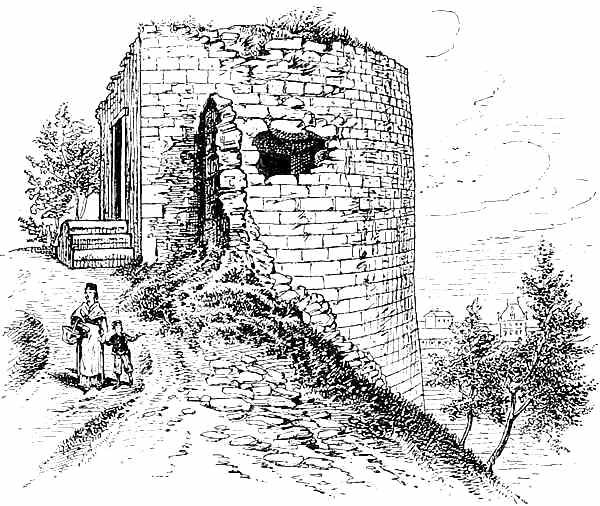

La Prison de Bonne Semaine—Mary Queen of Scots at Reims—Messrs. Pommery & Greno’s offices—A fine collection of faïence—The Rue des Anglais a former refuge of English Catholics—Remains of the old University of Reims—Ancient tower and grotto—The handsome castellated Pommery establishment—The spacious cellier and huge carved cuvée tuns—The descent to the cellars—Their great extent—These lofty subterranean chambers originally quarries, and subsequently places of refuge of the early Christians and the Protestants—Madame Pommery’s splendid cuvées of 1868 and 1874—Messrs. de St. Marceaux & Co.’s new establishment in the Avenue de Sillery—Its garden-court and circular shaft—Animated scene in the large packing hall—Lowering bottled wine to the cellars—Great depth and extent of these cellars—Messrs. de St. Marceaux & Co.’s various wines—The establishment of Veuve Morelle & Co., successors to Max Sutaine—The latter’s ‘Essai sur le Vin de Champagne’—The Sutaine family formerly of some note at Reims—Morelle & Co.’s cellars well adapted to the development of sparkling wines—The various brands of the house—The Porte Dieu-Lumière

188IX.

EPERNAY.

The connection of Epernay with the production of wine of remote date—The town repeatedly burnt and plundered—Hugh the Great carries off all the wine of the neighbourhood—Vineyards belonging to the Abbey of St. Martin in the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth centuries—Abbot Gilles orders the demolition of a wine-press which infringes the abbey’s feudal rights—Bequests of vineyards in the fifteenth century—Francis I. bestows Epernay on Claude Duke of Guise in 1544—The Eschevins send a present of wine to their new seigneur—Wine levied for the king’s camp at Rethel and the strongholds of the province by the Duc de Longueville—Epernay sacked and fired on the approach of Charles V.—The Charles-Fontaine vendangeoir at Avenay—Destruction of the immense pressoirs of the Abbey of St. Martin—The handsome Renaissance entrance to the church of Epernay—Plantation of the ‘terre de siége’ with vines in 1550—Money and wine levied on Epernay by Condé and the Duke of Guise—Henri Quatre lays siege to Epernay—Death of Maréchal Biron—Desperate battle amongst the vineyards—Triple talent of the ‘bon Roy Henri’ for drinking, fighting, and love-making—Verses addressed by him to his ‘belle hôtesse’ Anne du Puy—The Epernay Town Council make gifts of wine to various functionaries to secure their good-will—Presents of wine to Turenne at the coronation of Louis XIV.—Petition to Louvois to withdraw the Epernay garrison that the vintage may be gathered in—The Duke and Duchess of Orleans at Epernay—Louis XIV. partakes of the local vintage at the maison abbatiale on his way to the army of the Rhine—Increased reputation of the wine of Epernay at the end of the seventeenth century—Numerous offerings of it to the Marquis de Puisieux, Governor of the town—The Old Pretender presented at Epernay with twenty-four bottles of the best—Sparkling wine sent to the Marquis de Puisieux at Sillery, and also to his nephew—Further gifts to the Prince de Turenne—The vintage destroyed by frost in 1740—The Epernay slopes at this epoch said to produce the most delicious wine in Europe—Vines planted where houses had formerly stood—The development of the trade in sparkling wine—A ‘tirage’ of fifty thousand bottles in 1787—Arthur Young drinks Champagne at Epernay at forty sous the bottle—It is surmised that Louis XVI., on his return from Varennes, is inspired by Champagne at Epernay—Napoleon and his family enjoy the hospitality of Jean Remi Moët—King Jerome of Westphalia’s true prophecy with regard to the Russians and Champagne—Disgraceful conduct of the Prussians and Russians at Epernay in 1814—The Mayor offers them the free run of his cellars—Charles X., Louis Philippe, and Napoleon III. accept the ‘vin d’honneur’ at Epernay—The town occupied by German troops during the war of 1870–1

195X.

The CHAMPAGNE ESTABLISHMENTS OF EPERNAY AND PIERRY.

Early records of the Moët family at Reims and Epernay—Jean Remi Moët, the founder of the commerce in Champagne wines—Extracts from old account-books of the Moëts—Jean Remi Moët receives the Emperor Napoleon, the Empress Josephine, and the King of Westphalia—The firm of Moët & Chandon constituted—Their establishment in the Rue du Commerce—The delivery and washing of new bottles—The numerous vineyards and vendangeoirs of the firm—Their cuvée made in vats of 12,000 gallons—The bottling of the wine—A subterranean city, with miles of streets, cross-roads, open spaces, tramways, and stations—The ancient entrance to these vaults—Tablet commemorative of the visit of Napoleon I.—The original vaults known as Siberia—Scene in the packing-hall—Messrs. Moët & Chandon’s large and complete staff—The famous ‘Star’ brand of the firm—Perrier-Jouët’s château, offices, and cellars—Classification of the wine of the house—The establishment of Messrs. Pol Roger & Co.—Their large stock of the fine 1874 vintage—The preparations for the tirage—Their vast fireproof cellier and its temperature—Their lofty and capacious cellars—Pierry becomes a wine-growing district consequent upon Dom Perignon’s discovery—Esteem in which the growths of the Clos St. Pierre were held—Cazotte, author of Le Diable Amoureux, and guillotined for planning the escape of Louis XVI. from France, a resident at Pierry—His contest with the Abbot of Hautvillers with reference to the abbey tithes of wine—The Château of Pierry—Its owner demands to have it searched to prove that he is not a forestaller of corn—The vineyards and Champagne establishment of Gé-Dufaut & Co.—The reserves of old wines in the cellars of this firm—Honours secured by them at Vienna and Paris

205XI.

SOME CHAMPAGNE ESTABLISHMENTS AT AY AND MAREUIL.

