автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу My Wife and I; Or, Harry Henderson's History

[Frontispiece]

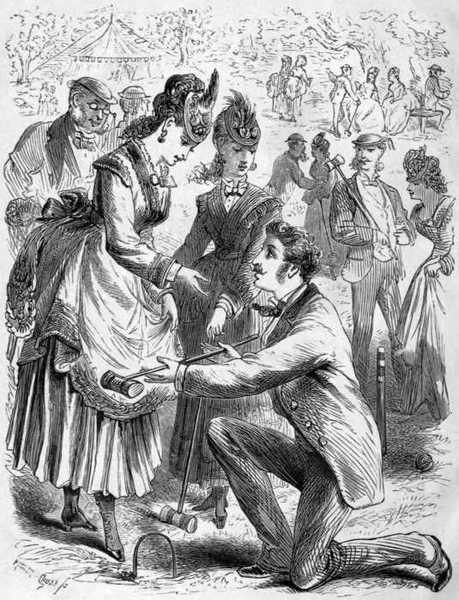

THE MATCH GAME.

"I knelt down, and laid my mallet at her feet. 'Beautiful princess!' said I, 'behold your enemies, conquered, await your sentence.'"

(Page 349.)

MY WIFE AND I:

OR,

HARRY HENDERSON'S HISTORY.

BY

HARRIET BEECHER STOWE,

AUTHOR OF "UNCLE TOM'S CABIN," "PINK AND WHITE," ETC.

New-York:

J. B. FORD AND COMPANY.

1872.

Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1871

BY J. W. FORD AND COMPANY,

in the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

PREFACE.

During the passage of this story through The Christian Union, it has been repeatedly taken for granted by the public press that certain of the characters are designed as portraits of really existing individuals.

They are not. The supposition has its rise in an imperfect consideration of the principles of dramatic composition. The novel-writer does not profess to paint portraits of any individual men and women in his personal acquaintance. Certain characters are required for the purposes of his story. He conceives and creates them, and they become to him real living beings, acting and speaking in ways of their own. But on the other hand, he is guided in this creation by his knowledge and experience of men and women, and studies individual instances and incidents only to assure himself of the possibility and probability of the character he creates. If he succeeds in making the character real and natural, people often are led to identify it with some individual of their acquaintance. A slight incident, an anecdote, a paragraph in a paper, often furnishes the foundation of such a character; and the work of drawing it is like the process by which Professor Agassiz from one bone reconstructs the whole form of an unknown fish. But to apply to any single living person such delineation is a mistake, and might be a great wrong both to the author and to the person designated.

For instance, it being the author's purpose to show the embarrassment of the young champion of progressive principles, in meeting the excesses of modern reformers, it came in her way to paint the picture of the modern emancipated young woman of advanced ideas and free behavior. And this character has been mistaken for the portrait of an individual, drawn from actual observation. On the contrary, it was not the author's intention to draw an individual, but simply to show the type of a class. Facts as to conduct and behavior similar to those she has described are unhappily too familiar to residents of New York. But in this as in other cases the author has simply used isolated facts in the construction of a dramatic character suited to the design of the story. If the readers of to-day will turn back to Miss Edgeworth's Belinda, they will find that this style of manners, these assumptions and mode of asserting them, are no new things. In the character of Harriet Freke, Miss Edgeworth vividly portrays the manners and sentiments of the modern emancipated women of our times, who think themselves

"Ne'er so sure our passion to create, As when they touch the brink of all we hate."

Certainly the author knows no original fully answering to the character of Mrs. Cerulean, though she has heard such an one described; and, doubtless, there are traits in her equally attributable to all fair enthusiasts who mistake the influence of their own personal charms and fascinations over the other sex, for real superiority of intellect.

There are happily several young women whose vigorous self-sustaining career, in opening paths of usefulness alike for themselves and others, are like that of Ida Van Arsdel; and the true experiences of a lovely New York girl first suggested the character of Eva; yet both of them are, in execution, strictly imaginary paintings, adapted to the story. In short, some real character, or, in many cases, some two or three, furnish the germs, but the germs only, out of which new characters are developed.

In close: The author wishes to dedicate this Story to the many dear, bright young girls whom she is so happy as to number among her choicest friends. No matter what the critics say of it, if they like it; and she hopes from them, at least, a favorable judgment.

H. B. S.

Twin-Mountain House, N.H.

October, 1871.

CONTENTS:

PageI.

The Author Defines his Position 1II.

My Child-Wife 5III.

Our Child-Eden 17IV.

My Shadow-Wife 32V.

I Start for College 43VI.

My Dream-Wife 52VII.

The Valley of Humiliation 66VIII.

The Blue Mists 76IX.

An Outlook into Life 84X.

Cousin Caroline 99XI.

Why Don't You Take Her? 113XII.

I Lay the First Stone in my Foundation 126XIII.

Bachelor Chambers 136XIV.

Haps and Mishaps 144XV.

I Meet a Vision 154XVI.

The Girl of our Period 166XVII.

I am Introduced into Society 182XVIII.

The Young Lady Philosopher 193XIX.

Flirtation 204XX.

I Became a Family Friend 216XXI.

I Discover the Beauties of Friendship 226XXII.

I am Introduced to the Illuminati 234XXIII.

I Receive a Moral Shower-Bath 240XXIV.

Aunt Maria 247XXV.

A Discussion of the Women Question 257XXVI.

Cousin Caroline Again 272XXVII.

Easter Lilies 280XXVIII.

Enchantment and Disenchantment 290XXIX.

A New Opening 307XXX.

Perturbations 319XXXI.

The Fates 327XXXII.

The Game of Croquet 336XXXIII.

The Match Game 345XXXIV.

Letter from Eva van Arsdel 351XXXV.

Domestic Consultations 360XXXVI.

Wealth versus Love 366XXXVII.

Further Consultations 373XXXVIII.

Making Love to One's Father-in-Law 379XXXIX.

Accepted and Engaged 388XL.

Congratulations, etc. 396XLI.

The Explosion 401XLII.

The Talk Over the Prayer Book 409XLIII.

Bolton 417XLIV.

The Wedding Journey 421XLV.

My Wife's Wardrobe 429XLVI.

Letters from New York 435XLVII.

Aunt Maria's Dictum 441XLVIII.

Our House 448XLIX.

Picnicking in New York 453L.

Neighbors 458LI.

My Wife Projects Hospitalities 464LII.

Preparations for our Dinner Party 468LIII.

The House-Warming 471ILLUSTRATIONS:

I.

The Match Game Frontispiece.II.

My Child-Wife 5III.

Matrimonial Propositions 15IV.

Uncle Jacob's Advice 47V.

My Dream-Wife 64VI.

The Umbrella 159VII.

The Advanced Woman of the Period 240VIII.

Bolton's Asylum 275MY CHILD-WIFE.

"The big boys quizzed me, made hideous faces at me from behind their spelling-books, and great hulking Tom Halliday threw a spit-ball that lodged on the wall just over my head, by way of showing his contempt for me; but I looked at Susie, and took courage."

MATRIMONIAL PROPOSITIONS.

"Early marriages?" said my mother, stopping her knitting looking at me, while a smile flashed over her thin cheeks: "what's the child thinking of?"

UNCLE JACOB'S ADVICE.

"So you are going to college, boy! Well, away with you; there's no use advising you; you'll do as all the rest do. In one year you'll know more than your father, your mother, or I, or all your college officers—in fact, than the Lord himself."

MY DREAM-WIFE.

"I told her that I was a poor soldier of fortune, but might I only wear her name in my bosom, it would be a sacred talisman, and give strength to my arm; and she sighed and looked lovely, and she did not say me nay."

THE UMBRELLA.

"Before a very elegant house in Fifth Avenue my unknown alighted, and the rain still continuing, there was an excuse for my still attending her up the steps."

THE ADVANCED WOMAN OF THE PERIOD.

"'You go for the emancipation of woman; but bless you, boy, you haven't the least idea what it means—not a bit of it, sonny, have you now? Confess?' she said, stroking my shoulder caressingly."

BOLTON'S ASYLUM.

