автордың кітабын онлайн тегін оқу The Alhambra

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

On page 357, "On the verge of great beetling bastion" was changed to "On the verge of the great beetling bastion".

On page 377, "on which occasion he have" was changed to "on which occasion he gave".

On page 388, "the talisman that hangs around my neck" was changed to the talisman that hangs around thy neck".

THE ALHAMBRA

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

LONDON . BOMBAY . CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK · BOSTON · CHICAGO

ATLANTA · SAN FRANCISCO

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd

TORONTO

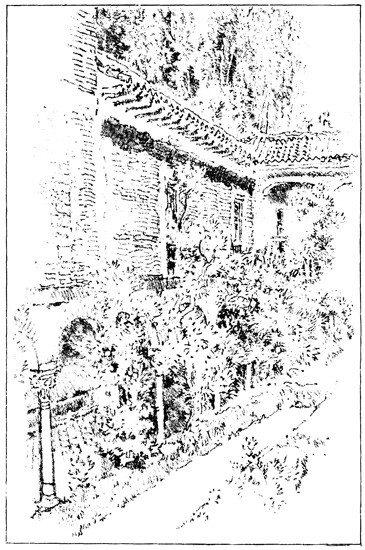

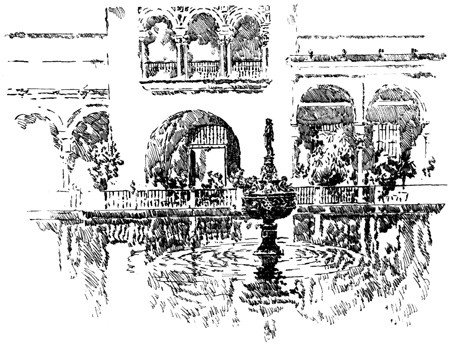

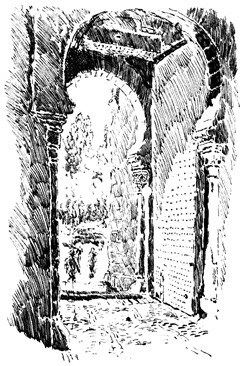

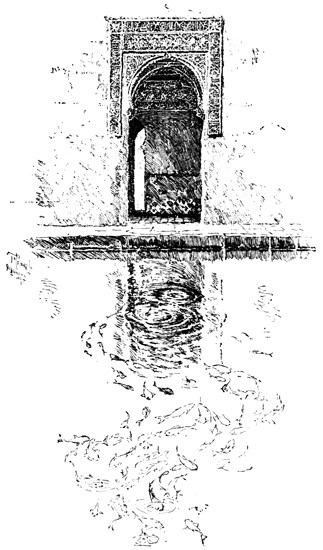

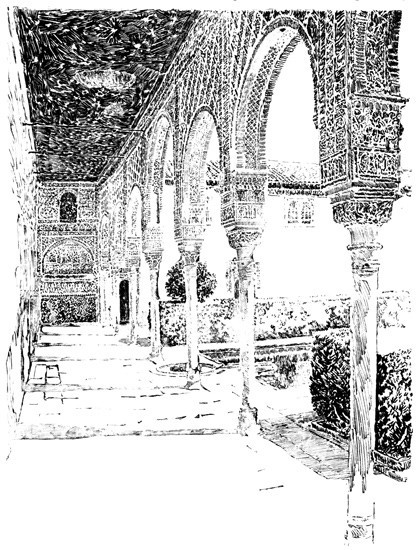

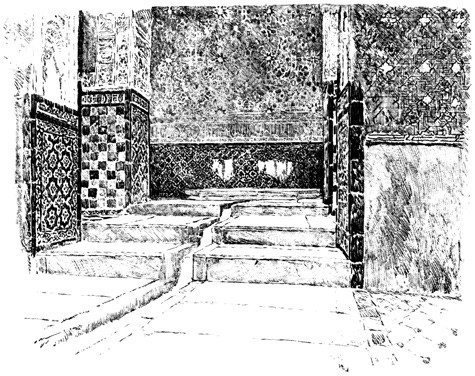

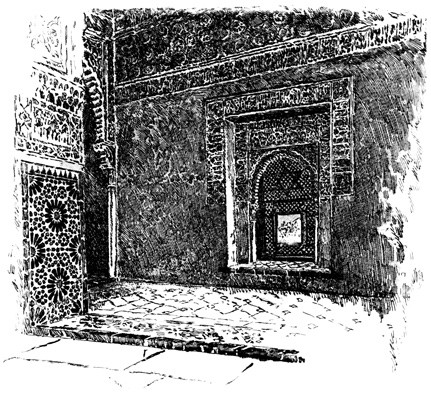

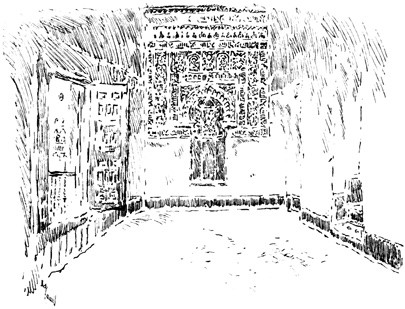

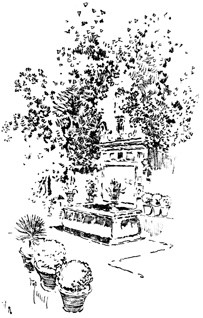

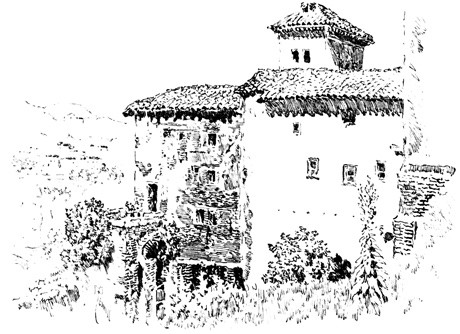

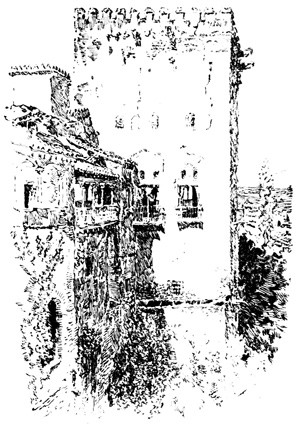

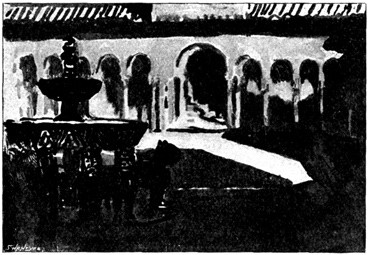

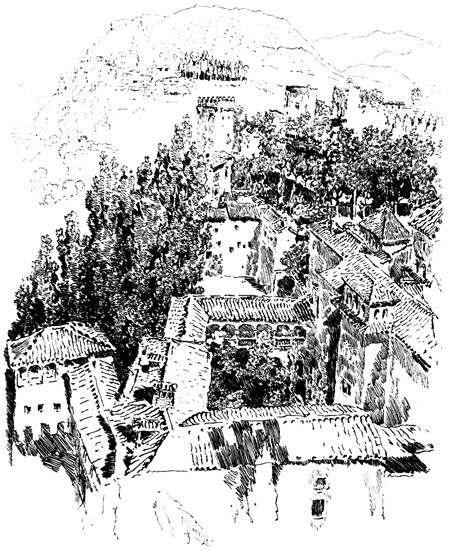

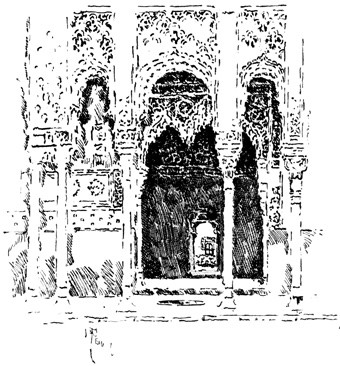

Washington Irving's rooms, overlooking the Garden of Lindaraxa.

THE ALHAMBRA

BY · WASHINGTON · IRVING

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

ELIZABETH ROBINS PENNELL

ILLUSTRATED WITH DRAWINGS

OF THE PLACES MENTIONED

BY JOSEPH PENNELL

LONDON: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd.

NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1911

Richard Clay and Sons, Limited,

BRUNSWICK ST., STAMFORD ST.,

AND BUNGAY, SUFFOLK.

First Edition (Cranford Series), 1896. Reprinted, 1906, 1911.

Pocket Classics, 1908.

INTRODUCTION

It is not possible to forget Washington Irving in the Alhambra. With a single volume, the simple, gentle, kindly American man of letters became no less a figure in the Moor's Red Palace than Boabdil and Lindaraxa of whom he wrote. And yet, never perhaps did a book make so unconscious a bid for popularity. Irving visited Granada in 1828. He returned the following year, when the Governor's apartments in the Alhambra were lent to him as lodgings. There he spent several weeks, his love for the place growing with every day and hour. It was this affection, and no more complex motive, that prompted him to describe its courts and gardens and to record its legends. The work was the amusement of his leisure moments, filling the interval between the completion of one serious, and now all but unknown, history and the beginning of the next.

Not many other men just then could write about Spain or anything Spanish so naturally. For, in 1829, while, within the walls of Alhamar and Yusef, he was listening to the prattle of Mateo and Dolores, in Paris, Alfred de Musset was writing his Contes d'Espagne, and Victor Hugo was publishing a new edition of his Orientales. A year later and the battle of Hernani was to be fought at the Comédie Française; a few more, and Théophile Gautier would be on his way across the Pyrenees. Time had passed since Châteaubriand, the pioneer of romance, could dismiss the Alhambra with a word. Hugo, in turning all eyes to the East, had declared that Spain also was Oriental, and to his disciples the journey, dreamed or made, through the land where Irving travelled in single-minded enjoyment, was an excuse for the profession of their literary faith. Irving, whatever his accomplishments, was unencumbered with a mission and innocent of pose. There is no reason to believe that he had ever heard of the Romanticists, or the part Spain was playing in the revolution; though he had been in Paris when the storm was brewing; though he returned after the famous red waistcoat had been sported in the public's face. At any rate, like the original genius of to-day, he kept his knowledge to himself.

Literary work took Irving to Spain. Several years before, in 1818, he had watched the total wreck of his brother's business. This was the second event of importance in his hitherto mild and colourless existence. The first had been the death of the girl he was to marry, a loss which left him without interest or ambition. There was then no need for him to work, and his health was delicate. He travelled a little: an intelligent, sympathetic and observant tourist. He wrote a little, discovering that he was an author with Knickerbocker. But his writing was of the desultory sort until, when he was thirty-five years old, his brother's failure forced him to make literature his profession. It was after he had published his Sketch-Book and Bracebridge Hall and Old Christmas, after their reception had been of the kind to satisfy even the present generation of writers who measure the excellence of work by the price paid for it, that some one suggested he should translate the journeys of Columbus, which Navarrete, a Spanish author, had in hand. Murray, it was thought, would give a handsome sum down for the translation. Murray himself, however, was not so sure: wanted, wise man, first to see a portion of the manuscript. This was just what could not be until Irving had begun his task. But already in Madrid, and assured of nothing, he found the rôle of translator less congenial than that of historian, and the Spanish work eventually resolved itself into his Life of Columbus. "Delving in the rich ore" of the old chronicles in the Jesuits' Library of St. Isidoro, there was one side issue in the history he was studying that enchanted him above all else. This was the Conquest of Granada, the brilliant episode which had fascinated him ever since, as a boy at play on the banks of the Hudson, his allegiance had been divided between the Spanish cavalier, in gold and silver armour, prancing over the Vega, and the Red Indian brandishing his tomahawk on the war-path. Now, occasionally, Columbus was forgotten that he might collect the materials for a new story of the Conquest to be told by himself. To consult further documents he started one spring (1828), when the almond trees were blossoming, for Andalusia; and Granada, of course, came into his journey. Thus chance brought him to the Alhambra, while (1829) the courtesy of the Governor and the kindness of old Tia Antonia put him in possession of the rooms of the beautiful Elizabeth of Parma, overlooking the oranges and fountains of the Garden of Lindaraxa.

