автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу Caricature and Other Comic Art in All Times and Many Lands

CARICATURE

AND

OTHER COMIC ART

IN ALL TIMES AND MANY LANDS

By JAMES PARTON

WITH 203 ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW YORK

HARPER & BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS

FRANKLIN SQUARE

1877

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1877, by

HARPER & BROTHERS,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

PREFACE.

In this volume there is, I believe, a greater variety of pictures of a comic and satirical cast than was ever before presented at one view. Many nations, ancient and modern, pagan and Christian, are represented in it, as well as most of the names identified with art of this nature. The extraordinary liberality of the publishers, and the skill of their corps of engravers, have seconded my own industrious researches, and the result is a volume unique, at least, in the character of its illustrations. A large portion of its contents appeared in Harper's Monthly Magazine during the year 1875; but many of the most curious and interesting of the pictures are given here for the first time; notably, those exhibiting the present or recent caricature of Germany, Spain, Italy, China, and Japan, several of which did not arrive in time for use in the periodical.

Generally speaking, articles contributed to a Magazine may as well be left in their natural tomb of "back numbers," or "bound volumes;" for the better they serve a temporary purpose, the less adapted they are for permanent utility. Among the exceptions are such series as the present, which had no reference whatever to the passing months, and in the preparation of which a great expenditure was directed to a single class of objects of special interest. I am, indeed, amazed at the cost of producing such articles as these. So very great is the expense, that many subjects could not be adequately treated, with all desirable illustration, unless the publishers could offer the work to the public in portions.

There is not much to be said upon the subject treated in this volume. When I was invited by the learned and urbane editor of Harper's Monthly to furnish a number of articles upon caricature, I supposed that the work proposed would be a relief after labors too arduous, too long continued, and of a more serious character. On the contrary, no subject that I ever attempted presented such baffling difficulties. After ransacking the world for specimens, and collecting them by the hundred, I found that, usually, a caricature is a thing of a moment, and that, dying as soon as its moment has passed, it loses all power to interest, instantly and forever. I found, too, that our respectable ancestors had not the least notion of what we call decency. When, therefore, I had laid aside from the mass the obsolete and the improper, there were not so very many left, and most of those told their own story so plainly that no elucidation was necessary. Instead of wearying the reader with a mere descriptive catalogue, I have preferred to accompany the pictures with allusions to contemporary satire other than pictorial.

The great living authorities upon this branch of art are two in number—one English, and one French—to both of whom I am greatly indebted. The English author is Thomas Wright, M.A., F.S.A., etc., whose "History of Caricature and the Grotesque" is well known among us, as well as his more recent volume upon the incomparable caricaturist of the last generation, James Gillray. The French writer is M. Jules Champfleury, author of a valuable series of volumes reviewing satiric art from ancient times to our own day, with countless illustrations. No one has treated so fully or so well as he the caricature of the Greeks and Romans. Many years ago, M. Champfleury began to illustrate this part of his subject in the Gazette des Beaux Arts, and his contributions to that important periodical were the basis of his subsequent volumes. He is one of the few writers on comic matters who have avoided the lapse into catalogue, and contrived to be interesting.

It has been agreeable to me to observe that Americans are not without natural aptitude in this kind of art. Our generous Franklin, the friend of Hogarth, to whom the dying artist wrote his last letter, replying to the last letter he ever received, was a capital caricaturist, and used his skill in this way, as he did all his other gifts and powers, in behalf of his country and his kind. At the present time, every week's issue of the illustrated periodicals exhibits evidence of the skill, as well as the patriotism and right feeling, of the humorous artists of the United States. For some years past, caricature has been a power in the land, and a power generally on the right side. There are also humorous artists of another and gentler kind, some even of the gentler sex, who present to us scenes which surprise us all into smiles and good temper without having in them any lurking sting of reproof. These domestic humorists, I trust, will continue to amuse and soften us, while the avenging satirist with dreadful pencil makes mad the guilty, and appalls the free.

There must be something precious in caricature, else the enemies of truth and freedom would not hate it as they do. Some of the worst excesses and perversions of satiric art are due to that very hatred. Persecuted and repressed, caricature becomes malign and perverse; or, being excluded from legitimate subjects, it seems as if it were compelled to ally itself to vice. We have only to turn from a heap of French albums to volumes of English caricature to have a striking evidence of the truth, that the repressive system represses good and develops evil. It is the "Censure" that debauches the comic pencil; it is freedom that makes it the ally of good conduct and sound politics. In free countries alone it has scope enough, without wandering into paths which the eternal proprieties forbid. I am sometimes sanguine enough to think that the pencil of the satirist will at last render war impossible, by bringing vividly home to all genial minds the ludicrous absurdity of such a method of arriving at truth. Fancy two armies "in presence." By some process yet to be developed, the Nast of the next generation, if not the admirable Nast of this, projects upon the sky, in the sight of the belligerent forces, a picture exhibiting the enormous comicality of their attitude and purpose. They all see the point, and both armies break up in laughter, and come together roaring over the joke.

In the hope that this volume may contribute something to the amusement of the happy at festive seasons, and to the instruction of the curious at all times, it is presented to the consideration of the public.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I. PAGE

Among the Romans 15

CHAPTER II.

Among the Greeks 28

CHAPTER III.

Among the Ancient Egyptians 32

CHAPTER IV.

Among the Hindoos 36

CHAPTER V.

Religious Caricature in the Middle Ages 40

CHAPTER VI.

Secular Caricature in the Middle Ages 50

CHAPTER VII.

Caricatures preceding the Reformation 64

CHAPTER VIII.

Comic Art and the Reformation 76

CHAPTER IX.

In the Puritan Period 90

CHAPTER X.

Later Puritan Caricature 105

CHAPTER XI.

Preceding Hogarth 120

CHAPTER XII.

Hogarth and his Time 133

CHAPTER XIII.

English Caricature in the Revolutionary Period 147

CHAPTER XIV.

During the French Revolution 159

CHAPTER XV.

Caricatures of Women and Matrimony 171

CHAPTER XVI.

Among the Chinese 191

CHAPTER XVII.

Comic Art in Japan 198

CHAPTER XVIII.

French Caricature 208

CHAPTER XIX.

Later French Caricature 230

CHAPTER XX.

Comic Art in Germany 242

CHAPTER XXI.

Comic Art in Spain 249

CHAPTER XXII.

Italian Caricature 257

CHAPTER XXIII.

English Caricature of the Present Century 267

CHAPTER XXIV.

Comic Art in "Punch" 284

CHAPTER XXV.

Early American Caricature 300

CHAPTER XXVI.