The bourgade of Ay and its eighteenth-century château—Gambling propensities of a former owner, Balthazar Constance Dangé-Dorçay— Appreciation of the Ay vintage by Sigismund of Bohemia, Leo X., Charles V., Francis I., and Henry VIII.—Bertin du Rocheret celebrates this partiality in triolets—Estimation of the Ay wine in the reigns of Charles IX. and Henri III.—Is a favoured drink with the leaders of the League, and with Henri IV., Catherine de Medicis, and the courtiers of that epoch—The ‘Vendangeoir d’Henri Quatre’ at Ay—The King’s pride in his title of Seigneur d’Ay and Gonesse—Dominicus Baudius punningly suggests that the ‘Vin d’Ay’ should be called ‘Vinum Dei’—The merits of the wine sung by poets and extolled by wits—The Ay wine in its palmy days evidently not sparkling—Arthur Young’s visit to Ay in 1787—The establishment of Deutz & Geldermann—Drawing off the cuvée there—Mode of excavating cellars in the Champagne—The firm’s new cellars, vineyards, and vendangeoir—M. Duminy’s cellars and wines—The house founded in 1814—The new model Duminy establishment—Picturesque old house at Ay—Messrs. Pfungst Frères & Co.’s cellars—Their finely-matured dry Champagnes—The old church of Ay and its numerous decorations of grapes and vine-leaves—The sculptured figure above the Renaissance doorway—The Montebello establishment at Mareuil—The château formerly the property of the Dukes of Orleans—A titled Champagne firm—The brilliant career of Marshal Lannes—A promenade through the Montebello establishment—The press-house, the cuvée-vat, the packing-room, the offices, and the cellars—Portraits and relics at the château—The establishment of Bruch-Foucher & Co.—The handsome carved gigantic cuvée-tun—The cellars and their lofty shafts—The wines of the firm

217XII.

CHAMPAGNE ESTABLISHMENTS AT AVIZE AND RILLY.

Avize the centre of the white grape district—Its situation and aspect—The establishment of Giesler & Co.—The tirage and the cuvée—Vin Brut in racks and on tables—The packing-hall, the extensive cellars, and the disgorging cellier—Bottle stores and bottle-washing machines—Messrs. Giesler’s wine-presses at Avize and vendangeoir at Bouzy—Their vineyards and their purchases of grapes—Reputation of the Giesler brand—The establishment of M. Charles de Cazanove—A tame young boar—Boar-hunting in the Champagne—M. de Cazanove’s commodious cellars and carefully-selected wines—Vineyards owned by him and his family—Reputation of his wines in Paris and their growing popularity in England—Interesting view of the Avize and Cramant vineyards from M. de Cazanove’s terraced garden—The vintaging of the white grapes in the Champagne—Roper Frères’ establishment at Rilly-la-Montagne—Their cellars penetrated by roots of trees—Some samples of fine old Champagnes—The principal Châlons establishments—Poem on Champagne by M. Amaury de Cazanove

229XIII.

SPORT IN THE CHAMPAGNE.

The Champagne forests the resort of the wild-boar—Departure of a hunting-party in the early morning to a boar-hunt—Rousing the boar from his lair—Commencement of the attack—Chasing the boar—His course is checked by a bullet—The dogs rush on in full pursuit—The boar turns and stands at bay—A skilful marksman advances and gives him the coup de grâce—Hunting the wild-boar on horseback in the Champagne—An exciting day’s sport with M. d’Honnincton’s boar-hounds—The ‘sonnerie du sanglier’ and the ‘vue’—The horns sound in chorus ‘The boar has taken soil’—The boar leaves the stream, and a spirited chase ensues—Brought to bay, he seeks the water again—Deathly struggle between the boar and a full pack of hounds—The fatal shot is at length fired, and the ‘hallali’ is sounded—As many as fifteen wild-boars sometimes killed at a single meet—The vagaries of some tame young boars—Hounds of all kinds used for hunting the wild-boar in the Champagne—Damage done by boars to the vineyards and the crops—Varieties of game common to the Champagne

235PART III.

I.

SPARKLING SAUMUR AND SPARKLING SAUTERNES.

The sparkling wines of the Loire often palmed off as Champagne—The finer qualities improve with age—Anjou the cradle of the Plantagenet kings—Saumur and its dominating feudal Château and antique Hôtel de Ville—Its sinister Rue des Payens and steep tortuous Grande Rue—The vineyards of the Coteau of Saumur—Abandoned stone-quarries converted into dwellings—The vintage in progress—Old-fashioned pressoirs—The making of the wine—Touraine the favourite residence of the earlier French monarchs—After a night’s carouse at the epoch of the Renaissance—The Vouvray vineyards—Balzac’s picture of La Vallée Coquette—The village of Vouvray and the Château of Moncontour—Vernou, with its reminiscences of Sully and Pépin-le-Bref—The vineyards around Saumur—Remarkable ancient Dolmens—Ackerman-Laurance’s establishment at Saint-Florent—Their extensive cellars, ancient and modern—Treatment of the newly-vintaged wine—The cuvée—Proportions of wine from black and white grapes—The bottling and disgorging of the wine and finishing operations—The Château of Varrains and the establishment of M. Louis Duvau aîné—His cellars a succession of gloomy galleries—The disgorging of the wine accomplished in a melodramatic-looking cave—M. Duvau’s vineyard—His sparkling Saumur of various ages—Marked superiority of the more matured samples—M. E. Normandin’s sparkling Sauternes manufactory at Châteauneuf—Angoulême and its ancient fortifications—Vin de Colombar—M. Normandin’s sparkling Sauternes cuvée—His cellars near Châteauneuf—Recognition accorded to the wine at the Concours Régional d’Angoulême

241II.

THE SPARKLING WINES OF BURGUNDY, THE JURA, AND THE SOUTH OF FRANCE.

Sparkling wines of the Côte d’Or at the Paris Exhibition of 1878—Chambertin, Romanée, and Vougeot—Burgundy wines and vines formerly presents from princes—Vintaging sparkling Burgundies—Their after-treatment in the cellars—Excess of breakage—Similarity of proceeding to that followed in the Champagne—Principal manufacturers of sparkling Burgundies—Sparkling wines of Tonnerre, the birthplace of the Chevalier d’Eon—The Vin d’Arbanne of Bar-sur-Aube—Death there of the Bastard de Bourbon—Madame de la Motte’s ostentatious display and arrest there—Sparkling wines of the Beaujolais—The Mont-Brouilly vineyards—Ancient reputation of the wines of the Jura—The Vin Jaune of Arbois beloved of Henri Quatre—Rhymes by him in its honour—Lons-le-Saulnier—Vineyards yielding the sparkling Jura wines—Their vintaging and subsequent treatment—Their high alcoholic strength and general drawbacks—Sparkling wines of Auvergne, Guienne, Dauphiné, and Languedoc—Sparkling Saint-Péray the Champagne of the South—Valence, with its reminiscences of Pius VI. and Napoleon I.—The ‘Horns of Crussol’ on the banks of the Rhône—Vintage scene at Saint-Péray—The vines and vineyards producing sparkling wine—Manipulation of sparkling Saint-Péray—Its abundance of natural sugar—The cellars of M. de Saint-Prix, and samples of his wines—Sparkling Côte-Rotie, Château-Grillé, and Hermitage—Annual production and principal markets of sparkling Saint-Péray—Clairette de Die—The Porte Rouge of Die Cathedral—How the Die wine is made—The sparkling white and rose-coloured muscatels of Die—Sparkling wines of Vercheny and Lagrasse—Barnave and the royal flight to Varennes—Narbonne formerly a miniature Rome, now noted merely for its wine and honey—Fête of the Black Virgin at Limoux—Preference given to the new wine over the miraculous water—Blanquette of Limoux, and how it is made—Characteristics of this overrated wine

251III.