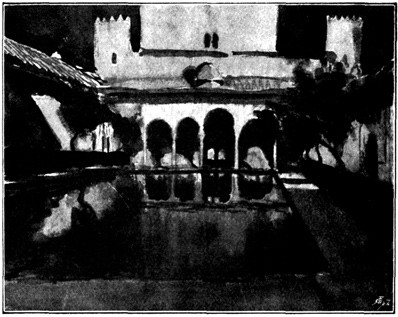

The Alhambra reveals but half its charm to the casual visitor. I know, of my own experience, how far custom is from staling its infinite variety, how its beauty increases as day by day one watches the play of light and shadow on its walls, as day by day one yields to the indolent dreams for which it was built. There was one summer when, all through July and August, its halls and courts gave me shelter from the burning, blinding sunshine of Andalusia, and the weeks in passing strengthened the spell that held me there. For Gautier, the place borrowed new loveliness from the one night he slept in the Court of Lions. But by day and night alike, it belonged to Irving; he saw it before it had degenerated into a disgracefully managed museum and annex to a bric-à-brac shop for the tourist; and he had heard all its stories, or had had time to invent them, before he was called away by his appointment to some useless and unnecessary diplomatic post at the American Legation in London.

The book was not published until more than two years later (1832). Irving, though a hack in a manner, had too much self-respect to rush into print on the slightest provocation. Colburn and Bentley were his English publishers, their edition preceding by a few months the American, brought out by Lea and Carey of Philadelphia. The same year saw two further issues in Paris, one by Galignani, and the other in Baudry's Foreign Library, as well as a French translation from the house of Fournier. The success of The Alhambra was immediate. De Musset and Victor Hugo had left the great public in France as indifferent as ever to the land beyond the Pyrenees. Irving raised a storm of popular applause in England and America, where, of a sudden, he made Spain, which the Romanticists would have snatched as their spoils, the prey of the "bourgeois" they despised. Nor was it the general public only that applauded. There were few literary men in England who did not welcome the book with delight.

I think to-day, without suspicion of disloyalty, one may wonder a little at this success. Certainly, in its first edition, The Alhambra is crude and stilted, though, to compare it with the pompous trash which Roscoe published three years afterward, as text for the drawings of David Roberts, is to see in it a masterpiece. Irving, more critical than his readers, knew it needed revision. "It is generally labour lost," he said once in a letter to Alexander Everett, "to attempt to improve a book that has already made its impression on the public." Nevertheless, The Alhambra was all but re-written in 1857, when he was preparing a complete edition of his works for Putnam, the New York publisher, and it gained enormously in the process. It was not so much by the addition of new chapters, or the re-arrangement of the old; but rather by the changes made in the actual text—the light touch of local colour here, and there the rounding of a period, the developing of an incident. For example "The Journey," so gay and vivacious in the final version, was, at first, but a bare statement of facts, with no space for the little adventures by the way: the rest at the old mill near Seville; the glimpses of Archidona, Antiquero, Osuna, names that lend picturesque value to the ride; the talk and story-telling in the inn at Loxa. Another change, less commendable, is the omission from the late editions of the dedication to Wilkie. It was a pleasant tribute to the British painter, who, with several of his fellows—Lewis and Roberts—was carried away by that wave of Orientalism which sent the French Marilhat and Decamps, Fromentin and Delacroix to the East, and had not yet spent its force in the time of Regnault. The dedication was well-written, kindly, appreciative: an amiable reminder of the rambles the two men had taken together in Toledo and Seville, and the interest they had shared in the beauty left by the Moor to mark his passage through the land both were learning to love. As a memorial to the friendship between author and artist, it could less well have been spared than any one of the historical chapters that go to swell the volume.

Even in the revised edition it would be easy to belittle Irving's achievement, now that it is the fashion to disparage him as author. Certainly, The Alhambra has none of the splendid melodrama of Borrow's Bible in Spain, none of the picturesqueness of Gautier's record. It is very far from being that "something in the Haroun Alraschid style," with dash of Arabian spice, which Wilkie had urged him to make it. Nor are its faults wholly negative. It has its moments of dulness. It abounds in repetitions. Certain adjectives recur with a pertinacity that irritates. The Vega is blooming, the battle is bloody, the Moorish maiden is beauteous far more than once too often. Worse still, descriptions are duplicated, practically the same passage reappearing again and again, as if for the sake of padding, or else as the mere babble of the easy writer. Indeed, many of the purely historical chapters have been crowded in so obviously because they happened to be at hand, and he without better means to dispose of them, and then scattered discreetly, that there is less hesitation in omitting them altogether from the present edition. An edited Tom Jones, a bowdlerized Shakespeare may be an absurdity. But to drop certain chapters from The Alhambra is simply to anticipate the reader in the act of skipping. There is no loss, since all important facts and descriptions are given more graphically and entertainingly elsewhere in the book.

Perhaps it may seem injudicious to introduce a new edition of so popular a work by pointing out its defects. But one can afford to be honest about Irving. The Alhambra might have more serious blemishes, and its charm would still survive triumphantly the test of the harshest criticism. For, whatever subtlety, whatever elegance Irving's style may lack, it is always distinguished by that something which, for want of a better name, is called charm—a quality always as difficult to define as Lowell thought when he found it in verse or in perfume. But there it is in all Washington Irving wrote: a clue to the lavish praise of his contemporaries—of Coleridge, who pronounced The Conquest of Granada a chef d'œuvre, and Campbell, who believed he had added clarity to the English tongue; of Byron and Scott and Southey; of Dickens, whose pockets were at one time filled with Irving's books worn to tatters; of Thackeray, who likened the American to Goldsmith, describing him as "one of the most charming masters of our lighter language."

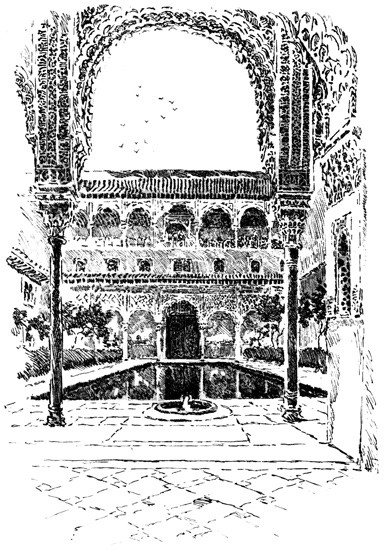

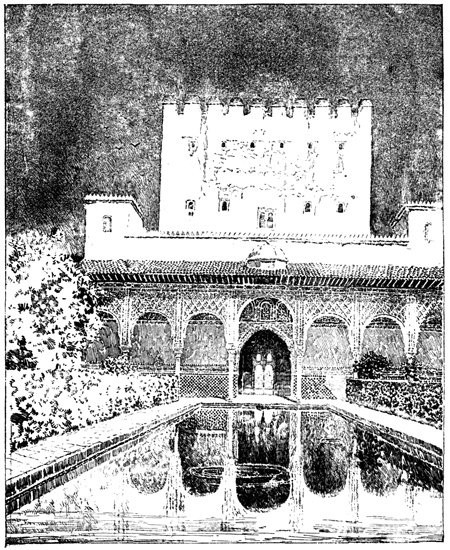

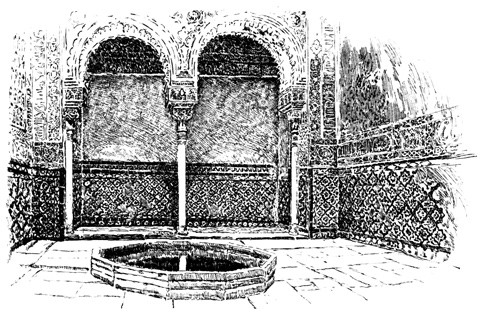

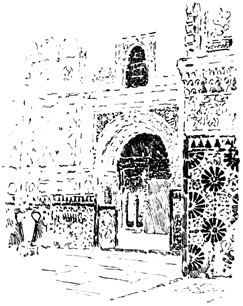

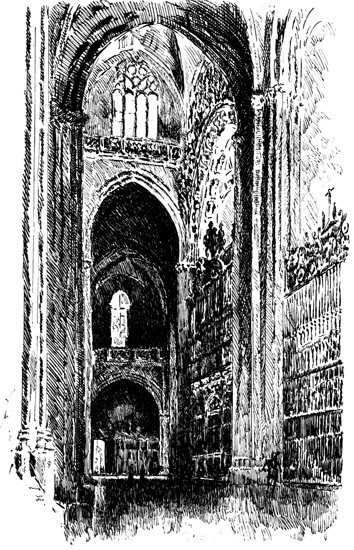

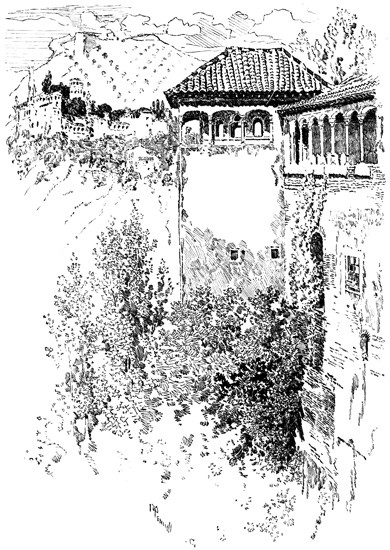

Much of this power to please is due, no doubt, to the simplicity and sincerity of Irving's style at its best. Despite a tendency to diffuseness, despite a fancy for the ornate, when there is a story to be told, he can be as simple and straightforward as the child's "Once upon a time," with which he begins many a tale: appropriately, since the legends of the Alhambra are but stories for grown-up children. And there is no question of the sincerity of his love for everything savouring of romance. For that matter, it is seldom that he does not mean what he says and does not say it so truly with his whole heart, that you are convinced, where you distrust the emotion of De Amicis, pumping up tears of admiration before the wrong thing, or of Maurice Barrès seeing all Spain through a haze of blood, voluptuousness, and death. It was the strength of his feeling for the Alhambra that led Irving to write in its praise, not the desire to write that manufactured the feeling. Humour and sentiment some of his critics have thought the predominant traits of his writing, as of his character. It is a fortunate combination: his sentiment, though it often threatens, seldom overflows into gush, kept within bounds as it is by the sense of humour that so rarely fails him. His power of observation was of still greater service. He could use his eyes. He could see things for himself. And he was quick to detect character. Occasionally one finds him slipping. In his landscape, the purple mountains of Alhama rise wherever he considers them most effective in the picture; and the snow considerately never melts from the slopes of the Sierra Nevada, which I have seen all brown at midsummer. He could look only through the magnifying glass of tradition at the hand and key on the Gate of Justice: symbols so gigantic in fiction, so insignificant in fact that one might miss them altogether, did not every book, paper, and paragraph, every cadging, swindling tout—I mean guide—in Granada bid one look for them. But these are minor discrepancies. In essentials, his observation never played him false. There may not be a single passage to equal in force and brilliance Gautier's wonderful description of the bull-fight at Malaga; but his impressions were so clear, his record of them so faithful, that the effect of his book remains, while the accomplishment of a finer artist in words may be remembered but vaguely. It is Irving who prepares one best for the stern grandeur and rugged solemnity of the country between Seville and Granada. The journey can now be made by rail. But to travel by road as he did—as we have done—is to know that his arid mountains and savage passes are no more exaggerated than the pleasant valleys and plains that lie between. For Spain is not all gaiety as most travellers would like to imagine it, as most painters have painted it, save Daumier in his pictures of Don Quixote among the barren hills of La Mancha. And if nothing in Granada and the Alhambra can be quite unexpected, it is because one has seen it all beforehand with Irving, from the high Tower of Comares and the windows of the Hall of Ambassadors, or else, following him through the baths and mosque and courts of the silent Palace, crossing the ravine to the cooler gardens of the Generalife, and climbing the Albaycin to the white church upon its summit.