"Halloo, Bolton!" said I. "Have you got a foundling hospital here?"

CHAPTER I.

THE AUTHOR DEFINES HIS POSITION.

It appears to me that the world is returning to its second childhood, and running mad for Stories. Stories! Stories! Stories! everywhere; stories in every paper, in every crevice, crack and corner of the house. Stories fall from the pen faster than leaves of autumn, and of as many shades and colorings. Stories blow over here in whirlwinds from England. Stories are translated from the French, from the Danish, from the Swedish, from the German, from the Russian. There are serial stories for adults in the Atlantic, in the Overland, in the Galaxy, in Harper's, in Scribner's. There are serial stories for youthful pilgrims in Our Young Folks, the Little Corporal, "Oliver Optic," the Youth's Companion, and very soon we anticipate newspapers with serial stories for the nursery. We shall have those charmingly illustrated magazines, the Cradle, the Rocking Chair, the First Rattle, and the First Tooth, with successive chapters of "Goosy Goosy Gander," and "Hickory Dickory Dock," and "Old Mother Hubbard," extending through twelve, or twenty-four, or forty-eight numbers.

I have often questioned what Solomon would have said if he had lived in our day. The poor man, it appears, was somewhat blasé with the abundance of literature in his times, and remarked that much study was weariness to the flesh. Then, printing was not invented, and "books" were all copied by hand, in those very square Hebrew letters where each letter is about as careful a bit of work as a grave-stone. And yet, even with all these restrictions and circumscriptions, Solomon rather testily remarked, "Of making many books there is no end!" What would he have said had he looked over a modern publisher's catalogue?

It is understood now that no paper is complete without its serial story, and the spinning of these stories keeps thousands of wheels and spindles in motion. It is now understood that whoever wishes to gain the public ear, and to propound a new theory, must do it in a serial story. Hath any one in our day, as in St. Paul's, a psalm, a doctrine, a tongue, a revelation, an interpretation—forthwith he wraps it up in a serial story, and presents it to the public. We have prison discipline, free-trade, labor and capital, woman's rights, the temperance question, in serial stories. We have Romanism and Protestantism, High Church, and Low Church and no Church, contending with each other in serial stories, where each side converts the other, according to the faith of the narrator.

We see that this thing is to go on. Soon it will be necessary that every leading clergyman should embody in his theology a serial story, to be delivered from the pulpit Sunday after Sunday. We look forward to announcements in our city papers such as these: The Rev. Dr. Ignatius, of the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, will begin a serial romance, to be entitled "St. Sebastian and the Arrows," in which he will embody the duties, the trials, and the temptations of the young Christians of our day. The Rev. Dr. Boanerges, of Plymouth Rock Church, will begin a serial story, entitled "Calvin's Daughter," in which he will discuss the distinctive features of Protestant theology. The Rev. Dr. Cool Shadow will go on with his interesting romance of "Christianity a Dissolving View,"—designed to show how everything is, in many respects, like everything else, and all things lead somewhere, and everything will finally end somehow, and that therefore it is important that everybody should cultivate general sweetness, and have the very best time possible in this world.

By the time all these romances get to going, the system of teaching by parables, and opening one's mouth in dark sayings, will be fully elaborated. Pilgrim's Progress will be no where. The way to the celestial city will be as plain in everybody's mind as the way up Broadway—and so much more interesting! Finally all science and all art will be explained, conducted, and directed by serial stories, till the present life and the life to come shall form only one grand romance. This will be about the time of the Millennium.

Meanwhile, I have been furnishing a story for the Christian Union, and I chose the subject which is in everybody's mind and mouth, discussed on every platform, ringing from everybody's tongue, and coming home to every man's business and bosom, to wit:

My Wife and I.

I trust that Miss Anthony and Mrs. Stanton, and all the prophetesses of our day, will remark the humility and propriety of my title. It is not I and My Wife—oh no! It is My Wife and I. What am I, and what is my father's house, that I should go before my wife in anything?

"But why specially for the Christian Union?" says Mr. Chadband. Let us in a spirit of Love inquire.

Is it not evident why, O beloved? Is not that firm in human nature which stands under the title of My Wife and I, the oldest and most venerable form of Christian union on record? Where, I ask, will you find a better one?—a wiser, a stronger, a sweeter, a more universally popular and agreeable one?

To be sure, there have been times and seasons when this ancient and respectable firm has been attacked as a piece of old fogyism, and various substitutes for it proposed. It has been said that "My Wife and I" denoted a selfish, close corporation inconsistent with a general, all-sided diffusive, universal benevolence; that My Wife and I, in a millennial community, had no particular rights in each other more than any of the thousands of the brethren and sisters of the human race. They have said, too, that My Wife and I, instead of an indissoluble unity, were only temporary partners, engaged on time, with the liberty of giving three months' notice, and starting off to a new firm.

It is not thus that we understand the matter.

My Wife and I, as we understand it, is the sign and symbol of more than any earthly partnership or union—of something sacred as religion, indissoluble as the soul, endless as eternity—the symbol chosen by Almighty Love to represent his redeeming, eternal union with the soul of man.

A fountain of eternal youth gushes near the hearth of every household. Each man and woman that have loved truly, have had their romance in life—their poetry in existence.

So I, in giving my history, disclaim all other sources of interest. Look not for trap-doors, or haunted houses, or deadly conspiracies, or murders, or concealed crimes, in this history, for you will not find one. You shall have simply and only the old story—old as the first chapter of Genesis—of Adam stupid, desolate, and lonely without Eve, and how he sought and how he found her.

This much, on mature consideration I hold to be about the sum and substance of all the romances that have ever been written, and so long as there are new Adams and new Eves in each coming generation, it will not want for sympathetic listeners.

So I, Harry Henderson—a plain Yankee boy from the mountains of New Hampshire, and at present citizen of New York—commence my story.

My experiences have three stages.

First, My child-wife, or the experiences of childhood.

Second, My shadow-wife, or the dreamland of the future.

Third, my real wife, where I saw her, how I sought and found her.

In pursuing a story simply and mainly of love and marriage, I am reminded of the saying of a respectable serving man of European experiences, who speaking of his position in a noble family said it was not so much the wages that made it an object as "the things it enabled a gentleman to pick up." So in our modern days as we have been observing, it is not so much the story, as the things it gives the author a chance to say. The history of a young American man's progress toward matrimony, of course brings him among the most stirring and exciting topics of the day, where all that relates to the joint interests of man and woman has been thrown into the arena as an open question, and in relating our own experiences, we shall take occasion to keep up with the spirit of this discussing age in all these matters.

MY CHILD-WIFE.

"The big boys quizzed me, made hideous faces at me from behind their spelling-books, and great hulking Tom Halliday threw a spit-ball that lodged on the wall just over my head, by way of showing his contempt for me; but I looked at Susie, and took courage."

CHAPTER II.

MY CHILD-WIFE.

The Bible says it is not good for man to be alone. This is a truth that has been borne in on my mind, with peculiar force, from the earliest of my recollection. In fact when I was only seven years old I had selected my wife, and asked the paternal consent.

You see, I was an unusually lonesome little fellow, because I belonged to the number of those unlucky waifs who come into this mortal life under circumstances when nobody wants or expects them. My father was a poor country minister in the mountains of New Hampshire with a salary of six hundred dollars, with nine children. I was the tenth. I was not expected; my immediate predecessor was five years of age, and the gossips of the neighborhood had already presented congratulations to my mother on having "done up her work in the forenoon," and being ready to sit down to afternoon leisure.

Her well-worn baby clothes were all given away, the cradle was peaceably consigned to the garret, and my mother was now regarded as without excuse if she did not preside at the weekly prayer-meeting, the monthly Maternal Association, and the Missionary meeting, and perform besides regular pastoral visitations among the good wives of her parish.

No one, of course, ever thought of voting her any little extra salary on account of these public duties which absorbed so much time and attention from her perplexing domestic cares—rendered still more severe and onerous by my father's limited salary. My father's six hundred dollars, however, was considered by the farmers of the vicinity as being a princely income, which accounted satisfactorily for everything, and had he not been considered by them as "about the smartest man in the State," they could not have gone up to such a figure. My mother was one of those gentle, soft-spoken, quiet little women who, like oil, permeate every crack and joint of life with smoothness.