Later American Caricature 318

INDEX 335

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

- Page

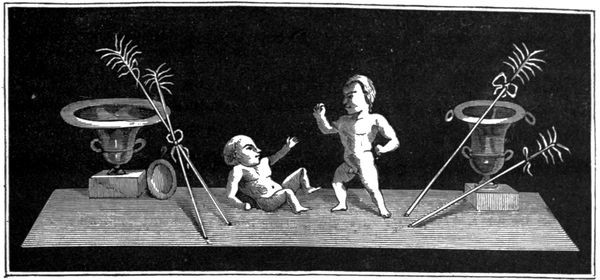

- Pigmy Pugilists, from Pompeii 15

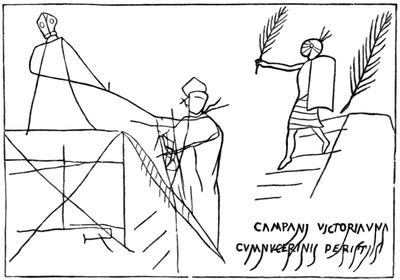

- Chalk Drawing by Roman Soldier in Pompeii 15

- Chalk Caricature on a Wall in Pompeii 16

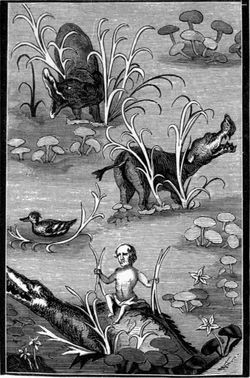

- Battle between Pigmies and Geese 17

- A Pigmy Scene—from Pompeii 18

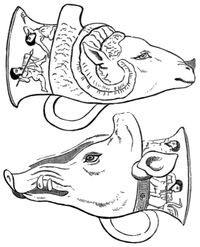

- Vases with Pigmy Designs 19

- A Grasshopper driving a Chariot 19

- From an Antique Amethyst 19

- Flight of Æneas from Troy 20

- Caricature of the Flight of Æneas 20

- From a Red Jasper 21

- Roman Masks, Comic and Tragic 22

- Roman Comic Actor, masked for Silenus 22

- Roman Wall Caricature of a Christian 25

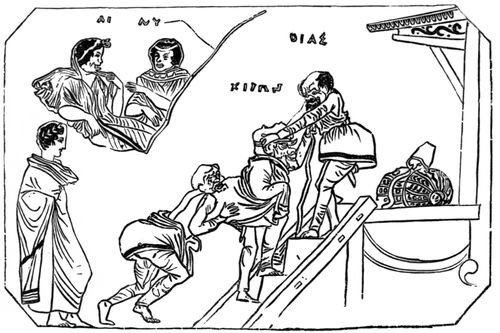

- Burlesque of Jupiter's Wooing of Princess Alcmena 29

- Greek Caricature of the Oracle of Apollo 30

- An Egyptian Caricature 32

- A Condemned Soul, Egyptian Caricature 33

- Egyptian Servants conveying Home their Masters from a Carouse 33

- Too Late with the Basin 34

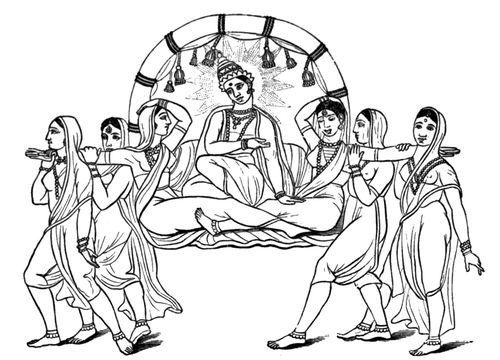

- The Hindoo God Krishna on his Travels 37

- Krishna's Attendants assuming the Form of a Bird 37

- Krishna in his Palanquin 38

- Capital in the Autun Cathedral 41

- Capitals in the Strasburg Cathedral, A.D. 1300 41

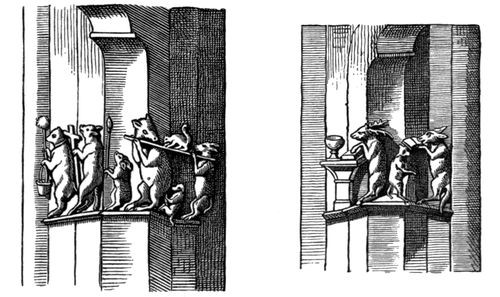

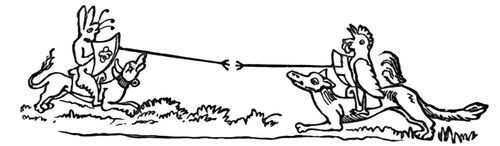

- Engraved upon a Stall in Sherborne Minster, England 43

- From a Manuscript of the Thirteenth Century 43

- From a Mass-book of the Fourteenth Century 44

- From a French Prayer-book of the Thirteenth Century 45

- From Queen Mary's Prayer-book, A.D. 1553 46

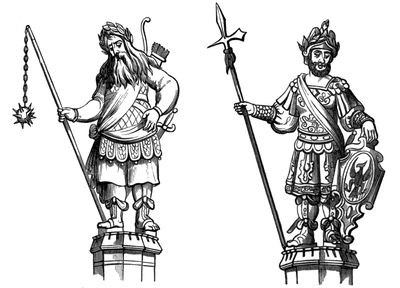

- Gog and Magog, Guildhall, London 50

- Head of the Great Dragon of Norwich 51

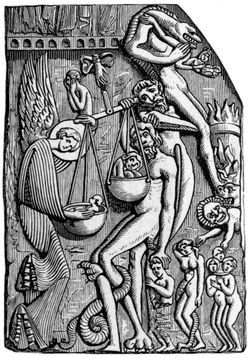

- Souls weighed in the Balance, Autun Cathedral 51

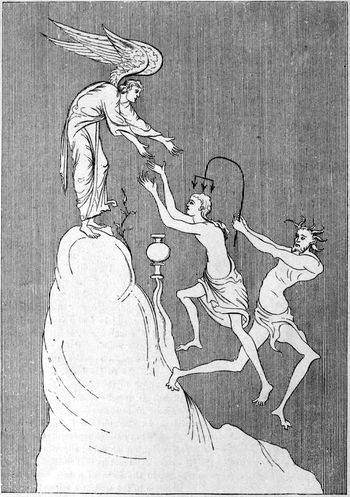

- Struggle for Possession of a Soul between Angel and Devil 52

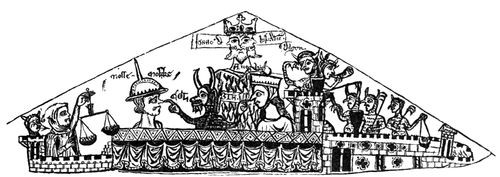

- Lost Souls cast into Hell 53

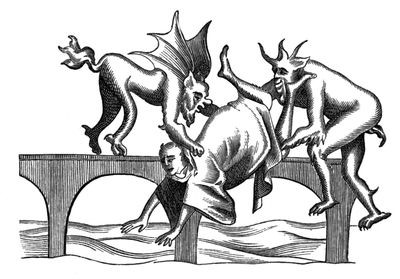

- Devils seizing their Prey 54

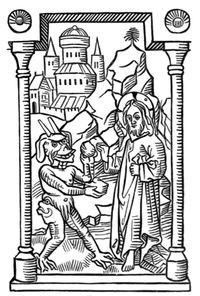

- The Temptation 55

- French Death-crier 56

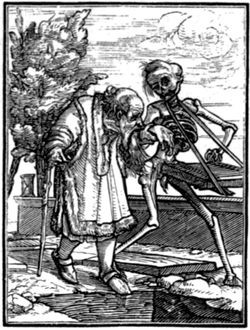

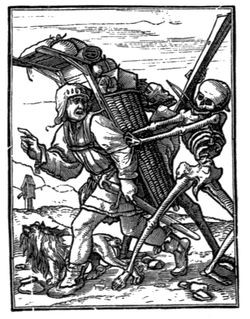

- Death and the Cripple 57

- Death and the Old Man 58

- Death and the Peddler 58

- Death and the Knight 58

- Heaven and Earth weighed in the Balance 60

- English Caricature of an Irishman, A.D. 1280 62

- Caricature of the Jews in England, A.D. 1233 63

- Luther inspired by Satan 64

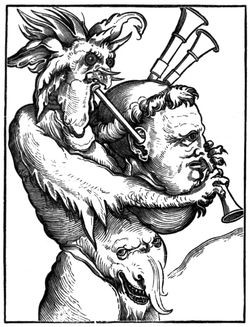

- Devil fiddling upon a Pair of Bellows 65

- Oldest Drawing in the British Museum, A.D. 1320 66

- Bishop's Seal, A.D. 1300 67

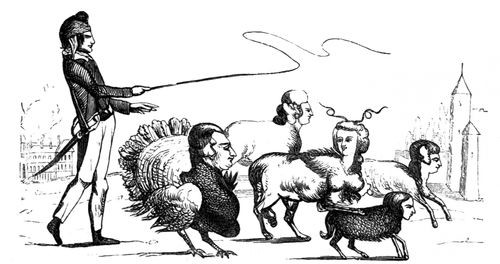

- Pastor and Flock, Sixteenth Century 70

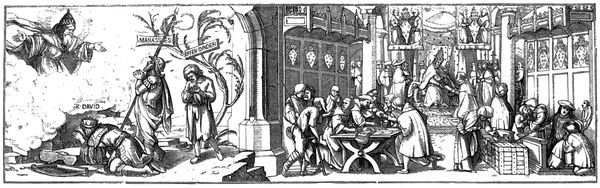

- Confessing to God; and Sale of Indulgences 72

- Christ, the True Light 73

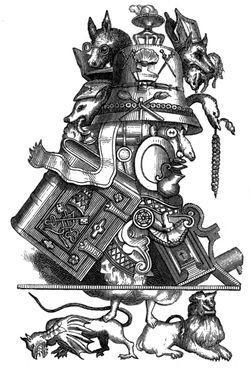

- Papa, Doctor Theologiæ et Magister Fidei 77

- The Pope cast into Hell 77

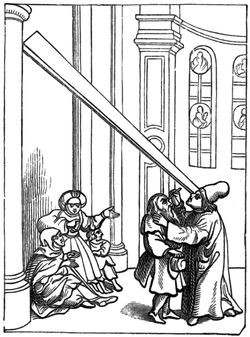

- "The Beam that is in thine own Eye," A.D. 1540 78

- Luther Triumphant 79

- The Triumph of Riches 81

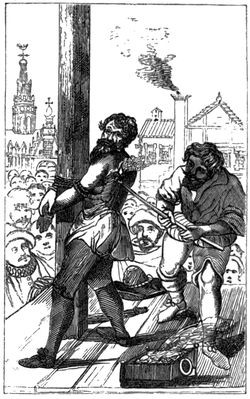

- Calvin branded 83

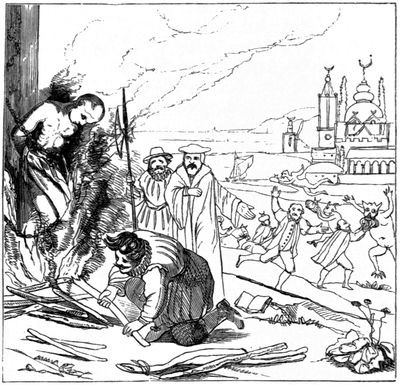

- Calvin at the Burning of Servetus 84

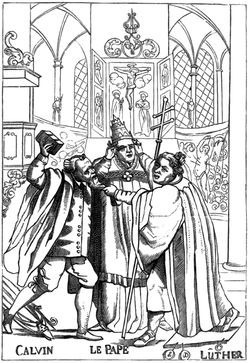

- Calvin, the Pope, and Luther 85

- Titian's Caricature of the Laocoön 89

- The Papal Gorgon 90

- Spayne and Rome defeated 94

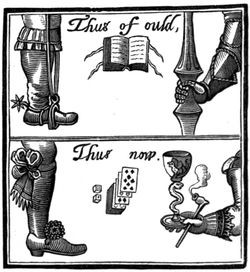

- From Title-page to Sermon "Woe to Drunkards" 97

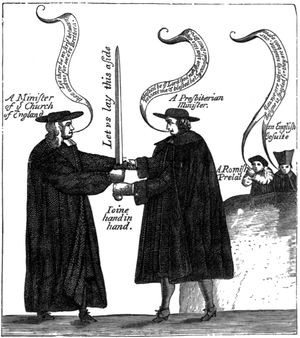

- "Let not the World devide those whom Christ hath joined" 99

- "England's Wolfe with Eagle's Clawes," 1647 102

- Charles II. and the Scotch Presbyterians, 1651 103

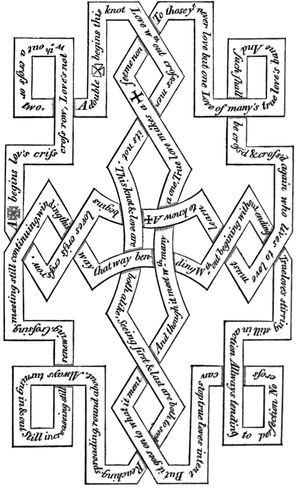

- Cris-cross Rhymes on Love's Crosses, 1640 105

- Shrove-tide in Arms against Lent 107

- Lent tilting at Shrove-tide 108

- The Queen of James II. and Father Petre 109

- Caricature of Corpulent General Galas 115

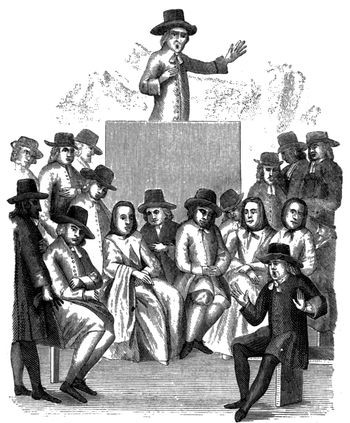

- A Quaker Meeting, 1710 116

- Archbishop of Paris 118

- Archbishop of Rheims 118

- Caricature of Louis XIV., by Thackeray 119

- "Shares! Shares! Shares!" Caricature of John Law 120

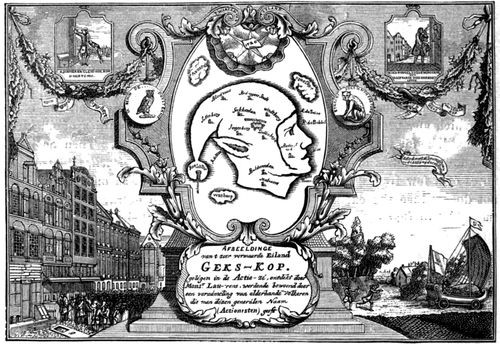

- Island of Madhead 122

- Speculative Map of Louisiana 126

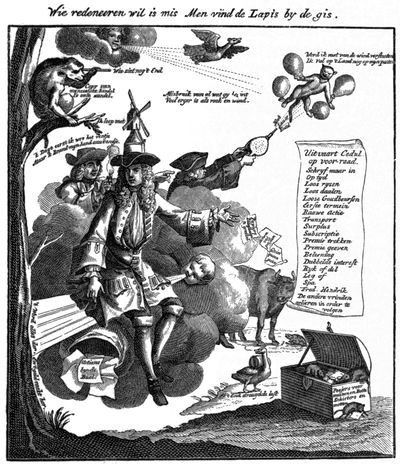

- John Law, Wind Monopolist 129

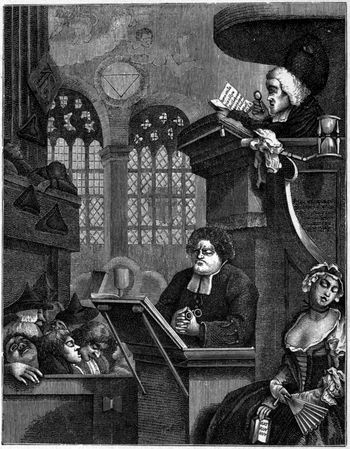

- The Sleeping Congregation 134

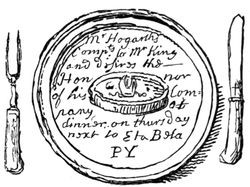

- Hogarth's Drawing in Three Strokes 137

- Hogarth's Invitation Card 137

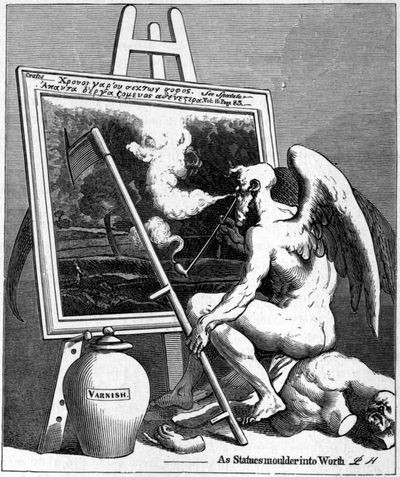

- Time Smoking a Picture 138