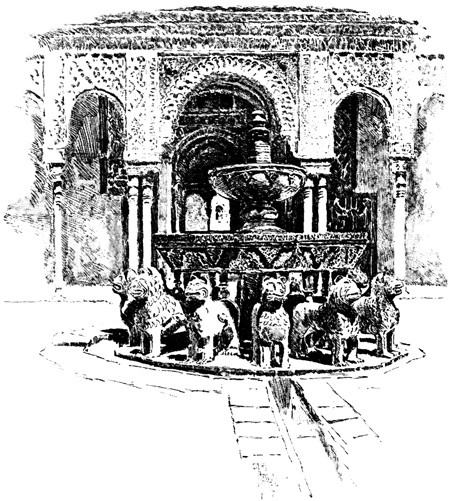

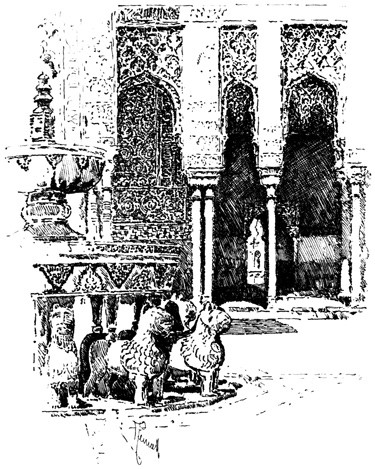

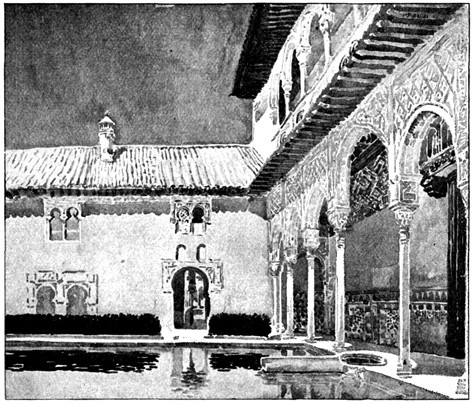

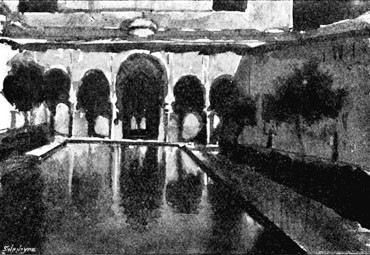

There have been many changes in the Alhambra since Irving's day. The Court of Lions lost in loveliness when the roses with which he saw it filled were uprooted. The desertion he found had more picturesqueness than the present restoration and pretence of orderliness. Irving was struck with the efforts which the then Commander, Don Francisco de Serna, was making to keep the Palace in a state of repair and to arrest its too certain decay. Had the predecessors of De Serna, he thought, discharged the duties of their station with equal fidelity, the Alhambra might have been still almost as the Moor, or at least Spanish royalty had left it. What would he say, one wonders, to the Alhambra under its present management? Frank neglect is often less an evil than sham zeal. The student, watched, badgered, oppressed by red-tapeism, has not gained by official vigilance; nor is the Palace the more secure because responsibility has been transferred from a pleasant gossiping old woman to half a dozen indolent guides. The burnt roof in the ante-chamber to the Hall of Ambassadors shows the carelessness of which the new officers can be guilty; the matches and cigarette ends with which courts and halls are strewn explain that so eloquent a warning has been in vain. And if the restorer has been let loose in the Alhambra, at the Generalife there is an Italian proprietor, eager, it would seem, to initiate the somnolent Spaniard into the brisker ways of Young Italy. Cypresses, old as Zoraïde, have already been cut down ruthlessly along that once unrivalled avenue, and their destruction, one fears, is but the beginning of the end.

But whatever changes the past sixty years have brought about in Granada, the popularity of Irving's book has not weakened with time. Not Ford, nor Murray, nor Hare has been able to replace it. The tourist reads it within the walls it commemorates as conscientiously as the devout read Ruskin in Florence. It serves as text book in the Court of Lions and the Garden of Lindaraxa. It is the student's manual in the high mirador of the Sultanas and the court of the mosque where Fortuny painted. In a Spanish translation it is pressed upon you almost as you cross the threshold. Irving's rooms in the Palace are always locked, that the guide may get an extra fee for opening—as a special favour—an apartment which half the people ask to see. As the steamers "Rip Van Winkle" and "Knickerbocker" ply up and down the Hudson, so the Hotel Washington Irving rises under the shadow of the Alhambra. Even the spirits and spooks that haunt every grove and garden are all of his creation, as Spaniards themselves will be quick to tell you; though who Irving—or, in their familiar speech, "Vashington"—was, but very few of them could explain. And thus his name has become so closely associated with the place that, just as Diedrich Knickerbocker will be remembered while New York stands, so Washington Irving cannot be forgotten so long as the Red Palace looks down upon the Vega and the tradition of the Moor lingers in Granada.

Elizabeth Robins Pennell.

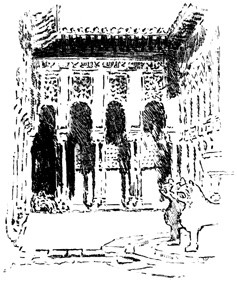

CONTENTS

PAGE The Journey 1 Palace of the Alhambra 46 Important Negotiations.—The Author Succeeds to the Throne of Boabdil 79 Inhabitants of the Alhambra 90 The Hall of Ambassadors 96 The Mysterious Chambers 106 Panorama View from the Tower of Comares 122 The Balcony 134 The Adventure of the Mason 144 The Court of Lions 151 Mementoes of Boabdil 163 The House of the Weathercock 172 Legend of the Arabian Astrologer 176 Visitors to the Alhambra 199 The Generalife 207 Legend of Prince Ahmed al Kamel, or, the Pilgrim of Love 217 A Ramble Among the Hills 259 Legend of the Moor's Legacy 270 The Tower of Las Infantas 293 Legend of the Three Beautiful Princesses 297 Legend of the Rose of the Alhambra 326 The Veteran 346 The Governor and the Notary 350 Governor Manco and the Soldier 359 A Fête in the Alhambra 377 Legend of the Two Discreet Statues 383 The Crusade of the Grand Master of Alcántara 401 An Expedition in Quest of a Diploma 413 The Legend of the Enchanted Soldier 417 The Author's Farewell to Granada 432

It seems that the pure and airy situation of this fortress has rendered it, like the castle of Macbeth, a prolific breeding-place for swallows and martlets, who sport about its towers in myriads, with the holiday glee of urchins just let loose from school. To entrap these birds in their giddy circlings, with hooks baited with flies, is one of the favourite amusements of the ragged "sons of the Alhambra," who, with the good-for-nothing ingenuity of arrant idlers, have thus invented the art of angling in the sky.

"The offer of the honest mason was gladly accepted; he moved with his family into the house, and fulfilled all his engagements. By little and little he restored it to its former state; the clinking of gold was no more heard at night in the chamber of the defunct priest, but began to be heard by day in the pocket of the living mason. In a word, he increased rapidly in wealth, to the admiration of all his neighbours, and became one of the richest men in Granada: he gave large sums to the Church, by way, no doubt, of satisfying his conscience, and never revealed the secret of the vault until on his death-bed to his son and heir."

I now proceed to relate still more surprising things about Aben Habuz and his palace; for the truth of which, should any doubt be entertained, I refer the dubious reader to Mateo Ximenes and his fellow-historiographers of the Alhambra.

The marvellous stories hinted at by Mateo, in the early part of our ramble about the Tower of the Seven Floors, set me as usual upon my goblin researches. I found that the redoubtable phantom, the Belludo, had been time out of mind a favourite theme of nursery tales and popular traditions in Granada, and that honourable mention had even been made of it by an ancient historian and topographer of the place. The scattered members of one of these popular traditions I have gathered together, collated them with infinite pains, and digested them into the following legend; which only wants a number of learned notes and references at bottom to take its rank among those concrete productions gravely passed upon the world for Historical Facts.

As to the alcalde and his adjuncts, they remained shut up under the great tower of the seven floors, and there they remain spellbound at the present day. Whenever there shall be a lack in Spain of pimping barbers, sharking alguazils, and corrupt alcaldes, they may be sought after; but if they have to wait until such time for their deliverance, there is danger of their enchantment enduring until doomsday.

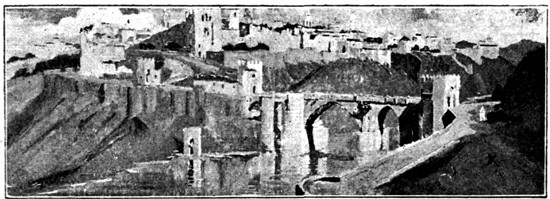

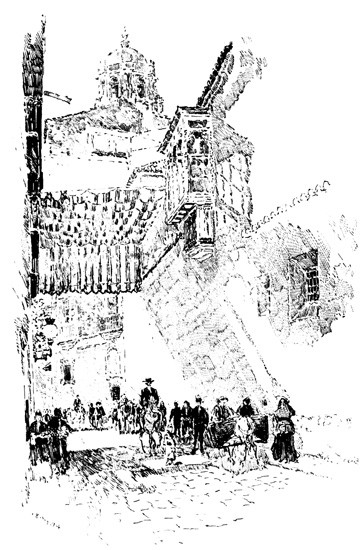

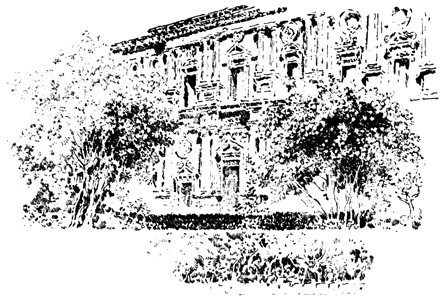

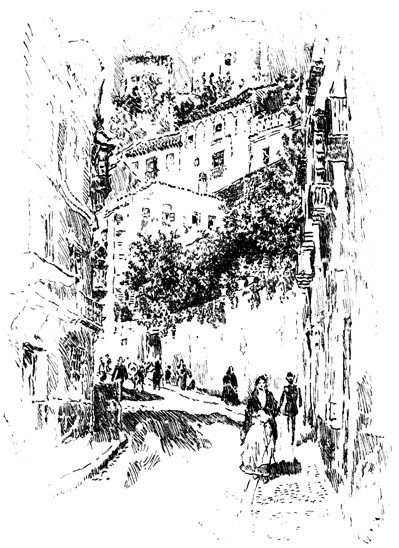

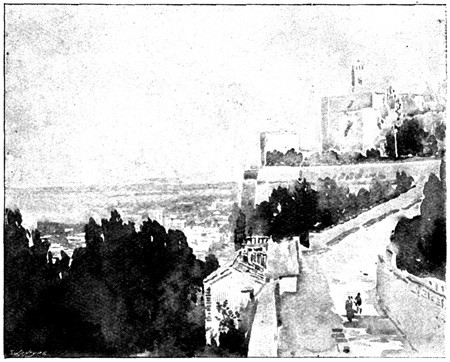

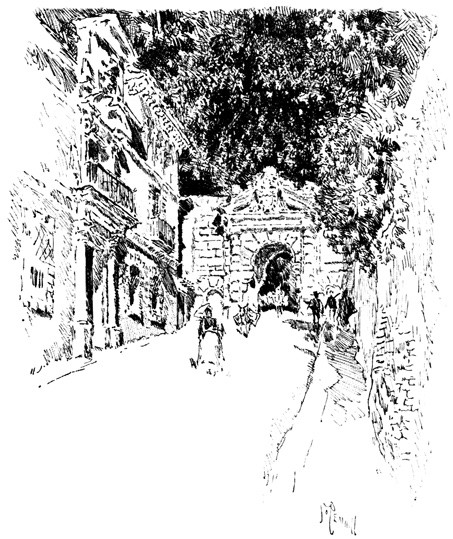

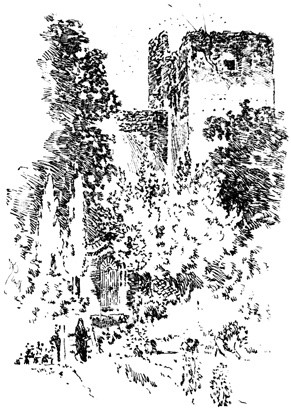

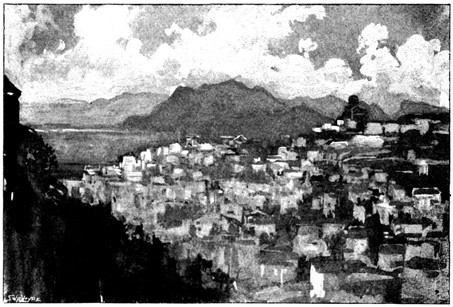

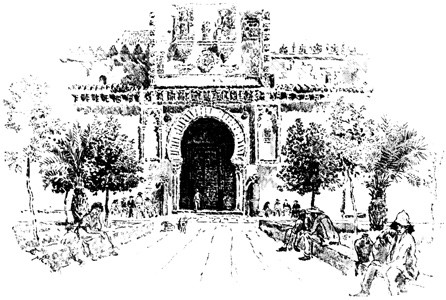

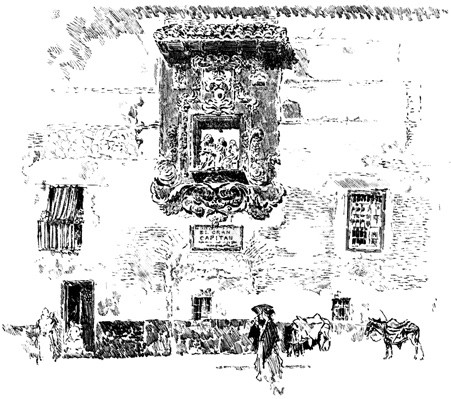

Seville

THE ALHAMBRA

THE JOURNEY

In the spring of 1829, the author of this work, whom curiosity had brought into Spain, made a rambling expedition from Seville to Granada in company with a friend, a member of the Russian Embassy at Madrid. Accident had thrown us together from distant regions of the globe and a similarity of taste led us to wander together among the romantic mountains of Andalusia.