FACTS AND NOTES RESPECTING SPARKLING WINES.

Dry and sweet Champagnes—Their sparkling properties—Form of Champagne glasses—Style of sparkling wines consumed in different countries—The colour and alcoholic strength of Champagne—Champagne approved of by the faculty—Its use in nervous derangements—The icing of Champagne—Scarcity of grand vintages in the Champagne—The quality of the wine has little influence on the price—Prices realised by the Ay and Verzenay crus in grand years—Suggestions for laying down Champagnes of grand vintages—The improvement they develop after a few years—The wine of 1874—The proper kind of cellar in which to lay down Champagne—Advantages of Burrow’s patent slider wine-bins—Increase in the consumption of Champagne—Tabular statement of stocks, exports, and home consumption from 1844–5 to 1877–8—When to serve Champagne at a dinner-party—Charles Dickens’s dictum that its proper place is at a ball—Advantageous effect of Champagne at an ordinary British dinner-party

258

PART I.

I.

EARLY RENOWN OF THE CHAMPAGNE WINES.

The vine in Gaul—Domitian’s edict to uproot it—Plantation of vineyards under Probus—Early vineyards of the Champagne—Ravages by the Northern tribes repulsed for a time by the Consul Jovinus—St. Remi and the baptism of Clovis—St. Remi’s vineyards—Simultaneous progress of Christianity and the cultivation of the vine—The vine a favourite subject of ornament in the churches of the Champagne—The culture of the vine interrupted, only to be renewed with increased ardour—Early distinction between ‘Vins de la Rivière’ and ‘Vins de la Montagne’—A prelate’s counsel respecting the proper wine to drink—The Champagne desolated by war—Pope Urban II., a former Canon of Reims Cathedral—His partiality for the wine of Ay—Bequests of vineyards to religious establishments—Critical ecclesiastical topers—The wine of the Champagne causes poets to sing and rejoice—‘La Bataille des Vins’—Wines of Auviller and Espernai le Bacheler.

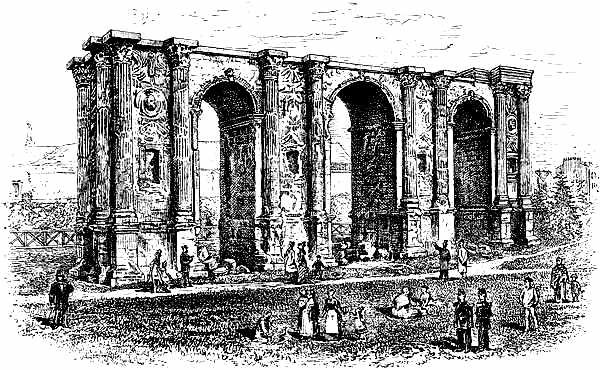

ALTHOUGH the date of the introduction of the vine into France is lost in the mists of antiquity, and though the wines of Marseilles, Narbonne, and Vienne were celebrated by Roman writers prior to the Christian era, many centuries elapsed before a vintage was gathered within the limits of the ancient province of Champagne. Whilst the vine and olive throve in the sunny soil of the Narbonnese Gaul, the frigid climate of the as yet uncultivated North forbade the production of either wine or oil.[1] The ‘forest of the Marne,’ now renowned for the vintage it yields, was then indeed a dark and gloomy wood, the haunt of the wolf and wild boar, the stag and the auroch; and the tall barbarians of Gallia Comata, who manned the walls of Reims on the approach of Cæsar, were fain to quaff defiance to the Roman power in mead and ale.[2] Though Reims became under the Roman dominion one of the capitals of Belgic Gaul, and acquired an importance to which numerous relics in the shape of temples, triumphal arches, baths, arenas, military roads, &c., amply testify; and though the Gauls were especially distinguished by their quick adoption of Roman customs, it appears certain that during the sway of the twelve Cæsars the inhabitants of the present Champagne district were forced to draw the wine, with which their amphoræ were filled and their pateræ replenished, from extraneous sources. The vintages of which Pliny and Columella have written were confined to Gallia Narboniensis, though the culture of the vine had doubtless made some progress in Aquitaine and on the banks of the Saône, when the stern edict of the fly-catching madman Domitian, issued on the plea that the plant of Bacchus usurped space which would be better filled by that of Ceres, led (A.D. 92) to its total uprooting throughout the Gallic territory.

For nearly two hundred years this strange edict remained in force, during which period all the wine consumed in the Gallo-Roman dominions was imported from abroad. Six generations of men, to whom the cheerful toil of the vine-dresser was but an hereditary tale, and the joys of the vintage a half-forgotten tradition, had passed away when, in 282, the Emperor Probus, a gardener’s son, once more granted permission to cultivate the vine, and even exercised his legions in the laying-out and planting of vineyards in Gaul.[3] The culture was eagerly resumed, and, as with the advancement of agriculture and the clearance of forests the climate had gradually improved, the inhabitants of the more northern regions sought to emulate their southern neighbours in the production of wine. This concession of Probus was hailed with rejoicing; and some antiquaries maintain that the triumphal arch at Reims, known as the Gate of Mars, was erected during his reign as a token of gratitude for this permission to replant the vine.[4]

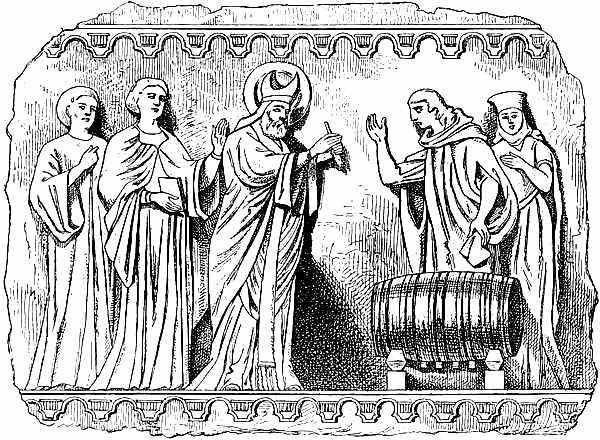

By the fourth century the banks of the Marne and the Moselle were clothed with vineyards, which became objects of envy and desire to the yellow-haired tribes of Germany,[5] and led in no small degree to the predatory incursions into the territory of Reims so severely repulsed by Julian the Apostate and the Consul Jovinus, who had aided Julian to ascend the throne of the Cæsars, and had combatted for him against the Persians. Julian assembled his forces at Reims in 356, before advancing against the Alemanni, who had established themselves in Alsace and Lorraine; and ten years later the Consul Jovinus, after surprising some of the same nation bathing their large limbs, combing their long and flaxen hair, and ‘swallowing huge draughts of rich and delicious wine,’[6] on the banks of the Moselle, fought a desperate and successful battle, lasting an entire summer’s day, on the Catalaunian plains near Châlons, with their comrades, whom the prospect of similar indulgence had tempted to enter the Champagne. Valerian came to Reims in 367 to congratulate Jovinus; and the Emperor and the Consul (whose tomb is to-day preserved in Reims Cathedral) fought their battles o’er again over their cups in the palace reared by the latter on the spot occupied in later years by the church of St. Nicaise.