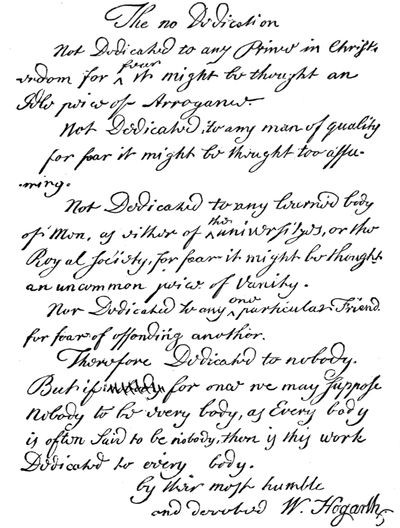

- Dedication of a Proposed History of the Arts 140

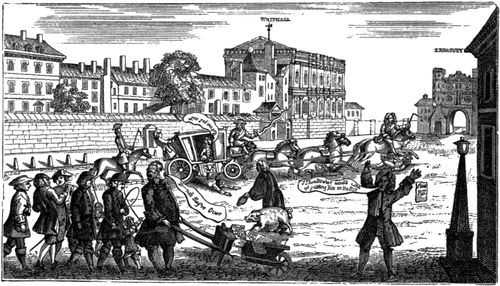

- Walpole paring the Nails of the British Lion 142

- Dutch Neutrality, 1745 142

- British Idolatry of the Opera-singer Mingotti 143

- The Motion (for the Removal of Walpole) 144

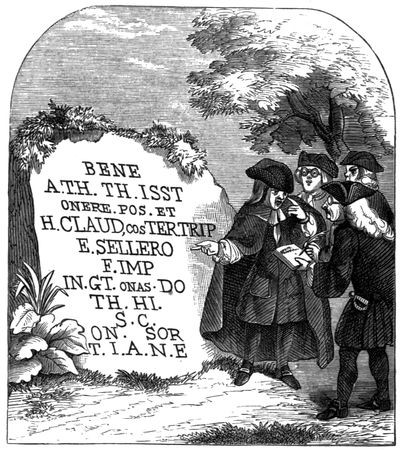

- Antiquaries puzzled 146

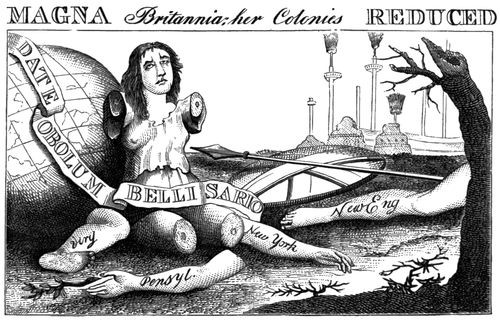

- Caricature designed by Benjamin Franklin 147

- Lord Bute 152

- Princess of Wales—Bute—George III 152

- The Wire-master (Bute) and his Puppets 153

- The Gouty Colossus, William Pitt 156

- The Mask (Coalition) 157

- Heads of Fox and North 158

- Assembly of the Notables at Paris 161

- Mirabeau 162

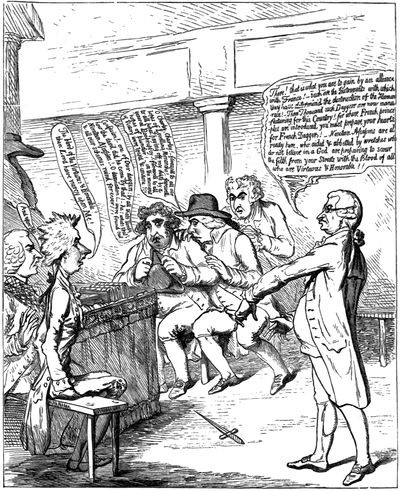

- The Dagger Scene in the House of Commons 164

- The Zenith of French Glory 165

- The Estates 166

- The New Calvary 166

- President of Revolutionary Committee amusing himself with his Art 168

- Rare Animals 169

- Aristocrat and Democrat 170

- "You frank! Have confidence in you!" 171

- Matrimony—A Man loaded with Mischief 173

- Settling the Odd Trick 174

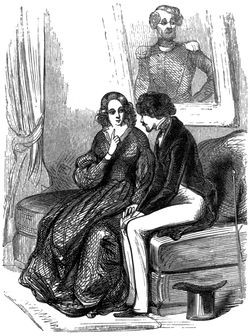

- "Who was that gentleman that just went out?" 176

- "Now, understand me. To-morrow morning he will ask you to dinner" 177

- "Madame, your Cousin Betty wishes to know if you can receive her" 179

- A Scene of Conjugal Life 180

- A Splendid Spread 181

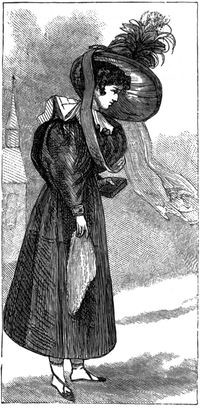

- American Lady walking in the Snow 183

- "My dear Baron, I am in the most pressing need of five hundred franc" 184

- "Sir, be good enough to come round in front and speak to me" 185

- "Where are the diamonds exhibited?" 185

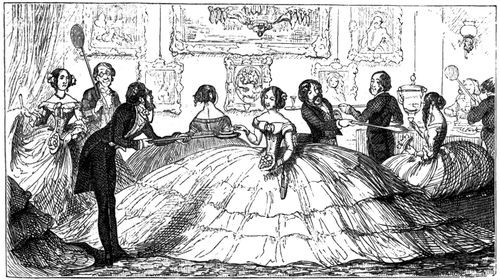

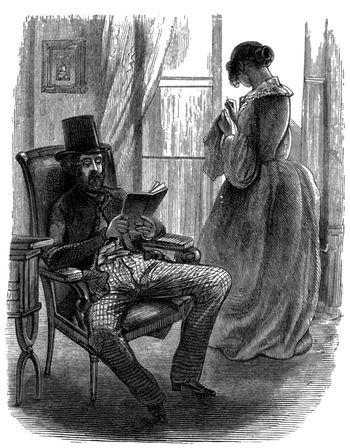

- Evening Scene in the Parlor of an American Boarding-house 186

- "He's coming! Take off your hat!" 188

- The Scholastic Hen and her Chickens 189

- Chinese Caricature of an English Foraging Party 191

- A Deaf Mandarin 196

- After Dinner. A Chinese Caricature 197

- The Rat Rice Merchants. A Japanese Caricature 206

- Talleyrand—the Man with Six Heads 209

- A Great Man's Last Leap 210

- Talleyrand 211

- A Promenade in the Palais Royal 213

- Family of the Extinguishers 214

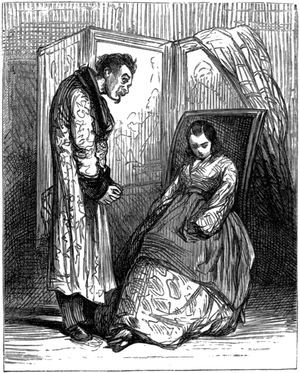

- The Jesuits at Court 215

- Charles Philipon 218

- Robert Macaire fishing for Share-holders 221

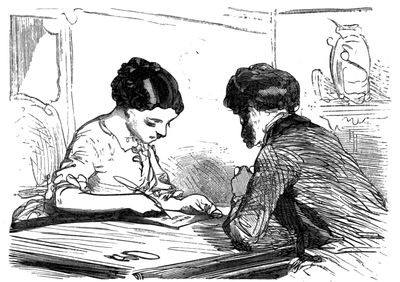

- A Husband's Dilemma 223

- Housekeeping 224

- A Poultice for Two 226

- Parisian "Shoo, Fly!" 227

- Three! 228

- Two Attitudes 230

- The Den of Lions at the Opera 231

- The Vulture 233

- Partant pour la Syrie 234

- Gavarni 236

- Honoré Daumier 237

- Evolution of the Piano 243

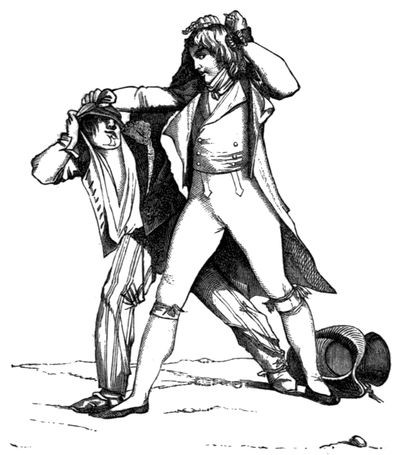

- A Corporal interviewed by the Major 244

- A Bold Comparison 245

- Strict Discipline in the Field 246

- Ahead of Time 247

- A Journeyman's Leave-taking 248

- After Sedan 250

- To the Bull-fight 251

- A Delegation of Birds of Prey 252

- "Child, you will take cold" 253

- Inconvenience of the New Collar 254

- Sufferings endured by a Prisoner of War 255

- King Bomba's Ultimatum to Sicily 259

- He has begun the Service with Mass, and completed it with Bombs 260

- The Burial of Liberty 261

- Bomba at Supper 262

- "Such is the Love of Kings" 263

- Mr. Punch 264

- Return of the Pope to Rome 265

- James Gillray 267

- Tiddy-Doll, the Great French Gingerbread Baker 268

- The Threatened Invasion of England 269

- The Bibliomaniac 270

- Hope—A Phrenological Illustration 271

- Term Time 273

- Box in a New York Theatre in 1830 276

- Seymour's Conception of Mr. Winkle 278

- Probable Suggestion of the Fat Boy 280

- A Wedding Breakfast 281

- The Boy who chalked up "No Popery!" 284

- John Leech 285

- Preparatory School for Young Ladies 286

- The Quarrel.—England and France 287

- Obstructives 290

- Jeddo and Belfast; or, a Puzzle for Japan 291

- "At the Church-gate" 292

- An Early Quibble 294

- John Tenniel 295

- Soliloquy of a Rationalistic Chicken 298

- "I'll follow thee!" 299

- Join or Die 304

- Boston Massacre Coffins 306

- A Militia Drill in Massachusetts in 1832 308

- Fight in Congress between Lyon and Griswold 312

- The Gerry-mander 316

- Thomas Nast 318

- Wholesale and Retail 319

- The Brains of the Tammany Ring 320

- "What are the wild waves saying?" 321

- Shin-plaster Caricature of General Jackson's War on the United States Bank 322

- City People in a Country Church 323

- "Why don't you take it?" 324

- Popular Caricature of the Secession War 325

- Virginia pausing 326

- Tweedledee and Sweedledum 328

- "Who Stole the People's Money?" 329

- "On to Richmond!" 330

- Christmas-time.—Won at a Turkey Raffle 331

- "He cometh not, she said" 332

CHAPTER II.