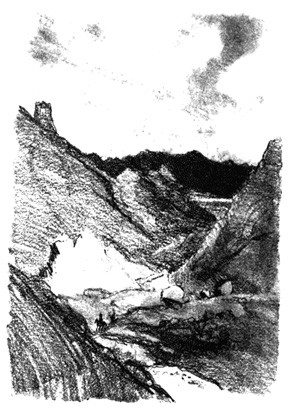

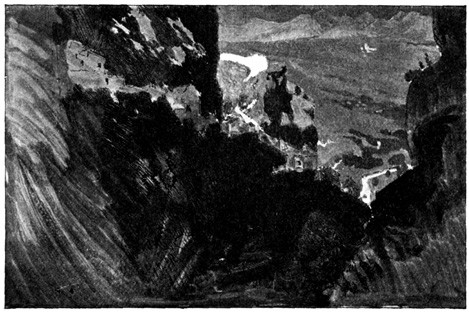

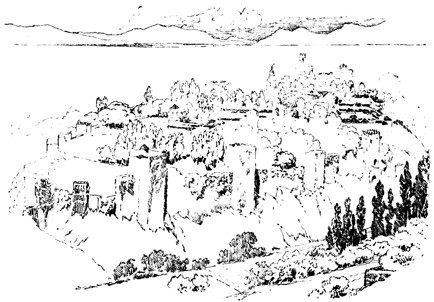

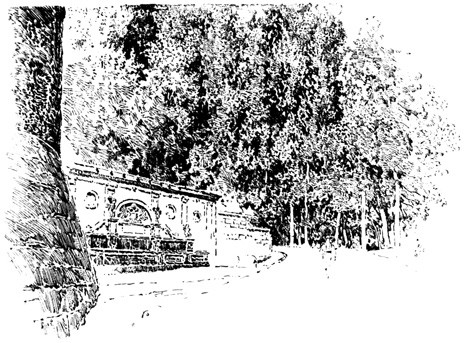

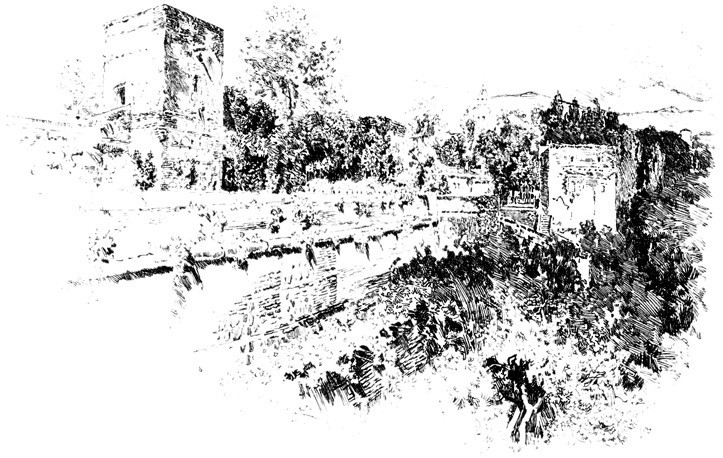

A stern melancholy country.

And here, before setting forth, let me indulge in a few previous remarks on Spanish scenery and Spanish travelling. Many are apt to picture Spain to their imaginations as a soft southern region, decked out with the luxuriant charms of voluptuous Italy. On the contrary, though there are exceptions in some of the maritime provinces, yet, for the greater part, it is a stern, melancholy country, with rugged mountains, and long sweeping plains, destitute of trees, and indescribably silent and lonesome, partaking of the savage and solitary character of Africa. What adds to this silence and loneliness, is the absence of singing-birds, a natural consequence of the want of groves and hedges. The vulture and the eagle are seen wheeling about the mountain-cliffs, and soaring over the plains, and groups of shy bustards stalk about the heaths; but the myriads of smaller birds, which animate the whole face of other countries, are met with in but few provinces in Spain, and in those chiefly among the orchards and gardens which surround the habitations of man.

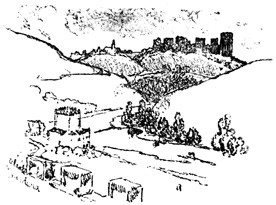

In the interior provinces the traveller occasionally traverses great tracts cultivated with grain as far as the eye can reach, waving at times with verdure, at other times naked and sunburnt, but he looks round in vain for the hand that has tilled the soil. At length he perceives some village on a steep hill, or rugged crag, with mouldering battlements and ruined watch-tower: a stronghold, in old times, against civil war, or Moorish inroad: for the custom among the peasantry of congregating together for mutual protection is still kept up in most parts of Spain, in consequence of the maraudings of roving freebooters.

But though a great part of Spain is deficient in the garniture of groves and forests, and the softer charms of ornamental cultivation, yet its scenery is noble in its severity and in unison with the attributes of its people; and I think that I better understand the proud, hardy, frugal, and abstemious Spaniard, his manly defiance of hardships, and contempt of effeminate indulgences, since I have seen the country he inhabits.

There is something, too, in the sternly simple features of the Spanish landscape, that impresses on the soul a feeling of sublimity. The immense plains of the Castiles and of La Mancha, extending as far as the eye can reach, derive an interest from their very nakedness and immensity, and possess, in some degree, the solemn grandeur of the ocean. In ranging over these boundless wastes, the eye catches sight here and there of a straggling herd of cattle attended by a lonely herdsman, motionless as a statue, with his long slender pike tapering up like a lance into the air; or beholds a long train of mules slowly moving along the waste like a train of camels in the desert; or a single horseman, armed with blunderbuss and stiletto, and prowling over the plain. Thus the country, the habits, the very looks of the people, have something of the Arabian character. The general insecurity of the country is evinced in the universal use of weapons. The herdsman in the field, the shepherd in the plain, has his musket and his knife. The wealthy villager rarely ventures to the market-town without his trabuco, and, perhaps, a servant on foot with a blunderbuss on his shoulder; and the most petty journey is undertaken with the preparation of a warlike enterprise.

Picturesque Ronda.

The dangers of the road produce also a mode of travelling resembling, on a diminutive scale, the caravans of the East. The arrieros, or carriers, congregate in convoys, and set off in large and well-armed trains on appointed days; while additional travellers swell their number, and contribute to their strength. In this primitive way is the commerce of the country carried on. The muleteer is the general medium of traffic, and the legitimate traverser of the land, crossing the peninsula from the Pyrenees and the Asturias to the Alpuxarras, the Serrania de Ronda, and even to the gates of Gibraltar. He lives frugally and hardily: his alforjas of coarse cloth hold his scanty stock of provisions; a leathern bottle, hanging at his saddle-bow, contains wine or water, for a supply across barren mountains and thirsty plains; a mule-cloth spread upon the ground is his bed at night, and his pack-saddle his pillow. His low, but clean-limbed and sinewy form betokens strength; his complexion is dark and sunburnt; his eye resolute, but quiet in its expression, except when kindled by sudden emotion; his demeanour is frank, manly, and courteous, and he never passes you without a grave salutation: "Dios guarde à usted!" "Va usted con Dios, Caballero!" "God guard you!" "God be with you, Cavalier!"

As these men have often their whole fortune at stake upon the burden of their mules, they have their weapons at hand, slung to their saddles, and ready to be snatched out for desperate defence; but their united numbers render them secure against petty bands of marauders, and the solitary bandolero, armed to the teeth, and mounted on his Andalusian steed, hovers about them, like a pirate about a merchant convoy, without daring to assault.

The Spanish muleteer has an inexhaustible stock of songs and ballads, with which to beguile his incessant wayfaring. The airs are rude and simple, consisting of but few inflections. These he chants forth with a loud voice, and long, drawling cadence, seated sideways on his mule, who seems to listen with infinite gravity, and to keep time, with his paces, to the tune. The couplets thus chanted are often old traditional romances about the Moors, or some legend of a saint, or some love-ditty; or, what is still more frequent, some ballad about a bold contrabandista, or hardy bandolero, for the smuggler and the robber are poetical heroes among the common people of Spain. Often, the song of the muleteer is composed at the instant, and relates to some local scene, or some incident of the journey. This talent of singing and improvising is frequent in Spain, and is said to have been inherited from the Moors. There is something wildly pleasing in listening to these ditties among the rude and lonely scenes they illustrate; accompanied, as they are, by the occasional jingle of the mule-bell.

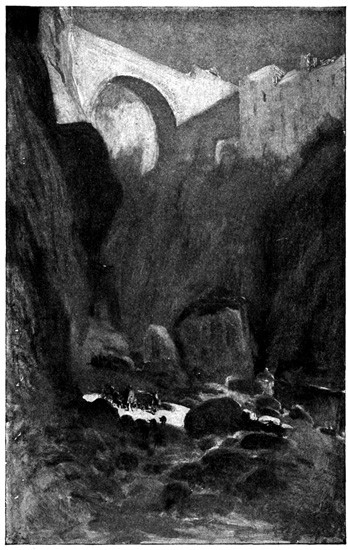

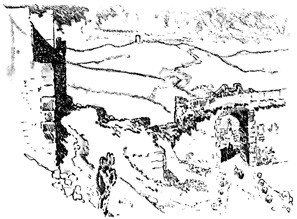

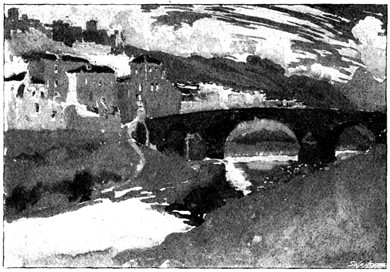

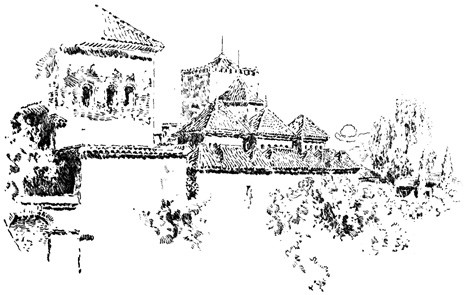

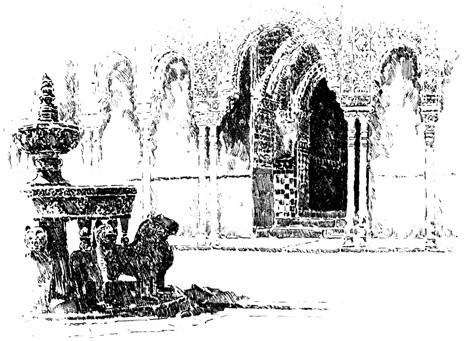

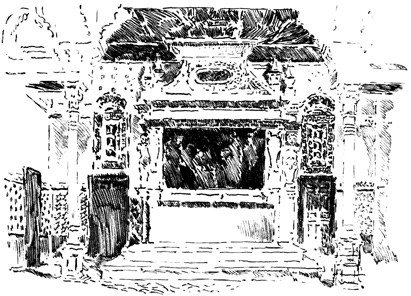

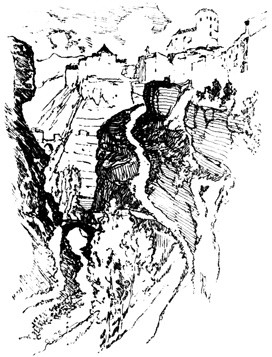

Roman Bridge, Ronda.