With a noiseless step, an almost shadowy movement, her hand and eye were every where. Her house was a miracle of neatness and order—her children of all ages and sizes under her perfect control, and the accumulations of labor of all descriptions which beset a great family where there are no servants, all melted away under her hands as if by enchantment.

She had a divine magic too, that mother of mine; if it be magic to commune daily with the supernatural. She had a little room all her own, where on a stand always lay open the great family Bible, and when work pressed hard and children were untoward, when sickness threatened, when the skeins of life were all crossways and tangled, she went quietly to that room, and kneeling over that Bible, took hold of a warm, healing, invisible hand, that made the crooked straight, and the rough places plain.

"Poor Mrs. Henderson—another boy!" said the gossips on the day that I was born. "What a shame! poor woman. Well, I wish her joy!"

But she took me to a warm bosom and bade God bless me! All that God sent to her was treasure. "Who knows," she said cheerily to my father, "this may be our brightest."

"God bless him," said my father, kissing me and my mother, and then he returned to an important treatise which was to reconcile the decrees of God with the free agency of man, and which the event of my entrance into this world had interrupted for some hours. The sermon was a perfect success I am told, and nobody that heard it ever had a moment's further trouble on that subject.

As to me, my outfit for this world was of the scantest-a few yellow flannel petticoats and a few slips run up from some of my older sisters cast off white gowns, were deemed sufficient.

The first child in a family is its poem—it is a sort of nativity play, and we bend before the young stranger, with gifts, "gold, frankincense and myrrh." But the tenth child in a poor family is prose, and gets simply what is due to comfort. There are no superfluities, no fripperies, no idealities about the tenth cradle.

As I grew up I found myself rather a solitary little fellow in a great house, full of the bustle and noise and conflicting claims of older brothers and sisters, who had got the floor in the stage of life before me, and who were too busy with their own wants, schemes and plans, to regard me.

I was all very well so long as I kept within the limits of babyhood. They said I was the handsomest baby ever pertaining to the family establishment, and as long as that quality and condition lasted I was made a pet of. My sisters curled my golden locks and made me wonderful little frocks, and took me about to show me. But when I grew bigger, and the golden locks were sheared off and replaced by straight light hair, and I was inducted into jacket and pantaloons, cut down by Miss Abia Ferkin from my next brother's last year's suit, outgrown—then I was turned upon the world to shift for myself. Babyhood was over, and manhood not begun—I was to run the gauntlet of boyhood.

My brothers and sisters were affectionate enough in their way, but had not the least sentiment, and as I said before they had each one their own concerns to look after. My eldest brother was in college, my next brother was fitting for college in a neighboring academy, and used to walk ten miles daily to his lessons and take his dinner with him. One of my older sisters was married, the two next were handsome lively girls, with a retinue of beaux, who of course took up a deal of their time and thoughts. The sister next before me was four years above me on the lists of life, and of course looked down on me as a little boy unworthy of her society. When her two or three chattering girl friends came to see her and they had their dolls and their baby houses to manage, I was always in the way. They laughed at my awkwardness, criticised my nose, my hair, and my ears to my face, with that feminine freedom by which the gentler sex joy to put down the stronger one when they have it at advantage. I used often to retire from their society swelling with impotent wrath, at their free comments. "I won't play with you," I would exclaim. "Nobody wants you," would be the rejoinder. "We've been wanting to be rid of you this good while."

But as I was a stout little fellow, my elders thought it advisable to devolve on me any such tasks and errands as interfered with their comfort. I was sent to the store when the wind howled and the frost bit, and my brothers and sisters preferred a warm corner. "He's only a boy, he can go, or he can do or he can wait," was always the award of my sisters.

My individual pursuits, and my own little stock of interests, were of course of no account. I was required to be in a perfectly free, disengaged state of mind, and ready to drop every thing at a moment's warning from any of my half dozen seniors. "Here Hal, run down cellar and get me a dozen apples," my brother would say, just as I had half built a block house. "Harry, run up stairs and get the book I left on the bed—Harry, run out to the barn and get the rake I left there—Here, Harry, carry this up garret—Harry, run out to the tool shop and get that"—were sounds constantly occurring—breaking up my private cherished little enterprises of building cob-houses, making mill dams and bridges, or loading carriages, or driving horses. Where is the mature Christian who could bear with patience the interruptions and crosses in his daily schemes, that beset a boy?

Then there were for me dire mortifications and bitter disappointments. If any company came and the family board was filled and the cake and preserves brought out, and gay conversation made my heart bound with special longings to be in at the fun, I heard them say, "No need to set a plate for Harry—he can just as well wait till after." I can recollect many a serious deprivation of mature life, that did not bring such bitterness of soul as that sentence of exclusion. Then when my sister's admirer, Sam Richards, was expected, and the best parlor fire lighted, and the hearth swept, how I longed to sit up and hear his funny stories, how I hid in dark corners, and lay off in shadowy places, hoping to escape notice and so avoid the activity of the domestic police. But no, "Mamma, mustn't Harry go to bed?" was the busy outcry of my sisters, desirous to have the deck cleared for action, and superfluous members finally disposed of.

Take it for all in all—I felt myself, though not wanting in the supply of any physical necessity, to be somehow, as I said, a very lonesome little fellow in the world. In all that busy, lively, gay, bustling household I had no mate.

"I think we must send Harry to school," said my mother, gently, to my father, when I had vented this complaint in her maternal bosom. "Poor little fellow, he is an odd one!—there isn't exactly any one in the house for him to mate with!"

So to school I was sent, with a clean checked apron, drawn up tight in my neck, and a dinner basket, and a brown towel on which I was to be instructed in the wholesome practice of sewing. I went, trembling and blushing, with many an apprehension of the big boys who had promised to thrash me when I came; but the very first day I was made blessed in the vision of my little child-wife, Susie Morril.

Such a pretty, neat little figure as she was! I saw her first standing in the school-room door. Her cheeks and neck were like wax; her eyes clear blue; and when she smiled, two little dimples flitted in and out on her cheeks, like those in a sunny brook. She was dressed in a pink gingham frock, with a clean white apron fitted trimly about her little round neck. She was her mother's only child, and always daintily dressed.

"Oh, Susie dear," said my mother, who had me by the hand, "I've brought a little boy here to school, and will be a mate for you."

How affably and graciously she received me—the little Eve—all smiles and obligingness and encouragement for the lumpish, awkward Adam. How she made me sit down on a seat by her, and put her little white arm cosily over my neck, as she laid the spelling-book on her knee, saying—"I read in Baker. Where do you read?"

Friend, it was Webster's Spelling-book that was their text-book, and many of you will remember where "Baker" is in that literary career. The column of words thus headed was a mile-stone on the path of infant progress. But my mother had been a diligent instructress at home, and I an apt scholar, and my breast swelled as I told little Susie that I had gone beyond Baker. I saw "respect mingling with surprise" in her great violet eyes; my soul was enlarged—my little frame dilated, as turning over to the picture of the "old man who found a rude boy on one of his trees stealing apples," I answered her that I had read there!

"Why-ee!" said the little maiden; "only think, girls—he reads in readings!"

I was set up and glorified in my own esteem; two or three girls looked at me with evident consideration.

"Don't you want to sit on our side?" said Susie, engagingly. "I'll ask Miss Bessie to let you, 'cause she said the big boys always plague the little ones." And so, as she was a smooth-tongued little favorite, she not only introduced me to the teacher, but got me comfortably niched, beside her dainty self on the hard, backless seat, where I sat swinging my heels, and looking for all the world like a rough little short-tailed robin, just pushed out of the nest, and surveying the world with round, anxious eyes. The big boys quizzed me, made hideous faces at me from behind their spelling-books, and great hulking Tom Halliday threw a spit ball that lodged on the wall just over my head, by way of showing his contempt for me; but I looked at Susie, and took courage. I thought I never saw anything so pretty as she was. I was never tired with following the mazes of her golden curls. I thought how dainty and nice and white her pink dress and white apron were; and she wore a pair of wonderful little red shoes; her tiny hands were so skillful and so busy! She turned the hem of my brown towel, and basted it for me so nicely, and then she took out some delicate ruffling that was her school work, and I admired her bright, fine needle and fine thread, and the waxen little finger crowned with a little brass thimble, as she sewed away with an industrious steadiness. To me the brass was gold, and her hands were pearl, and she was a little fairy princess!—yet every few moments she turned her great blue eyes on me, and smiled and nodded her little head knowingly, as much as to bid me be of good cheer, and I felt a thrill go right to my heart, that beat delightedly under the checked apron.