AMONG THE GREEKS.

CHAPTER III.

AMONG THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS.

CHAPTER IV.

AMONG THE HINDOOS.

CHAPTER V.

RELIGIOUS CARICATURE IN THE MIDDLE AGES.

CHAPTER VI.

SECULAR CARICATURE IN THE MIDDLE AGES.

CHAPTER VII.

CARICATURES PRECEDING THE REFORMATION.

CHAPTER VIII.

COMIC ART AND THE REFORMATION.

CHAPTER IX.

IN THE PURITAN PERIOD.

CHAPTER X.

LATER PURITAN CARICATURE.

CHAPTER XI.

PRECEDING HOGARTH.

CHAPTER XII.

HOGARTH AND HIS TIME.

CHAPTER XIII.

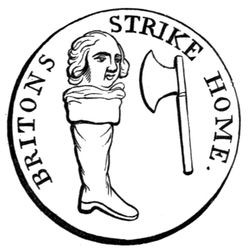

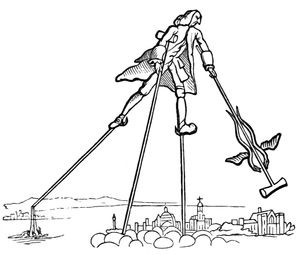

ENGLISH CARICATURE IN THE REVOLUTIONARY PERIOD.

CHAPTER XIV.

DURING THE FRENCH REVOLUTION.

CHAPTER XV.

CARICATURES OF WOMEN AND MATRIMONY.

CHAPTER XVI.

AMONG THE CHINESE.

CHAPTER XVII.

COMIC ART IN JAPAN.

CHAPTER XVIII.

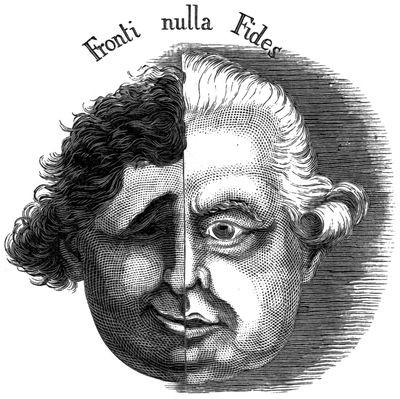

FRENCH CARICATURE.

CHAPTER XIX.

LATER FRENCH CARICATURE.

CHAPTER XX.

COMIC ART IN GERMANY.

CHAPTER XXI.

COMIC ART IN SPAIN.

CHAPTER XXII.

ITALIAN CARICATURE.

CHAPTER XXIII.

ENGLISH CARICATURE OF THE PRESENT CENTURY.

CHAPTER XXIV.

COMIC ART IN "PUNCH."

CHAPTER XXV.

EARLY AMERICAN CARICATURE.

CHAPTER XXVI.

LATER AMERICAN CARICATURE.

INDEX.

Pigmy Pugilists—from Pompeii.

CARICATURE AND COMIC ART.

CHAPTER I.

AMONG THE ROMANS.

Much as the ancients differed from ourselves in other particulars, they certainly laughed at one another just as we do, for precisely the same reasons, and employed every art, device, and implement of ridicule which is known to us.

Observe this rude and childish attempt at a drawing. Go into any boys' school to-day, and turn over the slates and copy-books, or visit an inclosure where men are obliged to pass idle days, and you will be likely to find pictures conceived in this taste, and executed with this degree of artistic skill. But the drawing dates back nearly eighteen centuries. It was done on one of the hot, languid days of August, A.D. 79, by a Roman soldier with a piece of red chalk on a wall of his barracks in the city of Pompeii.[1] On the 23d of August, in the year 79, occurred the eruption of Vesuvius, which buried not Italian cities only, but Antiquity itself, and, by burying, preserved it for the instruction of after-times. In disinterred Pompeii, the Past stands revealed to us, and we remark with a kind of infantile surprise the great number of particulars in which the people of that day were even such as we are. There was found the familiar apothecary's shop, with a box of pills on the counter, and a roll of material that was about to be made up when the apothecary heard the warning thunder and fled. The baker's shop remained, with a loaf of bread stamped with the maker's name. A sculptor's studio was strewed with blocks of marble, unfinished statues, mallets, compasses, chisels, and saws. A thousand objects attest that when the fatal eruption burst upon these cities, life and its activities were going forward in all essential particulars as they are at this moment in any rich and luxurious town of Southern Europe.

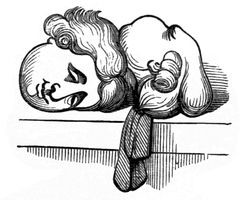

In the building supposed to have been the quarters of the Roman garrison, many of the walls were covered with such attempts at caricature as the specimen just given, to some of which were appended opprobrious epithets and phrases. The name of the personage above portrayed was Nonius Maximus, who was probably a martinet centurion, odious to his company, for the name was found in various parts of the inclosure, usually accompanied by disparaging words. Many of the soldiers had simply chalked their own names; others had added the number of their cohort or legion, precisely as in the late war soldiers left records of their stay on the walls of fort and hospital. A large number of these wall-chalkings in red, white, and black (most of them in red) were clearly legible fifty years after exposure. I give another specimen, a genuine political caricature, copied from an outside wall of a private house in Pompeii.

Chalk Caricature on a Wall in Pompeii.

The allusion is to an occurrence in local history of the liveliest possible interest to the people. A few years before the fatal eruption there was a fierce town-and-country row in the amphitheatre, in which the Pompeians defeated and put to flight the provincial Nucerians. Nero condemned the pugnacious men of Pompeii to the terrible penalty of closing their amphitheatre for ten years. In the picture an armed man descends into the arena bearing the palm of victory, while on the other side a prisoner is dragged away bound. The inscription alone gives us the key to the street artist's meaning, Campani victoria una cum Nucerinis peristis—"Men of Campania, you perished in the victory not less than the Nucerians;" as though the patriotic son of Campania had written, "We beat 'em, but very little we got by it."

If the idlers of the streets chalked caricature on the walls, we can not be surprised to discover that Pompeian artists delighted in the comic and burlesque. Comic scenes from the plays of Terence and Plautus, with the names of the characters written over them, have been found, as well as a large number of burlesque scenes, in which dwarfs, deformed people, Pigmies, beasts, and birds are engaged in the ordinary labors of men. The gay and luxurious people of the buried cities seem to have delighted in nothing so much as in representations of Pigmies, for there was scarcely a house in Pompeii yet uncovered which did not exhibit some trace of the ancient belief in the existence of these little people. Homer, Aristotle, and Pliny all discourse of the Pigmies as actually existing, and the artists, availing themselves of this belief, which they shared, employed it in a hundred ways to caricature the doings of men of larger growth. Pliny describes them as inhabiting the salubrious mountainous regions of India, their stature about twenty-seven inches, and engaged in eternal war with their enemies, the geese. "They say," Pliny continues, "that, mounted upon rams and goats, and armed with bows and arrows, they descend in a body during spring-time to the edge of the waters, where they eat the eggs and the young of those birds, not returning to the mountains for three months. Otherwise they could not resist the ever-increasing multitude of the geese. The Pigmies live in cabins made of mud, the shells of goose eggs, and feathers of the same bird."

Battle between Pigmies and Geese.

Homer, in the third book of the "Iliad," alludes to the wars of the Cranes and Pigmies:

"So when inclement winters vex the plain

With piercing frosts, or thick-descending rain,

To warmer seas the Cranes embodied fly,

With noise and order through the midway sky;

To Pigmy nations wounds and death they bring,

And all the war descends upon the wing."

A Pigmy Scene—from Pompeii.

One of our engravings shows that not India only, but Egypt also, was regarded as the haunt of the Pigmy race; for the Upper Nile was then, as now, the home of the hippopotamus, the crocodile, and the lotus. Here we see a bald-headed Pigmy hero riding triumphantly on a mighty crocodile, regardless of the open-mouthed, bellowing hippopotamus behind him. In other pictures, however, the scaly monster, so far from playing this submissive part, is seen plunging in fierce pursuit of a Pigmy, who flies headlong before the foe. Frescoes, vases, mosaics, statuettes, paintings, and signet-rings found in the ancient cities all attest the popularity of the little men. The odd pair of vases on the following page, one in the shape of a boar's head and the other in that of a ram's, are both adorned with a representation of the fierce combats between the Pigmies and the geese.

There has been an extraordinary display of erudition in the attempt to account for the endless repetition of Pigmy subjects in the houses of the Pompeians; but the learned and acute M. Champfleury "humbly hazards a conjecture," as he modestly expresses it, which commends itself at once to general acceptance. He thinks these Pigmy pictures were designed to amuse the children. No conjecture could be less erudite or more probable. We know, however, as a matter of record, that the walls of taverns and wine-shops were usually adorned with Pigmy pictures, such subjects being associated in every mind with pleasure and gayety. It is not difficult to imagine that a picture of a pugilistic encounter between Pigmies, like the one given at the head of this chapter, or a fanciful representation of a combat of Pigmy gladiators, of which many have been discovered, would be both welcome and suitable as tavern pictures in the Italian cities of the classic period.

Vases with Pigmy Designs.

The Pompeians, in common with all the people of antiquity, had a child-like enjoyment in witnessing representations of animals engaged in the labors or the sports of human beings. A very large number of specimens have been uncovered, some of them gorgeous with the hues given them by masters of coloring eighteen hundred years ago. In the following cut is a specimen of these—a representation of a grasshopper driving a chariot, copied in 1802 from a Pompeian work for an English traveler.

A Grasshopper driving a Chariot.

From an Antique Amethyst.

Nothing can exceed either the brilliancy or the delicacy of the coloring of this picture in the original, the splendid plumage of the bird and the bright gold of the chariot shaft and wheel being relieved and heightened by a gray background and the greenish brown of the course. The colorists of Pompeii have obviously influenced the taste of Christendom. There are few houses of pretension decorated within the last quarter of a century, either in Europe or America, which do not exhibit combinations and contrasts of color of which the hint was found in exhumed Pompeii. One or two other small specimens of this kind of art, selected from a large number accessible, may interest the reader.