It has a most picturesque effect also to meet a train of muleteers in some mountain-pass. First you hear the bells of the leading mules, breaking with their simple melody the stillness of the airy height; or, perhaps, the voice of the muleteer admonishing some tardy or wandering animal, or chanting, at the full stretch of his lungs, some traditionary ballad. At length you see the mules slowly winding along the cragged defile, sometimes descending precipitous cliffs, so as to present themselves in full relief against the sky, sometimes toiling up the deep arid chasms below you. As they approach, you descry their gay decorations of worsted stuffs, tassels, and saddle-cloths, while, as they pass by, the ever ready trabuco, slung behind the packs and saddles, gives a hint of the insecurity of the road.

The ancient kingdom of Granada, into which we were about to penetrate, is one of the most mountainous regions of Spain. Vast sierras, or chains of mountains, destitute of shrub or tree, and mottled with variegated marbles and granites, elevate their sunburnt summits against a deep-blue sky; yet in their rugged bosoms lie ingulfed verdant and fertile valleys, where the desert and the garden strive for mastery, and the very rock is, as it were, compelled to yield the fig, the orange, and the citron, and to blossom with the myrtle and the rose.

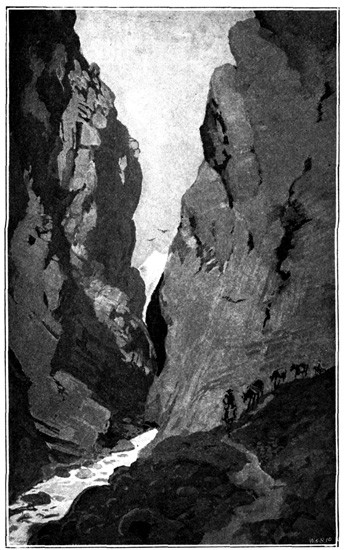

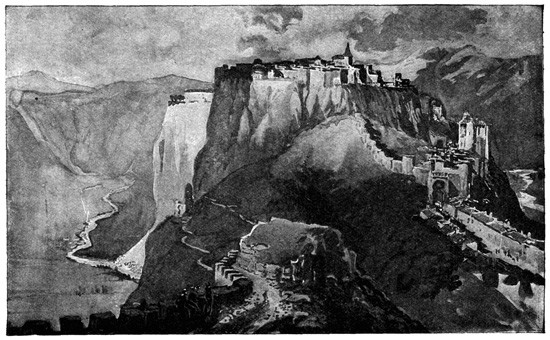

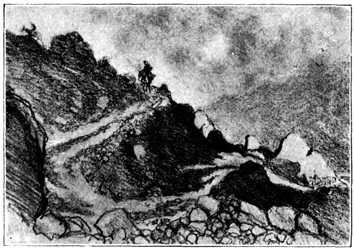

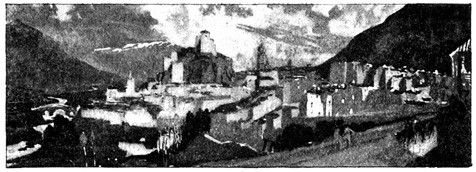

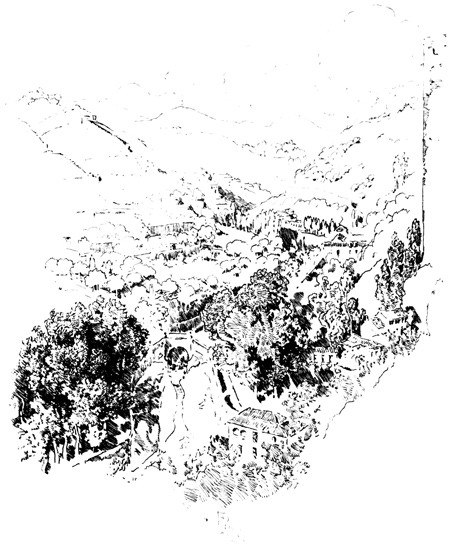

Serrania de Ronda.

In the wild passes of these mountains the sight of walled towns and villages, built like eagles' nests among the cliffs, and surrounded by Moorish battlements, or of ruined watch-towers perched on lofty peaks, carries the mind back to the chivalric days of Christian and Moslem warfare, and to the romantic struggle for the conquest of Granada. In traversing these lofty sierras the traveller is often obliged to alight, and lead his horse up and down the steep and jagged ascents and descents, resembling the broken steps of a staircase. Sometimes the road winds along dizzy precipices, without parapet to guard him from the gulfs below, and then will plunge down steep and dark and dangerous declivities. Sometimes it struggles through rugged barrancos, or ravines, worn by winter torrents, the obscure path of the contrabandista; while, ever and anon, the ominous cross, the monument of robbery and murder, erected on a mound of stones at some lonely part of the road, admonishes the traveller that he is among the haunts of banditti, perhaps at that very moment under the eye of some lurking bandolero. Sometimes, in winding through the narrow valleys, he is startled by a hoarse bellowing, and beholds above him on some green fold of the mountain a herd of fierce Andalusian bulls, destined for the combat of the arena. I have felt, if I may so express it, an agreeable horror in thus contemplating, near at hand, these terrific animals, clothed with tremendous strength, and ranging their native pastures in untamed wildness, strangers almost to the face of man: they know no one but the solitary herdsman who attends upon them, and even he at times dares not venture to approach them. The low bellowing of these bulls, and their menacing aspect as they look down from their rocky height, give additional wildness to the savage scenery.

I have been betrayed unconsciously into a longer disquisition than I intended on the general features of Spanish travelling; but there is a romance about all the recollections of the Peninsula dear to the imagination.

As our proposed route to Granada lay through mountainous regions, where the roads are little better than mule-paths, and said to be frequently beset by robbers, we took due travelling precautions. Forwarding the most valuable part of our luggage a day or two in advance by the arrieros, we retained merely clothing and necessaries for the journey and money for the expenses of the road; with a little surplus of hard dollars by way of robber purse, to satisfy the gentlemen of the road should we be assailed. Unlucky is the too wary traveller who, having grudged this precaution, falls into their clutches empty-handed; they are apt to give him a sound rib-roasting for cheating them out of their dues. "Caballeros like them cannot afford to scour the roads and risk the gallows for nothing."

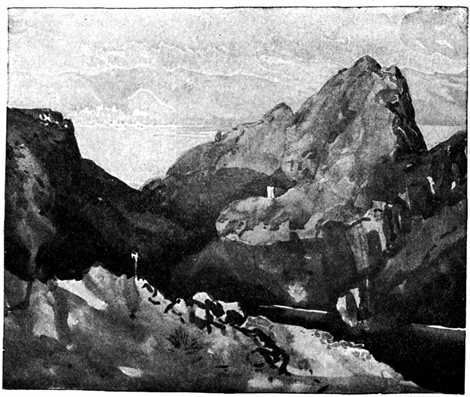

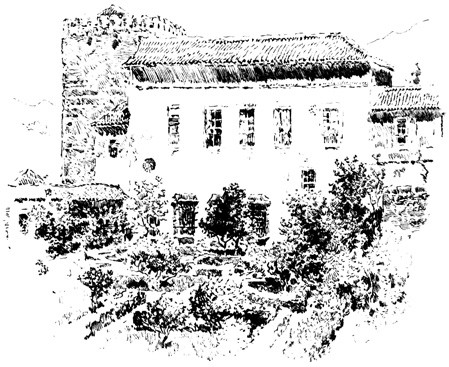

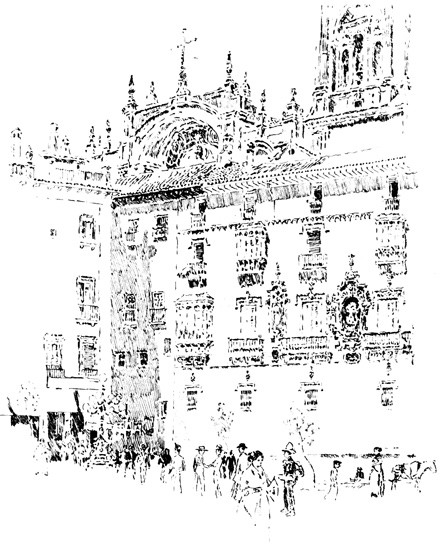

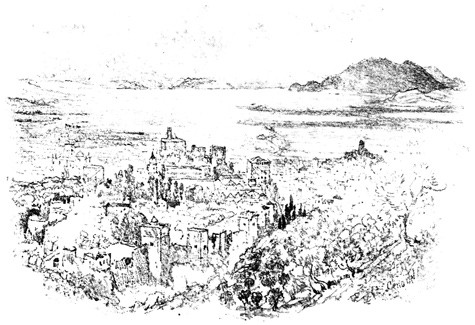

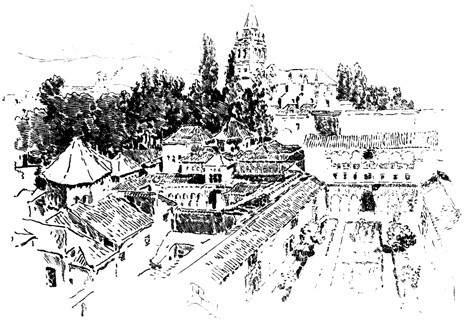

Approach to Granada. From near Elvira.

A couple of stout steeds were provided for our own mounting, and a third for our scanty luggage and the conveyance of a sturdy Biscayan lad, about twenty years of age, who was to be our guide, our groom, our valet, and at all times our guard. For the latter office he was provided with a formidable trabuco or carbine, with which he promised to defend us against rateros or solitary foot-pads; but as to powerful bands, like that of the "Sons of Ecija," he confessed they were quite beyond his prowess. He made much vainglorious boast about his weapon at the outset of the journey; though, to the discredit of his generalship, it was suffered to hang unloaded behind his saddle.

According to our stipulations, the man from whom we hired the horses was to be at the expense of their feed and stabling on the journey, as well as of the maintenance of our Biscayan squire, who of course was provided with funds for the purpose; we took care, however, to give the latter a private hint, that, though we made a close bargain with his master, it was all in his favour, as, if he proved a good man and true, both he and the horses should live at our cost, and the money provided for their maintenance remain in his pocket. This unexpected largess, with the occasional present of a cigar, won his heart completely. He was, in truth, a faithful, cheery, kind-hearted creature, as full of saws and proverbs as that miracle of squires, the renowned Sancho himself, whose name, by the by, we bestowed upon him, and, like a true Spaniard, though treated by us with companionable familiarity, he never for a moment, in his utmost hilarity, overstepped the bounds of respectful decorum.

Such were our minor preparations for the journey, but above all we laid in an ample stock of good-humour, and a genuine disposition to be pleased; determining to travel in true contrabandista style; taking things as we found them, rough or smooth, and mingling with all classes and conditions in a kind of vagabond companionship. It is the true way to travel in Spain. With such disposition and determination, what a country is it for a traveller, where the most miserable inn is as full of adventure as an enchanted castle, and every meal is in itself an achievement! Let others repine at the lack of turnpike roads and sumptuous hotels, and all the elaborate comforts of a country cultivated and civilised into tameness and commonplace; but give me the rude mountain scramble; the roving, hap-hazard, wayfaring; the half wild, yet frank and hospitable manners, which impart such a true game-flavour to dear old romantic Spain!

Thus equipped and attended, we cantered out of "Fair Seville city" at half-past six in the morning of a bright May day, in company with a lady and gentleman of our acquaintance, who rode a few miles with us, in the Spanish mode of taking leave. Our route lay through old Alcala de Guadaira (Alcala on the river Aira), the benefactress of Seville, that supplies it with bread and water. Here live the bakers who furnish Seville with that delicious bread for which it is renowned; here are fabricated those roscas well known by the well-merited appellation of pan de Dios (bread of God); with which, by the way, we ordered our man, Sancho, to stock his alforjas for the journey. Well has this beneficent little city been denominated the "Oven of Seville"; well has it been called Alcala de los Panaderos (Alcala of the bakers), for a great part of its inhabitants by lines of mules and donkeys laden with great panniers of loaves and roscas.

I have said Alcala supplies Seville with water. Here are great tanks or reservoirs, of Roman and Moorish construction, whence water is conveyed to Seville by noble aqueducts. The springs of Alcala are almost as much vaunted as its ovens; and to the lightness, sweetness, and purity of its water is attributed in some measure the delicacy of its bread.

Here we halted for a time, at the ruins of the old Moorish castle, a favourite resort for picnic parties from Seville, where we had passed many a pleasant hour. The walls are of great extent, pierced with loopholes; enclosing a huge square tower or keep, with the remains of masmoras, or subterranean granaries. The Guadaira winds its stream round the hill, at the foot of these ruins, whimpering among reeds, rushes, and pond-lilies, and overhung with rhododendron, eglantine, yellow myrtle, and a profusion of wild flowers and aromatic shrubs; while along its banks are groves of oranges, citrons, and pomegranates, among which we heard the early note of the nightingale.