THE GATE OF MARS AT REIMS.

The check administered by Jovinus was but temporary, while the attraction continued permanent. For nearly half a century, it is true, the vineyards of the Champagne throve amidst an era of quiet and prosperity such as had seldom blessed the frontier provinces of Gaul.[7] But when, in 406, the Vandals spread the flame of war from the banks of the Rhine to the Alps, the Pyrenees, and the ocean, Reims was sacked, its fields ravaged, its bishop cut down at the altar, and its inhabitants slain or made captive; and the same scene of desolation was repeated when the hostile myriads of Attila swept across north-western France in 451.

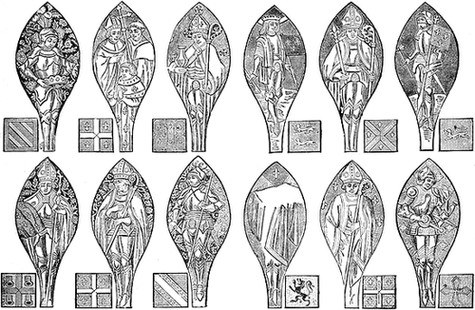

TOMB OF THE CONSUL JOVINUS, PRESERVED IN REIMS CATHEDRAL.

Happier times were, however, in store for Reims and its bishops and its vineyards, the connection between the two last being far more intimate than might be supposed. When Clovis and his Frankish host passed through Reims by the road still known as the Grande Barberie, on his way to attack Syagrius in 486, there was no doubt a little pillaging, and the famous golden vase which one of the monarch’s followers carried off from the episcopal residence was not left unfilled by its new owner. But after Syagrius had been crushed at Soissons, and the theft avenged by a blow from the king’s battle-axe, Clovis not only restored the stolen vase, and made a treaty with the bishop St. Remi or Remigius, son of Emilius, Count of Laon, but eventually became a convert to Christianity, and accepted baptism at his hands. Secular history has celebrated the fight of Tolbiac—the invocation addressed by the despairing Frank to the God of the Christians; the sudden rallying of his fainting troops, and the last desperate charge which swept away for ever the power of the Alemanni as a nation. Saintly legends have enlarged upon the piety of Queen Clotilda; the ability of St. Remi; the pomp and ceremony which marked the baptism of Clovis at Reims in December 496; the memorable injunction of the bishop to his royal convert to adore the cross he had burnt, and burn the idols he had hitherto adored; and the miracle of the Sainte Ampoule, a vial of holy oil said to have been brought direct from heaven by a snow-white dove in honour of the occasion. A pigeon, however, has always been a favourite item in the conjuror’s paraphernalia from the days of Apolonius of Tyana and Mahomet down to those of Houdin and Dr. Lynn; and modern scepticism has suggested that the celestial regions were none other than the episcopal dovecot. Whether or not the oil was holy, we may be certain that the wine which flowed freely in honour of the Frankish monarch’s conversion was ambrosial; that the fierce warriors who had conquered at Soissons and Tolbiac wetted their long moustaches in the choicest growths that had ripened on the surrounding hills; and that the Counts and Leudes, and, judging from national habits, the King himself, got royally drunk upon a cuvée réservée from the vineyard which St. Remi had planted with his own hands on his hereditary estate near Laon, or the one which the slave Melanius cultivated for him just without the walls of Reims.

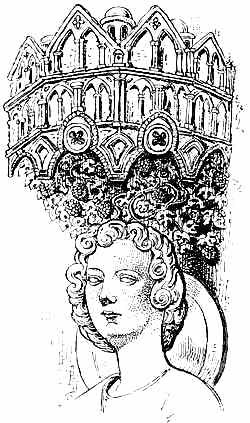

For the saint was not only a converter of kings, but, what is of more moment to us, a cultivator of vineyards and an appreciator of their produce. Amongst the many miracles which monkish chroniclers have ascribed to him is one commemorated by a bas-relief on the north doorway of Reims Cathedral, representing him in the house of one of his relatives, named Celia, making the sign of the cross over an empty cask, which, as a matter of course, immediately became filled with wine. That St. Remi possessed such an ample stock of wine of his own as to have been under no necessity to repeat this miracle in the episcopal palace is evident from the will penned by him during his last illness in 530, as this shows his viticultural and other possessions to have been sufficiently extensive to have contented a bishop even of the most pluralistic proclivities.[8]

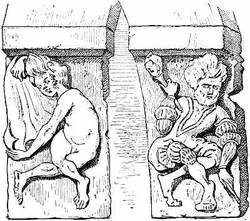

It is curious to note the connection between the spread of viticulture and that of Christianity—a connection apparently incongruous, and yet evident enough, when it is remembered that wine is necessary for the celebration of the most solemn sacrament of the Church. Christianity became the established religion of the Roman Empire about the first decade of the fourth century, and Paganism was prohibited by Theodosius at its close; and it is during this period that we find the culture of the grape spreading throughout Gaul, and St. Martin of Tours preaching the Gospel and planting a vineyard coevally. Chapters and religious houses especially applied themselves to the cultivation of the vine, and hence the origin of many famous vineyards, not only of the Champagne but of France. The old monkish architects, too, showed their appreciation of the vine by continually introducing sculptured festoons of vine-leaves, intermingled with massy clusters of grapes, into the decorations of the churches built by them. The church of St. Remi, for instance, commenced in the middle of the seventh century, and touched up by succeeding builders till it has been compared to a school of progressive architecture, furnishes an example of this in the mouldings of its principal doorway; and Reims Cathedral offers several instances of a similar character.

FROM THE NORTH DOORWAY OF REIMS CATHEDRAL.