"Please, ma'am," said Susan, glibly, "mayn't Henry go out to play with the girls? The big boys are so rough."

And Miss Bessie smiled, and said I might; and I was a blessed little boy from that moment. In the first recess Susie instructed me in playing "Tag," and "Oats, peas, beans, and barley, O," and in "Threading the needle," and "Opening the gates as high as high as the sky, to let King George and his court pass by"—in all which she was a proficient, and where I needed a great deal of teaching and encouraging.

But when it came to more athletic feats, I could distinguish myself. I dared jump off from a higher fence than she could, and covered myself with glory by climbing to the top of a five-railed gate, and jumping boldly down; and moreover, when a cow appeared on the green before the school-house door, I marched up to her with a stick and ordered her off, with a manly stride and a determined voice, and chased her with the utmost vigor quite out of sight. These proceedings seemed to inspire Susie with a certain respect and confidence. I could read in "readings," jump off from high fences, and wasn't afraid of cows! These were manly accomplishments!

The school-house was a long distance from my father's, and I used to bring my dinner. Susie brought hers also, and many a delightful picnic have we had together. We made ourselves a house under a great button-ball tree, at whose foot the grass was short and green. Our house was neither more nor less than a square, marked out on the green turf by stones taken from the wall. I glorified myself in my own eyes and in Susie's, by being able to lift stones twice as heavy as she could, and a big flat one, which nearly broke my back, was deposited in the centre of the square, as our table. We used a clean pocket-handkerchief for a table-cloth; and Susie was wont to set out our meals with great order, making plates and dishes out of the button-ball leaves. Under her direction also, I fitted up our house with a pantry, and a small room where we used to play wash dishes, and set away what was left of our meals. The pantry was a stone cupboard, where we kept chestnuts and apples, and what remained of our cookies and gingerbread. Susie was fond of ornamentation, and stuck bouquets of golden rod and aster around in our best room, and there we received company, and had select society come to see us. Susie brought her doll to dwell in this establishment, and I made her a bedroom and a little bed of milkweed-silk to lie on. We put her to bed and tucked her up when we went into school—not without apprehension that those savages, the big boys, might visit our Eden with devastation. But the girls' recess came first, and we could venture to leave her there taking a nap till our play-time came; and when the girls went in Susie rolled her nursling in a napkin and took her safely into school, and laid her away in a corner of her desk, while the dreadful big boys were having their yelling war-whoop and carnival outside.

"How nice it is to have Harry gone all day to school," I heard one of my sisters saying to the other. "He used to be so in the way, meddling and getting into everything"—"And listening to everything one says," said the other, "Children have such horridly quick ears. Harry always listens to what we talk about."

"I think he is happier now, poor little fellow," said my mother. "He has somebody now to play with." This was the truth of the matter.

On Saturday afternoons, I used to beg of my mother to let me go and see Susie; and my sisters, nothing loth, used to brush my hair and put on me a stiff, clean, checked apron, and send me trotting off, the happiest of young lovers.

How bright and fair life seemed to me those Saturday afternoons, when the sun, through the picket-fences, made golden-green lines on the turf—and the trees waved and whispered, and I gathered handfuls of golden-rod and asters to ornament our house, under the button-wood tree!

Then we used to play in the barn together. We hunted for hens' eggs, and I dived under the barn to dark places where she dared not go; and climbed up to high places over the hay-mow, where she trembled to behold me—bringing stores of eggs, which she received in her clean white apron.

This daintiness of outfit excited my constant admiration. I wore stiff, heavy jackets and checked aprons, and was constantly, so my sisters said, wearing holes through my knees and elbows for them to patch; but little Susie always appeared to me fresh and fine and untumbled; she never dirtied her hands or soiled her dress. Like a true little woman, she seemed to have nerves through all her clothes that kept them in order. This nicety of person inspired me with a secret, wondering reverence. How could she always be so clean, so trim, and every way so pretty, I wondered? Her golden curls always seemed fresh from the brush, and even when she climbed and ran, and went with me into the barn-yard, or through the swamp and into all sorts of compromising places, she somehow picked her way out bright and unsoiled.

But though I admired her ceaselessly for this, she was no less in admiration of my daring strength and prowess. I felt myself a perfect Paladin in her defense. I remember that the chip-yard which we used to cross, on our way to the barn, was tyrannized over by a most loud-mouthed and arrogant old turkey-cock, that used to strut and swell and gobble and chitter greatly to her terror. She told me of different times when she had tried to cross the yard alone, how he had jumped upon her and flapped his wings, and thrown her down, to her great distress and horror. The first time he tried the game on me, I marched up to him, and by a dexterous pass, seized his red neck in my hand, and confining his wings down with my arm, walked him ingloriously out of the yard.

How triumphant Susie was, and how I swelled and exulted to her, telling her what I would do to protect her under every supposable variety of circumstances! Susie had confessed to me of being dreadfully afraid of "bears," and I took this occasion to tell her what I would do if a bear should actually attack her. I assured her that I would get father's gun and shoot him without mercy—and she listened and believed. I also dilated on what I would do if robbers should get into the house; I would, I informed her, immediately get up and pour shovelfuls of hot coal down their backs—and wouldn't they have to run? What comfort and security this view of matters gave us both! What bears and robbers were, we had no very precise idea, but it was a comfort to think how strong and adequate to meet them in any event I was.

Sometimes, of a Saturday afternoon, Susie was permitted to come and play with me. I always went after her, and solicited the favor humbly at the hands of her mother, who, after many washings and dressings and cautions as to her clothes, delivered her up to me, with the condition that she was to start for home when the sun was half an hour high. Susie was very conscientious in watching, but for my part I never agreed with her. I was always sure that the sun was an hour high, when she set her little face dutifully homeward. My sisters used to pet her greatly during these visits. They delighted to twine her curls over their fingers, and try the effects of different articles of costume on her fair complexion. They would ask her, laughing, would she be my little wife, to which she always answered with a grave affirmative.

MATRIMONIAL PROPOSITIONS.

"Early marriages?" said my mother, stopping her knitting looking at me, while a smile flashed over her thin cheeks: "what's the child thinking of?"

Yes, she was to be my wife; it was all settled between us. But when? I didn't see why we must wait till we grew up. She was lonesome when I was gone, and I was lonesome when she was gone. Why not marry her now, and take her home to live with me? I asked her and she said she was willing, but mamma never would spare her. I said I would get my mamma to ask her, and I knew she couldn't refuse, because my papa was the minister.

I turned the matter over and over in my mind, and thought sometime when I could find my mother alone, I would introduce the subject. So one evening, as I sat on my little stool at my mother's knees, I thought I would open the subject, and began:

"Mamma, why do people object to early marriages?"

"Early marriages?" said my mother, stopping her knitting, looking at me, while a smile flashed over her thin cheeks: "what's the child thinking of?"

"I mean, why can't Susie and I be married now? I want her here. I'm lonesome without her. Nobody wants to play with me in this house, and if she were here we should be together all the time."

My father woke up from his meditation on his next Sunday's sermon, and looked at my mother, smiling. A gentle laugh rippled her bosom.

"Why, dear," she said, "don't you know your father is a poor man, and has hard work to support his children now? He couldn't afford to keep another little girl."

I thought the matter over, sorrowfully. Here was the pecuniary difficulty, that puts off so many desiring lovers, meeting me on the very threshold of life.