Flight of Æneas from Troy.

The spirited air of the team of cocks, and the nonchalant professional attitude of the charioteer, will not escape notice. Perhaps the most interesting example of this propensity to personify animals which the exhumed cities have furnished us is a burlesque of a popular picture of Æneas escaping from Troy, carrying his father, Anchises, on his back, and leading by the hand his son, Ascanius, the old man carrying the casket of household gods. No scene could have been more familiar to the people of Italy than one which exhibited the hero whom they regarded as the founder of their empire in so engaging a light, and to which the genius of Virgil had given a deathless charm:

"Thus ord'ring all that prudence could provide

I clothe my shoulders with a lion's hide

And yellow spoils; then on my bending back

The welcome load of my dear father take;

While on my better hand Ascanius hung,

And with unequal paces tripped along."

Artists found a subject in these lines, and of one picture suggested by them two copies have been found carved upon stone.

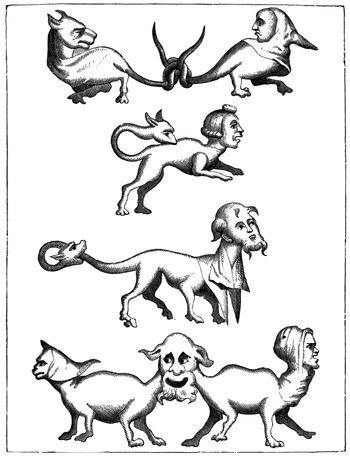

Caricature of the Flight of Æneas.

This device of employing animals' heads upon human bodies is still used by the caricaturist, so few are the resources of his branch of art; and we can not deny that it retains a portion of its power to excite laughter. If we may judge from what has been discovered of the burlesque art of the ancient nations, we may conclude that this idea, poor as it seems to us, was the one which the artists of antiquity most frequently employed. It was also common with them to burlesque familiar paintings, as in the instance given. It is not unlikely that the cloyed and dainty taste of the Pompeian connoisseur perceived something ridiculous in the too-familiar exploit of Father Æneas as represented in serious art, just as we smile at the theatrical attitudes and costumes in the picture of "Washington crossing the Delaware." Fancy that work burlesqued by putting an eagle's head upon the Father of his Country, filling the boat with magpie soldiers, covering the river with icebergs, and making the oars still more ludicrously inadequate to the work in hand than they are in the painting. Thus a caricaturist of Pompeii, Rome, Greece, Egypt, or Assyria would have endeavored to cast ridicule upon such a picture.

From a Red Jasper.

Few events of the last century were more influential upon the progress of knowledge than the chance discovery of the buried cities, since it nourished a curiosity respecting the past which could not be confined to those excavations, and which has since been disclosing antiquity in every quarter of the globe. We call it a chance discovery, although the part which accident plays in such matters is more interesting than important. The digging of a well in 1708 let daylight into the amphitheatre of Herculaneum, and caused some languid exploration, which had small results. Forty years later, a peasant at work in a vineyard five miles from the same spot struck with his hoe something hard, which was too firmly fixed in the ground to be moved. It proved to be a small statue of metal, upright, and riveted to a stone pedestal, which was itself immovably fastened to some solid mass still deeper in the earth. Where the hoe had struck the statue the metal showed the tempting hue of gold, and the peasant, after carefully smoothing over the surface, hurried away with a fragment of it to a goldsmith, intending (so runs the local gossip) to work this opening as his private gold mine. But as the metal was pronounced brass, he honestly reported the discovery to a magistrate, who set on foot an excavation. The statue was found to be a Minerva, fixed to the centre of a small roof-like dome, and when the dome was broken through it was seen to be the roof of a temple, of which the Minerva had been the topmost ornament. And thus was discovered, about the middle of the last century, the ancient city of Pompeii, buried by a storm of light ashes from Vesuvius sixteen hundred and seventy years before.

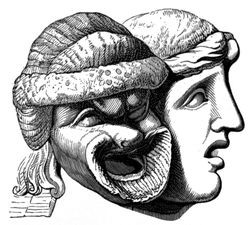

Roman Masks, Comic and Tragic.

It was not the accident, but the timeliness of the accident, which made it important; for there never could have been an excavation fifteen feet deep over the site of Pompeii without revealing indications of the buried city. But the time was then ripe for an exploration. It had become possible to excite a general curiosity in a Past exhumed; and such a curiosity is a late result of culture: it does not exist in a dull or in an ignorant mind. And this curiosity, nourished and inflamed as it was by the brilliant and marvelous things brought to light in Pompeii and Herculaneum, has sought new gratification wherever a heap of ruins betrayed an ancient civilization. It looks now as if many of the old cities of the world are in layers or strata—a new London upon an old London, and perhaps a London under that—a city three or four deep, each the record of an era. Two Romes we familiarly know, one of which is built in part upon the other; and at Cairo we can see the process going on by which some ancient cities were buried without volcanic aid. The dirt of the unswept streets, never removed, has raised the grade of Cairo from age to age.

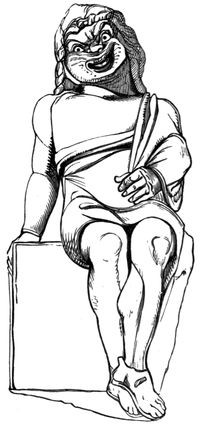

A Roman Comic Actor masked for the Part of Silenus.

The excavations at Rome, so rich in results, were not needed to prove that to the Romans of old caricature was a familiar thing. The mere magnitude of their theatres, and their habit of performing plays in the open air, compelled caricature, the basis of which is exaggeration. Actors, both comic and tragic, wore masks of very elaborate construction, made of resonant metal, and so shaped as to serve, in some degree, the office of a speaking-trumpet. In the engravings on this page are represented a pair of masks such as were worn by Roman actors throughout the empire, of which many specimens have been found.

If the reader has ever visited the Coliseum at Rome, or even one of the large hippodromes of Paris or New York, and can imagine the attempts of an actor to exhibit comic or tragic effects of countenance or of vocal utterance across spaces so extensive, he will readily understand the necessity of such masks as these. The art of acting could only have been developed in small theatres. In the open air or in the uncovered amphitheatre all must have been vociferation and caricature. Observe the figure of old Silenus, on preceding page, one of the chief mirth-makers of antiquity, who lives for us in the Old Man of the pantomime. He is masked for the theatre.

The legend of Silenus is itself an evidence of the tendency of the ancients to fall into caricature. To the Romans he was at once the tutor, the comrade, and the butt of jolly Bacchus. He discoursed wisdom and made fun. He was usually represented as an old man, bald, flat-nosed, half drunk, riding upon a broad-backed ass, or reeling along by the aid of a staff, uttering shrewd maxims and doing ludicrous acts. People wonder that the pantomime called "Humpty Dumpty" should be played a thousand nights in New York; but the substance of all that boisterous nonsense, that exhibition of rollicking freedom from restraints of law, usage, and gravitation, has amused mankind for unknown thousands of years; for it is merely what remains to us of the legendary Bacchus and his jovial crew. We observe, too, that the great comic books, such as "Gil Blas," "Don Quixote," "Pickwick," and others, are most effective when the hero is most like Bacchus, roaming over the earth with merry blades, delightfully free from the duties and conditions which make bondmen of us all. Mr. Dickens may never have thought of it—and he may—but there is much of the charm of the ancient Bacchic legends in the narrative of the four Pickwickians and Samuel Weller setting off on the top of a coach, and meeting all kinds of gay and semi-lawless adventures in country towns and rambling inns. Even the ancient distribution of characters is hinted at. With a few changes, easily imagined, the irrepressible Sam might represent Bacchus, and his master bring to mind the sage and comic Silenus. Nothing is older than our modes of fun. Even in seeking the origin of Punch, investigators lose themselves groping in the dim light of the most remote antiquity.

How readily the Roman satirists ran into caricature all their readers know, except those who take the amusing exaggerations of Juvenal and Horace as statements of fact. During the heat of our antislavery contest, Dryden's translation of the passage in Juvenal which pictures the luxurious Roman lady ordering her slave to be put to death was used by the late Mr. W. H. Fry, in the New York Tribune, with thrilling effect:

"Go drag that slave to death! You reason, Why

Should the poor innocent be doomed to die?

What proofs? For, when man's life is in debate,

The judge can ne'er too long deliberate.

Call'st thou that slave a man? the wife replies.

Proved or unproved the crime, the villain dies.

I have the sovereign power to save or kill,

And give no other reason but my will."

This is evidently caricature. Not only is the whole of Juvenal's sixth satire a series of the broadest exaggerations, but with regard to this particular passage we have evidence of its burlesque character in Horace (Satire III., Book I.), where, wishing to give an example of impossible folly, he says, "If a man should crucify a slave for eating some of the fish which he had been ordered to take away, people in their senses would call him a madman." Juvenal exhibits the Roman matron of his period undergoing the dressing of her hair, giving the scene the same unmistakable character of caricature:

"She hurries all her handmaids to the task;

Her head alone will twenty dressers ask.

Psecas, the chief, with breast and shoulders bare,

Trembling, considers every sacred hair:

If any straggler from his rank be found,

A pinch must for the mortal sin compound.

"With curls on curls they build her head, before,

And mount it with a formidable tower.

A giantess she seems; but look behind,

And then she dwindles to the Pigmy kind.

Duck-legged, short-waisted, such a dwarf she is

That she must rise on tiptoe for a kiss.

Meanwhile her husband's whole estate is spent;

He may go bare, while she receives his rent."

The spirit of caricature speaks in these lines. There are passages of Horace, too, in reading which the picture forms itself before the mind; and the poet supplies the very words which caricaturists usually employ to make their meaning more obvious. In the third satire of the second book a caricature is exhibited to the mind's eye without the intervention of pencil. We see the miser Opimius, "poor amid his hoards of gold," who has starved himself into a lethargy; his heir is scouring his coffers in triumph; but the doctor devises a mode of rousing his patient. He orders a table to be brought into the room, upon which he causes the hidden bags of money to be poured out, and several persons to draw near as if to count it. Opimius revives at this maddening spectacle, and the doctor urges him to strengthen himself by generous food, and so balk his rapacious heir. "Do you hesitate?" cries the doctor. "Come, now, take this preparation of rice." "How much did it cost?" asks the miser. "Only a trifle." "But how much?" "Eightpence." Opimius, appalled at the price, whimpers, "Alas! what does it matter whether I die of a disease, or by plunder and extortion?" Many similar examples will arrest the eye of one who turns over the pages of this master of satire.