Amidst the anarchy and confusion which marked the feeble sway of the long-haired Merovingian kings, whom the warlike Franks were wont to hoist upon their bucklers when investing them with the sovereign power, we find France relapsing into a state of barbarism; and though the Salic law enacted severe penalties for pulling up a vine-stock, the prospect of being liable at any moment to a writ of ejectment, enforced by the aid of a battle-axe, must have gone far to damp spontaneous ardour as regards experimental viticulture. The tenants of the Church, in which category the bulk of the vine-growers of Reims and Epernay were to be classed, were best off; but neither the threats of bishops nor the vengeance of saints could restrain acts of sacrilege and pillage. During the latter half of the sixth century Reims, Epernay, and the surrounding district were ravaged several times by the contending armies of Austrasia and Neustria; and Chilperic of Soissons, on capturing the latter town in 562, put such heavy taxes on the vines and the serfs that in three years the inhabitants had deserted the country. Matters improved, however, during the more peaceful days of the ensuing century, which witnessed the foundation of numerous abbeys, including those of Epernay, Hautvillers, and Avenay; and the planting of fresh vineyards in the ecclesiastical domains by Bishop Romulfe and his successor St. Sonnace, the latter, who died in 637, bequeathing to the church of St. Remi a vineyard at Villers, and to the monastery of St. Pierre les Dames one situate at Germaine, in the Mountain of Reims.[9] The sculptured saint on the exterior of Reims Cathedral, with his feet resting upon a pedestal wreathed with vine-leaves and bunches of grapes, may possibly have been intended for one of these numerous wine-growing prelates.

FROM THE NORTH DOORWAY OF REIMS CATHEDRAL.

The mighty figure of Charlemagne, overshadowing the whole of Europe at the commencement of the ninth century, appears in connection with Reims, where, begirt with paladins and peers, he entertained the ill-used Pope Leo III. right royally during the ‘festes de Noel’ of 805. The monarch who is said to have clothed the steep heights of Rudesheim with vines was not indifferent to good wine; and the vintages of the Champagne doubtless mantled in the magic goblet of Huon de Bordeaux, and brimmed the horns which Roland, Oliver, Doolin de Mayence, Renaud of Montauban, and Ogier the Dane, drained before girding on their swords and starting on their deeds of high emprise—the slaughter of Saracens, the rescue of captive damsels, and the discomfiture of felon knights—told in the fables of Turpin and the ‘chansons de geste.’ That the cultivation of the grape, and above all the making of wine, had been steadily progressing, is clear from the fact that the distinction between the ‘Vins de la Rivière de Marne’ and the ‘Vins de la Montagne de Reims’ dates from the ninth century.[10]

This era is, moreover, marked by the inauguration of that long series of coronations which helped to spread the popularity of the Champagne wines throughout France by the agency of the nobles and prelates taking part in the ceremony. Sumptuous festivities marked the coronation of Charlemagne’s son Louis in 816; and the officiating Archbishop Ebbon may have helped to furnish the feast with some of the produce from the vineyard he had planted at Mont Ebbon, generally identified with the existing Montebon, near Mardeuil. It is of this vineyard that Pardulus, Bishop of Laon, speaks in a letter addressed by him to Ebbon’s successor, the virtuous Hincmar, who assumed the crozier in 845, proffering him counsels as to the best method of sustaining his failing health. After telling him to avoid eating fish on the same day that it is caught, insisting that salted meat is more wholesome than fresh, and recommending bacon and beans cooked in fat as an excellent digestive, he proceeds: ‘You must make use of a wine which is neither too strong nor too weak—prefer, to those produced on the summit of the mountain or the bottom of the valley, one that is grown on the slopes of the hills, as towards Epernay, at Mont Ebbon; towards Chaumuzy, at Rouvesy; towards Reims, at Mersy and Chaumery.’ The Champagne vineyards suffered grievously from the internal convulsions which marked the period when the sceptre of France was swayed by the feeble hands of the dregs of the Carlovingian race. The Normans, who threatened Reims and sacked Epernay in 882, swept over them like devouring locusts; and their annals during the following century are written in letters of blood and flame.

Times were indeed bad for the peaceful vine-dressers in the tenth century, when castles were springing up in every direction; when might made right, and the rule of the strong hand alone prevailed; and when the firm belief that the end of the world was to come in the year 1000 led men to live only for the present, and seek to get as much out of their fellow-creatures as they possibly could. Such natural calamities as that of 919, when the wine-crop entirely failed in the neighbourhood of Reims, were bad enough; but the continual incursions of the Hungarians, whose arrows struck down the peasant at the plough and the priest at the altar, and the memory of whose pitiless deeds yet survives in the term ‘ogre;’ the desperate contest waged for ten years by Heribert of Vermandois to secure the bishopric of Reims for his infant son, during which hardly a foot of the disputed territory remained unstained by blood; the repeated invasions of Otho of Germany; and the struggle between Hugh Capet and Charles of Lorraine for the titular crown of France,—left traces harder to be effaced. Reims underwent four sieges in about sixty years; and Epernay, that most hapless of towns, was sacked at least half a score of times, and twice burnt, one of the most conscientiously executed pillagings being that performed in 947 by Hugh the Great, who, as it was vintage-time, completely ravaged the whole country, and carried off all the wine.[11]

Under the rule of the Capetian race matters improved as regarded foreign foes, though the archbishops had in the early part of the eleventh century to abandon Epernay, Vertus, Fismes, and their dependencies to the family of Robert of Vermandois, who had assumed the title of Counts of Champagne, to be held by them as fiefs. The fame of the schools of Reims, where future popes and embryo emperors met as class-mates; the festive gatherings which marked the coronation of Henry I. and Philip I.; the great ecclesiastical council held by Leo IX., which procured for the city the nickname of ‘little Rome;’ and the growing importance of the Champagne fairs, the great meeting-places throughout the Middle Ages of the merchants of Spain, Italy, and the Low Countries,—favoured the prosperity of the district and the production of its wine. Urban II., a native of Châtillon, who wore the triple crown from 1088 to the close of the century, was, prior to his elevation to the chair of St. Peter, a canon of Reims, under the name of Eudes or Odo, and, tippling there in company with his fellow-clerics, acquired a taste for the wine of Ay, which he preferred to all others in the world.[12] Pilgrims to Rome found penance light and pardon easily obtained when they bore with them across the Alps, in addition to staff and scrip, a huge ‘leathern bottel’ of that beloved vintage which warmed the pontiff’s heart and whetted his wit for the delivery of those soul-stirring orations at Placentia and Clermont, wherein he appealed to the chivalry of Western Europe to hasten to the rescue of the Holy Sepulchre from the hands of the infidel.

VINE-DRESSERS—THIRTEENTH CENTURY

(From a window of Chartres Cathedral).