"Mother," I said, after a period of mournful consideration, "I wouldn't eat but just half as much as I do now, and I'd try not to wear out my clothes, and make 'em last longer." My mother had very bright eyes, and there was a mingled flash of tears and laughter in them, as when the sun winks through rain drops. She lifted me gently into her lap and drew my head down on her bosom.

"Some day, when my little son grows to be a man, I hope God will give him a wife he loves dearly. 'Houses and lands are from the fathers; but a good wife is of the Lord,' the Bible says."

"That's true, dear," said my father, looking at her tenderly; "nobody knows that better than I do."

My mother rocked gently back and forward with me in the evening shadows, and talked with me and soothed me, and told me stories how one day I should grow to be a good man—a minister, like my father, she hoped—and have a dear little house of my own.

"And will Susie be in it?"

"Let's hope so," said my mother. "Who knows?"

"But, mother, ain't you sure? I want you to say it will be certainly."

"My little one, only our dear Father could tell us that," said my mother. "But now you must try and learn fast, and become a good strong man, so that you can take care of a little wife."

CHAPTER III.

OUR CHILD-EDEN.

My mother's talk aroused all the enthusiasm of my nature. Here was a motive, to be sure. I went to bed and dreamed of it. I thought over all possible ways of growing big and strong rapidly—I had heard the stories of Samson from the Bible. How did he grow so strong? He was probably once a little boy like me. "Did he go for the cows, I wonder," thought I—"and let down very big bars when his hands were little, and learn to ride the old horse bare-back, when his legs were very short?" All these things I was emulous to do; and I resolved to lift very heavy pails full of water, and very many of them, and to climb into the mow, and throw down great armfulls of hay, and in every possible way to grow big and strong.

I remember the next day after my talk with my mother was Saturday, and I had leave to go up and spend it with Susie.

There was a meadow just back of her mother's house, which we used to call the mowing lot. It was white with daisies, yellow with buttercups, with some moderate share of timothy and herds grass intermixed. But what was specially interesting to us was, that, down low at the roots of the grass, and here and there in moist, rich spots, grew wild strawberries, large and juicy, rising on nice high stalks, with three or four on a cluster. What joy there was in the possession of a whole sunny Saturday afternoon to be spent with Susie in this meadow! To me the amount of happiness in the survey was greatly in advance of what I now have in the view of a three weeks' summer excursion.

When, after multiplied cautions and directions, and careful adjustment of Susie's clothing, on the part of her mother, Susie was fairly delivered up to me; when we had turned our backs on the house and got beyond call, then our bliss was complete. How carefully and patronizingly I helped her up the loose, mossy, stone wall, all hedged with a wilderness of golden-rod, ferns, raspberry bushes, and asters! Down we went through this tangled thicket, into such a secure world of joy, where the daisied meadow received us to her motherly bosom, and we were sure nobody could see us.

We could sit down and look upward, and see daisies and grasses nodding and bobbing over our heads, hiding us as completely as two young grass birds; and it was such fun to think that nobody could find out where we were! Two bob-o-links, who had a nest somewhere in that lot, used to mount guard in an old apple tree, and sit on tall, bending twigs, and say, "Chack! chack! chack!" and flutter their black and white wings up and down, and burst out into most elaborate and complicated babbles of melody. These were our only associates and witnesses. We thought that they knew us, and were glad to see us there, and wouldn't tell anybody where we were for the world. There was an exquisite pleasure to us in this sense of utter isolation—of being hid with each other where nobody could find us.

We had worlds of nice secrets peculiar to ourselves. Nobody but ourselves knew where the "thick spots" were, where the ripe, scarlet strawberries grew; the big boys never suspected them, we said to one another, nor the big girls; it was our own secret, which we kept between our own little selves. How we searched, and picked, and chatted, and oh'd and ah'd to each other, as we found wonderful places, where the strawberries passed all belief!

But profoundest of all our wonderful secrets were our discoveries in the region of animal life. We found, in a tuft of grass overshadowed by wild roses, a grass bird's nest. In vain did the cunning mother creep yards from the cherished spot, and then suddenly fly up in the wrong place; we were not to be deceived. Our busy hands parted the lace curtains of fern, and, with whispers of astonishment, we counted the little speckled, bluegreen eggs. How round and fine and exquisite, past all gems polished by art, they seemed; and what a mystery was the little curious smooth-lined nest in which we found them! We talked to the birds encouragingly. "Dear little birds," we said, "don't be afraid; nobody but we shall know it;" and then we said to each other, "Tom Halliday never shall find this out, nor Jim Fellows." They would carry off the eggs and tear up the nest; and our hearts swelled with such a responsibility for the tender secret, that it was all we could do that week to avoid telling it to everybody we met. We informed all the children at school that we knew something that they didn't—something that we never should tell!—something so wonderful!—something that it would be wicked to tell of—for mother said so; for be it observed that, like good children, we had taken our respective mothers into confidence, and received the strictest and most conscientious charges as to our duty to keep the birds' secret.

In that enchanted meadow of ours grew tall, yellow lilies, glowing as the sunset, hanging down their bells, six or seven in number, from high, graceful stalks, like bell towers of fairy land. They were over our heads sometimes, as they rose from the grass and daisies, and we looked up into their golden hearts spotted with black, with a secret, wondering joy.

"Oh, don't pick them, they look too pretty," said Susie to me once when I stretched up my hand to gather one of these. "Let's leave them to be here when we come again! I like to see them wave."

And so we left the tallest of them; but I was not forbidden to gather handfuls of the less wonderful specimens that grew only one or two on a stalk. Our bouquets of flowers increased with our strawberries.

Through the middle of this meadow chattered a little brook, gurgling and tinkling over many-colored pebbles, and here and there collecting itself into a miniature waterfall, as it pitched over a broken bit of rock. For our height and size, the waterfalls of this little brook were equal to those of Trenton, or any of the medium cascades that draw the fashionable crowd of grown-up people; and what was the best of it was, it was our brook, and our waterfall. We found them, and we verily believed nobody else but ourselves knew of them.

By this waterfall, as I called it, which was certainly a foot and a half high, we sat and arranged our strawberries when our baskets were full, and I talked with Susie about what my mother had told me.

I can see her now, the little crumb of womanhood, as she sat, gaily laughing at me. "She didn't care a bit," she said. She had just as lief wait till I grew to be a man. Why, we could go to school together, and have Saturday afternoons together. "Don't you mind it, Hazzy Dazzy," she said, coming close up to me, and putting her little arms coaxingly round my neck; "we love each other, and it's ever so nice now."

I wonder what the reason is that it is one of the first movements of affectionate feeling to change the name of the loved one. Give a baby a name, ever so short and ever so musical, where is the mother that does not twist it into some other pet name between herself and her child. So Susie, when she was very loving, called me Hazzy, and sometimes would play on my name, and call me Hazzy Dazzy, and sometimes Dazzy, and we laughed at this because it was between us; and we amused ourselves with thinking how surprised people would be to hear her say Dazzy, and how they would wonder who she meant. In like manner, I used to call her Daisy when we were by ourselves, because she seemed to me so neat and trim and pure, and wore a little flat hat on Sundays just like a daisy.

"I'll tell you, Daisy," said I, "just what I'm going to do—I'm going to grow strong as Sampson did."

"Oh, but how can you?" she suggested, doubtfully.

"Oh, I'm going to run and jump and climb, and carry ever so much water for Mother, and I'm to ride on horseback and go to mill, and go all round on errands, and so I shall get to be a man fast, and when I get to be a man I'll build a house all on purpose for you and me—I'll build it all myself; it shall have a parlor and a dining-room and kitchen, and bed-room, and well-room, and chambers"—

"And nice closets to put things in," suggested the little woman.

"Certainly, ever so many—just where you want them, there I'll put them," said I, with surpassing liberality. "And then, when we live together, I'll take care of you—I'll keep off all the lions and bears and panthers. If a bear should come at you, Daisy, I should tear him right in two, just as Sampson did."

At this vivid picture, Daisy nestled close to my shoulder, and her eyes grew large and reflective. "We shouldn't leave poor Mother alone," said she.