The great festival of the Roman year, the Saturnalia, which occurred in the latter half of December, we may almost say was consecrated to caricature, so fond were the Romans of every kind of ludicrous exaggeration. This festival, the merry Christmas of the Roman world, gave to the Christian festival many of its enlivening observances. During the Saturnalia the law courts and schools were closed; there was a general interchange of presents, and universal feasting; there were fantastic games, processions of masked figures in extravagant costumes, and religious sacrifices. For three days the slaves were not merely exempt from labor, but they enjoyed freedom of speech, even to the abusing of their masters. In one of his satires, Horace gives us an idea of the manner in which slaves burlesqued their lords at this jocund time. He reports some of the remarks of his own slave, Davus, upon himself and his poetry. Davus, it is evident, had discovered the histrionic element in literature, and pressed it home upon his master. "You praise the simplicity of the ancient Romans; but if any god were to reduce you to their condition, you, the same man that wrote those fine things, would beg to be let off. At Rome you long for the country; and when you are in the country, you praise the distant city to the skies. When you are not invited out to supper, you extol your homely repast at home, and hug yourself that you are not obliged to drink with any body abroad. As if you ever went out upon compulsion! But let Mæcenas send you an invitation for early lamp-light, then what do we hear? Will no one bring the oil quicker? Does any body hear me? You bellow and storm with fury. You bought me for five hundred drachmas, but what if it turns out that you are the greater fool of the two?" And thus the astute and witty Davus continues to ply his master with taunts and jeers and wise saws, till Horace, in fury, cries out, "Where can I find a stone?" Davus innocently asks, "What need is there here of such a thing as a stone?" "Where can I get some javelins?" roars Horace. Upon which Davus quietly remarks, "This man is either mad or making verses." Horace ends the colloquy by saying, "If you do not this instant take yourself off, I'll make a field-hand of you on my Sabine estate!"

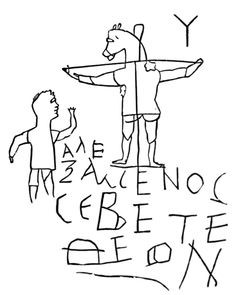

Roman Wall Caricature of a Christian.

That Roman satirists employed the pencil and the brush as well as the stylus, and employed them freely and constantly, we should have surmised if the fact had not been discovered. Most of the caricatures of passing events speedily perish in all countries, because the materials usually employed in them are perishable. To preserve so slight a thing as a chalk sketch on a wall for eighteen centuries, accident must lend a hand, as it has in the instance now given.

This picture was found in 1857 upon the wall of a narrow Roman street, which was closed up and shut out from the light of day about A.D. 100, to facilitate an extension of the imperial palace. The wall when uncovered was found scratched all over with rude caricature drawings in the style of the specimen given. This one immediately arrested attention, and the part of the wall on which it was drawn was carefully removed to the Collegio Romano, in the museum of which it may now be inspected. The Greek words scrawled upon the picture may be translated thus: "Alexamenos is worshiping his god."

These words sufficiently indicate that the picture was aimed at some member, to us unknown, of the despised sect of the Christians. It is the only allusion to Christianity which has yet been found upon the walls of the Italian cities; but it is extremely probable that the street artists found in the strange usages of the Christians a very frequent subject.

We know well what the educated class of the Romans thought of the Christians, when they thought of them at all. They regarded them as a sect of extremely absurd Jews, insanely obstinate, and wholly contemptible. If the professors and students of Harvard and Yale should read in the papers that a new sect had arisen among the Mormons, more eccentric and ridiculous even than the Mormons themselves, the intelligence would excite in their minds about the same feeling that the courtly scholars of the Roman Empire manifest when they speak of the early Christians. Nothing astonished them so much as their "obstinacy." "A man," says the Emperor Marcus Aurelius, "ought to be ready to die when the time comes; but this readiness should be the result of a calm judgment, and not be an exhibition of mere obstinacy, as with the Christians." The younger Pliny, too, in his character of magistrate, was extremely perplexed with this same obstinacy. He tells us that when people were brought before him charged with being Christians, he asked them the question, Are you a Christian? If they said they were, he repeated it twice, threatening them with punishment; and if they persisted, he ordered them to be punished. If they denied the charge, he put them to the proof by requiring them to repeat after him an invocation to the gods, and to offer wine and incense to the emperor's statue. Some of the accused, he says, reviled Christ; and this he regarded as a sure proof of innocence, for people told him there was no forcing real Christians to do an act of that nature. Some of the accused owned that they had been Christians once, three years ago or more, and some twenty years ago, but had returned to the worship of the gods. These, however, declared that, after all, there was no great offense in being Christians. They had merely met on a regular day before dawn, addressed a form of prayer to Christ as to a divinity, and bound themselves by a solemn oath not to commit fraud, theft, or other immoral act, nor break their word, nor betray a trust; after which they used to separate, then re-assemble, and eat together a harmless meal.

All this seemed innocent enough; but Pliny was not satisfied. "I judged it necessary," he writes to the emperor, "to try to get at the real truth by putting to the torture two female slaves who were said to officiate at their religious rites; but all I could discover was evidence of an absurd and extravagant superstition." So he refers the whole matter to the emperor, telling him that the "contagion" is not confined to the cities, but has spread into the villages and into the country. Still, he thought it could be checked: nay, it had been checked; for the temples, which had been almost abandoned, were beginning to be frequented again, and there was also "a general demand for victims for sacrifice, which till lately had found few purchasers." The wise Trajan approved the course of his representative. He tells him, however, not to go out of his way to look for Christians; but if any were brought before him, why, of course he must inflict the penalty unless they proved their innocence by invoking the gods. The remains of Roman literature have nothing so interesting for us as these two letters of Pliny and Trajan of the year 103. We may rest assured that the walls of every Roman town bore testimony to the contempt and aversion in which the Christians were held, particularly by those who dealt in "victims" and served the altars—a very numerous and important class throughout the ancient world.

CHAPTER II.

AMONG THE GREEKS.

Greece was the native home of all that we now call art. Upon looking over the two hundred pages of art gossip in the writings of the elder Pliny, most of which relates to Greece, we are ready to ask, Is there one thing in painting or drawing, one school, device, style, or method, known to us which was not familiar to the Greeks? They had their Landseers—men great in dogs and all animals; they had artists renowned in the "Dutch style" ages before the Dutch ceased to be amphibious—artists who painted barber-shop interiors to a hair, and donkeys eating cabbages correct to a fibre; they had cattle pieces as famous throughout the classic world as Rosa Bonheur's "Horse Fair" is now in ours; they had Rosa Bonheurs of their own—famous women, a list of whose names Pliny gives; they had portrait-painters too good to be fashionable, and portrait-painters too fashionable to be good; they had artists who excelled in flesh, others great in form, others excellent in composition; they took plaster casts of dead faces; they had varnishers and picture-cleaners. Noted pictures were spoken of as having lost their charm through an unskillful cleaner. They had their "life school," and used it as artists now do, borrowing from each model her special beauty. Zeuxis, as Pliny records, was so scrupulously careful in the execution of a religious painting that "he had the young maidens of the place stripped for examination, and selected five of them, in order to adopt in his picture the most commendable points in the form of each." And we may be sure that every maiden of them felt it to be an honor thus to contribute perfection to a Juno, executed by the first artist of the world, which was to adorn the temple of her native city.

They played with art as men are apt to play with the implements of which they are masters. Sosus, the great artist in mosaics, executed at Pergamus the pavement of a banqueting-room which presented the appearance of a floor strewed with crumbs, fragments and scraps of a feast, not yet swept away. It was renowned as the "Unswept Hall of Pergamus." And what a pleasing story is that of the contest between Zeuxis and his rival, Parrhasius! On the day of trial Zeuxis hung in the place of exhibition a painting of grapes, and Parrhasius a picture of a curtain. Some birds flew to the grapes of Zeuxis, and began to pick at them. The artist, overjoyed at so striking a proof of his success, turned haughtily to his rival, and demanded that the curtain should be drawn aside and the picture revealed. But the curtain was the picture. He owned himself surpassed, since he had only deceived birds, but Parrhasius had deceived Zeuxis.

Burlesque of Jupiter's Wooing of the Princess Alcmena.

Could comic artists and caricaturists be wanting in Athens? Strange to say, it was the gods and goddesses whom the caricaturists of Greece as well as the comic writers chiefly selected for ridicule. All their works have perished except a few specimens preserved upon pottery. We show one from a Greek vase, a rude burlesque of one of Jupiter's love adventures, the father of gods and men being accompanied by a Mercury ludicrously unlike the light and agile messenger of the gods. The story goes that the Princess Alcmena, though betrothed to a lover, vowed her hand to the man who should avenge her slaughtered brothers. Jupiter assumed the form and face of the lover, and, pretending to have avenged her brothers' death, gained admittance. Pliny describes a celebrated burlesque painting of the birth of Bacchus from Jupiter's thigh, in which the god of the gods was represented wearing a woman's cap, in a highly ridiculous posture, crying out, and surrounded by goddesses in the character of midwives. The best specimen of Greek caricature that has come down to us burlesques no less serious a theme than the great oracle of Apollo at Delphos, given on page 30.

This remarkable work owes its preservation to the imperishable nature of the material on which it was executed. It was copied from a large vessel used by the Greeks and Romans for holding vinegar, a conspicuous object upon their tables, and therefore inviting ornament. What audacity to burlesque an oracle to which kings and conquerors humbly repaired for direction, and which all Greece held in awe! Crœsus propitiated this oracle by the gift of a solid golden lion as large as life, and the Phocians found in its coffers, and carried off, a sum equal to nearly eleven millions of dollars in gold. Such was the general belief in its divine inspiration! But in this picture we see the oracle, the god, and those who consult them, all exhibited in the broadest burlesque: Apollo as a quack doctor on his platform, with bag, bow, and cap; Chiron, old and blind, struggling up the steps to consult him, aided by Apollo at his head and a friend pushing behind; the nymphs surveying the scene from the heights of Parnassus; and the manager of the spectacle, who looks on from below. How strange is this!

But the Greek literature is also full of this wild license. Lucian depicts the gods in council ludicrously discussing the danger they were in from the philosophers. Jupiter says, "If men are once persuaded that there are no gods, or, if there are gods, that we take no care of human affairs, we shall have no more gifts or victims from them, but may sit and starve on Olympus without festivals, holidays, sacrifices, or any pomp or ceremonies whatever." The whole debate is in this manner, and is at the same time a burlesque of the political discussions at the Athenian mass-meetings. What can be more ludicrous than the story of Mercury visiting Athens in disguise in order to discover the estimation in which he was held among mortals? He enters the shop of a dealer in images, where he inquires the price first of a Jupiter, then of an Apollo, and, lastly, with a blush, of a Mercury. "Oh," says the dealer, "if you take the Jupiter and the Apollo, I will throw the Mercury in."

Greek Caricature of the Oracle of Apollo at Delphos.