The result of these appeals was felt by the vine-cultivators of the Champagne in more ways than one, and their case recalls that of the petard-hoisted engineer. The virtuous, the speculative, and the enthusiastic who followed Peter the Hermit and Walter the Penniless to the plains of Asia Minor suffered at the hands of the vicious, the prudent, and the practical, who remained at home and passed their time in pillaging the estates of their absent neighbours. The abbatial vineyards suffered like the others; and the monks of St. Thierry, in making peace with Gerard de la Roche and Alberic Malet in 1138, complained bitterly of wine violently extorted during two years from growers on the ecclesiastical estate and of a levy made upon their vineyard.[13]

The efforts of Henry of France, a warlike prelate, who built fortresses and attacked those of the robber-nobles, and of Louis VII., who avenged the wrongs of the church of Reims on the Counts of Roucy, served to improve matters; and we may be sure that whenever the monks did get hold of a repentant or dying sinner, they made him pay pretty dearly for peace with them and Heaven. Colin Musset, the early Champenois poet, thought that the best use to which money could be put was to spend it in good wine.[14] Churchmen, however, managed to secure the desired commodity without any such outlay, for numerous charters of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries show lords, sick or about starting for the crusades, making large gifts to abbeys and monasteries; and many a strip of fair and fertile vineland was thus added, thanks to a judicious pressure on the conscience, to the already extensive possessions of the two great monasteries of Reims, St. Remi and St. Nicaise, and also to that of St. Thierry. The Templars, too, whose reputation as wine-bibbers was only inferior to that of the monks, if we may credit the adage which runs,

‘Boire en templier, c’est boire à plein gosier;

Boire en cordelier, c’est vuider le cellier,’

and who, prior to the catastrophe of 1313, had a commandery at Reims, possessed either vineyards, or droits de vinage, at numerous spots, including Epernay, Hermonville, Ludes, and Verzy; while the separate community of these ‘Red Monks’ installed at Orilly had estates at Ay, Damery, and Mareuil. The hospital of St. Mary at Reims also reckoned amongst its possessions vineyards at Moussy, bequeathed by Canon Pontius and Tebaldus Papelenticus. The wine, which in 1215 the treasurer of the chapter of Reims Cathedral obtained from that body an acknowledgment of his right to on the anniversaries of the deaths of Bishops Ebalus and Radulf, and that to which the sub-treasurer and carpenter were severally entitled, was no doubt in part derived from the vineyard planted in 1206 by Canon Giles at the Porte Mars and bequeathed by him to the chapter, and the one which Canon John de Brie had purchased at Mareuil and had similarly bequeathed.[15] Although papal bulls and archiepiscopal warrants had forbidden the levying of the droit de vinage on wine vintaged by religious communities, in 1252 Pope Innocent IV. had to reprove the barons for interfering with the monastic vintages in the neighbourhood of Reims, and to threaten them with excommunication if they repeated their offence.[16]

GATEWAY OF THE CHAPTER COURT AT REIMS.

These ecclesiastical topers, as a rule, were sufficiently critical of the quality of the liquor meted out to them, and an agreement respecting the dietary of the Abbey of St. Remi, at Reims, drawn up in 1218 between the Abbot Peter and a deputation of six monks representing the rest of the brethren, provides that the wine procured for the latter should be improved by two-thirds of the produce of the Clos de Marigny being set apart for their exclusive use. Ten years later, to put a stop to further complaints on the part of these worthy rivals of Rabelais’ Frère Jean des Entonnoirs, Abbot Peter was fain to agree that two hundred hogsheads of wine should be annually brought from Marigny to the abbey to quench the thirst of his droughty flock, and that if the spot in question failed to yield the required amount the deficiency should be made up from his own private and particular vineyards at Sacy, Villers-Aleran, Chigny, and Hermonville.[17]

We can readily picture these

‘jolly fat friars

Sitting round the great roaring fires

With their strong wines;’

or the cellarer quietly chuckling to himself as he loosened the spiggot of the choicest casks—

‘Between this cask and the abbot’s lips

Many have been the sips and slips;

Many have been the draughts of wine,

On their way to his, that have stopped at mine.’

The monks were in the habit of throwing open their monasteries to all comers, under pretext of letting them taste the wine they had for sale, until, in 1233, an ecclesiastical council at Beziers prohibited this practice on account of the scandal it created. Petrarch has accused the popes of his day of persisting in staying at Avignon when they could have returned to Rome, simply on account of the goodness of the wines they found there. Some similar reasons may have led to the selection of Reims, during the twelfth century, as a place for holding great ecclesiastical councils presided over by the sovereign pontiff in person; and no doubt ‘Bibimus papaliter’ was the motto of Calixtus, Innocent, and Eugenius when the labours of the day were done, and they and their cardinals could chorus, apropos of those of the morrow,

‘Bonum vinum acuit ingenium

Venite potemus.’

The kings of France may have preferred the wines of the Orleanais and the Isle of France, and the monarchs of England have been content to vary the vintages of their patrimony of Guienne with an occasional draught of Rhenish; but the wines of the river Marne certainly found favour at Troyes, where the Counts of Champagne, to whom Epernay had been ceded as a fief, held a court little inferior in state to that of a sovereign prince. The native vintage mantled in the goblets and beakers that graced the board where they sat at meat amidst their knights and barons, whilst minstrels sang and jongleurs tumbled and glee-maidens danced at the lower end of the hall. It fired the fancy of the poet Count Thibault, to whom tradition has ascribed the introduction of the Cyprus grape into France on his return from the Crusades,[18] and helped the flow of the amorous strains which he addressed to Blanche of Castille. Nor was he the only versifier of the time who could exclaim, with his compatriot Colin Musset, that ‘good wine caused him to sing and rejoice.’[19] Other local songsters, such as Doete de Troyes, Eustache le Noble, and Guillaume de Machault, sought inspiration at their native Helicon, and were equally ready with Colin Musset to appreciate a gift of

‘barrelled wine,

Cold, strong, and fine,

To drink in hot weather,’ [20]

in return for their rhymes. It was this wine that the gigantic John Lord of Joinville, Seneschal of Champagne under Thibault, and chronicler of the Seventh Crusade, was in the habit of consuming warm and undiluted, by the advice of his physicians, on account, as he himself mentions, of his ‘large head and cold stomach;’ a practice which seems to have scandalised that pious and ascetic monarch St. Louis, who was careful to temper his own potations with water. The king was most likely not unacquainted with the wine, as a roll of the expenses incurred at his coronation at Reims, in 1226, shows that 991 livres were spent in wine on that occasion, when, in consequence of the vacancy of the archiepiscopal see, the crown was placed upon his head by Jacques de Bazoche, Bishop of Soissons.

Henry of Andelys, a compatriot of the engineer Brunel, who flourished, if a poet can be said to flourish, in the latter half of the thirteenth century, has extolled the wines of Epernay and Hautvillers, and mentioned that of Reims, in his poem entitled the ‘Bataille des Vins.’ He informs us at the outset that ‘the great King Philip Augustus,’ whom state records prove to have had a score of vineyards in different parts of France,[21] was very fond of ‘good white wine.’ Anxious to make a choice of the best, he issued invitations to all the most renowned crûs, French and foreign, and forty-six different vintages responded to this appeal; amongst them Hautvillers and Epernay, described as ‘vin d’Auviler’ and ‘vin d’Espernai le Bacheler.’ The king’s chaplain, an English priest, makes a preliminary examination, resulting in the summary rejection of many competitors, till at length, as Argenteuil—‘clear as oil’—and Pierrefitte are disputing as to their respective merits, Epernay and Hautvillers simultaneously exclaim, ‘Argenteuil, thou wishest to degrade all the wines at this table. By God, thou playest too much the part of constable. We excel Châlons and Reims, remove gout from the loins, and support all kings.’[22] But lo, up jumps the ‘vin d’Ausois,’ the ‘Osey’ of so many of our English mediæval poets, with the reproach, ‘Epernay, thou art too disloyal; thou hast not the right of speaking in court;’[23] and enumerates the blessings which he and his demoiselle ‘la Mosele’ confer upon the Germans.[24] La Rochelle in turn reproves Ausois, and extols the strength of his own wines, and those of Angoulême, Bordeaux, Saintes, and Poitou, and boasts of the welcome accorded to them in the northern states of Europe, including England, to which the districts he mentions then belonged.[25]