"Oh, no; she shall come and live with us," said I, with an exalted generosity. "I will make her a nice chamber on purpose, and my mother shall come, too."

"But she can't leave your father, you know."

"Oh, father shall come, too—when he gets old and can't preach any more. I shall take care of them all."

And my little Daisy looked at me with eyes of approving credulity, and said I was a brave boy; and the bobolinks chittered and chattered applause as they sung and skirmished and whirled up over the meadow grasses; and by and by, when the sun fell low, and looked like a great golden ball, with our hands full of lilies, and our baskets full of strawberries, we climbed over the old wall, and toddled home.

After that, I remember many gay and joyous passages in that happiest summer of my life. How, when autumn came, we roved through the woods together, and gathered such stores of glossy brown chestnuts. What joy it was to us to scuff through the painted fallen leaves and send them flying like showers of jewels before us! How I reconnoitered and marked available chestnut trees, and how I gloried in being able to climb like a cat, and get astride high limbs and shake and beat them, and hear the glossy brown nuts fall with a rich, heavy thud below, while Susie was busily picking up at the foot of the tree. How she did flatter me with my success and prowess! Tom Halliday might be a bigger boy, but he could never go up a tree as I could; and as for that great clumsy Jim Fellows, she laughed to think what a figure he would make, going out on the end of the small limbs, which would be sure to break and send him bundling down. The picture which Susie drew of the awkwardness of the big boys often made us laugh till the tears rolled down our cheeks. To this day I observe it as a weakness of my sex that we all take it in extremely good part when the pretty girl of our heart laughs at other fellows in a snug, quiet way, just between one's dear self and herself alone. We encourage our own dear little cat to scratch and claw the sacred memories of Jim or Tom, and think that she does it in an extremely cunning and diverting way—it being understood between us that there is no malice in it—that "Jim and Tom are nice fellows enough, you know—only that somebody else is so superior to them," etc.

Susie and I considered ourselves as an extremely forehanded, well-to-do partnership, in the matter of gathering in our autumn stores. No pair of chipmonks in the neighborhood conducted business with more ability. We had a famous cellar that I dug and stoned, where we stored away our spoils. We had chestnuts and walnuts and butternuts, as we said, to last us all winter, and many an earnest consultation and many a busy hour did the gathering and arranging of these spoils cost us.

Then, oh, the golden times we had when father's barrels of new cider came home from the press! How I cut and gathered and selected bunches of choice straws, which I took to school and showed to Susie, surreptitiously, at intervals, during school exercises, that she might see what a provision of bliss I was making for Saturday afternoons. How Susie was sent to visit us on these occasions, in leather shoes and checked apron, so that we might go in the cellar; and how, mounted up on logs on either side of a barrel of cider, we plunged our straws through the foamy mass at the bung-hole, and drew out long draughts of sweet cider! I was sure to get myself dirty in my zeal, which she never did; and then she would laugh at me and patronize me, and wipe me up in a motherly sort of way. "How do you always get so dirty, Harry?" she would say, in a truly maternal tone of reproof. "How do you keep so clean?" I would say, in wonder; and she would laugh, and call me her dear, dirty boy. She would often laugh at me, the little elf, and make herself distractingly merry at my expense, but the moment she saw that the blood was getting too high in my cheeks, she would stroke me down with praises, as became a wise young daughter of Eve.

Besides all this, she had her little airs of moral superiority, and used occasionally to lecture me in the nicest manner. Being an only darling, she herself was brought up in the strictest ways in which little feet could go; and the nicety of her conscience was as unsullied as that of her dress. I was hot tempered and heady, and under stress of great provocation would come as near swearing as a minister's son could possibly do. When the big boys ravaged our house under the tree, or threw sticks at us, I used to stretch every permitted limit, and scream, "Darn you!" and "Confound you!" with a vigor and emphasis that made it almost equal to something a good deal stronger.

On such occasions Susie would listen pale and frightened, and, when reason came back to me, gravely lecture me, and bring me into the paths of virtue. She used to rehearse to me the teachings of her mother about all manner of good things.

I have her image now in my mind, looking so crisp and composed and neat in her sobriety, repeating, for my edification, the hymn which contained the good child's ideal in those days:

"Oh, that it were my chief delight

To do the things I ought,

Then let me try with all my might

To mind what I am taught.

Whene'er I'm told, I'll freely bring

Whatever I have got,

And never touch a pretty thing,

When mother tells me not.

If she permits me, I may tell

About my little toys,

But if she's busy or unwell,

I must not make a noise."

I can hear now the delicious lisp of my little saint, and see the gracious gravity of her manner. To my mind, she was unaccountably well established in the ways of virtue, and I listened to her little lectures with a secret reverence.

Susie was especially careful in the observation of Sunday, and as that is a point where children are apt to be particularly weak, she would exhort me to rigorous exactitude.

I kept it, first, by thinking that I should see her at church, and by growing very precise about my Sunday clothes, whereat my sisters winked at each other and laughed slyly. Then at church we sat in great square pews adjoining to each other. It was my pleasure to peep through the slats at Susie. She was wonderful to behold then, all in white, with a profusion of blue ribbons and her little flat hat over her curls—and a pair of dainty blue shoes peeping out from her dress.

She informed me that little girls never must think about their clothes in meeting, and so I supposed she was trying to be entirely absorbed from earthly vanities, unconscious of the fixed and earnest stare with which I followed every movement.

Human nature is but partially sanctified, however, in little saints as well as grown up ones, and I noticed that occasionally, probably by accident, the great blue eyes met mine, and a smile, almost amounting to a sinful giggle, was with difficulty choked down. She was, however, a most conscientious little puss and recovered herself in a moment, and looked gravely upward at the minister, not one word of whose sermon could she by any possibility understand, severely devoting herself to her religious duties, till exhausted nature gave way. The little lids would close over the eyes like blue pimpernel before a shower,—the head would drop and nod, till finally the mother would dispense the little Christian from further labors, by laying her head on her lap and drawing her feet up comfortably upon the seat, to sleep out to the end of the sermon.

When winter came on I beset my older brother to make me a sled. Sleds, such as every boy in Boston or New York now rejoices in, were blessings in our parts unknown; our sled was of rough, domestic manufacture.

My brother, laughing, asked if my sled was intended to draw Susie on, and on my earnest response in the affirmative he amused himself with painting it in colors, red and blue, most glorious to behold.

My soul was magnified within me when I first started with this stylish establishment to wait on Susie.

What young fellow does not exult in a smart team when he has a girl whom he wants to dazzle? Great was my joy and pride when I first stopped at Susie's and told her to hurry on her things, for I had come to draw her to school!

What a pretty picture she made in her little blue knit hood and mittens, her bright curls flying and cheeks glowing with the keen winter air! There was a long hill on the way to school, and seated on the sled behind her, I careered gloriously down with exultation in my breast, while a stream of laughter floated on the breeze behind us. That was a winter of much coasting down hill, of red cheeks and red noses, of cold toes, which we never minded, and of abundant jollity. Susie, under her mother's careful showing, knit me a pair of red mittens, warming to the heart and delightful to the eyes; and I piled up wood and carried water for Mother, and by vigorous economy earned money enough to buy Susie a great candy heart as big as my two hands, that had the picture of two doves tied together by a blue ribbon on one side, and on the other two very red hearts skewered together by an arrow.

No work of art ever gave greater and more unmingled delight. Susie gave it a prominent place in her baby-house,—and though it was undeniably sweet, as certain little nibbling trials on its edges had proved, yet the artistic sense was stronger than the palate, and the candy heart was kept to be looked at and rejoiced in.

Susie's mother was an intimate and confidential friend of my mother, and a most docile and confiding sheep of my father's flock. She regarded her minister's family, and all that belonged to it, as something set apart and sacred. My mother had imparted to her the little joke of my matrimonial wishes, and the two matrons had laughed over it together, and then sighed, and said, "Ah! well, stranger things have happened." Susie's mother told how she used to know her husband when he was a little boy, and what if it should be! and then they strayed on to the general truth that this was a world of uncertainty, and we never can tell what a day may bring forth.