Nor did the witty, rollicking Greeks confine their satire to the immortals. Of the famous mirth-provokers of the world, such as Cervantes, Ariosto, Molière, Rabelais, Sterne, Voltaire, Thackeray, Dickens, the one that had most power to produce mere physical laughter, power to shake the sides and cause people to roll helpless upon the floor, was the Greek dramatist Aristophanes. The force of the comic can no farther go than he has carried it in some of the scenes of his best comedies. Even to us, far removed as we are, in taste as well as in time, from that wonderful Athens of his, they are still irresistibly diverting. This master of mirth is never so effective as when he is turning into ridicule the philosophers and poets for whose sake Greece is still a dear, venerable name to all the civilized world. In his comedy of "The Frogs" he sends Bacchus down into Hades with every circumstance of riotous burlesque, and there he exhibits the two great tragic poets, Æschylus and Euripides, standing opposite each other, and competing for the tragic throne by reciting verses in which the mannerism of each, as well as familiar passages of their plays, is broadly burlesqued. Nothing in literature can be found more ludicrous or less becoming, unless we look for it in Aristophanes himself. In his play of "The Clouds" occurs his caricature of Socrates, of infinite absurdity, but not ludicrous to us, because we read it as part of the story of a sublime and affecting martyrdom. It fills our minds with wonder to think that a people among whom a Socrates could have been formed could have borne to see him thus profaned. A rogue of a father, plagued by an extravagant son, repairs to the school of Socrates to learn the arts by which creditors are argued out of their just claims in courts of justice. Upon reaching the place, the door of the "Thinking Shop" opens, and behold! a caricature all ready for the artist's pencil. The pupils are discovered with their heads fixed to the floor, their backs uppermost, and Socrates hanging from the ceiling in a basket. The visitor, transfixed with wonder, questions his companion. He asks why they present that portion of their bodies to heaven. "It is getting taught astronomy alone by itself." "And who is this man in the basket?" "Himself." "Who's Himself?" "Socrates!" The visitor at length addresses the master by a diminutive, as though he had said, "Socrates, dear little Socrates." The philosopher speaks: "Why callest thou me, thou creature of a day?" "Tell me, first, I beg, what you are doing up there." "I am walking in the air, and speculating about the sun; for I should never have rightly learned celestial things if I had not suspended the intellect, and subtly mingled Thought with its kindred Air." All this is in the very spirit of caricature. Half of Aristophanes is caricature. In characterizing the light literature of Greece we are reminded of Juvenal's remark upon the Greek people, "All Greece is a comedian."

CHAPTER III.

AMONG THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS.

Egyptian art was old when Grecian art was young, and it remained crude when the art of Greece had reached its highest development. But not the less did it delight in caricature and burlesque. In the Egyptian collection belonging to the New York Historical Society there is a specimen of the Egyptians' favorite kind of burlesque picture which dates back three thousand years, but which stands out more clearly now upon its slab of limestone than we can engrave it here.

An Egyptian Caricature.

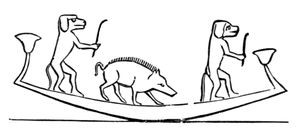

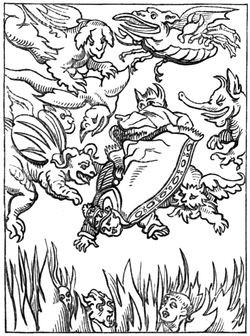

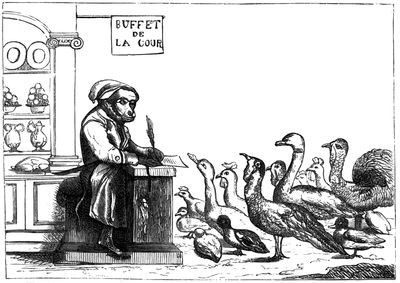

Dr. Abbott, who brought this specimen from Thebes, interpreted it to be a representation of a lion seated upon a throne, as king, receiving from a fox, personating a high-priest, an offering of a goose and a fan. It is probably a burlesque of a well-known picture; for in one of the Egyptian papyri in the British Museum there is a drawing of a lion and unicorn playing chess, which is a manifest caricature of a picture frequently repeated upon the ancient monuments. It was from Egypt, then, that the classic nations caught this childish fancy of ridiculing the actions of men by picturing animals performing similar ones; and it is surprising to note how fond the Egyptian artists were of this simple device. On the same papyrus there are several other interesting specimens: a lion on his hind-legs engaged in laying out as a mummy the dead body of a hoofed animal; a tiger or wild cat driving a flock of geese to market; another tiger carrying a hoe on one shoulder and a bag of seed on the other; an animal playing on a double pipe, and driving before him a herd of small stags, like a shepherd; a hippopotamus washing his hands in a tall water-jar; an animal on a throne, with another behind him as a fan-bearer, and a third presenting him with a bouquet. No place was too sacred for such playful delineations. In one of the royal sepulchres at Thebes, as Kenrick relates, there is a picture of an ass and a lion singing, accompanying themselves on the phorminx and the harp. There is also an elaborate burlesque of a battle piece, in which a fortress is attacked by rats, and defended by cats, which are visible on the battlements. Some rats bring a ladder to the walls and prepare to scale them, while others, armed with spears, shields, and bows, protect the assailants. One rat of enormous size, in a chariot drawn by dogs, has pierced several cats with arrows, and is swinging round his battle-axe in exact imitation of Rameses, in a serious picture, dealing destruction on his enemies. On a papyrus at Turin there is a representation of a cat with a shepherd's crook watching a flock of geese, while a cynocephalus near by plays upon the flute. Of this class of burlesques the most interesting example, perhaps, is the one annexed, representing a Soul doomed to return to its earthly home in the form of a pig.

A Condemned Soul, Egyptian Caricature.

This picture, which is of such antiquity that it was an object of curiosity to the Romans and the Greeks, is part of the decoration of a king's tomb. In the original, Osiris, the august judge of departed spirits, is represented on his throne, near the stern of the boat, waving away the Soul, which he has just weighed in his unerring scales and found wanting; while close to the shore a man hews away the ground, to intimate that all communication is cut off between the lost spirit and the abode of the blessed. The animals that execute the stern decree are the dog-headed monkeys, sacred in the mythology of Egypt.

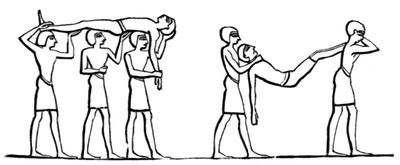

Egyptian Servants conveying Home their Masters from a Carouse.

That the ancient Egyptians were a jovial people who sat long at the wine, we might infer from the caricatures which have been discovered in Egypt, if we did not know it from other sources of information. Representations have been found of every part of the process of wine-making, from the planting of the vineyard to the storing-away of the wine-jars. In the valuable works of Sir Gardner Wilkinson[2] many of these curious pictures are given: the vineyard and its trellis-work; men frightening away the birds with slings; a vineyard with a water-tank for irrigation; the grape harvest; baskets full of grapes covered with leaves; kids browsing upon the vines; trained monkeys gathering grapes; the wine-press in operation; men pressing grapes by the natural process of treading; pouring the wine into jars; and rows of jars put away for future use. The same laborious author favors us with ancient Egyptian caricatures which serve to show that wine was a creature as capable of abuse thirty centuries ago as it is now.

Pictures of similar character are not unfrequent upon the ancient frescoes, and many of them are far more extravagant than this, exhibiting men dancing wildly, standing upon their heads, and riotously fighting. From Sir Gardner Wilkinson's disclosures we may reasonably infer that the arts of debauchery have received little addition during the last three thousand years. Even the seductive cocktail is not modern. The ancient Egyptians imbibed stimulants to excite an appetite for wine, and munched the biting cabbage-leaf for the same purpose. Beer in several varieties was known to them also; veritable beer, made of barley and a bitter herb; beer so excellent that the dainty Greek travelers commended it as a drink only inferior to wine. Even the Egyptian ladies did not always resist the temptation of so many modes of intoxication. Nor did they escape the caricaturist's pencil.

1: "Naples and the Campagna Felice." In a Series of Letters addressed to a Friend in England, in 1802, p. 104.

2: "A Popular Account of the Ancient Egyptians," by Sir J. Gardner Wilkinson, 2 vols., Harper & Brothers, 1854.

Too Late with the Basin.

This unfortunate lady, as Sir Gardner conjectures, after indulging in potations deep of the renowned Egyptian wine, had been suddenly overtaken by the consequences, and had called for assistance too late. Egyptian satirists did not spare the ladies, and they aimed their shafts at the same foibles that have called forth so many efforts of pencil and pen in later times. Whenever, indeed, we look closely into ancient life, we are struck with the similarity of the daily routine to that of our own time. Every detail of social existence is imperishably recorded upon the monuments of ancient Egypt, even to the tone and style and mishaps of a fashionable party. We see the givers of the entertainment, the master and mistress of the mansion, seated side by side upon a sofa; the guests coming up as they arrive to salute them; the musicians and dancers bowing low to them before beginning to perform; a pet monkey, a dog, or a gazelle tied to the leg of the sofa; the youngest child of the family sitting on the floor by its mother's side, or upon its father's knee; the ladies sitting in groups, conversing upon the deathless, inexhaustible subject of dress, and showing one another their trinkets.

Sir Gardner Wilkinson gives us also the pleasing information that it was thought a pretty compliment for one guest to offer another a flower from his bouquet, and that the guests endeavored to gratify their entertainers by pointing out to one another, with expressions of admiration, the tasteful knickknacks, the boxes of carved wood or ivory, the vases, the elegant light tables, the chairs, ottomans, cushions, carpets, and furniture with which the apartment was provided. This too transparent flattery could not escape such inveterate caricaturists as the Egyptian artists. In a tomb at Thebes may be seen a ludicrous representation of scenes at a party where several of the guests had been lost in rapturous admiration of the objects around them. A young man, either from awkwardness or from having gone too often to the wine-jar, had reclined against a wooden column placed in the centre of the room to support a temporary ornament. There is a crash! The ornamental structure falls upon some of the absorbed guests. Ladies have recourse to the immortal privilege of their sex—they scream. All is confusion. Uplifted hands ward off the falling masses. In a few moments, when it is discovered that no one is hurt, peace is restored, and all the company converse merrily over the incident.

It is strange to find such pictures in a tomb. But it seems as if death and funerals and graves, with their elaborate paraphernalia, were provocative of mirthful delineation. In one noted royal tomb there is a representation of the funeral procession, part of which was evidently designed to excite merriment. The Ethiopians who follow in the train of the mourning queen have their hair plaited in most fantastic fashion, and their tunics of leopard's skin are so arranged that a preposterously enormous tail hangs down behind for the next man to step upon. One of the extensive colored plates of Sir Gardner Wilkinson's larger work presents to our view a solemn and stately procession of funeral barges crossing the Lake of the Dead at Thebes on its way to the place of burial. The first boat contains the coffin, decorated with flowers, a high-priest burning incense before a table of offerings, and the female relatives of the deceased lamenting their loss; two barges are filled with mourning friends, one containing only women and the other only men; two more are occupied by professional persons—the undertaker's assistants, as we should call them—employed to carry offerings, boxes, chairs, and other funeral objects. It was in drawing one of these vessels that the artist could not refrain from putting in a little fun. One of the barges having grounded upon the shore, the vessel behind comes into collision with her, upsetting a table upon the oarsmen and causing much confusion. It is not improbable that the picture records an incident of that particular funeral.

CHAPTER IV.

AMONG THE HINDOOS.