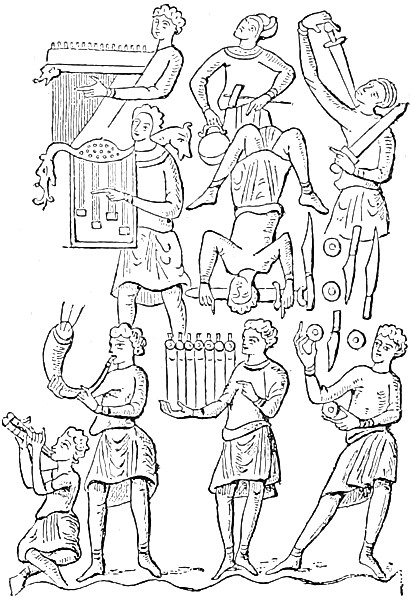

VINTAGERS OF THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY

(From a MS. of the Dialogues de St. Grégoire).

The vintages of the then little kingdom of France put in a counter-claim for finesse and flavour as opposed to strength, and maintain that they do not harm those who drink them. The dispute becomes general, and the wines, heated with argument, exhale a perfume of ‘balsam and amber,’ till the hall where they are met resembles a terrestial paradise. The chaplain, after conscientiously tasting the whole of them, formally excommunicated with bell, book, and candle all the beer brewed in England and Flanders, and then went incontinently to bed, and slept for three days and three nights without intermission. The king thereupon made an examination himself, and named the wine of Cyprus pope, and that of Aquilat[26] cardinal, and created of the remainder three kings, five counts, and twelve peers, the names of which, unfortunately, have not been preserved.

II.

THE WINES OF THE CHAMPAGNE FROM THE FOURTEENTH TO THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY.

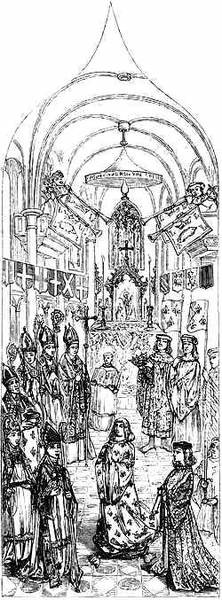

Coronations at Reims and their attendant banquets—Wine flows profusely at these entertainments—The wine-trade of Reims—Presents of wine from the Reims municipality—Cultivation of the vineyards abandoned after the battle of Poitiers—Octroi levied on wine at Reims—Coronation of Charles V.—Extension of the Champagne vineyards—Abundance of wine—Visit to Reims of the royal sot Wenceslaus of Bohemia—The Etape aux Vins at Reims—Increased consumption of beer during the English occupation of the city—The Maid of Orleans at Reims—The vineyards and wine-trade alike suffer—Louis XI. is crowned at Reims—Fresh taxes upon wine followed by the Mique-Maque revolt—The Rémois the victims of pillaging foes and extortionate defenders—The Champagne vineyards attacked by noxious insects—Coronation of Louis XII.—François Premier, the Emperor Charles V., Bluff King Hal, and Leo the Magnificent all partial to the wine of Ay—Mary Queen of Scots at Reims—State kept by the opulent and libertine Cardinal of Lorraine—Brusquet, the Court Fool—Decrease in the production of wine around Reims—Gifts of wine to newly-crowned monarchs—New restrictions on vine cultivation—The wine of the Champagne crowned at the same time as Louis XIII.—Regulation price for wine established at Reims—Imposts levied on the vineyards by the Frondeurs—The country ravaged around Reims—Sufferings of the peasantry—Presents of wine to Marshal Turenne and Charles II. of England—Perfection of the Champagne wines during the reign of Louis XIV.—St. Evremond’s high opinion of them—Other contemporary testimony in their favour—The Archbishop of Reims’s niggardly gift to James II. of England—A poet killed by Champagne—Offerings by the Rémois to Louis XIV. on his visit to their city.

THE coronations at Reims served, as already remarked, to attract within the walls of the old episcopal city all that was great, magnificent, and noble in France. The newly-crowned king, with that extensive retinue which marked the monarch of the Middle Ages; the great vassals of the crown scarcely less profusely attended; the constable, the secular and ecclesiastical peers, and the host of knights and nobles who assisted on the occasion, were wont at the conclusion of the ceremony to hold high revelry in the spacious temporary banqueting-hall reared near the cathedral. It is to be regretted that the menus of these banquets have not been handed down to us in their entirety; but a few fragmentary excerpts show that from a comparatively early period there was no lack of wine, at any rate. A remonstrance addressed to Philip the Fair, after his coronation in 1286, by the archbishop and burghers, asks that they may be relieved of a certain proportion of the sum levied on them for the cost of the ceremony, on the ground that there still remained over for the king’s use no less than seven score tuns of wine from the banquet. Some idea may be formed of the quantity of wine brought regularly into the city from the circumstance of the king having Reims surrounded by walls in 1294, and levying a duty on the wine imported to pay for them, and by the value attached to the ‘rouage’[27] of the Mairie St. Martin, claimed by the chapter of Reims Cathedral in 1300.

REIMS CATHEDRAL, WEST FRONT.

At the coronation of Charles IV., in 1322, wine flowed in rivers. Amongst the unconsumed provisions returned by the king’s pantler, Pelvau dou Val, to the burghers, ‘vin de Biaune et de Rivière’—that is, of Beaune and of the Marne—figures for a value of 384 livres 5 sols 2 deniers.[28] The arrangements of the coronation had been intrusted to the minister of finances, Pierre Remi, who certainly played the part of the unjust steward. In the first place, he made the cost of the ceremony amount to 21,000 livres, whereas none of his predecessors had spent more than 7,000 livres. His opening move had been to seize upon the greater part of the corn and all the ovens in Reims ‘for the king’s use,’ and to sell bread to the townsfolk and visitors at his own price for a fortnight prior to the coronation. After the ceremony he appropriated in like manner all the plate and napery, and all the cooking utensils and kitchen furniture, together with whatever had been left over, in the shape of wine, wax, fish, bullocks, pigs, and similar trifles. The wine thus taken was estimated at 1500 livres, part of which he sold to two bourgeois of Reims, and kept the rest, together with forty-four out of the fifty muids, or hogsheads, of salt provided.[29] Retributive justice overtook him, for the chronicler of his ill-doings chuckles over the fact that he was hanged as high as Haman on a gibbet he had himself erected at Paris. Things went off better at the coronation of King Philip, in 1328, when the total amount expended in the three hundred poinçons of the wine of Beaune, St. Pourçain, and the Marne consumed was 1675 livres 2 sols 3 deniers.[30] Part of this flowed through the mouth of the great bronze stag before which criminals condemned by the archiepiscopal court used to be exposed, but which at coronation times was placed in the Parvis Notre Dame, and spouted forth the ‘claré dou cerf,’ for the preparation of which the town records show that the grocer O. la Lale received 16 livres.[31]

[1] Diodorus.