Our little idyl, too, was rather encouraged by my brothers and sisters, who made a pet and plaything of Susie, and diverted themselves by the gravity and honesty with which we devoted ourselves to each other. Oh! dear ignorant days—sweet little child-Eden—why could it not last?

But it could not. It was fleeting as the bobolink's song, as the spotted yellow lilies, as the grass and daisies. My little Daisy was too dear to the angels to be spared to grow up in our coarse world.

The winter passed and spring came, and Susie and I rejoiced in the first bluebird, and found blue and white violets together, and went to school together, till the heats of summer came on. Then a sad epidemic began to linger around in our mountains, and to be heard of in neighboring villages, and my poor Daisy was scorched by its breath.

I remember well our last afternoon together in the meadow, where, the year before, we had gathered strawberries. We went down into it in high spirits; the strawberries were abundant, and we chatted and picked together gaily, till Daisy began to complain that her head ached and her throat was sore. I sat her down by the brook, and wet her curls with the water, and told her to rest there, and let me pick for her. But pretty soon she called me. She was crying with pain. "Oh! Hazzy, dear, I must go home," she said. "Take me to Mother." I hurried to help her, for she cried and moaned so that I was frightened. I began to cry, too, and we came up the steps of her mother's house sobbing together.

When her mother came out the little one suppressed her tears and distress for a moment, and turning, threw her arms around my neck and kissed me. "Don't cry any more, Hazzy," she said; "we'll see each other again."

Her mother took her up in her arms and carried her in, and I never saw my little baby-wife again on this earth! Not where the daisies and buttercups grew; nor where the golden lilies shook their bells, and the bobolinks trilled; not in the school-room, with its many child-voices; not in the old square pew in church—never, never more that trim little maiden form, those violet blue eyes, those golden curls of hair, were to be seen on earth!

My Daisy's last kisses, with the fever throbbing in her veins, very nearly took me with her. From that time I have only indistinct remembrances of going home crying, of turning with a strange loathing from my supper, of creeping up and getting into bed, shivering and burning, with a thumping and beating pain in my head.

The next morning the family doctor pronounced me a case of the epidemic (scarlet fever) which he said was all about among children in the neighborhood.

I have dim, hot, hazy recollections of burning, thirsty, head-achey days, when I longed for cold water, and could not get a drop, according to the good old rules of medical practice in those times. I dimly observed different people sitting up with me every night, and putting different medicines in my unresisting mouth; and day crept slowly after day, and I lay idly watching the rays of sunlight and flutter of leaves on the opposite wall.

One afternoon, I remember, as I lay thus listless, I heard the village bell strike slowly—six times. The sound wavered and trembled with long and solemn intervals of shivering vibration between. It was the numbering of my Daisy's little years on earth,—the announcement that she had gone to the land where time is no more measured by day and night, for there shall be no night there.

When I was well again I remember my mother told me that my little Daisy was in heaven, and I heard it with a dull, cold chill about my heart, and wondered that I could not cry.

I look back now into my little heart as it was then, and remember the paroxysms of silent pain I used to have at times, deep within, while yet I seemed to be like any other boy.

I heard my sisters one day discussing whether I cared much for Daisy's death.

"He don't seem to, much," said one.

"Oh, children are little animals, they forget what's out of sight," said another.

But I did not forget,—I could not bear to go to the meadow where we gathered strawberries,—to the chestnut trees where we had gathered nuts,—and oftentimes, suddenly, in work or play, that smothering sense of a past, forever gone, came over me like a physical sickness.

When children grow up among older people and are pushed and jostled, and set aside in the more engrossing interests of their elders, there is an almost incredible amount of timidity and dumbness of nature, with regard to the expression of inward feeling,—and yet, often at this time the instinctive sense of pleasure and pain is fearfully acute. But the child has imperfectly learned language. His stock of words, as yet, consists only in names and attributes of outward and physical objects, and he has no phraseology with which to embody a mere emotional experience.

What I felt when I thought of my little playfellow, was a dizzying, choking rush of bitter pain and anguish. Children can feel this acutely as men and women,—but even in mature life this experience has no gift of expression.

My mother alone, with the divining power of mothers, kept an eye on me. "Who knows," she said to my father, "but this death may be a heavenly call to him."

She sat down gently by my bed one night and talked with me of heaven, and the brightness and beauty there, and told me that little Susie was now a fair white angel.

I remember shaking with a tempest of sobs.

"But I want her here," I said. "I want to see her."

My mother went over all the explanations in the premises,—all that can ever be said in such cases, but I only sobbed the more.

"I can't see her! Oh mother, mother!"

That night I sobbed myself to sleep and dreamed a blessed dream.

It seemed to me that I was again in our meadow, and that it was fairer than ever before; the sun shone gaily, the sky was blue, and our great, golden lily stocks seemed mysteriously bright and fair, but I was wandering lonesome and solitary. Then suddenly my little Daisy came running to meet me in her pink dress and white apron, with her golden curls hanging down her neck. "Oh Daisy, Daisy!" said I running up to her. "Are you alive?—they told me that you were dead."

"No, Hazzy, dear, I am not dead,—never you believe that," she said, and I felt the clasp of her soft little arms round my neck. "Didn't I tell you we'd see each other again?"

"But they told me you were dead," I said in wonder—and I thought I held her off and looked at her,—she laughed gently at me as she often used to, but her lovely eyes had a mysterious power that seemed to thrill all through me.

"I am not dead, dear Hazzy," she said. "We never die were I am—I shall love you always," and with that my dream wavered and grew misty as when clear water breaks an image into a thousand glassy rings and fragments.

I thought I heard lovely music, and felt soft, clasping arms, and I awoke with a sense of being loved and pitied, and comforted.

I cannot describe the vivid, penetrating sense of reality which this dream left behind it. It seemed to warm my whole life, and to give back to my poor little heart something that had been rudely torn away from it. Perhaps there is no reader that has not had experiences of the wonderful power which a dream often exercises over the waking hours for weeks after—and it will not appear incredible that after that, instead of shunning the meadow where we used to play, it was my delight to wander there alone, to gather the strawberries—tend the birds' nests, and lie down on my back in the grass and look up into the blue sky through an overarching roof of daisies, with a strange sort of feeling of society, as if my little Daisy were with me.

And is it not perhaps so? Right along side of this troublous life, that is seen and temporal, may lie the green pastures and the still waters of the unseen and eternal, and they who know us better than we know them, can at any time step across that little rill that we call Death, to minister to our comfort.

For what are these child-angels made, that are sent down to this world to bring so much love and rapture, and go from us in such bitterness and mourning? If we believe in Almighty Love we must believe that they have a merciful and tender mission to our wayward souls. The love wherewith we love them is something the most utterly pure and unworldly of which human experience is capable, and we must hope that every one who goes from us to the world of light, goes holding an invisible chain of love by which to draw us there.

Sometimes I think I would never have had my little Daisy grow older on our earth. The little child dies in growing into womanhood, and often the woman is far less lovely than the little child. It seems to me that lovely and loving childhood, with its truthfulness, its frank sincerity, its pure, simple love, is so sweet and holy an estate that it would be a beautiful thing in heaven to have a band of heavenly children, guileless, gay and forever joyous—tender Spring blossoms of the Kingdom of Light. Was it of such whom he had left in his heavenly home our Saviour was thinking, when he took little children up in his arms and blessed them, and said, "Of such is the Kingdom of Heaven?"

CHAPTER IV.

MY SHADOW-WIFE.

My Shadow Wife! Is there then substance in shadow? Yea, there may be. A shadow—a spiritual presence—may go with us where mortal footsteps cannot go; walk by our side amid the roar of the city: talk with us amid the sharp clatter of voices; come to us through closed doors, as we sit alone over our evening fire; counsel, bless, inspire us; and though the figure cannot be clasped in mortal arms—though the face be veiled—yet this wife of the future may have a power to bless, to guide, to sustain and console. Such was the dream-wife of my youth.

Whence did she come? She rose like a white, pure mist from that little grave. She formed herself like a cloud-maiden from the rain and dew of those first tears.