A picturesque bridge was thrown across the little river, at one end of which was the ancient Moorish mill of the castle, defended by a tower of yellow stone; a fisherman's net hung against the wall to dry, and hard by in the river was his boat; a group of peasant women in bright-coloured dresses, crossing the arched bridge, were reflected in the placid stream. Altogether it was an admirable scene for a landscape-painter.

The old Moorish mills, so often found on secluded streams, are characteristic objects in Spanish landscape, and suggestive of the perilous times of old. They are of stone, and often in the form of towers with loopholes and battlements, capable of defence in those warlike days when the country on both sides of the border was subject to sudden inroad and hasty ravage, and when men had to labour with their weapons at hand, and some place of temporary refuge.

Our next halting-place was at Gandul, where were the remains of another Moorish castle, with its ruined tower, a nestling-place for storks, and commanding a view over a vast campiña or fertile plain, with the mountains of Ronda in the distance. These castles were strongholds to protect the plains from the talas or forays to which they were subject, when the fields of corn would be laid waste, the flocks and herds swept from the vast pastures, and, together with captive peasantry, hurried off in long cavalgadas across the borders.

At Gandul we found a tolerable posada; the good folks could not tell us what time of day it was, the clock only struck once in the day, two hours after noon; until that time it was guess-work. We guessed it was full time to eat; so, alighting, we ordered a repast. While that was in preparation, we visited the palace once the residence of the Marquis of Gandul. All was gone to decay; there were but two or three rooms habitable, and very poorly furnished. Yet here were the remains of grandeur: a terrace, where fair dames and gentle cavaliers may once have walked; a fish-pond and ruined garden, with grape-vines and date-bearing palm-trees. Here we were joined by a fat curate, who gathered a bouquet of roses, and presented it, very gallantly, to the lady who accompanied us.

Below the palace was the mill, with orange-trees and aloes in front, and a pretty stream of pure water. We took a seat in the shade; and the millers, all leaving their work, sat down and smoked with us; for the Andalusians are always ready for a gossip. They were waiting for the regular visit of the barber, who came once a week to put all their chins in order. He arrived shortly afterwards: a lad of seventeen, mounted on a donkey, eager to display his new alforjas or saddle-bags, just bought at a fair; price one dollar, to be paid on St. John's day (in June), by which time he trusted to have mown beards enough to put him in funds.

By the time the laconic clock of the castle had struck two we had finished our dinner. So, taking leave of our Seville friends, and leaving the millers still under the hands of the barber, we set off on our ride across the campiña. It was one of those vast plains, common in Spain, where for miles and miles there is neither house nor tree. Unlucky the traveller who has to traverse it, exposed as we were to heavy and repeated showers of rain. There is no escape nor shelter. Our only protection was our Spanish cloaks, which nearly covered man and horse, but grew heavier every mile. By the time we had lived through one shower we would see another slowly but inevitably approaching; fortunately in the interval there would be an outbreak of bright, warm, Andalusian sunshine, which would make our cloaks send up wreaths of steam, but which partially dried them before the next drenching.

Shortly after sunset we arrived at Arahal, a little town among the hills. We found it in a bustle with a party of miquelets, who were patrolling the country to ferret out robbers. The appearance of foreigners like ourselves was an unusual circumstance in an interior country town; and little Spanish towns of the kind are easily put in a state of gossip and wonderment by such an occurrence. Mine host, with two or three old wise-acre comrades in brown cloaks, studied our passports in a corner of the posada, while an Alguazil took notes by the dim light of a lamp. The passports were in foreign languages and perplexed them, but our Squire Sancho assisted them in their studies, and magnified our importance with the grandiloquence of a Spaniard. In the meantime the magnificent distribution of a few cigars had won the hearts of all around us; in a little while the whole community seemed put in agitation to make us welcome. The Corregidor himself waited upon us, and a great rush-bottomed arm-chair was ostentatiously bolstered into our room by our landlady, for the accommodation of that important personage. The commander of the patrol took supper with us: a lively, talking, laughing Andaluz, who had made a campaign in South America, and recounted his exploits in love and war with much pomp of phrase, vehemence of gesticulation, and mysterious rolling of the eye. He told us that he had a list of all the robbers in the country, and meant to ferret out every mother's son of them; he offered us at the same time some of his soldiers as an escort. "One is enough to protect you, señors; the robbers know me, and know my men; the sight of one is enough to spread terror through a whole sierra." We thanked him for his offer, but assured him, in his own strain, that with the protection of our redoubtable squire, Sancho, we were not afraid of all the ladrones of Andalusia.

While we were supping with our drawcansir friend, we heard the notes of a guitar, and the click of castanets, and presently a chorus of voices singing a popular air. In fact, mine host had gathered together the amateur singers and musicians, and the rustic belles of the neighbourhood, and, on going forth, the court-yard or patio of the inn presented a scene of true Spanish festivity. We took our seats with mine host and hostess and the commander of the patrol, under an archway opening into the court; the guitar passed from hand to hand, but a jovial shoemaker was the Orpheus of the place. He was a pleasant-looking fellow, with huge black whiskers; his sleeves were rolled up to his elbows. He touched the guitar with masterly skill, and sang a little amorous ditty with an expressive leer at the women, with whom he was evidently a favourite. He afterwards danced a fandango with a buxom Andalusian damsel, to the great delight of the spectators. But none of the females present could compare with mine host's pretty daughter, Pepita, who had slipped away and made her toilette for the occasion and had covered her head with roses; and who distinguished herself in a bolero with a handsome young dragoon. We ordered our host to let wine and refreshment circulate freely among the company, yet, though there was a motley assembly of soldiers, muleteers, and villagers, no one exceeded the bounds of sober enjoyment. The scene was a study for a painter: the picturesque group of dancers, the troopers in their half military dresses, the peasantry wrapped in their brown cloaks; nor must I omit to mention the old meagre Alguazil, in a short black cloak, who took no notice of anything going on, but sat in a corner diligently writing by the dim light of a huge copper lamp, that might have figured in the days of Don Quixote.

The following morning was bright and balmy, as a May morning ought to be, according to the poets. Leaving Arahal at seven o'clock, with all the posada at the door to cheer us off, we pursued our way through a fertile country, covered with grain and beautifully verdant; but which in summer, when the harvest is over and the fields parched and brown, must be monotonous and lonely; for, as in our ride of yesterday, there were neither houses nor people to be seen. The latter all congregate in villages and strongholds among the hills, as if these fertile plains were still subject to the ravages of the Moor.

At noon we came to where there was a group of trees, beside a brook in a rich meadow. Here we alighted to make our mid-day meal. It was really a luxurious spot, among wild flowers and aromatic herbs, with birds singing around us. Knowing the scanty larders of Spanish inns, and the houseless tracts we might have to traverse, we had taken care to have the alforjas of our squire well stocked with cold provisions, and his bota, or leathern bottle, which might hold a gallon, filled to the neck with choice Valdepeñas wine.[1] As we depended more upon these for our well-being than even his trabuco, we exhorted him to be more attentive in keeping them well charged; and I must do him the justice to say that his namesake, the trencher-loving Sancho Panza, was never a more provident purveyor. Though the alforjas and the bota were frequently and vigorously assailed throughout the journey, they had a wonderful power of repletion, our vigilant squire sacking everything that remained from our repasts at the inns to supplying these junketings by the road-side, which were his delight.

On the present occasion he spread quite a sumptuous variety of remnants on the greensward before us, graced with an excellent ham brought from Seville; then, taking his seat at a little distance, he solaced himself with what remained in the alforjas. A visit or two to the bota made him as merry and chirruping as a grasshopper filled with dew. On my comparing his contents of the alforjas to Sancho's skimming of the flesh-pots at the wedding of Camacho, I found he was well versed in the history of Don Quixote, but, like many of the common people of Spain, firmly believed it to be a true history.

"All that happened a long time ago, Señor," said he, with an inquiring look.

"A very long time," I replied.

"I dare say more than a thousand years,"—still looking dubiously.

"I dare say not less."

The squire was satisfied. Nothing pleased the simple-hearted valet more than my comparing him to the renowned Sancho for devotion to the trencher; and he called himself by no other name throughout the journey.

Our repast being finished, we spread our cloaks on the greensward under the tree, and took a luxurious siesta, in the Spanish fashion. The clouding up of the weather, however, warned us to depart, and a harsh wind sprang up from the southeast. Towards five o'clock we arrived at Osuna, a town of fifteen thousand inhabitants, situated on the side of a hill, with a church and a ruined castle. The posada was outside of the walls; it had a cheerless look. The evening being cold, the inhabitants were crowded round a brasero in a chimney-corner; and the hostess was a dry old woman, who looked like a mummy. Every one eyed us askance as we entered, as Spaniards are apt to regard strangers; a cheery, respectful salutation on our part, caballeroing them and touching our sombreros, set Spanish pride at ease; and when we took our seat among them, lit our cigars, and passed the cigar-box round among them, our victory was complete. I have never known a Spaniard, whatever his rank or condition, who would suffer himself to be outdone in courtesy; and to the common Spaniard the present of a cigar puro is irresistible. Care, however, must be taken never to offer him a present with an air of superiority and condescension: he is too much of a caballero to receive favours at the cost of his dignity.

Leaving Osuna at an early hour the next morning, we entered the sierra or range of mountains. The road wound through picturesque scenery, but lonely; and a cross here and there by the roadside, the sign of a murder, showed that we were now coming among the "robber haunts." This wild and intricate country, with its silent plains and valleys intersected by mountains, has ever been famous for banditti. It was here that Omar Ibn Hassan, a robber-chief among the Moslems, held ruthless sway in the ninth century, disputing dominion even with the califs of Cordova. This too was a part of the regions so often ravaged during the reign of Ferdinand and Isabella by Ali Atar, the old Moorish alcayde of Loxa, father-in-law of Boabdil so that it was called Ali Atar's garden, and here "Jose Maria," famous in Spanish brigand story, had his favourite lurking-places.

In the course of the day we passed through Fuente la Piedra, near a little salt lake of the same name, a beautiful sheet of water, reflecting like a mirror the distant mountains. We now came in sight of Antiquera, that old city of warlike reputation, lying in the lap of the great sierra which runs through Andalusia. A noble vega spread out before it, a picture of mild fertility set in a frame of rocky mountains. Crossing a gentle river we approached the city between hedges and gardens, in which nightingales were pouring forth their evening song. About nightfall we arrived at the gates. Everything in this venerable city has a decidedly Spanish stamp. It lies too much out of the frequented track of foreign travel to have its old usages trampled out. Here I observed old men still wearing the montero, or ancient hunting-cap, once common throughout Spain; while the young men wore the little round-crowned hat, with brim turned up all round, like a cup turned down in its saucer; while the brim was set off with little black tufts like cockades. The women, too, were all in mantillas and basquinas. The fashions of Paris had not reached Antiquera.

Pursuing our course through a spacious street, we put up at the posada of San Fernando. As Antiquera, though a considerable city, is, as I observed, somewhat out of the track of travel, I had anticipated bad quarters and poor fare at the inn. I was agreeably disappointed, therefore, by a supper-table amply supplied, and what were still more acceptable, good clean rooms and comfortable beds. Our man Sancho felt himself as well off as his namesake when he had the run of the duke's kitchen, and let me know, as I retired for the night, that it had been a proud time for the alforjas.

Early in the morning (May 4th) I strolled to the ruins of the old Moorish castle, which itself had been reared on the ruins of a Roman fortress. Here, taking my seat on the remains of a crumbling tower, I enjoyed a grand and varied landscape, beautiful in itself, and full of storied and romantic associations; for I was now in the very heart of the country famous for the chivalrous contests between Moor and Christian. Below me, in its lap of hills, lay the old warrior city so often mentioned in chronicle and ballad. Out of yon gate and down yon hill paraded the band of Spanish cavaliers, of highest rank and bravest bearing, to make that foray during the war and conquest of Granada, which ended in the lamentable massacre among the mountains of Malaga, and laid all Andalusia in mourning. Beyond spread out the vega, covered with gardens and orchards and fields of grain and enamelled meadows, inferior only to the famous vega of Granada. To the right the Rock of the Lovers stretched like a cragged promontory into the plain, whence the daughter of the Moorish alcayde and her lover, when closely pursued, threw themselves in despair.