[2] Idem.

[3] Max Sutaine’s Essai sur le Vin de Champagne.

[4] This arch is said to have been called after the God of War from the circumstance of a temple dedicated to Mars being in the immediate neighbourhood. The sculptures still remaining under the arcades have reference to the months of the year, to Romulus and Remus, and to Jupiter and Leda. Reims formerly abounded with monuments of the Roman domination. According to M. Brunette, an architect of the city, who made its Roman remains his especial study, a vast and magnificent palace formerly stood nigh the spot now known as the Trois Piliers; while on the right of the road leading to the town were the arenas, together with a temple, among the ruins of which various sculptures, vases, and medals were found, and almost immediately opposite, on the site of the present cemetery, an immense theatre, circus, and xystos for athletic exercises. Then came a vast circular space, in the centre of which arose a grand triumphal arch giving entrance into the city. The road led straight to the Forum,—the Place des Marchés of to-day,—and along it were a basilica, a market, and an exedra, now replaced by the Hôtel de Ville. The Forum, bordered by monumental buildings, was of gigantic proportions, extending on the one side from half way down the Rue Colbert to the Place Royale, and on the other from near the Marché à la Laine, parallel with the Rue de Vesle, up to the middle of the Rue des Elus, where it terminated in a vast amphitheatre used for public competitions.

[5] Henderson’s History of Ancient and Modern Wines.

[6] Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

[7] Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

[8] According to this document, published in Marlot’s Histoire de Reims, he leaves to Bishop Lupus the vineyard cultivated by the vine-dresser Enias; to his nephew Agricola, the vineyard planted by Mellaricus at Laon, and also the one cultivated by Bebrimodus; to his nephew Agathimerus, a vineyard he had himself planted at Vindonisæ, and kept up by the labour of his own episcopal hands; to Hilaire the deaconess, the vines adjoining her own vineyard, cultivated by Catusio, and also those at Talpusciaco; and to the priests and deacons of Reims, his vineyard in the suburbs of that city, and the vine-dresser Melanius who cultivated it. The will is also noteworthy for its mention of a locality destined to attain a high celebrity in connection with the wine of Champagne, namely, the town of Sparnacus or Epernay, which a lord named Eulogius, condemned to death for high treason in 499 and saved at the bishop’s intercession, had bestowed upon his benefactor, and which the latter left in turn to the church of Reims. To this church he also left estates in the Vosges and beyond the Rhine, on condition of furnishing pitch every year to the religious houses founded by himself or his predecessors to mend their wine-vessels, a trace of the old Roman custom of pitching vessels used for storing wine.

[9] Marlot’s Histoire de Reims.

[10] Henderson’s History of Ancient and Modern Wines.

[11] Victor Fievet’s Histoire d’Epernay.

[12] Bertin du Rocheret’s Mélanges.

[13] Varin’s Archives Administratives de Reims.

[14] ‘Bien met l’argent qui en bon vin l’emploie.’ Poems of Colin Musset, 1190 to 1220.

[15] Varin’s Archives Administratives de Reims.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] J. Gondry du Jardinet’s Agréable Visite aux Grands Crûs de France.

[19] ‘Chanter me fait bon vin et rejouir.’

[20]

‘Le vin en tonel,

Froit et fort et finandel,

Pour boivre à la grant chaleur.’

[21] Legrand d’Aussy’s Vie Privée des Français.

[22]

‘Espernai dist et Auviler,

Argenteuil, trop veus aviler

Très-tos les vins de ceste table.

Par Dieu, trop t’es fait conestable.

Nous passons Chaalons et Reims,

Nous ostons la goûte des reins,

Nous estaignons totes les rois.’

[23]

‘Espernai, trop es desloiaus;

Tu n’as droit de parler en cour.’

[24] The ‘vin d’Ausois,’ or ‘vin d’Aussai’ (for it is spelt both ways in the poem), is not, as might be supposed, the wine of Auxois, an ancient district of Burgundy now comprised in the arrondissements of Sémur (Côte d’Or) and Avallon (Yonne), and still enjoying a reputation for its viticultural products. MM. J. B. B. de Roquefort and Gigault de la Bedollière, in their notes on Henri d’Andelys’ poem, have clearly identified it with the wine of Alsace, that province having been known under the names in question during the Middle Ages. This explains its connection in the present instance with the Moselle.

[25] An incidental proof that the English taste for strong wine was an early one. As late as the close of the sixteenth century the Bordeaux wines are described in the Maison Rustique as ‘thick, black, and strong.’

[26] Probably either Aquila in the Abruzzi, or Aquiliea near Friuli.

[27] The ‘rouage’ was a duty of 2 sous on each cart and 4 sous on each wagon laden with wine purchased by foreign merchants and taken out of the town. It was only one of many dues.

[28] The old livre was about equal to the present franc; the sol was the twentieth part of a livre; and the denier the twelfth part of a sol, or about 1⁄24 d. English.

[29] Varin’s Archives Administratives de Reims.

[30] The Beaune cost 28 livres the tun of two queues; the St. Pourçain, a wine of the Bourbonnais, very highly esteemed in the Middle Ages, 12 livres the queue; and the wine of the district, white and red, 6 to 10 livres the queue of two poinçons. A poinçon, or demi-queue, of Reims was about 48 old English, or 40 imperial, gallons; while the demi-queue of Burgundy was over 45 imperial gallons.

[31] Varin’s Archives Administratives de Reims.

The importance of the wine-trade of Reims at the commencement of the fourteenth century is evidenced by the fact of there being at this epoch courtiers de vin, or wine-brokers, the right of appointing whom rested with the eschevins—a right which, vainly assailed by the archbishop in 1323, was confirmed to the municipal power by several royal decrees.[32] The burghers of Reims were fully cognisant of the merits of their wine, and certainly spared no trouble to make others acquainted with them. When the eschevins dined with the archbishop in August 1340 they contributed thirty-two pots of wine as their share of the repast, in addition to sundry partridges, capons, and rabbits. All visitors to the town on business, and all persons of distinction passing through it, were regaled with an offering of from two to four gallons from the cellars of Jehan de la Lobe, or Petit Jehannin, or Raulin d’Escry, or Baudouin le Boutellier, or Remi Cauchois, the principal tavern-keepers. The provost of Laon, the bailli and the receveur of Vermandois, the eschevins of Châlons, the Bishop of Coustances, Monseigneur Thibaut de Bar, Monseigneur Jacques la Vache (the queen’s physician), the Archdeacon of Reims, and the ‘two lords of the parliament deputed by the king to examine the walls,’ were a few of the recipients of this hospitality, which was also extended to such inferior personages as a varlet of Verdun and the varlet of the eschevins of Abbeville.