When we look at the apparent recklessness with which great sorrows seem to be distributed among the children of the earth, there is no way to keep our faith in a Fatherly love, except to recognize how invariably the sorrows that spring from love are a means of enlarging and dignifying a human being. Nothing great or good comes without birth-pangs, and in just the proportion that natures grow more noble, their capacities of suffering increase.

The bitter, silent, irrepressible anguish of that childish bereavement was to me the awakening of a spiritual nature. The little creature who, had she lived, might have grown up perhaps into a common-place woman, became a fixed star in the heaven-land of the ideal, always drawing me to look upward. My memories of her were a spring of refined and tender feeling, through all my early life. I could not then write; but I remember that the overflow of my heart towards her memory required expression, and I taught myself a strange kind of manuscript, by copying the letters of the alphabet. I bought six cents' worth of paper and a tallow candle at the store, which I used to light surreptitiously when I had been put to bed nights, and, sitting up in my little night-gown, I busied myself with writing my remembrances of her. I could not, for the world, have asked my mother to let me have a candle in my bed-room after eight o'clock. I would have died sooner than to explain why I wanted it. My purchase of paper and candle was my first act of independent manliness. The money, I reflected, was mine, because I earned it myself, and the paper was mine, and the candle was mine, so that I was not using my father's property in an unwarrantable manner, and thus I gave myself up to my inspirations. I wrote my remembrances of her, as she stood among the daisies and the golden lilies. I wrote down her little words of wisdom and grave advice, in the queerest manuscript that ever puzzled a wise man of the East. If one imagines that all this was spelt phonetically, and not at all in the unspeakable and astonishing way in which the English language is conventionally spelt, one may truly imagine that it was something rather peculiar in the way of literature. But the heart-comfort, the utter abandonment of soul that went into it, is something that only those can imagine who have tried the like and found the relief of it. My little heart was like the Caspian sea, or some other sea which I read about, which had found a secret channel by which its waters could pass off under ground. When I had finished, every evening, I used to extinguish my candle, and put it and my manuscript inside of the straw bed on which I slept, which had a long pocket hole in the centre, secured by buttons, for the purpose of stirring the straw. Over this I slept in conscious security, every night; sometimes with blissful dreams of going to brighter meadows, when I saw my Daisy playing with whole troops of beautiful children, fair as water lilies on the shore of a blue lake. Thus, while I seemed to be like any other boy, thinking of nothing but my sled, and my bat and ball, and my mittens, I began to have a little withdrawing room of my own; another land in which I could walk and take a kind of delight that nothing visible gave me. But one day my oldest sister, in making the bed, with domestic thoroughness, disemboweled my whole store of manuscripts and the half consumed fragment of my candle.

There is no poetry in housewifery, and my sister at once took a housewifely view of the proceeding—

"Well, now! is there any end to the conjurations of boys?" she said. "He might have set the house on fire and burned us all alive, in our beds!"

Reader, this is quite possible, as I used to perform my literary labors sitting up in bed, with the candle standing on a narrow ledge on the side of the bedstead.

Forthwith the whole of my performance was lodged in my mother's hands—I was luckily at school.

"Now, girls," said my mother, "keep quiet about this; above all, don't say a word to the boy. I will speak to him."

Accordingly, that night after I had gone up to bed, my mother came into my room and, when she had seen me in bed, she sat down by me and told me the whole discovery. I hid my head under the bed clothes, and felt a sort of burning shame and mortification that was inexpressible; but she had a good store of that mother's wit and wisdom by which I was to be comforted. At last she succeeded in drawing both the bed clothes from my face and the veil from my heart, and I told her all my little story.

"Dear boy," she said, "you must learn to write, and you need not buy candles, you shall sit by me evenings and I will teach you; it was very nice of you to practice all alone; but it will be a great deal easier to let me teach you the writing letters."

Now I had begun the usual course of writing copies in school. In those days it was deemed necessary to commence by teaching what was called coarse hand; and I had filled many dreary pages with m's and n's of a gigantic size; but it never had yet occurred to me that the writing of these copies was to bear any sort of relation to the expression of thoughts and emotions within me that were clamoring for a vent, while my rude copies of printed letters did bear to my mind this adaptation. But now my mother made me sit by her evenings, with a slate and pencil, and, under her care, I made a cross-cut into the fields of practical handwriting, and was also saved the dangers of going off into a morbid habit of feeling, which might easily have arisen from my solitary reveries.

"Dear," she said to my father, "I told you this one was to be our brightest. He will make a writer yet," and she showed him my manuscript.

"You must look after him, Mother," said my father, as he always said, when there arose any exigency about the children, that required delicate handling.

My mother was one of that class of women whose power on earth seems to be only the greater for being a spiritual and invisible one. The control of such women over men is like that of the soul over the body. The body is visible, forceful, obtrusive, self-asserting. The soul invisible, sensitive, yet with a subtle and vital power which constantly gains control and holds every inch that it gains.

My father was naturally impetuous, though magnanimous, hasty tempered and imperious, though conscientious; my mother united the most exquisite sensibility with the deepest calm—calm resulting from habitual communion with the highest and purest source of all rest—the peace that passeth all understanding. Gradually, by this spiritual force, this quietude of soul, she became his leader and guide. He held her hand and looked up to her with a trustful implicitness that increased with every year.

"Where's your mother?" was always the fond inquiry when he entered the house, after having been off on one of his long preaching tours or clerical counsels. At all hours he would burst from his study with fragments of the sermon or letter he was writing, to read to her and receive her suggestions and criticisms. With her he discussed the plans of his discourses, and at her dictation changed, improved, altered and added; and under the brooding influence of her mind, new and finer traits of tenderness and spirituality pervaded his character and his teachings. In fact, my father once said to me, "She made me by her influence."

In these days, we sometimes hear women, who have reared large families on small means, spoken of as victims who had suffered unheard of oppressions. There is a growing materialism that refuses to believe that there can be happiness without the ease and facilities and luxuries of wealth.

But my father and mother, though living on a narrow income, were never really poor. The chief evil of poverty is the crushing of ideality out of life—the taking away its poetry and substituting hard prose;—and this with them was impossible. My father loved the work he did, as the artist loves his painting and the sculptor his chisel. A man needs less money when he is doing only what he loves to do—what, in fact, he must do,—pay or no pay. St. Paul said, "A necessity is laid upon me, yea, woe is me, if I preach not the gospel." Preaching the gospel was his irrepressible instinct, a necessity of his being. My mother, from her deep spiritual nature, was one soul with my father in his life-work. With the moral organization of a prophetess, she stood nearer to heaven than he, and looking in, told him what she saw, and he, holding her hand, felt the thrill of celestial electricity. With such women, life has no prose; their eyes see all things in the light of heaven, and flowers of paradise spring up in paths that to unanointed eyes, seem only paths of toil. I never felt, from anything I saw at home, from any word or action of my mother's, that we were poor, in the sense that poverty was an evil. I was reminded, to be sure, that we were poor in a sense that required constant carefulness, watchfulness over little things, energetic habits, and vigorous industry and self-helpfulness. But we were never poor in any sense that restricted hospitality or made it a burden. In those days, a minister's house was always the home for all the ministers and their families, whenever an exigency required of them to travel, and the spare room of our house never wanted guests of longer or shorter continuance. But the atmosphere of the house was such as always made guests welcome. Three or four times a year, the annual clerical gatherings of the church filled our house to overflowing and necessitated an abundant provision and great activity of preparation on the part of the women of our family. Yet I never heard an expression of impatience or a suggestion that made me suppose they felt themselves unduly burdened. My mother's cheerful face was a welcome and a benediction at all times, and guests found it good to be with her.

In the midst of our large family, of different ages, of vigorous growth, of great individuality and forcefulness of expression, my mother's was the administrative power. My father habitually referred everything to her, and leaned on her advice with a childlike dependence. She read the character of each, she mediated between opposing natures: she translated the dialect of different sorts of spirits, to each other. In a family of young children, there is a chance for every sort and variety of natures; and for natures whose modes of feeling are as foreign to each other, as those of the French and the English. It needs a common interpreter, who understands every dialect of the soul, thus to translate differences of individuality into a common language of love.