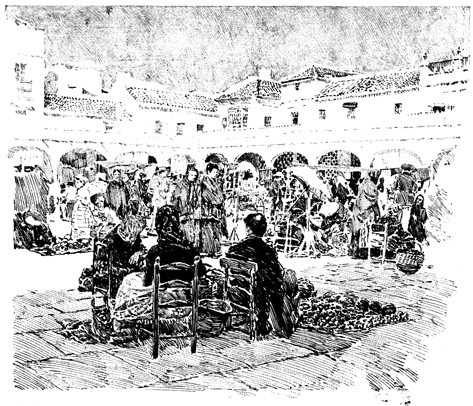

The matin peal from church and convent below me rang sweetly in the morning air, as I descended. The market-place was beginning to throng with the populace, who traffic in the abundant produce of the vega; for this is the mart of an agricultural region. In the market-place were abundance of freshly plucked roses for sale; for not a dame or damsel of Andalusia thinks her gala dress complete without a rose shining like a gem among her raven tresses.

On returning to the inn I found our man Sancho in high gossip with the landlord and two or three of his hangers-on. He had just been telling some marvellous story about Seville, which mine host seemed piqued to match with one equally marvellous about Antiquera. There was once a fountain, he said, in one of the public squares called Il fuente del toro (the fountain of the bull), because the water gushed from the mouth of the bull's head, carved of stone. Underneath the head was inscribed,—

En frente del toro

Se hallen tesoro.

In front of the bull there is treasure. Many digged in front of the fountain, but lost their labour and found no money. At last one knowing fellow construed the motto a different way. It is in the forehead frente of the bull that the treasure is to be found, said he to himself, and I am the man to find it. Accordingly he came, late at night, with a mallet, and knocked the head to pieces; and what do you think he found?

"Plenty of gold and diamonds!" cried Sancho, eagerly.

"He found nothing," rejoined mine host, dryly, "and he ruined the fountain."

Here a great laugh was set up by the landlord's hangers-on; who considered Sancho completely taken in by what I presume was one of mine host's standing jokes.

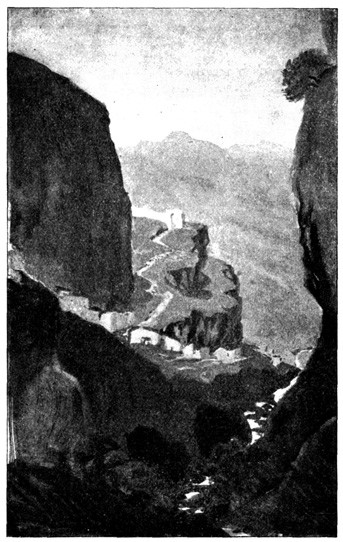

Leaving Antiquera at eight o'clock, we had a delightful ride along the little river, and by gardens and orchards fragrant with the odours of spring and vocal with the nightingale. Our road passed round the Rock of the Lovers (el peñon de los enamorados), which rose in a precipice above us. In the course of the morning we passed through Archidona, situated in the breast of a high hill, with a three-pointed mountain towering above it, and the ruins of a Moorish fortress. It was a great toil to ascend a steep stony street leading up into the city, although it bore the encouraging name of Calle Real del Llano (the royal street of the plain), but it was a still greater toil to descend from this mountain city on the other side.

At noon we halted in sight of Archidona, in a pleasant little meadow among hills covered with olive-trees. Our cloaks were spread on the grass, under an elm by the side of a bubbling rivulet; our horses were tethered where they might crop the herbage, and Sancho was told to produce his alforjas. He had been unusually silent this morning ever since the laugh raised at his expense, but now his countenance brightened, and he produced his alforjas with an air of triumph. They contained the contributions of four days' journeying, but had been signally enriched by the foraging of the previous evening in the plenteous inn at Antiquera; and this seemed to furnish him with a set-off to the banter of mine host.

En frente del toro

Se hallen tesoro

would he exclaim, with a chuckling laugh, as he drew forth the heterogeneous contents one by one, in a series which seemed to have no end. First came forth a shoulder of roasted kid, very little the worse for wear; then an entire partridge; then a great morsel of salted codfish wrapped in paper; then the residue of a ham; then the half of a pullet, together with several rolls of bread, and a rabble rout of oranges, figs, raisins, and walnuts. His bota also had been recruited with some excellent wine of Malaga. At every fresh apparition from his larder, he would enjoy our ludicrous surprise, throwing himself back on the grass, shouting with laughter, and exclaiming, "Frente del toro!—frente del toro! Ah, señors, they thought Sancho a simpleton at Antiquera; but Sancho knew where to find the tesoro."

While we were diverting ourselves with his simple drollery, a solitary beggar approached, who had almost the look of a pilgrim. He had a venerable gray beard, and was evidently very old, supporting himself on a staff, yet age had not bowed him down; he was tall and erect, and had the wreck of a fine form. He wore a round Andalusian hat, a sheep-skin jacket, and leathern breeches, gaiters, and sandals. His dress, though old and patched, was decent, his demeanour manly, and he addressed us with the grave courtesy that is to be remarked in the lowest Spaniard. We were in a favourable mood for such a visitor; and in a freak of capricious charity gave him some silver, a loaf of fine wheaten bread, and a goblet of our choice wine of Malaga. He received them thankfully, but without any grovelling tribute of gratitude. Tasting the wine, he held it up to the light, with a slight beam of surprise in his eye; then quaffing it off at a draught, "It is many years," said he, "since I have tasted such wine. It is a cordial to an old man's heart." Then, looking at the beautiful wheaten loaf, "bendito sea tal pan!" "blessed be such bread!" So saying, he put it in his wallet. We urged him to eat it on the spot. "No, señors," replied he, "the wine I had either to drink or leave; but the bread I may take home to share with my family."

Our man Sancho sought our eye, and reading permission there, gave the old man some of the ample fragments of our repast, on condition, however, that he should sit down and make a meal.

He accordingly took his seat at some little distance from us, and began to eat slowly, and with a sobriety and decorum that would have become a hidalgo. There was altogether a measured manner and a quiet self-possession about the old man, that made me think that he had seen better days: his language, too, though simple, had occasionally something picturesque and almost poetical in the phraseology. I set him down for some broken-down cavalier. I was mistaken; it was nothing but the innate courtesy of a Spaniard, and the poetical turn of thought and language often to be found in the lowest classes of this clear-witted people. For fifty years, he told us, he had been a shepherd, but now he was out of employ and destitute. "When I was a young man," said he, "nothing could harm or trouble me; I was always well, always gay; but now I am seventy-nine years of age, and a beggar, and my heart begins to fail me."

Still he was not a regular mendicant: it was not until recently that want had driven him to this degradation; and he gave a touching picture of the struggle between hunger and pride, when abject destitution first came upon him. He was returning from Malaga without money; he had not tasted food for some time, and was crossing one of the great plains of Spain, where there were but few habitations. When almost dead with hunger, he applied at the door of a venta or country inn. "Perdon usted por Dios hermano!" (Excuse us, brother, for God's sake!) was the reply—the usual mode in Spain of refusing a beggar. "I turned away," said he, "with shame greater than my hunger, for my heart was yet too proud. I came to a river with high banks, and deep, rapid current, and felt tempted to throw myself in: 'What should such an old, worthless, wretched man as I live for?' But when I was on the brink of the current, I thought on the blessed Virgin, and turned away. I travelled on until I saw a country-seat at a little distance from the road, and entered the outer gate of the court-yard. The door was shut, but there were two young señoras at a window. I approached and begged;—'Perdon usted por Dios hermano!'—and the window closed. I crept out of the court-yard, but hunger overcame me, and my heart gave way: I thought my hour at hand, so I laid myself down at the gate, commended myself to the Holy Virgin, and covered my head to die. In a little while afterwards the master of the house came home: seeing me lying at his gate, he uncovered my head, had pity on my gray hairs, took me into his house, and gave me food. So, señors, you see that one should always put confidence in the protection of the Virgin."

[1] It may be as well to note here, that the alforjas are square pockets at each end of a long cloth about a foot and a half wide, formed by turning up its extremities. The cloth is then thrown over the saddle, and the pockets hang on each side like saddle-bags. It is an Arab invention. The bota is a leathern bag or bottle, of portly dimensions, with a narrow neck. It is also Oriental. Hence the scriptural caution which perplexed me in my boyhood, not to put new wine into old bottles.

The old man was on his way to his native place, Archidona, which was in full view on its steep and rugged mountain. He pointed to the ruins of its castle. "That castle," he said, "was inhabited by a Moorish king at the time of the wars of Granada. Queen Isabella invaded it with a great army; but the king looked down from his castle among the clouds, and laughed her to scorn! Upon this the Virgin appeared to the queen, and guided her and her army up a mysterious path in the mountains, which had never before been known. When the Moor saw her coming, he was astonished, and springing with his horse from a precipice, was dashed to pieces! The marks of his horse's hoofs," said the old man, "are to be seen in the margin of the rock to this day. And see, señors, yonder is the road by which the queen and her army mounted: you see it like a ribbon up the mountain's side; but the miracle is, that, though it can be seen at a distance, when you come near it disappears!"

The ideal road to which he pointed was undoubtedly a sandy ravine of the mountain, which looked narrow and defined at a distance, but became broad and indistinct on an approach.

As the old man's heart warmed with wine and wassail, he went on to tell us a story of the buried treasure left under the castle by the Moorish king. His own house was next to the foundations of the castle. The curate and notary dreamed three times of the treasure, and went to work at the place pointed out in their dreams. His own son-in-law heard the sound of their pick-axes and spades at night. What they found, nobody knows; they became suddenly rich, but kept their own secret. Thus the old man had once been next door to fortune, but was doomed never to get under the same roof.

I have remarked that the stories of treasure buried by the Moors, so popular throughout Spain, are most current among the poorest people. Kind nature consoles with shadows for the lack of substantials. The thirsty man dreams of fountains and running streams; the hungry man of banquets; and the poor man of heaps of hidden gold: nothing certainly is more opulent than the imagination of a beggar.

Our afternoon's ride took us through a steep and rugged defile of the mountains, called Puerta del Rey, the Pass of the King; being one of the great passes into the territories of Granada, and the one by which King Ferdinand conducted his army. Towards sunset the road, winding round a hill, brought us in sight of the famous little frontier city of Loxa, which repulsed Ferdinand from its walls. Its Arabic name implies guardian, and such it was to the vega of Granada, being one of its advanced guards. It was the stronghold of that fiery veteran, old Ali Atar, father in-law of Boabdil; and here it was that the latter collected his troops, and sallied forth on that disastrous foray which ended in the death of the old alcayde and his own captivity. From its commanding position at the gate, as it were, of this mountain-pass, Loxa has not unaptly been termed the key of Granada. It is wildly picturesque; built along the face of an arid mountain. The ruins of a Moorish alcazar or citadel crown a rocky mound which rises out of the centre of the town. The river Xenil washes its base, winding among rocks, and groves, and gardens, and meadows, and crossed by a Moorish bridge. Above the city all is savage and sterile, below is the richest vegetation and the freshest verdure. A similar contrast is presented by the river: above the bridge it is placid and grassy, reflecting groves and gardens; below it is rapid, noisy, and tumultuous. The Sierra Nevada, the royal mountains of Granada, crowned with perpetual snow, form the distant boundary to this varied landscape, one of the most characteristic of romantic Spain.

Alighting at the entrance of the city, we gave our horses to Sancho to lead them to the inn, while we strolled about to enjoy the singular beauty of the environs. As we crossed the bridge to a fine alameda, or public walk, the bells tolled the hour of orison. At the sound the wayfarers, whether on business or pleasure, paused, took off their hats, crossed themselves, and repeated their evening prayer: a pious custom still rigidly observed in retired parts of Spain. Altogether it was a solemn and beautiful evening scene, and we wandered on as the evening gradually closed, and the new moon began to glitter between the high elms of the alameda. We were roused from this quiet state of enjoyment by the voice of our trusty squire hailing us from a distance. He came up to us, out of breath. "Ah, señores" cried he, "el pobre Sancho no es nada sin Don Quixote." (Ah, señors, poor Sancho is nothing without Don Quixote.) He had been alarmed at our not coming to the inn; Loxa was such a wild mountain place, full of contrabandistas, enchanters, and infiernos; he did not well know what might have happened, and set out to seek us, inquiring after us of every person he met, until he traced us across the bridge, and, to his great joy, caught sight of us strolling in the alameda.