If we go farther back into antiquity, it is India which first arrests and longest absorbs our attention—India, fecund mother of tradition, the source of almost all the rites, beliefs, and observances of the ancient nations. When we visit the collections of the India House, the British Museum, the Mission Rooms, or turn over the startling pages of "The Hindu Pantheon" of Major Edward Moor, we are ready to exclaim, Here all is caricature! This brazen image, for example, of a partly naked man with an elephant's head and trunk, seated upon a huge rat, and feeding himself with his trunk from a bowl held in his hand—surely this is caricature. By no means. It is an image of the most popular of the Hindoo deities—Ganesa, god of prudence and policy, invoked at the beginning of all enterprises, and over whose head is written the sacred word Aum, never uttered by a Hindoo except with awe and veneration. If a man begins to build a house, he calls on Ganesa, and sets up an image of him near the spot. Mile-stones are fashioned in his likeness, and he serves as the road-side god, even if the pious peasants who place him where two roads cross can only afford the rudest resemblance to an elephant's head daubed with oil and red ochre. Rude as it may be, a passing traveler will occasionally hang upon it a wreath of flowers. Major Moor gives us a hideous picture of Maha-Kala, with huge mouth and enormous protruding tongue, squat, naked, upon the ground, and holding up a large sword. This preposterous figure is still farther removed from the burlesque. It is the Hindoo mode of representing Eternity, whose vast insatiate maw devours men, cities, kingdoms, and will at length swallow the universe; then all the crowd of inferior deities, and finally itself, leaving only Brahm, the One Eternal, to inhabit the infinite void. Hundreds of such revolting crudities meet the eye in every extensive Indian collection.

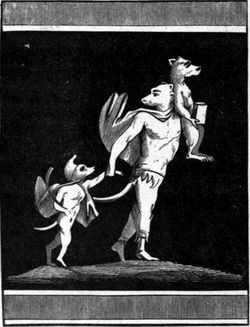

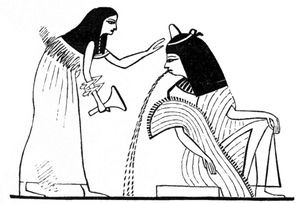

But the element of fun and burlesque is not wanting in the Hindoo Pantheon. Krishna is the jolly Bacchus, the Don Juan, of the Indian deities. Behold him on his travels mounted upon an elephant, which is formed of the bodies of the obliging damsels who accompany him!

The Hindoo God Krishna on his Travels.

There is no end to the tales related of the mischievous, jovial, irrepressible Krishna. The ladies who go with him everywhere, a countless multitude, are so accommodating as to wreathe and twist themselves into the form of any creature he may wish to ride; sometimes into that of a horse, sometimes into that of a bird.

Krishna's Attendants assuming the Form of a Bird.

In other pictures he appears riding in a palanquin, which is likewise composed of girls, and the bearers are girls also. In the course of one adventure, being in great danger from the wrath of his numerous enemies, he created an enormous snake, in whose vast interior his flocks, his herds, his followers, and himself found refuge. At a festival held in his honor, which was attended by a great number of damsels, he suddenly appeared in the midst of the company and proposed a dance; and, that each of them might be provided with a partner, he divided himself into as many complete and captivating Krishnas as there were ladies. One summer, when he was passing the hot season on the sea-shore with his retinue of ladies, his musical comrade, Nareda, hinted to him that, since he had such a multitude of wives, it would be no great stretch of generosity to spare one to a poor musician who had no wife at all. "Court any one you please," said the merry god. So Nareda went wooing from house to house, but in every house he found Krishna perfectly domesticated, the ever-attentive husband, and the lady quite sure that she had him all to herself. Nareda continued his quest until he had visited precisely sixteen thousand and eight houses, in each and all of which, at one and the same time, Krishna was the established lord. Then he gave it up. One of the pictures which illustrate the endless biography of this entertaining deity represents him going through the ceremony of marriage with a bear, both squatting upon a carpet in the prescribed attitude, the bear grinning satisfaction, two bears in attendance standing on their hind-feet, and two priests blessing the union. This picture is more spirited, is more like art, than any other yet copied from Hindoo originals.

Krishna in his Palanquin.

To this day, as the missionaries report, the people of India are excessively addicted to every kind of jesting which is within their capacity, and delight especially in all the monstrous comicalities of their mythology. No matter how serious an impression a speaker may have made upon a village group, let him but use a word in a manner which suggests a ludicrous image or ridiculous pun, and the assembly at once breaks up in laughter, not to be gathered again.

In late years, those of the inhabitants of India who read the language of their conquerors have had an opportunity of becoming acquainted with their humor. Wherever a hundred English officers are gathered, there is the possibility of an illustrated comic periodical, and, accordingly, we find one such in several of the garrisoned places held by the English in remote parts of the world. Calcutta, as the Athenæum informs us, "has its Punch, or Indian Charivari," which is not unworthy of its English namesake.

CHAPTER V.

RELIGIOUS CARICATURE IN THE MIDDLE AGES.

Mr. Robert Tomes, American consul, a few years ago, at the French city of Rheims, describes very agreeably the impression made upon his mind by the grand historic cathedral of that ancient place.[3] Filled with a sense of the majestic presence of the edifice, he approached one of the chief portals, to find it crusted with a most uncouth semi-burlesque representation, cut in stone, of the Last Judgment. The trump has sounded, and the Lord from a lofty throne is pronouncing doom upon the risen as they are brought up to the judgment-seat by the angels. Below him are two rows of the dead just rising from their graves, extending to the full width of the great door. Upon many of the faces there is an expression of amazement, which the artist apparently designed to be comic, and several of the attitudes are extremely absurd and ludicrous. Some have managed to push off the lid of their tombs a little way, and are peeping out through the narrow aperture, others have just got their heads above the surface of the ground, and others are sitting up in their graves; some have one leg out, some are springing into the air, and some are running, as if in wild fright, for their lives. Though the usual expression upon the faces is one of astonishment, yet this is varied. Some are rubbing their eyes as if startled from a deep sleep, but not yet aware of the cause of alarm; others are utterly bewildered, and hesitate to leave their resting-place; some leap out in mad excitement, and others hurry off as if fearing to be again consigned to the tomb. An angel is leading a cheerful company of popes, bishops, and kings toward the Saviour, while a hideous demon, with a mouth stretching from ear to ear, is dragging off a number of the condemned toward the devil, who is seen stirring up a huge caldron boiling and bubbling with naked babies, dead before baptism. On another part of the wall is a carved representation of the vices which led to the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. These were so monstrously obscene that the authorities of the cathedral, in deference to the modern sense of decency, have caused them to be partly cut away by the chisel.

The first cut on the next page is an example of burlesque ornament. The artist apparently intended to indicate another termination of the interview than the one recorded by Æsop between the wolf and the stork. The old cathedral at Strasburg, destroyed a hundred years ago, was long renowned for its sculptured burlesques. We give two of several capitals exhibiting the sacred rites of the Church travestied by animals.

Capital in the Autun Cathedral.

It marks the change in the feelings and manners of men that, three hundred years after those Strasburg capitals were carved, with the sanction of the chapter, a book-seller, for only exhibiting an engraving of some of them in his shop window, was convicted of having committed a crime "most scandalous and injurious to religion." His sentence was "to make the amende honorable, naked to his shirt, a rope round his neck, holding in his hand a lighted wax-candle weighing two pounds, before the principal door of the cathedral, whither he will be conducted by the executioner, and there, on his knees, with uncovered head," confess his fault and ask pardon of God and the king. The pictures were to be burned before his eyes, and then, after paying all the costs of the prosecution, he was to go into eternal banishment.

Capitals in the Strasburg Cathedral, A.D. 1300.

Other American consuls besides Mr. Tomes, and multitudes of American citizens not so fortunate as to study mediæval art at their country's expense, have been profoundly puzzled by this crust of crude burlesque on ecclesiastical architecture. The objects in Europe which usually give to a susceptible American his first and his last rapture are the cathedrals, those venerable enigmas, the glory and shame of the Middle Ages, which present so complete a contrast to the toy-temples, new, cabinet-finished, upholstered, sofa-seated, of American cities, not to mention the consecrated barns, white-painted and treeless, of the rural districts. And the cathedrals are a contrast to every thing in Europe also, if only from their prodigious magnitude. A cathedral town generally stands in a valley, through which a small river winds. When the visitor from any of the encompassing hills gets his first view of the compact little city, the cathedral looms up in the midst thereof so vast, so tall, that the disproportion to the surrounding structures is sometimes even ludicrous, like a huge black elephant with a flock of small brown sheep huddling about its feet. But when at last the stranger stands in its shadow, he finds the spell of its presence irresistible; and it is a spell which the lapse of time not unfrequently strengthens, till he is conscious of a tender, strong attachment to the edifice, which leads him to visit it at unusual times, to try the effect upon it of moonlight, of storm, of dawn and twilight, of mist, rain, and snow. He finds himself going to it for solace and rest. On setting out upon a journey, he makes a détour to get another last look, and, returning, goes, valise in hand, to see his cathedral before he sees his companions. Many American consuls have had this experience, have truly fallen in love with the cathedral of their station, and remained faithful to it for years after their return, like Mr. Howells, whose heart and pen still return to Venice and San Carlo, so much to the delight of his readers.

This charm appears to lie in the mere grandeur of the edifice as a work of art, for we observe it to be most potent over persons who are least in sympathy with the feeling which cathedrals embody. Very religious people are as likely to be repelled as attracted by them; and, indeed, in England and Scotland there are large numbers of Dissenters who have avoided entering them all their lives on principle. It is Americans who enjoy them most; for they see in them a most captivating assemblage of novelties—vast magnitude, solidity of structure only inferior to nature's own work, venerable age, harmonious and solemn magnificence—all combined in an edifice which can not, on any principle of utility, justify its existence, and does not pay the least fraction of its expenses. Little do they know personally of the state of feeling which made successive generations of human beings willing to live in hovels and inhale pollution in order that they might erect those wondrous piles. The cost of maintaining them—of which cost the annual expenditure in money is the least important part—does not come home to us. We abandon ourselves without reserve to the enjoyment of stupendous works wholly new to our experience.

Engraved upon a Stall in Sherborne Minster, England.

It is Americans, also, who are most baffled by the attempt to explain the contradiction between the noble proportions of these edifices and the decorations upon some of their walls. How could it have been, we ask in amazement, that minds capable of conceiving the harmonies of these fretted roofs, these majestic colonnades, these symmetrical towers, could also have permitted their surfaces to be profaned by sculptures so absurd and so abominable that by no artifice of circumlocution can an idea of some of them be conveyed in printable words? In close proximity to statues of the Virgin, and in chapels whose every line is a line of beauty, we know not how to interpret what M. Champfleury truly styles "deviltries and obscenities unnamable, vice and passion depicted with gross brutality, luxury which has thrown off every disguise, and shows itself naked, bestial, and shameless." And these mediæval artists availed themselves of the accumulated buffooneries and monstrosities of all the previous ages. The gross conceptions of India, Egypt, Greece, and Rome appear in the ornamentation of Christian temples along with shapes hideous or grotesque which may have been original. Even the oaken stalls in which the officiating priests rested during the prolonged ceremonials of festive days are in many cathedrals covered with comic carving, some of which is pure caricature. A rather favorite subject was the one shown above, a whipping-scene in a school, carved upon an ancient stall in an English cathedral.

From a Manuscript of the Thirteenth Century.