The inn to which he conducted us was called the Corona, or Crown, and we found it quite in keeping with the character of the place, the inhabitants of which seem still to retain the bold, fiery spirit of the olden time. The hostess was a young and handsome Andalusian widow, whose trim basquiña of black silk, fringed with bugles, set off the play of a graceful form and round pliant limbs. Her step was firm and elastic; her dark eye was full of fire and the coquetry of her air, and varied ornaments of her person, showed that she was accustomed to be admired.

She was well matched by a brother, nearly about her own age; they were perfect models of the Andalusian Majo and Maja. He was tall, vigorous, and well-formed, with a clear olive complexion, a dark beaming eye, and curling chestnut whiskers that met under his chin. He was gallantly dressed in a short green velvet jacket, fitted to his shape, profusely decorated with silver buttons, with a white handkerchief in each pocket. He had breeches of the same, with rows of buttons from the hips to the knees; a pink silk handkerchief round his neck, gathered through a ring, on the bosom of a neatly plaited shirt; a sash round the waist to match; bottinas, or spatterdashes, of the finest russet leather, elegantly worked, and open at the calf to show his stocking; and russet shoes, setting off a well-shaped foot.

As he was standing at the door, a horseman rode up and entered into low and earnest conversation with him. He was dressed in a similar style, and almost with equal finery; a man about thirty, square-built, with strong Roman features, handsome, though slightly pitted with the small-pox; with a free, bold, and somewhat daring air. His powerful black horse was decorated with tassels and fanciful trappings, and a couple of broad-mouthed blunderbusses hung behind the saddle. He had the air of one of those contrabandistas I have seen in the mountains of Ronda, and evidently had a good understanding with the brother of mine hostess; nay, if I mistake not, he was a favoured admirer of the widow. In fact, the whole inn and its inmates had something of a contrabandista aspect, and a blunderbuss stood in a corner beside the guitar. The horseman I have mentioned passed his evening in the posada, and sang several bold mountain romances with great spirit. As we were at supper, two poor Asturians put in, in distress, begging food and a night's lodging. They had been waylaid by robbers as they came from a fair among the mountains, robbed of a horse which carried all their stock in trade, stripped of their money, and most of their apparel, beaten for having offered resistance, and left almost naked in the road. My companion, with a prompt generosity natural to him, ordered them a supper and a bed, and gave them a sum of money to help them forward towards their home.

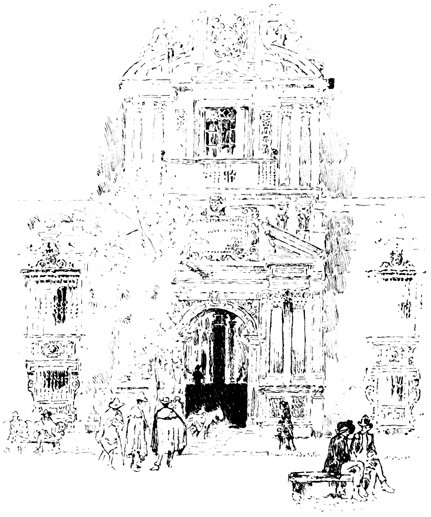

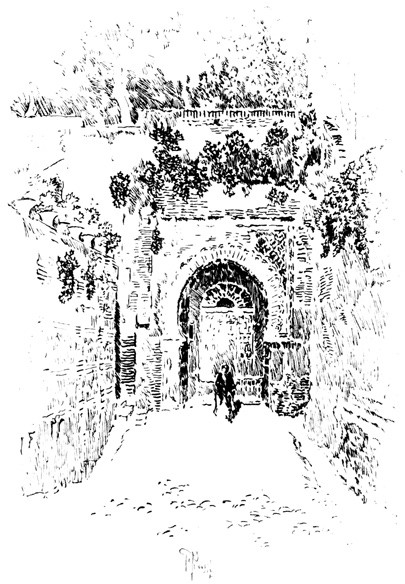

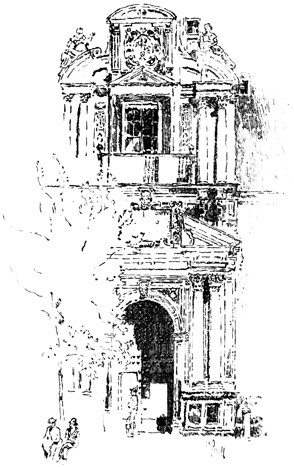

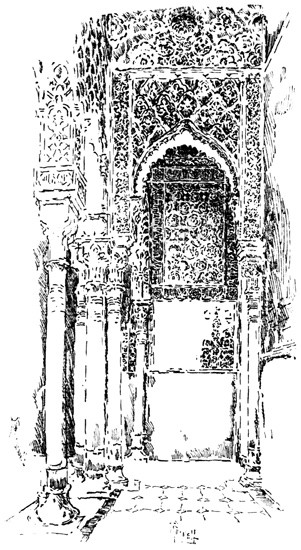

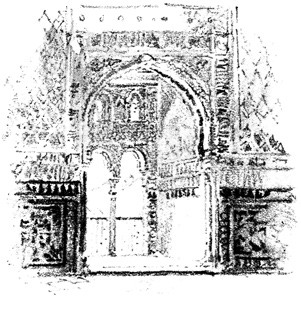

Moorish Gate, Ronda.

As the evening advanced, the dramatis personæ thickened. A large man, about sixty years of age, of powerful frame, came strolling in, to gossip with mine hostess. He was dressed in the ordinary Andalusian costume, but had a huge sabre tucked under his arm; wore large moustaches, and had something of a lofty swaggering air. Every one seemed to regard him with great deference.

Our man Sancho whispered to us that he was Don Ventura Rodriguez, the hero and champion of Loxa, famous for his prowess and the strength of his arm. In the time of the French invasion he surprised six troopers who were asleep; he first secured their horses, then attacked them with his sabre, killed some, and took the rest prisoners. For this exploit the king allows him a peseta (the fifth of a duro, or dollar) per day, and has dignified him with the title of Don.

I was amused to behold his swelling language and demeanour. He was evidently a thorough Andalusian, boastful as brave. His sabre was always in his hand or under his arm. He carries it always about with him as a child does its doll, calls it his Santa Teresa, and says, "When I draw it, the earth trembles" (tiembla la tierra).

I sat until a late hour listening to the varied themes of this motley group, who mingled together with the unreserve of a Spanish posada. We had contrabandista songs, stories of robbers, guerrilla exploits, and Moorish legends. The last were from our handsome landlady, who gave a poetical account of the infiernos, or infernal regions of Loxa,—dark caverns, in which subterranean streams and waterfalls make a mysterious sound. The common people say that there are money-coiners shut up there from the time of the Moors; and that the Moorish kings kept their treasures in those caverns.

I retired to bed with my imagination excited by all that I had seen and heard in this old warrior city. Scarce had I fallen asleep when I was aroused by a horrid din and uproar, that might have confounded the hero of La Mancha himself, whose experience of Spanish inns was a continual uproar. It seemed for a moment as if the Moors were once more breaking into the town; or the infiernos of which mine hostess talked had broken loose. I sallied forth, half dressed, to reconnoitre. It was nothing more nor less than a charivari to celebrate the nuptials of an old man with a buxom damsel. Wishing him joy of his bride and his serenade, I returned to my more quiet bed, and slept soundly until morning.

While dressing, I amused myself in reconnoitring the populace from my window. There were groups of fine-looking young men in the trim fanciful Andalusian costume, with brown cloaks, thrown about them in true Spanish style, which cannot be imitated, and little round majo hats stuck on with a peculiar knowing air. They had the same galliard look which I have remarked among the dandy mountaineers of Ronda. Indeed, all this part of Andalusia abounds with such game-looking characters. They loiter about the towns and villages; seem to have plenty of time and plenty of money; "horse to ride and weapon to wear." Great gossips, great smokers, apt at touching the guitar, singing couplets to their maja belles, and famous dancers of the bolero. Throughout all Spain the men, however poor, have a gentlemanlike abundance of leisure; seeming to consider it the attribute of a true cavaliero never to be in a hurry; but the Andalusians are gay as well as leisurely, and have none of the squalid accompaniments of idleness. The adventurous contraband trade which prevails throughout these mountain regions, and along the maritime borders of Andalusia, is doubtless at the bottom of this galliard character.

In contrast to the costume of these groups was that of two long-legged Valencians conducting a donkey, laden with articles of merchandise; their muskets slung crosswise over his back, ready for action. They wore round jackets (jalecos), wide linen bragas or drawers scarce reaching to the knees and looking like kilts, red fajas or sashes swathed tightly round their waists, sandals of espartal or bass weed, coloured kerchiefs round their heads somewhat in the style of turbans, but leaving the top of the head uncovered; in short, their whole appearance having much of the traditional Moorish stamp.

On leaving Loxa we were joined by a cavalier, well mounted and well armed, and followed on foot by an escopetero or musketeer. He saluted us courteously, and soon let us into his quality. He was chief of the customs, or rather, I should suppose, chief of an armed company whose business it is to patrol the roads and look out for contrabandistas. The escopetero was one of his guards. In the course of our morning's ride I drew from him some particulars concerning the smugglers, who have risen to be a kind of mongrel chivalry in Spain. They come into Andalusia, he said, from various parts, but especially from La Mancha; sometimes to receive goods, to be smuggled on an appointed night across the line at the plaza or strand of Gibraltar; sometimes to meet a vessel, which is to hover on a given night off a certain part of the coast. They keep together and travel in the night. In the daytime they lie quiet in barrancos, gullies of the mountains, or lonely farmhouses; where they are generally well received, as they make the family liberal presents of their smuggled wares. Indeed, much of the finery and trinkets worn by the wives and daughters of the mountain hamlets and farm-houses are presents from the gay and open-handed contrabandistas.

Arrived at the part of the coast where a vessel is to meet them, they look out at night from some rocky point or headland. If they descry a sail near the shore they make a concerted signal; sometimes it consists in suddenly displaying a lantern three times from beneath the folds of the cloak. If the signal is answered, they descend to the shore and prepare for quick work. The vessel runs close in; all her boats are busy landing the smuggled goods, made up into snug packages for transportation on horseback. These are hastily thrown on the beach, as hastily gathered up and packed on the horses, and then the contrabandistas clatter off to the mountains. They travel by the roughest, wildest, and most solitary roads, where it is almost fruitless to pursue them. The custom-house guards do not attempt it: they take a different course. When they hear of one of these bands returning full freighted through the mountains, they go out in force, sometimes twelve infantry and eight horsemen, and take their station where the mountain defile opens into the plain. The infantry, who lie in ambush some distance within the defile, suffer the band to pass, then rise and fire upon them. The contrabandistas dash forward, but are met in front by the horsemen. A wild skirmish ensues. The contrabandistas, if hard pressed, become desperate. Some dismount, use their horses as breastworks, and fire over their backs; others cut the cords, let the packs fall off to delay the enemy, and endeavour to escape with their steeds. Some get off in this way with the loss of their packages; some are taken, horses, packages, and all; others abandon everything, and make their escape by scrambling up the mountains. "And then," cried Sancho, who had been listening with a greedy ear, "se hacen ladrones legitimos,"—and then they become legitimate robbers.

I could not help laughing at Sancho's idea of a legitimate calling of the kind; but the chief of customs told me it was really the case that the smugglers, when thus reduced to extremity, thought they had a kind of right to take to the road, and lay travellers under contribution, until they had collected funds enough to mount and equip themselves in contrabandista style.

Towards noon our wayfaring companion took leave of us and turned up a steep defile, followed by his escopetero; and shortly afterwards we emerged from the mountains, and entered upon the far-famed vega of Granada.

Our last mid-day's repast was taken under a grove of olive-trees on the border of a rivulet. We were in a classical neighbourhood; for not far off were the groves and orchards of the Soto de Roma. This, according to fabulous tradition, was a retreat founded by Count Julian to console his daughter Florinda. It was a rural resort of the Moorish kings of Granada; and has in modern times been granted to the Duke of Wellington.

Our worthy squire made a half melancholy face as he drew forth, for the last time, the contents of his alforjas, lamenting that our expedition was drawing to a close, for, with such cavaliers, he said, he could travel to the world's end. Our repast, however, was a gay one; made under such delightful auspices. The day was without a cloud. The heat of the sun was tempered by cool breezes from the mountains. Before us extended the glorious vega. In the distance was romantic Granada surmounted by the ruddy towers of the Alhambra, while far above it the snowy summits of the Sierra Nevada shone like silver.